JANUARY 2025

DEPARTMENTS

gear guide ................ 16

book review ................ 22

exposure ................ 24

production credits .............. 58

stop motion .............. 64

FEATURE 01

DON'T THINK TWICE

JANUARY 2025

gear guide ................ 16

book review ................ 22

exposure ................ 24

production credits .............. 58

stop motion .............. 64

FEATURE 01

DON'T THINK TWICE

I want to start this letter by wishing everyone a very Happy New Year, emphasizing the “happy” part. This membership has weathered incredible hardships in the past few years, including the loss of other ICG members, loved ones and friends. ICG Magazine’s wonderful staff writer, Pauline Rogers, who passed away in December, was someone who reached out to ICG members of all ages and backgrounds to bring their stories to light. I remember when Pauline interviewed me years ago, I was nervous, but Pauline had a way to make you relax during an interview. Back in the days when we had our printed newsletter, Camera Angles, I was always looking for her interviews. And even now in our digital platforms, Pauline continued to provide ICG readers with more than just a story. She gave us deep insights into ICG members and the other union filmmakers she talked to. Pauline Rogers, along with the Local 600 members, friends and loved ones we lost this past year, will be greatly missed!

I am glad 2024 is behind us. We don’t know what the future may hold, but we do know what the past has brought. Being positive can be difficult at times, but we’ve had difficult times before, so let’s move forward! 2025 will bring some exciting meetings and events, starting with our first national membership meeting – for all regions – on February 8. Shortly after, on February 28, we will have our annual Publicists Awards luncheon. Even sooner, the Guild is now taking applications for scholarships for members and their children and grandchildren, while this issue of ICG Magazine spotlights the many talented ICG members who will bring their visions to the Sundance Film Festival.

I am confident that 2025 will usher in a new era in the motion picture industry, one that we all hope will be successful for all union crafts workers. Let us move into this new year in unity and solidarity, always looking to support our fellow sisters and brothers on set, and off.

Publisher

Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

NATIONAL DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Jill Wilk

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley

CONTRIBUTORS

Matt Hurwitz

Margot Lester

Kevin Martin

Mike Taing

1ST

2ND

NATIONAL

COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE

John Lindley, ASC, Co-Chair

Chris Silano, Co-Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard

Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook: @theicgmag

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007) Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2024, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com January 2025 vol.

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

“A visual masterpiece. Light and shadow are given incredible personality in cinematographer Jarin Blaschke’s exceptional work.”

Collider

NATIONAL BOARD OF REVIEW

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

JARIN BLASCHKE

CRITICS

CHOICE AWARD

NOMINEE

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

JARIN BLASCHKE

For Your Consideration in all Categories Including

JARIN BLASCHKE

Iwon’t take too many pats on the back (well, maybe one) for programming our January Sundance Film Festival-themed issue with A Complete Unknown on the cover. The new Bob Dylan biopic from Searchlight Pictures was written and directed by James Mangold, a filmmaker most fans associate with studio hits like Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Ford v. Ferrari and Walk the Line. But I’ve followed Mangold’s career since it started – at Sundance. First, in 1994, when he attended the Institute’s program for emerging filmmakers; then a year later, when he won a Special Jury Prize for Directing at the 1995 festival for his debut feature, Heavy; and then two years later, when he developed Cop Land at the Sundance Screenwriters and Directors Labs.

Still, even with that history, I was as surprised as Mangold (who said he was “floored and flattered”) when Sundance recently announced he would be their 2025 Trailblazer Award winner. According to the organization’s press release, the award recognizes “unwavering dedication and notable contributions to the field of cinema.”

I can name another filmmaker who easily qualifies for that honor: ICG Director of Photography Phedon Papamichael, ASC, who counts A Complete Unknown as his sixth feature pairing with the director. Mangold and Papamichael are Sundance guys at heart, using their old-school single-camera, shot-on-filmlike workflow to portray complex heroes whose journeys share upheaval and unpredictability. Matt Hurwitz’s story on page 30 dives deep into their process (along with Production Designer François Audouy, also working on his sixth feature for Mangold), revealing an indie sensibility that has always placed emotional depth above all else.

“Jim is very good with characters and story,” Papamichael told Hurwitz. “But besides portraying iconic figures, he’s more interested in the human aspect – what makes them tick, as artists, with all their flaws, and what makes an artist create.”

Both men were quick to praise longtime ICG Steadicam Operator P. Scott Sakamoto, SOC, for his near-prescient work with lead actor Timothée Chalamet. “Scott has an instinct about the story that always puts you in the right place when the

actors are doing their thing,” Mangold shared. “Watching Timmy so closely, seeing that he is about to turn to the audience and give this look, and moving to meet him; the camera and actor are just finding each other, making it feel alive and unrehearsed.”

Other signs of the kind of “hyper-alive” moviemaking Sundance champions can be found in my story on the new Hulu episodic Interior Chinatown (page 44), which had Sundance alumnus Taika Waititi as executive producer and pilot director. Shot by Guild Directors of Photography Mike Berlucchi and Tari Segal, this impossible-to-describe series (crime/fantasy/ comedy/family history/pop culture satire – did I leave anything out?) is based on a 2020 National Book Award novel by Charles Yu (Exposure, page 26), who, in his first time out as showrunner, leaned heavily on creative input from his entire production team. One episode (shot by Segal) features a “musical-oner-deodorant commercial,” while another (shot by Berlucchi) drops the show’s hero into a “rainbow-colored vortex,” achieved in-camera by capturing seven different lighting setups (simultaneously!) with a Phantom camera. I’d feel confident dropping any episode of Interior Chinatown into Sundance’s ground-breaking NEXT section (or even the Midnight category), knowing it would feel right at home.

Going home, sadly, is also how I want to end this space, by paying tribute to ICG Magazine’s 35-plus-year staff writer, Pauline Rogers, who passed away in mid-December after a protracted illness. Pauline not only more than doubled the years I’ve spent as editor, she was also Local 600’s longest-tenured employee (working often late into the night “because that’s when the phones and emails finally calm down, David!”). It may have been commonplace, once upon a time, to give the vast bulk of your working years to a single organization, but not anymore – so the dedication, passion, patience, and relentless zeal Pauline gave – for more than 30 years – to every story, and Local 600, is something to be honored and admired. As Pauline (in one of her many other lives) was also a publicist, ICG Magazine will feature an extended online tribute to her in February, before the Guild’s Annual Publicists Awards.

Until then, farewell and rest easy, P.R. You will be missed.

David Geffner Executive Editor

Email: david@icgmagazine.com

Don't

$1,499

Its power output – a class-leading 22,000 lux – and IP65 rating are notable, but what earned accolades for the Anova PRO 3 production light were its awardwinning suite of CineSFX™ (fire, lightning, TV, gunshot, paparazzi, etc.) and the patented “Magic Eye” optical light sensor. Built into the face, the Magic Eye automatically measures and matches any Kelvin or HSI color, making it easy to balance set lights. The PRO 3 also has a native V-lock battery operation, a touchscreen display, wireless LumenRadio and app control. Bridgerton Director of Photography Alicia Robbins uses the Anova Pro 3 in a very specific “but incredibly useful way,” she notes. “Because of its round shape and its directional but soft light, it is a perfect light to add a snoot, to help to pop up the light on a face that may need a little extra. We refer to it as the ‘Super Snoot’ because it can pick out a face among a group without spilling into the rest of the scene.”

The core set of 35, 40, 50, 60, 75 and 85mm has a maximum aperture of T1.8. (The 100mm is T2; a 28mm, 135mm and 50-135mm front anamorphic zoom are in the prototype phase; and a 180mm is planned.) These lenses provide excellent resolution across full frame (36 × 24) at the T1.8 while retaining vintage characteristics like smooth skin tones, medium contrast, classic gentle barrel distortion, signature flares, and oval bokeh. The compact and lightweight lens enables extremely close focus across the set from 28 to 100mm, and multiple focus/iris gear positions for ease of use on set. “The Legacy Anamorphics manage to combine a bit of character into a lens that has full-frame coverage, crazy-close focus, great resolving power, and minimal distortion in the wider focal lengths,” explains Local 600 Director of Photography David Vollrath. “They solve the problem of not enough coverage, not enough consistent focal lengths, and too much excessive falloff/distortion seen in vintage anamorphic lenses. A top choice for me on any anamorphic shoot.”

LIMELIGHT S: $1,160

LIMELIGHT L: $1,440

WWW.ELATIONLIGHTING.COM

Elation upgraded its LIMELIGHT high-powered color-mixing wash luminaires to deliver more color intensity with a wide color spectrum and better CRI. The improved products can be used for even stage washes, side- /front- / backlighting, silhouette effects, and accenting. The L is a full-sized fixture; the S is more compact. “We decided to give LIMELIGHT higher wattage LED’s to boost the brightness and deliver more vivid saturated colors,” notes Bob Mentele, Elation’s associate product manager. “The added Lime emitter boosts overall output even further and fills in the entire spectrum to create a more expansive color gamut. Output is highly homogenized with flawless distribution throughout the beam, so washes of color appear extremely uniform, and they include a wide zoom range for narrow to wide coverage. Both fixtures are IP65-rated so they can be used on sets indoors or out with no concerns about weather conditions, dust or moisture affecting performance.”

“I absolutely love the ZEISS Supreme Prime lenses because I feel like they’re freeing me to do whatever I want to do. They have sort of everything that I wish a lens would have as a versatile tool,” notes Steve Yedlin, ASC. The series has 25 primes and three zooms that feature lens data support, cover Super 35, Full Frame and larger sensors, and have two different lens coating styles to minimize or facilitate flares. “What’s great about the Supreme Primes is how close you get to wide-open before [optical degradation] starts. It allows us to frame our scene much bigger,” Yedlin adds. The Radiance group enables controlled flares in the image without sacrificing contrast or experiencing transmission loss. “The thing about the Radiance lenses is they’re reliable, and I always know exactly what I’m getting,” says Jon Joffin, ASC. “If I don’t want the flare; I can flag that flare off. I know they’re not going to blow out when I’m looking at a hot sky or if I’m pointing at a hot light.”

BY KEVIN H. MARTIN

PHOTOS COURTESY OF ROBERT HOFFMAN

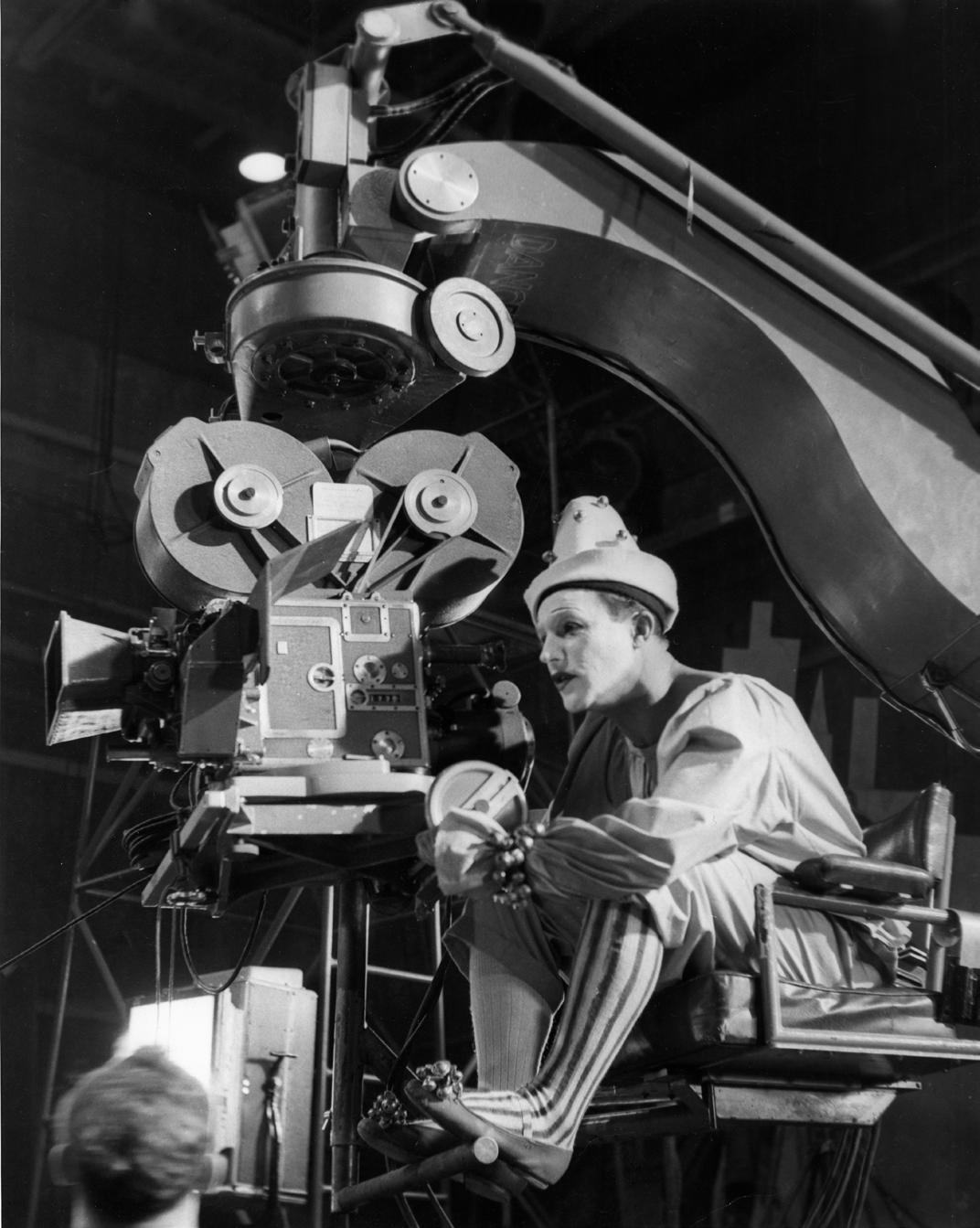

Bob Hoffman’s new book, Alchemy in Technicolor, isn’t just an exercise in film history (though it succeeds just fine on that score, too); this volume is as much an exploration of aesthetics as it is a document of a series of processes that helped shape the face of 20thcentury cinema. This is no mean feat, given how the very name has become something bigger than any of the processes and equipment associated with Technicolor.

The author, who has a long history in the industry ranging from sound work to publicity (the latter including a decades-long stint at Technicolor as the advent of digital was shepherding in a new era for film), weaves his telling of Technicolor’s story deftly, illustrating with incidents from multiple eras rather than just presenting a straight-line chronology. Hoffman explains time transitions by linking particular inventions or innovations or even a

period depicted in a film being discussed. For example, the earliest two-color film processes are covered, along with the advent of threecolor and the ongoing alliance between Technicolor and Kodak (which sometimes made for a less-than-welcome partnership). Hoffman’s scholarship, which builds on the work of other film journalists and historians, effectively refutes the coda in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (a favorite of Hoffman’s), that “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

“One misconception centered around the company’s history,” Hoffman describes, “is that some historians limited their analysis of the printing side of the operation and instead just focused on the [three-strip] camera, which was phased-out in the 1950s. The Technicolor camera was one of the technological wonders of the first half of the century; everyone was –

and still is – fascinated by it. I gave a talk at the Cinematheque in Paris, where we had one of the cameras, and people came in an hour early just to stand near the camera, gazing at it as this object of reverence. But there’s also the aspect of how Technicolor processes evolved after Kodak introduced Eastman Color.”

While introducing readers to names that will probably be new to those who haven’t scrutinized technological innovations, Hoffman’s tome is no polemic; he readily acknowledges several spectacular-looking film classics that originated on Kodak stock, including Don’t Look Now and The Black Stallion . “Looking at Technicolor’s place in history, there’s a tendency to think of it in terms of technology,” he continues. “But I think it has more to do with the creatives and how they chose to employ it. I can name a lot of cinematographers and production designers

LEFT: DIRECTOR/ACTOR GENE KELLY ON AN AMERICAN IN PARIS ; DIRECTORS OF PHOTOGRAPHY ALFRED GILKS, ASC, AND JOHN ALTON

ABOVE: VITTORIO STORARO, AIC, ASC, AIC (LEFT) AND DIRECTOR

BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI

BOTTOM: THE CONFORMIST – DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

VITTORIO STORARO, ASC, AIC

who understood the aggregate of all crafts coming together to result in spectacular color rendition. For the restoration Technicolor did of Lola Montes, you can see in the release print how Ophuls utilized [Eastman] color. There was no matrix element involved, though we used a lot of digital tools to restore it to its original length.”

Hoffman also quotes artist Jean Curran, whose "The Vertigo Project" consisted of dyetransfer prints made with permission from the Hitchcock estate and Universal Pictures, and exhibited in fine art galleries.

“To me Vertigo is the antithesis of the disposable digital age,” Curran declares. “The Vertigo Project works as a reminder of the importance of craft in a digital age – when Instagram has become such a central part of the global vernacular, it’s hard to know which images are good and we’re no longer challenged to learn to read imagery like we maybe once were. Also, let’s not ignore the Technicolor element. The fact that the prints were made as dye-transfer prints adds a layer of nostalgia for a time of greatness in film’s history.”

Alchemy in Technicolor explains stylistic differences between domestic Technicolor printing and its overseas brethren, with the British-made product often reflecting a more subtle look than the high-contrast and color saturation evinced in early U.S. films. Politics – both studio-based and national/global – also factor into the story, which creates a deeper narrative than one might expect in a typical film history book. The demise of Technicolor dyetransfer printing – which in the U.S. ended in the 1970s, only to be revived briefly at the turn of the century – was not predicated strictly on economics.

“Several foreign-based filmmakers were discovering and exploring Technicolor in the 1960s and 70s,” Hoffman notes, “and I think even now the best contemporary filmmakers seek out a lot of film history to see for themselves where the bar was set, regardless of era. That all sparked interest in developing a digital version of Technicolor.”

If digital emulation is the sincerest form of flattery, then the team that formed at Technicolor in the early 2000s were pioneers

of a sort. CFI color timer Dana Ross and ILM color scientist Joshua Pines came aboard in an attempt to deliver a digital equivalent to dye transfer. “Josh embraced Technicolor but had to be the bearer of bad news for filmmakers who went off the deep end and were creating a science project rather than staying in bounds and making prudent color decisions,” Hoffman shares. “But then other interests at Technicolor closed CFI and merged labs. These decisions were made in Paris and were way outside our pay grade, so you run headlong into the issue of creative [versus] corporate governance.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise to learn that Alchemy in Technicolor is lushly illustrated, with numerous images from some of the most gorgeous film classics ever lensed. If the print volume of this book resembles the digital version presented for review, then, to paraphrase Chief Brody from Jaws : you’re going to need a bigger coffee table.

Note: The print version of Hoffman’s book can be purchased through his website at: www. MovieAlchemy.com

CREATOR/SHOWRUNNER | INTERIOR CHINATOWN

BY DAVID GEFFNER PHOTO COURTESY OF TINA CHIOU

In the recent Hulu limited series Interior Chinatown, our hero Willis Wu (comic Jimmy O. Yang) is a background player on a meta-TV show that may – or may not – be part of a book he’s writing about the loss of his brother, Johnny (Chris Pang). Waiting tables in a restaurant run by his Uncle Wong (Archie Kao), Willis sees his old-school Chinatown neighborhood being swallowed up by a huge, amorphous (and nefarious) conglomerate called HBWC (Hulu Black and White Corporation). Showrunner Charles Yu, who has a J.D. from Columbia Law School and worked as a corporate attorney before becoming a TV writer ( Sorry For Your Loss , Legion, Here and Now), says the metaphor – the power megacorporations exert over individual lives, both seen and unseen –was just one of the many themes Interior Chinatown explores.

"The adage is that TV is a writer’s medium, but working with DP’s like Mike and Tari, who were so invested in the visual plan, it becomes so much more."

“Willis is trapped in a system, visible or otherwise, that he doesn’t understand,” Yu told me over a recent Zoom call. “How he finds love and connection, how he finds out who he is within these much larger forces is a theme that pops up in my work a lot.” Although Yu says his legal career never included “a company as powerful as HBWC,” he laughs, “I did spend thirteen years as a lawyer, so workplace stories have always figured into my writing. But it’s never as simple as ‘corporations bad, people good’ – this show was made by a huge corporation [Disney] that provided an incredible platform to tell our story.”

Interior Chinatown is based on Yu’s novel of the same name, which won the National Book Award for Fiction in 2020. Yu’s other accolades include two WGA Nominations for HBO’s Westworld, and his 2010 debut novel, How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, which made the Top 10 Sci-Fi/Fiction lists for Time Magazine and Amazon.com, as well as appearing on The New York Times Notable 100 Books list. He’s written essays, book reviews and journalism for everything from The Atlantic, Slate and The New York Times Style Magazine to The Wall Street Journal. With Interior Chinatown being his first-ever turn as a showrunner, Yu talked about that first day on set and the instant comfort he felt having an experienced (and truly diverse) union crew behind him.

ICG Magazine: When you wrote Interior Chinatown, did you imagine it could one day

be a TV series? Charles Yu: I did not! [Laughs.] It was hard to imagine how you could pull off just the lighting changes, for example. This is the best forum to talk about all that because it was more of a concept in my head when it was a novel. Once we were in the writers’ room [for the series], we expanded on that idea. Lighting, color, framing, et cetera are always part of a TV series, but in this show, all of those elements are done in a much more forward way. They are essential to how the story is told.

What’s the origin of how this went from book to series? It took me several years to write the book. What ultimately made it gel was finding the perspective of Willis. In my head, it was very much like the shot in the pilot episode when we’re outside with the cops and the [Golden Palace] restaurant is in the background. I even wrote in the pilot script that we see a reverse POV and now we’re with Willis, inside the restaurant, looking out through the windows at that exciting world he wants to be a part of. I remember being in the writers’ room on a show called Sorry For Your Loss, which was a great experience, and having turned in the manuscript – finally! Honestly, I was just relieved it was done.

Then what happened? Flash forward to early 2020 and Hulu was interested in turning it into a series, even as things were going crazy with the pandemic. After everything shut down, I had the time to work on the pilot script, which I did for about a year-and-a-half, until Hulu greenlit it. The book is so focused on Willis and his parents that I knew his universe, and all the characters

in it, would need to deepen and be broader for television. The book is such an internal journey, so how to film that – over 10 episodes – became the main question.

And that’s where many of your main creative partners come in. Exactly. The execution became a very collaborative discussion with the directors and the DP’s as to how to portray this space that is both physical and psychological at the same time. It was a challenge. I’m sure you heard from Mike [Berlucchi] and Tari [Segal] how tough it was to visually translate what’s in this crazy guy’s head! And that would be me. [Laughs.]

Another recent Disney episodic, American Born Chinese [ICG Magazine June 2023], was created by your brother [Kelvin Yu], and you co-wrote that pilot. How much did watching other showrunners help in your first time at bat? On paper, it gave me just enough. But I had months of sleepless nights knowing that at many points in this process, I’d be standing in a room with more than 100 people eager to hear my plan. That was scary, but also incredibly rewarding because literally every person on the crew knew more about their job than I did – they’ve all done it before and I never had! That’s a weird situation to be in. So I had to lean on everyone on the crew, listen to their input, hear their ideas, and try to synthesize that into something coherent in tone and feel. Making a TV series is so different from writing a book because it’s no longer a single creative voice. And that collaborative process is what made Interior Chinatown the TV series so much richer

than I ever could have imagined when I was writing the book.

We wrote about Taika Waititi, who was an executive producer – and he directed the first episode – for Next Goal Wins [ICG Magazine December 2023], where he did a lot of improvisation. The DP on that film, Lachlan Milne, called Taika “a force of nature.” What did you learn from that partnership? I had gotten to work with him on a feature project that’s still in development, so I got a taste of how Taika thinks. He reminded me and gave me permission and inspiration that this is something creative we’re doing. We’re not making widgets. Leave room for the unexpected and don’t be afraid to fail. Taika has a way of boiling this crazy meta-world down to: “What do I care about here?” And for him, it’s the smallest of details and always looking for a different way to pull off a scene or a shot. I’m not sure he thinks about it that way, but that’s how I perceived him.

Any examples? Well, there’s a shot in the pilot where Willis leaves the Tupperware dinner his mom has made for his father outside the door of the dad’s room [in the SRO the family lives in above the Golden Palace]. Willis puts it on the ground and Tzi Ma, who plays Willis’ dad, Joe Wu, has to reach out with his arm and pull it into the room. Taika shot that several times and he gave very specific instructions about how Joe’s hand came out of the door. I had no idea what he was going for, but after having watched the pilot being screened several times now, that shot never fails to get a laugh. That’s the sensibility I started to absorb over time from Taika.

How did the vision you had for these different worlds when writing the book measure up once you started working with Mike and Tari? I had an idea of the overall visual scheme I wanted. Willis’ world would be warmer and messier. We’d feel the dirt in the corners, and there was a granularity to it. The cop-show world is unnaturally clean and sterile; it feels like broadcast television. The idea was, in small and big ways, to blur the two worlds throughout the season. In the writers’ room, it was Willis’ world in the first third, a subtle blending in the second, and a complete melding of the two in the final third. But, as [Producing Director] John Lee reminded me, Willis enters the precinct by episode two and spends a lot of time there in episode three. So, what’s the rule here?

When [Detective] Greene is looking at Willis, what world is she in? That led to many on-set conversations and prep meetings. Mike and Tari were so great at translating what was in my head. My ability to process their technical choices– lenses, lighting, camera – was not very high. But we developed a language to clarify all the different worlds and their looks on set.

Both Mike and Tari mentioned Wong Kar Wai as a big influence, and CSI for the cop show. John Lee said he lifted whole scenes and edits from Bruce Lee for the “Kung Fu Guy” episode he directed. Were those references part of your vision from the get-go? I’m glad you noticed those references, and John was calling them out. Episode four was John’s episode, and he came in with this idea to make those scenes a true homage. The show is set in the 90s, and those flashbacks of Johnny fighting Kung Fu are set in the 80s, so it’s a love letter to all of the things you just mentioned. At the script stage, it’s mostly like: “This will feel like a kitschy 80s cop show.” But then to watch details that come out in production is incredible. I’ve been seeing, on social media, people making their own montages from individual shots in the show! That tells me people appreciate the cinematography. The adage is that TV is a writer’s medium, but working with DP’s like Mike and Tari, who were so invested in the visual plan, it becomes so much more.

Characters in the show, particularly the older generation like Willis’ mom and dad, speak English and Chinese, often changing within a scene. Yes, that did add another layer of complexity, even when we were doing ADR. And we had both Mandarin and Cantonese dialects being spoken. The idea was this is the reality of these characters’ lives. Willis’ mom and dad speak Cantonese to each other; Uncle Wong, who was born in America, speaks Mandarin, so he had another language journey. This came out in the writing phase – everybody’s going to speak a little differently because that’s the most honest way to portray this world.

The show wraps open-endedly. It could be sweet and hopeful for Lana and Willis to be together; it could also be very cynical as they are just part of another TV show, and the allseeing corporate giant wins out. Did you want to guide viewers one way or another? I think you nailed it, as it can be both. The number-

one goal was to pay off Willis’ emotional story and all the craziness that came before. What we learn at the end – spoiler alert – is he has been telling this story. I’m not a cynical person by nature; I prefer hopeful stories. But we live in a time when corporations have enormous power over our lives – seen and unseen. Willis is trapped in a system he doesn’t understand, and throughout the show, we see the layers of this dynamic. In the end, can he realistically get out? To me, that’s an open question.

This is a union magazine, and our focus is on the well-being of the people behind the camera, the Willis Wus of the world. In your first time as a showrunner, what was your impression of the crew that helped make this show come to life? As I mentioned, walking in on Day One was super scary. But very quickly I became inspired by the energy the crew brought. People came up to me, and not just Asian-American crew members, but people of all races, genders, sexual orientations – all backgrounds – to say how proud they were to be working on this show. How much they wanted to be there. It wasn’t inclusive in an “exclusive” way, like this is for us and by us. It was truly inclusive, like we’re all making this together because we love it. Yes, we had a lot of very experienced people, like Mike and Tari, John Lee and our production designer, Kate Bunch; but we also had many people who moved up to a role for the first time. And that was so inspiring.

Tari Segal said she knew this was an AsianAmerican story, but she wasn’t expecting to see so many Asian faces behind the camera. Similarly, John Lee said this was “our hip-hop moment, where we don’t have to tell the story [non-Asians] are expecting us to tell.” Where does Interior Chinatown land for you? That’s a fun quote! Of course, the underlying idea is the lens through which you can view the AsianAmerican experience. That’s definitely what the book was. But the show became something broader and deeper. It’s about people asking who they are, not in an identity-politics way, but in an existential way. Who am I? What do I care about? If someone had asked me a few years ago what I would consider progress for Asian-American filmmaking in this country, I would say exactly what we achieved with this show. To just tell a story where you care about the characters, regardless of their culture or background.

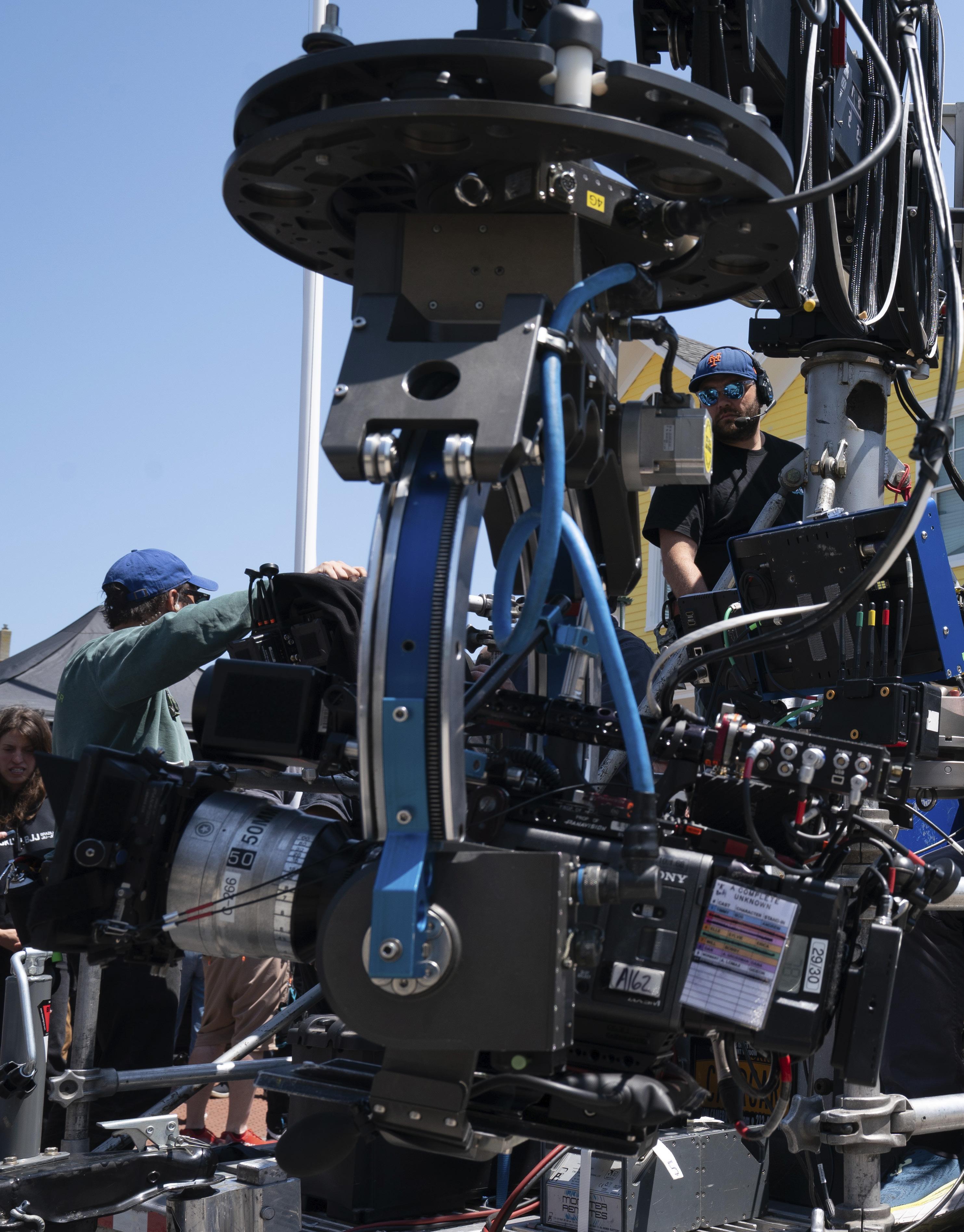

PHEDON PAPAMICHAEL, ASC, HELPS

“ELECTRIFY” JAMES MANGOLD’S NEW BOB DYLAN BIOPIC, A COMPLETE UNKNOWN.

BY MATT HURWITZ

PHOTOS BY MACALL POLAY, SMPSP / SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES

Timothée Chalamet’s Bob Dylan doesn’t say much – unless, of course, he’s singing. We see the camera flowing around the legendary troubadour, first showing the audience, warmly visible in a dark club, before turning to the actor’s face, just inches away. The camera settles, revealing a version of Chalamet not yet seen on screen, and to the actor’s credit, a chameleonlike inhabitation of the enigmatic singer/songwriter.

Co-Writer/Director James Mangold, whose career began at the 1995 Sundance Film Festival with the surprise indie hit Heavy, is no stranger to complex movie protagonists. From Girl, Interrupted to Ford v Ferrari, [ICG Magazine November 2019], the filmmaker has shown a flair for film heroes whose journeys share upheaval and unpredictability. In his new feature, A Complete Unknown, for specialized distributor Searchlight, Mangold takes us from Dylan’s arrival in an artsy, politically percolating Greenwich Village through his growth over the following four years – from struggling poet meeting his heroes to overnight cultural icon.

As ICG Director of Photography Phedon Papamichael, ASC, here lensing his sixth feature for Mangold, shares, “Bob asked him, ‘What is this movie about?’ And Jim said, ‘Well, it’s about this young man who leaves his family in Minnesota, moves to New York, and creates a new family – and then he leaves them.’ And Bob goes, ‘I like it!’” In addition to franchise tentpoles like Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Papamichael and Mangold’s other musical drama was Walk the Line, about Johnny Cash. “Jim and I are like brothers,” he states. “Our thought processes are scarily in sync.”

More than just a simple music film, Papamichael says, “Jim is very good with characters and story. But besides portraying iconic figures, he’s more interested in the human aspect – what makes them tick, as artists, with all their flaws, and what makes an artist create.” And perhaps because the pair had just come off Indiana Jones, where they had to be faithful to the formula of a historic franchise, for the Dylan shoot they desired something different.

“I decided early on that I didn’t want to shoot this in some shaky docu-style,” Mangold explains. “Better to make the world feel shaky, exciting, and vibrating, without turning it into a pseudodocumentary, and instead telling a real fable.” Instead of looking at Bob’s world, we’re in his world with him, “without being a POV movie, we do a lot of location shooting and just moving the actors around and letting it feel alive.”

To craft the film’s look, Mangold and Papamichael brought in several key players. Production Designer François Audouy had worked with Mangold on six previous titles, eventually creating 75 sets for this film, including whole city blocks representing Greenwich Village of the day. “Dylan arrived in New York at an extraordinary time,” Mangold relates. “Culturally, things were just bubbling in this petri dish of art, poetry and music.”

The city – and Dylan’s life in it – were well

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY PHEDON PAPAMICHAEL, ASC, SHOOTING HIS SIXTH FILM WITH WRITER/DIRECTOR MANGOLD SAYS "JIM AND I ARE LIKE BROTHERS. OUR THOUGHT PROCESSES ARE SCARILY IN SYNC.”

documented, allowing Audouy to assemble massive lookbooks with historical photography from Saul Leiter, William Eggleston, Ernst Haas and Daniel Kramer. Those references helped Papamichael establish a look that was saturated and contrasty, representative of the feel audiences will have known from those images of the day. He also worked to evolve that look over the four years in which the film takes place, as well as reflect seasons, working closely with Fotokem colorist David Cole.

“It’s winter when Dylan comes to New York, so we play that a bit muted, more in the brown and gray tones,” Papamichael describes. “And then, as his personality blossoms, and he becomes Bob Dylan, we heighten the visuals, in terms of saturation, color, contrast, harder lights and harder cuts, with the camera becoming more active.”

Adds Cole, “We wanted this idealized time, especially when Bob first comes to New York;

he is idealized about what he wants to do. We wanted to move through all the different palettes and colors, to keep it visually stimulating – draw the audience into the time and the story.”

Papamichael approached four different colorists in prep, asking them to create a sample LUT rooted in the feel of Kodachrome images found in Audouy’s lookbook, as well as in movies like The French Connection. He eventually chose the LUT Cole created, who says, “Working with our color scientist, Joseph Slomka, we generated various iterations. What we came up with emulated film from the 1970s – neg stocks and print stocks – as well as Kodachrome, pushing certain colors in certain areas. Kodachrome has strong, rich, primary colors, with some slightly off-key. So, it was a combination of all of those.”

The LUT’s were applied on set by DIT Patrick Cecilian, using Pomfort’s Livegrade Studio. As Cecilian shares: “I’m not doing big swings in the CDL. It’s all balanced. I also would adjust the white balance in camera, using bitbox. It’s a wireless camera control device that allows for adjustments without having to approach the camera, either on a crane or in a tight corner.”

Another key part of the look was provided by longtime Steadicam Operator P. Scott Sakamoto, SOC, whose past work with Papamichael includes Ford v Ferrari and Ides of March , as well as other musical films, including Bradley Cooper’s Maestro and A Star Is Born , shot by Matthew Libatique, ASC. “I think Scott gets the call from Bradley before Matty does!” Papamichael laughs. Notes Mangold, “Scott’s not just an exemplary operator on a technical level; he’s always thinking about what I need to tell the story. He has an innate consciousness

of how it’s going to cut.”

Mangold says Sakamoto’s sensitivity to the actors was vital to the film’s approach.

“Scott has an instinct about the story that always puts you in the right place when the actors are doing their thing,” he adds.

“Watching Timmy so closely, seeing that he is about to turn to the audience and give this look, and moving to meet him there; the camera and actor are just finding each other, making it feel alive and unrehearsed. That is where Scott is miles ahead of anyone else.”

Papamichael shot Ford v Ferrari at faster lens speeds, often at 2.8 or 4.0. “But for this,” Mangold states, “we were looking for a deeper depth of field, and also sharpness, even in places with very low light.”

Lensing at stops of T8, T11, or higher led to choosing the Sony VENICE 2 (supplied by Panavision). “The camera has two EI modes – 800 and 3200,” Cecilian explains. “We shot a lot in the 3200 base, but with some

scenes, shooting with a 5.6 or 8 on a night exterior, we’d set the camera at 12,800 EI!” Panavision’s Senior Vice President, Optical Engineering and Lens Strategy, Dan Sasaki, custom-built anamorphic lenses, because, as he describes, “Phedon was keen on coming up with a lens set that would share many of the characteristics he had gotten on Nebraska and the nostalgic flares of Walk the Line . He was also interested in getting lenses to photograph close to the actors.”

While shooting Ford v Ferrari , Papamichael discovered that traditional Panavision B Series and C Series anamorphic lenses didn’t play nice with a large-format sensor, so Sasaki offered to expand them. “The expanded lenses [used on Ford v Ferrari] were actually quite flawed,” Papamichael recounts. “They had vignetting, falloffs, and a softness on the edges that I loved.” After that film, Panavision took care of those flaws, and the lenses became quite popular. But, for

Papamichael, they became “optically perfect – and less interesting.”

For A Complete Unknown, he asked Sasaki to put together a hybrid set that combined the vintage qualities of the B Series and C Series, with the aberrations he preferred, while allowing for the close focus he was seeking. The set included six such custom lenses, ranging from 35 (T2.8) to 100 mm (T2.3). One important quality the lenses offered was unique flaring, inspired by the look of the spherical lens flares in Walk the Line. “They have a nice blooming effect,” Sakamoto observes. “You see the elements in line in the frame, and it’s quite beautiful.”

A Complete Unknown was shot on a 10week schedule – late March through late May 2024 – with Papamichael taking advantage of the early months to show more wintry periods. With rare exception, the production

(L TO R) A-CAMERA OPERATOR/STEADICAM P. SCOTT SAKAMOTO, SOC, DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY PHEDON PAPAMICHAEL, ASC, AND WRITER/DIRECTOR

shot in New Jersey, with carefully dressed Hoboken and Jersey City streets subbing in for Greenwich Village. Stage work was done at Palisade Stages in Kearney.

As they typically prefer, Mangold and Papamichael opted to shoot single camera. “Neither Phedon nor I are particular fans of multicamera,” Mangold explains. “We both feel happiest when we’re rolling one camera, one shot at a time, one composition at a time. Scott shot almost every frame in the movie.” (B-Camera 1st AC James Schlittenhart was full time on the main unit, with B-Camera Operator Ethan Borsuk day-playing as needed.)

With the iconic MacDougal Street long since changed from its 1960s look, the Art Department pored over the many references Audouy had assembled to recreate the historic street, mostly in what became their “MacDougal Street Hub,” built on Jersey Avenue, between Wayne and Columbus in Jersey City, with other key venues scattered

around nearby downtown Hoboken. The locations were captured with a combination of careful lighting and shooting with the VENICE 2 at 12,800 ISO, revealing city blocks that were indeed always alive, with plenty of detail visible.

“Phedon and I discussed how we wanted it to have a tungsten feel,” recalls Chief Lighting Technician John Alcantara. “He wanted to have dimmable control. You can’t do that with sodium, so we decided to go with a bigger traditional tungsten bulb. And the more I dimmed it, the more we would feel the warmth of the street.” Alcantara, who recently worked with Papamichael on Daddio (2023), says the approach to lighting throughout the project followed a simple mantra. “We just kept saying, ‘Natural, natural, natural.’ We didn’t want this to feel stylized in any way.”

Audouy took advantage of the massive amount of photographic documentation of Dylan’s Village apartment, reproducing it

on stage item by item. “We recreated every artifact we could find in those photos, as it’s like a holy place,” the designer describes. A soft drop with the New York skyline was used outside and lit with ARRI SkyPanels, while S360’s – with full color controls –were used to push soft light in through the windows. Inside the apartment, Alcantara’s team placed Astera Titan tubes, often in Lightsocks, and more S360s to provide a global ambient feel. Papamichael also utilized practicals inside the apartment as much as possible, swapping in Astera NYX bulbs to allow controllable color “without having to worry about getting too much of a warmer cast, like you would with tungsten,” Alcantara explains. Adds Mangold, “I admire the way Phedon is always looking for ways to use practicals and real lighting in the frame.”

One beautiful shot in the apartment took advantage of the VENICE sensor’s extreme sensitivity. With the camera rated at 12,800, we see Dylan grab a cheap gooseneck lamp to

RIGHT: CHIEF LIGHTING TECHNICIAN JON ALCANTARA SAYS THE APPROACH TO LIGHTING ALWAYS FOLLOWED A SIMPLE MANTRA. “WE JUST KEPT SAYING, ‘NATURAL, NATURAL, NATURAL.’ WE DIDN’T WANT THIS TO FEEL STYLIZED IN ANY WAY.”

LOWER LEFT: MANGOLD SAYS SAKAMOTO "HAS AN INSTINCT ABOUT THE STORY THAT ALWAYS PUTS YOU IN THE RIGHT PLACE WHEN THE ACTORS ARE DOING THEIR THING.”

sit on the floor with his television, watching coverage of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It’s a single shot, which starts high and wide, dives down into a close-up, then rotates around and reveals what’s on the TV, with the VENICE still making the rest of the room visible. “The way it was scripted,” recalls Papamichael, “was, ‘He’s in his apartment, taking down notes.’ But those kinds of scenes, we just throw them together quickly. ‘Try sitting on the floor here,’ and we just design a shot. That’s the beauty of discovering one shot that tells a story.”

Another dim, and beautiful, space is the interior of Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, where, one evening, Bob meets his two heroes, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. The location was the former Essex County Hospital, a mental institution in Patterson, NJ (also used in Joker), while the interiors were filmed at a closed school in Newark, the Dayton Street School. While the hallways were institutional – lit with 300 Astera Titans in place of the existing fluorescents, allowing varying adjustments of color, including the ability to add a green tint to match a

traditional fluorescent tube – Guthrie’s room was another story. The space is lit with vintage tungsten sconces by each patient’s bedside, allowing Papamichael to have the VENICE to provide a sense of the space as well as warmth between the characters.

Some of the film’s most memorable (and sure to be talked-about) scenes are of Dylan playing live (filmed, for the most part), with Chalamet playing live for the camera. The scenes take place, initially, in small clubs in Greenwich Village, and then later, in larger theaters and other venues. The club work was shot at a variety of Hoboken locations, with the iconic Gerde’s Folk City and The Gaslight shot in the town’s Elks Lodge. These scenes were lit with simple tungsten sconces and PAR cans, as well as traditional maroon Mole 407s, period-correct for that era.

In the clubs, and especially the larger theaters, Mangold avoided a traditional performance setup, i.e., perspectives from the middle of the house and the side of the stage. “That’s the language of rock

documentaries,” the director explains. “Phedon and I wanted the camera where you can’t put it if you were shooting a live event,” using wide lenses, close to the actor, and having Sakamoto swivel out to reveal the audience. “We’re not here to recreate a famous concert, as you’d see it from the audience. We’re here to recreate a famous concert as it felt to perform it.”

Since Chalamet was performing live, the team took full advantage of Sakamoto’s instinctive gifts. “Jim and I have a lot of respect for Scott – his experience and his instincts,” Papamichael shares. “We can’t have the operator waiting for us to say, on comm, ‘Okay, push in here, then rotate around.’ My instruction to Scott was, ‘Let’s start the song and go find it like we’re making a documentary.’”

Sakamoto’s keen ability to connect with the actor – and Chalamet’s gifts for awareness of the camera’s presence – created a memorable experience. “You learn from the actors how they’re going to move and where they’re going to move,” Sakamoto describes. “He’s playing the guitar, and my rig and

monitor are right up against his guitar – and he knows it. He can’t hit me, because he doesn’t want to ruin the shot. It became this wonderful dance we did together.”

Alcantara provided Papamichael with a 12-channel DMX-iT dimmer board, connected to programmer Michael Hill’s lighting console. “I could walk around with it, back to my monitor, constantly adjusting lights – keeping just enough eye light or eliminating it altogether,” Papamichael recounts. “I’m live-mixing my lights during the shot.”

A-Camera 1st AC Craig Pressgrove had to exercise similar instincts as Sakamoto, as seen in a handful of stunning focus pulls that substitute for coverage and cuts between actors. As Papamichael explains: “Jim and I like to be physically close to actors, and we like to have people create close-ups by walking towards the camera – and then you get to rack, and it becomes an overthe-shoulder.” That approach requires the 1st AC to be fully involved in the story, to know where and when beats will happen –and to be aware of the actors’ instincts, not anticipating the move, but landing on them as they occur. “Craig understands story,” Sakamoto shares, “which is why he’s such a fantastic focus puller.” “And,” Mangold adds, “it helps to have actors who know the limits of their frame and operators who trust that.”

Fotokem’s Cole handled final color timing, where the project was output to Kodak 3205 50 ASA camera stock, in a process known as Shift A.I. (Analog Intermediate).

As Cole explains: “We grade the film, make it look beautiful, under the lookup table – and then strip all that off and output to film.” That film is then scanned back in, and the color science is reapplied to the footage.

“We’re picking up all the little aberrations you get from film, even a little bit of projector movement, and real grain, not LiveGrain applied on top,” Papamichael describes of the process. “It breaks that sense of ‘I’m watching a movie’ for the audience,” Cole adds, bringing them into 1961 and Dylan’s first years in New York.

The hope, concludes Papamichael, “is that through this movie, Gen Z’rs will discover the spirit of that era. They’ll see how relevant Dylan’s experience was to today’s world – a young person finding themself in tumultuous times and expressing it. Hopefully, this will inspire a new generation to start listening to more than the one or two famous Dylan songs they’ve heard, and discover him as an artist.”

Director of Photography

Phedon Papamichael, ASC

A-Camera Operator/Steadicam

P. Scott Sakamoto, SOC

A-Camera 1st AC

Craig Pressgrove

A-Camera 2nd AC

Eve Strickman

B-Camera Operator Ethan Borsuk

B-Camera 1st AC

James Schlittenhart

B-Camera 2nd AC

Alec Nickel

Loader

Naima Noguera

DIT

Patrick Cecilian

BTS Director of Photography

John J. Moers

Still Photographer

Macall Polay, SMPSP

Publicist

Frances Fiore

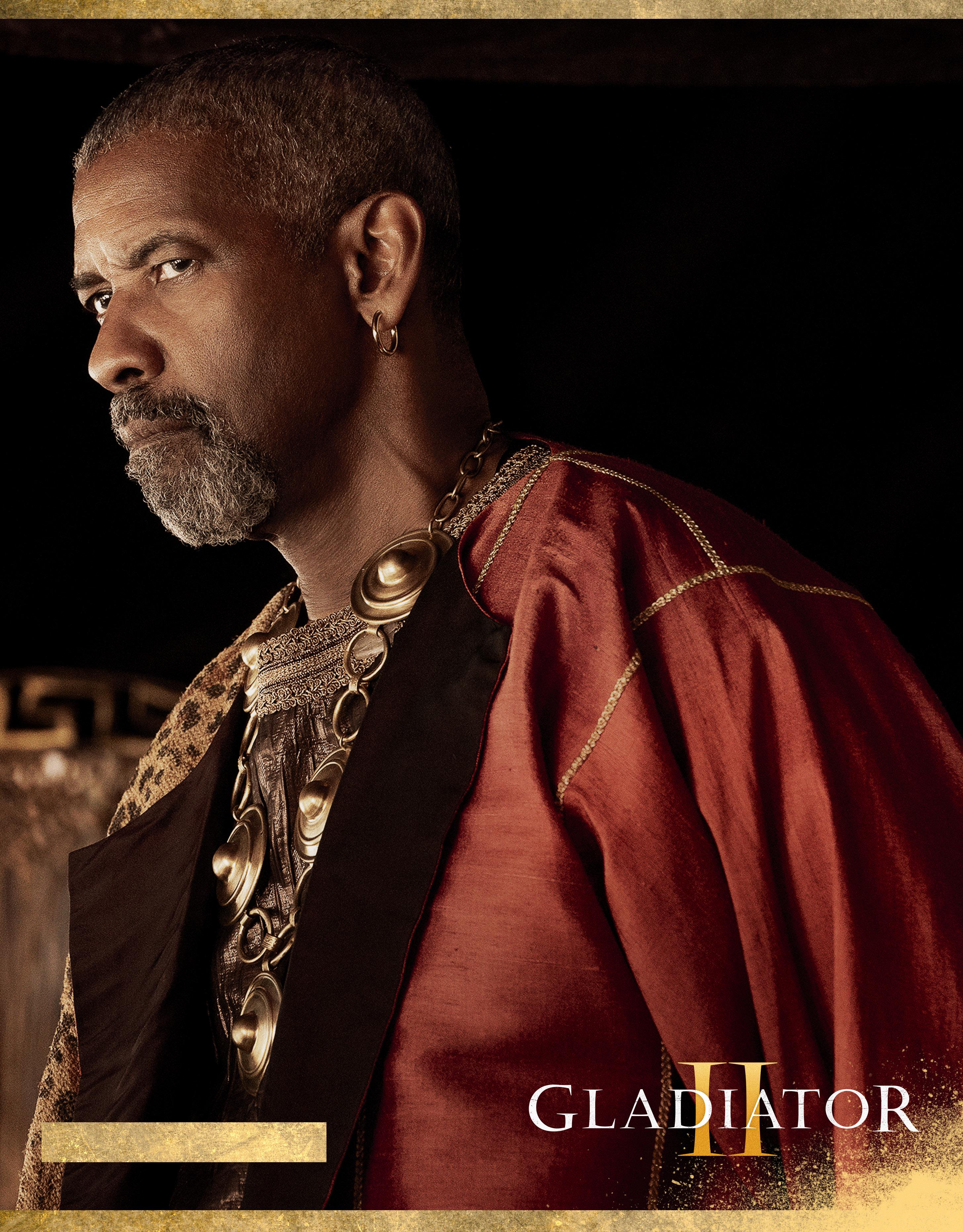

HULU’S INTERIOR CHINATOWN WAS 2024’S MOST INNOVATIVE EPISODIC SERIES. BUT VISUALLY TRANSLATING SHOWRUNNER CHARLES YU’S META-JOURNEY THROUGH THE 1990S WAS NO EASY ASK.

BY DAVID GEFFNER

Hulu’s 10-part series, Interior Chinatown, set in an unnamed American city circa 1990-something, looks straight away like a standard police crime drama, or, with the introduction of two Chinese twentysomethings having a cigarette break in the alley behind the “Golden Palace” restaurant, your standard Asian-American comedy. Or, even, with the abduction of a young Asian woman, witnessed by one of the workers, Willis Wu (comic Jimmy O. Yang), your standard noir-detective ride. But when the camera pulls back to reveal the entire “cold open” of the series has been taking place on a small portable TV screen, it’s clear that while Interior Chinatown intentionally looks like many familiar genres, it’s not like anything episodic television has seen before.

Let me explain: Novelist Charles Yu ( Exposure , page 26) won the National Book Award for his 2020 novel Interior Chinatown , a story Vanity Fair described as “a shattering and darkly comic send-up of racial stereotyping in Hollywood.” The book centers on Willis Wu, a self-described “Generic Asian Man” and “background Oriental making a weird face,” who’s relegated to being an “extra” in his own life. Every day Willis leaves his room in a Chinatown SRO (above the Golden Palace) to work as a waiter, and, presumably, as a silent background player in Black and White, a procedural cop show that’s always in production. As he watches an action-packed world unfold around him, Willis dreams of

being “Kung Fu Guy” – his beloved older brother who mysteriously disappeared 12 years earlier. As the novel moves forward, Willis gradually gets to become the main character of Black and White, discovering the secret history of Chinatown – and the lost brother he yearns to be – along the way.

As Director of Photography Mike Berlucchi, a 2022 ASC Award winner for the Apple TV+ series Mythic Quest, recounts: “I’ve been working with [Executive Producer and Pilot Director] Taika Waititi for the past three years. And while shooting Time Bandits, he mentioned [Interior Chinatown] in passing. I immediately grabbed the book and fell in love with it.”

Berlucchi was asked to shoot the season

solo. “While that may have made sense, on paper, to keep a visual through-line with one DP,” he adds, “I quickly realized that would not have been in service of the show. When the producers brought in Tari [Segal], for episode two, it was an instant fit. Tari has so much experience with police procedurals. But beyond that, she manages to do something different within that genre. I thought: ‘I can learn a lot from her!’”

Segal, who stayed on as alternating DP, lensing Episodes 2, 4, 6 and 8, says there were two main looks for the series – the grimy, handheld feel of Willis’ world, with 360-lit locations that characters move naturally through, and the TV series Black and White, which featured a hard, blueish “show light”

that flooded the frame whenever its main characters, street-smart detectives Sara Green (Lisa Gilroy) and Miles Turner (Sullivan Jones), show up.

“The idea was to lean into the TV procedural in a satirical way,” Segal describes, “as every time Green and Turner arrive, the ‘show light’ would come on. That meant shifting the color temperature of the lighting, adding strong backlights for every angle of coverage [regardless of continuity], having a strong key light, and remaining in Studio mode or Steadicam.”

The first example is in the pilot, when Green and Turner strut into the Golden Palace to investigate the Chinatown abduction. “The cop show look is teased in Mike’s episode,” Segal continues, “and then we dive into it in episode two, when Willis makes many attempts – unsuccessfully – to get into the precinct. Everyone in prep kept saying Law and Order [for the precinct interior], but I know the Dick Wolf world, and the look we wanted was much more like CSI. All the eyelines in the overs are close, and we’d do these walk-and-talks with Green and Turner where they go in circles around [the bullpen] but never right to their desk! We used all the established tools of the cop show and then went a little over the top.”

Willis’ world, which includes the SRO above the Golden Palace and flashbacks to his childhood of family dinners and learning kung fu with his brother, Johnny (Chris Pang), was influenced by Wong Kar Wai’s 1995 crime-drama Fallen Angels (shot by Christopher Doyle). There was also a weekend trip Berlucchi made with Production Designer Kate Bunch that served as inspiration. “We ate our way through every restaurant in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” he smiles, “and walked through the city, with that beautiful haze, at every time of day. We came back with photographs that became a big influence for the Chinatown exteriors.”

Berlucchi also pulled imagery from [Chinese Still Photographer] Fan Ho, “whose work is so incredible,” he adds. “The feel we wanted for the Golden Palace interior was a place that was loved, but dated. It needed to be very distinct from the cop show, which we see as an in-camera lighting change. The first time we did Green and Turner’s arrival at the Golden Palace, we didn’t go far enough. So, we came back on the last day of the pilot and made sure it was a bigger, more dramatic lighting shift to announce the TV show is here.”

Segal says each in-camera lighting cue had to be carefully broken down, because in some examples, “when the TV show comes on, we go abruptly from night to day. I would send all my notes to Mike since he would need to know what we did for the next episode. I’ve rotated a lot with other DP’s, and it’s not always seamless. But with Mike, it was an amazing partnership. Honestly, this show was so complicated, that was the only way we could have been successful.”

ArsenalFX Colorist Aidan Stanford says the incamera lighting changes were challenging because “Willis’ world has a 35-millimeter grain applied,

and the TV show was super clean. We also used two separate looks, extracted from the LUT’s Mike and I developed before the shoot. When going in and out of those drastic transitions, I’d add the outgoing/ incoming shot into a neutral group, and use the downstream nodes for the OFX [plug-in] look. Then it became a simple dynamic in and out of those worlds adjusting the primary grade as needed. Got tricky a few times with monitor comps, since those needed to be non-affected.”

Chief Lighting Technician Jeffrey Chin (American Crime Story, Hollywood) shares that the lighting units chosen for the Golden Palace, and many of the show’s sets, were practically-driven. “Working with Kate [Bunch] and [Set Decorator] Adrienne Garcia, we knew that the main space [of the Golden Palace] would have a square fluorescent practical; the booths would have hanging lamps and the hallways would have alternating ceiling cans and flush-mounted practicals,” Chin explains. “To control the intensity and color, we filled the ‘fluorescent’ fixtures with Astera Titans, the ceiling cans with Astera NYX globes, and the flush mounts with hybrid LiteRibbon. Everything was run back to a lighting console so we could change color and intensity, and cue lights on instantly. When the TV show enters, the light cues up brighter, and bluer, and a backlight comes up. [Detective] Lana Lane’s [Chloe Bennett’s] first entrance is also a cue where the lights go warmer, brighter and more glamorous with backlight. Willis’s decision to help Lana is a cue where his light gets brighter and he gets a backlight. When these characters leave, or the moment is over, the lights would default back to normal.”

For Port Harbour Police’s bullpen, Fixtures Foreman Kevin Cadwallader and his team retrofitted the overhead fluorescent fixtures with some 200 Astera tubes. “The concept behind the cues was that when the ‘TV show’ arrived, the light would come on in rows, and as the main characters walked, the show look would follow,” Chin explains. “In episode three, when Willis is finally granted entry into the precinct, the lights cue on as a way for us to know that the TV show is going into production and Willis is still allowed to be in the precinct. We also shot a few Steadicam sequences where Turner and Green burst into the precinct lobby and walk through the bullpen, down the hallway and into the tech room. The longest cue stack in those shots was almost 20 steps.” The light cues also played a narrative role. “We see this when Willis gained entry to the precinct,” Chin adds, “when Lana graduates from sidekick to become an arresting detective [Episode 3], and when Willis sees himself on the TV and decides to join Lana’s investigation.”

Since Interior Chinatown takes place in a nondescript 1990s timeframe, Chin says, “We talked about how there would have been many different light sources. Traditional incandescent was giving way to fluorescent tubes, while CFL’s and LED’s were not yet replacing sodium vapor or mercury vapor lights. So, it seemed natural to mix all the various sources. Many of

the Chinatown streets [without the Golden Palace in frame] were shot on location in [L.A.’s] Chinatown. We would ask owners to keep their storefront lights on, and then place Condors at each end of the street with an M40 and an ARRI S360. This gave us the flexibility to either backlight or fill-in a scene with either soft or hard light.”

Key scenes, like when Willis leaves Chinatown for the first time in Lana’s car [Episode 1], or when he rides his bike out of Chinatown [Episode 2] to the precinct, were shot on Universal’s “New York Street.”

“That was a huge undertaking,” Chin reflects, “as we had to dress several blocks of New York Street, and then beyond the Chinatown archway, as the city of Port Harbor. All fixtures were controlled by the lighting console, all signs were retrofitted with either Astera tubes or Quasar rainbows, and, as with the location work, we used Condors for soft backlight.”

For day work on the FOX lot, the team had to create a ‘sky’ by rigging an array of 110 SkyPanels S60 seven feet apart and pointing straight down. “The grips added an LT grid rag underneath that stretched 160 feet by 70 feet,” Chin describes. “Just underneath the rag, above the façade and across the street from the Golden Palace, was an 18K ARRIMAX for hard direct sunlight. The LED array allowed us to change the color temperature of the exterior. We could make it a bright sunny exterior or a cloudy cool exterior within seconds.”

In a show with many overt cinematic references, the first may be the most fun. In the pilot episode, Willis warned in voice-over that, “in Chinatown, Kung Fu can break out at any moment.” So, when a gang war ensues inside the Golden Palace, and Willis, his best friend Fatty Choi (fellow comic Ronny Chieng), and other workers join in, it is an opportunity for the filmmakers to dive into Bruce Lee fanboy territory.

“While Taika and I pulled from classic Hong Kong fight films for that first Kung Fu battle,” Berlucchi describes, “we wanted it to feel messier than the classic Bruce Lee scenes, like Willis, Fatty and the other workers don’t quite know what they’re doing. We also pulled from video games, specifically Neighborhood Rumble, which Fatty is always playing in the break room. We did a sidescrolling Steadicam shot across the booths that references that video game. While that first Kung Fu battle is meant to be heightened Hong Kong cinema, we were careful to never drift into satire, like the TV show.”

Producing Director John Lee, who helmed Episodes 4 and 8, says his talks in preproduction with Berlucchi were about “this journey of a spotlight that begins far in the background and becomes more prominent when Willis gets into the police station. By episode eight, the light is literally shining down on Willis, not unlike what many people of color experience when confronted with a police searchlight,” Lee shares. “Willis is now the star of Black and White, and this

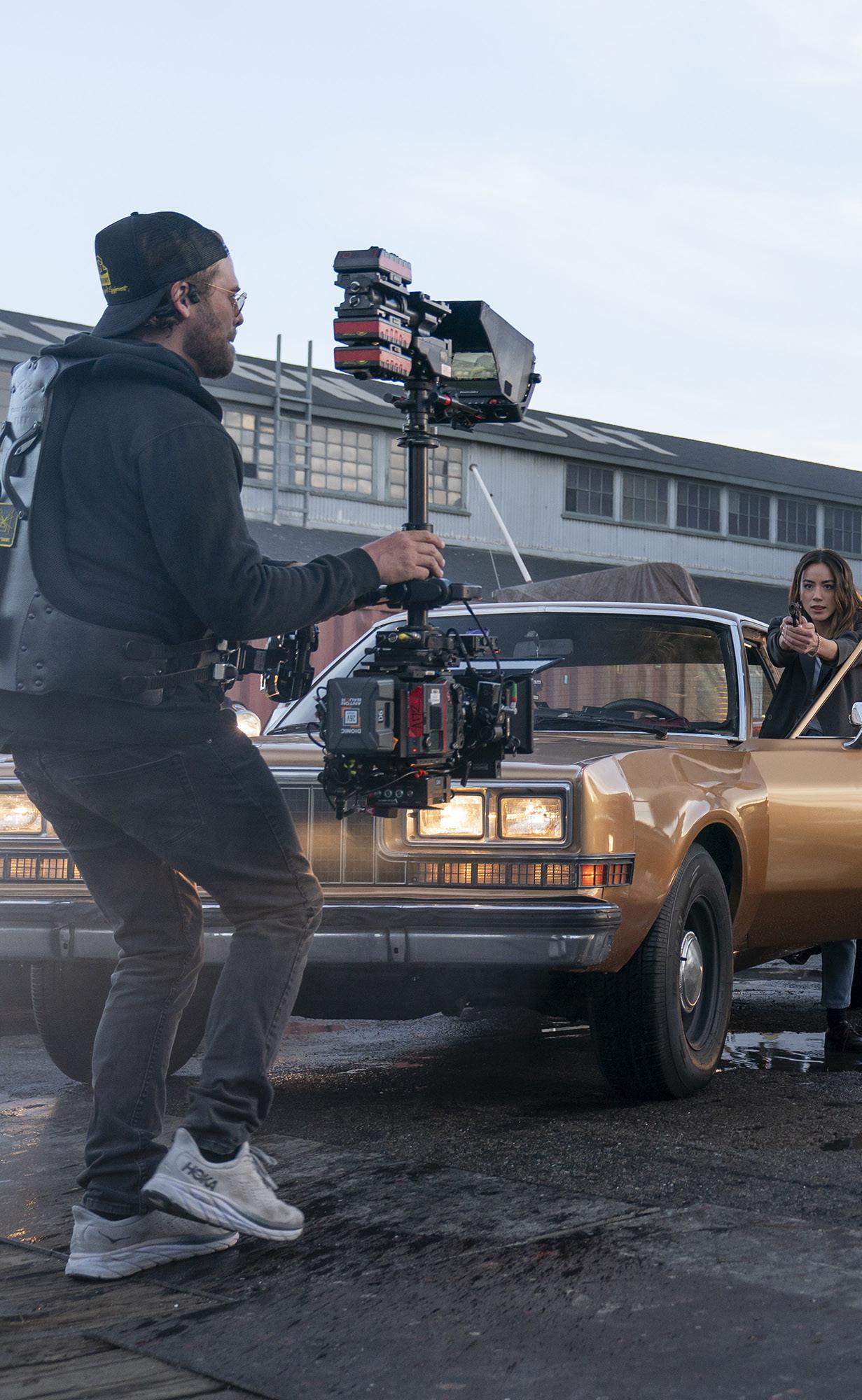

OPPOSITE PAGE TOP: FOR THE PILOT EPISODE'S FIRST BIG KUNG FU BATTLE, BERLUCCHI SAYS “TAIKA AND I PULLED FROM CLASSIC BRUCE LEE FIGHT FILMS, BUT WE WANTED IT TO FEEL MESSIER, LIKE WILLIS, FATTY AND THE OTHER WORKERS DON’T QUITE KNOW WHAT THEY’RE DOING."

OPPOSITE PAGE BOTTOM: FOR SCENES SET IN HIDDEN TUNNELS UNDER CHINATOWN, BERLUCCHI CALLS HIS COLLABORATION WITH THE ART DEPARTMENT "NEXT LEVEL. LIKE EVERYTHING ON THIS SHOW," HE SAYS. IT WAS ‘BEST IDEA WINS,’ AND THERE WAS NO EGO OR RIGID BOUNDARIES.”

spotlight represents him thinking he’s a fraud and has been discovered. Mike and I spent time talking about the different ways to visualize the light throughout the show. And Tari brought a lot to that, not just for her speed and intuition with the cop show scenes, but as a creative thinker. Every idea I threw at Tari, she matched and then some.”

The Segal-shot Episode 4, where Willis, having penetrated the precinct as “Tech Guy,” discovers archival footage of his brother working with Port Harbour Police, was another place for the Hong Kong cinema references to shine. For the kung fu fighting footage, Lee says, “We had three simultaneous teams, with Tari and [1st AD] Yuko [Ogata] overseeing it all. I would pingpong from setup to setup, dozens in total, all in a single location, all in one day.

“The book is very clear how Willis’ brother makes it out of Chinatown through kung fu,” Lee continues, “so that was important to maintain in the series. All of that footage Willis sees of his brother fighting kung fu is lifted from Bruce Lee films. Some of the cuts are even edited the same. I pushed hard in this episode to honor the older Asian cinema. It’s both an Easter egg for hardcore kung fu movie fans and an important narrative bridge for Willis, because kung fu is the legacy of his family [Willis’ father, Joe, ran a kung fu studio where Jonathan was trained], and the only real anchor he has to his brother.”

Segal says she wanted to frame Johnny’s footage in 4:3 to emphasize that Willis is

watching an older version of the TV show. “At that moment, when he’s watching the archival footage in the tech room, Willis is using an older version of Final Cut Pro, so he would be editing in a 16-by-9 world,” Segal explains. “We shot 4:3 with safety for both 16-by-9 and 1.85 and created a different look for the past that was more desaturated. We used the ALEXA 35 with Panavision PVintage primes in 1.85 until the end of episode six, when we switched to the C-Series Anamorphics and went to 2.35. By then Willis’ world and the TV show are starting to converge, and it’s a more elevated look [to the TV show] that references shows like True Detective and Mindhunter.”

Episode 4’s cliffhanger ending, where Willis, listening to a cassette tape of his brother desperately pleading for help, follows the audio down to a series of underground tunnels, is paid off in Episodes 5 and 6. Willis, having joined forces with Lana to solve his brother’s disappearance, returns to the tunnels, which terminate in Willis’ Uncle Wong’s (Archie Kao’s) office at the Golden Palace. Berlucchi, who shot all the tunnel scenes, says he stumbled across a video by French singer-songwriter Flavien Berger that was set in the tunnels of Paris. “It had all these beautifully twisted power cables running through the tunnels,” he recounts. “So, I brought images from the video to Kate and Adrienne and said, ‘Take a look at this.’”

Berlucchi says the art department went out and found the same cables and filled the tunnels, which were built on a stage in Chatsworth. “I asked them for fixtures that we could retrofit lights into, and then now and again for these small grates where we’d play shafts of light from the outside world. I remember seeing all these pallets of cables, and the art team saying, “Here you go. Your

dream came true,” he laughs. “The collaboration [with the art department] for those tunnels was next level. Like everything on this show, it was ‘best idea wins,’ and there was no ego or rigid boundaries.”

Chin says the fixtures added in the tunnels were the same Asteras from the Golden Palace, “but with more green, and either cooler or warmer color temperatures for a grittier look. All of the fluorescent light covers were aged as well,” he shares. “After seeing rehearsals, we would program-in random flickers or change a tube’s color. Shine was added to the walls to have random reflections from faraway sources. The tunnels were meant to be extremely dark.”

One of the main reasons Berlucchi chose the ALEXA 35 system “was because I knew we’d be spending so much time in those tunnels, especially in the final episode,” he states. “And that camera has the ES mode, which allows you to bump your ISO up to 3200. For the sequence when Willis comes down the ladder into the tunnel in episode five and flicks on his lighter, we wanted that entire scene lit only by the lighter, with maybe one bulb deep in the background to silhouette them. I couldn’t have done that scene with some of the older ARRI systems.”

The final three episodes of Interior Chinatown contain tour de force visuals that allow each episode to stand alone as a mini-movie. Episode 8 presents Willis as the new face of the Port Harbour Police Department, now starring in a series of commercial spots. Those include a whiskey ad in moody bar light, a 90s hiphop parody ad with Fatty’s new “secret sauce” product line, a high-end watch commercial shot in a glistening art deco building with billowing drapery, and a musical deodorant spot with dancers and singers that charts the history of Willis’

journey through Chinatown in a single take.

As Segal recounts: “Episode eight was challenging on so many levels. We had the same eight days to prep as all the other episodes, and the entire set for the musical oner had to be built from scratch.” She says Director Lee wanted to pay homage to a shot he and Segal did at the end of Episode 2 when Willis gets up the nerve to go through the tunnel on his bike that will take him out of Chinatown for the first time. “In that shot, the camera is above him looking down as he rides into the tunnel,” Segal continues, “so we replicated that with the oner. As Willis leaves Chinatown, the backgrounds change to the docks, the police precinct, and the big city, with night morphing into day and Willis now living his dream. We didn’t have the weight capacity or space for a crane arm, so we got a platform crane for our A-Camera/ Steadicam Operator, Tom Valko, to go up and down and then walk off, all with timed choreography, which was a challenge!”

Chin concurs with Segal about the complexity of the oner, noting that a model of the sets was built first to show the scale of

the move. “There were off-production dance rehearsals that took place on stage with tape marks where set pieces were going to be,” he describes. “Then, as the set was being built, we plotted and rigged the lights. One challenge was that sections of the set had to turn off to not contaminate the next set. So, when the shot opens, Willis is lit with rows of S60s, both key and fill. As he turns to go to the [docks], the Chinatown street dims into night.”

To light the docks, Chin’s team employed moving lights shining down a blue Mylar for water and some blinking LED’s on a backing. “We also had some Jo-Lekos shining into water pans to project a subtle water-ripple effect. We had one pre-light day to work through the light levels and get a basic timing. We cued each look manually instead of syncing the cue to the music. This ensured that Willis was in the right light on the correct area of the set.”

Lee notes that along with showrunner Yu, he and writer Eva Anderson wrote the lyrics for the deodorant ad, “with the goal of telling Willis’ complete story from beginning to end in one shot,” he describes. “As a guest

director, my ideas are always trying to push character, story, and psychology, which is why I like working with DP’s so much. I tend to talk about purpose, mood, and the psychological state of the characters with DP’s because I find, aside from what the lighting, camera or blocking will be, they like to get into the why of what we were doing, which then informs the what. Tari and Mike were dreamers in that respect, because they love the visual poetry of it all. I got in costume as one of the dancers for the oner because I wanted to ‘method direct,’” he laughs. “Oners are so much fun. They have this unique momentum, like a play in sports or a piece of music, where everything has to fit just right to work.”

Reflecting on his work in grading Episode 8, Stanford adds, “The big musical oner is the same LUT we used for the SRO, just pushed around into three specific grades. I used custom curves to get what we needed for a different style after the primary grade went as far as it could go. Tari had given specific references as well as written ideas for exactly what she shot. It was a huge help, and so

much of the final result comes from what was done on set.”

As Segal noted, Episodes 9 and 10 show Willis’ world and the Black and White TV show fully embedded, creating a hybrid look that reflects the inner (and outer) lives of each of the main characters coming unhinged. Turner has left the police force (he returns for the big finale in Episode 10); Willis is now the prime cop quizzing those who were around when his brother disappeared; and Lana, on forced leave from Port Harbour Police, is washing dishes at the Golden Palace. In Episode 9, we see Willis drive out to a high-desert diner to meet former Port Harbour Detective Aidan McDonough (Spencer Neville), who, according to the footage Willis reviewed, was shot by his brother and left to die that fateful night on the docks.

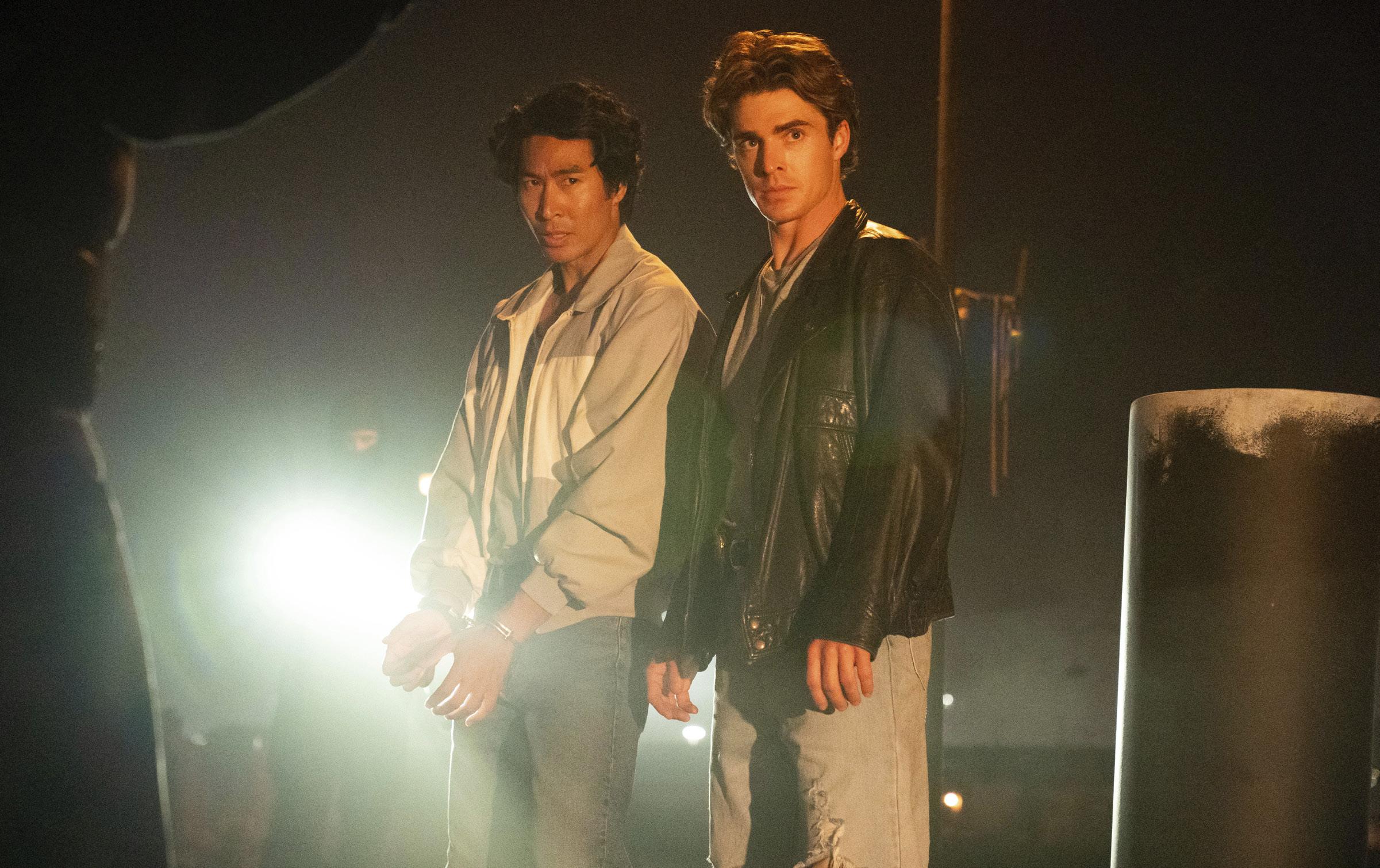

As McDonough talks, the scene spirals into a flashback, beginning with a compelling wide frame of the industrial surroundings at night. Willis soon learns the true story – his brother agreed to be cuffed and to return to

the precinct as McDonough’s prisoner for being involved with the mysterious “Painted Faces” gang, a group of Asian professionals bent on saving Chinatown from the massive corporation (HBWC, short for Hulu Black and White Corporation) that produces Black and White. However, at the moment Johnny is cuffed, hordes of thugs in ski masks roar up, car lights flooding the frame, as Johnny and McDonough join forces to battle them in kung fu. The final shot of the flashback is memorable: McDonough walking down an empty road with a bullet in his stomach as the streetlights behind him turn off, one by one.

“The guys pulling up and the kung fu battle represents the TV show coming to devour Johnny and McDonough,” Berlucchi describes. “After McDonough is shot, and Johnny runs off, as scripted, the final shot of the flashback was going to be in a city, where there’s ambient light, buildings, and other elements difficult to control. We shifted that concept to be out in the desert. We searched far and wide for a long empty road, and then I asked for an unreasonable amount of streetlights – about a half-mile –

all controlled by DMX.

“The shot is a oner in real-time,” he continues, “as we pull him forward down the road and then move around to feel the cop lights from the TV show flickering at his back. When McDonough turns around, there’s nothing there. He starts walking again, and we see one streetlight behind him flicker, indicating the TV show is coming. Then oneby-one, they all click off – chunk-chunk-chunk – as the show swallows him up.”

The kung fu battle at the docks, unlike in the pilot episode, was filled with professional fighters, so Berlucchi says, “We made sure it looked slick and produced.” Those scenes, shot at a dock in San Pedro, CA, required, as Chin notes, “recreating a lot of sodium vapor and mercury vapor lights with film lights. We built the hero lamppost for the Johnny/ McDonough confrontation and asked that the incoming vehicles be dressed with lights,” he describes. “Some were prop lights on cars and others were Par 56s rigged to roof racks. The red whirly gag behind McDonough, as he stumbles down the road, was a batterypowered walking red light. Then we cued

OPPOSITE PAGE/ RIGHT: “WE TALKED ABOUT HOW THERE WOULD HAVE BEEN MANY DIFFERENT LIGHT SOURCES [IN THE 1990S],” SAYS CHIEF LIGHTING TECHNICIAN JEFFREY CHIN. “TRADITIONAL INCANDESCENT WAS GIVING WAY TO FLUORESCENT TUBES, WHILE CFL’S AND LED’S HADN’T YET REPLACED SODIUM VAPOR OR MERCURY VAPOR LIGHTS. IT SEEMED NATURAL TO MIX ALL THE VARIOUS SOURCES.”

the lamp posts off via DMX to have him swallowed by the darkness.”

“Swallowed up” is a nice metaphor for what happens to Willis in the final episode, as, through a persistent use of news footage (shot on Panasonic VariCam PR Camcorder), HBWC pushes our hero toward the ending society would clamor for – the sad and terrible self-destruction of a young AsianAmerican from Chinatown. Highlights include driving through a sea of firecrackers at night on Chinese New Year; a wild chase through the Golden Palace, with Willis and Lana frantically trapped in the hallways of the SRO, each floor now capped by full-length mirrors; Willis’ pouring out his life story to the news camera on the roof of the SRO as a circling helicopter spotlights him from above; and Willis and Lana leaping off the roof of the SRO into a dumpster, culminating with Willis plunged into a “rainbow-colored vortex” where his brother plays Neighborhood Rumble in an eternal videogame loop.

“We used ARRI’s Ultra Prime 8R rectilinear lens for most of the footage inside the SRO, mainly to make the space feel massive, but also to get far enough away from the mirrors that we were so small and distorted, you couldn’t tell we were there,” Berlucchi explains. “The hallway mirrors were inspired by a visit to a fun house with my son, and my thinking how cool it would be if they felt trapped inside the SRO.”

By the time Willis and Lana make it to the roof, the TV show has surrounded them

– news cameras in their face, helicopter lights from above. That was done with blue screen around the perimeter of an elevated rooftop set piece, with the background plates shot in and around Downtown L.A., and added in VFX. “We used these point source mover [lights] up in the ceiling to create this impression of distance, as we couldn’t get quite far away enough inside the stage as I would have liked,” Berlucchi explains. “We had four on random cycles to mimic the various helicopters,” with Chin employing “a sweeping Xenon 4K light to reproduce the ‘closest helicopter’ beam.”