SEPTEMBER 2024 VOL.95 #7

FEATURING

SEPTEMBER 2024 VOL.95 #7

FEATURING

09.29.24

TELEVISION ACADEMY THE SABAN MEDIA CENTER WOLF THEATRE

Industry Leading Facilities

Class 100 Clean Room

2 Full Frame Lens Test Projection Rooms

MYT Works Opti-Glide System + PAT Charts

T-Stop Evaluation System

Lens Collimator

MTF Machine

Sony Authorized Warranty Service Center

Angénieux Factory Authorized Service Center

Zeiss, Cooke, Leitz, Sigma, and more

Masterpiece’s Entertainment Division understands the complex logistics of the industry including seemingly impossible deadlines, unconventional expedited routings, and show personnel that must be on hand. Masterpiece has the depth of resources to assist you in making sure everything comes together in time, every time.

Our range of services, include:

• Customs Brokers

• Freight Forwarders

• ATA Carnet Prep & Delivery

• Border Crossings

• Domestic Truck Transport

• International Transport via Air or Ocean

• Expedited Shipping Services

• 24/7 Service Available

• Cargo & Transit Insurance

• Custom Packing & Crating

I don’t have to tell anyone in this industry how challenging these last four years have been, with a pandemic, two work stoppages, and other historical interruptions. But all those (unplanned) disruptors just make what I have to highlight this month that much more special. How inspiring is it that our members continue to push forward their creative energies, as we see with ICG’s upcoming 2024 annual Emerging Cinematographer Awards? How great is it that this union continues to produce incredible work, our members reaching for their dreams of one day becoming directors of photography? I think back to some of those ICG members who were honored with an ECA and went on to fulfill that goal – Todd A. Dos Reis, ASC; Cynthia Pusheck, ASC; Amy Vincent, ASC; Rodney Taylor, ASC; Alicia Robbins; Hilda Mercado; Tod Campbell; Greta Zozula and Andrew Shulkind among them – and I am thrilled to be able to continue to showcase these current and future Local 600 members with the same aspirations. This year’s group is unique as it’s made up entirely of camera operators – Dominic J. Bartolone, Jr. (Sweet Santa Barbara Brown), Adam Carboni (Incomplete), Matthew Halla (The Unreachable Star), Jessica Hershatter (Pirandello on Broadway), Allen E. Ho, SOC (Iron Lung), Nick Mahar (Sands of Fate), Dylan Trivette (Bearing Witness: A Name & A Voice) and Andrew Trost (Bloom). The ECA’s, now in their 28th year, have (along with the annual Publicist Awards) “emerged” as one of the most important events Local 600 sponsors year after year. And because of that, this union will continue to foster the creativity of our members – now and in the future.

I hope to see all of you in attendance – Sunday, September 29, 2024, at The Television Academy, in North Hollywood, CA – to celebrate this incredible event.

Publisher

Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

STAFF WRITER

Pauline Rogers

COMMUNICATIONS

COORDINATOR

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley

CONTRIBUTORS

Ted Elrick (icgmagazine.com)

Margot Lester Valentina Valentini

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

Baird B Steptoe

VICE PRESIDENT Chris Silano

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Mark H. Weingartner

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER

Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Jamie Silverstein

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS

Betsy Peoples

NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Alex Tonisson

COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE

John Lindley, ASC, Co-Chair Chris Silano, Co-Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard

Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook: @theicgmag

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A.

Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2024, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

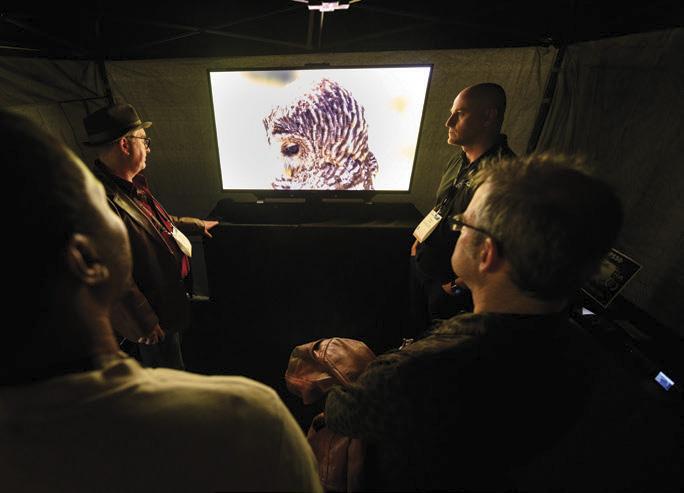

Join thousands in broadcast, media and entertainment at NAB Show New York, where infinite product discovery, networking and knowledge is within your reach. Ask questions. Get answers. Make connections. The latest innovations await on a show floor full of new-to-market tech and time-saving digital tools. Plus, access to amazing people and the most pivotal trends and topics you need in on now… AI, the creator economy, sports, photography, virtual production, FAST and more!

Invest in yourself through these incredibly in-depth conferences: • Local TV Strategies • Post|Production World New York • Radio + Podcasting Interactive Forum

EXHIBITS: OCTOBER 9–10, 2024

EDUCATION: OCTOBER 8–10

JAVITS CENTER | NEW YORK, NY

This year’s ECA (Emerging Cinematographer Awards) will be just two years’ shy of its 30th anniversary, continuing to showcase the enormous amount of talent in this union as well as the pay-it-forward mindset that’s always been a key part of the event. Founded in 1996 by Rob Kositchek, Jr., a 38-year ICG camera-operator-turned-director of photography, the event was inspired by the University of Southern California Cinema Arts’ “First Look,” a program that provided agents, producers and other industry stakeholders the chance to see new talent coming from one of Hollywood’s most prestigious film schools.

With the support of then-ICG President George Spiro Dibie, ASC, Kositchek created a “Film Showcase” aimed at helping non-directors of photography classifications take the next career leap. The inaugural event was held at the Directors Guild of America in L.A. (This year’s event will be held at the Television Academy.) In 2007, thenICG President Steven Poster, ASC, rebranded the event the Emerging Cinematographer Awards, using his extensive and trusted network (year after year) to help bring an all-star cast of vendors on board for support.

ICG Magazine has been there throughout the ECA’s soaring growth to help highlight the honorees, which is why it’s a pleasure to describe the 2024 ECA class as “one of the most forwardminded” in the event’s history. Although they hail from diverse regional locations – Asheville, NC; San Francisco, CA; and St. Louis, MO, among them – they share a creative mindset that puts collaboration at the top of the production pyramid. Short films like The Unreachable Star, shot by Western Region Operator Matthew Halla, utilized locations at the Manzanar National Historic Site, in California’s Eastern Sierras, to tell an important memory tale of a tragically difficult period in this nation’s history, and, as Halla tells it, a camera, grip and electric team who banded together to endure not only extreme summer temperatures but extremely tight quarters to help get the story told.

This year’s ECA-honored film Sweet Santa

Barbara Brown has a similarly inspiring backstory. Shot by Western Region Operator Dominic Bartolone, SOC, the movie was the second ECAwinning short film directed by 30-year Local 600 Operator Eric Dyson (the other was 2018’s Baby Steps , shot by 24-year ICG member Clifford Jones, a DIT at the time and now a director of photography). Dyson ( Zoom In , page 16) met Bartolone while working as an operator on HBO’s Emmy-nominated Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty [Deep Dive Live]. Bartolone referred Dyson to one of the stars of the show, Solomon Hughes (portraying Kareem Abdul Jabbar), who had written a script about a reallife racial profiling of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball squad in Santa Barbara, CA. The three men came together to produce the project, giving the experienced, all-union crew a “ton of freedom and respect,” as Dyson tells it, “because we’ve all worked on those shows that don’t give their crews either, and we know better.” Dyson says he’s been inspired by (and worked closely with) Directors of Photography Todd A. Dos Reis, ASC, and Cynthia Pusheck, ASC, both of whom continue to be spokespersons for the ECA years after they were honored.

One reason (of many) we’re so proud to bring you this September ECA-themed issue is hearing from people like Bartolone, who says in Margot Lester’s article (Risks/Rewards , page 54) that “collaboration” with his fellow production partners “isn’t merely optional, it’s essential for success.” It’s also hearing from industry professionals such as Writer/Director/Co-Producer Dina Rudick, who says of ICG Camera Operator Dylan Trivette, who shot Rudick’s ECA-honored documentary, Bearing Witness: A Name & A Voice, “We work with the mantra ‘strong opinions loosely held,’ and I can count on Dylan to care, to invest and definitely to have an opinion.”

Every one of these eight ICG members not only has deeply-held opinions about their craft, they also have clear and distinct voices about how best to support their union brothers and sisters on set. And that may be the very best reason why the ECA is nearing its 30th year of success, with only greater heights still to touch.

David Geffner Executive Editor

Email: david@icgmagazine.com

A Room with a View

“Don’t get me wrong: gee-whiz technology is amazing,” says the longtime North Carolina-based ICG freelancer. “But there’s just something about a project shot on film, especially for intimate explorations like His Three Daughters . The imperfections mirror our own and make these closely-told tales relatable and indelible.”

VALENTINA VALENTINI

Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice…”BEETLEJUICE!”

“There’s something about an auteur like Tim Burton having all the resources at his fingertips and still choosing a pared-down production. The original Beetlejuice relied on puppetry, miniatures and in-camera effects; and now, 36 years later, so does its sequel. With filmmaking’s ever-advancing technology, sometimes it’s just fun to do it like they did it in the ‘old days.’”

Eric Dyson has a history with the Emerging Cinematographer Awards that is unique within ICG. The 2024 ECA entry, Sweet Santa Barbara Brown , shot by Local 600 Operator Dominic J. Bartolone, Jr., SOC, marks the second short film Dyson has premiered at the ECA’s – as a director. (The first, Baby Steps, screened in 2018.)

That’s right. The 30-year IATSE member, who worked his way up from loader to 2nd AC, to 1st AC, and then operator, has also been writing and directing short projects throughout his long career in the camera department. Dyson says the twin inspirations of his father, a jazz musician and amateur black-and-white photographer who had his own darkroom, and his mother, an entrepreneur who started her

own payroll company, “was a combination in my home that was the real start of my career in this industry.”

Another big influence was working for Fritz Goode who ran Masai Films, one of the only Black-owned production companies in Hollywood at that time. “Joseph Wilcots, who worked with Fritz, shot the original Roots miniseries,” Dyson shares. “So, being there as a 16-year old was an incredible experience –Fritz would say, ‘This is Eric. He’s going to be a cinematographer.’ Even though I didn’t really know what that was!”

Dyson attended Brooks Institute of Photography on a three-year program, where all students had to buy a four-by-five camera and retouch negatives, regardless of whether their

focus was still or motion picture photography. But Dyson says he’s known since high school that moving images were his first love. “My parents bought me a Betamax camcorder in 1985, so I was the AV nerd holding the big camera at high school events,” he describes. “Between that and working for Masai, the roadmap was laid out by the time I got to Brooks and I just kept following in that direction.”

That roadmap also included a three-year stop at Amblin Entertainment, culminating as a set P.A. on the Amblin-produced TV series SeaQuest 2032 , shot by Ken Zunder and Stephen McNutt. Of his Amblin days, Dyson says, “Watching Steven Spielberg play with these little dinosaurs [to map out shots for Jurassic Park], and me recording that with a tiny

Looks like a traditional bulb, works like a professional luminaire. Designed to filmmakers’ requirements for practicals on camera, delivering perfect skin tones and the same controls as any other wireless DMX fixture. LunaBulb expands Astera’s smart ecosystem with the battery-powered PrepCase. Let your creativity shine wherever there’s a lamp socket.

Classic to Slim Look

Choose between a classic and di used look or a slim and brighter hotspot.

PrepCase Kit

The quickest way to set up 8 bulbs: assign DMX address, pre-configure dimming and color, pair them at once.

Preplnlay Kit

Simply add PrepInlays to your custom flightcase to use and prepare LunaBulbs in volume.

lipstick camera in a kind of ‘early previs,’ was pretty darn cool. So was having Stan Winston show us around his studio, seeing the original puppets for E.T., and getting to take golf carts around the Universal lot to secret places not everyone else knew about.”

Even though Dyson was a P.A. for the A.D. department on SeaQuest , he managed to spend plenty of time with the IATSE camera team – when a film loader went home sick toward the end of the show’s run, Dyson was asked to fill in, earning enough hours to join the

union. “These were still the days we’re loading 35-millimeter film in a dark room – the Golden Age of moviemaking,” he smiles.

Dyson’s introduction to the ECA’s came while working as a 2nd AC on Judging Amy. “I was starting to do my own writing at that time,” he remembers. “An operator named Walt Andrus, now retired, said he would love to shoot what I was writing so he could submit it for an ECA. So, when I set about wanting to make my

short, I understood that being a union camera technician gave me access to a lot of resources others might not have: Panavision said if you can insure what you need, you can have it; I had an experienced key grip offering to produce it. I knew I had the advantage of all these terrific professional relationships and the trust that comes from them.”

Years passed, with Dyson keeping busy on a run of high-profile shows including 24, Pushing Daisies , Community , Revenge and Extant, before he began writing again. “Baby

Steps took about a year-and-a-half to write,” he continues. “The DP was Cliff Jones, a DIT I knew who wanted to shoot as much as possible. We had a great working relationship talking about things like shot design, camera movement and color scheme. Cliff did a fantastic job on Baby Steps with minimal crew and lighting. He embraced the crappy aesthetic of the sets and what the actors were going for – the result was Cliff’s second ECA and now he’s shooting a Disney Channel show.”

Dyson’s next short was a dark comedy

“I UNDERSTOOD

TECHNICIAN GAVE ME ACCESS TO A LOT OF RESOURCES OTHERS MIGHT NOT HAVE...”

called Appy Days . “I hate asking people to work for free twice,” he recounts of bringing Jones back as his DP. “I offered to pay Cliff a little bit this time and he graciously declined. Two years later, I wrote Baggage Claim, which is on the festival circuit now and which Cliff also shot. We’ve done three projects together and each one has gotten smaller, in terms of my trying to use the least amount of dialogue to tell the story.”

Roughly six months after Baggage Claim, Dyson landed a gig on HBO’s Emmy-nominated sports drama Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty [ICG Magazine April 2022]. “Dominic Bartolone [SOC] was the A-Camera operator and he put my name in the hat. I came onto this massive set, with 500 extras, as one of 10 to 12 operators, and everyone on headsets. At some point, Dom said I should speak to Solomon Hughes [Kareem Abdul Jabbar in the series], as he had a short he wanted to do. It was about a racial profiling incident in the early 80s with the Harlem Globetrotters, in Santa Barbara, California. After he wrote it, Solomon, me, Dom, and some other folks started having Zoom meetings about how to bring this story to life.”

The film shot on King Gillette Ranch in Calabasas, CA, and at a church in Pasadena, CA, presented Bartolone with some “moody interiors to light,” as Dyson describes, and at least one major action scene involving drawn guns, police cars, background players and more. “Because Dom and I have had so many years in the trenches,” he adds, “we knew exactly how to light, stage and just generally approach a scene like that in the most efficient way possible. Of course, we knew to have an armorer on set and follow all gun-safety procedures to the letter, because we’ve all been on so many shows that have guns.

“We’ve also had our fair share of less-thangreat productions,” Dyson continues, “so just making sure everyone broke for lunch on time and was done when the schedule says they’re supposed to be done made our Santa Barbara

crew happy. Show up, do your job, and be respectful of all your other union brothers and sisters on set, is what people like me and Dom, who have put in so many hours, bring to a film like this. I think the result – ECA recognition by your ICG peers – speaks for itself.”

Another thing Dyson says camera pros like Jones and Bartolone bring to an ECA-winning production is having hands-on experience with new technologies. “If you’ve been a first, a second, a DIT or an operator, you’ve dealt directly with rental houses, you’ve broken down cameras, you know exactly what new lens, or rig or accessory will work best,” he explains. “So when you get the opportunity to DP, you can now use that technology you know so much about in the most creative way possible.”

Dyson says he’s become painfully aware – over the years – of the lack of racial and gender diversity in the camera department, but it wasn’t always so. “Growing up on sets run by Fritz Goode or [ICG Director of Photography] Johnny Simmons [ASC], it never occurred to me that wasn’t the norm,” he laughs. “It wasn’t until working on SeaQuest as a P.A. that I realized I was usually the only person of color on the set.”

Consequently, Dyson adds, “Working alongside people like Johnny Simmons; Todd A. Dos Reis [ASC], who was an ECA winner; Kirk Gardner; and Emil Hampton has given me a template for how to be a professional in this industry.

“I was a second when Cynthia Pusheck [ASC], who’s another ECA winner, was working for Pete Romano [ASC]. Cynthia left to go to AFI, and later, when she became a director of photography, I worked for her as a focus puller. There weren’t many female DP’s, certainly not in television, when Cynthia started, just like there weren’t many Black operators. So, not only did all of these people I mentioned provide mentorship, but I formed long-lasting relationships with them from which I have drawn so much knowledge and tried to pass it forward.”

COSTUME DESIGNER

BY VALENTINA VALENTINI

PHOTO COURTESY OF RAFAEL PULIDO

It’s hard to imagine luck would factor into the career of a four-time Oscar winner, but that’s exactly how Costume Designer Colleen Atwood describes her journey. She says the good fortune began when a chance encounter got her a PA job on Miloš Forman’s eight-time-Oscar-nominated feature Ragtime (1981), working with Costume Designer Anna Hill Johnstone. Luck, perhaps, but an aptitude for chameleon-like work, along with a fierce dedication to her craft, have also played a big part in Atwood’s success.

The Pacific Northwest native, who studied painting at the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, worked first in retail before turning to fashion advising and, eventually, moving to New York City. Her first film credit was Bruce Paltrow’s A Little Sex (1981), working for Oscar-winning Production Designer Patrizia von Brandenstein. Soon after, she began regularly working in theater, film and music, designing Bruce Springsteen’s 1986 world tour.

Never one to be pigeonholed, Atwood has followed her interests, whether that was Silence of the Lambs (1991) or Little Women (1994). She was the lead designer for all the new costumes created for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 2005, and in the same period joined forces with punk/emo band My Chemical Romance for “The Black Parade” tour and music video. Atwood received her first BAFTA for Sleepy Hollow (2000) and her first Oscar for Chicago (2003). She earned two Emmys for Tony Bennett: An American Classic and again last year for Tim Burton’s first venture into television with Netflix’s Wednesday Although Atwood first worked with Tim Burton (with whom she’s done 16 films over the last 34 years) on Edward Scissorhands, she claims to have no favorite child.

“When you’re as old as me and you’ve done as many projects as I have,” she says from the set of her latest project in Ireland, “you forget that you did these little movies or smaller projects. And then you see them and go, ‘Oh, I really like that one!’ I love doing what I do and I’ve been very lucky; it’s still exciting no matter the project.”

ICG Magazine: How and when did you meet Tim Burton? Colleen Atwood: I met Tim through a production designer he’d been working with who recommended me for Edward Scissorhands. It was back in the late 80s. I went in for an interview at Warner Hollywood, this great old studio on Formosa and Santa Monica, and Tim hired me in the room. He’s one of the few directors I’ve ever worked with who decided to hire me on the spot. And ever since, we have always gotten along. I think because we have a similar sensibility.

How so? The best way I can describe it is that although Tim does things that appear to be very goth, he has a modern eye. There’s a lot of negative space in the things that he films and designs, and you see details from all different periods, whether that’s a doorknob or a stuffed animal. Neither of us likes tons of clutter, and we like to focus on one thing in a room. A strong image isn’t surrounded by so much stuff that you don’t know where to look.

Did you have any inkling yours would be a creative collaboration lasting more than three decades? I had no idea at the time what it would be, or what it would mean. Edward Scissorhands was my fourth big job in the movie business, so it was pretty intense. I wanted to

make it as good as I could. We had a medium budget in those days, so we all kind of made stuff work. It was low-tech, which Tim likes.

Your latest project together, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, went back to those low-tech basics. Absolutely. Tim really wanted to revisit those parameters and that style of movie. Those of us who’d worked with Tim multiple times have done all kinds of budgets and scope on his projects, but the most fun is always on those movies where we just kind of made a lot of stuff by hand in a more analog world, where you solve problems in real time and not that “we’ll fix it in post” kind of attitude.

How, if at all, has your work with Tim changed over the years? Working with Tim has stayed the same – we still have the same relationship we’ve always had, and a shorthand because, after so much time, we know each other so well. I know when to go in and ask him a question and when to leave him alone. The thing that happens when you work with one director more than once – and Tim is the filmmaker I’ve done the most films with – is that you don’t ever want to do the same thing as before. You want to push it in another direction, to explore the artistry of that person, and create new things. But there is still always that Tim Burton stamp on it.

Aside from Burton, you’ve also had multiple collaborations with directors Jonathan Demme and Rob Marshall. Have you had repeat cinematographers to explore that creativity with? I’ve worked with Dariusz Wolski [ASC] on The Mexican and The Rum Diary , and then with Dariusz and Tim on Sweeney Todd and Alice in Wonderland. I really enjoyed collaborating with Dariusz, even though those are all such different films. I’ve done a couple of movies that are sort of my favorite films in terms of the visuals, and those were Sleepy Hollow and Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events with Chivo [Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC], for whom I have super high regard. I feel like Chivo’s in his own category.

What is the relationship like between the director of photography and the costume designer for you? Or what do you strive for it to be? Different cinematographers collaborate in different ways, but with the advent of digital filmmaking, some things have changed in that relationship. We used to have camera tests with hair and makeup: you shoot it in 35 millimeter, you look at it, you talk about it, and that’s how

the collaboration went. Today, with the speed of our preps, and everything being shot digitally, that phase of the collaboration is often skipped over. That aspect has declined. As for my ideal collaboration with a DP, it’s when you get to look at the costumes together. I’ve been lucky to work with Dion Beebe [ASC, AMC] on Rob Marshall’s films, and he is an amazing filmmaker and someone who always talks with me about the costumes. He and Rob love to always get wide shots in so you specifically get to see the costumes. But I’ve never been a person who gets bummed if the viewer doesn’t get to see the dress. If they want to tell the story in closeups, that’s fine. It’s not a story about a dress.

How did your collaboration with Haris Zambarloukos work on Beetlejuice Beetlejuice? I was on the show for a long time before Haris, so I didn’t have that much of a partnership in relation to the costumes. My main collaboration was more with special effects and makeup and [Oscar-winning Creature and Special Makeup Effects Supervisor] Neal Scanlan’s company, CFX.

Like when Dolores [Monica Bellucci] comes back together as the torso-legs, half-human walking around? That scene was mainly working with her amazing makeup team. We started with Tim’s concept, which was this woman who fell out of these boxes and stapled herself together. She has on a rag that covers up bits of her body that you need to cover up when you’re stapling yourself back together. Then she finds a wedding dress and puts that on, which is more like the wedding dress she wears in her prologue before Beetlejuice cut her up. The dress is a cross between a Victorian goth and a Renaissance dress – it could be any time period and totally modern. But it’s a big dress and I made it with a lot of different textures of black to catch light and to glean with the sets. I worked with her makeup team to recreate Tim’s drawing of how he wanted Dolores’ face done and the dress to look on her body. My work with CFX was with the Shrinkers [see cover image],and it was a huge collaboration because we needed to figure out how to build the shoulders up to come to the remote heads, which were created by Neal’s team. I needed to make a costume that incorporated a foam piece as the shoulders with clothes to go over it. So, every day the Shrinkers were in a scene, the whole team would be in there getting the clothes on, and then CFX would get the heads on and they’d go to work. It was a great collaboration.

Are your collaborations with special effects and makeup more involved on a Tim Burton film? It’s definitely a big part of the style of his movies. Tim relies on me a lot to help make sure that all that stuff looks like the world that he envisioned and that we’re trying to build together. As for our conversations for this new Beetlejuice, Tim and I don’t really do movie theory. I just sort of start throwing ideas his way. Like for the Shrinkers I said, “What if they’re like Century 21 realtors?” It was kind of a joke reference to where he’s from in Burbank; he’d know that 1970s real-estate company employee look. And he loved it. In an encyclopedic way, it’s about knowing what Tim’s references are going to be, and then just showing those to him. Ahead of time, I will show him fabrics and colors, but after that, it’s not like he’s in the room talking about clothes with me. He’s out dealing with everything else.

You didn’t design the first Beetlejuice. Did you have to go back and look at that film or talk to the costume designer, Aggie Guerard Rodgers? Aggie did such an amazing job at capturing Tim’s ideas for the original

Beetlejuice. I did talk to her about the movie, but not so much about the clothes because they were pretty simple in the original film. I had a lot more clothes in this movie than she had in that one. When it came to the character of Beetlejuice, that was a Tim idea that Aggie executed for him beautifully. So, for me, he was just an older version of the same thing. We made almost all the principal characters’ costumes in-house. The crowd costumes in the Afterlife for a rotating cast of 300 characters were a mixture of created and sourced from Angels in London and Western Costume Company and Motion Picture Costume Company in Los Angeles. For the “Soul Train” number, for about 200 people, we sourced tons of vintage 1970s stuff, but made some of it, too.

Your work has taken you outside of Hollywood a lot over the years – fashion, commercials and music tours. Does that inform your work in filmmaking or vice versa? I love musical artists and collaborating with them. Some of them, like Gerard Way from My Chemical Romance, whom I’ve done a few

things with, is an artist himself, very visual and creative. That kind of collaboration is faster and often with more limitations than filmmaking, and I love having a new challenge. I did a few videos this summer for [English Socialite and Fashion Designer] Daphne Guinness with [Photographer and Music Video Director] David LaChapelle, that were totally out of my normal realm of work. But I’ve known David for years and he called me during the strike to tell me about these videos he was doing. He was like, “You might be available for a change!” And I was able to see how he sees things, how he works with space and lighting. It was refreshing and fun for me because we used old-school tricks, like putting the big flower in front of the small person. Any time I work with anyone I learn new things, which is why I don’t like to ever do the same thing. It’s the same reason that I continue to work with Tim – when someone trusts you artistically, you’re a better artist than if you’re being second-guessed. I’ve been so lucky with the respect I’ve received, even when I was not particularly experienced. There has always been a true respect for the vision I was trying to create.

Ultimate Static Profile!

The movie that introduced the world to Tim Burton’s singular vision finally gets its sequel – 36 years later – and proves even more daring than the original.

BY VALENTINA VALENTINI

“BEETLEJUICE!”

There has been a Beetlejuice sequel in the works almost since the original film came out in 1988. Disney’s Bambi holds the record for longest period between original and sequel (63 years), but the longest period between films with the same director? That goes to Tim Burton and the summer 2024 Warner Bros. release Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, at 36 years.

Rarer still was Burton’s ability to return to the town in which the original film shot and bring back most of the original cast. Michael Keaton reprises his role as “Betelgeuse,” toiling away in the Afterlife’s boiler room with his shrunken-head sidekick, “Bob,” and a room full of shrunken-head lackeys. Catherine O’Hara’s also back as Delia, and Winona Ryder returns as Delia’s now-grown stepdaughter, Lydia. The new addition is Lydia’s teenage daughter, Astrid, played by Burton’s latest muse, Jenna Ortega, of Wednesday fame. Monica Bellucci, Willem Dafoe, Justin Theroux and a quick cameo from Danny DeVito round out the ensemble cast.

Audiences reunite with the eccentric Deetz family, picking up just after Charles Deetz (Jeffrey Jones) dies in an unfortunate boating accident. Three generations of Deetz return home to Winter River to lay their patriarch to rest, but burying Charles (and the past) proves much harder than imagined. Lydia, now a successful host of a hit TV show called Ghost House , comes home with her manager/boyfriend, Rory (Theroux), who’s intent on marrying Lydia to better monetize her fame as a spook-chaser. When Astrid returns home from a private girl’s school (where she’s taunted for her mother’s cheesy fame), she discovers a portal to the Afterlife. Mayhem and chaos soon follow as Beetlejuice returns to make good on his goal in the original film: marry Lydia and escape purgatory.

In many ways, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is the most Tim Burton-esque film Tim Burton has ever made. Having much more sophisticated filmmaking and VFX tools at his disposal than he did in 1988, the director manages to pack the sequel with all manner of visual and narrative oddities, including Beetlejuice’s ex-wife, Dolores (Monica Bellucci), who staples all of her various body parts together in a storeroom in the Afterlife, along with a New York City-style subway station where the “Soul Train” stops to transport eligible ghosts to their eternal resting places. As U.K.-based Director of Photography, Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC so aptly describes his inaugural collaboration with Burton, “I was a kid in a

candy store.”

Zambarloukos, a longtime admirer of Burton’s who knew all of the director’s oeuvre, rewatched Burton’s films again with a meticulous eye. Utilizing his own background in art education, Zambarloukos dove deep into the director’s obsession with horror filmmaker Mario Bava and historical Dutch/Flemish painters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

“I was warned that [Burton] was a man of few words, and I realized this from the interview process because it only took about three minutes on Zoom,” Zambarloukos recalls. “But I think that Tim is a person who has such a clear idea in his head that he doesn’t like speaking about it because he is more likely to draw it.”

Burton’s background as an animator has always driven his filmmaking, and Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is no exception. He illustrated the entire movie and shared those drawings with Zambarloukos. However, Burton’s longtime A-Camera Operator, Des Whelan, says that it’s not something he shows the whole crew. “Tim doesn’t want you to copy and paste what he did in the office two months ago, because the actors bring things you can’t anticipate,” describes Whelan, who has operated on seven Burton films over the last 20 years, starting with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory . “He gives everyone the freedom to do something else rather than be restricted by what the storyboard shows, which I love.”

So, Zambarloukos says, he spoke little and listened a lot.

“ IT COMES BACK TO THAT IDEA OF TIM WANTING TO HAVE EVERYTHING FEEL HANDMADE AND CONTAINED. ”

“Tim is so clear in his mind, he is so thought out, and for a very long time,” he shares, “that it is almost impossible to then express unless you can go through the nuances visually. I also discovered how everything is so personal – every idea and visual motif is based on personal experience – a thought, a memory, an encounter, an observation. He is a man who observes things in life, contemplates them, and then acts upon them all in a fluid, visual manner. That is a remarkable way of working; it is so astute and so detailed that you must always be listening.”

The Greek-Cypriot born cinematographer (who started as a camera intern for Conrad

Hall, ASC) asked Burton some questions about framing, lighting and color palettes, but mostly he describes the collaboration as a beautiful voyage of discovery. “It’s hard to emphasize how minimalist and quiet it was,” he says. “When people asked too many questions or wanted an answer in a particular way, that kind of shut off this fantastic creative flow that Tim had.”

The budget for Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, and the time frame for filming, were less than previous Burton shows; where a 15 to 20-week shoot is typical, this was only nine weeks with the majority done at and around Leavesden Studios in London, and a week allocated in New England. According to Production Designer Mark Scruton, who did Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children and Wednesday with Burton, the tight shoot was deliberate.

“Tim engineered it that way,” describes Scruton. “It wasn’t like we were boxed into a corner; He wanted it to be ‘back to basics.’ He didn’t want one of those lumbering Goliaths of a movie that we’ve all done before, instead, opting for a leaner production, less constrained by the huge machine that normally goes with bigger budgets.” Despite (or rather, in spite of) that, Scruton built dozens of sets at Leavesden and even gave the town of East Corinth, Vermont – which is Winter River in the film and where they originally shot in 1988 – a facelift that included a new covered bridge and a completely rebuilt Deetz house on the hill. The mantra was clear that this film was a continuation of the original, not a “reboot.”

“We took the things that made [the original] so vibrant, like the use of metallics and reflective surfaces, kinetic movement, the differentiation of color palettes between the real world and the Afterlife and pushed it further,” Scruton continues. “On certain sets, we’d use different color schemes and push the garishness up on some areas. In the original, whenever Beetlejuice was around, there was a green light. We kept that, but in other areas of those scenes, we used reds, purples and blues to push those spectrums. It expanded on this notion of vibrancy. And Haris and I were keen to have a sense of movement and dynamism. You’d never walk onto a static set; with lighting or an SFX

element, we always wanted [the sets] to have that slightly weird quality, like a TV screen crackling in the background.”

The real world, often seen in the Deetz’s house on the hill, offered a contrast with a more monotone palette. Though, as in the first film, Scruton had red primary pops throughout, which he felt gave it almost a comic book

“ WHEN I SAW THAT TREEHOUSE, I KNEW TO GET A LOW ANGLE THAT FEELS OMINOUS AND THE SLOW PUSHINS THAT MAKE IT... SLEEPY HOLLOWESQUE. ”

B-CAMERA

OPERATOR

BJ MCDONNELL

feel. Zambarloukos’ longtime chief lighting technician, Dan Lowe, used ECL Panels with Luxor lights for the larger sources and on larger sets to give the punch they needed. For the Afterlife, which is underground, Scruton had all practical builds with hardly any CG used to extend the sets. He helped Lowe to incorporate concealed lighting throughout, with Astera and Quasar tubes and LED strips. They stuck to metallics and reflective surfaces so that when lighting or camera was upping the ante with color, it could be absorbed into the design of each set. Most of the walls were sprayed in silver or gunmetal metallic and then washed with a soft hue to give either a warmer or a cooler look, depending on the scene.

“I think it was critical to [stay away from CG],” Scruton muses. “It comes back to that idea of Tim wanting to have everything feel handmade and contained. Otherwise, the temptation is to draw everything endless and huge and let your imagination go completely mad, but you’ve got to be careful that you don’t betray the original film. Even though we were using LED tape, modern lighting, and all the bells and whistles, we still wanted that theatrical quality from the original.”

While Zambarloukos still used the green tones famous from Beetlejuice, he never wanted the light and or tones too static. To create a lighting palette that undulates and changes in real-time as they were filming, he worked with Lowe to create programs on a lighting console so that everything would be available to them at the press of a button. “I did some tests for Tim and explained what we could give him in a matter of seconds by talking to our dimmer board operator Chris Craig, who has worked with me since Mamma Mia , and Dan [Lowe] instead of changing things out while shooting,” Zambarloukos reflects. “We spent maybe an hour, Tim came in and gave us some clear ideas about where he wanted it to go and what to do, and we saved those into the program and had a list of things ready for the shoot.”

One idea that came out of testing was to add a candle effect to the Afterlife scenes. The special effects department made Zambarloukos “Witches’ Fingers.” Burton immediately took to the name of the small lighting apparatus, of course. Zambarloukos felt the flickering suited the story and was indicative of the improvisation that happened on set.

“Especially when Michael Keaton came on set as Beetlejuice,” Zambarloukos continues, “you’d have to be ready to react at any given moment to his performance. For example, in the boiler room, we had rows of library desks with lamps on them with red shades. When Michael would speak to the Shrinkers, he would lean into that lamp’s glow. So, I asked Tim if we could augment that red on Michael’s face with a blue and yellow light behind him, and he loved that idea. When Tim liked something, he would say, ‘I like your repertoire, Haris.’ I think that was his way of telling me he liked having options to change something without warning.”

Adds Lowe: “After 25 years of working together, [Zambarloukos and I] have developed new lights and techniques, always working out the optimums, and applying knowledge to select the makes and types of lamps we use, to the point where sometimes we even ask certain manufactures to adapt their lights to our specification. Armed with this information, we have come up with that ‘repertoire of tools.’ We use lots of LED lamps with sophisticated lighting control, which enables speed

on set along with realms of possibility to be creative. We use automated rigs to quickly change and manipulate the lighting with great flexibility. What was great about this film was being able to push the boundaries, as we never had to stick with a continuity of lighting. It was nice that Tim was open to the new technology and what it could do. I think he saw the benefits and embraced it.”

The original schedule allowed for at least a week of shooting in Massachusetts and Vermont for the Winter River scenes – that was, until the 2023 SAG strike. Scruton wasn’t sure what he’d find when he stepped back into East Corinth, but, amazingly, the town had barely changed, nor had its residents. The owners of the hill on which the Deetz house had been built were still there and happy for a new build to happen for the sequel. Scruton describes a lovely couple in a corner house down the road who brought out their photo album from the original production.

Scruton and his team set about recreating Winter River, rebuilding the house on the hill from scratch, the covered red bridge from just a plain concrete bridge, and finding exteriors for Astrid’s all-girls private school, the quaint downtown and hardware store, the latter of which was almost collapsing. “We couldn’t actually touch that building because it was so fragile, so we had to clad it in its own replica,” Scruton recalls.

BJ McDonnell is a Local 600 multihyphenate, having directed, shot and operated A-Camera on scores of past projects. McDonnell, who was B-Camera/Steadicam operator for the New England portion of filming, recalls “being told it was a Tim Burton project and [I] said yes immediately,” says the Malibu resident. “It was like a childhood dream come true.”

McDonnell and the East Coast-based union crew, including Chief Lighting Technician Frans Weterrings and Key Grip Frank Montesanto, were tasked with capturing a key sequence when Astrid, angry with her mother’s life choices

(especially her phony fiancé), rides a bike throughout the whole of Winter River. She passes under the covered bridge from the original film, and, after narrowly avoiding traffic in town, crashes through a fence into someone’s yard. There she discovers a treehouse where she meets (and falls for) Jeremy (Arthur Conti), a peculiar boy who turns out to be someone (or something) much different than what he appears to be. The bike ride was filmed in the Boston neighborhood of Melrose to capture a very specific New England topography and architecture, while the bridge and treehouse portions were filmed in East Corinth.

Between a massive rainstorm and flooding in East Corinth while prepping, and the looming SAG strike, the three days in each location were cut down to two days in Vermont and two days in Boston, once SAG had settled their work action in November. The timing turned out to be serendipitous because the period in the film is Halloween, and by November the weather and trees

provided the right look. “We had to pack in as much as possible, and it was kind of amazing to watch everyone get it done,” recounts McDonnell.

The veteran operator hadn’t worked with Burton or Zambarloukos but says both were open to his suggestions and provided plenty of freedom to find what he needed. With the bike ride, the treehouse, and then the exteriors of the town on Halloween night and the house shrouded in black for the memorial sequence, McDonnell split off to get inserts - people walking around in Halloween costumes, and reactions all in a classic Burton style. “If you already love the movies of the director you’re working with,” McDonnell adds, “you get the vibe. For example, when I see that treehouse, I know to get the low angle that feels ominous and the slow pushins that make it spooky – very Sleepy Hollowesque. For me as a camera operator and also as a director, I take every piece of what I learn from directors and DPs to incorporate it into my knowledge, which I then take onto the next set. The good and the bad.”

Weterrings and Montesanto were also working for the first time with Burton and Zambarloukos. Even though they knew the schedule was tight, they aimed to make their work as seamless as possible. Lowe was there during a scout to convey the key elements of style, color schemes, lighting units and how Zambarloukos liked to operate from a lighting perspective. He also armed them with the lighting console information to help match what they’d accomplished in the U.K.

“During our whirlwind scout,” remembers Weterrings, “we put together ideas and came up with a plan. As most cinematographers now do, Haris wanted control over all the lighting elements. And LED’s have gotten so much better; I use Creamsource Vortex 8s and moving lights on Magni lifts. The only challenge, besides flooding rain and streets being washed away, was the house. It’s on top of a hill with no room around it, the sky behind it, and it’s shrouded in black cloth! I asked to shoot the house with some natural daylight to at least get it separated from the sky, and then I

added a couple of Magnis with the Vortex8s with Arrays and movers that helped give us an edge on the house and light the tree lines, and a Magni down on the town to edge it.”

Weterrings adds that with all the rain, “the Vortexes and the Proteus Maximus movers were ideal because they not only offer great color and intensity but can also stay out in inclement weather. Haris likes fixtures in the woods shooting straight up, so we also gave him that just inside the tree line surrounding the house. My programmer, Tim Boland, made it so everything was available for Haris to dial in. Matching colors and the few Beetlejuice effects was easy with the grandMA3 console that they had for the rest of the shoot.”

For the Boston shoot, Weterrings again used the Magnis with Vortex 8s and some movers to capture all the houses with Halloween decorations. Zambarloukos wanted a simpler look, so they changed streetlights out from LED to tungsten and some Beetlejuice interactive light, which Lowe had previously programmed.

Zambarloukos told Montesanto that he wanted a tracking bicycle to film the sequence of Astrid riding through town, and cameras rigged on the hero bike. His U.K. grips sent photos of a bicycle rig for Montesanto to duplicate. “Weight and balance are critical to make a camera bicycle rideable,” the key grip explains. “Since I didn’t have the remote head or camera available for testing, I went through several prototypes using a Specialized Globe cargo bike and my FlowCine Black arm, rigging it with weights to try to replicate the camera and remote head. The center of gravity and the balance between the front and the rear of the bicycle is critical for proper handling. I used a combination of Speed-Rail and aluminum extrusion to make the bike versatile and let me dial-in the ride.”

The day of the shoot in Vermont was the first time Montesanto was able to test the bike he had built, and he says the balance was a bit off, but still rideable. Because of the break from the strike, he had more time before shooting in Massachusetts to refine the bike setup.

“The mounts for the close-up on the hero bike ridden by Jenna Ortega had similar considerations,” Montesanto adds. “It’s always a challenge when the actor is riding the bike, but she did a great job. Luckily, they were able to send this bike to me in advance. I had to build this while they were filming in the U.K., so without measured camera positions and lens sizes, I used similar aluminum extrusion to keep the bike rideable and the camera position adjustable. I needed to keep the mount and camera clear of the handlebars and steering.”

Another necessary advancement in technology was the camera. Zambarloukos shot on three Sony VENICE 2s, citing the camera’s lowlight capacity and wanting to add a filmic quality. Enter Director of Photography Suny Behar, whose innovative software platform, LiveGrain, was a key part of the look. Zambarloukos asked Behar what vintage black and white stocks he had, to which Behar answered, “Almost all of them.” Zambarloukos and Behar zeroed in on two frozen cans of the oldest known Kodak stocks from 1938 – PLUS-X 1231 and SUPER-XX 1232. Behar had one shot at developing them, “and if that worked, we’d have enough samples for an accurate film grain application of 50 ASA and 100 ASA nitrate stock,” Behar describes.

“Nitrate stock is very interesting,” Zambarloukos observes. “Apart from its flammability, it is made of salt and crushed

bones; I knew Tim would appreciate that as a horror fan. When Suny processed and scanned it, I originally thought it would only be for the black-and-white footage [detailing the backstory of how Beetlejuice met Dolores] and that I would then find an appropriate grain to use for the color footage. But I loved it so much that I used it on the entire film. It gave this amazing layer of photographed silver.”

Zambarloukos had done two previous films with a bleach bypass, and Tim had used a bleach bypass on Sleepy Hollow . It added silver, which crushed the blacks and gave that luminous quality that only silver has, but it desaturated it and required a light saturation of red to be added back in. “I told Tim,” Zambarloukos continues, “that we can have fully saturated colors, the contrast, but have that silver quality too. It’s like a customized bleach bypass, color, silver nitrate film, as if we invented it specifically for this. I give credit to Suny for giving us this specific quality and for being so meticulous. I think we still would’ve achieved something good using a grain from a black and white stock, TRI-X, or something, but it’s that extra ...mile. It symbolizes the dedication of everyone on this project, which was completely inspired by Tim.”

Since Burton has only shot in 1.85:1, Zambarloukos knew that would be his aspect ratio. (While the DP predominantly shoots 2.4:1, he shot Belfast and A Haunting in Venice in 1.85:1.) For Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, he was keen on getting the highest fidelity from the VENICE 2, maximizing the 8K in 1.85:1. To do so, the image has to be cropped, which takes the resolution below 8K. But when Zambarloukos paired the VENICE 2 with Panavision’s Ultra Panatar lenses – the original Auto Panatars, of which there is only one set in the world, developed for Ben Hur and what Zambarloukos used on A Haunting in Venice – they had a 1.3 anamorphic, which converts the VENICE 2 into a 1.9:1 aspect ratio, taking capture above 8K.

“It’s such wonderful glass,” Zambarloukos marvels. “I would call the Ultra Panatars the ‘crown jewels’ of Panavision. Tim likes a lot of top space and a lot of negative space, and I think that’s implicit in telling a ghost story that is also, at its heart, a human condition story.”

Zambarloukos’ 1st AC for the last decade has been Dean Thompson, who worked in conjunction with 1st AC Bob Smathers for the U.S. portion. The focus pullers had two sets of Ultra Panatars 2 and one set of Ultra Panatars 1. “Both sets complement each other well,” says Thompson, “but we would

“ TIM LIKES A LOT OF TOP AND NEGATIVE SPACE – THAT’S IMPLICIT IN TELLING A GHOST STORY THAT IS ALSO, AT ITS HEART, A HUMAN CONDITION STORY. ”

HARIS ZAMBARLOUKOS, BSC

always use the older UP1s as first-choice lenses. The UP2s are great for close focus, and their size and weight were good for handheld and Steadicam.”

As Zambarloukos concludes of his first experience with the unique and totally singular mind of Tim Burton, “He displays the psyche of the human condition in such an incredible way, and that’s what informs everything else. So, no matter how intricate, elaborate or stylized the visual aspects of his films are, at the core, his questions to you, to himself, and to his actors will always be about that core human condition that he’s exploring. It’s that juxtaposition that makes his films so unique, so visceral, intimate and immersive.”

PRODUCTION DESIGNER SCRUTON AND HIS TEAM SET ABOUT RECREATING WINTER RIVER, REBUILDING THE HOUSE ON THE HILL FROM SCRATCH (ABOVE), THE COVERED RED BRIDGE FROM JUST A PLAIN CONCRETE BRIDGE, AND FINDING EXTERIORS FOR ASTRID’S ALL-GIRLS PRIVATE SCHOOL, THE QUAINT DOWNTOWN AND A HARDWARE STORE, THE LATTER OF WHICH WAS ALMOST COLLAPSING. / PHOTO BY NICOLE RIVELLI

Director

ABY MARGOT

NYC crew) to the roller-coaster family dynamics of Netflix’s His Three Daughters.

The trick with bringing something fresh to an age-old theme is finding a new approach that cuts through the current noise and lands directly with audiences. We all know – from ofttold tales or lived experiences – the pain, guilt, conflict and togetherness that accompany a loved one’s end of life. Fraught with family dynamics and individual personality traits, everything in that room is amplified by the specters of death and grief, patiently waiting in the wings.

In Writer/Director Azazel Jacobs’ new Netflix feature, His Three Daughters, these big themes are explored in a small apartment on New York City’s Lower East Side, as three sisters assemble for their father’s final days. Rachel (Natasha Lyonne) has been caring for their father, Vincent (Jay O. Sanders). But as the end nears, sisters Katie (Carrie Coon) and Christina (Elizabeth Olsen) return home, dredging up old tensions and contrasting personalities to the fore. Cannes and Sundance veteran and longtime NYC Director of Photography Sam Levy (Frances Ha, Lady Bird , Fantasmas) says his job was to help make the story “transcendent and magical, not a tale of woe. Our three main characters each have their own energy and rhythm in grieving for their father. My mission was to explore how to visually display their inner turmoil without the image being unnecessarily heavy or swollen.”

Levy says that, ultimately, the cinematography of His Three Daughters is

designed to evoke a sense of life’s fragility and beauty. “The essence of the narrative called for nothing less than the authenticity that only film can provide,” adds Levy, who used Kodak’s 5219/500 T 35-mm emulsion.

Key Grip Jake Sofaer, a frequent Levy collaborator, says shooting 35 mm is “almost like having someone that’s in your corner, a phantom that’s your friend. Film has a way of transitioning from light to dark that’s incredibly pleasing.”

Kodak’s 5219 stock was favored by Levy, as its “inherent grain and texture mirror the imperfections and transient nature of life itself,” he adds. “It allows for a richer, more organic feel. The texture adds a tactile quality to the images, making them more real and lived-in. The chemical process of developing film transforms each shot, adding authenticity and depth. This enhances the emotional weight of each scene, turning ordinary moments into profound reflections on the human experience.”

Levy used one camera on the shoot, the Arricam LT (three-perf at 1.85 aspect ratio) with Leica Summilux Primes. As 1st AC Christopher Eng, who worked with Levy on She Came To Me, describes: “The LT is a workhorse with a small form factor, and the Summiluxes allowed us the freedom to work with lower light levels for certain scenes without compromising the image. Sam is a true collaborator who works with all departments to achieve any given shot. He trusts the people he works with to do their jobs, and he’s constantly bouncing ideas off us to try and improve the setup.”

Trust between departments was a necessity on a film shot in a blistering 17 days – 18 if you count a single soundstage day for inserts without actors. As Levy explains: “We had to embrace the creative restriction of our tight schedule, using it to our advantage to foster creativity and efficiency. Balancing

the technical demands of lighting with the narrative nuances of the characters was a constant juggling act, requiring careful thought and adaptation throughout the filming process.”

Most of the story takes place inside a real apartment and the outdoor courtyard where Rachel escapes for a few puffs of a marijuana cigarette to ease the stress of what’s going on upstairs.

Levy says he wanted light and shadow to illustrate the interplay between life and death and to illuminate each sister’s mood or personality. “The light represents moments of clarity and beauty, fleeting yet impactful,” he explains. While each character has a specific glow, “as [Vincent’s] illness progresses, the light changes in subtle ways. All of this was designed to create a sense of wonderment and whimsy in the face of such impending loss and sadness.”

Like many of his generation (and many after), Levy’s approach to lighting and

exposure came from working with one of New York’s ...finest directors of photography, Harris Savides, ASC. ‘Harris told me to light using my eye, not the light meter,” Levy recalls. “Once the scene is lit to a place where it looks good to your eye, then and only then should you take out your meter to decide on your exposure. This project presented the ideal opportunity to apply those skills. It felt like everything I had learned [from Savides] was meant to culminate in this film.”

The crew visited the location in preproduction to assess the natural light and existing light fixtures. Chief Lighting Technician John Raugalis (who also worked with Savides) notes that “Sam likes to use the practicals on set as sources, which can be tricky shooting on film pushed one-half a stop. He also really trusts his instincts, and they never fail him – often going against convention and getting subtle and beautiful results.” Levy, who relied heavily on Raugalis to deliver the quality of light they were

after, calls Raugalis “one of New York’s most established gaffers. He has an artist’s soul and is a trusted collaborator. His perspective on lighting faces is incredibly unique and nothing scares him.”

Key Grip Sofaer adds that “there were times when there was just a chandelier over the dining room table that was the primary source. We wrapped it in diffusion and used unbleached muslin to bounce light to the actors’ faces. Or we’d book light HMI’s off of the wall through wag flags.”

Levy says His Three Daughters has “the most intricate choreography” of any film he’s done, and that the choreography was researched and rehearsed exhaustively.

“We broke down the action of this story into two parts,” he describes. “Blocking for the actors and then the resultant camera choreography. Each is separate and distinct, yet it was imperative to have them meet up and overlap to uncover the magical parts of the story.”

Writer/Director Jacobs and Levy were both committed to working from a dolly to keep camera movements “elegant and stable,” as Levy describes. “We didn’t just let the camera sit idly by while the actors move,” he insists. “The camera has a mind of its own. I wanted our Key Grip Jake keeping an eye on shaping light at all times. His sense of humor and incredibly positive attitude greatly lifted our spirits when we had some of our more intense moments of production.”

Because the space was small, rooms were revisited frequently.

“Each time we returned to a similar setup, the focus would be on what we could do differently,” notes Queens-based Camera Assistant Ronnie Wrase. “I think these situations helped define the sisters through the cinematography. Subtle changes in an almost identical shot illuminated the differences between them and their ever changing dynamic.” Adds Hoboken, NJ-based Eng: “We were crammed in this apartment for three weeks – which isn’t normally a selling point to a job! But that limitation both forced and allowed us to spend time perfecting our frames.”

Tensions between the siblings are an ever-present undercurrent in His Three

Daughters. And they roil close to the surface in two powerful interior sequences. Benji (Jovan Adepo) moves in and out of the apartment with a familiarity that indicates he’s a frequent and trusted companion of Rachel and Vincent’s. Katie isn’t happy about Benji’s presence and extends a passive-aggressive invitation to join her and Christina for supper. Benji declines and then schools the duo on Rachel’s contributions and shares memories of his time with their dad. As Jacobs describes: “I wanted Jovan to run with it and lead the way. It is a long scene, full of dialogue, that shifts in tone and mood dramatically. In short, lots of moving parts.”

Even though it’s a night scene, the union crew had to start before darkness fell and shot opposite huge windows overlooking the city. “We had to break the scene into different sections, playing to the angles we had available,” Jacobs continues. “It meant being nimble, and also very aware of things that would be needed in the edit to piece it together. We relied on work we had seen in Sam Fuller films – in particular, Stanley Cortez’s work using mostly a few masters that shift throughout enough to feel like there was a lot more coverage than there was.”

One of the most intense moments in the film is a physical struggle between the

sisters, set in a tiny corner of the hallway outside their father’s room. The tension builds gradually with Katie confronting Rachel (again) and escalates quickly into a scrum with Rachel and Christina screaming at each other until Rachel wriggles free of the fray and storms out. Levy says the scene dominated many of their prep discussions. “I wanted it to stand out because of its pivotal emotional moment,” he notes.

It was captured late at night at the tail end of a long production day.

As Levy continues: “When it came time to shoot, the hallway felt charged, heightened with an electric atmosphere. We couldn’t give the actors marks due to the violent nature of the scene. Our brilliant focus puller, Chris Eng, nailed it on an incredibly difficult shot, a dolly move-in on Elizabeth Olsen right at the most violent part of the fight.”

With only a few takes slated, the crew had to be dialed in.

“We let a lot of it play in a medium tracking shot while they moved throughout the frame,” Eng describes. “It was a fun challenge to choose who the scene belonged to at any given moment. Everyone had to work in tandem, and it’s always nice when those setups work out the way you plan.”

The resulting sequence has what Levy calls a “lustrous, silvery sheen, with the

OPPOSITE/ ABOVE: KEY GRIP JAKE SOFAER, A FREQUENT COLLABORATOR OF DP SAM LEVY, SAYS SHOOTING 35 MM IS ALMOST LIKE HAVING “A PHANTOM FRIEND IN THE ROOM. FILM HAS A WAY OF TRANSITIONING FROM LIGHT TO DARK THAT’S INCREDIBLY PLEASING.”

FOR A KEY EXTERIOR NIGHT SHOT (BELOW), LEVY (ABOVE) WORKED CLOSELY WITH POSTWORKS NY COLORIST PETER DOYLE, WHO UNDEREXPOSED THE NEGATIVE AND FORCE-PROCESSED THE FILM TO DELIVER AN ABSINTHE GREEN LIGHT ON THE CHARACTER’S FACE. AS LEVY NOTES: “A LOT OF WORK WENT INTO IT, BUT WHEN NATASHA’S CLOSE-UP COMES UP AND SHE EXHALES SMOKE, IT’S ALL WORTH IT.”

actors’ skin glowing, and the colors having a natural saturation that exceeded any other scene in the movie. It felt like creative intention finding its way onto the screen after hours of meticulous planning and testing. I just love how that scene turned out.”

Rachel’s wide-open courtyard retreat is a stark contrast to the cramped quarters inside. Every time Levy set foot there, he says he felt like “a character in a Polish film from the 1980s” thanks to the fencing and brutalist architecture. Holding to a simple and elegant lighting scheme was a challenge since the space lacked any practical sources. Consequently, Levy had to test-drive several approaches. But not before another issue revealed itself.

“It’s one of those courtyards with big openings on either end and tall buildings on either side, which creates a wind tunnel,” Sofaer explains. “One day we were out there with 12-bys up, and this monstrous wind blew through, strong enough to pick a grip up off the ground!” They had to strike that setup and map out a new scheme. “We pushed negative in front and made a big wall of four-by floppies, a bunch of sandbags and a grip standing on each stand,” Sofaer adds.

In one exterior sequence in the courtyard, Rachel gazes upward in contemplation – of the pain in the present and that yet to come. “It’s a deceptively tricky scene that seems simple at first but involved a lot of planning,” Levy describes. “I had to shoot film tests to try out different lighting instruments and exposures at night.”

Levy and PostWorks NY Colorist Peter Doyle analyzed the tests to arrive at the right cocktail of techniques. Then Levy choreographed Rachel’s action to a subway train as it trundles over the Williamsburg bridge (featured on screen). They underexposed the negative and forceprocessed the film in the lab to deliver an absinthe green light on Rachel’s face. “A lot of work went into it, but when Natasha’s close-up comes up and she exhales smoke, it’s all worth it,” Levy beams.

Making His Three Daughters required a purposeful approach, which served the specific rhythm Jacobs envisioned for the cut (he’s also the film’s editor). “The quick pace, having actors constantly on set with little waiting for everyone, created an exciting atmosphere,” Jacobs shares. “I imagine the challenge for Sam and his crew was quite different from mine, but I always got a sense that it was with the same goal as my own: people who like making films

want to make one they are proud of.”

This is Levy and Jacobs’ second outing. They shot a commercial together years ago. Levy says he had always hoped they’d make a film together. “I knew we’d have a successful collaboration,” he observes. “We’re the same age and have a similar creative sensibility and obsession with old movies.” In an early conversation, Jacobs said he wanted to emulate the way Writer/ Director Jean-Luc Godard and his director of photography, Raoul Coutard, shot French New Wave films in Paris in the 1960s.”

“When [Jacobs] told me he wanted to shoot on 35-millimeter film, with a single camera and a stealth team,” Levy continues, “he was describing my dream project. The more we talked, the more the idea took shape. I read the script and it took my breath away. Within a few days, we were in my office breaking down the script and shot-listing.”

“And that’s how it should be,” Sofaer concludes. “Every once in a while, you get to work on a film written and directed by someone in our New York community. And that’s what this project was. I love working with Sam. His approach made His Three Daughters an honest return to proper cinema. This kind of project is like vitamins for our craft. It’s why I got into cinema in the first place.”

Sam

1st AC

2nd AC

Loader

LEVY (CENTER AT CAMERA) WAS MENTORED BY AND WORKED WITH HARRIS SAVIDES, ASC. HE RECALLS HOW, “HARRIS TOLD ME THAT ONCE THE SCENE IS LIT TO A PLACE WHERE IT LOOKS GOOD TO YOUR EYE, THEN AND ONLY THEN SHOULD YOU TAKE OUT YOUR METER TO DECIDE ON YOUR EXPOSURE. IT FELT LIKE EVERYTHING I HAD LEARNED [FROM SAVIDES] WAS MEANT TO CULMINATE IN THIS FILM.”

WHAT’S THE COMMON THREAD AMONG THIS YEAR’S ECA HONOREES? A FEARLESS APPROACH TO CRAFT AND A DEEPLYHELD RESPECT FOR THEIR PRODUCTION PARTNERS.

BY MARGOT LESTER | PHOTOS & FRAMEGRABS COURTESY OF THE HONOREES

This year’s ECA honorees hail from diverse regional locations – Asheville, NC; San Francisco, CA; and St. Louis, MO, among them – yet they all share a creative mindset built upon collaboration as the most important link in the filmmaking chain. Western Region Operator Dominic Bartolone, who shot the ECA-winning Sweet Santa Barbara Brown, written by and starring Solomon Hughes (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty), says “collaboration” with his fellow production partners “isn’t merely optional, it’s essential for success.”

The same holds for Western Region Operator Matthew Halla, whose ECA-winning film The Unreachable Star was shot at the Manzanar National Historic Site, in California’s Eastern Sierras, and whose camera department shared tight quarters with the grip and electric teams in extreme summer temperatures. Halla says, “Being a cool person to work with is a large percentage of the job.”

And it’s not just respect for the human factor that these filmmakers value – they all revere an approach to filmmaking that knows no limitations. L.A.-based Camera Operator Allen Ho, SOC (who used a light meter signed by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, CBE to shoot Iron Lung, director Andrew Reid’s story about two Latina sisters), urges all his fellow Local 600 members to be “bold with your artistic choices, keep trying things you have never done before and don’t be afraid of taking risks.”

Likewise for North Carolina-based Operator Dylan Trivette, whose film Bearing Witness: A Name & A Voice reaffirms the passion and humanity inherent in the photojournalist’s craft. Working with Writer/Director and Co-producer Dina Rudick, Trivette says his approach is to always “stay curious, and trust my instincts while being unafraid to ask questions and passionately learn.” Rudick affirms Trivette’s intentions, noting that “we work with the mantra ‘strong opinions loosely held,’ and I can count on Dylan to care, to invest and definitely to have an opinion.”

Classification: Operator

Years in Guild: 20

Home Base: Los Angeles, CA

Origin City: Los Angeles, CA

Gear: Panavised ALEXA Minis with Panavision Primo primes, Angénieux Lightweight zooms, and Steadicam

Sweet Santa Barbara Brown focuses primarily on a 1983 incident in which Santa Barbara police racially profiled three Harlem Globetrotters and held them at gunpoint for 30 minutes. The project reunited Actor/ Writer Solomon Hughes and Operator/DP Dominic Bartolone, who first met on HBO’s Winning Time

“COLLABORATION ISN’T MERELY OPTIONAL BUT ESSENTIAL FOR SUCCESS.”

Shot mainly at King Gillette Ranch in Calabasas – just 20 minutes from Bartolone’s childhood home – the film, according to Bartolone, serves as “a stark reminder of the many untold narratives waiting to be heard. I firmly believe in the power of storytelling to raise awareness and provoke meaningful change, especially when it comes to addressing mistreatment.”

Bartolone adds that the movie calls for “deep reflection on necessary societal reforms and serves as a moving reminder of the essential need for transformative change in our collective consciousness and behavior.” To immerse the viewer in the action, Bartolone looked for ways to make the operator embody the feeling and action of the sequence. “This often involves approaching the subject closely and using a wider lens, effectively enhancing the visual impact and narrative intensity,” he explains. In the sequence where the teammates are forced to the ground, Bartolone used a low-mode Steadicam for several push-ins to give the audience a more intimate and intense perspective.

A former camera service and preparatory technician at Panavision, Bartolone jumped at a chance to co-DP a friend’s music video. “That sparked my journey towards becoming a DP,” he says. Hughes notes that “in the middle of very busy and chaotic shoots, Dominic was steady and constant. He is a visionary and an exceptional listener and observer.”

Incomplete examines the very real injustice of how people of color are treated by the American judicial system, through the lens of a horror film punctuated with moments of levity. Part of Hulu’s Halloween shorts showcase, it’s the second collaboration between Writer/Director Zoey Martinson and Director of Photography Adam Carboni, who explains that “we tried to capture symbolic visuals that support the larger themes while remaining grounded within the film’s realworld setting” – a strange Victorian mansion in Brooklyn where the protagonist (Marshánt Davis) is under house arrest.

“EXAMINE WHAT MAKES THE STORY WORK AND WHAT HINDERS IT. IT MIGHT TAKE YOU FOR A RIDE YOU WEREN’T EXPECTING.”

Carboni adds that, working with Chief Lighting Technician Rahul Sharma, he tried to create spaces with minimal practical or artificial lighting that created darker hallways and background rooms, which added suspense and tension. For a rapid montage depicting a frantic search for the main character’s phone, Carboni added variation and scope with negative-space framings and match-cuts. “These quick setups were probably the least technical of all the scenes,” he recalls, “but I was delighted at how the camera language heightened the playfulness of that section.”

Carboni got serious about film while in high school in his native Alabama. That’s when a Netflix DVD subscription introduced him to art-house and foreign films. “Harlan County, USA is the film that spoke to me most,” he remembers. “I wanted to tell stories and meet inspiring people like the ones in [Producer/Director Barbara Kopple’s] film.” Years later, Carboni approached Kopple after a screening and kickstarted his career with an internship at her production company.

Classification: Operator Years in Guild: 1

Home Base: New York City

Origin City: Guntersville, AL Gear: ALEXA Mini with Cooke Panchro

S2/S3 lenses in 3.2K mode, Cinesaddle/EasyRig, 750-watt LEKO ellipsoidal unit

Classification: Operator

Years in Guild: 1

Home Base: Los Angeles, CA

Origin City(s): Monterey and Santa Cruz, CA Gear: ALEXA Mini with Kowa Anamorphics, Dana Dolly

Based on the childhood experiences of Writer/Producer Kelsey Kawana’s grandfather’s time in a Japanese internment camp during World War II, The Unreachable Star, directed by Sharon S. Park, showcases the power of resiliency, togetherness and childhood imagination to survive extreme and unjust circumstances. The film was shot on location in California, in the Owens Valley and at the Manzanar National Historic Site, a Japanese internment camp that was used in World War II.

Director of Photography Matthew Halla recounts how he loves “shooting in crazy locations and all types of weather. I want to be a go-to DP for making cinema under extreme conditions.” Halla got what he wished for on Kawana’s film –temperatures soared past 100 degrees and the five-person crew, two AC’s and two grips joining Hall on camera – had to share tight quarters. The area’s unique geology composed the kids’ fantasy world, and its sparse vegetation and harsh mountains represented the real world. Colorist Ryan K. McNeal accentuated the contrast, making the dream life saturated and reality spare and cool.

“BEING A COOL PERSON TO WORK WITH IS A LARGE PERCENTAGE OF THE JOB.”