Industry Leading Facilities

Class 100 Clean Room

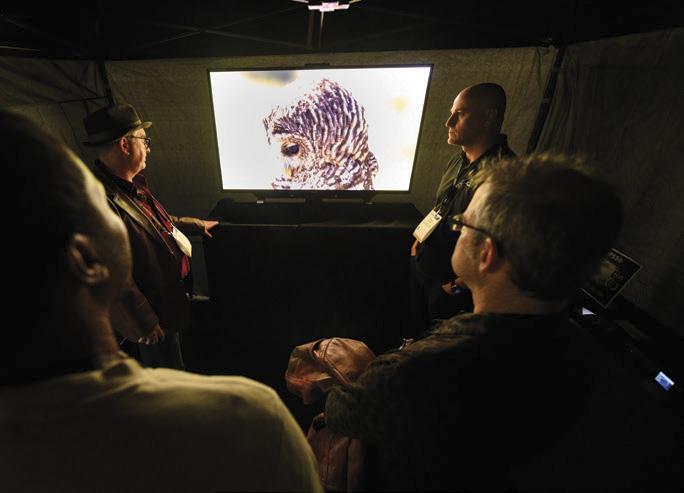

2 Full Frame Lens Test Projection Rooms

MYT Works Opti-Glide System + PAT Charts

T-Stop Evaluation System

Lens Collimator

MTF Machine

Sony Authorized Warranty Service Center

Angénieux Factory Authorized Service Center

Zeiss, Cooke, Leitz, Sigma, and more

The new EOS C400 is the ideal fusion of both functionality and form, seamlessly integrating into almost any production with its robust features and compact design. Innovation, Versatility & Imaging Excellence

• 6K Full-Frame Back-illuminated stacked CMOS sensor

• Triple-base ISO (800, 3200, 12,800)

• Improved autofocus with Dual Pixel CMOS AF II

• Variety of interfaces, including Timecode and Genlock

• Built-in Mechanical ND Filters

One week ago, last Thursday, before I started writing this letter, Local 600, as well as all the other IASTE craft unions signed onto the Hollywood Basic Agreement and the Area Standards Agreement, voted overwhelmingly to ratify the 2024-2027 contracts with the Alliance of Motion Picture Television Producers (AMPTP) – the trade group representing producers, studios and streaming services.

The numbers were beyond impressive: more than 88 percent of ICG’s voting members cast their votes in favor of ratifying the Hollywood Basic and Videotape Agreements (with 71.3 percent of eligible Guild members voting), while 85.9 percent of the voting members of the other IATSE West Coast Studio Locals voted to ratify the Hollywood Basic, and 87.2 percent of IATSE’s voting members approving the Area Standards Agreement. These are historically high figures and represent tremendous gains in many areas, including wage increases and quality-of-life enhancements, both of which are key to sustaining a long and healthy career in this industry.

Personally, I want to highlight new language in the Basic Agreement that requires productions that work beyond a 14-hour day to ask crewmembers if they want a “ride or a room,” and then to pay for it. This is one of several “guard rails” (as former ICG President John Lindley, ASC, described them) for our members working unsafe hours. Another “guard rail” this new contract provides is tripletime payment after 15 hours, which we hope producers won’t need to put into practice, both because of the obvious safety hazards and the cost to their bottom lines. I urge all members to read the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) for the Hollywood Basic and Videotape Agreement, as well as the Comparison of Gains in both agreements. They can be found on your MY600/Negotiation Page.

This 2024-2027 contract also saw historic gains for our publicist members (Local 600 Publicists Agreement MOA), who increased pension and health-care coverage in an additional ten states, totaling more than 20 states – hopefully, the entire country will be covered for our publicists members in future contracts. Speaking of the future, it’s important to emphasize that the gains in this contract were built upon the victories in contracts past. That means the achievements in 2024 will be built up even stronger in 2027, a contract negotiation for which this union (and the entire IATSE) is already beginning to strategize. As IATSE International President Matthew D. Loeb announced: “The gains secured in these contracts mark a significant step forward for America’s film and TV industry and its workers. This result shows our members agree, and now we must build on what these negotiations achieved.”

Building blocks of financial wellness, health and welfare, safety on set and quality of life don’t just happen. They take an incredible team of union professionals, working with complete dedication for a very long time. That included Lead Negotiator, ICG National Executive Director Alex Tonisson; Local 600’s Bargaining/Negotiation teams and ICG’s incredible staff, who met more than 25 times in 16 months; the ICG Communications department, which went above and beyond to keep this membership informed and connected before, during and after the negotiation and ratification process; and, finally, our Contract Action Team (CAT).

With this recent contract ratification, I can say that I am more proud than ever to call myself a member of a union that is – most definitely – “built to last.”

Now and forever.

Publisher Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

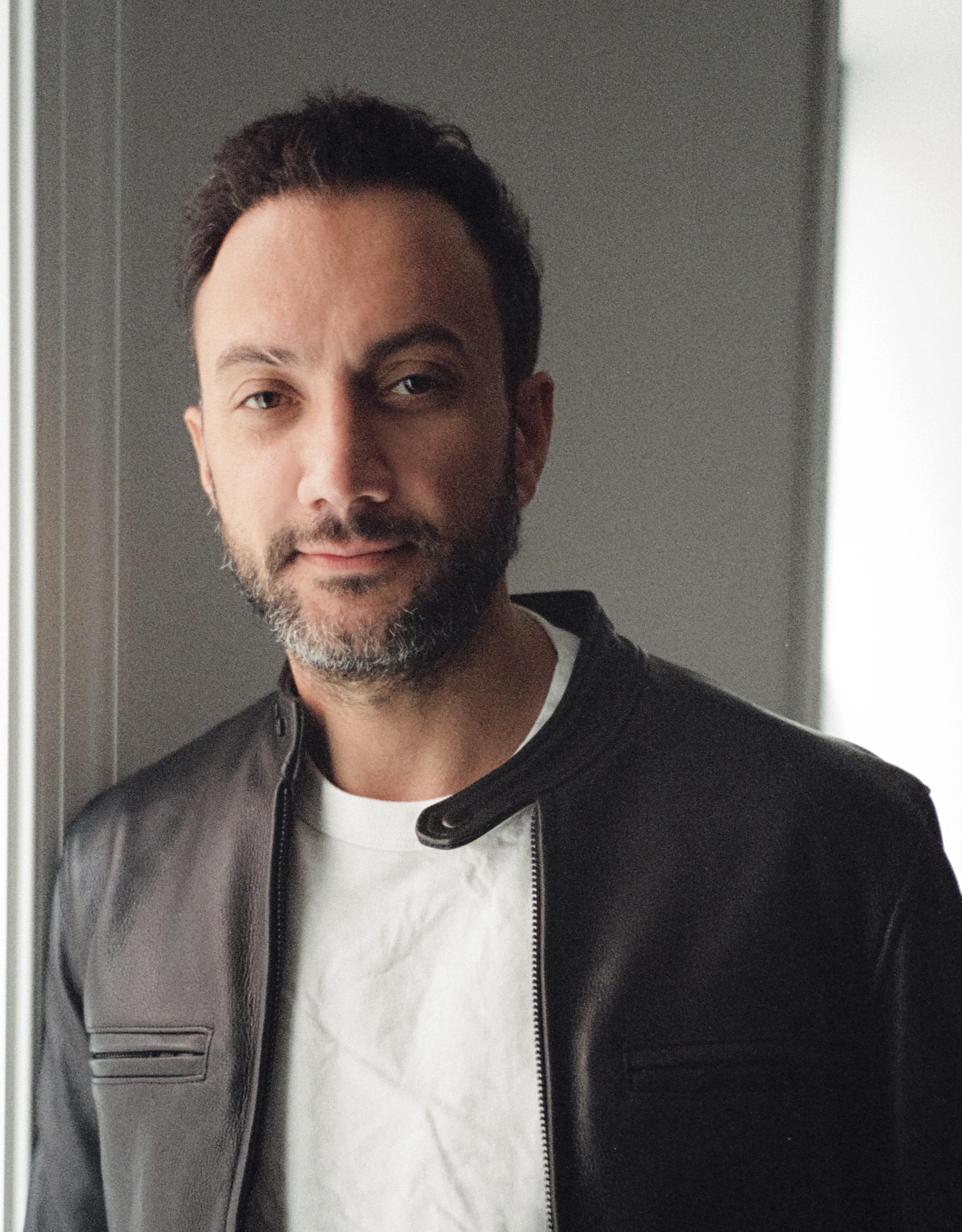

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

STAFF WRITER

Pauline Rogers

COMMUNICATIONS COORDINATOR

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley

CONTRIBUTORS

Ted Elrick

Margot Lester

David Geffner

Derek Stettler

COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE

John Lindley, ASC, Co-Chair

Chris Silano, Co-Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard

Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook: @theicgmag

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

Baird B Steptoe

VICE PRESIDENT Chris Silano

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Mark H. Weingartner

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER

Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Jamie Silverstein

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS

Betsy Peoples

NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Alex Tonisson

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2024, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com August 2024 vol. 95 no. 06

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

OUTSTANDING DRAMA SERIES

CINEMATOGRAPHY FOR A SERIES (ONE HOUR)

Adriano Goldman, ASC, BSC, ABC “Sleep, Dearie Sleep”

Sophia Olsson, FSF “Ritz”

“THE GOLD STANDARD FOR HISTORICAL DRAMA. It will be hard for another series to stand in its shadow.”

OBSERVER

As the editor of this magazine, I can hardly offer an unbiased opinion – basically, every issue we do is fantastic! But, I have to confess to some added love for our annual Interview issue, mostly because we highlight an amazing range of voices across the entertainment industry. This year was no exception, as I had the pleasure of “Zooming in” with all ten subjects, who shared their insights around the theme of “Future Tech.” The section starts with a trio of directors of photography, from three different generations, whose work has all been ground-breaking in their respective journeys, and who all share a love for combining traditional filmmaking with the latest in leadingedge tech in ways that will surprise many readers.

Let’s start with Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS. Few would dispute the Oscar-winning Aussie ushered in Hollywood’s current era of LED Volume storytelling with his Emmy-winning work on Season 1 of The Mandalorian (and even before with Rogue One: A Star Wars Story). And even though many felt Fraser took the Volume to greater heights on The Batman, when I asked about Dune 2, the highest grossing live-action film of 2024 – so far – Fraser said he put the Volume’s game-engine technology into service for a much more old-school aspect of filmmaking.

“What we could do with Unreal [Engine] was to scan the rock formations in Jordan with a drone, make them into a 3D model, put them in the right place on the planet, and then type in the day we wanted to shoot,” Fraser told me. “What we got back was the exact time a location is in shade and/ or sun.” Translation: Fraser used the most leadingedge digital tech to facilitate a make-or-break physical schedule that included an opening scene with 14 different real-world locations.

Alice Brooks, ASC, is a decade-plus behind Fraser in experience, but she’s no less resourceful when it comes to putting technology in the service of a story. For the upcoming feature Wicked (whose trailer alone would win an Oscar, if there were one), Brooks went searching for a way to make Director Jon M. Chu’s Oz different from any

other. She found it courtesy of Panavision lens alchemist Dan Sasaki, who built, in Brooks’ words, “new/old anamorphic lenses, used once on our film, and that’s it.”

Sasaki’s one-of-a-kind glass ultimately did morph into Panavision’s Ultra Panatar IIs (which Brooks has since used on another project), but they’re markedly different from the custom lenses used on Wicked. Brooks’ love for combining old/ new also extended to her approach to lighting. “We used a lot of gelled Tungsten on Wicked,” she adds. “But because the sets were insanely big and complex, we used Unreal Engine to figure out what type of light would fit where, before everything was built.”

Speaking of virtual world-building, when it comes to an Interview section themed around “Future Tech,” the acronym AI can’t help but come up. Thankfully, according to two of the industry’s most respected technologists – SMPTE President Renard Jenkins and Mariana Acuña Acosta, senior vice president of Global Virtual Production and OnSet Services for Technicolor and a woman who’s now on her fourth start-up company – computers won’t be replacing humans any time soon. Acosta reminded me that machine learning and artificial intelligence have been embedded in the VFX world for more than a decade. “There’s a feeling that AI is a brand-new technology,” she said, “but nothing that’s being done today would be possible without what came before. Just like the invention of the camera, the ATM, or the Internet of Things, where your fridge reminds you to go buy strawberries – none of these technologies has replaced human creativity and neither will AI.”

Jenkins, a longtime “Trekkie” with a soft spot for great cinematography, was even more bullish on humans as evergreen creators. “It may be easy –with the various generative AI tools available now,” the D.C.-based technologist told me, “to create still images that are fantasy based. But as far as producing narrative content, with real people, in the real world, what the cinematographer and his or her camera crew do? There’s no way that’s going away.”

And just to heap on one more (very biased) opinion: “We at ICG Magazine heartily agree!”

David Geffner Executive Editor Email: david@icgmagazine.com

Masterpiece’s Entertainment Division understands the complex logistics of the industry including seemingly impossible deadlines, unconventional expedited routings, and show personnel that must be on hand. Masterpiece has the depth of resources to assist you in making sure everything comes together in time, every time.

Our range of services, include:

• Customs Brokers

• Freight Forwarders

• ATA Carnet Prep & Delivery

• Border Crossings

• Domestic Truck Transport

• International Transport via Air or Ocean

• Expedited Shipping Services

• 24/7 Service Available

• Cargo & Transit Insurance

• Custom Packing & Crating

$12,838

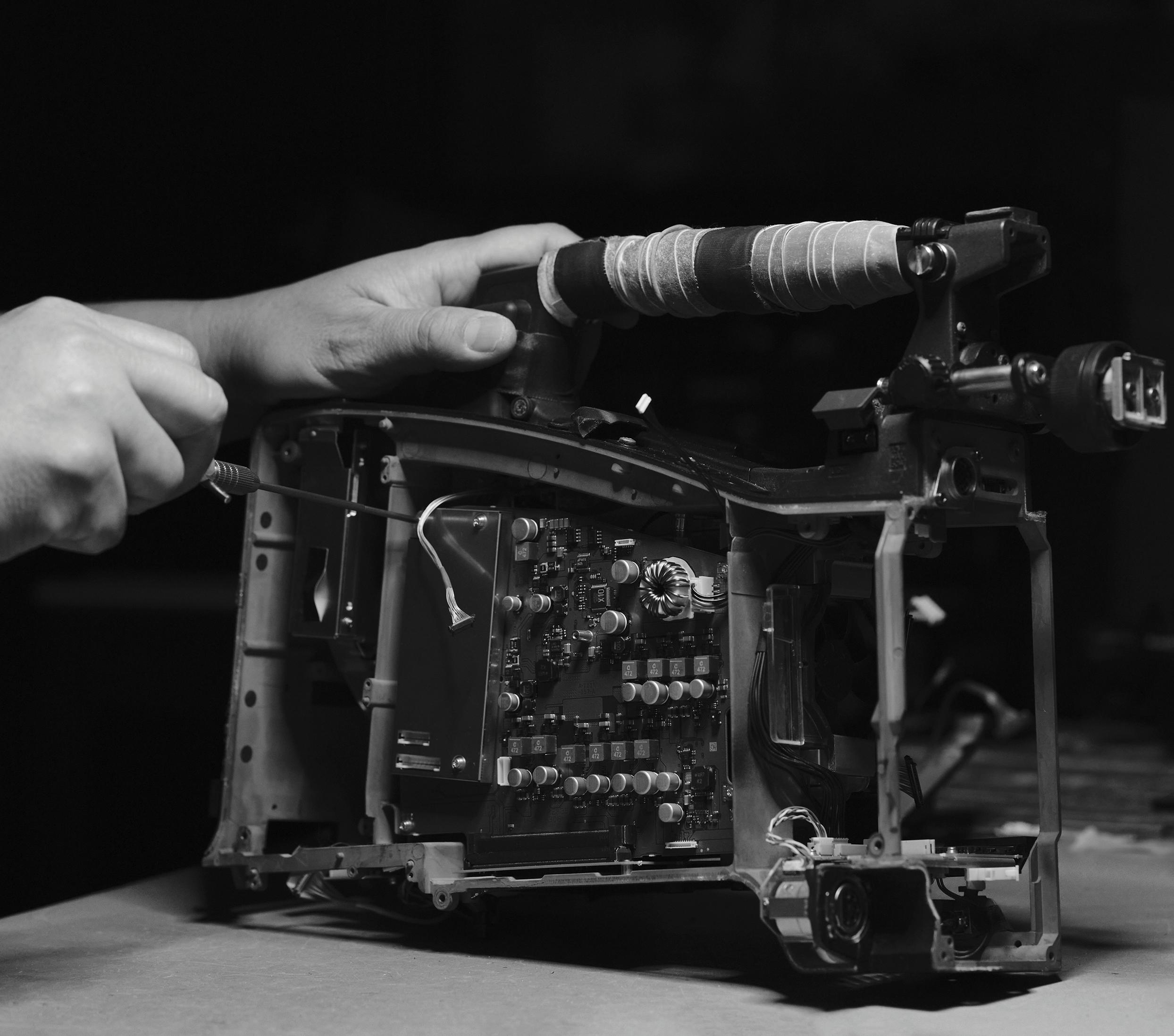

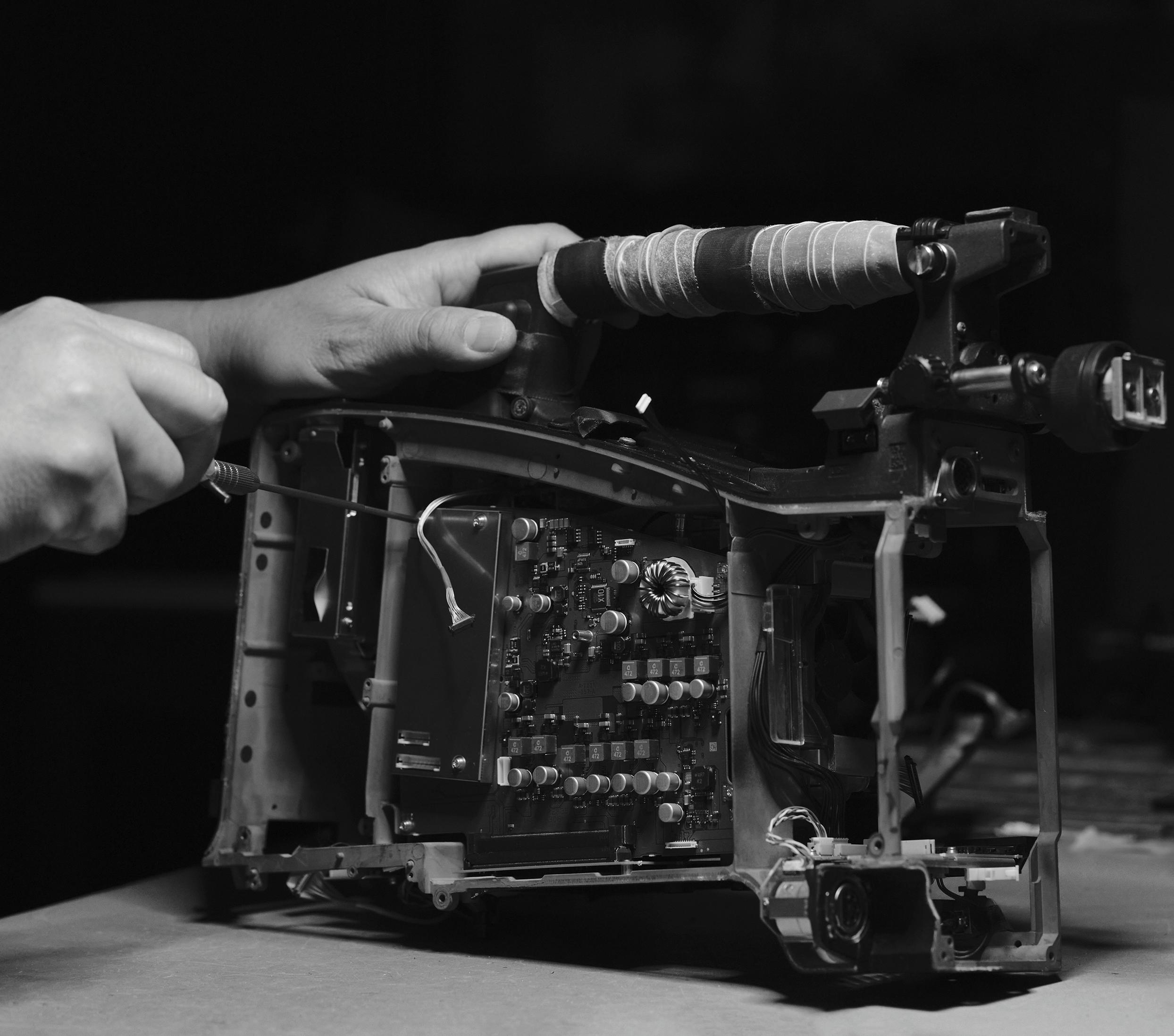

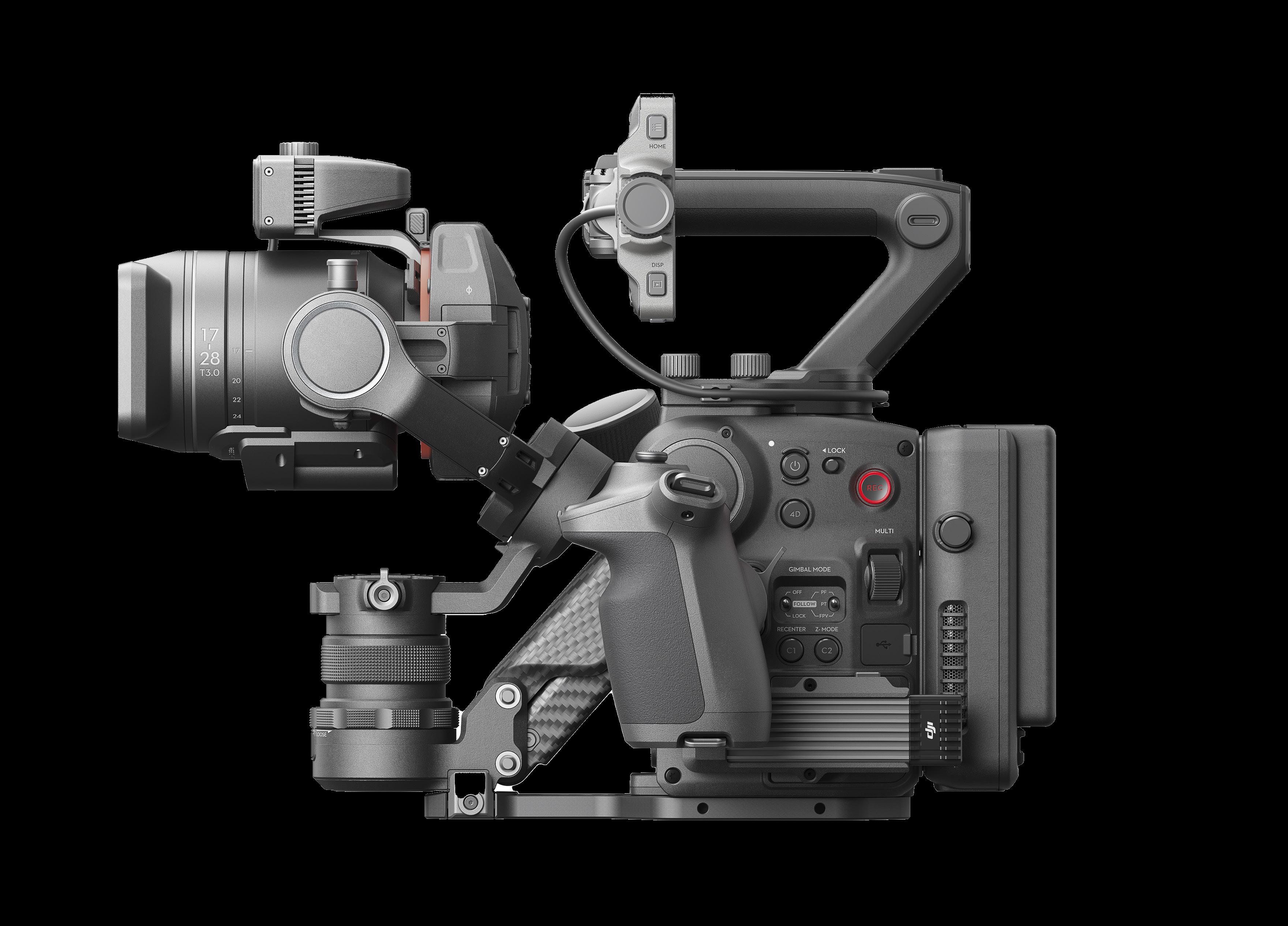

“What makes the DJI Ronin 4D special begins with having remote wireless control of nine stops of ND plus all the other camera parameters from kilometers away –and that all of these features fit inside a camera head smaller than two clenched fists,” notes Rodney Charters, ASC. “Its compact size allows for working in tight spaces and up close with actors – all in luscious 8K.” Launched last December, the all-in-one camera integrates DJI’s revolutionary four-axis stabilization. It delivers excellent image quality in complex lighting environments – as seen in recent projects including Civil War, Incision, and Wicked City – via full-frame 8K/60-fps and 4K/120-fps capabilities and DJI Cinema Color Science. The camera includes DL/E/L/PL/M interchangeable lens mounts, autofocus on manual lenses, and automated manual focus (AMF) with a LiDAR focusing system. As Charters adds: “Not since my first film with my father’s 16-millimeter Bolex and a 10-millimeter Switar have I had so much fun operating!”

“ONE OF THE BEST-LOOKING SHOWS EVER MADE. ”

$2,999-$3,499 RANGER FF LENS

$1,999-$2,499 RANGER S35

WWW.LAOWACINE.COM

Get a more extensive total zoom ratio with a larger aperture. The Ranger FF Compact Cine Zoom comes in 16-30-mm T2.9, 28-75-mm T2.9 and 75-180-mm T2.9 lenses with more than 11× zoom ratio in total. The lightweight and compact lenses are available in PL and wireless mounts. They deliver excellent neutral color rendition on skin tone and high image sharpness at both ends of the spectrum. They also have a built-in back-focus-adjustment system. The 3-lens Ranger S35 Compact Cine Zoom Series (11-18-mm T2.9, 17-50-mm T2.9 and 50-130-mm T2.9) delivers a lot of focal range at featherlight weight (750-850 g per standard lens and 650 g for the Lite lenses). “The Ranger T2.9 full-frame zoom lenses were indispensable during the filming of Wong Kar-Wai’s TV series Blossoms Shanghai,” says Peter Pau Tak-Hei, BBS; cinematographer, director, and Oscar-winning DP of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. “The 28-75-millimeter lens, with its exceptional detail, minimal breathing, and balanced contrast, quickly became my top choice for zoom lenses!”

It’s time to start using your head! This helmet cam is purpose-built for extreme, mobile video capture and real-time streaming. The patented base is helmet-contoured for solid fit, and the housing is low-profile. The compact, lightweight combo reduces snag hazards and increases mobility. You can mount it on multiple helmet types or deploy it as a remote video camera in vehicles, on robotics, and elsewhere. The product maximizes data throughput for uninterrupted footage but is easy to operate. Its intuitive web interface empowers you to customize everything from image quality to camera settings to video capture parameters. The new generation’s onboard sensors deliver 20× improved low light over their predecessors with customizable video output streams (2× H.264; 1× MJPEG). MOHOC and Silvus designed it to be plug-and-play-compatible with StreamCaster 4000-series MANET radios.

Join thousands in broadcast, media and entertainment at NAB Show New York, where infinite product discovery, networking and knowledge is within your reach. Ask questions. Get answers. Make connections. The latest innovations await on a show floor full of new-to-market tech and time-saving digital tools. Plus, access to amazing people and the most pivotal trends and topics you need in on now… AI, the creator economy, sports, photography, virtual production, FAST and more!

Invest in yourself through these incredibly in-depth conferences:

• Local TV Strategies

• Post|Production World New York

• Radio + Podcasting Interactive Forum

EXHIBITS: OCTOBER 9–10, 2024

EDUCATION: OCTOBER 8–10

JAVITS CENTER | NEW YORK, NY

The Middle MAX™ Menace extends your booming capabilities. Based on the same design principles as the Academy Technical Award-winning MAX Menace Arm, the Middle MAX has a maximum height of 18 ft/5.49m and can go to 6 ft/1.83 m below grade. With a payload capacity of 150 lb/68 kg (80 lb/36 kg when fully extended), it’s perfect for supporting lights, reflectors, cameras or set dressing. Its self-leveling head with baby pin and junior receiver features three lock-off or fixed positions. The rig rides on heavy-duty 10-in. × 3-in. puncture-proof tires. Fully assembled, this easy-to-use support even fits inside a standard cargo van. “I am amazed by the new design – the size and ease of movement make Middle MAX a must-have item for every production,” says Local 80 Key Grip David Donoho. “When time is limited on set, you really appreciate the value of high-quality equipment.”

DIRECTOR / PRODUCER / ACTOR

HORIZON: AN AMERICAN SAGA

BY PAULINE ROGERS

SANDY MORRIS / APPLE TV+

It feels like symmetry that Oscar-, Emmy-, and Golden Globe-winning filmmaker Kevin Costner’s most ambitious project to date – the four-part Horizon: An American Saga, releasing in Chapters 1 and 2 this summer from Warner Bros. – is a Western. After all, it was nearly 40 years ago that Costner first made his mark in Hollywood in the Lawrence Kasdan-directed Silverado, a film that many viewed as an attempt to revive a beloved cinematic genre that had, after its TV heyday in the 1960s, ridden off into the sunset.

Much like earlier Costner projects (most notably Dances With Wolves and Open Range), Horizon is as much an ode to the strength and toughness of the American West as it is to the men and women who settled there. It’s also yet another massive gamble by a filmmaker willing to put everything on the line to bring a story to audiences he feels compelled to tell, irrespective of its inherent commerciality.

Horizon’s box office fate aside, few can question Costner’s zeal for American history. His portrayal of the real-life Civil War veteran William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield in the 2012 miniseries Hatfields & McCoys broke cable TV viewership records and earned Costner a television trifecta – Emmy, Golden Globe and SAG awards. Six years later, the actor/writer/ director/producer kicked off the long-running Paramount+ franchise Yellowstone, starring as John Dutton III, the owner of Montana’s largest ranch. While Yellowstone centers on the family drama within the wealthy ranching clan, as well as the chafing away of Western and Native American lands by developers, Horizon, shot by James Muro (who operated Steadicam on past Costner hits Dances With Wolves and Field of Dreams) is about a specific period in the American West – pre-and-post Civil War –and the (often violent) struggles the emerging pioneers faced.

ICG Magazine: There was a lot to overcome in bringing Horizon to life, and it’s inspiring to see this story materialized. What was the genesis of this project? Kevin Costner: I commissioned a screenplay in 1988. That was another century if you think about it. I liked it very much. It was original, but still a recognizable Western story and I wanted to do it. But ultimately, when I tried to get it going in 2003, the studio wouldn’t do it for the budget we needed. I was baffled by that because I had just made a movie called Open Range that had done quite well for them. But at the end of the day, they didn’t want to do it. So, I went on to do other movies. And yet, I always loved the story. So, after some time, I thought maybe I would do it differently than what was originally intended. Maybe I would make a movie about how towns begin and show the drama of that, because all Westerns start with people already having a town, automatically. But we never see the history of a town that was fought for, that people died over; these towns didn’t just magically appear. That was something I thought was missing in [other Western] stories. With my writing partner, Jon Baird, we decided to

“I THINK THE IMAGERY

[MURO] GAVE US IN THESE MOVIES WILL LIVE FOREVER.”

develop that idea, which you see in the opening of Chapter 1 – somebody putting their stake in the ground. But even after I finished those four screenplays, which took about four years, I finally had to look to myself financially to get them made, which I’ve had to do before. And that hasn’t always been the most comfortable way to go. But, to serve the vision I’ve had in my head, I’m willing to do it.

Putting your own money on a project, betting so much on it, is such a strong investment in your vision. Does it feel risky? I take the risk because I believe in an audience’s ability to see this as something highly original, something that goes on – there are three more coming –and can look forward to that. That’s why I was willing to risk this. I believe that people want to see fresh things that mean something. That matter. That have empathy. That have danger. That have excitement. That have love and tragedy.

Given the state of television and the way it’s been going, what was behind the decision to release the story as multiple films in theaters, rather than as a television series? I just believe that some movies have a real life and that when we see them on the big screen, we’ll never forget them. And this story felt like one of those.

What is it about the Western genre that appeals so much to you, personally? Why do you think it’s captured the audience’s imagination more than any other era? I think it starts when you realize that the West was not just a land in Disneyland – it was real. It was a 300-year struggle. People from Europe were crossing an ocean, and they found that if they just kept going, they could find new lands. And if they were tough enough, or if they were mean

enough, they could control those lands. And America was formed on that basis, that if you were strong enough, you could take what you found and hold on to what you had. Not so much in Europe, where you were a second-class citizen, you lived under monarchies. America was like a promise, a promise that these pioneers could become kings themselves. And, ultimately, what we do know is that there were already people who had settled the land, the Native Americans, thousands of years before, and who paid a terrible price for our national appetite. So there’s this march across America, which was very much like the Garden of Eden before people came. The land was wholly natural, filled with animals and Native peoples, who all lived very lightly on the ground.

As an actor yourself, what qualities do you look for in the cast to evoke or match the setting and era of the story? Sometimes I’ll work with first-time actors. Sometimes I want a more seasoned actor because I feel like it’s going to require that. So I tend to mix my casts up. I’m very proud of who we had working on Horizon. There are some actresses in there that are going to be around for a long time. You probably noticed how heavy this Western leans on women. Entire plots revolve around women, so they’re not just tossed into cliché roles. Most Westerns feel like clichés. There are good guys and bad guys, but I know that the West was made up of all types of people. And those that were bad weren’t always stupid and dumb. They were conniving and mean. And that’s why the West was so incredibly dangerous.

Sounds like perfect fodder for complex villains. There was no law, at all, and that’s hard for people to conceive. It’s the mistake we make about Westerns. With no structured form of law, there was no one to tell you

what to do. If someone wanted what you had, there’s no one there to stop that. Imagine that you were my character in the scene on the hill and you realize this guy is going to challenge you. He’s either going to take what you have, he’s going to kill you, or he’s going to humiliate you. He’s going to do whatever he wants. And there was no police, no sheriff, no military around to stop him. To me, that’s very interesting to see on-screen.

How do you feel Horizon contributes to or diverges from traditional Western imagery? What are you proud of when you think of the film’s visuals? We tried to go to places that no one’s ever seen before; we tried to go to authentic places where great issues were solved. For example, crossing a river was really important 200 years ago! It’s not

so important now, you can ride a bike across these tremendous bridges that we’ve made, so we don’t apply our sensibilities to what life was like 200 years ago in the West. But we tried to show how it really was. One of the approaches we took was to keep the camera at horseback level, for the most part. I tried to keep the camerawork grounded. There are not a lot of straight overhead shots of something happening down underneath you, and not a lot of drone shots.

You go pretty far back with Horizon’s director of photography, Jimmy Muro. We absolutely do. It took me 106 days to shoot Dances with Wolves, and I shot Horizon: Chapter 1 in 52 days with Jimmy, who was a Steadicam operator on Dances with Wolves and Field of Dreams. I got Jimmy because I knew we wouldn’t be able to

wait for the [natural] light all the time, and we wouldn’t have all the bells and whistles, and that he would deliver despite all that. I’m sure there were days Jimmy ached to wait for the light to be at a certain place. But I said the story is the star, and asked him to bring as much magic as he could to it. What he managed to do, I thought was magnificent. Trying to make things interesting in midday light was one of our biggest visual challenges. And although it was unfair to Jimmy – or any cinematographer with that kind of canvas to work in – he pulled it off. I loved how we accomplished the battle. I was willing to let that battle go on for 35 minutes, but it was a living hell. And everybody went with me. The story is the star. And Jimmy embraced that and still managed to dazzle. I think his work in these movies, the imagery he gave us, will live forever.

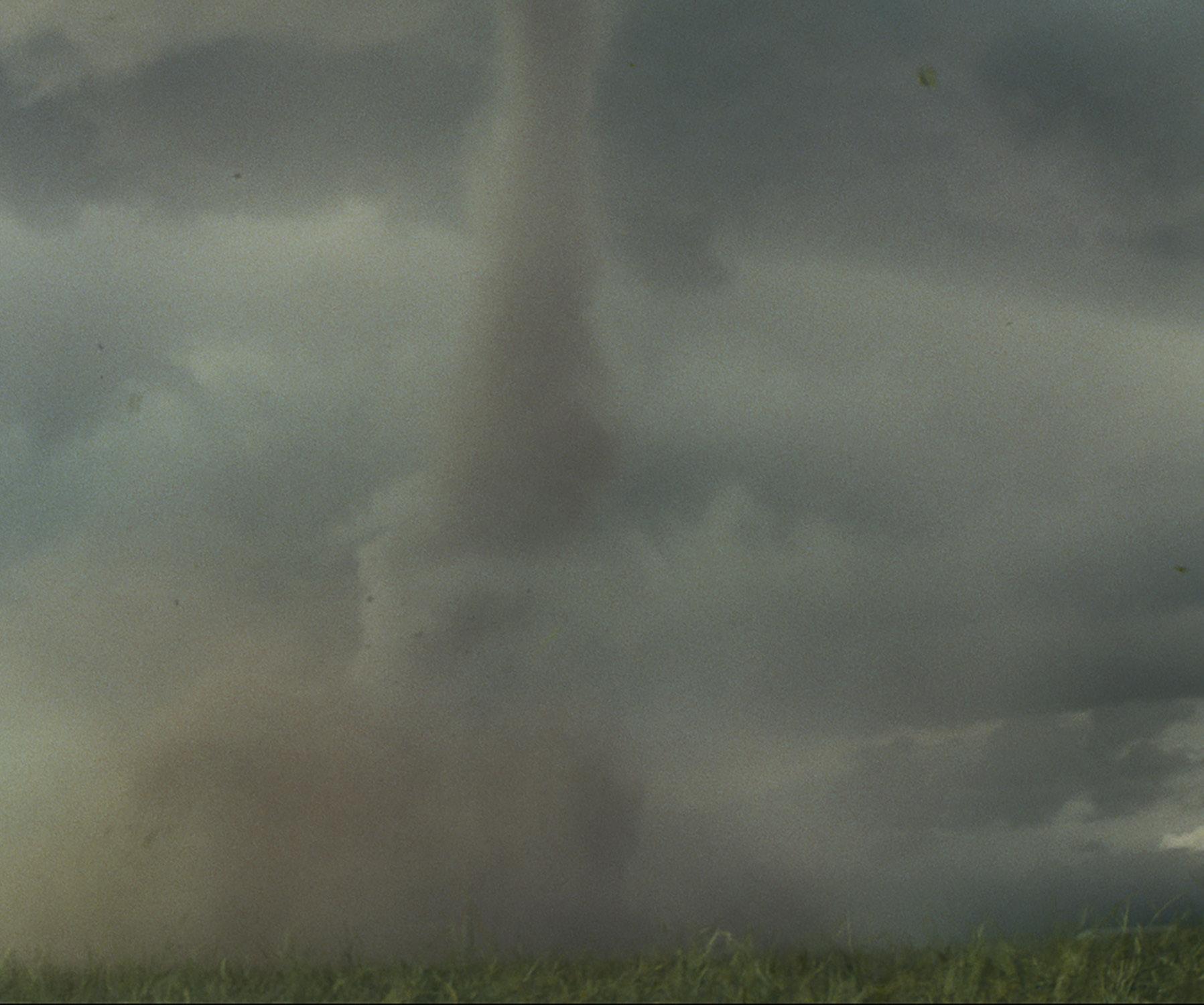

Dan Mindel, ASC, BSC, SASC, flies into a weather vortex for Universal’s disaster-flick update, Twisters.

BY KEVIN H. MARTIN

PHOTOS BY MELINDA SUE GORDON, SMPSP / UNIVERSAL PICTURES

“Everybody talks about the weather but nobody ever does anything about it.”

Roughly a century after Charles Dudley Warner, American essayist and novelist (and writing partner of Mark Twain), first voiced this pearl of wisdom, Hollywood provided the answer in the form of the 1996 disaster film Twister. In that fun popcorn flick, a group of tornado chasers manages to survive various encounters with nature’s most dangerous cyclones. The thrill-seekers release an array of weather sensor instruments into the core of an F-5 tornado, amassing a wealth of data on the 300-mph phenomenon that will presumably aid scientific understanding and the devising of lifesaving early-warning systems.

Even with Twister’s big theatrical grosses and a healthy tenure on home video (it was the first feature ever issued on DVD), the film’s only official follow-up was a longrunning thrill ride at Universal Studios. But in recent years, filmmaker Joseph Kosinski developed a new storyline that combined the requisite thrills with doses of science and pop culture – the latter in the form of a social media icon [Glen Powell] who documents his storm-chasing online.

Director Lee Isaac Chung, having scored a critical success with the 2020 Sundance hit Minari [ICG Magazine April 2020], decided to return to his Middle American roots to shoot Twisters on celluloid. “I learned on film in school,” Chung notes. “My first feature was shot on Super 16 millimeter, my second on 35 millimeter. So my choice of Dan Mindel as DP was specifically with this in mind, as Dan’s full commitment to shooting film helped with selling the studio. Also, we connected well together on our visual approach. Even though it’s a big action movie, this isn’t set in another galaxy and doesn’t feature superheroes. As much as was possible, we wanted to go into the real world to make this picture.”

For Dan Mindel, ASC, BSC, SASC, the director’s in-camera approach was a major selling point. “Between you, me, and the whole of Southern California, being outside from dawn to dusk is probably what I like most about my job,” Mindel shares. “One thing that enamored me right off was Isaac’s idea of shooting on location in Oklahoma and doing it in a nuts-and-bolts fashion, working from camera, grip and lighting trucks on the road.”

A-Camera Operator Geoff Haley was equally impressed with the old-school approach. “I am often pitched projects with the idea that we’re going to do things practically, without relying heavily on blue screen,” Haley muses. “But it doesn’t always turn out that way. So, I went into the project with some doubts. However, once I got to the location after prep, it was clear that everybody, from Isaac and the producers on down, was totally supportive of getting things done in-camera.”

Haley adds that there was a level of excitement over doing a movie out in the real elements, especially within the camera department. “Of course, as an operator,” he’s quick to add, “you wonder what horrific environments you’ll be placed in – I had visions of 100-mile-per-hour fans and ice machines pelting my face. I prepared myself

for that aspect plus the excitement of getting to shoot on film again at a time when 80 to 90 percent of my work is digital. We’ve shot film for a century, but the industry has a bit of amnesia about the medium. Some of the crew had never shot film at all. The cadence, rhythm and momentum associated with shooting film are different from what goes on when shooting digitally. One thing I love about film is that when you roll, everybody has focus and knows to pay attention because film is expensive.”

Mindel had suggested a vintage photojournalism approach to shooting on location. “Dan and I were trying to create painterly images that hearken back to vintage pictures we liked showing the life and culture in Oklahoma,” relays Chung. “There’s an element of nostalgia in what we were going for visually, and I think Dan and [Chief Lighting Technician] John Vecchio did a great job to achieve those scenes impressionistically. They use the strength of celluloid; Dan truly paints with light, and it isn’t just for the actors, but the light that hits within the frame and the highlights that roll off.”

As was the case on the original film, Twisters required a careful mix of visual and practical effects. Heading up the latter was SFX Supervisor Scott R. Fisher, who says he studied real tornado footage, “and the level of carnage is unbelievable. When you work on a disaster film, you rely on reference as a starting point, but then bring as many tools to the table as you can, because it is crazy what you’re trying to replicate. You need immense scale while making everything as visceral as possible in the foreground up to 40 feet away.

"You' can't just say up front that ten fans are going to be enough," he continues. "Our particulates were very high-velocity, sometimes propelled by jet engines that helped us achieve a 300-mile-per-hour look. It was a layered approach, with the area nearest the actors using our big fans from fifteen feet away, while further back we relied on the jet engines to cover the expanse.”

Another filmmaker instrumental in delivering the visual calamity was ILM VFX Supervisor Ben Snow, who worked as a digital artist on the original film. “Back then it was early days for computer graphics, and we didn’t have the greatest toolset to work with,” Snow recalls. “A few years later, I wished we could have done Twister again to take advantage of all the advances in CGI.

So to have several decades of progress to support this film was a dream come true.”

Snow says the original film used a particle system, “which is when P-render [an early volumetric approach for CGI] was developed,” he explains. “My role on that film was developing surface-based tornadoes and cloudscapes that were essentially geometry meshes with fractal shaders applied. Now we can use high-resolution fluid-dynamics simulations – plus terabytes of space! And one nice thing with this approach is that sims do sometimes generate something unexpected but useful – the digital equivalent of a happy accident on set.”

During prep, producers sent out a video crew and stills team to document real weather events in “Tornado Alley.” Snow says that yielded high-resolution skies to use for plate photography “and footage of some phenomenal cloud patterns for our library,” he marvels. “Oklahoma skies are so dynamic that they influenced our approach. One sequence was intended to be gloomy and overcast, but the plate shoot got us these amazing, blue-dappled skies. Leaning into that, we could maximize our use of the real environment in the live action.”

Chung himself drove much of the look, having conceived a clear idea for depicting the film’s various nemeses conjured by Mother Nature. “I knew each tornado needed its own look and personality,” he recalls. “Otherwise, it could end up feeling repetitive, seeing the same things happen six or seven times. So, each time our actors encountered a tornado, there would be a different context. That meant figuring out what each tornado did story-wise, with each action beat delivering a different portrait.”

Camera prep took place at Panavision Woodland Hills. First AC Sergius Tariq X Nafa reports that “anamorphic supplies are in such a critical state right now worldwide that getting matched sets doesn’t have the same meaning as it did back in the 1990s and 2000s. It’s more important that we get focal lengths that can produce a quality image regardless of series. We generally roll with the large and lavish Primo AO anamorphics [set for film]. For scenes that were shot inside vehicles, handheld and Steadicam, we opted for T Series and occasionally the custom C Series retro Panatars, a Mindel concept brought to life by Dan Sasaki back in 2014. Zoom-wise, the ATZ2 and the 11:1 Anamorphic Primo handled the telephoto shots.

“Aside from the skillset necessary to pull focus on film,” Nafa adds, “my main

“ I HAD

OF 100-MILE-PER-HOUR

MY

I PREPARED MYSELF FOR THAT ASPECT, PLUS THE EXCITEMENT OF GETTING TO SHOOT ON FILM AGAIN... ”

A-CAMERA OPERATOR GEOFF HALEY

teammate, B-Camera 1st AC Andrae Crawford and I were acutely aware of the elevated role protecting cameras and equipment would play in our duties to the show. We tested rain deflectors from Schultz, the Eliminator, and the Prodigy air blower from Bright Tangerine. Ultimately each system had instances in which they were the preferred method of keeping our cameras functioning smoothly. Speaking of which, we predominantly used Panavision’s Millenium XL2s [including all black Death Star and Millennium Falcon variants used by Mindel on The Force Awakens] as well as a Panavised 435 for high speed.”

During location scouting, Production found a basketball arena (the former home of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder) to serve as a makeshift stage in case of unsatisfactory weather and for process work. “That was large enough for our needs,” Mindel reveals, “because we needed a very long throw for our traditional lights. We also found an unused carpark nearby that worked out pretty well.”

Chief Lighting Technician Vecchio participated in the scout and had sidebar meetings with Mindel. As Vecchio recounts:

“We were armed with a large stack of computer-generated drawings from the art department to plot things out. I’d then turn the drawings with my notes over to my board operator so they could be put into Vectorworks. Even with plots noting what we’d need on any given shoot, I kept a 40foot truck full of lights in reserve, as you never know what might be needed when dealing with the unexpected. [Executive producer] Tom Hayslip and all of those guys at Universal were great at giving us whatever we needed.”

LED elements used included two- and four-foot Astera tubes to embellish a variety of building exteriors, along with many older HMI and Tungsten units to deliver a look Mindel felt newer systems could not achieve. “It was important to Dan that when lighting the principal performers, we use traditional tungsten or HMI units with a Fresnel,” Vecchio states. “Molebeams, 10K’s and Maxibrutes are old-school tech that Dan and I both love. When we were towing the lead actors in these trucks, we’d have gelled 10Ks and Minibrutes lighting them from outside. The way you place the light has to do with the shadow and fall-off, and Dan can perceive the special quality of a tungsten

light going through a Fresnel onto a sheet of diffusion before it falls onto the actor’s face. It’s the difference between illumination and lighting. But, it’s also a commitment that requires heavy generators. When you see the previous day’s footage in dailies, you see clearly what a difference that choice makes on the actors’ faces.”

“I am very reticent to light movie stars with LED’s,” Mindel adds. “My rule of thumb is that you use movie-star lighting on stars when shooting close-ups and dialog with them, as the balance of color can impact how a person looks. Using available light might sound like a sexy option, but it is not what you do with movie stars.”

Scenes following the heroes in vehicles as they pursued tornadoes were often captured using an Allan Padelford Camera Cars MTV insert truck, equipped with a 30foot Technocrane. Traveling ahead of the car carrying the actors was an SFX flatbed, which Fisher equipped with a wind/rain/weather rig that allowed him to blast the windshield and sides of the vehicle.

“We had a lot to deliver while coordinating with other departments and being careful not to complicate things for VFX,” Fisher shares. “We destroyed so much

of the foreground with our rubber debris that it was hard seeing through to the background in some cases. Testing early helped us nail things down; when [Chung] saw where we were going, he realized there would be these huge value gains for enhancing actor performance, as when they would have to lean in against the wind and react to being hit by stuff in the air.”

Haley, who was sometimes attached to the outside of a speeding vehicle, recalls seeing the SFX people “essentially getting ready for battle,” he smiles. “They’ve got their howitzers and catapults that are going to assault the operators and the actors, which can be daunting! It was always safe, but that didn’t mean it was without pain, because you get pelted with a lot of stuff. It’s an adrenaline rush, and it makes your operating feel more real, not unlike what the war cameramen did with handheld 16 millimeter in Vietnam. The actors, by the way, were troupers, always ready to go again.”

Nafa says he’s had experience pulling focus with film. “We had upgraded HD taps on the cameras,” he describes, “which work quite reasonably, plus LightRanger is a huge

aid. We also had a first AD and operators who were veteran filmmakers, so if I or [B-camera 1st] Andrae Crawford needed time to get positions, they’d give that to us.”

One tornado event is preceded by a rodeo sequence, which was an elaborate night exterior shoot. “We had 13 or 14 Condors loaded with Lightning machines,” Vecchio describes, “plus some 20Ks and 12-light Maxis. We had Super Troupers and other lights festooned over all the merchant vending areas, plus neon signs, plus more lighting for the people in the stands.

“[Chung] came up with a wonderful shot of leaves dropping down into the grandstand,” Vecchio continues. “Our stars look up and realize something bad is about to happen – and then everything goes dark. Per [Chung], the rest of the scene was to be illuminated only by lightning. We used traditional Lightning Strikes machines, plus Creamsource Vortexes – which can strobe and flash – that also pulled double duty for certain night exteriors. The new Vortexes and other LED’s have a higher IP rating, which means they have a higher resistance to rain. But the older lamps needed old-school

solutions, with our grip brothers, led by Key Grip Joseph Macaluso, putting Celotex over them as protection against the elements.”

Haley says operating on Twisters was a primal experience. “With digital, the operator has the worst seat in the house, because he’s either looking at a crummy little monitor or through an eyepiece with crappy resolution,” he relates. “But with film, I’ve got the best view of the action through the eyepiece, while everyone else relies on an HD video tap.”

When the weather changed during shooting and the sky darkened, Haley says he could see storm clouds forming in the distance. “I thought: ‘This looks amazing.’ But then I realized lightning would be following the clouds, and we’d only have a few minutes – with everything looking so dark and perfect – before we’d have to follow the industry-wide regulation for a mandatory 30-minute shutdown [when lightning strikes are within six miles]. That’s the biggest irony of this movie about inclement weather! By the third week, I knew

that whenever I got excited by what I saw through the eyepiece, I also knew we’d only have those ten minutes before production would get shut down. So, we might wait 25 minutes and be just about ready to go again when there’d be more lightning, triggering another automatic delay.”

Given the need for visual effects in so many shots, Chung relied on previsualization to prepare the various departments. “We had some previs on scenes that demanded technical choreography,” the director shares. “But when out on roads in nature, we tried to capture things in as natural a way as possible. Ben Snow was a real supporter of doing things practically and participated in every conversation I had with Dan on set about where the tornado was going to be and how we’d be framing the action.”

One sequence utilizing previs involved a sustained oner.

“Having done 104 movies, when I’m asked how to make the next oner ‘the best anyone has ever seen,’ I can sometimes feel stumped,” Haley laughs. “I saw the first iteration of previs, which has the heroes take cover from a night tornado in a drained pool.

Previs can’t really consider all the practical realities of shooting. So, even though the data at the bottom of the previs frame tells you what the taking lens will be, the actual move might not consider the physical size of the camera. How can a 35-millimeter camera with a magazine move between pipes that are eight inches apart? And how do you make the camera leap up over a table, then accelerate to 25 feet per second inside three seconds? On certain shows, everybody just loves seeing previs where you go zooming up into a helicopter view before suddenly entering the quantum realm, but sometimes you have to put on the brakes and consider reality.”

To that end, Haley and Snow went to the location with Chung to work through the scene before shooting commenced. “We took the previs with us to the pool so Isaac could review it in context,” Haley adds. “We said, this looks cool, but what if we did this instead? Using whip pans, careful lighting, and CG stitching, you can create a oner made from six or seven different shots and multiple elements.” The new plan included a crane move, Steadicam and handheld that

Haley did with a [Walter Klassen] SlingShot rig attached to a gimbal.

For a proof-of-concept, Haley and Snow used stand-ins and shot each pass on iPhones. “Doing this physically, almost like stunt vis, was the best way to work out details,” Snow reports. “We had a useful reference for how these seven or eight plates could be made to work as one, with lighting covering the handoffs or digitally stitching them together.”

“The advantage of having a world-class operator like Geoff Haley,” Mindel muses, “is that I can leave him to choreograph the move, while I go build a lighting scenario that will support the move and help with the transitions. I’ve seen the scene a few times in the last couple of weeks while coloring the movie, and I feel it was a particularly good use of that technique. I’ve learned that visual effects require careful treatment to give them what they need to make us look good. The payoff from working that way is not just great effects, but also that I can ask for a favor when I’m in trouble, like needing to remove a giant yellow crane from frame in the middle of the night. It’s a symbiotic relationship.”

“

WHEN YOU SEE AN ANALOG MOVIE, ONE SHOT ON LOCATION, YOUR BRAIN STOPS COMPARING IT WITH THE WAY OTHER THINGS LOOK, AND YOU GET IMMERSED IN THE STORY. ”

DAN MINDEL,

ASC

Snow concurs. “One of the most important parts of having the VFX Supervisor on set is reminding everyone there about this giant actor at the back of the shot that we’ll be putting in. Camera has to understand because they must allow enough space to frame for something that isn’t there. Intuitively, they want to frame for what they see, so communicating with images helped get everybody on the same page.”

Those post-added “monsters” benefited from the input of ILM animators. “Since the twisters have character, our animators essentially created their performances,” Snow continues. “That would be ingested into our sim engines and used as a basis for each tornado. Each storm required a bespoke solution, so it was not dissimilar to how Dan might use his lights, silks and flags to customize the light and optimize the camera image.”

Part of the VFX game plan revolved around what could be handled at ILM versus what could be addressed in the DI. “We knew that with all the sunny days, changing to overcast looks was going to be a big part of our end,” Snow adds. “That meant sometimes having to rotoscope every blade of grass or stalk of corn in an attempt to get rid of highlights created by sunlight. In the opening sequence, they are driving in incredibly thick fog, hail and rain, but a lot of that was done in sunshine. Since we had a perfect CG match for the car, we could replace all or part of the vehicle and avoid showing those hot glints of sunlight that would have been inappropriate for the

conditions of the scene.”

More VFX matching came about as a result of the SAG-AFTRA strike, which created a gap in shooting. “The seasons had changed, so to get things to match we’d be changing green grass to yellow or vice versa,” shares Snow. “The whole postproduction workflow benefited from the use of ACES. ILM had had a lot of involvement with the team that created ACES, and for this show, Company 3 was totally on board with the idea of using it as a basis for their color pipeline. As a result, this was probably the smoothest DI I’ve been involved with.”

Mindel, having worked with Company 3 Colorist/Executive Producer Stefan Sonnenfeld since their doors first opened, says: “I’m aware of what can and cannot be achieved in the DI. Stefan knows me well enough to have thrown his look into the mix in a way that I will appreciate when I turn up. For me, that has become the most fun part of the process – the discovery element, finding out whether our changes made the story better. At the same time, I know that for some other projects, Stefan’s input is the most important part of the finishing process, often dictating how the final result looks and feels, which marks a significant change in filmmaking.”

The DI, for Mindel, also made clear the differences between film and digital. “I was timing a digital movie a month before starting to grade Twisters ,” he reports. “The space that a digital movie lives in is beautiful and sleek, with high contrast values that make it quite enticing. But it’s very much its own thing. When you see an analog movie, one shot on location, your

brain stops comparing it with the way other things look, and you get immersed in the story. I think that’s because of the subliminal nature of film emulsion and the way intangible atmospherics appear within a scene – smoke, darkness, a shaft of light, wind, rain – become texturized. That sense of texture is missing from the digital space. But when you’ve got nothing to compare it to, you don’t know what you’re missing. That was clear seeing these projects back-to-back. The payoff shooting film was huge.”

Chung says working at Skywalker Sound with supervising sound editor Al Nelson and his team on Dolby Atmos and 7.1 mixes, left him impressed with the dimensionality of the soundscape. “It was like we were inside the tornado,” the director enthuses. “Al’s team conveyed a feeling of rotation within the storm, not just the sound of wind but also of debris hitting. That created an immersion and emphasized the danger of what our characters faced. Equally wonderful and surprising was how they were able to clean up our production sound, eliminating a lot of wind-machine noise so the on-set dialogue tracks could often be used.”

The making of Twisters reflects a “right tool for the right job” approach that has sometimes been neglected in the current love affair with digital technology. As Mindel concludes: “Being the oldest guy in the room is not an impediment. I’ve seen multiple times how best the various departments can work together, and that’s an advantage. If there’s an issue of doing something that nobody else is familiar with, I can sometimes raise my hand and say, ‘Hey, I know how to do that.’”

Director

A-Camera

B-Camera

B-Camera 1st

B-Camera

Director

A-Camera

A-Camera

A-Camera

B-Camera

B-Camera

B-Camera 2nd

C-Camera

VFX SUPERVISOR SCOTT FISHER SAYS THAT WHEN WORKING ON A DISASTER FILM, YOU RELY ON REFERENCE AS A STARTING POINT, AND BRING AS MANY TOOLS TO THE TABLE AS YOU CAN. IT’S CRAZY WHAT WE’RE TRYING TO REPLICATE.”

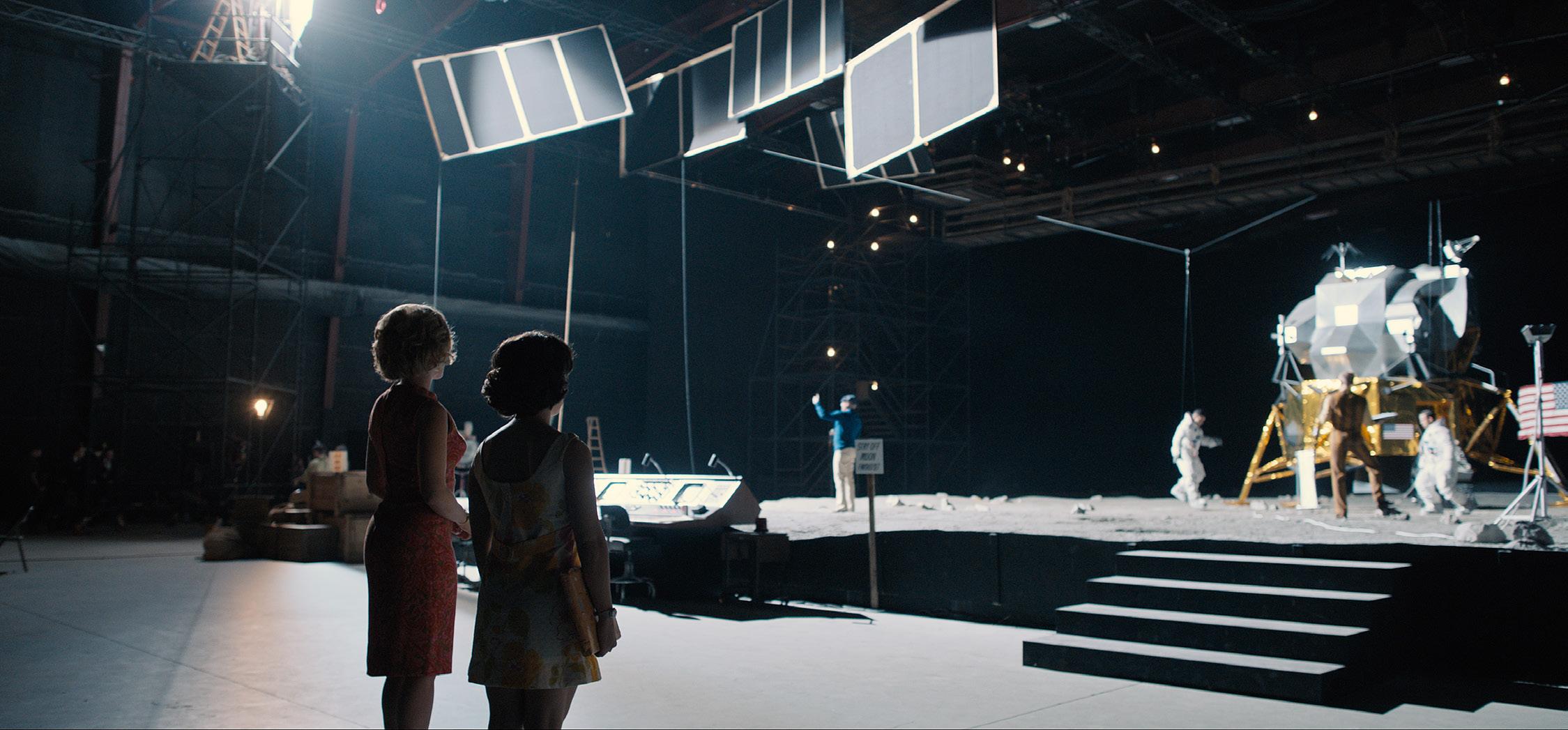

Dariusz Wolski, ASC, takes one career giant leap in the new romantic comedy, Fly Me To The Moon.

BY TED ELRICK

Although Director of Photography Dariusz Wolski, ASC, is best known for his many large-budget action features (The Martian, Prometheus, Napoleon, Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl) for directors like Ridley Scott and Gore Verbinski, he jumped at the chance to work on the new Sony Pictures romantic comedy Fly Me to the Moon, directed by longtime TV Producer/Writer/Director Greg Berlanti. The period story, set in Florida in the late 1960s, centers on a marketing hotshot named Kelly Jones (Scarlett Johansson), who wreaks havoc on NASA Launch Director Cole Davis’s (Channing Tatum’s) already difficult task of putting a man on the moon. When the White House deems the mission too important to fail, Jones is directed to stage a fake moon landing as backup. “It’s completely different from the movies I did with Ridley,” Wolski explains. “It’s a light romantic comedy, something I haven’t done, and was a bit of a challenge. Although it deals with space and the mission to the moon, there’s a bit of a twist.”

That twist included Berlanti casting Wolski as the cinematographer in the story who is tasked with faking the moon landing, à la shades of Capricorn One . “Dariusz was a natural, as so many of our conversations in prep were how we were going to shoot a fake 1969 moon landing as though it was done with the technical equipment of 1969,” Berlanti shares. “When are we going to be on real cameras, in camera; and when are we going to be on our cameras? There were a thousand logistical conversations.

“Many of the conversations they would have had if they were going to fake the moon landing were probably similar to what we were talking about,” Berlanti continues. “I had to also audition people for the role that Dariusz ended up playing, and it just seemed apparent to me that he should do both, because he was so much more real. It was so much fun to have him handle the onscreen stuff as well as shooting the movie.”

DIT Ryan Nguyen explains that when Wolski was acting, it was his job, along with A-Camera/Steadicam Operator James

Goldman and Chief Lighting Technician Josh Stern, to ensure Wolski was happy with what was being photographed.

“We worked together to cover Dariusz,” Nguyen says. “I think that may be the proudest thing for me, being there for him and making sure that he was comfortable in front of the camera and behind the camera during his two weeks of acting.”

Of his turn in front of the camera, Wolski laughs, noting, “I was completely conned into it by [Berlanti]. He killed me with kindness and put me in a place where I had no choice. It was fun, but also a little nerve-wracking, as my first take, I was looking straight in the camera to make sure [Goldman] operated it correctly. James was laughing. He couldn’t help it. The most amateur acting is looking straight at the lens. I did have to join SAG, but I don’t think I’m going to pursue it as a career goal. [Smiles.] It was fun while it lasted.”

Wolski, who shot with the ARRI ALEXA Mini LF and his own set of Angénieux lenses, says a lot of time was spent analyzing

period footage from NASA. “They restored a lot of 70-millimeter footage,” he describes. “And it was beautiful, almost too good. We analyzed it all, and when you look at period stock footage or documentary footage, it’s been shot in every possible format with all the different exposures and different film stocks. Once it’s been digitized, you have a lot of flexibility. You can change contrast, color representation, add grain or take away grain. We used quite a bit of the period footage, blending it with our own.”

While there was no IMAX footage from the 1960s, Wolski says many of the big helicopter flying shots over the launch pad were available in 70 millimeter. “With the large format [70mm] footage,” he continues, “you’re just trying to make it all consistent. Our terrific costume designer [Mary Zophres] and Production Designer [Shane Valentino] helped smooth the transitions from period to current footage as well.”

Unique for other films centered around NASA, Fly Me to the Moon was shot extensively at the Cape Canaveral/Kennedy

Space Center in Florida (as opposed to the Johnson Space Center in Texas, where other projects have lensed). Cape Canaveral is where NASA prepares to launch the mission, and Johnson takes over once the mission has launched. Berlanti’s film is set at Canaveral, and the production was given unprecedented access to launch sites.

Aerial Director of Photography David B. Nowell, ASC, whose credits go back to Apocalypse Now , had previously shot at Canaveral for Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen , and for the zero-gravity sequences of Apollo 13. “What was different this time,” Nowell shares, is the unlimited access his team had. “We had a guy from NASA, John Graves, come on board the helicopter,” Nowell recounts. “We thought we were going to have to carry him with us every time to prevent us from doing something wrong. But he was great. It was basically a history lesson. You know this is where the Redstone launched for the first two flights

to outer space with Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom. You know here’s where they did the launch for John Glenn’s historic flight. You know this is the pad where Apollo 11 launched, and it’s now being leased by SpaceX.”

Nowell says SpaceX would not allow his team within a mile-and-a-half of the pad “because they had an active rocket there that was going to launch people up to the ISS,” he states. “So, we ended up using another pad, 39B, that was used for other things besides Apollo. We shot plate after plate after plate because everything was pretty much the way it was back in 1969.”

The aerial team filmed in and around the 39B pad because, as Nowell explains, “they were going to add in the Saturn V rocket and everything that would have happened during Apollo. The only restriction was staying the mile and a half from around the SpaceX pad and one side of the VAB [vehicle assembly building], as there is something there that is top secret. We did the best we could to cover that up.” Nowell also

shot in Atlanta for sequences with a P-51 Mustang where Tatum’s character is flying Johansson’s PR maven around. “It was a lot of beautiful shots with the P-51 around all the lakes,” he says.

Nowell used the Shotover K1 stabilization system from Team 5. “Then I had my tech, Peter Graf, build Team 5’s special array platform called the Trident,” Nowell describes. “We had three Mini LF’s and three 21-millimeter Zeiss compact lenses, a huge array system. The cameras are turned on their side so they’re in portrait [orientation] rather than landscape; overlapped and stitched together it’s, like, 12K resolution.

“We did a lot of plates for that, both primary stuff for production and plate stuff for visual effects,” Nowell adds. “I had a list of what to get from Dariusz and sat with Sean Devereaux, the visual effects supervisor, who didn’t want to fly. He’d tell us what they needed, and then we’d go up, shoot it all, and come back and show it to him. Sean would then approve it or say, ‘We need to do something different.’”

“GOING TO NASA WAS MY FAVORITE PART OF WORKING ON THE JOB. WE SAW TWO SPACEX ROCKETS LAUNCH; ONE FELT LIKE IT WAS LITERALLY ACROSS THE PARKING LOT FROM WHERE WE WERE SHOOTING.”

A-CAMERA/STEADICAM OPERATOR JAMES GOLDMAN

While there were storyboards, Wolski says it was mostly him and Berlanti talking about the scenes and then having the actors come in to figure out the blocking. “There was a full-on read and some rehearsals,” Wolski recalls. “The actors would look at the scene, try this, try that – Scarlett was just amazing. She was so right on.” Berlanti, who studied theater in college before becoming a TV writer, screenwriter and producer/ showrunner (and also finding time to direct three features), says he’s a big believer in rehearsals and remembers Sidney Lumet’s comments about the value of rehearsing before shooting. “Before we get to set, we read through,” he explains. “It allows the actors to play with certain things that save you a lot of time on the day. We did a week’s worth of rehearsals with the main cast.”

Operator Goldman has worked with Wolski many times and notes how smooth the show was because he’s such a wellthought-out cinematographer. “He’s so

prepared on the day you show up,” Goldman describes. “Very thorough in his prep, which makes my job so easy. Dariusz is very clear with what he wants to accomplish, with each scene and each day.”

Goldman goes on to note that Wolski “is a forward-thinking filmmaker, as far as when you arrive on set. He likes to scout; he likes to pre-light; he likes to be in the moment so that he’s able to move with speed and efficiency. And Greg Berlanti is just a wonderful human being. He set the tone across the entire board. It was a delightful film to work on, a straightforward, oldfashioned romantic comedy.”

Several crewmembers of Fly Me to the Moon noted how Johansson’s character is all about raising awareness for the space program by marketing things like Tang, the orange drink of astronauts, and Omega watches. Others pointed out how they watched space movies before filming, such as Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff, shot by

Caleb Deschanel, ASC.

“Going to NASA was my favorite part of working on the job,” Goldman continues. “We saw two SpaceX rockets launch; one literally felt like it was just across the parking lot from where we were shooting. We shot at the Apollo Memorial, which is for those who died on the Apollo 1 mission before take-off. To see a space launch at such close range was a once-in-a-lifetime event.”

While many other space films are set in Houston, Fly Me to the Moon stands alone for its unique setting. “We’re at Canaveral, where nobody claps,” Wolski explains. “It’s just not done until the ship is safely in orbit, and that happens in Houston. There have been so many bad experiences, nobody claps until the ship is in orbit.” The DP adds that he was very young during the moon landing. “I was watching it on Polish television, but I do remember it.”

As for recreating a fake moon landing, Wolski says lighting, in particular, presented many challenges. “We didn’t really use arc lights, just one for the Moon landing but then for real we used the arc-light housing with an HMI inside, so that was kind of fun to look for all the old lights,” he recalls.

With the fake moon landing shot in Atlanta on a large stage, Chief Lighting Technician Stern says they needed to figure out what the light source would have been. “Other movies have used 50 K SoftSuns because they’re a very wide, single-shadow source,” Stern shares. “The problem was that we needed to do shots of people sitting at video village looking at the astronauts, who are on wires above this lunar landing set. It has cables holding them up so they can float, and we also wanted to be able to turn around and look at the light on the platform.”

What lighting was available to filmmakers in the 1960s?

“The most obvious thing we could think of was a Brute Arc Fresnel,” Stern continues. “Fresnels are beautiful, but they don’t have a wide enough spread and they don’t really work as a shadow caster, so we tested clear lenses. I knew the K5600 Alpha HMI’s have

a clear lens function with a small reflector and nearly 180-degree beam angle, and it turned out to be the perfect single-shadow source on our stage. Any serious lighting nerd would probably say, ‘Well, the shadows on the moon’s surface should not get wider because of the sun’s proximity,’ but the clear lens was convincing on camera.”

Stern says he called Sam Leu at Warner Brothers, “who’s in charge of all the studio’s vintage fixtures. I asked if they had any Brute Arcs, and Sam said they have four,” Stern adds. I asked if they could be modified to have HMI guts so we could use them on a stage. He modified two of their carbon arcs to have an 18K globe inside so we could photograph that and use it on stage, but not have smoke billowing out the top. Our stage in Atlanta didn’t have perms, let alone the evac systems that all of the old stages in Hollywood have.”

Leu’s modifications were key to the fake moon-landing shoot.

“We put one up on a 30-foot-tall steel truss tower riding on an old Molevator stand, the ones that have a drill motor,” Stern notes. “I also was able to get a lot of period fixtures from Cinelease, who let us

take their branding off and repaint so we could put them all in the background. We lit the entire moon set with the modified carbon arc or the Alpha, depending on the shot requirements.”

Berlanti is quick to point out just how important Wolski was to the entire project. “I don’t think I’ve learned more in the last decade in this business from anybody than I did watching Dariusz on set,” the two-time Emmy nominee concludes. “It was one of the highlights of my life to work beside someone of his caliber and to watch him create on the day. To see where his inspiration came from will always be one of my favorite experiences. He also has a wonderful sense of humor, which is key when making a comedy. If you’re not laughing on the set together, the audience won’t be laughing later.”

As Wolski concludes: “The challenge in this film was to be true to the historical elements. The other challenge, for me, was to shoot a romantic comedy, which I’ve never done. Many of the films I work on are so dark, and this was light. It was a departure from my normal style of working, and what I found is that shooting a comedy is all about the directors and actors.”

Director of Photography

Dariusz Wolski, ASC

A-Camera Operator

James Goldman

A-Camera 1st AC

Wilfredo Estrada

A-Camera 2nd AC

Trevor Carroll-Coe

B-Camera Operator

Jesse Roth

B-Camera 1st AC

Trevor Rios

B-Camera 2nd AC

Kevin Wilson

C-Camera Operator

Ramon Engle

C-Camera 1st ACs

Andy Hoehn

Daniel Guadalupe

C-Camera 2nd AC

Katrienne Soulagnet

DIT

Ryan Nguyen

Digital Utility

Breona Jones

Still Photographer

Daniel McFadden, SMPSP

Unit Publicist

Denise Godoy Gregarek

DIRECTOR GREG BERLANTI NOTES THAT, “I DON’T THINK I’VE LEARNED MORE IN THE LAST DECADE IN THIS BUSINESS FROM ANYBODY THAN I DID WATCHING DARIUSZ [ABOVE AT CAMERA] ON SET. IT WAS ONE OF THE HIGHLIGHTS OF MY [WORKING] LIFE.”

Director of Photography James M. Muro rides into the often treacherous breach of the American West for Kevin Costner’s sprawling cinematic anthology.

Thirty-six years in the making, Horizon: An American Saga is a sprawling chronicle of the Old West too expansive to be contained in a single film – and too cinematic for its creator, Kevin Costner, to conceive as an episodic series. The sweeping narrative is split into four films (two of which are yet to be shot), and spans more than a decade before and after America’s Civil War. The anthology aims to capture the complex story of western expansion and settlement with vivid, immersive detail and a palpable sense of place. Yet another ambitious passion project from twotime-Oscar-winning filmmaker Kevin Costner (remember Dances with Wolves and Waterworld?), Horizon, which Costner co-wrote, directed, and stars in, debuted with Chapter 1 this past June and paves the way for Chapter 2 (release still to be determined.)

Director of Photography James Michael “Jimmy” Muro’s partnership with Costner dates back to Dances with Wolves (1991), when Muro served as Steadicam operator. Muro’s journey from camera operator to director of photography culminated in his first feature Director of Photography credit on Costner’s Open Range (2003). The collaboration aims to hit new heights with Horizon, visualizing the American West in a raw, honest way not typically associated with a genre rife with visual and narrative clichés.

Muro’s approach to lighting emphasized natural, organic illumination, skillfully manipulating sunlight, often with 20×20 mirror boards to redirect light into interiors, while employing negative fill to shape and control contrast. To address the unique challenges of the vast Utah landscapes – where the film was made –particularly inherent in night scenes, Muro

worked closely with 2nd Unit Director of Photography Rob Legato, ASC, to develop a day-for-night technique that creates a distinct look characterized by edge lighting and deep blue-black skies. (This visual approach is thrillingly showcased in a dramatic horseback escape sequence.) For some night interiors, real gas lanterns were utilized as both practicals and light sources for the actors. For daytime exteriors, a shower-curtain material was the go-to choice to soften the harsh sunlight without it becoming too diffused.

Costner’s commitment to realism required creative problem-solving. A prime example is an early scene that sets the story in motion – an Apache attack on the home of the Kittredge family forces Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller) to lead her daughter to safety through a narrow tunnel. Safety concerns precluded the use of real gas lanterns in the

confined space. Muro’s unique solution was to use small LED cube lights purchased at Best Buy, which fit perfectly into the lanterns; flame flickers were added in postproduction to complete the effect. The scene also exemplifies the dedication to practical effects. During the ensuing gunfight, as the Kittredge house burns, real embers were blown onto the set from above instead of relying on visual effects. “If this was studiofinanced, they would have shut us down a long time ago,” Muro quips, highlighting the unique freedom afforded by the film’s independent nature.

Horizon stands as one of the most ambitious independent films ever made, partly funded by Costner’s personal $38 million investment. The rare degree of independence allowed the filmmakers unprecedented creative control. Despite the epic scale, which involved large numbers

of extras, wagons and horses in remote locations, the schedule for Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 was a remarkably efficient 50 to 60 days, with zero reshoots or pickups. “It was such a privilege to be there,” Muro adds. “We’d pinch ourselves daily as a reminder [that] this was one of the biggest independent projects ever made, and that’s where our energy came from.”

Production Designer Derek Hill’s work with Costner dates back to Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991), shot by Robert Richardson, ASC. Hill oversaw the creation of meticulous periodaccurate sets, including a mining town called Watt’s Parish that was constructed at an elevation exceeding 8,000 feet in Utah’s La Sal mountains. Perhaps the most ambitious undertaking was the construction of an artificial river within a valley when a suitable natural location couldn’t be found. “There’s something new on every project, but only Hollywood or the Pentagon would take on the task of building a river,” Hill remarks.

This artificial river, conceived as a 320-by-80-foot pool, was built using techniques typically employed for resort pools. Concrete and rebar were laid along an extended trench, with water pumped in from the nearby Colorado River, as it was built on a farmer’s land with water usage rights. The titular town of Horizon was then built on its banks, setting the stage for the spectacular Apache attack sequence that culminates in the town’s fiery destruction, which was shot over five nights. Although the town of Horizon was destroyed, the river is still standing and will be used for filming the remaining two chapters in the Horizon saga.

While New Mexico was considered for cost reasons, Utah’s visual grandeur ultimately proved ideal for Horizon’s epic scope. Costner even made an impassioned plea before the Utah senate, advocating for the value of shooting in the state, which helped to secure a crucial film tax rebate. The Horizon saga now stands as the largest film production in Utah’s history.

The impact extends beyond the film

itself. Costner is currently developing Territory Film Studios, a 150,000-squarefoot facility in Utah that will house sound stages, production warehouses and office space. This investment promises to further bolster Utah’s growing film industry and solidify Horizon’s legacy as a true catalyst for economic growth.

To better capture the towering buttes that are so prevalent in Utah’s landscape, "Muro opted to break free from the widescreen Western tradition, shooting Super 35mm cropped to 2.40:1 (as he did on Open Range) in favor of a taller aspect ratio. A-Camera Operator Alan Jacoby notes that, “The landscape and the locations are characters in this movie. Having the top and bottom of 1.85 just gives us more of that expansive feel for the western expansion story that we’re trying to tell.” To support that goal, Horizon: Chapter 1 was shot in 6K, 16:9, utilizing a Super 35 area of the RED V-RAPTOR’s large-format sensor and framed for a 1.85:1 extraction.

Muro’s selection of the V-RAPTOR (RED’s V-RAPTOR XL was used for Chapter 2) came

after testing he had done on the Paramount+ episodic drama SEAL Team. “I was shocked by how good the Raptor was,” Muro recalls. “It was light-years better than what I’d been using. I was so happy with that sensor.” The RED’s compact nature also appealed to Muro, who appreciates “the project box nature of RED’s many camera systems.” After selecting the V-RAPTOR, Muro consulted with 1st AC Alex Scott (working with Eric Messerschmidt, ASC and David Fincher at the time), who recommended pairing it with Leitz Summilux-C lenses. This combination proved crucial in achieving the film’s distinctive look. “Alex’s recommendation was great and I think we hit the jackpot when we found that combo,” Muro notes. “The look of Horizon is unlike many of the films in the last 20 years.”

Breaking away from the prevailing trend of shallow focus for daytime exteriors, Muro also opted to keep the backgrounds in focus with stops between 5.6 and 11. This approach lets the exquisite locations create depth naturally. As Jacoby asserts: “We want the viewer to understand that we’re not shooting on a soundstage, and it’s not with a backdrop, CG or AI. These are real locations.”

The Local 600 camera team employed a three-camera setup for nearly every scene, with Muro always operating C-Camera. This allowed for capturing spontaneous moments and unique angles, affectionately referred to as “Jimmy shots.” “It gives me great joy to just sneak in there with the third camera and then all of sudden it’s like the primary shot that the editor chose,” the longtime Steadicam-operator-turned-director-ofphotography reflects.

Costner’s vision called for a return to classic filmmaking techniques in other areas.

“Kevin is not a handheld filmmaker,” Muro explains. “So, we decided we’d go back to the classic John Ford approach. When the camera moved, it would always mean something; it would never be gratuitous.” As such, the team primarily relied on sliders, Steadicam and a jib, using tools like the Technocrane sparingly. For the majority of the shots, Jacoby operated A-camera on a Lambda head at the end of a 10-foot jib arm attached to an electric four-wheeler, providing extraordinary flexibility and efficiency across a variety of terrain.

The straightforward approach to gear and camera movement allowed for quick adaptations, which were important given

the lack of formal rehearsals. As Jacoby explains: “Kevin is an actor’s director, first and foremost. So, we would shoot what would normally be considered rehearsals, see what we captured, and then just refine it. Spontaneity was the key.” Minimal takes, multiple cameras, unfussy equipment and letting the natural beauty of the locations, the skill of the cast and the power of the script take center stage – these were the guiding principles on Horizon

The purity of Costner’s intent also extended to the film’s treatment of history. In establishing the reality of the time and place, extraordinary attention to detail was paid to the props and costumes. Western wagons were custom-built by the Amish community in Pennsylvania to specifications suitable for filming, while remaining authentic.

Costume designer Lisa Lovaas based all her designs on reference images from the era, going so far as to photograph original patterns of women’s clothing to ensure period-accurate prints on dresses. “Kevin wants people to experience something,” Muro details. “So the telling of this part of America’s history is not about changing history. It’s not about manipulating history; it’s about showing how difficult it was in those days and creating the reality of the

OPPOSITE PAGE/ ABOVE: UTAH’S VISUAL GRANDEUR PROVED IDEAL FOR HORIZON’S EPIC SCOPE. DIRECTOR COSTNER MADE AN IMPASSIONED PLEA BEFORE THE UTAH SENATE FOR SHOOTING IN THE STATE, WHICH HELPED TO SECURE A CRUCIAL FILM TAX REBATE.

period so people can feel like they go there when they watch this movie.” As Lovaas adds, “This is the Wild West, so Kevin is not sugarcoating the situation. What he wants is for people to absorb what it must have been like back then.”

From the very beginning, Costner’s focus was on making the Horizon saga a theatrical experience, with the grandeur of the visuals matching that of the story, and evoking the feeling of the films from his childhood. To achieve the desired cinematic look, a hybrid digital-film grading process was employed. In an unexpected discovery during post-production, FotoKem’s SHIFT Analog Intermediate process was suggested. The process involves printing the digitallyacquired and color-graded images to celluloid film and scanning them back to digital.

“Many of the great Westerns in cinema history were originally experienced on a film print,” explains FotoKem Senior Colorist Phil Beckner. “So, while this movie was acquired

digitally, we knew we wanted to incorporate a strong filmic look in the final product to bring that same experience to modern moviegoers.”

For Horizon: Chapter 1 , approximately 50 percent of the scenes underwent an additional printing to an interpositive film stock before re-scanning. This technique was applied to all night scenes and those at Watt’s Parish, based on aesthetic preferences. The strategy shifted for Chapter 2, exclusively utilizing a 50 ASA negative film-out process for all scenes. Muro says he’s delighted with the results: “I was already thrilled with the look from the V-RAPTOR, but the filmout gives the footage a very unique color structure, and I just couldn’t be more pleased with it,” he notes.

Muro says his approach was deeply rooted in serving the story and Costner’s vision. “We want to get the best light we can. The best performances we can. And we were lucky. But we try to control our luck,” he

continues. “I get a text from Kevin in post, and he says, ‘Every time I go through the footage to make sure the scene is right, or I’m struggling with anything, I find something that you’ve offered that makes it all work, and I can’t thank you enough.’ With Kevin, I’m never just a pair of hands. I’m there to be creative.”

The 33-year working relationship between Muro and Costner has fostered a shorthand and collaborative synergy that other department heads noticed. “Jimmy and Kevin’s collaboration is one of the most beautiful and seamless I’ve ever witnessed,” shares Lovaas. “The way they talk to each other, their common voice and taste that they share is quite beautiful and I think contributed to harmony on the set.” The sentiment is echoed by Muro himself: “I’m super proud to be working with an American treasure in Kevin Costner,” he concludes. “Our collaboration is what I always aspired to have in my career in camera.”