ICG MAGAZINE

PLUTOFRESNEL: 80 W equivalent to 300 W Tungsten

BUILT-IN BATTERY: 3h on MAX Brightness

LEOFRESNEL: 250 W equivalent to 1000 W Tungsten

BUILT-IN BATTERY: 2h on MAX Brightness

PLUTOFRESNEL: 80 W equivalent to 300 W Tungsten

BUILT-IN BATTERY: 3h on MAX Brightness

LEOFRESNEL: 250 W equivalent to 1000 W Tungsten

BUILT-IN BATTERY: 2h on MAX Brightness

Astera’s new Fresnels offer a 15° to 60° beam angle and superior colors, thanks to its Titan LED Engine. Both models contain a battery and feature numours mounting options, making them the most portable Fresnel option for film, studio and event lighting.

Backside display with TouchSlider

www.astera-led.com/plutofresnel www.astera-led.com/leofresnel

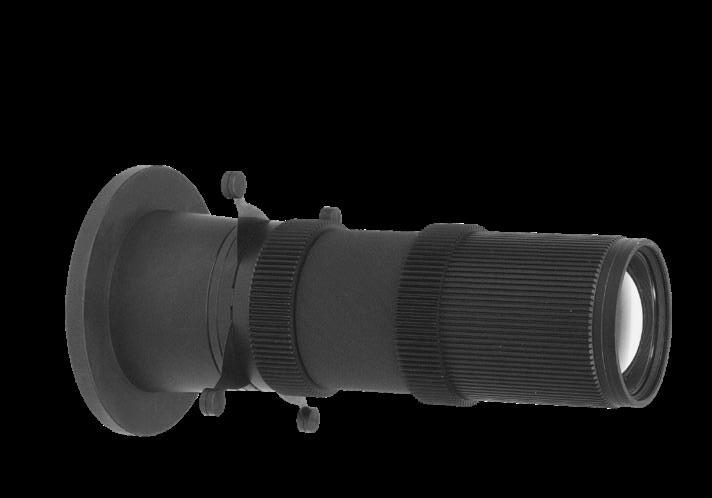

Projection lens with Zoom coming end of 2023

Television Academy

Saban Media Center Wolf Theatre • Los Angeles, CA

WWW.ECAWARDS.NET

SILVER SPONSORS

PREMIER SPONSOR

BRONZE SPONSORS

This issue of ICG Magazine highlights some of the many locations our membership visits for work. Although the current WGA/SAG strikes have frozen much of this industry’s union workforce in place, there will be a time (hopefully very soon) when IATSE production crews will hit the road again, bringing their world-class skills to locations near and far. Traveling for a job is something I know a little about, as being a camera technician has taken me all around this country and halfway around the world. And as most of this membership knows, it’s not the jet-set life those outside our industry might imagine.

Shooting on location can often mean some unplanned “adventures” – like a film I worked on near Acapulco, Mexico, where the smoke pots we used set a field on fire. After getting our camera equipment back to the truck, we (foolishly) rushed back to help put out the fire – until a military water truck came and finished the job.

There was also a time shooting on a river near Cuernavaca (also in Mexico). The script called for blowing up a bridge, which had to be built. That bridge became so popular with the locals, we had to post security guards to stop people from using it (until we could really blow it up)! For a show with Allen Daviau, ASC, shot in the Costa Rican jungle, I passed out and had to be air-lifted out by helicopter. Turns out I had been climbing up and down a volcano with a camera backpack that had the sternum straps so tight they closed off my airway. (My fault for grabbing the wrong backpack).

The teaching moment from that experience (and others for which safety was a factor) is that if I had not been working with a top-notch creative team (Director Frank Marshall and Producer Kathleen Kennedy) and a very experienced safety team on set, who knew exactly what they were doing, the outcome may have been very different.

That’s not to say international crews don’t have great technicians like our IATSE brothers and sisters. After all, filmmaking

is a universal language; and usually, the biggest obstacles on location are weather (my examples include a 120-degree shoot in Death Valley, CA; the worst snowstorm in half a century near Montreal, Canada; getting out of Hong Kong before a typhoon hit and shooting right after a hurricane on Kaui) and language. For example, crossing the border from Thailand into Cambodia to shoot in a refugee camp was an incredible experience. Looking back, communicating with the local Thai crews (who were great camera technicians) was the only real challenge.

A similar experience occurred when shooting Kodō drummers on Japan’s Sado Island. It was the first overnight flight I’d been on and, restless, I began wandering the aisles, where I struck up a conversation with a young Black brother (also from the U.S.). When the plane landed, I was met by my Japanese translator, who knew the young man I had befriended on the plane! Talk about a small world. As for the shoot, we waited on the island for four days to get a spectacular sunset (which finally came on the last day).

It is true that many international locations don’t have as deep an infrastructure for filmmaking as here in the U.S. Transportation and moving gear in and out of a remote location can be very challenging, especially if the (union) support and experience are lacking. And, let’s be honest, traveling to distant locations (especially when trying to raise a young family) is a chore.

But it’s not without some cool benefits.

Just ask my son, Baird Steptoe Jr., who, while in middle school, traveled from California to visit me on the Montreal set of The Sum of All Fears (shot by past ICG President John Lindley, ASC). I thought he was excited to see me at work. But it turned out his biggest thrill was being able to get a pair of the hottest new Nike sneakers – months before his friends could buy them in L.A.!

Here’s to hoping all our union brothers and sisters can be back out on location very soon, bringing our talents and expertise to parts unknown.

Masterpiece’s Entertainment Division understands the complex logistics of the industry including seemingly impossible deadlines, unconventional expedited routings, and show personnel that must be on hand. Masterpiece has the depth of resources to assist you in making sure everything comes together in time, every time.

Contact us to find out how our experienced team can securely and efficiently handle transporting to remote locations, made possible through our network of agents and partners around the globe. We have high-level access to restricted areas in all major international airports to oversee freight handling to make sure your precious cargo is always safe.

Our range of services, include:

• Performing Arts Industry Expertise

• Customs Brokers

• Freight Forwarders

• ATA Carnet Prep & Delivery

• Border Crossings

• Domestic Truck Transport

• International Transport via Air or Ocean

• Expedited Shipping Services

• 24/7 Service Available

Publisher

Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

STAFF WRITER

Pauline Rogers

COMMUNICATIONS COORDINATOR

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley CONTRIBUTORS

September 2023

vol. 94 no. 08

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

Baird B Steptoe

VICE PRESIDENT

Chris Silano

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Mark H. Weingartner

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER

Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Jamie Silverstein

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS

Betsy Peoples

NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Alex Tonisson

COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE

John Lindley, ASC, Co-Chair Chris Silano, Co-Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook: @theicgmag

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2021, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

Margot Lester Lara Solanki

This month’s issue is themed around Locations , and ICG readers would be hard-pressed to find a better place to make a hit TV show than Chicago.

The fact that FX/Hulu’s The Bear received 13 Emmy nominations in its first season is due mainly to the terrific creative team behind the lens of the food-themed series that’s captured America’s heart (and taste buds). But let’s not diminish the role the city of Chicago plays – in front of and behind the lens.

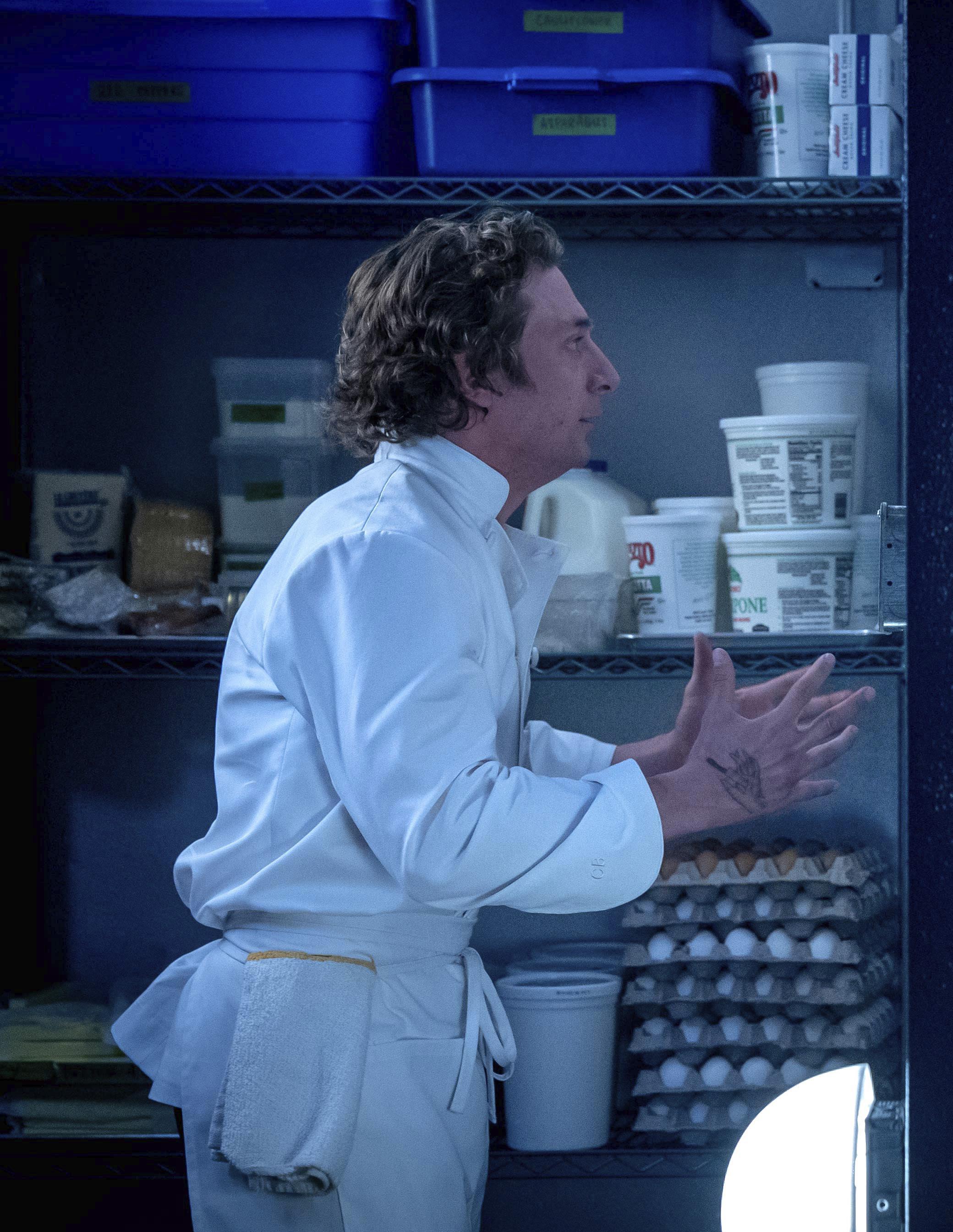

Pretty much everyone ICG Staff Writer Pauline Rogers interviewed for our cover story (page 18) said how proud they were to see their city presented in such a bright light. That starts with Director of Photography Andrew “Drew” Wehde, whom we first covered for the 2018 Sundance indie Eighth Grade [ICG Magazine Next-Level Filmmaking] and who now sits atop the episodic mountain with a show all about his hometown. Season 2 sees The Bear’s perpetually challenged chef, Carmen “Carmy” Berzatto (a terrific Jeremey Allen White), and his ever-feisty kitchen staff struggling to open a new finedining eatery. As Wehde told Rogers: “We wanted to make sure viewers understand how important Chicago is to everyone – not just to the characters but to the filmmakers who live here and make this series.”

Considering how quickly The Bear was produced – 10 episodes in 45 days – that goal was hardly a given. As A-Camera 1st AC Matt Rozek described about escaping the heat of the kitchen, “We had spent the better part of a day shooting Ayo [Edebiri, as Sydney Adamu] on the train for her episode where she traverses the city and hits a lot of restaurants. We had finished with the scripted work and were headed back to the station where we could unload, so we just wheeled the dolly with the Ronin up to the front of the train and started shooting out of the front – crazy upangles, slow pans as we came around corners in the Loop, Dutch angles as other trains passed on opposing tracks. When people saw the dailies the next day, they loved it. By the time we wrapped, we had shot the city

from every angle, from every mode of transport –train, boat, helicopter, city driving, freeway driving, everything.”

Finding the unseen was also the blueprint for Season 2 of Netflix’s The Lincoln Lawyer In an interview done before the WGA strike, showrunner Ted Humphrey described Los Angeles as “atmospheric,” but with a lot more to it than just Hollywood and celebrities. “It’s bright and sunny, but that just serves to accentuate the darkness lurking around every corner,” he says in the story (page 32), also written by Rogers. And while Season 1 stuck to mostly familiar Westside locations, viewers in Season 2 are treated to more off-the-grid L.A., everything from Frogtown to Valencia, Baldwin Hills to Chatsworth, and points in between.

What’s also cool about Season 2 is that both directors of photography have the same Latino/ Mexican ancestry that formed Los Angeles (or its original nomenclature, El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles). Abraham Martinez is a 25-year L.A. resident, known for projects like 61st Street , Queen of the South , and The Chi ; Pedro Gómez Millán, AMC, was born and raised in Mexico City and has credits that include Search Party , Little America , and Gentefied . As Millán explained the approach for Season 2, “We wanted to explore the east side and the gentrification in those neighborhoods. That meant delving more into an earth-color palette and finding the right spots to place the camera to feature those great locations.”

Exploring our annual Emerging Cinematographer Awards (ECA) section (page 48) is another treat, as it marks the first time the ECA’s have been awarded post-pandemic. (Last year’s in-person ECA’s went to the 2020 honorees delayed by COVID.) This year also serves as the 25th anniversary of an event co-founded by Guild member Rob Kositchek and ICG President Emeritus George Spiro Dibie, ASC. Currently cochaired by longtime ICG Director of Photography Jimmy Matlosz and former ICG President Steven Poster, ASC, all the proceeds and sponsorships of the ECAs go into ICG’s scholarship fund.

What’s unique about this 2023 class is that they all voiced how the events of these past years have changed them – as filmmakers and people. Some shot their movies in the darkest days of the pandemic, others wanted to be part of stories that tackled issues of race, gender identity, and crime that have been dominating the headlines. To a one, they view their ECA peer recognition as a validation of their career choices and of the union that supports them.

David Geffner Executive Editor

Executive Editor

Email: david@icgmagazine.com

2023 ECA Honorees

“It’s hard to believe I’ve been profiling ECA winners for more than a decade!. And you know what? I’m as impressed by the creativity and talent of this 2023 class, as was with that very first group years ago!”

Angels Flight, Stop Motion

“I absolutely love working on set as a unit photographer, capturing key details and moments. But the position comes with its own unique set of challenges, so I want to use this space to give a shout-out to all the Local 600 camera members – from DP’s to operators, from 1st and 2nd AC’s to DIT’s, loaders, and utilities – who have provided support to me throughout the years. From creating space on the camera truck for my gear and making space next to camera, to checking in with me to make sure I’m getting what I needed, that support has made all the difference to me and my job. You know who you are and know that you are all so appreciated!”

It isn’t often a Hollywood icon writes an honest biography (without pushing the sympathy button) that is painful (without daring you to feel for him/her), practical (a sharp-eyed take on the art and business of Hollywood) and also inspiring. I only wish I’d been able to read Duke’s book before my first encounter with him as a director. It may sound ridiculous, but as a white Jewish woman, I (like many others), coming into the entertainment industry in the 1980s, could relate well to what Duke endured, only from a woman’s place.

One of the tricks to drawing a reader into a book is the dedication, and Duke had me with his first quote. “To not the wisdom seekers but those who, in spite of losses, defeats, accomplishments, and victories, constantly ask the question ‘Why?’” That’s a question I still ask myself dozens of times a day, so by page one, Bill Duke: My 40-Year Career on Screen and Behind the Camera had me hooked.

Duke’s prologue is a powerful statement about Hollywood when he started, and, sadly, where we are again. It’s also an empowering lesson we all should learn.

As he writes: “In December 1982, with several

episodes of Flamingo Road, Falcon Crest and other television shows under my belt, I made my way to CBS Studios to direct my first episode of the primetime soap opera of that time, Dallas. Although Falcon Crest was a top-ten hit, Dallas was the holy grail of television. An opportunity to direct an episode of the number-one prime-time show – in its third year at the top of the ratings – was confirmation that I had proven my skills. At 8:00 a.m. I drove to the studio lot for my first day of work. When I arrived at the gate, the large white security guard asked, ‘Who are you delivering for?’ ‘I’m sorry,’ I replied. ‘Who are you delivering for?’ he repeated.

“I looked at the guard for what felt like an eternity. My mind flashed back to some of the many insults I had endured in my youth. I had been called nigger, coon, blackie, darkie, and tar baby, among other things; and in that moment, it felt like little had changed.”

In the book, Duke candidly expressed what he wanted to say, but in the story, he sits in silence, staring at the man’s smug face. Duke recalls what he had learned from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the sacrifices made. Without that, Duke believes his “career would never have been possible.” After a

few moments, he takes a breath. “There is obviously a misunderstanding,” he continued. “I am the first black director on Dallas, the number-one hit show on television, and what I’m delivering is my expertise and talent to that show.”

Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, on February 20, 1943, Duke’s early childhood was cloistered and almost idyllic – for the world he inhabited. There was dancing, baths in an old tin tub, and warm blankets. He grew up among hard-working foundry workers, and despite the harsh conditions, there was always laughter. However, a different reality crept in, as Duke began to experience what it was like to be a Black child in the 1950s.

He recounts a third-grade teacher, during history week, trying to be inclusive with the Black children in the room. She chose pictures of George Washington Carver and the book Little Black Sambo. As Duke writes: “As I look back now, I realize that it was not the teacher’s conscious attempt to diminish my significance or the significance of any other people of color in the class. She truly believed there was no difference between George Washington Carver

and Little Black Sambo…It was the ignorance of assumption – not of intentional malice – but an expectation of privilege and assumed superiority. We were recognized, but our true worth was unrecognizable.”

That dichotomy underlines every story Duke shares.

And each is worth reading. From his days panhandling on the streets to the jeering he took wandering the halls of Boston University and NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts in tights because he was taking dance to enhance his understanding of acting, to the many later inequities once he moved into the entertainment industry, Duke’s approach is always enlightening. His practicality is a lesson for not just actors but anyone in the industry.

“I learned that every movement of the body had meaning,” he writes. “Under her [Jean Erdman, a well-known dance and movement choreographer and principal with Martha Graham Dance Company], we learned what movement meant in terms of the character being portrayed and what silence and stillness meant to movement. She taught that movement was a physical expression of emotions and that sometimes movement was parallel to our feelings; other times, it was contradictory.” Duke talks about another plus – meeting and befriending Erdman’s husband – Joseph Campbell – author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, whose principles influenced future directing choices.

He also cites the many influences throughout his career, including other Black professionals who had previously broken ground in the industry, and those who were color blind and nurtured him along the way. Even the sad stories taught him lessons, such as one about a trip to Rome and a tour where an elderly white woman followed his group of Black people. Duke questioned the tour guide, who turned and said: “You’re not going to believe this. But she said [she’s following] because you’re all Black people [and] she was looking to see if she could find [our] tails.”

As for Duke’s acting career, it was eclectic. His résumé includes Car Wash , American Gigolo , Predator, Action Jackson, X-Men, Menace II Society, and many more. His thoughts on the craft are some that every actor should consider. It’s about the words – yes. But it’s also about the body, the emotion, and what’s behind each character.

Take Car Wash, a raunchy comedy, yes. But Duke digs into the character and the theme, and suddenly that comedy is a platform for a very deep message.

As he writes: “In terms of what young Black men were going through at that time, which my character, Raheem, symbolized. Raheem showed the rage and

anger that young Black men felt in the system. We were in a situation of desperation because no one could ‘hear’ our voices.”

Happenstance and hard work led to Duke becoming a director. He talks about getting a job in the rarefied world of nighttime soap operas. “One of the most popular and longest-running was Knots Landing, a spin-off of Dallas… I had the opportunity to direct it due to a mistake in which the executive producer mixed up my submission tape with someone else’s. I knew how difficult television was as an actor, and I found out that it’s a real challenge as a director, too.” Duke talks frankly about the craft of directing, the pressure of being in charge of so many creatives, and the travel to fascinating locations, including a story about taking some downtime in Hawaii that ended up in a plane crash!

That near-death experience invigorated his determination to grow his directing career. Duke talks about A Rage In Harlem and the message behind it, the challenges of a Black man directing older white women in The Cemetery Club, and being part of a phenomenon that no one saw coming with Whoopi Goldberg and her Sister Act series.

Not one to slow down, Duke takes the reader out of Hollywood and into his newest passion, the Duke Media Foundation, which he views as a career legacy project. “So, I could make a difference and leave something behind,” Duke writes, “I have always understood the plight of low-income children in this world, particularly in this country. In the past, I would send donations to various organizations, but I found it quite frustrating.”

Duke began his efforts by appealing to students interested in technology and preparing them for the working world. He bypassed Hollywood, describing where he spent his career as “too narrow. We are a media industry, from cell phone apps to video games to online distribution, webisodes, and podcasts,” he shares. “I wanted to make sure students understand the industry, how it has changed, and what it has become. This is how I make a difference,” he concludes. “Education….”

Ever honest and frank about his life, Duke’s other dedication, in this easily read and easily relatable book is: “To those who are told, whether out of love or doubt, ‘this cannot be done,’ ‘stop dreaming,’ or ‘that’s impossible’ and still keep believing they can.”

Bill Duke: My 40-Year Career on Screen and Behind the Camera Rowman & Littlefield

978-1-5381-0555-9 (paperback) $24.95

978-1-5381-0556-6 (ebook) $17.99

BY PAULINE ROGERS

BY PAULINE ROGERS

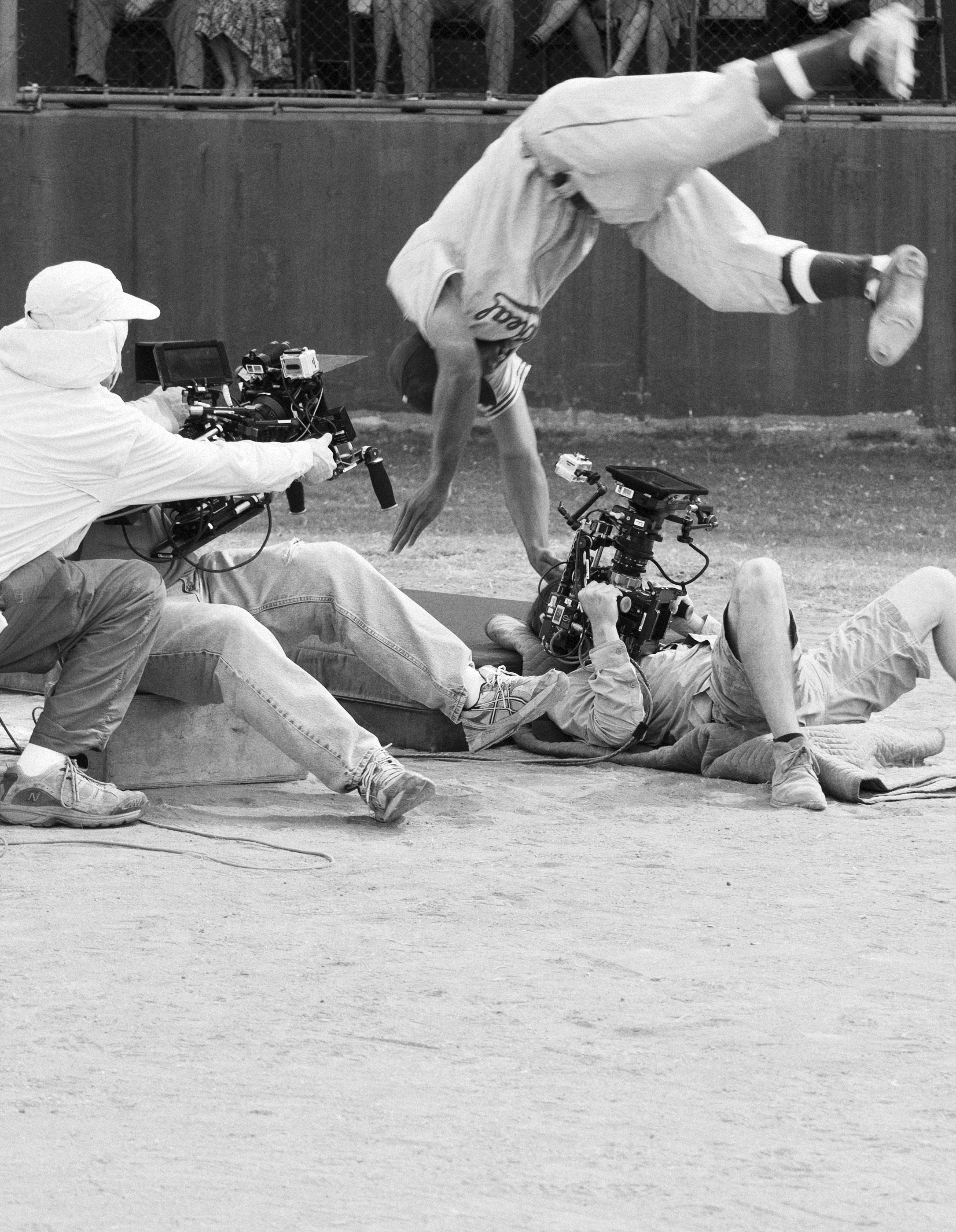

Melinda Sue Gordon, SMPSP , is a 2007 SOC Lifetime Achievement Award winner and 2009 ICG Publicist Guild Award winner, and one of the most prolific unit still photographers in the industry. With an enviable range of work that includes Field of Dreams, The Addams Family and Addams Family Values, Men in Black I and II , A Prairie Home Companion , The Reader, Oceans Thirteen, Moneyball, The Hangover Part II and Part III, Interstellar, There Will Be Blood and the upcoming Killers of the Flower Moon , Gordon says her approach to the craft is rooted in documentary photography.

During undergraduate school, Gordon spent a semester studying Aztec and Mayan culture in Guatemala, where she took along a camera and ten rolls of film. “This is when I first used shooting photographs to interpret what I was experiencing formally,” she recalls. “It also helped push me into engaging with people.”

In the early 1980s, Gordon attended AFI as a cinematography fellow studying under George Folsey Sr., ASC (Monkey Business, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers , Forbidden Planet ). “We all worked on each other’s projects, and I always had a camera with me,” she describes. “I would spend most of my free time printing up those ‘happy snaps’ and then handing them out. One project I worked on as both a second assistant and still photographer was Miss Lonelyhearts [directed by Micheal Dinner and shot by Juan Ruiz Anchía], which was shot in 35-millimeter black and white. It was picked up by American Playhouse, and they used my images for promotion. Several years later, they were producing Testament, and they remembered my name, and I got the job.”

A short stint as a cinematographer was creative and interesting but led to a professional crossroads. So, when Gordon was given the chance to shoot unit stills for Peter Weir’s The Truman Show , she jumped on board, calling the project an “incredible experience” with a director who inspired both the cast and crew.

“We lived in the set on location in Seaside, Florida,” she recalls. “I started a week before principal photography to create photos of Truman’s backstory from his birth through adulthood that play

in the film. It required setting up for images as varied as family photos to product photography to Hurrellstyle portraits. By the time we started shooting, I was completely invested in the story and characters.”

Locations have been a big part of Gordon’s career, and serendipity is a factor in the projects she’s worked on. When a friend, working at a rental house, was shipping lighting and grip equipment to Scottsdale, AZ, where he knew Gordon was from, he suggested she call to see if they needed a photographer. “It was a Friday, and I cold-called the office,” she remembers. “Silence on the other end of the line and then, ‘We’ll call you back.’ They had forgotten to hire anyone! They called Fox [the project was a negative pickup], and the photo editor, Bette Einbinder, suggested they hire me.”

Long story short, Gordon found herself on the set of Raising Arizona that next Monday, going on to do another five films with the Coen Brothers and four more with Director of Photography-turnedDirector Barry Sonnenfeld, ASC. “Perhaps my favorite Coen Brothers film is O Brother, Where Art Thou? ” she muses. “I loved the script, music, cast and crew. Not so much shooting during the

summer in Mississippi. Besides the heat, humidity and snakes, there was poison ivy, poison oak and poison sumac to contend with.”

Regarding the switch from film to digital capture, Gordon counts herself lucky because of her darkroom, retouching and restoration experience. “That background allowed me to pick up digital manipulation quickly,” she insists. “As for the cameras, they are tools – my main interest is the image. I love to be able to shoot with compositing in mind. On set, it is an in-spite-of-it-all situation –knowing I can create an image that tells the story by shooting various frames allows me to offer up those images to the filmmakers and photo editor. Many of them end up in the final press selection.”

As Gordon said in a 2009 ICG Magazine interview, “It’s a mixed bag, with digital being the format of choice now. The logistical time needed to do our digital work can be a challenge. I can often fold the work into the day when shooting on stage with downtime during lighting setups. On location, it is almost impossible to do. I take much more

work home than is healthy. On the flip side, another advantage not mentioned yet is the ability to change ASA and color temperature from shot to shot. No more coolers full of every flavor film imaginable, worrying about how hot the camera truck gets when it’s locked up on the weekends!”

A bigger change, psychologically speaking, was the move to mirrorless cameras.

“I liked hiding behind the blimp,” Gordon admits. “It made me feel less intrusive for the actors. I finally switched on Dunkirk when I knew I would have to carry everything I needed all day. At wrap one evening, I was walking with Kenneth Branagh the mile back to shore, along the mole that jutted out into the English Channel. He asked where my blimp was. I explained how the camera I had was silent since it didn’t have a mirror moving with each exposure. I also told him about my fear of being more of a distraction with my face exposed. He kindly assured me that wasn’t the case, and I decided to let that anxiety go – although I usually shoot using the viewfinder rather than the rear monitor with that in mind.”

Ever the innovator, Gordon has had several exciting opportunities to stretch her creativity in the past few years. A case in point was shooting stills in an LED volume for Season 1 of The Mandalorian [Opposite page 17 and ICG Magazine February/

March 2020]. “It was wonderful to be shooting in a space that looked real as opposed to a blue or green screen,” she recounts. “At that time, I was using a Canon 5D Mark IV for the gallery work and the Fujifilm XH-1 bodies for the Volume. I asked ILM’s ‘Brain Bar’ group, who were working the computers on stage, how to avoid the dreaded rolling shutter banding that occasionally appeared, especially in low light or at fast shutter speeds. The suggestion was to adjust the shutter speed to increments that weren’t available. I managed to come up with workarounds; but happily, with newer cameras, like the Fujifilm XH-2, these issues are less of a challenge. None too soon since now so many light fixtures also use LED technology.”

Most recently, Gordon went back to her documentary roots for Chris Nolan’s epic summer release Oppenheimer (page 15, above, and ICG Magazine August 2023], shot on location in New Mexico and other states. “Because it was based on true events and real people, we worked hard to create historically accurate images of the time and events,” Gordon shares. “Working with Chris Nolan is very specific. The set is minimal, with few people, no video village, no place to sit down. It’s not easy, but Chris understands and values what each crew person has to offer. I especially loved documenting the work of Visual Effects Supervisor

Andrew Jackson and Special Effects Supervisor

Scott Fisher in what I called their ‘mad scientist lab.’ It was marvelous.”

When Gordon isn’t traveling around the world on a production, she’s trying to support and promote her fellow still photographers. “When I first started shooting stills on set,” she explains, “we didn’t often run into other photographers. Usually just at the lab or at a studio photo department. That changed when Peter Sorel founded the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers [SMPSP] in 1995. It allowed us to get to know one another and our work, and help each other out. Considering we are all competitors for the same jobs, it has been an amazingly supportive group.” [Gordon also represents unit still photographers on Local 600’s National Executive Board.]

Despite some seismic industry shifts throughout Gordon’s career, technological and otherwise, it’s clear her passion has never waned – and she’s eagerly looking ahead to future challenges. “Unit still photographers have to love what they do,” she concludes, “because it requires skill, stamina and diplomacy to do well. It’s not just the time you put in on set, it’s also about really paying attention, figuring things out on the fly, and making sure you’re always there, out of the way and ready.”

BY PAULINE ROGERS

BY PAULINE ROGERS

FEATURE 01

The tight confines of a Chicago sandwich shop, in The Bear’s debut season, was a perfect environment to highlight a dysfunctional “family” trying to save a failing business. Season 2, however, serves up a buffet of different storylines. Yes, confrontation and confusion are still a prime ingredient of this 13-timeEmmy-nominated series, which in Season 1 centered around Carmen “Carmy” Berzatto (Jeremy Allen White), a young, award-winning chef from the fine-dining world who returns home to run his deceased brother’s neighborhood sandwich shop (modeled after the real-life eatery Mr. Beef). But Season 2 of The Bear changes up the menu, offering not just the inner workings of how Carmy and his rough-aroundthe-edges kitchen staff build a new location for the restaurant but also how the characters fit into one of the main stars of the show, the city of Chicago.

“We want to make sure viewers understand how important Chicago is to everyone – not just the characters but the filmmakers who live here and make this series,” explains The Bear’s Director of Photography Andrew “Drew” Wehde. “Throughout the 10 episodes [shot over 45 days], we take the audience on a tour of what makes the city so unique. We visit restaurants like Pequod’s, Kasama, Publican, Avec, and places like Margie’s Candies, Giant, and Elske. We wanted to pay tribute to those who have been relentlessly churning out incredible food for years and those new to the scene with that same devotion and desire.”

That’s a tall order, and the only reason the team could pull it off is the close creative relationship between creator/director Chris Storer and his longtime collaborator Wehde, who have been working together for more than a decade. Wehde understands Storer’s storytelling style, adding that “my whole camera team is encouraged to take those extra moments to discuss and understand every scene, every beat, and highlight all these beautiful moments.

“We talked a lot about season two and our desire to make it feel big, more cinematic than season one,” he continues. “Every location was prepped and pre-rigged for a variety of lighting choices, all of which were controlled remotely per our dimming board operator [Neil Adamson].” The idea was to go into each location with a plan, but always have options to show Storer on the fly, providing what Wehde describes as “the ability to rift and play with ideas in the moment on location and stage that may feel more aligned with the performances we were seeing during the rehearsals.”

Wehde’s crew has been together for years. They know each other well, which means he can rely on their creative input. “It allows us to work in a very non-verbal way,” Wehde adds. “Gary Malouf and I started together, and he’s operated on all of my work. Gary’s an extension of myself and is a major part of the look. We spend more time laughing on set than talking. Our shorthand is hard to explain.”

What’s not hard to explain (and key to making The Bear’s location work run smoothly) is the longtime team around Wehde who impact the efficiency of each set. Partners like Chief Lighting Technician Jeremy Long and Key Grip Dave Wagenaar have creative freedom, which is how

Wehde wants it. “As a cinematographer, it’s important to understand how much we are responsible for, and if I were to micromanage everyone, the work would suffer,” Wehde states. “I always say, ‘Embrace their focus and love. Let them run with it; I can always pull them back or help guide them on a specific path that I know will match the story best.’”

The intense collaboration with all departments also helps on the front end.

“Our Production Designer Merje Veski was on the same page with everyone when we started prep on the new season,” Wehde continues. “Her work is impeccable and precise. She can take any bit of information and transform it into exactly what we envisioned. The relationship between a cinematographer and production designer is crucial; it will directly translate onto the screen, so finding that bond is key.”

One prime example is the moment Wehde and Veski knew a new restaurant would need to be built for Season 2, they started conferring on the design. Wehde says his goal was to take Veski’s “incredible spaces” and find ways to marry light and space together. “I wanted the new kitchen to feel architectural with lighting,” he describes, “in a way that would remove any movie lights from the set. I wanted a space that would feel bright but also have shape and in-camera fixtures that would create interest.”

The pair were inspired by two classics of fine dining: Thomas Keller’s legendary The French Laundry (in Yountville, CA) and the double-Michelin-starred Chicago eatery Ever, created by Chef Curtis Duffy. In both examples, the linear lighting in the ceiling helps to define the kitchen spaces. So, the intention was to give the prep space a soft and beautiful light. Working closely with Wehde, Long built plexiglass soft boxes on the bottoms of all the hanging shelves. This became a focal point of the prep space and provided flexibility for shooting food in the last three episodes. “It gave the food a new look versus that of Season 1, elevating and matching the new restaurant perfectly,” Wehde says.

Veski also designed a linear window that divided the kitchen from the dining room. Wehde’s thought was to take the same linear lighting to the area around the window and into the swinging door. “Again, it gave us incamera practical lighting and a natural edge to bring a soft light source to the eye height of the actors,” he continues. “Construction

“WE WANT TO MAKE SURE VIEWERS UNDERSTAND HOW IMPORTANT CHICAGO IS TO EVERYONE – NOT JUST THE CHARACTERS BUT THE FILMMAKERS WHO LIVE HERE AND MAKE THIS SERIES.”

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ANDREW WEHDE

designed a swinging door with electrical for us. It was beautiful and played a huge part in our blocking. Everyone looked their best around the expedite station. At times, prep felt like we were not making TV, but rather we were racing the clock to design and create a restaurant.”

When it comes to lighting innovation, Wehde calls Long a magician. “We needed to be able to shoot 360,” Wehde recounts. “And that puts a lot of pressure on a gaffer to think outside the box and give us a multitude of lighting setups, all remote controlled, to allow us to adjust based on any new blocking during rehearsals. We embraced LED fixtures with high CRI levels [Astera Titan and Helios Tubes, Creamsource Vortex8 and Vortex4]. Quality of light is super important to Jeremy, and his team works hard to make sure everything is programmed and, at times, even configured differently through the board to get the best out of the lights.

“Our shorthand is funny,” Wehde admits. “I am a naturalist at heart and like to harness the light and beauty of what might exist at certain moments that we have seen. Jeremy has this ability to decipher my nonsense into a detailed lighting plot for all locations. We paint with lights and adjust all perimeters until the first take. Then we stop. But it’s an absolute blast how much lighting has evolved in the last few years and how much we can impact the look and grade of the show through these LED fixtures.”

Camera and lens choices play a big factor as well. As Season 2 needed to feel like a natural progression, Wehde says, “The ALEXA Mini LF felt like the right tool to continue with. I love the large format, as, coming from photography, it’s the way I see the world. Lenses match and make more sense in terms of focal lengths in a large format, and it’s the space [in which] I feel most comfortable. I also love how well the LF can handle highlights, and we’d embrace that with the way we exposed the camera.” Season 1 was shot at 3200 ASA on the Mini LF, and that EI carried over into Season 2. “It pushed my protection into highlights and gave us a more natural noise pattern in the midtones and highlights,” Wehde adds.

When it came to lenses, Wehde says Panavision, a key partner for many years, has helped him work toward building the perfect set. “In every show or movie I do, we take the serial numbers from the previous show and re-evaluate them and look to see if we can improve on specific focal lengths. I have been shooting with a modified H series set for the last three years, with specific serial numbers and new serial numbers that have come and gone over the years. Season 2 of The Bear brought the opportunity to dive even deeper into specific focal lengths with Dan Sasaki and Guy McVicker. This led us to find better-matched H-series lenses.”

Sasaki modified several one-off H-series lenses for Wehde. “One is a 50-millimeter H with a close focus of 14

inches and a T1 stop, which is an absolute gem,” Wehde beams. “The H series gives this classic soft feel with an organic focus roll-off. Not to mention they are very fast, which provides a ton of creative choices with depth-offield control. These optics give such a rich character to this show, and I truly believe they are a reason for the look.”

A-Camera 1st AC Matt Rozek adds, “Knowing the pace of the show, we prepped three cameras to have available basically at any time. [A-Camera 2nd AC] Matt Feasley and I dealt with the A-camera [handheld and studio] and the C-camera [dedicated to the Ronin], while [B-Camera 1st AC] Sam Knapp was almost always in studio mode on the Panavision 11:1. The Ronin, mounted on the dolly on the stage, allowed us to move through the shot list at a fast pace because we rarely had to put down track or even dance floor.”

“Then, when it was time to move on to handheld or studio,” Wehde picks up, “I could send Matt [Feasley] out to the cart to put a lens on and prep the other body while we finished the last take or two. When we did move on, Matt could walk in right away and put the camera onto the operator’s shoulder so he could immediately start lining up the next shot. I cannot stress this enough –there is very little wasted time on this set. So, everyone has to be on their game, ready to go from the moment the first AD says we are in.”

Wehde and Key Grip Wagenaar designed the system – the DJI Ronin 2 as a remote head-on A-camera dolly –so that depending on the surface, we could always roll on the ground, giving the dolly grip freedom of movement and the operators the chance to react to actors when a beat felt right. The stages were also designed to allow the dolly to roll anywhere. On location, the team adds a Custom Easy Raptor arm, the Raptor ISO 3, and a variety of vibration isolators depending on whether the Ronin is under- or over-slung, with the goal to always let the dolly be pushed on streets and sidewalks and, ultimately, provide the freedom of never shooting track.

Another essential element was on-set color and the desire to deliver dailies as close to the final color as possible. It’s a process Wehde developed gradually, adding a tool, or information, with each new show. In Season 2 of The Bear , what’s captured on set is what viewers see at home. “Thanks to [DIT] Tom Zimmerman’s knowledge of color and workflow, I can jump into the tent and make adjustments,” Wehde describes. “Tom keeps me honest and tracks it all precisely.”

As Zimmerman describes, “We utilize Pomfort Livegrade Studio as the software, and Tangent element TK panel to adjust shadow and highlights as well as Tangent KB panel to adjust color. Drew prefers this because he can isolate both the color channel along with high, medium, and low, using two factory-calibrated Flanders DM-240 monitors for color reference.” Wehde and Zimmerman also have Printer Lights set up on a Streamdeck to provide the DP with the ability to do quick RGB pushes, “but more importantly,” Wehde adds, “with

the speed we run, I can do full exposure pushes in one-third-stop increments. Post receives as close to a final product [as possible] every single day, Editorial gets to cut the show with the look that we love, and our producers and the studio review the day’s material in the intended way that we have envisioned the show.”

Zimmerman, who’s worked with Wehde for a long time, calls it a “pleasure” to see the Chicago-based camera crew get the recognition they deserve. “At the pace we run, we don’t have time for things not to work,” the DIT explains. “That means adding or upgrading requested pieces on my cart, having a backup plan in place and ready to implement, or building a smaller color station for us to use in small, third floor locations, like Carmy’s and Sydney’s apartments. I could not do this job effectively without the seamless back up of Digital Utility Sonia Jourdain and Loader Batoul [Raeyan] Odeh. Those are unsung positions, and they often carry the weight of the camera department without any complaint. I’ve never had any worries about camera footage being backed up or monitors or antennas being moved. I would go to do something and realize it was already done.”

Regarding the show’s other big star, Chicago, Rozek says, “the beautiful and unique look we had for the city this season came about almost by accident. We had spent the better part of a day shooting Ayo [Sydney Adamu] on the train for her episode where she traverses the city and hits a lot of restaurants. We had finished with the scripted work and were headed back to the station where we could unload, so we just wheeled the dolly with the Ronin up to the front of the train and started shooting out of the front – crazy up-angles, slow pans as we came around corners in the loop, dutch angles as other trains passed on opposing tracks. When people saw the dailies the next day, they loved it, so we started making plans to do more. By the time we wrapped, we had shot the city from every angle, from every mode of transport – train, boat, helicopter, city driving, freeway driving, everything. We got some unique perspectives that don’t always get showcased in Chicago.”

Zimmerman agrees, adding that “one of the “biggest surprises while watching Season 2 at home, was the use of all the helicopter, train, and other B-roll footage” of

the city. “It really is a valentine to Chicago. I loved that we didn’t just use stock footage or common angles of the city. There are shots of neighborhoods with the train slicing thru which is so representative of the way the city is laid out. “

B-Camera Operator Chris Dame says he has lived in Chicago for 30 years and is “proud of how many Chicago characters are a part of the story this season. For all the city exteriors, the B-Camera was on the Panavision 42-420. This is the same lens I had on season one. It has so much character and shines from 300-420 millimeter.”

Dame adds that one of the freedoms he’s given is that “I can roll the camera at any time. This means Sam [Knapp, B-camera 1st] is always ready to show off his talents. Being able to pop off inserts or go to any part of the frame, with the assistance of our dolly grip [John] Sircher] at any point, is a unique aspect of this show. Having a script supervisor and sound department that are ready for that is unique as well.”

Where would a story about rebranding a restaurant be without all those food inserts? As Wehde describes: “Shooting food is always interesting, and season one is where we found our style. It always landed in the world of graphic closeups on our 11-1 zoom lens. It was always the challenge of never shooting the food to shoot food but rather incorporating the food photography into the scenes, and always keeping the kitchen alive and busy.

“Season two kept this philosophy,” he continues, “but the introduction to the new restaurant meant an adjustment that aligned more with their desire to open a restaurant worthy of a Michelin star. This combined the season one long zoom lens work of digging into the details of the food, the details of the build, and the creation and execution of a dish with a second perspective that highlighted and celebrated a more static, curated food frame, which follows the process from raw to a finished plate. This gave Editorial the options on which visual style makes the most sense in those moments of the story.”

The biggest food prep and delivery comes at the new location in Episode 7, Fork, which was shot at Ever. Wehde says the goal was “to capture this space with the utmost respect to the existing interior and lighting design and to protect the vision of Chef Duffy and his team. We approached the food differently, using a 50- and 75-millimeter

“AT TIMES, PREP FELT LIKE WE WERE NOT MAKING A TV SERIES, BUT RATHER RACING THE CLOCK TO DESIGN AND CREATE A RESTAURANT.”

ABOVE/LEFT: FOR THE BEAR’S NEW MICHELIN-STARRED EATERY IN SEASON 2, PRODUCTION DESIGNER MERJE VESKI WAS INSPIRED BY TWO CLASSICS OF FINE DINING: THOMAS KELLER’S THE FRENCH LAUNDRY (IN YOUNTVILLE, CA) AND THE DOUBLEMICHELIN-STARRED CHICAGO EATERY EVER, CREATED BY CHEF CURTIS DUFFY.

WEHDE SAYS IN BOTH EXAMPLES, THE LINEAR LIGHTING IN THE CEILING HELPS TO DEFINE THE KITCHEN SPACES. “SO, THE INTENTION WAS TO GIVE THE PREP SPACE A SOFT AND BEAUTIFUL LIGHT. “

lens with diopters. This gave the world a different feel and made the food huge.”

Knapp recalls spending many days in Ever and shooting a lot of food.

“We would spend hours filming the actual chefs of Ever prep, cook, and clean,” he recounts. “Most of the time, we were on tight H series lenses with diopters – the reason being that most of the H series’ close focus goes to 2 or 2.5 feet. We wanted to throw on diopters and get as close as possible, sometimes mere inches. It was fascinating to watch and film those professional chefs doing their work, and something that I tell people was a highlight for me in working on this season. Those chefs are borderline running a military operation with hardly any words spoken. Each chef is focused on their job and performing it at the highest degree of difficulty and executed to perfection. It was a lot of fun seeing that world.”

One of the standout visual elements of Season 1 was a full episode oner. Season 2’s Episode 10 allowed the team to do another extended take, a 16-minute cut followed by 20 minutes of scene work. “This shot is a testament to how we raised the bar this season,” Rozek exclaims. “It’s not as long as last year’s oner, but it is technically more complicated. It takes a certain amount of insanity to do what we did as a oner – going from the most nuclear of lit spaces in that kitchen, where everything is bright white and reflective stainless steel, to the muted ambience of the dining room, where we stop and have conversations at a half-dozen tables, even back into the bathroom. The amount of lighting cues and camera choreography and details that went into the planning of the sequence was staggering. And that’s before you even add in all the food that must be precisely plated, the servers, the background, and the challenge of shooting in a working restaurant – because even though it is built on a stage, that is essentially what it is.”

Wehde explains that for the Season 2 oner, “we decided to maintain our light

levels throughout the take and utilize a Variable ND we could control remotely with my ARRI Hand Unit. This allowed us to maintain the depth of field at a T2.8. We had a base level in the dining room; the kitchen was three stops brighter, and the kitchen island was five stops brighter still.

“We couldn’t adjust the light level because it would change the ambient glow in the dining room,” he adds, “and I didn’t want a severe iris pull. Gary Malouf pulled off another handheld oner and even found ways to improve and make it bolder than in Season 1. Chris Storer put together a plan on overheads that helped all of us understand where each of the mini scenes would take place, and, with our experience from last season, we dialed this in with only one day of rehearsals, followed by five takes the next day, all by lunch.”

Besides the complex oner, Season 2 also includes several fun and unusual angles, like shooting through plexiglass as a menu is planned with a red marker; or from the inside of a wall that had been broken through. Two scenes that stand out include one from Episode 9, where the pressure is on to prepare the restaurant for its big opening. When Carmy sees a table that hasn’t been assembled correctly, he crawls, with Sidney, under the table to make it safe. The moment was a perfect opportunity to showcase the dolly and Ronin rig.

“We could scrape the floor very slowly, working our way to Carmy and Sydney,” Wehde recalls. “Without that rig, we would have needed an arm, and there never would have been room for that tool inside that set. It was also a great example of the organic development of a shot. It being a single uncut scene was never planned, but with Gary on A-camera and Mark on the dolly playing the movement, Chris saw the magic, as we did.”

Wehde also cites a shouting match between Richie [Ebon Moss-Bachrach] and Carmy, where Carmy is locked in the freezer. “We cut the wall out and did it practically in a split screen,” Wehde explains. “This scene came to Chris

Storer during the middle of shooting an earlier episode in the old restaurant. Every day we would come to check on the construction process of the new Bear. He had this brilliant idea of shooting the final fight between Carmy and Richie as a split screen, and our construction supervisor loved the idea and modified the build to accommodate. The scene was shot on our last day of principal photography.”

Rozek says it’s those types of shots and much more that make The Bear utterly unique in the world of episodic television. “I would challenge anyone to find another production that does the kinds of things we do on the timeline that we do them,” he concludes. “But then I look at our amazing [all-Chicago-based] crew, and it’s completely understandable. It makes me very excited for what is in store next season. We’ve all made it clear how much we love working on this show – and how anxious we are to return.”

Zimmerman’s thoughts echo Rozek, also describing The Bear as an outlier amongst all other shows he’s been on. “Two months from camera wrap to dropping on Hulu,” he concludes. “That fast turnaround comes from two things: Chris Storer’s vision and mental editing as we are shooting, and Drew’s embracing of on-set color correction and delivering a show that is close to final product. Drew also was committed to using a local Chicago crew full of people he knew and trusted. Our first season, we were a tiny show, on one little stage at Cinespace [Studios]. We all knew it was something special, watching the actors go through their paces. It’s gratifying to see it explode in popularity and critical praise.”

Wehde says The Bear’s massive success is directly proportional to the contributions of so many talented and hardworking filmmakers. “I am so proud to say this show is made in Chicago by a Chicago crew. As a community, we are showcasing that we can make and compete with the best in the world. I’m also proud to be born and raised in this city, and to have the chance to be working side by side with my friends and family on such a fantastic series.”

FOR A SHOUTING MATCH BETWEEN RICHIE [EBON MOSS-BACHRACH] AND CARMY, WHEN CARMY IS LOCKED IN THE FREEZER, WEHDE SAYS, “WE CUT THE WALL OUT AND DID IT PRACTICALLY IN A SPLIT SCREEN. OUR CONSTRUCTION SUPERVISOR LOVED [CREATOR/EP] CHRIS STORER’S IDEA TO DO THE SPLIT SCREEN IN-CAMERA, AND MODIFIED THE BUILD TO ACCOMMODATE.”

Season 2 of The Lincoln Lawyer visits rarely filmed pockets of L.A. – from Chatsworth to Frogtown and everywhere in between.

BY PAULINE ROGERS

BY PAULINE ROGERS

FEATURE 02

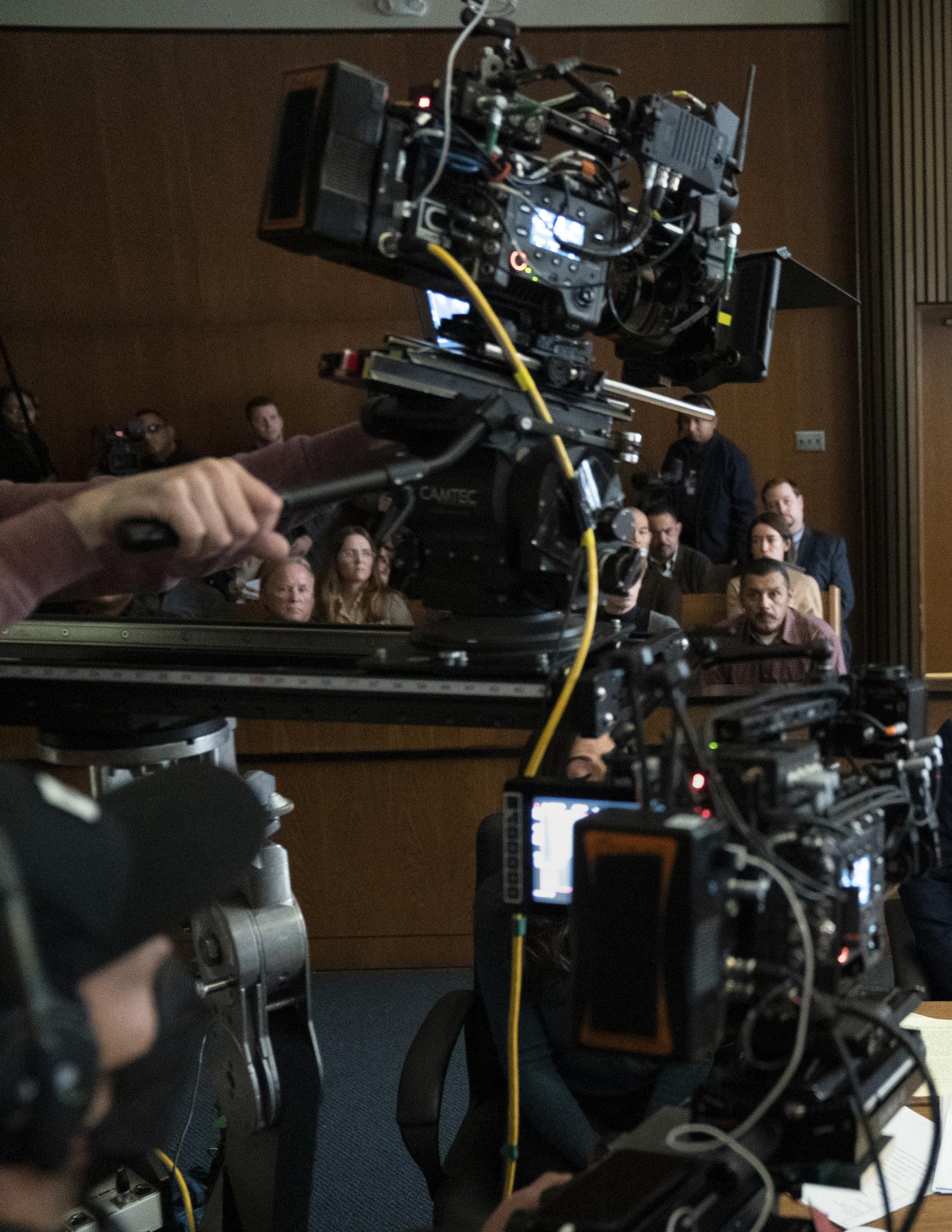

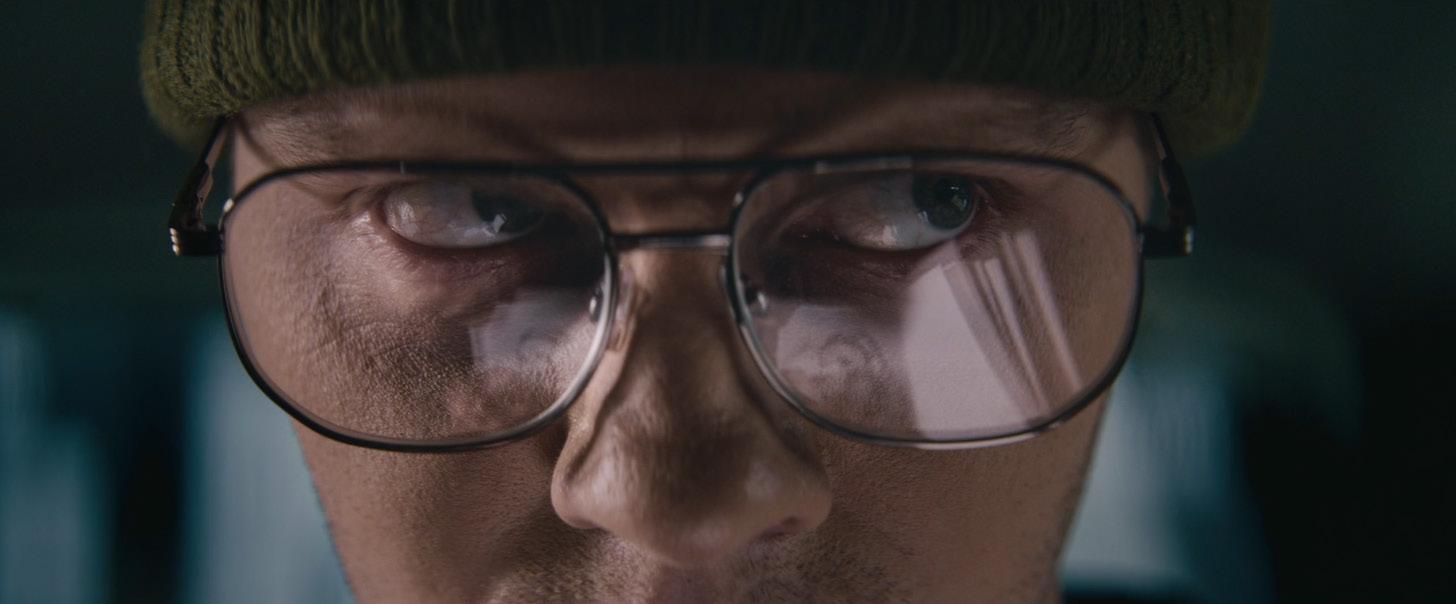

In an interview with the official Netflix fan site, Tudum, done before the WGA strike, Writer/Producer Ted Humphrey described Los Angeles as “such an atmospheric city – there is a lot more to it than the stereotype of Hollywood and celebrities. It is this mysterious, brooding entity. It’s bright and sunny, but that just serves to accentuate the darkness lurking around every corner.” What Humphrey was referencing was the backdrop for Season 2 of The Lincoln Lawyer, the popular Netflix crime series he oversees, created for television by David E. Kelley and based on Michael Connelly’s novel The Brass Ring The Lincoln Lawyer stars Manuel Garcia-Rulfo as Mickey Haller, a criminal defense lawyer and recovering addict (and the half-brother of Connelly staple Harry Bosch) who works out of the back of his Lincoln as he “navigates” the mean streets of L.A.

CO-SERIES DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY PEDRO GÓMEZ MILLÁN SAYS HE’S ALWAYS CRITICAL OF SHOOTING CARS, AND “WHEN IT ISN’T DONE RIGHT, IT THROWS ME OFF THE STORY. THE BIG THING,” HE NOTES, “WHEN SHOOTING CARS ON A VIRTUAL PRODUCTION STAGE [ABOVE] IS HOW TO INCORPORATE THE HAPPY ACCIDENTS THAT YOU GET WHEN YOU’RE DRIVING ON THE ROAD – THE SUN OR A RANDOM STREETLIGHT THAT HITS THE LENS IN UNEXPECTED WAYS.” / TOP IMAGE: COURTESY OF STARGATE STUDIOS

Season 1, delayed for more than a year by COVID, offered mostly familiar Westside locations for the L.A.-based story. For Season 2, with the pandemic mostly in the rear-view mirror, the creative team upped the ante, with even the few constructed locations looking and feeling like an undiscovered city. Whether it’s Haller’s new upscale law offices (with all those glass walls) or the many coutrooms where he plies his trade, the show’s locations provide a sense of time, place and character. In the same Tudum story, Location Manager Richard DePatri added that “L.A., while iconic, is also very recognizable – for better or for worse. I think the key is to present locations that fit the story and the scripts, but also to stay away from the main tourist attractions.”

In Season 2, Lincoln Lawyer fans get served the offbeat. From the Elysian restaurant in Frogtown (owned by Mickey’s lover/client Lisa Trammel, played by Lana Parrilla) to The Paseo Club in Valencia (where we see warm and fuzzy conversations with Mickey’s mentor, David “Legal” Siegel, played by Elliott Gould); and from The Cowboy Palace Saloon in Chatsworth, home of the Road Saints, the Sixth Street Bridge, and the L.A. River Walk to The Equestrian Center in Griffith Park, there’s something for every Angeleno.

Directors of Photography Abraham Martinez, a 25-year L.A. resident known for 61st Street , Queen of the South , and The Chi ; and Pedro Gómez Millán, AMC, born and raised in Mexico City, with credits that include Search Party , Little America and Gentefied , both agree Season 2 is a great ride. Millán shot the first six episodes and Martinez the last four.

“Season one was focused on the Westside of L.A., Malibu, and Santa Monica and the tech world,” Millán explains. “For season two, we wanted to explore the Eastside and the gentrification in those neighborhoods. That meant delving more into an earth-color palette and finding the right spots to place the camera to feature those great locations.”

Toward that goal, Millán tested different lenses and settled on the Angénieux Optimo primes. “I don’t always go for really sharp lenses,” he adds. “But I was fascinated by all the different looks and options [the Optimos] provided. We detuned the full set and did a bunch of tests at Camtec. They helped us find the right level of fall-off on the glass. We ended up shooting with IOP Glimmerglass 1/16 on the entire set. We wanted a more

dramatic look when framing portrait shots, and the 28 millimeter and 60 millimeter were detuned to increase the fall-off.”

Millán also chose Angénieux’s Type M1 50-mm F0.95 for more expressive moments, such as in an ER hospital scene. The lens was originally designed for low-light surveillance in the early 1960s, making it one of the earliest ultra-speed photographic lenses ever built.

“It has an incredible smooth focus falloff and natural, flattering skin tones,” Millán continues. “We usually shot them around T2 stop to give my focus pullers a fighting chance. In the ER room, we went all wide open as Mickey is critically injured. I didn’t want the focus to be sharp at all times, so the AC’s had to find it.”

The next step was to work with DIT Francesco Sauta to create the look.

“The idea was to soften the digital sharpness of the Sony VENICE cameras using the cinematic look of these Optimo lenses,” Sauta explains. “The classic soft filters 1/16th further detuned for more severe fall off on the ‘portrait’ lenses.

“As for the LUT creation,” Sauta adds, “we wanted the city of Los Angeles to be its own character. It was important that the different cultures and textures be made clear: the show’s content is, in fact, organic with this principle. We kept the warmth and vibrance of the colors while still protecting the cleanliness of the blacks. I worked with Picture Shop labs to keep uniformity and continuity between the on-set stills, CDL’s, and the dailies. The aim was to maintain The Lincoln Lawyer tone through many different locations while controlling the exposure.”

On set, Sauta used Livegrade Pro for CDL’s stills and a library/archive of the scenes. “It’s reliable software that makes every CDL and all stills quickly accessible,” he adds. “Silverstack XT was used for data management and quality control, with Odyssey 7Q+ used for on-set exposure check and noise control.”

For the courtroom sceness, Millán and Martinez wanted to keep a sharp contrast. Chief Lighting Technician Eric Sagot and his team used high and warm exterior lights while keeping the interior lights cool and low. For the exterior night scenes, color temperature was kept between 3600 and 3800K to maintain warmth. Thanks to the high sensitivity of VENICE 2, a base ISO of 3200 was used to catch the city lights in the background.

That city light is best seen off the deck and out of the glass windows of Haller’s house. Perched atop Baldwin Hills, it was a practical location in a residential area and tricky for the large-sized crew to access. “It had a large drop right after the terrace and no place to rig film lights,” Millán recalls. “We had a bunch of scenes at night on the terrace, so we had to be smart and fast, especially in episode one. Eric [Sagot] rigged a row of small AX3 LED lights that worked as practicals. We could dim every light individually, depending on the camera’s angle, and it helped to create mood, motivate light and still keep it naturalistic.” Because the view of Los Angeles is so powerful, they added cooler lights below the terrace that created a balance and color contrast with the warm practicals of the house.

For Haller’s newly redecorated law offices (born out of a successful case at the end of Season 1), Production Designer Andrew Leitch came up with a set that allowed the team to let more light into the space and open it up. “We decided to lower the ceilings and feature the skylight that was there in season one but that wasn’t featured,” says Millán.

The design incorporated a lot of glass with depth so that the action could be seen through different rooms. All the glass pieces were slightly gimbaled to give the camera crew a chance to fight reflections, but the crew admits it was still a bit of a headache.

“Once you bring two cameras and start lighting, there were reflections everywhere, and we could only gimbal the glass pieces so much until they started to look out of place,” Millán adds. “So, once lit, we had to go through the process of getting rid of reflections before calling the first team, which added some extra time and stress. Sometimes light reflections would bounce off two or three different layers of glass, and trying to flag those individually was timeconsuming. Typically, the best solution was to remove some of the glass pieces completely. It is very hard to tell if there is glass in the background, especially if it’s deep and out of focus, and people are looking at the action in the foreground.”

One key part of Season 2 is seeing L.A. through Mickey’s POV as he takes his business on the road. The executive producers and showrunners expressed dissatisfaction with how the cars were shot in Season 1, so there was a high expectation for change.

“As a cinematographer, I am always critical of shooting cars, and when it isn’t done right, it throws me off the story,” shares Millán. “The big thing for me when shooting the cars on a virtual production stage is how to incorporate the happy accidents that you get when you’re driving on the road – the sun or a random streetlight that hits the lens in unexpected ways.”

Production scouted companies that could provide that look and landed on Stargate Studios, founded by Sam Nicholson, ASC, who is also CEO of the Pasadena, CA-based VP company. According to Ross Fineman, executive producer, “the Stargate visual effects team enabled our Season 2 driving scenes to open up a more vivid, beautiful way to tell our stories with their ThruView virtual production process.” Stargate shot custom photographic plates with stabilized 9 × 8K camera plate shooting rigs combined into 64K horizontal 360 coverage. “On set, our ThruView, which consists of mobile LED walls, multi-camera tracking, 360 playback, and pixel-tracked kinetic lighting, was combined into the portable VP system,” Nicholson explains. “After a one-day installation on the shooting stage, we were able to cover eight pages of virtual production driving scenes per day with no post enhancements or fixes. Block shooting multiple episodes through the season allowed production to control costs with fantastic, photo-real results in camera.”

And what of the show’s namesake vehicle? Three Lincolns were used: one SUV with tinted windows and one without tinted windows, both on the virtual stage, and one vintage convertible used practically outside the virtual stage. Key Grip Chris Garlington rigged the camera mounts, allowing three cameras in the car. They used a small Sony FX3 to fit in small spaces and get more interesting angles. As 1st AC Joe Cheung describes: “The FX3 and FX6 were perfect small form factor to get us into small spaces for the driving shots, where we could shoot over the wheel, do low scraping hood shots, and [be] on the floor of the car.” They also brought the U-Crane arm for locations that included Pacific Coast Highway, Sunset Blvd, the Sixth Street Bridge, etc.

Of the few SUV exteriors, Millán recalls one in Episode 2 where Izzy Letts (Jazz Raycole) is driving Mickey, and some construction is slowing down traffic. The script was a 1/8 page read, a simple beat. But, as with many “simple” shots in Hollywood,

FOR THE COURTROOM SCENES (ABOVE/PGS. 42/43) CO-SERIES DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ABRAHAM MARTINEZ WANTED THE LIGHT TO FEEL COOL AND INTRUSIVE. “[GAFFER] ERIC SAGOT AND I MAPPED OUT THE EPISODES TO HAVE A DIRECTION OF TONE THAT WE WANTED,” HE EXPLAINS. “WE WANTED THE SUN FROM THE COURTROOM WINDOWS TO PUSH DEEPER IN AS THE CASE WENT FURTHER INTO THE SEASON.”

things got complicated. “During prep, we talked to Ted about this beat and realized that it was going to be so much bigger than anyone on the creative team imagined,” Millán recounts. “We had to close down a street on a Saturday and create our own traffic jam and shoot the scene practically with the U-Crane and on the virtual stage. The shot was 50 seconds in the final cut, but don’t even ask how long it took!”

Second Unit and on-the-fly shot s also opened things up for Season 2. Key to those were 2nd Unit DP David Sammons and Operator Brett Juskalian. As Sammons recalls: “Abe and I talked about a driving sequence that became a montage for episode one and blended real driving work with virtual, plates, and VFX. Abe connected me with Second Unit Director Alonso Alvarez-Barreda and Key Grip Chris Garlington. Alonso had a series of shots – Mickey in his ‘bubble’ looking out the window of the Lincoln and other shots connecting him to the outside world. We shot in the hills of Burbank, the 101 freeway from Hollywood heading south, and the streets of Downtown L.A.

“To maximize the time, we had the U-Crane rolling on as many plates and VFX shots on the resets as possible,” Sammons continues. “Shooting on an open freeway was intense, and our stunt team and precision drivers had extensive discussions over safety and how to best use our vehicles to create a safe buffer for us to move the U-Crane arm as needed. One shot involved the use of three lanes of traffic starting as a push-in on Mickey looking out the passenger side window and revealing the city as the car drives away from camera towards downtown L.A.”

Operator Brett Juskalian (who covered Millán when the DP was scouting, while Sammons covered Martinez when he was similarly occupied) says he loved the time he broke away from the studio for 2nd Unit and splinter work. “One of our larger splinter days, we headed to Mulholland Drive and filmed drive-bys while the drone unit followed the Lincoln through the mountains,” he explains. “Filming the vintage Lincoln practically was fantastic. It has such beautiful lines and large flat panels, which were great for finding reflections to visually tie the car into the locations.

“For a scene later in the second half of the series,” Juskalian continues, “Abe asked me to find a B-shot of the exterior of a hotel, while A-Camera Operator Dennis Noyes on Steadicam would concurrently pull Mickey from the hotel entrance across four lanes of traffic to a car stunt right next to the Lincoln. I set up a long lateral dolly along the fender line of the car and, moving right to the left, used the bumper, trunk, and hood reflections to hide Dennis as he crossed the street, and we converged on Mickey as he’s nearly run down by an unknown. It was a well-coordinated effort set in real-world Downtown L.A.”

Courtrooms play a big part in the fabric of The Lincoln Lawyer . Millán recalls how the main courtroom set had two 20Ks on motor chains above the windows on opposite sides to mimic sunlight. “We wanted to have sunlight fill the room as much as possible,” he notes. “Inside the courtroom, above each panel, we had SkyPanels S60 pushing through Magic Cloth. We had full lighting control, and I could quickly create mood and contrast.”

Martinez says that “coming into the backend of the season, and following Pedro, I knew the script would be heavy-handed with courtroom scenes. When it came to the moments when Mickey was outside of the courthouse, I found it important to highlight the two observable aspects of Los Angeles. First, there is L.A. during the day, a thriving and bustling place with lots of warmth and sunlight, which gives Mickey the feeling that he is moving along with his case. Then there’s nighttime, when he goes through periods of self-doubt, musing in a more mysterious reality. I wanted to depict nighttime Los Angeles as an edgy and dramatic environment that dwarfs Mickey as a maverick, who is chopping away at a case.

“The VENICE 2’s low-light capabilities, range of shadow detail, and clean blacks,” Martinez continues, “helped us achieve the subjective L.A. we desired. When it came to lighting, the city already had some interesting elements, like fog and sodium vapor streetlights. The fog at nighttime was relatively unpredictable and added a nice sense of atmosphere. We then had a lot of fun augmenting the natural light with our equipment to produce the look you see in the final shots.”

For the courthouse and courtroom, Martinez wanted the light to feel cool and intrusive. “Eric Sagot and I mapped out the

episodes to have a direction of tone that we wanted,” he explains. “We wanted the sun from the courtroom windows to push deeper in as the case went further into the season. Eric did great digging in the space with our truss lighting, Lekos, and AX3.5s. Leading to the verdict, we wanted a gradual feeling of warmth as Mickey wins. Eventually, the warmth we see that gels the exterior and interior of the courtroom provides a full circle of victory for Mickey, or so we think.”

Martinez says planning the multiepisode courtroom scenes was intense. He 3D-scanned the empty courtroom and had a midday look at the lighting from the windows. “This allowed me to virtually go anywhere in the courtroom in the palm of my hand. Next, I like to apply a street photographer’s mindset for the angles.”

The DP admits that having three cameras for the courtroom scenes was challenging. “Lighting for three cameras is not easy,” he continues. “We were able to find many sweet spots that allowed our camera operators to have freedom within their zones while block-shooting all the courtroom scenes. Every day I made a dry-erase board with a courtroom diagram for the team. This allowed us to get upwards of 89 setups in a day. We had a great third camera team operated by Dave Sammons or Matt Valentine.”

To define these shots, Martinez had the 10-foot Scorpio and kitted-out Ronin 2 gimbal. B-Camera was on decking, track, sliders, and dance floor as needed. C-Camera had the most range with zooms and pacing, often shooting tight. The idea was to give a sense of urgency with the camera movement, a feeling of claustrophobia. Longer focal lengths upped the tension of the courtroom scenes; wider lenses for when Mickey

was gaining momentum on his case. Martinez says they were also “mindful and purposeful with our camera lensing and pacing during the courtroom scene transitions to allow the audience time to speculate on the judgement of the case.”

As A-Camera Operator Noyes recalls: “One of my favorite courtroom moments is when we had to liven things up a bit and considered doing a whip pan. In rehearsals, I never hit the same place and was afraid of how to do it. I talked to ‘Big Show’ Joe Chueng, and we developed this way with whip panning on the Ronin 2 that would get us to the same position – no matter the lens size – and continue operating with the wheels before and after the shot.”

A favorite of several crew members is an homage to The Godfather when Dennis “Cisco” Wojciechowski (Angus Sampson) confronts a teacher who has been nasty to Lorna Crane (Becky Newton). “Late in episode 3, Director Kate Woods envisioned Cisco’s visit to Lorna’s former dean as an homage to the assassination scene of Don Fanucci from Godfather I I,” describes Juskalian. “It was a fun challenge because of the thematic differences between our scene and the original. In the film, Vito is taking a dangerous and bold step in his home neighborhood, so the viewer is kept in the moment with him.

“The point of our scene was revealing Cisco as the intimidating force that he is, so we built an initially more voyeuristic feel by staying back and creeping in with the dean as he approaches his dark porch. Then hopping back to reveal Cisco’s shoulder as the light flickers, we get ahead of the dean briefly before Cisco calmly and coldly emerges from the opposite end of the porch. Second Unit Gaffer Eddie Salerno and Dimmer Board Operator Walter Lin ended up rigging multiple lamps to achieve the flicker effect. Oddly, the scene in The Godfather used more of a pulsing, variac

dimming effect rather than a flicker. In our version, we could have a faster, immediate reveal of Cisco’s menacing silhouette instead of the tension-building intercutting and heartbeat-like throb of light in the original.”

The Road Saints Bar reveals more of Cisco’s life. In Episode 5, the police raid the bar (shot in Santa Clarita). “We had to shoot the interior of the bar day for night, action scenes, stunts, moving vehicles, highway closure and exterior night work and a dusk-by-dawn scene,” says Millán. “One of the tricks to make our day was to choose locations close to each other. The grip team tented the bar location where we shot during the day, and I worked with the art department to provide practicals to light the scene for me to move fast.

“We shot the dawn scene dusk-fordawn,” Millán continues. “Our first shot was the last beat of the scene when the sun was barely touching the edge of the mountains. After that, we had to move insanely fast to shoot the rest of the scene at blue hour. Because of the sensitivity of the VENICE, we had 30 minutes after the sun had set to keep shooting. We thought we were going to do one or two takes, but once we got those, I told the director to keep going and do more takes. I was so impressed with the VENICE sensor. It gave us much more time to keep shooting before we went into the full night.”

In true noir fashion, Season 2 of The Lincoln Lawyer ended with the team of union filmmakers banding together once more to shoot a teaser. “It leads to more mystery echoing through the dark side of Los Angeles,” concludes Martinez. “Mickey wins the case, loses the girl, and is once again confined to his most familiar place, his convertible Lincoln. But the city never sleeps, and the dark shadows come back to haunt Mickey as he makes a U-turn in front of Disney Concert Hall to lead us to his next case.”

MILLÁN EXPLAINS THAT, “SEASON ONE WAS FOCUSED ON THE WESTSIDE OF L.A., MALIBU, AND SANTA MONICA AND THE TECH WORLD. FOR SEASON TWO, WE WANTED TO EXPLORE THE EASTSIDE AND THE GENTRIFICATION IN THOSE NEIGHBORHOODS. THAT MEANT DELVING MORE INTO AN EARTH-COLOR PALETTE AND FINDING THE RIGHT SPOTS TO PLACE THE CAMERA TO FEATURE THOSE GREAT LOCATIONS.”

SEASON 2

Directors of Photography

Pedro Gomez Millan

Abe Martinez

A-Camera Operator

Dennis Noyes

A-Camera 1st AC

Joe Cheung

A-Camera 2nd AC

Brendan Devanie

B-Camera Operator

Brett Juskalian

B-Camera 1st AC

Penny Sprague

B-Camera 2nd AC

Ben Perry

DIT

Francesco Sauta

Loader

Raul Perez

Utility

Elana Cooper

Andrew Vera

Still Photographer

Lara Solanki

2nd UNIT

Directors of Photography

David Sammons

Brett Juskalian

C-Camera Operators

Jonathan Goldfisher

David Sammons

Matt Valentine

Miki Janicin

Eduardo Fierro

C-Camera 1st ACs

Michael Dumin

Noah Ramos

Jeanna Kim

Alex Lim

C-Camera 2nd ACs

Anthony Hwang

Gina Victoria

THE 2023 CLASS OF ECA HONOREES

ACKNOWLEDGES THAT TOUGH TIMES BREED STRENGTH, UNITY AND A PURPOSEFUL VISION TO REACH EVER HIGHER.

BY MARGOT LESTER

BY MARGOT LESTER

Wondering if there’s something a bit different about this year’s ECA honorees? No doubt about it.