1860 a pivotal moment in our history

November 16, 2022, marked the 162nd anniversary of the first arrival of Indian indentured workers in colonial Natal aboard the SS Truro. This commemorative supplement tells of their trials and tribulations, their toils and triumphs.

Women workers were once seen as ‘dead stock’ by recruiters of Indian indentured labour. They soon became indispensable on both the plantations and in the household carrying the burden of a double workload. Pictured are women workers preparing the soil for planting sugar cane in Esperanza on Durban’s South Coast. | 1860 Heritage Centre

November 2022

a pivotal moment in our history

Diaspora of the mutating marigolds

SIDDHI PILLAY

Silently mutating marigolds

You are a pioneer in foreign fields blessed and cursed to till this earth discarded beauty on roadside hills naturalised with artificial worth

THE journey of marigolds is intriguing and contested, not unlike our diasporic tale. Yet, undeniably, the Tagetes mari gold is pervasive in Indian rituals globally, conquering evolution as genes change to express new ways of being to brave new envi ronments.

As our population persists, mutations are inevitable. But in our survivalist and wary commu nity, a paradox emerges in which certain mutations are silenced, and unconscious tradition and orthodoxy (which, for me, differs from tradition that is consciously enacted to nourish one’s soul) is revered and perpetuated.

And in the silence of these mutations, bearing environmen tal pressure, we risk stagnation and disease.

Why are we still going on about indenture?

Surely, by now, we should know this story. But we are never done with it, at least, not until we understand it deeply within ourselves.

As much as attention is drawn to the suffering and challenges of the indentured labourers, there is also a subtle invitation for the present community to appreciate the trauma we collectively carry –our ancestral or intergenerational trauma – which has remained largely tangled and unaddressed.

This is not to disregard the extensive and vital literature on the topic that begins the diag nosis of this trauma, snowball ing mental illness and societal isolation. However, this operates primarily within the mind’s intelligence, accessible to only a stratum of diasporic descendants.

There is a gap in which the heart and spirit’s intelligences are neglected, indicated by our

unresponsiveness to the story of indenture or by the academic arguments on the minutiae of events. Consequently, we tread the surface of our existence, unwilling or unable to tackle the entangled roots of our indenture.

Engaging the heart and spirit’s intelligence

The performing classical arts have a significant role in activat ing heart and spirit intelligence. As Indian descendants, we have kept semblances of these forms active in our communities. Yet, a major trend persists that is a symptom of this unresponsive ness to our legacy of trauma (or trauma of legacy).

In South Africa, a proclivity remains towards restrictive ortho doxy in which we are expected to regurgitate stories that have become far removed from our experience.

This is not to say we should not be re-enacting the stories of the gods, but that we should, firstly, not do so unconsciously, and, secondly, explore these deeper to understand how they may facilitate intergenerational

and present healing, transforma tion, and transcendence.

Of course, we could also write new stories and reimagine flawed gods as our ancestors and as our selves. A few productions have indicated the value of such innate exploration to me, such as Flatfoot Dance Company’s Bhakti or John Newell’s Hebridean Treasure

We do have a handful of classical-integrating-contempo rary artists in South Africa trying to steer into this new and uncharted direction. However, without the platforms (including our communities and institu tions) to do so, many are forced back into convention or exhaus tion.

They are silenced in their transformations that could shift the plane of ancestral or inter generational healing that our communities (at various levels) need. We are marigolds sup pressing an innovative vibrancy merely because of entrenched and unquestioned expectation.

Mutation through crossing-over

cross over between the chromo somes of an organism.

Through the spread of indentured labour, the world is blooming with marigolds, all slightly different to their originals.

This offers immense oppor tunity to gain insight from other diasporic populations who have been tackling their indentured history through performing arts and literature, such as the Sarnami Hindostanen (Suri namese people descended from Indian indenture), allowing for a cross-fertilisation of ideas and an awakening of healing through empathy.

Artistes in South Africa have tried to promote this cross-fertil isation, but sustained effort has been difficult.

The South African Indian Dance Alliance conference (2020) was pivotal in turning my own thoughts.

It was the first time I encountered such a breadth and volume of Indian dias pora dancers. By listening to their challenges and successes, we were able to better

understand our own journeys.

Un-silencing our mutations

If our advancement appears straightforward, then, it risks a superficial approach to solving this complicated problem of his tories and healing.

Change to our interior spaces is inevitable, and eventually, mutations will no longer be silent; whether they are lethal or beneficial remains entirely in the hands of those holding the space right now.

Should we fear that our evo lution will erase the links to our past?

Warily, I would say that such fear risks a cancerous decay of our being.

Evolution should perhaps, then, not be looked upon as a disregard for our indentured past, but as an honouring of the pioneers who crossed over and began this process of transfor mation.

Pillay is a Durban-based author, innovation and management researcher and Bharathanatyam practitioner

2

To produce novelty, genes

November 2022

MARIGOLDS are placed in the sea at the Durban beachfront to commemorate the 162nd anniversary of the arrival of Indian indentured labourers to Natal. | DOCTOR NGCOBO African News Agency (ANA)

1860

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

Commemorating 162 years since indentured workers arrived in SA

and barbaric nature of the lion and how he spared its life when he caught it. The people who listen to him will trust him as they don’t know the other side of the story.

DR VUSI SHONGWE

Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter –African Proverb

FACED with a labour drought, the sugar cane planters managed to persuade the colonial govern ment to organise the importation of bonded labour from another British possession, India. The indentured workers, therefore, came from India from 1860 up to 1911 on board 384 ships carrying some 152 184 souls.

Their purpose was to provide labour in growing the colonial economy of British Natal. A life of pain and hardship followed as they experienced a new life in in Africa.

In a nutshell, as explained by Kathryn Pillay in her academic paper titled, The Coolies Here: Exploring the construction of an Indian ‘Race’ in Southern Africa, Indians came to Southern Africa to fill a labour shortage. Slavery had been abolished and sugar cane planters were left with a labour challenge as African peo ple refused to engage in the ardu ous physical labour that working in the plantations entailed, espe cially for the pay that was offered.

The explanation of the term ‘indenture’ and ‘coolie’

According to Rachel Sturman, in her piece, Indian Indentured Labor and the History of Interna tional Rights Regimes, in earlier periods in England, the term “indenture” was used in refer ence to an agreement binding an apprentice to a master.

The specific colonial usage referred to the contract by which an individual agreed to work for a fixed period for a colonial land owner in exchange for a passage

to a colony, and earned a wage accommodation and food rations.

Freedom of movement was not permitted in the term of indenture. While indenture was the system associated par excellence with Asian, especially Indian labour movements, imme diately after the era of slavery, it was also associated with English and Irish “servant” moving to the colonies.

The term indenture draws on the root dent, ultimately based on Latin dens (tooth), referring to the indented or serrated edges of the contract by means of which the original and duplicate copy could be separated by being torn or clipped off (note also the gen eral related word indentation).

As is well-known, points out Sturman, the indentured labour ers of Indian origin generally called the system of indenture gir mit (agreement in English). This word is known throughout the indentured diaspora in exactly this form – and hence clearly arose in India itself, before being taken to the colonies.

As is also well-known, as observed by Sturman, the migrants styled themselves as girmityạ in Hindi (according to Wikipedia, girmitiya or jahajus were indentured Indian labourers whom the British Empire sent to

Fiji, Mauritius, South Africa, and the Caribbean – mostly Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and Jamaica – to work on sugar cane plantations for the benefit of European settlers).

The agentive suffix -ya add ing the meaning “one associated with” – hence the term means one who signed the girmit

In Tamil, the equivalent term occurred as girmit ̣karan, the term karan referring to “man”, with the related term kari for “female”. Girmit ̣has been taken up as an iconic term by Indian South Afri cans, evoking the harsh world of plantation work, but not without pride in the commitment of the preceding generations.

There seems to be some kind of general consensus among South African scholars, especially of Indian descent, that while there are many studies focusing on indenture and indentured labourers, this vast and intensive body of work regarding people of Indian descent in South Africa lacks personal history, individual narratives, and experience.

It is, however, gratifying that more recent scholarship, such as that by Uma Dhupelia-Mes thrie, Goolam Vahed and Ashwin Desai, have attempted to move the historiography of indenture in Natal focusing on the intimacy

and terrain of the everyday lived experiences of Indians in Natal.

It is also important to men tion the role played by the 1860 Heritage Centre, an agency museum of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Arts and Culture, led by the conscientiously and passionately assiduous Selvan Naidoo.

The exhibitions run by the centre are breathtaking. Most importantly, they are educa tional. The public is encouraged to visit the centre to, as the late sagacious and repository of Afri can world history, the New York African-American scholar Dr Henik Clarke would say, “feel in the missing pages” of the history of indentured workers in South Africa.

Indeed, as the African prov erb aptly puts it: “Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter.”

As long as the lion can’t write, the hunter keeps telling his side of the story. His heroic acts in the jungle, his expeditions, medals and bravery are glorified in all of his stories. He could say that the lion runs away and hides on his arrival, scared of him.

He could tell stories of how he saved the animals under the attack of the lion. He may describe the stories of the cruel

But by the time lion learns to read and write, it can debate and reject many of the claims, revealing the true nature of the hunter. It can write its version of the story saying how scared the hunter is on seeing the lion, how he survived on dead animals, how cruel he was to the small and innocent creatures, and how he hunts down animals for fun. It can describe how he trapped the animals and tortured them to death and how he disobeyed the laws of the forest.

Although the explanation is the literal description of the sen tence, it has a more subtle mean ing. Every time a civilised society is established in history, a bar baric tribe or invaders attack and destroy their history and re-write what they intend it to be. It was the reason many of the flourished civilisations remained in history. Their cultures, lan guages and religions were lost. Some of the invaders who destroyed them are hailed as great emperors.

The stories of the war are told by the one who won it. Most of the emperors are described as great because no one dares to write against them. The invaders eradicate the cultural identity of native kingdoms and establish their rule as if they are doing them a favour.

Then the religious practices and ceremonies are ridiculed. Finally, they instil a sense of inferiority in the native people and exploit it in their favour. The colonisation, too, followed this pattern.

This concept is widely appli cable to many events in history. And it frankly describes to us that what we call history is just one side of the story.

3

Shongwe is the director of KwaZulu-Natal Sports, Arts and Culture

November 2022

INDENTURED workers arriving at the Bluff in the early 1900s. | 1860 Heritage Centre.

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

Debunking myths and stereotypes

PROFESSOR KALPANA HIRALAL

NOVEMBER 16, 2022, marks the 162nd anniversary of the arrival of indentured Indians in Natal. It is a history far too well known.

Yet, there is another group of immigrants that arrived in the wake of indentured Indians – the “passenger” Indians. There are, however, myths and stereotypes associated with indentured and “passenger” Indian migration to Natal, a few briefly alluded to below.

First, Indian migration to Natal consisted of two groups: indentured and “passenger”. The latter paid their own passage to Natal and were not bound by contractual labour. They arrived following the settlement of indentured labourers in Natal from 1860 onwards. Like their indentured counterparts, they were British subjects, but unlike the labourers, were subject to normal immigration laws.

The arrival of indentured Indians was sanctioned by Law 14 of 1859, which governed their socio-economic mobility in Natal. They came under the Office of the Protector of Indian Immigrants, which registered their arrival, births, deaths and marriages.

The differentiated status between “passenger” and inden tured immigrants also created a social hierarchy, stigmatisation and stereotyping of one group over the other decades later.

“Passenger” immigrants, because of their non-labouring status, endogamous social prac tices and religious affiliation (the vast majority were Gujarati-speak ing Hindus and Muslims) were perceived as the “superior” class of Indians and assigned labels such as “Arabs” and “Banias”.

Indentured Indians, in most instances, were labelled “coolies”, “samy” and “Madrassees”. These historical stereotypes hindered to some extent social contact between the two groups for many

decades.

Giving evidence at the Indian Immigrants (Wragg) Commission 1885-1887, George Mutukistna, an indentured Indian, alluded to a social hierarchy that existed between “passenger” and inden tured Indians: “The little feeling of caste which exists in Natal, is kept up by the Mauritius Indian merchants, who think them selves better because they are rich and who think that, by observing caste distinctions, they can set themselves apart from the Natal Indian people.”

Some “passenger” Indians, because they arrived under a dif ferent migration status, wanted to distinguish themselves from indentured labourers.

In an affidavit in 1907, Kuar jee Ramajee, of Durban, made a formal application for a domicile certificate and stated: “That I am a native of India ... That I am not an indentured Indian and also hold no pass under any act.”

Second, the “passenger” immigrant often conjures images

of the rich Gujarati trader. How ever, the “passenger” Indians are a misunderstood category.

They were not all wealthy, and they did not always have a solid commercial background. Many came from impover ished backgrounds. There were, amongst them, a few who had a commercial background, for example, the pioneer traders, amongst them Aboobaker Amod, and Moosa Hajee Cassim.

They were men of means, with multiple trade branches and international networks that established businesses in Natal and the Transvaal. But the vast majority of “passenger” Indians were struggling immigrants who were seeking an escape from the poverty of the rural villages in India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

They came mainly from agri cultural backgrounds. They were cultivators, petty farmers, peas ants, husbandmen, field hands and labourers. Among them were many skilled and semi-skilled

artisans who plied their castebased trade earning a livelihood as shoemakers, goldsmiths, car penters, potters, laundry workers and tailors.

They had little or no finance on arrival but, largely through kin, caste and village network, were able to secure employment as assistants, accountants, clerks, store managers, supervisors, and salesman.

Many who engaged in com merce in Natal, the Cape and the Transvaal were small-scale traders and often described themselves as a “storekeeper”. Others took on non-commercial menial jobs: hawking, “togt” (casual) work, stable hand, bricklayer, fireman, railway worker, and some had to eke out a living by working as cooks at hotels and as hired hands in shops. It was only after they had managed to save money that they established a business or went into partnership.

Second, Calcutta and Madras are associated with indentured migration. However, a small per

centage of “passenger” Indians also came from the southern parts of India, embarking from Madras in the south, originating from the Andhra districts of Chittoor, Gan jam Godavery, and Vizagapatam and were predominantly Tamil and Telugu speaking.

For example, Coottean together with her husband migrated as “passenger” Indians to Natal in the late 1880s, and in 1908, Manuel Arokiaswamy Francis described himself as “a free passenger … I have paid the cost of my own passage from India (Madras)”.

A re-assessment of aspects of Indian migration to Natal allows for a broader analysis of the indenture history. It debunks popular stereotypes and assists in breaking down labels used to separate immigrant groups.

Hiralal is a professor in the Department of Historical Studies, in the School of Social Sciences at Howard College at the University of KwaZulu-Natal

4

RANA Hardware at 134 Prince Edward Street, Durban. | 1860 Heritage Centre

November 2022

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

Where do we come from?

SELVAN NAIDOO and KIRU NAIDOO

THE Indian presence in South Africa came through various routes. In the millennium before the Dutch conquest of the Cape in 1652, one theory put forward by Cyril Hromnik points to Dra vidian gold miners having settled in southern Africa.

Their likely port of entry was present day Maputo traversing Komatipoort, a name derived from Tamil, and travelling beyond into the Karoo.

Much easier to demonstrate are the Indian slaves from Bengal, Surat, the Coromandel and Mala bar coasts trafficked by slave-trad ing Europeans to the Cape since the mid-17th century.

Anna Böeseken, a founder of the Genealogical Society, noted that over 50% of Cape slaves in the 17th and 18th centuries were Indian. Nigel Worden refers to Cupido, a slave from Mala bar who, in desperation about his enslavement, threatened his mistress with a knife and was subjected to a slow death being broken on the wheel.

Cupido remains a common surname in the Western Cape.

The better-known migration is that of Indian indentured workers to the plantations, railways, coal mines and domes tic service of colonial Natal between 1860 and 1911, num bering 152 184 souls transported on 384 ships.

While those numbers might sound large, they pale in com parison to the massive upheaval in African societies in Southern Africa during this period.

Colonial conquest was accom panied by the impoverishment of the African peasantry and the destruction of their economic base. In addition, forced taxation drove millions of Africans into the oppressive migrant labour system, mainly on the gold mines of the Witwatersrand. South Africa has yet to recover from the seismic impact of this colo

THERE were nearly 18 000 soldiers from India, commissioned by the British Army to serve in various capacities in the Anglo-Boer wars. At the end of the wars, a number of them remained and were integrated into the local community of Indian origin. This accounts in large part for the Sikh, Pathan and Gurkha presence in South Africa. | SS Singh Collection/ From the book Indian African by Paul David, Ranjith Choonilal, Kiru Naidoo and Selvan Naidoo

The myth of passive resistance

A HUGELY significant resistance milestone was the 1913 strike that had 20 000 Indian workers down tools. They brought the economy of Natal to a standstill. It was not always the peaceful passive resistance of the popular narrative.

The New York Tribune reported on 18 November 1913: “The East Indian residents of Natal today declared a general strike which was accompanied by rioting and the burning of sugar plantations. The police force is insufficient to deal with the rioters, and white women and children are in a

nial greed and the destruction of settled societies.

Across the Indian Ocean, Brit ain’s systematic extraction of the wealth of India and the violent destruction of its economy is starkly demonstrated by Shashi Tharoor in, among others, An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India

That destruction was a push factor for indenture. In an elaborate “coolie catching” system, recruiters

state of terror.

“Troops have been ordered to some of the disaffected dis tricts. In Durban itself practically the whole East Indian commu nity struck work and became so aggressive that a demand was made for the proclamation of martial law.

“In the country districts hun dreds of acres of sugar cane was burned. The revolt of the East Indians was brought about by the exclusive laws in force against them…”

Writing in Ilanga lase Natal, South African Native National

or “arkatiyas” deliberately targeted people driven to desperation. Note the common usage of the word “arkaat” in South African Indian English used to describe a person of bad character.

Peppered among these Indian migrations were the handful of workers brought to Natal before 1860 by individual planters to assist in agricultural experimen tation with crops like indigo. The first four Indians with experience

Congress (SANNC) president, Dr John Langalibalele Dube praised the resolve of the Indians to resist unjust laws. White colonialists were struck with the fear that Africans were waiting for a sig nal from the Indians to join the strike. United action among black peoples would have spelt disaster for colonial rule. There was how ever no organised formation for such mobilisation.

Excerpt from Indian Africans by Paul David, Ranjith Choonilall, Kiru Naidoo and Selvan Naidoo published by Micromega

in sugar cultivation were brought to the colony by Ephraim Rath bone in 1849.

Baboo Naidoo arrived in the colony from Mauritius in 1855. Candasami Kuppusami believes that Naidoo arrived with a Mr Clarkson.

A class of “free Indian” mer chants or people paying their own passage started to arrive in the 1870s outside of any arrange ment between the governments

of India and Natal. Landing vari ously from Gujarat, Bombay and Mauritius, their main interest was trade. There were, in addition, interpreters, teachers, clerks, accountants, lawyers, shop assis tants, and clerics brought out to service the needs of the growing Indian community.

Indian soldiers were also part of British regiments in the AngloZulu, Anglo-Basotho and AngloBoer Wars, as well as the two World Wars, with some opting to remain after being decom missioned. The Sikh, Pathan and Gurkha presences in South Africa are accounted for in part by these soldiers.

Nearly 18 000 Indian soldiers served in the Anglo-Boer wars. A war memorial on Observatory Ridge in Johannesburg records on a tablet: “To the memory of British Officers, Native NCOs and Men, Veterinary Assistants, Nalbands and Followers of the Indian Army who died in South Africa, 1899-1902.”

Whatever the motivation or avenue of arrival, a prominent narrative of Natal’s economic history in the 19th century was the unhappy saga of indenture.

In the third decade of the new millennium, new challenges abound. Covid-19 has compelled people all over the world to reset systems and priorities. The sen sible will see the world as one, that there is more that unites the human race than divides it.

A particularly oppressive sys tem of labour bondage in the form of indenture brought the majority of Indians to South Africa in the 19th century. Their descendants are the Indian Afri cans who have seized the oppor tunities beyond indenture but must yet still fully embrace the possibilities to change the world from within.

Selvan Naidoo is the curator of the 1860 Heritage Centre. Kiru Naidoo serves on the advisory board of the Gandhi-Luthuli Documentation Centre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. They are the co-authors with Paul David and Ranjith Choonilall of The Indian Africans recently published by Micromega and available at www.madeindurban.co.za

5

November 2022

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

My African story

Sharing the journey of two worlds

VERUSHKA PATHER

A JOURNEY started 162 years ago under African skies to what we enjoy today, from indenture to slave to freedom.

The tales are harsh of my peo ple and their blood still runs on our land, but their joy of culture and tradition allows their hearts to forever remain with us.

We have thrived, risen above all odds and excelled as children born from indenture. The Indian Ocean has brought with it the echoes of scripture and chant ing to our shores; apart from everything else that we have imbibed, the most valuable that Bharat (the name of India in ancient time) has given us is the quality of humility, patience, love and forgiveness.

Today 162 years later, a child who has been blessed to share the journey of two worlds – her ancestral land of India and born as a child of Africa – has a deep passion to share the weave of our land with the world.

This is our progression. We have evolved and as we celebrate the traditions of our foremoth ers, we still carry Kavady, we fire walk, and we prepare timeless foods such as idli, sambar, dosa and paniyaram. This is who we are.

But we have also imbibed the culture of the land we were born from, with the trials and tribula tions it comes with. This has cre ated the unique make-up of our beings, a unique personality that has the best of both worlds has

allowed us to become powerful creators – making ground-break ing inventions and thought pro voking conversations at many levels.

And 162 years later, adorned with all the best of our ancestors, we have a voice as an Indian African. We are a generation of influencers.

We have the collaboration of cultures. This is the pride of our people. The Indian African is the unique part of our nation bring ing two worlds together.

Khanya Designs has created the first African sari with the vision to bring about collabora tion using personalised Indo-Af rican creations as a medium to experience social cohesion.

eShweshwe is the original heritage weave of our country, telling tales of our land, our history, culture and the soul of our people. Along with exclusive African beading and the finest of Indian silk and cotton, Khanya Designs is a competitive global brand taking Africa to the world. Wearing a Khanya garment gives one a sense of pride, belonging, the sharing of history and you make a statement that you have arrived without saying a word.

Welcome to the African Renaissance.

Pather is a Bharathanatyam artist, fashion designer and owner of Khanya Designs

By Dr Betty Govinden

Tumbling from the great ghats in India, To the holding places in Port Natal, Ushered in by the capricious tide;

Crossing the kala pani, Children of the rain and storm, Buffeted by waves;

Stitching fragments of self, Patched together In the waters of the voyage;

Finding anchors in the wind, Fated to be vagabonds of identity

Their histories sinewed to their bones;

Tilling in coolie canefields, Learning the language and lore Of foreign shores;

Toiling for tea for empire, Castaways, Stonebodies in compounds;

Preserving the ancient hearth, With ladoos and rasgoolas –The remembrance of things past;

Lighting the family God-lamp, With suppliant hands, Watched by the stars;

Working with new kith and kin, For freedom to sprout on parched ground;

Mingling blood and water, To forge a new people, A new heaven and a new earth;

Heaving the sheaves of yesterday: This Harvest of Memory –New Beatitudes for our time and place…

is a writer and literary critic

6

Govinden

Crossing

ONE of the Khanya Designs. | Supplied

VERUSHKA Pather, seated, and models wearing Khanya Designs. | Facebook

November 2022

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

Natal Indian Congress rightly takes its place as an anti-apartheid fighter

Extract from the last chapter of Colour, Class and Community –

The Natal Indian Congress, 1971–1994

ASHWIN DESAI and GOOLAM VAHED

ASHWIN DESAI and GOOLAM VAHED

A 1990s NIC discussion docu ment on the future of the organi sation underscored that the ANC had yet to confront the challenge of reconciling non-racialism with other identities.

At one level the ANC is utterly remarkable for its non-racialism. It will be very difficult to find a parallel for the ANC anywhere in the world. At another level, sitting somewhat uneasily with this non-racialism are ethnic, regional, racial, gender, and other identities...

The ANC’s present non-racial ism is somewhat abstract and coming to terms with these other identities will provide a more materialistic foundation for its non-racialism... There needs to be much more open debate within the ANC about ethnicity, race, non-racialism, and nation-build ing, and there is a need for appro priate strategies to be developed in this regard.

A cameo of these challenges played out when Mac Maharaj wanted to appoint Ketso Gord han as director general of trans port. He informed Nelson Man dela of his intentions, as Mandela “was conscious that I’m of Indian

origin and I was appointing a person of Indian origin, although one with an impeccable record in the ANC”.

Mandela supported him, but Maharaj recounted: “Months later I got wind of murmurings among many of the ANC com rades. I think it was in ... a black magazine ... that ministers were appointing people from similar race groups, and in particular they made a remark about me ... and then − surprise, surprise − I learned from Madiba one day during a casual chat that one of the veterans of the ANC who was in Parliament and on the transport committee had gone to Madiba to complain about the appointment of Ketso. So the matter stayed on the public agenda.”

It is revealing that in spite of all the talk of non-racialism, Maharaj had to walk on egg

shells. Of course, he could rely on Mandela’s social and politi cal capital. Those without access to those resources felt the sting of marginalisation because of race and, unlike Maharaj, had nowhere to turn. The NIC might have collapsed into the ANC, but the wheel still bore the imprint of its racial spokes.

Marked by increasing eco nomic disparities, poor service delivery, unemployment and corruption, the political terrain has shifted dramatically since Maharaj’s exchange with Man dela and the NIC’s discussion document. But the changing real ity only reinforces and makes more urgent the issues raised. Such disparities provide fertile ground for authoritarian popu lists to stoke racial fires of hate.

Yunus Carrim, for example, spoke of the situation in KwaZu lu-Natal: “The emerging hostility

of African people, partly because of the EFF, partly because of the failure to reduce inequalities and create more spaces where we all interact... So we have this social explosion remaining in this prov ince. Nobody is doing enough to bridge the gap and as we fail to deliver on economic growth, job creation, reducing inequality ... if you don’t reduce the gap between Indians and Africans, we are in big trouble here... All over the world you are getting the same sense of belonging, of identity, of who belongs and who doesn’t, our country is not escaping it...”

Given the ANC’s seeming inability − some might say unwill ingness − to move beyond cel ebrating liberation as a “fancy dress parade and the blare of trumpets” accompanied by a few “reforms from the top”, the promise of a “better life for all” and an abiding non-racialism

appear a pipe dream.

Some would argue that there is little likelihood of “creat ing identities that are broader and more integrative”. But so it appeared in the early 1970s, when the apartheid state was at its height of draconian authori tarianism and a small group of men and women at the Phoe nix Settlement revived the NIC. Rather than letting the course of history determine their futures, they chose to make their own his tory, as part of a struggle to free all the peoples of South Africa.

The NIC was an anti-apartheid voice that not only fought and won significant battles against the co-option attempts of the apart heid regime but also kept the ideals of the ANC alive in the public domain. The NIC’s endorsement of the Freedom Charter and a non-ra cial inclusive nationalism spoke to people beyond the confines of its own ethnic base as it made a fun damental contribution to the UDF and the ANC underground and armed struggle. At a time when racial discrimination was ripping South Africa apart, and violence and repression were stalking the land, people were asked to step up to fight. The cadres of the NIC, whatever their shortcomings, enlisted and fought with courage and tenacity. Thus the NIC rightly takes its place in the pantheon of anti-apartheid fighters.

History will not be as kind to the present generation if they turn their backs on the ideals that powered the imagination and actions of people who came before them.

While today’s activists must find new ways of organising, new languages and new targets of dissent, and be critical of roads travelled, the memories and les sons of what went before are vital in formulating strategies and maintaining resolve.

Desai is a professor of sociology at the University of Johannesburg and Vahed a professor in the History Department at the University of KwaZulu-Natal

7

November 2022

PIETERMARITZBURG Treason Trial, 1985. Centre front, advocate Ismail Mahomed with, from left, George Sewpersadh, George Naicker, Leonard Gering (wearing glasses, between and behind Naicker and Ramgobin), Mewa Ramgobin (arms folded), Cassim Saloojee, Thumba Pillay (spectacles, chin on hand) and Essop Jassat (extreme right). | African News Agency

1860 a pivotal moment in our history

BRIJ MAHARAJ

BRIJ MAHARAJ

THE roots of the contemporary Indian diaspora can be traced to the colonial domination by the British and the exploitation of cheap indentured labour from the Asian sub-continent in differ ent parts of the colonial empire, including Fiji, Trinidad, Suri name, Mauritius, Malaysia and South Africa.

Studying the histories of indenture has emerged as a specialised area of research, in contrast to its earlier relegation as a footnote of imperial or colo nial history. Some of the lead ing scholars in the field are the progenies of indentured labour ers, who are contributing to an understanding of “history from below”.

As the indentured labour ers tried to adjust in an alien and hostile environment, they encountered conflict with their colonial rulers as well as with the indigenous majority, and this tension, persists to this day.

According to Susan Koshy, in the colonial and post-colonial eras, the Indian diaspora has raised questions of belonging: “Were they partial citizens, pariah citizens, per manent minorities, resident aliens or where they are simply excluded by recent culture from the possibil ity of citizenship altogether – what political rights did their economic contribution confer?”

The tensions between the indigenous communities and the indentured labourers were evident from the time of arrival.

Conventional history in South Africa, for example, portrayed the Zulus as “lazy”. However, the Zulus were smart because they refused to work for low wages. The indentured labourers worked for lower wages in Natal province, and the Zulus were displaced.

This was the beginning of IndoZulu tensions, which still persists and periodically resurfaces, even in the democratic era.

Yunus Carrim, a sociologist turned politician, has emphasised that the “presence of Indians poses interesting challenges for the tasks of nation-building and non-racial, democratic transfor mation in South Africa. The ways in which and the degree to which Indians are integrated into the post-apartheid society will be a not unimportant measure of how successful a non-racial democracy South Africa has become”.

From a sociological perspec tive, Indians essentially occupy a middle-man minority position in indentured territories – a buffer between the white colonial rul ers and the indigenous majority. So, they get portrayed as “scape goats” and villains in times of economic and political crises.

Historian Hugh Tinker raised the question of whether Asians were architects of their own prob lems in terms of their lifestyles. In spite of the distance and discon nection from India, they retreat into their religious and cultural cocoons – which meant that they were often isolated from main stream society and hence, the tendency to view them as aliens and exploiters.

This was compounded by the colonial government policy that kept different groups apart with the divide-and-rule strategy.

What is the nature of connec tions with India? And how does India connect with the inden tured diaspora? The majority of the descendants of indentured labourers have no links with India except as an abstract, spiritual motherland, which many pilgrims find disappointing as faith has been commodified

and where religion betrays the poor and disadvantaged.

Sometimes the indentured diaspora reminds India of a less sophisticated past. After all, the indentured were low caste peas ants and labourers, unworthy of the attention of the Indian ruling elite. However, the indentured diaspora did have some influ ence on the liberation of India from the shackles of colonialism.

Mahatma Gandhi developed his ideas about Satyagraha in South Africa. After India’s independ ence in 1947, the indentured were expected to integrate in their host countries.

In September 2000, the Indian government established a High-Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora to investigate and report on “problems and difficulties, the hopes and expec tations” of Non-resident Indians (NRIs) and Persons of Indian Ori

gin (PIOs) in their interaction with India.

The intention was to attract those with dollars, pounds and euros to invest in India. There was initially little interest in the descendants of indentured labourers in countries like Malay sia, Fiji, Trinidad, Suriname, and South Africa.

An interesting issue from which the motherland could ben efit was an acknowledgement from the High-Level Singhvi Committee (2001) that in the indentured dias pora, “a form of Hinduism… was being practised by people who had rid themselves of traditions and customs like jaati and sati, gotra and sutra… and dowry”.

The experiences of indenture is one of families torn apart by separation and the humiliation of poverty, alienation, resistance, and struggles to forge new lives under harsh conditions, which highlight the multiple ways in which Indians tried to retain a measure of self-respect and auton omy in a system that sought to deny them the rudiments of bare life and dignity.

Indentured labourers and their descendants were vulnerable dur ing the colonial and post-colonial eras, and their association with India has been tenuous. Women continue to be susceptible to vio lence and abuse. In both eras, there were common problems related belonging and identity – race, eth nicity, citizenship – which con tinue in the 21st century.

There is also a significant degree of coalescence between race and class as the colonial authorities had defined and maintained ethnic categories and used discriminatory regulations and institutional practices to structure inter-ethnic relations. The tensions, conflicts and prej udices of that era still persists, with third and fourth-generation descendants likely to be victims.

Maharaj is a geography professor at UKZN and Deputy President of the SA Hindu Maha Sabha. He writes in his personal capacity

8

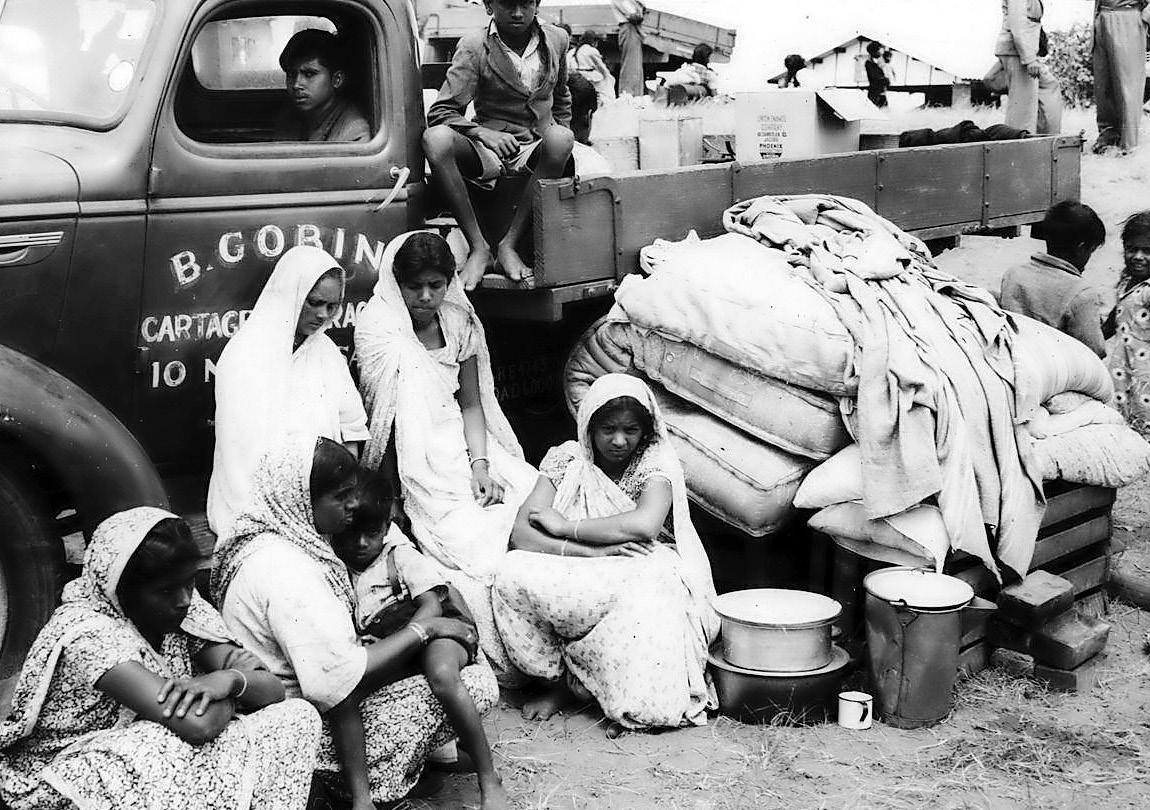

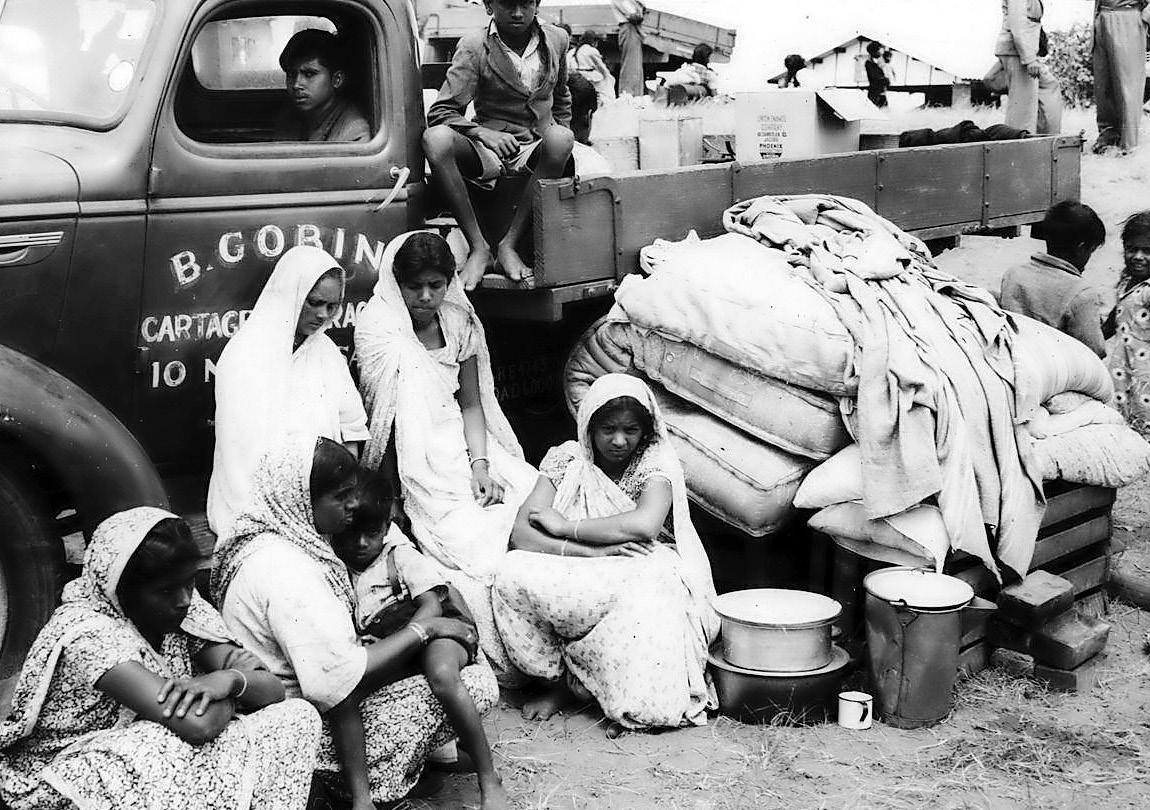

DISPLACED families housed in temporary relief camps during the race riots of 1949. | 1860 Heritage Centre

Reflections on the hardships of the indentured diaspora in SA November 2022

ASHWIN DESAI and GOOLAM VAHED

ASHWIN DESAI and GOOLAM VAHED