GLENN MURCUTT’S MAGIC THE LATEST KITCHENS

CONTEMPORARY BEACH HOUSES NEW ZEALAND

INSPIRATIONS KEVIN LOW IN DETAIL MALAY

CULTURAL EXCHANGE THAI DESIGNER ON SHOW

ROSITA MISSONI ON DESIGN TOURING BERLIN

GLENN MURCUTT’S MAGIC THE LATEST KITCHENS

CONTEMPORARY BEACH HOUSES NEW ZEALAND

INSPIRATIONS KEVIN LOW IN DETAIL MALAY

CULTURAL EXCHANGE THAI DESIGNER ON SHOW

ROSITA MISSONI ON DESIGN TOURING BERLIN

DESIGNERS AT HOME

CONVIVIUM - design Antonio Citterio

CONVIVIUM - design Antonio Citterio

“Where the kitchen is the home, it is the home which revolves around the kitchen.”

I DISCOVER AN ARRAY OF THOUGHTFUL AND INNOVATIVE DESIGN OBJECTS FROM THE REGION AND BEYOND. READ ABOUT THE LATEST BOOKS, TAKE A LOOK AT THE SOME NEW BOOKSHELVES AND REVEL IN WINE AND DESIGN.

24

DeSign newS

Our picks from the Decorate Life 2008 fair in Frankfurt, and the best furniture, objects, lighting and technology from around the globe.

32

re-Shoot

An old pastime is given a facelift –grab a book (or magazine), sit down and relax. habitus reviews an everyday object transformed by design. This issue we look at bookshelves.

35

conVerSation

There’s a certain breed native to many cities that has been spotted more recently in Sydney – the elusive wine bar. Associate Editor, Andrea Millar, visits Millevini in Surry Hills, to learn about the wine and design within the space.

39 montage

Paul McGillick takes a look at the idea of ‘layered experience’ found in four recent architectural books.

2.

PEOPLE &

I MEET A COLLECTION OF DESIGN ADVENTURERS WHO HAIL FROM SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND AUSTRALASIA, AND SEE HOW THEIR ENVIRONMENTS REFLECT THEIR LIFE AND WORK.

46 PartnerShiP

Stephen Crafti visits the studio of Pierre and Charlotte Julien, who have developed asuccessful business while also sustaining their shared passion for design.

65 creation

Furniture and lighting designer Kenneth Cobonpue studied in New York and Germany before returning to his homeland, the Philippines, to design. Stephen Crafti talks to him about his journey.

81

cLoSe UP

Chu Lik Ren visits Kevin Low’s body of architectural projects that explore the idea of ‘garden houses’.

68 Portrait

Andrea Millar visits Inge Holst of EDIT, whose creative path has taken her through many roles, and provided a sense of stability in somewhat tumultuous times.

89

52 on Location

Andrea Stevens takes a trip to Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand, and discovers that various places, people and cultures have been amongst the inspirations for David Trubridge’s timber creations.

72

SLow DiSSoLVe

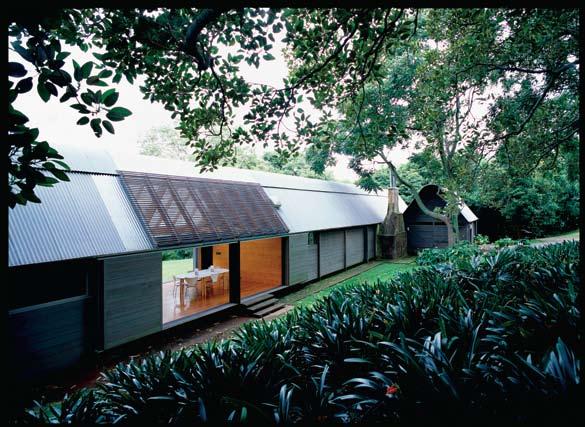

Rimbun Dahan, a creative sanctuary in Malaysia, fosters cultural exchange between South-East Asia and Australasia. Paul McGillick visited and was taken in by the literal and metaphorical beauty.

3. HABITUS HOMES

I A DIVERSE SELECTION OF THE BEST IN RESIDENTIAL DESIGN FROM AUSTRALASIA AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA.

cLoSe UP

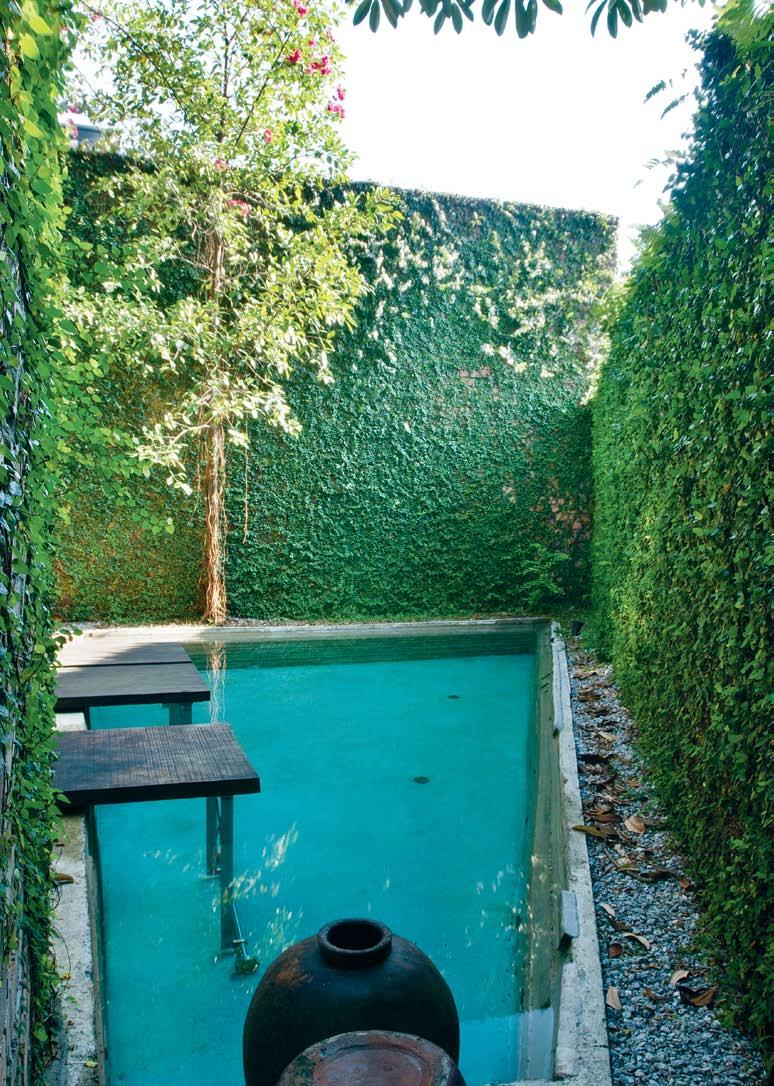

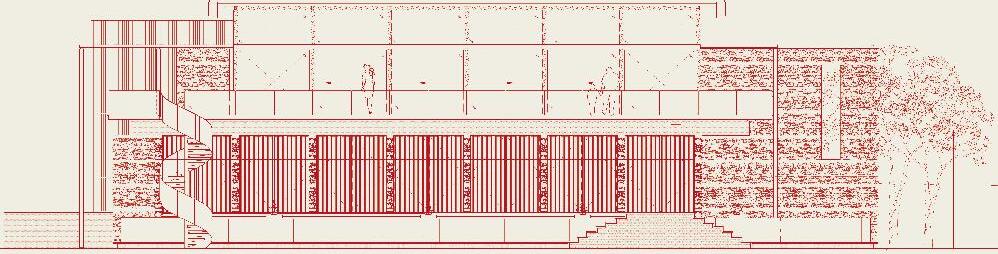

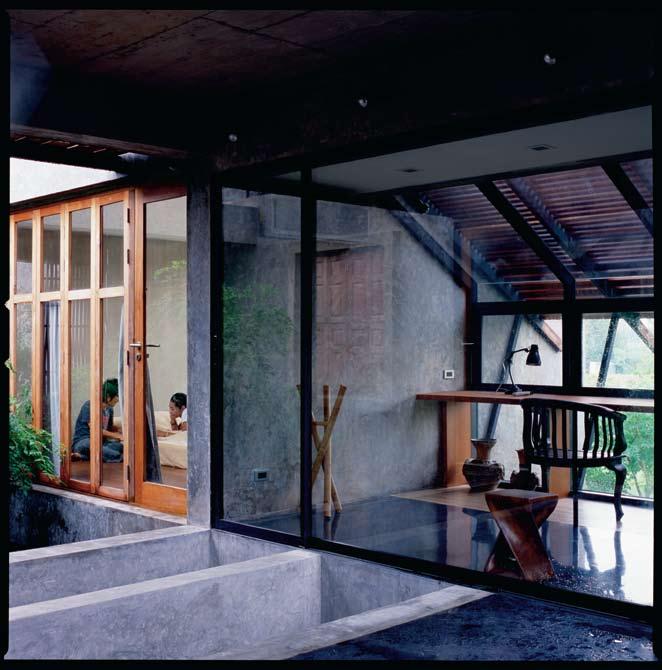

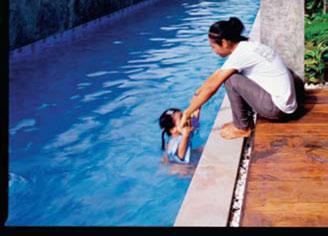

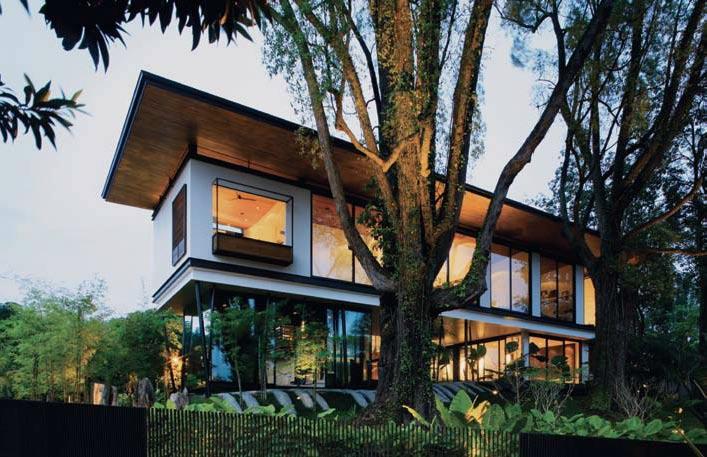

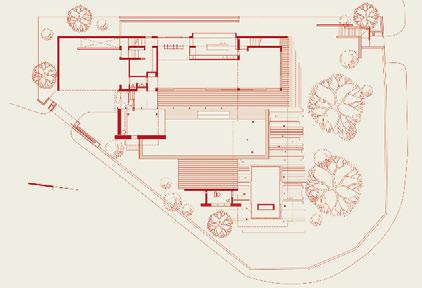

Tonkao Panin explores Boonlert Hemvijitraphan’s architecture, which expresses both a Thai climate and a particularly Thai way of living, encompassing traditional values in a contemporary context.

61 inSPireD

Andrew Parr, Director of SJB Interiors in Melbourne, has had a long career. But something that has always inspired him are the colours and textures of Missoni. Stephen Crafti talks to him about how this translates into his projects.

99

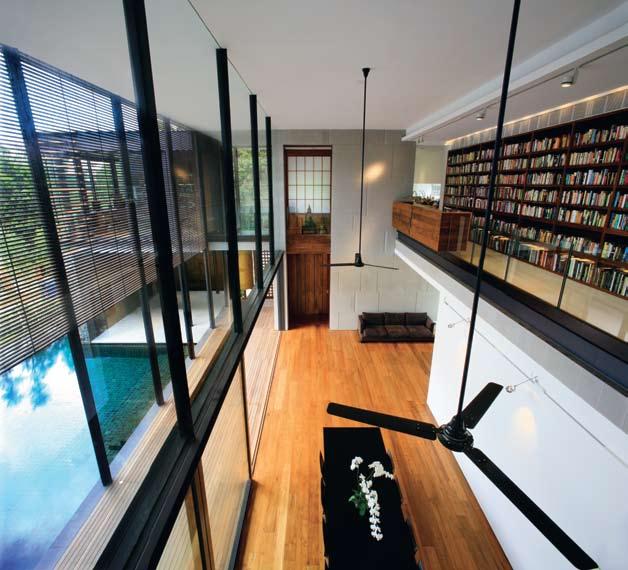

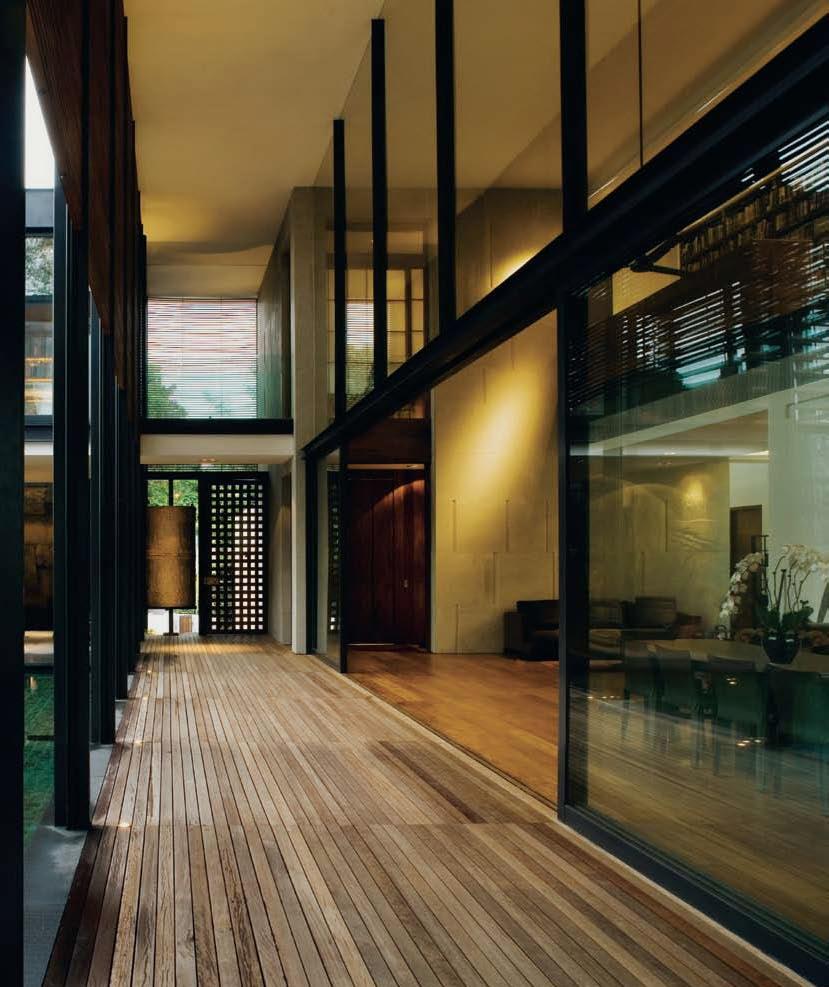

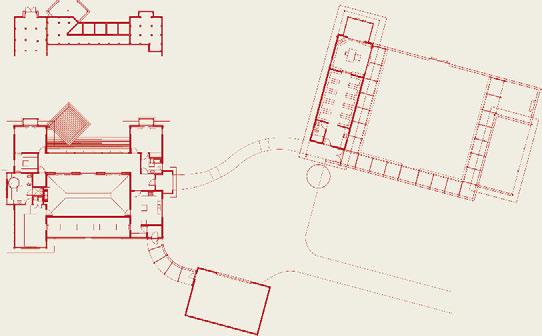

Scenario: naSSim roaD Darlene Smyth explores this project for a family designed by Ernesto Bedmar, which encompasses more than one residence.

115

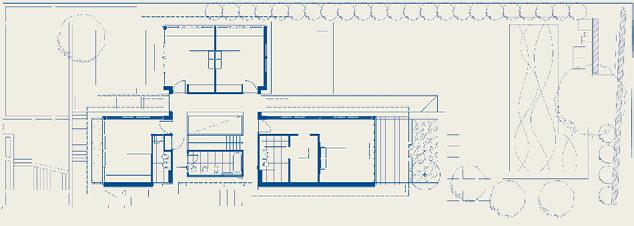

Scenario: ten hoUSing CASE, a group of Bangkok architects, has designed and lives in a project that explores the nexus between community and individual living. Tonkao Panin investigates.

124

Scenario: Batten hoUSe

Penelope Barker visits a house in NSW and finds a contemporary example of Bruce Rickard’s Sydney School style of architecture.

155

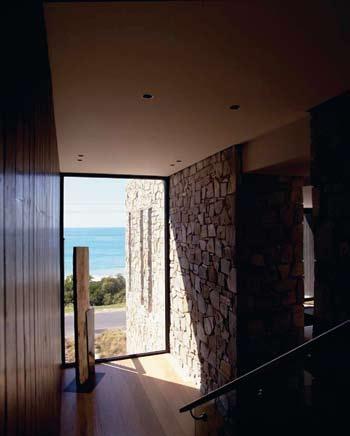

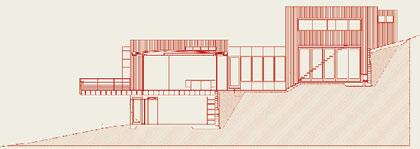

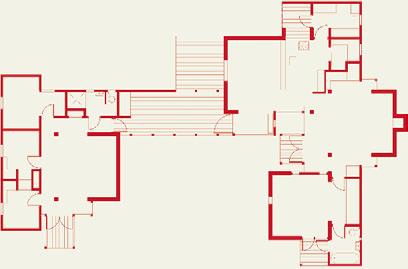

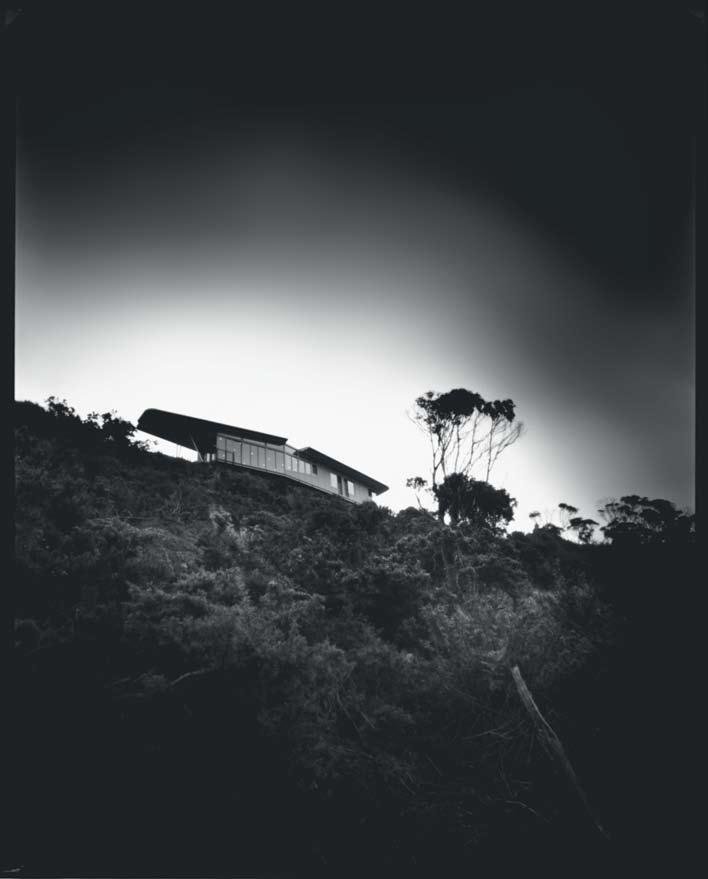

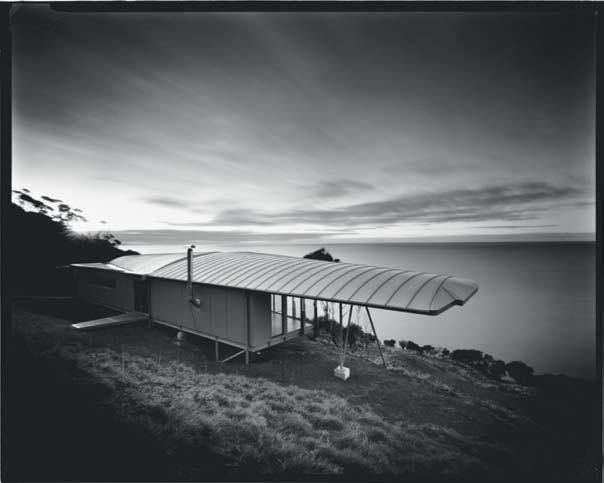

Scenario: Lorne

A holiday home in Lorne, Victoria, designed by architect, Simon Swaney, is much more than the beach houses from childood memories, Stephen Crafti discovers.

183

home moVie: qUentin DemPSter

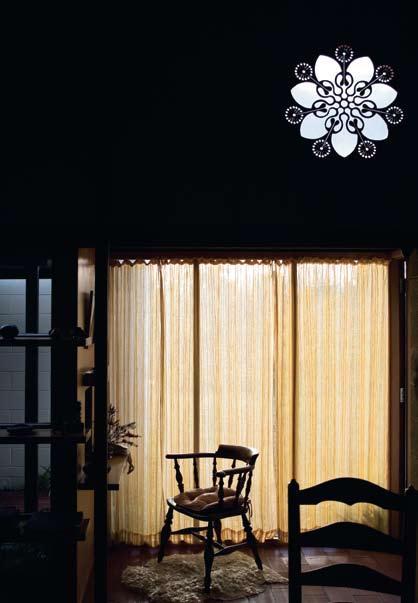

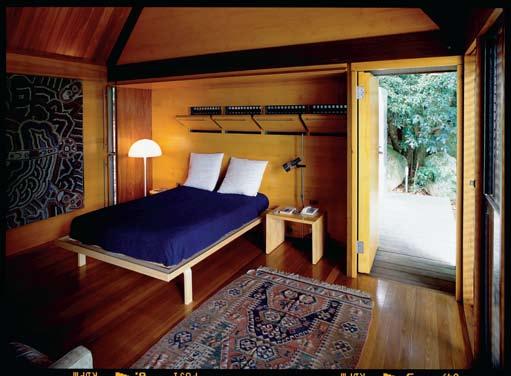

Perched on the Tasmanian coast is the home of television reporter Quentin Dempster, by artist and architect Richard Goodwin.

190

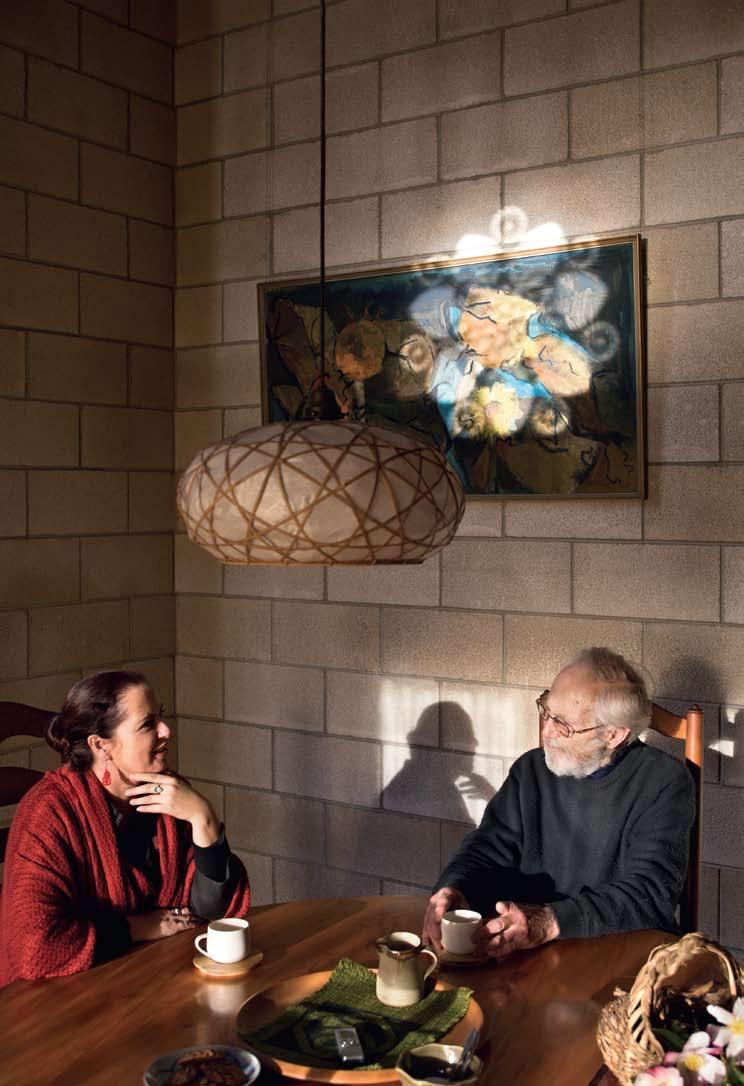

home moVie: DanieL thomaS Andrew Anderson’s house for art critic and museum director, Daniel Thomas is as much a gallery for his art as it is a home.

163

Scenario: BrUce martin

A 1970s home by John Scott, belonging to potters, Bruce and Estelle Martin, has stood the test of time. Andrea Stevens reports.

134

Scenario: eLLwooD

Jenna Reed Burns visits a house in Victoria, refurbished by interior designer Leigh Ellwood, fellow designer Donald Holt and landscape and furniture maker, Greg Hatton.

145

Scenario: LanDScaPe

Chu Lik Ren finds a house by K2LD Architects in Singapore that expresses a characteristic Singaporean respect for its environment.

174

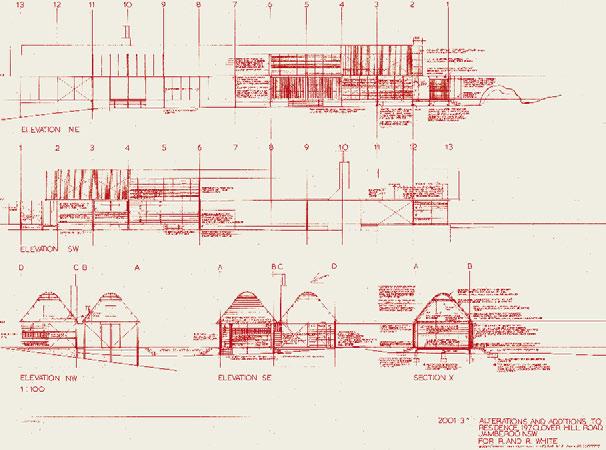

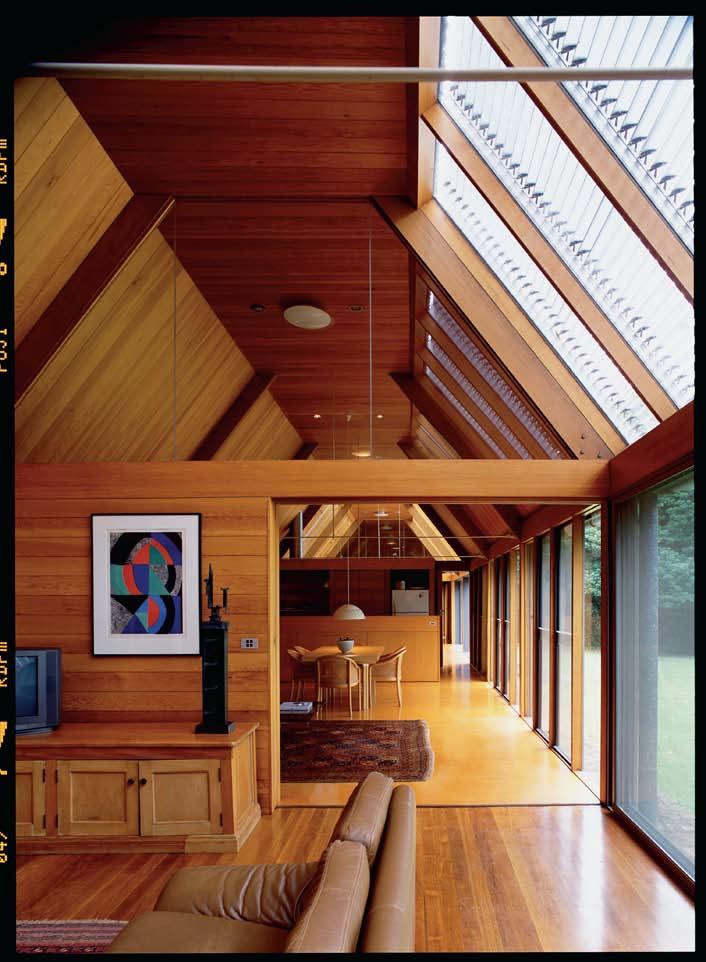

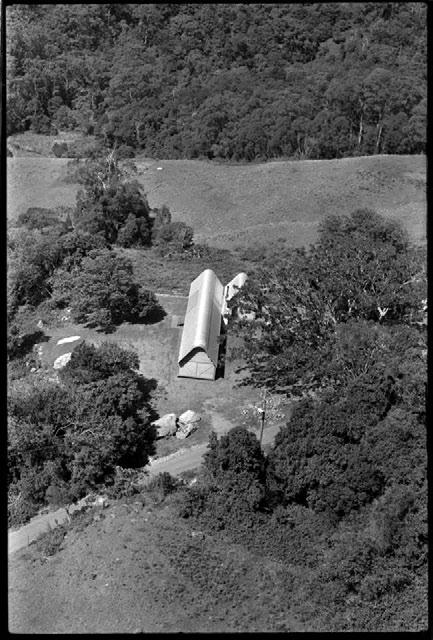

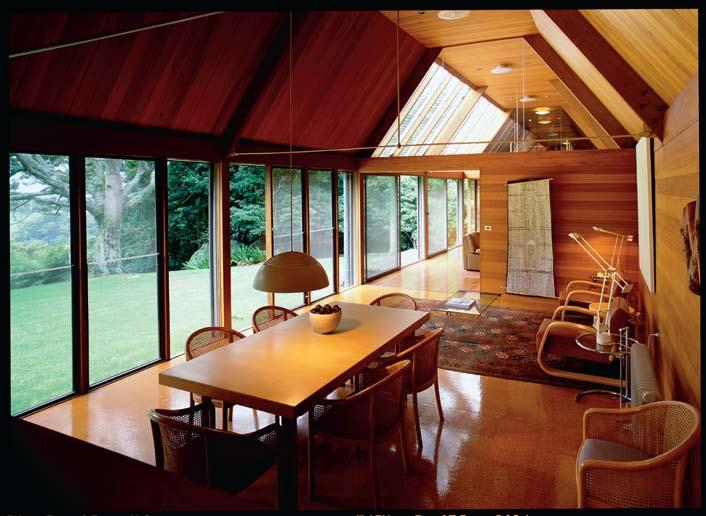

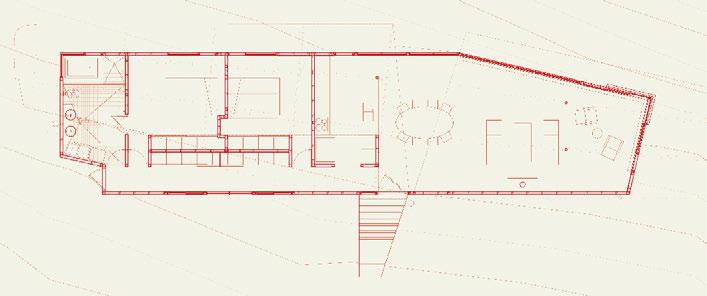

croSS FaDe: white hoUSe: A 1982 Glenn Murcutt-designed home south of Sydney has had a recent change in ocupants, and a subsequent addition, also by Murcutt. Paul McGillick explores the development of the structure.

200

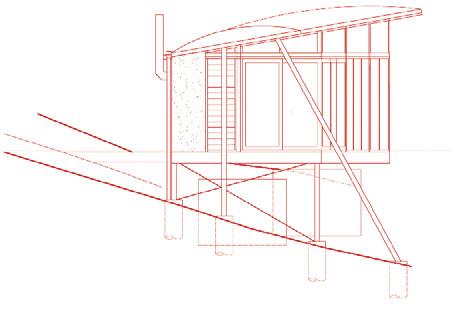

JUmP cUt: roBert Brown Same theme, different solutions… Philip Drew compares and contrasts two very different projects by Robert Brown – one in the Sydney suburb of Bellevue Hill, and the other, a hut in the iconic outback of Mudgee, NSW.

TAKE A VOYAGE TO SPACES THAT INSPIRE AND A CITY REBORN THROUGH ITS SPACES. LOOK TO KITCHEN TRENDS OF THE FUTURE SEEN AT MILAN’S EUROCUCINA EXHIBITION.

218

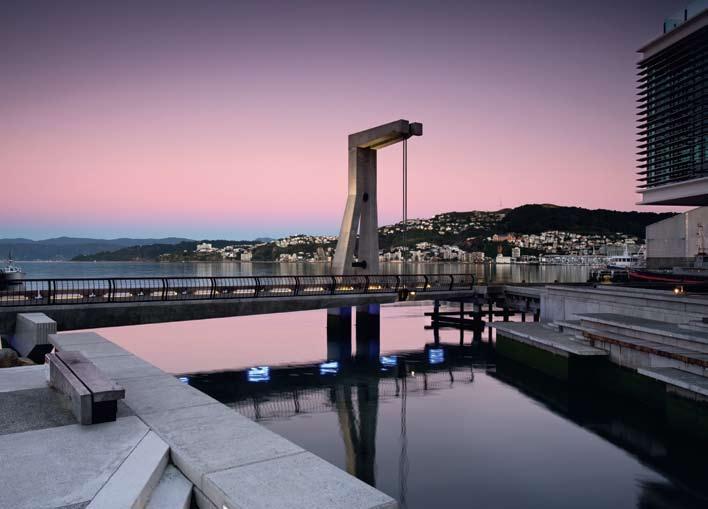

SPaceS we LoVe A collection of diverse and beautiful spaces from the Region.

226

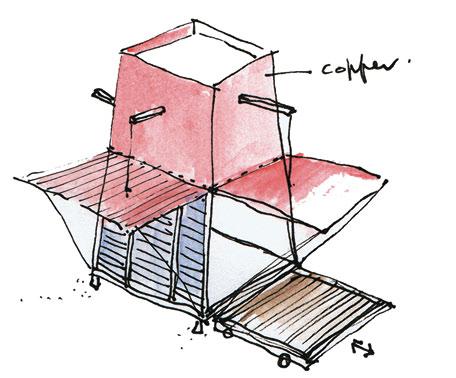

in camera: KitchenS Giovanna Dunmall takes us through Eurocucina and what we can look forward to in kitchen design.

236

SnaPShot: BerLin Mona Nümann discovers the re-use of old spaces is revitalising Berlin’s architectural landscape and culture.

the fascination of a new idea of form. An

alliance proving that good design can never be anonymous.

Like any magazine, Habitus is a work in progress and we look forward to constantly refining it.

But, of course, there is a highly developed idea behind Habitus and this will always be the foundation on which the magazine is built. Basically, Habitus is a magazine about how the design decisions people make are an expression of who they are. Whether it is the homes they build, the gardens and landscapes around those homes, the furnishings inside or even the clothes they wear – all of these things tell us a lot about these people as individuals, as families, as cultures and how they respond to contextual issues of place such as climate, landscape and cultural heritage.

In this issue, for example, I look at some books which deal with the layering of time and history. This will always be an issue lurking in the background of the Habitus stories, because even something which is apparently all about now – fashion, recent design and so on – actually comes from somewhere. Take David Trubridge, for example. He is one of the most outstanding designers in the Region with a substantial worldwide reputation, but all that he produces resonates with his own remarkable story and with the astonishingly beautiful part of New Zealand where he lives and works.

But if we take just a random sample of the architects whose work is represented in this second issue of Habitus – Ernesto Bedmar (an Argentinian living in Singapore), Kevin Low (a Malaysian-Chinese based in Kuala Lumpur), Glenn Murcutt (based in Sydney, but often designing for a rural Australian context) or Boonlert Hemvijitraphan (from Thailand’s vibrant capital) – each of them has a fascinating story which in turn responds to the stories of their clients and the context in which they are living and working.

Crucially, Habitus is about cultural engagement – about architects and designers from Australia, New Zealand and South-East Asia enriching one another in an on-going dialogue. The differences and commonalities all add up to a matrix of ideas which can lead to better outcomes for the environment we live in. Perhaps nothing sums up this part of the Habitus agenda more than our story on Rimbun Dahan in Kuala Lumpur, a remarkable story of exchange, sharing and cross-cultural inspiration and support. The kind of cross-cultural encounters which Rimbun Dahan engenders are the kind from which we can all benefit. In fact, we are already benefitting. It is often just a case of realising what is going on and then building on that in a conscious way.

Paul McGillick, Editor

I Habitus #01 has finally launched and, as the feedback comes in, the fine-tuning begins.

I “Habitus is a magazine about how the design decisions people make are an expression of who they are.”

AndreA StevenS

Writer

Last issue Andrea wrote about an inspirational treehouse by Joseph Lim in Singapore for Spaces We Love. This issue her stories were a bit closer to home: Andrea visited Bruce Martin’s 1970s house in Hawke’s Bay (page 163), and bought one of his beautiful wood-fired pots. Not far from there, she also spoke to David Trubridge (page 52), who is making his fine timber furniture in an old brick warehouse.

nicky ryAn

Photographer

Nicky first picked up a camera in high school, when her love affair with photography began – a recent fling taking place while shooting the Millevini wine bar on page 35. She has travelled the world through her photography and is currently based in Sydney’s Bondi Junction. Her favourite design object is a lead crystal lamp with a white shade which takes pride of place in her lounge room.

Prue ruScoe

Photographer

Prue is renowned for her fashion and beauty photography as well as her inspiring interior and lifestyle images – you can see her take on Inge Holst on page 68. Prue has been in the industry for 15 years, working her way up from an assistant, to contributing to various publications, including books. It’s fortunate she resides in Sydney’s Bondi Beach, with partner George and two children Luca and Eva, as her favourite pastime is spending time at the beach with her family.

StePhen crAfti

Writer

Stephen wrote three articles for Issue #2 of Habitus – Partnership on page 46, Inspired on page 61 and Creation on page 65. He also wrote the Lorne House feature on page 155 in the Scenario section. Stephen believes “...it’s important to broaden the discussion on design, whether the subject is architecture, interiors, furniture or fashion. Finding out what a graphic designer thinks about an artist is as interesting as how a person lives.”

GiovAnnA dunmAll

Writer

Giovanna, a freelance journalist living in London, travelled to Milan to research her In Camera story, on page 226. Giovanna hopes to launch an eco-website in 2009, and loves her pool rocker chair at home, made by young London-based designer Giles Miller. She asked him to make it for her after interviewing him and says – “It is so strong and durable. It is beautiful too as it is full of patterns and shapes. Anyone who thinks cardboard is for hippies is wrong!”

chu lik ren

Writer

Lik Ren worked on two projects for this issue of Habitus – the profile on Kevin Low on page 81 and the Landscape House on page 145. He says “It’s evident the best residential designs in Singapore and Malaysia are reaching their own high levels of maturity and sophistication. There’s the earthy Malaysian house and the pristine Singapore model. They are obviously each other’s counterpoint.”

trevor mein Photographer

Trevor Mein shot the Lorne House Scenario story on page 155, though his work first came to prominence in the late 1980s. Trevor trained in fashion design and graduated with a bachelor degree in architecture. He shoots for major designers, corporations and journals and is extensively published. His philosophy is to imbue images with atmosphere, to embrace the designer’s intentions with the subsequent layering of habitation and environment.

JennA reed BurnS

Writer

Melbourne-based Jenna is a writer and journalist with an interest in design and architecture. Jenna wrote about a house in her own suburb in the Scenario story on page 134. Jenna loves the “simple shape and deep rich colour” of her cobalt blue Holmegaard Gul vase, designed by Otto Brauer in 1962 and picked up from a garage sale in Sydney around 20 years ago.

Anthony Browell

Photographer

Anthony photographed three projects this issue for the Home Movie stories on pages 183 and 190, and the Cross Fade story on page 174. As with the Langston-Jones house in Issue #1 of Habitus, Anthony used a large pinhole camera to interpret Quentin Dempster’s house (page 183), capturing the extroverted, elegant assemblage of shapes. Anthony also personalised the project by adding a visual commentary of the team who conceived and crafted it – owner, architect, builder and critic.

Simon devitt Photographer

Simon worked on two photo shoots in this issue representing a rich vein of New Zealand design. First up was a Hawke’s Bay mid-century delight in Bruce Martin’s 1970s house on page 163, and a more modern touch nearby at the home and studio of David Trubridge on page 52, with his fine timber furniture and the landscape that inspires him.

tonkAo PAnin

Writer

Tonkao comments “As someone whose main job is teaching architecture, especially its history and theory, it is refreshing to contribute some points of views towards built projects such as TEN Bangkok (page 115), as well as Boonlert Hemvijitraphan’s design (page 72). Theoretical reflections, either critical or informative, only become ‘real’ once buildings are built, dwelled in and transformed. It is a point where the dialogue between theory and practice is possible.”

SPAceShift Studio

Photographers

Pirak Anurakyawachon of Spaceshift Studio shot two stories. He, along with partner Arunyarat P, explains “We present selected houses by Boonlert (page 72) – we really love his super delicate and so accurate signature of his works. Also, please enjoy the utopian TEN housing project (page 115) which we have learnt a lot from on how to share living space.”

lizette Bell

Photographer

Lizette photographed the Inspired story on page 61, the Partnership story on page 46, and the Ellwood House feature on page 134 of this issue. She lives in a sun-drenched Melbourne apartment a short walk from the beach. Her favourite design object is her Greg Hatton sugar gum log stool – she has an obsession with weathered, raw and recycled timber.

hAnS SchluPP

Photographer

Hans graduated from the oldest school of photography, the Lette-Verein in Berlin. He has worked as a freelancer in many parts of the globe and currently lives between Sydney, Hong Kong and Beijing. He also has a strong presence in Singapore, where he shot some of the images for the Kevin Low profile on page 81. Hans loves his old Eames lounge and says “...it’s the only seat I really relax in.”

fionA lim

Photographer Fiona Lim of FIFOTO

Photography shot the story of Rimbun Dahan on page 89. Her company is based in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, known for its colourful diversity both in food and the people who make it their home. Fiona loves the retro fibreglass Pastil chair by Eero Aarnio in her apartment saying, “It is super comfy to laze and spin around in!”

monA nümAnn

Writer / Photographer

Mona grew up in West Germany before emigrating to Australia, where she studied film and communications and began her career in the same area. After nearly three decades in Australia, she has taken up part-time residency in Berlin to rediscover her German cultural heritage, including the art, architecture and design she writes about for the Snapshot story on page 236. She loves her ageing Bang & Olufsen sound system because “... it strikes with its unique utopian design and still ensures ultimate listening quality.”

issuE 01 corrEctions:

On the Issue #1 Contributors page we said that Philip Drew lives with his daughter. In fact, she lives in Coffs Harbour and he in Annandale.

In Issue #1 Design News, page 24, The Strauss Chair was incorrectly attributed to Thonet Australia.

Thonet Australia Pty. Ltd. is the registered proprietor of Trade Mark A488756 being Thonet® in Australia. Thonet Australia gives notice that it will take steps necessary to protect the trade mark in Australia and any other jurisdiction where the trade mark is registered.

The Strauss Chair is available through Format Furniture, formatfurniture.com.au.

In Issue #1 Design News, page 25, the Andoo Lounge Chair is incorrectly attributed to Knoll/ dedece. The Andoo Lounge Chair is manufactured by Walter Knoll, available from Living Edge walterknoll walterknoll.de / livingedge.com.au.

In Issue #1 Director’s Cut, page 166, text is incorrectly attributed to Stephen Crafti. It actually was written by Paul McGillick.

Editorial dirEctor Paul McGillick habitus@indesign.com.au

associatE Editor Andrea Millar andrea@indesign.com.au

assistant Editor Nicky Lobo nicky@indesign.com.au

dEsign and art dirEction Wishart Design wishartdesign.com

Art Director: Karlee Bannon Junior Designer: Jessica Ryan

contributing WritErs Penelope Barker, Chu Lik Ren, Stephen Crafti, Philip Drew, Giovanna Dunmall, Tempe Macgowan, Mona Nümann, Tonkao Panin, Jenna Reed Burns, Darlene Smyth, Andrea Stevens

contributing PhotograPhErs Pirak Anurakyawachon, Lizette Bell, Patrick Bingham-Hall, Grazia Branco, Anthony Browell, Penny Clay, Simon Devitt, Max Dupain, John Gollings, Ian Hobbs, Simon Kenny, Albert Lim, Fiona Lim, Trevor Mein, Michael Nicholson, Mona Nümann, Louis Petruccelli, Prue Ruscoe, Nicky Ryan, Hans Schlupp

PublishEr / Managing dirEctor

Raj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

oPErations ManagEr

Adele Troeger adele@indesign.com.au

businEss dEvEloPMEnt ManagEr

Richard Burne richard@indesign.com.au

Production dEsignErs

Bronwyn Aalders, Lauren Mickan, Sarah Djemal, Camille Manley, Eunice Ku

Production assistant Kristy Macfie kristy@indesign.com.au

Financial dirEctor Kavita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

accounts Gabrielle Regan gabrielle@indesign.com.au

Darya Churilina darya@indesign.com.au

onlinE coMMunications ManagEr

Rish Raghu rish@indesign.com.au

onlinE coMMunications assistant Simon Layfield simon@indesign.com.au

EvEnts coordinators

Kylie Turner kylie@indesign.com.au Angela Raven angela@indesign.com.au

advErtising EnquiriEs

Richard Burne richard@indesign.com.au 0423 774 126

covEr iMagE thai architect, boonlert hemvijitraphan

Photography: Pirak anurakyawachon

indEsign Publishing

Level 1, 50 Marshall St

Surry Hills NSW 2010

(61 2) 9368 0150

(61 2) 9368 0289 (fax) indesignlive.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publication, the publishers assume no responsibility for errors or omissions or any consequences of reliance on this publication. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, the publisher or the publication. Contributions are submitted at the sender’s risk, and Indesign Publishing cannot accept any loss or damage. Please retain duplicates of text and images. Habitus magazine is a wholly owned Australian publication, which is designed and published in Australia. Habitus is published quarterly and is available through subscription, at major newsagencies and bookshops throughout Australia, New Zealand, South-East Asia and the United States of America. This issue of Habitus magazine may contain offers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. If you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services we have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as fulfilment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however, these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information and use it to inform you of other promotions and publications from time to time. If you would like to know what information Indesign Group holds about you please contact Nilesh Nandan (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax), subscriptions@indesign. com.au, indesignlive.com Habitus magazine is published under licence by Indesign Group.

ISSN 1836-0556

HERON CHAIR Australian designer Charles Wilson reinterprets the organic curves of the Victorian era into this graceful chair, whose profile is the streamlined form of a bird’s body cantilevering into the legs, livingedge.com.au

SCREW Ross Didier’s latest coat-hanger oozes masculinity, practicality and contemporary cool. Larger than life, this piece is sure to attract attention. The wall-mounted object is made from solid melamine polymer and cast aluminum, 225mm length x 120mm diameter, rossdidier.com

ZOE Cool, contemporary – bean bag? Designers Lievore, Altherr and Molina bring a whole new meaning to this once casual lounge piece with Zoe. Constructed from five internal chambers filled with glazed beads, Zoe is easily manipulated into various positions. Available upholstered with expressed seams in both fabric or soft leather, this über cool piece is sure to please, stylecraft.com.au

DELPHI A collaboration between Erik Jørgensen and Swiss architect Hannes Wettstein has produced a stylistic, versatile new concept modular sofa. Consisting of 11 different modules, it’s possible for the lounge to be used in an array of configurations to suit the busy lifestyles of modern families, corporateculture.com.au

“The urge for GOOD DESIGN is the same as the urge to go on living.”

FIREWOOD BASKET Made of 100% pure wool from German experts in felt, Hey-Sign, this basket is the perfect, stylish way to carry your logs to the fireplace, hey-sign.de

ZURI Both modern and classic, this freestanding bath-tub is manufactured from quartz and resin, in a simple form whose subtle geometric lines are ideal for the contemporary bathroom, rogerseller.com.au

FRACTURE Quirky Dutch designer Ineke Hans has created a lightweight, yet strong series of furniture that looks like it’s wrapped in bandages, cappellini.it / dedece.com.au

I

I 11

LOOP STAND Designed by Leif Jørgensen for HAY, the ultra chic Loop Stand has a three-dimensional, graphic look. Available in black or white powdercoated finish, corporateculture.com.au

HARRY BERTOIA

PALETTE PLATE Little eaters will enjoy mealtimes with this new plate, decoratively shaped like an artist’s palette. The microwave-safe plate comes with three boldly coloured drop-in bowls, allowing early eaters to sample, explore and discover new foods without fuss, skiphop.com

NEO COUNTRY This rocking chair designed for little people is made in solid wood and based on the kind of rural furniture found in traditional Dutch homes, cappellini.it / dedece.com.au

APEHANGER Contemporary Swedish design company Our Children’s Gorilla had function and a healthy dose of humour in mind with these cute ape clothes hangers for kids, ourchildrensgorilla.com

MOBILE HOME Made from colourful eco-friendly cardboard by Amsterdam-based Kidsonroof, this is a house made for knights, pirates and princesses, kidsonroof.com

PIPPOCAMPUS Designed to blend in with adult furniture, this is the rocking horse re-invented, with new materials and contemporary style, disguincio.com / milkfurniture.com

MIAMI With overscaled dimensions, this outdoor light has a shade made of waterproof white resin glass and a frame made of inox stainless steel, gineico.com

SUNDECK GARDEN LOUNGER This lounger from German company Flora, is just the thing for enjoying the summer sun with a good book, flora-online.de

VELA This new range of outdoor chairs hits the mark in terms of covetable design and materials that can withstand outdoor use. Made by Accademia in Italy, they’re made with AISI 316/L stainless steel tubing and weaved PVC rope, accademiaitaly.com / spacefurniture.com.au

ZOOP The self-titled Poet of Plastic, leading design figure Karim Rashid, does it again with this new watering can for Propper in a variety of wild colours, propper.de / outliving.com.au

RE-TROUVÉ Spanish designer Patricia Urquiola takes us back into the 50s with this entertaining reinterpretation of the delicately handcrafted lace metal designs of the era. The style is characterised by the repeated diamond patterns in the delicate curls and twists of the metal work. Unlike its predecessor Re-Trouvé is not handcrafted, although superior technology used to manufacture these pieces ensures a high-quality product, kezu.com.au

BAR WARE Oozing aesthetics and practicality, Michael Young’s striking Bar Ware range, complete with swizzle sticks, is sure to draw in the crowds. This British-born designer makes a unique comment on what to expect from the modern cocktail set, optique.com.au

IDOLL MOOD BOOK It’s good to see the art of journal writing is still a protected species with thoughtful (and quirky) designs still being produced. Each page has been carefully designed to cover all areas, pups.it

BLACK TITANIUM SERIES This elegant and functional set from Danish design company Menu is discreet and stylish, and includes a mobile phone charger tray, card beeper, luggage tag, keychain and cardbox, menu.as

ME&U Hanging about at home? This upholstered indoor swing may be the answer to the contemporary challenge of limited floor space. Designed by Danish duo Busk+Hertzog, it hangs from a cable wire attached to the ceiling, interstudio.com.au

RRP$3500

RRP$21,850

The X-System bookcase from Planex’s Australian design and manufacture program, is a chic choice for the modern home. Incorporating a modular design, the X-System can be adapted from a simple credenza to a full-wall shelving system. Available in 120 colour options.

The great charm in Swen Krause’s elegant bookshelf is in its endless possibilities for layout: a metal sheet mounts horizontally or vertically (or diagonally) on the wall, while the storage boxes, with their magnetic backing, attach to the sheet in any position. Mix and match as you please.

Bookshelf or sculpture? This item has a decisive energy thanks to its multi-directional shelving and crossed lines. The absence of solid backing gives it a light feel, making it an ideal solution to gently divide space. Available in tinted oak, open pores lacquer or matte lacquer finish.

Opus Incertum

Furniture formatfurniture.com

RRP$1810

Jasper Morrison’s bookcase is an integral part of his Crate Series: a collection of furniture originally inspired by the simplicity of a found wine crate. Incorporating the trademarks of the series, solid materials and striking usability, this bookcase will be a good fit for contemporary homes.

Sean Yoo Casamania casamania.it Insitu insitufurniture.com.au

RRP$570 white/black; RRP$615 grey; RRP$793 orange

Functioning as both bookshelf and stunning display case, Sean Yoo’s Opus Incertum is compact, sculptural and inspiring. Suitable for outdoor and indoor conditions, Opus is designed to be stacked in multiple formations, and in good news for the environment, Opus is constructed from 100% recycled materials.

right now there’s good reason to buy books

I What can you expect to find when a young, savvy interior designer, a high-end furniture retailer and two Italian restaurateurs come together to open a new wine bar in one of Sydney’s signature design precincts?

What you find are spaces that are meticulously designed – with a few surprises – to be the embodiment of a fine glass of red wine. Food that is creative and delicious wine to match (literally).

Millevini is the work of three partners from other well-known Sydney institutions, Khali Khouri from designer furniture house, Poliform, and Mauro Marcucci and Sabina Boncompagni of Italian trattoria, Pizza e Birra, also in Surry Hills.

The three partners enlisted the creative talents of interior designer, Cressida Kennedy of Space Control Design for the interiors, who responded to the brief with an intimate, contemporary interpretation of a classic winemaker’s den. “My brief was to create an Italian tapas feel to the place. From this I decided to keep the design quite raw, working with the architecture,” says Kennedy.

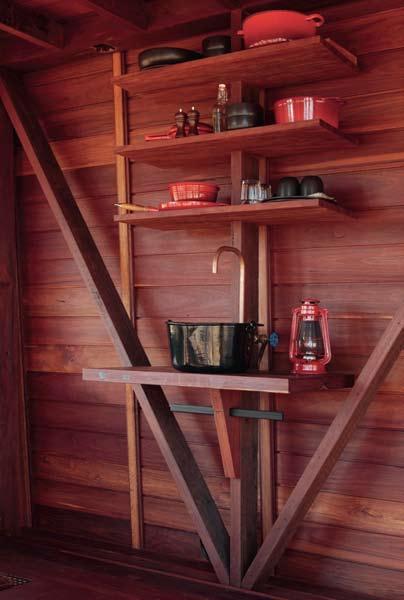

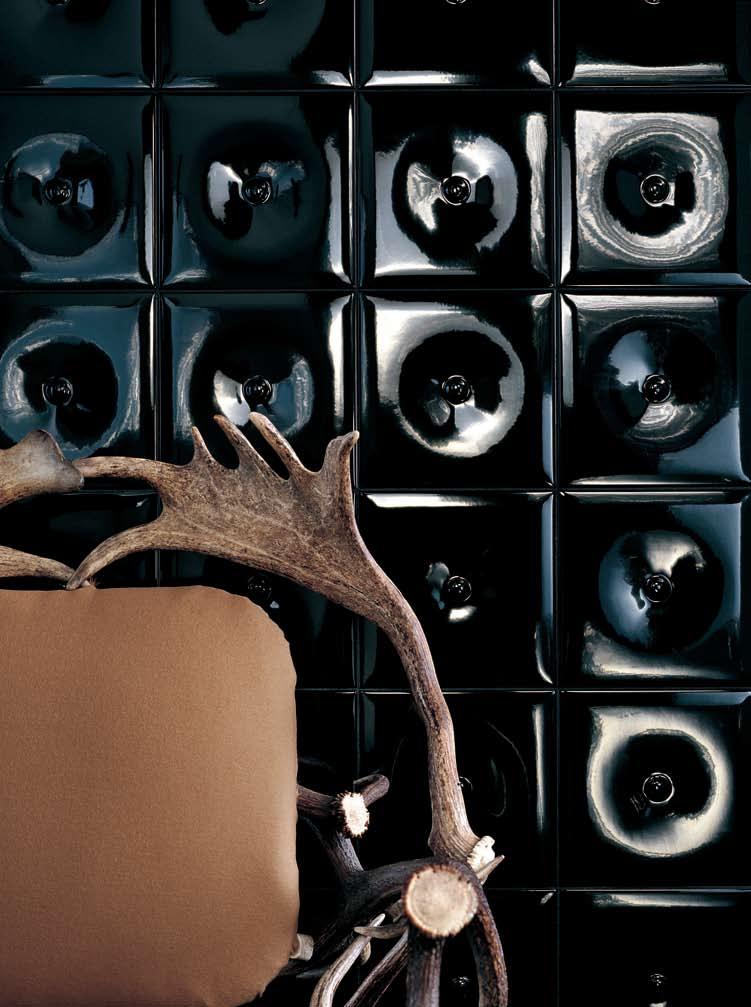

Key features of the new wine bar include raw, exposed rafters on the mezzanine level, a twostorey display of local and imported wine bottles and an exposed fireplace flue on the eastern wall. Considered details such as a custom crafted front door handle in the shape of grapes in metal, and mirrored ceilings in the bathrooms provide pleasant design surprises.

Fine wine consultant Guy Vaillant has introduced a range of local and important fine wines designed to match with the flavours of the dishes served. Head chef, Cristian Di Sandri has created an Italian tapas menu that combines modern classic Italian dishes such as risotto ai funghi porcini e tartufo bianco (risotto with porcini mushrooms and white truffles) with fast and tasty servings that have a distinct tapas inclination, such as spiedini d’anitra con prataioli e prosciutto (mini skewer with duck and champignon wrap on parma prosciutto). If Millevini is an indication, good design, good wine and good food will continue to forge new ground in the harbour city due to the relaxed licencing laws in the state, and its inhabitants don’t mind at all.

A The trick is to create a harmony of balance on the palate. When you taste the wine and you taste the food, none of the compounds should overpower the other. A wine becomes one more dimension of the taste of the food.

Q&A

If you were given an hour with a sommelier what would you ask? Andrea Millar talks to fine wine consultant, Guy Vaillant:

Q How does a sommelier choose wines for a restaurant?

A The wines I choose depend on the style of food served. For instance, in a seafood restaurant a third would be white wines in an aromatic style, wines without too much oak. Another third would be fruit driven reds such as Pinot Noir. The last third would be unusual wines say from up and coming vineyards. These I tend to include by the glass so customers can discover them.

Q What are the basic rules of food and wine matching?

I 02

Fine wines line sandstone walls on the mezzanine level.

Q Can you drink one single wine throughout an entire meal?

A There are notions that you need a different wine for fish or red meat for instance, but the reality is that people tend to stick with what they know or be a certain varietal lover. At a restaurant a sommelier can choose a wine to go with the dishes chosen – a Pinot Grigio works with a seafood entrée and a pasta for main, for example.

Q What is the height of bad taste – what shouldn’t you match?

A There are no general bad matches but if for instance you match a heavy, rich red with seafood the use of oak and tannins will make the wine taste bitter on your palate. Sometimes, if a wine tastes too acidic it could be the food you’re having it with.

Q If you were stranded on a desert island what bottle would you take with you?

A Montrachet, a French Chardonnay because it’s one of the most expensive. Also, a bottle of red like Serafino from McLaren Vale. These wines retain natural acid, they last longer and age well. Lastly, an aged Semillon like Tyrells Vat 1 that has complexity.

Q Are there any foods that are impossible to match with wine?

A Usually curries, but you serve them with white fruity styles to reduce the heat on the palate. The same applies for chilli dishes. However, anything with cheddar cheese, you have to match with beer.

Q What’s your choice of the best three wines to drink?

A A Pinot Noir from Pemberton in Western Australia, a Sangiovese from central Victoria or McLaren Vale and a Chardonnay from Western Australia – they tend to be more fruit driven, richer and have more weight on the palate.

...a custom crafted front door handle in the shape of grapes in metal , and mirrored ceilings in the bathrooms provide pleasant design surprises

Designer: Ingmar Relling

Rybo West Nofa is the Norwegian company which produces the “Siesta” range. Designed in 1964 by Architect Ingmar Relling, known as one of the greatest contributors to Scandanvian design. With its clean structural based design and well considered ergonomics, the Siesta chair has received numerous accolades and is exhibited in design museums and galleries around the world.

Melbourne

237 Napier Street, Fitzroy VIC Australia 3065

Freecall 1800 800 777

Phone 03 9417 0077

Fax 03 9417 0011

Email sales@thonet.com.au

Sydney 21 Boundary Street, Darlinghurst NSW Australia 2010 Phone 02 9332 1600

Fax 02 9332 4073

Email nsw@thonet.com.au

www.thonet.com.au

Adelaide Stylegroup Phone 08 8232 2155

Perth Katsui Phone 08 9385 3005

Newcastle HVD Phone 02 4929 6066

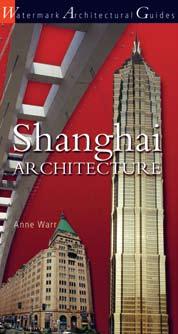

New or old, the most interesting architecture reveals layers of experience. Paul McGillick reviews four books which explore layering in both the public and private spheres.

I recently read J.G. Ballard’s autobiography, Miracles of Life. Ballard grew up in Shanghai and was still a boy when he and his family were interned by the Japanese for the duration of World War II. His childhood experiences were celebrated in his most popular book, his autobiographical novel, Empire of the Sun, subsequently made into a highly successful film directed by Steven Spielberg.

Ballard returned to Shanghai for the first time in 1991 and puts his finger on some intriguing paradoxes. Ballard asserts that the Chinese are uninterested in the past, and the destruction of Beijing would seem to support this. But Shanghai has tended to defy this trend. Substantially, of course, it was a European city, built up by European entrepreneurs who created a heady and hedonistic outpost laid over the top of almost inconceivable vice and poverty.

After 1949, the city was completely sinified and the vestiges of European life were driven out. But as Ballard points out, the old French Concession is “still today one of the largest collections of domestic art deco architecture in the world. The paintwork was shabby, but there were the porthole windows and marina balconies, fluted pilasters borrowed from some car factory in Detroit in the 1930s. Curiously, the TV towers, broadcasting the new to the people of Shanghai, seemed rather old-fashioned and even traditional, as seen everywhere from Toronto and Tokyo to Seattle. At the same time, the dusty and faded art deco suburbs were bracingly new.”

Ballard’s observations are supported by Anne Warr in her fascinating guide Shanghai architecture. It is, she says, “a city of contrast and paradox. Notorious in the 1990s for having the world’s largest agglomeration of construction cranes it is, nevertheless, one of the few cities in the world where a majority of the buildings of the 20s and 30s have not been pulled down.

“Stop for a moment before an apartment building in the former French Concession and look beyond the wires and air-conditioning units clinging to the exterior. Gradually you will see the sleek unencumbered lines of an original Art Deco building and realise that all around you, beneath the electronic cobwebs, are the bones of the old foreign city.” The paradox, of course, is that Shanghai is also home to one of the most phenomenal building sprees of all time – in the business districts of Puxi and Pudong, across the river from the Bund. As Ballard observes, looking down from his room on the seventeenth floor of the Hilton Hotel, “I could see at a glance that there were two Shanghai’s – the skyscraper city newer than yesterday, and at street level the old Shanghai that I had cycled around as a boy.”

Shanghai, of course, pre-existed the European concessions (which dated from the Opium Wars in the early 1840s) and significant layering of that past still exists. As Warr comments: “Over its history, each of the city’s distinct phases left an imprint on the built form. It is all here from the temples and gardens of the walled city to the Tudorbethan villas and faux French châteaux of the foreign settlements. That is not to mention the Art Deco apartment blocks, the Jewish ghetto, the Sino-Soviet Friendship Hall and the burst of Post-Modernism in the 1990s.”

The Bund (the word, Warr tells us, is Hindi for ‘embankment’ and is pronounced as in ‘fund’) is best known for its imposing array of Beaux-Arts and Art Deco buildings from the great days of the European trading companies. But the entire city is a marvel of the preserved past. And while there is a layering in the sense of accretion, there is also another layering in the form of the lilongs (unfortunately these have been more prone to destruction), which were an extraordinary blending of local and imported forms. Initially, the Chinese were forbidden from living in the foreign concessions. However, the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) precipitated a flood of refugees to the cities and the proscription broke down. The trading companies soon found they could earn more from real estate than opium. They developed entire city blocks into a unique form of mass housing: a perimeter of shop houses enclosing a network of lanes with row housing. To make the tenements more attractive to the Chinese, small courtyards were inserted, “accessed through pairs of black timber doors framed by stone portals – called shikumen.”

01, 02 Shanghai

Anne Warr

Published and distributed by Watermark Press 340pp softcover AUD$49.95 watermarkpress.com.au

03, 04, 05 FaçadE

Tom Evangelidis

Published and distributed by Jules Laverne 220pp hardcover AUD$110 juleslaverne.com

06, 07 t hE nE w Ma L ayS ian houSE

Robert Powell

Published by Periplus Editions 224pp hardcover US$34.96 peripluseditions.com

08 roM ancing thE t ropic S:

BE dM ar & Shi

Oscar Riera Ojeda (editor)

Published by Oro Editions 240pp hardcover AUD$112.50 oroeditions.com

“More than any other building form in Shanghai,” says Warr, “the lilong encapsulates the unique intertwining of Chinese and Western society. Today, the inner life of Shanghai cannot be fully understood without venturing through one of the lilong gates into the parallel world of serenity and order.”

Today, the Xintiandi precinct is best known as a restored lilong, incorporating restaurants, bars and boutiques – and including preserved shikumen houses. Since 1994, the Shanghai Government has actively sought to preserve the city’s heritage alongside the gobsmacking rates of development. At the same time, many fine pre-War buildings are being restored and adapted for new uses.

All of this is magnificently recorded in Warr’s book. This guide is the first thing you need to pack when you next travel to Shanghai. But it is far more than a guide, because Warr is a pioneer in researching Shanghai’s built heritage and the book represents a crucial body of research.

Of course, this remarkable heritage in Shanghai really comes down to us by default, cocooned as it was by more than 50 years of communism. The absence of capitalist development preserved the buildings, even though they were allowed to deteriorate (the Cultural Revolution was one period where a certain amount of destruction did take place). The same is true throughout the former (indeed, current) communist world.

Prague is probably the finest example. The communists built their hideous panelaks (cheap, high-rise apartment towers) out in the suburbs, but the city remained untouched, much of it gradually crumbling. By the time the communists were thrown out, there was no question that any of this heritage would be allowed to be developed. In fact, any form of development faces a real obstacle race – witness Frank Gehry and Vlad Milunic’s ‘Ginger and Fred’ House on the river, built on the site of the only bomb to fall on Prague during the War.

Tom Evangelidis lived in Prague for a time and first came to prominence with his exquisite photo archive of the city. This revealed the layers of history which characterise the city (it is not, as Milunic once explained to me, a coherent city architecturally, but derives its unity through a common scale and the topographical definition of the river and the hills on either side).

Now Evangelidis has produced a handsome collection of recent photographs in a large format book called Façade. The collection includes shots from Prague, but also St Petersburg, Moscow, Hanoi, Havana, Sofia, Bucharest and Istanbul. The book has no text (apart from a brief introduction by Barbara Messer) and one needs to go to the back to finally identify each image. Evangelidis wants to privilege the images. Again, we see a default heritage from communist times, as well as some extraordinary images of communist architecture. We see the layering of time. But we also see a strange entropic process as many of these buildings gradually deteriorate (as in Vietnam and Cuba), seeming to shed their layers until, presumably, there will be nothing more to shed.

As the title implies, Evangelidis prefers the façades of buildings, usually shooting them straight on. What he sets out to do is to allow the story of the building to emerge through the palette and texture of its façade. Some of the buildings are quite paradoxical, while all of them hint at histories which we will never really know.

On the other hand, these images can be read as portraits and the entropy of the buildings seen as a metaphor for ageing. The vanity and ego of the spurious idealism of communism is exposed and, like Dorian Gray, the corruption within becomes gradually manifest.

Layering – the resonance of the past through contemporary forms – is also the major presence in Robert Powell’s latest book, the new Malaysian house. Along with Singapore-based architect, author and publisher, William Lim, Powell has been the most important researcher

and advocate of the new wave of South-East Asian architecture, especially domestic, since it first emerged in the early 1990s.

Post-colonial debate about culturally and climatically appropriate housing forms in South-East Asia initially triggered a wave of vernacular revival. This saw a revived interest in traditional building forms, local materials and passive climate control strategies. But a new generation of architects and clients in the early 1990s saw a flowering of highly sophisticated and invariably quite beautiful housing. Singapore led the way, but Thailand and Malaysia are now also fascinating for the imagination of their new housing solutions.

Those solutions are highly varied, as can be seen in Powell’s new book. All the residences are in Malaysia, although some of the architects are actually based in Singapore. Powell provides an all-too-brief introduction (for fuller discussions on the development of the new SouthEast Asian house and the role of the seminal, Geoffrey Bawa, one needs to go back to Powell’s earlier books) and then looks at the houses in categories: detached houses, extended family houses, houses in gated settlements, refurbished houses, second homes and retreats.

What is revealed – thanks in great part to Albert Lim’s sublime photography – is an extraordinary diversity. Above all, it reveals a hugely imaginative response to the challenge of reconciling universal modernism with the particularities of place, culture and climate. Each building is given ample pages, generous photographs, plans and a detailed discussion from Powell. What Lim is able to bring out is the sheer beauty of these buildings, superb detailing and sensitivity to materials and landscape.

Robert Powell has also supplied the foreword to a new monograph on Singapore-based Ernesto Bedmar in Romancing the Tropics: Bedmar & Shi. Bedmar hails from Argentina, but has lived in Singapore for more than 20 years. The sheer beauty, serenity, intelligence and pure good taste mark him out in a category all of his own. Powell comments that he “has always seemed to me an exotic transplant from one culture to another, with an acute appreciation of the nuance of climate and culture.”

For Geoffrey London, who has written the essay for the book, climate is central to the way Bedmar has inflected universal modernism. But London adds that he has always been “drawn consistently to the idea of the vernacular” and in “the way weather expresses itself in the architecture and the use of materials like stone, timber and water, a part of Asian culture and not a part of his own Argentinian tradition.” Likewise, says London, he is drawn to the “privateness and quietness” of Asian cultures, “the oppositie of his own Latin cultural beginnings”.

In a statement of his own, Bedmar attributes his love of material texture to his rural origins, along with the dialogue between exterior expanse and “the intimacy of the habitat, house and shed”. Here he acknowledges the seminal influences of Barragán and Geoffrey Bawa, commenting that “I am able to perceive visual poetry – a language of sort, in which textures, shadows and forms coalesce with simple elegance, which captures my senses and leads me on an enjoyable journey with discoveries at every junction.”

This brief, lyrical essay by Bedmar himself is complemented by an insightful interview with Erwin Viray from the National University of Singapore. Fittingly, this small-scale book is as exquisite as the work of this most exquisite of all architects –beautifully laid out, excellent photography, an illustrated timeline and luscious colour drawings.

In Ernesto Bedmar we have another species of layering, both in the origins of the work, but in the houses themselves which offer not so much layers, as veils of experience which part gently in the breeze to engender an invariably sublime experience. As the landscape architect from Kuala Lumpur, Ng Sek San, remarked to me when we visited the Subang Jaya house outside KL together: “He is the Master.”

Melbourne Showroom

285 -287 Swan St. Richmond +613 9421 1191

www.morticeandtenon.com

HiRise Dining Table, Buffet & Heron Chair designed by Tony Stuart Manufactured in Australia by Mortice & Tenon

After 22 years of marriage, it’s understandable when partners finish off each other’s sentences. For Charlotte and Pierre Julien, the words are sometimes out before the sentence even emerges. “It’s something that happens when you’ve been together for so long. Working together also makes you that much closer,” says Charlotte, who has been designing furniture and lighting with Pierre since the early 1990s.

Many of the Juliens’ designs appear in their apartment in Melbourne’s St Kilda East. Some of the pieces, such as a desk in the living area, are built in. Other pieces, such as their Cardinal sideboard (also in the living area), are used to display an eclectic assortment of objects and artefacts. A precious Victorian candelabrum, once Charlotte’s grandmother’s, is placed next to a china cat, a feline symbol of good fortune. “We eventually find a place for most things,” says Charlotte.

While the couple’s home includes several of their chairs, lights and tables, they have now produced too many designs to include everything

at home. The Juliens’ North Melbourne studio, however, provides the required space and also doubles as a showroom.

While some designs displayed in North Melbourne are recent, others were designed at the start of their careers. The Cardinal sideboard, for example, was designed in 1992 and still remains one of their most popular styles. This typifies their approach says Charlotte. “We’re not interested in creating faddish pieces. Things should have a sense of longevity, rather than being the fashion of the moment.”

Ironically, however, it was fashion that brought the Juliens together. Charlotte modelled in the early eighties for designers such as Romeo Gigli and Thierry Mugler, and Pierre modelled for Jean Paul Gaultier. While Charlotte loved the buzz of the runway shows, Pierre was keen to get out of the industry. “Pierre hated modelling. He’s quiet and reserved. In modelling, you need to be an extrovert,” she says.

Charlotte kept modelling until her late 20s

while Pierre switched to restoring ornate French furniture in Paris. Although not formally trained, Pierre made the transition to furniture effortlessly. “I’ve always loved working with my hands. And it was a pleasure restoring exquisitely made furniture, whether from the seventeenth or the nineteenth century,” says Pierre.

Post-modelling, but also still based in Paris, Charlotte began painting film sets. “I’d assist the master set painters, mixing their colours,” says Charlotte, recalling the vast amount of paint required to complete entire street scenes.

Both Pierre and Charlotte put their new careers on hold when they migrated to Australia (where Charlotte was raised) in 1992. “I’d been modelling in Europe since I was 16. I was keen to come home and start a family,” says Charlotte, who now has a 15-year-old daughter, Billie. “I fell pregnant as soon as I stepped off the plane,” she adds. The early nineties coincided with one of Australia’s worse recessions. “We knew the first few years would be difficult financially,” says

I After 15 years designing furniture and lighting, the Juliens compare their work to solving a jigsaw puzzle. Each design fills in the picture, adding meaning to the Pierre and Charlotte collection. Stephen Crafti caught up with them at home in Melbourne.

Charlotte, who was keen to work with Pierre in a creative industry. “But we were also mindful of making a living, something that would allow us to support ourselves.”

That something was furniture and lighting. With Pierre’s sharp technical skills and Charlotte’s highly trained eye, they found a small niche in the market for well made, highly crafted design. At the couple’s dining table sits the first chair Pierre made in Australia. A reproduction of a Swedish chair owned by Pierre’s great grandfather, it is made from Sycamore and features a finely carved backrest.

Other designs, such as the classic Cardinal sideboard, exhibit a strong Japanese influence. Made from stained American Oak, the sideboard reflects the couple’s aesthetic for minimal and highly considered design. “I lived in Japan for four years. It’s something that still resonates with me,” says Charlotte, who finds inspiration from reading books on Japan. Inspiration sometimes comes from unexpected holiday finds too. Recently in Tasmania (where Charlotte was raised), the couple discovered, half buried in the sand, a 19 th century ‘snuffer’, used to extinguish candle flames. “Both of us were instantly drawn to its shape, like a bell,” says Pierre, who sees the form of the snuffer as a possible wall light.

It’s not just form that attracts Pierre and Charlotte, but also the way natural light reacts with a surface, whether it is stained American Oak, polyethylene or steel. Natural light was fundamental in organising the spaces within their apartment. Initially, there was a corridor running through the centre, opening to three small bedrooms. However, requiring a large living area and one less bedroom, walls needed to be knocked out. “Charlotte and I removed the bricks ourselves. It was definitely a hands-on exercise,” says Pierre, who also remodeled the kitchen and bathroom. Now the apartment enjoys full light during the entire day, with the kitchen receiving morning sun and the living areas, northern sunlight.

I 02

The couple’s French bulldogs, Ferdinand and Nancy take full advantage of a large daybed made of American Oak with a leather seat. A photo of Ferdinand is proudly displayed on the living room wall, in a steel frame designed by the Juliens. While Nancy is not featured on the wall, she appears in one of the Julien’s magazine advertisements. The greatly over-scaled Nancy dominates a small figure of Pierre, picking up ‘stools’ of the furniture variety. “There should be an element of humour in design. That sense of irreverence is a particularly Australian characteristic,” says Pierre.

Since living in Australia, Pierre has developed a love of Australian Rules football. A St Kilda fan, he fondly recalls watching the game on television for the first time. “At first, it looks like complete chaos. But when you understand the rules, there’s a level of skill and finesse,” he says. “It’s like furniture. Those who understand furniture appreciate the level of detail involved.”

The same level of detail can be appreciated in the renovation of their apartment. While not large, it has been thoughtfully considered. The kitchen for example, features Oregon cupboards, with ribbon-like handles for the doors. “We use the same handles on some of our credenzas,” says Pierre. As distinctive, Bucket wall lamps are also in the kitchen. “They were designed as up or down lights,” says Pierre, who placed the bucket on a vibrant orange base. Other lights in the Julien’s apartment have greater subtlety. Wall lights in the living areas are made of hydro-stone, creating elegant as well as functional wall sculptures.

Ideas, like the furniture they bring from studio to home, go back and forth. “We need to fully agree on a design before it goes into production,” says Charlotte. And while there may be

“We’re NOT interested in creating faddish pieces. THINGS should have a SENSE OF LONGEVITY, rather than being the fashion of the MOMENT.”I 01 Previous Charlotte and Pierre with French bulldog, Ferdinand. I 02 Pigeon Light by American artist, Ed Carpenter. I 03 Red Toto stool

a stalemate for a short period, things get resolved fairly quickly. “We rarely leave things to discuss later,” says Charlotte. For designs to move forward they must be practical and there must be a need for them in the first instance. “We’re not interested in designing things just for the sake of design,” says Charlotte, who compares each design to pieces in a puzzle. “Each chair, table or light is another piece in that puzzle. We see our work as a progression. The image in the puzzle becomes clearer with each new shape that’s placed on the board,” she adds.

Sometimes, a design isn’t an instant success. It can be a few years before a certain design really takes off in the marketplace. “People like a sense of familiarity. They often need to be reassured of their decisions,” says Pierre, who likes to push boundaries where appropriate. “After 15 years, we’re more assured of what works and what will take some time before it’s accepted,” says Charlotte. “We tend to work in a fairly intuitive way. We generally steer away from things that are too hard edged,” she adds.

After 15 years in the furniture business, the Julien’s fashion careers are truly over. Charlotte and Pierre are far more comfortable in jeans and loose fitting jumpers than wearing clothes from the fashion runways. “We buy less clothing, but we still prefer quality clothes, whether it’s a woollen jumper or well made shoes. Clothes should be as comfortable as sitting in one of our chairs,” says Pierre.

Pierre & Charlotte, pierreandcharlotte.comI 07

08

“There should be an ELEMENT OF HUMOUR in design. That SENSE OF irreverence is a particularly AUSTRALIAN characteristic.”

I met David Trubridge at Cicada Works, his workshop and studio in Whakatu. Within a collection of red brick industrial buildings, the most beautiful objects are being crafted. A team of local and international furniture makers are steaming and bending timber, riveting and oiling, to create the light, graceful forms that are the hallmark of David’s work.

Abstractions of natural form and pattern are expressed using skeletal and skin-like structures to make light shades, recliners, seats and bowls. They embody a sense of place, as objects of the South Pacific, yet they also allude to other cultures and times. Some pieces have a timeless Japanese quality, some remind me of patterning from the 1970s or the elegance of Danish design.

David has been making furniture across four decades with a personal design evolution tied to his values and travels. What he sees and believes, finds an expression in his art form. His work has grown out of a vision to create the lightest of structures. In his words, “Simple and low impact, made of natural materials and processes, leaving a delicate footprint.” It is a unique body of work, establishing him as one of the world’s top eco designers.

When his children were two and four years old, he and his wife Linda sold their house in Northern England and bought Hornpipe – an ocean-going yacht. They set off on a voyage that lasted 10 years. Much of that time was spent in the Pacific Islands and New Zealand’s Bay of Islands. During those years, Trubridge made bespoke furniture when they needed money. He started using local materials and experimenting with traditional techniques. Instead of post and rail construction, he began lashing wood together in tension structures. Boats, fish traps, a clump of tied reeds became generators of form.

I David Trubridge’s iconic furniture and lighting have been exhibited in the Pompidou Centre in Paris, ICFF in New York and the Salone del Mobile in Milan. Andrea Stevens caught up with him in his studio in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand, where he talks about his favourite sources of inspiration for the fine sculptural objects he produces.

In 2001 he took his Body Raft to the Milan Furniture Fair. The piece is made of curving timber slats screwed to internal frames, referencing traditional boat building. It caught the eye of Italian furniture manufacturer Cappellini, who now manufactures it under license. Linda describes the reaction to Body Raft: “They liked it because it evoked the exotic. It had a sophistication of design, but it also had a feeling of nature in it. People live in cities and want stylish things and yet they want something more that has a heart and soul.” Since then, his career has been propelled from a craftsman/maker to a designer with an international reputation.

The demand for his work causes major reflection for David – “Who needs another design object? The only justification for me is not the object itself but its message. If it acts in some way as an agent for change, if maybe it causes a few thoughts and reflections, then it has a value.” He gets plenty of opportunity to talk about sustainable design. He teaches at the Vitra Design Museum summer design classes in France. Already this spring he has spoken at a design week in Brussels, as part of 100% Design in London with Essenze (his export partner) and at a symposium in San Francisco. He will return to Milan again next year with new work.

He believes the importance, or the role, of ‘design’, is in (re)designing processes not objects – finding better ways of doing things. At the Vitra summer school, he has been running a workshop on sustainable design. He questions why we need to design yet another table when there are already so many. Instead, he leads a workshop on re-designing the ritual of eating. “Hopefully, in thinking about the ritual, you’ve improved on the way in which we go about things, so we don’t need as many objects. And the objects you’ve identified a need for, there’s now a reason to design them. This is how to design in ways to actually ensure survival rather than cause our destruction.”

I 02

At Home David designed his retreat, set in the striking New Zealand landscape.

I 03

In the Studio David’s maquettes on display in his studio –each representing his craft-like aesthetic.

I 04

Mahia Peninsula Looking south along the coast towards Napier.

I “Every creative person needs some sort of studio where you have your own bits and pieces that inform and are important to you – the ‘way points’ along your course.”

DAVID

Fashion for David is, of course, a four-letter word. He makes his furniture to last and aims to give it an emotional content that will make people want to keep it.

He finds his creative energy in the open spaces of the coast and mountains. This is largely why he and Linda moved to the South Pacific. They live on the Heretaunga Plains, in Hawke’s Bay on the eastern coast of the North Island. The Pacific Ocean lies to the east and the Kaweka Range to the west. There has always been a strong artistic community in the region, centred in and around the Art Deco city of Napier. The closest major city is Wellington, a four-hour drive away.

His view on creativity is layered, “I really believe in a process that transcends traditional boundaries of art, craft and design. People try to categorise things. Are you an artist? Is that design? You’ve got to be everything. I think it’s crucial that you work as an artist first to find your place, to know what you are saying and how you say it. As a designer, how do I use those forms, that vocabulary, for making something? And as I am designing, I need to know how to make it.”

When Body Raft was first received with great acclaim in Europe, someone commented, “This is the way it is going, this is the future.” His reply was “If you say so. I’m just doing what I do. I’m just doing my own work.” I look forward to the next leg of his journey.

My family, Linda and our kids, are the most important. Even though the boys are away doing their thing, this is still their home base. Home is important and part of that is the whole home studio. Every creative person needs some sort of studio where you have your own bits and pieces that inform and are important to you – the ‘way points’ along your course. It is space in which I can develop ideas.

I deliberately said ‘develop’ ideas above because to me part of that creative process can’t happen in my studio. I actually need also to go

I “It is the place where there’s much more empty space to allow things to slowly filter to the surface. You see things more clearly and you can have ideas from there.”

DAVID

further away and have more space and more freedom and let that surface clutter of life float away. Our retreat at Mahanga is really important in that sense. It is the place where there’s much more empty space to allow things to slowly filter to the surface. You see things more clearly and you can have ideas from there.

And, if you take that path to its ultimate, it’s Antarctica. Even Mahanga doesn’t have the emptiness of Antarctica. To me, that has been the most amazing place I have been to, the most inspiring, the most awesome in the true sense of the word. In that emptiness I saw things about my creative process that I wasn’t able to see anywhere else, and to reassert that connection with the landscape is always important for me. The wilder, the emptier the place, the more I find that connection, the more energy I get from that.

My model canoe is from Vanuatu. It’s a very simple thing, a beautiful object in its own right. I love the visual tension between the grid of those outrigger frames, the platform and the loose curve of the hull, of the waves and the paddle. In a way it’s what New Zealand is – between the Cartesian, Western way of thinking, of living where everything is quite rigid and set into grids; and the Polynesian way which is completely opposite, much more feminine and loose, open and flowing. The canoe sums up that place we are in the world between Polynesia, Asia and Europe.

Our yacht Hornpipe was a number of things – it was a self-contained home, it was our transport we could take anywhere in the world. That lifestyle, it’s not something I could do forever. By the end we had done it, we enjoyed it and we got an enormous amount out of it. Looking back on it now, the most important thing was the family time. For the first 10 years of the kids’ lives we lived together completely, and mostly they never went to school. The other thing is understanding that when you are living on a small boat, you can’t have much stuff. There isn’t the room and you don’t need it because you are living this fantastic life. It was a simple life and that has become a great lesson.

Some people’s inspirations may be predictable. But Andrew Parr, Director of SJB Interiors in Melbourne, takes his professional cue from a slightly more colourful source. Stephen Crafti investigates.

Andrew Parr’s parents had great faith in his talents as a designer. When he was only 16, they handed him a brief to design the new family home in East Doncaster, Melbourne. His concept, a courtyard style house with a discreet façade, was actually built. “There were four garage doors at the front. And in the centre was a pathway leading to two courtyards, one used by the living areas, the other, the bedrooms,” says Parr, Director of SJB Interiors. “My father worked as an engineer so I had help with the documentation,” he admits.

Parr’s talent for design was formalised, when he graduated in Interior Design from RMIT in 1987. Unlike many emerging designers who start off in small firms and are given projects sized to match, Parr went to work with Synman Justin Bialek Architects (now SJB Architects) soon after graduating. His first project was designing plush new headquarters for Smorgon Industries in West Footscray, Melbourne. “It was a quite a lavish project. Particularly as the site was once an abattoir,” says Parr, who has since designed numerous interiors around Australia and abroad – the Establishment Hotel in Sydney, the Royce Hotel in Melbourne, as well as the chain of Adina hotels in Germany (two in Berlin, Hamburg and Frankfurt), and in New Zealand.

collection of Missoni crockery, evocative of the 1950s. “I bought this crockery a few years ago. I love the intensity of the colours – turquoise, brown and ambers,” he says. Parr also delights in his Missoni towels, which feature up to 20 to 30 colours, from reds, pinks and yellows to every shade in between.

Parr enjoys experimenting with colour. “I designed a carpet for a hotel in Canberra. It’s grey, cream and charcoal, in a geometric pattern. It’s not almost primitive like Missoni’s designs. But it has quite a Peruvian feel, like many of Missoni’s designs,” says Parr.

Habitus caught up with design luminary Rosita Missoni, now as influential in the world of interior design as she was once in the world of fashion.

Q What was the catalyst for the Missoni Home label?

A Ten years ago I handed over the reins of the fashion collection to my daughter Angela. After enjoying a short sabbatical period I started suffering a kind of vertigo.

Q At the time, why did you make the move?

“I generally take a brief, absorb it, and then mull over it for a week or so. But I give myself quite a strict deadline,” says Parr, who regularly writes the words ‘concept today’ in his diary. A recent diary entry is for the much celebrated Australian chef, Luke Mangan, who is opening a new bar and restaurant in Melbourne. “I already have the floor plan worked out. But the concept will become clearer as the week moves on,” says Parr, who is thinking of creating a moody Melbourne experience, with exposed bricks, black steel windows and recycled timber floors. The exposed brick walls will also feature large fabric panels, as according to Parr, “Textiles are a form of art. It just depends how they’re used.”

While the raw finishes for Mangan’s bar and restaurant are mulling over in Parr’s mind, so too are sumptuous Missoni designed textiles, the fashion label that moved into homewares 25 years ago. “I’ve always loved Missoni, particularly its primitive African inspired designs, often in black and white,” says Parr, who has several Missoni designs in his own house – towels, sheets, throws and bedspreads. He also has a

While the carpet in Canberra is restrained in its use of colour, Parr’s Sydney apartment, however, is definitely not. Pink and lilac feature on the bedroom walls, complementing the Missoni bedspread, the dining room walls are a pale turquoise and the apartment’s light timber furniture and floors create an interesting juxtaposition. “I love putting unexpected combinations together,” says Parr.

Like Missoni, Parr has a preference for geometric rather than floral patterns. “Florals aren’t in my repertoire. I find them far too busy, particularly when you have a series of floral patterns going on in the one room,” says Parr.

The Adina hotels also feature strong colour. The Adina in Berlin, already completed, has tan orange walls with strong accents of lilac. And like a Missoni towel, black is used to separate the vibrant hues. “It’s not just about colour. Missoni has built a reputation for texture,” says Parr. “I like mixing things up. Like Missoni designs, interiors should be animated. There should be a level of the unexpected.”

SJB

Interiors, sjb.com.auA I felt the home was becoming more fashion orientated. The existing Missoni Home collection needed direction – and I knew I had the passion and creativity to work on it.

Q If you heard that an influential Australian designer cited Missoni as one of his biggest creative influences, what would you say?

A I would hope to meet him/her and share feelings.

Q What do you have a greater passion for, fashion or homewares?

A I still do have a passion for fashion but I feel I lost track with creativity in that field –my life does not correspond anymore. The home is now my passion and I enjoy every single minute of my creative work.

Q What’s the greatest distinction between the two, besides the obvious?

A Fashion is ephemeral and this is its great charm. Home is long lasting, like elegance.

Q What or who inspires Rosita Missoni?

A I am a sponge and I enjoy life, nature, art, sports and people. I have the rare privilege to work in a field that is also my hobby.

Q At home, what other styles of furniture and accessories do you mix in with Missoni Home?

“Textiles are a form of art . It just depends how they’re used.”

A I simply mix. I love design, textures, patterns, colours and comfort. I like to associate old and new pieces of furniture, objects and lamps. I have testimonials of great designers like Le Corbusier, Giò Ponti, Hans Wegner, Gaetano Pesce, Verner Panton mostly found in flea markets that live happily in my homes on Missoni rugs, fringed curtains and pillows.

Q What was it like to be a visionary, a strong woman in Italy in the 1950s and 60s?

A I was more a dreamer than a visionary woman. My strength came out step by step. I grew up in my family’s factory among yarns, fabrics, embroideries and fashion magazines. The factory was my playground and my fashion school. At 21 in 1953 I married Tai Missoni, an eclectic, handsome athlete, an artist with a great sense of humour who had just started a small business of knitted jumpsuits. Mixing our experiences we started building little by little, sweater by sweater what became the Missoni style.

Q Missoni Home is sold all around the world. How does the label transcend cultural boundaries?

A Missoni is a style, a way of life for us and our worldwide clientele.

It’s a style that transmits joy and optimism and by following our basic suggestions, many of our customers share with us the pleasure of playing around with things and objects in a timeless and endless creative game.

I 01 Previous Andrew Parr

I 02

Bedroom

Pink and lilac walls complement the Missoni bedspread.

I 03

Missoni Home

A bold addition.

I 04

Rosita Missoni

I 05

Missoni Homewares

Characteristic Missoni vibrancy.

I 05

Kenneth Cobonpue sits surrounded by bamboo twigs, sea grasses, hemp and rattan. In his studio on Cebu, a bustling island in the Philippines, Kenneth creates contemporary furniture and lighting using traditional materials. Organic shaped rattan lights are shipped to furniture stores in almost every country of the world, including KE-ZU in Sydney and Hermon & Hermon in Melbourne. Wall lamps, pendants, screens, chairs and beds are ready to go, each piece conveying a sense of the handcrafted. Bamboo twigs are tied to a welded metal frame, creating a screen, and rattan lamps are inspired by jellyfish and sea anemones.

For Kenneth, the choice to pursue a career in furniture wasn’t a difficult one. His mother, Betty Cobonpue, founded a furniture design and manufacturing company in the Philippines in the early 1970s. “She built a reputation for her innovative use of rattan. It was the type of furniture that could be placed in a thatched hut or a contemporary Western home,” says Kenneth. However, rather than stay and learn from his mother’s skills, he went to New York in 1987, studying industrial design at the Pratt Institute and in 1994, studying furniture marketing and production in Germany.

Ten years ago, the prodigal son returned. And like his mother before him, Kenneth has developed a reputation for beautifully made furniture and lights. While his New York studies and work experience at a leather and wood studio in Florence were crucial to his development, his career path was determined as a child. “I can still remember when my mother set up her first work station in our

I The organic forms created by Kenneth Cobonpue are inspired by his native Philippines, but also have a place in the wider world. How has he achieved this relevance, Stephen Crafti asks.

backyard. I used the wood and rattan scraps I collected from the carpenters to make toys,” he says. As a child, one of his first larger scale projects was a bridge, made from wood and placed over a fishpond. “I had no knowledge of structure. I fell into the water several times before the bridge was resolved.”

Fortunately, mishaps are now few and far between. Kenneth’s first commercially successful design turns ten this year. The ‘Yin & Yang’, a steel and wicker range of furniture, wrapped in rattan skin, is as popular today as it was ten years ago.

Like most of his furniture and lights, the process from design to development can take months. And the use of rattan continues to evolve in the collections. “Rattan is extremely flexible. It can be easily stripped to its various forms. It continues to be a springboard for new ideas,” he says. “I love working with natural fibres, whether it’s rattan or hemp. They’re extremely sensual. You can touch, smell, bend and twist them in so many ways,” says Kenneth, who is also interested in fusing technology with renewable and environmentally friendly materials.

While particular materials inspire Kenneth’s creativity,

he can’t exactly pinpoint where or when an idea might emerge. “Sometimes it’s a certain material, but ideas tend to lurk in my mind. Other times, it could be something like a simple object on my breakfast table,” he says. However, when the idea starts to crystallise, it’s articulated as quickly as possible. “I try to sketch the idea and then build a model. My designs have a very three-dimensional quality to them. There’s no substitute to actually making something yourself,” says Kenneth, who works with three designers from a small studio. “I still do pretty much everything from answering emails to meeting clients,” he adds.

Time spent traveling to the studio doesn’t eat into Kenneth’s day. His house, located in a hilly village nearby, takes in the city lights down below. “You could say that it’s a fairly contemporary structure, full of glass and filled with light. It was inspired by traditional Asian pavilions,” he says. And though he has forged a reputation for his design acumen, many creative decisions are made at home. “My wife is my most trusted critic,” he admits.

Living and growing up in Cebu made Kenneth culturally sensitive to the Asian traditions of craft and history. Having left the Philippines to study and work heightened his design sensibilities, and provided him with a contemporary global context. However, the times he lives in have also shaped his philosophy, both in design and otherwise. “I am a child of our time. And these times call for a return to caring for our planet and finding sustainable ways of living. My work will always be contemporary in aesthetic. But it will always stem from nature and be crafted by hand.”.

Inge Holst, object designer and business manager for Edit, has arrived at a particularly interesting, often quirky and very beautiful place. Edit is the latest venture of one-off design objects, fabrics and artworks by partners, Belinda Seper and Sharyn Storrier Lyneham. The combination of skills by the talented trio is seeing the works gaining international acclaim and being snapped up by Liberty of London. Australian fashion protagonist, Belinda Seper, has brought some of the world’s most celebrated fashion labels to Australian shores and Sharyn Storrier Lyneham, ex-editor of Vogue Living and Vogue Entertaining and Travel, has literally helped define an Australian creative industry.

ing costumes. It was this passion and skill that attracted the eye of Storrier Lyneham after seeing some handmade coat hangers Inge produced for Seper’s The Corner Store. ‘The sensitivity’ was as clear as day to the former editor and it was this validation of a creative talent, sprung simply from a coat hanger, that began the collaboration between the two more established women and the young designer.

Edit is a natural destination for Inge who, after working as a freelance costume designer on Australian films, musicals and commercials, ultimately became disillusioned with the craft. “As a maker of costume for film and TV, you are often

Edit uses the pop-up store concept with great success to ‘exhibit’ the Edit range of wares that sell out within days. In a society where interior furnishings and objects – the layers that create the story of a life being lived – are mass produced, the one-size-fits-all approach has started wearing thin, not just for the elite, but for many who’d rather have an empty shell than a house full of generic furniture and soft furnishings.