# 22

living in design

Industrial repurpose, with purpose. A master chef and his kitchen. The dark side of timber. Slow architecture. Textile dynasty. The great outdoors.

THE ART OF OUTDOOR LIVING

Industrial repurpose, with purpose. A master chef and his kitchen. The dark side of timber. Slow architecture. Textile dynasty. The great outdoors.

Winner of 19 international design awards, the 1.5-metre Haiku® ceiling fan is everything you expect from a Big Ass Fan®, designed specifically for your home. Haiku integrates a silent, powerful motor with aerodynamic aerofoils, crafted and balanced by hand to ensure perfect performance at all seven speeds. Without the wobble. Guaranteed. Together, Haiku’s features result in the world’s most efficient ceiling fan—verified by ENERGY STAR®.

Need a ceiling fan as refined as the rest of your design?

Visit haikufan.com.au to build the perfect Haiku. (07 ) 3292 0156 | HAIKUFAN.COM.AU

“Haiku is flawless. It is the perfect fit in our modern home. Haiku’s aesthetics, combined with its extraordinary features, make it the only ceiling fan we would consider.”

- Mark P.

What are products if not a physical manifestation of our values? Iconic forms, narrative concepts and symbolic materials combine to make products with meaning.

24. DESIGN NEWS

C heck out the latest and greatest contributions to the world of design.

35. RESHOOT

One concept, three ways. Inspired by the tribal, we create totem forms using ceramics, lights and cushions. Their delicate and fragile texture belies the strength of the silhouettes they create.

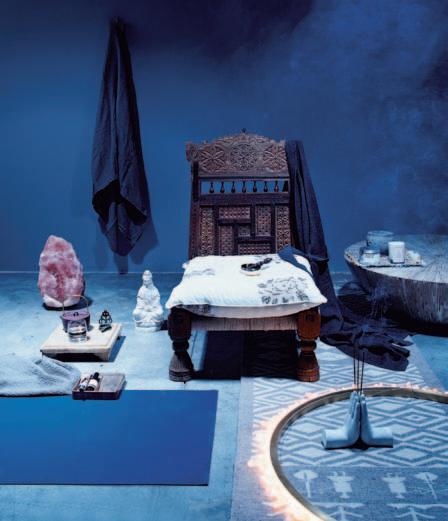

41. COOL & CALM

The best way to end the year is to spend some time on the three ‘ R ’ s: relax, rejuvenate and restore.

51. H ABITUS PAVILION

We explore the fascinating links between creative people and where and how they live. From a master chef in Sydney through to left-of-field product designers in Bangkok, it's a creative smorgasbord.

58. 56thSTUDIO

In the riotous mix of Bangkok, 56thStudio get their inspiration from the city. Nicky Lobo reports that the ethnic melting pot with its mix of tradition and the modern, craft and the manufactured, gives the designers the raw materials for products with an edge of social commentary.

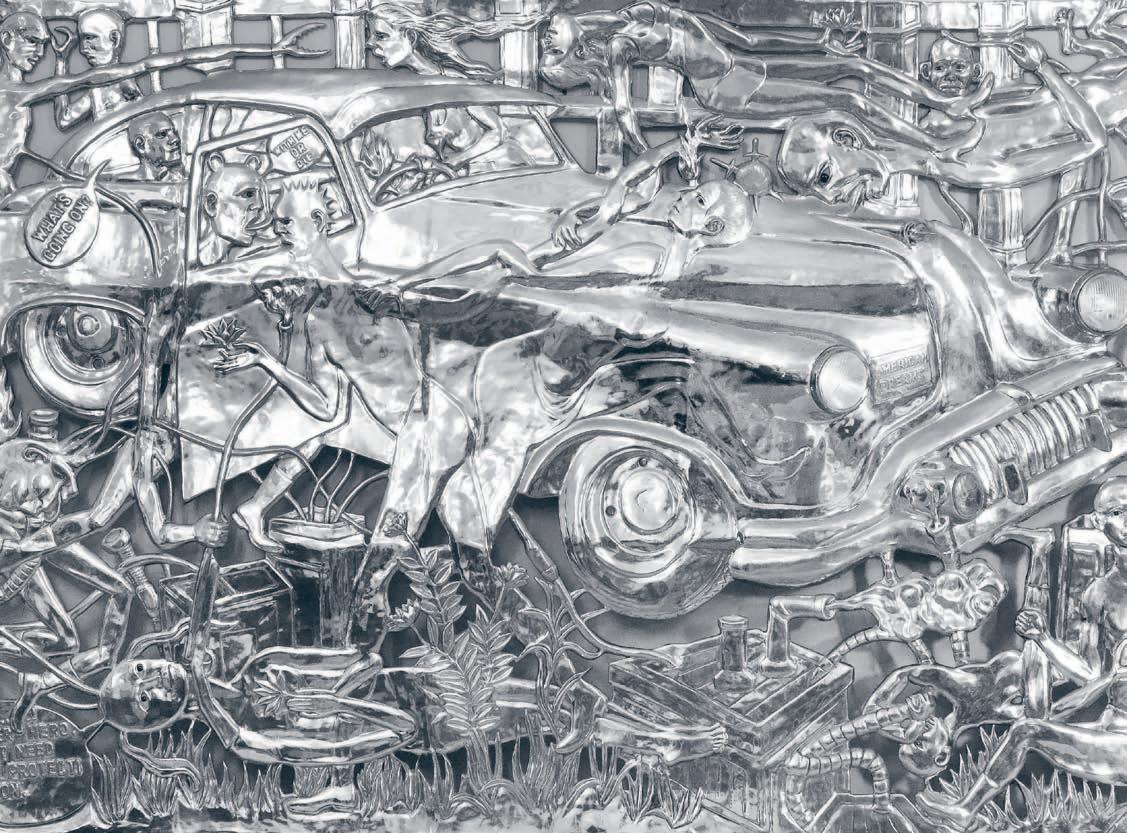

67. ENTANG WIHARSO

Yogyakarta-based painter and sculptor, Entang Wiharso, lives in one of the most diverse countries in the world. He is remarkable both for the range of materials he uses and for the bold exploration of the political and social implications of his country’s ethnic, cultural and religious mix.

75. ROSS STEVENS

We give you the background on the inaugural Habitus Pavilion at Sydney Indesign 2013. #75

He is a master, says Andrea Stevens, at repurposing refuse. Industrial designer, lecturer and builder, Ross Stevens, lives 90 minutes from Wellington in his dazzling own home, a model of upcycling.

87. M ARK BEST

Mark Best, of Marque restaurant in Sydney, consistently takes out top honours in the Australian food business with his cuisine, notable for its innovative approach. Paul McGillick met up with him in his equally innovative apartment in a converted woolstore warehouse.

#154

Once again we survey the way architects and their clients respond to the unique character of where they live, and to the special needs of their homes.

98. LONGFORD HOUSE

Set in an idyllic landscape near Launceston in Tasmania, this is a house which celebrates its location, especially a 120 year-old Oak tree. At the same time, observes Paul McGillick, its designer, Sarah Foletta has played with Palladian proportions and the idea of the French ferme

112. KENCANA HOUSE

Part of a gated community in Jakarta, Indonesia, this house designed by Budi Pradono – with heaps of input from his totally engaged clients – grapples with the opposition of privacy and community. The result, says Paul McGillick, is a wondrously layered experience of refuge and prospect.

129. JAMBEROO HOUSE

#98

Set in beautiful countryside south of Sydney, this house designed by Casey Brown Architecture is very much of its place, responding to existing farm buildings and to local materials. And, says Philip Drew, it is also a study in tonal contrast, intrigued, in a very non-Australian way, with the dark side of a very Australian material.

143. MARIMEKKO-INSPIRED HOUSE

No, it’s not in Scandinavia. It’s in Perth, Western Australia, and it gets its name from the design of a custom privacy screen. But the real back story, says Anna Flanders, is about architect, Ariane Prevost ’ s principles of Slow Architecture.

154. WONDERWALL HOUSE

On the outskirts of Chiang Mai, this house, designed by Situation Based Office, is a response to its site and existing buildings. Aroon Puritat says it is also an experiment in reconciling Lanna architecture with contemporary practice.

#179

We have something of an emphasis on the outdoors in this edition of Reportage, surveying ideas for outdoor living and reviewing books on landscape and garden design. And, for a dash of colour, we profile textile company, Maharam.

166. OUTDOOR LIVING

Summer has arrived in the southern hemisphere, so we look at ways to make the most of outdoor living.

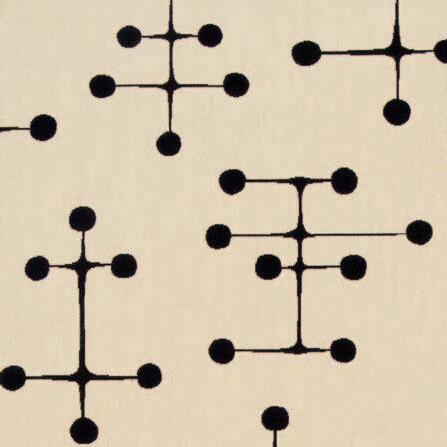

179. FAMILY STORY

Stephen Lacey looks at innovative textile company, New York-based Maharam.

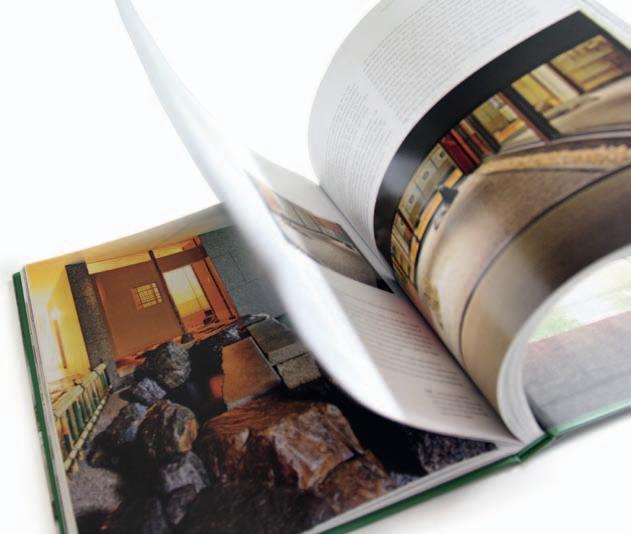

185. BOOK REVIEW

How we plan our landscapes is essential to our identity, Tempe Macgowan reveals in a review of three recent books.

Each element that surrounds us contributes to build our reality. That’s the authentic existence, the existence that defines who you are.

Silestone® lets you express character and emotion through your kitchen and bathroom. The only benchtop with bacteriostatic protection, and available in varied and exclusive textures.

surrounds contributes authentic that bacteriostatic varied exclusive Silestone®.

Live the authentic life, live your life with Silestone®.

and fashion, the in in what is

“I love architecture and fashion, but the authentic things are in the houses we live, in the clothes real people wear. That’s what I tell people on my blog. That is Authentic life.”

Macarena Gea (Blogger and Architect)

Benchtop UNSUI / INTEGRITY Sink / SUEDE Exclusive Texture

Benchtop UNSUI / INTEGRITY Sink / SUEDE Exclusive Texture

Every

The world’s most advanced drinking water system.

wALL sYsTem FROM $9,490 desIgn CR&S POLiFORM

PArIs-seouL sofA FROM $15,500 desIgn jean-MaRie MaSSaud

PArIs-seouL smALL TAbLe FROM $4,975 desIgn jean-MaRie MaSSaud

sAnTA monIcA Lounge ArmchAIr FROM $4,590 desIgn jean-MaRie MaSSaud

bIgger coffee TAbLe $5,395 desIgn CaRLO COLOMbO

dAmA coffee TAbLe $1,885 desIgn CR&S POLiFORM

TrAces de dAmIer rug FROM $4,565 desIgn CC-taPiS

It strikes me that this is a great metaphor for design, both product and architectural. Deep down we have the everyday needs which drive design – if you like, the structures of thought and emotion typical of different societies. These structures then get expressed at the surface level – the visible level – in the form of unique designs which reflect the personality of the designer and the cultural character of individual communities.

In these days of instantaneous global communication, regional design can be strongly inflected by the dominating aesthetic of the great metropolitan centres. It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that you haven’t made it unless you have made it in London or New York.

The irony of this is the fact that mainstream design (including architecture) has been so often shaped and inspired by regional traditions, Scandinavian design being an outstanding example. Of course, it has always been to some extent a two-way traffic flow. After all, the provinces always want to feel up-to-date. But this is more a question of fashion, and good design has nothing to do with being fashionable.

On the one hand, regional and vernacular design can often serve to refresh mainstream design. On the other hand, designers in regional contexts may consciously react against mainstream design and seek authenticity and immediacy in local materials and traditional forms and practices. In this issue of Habitus, this motivation is illustrated in completely different ways by Ross Stevens in New Zealand, 56thStudio in Bangkok and Rob Brown with the house he designed at Jamberoo, south of Sydney.

But then we also feature houses from Tasmania, Jakarta, Chiang Mai and Perth, each of them engaged in a robust and productive conversation between a mainstream Modernist agenda and a local context and tradition.

The cross-cultural conversation is at its most generative (to borrow another Chomskyism) when the interlocutors are on an equal footing. That’s when things really become creative. To extend the metaphor a little further: the more diverse the genetic ingredients, the healthier the offspring. Which is why Habitus throws the spotlight on South-East Asia and Australasia – because this is where we think some of the most exciting design in the world is currently being practised.

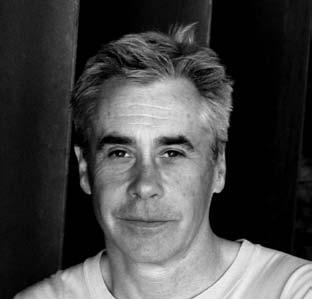

Paul

| Editor

Paul

| Editor

McGillick

Before he became a political activist, Noam Chomsky was a linguist who radically re-framed the way we looked at language. For example, he dug deeper into the mystery of language by demonstrating how it was species specific. But one of his more suggestive, if less convincing, ideas was to describe language as having a deep structure and a surface structure.left | editor, paul mcgillick. rIght | deputy editor, nicky lobo.

I fi rst met Alistair when we were in an exhibition together in 2003 at Object Gallery. His approach was already well developed and it has been like watching a story unfold to see it evolve over the years. The way he works volume and movement into beguiling, shifting forms seems startling and yet curiously easy and self-evident –something we have been striving for in our own work for years. Your story (page #77) gets to the heart of his world. It ’s important to know from where and how such a singular voice emerges. In the end, it will be the work of outsider individuals like him, carving out their own fascinating worlds, that lead us to somewhere new.

Stefanie flaubert DESIGNER /A RTIST, KORBAN/ FL AUBERT

I feel more connected than ever to the people who inhabit the spaces we design. What makes them tick? How does the space make them feel? What ’s their favourite part? What have they brought to it? In magazines, it ’s often hard to see the personality of someone in their space through increasingly heavy styling and endless over detailing, so it was refreshing to see the home of artist, Sydney Ball (page #54), and get a glimpse into his world. Functional, utilitarian, human, real. A home and workplace housing so many precious pieces, but one that is anything but precious itself. Years of accumulated objet that you know wasn’t just brought in for the shoot, each with a story. Maybe it ’s just the drudgery of the 9-5 work day, the repetitious daily commute or the endless meetings that ’s fogging my view. I look at his house and studio in the bush and realise he doesn’t have to put up with any of that monotony. How lovely.

matthew She argold DESIGNERHaving lived for the last three years in an inner-city terrace, I found the story on the Glebe terrace (by Michael Bechara, page #125) particularly interesting. The fusion of the modern timber panelling with the original bricks works nicely. And I also found the recessed timber wall with minimalist built-in storage for the open living space an intriguing and innovative solution. I particularly love when original heritage features are retained as much as possible (let ’s face it: these elements add so much character) – but I have to say that the double-height open living space blew me away. The skylights and full-height glass doors create such harmony with the outdoor environment, and this combined with the integration of old and new give the space a surprisingly grand and open feeling.

Simon byrne S R EADERAs a new reader, I am impressed with the quality of the publication, and of the selected works. Your recent focus on some great Modernist designs –the article on Westmere in Auckland (page #98) for example – shows the strength of this approach. As a young designer just beginning my own practice, however, I would love to see more focus on the built works of architects and designers who are at the beginning of their careers – particularly as a way of introducing a critique of this Modernist trend. Although I’m not keen to see more faceted digital-esque facades, perhaps there is the possibility of charting the progress of the youngest in our profession to see what kinds of ideas Habitus might be publishing in the next 20 years.

andrew daly

Each response receives 4 x collector ’s Ottawa cups by Karim Rashid from BoConcept, and a 1-year subscription to Habitus. Send in your responses to our stories this issue at conversation@habitusmagazine.com

AngeliTA BoneTTi

m arimekko-i NSPir e D houSe #143

Growing up on the beautiful surrounds of Lake m a ggiore, it aly, a n gelita has always been inspired by e u rope’s art and design scenes. a f ter graduating in a r t and mu ltimedia Communication from the Brera a c ademy of Beautiful a r ts in m i lan, a n gelita worked for many international magazines and brands. Now living in Perth, her dream is to “buy a new eco and sustainable house by the beach, and to make it beautiful.”

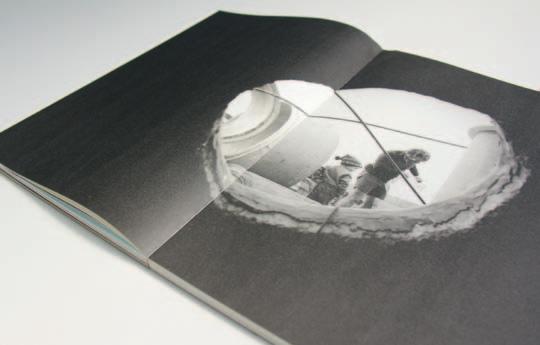

SiMon deviTT

ro S S St eve NS #75

Simon Devitt is a photographer based in auckland, New Zealand. tr avelling extensively to photograph work in both a u stralia and further afield, his pictures have featured in numerous books. Collaborating with a ndrea Stevens in 2011 to create their book, Summer Houses, Devitt is a man of many talents, also lecturing in Photography of a r chitecture at the un iversity of a uckland.

John doughT y

h a Bi tuS Pavi L ioN #51

John has been a practising commercial photographer since 1982. i n the beginning it was a love of processing film, slides and printing black and white photos that kept him shooting. a family man at heart, his focus is on the detail of the job. h i s expertise includes action sports, boardrooms and a long list of products from computers to wine bottles, and everything in between. a keen eye for detail, spacial lines and a thorough understanding of light, his photos have depth beyond the obvious.

Philip Drew is an architectural historian and author. Currently, Philip is researching, with noted photographer a nthony Browell, a pictorial biography of Sydney, Fragments: Intimate Sydney, consisting of close-up images of city architecture that tell its story as part of an open art gallery. he s ays about the Jamberoo house, “What i enjoyed most was the unique collection of farm buildings that form a small museum in their own right and the way that r o b Brown succeeded in making the new house the natural climax of this group.”

A nnA Fl A ndeR S

m arimekko-i NSPir e D houS e #143 “ i n spiration comes from people, performance, textiles, cultures and new trends,” says a n na, “ i love finding old stories that can be seen in spaces, places and design or architectural pieces.” a n na, and her pooch Suki, live in a studio apartment in Perth’s, Fremantle, and they are only a three-minute walk from the beach. But most of all, a n na just loves good conversation, and lots of laughter.

STePhen l ACey

Fa mi Ly Br a N D #179

Stephen has a m a sters degree in e n glish from Sydney un iversity. he has also published three novels, and has been short listed for the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize. h i s feature articles on design and architecture have appeared in numerous national and international publications. With a keen eye for design, he lives in a warehouse apartment in a n nandale, boasting an extensive collection of indigenous art and k i vi tealights.

TeMPe M ACg oWA n B o ok revie W #185

tempe has been writing for design magazines since the mid-1980s when a colleague in London encouraged her to write about the competition for the Par de la vi llette. a f ter the exhilaration of interviewing and working on this piece, she hasn’t stopped writing, including a stint for the Sydney morning herald on gardens and writing her book, Transforming Uncommon Ground: the gardens of Vladimir Sitta. She also worked on the redevelopment of hyde Park South. But, most of all, she loves to walk her dogs in Sydney ’s Centennial Park.

WoN De rWa L L houSe #154 a r oon loves to talk about all things art and architectural, a love that no doubt began during his time at the Department of a r chitecture at Silpakorn un iversity. Writing for magazines such as Art4D, and t hailand’s Wallpaper, a roon is also an important member of the Land Foundation project, which seeks to cultivate a place, or land, of and for social engagement.

L oNGFor D houSe #98

Sharrin is an architectural and environmental photographer who loves collaborating on exciting projects. r e siding in Sydney’s famous Bondi Beach, with her fiancé, writer tom Parker, and their trusty Jack r u ssell terrier, Sharrin is constantly inspired by life, light, form and colour. She first fell in love with photography at nine, when her parents gave her a ‘magic’ little camera. a nd since then, has only continued to love her craft, and to capture beautiful images from around the world.

ST uA RT SCoTT

m ark Be St #87

a f ter 18 years of the hustle and bustle in Sydney's i n ner West, Stuart now lives a stones throw away from avalon Beach. a nd living with seven females, Stuart’s life is definitely full. Between his partner m i ndy, her daughter Georgia, their Springer Spaniel Frankie, four chickens, and five children aged between 14-25 who come and go, it is surprising that Stuart gets any time to follow his passion – photography.

SooPA koR n SR iSA k ul

WoN De rWa L L houSe #154

a f ter graduating with an architectural degree, Soopakorn decided that his love for this design field was best found through photography. Capturing experiences and encouraging contemplation, Soopakorn’s photographs are both personal and intimate, revealing insights and depths that only an observer can see.

A n dR e A STe venS

ro S S St eve NS #75

a f ter a ten-year stint as an architect, a ndrea moved into digital media and architectural publishing, where she now mixes an interesting and full career with raising her two children. Living in an old-fashioned peninsula suburb in a uckland, New Zealand, a ndrea is always inspired by eccentricity and fresh ideas – it was her friend ’s experimental house that first sparked her passion for design and architecture. “Food prepared with care,” says a ndrea, “that is what i most look forward to.” From an architect, to an architectural writer, a ndrea loves this field.

Hydroline, the invisible massage. Discover Teuco’s know-how affording superior efficiency while replacing classic jets with minimal slits. Available on bathtubs in Duralight® the beguiling smooth material. Now also available on acrylic tubs.

MADE

ediToR i A l diR eCToR Paul mc Gillick habitus@indesign.com.au

dePuT y ediToR Nicky Lobo nicky@indesign.com.au

ediToR i A l ASSiSTA n T Philippa Daly philippa@indesign.com.au

oR iginA l de Sign TeM Pl ATe one8one7.com

SenioR de SigneR F rances yeoland frances@indesign.com.au

de SigneR a lex Buccheri alex@indesign.com.au

J u nioR de SigneR rollo ha rdy rollo@indesign.com.au

J u nioR de SigneR & AdveRTiSing TR AFFiC

Natalie Lau natalie@indesign.com.au

Con TR iBuTing de SigneR m ichelle Byrnes

on line ediToR

Lorenzo Logi editor@habitusliving.com

Con TR iBuTing W R iTeR S

P hilip Drew, a n na Flanders, Stephen Lacey, te mpe m a cgowan, a r oon Puritat, a n drea Stevens

Con TR iBuTing

PhoTogR APheR S Patrick Bingham-h a ll, Jason Busch, a n gelita Bonetti, Simon Devitt, a l bert Lim, Sharrin r e es, a t irojt r ot ratanawalee, Stuart Scott, Piyawut Srisakul, Nicholas Watt, Brent Winstone

COVER IMAGE

Sustainable Decadence (page #75)

Photography: Simon Devitt

Ceo / Pu BliSh eR r aj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

oPeR ATionS M A nAgeR a dele tr oeger adele@indesign.com.au

PRoduCTion M A nAgeR S ophie me ad sophie@indesign.com.au

Su BSCR iPTionS / PA To Pu BliSh eR e l izabeth Davy-hou liz@indesign.com.au

FinA nCi A l diR eCToR k avita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

BuSine S S MA nAgeR Da rya Churilina darya@indesign.com.au

ACCoun TS G abrielle r egan gabrielle@indesign.com.au vi via Felice vivia@indesign.com.au

on line CoMM u niCATionS r adu e n ache radu@indesign.com.au r a mith ver dheneni ramith@indesign.com.au

r yan Sumners ryan@indesign.com.au

Jesse Cai jesse@indesign.com.au

e v en TS A n d MAR k eTing te gan r ichardson tegan@indesign.com.au

a ngela Boustred angie@indesign.com.au

BuSine S S develoPM en T MA nAgeR ma rie Jakubowicz marie@indesign.com.au

(61) 431 226 077

AdveRTiSing enquiR ie S Colleen Black colleen@indesign.com.au

(61) 422 169 218

HE AD OFFICE

L evel 1, 50 ma rshall Street, Surry h i lls NSW 2010 (61 2) 9368 0150 | (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax) | indesignlive.com

MEl bOUR n E Suite 11, Level 1, 95 victoria Street, Fitzroy viC 3 065 | (61) 402 955 538

SInGA pORE

4 L eng ke e road, #06–08 Si S B uilding, Singapore 159088 (65) 6475 5228 | (65) 6475 5238 (fax) | indesignlive.asia

HOnG KOnG un it 12, 21st Floor, Wayson Commercial Building, 28 Connaught r oad West, Sheung Wan, hong kong | indesignlive.hk

publisher

the publication.

submitted

sender’s risk, and i ndesign Publishing cannot accept any loss or damage. Please retain duplicates of text and images. ha bitus magazine

a wholly owned au stralian publication, which

designed and published in au stralia. ha bitus is published quarterly and is available through subscription, at major newsagencies and bookshops throughout au stralia, New Zealand, South-e a st a sia and the un ited States of a merica. t h is issue of ha bitus magazine may contain offers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. i f you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services we have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as fulfilment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however, these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information and use it to inform you of other promotions and publications from time to time. i f you would like to know what information i ndesign media a sia Pacific holds about you please contact Nilesh Nandan (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax), subscriptions@indesign.com.au, indesignlive.com. ha bitus magazine is published under licence by i nde sign media a sia Pacific. iS SN 1836-0556

Teuco asked beauty to conceal power.

The result is Hydroline.

Aged copper, brass & waxed rust finishes Chant New Zealand, Brionne France & Fersa Argentina

Aged copper, brass & waxed rust finishes Chant New Zealand, Brionne France & Fersa Argentina

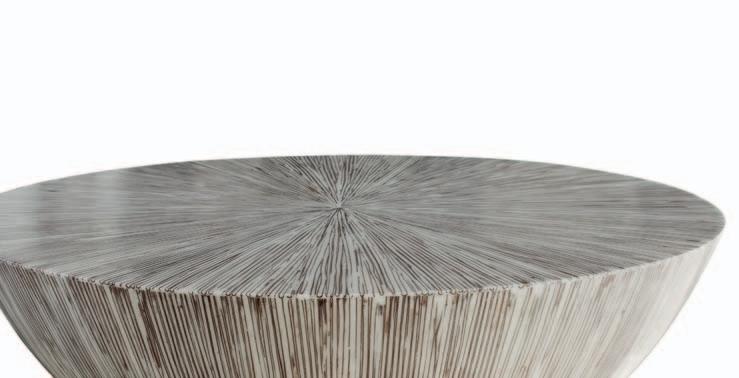

The RE-TURNED collection, from European house Discipline , takes an often ignored material, left over wood, and elevates it into a piece of beautifully crafted design. A 100% recycled item, the collection by Norwegian designer Lars Beller Fjetland is the perfect piece for someone with a big heart for Mother Nature. And Fjetland ’s latest design celebrates even the smallest of nature’s creatures in style and beauty.

discipline.eu / stylecraft.com.au

Observing the specific details in the simplest everyday actions was how the WORKAHOLIC collection by Thai design house, THINKK Studio, was first born. With a collection that includes lamps made from concrete and wood, concrete vases with wire frames, and little wooden trucks to hold your pens and paper clips, THINKK ’s new collection has even the busiest of workers covered. “This is a collection of little desk organisers that allow us to have fun,” say THINKK ’s designers, Decha Archjananun and Ploypan Theerachai . “It also helps to recharge and refresh our imaginations, as if we were young again.”

thinkk-studio.com

The English Tapware Company launches their new BLACK collection, encompassing Perrin & Rowe’s traditional kitchen and bathroom collections. BLACK offers lustrous black ceramic detailing, ensuring that any kitchen or bathroom has that sleek, discerning edge. Classical design does not go out of date. Rather, its timeless elegance will for long sit comfortably alongside a wide range of architectural styles. And BLACK will certainly add sophistication to any space.

englishtapware.com.au

In Basque, LASAI means quiet, calm and peaceful. And peaceful is exactly what this chair produced by Alki is all about. Bold in form, its large solid Oak structure exudes an air of refined sophistication; its manner; composed tranquillity. Designed by Jean Louis Iratzoki , LASAI seeks only to reveal its true character – a simple chair of exceptional quality, crafted by a group of people who share a humble vision to work and live in the beautiful Basque country. Years of work have allowed Alki to produce pieces that represent an age-long commitment to tradition, culture and know-how. Started from a small town near Biarritz, Alki’s collection defines contemporary, while speaking the language of harmony, texture and the senses. LASAI is simply the next piece in their honest and treasured history.

alki.fr / coshliving.com.au

A simple design with a luxury finish, the brass SMED stool combines industrial chic and opulence to commend any modern space. A classic collaboration between Great Dane Furniture and OX Design Denmark, the SMED stool took 12 months of discussions, samples, proportion and material testing. But the result is a truly beautiful and authentic piece. Classic yet contemporary, this is a unique and sophisticated piece for any and every interior.

greatdanecontract.com

Poliform welcomes French rug brand CC-Tapis to their collection. Created in 2001 by the Maison Chamszadeh , known in France for over 40 years for their commitment to traditional carpet making, CC-Tapis takes ancient craftsmanship and artisan know-how to create fresh, new and engaging designs for the contemporary home. Their rugs – hand woven with a Tibetan knot upon a cotton weave and loomed with wool, silk or hemp –present as a beautiful addition to any modern interior.

cc-tapis.com / poliform.it / spacefurniture.com

North Shore Interiors’ Linda Delaney recently launched the NSI HOUSE OF DESIGN, a unique range of bespoke cushions, the BEACH HOUSE BOYS just one of the many collections. Each cushion is 100% cotton and beautifully detailed with a splash of colour, making it the perfect addition to any little child’s bedroom or playroom. “Kids love cushions,” says Delaney, “whether it is just for cuddling, resting upon to daydream or snuggling into as they read their favourite books.”

nsinteriors.com.au

“With every approach, I try and create work that has life,” says Kenny Yong Soo Son of Studiokyss. “I try to create work that has the potential to exist in this world.” With a background in jewellery and metalcraft, the Sydney-based designer hopes to interact physically and emotionally with his users through his objects. Combining robust, textured materials with minimalist restraint, his CONCRETE CONTAINERS engage on all levels. “I believe there are too many ‘lifeless’ objects in this world – there must be a reason to be part of this world.”

cargocollective.com/kyss

Riva 1920 believes in spare form and function. And their latest release, in collaboration with Jamie Durie, is once again testament to their passion for sophisticated design. Durie’s TUBULAR TABLE juxtaposes the unique elements of the wood with the modern aesthetic of the integrating powdercoated metal in ways that are truly beautiful.

riva1920.it / fanuli.com.au

Retaining all the core elements of their original HAIKU award-winning design, Big Ass Fans now release their new, and bigger, fan which features a neodymium magnet motor and larger aerofoils. Fashioned from aircraft-grade paint, HAIKU 2.1 offers paramount durability, efficiency and style. And consuming only 60W of power, HAIKU is the most energy-efficient fan in the world, delivering twice the airflow of a standard ceiling fan at only half the weight.

bigassfans.com

Ink & Spindle’s work is inspired by a love for Australia’s native flora & fauna. To designers Lara Cameron and Tegan Rose , one of the most important aspects to their creations is sustainability. Their desire to live, work and create in an ethical and sustainable manner has always influenced Ink & Spindle, from their materials to the production process.

inkandspindle.com.au

Exclusively designed for Bespoke Global , these handcrafted beach ping pong racquets are designed with a stunning array of domestic and sustainably sourced exotic woods. As the world’s leader in luxury artisan products, Bespoke Global ensures exceptional craftsmanship. So, what are you waiting for? While away an afternoon and kick up some sand with these Californian beauties.

bespokeglobal.com

MARBELOUS WOOD – REFRACTION reinterprets the classic wooden floor with an explosion of colour. In this project by Pernille Snedker Hansen , both the form of the parquet floor and the applied pattern are inspired by the refraction of light through a prism, a graduating colour scale from one colour to the next. Its highly organic yet graphic patterning creates an optical experience as your feet move across the floor, while the transparent marbling pattern merges with the wood. snedkerstudio.dk

DRY TABLE by UK-based designer, Alex Bradley, can be used as a normal table and a drying rack. A spacesaving table, DRY TABLE is designed to be used both indoors and out. The table’s steel rods replace traditional table surfaces to one where you can hang items or dry washing. Highly aesthetic, Bradley has created a table that cleverly offers both design and functionality.

alexbradleydesign.co.uk

CLUC, by Barcelona designer, Laia Fuste , is an object collection designed for cats, which not only considers their psychology, perception and morphology, but also their shared life with us humans. Fuste has created unique objects that belong to not only us, but also to our furry friends. “We sleep with them, play with them, travel with them, and take care of them,” says Fuste, “we can also now learn from them.”

cargocollective.com/laiafuste

WORKBENCH is the result of a combination between two traditional craft materials: wicker and clay. Through an experimental research approach, Alberto Fabbian and Paola Amabile have created a product that reinterprets the technical possibilities of both materials, creating new languages and forms previously unimagined. The collection of objects was also made in collaboration with Antoniazzi&Piovesana and Ceramiche Vicentine

albertofabbian.com

/ cargocollective.com/amabilepaola

Melbourne-based Stephanie Ng uses a combination of colour, form and texture to make the ordinary special. Her signature: a personal feel to finished products, as portrayed through her latest product range, LUNA LANA Creating products that retain their functional edge, she also believes in design for emotion, designs that move people.

stephaniengdesign.com

“We design things that exploit the raw and rudimentary outline of the object,” says Singaporean designer, Jaren Goh . “A chair should look like a chair and nothing else.” The WANG CHAIR , from Munkii , is a sleek, sexy lounger designed from a combination of cleverly positioned tripod steel frames and Oak laminated seating.

munkii.com.sg

Based on the Californian spirit of original ‘cruiser’ skateboards, HANDMADE WITH LOVE , by French company La Planche à Roues is a new collection that adopts a similar style. Offering an alternative mode of transport to move around the city, the skateboard has undergone a constant evolution in design. These handmade skateboards are cut from solid pieces of Oak, Ash or Pine timber and customised with an engraved logo and geometrically painted shapes. Traditional craft with a contemporary edge, these skateboards are certainly unique, commenting as much on design as the original ‘hipster’ culture that invented them.

facebook.com/LaPlancheARoues

Utilising her love of textas and pens, Melbournian Jane Reiseger creates semi-abstract images and playful line works. Drawing inspiration from her surroundings, as well as her young son, Reiseger’s latest project brings her unique talent into everyday homes, with a range of wallpaper designs produced in collaboration with The Wall Sticker Company. SUPER FRESH SUNNY WALLS features nine different designs, all featuring Reiseger ’s hand-drawn fruit characters. janereiseger.com / thewallstickercompany.com.au

GLASSWOOD : where glass and wood complement each other. In this project, Hamburg-based designer Alexa Lixfeld experiments with textures and colours through her collection of handmade and mouth blown vases.

alexalixfeld.com

Dinosaur Design’s MODERN TRIBAL range plays with ideas around the meaning of ‘tribes’, and the perennial need for humans to belong. With its juxtaposition of colour and shape, Louise Olsen and Stephen Ormandy have created distinctly modern pieces that hint at the ancient. Bold block-shaped vases contrast with soft rounded shapes punctuated with holes, and strong primary colours work in harmony with earthy neutral tones.

dinosaurdesigns.com.au

HIDE is a series of moulded leather pendant lights designed by Ben Wahrlich for Melbourne studio, AN/AESTHETIC. The pendant lights offer a unique marriage of vintage charm and contemporary design, by incorporating both modern and traditional production techniques.

anaestheticdesign.com

Made in Ratio has been forged with a desire to take ideas from inception to production. Embracing experimental processes, and working alongside some of the finest craftspeople in Europe, their products are imbued with the spirit of innovation. COWRIE , by Australian designer Brodie Neill , is inspired by the concave lines of sea shells. The curvilinear forms are the result of extensive research, utilising an innovative process, which bridges the handmade with the digital.

brodieneill.com / madeinratio.com

“I was lucky enough to collaborate with local shibori artist Vic Pemberton on these hand dyed indigo cotton rope vessels,” says Australian designer, Gemma Patford . Bridging the gap between hand-made charm and modern style, Patford and Pemberton’ s COTTON ROPE VESSELS are the perfect addition to any contemporary home.

gemmapatford.com

LifeSpaceJourney is a niche design and manufacturing practice located in Melbourne ’s inner west. Their latest release, THE SHEARER takes the simplicity of a wool bale and combines it with practical strapping to create form and structure, whilst adding detailing reminiscent of vintage sports car upholstery. Made from premium custom tanned leather and custom quilted duck down, THE SHEARER is designed for comfort with a robust character that remains true to its simple origins.

lifespacejourney.com

Passionate about quality, creativity and lifestyle, Sydney-based furniture studio Christelh releases HOVER . Inspired by the round windows of a passenger ship, this beautiful pendant light is a celebration of classic materials, modern processes and future design possibilities. This design demonstrates a simple and modest aesthetic.

christelh.com

Introducing the Pleasure sofa by FLEXFORM.

Designed by Antonio Citterio, the Pleasure Sofa is the epitome of comfort and style. Available exclusively at Fanuli, its clean, relaxed lines add elegance and adaptability to every setting.

Flexform is one of the world’s most sought after and renowned furniture brands. It’s a perfect fit with Fanuli, where you’ll find a range of world-class soft furnishings, imaginative tables, bookcases and storage solutions for the home and contract interiors.

Made in Italy.

From top | Weather Diary Collection jug $95, Bowl $37, both from Marimekko; Elcho Island bowl by Mavis Djuramalwuy Yunupingu, $310, Koskela; Davidoff large brushwork porcelain vase, $44, Planet Furniture; Three stacked organic pasta bowls by Craig Pearce, $55, Workshopped; handmade white ceramic bowl, $80, Judy Sciberras; Robert Gordon x Living Edge bowl , $55, Living Edge; large mixing bowl in bottle, $145, MUD Australia; Weather Diary Collection salad platter, $125, Marimekko; small mixing bowl in orange, $114, MUD Australia; cereal bowl in blue, $16, Orson and Blake; Isadora Corfu serving bowl in blue and orange, $189 each, Citta Design; (on wall throughout) Eggshell Acrylic in Ming Dynasty, $43.20/L, Porter’s Paints; (on floor throughout) wooden floorboards in hornblende, Techtonic Flooring.

Barazza is award-winning design and functionality. Made in Italy for over 40 years. Barazza’s Made to Measure offers a unique ability to seamlessly incorporate cooktops, sinks and accessories into a stainless steel benchtop. It gives the designer the ultimate freedom to create a functional piece for the kitchen, which boasts an unrivalled minimalist elegance. Exclusive to Abey Australia. – Barazza Made to Measure

From top | Grecian tile cushion , $130, Rouse Philips; Dutch wax print cotton cushion , $149, Planet Furniture; Jaunt to Jaipur Zig Zig cushion , $99.95, The New Punjab; Trekken hand woven cushion , $280, Marijke Arkley; dipped cushion in teal, $49.95, Southwood Home; Coburn cushion , $130, Rouse Philips.

From top | Grecian tile cushion , $130, Rouse Philips; Dutch wax print cotton cushion , $149, Planet Furniture; Jaunt to Jaipur Zig Zig cushion , $99.95, The New Punjab; Trekken hand woven cushion , $280, Marijke Arkley; dipped cushion in teal, $49.95, Southwood Home; Coburn cushion , $130, Rouse Philips.

Eggshell Acrylic in shell grey (on wall, throughout), $43.20/L, Porter’s Paints; Beat vessels by Tom Dixon: Tall, $1,342, Drop $1,683, Top $1,144, dedece; Vintage Indian wall window panels , $150 each, The R.E.A.L. Store; Iron Lace marble in honed finish, $250/m 2 , Gitani Stone; limited edition Traditional Sources incense burner, $80, Nadia Hernandez; Rock from Gosford Quarries; linen duvet cover, $530, Ecoluxe; wooden rosary, $95 , The R.E.A.L. Store.

Marrying pri M i tive with the conte M p orary, our primal instincts coM bine to create dark, cool spaces t hat proMo te a sense of calming energy and reinvigoration – a retreat froM t hose hot su M M e r days.

Clockwise from top left | C2 FAT copper light , $462, Workshopped; wide width linen sheer by C&C Milano, POA, South Pacific Fabrics; calligraphy on washi paper by Naoaki Sakamoto, $1,950, Small Spaces; Turkish wheat thresher, $550, and Turkish oil urn , $330, The R.E.A.L. Store; Beni Ouarain carpet (Morocco c.1930), $4,900, Jason Mowen; Deco circle side table in antique brass, $610 (nest), Globe West; Wina post finial statue (Papua New Guinea c.1940), $1,950, Jason Mowen; books throughout , POA, Beautiful Pages; Long Island modular lounge upholstered in linen, $16,790, Fanuli Furniture;

Tom Dixon gold tray, $220, tea pot , $253 and caddy, $88, dedece; silk and linen throw cushions , $149 each, Planet Furniture; Iron Lace marble in honed finish $250/m 2 , Gitani Stone; Metallix bricks in bronze, $1,547/1000 bricks, Austral; beeswax candles , $25-29, Planet Furniture; brass dish oil lamp , $55, Mulbury; Chinese water trough , $480, The R.E.A.L. Store; oranges and cumquats supplied by Crinis Fruit Tarrawanna; cashmere blanket queen size in wheat, $990, and Society RAW bedcover in natural, $765, Ondene.

c lockwise from left | wide width linen sheer from C&C Milano, POA, South Pacific Fabrics; Cumulus large pendant light , $485, Planet Furniture; Lui wooden stool by Tribu, $1,490, Cosh Living; Chinese ceramic cup , $50, The R.E.A.L. Store; beeswax candle , $25, Planet Furniture; Nok head sculpture on stand (Nigeria), $750, antique Koranic tablet (Morocco c.1900), $600, and hanging mask (Papua New Guinea c.1970), $750, all from Jason Mowen; American Oak ladder by Chris Colwell, $275, Small Spaces; woven dilly bag by Rosemary Mumunini,

$250, Koskela; linen duvet cover (hanging), $420, Ecoluxe; Henry Wilson marble top table , $1,775, Corporate Culture; vintage Turkish spice grinder, $240, The R.E.A.L. Store; rock from Gosford Quarries; wooden Indian grinder (w/out grinder), $285, The R.E.A.L. Store; blue stripe ceramic soba cup by Keiko Matsui, $40, Small Spaces; Leila queen size bed , $4,003, Jardan; rustic linen throw with red (over bedhead), $250, and linen cushion with string cross stitch, $180, both from Ecoluxe; Society REM cushion in bianco, $138, woollen bed blanket in

bianco, $550, Society REM quilt in bianco (and underneath) in sable, $845 each, all from Ondene; Kakuda Maple tray by Oji Masanori, $155, ceramic tea pot by Hilary Jones, $110, ceramic cup and saucer by Alison Fraser, $45, all from Small Spaces; Iittala glass tumbler, $29 (set of 2), Anibou; wooden scholars stool , $295, The R.E.A.L. Store; pure alpaca rug in white, $799, The Latin Store; Turkish pinat dough riser tray, $270, The R.E.A.L. Store; large Tjanpi basket , $1,320, Koskela.

c lockwise from top left | hanging chair, $145, Swingz and Thingz; linen cushion with red seed beads, $230, Ecoluxe; hemp and wool bean bag , $750, Koskela; Turkish garden harvesting forks , $240 each, The R.E.A.L. Store; Magis Rocky rocking horse by Marc Newson in white, $1,683, Corporate Culture; birdhouse in natural terracotta, $310, Abalos; FOG linen tea towel (sack on stick), $18, Mr Kitly; teepee , $250, Lightly; agave ocahui 330mm, $225, Garden Life; Sahara 3 pot in warm grey by Gandia Blasco, $525, Parterre; Treehorn balance blocks , $55, State of Green; Society REM cushion in bianco, $138, Ondene; white tree block print quilt , $200, Shakiraaz; rocks from Gosford Quarries; thermos bottle , $148, FOG linen yellow plaid kitchen cloth , $10, and CARA mug cup , $75, all from Mr Kitly; selection of Tangier dishes , $25-45, Jason Mowen; cumquats supplied by Crinis Fruit Market Tarrawanna; EcoSmart Fire Stix heater, $1,595, Cosh Living.

c lockwise from top left | wooden Oak wall hook , $30, Small Spaces; Society Lipe bath towel in fumo (hanging and on ground), $175 set, Ondene; Indian macrame chair, $700, and cushion , $125, The R.E.A.L. Store; gold metal singing bowl with wooden hitter stick, $32, Anjian Australia; cashmere robe in charcoal (draped on chair), $550, Ondene; Carillo Zen table , $2,398, Nicoya Furniture; New Friends weaving , POA, Mr Kitly; marble mortar, $60, The R.E.A.L. Store; Lilla Bruket bath salts , $36, Funkis; Jonathan Ward candle , $65, Ecoluxe; natural wool floor runner, $700, Planet Furniture; Christopher Boots

Prometheus III pendant light , $4,950, Inlite; prayer hands , $33, Mulbury; JADE yoga mat , $70, E.M.P. Industrial Australasia; Vide Poche in gunmetal bronze, $250, Henry Wilson; Reverence hand balm , $29, and deodorant , $35, Aesop; antique marble tray with feet, $270, The R.E.A.L. Store; Premio tumbler glass , $19.50, Citta Design; Zisha teapot by Neri & Hu, $165, SeehoSu; brass dish oil lamp , $55, Mulbury; meditating Quan Yin statue in ivory finish, $150, Anijan Australia; Himalayan salt lamp , $59, Natures Energy.

Our top of the range washing machines hold features that are so gentle on your clothes, they actually make them last longer and are extra gentle even for woollens and silks. OptiSense ensures that clothes are never overwashed, the ultra gentle XXL Soft Drum allows for bigger loads and the Direct Spray feature ensures even distribution of water spray which dissolves even the toughest stains. See why we are endorsed by the prestigious Woolmark at www.aeg.com/au

(European model shown)

tongue n groove timber constructed of FSC European Oak treated with natural oils in 15 beautiful colours allowing for easy maintenance

Showrooms

Shop 2 188 Chalmers Street, Surry Hills NSW 2010

P 02 9699 1131 F 02 9690 0929

575 Church Street, Richmond VIC 3121

P 03 9427 7000 F 03 9427 0100

tonguengrooveflooring.com.au

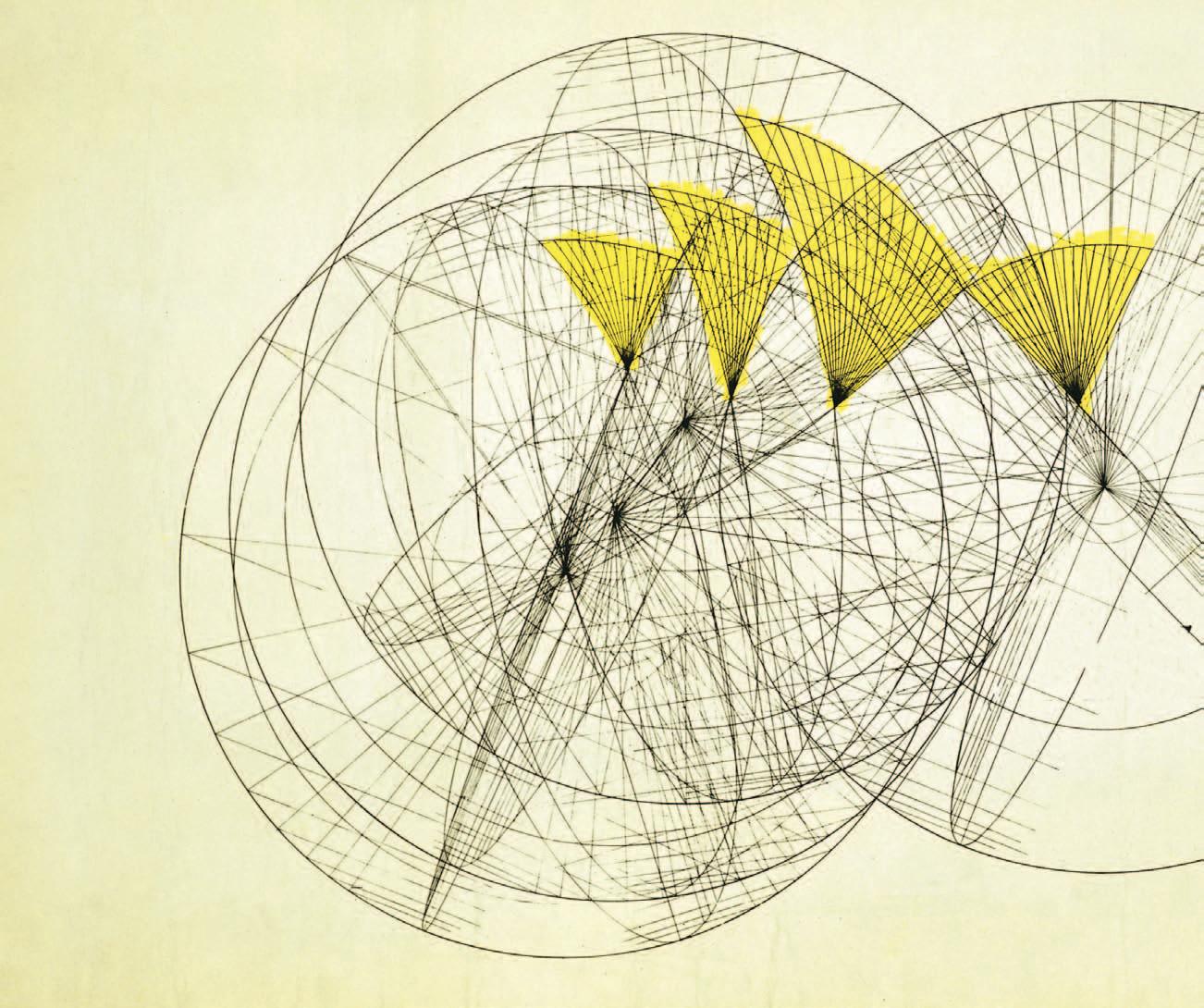

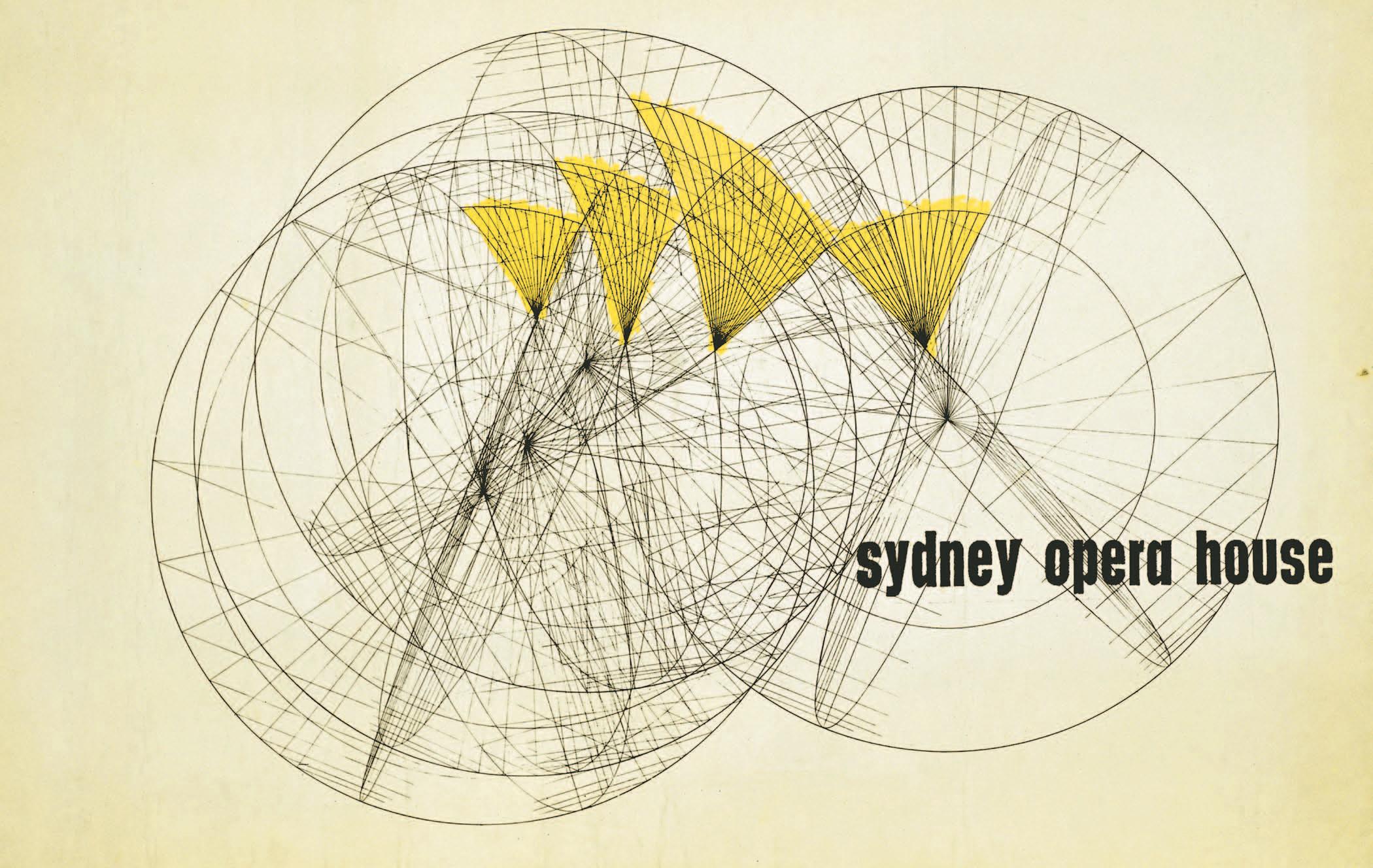

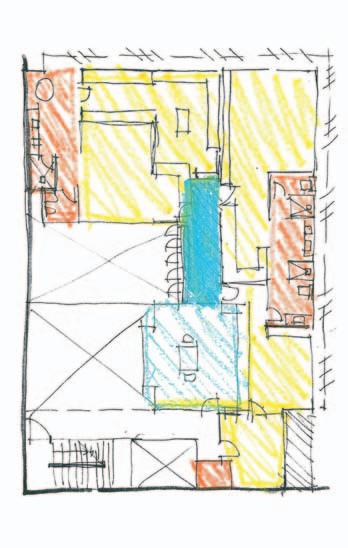

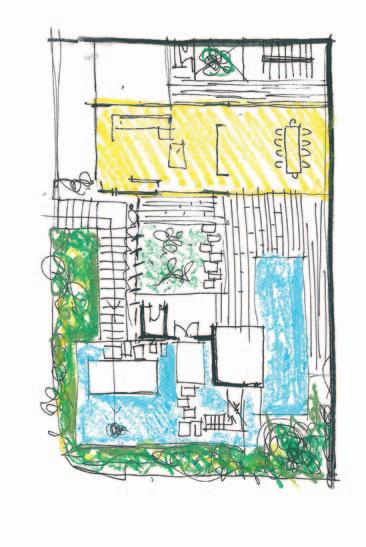

What is Habitus as an experience? This question was presented to the creative studios involved in the Habitus Pavilion for The Project at sy dney i ndesign 2013 .

The Project is a collaborative creative exercise that draws together players in the design community (in this case, Habitus magazine) with design professionals to create installations for Sydney Indesign. This event attracts thousands of industry members and designinterested consumers – so the level of quality and visual engagement aims high. This year, The Project asked participating companies and brands to explore the keyword ‘Process’.

Habitus was initially given 100 square metres in the Galleria exhibition space at Australian Technology Park. There were a number of considerations for the project. Firstly, it was the first time the brand had a dedicated space. Secondly, as one of the organisers – being part of the Indesign Media brand – it was important that the space set the benchmark in terms of creativity. Thirdly, being a magazine and a website, rather than a commercial and/ or residential product supplier (who were the majority of the other exhibitors) there was quite a different intention, personality and feel required for the space.

Habitus aimed to use the space to communicate the print and digital components of the brand, and explore the notion of home with its signature appeal – which is intelligent, immersive and creative.

Habitus first approached loopcreative, who have an impressive track record in producing engaging hospitality design with a strong focus on interaction. They introduced lighting designers, lo-fi, to bring their expertise to the space. When the opportunity arose for the project to triple in size and scope, the team conceptualised a garden oasis and brought on Landart to work their magic. Finally, Promena building and construction management came on board to help the project come together.

The initial concept from loopcreative took inspiration from pavilions at La Biennale di Venezia. They proposed a steel structure that referenced the construction element of residential design, which was to be covered in sheets of folded white paper, representing the

unwritten pages of the magazine. loopcreative wanted to create “a residential concept with links to the elements that make up the magazine, translated into a built form,” as Rod Facheaux explains. “We could have done mock-up rooms of home interiors,” he continues, “ but we didn’t think that’s what Habitus is about.” From lofi’s perspective the key goals of the space were “identification, information, entertainment, experience,” says Greg Dunk, and a lighting scheme was devised to provide this.

The biggest challenge was a massive increase in the size of the space midway through the project. Wanting to give this extra space a purpose that related to the brand, and to the reader, the ‘Habitus Home’ exhibition was born. Readers and artists featured in the magazine were asked to submit artworks (both visual and text-based) that represented their idea of home. The Habitus team curated the entries to be displayed in a garden exhibition, fixed with pegs onto Hills Hoist clotheslines, a nostalgic and domestic element of many Australian homes and an icon of Australian design.

Another major challenge, as with any project, were time and budget constraints –made more intense with the extra space that was taken on, and the strict schedule, which only allowed two days for installation and one day for breakdown.

The 450-square metre pavilion was divided into four key areas: a shipping container representing the digital arm of the brand; an

area to relate back to the original pavilion concept; a bar area and the garden exhibition. The container included a laser projection and smoke machine – an immersive experience which invited visitors to begin the intriguing journey through the space. The steel pavilion became a cardboard box structure due to budget restraints and a potential sponsor falling through. Although this amendment to the design was not as originally planned, the team took it on as a challenge and saw it in a positive light. It still bore a relation to the construction element of residential architecture, whilst also relating to the paper element of the magazine itself. Ironically, it was also a complete interpretation of the keyword, ‘Process’ as the design was revised multiple times on site to best make use of the available materials while providing a sound support.

This space opened up to the bar area, which marked the beginning of the garden exhibition. “We wanted to create a soft and inviting space that would encourage guests of the exhibition to meander and explore, to sit and meet with other business or colleagues,” says Matt Leacy of Landart. “Habitus magazine has always seemed to explore an alternate route to the common, more everyday, version of design,” Matt continues. “It beats to its own drum and doesn’t mind showcasing something a little left of field.” With the native and exotic planting – some over five metres tall – throughout the industrial space, “the plants gave the feeling that they were reclaiming the building… it was quite surreal in appearance.”

Creative partners Landart Landscapes, loopcreative, LO-FI Design and Engineering, Promena Projects

Product partners Advance Audio, Alpine Nurseries, Antique Floors, Barco, Classiqe, Garden Life, HG, Hills, Royal Wolf, Wats on Tap Exhibition Partners Archi-Ninja, KW Doggett, Olsen Irwin Gallery, SOS Print + Media

Design has many functions in our society. There are practical considerations – to provide the spaces, products and accessories required to live our daily lives as efficiently and pleasantly as possible. There is the motivation to explore the new frontiers of technology in the aim to continue moving ever forward. But another concern is sustainability.

Although most often used these days in an environmental sense, design also plays an important role in cultural sustainability. For all the benefits of globalisation – the blurring of boundaries between continents, language and economies – there is a real risk of cultural homogeneity, the potential that we develop into a single, dominant society with no variation. As with genetics, diversity is key to our cultural development, and so the need to preserve traditional crafts of various geographical areas is widely recognised.

Designer Rugs offers six ranges that celebrate the art of Tibetan knot weaving. This ancient technique is unique, using a rod to assist the warp and weft yarns in the construction of the rug. The knots are hand-tied over a rod, and as each row is completed, the pile is cut and the rod slipped out. Once the rug is finished and applied with hand shearing or carving, the resulting surface is full of interest, depth and variation. Not only does this technique achieve a beautiful finish, but also has a more dense, luxurious and durable quality than is possible with machine weaving.

Designs can take up to 16-18 weeks to manufacture, due to the intricacy of the construction method. But, far from being seen as negative, this approach accords perfectly with the popular Slow movement. A reaction against our fast-paced lives, this movement thrives on slower, more conscious action and behavior. It means that, contrary to a hyperinstant mentality, waiting a bit longer for a special piece is not only completely bearable, but also provides time to fully anticipate and appreciate the finished product.

Designer Rugs’ Mystique, Wool and Silk and Contemporary Hand Knot ranges from the In-House collections are crafted in Nepal using New Zealand and Tibetan wool with pure

silk highlights. They are available in stock sizes (200x300cm and 240x300cm), or can be fully customised. This enables you to be involved in the conceptualising of each individual piece, becoming part of the creative process and ensuring the finished product is perfectly suited to your interior.

As well, the Designer Collaborations with Catherine Martin (Deco), Caroline Baum (Sand Script) and Bernabeifreeman feature the same artisanal Tibetan hand-knot technique. These highly sought-after designs are created by some of Australia’s best-known and regarded personalities from the design and arts communities, bringing their expertise and insight together with the centuries-old wisdom of an ancient society.

In many ways, the world of Tibetan knotting is far removed from our every day lives. But it is the values that it represents – quality, a slower pace, complexity and texture – that we are craving. And by appreciating items like these, and incorporating them into our living environments, we choose to invite these values in and affirm their benefits.

Rejecting the ready-made convenience of mass-produced products, Tibetan hand-knotted rugs urge us to slow down and appreciate an ancient craft.

Bangkok is an intriguing melting pot of culture and industry, craft and mass manufacture, tradition and humour.

nicky LoBo t alks to 56thStudio, who use a dash of all of these in their socially aware furniture and products.

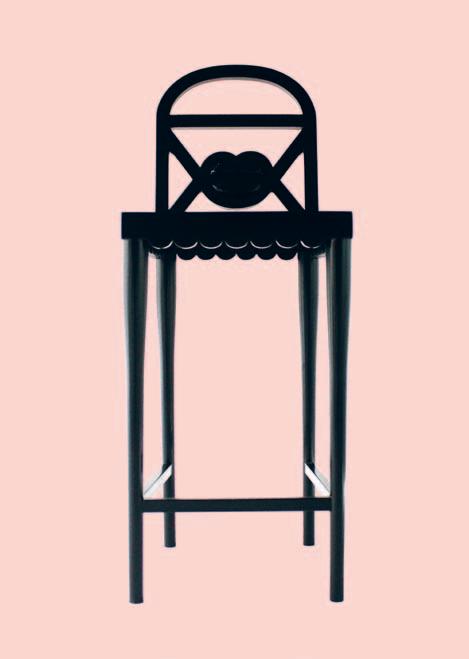

There are many quirky design studios in Thailand (see the story on Propaganda in Habitus #01 for a good example). With an antiestablishment approach, their skill has been to utilise design as a tool to comment on social and political issues. Although often done in a humorous, non-offensive way, sometimes it means their products are only shown outside of the country. “We cannot exhibit them here in Thailand if we still want our heads on our shoulders,” jokes Saran Yen Panya of 56thStudio.

He’s referring in particular to the studio’s new lounge titled Faith-inc, which responds to a recent scandal about a Thai monk who was found spending donation money on personal items, amongst a host of more serious allegations. The lounge aims to criticise traditional institutions which are revered in Thailand, such as religion, the government and monarchy – and so was displayed in Berlin during the Illustrative Festival in September, rather than their home country.

Some of 56thStudio’s designs are more lighthearted, yet still comment on serious issues, such as the Cheap Ass Elites chair. It combines a low symbol – plastic – with a high symbol – a traditionally expensive form – making a statement about the nature of social class distinctions, and portraying the designers’ view that “Looking up to those who

own those expensive chairs is just as stupid as looking down to those with plastic chairs.”

Whether funny or serious, most of the studio’s products begin as casual conversations between Saran and his studio partner, Napawan Tuangkitkul. The two met during their undergraduate study at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok where they both “found the craft of designing architecture strictly boring.” Since then, they’ve become close friends and studio partners, although they both have other projects on the go as well –Napawan runs a family business in textile and wall decoration, and Saran also works as an art director for several companies, as well as teaching himself the important art of cocktail design (“It’s very similar to the craft of design,” he says, “not every recipe works on the first batch.”)

The source of continual inspiration for 56thStudio is “conversation as a two-way communication that, in our case, leads to fruitful arguments, discussions or even healthy quarrels,” comments Saran. “Our process always starts from having something to say, and being very desperate to deliver the message, yet not knowing what it’s going to end up as,” he adds.

They believe every object can be a tool for communication – not just a functional object or decoration. For Saran and Napawan, ‘Form follows Story’ is the complete package.

“It’s like dating a super pretty guy/girl with brains, profound thoughts and a complicated, self-made background” is Saran’s analogy. In other words, it’s design with narrative and a certain purpose.

It has now been two years that the duo has been working under the moniker 56thStudio – bestowed on them by a fortune-teller – and they have already attracted international attention. Cheap Ass Elites was showcased in the Konstfack University (Sweden) exhibition titled ‘ d e sign for a Liquid Society’ in Spazio r o ssana Orlandi this year, arguably the most creative of the satellite spaces that make up Salone Internazionale del Mobile. They have also exhibited in Italy, Paris, and most recently, Berlin.

Their international appeal may be partly due to the fact that Saran and Napawan call their products ‘neo-ethnic’, taking on a variety of influences and histories, which resonates with so many people today. “growing up in Bangkok, a city with a big clash of different cultures, we are naturally influenced by things that were meticulously done in the past, the contrast of prestigious heritages, vernacular design languages, exotic crafts and street cultures,” Saran shares. “Updating these topics and introducing them to new audiences and younger generations gives us great pleasure.”

above lef T | supermodel naomi from the caricature as range of chairs, available in a variety of colours and timber finishes. above righT | the caricature as series. below lef T | bad romance chairs, displaying the happy marriage between “ super ugly chairs... and our quirky prints ”. below righT | koon print screen printed portrait on gold wrapping paper “ that is commonly found in a tacky craft store”.

above lef T | supermodel naomi from the caricature as range of chairs, available in a variety of colours and timber finishes. above righT | the caricature as series. below lef T | bad romance chairs, displaying the happy marriage between “ super ugly chairs... and our quirky prints ”. below righT | koon print screen printed portrait on gold wrapping paper “ that is commonly found in a tacky craft store”.

Our process always starts from having something to say, and being very desperate to deliver that message

SA r A N | dESIgN E r

“People seem to respond to it better than acting as serious academic activists,” says Saran of the studio’s habit of commenting on serious taboos in whimsical or humorous ways. But there’s still a lot of work to be done in their opinion. They believe that the Thai creative industry needs proper regulation to make the most of the talent that is already there, otherwise individuals run the risk of remaining undiscovered if they are not connected to the inner circle or ‘creative mafia’. “My favourite Thai illustrator is now living in the north and making a living by being a barista instead,” rues Saran.

It is clear that talent and vision is to be found in Thailand – in abundance. Like the best of their Asian, Australasian, European and American contemporaries, they practise design as a form not just of artistic expression, but also social and cultural expression. But the Thai industry needs to be unified for it to make a real impact. In the meantime, 56thStudio will continue to tell their stories so long as there are “issues which give us the itch to say something back to society,” Saran says. And they needn’t worry – we’ll be listening.

56thStudio | 56thstudio.com

Hear more from 56thStudio at habitusliving.com/issue22/56thstudio

SPEAKERS INCLUDE: JUHANI PALLASMAA

SPEAKERS

Your fridge is never alone. It stands centre stage in your kitchen. That’s why we’ve designed it to fit your life and match the full range of Fisher & Paykel kitchen appliances. Introducing the new range of ActiveSmart™ fridges with SmartTouch Control Panel and Ultra Slim Water Dispenser.

Drawn to the dark side of human life, ENTANG WIHARSO’s art explores prevailing sociopolitical mores in his home country, Indonesia. To ENTANG, creating is a way of understanding the human condition – and human problems like love, hate, fanaticism, religion, and ideology.

New ZealaNd industrial designer Ross steveNs has never let scale deter him. Whether it’s designing screws, amplifiers or houses, he will put his hand to it. aN d R e a s teve N s speaks to a designer who artfully blends high tech and low tech.

it is hard to keep up with Ross Stevens. The industrial designer, university lecturer and house builder has dozens of projects on the go, from making his own windmillpowered spa pool to futurist proposals in 3D printing. He has become a master at repurposing industrial refuse to his own ends as well as fabricating tessellated forms from the latest ABS plastics to define a visual and emotional language. From low tech to high tech, from design to making, he is a true chameleon.

His latest project is a new wing on his house in the Wairarapa, about an hour and a half’s drive over the Rimutaka Range from Wellington. It is a remote place, and a world away from Glasgow and Paris where he and his German wife Petra met, and where his career took off. But not so surprising for a boy who grew up on Napier Hill. “I love New Zealand, I am one of those classic Kiwis that only fits here,” he says.

It has been a fascinating career path and one that has tested his resolve and ingenuity as he found himself hurled from ‘big budget’ projects in Europe (where the sky was the limit), back to ‘no budget’ projects in Wellington, where there was literally no budget. But it seems to be just this situation that he and so many New Zealander’s face that creates a country of inventors who punch well above their weight internationally. “I also think it’s because we are a bit naïve,” says Ross, “and we need to be protective of that, we don’t want to lose it.”

He found his calling in an engine reconditioner’s workshop of all places. Fed up with school by age 14, he spent more and more time “making stupid things” with lathes and spray guns. “The engineer who ran the workshop was semi-retired so he didn’t really mind having me there, I think he just enjoyed my enthusiasm,” Ross says. With a lot of technical knowledge and craft skills on board he got into the only industrial design school in the country at the time, Wellington Polytechnic. He was one of four graduates in 1986 and landed a job at Fisher & Paykel before a travel award jettisoned him off to Europe and eventually into Philippe Starck’s studio. The years in Paris were extraordinary, and Starck’s studio in the early nineties… well there was just no better place on earth as far as the then-26 year old New Zealander was concerned. By the time he left he had codesigned the Thomson Zeo television with Starck, and he continued working on concept designs for him when back in Wellington.

“It was woeful coming home,” he says. “ In my first local job they suggested I spray-paint MDF silver because they couldn’t afford anodised aluminium”. He started teaching industrial design at Victoria University in Wellington and found his professional feet again, designing high-end audio products and his own architecture projects. He built a container house for his family on the oddest site imaginable in Owhiro Bay. Now a Wellington

previous | Ross tRi ms the tops of the mac Ro caRpa sleepeR s W h ose laRg e scale visually buttResses the house against the pRe vailing Wi nds. above left | the family live in the Remote Wai R aRapa su RRo unded by RegeneR ating bush and faRm land. above right | Ross and his Wife petR a keep mountain goats. opposite | RaW timbeR Rusting steel and stone gR avel looks completely at home amongst the gR asslands and mountainous landscape.

It is what you would expect from an industrial designer making architecture.

| designer & residen T

icon, the three stacked containers sit against a rock cliff on a three metre-wide strip of land. He built it himself on weekends out of industrial leftovers to worldwide acclaim. “It is what you would expect from an industrial designer making architecture,” he reflects.

Ross sees this type of upcycling as one path to sustainable decadence and has taken the concept even further in this house in the Wairarapa. “If I start with something that people think has no value at all, and at the end of it they go ‘wow, I never understood it had that value’, then that’s really cool. So I am constantly looking for things that someone doesn’t have a use for, but that I have.”

The house site is a small plateau in the foothills of the Rimutaka Range overlooking a lake, the plains and the sea. Ross built his workshop out there about 16 years ago, but eventually he and his family moved out and he now commutes into Wellington for work. He has just completed the next wing of the house, adding bedrooms and a lounge, and eventually there will be a third and fourth wing to seal in a protective courtyard from the legendary Cook Strait winds.

Almost every material and product in the house has been upcycled, from the insulated sandwich panel structure, to the Rimu veneer door skins (used here for wall lining) to the wiring. “I can’t be picky because I just take what people don’t want, so it is a compromise each time,” explains Ross. “Sometimes it’s not quite what I would have wanted, but other times I get these incredible results I would never have thought of.” The rusting steel sheet with cut-out holes is a great example where the leftover materials of someone else’s process take on a new life within a different context.

Ross’ design responds to the big landscape and intense winds – rated for winds up to 200 kilometres an hour, it hunkers down and leans away from the prevailing gales. He has used over-sized macrocarpa sleepers to cover the insulated panel, ground it and camouflage it

previous | s o uth of the house and facing the pRe vailing Wind is a sculptu R al savonious Roto R Windmill, Which heats the spa. opposite above | in the main bed Ro om a photog R aph by pe tR a alsbach-stevens sits on the c Redenza Ross built. th e th omson zeo television is designed by ph ilippe staRc k. opposite beloW | compRessed sheet, timbeR dooR skins and Recycled Rimu battens cReate Rich colouRs and textuRes. above | the laRge ciRculaR light in the lounge is designed by Ross and his colleague beRnaRd guy in an expeRiment With 3 d pRinting.I start with something that people think has no value at all...

ross | designer & residen T

in the site, and designed the interior almost cave-like as a retreat from the immensity of the environment. “I was really interested in the way it sat on the land,” he says, “but also the way a building can house people with really complex histories and complex dreams for the future. It was hard because I didn’t know the answers going into it.”

The key space inside is the lounge, where the couple keep their treasures and heirlooms, called ‘the room of ancestors’, an idea inherited from the Māori wharenui/meeting house. Ross started with four inherited objects: two large pieces of German furniture that once belonged to Petra’s grandparents, and two paintings in gilt frames painted by Petra’s great-greatgrandfather. They provoked Ross to paint the walls black to bring out the depth of the old timber and contrast with the gilt. It is a remarkable room not least for the colour, but in the variety of detail and the panelled ceiling – tessellated champagne-coloured plastic pressed with the topography of the surrounding landscape. “I am really interested in the idea of sustainable decadence,” says Ross, “and digital decoration allows me to create that with very little material.”

The way he has reconfigured salvaged materials often bares little resemblance to their original use. Most things require a second take, and even then their origins are hard to pinpoint. Compressed sheet is fixed up back-tofront so you see a textured surface; ABS plastic is pressed into a triangulated pattern and used as room cladding; ceramic tiles from the dump are inlaid into a recycled Rimu credenza; and three-millimetre MDF is laser cut into stars and flowers in the children’s bedroom ceiling. There are no off-the-shelf results, because he has a myriad of craft options available to him, from handmade to digital.

For more images of Ross and his home visit habitusliving.com/issue22/rossstevens

But lighting is a technically difficult yet astonishing medium that requires a mastery of a varied and continually evolving discipline. Truly good lighting is a subconscious emotion that needs to be in context with its surrounding, implementing design far beyond concerns of visibility and horizontal foot-candles. Only then, can lighting be a truly integral part of a whole.

And at Classiclite, great lighting is not just a job, it is a passion. Founded in 2003 by Sam Carpinteri, Classiclite’s designs fuse the architectural with the formal, the aesthetic with the functional, to create forms that provide the perfect mix of light and design. This is in fact a knowledge that has been 35 years in making: with years of experience in the technical industry, Sam has brought a new dimension to lighting and lighting application. Initially starting as an outdoor and cabinet based lighting product retailer, Classiclite is now the Australian distributor for the exclusive European brands Penta and Ole. And as an independent lighting design company, Classiclite is able to apply their knowledge, respect and passion to each and every project.

This is a passion that has extended throughout the Classiclite family, with Sam’s daughter, Jessica, joining the company in 2007. Bringing with her a modern and creative flair, together they now work at maintaining a strong personal customer focus, but, lighting quality has, and always will be their main priority. In every design, Classiclite always tries to improve the visual perception and understanding of the environment, to use light as an expressive and poetical tool. Lighting is a subtle design tool, that when, done well, will bring to life even the most mundane of design schemes. And, as Classiclite says, “light is a matter of balance – between atmosphere and functionality.” At ClassicLite, they work together with architects, interior designers, developers and home

owners to help deliver an exceptional result on each project, every time.

You can feel this growing experience of Classiclite in its rich collection of lights that merge material with different characteristics. The result is living light - lights that create a new space to live, lights that model themselves according to their different needs. With products ranging from the technical to one-off Murano glass pendants, Classiclite has every one of these needs covered.

Light is integral to life. It can stir emotion, set a mood, create atmosphere, and offer direction and guidance.

He is one of Australia’s finest and most innovative chefs. And after visiting his Sydney home, PAUL McGILLI c K suspects that this apartment, elegantly re-worked by JULIUS BOKOR , is a perfect reflection of the man and his cuisine.

every home has a story. But the innercity apartment home of leading chef Mark Best, seems to resonate with a host of stories.

A food critic reviewing Mark’s new restaurant – Pei Modern – in Melbourne in 2012, noted his commitment to “flavours with an edge and a difference.” It could well be a description of the man himself. And it explains a lot about Mark’s distinctive apartment.

There is nothing formulaic about this apartment. But, then, there is nothing formulaic about Mark Best. First, his back story: he began his working life as an electrician on the goldfields of Western Australia, only beginning a four-year apprenticeship as a chef in 1990 at the Macleay Street Bistro in Sydney’s Kings Cross at the age of 25. In his fourth year as an apprentice he won the Josephine Pignolet Award for Best Up and Coming Chef in NSW. After stints in France and the UK, he and his wife Valerie returned to Australia to open Marque restaurant in Sydney’s Surry Hills in 1999, which has continued to accumulate awards since then at a steady rate.

Another story is the building. The Goldsborough Mort building on the edge of the Sydney CBD overlooking Darling Harbour was built in 1883 as a woolstore. Then, as Sydney Harbour transitioned from being a working harbour, the building was converted into apartments in 1995. Like so many adaptive reuse projects, the romance of the building did not fully translate into optimum living spaces,

although it did boast a much-admired roof garden (by landscape architects 360° headed up by Daniel Baffsky, see Habitus #01).

Architect Julius Bokor thinks that the roof garden may have been initially what attracted his client and friend to the building. Ask Mark and he says, “We liked the infrastructure of the building,” and that he liked the original design of the apartment which he and Valerie bought around seven years ago.

The reality, though, was that the apartment was dark and claustrophobic. “You couldn’t see out of the bedroom … bad vibes,” says Bokor. The trigger for the make-over came when Mark and his wife Valerie acquired the onebedroom flat next door. “Although we couldn’t really afford it,” says Mark, “we didn’t want just anyone moving in next door. So, we picked it up and rented it out. Originally, we were just going to knock the wall down – which we did initially – but then the different coloured floors, the doubling up of kitchens, and so on [didn’t work], so eventually we bit the bullet.”

The result – rather like Mark’s cuisine – is an intriguing mix of innovation and conservation where the end product was driven by the process rather than any prescribed solution. In what he calls a “meeting of minds” it was agreed to simply strip the place back to its industrial origins and see what was there –given that the original conversion had imposed layers (like gyprock walls, ceiling and cladding) which obscured the character of the building.

So, a two-bedroom apartment has been joined to a one-bedroom apartment with the entry to the one-bedroom apartment now the laundry/powder room and the remnant concrete walls acting as room dividers, making it, says Bokor, “a more complex space.”

The stripping back included a polished concrete floor on the upper level where the floor inserted during the 1995 conversion was stripped back to “what was there,” making a virtue of the flaws to add texture and depth. The original fenestration has been restored along with the original air vents under the windows along the western wall, which had been gyprocked over. Similarly, the brickwork along the inside western wall had been painted over. This, too, has been stripped back allowing the texture of the bricks to add to the material character of the space.

The result...is an intriguing mix of innovation and conservation.

brown box which, when you open it up, is all white.

The agenda had been to optimise space and maximise light. There is now a sense of continuous space, but punctuated by partial walls to create the nooks and crannies apartments so rarely have. The mezzanine level helps spread western light through the apartment, but is now helped by a raised ceiling and continuous strip lighting which creates the illusion of more light coming in from the outside.

Stairs (the treads are concrete made in an oven) at the entry go up in opposite directions – to the right to the son’s room, to the left to the master bedroom and a sitting/television room, all connected by a gallery. Julius describes the upstairs as having a Japanese aesthetic – “a brown box which, when you open it up, is all white.” The Japanese aesthetic is enhanced by the Smoked Oak veneer and the way everything slides away to optimise space and to keep things simple and elegant.

Space and light optimisation is also served by a variety of strategies, such as the mirror at the end of the entry vestibule to the bathroom. No room is ever fully enclosed, thus allowing the western light to penetrate as thoroughly through the floorplate as possible.

In fact, the amount of space is remarkable. The joinery in the superbly comprehensive kitchen, for example, not only has the function of concealing (pantry, fridge etc.), but also offering ample storage. Similarly, the surprisingly large walk-in robe, described by Mark as a “girl’s dream wardrobe.”

All of this generates yet another story – the spatial narrative of the apartment. As we know, it is hard to make an apartment uniquely one’s own, just as it is hard to find an apartment which offers the richness of spatial experience human beings seem hardwired to need. But this one, while it certainly maximises the amount of space and light, manages never to fully reveal itself. Instead, it offers a surprising number of journeys, each one tantalisingly flagged by visual fragments of the space beyond, and signalling yet another way of inhabiting this particular home.

Speaking of the make-over, Mark says “that it has completely transformed the feeling of well-being, which is the most important thing for me.” This is a home which clearly works for this family of three. At the same time, though, one suspects that in some impossibly subtle way it totally embodies Mark Best, the man and his food.

b okor architecture + interiors | bokor.com.au

Marque | marquerestaurant.com.au

Meet Mark at habitusliving.com/issue22/markbest

formfunctionstyle.com.au

A garden is one of the most important areas of any home. It’s an extension of who you are, your lifestyle, family and friends. More importantly it’s a space where you can go to simply relax. My name is Chris Slaughter and it’s my passion to create your ideal escape.

To give you an idea of the gardens I have created for other clients please visit scenicbluedesign.com.au and click ‘Escape’ to view my portfolio.

If you would like to make an enquiry call me direct on 0405 663 222 or visit scenicbluedesign.com.au for more inspiration.

Kind regards

Sensational and varied landscape is what TASMANIA is famous for. Designer, SARAH FOLETTA, celebrates this with a house which, says PAUL MCGILLICK, seems part of a rural idyll.

text Paul McGillick | Photo Gr a Ph y Sharrin r ee S

text Paul McGillick | Photo Gr a Ph y Sharrin r ee S