SMEG THERMOSEAL ATMOSPHERIC CONTROL & DYNAMIC AIRFLOW FOR PERFECT RESULTS

smeg.com.au

SMEG THERMOSEAL ATMOSPHERIC CONTROL & DYNAMIC AIRFLOW FOR PERFECT RESULTS

smeg.com.au

Mezzanine level

171 Robertson Street

Fortitude Valley, QLD 4006

P | +617 3216 1551

1f Danks St Waterloo, NSW 2017

P | +612 9699 1131

575 Church Street Richmond, VIC 3121

P | +613 9427 7000

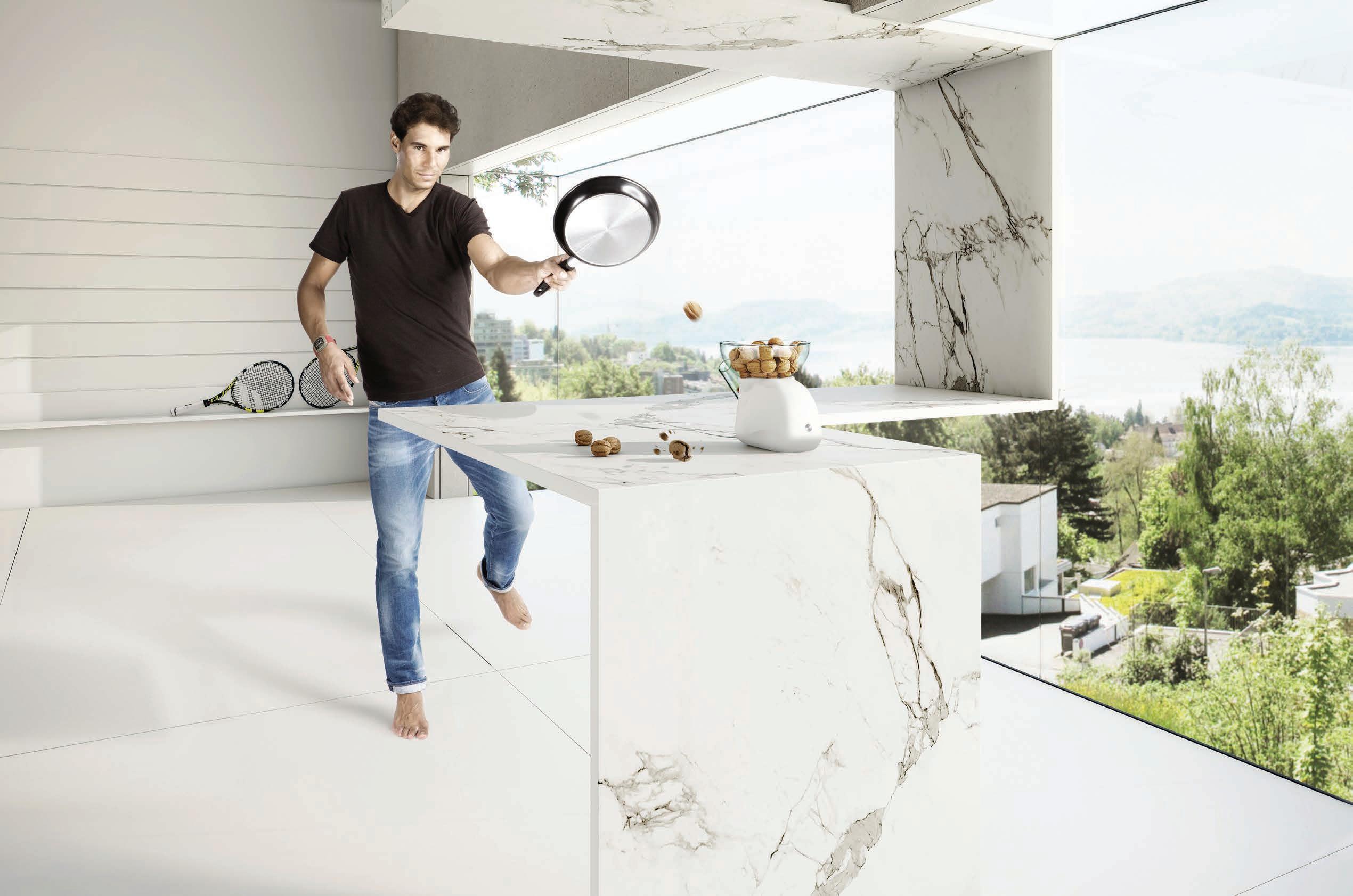

Chamoisee Prime The gentle warmth of a honey-brown hue enhances the natural oak finish of our Chamoisee timber.

Tongue n Groove™ floorboards are designed with three solid layers of fine European Oak for a premium level of finish, longevity and structural integrity.

tonguengrooveflooring.com.au

New concepts, creations, movements and forms of expression in the world of design.

26 DESIGN NEWS

Design can be practical, and design can be elaborate. Often it tends to be one or the other but there’s no reason it can’t be both. In our customary Design News pages, we’ve collated a selection of pieces that prove it.

36

Using three recent books as case studies, Sandra Tan explores concepts of nostalgia in architecture and design, our relationship with the past, and why we choose to dwell.

A warm invitation into the private homes of our contemporaries, join us as we learn how others lead their lives.

42

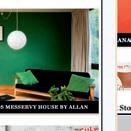

At home in Kew, Melbourne, architect John Wardle invites us into the house he has shared with his wife, Susan, for more than 25 years. Originally designed in 1951 by Horace Tribe, it has undergone two renovations since the Wardles took up residence.

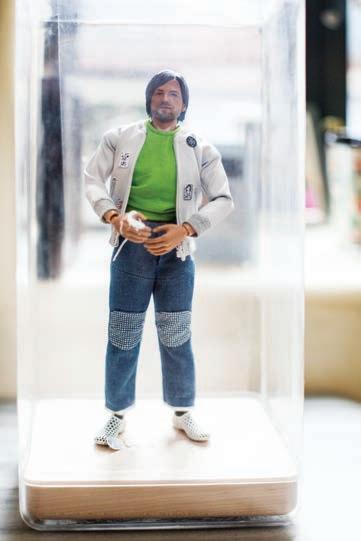

57 PENG LOH

An unlikely insight into Singaporean raised and based – yet widely traveled – hotelier Peng Loh, and the nostalgic memories that inform his work and design decisions.

67

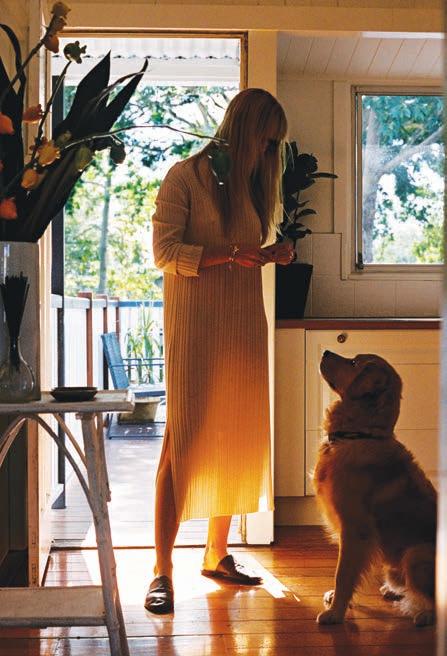

A relatively recent move, jewellery designer and maker Holly Ryan’s new home along the banks of Brisbane is a dedicated mix of old and new. Much of her furniture pieces are orginal Mid-Century designs complimented by smaller ceramics and scultpural pieces she’s accquired over the years.

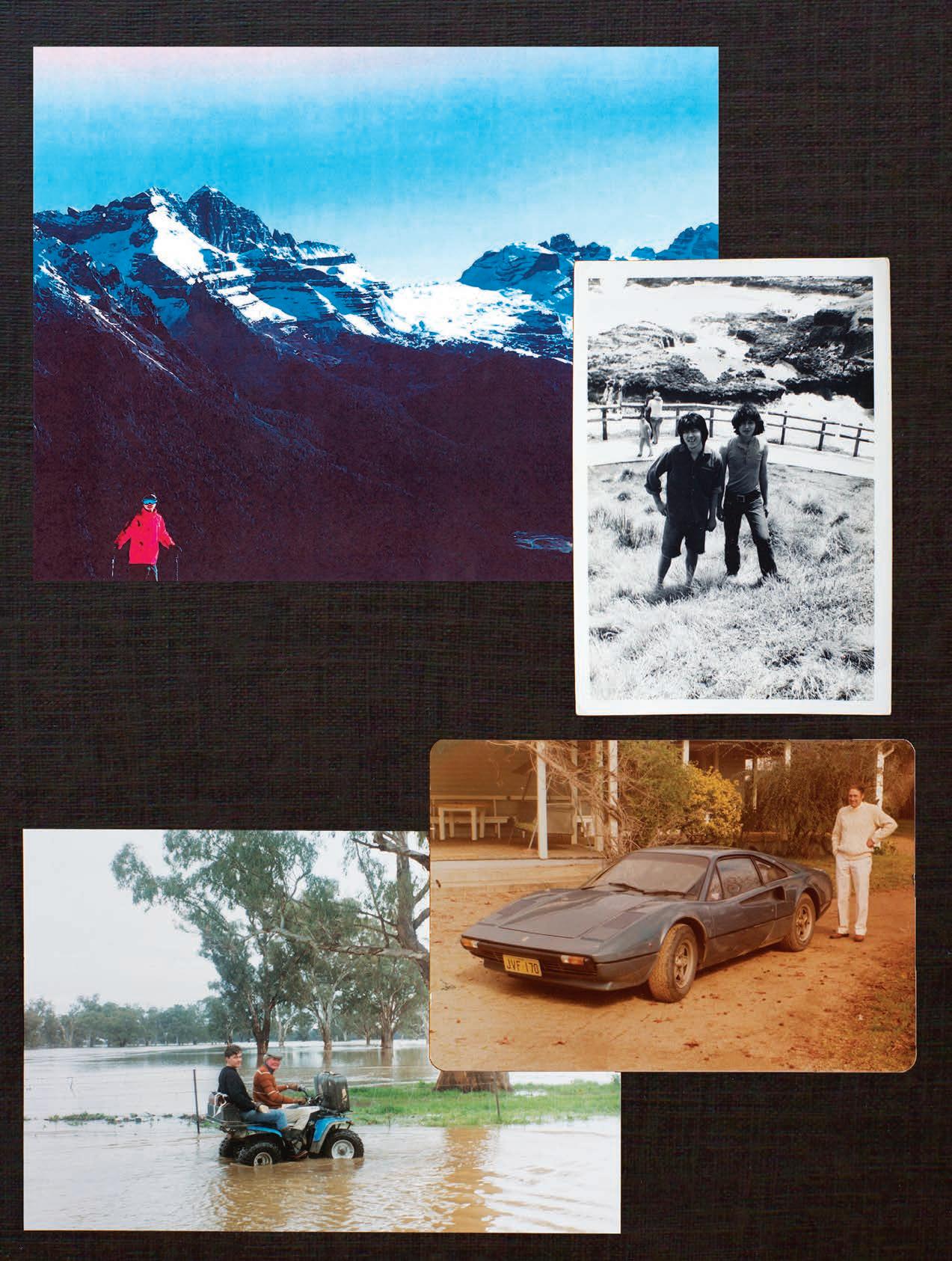

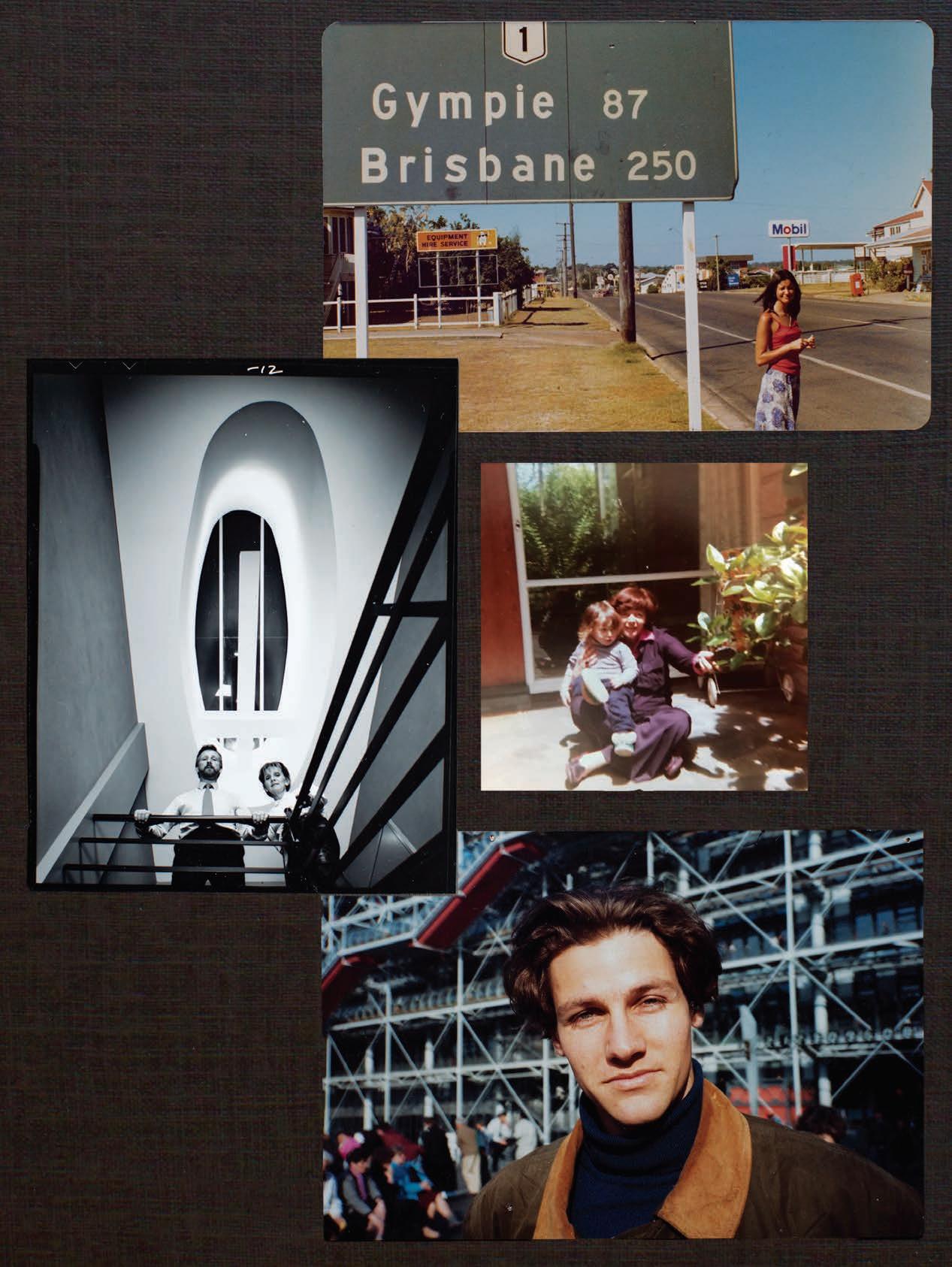

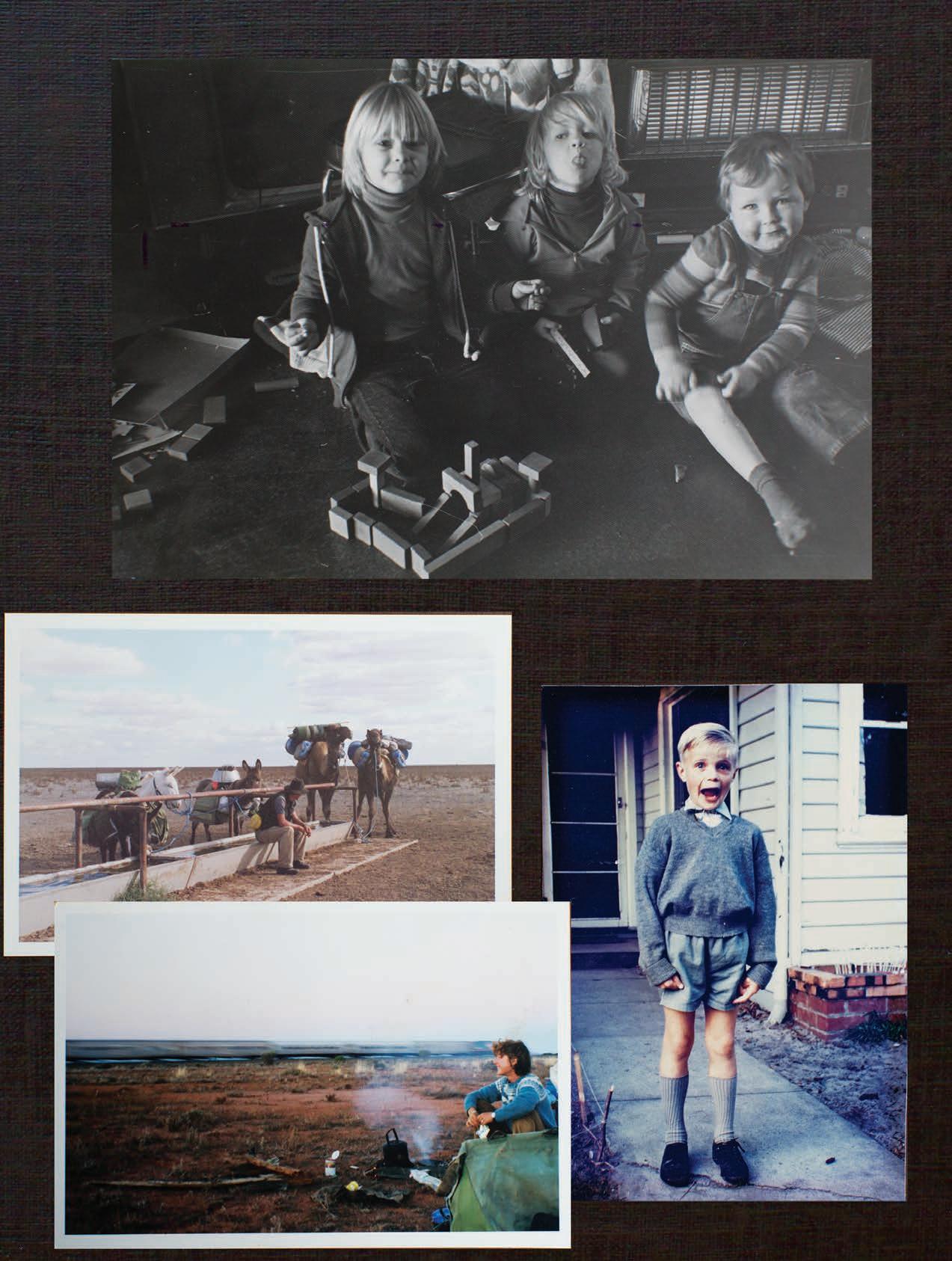

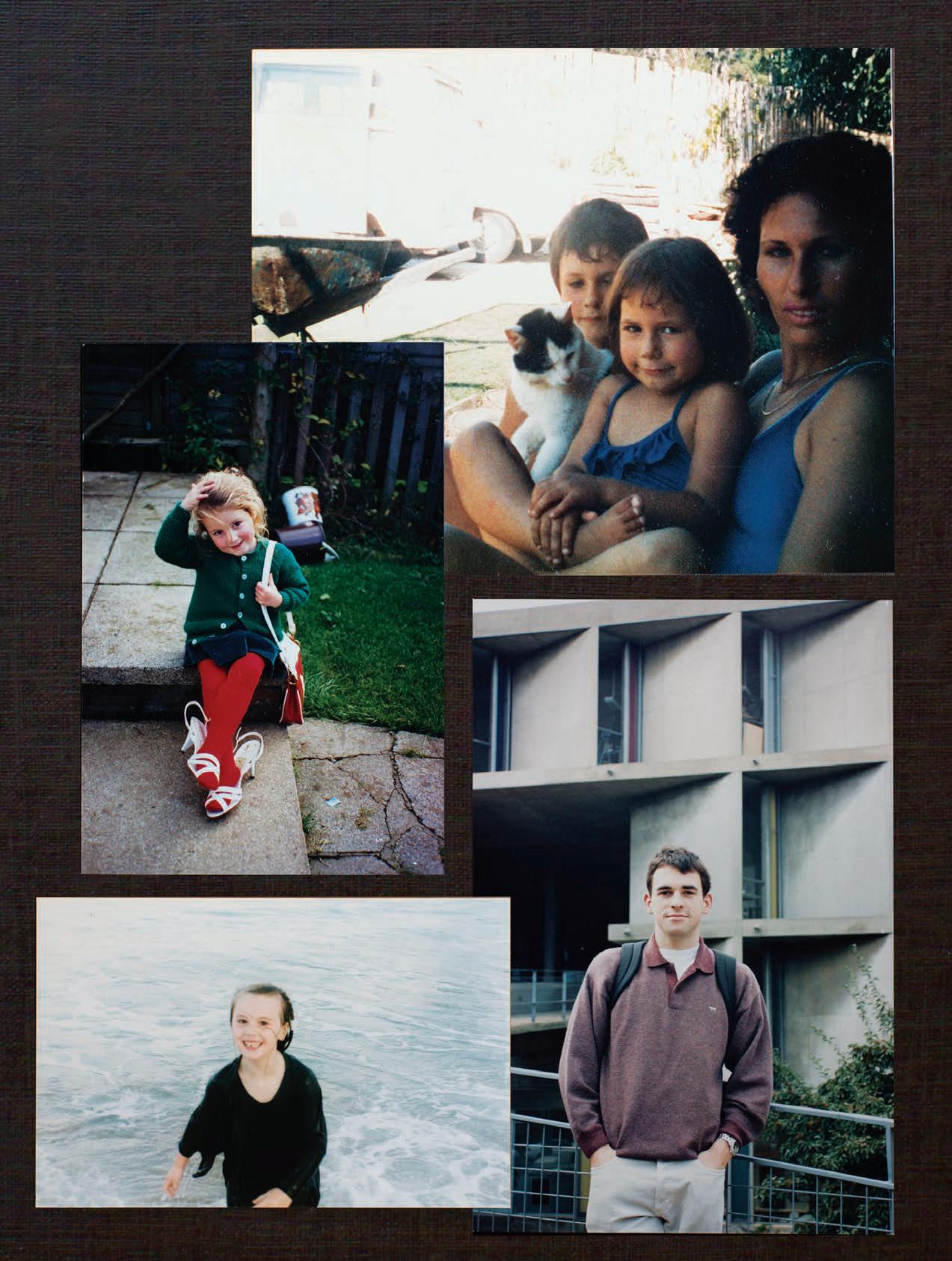

82 HABITUS FAMILY ALBUM

In the first edition of the Habitus Family Album, Stephen Todd has collected photographic evidence of pivotal moments in the lives of some of our favourite creatives from the region.

91 PASSE COMPOSÉ E

Drawing inspiration from Patricia Urquiola, Felix Burrichter and their work for Cassina, we explore the concept of the past informing the future of design.

96 MARC NEWSON

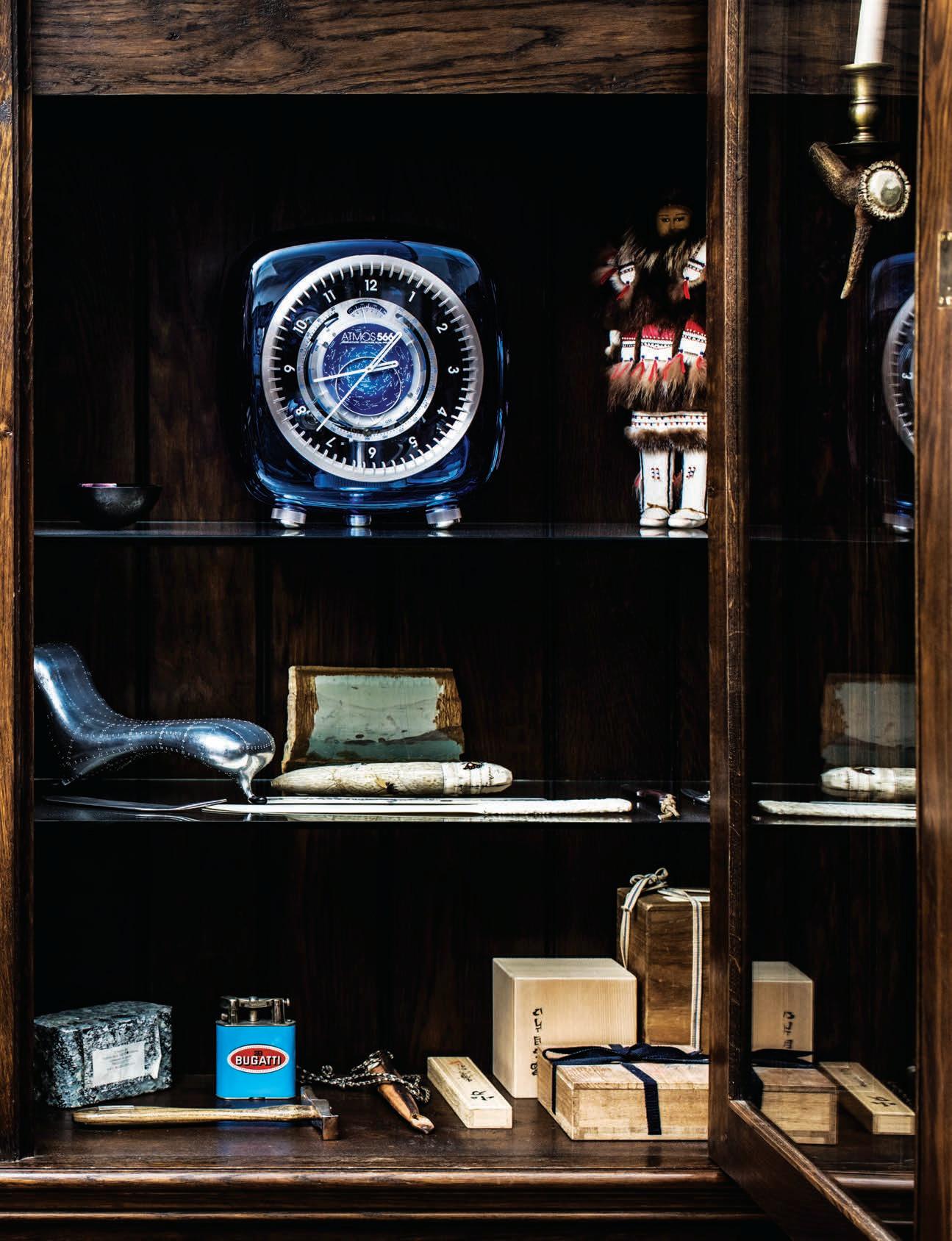

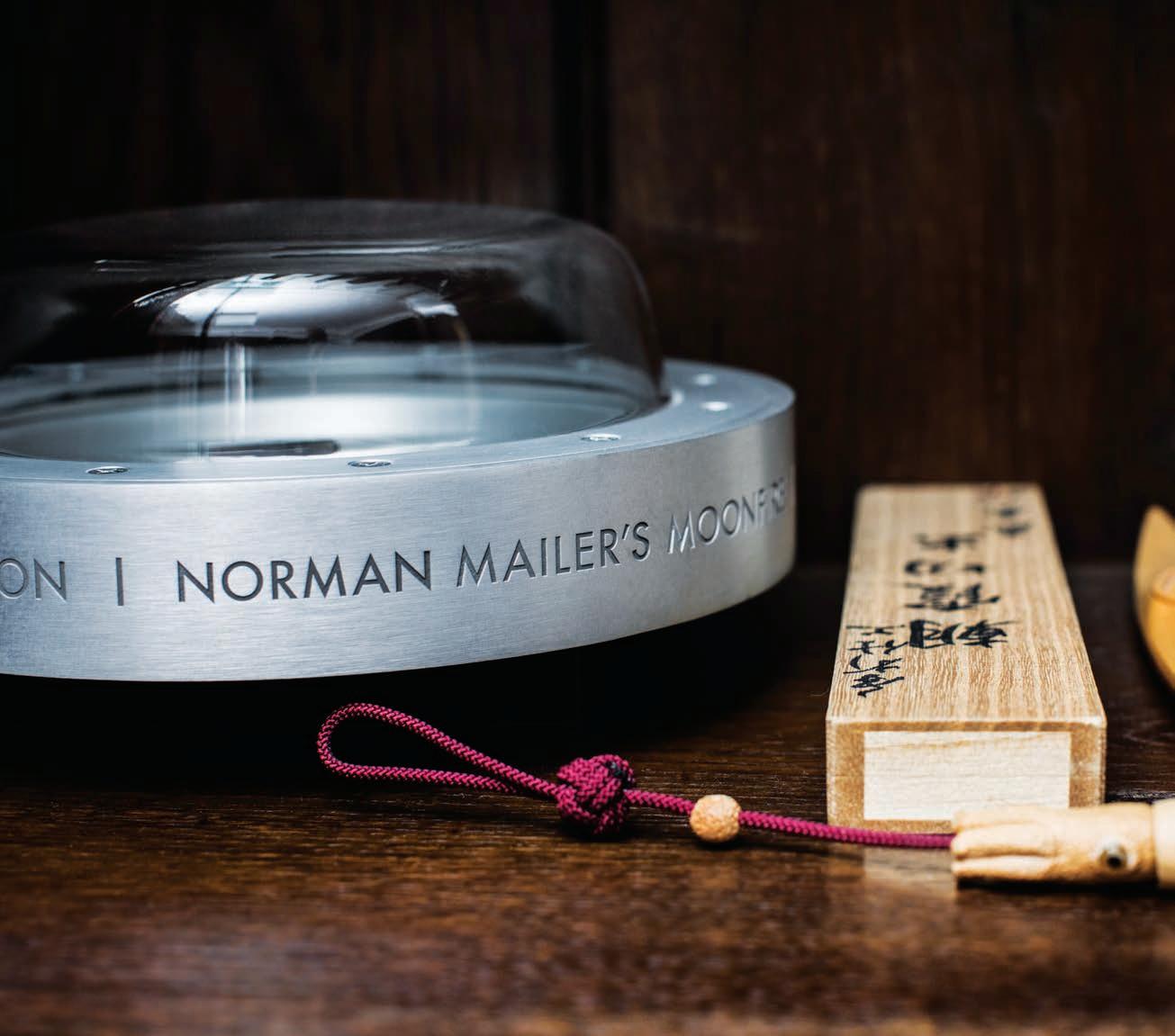

As one of the world’s most celebrated designers, it’s fitting that Marc Newson sees design as a global industry. In an exceedingly rare glimpse into his private life, Stephen Todd is invited into the home he shares with wife Charlotte Stockdale and their two daughters.

A place in which families are born, memories are made, and the future is found; explore with us these homes from accross the region.

114 COOGEE CASTLE

Perched atop the dramatic cli s of Australia’s Eastern Seaboard, a young family of five relax into a fresh interior scheme designed to aid them in the next phase of family life.

138 MT MARTHA HOUSE

This beach front home in coastal Victoria spills down to the shore, both physically and visually. Yet it’s exactly the opposite of what you’d expect to see.

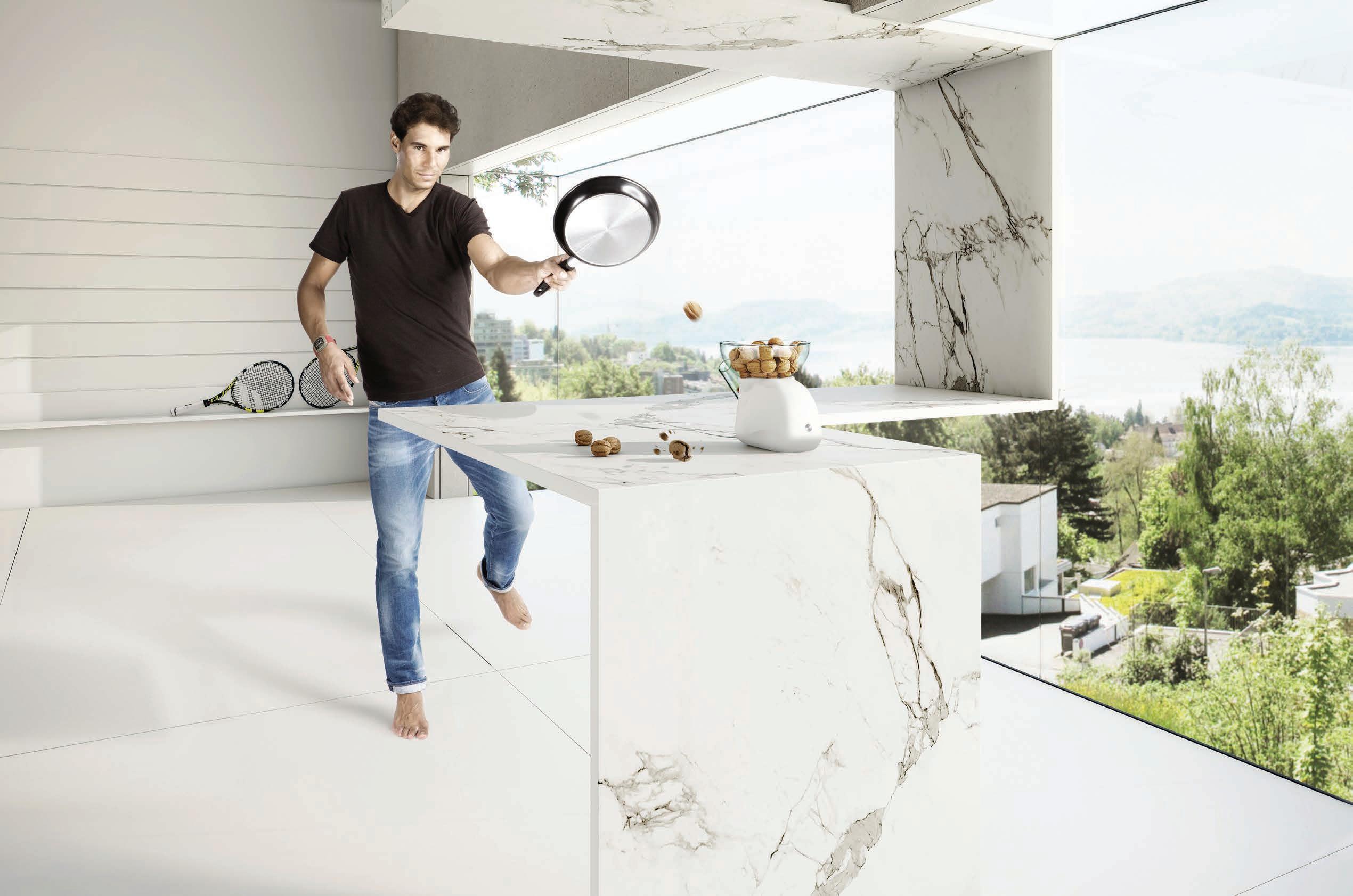

148 LIVING SCREEN HOUSE

Memories were designed to be made in this North Bondi abode. The longtime residents of the area wanted a new home in which their young-adult o spring could live comfortably now and always return to.

162 MANILA HOUSE

In a city where space is a rare and coveted commodity, this modern take on a traditional Filipino home feels spacious and open.

178 GRACE HOUSE

A home in Kew, Melbourne, initially designed in the 1980s by a well known and celebrated architect – to much industry acclaim – is sensitivley re-worked for its new owners.

Tama Living is the ideal setting for that special moment, a soothing and pleasant experience. Its lavish, elegant cushions set the rhythm for the sofa to unravel like a piece of classical music. With side tables and trays crafted from exquisite materials, it embodies the spirit of refined living. Design: EOOS.

What began with a spark...

We have been perfecting one oven for 30 years. Our latest rendition accentuates its distinctive design: the door is now created from one imposing 90 cm wide sheet of 3 mm high-grade stainless steel. It represents one vast entrance to culinary potential.

This remodelled, hand-crafted work of art is the culmination of our finest principles, skills and ethos. We’ve christened it the EB 333 in recognition of our 333 years of working in metal. This has always been more than an oven; it is a promise to create masterpieces.

For more information, please visit www.gaggenau.com/au

Th e Vi ct or ia + Al be rt Pemb ro ke ba th is aptl y nam ed af te r th e bi rt hp la ce of Eng la nd ’s fi rs t tu do r ki ng as it ev ok es a re ga l el eg anc e. Th is tr ad it io na l dou ble -e nd ed ba th is ac ce nt ed by cr is p co rn er s an d a de co ra ti ve ri m. De sign ed by Me ne gh el lo Pa olel li As so ci at i.

Why do we have such a far reaching fondness for the past? Where did it come from and why does it compel us so strongly – everything looks better in hindsight, right? As time passes and memories sweeten, a soft spot for bygone eras draws dangerously close to putting them on the proverbial, unattainable, pedestal. Which begs the question: Is it impossible to move forward if we keep looking back?

In this issue we wanted to explore the idea of retrospection further, as the design industry is one with a particular penchant for all things ‘nostalgic’.

The celebrated names and faces of architect John Wardle and designer Marc Newson grace this issue and we count ourselves lucky to have borrowed their time. Both men have reputations that precede them and we ask how has this impacted their approach to future projects. Does it help or hinder?

In his essay Passé Composée, Stephen Todd relays Patricia Urquiola’s suggestion that it is impossible to ignore the past, that we must use it to inform the future.

Later on, Andrea Stevens writes about childhood memories revisited – and reworked. New Zealand’s Opahi Bay was once the small town frequently visited by a young couple and their three daughters. Now, a generation on, it’s the slightly larger small town in which the same three daughters have subdivided the land on which their holiday home once stood. One lives there permanently with her young family in a new home that evokes the past yet allows space for the future. Without holding on too tightly, I think it’s possible honour the past, perhaps even draw inspiration from it, and use it to better the future. I hope that’s what we’ve shown you. I hope that’s what you get from these pages.

HOLLY CUNNEEN | DEPUTY EDI TORMARNIE HAWSON

THE LUXURY OF TIME #42

For photographer Marnie Hawson, it is the rich history and context of her 130+ year old former post o ce turned home and work studio that gives her a daily sense of nostalgia. “There is perfection in the imperfect, and history everywhere – wobbly floors, gaps in the weatherboards and a once missing front path.”

R ACH AEL BERNSTONE

THE LUXURY OF TIME #42

Nostalgia is in the history of the object and maker, we can access this through the choices we make in organising our spaces. For Rachael Bernstone, her emerald green velvet Featherston Contour chair from Gordon Mather o ers her a piece of – and part in – Australia’s design history. “I love that it was designed in my home town and it’s a beautiful, sculptural object as well as a delight to sit in.”

R EBECCA GROSS

MAKING MEMORIES #148

Rebecca Gross learns history and understands culture through the lens of architecture and design. As one who as always loved the challenge of change, she finds nostalgia in the buildings and objects that remind her of her childhood and that have a strong sense of place. “Mostly its vernacular architecture: the corner dairy in New Zealand and the seaside towns in Maine.”

CALEB MING

THE GRAND HOTEL(IER) #57

For design to be engaging, for it to mean something, it has to connect to fragments of your own memory. For photographer Caleb Ming, colours o er a link back to another time and place; “A certain aged colour, even a vibrant colour, makes me think of the times from before.” A house can mean many things to many people, and through the inclusion of colours, one can open a space up to endless connections that even the designer cannot control.

JODY D’A RCY

A CASTLE ON CROWN LAND #114

Good design is timeless, that’s why trends move on rotation and what’s old will inevitably turn new again. “Architecture and design are embedded in Nostalgia,” says Jody D’Arcy. For her, good design is something that just feels and forms organically, and intertwines in our emotions; “whether it’s a comfortable chair or an interesting object, having an appreciation for its creation and function literally evokes joy and happiness.”

THE ODYSSEY #96

Living in a space gives one access to a history that they might have not even been a part of. For Richard Boll, living in a 1935 building on the seafront in Brighton, England, once home to actor Rex Harrison and writer Graham Greene, o ers him a sense of being a part of a larger narrative; “there’s a certain pride that goes with living in an architectural museum piece, albeit one that’s not always been universally appreciated.”

SIMON DEVITT

BUILDING A HAPPY HOME #126

Houses and artefacts that reveal a sense of their age and history are particularly interesting to Simon Devitt, where scars of experience are transformed into reminders of good times and patterns of beauty. “I really love visiting architecture that’s proven itself over time, a 40-year-old home still lived in by its original owners, for example. The evidence to suggest life has been lived, time has played out. Children have grown up in those homes and visit with their children.”

habitus takes the conversation to our contributors discovering their inspiration and design hunter®

Each home of Stephen Crafti is filtered in a distinct experience that is deeply tied to place and context. And it is from a wealth of experience with past home spaces that we can better curate our ideal means of living. “I prefer to grow roots in one place. Hopefully my latest home will be my last. The renovation includes a bedroom and a bathroom on the ground floor so that even in old age, I can stay.”

For Stephen Todd, it is the iconic imagery of di erent landscapes that render in him the memories of his own past. It is the symbolic connotations of places rather than the places themselves that hold the most value. “I have no particular attachment to place. I am as capable of picking up stick and moving to Paris for 20 years as I am likely to decide to move to a farm in Central West NSW – which is where I live now.”

Nostalgia is a pivotal starting place from which we build ideas and designs, inspired by the new and foreign. For German-born Sylvia, Sydney has become her new home but also an international hub of design, not neglecting her a ections for European and Asian architects and creatives. “It is great to have two homes, two languages and two cultures for reference and ideas, both inspiring… And I always appreciate that we are lucky enough to be so closely tied to Asia and all its influences.”

WWW.WOUD.DK

Retailers Victoria FLOC, Collingwood Luke, Prahran Simple Form, Seddon The Plant Society, Collingwood

New South Wales

Luumo, Waverley

Western Australia

Arrival Hall, East Perth designFARM, Hay Street

Tasmania LUC, Hobart New Zealand

Capricho, Takapuna Concrete Blush, Christchurch

CHAIRMAN / PUBLISHER

Raj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

DEPUTY EDITOR

Holly Cunneen holly@indesign.com.au

GUEST FEATURE EDITOR

Stephen Todd stephen@indesign.com.au

SE ASIA EDITOR

Janice Seow janice@indesign.com.sg

EDITORIAL A SSISTANT

Andrew McDonald andrew@indesign.com.au

EDITORIAL INTERN

Ella McDougall

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Sylvia Weimer spacelabdesign.com

JUNIOR DESIGNER

Camille Malloch camille@indesign.com.au

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Rachael Bernstone, David Congram, Stephen Crafti, Rebecca Gross, Mark Scruby, Andrea Stevens, Sandra Tan

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRA PHERS

Kurt Arnold, Richard Boll, Emma Cross, Jody D’Arcy, Simon Devitt, Murray Fredericks, Marnie Hawson, Benjamin Hosking, Haidee Lorenz, Caleb Ming

COLLAGE A RTISTS

Dina Broadhurst, Fausto Fantinuoli

ILLUSTRATOR

Sandra Tan

M ANAGING DIRECTOR

Kavita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

GROU P OPERATIONS M ANAGER

Sheree Bryant sheree@indesign.com.au

A SSISTANT PRODUCTION MANAGER

Natasha Jara natasha@indesign.com.au

ACCOUNTS

Ting Zhang ting@indesign.com.au

Cassie Zeng cassie@indesign.com.au

ONLINE MANAGER

Radu Enache radu@indesign.com.au

W EB DEVELOPER

Ryan Sumners ryan@indesign.com.au

BRAND DIRECTORS

Colleen Black colleen@indesign.com.au (61) 422 169 218

Dana Ciaccia dana@indesign.com.au (61) 401 334 133

SALES SU PPORT & R EPORTING

M ANAGER Genevieve Muratore genevieve@indesign.com.au

COVER IMAGE

John Wardle (p.42)

Photography by Marnie Hawson

The new Silent Gliss 5600 system provides benchmarking technology based on outstanding Swiss innovation which meets the complex demands of modern architecture.

The world’s most silent curtain track system. silentgliss.com.au

HEAD OFFICE

Level 1, 50 Marshall Street, Surry Hills NSW 2010 (61 2) 9368 0150 | (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax)

MELBOURNE 1/200 Smith St, Collingwood, VIC, 3066

SINGAPORE

4 Leng Kee Road, #06–08 SIS Building, Singapore 159088 (65) 6475 5228 | (65) 6475 5238 (fax)

HONG KONG

Unit 12, 21st Floor, Wayson Commercial Building, 28 Connaught Road West, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong indesign.com.au

States of America. This issue of Habitus magazine may contain o ers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. If you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services we have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as fulfilment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however, these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information and use it to inform you of other promotions and publications from time to time. If you would like to know what information Indesign Media Asia Pacific holds about you please contact Nilesh Nandan (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax), info@indesign.com.au. Habitus magazine is published under licence by Indesign Media Asia Pacific. ISSN 1836-0556

Dr TerryWu, Plastic Surgeon and BoardMember of ACMI and Heide Museum of Modern Art

My lifeisamelting potofinspirations. Artinall itsforms influences my lifeand the life of my family.The work Idoasaplastic surgeon and forthe arts hold equal importance and provide balance. Ifeeladeepresponsibility to nurtureand supportcultural endeavours, both forthe community and forour children’s future. spacefurniture.com

Habitus and our republic of loyal Design Hunters celebrate authentic design as a way of life.

From our base in Australia we seek out the uniqueness of the Asia Pacific – be it interiors, architecture or products –and curate the stories behind the stories.

Join us on our hunt.

When Antoni Palleja was designing the WALLACE sofa for Carmenes, the brief was to create a sofa that was first and foremost extremely comfortable, without losing any innate elegance. Somewhat reminiscent of 80s design, the solid form is loud and proud with exaggerated arms that can be toned up or down for di erent settings. Available from Ajar ajar.com.au

Looking for a moment of pause? The VENA chair from Curious Grace could be the perfect solution. With a high backrest and sides, the design translates an intimate podlike shape into an elegant piece of furniture. Formed on a solid timber frame and available in a range of custom fabrics and colours.

curiousgrace.com.au

The playful TRAMPOLÍN bench brings a little vibrancy to any waiting space. Designed by studio Cuatro Cuatros for Spanish retailer Missana , this three-seater exudes a jovial spirit in its twisted, Bauhaus-inspired form. The lightweight frame and removable seat and backrest help to create a seating alternative that can easily slip into any narrow hallway.

missana.es

Inspired by the majesty of Egypt and named after the Egyptian city Thebes, the THEBAN daybed from German brand E15, illustrates a perfect melding of strength and subtlety. Building on the founder’s strong understanding of architecture, this piece is a noble accompaniment to any poolside setting.

livingedge.com.au

Finely crafted with a focal point on the arc form, the HALO range was designed by Laelie Berzon and Lisa Vincitorio of Something Beginning With . The designs carry a visual lightness complemented by their solid American oak and circular steel tube structures.

somethingbeginningwith.com

Building on the wonderfully spirited collection of chairs CATIFA , designed by Lievore Altherr for Arper, Stylecraft is exhibiting six new colours to mix and match into their range. Now available in rose, petrol, yellow, ivory, dove grey and green, the new colours have been perfectly matched to compliment the existing collection with an expanding palette for the artistically minded.

stylecraft.com.au

Fusing elements of a writing bureau, sideboard and cupboard, the S3 storage unit from Danish brand Andersen is the ideal amalgamation of beauty and utility. Designed by byKATO and available from Danish Red , the directional geometric handles transform this unit into a salient expression of sleek European design.

danishred.com.au

Revolutionising the art of music, while literally merging the two, the BEOSOUND SHAPE wireless speakers from Bang & Olufsen reinterprets a speaker system into a sculptural element of beauty. bang-olufsen.com

The CALA chair from designers Doshi Levien for Kettal , carves a graceful curve that perfectly compliments the organic form of the outdoor world. Latticed rope establishes a light airiness and spatial presence – helping the piece simultaneously stand out from and merge into its environment.

ketall.com

Australia’s design aesthetic, born somewhat from a place of isolation, is inspired from an extreme landscape and a resourceful approach to creation. To celebrate this unique spirit, CULT has launched a locally focused brand NAU. Featuring a cast of Australia’s most brilliant designers from Adam Goodrum, Jack Flanagan, Adam Cornish and Gavin Harris, the collection pieces together a beautiful assembly of furniture, lighting and accessories. cult.com.au

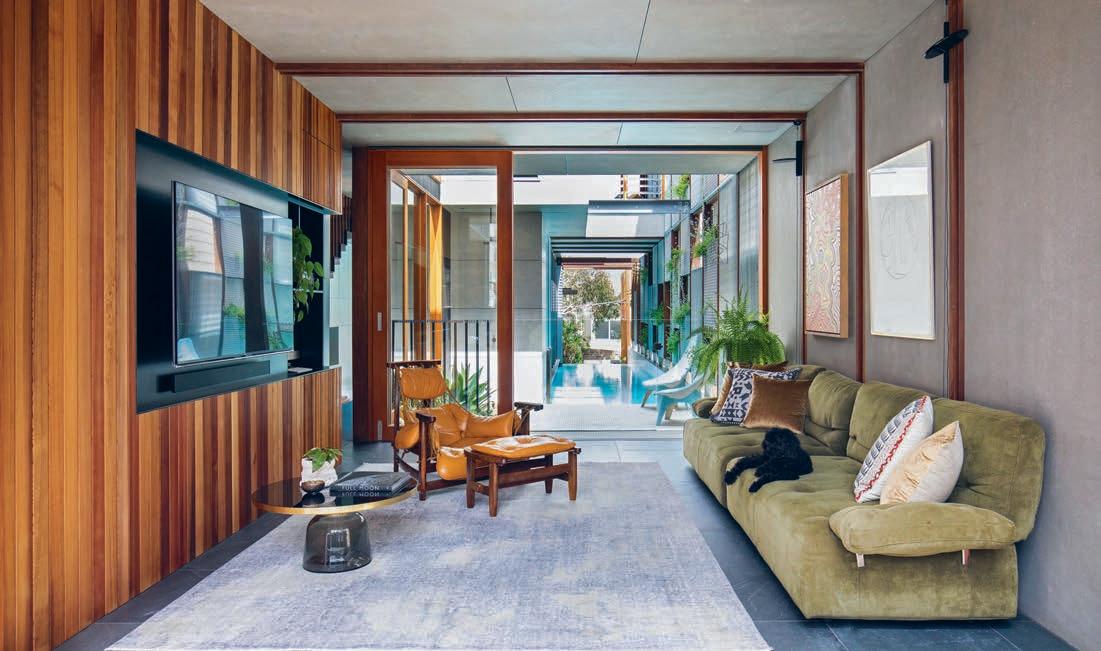

The TWIN RANGE from Italian brand Flaminia , available from Parisi , cements the exceeding reputation of Italian craftsmanship. With fluid curves that compliment the movement of water, the selection of basins o er a welcome softening to the strict lines of the bathroom.

parisi.com.au

As a people who seek change and evolution, we are often moving from dwelling to dwelling. And in this, experience a hugely varying setting of indoor and outdoor spaces. The BRIXX collection designed by Lorenza Bozzoli for Dedon is a mix of modular seating pieces that can be accessed from all sides to create islands and bring people together in seemingly limitless combinations.

dedon.de

The HALVES side table is the collaborative e ort between Danish Muuto and Canadian MSDS design studios. A youthful design of asymmetrical shelving allows for the piece to o er varying storage capabilities depending on its angle.

muuto.com

Th e MONO dining chair for Danish brand WOUD, warps both timber and expectations to create an altogether pioneering piece of furniture. The elegantly overlapping seat, created entirely from a single piece of timber, is created through the use of UPM Grada form-pressing technology. Available from FLOC flocstore.com.au

VOLA commitment to sculptural modularity is epitomised by the T39 Towel Rail. The system features minimalist cantilevered bars which can be configured in any quantity and spaced to suit any bathroom design. T39 is the perfect accompaniment to VOLA award-winning range.

Melbourne-based jeweller Abby Seymour has released her first homewares series o ering pieces to embellish the home alike the body. Featuring four wall hangings and a line of faceted jewellery dishes, the collection exhibits her masterful hand working with brass and ceramics, while translating her signature geometric styling into the home.

abbyseymour.com

The SOCKET occasional lamp from Menu is a multifaceted object of beauty to counter a desk of clutter. Inspired by the designers from Danish studio Norm Architects’ exploration into geometric jewelry, this lamp acts as both practical lighting solution and sculptural artifact. Cast in glistening brass with an easily removed socket, it can also double as a stylish paperweight.

menudesignshop.com

Available in three sizes (small, medium and large) each one of the BATEA co ee tables designed by Daniel Garcia for Woodendot , feature expanding potential – read sleek hideaways for the chaos and clutter of everyday life.

woodendot.com

Gorgeous folds of fabric physically articulate the comfort of the ELYSIA lounge chair, designed by Luca Nichetto for De L a E spada . This chair proudly exposes the inner skeleton of the frame – traditionally hidden within the upholstery – to expose the craftsmanship and character of timber.

thefutureperfect.com

Nothing ever goes out of style, it just gets reinvented. That’s the age-old philosophy underpinning Sunbrella ’s new SHI FT collection of textiles. A fresh take on much loved patterns, each injects the sophistication of tried and tested favourites in refreshed colourways. The collection also plays with a gorgeous novelty yarn to give an elevated sheen, used in their Radiant print – a twist on the traditional palm leaf pattern.

sunbrella.com

Stretching out a glorious melange of ochre reds and yellows, the CHARLIE RUG from BluDot imitates the rich colouration of the desert floor to create a natural and textured indoor scape. Ideal as both a floor and wall feature, the elongated geometric patterning extends the visual length of the room while igniting a warm interior palette.

bludot.com.au

We wear vintage, adore Mid-Century design, and share daggy photos on #ThrowbackThursday – but why do we dwell in nostalgia? Sandra Tan reviews three new books that celebrate our relationship with the past; through the places we build and the memories we share.

TEXT AND ILLUSTRATIONS SANDRA TANWh at do you remember of your childhood home?

Though mine burnt down more than a decade ago, I still recall its kitsch fl oral wallpaper, mismatched tiles and dramatic drapes in vivid detail. With focus, I can almost feel the texture of these long-lost things, like a phantom limb. Such is the immersive sensory power of nostalgia.

Particularly during our formative years, the places we inhabit leave a lasting impact, informing the way we think about and interact with space throughout our lives. They also mark a moment in time – our homes, social centres and watering holes preserve an uno cial concrete record of our everyday existence. It is these observations of domestic life that form the basis of The Rumpus Room and Other Stories from the Suburbs, through the unique lens of Australian presenter and architecture enthusiast, Tim Ross.

In the vein of his ABC television series Streets of Your Town, which charts the modern history and progress of Australian civic architecture, Tim’s new book is a more intimate ode to suburbia in the 1970s and 80s. When, like a teenager liberated by self-discovery and reinvention, Australian families embraced the

art of DIY. As Tim tells, it was “the era of being able to do anything yourself, as long as you had a spirit level, a string line and the ability to call out to your next door neighbour when you were trapped under a toppled tank stand”.

Tim’s characterful personal anecdotes of his own youth and family life are interspersed with photography from the period, imbued with the grain of analogue fi lm stock and largely collected by the author himself. The book’s gloriously retro aesthetic is accompanied by vivid storytelling, and some of its most enjoyable moments are where Tim’s design nous meets his comedic turn of phrase.

“In his book The Australian Ugliness, Australian architect Robin Boyd rallied against Featurism in houses. In 1986, my mate Graham’s family built a new house that not only embraced Featurism but grew it a new set of tits.”

Faithfully capturing the nuances of colloquial Aussie humour and how the spaces we live in refl ect our changing needs, The Rumpus Room is an insightful, culturally valuable time capsule.

More abstract, but equally evocative of a sense of place is Among Buildings, a collaborative work by architect and poet Michael Roper,

photographer Tom Ross, and graphic designer Stuart Geddes. Presented as a sequence of posters pleated into unbound rectangles within a hardcover sleeve, the inventive publishing format invites a more participatory interaction than a conventional book might. There is something almost ceremonial about opening these self-contained segments, which each unfold to reveal photographic and poetic responses to one of 26 iconic Melbourne buildings.

Though the subjects may be familiar –recognisable places include the Queen Victoria Market and Federation Square – Tom’s large-scale photography looks closer than we are used to, magnifying the fine details of each building. We are shown the textures of cladding, the light on window panes, the subtle blurry motion of surrounding foliage, and this peripheral perspective of such well-known landmarks allows a more intimate experience of the structure.

Void of colour, but for one surprise section that seems to glow by contrast, the black and white images throughout Among Buildings give Melbourne a timeless look – these pictures could almost be taken from a bygone era. The effect also brings the strength of composition to the fore. With contemporary buildings cast in the same light as classics, you can begin to see a visual association between, for instance, the angular geometry of RMIT’s Storey Hall (Ashton Raggatt McDougall, 1995), and the striking cathedral ceiling of Capitol Theatre (Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, 1924).

The poetry creates a powerful impression of the built environment, and imbues the publication with a contemplative, dramatic quality. In the excerpt for Chadwick House (by Harold Desbrowe-Annear, 1903), Michael writes:

Our homes are distortions

Of our bodies, our affections

Ballooned and kinaesthetic

The stent and the wound

Of visceral love

Wholly mortar nor memory

No more certain than hands

That build and repair

Shaped and reshaping us (epigenetic)

Impermanent as skin

With a few carefully chosen words, Michael crafts sharp expressions of a building’s presence and our sentimental connection to space. Together, these fragmentary revelations portray Melbourne’s urban identity.

Our literary trip down memory lane has thus far taken us from the suburbs to the city, but what of the global experiences we share? Sometimes these are big world events: devastating wars or jubilant sporting contests. But often, the things that unite us are small and ubiquitous.

Written by self-described pencil connoisseur Caroline Weaver, owner of CW Pencil Enterprise Shop in New York, The Pencil Perfect traces the history of an unassuming tool that has enabled creativity worldwide for generations.

The book tells a comprehensive story, beginning in the 16th Century with the discovery of graphite in England, to the first rudimentary wood-cased pencils, eventually refined by German pioneers like Staedtler and Faber-Castell, names that we recognise today. From Europe to the US, and the exemplary standard of Japanese pencils, what is striking is how a simple implement has maintained global relevance over such a lengthy timeline. But as Caroline suggests, “The pencil is one of those non-essential objects that will always exist because of its permanence in so many cultural landscapes and for its ability to be there when your phone is dead or your pen runs out of ink.”

In place of photographs, there are fantastically detailed pencil illustrations throughout, drawn with superb realism by Oriana Fenwick, a Zimbabwe-based artist. A particularly enlightening one cleverly depicts the staged process of how singular pencils are formed from a block of wood. Others portray important figures who have championed the use of pencils, including a delightfully apt drawing of cartoon mogul, Walt Disney.

Though we use them to write our first words, pass hand-written notes to our loved ones and sketch our grand plans, society has been remarkably uncurious about the origins of the humble pencil. Caroline cites only one other book, The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance by Henry Petroski, as the sole other resource for all of pencil history. But as the author writes, “Nostalgia is the most powerful sensation with an object like this. I dare you to find a single person on this planet who doesn’t associate a memory with the smell of a wood-cased pencil.” With The Pencil Perfect, Caroline ably fills a gap in our collective knowledge of a medium that has remained crucial to communication, even in these touchscreen times.

Our past recollections are the context from which we shape our own personal narratives. But not only do our memories provide us a sense of self, they connect us to others – a concept we draw on frequently in the era of sharing, as we habitually publish our own experiences through social media. Similarly, the publications here offer a window into the places, stories and objects that unite us: communities of otherwise incongruous people with shared milestones.

AMONG BUILDINGS

Tom Ross, Michael Roper, Stuart Geddes

Uro Publications

232pp loose-leaf in slipcase AU$49 uropublications.com

THE PENCIL PERFECT

Caroline Weaver

Gestalten 160pp hardcover AU$69 gestalten.com

THE RUMPUS ROOM

Tim Ross

Self-published 98pp softcover AU$36 themanaboutthehouse.net

or the most part, architect John Wardle is a forward thinker, a designer whose practices’ buildings – including the under-construction Melbourne Conservatorium of Music and the Melbourne School of Design – are shaped and crafted using the latest computeraided design technologies and innovative construction techniques.

In some ways though, John looks backwards and forwards, subconsciously, to advance and compress time. As founder and principal of John Wardle Architects (JWA), John maintains that good architecture needs su cient time to percolate and evolve.

At JWA, there is a constant endeavor to expand time: ideas are given space to emerge; the client’s needs might change or become more readily understood; spatial outcomes and minute details are refined. “The design development stage can only benefit from an extended period of deliberation and consideration,” he notes. His own house in Kew, in Melbourne’s inner east, is an extreme example of the transmutations that can occur in the architect’s mind and a building over a prolonged timeframe.

Home to John and his wife Susan for more than 25 years, the house was originally

designed by Horace Tribe in 1951. Today, it’s almost unrecognisable as the building the Wardles purchased, having undergone two major renovations, most recently in 2000. At that time John was exploring “a fascination with a sense of enclosure”; a new wing was added to project the primary elevation outwards towards the street, partly to capture city views.

The resulting living room presents as a cross-section of the house. “All of the structure, internal finishes and furniture elements are capped by a single sheet of glass, which invites an understanding of the inner program,” says John.

Inside, the perimeter of this space is emphasised by articulated shelves and benches used for formal display, while a collection of contemporary furniture pieces – including a large sofa and iconic chairs such as the Fjord chair by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso and the Take a Line For a Walk armchair by Alfredo Häberli for Moroso –are arranged and rearranged to facilitate entertaining or relaxation modes. A grand piano takes centre stage: a house concert is being planned with an old friend, singersongwriter Rebecca Barnard, who will be joined by Monique diMattina.

Rachael Bernstone shares a rare glimpse into the private world of John Wardle, the celebrated Melbourne-based architect whose constant curiosity underpins a relentlessly inventive practice.TEX T RACHAEL BER NSTONE | PHOTOGRA PHY MA R NIE H AWSON

John explored the same preoccupation –with di erent results – on later JWA projects, including the City Hill House and Vineyard House. “To use your own projects as a test bed for the sorts of ideas that we often encourage our clients to consider gives validity to those concepts,” he says. “When you test your ideas with genuine enthusiasm and a degree of strategy on a project for your own family, it can draw those moments of individual endeavor into something that becomes part of a larger o ce discussion, such as a joinery element or ways of lighting a room.

“I enjoy that aspect of practice,” he adds, “where personal experience rolls into larger discussions with colleagues.”

Now that the couple’s children have grown up and recently moved out, the architect is developing plans for a third major reworking of their home. “The intention this time is to make it bigger by turning the kids’ playroom and elevated terrace into a place for drawing and study,” he says. “The original floor plan is still there, but it’s been slowly consumed as I’ve worked and reworked it over many years. The house is basically a constantly shifting experiment, and I think we will continue to stay there for many years.”

Despite this long-term preoccupation with one building, John and his family also enjoy visiting their farm on Bruny Island in Tasmania. The same location in which the JWA-designed Shearers Quarters won Australia’s highest award for residential architecture: the Robin Boyd Award in 2012.

John has spent the past 18 months overseeing the renovation of the property’s historic Waterview cottage, originally constructed in the 1840’s by the ship’s carpenters, on the edge of a cli overlooking Storm Bay. “I need to visit Waterview as an antidote to city life,” he says.

John grew up on the outskirts of Geelong, on the banks of the Barwon River; his father was an agricultural scientist turned science teacher and his mother was a school librarian. His childhood home was a place where accepted knowledge and conventional wisdom were endlessly challenged by constant questioning and new evidence. It was an environment that stimulated his ingrained sense of curiosity, one that was instrumental in setting the tone for JWA’s inclusive practice model, where the studio structure enables John to “lead from the middle”.

“Rather than just an understanding of architectural history, I bring a broad range of interests into the practice discussions,” he says. “I’m a very curious person and many of the methods of our practice are informed by that curiosity, as well as that of fellow Principal Stefan Mee, and by drawing craftspeople, artists and makers into our circle. I’m not an architect who works in isolation and we very much require many levels of input from a broad group of others within the practice.” John’s home and o ce are testament to his broad interests, with their substantial arrangements of unusual objects collected over time.

Home to John and his wife Susan for more than 25 years, the house was originally designed by Horace Tribe in 1951.

“I enjoy that aspect of practice, where personal experience rolls into larger discussions with colleagues.”

Over several weekends each year, members of the JWA team visit John’s Bruny Island property en masse, to undertake building projects. “Those trips are beneficial in so many ways: they remove us from the conventions of the space and the orthodoxies of an architecture o ce to somewhere that is completely other,” he says. “When we are there I try to not dictate, but rather to suggest and encourage, so those weekends are very playful. They are less about pure design and much more about the process of making, and sparking connections with the skilled tradespeople who craft our buildings.”

John also seeks respite from the pace of city life and his own restless energy by taking long walks through far-flung landscapes, including a recent overseas holiday where he and Susan walked along age-old tracks in three European countries. “It is such a pleasure to walk within ancient places,” he says.

Walking for pleasure is a simple way to return to a less demanding era. On foot, it’s possible to reconnect with nature and relish the present moment. Short of time travelling, it’s one of the best ways to return to the foreign country of the past, and to luxuriate in the pleasure of having enough time.

JWA | johnwardlearchitects.com

“The house is basically a constantly shifting experiment, and I think we will continue to stay there for many years.”

we are the air chitects

Showcasing the advantages of induction cooking, the NikolaTesla innovatively combines a centralised extraction system that features high extraction perfomance, low noise levels and class A+ energy efficiency. The key to this system is synergy: the cooktop communicates directly with the rangehood, automatically calibrating to the ideal extraction level. As a result, you can focus your energy on cooking and leave the rest to us.

Sitting down with Loh Lik Peng, one of the world’s leading hoteliers, David Congram discovers the art of the architectural striptease. Nostalgia, it seems, is an act of seduction.

Icould never have expected such a litany of details. When I enquired o -hand about Loh Lik Peng’s earliest memories of hotels, I received a story so furnished with particulars and wry observations of human oddities that, at times, it felt like I was interviewing E.M. Forster (sultry, colonial heatwaves inclusive).

You see, apparently, they wore white gloves. And in those white gloves, they – a small army of twelve year olds – diligently flitted about a (now extinct) Sri Lankan villa, barefoot and in long, Nehru-collared tunics crispened from litres of starch. In white gloves they carried telephones with rotary dials and heavy receivers between viewing decks and breakfast rooms; they silently turned-down beds; re-arranged mosquito nets; shuttled silver buckets of hand-cut ice up and down stairs. And in white gloves, greeted people with broad grins under the sub-tropical sun.

“It was all very colonial – this big, beautiful old place. It probably wasn’t very luxurious but in my mind it was a whole other world. This is one of my earliest memories”, Peng tells me. “It’s a strange fate, I suppose, that it’s one of a hotel my family visited when I couldn’t have been more than seven years of age.”

Fate indeed. That seven year-old sitting poolside an upper-shelf Sri Lankan hotel has, 38 years later, become one of the world’s most critically acclaimed hoteliers and restauranteurs. With a string of more than seven boutique hotels and 20 fine-dining restaurants in the major cosmopolitan cities of Singapore, London, Shanghai and Sydney (known collectively as Unlisted Collection), Peng has become renowned for reinterpreting tired, heritage sites into modern lifestyle

concepts – always with a high degree of finesse and stylish whimsy.

“In a way,” he tells me one morning, “I suppose I’m always turning back to that childhood memory of the Sri Lankan hotel –to that feeling of visiting a whole other world.

“Today I am drawn to refining an idea of hospitality into a deep experience of multiplicity – mainly because I enjoy that immersion so much. Travelling, seeing new places, sampling local neighbourhoods are all distinct but absolutely interconnected experiences. Each of my hotels or restaurants aims to provide that feeling of immersion and wonder.”

And wonderment, it would seem, is something that Peng has found in no short supply. Last year, a Forbes journalist categorically declared “Anything-Goes Loh with a Midas touch.” But I find that denomination a little wanting. Peng may very well be a little bit of a blithe oddball, but ‘anything’ will not necessarily always ‘go’.

Approaching even the most miniscule of details with laborious deliberation, Peng is a master of precision and intent. Not a single element – such as the length of fork tines in his Waterhouse Hotel in South Bund of Shanghai, or the embroidery on the laundry bags of his latest establishment in Sydney, The Old Clare Hotel – escapes Peng’s ruminative methods.

And the man himself is no exception. For almost two hours, Peng responds to each and every one of my questions with a fillet knifesharp clarity and measured syncopation, never erring from his perfect metier of insightfulness and levity. It’s obviously a linguistic method he’s curated over many years and even more flyer miles.

The son of two Singaporean doctors, Peng is Dublin-born, Singapore-raised, and London-trained. Earning a law degree from the University of She eld before continuing in post-graduate business studies at the London School of Economics, Peng eventually left the world of practicing at a bar he found “rather boring”, to practicing at a bar of quite a di erent kind.

From jurisprudence to hospitality, he speaks to me today in his Singaporean apartment, enveloped in a decorative scheme I – ironically – haven’t the words to define. To his left is a family of industrial electric fans of similar sizes, each with that gloss enamelled tulip base and graphic wirework cage (the pewter has lost its lustre but the sheen of their lacquering has not drained one iota since manufacture almost a century ago). By a wall, antique advertisements for all manner of goods (or, indeed, morals) provide the backdrop for a system of atomic age furniture with sweeping vital lines.

“They were my avenue through to loving design and design history. I don’t know why, but I find them endlessly fascinating,”, he says. Whether it’s this rather chic apartment he shares with violinist wife Min Lee and their two small children, or his Bethnal Green Town Hall in London he shares with guests in more than ninety-eight rooms, there is no mistaking Peng’s characteristic orientation to design.

Mid-Century revival, eclectic minimalism, disruptive post-modernity … all buzzy terms fail to capture the dynamism, grace and joy of the Loh Lik Peng aesthetic. And potentially, this is because they are experiences more than mere sites.

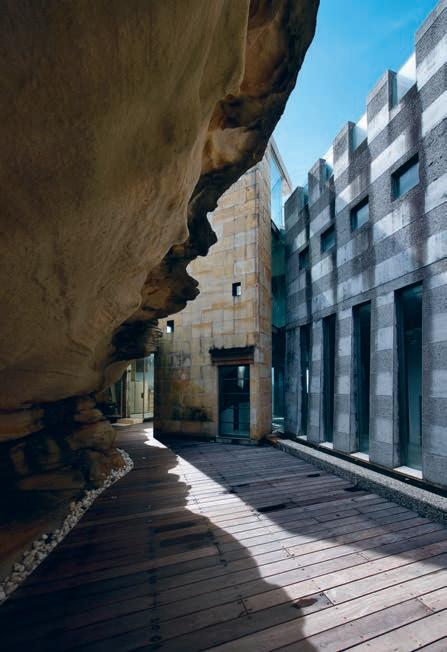

“When scouting for a new location, I’m on the hunt for stories – for buildings that are a little unloved but that also have character and breathe the story of their neighbourhood. Each one of the Unlisted Collection’s hotels or restaurants is a reflection of its city, and I think that what makes them unique is that each location is alive, in a way, […] with the people who live there, or work there, or even just are passing through as visitors.

“The history is always the most important thing because it provides the narrative and the romance.”

This became all-too apparent to me a week earlier as I sat on a barstool drinking wine in The Old Clare Hotel – Peng’s recent hotel project in one of Sydney’s abandoned breweries. As I glance around the room, I can’t shirk the sensation that the structure itself is performing an act of seduction … a striptease, if you will. It has a coquette’s charm and a stripper’s bravado, teasing me nonstop by dressing and undressing.

Here, a spirited, modern interpretation of a barbershop chair sits beside a raw sandstone wall (divots and scratches from the original nineteenth-century masonry are exposed from

Mid-Century revival, eclectic minimalism, disruptive post-modernity … all buzzy terms fail to capture the dynamism, grace and joy of the Loh Lik Peng aesthetic.

having removed the pea green cladding slapped up in the 1960s). There, some ancient safes in the lobby are mounted in pride, illuminated by the aureated glow of ultra-contemporary lighting. “That was a total surprise!” Peng exclaims mid laugh. “We uncovered these filthy old safes in the basement of The Old Clare where they must have been walled-in and sealed-up for almost a hundred years. We broke into them, as gently as possible, and discovered reams of old documents: a budget, receipts, contracts, all sorts. I thought that these relics of local history were incredible (even if the contents were a bit … what’s the word? Mundane?) so I couldn’t bring myself to throw them away. And there they are, in the lobby in pride of place, to celebrate the stories and the people who once brought this building alive.

“But those safe doors! They must’ve weighed three- or four-hundred kilograms each!”

With a curator’s sense of preservation and an enthusiast’s desire for discovery, the odd tale of the safes is but one of the jolly stories of learning to love the past hand-in-hand with the present which gives Peng’s creations an aura not of timelessness, but otherworldliness.

When visiting the High-Victorian council chambers in London’s East End (Peng’s Town Hall hotel), I discover that the walls are adorned with artefacts of bravery and pluck. Everywhere, sooty and tattered evacuation posters tell me that this is the correct way to wear my gasmask and I should hot-foot it to the nearest Tube station until the third siren.

“Now that I think about it, perhaps that experience of being seven in the Sri Lankan hotel has shaped my approach more than I thought. They might be mine or someone else’s, but the muse is always memory.”

“I suppose I’m always turning back to that childhood memory of the Sri Lankan hotel – to that feeling of visiting a whole other world.”

The future belongs to the curious.

luxxbox.com

And after 10 years in the game we are still pokin' around.

Jewellery designer, maker and owner of an eponymous label, Holly Ryan invites Holly Cunneen into her recently acquired and most personally styled living abode on the banks of Brisbane.

When you put pen to paper and list pivotal moments in Brisbanebased jewellery designer and maker Holly Ryan’s life, you’d be forgiven for an esoteric declaration that her path was decided and that she was destined to become a jewellery designer. But in the face of being told what to do, she did in fact side-step it for some time – perhaps in subconscious rebellion against life predetermined.

Both of Holly’s parents were jewellery makers and back in 1988, just before she was born, they were in Mexico studying silver smithing. Returning to Australian shores Holly grew up in her mum’s jewellery studio in Coolum Beach, Queensland. Fast track a decade or so and she was studying a bachelor of fine arts and majoring in Fashion at the Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane. In her final year she collaborated with her mum on a line of jewellery to accompany her graduating clothing collection. “When the buyers came to the graduate runway show, they were interested in the jewellery and not the clothing. So it was kind of decided for me,” remembers Holly.

“I resisted it at first. I moved to Sydney and worked for a clothing designer called Sara Phillips.” But the call of destiny was unavoidable and soon Holly was working on her eponymous brand. “It was an opportunity to put my name to my own designs rather than create designs for another label.” Holly Ryan the jewellery label was o cially born in 2011.

“Most of the furniture are pieces that I’ve particularly wanted in my head – like the cream couch, a 1970s Don Rex original.”

Although she flew the proverbial coop some years ago when she was just 17, it was only recently that she moved into her current abode in Windsor, Brisbane. The move was born out of practicality; with most of her sta based in Queensland’s capital, it began to feel “selfish” to ask them to commute daily to the Sunshine Coast, where she was previously based. Instead, she found a new home and studio and moved closer to them.

Self described as Mid-Century Modernism meets 70s minimalism and “a little bit quirky”, her home is dotted with vintage pieces she’s painstakingly searched for until found in a reasonable condition. “Most of the furniture are pieces that I’ve particularly wanted in my head – like the cream couch, a 1970s on Rex original,” says Holly. Or the Corbusier chairs, or the Eileen Gray table. “Every piece has a purpose.”

These instantly recognisable designs hero her interiors and speak to an elevated appreciation for design. Yet her obsession with collecting ceramics and penchant for creative exchange between artists – often in the form of trading with friends, jewellery for artworks – makes the space her own.

Despite her knowledge and deep-seated appreciation for design, it’s a nameless wicker chair that carries the most sentimentality. “A wicker cane rocking chair with a Mongolian sheepskin thrown over it, that’s my great grandmother’s chair and I’ve had it in every house that I’ve lived in since I was 17. It’s really special to me.”

Without being over styled or overwhelming, Holly’s home is a constant source of inspiration for her work. As is her studio.

“Everything that I do with my jewellery is inspired by sculpture, architecture, conceptual art and interiors,” says Holly. “I love ceramics so whenever I’m looking at sculpture and ceramics I generally find inspiration for my jewellery. So it’s just nice to have that around the house.”

A marker of her generation – or perhaps one of life as a designer – work and home life tend not to be separate entities. “Both [home and work studio] are creative spaces for me and I’m the sort of person that doesn’t really stop working,” says Holly. “It’s not like I go home and switch o , I go home and in a di erent area work on di erent things.” That’s why it’s so important for both spaces to foster a sense of creativity and feed her need for inspiration.

Reminders of the first time she dabbled in 3D printing are sprinkled around her home, too. Following a trip to Japan and heavily inspired by the work of Tadao Ando, a series of geometric bangles ended up being too small and slightly too impractical to continue into production. “I cast them to brass from the original plastic and they look really nice now that the metal is tarnished. I use them as paperweights around the house and they’re just sitting on the table in front of the sculpture now.” Likewise one of her first designs is on display in a saucer on the main bookshelf. Made from 28 di erent pieces and featuring cold connections and solder joins, it serves as a constant reminder of where she came from and how hard she pushed herself to keep going.

It’s a full on – and seemingly never-ending – approach to life. But with elements of her jewellery design finding their way into her home and vice versa, these are just some of the moments that make one lean back and smile with satisfaction.

Holly Ryan Jewellery | hollyryan.com.au

Holly Ryan Jewellery | hollyryan.com.au

A marker of her generation – or perhaps one of life as a designer – work and home life tend not to be separate entities.

Danish brand Vipp finds a new home at CULT. With them, they bring a varied – yet considered – collection ranging from bins, lighting, home accessories to complete kitchen and bathroom modules.

It is no short stretch to say that we are inundated with options when designing and decorating interior spaces. And despite the perceived benefits that come with an excess of choice, it can more often than not choke the design process.

Vipp is one of the few brands today that understands this pervading anxiety. Entirely comfortable in their own skin, Vipp’s industrial-based range cites a single product for each item category.

It makes perfect sense, then, that to celebrate CULT’s 20th birthday, they have welcomed in the Danish brand. An expansion with an expanding brand, who’s adherence to quality and function has seen its long line of products linger on – unchanged – in the contemporary home.

Vipp came to standing in the 1930s after designing their – now iconic – steel-cylinder pedal bin for a private hair salon. Customers and neighbouring hair salons alike took notice of its exceptional strength and considered design, creating a best seller that continues to decorate the front pages of Vipp’s website and stores.

The pedal bin was an important lesson for designer Holger Nielsen; that objects should be first and foremost functional, and if an object has truly been designed well –from every angle and perspective – then it shouldn’t need to be reinvented. The job of the designer should then be complete; do it once and do it well.

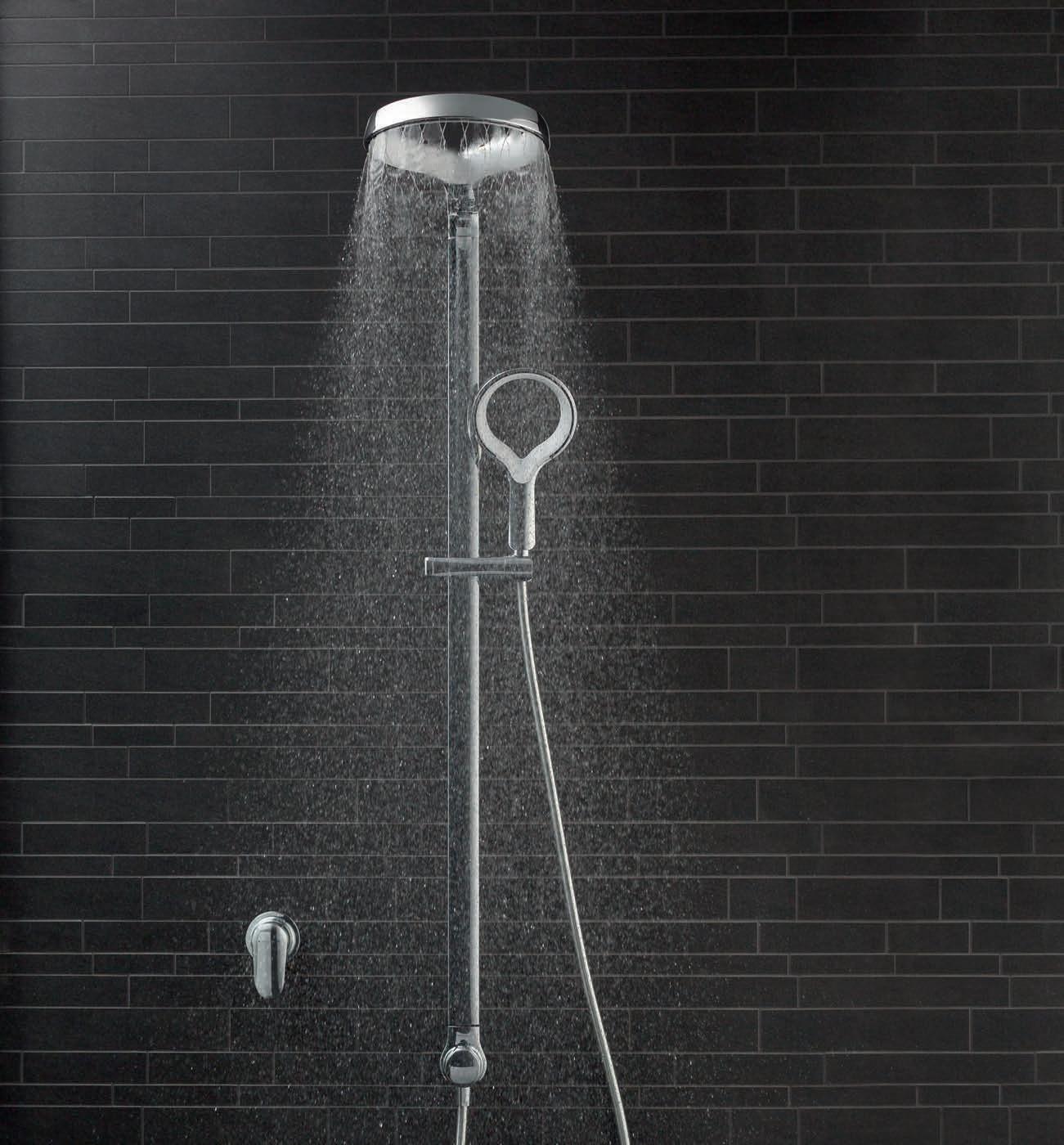

The DNA of this progenitive pedal bin lives on and has been extended throughout the entire home through Vipp’s collection of decisively timeless, sleek and impeccably resolved products. They have more recently released module sections within the bathroom including a sink, tap and shelving solution. While in the kitchen, their concept bundles enable you to lift their own perfectly curated, interconnecting spaces and drop them right into your home directly from theirs.

And this same concept of making prefabricated and completed designs accessible is truly realised in their latest and most daring project to date; the Vipp shelter. Amalgamating their breadth of products within the one site, shelter transforms individual items into a holistic object itself; a two storey, steel structure getaway.

The Vipp collection is simultaneously as expansive as it is slim; taps, soap dishes, towel rails, lighting, linen, floor lamps, toothbrush holders and breadboxes – each considered to be the best that they can be. Evidence of how an edited down collection – under a conscious and critical eye – can o er you choice, function and high design.

If an object has truly been designed well – from every angle and perspective – then it shouldn’t need to be reinvented.

Dessein Furniture holds pride of place firmly at the forefront of local design. Having collaborated with the likes of Adam Goodrum, Tom Fereday, Simon Archer, Nathan Day and Jon Goulder, their furniture is the epitome of contemporary, thoughtful design. The Pieman Collection is Dessein’s premier range, and features stunning tables, chairs, armchairs, shelving and home accessories. Dessein is proud to be associated with Habitus as part of our commitment to the promotion of high quality Australian design and production in the furniture industry. desseinfurniture.com

only

As a child of the aspiring middle class, I was often portrayed by my parents with the symbols of nascent status arrayed around me. Is this where my fascination with material culture comes from?

We all have defi ning moments, many lurking in the depths of the family photo album. In this inaugural Habitus Family Album we share a rare glimpse of seminal moments in the lives of some of our favourite creatives.

Further on, Australia’s most notorious expat designer, Marc Newson gives insight into his global existence, and Patricia Urquiola reveals how she is mining Cassina’s back catalogue to create visions for our future.

Welcome to the third installation of In Habitus Veritas.

— Stephen Todd

I must have been 19 or so and for some reason we thought it an adventure to hitch hike through Queensland having caught a bus and a train down from Darwin. Being in that place at that time made me question my notion of place. How di erent my highly charged life in Melbourne was compared to middle Queensland and the Northern Territory seen by train. It dawned on me how vast Australia is, how many countries there are within our single entity. I suddenly felt very small, and knew instinctively I had a long way to go, and that wasn’t just about the distance to get back to Melbourne. The memory of place has a fantastic imprint on imagination, and the silence and colour, the scent of the desert through which we travelled was truly incredible. I’m still wondering what on earth we were thinking hitch hiking through Queensland. What does that say about the designer I am today? Perhaps it’s something to do with an adventurous spirit, an enquiring mind.

In 1992, with a degree, a one-way ticket and apparently a thick lump of hair I set o to travel and work in Europe. I wanted to work for someone amazing, learn a foreign language and explore all things foreign. This photo was taken during a month in Paris involving intensive French classes every morning followed by afternoons exploring the city with students from all over the world. The Pompidou Centre blew my mind on so many levels: the big audacious idea, the extraordinary resolution of details, the city’s investment in culture and how this edifice transformed a whole quartier. At that time, skinny pale kids in Levi’s would hangout, drink and smoke in the big plaza that leans towards this monument of new-modernity. When I look back I recognise that my five years abroad was a time of immense freedom and fun, and when I worked out what it was that I really, really loved to do.

I love being in nature, I draw a lot of inspiration from outdoors. Since I decided to be an architect, I have been traveling around the world to discover new sources of inspiration. Nature often appears grand yet it is so fragile. While I looked at such an iconic setting as the Dolomites in awe, I realised how the gracious mountains were a ected by global warming. It is such a moment that poses the question of our responsibility in the face of imminent disaster, as well as the duty of architecture to respect nature.

19.

This image is of my older brother, the great chef Cheong Liew (in front) and myself. It was taken on a very beautiful summer’s day, a year after I arrived in Australia. I had just finished my year of boarding school in Glenelg, South Australia, and I was reveling in a newfound sense of freedom of expression, the prospect of unbridled opportunity, and the sheer sense on wonderment and joy of being in Australia. There was so much to discover and enjoy. This feeling about the country has never left me, and as each year passes I love it more. I have found much inspiration in its historical material culture, its social and physical landscape. This sense of wonder about the country and its people continues to inspire me. I have been very fortunate and feel so grateful.

I took this shot with my Kodak Instamatic sometime in the late 70s, 1979 I think. A family friend drove from Sydney to our farm near Forbes in his Ferrari 308. Mid-engine Italian sport-cars were such futuristic, alien objects back then and this car was the most exciting, beautiful thing I’d ever seen. A vision of the future had landed in the front drive. People sometimes ask if growing up in rural Australia influenced my designs but in truth it sometimes feels the opposite. Design for me has always been more like a fantasy of another time and place.

I remember so clearly the time this photo was taken. I remember feeling not only was it the launch of a new studio but also the launch of an exciting new chapter in my life; I clearly recollect a feeling of confidence, conviction and excitement for the future. It was knowing that I could do it, that I could achieve a successful balance between commercial reality and creative excellence. I felt that finally clients were becoming more aware of the value of good design and the role it played – the importance of design in the creation of home as sanctuary, in the productivity of a workplace, in the hotel guest experience and the education of our students.

I’m sitting in front of the gas fire, on the cork floor at my family home. The house was built by my Dad, the blocks we’re assembling were made by Mum and the photo shows my cousins – Sarah, Libby and me – building a church. I guess my little brother Matt and cousin Angela were already in bed – the older kids were allowed to stay up late! I love this image, it is full of warmth and great memories of holidays with people I love. My childhood was generally split between Ararat and Shepparton and spent in houses in various states of construction. Both families built and made their lives – homes, curtains, furniture, stain glass windows, jumpers etc. – so holidays were invariably dotted with construction projects.

Taken during the great flood that a ected much of New South Wales and Queensland, I would have been returning to Sydney College of the Arts after the Easter break. Here, Dad is taking me to the front gate via ATV where a rescue vehicle was waiting. My expression pretty much says, Get me the hell out of here!

My paternal grandparents were Polish Jewish holocaust survivors. This beautiful, modernist house was a place of great warmth and love. It featured walls made from Jerusalem stone, a not uncommon gesture amongst Diaspora Jews wanting to illustrate their connection to the homeland. If I were to ask an architect to select a material that represented my social allegiances (my belief in pluralism, in urgently addressing climate change), what would they choose? For me every building is social, is political.

The longest stretch. The railway access road took us from Menindee to Broken Hill. We didn’t meet another person for five days, we did have the rhythmic coming and going of the Ghan on its way from Adelaide to Darwin and back, so silent until it was basically upon us. This did a good job of scaring the bejesus out of the animals who would flap around wildly on their tether ropes like balloons in the wind. Our trusty billy (which to this day continues to make us our everyday cups of tea) sits on the fire, a pack bag front right. Bought one, made the other. Both objects stood the test of time on the road, practical without the need for anything else, simple enough they can hold our memories. The camel and donkey trip was defining experience - and a good indication that our relationship was a goer!

01 Koichi Takada , ARCHITECT SKIING AT MADONNA DI CAMPIGLIO, ITALY, 2009. 02 Khai Liew MASTER CRAFTSMAN PHILLIP ISLAND, VICTORIA, 1971. AGED 03 Charles Wilson , DESIGNER AT HOME IN CENTRAL WEST NSW, DREAM VEHICLE, 1979. 04 Charles Wilson , DESIGNER AT HOME IN CENTRAL WEST NSW, REALIT Y VEHICLE, 1990. 05 Kerry Phelan , INTERIOR DESIGNER HITCH HIKING TO BRISBANE, 1979. AGED 19. 06 Sue Carr, INTERIOR ARCHITECT WITH KEN LLOYD, PARTNER IN INARC AT THE INARC STUDIO, FLINDERS LANE, MELBOURNE, 1984. 07 Lou Weis, CREATIVE DIRECTOR, BROACHED COMMISSIONS WITH SISTER, SARA AT GRANDPARENTS ’ HOUSE, HOWITT ROAD, CAULFIELD, MELBOURNE, 1978. 08 William Smart, ARCHITECT CENTRE GEORGES POMPIDOU, PARIS 1992. AGED 24. 09 Adam Haddow, PRINCIPAL, SJB AT THE FAMILY HOME, ARARAT, VICTORIA, EASTER 1978. AGED 5. 10&11 Elliat Rich & James Young , SOMEWHERE BET WEEN MENINDEE AND BROKEN HILL, WINTER 2001. EDITED BY STEPHEN TODD | COLLAGE DINA BROA DHUR ST16

I was the youngest of five kids. Every day I would watch my sisters and brother go off to school, I was envious of them being out in the big, wide world. At last it was my turn, and here I am heading off to my first day in bubs at Carrum Primary School. Even today, nothing excites me more than being somewhere I haven’t been, seeing something I haven’t seen or making something I haven’t made before. My uniform is still a rainbow of greys.

I’m three in this picture, seated outside our house right on City Beach with views out to the Indian Ocean and Rottnest Island. I was born in Sydney, but my parents drove us across the Nullarbor Plain when I was nine months old, to settle in Perth. I can still feel all the potholes in the unsealed road, rattling my young bones. The house was this modern masterpiece, single storey white brick, the double columns of the pergola make think of Carlo Scarpa’s comments that columns should act as vertical accents, always be paired so that one doesn’t get lonely on its own. I reckon my parents paid about $30,000 for the house back then, unthinkable today.

I was sent to boarding school in the Southern Highlands when I was eight. This was taken in my dorm room in my second year. It was a boys’ school run by an old hippy headmaster and his wife. We were encouraged to build cubby houses, work in the wood shop, the pottery studio and generally get up to mischief. I feel like the foundation of my practical knowledge came from these years. I remember we were allowed a pocket knife with a blade length no longer than eight centimetres and were encouraged to go camping and make fires alone on weekends in the outlying paddocks. Just writing that now I’m almost in disbelief at how things have changed in the liberties of kids these days.

I grew up in two houses which were both designed and built by my family while we lived on site, hence the wheelbarrow and the half built path in the background. My parents where always inventive you can see the paperbark branches for fencing, and we always had a garden we could eat straight from, an old water tank for swimming and a chook pen for turning our scraps into eggs! This connection to the wider world around me and the idea of working together was very important. The inspiration for becoming a creative was definitely my parents.

19 Tom Ferguson, architect and photographer at harvard univerSity in front of le corbuSier’ S carpenter center for the viSual artS building. 1988.

After finishing third year at UNSW I took a year away from campus, working six months at Cracknell Lonergan to fulfill my practical experience requirement and then going on exchange to McGill University in Montreal. I joined a second year studio run by Ricardo L Castro, a “Colombian-born, Canadian architectural photographer, critic, and educator” to quote his Wikipedia page. I had a great time and while the design projects (being second year) weren’t particularly complex it allowed me to focus on other elective subjects which didn’t have a year bias. Ricardo took us on a road trip to Boston to see all the classic works of architecture there including the Carpenter Centre shown in the photo. Apart from all the buildings in Boston we also visited the Davis Museum at Wellesley College by Rafael Moneo and the Exeter Library by Louis Kahn so it was a pretty amazing trip.

20 Holly Cunneen, deputy editor, habituS Seven mile beach, nSW, 1996. aged 5.

I’m awaiting my date, Stephen Azaparti to take me to the Catholic debutante ball. I love voluminous dressing, even then, and clearly knew how to reveal/conceal – and the power of the neck! Just add a statement earring or chandelier but I wasn’t allowed to have my ears pierced! I also love a single focused posie and still don’t like to mix floral messages with various blooms. The real context is that everyone else had miniskirts on, pre-teen shoulder action and updo’s but I didn’t flinch and was totally happy with my look. First to arrive and the last to leave, I love an occasion with a colour-specific theme! It also proves that stylists are born not made, I found my getup from one of my cousins throw outs!

23 Nick Tobias, architect medloW bath, blue mountainS , circa 1979. aged 3.

This image is very precious to me, it shows my Pop teaching me my trade. My Pop was blind but he could still teach me the old ways of traditional upholstery. It was very important to him that I learn and that he teach me. This style of work is all about touch and feel. He was very proud I was becoming the fourth generation furniture maker in my family, he told me I have a reputation to live up to. I bear that in mind every day.

Apparently I went through a period of wearing these blue plastic glasses without lenses, religiously. I believe the cardboard box is doubling as an Alfa Romeo GTA 2000. The image relates to growing up in an environment of making, not specifically design. My father and grandfather both had timber and metal workshops so there was always any number of projects going on and my father specifically involved the children to varying degrees. Some of the time I enjoyed the projects and others not so much, however these are times that I now hold close.

Like most children I loved dressing up, mimicking type cast personalities. I was always such a little tomboy, climbing trees, playing soccer, that sort of thing. We moved around a lot when I was little, from Sydney, to California, then to Wales in the U.K. This photo always makes me giggle. I was just playing a character and would have no doubt thrown the shoes and bag away immediately after the photo and climbed back up my tree. Creating characters, whether through a person or a room or a space, has always been something that has stayed with me as a stylist.

This was taken on one of the many trips my parents took me, my younger brother and two older sisters on. My parents have such a quietly adventurous spirit and – what I now recognise to be – a deep-seated desire to explore their country. Our holidays, long weekends and birthdays were spent neatly (if not tightly) packed into a long white Holden Commodore road tripping up, down and across Greater Australia. Although we, as kids, loved to complain about the long hours on the road and nights spent in a tent or caravan park, I don’t think I have any fonder memories. And I don’t think I’ve ever properly thanked them.

This was taken at the Blue Mountains house that my grandmother maintained as a secret home away from home. She would steal me away from my parents and we’d hang out together at this house and be creative. This is where she handed me a sledge hammer and said, ‘Demolish the bathroom!’ It’s also where we’d make mosaics, play jazz, paint, do all sorts of fun stuff. My grandmother really nurtured my creative side and I owe her a big debt for it. That’s not her up the ladder though. That would be her cleaner-turnedfriend Connie Ellero, who I would have been helping clear the gutters. Nothing’s changed really, I still spend my life assuring clear passage for waste.

24 Alexander Lotersztain , deSigner venice, italy, circa 2002.

This photo was part of the test shoot prior to my wedding, and shows a 23 year old with her future in front of her. Three months after the photo was taken I had completed my architectural studies, another month later I was married. Clearly I was in a hurry to get somewhere! Piers and I celebrate our 20th wedding anniversary this year. Without him, my practice would be nothing. When I look at this photo, I think about Ed the photographer. He said, “Mel, you’re gonna be one of these cool brides. You don’t want the sandstone arches that every other Newie bride wants. How about that shiny building Newmed 1?” And that was it. Yes, even on my wedding day, I found myself promoting great design and good architecture.

I was living in Milan at the time, and my twin sister was in London so she decided to come to visit and we went to Venice for a few days. I’d lived two years in Tokyo before arriving in Milan, it was the start of my kind of ‘real’ design journey, finding my way in the global design hub. Venice was extremely inspirational, from the architecture and history the city to the way people lived and went about their daily lives. Like a journey back in time. I remember vividly walking through the backstreets and peeping into the window of a violin workshop, and the craftsman sanding his masterpieces. That trip made me consider ways of slowing down or re-booting, and of maybe finding the essence of the many reasons I became a designer.

12 Tony Amos, photographer at home in Seaford, melbourne. aged 5. 13 Henry Wilson, deSigner at tudor houSe boarding School, 9 yearS old. 14 Jon Goulder, maSter craftSman at e W goulder & SonS furniture upholSterS and furniture makerS 1986. 15 Ross Gardam, deSigner at home in barham, nSW, 1979 aged 2. 21 Melonie Bayl-Smith, architect at the david maddiSon clinical ScienceS building, univerSity of neWcaStle, September 1997. aged 23. Adam Goodrum, deSigner at home, city beach, perth, 1975. aged 3. 17 Nicole Monks, deSigner in the backyard of the family home at tarbuck bay, nSW. aged 3. 18 Emma Elizabeth , creative director of local deSign SWanSea, WaleS backyard dreSS upS , 1989. 22 Megan Morton, interior StyliSt my grandmotherS houSe, kenSington Sydney, 1980SThe mosaic is an ancient art form with roots going back to third millennium BC Mesopotamia. A unique combination of art, fine craftsmanship and industrial design, mosaics are timeless examples of the beauty that arises from crossing over the worlds of art and design. Artistic mosaics find a place of their own in the Mosaico+ universe, o ering the highest level of personalisation and prestige. Mosaico+ explores all the expressive potential of the mosaic form, with the aid of an all-Italian production system that combines innovative techniques with an traditional culture and craftsmanship.

Juxtaposing chips, assembling fragments, selecting materials, expertly adapting shapes to specific spaces: these are the actions that make each Mosaico+ project unique and unrepeatable. An artistic mosaic can only be done by hand, but Mosaico+ has succeeded in integrating traditional craftsmanship with modern technology; adapting IT tools and advanced procedures typically used in industrial design to elaborate or develop requests made by clients during the planning phase.

A recent launch from Mosaico+, the Dialoghi collection, comes from a design search focused on the experience of the material. Experience as a tool for exploring the worlds of design, and material as a means of enhancing the essential elements of the mosaics. The texture layout and original chip designs of the Dialoghi range lets architects and designers create their own mosaics, expressing the legacy of the form while channeling contemporary luxury.

Mosaico+ makes all its design and manufacturing experiences available to customers to best assist them in the development of their projects, with a before and after-sales service comprising design and technical advice for the choice of the most suitable materials and sizes as well as technical assistance and supervision during installation.

Mosaico+ | mosaicopiu.it/enThe worlds of art and design always work alongside one another, but for Mosaico+ there’s no need to separate.

Futurolists are doing a roaring trade these days, so anxious are we to know what tomorrow will bring. Oracular trend predictors habitually ri o our fears of technology, climate change, immigration and economic precarity in order to provide panacæ for an as yet unknown era. F uture perfect, the Milan Furniture Fair is by its very raison d’être a time machine churning out new product at a rapid rate of knots. But one of the most compelling shows at the Salone this year was not a stand delivering glittering consumer durables, it was an exhibition proposing new ways of inhabiting our homes.

This Will Be The Place was the title of the exhibition orchestrated by Patricia Urquiola in her capacity as art director of Cassina, based on a sibling publication edited by Felix Burrichter, editor and creative director of PIN-UP magazine. What was interesting about this double-edged manifesto was that at no point in formulating a future did Urquiola or Burrichter obliterate the past. Their future entails no tabula rasa, more a recalibration.

“The past is not made out of marble, to use an architectural metaphor,” Urquiola tells me. “The past is a mix of possibility and memory. Design should respond to the present, and there can be no future without a knowledge of the past. The intersection between heritage and innovation is very important to me.”

“The past used to be the future,” Felix Burrichter adds, by phone from his o ce in New York. “And most of the things that we think are going to happen to us in the future already in part exist. We already live according to a future vision. For instance, ‘collective living’ might sound more radical than Airbnb but ultimately that’s what it is. It’s a matter of nomenclature.”

In Part I of the publication which serves as a de facto catalogue to Urquiola’s show, Burrichter interviews architectural historian Beatriz Colomina who believes the 21st Century to be that of the bed. Berlin-based architect Arno Brandlhuber predicts the house of the future will

be a fluid structure composed of few divisions. Chinese architect Zhao Yang foresees a return to nature and tradition – perhaps not too surprising given he was born in the most violently industrialized economy of the past 30 years. Konstantin Grcic suggests that to think about the future e ectively, one needs to know the past and be rooted in the present.

“The problem is that when we think of the future,” says the Munich-based industrial designer, “we picture a certain cliché of it and that is often connected to technology, electronics, the digital and so on. In contrast to that, I work in an industry that’s much more analog – namely, furniture. Mine is a slow world, a world in which one scrutinises and revises the things that have existed for hundreds of years.”

Grcic’s a ection for the analog has its roots in his classical training as a cabinetmaker at the John Makepeace School in Dorset, England. Yet, as we witnessed in his Panorama show at the Vitra Museum in 2015, he is not immune to a fascination with the future. In that show he staged a series of dioramas around the ideas of Life Space, Work Space, and Public Space. “It was an opportunity for me to take stock,” admits Grcic. “But also to look ahead.” Domus described Panorama as “a retrospective that looks to the future, but with an individual suggestion that narrates the present.”