INDESIGN Luminary Richards Stanisich

Commonwealth Bank, South Eveleigh, Woods Bagot & Collaborators

Paul Priestman, PriestmanGoode

The Gandel Wing, Cabrini Malvern, Bates Smart Ozanam House, MGS Architects

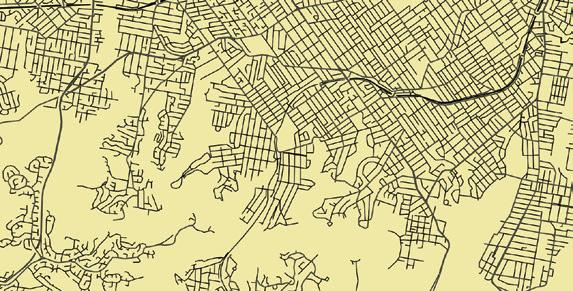

The ‘City Futures’ Issue.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM A

Issue #79 / Australia $16.50 / New Zealand $17.50 / Singapore $12.95 / U.S. $21.99

professional resource for the design curious.

Instant Comfort, Everywhere HermanMillerAsiaPacific Meet Cosm – our latest office chair that provides instant comfort, everywhere. hermanmiller.com/cosm

©2019 Herman Miller, Inc.

©2019 Herman Miller, Inc.

Rumba Workstation

Pictured with: Precinct Screens, Vox Task Chairs, Wes Armchair, Archie Table, SOL-Dash Mobile Stool & Dress Standing Aid

by ZENITH Design

Pictured with: Precinct Screens, Vox Task Chairs, Wes Armchair, Archie Table, SOL-Dash Mobile Stool & Dress Standing Aid

by ZENITH Design

A CONCEPTUALLY DEVELOPED COLLECTION OF LUXURY VINYL TILES, DESIGNED TO INSPIRE ENGAGING AND STYLISH INTERIOR SPACES

For more inspiration visit polyflor.com.au

Introducing OE Quasi Light

Design to Shape Light

OE Quasi Light

Design by Olafur Eliasson louispoulsen.com

Design to Shape Light

OE Quasi Light

Design by Olafur Eliasson louispoulsen.com

THE NEW KITCHEN ESSENTIAL

All your drinking water needs, All-in-One beautifully designed system. Remove the need for multiple taps in your kitchen with a single, beautifully designed system that delivers boiling, chilled and sparkling filtered drinking water, as well as hot and cold unfiltered water for your sink.

The Zip HydroTap All-in-One offers every water option you need from one multi-functional tap and a single intelligent compact under-bench system. That’s why the Zip HydroTap will be the one and only hydration solution for your kitchen. Discover more at zipwater.com

THE WORLD’S MOST ADVANCED DRINKING WATER SYSTEM

ZIP HYDROTAP | PURE TASTING | INSTANT | BOILING | CHILLED | SPAR KLING

CEO and Founder

Raj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

Managing Director

Kavita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

Editor Alice Blackwood alice@indesign.com.au

Consulting Editor Paul McGillick

Indesignlive Editor

Aleesha Callahan aleesha@indesign.com.au

Brand Director Colleen Black colleen@indesign.com.au

Sales Manager Dana Ciaccia dana@indesign.com.au

Business Development Managers

Kim Hider kim@indesign.com.au

Valeria Valera valeria@indesign.com.au Brune a Stocco brune a@indesign.com.au

Production and Projects Manager

Brydie Shephard brydie@indesign.com.au

Production Assistant

Becca Knight becca@indesign.com.au

Accounts

Cassie Zeng cassie@indesign.com.au

Ting Zhang ting@indesign.com.au

Lead Designer Louise Gault louise@indesign.com.au

Designer Louis Wayment louis@indesign.com.au

Online Manager Radu Enache radu@indesign.com.au

Web Developer Ryan Sumners ryan@indesign.com.au

Indesign Correspondents

Stephen Cra i (Melbourne)

Mandi Keighran (London) Andrea Stevens (New Zealand)

Contributing Writers

Leanne Amodeo, Rachael Bernstone, Aleesha Callahan, David Congram, Stephen Cra i, Mark Healey, Annie Hensley, Mandi Keighran, Andrew McDonald, Paul McGillick, Emily Su on, Marg Hearn, Pia Sinha, Andrea Stevens, Sophia Watson, Tone Wheeler

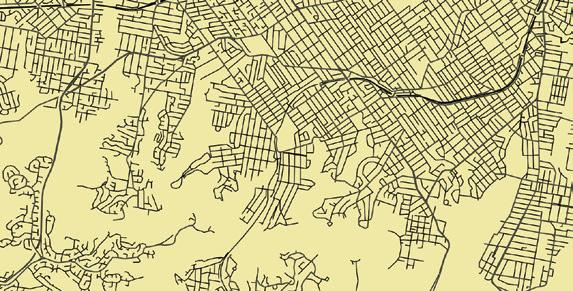

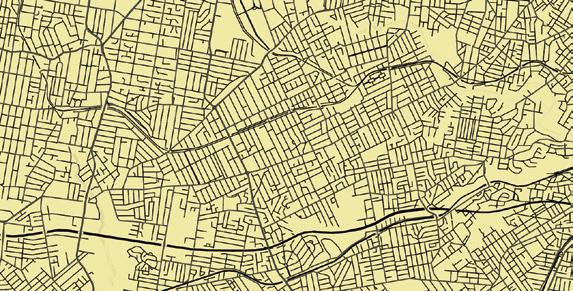

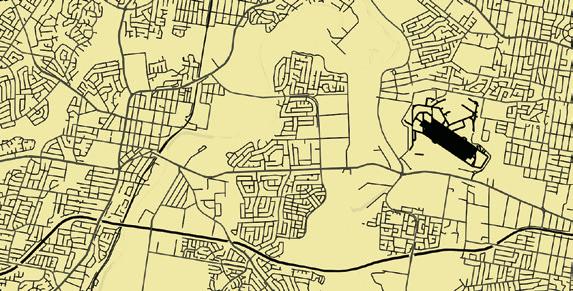

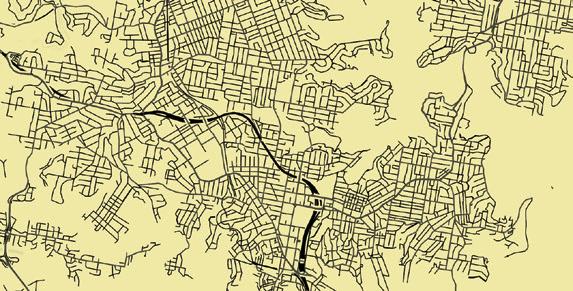

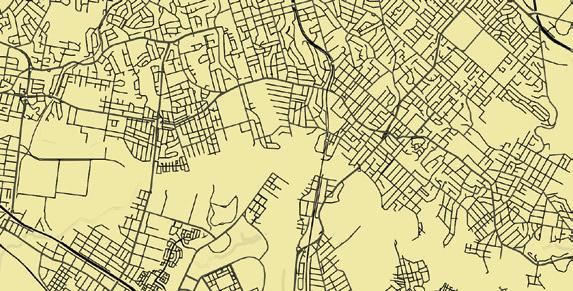

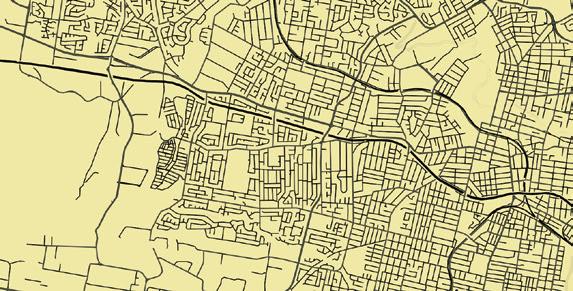

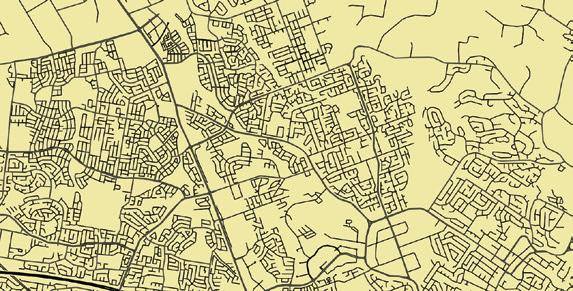

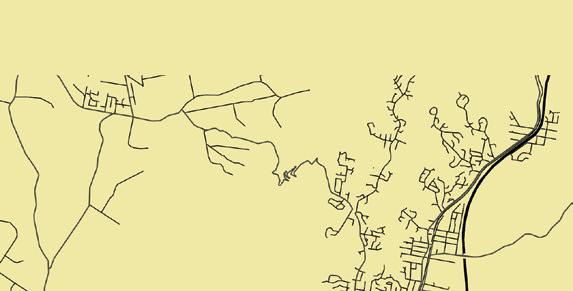

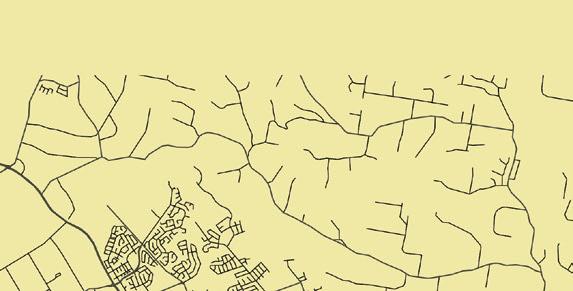

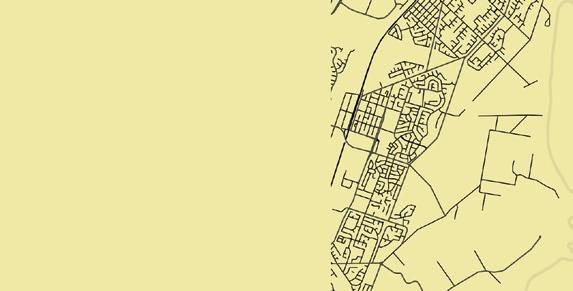

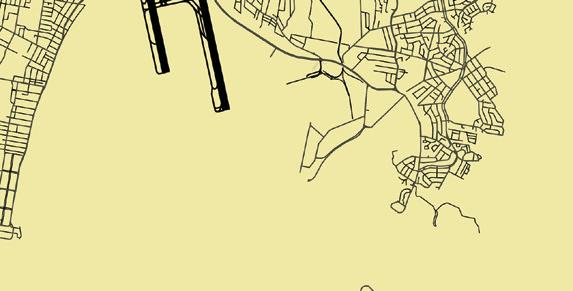

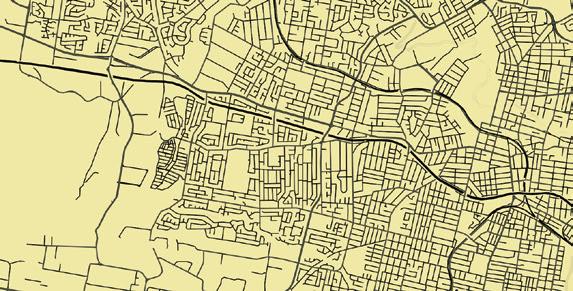

Featured Photographers & Image Producers Michele Aboud, Peter Benne s, Bre Boardman, Peter Clarke, Charles Dennington, Alana Dimou, Giuseppe Dinnella, Thurston Empson, Nicole England, Felix Forest, Dan Hocking, MakeMapsStudio, Adam Mørk, Shannon McGrath, Trevor Mein, Tim O’Connor, Ian Ten Seldam, Gregor Titze

Head O ce

Level 1, 50 Marshall Street Surry Hills NSW 2010 (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax) indesignlive.com

Melbourne

1/200 Smith Street, Collingwood VIC 3066

Singapore

4 Leng Kee Road, #06–08,SIS Building, Singapore 159088 (65) 6475 5228, (65) 6475 5238 (fax) indesignlive.sg

Hong Kong Unit 12, 21st Floor Wayson Commercial Building, 28 Connaught Road West, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong indesignlive.hk

Join our global design community, become an Indesign subscriber!

To subscribe (61 2) 9368 0150 subscriptions@indesign.com.au indesignlive.com/subscriptions

Yearly subscription: Australia $55 (incl. GST) International AUD $110

Printed in Singapore Indesign is printed with ENVIRO Soy-Based Process Black ink, UV Solventless Varnish and on paper which is awarded an Environmental Management Certificate to the level ISO14001:2004 GBT24001-2004 and Eskaboard and Eskapuzzle produced from 100 per cent recycled fibres (post consumer).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmi ed in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. While every e ort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publication, the publishers assume no responsibility for errors or omissions or any consequences of reliance on this publication. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, the publisher or the publication. Contributions are submi ed at the sender’s risk, and Indesign Publishing cannot accept any loss or damage. Please retain duplicates of text and images. Indesign magazine is a wholly owned Australian publication, which is designed and published in Australia. Indesign is published quarterly and is available through subscription, at major newsagencies and bookshops throughout Australia, New Zealand, South East Asia and the United States of America. This issue of Indesign magazine may contain o ers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. If you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services you have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as fulfillment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information and use it to inform you of other promotions and publications from time to time. If you would like to know what information Indesign Media Asia Pacific holds about you please contact Nilesh Nandan (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax), subscriptions@indesign.com.au, indesignlive.com Extended Digital Extended Print Extended Events Indesign Family CAREERSINDESIGN INSTANT CONVENIENCE Zip HydroTap provides pure tasting filtered water with instant boiling, chilled and sparkling water. Discover more at zipwater.com Strategic Partners MILANINDESIGN INDESIGNLIVE.COM INDESIGN IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY

It has been a year of milestones for Indesign Media. In June we brought home our most successful INDE.Awards yet. With 430+ entries from more than 14 countries, the awards program has carved out a uniquely democratic platform for the Indo-Pacific region – something which no other awards program does. Design excellence is not dependent upon big budgets and slick imagery; weight is given to the role of design in respect to local culture, community, and user needs.

Closely following the INDEs was Saturday Indesign, making its exciting comeback to Melbourne after a two-year hiatus. Its festival-like atmosphere creates an event dynamic as yet unmatched in our region. And the opportunities for connection and collaboration are plentiful.

On the commercial design front, we staged the second annual FRONT.design at Barangaroo, Sydney. It’s an ambitious event – the first and only of its kind in Australia – with a rich and multi-faceted program that addresses our complex commercial ecosystem. It has been effective in bridging the gaps between a vast playing-field of stakeholders and building productive links where before none existed.

The success of these initiatives is leading us with renewed vigour into 2020, the year in which we celebrate 20 years in business and in print. Stay tuned for some exciting reveals!

On the topic of futures: what are the imperatives for our cities in 2019 and beyond? I put the question to the design leaders and industry experts for the ‘City Futures’ issue. What arose were vital and important themes around urban density (pages 142 and 152), housing affordability (page 132), multi-functional aged and healthcare environments that foreground the dignity of the user (page 145), and the critical importance of moving forward in a ‘co-design’ partnership with Indigenous people (page 154).

This is an issue that is alive with the voices of our design community. You’ve put words to it, we’ve given it the platform it deserves. Enjoy!

INDESIGNLIVE.COM 22 FROM THE EDITOR & PUBLISHER

indesignlive.com /indesignlive @indesignlive @indesignlive 250,950+ readers engaged across print, digital and social... On The

Yagan

article on

Raj

Cover

Square, Perth by Lyons Architects with iredale pedersen hook and ASPECT Studios is featured in our

Co-Designing Community With Our First People, page 154, photo: Peter Bennetts.

Nandan CEO and Founder, Indesign Media Asia Pacific

Alice

Blackwood Editor, Indesign magazine

SYDNEY 5/50 Stanley Street Darlinghurst +61 2 9358 1155 MELBOURNE 11 Stanley Street Collingwood +61 3 9416 4822

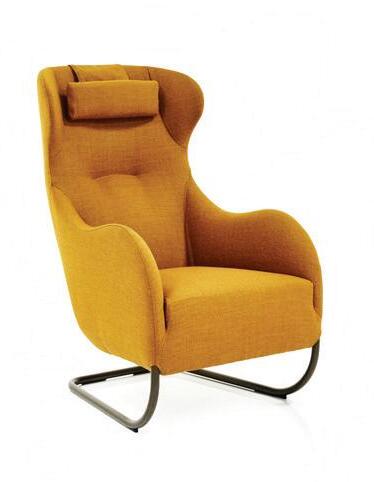

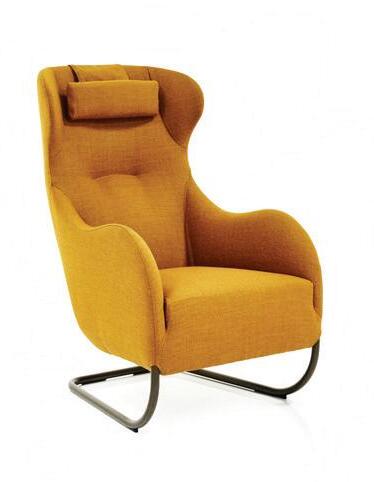

Elba Soft Armchair by Crassevig

Annie is a principal at fjmtstudio leading fjmtcommunity, a discipline dedicated to reinforcing place specific design through consultation, placemaking and art integration. Much of her 17 years at fjmt has been dedicated to community, cultural and urban design projects. No matter the typology, Annie continues to reinforce the importance of the public as a primary stakeholder.

Her contribution to fjmt’s distinct, site-specific response includes in-depth research into the locale and its community, engagement, place strategies and post occupancy evaluation. She continues her involvement in a number of completed projects to optimise their ongoing success, including Bunjil Place in Victoria.

Bringing Back The Town Square

Page 162

Introducing the Voices of Indesign –The ‘City Futures’ Issue

Stephen Crafti started writing on architecture and design in the early 1990s after purchasing a Modernist 1950s house in North Balwyn, Melbourne, designed by Montgomery King & Trengove. “I would never have thought that decades later I would still be writing in this specialised area, continuing to ‘live the dream’ on a daily basis!” Stephen says.

So Artificial!

Page 68

Clare Cousins Architects

Clare Cousins established her Melbourne practice, Clare Cousins Architects, in 2005. Engaged in projects large and small, the studio has a particular interest in housing and projects that nurture community. Clare is a life fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects, and its immediate past national president.

Clare was an inaugural investor in the Nightingale model, a socially, financially and ecologically sustainable multi-residential housing model. She is now undertaking her own Nightingale project as one of six architecture practices collaborating to deliver Nightingale Village as both designers and developers.

Clare is a special issue advisor for Indesign #79, helping to define the themes and topics we have covered in this issue. –

Fight For Affordable Housing

Page 132

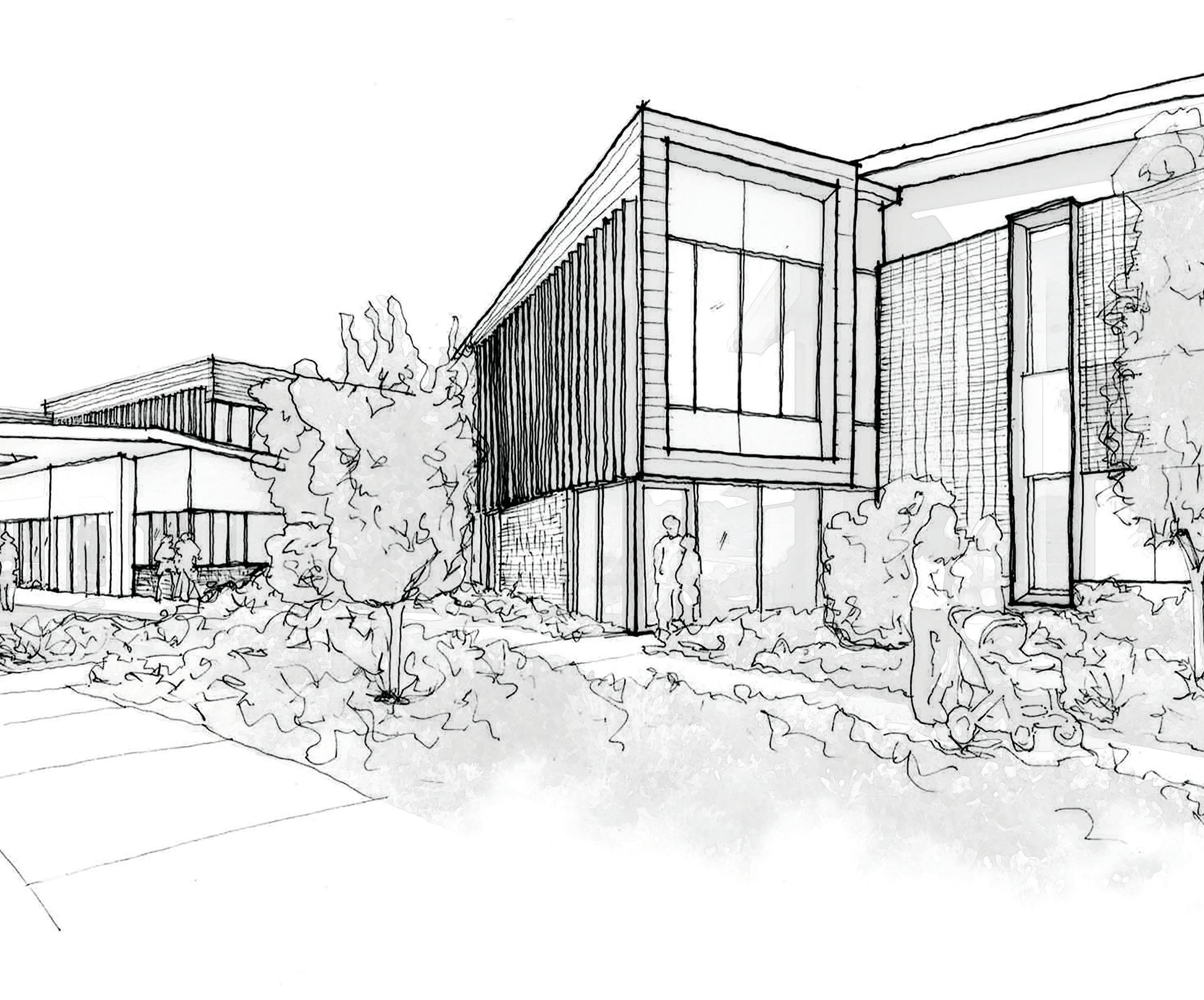

Bates Smart

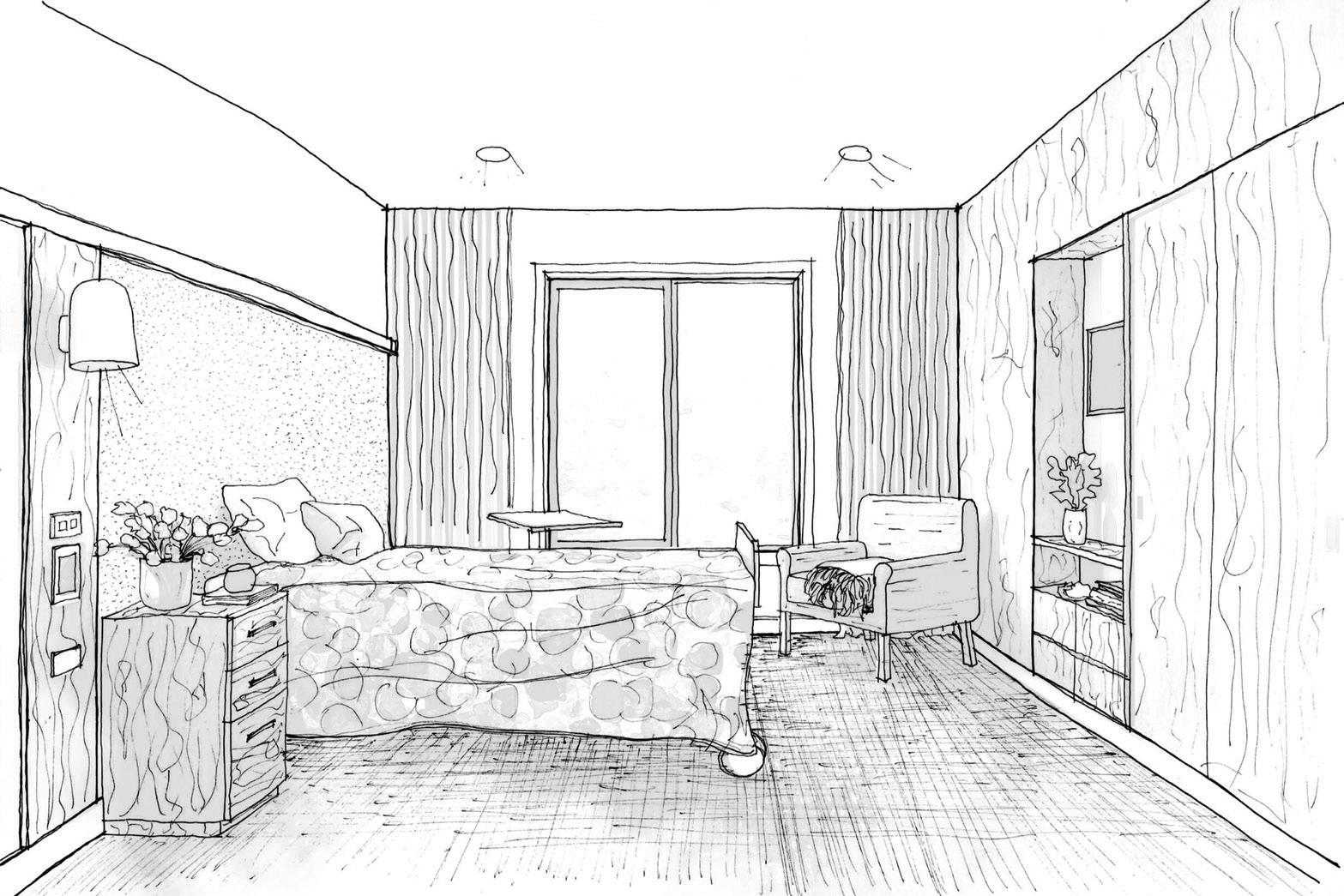

Mark Healey is a studio director at Bates Smart in Melbourne. As a senior interior designer with over two decades’ experience in Australia and internationally, Mark specialises in leading and delivering high quality healthcare, hospitality, multi-residential, civic and commercial developments.

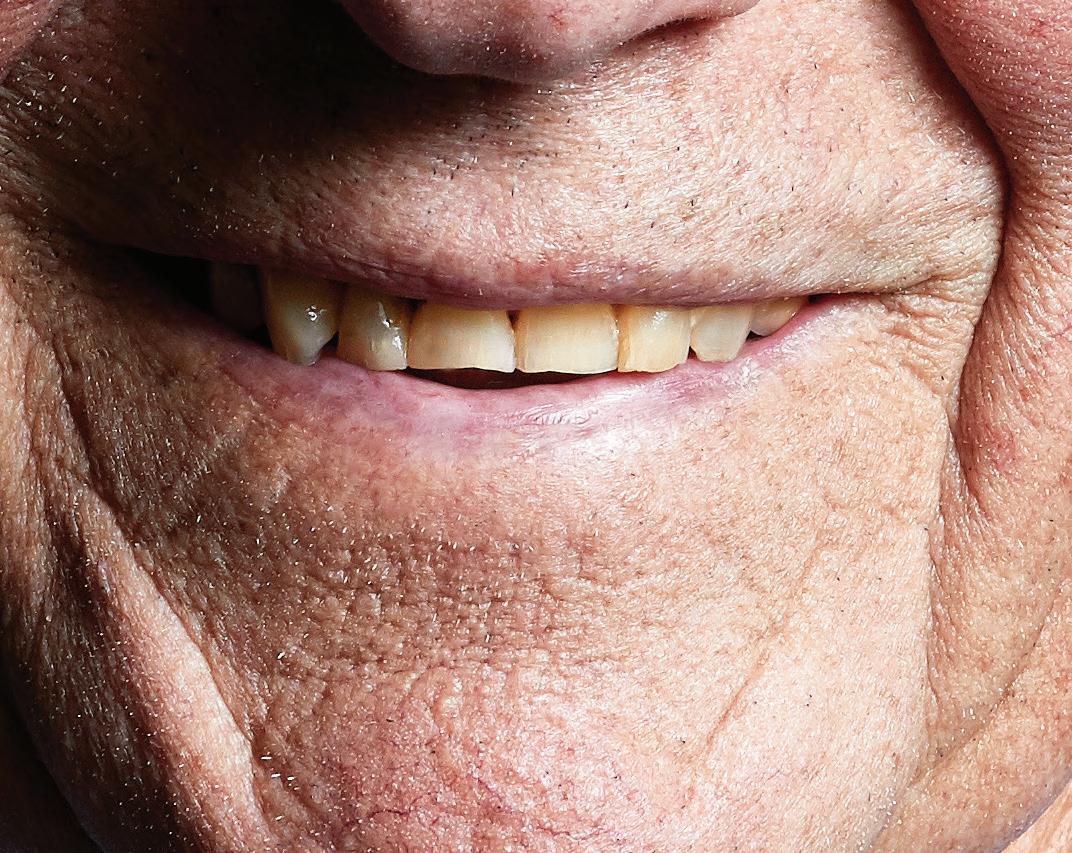

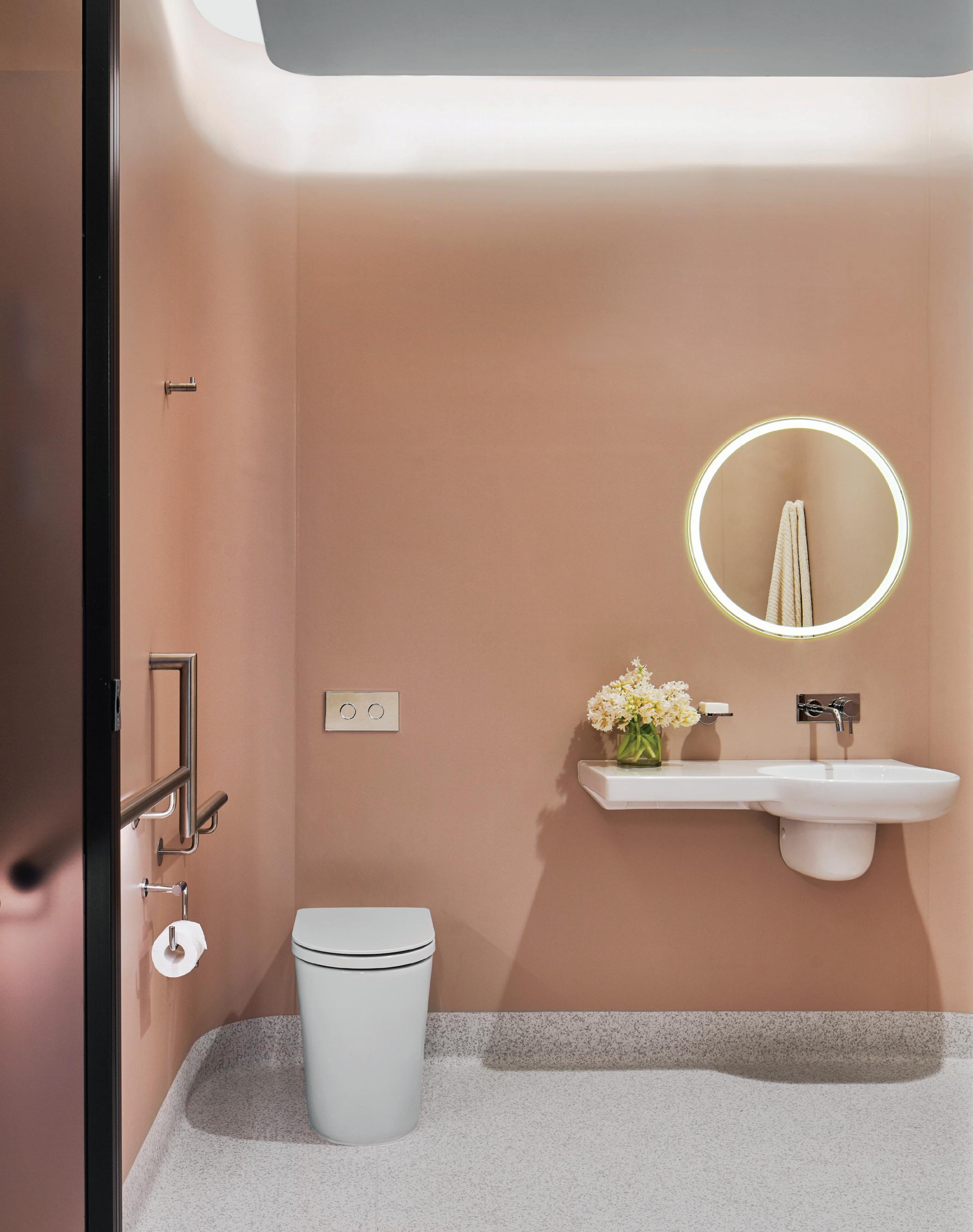

Mark has achieved numerous career highlights since joining Bates Smart in 2003. He has been lead designer for projects including the awardwinning Royal Children’s Hospital, Bendigo Hospital, and The Gandel Wing at Cabrini Malvern.

Mark is an active member of the Design Institute of Australia and alumni of the Committee for Melbourne’s leadership program, the Future Focus Group.

Healing With Dignity

Page 120

Tone Wheeler is a director at Environa Studio with Jan O’Connor, and a passionate advocate for environmental architecture. He has taught at universities for 30 years, served on boards and appeared regularly on television and radio.

Australia’s Rack-Stack-And-Pack Syndrome

Page 142

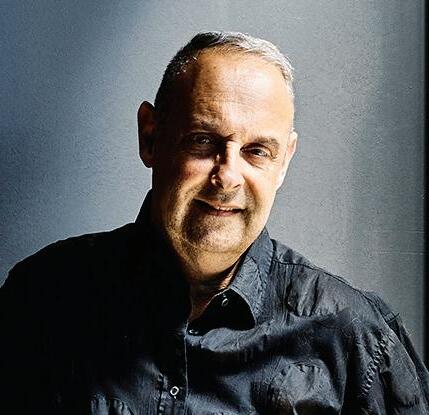

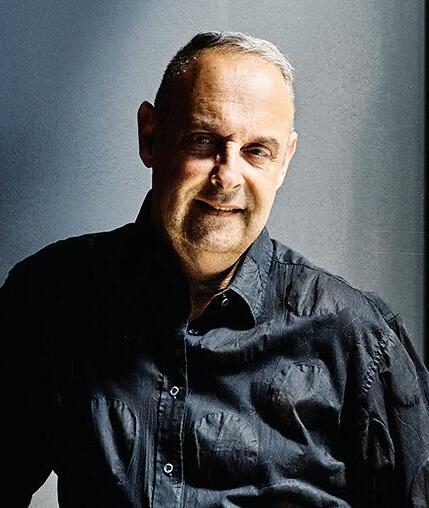

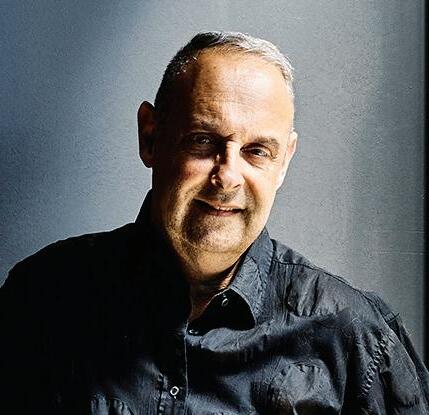

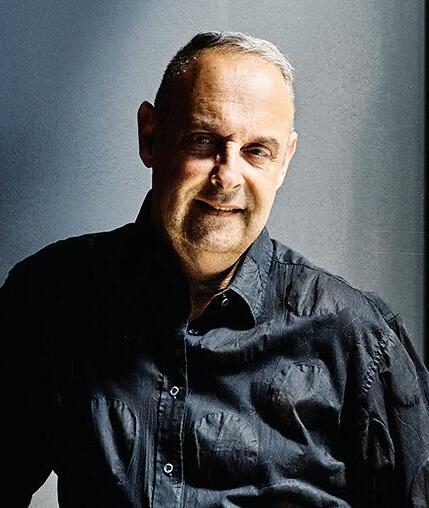

As a designer and chairman of PriestmanGoode, Paul Priestman leads a wide range of projects, from product design through to transport. He has built a reputation for his award-winning future concepts – visionary ideas to improve our everyday and encourage sustainable, long-term thinking. He is an inspirational speaker on the subject of design and creative future thinking. In 2015, Paul was voted one of London’s 1000 most influential people by the Evening Standard for the third consecutive year. In 2016 he was recognised as one of Britain’s 500 Most Influential individuals by The Sunday Times

Paul is a special issue advisor for Indesign #79, helping to define the themes and topics we have covered in this issue.

–

What’s The Rush?

Page 128

Annie Hensley Principal fjmt

–

Stephen Crafti Architecture and design writer

–

Clare Cousins Founder

Mark Healey Studio Director

–

Tone Wheeler Director Environa Studio

–

Paul Priestman Chairman PriestmanGoode

INDESIGNLIVE.COM 24 contributors

Your design statement lies within.

The difference is Gaggenau.

Grand architecture demands grand interior pieces. Refrigeration is one such design element and should speak to who you are. Every Gaggenau piece is distinctively designed, crafted from exceptional materials, offers professional performance, and has done so since 1683. Make a statement: gaggenau.com.au

In Short

The ultimate industry cheat sheet.

29-54

In famou S Big thinkers and creative gurus.

61-80

INDESIGN Luminary Jonathan Richards and Kirsten Stanisich of Richards Stanisich, Stephen Crafti, Sebastian Herkner, Sandra Furtado and Peter Sullivan of Furtado Sullivan

In SI tu

Provocative, innovative and inspiring design.

85-122

Commonwealth Bank at South Eveleigh Axle – Building 1, Sydney by Woods Bagot with Davenport Campbell (interior design), fjmt with Sissons Architects (base building), Mirvac (developer)

Tūranga, Christchurch, New Zealand by Architectus in association with Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects

McCorkell Brown Group offices, Melbourne by Ha Architecture

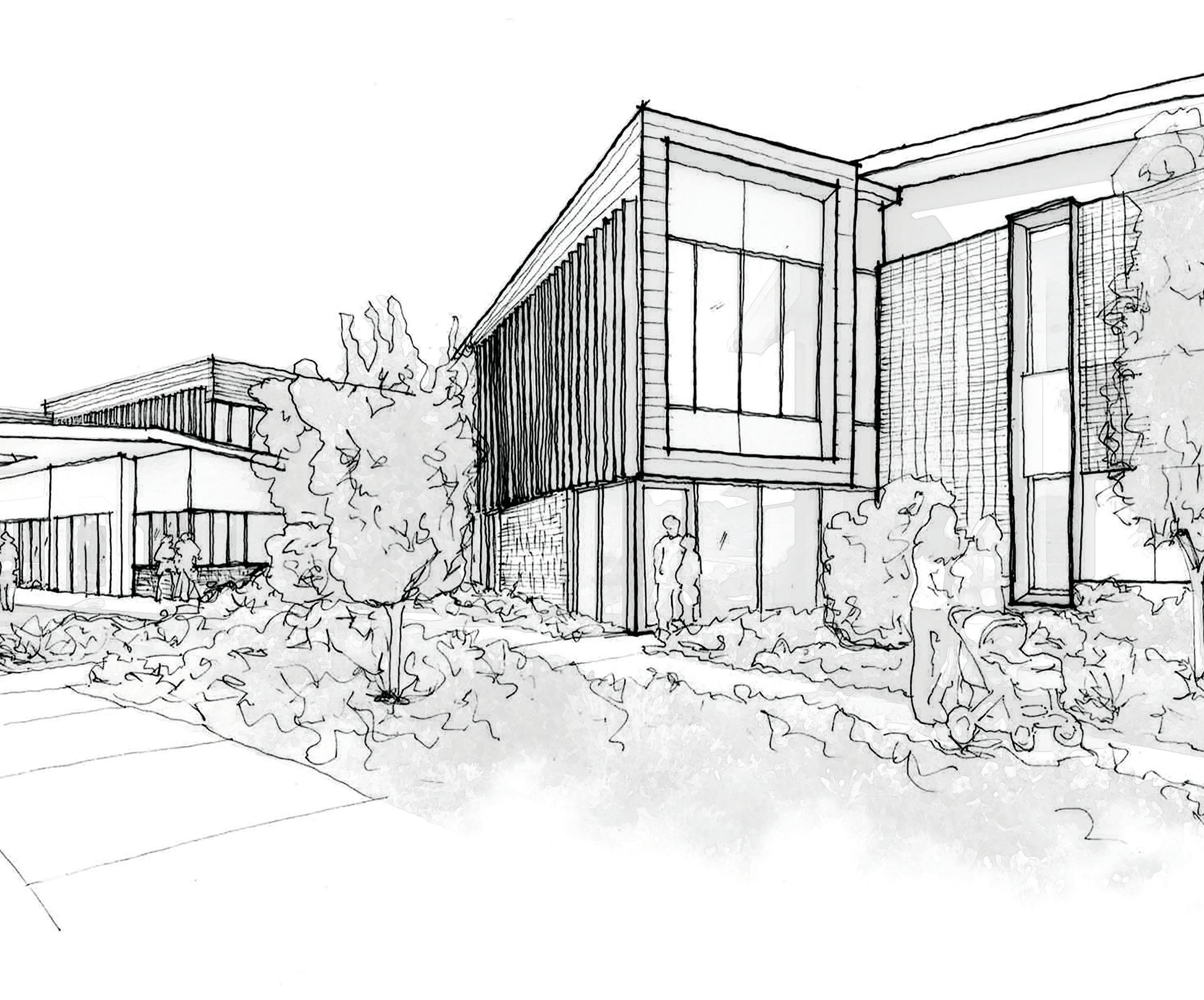

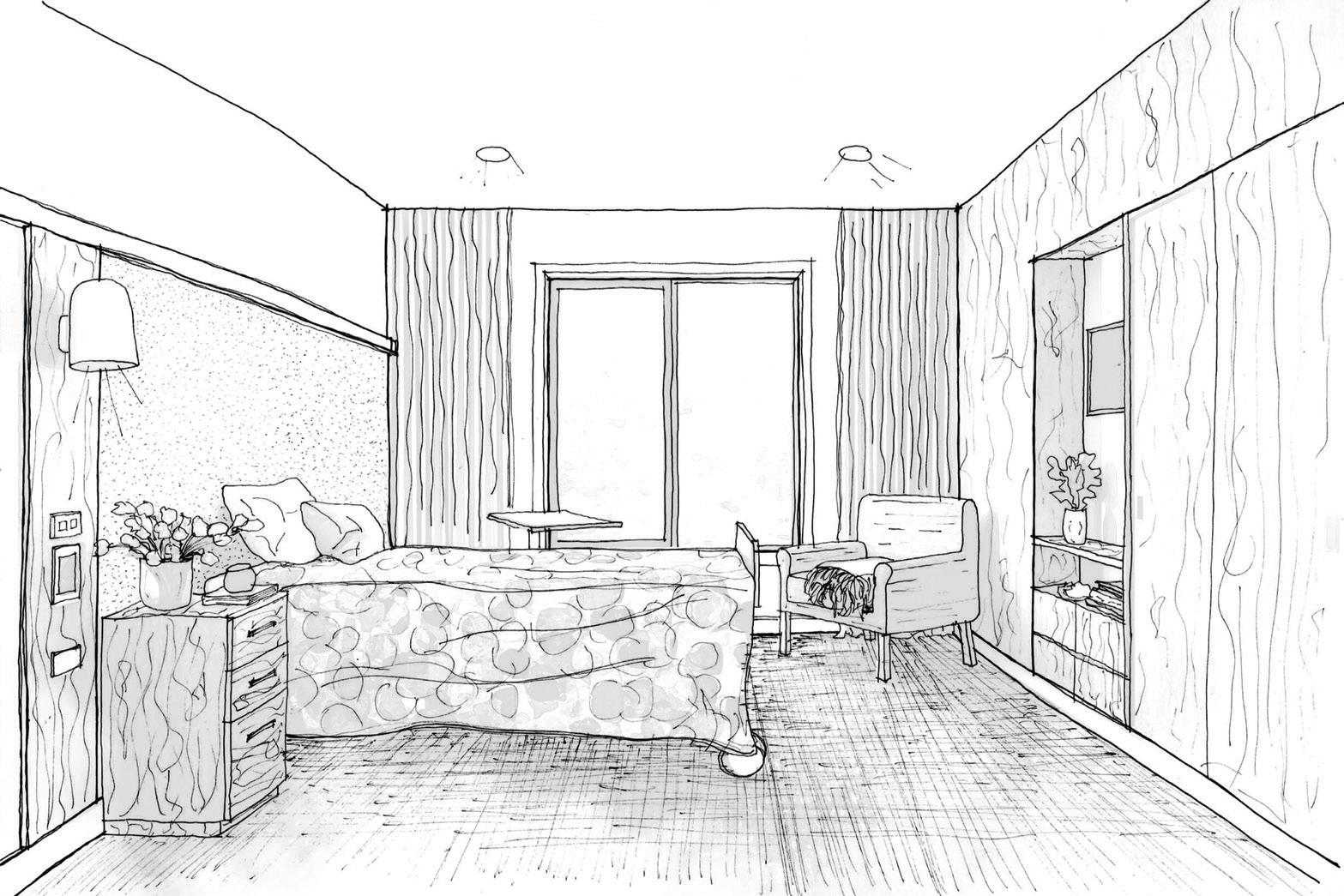

The Gandel Wing at Cabrini Malvern, Melbourne by Bates Smart with special comment from Mark Healey of Bates Smart

I n Depth

Housing, health and cultural imperatives for our cities’ futures.

127-167

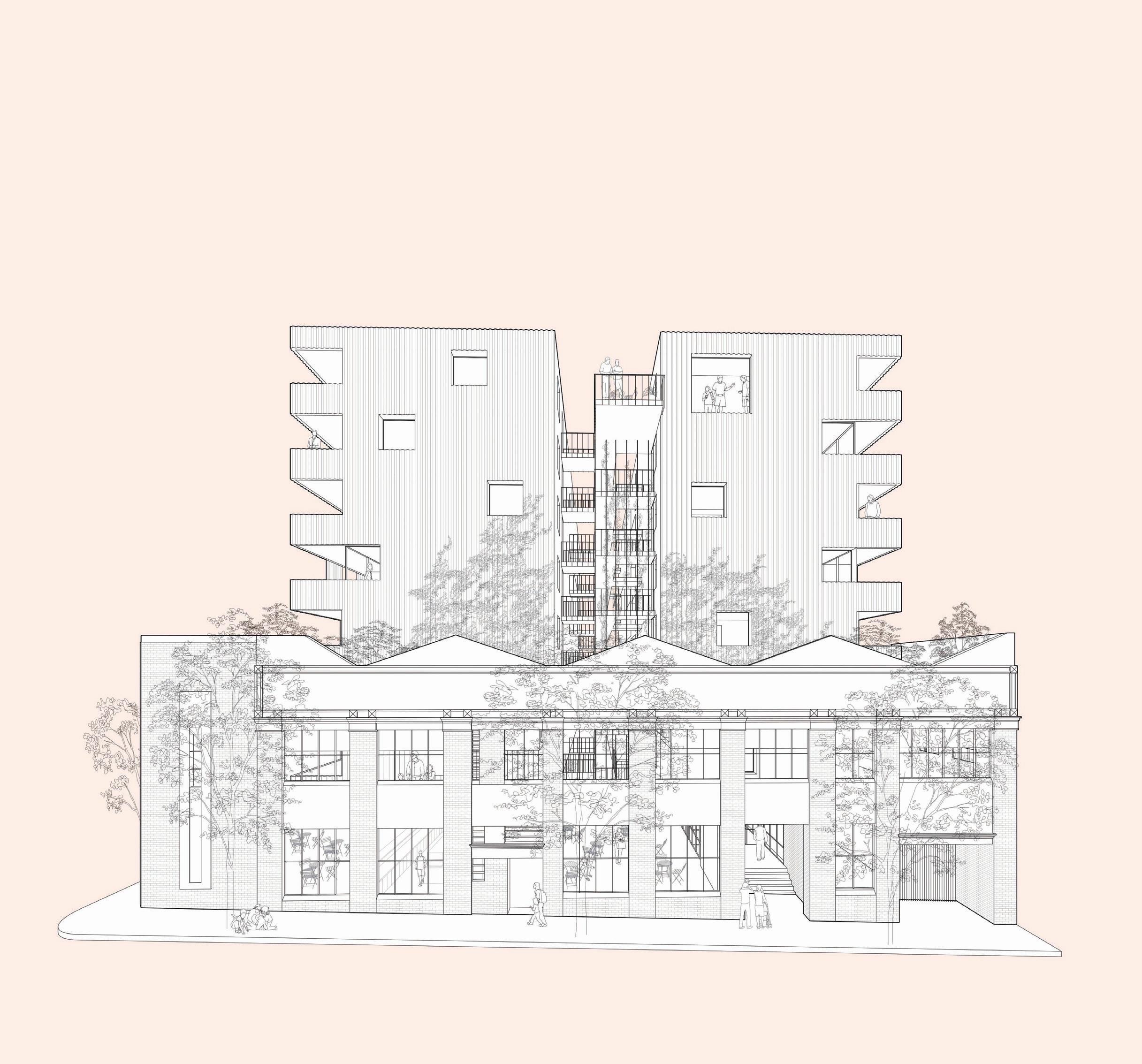

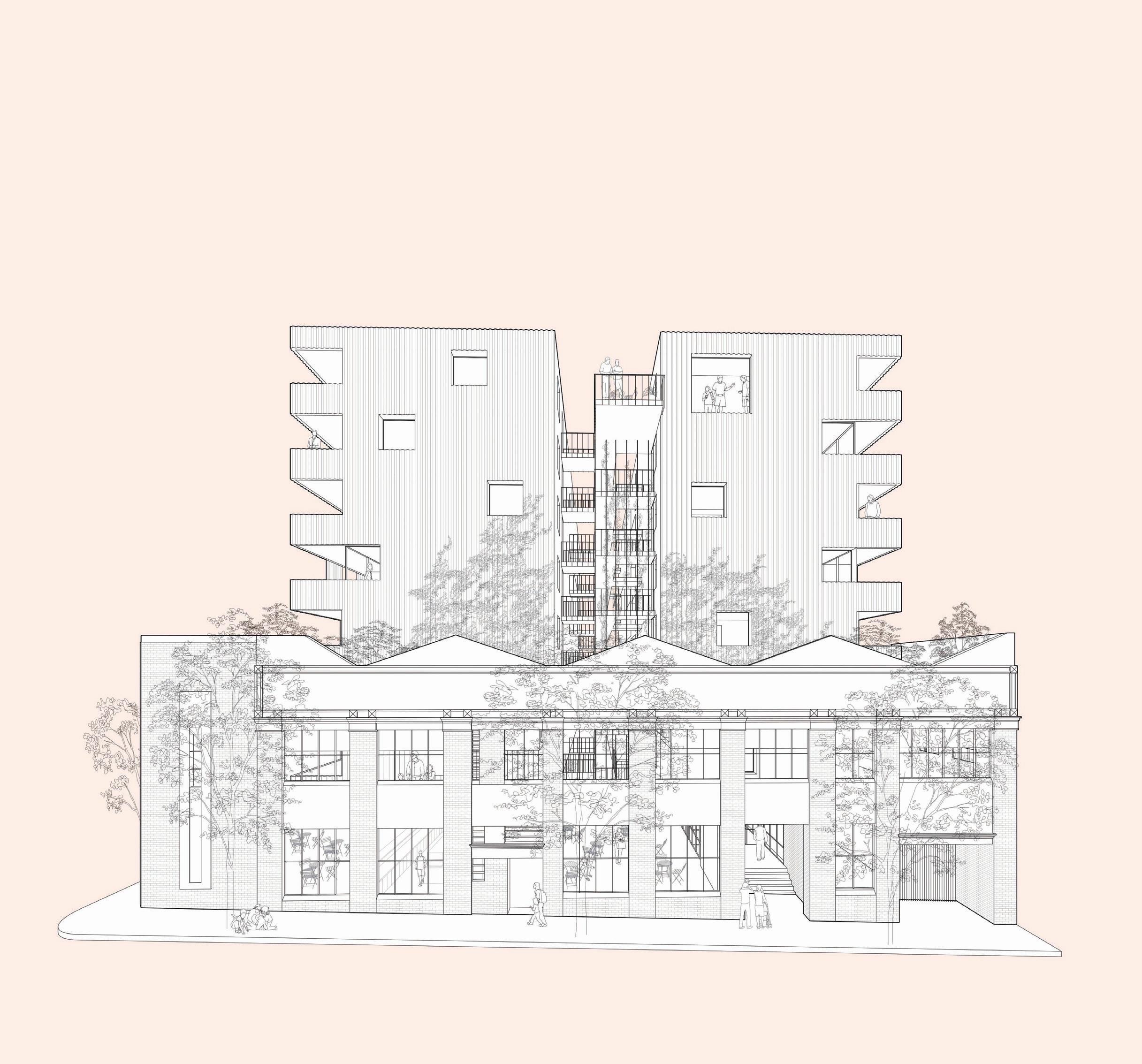

Featuring Ozanam House, Melbourne by MGS Architects

Orygen and Orygen Youth Health, Melbourne by Billard Leece Partnership

BaptCare, Melbourne by ClarkeHopkinsClarke

Yagan Square, Perth by Lyons Architects with iredale pedersen hook and ASPECT Studios

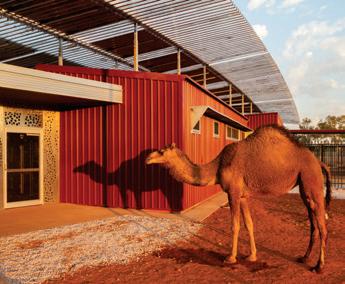

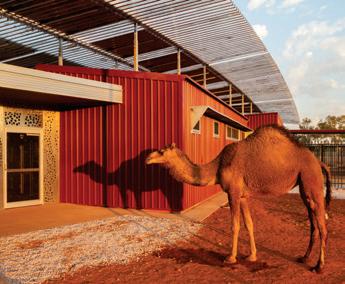

Punmu & Parnngurr Aboriginal Health Clinics, Western Australia by Kaunitz Yeung Architecture

With special comment from Paul Priestman of PriestmanGoode

Tone Wheeler of Environa Studio

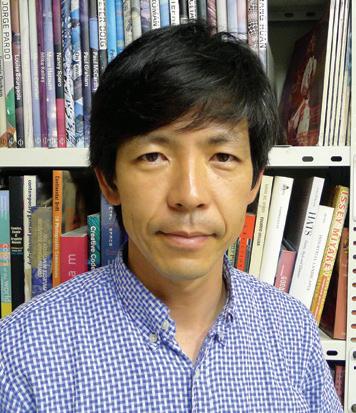

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto of Atelier Bow-Wow

John Doyle of NAAU

Graham Crist of Antarctica Architects

Annie Hensley of fjmt

-

-

-

-

INDESIGNLIVE.COM 26 CONTENTS

Introducing the stylish new black oven range. Combining a sleek, premium design with intuitive features, the new Series 8 black glass ovens provide a contemporary edge over the traditional stainless steel look. Perfect for those looking for something different. www.bosch-home.com.au

the ultimate industry cheat sheet

INDESIGN 29 IN SHORT SHORT IN

Hospitality’s 15 Minutes

Anyone paying attention to modern hospitality typologies will know that it is no longer a singular experience. The name of the game now is duality, where success is as much about the digital experience as it is about the physical. So how are we as designers responding?

Situated within the Nanshan district of Shenzhen, China, Waterfrom Design has envisioned the interior of Doko Bar, a bespoke dessert shop and local hotspot.

Inspired by the famous Andy Warhol quote, “In the future everybody will be world-famous for 15 minutes”, the project focuses on placing diners at the centre of a grand show. With social media and celebrity culture in mind, the venue becomes a 360-degree theatre experience of observing and being observed. From the transparent, open spaces, to the bright colours and ‘Instagrammable’ plates of food. Every step of the process is designed to see and be seen.

The floorplan places diners in a prime position to observe their surroundings. Windows, which are so often the best seats in a restaurant, are also brought into the interior. Frames punctuate the interior space, mimicking the squares of photos found in social media. These elements are also illuminated with light, putting the spotlight on the guests themselves.

The first floor revolves around the chef’s bar; on the second floor the stairs are lined with glass, providing views down to the lower level and transparency throughout the interior volume. Inspired by fashion catwalks, the walkway leading from the stairwell is designed to resemble a runway. In the midst of these layers of glazing, a giant red box seemingly floats mid-air. It is intended to appear as a VIP room, like the balcony of a classical opera theatre – a privileged place from which you can observe and be seen.

In essence, Doko Bar aims to mirror our ever-present social media relationships that are both real and virtual. In doing so it astutely captures our experience with modern hospitality spaces.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 30

INDESIGN 31 IN SHORT

Why So Serious?

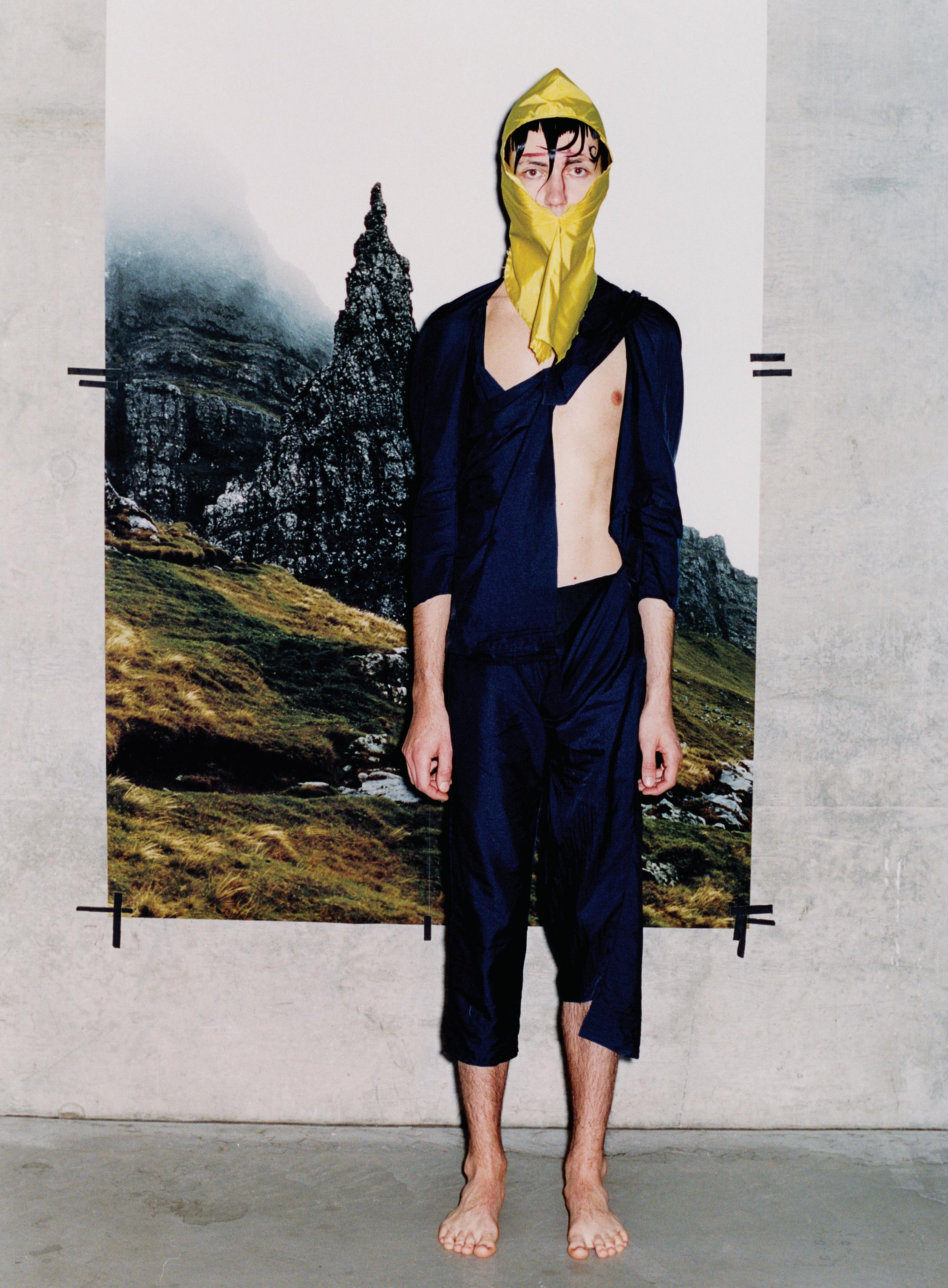

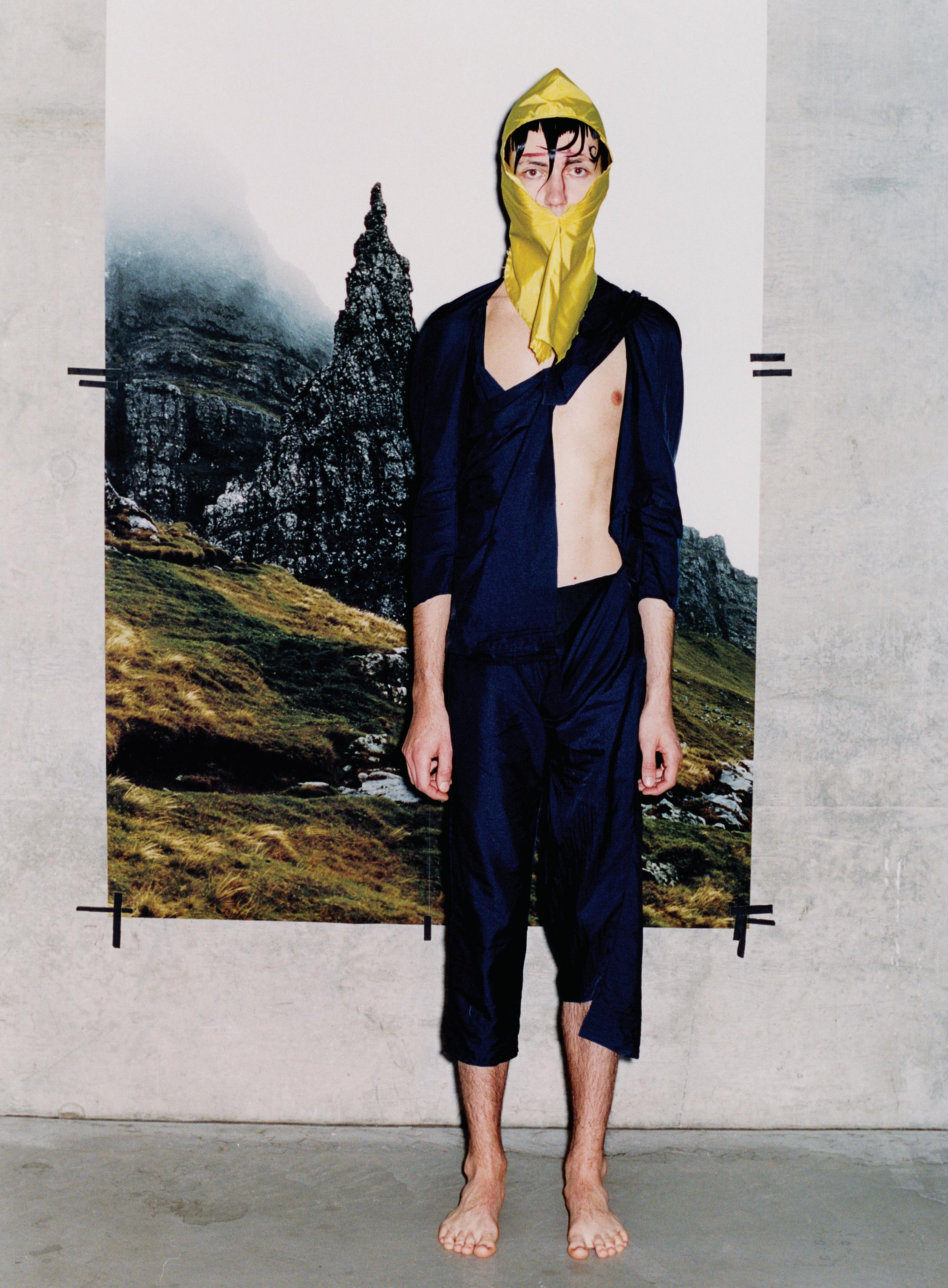

From the moment Walter Van Beirendonck graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp back in 1980 he has continually shocked, surprised and seduced us. His larger-than-life character, defined by strong graphics, innovative cuts and an irreverent approach to fashion, sends us a little off-kilter and has us questioning the world around us. From the long latex jackets, tube skirts and muzzle headpieces of his controversial 1982 debut Sado, to the muscle-tight latex suits of his fetish-inspired Paradise Pleasure Productions (A/W 1998) , his phallocentric Sexclown collection (S/S 2008) and more, Van Beirendonck offers humour and irreverence in the face of tooserious creativity.

They say that behind every joke is a flicker of truth, and that’s what’s so valuable about the exciting catalogue of Van Beirendonck’s work. Each and every collection is so immediately arresting that it forces you to really stop and think.

The man himself says: “I’m a very dedicated fashion designer and it’s still my passion. For me, it’s important that I am a human designer; approachable and very much related to our contemporary world. I believe you can communicate a lot through fashion and that’s what I really like about it.”

For Van Beirendonck, the future of fashion is found in the most raw, unstructured moments. He says that humour is often the jumping-off point to access these greater truths about people and often yields the most authentic results. Just imagine the possibilities for designers in taking this more human-centred approach.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 32

–

–

“All the shows I have ever done are a communication tool,” says Walter Van Beirendonck, a master of humour and irreverence.

Be immersed. Abey Australia’s diverse range of sinks provides you with a selection from around the world. Visit an Abey Selection Gallery to immerse yourself in the collection. Lucia Bowl & 3/4 VICTORIA Selection Gallery 335 Ferrars St Albert Park Ph: 03 8696 4000 WESTERN AUSTRALIA Selection Gallery 12 Sundercombe St Osborne Park Ph: 08 9208 4500 NEW SOUTH WALES Selection Gallery 1E Danks St Waterloo Ph: 02 8572 8500 QUEENSLAND Selection Gallery 94 Petrie Tce Brisbane Ph: 07 3369 4777 www.abey.com.au

The Science Of Socialising

Indesign Zenith

“The idea for [Bayou] was inspired by conversation, the way we meet and greet, and the sociology of interaction. These abstract notions nd their physicality in the gentle, so and open forms of the sofa’s elements,” says designer, Frag Woodall. The Bayou collection is made up of harmonious uid forms and can be con gured in a number of ways to enhance interactivity. Bayou is in its element in de ned commercial spaces as well as open-plan environments.

Royal Nut Company By Breath Architecture

Have you heard? When it comes to bringing a brand to life, exteriors are the new interiors. This was certainly the case for Melbourne’s Royal Nut Company (RNC) when it approached fellow locals Breathe Architecture to give its brand a more iconic home. A Brunswick institution, the Royal Nut Company is a beloved family business that’s been selling wholesale nuts to locals for three decades. In recent times, Melbourne watched RNC change to a sustainable business model reducing its plastic packaging, and sourcing and buying home-grown local nuts. Most notably, it has been working with local beekeepers for its honey and producing its own nut butters.

A fan of the long-standing business, Breathe Architecture was right by RNC’s side when its warehouse was sold to make way for apartments. The designers were keen to help RNC move into its new factory – a vacant site awaiting revitalisation. Celebrating the site’s industrial history, the original character of the warehouse was retained: exposed roof trusses, high-level steel windows, original brickwork and concrete oors. The existing brick warehouse was painted gold, establishing the company’s presence within the industrial area; also a nice nod to the brand’s ‘royal’ status and its in-house honey products. As Breathe founder, Jeremy McLeod, explains: “We wanted to make it functional, we wanted to keep it honest and of course, we wanted to make it gold, very gold.”

Combined with oversized super-graphic elements borrowed from former decades, the façade becomes a memorable landmark, resonating with the royal character of the brand. Internally, a whitewashed material palette was adopted alongside the gold motif that appears throughout. This places emphasis on the Royal Nut brand and the products themselves.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 34

Scape

DESIGNED BY ADAM GOODRUM

ENCOURAGING CONNECTION INSPIRED WORKING RESPITE AND REJUVENATION ENHANCED WELLBEING

An Urban Room With Local Flavour

What makes a city great? Is it the architecture? Hospitality and retail? Quirky locals? It’s no surprise to hear that these are just some of the elements that make a city desirable. Culture is arguably the most significant ingredient in the distinction of any city. Sure, you can have a transit system that runs like a Swiss watch, but it’s really the holistic proposition of lifestyle and local culture that lives at the heart of a metropolis – and its devoted visitors.

In south-western France, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and FREAKS Architecture have designed a major new cultural venue that contains a trio of institutions. Centrally located in Bordeaux, the new 18,000square-metre MÉCA Cultural Centre brings together three regional arts agencies: FRAC for contemporary art; ALCA for cinema, literature, and audiovisuals; and OARA for performing arts.

“Now that MÉCA has opened, the fourth and final element is here: the city and the citizens of Bordeaux,” says Bjarke Ingels, founding partner and creative director, BIG. “Within this new urban room,

we have already seen the arrival of the first skateboarders, the first romantic couple sharing a bottle of Bordeaux on the steps, and the first demonstration on the sloping promenade. So consider MÉCA’s urban room as a blank canvas, or rather an empty frame, for the Bordelais to fill it with their ideas, their creativity, their culture, and to make it their own.”

BIG and FREAKS conceived the building as a single loop of cultural institutions that forms an extension of the promenade. “Not only does MÉCA spill its activities into the public realm and the urban room, but the public is also invited to walk around, through, above and below the new cultural gateway,” Ingels says. “By inviting the arts into the city and the city into the arts, MÉCA [provides] opportunities for new hybrids of cultural and social life beyond the specific definitions of its constituent parts.”

A rich and real designed melting pot of architecture and culture, peppered with plenty of hospitality, retail, and quirky locals to boot.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 36

iQ Surface

HOMOGENEOUS VINYL

Previewed at Milan Design Week, the iQ Surface range is created for designers. The result of a collaboration between Tarkett and Note Design Studio, the range gives equal weighting to function, form and expression of colour. Taking homogeneous vinyl flooring to new heights the iQ Surface range can be used across floors, walls and furniture opening up greater possibilities to play.

WWW.TARKETT.COM.AU

Created for Designers

Living The Gourmet Life

Indesign Gaggenau

Striking a balance between old and new, The Malton contributes to the history of its area (in Beecro , NSW) while also providing residents with “everything they need to lead a contemporary, laid-back lifestyle”, says Dean Chivas of developer Central Element. Lending sophistication to every residence is an elegant kitchen complete with professional-grade Gaggenau kitchen appliances. Think, the Gaggenau 200 series oven and microwave with full surface grill and 90cm gas cooktop – for a world-class gourmet experience.

Holzweiler Flagship Oslo

Is digital design now part of the interior designer’s remit? Snøhetta has designed both physical and digital retail spaces for Oslo-based fashion label Holzweiler, featuring a muted colour palette and gridded elements. Holzweiler was keen to o er its customers a similar retail experience both online and in store, so asked Snøhetta to design a showroom and agship store, but also to create a website to match. “The aim with the showroom, the agship and the online sales channel was to create a seamless and holistic customer experience that brings the brand and people closer together,” explains Snøhetta cofounder Kjetil Trædal Thorsen. A multidimensional brand universe.

Dot-Dot Dash-Dash

Indesign Nightworks

“The modularity of Code enables architects and interior designers to choose from six standard con gurations or use the individual components to create a light that will suit their space,” says Nightworks founder, Ben Wahrlich. The range has been cra ed using hand-blown glass and solid brass and is inspired by the dots and dashes of Morse code. An original design approach sure to make your projects shine.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 38

Life On Mars

With climate change high on the agenda, designers are addressing the challenge in numerous and imaginative ways. Not least of all, considering what life on Mars might be like.

HER, which is located in the centre of the Fashion Walk of bustling Hong Kong, is the ambitious project of stylist Hilary Tsui and created by Clap Design. Angela Montagud, Clap Design cofounder and studio director, says: “We came up with three key points that reflected the essence of HER: femininity, purity and strength. We imagined immediately a sinuous landscape, with impressive mountains and pure materials. The aim with this store is to transport the user to a new planet, so we designed an entire experience around this principle.”

From the façade that shows the mountainous landscape of the interior, to the moment in which the user receives their purchases specially ‘space packaged’, shopping at HER is a curated series of experiences that are altogether martian-esque.

Stacked terracotta display plinths and celestial aluminium partitions create an other-worldly atmosphere which Clap likens to “reddish mountains”, where accessories can be displayed or visitors can pause and dwell. The tiles have also been applied across the floors and the lower half of the store’s exterior.

Clothing items are hung from suspended racks shaped in waves. Jewellery is presented on pale circular tables supported by thin metal stems, intended to resemble “small white lotus leaves that grow from the mountains,” says Montagud.

As well as the service counter in the café, structural columns and an arched partition have been clad in spacecraft-style aluminium. Continuing the space theme is a handful of portholes – akin to those seen on a rocket – which have been cut-out of the peripheral walls and covered with orange-tinted glass. Rounding out the customer journey is the take-home surprise: your purchased goods vacuumpacked – much like an astronaut’s food.

INDESIGN 39 IN SHORT

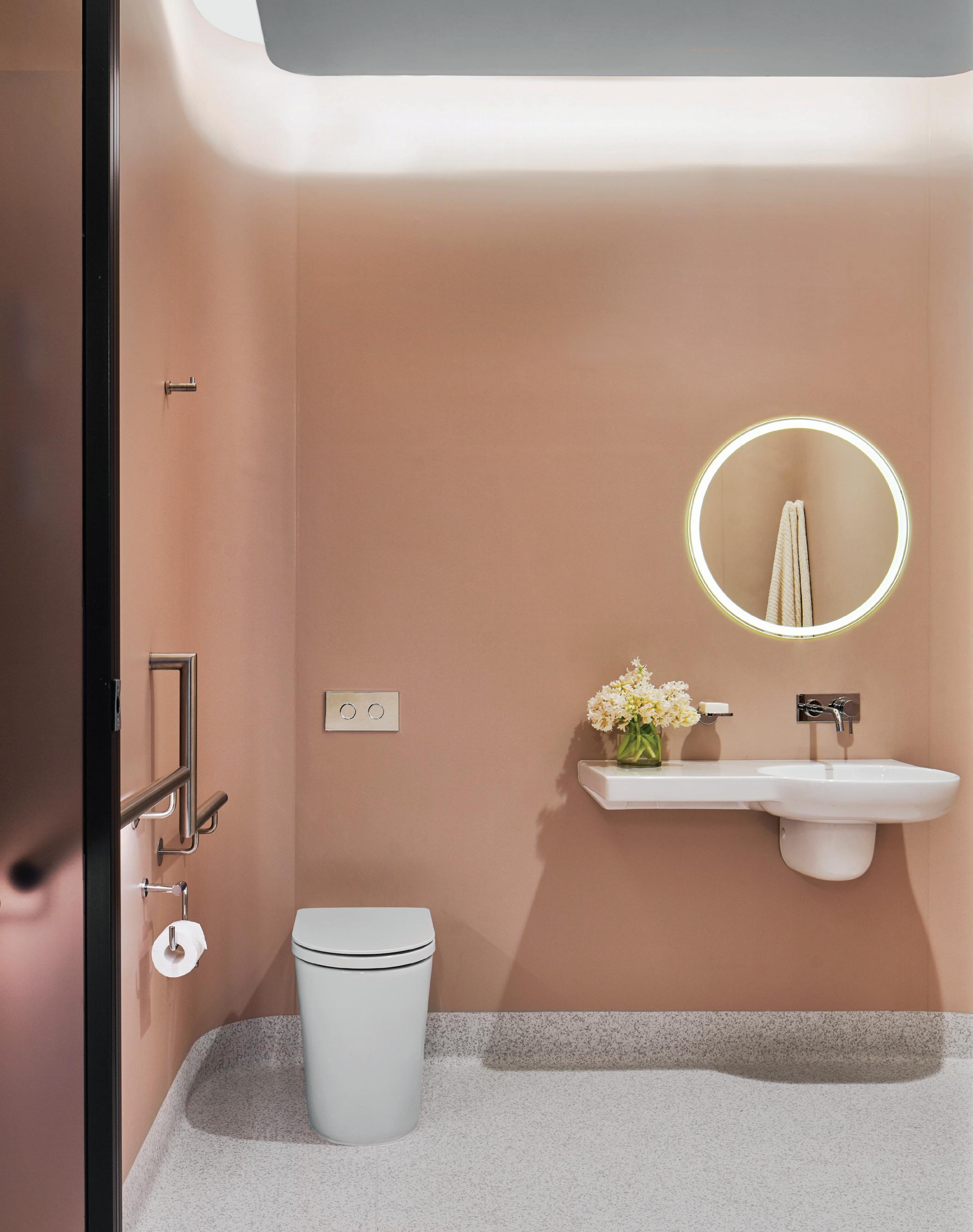

It’s Only Natural Kangaroo Valley Outhouse

Sustainability is a tough nut to crack. While we all talk a big game about reusable or sustainable materials, we rarely discuss spatial impact – specifically the affect of our designs on a site’s natural habitats and cultures. Designed by Madeleine Blanchfield Architects, the Kangaroo Valley Outhouse is a bathroom in the bush which services a nearby cabin for overnight stays. The concept was to separate the bathroom from the cabin

and mimic the experience of camping. It is situated low on a hillside, about 30 metres from the accommodation and accessed via a pathway though dense landscape. This mirrored cube, elevated above the existing ground and nestled in vegetation, completely disappears during the day. Reflecting the lush landscape, only the subtle lines of the cube’s edges are visually legible. Once inside, its all-glass walls afford 360-degree views.

Could an uninterrupted design approach herald a new-generation approach to sustainability within the built environment?

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 40

–

–

Oasis Of Calm

Indesign UCI

Designing for wellness and the human experience – it’s by no means a new concept but what does it look like in the modern age? Making a landmark statement from the outside in, the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (VCCC) has been able to achieve a welcoming, comforting and restorative space that puts human needs front and centre.

Designed by DesignInc and Silver Thomas Hanley with McBride Charles Ryan, and completed in 2016, the space features sweeping curves, so light and natural timbers, which all come together to de ne the specialist hospital. Punctuating the calming space is a series of custom furniture items, created in collaboration with UCI Projects. Throughout the large-scale medical precinct 1800 chairs dot the space, specially made to withstand the niche needs of a medical environment.

The building’s exterior is a physical manifestation of the concept of networks and clusters converging. Taking this line of thinking inside, zones for di erent purposes like waiting, eating and socialising have been integrated at careful junctures to encourage engagement. In collaboration with the design team, UCI delivered comfortable, durable seating options for VCCC’s high-tra c spaces. Within the cavernous building, the so furnishings help to anchor the functions throughout. As such a signi cant healthcare environment, getting the right balance for patient-visitor wellbeing has made all the di erence to the project’s success.

On A Sit-To-Stand Health Kick

Indesign Stylecra

Studies on the bene ts of sit-stand desks have revealed a noticeable improvement in productivity along with reduced back pain among users. People also admit to feeling more focused compared to sitting hunched over a laptop all day.

Built for today’s agile workspace, Stix is a workstation and table system by Thinking Works available with a height-adjustable framework. For added privacy, the sit-stand desk comes with screens upholstered over an acoustic PET board or manufactured with exposed acoustic PET from a range of PET colours.

What Lies Beneath

Indesign Milliken-Ontera

To feel both safe and upli ed within a healthcare environment is a unique combination that inspires con dence and promotes wellbeing among patients, sta and visitors alike. The right ooring, for instance, has been shown to help with patient recovery while also improving sta e ciency. With elegant organic tones and seamless textures, the Manaaki collection by Milliken-Ontera helps create a calming experience in healthcare spaces. Its antimicrobial treatment also contributes to a healthier interior environment.

INDESIGN 41 IN SHORT

Hashtag Cool-porate Campus?

Instagram-ready offices are really hitting their stride. Why? Because they are designed to encourage Millennial employees to forget they’re in an office park and, it seems, the Millennial workforce responds best to blurred environments that mimic their non-professional lives.

Perkins+Will has overhauled the North American headquarters of consumer goods company Unilever with new communal areas designed to challenge workers’ perceptions of the traditional suburban office park. Unilever has long had its headquarters in New Jersey, just across the river from New York City. But increasingly the company has needed a more dynamic work environment to help recruit employees.

Perkins+Will was charged with rethinking the corporate campus, which accommodates about 1450 employees and several hundred independent contractors. The goal was to create a showpiece headquarters that would be “smart, sustainable and Instagramready with a feeling like you were in Manhattan”, say the architects.

Rather that razing the site and starting fresh, the architects chose to renovate four existing 1960s and ‘70s rectilinear buildings. They also added a lofty central atrium that rises 12 metres on the site of a former courtyard. “The [30,000-square-metre] renovation included interiors, as well as the construction of an entry pavilion and common area that stitched together the open space between individual buildings to create an entirely new, enclosed structure.”

The existing buildings have been revamped with open workspaces, huddle rooms, lounges and lockers. The central volume houses The Marketplace where employees can shop, work and socialise. Additional amenities include coffee stations, a fitness centre, hair salon and cafeteria. The building features a range of smart technologies including thousands of sensors that measure light, temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide and human presence. If this is what companies are facing to attract and retain talent, the challenge for designers is then to find new ways of making the workplace a compelling and hashtag-worthy experience.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 42

Visit: 27/69 O’Riordan Street Alexandria NSW 2015 | Call: (02) 9313 5400 | Web: bludot.com.au

Rest And Find Relief

Indesign Krost

O en transitional spaces in healthcare facilities – those areas where patients and families are caught in a seemingly endless ux of waiting – feel uncomfortable and appear unappealing. With the concept of care embedded so deeply within the healthcare experience, simple and e ective choices can make all the di erence.

Good furniture design can o er comfort by supporting a range of postures and activities – conversation, information sharing, resting. It can also provide a smooth transition from pain and emotional uncertainty to relief and vital information.

Enter Nina, a unique and practical occasional chair by Krost. The chair o ers supreme comfort through its highdensity foam padding and full micro bre upholstery. Its generous sizing – coupled with the use of commercial-grade fabric and rigorous quality testing – means it is exible to its application and context.

Let’s Talk

Bathroom Ergonomics

Indesign antoniolupi

Ergonomics as a concept is expanding in its contextual relevance, moving beyond the ‘expected’ realms of desking and task-seating to address the environments and products that are most connected with our bodies. In particular, ergonomics has become a central principle for bathroom designers specialising in those elements such as baths, toilets and more.

With designers prioritising the creation of healthier and safer bathing environments, end users today have the ultimate luxury of a space that looks and feels good. Just like the Mastello bath designed by Mario Ferrarini for antoniolupi. The design is rmly anchored by the concept of safety and ergonomics with emphasis placed on added functionality, as well as relaxation and a memorable bathing experience.

Ferrarini has designed the Mastello with a comfortable, integrated seat and an edge that rises gently to act as a headrest. The internal seat makes for comfortable submerged reclining while an external wooden step means you can hop in and out of your tub with ease. At 135 centimetres in length, the bath is ideal for integrating into smaller spaces. And, it can comfortably accommodate users up to a height of 195 centimetres.

Envisaged as a spacious bath and a micro oasis for relaxation, the Mastello really embraces its uid lines with so shapes and smooth surfaces that appeal to our haptic senses. Through its very design, the bath gives back to the body and mind. An embracing of wellbeing and ergonomics in both form and functionality.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 44

WHERE PORCELAIN BECOMES ART

Lladró Boutique 143 York Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 Australia

lladrosydney@formfluent.com

now open in sydney

Seeds Of Success

Ahh the pop up. It’s retail’s most valued currency right now – particularly when it comes to bringing customer experience strategies to life. While we may not have a hand in creating these strategies we are certainly charged with the responsibility to develop their physical manifestation. The secret it would seem is in high-impact solutions that speak to the tenets of a brand and resonate with its customer base in a meaningful way.

Recently cult beauty brand Glossier teamed up with landscape designer Studio Lily Kwong to create a pop-up shop in Seattle, USA. Most notable was its seemingly sub-tropical interior – a proverbial walk in the park. In collaboration with Kwong, Glossier’s in-house team drew inspiration from the area’s natural topography, including the close-by Mount Rainier and their much-loved neighbourhood park.

“A er talking to people in the area and doing some on-the-ground research, we were really inspired by everyone’s love for nature and how it seemed to be a unifying theme within the community,” said Kendall Latham, Glossier’s senior environmental designer. “With Glossier Seattle, we wanted to capture the mood of the surrounding landscape and represent the juxtaposition of nature and technology in the city.”

Visitors stepped into a bright space lled with plant-covered mounds of varying sizes. Live moss, Mexican feather grass and owering shrubs adorned hills constructed from wooden ribs and wire mesh. White display pedestals topped with Corian surfaces mimicked walls of stark white – a clarifying contrast to the verdant hills and raw pine ooring. The team also incorporated large-format imagery in tones of pink and purple, a signature of the Glossier colour palette. The perfect fusion of global brand and local community with a side of installation that feels refreshingly le -of- eld and yet relevant.

The Urban Edge

Indesign Phoenix

Conservation is all about striking a balance between preserving the special character and signi cance of a heritage area while bringing about change in a way that sustains it into the future. The Chestnut Townhouses in Cremorne, Melbourne, designed by NTF Architecture make for an interesting study, exploring new forms of interaction between urban dwellings and their heritage surroundings. Their built form appears unembellished so as not to visually compete with the decorative heritage buildings in the vicinity. Even materials used are simple, unre ned and robust to complement the surrounds. In contrast, the townhouses’ interiors feel contemporary and modern, o ering a combination of luxury, comfort and convenience to residents. This is particularly evident through the selection of tapware and bath accessories. In fact, in a couple of the boutique townhouses, Phoenix was the brand of choice for the kitchen and bathroom designs. The bold matte-black nish of the Vivid Slimline Sink Mixer (pictured above) succeeds in lending character and an industrial urban edge to NTF’s kitchen design and the surrounding living zones.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 46

(Photo: Shannon McGrath)

‘Reefs’ by Dauphin is inspired by the infinite variety of coral reefs, and provides solutions for the open office environment by offering comfortable structures with visual and acoustic privacy.

The Reefs modular system adapts to the unique requirements of organisations, individuals and tasks and allows unlimited design options, from configurations that foster collaboration to hideaways for quiet focus.

Available now from Business Interiors – the home of innovative furniture solutions.

businessinteriors.com.au/indesign 1300 301 110

Sustainable Coatings For Healthy Spaces

It’s that rst moment of arrival in a space that de nes your direction – that transcendent moment of breaking through the threshold and soaking in the artistry, design and cra smanship that is embedded within a building’s walls and ceilings. Yet powerful, considered and thoughtful design comes down to more than just aesthetics – it has the ability to make you feel good and positively a ect your physical, mental and emotional state.

Revolutionary architect, Luis Barragán once said: “Architecture is an art when one consciously or unconsciously creates aesthetic emotion in the atmosphere and when this environment produces wellbeing.” That shi towards health and wellbeing within the built environment continues to be paramount, and the ability to engender change through design comes in the most intelligent of forms. In search of an artful balance of promoting wellbeing and providing an aesthetic sanctuary, Australian-based company, Wattyl is committed to creating the best products and materials that achieve this.

An advocate of good design, healthy spaces and product innovation, Wattyl has introduced I.D Advanced. Paint is a key consideration in human health – it is a material that promotes a nurturing atmosphere within a space that extends to the futureforward thinking for wellness spaces of tomorrow. The instinctual and sensorial response to a newly nished space needs to have a welcoming and comforting feeling that eliminates the toxicity of paint smells.

“Our inspiration was to build on the platform of the previous Wattyl I.D range to have a further positive e ect on the indoor environment and the health of inhabitants,” says technical director at Wattyl, Matthew Fitzgerald. Determined to mitigate toxins and enhance air quality, Wattyl’s most advanced paint

has an impressively low VOC formula that surpasses the Green Star requirements of the Green Building Council of Australia. I.D Advanced is the latest in Wattyl’s centennial company history in protecting, enhancing and elevating high performance coatings of Australian buildings.

Wattyl o ers a paint that eliminates the shock of ingesting the chemical smell and toxins within a newly nished project and a product that genuinely cares about the people inside the space. Durable, versatile and dynamic, the product’s Total Protection Technology™ delivers a new level of protection o ering advanced cleanbility, washability and stain resistance. Designed for tactile experiences, the interior paint formula elevates any space with its extensive and contemporary range.

“The bene ts of low emissions from I.D Advanced, containing VOC<1g/L minimises impact on indoor air quality. I.D Advanced has been formulated and tested to meet globally recognised antimicrobial standards, improving environments such as hospitals, healthcare, educational and institutional spaces and meets the requirements of long service life,” Fitzgerald adds.

Environmentally sound and re ned, Wattyl I.D Advanced boasts architectural and ethical advancements all in one product. It o ers technical innovation with a touch of sophisticated elegance that celebrates building materials that enhance the way people live and use spaces.

With health and wellbeing at the forefront of the product and brand’s philosophy, it recognises that healthy, human-centric spaces are a right and in this contemporary context, it should be at the start of every conversation. The nished product of I.D Advanced is designed for the present married with an exceptional awareness for a better, cleaner and healthier future.

WATTYL.COM.AU 48 INDESIGN WATTYL

Words Emily Sutton Photography Courtesy of Wattyl

Wattyl worked on the Charles Perkins Centre at Sydney University to use its revolutionary building materials to support the research centre’s committment to improving global health.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 50

Humble Pizza Hearts Formica

Nostalgia is a powerful tool for creating hospitality venues that appeal to our emotions and gain our loyalty. Nineteenfifties-style milk bars, rock ‘n’ roll burger diners and kitsch bars are nothing new. So how are we taking nostalgia to the next level?

Designed by Child Studio, Humble Pizza is London’s latest hospo-hotspot. Situated on King’s Road, a boutique-lined street in the affluent Chelsea neighbourhood, Humble Pizza boasts a menu of exclusively plantbased pizzas.

Its almost entirely pink interiors have been designed by Child Studio to emulate the aesthetic of the workmen’s cafés, commonly known as greasy spoons, which sprung up across London in the 1950s.

These cafés served no-frills food and typically featured pastel-coloured surfaces made from Formica, a laminated composite material invented in 1912. “We have long been attracted to the cinematic quality of London’s ‘Formica cafés’, the duality of Modernist design language and the playful, almost cartoonish spirit,” explains Chieh Huang and Alexey Kostikov of Child Studio. Apart from the white tile floors, surfaces throughout the eatery are clad with cherry wood-framed panels of pink Formica. The material has also been used to cover the countertops of the circular dining tables and the service desk that sits beside the entrance. The studio worked closely with the Formica factory to give the panels a subtle, linen-like pattern.

A candy-pink seating banquette runs towards the rear of the eatery, where a partition with recessed opening looks through to a forest-green kitchen. The opening is fitted with lights to draw attention to the chefs at work, creating what the studio hopes will be a “cinematic focal point”. “This project aims to create a contemporary version of this unique typology,” say Huang and Kostikov.

It certainly does that, along with its décor of pink broadsheet newspapers hung intermittently across the walls. Definitely a fit-out that tugs at locals’ heart-strings, and awakens the interest of visitors who ‘heart’ Formica extra hard.

INDESIGN 51 IN SHORT

Arch-tivist: Odile Decq

French architect Odile Decq studied architecture and urban planning in Paris, back when having these dual qualifications were in every architect’s interest. They’ve been pivotal in establishing Decq as an international leader in design, and a luminary to women in design. Decq was in Sydney recently for the SCCI Architecture Hub. She delivered a keynote address on architecture as place rather than building.

In an exclusive interview with Indesign, she tells us: “I am an activist. My architecture is [about] activating cities. When I do a museum, office building or home, architecture is [literally the] activist” – of a site, community and the individuals within. “I always look at a building as a place, not an object,” she says. “It’s a place of living: doing something in your life.” Understanding a site and its urban context is vital to conceiving a built environment. Before any project, she visits “the place [site], the surrounds and the people for whom I have to build, and after that I start.”

Decq likes to break bread with the people who will interact with her architecture.

“I always have a meal with them – by having a meal with them I understand how they socialise. After that I go to the site, walk on the site and understand what is around. This is really a journey, to the place and the people that are living there.”

Activism manifests in many different ways for Decq who also considers herself an activist for women in architecture. She believes young female designers need strong role models from above. “We need woman in powerful positions to aspire to,” she says.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 52

–

–

A champion for women in design, and for architecture as a product of place and people.

SIMPLE, INTUITIVE, ADAPTIVE. MOVING WALLS - FOR THE CREATIVE AND DYNAMIC WORKPLACE. www.t-c-w.com.au SYDNEY 02 8070 9314 MELBOURNE 03 9614 3333

The Art Of Cra

Indesign Rocks On

Cra smanship is a marker of quality and at the core of successful design. Just like the wide range of meticulously cra ed porcelain and ceramic, wall and oor tiles from the house of Rocks On. With a new range of uniquely designed oor tiles and nishes in an assortment of sizes, the brand has also launched wall and feature tiles, inlaid timber wall panelling, and bookmatched luxury stone slabs. Interestingly enough, all the tiles have been created from hard-wearing scratch, stain and acidresistant porcelain, ensuring surfaces stay evergreen and beautiful for years together.

Wear Your Emotions On Your Sleeve

Fashion as personal expression takes on new meaning in Beatrice Sangster-Bullers’ recent collection, The Order of The Singularity, which sees arti cial intelligence integrated into the garments to map wearers’ mental states and display their emotions. Models were given an electroencephalogram (EEG) brain-activity recording device to measure their brainwaves. This was linked via Bluetooth to a screen interface tted into the chest of the garments. Algorithms converted the EEG signals into audio and visual outputs, allowing users to hear and see their brainwave data in real-time on their smart devices. Sensors also tracked heart rate, body movement and breathing. The wearer could choose what visual output they projected onto their clothing – a virtual display of emotion.

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN SHORT 54

The World Of Tom Dixon

Words Emily Sutton Photography Peer Lindgreen

The new creative studio of Tom Dixon at The Coal O ce is a celebration of experimentation and innovation of art, design, culture and community as a collective movement. Reimagining the 21st century retail experience, Tom Dixon looks beyond the boundaries and cra s a truly immersive experience that encapsulates the future-forward way of living, working and entertaining.

LIVINGEDGE.COM.AU 56 INDESIGN LIVING EDGE

LIVINGEDGE.COM.AU 58 INDESIGN LIVING EDGE

Design has the power to create a feeling, to make you question the details and push the boundaries of innovation and creativity. It is a medium in which designers showcase their narrative and their personality – giving them an opportunity to de ne their own style.

A pioneer, leader and boundary-pushing creator, Tom Dixon continuously brings exciting design propositions to areas of lighting, accessories and furniture. The Tom Dixon brand itself encapsulates a distinct nature and a joyous, quirky and rigorous of design.

Breaking barriers in conventional shapes and textures of lighting and furniture, the meticulous and exuberant cra smanship of Dixon’s pieces are celebrated within the new studio of The Coal O ce by Design Research Studio (DRS). A restless innovator, Dixon established DRS in 2003 under his design direction as a trailblazing creative powerhouse across high concept interiors, architectural design and branding projects for the spaces and brands of tomorrow. Against the historic industrial backdrop of Coal Drops Yard in the iconic area of Kings Cross in London, The Coal O ce is the new home for Dixon’s latest experiments and collaborations, and a multi-disciplinary platform that puts the spotlight on innovative and thoughtful design.

As one of Britain’s brilliant, anarchic and creative minds, Dixon has cra ed a hub of creativity, combining a shop, workshop and o ce with a restaurant and café to showcase his brand’s latest ideas in interior design and product innovation.

It’s a truly immersive experience, elevating our interaction with the brand to a holistic and spatial level. Dramatic and robust within the site’s existing fabric, the interior space allows Dixon to put his re ned, sculptural pieces into action. Stepping into the doors of The Coal O ce is a transcendent experience of past, present and future,

where ornamental collections of lighting and furniture illuminate the space and highlights the brand’s ingenious engineered materiality and cra smanship.

As a multi-disciplinary agship that encompasses the future of living, working and entertaining, The Coal O ce works to rede ne the way we experience multi-functional spaces in the contemporary context. Dixon’s vision is focused on product development and integration tailor made for the multi-use, adaptive and agile spaces. Curated with furniture and lighting pieces to represent the story and journey of authentic design, the space encourages visitors to indulge in the brand philosophy and versatility of the new workspace.

Consistently changing the pace in food, functionality and future living, the pieces on show enhance the workplace experience and focus on fashion, cra and culture as a collective movement. Statement lighting hangs from the exposed ceiling to create a visual beacon within the space. De ned by sculptural archways, each zone celebrates design through vibrant colours, distinct forms, luminosity and a multitude of furniture pieces. A veritable journey across the full breadth of Dixon’s creative spirit and distinct approach.

Sharing Dixon’s passion for sophisticated and extraordinary design, Living Edge is proud to bring his inimitable work to Australian shores. Living Edge believes in brands that represent a lifestyle and a story. A new edition to Living Edge, Tom Dixon rede nes the traditional workplace with contemporary pieces and elements that take the nature of the o ce to the next level. Driven by sophisticated design and exceptional, authentic and innovative spaces, Living Edge celebrates interior pieces that enhance the way people live in the present and for the future generations –synonymous to the philosophy of Tom Dixon.

LIVINGEDGE.COM.AU 59 INDESIGN LIVING EDGE

FACADES BY

FACADES NOW AVAILABLE

REDEFINING ARCHITECTURE

Transforming imagination into functionality, Neolith Facades are now available. After years of development, Neolith is the superior standard in surfaces. Neolith Facades have redefined European architecture. Neolith is suited to a range of cladding applications and can be used with multiple cladding systems.

Talk to our Neolith Specialists today to discuss Neolith’s certifications and which cladding system best suits your application. Add a complete and consistent finish to your next project with Neolith Facades.

Proudly brought to you by CDK Stone.

ESTATUARIO | CLADDING Discover more at www.cdkstone.com.au

Big thinkers and

C reati V e gU rUs

INDESIGN 61 IN Famous FAMOUS IN

An Arranged Marriage

Thrown together by circumstance, Kirsten Stanisich and Jonathan Richards formed a professional partnership that has seen them grow, flourish and forge a brand of their own.

INDESIGN 63 IN Famous

Words Paul McGillick Portrait Photography Charles Dennington

INDESIGN Luminary

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN Fa MO u S 64

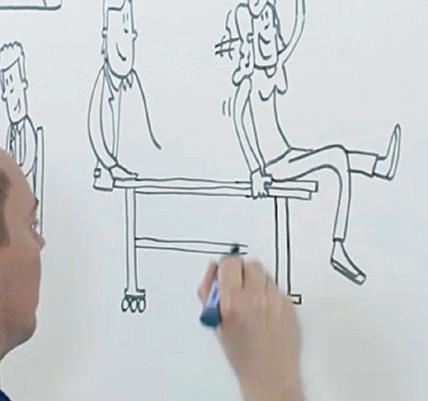

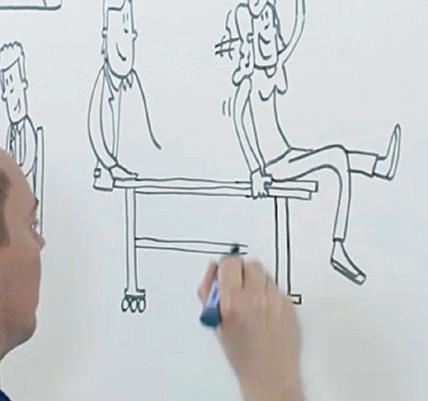

Quizzed about whether the success of his partnership with Kirsten Stanisich is because they are similar or different, Jonathan Richards comments that they are quite different. “I didn’t ever go to Kirsten and say, ‘Hey do you want to start a partnership?’ We just found ourselves together. It’s like an arranged marriage. A company just joined us and said, ‘You guys will work well together’.”

He says they are good friends and with an equally good working relationship. “We have lunch all the time, we hang out together – it’s a very easy conversation and throwing up of ideas.” But Stanisich quips that “it’s like having a big brother who can tell you to pull your head in”.

The company that brokered this professional marriage was SJB, the Melbourne-based architecture and interior design firm which 23 years ago sent a fairly raw young architect and designer, Stanisich, to Sydney to start up a new branch of the practice.

For Stanisich, architecture hadn’t been an obvious choice. She was halfway through a classics degree when she bailed out into architecture at Melbourne University. “If the world was a different place,” she elaborates, “I would love to be a fashion designer. When I say fashion, I don’t just mean things changing, I am talking about the essence of materiality, silhouettes, fabrics. To me fashion really reflects what’s happening socially.” But at university she was sustained by a group of fellow architecture students who helped her clarify the path forward.

Following graduation she worked for an architect in Melbourne for two years before joining SJB. “I ended up working with Andrew Parr on the casino in Melbourne and I realised I really liked the interiors side, so I [stayed] in interiors. Andrew’s got an incredible energy about him. And he just loosened me up about the possibilities of what things could be.”

Sydney was a challenge and she says she was “thrown in the deep end a bit”, but it was the “right place at the right time” and she got to work with Andrew Parr on iconic projects such as MG Garage and the Establishment Hotel.

Richards’ early years were equally circuitous. He didn’t really know what he wanted to be, but at school he was good at drawing and liked maths. “I didn’t even know what architecture was, really. I wanted to be an artist. But my dad didn’t support me, saying I’d never make any money as an artist. I didn’t really believe him, but I was too scared to just embark on being an artist. So, I enrolled in interior design [at University of Technology Sydney] thinking it might be an artistic form of architecture. I did like modern buildings and I liked being in them, but I didn’t think I was capable of architecture. With interior design I thought I could draw and use my artistic passions in some kind of three-dimensional shape. And I really enjoyed it.”

His first job was with BVN (originally Bligh Voller), which he loved. Then he thought he should get back to his “artistic leanings”, so he went into exhibition design, working for Freeman Ryan before

INDESIGN 65 IN Famous

“If the world was a different place I would love to be a fashion designer... To me fashion really reflects what’s happening socially.”

Page 62 and page 66: “We have lunch all the time, we hang out together – it’s a very easy conversation and throwing up of ideas.”

– Jonathon Richards of Richards Stanisich. Opposite: Hotel Rose Bay, Sydney, builds on its historical narrative with Art Deco-era references, photo: Felix Forest. Page 67: The Bell Table by Richards Stanisich, handcrafted by The Wood Room, photo: Tim O’Connor.

becoming the exhibition designer for the New South Wales State Library. He then went to live in London, returning in 2002 with a view to working with Burley Katon Halliday (BKH). But a friend suggested SJB instead. His friend said “they were completely different to BKH. It had a Melbourne aesthetic, darker. So I went to an interview with Kirsten and Andrew [Parr]. I got the job and I started working from 2003.”

All up, Stanisich worked for SJB for 23 years, 15 of them as a partner, while Richards worked there for 15 years, 10 of them as a partner. In time, they became the sole owners of SJB Interiors Sydney.

But for a long time they remained partners with Andrew Parr and Michael Bialek who Richards describes as “a real mentor to both of us, a kind of father figure, a gentleman”. In effect, the many years at SJB were an apprenticeship and one of the benefits was that “there were older people who could teach us the economics of running a business and the financial side of running a design practice – making it profitable so that you could keep doing it”. All of this put them in an excellent position to branch out as an independent practice.

Essentially it meant simply re-branding so that now, just over a year after the launch of their own practice, they retain their clients, the same staff, even the same studio. “It had an emotional impact,” says Richards, “but on a pragmatic level we simply changed the name on the door.”

Psychologically, it has certainly made an impact – the kind of impact necessary to refresh the practice and bring it toward new horizons, which now include furniture and product design. Richards says they now feel more “hands-on, there’s a new ownership, a new way of working”. He has noticed that they take extra care when presenting and he and Stanisich have established their own studio space where they can experiment privately with materials, samples and finishes – what Stanisich describes as “a sanctuary space where we can go and think”.

So, what makes the ‘marriage’ work? Is it because they are alike, or because they are actually different and complement one another?

“I think,” says Stanisich, “the main thing is that we have a strong aesthetic together – not just in the look and the feel, but the whole idea of what we are designing and why we are designing.” The fact that they work at a boutique scale means they can change the way they work if appropriate – something more difficult to do in a larger organisation. This is evident, says Richards, in the way they are becoming “more detailed, more tailored” and, adds Stanisich, with “more of an obsession for fabric”.

richardsstanisich.com.au

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN Fa MO u S 66

Raw, Primal, Simple

“We like to keep things a little raw and primal — objects so natural that you have an immediate association with the design,” say Richards and Stanisich of The Bell Table. With its sculpted base, plinth footing and carefully softened edges it draws people in to face one another in a joyful and almost primal communion.

–

So Artificial! Stephen Crafti questions the motives behind overly styled spaces that strip out true personality for the “ubiquitous” throw.

Words Stephen Crafti

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN Fa MO u S 68

In the early 1990s, I was covering a significant architectdesigned home for a magazine. The distinctive house, with its curvaceous white walls and dramatic voids, was filled with the finest Italian designer furniture most could only dream about. With notepad in hand, I witnessed virtually the entire contents carried to the garage. Flimsy and inexpensive white soft vinyl furniture was brought in, not surprisingly, curved. The owner of this home looked on in despair while the photographer and stylists patted themselves on the back!

Decades later, furniture that doesn’t quite ‘fit’ the theme of a photographic shoot continues to be shunned in favour of what’s perceived as the latest and greatest. Houses, along with apartments and even workspaces, become less authentic with the goal to creating generic images that are intended to appeal to the imaginary visitor, be it an editor, a reader, a potential client looking for an architect or designer, or perhaps a buyer. Given how many high-rise apartments look virtually identical to one another, one would think the idea would be to create something new and exciting. But how many versions of a lounge or bed stacked with cushions and the ubiquitous throw can be recreated? Just pause a moment and think about entering an apartment for the first time – whether in reality or on a sales flyer – and seeing something unexpected. It could be an armchair handed down through family generations or a piece of art that speaks of another time in history. Not all antique furniture has to look as though it’s covered in cobwebs!

Stylists and others in the design community certainly have a role to play in this industry. Let’s face it, no one really wants to discover a room full of junk that makes a space feel uncomfortable. And who doesn’t like to see clean windows, beautiful flower arrangements and a few great designer furniture items? But ‘sanitising’ these spaces as though people have never entered them has become more the norm than the exception.

Obviously images need to be controlled to highlight architectural and design qualities. But where’s the ‘voice’ that tells you about the bigger picture of the design? In

an office, for example, not everyone works in a breakout space or a comfy armchair. Work also takes place around workstations with files and plans strewn across tables and benches. Many architects and designers have a tendency to strip an office completely and create empty rooms or, alternatively, bring in the stylists and see a functional space become a showpiece.

Those images make many people feel uncomfortable. If a house is on the market for sale, I would much prefer to experience a sense of the owners, how they use the spaces and the odd little quirks that express human nature. Seeing a house void of personal contents, with ‘props’ orchestrated within an inch of their lives, does nothing for the design senses.

Thankfully, there is now a subtle shift in the way spaces are presented, taking small but incremental steps towards authenticity. We see some stylists and photographers creating unique settings that capture both the spaces and the owners who dwell within. But unfortunately, there are still those stylists who see themselves as designers. Everything gets moved out and a ‘look’ is moved in.

What’s the remedy? I feel it’s a case of two steps forward and one step back. Do architects and designers need to be more vigilant when stylists move in? Do owners, be they sellers or proud homeowners, need to be more forthright when they see their belongings shuffled into a spare room or garage? Or is it simply waiting until the market reacts to these mocked-up rooms – only then might the focus shift?

Fortunately, I have not been a witness to a mass clearing of a house since that day in the early 1990s, when I was then relatively new to this industry. But I regularly walk into homes where an amateur stylist has made their mark. Everything is so artificial, with no sign of life.

Agents or property managers may argue that these makeovers allow people to envisage how a space could be used. But aren’t people more design savvy now? Surely they realise there’s simply no one home.

INDESIGN 69 IN Famous

Stephen Crafti is a prominent Australian architecture and design writer.

Reading The Zeitgeist

INDESIGN 71 IN Famous

Words David Congram Portrait Photography Alana Dimou

In a world that feels less and less clear-cut, designer Sebastian Herkner upholds a philosophy of the specific that presents us with a cure for identity crisis.

“When I was a child,” says Sebastian Herkner, “I would travel around Europe with my parents. We would stop at a village, and often this village was dedicated to crafts. This one would be dedicated to ceramics, that one to gloves – and things like that. Even as a little child, I was always interested in the crafts of these places. I think that’s where it all started – my journey into the design world.”

As far as journeys go, this one is fairly enviable. From boyhood reconnoitres of Europe’s company towns to, earlier this year, being awarded one of the design industry’s highest accolades –Maison&Objet’s 2019 Designer of the Year – Herkner’s career trajectory can only be summed up as preternatural.

“He’s made it!” say some. And perhaps they’re right. After all, in the possession of accolades some designers spend half-centuries chasing, it would appear that at the youthful age of 37 Herkner is already flirting with luminary status. The credentials stack up to suggest as much: a German Design Award, Cologne IMM’s Das Haus, a Red Dot, the IF Award, the Iconic EDIDA Award –not to mention stints with Stella McCartney, Moroso, ClassiCon, Cappellini and now Wittmann, among other stalwart brands. Laurels aplenty – but he refuses to rest.

So much so, in fact, it was a stroke of luck I even caught him in Sydney. He had just arrived from Perth, via Europe, Asia and a brief visit to Zimbabwe. He was off again in the morning. I ask if he finds it exhausting to travel so often. “No. It is so important to how I work. Opening myself up to new experiences, people and objects, I find inspiration every time.”

And without fail seemingly every time, he’ll find something more concrete, too. During our talk he excitedly describes Bulgarian cake pans, French secateurs, Malawian woven baskets and Chinese brushes travelling in his suitcase from the farthest-flung climes, eventually finding home back in his Offenbach studio in Germany. From here, they’ll rouse into new life inspiring, say, a chair for Thonet or lamp for Gubi.

Macarons are a recent acquisition – I could just tell.

“Do you know Ladurée, the pâtisserie in Paris?” he asks me (and boy, do I ever!). “When I was there looking at the macarons, I thought their form was so perfect – they have a kind of elegance and confidence, you know? – and it was something very similar to what I wanted to achieve for Wittmann’s Merwyn collection.” I look down at my chair. Sure enough, it’s a macaron: two round, flat-

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN Fa M O u S 72

Page 70: “I don’t know if my work is political or if it is about the way we are living. But I know we live in a quite paradoxical world.” – Sebastian Herkner. Above: A development on the Merwyn collection for Wittmann, the Miles Sofa is inspired by the elegant macarons of French pâtisserie, Ladurée, photo: Gregor Titze. Opposite: Herkner’s Stellar Grape lighting for Pulpo is reminiscent of tightly bunched Concord grapes, photo: courtesy of the designer. Page 74: Herkner combines high seating comfort with an optical lightness for Wittmann’s Merwyn collection, photo: Gregor Titze.

“It is so important to how I work. Opening myself to new experiences, people and objects, I find inspiration every time.”

Sebastian Herkner, designer.

top domes sandwiched together and ringed with a strip of leather piping, à la cream. Elsewhere is a table I immediately imagine to be inspired by boiled sweets melting in the sunshine (Pastille Table, Edition Van Treeck), and a lamp evidently taking cues from those tightly bunched Concord grapes with pearlescent, chalky flesh (Stellar Grape lighting for Pulpo).

I need little prompting to learn the back stories. In each instance, Herkner launches right into a narrative so furnished with details – what object caught his attention, the life of the community using it, how it was made – and suddenly it hits me. That is what inspires him. Not travel, not objects, but that curious and fragile nature of happenstance when people, material and place collide. For him, a cake pan is anything but. “What is specific about it?” he asks. Well, it’s a celebration of Bulgaria’s metallurgic ecology; it’s generations of blacksmithing between the mountains of Rila and Vitosha where craft histories of the Mediterranean, the East and Europe converge; it’s comradeship, hospitality, open-heartedness. Not a cake pan in the world, but the whole world in a cake pan.

Germans call this geist. Aristotle called it haecceitas – or roughly, ‘thisness’. Herkner calls it responsibility. “Craft is so much about identity,” he says. “As a designer, it is my responsibility to understand and examine how craft is this element that connects us together and then connects us to a place. We need to respect it.”

“In Offenbach where I studied, and where I still have a studio, you enter the city by driving past a sign saying, German Weather City. The weather forecasting institute is there. But it also says German Leather City, too, because there was, in the past, a production of belts, wallets, shoes and bags and all these leathergoods. Eventually, it lost its identity. All the leather production left. There are still a few beautiful factory buildings, but they’re quickly becoming

apartments, lofts and offices. There is no longer this thing which connected so many people together and made them proud of their town and each other. Craft and design is so important in this – and not just furniture. It can be a bakery, a butcher or even a farm, but it’s all connected with craftsmanship, quality and people.”

As he tells me this, I can’t help being saddened. I think of Friuli Venezia Giulia (the Chair District) where more than 10 municipalities produce a smaller and smaller percentage of the world’s chairs per annum. I think of places like Torino, Leipzig, Bilbao, Lille and St Etienne, where the 2008 crash and the ‘eurozone crisis’ have made it difficult for these once-bustling industrial cities to now round a corner. And closer to home, I think of communities wringing their hands in abandoned steel towns throughout Australia.

“I don’t know if my work is political,” Herkner tells me toward the end of our conversation, “or if it is about the way we are living. When I give lectures, they are about things like quality, patience, craft taking time. But I know we live in a quite paradoxical world. You can buy something on AmazonPrime and you get it the same day. If you don’t like it, you can send it back. Where is the respect for craft and people in this? We just consume it all too quickly. I think this is where the interest in materials has grown a lot recently. We want to be connected back to the thing, that place and the craftspeople’s skills. That’s the paradox. We want these traditional things, the old things. But we are being pulled into the future. I think it is our responsibility to shape what it can be.”

Sebastian Herkner was recently in Australia to launch Wittmann at DOMO.

sebastianherkner.com

INDESIGNLIVE.COM IN Fa MO u S 74

Cla ics newly interpreted: KALDEWEI MEISTERST Ü CK CLASSIC DUO OVAL 3.5MM ENAMELLED STEEL | 30 YEAR GUARANTEE | MADE IN GERMANY @BATHEAUSTRALIA WWW.BATHE.NET.AU | 1300 BATHE

The Place-Makers

Sandra Furtado and Peter Sullivan’s practice might be in its infancy, but they are already tackling the big issues that will have a lasting effect on our cities.

Words Aleesha Callahan Photography Michele Aboud

Words Aleesha Callahan Photography Michele Aboud

Seeding Ideas

For Furtado Sullivan it’s really important to set up open lines of communication, and as the role of the architect continues to be “eroded” it’s even more important that space and time is given over to idea generation at the start of a project when “you can plant the seed for concepts”, says Sandra Furtado.

–

INDESIGN 79 IN Famous

For an incredibly young practice, Furtado Sullivan brings honed insight, collaboration and a holistic approach to its projects – and our cities are all the better for it. Formed in mid-2018 and helmed by Sandra Furtado and Peter Sullivan, what underpins the newly formed practice is an adept understanding of where architects sit –and need to sit – in the ever-changing built environment.

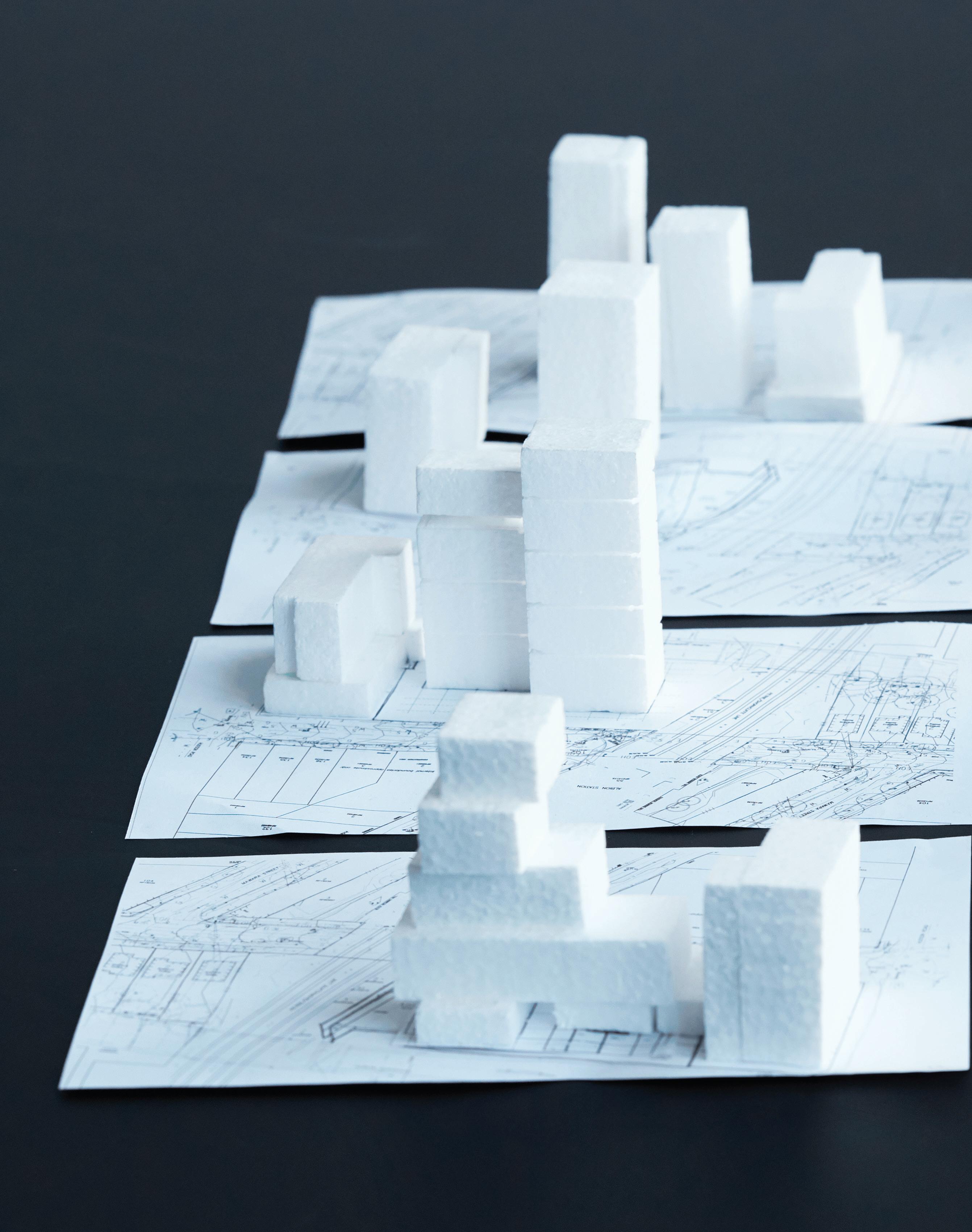

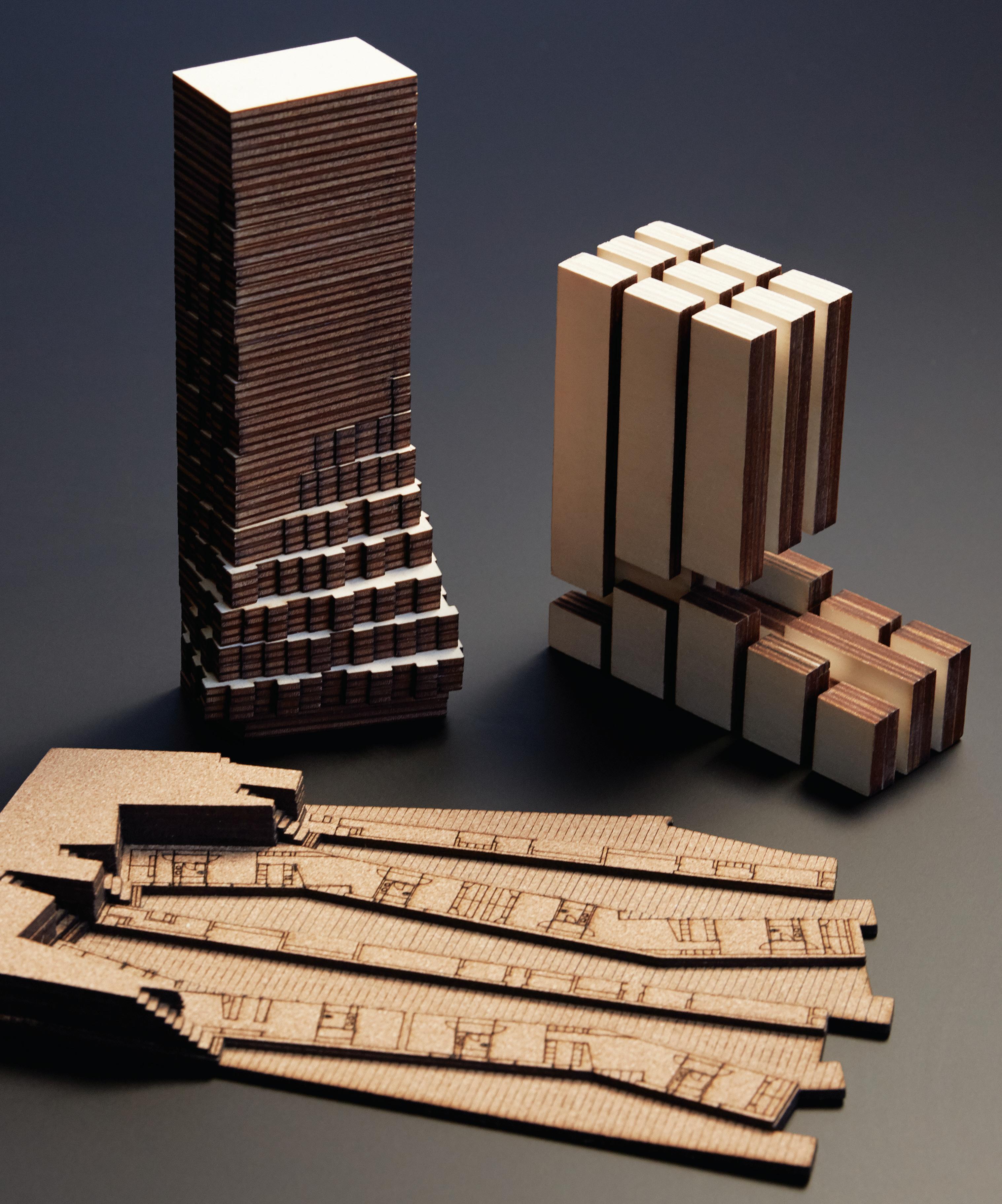

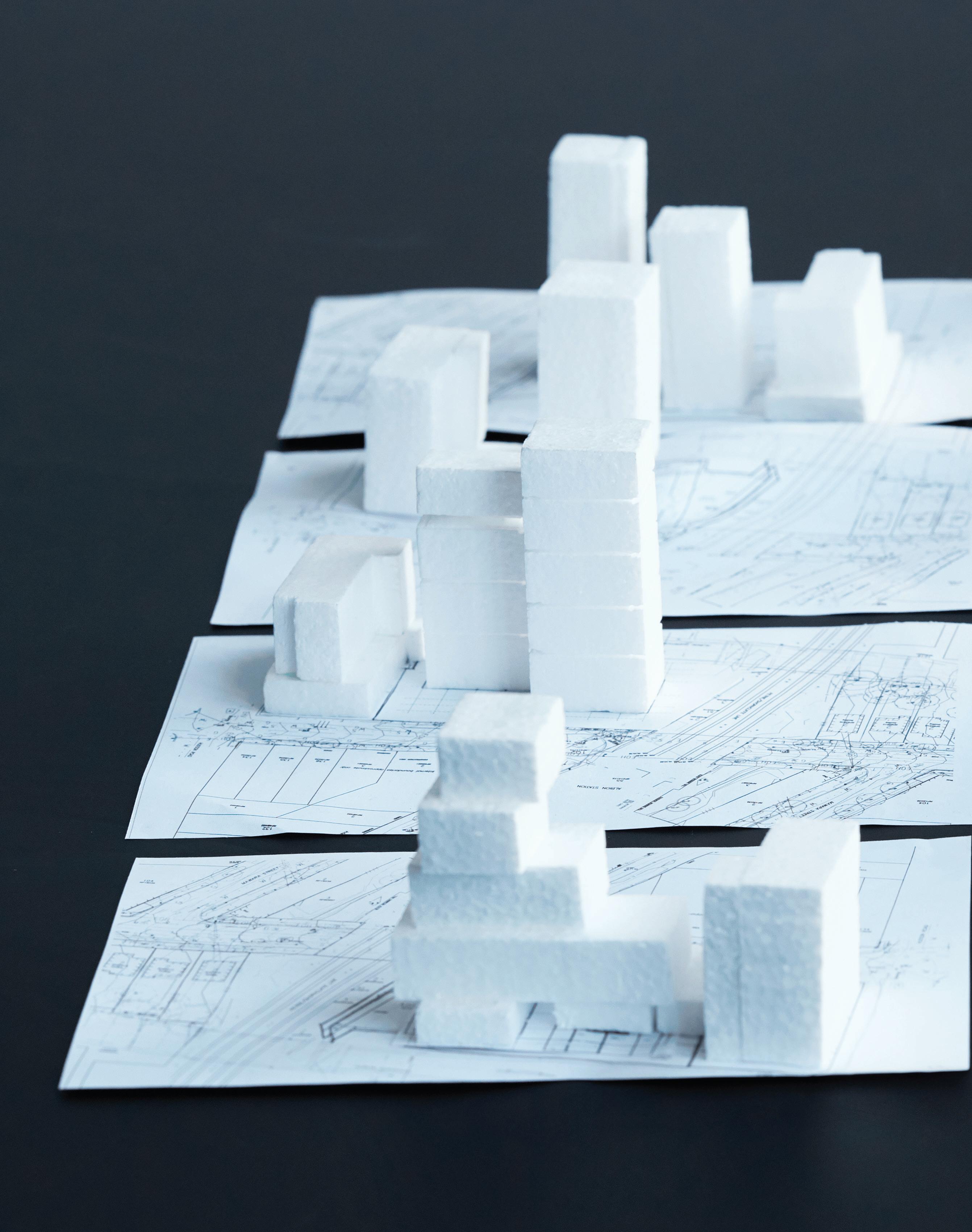

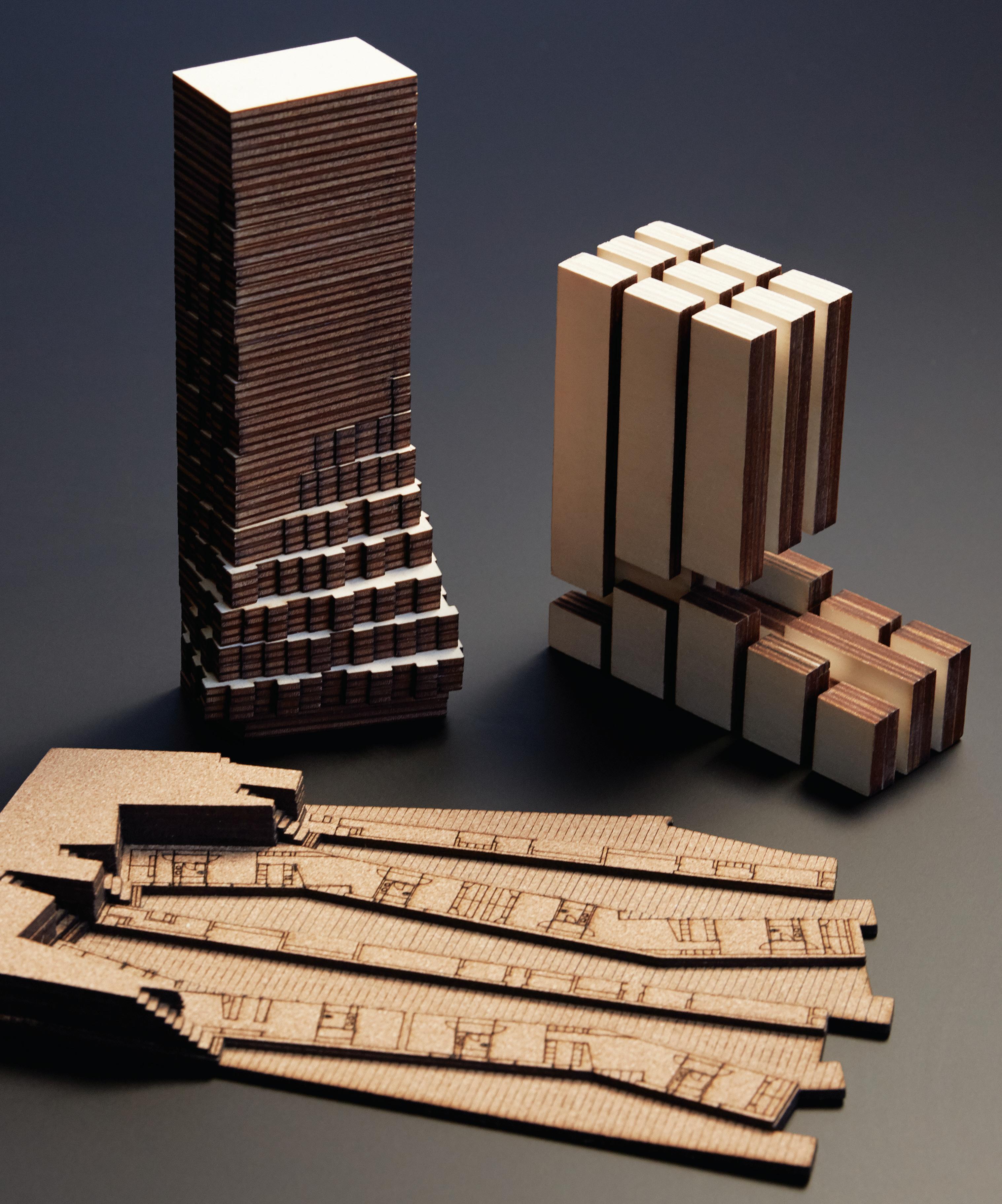

Top of the agenda is tackling large-scale projects that bring a level of complexity, such as mixed-use commercial and multi-residential towers, alongside urban scale and precinct or place-making work. The types of projects that can truly leave an impact and change entire urban experiences.

The term ‘biting off more than you can chew’ comes to mind when thinking about the sheer intricacy that goes with projects of this scope. For Furtado Sullivan, it’s all about bringing a holistic perspective. Furtado draws the image most clearly when likening a building to a tree. From afar you can see the shape, the form, you get a sense for what it is, maybe even what kind of tree it is. But as you approach other details and elements come into focus: “The colour and texture of the trunk, the sizes of the leaves, the geometry of those leaves. It’s the same with a building: the closer you get, you start to understand it in a new way and see all the details.”

Operating at this level means there are inevitably many stakeholders coming together. It may come as no surprise that a key pillar of the studio is collaboration. As a concept, collaboration seems simple in theory but is not always so in practice. When egos and conflicting agendas collide, it can be all too easy to lose sight of the common goal. The pair recognises that it’s an oft thrown-about term or philosophy for many practices, but they hold steadfast in its importance for their own. How does this ethos materialise in the everyday? “The success of a collaboration comes down to the individuals you work with and how humble you are in taking someone else’s advice. But it’s also how willing the other people are in reciprocating,” says Furtado. “Ultimately, the goal is to build a better outcome,” adds Sullivan.

A hallmark project currently on the books for Furtado Sullivan is One Circular Quay Hotel. The hotel sits within a precinct-wide revitalisation that brings together a consortium of stakeholders. When working to such a large scale the duo explains that it’s critical to look beyond and ensure that the final outcome will become “more than the sum of its parts”.