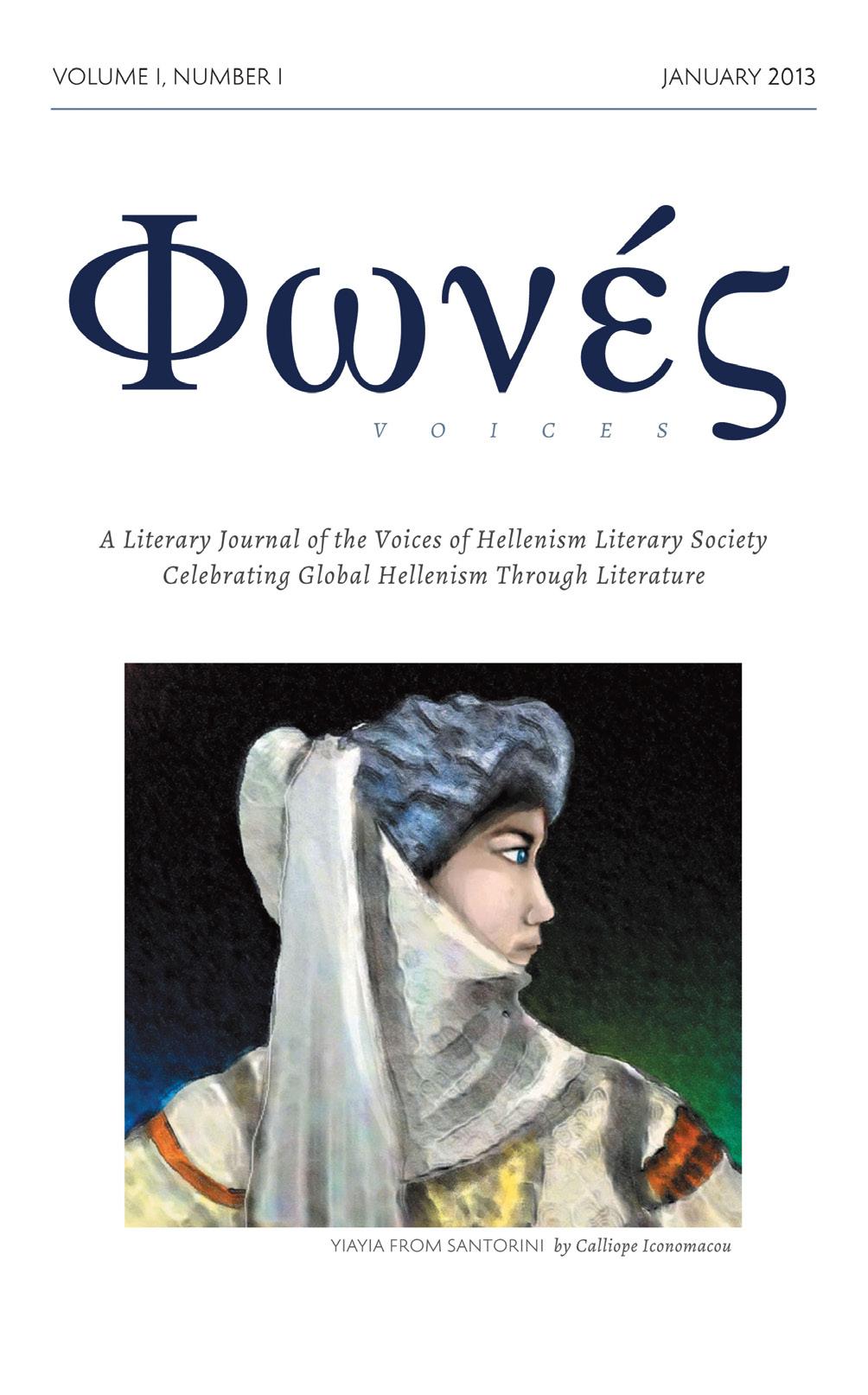

Φωνές Voices

Volume I, Number II 2014

A Literary Journal of Voices of Hellenism Publications

WHITE ISLAND by Constantin Alexiades

Copyright © 2013 by Voices of Hellenism Publications

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Rights will revert back to the authors after publication. Permission to use individual works should be obtained by contacting the respected authors. For requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below Voices of Hellenism Publications P.O. Box 1624, San Mateo, CA 94401 www.voicesofhellenism.org

Ordering Information: Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, and others. For details, contact the publisher at the address above. Orders by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesalers. Please contact distribution: Tel: (650) 504-8549; Fax: (650) 358-9254 or visit www.voicesofhellenism.org.

Subscriber Services: A single subscription provides three annual issues for three years, $50 in the U.S. and $80 in all other counties. All payments in U.S. Dollars. Direct all inquiries, address, changes, subscription orders, etc. to: email info@vhpprojec.org; telephone: (650) 504-8549; mail: Voices of Hellenism Publications, PO Box 1624, San Mateo, CA 94401. Editorial and Publishing Office: 1040 S. Claremont Street, San Mateo, CA 94402. Postmaster: Send changes of address to Voices of Hellenism, PO Box 1624, San Mateo, CA 94401.

Printed in the United States of America

Second Edition

ISSN: 2330-4251

Volume I, Number II is dedicated in loving memory of Ciro A. Buonocore

Woman From Macedonia by Calliope Iconomacou

Ό

Φωνές Voices

Poetry

Landmark (After Hitchcock) 9 Nick Mamatas

To a Poet 10 Jonathan Beale

Costa Rica Animals 12 Thanasis Maskaleris

A Boy in Greece 13 Andrea Potos

Fight 14 Belica Antonia Kubareli

Caldera’s Happiness 15 Achilleas Katsaros

My People 16 Katie Aliferis

Doria 16 Ezra Pound

The Good Ol’ Days 17 Phyllis Sembos

πράσινος κήπος (The Green Garden) 18 Vrettakos (Translation Anastasia Soundiati)

Return From Exile 19 Lee Slonimsky

Wisdom at Sweeties 20 Kimberly Escamilla

Ιδανικό Ζευγάρι (The Ideal Couple) 21 Marika Symenidou

Διγλωσσία αλά ελληνοαμερικανικά 22 Yiorgos Anagnostou (Bilingualism à la Greek-American)

Greek Widows of America (1950s) 24 Dan Georgakas

Heaven’s Hands 24 Nick Johnson

Memory-of 25 Angelos Sakkis

Μητέρα (Mother) 26 Peter Nanopoulos

The Translation 28 Brendan Constantine Mοίρες (Moires) 29 Stavroula Zervoulakou

Το Σφαγείο (The Slaughterhouse) 30 Despoina Anagnostakis

Water Becomes Us 31 Katherine Hastings

My Gary Kitchen 32 Paul J. Kachoris

Οδοιπορικό (Travelogue) 34 Despoina Anagnostakis

Στο Δάσκαλο (To The Teacher) 38 Kostis Palamas (Translation Peter Nanopoulos)

Μυρωδιά του Κυριακάτικο ψητό 39 Sotirios Pastakas (Translation Angelos Sakkis) (The Smell of Sunday Roast)

1 2014 | VOICES

Fiction

Palimpsest 41 Kathryn Koromilas

Bazaar 45 Belica Antonia Kubareli

Eye of the Hydra (Feature Novella) 47 Akos Kirsh

College Life: November, 1941 79 George Karnezis

Sunday, Saturday, Sunday 87 Akrevoe Emmanouilides

The Communist Leader’s Wife 93 Irena Karafilly

Bringing Cheese to a Séance 97 Steve Pastis

Princess and I at the Dance of the Crazies 99 Vangelis Manouvelos (Translation Angelos Sakkis)

Courtship 105 Harry Mark Petrakis

The Way Things Are 115 Will Manus

Creative Non-Fiction

About My Mother 117 Irene Sardanis

Return to Symi 121 Richard Clark

Journey to a New Reality 127 Dena Kouremetis

In a Tragic Split Second 133 Mary Pruitt

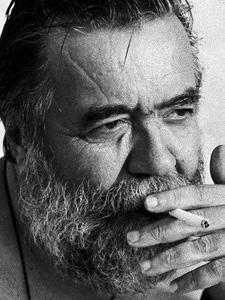

An Extraordinary Man and Friend 135 Stephanie Quinn

Academia and Scholarship

On Being Greek in America 139 Dan Georgakas

The Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles 153 Foti Jean-Pierre Fotiu and Lazar Larry Odzak

Embracing the Humanities and the Arts 157 Yiorgos Anagnostou Strange Prisoners 159 Christine Salboudis

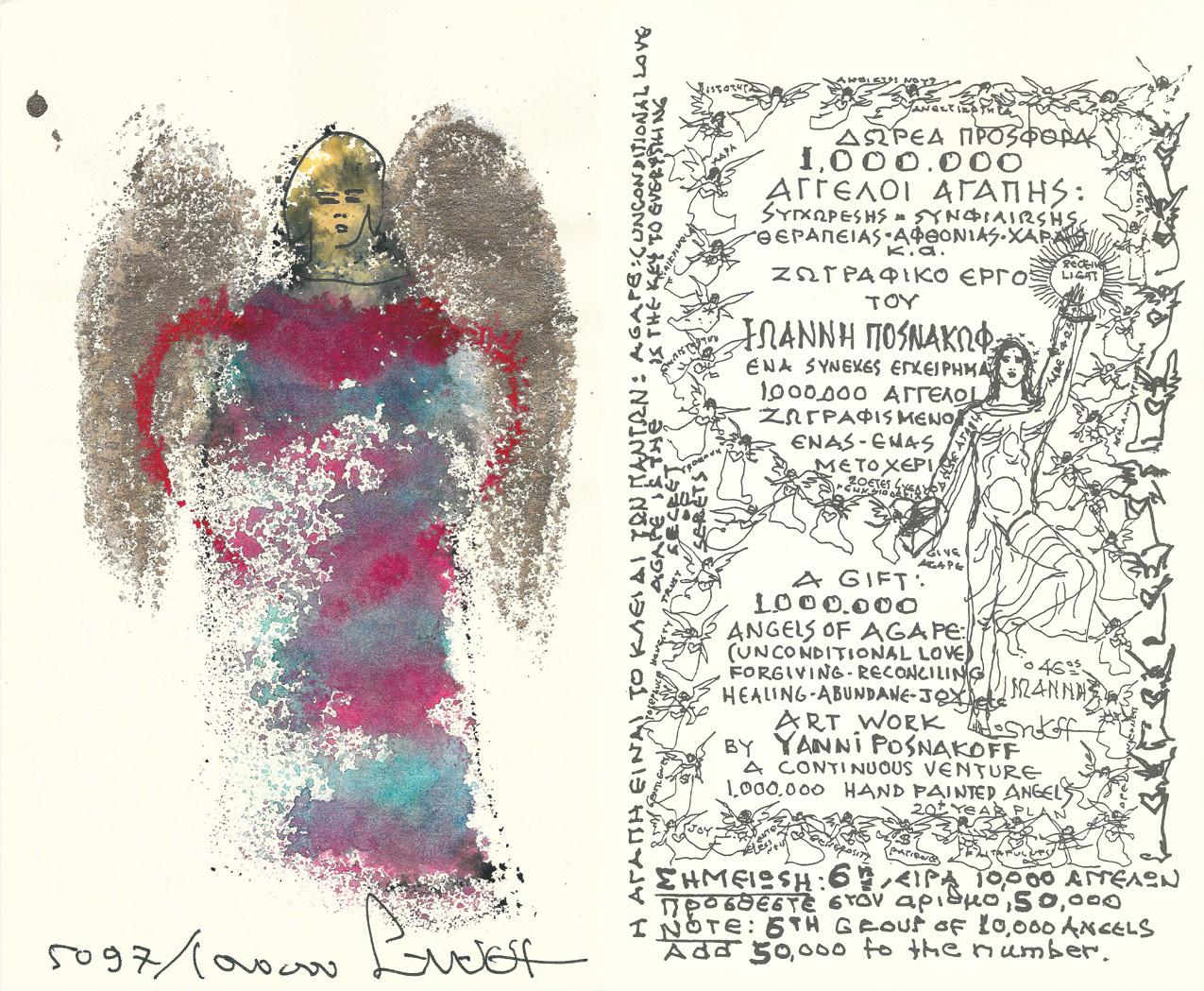

Art

Woman From Macedonia Calliope Iconomacou (Inside Front Cover)

Seated Figure 44 Peter McNeill

Up in the Air 46 Peter McNeill

Toilet in Place 46 Eleftheria Lialios

Eye of the Hydra 57 Akos Kirsch

(Representation) 78 Odysseas Anninos

(The Beekeeper) 92 Odysseas Anninos

(The Troupe) 114 Odysseas Anninos

(Love in Spring) 119 Odysseas Anninos

Greece 129 Odysseas Anninos

Cold Fire 152 Annamarie Buonocore

Kalamata Earthquake Photo Essay 164 Eleftheria Lialios

Window Sharon McNeil (Back Cover)

Ο μελισσοκόμος

Ο θίασος

Αγάπες στην άνοιξη

Aναπαράσταση

Biography

Pythagoras Caravellas 173 John B. Vlahos

Book Review

A Coffee Date with the Soul 177 Annamarie Buonocore

Film, Theatre, and

Culture

M a n o l i ... ! 181 Giorgos Neophytou From the Shores of the Aegean to the 187 Ilias Chrissochoidis Edge of the Pacific

3 2014 | VOICES

NOTICE OF CONTROVERSIAL CONTENT DISCLAIMER

We recognize that some of the content herein may be controversial in nature. Please read the following disclaimer. Voices of Hellenism Literary Journal (Φωνἑς), its editors, board members, associates, and interns are not responsible for:

Ǒ personal, political, social, or economic views expressed by its contributing authors and artists

Ǒ views and opinions expressed by any advertisers or partner organizations

Ǒ the content of websites and links referred to by the Voices of Hellenism website

Ǒ copies of or references to existing or deleted pages on our site published by third parties

Ǒ controversial or political content on our website or in-print publications

The views expressed herein are the respected views of the individual contributing authors and artists and not necessarily the views of our publisher, editors, board members, affiliates, volunteers, or interns. Although we take great care to avoid published content that might be offensive or inappropriate in nature, we would be most grateful if you would notify us at info@vhpprojec.org in case you encounter such content on our website or in our publications or have any other concerns. For more questions on our policies regarding controversial content, please email us at info@vhpprojec.org. Thank you.

ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II 4

Φωνές Voices

Founding Editor and Publisher

Annamarie P. Buonocore

Associate Editor

Angelos Sakkis

Assistant Editor

Peter Nanopoulos

Editorial Board

Cassandra Vlahos, Dena Kouremetis, David Windsor, Paula Wessels, Nick

Tarlson, Giota Tachtara, Irini Hatzopoulos, Steve Pastis

Translation Board

Angelos Sakkis, Peter Nanopoulos, Irini Hatzopoulos, Krystalli Glyniadakis

Graphic Designer/Art Director/ Photo Editor

Ranya Karafilly

Intern

Lea Buonocore

Voices of Hellenism Publications Board of Directors

John Vlahos, Paul Manolis, Steve Pastis, Alexandra Kostoulas, John Kyriazoglou, Vickie Buonocore, Virginia Lagiss, John Bardis, Thanasis Maskaleris (Honorary Chairman), Annamarie Buonocore (Executive Director)

Advisory Board

Peter Nanopoulos, Thanasis Maskaleris, Angelos Sakkis

Scholars Emeritus and Deceased

Fr. Leon Contos

Sponsors 2013

Dr. Peter Hadreas, Olympia Tachopoulou

Advertisers

Friends of Kazantzakis Bay Area

Printer

Western Web Printing 707-444-6236

For all your printing needs

www.voicesofhellenism.org

Volume I, Number II

ISSN: 2330-4251

We accept submissions on a rolling basis with an August deadline for each issue. Voices of Hellenism is published once a year. We also welcome editors, board members, volunteers, and interns for two-year terms. Voices of Hellenism Publications is a 501c3 nonprofit corporation in the state of California.

TOWARD THE NEW VOICE

Dear Readers,

Under normal circumstances, I consider myself to be a fairly decisive individual. I rarely take more than three or four minutes to decide what I will eat in a restaurant, and most home decorating decisions are a walk in the park for me. But in the midst of such profound thinking, I found many unresolved contradictions. Often the best way to deal with many of these paradoxes is to just let them be. I love writing, but I hate it. I find the crisis in Greece depressing yet exhilarating in the artistic boom that is looming yet going unrecognized by many. I am essentially a rebellious non-traditionalist but am often humbled and even silenced by the powerful momentum of tradition that comes from humble chanting in an Orthodox liturgy. I decided to let the problems roll as I rolled with the punches of publishing the second issue.

One day while driving down a scenic road, I thought about addressing the two above questions. While it is true that print media and publishing have seen better days, it is also true that there is an empowering sense of having the whole world at one’s fingertips in this eclectic corner of the world. When studying any field within the greater field of humanities, we are often faced with the dreaded question, “What are you going to do with that degree?” Many who have asked me that question over the years see teaching and academia as that default profession that serves as a refugee camp for those who live in fascination of letters and liberal sciences.

They see these fascinations as impractical. What many of these people forget is that the world can become open in more ways than imaginable through books, magazines, and journals of the humanities. I am not saying that publishing is the only other choice for those of us who get the question, but it is a powerful profession that places the purpose in the humanities and proves the closed-minded wrong. People become who they become based on their knowledge, and books and other literature stands behind every ounce of that knowledge, the knowledge that fuels the world’s progress. That is why there will always be a need to continue publishing in-print journals such as Φωνές

When I think about the mess literary journals have faced for decades, I think of my earliest struggles to encourage fellow students and members of the local community to submit to and read schoolbased blogs, newspapers, and student literary magazines. The struggle to keep the momentum and that little thing called funding are always challenges. The question all publishers and writers alike must ask is whether we see these as challenges or opportunities. Here at Φωνές, we see these as opportunities, and this leads me to my next point as to how it sets us apart. The knowledge that fuels the world’s progress is the reason we must continue publishing and printing. Here at Φωνές, we receive many quality submissions that come across my desk. We receive so many that we cannot possibly publish all of

ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II 6

them. In these submissions of fiction, art, poetry, and scholarly essays, there are voices of our people that speak of human progress. As a freelance writer and poet myself, I realize like many others that writing is not a sure path to fortune or even financial security. There is a higher currency. That currency is the human voice. The human voice is the one that will answer the questions, “why go on living?” and “who am I?”

Because we are a literary journal with a Hellenic theme that caters to Hellenes and Philhellenes, we have an overwhelming amount of voices that not only speak of the oppressive struggles of the Greek migration and diaspora but also of today’s modern-day crisis in Greece, which is fueling a new diaspora of our people. Much of the literature by our people becomes overlooked in a changing world. Literary magazines that focus on such a niche like Φωνές are hard to come by, and much of the role of the literary magazine is being subsidized by academic publishers that may or may not be doing a quality job that gives justice to the community writer. Here at Φωνές, we are a community journal with an academic and eccentrically intellectual backbone. We continuously make our mission to bridge the gaps that exist between our community and Modern Greek academia in many of the finest universities in the United States, Canada, England, Australia, and Greece where our people have excelled in academia to make our mark on the world. It is our goal moving forward to include more works emerging from the current Greek crisis. We also strive to engage the works of scholars and researchers in the

fields of Modern Greek Studies and Greek American Studies and offer the different perspectives on the various issues taking place within these departments that offer our community a plethora of knowledge and opportunities.

We are a global publication that is brought to greatness in every issue because of our talented writers that deserve more than just the dark shadows of a file cabinet. Our editors are the ones that bring a plethora of backgrounds and experiences to the table that shapes this journal. As always, I would like to thank all of the writers, editors, financial sponsors, board members and volunteers who helped shape this second issue. From the poetry that reflects on our cultural history, such as the poem, “Greek Widows” by Dan Georgakas to fascinating essays that consider modern-day issues and trace them back to the foundations of our people and democracy, such as the essay, “Strange Prisoners” by Christine Salboudis, this journal offers a wide variety that speaks of the diversity and broadness of Hellenism in a global landscape. We look forward to your feedback as always.

Sincerely,

Annamarie Buonocore Publisher, Founding Editor

Annamarie Buonocore Publisher, Founding Editor

7 2014 | VOICES

Landmark (After Hitchcock)

by Nick Mamatas

Even the minor films feature famous landmarks.

Ever see a movie in which characters run into a cinema? And the film on the screen mimics and mocks the men and their scrambling runs?

Hitch did that, in Saboteur In fabulous Radio!

City!

Music Hall!

Nineteen forty-two.

Everyone knows Mount Rushmore. Thanks to those fingertips. Those flailing shoes.

If you’re a man who knows too much you might end up shot at at the Royal Albert Hall

Strangers on a Train Didn’t stay there for long. One stalks the other at the Jefferson Memorial

How many other criminals have been captured at the Statue of Liberty?

And yet, here I am in the British Museum

Everything is so calm and orderly. Not like Blackmail so long ago. That fellow hanging from a rope. The Sphnix’s wry smile.

But they have my Elgin Marbles. And I have my gun.

And so many tourists waiting here, gaping. So I guess it’s up to me.

9 2014 | VOICES

POETRY

To a Poet

by Jonathan Beale

“Those who dare give nothing Are left with less than nothing.”

— Robert Graves

So then. How should I address?

Mr. Heaney, Famous or Seamus

Is the naming required or a real necessity?

So from the word and idea. What?

Sculpted by the poet in a darkened Moment when the key drops to reveal

From Silence, peace, patience

To be cast amongst stratosphere

Where it will flow silently on from one-to-another

Myth-makers dream of such —

Their manna, their beverage

And all the holy men stand to

Preach their light's light.

Yet the poet can cast more light.

Sagacity moulds him in the wind

Cut hard for and from the cold wind

No charlatan can ever fool

As the first flint then crashes Against the stone

From some silent moment

The birth is sent

Crying out to the worldThe scream that is silence

Breaks the silence.

The vessel; poroused and ready.

As is the accident of birth

The ink to the mind

Alchemy? Or what?

10 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Some trickery?

Of whys and wherefores

Who then speaks and from where?

So then who devised the torment?

The discovery, the truthbearer

The line then the anomaly

Or receive in the mind’s eye

That blended upon the soul

To taste and forget the second

That as celebrant

One and all and so

For the tabula rasa

And for the unwritten of tomorrow

Have the sod from whence

To grow their own ideas

And so their ideas will grow.

So said the voice from all the poets past.

The effort and obvious rhyme

So laboured the charlatan uncovered

And so. The poet. The craftsman

Born to give, the moment

Is caught forever

To be grown down the history line

Made fuller in tongues to come

“And empty shells reply

That all things flourish.”

— Philip Larkin

11 2014 | VOICES

Costa Rica Animals

by Thanasis Maskaleris

You, peaceful children of this paradise land, you stare at us, visitors, with the most amiable glances … You, dogs at Lenny’s and Joan’s hacienda, who accompany me to my morning wanderings … you are the most devoted guides I ever had, rejoicing in my appreciative response … And you, caged and uncaged birds, you look at us, puzzled by our human gestures, as though you want to decipher us …

You are the barking, singing signal givers Initiating us to your terrestrial riches You are in harmony with everything around you, Even with us, the intruding strangers. Here we, wanderers with dissonant psyches, can attune to the harmony that Nature gives … You can be our teachers of naturalness and peace, toward co-existence with all—with Mother Earth and with all of humankind …

12 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

A Boy in Greece

by Andrea Potos

My grandfather was a boy in the mountains not far from Delphi, great navel of Mother Earth. He lived in a village encircled by a silvery-green sea of olive trees and dust, and lit by a billion stars. He told me he could read by their light alone. I love to think of him under that luminous sky, eons before I was born to his gentleness. Even the darkness cradled him, a book creased open on his lap.

For Papouli

13 2014 | VOICES

Fight

by Belica Antonia Kubareli

She said: “The chicken is in the oven” and once again he replied with silence. She knew she had lost him but wouldn’t admit it even in her dreams. It wasn’t a matter of keeping up appearances. It was her need not to let silence penetrate her life. So every now and then, with the kids playing in the garden, the dog sleeping on the sofa, the kettle boiling and the windows rattling, she would drop a word to him, staring at his back typing on his laptop. She would never stop fighting his silence, trying to get him back to her world.

14 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Caldera’s Happiness

by Achilleas Katsaros

I saw the happiness and I only took a few steps behind to feel this emotion deeply in my soul. It was she who gave her beauty and brightness from inside her heart. She gave her beauty to Unknown Out of Us with no sense of despair. The little moon fights against the sun here in Caldera.

Then I said, yes, happiness has a face, has also eyes, nose, hair … has body … has mouth and speaks and says only the good news that you love to hear … and then blows a little wind in the Aegean Sea and takes the words to make them treasures of the whole world. The little wind flies over the rocks here in Caldera and paints the sunset as a bay of innocence. it purifies the mind and at the same time is a promise of eternity. That moment is the medicine of sorrow and the little wind continues his game with your hair … it becomes the white that blinds you it becomes the friends who have a passport to your life …

15 2014 | VOICES

My People

by Katie Aliferis

Sapphire and teal

Water crashes against the White rock strewn shore

Towers of stone

Crown the horizon

Protecting what is ours

Victory or death

We will accept no less Maintaining our freedom

Defending the Mani.

Δώρια - Doria

by Ezra Pound

Be in me as the eternal moods of the bleak wind, and not As transient things are— gaiety of flowers.

The poem "Doria" was first published in The Poetry Review in 1912. It is considered in the public domain because it was published before January 1, 1923. The copyright has expired.

16 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

The Good Ol’ Days

by Phyllis Sembos

Oh, for the carefree days

Of nineteen thirty-nine. When there was no haze

And movies cost a dime. When mild wasn’t strontium

And water was clean

That nightmare ‘plutonium’

Was only a dream, When food was delicious

Without MSG

The bread was nutritious, And ‘what’s LSD?’

Franks were real beefy

Not sodium nitrate, Nothing made cheaply

Or sprinkled with phosphate. No florides or chlorides.

Or bromides or DES, No chlorophil, portomil

Or spilled oily mess

Oh, for the carefree days

When life was a bore.

We all got together

For a hell of a WAR.

17 2014 | VOICES

Ό πράσινος κήπος - The Green Garden

by Vrettakos

Translated by Anastasia Soundiati

I have three worlds. A sea, a sky and a green garden: your eyes. If I could walk all three of them I would tell you where each one of them is bounded. The sea, I know. The sky, I suspect. As for my green garden don’t ask me.

18 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Έχω τρεις κόσμους. Μιά θάλασσα, έναν ουρανό κι' έναν πράσινο κήπο; τα μάτια σου. Θα μπορούσα αν τους διάβαινα και τους τρεις, να σας έλεγα που φτάνει ο καθένας τους. Η θάλασσα, ξέρω. Ο ουρανός, υποψιάζομαι. Γιά τον πράσινο κήπο μου, μη με ρωτήσετε.

Return From Exile

by Lee Slonimsky

Exhilarated on his long-walked path, Pythagoras, rejuvenated, basks in lush sunlight and for a moment asks why numbers matter, if the height and width of triangles explains this awe, this Is of branchery, smooth stones, the love of blue for sky and water. How the wind, once true to winter, now’s the tickle of soft breeze.

Exiled so long, he’ll soon be gone, but still the shimmer of the pond slows sullen time almost to sweet oblivion. His will Can make a lot of what is left. Sublime, the way age can lift attitude, rouse hope: he gazes at some swallows’ perfect loops.

19 2014 | VOICES

Wisdom at Sweeties

by Kimberly Escamilla

The neighborhood bar in North Beach is barren except for one clutch of retired Italians whose late lunch has blurred into an evening of beer and gossip.

I know what my husband is going to order before we leave the tattoo shop, before Mary Joy unties the baggie of our daughter’s ashes, lowers her head and needle that will bind us for life.

Ouzo, tinged blue, like the inside of ice is poured neat from a dusty bottle.

The bartender-mother asks—are you Greek?

We extend our saran-wrapped wrists, the Hellenic epitaph still wet and nubile.

As the sweet anise burns, I think of the monks at Mount Athos who could never have predicted their pet-project some 700 years later would treat sour stomachs and jack-knifed hearts around the globe.

The bartender-mother and eavesdropping Italians listen rapt and teary, they raise their glasses to the purity of grief, the kind that a tattoo and Ouzo can only begin to admit.

20 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Ζευγάρι - The Ideal Couple

by Marika Symenidou

Translated by Krystalli Glyniadakis

With years apart, they attended the same university

They had a boy, a girl, separately

They both love music, movies, poetry

But most of all, the sea.

She rejected him at first so she could find him

He found her so he could lose her in the dark.

The ideal couple, went on to marry –he. Who went on honeymoon? Well, she!

21 2014 | VOICES Ιδανικό

διαφορά χρόνου φοιτήσανε μαζί Έκαναν από ένα αγόρι και ένα κορίτσι χώρια Αγαπούν την ποίηση , τις ταινίες και τη μουσική Μα πιο πολύ τη θάλασσα.

αρνήθηκε στην αρχή για να μπορέσει να τον βρει Την βρήκε για να μπορεί να την χάνει στο σκοτάδι

ιδανικό ζευγάρι παντρεύτηκε αυτός Πήγε γαμήλιο ταξίδι αυτή!

Με

Τον

Ω,

Bilingualism à la Greek-American

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

Να

ο πότης;

Μονόκλ αγγλικής αγαπητοί

διπλή ’ναι μυωπία

Όταν

κιτάπια

22 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

ελληνοαμερικανικά

Διγλωσσία αλά

είπα

εγώ δυο δίγλωσσα στιχάκια πόρτες χτυπώ εκδόσεων Αρgό κουφότητα πικρά σφηνάκια.

’ναι οι δίγλωσσοι θεσμοί, η δίγλωσση κοινότης; Πού των ντ και d οι καλπασμοί, της ποικιλίας

δημοσιεύσω

κι

Πού

ξένοι εξόριστοι Ε.Τ.

ήτα κοινωνία.

ελλείψει

λοιπόν κληρονομιές διθύραμβοι υμνούνε

τσιριμονιές

ομόφωνες

γλώσσας πού ’ναι;

LA μόδα έριξα τα παρδαλά στανζάκια στης Ορλεάνης τα βαθιά το δίστιχον μπλοκάκι στο Φρίσκο κι αν σπινάρισα οργανικά τιτλάκια στημένο ραντεβού παντού το δύστυχον ποιητάκι. Λέω λοιπόν ένα τουίστ του ράιντ προς βόρεια του East astride στης λεγομένης διασποράς οικόπεδα μην και προφτάσω τις κόπιες να περάσω στη λεγάμενη Andromeda μιας κοπιά ζουσας αγοράς

Στο

To publish I dared to think a bit of verse in bilingual ink I knock on doors of Argot publications deaf ears, ah, cheers in bitter potions.

Where’s the bilingual fora, the bilingual community? Where’s the galloping ρα and ra, the ippotis of multiplicity?

Double myopia of a coquettα the monocle of English, dear sirs, yeah it is! those societies defeating eta exiled foreigners E.T.s.

So when dithyrambs heritage extol I only hear “clapping of thumbs” loss of language taking its toll.

In L.A. for fashion I tossed some spotty stanzas disco, in New Orleans the notepad sings the blues, and did I ever spin some organic titles in Frisco! the poor little poet still in pale hues.

So I hitch my fate a ride destination northeast astride to the so-called diaspora estate “asétora” just so I get a chance, any aim to offer the copies for a penny to, let’s say, the Andromeda of an exhausted agora ...

23 2014 | VOICES

Greek Widows of America (1950s)

by Dan Georgakas

Consider these Greek widows of America completing black-clad lives in the rented rooms of the old neighborhood Or dreaming alone in their aging homes now that children sleep in the wedlock so eagerly sought for them, but which strangely had no place for those rough-skinned peasant girls who once were matched to older men and now endure November graveside days sipping the last of the home made wine.

Heaven’s Hands

by Nick Johnson

My hands have created a new path

My eyes will lead the way

My heart will speak when my eyes sleep

My mind will mend and be my friend

My soul will know just where to go

My legs will bear me

My lungs will breathe

My hands will toil until they bleed

My hunger will wait until the night

My sleep will be in heaven I dream.

24 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Memory-of

by Angelos Sakkis

Leafing through an old book about a dictatorship in the Caribbean, written in Greece more than a year before the hated dictatorship there came to pass—the book sounding an utterly unheeded alarm—he spots a passage side-barred and underneath a comment in his late father’s hand “apofasizomen kai diatassomen,” the catchphrase of the odious ringleader meaning “We decide and decree”.

Apart from any feelings stirred by those words, what catches him by surprise, in retrospect, is a memory of the smell of his father’s hands coming to him in stream-of-thought kind of way on looking at the writing, can almost see the hand holding the pencil, most often just a pencil stub, keeping accounts in the familiar longhand, and he remembers smells of the old grocery store; unraveling the strands no more in actual sense, but as a memory-of

stale olive oil, cheese, nasty “trinal” all mixed with hand sweat, pungent touloumotyri, tarama and olive brine salamoura, the dry whiffs of burlap sack, damp sawdust on the tile floor in rainy weather the stifling darkness of the basement at the other store.

25 2014 | VOICES

Μητέρα - Mother

by Dr. Peter Nanopoulos

Translated by Dr.

Peter Nanopoulos

26 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Εάν λυγίσης στη ζωή, εάν ποτέ κιοτέψεις, θυμήσου τι σού΄λεγε η μάνα από παιδί, πάρε τα λόγια τα σοφἀ και κάνε τα χρυσάφι, βάλτα εμπρός σου οδηγό και βάθισε ορθός σε στεριά ή θαλάσσι. Όση αγάπη κι’αν θα βρείς, και όση καλωσύνη, πέτρα μη ρίξεις πίσω σου γιατί πίσω είναι πάντα εκείνη. Εκείνη που σε νανούρισε από μικρό παιδί και πιότερες φορές σ’ εφίλησε μ’ αγάπη και στοργή. Εκείνη που στον ύπνο της ακόμη σ’ονειρεύει και λαχταράει να σε δεί σαν τότε που ήσουνα ένα μικρό παιδί. Όπου και νά’σαι τώρα πιά κοντά ή μακρυά της, σκείψε και προσκύνησε την Άγια Παρθένα και κοίταξε την αγκάλη της το ταλαιπωρημένο βλέμα: Eσένα και τη μάνα σου με εκσταση θα δείς. Για τη Γιορτή της Μητέρας

If you feel like giving up in your life if you ever have the urge to retreat, remember what your mother said since you were a child, take these wise words and turn them into gold, place them in front of you as a guide and walk straight, on land or at sea.

As much love as you may ever find, and as much kindness, do not throw a stone behind you because behind (you) she is always there.

She, who lulled you since you were a small child and many a times did she kiss you with love and affection.

She, who in her sleep still dreams of you and longs to see you like then when you were a small child.

Wherever you may be now near or far away from her, bend down and worship the Holy Virgin and look at her embrace her weary eyes: You and your mother with awe you shall see.

For Mother’s Day

27 2014 | VOICES

The Translation

by Brendan Constantine

I once loved a girl with Russian Flu. Every day I climbed her tree house, to sit at her side and read Chekhov in search of a cure. Neither of us knew what the strange words meant or if I said them right, but she would sometimes nod weakly, her forehead damp with candlelight, and say Now we're getting somewhere, though we never did before she slept. How many nights did I climb down, fearing my pronunciation kept her ill? How many branches hold the heart above the belly? What noisy book is read in the house of the heart, fruitlessly? One morning I woke to snow, the entire forest revised. When I got to her, she had passed completely from translation, even her name no longer the right word for her. I spoke it anyway, over and again until it sounded wrong to me, spoke it back into noise, then left it in the woods for storms to say.

28 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

This poem appears in the collection Birthday Girl With Possum (Write Bloody Publishing, 2011)

Mοίρες - Moires

by Stavroula Zervoulakou

Translated by Angelos

Sakkis

Αγάπες

Yesterday I looked for what you took from me Tonight the Fates lay me to sleep.

Clotho, Atropos, Lachesis, by tomorrow all hope will be lost, they gnaw all night at life’s thread.

For company cigarettes and drink my mind daily on the brink.

Love gone bankrupt, rivers gone dry roses were smashed and the blood flows.

New love is back the rivers flow again rose bushes bloom for someone’s heart.

29 2014 | VOICES

έψαχνα απλά το τι μου πήρες, απόψε με κοιμίζουν μοίρες Η Κλωθώ, η Άτροπος, η Δάχεση αύριο χάνονται οι ελπίδες, ροκανίζουν το νήμα της ζωής τις νύχτες.

ποτό και το τσιγάρο συντροφιά το μυαλό μου καθημερινά σκορπά.

που πτώχευσαν, ποτάμια που στέρεψαν, ρόδα που έσπασαν χαι αίμα χυλά.

Χθες

Το

Αγάπες

που ήρθανε, ποτάμια που τρέχουνε, ροδιές που ανθίσανε για μια καρδιά.

Το Σφαγείο - The Slaughterhouse

by Despoina Anagnostakis

Translated by Irini Hatzopoulos

Long live Greece

Of the past, of the oracles

Virtuous Hellenic way, illustrious lifetime

Down with the jungle of these soundrels

Onward animals, assemble

And marshal yourselves as Europeans

The lorry to the slaughterhouse is here

Loaded with the youth of Greece

Be brave! Resist!

Before you’re vended

Marousi, November 2011

30 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Ζήτω η Ελλάδα του παρελθόντος και των μαντείων Οδός Ελλήνων με αρετάς, ενδόξων βίων Κάτω η ζούγκλα του παρόντος και των αχρείων Εμπρός τα ζώα για συναχθείτε Και ευρωπαϊκά παραταχθείτε Το φορτηγό για το σφαγείο έφτασε Με ελληνική περίσσια λεβεντιά Αντισταθείτε Πριν πουληθείτε Μαρούσι, Νοέμβριος 2011

Water Becomes Us

by Katherine Hastings

We wander the tangled meadow of a newly birthed common spring in our blood, the taste of spring on our skin, in our hair. Spring is in the song of the wending words floating between us, words taken from the latest film, the latest book, the news. We give each other the music of our mouths, hard land crunching beneath our heels, note the young trees with their first blooms. For decades I have watched you—young girl in the frilly dress belted by guns and holsters— leap from the blue bridge into the Niagara. Your determination was a lovely dive, a dare, your platinum hair an unwilling

accessory to grace. As you flew off between paper mill and docks, I climbed hills backwards to face the bay, the Gate.

We hadn't met, of course, but I thought I heard you say, Lean into me like a wave. We rode the water as the water wanted— smooth at times, then rough. Stars landed their light on the smooth deep blue of it or turned to us their black backs.

We walk and I say The apple blossoms of young trees fade so soon, but you are in the middle of a story pulling a girl to shore, pulling me, those falls roaring in the distance, and I know, as that water always knew, something about electricity, how we'd go over together.

31 2014 | VOICES

My Gary Kitchen

by Paul J. Kachoris

Passing through my cob webs once again. Remembering the ironclad rules of steel-dusted Gary. Lock-stepping into my old neighborhood. Venturing out of my Greek kitchen to find a new land, lurking out there, just behind the white and sheer kitchen curtains gaily tied back at their sides.

Bumping up against a language so painfully tinged with guttural grunts.

Unintelligible to my refined and vowel-kissed ears.

Not like the yellow canary’d Greek spoken to me by my proud, house-dressed and aproned mother, who scurried around singing her Greek kitchen song to me: “kanarini mou gliko, se mou peres to mialo, to proi pou keladas ....” (“my sweet canary, you have taken my mind, in the morning when you warble ...”)

Lulling me and loving me with her queenly smiles; spinning golden notes around my heart and blessing me, her little Greek prince.

Outside in the streets and in the school yard— Aliens!! Creatures making up new words. And I, staring at their mouths transfixed, wondering: “what babble are they spouting?” These are not the sounds from my Greek kitchen!

They are deep attacks of a very painful exclusion: pithy spears aimed, oh! so straight into my heart; shattering the little, yellow canary of a boy, who only wanted to romp around, play, love and be loved and just be engulfed in kitchen magic.

32 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

But these guttural Teutonic grunts were so unkind, so un-soothing. Heavy, heavy stones of sharp edged cacophonies, shaming and shoving me into strange and frightening corners. Cowering, shaking and trembling unprotected. Slaying my sweet, innocent Greek kitchen happiness. And finally, pinning me—naked up against a foreign wall to be shot summarily, for crimes I never knew I had even committed, when I first ventured alone, out of my safe, little Greek Gary kitchen.

This poem was the Second Prize winner in the Lyric Poem Category; Poets and Patrons 50th Annual Chicagoland Poetry Contest 2006 [2002-2006]

33 2014 | VOICES

Οδοιπορικό - Travelogue

by Despoina Anagnostakis

Translated by Angelos Sakkis

34 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

Ο δρόμος μάκρυνε αφόρητα απόκαμα πια και το κορμί μου γέρνει γέρικο καθώς γίνεται είναι φορές που θέλω ο δρόμος να κοπεί στα δυο κι εγώ σα πεταλούδα ανάλαφρη να νιώσω του γκρεμού το δέος δεν έχω μάτια γι άλλο δρόμο αυτόν μου όρισε η μοίρα να πορευτώ αγόγγυστα μού’ταξε οδόστρωμα καλό δίχως καμπές και σκάρτο υλικό για να πατώ γερά μα εγώ, χιλιάδες οι φορές που σκόνταψα και λύγισαν τα πόδια μου σα τραυματία γλάρου στης λίμνης τα λασπόνερα η μοίρα πάντα αδέκαστα ορίζει που θα περπατήσω κι εγώ κι εσύ άξιε συνοδοιπόρε Ο δρόμος είναι αφόρητα μακρύς σας λέω κι εγώ δεν ξέρω αν θα φτάσω εκεί που όλοι ξαποστάζουν αν φτάσω κάποτε, αν, λέω, θα’ναι σα να’ κλεισε ένας κύκλος ο κύκλος της ζωής περπατώντας ως το θάνατο κουράστηκα να περπατώ, κουράστηκα να περιμένω είναι φορές που φτιάχνω όμορφες ατσάλινες φτερούγες για να πετάξω και πιο γρήγορα να φτάσω μα προλαβαίνουν δυνατοί αέρηδες, τις σπάνε και είμαι μόνη στο κενό σαν καρυδότσουφλο σωστό στο μένος των ανέμων Κι η ανατολή, αυτή δε μπόρεσα ποτέ κατάματα να την κοιτάξω πως να κοιτάξω κάθετα το μέγα ήλιο μετά τα βόρια και νότια ταξίδια

35 2014 | VOICES η μόνη σίγουρη πορεία είναι στη δύση εκεί ο ήλιος δεν πονά μόνο καλωσορίζει και με το πέπλο το χρυσό που πια πορτοκαλίζει όλη τη φύση τη νεκρή μαζί και μας σκεπάζει Νύχτωσε και φοβήθηκα μη χάσω το δρόμο μου γιατί όσο κι αν τον βαρέθηκα αυτόν τον ίσιο δρόμο δεν ντρέπομαι να σας το πω φοβάμαι μη λοξέψει και στο σκοτάδι πια χαθώ και χάσω τη ψυχή μου αυτή που η μάνα μου μ’ευχές κι αγάπη φόρτισε και σπίθα σπίθα ηλεκτρισμού η αγάπη της φώτισε τη ζωή μου σας λέω πια άλλον εγώ δρόμο δεν έχω μάθει και το φεγγάρι με βοηθά αν τύχει και ξεφύγω πάλι τα χνάρια μου να βρω ξανά να περπατήσω τον ανεκπλήρωτο σκοπό ευθύς να συνεχίσω Πολύς, ατέλειωτος ο δρόμος σ’αυτό μου το ταξίδι τέλος δε βλέπω πια έχει κρυφτεί στου χρόνου το μπαούλο και σα θ’ανοίξει κάποτε αυτό αντί για τέλος μια αρχή σάμπως μεταλλαγμένη θα ξεπροβάλλει, η αρχή της ανυπαρξίας σ’αυτή που ήμουν άχρονα προτού τη γέννησή μου Μαρούσι, Απρίλιος 2009

The road has become so unbearably long

I’m dead tired and my body lists as it gets older at times I wish the road would break in two and like a weightless butterfly I’d get to feel the awesome precipice

I’m not looking for another road fate has ordained this one for me to tread ungrudgingly its smooth surface has been assigned to me with no turns or bad construction, so I could firmly plant my feet but me, I’ve stumbled more than a thousand times and my legs have buckled under me like those of an injured seagull at the water’s muddy edge fate always impartially ordains where I’m to walk both me and you my worthy fellow traveler

The road has become so unbearably long I tell you and I don’t know if I will ever reach the place where everybody rests if I ever do, if, I say it’s going to be as if life’s circle has closed and there’s nowhere to walk but to death I’m tired of walking, I’m tired of waiting at times I construct beautiful wings of steel so I can fly high and get there faster but strong winds catch up with me, they break them and I’m left alone in the void like a nutshell in the raging gales

And the sunrise that one I could never face straight on how could I gaze squarely at the glorious sun after the journeys to the north and south

36 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

the only reliable course is to the west the sun from there doesn’t wound, it only welcomes and with its golden mantle that slowly turns to orange it cloaks the entire still nature along with all of us

Night has fallen and I fear of losing my way because no matter how sick I am of it of that straight roadway

I’m not ashamed to tell you

I’m afraid it might swerve and in the darkness I’d get lost I’d lose my soul

the one my mother charged with blessings and with love her love a spark, a spark of electricity that has illuminated my life

I tell you, I’ve known no other road and the moon helps me, in case I drift off so I can find my tracks again and soon I resume the walk toward the unfulfilled end

A long and endless road during this journey of mine

I no longer see an end it must be hiding in time’s steamer trunk someday when that’s opened instead of an end perhaps a somewhat altered beginning is going to appear, the beginning of non-existence like where I was outside of time before I was born.

Marousi, April 2009

37 2014 | VOICES

Στο Δάσκαλο - To The Teacher

by Kostis Palamas (1859-1943)

Translated by Dr. Peter Nanopoulos

Chisel, again, teacher, souls!

And whatever is still left in your life, Don’t deny it! Sacrifice it to your last breath! Build the palace, wise teacher!

And if some strength in your body remains, Don’t get tired! Your soul is made of steel. Lay now deeper foundations, So that war cannot destroy them.

Mine deeply. So what if many have forgotten you?

Sometime they too will remember The burdens that you bear like Atlas on your shoulders, Patience! Keep building, wise one, society’s palace.

Kostis Palamas, a beloved and highly respected figure in Modern Greek literature, lived in Athens during the first half of the 1900s. He wrote the inspiring lyrics to the Olympic Anthem and a long array of deeply patriotic poems that earned him the unofficial title of the National Poet of Greece. He also wrote many moving short stories and incisive studies related to the work of influential writers who had preceded him, including Andreas Kalvos and Dionysios Solomos. Palamas was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in Literature and his work has been translated in many languages. The poem "Στο Δάσκαλο" ("To The Teacher") serves as an appreciative testimony to teachers everywhere. (See Kostis Palamas, A Study of his Life and Work, by Thanasis Maskaleris; Twayne Publishers, 1972.)

38 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER II

πάλι, δάσκαλε, ψυχές! Κι ότι σ' απόμεινε ακόμη στη ζωή σου, Μην τ' αρνηθείς! Θυσίασέ το ως τη στερνή πνοή σου! Χτισ' το παλάτι, δάσκαλε σοφέ! Κι αν λίγη δύναμη μεσ' το κορμί σου μένει, Μην κουρασθείς. Είν' η ψυχή σου ατσαλωμένη. Θέμελα βάλε τώρα πιο βαθειά, Ο πόλεμος να μη μπορεί να τα γκρεμίσει. Σκάψε βαθειά. Τι κι' αν πολλοί σ’ έχουνε λησμονήσει; Θα θυμηθούνε κάποτε κι αυτοί Τα βάρη που κρατάς σαν Άτλαντας στην πλάτη, Υπομονή! Χτίζε, σοφέ, της κοινωνίας το παλάτι!

Σμίλεψε

The Smell of Sunday Roast

by Sotirios Pastakas

Translated

by Angelos Sakkis

It smells like Sunday roast on my balcony. I stretch my hands and find the stove turned off, the plates cold. I forgot again to cook. I feel full just with the aroma, even though nobody’s asked me to share the chicken and potatoes split in three. It wasn’t by chance, I figure, that I’d served in a battalion of undesirables.

39 2014 | VOICES Μυρωδιά του Κυριακάτικο ψητό

ψητό της Κυριακής στο μπαλκόνι μου. Απλώνω τα χέρια και βρίσκω την κουζίνα σβηστή, τα πιάτα κρύα. Ξέχασα να μαγειρέψω πάλι. Χορταίνω με τις μυρουδιές κι ας μην με κάλεσε κανείς να μοιραστώ το κοτόπουλο με πατάτες στα τρία. Σε τάγμα ανεπιθυμήτων, λέω, δεν υπηρέτησα τυχαία.

Μυρίζει

Palimpsest: A Novel

BY KATHRYN KOROMILAS

Greek light. The ancients likened the light of day to Being. Light gave life. Darkness took it away. I could never have understood this had I not arrived in my father's village and sat under its sun. In Zelopolis the sun was no metaphor, it was real. It forced clarity upon the landscape, making its topographic idiosyncrasies completely seeable; exposing everything as far as the eye could see, even beyond the eye. Forced knowledge that only the mind could comprehend, that only the spirit could intuit.

My first encounter with Greek light, however, was merely theoretical. It came through the world of books in my father’s artificially lit library back in Coober Pedy. It was there in the dim, dry ambience of that room that I first read the poets and the philosophers. It was there that I came to understand that the sun generated the best conditions under which a person may discern objects and scrutinise truths. It was there that I played out the drama of light and of darkness, the drama that determined, for the poet Elytis, what it was to be Greek. I followed the Homeric myths underground—down the dark and dank stairways—curious about the underworld, but always, reluctantly, coming back up. Greeks were supposed to be children of the light, and would always choose light over darkness, sight over blindness, reason over confusion, life over death.

It was in Akindynos’s aphotic room, drilled into the dismal underground of Coo-

ber Pedy land and fitted with shelves filled with book and book and book, where I spent the long days of my youth. I’d always been drawn to my father’s library as it revealed a world of colour in the darkness. I imagined that Greece must be a lot like Coober Pedy. In Coober Pedy, many people spoke Greek, and looked Greek, and had Greek names. These Coober Pedy Greeks were also curious about darkness. They sought treasures in the antipodean shadows, underground where ochre turned black. But more than that, they recoiled from the day, and sought refuge in darkness, where they built their homes. I then understood that it wasn’t Coober Pedy light that they shrank from, it was the heat.

Even back then, Akindynos burrowed into the darkness seeking out the Greek light. He sought all possible knowledge of the Hellenic world, and of the Hellenes. He added books to his library that were either about Greeks or about other things, but written by Greeks. Amongst all the Greek volumes, Akindynos also included encyclopaedic texts that, by virtue of their broad scope, appended information of a world that took me far beyond the confines of Coober Pedy and the Coober Pedy Primary School, the disseminating-curriculum and the teaching staff, those blood-filled narratives of colonisation, the dark stories of indigenous culture, of witjuti grubs, red kangaroos, and the Dreaming. There was the world of Coober Pedy in which Akindynos was a visitor and

41 2014 | VOICES

FICTION

the world of Hellas in which Akindynos, and by extension me, belonged.

But there in my father's library I also found my own world, another world, between this one and that one, a world that opposed the vivid Greek optimism of light. One day I turned a page in an illustrated book of world religions only to be shocked into recognition, to recollect some old knowledge, to rediscover a black goddess who held a bloody knife in one arm and a decapitated head in another. That was Kali, the Hindu goddess. Kali, she who is black. Kali, with a long red tongue lolling out of her open mouth. Kali, symbolising violence and death. But also, life. Kali, motherly love. Kali. Her name full of the same sound of my own name, my nature already drawn to the same darkness. My namesake may have been the bright-starred constellation that my father called Callisto, but darkness was always more becoming of me than light.

As it was of Thalia. From the very moment she was born, or maybe a little later, a few months after she was born, she would cry whenever I took her outside into the sun, or even inside when I pulled aside the curtains to sit in the light. Julian and I had moved into a three-bedroom house in Adelaide. A light, airy, sunny home, optimistic and welcoming, a family home. Thalia’s was the front room where the light of the day would stream inside, making her unhappy. The two back rooms were for Julian and for me, a bedroom and an office, filled with artificial light that could be manipulated and focused onto whatever needed to be seen.

During my pregnancy, I had sought out the sun, spent most of my time in the front room, bringing my books with me, but then, usually leaving them aside, the room too bright for reading. When Thalia was born, I would drink tea in the front garden under the shade of the Jacaranda with the spectacle of light all around. But Thalia was always

distressed. She was always in a battle with the sun. Thalia was not a child of the light. Not a Greek at all.

And so, there we were—mother and daughter—and we developed a new habit. We slept throughout most of the day, and stayed awake until late at night when she was able to function, performing all the normal actions that children perform during the day, and I could be a normal mother. In the evening’s darkness, Thalia would happily play, laugh, listen to my stories, listen to me sing, crawl into Julian’s embrace, feel about his face. I understood very early on, much earlier than Julian, much earlier than the doctors, that Thalia’s rejection of light was a matter of confusion, not contempt. She did not know how to filter the shafts of light. They came to her potent and dangerous. When the diagnosis came, Thalia had already learnt to negotiate her way around the space, seeking the dark, covering her eyes in the light. Along with the diagnosis came a dark pair of glasses to help with the day, but even then Thalia would keep her tiny hand to her forehead—a constant salute—keeping every single ray of sunlight from making contact. I should have expected it, should have been prepared that day. We were in Coober Pedy—a visit to see Thalia’s grandmother, Anastasia. Thalia, having mastered her walk was already so confident in making her way about the space; not seeing and yet seeing by counting steps, and feeling around obstacles, smelling paths and intuiting spaces. It must not have been more than a minute, less than that. I had turned my back. It is a wonder mothers ever do that—turn their backs—but they do.

And it was in that moment, and not the previous moment, not the moment when I was looking right at her as I spoke to Anastasia about her. It was the moment when I had turned away. Anastasia had begun talking about the mine, a new machine, and I

42 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER IΙ

had turned to see the thing she described. This was the moment that Thalia sought the darkness, and the deep shaft, the treasure below. I knew she’d fallen even before I turned around to see that she wasn’t there. To see that her short figure with her large blonde head had disappeared from the landscape. I understood it in my body first, and then, when I turned back to find a flat landscape without a child, I knew it in my head. Thalia, who’d become so confident in navigating herself in the dark, must have run toward that black hole in the bright landscape, her joy must have been so great, her trust in the blackness so complete that she had stepped right into it, and fallen down, there.

Broken.

Later, when I returned to Coober Pedy, to the hot ochre land with the holes in the ground, I would sit for long hours, just sit, next to that single hole. In the begin-

ning, it was inconceivable that I would do anything but sit, and stare, and replay the moment again and again, rearranging the facts, placing myself, or Julian, or Anastasia over the hole that took Thalia. I’d replay even further back, and rearrange the entire day, shifting the visit to another day, an overcast day when the black hole would be less attractive. And I’d go even further back, to the moment of Thalia’s conception, shifting that day to another day, rearranging the chromosomes, so that different genes would connect, disease-free genes that would have avoided the blindness. And I’d go even further back, murdering off the conception entirely, removing all evidence of there ever having been a Thalia. The past was not satisfactory. It was not satisfactory at all. But it had past, and could not be changed now. Not now. Not ever. Enough. �

Excerpted from the novel PALIMPSEST

43 2014 | VOICES

Seated Figure by Peter McNeill.

Seated Figure by Peter McNeill.

Bazaar

BY BELICA ANTONIA KUBARELI

An old beggar bumps into me saying, “Your eyes are yellow” and starts crying. A fat African woman dances to her internal music oblivious to the hubbub with her hands stretched up in the skies and her eyes closed. A young couple rolls half naked under the sunny bushes and I enjoy their hugs like a child in the middle of Mom and Dad. My dog falls in love with a cat who scratches her wildly while she licks him. A pair of boots land on my head. Not my size. Dazzling smells cause me hunger—hunger for you. A peddler sells the books I had given to my best friend when I left Greece. The Sunday bazaar leads to Acropolis. The gods still overlook Athens. �

45 2014 | VOICES

FICTION

Up in the Air by Peter McNeill

Toilet in Place by Eleftheria Lialios

Up in the Air by Peter McNeill

Toilet in Place by Eleftheria Lialios

Eye of the Hydra

BY AKOS KIRSH

PROLOGUE

Tolo, Greece

The sunrays of Apollo caressed my skin as I laid on the beach near to the road, which led into the town. I couldn’t stop admiring the beautiful girls who passed by me in the sand, but sadly none of them were alone so I couldn’t use my charming personality to get their attention.

Without a single cloud in the azure sky, some whistling seagulls circled above the water surface. Windsurfers flickered from one end of the bay to another while swimming tourists enjoyed the water constantly at the beach. The wind brought to them the sound of a ship’s horn from a remote port. Behind the nearby islands the outline of mountains emerged on the distant horizon. I was watching the people and enjoying every minute of my free time.

Only two days had passed since I'd arrived in Tolo to release the dead steam, which I was filled by during my job. The life of a private detective is never an easy one. Usually full of danger and tension. That is why every year I tried to scrape together a small amount of money for a vacation. Sometimes it was really hard. Practically every day I wandered the streets of London, even on the weekends. In any case, I had managed to get to Greece once again.

A few years ago, I had travelled to Athens and Rhodes also, but for the charming lit-

tle town of Tolo I hadn’t had any luck until now. I was ready to go and jump into the warm waves when suddenly a shadow fell on me and a pink paper kite crashed into my head. I was thoroughly surprised and fell to the ground in fright, as I started to struggle with the monster which was stuck to my face.

“Oh my God! Are you alright, sir?” Asked a tinkling female voice.

I hardly heard the words, but to serve as an excuse for me, some sand went into my ears. Once I realized there was nothing to fear, I dropped the kite and stood up. I was about to start shouting at its master but an etheric phenomenon appeared before my eyes, on which I could just blink and dared not quarrel with. Slender body, long blonde hair and a blue bikini … a view which I could not resist. Her tanned skin was almost glowing in the sun.

“What’s wrong with you? Are you deaf?” She asked impatiently.

“Oh … sorry! I got carried away. This thing is yours?”

“Yes it is. I’m sorry for what happened but a strong wind came and …”

“Don’t worry!” I smiled kindly and the impact on her was obvious, as she returned the gesture. “Let me introduce myself! My name is Ron Wyatt.”

“Jennifer Borchardt.”

“You have an interesting name. Does it come from a German father perhaps?”

“That’s right. How did you guess?”

47 2014 | VOICES

FICTION

“Good instinct. May I invite you for a cocktail?” I asked by a rush of idea, but I noticed for her it wasn’t unexpected because she agreed immediately. Probably she realized what a big impression her presence had on me.

Leaving the coast we crossed the road and sat in a nearby tavern, where I ordered the drinks and, accompanied by the roaring sound of the sea, we started talking. It turned out that she worked as a restorer at the British Museum, but now she was spending her holiday here. Jennifer seemed happy in my company, although at times it looked like she was spiritually somewhere else—but I didn’t give much credit to that.

When I talked about my job she was thoroughly surprised. Then we ordered another round. The more we talked, the more she fascinated me. Especially when she began twisting a strand of her hair and flirtatiously smiled at me.

“Would you like to go dancing tonight with me?” I asked, though I had no idea why since I wasn’t good at dancing. On the floor my movements reminded one of a nervous chicken.

“Absolutely. Where?”

“There is a nightclub not far from here, it goes by the name of Disco Club, I think.”

“Yes I know where it is. In which hotel are you staying?”

“In the Demos Apartment house on the other side of town.”

“Nice. My place is the Apollon Hotel. Just five minutes away from here.”

“I guess I know which one it is. Ten o’clock would be okay for you?”

“That will be fine,” Jennifer nodded, smoothing a stray hair from her forehead, then looked at her watch. “Well … time went fast. I think I will go and swim a little bit, and after that I will return to my room. Left all my stuff on the shore anyway.”

“I’m afraid me too. Let’s hope everything will still be there!”

Fortunately, none of our stuff seemed to be missing. As I began to pack, Jennifer walked into the sea, cheerfully waving her hand. She jumped into the waves like a mermaid. When she reappeared, she was already in the deeper section of the water. Nobody was around her, so she could swim wherever she wanted. Only a white speed boat, with two fishing men, rocked in her vicinity. They were far away, so I couldn’t see them clearly enough to be sure, but it looked like one of them was wearing a diving suit. I shrugged my shoulders and grabbed my backpack.

I strolled in the sand, then turned back to take a last glimpse of her, but a terrible sight met my eyes. Jennifer was desperately flapping her arms in the water, then she sank in a moment. I cried out and raced breathlessly toward her direction. I dropped my bag and clothes, then jumped into the water. With powerful strokes I swam towards her. In the meantime, she turned up again and again, crying for help in horror.

I doubled the pace. Then she submerged once more and didn’t come up this time. When I reached her, I took a deep breath and dived. A blank unbroken silence reigned under the water. The salt heavily stung my open eyes, but I tried to control myself not to close them. Soon, I discovered her slowly sinking body. I managed to grab her arm and pulled her towards the surface. As I emerged from the water, I saw some people watching from the shore, then a sailor man popped up next to us and helped us out of the sea. Together we pulled Jennifer onboard and laid her down. Unfortunately, she wasn’t breathing.

I was terrified and tried to artificially respirate her to get the swallowed water out of her lungs. All in vain. Filled with disappointment and exhaustion, I had to sit down on the deck. Meanwhile, the unknown Greek man steered towards the shore. It was unbelievable that the woman I had just met and invited on a date was now, on the same day,

48 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER IΙ

dead. I cursed Fate and mourned for Jennifer, when something captured my gaze.

I leaned over her and examined her body. My eyes widened, as I stared at the red stripe that ran around Jennifer’s neck. There was no doubt; it hadn’t been there before she went to swim. As I looked closer, I already knew what I was looking at. Someone had strangled Jennifer professionally. I jumped up and looked for the speed boat with the fishing men, but couldn’t find it.

They had disappeared like a grey donkey in the mist, and left behind nothing but the body of a charming woman. As I reached the shore, I couldn’t stop wondering what the hell had happened before my eyes.

CHAPTER ONE

Inspector Stratos Fotopoulos was a middleaged man. His straight hair had started to bald strongly on top of his head, and he tried to compensate for it with a surprisingly thick beard. His manner was rough and straightforward. Fotopoulos didn’t even attempt to hide that he didn’t sympathize with me, but at least he believed my story. There wasn’t much furniture in the white-walled office. Apart from a file cabinet and his desk, I saw nothing else in the room, except one chair, on which I was sitting opposite the inspector.

“You are lucky to be a private detective and pure as freshly fallen snow,” Fotopoulos growled, after making me wait for an hour until they checked my data. “So you didn’t see anything?”

“Just what I told you already. I imagine those two guys from the boat could tell you more.”

“The problem is that we don’t have any description of their appearances. However, many witnesses also claim that they saw one of them climbing out of the water in a diving suit. Only the foam they churned up remained after them. In other words, we are

completely in the dark. But something else did turn up,” he said, leaning closer to me. “My colleagues called the British Museum and asked about Miss Borchardt. They have never heard of her.”

“What?” I couldn’t believe my ears. This information was something I didn’t expect.

“You heard me right. Whoever she was, she lied to you, Mr. Wyatt.”

“But why?”

“Good question,” he nodded, then stood up and held out his hand. “You can go now. Your statement was recorded but … don’t leave town for a while!”

I said goodbye and left the building. Immersed in my thoughts, I walked through the main street of Tolo, passing taverns and shops. The whole situation seemed surreal and absurd. My holiday couldn’t get any worse than this. Who were you really, Jennifer? I decided I had to find out, so I headed straight for the Apollon Hotel.

It didn’t take long to find the building, which was marked by a billboard featuring a golden harp and lettering on a brown background. I arrived at the parking lot, from which people could access the building through a glass door. Pleasantly cool air waited for me inside. The marble hall was furnished with a white piece suit and a largescreen TV.

Behind the reception desk, a bald bespectacled man was seated. He immediately arose as he saw me.

“Good afternoon! How can I help you?” He asked in slightly accented, but understandable, English.

“Greetings! My name is Ron Wyatt. Inspector Fotopoulos sent me to look around the room of Miss Jennifer Borchardt.”

“I believe the police closed the suite already,” he frowned, but I didn’t let myself be distracted.

“I’m here unofficially. The inspector is a good friend and a colleague of mine. You

49 2014 | VOICES

know, I’m a detective in London. Actually, he isn’t satisfied with the performance of his men and asked me to help. Neither would he be happy to learn that you were not willing to cooperate with the authorities. We are talking about a serious crime here, sir! But if you think it necessary, I shall make a phone call …” I shrugged my shoulders and reached for my mobile phone.

“No need for that!” Replied the man suddenly, from which I found out that he didn’t wish to experience the wrath of the inspector. “Here is the room key. Second floor!”

So I went up the stairs. I could have used the elevator, but two years ago I got stuck in one during a power failure. Since then, I couldn’t force myself to use the mechanism. After a few minutes, I was standing in the corridor outside of the room. A yellow ribbon was stretched across the door, indicating that the police had already scanned the place. Without hesitation, I tore off the ribbon and stepped inside. I found myself in an elegant room with a double bed and a balcony. From there, one could enjoy a stunning view of the open sea. Before entering, I took out a handkerchief to avoid leaving fingerprints, and opened the cabinets and drawers.

I'd hoped to find something that would explain the whole situation, but there wasn’t much to check. It appeared she had moved in recently and didn’t feel like unloading her luggage. In the open suitcase, only her clothes were lying. I searched through and through the room but couldn’t find anything that would bring the case further. Until I discovered some strange scratches on the floor at the foot of the bed. I crouched and looked under it. To my surprise, one of the tiles was located differently in comparison with the others. The local authorities had been really careless.

I quickly pulled aside the bed and took a closer look. As I displaced the tile, an envelope caught my eye. I picked it up and

extracted an old newspaper as well as a letter with the following writing on it:

Meet me at midnight on Thursday in the port! I know why your father died. His diary is in my possession. Come alone!

Professor Alain Bergman

I was thoroughly surprised by the content of the letter. It seemed I had gotten myself into a complicated affair where nothing was as it appeared to be. I also read the newspaper article, which was about a fire that had occurred on the island of Hydra twenty years ago. A French man had died in the flames, but the article didn’t mention his name. The rest of the newspaper was missing.

I sat down on the bed and began to wonder. Whoever Jennifer was, it was certain she didn’t stumble across my path by chance. I felt it. Nevertheless, I knew how to continue the investigation. I decided to go to the meeting and see who this Professor Bergman was with my own eyes. Because today was Thursday! I needed answers, and only he could provide them.

I took the contents of the envelope, put everything back in its place, and then left the building. The receptionist gave me a puzzled look but I didn’t care about it. My thoughts were focusing on the meeting already.

Now I really regretted not bringing my gun with me. But who would do such a thing, when he was going on a vacation? However, Fate had yet again intervened.

CHAPTER TWO

The silky cloak of the night fell quickly. Tolo’s nightlife became more lively. Locals and tourists sat in the taverns to have their dinner, listening to pleasant music and talking, or just visited the bazaars to buy some souvenirs. Dozens of cars and mopeds travelled

50 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER IΙ

on the sidewalk-less main street. A parade of French, English and Hungarian words buzzed around me. The vibrant nightlife proved to be attractive, though it was the least interesting thing to me.

I looked at my watch while heading to the harbor. Only ten minutes left until the meeting. As I approached the edge of town, there were increasingly few pedestrians, until I found myself alone on the street. I passed a long row of parked cars, shooting a quick glance at the pink flowers of a bougainvillea which ran along the wall of a house. Tolo had lost none of its scenic beauty and charm in the light of the street lamps. A few minutes later, I reached the port. Dozens of fishing boats and cruise ships rocked on the waves, while the night lights calmly danced on the water. The colored lights were strengthened by the reflector of a passing vehicle, as the port was located next to a road which bypassed the town on the nearby hillside.

A row of benches and lamps stood on the long promenade of the harbor. I didn’t see a single soul, but I tried to be cautious. I was walking in the shadow of the concrete wall along the promenade, listening to the sound of the sea as the waves lapped the shore. I almost felt like I was on an island of peace and tranquillity. Almost. Finally, I reached the end of the promenade, where the shadows deepened.

Suddenly, the sound of footsteps reached my ears. Someone was walking up and down near the rocks, outside the light of the lamps. Slowly I managed to make out the contours of his figure. He was short and had his hands clasped behind his back. I thought it was time to reveal myself.

“Professor Alain Bergman?” I asked, and my voice made him stop. His glasses glinted as a stray beam of light wandered over his face.

“Who are you?”

“I came to the meeting. My name is Ron Wyatt.”

“I was expecting a woman.”

“I know. She sent me,” I lied. “She was afraid it might be dangerous to meet here, so I agreed to come in her place.”

“I still don’t understand what you are doing here.” He wrinkled his forehead and stepped out of the shadows, revealing his skinny body and grey hair. He appeared to be in his seventies.

“I’m a private detective.”

“Oh … I get it! This means that Miss Sicard hired you?”

Sicard. Now I had learned Jennifer’s real name at least! Of course I answered with a yes, but confessed that there was much information in this matter that I still didn’t know.

“In the letter you sent her, you mentioned a diary,” I came to the point.

“Yes, it’s here with me,” he said, pointing to his pants pocket. “It belonged to Luc, Miss Sicard's father. We were colleagues and friends for a long time until … he was killed.”

“How did he die?”

“He was run over by a car on his way home. There weren’t any witnesses. His body was found lying on the Paris road the next morning. The police investigation didn’t last long. Allegedly they found alcohol in his blood and they thought he was drunk that night, though I’m sure he wasn’t. He never drank. On the same day as his murder, someone broke into his house and made a mess, but didn’t steal anything. I suspect that someone bribed the police, which is why they dropped the case. The killers were looking for the diary, which Luc sent me via post a day prior to his death.”

“He sent it to you and not his own daughter? Why?”

“Their relationship was not the best.”

“I see. And what can be found in the diary? What was your profession by the way? Miss Sicard wasn’t too talkative.”

51 2014 | VOICES

“We worked as art historians at the University. At times, the Louvre used our services as restorers as well.”

“Professor Bergman … this story becomes more and more confusing. Why the hell did your friend die?”

“Read it!” He said, handing over the diary. “Then you will find out. I can’t say more because there is little time left I’m afraid they are on my trail.”

As soon as my fingers touched the leather-bound book, a soft pop sounded from somewhere above us, and Professor Bergman lurched. On his chest a red blood spot appeared, increasing in size. I immediately dove for cover and flattened myself against the wall. I don’t know how I was able to move at all. It’s not an everyday thing that someone is killed before your eyes, and the sight thoroughly shocked me. Despite the situation, the adrenalin flowing through my body gave me enough strength to act. However, there was nothing I could do for the old man. He collapsed before my eyes and breathed out his soul. It was time to leave the port!

But I couldn’t go backwards, because new bullets hit the ground around me. I saw a dark figure stirring behind a bench. I cursed my bad luck, then made a decision and moved towards the rocks. I ran as much as I could, while bullets flew around me like angry wasps. Fortunately, the night’s darkness served as a perfect cover, though it also made my escape harder. I could barely see anything as I climbed down the rocks and found a small crack to hide in. The sea washed my shoes.

Above me, loud and angry words were spoken and the figures of two men emerged, then stopped at the edge of the hill and looked down into the darkness. In their hands, they held silenced pistols. After looking at each other, the higher one motioned to his companion, who started to climb down. He moved like a panther, skillfully and

silently. He was a professional. The man was only a few centimetres away from me, and I didn’t even dare take a breath. His companion joined him.

They knew I was there somewhere, but they couldn’t rely on their eyes. Unfortunately, the situation quickly turned to their advantage when one of them pulled out a flashlight and turned it on. The white light pierced the night like a sword. Only seconds separated me from death, so I had to act. Using the power of surprise, I broke out and pushed them with my full power. It was fun to listen to their cries as they fell into the water with a loud splash. Without wasting a second, I climbed back to the promenade, hoping that they didn’t have any friends, otherwise I was doomed!

But Goddess Fortuna stood next to me that night. With the diary in my pocket, I quickly disappeared into the shadows, like a wandering spirit in an old castle.

CHAPTER THREE

I returned to my apartment, located on one of the steeply rising side streets, with my nerves on edge. Once I'd sat down on the balcony and drunk a glass of beer, I managed to calm down a bit. The area was quiet and the noise of the bustling main street reached my ears dully. Across the rolling dark sea, the lights of other settlements vibrated on the mainland. A little closer, the cross of Koronisi Island’s only church shone with blue light, like an improvised lighthouse.

At this moment, I would have gladly returned to my house in London to enjoy the company of my cat, Tom, whom I'd left with one of my friends in my absence. Finally, I gathered myself together and started reading the diary. Surprisingly, it described the life of Luc Sicard’s father, François Sicard. He was born in Paris, into a moderately wealthy family. François lost his mother at a young

52 ΦΩΝΈ Σ | VOLUME I, NUMBER IΙ

age and his father became an alcoholic, so as a teenager he was forced to look for a job.

After a long search, a local press employed him as an assistant, but in his spare time, François devoted himself to painting. He often made drawings in the streets for money. In time, a benefactor and patron of the arts discovered his talent and searched for a teacher to train him. Meanwhile, his father slowly drank himself to death.

The young François soon became independent, and under the tutelage of his teacher, he grew up to be a true artist. Until the age of twenty-six, François lived a modest life despite the inherited family wealth, because he didn’t want to throw away the money. At a cafeteria, he met with his future wife, Patricia Laroche. A year later, they married and began to travel. The painter was charmed, especially by the Mediterranean atmosphere and historic monuments of Greece.

Despite his talent, he didn’t become famous. His complicated nature made things even more difficult. Apart from Patricia, not many people were capable of develping a good relationship with François—probably as a consequence of his hard childhood. A breakthrough came at the age of thirty, when a large number of his paintings were sold. It was even mentioned in the newspapers, because two English Lords and a German lawyer were the ones to purchase them.

However, the happiness of François was overshadowed by his wife’s illness. In every second month, a hot fever knocked Patricia off her feet. The doctors didn’t know the reason for it, and the medicines could only ease the symptoms. She became skinny and weaker over time. For three years, Patricia battled the disease, but on an autumn day she finally closed her eyes. In his grief, her husband reached out to alcohol, as had his late father, and became addicted too.

He had only a few friends, who unsuccessfully tried to steer him back towards a

healthy lifestyle. Even his only son, the fiveyear-old Luc, wasn’t able to change his mind. Once the painter became incapable of raising a child, a cousin of François looked after the children. Finally, everyone turned away from him and there wasn’t a gallery that would exhibit his creations.

As a last hope, he sold his house and moved to Greece, to the island of Hydra, which had long been known as a centre for culture and the arts. He built a new home for himself three kilometres out of town. The sea air and the hospitable residents helped him find peace, and slowly François gave up alcohol.

Then he began painting again, and in a telegram made contact with his son and cousin. On the island, he made numerous paintings, which were purchased by several galleries throughout Europe. Some even reached America. However, fame never found him again.

Though he established an acceptable relationship with his son, the gap that separated them remained. Then, on a summer night, tragedy occurred. The sixty-year-old François, who was said to adore cigars, fell asleep in his bed, and the sheet caught fire. The whole building burned down. His family transported his remains home, and the memory of the artist was slowly forgotten on the island.

His works were also destroyed by the flames, but some said one painting survived the fire.

The diary ended here. I was sitting with my thoughts, staring at the dark sea. According to Bergman, I would know what was going on after reading the diary, but I could only guess. For lack of any better ideas, I flipped through the book again. Then I came across an inscription at the bottom of a page, written in small letters. It was hard to read, but in the end I succeeded: The victorious Heracles (1991 – François Sicard & Giannis

53 2014 | VOICES

Pavlis). Now I realized what was going on! The victorious Heracles was probably the last painting of François, which wasn’t destroyed in the fire. Luc Sicard discovered the person who knew something more about it. Unfortunately, he didn’t have the time to get to the bottom of things, just like his daughter, who shared his fate. Professor Bergman also passed away. It seemed I was the last person who could reveal the secret.

I was ready to fulfill the task. Not because of pride or a reckless desire for adventure. Simply due to my commitment to justice. I owed it to the memory of the Sicard family.

CHAPTER FOUR

The sun clothed the landscape in a red robe as it leisurely rose above the horizon, stroking the bottom of the cloud fragments lazily sliding on the yellow sky. I hadn’t slept much last night, but I was ready to go to the island of Hydra.

Alas, I had to wait; it was too early in the morning and everything was closed still, so I couldn’t pay for the tickets to the ship. However, I suspected that inspector Fotopoulos would be in his office already. I was right.