Water & Sanitation Africa

Complete water resource and wastewater management

INDUSTRY INSIGHT

WATER IN THE DIGITAL

Complete water resource and wastewater management

When mechanical strength and corrosion resistance is vital, you’ve got to double down on quality. Macsteel’s patented TosawrapTM has a unique triple part system that provides an inner and outer coating, and seals around welds and other surface irregularities. Perfect for rural water supply and petrochemical applications, these powerful sleeves are made in-house, allowing flexibility when it comes to sizes.

Scan the QR code to learn more about how our steel products and services can help drive your business forward

Water supply in Southern Africa is unequally distributed, with 70% of water resources being shared between a number of different

Transboundary water management is crucial for development in the region. DBSA has a strategic partnership model to strengthen the implementation of various water and sanitation programmes.

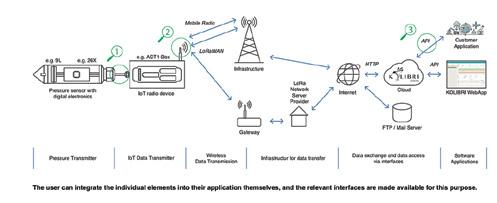

stand-alone or wireless

Pressure Ranges

0…5 to 0…100 mH2O

Total Error Band

±0,1 %FS @ 0…50 °C

Recording Capacity

57‘000 measuring points

Dimensions ø 22 mm

Special Characteristics

Also available in ECO design

3G 4G

Pressure Ranges

0…1 to 0…30 bar

Total Error Band

±0,2 %FS @ 0…50 °C

Accuracy

±0,05 %FS

Interfaces

RS485, 4…20 mA

Special Characteristics

ø 16 mm

Communication Mode

2G / 3G / 4G / LoRa NB-IoT LTE 2M

Sensor Interfaces

RS485, SDI-12, analog, digital

Battery Life Up to 10 years

Editor Kirsten Kelly

kirsten.kelly@3smedia.co.za

Managing Editor Alastair Currie

Editorial Coordinator Ziyanda Majodina

Head of Design Beren Bauermeister

Designer Jaclyn Dollenberg

Chief Sub-editor Tristan Snijders

Contributors Ralf Christoph, Jessica Fell, George Gerber, Lester Goldman, Ednah Mamakoa, Gina Martin, Chetan Mistry, Dan Naidoo

Production & Client Liaison Manager Antois-Leigh Nepgen

Distribution Manager Nomsa Masina

Distribution Coordinator Asha Pursotham

Group Sales Manager Chilomia Van Wijk

Bookkeeper Tonya Hebenton

Advertising Sales Hanlie Fintelman

c +27 (0)67 756 3132

Hanlie.Fintelman@3smedia.co.za

Publisher Jacques Breytenbach

3S Media

Production Park, 83 Heidelberg Road, City Deep Johannesburg South, 2136 PO Box 92026, Norwood 2117

Tel: +27 (0)11 233 2600

www.3smedia.co.za

ISSN: 1990 - 8857

Annual subscription: R330 (SA rate) subs@3smedia.co.za

Copyright 2022. All rights reserved. All material herein is copyright protected. The views of contributors do not necessarily reflect those of WISA or the publishers.

WISA Contacts:

HEAD OFFICE

Tel: 086 111 9472(WISA)

Fax: +27 (0)11 315 1258

WISA’s Vision Inspiring passion for water

Physical address: 1st Floor, Building 5, Constantia Park, 546 16th Road, Randjiespark Ext 7, Midrand Website: www.wisa.org.za

BRANCHES

Central Branch

(Free State, Northern Cape, North West)

Chairperson: Dr Leana Esterhuizen

Company: Central University of Technology

Tel: +27 (0)51 507 3850

Email: lesterhu@cut.ac.za

Eastern Cape:

Branch Contact: Dan Abrahams

Company: Aurecon

Tel: +27 (0)41 503 3929

Cell: +27 (0) 81 289 1624

Email: Dan.Abraham@aurecongroup.com

Gauteng

Branch Lead: Zoe Gebhardt

Cell: +27 (0)82 3580876

Email: zoe.gebhardt@gmail.com

KwaZulu-Natal

Chairperson: Lindelani Sibiya

Company: Umgeni Water

Cell: +27 (0)82 928 1081

Email: lindelani.sibiya@umgeni.co.za

Limpopo

Chairperson: Mpho Chokolo

Company: Lepelle Northern Water

Cell: +27 (0)72 310 7576

Email: mphoc@lepelle.co.za

Mpumalanga

Chairperson: Lihle Mbatha (Acting)

Company: Inkomati-Usuthu Catchment Management Agency

Tel: +27 (0)13 753 9000

Email: mbathat@iucma.co.za

Western Cape

Chairperson: Natasia van Binsbergen

Company: AL Abbott & Associates

Tel: +27 (0)21 448 6340

Cell: +27 (0)83 326 3887

Email: natasia@alabbott.co.za

Namibia

Please contact the WISA Head Office at admin@wisa.org.za for more information

“We

must free ourselves of

the hope that the sea will ever rest. We must learn to sail in high winds.”

– Aristotle Onassis

In keeping with the WISA 2022 Biennial 2022 Conference’s nautical theme – #NavigatingTheCourse – the wise words from Greek shipping magnate Onassis, who amassed the world’s largest privately owned shipping fleet, are particularly fitting.

Over the past few years, the water and sanitation industry has only experienced high winds. Nearly every speech, press release and report starts with listing at least two of the four depressing facts:

• South Africa is the 30th driest country in the world, with a semiarid climate and average annual rainfall of about 465 mm – half the world average.

• South Africa is approaching physical water scarcity in 2025, with an expected water deficit of 17% by 2030.

• South Africans use more water than the global average –234 litres per person daily – which means the country’s per capita water consumption is higher than the global average of 173 litres.

• South Africa needs at least R1 trillion to recapitalise the water sector.

But its these high seas that have inspired innovation. South Africa has built a highly active research and innovation capacity in the water sector, which is spearheaded

by the Water Research Commission (WRC). As a result, South African scientists have been among the significant contributors to new knowledge creation in the water innovation domain, especially in water treatment technologies.

An early example of local water innovations is the Khoisan methods of detecting and harvesting water under the desert floor and using empty ostrich eggshells for storage for long journeys across the Kalahari. In addition to dam building for agricultural growth and interbasin transfers to enable mining and industrial development, South Africa has boasted world firsts such as reverse-osmosis membranes and dry-cooled electricity generation. Sanitation could now also become the nucleus of a new circular economy, comprising a cycle of technology design, water treatment, water distribution, water use and consumption, wastewater collection, recycling and water reclamation, and product recovery and residual waste use (page 24).

The Darvill Wastewater Treatment Plant’s upgrade is now completed (page 44), showcasing a number of innovations as well. It is, however, important to remember that these innovations bring their own challenges, such as underappreciated cybersecurity issues (page 26).

As Dan Naidoo, chairman of WISA, points out on page 9, none of these innovations would be possible without our committed water professionals. I look forward to meeting you all in person at the WISA conference.

In each issue, Water&Sanitation Africa offers companies the opportunity to get to the front of the line by placing a company, product or service on the front cover of the magazine. Buying this position will afford the advertiser the cover story and maximum exposure. For more information, contact Hanlie Fintelman on +27 (0)67 756 3132, or email Hanlie.Fintelman@3smedia.co.za.

The opinions and statements shared by thought leaders in the water industry to Water&Sanitation Africa.

“The water industry will never have the optimal amount of funding, number of water and wastewater treatment plants, nor people on the ground. This should motivate the entire country towards collaborating and working together to solve the water crisis. There needs to be less focus on the blame game and challenges, and more emphasis on the cooperation and integration of efforts. This cooperation does not need to happen within the water sector but within the value cycle of water.” Dr Lester Goldman, CEO, WISA

PAGE

“We are now on the cusp of creating a new industry (the Tesla of sanitation) that can deliver safe sanitation solutions to communities and households in the form of a reinvented toilet. A reinvented toilet kills pathogens, requires no input water, and transforms human waste into a safe by-product, such as clean water and ash, and does not require a sewer or septic connection.” Dr Shannon Yee, lead on the G2RT programme supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

24 PAGE

“I would like to take a moment to acknowledge the water professionals that show up every day and do their jobs. They are our South African heroes. There are still a lot of experienced, talented people in key positions that are managing (against all odds) to keep services going. We desperately need more of these people, who speak truth to power, who are practical and honest.”

Dan Naidoo, chairman, WISA

PAGE

“To illustrate the importance of cyber training, there was a recent case in Saudi Arabia, where an oil company underwent a series of penetration tests. The company’s network and software managed to thwart all attempts. As a last resort, a person handed out USB sticks (that hosted a virus) to the company’s employees and managed to infect computers with malware. Within minutes, the company was penetrated.”

Johan Potgieter, cluster leader: Industrial Software, Schneider Electric 31 PAGE

“Reducing water consumption in a water-scarce country needs to be a business priority – not merely from a cost perspective, but for environmental, risk management and operational sustainability. By reusing water – especially water originally from rainwater catchment – businesses build resilience, reduce the risks posed by water interruptions and the impact on operations.” Chester Foster, GM, The SBS Group

33 PAGE

“Depending on its quality, groundwater is generally more affordable than water reuse or desalination. It is a ‘sleeping giant’ and has huge potential in improving the region’s water security. Groundwater flows a lot slower than surface water and can provide water when the surface water sources are stressed. Then, when rainfall levels improve, and the rivers start flowing again, the groundwater can be recharged, while the surface water sources again become the primary water source. Groundwater can buffer the impacts of drought.”

PAGE

Neville Paxton, chairman: Eastern Cape Branch, Ground Water Division

“Chlorine remains the most popular choice for treating water. It’s cheap, abundant and ruthlessly effective. Ozone and UV don’t necessarily compete with chlorine. Instead, they help reduce chlorine use, lessening risks and environmental impact, and offer alternatives where chlorine is impractical or dangerous.”

Chetan Mistry, strategy and marketing manager, Xylem Africa

“If water treatment facilities do not reduce the organic content of wastewater before it reaches natural waters, microbes in the receiving water will consume the organic matter. As a result, these microbes will also consume the oxygen in the receiving water as part of the breakdown of organic waste. This oxygen depletion, along with nutrient-rich conditions, is called eutrophication – a condition of natural water that can lead to the death of animal life.” Ralf Christoph, GM, Hanna Instruments

“In South Africa, there is a focus on the current cost of a product, without taking into account its life-cycle costs. Stainless steel is an optimal material in water system applications and, while it comes at a price, it is an investment in the country’s infrastructure. If the overall system is designed properly, the thickness of the steel can be reduced to withstand pressure. Drakenstein Municipality is a wonderful example of the savings that can be achieved when using stainless steel for bulk water reticulation.”

Anesh Prithilall, business unit manager: Valves, EMVAfrica

“Darvill is a flagship WWTW for Umgeni Water due to its size, the iconic egg-shaped digesters and, more importantly, its processes that embrace a circular economy. Bulk water is our core business, and we therefore focus on maintaining and improving the quality of water throughout the water cycle. Catchment management is extremely important. We therefore have to treat our wastewater properly so that, when it is discharged back into the catchment, we can use that water again.” Megan Schalkwyk, process engineer, Umgeni Water

“The risk posed by water hammer should be assessed at the conceptual design stage, prior to finalising the pipe material, diameter and wall thickness, as well as at the technical design stage, prior to detailing the mechanical and electrical plant to ensure maximum safety and economy of the pipeline project.”

George Gerber, CEO, Water

The water industry has undergone enormous changes in the past 20 years. It used to be the norm to have a large team of operations staff to carry out time-consuming tasks such as manual measurements. But today, W/WW treatment plants can be mostly operated remotely, increasing productivity, efficiency and accuracy.

Increasing populations, industrialisation and climate change intensify water scarcity. Communities across the world have an urgent requirement for safe, reliable and affordable W/WW services. W/WW is a non-cyclical industry: authorities will continue to invest in upgrades if populations increase and infrastructure ages. It is

therefore critical to leverage the right solutions at the right time to ensure these investments are effective in improving operations and justifying capital expenditure.

The W/WW industry should be focusing on the internet of things (IoT) and how it can improve operations. The IoT connects digital objects such as sensors and flow meters to the internet, turning them into ‘smart’ assets that can communicate with users and application systems. This allows for more efficient process control and optimised network management. General water monitoring operations that were previously manual and inefficient can now be automated, continuously reporting on their own status in real time.

Endress+Hauser understands the practical and quality needs that the water industry is demanding. That is why its primary goal is to create practical solutions to ensure everything works perfectly.

Netilion Water Network Insights optimises processes across the entire water cycle while collecting measuring variables and displaying the data in a customisable visualisation. This allows

a W/WW treatment plant to react quickly to incidents and save on operating and energy costs.

Promag W 800

Water’s journey is endless. It often travels long distances through huge pipelines in remote areas without any other infrastructure. To guarantee sufficient water quantity and quality, active management is needed.

This is exactly where the batterypowered Promag W 800 makes your life easier. It provides everything you need to maintain full compliance with legal requirements while increasing your operational efficiency.

Whether in urban or remote areas, a desert or the tropics, the accurate measuring and billing of drinking and process water consumption is becoming increasingly important. Endress+Hauser has developed the new Promag W 800 with battery power precisely for such applications. This electromagnetic flow meter allows for versatile and autonomous use even at locations without power supply:

• in areas with sea, river, spring or ground water

• in distribution networks and transfer stations

• in irrigation systems.

Water quality monitoring

Water quality monitoring is also an important aspect for water and wastewater plant managers. Online monitoring in the distribution network ensures that water quality is permanently measured. Real-time

Established: 1984

Supported regions: Botswana, DRC, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Number of employees: 111

warning of pollution events is possible to ensure that they are quickly resolved, and downstream operations are not adversely affected.

Furthermore, online monitoring parameters are used as an input for network asset condition assessment –for example, pH and conductivity in wastewater pump stations. This can allow for improvement to network operations.

Water quality monitoring generally consists of several key parameters:

• pH

• turbidity

• free chlorine.

These parameters ensure that drinking water is safe or that treated wastewater meets environmental guidelines. They are either measured online by process instrumentation or manual grab sampling, which may examine a composite sample over a weekly period.

Transforming the network IoT IoT technology solutions like Netilion can provide enormous benefits that were not previously possible. Whether in densely populated or remote regions, Netilion Water Network Insights ensures full transparency in water networks around the clock. It can be used for the reliable monitoring of water quantity, pressure, temperature, level, or water quality.

Netilion Water Network Insights connects all levels of a water supply system and offers service providers and water associations tailor-made solutions from a single source. These include everything from field devices, components for data transfer, data recording and data archiving, to data evaluation as well as one-of-a-kind forecasting functions.

In these testing times of decreasing water security, IoT technology has been proven to boost operational efficiency and provide smart investment decisions. As utilities continue to make quantum leaps in their use of IoT technology,now is not the time to be left behind.

Rely on a partner that offers the best measuring devices and solutions,

Online monitoring in the distribution network ensures that water quality is permanently measured

assists you with technical support on-site, and has in-depth knowledge of the requirements in the W/WW industry. With Endress+Hauser, you get high-quality solutions capable of increasing your plant efficiency and optimising costs.

www.endress.com

info.za.sc@endress.com

As an economic enabler, water drives job creation and social upliftment; however, it is the one resource that is treated with a siloed approach from government.

From a local government perspective, water is siloed in the way it integrates with bulk suppliers and bulk users (like the agricultural sector). The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment does its own environmental planning regarding water conservation and climate change. The Department of Science and Innovation works on its own water technology innovations. The Department of Higher Education and Training – which is responsible for all of the industry-specific Sector Education Training Authorities (SETAs) – uses a siloed approach for capacity building and training for the water industry.

This silo mentality wastes resources and efficiencies where two departments often work on the same water issue but with two different approaches, and there is very little knowledge sharing.

Collaboration and the breaking down of silos will go a long way towards averting a water crisis. It does not require additional resources and infrastructure but a commitment from everyone to work together, integrate efforts and consolidate resources.

The water industry will never have the optimal amount of funding, number of water and wastewater treatment plants, nor people on the ground. This should motivate the entire country towards collaborating and working together to solve the water crisis. There needs to be less focus on the blame game and challenges, and more emphasis on cooperation and the the integration of efforts. This cooperation does not need to happen within the water sector but within the value cycle of water.

Our sector has been internally focused; stakeholders within the sector are working well together, but we must now look outwards. The challenge lies outside – with local government, CoGTA, the agricultural and mining sectors, as well as the industrial use of water. We need to integrate, so let’s welcome everyone into the water sector and offer assistance.

Due to the very nature of water, we simply cannot solve this crisis alone.

In keeping with the WISA 2022 Biennial Conference and Exhibition’s naval theme –

Every industry, every company and every single human being needs water. And yet, for the most part, water is not a shared responsibility. It is a responsibility the water industry typically bears alone.

By Dr Lester Goldman, CEO, WISA

#NavigatingTheCourse – I want to encourage the water industry to build straits with other government entities and industries, as well as the public. A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water.

Let us use this conference to extend hands to entities that are outside the water sector. We simply cannot carry this heavy burden by ourselves. There needs to be collective responsibility and collective decision-making regarding water.

When describing South Africa, phrases such as ‘failed state’, ‘failed system’ and ‘infrastructure on the verge of total collapse’ are often used. And yet, our country miraculously keeps limping along. This can only mean that we still have some dedicated and competent people working on our infrastructure.

By Dan Naidoo, chairman,

Upon completion of the book Sabotage:The OnslaughtonESKOM by Kyle Cowan, I formed a newfound respect for Eskom employees, who turn up at work every day and (mostly) keep the lights on. I could not help but draw parallels to the water sector, where water professionals often work in trying conditions and manage to keep the industry from collapsing. These people are passionate about their jobs, their country and want to make a positive difference.

Hats off to our professionals I would like to take a moment to acknowledge the water professionals that show up every day and do their jobs. During the series of hard lockdowns, many of these people left their families to stay in quarantined

hotels so that they could operate water and wastewater plants and minimise the risk of infection.

They are our South African heroes. There are still a lot of experienced, talented people in key positions that are managing (against all odds) to keep services going. We desperately need more of these people, who speak truth to power, who are practical and honest. There are many people in our sector that are making a solid, positive difference. I am looking forward to greeting you all at the WISA Biennial Conference. After four long years, we can all meet face to face, discuss frustrations and solve technical issues over a cup of coffee and inspire each other to continue with the fight. While we should always strive to work at optimal levels of efficiency, the local water sector is faced with a myriad of complex problems and are compelled to find creative solutions with limited resources. Let us take comfort in the fact that if we can keep our basic services running in these difficult times and conditions, improving service delivery should be easy.

WISA will once again host the flagship event of the Southern African water sector, bringing together regional and international water professionals, companies, regulators and stakeholders.

For individual or group registration, scan the QR Code, or visit: wisa2022.co.za/registration

The WISA Gauteng Branch hosted the ‘Gauteng Water Security in 2022’ webinar that unpacked water security strategies in the Gauteng’s metropolitan municipalities.

By Gina Martin,

publications lead:

Gauteng Branch Committee, WISA

The three Gauteng metros –City of Johannesburg, City of Ekurhuleni and City of Tshwane – presented their respective current water security status, challenges associated with water security, and water security plans for 2022. This was followed by a presentation on the National Water Security Framework (NWSF) by an independent integrated water resources management specialist from the CSIR.

City of Johannesburg (CoJ)

According to Ondela Tywakadi, principal specialist: Water Services, Policy Development and Regulation at CoJ, the municipality has close to six million commercial, industrial and domestic customers. CoJ is also the largest consumer of Rand Water in the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS), has exceeded its abstraction licence limit, and is facing serious challenges in lowering water demand in the municipality.

Water pollution, loss of river catchments, ageing infrastructure, population and economic growth, as well as high non-revenue water (NRW) are all contributors to the municipality’s water demand problems.

In response, CoJ’s 2022 Water Security Strategy aims to align to the Joburg 2040 Growth and Development Strategy goals and outcomes, providing a long-term roadmap towards a more resilient, liveable and sustainable city. Some of the steps CoJ is taking to mitigate the water demand challenges in the metro include:

• Implementing a Water Conservation and Water Demand Management (WC/ WDM) strategy, with programmes for active leak detection, infrastructure upgrade and renewal in Soweto, pipe replacements, new pressure-reducing valves, as well as public education and awareness.

• Inclusion of alternative water use in the review of the current Water Services Bylaw, specifically the use of groundwater,

rainwater harvesting (CoJ has developed a guideline), greywater use and effluent reuse. Groundwater exploration and the development of boreholes commenced in 2016, following a feasibility study. CoJ has drilled 26 boreholes thus far to supplement supply.

• Development of a drought management plan, as required by the Department of Water and Sanitation’s Disaster Management Plan. The objectives of this plan are to prevent and reduce water-related disaster risks, mitigate impacts by preparing effective responses to water-related disasters, minimise loss and property damage, and facilitate quick recoveries from the impacts of water disasters.

When explaining why water security within CoE was at risk, Aser Sekgoela, divisional head: Water Quality and Revenue Management at CoE, referenced: • Population growth – the population in

CoE has doubled in two decades.

• Low rainfall – South Africa’s average of 464 mm/annum is substantially lower than the global average of 860 mm/annum.

• The water requirement of half of South Africa’s water management areas exceeds availability.

• The demand on the IVRS, which CoE is part of, exceeds supply, and Rand Water’s abstraction licence will not be increased until the Lesotho Highlands Water Project Phase II is commissioned (expected to be in 2025/26). CoE is therefore implementing a resilience strategy to increase water storage from an average of 24 hours to 36 hours. CoE has also identified future water resources, aiming to have an 80:20 split between Rand Water and alternative supply such as rainwater and stormwater harvesting, treated effluent reuse, groundwater abstraction, and acid mine drainage treatment. Feasibility studies, pilot projects, borehole drilling and by-law revisions are currently under way to make alternate water supply and water resilience a reality. A WC/WDM strategy was developed, identifying 21 initiatives

earmarked to reduce NRW and water losses. The implementation of these projects and initiatives has resulted in the reduction of NRW from 40.3% in FY 2013/14 to 33.96% (as at August 2021), with the goal of 25% by 2025.

City of Tshwane (CoT)

Stephens Notoane, group head: Water and Sanitation Department at CoT, indicated that 72% of the municipality’s annual average demand is supplied by Rand Water. The remainder is acquired internally from CoT’s own fountains, springs, boreholes and water treatment plants, as well as from water treatment plants owned by Magalies Water.

Facing the same challenges as the other municipalities, CoT experiences water losses of around 32% on average. Gauteng is one of the few urban places in the world not built alongside a water source or river system.

Notoane highlighted that all the cities within Gauteng depend on transfers to meet their water requirements. The volume of water required by 2026 will not be met if additional storage infrastructure

is not built and investment into water security not prioritised. Gauteng is set to face a water deficit.

Changes in community/public behaviour are required, as the current water consumption per person in Gauteng exceeds the world average. New settlement and housing designs should take this into consideration by reducing water requirements and usage, as well as implementing water reuse systems and more efficient fittings.

The Vaal River Reconciliation Strategy concluded it is vital that WC/WDM strategies be implemented extensively, alongside large-scale water reuse. The CoT Water Resources Master Plan (2015) and Tshwane Vision 2055 (2013) aim to:

• investigate reuse as a possible additional water resource

• reduce demand on the IVRS (via Rand Water)

• take cognisance of water availability and requirements

• increase capacities and supply areas of water treatment plants.

Strategic plan alignment

Although South Africa has been at the forefront of water sector innovations and initiatives in the region and internationally, it has struggled to implement some of the policies it advocates. Ashwin Seetal, an integrated water resources management specialist with the CSIR, highlighted the need for a deliberate and concerted effort to

For continued updates and constructive engagement, the Gauteng Branch hopes to make this an annual event. Should you have any comments or ideas for events you would like to see, please contact Zoe Gebhardt (zoe.gebhardt@gmail.com). Watch your mailboxes for details of the next WISA Gauteng Branch event.

address these challenges, to provide water security for South Africa’s current and future socio-economic development needs, and for the NWSF objectives to be realised. Seetal added that it was clear that this was starting to happen; however, buy-in from role players outside the water sector was needed to see these initiatives succeed.

The Gauteng City-Region Observatory (GCRO) was approached to develop a Water Security Perspective using specialist, expert and provincial inputs as well as a review panel. There are five programmatic areas for intervention, which are aligned to the points already raised by the metropolitan municipalities:

• reduce water demand

• manage variability to prepare for drought and/or water scarcity

• invest in alternative water sources and water conservation

• manage water quality to limit pollution and achieve environmental goals

• create effective institutions.

All water users depend on a common resource and set of infrastructure, and Gauteng’s excessive water usage must

be reduced, with smarter planning and management of urban growth. Its existing supply of water must be better managed, and the water supply mix must be diversified.

Wastewater management systems must be repaired, water quality improved and stormwater management enhanced. Ultimately, water security is a neverending challenge that requires effective institutions and collaboration. There is

Prestank tank capacities range from 1 500 litres to 4.2 million litres designed to SANS 10329:2004 guidelines and SANS structural codes. Our Hot Dipped Galvanising units are easily transported and assembled on even the most remote sites.

no single solution to fix Gauteng’s water security issues; rather, a combination of all of these aspects is required.

By paying attention to the NWSF Focus Areas, acknowledging the sector’s many strengths and capabilities, weeding out obstructions, upskilling youth as sector resources, and providing impactful implementation and operational leadership, the vision for the water sector can be realised.

The newly elected YWP National Committee members (2022-2024) will aim to empower young water professionals through a range of networking, training, thought leadership and empowerment opportunities.

By Jessica Fell,

national marketing lead, YWP

The new committee members will meet in person at the WISA 2022 Biennial Conference in Sandton, after which an annual strategic session will be held. Here are the committee members (2022-2024)

Anya Eilers (national lead)

A water resource scientist from Zutari, Anya has worked on a range of integrated water resources

management and climate change projects across sub-Saharan Africa. She spent two years with the Global Green Growth Institute in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, working in the water sector under the Investment and Policy Solutions Division. She has an MSc in Geology from Stellenbosch University and has been part of YWP since 2017.

Ashton Mpofu (outgoing national lead)

Holding a masters’ degree in chemical engineering (cum laude), Ashton is currently completing his PhD. He is passionate about water in the green economy for inclusive and sustainable socioeconomic development. Ashton works as a senior analyst at Green Cape and has 10 years of combined experience spanning teaching and training, mineral processing, research and development, consultancy, intellectual property and commercialisation, market intelligence, and business development.

Nsuku Nxumalo (national vice lead) Nsuku is a consultant in the

water practice Pegasys. With an MSc in Water Science, Policy and Management from the University of Oxford, Nsuku has experience in water and environmental management from her role as environmental officer at Anglo American (Thungela Mining). Nsuku is also a candidate natural scientist who is passionate about all things water.

Magray Owaes Hassan (national vice lead)

Magray is a highly reliable, dedicated and results-driven PhD candidate in environmental engineering specialising in nitrogen removal in wastewater via Anammox technology. He has over five years of experience conducting basic and applied research in the water and wastewater treatment sector.

Eugene Fotso Simo (national coordination lead)

Born in Cameroon, Eugene works as a water engineer at Zutari and holds an MSc in Water Quality Engineering from the University of Cape Town. He aims to leave a positive mark on the African continent by improving service delivery in the water sector.

Jessica Fell (national marketing lead)

A PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town with research focusing on evaluating blue-green infrastructure for sustainable cities, Jessica has four years of experience in the water sector in academia and the private sector, and her research interests include water-sensitive city transitions, planning, policy, and data and information visualisation.

Craig Tinashe Tanyanyiwa (national finance lead)

Craig is an earlycareer hydraulic engineer and a PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town. Growing up in a water-scarce city made him cognisant of the fragility of the water system and cultivated an interest in water resource management. As a result, he has dabbled in groundwater management, low-cost sanitation, water demand and pressure management, and stormwater management.

Mmakgomo Malatji (Limpopo lead)

Mmakgomo works for Lepelle Northern Water Board, has a postgraduate degree in public development and management from the University of the Witwatersrand, and is currently pursuing her LLB studies with the University of South Africa. She aims to transform and work on gender equality for female water and sanitation professionals, connect people, support their professional aspirations, and build up a support group of female water and sanitation professionals.

Lindiwe Nkabane (KwaZulu-Natal lead)

A graduate trainee at Umgeni Water under the Catchment Management Department, Lindiwe holds holds an MSc in Hydrology. Her work is highly driven by her rural upbringing, which was characterised by a lack of fresh water for drinking and domestic purposes, and poor sanitation services. She strives to improve life and bring about dignity through her work to impoverished communities with poor/no water and sanitation services in alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 6.

Thapelo Mongala (North West lead)

Thapelo is a junior lecturer at the Centre for Water Science and Management at North-West University. His previous experience was at the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment where he coordinated environmental management functions including capacity building, advocacy and facilitating schools, youth and community-based projects and programmes.

Penester Tjale (Gauteng lead)

Penester holds a BTech in Geology from Tshwane University of Technology and is currently an MSc Environmental Science student with the University of South Africa. She is passionate about young people and their role in the water sector.

Aluvuyo Bixa (Eastern Cape lead) Currently enrolled for a BSc (Hons) in Geography, Aluvuyo has recent work experience as a candidate scientist at the Department of Water and Sanitation in Gqeberha. She is passionate about water and sanitation preservation, and aims to find solutions as to how she can help with mitigation measures to preserve our water resources.

Mohamed Gulamhussein (Western Cape lead)

As a water and wastewater treatment engineer at Zutari, Mohamed has been involved in the process design and conditional assessments of multiple water treatment works. He is passionate about process design, treatment technology and project coordination.

The new committee is inspired by the passion, talent and potential of our young water professionals and looks forward to serving, learning and growing with them. Connect with us on Twitter @YWPZA.

Southern Africa’s water supply is unequally distributed, with 70% of water resources shared between different countries. Transboundary water management is crucial for regional development. WASA speaks to the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) about its strategic partnership model to strengthen the implementation of various water and sanitation programmes within the SADC region.

What is the SADC Water Fund?

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) Regional Fund for Water Infrastructure and Basic Sanitation (SADC Water Fund) is the financing facility for the development and integration of the water and sanitation sector in the Southern African region. The SADC Water Fund finances infrastructure projects to improve the supply of drinking water and water for agricultural use for the poor.

SADC member countries established the SADC Water Fund mainly as a regional development financing facility, with the mandate

of strengthening the coordinating function of SADC by funding projects to improve regional water and sanitation infrastructure, as well as facilitate information and knowledge sharing.

What is the DBSA’s role within the SADC Water Fund?

The DBSA, together with the SADC secretariat and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) Development Bank, entered into a financing and project management agreement in December 2012. The DBSA is the mandated lead arranger that is responsible for managing its regional fund for water.

As the project executing authority, the DBSA’s Infrastructure Delivery Division is responsible for the overall programme management and implementation of the Fund. This allows the Fund to leverage the bank’s institutional capacities and promote synergies with the DBSA’s other activities, such as receiving co-funding from the bank’s other product offerings.

What are some of the key objectives of the Fund?

The Fund’s development objectives are to:

• promote and support strategic transboundary and pro-poor water supply and sanitation infrastructure development in the SADC region

• promote climate resilience in the water supply and sanitation sector in the SADC region

• facilitate the application of integrated water resources management principles for infrastructure development.

How does the dedicated Fund Management Unit work?

The Fund identifies bankable projects and provides support through the entire value chain. The SADC Water Fund supports the following activities:

• identification and selection of bankable water and sanitation project proposals (quality feasibility studies must be available)

• provision of support to the applicants in finalising project documentation

• contract and procurement management under the Fund

• raising of additional funding from other development partners

• facilitation of cross-border coordination and agreements during project preparation and implementation

• post-implementation monitoring and evaluation.

Why is a Fund like this essential, especially for the SADC region?

More than a third of people in the SADC region do not have access to safe drinking water and over half of the region’s population do not have access to improved sanitation

SADC- Southern African Development Community

Objective:

To achieve development, peace & security, economic growth, to alleviate poverty, enhance the standard and quality of life of peoples of SADC, support the socially disadvantaged through regional integration.

SADC Regional Development Fund RDF

Receipts & expenditures of SADC relating to development of SADC region.

RDF shall be main SADC instrument for socio-economic development and integration of SADC region.

X Border WASH

Improve water and sanitation transboundar y infrastructure along major trade corridors in the region key to promote regional integration and address rapid urbanization due to increased cross-border trade and traffic volumes

facilities. However, these urban statistics generally exclude the urban poor living in informal settlements.

That’s why there’s such a huge need for water and sanitation infrastructure in urban and rural areas in SADC. Infrastructure needs to be developed, rehabilitated, expanded and climateproofed to be resilient to floods and droughts. The recent Covid-19 pandemic is a strong reminder of the importance of access to WASH facilities, especially for the poor, to ensure community resilience to adverse events such as outbreaks or the effects of climate change.

Addressing such a huge need also presents a challenge and opportunity for innovation in infrastructure technological approaches, financing and implementation models.

The Fund’s sustainability and growth strategy is anchored on:

• a diversified portfolio of projects within the water and sanitation sector

• diversified and innovative funding instruments

• diversified international and local development partners. To achieve this, the Fund has developed a programmatic approach with three programmes that have a nexus approach. These are backed by an immediate financing pipeline of about €120 million (R2.1 billion).

SADC Regional Water Infrastructure and Basic Sanitation Fund

Key financing facility for development & integration of water sector in SADC region. SADC Water Fund’s long-term vision is to become a special “water sector window” of RDF.

Water Fund hosted in DBSA

Regional Water Innovation for Resilience

Investment in pilot projects (locally relevant innovative technology, financing and governance models) for resilient water sector in major cities in transboundar y catchments

What projects are currently being financed under the Fund?

As part of its programmatic approach, the Fund has the several ongoing activities:

• Cross-border infrastructure for water supply: By 2042, approximately 76 000 people living below the poverty line and without access to water will benefit from the Kazungula Water and Sanitation Project in Zambia, as well as the Lomahasha and Namaacha water supply projects in Mozambique and Eswatini.

• Innovation for climate resilience: The Ramotswa (in Botswana) Transboundary Aquifer – where in situ groundwater remediation typifies a conjunctive approach for improved water resource use and management – will boost water security for about 30 000 people in communities in Ramotswa. Through implementing innovative remediation and sanitation technology that combines in situ groundwater remediation with improved sanitation, thereby protecting this water resource, groundwater can be used as potable water after minimal treatment.

• Regional transboundary water information systems: The Climate Resilience Information Systems Project (part of the overall Regional Water Investment Programme) will support sustainable investments

Objectives:

•Strategic pro-poor WASH infrastructure development

• Climate resilience in WASH sector

•Application of IWRM to infrastructure development

Transboundar y Water Information System

Support to transboundar y hydrological and metrological data collection &, development of information for sustainable infrastructure, risk preparedness and climate adaptation.

for reliable climate information and early warning systems. This will encourage investments that promote water resilience.

Any final thoughts?

Achieving sustainable financing for investments in water supply, sanitation and for the development, protection and restoration of national and transboundary water resources is the core focus of the SADC Water Fund. Current institutional arrangements are often inadequate, and the financing of water investments is often unsustainable. Also worth noting is low public capacity to finance required investments in the development and management of water resources, including protection and restoration. Lack of investment in water infrastructure has led to significant, economic, social and environmental losses. For the SADC region to see improvement in the performance in the water sector, facilities such as the SADC Water Fund are important.

Emerging sanitation technologies promote a new paradigm for the collection and disposal of menstrual waste products that is both safe and sustainable.

By Ednah Mamakoa, technical officer, SASTEP

The disposal of used feminine hygiene products raises socioeconomic, cultural, religious and environmental concerns. Menstrual hygiene waste is usually thrown away with other solid wastes and ends up in landfills. In other cases, they are flushed into a toilet, resulting in sewage reticulation system blockage, or they are disposed of in pit latrines, contributing to rapid pit filling. Other than throwing menstrual waste in the garbage, there is currently no clear plan in place for the safe disposal of menstrual waste, particularly in communal and public spaces. Waste streams, both solid and sanitary, are anticipated to grow as urbanisation and access to disposable products increase. As a result, new sanitation technologies should be able to handle these wastes.

In its ‘Policy on the Disposal of Sanitary Waste’, the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) indicates that incineration is the recommended method of treatment for large volumes of sanitary waste. The incineration of sanitary waste is specifically stipulated in the draft Health Care Risk Waste Management Regulations (part of NEMWA [No. 59 of 2008]) drawn up by the Department of Environmental Affairs. The Occupational Health & Safety Act (No. 85 of 1993) states that commercial or

industrial volumes of sanitary waste may not enter the general municipal waste stream and commercial sanitary waste must therefore follow the requirements for healthcare risk waste. The regulations mean it is no longer practical to legally dispose of large volumes of sanitary waste in landfills.

The South African Bureau of Standards passed the first reusable sanitary standard, SANS 1812. This regulation is one of the first in Southern Africa for washable sanitary pads, and it is paving the road for other African countries to follow suit.

The South African Sanitation Technology Enterprise Programme (SASTEP) has shortlisted the SHE (Safe Hygiene for Everyone) device as part of the suite of technologies to be assessed for commercialisation in South Africa. The SHE sanitary pad disposal system is a fully automated, sterile sanitary pad disposal device designed to give dignity, privacy, waste reduction and safe hygiene.

With a batch processing time of under 30 minutes, SHE

thermally treats menstrual hygiene waste with reduced emissions and low particulate matter (PM2.5). It reduces menstrual hygiene waste to ash, keeping it out of landfills, toilets, pit latrines and water bodies. The technology is envisaged to be licensed from an international technology partner, Biomass Controls PCB, to a local partner for commercialisation and local manufacture.

The SHE device will introduce an innovative technology into the South African sanitation value chain that adds value in a sanitation subsegment that is largely overlooked. Providing women and girls with tools such as mandatory premenarchal training and access to adequate disposal facilities, to manage their menstrual cycles and dispose of the wastes safely can improve attendance in schools. This will contribute to the creation of a world in which no one is held back simply because they menstruate.

This is an extract from The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022, providing a global overview of progress on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, using the latest available data and estimates. AT CURRENT RATES, IN 2030

OVER THE PAST 300 YEARS, OVER 85% OF THE PLANET’S WETLANDS HAVE BEEN LOST THE WORLD’S WATER-RELATED ARE BEING DEGRADED AT AN ALARMING RATE

MEETING DRINKING WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE TARGETS BY 2030 REQUIRES A 4X INCREASE IN THE PACE OF PROGRESS

FOR AT LEAST 3 BILLION PEOPLE, THE QUALITY OF THE WATER THEY DEPEND ON IS UNKNOWN DUE TO A LACK OF MONITORING

733+ MILLION PEOPLE

WILL LACK SAFELY MANAGED DRINKING WATER WILL LACK SAFELY MANAGED SANITATION WILL LACK BASIC HAND HYGIENE FACILITIES 1.6 BILLION PEOPLE 2.8 BILLION PEOPLE 1.9 BILLION PEOPLE

LIVE IN COUNTRIES WITH HIGH AND CRITICAL LEVELS OF WATER STRESS (2019) ONLY ONE QUARTER OF REPORTING COUNTRIES HAVE >90% OF THEIR TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS COVERED BY OPERATIONAL ARRANGEMENTS (2020)

The UN is excited by South Africa’s SDG 6 organisational structure, which increases collaboration with other government departments and agencies responsible for other SDGs. It is one of the best worldwide and has been made available as an example for other countries to emulate.

As our local custodian of water resources, the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) is the leading agent for SDG 6. All the planning, collecting of data and reporting completed for SDG 6 is the responsibility of the Minister of Water and Sanitation, Mr Senzo Mchunu. Reporting is coordinated through Stats SA as the custodian of statistical information of our country.

SDG 6 contains eight targets, all focusing directly on water services (including sanitation) and water resource management.

“The DWS has developed the SDG 6 Working Group to coordinate activities related to the eight targets of SDG 6,

SDG 6 is divided into eight targets that reflect the water cycle:

6.1: Drinking water – achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all

6.2: Sanitation hygiene – achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations

6.3: Wastewater and water quality – improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimising release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally

6.4: Water use and scarcity – substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity

6.5: Water management – implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate

6.6: Ecosystems – protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes

SDG 6 has 11 indicators (black) that will be used to measure the progress made on each target. In addition to the 11 targets, South Africa has proposed additional targets (in blue)

6.1.1 Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services

6.2.1 Proportion of population using safely managed sanitation services, including a hand-washing facility with soap and water

6.3.1 Proportion of wastewater safely treated

6.3.1 (DWS) Proportion of water containing waste lawfully discharged

6.3.2 Proportion of bodies of water with good ambient water quality

6.3.2 (DWS) Proportion of bodies of water complying to water quality objectives

6.4.1 Change in water-use efficiency over time

6.4.2 Level of water stress: freshwater withdrawal as a proportion of available freshwater resources

6.5.1 Degree of integrated water resources management implementation (0-100)

6.5.2 Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation

6.6.1 Change in the extent of water-related ecosystems over time

6.6.1.1 (DWS) Change in the spatial extent of water-related ecosystems over time, including wetlands, reservoirs, lakes and estuaries as a percentage of total land area

6.6.1.2 (DWS) Number of lakes and dams affected by high trophic and turbidity states

6.6.1.3 (DWS) Change in the national discharge of rivers and estuaries over time

6.6.1.4 (DWS) Change in groundwater levels over time

6.6.1.5 (DWS) Change in the ecological condition of rivers, estuaries, lakes and wetlands

The targets have to be implemented through:

6a: International cooperation – expand international cooperation and capacity-building support

6b: Community participation – support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management

6.a.1. Amount of water- and sanitation-related official development assistance that is part of a government-coordinated spending plan

6.b.1 Proportion of local administrative units with established and operational policies and procedures for participation of local communities in water and sanitation management

and the inclusion of the other 16 SDGs. It comprises 13 Task Teams (one for each target and five cross-cutting). This will improve the implementation of SDG 6, as well as offer support with the other 16 goals that have links to SDG 6,” explains Mark Bannister, chief engineer and SDG 6 coordinator at the DWS.

The Task Team’s key objectives are as follows:

• Interrogate and, where necessary, further develop or localise methodologies for reporting on the SDGs.

• Collect data and report on trends towards achieving the SDGs.

• Provide inputs to country reports and other SDG reports by researchers.

• Monitor the current status and quantify the target gaps towards achieving the 2030 goal.

• Identify potential interventions/ tangible projects for the sector to implement in order to close gaps.

• Ensure sector alignment between the

National Water and Sanitation Master Plan (NW&SMP) and SDG 6.

• Support water and sanitation needs of the other 16 SDGs.

According to Bannister, members of the Water and Sanitation Leadership Group (WSSLG) crosscutting Task Team (comprising broad representatives from the sector) should preach the key messages and mobilise others within their area of expertise to deliver projects on the ground aligned with the NW&SMP and the SDG 6 programme. “The WSSLG influences key sector role players to align themselves with the key instruments for change such as the NW&SMP. The themes in the NW&SMP align themselves to the SDG 6 targets accordingly.”

the synergy and tradeoffs between them, and translate these needs into projects that influence positive change through the NW&SMP.

The cross-cutting SDG 6 Interlinkage Task Team has developed a tool to gather the water and sanitation needs of each of the other 16 SDGs, identify

“When people ask me, 'Are we going to meet SDG 6 by 2030?’ I always say, ‘Yes, of course we are,’ but we all need to play our part. This is a ‘sector programme’ not a ‘DWS programme’. We either win together or lose together, and it is very much the department’s intention to win. While progress is not as quick as we need it to be, as a sector, we must prioritise our actions, accelerate the process, and align ourselves with SDG 6 and the NW&SMP – we still have eight years to achieve this goal, and it’s up to all of us whether we achieve it or not,” says Bannister.

The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have one ambitious target – to end extreme poverty and achieve sustainable development worldwide by 2030. Not only is achieving SDG 6 essential for the water and sanitation sector, but it also has a major positive impact on the other 16 SDGs.

With access to clean water, agriculture is improved, enabling communities to produce income from their crop’s yield. Improved agriculture produces nutritious, safe food that makes physically and mentally strong, healthy people that can work and get an income. In developing countries, 80% of sicknesses are due to drinking and washing with contaminated water. Waterborne illnesses cause preventable deaths. Proper handwashing effectively prevents viral illnesses and reduces the spread of viruses. When a family’s incomeprovider is sick or dies from unsafe water, it can plummet them into deeper poverty. The burden to collect water lands on women and children. The hourslong trek to provide water for families keeps women out of the workforce and girls out of school, diminishing their ability to gain the necessary skills to support themselves financially.

Water and energy are mutually dependent, with all energy forms requiring water to varying degrees. In turn, water management, including treatment and pumping, requires energy.

Within agriculture, adequate water is needed at the right time for seeds to germinate, crops to grow and produce vegetables, fruits, grains, fibres such as cotton, and oilseeds. Similarly, water is essential for livestock to be able to produce milk, meat and eggs. Poor water quality can also negatively affect fish stocks.

Boosting access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities in schools can improve the health, attendance and welfare of students and teachers, and can therefore contribute to better educational outcomes. WASH in schools is particularly important for girls and young women, as is providing privacy for menstrual hygiene management. School pupils are well placed to start learning about safe water and sanitation through the school curriculum.

Water facilitates all types of economic activity – secure water of proper quality is essential for development.

Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation and hygiene are fundamental to protecting health. Contaminated water that is consumed may result in waterborne diseases, including viral hepatitis, typhoid, cholera and dysentery. Water can also provide a habitat for mosquitoes and snails, which are intermediate hosts of parasites that cause diseases like malaria. Without adequate quantities of water for personal hygiene, infections and viruses can spread easily.

Many women in poor households bear the burden of retrieving water from distant sources and often have little option but to use polluted wastewater for domestic purposes, exposing them to unsafe water. They are most affected by the lack of adequate sanitation facilities and/ or sufficient wastewater treatment. Water is heavy. Carrying it consumes time and valuable personal energy that can prevent girls from attending school. Bringing water sources closer to people reduces the time needed to collect water and makes more time available for educational activities, especially for females. Paths to water sources that are long and through remote areas put women and girls at risk of sexual and physical violence.

Industry is a significant and, at times, major consumer of water and needs to have appropriate water quantity and quality. Simultaneously, industry may have the potential to pollute water resources.

Access to basic services (like water and sanitation) will contribute towards reducing inequalities across lines of geography, gender, race and wealth.

An adequate and sustainable supply of water and sanitation is a requirement for a sustainable city. Cities are also increasingly playing a role in the management of water-related ecosystems.

Climate change is often discussed in terms of carbon emissions, but people feel the impacts largely through water. The effects of climate change are altering the hydrological cycle, resulting in more frequent and severe extreme events and disasters, such as droughts and floods, damaging water supplies and sanitation services.

Improved water governance can reduce conflict, displacement and migration. Good water management can support socio-economic development, and bring peace and security to countries and across countries that share freshwater ecosystems, particularly those under threat.

Water-related ecosystems – including wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes –sustain a high level of biodiversity and life. They are vital for ensuring a range of benefits and services such as drinking water, water for food and energy, habitats for aquatic life, and natural solutions for water purification and climate resilience. However, water-related ecosystems are increasingly under threat, relying on sufficient water quantity and quality to main¬tain full functionality. These ecosystems are enduring effects from human activities such as pollution, infrastruc¬ture development and resource extraction. Increased access to safely managed sanitation services should enable the reduction of marine nutrient pollution. Reducing untreated wastewater will also protect aquatic ecosystems.

Water is an integral part of consumption and production cycles of food, energy, goods and services. Managing these processes sustainably is important in protecting the quantity and quality of water resources, and using water more efficiently. For example, the safe reuse of wastewater can help create more circular, sustainable production and consumption patterns. Improved sanitation systems and treatment plants can generate fertiliser from human and animal waste that could be used in farming or turned into biofuels.

Water and land management are closely associated, with activities taking place on land using and potentially polluting water resources. Land-based ecosystems depend on freshwater resources in suffi¬cient quantity and quality. In turn, activities on land, including how land is used, influence water availability and quality for people, industry and ecosystems. Protecting forest catchments and encouraging sustain¬able land management practices, such as buffer strips along waterways and conservation agriculture, can re¬duce the impact on water quality.

The pursuit of partnerships that aim to improve finance, capacity-building, data acquisition and monitoring, science, innovation and technology in the water sector are essential to achieving SDG 6.

The current industry gold standard of sanitation is the flush toilet connected to waterborne systems. The other extreme is the ventilated pit latrine, which conjours up images of bad odours and flies, and is the antithesis of aspirational. But we can imagine a new industry that takes the best of both worlds – a standalone toilet system giving you the convenience of the flush toilet.

A typical waterborne sanitation system uses flush toilets, kilometres of sewer piping, high-energy pump stations, and large wastewater treatment plants –requiring vast amounts of land, water and trillions of rand in infrastructure investment. The vision for G2RT is that it can essentially provide the same basic sanitation functions of those large, costly systems in a space no bigger than the toilet itself. This innovative self-contained system that can

treat human waste safely in a house provides empowerment and ownership for the household. This brings back dignity to sanitation and offers an alternative to sewered networks. Indigent communities with no sewer system will no longer have to use toilets that offer an undignified experience. They will have their own toilet, and a better sense of responsibility and ownership for that toilet.

This sense of ownership will shift the perception that government is 100% responsible for the provision of sanitation to a more shared responsibility between South Africa’s citizens, the government and the private sector.

At a municipal level, engineers will be able to offer an alternative solution to developers and investors interested in growing new economic zones and creating jobs. But the biggest opportunity will be for businesses and investors seeking the transformative ‘Sanicorn’ opportunity as toilets such as these will revolutionise sanitation in the future.

• 4.5 billion people worldwide lack access to improved sanitation (nearly half of the world’s population)

• Close to 2 billion people lack even the most basic sanitation, such as toilets or latrines

• About 673 million people still defecate in the open, often in rivers where people fetch their drinking water

• In 2016, inadequate sanitation and hygiene are estimated to have caused more than 500 000 deaths from diarrhoea alone

• Preventable diarrhoeal diseases are the second-leading cause of death in children under age five

• The UN estimates that between now and 2050, the world’s population will grow by 2 billion people. More than 90% of that growth will be concentrated in cities and in developing countries – places that are least likely to have good sanitation

Generation 2 Reinvented Toilet (G2RT) builds on the exceptional innovations developed during the original Reinvent the Toilet Challenge programme. Without inlet water or output sewer lines, G2RT is designed to be a new, affordable toilet. Could this be the solution to the world’s sanitation problems?

There has been strong level of South African engagement from partners such as the Department of Science and Innovation, the Water Research Commission, eThekwini Municipality, Khanyisa Projects and the UKZN WASH Centre

• In 2011, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation initiated the Reinvent the Toilet challenge

• The aim was to spur the creation of new toilet technologies that safely and effectively manage human waste

• The foundation awarded grants to 16 researchers around the world to develop reinvented toilet technologies based on innovative approaches and engineering processes

• In 2012, a two-day Reinvent the Toilet Fair was held in Seattle, USA, where representatives from communities were encouraged to ultimately adopt these innovative approaches to sanitation

• In 2013, a Reinvent the Toilet Challenge was launched in India and China

• In 2014, the Water Research Commission (WRC), Department of Science and Innovation, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation entered into a partnership to test reinvented toilets on its South African Sanitation Technology Evaluation Programme

• In 2018, there was a Reinvented Toilet Expo in Beijing, China, where there were product announcements and funding commitments aimed at accelerating the adoption of innovative, non-sewered sanitation technologies in developing regions around the world

• In 2019, the WRC and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation relaunched the first reinvented commercial demonstration platform to pilot reinvented toilet models in various settlement types such as schools, rural, informal and urban environments and transition commercial partners into viable manufacturers and suppliers of reinvented toilet technologies

The prototype G2RT is the result of a global collaboration led out of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) in the US. “We have gathered the best concepts from around the world and used expert engineering to integrate them into a single, standalone system,” explains Dr Shannon Yee, associate professor at Georgia Tech and lead on the G2RT programme supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

According to Yee, finding the right collaborators and then wrangling them to make decisions collectively as a global team was the hardest part of this programme. “But without this type of collaboration, solving such a complex problem would have been impossible.”

There has been a strong level of South African engagement from partners such as the Department of Science and Innovation, the Water Research Commission, eThekwini Municipality, Khanyisa Projects and the UKZN WASH Centre. Students that are part of the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s WASH Centre travelled to Georgia Tech to assist in the development of G2RT and are spearheading prototype testing in Durban.

The concept of G2RT is based on the premise of creating a wastewater treatment plant in a box, which safely treats faeces and recycles the water. The G2RT prototype has two parts: a front end, which looks like a typical flush toilet, and a back end, where the waste and water are processed.

When the toilet is flushed (with a small amount of water), the urine and faeces are separated.

The urine and flush water go through a multistep liquid filtration process that produces clean water. This water is then recirculated to flush the toilet.

Here, the faeces will get pasteurised, killing off all pathogens and eliminating odours before being pressed into cakes, which are then dried. These faeces cakes then fall into a receptacle that users can dispose of in the trash or compost. The waste itself is odourless and pathogen free.

One of the challenges facing G2RT is the high cost, but the team has set an aspirational affordability target that will make it economical for all communities – indigent, low- and high-income areas. A key goal is to continue to simplify the

The concept of G2RT is based on the premise of creating a wastewater treatment plant in a box

TOP Dr Shannon Yee, associate professor at Georgia Tech and lead on the G2RT programme

ABOVE G2RT builds on the exceptional innovations developed during the original Reinvent the Toilet Challenge programme

system and pursue economies of scale to eventually lower the cost. “Together with research and development partners, we want to work alongside large manufacturing corporations to evolve the reinvented toilet design to make it less expensive, highly reliable, and adaptable to the diverse markets around the world,” Yee adds.

The G2RT prototype is remarkable, as it shows what is possible when a clear vision is set and global collaborative partnerships work towards solving the world’s sanitation challenges; however, it requires a few enablers, such as a visionary business with associated investors who transform the industry through mass production and supply models. But for this to become a reality, demand must be created and this is where national and local government is encouraged to become early customers, and to put policies in place to accelerate local manufacturing and adoption.

So, what is the goal behind the new toilet challenge? “To build an industry and create a thriving market that delivers life-changing sanitation innovations to the billions of people who need them. To transform sanitation from an unreliable and unequal system that endangers the health and livelihoods of billions, into a valuable enterprise,” concludes Yee.

This would be terrifying. A cyberattack on water infrastructure could lead to widespread panic and potentially significant illness and loss of life, with substantial effects on other critical services such as firefighting and hospitals. It could shut down our economy. It begs the question: is the water industry taking cybersecurity seriously?

By Kirsten Kelly

South Africa has the third highest number of victims of cybercrime in the world, costing us R2.2 billion a year, according to the Accenture State of Cyber Security Report 2021. Here are some more red flags:

• The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development recovered from a debilitating ransomware attack that unfolded in September last year, affecting all its electronic systems.

• Transnet was the target of a cyberattack that affected crucial systems and caused our ports to shut down. The attackers encrypted files on Transnet’s computer systems, thereby preventing the company from accessing their own information while leaving instructions on how to start ransom negotiations. The ransomware used in the attack likely originated from Russia or Eastern Europe.

• The National School of Government was targeted in a ransomware attack costing around R2 million.

• Private hospital group Life Healthcare was also targeted last year in an attack

that affected their admissions systems and email server.

These incidents paint a worrying picture of how vulnerable South Africa is to cybercriminals and even cyberwarfare. While digitalisation is reshaping the water sector for the better, it also increases cybersecurity vulnerabilities. A 2019 paper, titled ‘A Review of Cybersecurity Incidents in the Water Sector’, highlights an increase in the frequency, diversity and complexity of cyberthreats to the water sector.

Water utilities typically face the following cybersecurity threats:

• Criminals access water systems and flow operations, manipulating water flow and chemical dosages in water treatment works.

• Cyberattackers can gain access to customer data through water companies’ online payment systems.

• Attackers can also gain administrator credentials and work their way laterally through the water network.

Why is the water sector vulnerable?

“Unlike its critical infrastructure counterparts, the water sector is in the

hands of a vast array of organisations, many of which are small and underresourced. There is some level of data sharing and integration between these organisations and networks. When there is a cyberattack, it is dealt with in isolation; there is no sectorwide communication and sharing of the incident. This prevents the water industry from being proactive and learning from each other,” says Professor Annlizé Marnewick at the University of Johannesburg.

“Furthermore, the water sector relies on a variety of physical infrastructure and operational technology systems (sensors, actuators, logging devices, meters, pumps) that are connected to the internet to gather remote data

• Every 24 seconds a host accesses a malicious website

• Every 1 minute a bot communicates with its commandand-control centre

• Every 34 seconds an unknown malware is downloaded

• Every 5 minutes a high-risk application is downloaded

• Every 6 minutes a known malware is downloaded

• Every 36 minutes sensitive data is sent out of the organisation (Source: SecurePalm)

to support activities like metering and billing, or predictive equipment maintenance. There are many entry points for cybersecurity attacks within our sector,” explains Dr Jeremiah Mutamba, senior manager: Strategic Programmes, Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority.

Sunitha Venugopal, director at SecurePalm, adds that an organisation must close hundreds of hypothetical doors (entry points) to avoid a cyberattack, where a hacker only needs to find one open door to conduct a cyberattack. “The odds are stacked against all organisations, but the water industry is extremely vulnerable. Typically, this sector operates a lot of legacy-based operational technology with well-known vulnerabilities that cybercriminals can easily exploit. People are opposed to updating or changing these systems because they are expensive and still in working

Russia has attacked Ukraine by land, sea, air and cyberspace. In the hours before Russian troops invaded, Ukraine was hit by never-before-seen malware designed to wipe data. Russian cyberattacks have undermined the distribution of medicines, food and relief supplies. Their impact has ranged from preventing access to basic services to data theft and disinformation. Many of these cyberattacks have been designed to disrupt the provision of emergency services in the immediate aftermath of airstrikes.

Given that the USA and EU have banded together in support of Ukraine, the scope of a cyberwar could be broad. While all eyes have been on the RussiaUkraine war, the water sector in the USA has been preparing for an onslaught of cyberattacks from Russia that could lead to drinking water contamination, service disruptions and ransom demands.

As tensions between Russia and the USA rise, the threat of cyberattacks against water and wastewater infrastructure from all directions increases. The Biden administration has unveiled a 100-day action plan – a voluntary strategy – to increase the protection of water systems from attacks.

• A water treatment plant in Florida, USA, was attacked. In that incident, a hacker broke into the IT system of a water treatment plant and remotely accessed the computer system. The plant operator observed the mouse moving around on his screen and access various systems that control the water being treated. The hacker tried poisoning the supply, by adjusting sodium hydroxide levels from 100 parts per million to 11 100. Because the plant operator observed what was going on, the attack was thwarted in time.

• A wastewater treatment plant in Maroochy, Australia, was attacked by a person whose application for employment was rejected. This caused the plant’s pumps to stop working, where wastewater was discharged into the sea.

• A waterboard in Michigan, USA, had a ransomware attack where $25 000 was paid to cybercriminals in order to resume operations.