The Peaks Beyond Old Gold Mountain

A tribute to Chinatown and a celebration of cultures

When the first immigrants from China arrived in California, they called the state Gold Mountain for the recently discovered riches in the Sierra Nevada. Some set off for the gold fields or while others settled in San Francisco. No matter their origins, these pioneers would bring with them their languages, their way of life, their families, their values and above all, the dream of a brighter future.

Old Gold Mountain remains inseparably connected to San Francisco’s Chinatown, the first and oldest in the United States, where generations of Americans would call home. Throughout history, the community has faced everything from natural disasters, crime and instability to anti-Asian discrimination and violence – the bonds between its residents growing stronger as it worked together to overcome and endure.

This publication is, with Chinatown as its inspiration, a celebration of cultures finding their footing in parts unknown as well as a place of gathering for a community to share, create and thrive together. This first issue shines the spotlight on creatives at different chapters on their journeys. Some names may be familiar to you and others you may be meeting for the first time, but they are all united in their desire to bring the light forward, toward the many peaks that lie beyond Old Gold Mountain. The Golden Generation is just beginning.

San Francisco circa 1930. Grant Avenue at Sacramento Street.

San Francisco circa 1930. Grant Avenue at Sacramento Street.

A Golden Generation featuring:

“SILENCE

CARMEN CHAN P-LO

SHENG WANG

10 12 20 28 30 36 38 42 48 54 56 64 72

EILEEN SHO JI

FOREWORD

DANIEL WU FLUSHFIX™ ABIGAIL HING WEN

IS GOLDEN” IN CONVERSATION WITH SAI MING LEE & SUZETTE LEE THE NIKE DUNK HIGH AND AIR FORCE 1 “GOLD MOUNTAIN” FEATURING LIONDANCEME CHRISTINA CHOI KELVIN YU

TATTOO TRANSLATOR 3000™

I didn’t experience San Francisco Chinatown until I was an adult, contrary to most recollections commonly shared by those who spent their childhood nearby. I was born and raised in Florida, where the Asian American community was sparse and not big enough to warrant its own ethnic micro-neighborhood. This has significantly shaped my understanding of it and its importance. And while the outsiders’ understanding of the purpose of Chinatown has changed throughout the years (and certainly in the past decade), its meaningfulness to the Asian American community has not. It’s a haven, a town square, a reminder of what our ancestors must have felt growing up in a society where Chinatowns were a place to surround themselves with shared values and culture, when others shunned them. And even for those that aren’t of Asian descent, Chinatown can still be a welcoming place, somewhere to be part of a community where the old teach the young and the young help the old. Although there is an unspoken warmth of familiarity we may feel while being in this particular neighborhood, the experience is still undoubtedly American. Walking through Chinatown doesn’t necessarily invoke a longing to be back in Asia for Asian Americans, but almost certainly a pride about how the strength of a community can persevere in any environment.

“The Golden Generation” signifies a movement that has been happening for many years within the APA community. APA youth are combining their cultural values with their American experiences and breaking through the barriers of what was often deemed a typical or traditional path forward. We are excited to share a few of these stories and bring light to what’s to come.

I’d like to thank our partners at Nike, MAEKAN, Intertrend, Adam Studios, and all of the interview subjects for taking part in this important moment to share stories from our community.

Thank you for taking the time to read these stories and learning more about what’s going on within the APA community. Believe me when I say that this is, by definition, a groundswell.

“As American as Chinatown.”

Richard Liu Co-owner, The Darkside Initiative

Richard Liu Co-owner, The Darkside Initiative

The Darkside Initiative

The Darkside Initiative

11

This is the Chinese supermarket in South Florida where I grew up. It represents the only cultural immersion I was able to experience without a Chinatown.

FOREWORD

EILEEN SHO JI

Singer-Songwriter and Producer

Inspirational lifestyles surround us. As a creative, immersing yourself in the feed churns up equal parts excitement and inspiration, self-loathing and disappointment. We see final products, but the paths to reach them are long and winding ones, often through valleys of uncertainty and pain.

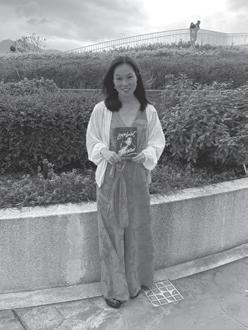

Eileen Sho Ji is a multi-faceted creative, born to a Taiwanese mother and an American father. Having grown up surrounded by artistic influences, she early on decided to pursue a creative career. That pursuit brought with it constant reevaluation of her desires and her goals, so while Eileen’s objectives have changed, her internal compass is more finely tuned than ever before.

For many of us, developing a career wasn’t why we got going in the first place. When getting paid for your passion doesn’t materialize, coming out the other side with a renewed excitement for creating on your own terms is the reward.

13

EUGENE KAN

What was your childhood like growing up?

EILEEN SHO JI

I had a very atypical Asian American experience in a lot of ways. My mom came from Taiwan after she met my White dad on an airplane. Maybe a year later, he visited her in Taiwan and was like, “Let’s get married.” Up until then, she’d never stepped foot in America, but she flew over and started her life here. She’s very sporadic and spontaneous.

I was really fortunate in a lot of ways because I grew up having a lot of creative outlets and she was always sending me to arts programs, taking me to museums, the opera, and just filling my life with art. She’s an artist. My dad’s a writer. My older brother’s a designer. So I grew up surrounded by creativity and my parents always encouraged me. When I started making music, they were super proud of me and wanted me to really pursue it. They even said, “If you don’t want to go to UC Berkeley, you don’t have to. That’s your decision to make.” Ultimately, I’m happy I did it, because I’ve built a skill other than music in a completely different avenue. All this is to say that I had a nontraditional upbringing with nontraditional parents.

Growing up, I didn’t go to school with a lot of Asian people, which I think is a bit of the opposite experience for some Asian Americans. When I got to UC Berkeley, it was a culture shock for me because there are tons of Asians and White people at Berkeley. Where I grew up in Hayward, California, I was one of just a few Asian people at my school, which was predominantly Black and Latinx.

Since I wasn’t really used to being around people who shared my same cultural background, it was an unfamiliar experience for me to start connecting with people on that basis. I’m still navigating that now. In addition, there’s the cultural clash of having a White father and an Asian mother, with cultural differences that manifest within myself, what I value, and how I see different sides of who I am.

Was it difficult not having a straightforward clear definition of who you are and what your position is in the world?

In this really beautiful and magical way, I feel super blessed to be from the Bay Area. It’s so diverse and I didn’t really have a community that was structured around my ethnicity. I didn’t have a lot of extended family either, with my mom’s side of the family in Taiwan and my dad’s side of the family all across the United States.

I lived in a typical nuclear family and, where I went to school, I didn’t know that many people that looked like me

or, had the same cultural background as me that I could relate to on that front. It really forced me to be able to relate on other fronts.

I think that wound up being amazing because it drove me into art. I found something that I was into that had nothing to do with my background or my upbringing with my family. I found art and I immediately started connecting with people in that way.

So in a way, not having a built-in community through my culture allowed me to build community in something completely new.

In recent years, how has your understanding of your Asian identity changed?

I’m starting to tap into the Bay Area’s Asian community more than I was before and there’s this kind of automatic understanding where we had a lot of the same experiences so you don’t have to even explain certain things, cause it’s like, “Oh, I know. My mom did the same.”

It’s fun to now be a little bit older and hanging out with more Asian people or creating with more Asian artists. It’s fun to get to tap into the subtle ways our upbringings overlapped, but even more so in the ways that they were vastly different based on what kind of Asian you are or where in the Bay you grew up. I think it’s really beautiful how different every Asian American experience is.

How has finding this community affected your creative path?

I started making art because I was searching for a community and searching for a way to connect with people.

Right after graduating, I had to grapple with these questions, “Do I want to do this music and creator thing full-time? Do I actually even care about music or am I just doing this because I want friends? Am I lonely and offering my craft as a service so I have an excuse to work with and hang out with people?”

I think that’s why I would collaborate with so many people and go hard on social media, even though I didn’t like the music I was making. I had to stop. I’ve taken a long break because I really want to make sure I want to do this. And now that I’ve separated myself from that pressure of trying to create as a means of connecting, I’m realizing I really do love this.

That pressure of trying to build community through art was taking the joy out of it. Now when I’m creating, I do it because I want to. Sometimes it’s open and

1 One of my favorite pages in “Be Here Now” by Ram Dass, a book my dad used to reference all the time when was growing up.

2 My library card from the newly remodeled Hayward Public Library. I lost the one used growing up but don’t feel too bad about it because the design on this new one is so cute.

3 I grew up with this print everywhere in my home. My mom used to give me laminated pocket sized versions to keep in any backpack or wallet owned as a form of protection as moved throughout the world.

4 I’ve always been obsessed with clouds and the color blue, especially light/pastel/sky blue — there’s something so comforting about it.

5 can’t remember how this wooden flower came into my life, but it’s been around for as long as I can remember. love how simple it is and how perfectly the colors go together. Huge fan of the pastel yellow, green, and blue combo. It’s one of my favorite things I own.

6 Check-out slip from a Dorothea Lange biography borrowed for a research paper. It’s one of the most inspiring projects I worked on during my time at Cal. love that the stamps go all the way back to ‘93.

7 I wear this necklace with Guanyin, the goddess of compassion, every day.

8 Practicing piano in my childhood home in 2004 I believe. Actually not much has changed since then.

15 14

7 3 2 4 1 6 5 8

I

THINK IT’S REALLY BEAUTIFUL HOW DIFFERENT EVERY ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IS.

collaborative, but a lot of the time it’s a very private, intimate, personal thing.

Do you feel the need to adjust your positioning for different audiences?

I’ve always struggled with feeling like I’m not really present when I interact with people. I’m paying very close attention to what they’re saying and how they’re responding, and then I’m basing my identity off of this specific interaction to try and appeal to whoever I’m interacting with. And in some ways that made me a great performer and collaborator. I just worked on other people’s music because I knew how to shape and fit into the mold for this other person making their music.

In the past, I’ve felt like I’ve always had to perform, whether it’s musically or socially, being someone who’s bubbly and who people feel is worth being around. That’s something I’m working on. Around fellow Asian creatives or Asian people in the Bay Area, I feel like I don’t have to perform as hard. This sense of community is new to me.

I wish I had removed the pressure from myself in order to find out what was going to work for me. It took 23 years of intense anxiety, sadness, depression, pain and confusion. And I will still go through these things. But something has recently shifted.

I’ve had the realization that it’s going to be hard and it’s okay that I’m not super productive or going to have this crazy creative output. I’m going to make mistakes, say stupid things, and disappoint people. All my pain has come from thinking I wasn’t supposed to feel pain or disappointment in myself. Now I’m being kind to myself and telling myself it’s okay, because I’m here and I’m going to keep on trying to see what works for me.

Would you say that Asian culture has had any impact on your work?

It definitely has. I actually first started making beats during a visit to Taiwan when I was 14. I was so inspired by everything I was seeing and feeling, but I also felt lonely and out of place, even around my family there, because I couldn’t speak Mandarin very well. During that trip, I spent

up all night having anxiety attacks and I’d be so afraid about how I was gonna present myself to people and then present myself on the internet.

What does your creative pursuit feel like now?

For so many years there was something in me that told me I had to be pursuing this ideal life of a creative that you see on TikTok. All these people in New York that are popping off and everybody’s hot and everybody’s super fashionable, somehow affording all the clothes that they’re wearing. They present this idea of what it looks like to be a full-time artist. And then you’re seeing people that are actually grinding. It’s not that glamorous; there is a ton of work that goes into it. It’s super respectable.

I wanted to be somebody who could wake up and just create all day and be able to support myself in that way. But that pressure of having to monetize what you love just completely alters your relationship with it. We’re sold this idea of aspirational creative worlds and identities, but I know that the creative world looks different for everybody. You’re susceptible to believing that you’re supposed to be something that is not what you actually feel good being.

I felt really self-conscious in college of my socioeconomic status, of being Asian, of being a woman, of pursuing art while going to school with people from immensely wealthy families. I felt weird about being an artist in this whole world of capital while also not feeling good as an artist in my artistic community because I wasn’t dropping any new music. I was constantly conflicted over feeling like I wasn’t presenting in the right way to anyone, but it was coming from the fact that I was doing things I didn’t really want to be doing. I wanted to be somebody who locked myself in my room and played piano for hours, but I was too focused on what the next thing I was going to drop was. Now I’m giving myself space to explore myself, both what that looks like in a musical sense and outside of music.

It seems like you have a new understanding of what needs to change so that you can find calmness and comfort. What would you tell a younger version of yourself to address the uncertainty you felt when you were younger?

What works for others does not necessarily work for you. What works for you is so specific to you.

a lot of time making beats on my phone in an attempt to process and capture all of those emotions through sound, recording samples of different conversations, noises, and music I’d hear wherever I went.

My experience there felt so cinematic, from everything I was soaking up in this new yet familiar environment, to all of the different feelings that being there evoked, both good and bad. This desire to explore my identity in relation to Asian culture played a huge part in inspiring me to start making music.

What did you think it’d be like to be a career artist and what has been the reality?

There’s a part of me that still wants it in some ways, but then I have to keep telling myself, “When you wanted that, you were really unhappy.”

I wanted to be a full-time artist and I was in these spaces where I could have done that. I felt like I accomplished so much in the last couple of years pursuing modeling and music and all these creative projects, but I felt horrible throughout all of it because I had such deep anxiety and just a complete utter lack of confidence in myself. I’d be

Right now, I don’t have things completely figured out, but I’m moving in a direction that feels better. I feel like there’s just so many ways to make your craft into something you pursue full time, and it’s exciting to give yourself the grace and the space, to remove pressure and figure out what works for you.

I’m in this place where I’m like, “I literally don’t care.” I love what I’m making and there’s no time limit and there’s no rush.

18

“ We’re sold this idea of aspirational creative worlds and identities, but I know that the creative world looks different for everybody. ”

DANIEL WU

Actor, Director, and Producer

Actor, Director, and Producer

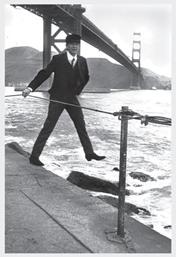

To many, immigrating to America conjures up a time of doors opening and opportunities blossoming — a chance to leave the challenges of ancestral homes behind and to step foot into the land of the free. America, in the imaginations of hopeful immigrants, is the place where dreams become reality through discipline, hard work, and a bit of luck. For Daniel Wu, it was moving counter to this narrative that opened doors.

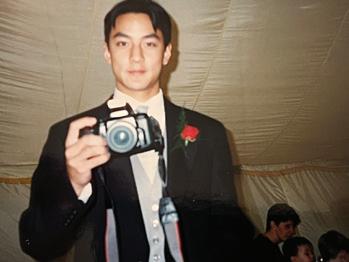

A chance scouting at a bar in Hong Kong kicked off a multidecade career as a movie star in Asia. Success is built off of untold effort, sacrifice, and desire, but also a great deal of timing. In 2016, Daniel returned to his homeland to continue building, adding to his credits notable roles across television and film including Into the Badlands, Westworld, Reminiscence, and American Born Chinese.

New social responsibilities and concerns came alongside more acting roles. The rise in Asian hate crimes in 2020 prompted Daniel to start speaking up for his beliefs, resulting in his increased involvement in championing Asian American opportunities. A future where Asian American roles in entertainment are no longer talking points is a multigenerational undertaking. Count Daniel Wu in for the journey.

21

EUGENE KAN

Looking back on your youth, do you think it was in your cards to become an actor?

DANIEL WU

Growing up in San Francisco, I didn’t see anyone on TV who represented me or my story, so I never considered becoming an actor. I was, however, always interested in film and took film courses in college as part of my architecture degree.

I was in Hong Kong for a trip when I got spotted in a bar and asked to be in a TV commercial for Hang Seng Bank. The director of my first movie saw me in that commercial and cast me in his movie. At first, I turned down the offer, thinking that I would ruin his project. This was the director’s dream, his story, and he wanted to tell a beautiful story on screen. As an actor, I was a part of the team that was there to help him tell that story.

Over time, he convinced me that I could do it. And so I gave it a try, promising to do my best and work hard to be good at it. I attribute this mentality to both my martial arts background and my upbringing as an Asian American, where I was told to work twice as hard as everyone else.

Hong Kong empowered me to believe that I could be an actor. If it wasn’t for my 20 years in Hong Kong, I don’t think I would’ve even come back to the United States. But having developed my craft and talent over there, I had something to bring back and work on here.

Starting out without a professional acting background, what was your creative process like?

I had two to three months to prepare for the movie, and I used what I knew, which was the creative process I learned in architecture school. I didn’t know anything about acting, but I looked at this character like it was a building. The foundation of the building is like this person’s backstory. And if that foundation is f***ed up, then the whole building’s going to be f***ed up. Then you have the structure of the building, like whether it’s wood or steel or bamboo — that’s the internal strength of the character. Next is the skin of the building, which is what the person is trying to present to the rest of the world.

So I used that process and I just used what I knew, because I look at filmmaking and I look at architecture and I look at any kind of creative field — it’s really the same thing. The medium and form of expression are different, but if you can get to the core of what it is you’re actually trying to do, then you can apply it to anything. Unlike being a fine artist, architecture and filmmaking as commercial art forms require knowledge

of production, teamwork, and creating commercially viable products. You have to rely on a group of people getting together to help you realize your vision. I am really thankful for my architecture education setting me up to be a better actor.

Looking back, were there any specific moves you made that really paid off or any missteps that might have negatively impacted your success?

You have to get used to falling down and getting back up, getting knocked down and getting back up. You gotta have a strong character and a strong desire to succeed in order to keep going, regardless of whether you’re in Asia or Hollywood.

People think it was a fairytale story for me, where I was discovered on vacation and chosen to become a movie star and that was it. No! My first day on set I looked around and made the decision that this was what I wanted to be doing. What I loved about architecture school was the creative environment where there’s this energy and buzz and I wanted to be in a field where I could feel that all the time. I walked onto that movie set and I recognized that environment immediately. From that moment on, I committed to the craft of acting.

I was observant, I read books about acting, I talked to a lot of senior actors about their processes, but there’s no such thing as perfection. I’ve seen people burn themselves out by trying to stick to a perfect ideal. You have to find moments to relent and places to stick to your guns. I kept trying for perfection and not being able to achieve it, and I realized that you have to be adaptable.

Having successfully worked in both contexts, could you compare your experiences working as an Asian in Asia versus in North America? What made you choose to speak out for more opportunities for Asian Americans?

I don’t really look at myself as an outspoken leader. I just speak my mind. It’s important to do so, but it was a huge transition. Coming back in 2016 was like culture shock to me. When I was doing Into the Badlands, all the Asian American media was making a big deal about what I was doing, “You’re one of the few Asian American males leading a TV show in America right now.” Yeah, but it’s not any different from what I’ve been doing for the past 20 years leading movies in Hong Kong. They kept trying to put me up on a pedestal and making me carry the flag for Asian American males. I didn’t want to do that. I’m just an actor.

But as I spent more time thinking about it, it became really apparent during the Asian hate crimes in 2020 that

if we don’t speak up for our own people and collectively get together, nothing will happen. Asian America is very diverse in terms of language and culture. We aren’t a monolith. So it was difficult to see us as one culture that could get together and do something, but once we started being treated as a monolith, it became clear that everybody needs to get together and stand up.

There was a case in New York where an old Chinese lady was lit on fire and slapped in the face. I reached out to the community center that was offering a reward for information to catch the guys that did it and I increased that reward because I was appalled by what was happening. This is way beyond calling someone a “chink.” They caught the guys before the reward was enacted because they were caught for something else, but ultimately nothing happened and it was depressing to see that.

that way at all. There’s still some part of white Hollywood that wants to see the Long Duk Dong9 character and they think it’s funny, so we have to make a conscious effort to make a change. That comes from working and collaborating with people on the same page.

One case of this was when I worked with director Lisa Joy on Reminiscence. She had an agenda herself. She said to me something like, “I’m tired of seeing emasculated Asian males on screen and I want to see him be sexy. We’re not seeing that on American screens.” I spent years doing that in Asia and then people don’t see you that way here. They see Asian males as nerdy or funny or weird but never the hero or the sexy guy. So for me, I make sure that I can see the character as a character that I can be proud of and is pushing the bar and changing things a little.

It wasn’t until Vicha Ratanapakdee was killed in San Francisco and then three elderly Asian people got pushed down in Oakland Chinatown that I was like, “What the f***?” I was really pissed and I posted about the attacks. Daniel Dae Kim called me right away. He’s like, “I’m pissed too. Let’s do something about this.” We put up a reward to catch that guy. Nothing came of it, but that’s what started the whole movement of people standing up and saying we’ve had enough of this s***. None of the mainstream media was talking about it, so we wanted to get them talking about it. It wasn’t by plan. I was just mad and I have a platform of like a million people on my Instagram, so I talked about it until somebody noticed.

It was scary at first because I don’t really know a lot about race relations and activism and people were calling me an activist. I’m not an activist, I’m just trying to stick up for my people. There are other people that have been in this space for many years such as Asian Americans for Advancing Justice and all these other groups that have been fighting this fight. I’m just going to use my platform to highlight all the work they’ve been doing and spread the word.

How do you make sure you’re telling the stories and crafting the characters you want to see while navigating what Hollywood wants?

I’m tired of seeing the same stereotypical characters on screen over and over again. I’m lucky that I’m in a position where I can turn down stuff because I’m not waiting for the next check, but it’s messed up that I have to think in

Whether you liked it or not, Crazy Rich Asians was profitable and a turning point in that it opened doors for more opportunities. Hollywood is about making products that sell, not just win awards. If we can prove that there is a market for our stories, they will let us make them. But we need to be careful with how we use those opportunities, not just accepting the status quo, but pushing boundaries.

What do you think would accelerate that?

We’re starting to see change in the three fields that America values the most: entertainment, politics, and sports. People like Congressman Andy Kim and Representative Judy Chu are making headway as are athletes like Shohei Ohtani. We need to support our community in all those fields, not just in Hollywood.

The main message is that we all have to support each other, no matter what our background is. Not just Chinese Americans supporting Chinese Americans or Korean Americans supporting Korean Americans. We have to act in a way where we support each other because we can’t do it separately.

How has your perspective on what it means to be Asian American changed throughout your life?

Being in Asia, where I wasn’t a minority, was very empowering. You’re not thinking about a bamboo ceiling or things like that. You’re doing stuff based on what you want to do. I wasn’t trying to fit into Hollywood like what all my Asian American peers had to deal with for so many years.

23 22

“ If we don’t speak up for our own people and collectively get together, nothing will happen. ”

ONCE WE STARTED BEING TREATED AS A MONOLITH, IT BECAME CLEAR THAT EVERYBODY NEEDS TO GET TOGETHER AND STAND UP.

In Asia, I just got to work on myself. And everyone I worked with in Hong Kong encouraged me and instilled that belief in me that I could be an actor. That was instrumental in who I am now because, coming back to America, I realized the value of my experiences and that empowers me to work here. There are uphill battles here. If I hadn’t gone to Asia and been given opportunities there, I’d probably be cynical as hell and thick-skinned and angry.

What did you think being an actor would be like and what has been the reality of it?

I think everyone has this misconception that it’s this glamorous thing to do. I was also ignorant in thinking that it’s all about the art form. There’a a lot of hustle and business involved too — it’s a balance of both. I think that being an architect helped me with this because I understood the balance between art and commerce and how to make them work together. You have to understand that your product has to sell and I think I didn’t understand that so much at first. Going in, I was like, “I just get to make cool s***,” before realizing it’s not that easy. You have to make stuff that’s cool, pushes the limits, but also sells.

In 10 years, how will you know your work on and off screen in empowering Asian entertainers has been successful?

Success to me is when Asian American kids are inspired to be actors, performers, singers. It’s already happening now. Kids that looked like me in my generation never said stuff like they want to be an actor or singer or anything like that. I’d like to see more of us in everything and it’s not even a thing you have to talk about anymore. I want to get to the point where I don’t have to count Asian representation anymore. It’s just there. Not just with films like The Farewell and Minari, but also mainstream productions where Asian American stars appear alongside Black, White, and Latinx people, reflecting what our society is today.

I see that the younger generation is kicking down the door and saying, “If you’re not going to give me space, I’m going to make my own space and I’m going to have my own followers.” There is nothing to be afraid of anymore. Just go do it.

27 26

9 Long Duk Dong is a fictional character of a Chinese foreign exchange student played by Gedde Watanabe in Sixteen Candles, a 1984 American coming-of-age comedy film written and directed by John Hughes. This character has been widely called an offensive stereotype of Asian people.

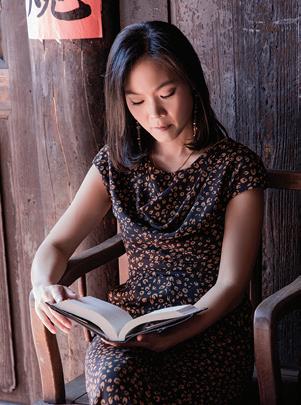

ABIGAIL HING WEN

Author and Filmmaker

Not thinking a creative passion will wind up being a prosperous career is sometimes exactly the right start. When you’re young, you don’t necessarily know what you want to succeed in, especially if it looks like some routes are more likely to be fruitful than others. One way forward is to continuously ask yourself, “What’s authentic to me?” and let that guide you towards the right people and the right projects — that’s the path Abigail Hing Wen took.

Abigail never thought she’d write professionally. She worked her way through law, tech, and venture capital, her passion for writing staying with her all the while. These diverse experiences she accumulated would later find their way into the plots, themes, and characters of her works.

Despite multiple rejections, her tenacity finally paid off with the publication of of her debut young adult novel Loveboat, Taipei, an instant New York Times Bestseller. She’s now executive producing the book-to-film adaptation with ACE Entertainment and Lionsgate. Abigail’s not done yet. She’s got a lot to say, allies to gather, and stories to tell in tech, AI, women’s leadership, implicit bias, and culture.

31

American and Canadian students arriving by plane to Taiwan in 1967 to attend the first Overseas Compatriot Youth Taiwan Study Tour, informally known as The Love Boat

How did you get started as a writer?

ABIGAIL HING WEN

In retrospect, I realize I’ve been writing my whole life. I used to tell stories to my brother and sister and have kept a journal since I was nine. Every time I could turn in a fictional assignment instead of an essay, I always took that opportunity.

I never thought I could be a professional writer – none of the authors I read were anything like me. When I was in law school, I was trying to decide between writing this article I needed to go on the market to be a law professor or write this fantasy novel I had swimming around in my head.

And my husband was like, “You know, you’re really excited about this novel. Why don’t you just try it and see what happens?” I did it and it just came pouring out of me and I was like, “Wow, I had no idea that I could do this.” So that was the beginning.

What’s your writing process like?

Since I left my corporate job about two years ago, I haven’t looked back. It’s been fun, and while I find that I don’t write as much every day, I am doing more producing work. I try to do my writing in the morning when my brain is fresh and I have a lot of creative ideas.

I’m in Vienna with my family right now, with my son who’s studying music and composition, so it’s been like my writing retreat. You’re actually the first person I’ve talked to about what this time here has been like. Here, I get most of my writing done around eight to one o’clock, Then, I take a break for lunch. Some days, I’ll go for a walk with my husband or see a museum. Then, once the United States wakes up in the afternoon, I take meetings for producing type things like book launches and other projects I’m working on. In the evening, we go to the opera and watch a show. There are standing room tickets here, so you can watch a show for five bucks every night. It’s probably not going to be my schedule in the States, though, where there are more distractions and in-person meetings. So for now, it’s been a monthlong protected retreat and I’m really enjoying it.

How do you like to write? Are you more of an architect following a carefully laid out plan or a gardener going with the flow?

I am definitely the organic type and I often write backwards. I use a program called Scrivener and write different scenes, moving them around as needed. When I start a new project, I dive right in and figure out the

key emotional points and the character’s emotional arc. For example, I have a script I’ve been working on where I came up with the climax first and then thought about which character was going to reach that moment. Then, I work with beta readers to uncover any parts they don’t get. I think resolving those disconnects is what makes the fun parts of the story come out.

How do you approach writing characters that are authentic and serve your story well?

Initially, I drew inspiration from stories I had read when I was younger because that’s what I knew. However, as I got closer and closer to my own experiences, I was able to tap into more unique characters that are fictional. For instance, Ever from my Loveboat series has a similar internal journey to me where she’s trying to navigate being a girl between cultures, trying to honor her parents while pursuing her passions, but her external journey is really all her own. I never did all of the crazy things she does. But I think all of my characters have a piece of myself in them, which helps me to write them authentically.

When I first started writing, my characters were perfect. And this might be because of my cultural background as an Asian American writer. I would get feedback from editors saying they wanted to see more flaws. I was like, “What do you mean? If I make them imperfect, then you might not like them.” And I think that had to do with me feeling like I needed to be loved and liked. The more I worked on that and studied character arcs and development, I realized they needed imperfections to grow and have an emotional journey. Even at the end, they might still have imperfections, and that’s okay. That’s part of what makes them human.

I’ve been watching all these operas while I’m in Vienna that have deeply flawed characters that are still loved by audiences. It’s been helpful to let me write deeper, more authentic characters that are free to be themselves.

You mentioned that when you go back to the States, things will be more distracting. When that happens, how do you carve out time for writing, rest, and family?

I found that I had to prioritize time for writing, because it was the easiest thing to slip. When I was working full-time as a lawyer in tech moving over to the business side, I found that as my writing life got bigger, I began to take steps to shrink that part of my life. I remember telling my manager that I probably needed to leave, and he found more time-bound projects for me instead. So the last thing I did before I left my company was develop and host their artificial intelligence podcast

33 32 NATE KAN

I STILL GET CALLED A “SWEET GIRL,” EVEN THOUGH I'M PRODUCING MOVIES AND FIGHTING TO MAKE THINGS HAPPEN.

IMPLICIT BIAS IS A HUGE ISSUE IN OUR COMMUNITY AND THERE ARE DAMAGING MISPERCEPTIONS ABOUT ASIAN AMERICANS NOT BEING LEADERS OR BEING PASSIVE.

Intel on AI, which has since been passed onto my amazing manager. It’s been a constant reevaluation, deciding what can stay and what I should strip out of my life so I can focus on the things that really matter to me.

Talking about your time in tech, what are some ways AI and machine learning have intersected with the Asian American experience?

I have not specifically researched it myself, but I know people have been testing things and posting about it. I know for a fact AI draws from historical data written by humans, which will inherently reflect biases. For instance, searching “Asian baby girl” versus “Asian baby boy” can yield wildly different outcomes and problematic results, with the former being more sexualized. I remember one of my colleagues in the book industry posting about what GPT was saying about Asian girls. It was often sexualized because that was a thing that was written about Asian women in the past.

Having dealt with those issues in different fields, what are your methods for speaking out?

I don’t think I have the perfect answer, but I have a couple thoughts on it. For instance, while I’ve been here, I’ve been explaining the reason I don’t speak German is I’m not from here and the reason I speak English so well is that I was born in the States. And it’s just part of familiarizing people with the idea of, “Okay, there are different types of people in the world.” And while being constantly asked why I speak English so well is a microaggression, I think the most important thing is not to internalize it, which is what I think a lot of people have done.

Growing up, I used to think, “Oh, the problem is me somehow,” or, “Was I coming across too strongly because I wasn’t being a sweet girl?” I think the first step is not to internalize and then, if there is an opportunity to educate, do that — which is harder for sure.

I was worried when I wrote Loveboat, Taipei about how Asian American it was. It was more Asian American than anything I’d ever written before. I really didn’t know if it would be widely read or just read by our community or not even get published. I think that was my fifth attempt at getting published and I had come close twice before and couldn’t get through marketing. And then I had no idea if this one was gonna do well either.

With Loveboat, Taipei I was able to appeal to audiences of different backgrounds by creating Asian American characters with unique personalities where their Asianness was not the most interesting thing about them and, at the same time, bring audiences into this very deeply Asian American experience through the centrality of food, the pressures of family, and what it means to be disconnected from your heritage because you’ve immigrated across the seas and may not know the language of your ancestors anymore.

Having now achieved quite a list of significant things, what would you tell a younger version of yourself?

This is why it’s so important for diverse individuals to work on AI. It can be difficult, as the community can feel small and difficult to penetrate. But I encourage more people to go into the field, especially people from different backgrounds because without diverse individuals at the table, issues like facial recognition software not working on certain faces will go unnoticed. Even if you’re not directly working in the field, at least you can say, “Hey, why is ChatGPT saying x, y, and z about my community when that’s totally not accurate.”

Does it ever feel challenging to balance being an artist who wants to work on their craft while continuing to “fight the good fight?”

I feel like you were like reading my emails or something because this is a challenge I face all the time!

I would love to just bury my head in the sand and just do my work and my art. Implicit bias is a huge issue in our community and there are damaging misperceptions about Asian Americans not being leaders or being passive. I still get called a “sweet girl,” even though I’m producing movies and fighting to make things happen. When they think you’re a “sweet girl” and you don’t act like one, you run into problems. I think Asian American women face more backlash when they speak out or fight back, so I have to continue to build allies and educate people about implicit biases.

I work with people who think they’re always right. You can pray for a moment when they’ll actually humbly ask, “How can I get better?,” but unfortunately that’s not how the world always works. So then I think the last part is really having allies to speak up for you to say, “Hey, do you realize that you cut that person off? Do you realize that you just trampled all over their idea?,” or even just to take them aside quietly and explain in a way so that they’ll feel less defensive because it’s coming from a third party. Having someone speak on your behalf goes a really, really long way.

How do you stay true to telling the stories you want to tell while balancing the demands of the publishing and film industries?

I’m actually struggling with this now because there are certain stories that I would like to tell that may be harder to find a market for. I’m asking myself, “Is now the right time to tell them or do I need to wait till I have a bigger profile?” I do find that most of my ideas tend to be high concept and commercial. I worked in venture capital for many years, so I think I have a kind of natural sensibility for that. But I do have some stories that I don’t know if they’re going to have big markets. I feel very strongly that they need to be told, so I’m thinking about creative nontraditional routes.

Worry less. There’s so much uncertainty when you’re young and you don’t know if you’re going to be successful at the things you want to be successful at and maybe you don’t even know what you want to be successful at! I would tell myself, “You’re going to get there and you’ll be happy.” I had a lonely childhood in Ohio that was not always easy. If I could, I’d go back and hand that little girl Loveboat, Taipei and say, “Things are going to turn out okay.”

For young creators: do what you love and don’t be afraid to be yourself. When you are yourself, you’ll find the people who connect with you. It’s not a judgment if you don’t connect with someone, it means you’re not a creative fit. When you are your most authentic self, then you find people who resonate with you and then you can go do really cool things together. I have to tell myself that too because it gives me the go ahead to find the right people for the right projects.

35 34

“ I never thought I could be a professional writer –none of the authors I read were anything like me. ”

“SILENCE IS GOLDEN”: IN CONVERSATION WITH SAI MING LEE & SUZETTE LEE

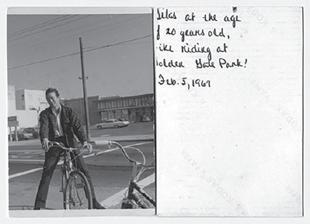

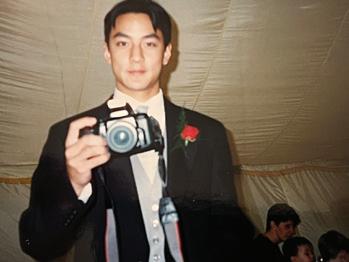

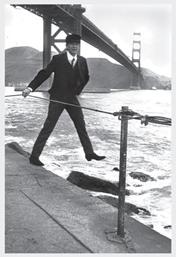

Silas Ming Lee was born in Kobe, Japan but came to San Francisco with his parents around the age of four. The eldest of nine children and the only one born outside the United States, he was the only one to receive a Chinese name until an English teacher gave him the name Silas after “silence.” He has lived in Chinatown for most if not all of his life. His passion for photography is shared with his children Suzette, Stephan, and Sean.

SUZETTE LEE

What was life like for grandpa and great grandpa?

SILAS LEE

My father’s parents ran a sewing factory in Ross Alley. After they retired and passed away, my uncle moved out of there and that became Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory. When you walk inside today, you see the office area upstairs at the back. My uncle built that, and my grandmother and my grandfather slept there. My mom used to do the sewing there, but after she moved to Ping Yuen, people would still bring stuff to her and she would sew at home. My father used to work as a dishwasher at a famous French restaurant called Place Pigalle in Marina. The original sewing factory was across the street from the Bank of America at Kearny and California. Before that building was built, it was all Filipino stores on those three blocks. I used to go out there all the time to walk around and explore the stores or eat Filipino food.

What else can you tell me about your childhood?

I was born in Japan, in Kobe...1947. And we came here when I was about three or four. We lived at the Lafayette Hotel until we eventually moved into Ping Yuen, which was low-income housing. Baba used to walk me to kindergarten at Commodore Stockton in Chinatown.

All the stores in Chinatown used to be on Grant Avenue, but now everything’s on Stockton Street. Grant Avenue is mostly just souvenir places for tourists now. There are no meat shops like the Italian meat market that was on Jackson and Grant. I used to walk around the whole block by myself even when I was five. Just roaming around and everyone knew me too. I’d just play on the street or buy some pickles from the big barrels outside the stores.

What was it like fitting in at that time?

I do remember I used to get my ass kicked a lot by the ABCs (American-Born Chinese) because they thought because they thought I was a Japanese spy. In high school, I started hanging out with Black people more. There was one that used to come to the house all the time. He would back me up. I said, “My own people are picking on me,” and he protected me. Later on, I started hanging out with the fresh off the boat Hong Kong Chinese and I got along with them because I knew the Hong Kong slang and everything.

Where did you learn to speak Chinese so well?

I was just always speaking it. Dad spoke both Hoisanese and Hong Kong Cantonese, so I learned that way. I went to Chinese class and always spoke Chinese with your grandparents and your mom too.

At Chinese school? Is that how you met mom?

No. I met Mom when I went back to John Adams to get my GED, ‘cause I quit high school. I was a bad boy who didn’t like school. So I spent my time hanging out on the street, standing on a corner, you know, acting bad. But then I went to John Adams and they put me in an English class for foreign students.

Mom was sitting next to me but I didn’t know her that well. We never talked and I always spoke really good English with the teachers. Then one day, she heard me in the hallway talking Chinese and she said, “Oh, you speak Chinese? Your Chinese is so good! Are you from Hong Kong?” So we got to talking and I offered to drive her home. And that was the beginning. I started taking her out all the time. We used to go to those Chinese romance movies, you know, where the parents don’t like the guy or they don’t like the girl.

I feel like after you met Mom, a lot of your photography was focused on taking photos of her.

I took a lot of pictures of her. She liked taking pictures. And I always had my camera with me. We’d go for a walk, and all of a sudden I’d say, “Oh, stop a minute. I want to take a picture of the background with you in it.” Do you remember that tan raincoat?

The trench coat? Yeah. It’s in my closet now.

That’s the one. I bought that for her because I told her, “You look good in it.” And I took a picture of her, right? I wonder if Mommy still fits in it.

Probably not, because it barely fits me! But going back to photography. What struck up that passion and how did you learn?

I just liked taking pictures of everything when I was a kid. I bought a Kodak Instamatic when I was a teenager. In those days, there weren’t so many films to choose from, so I was shooting on Kodak like everyone else. I was the only one in my friend group into photography. I learned everything myself by reading books. I never went to a photography school. I had a dark room where I developed my own slides. Color in this house here and black and white at Yeung Yeung’s.

Seeing as Stephan is a chef and both Sean and I are photographers, do you think you might have had something to do with us turning out creative?

Yeah, I was always taking pictures, then they started doing it and then you started. You all took after me!

37 36

China Beach, under the bridge

(Self captioned in text)

The Tan Coat

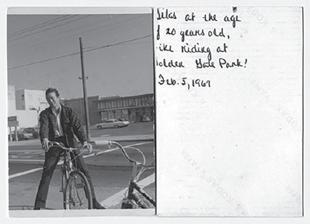

Teenager Walking around Chinatown

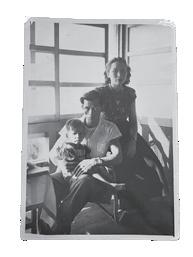

Mama and my brothers and sisters

Guess how many cans of hairspray?

Bad Boy

Baba, Mama, and me in Japan

For over a decade, LionDanceME has trained and performed the traditional art of lion dance in San Francisco. Its own studio is located in the heart of Chinatown.

Students of all ages participate in local competitions and community events, including the annual Lunar New Year Festival in San Francisco. Sessions can last up to six hours at a time, with many routines practiced to perfection to ensure safety during live performances.

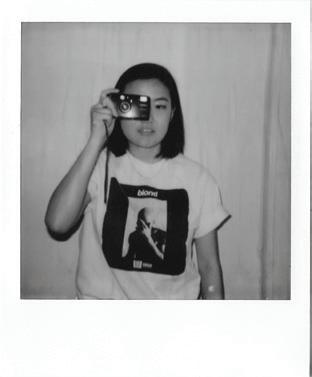

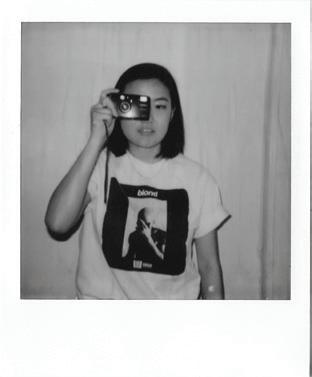

Los Angeles photographer Christina Choi has palpable courage. Her camera is never far from her hand, at every moment she’s in creative mode. From the day she set her sights on being a key player in the world of commercial photography, an industry fundamentally built on collaboration, she knew that asking is much quicker than waiting around.

Christina started out as a teenager pursuing the opportunities she wanted, unafraid of rejection, and embracing a straightforward attitude, “The worst they can say is no, at least I tried.” Since then, her love for photography has only grown. She sees it as endlessly rewarding, from shooting to collaborating, from the potentially lengthy editing process to reflecting on her work many years later. Photography is her time machine and her calling.

The kind of courage Christina has is the sort of gumption that carries young Asian Americans through all kinds of boundaries to reach incredible opportunities.

CHRISTINA CHOI Photographer

43

EUGENE KAN

When you were growing up, what was the initial spark of interest in being creative?

CHRISTINA CHOI

At a young age, my parents instilled this sense of being well-rounded. It meant going to Kumon but also playing sports and attending art classes that my mom put me in. I’m so grateful that she pushed me to unlock that side of me so young. I feel like that wasn’t like a lot of Asian parents, but I was very lucky.

Between the sports, the Kumon, and the art, why did art stick out?

I remember my mom put me in art classes when I was five-years-old. Us six kids had the same art teacher from age 5 until 12. One week we would do it in this kid’s garage, another week in my garage. So I grew up with the same art teacher. She’s a Korean American artist named Young Shin. She really believed in us and she encouraged us to interpret prompts ourselves and create something unique. We all had the same materials but we always had different outcomes.

How important was mentorship to you?

So I have a brother that’s 12 years older than me, and I always wanted to hang out with him. But I was that annoying little sister that, you know, he didn’t want to hang out with. I looked up to him so much and I remember when I was 10, he was 22, just about to finish college, he had a lot of cameras, point-and-shoots, DSLRs, and he inspired me to pick up a camera. As I got a little older, at age 14 or 15, he had a Canon D60 that was released in 2002. The LCD screen is literally half an inch by half an inch. I took it from him and through trial-and-error and YouTube Academy, I kind of taught myself photography.

You’re from the YouTube generation that has all these tools at your disposal. Does it overcome the need for a mentor when you have all these online resources?

Early on I was super into gear and learning about the best lenses, the best cameras, how-to videos, and unboxings. But the internet was less about helping me in a stylistic way. YouTube really showed me how to use the camera. So apertures, shutter speeds, ISOs, all those scientific things. On YouTube at that time, there were really no female photographers doing any of those unboxings or gear reviews. Or Asian women for that matter. I feel like there are a lot more Asian men, but definitely no girls that look like me who are really into tech. In that aspect, I really felt alone. I was like, why isn’t there anybody that looks like me doing these reviews or unboxings?

How did you get going in photography after borrowing your brother’s camera?

Fast forward to when I was 18 or 19, I really wanted to do something with what I’d been learning. I started cold emailing a bunch of people that I admired who I wanted to shoot for. I just told myself the worst they can say is no. I had that mentality at a very young age. I asked without any expectations and I try to keep that mindset with me to this day. Don’t be afraid to ask because the worst they can say is no. I was slowly building. I’m so proud of where I am today. I just turned 28 so I guess I truly started to believe in myself 10 years ago.

If you look at your portfolio there are some heavy hitters in there. How did you get the opportunity to shoot people such as Pharrell, Sosupersam, Aimee Song, and more?

It started with me cold emailing those people I respected on the internet who I wanted to shoot. I remember hitting up Kelia Moniz, this world champion surfer, because she lived nearby and we ended up shooting. I also emailed Aimee Song, the fashion blogger, and was her first-ever intern and helped her grow her following to a few million followers. Then, I met the MISSBISH team at COMPLEXCON and, while shooting that, met a lot of people there. That’s when I met Rachel Muscat and Pharrell. I started shooting for MISSBISH regularly. I’d go to class, take an Uber to a shoot, go back to class and edit. I think it was just consistency and having a can-do attitude.

How would you describe your approach to photography?

I try to capture nostalgic moments and make you feel like you were there, but you weren’t. Or it might be like a deja vu kind of thing. I always try to capture a relatable moment. In photography, you’re interacting with people more than anything and I feel like you just have to be approachable and open-minded and then the photos will follow.

When did you realize the power of photography as a medium?

I take photos for my niece and nephew’s birthday every year. ‘ve been reflecting a lot recently after my dad’s passing, looking through his old photos, looking through my childhood photos, and I’m so grateful I have them. And I’m grateful for the people that took them at that time because I can reflect on them now and appreciate it. Cause, at the time, it’s just something that’s there, but you don’t really appreciate it until the future after that moment has passed or that person’s gone. I was thinking about this recently when I started looking through my niece and nephew’s photos that I’ve taken.

44

I SAY TAKE THE OPPORTUNITY —

WE’RE IN THE SPOTLIGHT NOW. JUST OWN IT.

I’m doing that for them so that when they’re my age they’ll appreciate it.

Does being Korean American inform your work?

In my last zine project I really dug deep into my Korean heritage and my parents. I used their Korean passports that they used to immigrate to America. I’ve never really talked about my “Koreanness” through my art before. I feel like I’ve just become comfortable with myself in the last few years and I’ve started really owning who I am and where I come from.

Where do you think your discomfort in the past might have come from?

I never really grew up with a ton of Korean friends. The only Korean I spoke was at home. I always wanted to assimilate growing up and be “whitewashed”. It’s not until recently in my twenties where it’s been a transformative time for me to really get to know myself and be proud of my heritage. I have no doubt that I will continue using my parents’ influence and my home country’s influence in my future works because of the confidence instilled in me from this recent project. This is just the beginning.

Also, the art teacher I mentioned, Young Shin, was the first person who showed me what art was and she’s a Korean American woman. I was really grateful for that. I was very lucky to be surrounded by people who trusted my creativity.

We’ve seen an increase in Asian American artists and people of color getting visibility in pop culture. Has that changed the creative landscape for you at all?

In recent times, I’ve definitely seen people wanting an all minority production or seeking women of color to shoot specific campaigns. I say take the opportunity — we’re in the spotlight now. Just own it. It’s an amazing thing to see the increased representation and to recognize that we’re living through history.

What did you think it’d be like to be a professional photographer and what has been the reality?

I love taking photos, so I feel like even though I’ve made photography a career, it’s still my favorite hobby. I’m excited to go home and dump my photos in a hard drive and edit them the same day because I took those

Do you think it was harder for you to come up as an Asian American woman?

I never try to put any pressure on it, but I do feel like when I’m on production sets in LA I am usually the only woman with a camera on set, period. You have other women who are makeup artists, hair stylists, but I’m usually the only girl on set that has a camera. But that’s never deterred me. I know I belong there, but I definitely wish there were more of us.

There’s a stereotype of Asian Americans being quiet and shy. Where did you find your confidence to step up for yourself?

I wasn’t the photographer at first, you know. I was the assistant, I was the PA, I was the digitech. I feel like I had to do all those things to know everything about production and then that instilled in me the confidence to be a photographer on set.

photos for myself. And I think that’s how I’m able to shoot photos as a career and still enjoy doing it. I feel like a lot of people, when their hobbies become their career, they lose passion for it. I keep good boundaries between my career and my hobby.

Lastly, what do you think has been the biggest challenge for you in your career as an artist and creative? What would you say to a younger version of yourself?

Oh my god, I have imposter syndrome every day. In hindsight, I think it does stem from not growing up with representation. I’ve always thought that maybe I’m not someone’s first choice. So instead of waiting for people to approach me, I have to be the one to ask and have that zero expectations mentality. I’d tell my 15-yearold self that rejection is ok and you move on from that. You’re going to think, “How am I going to manage this?” and then learn to balance that with thinking, “They must think I can do it and I have to do it.” And then you surprise yourself.

47 46

“ On YouTube at that time, there were really no female photographers doing any of those unboxings or gear reviews. Or Asian women for that matter. ”

Cover art for Ta-Ku and Masego's Single, "Flight 99"

Lucy in Rick Owens

Pharrell in Washington D.C. on Juneteenth

KELVIN YU

Actor, Writer and Producer

Actor, Writer and Producer

For film and television multihyphenate Kelvin Yu, his career might be traced back to a tap on the shoulder at 13 and a few encouraging words from a teacher. After trying out for that first school play, the burgeoning drama geek from Southern California locked in his path towards a career as a working actor. Taking on every opportunity that went his way, from single lines and single scenes to being typecast as the vengeful spouse or sibling on crime serials, the entertainment industry veteran endured the demoralizing gauntlet many working actors in America face — the side jobs, the auditions, and the anxiety around the phone ringing far less often than one would hope.

Partially a way to pass the time and eventually a kind of salvation, writing lead him towards more peers, more opportunities, and, of course, more roles. Kelvin wrote for shows that helped redefine American television such as long-running animated television series Bob’s Burgers, Master of None, and, most recently, American Born Chinese, all while continuing to work extensively as an actor. A “new-ish” father of two, he continues to find inspiration in necessarily stolen moments of boredom and the “squishy place,” a pure and emotional if nonsensical space residing inside everyone.

49

How did you get started acting?

KELVIN YU

I grew up in Southern California, but not in LA proper. I wasn’t a Hollywood kid, but I was a drama geek. I got tapped on the shoulder, literally, when I was 13, by a teacher who suggested I audition for the school play. It’s a really powerful thing for somebody older to tell you that they see something in you. For me, especially as an Asian American growing up in a fairly white area, for Mrs. McIntyre to say, “Hey, I think you should audition for the school play,” is validating or, as I guess the kids are saying, I felt “seen.” And then from that moment on, I never seriously considered anything else.

So acting was largely the only career path you considered?

I always knew I was gonna audition for theater departments at the end of high school. I always knew I was gonna become a professional actor. And I did. That said, it wasn’t easy. Over 20 years ago, it’s hard to remember because the movement towards diversity has taken effect to some extent now and the internet has changed the entire game, but there was just nothing for me then. If you stacked a hundred scripts on a table, there might be five to ten roles in those hundred scripts for me, right? And so I was not playing a good numbers game, so I did everything that everybody else does — I waited tables for seven years. Auditioned. I did everything I could. I did one-liners. I had one line on Frasier. I had one scene in ER. And then there came a point where I realized that the business model that I was engaged in was not sustainable.

They were never gonna give me the role that you lived through as a viewer and I’m not just talking about leading man roles. They were just never going to give me a role where people were actually experiencing my experience. I was always gonna be sort of peripheral or ancillary to whatever story was being told. And that was just a gross feeling.

What sort of roles were you doing at the time?

What I was doing around that time, which makes me laugh a lot now, was being hired to kill my spouse or my sister on these cop procedurals. Whether it’s CSI, Without A Trace, or The Closer, they do like, one Mexican episode a year, one Chinese episode, or one Middle Eastern episode. So whenever they did the Chinese episode or the Korean episode, it was always some jilted husband whose wife got an email address and he was so ashamed of her – because they didn’t really know what they were writing. I came from drama

school and grew up in the theater and so I could blubber my way through a confession in those auditions. And so I got that role like, six times. So I was working a lot, but you get to a place where you think, “I have more to offer.” And I think in general, the actor’s life can be more fulfilling because the act of acting is to embody the experience.

What is it about being an actor that’s rewarding or challenging?

Whether you’re a producer, writer, director, or crew member, you don’t get down on the playing field and throw the touchdown pass. The actor gets to do that. Even though an offensive coordinator and a bunch of assistant coaches and a head coach designed that play for you, you get that ball into the end zone or you take that three-pointer at the buzzer and that can be incredibly meaningful in life.

The problem is it only happens once in a blue moon and you have no control over when it happens, and so you wake up every day waiting for the phone to ring and wondering if someone out there likes you or thinks you’re interesting. So you do that calculation, “Is that touchdown pass worth it if you are just gonna sit around and wait for somebody to call your number for your whole life?”

While you were continuing to act, how did you transition into writing?

I started writing poor, terrible, unreadable scripts around 2005, 2006. While I waited for somebody to like my acting, writing gave me the gift of waking up in the morning with some agency. I got to wake up, start writing, and think, “Maybe today’s the day I come up with that great idea or I fix that broken idea into something slightly better.” It gave me empowerment, agency, and mental health. It was like a therapeutic device to get through the waiting in an acting career.

Could you talk about how that led to Bob’s Burgers?

It was a couple years of writing along with another guy named Steven Davis. I had told him at the time to take my name off our scripts because I was ashamed of them and I didn’t think they were any good. And then he calls me and he says, “Look, I have a meeting with Family Guy and I just feel like you should take the meeting with me.” We took the meeting with Family Guy and right away they told us that it was for another show. So we’re like, “Great. We got bait-and-switched here.” They said, “It’s for this new show called Bob’s Burgers.” We watched the presentation for it and it seemed like something genuinely special.

We got that job and we thought it was going to be a fun three or six months max, and it’s been 14 years and the show’s still on the air. So somehow my writing career just got on the expressway. You just can’t plan these things.

What is it about the writing for Bob’s Burgers that sets it apart from other sitcoms?

Comedy is contextual, and generally things are funny because of the exact moment they’re funny in and most of the time they’re not funny over the test of time. A lot of times they become problematic. Bob’s Burgers was created by Loren Bouchard in 2008, and I started writing for it in 2010. The notes we received were like, “Can this

into stinkers. I’ve seen kind of medium to lukewarm ideas turn into some of our best episodes. So I think that’s sort of my experience of Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000 hour rule10,” just watching people come up with something.

The other part of this is the staff, which is lightning in a bottle. In short, I think the recipe is that we made each other laugh. It’s always being true to what makes you laugh in the moment and then just having the faith that even if it fails in the marketplace, you’ll be able to sleep at night because you made the thing that you liked. Versus pandering and having that fail and feeling, “I didn’t make the thing I liked and it failed. What would’ve happened if I made the thing I liked?”

be more like South Park? Can this be more like Family Guy?” That’s what people were enjoying about “adult animation,” like, “Oh, they made fun of this celebrity. They said something snarky about this woman’s body.”

Loren Bouchard was coming from his own sensibility and worldview, and he was challenging us to be funny without punching down. Bob’s Burgers is an anomaly because the family loves each other. They go towards compassion and greater empathy. I think the world and comedy in general were turning that way, so we were lucky to be part of that.

We got tweets and emails from people saying they would leave it on at night, because it was soothing and helpful during whatever they were going through, whether it was their adolescence or anxiety. And I’ve taken that with me as a writer, the ability to be funny and kind at the same time.

How do you accomplish something like that where you need to balance being funny and kind, cover different relevant issues, and all without being too heavy-handed or feeling like you’re pandering?

We made 250 episodes of Bob’s so far, and we’re not done at all. 250 times I’ve watched somebody come up with an idea, generate some pitches, put that on a board, turn that into a pdf, read that in front of ad people, have artists come and draw that idea, and then we put that on tv. I’ve seen it all happen. I’ve seen great ideas turn

You’re currently an Executive Producer on projects such as American Born Chinese. What’s the journey like getting into leadership positions like that?

There’s almost a militaristic structure to TV writing where you come in as a Staff Writer and then you move up to Story Editor – this is how your representation negotiates for you – then Executive Story Editor, and then I think it’s Producer, Supervising Producer or Coproducer, Co-executive Producer, Executive Producer, and then Showrunner.

So I started to work on other projects like Master of None with Aziz Ansari and Alan Yang, which was also really illuminating for me because they’re sort of my cohort demographically. They look like me, they talk like me, they grew up like me. And so to watch them make their own show and be specific about who they are and the things they want to say was really informative for me. You can go and tell that story and if you tell it well, people will watch. It was a really successful show and kudos to them for changing the American view of people that look like us — that you can be a bon vivant living in New York having martinis and eating at the best restaurants and dating whoever you want. Aziz shifted the perception.

Granted the road ahead is still a long one, how do you think representation has changed since you started out?

51 50 NATE KAN

“ I think that one of the best things we can do is find a space for that boredom and then really sit in it at the moment – to not be entertained by anything and see what happens. ”

I was on a plane recently on a nine hour flight and I have a one-year-old so I’m the guy walking up and down the aisle with the baby so she doesn’t bother anybody. I got to see what everybody’s watching and I saw a lot of Wakanda Forever because that’s the big movie right now, but like everybody else was watching Friends. It was so mind boggling to me. It’s such a cultural force and it has wired our brains to see the world in a certain way.

Yes, diversity is happening. Yes, Crazy Rich Asians did well in the box office. But Friends and Seinfeld and The Office and sitcoms of the 80’s and 90’s are in our DNA. Yes, we’re starting to chip away, and I don’t want to diminish Shang Chi or Master of None or Fresh Off the Boat but it’s drops in an ocean. I used to be hunting for crumbs at the bottom of a table and I dare say that most of us still are. If you take a quick snapshot of the whole field, things have not shifted in a grander sense. I’ve had a really wonderful experience over my now 25 year career but it’s definitely been in the context of limited opportunities.

Do you think anything could possibly accelerate Asian American representation in popular culture?

I think we’re in this phase where Asian Americans are perceived as trendsetters, DJs, or elite chefs or something like that. We’re almost fetishized for our sense of culture and trends, but I think you have to accept the process to some extent. Italian Americans in the ‘70s probably rolled their eyes when there was “yet another mafia story”. But those stories helped to imbue American society with Italian American culture. In the same way, you and I might roll our eyes at another martial arts movies, but that’s the process of the American canon — normalizing you and then you can have your seat at the table.

Once people have seen your face in an interesting narrative, they might become interested in something that’s five degrees off that — a little less martial arts or mafia each time — until we get to a completely different story. It’s not so linear, but that’s how it might be happening. We’ll get to a place where an Asian American story is just an American story. I think we’re moving exponentially faster. It’s a balancing act because you want to stay true to your community, but you’re trying to sell your product to a wider market.

What do you keep in mind as you’re maintaining this balancing act?

It all really starts with what I call “the squishy place”. It’s that place inside you that is warm, fuzzy, squishy, and almost cringey. I think everybody has it and everything

you’re making has to come from there. It can’t come from a market analysis. It has to come from your, like, rat brain, like five-year-old Nate or five-year old Kelvin that’s just living in pure presence.

And it can be painful. I’m not saying it’s all happy – it can be from somewhere painful like your parent’s divorce or political strife – but when you build something out from there it might become a movie, it might become a rap album, it might become a pot of clay. But it has to come from there because you work too f***ing hard and it’s too stressful to not be devoting your time and energy to that thing.

That’s definitely a strong message for not just this generation but the next. What would you say to a younger version of yourself?

I think a lot of people, especially for this younger generation, the daily to-do is to crack the algorithm and beat the system somehow. I think that’s the wrong way to go about making art in general, because eventually technology will – like it always does – fill that space because that’s what we build it for. But the one place it will never infringe upon, I think, is that human squishy place. By definition, technology can’t go to that nonsensical, purely God space or whatever you want to call it. And so I think this algorithmic generation could be an enlightened renaissance of the squishy place for humans because we are now so free to just live in that space and use the machinery we’ve built to help us create art with it. So I think that’s the fuel we should keep mining rather than trying to crack a code. I think that it’s about embracing where we’re at in the moment and to some extent embracing boredom.

53 52

I WAITED TABLES FOR SEVEN YEARS. AUDITIONED. I DID EVERYTHING I COULD. I DID ONE-LINERS, I HAD ONE LINE ON FRASIER. I HAD ONE SCENE IN ER. AND THEN THERE CAME A POINT WHERE I REALIZED THAT THE BUSINESS MODEL THAT I WAS ENGAGED IN WAS NOT SUSTAINABLE.

10 In his book “Outliers: The Story of Success,” Malcolm Gladwell refers to the 10,000 hour rule to mean that the key to becoming a true master of something is to practice it for 10,000 hours.

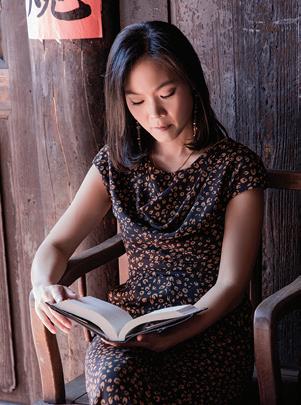

CARMEN CHAN

Photographer

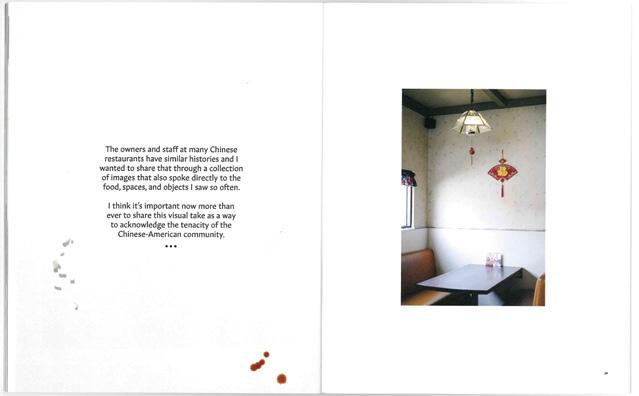

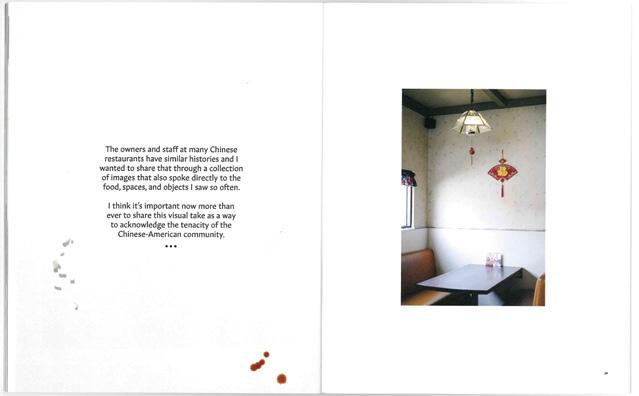

Carmen Chan’s career in photography didn’t start with inheriting an heirloom camera, attending a class, or meeting a professional. Instead, it was coming across an admittedly mundane photo of cups that sparked the thought that perhaps there was something else she’d rather be doing. As the child of Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong, she spent much of her early life inside her parents’ restaurant, Cathay House, as well as many other Asian restaurants in their tight-knit Las Vegas community.

Throughout the chapters of her life spent in Hong Kong, Los Angeles, New York, and Boulder, Colorado, where she’s now based, her determination in perfecting her technical craft has gone hand-in-hand with her increasing desire to uplift the underrepresented and to support her community. Carmen has been volunteer Program Manager at Diversify Photo and is also co-founder of F*ck Gatekeeping, an online knowledge base for emerging BIPOC photographers.

Her desire to share the stories and work of female artists resulted in publishing her first book EXPOSURE, while the memories of her family’s restaurant inspired her second book Chinese Food, which documents small Chinese restaurants throughout California. Now, more than ever before, Carmen is confident in her eye and her value, fully embracing her perspective and trusting that her honesty will resonate with the right people.

57

EUGENE KAN

How did you get into photography?

CARMEN CHAN

I didn’t get into photography when I was really young, although I do recall when I was maybe 10 my mom gave me an Olympus View point and shoot that I still have, and it’s now made a comeback as a film camera trend. I did take photos for social purposes like documenting friends and family with digital cameras, but never from an artistic angle, like trying to make art.

So for me, photography as a career began when I was tired of my job in production, scripted film and television production, and I saw a photo that my friend who I went to high school with posted on Facebook or Flickr. It’s a photo of cups hanging in a kitchen. It’s so mundane, but for some reason I thought it was an amazing photo. I hit him up and was like, “Hey, wanna meet up and catch up?” The next time we met, he had extra camera bodies and taught me how to use the camera in manual mode. From there, I became obsessed and would bring the camera to work, take pictures of my coworkers and random s*** like flowers.