Student Scholarship & Art Exhibition

Student Scholarship & Art Exhibition

As we celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, we want to extend a heartfelt thank you to all the students who submitted their artwork for the Make Noise Today Student Scholarship & Art Exhibition.

Your creative expressions have not only enriched our hearts but have also served as a powerful testament to the diverse and vibrant cultures within the AAPI community. Your dedication to sharing your stories and perspectives through art is truly commendable.

Your participation has made this contest a beautiful reflection of Amplifying Heritage and Empowering Futures, and for that, we are immensely grateful. Thank you for your contributions, and may your artistic endeavors continue to inspire us all.

As Asian Americans, we are considered ‘the quiet ones.’

When negative media and hate crimes against Asians escalated during the pandemic, we felt it was time to be heard. This initiative was launched in May 2020 in honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, and our powerful voices continue to be loud and strong to take control of our own narrative and combat racism by telling personal stories of our heritage and accomplishments, challenges, grit, inspiration, and culture.

We believe that change begins with youth and that the way in is through storytelling. Stories move hearts and change minds. By achieving a larger volume of stories, we can attain narrative plenitude to educate and increase empathy, uniting Asian Americans and other minority groups in moving towards sustained action and change.

Intertrend is a multicultural agency that understands the intersection of cultures, emerging trends, and the interaction between brands and consumers. Based in both Long Beach, CA and Plano, TX, the agency has worked with leading brands and also houses a family of entrepreneurial brand units that build to its core expertise across digital, content and experiential. Interpreters and interrupters, interdisciplinary and international, Intertrend is where culture and content meet.

The purpose of Creative Class Collective is to facilitate, support and encourage new and innovative ideas in the realm of arts, music, education, and other creative outlets with the goal to aid in elevating community planning and economic viability. Our goal is to establish a creative movement with a positive civic impact and strengthen cultural equity by focusing on communities in need.

In a world that is constantly evolving, the intricate tapestry of Asian American culture thrives through the threads of tradition, memory, and aspiration.

This scholarship contest invites Asian American high school students to explore, express, and celebrate what ties them to their cultural roots. By highlighting their connection to Asian American heritage, students are also reminded of their role as the next generation’s stewards in keeping this rich culture vibrant and alive.

We wanted to highlight the invaluable efforts of the Intertrend Communications that sorted through 465 submissions, and our esteemed judging panel time to review our semi finalists. Thank you!

CHELSEA SIK Actor / Executive Producer / Digital Creator

CHELSEA SIK Actor / Executive Producer / Digital Creator

Born and raised in Malaysia, Chelsea Sik left her home country at age 15 in pursuit of an acting career. Her journey began by learning the craft at Idyllwild Arts Academy as a sophomore Musical Theatre major, then furthering her education at USC as a BFA Acting major. Since graduating, Chelsea Sik is a working actor, executive producer and digital creator, known for her award winning short film Foreign Planetary and growing social media presence. Under her brand as a “Clown”, Chelsea has amassed over hundred thousands of followers and multi-millions of views across platforms. You can follow her journey on Instagram @chelseasik!

BRIAN LIN Education Consultant

BRIAN LIN Education Consultant

Based in Los Angeles and raised in small-town Oklahoma as a child of Taiwanese immigrants, Brian is a lifelong advocate for the arts and education, particularly in their power to help youth find and express their voice. Since childhood, music has been a critical path for expression and community for Brian, and he holds a deep appreciation for teachers like Ms. Askins and Ms. Anduss, who showed him how powerful it was for a student to feel seen and heard, particularly when most of his classmates didn’t look like him. Brian believes in the importance of APIA representation in leadership and media, and along with Tommy Chang and Albert Kim, he hosts the miseducAsian podcast to help amplify the voices of APIA communities across the country. He is currently a consultant who supports education institutions across the country to make more equitable and inclusive decisions for all students.

Communications team panel who took the

JASON KEAM Painter / Animator

JASON KEAM Painter / Animator

Jason Keam is a Long Beach, California based free form hard-edge figurative and abstract painter with a background in animation and visual effects. His work celebrates and liberates all living beings, cultural tools, and their relationship with each other. Everything starts with a drawing on paper then digitized then redrawn and repeat until refined, reduced, or simplified. His world is filled with vibrant animated figures with curious and playful abstracted lines. His paintings have the quality of a screen print on a freshly printed skate t-shirt.

KATERINA JENG Author / Marketing Agency Co-FounderKaterina (they/she) is a dedicated advocate for inclusivity and healing through creativity, known for founding an acclaimed Asian American creative collective in 2016 and co-founding Spectacle, an inclusive marketing agency, in 2018. Their work spans from editing a literary journal that amplifies Asian American stories to advising companies like Vans and Denver Health on culturally sensitive messaging. With a background in English and music from Cornell University and a fellowship at Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop, Katerina’s efforts in community organizing and marketing are rooted in a deep commitment to social justice and equity. A New York native, they find joy in simple pleasures like sunshine, good food, and quality time with loved ones.

“A Gold Star For You” represents my experience as an Asian American. A certain type of guilt accompanies being biracial, and I often find myself doing anything possible to make up for the Asian I don’t possess in my blood. Though I’m extremely proud of my culture, I worry about living up to my family’s legacy, striving to achieve what they weren’t given the opportunity to. I contemplate the right I have to hurt from Asian hate, to speak up on injustice, teach others about Chinese heritage, and if my passion for my culture is appropriate.

The stars in this piece take inspiration from both the Chinese and American flag, coinciding with the artwork’s color placement to represent the identity conflicts associated with being biracial. Additionally, the stars relate to the idea of Asians being the “Model Minority” and the desire to leave behind no gaps in my successes. I hope to be noticed as a person of color, but note how I have white-passing features. Recognized only by fellow Asian-Americans, I feel selfish that they aren’t enough for me.

How do you measure fulfillment?

How do you know when you’ve accomplished true success?

How do you choose who gets a gold star?

The thick, sticky air sends sweat down my back as I’m sitting on the too-high cushioned seat at the front desk. The summer breeze could’ve been like any other gust in November or January, but it’s July, and the wind is serene, my morning Chrysanthemum tea tastes sweeter and the hours to my long work day are even longer. I remember thinking to myself, sitting behind my mother’s nail salon’s front desk, how my summer should have gone. Jumping into pools, joyriding around parking lots, gazing at sunsets, the beach with an acai bowl and friends. But there I was, my two weeks left of summer in that chair again just like I had the first week of June, answering the phone for my English faltering mother for the business she had spent half her life building.

Lu nch is early for the slow day and I sit in the back in a teal painted room with harsh fluorescents and the spatial depth of the average Manhattan shoebox apartment. I sit across from my mother, sharing a meal of slow-cooked meats and marinated eggs alongside garlic bok choy from the night before. I give her the traditional “thank you for this meal” in Vietnamese and we eat in silence of each other but in the loud thoughts of our brains. There’s a tensity in the air. As I bite into the cold bok choy, I hear her mutter then stop, a hesitance in her stare when I look back at her.

Then, almost as if to play it off, she fixates on the marinated pork belly and says fondly to me, “thank you for sharing this meal with me”.

I pause.

“You know I always love eating with you.”

At the moment, I have nothing to say except an “of course” and continue eating. However, from that point on, the point in which I dreaded the entirety of my summer of what I thought was wasted youth or internship chances had become something irrevocably different. I was reminded of the hands that belonged to another life before my own: in the Saigon tropics and under man-made tin roofs, then to the trials of a less than manageable wage from textile

companies of a foreign land, the keys to a business and Sundays spent painting endless nails, and finally, to a rare summer season where joy is sparked from something as simple as the shared spoons of rice and pork with her daughter. I had little knowledge on what it truly meant to be Asian American before, and what my purpose had been in life. But those words of gratitude on a random July Tuesday afternoon vocalized more than a thankful remark. It stressed the decades of work that led to a moment of simple peace, a uselessness in the non-material aspects of the eccentric unmatching decor, and the significance of a shared Asian meal. The display of love and affection is hard to come by in an Asian household, a belief held by many, but I think that it’s all around us. In the silent build up of courage before saying an apprehensive ‘thank you’, the cool condensation of freshly cut fruit, the stillness of a suppressed struggle or a reminder to wear a jacket, love may have not been in the form of words or touch, but in the subtle impacts of actions. To be Asian American for me wasn’t just eating French fries with chopsticks, the duality of American freedom and Chinese Confucius beliefs, or my Californian accent with broken Vietnamese, it was also the exploration of two worlds of myself. One world where physical touch was my first love language according to Buzzfeed quizzes, while another coexisted in giving my father the last Banh Tet or packing my sister’s lunches. One world where I smile fiercely on crashing waves, and another where I sit, tranquil yet grateful, on the front desk of that nail salon in the thick, sticky summer air with a back full of sweat just like how my mother’s did in Ho Chi Minh all those years ago, finding a purpose in accepting the two raging sides of myself.

Têt = Lunar New Year

Ông Bà Ngoại = grandparents

Bánh Xèo = Vietnamese sandwich

Ngon = flavorful

No = full

Nước Mắm = fish sauce

Bún Bò Huế = spicy Vietnamese soup

Ché = Vietnamese dessert

Amber Y.

The imagery found in my work consists of themes relating to childhood, whimsical imagination, and my Chinese heritage. In this instance, I collected wrappers and packaging of my favorite childhood Asian snacks.

The idea for this piece originated from how the cravings I used to feel for these delicious snacks reflect my current craving to connect with my culture on a deeper level. The process of layering and gluing the wrappers onto the paper contributed

to more vibrant, saturated colors and wispy textures that enhanced the narrative of my piece. Through my own artistic expression and learning to advance my culinary skills in Chinese cuisine, I continue to remain steadfast in enriching myself in the history and culture of my heritage.

Only diamond can break diamond Only human can break human The destiny of history Is bound to repeat.

My great grandma had a dove It seemed fleeting yet so loved But how quickly could it slip From the loving of her kiss

As the first generation Beginning where salvation Was precious then but distant For who would really listen?

Even when they bluntly fell Experienced human Hell The worst of humankind Had seemed to make them blind

The dove had seemed to flee To where they couldn’t see The end-of-tunnel light They needed now to fight

It burned, oh, it burned ‘Cause somehow it had turned Toward the hands of Lucifer That scared her dove away from her

But why then must it go In face of fearful foes?

Only diamond can break diamond Only human can break human The destiny of history Is bound to repeat.

My grandmother was born To a family that was torn But the embers still burned hot And suddenly they fought.

There did Vietnam split But even more did it Punish those poor families Who only had one need-

To laugh, to love, to live so free To touch, to care, just to be seen

So how could they have done This all? It left her stunned

She saw the North had come Her body frightened numb Her burns will tell her story As she fled her territory

She saw them, even children, At gunpoint at their own chin, Must some go such dark ways To gain power over prey?

Brutality then continued Reflections on the issue Evolved from reigning terror Existentialist endeavors

And what was “free” Was nothing to see But refugee camp Squalid, unkempt.

But they needed the shelter, ‘Cause born was my mother The third generation Stuck in this situation,

Then a call from her cousin! A call straight from heaven! The American states Had offered a place.

The doves were flying! Their spirits were rising! Their one lucky chance To make this advance,

But we still had a mountain They didn’t account in The states didn’t mean That we were really Free.

My mother neglected Her mom disrespected ‘Cause no matter what They’re just nothing but Outsiders.

My mom With not Not a single Except for Her world Her parents The tension Always seemed She cared Helped through Despite her From her Wealth slipped As soon as Mom pled Begging, But what Confronting

Her brother, Their voices

Yet with all They couldn’t That around How alone

“You’re lucky That’s all But why was When all Freedom And indeed ‘Twas then It’s her life She worked Strengthening Left her past She focused

Replanting With hope Raised me, The fourth

lived through school a single jewel single sport for those chores world fell apart parents would part tension in rooms seemed to loom cared for her siblings through broken billings her remorse mom’s divorce, slipped from their fingers as it lingered pled on her knees just please, good was it there Confronting thin air? brother, her sister voices within her all their demands couldn’t understand around all of them alone she felt then lucky to even be here” she heard from her peers was this called luck she felt was stuck is expensive indeed came with expenses then when she realized life to devise

worked her way to college Strengthening her knowledge past behind focused all her mind

Replanting her own roots hope to bear new fruit me, my brother and sister fourth after great-grandmother.

It took four generations To mend the situation, Diamonds can’t heal diamonds But humans can heal humans

The fire of dark Embedded in hearts Continues today With Russia, Ukraine,

The obstacles we faced, Just a frequent case Of what families see When violence springs

We can only wait The dove may come straight And then can we see Just how good Peace would be.

Only diamond can break diamond Only human can break human Unless we change our history It’s bound to still repeat.

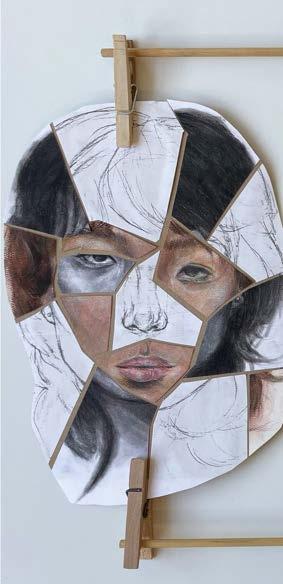

“In this piece, I deconstruct and unmask racial stereotypes that have constrained my genderqueer expression as a Chinese American.

Drawing inspiration from the flashiness of Beijing opera and Chinese mythology, I juxtapose them with slogans and imagery from the Chinese Exclusion Act–taking something popularly used to dehumanize Chinese Americans and repurposing it into an act of celebrating my intersectionality. In the center, I position myself in place of the ‘yellow’ Chinaman from Frank Leslie’s 1882 caricature, ‘The Only One Barred Out,’ transforming this dehumanizing figure into a symbol of empowerment amidst the chaos. Dressed in male and female garments, I embody self-affirmation, celebrating my gender-identity without being confined by racist interpretations.”

Ardachandran Alapadm

Aariya M.

Piece Description: Ardachandran Alapadma refers to the hand gestures depicted. These hand gestures are found in the art of bharatnatyam, an Indian dance style. Ardachandran Alapadma translates into “A fully bloomed woman (or person).” The purpose of this artwork was to depict my personal view of artwork as I grew up, and how it made me into the person I am today. In Indian households, regardless of dialect or region, you will often find a framed “Madhubani” art piece.

Growing up, I was infatuated by these pieces and would collect them in my mind as my family

traveled to relatives and friends’ houses. As I got older, I began recreating these works and started to convey my emotions and feelings through my Madhubani art. Now, as I am older, I have made this piece to represent my life so far. I’ve included customs from both sides of my family and have represented my heritage through patterns. The monotone palette represents how I shamelessly and boldly represent my culture, even if it means standing out. By combining cultural patterns, a Madhubani style, and the art of Bharatnatyam. I can confidently say that this piece empowers me, and puts my heritage on a pedestal.

生日快乐. That’s “Happy Birthday” in Mandarin, 4 curling-and-swirling loops that my stubby hands just cannot seem to replicate. At 7-years-old, I scribble onto the cardstock adorned with glitter glue and photos of my mother.

The Google Translate search “how to write happy birthday in Chinese” glares mockingly at me. I glare right back. I skip over to my mother, eager to present my work.

She accepts the card, giving me a warm hug. She beams, “Thank you, honey.” Not ‘谢谢 宝贝’ thank you, honey in her native tongue, in her language. (In our language.) The English is especially jarring with her Chinese accent and soft smile—just more salt in the wound.

I guess what the other children whisper about me at Chinese school is true: My Chinese is so poor I am lucky I am good at reading English. They taunt that my parents are too soft. They mock that I will become one of them, a full-blooded American.

They say that I am good at being Asian, but not good enough.

As an Asian-American, It feels like a sin to declare that Lunar New Year is my least favorite holiday. Red is so unflattering on me that I curse my ancestors for making red the traditional color. I practice smiling in the mirror, cheeks stretching unnaturally to the point of a grimace, as I prepare to greet family friends. I have no idea who they are. They assure me that I look adorable in red. They don’t know who I am either.

Years ago, I was rosy-cheeked and rosy-eyed, willing to attempt to satisfy an impossible standard. Now, I grumble under my breath at all the rituals I am forced to follow: wear red, don’t wash your hair, clean your room. Everytime I attempt to ask why, why we do things the way we do, I get the same response: that’s just the way things are.

“Don’t make a scene,” my mother warns.

I snort. I was the one who taught her that phrase.

“我知道,” I respond out of habit. I know.

To my parents, it has always been endearing that I can speak their Asian dialects, albeit brokenly. A mishmash of Mandarin, Cantonese, and Shanghainese that I’ve come to associate with home and take pride in. Don’t make a scene. And so, I let myself be the butt of the joke and an easy conversation starter. “She uses chopsticks so well, for an American.” I stab my chopsticks into my stir-fried noodles. “She speaks so well, for an American.”

“我可以听见你,” I grumble. I can hear you. The adults all laugh. Even without looking I know that my mother is glaring at me, mouthing the words. Don’t make a scene.

For the sake of tradition, I am supposed to let everything pass. That’s just the way things are: the ‘Asian’ way. My mother doesn’t stop the Aunties from making their jokes. We never mention what happens at New Year dinner. Don’t make a scene. All I can do is sit there like a good girl, quiet and quieted. Funnily enough, I always feel most Asian when I am being ridiculed for being too American.

“再过 几年,她就不会再理解我们了,” a drunk woman who insists she is my Auntie intones. Give it a few years and she will no longer understand us.

When I told my mother that I couldn’t sleep, she bought me a new bed. I thought that maybe my broken Cantonese—the Cantonese everyone was so eager to laugh at—wasn’t getting through to her, so I spent that night scrolling through Google Translate, just like I did with writing that birthday card all those years ago. ‘Insomnia in Mandarin.’

Even if I could explain to her what I mean in perfect Cantonese, she would still not understand. The ‘Asian Way’ does not tolerate or comprehend nuanced conversations about mental health. Don’t make a scene. I cannot be a liability, a burden. “What do you mean you can’t sleep?” she asked. “Just close your eyes.”

I watch American TV shows, where the characters always find a way to have emotional heart-to-hearts. I scoff at the corniness, wondering are there actually families who do this?

I know she cares. But my mother, no matter how hard she tries, cannot fix the mess in my head the way she can fix the mess in my room. She cannot fix me. If only Google Translate could tell her that. If only I could tell her that.

At 17, My Mandarin has become so rusty that I can barely hold a conversation, while my mother’s English is nearly flawless now. But I don’t need words to feel, say, my mother’s anguished homesickness when she facetimes her family all the way from Malaysia. Pain is a universal language. She’ll immediately leave the house to ‘take out the garbage,’ which we both know is a thinly veiled excuse. We never talk about the garbage still in the bin, her tear-stained face, and the scent of cigarettes that follow her. Empathy is a universal language.

We are not a family that talks about hard topics. We are not a family that knows the words to do so—words I don’t know how to say due to a language barrier and words that I can’t say due to a communication barrier. What transcends language, of messy labels like “Asian” and “American,” is pure humanity. For me, that’s more than enough.

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl I am terrible at math,

And not the top of the class I’m average

Just in the middle.

Numbers to me are just another riddle.

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl I hate eating rice every day; I enjoy varieties in every way.

I enjoy a savory burger with crispy fries. Weird right?

There really isn’t a delay when I relay my choice which food I eat.

Yet people expect me to be the little quiet girl in the back who just eats rice seaweed.

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl I can see perfectly fine and all the signs I can see all the hate that is thrown at my people.

It’s like we are being treated as if we were never of American History.

A very important part of OUR story, we were ones who built the railroads, connecting the East coast to the West coast.

East connecting with the West, who can forget?

Therefore I detest.

So please don’t make a funny face at me when see me at a red light.

Because I can see your face and I’ll remember night.

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl I am not docile nor delicate, However, I am intelligent and intricate I have bursts of energy that come out in joy. My feelings are not something to be toyed. I am loud and could talk 100 miles per hour. But how my people are being treated has gotten sour.

I will not sit back and let you ruin mine and my own. Life is precious--too short to be pretentious. This matter to me is serious, and I’ll stand for what I believe in

Because I’m courageous.

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl

To the those in my class, stop blaming me for the virus.

I am not a virus, nor do I want to be “viral.”

Stop mocking my native language, due to your ignorance,

Your poor choice of words are a mere hindrance, at most a nuisance.

My culture has 5000+ years of history. That’s 5000+ of years of amazing heartfelt stories, One with many dynasties. It used to be an honor being bilingual, respected like a mogul.

Now I rather not talk or I encounter a Smeagol

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl I’m not “exotic,” “chic,” or “oriental.”

choice of rice with people. never part the forget? when you remember it all gotten me

I live in the metro, call me continental. Don’t say my eyes are unique.

Social media made it a trend to have fox eyes, Beautifying its shapes and sizes.

Yet they laugh at those whose genes contain them And stripped them of their prizes. They shame them. And blame them.

Even have the nerve to point their fingers at them

I am my own being.

Not what I’m known to be but known for what I will become.

I am powerful, intelligent, important, a girl, a woman, a mother someday, a writer, an astronaut, a president even?

I am not your stereotypical Asian girl. Instead I am someone who represents me And this is my being.

This is my writing,

This is me fighting. See me.

Words

Words, They come out of my mouth,

I use them to speak. To make conversations. Sometimes they come out unexpectedly. Words, They’re the most powerful weapon. They could be as sweet as honey or as sharp as a sword.

They could be bullets piercing through, Or medicine to help the old.

Words move around the world like the ocean, Drifting from one to another, Making conversations seem to last forever. Yet we always find ways to down one another. Pulling each other deeper into the ocean.

All alone,

Maybe it’s better to be alone, ‘Cause you won’t get hurt. And when you don’t get hurt, you aren’t sad, And when you’re not sad, you are happy. But why does hurt to be alone

Like I’m suffocating even more. I’m not heard.

My words turn into bubbles that never float ashore

Say why does society, Always pull the trigger, Shooting means words at each, Like a war.

Arguing back and forth.

Why can’t we say nice words? Meaningful words?

Why can’t we just say, “I’m sorry, please forgive me.” Why do we have the war continue?

And why must we always believe the bullets pierce through our skins, Whereas we could be bulletproof and happy with our kin.

I learned that society would never back down from a fight.

Where they shoot each other till one or both die. But I refuse to listen to whom pulls the trigger, I refuse to listen to their taunting and teasing, Their bickering back and forth.

Because I know one day, And I hope that maybe it will cease. And there’s peace.

Where we could go back to the innocent past. Like a child’s laughter by the stream, Where sunlight is gleaming. Where your smile is beaming, Finally at peace.

The title “Blending In” has two meanings in this oil painting.

1, the fact that my younger self is literally merging with elements in the background, and 2, how growing up in a place with people who didn’t look exactly like myself required some “blending in.”

I always start my paintings with a physical collage to reference, this time incorporating items such as the stars from the Chinese flag on my brother’s hand, the text of the Los Angeles Times on the top right, and the blatant word of “TEXAS” upside down at the bottom. The elements in the piece represent not only the many places I’ve grown up in but also the diverse cultures I’ve been privileged to experience.

because Olivia L. because

theseletterswerecarvedbyahighschoolboyinBakersfieldandbecauseheexcavatedtheir entrailstosparemyclothesfromstainingIinherited26emptyframesskeletonsascaffoldto reconstructthebodyofhismemorybodyofsunkenversesIhauledauniverseoutofauniverse wherehedoesn’tstayuptillmidnightonmysubmissiontothe3rdgradeyearbookcoverbecause thisisn’tthefirsttimehe’sdrawninmonthsauniversewhereaviolinforceshischinup andweadmirethe permanentdentinhisclavicleauniversewherehetakesthecarvingclass in highschoolwherehetakesthecarvingclass universewhereIlearnrhythmsfrommymotherratherthan learningmymotherthroughrhymebecauseshesingsinthecarbecauseshepaidformylessons andIcouldn’tholdapitchifitwastheonlythingonmyback becausetheirbacksbroke witheverywavebreakingagainstthem

ofcourseonlybecomingadoctor couldsupportaweatheredspineofcoursethey’dworkforwhattheyriskedeverythingforofcourse they’dnevergotoahighschooldance

ohtoinheritmyparents’silentrevolutions toodeepatruthformetorealizeatruththatconsumedeveryscrapofyearningcastoff thecoastofSaigonandCalifornia atruththatconnectsthe2.5millionfleeingbeforetheirhomefellontopofthem theocean’sbellycradleseveryoneeverydreamtuniverse betweenpeopleofthisdiasporaisadialoguespokenonlybythesea listenfor

theabyssaldarkness

the deafeningcrashofwateronsolidrock acrabsteppingoutofitsshell tomoltanewone theimpossiblephenomenaofasingleocean notforthosesearchingforhome butforeveryonewhodiscoveredhomeineachother justwantedaplacetoprotectit apeoplethatwouldmakespaceforitssong aLòngMẹtuckedinthekeysoflullaby

Idon’twritetobemorethanIam buttorememberwhatIampartof mypoemsareanechooftheentireocean–mypoemswerenevermine notentirely

At the outset, I showcased my dance proficiency with energetic movements and precise steps,

红包

on your name

Cloris S.i.

there goes a saying: a name must flow like ivory, crisp like jade, full like a mouth of steam before it cascades, a tumbling ball of fire, but baba and i gave you an american name and the syllables bounce on my miso-coated tongue shape-shifts in rhythm, stone-skipping across tea-infused teeth and i drag out your last letter like silk threads of lotus roots, your name ends too soon.

they’ll pronounce your last name wrong lips puckered, too much air between their teeth they’ll say nameless face she, blind complying she you’ll never tell them to say “shí” tongue curled around back palate, you’ll never tell them to call you rock of security and stability, womb of monkey king, tell them: go travel forests of limestone shí lín catch the wave of your antelope sandstone, sightseeing — they’ll see you eyes closed — they’ll hear you listen dragon — breathe fire through sequoia body, burn wildflower poppies exhale jasmine breeze

in your roar, i’ll listen for ashes of paper money we lay on your grandpa’s grave every qīng míng and remember: keep pacific salt and atlantic wind between your cheeks (you’ll need to blow out the fire too)

ii.

i saw our city’s name on the newspaper a man spat at an asian woman on her way to the market last morning before a group of mothers screamed for their kids to get away from her, before she told her daughter to set her goals as low as her mother’s paycheck.

by preschool, chalk fingers will learn to draw out the corners of eyelids quicker by first grade, they’ll stick “made in china” labels on your shoulders by middle school, you’ll forget the symphony you hold between your two ears by high school, you’ll kowtow your golden head to your homeland’s landmines.

I hate the sound “nga.” The most basic of principles within Tagalog, and I have never understood how to perfectly execute the sound. Out of all of the twenty-six letters, the language rearranged them to this, creating my veritable hatred for it. The frustration of never connecting with your culture over a single sound. One of the first words you learn to pronounce as a child growing up in the Philippines. I did not get that. I never got it. Am I separated from my culture if I cannot even begin to say my real middle name? This spiraling of unknowing leaves me miles away.

The constant reminders from family and friends: “Do you speak Tagalog? Can you understand it?” If someone were to ask me if I was bilingual, again, my answer would be unfinished. Sometimes I answer with “one and a half” as understanding and being able to read by carefully sounding out the syllables is not equivalent to speaking and writing. Never complete. Daily reminders of me falling short of the expectation. I question if the people to blame are my parents for never fully teaching me, or myself. Why should I apologize for not understanding my cultural language? Nobody apologized for never teaching me.

As I drowned in these foreign words, Simbang Gabi (Night Mass) approached, a nine-day series of reverence positioned right before Christmas. This daunting event in which aunties and uncles would be disappointed at my lack of awareness perpetuated my alienation. Even so, my family and I had to prepare for the event. We visited Seafood City, an Asian supermarket known for its tacky plastic cups of translucent jelly and porcelain mahjong tiles, to offer home-cooked Filipino meals for this special occasion at Church, and from 3:00 a.m. to 5:00 a.m., we rejoiced among the pews, collecting in the churchyard after the service to share food with the congregation. Everyone in the Filipino-Catholic community contributed to the potluck, offering clusters of fresh lychee carved into the shape of blooming flowers, steamed delicate rice pastries of bibingka, and large trays of crispy pata, each plow of the blade revealing the glazed umber

skin and its delectable meat. Our sumptuous repast combined with the heartwarming moments of dining together as a spiritual family nourished the bonds within my cultural community.

The humility of my Filipino-Catholic bond forged through communal meals helped me fill the language barrier with a new purpose. I learned to stop chasing away “nga” and embrace the shared identity of Asian-American culture. I no longer immortalized the blame game, rather, I practiced archaic Filipino recipes in the kitchen, unearthing their origins as I circumnavigated my own life. I saw the wondrous adventure of the Bicol Express with its creamy coconut milk and spiced red peppers purchased by hungry train travelers in Manila. I witnessed the universality of lumpia and how its delicate pastry skin enveloping minced spring seasonings topped with a glossy sunset-colored sauce transcended multiple cultures in Asia. While difficult translations eluded me, food spoke for itself. In all its creation and symmetry, meals are a clear-cut example of our purpose within the vast universe. The symmetry of the luscious glossy fruit of lychee and its impossibly packaged milky half-moons exemplifies how food is the perfect opportunity to share with friends and family. These newfound realizations transformed me into an emotionally empowered individual capable of circumnavigating life’s challenges through food.

The sublime nature of meals and the gift of sharing them with those around me is a testament to my Filipino culture and a reminder that I can inevitably count on food as a universal language to evoke love and care for my community. With this in mind, I will continue the legacy of Asian cuisine with my newly found deep-rooted knowledge and understanding of the recipes I create and share. I am not an alien to my culture, I am a Filipina human being who tries to get to know it every day.

自豪(Pride)Katie H.

Glows of valiant red and gold illuminate the dark like beacons of good fortune and joy. Like the qipao that envelops me, its silk the crisp spring air, cool against my skin. Like the loud radiance of my heart, beating blood profound and pure and lavishing lustrous pride.

Streams of traditional instruments swirl through the lantern glow like rays of ancestry and nature embracing my soul. Like the classical poem that flows through my lips, rising and falling in inflection like the Yangtze river’s currents.

Like the light teal beads of my jade bracelet, twirling along my wrist as I sway it in the air, glinting in the light like tiny moons.

Applause floods the vibrant room and accompanies its gliding music like the sun that washes warmth over the Huangshan mountains. Like the literature, the history, the beauty of it all, that enliven and ignite me, a firework of exploding pride and love.

Like the unity between us and each other, so red and golden and fluent, like my bond to my culture, Like me.

红色和金色的光芒,在黑暗中闪耀 就像是幸运和欢乐的灯塔 就像是包裹着我的旗袍 - 丝绸般地滑过我的皮肤,带来春天的清凉 就像我有力的心脏,跳动的血液,放射出纯粹而骄傲的声响 传统乐器的溪流,在灯笼的光芒中旋转 就像祖先和历史拥抱着我的灵魂 就像我心中流淌的古典诗篇,似长江流水绵延千里,蜿蜒不息

就像我玉镯上淡青色的珠子,随我在空中摇摆,沿着我的手腕转动,如小小月亮一样闪闪发 光

掌声伴随着优美的音乐,在充满活力的房间飞扬

就像太阳给黄山沐浴着温暖

就像文学,历史,这一切的美,使我激动并点燃我心中骄傲和爱的火光 就像我们彼此之间的团结和友谊,红色的,金色的光影,正是我的文化和我的纽带,将我紧 紧拥抱 这就像我

The sun painted the sky with hues of pink and gold as my mother and I strolled along the meandering path of the garden near my school. Under the bridge, the lake moved lazily with its floating shapla flowers, the lonely and the paired leaf petals and the gradient of bright pink to pure white petals moved in harmony with the water. The air carried the fragrant symphony of jasmines, pink roses, rosemary, and marigolds that adorned the trees and danced along the breeze.

As we walked, the shapla flowers whispered secrets to the water and the water gossiped with the rocks. The jasmines released a sweet fragrance that mingled with the earthy scent of rosemary, while the pink roses blushed with tales of love and longing. The scattered petals created a vibrant canvas on the sidewalk; a tapestry of lost memories.

Roses are a concept of love so familiar yet distant. The soft pink is my mom’s fingers braiding my hair. The petals are the beds my mom tucks me into when I’m sick. My fingers reached out and plucked one, admiring its velvety petals, and reached for another for my mom. As I attempted to detangle another rose from the bunch, a gentle slap on my hand stopped me.

“Flowers have feelings too,” my mom’s voice carried a tone of soft reprimand. “Imagine how you would feel if you were plucked from your family. Imagine a random person coming and hurting you for no reason.”

I looked down at the half-plucked rose, guilt settling in like dew on petals. Innocent tears of water trickled down its stem, making my fingers sticky. Apologetically, I cradled the rose against my chest.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered. Though I did not understand its pain, I clutched the lonely flower the whole way home.

My best friend’s favourite colour was red. Red was the matching dress for school fairs. Red was the flush on our cheeks from racing through fields and laughing till our stomachs hurt. Red was the lipstick, “borrowed” from her mother, smudged all over our faces. So, red was my favourite colour.

Roses were my best friend’s favourite flower. Roses were the petals we tossed at grooms during weddings. Roses were the childish fantasies of love. Roses were the petals we tucked ourselves under to dream and giggle about nothing and everything. So, roses were my favourite flower.

Yet, red became the colour of my embarrassed cheeks of not being the one that was called out to. Red became picking at my skin as I questioned why I didn’t belong. Red became my bloodshot eyes wondering when I wasn’t needed anymore.

Red was the blood of my blood after I pricked it on a rose thorn. My mother said the innocent beauty of a rose was protected by its own thorns. “You need some thorns,” she said, “because waiting for someone to stop your plucking isn’t an option.” So, I became a rose.

Roses are not my favorite flower.

My hair in the US spoke a language of its own. It navigated phases, not styles but rather the question of whether to wear a hijab or to not wear a hijab. The hijab became a link across oceans. Though I did not wear it in Bangladesh, it held a different weight under the American sky.

The dilemma evened out in sixth and seventh grade, when COVID didn’t give me an option to contemplate on those thoughts. At the arrival of eighth grade, I chose not to wear a hijab. I’m not sure why. Maybe it was a mesh of stares, judgements, the impossible standards on how I present my head. My hijab is wrong or my hair is inappropriate. I’m too young to wear a hijab or how could I not wear one? Are you not muslim?

So, on the fresh first day of eighth grade, I did not wear a hijab. Walking in, the first thing I heard was, “who is that? Is that Labiba?” My friends were baffled. I lowered my head, seeking refuge in a seat away from my friends as the murmurs trailed me, winding through the corridors and lingering in the cafeteria. It persisted through the school walls, infiltrating the silence of my home and screaming in the loud of my thoughts.

I was wearing a hijab two weeks later. Initially my hair was wrapped to block the whispers, but soon, it became a statement of my identity and my beliefs. I carefully pinned my hijab around my head every morning.

My Hijab

I was in the thrill of an eighth-grade trip to Six Flags; my first ever trip to Six Flags, in fact. My hijab was wrapped and pinned tightly to my head just in case it tried to fall off. While walking through the park, I brushed past a man and his wife. The man’s hateful accusations and curses sliced through the air. A terrorist is what he said. His words, sharp as daggers, halted me. I promise I had not touched his wife. Vines of accusations entwined my feet, a gray cloud enveloped my head. I swear there was a thorn lodged in my throat. They walked away, going about their day, back into the sounds and colors of the park that I couldn’t see. For a moment, I was rooted in place, held captive by the weight of his hate. Eventually, my friends’ voices dispersed the fog in my head. I leaned into their chatter; I smiled and nodded as they insulted the man and jokingly plotted against him. Though I did not cough up a bloodied rose, I couldn’t help but notice the sky had taken a greyer tone.

Returning home, within the comforting walls, I let my thorns recede. It was ironic, wasn’t it?

Despite my defenses, tears cascaded down like the blood-like water from the broken rose. I wonder if he knew flowers had feelings too.

Every week, I call my grandmother across the ocean. Her voice carries the essence of a world I straddle between the US and Bangladesh. Every month or so, I get news across the ocean—of sickness, loss, death. Amidst the familial connections of these calls, there lies a weighty burden of being the eldest grandchild. I am expected to be a model of success, a repository of cultural values, and a paragon of virtue. The weight of these invisible waters is a constant reminder that my actions ripple through the family. I find myself perched on a tall, thorny stool—a beacon or an example.

In the US, I feel it is my responsibility to represent Bangladesh. Bangladesh was catching fish by the water and being terrified it would try to eat your hand.

Bangladesh was eating my favourite foods in the cool air of the mall to take refuge from the blistering heat. Bangladesh was making and eating warm pitas in the cold winter. Bangladesh was pressing my nose up against the bus window to look at the rice farms and the hills of tea leaves and through the forests hoping to see a wild animal. Bangladesh was the rain soaking me as I huddled on the seat of the rickshaw so I didn’t get soaked in the flood water. Bangladesh was the laughter of an aunt. Bangladesh was the warmth of a grandmother’s embrace. Bangladesh was everything. How do you encapsulate your everything to someone who has never seen it past its geographical name and its poverty?

And yet, Bangladesh is held at an arm’s length. Bangladesh is not being able to communicate properly with my closest family. Bangladesh is a culture that I’ve never had the chance to memorize until it was in the curves and bumps of my hands. How do I embody something I have not had the chance to understand yet? Do I feign understanding, fabricate experiences, or embrace a sense of belonging that feels fragmented?

** All inconsistencies in tense and British/American English are intentional! (British English refers to the experiences that stayed in Bangladesh and American English for the ones that are in America.)

To create this piece, I envisioned myself in a peaceful setting, extending a hand to welcome others into my future. My serene expression reflects my introspective nature and deep desire to be content with who I may become and where I may go.

I also chose to depict a dragon, qipao, and specific flowers to symbolize my Chinese heritage. The flowers — a lotus, a plum blossom, and a magnolia — signify perseverance, prosperity, and resilience, representing my dedication to personal growth and a broader Asian American narrative of flourishing even in the face of adversity. The dragon and qipao reflect my desire to understand my heritage, from its rich folklore to its cultural influence today. To complete the work, I incorporated elements of art and music, both sources of creativity and self-expression, to embody the possibilities that await me and the freedom I seek in shaping my life.

Together, every aspect of this piece echoes my vision for a future of exploration and growth.

Alexie I.

This song is about my experience of being bullied growing up as an Asian immigrant. I was always bullied for my the way I looked and spoke. I am claiming back my “yellow” skin - the color that was used as a derogatory term, as “golden”. I was also often bullied for my eyes. I often wished they were bigger, lighter, and whiter. Eurocentric beauty was a constant standard, both in the Philippines and America. Growing up, I was insecure about my appearance and would try to change it as much as I could. However, as I matured, I realized that these insecurities would become the aspects I learned to love the most. Once I started loving myself and my heritage, the stars aligned and I started becoming the best version of myself. When I’m in touch with where I come from, I know where I want to go and my ancestors are the roots of that path. That is where the idea of a “Golden girl with a golden future” comes from.

I chose the art form of a song because Filipinos love singing and karaoke. It is one of my favorite forms of art as a multifaceted artist. It is also a very literal way to...Make Noise!

I play the guitar in the first half for to achieve a soulful and deeper sound that matches the mellow lyrics. The wave sounds are for the viewers imagery when listening, reminiscent of the Philippines. Waves are symbolic for growth and transformation. In the second half, I play the ukulele and even though it’s the same chords, it’s a more tropical and brighter sound which matches the empowering lyrics. Naturally, I wanted to include bits of Tagalog/Filipino followed up with translations for intersectionality in my identity as a Filipino-American. “Gintong Babae” means “Golden Girl” and “mahalin mo ang sarili mo” translates to “love yourself.” Those are two powerful messages to leave my fellow Asian women with. For the ending, I wanted a full circle moment in the end with the idea of looking in the mirror and pride in how far I have come.

Bindi. The tiny red dot between my eyebrows was an attempt to clear up the audience’s confusion as to why I was dancing on that stage. Exactly half of my identity could be expressed through that minuscule mark of pigment on my forehead. Sometimes it felt like my bindi was like the little dot in the corner of videos, flickering on and off. Ghungroos. The heavy bells on my ankles pinched as I attempted to shuffle across the stage. Their weight bore down on me. Sari. Its metallic fabric glistened in the intense lighting aimed at us. I felt trapped in the fabric. Bharatanatyam. The rich ancient cultural art I practiced was supposed to make me feel deeply connected to my culture, but somehow what I felt was far from it. I watched in envy as my peers danced with their perfectly formed mudras in sync to the beat of the mridangam. I felt like a fraud. How could I form my mudras well if I had no idea what they were symbolizing? I didn’t even know how to pronounce mridangam, let alone dance to the beat of one. As we took our final bows, I felt no pride in my meaningless movements to lyrics I couldn’t understand, even though I could clearly make out my dad’s high-pitched whistle he reserved for one-of-a-kind performances. Everything comes with time. I’ll learn to love it.

I quit two months later.

For about eight years of my life, Fridays meant dance class. Alongside two other girls, I piled into a minivan, screamed the lyrics to that week’s pop hit, and raced down a hill to the sliding glass door where our teacher awaited us. And for a while, it was just that. But as singing turned to gossip and our shadows grew longer on the hill, I began to dread these classes more and more. In an attempt to quicken the pace of our learning, our teacher now pit us against each other in “friendly” competitions and tried to incentivize us by awarding a “best dancer” each week. She only granted this elite status to two types of people: the truly talented or the so-called “most improved players.” I was the pinnacle of mediocrity. I didn’t know where I fell in this hierarchy. With every Friday that passed, this feeling grew more intense until I had no desire to keep dancing. Despite the intense disapproval from what felt like my entire Indian ancestral line, after months of begging I finally got what I wanted. My dance career was officially over.

What followed was an immediate resentment toward not just bharatanatyam, but my entire Indian identity. I let my earring holes close up—I didn’t need to wear those heavy jhumkas anymore. I even began to abandon my femininity altogether, I vowed to never wear makeup again and avoided wearing dresses at all costs. The friends I once begged my parents for sleepovers with became strangers I passed occasionally in hallways. My onceblinking red dot had now vanished entirely. To account for its absence, I began to reinvent myself by exploring my East Asian side, something I had never taken an interest in before. Suddenly I could name all 7 members of BTS and started hanging out with people who used “chink” as a term of endearment. While I was happier now that I had quit dance, something still felt wrong. It felt like I had successfully removed a tumor growing inside my brain by chopping off my entire head. I finally realized that associating one negative experience with all of Indian culture would not help me resolve the turmoil I still felt.

I soon discovered a new means of cultural expression: cooking. In the kitchen, there are no pressures to outperform your peers or reach a certain standard. Using cooking as an outlet for my cultural struggles, my confidence grew along with pride for my heritage. I found that despite my toxic relationship with dance, Indian culture could still be an important part of my identity.

The beat of the mridangam echoes through the auditorium. The familiar jingling of ghungroos surrounds me. I whistle as my peers take their final bows. Part of me feels jealous as I watch all my former classmates achieve their long-awaited arangetram, but another part of me understands my place is in the audience. Directly on my ajna chakra, lies a singular red dot. Bindi.

Big Fish and Begonia

Alice Y.

“Mallakhamb” Aerial Arts

Mrunal P.

Alice Y.

“Mallakhamb” Aerial Arts

Mrunal P.

My Filipino dad smiling

As my younger sister backs out of the driveway

His calloused hands fall loose at his sides

As he’s illuminated by the sun

My mom sits in the passenger’s seat

Prayers prancing in her mind

The rosary hanging from the rear view mirror

Enchants her revered whispers

My younger sister in the driver’s seat

Painted nails adorning her hands clutching the wheel

She stares at the backup camera

Looking behind has become obsolete

I sit in the backseat

Spectating these pillars ahead

And notice my dad standing in the driveway

Beaming, bright and bold

My Filipino dad’s smile

Is to be framed in museums

A phenomenon it has become to us

A phenomenon I wish it wasn’t

I take a photo

Maybe he seldom smiled

Maybe he seldom laughed

So ours might make the stars shake and dance

Maybe if they were more acquainted with our luminescence

We’d be able to open all the doors he had to walk past

The stars would be the keyholders

No need for extra courses to account for our intelligence

But the stars are too acquainted with us

I only wish they would hear him more

To raise future generations in a household lacking in laughs

Would be to disrespect the calloused hands

That held us

That scolded us

That fed us

That loved us

But I’d want my dad to be raised

In a household nurtured with laughs and calloused hands

And cut fruit and elephant statues

So for future generations, I’ll raise them how I wanted my dad to be raised

My Filipino dad smiling at us

Has become one of my most favorite photos

Because that stars heard him

And knew him by name on that bright, blue day

“As a Korean American raised by immigrant parents, I wanted to be connected with my heritage. I wanted to do something traditional, where I could learn new things about my heritage and the history of Korea. This goal led me to the captivating realm of traditional Korean dance, a realm where the rich tapestry of Korean history and tradition unfolded.

Through the canvas of “Cultural Choreography,” I encapsulate the essence of my journey, portraying the fusion of travel, culture, and identity. The overstuffed suitcase serves as a poignant symbol of their adventures, brimming with fans, small drums, shoes, clothing, and hair accessories, each item a cherished relic of their heritage. With each brushstroke, the artist communicates not only their joy in the exploration of their cultural roots but also their reverence for the ancestors who paved the way. “Cultural Choreography” is more than just a painting; it is a testament to the enduring power of culture to illuminate our paths and connect us with our past, present, and future.”

As I explored the intricacies of Korea’s language and culture, I stumbled upon a realization: even within language, biases against women persist, hidden in plain sight. This piece explores the disparity in Hanja characters between ‘son’ and ‘daughter’ in Korean culture, emphasizing gender bias. As I researched the history behind these symbols, the symbol denoting ‘son’ carries a weighty significance, straightforwardly translating to ‘son’ with directness and prominence. It embodies a sense of importance and authority, reflecting the elevated status traditionally afforded to sons within Korean society.

However, juxtaposed against this, the Hanja character for ‘daughter’ struck me with its simplicity and seeming insignificance, merely signifying ‘girl’ without the same as its counterpart. Beyond language, it reflects a cultural perspective positioning daughters to a lower status. The artwork, inspired by personal experiences, portrays me contorting into the ‘son’ symbol, representing the discomfort of conforming to societal expectations favoring sons.

Surrounding the ‘son’ symbol with cleaning products and pots signifies the weight of traditional gender roles, serving as a visual commentary on struggles faced by my sisters and me conforming to expectations that favored my brother as the preferred ‘son.’ As I continue to create my body of work, one of my goals is to continue exploring the dynamics of familial connections, drawing inspiration from my Asian American background.

My goal is to explore how these connections resonate within the broader cultural and societal context that shapes my identity. I hope to continue not only delving into the diverse ways in which we communicate and connect as a family but also to convey these experiences and stories, inviting viewers to find resonance in their familial bonds.

Bollywood’s Heroine: A Gemini Simar S.

In my dreams, I am on a 1960s film screen: a chiffon dupatta flowing against the sweeping Swiss alpine, a panorama of weeping mustard leaves-- drowning in gold, weighted by a wedding veil, and running far too fast. Bollywood formed me into a hopeless romantic, painting scenic landscapes carved with poetry you can never find in the Western world and laced with the two women I wished to be: The perfect daughter and the runaway bride.

The first: a woman so brave that she is silent. She sacrifices her own happiness for the honor of her family. And so quietly, as the story reaches an end you could never see coming, she becomes a muted martyr, promising to pass her modern values to her children.

The second: a woman so brave that she chooses love. Chooses to declare her passion to a crowded room and picks the plot that provides her contentment. Oh so very loud, as the story reaches a close, she runs away from the altar to marry her own happiness.

I have spent my life balancing between the two women, wishing to be one, only to jump across a fictitious, lying line, hoping to be another.

I am eight years old. My mother hands me a platter of red meat. I cry, I cry, and I cry. The thought of eating a living being taints the meal, no matter how seasoned it is. Today, I am still a vegetarian.

As a Punjaban, I was surrounded by women as strong as stone. Women who could never imagine crying over meat. I slowly became embarrassed of my tired tears and sensitive soul, insecure that that made me a disgrace towards the women warriors behind me.

Growing out of girlhood; my budding identity creeped up on me like a shot and that crisis transformed into a civil war. The faceted failures of these fickle feelings. I craved the freedom to run away, yet simultaneously, I desired conventional perfection. I returned, once again, to the two heroines of Bollywood.

And so, I spent sleepless nights challenging myself academically. I searched the internet tirelessly for internships. I went to every function, dressed in jewels and silk. From Sunday school, to honor societies, and student government, I strived for perfection, hoping that it would

compensate for my sexuality, peaceful persona, and refusal to eat meat at 8 years old-- all things I considered to be weaknesses.

Eventually, I realized that my aim for excellence was cowardly. The intent made it so. Truthfully, I dreamed to be brave like the women of bollywood instead of perfect like their image. I concluded that my delicate disposition was my way of defying the same strangling societal standards the women of my family faced.

The crisis in my heart came to a close when a local Sikh activist taught me the concept of Jujana, to fall in love with the struggle. I began to value the battle instead of the outcome. Stubbornness became a source of courage, proof that I had a reverence for hard work, giving me peace with the intersections of my identity.

Jujana taught me that my identity will never fit with perfection. This once painful fact is now an ode-- an opportunity to grow. Since then, I have taken as many risks as possible, not aiming to win nor constraining the emotions failure brings. I lost my first pageant. Created (and abandoned) an initiative. Struggled with my business. However, none of these, no matter how disappointing, deterred me from trying.

I have fallen in love with myself just as I have fallen in love with the struggle. This love is a quiet hum in the background of my journey. It is not the melody, but the baseline of all my future endeavors.

On this never-ending road, I have created my own kind of bravery. Not the one of the faultless daughter or fearless bride. Rather, the one of a girl who has redefined the “hopeless romantic” into fortitude.

The Halmeoni Within Me

Isabel C.TheHalmeoniWithinMe

TheHalmeoniWithinMe

InKorea, Iwastaughttosleeponthefloor. Myhalmeoni,orgrandmother, wouldtellmethatthiswasthewaytosleep, thewaytosleeplikeaKorean, thewaytosleeplikemyancestors. Ididnotlisten. Iwasstubborn, stubbornlikemyhalmeoni. WithmyAmericanphoneandpajamas, IchosetosleeponthebedbecauseIthought, “MyfriendsinAmericawouldneverdothis.” IfeltdestinedtobeatrueAmerican, sopretendingtofeelguiltless, Isleptinthebed.

Isilentlygiggle, bothoutofmyabilitytonurturetheKoreaninme andoutofmyembarrassmenttoadmitmyjoy.

InKorea, Iwastaughttosleeponthefloor. Myhalmeoni,orgrandmother, wouldtellmethatthiswasthewaytosleep, thewaytosleeplikeaKorean, thewaytosleeplikemyancestors.

Ididnotlisten. Iwasstubborn, stubbornlikemyhalmeoni. WithmyAmericanphoneandpajamas, IchosetosleeponthebedbecauseIthought, “MyfriendsinAmericawouldneverdothis.”

IfeltdestinedtobeatrueAmerican, sopretendingtofeelguiltless, Isleptinthebed.

Onenight,however, Ichoosetobedifferentlike myparentswhoimmigratedtoAmerica. Islowlylowermybody, lyingdownnexttomyhalmeoni. Iamsuddenlybelowthesky, yetIcanseemore.

Onenight,however, I choosetobedifferentlikemyparentswhoimmigratedtoAmerica. Islowlylowermybody, lyingdownnexttomyhalmeoni. Iamsuddenlybelowthesky, yetIcanseemore.

IcanseethewarmgazeoftheMoonhugging Daegu. Icanfeelthesoftsummerbreezeunderneath swallowmewhole.

IcanseethewarmgazeoftheMoonhugging Daegu.

Icanfeelthesoftsummerbreezeunderneath swallowmewhole.

MygrandmothertellsmethatIamKorean withKoreanblood,aKoreanmind,andKorean ways.

MygrandmothertellsmethatIamKorean withKoreanblood,aKoreanmind,andKorean ways.

IthinkthatIamKoreanforsleepingonthefloor. Iamnotwrong, butIrealizethatshecallsmeKoreanbecauseI acceptit.

Isilentlygiggle, bothoutofmyabilitytonurturetheKoreaninme andoutofmyembarrassmenttoadmitmyjoy.

Myhalemoni,however,sensesmyhappiness, andshesmilesinthedark, thinkingIcannotseeher, butIcan, andIsmilewithher.

Myhalemoni,however,sensesmyhappiness, andshesmilesinthedark, thinkingIcannotseeher, butIcan, andIsmilewithher.

I amKoreanbecauseIacceptmyKoreannesswith openarms.

IthinkthatIamKoreanforsleepingonthefloor. Iamnotwrong, butIrealizethatshecallsme KoreanbecauseI accept it.

IamKoreanbecauseIacceptmyKoreannesswith openarms.

Vikramaadhithyaa J.

Vikramaadhithyaa J.

June P.

This piece describes the connection between mother and daughter, intertwining culinary elements and familial heritage.

As the daughter of an immigrant mother born in Korea and adopted into the U.S. at a very young age, I’ve always felt a certain detachment from our cultural roots, which I and my mother have sought to rekindle through our shared exploration of Korean cuisine and cooking.

The background, depicting the inside of my fridge, is representative of my mixed identity; housing both Korean staple ingredients as well as more Westernized items. I allowed some items to come into the foreground of the painting and blend into the clothes and skin of my younger self, symbolizing my Asian-American identity and how integral of a piece food has served in embracing my ethnicity and reconnecting with more foreign parts of my culture.

“This piece depicts my dad cooking Korean BBQ (KBBQ) for my sister. The title “redolence” has 2 definitions: pleasant odor or the state of being strongly reminiscent. Since my childhood, my dad would cook KBBQ and remember how his mother did the same for him. The scent of the meat brings my dad nostalgia for his own childhood. This piece shares my core values in how preserving and sharing familial tradition throughout generations is a crucial means of communicating love and developing important memories that serve as a foundation to continue maintaining the root of culture.

Through traditional Korean patterns and saturated colors, I explored the versatility of composition through both arrangement of color and patterns. For a contemporary look with a conventional medium, oil paint, I utilized different brush shapes to create solid or graduated shapes and created continuity throughout my art by hiding similar patterns or objects. Throughout the piece, the general color scheme consists of magenta (universal harmony), green (growth), and blue (wisdom). The warm-tones are in the primary subjects, who are in the present; however, the cooltones symbolize the lingering memories that remind the father of the bittersweet redolence when he was a child. The viewers can witness a chain of movement from the bottom right corner to the left side as the recollections encompass both the daughter and father. Also, it harmonizes the past and presents it into one cohesive whole.”

I’ve always wanted to direct a movie.

The set would be my own living room. A used dark gray couch and wooden tiled floor. Dust growing on the cobalt blue curtains that were never drawn, they hid your true identity from everyone else. To them, you were the best mother a daughter could have.

Let’s make me the victimized protagonist, the innocent and unlucky character who’s put through every single obstacle.

You are cast as the antagonist that ruins my life, molding your grievances into cookies of complaints you forced down my throat each night.

How your neglecting demeanor forced me into picking up countless hobbies as a means of escapism. How you tried to cage me in your dull Chinese world each time I tried to add any color. Your hands aching to break the canvas of the world I began painting for myself, labeling it quixotic and reminding me of the myriad of bills you were paying because we were now in America. I still remember every time your eyes shot daggers at my face, carefully etching my features into your version of perfect asian girl. Sadly for you, I had already applied my final layer of varnish. But each time I hung my canvas over the fist-sized hole in the wall, it still reminds me of the reason I should be afraid to paint.

Do not forget the scene where you used the words “PAST DUE” from your bills to catch and hold me hostage. Some days, I was let out and allowed to act my age, ask for a hug and sweets other than cookies. Other days, I inherited the phrase “PAST DUE” from you as you sprinkled them into my hand. I still tried to make something of it, etching each letter into the words, “HAPPY BIRTHDAY.” But I had overdosed on false hope because your only reaction to my gift was, “How much did it cost?”

Remember the scene in which your chokehold almost cost us our lives? Light was pouring through the car windows, the warmth offering me the hug I was craving. You asked me if I had thought about my future yet. Feeling your gaze on me, my mouth twitched to say what I had prepared for this exact question. But perhaps because I wanted to prove myself a worthy hero, to finally defeat the villain, I met your stare and said…

“I’m going to be a painter.”

The moment the words left my mouth, you froze, stealing the warmth embrace of the sun. Your knuckles turned white as you gripped the steering wheel, breathing hard. At that moment, I felt

like the antagonist. You slammed your fists on the dashboard, forcing the car to a sudden halt. The screeching of wheels and honks pierced my ears along with my own scream. Suddenly, I was propelled forward by another car crashing into us from behind. The last thing I saw were your eyes finding mine through the reflection of the car window.

Let’s cut out the scene where it took the sound of a casket being shut for me to hear your cry of help. To recognize that the muffled pleas from behind the set’s thick walls weren’t mine, but yours. To recover memories of every night you had stayed up, trying to change previous scenes and attempting to make better ones for tomorrow. To remember every time your eyes would look through me, but looking nonetheless. How they became marred with tears as they bored into mine through the reflection of the car window. I called you weak, what kind of villain breaks down in front of the hero?

Let’s remove the scene where I became frightened by the words I saw on your epitaph.

“PAST

Let’s forget the plot twist where I realize I should have valued your efforts more, which would have stopped the cycle of forcing our antithetical ideals onto each other. Where I realize not every scene was your fault, rather twisted to fit my perception of you as a villain. Where I realize that my life is not a movie.

Another day at school has slowly gone by The weekend a long way away

I enter the house with a great big sigh It had not been a very good day

I see mom stirring the pot of tteokbokki on the stove

Lulu sits on the couch on her phone

I see Hami hunched over her sewing I look to my room and start going

“Ah Romi-ah you’re back home already? How was your day? Come here and sit by me!”

Hami wraps me in her arms, and she can see

She pats my cheek and holds my hand I tell her my day wasn’t grand

“It’s not fair, Hami! I feel my classmates judge and stare!

I don’t understand! Why? Why do they care?

I’m just quiet and I like to listen

Do they think I’m depressed? They say I don’t speak

I hear them murmur I’m weird, silent, and meek!

But today, was something new, something different that I didn’t wish

My teacher whispered, ‘“Abby, is your first language not English?’”

“Why would she ask that? Is it because I’m Asian?

Would she have asked that if I were Caucasian?

She thinks I don’t know the language!

Like I don’t comprehend!

She speaks to me slowly, and tries not to offend

Hami what should I do? Why can’t they see?

How do I show them I’m just being me?

She holds me in her arms and rocks me as I whine

Then she looks at me with a smile that shines, “I know my sweetie, this is all so tough!

People can be ignorant, rude and rough!

But trust me, it’s not just you

So do not cry, there are things you can do

Silence is something that’s misconstrued

It’s seen as lacking any attitude

People get called depressed, They’re called weird

Especially by Americans who do not want to hear.

There is strength in silence and wisdom in knowing

When to speak and when not to be crowing

Take rice cakes for instance

Sometimes you like them soft, chewy and plain

But in tteokbokki, you add some gochujang, soy sauce, and sugar

And suddenly, the rice cakes are just not so tame

You are my little rice cake, Romi-ah

Your heart is soft and kind

When you’re ready to share your voice with others

Bear this in mind,

Be like tteokbokki that is seasoned, spicy and sweet

For when you speak, it’ll be a joy for everyone you meet

Now let’s go have some tteokbokki to eat!”

Gayageum Sanjo (가야금산조)

Sou Lynn B.

Sad Self Trinity B.

Gayageum Sanjo (가야금산조)

Sou Lynn B.

Sad Self Trinity B.

To be honest, when I started working on The Dragon Boy, I didn’t really have an intent or idea for it. I hadn’t worked with acrylic in the past and my painting experience was limited. However, it wasn’t so easy. My lack of experience using acrylic caused me to struggle, particularly with small details and there were times that I contemplated giving up. I struggled with setback after setback, one of which was when I smudged a large portion of the dragon’s eye. But as I kept working on it, I realized that it was an illustration of Chinese culture and I wanted to do it justice. I couldn’t give up.

The dragon, a symbol of power and wisdom in Chinese folklore, gave me strength as I painstakingly painted its fur. I grew quite attached to the painting. I spent a long time on the face of the boy, but no matter what I did, I couldn’t change his frown without possibly ruining the entirety of his face. After working on it for several hours, I realized that he didn’t have to have a smile–he was fine the way he was.

When I finally completed the full painting, my hands were tired. My clothes were covered in acrylic from when I’d put my entire forearm in my palette when reaching for my water bottle. However, I was happy with it, and I felt accomplished.

Now, when I’m looking back at my experiences creating The Dragon Boy, I realize that I did have an intent. The Dragon Boy is an exploration of identity–my identity. It illustrates my growth and my struggles. It’s not perfect, and it’s not meant to be. Maybe, I’d realize, I’m not meant to be perfect either.

Bollywood’s Heroine: a Gemini Simar S.

Enchanting Essence: Embracing the Beauty of India

Juhi B. Kannukku Niram

Janani M.

Kannukku Niram

Janani M.

With dramatic lighting and a surprising color combination, I created the piece Kannukku Niram (Tamil) or Color to the Eyes as a way to highlight the importance of color and expression in Indian culture.

Whenever I step foot into a clothing store in India, I see only color: bright greens, dull reds, and beautiful blues—all with the most unexpected pairings. One combination that I always dreamed of, whether on my Bharatanatyam dance costume or on my chudidhar, was pink, blue, and yellow. For that reason, I wanted to incorporate these colors in my self portrait artwork using colored pencils on black paper.

The dramatic lighting in the piece (from the diya lamp) allows the colors to stand out, emphasizing the overwhelming yet comforting feeling I felt when walking into those shops.

This feeling is innate to the experience of being South Asian, hours together watching our mothers and grandmothers pick their favorite sarees, walking around the marble wondering when it would be our turn to do the same. Ultimately, through this piece, I wanted to revisit my experiences during hot sunny Indian summers, and highlight the function of color in my heritage.

The chaotic collision of growing up with two languages, but losing your mother tongue. This piece relates to anyone who lost their connection to their culture and language, that even simple conversation is a struggle. Focusing on how it feels with words being hurled at me that I can’t respond to without being confused, by using facial expressions pretending to understand but failing.

I’m submitting this, even though it doesn’t technically go in the category of tradition. But consider it, as many asian americans lose touch with their first language, it can go for generations (in the present and future). An unfortunate tradition.

Translations of the Korean: sorry; what?; yes?; hello (with incorrect spelling); I can’t do Korean well; I don’t know; sorry (with incorrect spelling); what does that mean?

Nirvana Kim P.

Nirvana Kim P.

In the heart of South Korea’s bustling city of Incheon lies a gateway to countless journeys, both physical and emotional. Incheon International Airport, a bridge of connectivity. For me, Incheon Airport holds a special significance. It was here, in 2015, that my family started a life-changing journey from Vietnam to America. I was just 7-years-old then but yet in a foreign land, with a language barrier as vast as the ocean we crossed, my parents navigated the immigration journey with grace and resilience. Their sacrifice laid the foundation for my academic growth and future opportunities.

Fast forward to 2023 the familiar halls of Incheon Airport welcomed us once again. But this time, instead of heading westward, we were bound for the east, returning to Vietnam. As the only child, the responsibility of guiding my family fell on my shoulders. The weight of this newfound role was nerve wracking, to the trust my parents placed in me, a 16-year-old girl navigating the process of immigration. Sitting in the waiting terminal, I couldn’t help but reflect at the contrast between then and now. In 2015, we were strangers in a strange land, carried with us only determination and hope. But now, as we navigate on our journey back to Vietnam, my parents emit a sense of calm assurance, their trust in their immigrant daughter unwavering.

Incheon Airport, once again, with its busy crowds and activity, mirrored the convergence of our two worlds, my parent’s world of sacrifice and resilience, and my world of opportunity and growth. Like the airport itself, I stood at the intersection of past and present, a bridge between two cultures, two worlds. Incheon Airport, with its never ending energy and promise of new beginnings, will forever hold a special place in my heart: A symbol of the powerful spirit of migration and the enduring power of family.

The excitement I felt as I stepped foot into Ca Mau, a small providence in Vietnam, is truly nostalgic. I feel at ease as I watch the gentle breeze and peaceful wind dance across the atmosphere. My parents’ first choice for places to visit in Vietnam is the temple. I had a bit of extra time on my trip to the temple to reflect back on the previous 48-hour travel and the past nine years in America. Even though I am happy to have my family here in America, I feel as though a piece of my soul was left in the temple that my mother and I visited before we came. The thought about revisiting the temple made my heart jump with excitement and nervousness cursing through my veins as I did not know what to expect.

As I stepped into the temple courtyard, a sense of calm washed over me like an ocean wave. The air was thick with the scent of incense, and the soft murmur of prayers filled the atmosphere. It had been years since I last set foot in Vietnam, my ancestral homeland, and being here again felt like coming home in the truest sense. As an Asian American, I had always felt a deep yearning to