Make Noise Today is a platform that creates empathy and equity through Asian storytelling.

As Asian Americans, we are considered ‘the quiet ones’. When negative media and hate crimes against Asians escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, we felt it was time to be heard. This initiative was launched in May 2020 in honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, and our powerful voices continue to be loud and strong to take control of our own narrative and combat racism by telling personal stories of our heritage and accomplishments, challenges, grit, inspiration, and culture.

Learn more at makenoisetoday.org

Follow us: @makenoisetoday

CONTENTS Introduction .............................................. 4 Judges ....................................................... 6 Winners ...................................................... 7 Other Select Work ................................. 28 Thanks to Our Partners ....................... 97 Click on page numbers to navigate to page.

4

AAPI STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP AND ART EXHIBITION

We held a scholarship contest where high school students nationwide were invited to submit original creative work on the subject of mental health wellness from the lens of AAPI youth. Winning and select submissions are featured in this exhibit to amplify young voices and subvert the stigma surrounding mental health within the AAPI community.

There is much to learn from today’s Gen Z youth, who are empowered to take charge of their lives. In many ways, this generation recognizes that mental wellness is critical to one’s health and fulfillment, propensity for success, and a cornerstone of society’s ability to thrive. The lackluster stats of Asian Americans addressing mental health are well known, but it is time to help shift our cultural norms, perceptions and inhibitions to open real conversations about the importance of mental wellness.

5

JUDGES

We wanted to highlight the invaluable efforts of the Make Noise Today team who sorted through all the student submissions, and our esteemed judging panel who took the time to review our finalists. Thank you!

Anthony Christian Ocampo, Ph.D Professor of Sociology, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

Anthony is the author of Brown and Gay in LA: The Lives of Immigrant Sons and The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race, which has been featured on NPR, NBC News, Literary Hub, and in the Los Angeles Times. He is an Academic Director of the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity and the co-host of the podcast Professor-ing. His writing has appeared in GQ, Catapult, BuzzFeed, Los Angeles Review of Books, Colorlines, Gravy, Life & Thyme, and the Chronicle of Higher Education, among others. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Jack Jones Literary Arts, Tin House, and the VONA/Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation. He was recently featured in the Netflix documentary “White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch,” as he was one of the employees involved in suing the company for racial discriminatory hiring practices. Raised in Northeast Los Angeles, he earned his BA in comparative studies in race and ethnicity and MA in modern thought and literature from Stanford University and his MA and PhD in sociology from UCLA.

Jocelyn Tsaih Artist

Jocelyn is a Taiwan-born, Shanghai-raised artist. She received her BFA in Graphic Design at the School of Visual Arts. She is a painter, illustrator, and muralist. Though she works in various mediums, the connecting thread throughout her work is her depiction of amorphous figures. Often portrayed in abstracted, liminal spaces, she aims to touch on the emotions as well as the otherworldliness of our human experience. The figures in Tsaih’s work act as extensions of herself. As someone who grew up between multiple cultures and worlds, she’s created her own version of the “in-between”. This is where the figures, and herself, are free to just be. She utilizes color, form, and composition to create images that convey strong moods, possibility for curiosity, and space for introspection.

Dr. Tommy Chang, EdD CEO, New Teacher Center

Tommy brings over 25 years of education experience and leadership to this role, including significant positions in schools, districts, and nonprofit organizations. His journey began with and continues to return to the lifechanging moment he answered the call to become a teacher. Before his most recent position as acting CEO and President of Families In Schools, Tommy spent three years as a consultant and coach to school system leaders and advised organizations such as Great Public Schools Now LA, FourPoint Education Partners, and Whiteboard Advisors. He has served on several nonprofit boards such as Leading Educators and Silicon Schools Fund as well as Education Leaders of Color, an organization dedicated to elevating the leadership, voices, and influence of people of color in education to lead more inclusive efforts to improve education. From 2015-2018, he served as superintendent for Boston Public Schools during which time the district saw increases in student graduation rates and decreases in school dropout rates. He also supported the development and implementation of The Essentials for Instructional Equity, an innovative framework for teaching and learning aimed at closing opportunity and achievement gaps. A native of Taiwan who immigrated with his family to the U.S. at age six, Dr. Chang grew up in Los Angeles and holds an Ed.D. from Loyola Marymount University, M.Ed.’s from the Principals Leadership Institute and the Teachers Education Program at the University of California Los Angeles, and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

6

WINNERS

Congratulations to the winning students! Your creative piece was selected as one of the most stirring and contemplative among hundreds of submissions from students nationwide.

We want to thank all of our participants in the Bring the Noise student art scholarship contest. Your submissions on the subject of AAPI mental health were brave and awe-inspiring. We heard you. And we look forward to you continuing to Make Noise Today and every day!

7

8

MemorialCare

Platinum Prize

The Marionette by Grace P.

As a Korean American, I struggled to strike the right balance between two distinct cultures. Growing up in a conservative Korean household taught me to be deferential, reserved, and mature “unnie” (i.e., older sister), whereas American culture emphasized a socially adept lifestyle. Having been exposed to cultural differences since a young age, incidents such as being chastised for bringing my mother’s homemade kimchi and kimbap to school caused me to further isolate my two identities. My piece depicts my internal conflict, a struggle to break free from the grip of my insecurities and fears about how different communities of people perceive different aspects of myself, and to find the courage to overcome them. Furthermore, my piece depicts different stages of emotion, such as frustration, loneliness, and relief. Ropes are prominent in my piece, and they represent the restrictive force that untangles through each stage. As an Asian American, I have discovered the value of combining qualities from both cultures to bring out the best in myself.

9

The day that I brought Vietnam home

by Taylor N

It took many years of growth and hours of introspection on my own part before I finally realized the reason why my grandmother would search through the trash every week before she took it out to the alley. To a young child, the war-hardened survival techniques that she had never unlearned had just come off as oddities that I could never shake. The houses my friends lived in were clean, white- without shriveled ladies with discerning eyes that would pick through the garbage can after every meal to make sure we never threw anything away.

Popo never liked to talk about Vietnam. At least, not unprompted. It wasn’t a part of her life that she liked to remember, and for the longest time, I was unsure of what exactly my family was. I knew that we were Chinese, the red and gold calendars on the wall reminded me of that every day. They always had scripts that I could never understand, holidays that I had never heard of. For the time, being Chinese was a way of eating my food: never leaving rice behind in my bowl, picking apart oranges and saving the peel, dropping crab shells onto the plates of my grandparents, who would suck on the cartilage until they could gum the legs into paste. China was not a place in my head, nor was I sure that it was exactly where my family came from.

In the seventh grade, I was assigned a project from my physics teacher: make a roller coaster with a central theme. My current obsession that year was TellTale’s series The Walking Dead, a game focused on a world overrun with the undead. Many of the scenes depicted in the games resembled war-torn battlefields, overrun with the bodies of the damned. That was what I had based my entire project on. Melted glue held dirt and moss to a flat piece of cardboard, with sticks that attached themselves to a pool noodle that I painted with various shades of brown, red, and black. I used small props to represent the items left behind by victims in the video games- reminders of the inspiration I had received from them.

While the poster was drying, my Popo had come downstairs to bring me some tea. She has this wonderful habit of putting an amalgamation of herbs and fruits into a pot of boiling water and then claiming it would cure any disease imaginable. I used to be irked by these cups of broth. They were too bitter, and I would gag on the debris that floated at the bottom. But now, I miss them dearly. That day, the tea was sweet.

She paused when she opened the door to the basement, looking squarely at the project that I had put my entire heart into. I thought for a moment that she was disappointed in me, with the way that her thin lips pressed together and turned down. Her legs had given out under her, and she moved to sit in the doorway, looking with exhausted eyes toward my science project. Then, she told me all about Vietnam.

“Yunyi, you do this?”

“Yes Popo, is something wrong?”

“Look like Vietnam,”

It was then when she told me of the past I had no idea existed. Of a time where America fought a war that they were bound to lose. Of a time where my grandfather was a man of grandiosity, and spoke much more than he does now. She told me of the boat that she took my mother on immediately after the fall of Saigon, and how a woman died aboard their ship, leaving them with no other choice to abandon her body or risk illness by leaving all others exposed to it. She told me about the burning fields and the torn-up casinos, and of the police that raided her home.

10

Somehow, she managed to say this all with a smile on her face. When I had asked her in a hushed tone if she was alright, she waved her hand at me.

“Chinese never cry. We grateful,” she placed her hand over mine, “grateful because America take care of us.”

For some reason, those words stuck with me. I felt like all of the suffering that I had endured in my own time was nothing, that I would never be allowed to feel pity for myself when my grandmother had already lived through fifteen lifetimes of trauma. It didn’t feel fair.

So, when I ended up in the hospital for a suicide attempt, I had never expected to hear anything from her or Gonggong. I was ashamed. I knew I could never face them after what I had done. After all that they’ve been through, what did I give them to show for it? A destroyed daughter and miserable grandchildren. While I sat in bed for the week I was mandated to stay in the hospital, I kept repeating to myself: “Chinese never cry.”

I told the doctors that I was better, that everything would be okay when I returned home, and that I would not need any further intervention. There was this aching fear inside of me that my mother had told my Popo and Gonggong that I had failed them, that I was not the American dream. I tried everything I could to make my return as normal as possible. I wanted to pretend that nothing had ever happened.

But when I got home, Popo was waiting for me upstairs, sitting next to my bedroom with her hands clasped in her lap. I smiled sheepishly at her and tried to push past silently and just settle into my bedroom, but she called out softly for me not to close the door.

“Mat yeh?”

“Taylor- you not happy?”

Five minutes passed before I could even begin to think of anything to tell her. Of course she noticed I was gone, I lived with her for god’s sake. And why wouldn’t my mother tell her? She was her daughter, she had to tell her mom. I wondered if my Popo held my mother as she cried, just as my mom did to me.

“No, Popo, I’m not happy.”

“Popo loves you, we all love you.”

And that was all I needed to hear to know that everything would be okay.

“I love you too, Popo.”

Dear Asian Americans Gold Prize

Dear Asian Americans Gold Prize

The Masque of Contemplation

by Hyunyoung M.

The Masque of Contemplation is a piece I created to reflect the difficulties surrounding Asian communal identity whilst growing up. Within the piece, I’ve included elements of Korean “탈춤“ (talchum), a form of Korean performance, to represent the Asian society I was brought up in and was expected to participate in as I became older. The pressure to assimilate and become more “Asian” despite being raised simultaneously in an American culture raised clashes within my American and Asian identities to the point where I felt depressed and anxious in order to make a decision. Therefore, the mask and perspective of the piece shows the main subject (me) in the mirror, hesitant to put on the mask and join the daunting performance. By putting the mask on, I could finally feel assimilated to Korean culture but the

hesitance and cultural differences prevent me from making a definite decision to do so. The internal turmoil has been included in my journey in finding where I belong, anxious to commit to one identity. However, it can be inferred that my piece offers options: one could choose to assimilate to Asian culture, omit doing so, or identify with both. Therefore, a significant part of my journey in finding solace in incorporating both aspects of my cultures into one identity was understanding I do not have to follow any choice set for me; I can choose my path. With my piece, I hope to bring attention to the pressures of Asian society and express the importance for other Asian-Americans to take time to decide for oneself in terms of their identity, because they have the power and liberty to do so.

13

Tanghulu

Tanghulu, also called candy haw is a snack that’s commonly found in Northern China in the winter.

Ingredients:

Fresh handpicked hawthorns, bamboo skewers, edible thin rice paper from the closest Chinatown, 2 cups of sugar, and a cup of water.

One of my happiest memories is munching on my tanghulu with my classmates.

We would tear up the rice paper, Lick it and stick it under our nose like little mustaches. We were policemen that caught the bad guys, superheroes that fought the villains, pirates that sailed the ocean.

But when I finally sailed across the ocean one day, I found that I was all alone. A captain without her crewmates, surrounded by riches that didn't shine anymore.

Step one:

Wash the hawthorns thoroughly, dry them, and put them on the skewer.

Washing is the first step of assimilation. You throw away all parts of you that used to make you proud but now are deemed to be weird and Chinese. Take in the American culture as fast as possible. The faster you assimilate, the quicker you’ll have friends again. Put on a new look. Hollister, American Eagle, and Lululemon are your new favorite stores. Get some new lunch.

Chicken nuggets and PB&J are okay, but wait, all the cool kids only eat salad for lunch. Pierce your ears like piercing the hawthorns with the skewer. Those silver hoops will make your face look smaller like all of your other “friends”.

Step two:

Prep the tabletop with a piece of parchment paper. Lay it down lightly just like how Chinese women talk. How they always talk and walk lightly in tradition, how they always have to be elegant, how your mom tells you that you are too direct, too fierce, and too loud to be a Chinese woman.

Step three:

Mix the sugar and water like how you mix your smile with depression. Set it on the stove and let it heat up, but don’t make it boil, because there is sugar in there that oppresses your true feelings. Because your Chinese mom keeps telling you that,

14

“No, you’re not depressed, you just want attention like all other teenagers in this country.”

But mom, I’m not like the other teenagers in this country, my culture keeps coming back to haunt me instead of bringing me joy, my accent keeps coming back and getting made fun of, my country keeps appearing in the news headlines, my depression is not validated by anyone except the dark voice in my own head.

Step four:

Dip the hawthorns into the syrup while holding the skewer. Rotate quickly while dipping to cover the fruit entirely with syrup, then place the sugar-coated Tanghulu onto the parchment paper that you have prepared.

Step five: Wait.

When I was little, one day my mom brought me this big tanghulu on our way back from the park. I was so happy, and I started munching on it like a little chipmunk because the hawthorn fruits are so big compared to my little face. But when I was going upstairs to our apartment, I tripped and dropped the tanghulu onto the ground. I started crying like a petulant child, and my mom thought it was because I scraped my knee. I wasn’t crying because of pain, I was crying because I dropped the tanghulu on the ground.

Now I cry, and my mom thinks it's because I oppose Chinese culture, I wasn’t crying out of disapproval, I was crying out of shame.

Step six: When the candy coating hardens, remove the parchment paper, then wrap it with thin rice paper, completing the final touches of the tanghulu.

I am not ashamed of my culture; I am ashamed of loving it so deeply, of embracing the things that I truly love.

When you take a bite of the tanghulu, you bite through the crunchy layer of sugar, and just before you savor the crispy sweetness, you are greeted by the soft, sour, mealy hawthorn fruit.

Like my Chinese American identity, I wear a hard, loud, and independent armor on the outside, while inside, I possess softness, elegance, and strength.

Like the growing awareness of mental health within the Asian American community, we cry and break, but we are together. We speak and rise together, fight and unite together, love and belong together, grow and thrive together, persevere together,

TeachAAPI Silver Prize

and get back up together.

Like my journey to better mental health, I almost gave up on the hard and sticky hardships, but I was uplifted and saved by the love of friends, family, and culture.

“I love you!”

“Everything is going to be okay.”

“It's not your fault.”

“Mommy can be harsh sometimes, but she loves you!”

“Thank you for everything you've done, and for giving our community a voice.”

For a long time, I searched for ways to heal, and I discovered that more than love from others, there is love from within.

For me, that love began with expression.

It all started with a stage, a place, a chance, a representation, a declaration, a liberation, a voice to speak, to love myself,

to save myself and others from mental illness.

TeachAAPI Silver Prize

(continued) 16

Dear Popo

by Jupiter Z.

This song and this poem illustrate the importance of communication, storytelling, and vulnerability as it relates to my relationship with my grandmother.

PLAY VIDEO

Prize

TeachAAPI Silver

Lost Cause by Reihinna H.

This song is about a personal experience I have had with my own mental health, especially during quarantine. It is written in the second person and is addressed to my mother, so that it is as though I am speaking directly to her.

Before COVID-19, I would silence my thoughts or ignore them, but, being inside a quiet house every day, I was forced to listen to what was going on inside my head. When I noticed this, I was afraid of telling my mother at first. Many people from her side of the family, who are all from the Philippines, did not want to admit each other’s mental health problems. They would deny that these problems even existed, and their solution to them was to either ignore them, or pray to God for help [Verse 2/Prechorus]. This is a common belief within the Filipino-American community, but many do not realize the harm that comes with this.

PLAY VIDEO 18

In my song Lost Cause, I utilize the repetition of “silence” in the beginning by saying how it may seem that it’s easier to remain silent than to express your feelings, but at the end, after witnessing how my family has tried to silence a family member, I realize that silence just constricts how you truly feel. I have been lucky to have an understanding mother, however, who does not give into others’ harmful mindsets.

When I approached my mother and told her about how I was feeling down, she told me how she’s felt the same way before [last chorus]. Both my mother and my father opened up to me about their mental health struggles and made me feel seen, and I believe that is something that the AsianAmerican and Pacific Islander community can learn from. To approach mental health, we must first understand that it is a real problem that must not be ignored. Only then can we share our voices and make noise.

TeachAAPI Silver Prize

Night Walks by Lila M.

We step out into a dark night. The humid Houston air immediately surrounds us. Which way today?

Our tradition started during the pandemic. Like many other families, we got a pandemic dog, a scruffy little mutt named Wizard. My dad was against it. Not the dog itself, but the idea of feeding him meat he found thoroughly unethical. “I don’t believe in killing one animal to feed another,” he would say. But we got a dog anyways, under the agreement we would research healthy, mostly vegetarian diets for canines.

Naturally, the dog needed walking. To avoid the oppressive heat of that summer, I chose to walk at night. I didn’t want to walk alone, so I asked my dad to join me. And in this strange COVID summer, where the days seemed to stretch and twist around each other, we had time for very long walks.

Despite the dark, we found ourselves noticing many little wonders in the night. Two great horned owls, spiraling around each other in a mating dance. The city of frogs living underneath the cracked sidewalks. The moon, bright and fat in the sky, casting dappled shadows through the trees.

This is what my dad loves. He is an editor for our city’s newspaper. It’s a grueling job, and often, I was frustrated with him for constantly working. But walking with him, I could see why he keeps going: he is a man who lives in his city, he is a man who cares deeply. On these nighttime walks, I learned how to truly be a part of my place, and how to be a part of our place together.

But most importantly, on these walks, we talked. I told him stories of my online high school. In return, he traded stories of his own high school days, stories I had never heard, even some stories he hid from his mother. I learned how he was similar to me, a high achiever, and someone who cared deeply about words, language, and how he fit into them. I told him what I struggled with somehow, the words came easier walking side by side in the dark. He told me I’m proud of you. I told him of my worries for the future, and he told me his life story, slowly, like a river of stories trickling over the weeks. He told me why he quit medical school to become a writer, how his mother reacted. I asked him for advice, often. I didn’t always agree with what he gave, but I always valued his words. We talked about writing. He told me choose one writer and read them deeply. See what you learn.

We talked about where we fit in America. It was a question that had been weighing heavy on my mind, as a biracial third generation immigrant. In a world so often divided by race, who was I? Did I deserve to claim an identity whose language I did not speak? In response, my dad told me his own lived experiences. What the kids in his hometown of Mobile, Alabama told him, often a mixture of racism and ignorance. Helping my Dada practice jokes in English. All of these seemed

“more” Asian-American experiences. But to 20

like quintessentially

how he fit into them. I told him what I struggled with somehow, the words came easier walking side by side in the dark. He told me I’m proud of you. I told him of my worries for the future, and he told me his life story, slowly, like a river of stories trickling over the weeks. He told me why he quit medical school to become a writer, how his mother reacted. I asked him for advice, often. I didn’t always agree with what he gave, but I always valued his words. We talked about writing. He told me choose one writer and read them deeply. See what you learn.

We talked about where we fit in America. It was a question that had been weighing heavy on my mind, as a biracial third generation immigrant. In a world so often divided by race, who was I? Did I deserve to claim an identity whose language I did not speak? In response, my dad told me his own lived experiences. What the kids in his hometown of Mobile, Alabama told him, often a mixture of racism and ignorance. Helping my Dada practice jokes in English. All of these seemed like quintessentially “more” Asian-American experiences. But to my surprise, he felt the same way I did. He understood my feelings of disconnect, and of not being enough. He described his sense of shame he felt not knowing Gujarati, his despair at not being able to talk to his own grandmother. And he told me a story: When his grandmother almost died of a heart attack, he dedicated himself

to learning Gujarati enough to write her one letter. He worked hard with the limited Gujarati learning resources he had, he even traveled solo to a small town in India to truly immerse himself. And eventually, he succeeded in his goal: He wrote his grandmother a letter in Gujarati. This story had a powerful impact on me. It showed me that I couldn’t let other people define my identity. That was up to me.

As the pandemic eased, we were both drawn back into the chaos of life. I took on AP classes, and his work intensified. We both worked late. Yet every single night, we still made time for our walk. Whether an hour or five minutes, whether we were mad at each other or tired out of our minds, we still walked. They meant: I will always take the time for you. I care about you. I love you.

These walks, these conversations were now vessels for understanding. They had become almost ritual, a way to ground ourselves in this ever-chaotic world. And so, each night, as I step out into the dark, I know it doesn’t really matter which way we go, where I walk. What matters in this world is that we walk side by side and talk.

Honorable Mention

22

Skeletons In My Closet

by Michelle W.

My grandparents were refugees during the Korean War and immigrated to America after my parents became teenagers. As I grew up, I placed great pressure on myself to meet the high standards of my parents and be the “perfect daughter”, the daughter that always got straight A’s, performed well in sports, and had an interesting hobby like art.

This immense pressure to be perfect was taking an toll on my mental health and was falling into multiple cycles of depression and anxiety. I was scared to tarnish my image of being a perfect daughter to my parents when they worked so tirelessly to allow me to flourish in a new country. I felt as though my problems with my mental health were so miniscule in comparison to their hardships that I couldn’t dare to ask to see a therapist. I was so blinded by my longing to be “perfect” that I was hurting myself mentally as each day went on.

I painted my depiction of the idiom “skeletons in the closet” to help me through my dilemmas. I painted myself dragging a giant lifeless skeleton to show how I felt so chained down by my mental health struggles. I wanted the scattered bones to act as my broken mental state. The immense scale of the entire closet in comparison to my painted selfl was to represent how guilty I felt for wanting to ask for help. It felt like an endless walk through the grim and lonely closet.

Honorable Mention

24

Carbon Copy

by Lauryn K.

College applications are brutal. We pour everything into compiling our entire lives into essays and lists that someone will look at for a matter of minutes. Comparison is inevitable and crushing. At a certain point, I started feeling like a carbon copy of every Asian girl in the country. The bubble I was living in popped and I couldn’t help dwelling on the fact that there were countless people who I’ve lived parallel lives with. I was always a good student, yet next to hundreds of thousands of other applicants, I felt like a fly.

As we all know, Asian households have a penchant for eliciting excellence. Both through myself, and through my friends, I’ve seen what this process of trying to conform to the mold of a perfect college applicant can do to a person. And despite reassurances of “oh, there is only one you” or “you are unique and special,” sometimes, these platitudes just can’t combat this feeling-- that sinking feeling of being insignificant and believing that there are a million mirror images of you.

Everyone has different ways of coping, and for me, art has always been my outlet when words escape me. The cathartic process of illustration allows me to address mental stressors like these while sharing my sentiments with others, often leading me to realize that I am, in fact, not alone.

Honorable Mention

We are running side by side, Popo

Down the river path of orange muskmelon and flaming grapefruit, adorned with pearl necklaces of tang yuan, to the mountains of nian gao. Back in my chair, back sitting across from you, back celebrating Chun Jie at your house I’ve always thought the branches outside your kitchen window look like faces, peering in, from stinging night air, at our family

Tell me, Popo, why do these foods mean togetherness, but when squeezed between auntie and uncle, I am alone? Tell me, why as mouths close around this feast, the words out of those mouths aren’t the ones I need to hear? Tell me, “how are you doing?” and I will grasp onto the ‘er’ “Climbing higher, pushing further, working harder.” These questions don’t really want an answer.

Shouldering a load of ‘musts,’ I struggle through hard country, looking for the path, the one this family has trod on through generations Blind I am, I can only tumble down twisting slopes Let the brambles cut into my body, I will swipe through with arms inked bloody. When I emerge on the other side– I am lost. I live on the side paths. My home is the bathroom stall I don’t squeeze in, counting to ten, drowning in the air. Late at night, I don’t spend time unable to journal, hands too shaky to write

When doors slammed in the pandemic, when features of those who shared my face became symptoms, when I watched my people lying abandoned, puppets on the news, characters in a larger narrative, when I lay dead alongside them in my bed, tell me they do not exist

Remember that word spray-painted across the wall-ball courts of my elementary school. That word was quickly power washed away, one more stain on the old schoolyard, but that feeling of my playground violated remained. That word never disappeared, but tell me, my feelings do not exist.

Tell me again how you came to the US, my age, my twin. Recount your story so I picture myself. Tell me how we were sent to school with a sign slapped on our backs, “warning: does not speak English.” But don’t tell me, “animal in a zoo, handle with care.” A caution to people gawking. Tell me instead how we shortened our name to something more comfortable for strange lips Don’t tell me the power your name held for you. How erasing it stole ownership of your identity. Tell me rather of a strong mother, who held her husband, her 11 year old daughter when their sister, daughter was lost. But never tell me of losing your baby, of grieving, of breaking. Because there should be nothing to tell

Even with your surgery, one supposed to render you bedridden, you prepared this meal for us Even in your recovery, you must press on, crawling on your knees.

Because we’re full and complete.

26

Even with your surgery, one supposed to render you bedridden, you prepared this meal for us. Even in your recovery, you must press on, crawling on your knees.

Because we’re full and complete.

We’re humble and grateful.

We’re hard-working and assured.

We’re excited for tomorrow and excited about yesterday and today

Say I am recovering,

Say I am improving,

Say I am feeling better,

Say I am feeling nothing.

I am nothing.

I look up. Red eyes meet red eyes, there is no room to talk when you are running forward, but there is room for so many words in an incomplete story

Dinner ends and we retreat upstairs into the night.

I lie awake, listening to the sounds of the house They slip through the cracks in my room, barely audible but there, splintering. Stifled sobbing. Soft muttering. Shaky breathing. In the nights at that house, I hear my grandmother crying until sleep frees her.

Tonight, both of us stay up together, separated by a flight of stairs in the dark I cry alongside her, only a few steps away through the black How many members of this family of liars, smothered cryers, are screaming with us, in this quiet, quiet house. We are stranded in this close knit family. Silence, bare feet slide over a shag rug, shuffling towards the stairs. In the dark, you can’t see the bottom of the steps, so at the top, you are standing before an abyss

But finally, I see the path, different than expected. Watch it wind, watch it double back, watch it wrap into itself, confused. I’ll find you in the dark, Popo. We will run side by side.

by Julia H.

27

Honorable Mention

OTHER SELECT WORK

I was born in America to Chinese immigrant parents. Growing up, I was called an ABC (American Born Chinese), and this label has continued to stick with me. I have always felt as though I’m not “Chinese enough”, especially with my degrading ability to speak Cantonese, which caused a barrier between me and the main exposure to my culture, my parents. What drove me farther away from understanding my roots and myself was that I grew up in a predominantly white small-town community. Apart from my confusion about identity, these two aspects of my life both had their impacts. The disconnect between me and my parents affected my relationship with them and the mental strain from being regarded as “different” outside of my home life has shaped who I am and how am today.

Putting all these emotions into my piece, I created a sculpture titled “Split.” The clay hands unravel a crochet doll in two directions to represent a divide in identity and the toll it takes on the individual. Though I am incredibly proud of both aspects of my life, they no doubt have had adverse effects on my mental health. Despite this truth, the idea behind using a crochet doll is that it was not only easy to portray the unraveling of oneself but also that it was able to be repaired. Though not as easy as it is taken apart, the strings can be rewoven to become whole once more, representing thriving and self-accepting potential.

28

SPLIT by Sharon G.

29

The Weeping Willow by Faleha K.

Nestled amongst the expansive field is a single weeping willow tree

The weeping willow is versatile She can turn into paper, which can turn into the greatest classical works of all time by Aristotle and Shakespeare She can also turn into tissue paper, paper towels, and toilet paper; single use, but effective nonetheless

She is quiet, yet bold When in her presence one feels safe, as if the space beneath her branches is a sanctuary where all their worries and sorrows fly away along with the deciduous leaves. Still, the willow dares to stand out. Where there might be a monoculture of trees or trees of different species, the willow is the most distinct and most intriguing. She grazes the sky, whispering to the world. Her roots wander the vast ground, seeking exploration and independence.

She is what little girls envision in their dreams. Her beautiful branches flowing in a warm spring breeze, the smell of lavender and honey in the air. A book and a girl sit against her trunk, the willow hugging them as her light branches sway and kiss the girl's forehead. She provides a sweet, sweet escape She is the girl's secret meadow, her solace, her freedom

She is tied down to a single place, yet her growth doesn't cease. Instead, her resilience is felt farther than the area she resides

She channels her energy into creating a brighter and more secure environment for those creatures inhabiting her abundant leaves and branches

When faced with change the willow is adaptive, photosynthesizing during the warmer seasons and shutting down during the colder ones. She uses her energy stored in autumn to grow and create vibrance in spring Her glorious aura expands throughout her fellow flora and fauna, tantalizing and comforting

30

The willow refuses to decay and break, she only bends. She is able to sustain herself, overcoming obstacles without much help from others. While she may prefer dewy grass and clear ponds, she can thrive in drier areas, adjusting to the earth as she may need.

She is sturdy. As much as the dark stormy nights try to knock her down, the willow’s confidence and persistence allow her to fight the wind. Although she wails as the wind howls and lightning strikes, her resistant nature does not allow her to burn, only smoke. She does not only survive, but she grows from these treacherous battles with the natural elements

When her roots expand, she doesn't let sediment and bedrock cease her journey, instead she proudly lays down her roots and flourishes

As much as the insolent people try to carve away at the willows bark, mocking her, the willow stands, the marks fading over time, but forming scars that remind her of her resilience She may be scarred, but her roots remain untouched and as rich as the soil that surrounds them, never letting sediment and bedrock cease her journey The willow doesn’t know what fate lies in front of her, but she does know that her future is bright, she can spread as far as her heart desires

People may see her as the weeping willow, but she's more than what meets their gaze She is a being, forging her own path with integrity, hope, and persistence

I am the weeping willow

31

How to Deal with Spiders

by Winnie L.

How do you deal with a spider? No, not your everyday house spider, but the spider manifested from your deepest, darkest thoughts. Like a fly in a web that tangles and twists, you are trapped within the silk of despair. Yet the silk is not made of iron or diamond—some days you can fly away, but others you are trapped longer.

That spider feeds off your negative thoughts, and thus, you should cut off its food source. Now, I shall pass you my guide on how to deal with this spider! Instead of moping around like a turkey on a plate, how about joining some online communities?

Platforms such as Reddit and Discord consisted of welcoming communities created for Asian Americans struggling with mental health. You don’t have to deal with it alone, it is okay to talk about it, and joining an online community is an easy way to start.

Hey! How about doing some fun stuff? I enjoy listening to music and drawing, it helps me take my mind off of unhappy thoughts. I even tried new things such as fashion and cooking (despite not being good at it). Keep a journey or write (or scream) your feelings out! Nurture your body with good sleep and exercise! There are many things you can do to starve that spider! Eventually, that spider can no longer trap you. Just remember to stay positive, everything will be okay!

33

Free(dom) of Speech

By: Jessica T.

Falling from the clouds, earth caused fear yet to the roads he bowed and relief caused tears.

Grasping those years, memory caused him to ascend the mount rice grew near, water balanced on both ends.

He carries the light which others depend, never reaching free-range ‘til nights clashing with friends yet the sun brings fights for change:

A change for freedom, the choice to arrange his own desires, his own claims, to let curiosity seek the strange. to make dream and life one and the same.

He sought the reality free of shame, so he leapt from his roots for almighty fame to freedom’s foreign terrain, to find the loot.

Yet he fell from the soot, and the clouds parted

to reveal the arrogance put where tears had departed.

Now see my broken-hearted ashamed of his shame, from trauma he never parted, yet a trauma never claimed.

A trauma only proclaimed in tears watering this land of the free Yet tears can never name these feelings I fail to see.

“Don’t be like me, anak, my child; just be happy to be in the land of the free.”

Yet how free can I be, with emotions suppressed?

“Tatay, father, use your freedom of speech tell me you are not okay, please, be the human I see.”

34

the healing wound by Leeyana

M.

In my day to day life, I find myself meditating upon the collective trauma of my family There is a reason why most Asian parents do not believe in mental health issues, much less support strategies to relieve the associated burdens In just under a century, a look back into our history reveals a dark past of exploitation, displacement, and colonization, both from the West and countries in the Asian continent What happens to a hurt animal? It becomes violent It nips It barks It bites because it thinks that help is just another hand that will hurt them As a community, we have become that dog We push our trauma aside, as we don’t know how to heal We push it away so the hurt lessens But when a wound is left untreated, it becomes infected It seeps into our bloodstream so that every moment is unbearable, and when the infection is too far gone, the stench of it starts to affect the ones around us I can clearly see the way trauma has affected my family and furthermore, how it has affected me I see the pattern, and I have started to heal

My parents were born in the fading years of the Marcos regime Although I was not given much of a glimpse into their lives during the regime, I cannot imagine that it was easy I find myself thinking: is this why they are the way they are? Is the endless poverty of the Filipino people the reason why my father is so resourceful to the point of stinginess? Is it why my mother loves to flaunt the money she has? Is that why they stock up on food we won’t eat or clothes we won’t wear? When I tell them about my struggles, is that why they laugh, like it’s something so menial that it’s not even worth an understanding nod? Oh, their privileged daughter, with no worries of the world around her “You don’t know what struggle is”, that was what I was always told See, trauma works in ways that are incomprehensible and erratic My father brushed me off with a scoff and a swig of his nightly beer because “his uncle was worse” My mother told me I should be grateful and to never “complain”, because “I’m not carrying my family on my back” like she did When I was a child, I hated them for it I hated seeing my father drunk He was so embarrassing to me When he put the bottle on the table, I cringed at him When he drank at our family gatherings, I rolled my eyes, already imagining how disheveled he’d become by the end of the night I bit my tongue as hard as I could when my mother berated me for being “lazy” I imagined getting struck by a semi truck when we got into screaming matches in the car The smell of their wounds was making me gag I vomited everything they gave to me, their privileged, weak daughter All we could do was stare at the mess I made, and sigh, both of us disappointed

But I don’t hate them for it, at least not anymore I’ve made peace with the way they are I can’t heal their wounds, not completely That’s not my job The smell of rotting flesh and pus has gone away The wounds have scarred, thick keloids roping on their bodies I laugh along with my parents now I hold their hands I talk to them instead of blocking them out On my chest, there is a scar above my heart It is small and clean I touch it tenderly Underneath it, inside my heart, is a little girl I have kept her there so she is safe She still knows the smell of rot She is so small, and still so scared I can’t heal my parents’ wounds What I can do is wrap it in cotton and kiss it like they kiss my head I kiss my past self, her little hand covering the crust around her dry lips I can tell her that it’s okay now My parents are like giants to her, with fangs for teeth and claws for nails and scars from past battles covering every inch of their body But I see them for what they really are: hurt They had to use their fangs and their claws to stay safe

They just didn’t know that they were already safe. They didn’t know who they were hurting. I hug my parents closer. I hug the little girl closer. Trauma works in ways we can’t understand, but so does healing. A wound will always close, no matter how long it takes.

35

Melting

by Brianna B.

What is my mental-health path?

Melting is a self-portrait representing my experience with being Asian American. Being apart of two cultures, yet not belonging to either can be isolating and awkward. I showed this by using oil pastels as my main medium making the piece look messier and using a sharp tool to scrap away swirls into the oil pastel making it look disorienting.

I realized how I felt about my race when I went to Thailand with my mom and my sister in the summer of 2022. I am from Thailand but moved to America at a very young age, so for a long time I denied my culture which included little things like, not wanting to bring seaweed to

school because other students would judge it and call it “disgusting”. When I visited Thailand that summer I realized how much I despised being Thai and how much the “Thai side” slowly disappeared while growing up in America. I showed this through the stretching of the left side of my face. I felt like I needed to fit into whatever culture niche I was immersed in. Whether I was in Thailand or America. I either felt too American or too Thai. So with the words:

“If

I’ll Be Somebody I’ll Never Let My Skin Decide

For Me” above my head, I communicated how my appearance defines who I am, how I feel, and if I want to be “somebody”.

36

“I’m Proud” an original song by Katie C.

I’ll push down my feelings

So people think I’m fine

“Oh she’s that one happy girl”

But really I’m crying inside

I’d embrace my stereotypes

Mental health talk is a waste

With asian parents like that 你以為你是誰

(Translation: who do you think you are)

Are you Chinese? They’d all ask No, I’m Taiwanese, is what I’d say Confused faces reply

Where the heck is that?

My tears turned to lies

I’d make a lengthy story

Oh, I’m Chinese, Japanese, Looking back, I wish I could say sorry

I should’ve been proud

Oh here I’ll show you on a map

Culture isn’t a barrier

How I shielded it is what makes this story sad

(I am Taiwanese) 我是美國人

(I am American)

(No matter who I am)

I should never run

Never run from who I am

Don’t let it get to my head

Don’t let them flood my mind

Yet I reflect on who I am

I’ve cried but never let the tears flow

I’ve screamed but never let my voice show

I’m tired of pretending that I’m perfectly fine

I should be speaking up; and now’s that time.

I used to overlook my mental health

“Oh it’s okay, when I grow up I’ll understand”

But looking back I see all of my wrongs

Dear future, this is what I demand

I demand to be proud

I’ll say this is not the end

I’m proud of my culture

我一定要勇敢

(I must be brave)

Call this the sequel

Of a story I used to hate

The new and improved reboot

And again and again I’ll say

我是台灣人

(I am Taiwanese)

我是美國人

(I am American)

不管我是誰

(No matter who I am)

I should never run

Still I look back on the past Stories I will carry

I can’t help it, no I can’t

Still their words I find it scary

Taiwanese or Thai?

Slanted eyes or a narrow nose

Why don’t you ever wear a kimono?

Are the asian stereotypes true?

It was questions like these that made me afraid Made me want to hide all of my colors

If there’s nothing on the surface for them to see Then what is there to judge?

But now I’ve learned

I think I’ve grown And now again

I’ll say

我是台灣人

(I am Taiwanese)

我是美國人

(I am American)

不管我是誰 (No matter who I am)

I should never run

Never run from who I am

Don’t let it get to my head

Don’t let them flood my mind

Yet I reflect on who I am

I hope I’ve learned

I hope I’ve grown

But no matter what

I’m Proud

我是台灣人

不管我是誰

PLAY VIDEO 38

Forever Twelve by Alina Q

I am twelve, and the ivory keys of our grand piano do not stir. Days of practicing my triplets and arpeggios expire as my idyllic childhood rots away before my own eyes. I am twelve when I first recognize the talk of a career in computer science or mathematics or engineering that erupts over dishes of scallion pancakes and egg tofu.

But I am only twelve, and I do not understand.

I am thirteen and the pressure of my parents and their parents before them weigh down on me like dumbbells as I lean over my desk, sprawling and poring over the pages. I recite the equations to myself like a war song.

I am bright, and I know it as well as my classmates at school; but I am not bright enough for the prying eyes of the aunties that come over and wonder offhandedly about my whereabouts. I am thirteen and I try to force myself to care.

I am thirteen when I pick up the blade in the mirror of my bathroom. I stare at my reflection and I do not recognize the person staring back with wide and unblinking almond eyes. I stand on the cold tile floor as I watch blood bloom into little crimson beads along my skin, the serrated blade dragging across flesh in one swift motion. I know my mother and father would never understand, even if I summoned the smothered embers of courage remaining within me. This I can control, I assure myself. At least this. I pray fervently to whatever God is in the heavens that as I stare at my bedroom ceiling into the late hours of night.

I am thirteen and yet I still do not understand.

I am fourteen and I curse myself for not being able to be as hardworking as I wished I could be, or as my mother wished I could be. I am fourteen and still the expectations weigh impossibly heavy upon my shoulders, my own towering ambitions adding to my load. This and this and this. I keep up, but just barely so, trembling under my burden. My mother watches me with critical eyes, her voice filled with venom as she speaks sharply in a concoction of both Chinese and English. I am fourteen and I know am not the person she wishes I was and neither God nor I can help it.

I am fourteen and I am exasperated.

I am fifteen and I meet people just like me. They share my skin along with their stories and struggles and worries. We are fifteen as we speak in low, hushed tones of the future ahead of ourselves and our eyes meet in unsaid acknowledgement. We are fifteen and we confide in each other for everything, for we know that together we will always understand. I am fifteen and I find that I am not as alone as I think.

I am fifteen and there is hope.

I am fifteen and I understand.

39

PLAY VIDEO

40

A Pencil vs. Pen by Nguyen H.

A Pencil vs. Pen by Nguyen H

A pen is designed to write smoothly on paper, With ink filled in its cartridge, Leaving a permanent trace wherever it trails, A pen’s mark can’t be undone, Its stains can not be erased, A pen is made for perfection, Its bearer must make no mistake.

In contrast to a pen, A pencil has a built in eraser, Its traces can be erased, A pencil prepares for blunders, Its bearer can review their faults, Ameliorate them.

pen is designed to write smoothly on paper, With ink filled in its cartridge, Leaving a permanent trace wherever it trails, pen’s mark can’t be undone, stains can not be erased, pen is made for perfection, bearer must make no mistake. contrast to a pen, pencil has a built in eraser, traces can be erased, pencil prepares for blunders, bearer can review their faults, Ameliorate them.

When offered a pen or pencil, I choose the pen, I’ve left myself, Without room for error, No, I am not cocky, I’m a perfectionist, Just like a pen, My cartridge is filled with ink, So when I don’t fit in the standards created for me, Just like a pen, My ink bleeds, Leaving an indelible mark that ruins my pristine sheet, To be Asian,

Even if I wanted to fix them, I couldn’t, Scratching those errors would just emphasize them, They’d remain here, Sabotaging my paper for eternity, Soon, my paper is filled with scribbles, As I desperately try to fix my drawing, My brain aches, Wondering why the lines don’t look right, I’m revolted by the image created, I stare at my creation blankly, Continuously loathing it more and more, I realize, I’m no match for perfection, I can’t afford to bleed ink,

I am expected to excel in my academics, The percentage on the top corner of my test, Dictates my self worth, I am defined by my intelligence, To fit the Asian beauty standards, I am expected to be thin and pale, They are what my pen must follow, But of course,

There is bound to be flaws, My pen is forced to wield in such unfamiliar strokes, When I receive a lower score on a test, My pen slips, When I gain another inch of fat, Another mark skids across the sheet, They make up the impurities on my paper, They distract the viewer from the whole picture,

I watch those around me, Wield a pencil, Unlike me, They don’t dwell over a mere mark, They erase it, If their hand slips, They redo that stroke, I notice, They slip about the same times as I do, But all their imperfections are erased, Leaving just a beautiful image behind, Their erasers enabled them to advance, Learn from their mistakes, And so I realize, I don’t have to be bound by my errors, I am not defined by a grade, There’s more to being Asian than just intelligence, I don’t have to set myself into a permanent mold, As I stride along those thoughts, My brain relaxes, I finally accept myself, With every flaw, Instead of letting them dictate my self worth, I understand that I can improve, Erase them on my final paper, So when I’m offered the choice between a pen or a pencil again, This time, I gladly reach for the pencil.

When offered a pen or pencil, choose the pen, I’ve left myself, Without room for error, No, I am not cocky, a perfectionist, Just like a pen, cartridge is filled with ink, when I don’t fit in the standards created for me, Just like a pen, ink bleeds, Leaving an indelible mark that ruins my pristine sheet, be Asian, am expected to excel in my academics, The percentage on the top corner of my test, Dictates my self worth, am defined by my intelligence, fit the Asian beauty standards, am expected to be thin and pale,

41

The Exigency for Empathy

My family is pure Korean: my 아빠 (Dad) is Korean, as is my 엄마 (Mom). Being from a conservative Korean household, mental health was taken just about as seriously as double-eyelid surgery. Not as popular, but not taken seriously at all.

Sometimes, I have wished that instead of panic attacks, perhaps it would have been better to break a bone or tear a ligament; at least with excruciating physical pain, there would be people who would sympathize with and understand my affliction. There were no words to describe what I had felt on the inside, and a doctor's diagnosis would find no signs of a physical ailment. Every complaint and concern that I raised would simply enter into my 아빠’s one ear and slide out the other with the default consternation of "go to [my] happy place". My "happy place" was usually closing my eyes and imagining myself on the sandy shores of Jeju Island, where our family frequently vacationed, surrounded by crystal-clear waters and enjoying a cool, frozen Korean pear-flavored Tank Boy while floating on the waters. This meditation has never worked for me.

The feeling of falling from a high altitude and the immediate washing over of a shroud of doom, adrenaline and cortisol coursing through my veins, leading to an inescapable box of horror, exacerbated my already-anxious thoughts. My mind would race with worries about when the next panic attack would strike, and there was no preparing me for its excruciating terror and unpredictable haunting. My 아빠 would tell me, "It’s all in your head. Snap out of it"—in Korean, of course. In a strict, stern, disciplinarian tone, that would make me feel as though what I was going through was my fault—that it was because I wasn’t controlling myself that these terrors were befalling me.

"You’re not actually going to class today", 아빠 assured me. "It will only be a visitation. After our visit, you can go play your ‘Nintendo console device’". It was actually a Wii U, and his promise placed me at ease—after all, pinky promises were unbreakable and irrevocable. He even sealed this pinky promise with his thumb. It was my first time visiting an American classroom after having only seen Koreans throughout my life.

As I began to stroll down, my hands clasped and interlocked with my 아빠’s at the sight of the first Caucasian. A strange feeling began to wash over me. For some reason, I was afraid. Why did he have golden hair? Why were his eyes green? Why was his face so pale? Was he a 도깨비 (goblins in Korean culture)? In Korean folklore, these monsters ate children. I was terrified for my life—of course, I was only a foolish and ignorant child. Many of my close friends are Caucasian today

Suddenly, 아빠 left. Hands unlocked, like his iPhone, I was left in this prison cell, and the door slammed behind him. There, behind the locked doors, my first wave of panic washed over me. Looking around the room, I did not see any Koreans around me. I saw more 도깨비s. I frantically wanted to leave, but I was trapped in a room full of 도깨비s.

Tick, tock, tick, tock. I anxiously watched the clock, but each second felt like minutes, and minutes felt like hours. I anxiously watched the door—where was 아빠? He had to save me from these 도깨비s I closed my eyes for a while and covered my ears, but when I opened them, the 도깨비s were still there. I watched the clock again. Tick, tock, tick, tock. Only 2 minutes

42

have passed since 아빠 left. A tidal wave of hopelessness began to wash over me, and suddenly, at that moment, the feeling of betrayal from 아빠, who had pinky-promised and sealed with his thumb that I would not start class today, began to envelop me, and I began to weep. I began to bawl. Urine began to trickle down my ankles as laughter began to trickle into the classroom.

I began to resent 아빠 who threw me into this prison. I began to resent 아빠, who told me that my panic attacks were all in my head. There was no way for me to leave. All the students in the classroom stared with detached and unsympathetic eyes. As a matter of fact, some of them laughed at me with jeers and sneers that only compounded my sorrows; they stretched out the ends of their eyes with their fingers and mocked the physical shape of my eyes. I just wanted all of this to end.

It is estimated that 19.1% of Americans, or over 40 million people, suffer from the diverse spectrum of anxiety disorders every year Those studies under-represent the prevalence of anxiety disorders within Asian demographics because the stigma against mental health leads many Asians to not go to their doctors for a diagnosis. Many people who are undiagnosed feel the emotions that I experienced as a child without ever realizing that there is help and support for their condition. I take a small pill (Lexapro 10mg) that completely removes all of the feelings of dread that wash over me during a panic episode. When I first saw my therapist, I was astounded to learn that what I was going through was not unique to me: this gave me reassurance, as I began to learn that there were communities of people who suffered from my same ailments and were able to provide love and guidance toward recovery- many of the people who helped me in my recovery were Caucasian. Unfortunately, mental health is stigmatized within the Korean community, and as such, more education and outreach as to the prevalence of mental health issues can allow for greater probabilities of acceptance among Koreans and the AAPI community at large. I believe that strong leadership in providing quality education can break down the barricades of ignorance that have plagued Korean society. Today, South Korea leads the world in suicide statistics. Addressing the core mental health issues prevalent within our culture will not only allow us to honestly assess ourselves but also move forward as a society, liberated from the torments of mental disorders.

43

“All You Can Eat” is a mixed media painting made of watercolor, then outlined with red and black india ink. It’s hard to explain this piece into so few words, because of how many meanings it can take on. I like to invite viewers to search for symbolism in my art and discover their own interpretation.

Personally, my main statement was pertaining to generations like mine assimilating into American culture and losing our original asian heritage, only to later “consume” all information at once after being starved, taking a toll on our mental health. A specific example of this over-consumption happened during the COVID pandemic, when the phrase “ Stop Asian Hate” was increasing in popularity. Our heads were

collectively being filled with atrocities committed around the country. In America, Asians are minorities and thus we become a melting pot. We can’t care about just one nationality, Asians in America are hurt as a race. We’re all connected at one big circular table.

Another meaning can be found about the beauty standards in Asian cultures. Many prefer thin bodies and double-eyelids, and so we gain eating disorders and body dysmorphia. A common phrase for Asians living in the gluttonous America, land of the large food portions, is “You’re getting fat”. How ironic is it that Asian food is so delicious and culture to be celebrated, yet we cannot eat too much for fear of shame?

44

“All You Can Eat” by Sofia D.

Asian Armor by Edward C.

Asian Armor by Edward C.

Sweat ran down my body in streams, scurrying to escape the heat of my skin. It found refuge on the wooden tiles of the dance floor. The teacher was teaching us a dance step, and my mind tracked the sound her shoes made it was a box step. I grinned as I copied the shape of the footwork, feeling the weight of my feet hit the wooden floor to create a box. Time became inconsequential. All I could hear was the allure of the music, comforting in its embrace of my steps.

“Thank you so much for coming!”

I snapped from my trancelike awe. I glanced at the clock -- one hour had passed. Staring at the mirror, an entirely different figure stared back. Sweat fuzzled his unkempt hair and drenched his white shirt. I beamed. My figure beamed back, only wider and happier. I stared back in wonder, realizing that that figure was me. The past hour felt like an out-of-body experience. It was surreal! How could I experience that again?

10 years ago, that out-of-body experience marked the beginning of my dance journey. From that moment, I would pester my mom about continuing to take Hip Hop classes. I would find happiness. Had it not been for the founding of that new dance studio, I might not have discovered this gemstone of an art. But this was beyond me. This was beyond my fervor. This was passion. Along the rollercoaster of life, this passion was the seatbelt that secured me to my seat, fastening me as I rushed through winds of change and gusts of joy, and I relished its significance in my life.

Passion begets passion. As I progress through my journey, I hope to ignite that spark I felt so many years ago in the communities around me. After all, without the spark of art, our souls’ tinder would be reduced to mere sticks and twigs, incapable of lighting the fire of life.

Growing up, the main priority my parents set was to find me my spark. I was given outlets, each one an electric current of expression and release, and I chose to plug into the vivacity that was Hip Hop. It was my lighthouse of hope and excitement, slicing through any fog of uncertainty and hopelessness. I was a dancer and proud of it.

I grew up in homey Irvine, California, with its cookie cutter HMarts and ni haos. Asian was the fashion style. I was the geek, the know-it-all who knew it all. At night, a plethora of dance classes dotted my schedule. I was the dancer, popping in my seat whenever music played. Through such a childhood, I reveled in the A’s that dotted my report card and the trophies that filled my room. I was an Asian dancer, and as I grew older, that identity grew into a battle between my artistic endeavor and my academic intellect.

We, as a community, are shoved into a stereotype of excellence. Under this plate of academic armor, we charge into the hinterland, wading through terrain of education and erudition. It’s sturdy armor. Yet, such an armor only fits a certain few – a demographic of doctors, lawyers, and engineers. The rest remain unprotected against the swaths of AP classes

46

and extracurriculars, unsupported by the elderly. As they should be, right? After all, practicality reigns supreme.

Yet, this plate of academic armor can compress us teenagers, forcing us to comply with the demands of the academic battlefield. It can choke us into concurrence as we march on towards the horizon that is colleges, careers, and cash. The iconoclasts fall out of line. The artists are impaled by the spear of utility. The rejected sulk back to their barracks.

As I near the end of my high school journey, such a dilemma plagues me. I enjoy both my academic pursuits and artistic passions; yet, with this growing pressure to prioritize academics, how can I find a balance? How can I make both my family and myself happy?

My family and I talk. We touch the tainted lens of our thoughts, peering through a spyglass of curiosity and peeking at the tattered remains of our conscience. What does it mean to be Asian-American? Is it the A’s that dot my report cards, staining the Aeries portal a deep navy blue? Or is it the 3 AM freestyles, rejuvenating my soul as I step into an aura of purpose and drive?

As I delve into these questions, I find myself leaning into my soul’s expression, my art. Self-expression is one of the most powerful tools in relieving ourselves of the burden of societal pressures and stress. I’ve continued to live by the belief that passion begets passion as I spread the love of Hip Hop at my school, my studio, and with my peers. I hope to empower the AAPI community to find light in their own avenues of expression. We are all human, but we are each huger than life, unique in our own imperfect, expressive ways.

Maybe this isn’t a battlefield.

When we strip away our armor, who are we? Are we militant warriors, marching towards the frontier of competition and comparison – or rich arsenals of care and compassion, maintained to defend a space for expression and service? Only we can tell.

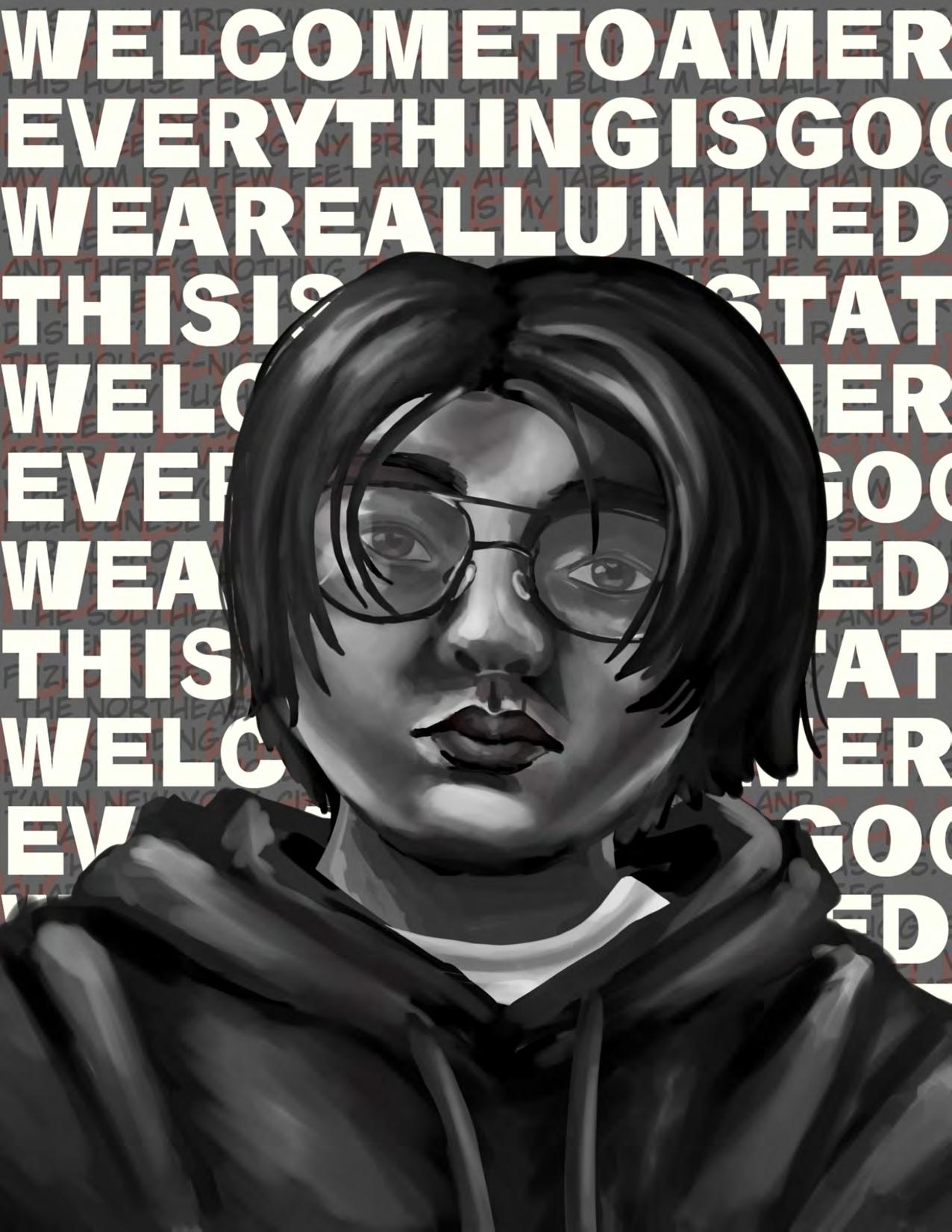

47

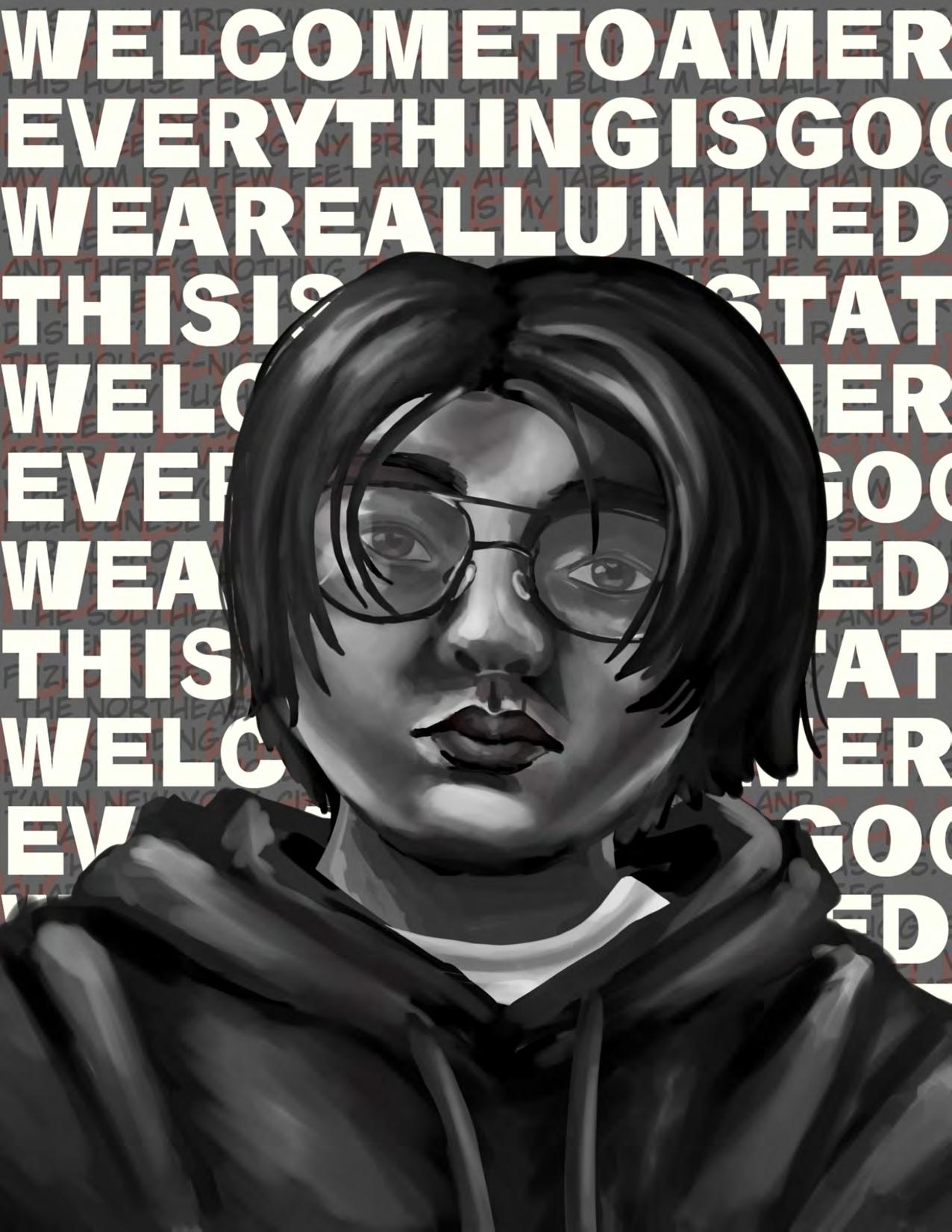

I painted “Mask” for a gallery exhibition around Covid-19’s impact on teenage mental-health. It began as an outlet to express an omnipresent feeling of overwhelmedness: During the pandemic, I was terrified for myself and those close to me, angered at political apathy and inaction, and disheartened by how AAPI trauma was being weaponized to support policing and pit Black and AAPI communities against each other. Simultaneously, I was crumbling under academic stress, in a school environment that lacked AAPI representation or support. When I attended class and went through life, I felt pressure to mask what I went through, feigning composure despite being engulfed in a mess of emotion. The double-exposure effect I mimicked aimed to capture the complex experience of feeling everything all at once.

As I painted and processed, I realized “feeling everything” also encompasses feeling strength and renewal. While the piece began as a visualization of hardship, it also gave me an opportunity to reflect on how my pandemic experience motivated me to build AAPI community and anti-racist education at my school, brought me closer to my loved ones, and cemented the value of culture and intersectional justice in me. The “mask” I put on evolved into genuine leadership skills and confidence that coexists with my stressors. I hope this piece helps others feel seen in both their trauma and strength, and shows that AAPI mental-health is nuanced. A person cannot be reduced to a single experience or stereotype: truly seeing people requires a multifaceted lens.

49

Mask by Tula K.

Foolin’ my skirt by Michelle Q

I spin and I twirl in the pretty pink skirt my mother got for me. So feminine, so innocent.

A classmate’s eyes gazed and stared at the way it swished in the air. Another classmate’s pencil scratched his sketchbook pages. A group of boys in the back of class chatted amongst themselves, and their not-so-faint whispers traveled through the class.

“She’s like that girl in that video you watched.”

A woman wearing a sexified Japanese schoolgirl uniform radiated from the computer screen the boys were gawking at. We looked nothing alike, except for the fact she was also Asian. Was it because of my skirt?

He wasn’t looking at my skirt but imagining what was underneath. He wasn’t shading my skirt’s ruffles but using me as reference for his drawing of a sexualized Asian fantasy. All they saw was a slut—no, an Asian slut, which is supposed to be even sluttier than a white girl—to be looked at, unheard and uncared for.

Sometimes other girls called me lucky. Not lucky in the way my mother had gifted me that skirt for good fortune; it was to remind me of how much of a wonderful daughter I was, she said. But lucky that I attracted attention from boys, just by being Asian. To them, it was a blessing from the gods of seduction.

When I finally got the courage to wear a skirt again, I decided on a black skirt perfect for a family reunion. It was more subtle with no erotic ruffles or promiscuous colors. It was nice and plain, just as I should be to not be an attention-seeking, pink-loving Asian slut. It was feminine but not too feminine.

“You’re built like a stick.” My aunties handed me another bowl of rice.

“Who ate the old Michelle?” My uncles instructed me to do laps around the house.

“Here. Take this to massage yourself. It’ll help your curves come in.” I looked back at the mysterious green concoction in a potion bottle that was somehow going to remedy my door-like body structure.

Never did they ask about my grades or academic achievements—that was reserved for phone gossip. Or the new dance I learned for Multicultual Fair. Or the chè ba màu I made for the party.

I was just someone whose arms and face resembled a skeleton and whose legs weren’t straight and skinny like the white girls at my school. My thighs and calves weren’t for walking but for family members to criticize when they jiggled. My looks headlined every conversation. Perhaps all their energy was exerted wandering their drunken eyes and

1

50

blabbering their gluttonous mouths, leaving their ears no power to listen to whatever I had to say about the type of person I was.

I might as well had been a statue. Then, they could fully sculpt my body into something exceptionally tolerable.

Why wear a skirt when you have nothing nice to show? Aren’t sluts Asian sluts supposed to be pretty?

I got a direct message from a faceless Instagram page asking “You’re Asian, right? Are you single?”

Scrolling through his following list, I found they were all Asian girls from my school. His entire reasoning for wanting to date an Asian girl stemmed from his unfortunate dating history. While he was dating non-Asian girls, he always saw his other white male peers dating Asian girls and thought they looked overjoyed. To him, Asian girls are petite, cute, and never mistreat white men.

While he was on his hunt for delicate, docile Asian girls, the prey bit back. I found myself among tens of Asian women calling out the guy for fetishizing Asians, realizing his words aren’t compliments but were creepy comments. As much as he loved us Asian girls so much, he became livid over the fact that we weren’t the Asian schoolgirl sluts he believed we were that I believed I was.

I always thought I was just something to look at, so I never spoke up for myself as an Asian femme. But, these Asian women knew exactly how I felt, and we shared in our pain of feeling trapped in the deep-seated hatred that lies underneath all the sexualized “love and appreciation” white men offered to us.

We deserve to feel like real people in our femininity, our skin, our Asianness and make a fool out of those who try to make us feel like we’re anything but that.

Because it was never the skirt.

2

51

Familiar Flowers by Sarah C.

Growing up in a family of seven has made me realize that familial bonds are important to maintain and cherish throughout life. My family has been there to encourage me on my artistic journey; they are people I can rely on and confide in. The people depicted in this piece are my two sisters, one older and one younger. They are drawn in a field full of chrysanthemums,

a flower that represents friendship and happiness. My sisters are family, but also close friends who I can lean on in tough times. Their body language and expressions imply trust in one another. My artwork strives to show how family and friends can be a place of refuge when situations may bedifficult and a place of relaxation to share laughter.

52

53

Not Just by Remy P.

I am bipolar I struggle with PTSD I am crippled with anxiety I have to fight every day to get out of bed I cannot focus in class for my life I will never be anything other than these things

I am Remy P. I do not let the past haunt me for I am past it. I fight for myself, not against. I am a high achieving student who has been accepted into college, participates at school as a member of the student council, and is part of two international organizations from my high school chapters. I play sports, lift, paint, sing, and do countless other activities. I am Chinese American; I refuse to discard this label by focusing on any others I have been assigned. I cannot be condensed into just a few words.

I can’t be helped none of the medicines have been able to change me what if they never do what if I’m never enough I never should have told anyone all it has been is a waste of time money energy

My mom, my doctors, and my friends– they have been with me throughout this whole journey because they care. They cared before and still care now; everyone only wants the best for me. They haven’t given up on me– I can’t give up on me. I suffered for years on my own, wrestling with the idea that my own mother had abandoned me as a days-old baby, along with the hellish feelings that parasitized my internal war. I do not regret reaching out for help because even if the process has been long and exhausting, it is infinitely times better than being exhausted for so long alone. I am not just dragging those around me down, but being carried through their strength.

Why do I have to change this isn’t fair why am I not good enough to be allowed to be myself why was I not good enough to be kept I’m just a robot trudging through life and just as inhuman

I am not a robot– I still feel feelings like anyone else. I have crushes just like any other teenager. I can feel sadness without it being tied directly to my depression. I can be happy in my life and proud of what I have accomplished. I’m not changing to bend to what society expects of me but so that I can celebrate the time I have. I am not good enough– I am more than enough. I understand my mother was only acting in my best interests despite the hurt she may have felt. I am not just surviving– I am living a life I deserve to enjoy.

Why am I like this would I have been different if I hadn’t been adopted what if I had known about any of my genetic risks could I have been more careful knowing what might happen what I would become

I lead a life here in America that would never have been possible in China. Even if I knew my

immediate family’s medical history, I would only have been more stressed about it for longer. My 54

just as inhuman

I am not a robot– I still feel feelings like anyone else. I have crushes just like any other teenager. I can feel sadness without it being tied directly to my depression. I can be happy in my life and proud of what I have accomplished. I’m not changing to bend to what society expects of me but so that I can celebrate the time I have. I am not good enough– I am more than enough. I understand my mother was only acting in my best interests despite the hurt she may have felt. I am not just surviving– I am living a life I deserve to enjoy.

Why am I like this would I have been different if I hadn’t been adopted what if I had known about any of my genetic risks could I have been more careful knowing what might happen what I would become