INDEPENDENT SCHOOL MANAGEMENT

Decarbonisation for the school estate

Climate change and the management of risk

Reduce your school’s operational carbon footprint

Responsible investment is about sustainability, not compromise

Decarbonisation for the school estate

Climate change and the management of risk

Reduce your school’s operational carbon footprint

Responsible investment is about sustainability, not compromise

Welcome to the autumn edition of Independent School Management. Thank you for all your positive comments about the magazine.

In this edition, we focus on positive strategies to consider for the new school year.

The increasingly high temperatures recorded this summer, along with forest fires, floods and other natural disasters all spell out a clear message about the effects of climate change on the planet. This year may be the hottest in the past 100 years, but might also be the coolest for the next 100 years.

As medium to large businesses, schools have their part to play in reducing their own carbon footprint. But sustainability isn’t just about doing the right thing, aiming for net-zero in energy use can also reduce operating costs as it can lower your energy cost base too, after the initial investment.

We have a special focus of features that consider various green measures, including decarbonising your school estate (ceasing to use fossil fuels for the operation of the school’s heat, transport and power requirements), marrying a sustainable approach with your works programme, identifying and mitigating risks, and considering an ethical approach to investment (by avoiding investment in fossil fuels, but also on whether an investment business is involved in other areas such as tobacco, the arms industry, animal testing and gambling).

Across the water International school projects continue apace. If your school is considering an international iteration, it’s vital that you and your team are aware of the potential risks from the very beginning. Some of the key risks include:

• Reputational damage to the home school if the overseas iteration is unsuccessful or is mired in scandal

• Insufficient demand from inadequate prelaunch research that fails to predict the potential demand for places

• The risk of planning/managing an overseas school diverting

management time and investment away from the UK operation

• Parents at the home school feeling concerned that their school fees are being spent on the overseas school rather than on the one educating their child in the UK

• Local regulations can be complex, inconsistently applied and are always evolving, so require ongoing supervision. This absorbs both management time and expense.

Protecting the school brand is key. It’s imperative that you register your school's trademarks in countries of interest preproject to avoid an interloper stealing your legal identity there.

There will also be a need for project documents, including a ‘memorandum of understanding’, which helps discussions to reach an initial agreement with a potential project partner at an early stage, and sets out the intentions of the two parties. Another is a ‘heads of terms’, which sets out the main commercial terms of the project. The final ‘project agreement’ sets out a clear, practical and detailed framework for the relationship between the parties and the operation of the school prior to and after the launch of the school.

Apart from the potential financial benefits of a successful international project, the relationship between the home and overseas operations enables valuable opportunities for sporting and cultural links, exchanges of staff, and the development of an international community of alumni.

Back closer to home, key changes for the inspection of governance under the Independent School Inspectorate’s (ISI) new F23 have just come into effect. We

analyse the key changes and amendments affecting an independent school’s operation. One of the more significant changes is that single word qualitative judgements are being dispensed with: something that heads and teachers in the maintained sector have been demanding from Ofsted in their inspections, especially since the death of a headteacher in Berkshire after a harsh designation was assigned to her primary school.

Governance itself will not be judged by ISI, as with the previous framework. However, since the framework focuses on “the responsibility of the school’s leadership and management and governance to actively promote the wellbeing of pupils at the centre of ISI’s evaluation of the school”, this is very likely to lead to an expectation by the inspectorate of an extensive provision of evidence that demonstrates how this is achieved. Nothing is ever straightforward when it comes to ‘new’ and ‘improved’ frameworks.

To keep up with the latest sector news and people moves, follow us on Twitter @IndSchMan

Editor,We trust you will find this issue of Independent School Management informative and useful.

To keep up-to-date with the latest independent schools news, ensure you receive future copies and sign up to our newsletter, please visit our website.

independentschoolmanagement.co.uk

Chief executive officer

Alex Dampier

Chief operating officer

Sarah Hyman

Editor Andrew Maiden andrew.maiden@nexusgroup.co.uk

Reporter and subeditor

Charles Wheeldon charles.wheeldon@nexusgroup.co.uk

Advertising & event sales director

Caroline Bowern 0797 4643292 caroline.bowern@nexusgroup.co.uk

Business development manager

Steven Godleman steven.godleman@nexusgroup.co.uk

Event manager

Conor Diggin

Operations executive

Sophia Chimonas

Senior conference producer

Teresa Zargouni

Head of digital content

Alice Jones

Marketing design manager

Craig Williams

Marketing campaign manager

Sean Sutton

Lead developer

Jason Hobbs

Publisher

Harry Hyman

Investor Publishing Ltd, 5th Floor, Greener House, 66-68 Haymarket, London, SW1Y 4RF

Tel: 020 7104 2000

Website: independentschoolmanagement.co.uk

Independent School Management is published three times a year by Investor Publishing Ltd. ISSN 2976-6028

© Investor Publishing Limited 2023

The views expressed in Independent School Management are not necessarily those of the editor or publishers.

@IndSchMan linkedin.com/company/ independent-school-management

6-9 News in brief

10-11 Go your own way

12-13 Keep it simple

14-15 Cashing in Bursars should use deposit platforms

16-17 Why net zero?

Decarbonisation for the school estate

18-19 Weather the storms

Climate change and the management of risk

20-21 Onward march

Reduce your operational carbon footprint

22-23 The right choices

Responsible investment is about sustainability, not compromise

24-25 Beyond the small print

How parent contracts should work for your school

26-29 Standard bearers

Inspection of governance under the Independent Schools Inspectorate’s F23

30-31 Worldwide opportunities

Emerging market opportunities for international schools

32-33 Destination Dubai

The emirate is welcoming UK independent schools

34-35 Find your resilience

Overcoming daunting challenges

36-37 All change in the classroom?

A Labour government might redefine school recruitment models

38-39 Embrace apprenticeships

How they can be used as part of the school workforce

40-41 Make change positive

Protocols for making effective change while keeping stakeholders on board

42-43 Build a development office

Strategy for the effective launch of external relations

44-45 Beyond hope

Development should be at the heart of a school’s central management function

46-47 People moves

48-49 The last word

Suzie Longstaff of London Park Schools

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer has claimed that his party’s policy on independent school taxation is not an ideological attack, Jewish News has reported.

Starmer was answering questions from Year 6 pupils on a visit to Independent Jewish Day School in Hendon, north London – and when the subject was raised he backed the policy outlined by Labour’s education secretary Bridget Phillipson to end charitable status and impose VAT on fees.

Starmer said: “Ending the tax break is not aimed at independent schools on any ideological grounds. It’s simply trying to answer the question of, if in your state schools you don’t have teachers in basic subjects like maths, then are you going to do anything about it?

“And if so, how are you going to pay for it? That tax break will be used to support the recruitment of 6,500 new teachers into state secondary schools in subjects like maths.

“Any parent, whether they send their child to an independent or a state school, would say every child deserves to be taught in the core subjects by a teacher who has got the relevant qualification. This is not intended as any reflection on independent schools. We want them to thrive and to work with them.

“It’s a way of ensuring we get enough

good teachers into secondary schools to make sure every child has the chance to thrive. My ambition, because we will have five missions in government, and one of them is about education and skills.

“One day, if we get this right, it shouldn’t matter whether you go to independent school or state school, and that every child will have the same chance, whichever school they go to.

“That’s not to the detriment of independent schools; on the contrary, I want to make sure every child has the best chance.”

Katharine Birbalsingh, head of Michaela Community School in Northwest London and known as Britain’s strictest headteacher, says private schools are scrapping GCSEs because “they are failing to meet the standards,”The Telegraph has reported.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, Birbalsingh said: “If you do not perform at GCSE, then that is why they are doing this. Because over Covid, we learned what teacher bias does, about how the grades are then inflated. In particular, in the private sector, the grade sevens in the private sector went from 46% to 61%.

“And this move will allow them to do exactly the same thing again, which will advantage richer pupils, the pupils that can

afford £25,000 a year over the normal kids [at] state schools. And they will then get the jobs and get the positions of authority out there, having not achieved any kind of national standard.

“And this is the private schools pushing through an agenda, because they are failing to meet the standards that they should do for their pupils that is really important to note. People think that they are, but they are highly selective and they are not coming out with those nines or the sevens frankly for their pupils.

“And now they’re saying what we need to do is create our own exams because they are not performing at the level that they should do at GCSE level.”

Latymer Upper School, a private school in Hammersmith, west London, recently announced it is dropping all GCSEs apart from English and maths and creating its own qualifications.

Latymer’s deputy head Ian Emerson said that GCSEs “remain narrow and are marked according to rigid and limiting mark schemes”.

He said: “They reward rote learning rather than deeper, more original thinking. And they do not effectively teach students the core skills which are sought after by employers in the modern workplace.”

Earlier, Hampshire private school Bedales stated that it plans to move to its own ‘Bedales Assessed Courses’ in most subjects.

Nord Anglia Education has officially launched Oxford International College (OIC) Brighton, a new independent day and boarding school for pupils aged 13 to18.

The Lord Lieutenant of East Sussex, Andrew Blackman, hosted a special tree-planting ceremony to commemorate the opening of the school, after which the Mayor of Brighton & Hove, Jackie O’Quinn, officially opened the new building before attendees were taken on tours of the school campus.

The school, which will expand to accommodate a maximum of 400 boarding and 100 day students over the coming years, is built upon the model of its sister school, Oxford International

College, in Oxford.

OIC Brighton offers pre-GCSE, GCSE and A-level courses for British and international students and enrolled 160 pupils for the start of term.

Tess St Clair-Ford, founding principal of OIC Brighton, said: “We are thrilled to welcome our first cohort of students to our newly renovated Brighton campus as they

embark on their learning journey with us. Following extensive investment, all of our students benefit from state-of-the-art facilities thoughtfully designed to support their learning, while our enviable location in the British countryside, close to the city of Brighton and the coast, provides our students with many opportunities to relax, study and stay fit.

“Our passionate teachers, who are leaders in their fields, will guide our students to stand out as pioneers, original thinkers and highly skilled learners. By matching the ambition we see in our students with an equally ambitious and motivated teaching team, we will build a culture of dynamism, making our college an inspiring place for both learning and teaching.”

Andrew Fitzmaurice, chief executive of Nord Anglia Education, commented: “OIC Brighton will be an outstanding school, focused on high-quality

teaching and learning, academic excellence and wellbeing. Our new school is an international place of learning dedicated to nurturing students’ global citizenship, confidence, resilience and team spirit.”

“We are a school community with wellbeing at its heart. I truly believe that there is a deep connection between academic progress and strong mental health and wellbeing. This focus on wellbeing is at the core of everything that we do as a school; creating an environment where all our students feel fully supported and ready to take on any challenge.”

Eton College is partnering with state school trust Star Academies to open free sixth form colleges in Dudley, Middlesbrough and Oldham which will educate young people from deprived communities in the Black Country, Teesside and northern Greater Manchester, supporting them to achieve places at the very best universities. The colleges will be called Eton Star Dudley, Eton Star Oldham and Eton Star Teesside.

Partnerships between independent schools and the state sector offer little benefit for the state schools involved, a report has claimed. Of the state schools polled for the report, only 3% said they benefited

from access to private schools’ facilities and just 1% benefited from teacher secondment. Many of the partnerships involved little more than joint football matches or invitations to school concerts, the report stated. On the plus side, some state schools reported events aimed at helping state school pupils with university applications, and week-long summer schools at the private institutions. Freedom of Information requests were sent out to 400 state schools, with 277 replying. Of those, 36 (13%) said they were involved with a partnership with a school in the independent sector.

£13M

The bill to the taxpayer for the children of diplomats attending UK private schools amounts to £13 million annually, The Times reported. The Foreign Office, which funds the scheme, also spends an additional £25 million annually on the fees of schools overseas for children whose parents are posted there. The average cost for the fees of the 514 diplomats’ children attending UK independent schools is £26,800 a head. The support is available under the Foreign Office’s continuity of education allowance to diplomats who cannot take their children with them to their posting on security grounds, or where “local schools of an acceptable standard are not available”. The statistics were revealed following a parliamentary question posed

by the shadow attorney general Emily Thornberry.

The Labour Party has used a written parliamentary question to ask education secretary Gillian Keegan to provide evidence for her claim in the House of Commons that “many” private schools “cost the same as a family holiday abroad”, Yahoo reported. Schools minister Nick Gibb, replying to shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson, said: “Many private schools are attended by middleincome families who make financial choices to do so. The Independent Schools Council has confirmed there are around 50 private schools that charge £1,500 or less per term. Research from the travel company Expedia suggests that families spend an average of £4,800 on family holidays each year.” However, with 2,408 independent schools in England, 50 schools represent around 2% of the total.

over a three-year period and charged with 48 separate offences including 37 sexual assaults and 10 counts of causing a child to engage in sexual activity. A jury found him guilty of all but four of the offences following a four-week trial at Bradford Crown Court.

Kingswood School, an independent co-educational day and boarding school in Bath, has been fined £50,000 after exposing seven children and two staff members to high levels of radioactive radon gas, Yahoo News reported. Five pupils were exposed to levels of radon almost eight times the legal limit, while boarding in 2019 and two children of staff who lived on site were exposed to levels almost 14 times the limit, while their parents were also reportedly exposed to high levels.

Labour’s deputy Angela Rayner has declared that private schools are a waste of money and that youngsters can do just as well attending a local comprehensive. Raynor made the remarks on Sky News while commenting on former TV presenter Carol Vorderman’s criticism of veterans’ affairs minister Johnny Mercer for being privately educated but not attending university. Rayner left school

Alexander Ralls, 47, who was deputy head of boarding and deputy child protection officer at Queen Ethelburga’s School in Thorpe Underwood, North Yorkshire, has been convicted of more than 40 sexual offences against pupils, the Harrogate Advertiser reported. Ralls was accused of sexually abusing 20 girls

in Stockport at 16 with no qualifications after becoming pregnant. She later studied part-time at Stockport College, learning British Sign Language, and gaining an NVQ Level 2 in social care.

The National Secular Society has warned the Welsh Government that some independent schools are omitting education which conflicts with religious teachings. Responding to a consultation on proposed changes to standards for independent schools in Wales, the NSS warned that allowing the teaching of personal, social, health and economic education in a manner that reflects a “school’s aims and ethos” could lead to faith schools not teaching about protected characteristics set out in the Equality Act 2010.

The Methodist Independent Schools Trust, which owns Culford School, near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, filed a serious incident report to the Charity Commission. This follows the sacking of the school’s headmaster Julian JohnsonMunday following an independent investigation. A letter sent to parents by Mark Donougher, chairman of governors, said an investigation by an independent lawyer has found that Johnson-Munday breached several the school’s internal policies which constituted “gross misconduct and a breach of trust that was incompatible with his leadership role”. However, the school has emphasised that the allegations did not concern pupils.

The Thurlow Educational Trust, which runs Rosemead Preparatory School in Dulwich, south London was fined £80,000 by the Health and Safety Executive after a ceiling collapsed onto 15 children in a Year 3 class, ITV reported.

Tables and chairs fell from an attic above the classroom injuring pupils and their teacher who suffered fractured limbs, cuts and concussions. Several pupils were taken to hospital for assessment and treatment following the incident which happened in November 2021.

Special educational needs group Witherslack Group is planning to open a school for primary and secondary pupils near Tonbridge in Kent, Kent Live reported. The company has applied to refurbish Mountains Country House in Hildenborough set in 28 acres of parkland, the former home of Fosse Bank School until it closed suddenly in March. The new school will cater for 90 pupils with SEN, aged between eight and 18.

The Welsh government says it intends to amend the current regulations governing independent schools in Wales in a bid to enhance the quality of education and improve the welfare, health and safety of independent school pupils, Herald Wales reported. The proposed amendments primarily focus on two sets of regulations: the Independent School Standards (Wales) Regulations 2003 and the Independent Schools (Provision of Information) (Wales) Regulations 2003. The Welsh government also intends to introduce a new set of Independent Schools (Prohibition on Participation in Management) (Wales)

Regulations, which outline the grounds for prohibiting certain individuals from participating in the management of independent schools.

The Edinburgh Academy has apologised for “brutal and unrestrained” historic abuse as the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry took closing submissions in its investigation into the school, The National has reported.

Almost 50 witnesses have given evidence and 20 teaching staff at the school have been subject to allegations, including a child being beaten with a cricket bat, another pupil suffering a “small bleed on the brain”, a child being strangled, and boys being paid to swim naked. Most of evidence has covered the years between 1954 and 1995.

Corporal punishment was banned in Scottish private schools in 2000, but the hearing heard that “disproportionate sadistic violence” was common in the school in the 1970s and a “culture of fear” prevailed, with former teacher, Iain Wares, described by a lawyer for survivors as “one of the most prolific abusers in Scottish criminal history”.

The Edinburgh Academy acknowledged the “brutal and unrestrained” violence and admitted “serious sexual abuse was widespread”, and expressed regret that police were not brought in to deal with Wares in the 1970s. He was instead recommended to Fettes College. Wares and fellow teacher Hamish Dawson, who died in 2009, were publicly named during the inquiry. Wares was dismissed in 1979 and now lives in South Africa.

Courteney Donaldson reveals the secrets to owning your own school: How do you go about it? What are the risks? What are the opportunities?

It may sound a bit of a cliché but, for your school business to succeed, whether for-profit or not, you’ll need to have a genuine passion for what you’re doing. Successful business owners never underestimate the amount of work they’ll need to put in and the potential impact on their family and friends. It’s not enough to be acquiring or starting your own business because you are fed up with working for someone else, or because you are tempted by the idea of a millionaire lifestyle, albeit rare in education. You won’t get there unless you have the deep enthusiasm and drive which are necessary to succeed.

For many company directors, school proprietors and trustees, the decision to sell their school can be a difficult one. Typically, they will want to keep the sale highly confidential to mitigate any risks associated with the potential departure of staff and/or pupils, uncertain as to what the implications of a sale may mean to them as employees, or concerns from parents on the implication that a sale may have on their children’s education.

Because of the confidential nature of the independent school sales market, it’s essential that, alongside making web and press-based searches for possible acquisition opportunities, you work with an agent that specialises in the sale of education businesses. Concisely advise them of your specific requirements:

• What type of school are you looking for?

• Where?

• What operational profile?

• What capacity and tenure?

• One with an established track record or a turnaround?

Once the agent understands your strategy, they will be able to determine the opportunities currently available which are best suited to you. They are likely to ask you to sign a non-disclosure agreement prior to any sensitive information, such as management

accounts, being released to you. The agent’s role when acting for the vendor (business owner/trustees) is to introduce suitably vetted and serious prospective purchasers that have the prerequisite experience and financial ability to conclude a transaction successfully.

Ordinarily, most educational establishment acquirers will require bank or investor funding to finance their acquisition. First, speak to a financial broker that specialises in securing commercial mortgages for business acquisitions. This will ensure that your aspirations on the funding front are realistic from the outset.

Post-pandemic, and amid banks’ desire to mitigate risk, providing evidence of your educational experience and business acumen will be essential, and a comprehensive business plan will help to demonstrate this. Presenting both yourself and your business acquisition intentions and ideas in the best possible way to potential lenders is a vital part of securing any funding that you may need to acquire and invest in a business.

The agent’s primary objective is to achieve the best possible price for their client, often the vendor, and then subsequently support the transaction, from headline

deal terms and price being agreed, through to completion. Most acquisitions will be subject to financial, operational, property, and legal due diligence and, if a bank or lender is to provide a commercial business mortgage/loan, it’s likely that they will require a formal RICS ‘Red Book’ valuation for secured lending purposes, along with a building survey so that the condition of the asset can be assessed and any defects or requirements for capital expenditure identified.

Location: this is of prime importance to the success of a school and dictates the catchment areas from which students will predominantly come from. Think about demographics, competitors, local trading conditions, fee levels, average house prices in the area and so on. If you intend to be a hands-on proprietor, locality will be a matter of personal choice for you and your family. Also, consider the direction of travel for the school. If you’re contemplating growing boarding provision and seeking to serve international pupils, then ease of access to international airports, roads and rail will be key.

Tenure: does the school trade from freehold or leasehold premises? Think about both the long term and the short terms, how much money you can afford, loan serviceability and surplus for

“For many company directors, school proprietors and trustees, the decision to sell their school can be a difficult one.”Courteney Donaldson

reinvestment and any capital investment plans.

Property: consider the condition of the building and any repairs needed. If you are planning to acquire a school which has listed building status, do not underestimate the complexities and costs that ongoing regular maintenance and refurbishment may entail. Does the asset have scope for further development, or does it already benefit from purpose-built facilities which set it apart from other local competitors? Are sporting facilities held on the same legal title as the rest of the school campus, and, if they are leased or held on a licence, how secure are your rights as a buyer to occupy and use them?

Many factors determine the value of a school: its location, its buildings, their configuration and condition, the school’s tenure, its assets and liabilities, its fixtures and fittings, and goodwill. But the single most important factor associated with the value of a school when being sold as a going concern is its financial information. This comprises the business’s accounts, management accounts, cash flow forecasts, and profit and loss projections.

To be able to read your prospective school’s accounts, you need to have a good grasp of accounting principles, forecasting and business planning. A concise understanding of how the school is currently performing is essential, but the best way to look at accounts is to take as long a view as possible and to examine accounts from the previous few years. Good, dependable and accurate termly management information will be vital. You and your accountant will have to decide whether the accounts represent the true situation and, from there, you should be able to determine whether the business is well run, is overpriced given the level of current earnings, and/or if it has potential for a more efficient commercial operation or growth via changes or expansion.

You may be considering buying an independent school, developing a new SEND school or sixth form, selling or

transferring ownership of a school, or simply seeking to reflect the worth of your school in your accounts. In fact, any aspect of holding an interest in a property is likely to require a valuation at some stage. So, what aspects of the business form part of the valuation?

The calculations for the value of the school business will be based on the number of students in each year group, additional income, bursaries and so forth, and the valuer’s assessment of the sustainable level of occupancy or roll numbers. This will have regard to historic rolls and factors that might affect future rolls. The level of fees being charged will also be considered, as will the scope for fee increases and other potential revenuegenerating activities.

The four main categories for assessment are:

• Staffing

• Direct costs

• Premises costs

• Administration costs.

The end figure, or ‘market value’, includes the property, the fixtures and fittings and any goodwill attributable to the business. To calculate this, the level of operating profit is multiplied by the appropriate multiple, known as a ‘years purchase’ (YP) for that property. The YP is selected by benchmarking against comparable evidence from the sale or acquisition of other broadly comparable independent schools. This YP needs to be evaluated carefully to reflect the security of income streams, potential for growth or diminution in trade, the attributes or shortcomings of the school (and/or its assets), the strength of demand from purchasers/desirability of the business (and assets), location, availability of finance and potential serviceability of

loan/mortgage. The valuer will primarily have regard to transactions involving other broadly comparable schools. This evidence of actual sales is then interpreted in relation to the subject property.

Before you formally begin the process of buying an independent school, speak to a specialist business property advisor about the market so you have a good understanding of pricing, competition etc.

During 2022, the volume of operational independent school transactions was suppressed in comparison to previous years, primarily due to financial performances being largely distorted for the academic years 2021-22 postpandemic. Across the UK we saw an increase in smaller independent schools making the difficult decision to close and when those properties were presented to the market, a lot of interest came from SEND and specialist education providers.

The UK independent schools market continues to be highly fragmented and, therefore, opportunities for corporate groups and investors to acquire via portfolio buy and build strategies are not as prevalent when compared to the volume of opportunities in other operational real estate sectors. Established schools, with high rolls and a solid track record of stable and established earnings, continue to be highly sought after by buyers, as do smaller schools which may have closed but could be converted to a more specialist education use, or offer potential for alternative use.

Continually thinking about strategy is critical to your school’s consistent improvement. Leadership consultant Mike Buchanan argues, however, that you shouldn’t complicate your approach

As we have emerged from the immediate demands of the pandemic, many independent schools have been considering their futures in the face of a changed market for independent education, the ravages of unpredictable inflation and heightened threats from possible future changes to taxation and/or their charitable status.

I’ve been working with a number of schools and their leaders to help them think about those futures and to plan for them. Often, people rush to producing a detailed, often complex operational plan using SMART targets and other familiar paraphernalia. This seems to satisfy a need and they often look impressive, yet they often fester unread and unused once launched.

Distilling something simple which becomes a constant touchstone for actions, behaviours and standards is much more challenging and vastly more effective. The process of distilling is an essential element of a simple, effective strategic plan.

Plans have multiple audiences so you should be clear about who they are: staff, parents, children, governors, inspectors, the public. A well written plan can meet the needs of all without compromising the distinctive message and meaning you wish to convey.

Such a plan might have just three elements. Your challenge is to produce something on a single side of A4.

This is your three-minute pitch to prospective parents that encapsulates all that the school is about. It should use the language you use to reinforce these elements with staff and students every day. One of your measures of success is how quickly, loudly and often this language is parroted by others without prompting, and how everyone’s behaviours reflect these key elements. For example:

Learning: every child develops an understanding of themselves and their capabilities, and progresses to a school, university, college or employment of their choice with the confidence to take on their future.

Performing: every child achieves more than they ever thought possible, inside and outside the classroom, across a wide range of exacting intellectual and other pursuits, whatever their starting point.

Thriving: every child is happy; they are kind, principled, loyal, generous, determined, responsible, compassionate and bold; they relish collaboration, enjoy the intellectual freedom to be creative, the enterprise to act and the resilience to cope with adversity.

Here is where you can be clear about what you are expecting to see and feel in the school. Each of these elements is likely to have more detailed plans for delivery at sub-school level, providing accompanying

explanations of what they look like in practice and as measures of success. Your school may have a different number of elements in the ‘How do we do it?’ section, but I’d urge you to minimise these as this will force you to write with clarity and precision – every word must be carefully chosen to convey your specific meaning, and please do ruthlessly expunge all edu-jargon. Using plain English and active verbs will make it more powerful, lead to greater consistency of application, and make it accessible to all of your intended audiences, particularly parents.

Ensuring expert, supportive teaching, assessment and care for every child, and learning that is challenging, inspiring and leads to success.

Prizing individuality, connection and community, apparent in how we behave and include each other.

Providing a curriculum of powerful knowledge that is demanding, meaningful, nourishing and exciting.

“Distilling something simple which becomes a constant touchstone for actions, behaviours and standards is much more challenging and vastly more effective.”Mike Buchanan

Valuing curiosity and perseverance, and aiming to help each child to develop independence of mind and spirit.

Developing children who are eloquent, bold, relish responsibility and learn from taking measured risks. Ensuring the school is a great place to develop professionally and flourish personally.

Welcoming challenge and change as opportunities for growth; combining high trust and high accountability.

Enabling children to discover their creativity and abilities through exacting, varied physical, artistic, cultural and social activities.

Realising, recognising and rewarding the best from everyone and the best in everyone.

Expecting proactive, optimistic leadership and explicit modelling in every role and continually looking for improvement.

The final element of the three is how you will know when you are being successful and therefore need to re-plan. This is your opportunity to describe the sunny uplands that you are seeking. Your context will provide this. It may be that you are embarking on a significant period of change as you switch from being a predominantly boarding school to one more focused on the local day market, or that you are extending or collapsing your age range. It may be that you are seeking to evolve your already successful offer on the arrival of a new head or as you embark on a bursary campaign. This is where you can describe what success looks like so that your audiences are inspired by the possible and what is to come. It might be quite simple, for example:

Excellence in teaching, learning, assessment and care is our overarching focus; it drives our behaviours. Our prize is to be recognised for this, demonstrably to surpass the attainment for similar pupils in competitor schools, and to be the first choice of parents seeking an independent education in the area. The indicator of our success is delighted parents and growing demand for places because of the positive experiences of the children and their performance in exams and elsewhere.

The successful delivery of the plan involves four steps:

• Modelling behaviours, attitudes, language, relationships – bringing your values to daily life

• Building understanding of the plan and conviction through story-telling each day

• Building simple tools to enable people, weeding out obsolescence and removing blockages and blockers

• Developing skills, including risk-taking without fear of blame.

So a simple, touchstone plan on a single side of A4, written for multiple audiences in clear, compelling, plain English is the initial challenge. Bringing it to life will require more elaborate delivery plans at all levels in the school but, now, these plans can be created and evaluated against this touchstone strategy, and you can be holding people to account against the behaviours and attitudes encapsulated in your plan. Good luck.

It is well known that there are a huge number of economic pressures on the independent school sector. With inflation increasing the school cost base, as well as affecting the disposable income of our parents, with potential VAT imposition on the horizon and a relentless rise in interest rates since the end of 2021, there are plenty of issues to focus the attention of bursars nationwide.

A rising base rate is making borrowing more expensive for schools and creating a ‘mortgage payment time bomb’ for parents who are exiting longer-term fixed rates over the next 12 months.

One thing that hasn’t kept up with the pace of the increase in bank rates is the return offered by banks on their deposit accounts.

Banks partly rely on lethargy among their customers. It’s often claimed that you are more likely to get divorced than change your bank account. Add to that the difficulty faced when trying to search for banks that take deposits from schools and then actually trying to open an account, it’s not difficult to see that there’s no real incentive for the ‘Big Four’ to increase their deposit rates at the same pace as their borrowing rates.

A significant amount of income a bank makes is generated by rate margin – the difference in rates at which they lend money compared to the rates they pay

for deposits. As rates have increased, the opportunity for banks to grow that margin has increased.

Schools with healthy reserves will often trust their long-term investments to a fund manager, often shorter-term cash reserves and operational cash are left without much focus.

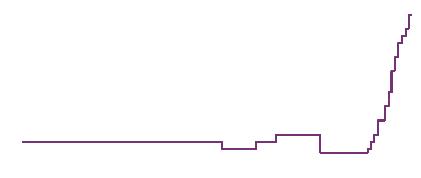

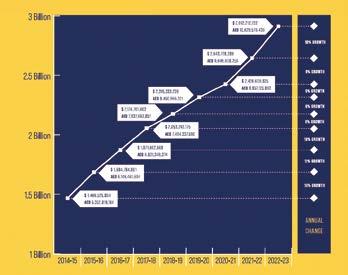

Short-term cash reserves and operational cash can be quite sizable. If we take an example of a school generating £7.5 million a year in fee income (collecting fees at the start of each term), its cash flow could look something like the graph below:

This leaves a significant amount of cash sitting in a current account, probably earning close to zero.

Having worked in the banking sector for 35 years, focusing on the education and not-for-profit sectors for the last 20, I have supported hundreds of independent schools and academies in reviews of their

deposit strategy with a view to increasing significantly the amount of interest generated for their money. The past year has seen a significant growth in appetite from schools hoping to maximise returns as the bank rate has risen.

A deposit platform is a technological offering to overcome the need to produce an ID and address verification while completing an application form each time you want to open a deposit account. The platform provider verifies the school and its chosen signatories and then allows the school to open deposit accounts with a multitude of banks directly from a single, online platform.

With the increased use of deposit platforms, hundreds of schools have removed the biggest barrier to shopping around as the school is free to use the

platform to open new accounts at will, alongside using its existing accounts. You will often find that banks offer an enhanced rate of interest for accounts opened through one of these platforms compared to going directly to the bank. The reason for this can be twofold. First, it is a ‘low cost to serve’ method for the bank to collect deposits. After all, there’s no need for the services of a relationship manager or a branch, so deposits can be managed at lower costs. In addition to this, banks know that someone considering a deposit platform is looking for a competitive rate so they will often put their most competitive rates through the deposit platform, knowing that the majority of their existing clients are unlikely to be exploring these higher paying options.

While deposit platforms have been used in the UK for many years by companies and individuals, they are a relatively new consideration for the school sector. If this is an area you would like to explore, here are several questions to be considered:

1. Does your investment policy cover short-term cash deposits? If it doesn’t, then you should consider creating one. A policy should be specific and not open to wider interpretation, giving you clear guidance on the type of institution you can place deposits with.

2. What happens if the deposit platform goes bust? Make sure the platform you use holds your funds in accounts in your name or as client accounts (much like a solicitor’s client account), ensuring that the funds are yours and that any liquidator could not use them if they need to wind the company down.

3. Security of withdrawals and deposits. It makes sense to choose a platform that allows you to stipulate ‘dual control', that is, two people authenticate each transaction.

4. Which banks should I choose to place deposits with on a platform? Your

investment policy for cash deposits needs to stipulate the criteria in place for you to place funds (for example, jurisdiction, credit ratings etc).

5. Is it financially worthwhile? As at 30 June 2023, some instant access accounts were paying over 3% and some 12-month fixed rate deposits were paying around 6.5%. If these rates remain unchanged for a year and you kept a deposit of £1 million in them, this would give you an indicative return of somewhere between £30,000 and £65,000 over a year.

A selection of interest rates from a variety of banks on one deposit platform is detailed below. These rates were correct on 30 June 2023 and the indicative returns* assume that rates do not change and funds are left for a full year at these rates.

For any school with an element of surplus cash, it makes sense to explore a wider range of deposit options to help offset some of the cost pressures that are being experienced now as well as those on the horizon.

Next Steps:

1. Review your cash flow forecasts to understand your level of cash for potential deposits.

2. Ensure you have a robust investment policy that covers cash deposits.

3. Consider a deposit platform to help you maximise your deposit interest earned while minimising the administration of account opening and management.

Ian Buss runs the consultancy Education Banking Support – linkedin.com/in/ianbuss

“Banks partly rely on lethargy among their customers. It’s often claimed that you are more likely to get divorced than change your bank account.”

In the first of a series of three features, Nigel Aylwin-Foster outlines how to plan the decarbonisation of your school estate

Five years ago, I doubt the term ‘EDP’ had ever have been heard of in the independent education sector: it stands for ‘Estate Decarbonisation Plan’. Now, with the marked increase in focus on becoming net zero within the UK, not least in the education sector, the EDP has become an important planning tool for schools. Every school will need one, and staff must understand what it is and why it matters. It’s not a long-shot to suggest that within the next five years every school in the sector will have developed one, even if the school doesn’t intend to implement the plan for several more years. After all, even if the intent is to leave an action until the last safe moment, without a plan, how does one know what the last safe moment is?

This article will explain the Why? and the What? The two subsequent articles will look at the How? in more detail.

Being net zero carbon means ceasing to use or rely on fossil fuels for any part of the school operation, including in the supply chain and off the estate (for example, staff commuting and school trips on commercial transport), or offsetting where the irreducible minimum of fossil fuel usage has been reached. Estate decarbonisation therefore means ceasing to use or rely on fossil fuels for the operation of the school estate – in essence, for all the estate’s heat, transport and power requirements. Notwithstanding the challenges, all schools in the UK should eventually be able to achieve this, although it will take time, money, effort and appropriate prioritisation.

“Developing an EDP is the work of some months of study, culminating in the production of the plan.”

The purpose of an EDP is to describe how a school intends to achieve this. This needs to be worked out in enough detail to determine a programme for implementation, along with the management, resourcing and budgeting requirements. The latter is important, so that the school can invest accordingly to its broader development plans.

In most cases, the resulting programme of decarbonisation will last at least a decade, probably two. The EDP will inevitably require some adjustment en route to the school achieving net zero carbon, but that does not negate the worth of drawing one up in the first place.

Developing an EDP is the work of some months of study, culminating in the production of the plan. Undertaken with the necessary engineering and commercial rigour – and with a keen eye on pragmatism and practicality in an educational setting – the task is akin to crafting an estate master plan, except that the subject matter is mechanical and electrical rather than an exercise in managing the time frames for when to build.

A well-crafted EDP will:

• Take account of the school’s current situation and general development plans, both in the physical and broader educational sense

• Provide an update on the political, legislative and commercial context of the work. These all have some bearing on the decarbonisation options

• Provide a clear description of the opportunities, costs, timescales and impact of the full range of decarbonisation work required on the estate, with supporting technical, engineering, and commercial logic. This includes the scope for improving energy efficiency on the estate, so that less energy is required in the first place, as well as the scope for the conversion of the estate’s energy systems to alternative low-carbon technologies

• Provide preliminary scopes of work and design concepts for the more complex infrastructure projects, largely driven by conversion of the heating plant and the changes to the power infrastructure required to support the heating plant conversion. (Note that conversion of the heating plant will almost always be the most challenging and expensive project within the plan. Even though, in some cases, it could be a decade or more before the fossil fuel heating plant needs to be phased out, it’s not feasible to estimate the conversion costs realistically without drawing up at least a preliminary design concept. This matters, because the costs are such that they are almost bound to require some significant changes to the school’s existing development plans: it’s in a school’s interests to understand the potential impact sooner rather than later)

• Take account of the interactions between the various technologies involved, to produce an integrated design concept for the use and development of heat, transport and power systems across the estate.

• Produce a cost/benefit analysis for each major project enshrined in the plan, including an estimate of the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and potential reduction in operating costs

• Provide metrics to measure year-on-year progress, with reductions in energy usage and carbon emissions

• Set out a year-by-year implementation programme for all the major energy efficiency and decarbonisation projects, including annual estimates for the required capital outlay. The work can then be incorporated into the broader estate development plan, so that funds can be raised and allocated in a timely fashion and projects can be executed in good order when required, rather than being rushed. Low-carbon conversion projects in schools do not respond well to being rushed, especially the core business of converting the school’s heating.

• Advise on the immediate next steps required to start turning the EDP into action.

The terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘net zero’ often seem to be used interchangeably, but in practice they are not synonymous and it’s worth being clear about the interrelationship. Both will come to matter more and more in schools, and resources need to be targeted with a clear sense of purpose.

Environmental sustainability encompasses everything from reducing emissions to encouraging biodiversity, reducing the extinction of species and even investing sustainably. The most commonly used agenda for this in the independent education sector is the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals shown below:

We’ve already discussed the purpose of net zero carbon, but there’s now another net zero on the block – net zero for energy. Being net zero for energy means a school generates as much energy as it uses, even though it may still need to buy energy from external sources. This is not the same as being net zero carbon – a school could in due course become net zero carbon but still be heavily reliant on the procurement of energy from external sources. In contrast, a school could be net zero for energy but still not be net zero carbon. The distinction between the two is somewhat nuanced but it’s important to be clear about the school’s priorities before an EDP is developed because it will influence the development of the plan. Net zero carbon is ultimately about reducing the impact of climate change; net zero for energy is motivated by the desire to reduce operating costs.

The Venn diagram below illustrates the interrelationship between these three purposes, within a school context:

As already outlined, all schools in the UK should be able to achieve net zero carbon (given time, money and effort) whereas most schools in the UK will not be able to achieve net zero for energy, simply because they lack the real estate to be able to install the required onsite power generation and storage systems. However, they will still be able to get part of the way and it will remain a worthwhile goal.

In the two next editions, I’ll outline how to plan for these respective net zero goals.

“The terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘net zero’ often seem to be used interchangeably, but in practice they are not synonymous and it’s worth being clear about the interrelationship.”

John Fraser considers how the threats of climate change should affect your approach to managing risk in your school estate

In 2020, the earth’s surface temperature was 0.98oC warmer than the 20th century average. December 2021 saw 12.2 million square kilometres of sea ice adrift in the Northern hemisphere, a 4% increase from the previous year. Our climate is changing and, regardless of where your school is located in the UK, this is likely to have a significant impact on your property risks. Increased rainfall and flooding, drought and heatwaves, and extreme weather events are climate-change challenges that will all require risk mitigation.

Climate change has led to an increase in the frequency and severity of floods and rainfall in the UK. This poses a significant risk to all schools, not just those located in flood-prone areas, increasing the likelihood of damage and the cost of insurance premiums. In particular, heavy downpours can overwhelm drainage systems and cause flash flooding in schools. This increase in surface water runoff poses challenges for drainage, including sewers and surface water management systems. These systems may become overwhelmed, leading to localised flooding, sewer backups, and increased risks to properties.

The increased rainfall intensity and the risk of flooding associated with climate change can pose a threat to school buildings located in flood-prone areas. Flooding can result in structural damage, damage to equipment and resources, and

the disruption of educational activities. Schools may need to implement flood mitigation measures, improve drainage systems, or consider relocation in extreme cases.

Climate change has also contributed to more frequent heatwaves and drought conditions in the UK. Higher temperatures and prolonged dry spells can affect school buildings and infrastructure, leading to issues such as subsidence, structural damage and increased fire risks. During periods of drought, soil moisture levels decrease, causing the soil to shrink. This shrinkage can result in subsidence, particularly in areas with clay soils that are highly sensitive to moisture changes. Additionally, extreme heat can affect the wellbeing of staff and pupils, increasing cooling demands and affect future energy costs.

Rising temperatures can create uncomfortable and potentially unsafe conditions for pupils and staff, particularly in schools without adequate cooling systems. Heatwaves can affect concentration, physical wellbeing and productivity. Schools may need to invest in cooling measures or adapt their schedules to mitigate the impact of heat stress.

The UK has experienced an increase in severe storms and extreme weather events as a result of climate change. These storms, coastal storm surges, intense hailstorms, high wind speeds and wildfires can all cause significant damage to properties, including roof and solar panel damage, flooding and structural issues. Such events can lead to higher insurance premiums and increased costs of property maintenance and repair.

Schools may face disruptions in their operations due to school closures, power outages, or damage to infrastructure

caused by severe weather events. This can affect the learning environment and potentially lead to the temporary closure of part or all of a school.

Climate change can also worsen air quality, particularly in urban areas. Increased pollution and higher pollen levels can affect the health of pupils and staff, leading to respiratory issues and reduced wellbeing. Schools may need to implement measures to monitor and improve indoor air quality, such as proper ventilation systems and filtration.

It remains crucial for schools to stay informed about climate change impacts and take appropriate measures to protect properties and manage associated risks.

Schools may need to consider retrofitting existing buildings to improve energy efficiency, adapt to changing climate conditions, and reduce their carbon footprint. This can include upgrades such as insulation, energyefficient lighting, renewable energy installations, and rainwater harvesting systems. Such measures can enhance the sustainability and resilience of school infrastructure.

Climate change and the associated risks can also have psychological and emotional impacts on pupils, staff and the

“The increased rainfall intensity and the risk of flooding associated with climate change can pose a threat to school buildings located in flood-prone areas.”John Fraser

school community. Concerns about the future, eco-anxiety and a sense of urgency may affect mental health. Schools can play a vital role in providing support systems, promoting climate literacy, and fostering a sense of empowerment and resilience in the face of climate change challenges.

It's important for schools to engage in climate change adaptation planning, assess vulnerabilities, and develop strategies to manage and respond to the effects. Collaborating with local authorities, educators and the wider community can help ensure a comprehensive and coordinated approach to address climate change impacts on schools. Remember to:

• Stay informed: stay up to date on how climate change affects your region specifically. Understand the potential risks, such as flooding, coastal erosion or extreme weather events that your school may face due to climate change.

• Assess vulnerabilities: conduct a thorough assessment of your property’s vulnerabilities to climate-related risks. Identify areas that are at higher risk, such as cellars, low-lying areas, or locations near water bodies. This assessment will help you prioritise risk management efforts and take appropriate actions.

• Be insured: speak to your insurance broker to review your coverage to ensure it adequately protects your property against climate-related risks. Understand the terms, exclusions and limitations of your policy. Consider additional coverage options, such as flood insurance, to enhance protection. Regularly review and update your insurance coverage as needed.

• Maintain and upgrade property: regularly maintain your property to ensure it is in good condition and resilient to climate-related risks. This may include maintaining drainage systems and gutters, inspecting and repairing roofs, reinforcing vulnerable structures, and protecting against wind and water damage. Consider

For schools with Grade I and Grade II listed buildings, the risks driven by the effects of climate change are likely to be higher when compared to other buildings. Factors such as location, specific construction materials and methods, previous maintenance, and ongoing conservation efforts can influence their vulnerability. Engaging with conservation professionals, architects and heritage organisations can provide valuable guidance on assessing and managing climate change risks specific to these buildings while preserving their historical significance. Things to consider:

• Age and vulnerability: a listed building’s age and construction methods can make it more susceptible to damage from floods, storms, wildfires, and other climate-related hazards.

• Limited adaptability: listed buildings are subject to preservation regulations that limit alterations to their original fabric and appearance. This can restrict the implementation of modern retrofitting and adaptation measures that could enhance their resilience to climate change effects.

• Location and exposure: Grade I and Grade II listed buildings are often located in areas with historical significance, such as city centres or near water bodies. These locations may expose them to other indirect climate-related risks, such as air pollution or flooding.

• Maintenance challenges: listed buildings require careful maintenance to preserve their heritage value. Climate change impacts, such as increased humidity, higher temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events, can accelerate the deterioration of building materials. Maintenance and repair costs for these buildings may increase as a result. In addition, the specialist skills to perform the maintenance – such as stonemasons – maybe in short supply increasing costs and lengthening timelines.

energy-efficient upgrades that enhance climate resilience, such as insulation, storm windows or renewable energy installations.

• Ensure sustainable drainage: implement sustainable drainage solutions, such as rainwater harvesting, permeable paving, or green roofs. These measures can help manage storm water runoff, reduce flood risk, and contribute to the overall sustainability of your school.

• Landscape and plant vegetation: utilise landscaping techniques that enhance climate resilience. Planting native vegetation, creating more green spaces, and implementing appropriate irrigation systems can help manage soil moisture, reduce erosion, and mitigate the effects of extreme temperatures.

• Have an adaptation and resilience plan: develop a climate adaptation and resilience plan for your school which

should include strategies to address identified risks and potential future scenarios.

• Engage with the local community: collaborate with your neighbours, community groups and local authorities to implement neighbourhood-level resilience measures, share information, and support each other in managing climate-related risks.

• Develop financial planning: incorporate climate-related risks into your long-term financial planning. By implementing an appropriate blend of these risk management strategies, schools can enhance the resilience of their properties and operations and reduce the potential effects of climate change.

John Fraser is managing director of the education practice at insurance broker and risk advisor Marsh.

The planning of maintenance regimes and their associated costs have always been important for independent schools. However, rather than simply maintaining the condition of the estate, schools should now be looking to incorporate planned maintenance works alongside opportunities to improve the energy performance of their buildings too. This will help them reach their ambition of being environmentally sustainable enterprises.

To help maintain school buildings in good condition, planned preventative maintenance programmes should be used to help forecast key moments of expenditure in a manageable way. This sets out which building fabric, mechanical and electrical items require replacement and remedial works over the next five to ten years and helps to identify periods of greater expenditure required to maintain the functionality of the buildings.

Independent schools are also now trying to improve the operational efficiency of their buildings to become more sustainable and with a lower carbon footprint.

Ongoing maintenance requirements and the aspiration to improve the operational efficiency of an estate do not exist in isolation and should be considered together as a single exercise when forecasting budgets for capital expenditure.

Planning for cyclical maintenance should be considered as part of a wider strategy that reviews opportunities for either upgrading or installing new building fabric elements and mechanical systems. Most importantly, this will help target expenditure where it will make the most difference and prevent expenditure on items that may be superseded with later refurbishment or upgrade works.

There are a number of ways to reduce operational carbon and improve the efficiency of school buildings. Often, the choice of the primary energy source of the building has a significant impact on this.

The use of gas or oil-fired boilers in buildings is a carbon intensive energy source. Switching to modern electric heating options, such as electric boilers or variable refrigerant flow systems, can reduce the carbon footprint of a building. The CO2 emissions associated with grid supplied electricity have significantly reduced in recent years due to greater renewable technologies being incorporated onto the grid system, which has also moved away from reliance on fossil fuel-based power such as coal.

While there are other mechanical and electrical installations that can be used to improve performance, such as the installation of photovoltaics and LED lighting, there are also options to make improvements to building fabric elements. These building fabric options include reviewing the levels of insulation within ceiling voids and cavity walls and the glazing to windows. Upgrades to existing insulation to comply with the U-values for roofs and cavity walls as set out in the updated Approved Document Part L published last year could see a reduction in heating requirements. Additionally, installing new double or triple glazed windows could reduce heating requirements by increasing the air tightness of a building, but should not reduce useful ventilation of the building as discussed in Approved Document Part F.

The benefit of each potential improvement option should be considered as part of a modelling exercise. This exercise is usually undertaken in producing an Energy Performance Certificate, which despite only being a legal requirement in certain circumstances, may be useful in understanding the most effective options for reducing the operational carbon footprint of a building.

Understanding and capturing the operational efficiency of a building is essential to mapping out any potential improvement works. A way to do this is through the use of Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) and Display Energy Certificates (DECs).

EPCs provide a rating for the modelled energy performance of a building based on its construction and specification. The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards currently require a minimum E-rated EPC to be produced for the construction, sale and letting of non-domestic private rented properties.

While EPCs can be considered an imperfect tool, in the absence of anything else they can still provide a useful benchmark rating (from A to G) indicating the modelled energy efficiency of a building.

Alternatively, DECs measure the actual energy performance of a building by taking into consideration how a building

“Independent schools are also now trying to improve the operational efficiency of their buildings to become more sustainable and with a lower carbon footprint.”Richard Fitz-Hugh

is used over a 12-month period. DECs are required to be displayed in buildings over 250 square metres that are occupied by public authorities and frequently visited by the public. While independent schools might not fall into this category, DECs are nonetheless another useful benchmark to demonstrate the operational efficiency of a building.

Despite the upfront capital expenditure associated with undertaking upgrading works, there is the potential to achieve a reduction in primary energy use in the long term, that is, the primary loads such as lighting, heating, ventilation and air conditioning.

Modelling exercises carried out to consider the effects of various installations on an EPC rating can also indicate the corresponding effect on primary energy use for the building for each installation or combination of installations, that is, electric boiler, photovoltaic panels etc. While this is a simulated scenario with certain assumptions on daily usage, occupancy

rates etc, it helps identify the potential reduction in running costs of a building with those particular installations.

An understanding on potential longterm reduction in running costs may help inform decision-making on short and medium term capital expenditure.

Understanding the condition of existing building fabric and mechanical and electrical systems, their maintenance requirements, their effect on the operational efficiency of a building and the scope for altering and improving those elements requires careful consideration.

Undertaking refurbishment works to buildings is often not a straightforward task. For example, removing a gas-fired heating system and replacing it with a new VRF system may require a feasibility study that considers the physical space required for pipework routes and external plant, the timing of works around school term dates, and any statutory requirements for planning permission. It may also be that an upgrade to the

building’s existing electrical power supply is needed – and the ability to do this may depend on wider electricity supply network capacity.

Additionally, many independent schools comprise listed buildings that can be more challenging to adapt and alter. Technical challenges arise in installing the new installations while ensuring minimal impact to the original features of the building. In most cases, a listed building consent application will need to be submitted to the local authority.

Considering these challenges and the ways to improve the operational efficiency of a building should be done alongside a traditional planned preventative maintenance programme. Reducing carbon emissions of a property portfolio is becoming an increasingly important task and should be considered alongside basic maintenance requirements to ensure a joined up approach to estimating capital expenditure requirements.

Heather Lamont says responsible investment is about sustainability, not compromise

Ethical investment? Responsible investment? ESG? Sustainability? Impact investing? If you’ve been discussing your school’s investment policy recently, no doubt some of this jargon will have crept into the debate. But when the industry can’t even agree what to call it, never mind what it means, it’s no wonder there’s a good deal of scepticism around. Many an investment committee will be inclined to reject any reference to non-financial issues as a marketing gimmick which risks detracting from spending resources.

However, ignoring the subject isn’t really an option – at least not if you want to comply with investment guidance from the Charity Commission and other regulators. The good news is, it shouldn’t actually be that difficult to understand and agree on what’s important (and what’s not) for your school and how to express your priorities in your investment policy.

A straightforward framework for thinking about the non-financial aspects of your policy typically encompasses three distinct, but often overlapping, approaches.

The longest established and most traditional approach, as well as the easiest to implement, is what most people would historically have meant by ‘ethical investment’. It’s principally about identifying any types of business activity that you don’t want to see among the companies in your portfolio because

they conflict with your school’s values or would expose you to reputational risk.

For some schools a light touch will be sufficient and appropriate here, indeed many parents and governors will be content if there are no explicit exclusions. It’s perfectly legitimate to conclude that you don’t need an ethical policy, but you should still have the conversation and record your rationale. Conversely, many investors, including most faith schools, will want their investment policy to reflect their founding ethos, and they will often be able to refer to faith-consistent investment guidance specific to their own institution or denomination for help in expressing their policy.

It’s important to work with your fund manager to understand how they will implement your intended policy. Do they have the information resource to identify and monitor which companies may fall foul of the agreed policy? What revenue thresholds can they apply when screening for excluded stocks? A typical approach is to exclude any business which generates more than a given percentage (often 10%) of its turnover from the offending activity. This works well for most themes, for example if you want to exclude tobacco companies but not supermarkets, a 10% screen for tobacco would usually do the trick. But there may be activities for which a zero tolerance is preferred; this is often the case in respect of illegal weaponry such as cluster bombs and landmines.

One common pitfall is to apply any exclusion policy only to ‘direct holdings’ in individual company names. In practice almost all schools’ portfolios are invested significantly, in many cases wholly, through pooled investment funds. If you do have exclusion criteria, you should discuss with your fund manager whether these are being applied consistently across the portfolio, and identify any reputational risk that you face if pooled funds are not screened according to the same criteria as direct holdings.

Incidentally, there’s no evidence that any reasonable screening policy need be damaging to your long-term investment

returns. Over shorter time periods there can be some divergence – this can be positive as well as negative – between screened and unscreened portfolios, but these variances tend to even each other out over time. In any case, the regulator is clear that charity trustees should at least consider whether any screening is appropriate for their organisation, not just dismiss the idea out of hand.

This is a key element of responsible investment management. Your fund manager should assess the risks to your portfolio associated with the environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards of investee companies and potential holdings. Unlike the ‘alignment’ approach above, this isn’t about what business they’re in, but rather about how they do business.

Good fund managers will address these issues as an integral part of their investment process, because this assessment is about enhancing the sustainability of your portfolio returns. However attractive they may look through the lens of conventional financial analysis, companies which have poor standards of behaviour tend to underperform over the long term. They are also more prone to financial shocks and sudden reputational damage which can destroy shareholder value. So your investment policy should recognise the

“Many an investment committee will be inclined to reject any reference to non-financial issues as a marketing gimmick which risks detracting from spending resources.”

importance of ESG considerations and your fund manager should be happy to discuss how they incorporate these in decision-making.

Schools and other charitable investors are increasingly aware that investment markets and portfolios can only be as healthy as the environment and

communities in which they operate. For many, therefore, the long-term sustainability of returns requires realworld change to help address systemic challenges like climate change, modern slavery and health crises such as soaring global rates of obesity and poor mental health.

A number of industry-led initiatives have already demonstrated that commitment and collaboration by investment managers who engage with companies and regulators on behalf of the investment community can indeed drive change in company behaviour over time. In practical terms, driving improvements in behaviour across the corporate sector has much more impact on the issues of concern than any policy on what sort of companies are or are not permitted in a school’s portfolio. Most investment decisions simply involve your school buying assets from other investors or selling to them. These transactions don’t change the amount of

capital that is allocated to the activities in question, whether ‘bad’ or ‘good’. Even policies which aspire to include ‘positive’ investments in the portfolio tend to have very limited real-world impact.

So another question for your fund manager should be around their commitment to driving real change on these systemic issues, and what impact they are having.

Which of these approaches – it could be one, two or all three of them – is relevant to your school? That’s the conversation you should be having, if you haven’t already. It doesn’t even matter what you call it. The important thing is to get past the jargon, consider what matters to your school and understand how your fund manager can support those objectives – and then hold them to account for delivering against what you’ve agreed.

“Schools and other charitable investors are increasingly aware that investment markets and portfolios can only be as healthy as the environment and communities in which they operate.”

Banish from your minds the phrase ‘terms and conditions’, which may evoke the impenetrable language of the ‘small print’, which is meant to be seen but not read. Consider instead that your parent contract is your script, your guide, your toolkit for shaping your business and the relationships on which it is built and on which it relies. It should say what you do and by doing what it says you should be best placed for success. From a tick box on a to-do list, elevate the parent contract to its rightful place as a priority, and a worthy investment of your time. Read on to remind yourself what the parent contract is and what it can do for your school.

A school’s existence is a matter of registration and regulation, but educational services are provided by independent schools through a private legally enforceable relationship with parents of pupils – this is the ‘parent contract’. It is no exaggeration to say that it is this legal relationship which is the foundation of your business. It bears weight in securing the health and future of your business and optimal outcomes for your beneficiaries, regardless of corporate/organisational structure.

It's a contract with individuals, not with businesses – a ‘consumer contract’, and as such it must also deliver a fair deal for the parent and be drafted in plain and