INDEPENDENT SCHOOL MANAGEMENT

Insights from a successful school merger

Maximise revenue from hiring school facilities

A new perspective to VAT on school fees

Managing claims of discrimination

Insights from a successful school merger

Maximise revenue from hiring school facilities

A new perspective to VAT on school fees

Managing claims of discrimination

What should be on your agenda?

Welcome to the first edition of Independent School Management of 2024. Thank you for your continuing support for the magazine; it really is appreciated.

The start of this new year feels, finally, like the beginning of the countdown to the general election. Rather than a notional future event, it is soon to be real and is approaching with some rapidity. At this stage, it still seems likely that Labour will win and, therefore, the threat of VAT on fees will become a reality. Every independent school with a charitable status should have been preparing for this eventuality for some time. If not, you are now in the last chance saloon.

We refresh some of the key options to mitigate the risks, but add some extra insights to help the sector survive and thrive. Considering a payment scheme, for instance, where fees are charged in advance might work for some schools. The fees would need to be paid in full for the school to use as it sees fit and should not be held under an escrow account or similar arrangement. There may also be an opportunity to recover VAT incurred on certain capital expenditure from the previous 10 years if subsequently used for taxable activity.

But life must go on regardless so, in this edition, we focus on aspects of effective school governance, beginning with the risks and opportunities of artificial intelligence. We show how governors can navigate the ever-evolving educational landscape effectively, including understanding the ethical considerations surrounding the technology.

While this approach requires governors to be forward-thinking, it is also important to recognise that times have changed and attitudes expressed

by some governors in previous eras may have exposed occasions of accidental discrimination and other biases. We tackle this risk of outdated attitudes head-on and also provide a case study of how a school should respond to claims of discrimination and examine the key considerations for governors.

Notwithstanding the pending threat of VAT on fees, taking a more commercial approach to a school business is vital anyway. Rising fees have represented an unsustainable trend for some time. Finding alternative ways to boost the bottom line should always have been a given. We put the spotlight on the commercial activities that Mill Hill School has introduced. Its projects have paid dividends and have also boosted the school’s profile. Not all schools are fortunate enough to have similar facilities to launch such ventures, however, so we will be profiling other schools’ entrepreneurial acumen in future editions.

Many schools will have been considering a merger, of course. In our summer edition last year, we outlined the practicalities and considerations of mergers, with attention given to those of legal, financial and reputational concern. In this edition, the head of a merged entity in Bedford provides the inside story of its own successful outcome, sharing how the process panned out, including combatting the risk of a ‘them and us’ mentality between staff and parents of the formerly separate schools.

The vast majority of our editorial content is intended to challenge outdated strategic orthodoxies. That’s because strategies must change and adapt on a

continual basis. This is, necessarily, a challenge. However, by following a series of techniques, it’s possible to harness change and not be a victim to the vagaries of it.

Schools that are adept at strategic thinking are able to identify or predict opportunities and obstacles before they materialise. This means that they can prepare themselves for future threats, but also that they can act to shape a future where the most beneficial outcome for their school becomes more likely. After all, there are lots of different possible futures. The trick is to identify those you should focus on for your school. By applying strategic thinking skills to develop an understanding of how the future might unfold, your school will be well placed to position itself for success by developing a strategy that exploits the opportunities you’ve identified while overcoming the obstacles.

To keep up with the latest sector news and people moves, follow us on Twitter @IndSchMan

Andrew Maiden Editor, Independent School Management

Chief executive officer

Alex Dampier

Chief operating officer

Sarah Hyman

Editor

Andrew Maiden andrew.maiden@nexusgroup.co.uk

Reporter and subeditor

Charles Wheeldon charles.wheeldon@nexusgroup.co.uk

Advertising & event sales director

Caroline Bowern 0797 4643292 caroline.bowern@nexusgroup.co.uk

Marketing Content Manager

Sophie Davies

Business development

Robert Drummond

Luke Crist

Mike Griffin

Kirsty Parks

Event manager

Conor Diggin

Marketing campaign manager

Sean Sutton

Publisher

Harry Hyman

Investor Publishing Ltd, 5th Floor, Greener House, 66-68 Haymarket, London, SW1Y 4RF

Tel: 020 7104 2000

Website: independentschoolmanagement.co.uk

Independent School Management is published six times a year by Investor Publishing Ltd. ISSN 2976-6028

© Investor Publishing Limited 2023

The views expressed in Independent School Management are not necessarily those of the editor or publishers.

@IndSchMan

linkedin.com/company/ independent-school-management

6-7 News in brief

8-9 Stronger together

Merging two schools

10-12 Schools for hire

Increase revenue from lettings

14-15 Hire safely

Guidance for school facilities hire special report

16-17 Do it yourself

Get a grip on artificial intelligence

18-19 People like us

Reflect the people you serve

20-23 Do the right thing

How to respond to discrimination claims

24-26 Think strategically

Continually review your school’s strategy

27-28 Employee tax risks

The pitfalls of managing employmentrelated tax matters

29-30 Beware of fraudsters

Procedures for apparent suppliers

31-33 Get rid of carbon

How to develop an effective plan

34-35 A matter of judgement

Guide to investing charity money

36-37 Next in line

Prepare the next generation of school leaders

38-39 Rateable values

The effects on your school estate

40-41 A taxing problem

A new perspective of VAT on fees

42 Out of order

The moral and business case for charging orders

43-44 Before the deluge

Mitigate the threat of flooding

45 Deal with bad news

Combat the fallout from an unforeseen crisis

46 Have a plan

Improve school admission practices

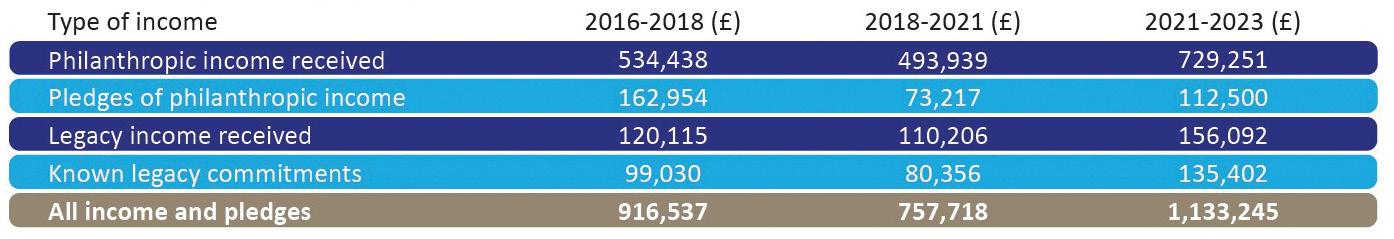

47-48 Maximise fundraising

Celebrate record levels of income generation

49-50 Relationship for life

Short-termism doesn’t work in development

51-52 People moves

53-54 The last word

Dai Preston of Arnold Lodge School

Peter Roberts, the headmaster of private school Ampleforth College in Yorkshire has pledged not to pass Labour’s threatened tax hike on to parents, saying the school will do everything it can to absorb the proposed 20% VAT which the party plans to impose on school fees, the Daily Mail has reported.

Roberts told the Daily Telegraph: “If there is a VAT thing, we will not pass it on to the parents. We will just do all we can to make sure we get through, just as we always do.”

Labour’s VAT plan aims to raise £1.5 billion a year with the tax which it plans to spend on state schools.

Shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson said if Labour win power, it will ensure that parents will pay VAT on independent school fees, even if they have paid in advance, by making a change to tax law.

In a speech at the Centre for Social Justice in London, Phillipson said: “George Osborne, when he made VAT changes, did something very similar. So, we’re clear there was precedent when the legislation was drawn in such a way that it is effective in raising the money that we need to invest in our state schools.”

Osborne’s changes meant that the VAT rate for goods or services provided were applied from 2011 onwards, even if invoices or prepayments had been received before then.

The Independent Schools’ Bursars Association chief executive David Woodgate said: “The number of parents who can afford to use fees in advance schemes is very small and any political focus on this niche issue is a clear attempt to exploit stereotypes about independent schools.”

Woodgate added: “Most of our parent base are from dual-income households who pay school fees each year from taxed income and it is these families who should be concentrated on: these are the people Labour’s tax on education would hit hardest.”

Meanwhile Labour Party leader Sir Keir Starmer said that funds he will raise from taxing independent school fees will be spent on mental health support for every school in England, The Telegraph has reported.

Speaking to the BBC, Sir Kier added that this policy will help reduce self-harm and suicide among young people and is one of a number of policies forming part of a “children’s recovery plan”.

A senior Conservative Party source said Labour was “stretching the limits of credulity”, adding: “Their numbers simply don’t stack up, so Labour will either have to ramp up national debt or slam working families with higher taxes.”

During a House of Commons debate on choral music in cathedrals, Sir Michael Fabricant, the Conservative MP for Lichfield said, while asking a question, that cathedral schools are “very concerned that if they have to charge 20% on their fees, and possibly lose their charitable status, they may no longer be viable and will go bust”.

Responding to Sir Michael, Andrew Selous, the second church estates commissioner said:” There is a concern that cathedral schools may not be able to afford to pay business rates. If the payment of business rates and the addition of VAT on fees cause choir schools to close, that would be an issue for a number of cathedrals.”

The Independent Schools Council chief executive Julie Robinson later said:

“The majority of independent schools, including cathedral schools, have thin operating margins and cannot absorb the effects of VAT and the loss of business rates if they are to remain viable. But nor should they have to ask hardworking families to bear the brunt of a legal requirement to place VAT on fees.”

Eton College told its 1,350 pupils to stay at home at the start of term because the lavatories have backed up following flooding, Yahoo reported.

Thames Water warned that sewers in the centre of the Berkshire town wouldn’t have the capacity to cope if the boys returned, so the school switched to remote learning until the issue was resolved.

A spokesperson for Eton College said: “Following extensive flooding in the region, the Thames Water sewers which serve the town of Eton, flooded.

“Therefore, boys could not return for the scheduled start of term.”

Caterham schools has acquired Copthorne Prep School (CPS) in Sussex, cementing a long-standing relationship between the schools.

Copthorne Prep School headmaster Nathan Close will continue to lead the school.

Caterham schools encompasses Caterham senior school, led by headmaster Ceri Jones and Caterham Prep led by headmaster Ben Purkiss, and now CPS.

Close said: CPS has been providing first-class education for children for the last 121 years. This next step is a fantastic opportunity to build on our proud legacy by joining a highly successful, forwardthinking family of schools which shares our core commitment to the happiness and success of our children. Crucially, parents can have full confidence that their children will continue to enjoy the happy, successful school they chose, and that their children will be fully supported and prepared for whichever senior school they chose beyond CPS.”

Caterham School is the founding school of the East Surrey Learning Partnership, a group of independent and state-maintained schools which work together as equal partners to further educational opportunity for all young people in the local area.

Belmont School in Dorking, Surrey has announced it is closing after 143 years of operation.

Belmont is an independent coeducational school for pupils aged from three to 16.

On the school’s website Belmont’s head of school Marc Broughton wrote: “It’s with a heavy heart that we have contacted the parent body to confirm the closure of Belmont School on the 15th of December. We have worked tirelessly to exhaust all avenues to find an answer to this situation, but the Governing body, Save Belmont team and school leaders have sadly been unable to come up with a viable solution.

“In my short tenure as Belmont Head, I have been so immensely proud to lead

a school with such wonderful staff and pupils. Since the moment I set foot on site it was clear that Belmont held a very special place in the hearts of so many people. Over the course of the last few weeks, I have been touched and overwhelmed by the Belmont community and the lengths that they have gone to in order to try and save the school. They have come together and displayed such strength and resilience at such a difficult time and for this they should be truly proud.”

Five men aged between 69 and 90 have been arrested and charged in connection with abuse spanning 24 years at private day school The Edinburgh Academy, STV has reported. The abuse incidents are alleged to have taken place between 1968 and 1992.

A sixth man, aged 74, will be reported to the Procurator Fiscal.

Police Scotland said reports are being submitted to the Procurator Fiscal.

Detective inspector Colin Moffat said: “We would like to thank everyone who has come forward and assisted our enquiries to date. While the investigation of child abuse, particularly non-recent offences, can be complex and challenging, anyone who reports this type of crime can be assured that we will listen and we will investigate all reports, no matter when those offences occurred or who committed them.

Edinburgh Academy was the subject of hearings at the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry last year. Former pupils alleged sexual and physical abuse during witness statements to the Inquiry.

Broadcaster Nicky Campbell previously alleged he was abused while at the school by former maths teacher and rugby coach Iain Wares, who also taught at Fettes College, and now lives in South Africa.

Wares, aged 84, faces more than 80 charges of historic abuse relating to more than 40 victims aged as young as nine. He also faces separate charges of sexual misconduct in Cape Town.

A South African court approved Wares’ extradition to the UK in 2020, but that has been delayed by an appeal.

Ian Daniel reports on the successful merger of two schools, with insights on how it was achieved

In 2013, the governors of Rushmoor School and St Andrew’s School, both based in Bedford, formed an alliance, so that one governing body would oversee both schools, with one leadership team. As head at Rushmoor, I was then appointed principal of both schools. I explained to the joint community that there were many difficulties to overcome, but my most important message was that the education and welfare of the pupils was at the centre of all decisions.

Over the past 10 years, the pupils have been very open to the benefits that the merger has brought and in May 2021 the two schools formally merged under one new name, Bedford Greenacre Independent School. Changing the name was key in order to build a new brand identity and it would have been unfair to choose one name over the other. Currently, the pupils are spread across two small urban sites, but in the next academic year they will move to a new £24 million, 40acre facility, which will be the final piece in a very successful merger.

Success didn’t just happen and I believe that communication with parents has been key. I routinely will be seen outside the school gates chatting to parents. I aim to be approachable and want to keep parents involved, crediting the parent council as being invaluable in the decision-making process, which has been particularly important when combining

a girls’ school with a boys’ school and navigating the introduction of a coeducational environment.

Open debate is important to find positive solutions; listening to the views of parents, staff and pupils is the most important aspect of leadership. From the outset, the school was keen to promote the wider opportunities as a positive factor in the merger, helping benefit pupils by allowing them to forge new friendships across clubs, performances, school teams, fixtures and residential trips.

Of course, there were difficulties along the way, the first being overstaffing, with redundancies having to be made in the early days of the alliance. Streamlining has ultimately led to greater efficiencies, with specialist staff working across the two sites, leading to parity in the standard of teaching and learning.

Raising pupil numbers was important and has been managed by improving marketing, such as introducing a social media presence and ensuring that the school leadership is hands-on in meeting prospective families and being more visible at community events. The leadership wants to convey to the wider public that, as a non-selective school, we cater for all abilities by providing an individual approach.

Day-to-day management of the two schools was challenging for a number of years, policies had to be combined,

expectations had to be adhered to, the “we always do it this way” from some staff had to be challenged and workable solutions found. I felt that some saw the alliance as a Rushmoor takeover, which was not the case, so I was keen to promote debate between the leadership and staff to allow solutions to be found that would ultimately work in the best interests of the pupils. So a flexible approach was adopted and this is why, after a number of years, it was agreed that the junior pupils from both school sites would be brought together on one site, as the school moves fully towards co-education and in preparation for the move to the new building. It was agreed that this decision would be the least disruptive for the younger pupils, which has proved correct as the combined junior school is a thriving environment. Of particular note is that junior staff from across the two sites are now very happy to be working together, using their areas of expertise more effectively and providing the pupils with greater opportunities in many areas.

The merger brought with it economies of scale; while two small schools might have struggled with some financial elements, such as introducing modern school management information systems, or improving IT resources for pupils, working together has meant that this

has not been a problem. The end result means that improved systems allow staff to monitor pupils’ progress better and to develop more efficient working methods. For example, pupils immediately had laptops and smartboards updated when the new structure was established. Small improvements, such as IT facilities, hold huge benefits to pupils who have specific learning needs, but also help to provide extension opportunities for gifted and able pupils. When the final step of the merger takes place, these economies will be even greater as the school will only have one site to maintain and new energy-efficient technologies are being incorporated to help further.

Initially, there was a ‘them and us’ mentality, but with the passing of time, and movement of both staff and pupils between the two sites, this has ceased. Now with the new name and branding, the staff and pupils are proud of what the alliance has become.

Getting the rebranding correct was crucial, using Bedford in the name is geographical, but also underlines that Rushmoor and St Andrew’s had very long histories in the town. Greenacre links to the semi-rural setting of the new site and also Greenacre was the family name of the previous landowners dating back to the 14th century. The logo shows a tree to signify growth, with its roots used as a reference to the school’s strong past. The vertical lines signify stability, longevity

and strength for the future. Interest in the school has soared due to the rebranding and the imminent move, as well as the reputation of individual support that the school provides, having been rated as excellent in all areas in its 2022 inspection.

Pupils’ voices have contributed to the successful merger; the leadership team is interested in their opinions, such as including them in the design process for the rebranded uniform. Another example happened in 2016, following consultation with pupils, a joint sixth form was opened. Since its introduction, new subjects have been included in line with pupils’ wants and needs and this has meant it has been a successful addition, with the most recent cohort being the largest yet.

Over the past 10 years, the willingness to adapt plans as the educational landscape has developed has been vitally important. Moving to a fully co-educational structure will be the biggest change with the move to the new site, so the school is already timetabling co-educational lessons where logistics allow. The school has also had to adapt plans when timings have been pushed aside due to problems like planning issues creating uncertainty. The pandemic caused issues too, but was managed well with a virtual full timetable, online assemblies,

“Open debate is important to find positive solutions; listening to the views of parents, staff and pupils is the most important aspect of leadership.”

competitions, talent shows and sharing news via social media to maintain the school community spirit.

Since 2013, a great amount of determination and perseverance to overcome difficulties has been required; I have highlighted the importance of having governors who have wide-ranging areas of expertise as a contributory factor to the success of the merger.

Through the alliance, to the formal merger and rebranding, one point has been made clear. The school is far more than the facilities it has, it is about a dedicated staff, who go above and beyond to ensure that pupils are pushed to reach their potential. Any schools that plan to merge will face challenges, but putting the pupils at the centre of all decisions will be the key to overcoming them.

Ian Daniel is principal of Bedford Greenacre Independent School.

Adele, you’ve been working with Mill Hill for some years now, making lettings count. Where did it all start?

After over 17 years working in the commercial school sector there’s not much I haven’t seen. When I started out, some schools were renting out their halls and sports centres on a very ad hoc basis, with the bursar or the school office often trying to juggle this alongside their other commitments.

When I was approached by the bursar of Mill Hill, I was working in the events industry and so the transition seemed easy and then I very quickly ended up doing my first film shoot. It was baptism by fire, no small affair, but a big ITV drama which brought a lot more drama than I had anticipated. But I survived, as did the school happily, in receipt of an injection of cash. Suddenly, commercial opportunities were taken seriously.

Starting with filming, that’s a braveor - foolhardy decision?

Yes, it was in retrospect probably quite foolhardy. The school had no prior experience of filming and neither did I, but now, more than 150 film shoots on, Mill Hill has established a reputation as a great location and we have generated significant returns for the school. We’ve also started to engage our students in the process, where appropriate, offering them opportunities to work on a professional film set, and we now have an annual London schools film competition, londonschools.film, judged

“We’ve also started to engage our students in the process, where appropriate, offering them opportunities to work on a professional film set.”

and supported by our contacts from the industry.

A word of caution, though, filming isn’t for every school and you do need to remember that (a) You need the school’s buy-in – which needs to review the script carefully and sign off the project; (b) If you’re managing a film shoot, you need to remain firm about what is allowed to happen onsite and what you will and won’t accept; and (c) You will need to be flexible. There will be times when they’re on set and they may decide they need to change something or move location slightly; adapt to it.

So, filming is one way of generating revenue from the school’s buildings and facilities, but probably not where most schools will start?

No, probably not. Fast-forward and I am now asked what the best strategy is to ensure that commercial income is consistent and in line with the needs of a school and that we optimise the return on our assets.

Like all businesses, the first income streams should be the easy wins, the building blocks on which to build.

For many schools, a day camp and/or a residential let run by reputable third parties can bring in reliable and substantial amounts of income. The external company, operating

independently as a business, will take the pressure off the school’s team, allowing them to focus on other areas. Then comes the dry hire – classroom lets, regular theatre bookings, sports pitches and swimming pool hire – followed by specific bespoke programmes and events – and perhaps filming – all of which are slightly riskier but with potentially higher financial returns.

How do you get going on the commercial journey?

Schools need to start by identifying the opportunities. Every school has at least five asset classes they can explore, all of which can deliver a significant return when managed carefully and in the context of a wider whole-school strategy: education, probably the school’s most significant asset and often the most overlooked when it comes to commercial opportunities; co-curricular, normally evidenced by the school’s considerable investment in appropriate facilities; provenance, the vital role that the history and connections embedded in the school’s past can play in the future success of the school; community, partnerships and public benefit – a significant and growing group of assets that, when carefully considered and integrated into the commercial strategy, can deliver excellent returns

“Every school has at least five asset classes they can explore, all of which can deliver a significant return.”

for both parties; and finally, of course, the buildings and facilities, which most schools have in abundance and which, in many schools, lie dormant for a significant part of the year.

For some schools, it may be that the only agreed and accepted income generation opportunities initially arise from, for example, the hiring out of sports facilities – the letting of the sports hall, swimming pool, tennis courts etc – but for others it may be a lot broader and deeper, involving different departments across the school in developing bold projects and programmes that knit

together different assets to deliver more significant returns. These bespoke projects are riskier, but the returns are significantly higher.

A whole-school approach to commercial activity is so important, with results often leading to a sum greater than its parts. How, in your experience, can this work in practice? When we get it right, the returns are significant. Not only can we generate much better revenues when we develop a broad-reaching programme, which engages the school and the wider community, we also get a chance to better position the school and reinforce its brand and USPs (unique selling points). Getting this right can be challenging and it is important to look at the strengths within your school community: the well-placed head of sports or drama, for example, to see what connections can be made in their respective fields.

This level of attention and planning will not only bring good PR to the

school, with amazing opportunities for current pupils from the school’s contacts, these initiatives and programmes will also engage the local community and extend the brand’s reach far beyond the school walls. Often working with the right, carefully selected partners, you will find that they can add real value, respecting and potentially even investing in your facilities, and introducing prospective pupils into the admissions department.

Any director of commercial operations needs to be involved in key planning of the school’s future, especially the planning of new buildings or current building upgrades to future-proof dual use to maximise commercial opportunities. Commercial use must become an integral part of the school’s timetabling – vital, additional income and value, not inconvenience – and the development of programmes and initiatives must be undertaken with transparency.

There need to be open conversations about the importance of this non-fee revenue.

We often talk about ‘dual use, school first’ – is it a given that you have dual use approval?

No. I started out by understanding the school’s estate, or estates in our case as we now have eight schools within the Mill Hill Education Group and we are working hard to drive returns on our assets across all of our schools. I start by understanding how the estate is used by the school, when the facilities are lying empty and which are in demand on the open market or unique to the school within its particular target market. I also appraise what opportunities there are in the local community, such as local community school needs, strong sports associations or clubs, local area community groups or simply a lack of local venues to hold meetings, workshops, revision classes or events.

This work is the basis of fulfilling the ‘dual use, school first’ promise, but it is only the beginning. You then need to consider safeguarding and child protection, contracts and commercial parameters, which will often require legal advice. You need to develop appropriate risk assessments, consider health and safety impacts, and ensure that the good reputation of the school is protected above everything else. Your colleagues will expect you to have covered these bases and you will need to

reaffirm your commitment, consistently and continuously, to delivering a professionally run school site, irrespective of whether it is for school use or a third party.

What is critical to the success of a commercial programme?

You need a clear mandate from the very top of the school – the chief executive/ chief operating officer, the head(s) and the senior leadership team. The leader of the commercial operations team needs this senior level of support and then the grit, vision, creativity and bravery to develop exciting, bold and interesting projects, which inspire the internal audiences and encourage participation

and engagement from your external audience. Crucially, the commercial team will need the support and participation of the school’s marketing team since they are the custodians of the school’s brand(s) and your marketing partners are invaluable in helping to take the product(s) to market and engaging the wider community.

Have you seen a change in how schools approach their commercial activities?

With the pressures on schools to generate additional income, there’s never been a more important time to look at every possible source of revenue. The school’s doors should be as open as the minds of all those looking to make the most of their considerable assets.

I have been excited by the formation of the Schools Enterprise Association in recent years, which supports the commercial managers and all those working in this unique sector within schools. It is important that everyone is actively engaged so that schools and pupils benefit from the opportunities to really add significantly to the school’s non-fee revenue streams as every penny will become even more vital over the next few years.

Adele Greaves is the director of commercial operations at The Mill Hill Education Group; Dorothy McLaren is the founder and chief executive of The Schools’ Enterprise Association.

We work in partnership to forge strong relationships to truly understand your school’s community and what sets it apart.

Creating uniforms that students are happy and proud to wear.

Call us on 0113 238 9520 or email info@perryuniform.co.uk perryuniform.co.uk

As schools seek to maximise their commercial offering, they must consider the latest statutory guidance to ensure that effective and compliant hire facilities agreements, that specifically reference and implement safeguarding requirements, are in place. This is an overview of recent updates to both statutory and non-statutory safeguarding guidance that schools should consider when letting school facilities for non-school activities.

The Department for Education (DfE) has recently updated the following guidance:

• Keeping Children Safe in Education 2023 (KCSIE) – statutory guidance for all schools and colleges.

• ‘Keeping children safe in out-of-school settings’ – non-statutory safeguarding guidance for providers of after-school clubs, community activities and tuition, to keep children safe where individuals or organisations provide these services.

Schools increasingly seek alternative streams of income to thrive and maximise their assets. Many options are available to generate additional income, one of which is hiring out facilities.

Hiring facilities is traditionally attractive as it makes use of facilities already at the school’s disposal which may be unused for periods of time. For example, a school may choose to hire out its sports hall to a community activities group in the evening, or boarding accommodation during school holidays.

“Schools increasingly seek alternative streams of income to thrive and maximise their assets.”

We frequently find that in this regard, independent schools can operate as a year-round business. The risk of a future Labour government’s plans to increase VAT on school fees by 20%, also lends additional urgency to plans to increase income to offset this potential threat.

There are a number of key considerations which all schools should keep in mind when putting in place any hire arrangements.

KCSIE is updated annually (usually in September) and last year the updates included provisions which directly affect facilities hire. KCSIE now references ‘Keeping children safe in out-of-school settings’ and confirms that it sets out safeguarding arrangements that schools should expect providers of services such as after-school clubs to have in place.

In relation to safeguarding, new provisions have been inserted in KCSIE which stipulate that when a school receives an allegation relating to a safeguarding incident that happened when an individual or organisation was using the school premises to provide activities for children, the school should follow its own safeguarding policies and procedures, including informing the local authority designated officer (LADO). Hirers are expected to report any incident to the school’s designated safeguarding lead (DSL) within a set period and we would usually recommend this is within 24 hours.

Hirers are expected to meet safeguarding requirements as a matter of best practice set out in ‘Keeping children safe in out-ofschool settings’. It is important that schools ensure that this guidance is reflected in hire facilities agreements. There are a number of core features of this guidance.

The staff of hirers should undergo basic safeguarding training. The updated

guidance takes expectations further, and now recommends that all staff present, or in a position of responsibility when using the school premises, completed basic health and safety training relevant to children.

Furthermore, the hirer should conduct regular performance reviews of staff and volunteers to check their suitability and training requirements. Most employers will already be conducting regular appraisals of staff performance, which should focus on the suitability of staff to participate in activities in out-of-school settings and ensuring the training is adequate.

The hirer should conduct a risk assessment appropriate to the proposed activity, reviewing and updating it annually (or earlier if the circumstances or public health advice changes) and put in place active arrangements to monitor whether the controls for managing risks are effective and working as planned. The hirer should also have in place a fire safety and evacuation plan, as well as a plan to respond effectively to an emergency on the school premises.

Schools should expect hirers to have a number of policies in place before hiring school premises. The key policy,

of which schools should request a copy, is the hirer’s child protection and safeguarding policy. Schools should also seek confirmation that the hirer has a complaints procedure in place that includes provision for children, young people and families to raise safeguarding concerns, together with a whistleblowing policy so staff can raise concerns about the maltreatment of any children, as well as a staff behaviour policy.

There are also certain expectations which schools should place on hirers where the activity involves children under five years of age. In these circumstances, schools should expect hirers to provide paediatric first aid training to their staff, unless there’s an exemption from registration with Ofsted. The hirer should also have in place a GDPR-compliant registration form for children in its care, including essential contact information and medical details, where it has five or more members of staff.

All too often, schools rely on inadequate hire agreements with hirers which offer limited clarity regarding the obligations of the parties and provide little protection to the school.

To ensure safeguarding is in place and to protect the school commercially, a robust hire facilities agreement will ensure consistency and certainty that obligations will be met. The agreement's terms should

cover payment, liability, force majeure and termination, in addition to appropriate safeguarding provisions.

Alongside the hire facilities agreement, schools should put in place a supplemental letter of undertaking, which the hirer must sign when entering into the hire agreement. This requires the hirer to undertake to comply with its safeguarding obligations pursuant to the hire agreement.

The hire agreement may also be supplemented by a safeguarding checklist, solely for use by the school to ensure and document that all safeguarding obligations placed on the school are achieved. For example, this checklist would include ensuring the hirer has in place a child protection and safeguarding policy, and that a copy has been requested and checked by the school to ensure it is appropriate for the purposes of the hire facilities agreement.

A school’s governing body has a strategic leadership responsibility for its school’s safeguarding arrangements. Governing bodies must ensure governors receive appropriate safeguarding training so they have the knowledge to provide strategic challenge to test and assure themselves that the safeguarding policies and procedures in place are effective and support a robust whole-school approach to safeguarding. Governing bodies should

“The key policy, of which schools should request a copy, is the hirer’s child protection and safeguarding policy.”

have safeguarding as a standing item on its agenda and the hiring of facilities should be included as part of a review of processes. These arrangements should be monitored and included as part of any assurance framework.

In the current political and economic climate, schools must consider carefully ways to review their strategy, and look to increase their income while managing and balancing any risks and ensuring compliance with legal obligations.

Schools that hire out their facilities, or are considering doing so, should review and update their existing hire agreement, or prepare one to ensure that it reflects all of the recent updates made by the DfE in both the statutory and nonstatutory guidance.

Emma Swann is a partner and head of academies at law firm Harrison Clark Rickerbys.

Everybody’s

Independent school governors should be well informed about artificial intelligence to navigate the ever-evolving educational landscape effectively. First and foremost, they should understand the potential benefits of AI in education, including personalised learning, data analytics for student performance assessment, and administrative efficiency. Moreover, governors should grasp the ethical considerations surrounding AI, ensuring the responsible use of AI technologies and data privacy. It’s crucial for them to be aware of the latest developments and timeline in AI, as these can affect the curriculum and teaching methods, influencing decisions on technology investments. Lastly, independent school governors must be mindful of equity and inclusion, ensuring AI is used to bridge educational disparities and provide equal opportunities for all students. By staying informed about AI’s potential and pitfalls, they can shape a brighter and more equitable future for their schools.

When I told a colleague that I was going to get ChatGPT to write the (above) introductory paragraph of this article, he (rightly) told me that that was “corny”. But it is the first time I have done such a thing and I learnt that within 30 seconds of briefing ChatGPT I had before me a convincing text, albeit not quite in my style (it might have taken another minute or so to craft that). I knew this could be done, but I hadn’t ever used AI to achieve in seconds something which might

“Governors should grasp the ethical considerations surrounding AI, ensuring the responsible use of AI technologies and data privacy.”

otherwise have taken me a great deal of time. So my first point is a simple one: governors should not just know what AI is and how it can be used, but know how they themselves could use it in their own lives.

I have sat in several rooms witnessing AI enthusiasts demonstrate how much can be achieved, how quickly, and how much refined, but too often to people who marvel at it largely through their own unfamiliarity – almost as if it were alchemy. Once people have an idea of how they might use AI themselves, they can appreciate better what its profound implications are.

AI is developing at high speed. The transformation wrought by ICT occurred slowly in comparison and we can’t afford to ‘wait and see’. On the global stage, the UN secretary general, Antonio Guterres, launched his Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence in October, speaking of AI as “an enabler and accelerator” for the world, able to predict and address crises and scale up the work of governments, stating that “the transformative potential of AI for good is difficult even to grasp”, although he warned also of the dangers of the “malicious use of AI”. This was on the same day that UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, launched the AI Safety Unit, telling his audience: “I genuinely believe that technologies like AI will bring a transformation as far-reaching as the industrial revolution, the coming of electricity, or the birth of the internet… But like those waves [of technology], it also brings new dangers and new fears.”

His speech echoed some of the conclusions of former PM Sir Tony Blair and former foreign secretary Lord Hague in their joint report, published in June last year, ‘A new national purpose: Innovation can power the future of Britain’, which urged the building of foundational AI-era infrastructure as part of a more strategic state and how we plan for the future. They stressed the importance of “retraining and lifelong

learning, issues that will become of huge importance for future economic prosperity”, urging all political parties to address this with the “necessary speed and sense of priority, in a period of dramatic change and opportunity that has already begun”.

To some extent these national and global developments reflect what canny educationalists have been saying for some time. Sir Anthony Seldon, the prolific political biographer and current head of Epsom College, as long ago as 2018 in The Fourth Education Revolution (coauthored with Oladimaji Abideye) was urging educationalists to wise up to the likely consequences of AI for society, for humanity and the implications for education.

So if AI has not featured in the deliberations of your school board in the past year or so, it should have done and chairs should be looking to heads to ensure that it does this year. Many schools are commendably ahead in this area but if that is not the case in your school it’s important not to be left behind.

AI is spoken of as the solution to teacher shortages, an aid to pupil and teacher wellbeing, something which can revolutionise assessment and administration in schools, bring about

personalised learning, an end to school life punctuated by the physical movement of pupils at regular intervals to the sound of bells – and much more. And it is feared for all of those things, with profound implications for how we run schools and the role of the teacher in the digital age. And yet, even though they are going to be making key strategic decisions in this area, many governors don’t know exactly what AI is, unless they have had reason to come across it in their own lives, and many more don’t know how it might apply to schools in general and to their own school in particular.

The future is exciting but uncertain and the opportunities are equalled (in some eyes) by the risks. But if it is true that in education AI can offer better personalised assessment of pupil learning as a starting point, it’s difficult to understand why it is not more widely in use in schools. Some of this is linked to inexperience in ed tech, some to expense, some to teachers’ fears about the use of AI in teaching as well as learning.

The government has already indicated that it sees AI as key to resolving teacher workload issues in the announcement of the £2 million grant to Oak Academy to develop planning tools for teachers by using AI. As the education secretary Gillian Keegan said when announcing this: “Whether it’s drafting lesson plans or producing high-quality teaching resources, I am confident that by tapping

into the benefits of AI we will be able to reduce teachers’ workloads so that they can focus on what they do best – teaching and supporting their pupils.”

If this is to become the norm in the state sector, independent schools will want to be ahead in this area, and the development of AI-led teacher resources offers individual and groups of schools (and arguably the whole sector) some brilliant opportunities to form independent/state school partnerships.

What governors need to do is to reassure themselves that someone in their senior team is leading thinking about this in the school, can give a clear account of what the school is and is not providing, what it is and is not aiming to provide in the future, what these are going to cost, and how they are going to take the school community with them in this area. As for any other area of strategic development, governors will want to see success criteria and progress milestones.

Al Kingsley, chief of NetSupport and a member of the DfE’s regional schools directorate advisory board for the East of England, who writes and speaks extensively about ed tech and governance, in My School Governance Handbook, quotes the co-host on his EdTech Shared podcast, Linda Parsons, who wrote: “Don’t start writing a digital strategy until you have tailored your school’s digital vision.”

I would go further and urge the creation of a digital communication plan. And schools which have embraced

“Governors will be interested in the sense of direction and knowing what they can do to support developments. To do so, they need to understand what AI is and be, however amateur, users themselves.”

developments in this area most effectively have not only invested in technology but also extensively in ongoing training to ensure that staff are appropriately skilled to work confidently with AI, so you’ll want to know what the digital training plan is and what its continuing (not oneoff) costs wilI be.

No school can embark on any of this until a plan is in place and has been costed and communicated. And it’s by no means certain that all schools will embark on this soon. But governors will be interested in the sense of direction and knowing what they can do to support developments. To do so, they need to understand what AI is and be, however amateur, users themselves.

Durell Barnes is head of governance for RSAcademics.

The social profile of governors has changed little over the years and, in changing times, is your governing body doing all it can to reflect the make up of the people it serves? Mike Buchanan digs a little deeper

Most governing bodies of feepaying schools in the UK are made up of people like me: white, male, 50-plus years old, highly educated, affluent and from a narrow range of backgrounds and professional experiences. A survey covering statemaintained schools by the National Governance Association (NGA) found that 93% of respondents were white and that this proportion has hardly changed over the past 20 years. According to the NGA, just 1% are from mixed or multiple ethnic groups, 3% are Asian, 1% are black, 91% are aged 40-plus and 99% are aged 30-plus.

I don’t think these statistics are collected for independent schools in the UK, but they should be, and I’ve no reason to suppose they would differ in any substantial way. In other words, most schools are largely governed by people like me.

So what? I consider myself to be open-minded, thoughtful and inclusive in the way I behave so, given this, surely the most important thing I bring to the boards I sit on are my skills, knowledge and experiences gained over many years working in and with schools across the world. Surely these characteristics are more important than someone’s background. Diversity is a nice-to-have, but let’s not have the tail wagging the dog. This is exactly the argument I have encountered in 2021 when working with governing bodies.

“Some things must be changed post-pandemic and the place of equality, equity, diversity and inclusion as a central feature of our schools should be one of the changes.”

Many things will automatically change as a result of the pandemic. Some things must be changed post-pandemic and the place of equality, equity, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) as a central feature of our schools should be one of the changes. And it must be led from and by the governing bodies of our schools.

There are many business-led reasons why greater diversity and inclusion are positive steps for schools to take, not least that employees and students in those schools will have a richer experience, contribute more, and achieve more highly as a result. If you need a rational argument for change then this is a good one. Alongside this is the emotional, moral argument. As a governor of a school, would you set out with the intention of making people in your school community feel excluded, unheard, unseen, unsafe, untrusted, unvalued and lacking respect for who they are? In other words, feeling as if they do not belong. I hope the answer is “no”. Nonetheless, this is the reality for some students and their families in our schools.

Diversity and inclusion are not ‘niceto-haves’. They are the foundation upon which positive, productive and joyous communities are built. For too long we have paid lip service to the idea of their importance and waited in hope that the statistics might naturally evolve over time. This strategy of hope over action has failed too many people in our care: colleagues, students and their families. Some schools have set out deliberately on a different path, often driven by a combination of enlightened head and chair.

A good starting point is for the board members to explore their individual understanding of the terms and come to a shared language. This process takes time and careful exploration; it may be best facilitated by an outsider. I find it ironic

that as a white, privileged, older man I am increasingly being asked to talk with boards about diversity and inclusion. I am told that’s because I can provide a degree of psychological safety and, hence, prompt an open conversation. This fear of ‘getting it wrong’ is a powerful driver of hesitancy and inaction. So how might a board start such a conversation?

In order to promote productive dialogue, governors might start by exploring:

(i) How employees, students and parents experience inclusion as well as their own perspectives, and

(ii) Begin to outline a vision for the future based on these findings and their agreed common language. In other words, governors might address:

• Why EEDI matters and to whom.

• The role of governors in leading on EEDI.

• What EEDI mean to the employees, students and parents.

Coming to your own, visceral definition of the terms is a crucial step in bringing good intentions to life in your school. These are the litmus tests of future success. Recently, a board I worked with came up with this agreed understanding:

• Equality = treating people as equals over and above statutory requirements.

• Equity = recognising different starting points and removing their impact by positive actions.

• Diversity = recognising all the differences that any group of people represent and the benefits of these differences.

• Inclusion = an emotional response to feeling respected, valued, safe, trusted and having a sense of belonging.

The board also agreed that ensuring that all parts of the school community (students, employees, families, governors and supporters) should feel included and that this goal should drive the activity of the school from the board downwards.

In order to achieve this intention, the board set out the ambitious goals below and now plan, with the school leaders, to co-create and support the steps required to make rapid progress towards these goals:

• There should be no gap in attainment between students which arises only from their background.

• Students, employees, families and governors should feel included.

• The curriculum should be inclusive as reflected in the two bullet points above.

• Adults should report confidence in their ability to manage EEDI without fear.

• Students and employees should feel safe and safeguarded when reporting on their degree of inclusion.

• Students and employees should report a sense of fairness in access to and allocation of opportunities.

There are many practical steps that follow from such a statement of intent, from challenging mindsets and tackling systemic biases, to agreeing measures of progress. Proper investment of time and other resources is also needed. Crucially, where schools are being successful it is because they have ensured that their approach is part of their culture. Where schools have not yet had success it is typically because EEDI is seen as an addon, is tokenistic and formulaic. Importantly, governors should be

“Where schools have not yet had success it is typically because EEDI is seen as an add-on, is tokenistic and formulaic.”

seen to be intentionally leading and not merely supporting steps towards greater inclusion and diversity as shown by who is on the board. However difficult, this means actively seeking to ensure the board has a mix of genders, ethnic, social, educational and professional backgrounds, as well as other protected characteristics, and a wide, balanced range of ages so that the phrase ‘people like us’ becomes a positive affirmation of inclusive practice rather than an accusation of exclusion.

Mike Buchanan is the founder of PositivelyLeading and was formerly the executive director of HMC.

Charlotte Melhuish discusses how schools should respond to claims of discrimination and the key considerations for governors

Perhaps reflective of broader global trends, schools have seen an increase in former pupils reporting their experiences of discrimination at school. Some of these experiences relate to incidents that are alleged to have taken place many years ago, whereas others are more recent. In this article, we explore the issue through a fictional case study.

The chair of governors of the Red School receives an email from a former pupil (who left last academic year) stating that he was subject to racism while at the school and that “he does not wish any other pupil to be subject to such discriminatory behaviour”. The former pupil names the alleged perpetrators, some of whom are still pupils at the school. He alleges that teachers did not take appropriate action at the time to deal with the behaviour. He has also shared his concerns on social media, to which other alumni have responded, suggesting there is a culture of racism at the school.

The most important, overarching principle is that all allegations of racism should be taken seriously – racism has no place in society or schools. Staff and governors are in a front line position to encourage and maintain an equal and inclusive culture in school, and respond appropriately and robustly if incidents arise.

“The most important, overarching principle is that all allegations of racism should be taken seriously – racism has no place in society or schools.”

• Gather facts – Given the potential for police involvement (see below), the chair should ask a member of the senior leadership team to gather sufficient information to establish the broad facts. For example, what has the former pupil alleged? Was the school aware of the incidents at the time and, if so, are there contemporaneous notes of the action taken in response? Have the alleged perpetrators been identified by the victim(s) online, and which of these are current pupils? These factors will help to determine the next steps.

• Take advice and liaise with other agencies as needed – The chair or head should consider whether to take legal advice at the outset, given the seriousness of what is alleged and the potential implications (including potential reputational damage to the school if the response is not properly and sensitively handled). Discussions should also include whether to liaise with external agencies, such as the police (if a crime may have been committed) or social services (if there are safeguarding concerns about a child or young person).

As for all serious cases, the school may wish to refer to the non-statutory guidance from the National Police Chiefs’ Council ‘When to call the Police, Guidance for Schools and Colleges’, which provides guidance to schools when considering contacting the police. The guidance explains when an incident is considered to be a hate incident (which includes when the victim or anyone else believes the incident was motivated by hostility or prejudice based on race), and also when it’s considered to be a hate crime.

Whether the chair or head reports the matter to the police is a matter of professional judgement taking into account all the factors in the guidance, the outcome of the school’s initial fact-finding exercise and all relevant circumstances.

Where the police are involved, the next

steps will, to an extent, be led by them. This does not completely prohibit a school-based investigation but the school should liaise closely with the police regarding timings to avoid prejudicing any police investigation. If the police don’t need to be involved (or where the police confirm the school may proceed with its own internal investigation), the chair or head should ensure the schoolbased investigation is conducted in accordance with school policies.

• Alleged perpetrators who are current pupils – The school has a duty of care to its current pupils, which includes the alleged perpetrators. The head should therefore ensure that steps are taken to monitor these pupils and, where necessary, that appropriate arrangements are put in place (for example, if there’s a risk that they may be bullied or targeted themselves, particularly if the allegations have been shared online). Depending upon a pupil’s age, this may require the parents’ involvement. If the outcome of the school’s investigation confirms that current pupils were acting in breach of school policy and displayed inappropriate discriminatory behaviour, the head may impose sanctions in accordance with the school’s behaviour policy. The chair should be informed of the outcome of the school’s investigation.

• Preparing a response – The chair’s

“Whether the chair or head reports the matter to the police is a matter of professional judgement taking into account

all the factors in the guidance, the outcome of the school’s initial fact-finding exercise and all relevant circumstances. ”

response to the former pupil should be approached with care bearing in mind the sensitivity of the allegation and that any response may be shared by the former pupil in a public forum, for example, via social media. PR and/or legal advice should be sought as appropriate. Any disciplinary action taken against current pupils should not be disclosed to the former pupil.

• Social media – If the allegations are being shared publicly on social media, the chair or head should ensure that staff have been advised not to respond to any public or press interest (including responding to comments made by alumni), but direct all

communications to a designated central point of contact in school who has been provided with clear guidance on an appropriate response (following PR advice, as required). PR and/or legal advice should be sought if the school is considering taking steps to remove the social media post and/or restricting any further comments from others.

• Raising awareness/teaching – The chair and head will no doubt be aware that there is always more that can be done to promote and improve a culture of equality. This should include ensuring senior leadership takes a proactive approach in considering what more can be done ‘on the ground’ and what lessons can be learned as a result of this allegation. For instance, it may be appropriate to involve pupils by asking them what they feel should change (such as via a pupil committee); ask senior leadership to speak with staff about their experiences; review the curriculum and PSHE lessons; and set up an action group of staff who can drive forward any proposed changes.

While senior leaders will handle the operational on-the-ground response, governors will have a key strategic role in responding to and managing such incidents, not least as they have ultimate

responsibility for ensuring appropriate action is taken where it is alleged that there is (or was historically) racism/ discrimination in the school. For instance:

• Governors should hold the senior leaders to account in ensuring serious allegations are handled correctly, and ensure they are confident staff have the appropriate training and resources to do so.

• Bullying records should be reviewed for patterns of racist incidents.

• If a culture of racism/discrimination in the school has been found to exist, governors may want to consider whether to commission an independent review to identify issues and advise on ways to improve the culture of the school going forward.

• If the school is a charity, governors (as trustees) will need to consider whether to make a serious incident report to the Charity Commission. The Commission has guidance online which summarises the relevant factors, such as whether the incident results in or risks significant harm to the charity’s beneficiaries (that is, pupils/former pupils), and/or harm to the charity’s work or reputation. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the trustees to decide whether an incident should be reported based on the incident meeting the seriousness threshold. If governors decide not to make a report, the reason should be recorded appropriately (for example,

Turnkey

Sports canopy • School Canopy • Sports Complex • Padel Centre • Tennis hall • Play Area • Gymnasiums • Changing rooms • Club-houses • Dojos • Grandstand • Skateparks • Football pitches

For further information:

www.smc2-construction.co.uk

contact@smc2-construction.co.uk

Phone: +44 (0)3333 051 015

Focus on the school canopy !

An easy solution to allow children to play outside no matter the weather

+ Easy to install

+ Made in tensile membrane an optimal natural light

+ Built with a timber frame for a low carbon impact

in meeting minutes). If the Commission later becomes involved, trustees will need to be able to explain why they decided not to report at the time.

• Should more be done to hold leaders to account for diversity, equality and inclusion more generally? Governors may wish to consider having a designated governor who takes the lead in this area, and reports back to the wider governing body periodically.

Failure to create and maintain a culture of equality can have additional wider implications for the school, including:

• Legal and regulatory requirements –There are various legal and regulatory requirements for independent schools relating to unlawful discrimination and promoting mutual respect and tolerance (for example, Parts 1 and 2 of the Independent School Standards Regulations 2014 and obligations under the Equality Act 2010). On inspection, inspectors may look

at whether incidents of bullying or prejudiced and discriminatory behaviour are common and whether these are indicative of ineffective safeguarding practices.

It is for the governors and head to satisfy themselves that the school is meeting these standards, bearing in mind that inspectors may challenge both senior leadership and governors to reflect upon whether they are doing enough to promote equality and the effectiveness with which the school deals with discrimination, including racism, in all its forms, particularly in light of Independent Schools Inspectorate’s new inspection framework with its central focus on pupil wellbeing. Schools which are found to be failing to encourage respect for others and/or to deal effectively with racism risk not meeting the independent school standards and, therefore, are at risk of sanctions issued by the Department for Education.

Heads and governors should therefore ensure the school is regularly reviewing its procedures and relevant policies

such as those regarding equality, antibullying, behaviour and the staff code of conduct; that these are being effectively implemented in practice; and that these are contributing to the creation of an inclusive ethos and culture across the school.

• Legal claims – Parents, pupils or alumni may seek to bring legal claims against a school in relation to discriminatory behaviour, including claims for discrimination, negligence and/or breach of contract. The merits of such cases are of course dependent upon the facts, but even cases without merit can be time-consuming and costly for the school to respond to.

It's therefore important for heads and governors to ensure the school takes active measures to promote and maintain a culture of equality, and effectively and promptly deal with any incidents of alleged discrimination if they arise. This commitment should not simply be set out in a policy, but actively implemented in practice.

Charlotte Melhuish is a partner in the education team at law firm Stone King.

You’ll often hear people being told that they need to think more strategically, usually when they’re faced with a significant problem that threatens their organisation. But waiting until you’re facing an existential threat before you start to think more strategically is probably too late. That’s why it’s no secret that the most successful organisations make a habit of thinking strategically as a matter of routine. But what is strategic thinking, why is it so important and how do you do it?

Put simply, strategic thinking is about shifting your focus from what’s happening within your organisation to what’s happening around it, now and in the foreseeable future. In doing this, you’re trying to identify the opportunities that you might be able to exploit as the environment around you changes, as well as the obstacles that you’re going to need to overcome to remain successful. The Harvard Business Review’s guide to thinking strategically puts it neatly: “When you think strategically, you lift your head above your day-to-day work and consider the larger environment in which you’re operating.”

Max McKeown, a strategy author, concurs but also believes that “becoming a strategic thinker is about opening your mind to possibilities”. This is an important aspect of effective strategic thinking because all too often if we bother to think about the future at all, we have a habit of viewing it through rosetinted spectacles, assuming it will unfold

“It’s no secret that the most successful organisations make a habit of thinking strategically as a matter of routine.”

in the way that we want it to. We can be forgiven for this because we are born with a natural optimism bias, but the problem is that the future has a habit of unfolding in a way that constantly surprises us. Indeed, the future is so uncertain and unpredictable that the formal study of the subject is now known as ‘futures studies’, with the pluralisation of the word reflecting the fact that there are many alternate possible futures, all of which could present opportunities, as well as obstacles.

Organisations that are adept at strategic thinking identify possible opportunities and likely obstacles well before they materialise. Not only does this mean they can prepare themselves well in advance, but it also means they can start doing things to help shape the future so the outcome that most benefits them becomes more likely. Returning to McKeown, this is why he believes that “becoming a strategic thinker – a strategist – is about getting better at shaping events” and why Harry Yarger, author of the seminal The Little Book on Big Strategy, believes that the aim of good strategy is to “create more favourable future outcomes than might otherwise

exist if left to chance or the hands of others”. So, if your school is good at strategic thinking, then not only will it be able to identify and then exploit opportunities that others miss, but it will also be able to make these opportunities more likely to materialise.

To take an example many will be familiar with, in the early 2000s, Charlie Ward, an engineer at Amazon, noticed that people were becoming increasingly time-poor. In 2005, Amazon exploited the opportunity it felt this presented by launching Amazon Prime, a service deliberately aimed at people who are more time-sensitive than price-sensitive. Customers didn’t ask Amazon to provide

the guaranteed two-day delivery service but, by 2021, the scheme had more than 200 million paying members globally, establishing it as one of the world’s biggest online subscription services. It’s a similar story with obstacles. Those organisations that have looked to the future and identified a possible challenge that might need to be addressed will be better placed to overcome it, or even shape the future so that it’s less likely to materialise.

As we’ve already established, effective strategic thinking requires us to try to understand what the future might look like. But as we’ve also established, there are lots of different possible futures. The trick is therefore to try to identify those we should focus on. The Futures Cone illustrated in Diagram 1 can help with this. Developed by Joseph Voros in the early 2000s, it identifies alternative futures that could unfold, including the ‘projected’, ‘probable’, ‘plausible’, ‘preferable’, ‘possible’ and ‘preposterous’. Describing what each of these might look like in, say, five years’ time can be a powerful way of starting to understand how the environment in which your organisation operates might change. But to do this in an informed way, you need to develop a better understanding of what’s happening around you, both at the global level and at the more local level, specifically the sector in which your organisation operates.

At the global level, a good starting point is to consider the megatrends that seem to be shaping the world in which we all live and work. There’s lots of analysis on this and even a quick online search would identify things like: climate change and increasing electrification; global population increases; greater urbanisation; the increasing ubiquity of artificial intelligence and machine learning; the blurring of work/life boundaries etc. Thinking more locally, the best way to understand what’s happening in the education sector is to become

super-inquisitive and to hunt for, rather than gather, information about emerging trends affecting the sector by reading more widely, listening to expert podcasts, attending conferences, following bloggers etc.

Once you’ve spent time in the ‘understand’ phase, you can then apply a technique called ‘visioning’ or ‘scenario planning’ to describe what you think some of the alternative futures might be as they relate to the world in which your organisation exists. Going back to the futures cone, a good place to start is by describing what you think the ‘probable’ future might look like, so the one that you think is most likely to unfold based on everything you’ve read, heard or seen. It can be quite difficult to do this if you’ve never done it before, but applying the PESTLE headings can help, where the acronym stands for ‘political’, ‘economic’, ‘social’, ‘technological’, ‘legal’ and ‘environmental’. The idea is that you take each heading in turn and think about how the trends and changes you’ve

identified under that heading (both global and local) will shape the sector.

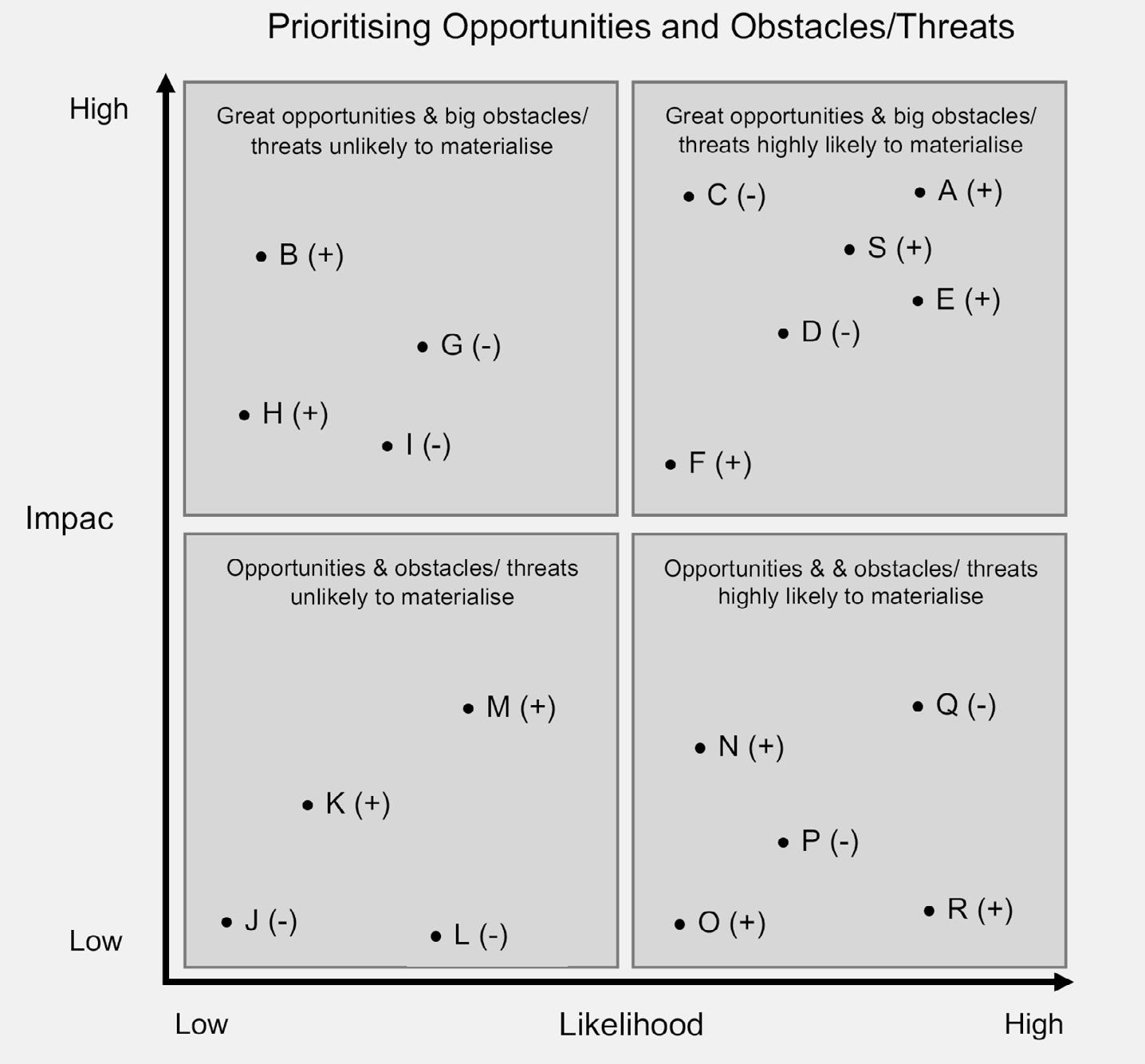

To take a topical example, under the ‘political’ or ‘economic’ headings your description of the ‘probable’ situation in, say, five years’ time might include something like: “having won the general election in 2025, the Labour government imposed VAT on school fees and removed the exemption from business rates that charitable fee-paying schools enjoyed”. Once you’ve described it in a few paragraphs, you can go back to each of the different headings to try to find opportunities you could exploit and obstacles you might need to overcome, capturing them on an impact/likelihood matrix such as that illustrated in Diagram 2 as this will help determine which to focus on, with the opportunities denoted by a (+) and the obstacles denoted by a (–). As you do this, it helps if you have an idea of what you want your school to be like in the time frame you are considering as this helps you identify how specific opportunities might help you achieve

your desired endstate (think of them as the ladders in the game Snakes and Ladders).

It's then worth considering the different actors, or stakeholders, that might impact on your environment and ascertaining whether, in the alternative

future you are examining and, given the endstate you are trying to achieve, they are likely to represent opportunities (perhaps for collaboration) or obstacles (because they are likely to oppose you).

Plotting them on a ‘power/interest’ matrix like that in Diagram 3 can help

you determine which are likely to be most important to you, where (+) or (–) are used to denote whether the stakeholder is likely to support or oppose you.

Having applied your strategic thinking skills to develop an understanding of how the future might unfold, you are well placed to position your organisation for success by developing a strategy that joins the dots, exploiting the opportunities you’ve identified and overcoming the obstacles, as well as shaping the future where you can make the former more likely to materialise and the latter less so. However, the chances are that although you might get some of it right, the future will always surprise us so it’s important that you also consider the ‘plausible’ and ‘possible’ futures, not just the ‘probable’, and that you’ve thought about what you would do if they were to unfold.

Once you’ve started to implement your strategy, remaining attuned to what’s happening around you and being prepared to adapt your strategy when it becomes apparent that your predictions about the future were incorrect is imperative. That’s why the most successful organisations create time for strategic thinking and do it regularly – something worth thinking about as, having read this article, you switch focus back to the dayto-day operations of your school.

Craig Lawrence is founder and managing director of Craig Lawrence Consulting.

Successful independent schools depend heavily on their staff and ensuring they offer competitive packages with a clear understanding of the tax treatment. The net reward for employees plays a pivotal role in this equation.

Additionally, it’s important to note an increase in HMRC activity as it has expanded its compliance team by more than 3,000 additional personnel. Given this heightened scrutiny, it is advisable to maintain a strong grip on your responsibilities regarding employment-related taxes, ensuring that your institution has well-established and resilient processes, policies and procedures in place.

This article looks at some of the key employment tax areas that frequently appear within the setting of independent schools.