9 Foreword

Judy Hecker, Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich, Director of Exhibitions and Programs

19 At the Threshold

Carmen Hermo, Curator

57 Works in the Exhibition

4

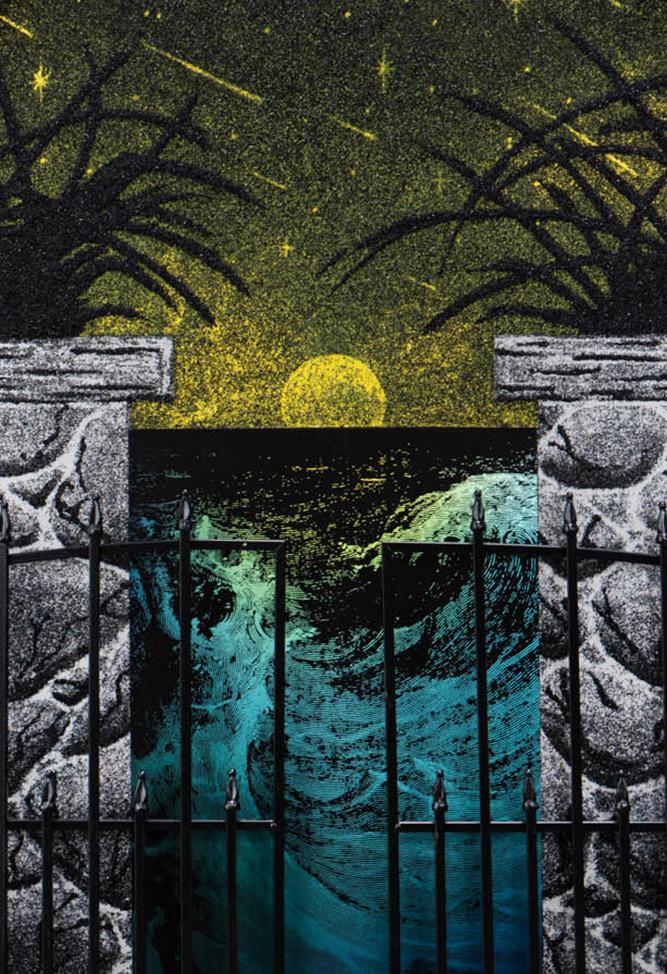

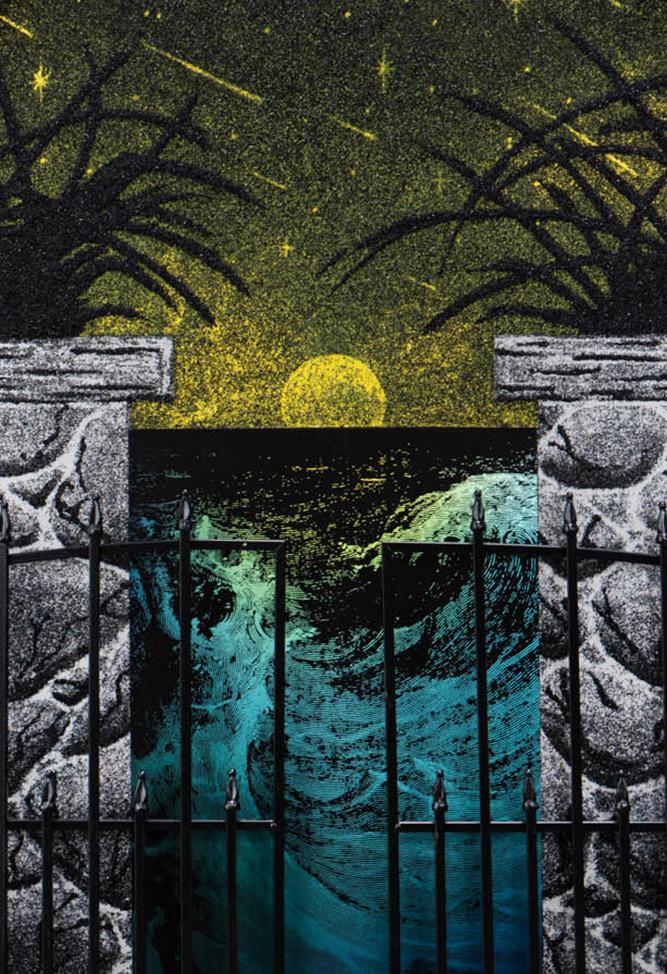

Aaron Coleman

Gateway for Premonition, 2022

Gateway for Evasion, 2022

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman

Gateway for Remembrance, 2022

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman

Foreword

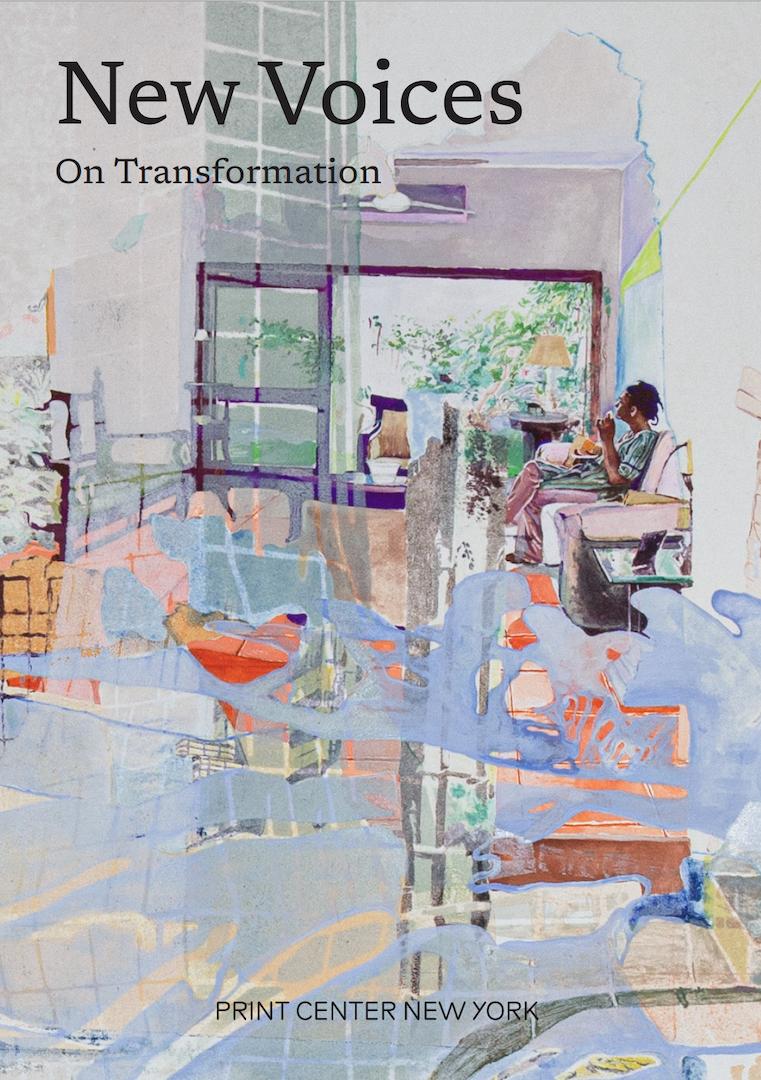

Print Center New York is thrilled to present the first season of New Voices, a new annual open call program that builds on our organization’s more than twenty-year history of supporting emerging and underrecognized artists who consider printmaking and its strategies a central part of their practice. New Voices, an evolution of our prior New Prints program, provides opportunities for a focused group of artists to develop and contextualize their work through a curated group exhibition, artist-led public programming, cohort convenings and community-building, and individualized resources for professional and artistic development.

For our pilot year, we were fortunate to work with invited curator Carmen Hermo, Associate Curator for the Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, who developed this season’s guiding curatorial framework and then led the selection process.

9

Hermo’s framework encouraged applicants to consider their work in relation to the theme of transformation—an open-ended concept that drew a competitive pool of nearly 500 applicants from 42 states across the United States. With New Voices: On Transformation, we are proud to present the work of the eight artists in the inaugural New Voices cohort: Aaron Coleman, Julia Curran, Juana Estrada Hernández, Lois Harada, Nina Jordan, Farah Mohammad, Jacquelyn Strycker, and Eriko Tsogo.

We are grateful for Hermo’s thoughtful engagement with our open call process from start to finish, and for her spirit of generosity and collaboration. We also thank Robin Siddall, Exhibitions and Programs Coordinator, who has not only been an energetic steward of this new program’s development and the organizer of its many logistical hurdles, but also became an invaluable collaborator in Hermo’s curatorial process.

New Voices grew out of a series of energizing focus groups organized by Megan Duffy, our former Artist Programs and Education Manager, who in 2021 convened artists, curators, and arts programmers to review and provide critical feedback on an early prospectus for our new artist-centered programming. We thank her and each of those 23 participants for their time, observations, and ideas, which sharpened our thinking and ultimately helped us define and shape this program.

We are grateful to all of our supporters for making this inaugural presentation of New Voices possible. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. Additionally, this project is supported,

10

in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature. We are also grateful to The Wolf Kahn Foundation and The Emily Mason | Alice Trumbull Mason Foundation for establishing the Emily Mason – Wolf Kahn Artist Development Fund. This Fund fosters connections and advancement within the printmaking community by supporting artists' professional development opportunities with cohorts, critics, gallerists, printers, and publishers.

Finally, we extend gratitude to all of Print Center New York’s talented staff, and our Board of Trustees for supporting programming like New Voices that aims to elevate the work of rising talent and advance printmaking as a vibrant form of contemporary artistic expression.

Judy Hecker Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich Director of Exhibitions and Programs

11

Foreword

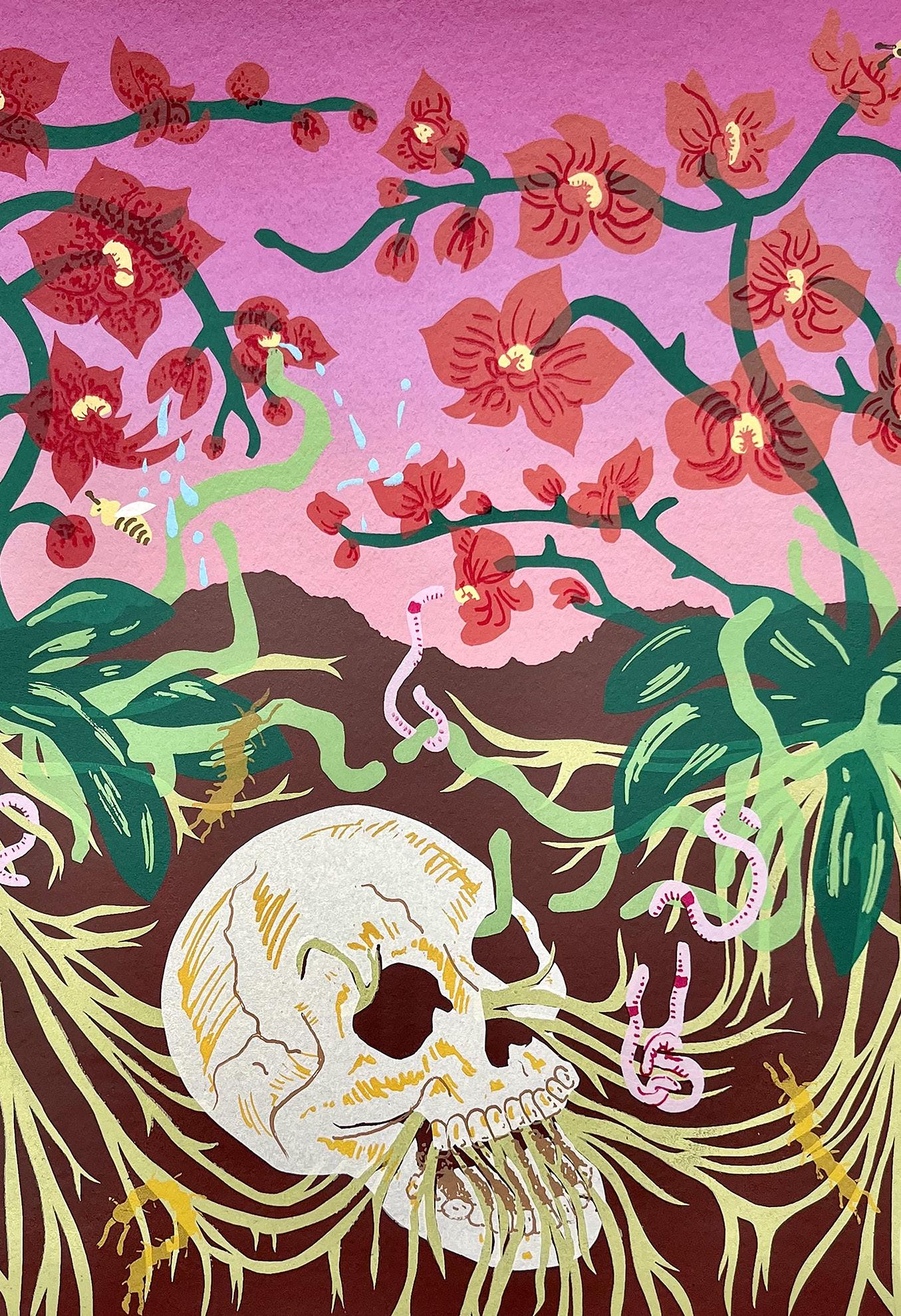

Julia Curran

exterior of Memento Mori for Evil Men

(One Day You Too Will Die, She Will Eat You, Then Shit Out Your Bones), 2022

12

Julia Curran

interior of Memento Mori for Evil Men

(One Day You Too Will Die, She Will Eat You, Then Shit Out Your Bones), 2022

Julia Curran

Julia Curran

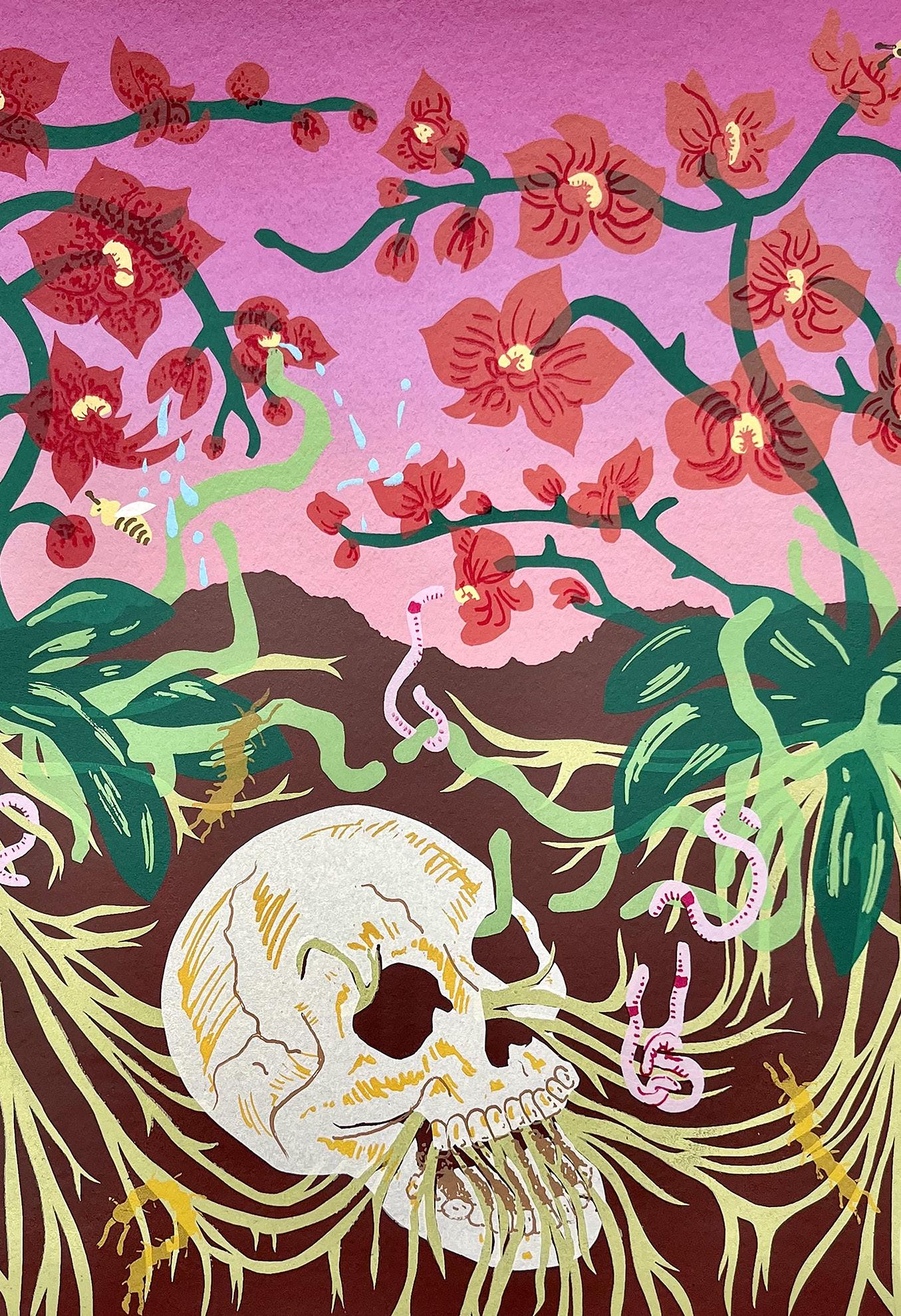

Spring's Revenge, 2023

16

At the Threshold

In Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler’s 1993 harbinger of things to come, the protagonist of this speculative and dystopian novel is Lauren Oya Olamina, a Black teenager who withstands her time’s horrors of violence with an unusual threshold for empathy and understanding; who is seemingly uniquely able to question and destabilize the truths told to her and framing society. In the book’s epiphany, Lauren sets out tenets for a new religion, her experiences and emotions accumulating into the realization: “All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change.” This revelation does not unmoor people from a sense of empowerment in the face of change, but rather entangles the relations of transformation, revolution, and development as truth, as omnipresence, and as something that happens to and through you.

19

Carmen Hermo

Carmen Hermo

The United States is often described as being on the brink of civil war, its conditions uncannily calling to mind the social armaments and tribalism of Parable of the Sower. Rampant breakdowns of democracy and justice, looming climate collapse, capitalist exploitation, and technological acceleration have changed how we relate to ourselves, each other, and our environments. There is a sense that we are coming to a limit, exacerbated by the constant swirl and scroll of repeated and recurring destabilization. As image and idea makers, artists can inspire a pause in the midst of this—a reflection, a reconsideration of what is accepted or known. Their work can re-situate a viewer within themselves and within the matrix of possibilities for our shared futures.

Printmaking, too, is by definition an act of change, of transformation—relief and reversal upend first impressions, and duplication, stencil, and transfer germinate new ideas and images—and the social, political, and personal context of an artist’s practice ensure that this thousands-year-old medium continues to track our chaotic times. As reflections on and within these contexts, the works of the artists in On Transformation represent thresholds: spaces where materials and techniques meet up with inquiries about accepted truths and realities, with what the artist is to do about it. This threshold can be a boundary of understanding and recognition that perforates preconceptions and biases. On this verge, on this tipping point, the paths and decisions of the past meet the next steps of the future; the was conjoins the now for a moment, while we see and ponder the what will come next. For some

20

artists in On Transformation, that pause is the crux of their work, liminal and full of potential; others mine the past to inform our actions in the present, and still others navigate and refuse the binaries that the threshold seems to create. These artists situate the viewer at a site of potential, received, or active transformation, exploring life and death, truth and history, and belonging within the home, our surroundings, and ourselves.

In Aaron Coleman’s work, the thresholds of self recognition and social potential collide in object-prints that are themselves portals into possibility. Combining gothic wooden frames, wrought iron fencing, Astroturf, and textured rubber crumb with screenprinted images and techniques, the artworks are imbued with a sense of both foreboding and luminosity. In part inspired by Saidiya Haartman and Fred Moten’s project “The Black Outdoors: Humanities Futures After Property and Possession,” and the artist’s own experiences as a biracial person of color, barriers and fences evoke divisions of public space, social bias, and land access. In Gateway for Evasion (2022) and Gateway for Remembrance (2022), Coleman incorporates details of Gustave Doré’s wood engravings for the 1866 La Grande Bible de Tours, distilling heavenly light and thrashing waves into ruminations on the beauty of urban spaces, and life and death remembered. Recontextualizing images from a canonical religious aesthetic, Coleman redirects the historical to the present, the space of history being made now.

The opening gate in Coleman’s Gateway for Premonition (2022) positions the viewer within an image that is ambiguous—are the Astroturf mounds inviting

21

At the Threshold

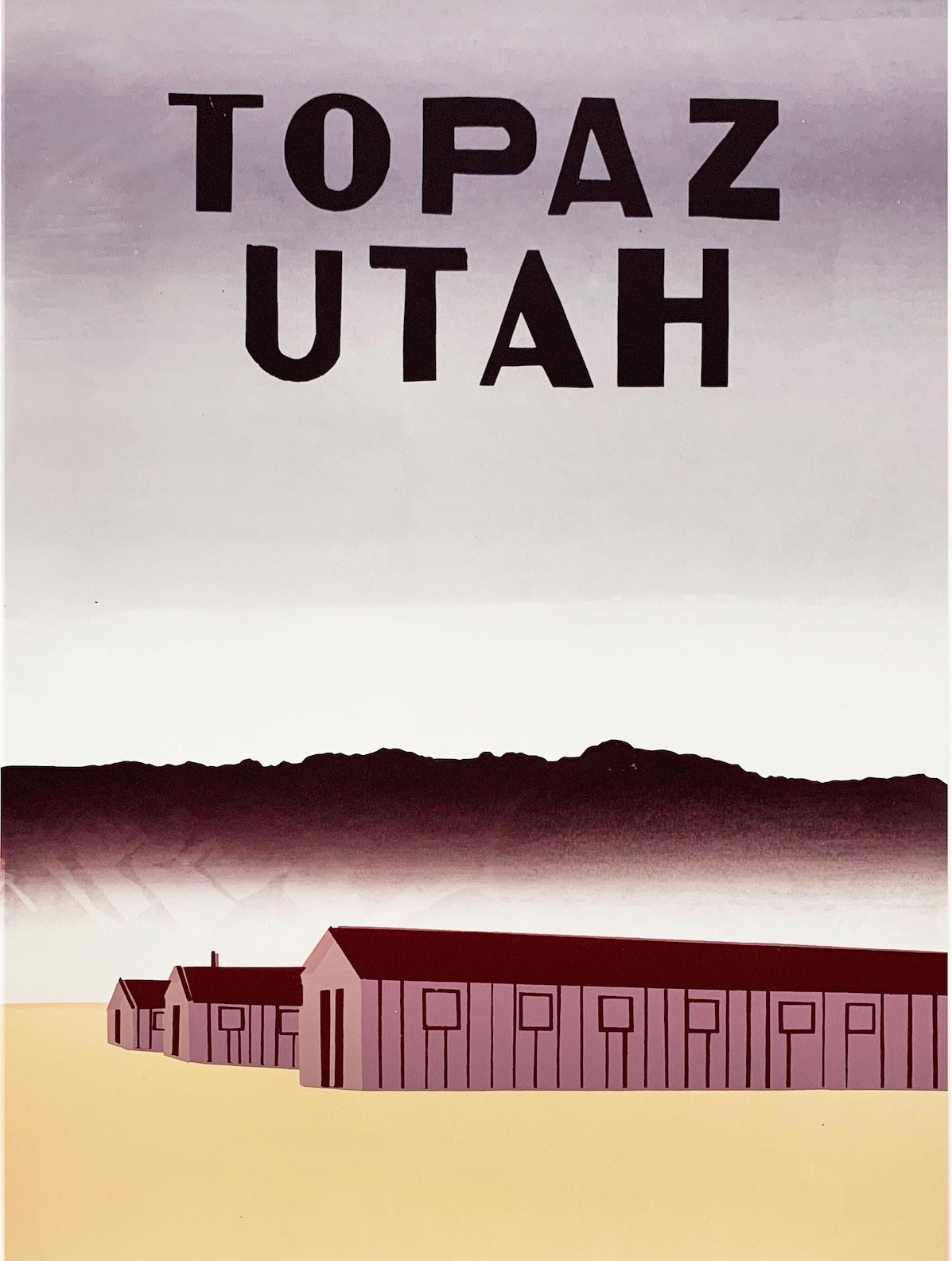

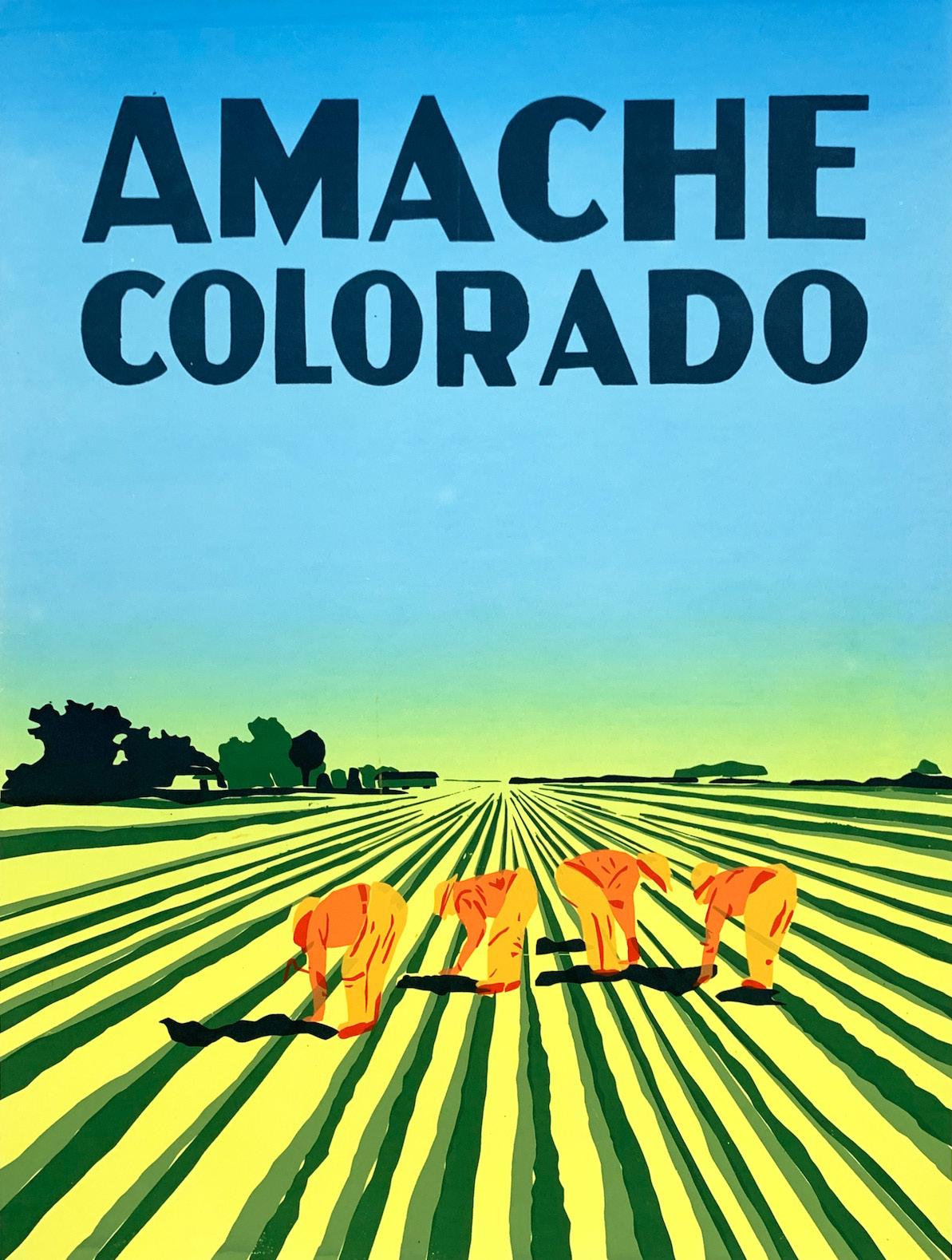

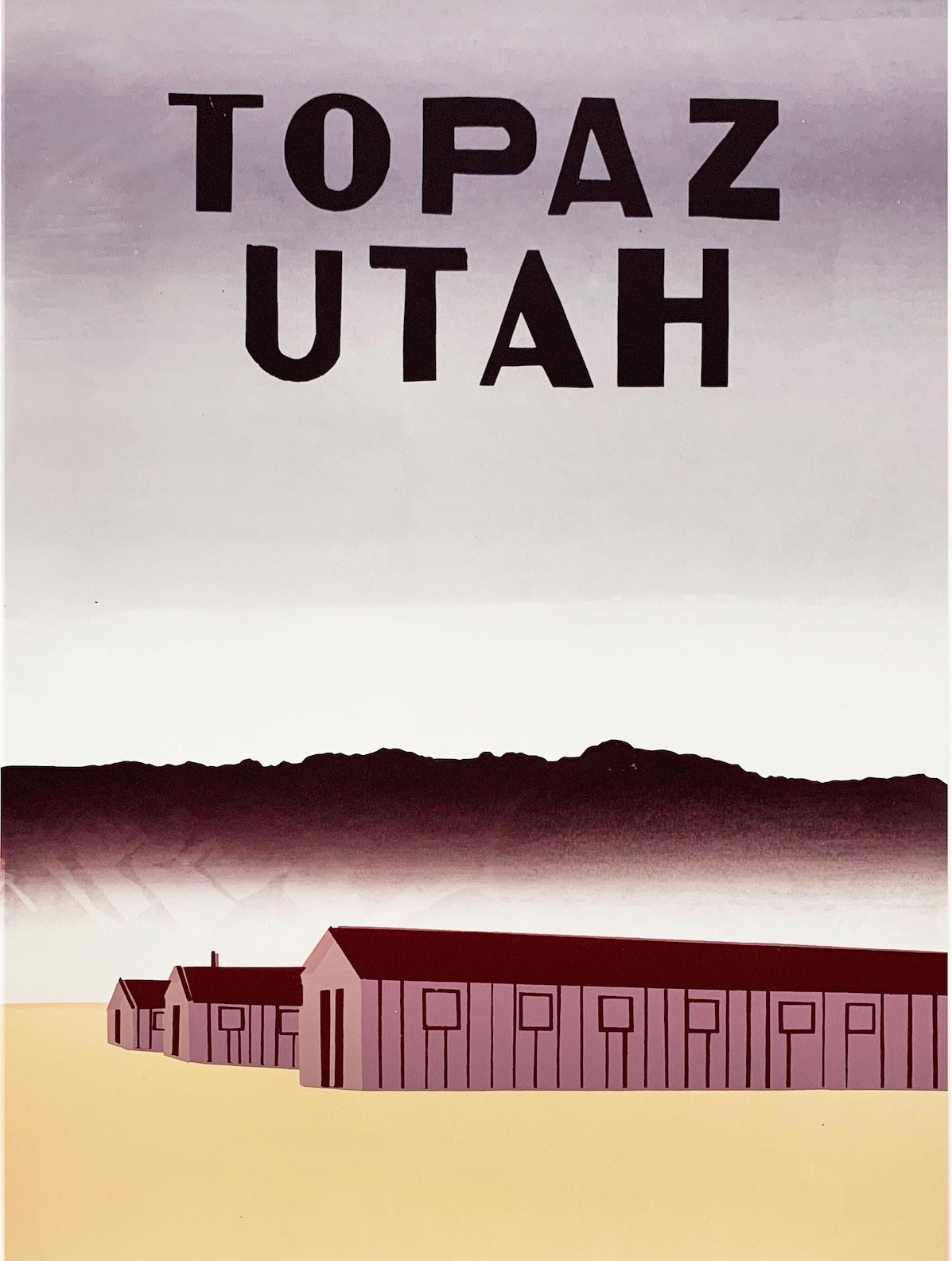

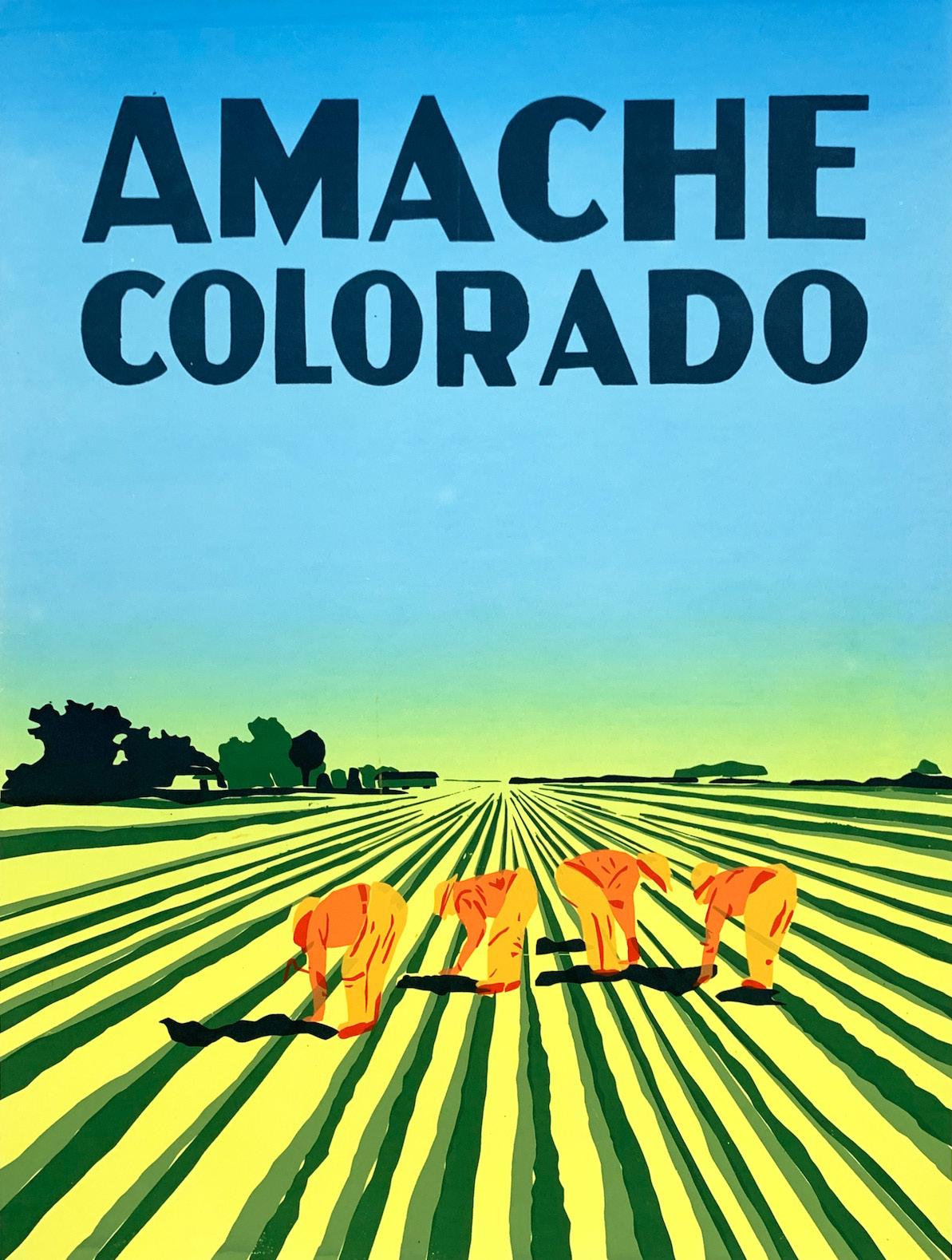

exploration, or occluding passage? Is the rain cleansing, or unwelcoming? The ambiguity and material specificity in Coleman’s work, in his words, “address how mundane and seemingly anodyne artifacts embody the complex and pervasive history of racism and classism in the United States,” and allude to the racist foundations of placemaking and urban design in the US. This is further reflected in the encroaching form of In The Wake (2023), a found shard of payday loan/check cashing signage. The sign’s Pan-African colors point to these businesses’ predatory marketing and presence in communities to which Black Americans are relegated due to systemic racism in housing and urban planning. Coleman screenprinted a Kente cloth pattern on the sign’s verso in a nod to the origins of these cultural signifiers, and determined that its natural sharkfin-shaped form required a floor-based installation. Metaphorically circling the exhibition space, it cleaves the gallery, perhaps questioning how art institutions are not so different in their manipulation of narratives, identities, and resources. In Lois Harada’s work, transformation operates on accepted truth and history, co-opting propagandistic art and re-creating the foundations of capitalism and so-called America. The artist’s Wish You Were Here series intervenes on propagandistic images of Western landscapes, inspired by the mythologizing artistic project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). These screenprints engage bold colors and forms reminiscent of the manifest-destiny imprints created by WPA artists, yet Harada instead foreground the barracks, guard towers, and wire fences of Japanese American internment camp sites. Wish You Were Here, Amache (2022),

22

Carmen Hermo

depicts the hard labor and stark conditions experienced by Harada’s paternal grandmother’s family, who were forcibly relocated from their farming life in San Diego to a camp in Poston, Arizona. Heart Mountain (2022) disrupts the postcard picturesqueness of a majestic mountain with encroaching carceral reality. The foundations of these screenprints are appropriated from images in the archives of the Library of Congress, recasting institutionally-approved histories, and complicating the visuality of travel and tourism in the American West with the realities of violence and forced labor of that land, making the viewer question their previous ideas about it: How did we not see this before? What other seemingly apolitical landscapes are also sites of carceral violence and dispossession? Making labor even more visible within this narrative is Harada’s accompanying custom penny press, which allows visitors to print their own souvenir pennies of these sites. This turning of the gears transforms the penny from its role as circulating legal tender into a document, a pocketable monument to be carried forward. A nod to the dark tourism of internment sites like Manzanar, Harada’s work also acknowledges the complicity of citizens whose labor and tax dollars fund human rights abuses, then and now.

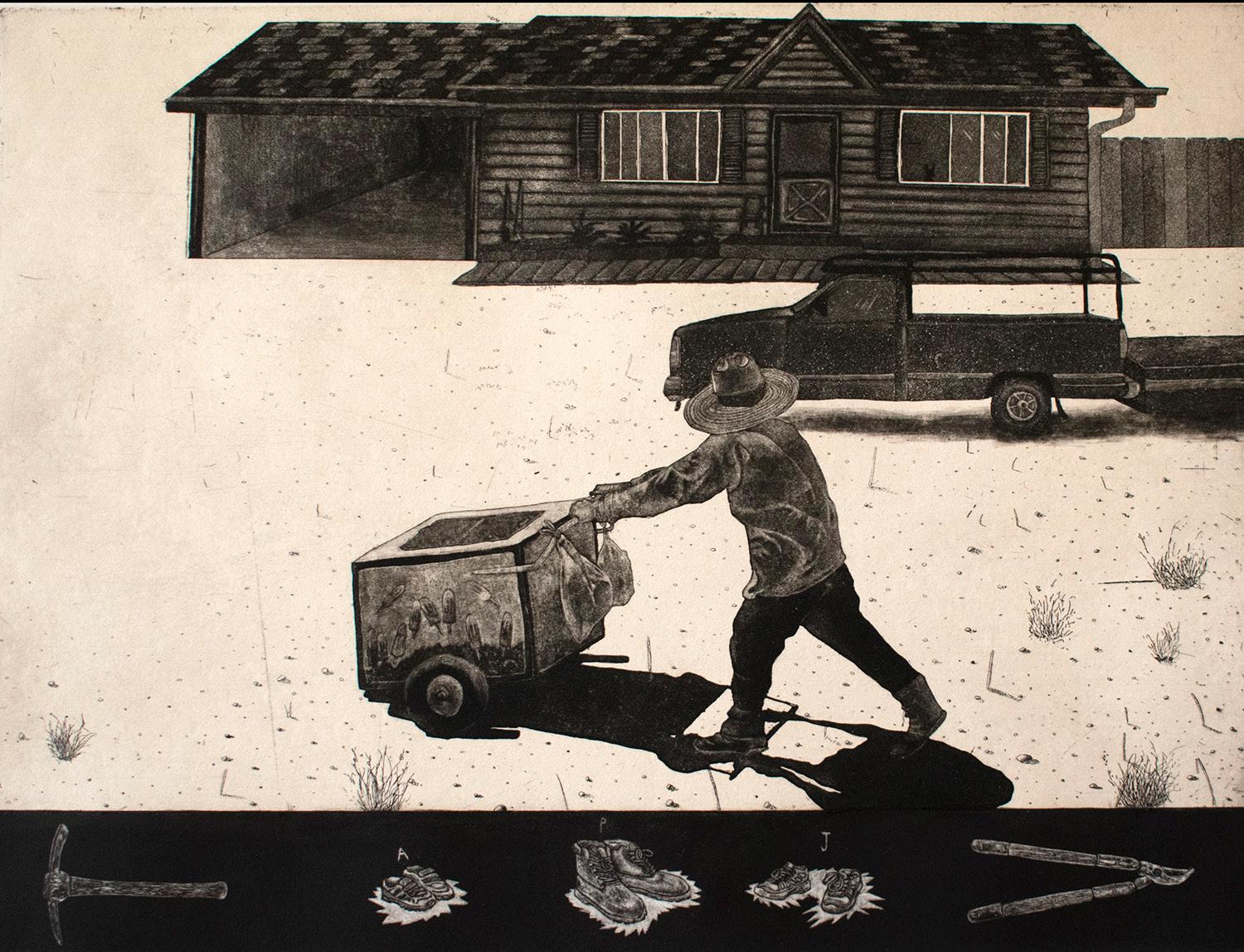

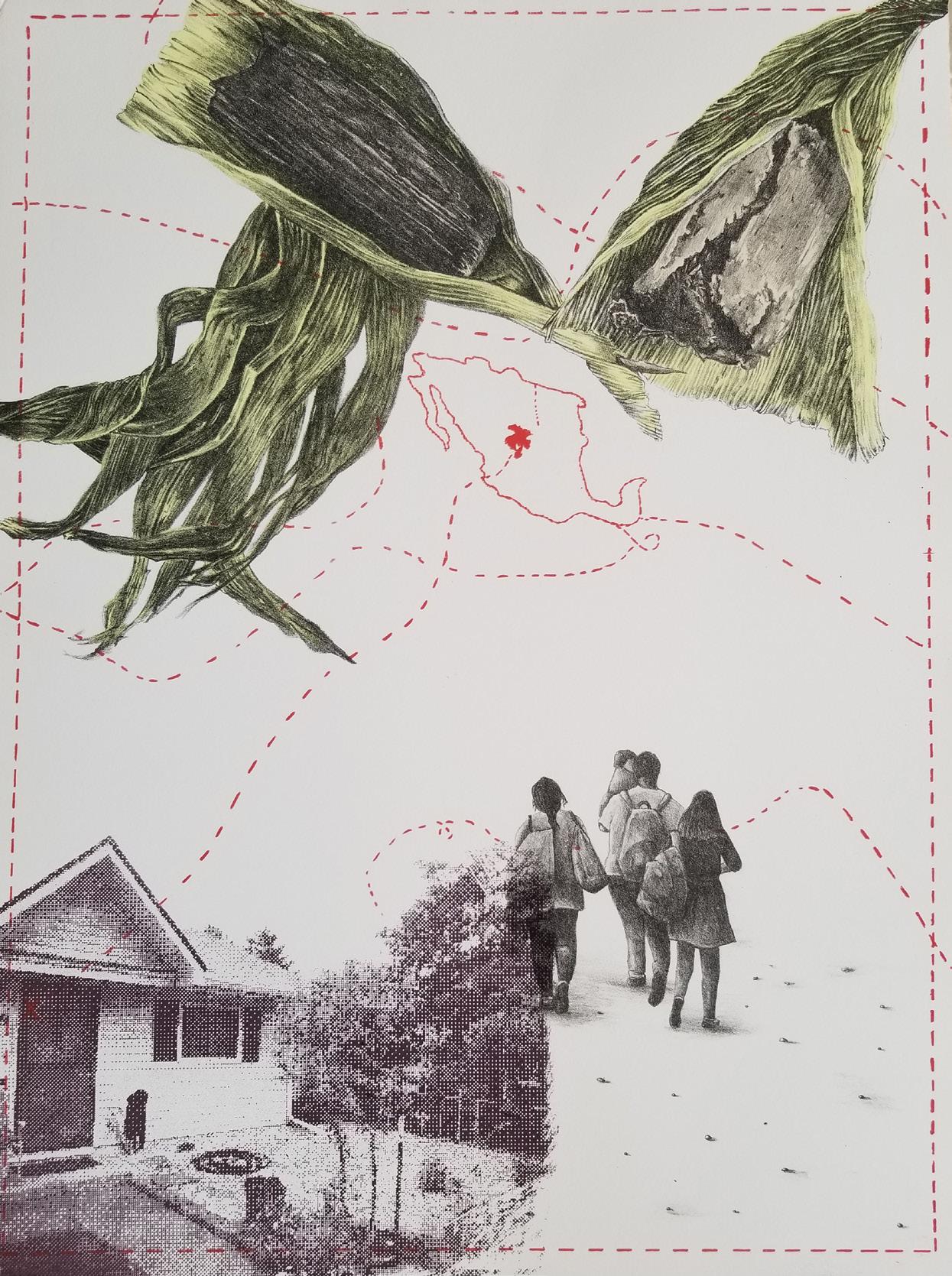

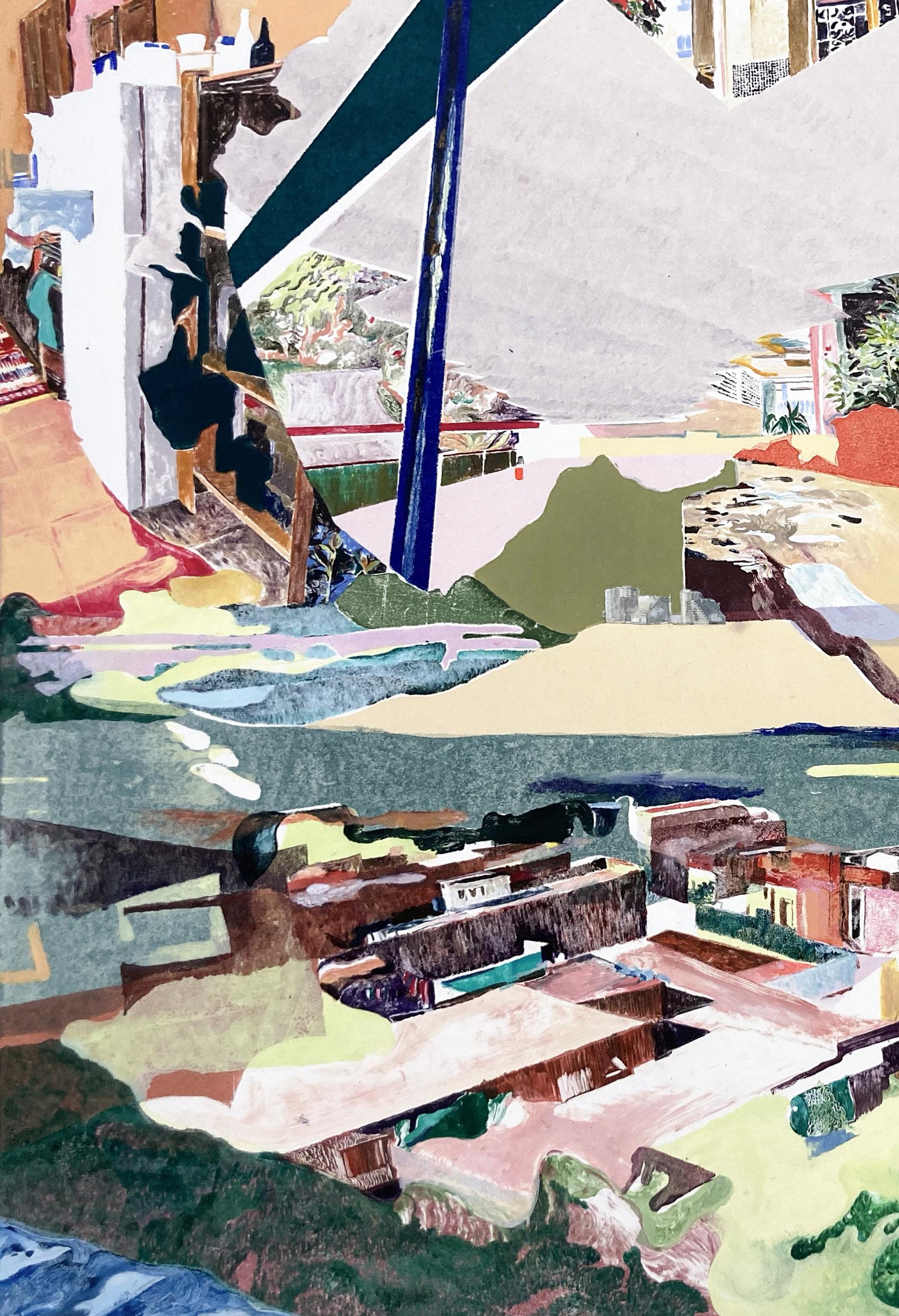

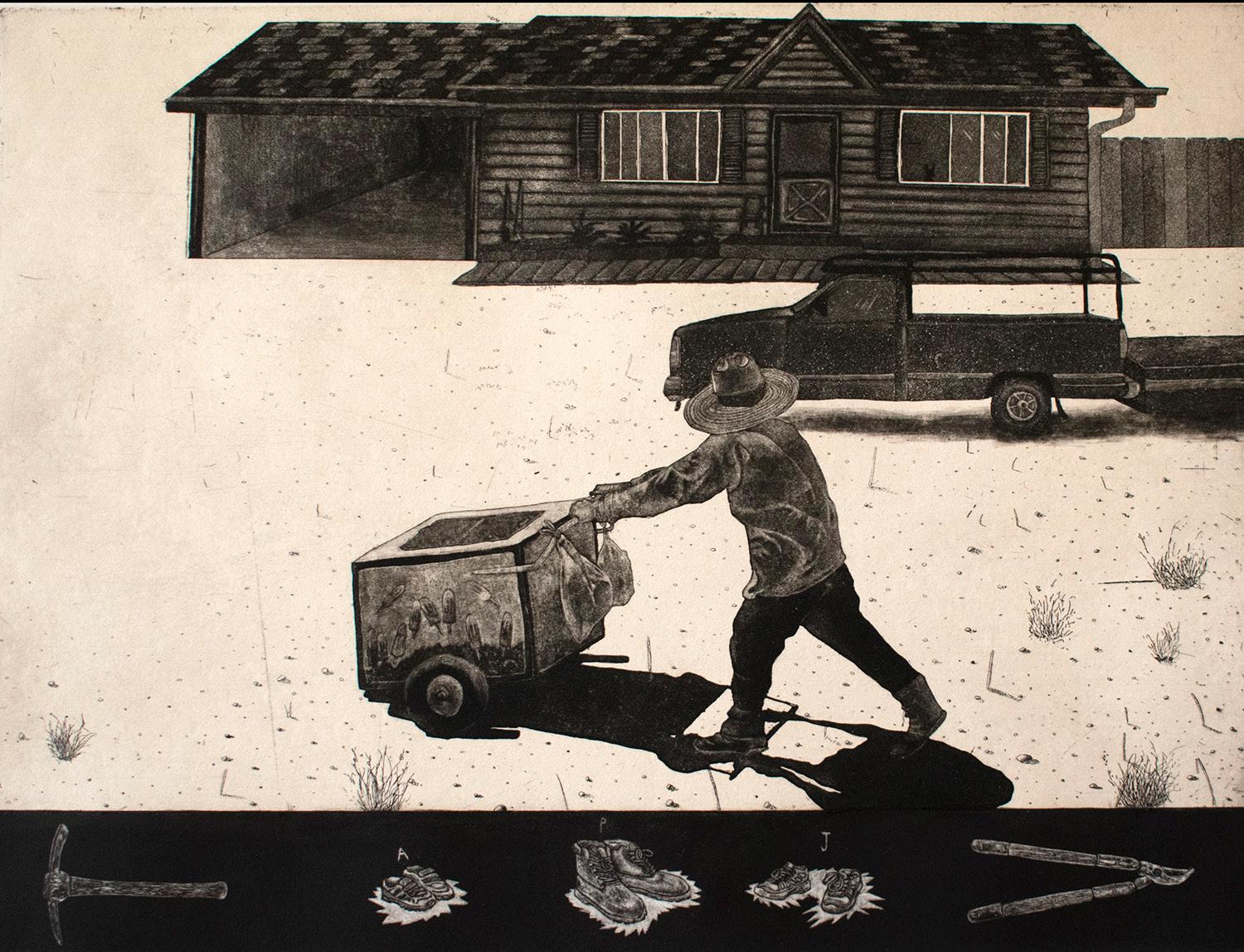

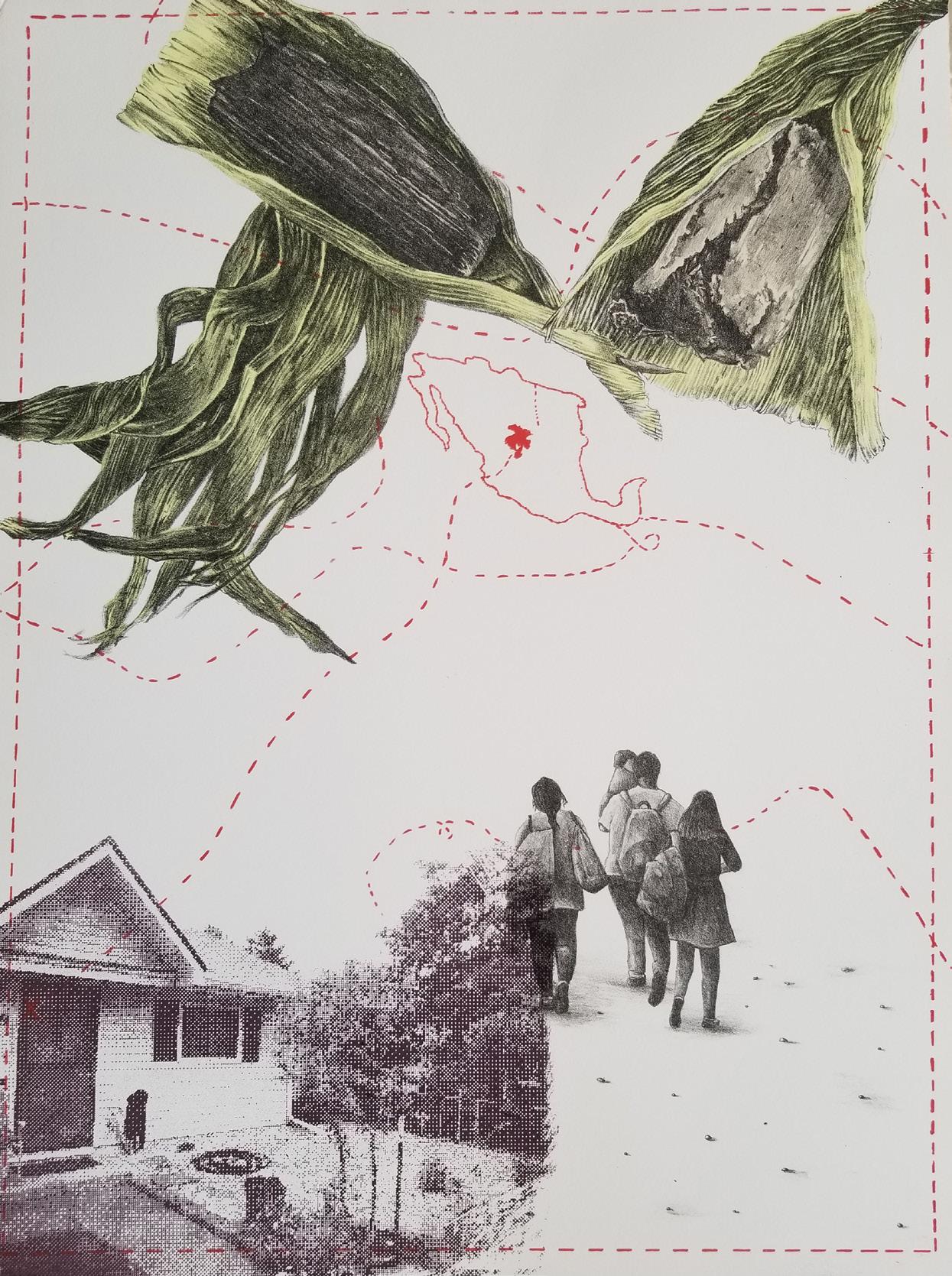

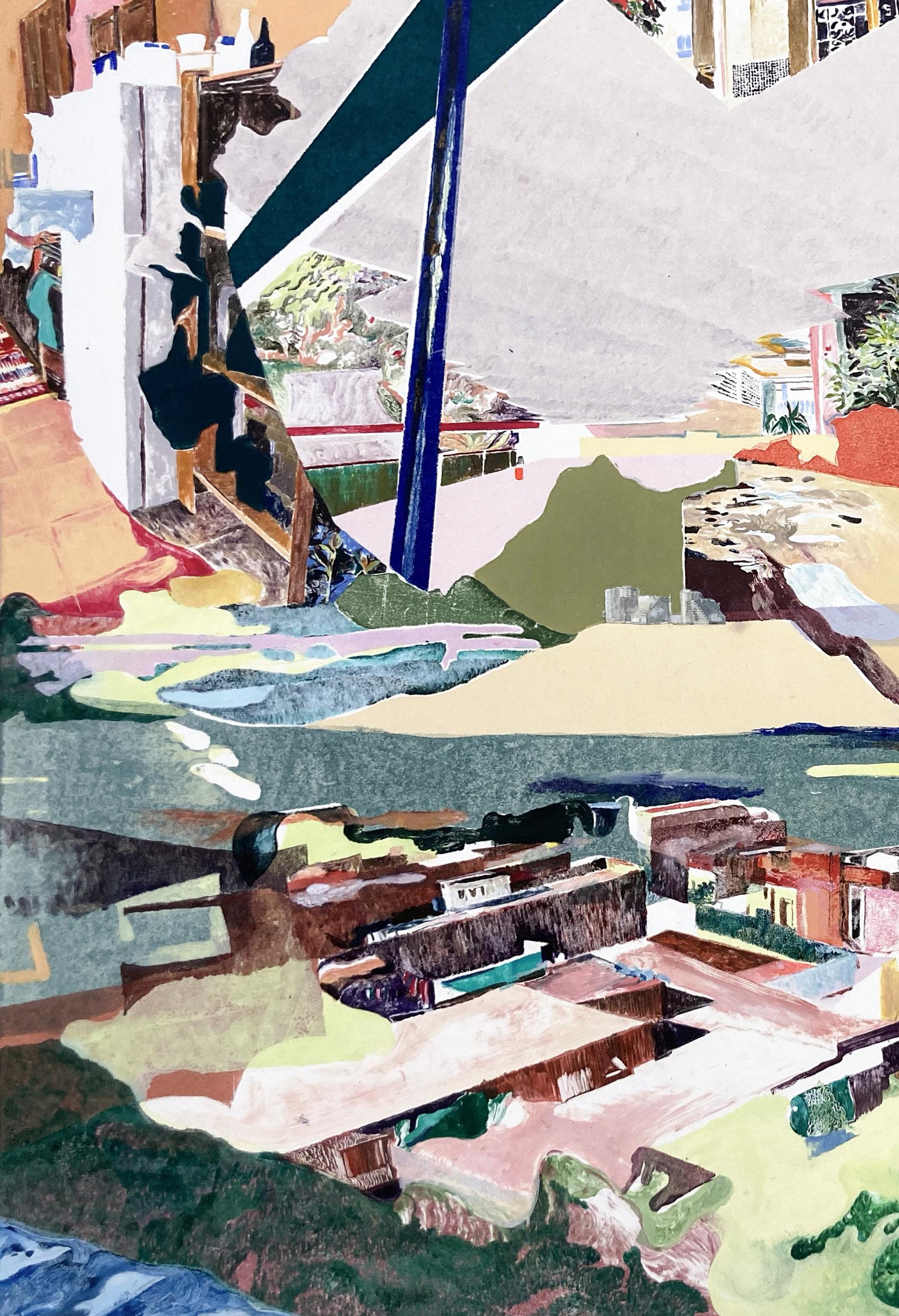

Juana Estrada Hernández’s work takes shape around the US/Mexico border, a threshold manifested by military and political forces that cleaves yet unites families, histories, and generations. Seeking to sustain familial knowledge about the border crossing, Estrada Hernández spoke to younger generations and realized their understanding of the journey was skewed by the relative safety of their lives in the US, and media

23

At the Threshold

manipulation. Estrada Hernández embarked on a series of questions, unfurling the series Nuestra Historia (2019) as a way to document and disseminate the oral instructions and guidance given to her before she left Mexico for the US in her own youth. Purposefully colorful and seemingly fun, these prints plumb the terror of lived risk by considering how children would experience or understand the rules of encountering la migra or what to bring along on the punishing desert crossing. In the large-scale paper installation Lo que no les enseñan parte 2 (2019), Estrada Hernández navigates her own story—“what they don’t show,” she says, critiquing media characterizations of refugees—by imprinting bunched and discarded clothing in paper, mixing ink with earth to convey the physicality and terrain of the journey. These pressings are sunken into paper, installed as grid; below them sit paper water jugs made of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) documents, showing the tragic connection between documentation status and the resources required to thrive.

However, Estrada Hernández also wants to remind herself, her family, and all who view her work that survival, shelter, and safety are true goals of the refugee’s journey. Ah chambiar para nuestra casita (2020) and Comida de mi Madre (2020) bring together images of well-worn work boots and the comforting family casita, respectively, foodways so linked to memory and the maintenance of tradition despite distance. Though the border is a threshold for separation—engendering dangerous journeys and state surveillance that can prove fatal—it also represents a hybrid, liminal space between the US and Mexico, lived in the interchange

24

Carmen Hermo

and flow of love and communication by families and communities, and artists such as Estrada Hernández.

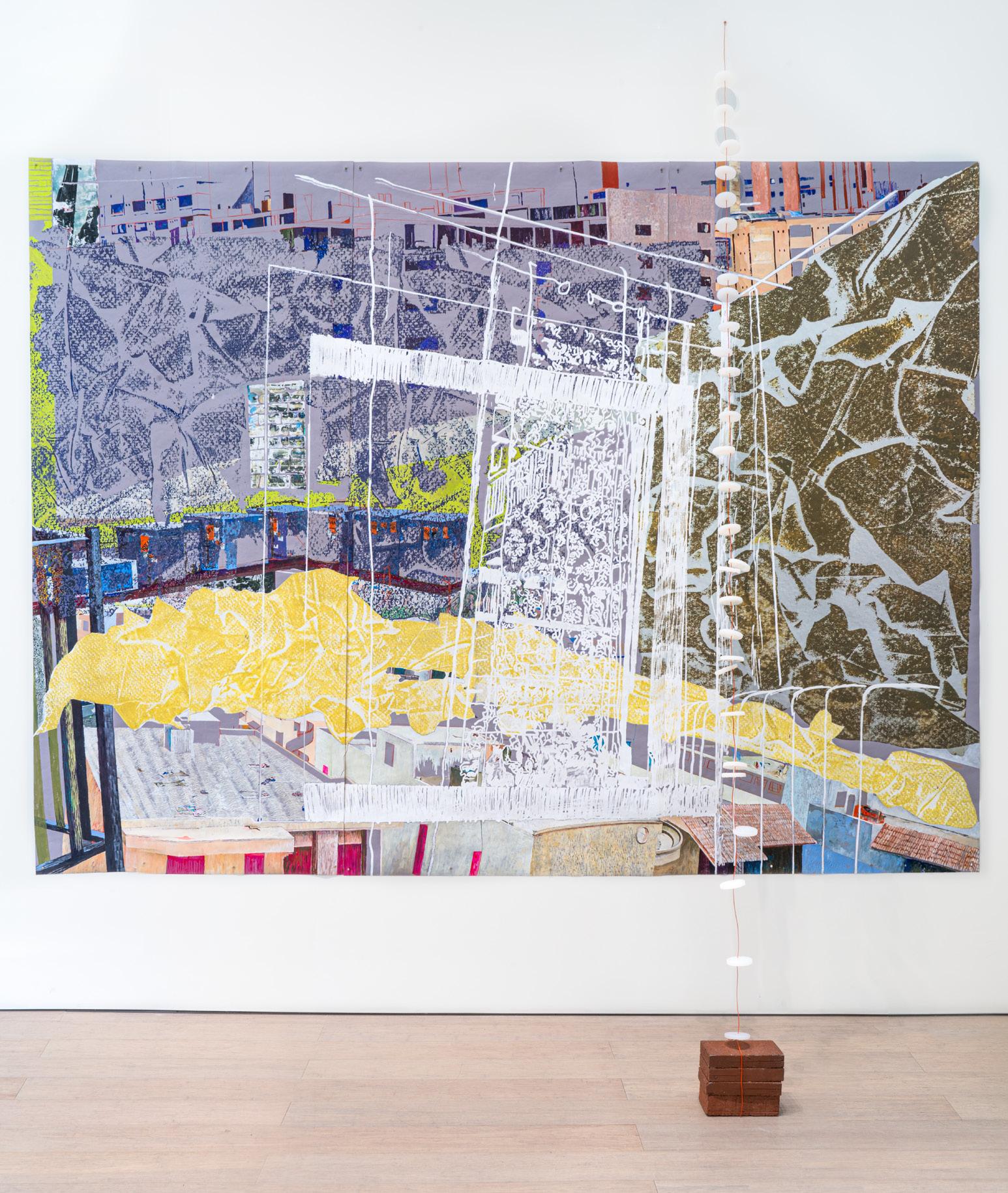

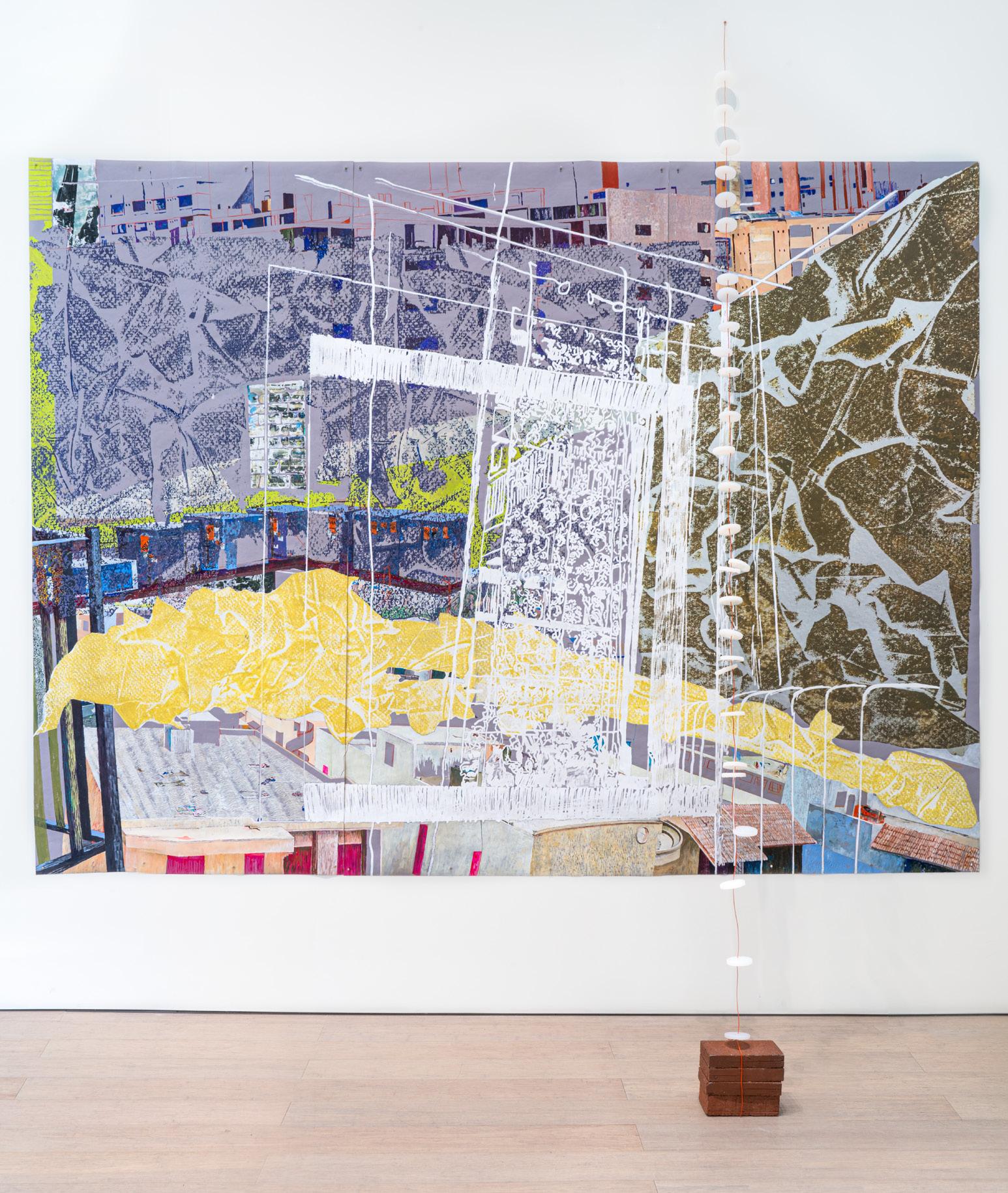

Farah Mohammad’s expansive, experimental work maps the sensations of familiarity, place, and changing environments through elusive, evocative marks. Drawn from and sometimes weaving together images of life at home in Karachi, Pakistan, or Harlem, New York, traces of previous prints bleed like memories into one another. Fortnight (2022) began with an acrylic image transfer of an elevated lookout where government officials live in Diyarbakir, Turkey—a retreat from the implications of their destruction of Kurdish cultural sites. In more than twenty-six runs through the printing press, the monoprint accumulated layers of more personal domestic sites, with images made from reflections of home and belonging surrounding the ominous architecture of power and control. Morning Dew (2023) plays with pressing and reversal techniques, creating a ghostly impression overlaid with an unfurled sprawl of blue that also creeps into GREENER GRASS IN MOTHER’S GARDEN (2022). Transforming her mother’s dupatta textile, Mohammad cuts, resist-dyes, and bleaches the textile to evoke the sensation of looking through a window screen outside to her mother’s garden— separated by the registers of sight as much as the passage of time and growth. On a larger scale, MOTION AND REST CHAOS AND LONGING (2021) combines a watercolor painting of a pile of unfolded laundry with acrylic transfers of the balconies, walls, and windows of everyday life in Karachi. These spaces congeal into an all-over landscape that crosses time and space to situate the viewer in unresolved, unspooling memory.

25

At the Threshold

Carmen Hermo

The nature of memory itself is one of liminality—the thresholds of remembrance are constantly re-treaded, turned over in the conscious and unconscious mind, sparked by senses and, for Mohammad, by what she calls an “emotional inventory of… personal symbolism” that brings together “unrelated sites that symbolize resilience.” Mohammad’s work explores the interconnectedness of our sensorial understanding of our everyday surroundings with the remembered version of it—and the slippage between the two.

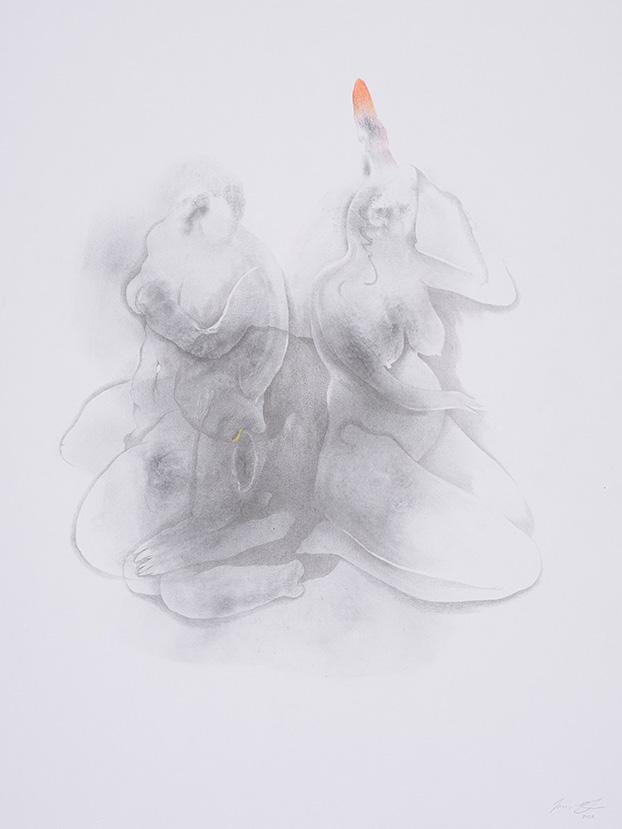

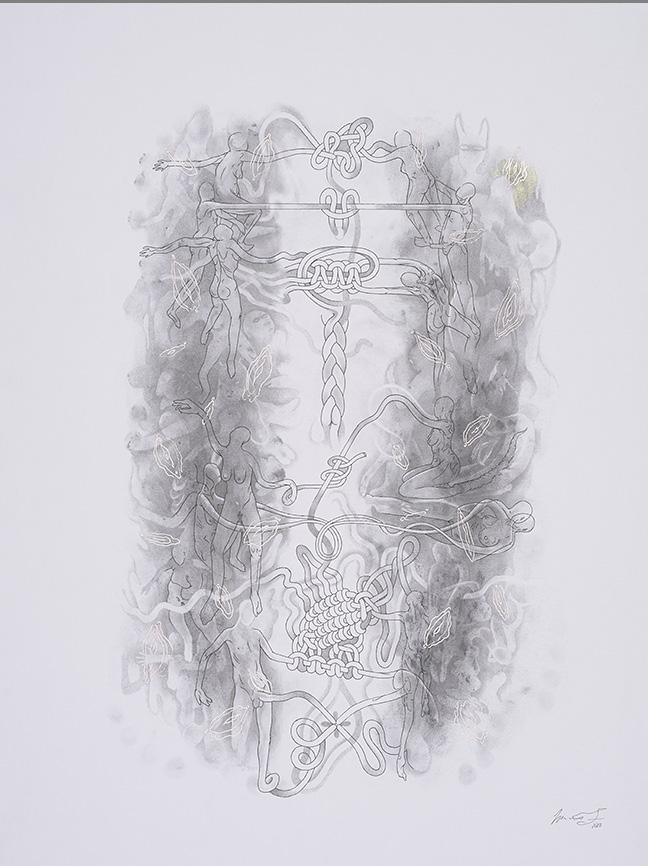

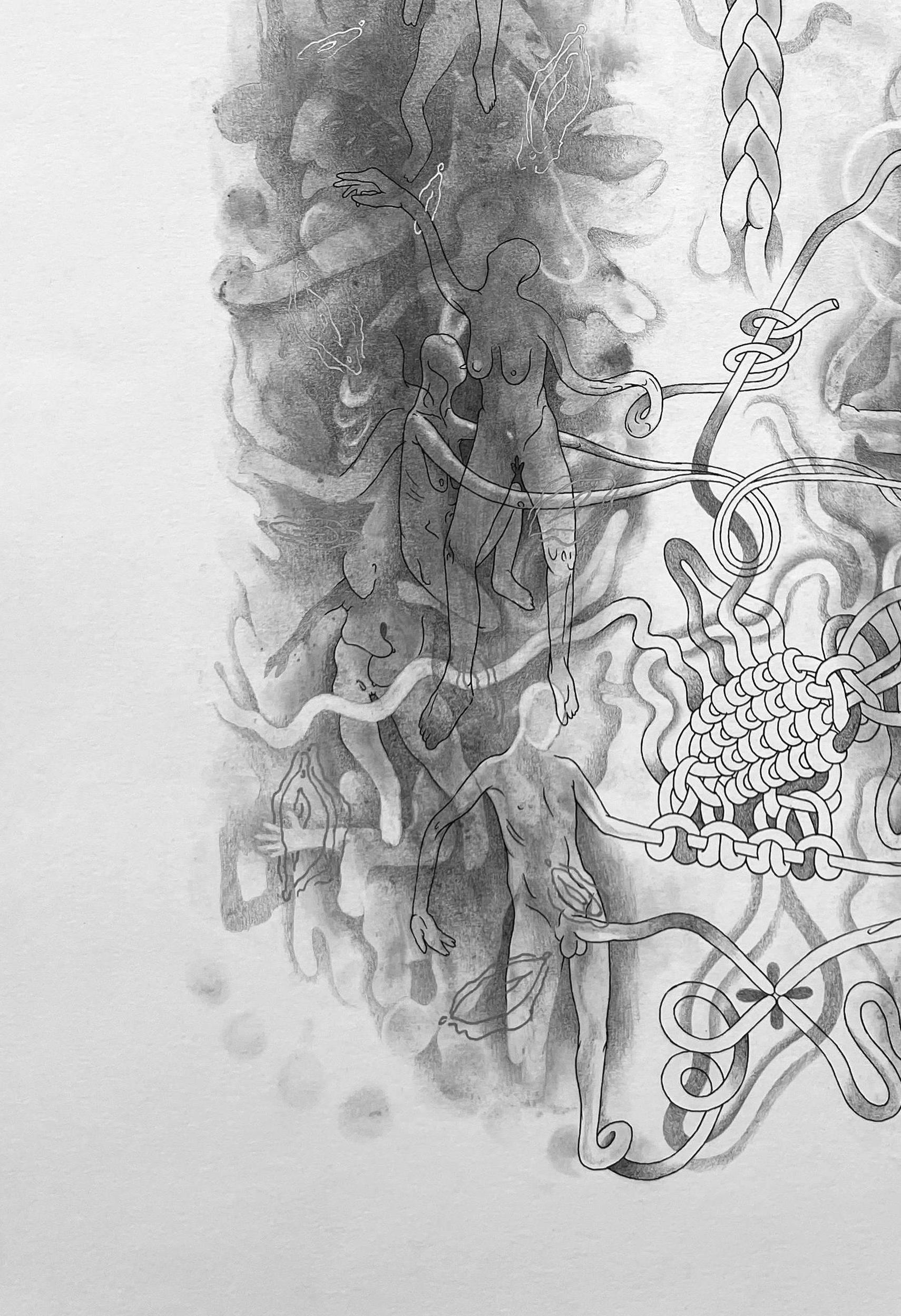

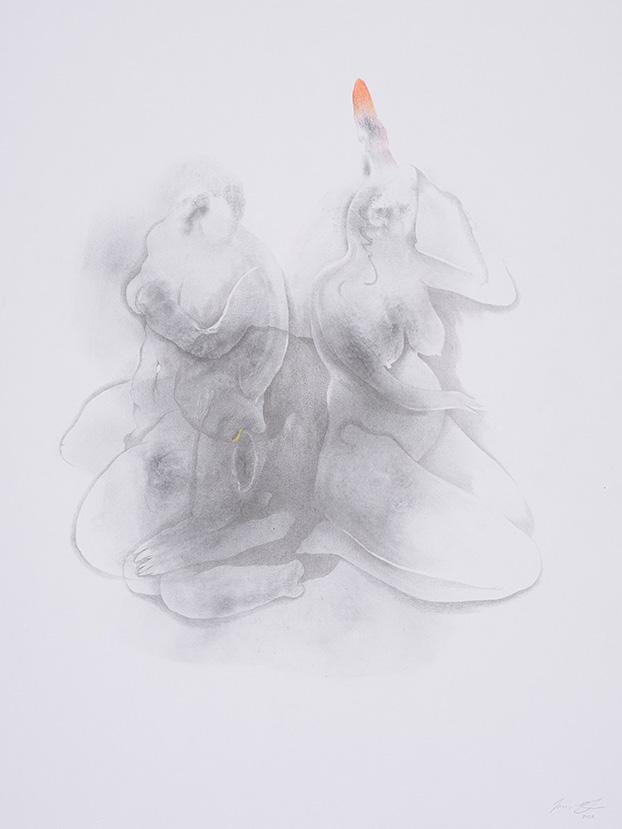

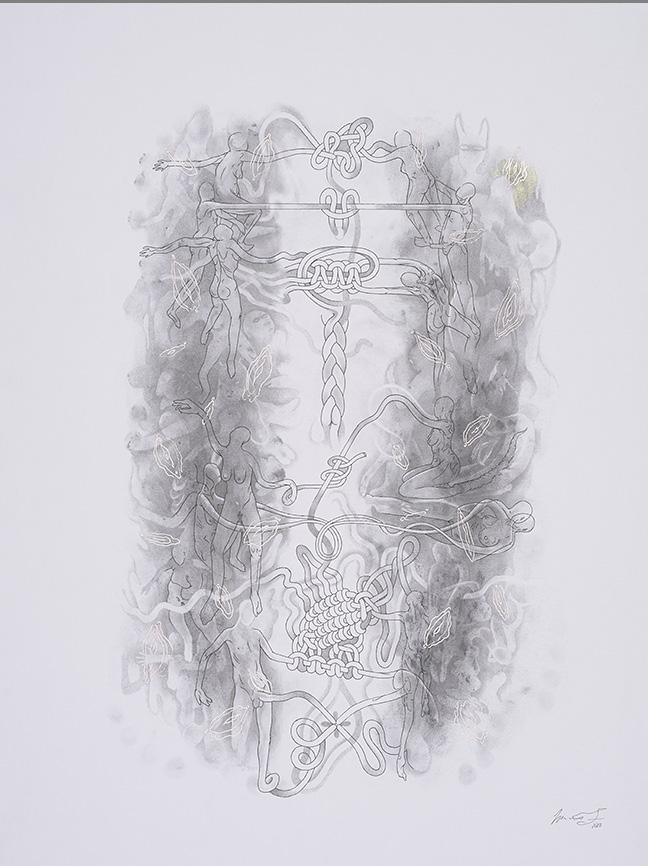

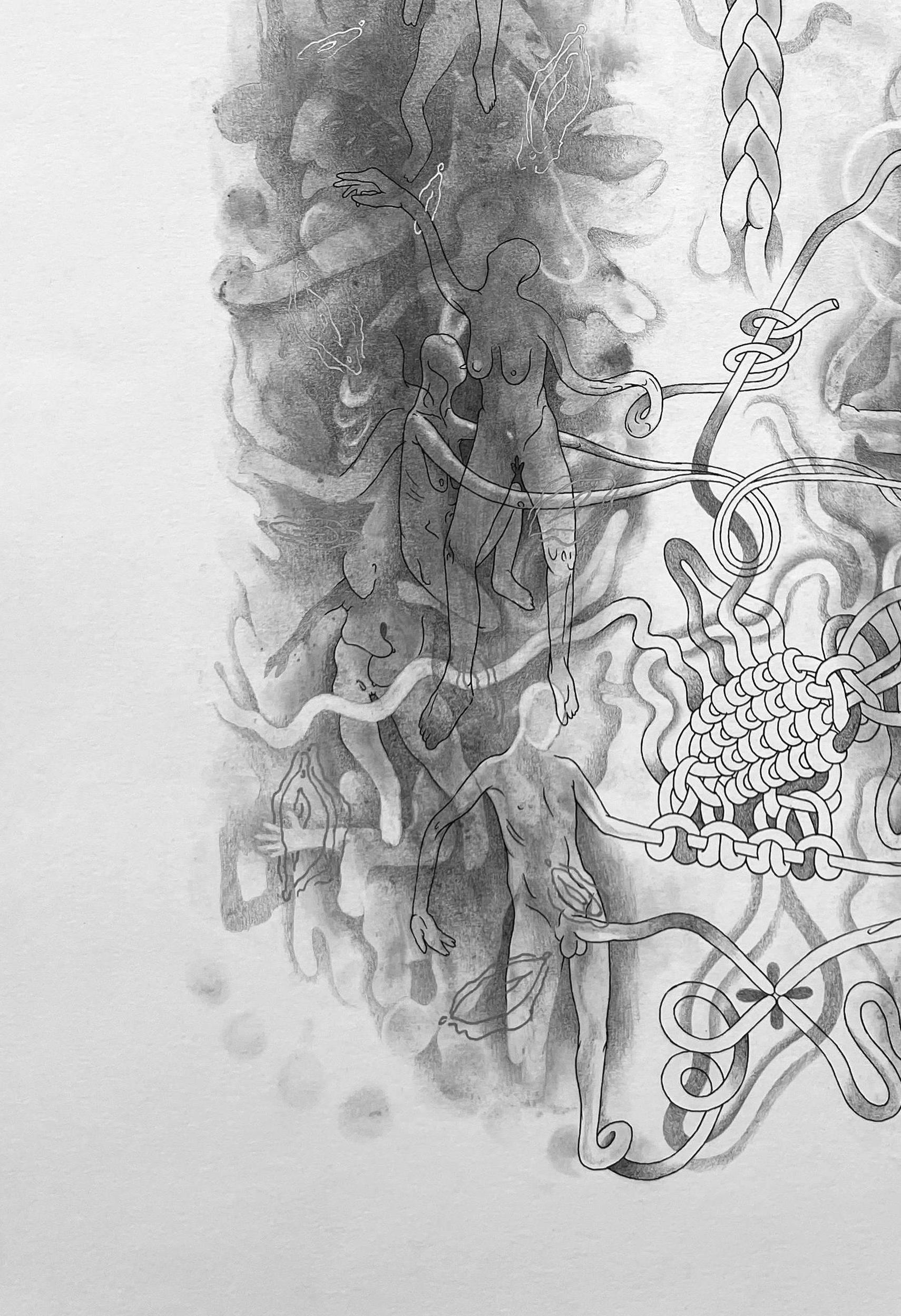

For Eriko Tsogo, the memories and experiences that create the self are solidified in the body as a site of both pleasure and conflict. Their expansive, ongoing series Wrong Woman, Myths from the Sky explores their life experience in a seemingly never-ending array of drawn and stenciled forms, at times surreal, or seemingly humorous, yet always based on the traditional techniques of Buddhist thangka painting, where sacred images begin as outlines before backgrounds, then figures, are filled in. Between this tradition and their work is what the artist terms a “self-affirming system” in the face of marginalization within marginalization, connecting their experiences as a Mongolian immigrant in the Midwest, a DACA recipient relying on state approval, and the emotional trials of trauma, sexual abuse, and building a place of belonging amidst it all. In American Me (2022), a work combining digital collage and pen drawing, the margins of the image contain multitudes, a frame of forms that convey intricacy and interconnectedness, and what the artist terms in their work overall as “the embattled emotional middle space of marginal identity; one who lives in two worlds while

26

being more or less a stranger to both.” At the center of that work, a gnarled and wizened tree sprouts from optically buzzing roots, topped by a sixteen-handed figure who reaches up in a plea or protest, finding growth and creation in the personal journey as well as within these “hybrid print-drawings.” As Tsogo’s work as a performance and installation artist emboldens, they convey “emotional trials through physical embodiment,” now extending to a series of expansive body print works on paper. Dusting graphite on their feet, breasts, and butt, they then use layered drawing to transform the ghostly imprints into explorations of displacement and connection, gender ambiguousness, and objectification, respectively. Together, these works made across years of vulnerability form the Wrong Woman series, creating a visual reclamation of feelings and experiences, and rejecting social definitions of acceptability in favor of the self-attuned.

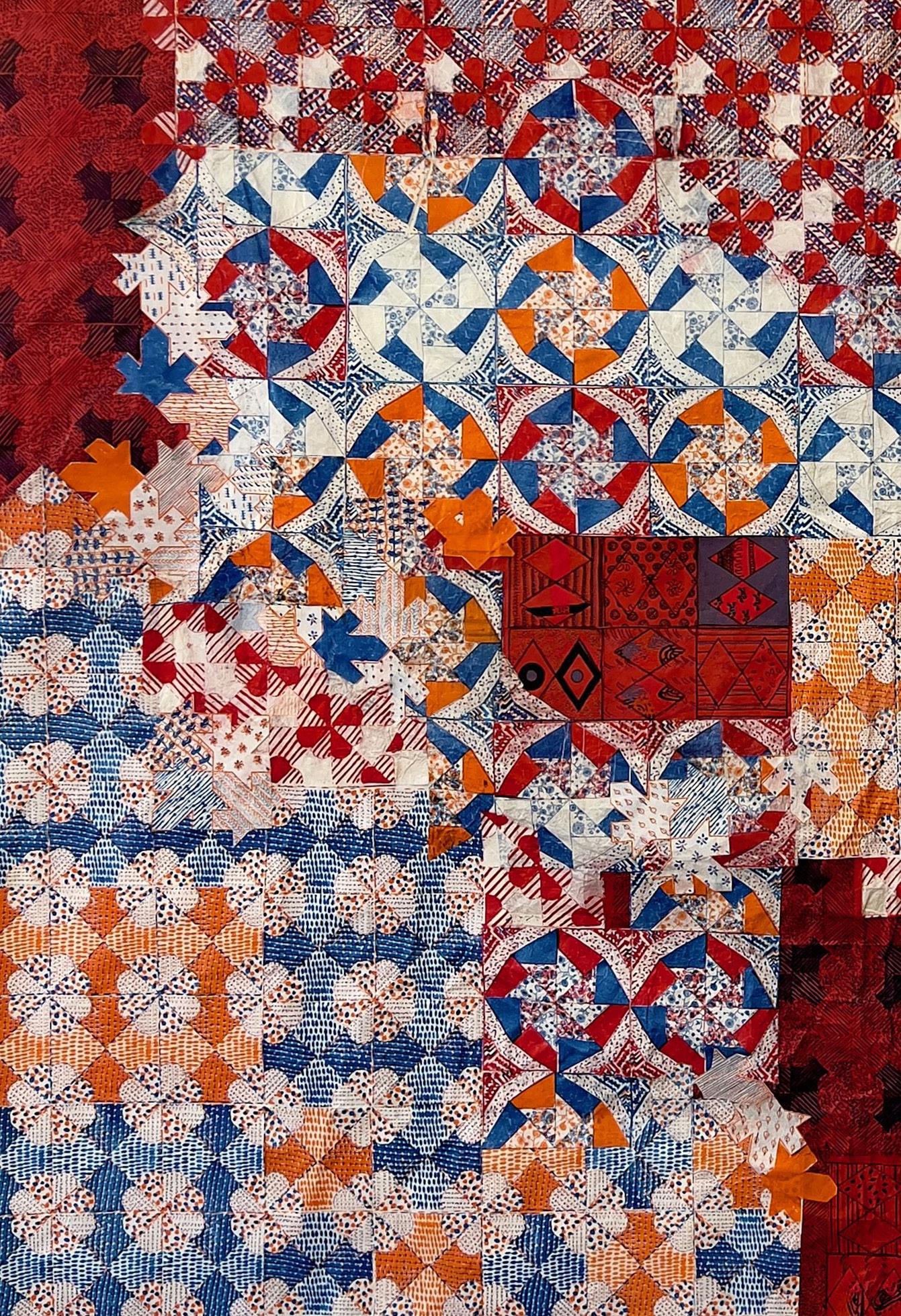

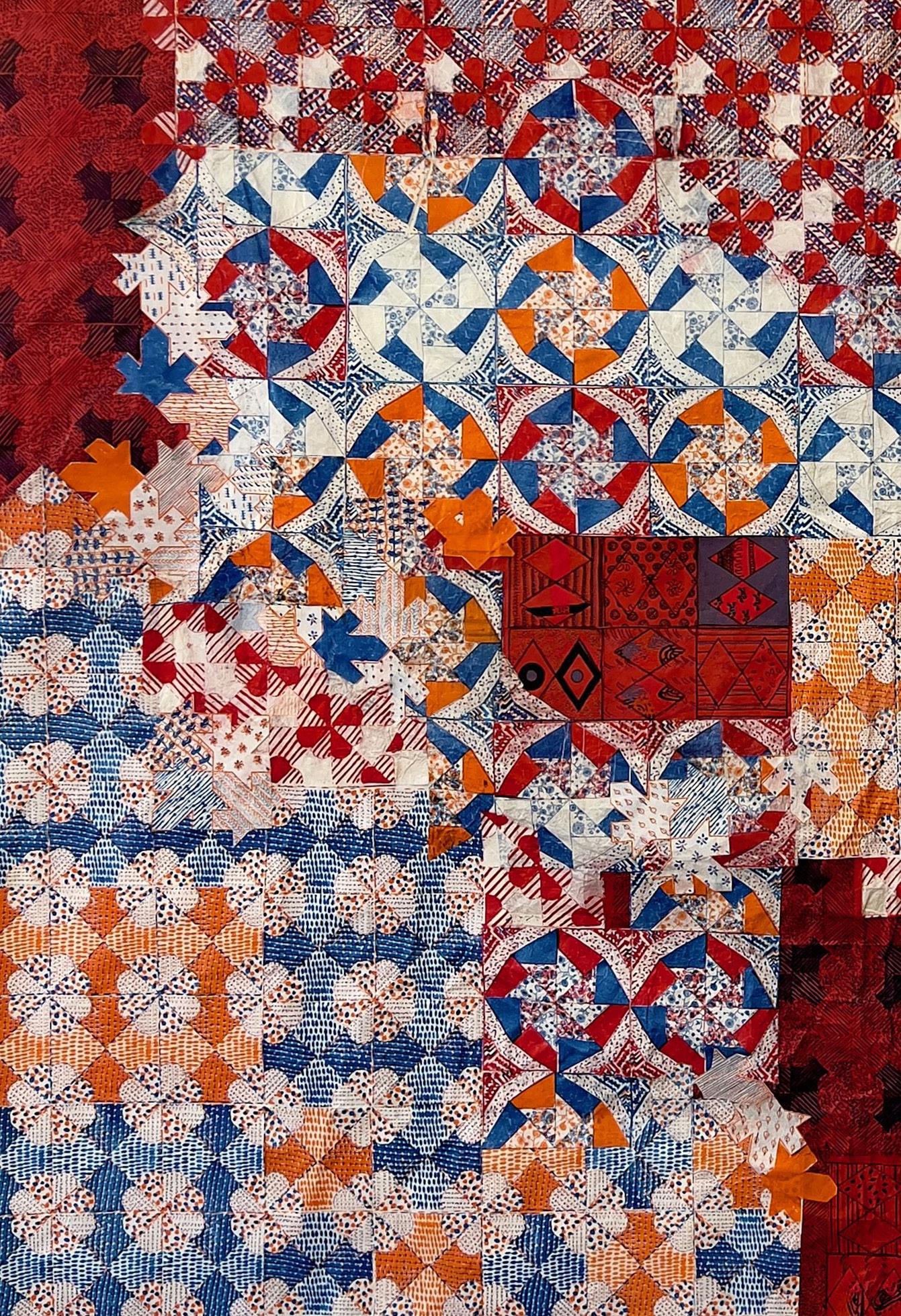

This overlapping sense of selves and textures thrums in the abstract explorations of Jacquelyn Strycker. Strycker’s 2019 work Quilted Medley (Red) is a riot of collaged risograph and screenprint patterns abutting, jockeying, and overlapping one another on a combination of Japanese and handmade papers. This breakthrough piece led Strycker to expansive works printed on cotton like Shift (2022)—in which one repeated pattern is made errant, variegated only by its color shifts—and Dream House (2023)—in which a Crown Quilt pattern is fortified with polyfil entrails and becomes a print-object that feels like an exhausted castle, or a piecemeal blanket. Strycker’s embrace of risograph printing actually began with an ending. After having

27

At the Threshold

Carmen Hermo

her child in 2015, she had to set aside her printmaking practice and give up her studio. Risograph proved an accessible way to return to artmaking, and she began working modularly: drawing first, then scanning to make risographs and screenprints, printing and re-printing small squares of paper (and often re-using the “make ready”), tessellating them into undulating, vibrating prints whose visual power drew from this buildup of patterning. In 2020, Strycker took on what she called a “scrap pile” of prints on fabric, sewing them together, and conjuring the haptic intimacy of quilts and blankets as supports for dense and intricate visual compositions. “I’ve decided to lean into the chaos and impermanence rather than fight against it,” the artist explained—an ad-hoc avant-garde gesture that has resulted in works like Crazy Quilt (2021), where the forward movement of the repeated and re-used prints leaves behind a kind of map. “Leaning into” disarray and transitional states, Stryker’s use of the risograph became an “intermediary between manual and digital processes” that she could use to create visual space dissolving the boundaries between “decoration and function,” family life and studio practice, blurring it all together.

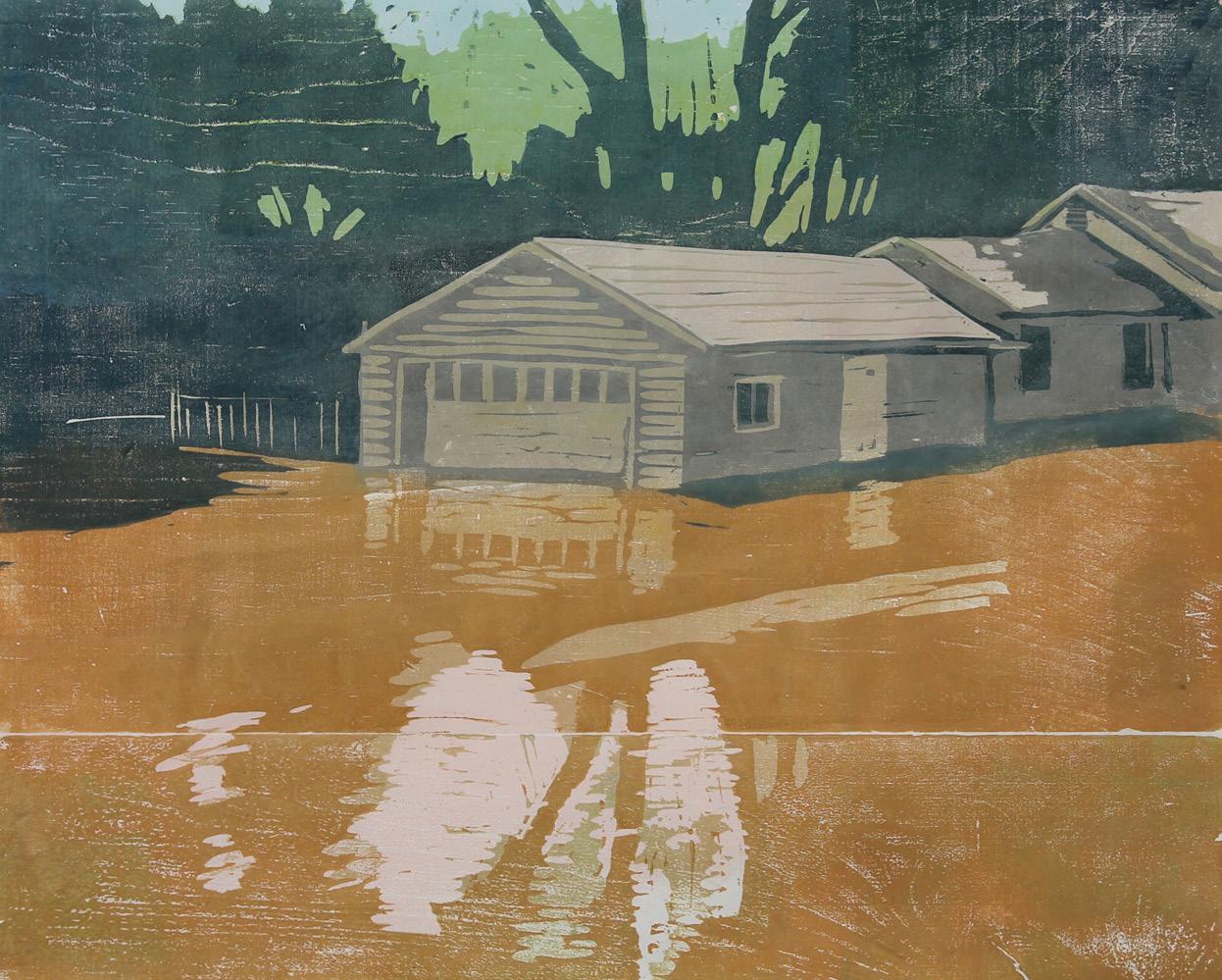

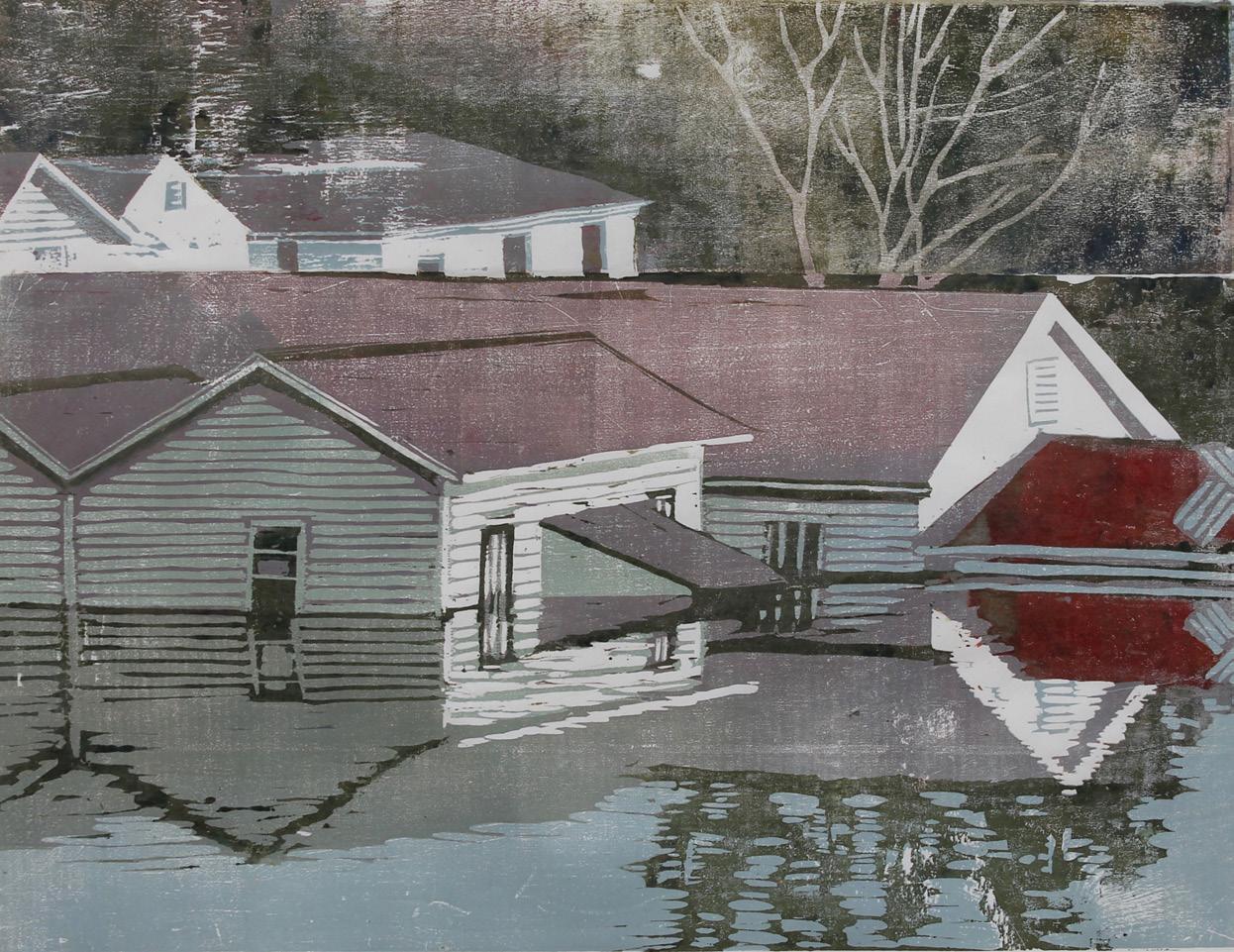

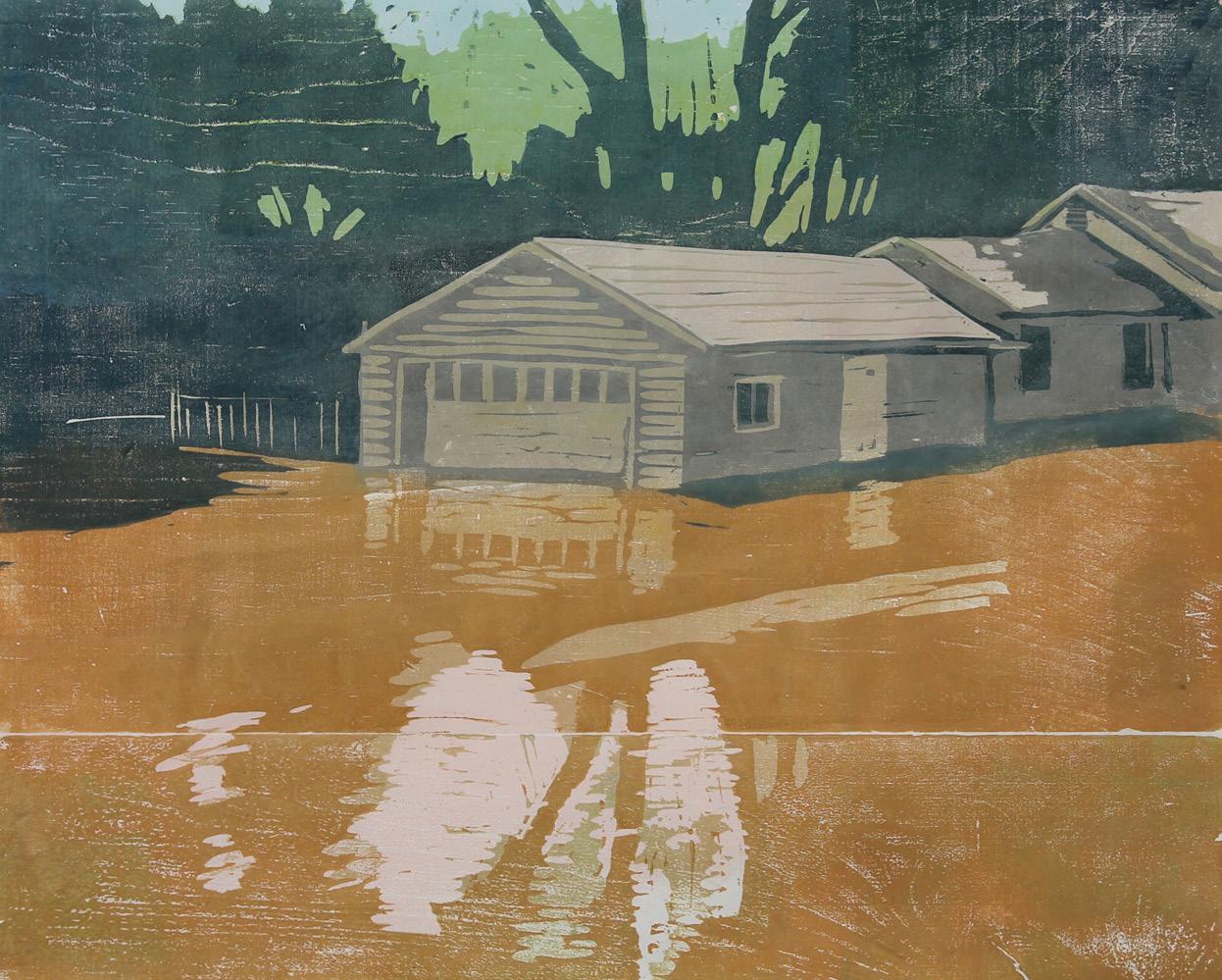

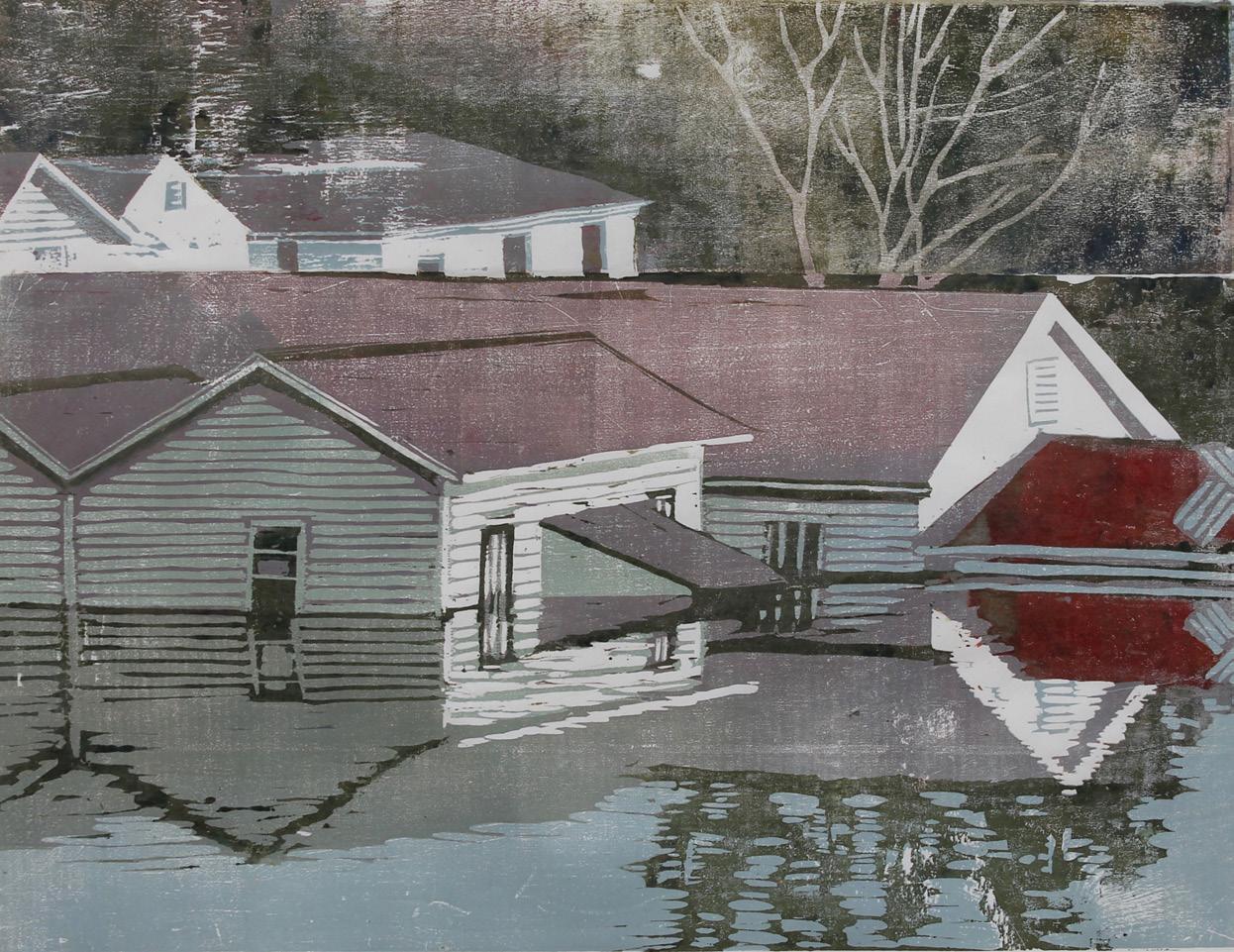

Nina Jordan’s woodcut prints visualize a rising water line, a stark threshold that is crossed with increasing frequency and dismaying levels of acceptance. Her prints begin with discarded and found lumber foraged around the streets of New York. This use of materials originated from her experience working on a construction project, where she began experimenting with wood scraps from the dumpster, pulling prints by hand on the floor of the site. Jordan’s carving of the cast-off

28

building materials coaxes out the undulating movement of rushing flood waters, the shimmering of sunlight in a driveway-turned-pool, or the still and stagnant calm of inundated futures. These images are drawn directly from US news reports of floods caused by extreme weather, but focus on the everyday beauty and horror of climate collapse over geographic specificity. Growing from an ongoing body of work exploring real estate listings, the disappearing American Dream of home ownership, and the lingering gaze of a childhood fretted with housing insecurity, these prints explore shelter, vulnerability, and disappearance. They relate to the notion of being “underwater”—overwhelmed, behind on bills, too busy with labor to live—while also literalizing that image. The homes mark life, acting as stand-ins for human impact; the only living creature in the series is a magnificent sturgeon, an ancient species that washed up on the sidewalks during one flooding event, inspiring FLOODED HOMES AND LAKE STURGEON (2022). Swimming in the blue depths of a washed-out suburbanscape, the fish reminds us of the plants and animals dragged down by human action and inaction. The eerie isolation of Jordan’s homes surrounded by water—with no figures or signs of life—raises questions of whose lives and living have been interrupted and altered; where they have gone, and where are they now?

Julia Curran’s works, then, remind us of the earthy ends that await us all, and that the forces of composition and decomposition occur to humans, animals, and plants alike. In Curran’s layered acrylic, screenprint, and cut paper triptychs and prints, divisions between above-ground life and the thrumming cycles of life

29

At the Threshold

Carmen Hermo

below ground disintegrate. Drawing from her experiences struggling against and eventually accepting her autoimmune disease, Curran destabilizes societal hang-ups about the body’s systems as shameful, instead reveling in the colors and creative force of bodies that are unruly, leaky, and abject, yet powerful and tender. This understanding of our bodies and selves is nearly sacred, and Curran’s use of hinged, three-dimensional triptych presentations makes her work into a self-contained system of meditation and honoring, first in its making and then in its altar-like contemplation. In Curran’s hands the triptych form unfolds an axis of experience where images on the exterior must be opened in order to access the narrative balanced across the interior. Inside works like Memento Mori for Evil Men (One Day You Too Will Die, She Will Eat You, Then Shit Out Your Bones) (2022)—an intimate triptych with forms inspired by historic anatomical woodblock print illustrations— the cycles of death, decomposition, time, and forgetting come for abusers of power as an underground figure representing Mother Nature swallows bones and a vine encircles a crumpled MAGA hat. This transformation of death into life is echoed in other works, where human skulls sustain blossoming seedlings (What the Garden Gave Me, 2022) and a sensual, squirting bacchanalia of flowers, bees, and worms center pleasure as a generative force (Spring’s Revenge, 2023). Curran’s work seeks to question what is lost in a “society that separates the brain from the body, and sees itself divorced from the rest of the natural world.” For Curran, these memento mori works plumb the inevitability of death, reminding us that in the end, all such binaries and boundaries will

30

At the Threshold

dissolve, as the earth’s systems of decomposition and regeneration pulse on beyond our lifetimes.

31

Juana Estrada Hernández

Ah chambiar para nuestra casita, 2021

Juana Estrada Hernández Comida de mi Madre, 2020

Wish You Were Here, Topaz, 2022

36

Lois Harada

Lois Harada

Wish You Were Here, Heart Mountain, 2022

Lois Harada

Wish You Were Here, Amache, 2022

Nina Jordan

Nina Jordan

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOUSE III, 2021

40

Nina Jordan

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOUSE VI, 2021

Nina Jordan

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOUSE VII, 2021

MOTION AND REST CHAOS AND LONGING, 2021

44

Farah Mohammad

Farah Mohammad

Fortnight, 2022

Jacquelyn Strycker

Dream House, 2023

Jacquelyn Strycker

Dream House, 2023

Quilted Medley (Red), 2019

Jacquelyn Strycker

Jacquelyn Strycker

52

Me, 2022

Eriko Tsogo American

Eriko Tsogo

Forbidden Fruit, 2022

Eriko Tsogo

Shadow Dance, 2022

Works in the Exhibition

Aaron Coleman (b. 1985)

Gateway for Evasion, 2022

Screenprint, turf rubber crumb, spray-paint, wrought iron and lumber on panel

72 × 48 × 5 inches

Gateway for Premonition, 2022

Screenprint ink, turf rubber

crumb, Astroturf, wrought iron and lumber on panel

72 × 48 × 5 inches

Gateway for Remembrance, 2022

Screenprint, turf rubber crumb, wrought iron and lumber on panel

72 × 48 × 5 inches

In the Wake, 2023

Found shard of payday loan and check cashing sign, plywood, screenprint, and rubber mulch

78 × 48 × 54 inches

Julia Curran (b. 1988)

Memento Mori for Evil Men (One Day You Too Will Die, She Will Eat You, Then Shit Out Your Bones), 2022

Screenprint

18 × 24 inches

Edition of 12

Published by Grafik House USA, St. Louis MO

Memento Mori for Evil Men (One Day You Too Will Die, She Will Eat You, Then Shit Out Your Bones), 2022

Acrylic, screenprint, and paper on hinged panel

Open: 18 × 48 × 1 ½ inches

Closed: 18 × 24 × ¾ inches

Mother Nature, 2022

Woodblock and oil paint

13 × 9 inches

Spring’s Revenge, 2023

Screenprint

13 ¾ × 13 ¾ inches

Edition of 24

What the Garden Gave Me, 2022

Acrylic, screenprint, and paper on hinged panel

Open: 42 × 36 × 1 ½ inches

Closed: 42 × 18 × ¾ inches

Juana Estrada Hernández (b. 1995)

Ah chambiar para nuestra casita, 2020

Intaglio, mezzotint, and chine collé

18 × 24 inches

Edition of 10

Comida de mi Madre, 2020

Lithograph

20 × 15 inches

Edition of 20

57

Lo que no les enseñan parte 2, 2019

Pressure monotypes, kozo paper

gallons, and woodcut

72 × 108 inches

Nopalaso en nombre de nuestras

familias!, 2021

Lithograph

15 × 20 inches

Edition of 10

Untitled, 2019

Lithograph

12 × 12 inches

From the series Nuestra Historia, 2019

Edition of 10

Lois Harada (b. 1988)

Amache, 2022

Heart Mountain, 2022

Topaz, 2022

Screenprints

26 × 22 inches each

From the portfolio Wish You Were Here, 2022

Edition of 10

Wish You Were Here, Pennies, 2022

Pressed pennies

Each penny ¾ × 1 ¼ inches

Open edition

Custom penny press for Wish You

Were Here, Pennies, 2022

60 × 14 ½ × 14 ½ inches

Created with support from Interlace Grant Fund/The Andy

Warhol Foundation

Nina Jordan (b. 1964)

FLOODED HOMES AND LAKE

STURGEON, 2022

Woodcut

39 × 48 inches

Edition of 3

SUBMERGED HOME/EXTREME

WEATHER, 2023

Woodcut

30 × 48 inches

Edition of 2

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOME III, 2021

Woodcut

15 × 19 inches

Edition of 4

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOME VI, 2021

Woodcut

13 × 17 inches

Edition of 4

UNTITLED, FLOODED HOME VII, 2021

Woodcut

13 × 17 inches

Edition of 4

Farah Mohammad (b. 1993)

Fortnight, 2022

Monotype

22 × 30 inches

58

GREENER GRASS IN MOTHER’S GARDEN

, 2022

Printed lawn fabric, bleach, fabric dye, thread, green painted wire

38 × 39 × 7 inches

Morning Dew, 2023

Monotype and gouache

22 × 30 inches

MOTION AND REST CHAOS AND LONGING, 2021

Acrylic and gouache on printed

Tyvek, silicone, orange painted wire, bricks

96 × 120 × 26 inches

Jacquelyn Strycker (b. 1981)

Crazy Quilt, 2021

Sewn risograph on cotton stuffed with polyfill

41 × 38 ½ inches

Dream House, 2023

Sewn risograph on cotton stuffed with polyfill

48 × 48 ½ inches

Notions, 2022

Collage of risograph on handmade papers with gouache

34 × 30 inches

Quilted Medley (Red), 2019

Collage of risograph and screenprint on handmade and Japanese papers

60 × 60 inches

Shift, 2022

Sewn risograph on cotton

28 × 46 inches

Eriko Tsogo (b. 1990)

American Me, 2022

Gel pen, micron pen, digital collage on paper 24 × 19 inches

Forbidden Fruit, 2022

Mechanical pencil, graphite powder on paper

Drawing based on initial breast body print 24 × 19 inches

Shadow Dance, 2022

Mechanical pencil, gel pen, graphite powder on paper

Drawing based on initial foot print 24 × 19 inches

The Great Sacrifice, 2022

Gel pen, graphite powder, mechanical pencil, chili powder, digital collage on paper

Drawing based on initial gluteus maximus body print 24 × 19 inches

Courtesy the artist and Tappan Collective

59

Curator

Carmen Hermo is Associate Curator for the Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Hermo curated Baseera Khan: I Am An Archive (2021–22); Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Are We Reading Closely? (2020); and Roots of The Dinner Party: History in the Making (2017); and was part of the curatorial collective behind the critically-acclaimed Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall (2019). She organized the Brooklyn presentations of Andy Warhol: Revelation (2021–22); and Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (2018). Previously, Hermo was Assistant Curator for Collections at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and has worked with the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Other curatorial projects have been presented at A.I.R. Gallery and Hirshhorn Museum, and her writing has appeared in ArtNews, BOMB Magazine, Women's Art Journal, and more. She received her BA in art history and English from the University of Richmond and her MA in art history from Hunter College.

60

Artists

Aaron Coleman is a multi-disciplinary artist, Associate Professor, and Kenneth E. Tyler Endowed Chair at the Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis. He received his MFA from Northern Illinois University in 2013. Coleman has participated in international residencies and exhibitions and received numerous awards for his work in printmaking, sculpture, and installation. He is the 2021 recipient of the Black Box Press Foundation Art as Activism Grant and was nominated for a 2022 Joan Mitchell Foundation Fellowship. His work can be found in the collections of the Janet Turner Print Museum, the Ino-cho Paper Museum, The Yekaterinburg Museum of Art, the National Library of France, and the Artist Printmaker/Photographer Research Archive at Texas Tech University, among others.

Julia Curran received her MFA in printmaking from Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi in 2015 and was a Fulbright scholar in Paris in 2011–12. She has exhibited her work widely including at SPRING/ BREAK Art Fair, Los Angeles; the Fort Wayne Museum of Art; Rochester Contemporary Art Center; the El Paso Museum of Art; Musée Roger Quillot, ClermontFerrand, France; Duane Reed Gallery, St. Louis; and Field Projects, New York. Her work has been published in Hey! Magazine, Studio Visit, and Friend of the Artist. Recently, she was awarded residencies at Tongue River Artist Residency in Dayton, WY; the Wassaic Project in Wassaic, NY; and the Jentel Foundation in Banner, WY. Curran currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

61

Juana Estrada Hernández is a Mexican artist and Assistant Professor of Printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design. She received her MFA in Printmaking from the University of New Mexico and her BFA in Printmaking from Fort Hays State University. Estrada Hernández has exhibited her work across the United States, Mexico, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Poland. She has appeared in multiple publications including Migratory Yellow Pages, Hyperallergic, and Printmaking Today, and on the Hello Print Friend podcast. Her work is held in several collections including those of the Janet Turner Print Museum, Chicago Printmakers Collaborative, Zygote Press Archives, Laval University, and Engramme, National Library and Archives of Québec.

Lois Harada is an artist based in Providence, RI. She has worked at DWRI Letterpress, a commercial letterpress print shop, since 2011. Her letterpress portfolio Signals was acquired by the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in 2021. Harada is the recipient of a 2022 Printmaking Residency at Anderson Ranch; a 2022 Interlace Project Grant, a regional regranting program supported by Providence College Galleries and the Warhol Foundation; and a 2023 Rhode Island State Council on the Arts grant supporting the development a new typeface based on her work with WPA-style posters. Harada earned her BFA in 2010 from RISD and returned to teach in the Graphic Design and Printmaking Departments in 2022.

62

Nina Jordan is a Brooklyn-based painter and printmaker who began working in woodcut twenty years ago. She is the recipient of a NYFA fellowship in printmaking and artists’ books, and a 2023 printmaking residency at In Cahoots in Petaluma, CA. Her work is in the collections of The New York Public Library, the Beinecke Library at Yale University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The University of Richmond Museums. Jordan received her MFA from Brooklyn College.

Farah Mohammad is a printmaker, installation artist, and educator based in NYC. She received her BA from Bennington College and her MFA from Columbia University. Her exhibition highlights include a solo exhibition at Nyama Fine Art, New York, and group exhibitions at the Moss Art Center, Blacksburg, VA; Half Gallery, EFA’s Blackburn 20|20 Gallery, The Jewish Museum, ChaShaMa, Field Projects, and Local Project Art Space, all in New York. She was a 2022–23 resident at Cornerstone Studios and a 2021 recipient of the Lower East Side Printshop's Keyholder Residency. She has also received a 2021 EFA Robert Blackburn Printmaking Award; a 2020 Lucas T. Carlson Grant from Columbia University; and a 2020 Coursework Award from Print Center New York. Mohammad’s work is in the permanent collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

63

Jacquelyn Strycker is a Brooklyn/Queens-based artist working primarily in printmaking, collage and fiber-based media. She is currently a faculty member at Pratt Institute and a faculty member and the Director of Operations and Online Curriculum for the MFA Art Practice department at the School of Visual Arts. She has exhibited work across the United States and internationally, and is a frequent speaker at the annual College Art Association conference. Strycker received her BA in Visual Arts from Columbia University and her MFA in Printmaking from Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, PA.

Eriko Tsogo is a Mongolian-American multidisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn. She holds a BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and Tufts University. Tsogo grew up in Budapest, Hungary and immigrated to the United States with her family in 1999. She has participated in numerous exhibitions and residencies throughout the United States, and has exhibited at the Currier Art Museum, Manchester, NH; the Contemporary Mongolian Art Biennial; Art Basel Miami Beach; and The Other Art Fair, Brooklyn. She received a “Juuh” Honorarium from the Mongolian Ministry of Education Culture and Science; an Alliance for Artist Communities Fellowship; and a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant. She is one of the creators of Mongovoo Temple at Meow Wolf Denver. She is represented by Tappan Collective, Los Angeles.

64

Board of Directors Staff

David G. Sabel Chair

Mary Beth Forshaw Vice Chair

Andrea Butler Secretary

Stewart K.P. Gross Treasurer

Anders Bergstrom

Judith K. Brodsky

Anne Coffin, Founder

Donald T. Fallati

Jennifer Farrell

Starr Figura

Mark Thomas Gibson

Joseph Goddu

Evelyn Lasry

Sabina Menschel

Brooke A. Minto

John Morning, Founding Chair

Daniel Nardello

Martin Nash

Janice C. Oresman, Emerit

Maud Welles

Diana Wege

Judy Hecker Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich Director of Exhibitions and Programs

Danielle Cooke Curatorial Fellow

Aaron Fisher Registrar and Facilities Manager

Tiffany Nesbit Director of Development and External Affairs

Taia Pollock Visitor Engagement Assistant

Robin Siddall Exhibitions and Programs Coordinator

Ema Wang Public Relations Specialist

Published on the occasion of the exhibition New Voices: On Transformation

Print Center New York

June 1–August 26, 2023

Curated by Carmen Hermo with Robin Siddall

© Print Center New York and the authors

ISBN: 978-1-7341224-3-5

Edited by Jenn Bratovich and Robin Siddall

Design by CHIPS

Print Center New York thanks The Wolf Kahn Foundation and The Emily Mason | Alice Trumbull Foundation for their grant establishing the Emily Mason and Wolf Kahn Artist Development Fund.

All artworks courtesy and © the artists unless otherwise noted.

56–57: © Eriko Tsogo. Images courtesy Tappan Collective, Los Angeles.

Cover: Detail of Farah Mohammad, Morning Dew, 2023. Monotype and gouache, 22 × 30 inches.

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman

Aaron Coleman

Julia Curran

Julia Curran

Nina Jordan

Nina Jordan

Jacquelyn Strycker

Dream House, 2023

Jacquelyn Strycker

Dream House, 2023

Jacquelyn Strycker

Jacquelyn Strycker