The Materiality of Sound in Print

Print Center New York is thrilled to inaugurate our new, ground-floor space at 535 West 24th Street with Visual Record: The Materiality of Sound in Print, organized by Elleree Erdos and presented in the Jordan Schnitzer Gallery. This interdisciplinary exhibition exemplifies the ambitions of our organization, presenting printmaking as a fluid medium that connects to broader ideas and practices. In this show, expansive monotypes and intricate etchings live alongside cast objects and installations that bring sound into the gallery. It is a coming together of fifteen artists whose works show that the relationship between the physical and sensorial properties of print and sound is an open-ended proposition, playing out in key themes of the body, identity, history, and place.

Visual Record began in early 2020 when Erdos came to us with the idea of exploring this new area of schol arship. It feels like a lifetime ago: before Print Center

New York embarked on a journey to a new space; before Erdos stepped into the position of Director of Prints and Editions at David Zwirner. Over two years, one transformational move, and many conversations later, we are delighted to be able to give this exhibition a fuller presentation than we could have imagined at the start.

Visual Record arrives as Print Center New York looks to the future and begins its next chapter. We’re asking: What does contemporary (and historical) printmaking contribute to our moment? How is print woven into cultural production at large? This exhibition poses its own questions: What do sound and print have to say about each other? How do artists move among mediums and processes? What is a record, an impression? This publication expands the dialogues in Erdos’s show by bringing together contributions from art historian Jennifer L. Roberts and composer and writer David Toop. As her insightful text here shows, Roberts has brought new ways of thinking to bear on the study of printmaking, envisioning the craft of print as an embodied set of practices with philosophical implications. We are happy that she has made this medium a home. Toop’s essay hums with the rhythm of a writer who is also a practitioner—a maker of music, and a student of sound—lending us a welcome perspective from outside our field and enriching our thinking.

I am grateful to Erdos, a longtime ambassador of our medium, for her original perspective and collabora tive spirit. We extend our deep thanks to all the lenders who made these works available to us, and in particu lar we highlight Anthony Allen, Sasha Baguskas, Alexis Johnson, Lisa Kolhi, Kristin Soderqvist, Julia Speed,

and Valerie Wade for their assistance. Moreover, we thank the artists in Visual Record for their enthusiastic embrace of this project and for creating the works that inspired it.

We thank our preparators for their work installing this first exhibition in our new space, with special thanks to Liz Naiden, who sensitively handled the exhibition’s sound and tech support. Finally, this publication—the first in Print Center New York’s new series—owes its design to Adam Squires at CHIPS, who also thoughtfully led our organization’s rebrand this year. We are grateful to the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation for supporting this publication, enabling us to expand upon the ideas in Visual Record and share this project with new audiences.

I am deeply appreciative of Print Center New York’s talented staff, in particular Jenn Bratovich, Director of Exhibitions and Programs, who brought this un conventional project to fruition while we undertook a move and reopening that was unprecedented in our institution’s history. Finally, as we open the doors to our next chapter, I extend my gratitude to Print Center New York’s Board of Trustees, for supporting such an ambitious and exciting first season of programming, and to Jordan Schnitzer for his leadership support.

The coronal suture of the skull…has—let us assume—a certain similarity to the closely wavy line which the needle of a phonograph engraves on the receiving, rotating cylinder of the apparatus. What if one changed the needle and directed it on its return journey along a tracing which was not derived from the graphic translation of sound, but existed of itself naturally—well, to put it plainly, along the coronal suture, for example. What would happen? A sound would necessarily result, a series of sounds, music…

In 1919, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke pondered what sounds might occur if we looked beyond the groove of the phonograph cylinder to a naturally occurring incised line: the coronal suture of the human skull.

With a phonograph or a record player, the waveforms of sound vibration correspond to etched or incised marks on a rotating cylinder or disc. To play back the sound, a stylus vibrates as it traces the groove around the object. The channels inscribed in a record are thus the material embodiment of sound, inseparable from the potential sound they contain. Rilke’s mystifying proposition suggests that our own bodies—our skulls—contain similar conduits that offer an unmediated conversion of human subjectivity into sound.

The artists in Visual Record: The Materiality of Sound in Print seek out ways to take up Rilke’s proposition—not literally, of course, but by revealing that sound and print are both composed of generative, physical forces that can, as Jennifer L. Roberts writes in her text for this publication, “show us the world as made and perceived by touch.” In other words, print and sound can transform the way we feel.

Grounded in the mechanical similarities between sound recording and printmaking, the exhibition features fifteen artists whose work translates between sound and print through distinctly physical means. Some explore how cast, perforated, and printed material surfaces affect sound’s dispersal and our experience of it, while others extract meaning from the visual representations of sounds elicited by external emotional and physical stimuli. Several artists in the exhibition explore the gap between sound and vision as a productive space from which to examine the shortcomings of social and political systems. Across a wide range of subject matter—from the rhythms of jazz and American nostalgia to the sound of silence and the encoding of race in aural matter—the

works examine the idea of the “record” through innova tive technical and conceptual approaches to print. The comparison between sound and print is, on one level, technically direct: the mechanics of analog sound recording resemble the creation of a printing template. And for decades, artists have sought to subvert the reproductive qualities of the record. John Cage—considered the father of experimental music for his embrace of chance, ambient noise, and silence—possessed an infamous disdain for records and encouraged their use only in order to make something new and original:

…though people think they can use records as music, what they have to finally understand, is, that they have to use them as records…the only lively thing that will happen with a record, is, if somehow you would use it to make something which it isn’t. If you could for instance make another piece of music with a record…that I would find interesting…But unfortunately most people who collect records and use them, use them in quite another way. They use them as a kind of portable museum or portable concert-hall.¹

Christian Marclay, as both a visual artist and a DJ, has since the 1970s exhaustively mined the vinyl record’s potential as a productive medium, looking far beyond its conventional function to embrace sound as

1 Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier, Broken Music: Artists’ Recordworks (New York: Primary Information, 2018), 73.

something that is not just passively heard, but which can reflect the accumulation and individuality of lived ex perience. He recognized the futility of physical objects to preserve something as fleeting as sound. In the 1980s, Marclay cut, scratched, and walked on records; he collaged them, broke them, and glued them back together; and he allowed dust and scratches to collect on records sold without sleeves—“whatever I could do to them to create a sound that was something else than just the sound that was in the groove.”²

Marclay, like Rilke, sought a sound that was raw, palpable, and human. The other artists in this exhibition similarly reimagine the way we encounter sound and visual representations of it. Through physical gestures— burning, tracing, cutting, perforating, erasing—they create works that embody sound, rather than merely represent or record it. This physical, material approach impels us to reflect on the conventions, stereotypes, and assumptions encoded in our senses. While Visual Record features work by primarily visual artists, it parallels developments in contemporary sound art, where artists are cultivating a wider perceptual engagement that challenges medium specificity and engages with the politics of sound, listening, and silence.³

We can only begin to understand sound as a reflection of our time—its social, political, and cultural implications—when we consider that sound belongs not just to the ears. Sound is a total perceptual experience, 2 Rob Young, “Don’t sleeve me this way,” The Guardian, February 14, 2005, www.theguardian.com/music/2005/feb/14/popandrock.

captured not only through listening and hearing, but through touch and feeling. Prints, too, contain evidence of a tactile encounter—the transfer of ink, the imprint of a plate. The artists here ask and answer questions through physical interventions deeply intertwined with the history of print: pressure, contact, transfer, and interference.⁴ The works in Visual Record range from unique transfer drawings to editions of varying sizes, but each is most importantly an intimate record of human experience. They capture the anguish of the wrongly accused and the silence of death, the bated breath of broken Constitutional promises and the fragility of a moment in time. They express the exhilaration of musical impro visation and the joys of listening to a sung melody. In doing so, each work thus brings us closer to an unmedi ated “primal sound.”

3 Walker Downey addresses the work of Kevin Beasley, Christine Sun Kim, and Nikita Gale as examples of sound artists embracing an expanded, multimodal conception of sound. Walker Downey, “For Eyes and Ears: New Sound Art Serves Different Senses with a Multimodal Approach,” ArtNews, June 7, 2022, www.artnews.com/ art-in-america/features/sound-art-multimodal-approach-1234630791.

4 Jennifer L. Roberts brilliantly unpacks some of these concepts, among others, as they apply to print in her 2021 Mellon Lectures. Jennifer L. Roberts, Contact: The Art and Pull of the Print, 2021, www. nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/ roberts-2021.html.

Ballet of the Unhatched Chicken, from the portfolio Pictures at an Exhibition, 1975

Sadness from listening to a sung melody, (Le Vallon) Gounod, 1896, from the portfolio The First Time, the Heart (A Portrait of Life 1854–1913), 2017

Sound becomes strange when it is captured in print. As it slips into the silent stillness of the visual record, it recomposes itself in unexpected ways. New shapes and relationships emerge, and images loom up even from the inaudible vibratory fringes of the sonic register. But such revelations go both ways, because sound also disturbs the ostensibly familiar realm of print, interrupting its longstanding complacency as a medium of visual reproduction. When print captures the movements of sound, it also discloses its own deep roots as a practice of revelatory conversion between the invisible and the visible. There’s a lot we can learn about sound by looking at prints, but there’s also a lot we can learn about print by looking at sounds. Sound is made and received through touch and pressure—the plink of a key, the pluck of a string, the transmission of pressure waves through the air, the vibration of the tympanic membrane in the ear. And

when sound intersects with print, it reveals that print, too, is more a matter of touch than we commonly recognize. Although print is usually associated with replicability and a certain air of dematerialization, the tactility of sound helps remind us of the primordial nature of all prints as impressions—imprints born from physical contact. Every print is a recording of a contact event between a matrix (the surface that “gives” the image) and a support (the surface that “takes” it). That transfer is a haptic one: in a printing press, for example, the press “feels” the image (by sensing differences in the plate’s topography or chemistry) in order to transmit it from one surface to another. 1

In his pigment-on-paper piano works, Jason Moran literally performs this mutual tactility of sound and print. For each work in this series, Moran, a jazz pianist and composer, spread a sheet of Japanese gampi paper over his keyboard, covered the paper with pigment, and played. The resulting image is a recording of the music taken at the intersection of the body and the instrument. The kinetic deformation of the keyboard in the course of playing is retained in the density of pressed pigment and in the residual wrinkles and contortions in the paper. The print also captures certain aspects of piano performance that are never strictly audible: the silence between notes, for example, is registered as a

1 For an extended discussion of printmaking as an art of contact, see Jennifer L. Roberts, Contact: Art and the Pull of Print (70th Annual A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), 2021. www.nga.gov/research/casva/ meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html.

cloudlike blur of pigment spread by Moran’s hands and fingers as they flew between the keys.

As gestural monuments to the songs they record, Moran’s images recall the long history of rubbings made from memorial reliefs, in which pigment and pressure applied to paper serves to “lift” inscriptions through from the invisible surface below. 2 And indeed this quality of emergence from an invisible realm, this sense of revelation or resurrection, has also long been the work of print. We tend to think of print as a visual art, but printmaking itself, in the culminating moment of the impression, is as blind as music: with the paper surface squeezed tight against the matrix, most prints are made under pressure in a dark, unobservable space. Print shows us the world as made and perceived by touch, and only later given over to the eye.

Audible and palpable experience (unlike optical experience) is multidirectional. Sound happens in the round, and print can capture this directly in ways that most other “visual” media cannot. Because prints are made under conditions of pressure and counterpressure, they can register impressions that come from either side of the paper in the act of printing. An incident detected on one side of the paper can always emerge through to the other (as in rubbing or embossing). This means that the “picture plane” in print is very different than it is, say, in painting, which is as resolutely frontal

2 On rubbings, see Allegra Pesenti, Apparitions: Frottages and Rubbings from 1860 to Now (Los Angeles; Houston: Hammer Museum; The Menil Collection, 2015).

as is vision. If the surface of a painting is analogous to a retina, the surface of a print is closer to an eardrum (a membrane that senses vibrations coming from all directions). Perhaps the best way to put this is to say that a print, unlike a painting, can sense things that come from behind it. Audra Wolowiec’s cast concrete relief works, based on the structure of acoustical tiles, emphasize this by exploring the multidirectional quality of the surfaces that are necessary for the capture of sound. And her waveforms, which she made while in residence at the Dieu Donné paper mill after watching pulp sloshing in vats and screens, reveal that paper itself is born from an immersive field of vibration—from an aqueous surround.

Dario Robleto’s portfolio The First Time, The Heart explores the bodily origins of sound recording’s immersive desires. After years of working physical ly with sound as a sculptural material (melting, pul verizing, cutting, and casting vinyl records; stretching cassette tape into filaments), Robleto began researching the graphic history of waveform sound recording. In doing so, he learned that sound recording, at its origins in the nineteenth century, developed along with physiological practices of pulse recording. His prints feature waveform images that he found in medical archives, capturing pulsations of the brain and heart that had been elicited in response to sonic, tactile, and emotional stimuli (“holding breath while listening to tuning fork”; “sadness from listening to a sung melody”). These were palpated images, created by deep vibrations coursing up through the flesh, received by sensitive detectors that rested at the surface of the skin and then traced in

oscillating lines on moving scrolls of soot-covered paper. The same instruments that captured these movements from the mysterious depths of the mind and heart would later facilitate the birth of sound recording: pulse waves in soot became soundwaves in wax and vinyl. Robleto’s work explores the impulse, broadly shared across multiple practices, to capture ephemeral signals of life from the vibratory realm. He emphasizes the capacity of the “visual record” to evoke an emotional and corporeal relationship to the past, and to store and release ineffable information through time. 3 Glenn Ligon’s Come Out project also explores sound as testimony from the body, while emphasizing its unique capacity to generate critical social awareness through harmonic interference. The project includes screenprints made by layering a series of screens bearing the phrase “come out to show them.” The screens are printed off-register, so that as the words are stacked up, interference (or moiré) patterns emerge that produce a rippling effect. Printmakers have been aware of these patterns for centuries, especially in line

3 Working with Island Press in St. Louis, Robleto first printed the pulse waves in transparent ink. Then he inverted each sheet and hand-flamed it from below with a burning candle, creating an atmospheric swirl of soot that buried the line. Then he flipped it over again and carefully dug each line back out of the soot with miniscule brushes. Robleto’s process gives us sound as an image that is both buried and retrieved, both archaeological and atmospheric, suggesting both latency and release. On Robleto, see Michael Metzger, ed., The Heart’s Knowledge: Science and Empathy in the Art of Dario Robleto (Evanston, IL: Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, 2022).

engraving, which builds images from ranks of near-par allel lines that intersect in ways that sometimes spark interference, and in screen printing and halftone-based photoreproduction, where the gridded structure of the images mean that the slightest misregistration can cause moiré effects to erupt. Usually, these unruly effects are suppressed by printers, but Ligon cultivates them here in order to highlight the disruptive spatiality that is possible in both print and sound. The phrase “come out to show them” is taken from a sound recording of the 1964 testimony of Daniel Hamm, one of six young Black men wrongly charged with murder and beaten by police. Denied medical treatment because he had no open wounds to prove his ordeal, he resorted to opening his own bruises so that the blood would come out. In his prints, Ligon nods to Steve Reich’s 1966 sound work Come Out, which looped the same recording through thirteen minutes of phase shifts and channel splits, releasing Hamm’s voice into a multidimensional aural space organized around structures of overlapping frequencies. Both Ligon and Reich give structure to Hamm’s ordeal without backing away from the agony of its embodied immediacy. And the interferences in their work generate a new kind of space from that agony—a powerful and transformative space that eludes all visual convention—that can only be evoked through this haptic-harmonic layering. 4

Jess Rowland’s Sound Tapestries are flat, flexible speaker arrays made from circuits of conductive materials that

carry audio signals. Sound is electronically generated along the surface of these hanging speaker “tapestries,” each of which serves as a separate channel for the com position. Such circuitries, generating as they do a kind of strange, pictorial electromagnetism, would seem to carry us a long way from the world of pressure and contact that we have explored so far in this essay. They seem to have taken the leap into computation (and the “digital”) that is often understood as synonymous with the so-called “death of print.” But, as Rowland’s printed circuits make plain, the circuits that are supposedly killing off print are themselves prints—circuit printing is part of the extended history of printmaking. The printed circuit was invented during WWII by the engineer Paul Eisler, who developed his prototypes by spending weeks on end in the library of the British Museum studying the history of tradition al techniques like etching, engraving, and lithography. 5 Contemporary circuit manufacturing maintains this inheritance from the print room. So the digital world, in a very real sense, still runs on print. Of course Rowland’s work also demonstrates that a printed circuit is more than “just” a print: once it is printed it is able to execute other instructions and essentially “play” other phenomena. This speaks to the capacity of print for continual regeneration—not in

4 On Ligon’s project see Ellen Y. Tani, “‘Come Out to Show Them’: Speech and Ambivalence in the Work of Steve Reich and Glenn Ligon,” Art Journal 78.4 (2019): 24–37; and Janet Kraynak, “How to Hear What Is Not Heard: Glenn Ligon, Steve Reich, and the Audible Past,” Grey Room 70 (2018): 54–79.

the way it is usually understood, as the production of multiple copies from a single matrix—but in the sense of an ongoing chain of material agency in which prints can themselves become matrices, generating new im pressions. This model of print as a propagating series of impressions (print becomes matrix; matrix begets print, ad infinitum) is also a very old one. It stretches back to medieval theories of the commutative image and to Enlightenment models of knowledge as a series of transfers of “impressions” in the mind. 6 It is worth emphasizing that sound is also communicated through chains of generative relay: when you hear a sound, it impresses itself on your ear. 7 But at the moment that it receives these vibrations, the ear generates a set of sympathetic vibrations and passes them on the brain: at that moment, the ear both receives and originates a sound-image.

This rolling renewal at the heart of both sound and print is intriguingly performed in Allen Ruppersberg’s Great Speckled Bird, made in collaboration with Gemini G.E.L. The print consists of a twenty-foot-long perforated player piano roll for a popular hymn that Ruppersberg then screen printed with images of vintage

5 Paul Eisler, My Life with the Printed Circuit (Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 1989).

6 See Elina Gertsman, “Multiple Impressions: Christ in the Winepress and the Semiotics of the Printed Image,” Art History 36.2 (2013): 310–37; and William B. MacGregor, “The Authority of Prints: An Early Modern Perspective,” Art History 22.3 (1999): 389–420.

7 On the nature of sound recording as tympanic relay, see Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 34, 62–67.

hotel stationery. Player pianos, common in the early twentieth century, were self-playing pianos controlled by perforated scrolls of coded music (“piano rolls”). Piano rolls were essentially long, reproductive prints in which information was “printed” by perforating rather than inking the paper. Ruppersberg then screen printed the roll with images of vintage hotel stationery. The piano roll (recalling Rowland) has very strong ties to the active matrix of computation. The concept of the executable print was first embodied in the form of the punch card, most famously in the Jacquard loom, and later in the early IBM system (several other works in this exhibition, including Terry Adkins’s disk print and Annesas Appel’s music-box scores, also explore this per forated territory of sound reproduction). When it is hung on the wall, the visual effusion of Rupperberg’s screen printing dominates the work, with its punctured code lurking inconspicuously as a form of latent storage. But when the print is spooled into a player piano, the silent perforations are activated. The music held visually in the perforations is released as a sound event. This again highlights the status of both print and music as technologies that alternate between impression and matrix, storage and release. Prints wait in dark storage drawers, holding their images in abeyance, until they are brought out and seen, impressing themselves anew on their viewers. Music waits in memories and cylinders and discs and tapes, stored in spatial arrays, until it is brought out and executed as a temporal event to be impressed on an ear (or another recording device). In fact, as musicologists Alexander Rehding and Daniel Chua point out, this alteration

between image and sound is the fundamental structure of music that allows it to pass through time and to form such a strong fabric of human culture. Music is “a space-faring and time-traveling vessel,” “a conjunction of event and storage in which sounds glimmer in time, then dim into space,” and then repeat the cycle. Sound is “locked in space and transported in silence out of its own time in order that it can be played back anywhere.” 8 Ruppersberg gestures to this in the printed rhythm of his road-trip motel stationery, which tells a similar tale of movement and stillness, emergence and retreat, rest and release. His scroll speaks to the endlessness of both print and music, its capacity for eternal reemergence, renewal, and relay.

Bethany Collins’s America: A Hymnal emphasiz es that this relay of culture through print and sound is always tactile and material, and thus is as much a process of deformation and change as it is a process of reproduction. A bound book in the format of a nineteenth-century shape note hymnal, it features 100 lyrical variations, written from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, of the song “America (My Country ’Tis of Thee).” Each page features the same tune, but the lyrics are different; the book tracks the melody as it was appropriated through American history in support of various often conflicting causes (it was used to support, for example, both abolitionism and the Confederacy).

8 Daniel K. L. Chua and Alexander Rehding, Alien Listening: Voyager’s Golden Record and Music from Earth (New York: Zone Books: 2021), 197–98.

The musical notation—the notes and stave lines—are the sounds held in common in this babel of conflicting claims to Americanness. They have been printed not with ink but singed away by a laser cutter, each coming into presence as a hole. Each page becomes a stencil, a punch card, through which a common American identity can be passed along as an executable perpetuity. But laser cutting is a form of burning, and Collins has deployed it here in such a way that the pages are singed and incredibly fragile. This means that each turn of the page, each playback of the print and the music, contributes visibly to its destruction, leaving gaping, toothless staves and musical debris littering the gutter. 9 Collins reminds us that the same material forces that make print and music transmissible—all those forms of pressure and vibration we have been following in this essay—are the forces that insist on its constant trans formation and precarity. Print and sound recording can never be truly reproductive; each retrieval of a song or an image changes it forever. The tape wears out; the ink fades; the times change. These forces, of course, are social and political as well as material. Collins implores us to look and listen carefully, because no revelation will be the same as the last.

9 For an especially sensitive discussion of the material fragility of Collins’s book, see Molly Schwartzburg, “A Book for This Moment and for This Library: Bethany Collins’s ‘America: A Hymnal.’” www.smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/2018/01/25/a-book-for-thismoment-and-for-this-library-bethany-collinss-america-a-hymnal.

Boogie woogie, its rhythms as precise and relentless as assembly lines, heavy machinery, the click-clack of steel wheels on a railroad track. When graphic artist Alex Steinweiss designed the cover for a four-shellac disc titled Boogie Woogie, released in 1942, he understood not only the graphic drama of the piano keys but also their symbolic representation of entanglements, both fraught and productive, between black and white musicians. In his artwork, one white hand, one Black hand loom over a diminutive piano like phantoms. As Alfred Appel Jr. points out in his book, Jazz Modernism, the record featured Black and white musicians playing together—Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, and Harry James on “Woo-Woo” and “Boo-Woo”.¹ Not only was this record part of Piet Mondrian’s personal collection, 1 Alfred Appel, Jr., Jazz Modernism

Alfred A. Knopf,

it was also his soundtrack to the creation of Broadway Boogie Woogie and what Fred Moten has described as “… the amazingly, beautifully jooked joint called Victory Boogie Woogie, Mondrian’s transblackatlantic thing…” ² Those titles, “Woo-Woo” and “Boo-Woo,” are ghostly evocations in themselves of the steam whistle’s shriek— thrilling/chilling alarm call of settler-colonialism and carbon catastrophe delivered coast to coast. With modernism’s reach came the mass market, a proliferation of recorded sounds and printed images that entered the consciousness of vast audiences. Mondrian’s “transblackatlantic” geometrical abstractions were hugely influential in the fields of twentieth-century painting, sculpture, design, fashion, and architecture. As objects created with paint and colored paper on canvas, however, they were located firmly in the fine art tradition of the unique work. In one sense, they corresponded to and evoked performances of the jazz Mondrian loved, yet there were key differences. A painting remains present and visible to the longest gaze; over time it might become regarded as priceless, its unique status conferred by the artist’s touch. Sound vibrations also possess physicality, but as cycles of vibratory disturbance, they evaporate into the air. They can be recorded and reproduced on discs or other physical media in editions calculated to suit their potential market, but the current market value of Boogie Woogie—less than $600 for an original Columbia Records copy in mint condition—is a fraction of the $50.6m paid for Mondrian’s Composition No. III

2 Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017), 232.

with Red, Blue, Yellow, and Black, sold in 2015. There exists a long tradition of artworks wrestling with the problem of representing the intangibility of sounding and listening in a silent, fixed medium. A ragamala album of thirty-four paintings in the Provisional Mughal style, created in c. 1610, uses poetic images to depict the nature of each Hindustani classical raga, or musical mode. ³ To illustrate the morning raga named Todi, for example, a woman lures a wide-eyed antelope with the sound of a string instrument called a rudra veena. In ancient China, the depiction of nature-loving figures in landscape settings was a major theme; for Chinese art specialist Susan Nelson, these figures were listeners as much as they were gazers. Sound was, in itself, a subject. As she writes of Li Tang’s hanging scroll Wind In the Pines of Ten Thousand Valleys (1124), “Li’s chief subject is the windy murmuring of the great pines massed in the foreground, echoed by the groves on the ledges above and underlined by the steady splashing of the stream.”⁴ In Sinister Resonance, I wrote of the Dutch painter Nicolaes Maes, whose early genre scenes painted between 1655 and 1656 depicted the intimacy of silence, the intense prurient curiosity of eavesdropping, and the invasive nature of sound.5 All of these works could be considered as forms of imprecise notation or recording—precursors to the invention of audio recording in the nineteenth century, but also to

3 Joep Bor, ed., The Raga Guide: A Survey of 74 Hindustani Ragas, (Monmouth: Nimbus Records, 1999), 167.

4 Susan Nelson, "Picturing Listening: The Sight of Sound in Chinese Painting", Archives of Asian Art 51 (1998–99): 32–33.

the extraordinary explosion of sonic experimentation in the twentieth century.

The impact of mass production was echoed in art by ready-mades, multiples, and the plasticity of new re productive technology, particularly the phonograph and magnetic tape, which enabled the dramatic expansion of electronic music. In that sense, printing was a closer analogue to recorded music than painting. The precision required to register color layers in offset lithography and screen printing could be manipulated, as Andy Warhol demonstrated with silkscreen prints derived from photographs of car crashes, an electric chair, Jackie Kennedy; or with his Birmingham Race Riot of 1964. In both their mass-produced, high contrast, smudged look and their subject matter they mirrored the urgency of news stories, barely able to keep up with the tumultuous events of the era. Similarly, Steve Reich’s tape compo sition, Come Out (1966), ran two identical tapes on two tape machines: the two words of the title are excerpted from speech recordings of a young black man, Daniel Hamm, one of the Harlem Six arrested and beaten by police after a murder in Harlem in 1964. Minute variations in the tape speed of the two machines caused a gradual phase shift, the emergence of polyrhythms and effects comparable to the moiré patterns of graphic media or the imperfect registration of a printed image. Whether in the form of tape, shellac or vinyl records, spectrogram, voiceprint, or wave form, the materiality

5 David Toop, Sinister Resonance (New York and London: Continuum Books, 2010).

of recording media affords a translation from intangibil ity and ephemerality into graphism. Christian Marclay’s cyanotypes, for example, take inspiration from the photograms of nineteenth century biologist and photographer Anna Atkins. Where Atkins used the cyanotype process to photograph dried algae, specifically seaweed, Marclay lays unspooled cassette tapes and plastic cassette boxes on the light-sensitized paper. In both cases there is a poetic contrast between the transience of the materials—the fluidity of seaweed in its liquid environment and the musically imprinted potentiality of tape winding through its mechanism— and their fixity as visual patterns or blueprints. A residue of the original recording artists remains—Rush, Barbra Streisand, Tina Turner, and others—if only through Marclay’s acknowledgement of their names in his titles, yet they are fully absorbed into the original material and its transformation, as if fossils of long-extinct behemoths collected on a nineteenth century seashore. Dario Robleto’s work also reaches back into the nineteenth century, to graphic recordings and representations of bioacoustic events. These include printings of historical waveform recordings, including the first waveform recordings of blood flowing from the heart during sleep and dreams; blood flowing from the heart in newborns and respiration; and blood flow during auditory experiences. Robleto’s preoccupation with those early devices that inscribed states of the body reminds us that there is a confluence here, a blurring of writing with audible pulsation, invasive inscription, cal ligraphy, music notation, and drawing. The Buzzcocks described the recording process as a spiral scratch:

a needle scrapes through the continuous groove of a record as if following the historical precedent of intaglio printmaking—etching, drypoint, or engraving—miracu lously unlocking the complexity of music as it does so. This burial ground of living sound, inert until activated, is evident in America: A Hymnal, a book and performance work by Bethany Collins in which the printed lyric of “America (My Country ʼTis of Thee)” is sung in all of its one hundred versions, each one rewritten to support a specific political cause—as Collins has said, “a hundred dissenting versions of what it means to be American, bound together.” 6 Voices are entangled as heterophonic vibrational confusion, released as if birds from the confines of paper, printer’s ink, and binding, yet still subject to the borderlands of physical space and intelligibility. Sound insinuates itself into the substrate of air as both transparency and felt vibration, transient and suspended materiality, tactile and ephemeral. To watch and listen to an improvised piano performance by Jason Moran is to become fully conscious of that contradiction. The listener hears resonance activating a room, yet this listening is also sympathetic movement, absorbed by the physicality of hands as soft and hard tools. Fingertips are also fingerprints, probing and pressing in intimate relationship—pressure, caress, attack, and withdrawal—with the black and white keys of the piano, their

6 Bethany Collins, quoted in Dinah Cardin, “A Word with Bethany Collins”, Peabody Essex Museum, March 11, 2020, www.pem.org/blog/a-word-with-bethany-collins

resistant and giving mechanism, their troubled history as ivory and ebony embodiments of colonial plunder. As he repeats and intensifies movement in one area of the keys, ghost harmonics emerge, floating in circulato ry motion through the room. Moran’s Choruses in unison (2020) and Note Count (2021) address and accentuate the complex entanglements of this process. Created by laying gampi paper on the piano’s keyboard, coating the paper with pigment, then playing the keys through the paper, they persist as trace memory of what has long become another kind of trace memory. The image is a record, potentially existing in parallel to an audio record, yet what it records through physical contact over time is the unique touch of the musician, never to be repeated exactly. Ephemerality and eternity exist within the same space, if only for a moment.

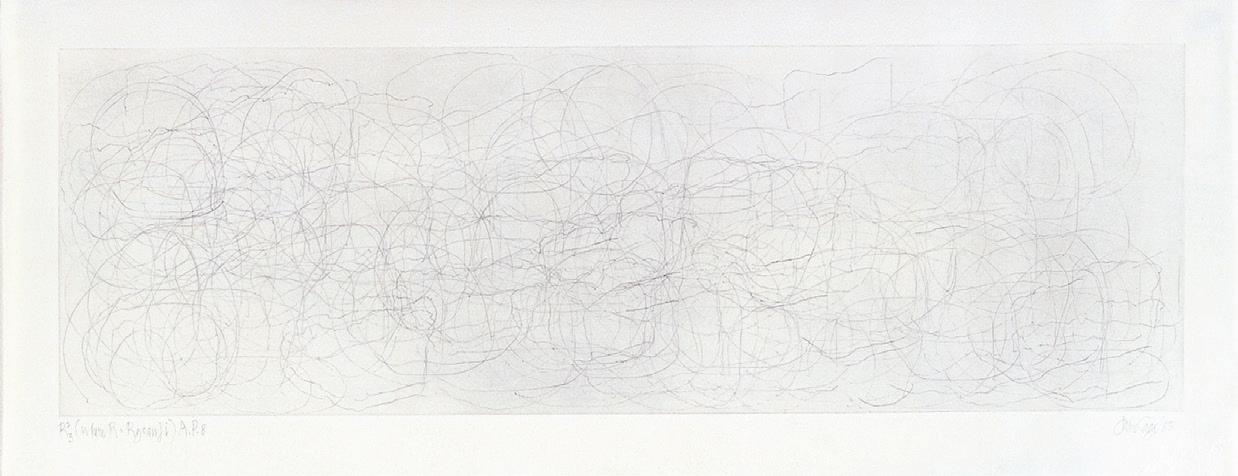

Where R=Ryoanji: R2/1, 1983

Where R=Ryoanji: R2/2, 1983

Works in the Exhibition

Terry Adkins (1953–2014)

Untitled (Disk Print, Red), 2001

Ink on paper, printed from metal music box disc

30 × 30 inches

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Annesas Appel (b. 1978)

Metamorphosis Music

Notation, 2015

Piezo print in 50 strips with perforations; hand-cranked music box

Each strip 89 × 3 inches

Installation dimensions variable Printed by Bernard Ruijgrok, Amsterdam

Courtesy the artist and Gallery DudokdeGroot, Amsterdam

K.P. Brehmer (1938–97)

Gnome, 1975

Ballet of the Unhatched Chicken, 1975

Great Gate of Kiev, 1975 Etchings

20 7⁄8 × 26 3⁄8 inches each

From the portfolio Bilder einer Ausstellung [Pictures at an Exhibition], 1975/1988

10 etchings by K.P. Brehmer,

11 hand-colored photostats by Philip Corner, and one LP Edition of 30 planned; a few impressions printed

Published by Edition Block, Berlin Courtesy Edition Block

John Cage (1912–92)

Where R=Ryoanji: R2/1, 1983 Drypoint

Image: 7 × 21 ½ inches

Sheet: 9 ¼ × 23 ¼ inches Edition of 25

Printed and published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco Courtesy Crown Point Press

Where R=Ryoanji: R2/2, 1983

Drypoint

Image: 7 × 21 ½ inches

Sheet: 9 ¼ × 23 ¼ inches Edition of 25

Printed and published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco Courtesy Crown Point Press

Where R=Ryoanji: R2/3, 1983 Drypoint

Image: 7 × 21 ½ inches

Sheet: 9 ¼ × 23 ¼ inches Edition of 25

Printed and published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco Courtesy Crown Point Press

Where R=Ryoanji: 2R+13.14, 1983

Drypoint

Image: 7 × 21 ½ inches

Sheet: 9 ¼ × 23 ¼ inches

Edition of 25

Printed and published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco Courtesy Crown Point Press

On the Surface No. 10, 1980–82

One from a series of 35 related etchings printed in two impressions each

18 ½ × 24 ½ inches

Published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco Courtesy Crown Point Press

Blake Marques Carrington

Strata Systems v04_LOOM #4001, 2016

Inkjet print on coated cotton, with acrylic and black gaffers tape

48 × 32 × 3 inches

Courtesy the artist

Strata Systems v04_LOOM #4002, 2016

Inkjet print on coated cotton, with acrylic and black gaffers tape

48 × 32 × 3 inches

Courtesy the artist

Bethany Collins (b. 1984)

America: A Hymnal, 2017 Artist book with 100 laser-cut leaves

6 × 9 × 1 inches

Edition of 25

Published by PATRON Gallery, Chicago

Courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery

Peter Fischli/David Weiss

(b. 1952/1946–2012)

Record (for Parkett), 1988

Cast rubber record

11 13⁄16 inches diameter

Edition of 120

Published by Parkett

Publishers, Zürich/New York Courtesy Parkett Publishers

Jennie C. Jones (b. 1968)

Five Point One Surround, 2014

Portfolio of five aquatints

30 × 22 inches each Edition of 15

Published by Universal Limited Art Editions, Bayshore, NY

Courtesy Universal Limited Art Editions

Glenn Ligon (b. 1960)

Detail, 2014

Three-color screenprint on Coventry Rag 335gsm 13 × 16 inches

Edition of 50 and 40 APs Published by Camden Art Centre, London Courtesy the artist

Christian Marclay (b. 1955)

Allover (Rush, Barbra Streisand, Tina Turner, and Others), 2008 Cyanotype

51 ½ × 100 inches

Published by Graphicstudio, University of South Florida, Tampa

Collection of the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, Tampa

Silence (The Electric Chair), 2006 Screen printing ink on vellum

Image: 23 × 30 inches Sheet: 30 × 30 inches

Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Jason Moran (b. 1975)

Note Count, 2021 Pigment on gampi 25 ½ × 38 ¼ inches

Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine Gallery, New York

Choruses in unison, 2020 Pigment on gampi 42 ½ × 77 ½ inches

Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine Gallery, New York

Dario Robleto (b. 1972)

Experiment with cannabis (sudden freedom from any unusual feeling, beginning to feel an indefinable sensation of comfort), 1874; Perfect mental repose, 1879; Holding breath while listening to tuning fork, 1880;

Palpitations (panic attack), 1902; Sadness from listening to a sung melody, (Le Vallon) Gounod, 1896

From the portfolio The First Time, the Heart (A Portrait of Life 1854–1913), 2017

Photolithographs on Rising Drawing Bristol with transparent base ink, hand-flamed and sooted paper; image brushed with lithotine and lifted from soot, fused in a mild solution of shellac and denatured alcohol

Each sheet: 11 ½ × 14 ¼ inches

Edition of 6

Published by Island Press at Washington University, St. Louis Courtesy the artist

Jess Rowland (b. 1971)

Sound Tapestries, 2022

Copper foil on acetate, with electronics

18 × 48 inches each

Installation dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist

Allen Ruppersberg (b. 1944)

Great Speckled Bird, 2013

Screenprint on perforated player-piano roll

Panel A sheet: 11 ¼ × 75 ½ inches

Panel B sheet: 11 ¼ × 72 ½ inches

Panel C sheet: 11 ¼ × 43 ¾ inches

Panel D sheet: 11 ¼ × 46 inches Edition of 12

Printed and published by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles. Courtesy Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York

Audra Wolowiec (b. 1979)

AIR, 2020

Five-channel sound installation 2 minutes, 27 seconds

Breath practitioners: Carlye Eckert, Denise Hopkins, Elizabeth Casasnovas-Calderon, Katie Mullins, and Mark Trecka

Courtesy the artist

voiceprint (we the people), 2021

Offset woodblock print with laser-cut commas 24 × 19 inches

Edition of 26 Courtesy the artist waveforms, 2017 Handmade paper of cotton and linen with pigment 40 × 30 inches each

Courtesy the artist concrete sound, 2020 Cast concrete with pigment 18 ½ × 18 ½ × 7 inches

Courtesy the artist

Elleree Erdos is Director of Prints and Editions at David Zwirner. She was previously curator of a private art collection and Associate Director at Craig F. Starr Gallery, and has held positions in the print departments at the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Clark Art Institute. Erdos earned an M.A. from Columbia University and the University of Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne and a B.A. from Williams College.

Jennifer L. Roberts is Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University, where she teaches art history, print history, and material studies, with an emphasis on intersections between the arts and the natural sciences. She is the author of numerous books and essays on American art from the eighteenth century to the present, and has curated multiple exhibitions in contemporary art at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. In spring of 2021, she delivered the 70th Annual A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts for the National Gallery of Art, with a series titled Contact: Art and the Pull of Print.

David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music, and materials since 1970, encompassing improvised music performance, writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations, and opera. It includes eight acclaimed books, including Ocean of Sound, Sinister Resonance, Into the Maelstrom, Flutter Echo, and Inflamed Invisible. His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism were released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows. Solo records include New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments, Entities Inertias Faint Beings, and Apparition Paintings. Recent collaborations include Garden of Shadows and Light with Ryuichi Sakamoto. www.davidtoopblog.com.

Staff

Maud Welles

Chair

David G. Sabel

Vice Chair

Mary Beth Forshaw Secretary

Stewart K.P. Gross Treasurer

Anders Bergstrom Judith K. Brodsky Andrea Butler

Anne Coffin, Founder Jennifer Farrell Starr Figura

Leslie J. Garfield Mark Thomas Gibson Joseph Goddu Evelyn Lasry Sabina Menschel John Morning, Founding Chair

Daniel Nardello Martin Nash

Janice C. Oresman, Emerit Diana Wege

In Memoriam

Leonard Lehrer

Barbara Stern Shapiro

Judy Hecker

Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich

Director of Exhibitions and Programs

Brooke Christensen Senior Administration Fellow

Tiffany Nesbit

Director of Development and External Affairs

Diana Perea

Exhibitions and Publications Coordinator

Robin Siddall Program Fellow

Tuesday Smillie Registrar

Ema Wang

Marketing and Communications Manager

Published on the occasion of the exhibition Visual Record: The Materiality of Sound in Print, Print Center New York, October 8, 2022–January 21, 2023 Curated by Elleree Erdos

© Print Center New York and the authors

ISBN: 978-1-7341224-2-8

Edited by Elleree Erdos and Jenn Bratovich

Copyedited by Anne Osherson

Design by CHIPS

Edited by Elleree Erdos and Jenn Bratovich

Copyedited by Anne Osherson

Design by CHIPS

All artworks © and courtesy the artists unless otherwise noted.

7: © Annesas Appel. Photo by Daria Tuminas

15: © Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Image courtesy Parkett Publishers, Zürich/New York, and the artists

17–18: © Glenn Ligon. Image courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

27–29: © Edition Block, Berlin 30–32: © 2013 Allen Ruppersberg and Gemini G.E.L., LLC 46–47: © Bethany Collins.

Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago.

Photo: Evan Jenkins

48–50: © Jennie C. Jones and Universal Limited Art Editions. Image courtesy Universal Limited Art Editions 58–59: © Jason Moran. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photo: Farzad Owrang 60–61: © 2008 Christian Marclay and Graphicstudio, U.S.F. Photo: Will Lytch 63: © 2022 The Estate of Terry Adkins / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert 64–65: Jess Rowland, Sound Tapestries, 2013–ongoing, installed at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, UC Berkeley, 2013. Copper foil on acetate; electronics. Installation dimensions variable. © Jess Rowland. Photo: Sibila Savage. 66–67: © John Cage Trust

Cover: Detail of Jason Moran, Note Count, 2021. Pigment on gampi, 25 ½ × 38 ¼ inches. © Jason Moran. Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photo: Farzad Owrang