Heaven in a Wildflower Krishna Reddy

Krishna Reddy

Heaven in a Wildflower

9 Foreword

23 Heaven in a Wildflower

Sarah Burney

53 We Want to Find Out: Reflections of a Student Mark Johnson

67 Art Expression as a Learning Process Krishna Reddy

89 Works in the Exhibition

Germination I [Seed Pushing], 1961

Radiating Flowers, 1967

Water Lilies, 1959

Foreword

Print Center New York is proud to present Krishna Reddy: Heaven in a Wildflower in our Jordan Schnitzer Gallery. Organized by independent curator Sarah Burney, it is the first exhibition at a New York institution to focus entirely on the late Indian artist in over 40 years (the last was Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective at the Bronx Museum in 1981). Reddy is best-known in the printmaking field as a printer who, alongside Stanley William Hayter and Kaiko Moti at Atelier 17, co-developed viscosity printing—a highly technical intaglio process that revolutionized the ability to print multicolor images from a single plate. Yet this dazzling achievement has overshadowed Reddy’s work as an artist in his own right.

Burney’s exhibition and publication aim to draw out the why of Reddy’s work, and the results attest to the clarity of her understanding of Reddy as an artist. Burney argues that Reddy—who was born in rural India

Krishna Reddy: Heaven in a Wildflower

and spent significant time in Europe before landing permanently in New York in 1976—has often been read in Eurocentric terms that can’t capture the complexity of his approach. Likewise, emphasis on his technical innovation has overridden the nuance of what motivated him in the studio. But as this project makes clear, Reddy was disinterested in technique for technique’s sake; rather, technique grew organically from his finely attuned sensitivity and presentness to materials, process, and the world around him. We thank Burney for her committed understanding of the contexts in which Reddy worked and the deeply rooted worldview that gave him the curiosity and freedom to ask his inks and plates what might be possible.

Part of Print Center’s mission is to act as a platform for rising curators in our field and to provide intellectual support for developing their research and thinking. We therefore thank the curatorial working group who acted as a sounding board for Burney as she developed this project, including: Rattanamol Singh Johal, the Shireen and Afzal Ahmad Professor of South Asian Arts and Assistant Professor of History of Art at the University of Michigan; curator Sumesh Sharma; and the artist Mark Johnson, Print Studio Coordinator and instructor at New York University, who was a student and close friend of Reddy. In particular, Heaven in a Wildflower would not be what it is without Johnson, who contributed a personal reflection to this publication, produced a demonstration video of viscosity printing with NYU student Avery Munson Clark for the exhibition, and will act as a key participant in our public programming.

The success of this project is also indebted to Judith Blum Reddy, who warmly opened her home, studio, and flat files to Burney and our team. Her contributions as the sole lender to the exhibition and as a research resource have been invaluable. We also thank our colleagues in galleries, archives, and libraries who have facilitated Burney’s research. In particular, we thank Priyanka Raja, Prateek Raja, and Joshua Nassiri Giri at Experimenter, Kolkata; Projjal Dutta at Aicon Contemporary, New York; and Amethyst Rey Beaver, Dev Benegal, Jennifer Farrell, Benjamin Levy, and Christina Weyl.

We thank the dedicated staff at Print Center New York for realizing this ambitious project over the last year. Our curatorial intern Thomas Sendgraff came onboard last fall and pushed our programming and engagement efforts to the finish line. We thank our friends at EFA Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, especially Essye Klempner, for their collaboration during this programming season. In finalizing this publication, we also thank Gabriella Angeleti for her speedy copyediting and Argenis Apolinario for new photography. Finally, we owe thanks to Judith K. Brodsky, who brought the potential for a project on Reddy to our attention by way of her acquaintance with Umesh and Sunanda Gaur, impressive collectors of Indian art. The Gaurs made it their mission to assemble impressions from all 54 of Reddy’s viscosity plates, and to advocate for a series of institutional exhibitions in 2025—Reddy’s centennial year. As we join an international network of projects on Reddy this year, we thank the Gaurs for their

warm reception and for their belief in the importance of this work.

We are grateful to all of our supporters for making this exhibition possible. Heaven in a Wildflower is generously supported by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation, with additional support provided by the Guston Fund and the IFPDA Foundation. Print Center New York is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature. Major support provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Print Center New York gratefully acknowledges the leadership support of our Board of Trustees, the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation for the Jordan Schnitzer Gallery, and the Garfield Family Foundation for the Leslie and Johanna Garfield Lobby.

Judy Hecker Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich Chief Curator

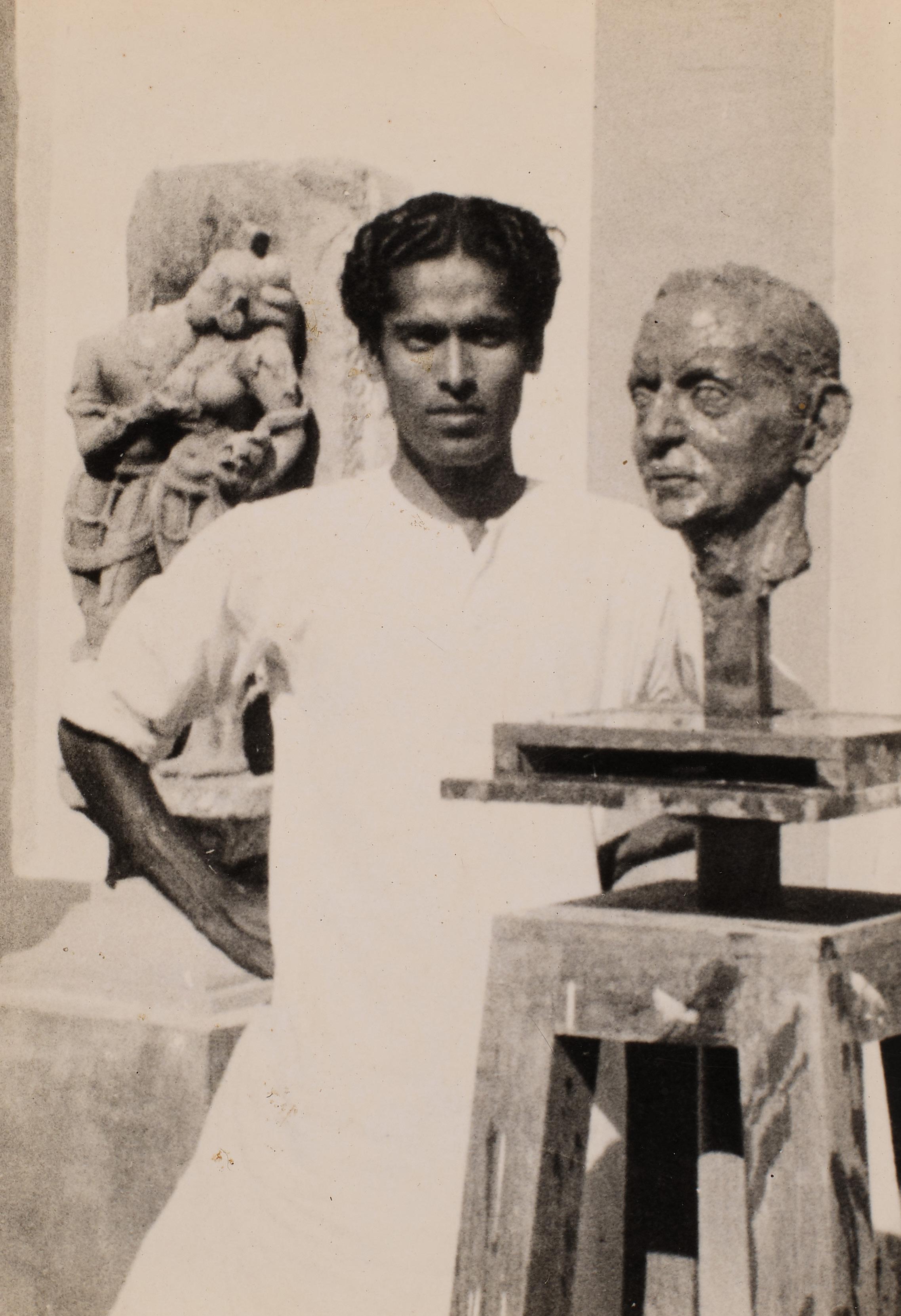

Krishna Reddy Kalakshetra Madras, Chennai, late 1940s

Reddy in Paris, early 1950s

Reddy and classmates during a workshop critique with Ossip Zadkine, Paris, 1951

The Printmaking Workshop, New York, 1971

Reddy with Eleanor Magid and Robert Blackburn

Reddy teaching, unknown date

I said, “Oh well, I am drawing the tree, drawing its flowers, trying to learn the way the petals part in the center and the way they are arranged.”

He [Nandalal Bose] said, “Maybe the tree is refusing you. Maybe after a few days if you persist it will say, ‘Oh good, come along with me.’ If you are willing it may accept you in its shade and might even let you walk in.” [...]

I said to myself, “My God, how little I know!” [...] I was only indulging in the tree’s superficial aspects. It was this man who pointed me towards the depths of nature.

— Krishna Reddy

Sarah Burney

Heaven in a Wildflower

In dramatic compositions buzzing with intersecting lines and glowing colors, Krishna Reddy engaged in a lifelong exploration of nature, humans, and our universe. He considered insects, aquatic creatures, plants, expansive landscapes, the powerful movement of water and protest, the stillness of prayer, the individual and the collective, the child and the clown, and the personal and the global. Reddy pictured our world as continually changing: its inhabitants are dynamic processes interconnected with their surroundings, which are themselves in flux.

Reddy’s distinctive imagery—almost abstract and cellular meditations—and subject matter point to a profound personal philosophy that positions looking as the beginning of learning. That is, looking closely at the world around us, especially the natural world, was how Reddy found the beauty in the interconnectedness

Sarah Burney

and constant change that defines our universe. It is this approach that shaped his conceptual and aesthetic inquiries, and also motivated the groundbreaking, innovative approach to printmaking for which he is best remembered.

Discussions of Reddy’s legacy often bifurcate his art from his contributions to printmaking—the latter often far eclipsing the former. In the 1950s, while working at the famed experimental printmaking workshop Atelier 17 in Paris, Reddy co-discovered viscosity printing, a complicated printing technique that exploits the tackiness of intaglio inks to produce multicolored prints in a single pass through the press.1 Reddy used this new process to great effect in his artwork, taught it at New York University for over twenty-five years, introduced it to the larger printmaking community through workshops in India, Europe, and the United States, and published a book on the subject.2

Despite this, Reddy was uninterested in technical discussions on printmaking. He urged his students to explore their materials rather than master them. This is not surprising when we understand how Reddy

1 This process has been referred to with many different names, including intaglio color viscosity printmaking, mixed color intaglio, simultaneous color printmaking, color viscosity, and simply viscosity printing, to name a few.

2 Krishna Reddy, Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes (State University of New York Press, 1988). Repackaged as New Ways of Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Process (Ajanta Offset Packaging Limited and Vadehra Art Gallery, 1997).

worked in his studio: he was unconcerned with the rigors and commercial considerations of editioning. He created numerous colorways of the same plate, changed the titles of artworks mid-edition (when he made editions at all), and continued to innovate with unconventional tools and techniques throughout his life. Ultimately, his use of viscosity was not a technical flex but, through the technique’s ability to create endless variations of glowing gradients, a means to convey the dynamism Reddy saw in our world.

Perhaps Reddy’s art has also not been fully appreciated due to a prevailing Eurocentric reading of his biography and artwork. Born and raised in India, Reddy traveled to Europe in the early 1950s, living in London and Milan before settling in Paris for twenty-six years. In 1976, he moved permanently to New York. His success in Europe, and especially his tenure at Atelier 17, is undeniably significant—he was the only person of color to ever be co-director of this important space. He was part of a vibrant community of Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist artists, yet did not identify with either artistic movement.3 He appreciated his peers’ novel approaches to artmaking, and often shared formal similarities with them, yet the context of their artistic production was distinct. While his European contemporaries were shaped by their lived experience of World War II, Reddy was a product of different circumstances.

3 Laura Bottome, et al., “A Dialogue with Krishna Reddy,” in Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective (Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1981).

Sarah Burney

Yet Reddy did not fit in with his peers in India either; he was close friends with many in the ascendant Progressives Artist Group but never formally identified with them.

Attempts to contextualize him in these ways—like attempts to focus solely on his technical achievement— have missed the philosophical underpinnings of his work. Straddling all these worlds, Reddy charted his own singular path, but was ultimately continuing an exploration of the world and creativity that was sparked in India. It is by retracing Reddy’s biography, with an emphasis on his early years, that we come to understand what motivated his experimentation and vision, allowing us to truly appreciate his artistic contributions.4

Reddy was born in 1925 in Nandanoor, a small rural village in the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh, India. The rich culture of Hindu rural society ensured that art and philosophy were an integral part of Reddy’s life from the beginning. Every day, his family decorated their front yard with ephemeral designs made out of colored rice and powder. Seasonal festivals celebrated color, light, and individual deities. Traveling open-air theater troupes, folk musicians, and dancers often came through the village to perform. Reddy’s father made sculptures for the local temples5 and his mother often

4 Roobina Karode, “The Embodied Image,” in Krishna Reddy: The Embodied Image (Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2011).

5 Past publications have noted that Reddy’s father painted murals in temples. Judith Blum Reddy confirmed that Reddy senior sculpted.

took him to neighboring villages to hear talks by visiting priests, astrologers, and philosophers.6

Reddy’s schooling was avant-garde from an early age. At eight years old, after studying at the local village school, he enrolled at the Rishi Valley School, founded by the internationally renowned philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. In 1943, he made the long journey north to West Bengal to attend Kala Bhavana, the art institute at Santiniketan7 founded by Bengali polymath and Nobel Prize Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. These institutions were established to counter the prevailing colonialist, efficiency-driven educational model in vogue in modern Indian schools. Krishnamurti’s teachings of absolute awareness, rejection of caste, nationality, or religion, and understanding of one’s self through observation had a profound impact on Reddy. These ideas forged the foundation of his personal philosophy, and were further enhanced by Santiniketan’s emphasis on Vedic thought. Both schools were set in verdant rural enclaves and a connection to nature was foundational to their missions. Santiniketan drew inspiration from the traditional ashram: classes were held outdoors under the shade of a tree, students worked in the fields of neighboring villages, and, in lieu of a diploma, a leaf was given to commemorate graduation. Reddy’s instructors here included Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, and

6 Bottome et al., “A Dialogue with Krishna Reddy.”

7 Visva-Bharati (now Visva-Bharati University) is commonly referred to by the name of the city in which it is located, Santiniketan.

Sarah Burney

Benode Behari Mukherjee—artists leading the intellectual articulation of Early Indian Modernism.

Reddy’s sketchbooks from Santiniketan reveal the institution’s novel approach. Tagore and his faculty were cultural internationalists, in dialogue with their intellectual contemporaries across the world while celebrating India’s cultural heritage as both subject and inspiration. For example, in a sketchbook labeled “Designs” we see both the growing understanding of Indian decorative forms and the beginnings of abstraction. In Reddy’s studies of human anatomy, bones, muscles, and ligaments are meticulously illustrated and labeled in English as befitting a medical student. At Santiniketan, Reddy was able to fully nourish his scientific interest in the natural world by studying biology, botany, and biochemistry.

Against this backdrop of cultural enrichment, Reddy came of age at a politically volatile time in India, when the indignity of British rule was being forcefully challenged. He witnessed firsthand the catastrophic 1943 Bengal Famine, was repeatedly arrested for his role in Mahatma Gandhi’s Quit India Movement, and experienced the upheaval of Partition before he turned twenty-two. Like many Santiniketan students, Reddy joined the relief efforts for famine victims, distributing aid and assisting in funerary rites for the deceased. He never forgot the injustice that created this calamity nor the emaciated, skeletal bodies of the famine victims—he preserved them in drawings seven years later, and these forms would echo through his future figural work.

Upon graduation, Reddy returned to the south to lead the Art Department at the College of Fine Arts,

Kalakshetra Madras—the first step in his lifelong career as an educator. He forged a relationship with Krishnamurti, who advised the young artist to continue his education abroad. Reddy traveled to Europe in 1949 and specialized in sculpture, initially at the Slade School of Fine Art, London, studying under Henry Moore; then the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, under Ossip Zadkine; and the Academia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan, under Marino Marini.

Reddy settled in Paris where he visited Atelier 17, the printmaking workshop founded by the English chemist-turned-artist Stanley William Hayter. The international and experimental nature of Atelier 17 resonated with Reddy: much like Santiniketan, it was an intellectual hub where artists gathered to discuss art and philosophy, collaborate, and experiment with the medium of print. Hayter had relocated Atelier 17 to New York during World War II, forging strong ties with the American printmaking community. The reestablished Parisian iteration of the studio was a destination for many traveling American artists, most notably the Black artist and printmaker Robert Blackburn, with whom Reddy formed an immediate friendship. Reddy quickly became an integral part of the Atelier 17 community, working closely alongside Hayter and eventually becoming co-director.

By the 1950s, printmaking, specifically intaglio, became Reddy’s primary medium. Although he continued to create spare, elegant sculptures and maintained a prolific drawing and watercolor practice, intaglio allowed Reddy to indulge color that beloved artistic element that sculpture deprived. For Reddy,

Sarah Burney

intaglio combined sculpture and color.8 Reddy produced 54 intaglio plates between 1952 and 1997 and pulled innumerable variable impressions from them. In them, we see the evolution of his unique artistic voice.

From the start of his printmaking practice, Reddy rose to Bose’s poetic provocation. His first suite of color intaglio prints (produced in the 1950s at Atelier 17) predominantly depict small creatures: a fish, insect, tuatara lizard, jellyfish, and butterfly. In each, the subject is abstracted to the point of obfuscation and exists in a pulsing technicolor world where foreground and background bleed into each other. Working his copper plate with etching acids, burins, gouges, and other traditional hand tools, Reddy created compositions full of sweeping arced lines forming organic shapes. The fluidity of these compositions reflects the interconnectedness he saw in our world: all things formed of the same elements, viewed as both micro and macro. In Absterix [Tuatara Forming/Bulging Tuatara] (1953) and Jellyfish (1955), Reddy simultaneously contemplates his titular subjects and astronomy, connecting the visual parallels between the two: the curved shapes of our galaxy and an abstracted reptile body, Sputnik hurtling into space and a jellyfish as it moves in water. When he considered a fish he wondered at how bundles of cells “come together, shape themselves into many forms like bones,

8 Sucharita Ghosh Stephenson, “Out of India: Krishna Reddy,” NDTV and BBC World, YouTube, 23 min., 44 sec., https://youtu.be/Cb94R_uOjuA.

muscles, and fins to navigate and live in the abundance of water.” He concluded: “I had the feeling that space itself is creating the fish.”9

Reddy considered his artistic tools and materials with the same reverence and curiosity as his subjects. In fact, it was his close attention to a studio accident that sparked the development of viscosity printing. Reddy noticed how inks of different viscosity (tackiness) did not mix, suggesting an opportunity to layer multiple colors on a single plate. In collaboration with fellow printmakers Kaiko Moti and Hayter, Reddy began experimenting with using linseed oil to alter the viscosities of ink, until colors could be predictably layered, and thus simplified one of printmaking’s biggest challenges: printing multiple colors with precision.10

Unsurprisingly, Reddy was also innovative in his handling of the plate. He approached the metal surface of the intaglio plate as a carving medium as opposed to a drawing surface. Initially working with traditional printmaking hand tools, Reddy gradually incorporated stone carving tools (such as chisels and grinders) and a variety of attachments for electric instruments (typically used by machinists and jewelers) into his platemaking toolkit. He even created his own carving chimeras: the most famous is “Pierre,” a machine tool

9 Krishna Reddy, “Catalog Raisonné,” in Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective. 10 Previously every color required its own plate; creating a multicolor image required a careful and laborious registration process to ensure the color layers lined up correctly.

Sarah Burney

with interchangeable heads attached to the body of a dentist’s drilling machine.

This sculptural approach to platemaking further enhanced the possibilities of viscosity printmaking by incorporating the mechanics of relief printing. Carving or etching plates to varying depths and then using rollers of varying densities to apply ink expanded the colorways an artist could achieve. Inks applied with a soft roller could cover the plate’s whole surface, reaching both the deeply carved areas of the plate as well as its shallow areas. A harder roller would deposit ink only on the topmost surface. Reddy often carved such deep lines and hollows in his plates that rollers were unable to deposit any ink at all, allowing the bare, bright whites of the paper to punctuate his vibrant gradients.

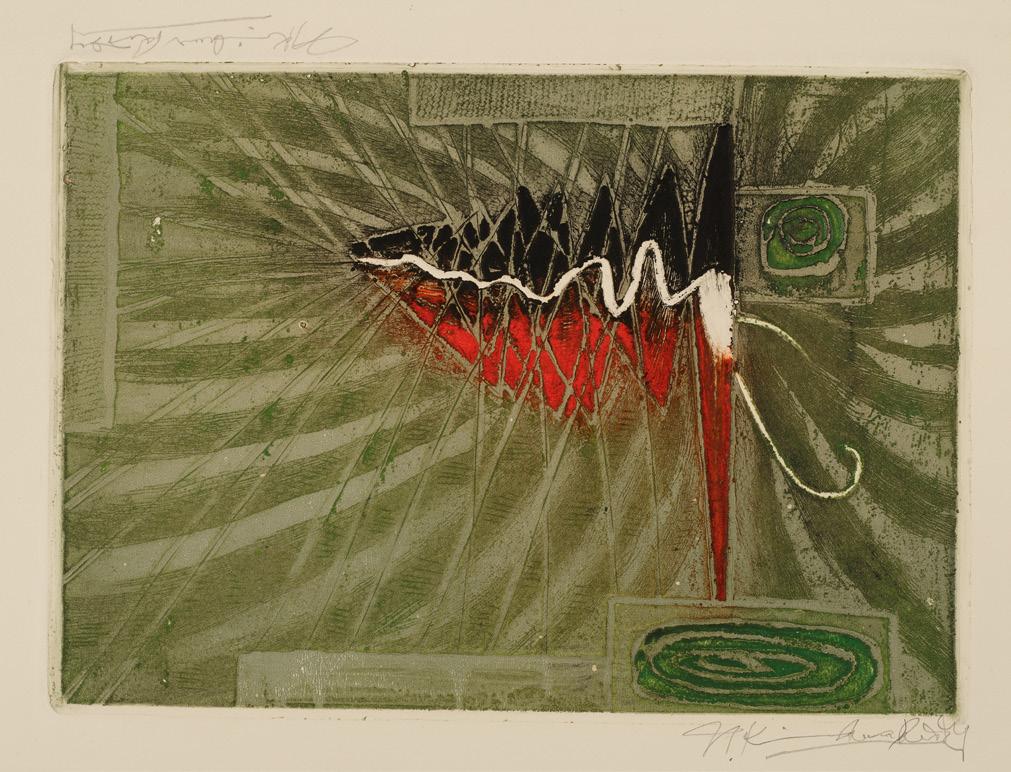

In the 1960s, Reddy created a series of prints that highlight the comprehensive way he considered a subject. Again, favoring a scientific-inflected abstraction over representation, Reddy considered the genesis of a flower in Germination I [Seed Pushing] (1961) and Germination (1964). At first glance, these images can be mistaken for illustrations of planets or the Big Bang. They are dramatic, explosive—an invisible and microscopic moment that Reddy rightfully saw as the unleashing of a powerful cosmic energy found in every moment of atomic birth and death. Others such as Blossom [Blossoming] (1965), Flower (1961), Water Lilies (1959), and Radiating Flowers (1967) articulate the glowing, prismatic energy of his subject. The water lily was a personal, nostalgic subject. His village pond was full of water lilies and lotus flowers. He had carried his

childhood wonder of their forms across continents and into adulthood.

From the onset of his arrival in Europe, Reddy traveled frequently, leading printmaking workshops and exhibiting his art across India and Europe. His first visit to North America in 1964 (to participate in the International Sculpture Symposium) led to invitations to lecture, teach, and exhibit from academic institutions across the United States. Reddy was soon traveling to the country yearly. Travel indulged his love for experiencing the natural world, and he created multiple prints that memorialized specific vistas from his travels. The most representational of these prints, Sunset (1961), was inspired by a beach in Portorož, Yugoslavia. Arguably his most powerful landscape, Pastorale (1958) was inspired not by a place but by Ludwig van Beethoven’s symphony of the same name.11 Beethoven’s ode to rural life was, unsurprisingly, deeply moving for Reddy, who translated the music into an abstract yet somehow still panoramic vista. Reddy’s quasi-abstract landscapes affirm how the artist extended his animist gaze to the land—a dynamic and vital subject.

Alongside these landscapes, Reddy was drawn to phenomena that underscored the force and movement of water, evidenced by Whirlpool (1962), Wave [La Vague] (1963), and Splash (1963). His composition intensifies the drama: these are action shots, tightly

11 The title is Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, but the work is popularly known as Pastorale.

Sarah Burney

cropped to heighten the power of the subject. Reddy conveyed the vital energy of water in motion by once again altering his platemaking approach and working with a highly polymerized cellulosic paint. He applied the paint to the plate rapidly through a wax paper funnel, its flowing strings creating liquid lines that Reddy etched so deeply they remained uninked during the printing process, mimicking the bright white crests of water in the finished print.

As Paris, and later the rest of France, became engulfed in protests against Charles de Gaulle’s government in 1968, the conflict triggered a major shift in Reddy’s practice. The unrest was familiar for the artist, who had lived through the political tumult marking the end of colonization in India. In the streets, Reddy marched with the Parisians.12 In the studio, the gaze of his prints shifted from the nature of our universe to the nature of humankind.

Reddy’s first figurative viscosity works, Three Figures (1967) and Demonstrators (1968), memorialize the Paris protests. Teeming with the same energy as Whirlpool, Splash, and Wave, Reddy’s depiction of the protesters as unified, glowing forms embodies his belief in the power and strength of the collective. His elongated semi-abstract figures—which bear a striking resemblance to 12 Europe was, of course, not perfect. Reddy experienced racism daily in Europe. In his early years in Paris, he was harassed and arrested multiple times for his support of the Algerian Revolution—often simply because, as a dark-skinned man, he looked Algerian. Still, he did not let these experiences embitter him.

Radiating Flowers—are often attributed to the influence of the European modernists Constantin Brâncuși and Alberto Giacometti, with whom he formed friendships in Paris. Yet, we can also recognize the stretched bodies of Reddy’s Bengal Famine drawings from the 1950s. In the same way that he moved between a flower and a landscape, Reddy shifted fluidly from the collective to the individual. He transposed his demonstrators into sculpture, casting both a many-headed mass and single demonstrator in bronze. He further explored our interconnectedness in the prints Between Many and the One and Life Movement (both 1972), continuing to abstract the human form, and at times reducing the body to a single vertical line. In the 1970s, Reddy’s compositions—previously marked by fluid hand drawn lines—became anchored by soft yet ruler-straight grids. In Life Movement, he utilized another new printmaking process of his invention: Simultaneous Pointillism and Broken Color Printmaking. This method modified viscosity printing by incorporating a halftone pattern on the surface of the plate, producing especially vibrant color fields. Here, a radiant, glowing individual emerges from the collective.

The experience of fatherhood deepened Reddy’s meditations on the human experience. In 1975, he produced two prints that memorialized the infancy of his daughter Aparna, whom he affectionately called Apu: Untitled [Apu’s Space] and Apu Crawling. Combining photographic transfer processes and machine tools for plate preparation, Reddy created fantastical images of multiple young Apus in an architecturally ambiguous space that follows the laws of perspective but has waves

where a sky or ceiling should be. A soft color palette and ample negative space heighten the whimsical, dreamlike quality of these works. Watching his young daughter explore the world reaffirmed what Reddy had learned from Krishnamurti: humans are innately curious. In his own writing, Reddy would go on to call true creativity “child’s play,” asserting that “Play is infinitely important as it is the very heart of creativity. An artist who has stopped playing denies his own being.”13

In 1976, Reddy moved to New York permanently to join the faculty at New York University and to establish the study of printmaking within its Department of Art.14 Blackburn was by then running his own studio, The Printmaking Workshop, in downtown Manhattan, and the two friends worked closely together. His move to New York further cemented his significance within the South Asian creative diaspora. Like Hayter and Blackburn had, Reddy and his wife, the artist Judith Blum, served as the welcoming committee and connector for many artists. Their SoHo home and studio became a landing pad for countless transplants from the subcontinent.

Reddy’s abstraction and use of color reaches its most playful form in a body of work focused on clowns.

13 Reddy, Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes.

14 Reddy continued to travel almost yearly to India, where in 1972 he had been recognized for his contributions to the art community with a Padma Shri Award—the fourth-highest civilian award given by the Republic of India.

Sparked by an outing to the Big Apple Circus with Apu, this would go on to become his longest thematic inquiry. For his monumental print Great Clown (1981), Reddy created over 44 different variations ranging from dark, almost sinister black-white-red works to riotous rainbow blends. Likewise, the kaleidoscopic Clown Falling [Fallen Clown] (1981) exists in over 100 colorways. Despite the lightness of this imagery, for Reddy, the clown was also a motif for somber reflections on the individual. Reddy saw parallels between the labors of the clown in a crowded ring and the artist in a modern world. The trappings of modernity—institutions of government, school, and religion—were continuously forcing us to perform yet sapping our innate curiosity and creativity.15 The 1990 Gulf War, which Reddy staunchly opposed, extended his lamentation. He grieved how modernity amplified our pointless predilection for violence in the works Sorrow of the World [Sorrow in Lebanon (the World)] (1990) and Violence and Sorrow [Violence and Sorrow: Persian Gulf] (1995).

Reddy’s final print, Untitled [Woman of Sunflower] (1997), is a fitting capstone work. It depicts a figure in a seated, meditative pose against a glowing background that evokes both a honeycomb and the spiraling arrangement of sunflower seeds. Combining Reddy’s molecular botanical imagery with his elongated human forms and softened grid-like subdivisions, it is a culminating synthesis of the artist’s explorations of humanity

15 Bottome et al., “A Dialogue with Krishna Reddy.”

and our world set against a stunning multicolored image of spiritual enlightenment. Reddy did not subscribe to any specific religious doctrine as an adult, but he retained the bodily experience of being in deep prayer as a child throughout his life and created multiple works that strove to capture this feeling. In an ever-changing world, Reddy believed only a reverential stillness would enable artists to look intensely and learn.

In 1998, a year after producing Untitled [Woman of Sunflower], Reddy published his essay “Art Expression as a Learning Process.”16 Drawing on lectures and essays from across years of teaching and writing, the text is a beautiful articulation of Reddy’s unique philosophy, a manifesto for artists, and a poignant final lecture by a life-long educator. He used the opening lines of William Blake’s poem “Auguries of Innocence” for his epigraph: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.” In these lines, Reddy perfectly encapsulates the crux of his philosophy: to observe with a mind free of preconceived notions; to consider the essence of a creature, plant, being, material, and idea; and to find the alchemical potential in ink and a plate, oneself in the clown, and heaven in a wildflower.

16 Krishna Reddy, “Art Expression as a Learning Process,” India International Centre Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1998): 95–105.

Untitled [Fish], 1952

Fish, 1952

Jellyfish, 1955

Sunset, 1961

Wave [La Vague], 1963

Pastorale, 1958

Untitled [Three Figures], 1967

Three Figures, 1967

Untitled / Demonstration (with multiple figures), 1968

Demonstrators, 1968

Mark Johnson

We Want to Find Out

Reflections of a Student

After we finished printing in his studio, and all was done, Krishna would ask if I wanted a little juice. I would say yes and he would go fix two small glasses of orange juice and bring them to the table, saying “please” while gesturing to a chair. After sitting down, we would start talking. No matter the circumstance or situation, somehow, he would circle around to the central aspects of art and creativity.

Many years have passed since I last spoke with Krishna, but I still hear his voice when I think about him. The exact specifics of our conversations come in and out of focus, but the essence remains clear. For me, Krishna’s gift was making it all seem so simple and possible. “We don’t know and we want to find out,” he would say. He always came back to this foundational statement about the collective endeavor of artists, stressing his belief in our limitless creative potential and our desire

Mark Johnson

to manifest this curiosity. He strongly believed that nurturing and developing a deep level of curiosity is an essential aspect of life that can be applied to any activity or situation, allowing us to take a journey in the infinite experience of the unknown. And as Krishna so often stated, with finding out there is learning, and learning is creativity because you are creating new knowledge and understanding.

Krishna encouraged students to avoid proclaiming themselves as masters over their materials, instead remaining open to what they could discover in using them. He put great emphasis on getting lost in finding ways to express oneself, and if existing ways did not suffice, then an artist should seek out new ways, techniques, and processes. Techniques are invented from this desire to express, as opposed to being abstractly developed without connections to ideas.

To illustrate how he came to understand the significance of materials and processes, Krishna recounted traveling to the southern coast of Spain and contemplating the form of a fish. He told of beginning to see the formation of the fish occurring because of all the external forces exerting themselves on the fish—the water, currents, and gravity—in tandem with the forces the fish was exerting on its environment. All are interconnected parts of a process and gather up to create form. “Pondering the shape of a fish in movement, I began to see its form as a dynamic expression of the

total environment.”1 He explained how he started to make the connection between natural formations and how an image takes shape in terms of materials and tools. “It fascinated me to watch how each new image, in trying to realize itself, set me into motion—inspiring me to find new ways and means to build it.”2

This artistic philosophy was a prime contributor to Krishna pioneering new ways of color printmaking, specifically realizing multiple color prints from a single plate. Krishna explained the origin story to me: he was printing one Sunday in the late 1950s at Atelier 17 with a master printer who was very exacting and set in his ways. On this day, unbeknownst to all, there was a small amount of linseed oil on the glass surface where ink was going to be rolled out with a brayer. As Krishna rolled the brayer over the surface, he noticed that the ink did not “stick” to where the linseed oil was. The master printer saw this and reprimanded Krishna for not carefully cleaning up and rolling the brayer. Krishna saw the situation very differently, and thought to himself: “What exactly happened here?”

Following this, Krishna told fellow Atelier 17 artist Kaiko Moti and director S.W. Hayter, and they began to experiment with the significance of what had occurred.

1 Krishna Reddy, Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes (State University of New York Press, 1988), 8. 2 Reddy, Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes, 8.

Mark Johnson

Each Sunday (the day the staff used the workshop without students present), they investigated modifying the viscosity of the inks with linseed oil, discovering that the inks, when rolled one over the other, would either mix or repel each other in predictable ways. This activity occurred in the midst of a larger shift, as artists sought to make printmaking— especially color printing— more spontaneous and open to exploration, expansion, and experimentation.

Because of his sculptural background and the experimental atmosphere of Atelier 17, Krishna began thinking concurrently about the intaglio plate as a sculpture rather than just a flat surface. This approach created areas of the plate where inks of different viscosities could be deposited by rollers of varying densities. To accomplish this, he used acid, engraving tools, and, most importantly, mechanical rotary tools such as his prized dentist drill fitted with carving bits or heads that he often purchased on Canal Street in New York City. His literal deep dive into making plates in relief continued until his last plate. His plates are so sculpturally worked that they are works of art in themselves, and inked rollers respond in unimaginable ways when traveling over them.

Krishna continued a lifelong journey of experimentation and development in this realm of single plate color printing, which eventually became known as color viscosity printing—one of his lasting legacies. While it is a specific technical achievement, I want to make the point that, more importantly, it is a unique way of conceptualizing printmaking—one that acknowledges printing as a process that is as important and dynamic

as the making of the plate itself. Additionally, it became an integral part of a new focus on combining techniques and perceiving all aspects of printmaking as in play and available for exploration. Krishna utilized this methodology in all his print work, applying his energy and experimentation across both the making of the plate and the printing process. He would so often say to his students that a final print is 50 percent plate making and 50 percent printing.

Krishna advocated for perceiving the significance of materials and processes not as a means to an end, but as major contributors—alongside ideas—to the creation of art. To do this you have to be present and available to engaging with all the nuances and variables of the creative process. To express this idea he would rub his thumb and index finger together and then hold them to his ear and rub them again, saying that if we can develop such deep sensitivities, they can be applied anywhere, to any circumstance, not just in art.

Krishna not only employed this very experimental approach in his work, but as a lifelong teacher, he wanted to support his students in developing their own curiosities and methodologies. When teaching, he often stated, “I am just showing you the ABCs—it is up to you to experiment and find your own way.” His class lectures and demonstrations would start off with basic concepts, moving on to philosophical concerns and inspirational ideas such as the need to be free and able to explore as a child does—without fear, societal pressure, and ego. He cultivated an open atmosphere and encouraged students to realize that subject matter is everywhere and can be anything, while the most important component

Mark Johnson

is engagement. His teaching always included a discussion of the philosophical foundation of artists and the connection they had to the issues of their time.

As we finished our post-printing glasses of juice, Krishna would ask, “A little more?” I would decline and soon be on my way, walking down the six flights of stairs and then back out onto Wooster Street. My memories and personal understanding pale in comparison to being with Krishna in person. I always loved hearing him speak about his life experiences; he would say, “I grew up in a small village in southern India and somehow walked out.” I wish I had recordings of him speaking to his class or the times when we were talking casually in his studio. But now, reflecting back, I am left with his overall philosophy toward art and life. As he wrote in his notebook from the 1950s: “Great forces are churning this earth, creating this cream of vast unknown forms of nature, and we are left to wonder, and if possible, calculate this with our own limited mind.”3 We don’t know and we want to find out.

3 Krishna Reddy, personal notebook, ca. 1950s.

Entrance to Atelier Krishna Reddy

SoHo, 2014

Atelier Krishna Reddy, 2009

Hand tools in the studio, 2011

Drill bits for “Pierre,” 2011

Krishna Reddy

Art Expression as a Learning Process

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower...”

—William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence”

Human beings, essentially dynamic processes, are of the Universe, which is a continuous changing process. We are of this great organism, and its space is the background from which we emerge. In our attempt to discuss art-making as a learning process, it may be interesting to explore the interrelationship between mind and the Universe, which touches human life very closely. This subject deserves deep study and contemplation. Born into a world of scintillating and dynamic energy patterns, the early human was differentiating himself from it, acquiring new emotional and mental characteristics, obeying an initial inner formative

Krishna Reddy

impulse. The everchanging natural phenomena, part of a vast Universe in constant upheaval, inspired in him feelings of awe and fear. They robbed him of all assurance and tranquility. He struggled for survival within a harsh and unyielding Nature. He strove to wrest the things of the outside world from the flux of happenings. He sought permanency, solidity, and stability in the natural world.

The impulse of self-preservation created a selfconsciousness and the assumption that “I” existed apart from the Universe. His self-centeredness was compelled by a felt urge toward balance and harmony, and by instinctual physical drives necessary for his comfort, well-being, and life. (In search of order and harmony, he was driven to wrest order from the flux of happenings.) He created a physical world from his consciousness, with mental concepts of space, time, and matter. In a desire to extoll order and harmony and ward off chaos, he created an environment and objects in his own image. His was a humanly conceived world system, the universe of the mind’s own image. Here he could find repose.

The process of creating an artificial environment has continued, leading to a technocratic world system. This synthetic world of ours is rife with distortions that we have created through organization. We have not only lost touch with the spiritual nature of the earth, but the earth itself is now in danger of losing its very physical substance through our actions. We lack a planetary vision. We lack awareness of the connection between our self-centred consciousness and the world around us. We have alienated ourselves from Nature.

At the same time man wanted to understand the natural world around him, and through this desire

developed spiritual curiosity. He wished to experience a deep sense of interrelationship with his surroundings; he longed for complete union with the Cosmos.

In the search for meaning and understanding, it is the capacity of intelligence to discern, learn, and create. Our intelligence helps our sense of wonder to emerge, which is the start of the learning process. Our childlike awe and wonder about Nature mark our awakening to planetary awareness. This awareness manifests itself every time we discover the marvel of a flower or the spectacle of the most distant stars and galaxies. The visionary faculty is within the reach of anyone who can retain a sense of wonder and awe…

Artists demonstrate this point. The artist learns by looking intensely at Nature, by being aware of it, by being open to it with all his senses. He has an appetite for learning and a passion for discovering; he is engaged and experimenting. In this he draws upon the deeper sources of his individuality, his instant “tune-in” to vast fields of the phenomena of life. This state of mind where he is free to express a vision of a new order of reality is essential for the artist. He can enjoy the freedom to go beyond craft, to explore, to approach that mysterious entity, the thing in itself, the ultimate reality. That is the goal of his quest for meaning and learning. Mondrian said: “I do not want pictures, I just want to find things out.” And Picasso states: “When I paint my object is to show what I have found and not what I am looking for.”

Through his creation the artist transmits that insight into the mysterious sources and inner workings of reality. His task is to show that art-making can be a breakthrough to creativity and learning; that art has a

Krishna Reddy

great deal to do with emotional life as it springs from the depths of man’s spiritual nature. In the capacity of our intelligence and the radiation of its enormous energy, there is revelation and learning. Art-learning illuminates what is most subtle, and penetrates it most significantly. The challenge is how to recover the astounding capacity we have for creative intelligence and aspiration. To marvel and wonder is the beginning of learning. For all our measuring sticks and scientific theory, we are still young. We are, in Newton’s words, like children playing with pebbles on the seashore, while the great ocean of Truth rolls unexplored beyond our reach.…

The industrial revolution obliterated Western spirituality. We tend to think of the spiritual life as a seeking of the unknown, as a flight from reality. In fact it is an attempt to define and explore reality.

Living in an ambitious society, full of conflict and corruption, the artist also is corrupted with the vagaries of private greed. In a culture now dominated by the notion of art as commodity, the artist becomes selfindulgent and preoccupied with himself, and with goals involved in self-promotion. He learns to use his art as a means, as an acceptable product, geared to impress others. He designs his works of art to satisfy the tastes, desires, and needs to his market. The modern artist is miserably dependent on the dealer, the curator, the critic, and the media of publicity. He puts himself on a track to satisfy the passing fashions of the commercial world, where improvisation and interplay are mistaken for creativity. But true creativity cannot exist where there is motive, ambition, and competitiveness.

Our organism is a complex assemblage, a celestial alchemy of space and time. Our mental environment is a diverse network of memories, thoughts, instincts, emotions, and deep intuitions—reflecting the inner processes of our heredity and experience. Our sense of self—our consciousness, arises from the cerebral patterns permanently inscribed as a result of many life experiences. Our consciousness is the movement of all these in space-time, and our reaction to everything around us with a sense of being in the here-and-now—a sense that we actually exist.

Continuous change characterizes the natural world, not permanence, solidity, or stability. Fear causes us to see chaos in the outside world. In our reaction to reality, in our struggle to bring forth from chaos a sense of order, an organizing faculty within our nervous system intervenes—forming these impressions into coherent patterns of proportion, symmetry, equilibrium, and harmony, which we call “aesthetic harmony.” Our symmetry-seeking minds attempt to reduce the images given in visual perception to a schematic or structural order. To the sense of sight, our “noblest sense,” we apply the language of geometry in the structural sense. For example, such a complex organism as a tree, with all its interrelated cellular and spatial structures, is reduced to a spheroid posed atop a cylindrical column. But the essential nature of the tree is more than what we see. Given a piece of forest land, we clear it and straighten it out, as we cannot perceive its complex structure and are terrified of its apparent chaos. We transform the living jungle into an elegant, formal garden. We build everything geometrically with basic shapes, primary

Krishna Reddy

colors, and in simple linear ways. This is reflected in the way the planet is spread over with our constructions and cities. In organizing our environment to suit our needs, we have deeply interfered with this planet and life on it.

In Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, certain thinkers realized the importance of freedom as they attempted to learn the sum total of visible truth open to human intelligence. They recognized that to observe clearly, one must be free from all self-imposed limitations, preoccupations and prejudices. Using this new-found freedom, they wanted to examine, understand, and create in the context of their relationship with the world outside themselves. Among these thinkers were the artists of Europe in the late nineteenth century, who, in their attempt to correlate art and reality, were also struggling to free themselves from their instinctual limitations. These artists were in their own way philosophers and explorers. They wanted to learn from the visible, the actual, palpitating reality of things: the phenomenal image, the true nature of the objects they perceived. They were explorers who invented an entirely new reality by relating the analysis of human life to the analysis of Nature. They developed an experimental and exploratory attitude towards Nature.

In the spirit of research, they invented visual abstraction by paring down the visible world to its essentials: from chaos to glorious harmony. They felt they were creating icons of distilled beauty by reducing the appearance of objects to their pure and essential forms. They created images the way we translate concepts into symbolic forms. In their attempt to reduce the images given in visual perception to a schematic or structural

Art Expression as a Learning Process

order, the instinctive laws of perception intervened. Their experiments reflected their formal and intellectual roots. Cezanne, for example, said his aim was “to make order out of confused sensations which we bring with us when we are born.” He believed that reducing the phenomenal image by stripping it of its concrete details would allow him to come to its pure, essential form, its solidity and reality, its structure. He made laborious efforts to reproduce this essential form with scientific exactitude. He did not realize that in his patient search for the form inherent in the object he was only extending himself—his instinctual need for structural order and geometry.

Mondrian, too, in his quest for self-contained abstract forms, ended up making reductive visual conclusions. Malevich aimed to transcend entirely the natural world. His Black Square was hung high, like an icon, across a corner, and became the emblem of Suprematism, the most reductive, uncompromising style of abstract painting. Malevich called it “the beginning of true sense.” Mondrian and Malevich did not realize that in their search for the essential nature of objects, they were only extending themselves—that in each experience they were forcing reality to submit to their instinctual concerns.

Juan Gris stated, “Why not let geometry and architecture speak for itself in terms of pure form and colour?” Through improvisation and interplay, he produced some beautiful images. Kandinsky and Picasso did recognize the interference in their creative work of these limiting forces. Having done patient research with Cubism to reduce images to geometric structures,

Krishna Reddy

Picasso began to see its limitations. He watched his own conditioned faculties take over his Cubist approach, and tried to depart from Cubism and surpass it. With a newly learned visual language he worked on poems of his life experiences, and would continue to do so the rest of his life.

The Surrealists went farther in learning the secrets of the Self, which are hidden deep within everyone. They wanted to draw their imaginative powers from long-buried memories, from the deepest layers of the unconscious, the Id itself. But in their declaration to “cut off reason and logic—one plunges into the deepmost wells of creativity,” they could not escape their brains, crowded with overwhelming experiences.

Artists and thinkers recognized that the projection of a symbol or image from the subconscious was not an act of creation but merely the transfer of an already existing object. They saw that in order to observe clearly one needs to be free to look—free from memories, ideas, conclusions, and beliefs interfering between one and the world. Their curiosity and wonder drove them to discover the visible, actual, living reality of things. They wanted to learn the mysterious sources and inner workings of Nature. They wanted to examine, understand, and create. In their penetrating experiments they appreciated the way the eye becomes educated through contact with Nature.…

The creative potential is innate in each of us, and we should struggle to make it function in our lives. Creativity contains the sense of wonder, which eventually drives us to transcend ourselves and explore Nature

Art Expression as a Learning Process

and the Universe. Curiosity—that wanting to know—is the seed that grows through marvelling and wondering into learning. The human mind is an extraordinary phenomenon, equipped with supreme intelligence— to observe, to question into life, to find things out, to enter into the depths of what lies behind. With all our senses as windows, the mind is a visual organ to look at the universe.

Responding to the excitement, mystery, and amazement of the Cosmos, we seek out the hidden structure of the external Universe and explore the mysteries of Nature’s processes. The outcome of this learning process through our minds will be to transcend altogether our mental environment, its memory and remembrances, to move beyond the “me” and the selfconscious, to learn the world. The goal of our minds is to transcend our human condition and to move towards a state of being without the ego.

In pure observation free from the activities of the self, there comes to us the revelation of the presence of the other, the unknown, the reality. This is pure perception, unrelated to thought and time. In this process there is creativity and learning. It is a transcendent state of observation that allows us to penetrate into the inmost essence of things, the mysterious sources and inner workings of Nature. We explore the mysteries of a Universe that is in constant upheaval. We witness movements of the inward life of things, a Nature where nothing stands still and reality is a continuously changing process.

The serious thinker gives away all he has—his possessions, his normal self—in order to be open before

Krishna Reddy

the presence of Nature and the Universe. In this way he makes a breakthrough to creativity, to engage in a true dialogue of man and cosmos. He projects himself into the future, not knowing what he might find. He questions life: to discover, to learn, to understand, to find enlightenment, to live.

Artists recognised that the human being is qualitatively distinguished from other life-forms by a certain spirituality and a higher consciousness. As true artists they were of great spirituality, and their art sprang from the depths of their spiritual nature. Sartre said: “A revolutionary philosophy must be a philosophy of transcendence.” Art-making in this sense becomes the most precious evidence of freedom.

Van Gogh meditated on the unearthly beauty of reality. In his longing for complete union with Nature, he was free to express a new vision, a new order of reality. He created a world of a scintillating and dynamic vision of Nature. He pursued art as a religion and a mission in life. In his work we see the expression of an ecstatic state of mind.

Brancusi created serene images, like his Bird in Space, by raising the fusion of elementary geometric forms to spiritual heights. Giacometti, likewise, operated on a spiritual plane, in his dialogue with life in terms of dynamic, linear movements. He created philosophical works of extreme penetration. He insisted on the primacy of pure being and creative procedure. He probed the unknown and the hidden, creating an archetypal vision of it. He produced monumental pieces of art with tremendous feeling.

Art Expression as a Learning Process

Paul Klee was a great thinker and a poet in his art. He questioned everything in life. With his deep feeling for materials, every new thought he had realized itself in new ways and means. He expressed his vision of existence with penetrating insight and accomplished art. His work was a dialogue of man and Cosmos. While working in Kairouan, North Africa, on one of his paintings, he said: “I now abandon work. It penetrates so deeply and so gently into me, I feel it and it gives me confidence. Colour possesses me. That is the meaning of this happy hour. Colour and I are one. I am a painter.” In the art he created throughout his life, we feel the expression of a life lived with a highly developed sense of awareness, and we experience the joys of discovery and learning.

This earth of great beauty is a marvel. As we descend into this paradise, every day, every moment of our life becomes a constant celebration. The earth is a living totality, with its own vital functions, while at the same time it belongs to a greater community in time/space. The flowering part of this mysterious Nature is the splendour of human life, equipped with an open frame of mind, with planetary vision. We have developed a profound sense of wonder and curiosity. We have the capacity to enquire, to learn the true nature of the objects we perceive, to enter into the depths of what lies behind them; to learn, to find enlightenment, to live. The basic role that mind and self play at some unfathomable level is the workings of the Universe.

An artist can, like a true poet, in his leisure hours carry on his experiments in silence, and marvel.

Life Movement, 1972

Apu Crawling, 1975

Untitled [Apu's Space], 1975

1981

Clown Falling [Fallen Clown],

Great Clown, 1981

Violence and Sorrow

[Violence and Sorrow: Persian Gulf], 1995

Untitled [Woman of Sunflower], 1997

Untitled [Woman of Sunflower], 1997

Works in the Exhibition

All works courtesy Krishna Reddy Estate, unless otherwise indicated.

Note on titles: Reddy often used different titles for prints pulled from the same plate. Brackets indicate alternate titles by which works are known.

Note on editioning: Reddy did not always follow a standard system for numbering his prints. Here, we have transcribed the edition information as it appears on the impression on loan for this exhibition.

Mixed color intaglio (viscosity prints)

Germination I [Seed Pushing], 1961

14 ⅛ × 19 inches

(sheet: 19 ⅝ × 26 inches)

Germination, 1964

Impression by the artist 23 of 25

12 × 17 ½ inches

(sheet: 19 ⅝ × 26 inches)

Blossom [Blossoming], 1965

Impression by the artist from an edition of 50

17 ¼ × 13 ½ inches

(sheet: 18 × 22 inches)

Flower, 1961

Artist’s proof 9 of 15

15 ⅝ × 18 ¾ inches

(sheet: 21 ⅞ × 28 ½ inches)

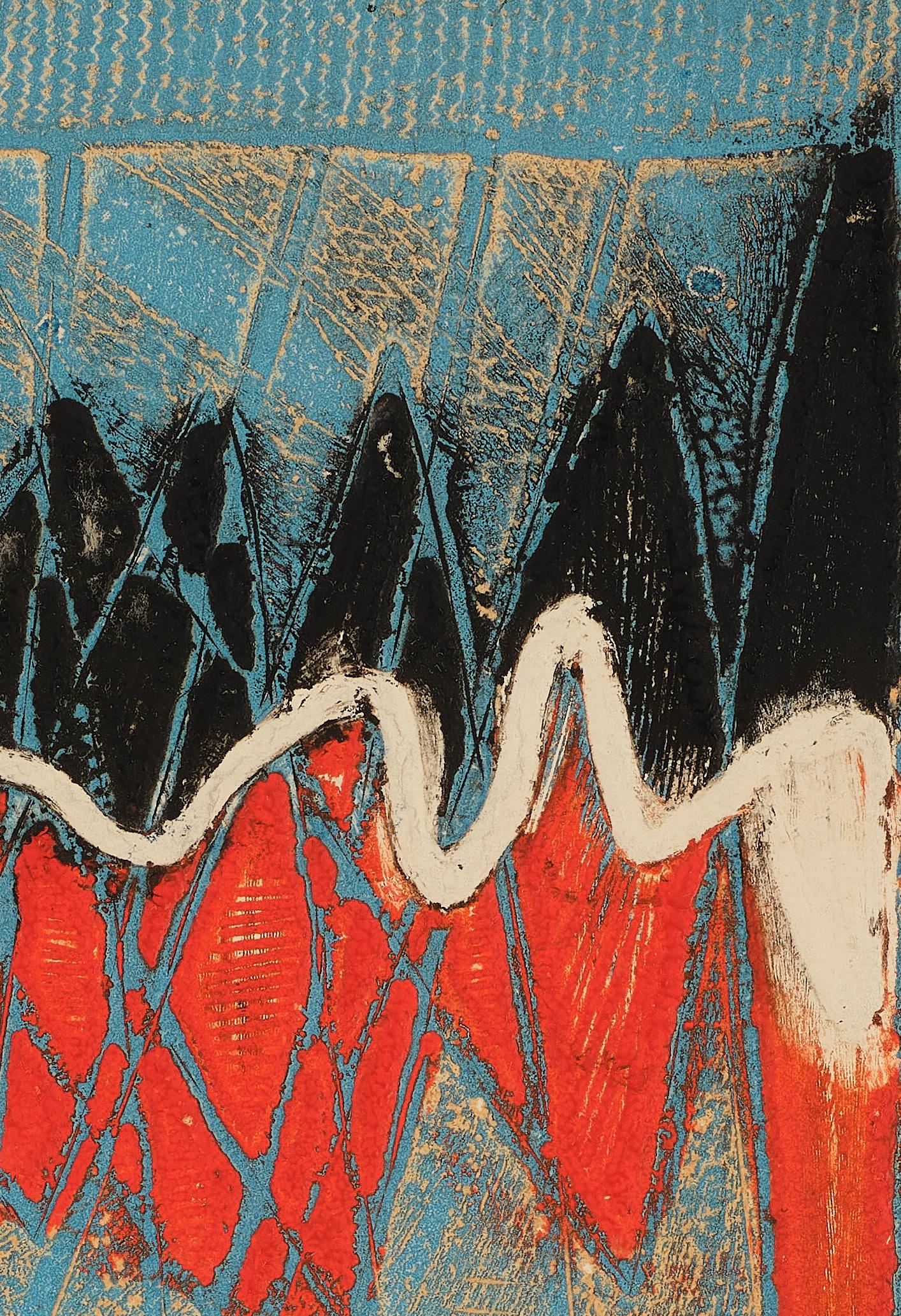

Radiating Flowers, 1967

Artist’s proof 6 of 10

12 ¼ × 18 ⅞ inches

(sheet: 15 ⅛ × 23 ¼ inches)

Printed by the artist

Published by Antares Editions d’Art, Saint-Cloud, France

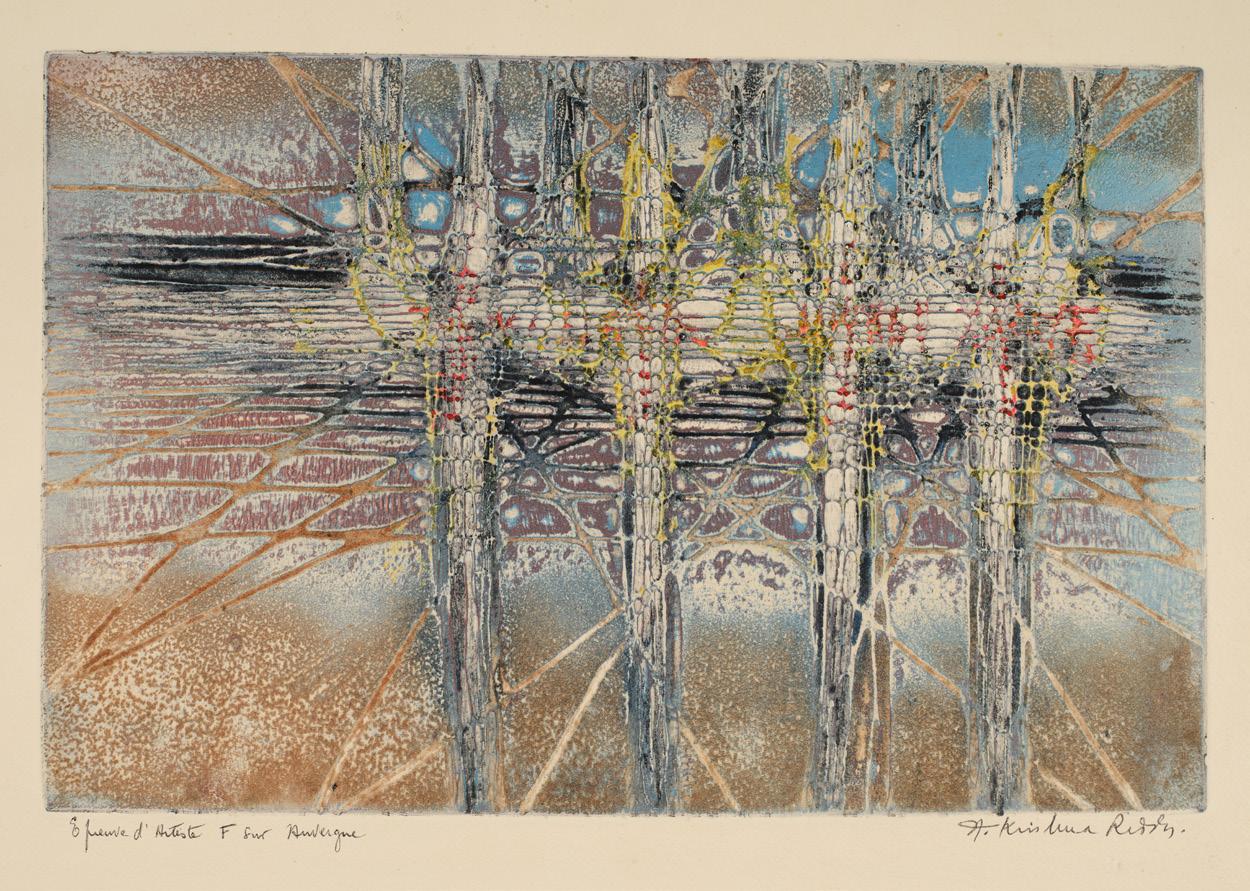

Water Lilies, 1959

13 ¼ × 18 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Fish, 1952

Artist’s proof 4 of 15

9 ¾ × 13 ¾ inches

(sheet: 18 × 22 inches)

Fish, 1952

Impression by the artist 1 of 10

9 ¾ × 13 ¾ inches

(sheet: 18 × 22 inches)

Untitled [Fish], 1952 Edition of 25

9 ¾ × 13 ¾ inches

(sheet: 18 × 22 inches)

Insect, 1952

Artist’s proof 12 × 16 inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 26 ¼ inches)

Space Creates Form [Insect], 1952

Artist’s proof from an edition of 25

12 × 16 inches

(sheet: 17 ¼ × 22 inches)

Untitled [Insect], 1952

Impression by the artist 23 of 25

12 × 16 inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 26 ¾ inches)

Absterix [Tuatara Forming/ Bulging Tuatara], 1953

Artist’s proof from an edition of 50

15 ¼ × 11 ¼ inches

(sheet: 22 × 17 ¾ inches)

Jellyfish, 1955

Impression by the artist, HC 4 of 5

17 ⅜ × 13 ⅛ inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ¼ inches)

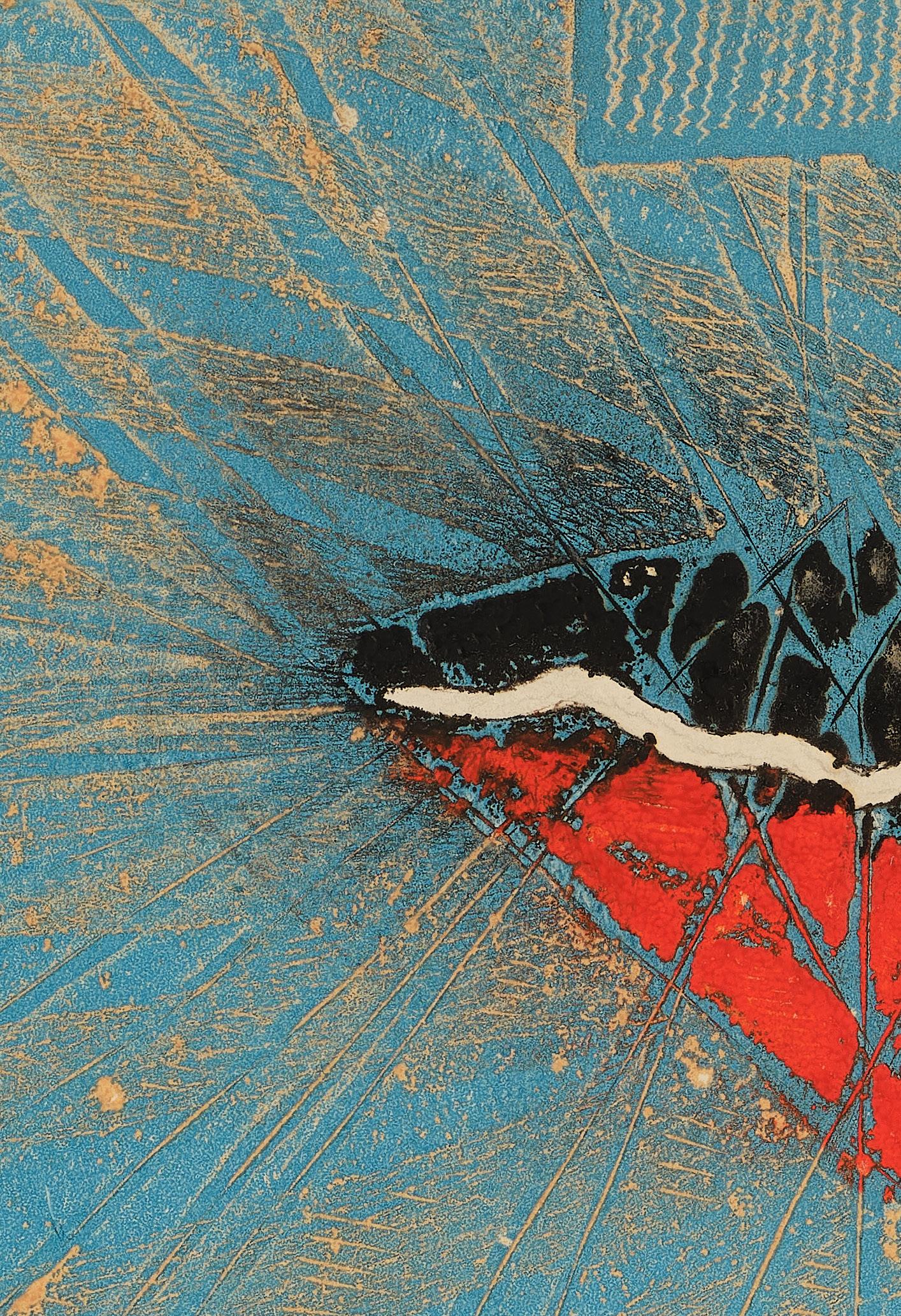

Butterfly Formation

[Le Papillon], 1957

Artist’s proof from an edition of 110

17 ½ × 13 ½ inches

(sheet: 25 ⅜ × 19 ½ inches)

Pastorale, 1958

Artist’s proof 2 of 10

14 ¼ × 18 ⅞ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 26 inches)

Sunset, 1961

Impression by the artist 1 of 10

17 ¼ × 13 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ⅝ inches)

Sunset, 1961

Artist’s proof

17 ¼ × 13 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ⅝ inches)

River, 1960

Edition 88 of 120

13 ¼ × 18 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 inches)

Whirlpool, 1962

Impression by the artist, HC 4 of 5

14 ½ × 18 ⅛ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 26 inches)

Splash, 1963

Impression by the artist 17 of 25

14 ½ × 18 ⅛ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 24 ½ inches)

Wave [La Vague], 1963

Artist’s proof 1 of 10

14 ⅝ × 18 ¾ inches

(sheet: 22 × 28 ½ inches)

Three Figures, 1967

Artist’s proof 8 of 10

13 ⅝ × 17 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Untitled [Three Figures], 1967

Edition of 75

13 ⅝ × 17 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Demonstrators, 1968

Artist’s proof 10 of 10

13 ⅝ × 17 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ⅝ × 26 inches)

Life Movement, 1972

Artist’s proof 3 of 10

11 ¾ × 19 ¾ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Between Many and the One, 1972

Edition 82 of 135

12 ½ × 19 inches

(sheet: 15 × 22 ½ inches)

Printed by the artist

Published by Antares Editions

d’Art, Saint-Cloud, France

Rhythm Broken

[Rhyme Broken], 1977

Impression by the artist, HC

13 ⅞ × 19 ⅞ inches

(sheet: 20 ¾ × 30 inches)

Untitled [Sorrow of the World/ Sorrow in Lebanon (the World)], 1990

Impression by the artist 2 of 25

11 ½ × 9 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 25 ⅞ × 19 ¾ inches)

Violence and Sorrow [Violence and Sorrow: Persian Gulf], 1995

Artist’s proof

14 × 19 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Maternity, 1955

Impression by the artist 1 of 10

17 ⅞ × 13 inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ¾ inches)

Child Descending

[Apu Descending], 1976

12 ⅝ × 19 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Apu Crawling, 1975

Impression by the artist 25 of 25

13 ⅞ × 18 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ⅝ inches)

Untitled [Apu’s Space], 1975

Edition of 50

12 ⅞ × 18 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Woman and Parting Son, 1971

Artist’s proof 5 of 10

13 ⅝ × 17 ½ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Clown Juggler [Clown—Jongleur], 1978

Impression by the artist 3 of 10

11 ⅜ × 9 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ¾ inches)

Clown Forming, 1981

Impression by the artist, state 4 of 32

15 ½ × 19 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ⅞ inches)

Clown Falling [Fallen Clown], 1981

Impression by the artist, HC 2 of 30

13 ¾ × 18 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Clown Falling [Fallen Clown], 1981

Impression by the artist, HC 1 of 30

13 ¾ × 18 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Clown Falling [Fallen Clown], 1981

Impression by the artist 15 of 40

13 ¾ × 18 ¼ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Great Clown, 1981

Impression by the artist 4 of 25

39 ¼ × 29 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 50 ⅞ × 39 inches)

Untitled [Clown and His Mask/ Clown with Mask], 1982

Impression by the artist from an edition of 20

10 ⅛ × 14 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Clown Dissolving, ca. 1994–97

Edition 8 of 80

12 ½ × 19 ½ inches

(sheet: 22 ¼ × 30 inches)

Printed by Mark Johnson

Praying Woman, 1970

Impression by the artist 1 of 10

17 ⅜ × 13 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 23 × 19 ⅜ inches)

Sitting Figure [Meditation], 1972

Impression by the artist, HC 2 of 10

17 ⅝ × 13 ⅞ inches

(sheet: 25 ¾ × 19 ¾ inches)

Dawn Worship, 1974

Impression by the artist 3 of 20

13 ⅝ × 17 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ¾ inches)

Sun Worship, 1975

Impression by the artist 1 of 15

13 ¾ × 17 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 26 inches)

Untitled [Woman of Sunflower], 1997

Artist’s proof from an edition of 10

14 ¼ × 18 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ⅝ × 25 ¾ inches)

Untitled [Woman of Sunflower], 1997

Impression by the artist from an edition of 5

14 ⅛ × 18 ⅜ inches

(sheet: 19 ¾ × 25 ⅝ inches)

Sculpture & Works on Paper

Untitled / Demonstration (with multiple figures), 1968

Resin

12 × 16 ½ × 4 inches

Untitled / Demonstration (with single figure), 1968

Cast bronze

16 × 4 × 4 inches

Untitled, 1942

Multicolor woodblock

8 × 5 ½ inches

(sheet: 11 ¾ × 7 ⅝ inches)

Drawings of human anatomy, 1943–44

Ink on paper

8 ⅛ × 6 ⅝ inches

Studies of human anatomy, 1944

Ink and watercolor

7 ⅛ × 9 ⅞ inches

Drawings of swans, 1944

Ink on paper

8 ⅛ × 6 ⅝ inches

Design studies, ca. 1943–47

Ink on paper

13 ¼ × 8 ¼ inches

Design studies, ca. 1943–47

Ink on paper

10 ⅛ × 7 ⅝ inches

Portfolio of drawings, ca. 1943–47

14 × 9 × 2 inches

Untitled [Bengal Famine], 1950

Ink on paper

13 ½ × 8 ½ inches

Untitled [Bengal Famine], 1950

Ink on paper

17 ½ × 11 ¾ inches

Untitled [Bengal Famine], 1950

Ink on paper

13 ½ × 8 ½ inches

Le Musician, 1953

Etching with aquatint

Artist’s proof 9 ½ × 5 ¾ inches

(sheet: 13 ¾ × 10 inches)

Seated Figure, 1952

Etching

Artist’s proof

10 × 6 ⅝ inches

(sheet: 16 ⅝ × 11 ⅜ inches)

Landscape, 1965

Lithograph

Edition 14 of 20

16 ¼ × 24 ¼ inches

(sheet: 17 ½ × 25 ⅜ inches)

Printed and published by Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Inc., Los Angeles (now Albuquerque, NM)

Other Materials & Ephemera

Graduation certificate from Santiniketan, December 24, 1947

11 ½ × 9 inches

Selection of tools, including “Pierre” drill and assorted bits

Plate for Radiating Flowers

12 ⅝ × 19 ⅜ inches

Plate for Clown Dissolving 12 ⅝ × 19 ⅝ inches

Plate for Clown Falling [Fallen Clown]

13 ¾ × 18 ½ inches

Printing Clown Dissolving, 2024

Digital video (color, sound)

5 minutes, 17 seconds

Produced by Mark Johnson and Avery Munson Clark

Krishna Reddy, Kalakshetra Madras, Chennai, late 1940s

Gelatin silver print

4 ½ × 3 ½ inches

Krishna Reddy and classmates during a workshop critique with Ossip Zadkine in Paris, 1951

Gelatin silver print

5 ⅛ × 7 ⅛ inches

Krishna Reddy, S.W. Hayter, and other artists at a café in Paris, early 1950s

Gelatin silver print

8 ½ × 11 inches

Krishna Reddy in Paris, early 1950s

Gelatin silver print

6 ¼ × 5 ¾ inches

Eleanor Magid, Krishna Reddy, and Robert Blackburn at The Printmaking Workshop, New York, 1971

Gelatin silver print

5 ⅜ × 9 ⅝ inches

Krishna Reddy teaching, unknown date

Photograph

7 ½ × 9 ½ inches

Contributors

Sarah Burney is an independent curator and writer based in New York and raised in Kuwait and Pakistan. Burney is a specialist of contemporary printmaking and contemporary art from South Asia and the Middle East. She writes an ongoing column on Kajalmag.com titled One Piece By and recently published the exhibition essay Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences (2022) for Union Pacific Gallery (London). Burney partnered with Zarina to co-author one of the artist’s last major publications, Directions to My House, published by Asian/Pacific/American Institute, New York University (2018). Burney co-curated the exhibitions Adeel uz Zafar: Triad (2024) at Aicon Contemporary (New York); Encounter/Exchange (2022) at Praise Shadows Art Gallery (Brookline, MA); curated The New Minimalists (2018) at the Abrons Art Center (New York); and received a Tulsa Artist Fellowship (2019) (Tulsa, OK). She is interested in exploring artists’ materials and processes and diversifying discussions in contemporary art. Her writing and curatorial work is informed by the variety of perspectives she has gained in the field, including in the studio of Zarina, the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective, and the Guerrilla Girls.

Mark Johnson was born in New York in 1964 and currently lives and works between New York and Portland, ME. He received a BA from Oberlin College and an MA from New York University. His paintings and prints have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including at Planthouse Gallery (New York); Susan Maasch Fine Art (Portland, MA); and Print Center New York. His work is included in the book Color: A Workshop for Artists and Designers (2005) by David Hornung. Johnson is the Print Studio Coordinator at NYU and printmaking instructor at NYU and Marymount Manhattan College. He is the co-founder of aquatintbox.com.

Board of Directors Staff

David Sabel Chair

Mary Beth Forshaw Vice Chair

Andrea Butler

Secretary

Stewart K.P. Gross

Treasurer

Anders Bergstrom

Judith K. Brodsky

Anne Coffin, Founder

Donald T. Fallati

Jennifer Farrell

Starr Figura

Mark Thomas Gibson

Joseph Goddu

Lily A. Herzan

Evelyn Lasry

Sabina Menschel

Brooke A. Minto

John Morning, Founding Chair

Daniel Nardello

Martin Nash

Janice C. Oresman, Emerit

Zina Starosta-Egol

Maud Welles

Judy Hecker Executive Director

Jenn Bratovich Chief Curator

Tiffany Nesbit Chief Operating Officer

Aaron Fisher Gallery Operations Manager

Alexa Gross External Affairs Coordinator

Taia Pollock Visitor Engagement & Events Coordinator

Alex Santana Curatorial Associate

Robin Siddall Exhibitions & Programs Manager

Published on the occasion of the exhibition Krishna Reddy: Heaven in a Wildflower Print Center New York January 23–May 21, 2025

© Print Center New York and the authors

ISBN: 978-1-7341224-6-6

Edited by Jenn Bratovich and Alex Santana Design by CHIPS Layout by Robin Siddall

Unless otherwise noted, all images © Krishna Reddy Estate. Photo: Argenis Apolinario.

22: Bottome, Laura et al., “A Dialogue with Krishna Reddy.” In Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective, edited by Janet Heit. Bronx Museum of Art, 1981.

61–66: Atelier Krishna Reddy, SoHo, 2009–14. © and courtesy Dev Benegal.

67–77: This reproduction of “Art Expression as a Learning Process” was first published in India International Centre Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1998).

83: © Krishna Reddy Estate. Image courtesy Experimenter (Kolkata, West Bengal, India).

Cover: Detail of Krishna Reddy, Fish, 1952. Mixed color intaglio, 9 ¾ × 13 ¾ inches (sheet: 18 × 22 inches).