At the University of Manitoba, a venue by Teeple Architects with Cibinel Architecture integrates into a challenging site with elegance and poise. TEXT Lawrence Bird

A new museum in Peterborough by Unity Architects puts an international-calibre collection of watercraft on display. TEXT Javier Zeller

eaupré Michaud et Associés and MU Architecture revamp Montreal’s Hôtel de ville hrough a process that foregrounds transparency. TEXT Peter Sealy

4 VIEWPOINT

Fresh perspectives on labour in architecture.

6 NEWS

Remembering His Highness

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV (19362024) and Justice Murray Sinclair (1951-2024).

15 AIA CANADA SOCIETY JOURNAL

The winners of this year’s AIA Canada Society design awards.

41 INSITES

Larry Wayne Richards reflects on architecture’s digital futures.

46 PRACTICE

Rick Linley on optimizing the design of your architecture practice to align with your business model.

48 BOOKS

A new textbook on modern architecture, and monographs by Martin Simmons Sweers and Blouin Orzes.

50 BACKPAGE

In The Exchange, DTAH has designed a vital new hub for Niagara Falls, Ontario, reports editor Elsa Lam.

COVER Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, Ontario, by Unity Architects. Photo by Salina Kassam

How can architects actively design their own practices and why should they do so? An article by Rick Linley in this issue (see page 46) tackles the nuts-and-bolts of this question, and two recent sessions in Toronto addressed the topic head-on.

At the Interior Design Show, a panel entitled “Designing the Plane while Flying It: Leading in Turbulent Times” included KPMB’s Phyllis Crawford, Nina Boccia, and Rachel Cyr, along with consultants Rob Luke and Elaine Pantel. The presentation traced KPMB’s strategic planning over the past several years, sharing how the firm sought to sharpen its value proposition in relation to changing markets. With the help of trusted advisors, KPMB identified the specific skill sets and character strengths that would be needed to help the firm continue to grow and thrive, and systematically assessed their staff’s abilities against this framework.

As the process unfolded, the firm began to identify where they needed to invest in targeted growth, both for individuals and teams. For instance, they saw good overall performance in core technical and design skills, but more work needed to develop partnership qualities. They’ve since embarked on a process of systematically training up future firm leaders, including building business acumen and financial literacy, to fill in the gaps for the firm’s future success.

A separate event, co-curated by the Toronto Society of Architects and DesignTO, looked more broadly at the question of labour in architecture. “How teams work together, and under what conditions work is getting done, has been an area of increased focus over the past years,” writes the TSA. “Particularly in the field of architecture where many of the common pitfalls of creative disciplines also intersect with regulatory requirements and exceptions to Ontario’s Employment Standards Act there is an understanding that we must do better.”

Reza Nik, founding director of Torontobased SHEEEP, spoke about how he is using his studio as a platform for building community

ABOVE A spring panel hosted by the Toronto Society of Architects and DesignTO focused on progressive approaches to labour in architecture.

and sharing best practices. Through initiatives such as SHEEEP.radio and SHEEEP.school, he is aiming to exchange knowledge and empower architects to carve their own paths.

Architect Je Siqueira, from Bernheimer Architecture in New York City, detailed the process and advantages of becoming a unionized workforce, highlighting the leverage it affords in negotiating for contracts with fairer terms for employees. Yvonne Ip, a founding member of Guelph, Ontario’s Arise Architects Co-Operative, gave an overview of the collective decisionmaking involved in a co-op business structure.

Hazel York, a managing partner at UK firm Hawkins/Brown, was instrumental in shaping the firm’s recent transition to employee ownership a model echoed by succession strategies in Canada, in which company shares are distributed from one generation to the next. Here in Canada, 5468796 Architecture cofounder Johanna Hurme detailed her firm’s progressive approaches to profit-sharing, financial transparency, and formal and informal benefits for staff.

Regardless of a firm’s business structure, common themes reverberated throughout these presentations. As firm owners age, planning for succession is critical but this process requires strategic thinking and a long runway. Such a process is often best rooted in transparency: staff are motivated by understanding where they fit into the continuum of a firm, and what they need to accomplish to move up the ladder. People are also more productive when they share in the benefits from that productivity. Arise Architects’ Yvonne Ip suggests that all firms could benefit from considering the philosophy of cooperatives. “Cooperatives ultimately dismantle this idea of employee versus employer, [instead] you are one and the same,” says Ip. “Ultimately, it’s really about the work whether the work is the project or the business.”

EDITOR

ELSA LAM, FRAIC, HON. OAA

ART DIRECTOR

ROY GAIOT

CONTRIBUTING

EDITORS

ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC

ODILE HÉNAULT

LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC

DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC

ADELE WEDER, FRAIC

ONLINE EDITOR

LUCY MAZZUCCO

SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR

ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C

VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER

STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3

SWILSON@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

FARIA AHMED 416 441-2085 x5

FAHMED@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM CIRCULATION

“The best part of Savings by Design is that the money saved through energy efficiencies can be spent on school resources and, ultimately, directed back to the classroom.”

Gerry

Sancartier

Property

and

Operations Officer

†

*

Success Story | Ottawa

Ottawa Catholic School Board By the numbers†

Participating in Savings by Design has been a key part of Ottawa Catholic School Board’s long-term energy-management strategy. The three schools that have completed the program are now a model for the board’s other new construction projects, setting a green standard in line with its sustainability vision for building beyond code.

To get the most out of your next project, contact Venoth Jeganmohan, Energy Solutions Advisor. enbridgegas.com/sbd-commercial venoth.jeganmohan@enbridge.com 647-502-6759

enbridgegas.com/sbd-commercial for details.

Vancouver Art Gallery issues invitation-based RFP to Canadian firms for new building design

On January 22, 2025, the Vancouver Art Gallery Association’s Board of Trustees passed a motion to invite a select group of Canadian-based architecture firms to submit proposals to design a new building, following the removal of Herzog & de Meuron from the project. The decision marks a significant milestone in the gallery’s journey to create a new building that celebrates art while prioritizing achievability, practicality and fiscal responsibility. The new site remains 181 West Georgia at Larwill Park in downtown Vancouver, which is approximately a 10-minute walk from the current building.

The 14 firms include: Diamond Schmitt Architects, Formline Architecture & Urbanism, Hariri Pontarini Architects, HCMA , Henriquez Partners Architects, KPMB Architects, Michael Green Architecture (MGA), Office of Macfarlane Biggar (OMB), Patkau Architects, Perkins+Will, Revery, Saucier+Perrotte Architectes, Teeple Architects, and 5468796 Architecture. vanartgallery.bc.ca

5468796’s Pumphouse among five MCHAP finalists

Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize (MCHAP) director Dirk Denison and 2025 MCHAP jury chair Maurice Cox have announced the five finalists for the 2025 Americas Prize, which include Canadian project

Pumphouse in Winnipeg, Manitoba, by 5468796 Architecture. The 2025 Americas Prize honours the best work of architecture completed in North, Central, or South America from 2022 to 2023. Winnipeg’s historic James Avenue Pumping Station was slated for demolition after 14 failed attempts to revive the historic building. 5468796 developed a conceptual design that was paired with a financial pro forma and presented the business case to an existing client, connecting them with the City as an owner and eventually leading to the

building’s successful preservation through private investment. The new approach considers the pumphouse a “found object” and uses the existing building’s structural properties, while proposing an expansive public realm that weaves into the fabric of the Exchange District National Historic Site. The project includes two residential blocks flanking the historic pumphouse building, which has been repurposed as an office and restaurant.

“A plot that had no future, pushing zoning and regulatory envelope, the project builds a contemporary new way of living within the memory of an industrial archaeology. A series of smart strategies allow to maximize the identity of the Pumphouse, the new residential use, views and private and shared spaces in this complex urban plot,” said the jury about the project. “The abandoned pump house seems to extend its precise and rigorous material language beyond its original enclosure.” mchap.co

With climate change and housing shortages being two of the top issues in Canada and around the world, how does it make any sense to continue to have the virtually unfettered right to demolish buildings in Canada? Unless a building has heritage status (less than one percent do) you can obtain a demolition permit over the counter on demand anywhere in the country. The right to demolish is rooted in outmoded planned obsolescence practices that originated in the postwar building boom. A right to demolish has no place in the era of climate change. Conservation of all resources is critical to survival.

Society rationalizes demolition by saying, “The old must make way for the new.” We would never apply that rationale to the elderly

or infirm. We do all we can to extend the life of people as long as possible; surely, we should do the same for our buildings.

Buildings contain irreplaceable environmental resources. In some Canadian jurisdictions, cultural heritage value or rental housing protection policies intervene between buildings and the wrecking ball. Heritage laws emerged in the 1960s and ’70s to try to keep important buildings out of the demolition stream. In the 21st century, the question of cultural value is eclipsed by the environmental dangers of demolition. It’s not only an issue of running out of landfill space to deal with the approximately 30 percent of landfill from the construction industry, but it is also the loss of material that could, and should, be reused, recycled, and repurposed. The best way to conserve material is to maintain our building stock where it stands. I am writing this article from home in a 100-yearold repurposed school building. Down the street an older hotel has been repurposed by the City of Toronto for social housing. Smart developers are rehabilitating office space for housing.

With every new build, our debt to the environment mounts. In the middle of a housing crisis, in Toronto’s Regent Park, buildings that could and should be rehabilitated sit boarded up, waiting for demolition and new construction to create new housing units. With a bit more imagination, we could build over and around what we have.

How is it that Canada has excellent policies on recycling small stuff like pop cans and paper but not buildings? How is it that school boards and other institutional property owners are permitted to defer maintenance to the point that demolition and its associated waste and disruption become inevitable? The Toronto District School Board has a mounting maintenance backlog of more than $4.2 billion in 2023.

Thinking is changing. The Declaration of Chaillot, passed March 2024 in France at the United Nations Environment Program’s Building and Climate Global Forum, represents a major shift in approach.

We pioneered the first PVC-free wall protection. Now, we’re aiming for every 4x8 sheet of Acrovyn® to recycle 130 plastic bottles—give or take a bottle. Not only are we protecting walls, but we’re also doing our part to help protect the planet. Acrovyn® sheets with recycled content are available in Woodgrains, Strata, and Brushed Metal finishes. Learn more about our solutions and how we’re pursuing better at c-sgroup.com.

Endorsed by over 70 countries, including Canada, it calls for, among other things, “prioritizing the reuse, repurposing and renovation of existing buildings and infrastructures to minimize the use of nonrenewable resources, maximize energy efficiency and achieving climate neutrality, sustainability, and safety with particular focus on the lowest performing buildings.” The report cites a worldwide production of “100 billion tons of waste annually generated from construction, demolition, and renovation processes,” and notes that “most of the materials are wasted at the end-of-use phase of these processes, with about 35 percent sent to landfills.”

There are two things our Canadian governments can do right away. The first is to introduce planning policies that prioritize building adaptation and reuse over demolition and new build, with financial incentives to match; the second is to introduce a notice period of 60 days prior to issuing a demolition permit. That nominal notice period can be easily worked into the construction planning calendar and would give municipalities a chance to ensure that all measures are taken to avoid the environmental damage of demolition.

As your grandmother said, “waste not, want not.”

volunteer advocate, and recently retired architect who specializes in the conservation of buildings from her two offices (both rehabilitated buildings) in Muskoka and Toronto.

The formal method of verifying the currency of licensed architects through continuing education requirements has been in place in most provincial associations since the turn of the millennium. The introduc-

tion of these requirements parallels the revision of educational requirements for licensure, from professionally focused five-year undergraduate university programs to diverse graduate programs. The task of determining what is germane to professional competence is a notable regulatory challenge, but the fact that all our professional associations have resorted to fines in excess of registration fees to leverage compliance with continuing education requirements suggests that something is amiss, and worthy of rigorous and objective review.

The original intent of continuing education as a non-profit, lowcost-to-architects way to keep practitioners up to date is not immediately obvious. The Architectural Institute of British Columbia states the purpose of required continuing education as “a response to the public’s increasing expectation that architects remain current with contemporary technology, business practices, methods, and materials.”

But in other cases, there has been noticeable mission-creep. The Ontario Association of Architects describes the intent of continuing education as part of the organization’s “dedication to promoting and increasing the knowledge, skill, and proficiency of its members, and administering the Architects Act to serve and protect the public interest.”

One large association thus defines their mission as keeping members up to date. The other offers a broader and more open-ended mission statement that extends well beyond the issue of currency. This reflects two quite different paths.

Regulating educational requirements is a tough challenge, certainly, for any organization. “The broader the range of issues to be accommodated, the greater the difficulty to regulate,” is a familiar axiom. In our profession, regulating education should be premised on the fact that architects process information and come to understand their craft in unique ways. Visual literacy, for instance, is core to an architect’s formal

ACO. we care for water

Suitable for heavy duty areas Disability Act compliant grates Standard trash bucket Optional foul air trap & silt bag

May be used on waterproofed terrasses

education and professional skill set. The accreditation process for evaluating architecture university programs in Canada, as one example, requires an exhibition of ideas and concepts as a principal component. This is how we communicate, learn, and grow as architects. Yet, ironically, attendance at such an exhibition would be ruled invalid as counting towards provincial continuing education requirements, because its inherent value cannot be readily quantified.

A sizable amount of regulation focusing on professional development is also premised on the notion that one can somehow quantify reading, and accurately corroborate the time taken to research a topic, author a book, or publish an article. In contrast, travel which most architects view as an important way of coming to understand architecture is only deemed valid by regulators if it can be corroborated by a tour guide receipt. A mode of regulation that would more accurately reflect lived experience would not be driven by administrative expediency, and would assign value beyond that which can be easily quantified.

Activities cited in the “unstructured learning” category aside from association meetings and committee work are, on the whole, largely impossible to regulate with specificity, and in most cases, fail to credibly validate either currency or knowledge. Elimination of these activities would be a positive first step, and serve to focus attention on legitimate profession-specific requirements. A compelling argument can be made that compliance with unstructured continuing education requirements achieves nothing but increased workloads for regulators, ill will of individual members, and no credible validation of whether the individual in question is up-to-date or not.

Structured professional development, on the other hand, can and should be monitored in a comprehensive and straightforward manner.

The profession of architecture, while complex and ubiquitous in comparison to other professions, is not so complicated when it comes down to what we actually do. All North American schools of architecture seeking accreditation, for instance, are presently required to meet student and program performance criteria that are specific, quantifiable, and accepted by 185 post-secondary institutions with widely differing missions and geographic settings. Consensus on this kind of complex and diverse subject matter has thus proven to be possible. The professionally specific Internship Architecture Program (IAP) provides another example of how the scope of professional activity can be defined in 15 rationally weighted categories that all associations agree on. The referencing of continuing education activity to any of these 15 categories could serve to ameliorate concerns of whether subject matter is profession-specific.

The question arises of whether verifying compliance with continuing education requirements is fair to all associations. Smaller provincial associations with limited resources, in particular, are not well positioned to credibly monitor professional development activity, or to deal with clarification and interpretation of regulations. Most associations rely entirely on computerized transcripts to record and tally up activity hours in each category, and restrict entries beyond the deadline of each cycle. The few unfortunate individuals targeted for audit rely on local interpretation, which can vary significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

The concept of a national organization such as the RAIC as a central repository for course material and records has obvious merit. The RAIC already offers mostly online courses. Professionally qualified staff could efficiently manage queries on regulatory requirements. Local jurisdictions could then, as most already do, focus on continuing education related to regional issues, such as changes to legislation, building codes,

25_001639_Canadian_Architect_APR_CN Mod: February 21, 2025 9:00 AM Print: 03/03/25 2:16:49 PM page 1 v7

Uline’s cushioning gives you the best seat in the house. And with tons of products always in stock, you’ll love our variety. Order by 6 PM for same day shipping. Best service, products and selection – experience the difference! Please call 1-800-295-5510 or visit uline.ca

construction documents, and bidding and contract negotiation. Updating continuing education requirements first requires acknowledgement that the existing system appears to be falling short of its intended mission. A quarter century of experience should provide hard evidence that we are failing to reach the desired results. The autonomy of provincial associations should be prepared to yield to a greater need for consistency, fairness, and objectivity across jurisdictional boundaries. Wellcrafted and intelligent regulation can and should eliminate any question of competence and currency from public concern.

Ian Macdonald, FRAIC, is Professor Emeritus at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Manitoba.

His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV (1936-2024)

His Highness Prince Karim Al-Hussaini, the Aga Khan IV, 49th hereditary imam of the Shiite Ismaili Muslims, and philanthropist, passed away on February 4, 2025, at the age of 88, surrounded by his family in Lisbon, Portugal. His Highness became the 49th Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims on July 11, 1957 at the age of 20, succeeding his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mohamed Shah Aga Khan. He was also the founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), whose agencies work to improve the welfare and prospects of people in the developing world.

On February 5, 2025, his son Rahim was named the Aga Khan V, the 50th hereditary imam of the Shiite Ismaili Muslims, which was in accordance with his father’s will.

His Highness the Aga Khan IV was granted honorary Canadian citizenship in 2009. In 2013, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) awarded him its highest honour the RAIC Gold Medal. The selection of His Highness marked the first time in more than 30 years that a non-architect had been chosen to receive the Gold Medal, and recognized the Aga Khan IV ’s extraordinary achievements in using architecture as an instrument to further peaceful and sustainable community development around the world.

In recognizing His Highness, the RAIC took note of his remarkable accomplishments in various aspects of the field of architecture as part of his broader social and economic development work through the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). This included the specialized cultural programming undertaken through the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, the restoration of many heritage sites throughout the Muslim world by the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

“There has been a strong link between the Shia Ismaili Muslims led by His Highness the Aga Khan IV and this country, a true convergence of pluralist values and respect for the diversity of culture,” wrote Canadian architecture critic Trevor Boddy, citing a series of projects completed under His Highness’s patronage, including the Ismaili Centre in Vancouver (Bruno Freschi, 1983), the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat in Ottawa (Maki & Associates with Moriyama Teshima Architects), the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto (Maki & Associates with Moriyama Teshima Architects), and the Ismaili Centre in Toronto (Charles Correa with Moriyama Teshima Architects). In recent years, the Global Centre for Pluralism (KPMB A rchitects) has opened in Ottawa, and The Aga Khan Garden (Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects) and The Diwan (AXIA Design Associates, Arriz + Co., and Kasian Architecture, Interior Design, and Planning) have opened in Devon, Alberta.

“I think it is right to begin by clarifying that my definition of architecture goes beyond a concern for buildings designed by architects,” said the Aga Khan IV. “I see architecture as embracing practically all aspects of our entire built environment. People everywhere independent of their particular background or educational level almost instinctively understand the importance of place, and how the spaces of our lives are shaped and reshaped for better or for worse. This universal sensitivity to changes in the built environment also helps explain the profound impact of architecture on the way we think about our lives. Few other forces, in my view, have such transformational potential.”

the.akdn

ABOVE Justice Murray Sinclair was the 2024 recipient of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Gold Medal, recognizing the impact of decolonization and reconciliation on Canadian architecture.

The Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair, former chair of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), recently passed away.

Sinclair was the recipient of the 2024 RAIC Gold Medal, awarded for his dedication and leadership in promoting truth and reconciliation, dismantling colonial relationships, and advocating for the rights of

Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. The Gold Medal recognizes the impact of the TRC and Sinclair’s work on the present and future Canadian architectural landscape.

Sinclair was born and raised on the former St. Peters Indian Reserve north of Selkirk, Manitoba. In 1980, he was called to the Manitoba Bar and focused on civil and criminal litigation, Indigenous Law, and Human Rights.

In 1988, Sinclair became Manitoba’s first, and Canada’s second, Indigenous judge. That year, he also served alongside the Associate Chief Justice as Co-commissioner of the Public Inquiry into the Administration of Justice and Aboriginal Peoples of Manitoba. In 1995, he was appointed to the Court of Queen’s Bench.

In 2009, Sinclair was appointed to Chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada into Indian Residential Schools (TRC).

In 2016, he was appointed to the Senate of Canada as an Independent Senator, where he advocated for various important issues. “The Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair has left an indelible mark on the architectural community and on Canada as a whole,” said Jonathan Bisson, president of the RAIC Board.

“His courage and wisdom inspire us to continue our commitment on the path of truth and reconciliation. For many years, we have carried forward his legacy, but it is essential to remember that this journey is a collective duty, a lasting commitment to listening, respect and action. I am confident that his dedication to truth and justice will continue to guide our work for generations to come,” said Bisson. raic.org

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe

Earth tones never go out of style.

In 2025, natural colours are on-trend. Our phenomenal range of earth tone options, in traditional and modern styles, lets you design premium masonry exteriors that never age. Our calcium silicate brick and stone products, made with natural materials, deliver unparalleled beauty and performance. Proudly made in Canada since 1949. solutions@arriscraft.com

“It allowed us to explore innovative ideas and strategies for achieving our sustainability and energy e ciency goals.”

– Marwan Kassay Project Manager, Housing Development

Free expert assistance and incentives up to $120,000*

While designing Credit River Way, Peel Region and FRAM Building Group collaborated with sustainable building experts from the Savings by Design program. This allowed them to explore strategies in achieving sustainability and energy e ciency goals—including ventilation and heating upgrades along with an innovative solar wall that preheats make-up air.

To get the most out of your next project, contact Alex Colvin, Energy Solutions Advisor. enbridgegas.com/sbd-a ordable

m3

Projected annual natural gas savings

Projected annual GHG reduction

alexander.colvin@enbridge.com 519-670-2484

Dora Ng President, AIA Canada Society

Ispent the early months of 2025 shaping goals, planning initiatives and strategizing pathways for personal and professional development. In our evolving political landscape, there is a palpable sense of uncertainty, where, in the four-quadrant classification of risks, “unknown-unknowns” appear to be prevalent. But architects are trained to be versatile and adaptable. We are problem solvers and solution providers. We help shape how people live, interact, work and play. Architecture is also a team sport. We are integrators who listen to many asks, and collaborate with engineers, developers, contractors and other building professionals to translate ideas into space. Our teams need the diversity of individuals in our communities for all voices to be heard, and to make our own work complete.

In this April issue of AIA Canada Journal, we celebrate the winners of our 2024 AIA Canada Design Awards, which represent design excellence across a diverse range of typologies, scales and levels of complexity. This spring, we will also be launching a dedicated Student Award program to recognize and promote future generations of architects. Check back in the next AIA Canada Journal for the winners.

The AIA Canada Design Awards program is held annually in the fall, celebrating outstanding achievements in design, innovative thinking, and best practices showcased by AIA Canada members and emerging design professionals. Since its launch in 2020, the program has attracted a remarkable range of high-quality submissions. We are delighted to see growing engagement from both established firms and emerging talents, including students from across Canada. The award recipients were officially announced during the AIA Canada Annual General Meeting on November 27, 2024. We invite you to explore the following pages to discover the inspiring projects recognized in each category. Congratulations to all of this year’s outstanding winners!

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to our distinguished panel of judges whose dedication, expertise, and discerning perspectives have been instrumental in shaping the 2024 AIA Canada Design Awards.

Dr. Christine Bruckner (FAIA, HKIA, R.A., LEED® AP, BEAM PR, BREEAM AP, WELL AP Faculty, RESET Fellow) is a Director at M Moser Associates. She is an accomplished architect and sustainability consultant com -

AIA International Spring Conference 2025

AIA Canada Student Design Award Program 2025

mitted to advancing best practices in environmentally responsible, energy-efficient design across all scales. Dr. Bruckner currently serves as the Chair of the AIA International Committee Advisory Group and is a member of the interim board for the AIA International Region.

Carlo Parente (OAA, AIA, NCARB) is Founder and Principal Architect at Parente Architecture, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Architectural Science, Toronto Metropolitan University. Parente’s impressive portfolio of projects spans North America, Europe, and Asia. His community-centred work is driven by a holistic approach that integrates performance-based design, emerging technologies, architectural theory, and cultural context.

Warren Schmidt (MArch, BED, Architect AIBC, AAA, MRAIC, CPHD) is a Principal at B+H Architects. Schmidt is a passionate advocate for design excellence. His design philosophy emphasizes the importance of creating spaces that are not only aesthetically compelling, but also functional, sustainable, and deeply connected to the people and communities they serve.

If you missed the virtual AIAI conference in March 2025, you can view the recorded sessions at www.aiainternational.org. The three-day virtual gathering included lectures, panel discussions, and building tours from around the world, featuring speakers from the seven international chapters (Canada, Europe, Hong Kong, Japan, the Middle East, Shanghai and the UK) and three international sections (Southeast Asia, Taipei and Latin America).

AIA Canada Society is committed to supporting and promoting future generations of design professionals. In April, we will launch our renewed Student Design Award program. To learn more, visit www.aiacanadasociety.org.

RAIC Conference: Montreal, June 1-4, 2025

AIA Canada Society would like to thank the RAIC for the partnership opportunity

at this year’s RAIC Conference. AIA Canada will be hosting a social event at the conference venue on June 1, 2025, and we welcome all to attend. Visit www. aiacanadasociety.org to RSVP.

AIA National Conference: Boston, June 4-7, 2025

AIA25 features inspiring keynotes, industry-best continuing education, dynamic networking, immersive tours, and the industry’s largest expo. Look for the new AIA International Symposium, which will be held on June 4, 2025.

ARCHITECTURE (AWARD OF EXCELLENCE)

təməsew ’ txw Aquatic and Community Centre, New Westminster, British Columbia hcma architecture + design

Selected to participate in the AIA International Design Awards 2025

Woven into the landscape with a dramatic, unifying roof, təməsew ’ txw is designed to be the heart and soul of its community. Created for all ages and abilities, it reflects how communities engage in recreation today and into the future, with a focus on human connection and wellness alongside traditional sporting activities. Extensive public and stakeholder engagement took place over two years, involving more than 3,000 people, including urban Indigenous communities, Host Nations, multicultural groups, and an accessibility committee. təməsew ’ txw is Canada’s first completed all-electric aquatic centre to achieve CaGBC Zero Carbon Building - Design Certification, targeting a 92% reduction in GHG emissions compared to its predecessor, and has earned Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Gold Certification.

URBAN DESIGN (AWARD OF MERIT)

Waterworks, Toronto, Ontario

Diamond Schmitt

Waterworks is a hybrid, mixed-use development that rehabilitates, conserves, and expands an industrial heritage site through the integration of diverse programs—supporting not only the lives of its residents but also enriching the broader community and urban environment. Located at the northern edge of Toronto’s oldest public playground, the project is anchored by the 1932 City of Toronto Waterworks building. The original Art Deco structure has been fully retained and meticulously restored. Three new building wings, each twelve stories high, are positioned above the heritage structure to preserve daylight access to the historic skylights. These new additions house a gymnasium, a 25-metre pool, and various program spaces for the YMCA, alongside 288 residential units that frame a south-facing outdoor courtyard on the fourth floor.

ARCHITECTURE (AWARD OF MERIT)

Walker Sports and Abilities Centre, Thorold, Ontario

MJMA Architecture & Design and Raimondo + Associates Architects

The Walker Sports and Abilities Centre served as the central hub of the Niagara 2022 Canada Summer Games, hosting numerous indoor and outdoor events for the nation’s top athletes—both able-bodied and those with mental or physiCal disabilities—to compete at the highest level. The facility was conceived to also offer long-term amenities and research facilities for promoting sport and wellness. Despite its monumental scale, the building is made exceptionally navigable and welcoming through the strategic use of natural daylight, visual transparency between program spaces, and views to the outdoors. The three large sports halls—a quadruple gymnasium, a 1,000-seat spectator ice pad, and a practice hockey arena—are united by a large, folded roof, and the design creates an expansive interior public space connecting the primary amenities.

COMMUNITY-ENGAGED DESIGN (AWARD OF MERIT)

Ziibiing – Taddle Creek Indigenous Landscape at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Brook McIIroy

A space for learning, gathering, and ceremony, Ziibiing is located at the eastern gateway to the St. George Campus. Ziibiing means “at the river” in Anishinaabemowin, and the design seeks to commemorate the memory of Taddle Creek, which once flowed through the site but is now buried deep below. To foster an inclusive space, the design draws from cultural elements significant to many Indigenous communities, such as fire, water, and the stars. Situated atop a hill, a bronze open-air pavilion forms a welcoming beacon for all, and features a sacred fire and wooden seating. Inspired by the Anishinaabemowin words Awaadiziwin (knowledge you can see) and Akinoomaage (to look to and take direction from the earth), this landscape encourages the reclamation of Indigenous knowledge.

University of Victoria Student Housing and Dining, Victoria, British Columbia Perkins&Will

Driven by the growing demand for on-campus housing, this mixed-use complex integrates 782 beds, a 600-seat dining hall, conference spaces, academic facilities, and common areas. The design fosters social connections as an integral part of the academic journey, encouraging community and collaboration among students. The project achieves BC Energy Step Code Step 4, Passive House, and LEED v4 Gold certifications, contributing to reduced campus-wide CO₂ emissions while improving the health, comfort, and well-being of residents. Through a thoughtful mix of uses, regenerative design strategies, simple material detailing, and a student-centred approach, the project sets a new benchmark for sustainable student housing—highlighting UVic’s dedication to fostering a vibrant, inclusive, and environmentally responsible community.

Weldon Library Revitalization Phase One, London, Ontario Perkins&Will

Located at the heart of Western University, this project reimagines John Andrews’ 1967 Weldon Library as a cutting-edge hub for interdisciplinary learning. The revitalization was shaped by three key design principles: celebrating the existing architecture and creating an inspiring destination; implementing strategic interventions to support contemporary pedagogy, research, and operations; and adopting a holistic approach to space, systems, materials, and furniture to yield a healthier, more sustainable environment. At the heart of the library, a dynamic new Learning Commons reconnects the Great Hall with a previously enclosed mezzanine. New spaces dedicated to study, socialization, and community engagement foster 21st-century learning, while improvements to daylight access, air quality, and acoustics enhance well-being.

RESIDENTIAL (CITATION)

Arbour House, Victoria, British Columbia

Patkau Architects

Intertwining landscape, light, and family life, Arbour House is a loosely knit fabric of spaces overlooking Cadboro Bay. Variously scaled spaces are unified by a rhythmic, pleated ceiling. This intricate wooden arbour is crafted from finger-jointed hemlock and suspended below arrays of operable skylights, and alternates between areas of greater and lesser porosity. The changing rhythms of the sun interact with this latticework, casting dynamic geometric patterns that shift throughout the day and across the seasons. Positioning the house toward the top of the sloping site improved views and solar exposure, created space below for a garage and secondary suite, and allowed for plantings extending a grove of protected Garry oaks.

RESIDENTIAL (CITATION)

Lambkill Ridge, Terence Bay, Nova Scotia

Peter Braithwaite Studio Ltd.

Named after the area’s abundant flowering Sheep Laurel, this project is a nature retreat designed for a young family. Elevated on stilts, the two volumes position occupants within the tree canopy, offering sweeping views of rugged terrain and the ocean, while allowing the natural landscape to thrive. Off-grid features include strategically placed windows for optimal thermal gain and passive ventilation, an incinerating toilet, and a rainwater collection and filtration system. To harmonize with the surrounding landscape, the home is clad with locally sourced rough-hewn hemlock siding with black metal accents. The layout is designed to maximize natural light and ventilation, ensuring year-round comfort.

ARCHITECTURE (HONORABLE MENTION)

Centre for Computing & Data Sciences at Boston University, Boston, USA

KPMB Architects

This 19-storey tower is Boston’s largest fossil fuel-free building, meeting Boston University’s Climate Action Plan targets and aiming for LEED Platinum certification. Powered by geothermal energy, the building features a high-performance envelope with integrated sun-shading and advanced HVAC systems to enhance energy efficiency. Elevated ground floors are designed to ensure future climate resilience and flood protection. Designed as a “vertical campus,” the Centre’s cantilevered volumes create distinct departmental “neighbourhoods,” each with access to outdoor spaces, and fostering a dynamic academic community of over 3,000 students, faculty, and staff.

URBAN DESIGN (HONORABLE MENTION)

The Durham Meadoway, Durham, Ontario SvN Architects + Planners

This proposed 27-kilometre active transportation route and linear park stretches from Pickering to Oshawa through the Gatineau Hydro Corridor. The project aims to transform underutilized land into a regenerative landscape, connecting with existing trails and parks, while creating vibrant new social spaces and becoming a signature destination with a distinct sense of place. It will celebrate the cultural diversity of Durham’s communities—including First Nations, Inuit, Métis, settlers, and immigrants—through thoughtfully designed public spaces and programming. It will also enhance biodiversity by establishing a meadow habitat that supports insects, birds, mammals, and herpetofauna.

In response to a major heatwave, Roberto Clemente Community Academy faced challenges with its air conditioning system, prompting the installation of new portable cooling units. Blackhawk HVAC created an opening in the roof and installed a BILCO Type D roof hatch to facilitate the safe handling of the cooling units.

The project required a significant amount of planning and precise execution, including cutting through the roof and removing concrete to make room for the BILCO hatch. With this successful installation, the district now has a reliable and secure way to manage future mechanical upgrades, with the added benefit of a long-lasting investment that will pay off in future projects.

“BILCO met and exceeded my expectation with the roof hatch. I was impressed with the quality of the door. I can be very critical of products, but we set it, squared it, set the bolts and it was done. There was no messing around with the latch or any other part of the hatch.”

– Rich LaCien, Blackhawk

• Roberto Clemente Community Academy in Chicago needed to upgrade its air conditioning system during a record-breaking heatwave.

• To ensure full reliability, the school district undertook a major upgrade, including the removal and installation of two 750-ton chillers.

• Type D roof hatch for mechanical equipment installation and removal.

• The double-leaf hatch measured 9-feet, 8 inches x 18-feet, 3 inches.

Keep up with the latest news from The BILCO Company by following us on Facebook and LinkedIn.

For over 90 years, The BILCO Company has been a building industry pioneer in the design and development of specialty access solutions for commercial and residential construction. For more information, visit www.BILCO.com.

The BILCO Company is now part of Quanex (NYSE: NX), a global, publicly trade manufacturing company serving OEMs in the fenestration, hardware, cabinetry, solar, refrigeration, security, construction, and outdoor products market.

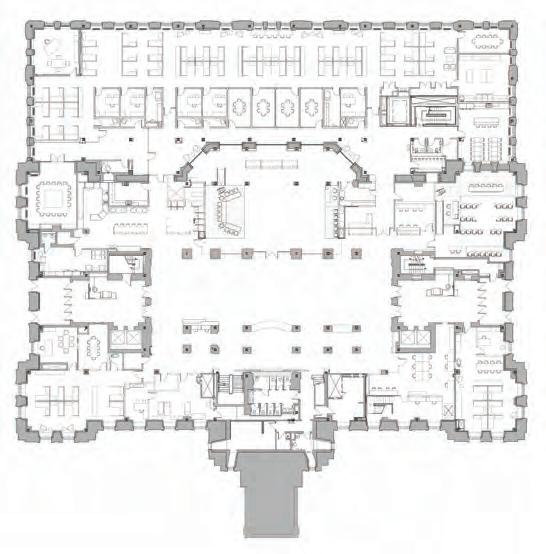

AN ELEGANT NEW CONCERT HALL MAXIMIZES A CONSTRAINED SITE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA.

PROJECT University of Manitoba Desautels Concert Hall, Winnipeg, Manitoba

ARCHITECTS Teeple Architects in association with Cibinel Architecture

TEXT Lawrence Bird

ABOVE A Sol LeWitt drawing is prominent in the L-shaped lobby, which spans between the main entrance to the west and a landscaped court to the north. OPPOSITE The wood-lined concert hall can be configured to accommodate a full orchestra, and up to 475 spectators. OPPOSITE BELOW The concert hall connects to the Taché Center Block building, making use of an existing lobby, visible at rear, along with existing mechanical spaces.

When the University of Manitoba set out to realize benefactor Marcel Desautels’ dream of a world-class concert hall, Dean Edward Jurkowski knew he was creating a tough design brief for Teeple Architects and Cibinel Architecture. The site allocated to the concert hall was an almost land-locked parcel, walled in to the north and west by the perpendicular wings of Taché Hall, home to the university’s Faculty of Music, and to the east by Taché’s Center Block building.

Adding to this tight urban condition was a set of extreme constraints below ground. Lead architect Tomer Diamant of Teeple Architects quickly determined that the hall’s orchestra pit needed to slip down into a knot of existing tunnels, while the auditorium expanded overtop of them a very tricky condition.

Moreover, the space needed to deliver perfect acoustics. Diamant and his team modelled and fine-tuned the hall in close collaboration with acousticians SLR Consulting. The white oak millwork flowing along walls and ceiling has acoustic properties, and its curves lend the space a quality that Diamant identifies as “both generous and intimate.” The billows of white oak contrast with the much darker tone of the hall’s upper level. Walls surrounding the loges, for example, are clad in dark, convex vertical pine profiles. Their scalloped surface scatters sound, and is also likened by the designer to log-cabin siding perhaps a wry regional detail.

For this audience member, the sensuality of the hall evoked the impression of being within a musical instrument and recalled those early exercises in architectural drawing when one is asked to cut a section through a violin. A section through this hall would reveal a large plenum beneath the rear seats, and a largely passive ventilation system that satisfies both acoustical and sustainability objectives. (The hall targets LEED Silver.)

The same section would also unveil an intricate dance of interior and exterior spaces, setting the stage not just for musical performances, but also for social performance. The angular lobby invites concert-goers to strut against the backdrop of a Sol LeWitt drawing, which was removed from another location and meticulously reproduced according to LeWitt’s original directions. (LeWitt’s work can be seen as an early instance of media art buyers of his wall drawings receive instructions for constructing the piece, not anything physical.) This lobby interlocks with an armature of exterior spaces slipping obliquely alongside the existing buildings. Letting in the sun, while politely declining to loom over the landscape, the hall’s roof dips down a modest but extremely effective gesture that serves well to draw in visitors.

Liz Wreford and Taylor Laroque of Public City Architecture stickhandled the landscape, which deftly creates approaches to not just the concert hall, but to nearby student residences and classrooms as well.

The landscape accommodates a number of pieces of public art, including an Ai Weiwei bicycle sculpture. Like the LeWitt, this is on loan from Michael Nesbitt who, like Marcel Desautels, is a great patron of the arts in Winnipeg, and a significant donor to this building. While these outdoor spaces are slim, they recall the richness of far denser urban environments. Visitors might be reminded of the winding European passageways documented by Camillo Sitte, opening up to create space for architectural gems.

The hall accommodates three distinct performance conditions, holding up to an 85-person orchestra and offering as many as 475 spectator seats. Recently, I attended a performance in which the stage held just the four performers of the Attacca String Quartet, who presented a program of short experimental pieces during the 2025 Winnipeg New Music Festival. Dynamic, with rapidly changing tonality, these pieces demanded that the hall produce an extremely precise, robust and responsive sound. To my ear, it met the test from every corner of the space. After the performance, I spoke to Julliard-trained Amy Schroeder a founding member of the quartet who praised the hall for its clarity of sound. It was “a really great place to play,” she noted, “not too reverberant, but also not too dry.” Tomer Diamant, comparing the theatre to a Swiss watch, explains how “many intricate parts must come together seamlessly” for the hall to work. “While the design is driven heavily by physics, you never truly know if it will succeed until opening night.”

Succeed it did. Indeed, Desautels Concert Hall can be seen as an artefact whose many components slip cleverly into each other: interiors, architecture, mechanical and acoustical systems, landscape and urbanism. The ensemble is tightly wound, but feels absolutely relaxed. It is no wonder that its balance of poise and flow satisfies musicians and concert goers alike.

ARCHITECTS: STEPHEN TEEPLE (FRAIC), TOMER DIAMANT (MRAIC), JASON NELSON, HELENA DINI, AMANDA KEMENY. CIBINEL

ARCHITECTURE: MICHAEL ROBERTSON (MRAIC),

Looking for a budget-friendly ceiling with the natural beauty of wood? Lyra® PB wood-look ceilings are a great option with superior sound absorption. They’re part of the Sustain® portfolio –meeting the most stringent industry sustainability compliance standards today. Order a sample now at armstrongceilings.com/lyrawoodlook

PROJECT Canadian Canoe Museum, Peterborough, Ontario

ARCHITECT Unity Design Studio Inc.

TEXT Javier Zeller

PHOTOS Salina Kassam

There are perhaps no material objects from this country more elegant than the canoe and the kayak, the jiimaan (Anishinaabemowin) and qajaq (Inuktitut) as they are known to Indigenous peoples. Their forms were already perfected before being adopted by Europeans as the selfevidently superior means of travelling across lakes and down rivers in this water-rich land. The Canadian Canoe Museum, in Peterborough, Ontario, is home to the world’s pre-eminent collection of these human-powered watercraft.

Begun by private collector Kirk Wipper, the collection became formalized as a not-for-profit public museum in 1997. For several decades, the Canadian Canoe Museum languished in a nondescript former out-

the frame-and-birchbark construction of many of the historic canoes

the museum’s

white-oak-slat ceiling contributes to acoustic control, and is part of a wood palette evoking a gathering lodge.

ABOVE The main stair spirals around a wood-slat-clad service core, offering visitors views of the collection archive, as well as varying vantage points to the canoes suspended in the main atrium.

board motor factory in Peterborough. By 2010, efforts were underway to move to a waterside site and a new building that reflected the cultural importance and global significance of this collection. In 2015, the Museum launched a two-stage competition, chaired by architectural writer Lisa Rochon, that selected Ireland’s heneghan peng architects in joint venture with Kearns Mancini Architects as designers for the new building (CA, May 2016). It was to be sited immediately adjacent to the Lift Lock National Historic Site on the Trent-Severn waterway, a necklace of interconnected rivers and lakes that permits boat travel between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay on Lake Huron. However, shortly before construction was slated to begin a few years later, the selected site was discovered to be contaminated with industrial solvents. This in combination with financial challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, led to the selection of a new site further south on the Trent-Severn and a new architect team, Unity Architects, one of the original competition’s shortlisted finalists. Unity Architects, formerly Lett Architects, is a storied Peterborough firm, well-known for their thoughtful design work on cultural projects including The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery on Toronto’s waterfront, Victoria College’s Isabel Bader Theatre and the (unfortunately repurposed and

much missed) Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation. Their work is characterized by clear, unfussy, carefully detailed elegance.

On the Canadian Canoe Museum project, Unity faced a challenging set of conditions: a constrained budget, a site different than the one they had initially designed for, and a compressed timeframe for construction. Unity nonetheless delivered a much better building than would have been expected in the circumstances they faced. With a restrained palette of materials and controlled spatial sequence, Unity Architects has created a place that connects the visitor to the artifacts through material and movement.

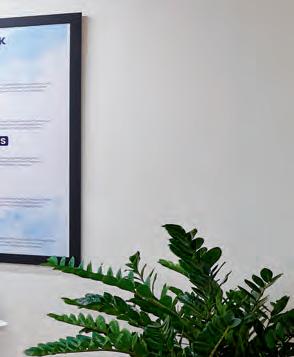

The new building, fronting a broad bend in the Otonabee River called Little Lake, is set towards Ashburnham Drive, away from the river’s floodplain. The building presents a long, mostly mute, weathering steel façade to the road. These vertically oriented siding panels are well on their way to becoming fully patinated, and their warm orange colour provides a textured backdrop to the Museum’s trilingual signage, which incorporates a pictograph (mazinaawbikinigin) from the indigenous Fort William First Nation.

A full-height glazed volume marks the main entrance, held in a frame of prefinished metal and wood cladding. The curtainwall glazing of the

two-storey entrance vestibule is fritted with a large-scale hydrological map showing the waterways of central Canada, from Hudson’s Bay to the Great Lakes. This is the first of many references to wood, waterways and cultural history understood especially through an Indigenous perspective that repeat through the experience of the Museum and the display of its collection. South of the entry, the building’s volume erodes away, and a faceted curve of weathering steel siding lifts, tilting above a broad triangle of curtainwall.

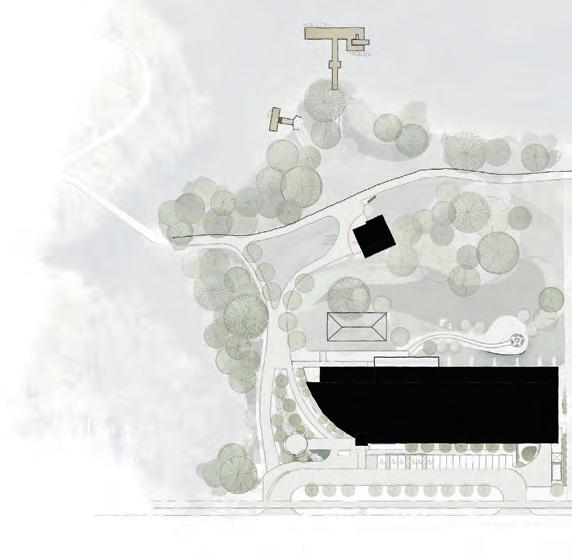

Inside, the building is a long bar composed of two double-storey levels. On the ground floor, two-thirds of the building houses the Museum’s archive: 500 watercraft cradled and stacked high on custom racks. Directly above this volume, the 1,850-square-metre exhibition space contains the approximately 100 vessels on display.

South of the exhibition and archive hall, the public spaces of the museum are anchored by a 7.6-metre-tall entry hall, which includes a café, gift shop, workshop and staff spaces. This open atrium is a glulamframed mass timber structure, clad in cross-laminated timber panels.

Given the complex technical requirements involved in providing a “class A” archival climate-controlled space for the collection, Unity focused their design towards a strategic use of the remaining resources; the large-scale public entry hall and spiralling promenade to the

exhibit hall on the second floor are especially successful. The entry hall’s timber frame and cladding particularly at the southeast corner, where the curtainwall glazing displaces the spruce CLT panels, exposing the Douglas fir glulam structure as a frame is an elegant echo of the frame-and-birch construction of many of the canoes and kayaks in the collection. An acoustic ceiling with white oak wood slats helps control sound and keep the space intimate, and the wood material palette evokes a gathering lodge. Along the west façade of the entry hall, a three-storey hearth is flanked with glazing that overlooks the Otonabee River and Little Lake. A two-sided dry-laid stone chimney anchors the building’s south-west corner. The warmly appointed space was being well enjoyed on the wintery day I visited.

To access the exhibition space, visitors ascend a stair that spirals around a three-storey stack of wood-slat-clad service spaces and washrooms, shaped like a lozenge or a boulder in a river. This journey provides an overlook into the collection archive at different heights, as well as views of the entry hall, with its ceiling-suspended canoes and kayaks. You pass alongside them, see them from below and then from above, always moving alongside a wood surface and grasping a wood handrail that provides a direct physical connection to the material world of this collection.

In addition to the main exhibit hall, the second floor contains a multipurpose space and library. The exhibit hall is a black-box space under the building’s asymmetrical gable roof, entered through the threshold of a simple millwork frame. It’s worth mentioning that while exhibitions can sometimes come across as diffuse or sparse in these types of largescale black painted volumes, the Canadian Canoe Museum’s exhibition design, by Montreal’s GSM, is extremely well arranged. Another hydrological map this time of North America, where Canada appears like a vast sponge with spidery rivers and myriad lakes anchors the hall under a spiral of suspended canoes and kayaks. Watercraft are displayed along with a mix of video, audio, and interactive components all with a welcome emphasis on Indigenous voices and perspectives. The elegance of the objects themselves is undeniable, and the skill of their makers is evident and remarkable.

While my winter visit meant arrival by car, a network of interconnected parks and a riverside section of the Trans Canada Trail give an unusual prominence to the building’s river face, which Bill Lett and Michael Gallant from Unity describe as the building’s true front door in the summer months. A smaller volume on the river holds 50 canoes at the waterside, along with two fully accessible docks. For the first

time in its history, the museum has an onsite facility where visitors can get firsthand experience of paddling a canoe or kayak.

Perhaps the most successful attribute of Unity Architects’ design for the Canadian Canoe Museum is their distillation of the artefacts, the canoes and kayaks, into the experience of the museum itself. Their subtle evocation of form, craft, and movement is carefully considered and achieved without superfluous gestures. The building embodies the elegant logic of its collection and provides a fitting new home for these foundational objects of Canadian culture.

Javier Zeller, MRAIC, is an architect working in Toronto with Diamond Schmitt Architects.

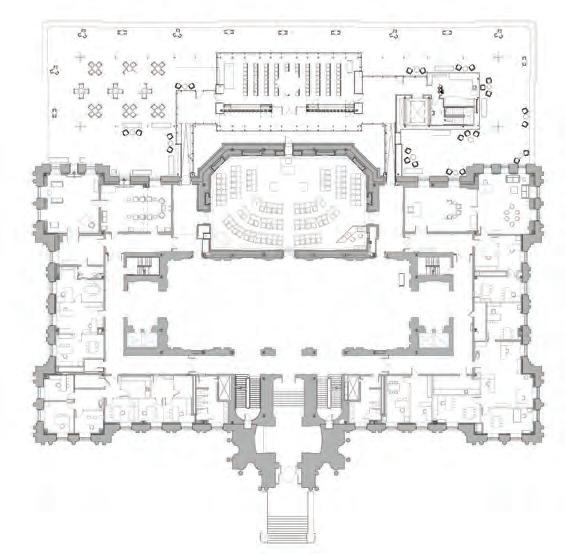

THE SEVEN-YEAR-LONG MODERNIZATION OF MONTREAL’S CITY HALL BUILT TRANSPARENCY INTO THE LANDMARK BUILDING—AS WELL AS INTO THE PROCESS OF RESTORING IT.

PROJECT Montreal City Hall modernization, Montreal, Quebec

ARCHITECTS Beaupré Michaud et Associés, Architectes in collaboration with MU Architecture

TEXT Peter Sealy

PHOTOS Raphaël Thibodeau

The successful restoration of Montreal’s City Hall by Beaupré Michaud et Associés, Architectes in collaboration with MU Architecture and a team of ten other specialist firms presents not only an ecologically and aesthetically superb work of civic architecture, but also a welcome opportunity for reflection upon the meaning of public buildings and why they should be valued.

When we speak of architecture as “public,” we are sometimes referring to buildings in government ownership a category which would include spaces with little or no access, such as fire stations, prisons, schools, and wastewater treatment plants. In other cases, a building’s publicness is adjudged precisely because it can be entered by anyone, with limited restrictions, no matter who its owner may be. Fast food restaurants,

shopping malls, and subway stations belong to this latter category.

While libraries, museums, and recreation centres comfortably straddle these two definitions, major government buildings such as embassies and legislatures test architecture’s capacity to meaningfully welcome citizens in the face of onerous and ever-increasing security requirements. With Montreal’s City Hall (known as the Hôtel de ville in French), this dual challenge of creating a building that is open to citizens, and yet also functional for municipal governance, has been ably handled by the architects charged with revitalizing this century-old edifice.

Situated at the edge of the Old City between the Champ-de-Mars and Place-Jacques-Cartier, Montreal’s Hôtel de ville offers impressive vistas southwards towards the St. Lawrence River and northwards to Mount Royal. Constructed in 1872–78 to designs by Alexander Cowper Hutchison and Henri-Maurice Perrault, the Second-Empire-style Hôtel de ville was rebuilt following a devastating fire in 1922 and later expanded in the 1930s; major restoration works took place from 1990 to ’92. Its best-known feature is forever ingrained in our history: the south-facing balcony from which the French President Charles de Gaulle delivered his famous “Vive le Québec Libre!” speech to a rapturous crowd in July 1967.

The early 2010s were a difficult period for Quebec politics, as fraught debates over religious symbols and reasonable accommodations were layered atop student strikes and municipal corruption scandals—especially

around the awarding of construction contracts—resulting in a profound sense of public unease and distrust. Maclean’s magazine would later apologize for a controversial 2010 cover showing Bonhomme Carnival carrying a briefcase stuffed with cash, accompanied by the incendiary headline “The Most Corrupt Province in Canada.” It was against this background that restoration work on the Hôtel de ville’s copper roofs revealed the need for far larger interventions. In launching a wide-ranging revitalization of the Hôtel de ville in 2017, the City of Montreal set transparency as its order of the day, both spatially and financially.

Spatially, this meant opening the building to make it more accessible and welcoming to visitors. While open doors and glass walls are no guarantee that malfeasance has been banished, such gestures were supported by first Mayor Denis Coderre’s and later Mayor Valérie Plante’s administrations, under whose aegis the project was executed. As a result, the areas accessible to all members of the public have been more than doubled, including a vastly enlarged reception lobby, public café, and planned exhibition space.

While far from ideal—the presence of a metal detector, x-ray machine, and several security guards hardly screams “bienvenue!”—this necessary compromise marks the point of departure for a laudable and stunning sequence of public spaces spanning two floors. From the large ground-floor vestibule, upstairs to the massive and ornate Hall of Honour and council chamber, visitors may wander and appreciate a restoration which appears imperceptible. Thanks to painstaking work, marble, brass, wood, and iron-

work appear as they might have a century ago, when the building was freshly made: thousands of hours of intellectual and physical labour have been expended to make it appear as if nothing had changed, and nothing had been touched.

This promenade patrimoniale concludes with the newly built Salle du pin blanc, a rooftop pavilion offering stunning views of the city and the Hotel de ville’s own façades. Clad in brass, the pavilion is a solid yet unobtrusive presence upon the historic building. Visitors who turn away from the vista are afforded a special treat: the chance to gaze upon the five historic stained-glass windows which adorn the council chamber’s exterior façade.

Financially, the imperative for transparency meant that throughout the project, agreements with over fifty sub-contractors—from heritage masons to plumbers—had to be approved by separate votes of the city council. The resulting series of arrangements for this Integrated Design Process (IDP) was complex for the architects to supervise, but also led to closer-than-usual collaboration between the designers and sub-trades. Throughout, modern amenities—be they the cabling needed to broadcast council sessions, or updated ventilation to introduce fresh air—are largely imperceptible and completely unobtrusive. The level of care and coordination from architects and tradespeople needed to bring about such a result deserves high praise.

As the project unfolded, two principal veins of work emerged. At one scale, the overall restoration involved the removal of a century’s worth of accreted partitions and wall coverings—each of which detracted from the grandeur and vision of the original Hôtel de ville. This is clearly

apparent in the transformation of the salon de la Francophonie, which leads to the Balcon du discours from which De Gaulle made his provocatively emancipatory proclamation. The meanness of what was previously a dim series of small rooms has given way to a generous and well-lit salon leading to the balcony: here, restoration is a matter of subtraction.

This was far from the only moment in which restoration uncovered elements of the original Hôtel de ville, which had been hidden behind decades of previous interventions. For example, on the ground floor, the original north façade, obscured during the construction of an addition to the rear of the building in the 1930s, has now been revealed. Heavy greystone blocks together with patches of brick and mortar are now visible from the Salle des armories on one side and the city clerk’s office on the other. Five openings in this long-hidden façade are adorned with a series of tableaux by the artist Chih-Chien Wang, which echo historic stained-glass windows in the city council chamber immediately above.

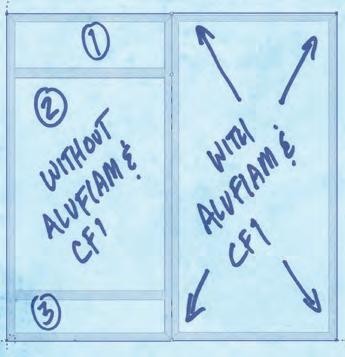

At a finer-grained scale, the team laboured to reuse, recycle, and refurbish existing finishes and furnishings. The most impressive act of reuse is found in the restoration of the Hôtel de ville’s 169 double-height sash windows, which date from 1925. Framed in white oak, these windows had previously been blighted by poor energy performance and pierced by an unsightly array of air conditioners. The process of retrofitting began with the meticulous testing of two mock-ups. Even after careful analysis proved that the proposed window retrofit would be effective, it took a leap of faith from the municipal client to accept that this would be possible for such a huge number of windows. The result has

ABOVE The building’s office areas have been revitalized with a priority on creating open meeting and working areas, and the introduction of abundant daylight throughout the floorplate.

been an immense success, with the building’s energy use reduced by 79 percent. By undertaking this process, the city leads by example, retaining heritage elements in the same way it often requires of homeowners undertaking renovations. The resulting effect is magnificent.

Out of sight of most visitors, the Hôtel de ville includes significant office space for Montreal’s elected officials, including the mayor, along with their staff and municipal employees. This is executed brilliantly, replacing dark and cramped office areas with well-lit and apportioned spaces. The careful use of fritted glass partitions allows daylight to penetrate into interior spaces, which are arranged between the external façades and a core of white-oak-clad meeting rooms and service spaces.

Two features jump out in the office areas: first of all, the emphasis on biophilic design, realized through an impressive quantity of plants arranged throughout. Secondly is the care with which mechanical services have been integrated into the building’s various spaces. One glance at the ceiling reveals the thoughtful arrangement of radiant heating panels, luminaires, and mechanical services. Once again, architecture is revealed to be—at least in part—a matter of coordinating labour to produce a seamless effect.

Many of Canada’s most significant representational buildings are either currently under restoration (the Parliament buildings in Ottawa) or in dire need of it (the Prime Minister’s official residence at 24 Sussex Drive). At a moment of financial stress, which overlaps with parallel—and somewhat related—anxieties about political polarization and our ability

to complete large-scale public works, such projects necessarily attract scrutiny, and often scare governments away from investing the needed funds to maintain our national heritage. The success of Beaupré Michaud and MU ’s transformation of Montreal’s Hôtel de ville suggests a way out: project by project, contract by contract, window by window, if needs be. The question remains to what extent the citizens of Montreal will adopt their Hôtel de ville as a properly civic space. What is clear is that this civic symbol has been revitalized in an exemplary manner. Whatever Montrealers think of their elected officials, they can be justifiably proud of their city hall.

Architectural historian Peter Sealy is an Assistant Professor at the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto.

CLIENT VILLE DE MONTRÉAL ARCHITECT TEAM BEAUPRÉ MICHAUD ET ASSOCIÉS: MENAUD LAPOINTE (MRAIC), NELLY CHARPENTIER, PATRICK MA, NICOLAS GAUTIER, SABRINA RICHARDSON, CAMILLE CHAREST, MAXIME BONESSO, CATHERINE LAMARRE, MARTIN TURENNE, PARISA ROOSTA, BAPTISTE AITKEN, ÉTIENNE MILOUX. MU ARCHITECTURE: CHARLES CÔTÉ, MICHELLE BÉLAIR, VÉRONICK LALONDE, SAKIKO WATATANI, MAUD BENECH STRUCTURAL NCK INC. | MECHANICAL/ ELECTRICAL MARTIN ROY ET ASSOCIÉS | INTERIORS BEAUPRÉ MICHAUD ET ASSOCIÉS, ARCHITECTES IN COLLABORATION WITH MU ARCHITECTURE | CONSTRUCTION MANAGER POMERLEAU | DECONTAMINATION LE GROUPE GESFOR | ACOUSTICS SOFT DB | A/V GO MULTIMÉDIA | LIGHTING CS DESIGN | FURNISHINGS DAVID GOUR | VERTICAL TRANSPORTATION JMCI | AREA 27,700 M2 BUDGET $221 M COMPLETION JUNE 2024

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 98 KWH/M2/YEAR | WATER USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 0.11 M 3/M2/YEAR

TEXT Larry Wayne Richards

AND IMAGINATION IN DIGITAL SPACE TEXT Lawrence Bird

“The new age arrives on no specific day; it creeps up slowly, and then pounces suddenly.”

-The New Yorker, The A.I. Issue, November 20, 2023

The digital realm and the extended realities of architecture are changing at breakneck speed. There is a sense of something radically different now an accelerating cyber-avalanche, generating previously unimagined spatial complexity. With the convergence of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and robotics, a new era of both real danger and great opportunity has arrived.

In 1966, Canadian Architect published a two-part essay by Toronto philosopher Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980), titled “The Invisible Environment.” His musings extended from Plato and education, to John Cage and silence, to computers and electronic circuitry as an extension of the human nervous system. McLuhan reworked the essay for Yale University’s prestigious Perspecta journal in 1967, with an adjusted title: “The Invisible Environment: The Future of an Erosion.”

These essays are labyrinthian. McLuhan speaks of “the new and potent electronic environment we now live in” and the “intricate and

complex integral world of electric information,” with assertions like “The future of city (sic) may be very much like a world’s fair a place to show off new technology not a place of work or residence whatever.” All of this gets bracketed with digressions into pop culture’s invisible systems and brainwashing, with comments on The Beatles and even an illustration of Sean Connery as James Bond, pointing a gun skyward. Expanding on the invisible systems and environments that he believed to be increasingly controlling our minds and society, McLuhan writes about consciousness: “Let me suggest that it may be possible to write programs for changes not only in consciousness but in the unconscious in the future. One could write a kind of science fiction story of the future of consciousness, ‘the future of an erosion’. The future of consciousness is already assuming a very different pattern, a very different character.” It’s as though McLuhan was talking about today.

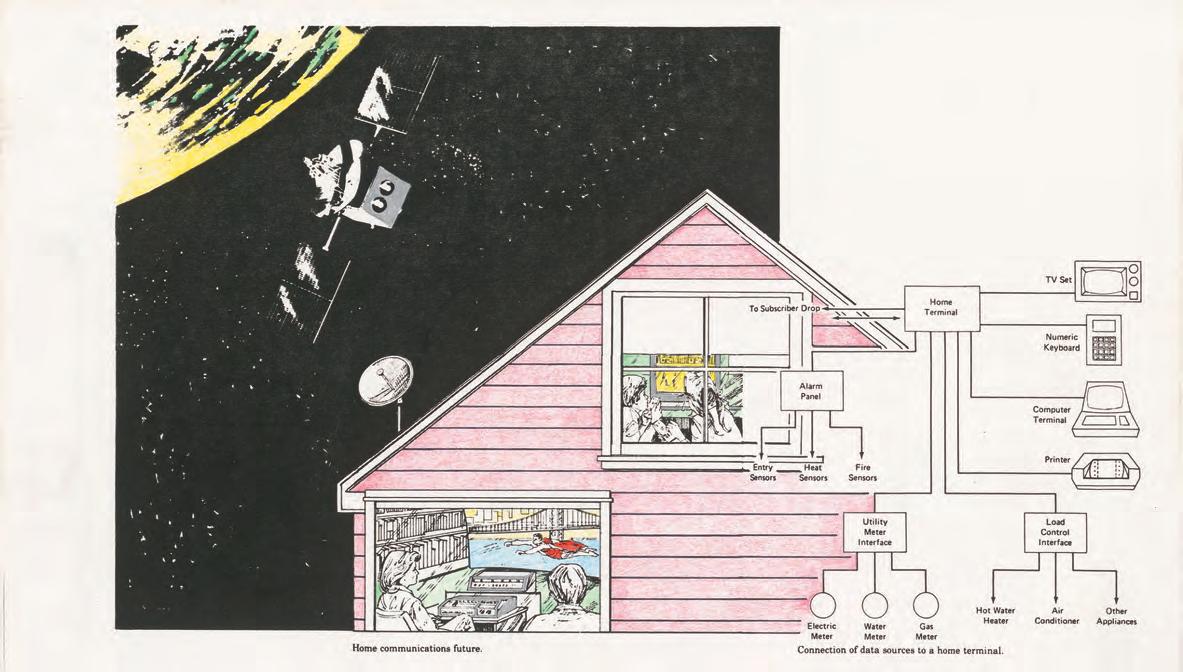

Two decades later, in 1983, the “birth year” of the internet, I presented a project entitled “The Positive and Negative Influences of Electronic Systems on Architecture” at an international research meeting in Poland. The project focused on how computing was transforming architectural design and production, and speculated on new kinds of digitized, simultaneous experience. I included a colour-enhanced illustration of an electronic cottage, offering a glimpse into a world that has now fully arrived

ABOVE A 1983 pre-internet-era illustration, colour-enhanced by the author, reflected on the possibilities of an “electronic cottage” connected to global information systems.

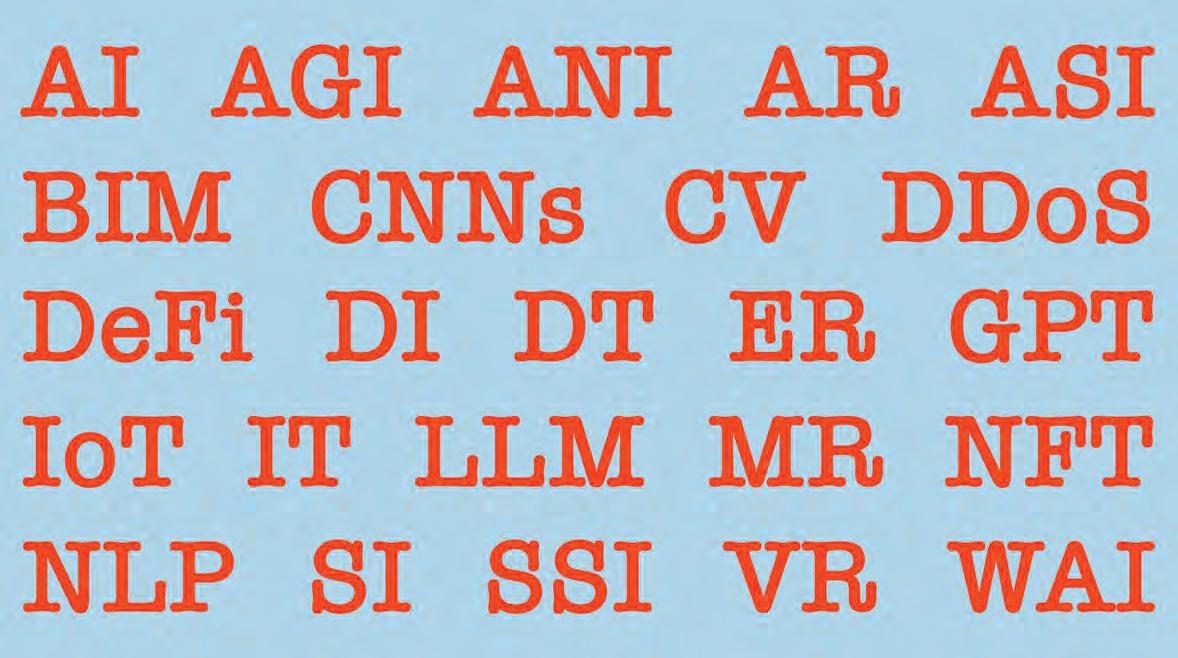

ABOVE A graphic by Richards and Julie Fish, entitled Some Acronyms, points to the disorientation of rapid technological change. OPPOSITE, TOP TO BOTTOM A rendering by Khloe Bouchard of Montreal-based Moment Factory points to the normalization of socializing in virtual spaces; a recent rendering generated by student Zee Virk in Midjourney points to the discontinuities of A.I.-generated imagery; SPAN’s interactive installation, The Doghouse, explores the possibility of folding 2D images from Midjourney into a 3D physical object, and incorporates robotics and advanced fabrication techniques.

given today’s techno-laden skies, with more than 10,000 satellites plus two occupied space stations orbiting Earth, and the preponderance of work-and-shop-from-home. Through that 1983 project, I was starting to realize that, as David Wortley, British consultant on immersive technologies, said to me, “We can be several places all at once.”

Since the 1980s, research and publications on digital architecture have exploded, as documented in the 1,660-page book Digital Architecture (Mark Burry, ed., Routledge, 2020). Canada’s architectural practices became more efficient with electronically assisted computation. Imaginative proposals for virtual places have proliferated, like Toronto-based theoretician Brian Boigon’s 1993-95 Spillville, a conceptual design for the first avatar town, in which one could interact with cartoon characters on the internet. Boigon explained, “You’ll have your own personal cartoon, and you’ll be able to manipulate it in cyberspace.”

During 2010-11, the Canadian Centre for Architecture presented 404 ERROR: THE OBJECT IS NOT ON LINE . The exhibition, which included aspects of my 1983 project, questioned online habits and new ways of thinking about the web. Two years later, the CCA generated an exhibition and accompanying book, Archaeology of the Digital (Greg Lynn, ed., CCA and Sternberg Press, 2013) that explored the genesis and establishment of digital tools at the end of the 1980s.

Fast forward to 2019 when, in a coda to my chapter on postmodernism in Canadian Modern Architecture (E. Lam and G. Livesey, eds., Princeton Architectural Press), I referred to “cyber-postmodernity” and “techno-postmodernity.” These references were spotted by David Minke, associate at GEC Architecture, who invited me to give a talk

in an office lecture series and to elaborate on my cyber-techno preoccupations. Minke asked: “What era are we in?” Thus, the prickly matter of Zeitgeist arose: What is our time, space, and spirit?

I gave the lecture for GEC at their Toronto studio and via Zoom for their Alberta offices. Titled “Extended Realities,” I spoke about the extraordinary time that we are in the rapid technological change characterized by acceleration, convergence, and disorientation, and symbolized by a mind-boggling profusion of defining acronyms. I asked that audience and now I ask readers here to ponder what these extended realities might mean for the changing practice and creative art of architecture.

Although some see our current socio-technological condition as simply another inevitable step in the so-called March of Progress the evolution of humankind over millions of years I’m not convinced. Granting that the momentous technological inventions of the past two centuries such as the telegraph, electricity, radio, automobiles, airplanes, television, computers, robots, and smart phones were disruptive at the time, but soon smoothed into daily life, today’s changes seem to be of a different magnitude. According to the Oomph Group (January 14, 2025), there has recently been “a huge influx of venture capital into the AEC industry” in Canada, fuelling tech start-ups and generating highly competitive, disruptive circumstances. Indeed, the rapidly unfolding, immersive, resource intensive, micro-chip world of artificial intelligence, robotics, and virtual reality is unprecedented.

These new, fluid technologies propel us far beyond the array of familiar altered states such as dreams and anaesthesia, or the tech-placeotherness of smart phones and Zoom, and into augmented, extended, and simultaneous realities. There are new, architectural-digital-spatial implications particularly in the arena of the material versus the immaterial. There is no longer an inevitable, innocuous technological continuum. Something new is happening, erasing boundaries between the real and the unreal, truth and fiction.

Artificial intelligence is getting smarter faster, but harbours its own demise. In “When A I.’s Output Is a Threat to A I. itself,” Aatish Bhatia (New York Times, August 25, 2024) forewarns of degenerative A.I. which “hallucinates” on its own data and, through unintended feedback loops, “The model becomes poisoned with its own projection of reality.” This is true of images as well as text.

Both the magic and madness of accelerating digital technologies were brought home to me in a rendering generated by Zee Virk, a student of Dr. Douglas MacLeod at Athabasca University. Using Midjourney A.I., she entered the elaborate prompt: a community wellness centre, with a rotunda in middle bringing in natural light, views of the surrounding pine trees beyond, glass door opening to a seating area, people of all ages, timber and brick structure, café with plants at front, concrete floor, --ar 16:9

The almost instantly produced image seems lovely until one looks closely and sees bizarre, structural anomalies. Where are those timber fragments heading? MacLeod notes that such discontinuities raise the question: “Will being articulate with input become the most important characteristic of an architect?”