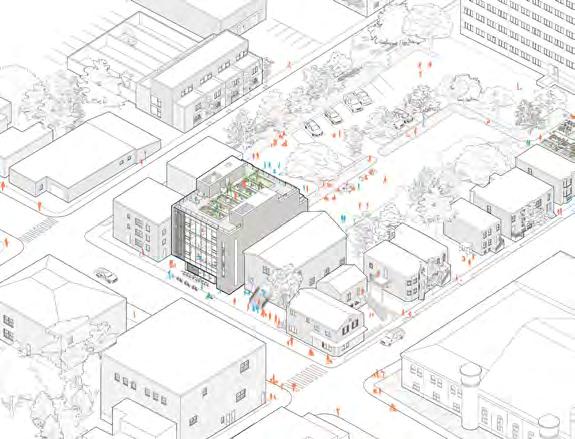

An five-unit infill by LGA Architectural Partners offers a look at how Toronto’s “missing middle” can be addressed with sensitivity and finesse. TEXT Jaliya Fonseka

Halifax firm FBM designs their own office as a prototype for mixed-use, mass timber construction in Atlantic Canada TEXT T. E. Smith-Lamothe

New work by Kingman Brewster demonstrates that the tiny community of Fogo Island is becoming a hub for contemporary architecture. TEXT Michael Carroll

4

Architects champion pro-renovation, anti-demolition policies in Europe.

6

Remembering Shannon Bassett, 1972-2024.

Field reports from Tokyo and Brussels, 2025-2027 strategic vision.

Banff Centre’s Haema Sivanesan revisits the architectural legacy of the Leighton Artist Studios.

The provincial auditor general points to unfair procurement processes and opaque decisionmaking behind the ongoing redevelopment of Ontario Place.

48

New volumes on architectural theory, upfront carbon, Toronto’s Casa Loma, and more.

Peter Sealy reviews a new exhibition on Arthur Erickson’s travel photos and diaries.

COVER Ulster House, Toronto, by LGA Architectural Partners. Photo by Doublespace Photography.

On February 1, an architect-led group called HouseEurope! launches its “No to demolition, Yes to renovation” campaign. Using a mechanism called a European Citizens’ Initiative, they are filing a proposal for all European countries to introduce tax incentives for renovation, harmonize assessment standards for renovations, and require lifecycle analysis before demolition. They have a year to collect a million signatures from across the EU in support of their proposal. If they succeed in doing so, the EU parliament is obliged to discuss the implementation of the proposal.

The story of this effort is told in a documentary film commissioned by Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). The film, directed by Joshua Frank, is the centrepiece of a new exhibition at the CCA called To Build Law, on display until May 25, 2025. It is the second part of an ongoing exhibition and film series by the CCA that explores alternative forms of architectural practice.

How did architects end up making a major policy proposal and embarking on an ambitious PR campaign to convince a million others to support it? The effort was spearheaded by two groups: Berlin-based collaborative architecture practice bplus.xyz and the ETH Zurich-based chair for architecture and storytelling s+. As is becoming increasingly clear, the construction and operation of buildings is a significant contributor to the climate crisis, accounting for at least 38 percent of carbon emissions globally. The construction sector is also the biggest producer of waste in the European Union. Architects have a clear view of the environmental impact of buildings as well as the upfront carbon that can be saved by reusing and transforming buildings, rather than demolishing them.

The architects involved in the HouseEurope! campaign contend that the needed change cannot happen through the scope of traditional architectural practice, which is limited to addressing a single building at a time. A shift in

cultural norms is needed, supported by larger policy and legal structures.

How do such laws get made? Frank’s documentary follows the architects going through many of the processes that will be familiar to architects: establishing partners, drafting positions, testing ideas and slogans, convening meetings, strategizing campaigns, presenting at conferences.

The organizers note that every minute, a building in Europe is demolished. “Demolishing buildings wastes homes, jobs, energy, and history,” they write. The “demolition drama,” as they term it, is supported by the way that buildings are held as assets, to be torn down and redeveloped for the sake of profit, with limited consideration of community and environmental impacts even in the face of housing crises throughout Europe.

Over 50 percent of global assests are currently invested in real estate. “The built environment is one of the most valuable assets in today’s globalized speculative economy,” says Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou, Director of the Center for Capitalism Studies at University College London.

“We happily forget about and exclude [thinking about] those speculators and real estate developers who are planning at this moment to destroy the very fabric of our society so that they can make more money,” says economist and political advisor Ann Pettifor. “If your land is finite, the only way you can keep reinvesting it and keep generating returns is destroying everything and starting again.”

HouseEurope! argues that a fundamental change of values is needed that prioritizes social and environmental good, and that this change becomes possible when citizens demand it.

“Renovation and transformation are real alternatives,” they write. “We can change our value system through activism and direct democracy.”

EDITOR

ELSA LAM, FRAIC, HON. OAA

ART DIRECTOR

ROY GAIOT

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC

ODILE HÉNAULT

LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC

DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC

ADELE WEDER, FRAIC

ONLINE EDITOR

LUCY MAZZUCCO

SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR

ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C

VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3

SWILSON@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

FARIA AHMED 416 441-2085 x5 FAHMED@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

CIRCULATION CIRCULATION@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

PRESIDENT & EXECUTIVE PUBLISHER ALEX PAPANOU

HEAD OFFICE 126 OLD SHEPPARD AVE, TORONTO,

First all mass timber acute care hospital in North America breaks ground

The Quinte Health Prince Edward County Memorial Hospital in Picton, Ontario, which has officially broken ground, will be the first all mass timber acute care hospital in North America upon completion in 2027.

The new hospital is designed by HDR and currently under construction with M. Sullivan & Son and Infrastructure Ontario. This healing environment will serve its community with advanced medical technologies, energy-efficient operations, biophilic design principles, a low-carbon mass timber structure and access to nature throughout the facility. Its clinical capabilities will include 23 inpatient beds, an emergency department, diagnostic imaging procedures, comprehensive ambulatory care services, and healing gardens. Its sustainable infrastructure will feature geothermal energy, solar panels, green roofs, electric-vehicle-ready parking, and a high-performance building envelope for future electrification and net-zero carbon emission status. Located in the heart of Picton, Ontario, the new Prince Edward County Memorial Hospital will be adjacent to the existing hospital, which will remain operational during the new facility’s construction.

“It has been an amazing journey with Quinte Health and the Prince Edward County community to be able to bring such a groundbreaking energy and carbon reduction approach to the design of acute care facilities,” said Jason-Emery Groen, design director, HDR , Canada. “Through a multidisciplinary approach to building trust among key stakeholders, agencies and Authorities Having Jurisdiction, HDR was able to shift age-old limitations into phenomenal opportunities, not only for this community, but the future of healthcare design and beyond in North America.” hdrinc.com

Following three years of planning and design, Calgary Municipal Land Corporation (CMLC), Arts Commons and The City of Calgary have announced that the Arts Commons Transformation (ACT) expansion has broken ground.

Construction on the ACT expansion, designed by KPMB Architects, Hindle Architects and Tawaw Architecture Collective, will be managed by EllisDon with project management by Colliers Project Leaders, and is expected to be completed in 2028. The ACT expansion is the first of the three campus transformation phases to begin construction. The other two phases include the Olympic Plaza Transformation (OPT) project, which is now fully funded, and the ACT modernization, for which efforts are underway to secure the remaining required funds. Design is currently underway for the OPT project, which is aiming to create a more modern, inclusive and accessible arts-focused outdoor gathering space as part of the contiguous Arts Commons campus upon its completion in 2028. The design for the Olympic Plaza Transformation project will be revealed this spring. www.calgarymlc.ca

The Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG) has announced that it will not be going forward with the design of its proposed new building and that it will be bringing in a new architecture partner.

Estimates for the the project have now reached $600 million. Anthony Kiendl, VAG’s CEO and executive director, announced on December 3, 2024, that Herzog & de Meuron has been removed from the project, which is taking a new direction. “Following the temporary pause of on-site construction activity announced at the end of the summer, we have been reassessing the project’s direction. Throughout this process, we have been listening to feedback from our supporters, artists, members and stakeholders, who are helping to shape the next phase of this transformative project,” said Kiendl. In the statement, Kiendl went on to state that VAG ’s goal is to create a building that “embodies a diverse and inclusive artistic vision while ensuring financial sustainability within a fixed budget.”

Kiendl also noted that VAG recognizes that inflation has put “tremendous pressure” on their plans, and as a result, it has become clear that they require a new way forward to meet both their artistic mission and vision and practical needs. “For the past decade, we have had the benefit of collaborating with the esteemed Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron on plans for a new Gallery. We are grateful for our partnership with them, which has helped shape our thinking around what a museum could look like in the 21st century and provided valuable research that can be applied moving forward,” said Kiendl. “However, in view of our reassessment, the Gallery Association’s board has made the difficult decision to part ways with Herzog & de Meuron.”

The statement also noted that at its last meeting, the board approved updated Strategic Priorities that will guide the gallery as they move forward. “These underscore our commitment to build a new cultural hub that will be the heart of our communities and serve and inspire diverse audiences,” said Kiendl. Kiendl concluded by stating that in the coming months, they will schedule a series of opportunities at the gallery to share more about the next phase of the project and discuss it with its members and communities. www.vanartgallery.bc.ca

The inaugural Architectural Foundation of BC Achievement Awards event a continuation of the AIBC’s legacy program took place on November 21st, 2024. The 2024 Awards recognized four individuals. Nancy Mackin, founder of community-based design practice Mackin Architects, received the award for Community Stewardship. Darryl Condon, the Managing Principal of hcma, and a leader in professional

organizations including the Rick Hansen Foundation and the Regulators of Architecture in Canada, received the Barbara Dalrymple Memorial Award for Community Service. William R. Rhone, co-founder of Rhone & Iredale, received a Lifetime Achievement Award. Finally, RAIC Gold Medallist Peter Cardew was recognized posthumously with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

www.architecturefoundationbc.ca

Four Canadian projects were recently recognized at Singapore’s 2024 World Architecture Festival (WAF). The 2024 winners presented live to judging panels at the festival. The Canadian winning projects are 5468796 Architecture’s Pumphouse (Completed Building: Creative Reuse), 5468796 Architecture’s Arthur Residence (Completed Buildings: House & Villa, Urban/Suburban), NEUF architect(e)s’ Institut Thoracique de Montréal (Future Project: Office), and Coronation Park Sports & Recreation Centre, by hcma and Dub Architects in conjunction with FaulknerBrowns Architects (Future Project: Sport).

www.worldarchitecturefestival.com

based activities, and sporting and fitness activities. It is only the third Canadian project to earn recognition in the competition’s history.

The t m sew’txw facility has also recently been certified gold for accessibility by the Rick Hansen Foundation, which reinforces the principles of inclusive and accessible design that were core aspects of the facility’s planning and detailing. The 10,684-square-metre aquatic community centre is Canada’s first completed all-electric aquatic facility to achieve the Canada Green Building Council’s Zero Carbon Building-Design Standard. t m sew’txw is also the first to use the gravity-fed InBlue filtration system, which reduces the need for chlorine usage and creation of associated harmful byproducts.

Winners for this year’s edition of the Prix du Québec, the highest distinction awarded by the Government of Québec in the fields of culture and science, include Serge Filion, who was awarded the Ernest-Cormier Prize, and Raymond Montpetit, who received the Gérard-Morisset Prize. Serge Filion became director of the land use planning division for the City of Québec in 1969, where he designed Quebec City’s first land use plan and first zoning plan. From 1996 to 2005, he was director of planning and architecture at the National Capital Commission of Quebec. Raymond Montpetit is a researcher, museologist, author, and professor, who played a major role in establishing the province’s first master’s program in museology, and contributed to the design of the Centre d’histoire de Montréal, the Pointe-à-Callière Museum of Archaeology and History, and the Centre des mémoires montréalaises. www.Quebec.ca

t m sew’txw Aquatic and Community Centre, which recently opened in New Westminster, British Columbia, has been awarded a Special Prize for Interiors in the Sports category at the Prix Versailles in Paris. t m sew’txw, derived from the h n’q’ min’ m’ language and meaning “Sea Otter House,” was designed by hcma architecture + design, for all ages and abilities with a focus on community connections, wellness24_014607_Canadian_Architect_FEB_CN Mod: January 3, 2025 2:17 PM Print: 01/03/25 3:43:40 PM page 1 v7

We provide quality shipping, packaging and office furniture products to businesses across North America. From crates and tubes to tables and chairs, everything is in stock. Order by 6 PM for same day shipping. Best service and selection. Please call 1-800-295-5510 or visit uline.ca

Ontario Land Tribunal decides against preservation of Moriyama landmark

On Friday October 18, the Ontario Land Tribunal green-lighted the redevelopment of the former Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, a heritage-designated building designed by the late Raymond Moriyama, at 123 Wynford Drive. The proposed new development is a pair of condo towers, one of which is a 48-storey tower to be located on top of the heritage building.

To accommodate these proposed towers and below-grade parking, the developer plans to completely demolish the old Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre and later reassemble portions of the original building at an elevated grade. The City of Toronto refused the development application, citing the property’s heritage designation. “The proposal to demolish the building (with the exception of the north-west concrete pylon) and alter the property would result in the permanent loss of this significant cultural heritage resource,” wrote the Interim Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning. “The proposal to demolish and re-attach select portions of the original building onto a new tower structure in its former location at a much higher grade would remove the building’s integrity as a whole building and all its interior and exterior heritage attributes as well as alter its placement on the site.”

The heritage building, recently renovated by Moriyama’s firm, holds deep cultural, historical and architectural significance. This holds particularly true for Japanese Canadians, who have been advocating for the retention and restoration of the existing structure.

“Less than 20 years after Japanese Canadians were unjustly incarcerated during the Second World War, the Japanese Canadian community built the JCCC as a living monument to celebrate their ancestry, regain a sense of self-respect, and promote friendship with all Canadians through culture,” writes the National Association of Japanese Canadians’ Greater Toronto Chapter. “Due to a funding shortfall at that time, 75 community members stepped forward and put second mortgages on their homes and businesses to finance the building.”

The developer contested City Council’s refusal of their application by bringing the case to the Ontario Land Tribunal. In its decision to approve the development plans, the Tribunal wrote: “The Tribunal acknowledges the cultural and architectural significance of the existing structure. However, in the absence of any firm alternative plans, it believes that the proposal preserves the importance of the Subject Site. The Tribunal encourages both parties to continue discussions with this goal in mind.” www.olt.gov.on.ca

In October, NDP Ontario leader Marit Stiles filed a complaint with the Ontario Integrity Commissioner about the process in which Austrian spa company Therme was chosen to redevelop Ontario Place.

In her affidavit to the Integrity Commissioner, Stiles questions the callfor-development of Ontario Place, the evaluation process, and the lease agreement with Therme. Stiles claims that Infrastructure Minister Kinga Surma has shown “preferential treatment” to Therme during the Ford government’s process of partnering with private companies to redevelop Ontario Place. As a result, Stiles is asking for an investigation to identify whether the infrastructure minister broke ethics laws by choosing Therme as the main proponent for the redevelopment of Ontario Place. The complaint includes a nine-page-long affidavit and over 1,000 pages of documentary evidence. The documents reveal that the province is required to provide Therme with 1,600 parking spaces in a planned garage that will have over 2,000 spaces even though the call for development was explicit in only offering existing parking to applicants. “This evidence suggests that Therme received preferential treatment, and its private interests were improperly furthered, as a result of decisions for which Minister Kinga Surma is ultimately responsible,” reads the letter. The complaint also cites evidence reported in Canadian Architect that the Provincial government unnecessarily closed the Ontario Science Centre, based on a deliberate misinterpretation of engineering reports about the roof condition. The letter concludes with a request that the office investigate whether Minister Surma breached sections 2 and 3 of the Members Integrity Act.

www.canadianarchitect.com

Canadian-American architectural and urban designer Shannon Bassett passed away peacefully with family members by her side at the General Hospital in Ottawa on December 26, 2024, at the age of 52.

Bassett was a tenured professor of architecture at McEwen School of Architecture, Laurentian University, in Sudbury. Her research, teaching, writing and practice operated at the intersections of architecture, urban design and landscape ecology.

Bassett’s writing on China’s explosive urbanization and changing landscape, as well as shrinking cities and the post-industrial landscape in North America, have been published in Topos, Urban Flux, Landscape Architecture Frontiers Magazine, and Canadian Architect. Her design work

and research has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Hong Kong Shenzhen BiCity Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture in 2012. Her architectural and urban design practice included designing an urban masterplan for the Village of the Arts in Bradenton, Florida, as well as a series of speculative design studies for the City of Tampa Riverwalk. Prior to arriving at Laurentian, Bassett had taught at the University at Buffalo, the University of South Florida, and Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston. She has lectured in countries including China, India, South Korea, and the US. She has run design research studios in China, and for many years served as an invited professor each summer in Busan, South Korea.

A consummate collaborator, until her passing Bassett was actively collaborating with the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) on the conservation and urban redevelopment of the old walled city of Delhi. She was also collaborating with colleagues at Toronto Metropolitan University on a symposium examining the state of women in Canadian architecture, a topic she also advanced as a co-founder and advisory member for the organization Building Equality in Architecture North.

At Laurentian University, Indigeneity became a vital part of Bassett’s teaching and spirituality. “It is with heavy hearts we reflect on the passing of our colleague Shannon Bassett,” writes Laurentian University

McEwen School of Architecture director Tammy Gaber. “Shannon joined the McEwen School of Architecture as a faculty member in 2018, having studied architecture at Carleton (B.Arch) and urban design at Harvard University (MAUD). While at MSoA , Shannon enthusiastically taught a range of courses in the undergraduate and graduate programs and supervised M.Arch thesis students.”

“Beyond the classroom, Shannon actively mentored students in several international design competitions and was one of the co-founders of the Building Equality in Architecture North BEA(N) group, which continues to have a growing membership,” adds Gaber. “She will be deeply missed by our community.”

“Shannon Bassett was a critical member of the Building Equality in Architecture (BEA) collective, which aims to promote and support gender equity in architecture across Canada,” write Building Equality in Architecture Toronto (BEAT) Executive Chair Jennifer Esposito and Advisory Chair Heather Dubbeldam. “Co-founding BEA North in 2020, she played a key role in supporting the growth of BEA from a Toronto-based grassroots group to one with a national presence. Shannon was an advocate for gender equity and diversity in the profession, particularly in northern communities. She was also a committed educator, sharing her expertise and enthusiasm with the next generation of architects through her roles in academia. Kind, generous, and courageous in her beliefs, Shannon’s contributions to education, research, and advocacy will leave a lasting impact.”

The family has requested donations to the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada.

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe

ACO DRAIN Multipoint

Suitable for heavy duty areas

Disability Act compliant grates

Standard trash bucket

Optional foul air trap & silt bag

May be used on waterproofed terrasses

Type FT-30 flood tight floor access doors are constructed for use in applications where there is concern of water or other liquids entering the access opening. Type FT-30 doors are rated to withstand a 30-foot (9.14m) head of water from the topside without leakage and up to a 5-foot (1.52m) head of water from the underside (when specified) and will resist low-pressure gases and odors. Doors are reinforced for AASHTO H-20 wheel loading and feature aluminum construction, type 316 stainless steel hardware, and engineered lift assistance for easy one-hand operation.

Registration open: Conference on Architecture

With over 50 education sessions, as well as architectural tours and many special events, you don’t want to miss this annual flagship event. Make sure to register before March 22 for the best rates. raic.org/2025-raic-conference-architecture

L’inscription à la Conférence sur l’architecture est ouverte

Plus de 50 séances de formation, des visites architecturales et de nombreux événements spéciaux au programme de cet événement phare annuel que vous ne voudrez pas manquer. Inscrivez-vous avant le 22 mars pour profiter des meilleurs tarifs. raic.org/fr/raic/conference-sur-larchitecture-de-lirac-2025

Elevate your career: Renew your RAIC membership for 2025

Your RAIC membership helps you stay connected, informed, and up to date with the latest developments in the field. Ensure uninterrupted access to exclusive benefits, cost savings, and learning opportunities in 2025 by renewing your RAIC membership. raic.org/renewal

Rehaussez votre carrière : renouvelez votre adhésion à l’IRAC pour 2025

L’adhésion à l’IRAC vous permet de rester en contact avec la profession et d’être au fait des dernières nouvelles dans le domaine. Renouvelez votre adhésion pour un accès ininterrompu à des avantages exclusifs, des réductions de coûts et des activités de formation en 2025. raic.org/fr/renouvellement

New Courses for 2025

Looking to take your architecture practice to greater heights? Good news! We’re bringing you two new courses: HR Essentials for Architects and Financial Management for Architects. Led by certified industry experts, these courses will give you actionable insights and tools tailored to the architecture profession. raic.org/live-online-courses

Nouveaux cours en 2025

Vous souhaitez faire croître votre firme d’architecture? Bonne nouvelle! Nous présentons deux nouveaux cours : HR Essentials for Architects et Financial Management for Architects. Animés par des experts agréés de l’industrie, ces cours vous fourniront de l’information utile et des outils pratiques adaptés à la profession d’architecte. raic.org/live-online-courses

Registration is open for this year’s Conference on Architecture

L’inscription à la Conférence sur l’architecture est ouverte

Giovanna Boniface

RAIC Chief Commercial Officer Chef de la direction commerciale de l’IRAC

Established in 2013 as the RAIC Moriyama Prize, the RAIC International Prize was created based on Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama’s belief that remarkable architecture has the power to transform society by promoting humanistic values of social equality, respect and inclusiveness. It aims to create environments that contribute to the wellbeing of all people.

Le Prix international de l’IRAC, créé en 2013 sous le nom de Prix Moriyama IRAC, repose sur la conviction de l’architecte canadien Raymond Moriyama que l’architecture remarquable a le pouvoir de transformer la société par la promotion des valeurs humanistes d’égalité sociale, de respect et d’inclusion. Il vise à créer des environnements qui contribuent au bien-être de toutes les personnes.

The RAIC is the leading voice for excellence in the built environment in Canada, demonstrating how design enhances the quality of life, while addressing important issues of society through responsible architecture. www.raic.org

L’IRAC est le principal porte-parole en faveur de l’excellence du cadre bâti au Canada. Il démontre comment la conception améliore la qualité de vie tout en tenant compte d’importants enjeux sociétaux par la voie d’une architecture responsable. www.raic.org/fr

In 2023, the Prize expanded to encompass the broader and ever-evolving mission, vision and values of the RAIC and Canadian architects, focusing on an annual theme. The theme for 2024, Indigenous Architecture, acknowledged and celebrated Indigenous practitioners who incorporate Indigenous knowledge, ways of knowing and doing in the built and natural environment. The theme for 2025 is Climate Action. It seeks to highlight a project outside of Canada that exemplifies design excellence in climate action and regenerative development and design.

The recipient of the 2025 International Prize will be identified by a selection committee, and presented at the June RAIC Conference on Architecture in Montreal.

En 2023, les modalités du Prix ont été modifiées pour englober la mission, la vision et les valeurs élargies et en évolution constante de l’IRAC et des architectes canadiens. Le thème pour 2024, Architecture autochtone, visait à reconnaître et à célébrer les praticiens autochtones qui intègrent le savoir des Autochtones et leurs modes d’apprentissage et leurs façons de faire dans l’environnement bâti et naturel. Le thème pour 2025, Action climatique, vise à mettre en lumière un projet réalisé à l’extérieur du Canada qui se distingue par l’excellence de sa conception en matière d’action climatique et de développement régénératif.

Le lauréat du Prix international 2025 sera choisi par un comité de sélection et le prix lui sera remis dans le cadre de la Conférence sur l’architecture de l’IRAC à Montréal.

We are going to do this together:

Ryan McClanaghan

Architect AIBC; Associate, DIALOG

Architecte AIBC; Associé, DIALOG

In the spring of last year, I travelled to research the emerging field of bio-regional design, experiencing first-hand how exceptional architectural and material practices are forging a path forward to a healthier, lower-carbon future for our built environment. I am the latest recipient of DIALOG’s Iris Prize, an internal research and travel grant for practitioners, awarded annually to explore innovative ideas that meaningfully improve the wellbeing of communities and the environment we share. What follows is a dispatch from my research trip.

The bio-regional design framework is straightforward: it focuses on locality, biomaterials and new construction processes to achieve exceptional results. The challenge lies in implementation—breaking free from the status quo of a global network reliant on high-carbon, unsustainable construction materials. In a bio-regional approach, the process of construction becomes as important as the design itself, with novel techniques and, often, new materials being created.

In Basel, Switzerland, Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane has designed the Vitra campus’s most sustainable building to date: a small garden house made from thatch and timber, using materials that are grown instead of those extracted from below ground. Meanwhile, in Basel, Herzog & de Meuron are constructing HORTUS, a five-storey building designed to be net energy-positive within 31 years. It features a rammed earth structural floor system, developed together with the client Senn AG and ZPF Ingenieure, and a reduced material palette of clay, wood, and cellulose. It is, without question, the most ambitious example of building at scale using natural materials that I’ve seen: the approach is imaginative and technically rigorous, resulting in a stunning building.

BC Architects, Materials, and Studies in Brussels operate as a tripartite practice, specializing in earth construction, using surplus excavated soil from building sites. They began as an architecture studio but discovered that Brussels’ urban geology is ideal for creating rammed earth and other earthbased building products. This led the architects to establish a materials company, BC Materials, which manufactures products like earth blocks (replacements for traditional concrete masonry blocks), fired bricks, mixes

for unstabilized rammed earth (made without cement binders and fully reusable), and earth plasters and paints for interior finishes. They also founded BC Studies, a branch dedicated to education and teaching others.

On a hot summer day, I joined one of BC Architects’ “Earth Discovery Day” workshops at their shared workspace with BC Materials. Alongside a small group of architects, builders, and students, I participated in hands-on exercises to experiment with different earth product mixes. I left with clay under my fingernails, sand in my shoes, and excitement for the potential of earth-based construction.

Rotor, another Brussels-based practice, focuses on salvaging construction materials from the built environment. They operate both as a supply outlet for dismantled and reclaimed building components, and as consultants helping other design practices integrate circular construction strategies. Their large warehouse in northern Brussels showcases salvaged materials, which are often sold at lower costs than new products, to those who appreciate the patina and texture of second-hand materials. Rotor has also conducted several EU studies on circular construction, and is involved in ambitious

HORTUS, by Herzog & de Meuron, is a rammed earth timber building under construction in Basel, Switzerland.

HORTUS, par Herzog & de Meuron, un bâtiment en bois et en pisé en construction à Bâle, en Suisse Herzog & de Meuron

projects like the adaptive reuse and retrofit of an 18-storey office tower in collaboration with Snøhetta. Their goal: to allocate 3% of the building’s overall weight and cost to repurposed materials. When I visited their studio, the team was busy preparing an exhibition to highlight the work they and others across Europe are doing to advance circular construction practices.

What stood out most during the trip wasn’t the novelty or innovation of these construction techniques—it was the openness with which everyone shared their learnings, taught others, and inspired action. There was an urgent sense of responsibility to move toward a more sustainable future. Now that I’m back in Canada, the challenge is figuring out how to create our own regional approaches to low-carbon building.

Au printemps dernier, j’ai effectué un voyage de recherche sur le domaine émergent de la conception biorégionale afin d’observer directement comment les pratiques exceptionnelles en architecture et dans le choix des matériaux tracent la voie à un avenir plus sain et plus sobre en carbone pour notre environnement bâti. Je suis le dernier lauréat du Prix Iris de DIALOG, une bourse de recherche et de voyage destinée aux praticiens et décernée chaque année pour explorer des idées innovantes qui améliorent véritablement le bien-être des collectivités et l’environnement que nous partageons. Voici un compte-rendu de ce voyage.

Le cadre de la conception biorégionale est simple : il se concentre sur la provenance locale, les biomatériaux et les nouveaux processus de construction qui permettent d’obtenir des résultats exceptionnels. Le défi réside dans la mise en œuvre –s’affranchir du statu quo d’un réseau mondial qui dépend de matériaux de construction non durables à fortes émissions de carbone. Dans une approche biorégionale, le processus de construction devient aussi important que la conception elle-même du fait de la création de nouvelles techniques et, souvent, de nouveaux matériaux.

À Bâle, en Suisse, l’Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane a conçu le bâtiment le plus durable du campus Vitra à ce jour : une petite maison de jardin faite de chaume et de bois, qui utilise des matériaux cultivés plutôt que des matières premières d’extraction. Pendant ce temps, à Bâle, Herzog & de Meuron construisent HORTUS, un édifice de cinq étages conçu pour être à énergie nette positive dans les 31 ans.

Il se distingue par un système de plancher structurel en pisé, développé en collaboration avec le client Senn AG et ZPF Ingenieure, et par une palette de matériaux réduite à l’argile, au bois et à la cellulose. Ce projet est sans aucun doute l’exemple le plus ambitieux de bâtiment d’envergure construit à l’aide de matériaux naturels que j’ai vu : l’approche imaginative et techniquement rigoureuse donne lieu à un bâtiment remarquable.

BC Architects, Materials, and Studies de Bruxelles est une firme tripartite spécialisée dans la construction en terre, qui utilise les

BC Architects, Materials, and Studies: building with earth and inspiring others in Brussels, Belgium

BC Architects, Materials, and Studies : Bâtir avec de la terre et inspirer les autres à Bruxelles, Belgique

Rotor, a practice based on reuse and the circular economy in Brussels, Belgium

Rotor, une entreprise axée sur la réutilisation et l’économie circulaire à Bruxelles, Belgique

excédents de terre excavée des chantiers de construction. À l’origine, la firme était un atelier d’architecture, mais lorsque les architectes ont constaté que la géologie urbaine de Bruxelles était idéale pour créer des bâtiments en pisé et autres produits de construction à base de terre, ils ont créé une entreprise de matériaux, BC Materials, qui fabrique divers produits dont des blocs de terre compressée (qui remplacent les blocs de maçonnerie en béton traditionnels), des briques cuites, des mélanges pour pisé non stabilisé (fabriqués sans liant cimentaire et entièrement réutilisables) et des enduits et

peintures à base de terre pour les revêtements intérieurs. Ils ont également fondé la firme BC Studies, une division dédiée à l’éducation et à l’enseignement.

Par une chaude journée d’été, j’ai participé à l’un des ateliers de la Journée de découverte de la terre organisée par BC Architects dans les espaces partagés avec BC Materials. Avec un petit groupe d’architectes, de constructeurs et d’étudiants, j’ai participé à des exercices pratiques pour expérimenter différents mélanges des produits de terre. Je suis reparti avec de l’argile sous les ongles, du sable dans mes chaussures et un vif intérêt envers le potentiel de la construction en terre.

Rotor, une autre entreprise établie à Bruxelles, se concentre sur la récupération des matériaux de construction de l’environnement bâti. Elle est un point d’approvisionnement en composantes de bâtiments démantelées et récupérées et elle agit comme consultant pour aider d’autres firmes de conception à intégrer des stratégies de construction circulaire.

Dans son grand entrepôt situé au nord de Bruxelles, on peut trouver des matériaux récupérés qui sont souvent vendus à des prix inférieurs à ceux des produits neufs pour autant que l’on apprécie la patine et la texture des matériaux de seconde main. Rotor a également mené plusieurs études de l’UE sur la construction circulaire et participe à des projets ambitieux comme la réutilisation adaptative et la rénovation d’un édifice de bureaux de 18 étages, en collaboration avec la firme Snøhetta. Leur objectif : allouer 3 % du poids et du coût total du bâtiment à des matériaux reconvertis. Lorsque j’ai visité les bureaux de Rotor, l’équipe était occupée à préparer une exposition pour mettre en lumière le travail qu’elle et d’autres firmes européennes réalisent pour faire progresser les pratiques de construction circulaire.

Ce qui m’a le plus marqué durant ce voyage, ce n’est pas la nouveauté ou l’innovation de ces techniques de construction, mais plutôt l’ouverture d’esprit avec laquelle toutes ces personnes ont partagé leurs apprentissages, enseigné à d’autres et suscité l’action. Elles étaient toutes animées d’un sentiment d’urgence face à la responsabilité d’aller vers un avenir plus durable. Maintenant de retour au Canada, le défi consiste à déterminer comment créer nos propres approches régionales au bâtiment à faibles émissions de carbone.

accessible à l’ère

Fukagawa

Enmichi community centre

Centre Communautaire Enmichi du quartier

Fukagawa

Dr. Henry Tsang Ph.D., Architect AAA, FRAIC, RHFAC Professional Ph. D., architecte AAA, FRAIC, professionnel agréé en accessibilité de la FRH

Canada’s population is aging rapidly, yet our built environment is not adapting quickly enough. By 2050, the number of seniors will be double that of today’s, reaching one-fourth of the population. Japan—the most advanced ageing country in the world—has already reached this milestone, and entered what is known as the “super-ageing era.” A stroll around Tokyo gives a glimpse of what the future holds, and provides clues to what Canada’s cities and built environment will need to do to adapt to this forthcoming reality. I will introduce a few instructive projects here.

To begin, Tokyo is the largest city in the world, and its complexity is mind-numbing. Yet it is safe, walkable and accessible. Nearly all of Tokyo’s 822 train stations have elevators, and major sidewalks are all connected by an expansive network of yellow tactile

indicators. Intersections have generous curb ramps with visual and audible signals at crossings. But perhaps most impressive for Canadians is the quality of the sidewalk pavement: flat, smooth, rigid and spotless.

As a first case study, I visited Fukagawa Enmichi, an award-winning multi-generational community centre designed by JAMZA. Architect Shun Hasegawa gave me a tour and described his concept for a community hub fit for “0 to 100-year-olds.” The building spaces are shared among several operators, including an infant daycare, an after-school club, and a day service for seniors. What makes it work is the intentional programming and layout, which encourage the three groups to intersect and interact. The functional spaces are connected by an interior “street” that doubles as a library and an alleyway shortcut. “From the outside, it looks like a café, so many people are curious and wander in, but when they find out it’s not, they walk through our ‘street’ and exit from the back door,” says Hasegawa. “It’s funny how people get embarrassed to leave from the

door they entered. Some people use our corridor as a shortcut. But that’s what we wanted it to be, a street-like connector and public space that contributes to the neighbourhood.”

A second case study is the Nishi-Kasai Inouye Eye Hospital, a healthcare facility specializing in age-related diseases such as glaucoma and macular degeneration. I visited with Kevin Ng, the Rick Hansen Foundation’s accessibility expert. The building was designed by architecture firm Kajima, and implemented a series of innovative accessibility solutions specific to senior patients with low vision. According to Mari Chiba, the hospital’s corporate manager, “One thing you would notice is that there is very little use of braille, despite being an ophthalmology hospital. In reality, our patients have very low braille literacy because they have low vision, they are not blind. Therefore, we focused the design on enhancing visibility, such as color contrast and lighting, as well as audible signals.” Soft and hard materials were used for flooring to vary the sound and feel of directional wayfinding. Ceiling lights and handrail lighting are aligned to be used as track lighting, and in emergencies, this lighting flashes to provide directional indication.

In the super-ageing era, there will be need for super-accessible solutions for the built environment. But we may not have to reinvent the wheel. This month, the RAIC Long Term Care Working Group will be hosting its first online panel discussion on the future of architecture for ageing in Canada. Stay tuned.

Dr. Henry Tsang, Architect, AAA, FRAIC, is an RAIC Advisor to Professional Practice appointed to the RAIC Long Term Care Working Group. He is also an associate professor at the RAIC Centre for Architecture at Athabasca University, and is currently on sabbatical leave as a visiting professor at the University of Tokyo.

indices sur les mesures que devront prendre les villes et les intervenants de l’environnement bâti du Canada pour s’adapter à cette réalité à venir. Je vous présente ici quelques projets instructifs à cet égard.

Précisons d’abord que Tokyo est la plus grande ville du monde et qu’elle est d’une complexité saisissante. Pourtant, elle est sécuritaire, propice à la marche et accessible. La quasi-totalité des 822 gares de Tokyo ont des ascenseurs et les principaux trottoirs sont tous reliés par un vaste réseau d’indicateurs tactiles jaunes. Les intersections sont dotées de rampes d’accès de dimensions généreuses et de signaux visuels et sonores aux carrefours. Ce qui impressionne toutefois le plus les Canadiens, c’est probablement la qualité du revêtement des trottoirs : plat, lisse, rigide et impeccable.

Comme première étude de cas, j’ai visité l’Enmichi de Fukagawa, un centre communautaire multigénérationnel primé conçu par JAMZA. L’architecte Shun Hasegawa m’a fait visiter les lieux en décrivant son concept de centre communautaire adapté aux « 0 à 100 ans ». Le bâtiment accueille divers services, notamment une garderie, une halte scolaire et un service de jour pour les personnes âgées. Le succès de ce projet repose sur la programmation et l’aménagement intentionnels qui encouragent les trois groupes à se croiser et à interagir. Les espaces fonctionnels sont reliés par une « rue » intérieure qui sert à la fois de bibliothèque et de raccourci. « De l’extérieur, on dirait un café, de sorte que bien des gens sont curieux et entrent dans le bâtiment et lorsqu’ils découvrent

que ce n’est pas le cas, ils passent par notre “rue” et sortent par la porte arrière », explique Hasegawa. « C’est amusant de voir les gens étonnés de sortir par la porte par laquelle ils sont entrés. Certaines personnes utilisent notre corridor comme un raccourci et c’est ce que nous voulions qu’il soit, un lien avec la rue et un espace public qui joue un rôle utile dans le quartier. »

Le deuxième projet étudié est celui de l’hôpital ophtalmologique Inouye du quartier Nichi-Kasai, un établissement de soins de santé spécialisé dans les maladies liées à l’âge, comme le glaucome et la dégénérescence maculaire. J’ai visité les lieux avec Kevin Ng, l’expert en accessibilité de la Fondation Rick Hansen. Conçu par la firme d’architecture Kajima, le bâtiment a mis en œuvre une série de solutions d’accessibilité innovantes particulières pour des patients âgés et malvoyants. Selon Mari Chiba, gestionnaire de l’établissement, « une chose que l’on peut noter, c’est qu’il y a très peu de braille, bien qu’il s’agisse d’un hôpital ophtalmologique. En réalité, nos patients ont une faible vision, mais ils ne sont pas aveugles. Par conséquent, nous avons mis l’accent sur une conception qui améliore la visibilité, comme le contraste de couleurs et l’éclairage, ainsi que sur des signaux sonores. » Des revêtements de sol souples et durs ont été utilisés pour varier le son et le sentiment d’orientation. Les plafonniers et l’éclairage des mains courantes sont alignés pour servir d’éclairage dans le parcours et en cas d’urgence, cet éclairage clignote pour indiquer la direction à suivre.

La population du Canada vieillit rapidement et pourtant notre environnement bâti ne s’adapte pas assez vite. D’ici 2050, le nombre de personnes âgées aura doublé et représentera le quart de la population. Le Japon, le pays le plus avancé au monde en matière de vieillissement, a déjà atteint ce seuil et est entré dans ce qu’on appelle « l’ère du super vieillissement ». Une promenade dans Tokyo nous donne un aperçu de ce que nous réserve l’avenir et nous donne des

À l’ère du super-vieillissement, nous aurons besoin de solutions super accessibles pour l’environnement bâti. Toutefois, il n’est peut-être pas nécessaire de réinventer la roue. En février, le Groupe de travail sur les établissements de soins de longue durée de l’IRAC tiendra son premier panel en ligne sur l’avenir de l’architecture pour le vieillissement au Canada. Restez à l’affût.

Henry Tsang, Ph. D., architecte, AAA, FRAIC, est un conseiller à la pratique professionnelle de l’IRAC nommé par le Groupe de travail sur les établissements de soins de longue durée de l’IRAC. Il est également professeur associé au Centre d’architecture de l’IRAC à l’Université Athabasca et il est actuellement en congé sabbatique en tant que professeur invité à l’Université de Tokyo.

Visit to the NishiKasai Inouye Eye Hospital.

Visite de l’hôpital ophtalmologique Inouye

Kelly Alvarez Doran

OAA, MRAIC, Co-Founder of Ha/f Climate Design OAA, MRAIC, Cofondateur de la firme Ha/f Climate Design

Earlier last year, Ha/f began working on the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC)’s Low-Rise Housing Design Catalogue. As part of a cross-country team assembled by LGA Architectural Partners, we’ve been supporting design teams with energy modelling, climate risk assessments, life cycle assessments, and the development of a material catalogue to guide future builders to lower-carbon, lower-cost choices. Working coast to coast with some of Canada’s leading practices has revealed that we’re all building the same way. Though thousands of kilometres apart,

the housing of British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Nunavut currently employs the same means and methods in its making.

In developing the material guidance for the catalog we’ve looked back at previous versions of the CMHC’s Wood-frame House Construction guides. In comparing the current version published in 2013 with the initial version of the document published in 1967, we immediately recognized how our detailing and material options have narrowed over that timeframe. The 1967 version has a whole section dedicated to the “basementless house” and defines rigid insulation as “made from wood or vegetable fibres, expanded polystyrene, polyurethane, mineral wool or cork.” 46 years later, the basementless section has disappeared,

foamed-in-place insulation has emerged, and rigid insulation is defined as being “manufactured in sheets or boards using materials such as polyisocyanurate and expanded or extruded foamed plastic”— with no mention of wood, vegetable fibres, or cork as options.

We’ve plasticized our housing, and our thinking. From the OPEC crisis onward, our narrowed focus on energy-use reductions has, ironically, blinded us to our ever greater reliance on fossil fuel-derived products throughout the built environment. Siding, roofing, insulation, window and door frames, flooring, countertops, and even the paint on our walls have become heavily reliant on petroleum. The net result: our housing is far more carbon-intensive to build, and is far

New Frameworks S-SIPs (Straw Structural Insulated Panels), architect

Love|Schack Architects

Nouveaux panneaux structuraux PSI (Panneaux structuraux isolants en paille), architecte : Love|Schack Architects.

more toxic and harmful to our health and the broader environment. It has also diverted the enormous economic benefits of construction’s supply chain towards refineries.

Our agency as architects sits almost entirely in what we build with, who we source from, and who we build with. While we have some influence over how buildings are operated and maintained, our ability to control and mitigate ultimately stops the moment a building is occupied. It is through drawings and specifications—and the millions of dollars they direct—that we can most effectively address the climate-related challenges we face. This reality overlaps with the lifecycle emissions of a building: across much of Canada, the embodied emissions of constructing and maintaining a building will eclipse the emissions associated with a lifetime of its operations. It is therefore imperative that we question what we’re building with, interrogate the methods we’re currently using, and work together to find lower-carbon alternatives. Are we sourcing our materials from parts of the world with questionable labour practices? Can we work with regional producers and suppliers with whom we can see first-hand the impacts of decision-making?

To help us make more informed and more efficacious choices, Ha/f is working with the RAIC and the National Research Council of Canada to deliver Life Cycle Assessment workshops to architects across the country. Undertaking LCAs during design serves to both ask and answer the questions: Where does this material or product come from? Through whose hands has it passed? Working together to ask these questions and share our findings, we can move Canadian architecture back to a family of materials sourced from our fields, forests and quarries, and start to shift towards regenerative and lower-carbon design.

For more information on the RAIC Life Cycle Assessment workshops visit raic.org/LCAworkshop

L’année dernière, Ha/f a commencé à travailler sur le Catalogue de conception de logements de faible hauteur de la Société canadienne d’hypothèques et de logement. Faisant partie d’une équipe pancanadienne réunie par Levitt Goodman Architects, nous avons aidé les équipes de conception à modéliser l’énergie, à évaluer les risques climatiques, à analyser le cycle de vie et à élaborer un catalogue de matériaux pour orienter les futurs constructeurs vers des

choix à plus faibles émissions de carbone et moins coûteux. La collaboration avec des firmes de pointe des quatre coins du Canada a révélé que nous construisons tous de la même façon. Bien qu’elles soient situées à des milliers de kilomètres les unes des autres, les habitations de la Colombie-Britannique, de la Nouvelle-Écosse et du Nunavut utilisent actuellement les mêmes moyens et méthodes de construction.

Dans le cadre de l’élaboration de l’orientation matérielle du catalogue, nous avons examiné les versions antérieures des guides de la SCHL sur la construction de maison à ossature de bois. En comparant la version actuelle publiée en 2013 avec la version initiale du document publiée en 1967, nous avons immédiatement remarqué que nos options relatives aux détails et aux matériaux avaient été réduites au fil des ans. La version de 1967 comporte tout un chapitre sur la « maison sans sous-sol » et définit l’isolant rigide comme étant « fait de fibre de bois ou de fibre végétale, de polystyrène expansé, de polyuréthane, de laine minérale ou de liège ». Quarante-six ans plus tard, le chapitre sur la maison sans sous-sol a disparu, l’isolant pulvérisé sur place est apparu et l’isolant rigide est maintenant défini comme étant « fabriqué en feuilles ou en panneaux à partir de matière comme la polyisocyanurate ou la mousse plastique de polystyrène expansé ou extrudé », sans aucune mention du bois, des fibres végétales ou du liège comme options.

Nous avons plastifié nos habitations et notre pensée. Depuis la crise de l’OPEP, nous nous sommes concentrés sur les réductions de la consommation d’énergie ce qui, ironiquement, nous a empêchés de voir à quel point nous dépendions de plus en plus des produits dérivés des combustibles fossiles dans l’ensemble de l’environnement bâti. Les matériaux de bardage, de toiture et d’isolation, les cadres de portes et fenêtres, les revêtements de sol, les comptoirs et même la peinture de nos murs sont devenus très dépendants du pétrole. Le résultat net : la construction de nos maisons a une empreinte carbone beaucoup plus importante et elle est beaucoup plus toxique et nocive pour notre santé et pour l’environnement en général. Les énormes avantages écono miques de la chaîne d’approvisionnement de la construction ont également été détournés vers les raffineries.

Notre rôle, comme architectes, s’exprime presque essentiellement par les matériaux que nous utilisons, les sources auprès des-

quelles nous nous approvisionnons et les personnes avec qui nous bâtissons. Nous avons une certaine influence sur la façon d’exploiter et d’entretenir les bâtiments, mais nos capacités de contrôle et d’atténuation s’arrêtent en fin de compte au moment où un bâtiment est occupé. C’est par nos plans et devis – et les millions de dollars qu’ils représentent – que nous pouvons relever le plus efficacement les défis climatiques auxquels nous sommes confrontés. Cette réalité est imbriquée dans une certaine mesure avec les émissions du cycle de vie d’un bâtiment : dans la majeure partie du Canada, les émissions de carbone intrinsèque liées à la construction et à l’entretien d’un bâtiment éclipseront les émissions associées à son exploitation sur sa durée de vie. Par conséquent, il est impératif que nous nous interrogions sur les matériaux avec lesquels nous construisons et les méthodes que nous utilisons et que nous unissions nos efforts pour trouver des alternatives plus sobres en carbone. Nos matériaux proviennent-ils de régions du monde où les pratiques de travail sont critiquables? Pouvons-nous travailler avec des producteurs et des fournisseurs qui nous permettent de constater directement les impacts de nos décisions?

Pour nous aider à faire des choix plus éclairés et plus efficaces, Ha/f collabore avec l’IRAC et le Conseil national de recherches du Canada pour présenter des ateliers sur l’analyse du cycle de vie (ACV) aux architectes de tout le pays. L’ACV effectuée au début de la conception permet de poser les questions suivantes et d’y répondre : d’où ce matériau ou ce produit provient-il? Par quelles mains est-il passé? En travaillant ensemble pour poser ces questions et partager nos observations, nous pourrons ramener l’utilisation d’une famille de matériaux provenant de nos champs, de nos forêts et de nos carrières dans l’architecture canadienne et commencer à nous engager dans la voie de la conception régénérative et sobre en carbone.

Pour un supplément d’information sur les ateliers sur l’analyse du cycle de vie de l’IRAC, visitez : raic.org/LCAworkshop

Jonathan Bisson FIRAC, Hon. RAIA, RAIC President Président de l’IRAC

Mike Brennan Hon. MRAIC, Hon. RAIA Chief Executive Officer Chef de la direction

Architecture has the power to transform communities, honour diverse histories, and inspire innovation. The RAIC is proud to lead this transformation, shaping a built environment that reflects our collective aspirations. Our 2025-2027 Strategic Plan serves as a roadmap for achieving design excellence, advancing sustainability, and fostering inclusivity across Canada. Rooted in RAIC’s core values—Integrity, Agility, Design Excellence, Social Equity, Reconciliation and Environmental Responsibility—this plan emphasizes the vital role of architecture in addressing the challenges of our time, while creating meaningful spaces for future generations.

Strategic Priorities

• Invigorate the Membership Model

Strengthening the RAIC’s membership offering to better serve a diverse community of architects, designers, and industry professionals while ensuring financial sustainability.

• Progress Meaningful Advocacy

Championing policies and practices that address critical issues such as climate action, accessibility, and equity, and advancing reconciliation in the built environment.

• Foster a Culture of Design

Celebrating Canadian design excellence and positioning it as a global leader, inspiring innovation and collaboration across disciplines.

• Communicate and Market Achievements

Amplifying the contributions of architects to ensure their work is recognized and valued by the public, stakeholders, and policymakers.

• Support and Strengthen Practice

Equipping architects with the tools, resources, and professional development opportunities they need to excel in a rapidly evolving world.

Values in Action

Through Leadership and Integrity,

our actions align with RAIC’s mission to foster impactful design. Excellence drives our celebration of world-class architecture, while Sustainability prioritizes environmentally responsible practices that benefit communities. Also important is being agile for proactive collaboration, continuous knowledge-sharing, and the ability to adapt to emerging design trends. Inclusion and Reconciliation are integral to our work, ensuring the built environment reflects Canada’s diversity and respects Indigenous knowledge, culture, and traditions.

The 2025-2027 Strategic Plan is more than a roadmap—it is an invitation to action. It calls upon architects, designers, and all stakeholders to unite in shaping a future that prioritizes design excellence, environmental stewardship, and social equity. As we navigate the pressing challenges of our era, we believe this plan positions the RAIC as a catalyst for transformative change.

For more information about the RAIC’s strategic vision, visit raic.org/about-raic

L’architecture a le pouvoir de transformer les collectivités, d’honorer les diverses histoires et de susciter l’innovation.

L’IRAC est fier de mener cette transformation axée sur la création d’un environnement bâti qui reflète nos aspirations collectives. Notre plan stratégique 20252025 sert de feuille de route pour atteindre l’excellence en design, promouvoir la durabilité et favoriser l’inclusivité à la grandeur du Canada. Enraciné dans les valeurs fondamentales de l’IRAC – intégrité, agilité, excellence du design, équité sociale, responsabilité environnementale et réconciliation – ce plan met l’accent sur le rôle vital de l’architecture pour relever les défis climatiques de notre époque tout en créant des espaces significatifs pour les générations futures.

Priorités stratégiques

• Dynamiser le modèle d’adhésion Renforcer l’offre aux membres de l’IRAC

afin de mieux servir une communauté diversifiée d’architectes, de designers et de professionnels de l’industrie tout en assurant la viabilité financière.

• Progresser dans une action de sensibilisation significative Promouvoir des politiques et des pratiques qui tiennent compte d’enjeux cruciaux comme l’action climatique, l’accessibilité et l’équité et promouvoir la réconciliation dans l’environnement bâti.

• Favoriser une culture du design Célébrer l’excellence du design canadien et faire du Canada un leader mondial qui inspire l’innovation et la collaboration interdisciplinaire.

• Communiquer et promouvoir les réalisations Attirer l’attention sur les contributions des architectes afin que le public, les parties prenantes et les décideurs puissent les reconnaître et les valoriser.

• Soutenir et renforcer la pratique Donner aux architectes les outils, les ressources et les occasions de perfectionnement professionnel dont ils ont besoin pour exceller dans un monde en évolution rapide.

Les valeurs en action

Nos valeurs orientent chacune de nos priorités. Le leadership et l’intégrité nous assurent que nos actions sont en phase avec la mission de l’IRAC de favoriser un design qui a de l’impact. L’excellence stimule notre célébration de l’architecture de classe mondiale, tandis que la durabilité priorise les pratiques respectueuses de l’environnement qui profitent aux collectivités. L’agilité est importante pour une collaboration proactive, un partage continu des connaissances et la capacité de s’adapter aux nouvelles tendances en design. L’inclusion et la réconciliation font partie intégrante de notre travail pour assurer que l’environnement bâti reflète la diversité du Canada et respecte le savoir, la culture et les traditions autochtones.

Un appel à l’action

Le plan stratégique 2025-2027 est toutefois plus qu’une feuille de route – il est un appel à l’action. Il invite les architectes, les designers et toutes les parties prenantes à s’unir pour façonner un avenir qui accorde la priorité à l’excellence du design, à la gérance de l’environnement et à l’équité sociale. Alors que nous sommes confrontés aux défis urgents de notre époque, nous croyons que ce plan positionne l’IRAC comme un catalyseur du changement transformateur.

Pour un supplément d’information sur la vision stratégique de l’IRAC, visitez raic.org/about-raic

PROJECT Ulster House, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECT LGA Architectural Partners

TEXT Jaliya Fonseka

PHOTOS Doublespace Photography

Walking past the corner of Ulster and Lippincott, you might mistake the building tucked behind a mature, blue spruce for a thoughtfully designed three-storey single-family house in the neighbourhood. A relaxed garden spills over the edges of the property, alive with pollinators, giving the impression that it’s been there for years rooted and full of character. The house itself is contemporary yet quiet in its presence, woven into the Harbord Village fabric like a good neighbour: calm, gentle, and human. Despite its appearance, Ulster House is not a single-family home it’s a five-plex, with two units sharing the upper floors, a ground floor unit, a laneway dwelling, and a basement apartment. It is the result of years of advocacy and experimentation, rethinking Toronto’s most ubiquitous housing typology the single-family infill home as a multi-unit urban dwelling. This small condominium is architects Janna Levitt and Dean Goodman’s prototype for dense housing, done differently.

The imperative of good design

Urban densification is no longer a choice, but a necessity. With rising populations, housing shortages, and our intensifying climate crisis, how we design

our homes and communities is increasingly critical. Buildings account for over 40% of global carbon emissions, positioning architecture as both a major contributor to the problem and potential part of the solution. Designed by Levitt and Goodman, founding principals of LGA Architectural Partners, Ulster House is an example of this pursuit by individual architects to make a tangible impact. The project pioneers sustainable ways of living and sets a precedent for buildings to contribute positively at scales larger than their own footprint.

As a five-unit condominium, Ulster House addresses Toronto’s “missing middle” the critical range of housing types between single-family homes and high-rises. This category, defined in the city’s 2030 Housing Action Plan, is crucial for alleviating both the current housing crisis and the climate crisis. It’s the middle ground where affordability and sustainability intersect, where families are not priced out. Ulster House revives the kind of multi-family housing that once defined this neighbourhood, where immigrant families would share homes and multi-generational

OPPOSITE Each unit in the development has its own front door. The two upper units, entered from Ulster Street, include private, open-air patios that are framed into the top level of the building. ABOVE The house’s slightly canted form, clay shingle cladding, and abundant landscaping with native plants nod to the neighbourhood context of century-old brick homes.

living was the norm, creating a sense of belonging in the urban sprawl. Until recently, however, low-density single-family zoning and smaller family sizes have dominated. This restrictive zoning once covered some 70% of Toronto’s residential land, and those rules only began to be relaxed five years ago. Ulster House disrupts that norm while continuing to offer an adaptable structure through simple stick-frame construction that allows renovation, change, and growth. It shows how families may stay rooted in their neighbourhood, even as their needs evolve.

Serving as both their own home and a demonstration project, Ulster House builds on lessons from Levitt and Goodman’s former residence. Their Euclid House (2006) tested compact footprints and flexible living options, and introduced Toronto’s first residential green roof. “All architecture must contribute to good city-building,” says Levitt. “What you’re doing has to add up to be bigger than the project itself.” Goodman and Levitt are not only the designers, owners, and residents of Ulster House they are also the developers, shifting the paradigm of a ruthless profit-maximizing profession to one where the design decisions are driven by the ambitions of the owners as citizens. Ulster House harmonizes with the neighbourhood’s existing scale while introducing density that feels human and livable. The handmade, electric-fired clay shingle cladding, warm to the eye, recalls the textures and tones of the surrounding brick. Sloped roofs designed to house photo-voltaics for an all-electric HVAC system echo the homes around it, subtly reinforcing the community’s char-

acter. A layered landscaping of native plants and deadwood logs, designed by Lorraine Johnson and selected in accordance with permaculture principles, creates a biodiverse retreat amidst the urban fabric. A sumach screen offers a verdant alternative to the ubiquitous wood fence, softly defining private outdoor space.

Each unit features a dedicated ground-floor entrance, connecting directly to the street. Large glass entry doors with transom windows, framed by vertical stained cedar planks, are sheltered by overhangs. This transparency fosters a sense of trust with the surrounding context, striking a delicate balance between privacy and connection.

The architects currently occupy two of the units the ground floor of the main home, which houses their kitchen and living spaces, and the laneway unit, almost bunkie-like, across a courtyard. Clad in Yakisugi (charred) cedar, the laneway house contains a bedroom, a bathroom, and a home studio that also functions as the library and guest room. Goodman and Levitt’s daily routine involves traversing the courtyard that connects their sleeping spaces with their living spaces a continual communion with the seasons. This experimental design tests the limits and possibilities of outdoor living in Toronto’s climate, where such a routine is otherwise uncommon. The stone walkway, nominally heat traced for winter, is sheltered by a wood trellis and clear acrylic covering, providing partial protection from the elements.

In a recent interview, Egyptian architect Abdelwahed El-Wakil describes the courtyard as “the open living room,” and “the soul of the house.” He speaks of the courtyard as a kind of aperture, a soft-edged threshold that draws us back toward the natural world we have so distanced ourselves from. Reflecting on his own home in Agami, Egypt, centered around a courtyard with a small fountain and windcatcher, El-Wakil highlights the timeless principles of daylight, passive ventilation, and harmony with the sun we all share.

Despite the cold Canadian winters, Goodman and Levitt have always embraced these same principles. “Walking through the courtyard, or looking out from the living and dining rooms in the main house immediately connects us to the seasons, the weather, and a landscape,” shares Goodman, attributing their enhanced quality of life to a deepened relationship with nature. “It’s centering, and is the reciprocal element to the constructed world.”

The path between the two also serves as a three-season exterior workshop area and is lined on one side with a cedar storage wall containing, in part, Goodman’s woodworking tools. A 10-foot shipping container, converted by Goodman into a sauna, provides warmth and purpose during colder months. “The natural ventilation is luxurious,” notes Levitt, when describing the sensation of air and light flowing through the home from the courtyard. Yet the integration of the courtyard offers more than such comforts. It embodies a philosophical

shift: that our response to climate change must include a rethinking of human comfort, and of our relationship to nature.

For the two upper units, open-to-sky outdoor terraces extend the building’s living areas, offloading interior functions while maintaining a sense of openness. These areas ease the compact footprints of the leasable units, inviting natural light and ventilation and reducing reliance on conditioned spaces. The building’s cohesive massing, unbroken by projecting balconies or expansive glass, maintains a robust enclosure, and retains its intimate residential character.

The project as a whole is anchored by passive design principles and detailed studies of embodied and operational carbon emissions. The architects evaluated the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of the development against the Architecture2030 challenge, which calls for a 40% reduction in carbon emissions compared to industry standards. This analysis prompted key adjustments, including replacing steel framing with wood and decreasing the quantity of cement in concrete components. Such decisions reduced the building’s GWP by almost half, surpassing their targeted benchmark. For the architects, these results reinforced the value of integrating carbon accounting early in the design process.

Perhaps most impactful is the overall concept of designing livable, efficient spaces within a compact footprint, reducing overall building materi-

als and ongoing operational energy needs. Compact spaces require thoughtful design. The architects describe their material choices as “elevated but pleasant to the touch,” as is evident in the kitchen, where stainless steel countertops provide a tactile contrast to warm wood finishes that replace drywall to further reduce embodied emissions. The bunkie follows the same philosophy: wood throughout, with the exception of an elegantly crafted bathroom wrapped seamlessly with sea-green mosaic tiles.

Many of the outcomes of the Ulster House were hard-won, requiring the creation of a typology, advocacy for zoning variances, and adaptation to permitting requirements. The bunkie’s narrow pocket garden the result of laneway setback requirements is just one example of how Levitt and Goodman’s thoughtful design maximized even the most constrained possibilities.

Aligning authorities and consultants with the vision took time, and delays were frequent. But each challenge only reinforced the architects’ belief that a different kind of housing was not only possible, but long overdue. Since the project was first proposed, changes to as of right conditions for small multi-unit buildings, development charges, and financing options (such as loans and lines of credit) have made buildings like Ulster House more feasible. However, legislation such as Bill 212, the removal of bike lanes, and the extended delays of the

Eglinton Crosstown LRT, puts into question the provincial government’s position on ‘good’ city-building.

Ulster House offers an exciting glimpse of what gentle densification might look like in our cities: an urban future that embraces creativity, sustainability, and a redefined connection to the natural world. For architects who continually push the boundaries of what’s possible, a project like this becomes a living testament, showing skeptical clients an alternative, improved way of living. Ulster House sets a high bar, asking architects, city planners, and community members alike to think beyond their projects’ immediate footprints, and challenging us all to become better city builders.

Jaliya Fonseka is the principal of Fonseka Studio and an Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, at the University of Waterloo, where he teaches in the architecture and archi

tectural engineering programs. He leads with community-oriented scholarship, inves

tigating topics of home, belonging, and climate.

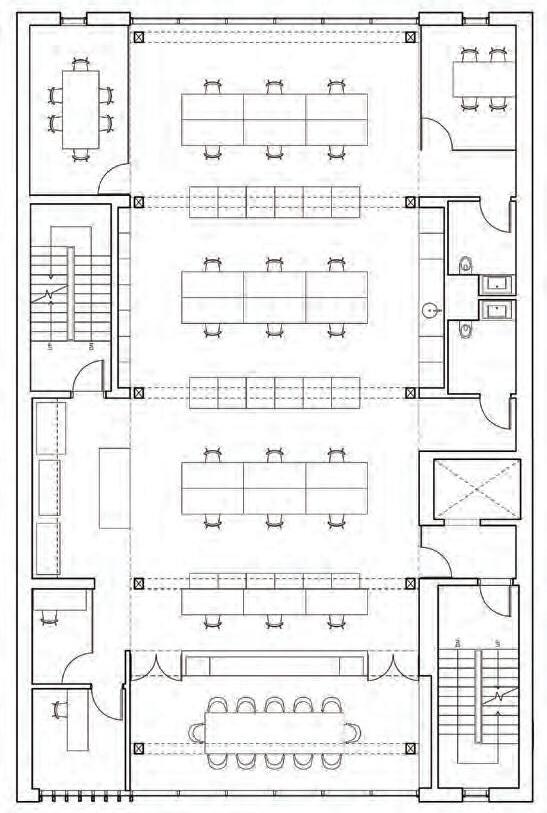

PROJECT Cunard Street Live/Work/Grow, Halifax, Nova Scotia

ARCHITECT FBM Architecture – Interior Design – Planning

TEXT T. E. Smith-Lamothe

PHOTOS Doublespace Photography, unless otherwise noted

Modern mass timber has made inroads throughout Canada, including, most recently, the Atlantic provinces. At the vanguard of this movement is a recently completed project led by Susan Fitzgerald, principal at Halifax firm Fowler Bauld & Mitchell (FBM).

FBM had long wanted to do a project using mass timber, but clients were hesitant to be among the first in the region to construct a multistorey building from the material. So, FBM bravely decided to become its own client. In 2019, the firm was operating from a typical 1970s office tower downtown. A new mass timber workplace would accommodate their growing staff, at the same time demystifying and de-risking this construction method in the region. FBM committed, with Woodworks Atlantic, to documenting the process and costs as a test case.

As local modern mass timber examples were, at the time, few and far between, all involved knew there would be a steep learning curve. Fitzgerald sums it up: “We didn’t know any of this before, so, we really had to go through it ourselves.” The design team which also included structural engineer Gilles Comeau, and Fitzgerald’s husband, Brainard, in the lead for contractor Aitcheson Fitzgerald Builders first refined the program and concept in animated, sometimes intense, discussions. With the support of Ontario supplier Timber Systems, they toured

a certified sustainable forest, the production mill, and several completed projects to absorb first-hand both the challenges and rewards of mass timber. As Comeau learned, any engineering calculations are impacted by the dimensions of product available, the species used, and how the members are glued, nailed or bolted together.

The new building began with a three-storey office program. Given the tight housing situation in Halifax, seven residential units were integrated into the program on the fourth and fifth floors. Tenants and staff share the elevator and stairwells, fostering a diverse and congenial micro-community. This extends outside to the roof, too, conceived as an outdoor oasis for both the staff and residents. Vegetables and flowers are thoughtfully arranged in raised beds and nurtured by a professional gardener. Fitzgerald points out that “some people, who never brought lunches to work downtown, do now outside, on the roof.” In addition to the outdoor space being a visual respite from computer screens for the staff, it is also a valuable amenity for the residential tenants. A panoramic view of the blue Halifax Harbour to the east and comfortable outdoor furniture facilitate conversation.

The site itself is a 15-by-30-metre lot sandwiched between Souls Harbour Rescue Mission, a daily meals and shelter charity, and a older multi-unit apartment building. The FBM office takes up the entire width, but pulls back from the rear boundary to permit a sunken patio which, besides being accessed from the staff kitchen, allows ample light into the lower level. An overhang at the street articulates the glass façade, and sometimes even provides shelter for patrons of Souls Harbour as they line up for lunch.

As contractor Brainard Fitzgerald notes, the construction was slowed by the Covid pandemic’s arrival shortly after construction began, disrupting suppliers and personnel, and making costs unpredictable. The construction process was also complicated by building with zero-side yard setbacks, and little room at the front or back of the site. There was not a conventional lay-down area for materials: concrete formwork for the core circulation areas had to be disassembled and stored off-site, only to be brought back for each of the five levels. But he was pleasantly surprised by how robust and resilient the mass timber components were when assembled on site protection from mold, moisture and damage were manageable, and did not add significantly to the budget.