INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS REVIEW

FEATURING:

by ANFANIOLUWA LAWAL by SARAH LOPEZReview: The Egyptian Coffeehouse

by HANADI AMIN

Letter from the Editors in Chief

Note from the Creative Director

Foreword by Rosella Cappella Zielinski, Ph.D

Note From Our Founder by Andrew Facini

Interview with Noah Riley with Bridgette Lang, Josh Wright & Barrett Yueh

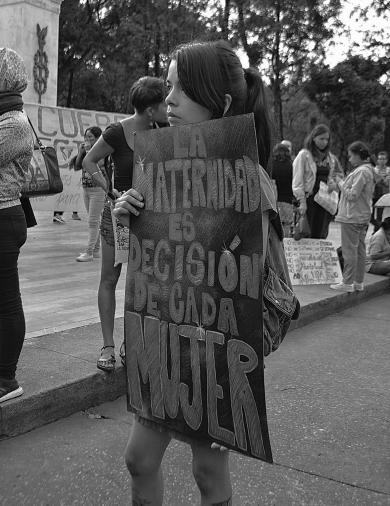

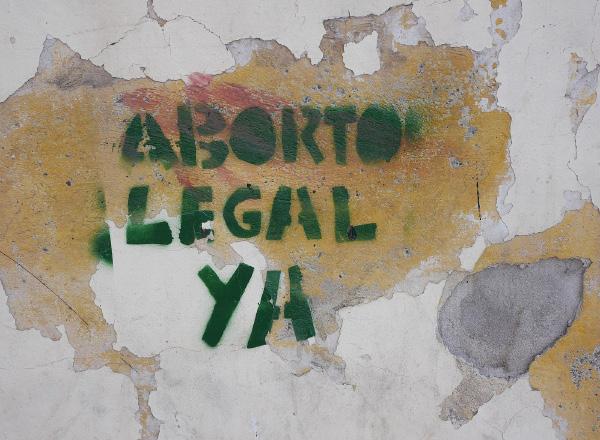

Editor's Note Conditions for Abortion Reform in Latin America by Maecey Niksch

Hispaniola and Climate Change by Sarah Lopez

Editor's Note Hospitality for a Price by Diana Reno

In the Wake of the “Bulldozer” by Bella Newell

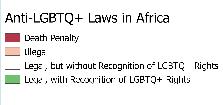

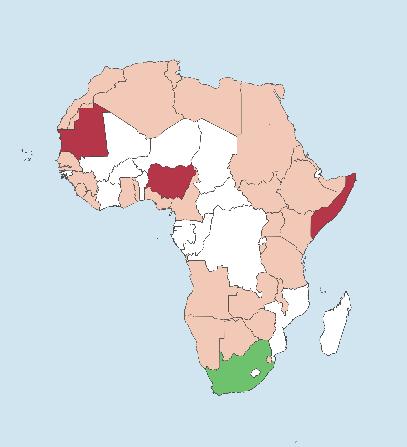

LGBTQ+ Rights in West Africa During COVID by Anfanioluwa Lawal

Refugees, Hydro-Terrorism, and Unstable Governments by Keegan Mitsuoka

Book Review: The Egyptian Coffeehouse by Hanadi Amin

Editor's Note A Temporary Ban On Its Own Citizens by Nick di Paolo Consensus and Clean Air by Sydney Steger

Thailand: An Unforeseen Victim of Myanmar ’ s 2020 by Ashari Bilan-Cooper

Editor's Note

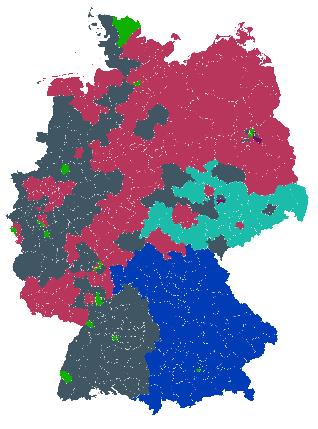

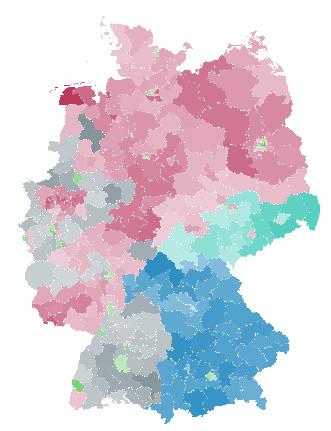

To Build Bridges or Walls? by Jude Hoag Taking Up Merkel’s Mantle by Erica MacDonald

French Positionality on Security by Sydney Pickering

Editor's Note The Fragile State of Kyrgyzstan by Azima Aidarov The Arms Race Five Times Faster Than Sound by Joseph Su

Photography

Senior Editorial Board Contributing Staff

Dear Reader, We are thrilled to bring you the Fall 2021 issue of the International Relations Review (IRR) Journal. Since 2009, the International Relations Review has contributed to the breadth of international scholarship through a bi-annual publication written and edited by Boston University's undergraduate students. Founded with the intention of promoting dialogue between students, scholars, and policy-makers in an increasingly globalized world, the platform that the IRR creates for emerging scholars is needed now more than ever.

The traditional lenses of understanding international relations have shifted in the decade that separates this issue from the first. From antigovernment demonstrations and far-right nationalism to the implications of climate change and the global pandemic, the past twelve years have illuminated the extent to which technology and social mobilization have redefined resistance for the generations to come.

Despite the unique hardships posed by the global pandemic, the 25th edition preserves the IRR's commitment to illuminating key currents in international affairs that are often neglected by global media. This issue seeks to explore the role of resistance in promoting political reform, thwarting suppression, and accelerating solutions to the world's most pressing crises, whether through the coffeehouses of Egypt or the colonial histories of Latin America.

In celebration of the 25th edition, the International Relations Review team has reworked nearly every facet of the journal to reach

uncharted territory in academia and journalism. In an age of misinformation and unprecedented social mobilization, we hope the IRR remains at the forefront of global debates on international affairs through research-driven and policy-forward analysis.

As always, thank you for supporting the International Relations Review, and enjoy the issue. We look forward to publishing again in Spring 2022.

Until next time,

Boston University College of Arts and Sciences, Kilachand Honors College, and Pardee School of Global Studies Class of 2023 and Editor in Chief at the International Relations Review , 2021–22

Boston University College of Arts and Sciences and Pardee School of Global Studies Class of 2022 and Editor in Chief at the International Relations Review , 2021–22

BARRETT YUEH

Boston University College of Fine Arts and College of Arts & Sciences Class of 2022 and Creative Director of Print at the International Relations Review , 2021–22

The title Creative Director did not exist for this journal until this year. The idea of having someone so versed in and focused on art, design, and typesetting for an academicstyle journal has, at times, seemed laughable. Ellen Lupton, author of every designer’s favored typography guide Thinking With Type says, typography and design is all about making information make sense visually. As I have spent the last semester organizing the activities of our layout designers and coordinating the production of this journal, I can testify that there is an impressive

range of incredibly high-level, scholarly writing to be consumed in this journal, and it has been no easy task to make it make sense .

In my two and a half years with the International Relations Review , my job has varied substantially in scope and definition. I entered the editorial board as a layout editor as a sophomore in the fall of 2019 and within months accepted an offer to be the next senior layout editor, a position whose duties would range from “supervise the layout team” to “wake up at 5am to meet with the Editor in Chief and review the final proof.”

My long-term affiliation with the IRR in this capacity has allowed me to see the journal flourish in three distinct eras of leadership—Soo Min Cho and Kavya Verma in 2019, Noah Riley in 2020, and now Bridgette and Josh in 2021. Each of these teams has brought with them their own unique perspectives and contributions to the branch and to the journal, and it has been a true joy to bring them to life visually.

It has been an immense honor to work with the entire editorial board to help design and produce the IRR’s 25th issue,

and I of course look forward to completing my work with the IRR in our Spring 2022 issue. I hope to address you all again then.

With love,

As a graduate student, I took a course called “Teaching Political Science.” My then professor imprinted on me how best to reach others when talking about International Relations—we should “bring the good news.” The term “evangelical,” he went on, is derived from the Greek word euangelion, meaning “gospel” or “good news.” The Greek root word was initially used in the first centuries AD in a secular context to share announcements celebrating military victories. The Boston University International Relations Review , while of course not celebrating military victories, brings the good news. How? It brings together student voices that are eager to understand and solve pressing problems. And there are no shortages of problems. The pandemic and public health emergencies with large, rising authoritarianism, extremism, poverty, racism, and climate change all require multifaceted collective solutions. No one person, government, or institution can solve them. The voices in the

ROSELLA CAPPELLA ZIELINSKI, Ph.DAssociate Professor of Political Science at Boston University, Visiting Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security at the University of Texas at Austin, and Non-Resident Fellow at the Krulak Center for Innovation & Future Warfare at Marine Corps University. Most importantly, she is the faculty advisor to the Boston University International Affairs Association.

IRR are at the forefront of bringing attention to issues global in scope and shaping how we understand them. The contributors and staff are not buckling under the daunting nature of these grandiose problems but bravely facing them.

Critical to bringing the good news is the IRR staff. With social media and a 24-hour non-stop news cycle, it often feels like there are too many voices, and breaking through the noise seems impossible. The staff of the IRR makes sure that every contributor feels confident in their piece. Pieces are vetted for academic rigor and promoted online and in hardcopy. The hard work of the staff over the years has paid off. Since 2011, the Library of Congress has retained physical copies of the IRR catalog. Visitors to the Library of Congress can request past IRR issues in the Jefferson and Adams Reading Rooms.

IRR, you inspire us to take the hard step of having a public conversation and proposing solutions to pressing political problems. Indeed, a keystone of democracy. Thank you for bringing the good news for twentyfive issues now. Happy Anniversary!

ANDREW FACINI, CAS '10

Director of Communications at the Institute for Science and Technology and former Publishing Manager at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Our community is built upon excellence. Together, let's prove what the best IR department in the nation is capable of,” I wrote in the inaugural issue of the IR Review . Pretty rich, coming from an Editor in Chief cruising into senior year with a 2.7 GPA.

When I was approached in early 2009 by Frank Pobutkiewicz, the then-leader of the Boston University International Affairs Association, about launching an academic journal, I was initially excited to have a new project to work on “outside” of classes.

In 2006, I found the IR program under CAS—the Pardee School was still eight years away—to be both inspiring and overwhelming. Like today, it was BU's largest undergraduate department, and the opportunities were plenty. But I found my mind wandering and the curriculum structure vague. I changed academic “tracks” within the major more than once and struggled to stay focused across the disparate possible paths ahead of me. I ended up turning to student organizations and journalism work for much of those first three years.

So by 2009, starting something new like the International Relations Review was a no-brainer. I brought over fresh editorial skills from The Daily Free Press and was thrilled to connect with the go-getters at the International Affairs Association, all of whom were much more rooted in the IR programming than I had been. We imagined a few issues that could fill (maybe) eight pages and set things on a sustainable course that wouldn't immediately end when we graduated.

The work itself was decidedly makeshift. We put out fliers to ask students to repurpose their term papers for articles. We wrote to study abroad coordinators, asking for reflections. I polled my friends, in case anyone had some decentquality photos left on their digital cameras from their travels. The InDesign program I used to lay it all out was almost certainly pirated. Our office was my dorm, and the payment (if I could scrounge cash) was beer.

But from there, we caught something unexpected—a great vibrant enthusiasm from those first contributors and editors to get those stories out; to share their journeys figuring out the program, and finding themselves in the field for the first time.

Suddenly, the discordant threads in the IR department were speaking up, revealing to me so many newfound passions and possibilities. In a way that's never truly captured by the sanitized advertising from the university itself, those articles displayed that authentic “excellence” that I only—until then—pretended to understand.

By the second issue, it was clear that we had tapped into something compelling. At an institution that exudes a thick, almost commercial veneer, an independent space to share honest reflections of our diverse paths is something I'm incredibly proud to have helped establish. Thinking back to those late-night editorial binges in my South Campus room, I really hoped the IRR would, first, survive in the years after graduation. I would never have believed the IRR would reach 125 pages by its 25th issue. A profound congratulations is owed to the hundreds of students who kept this inspiring and genuinely authentic endeavor rolling year after year.

My only advice is just what I found while putting together that first issue: keep sharing those journeys. In a world as boundless as this, it's too easy to feel disconnected and directionless. But if you're here to learn about people and countries and how everything is connected, all you need to do is look for those stories of growth and learning, and find reflections of yourself in them.

NOAH RILEY, CAS '21

Editor in Chief at the International Relations Review , 2020–21

In April 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Noah Riley, a rising senior at Boston University, was elected Editor in Chief of the International Relations Review . For three years, Noah wrote for the IRR’s online and print publications and was one of the founding anchors of the investigative YouTube series, REACT News. Now a Boren Scholar, Yenching Scholar, former Pardee School Dean’s Ambassador, and current graduate student at Peking University, Noah sat for an intimate interview with Bridgette, Barrett, and Josh.

Since many of our readers are undergraduate IR students, what advice would you give to younger students thinking about pursuing opportunities in the field and forging a unique path for themselves?

If we're talking specifically about professional opportunities, take the time to apply to as many different fields or sort of different organizations as you can. When I was in school, I imagined I would be really, really interested in working at a think tank, and right now, I'm fortunate to be able to intern at one, but I now know that I would never want to work at a think tank as a junior staffer. By trying out different opportunities, you put stuff on a resume and build your personal skills, but also it's really valuable as a tool for you as you go off into the world and figuring out what you really like and don't like.

I would also say you should take classes outside the field of IR. If you're interested in being a decision-maker, you're not gonna think, “Oh, remember that time John Mearsheimer wrote that one thing and that one book?”

Literally, you'll never ever say that, so finding other classes and other opportunities, outside of IR, to expand the way you think, is really important too.

What advice would you give to our staff writers, especially the younger staff that are publishing their first piece in the Fall 2021 issue and hope to continue with the IRR in the future?

I think people underestimate how important of a skill writing is. The more and more you write, the better you're going to get at it. It's a very different type of writing than you'll experience in class, and probably more important than the type of writing you do for class. The IRR is a great opportunity to do that, and to figure out what the most important things are to you, and taking the time to get really invested in them and write about them. It will give you opportunities both professionally and personally moving into the future.

What future do you see for the IRR? What are you most excited to see accomplished?

One thing that's super exciting right now is it's infinitely more organized than the way I left it. It's so much bigger and more impressive, and I think there's a lot of different moving parts that have come together really nicely in a way. I think that previous renditions of the IRR weren't able to do that. The expansion into

digital space means the IRR has different platforms now for people who might not necessarily be like long-form writers but who still want a chance to talk about their perspective and the issues that are important to them.

What is the greatest lesson you learned from the IRR?

The lesson I learned specifically about the IRR is that it's a really unique platform for undergraduate students to be able to voice their opinion in a professional way. Oftentimes people don't have the time for it, or don't necessarily know the process for outside publication is, so I think it's a really powerful thing for students to be able to get published in a journal like this.

I think personally, the IRR also gave me an opportunity to figure out how best to present people's voices and what people have to say because a lot of people have very interesting ideas. They have really insightful things to say, and then sort of wanted an opportunity to say that. Being Editor in Chief helped me realize how I can help manage those things, how it can help promote those things, and then I guess lead to like future lessons about that.

What knowledge about academia, more broadly, have you carried with you into graduate school or other professional opportunities?

My classes, for the most part, in international relations, gave me a foundation to understand real world problems. I had a mix of classes that were really theory-based and heavy on reading and then through BU, there are a lot of professors of the practice that help you tackle real-world problems, I suppose. It gives you a solid foundation and background and a way to approach problems from different perspectives that I think is different from something more STEMfocused that uses very specific frameworks to approach problems.

In what ways did the IRR help you excel in your senior thesis?

I really figured out how to structure my ideas and put together analysis. The IRR isn't necessarily always about making an argument in the paper, but for the purpose of analysis, it can be really helpful. You know you'll get feedback from your editors or people who are like more senior staff-level people

at the IRR who will say, “Oh, you should fix this,” or, “I don't find this necessarily convincing.” That will improve sort of your ability to analyze and in some ways your arguments. Again, it also just goes back to figuring out how to write about international relations. That can sort of add to your portfolio of things to do with your thesis.

Professionalism is undoubtedly essential for students entering the workforce. Since you’ve had such substantive internship and practical experiences in international affairs, what are your recommendations for maintaining a competent attitude?

There's like a whole host of advice people can give, but I think there are two things that have really helped me.

First: never be afraid to reach out to people, whether it's on LinkedIn or somebody's website contact information. You should understand that there are also people too, who are generally pretty passionate about you know the fields that they work in, and they would be more than happy to chat with you about that field or

that organization. As long as you reach out in an appropriate and respectful way and are sensitive to their time, they’d be more than happy to chat over Zoom or get a cup of coffee or whatever.

Secondly, something that's really helped me is that, say you do take a job or an internship— within the first week or so, reach out to your supervisor about ways to succeed in your internship. Then you'll have an idea of how to succeed in what they're looking for, and the easier it is for you to fulfill those expectations and hopefully exceed them.

I guess the last thing is just getting to know people in a more personal way. When there's a feeling that you want to get to know them for who they are, as a person, then they also are really interested in your work and personal life.

Unfortunately, you were unable to have a launch party or opportunity to speak to your staff last year. Given the chance now, what would you say?

I would say that they've done a great job. I hope they appreciate

the sort of platform and opportunity the IRR offers because I think it is like a really unique space for people to develop their voice.

How is graduate school treating you? What advice do you have?

One: make sure that if you're applying right out of undergrad that this program or this certain topic is something you're definitely interested in, because if it's not, then those years can maybe feel like wasted years when you could be getting professional experience before really defining what your interest is and then going back to grad school. If you're going to do it right out of undergrad, really understand that that's the field you're interested in.

In the same vein, start applying early and really value your relationships with your professors. It's always important to have relationships with professors anyway but it also helps like for practical applications with networking or writing letters recommendation.

And lastly, I've really enjoyed grad school because like I

said, I knew the topic I was really interested in and have been able to really specialize in that. All my courses are geared towards that, and I've really enjoyed it.

And lastly, what do you miss most about BUIAA?

I miss my weekly Zoom appointments with Barrett and Branden! But seriously, I do think that the different branches of BUIAA actually helped me develop a lot as a person, and I think I realized attributes about myself that

I like and maybe want to develop or that I don't necessarily like. The IRR was a great place where I was able to find my voice as a writer, and iin my later years, I figured out how I can be a better leader, managing different personalities and moving parts. Even if the relationships among people aren't necessarily the greatest, there's always ways to work better and towards a goal. I think there are a lot of situations that BUIAA puts you in that really help you grow as a person. Love you all.

North and South America, collectively distinguished as the Americas, face a diverse set of challenges, many of which we seek to explore in this section. One of the Caribbean's most pressing concerns is the impact of climate change and the associated infrastructure needed to combat these effects, which Sarah explores in her analysis through a modern and historical context. Uneven development of the region has led to uneven effects in the light of natural disasters.

This section seeks to explore the influence of social movements on the politics and development of Latin America through the lenses of climate, infrastructure, and social reform. While two articles only begin to explain the breadth of historical and political development in the hemisphere, we sought to shed light on two lesser-known matters in contemporary Latin American affairs.

MARLA HILLER, CAS '22 Senior Editor, Americas

“This article intends to provide arguments about the success of legal reform in Argentina in comparison with what is called a moderate legal reform in Chile. The importance of the topic speaks for itself in a region with the most restrictive laws in the word and higher rates of induced abortion and adolescent pregnancy.”

BEATRIZ GALLIThe prevalence of the Catholic Church in Latin American governance has long prohibited the abortion debate from entering political discussions. Abortion restriction is persistent in Latin America because it is politically divisive; those in power avoid moving against the anti-abortion status quo, as the resulting antagonization of religious actors would threaten their political viability. 1 However, in the twenty-first-century, abortion reform has developed across Latin America in varying degrees of moderation, as is seen in the cases of Chile and Argentina. In 2017, Chile revised its abortion regulations to make exceptions in cases of saving maternal lives, as well as in cases of rape and fetal malformation. 2 More recently in December of 2020, Argentina completely legalized abortion on demand for the first fourteen weeks of gestation. 3 Feminist social movements have been the most critical actors in the advancement of abortion reform policies, but the asymmetrical adoption

of abortion reform across Latin America reveals a dependency on collaboration between women’s movements and the incumbent government, as well as the countries’ respective political environments, to adopt such reforms.

The ability of women’s movements to form productive connections with state institutions depends on the country’s institutional rules for the participation of women in government. These rules, such as gender quotas, facilitate the success of legislative bills for abortion reform and place female politicians in positions of power where they can act as state allies. Gender quotas in particular give women a fixed share of seats in legislative bodies by implementing a limit for the number of representatives that can be of a single sex. However, collaboration between women’s movements and the government tends to steer women’s movements away from promoting radical change because they are expected to act in the interest of the state and its anti-abortion status quo. In Chile, the women’s movement MILES ( Miles por la Interrupción Legal del Embarazo ) attempted to collaborate with the Bachelet government, but the Bachelet administration proposed its own bill

despite the similarity in their demands. In instances where state collaboration has proven to yield less radical reform, feminist movements, especially Ni Una Menos in Argentina, have strengthened and mobilized so that policymakers can no longer ignore their demands for total abortion decriminalization, resulting in a more radical liberalization of abortion than when collaboration occurs. While the adoption of gender quotas has increased the number of women represented in legislatures, these quotas have not guaranteed the implementation of abortion reform, nor have they been effective at instituting reform without the presence of women’s rights activism. In Chile, institutions such as formal rules, along with informal practices and norms, have dictated the extent of women’s presence in all political arenas. Chile’s binomial majoritarian electoral system, which was created during the Pinochet dictatorship in order to decrease the number of political parties competing and overrepresenting the political right, continued to dictate national elections in the post-Pinochet period of democratic consolidation. 4 During her second term in 2015, Chilean President Bachelet replaced this electoral system law with a more proportional electoral system by increasing the size of both chambers of Congress. 5 Additionally, Bachelet’s new law

included a gender quota, stating that “parties cannot have lists where more than 60 percent of the candidates are from a single sex,” effectively instating a 40 percent quota for women. 6 Gender quota laws, though, do not seem to have advanced political discussion about abortion reform in any way. This quota was only implemented under Bachelet’s second administration in 2015, and the abortion reform effectively passed two years later in 2017. This is not enough time to indicate that a redistribution of the proportion of women in the legislature caused the proposal of the abortion reform bill, though it did make it more likely to pass. It was President Bachelet’s second administration that also put forward the bill to end the total abortion ban that Pinochet had put in place in 1989. 7

The case of Argentina also demonstrates how an increase in the number of women in government does not guarantee support for women’s rights movements and their agendas, especially regarding abortion reform. Since the 1990s, the institution of gender quotas in Argentina has largely increased legislative representation for women’s movements at both the national and subnational levels in the locations where they have been implemented, allowing women to be brought into the political conversation. The world’s first gender quota law was signed in Argentina by President Carlos Menem in 1991, which dramatically increased the proportion of women legislators in the Argentine Chamber of Deputies and Argentine provincial legislatures over the following decades. 8 By 2015, 37 percent of the seats in the National Chamber of Deputies, 40% of seats in the National Senate, and an average of about 25 percent of seats across all provincial legislatures were held by women. 9 However, quota adoption alone did not emanate either immediate or uniform increases in women’s numeric representation in all legislatures due to significant variation in legislative election cycles, the use of placement mandates, and variation in district sizes. 10 In a federal system such as that of Argentina, the decentralization of policymaking from the central government to the provincial level—especially regarding jurisdiction over health, education, and social policies—makes women’s appointment to subnational cabinet ministries

integral to understanding women’s influence over abortion reform and other reproductive rights policies. 11 Nonetheless, women are still marginalized from political party leadership posts in Argentina, and those women who have made it to executive positions—such as Isabel Perón and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner—have done so through informal institutions and under-the-table processes, both having been selected as successors to their husbands. 12 Furthermore, not all women who achieve prominent representative positions in Argentina have ushered in abortion reform. For instance, President Fernández de Kirchner was widely seen as uncommitted to promoting progressive women’s rights, as she strongly opposed abortion and took a conservative stance on reproductive rights. 13 Though gender quota laws did provide women with more representation in legislatures, they ultimately did not advance the abortion debate in Argentina, nor did having a woman in the presidential position. Rather, Argentine women’s movements were the critical actors who finally pushed for the adoption of reform. Abortion reform has occurred either when women’s movements attempted to collaborate with state institutions to push their demands, as in Chile, or when feminist movements have strengthened and mobilized for their demands, as in Argentina. The former method has resulted in a more moderate abortion reform, whereas the latter has driven more liberal abortion decriminalization. Even with a female executive, such as Bachelet who was critical to the introduction of the abortion reform bill, Chilean abortion reform remained moderate, largely because the Bachelet administration crafted the bill without the direct input of women’s movements in order to dampen more ambitious demands from women’s movements. 14 Bachelet’s second administration introduced its own abortion bill in lieu of the one proposed by MILES to Congress in 2014, despite its similarly moderate demands to legalize abortion in instances of threat to maternal life, fetal malformation, and rape. 15 The Bachelet administration conducted negotiations within the electoral coalition, which limited interaction with the existing campaigns and feminist organizations, 16 especially due to the Socialist

Party’s lack of roots in civil society and its strong Catholic influence. 17 Women’s movements alone were not capable of introducing abortion reform to the legislature, due to women’s movements’ exclusion from representation in political parties. Additionally, women’s movements were notably weakened and discouraged by the institutional legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship, which emphasized political parties and prevented social movements from organizing specific campaigns for policy reforms. 18 Therefore, the Chilean abortion reform bill ended up being more moderate, making it more likely to pass in Congress; the bill would only legalize abortion under the circumstances of a threat to the woman’s life, rape, and fetal malformations incompatible with life outside the womb. 19 Furthermore, President Bachelet played a key role in defining abortion policy through a law that allows Chilean executives to introduce bills and force a debate on them by declaring them as “urgencies.” 20 If it were not for President Bachelet’s pursuit of abortion reform via the wide legislative powers of Chilean presidents, the abortion reform bill would not have passed Congress, although institutional barriers undermined a complete collaboration with women’s movements and the Bachelet administration distanced itself from MILES’s initial proposal.

For Argentina, the predominant force pushing for abortion reform has been women’s movements, such as Ni Una Menos, which have notably demanded abortion reform through street activism, a method which has proven more effective government collaboration in mobilizing for complete abortion legalization.

When abortion reform finally rose to the forefront of the Argentine political discussion in 2018, it was under the conservative right-wing PRO president, Mauricio Macri, which shocked many because previous center-left governments, including the administrations of female executives, had not touched on the abortion debate. 21 While this political timing is perplexing, the surfacing of the abortion debate in political discussion can be explained by the strengthening of feminist movements in Argentina during this period. The implementation of abortion reform in Argentina was a consequence of strengthening feminist mobilization, which brought the abortion issue to the forefront of the political agenda and made it impossible for policymakers to ignore. 22 The Ni Una Menos movement emerged on the political scene in 2015—organizing a massive march of over 200,000 women in Buenos Aires in front of the Argentina National Congress—initially to make visible the country’s femicide issue, but it evolved to create a platform for the mobilization of Argentina’s abortion debate by allying itself with other women’s groups and forming a natural social movement base for abortion decriminalization. 23 Ni Una Menos was such a powerful abortion rights movement in Argentina because its activists framed abortion as a social justice issue, emphasizing the deaths of women due to clandestine abortions and arguing that women would undergo abortions regardless of the law, though in unsafe conditions. 24 Framing abortion as a social justice issue broadened public support for abortion decriminalization, as it illuminated the relationship between abortion rights and other injustices suffered by poor women in particular, including domestic violence and wage inequality. 25 As a result, the discussion of abortion decriminalization became more politically accessible, and in 2018, President Macri opened the abortion debate in a legislative session for the first time. 26 However, attitudes toward abortion only began to change substantially after 2018 as feminist social movements increased street protests while the legalization and decriminalization bill was debated in the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. 27 As state institutions failed to meet their demands, Argentine feminist movements became stronger, increasing political unrest and further

mobilizing women’s movements in the streets. With the prevalence of their street protests, the abortion rights movement started to garner a bloc of support in the political arena, even gaining the recognition of former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who changed her position from being against abortion decriminalization to being in favor of it and acknowledged the importance of the massive mobilizations that took place in Argentina. 28 Thus, Argentina exemplifies the significance of feminist mobilization in pushing abortion reform onto the political agenda in the instance when collaboration with state institutions fails to enact any change, or to enact change that is radical enough to champion women’s reproductive rights to the greatest extent.

Women’s movements have been the most critical actor in lobbying for full abortion decriminalization, with or without the state’s support, though feminist movements’ attempts to collaborate with state institutions has resulted in more moderate abortion decriminalization. The ability of women’s movements to form productive connections with state institutions has largely depended on the country’s institutional rules for the participation of women in government to facilitate the success of legislative bills for abortion reform and place female politicians in positions of power where they can act as state allies. The failure of a state to collaborate completely with women’s movements may even serve to strengthen and mobilize these movements further, as demonstrated in Argentina. Understanding how women’s movements have successfully demanded full abortion legalization in Argentina may inform women’s movements in other countries, in the Americas and beyond, on how to effectively advance women’s reproductive rights.

1 Cora Fernández Anderson, Fighting for Abortion Rights in Latin America: Social Movements, State Allies and Institutions (Routledge, 2020), 41.

2 Susan Franceschet, “Informal Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Chile (1990-2015)” in Gender and Representation in Latin America , ed. Leslie A. SchwindtBayer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

3 Mariela Daby and Mason W. Moseley, “Feminist Mobilization and the Abortion Debate In Latin America: Lessons from Argentina” in Politics & Gender (2021), 1-35.

4 Francescet, 8.

5 Ibid, 9.

6 Ibid.

7 Anderson, 97.

8 Tiffany D. Barnes and Mark P. Jones, “Women’s Representation in Argentine National and Subnational Governments” in Gender and Representation in Latin America , ed. Leslie A. Schwindt-Bayer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 2.

9 Ibid, 8.

10 Ibid, 13.

11 Ibid, 10.

12 Ibid, 12; Gervasoni, Carlos. “Argentina’s Declining Party System: Fragmentation, Denationalization, Factionalization, Personalization, and Increasing Fluidity” in Party Systems in Latin America: Institutionalization, Decay, and Collapse , ed. Scott Mainwaring (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 258.

13 Barnes & Jones, 18-19; Gudiño Bessone, Pablo. "Los Debates Por La Legalización Del Aborto En Argentina. Notas Sobre La Relación Entre La Iglesia Católica Y Los Distintos Gobiernos Presidenciales En Democracia (1983-2018)," Apuntes (Lima) 47, no. 87 (2020): 94-96.

14 Anderson, 120.

15 Ibid, 97.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid, 98.; Valenzuela, J. Samuel, Somma, Nicolás, and Scully, Timothy R.“Resilience and Change: The Party System in Redemocratized Chile'' in Party Systems in Latin America: Institutionalization, Decay, and Collapse , ed. Scott Mainwaring (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 150.

18 Anderson, 104.

19 Ibid.

20 Anderson, 101.

21 Daby & Moseley, 2.

22 Ibid, 3; Gudiño Bessone, 99-100.

23 Daby & Moseley, 8.

24 Ibid, 13.

25 Ibid, 14.

26 Ibid, 16; Gudiño Bessone, 99.

27 Daby & Moseley, 20; Gudiño Bessone, 99.

28 Daby & Moseley, 28; Gudiño Bessone, 101.

The week of August 16, 2021, Haiti was hit with a 7.2-magnitude earthquake that caused an estimated death toll of nearly 1500 people. 1 The country was already reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic, the political crisis following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, and the 2010 earthquake, which continues to challenge the country. The Dominican Republic, the neighboring country on the island of Hispaniola, has not suffered to the same extent as Haiti. The countries were established at similar moments in time with similar histories, yet Haiti is constantly devastated by tropical storms, hurricanes, and earthquakes—disasters that also hit the Dominican Republic. In comparison to Haiti, the Dominican Republic has been more adept at recovering from natural disasters. As climate change worsens, islands like Hispaniola will continue to suffer from extreme climate catastrophes. If Haiti is unable to recover from an earthquake that occurred over a decade ago, it will likely fare far worse in the future as natural disasters ensue with increased frequency. Examining the root causes of Haiti’s severe vulnerability will allow for a better understanding of how Haiti can work to prevent such destruction in the wake of natural disasters more effectively. While both countries on Hispaniola have similar

backgrounds, the lasting effects of colonialism on Haiti, the lack of efficient implementation of environmental policies, and the tense politics on the island and within the country affect Haiti’s ability to recover and support its population after the many natural disasters the country has endured in the last two decades.

Hispaniola’s history is fraught with slave revolts, violence, and many government overthrows. The 1791 Haitian Revolution, which lasted thirteen years, toppled the French colonial elites, abolished slavery, and became a beacon of Black independence for the many enslaved Africans in the Western Hemisphere. 2 The Dominican Republic remained a Spanish colony until 1822 while Haiti occupied the capital city, Santo Domingo. The Dominican Republic was under Haitian rule until February of 1844, when Dominican militants and guerilla men chased Haitians out of Santo Domingo and declared itself independent from both Spain and Haiti. After their respective declarations of independence, both the Dominican Republic and Haiti were occupied by the United States in the early 20th century, but the U.S. military occupations had varying effects for both nations.

The U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 and of the Dominican Republic from

How Haiti's complex and tragic history creates an increasingly vulnerable nation

1916 to 1934 overlapped, and the U.S. controlled both countries’ economies at the same time. As opposed to the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic which saw rapid development, the U.S. occupation of Haiti was characterized by accelerated urbanization without modernization. Haitians were migrating to Port-au-Prince and other large cities in Haiti, as the U.S. centralized power in the capital and opportunities for labor became concentrated in the larger cities. However, due to the racism Haiti faced from the large powers in the international sphere that deeply affected its standing, Haiti was unable to access the technology that many countries developing in this era utilized to keep pace with modernization. On the other two-thirds of the island, the Dominican Republic was experiencing industrialization and rapid economic growth because it did have access to the American technology that worked to remodel many developing economies. The Dominican Republic appealed to American interests and aligned with the capitalist United States during the Red Scare. After the American occupation of the island, both nations underwent dictatorships—again with varying consequences. The dictatorship of Francois Duvalier in Haiti resulted in an inefficient bureaucratic system and an even more cemented distrust in the central government from the Haitian population. 3 The Trujillato , the reign of Rafael Trujillo, in the Dominican Republic, while incredibly violent and authoritarian, continued the trend of economic growth and increased public education and literacy rates. The Haitian dictator Duvalier did not as there were rarely any opportunities for foreign corporations to buy and develop land in Haiti—the Dominican Republic, however, did provide land for foreign corporations, which helped the Dominican economy grow, though often at the expense of the local businesses. Despite having been the first nation in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery through a successful slave revolt, Haiti is, and has been since the 1990s, at the mercy of foreign aid and intervention. The racism that faced the Black Republic after its independence severely impacted its first fifty years as a new nation in the global sphere which also affected its development in the 20th century. 4 The white and predominantly

slaveholding countries at the time, such as the United States and France, refused to grant Haiti its sovereignty, limiting the country’s main form of income—agricultural exports. With plantation slavery, Haiti was a primary exporter of sugar and coffee, and without recognition of sovereignty, global markets were largely unavailable to the nation. In 1824, the French recognized Haitian independence with the condition that Haiti would need to pay 150 million francs—the equivalent of $21 billion—within five years as reparations for France’s loss of profit since it would no longer be able to exploit Haiti and use slave labor. 5 In the first century of its existence as an independent state, Haiti’s revenue from its limited agricultural exports went to paying off the debt instead of investing in infrastructure and public goods like education, healthcare, and job security. The debt to France was paid off in 1947. 6

The other persisting structures of plantation slavery and colonialism are present in the statebuilding of Haiti like the hierarchical divisions based on race—where mulatto , or mixed-race, people formed the elite class and the freed blacks were often working-class and below the elites. 7 Cities were reserved largely for the mercantile, mulatto elite while many freed blacks were pushed to rural areas and then forced to work on agricultural land owned by mulattos , similar to the share-cropping system in the southern United States. 8 The reliance on agricultural exports, developed under colonialism and maintained after Haitian independence, influenced Haitian statebuilding in that most cities and locations with jobs were developed along the coast instead of spread across the nation’s territory. The Haitian coast is along a fault line, so while geography does play a role in Haiti’s vulnerability to climate catastrophes, the disasters are more devastating because the majority of the population and labor live along the fault line where most large and destructive earthquakes occur.

Geography also plays a role in the permeation of guerilla tactics in Haitian society. The mountainous regions of the island were useful during the initial slave revolts that garnered Haiti’s independence. Guerilla tactics continued to be used throughout the nineteenth century as the

Haitian population often violently protested the government that was only interested in protecting elite interests. 9 Guerilla tactics developed an extreme distrust of the Haitian government amongst Haitians, and the distrust of government has cemented itself as a social norm of Haiti now. The structures rooted in the colonial years of Haiti were further exacerbated by U.S. occupation in the early twentieth century and Haitian political elites catering to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). U.S. occupation of Haiti centralized political power and economic power in Port-auPrince, where many mercantile elites lived. 10 This centralization of power in one city of Haiti led to the neglect of other provinces. The country’s inability to access technology that would modernize the nation because of racism from the U.S. and France, who would not acknowledge Haiti, led the country to be underfunded. Haiti was also still working to pay off its debt to France at this point. The already weakly connected country began to crumble at this centralization of power due to the neglect of the other provinces. As power was centralized in the capital, black Haitians migrated from rural areas to the capital to find work, and many mixed-race elites fled to rural areas. This migration caused the population to concentrate in urban areas, so when a natural disaster hits these urban centers, like the earthquake in 2010 that hit the capital, the disaster decimated much of the population.

The American presence in the early twentieth century was then replaced by NGOs in the middle of the century to provide financial aid to the Haitian population. The Haitian American Voluntary Association estimates that in 1984, about 200 to 300 NGOs were working in Haiti. In 2010, that number was estimated to be 10,000. 11 These NGOs are often viewed as an extension of state power, especially in a government as weak as Haiti’s, because these NGOs work in areas considered to be government responsibilities, such as healthcare, water distribution, and natural disaster recovery. NGOs also tend to operate out of foreign interest as they receive funding from former colonial powers like the U.S. and the U.K., and this conflict of interest—working in Haiti but also keeping funding—is not beneficial to the Haitian

population long-term. 12 These organizations are unsuccessful in providing long-term and concrete aid to Haiti, as shown by their long duration in Haiti—the first recorded NGO arriving in 1954 after a hurricane. 13 The continued inefficiency of the government to provide its population with recovery and prevention from natural disasters led the Haitian political elite to pander to the NGOs as they had the resources to, in the short term, provide relief for the Haitian population. 14 In contemporary times, Haiti’s political elite depends on NGOs instead of working to restructure its inefficient systems.

The difference in climate vulnerability between the two nations on Hispaniola largely relates to state development as climate adaptation is “limited by institutional rigidity, governance inefficiencies, or pathway dependence,” meaning the development of efficient bureaucratic systems is largely what determines a nation’s vulnerability to natural disasters. 15 Efficient government structures can implement environmental policies effectively and educate the population on prevention and aid, which decreases the state’s vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change. Due to the Dominican Republic’s dependence on ecotourism as well as its colonial history based in land-holding and ranching, instead of crop plantations like in Haiti, the concept of land protection and conservation has deeper roots in Dominican politics. 16 The implementation of reforestation in the Dominican Republic is one of the earliest forest conservation laws in the Western Hemisphere, and the robust forest protection policies were further enforced through the authoritarian government of the dictator, Trujillo. 17 The culture of forest protection, as well as the implementation of public school enrollment—both figures cemented through an authoritarian and violent regime—point to an efficient government in terms of natural disaster aid and education around climate. 18 The racist colonial structures that prioritized the mulatto elite add to Haiti’s climate vulnerability as elites often owned the land previously used by the French colonials for slave labor, which needed to be cleared to continue with agricultural exportation of sugar and coffee—an economic system created under French colonization. 19 Currently, just 1.25 percent of the

Haitian territory is covered by forests. 20 In Haiti, deforestation remains necessary to clear land for agricultural exports and for the charcoal that is the country’s primary form of fuel. 21

The Dominican Republic in the last century and recent years has also inhibited Haiti’s development. The tension between the two countries on the island is fueled by racism and anti-Blackness, which was exacerbated by the Trujillo dictatorship’s aim to appeal to inherently racist eurocentric ideals. In recent years, the Dominican Republic has revoked the citizenships of hundreds of Dominicans because they could not trace Dominican ancestry from 1929. Many Dominicans who have Haitian grandparents or great-grandparents are now being deported to Haiti in droves, further destabilizing the country and putting more economic strain on the nation. The Dominican Republic’s actions indirectly affect Haiti’s vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change by putting more strain on an already crumbling government.

In addition to infrastructure issues and tension on Hispaniola, Haiti also experiences extreme political instability, which has worsened in the last five years when President Moïse came to power in 2017 after a contested election. 22 New presidential elections were expected in March 2021, but the politician demanded his term end in 2022 as it took a year for him to officially take

office—a demand that reminded Haitians of the Duvalier dictatorship. 23 Moïse dissolved Parliament and consolidated all his power by dismissing the country’s elected mayors. 24 He was assassinated on July 7, 2021, throwing the nation into even more political instability in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Grace and an earthquake earlier that week. The interim Prime Minister, Ariel Henry, plans to hold elections swiftly, but much of the population fears that elections will not be held amid the violence that currently grips the capital city. 25

As Haiti attempts to recover from the recent events, the continuation of a dangerous pattern can be seen. There is a repetition of what occurred in the twentieth century—American policy and intervention creating harmful repercussions as U.S. policymakers continue to operate in their national interest and not help the Haitian population in the long term. In July 2021, following the assassination of Moïse, the U.S. announced its intention to send a “Special Envoy” to Haiti to aid “Haitian and international partners [in facilitating] long-term peace and stability and support efforts to hold free and fair presidential and legislative elections” as well as “work with partners to coordinate assistance efforts in several areas, including humanitarian, security, and investigative assistance.” 26 Like NGOs did after Duvalier’s dictatorship, the Special Envoy is meant to assist in many areas considered the Haitian government’s responsibility and yet, there are no concrete actions in this announcement of the Special Envoy. Haiti is already shrouded in uncertainty, and American intervention only adds to the uncertainty. In the same month, the United States deported over 7,000 Haitian migrants. 27 The strain that these now 7,000 people will put on Haiti is an extremely harmful move on the side of the United States, who is aware of the political instability and violence that is rampant in Haiti currently. 28 This policy move was condemned by many, including the head of the Special Envoy team who resigned in protest of the U.S.’s immigration move amongst other reasons, leaving the fate of Haiti in more uncertainty. 29 The recent disasters and the mishandling of American aid in response to the current political upheaval in Haiti demonstrate how ineffective foreign intervention can be in a country with such a complex history.

The historical complexities of Haiti inhibited its development as a state. The nation suffered through persisting racist structures and inefficient bureaucracy, which was worsened by a century-long debt to a colonizer and destroyed Haiti economically. It is vulnerable to climate disasters because of deforestation, which is a product of the colonial plantation system as land needs to be cleared of trees to make room for Haiti's agricultural exports. Policy change and cooperation is difficult because the population does not trust the government, another by-product of colonialism. A by-product of U.S. occupation, Haiti’s weakly connected institutions create vulnerability and force Haitians to consolidate in urban centers. As a result, natural disasters become devastating because the death toll is higher when there are more people concentrated in one area. Keeping in mind the complexities of Haiti’s struggles, future analysis should focus on the intricacies of state failure that originates in the very beginnings of Haiti’s existence as well as how to protect the population from climate catastrophe while working around a failed state. The assassination of Moïse provides the opportunity for an overhaul of the government, which can then work long-term to recover from the myriad of natural disasters that have and will continue to plague the nation.

1 “Haiti earthquake: Tropical Storm Grace hampers rescue,” BBC, 17 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/ world-latin-america-58222888#:~:text=Tens%20of%20 thousands%20of%20people,unknown%20number%20 are%20still%20missing.

2 Mark Schuller, “Haiti’s 200-year Menage-a-Trois: Globalization, the State, and Civil Society,” Caribbean Studies 35, No. 1 (2007).

3 Francois Pierre-Louis, “Earthquakes, Nongovernmental Organizations, and Governance in Haiti,” Journal of Black Studies 42, no. 2 (2011).

4 Hans Tippenhauer, “Freedom is not enough: Haiti’s sustainability in peril,” Local Environment 15, No. 5, (2010).

5 Robert Fatton Jr, “Haiti in the Aftermath of the Earthquake: The Politics of Catastrophe,” Journal of Black Studies 42, No. 2 (2011).

6 Mark Schuller, “Haiti’s Unnatural Disaster,” Humanitarian Aftershocks in Haiti (Rutgers University Press, 2016).

7 Ibid.

8 Schuller, “Haiti’s Unnatural Disaster.”

9 Tippenhauer, “Freedom is not enough.”

10 Schuller, “Haiti’s Unnatural Disaster.”

11 Pierre-Louis, “Earthquakes, Nongovernmental Organizations, and Governance in Haiti.”

12 Schuller, “Haiti’s 200-year Ménage-à-Trois."

13 Pierre-Louis, “Earthquakes, Nongovernmental Organizations, and Governance in Haiti.”

14 Ibid.

15 Mimi Sheller, Yolanda M. Leon, “Uneven socioecologies of Hispaniola: Asymmetric capabilities for climate adaptation in Haiti and the Dominican Republic,” Geoforum 73 (2016).

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ewout Frankema and Aline Mase, “An Island Drifting Apart: Why Haiti is Mired in Poverty while the Dominican Republic Forges Ahead,” Journal of International Development 26 (2014).

19 Ibid.

20 Tippenhauer, “Freedom is not enough.”

21 Ibid.

22 Laurel Wamsley, “Even Before Jovenel Moïse's Assassination, Haiti Was In Crisis,” NPR, July 7, 2021.

23 Ibid.

24 Maryam Gamar, “What the assassination of Haiti’s president means for US foreign policy,” Vox, July 10, 2021.

25 Anthony Esposito and Daniel Wallis, “Haiti since the assassination of President Moise,” Reuters, 14 August 2021.

26 Ned Price, “Announcement of Daniel Foote as Special Envoy for Haiti” (Press Statement, U.S. Department of State, 2021).

27 Diana Beth Solomon, “Migrants' hopes dashed by surprise deportation to Haiti from U.S. border,” Reuters, 8 October 2021.

28 Ibid.

29 Yamiche Alcindor, “U.S. special envoy to Haiti resigns, citing ‘inhumane’ deportation of Haitians,” PBS, 23 September 2021.

Though Africa is often inaccurately considered a homogenous region, the following articles explore diverse topics spanning from international human rights to meaningful political shifts in the region. Contributors examined the harmful anti-LGBTQ+ laws and homophobic tendencies that plague West Africa, Uganda's open-door refugee policy, and the implications of Tanzania's political transition after Magufuli's shocking death. Together, these pieces expose the continued diffusion of progressiveness throughout African politics. From discriminatory policies and progressive refugee laws to democratic state-building in East Africa, we hope to demonstrate the diversity and development of the African political sphere from unique angles.

LÉA NAMOUNI, CAS '23Furthermore, the Middle East section examines the cultural, environmental, and economic factors that form modern Middle Eastern politics and society. Through deconstructing The Egyptian Coffee House , Hanadi explores coffee houses' cultural and political implications in Egypt. Keegan draws from the literature on hydro-terrorism and resource politics in the Middle East to address the imminent consequences of the climate crisis in Syria and Iraq. With a book review and a call to action, the Middle East section utilizes academic frameworks to discern the basis of substantial political conflicts in the region.

by DIANA RENO

by DIANA RENO

In the eyes of international media, political scientists, and the United Nations, Uganda has the most progressive refugee policy in the world. In the 1960s, Uganda created a refugee settlement program with lofty economic and social integration goals, leading them to welcome thousands from Poland, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Sudan. 1 Today, estimates put Uganda’s current refugee population at over one million. 2 Refugees are accepted in Uganda, but they are also free to move around the country, obtain jobs, open businesses, and access social services, including schools and healthcare. 3 Most refugees are given modest homes and small plots of land to farm. 4 This generous allotment allows refugee families to acquire food and generate income by trading their surplus crops with Ugandan merchants. The development of self-reliant refugee settlements aims to create communities of settled families that are not dependent on Uganda’s resources and aid for survival.

In 2021, Uganda made international headlines for agreeing to take in 2,000 Afghan refugees fleeing the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan’s government. The United States asked Uganda to be a stopover for the refugees, promising financial support for three months—September through December 2021—until the United States and Canada processed incoming visas. The United States Embassy in Kampala publicized their gratitude, posting to Twitter that “the Government

of Uganda and the Ugandan people have a long tradition of welcoming refugees and other communities in need.” 5

Amidst this sea of praise, some scholars argue that the situation in Uganda is anything but ideal. Ugandan citizens are remarkably poor, and resources are stretched thin between citizens and refugee settlements. Moreover, President Yoweri Museveni allegedly operates one of the most corrupt governments in the modern state system. His regime holds close and complicated political ties to the United States, making their refugee-hosting collaboration significant. There has been speculation that the Ugandan government’s kindness towards refugees may be a publicity tool to draw attention away from Museveni’s

allegedly brutal suppression of political opposition during the last election season. 6 In light of this information, one has to make a difficult decision: should Uganda still be considered a progressive role model for humanitarian refugee policy? Perhaps more importantly, can Uganda maintain its high level of refugee support without first addressing the dark political undertones that make it possible? Uganda’s self-reliant refugee policy will lose its viability if its proponents do not resolve the administrative, historical, and foreign policy factors corrupting the program.

Uganda’s refugee settlement program could not have lasted as many decades or hosted as many migrants without the overwhelming support of the Ugandan people. Many native Ugandans feel solidarity with displaced refugees, due to their own experiences with mass displacement. Warlord Joseph Kony’s insurgency of the Lord’s Resistance Army in the early 2000s terrorized citizens, abducted children to become soldiers, and mutilated and murdered untold numbers of Ugandan and Sudanese people. Around 1.8 million individuals were internally displaced, profoundly impacting how Ugandans perceive refugees to this day. 7 Empathy for incoming migrants has allowed for the development of mutually beneficial trade relationships and a collective willingness to share Uganda’s few resources. Many Ugandans take great pride in these amicable relationships and their nation’s openness to refugees. 8 Economic

integration also plays a crucial role in the success of Uganda’s refugee communities. Refugees are often able to trade with Ugandan merchants, who prefer their lower-priced agricultural products. Many long-term refugees start small businesses that employ both Ugandans and other refugees. This economic interdependence encourages Ugandan citizens to be supportive of their nation’s inclusive refugee policy. Recently, however, popular perception of refugees has shifted. Despite moderate economic growth, Uganda remains plagued by poverty, especially in and around refugee host communities. These communities live in extremely poor conditions with limited access to fresh water, food rations, and other necessities. Due to the overextension of resources, the national government recently reclaimed plots of land from some permanently settled refugees, leaving many incapable of feeding their families or generating income. 9 In certain cases, the food scarcity reached such a dire level that some refugees were forced to return to the countries they fled. In the northern region especially, conflict over water access and food caused tensions among citizens and refugees. 10 Unpredictable patterns of flooding and droughts have wrought havoc on the agricultural sector, leading disgruntled Ugandans to now work for refugees in exchange for some of their government-provided food rations. In July 2017, a group of Ugandans blocked water trucks

from reaching a refugee settlement in protest of the disproportionate allocation of resources to refugees. 11 If the Ugandan government does not publicly recognize the unmet needs of their citizen population, the Ugandan people will continue getting hungrier and more discontent. Regardless of whether they direct that anger at the politicians or the refugee settlements, the government will eventually be forced to take notice.

As an additional point of contention, the influx of Afghan refugees has awoken concerns of conflict spill-over into Uganda. Conflict spillovers occur when refugee warriors and armed exiles continue military activities within host countries. 12 The last thing Ugandans want is the newly empowered Taliban turning their attention to the nation sheltering Afghanistan’s expatriates. Fear of terrorist attacks like the bombings of Kampala in 2010 has dampened enthusiasm around the incoming 2,000 Afghan refugees. 13 Failing to acknowledge the Ugandan people’s concerns around new refugee communities causes internal distrust of the refugee settlement system. This loss of public support detracts from the efficacy of the refugee program as a whole.

The current administrative failures plaguing Uganda’s refugee settlement program are strongly interconnected with the nation’s fluctuant history of refugee support. Throughout these changes, Uganda’s ruling body has consistently used refugees to gain power, legitimacy, and international funding. In 1971, Idi Amin, the “Butcher of Uganda,” staged a military coup to become the president. His reign was marked by extreme violence, expulsion of the Asian business community, and collapse of the national economy. 14 Amin used refugee populations to grow his power and influence by recruiting soldiers from countries like Sudan, Rwanda, and the Congo. These countries continue to experience substantial refugee movement into Uganda today. Amin created, and later modernized, several refugee settlements that are still in use. He also oversaw Uganda joining the 1951 Refugee Convention and created the Determination of Refugee Status Committee. Despite his reputation for violence within Uganda, Idi Amin was praised for his commitment to the human rights of refugees at

every level of authority extending up to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 15

In the wake of Idi Amin’s rule, Uganda struggled to maintain the crumbling refugee settlements that the UNHCR created but could not sustain. 16 Milton Obote, deposed as acting president of Uganda in 1971, became president again in 1980. Obote appealed to the International Conference on Refugees in Africa for more funding, but concerns about the mistreatment of Rwandan refugees hindered his efforts. 17 Uganda experienced Rwandese immigration by the thousands in the decades leading up to the Obote II period, forcing the government to build more refugee settlements and hire additional administrative and technical staff. 18 The strain on government resources resulted in a significantly reduced quality of life for Rwandese in Uganda. Additionally, the 1980 election made clear that the Rwandese voter base posed a significant threat to Obote’s party, thus Obote’s Minister of International Affairs introduced “The Alien Registration and Control Bill,” which stripped naturalized citizens of their access to the benefits of Ugandan citizenship, including the right to vote. 19 The bill implicitly gave Ugandan citizens permission to abuse and seize land from settled Rwandese “aliens.” Even as Uganda continued to support refugees in developed settlements, Rwandese refugees under Milton Obote were forced to run for their lives.

In 1986, Yoweri Museveni seized the presidency, ruling Uganda ever since. This abrupt regime change seemed like a promising opportunity to improve the quality of life for refugees in Uganda because Museveni showed commitment to refugee support programs as a national development issue. 20 His novel approach to refugee settlement laid the groundwork for the United Nations’ development and adoption of the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. The Declaration outlines a “Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework,” which pledges the UN’s commitment to supporting countries that host a large number of refugees. 21 Similar to the former presidents, Museveni tried to use the large-scale influx of refugees to garner financial support from the international community. In June 2017, Museveni collaborated with UN Secretary-General

Antonio Guterres to co-host the Refugee Solidarity Summit in Kampala. Based on the overwhelming international support for the New York Declaration and the increase in refugees seeking shelter in Uganda, Museveni seemed to be in an advantageous position to ask for more pecuniary support in the international community. This led him to set a goal to raise $2 billion for maintaining refugee settlements in Uganda. By the conclusion of fundraising, Uganda only received $358 million. 22 Despite all of the praise Uganda received in the wake of the New York Declaration, simply continuing to host and support refugees would not win Museveni the international funding he had hoped to receive. This encounter changed the way Museveni approached refugee policy, and Museveni would go on to alter his policies with the apparent intention of gaining more money and power. In pursuing his goals, Museveni often uses Uganda’s long-term commitment to refugee support as leverage in the sphere of foreign policy. Take, for instance, the relationship between Uganda and the United States. The two nations maintain a close relationship, despite the United States sanctioning Uganda in April of 2021 for “undermining the democratic process” in their most recent election. Museveni faced serious allegations by his political opposition, Bobi Wine, of kidnapping, torturing, and killing Wine’s supporters. The United States acknowledged that violence was committed against members of the democratic political opposition and members of the press, along with significant election tampering. 23 However, these sanctions did little more than appease the American public’s

desire to defend democracy. Ugandan-American relations were quickly repaired with the United States financially supporting the 2,000 Afghan refugees that Uganda is temporarily hosting. Both the United States and Uganda have valid reasons to stay in each others’ good graces. Museveni provides the United States with regional enforcement to further U.S. interests in East Africa. Museveni readily sends troops on behalf of the United States to regions such as Somalia, South Sudan, Congo, and Burundi in order to influence regional conflicts. The United States is also following a popular trend among wealthy nations of outsourcing refugee management to client African countries in order to avoid xenophobic backlash. This system works well for the United States, as it has someone to clean up its messes in Africa and the Middle East while keeping its voter base content. 24 Though Uganda expends significant resources in providing these services to the United States, the relationship remains beneficial by giving Museveni access to international funds and influence. Instead of focusing on his party’s human rights abuse allegations, the international press praises Uganda for its progressive refugee settlements. Moreover, Museveni reframes his image as the protector of displaced Afghans. Considering how quickly the United States lost interest in sanctioning Uganda, Museveni effectively has permission to continue dismantling Uganda’s democracy so long as he continues doing favors for the United States. As a useful ally of the United States, Uganda increases its political and diplomatic standing in the international system.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, taking in refugees for the United States is financially beneficial to Uganda. The United States ensures that Uganda has continuous access to large IMF loans, which play a critical role in supporting Museveni’s regime. The United States offered to financially support the 2,000 Afghan refugees as well, which resulted in the refugees being sheltered in five-star hotels. Considering the significant lack of resources for the settled refugees and Ugandan citizens, this program seems absurd. However, considering Museveni’s apparent interest in maintaining a strong relationship with the United States, this exorbitant display of dedication serves his purpose. 25 The Ugandan national government is not committed to promoting the well-being of all refugees within its borders, causing an imbalance in the refugee support program that makes it unstable long-term.

Change under Uganda’s current autocratic regime would likely be slow-moving and face substantial resistance. However, if Uganda opened itself to resolve the current political and developmental issues within its refugee settlement program, the nation would benefit. One possible solution would be to create a refugee settlement system independent of the national government. Future research should examine which aspects of the broken current system could function outside of direct government control. Moreover, researchers should analyze the contrast between different phases in the history of refugees in Uganda, such as periods of more or less funding and popular support, to demonstrate how a theoretical nonpartisan organization may meet the needs of both Uganda’s refugee and citizen populations. The separation of refugee management and government may not be a politically viable solution for Uganda, but it would promote the humanitarian objectives that the international community admires in Uganda’s self-reliance refugee system. Uganda could be the model for treating refugees with basic human decency. As it exists now, Uganda’s refugee policy is too encumbered with administrative, historical, and foreign policy deficiencies to remain viable.

1 Ahimbisibwe Frank, “Uganda and the Refugee Problem: Challenges and Opportunities,” African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 13, no. 5 (2019): 63.

2 Sulaiman Momodu, “Uganda Stands out in Refugee Hospitality,” African Renewal (2018-19).

3 The World Bank, “Uganda’s Progressive Approach to Refugee Management,” The World Bank (2016).

4 Ulrike Krause, “Limitations of Development-Oriented Assistance in Uganda,” Forced Migration Review (2016): 52.

5 Isaac Mugabi, “Arrival of Afghan Refugees in Uganda Raises Security Concerns,” DW: Made for minds (2021).

6 Ibid.

7 Christopher E. Bailey, “The Quest for Justice: Joseph Kony & the Lord’s Resistance Army,” Fordham International Law Journal 40, no. 2 (2017): 247.

8 Tessa Coggio, “Can Uganda’s Breakthrough RefugeeHosting Model Be Sustained?” The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute (2018).

9 Melanie Gouby, “What Uganda’s Struggling Policy Means for Future of Refugee Response,” The New Humanitarian (2017).

10 Coggio, “Can Uganda’s Breakthrough Refugee-Hosting Model Be Sustained?”

11 Gouby, “What Uganda’s Struggling Policy Means for Future of Refugee Response.”

12 Frank, “Uganda and the Refugee Problem: Challenges and Opportunities,” 66.

13 Mugabi, “Arrival of Afghan Refugees in Uganda Raises Security Concerns.”

14 Christopher Riches and Jan Palmowski, “Amin, Idi,” in A Dictionary of Contemporary World History (5 Ed.).

15 Alexander Betts, “The Political History of Uganda’s Refugee Policies,” Refugee History

16 Byaruga Emansueto Foster, “The Rwandese Refugees in Uganda,” Scandinavian Institute of African Studies (1989): 150.

17 Betts, “The Political History of Uganda’s Refugee Policies.”

18 Emansueto Foster, “The Rwandese Refugees in Uganda.”

19 Ibid.

20 Betts, “The Political History of Uganda’s Refugee Policies.”

21 UN Refugee Agency, “New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants,” Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (2018).

22 Coggio, “Can Uganda’s Breakthrough Refugee-Hosting Model Be Sustained?”

23 Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, “Imposing Visa Restrictions on Ugandans for Undermining the Democratic Process,” U. S. Department of State (2021).

24 Nyasha Bhobo and Kudakwashe Magezi, “As Afghan Refugees Grow Increasingly Desperate, Museveni’s Uganda Sees Lucrative Gains,” The New Arab (2021).

25 Ibid.

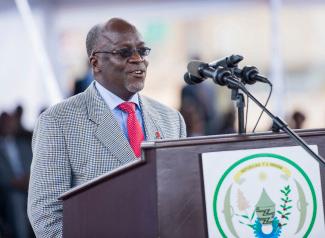

Lecturer in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, at the University of Aberdeen, and Author of “Tanzania: The Authoritarian Landslide” in the Journal of Democracy (2021) and “Again, making Tanzania great: Magufuli’s restorationist developmental nationalism” in Democratization (2020)

“I appreciate the effort made to grapple with the contestable and open question of President Hassan’s presidency, in the context of Magufuli’s presidency and the longer legacy of CCM rule. In my judgement, this essay captures a variety of issues at stake in contemporary Tanzanian politics.”

When John Magufuli took office as the President of Tanzania in 2015, he promised to make change. Early on, his policies attempted to curb government spending, crack down on corruption, and modernize the country. He was applauded by Tanzanian and international onlookers alike for these actions, and reporters dubbed him the “Bulldozer” for his brazen razing of unnecessary frivolities. 1 He was exactly the type of man Tanzania needed to continue their projected and much discussed upward trajectory. But by March of 2021, when he unexpectedly died in office, the headlines read differently. Instead of bringing political change to

Tanzania, Magufuli had led the country down an increasingly undemocratic path.