28 minute read

1.3. URBAN DEVELOPMENT HISTORY OF RIO DE JANEIRO IN 20th CENTURY 1.3.1. Hausmanization strategies and Pereria Passos Period 1.3.2. Carlos Sampaio Period 1.3.3. Antonio Prado Jr. Period 1.3.4. Effects of National Automobile Industry on Urban Development 1.3.5. 1977 Basic Urban Development Plan 1.3.6. 1992 Summit Conference on Sustainable Development of the Earth

1.3. URBAN DEVELOPMENT HISTORY OF RIO DE JANEIRO in 20th CENTURY

Rio de Janeiro has exposed to several urban design strategies and applications throughout the history. It is quite significant to understand the planning decisions under specific circumstances which result in positively or negatively in order to interpret today’s problems. This session will be discussing the different urban factors of 20th century involved in the urbanization process: How the different actions resulted in to shape the urban design of Rio de Janeiro, as well as the effects of the world-wide developments on the urbanization of the city. Moreover, one of the biggest problems of the city of Rio de Janeiro is the shanty towns (favelas), inequality and lack of housing. The root of those problems will be analysied in this session by looking closer to the source and beginning of these facts.

Advertisement

1.3.1. Hausmanization Strategies and Pereria Passos Period

Engineer Pereria Passos was the mayor of Rio de Janeiro between 1902 - 1906 who had important effects to shape Rio’s urbanization. The core of the city went through a period of intensive construction work which leaded the destruction of the last vestiges of Rio’s colonial urban design.

In Passos period, the redesign and development of centre of Rio was the main purpose in terms of urban design. It was desired to increase the importance of Rio in international level. At that time, political buildings were mixed with the poor slum houses and this image was not matching with the purpose of Passos. So as a result of it, Rio had a radical urban transformation.

Since the aim was to heighten the prestige of Rio, the great Europen capitals were taken as examples. Especially Paris became the city which Rio was desired to be transformed like. So grand avenues ending in impressive urban squares surrounded by public buildings were all aimed to beautify the city of Rio.

In the same period, some large scale urban interventions funded by Federal Government existed in the city. Their effects were huge for Rio although they were not so many in the numbers. The most important of them was the opening of Central Avenue. Parisian type of boulevard designed by Haussmann was the main goal to achieve. In order to do that, so

In Passos period, the redesign and development of centre of Rio was the main purpose in terms of urban design.

In order to have Parisian type of boulevard designed by Haussman, so many colonial buildigns were destroyed. many colonial buildings were destroyed to have this kind of streets. It became one of the most impressive urban highway and heart of the nightlife of the city at that time which was surrounded by buildings maximum of 3 storeys. Today the name of the street is changed to Rio Branco Avenue and it still has the same significance, however, it is drawn into the traffic problem and inexpressive office buildings.

Figure 1.26. Avenida Central in 1900s

Figure 1.27. Avenida Central in 1900s

Figure 1.28. The opening of the Avenida Central and the impact on the city’s urban fabric

Seafront Avenue was another boulevard which was built in this time as well. Marechal Floriano Square is located in the junction point of Seafront Avenue and Central Avenue. This section of Rio Branco Avenue (Central Avenue) is the only part which still has the architectural importance and aesthetic values. Municipal Theatre (Teatro Municipal), located there, inspired by the Paris Opera House and it has been the Brazil’s most prestigious artistic venue since it was opened in 1909. In addition, it is possible to encounter other French inspirations in the architecture of Rio de Janeiro. Fine Arts National Gallery (Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) built in 1908, is another example of the french inspiration based on design and the effects of the architectural icon the Louvre Museum in Paris is visible here. Also National library is located in this square as an architecture piece which could succeed in surviving until today. This urban region of Rio was a good example of “Belle Epoque” style.

Since they were the primary inspiration sources of Rio’s urbanization and architecture, perhaps it is important to talk about the “Haussmanization” and “Belle Epoque” style.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, or known as Baron Haussmann was a French official who served as prefect of Seine (1853–1870), chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to carry out a massive urban renewal program of new boulevards, parks and public works in Paris commonly referred to as Haussmann’s renovation of Paris. Due to the traffic and sanitation problems, as well as with the aim of linking the important landmarks, Napoleon and Haussman designed new urbanization systems for Paris. Since population of Paris had doubled since 1815 with the same surface area, the needs of the city in terms of infrastructure were increasing day by day. Also with the aim of modernizing Paris, so many radical attempts had been applied. Multiple neighbourhoods and historic buildings were demolished with the aim of building new boulevards, also the houses of low-income families and their traditions were lost with the teared down buildings. This created much controversy and disappointment among citizens, but it allowed beautiful, modern buildings to be easily viewed.

The new road system of Haussmann was based on straight long streets, which features also as a linkage between the important buildings of the city. These roads were also efficient to solve traffic problems, because it speeded up the circulation flow. Also this new system let the sewage system to be constructed underground. Those applications helped Paris to become a cleaner city. His ideas were very modern

compared to traditional systems existed before Hausmann urbanization.

From social point of view, Haussmann was not so motivated to negotiate with the people of Paris. His design approach caused eviction of so many poor people from their houses and neighborhoods, which aroused the hatred of the citizens. Application of his plans were based on force and imposition. While destroying the regions and houses, so many small businesses and traditions were also doom to disaappear. (Brandao, 2006)

When we look at Rio de Janeiro, we see the similar attitude and design approach in Pereira Passos reforms. Although Passos brought important changes in terms of infrastructure and aesthetic in the city center, creation of wide streets and boulevards caused huge number of low - income families to lose their homes. In Passos period, approxiametly 3000 poor colonial houses were wiped off from the face of the earth (FINEP, 1985 cited in Brandao, 2006). The alternative solutions as housing which brought to the citizens were not adequate neither logical, because the social housings municipality offered were pretty far away from their daily life activities and works. Although they wanted to stay within the region, they could not afford to live there anymore due to the

transformations of the city made by Passos period.

The consequence of this action was going to be the greatest urbanization problem of Rio de Janeiro in the following years until nowadays. The solution people found was to build their own houses in the areas which were not being used within the region they were kicked off due to the evictions. The homeless quickly started to occupy the previously deserted main hills located in the center in a very risky and unstable way. It conduced toward rise of first shanty towns which are known as favelas today.

The reforms of Pereira Passos are the initatives of first governmental urban interventions in the history. Before this period, the government was only inspecting private sector activities. This way of city planning changed the whole traditional system, as well as 20th century city planning and urban design approach in Rio de Janeiro. Except the times when there was World War I, the other mayors acceded after Passos followed the same aggressive attitude towards planning. (Reis, 1977 cited from Brandao, 2006)

1.3.2. Carlos Sampaio Period

Carlos Sampaio was the mayor of Rio de Janeiro in the years between 1920 - 1922 who had serious effects in the urban planning history of Rio de Janeiro. As it was discussed in the previous section, the main goal of Passos was to make Rio an internationally important city, on the other hand Sampaio's aim was the preparation of Rio for the upcoming celebration of the first Centenary of Brazil’s Independence. This event could enable so many international and national tourist to come to Rio and make an influence world wide. Moreover, the site for this event hadn’t been decided when Sampaio was elected, so he saw this situation as an opportunity to continue Passos design about redesigning of Central Rio (Brandao, 2006).

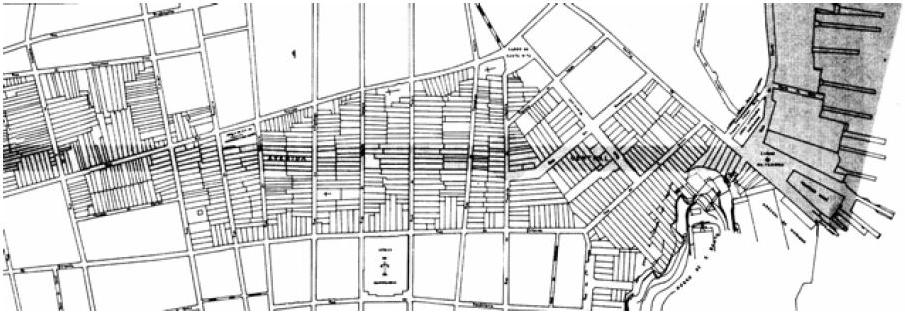

The most important application he has done in the urban history of Rio de Janeiro was the demolishment of Morro do Castelo (Figure 1.26,27,28,29). Morro do Castelo was built in the 16th century and it was practically the place where everything started and is linked to several important points of the city’s memory.

The excuse of municipality for this action was the safety of the citizens, because since the time of Dom João VI, it was considered harmful to the health of Cariocas because it hindered the circulation of the winds and prevented the free flow of waters. (GOMES ) Over the centuries it was gradually considered unfeasible for the city’s progress and urbanism. Finally in 1922 with those excuses and as well as being a proleter area in the city center, it was destroyed by water tanks. Not only Morro do Castello, but also Misericordia, which was one of the city’s oldest and poorest neighbourhood was removed from there. Although it was being occupied by low-income families, it turned out one of the most expensive neighbourhoods of Rio de Janeiro because of the urban renovations. It was also an opportunity for the mayor Sampaio to use that area for the Centenary of Brazil’s Independence, which he did eventually, and this caused some speculations among citizen. He was blamed as a mayor who destroyed the historical valueable buildings as well as poor neighbourhoods in order to have a site for an organization which has the possibility to drive a financially profit for the government and increase the fame of the city. This decision generated so much repercussion that Mayor Carlos Sampaio even wrote a book in which he presented his point of view justifying loans and other negotiations that involved the devastation of the Castelo hill.

The main aim that Sampaio tries to achieve was to prepare Rio for the upcoming celebration of the first Centenary of Brazil's Independence.

The demolishment of Morro do Castelo was the most important event which was done during this period.

Figure 1.29. Demolition of Morro do Castelo, 31/08/1922

Figure 1.30. Demolition of Morro do Castelo, 09/10/1922

Figure 1.31. Demolition of Morro do Castelo, 24/10/1922

Figure 1.32. Demolition of Morro do Castelo, 22/11/1922

After the the demolition of the Morro do Castelo, some working class communities who could hardly survive after Passos urban reforms were also forced out. It could solve the problem of the area for Centenary of Brazil’s Independence and site for new urban developments, however, it was going to cause even bigger urban problems in the future of Rio de Janeiro since they keep evicting poor population without providing an equivalent option for housing.

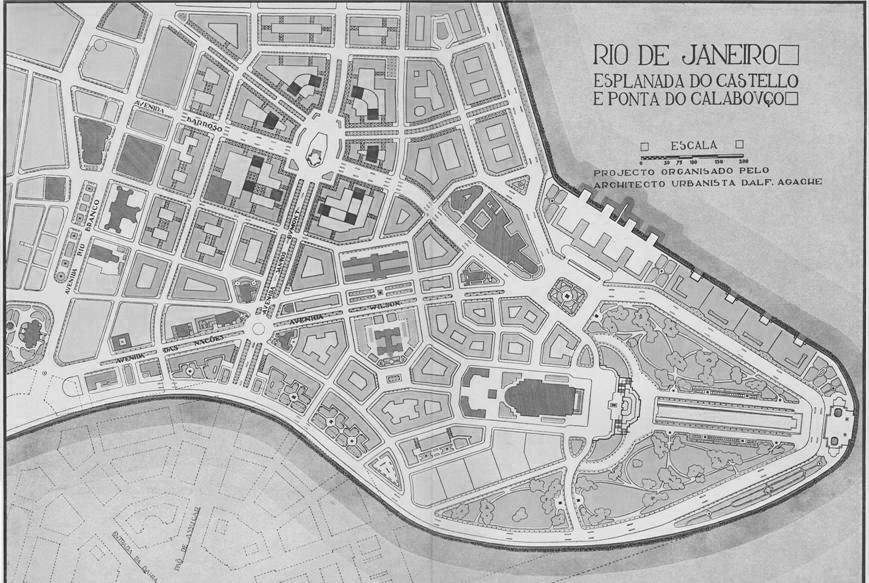

1.3.3. Antônio Prado Jr. Period and Agache Plan

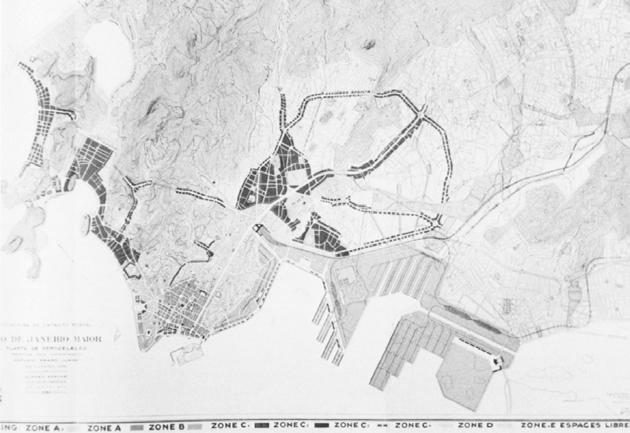

Antônio Prado Junior is another important figure for the urban planning development of Rio de Janeiro who served as mayor of Rio de Janeiro between 1926 and 1930. In the late 1920s, he was commissioned French urban planner Alfred Agache and his team for a new plan for Rio. The main concern of this team was to beautify the Rio, specifically its centre and southern areas. In addition, having certain zones for the specific activities was another aim of Agache plan. According to this, for instance, central zone would be divided into 6 different areas : Business Centre (Centro de Negocios), Administrative Centre (Centro Administrativo), Monumental Centre (Centro Monumental), Financial Centre (Centro Bancario), Embassy District (Bairro das Exbaixadas) and Calabouco Gardens (Jardins do Calabouço).

Agache pursued zoning policy also for residential concerns. The southern zone which has more tourist attraction and nice beaches such as Copacabana, Ipanema and Leblon was going to host more affluent strata of Rio by designed in a similar way to European Garden Cities. The early neighbourhoods like Catete, Botafogo, Flamengo, Laranjeirasi Vila Isabel and Tijuca were allocated for middle class by making minimum changes and following the already existing organization. The intention for the poor society was to allocate suburban areas of the city by constructing social housings and improving infrastructure and providing proper public transportation to increase the connection of those areas to city centre.

High Class - Southern Zone Middle Class - Northern Zone Low Class - Suburbs

Figure 1.33. Agache Plan zoning diagram for residentials

French urban planner Alfred Agache was commissioned by Antonio Prado Jr. His main purpose was to beautify Rio by having certain zones for the specific activities. Also seperating the stratas by economic situation into the different areas of the city.

Construction of the Avenue Presidente Vargas caused tearing down of more than 500 buildings and this action assumed as one of the biggest mistake in Rio de Janeiro's urban planning history. Agache Plan was never applied due to the lack of time and financial budget, however, this beyond ambitious plan still takes a very important place in the urban planning history of Rio de Janeiro. With this plan, the municipality of Rio de Janeiro for the first time admitted the existence of uncontrolled growth of the city and felt the necessity to take required actions like cooperating with an international design team for the city planning.

Although Agache plan was not applied in the time it was planned, following the other decades some of its proposals were carried out. The French designer proposed to open a huge avenue which would work kind of an urban expansion axis perpendicular to the Central Avenue (Brandao, 2006). Nevertheless, it required the demolishment of every single block located between the General Camara and Sao Pedro streets. This urban reform resulted in tearing down of over 500 buildings, which was assumed the biggest mistake ever happened in Rio de Janeiro urban planning history by some authors (Reis 1977). Besides, the development foreseen before the construction of this avenue did never happen. While surrounding fabrics were all demolished, the important historical part of the city also dissappeared as a result of this action. Finally, the monumental buildings planned to be built here never put into practice.(Brandao,2006)

In 1930s, rural areas were exposed to depressions. Towards the end of 30s, 50% of the cultivated areas were gone lost. At the same time, Rio de Janeiro was

Figure 1.34. Urban fabric before the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

Figure 1.35. Urban fabric after the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

passing through an industrial development period. All these facts are encouraged people in rural areas to migrate Rio city center. Rio had its period of most dramatic increase in its population growth from 1940s to 1980s. Therefore, the population growth was so fast that planning was left behind (Brandao 2006). Rio’s population increased 0.6 million in 10 years. The population which was 1.8 million in 1940 raised to 2.4 million in 1950, and became 3.3 million people in 1960. At the same period, the population of greater Rio is expanded from 2.2 million to 4.9 million (IBGE, 1966).

Figure 1.36. Urban fabric after the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

Figure 1.37. Urban fabric before the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

Figure 1.38. Urban fabric before the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

Figure 1.39. Urban fabric before the construction of Avenue Presidente Vargas

Greek architect and urban planner Constantino Doxiadis designed a master plan for the city considering massive car and circulation problem of Rio de Janeiro.

1.3.4. Effects of National Automobile Industry on Urban Development of Rio de Janeiro and Beginning of Gated Communities

The increasing number of cars started to show its effects on the urban context in the beginning of the 1960s especially in the metropolitan cities. Also in Brazil, the national automative industry was born and streets were congesting by cars. In addition, the specific geography Rio de Janeiro has, such as the mountains and the sea, was making even harder to have a proper circulation and the traffic problem was becoming unbearable for citizens. Pedestrians gradually had to share their own spaces with cars and the focus of the urban context turned into cars, rather than the people.

In order to be able to control this increasing number of cars on the streets, the core element of urban planning became the transportation. The automobile industry remained in the forefront of daily life so much that traffic engineers took over the lead of urban design teams. In this period, mostly the infrastructures such as bridges, roads, tunnels etc. became the main components of the urban design (Brandao, 2006). In the late 50s, the governor of the State of Guanabara, Carlos Lacerda (1960-65) hired Greek architect and urban planner Constantino Doxiadis and his team to design a master plan for the city considering the massive car and circulation problem. It was a redevelopment plan including also housing issues, basic sanitation and the creation of road systems for railways, highways and subways, preparing the city for the expected growth for the year 2000. Like Agache plan in 1920, this plan was also mainly focused on consolidated urban structure. (Brandao 2006)

Plano Doxiadis was completed in 1963, however, it was not published until 1965. The head of the design team Constantino Doxiadis proposed 8 concrete projects to solve the urgent needs of Rio de Janeiro.

Figure 1.40. Constantino Doxiadis presenting his plan

The list includes different subjects such as creation of an industrial area in Sepetiba, the construction of 10.000 houses for favela residents or installation of more than 7.500 classrooms.

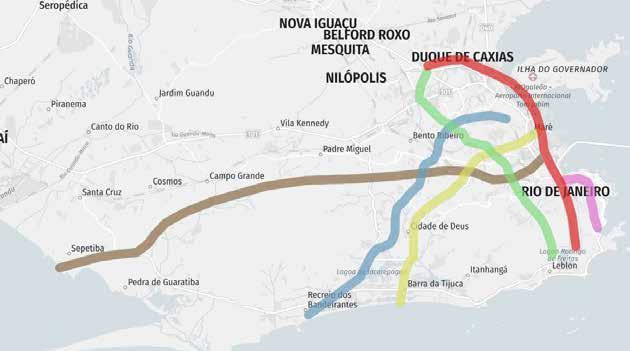

Doxiadis plan is also known as Polychromatic Plan due to the large circulation routes that would integrate the city: the Red, Blue, Brown, Green, Yellow and Lilac lines. Admitting the use of the car as an individual means of transport and the bus as a means of mass transport, in an increasing and irreversible way, this system provided for 403 km of expressways and another 517 of main roads in the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, to be complemented by 80km of subway lines.

Although the plan was never fully implemented, several governments carried out important parts such

Doxiadis plan iis also known as Polychromatic Plan due to the large circulation routes that would integrate the city: the Red, Blue, Brown, Green, Yellow and Lilac lines.

Figure 1.41. Doxiadis plan, or also known as Polychromatic Plan for the large circulation routes

as tunnels, viaducts, opening of the Lilac Line and implementation of part of the Green Line and, decades later, the Red and Yellow Lines.

The Lilac Line was one of the first to be built. It connects the Laranjeiras neighborhood with the Santo Cristo neighborhood, passing through the Santa Bárbara tunnel. Initially, it would unite the Botafogo neighborhood with the Gasômetro viaduct without interruption. In its original project, there was almost total destruction of the Catumbi neighborhood, but due to protests from residents, its layout was reformulated.

The Green Line (RJ-080) would connect via Dutra to the Gávea neighborhood, passing through Tijuca. A tunnel over the Tijuca massif would link Uruguay Street in Tijuca to Santos Dumont Square in Gávea. From it, only the Noel Rosa tunnel and Pastor Martin Luther King Júnior avenue remained as important routes. Via Pavuna, you would reach via Dutra where you would meet the Red Line.

The Brown Line would connect the center to Santa Cruz, east to west, passing through the Rio Comprido, Tijuca, Andaraí, Água Santa, Piedade, Madureira, Sulacap, Bangu, Campo Grande neighborhoods, all the way to Santa Cruz.

The Blue Line would connect Recreio dos Bandeirantes to the municipality of Duque de Caxias.

The Red Line, officially Via Expressa Presidente Joao Goulart, was inaugurated, in its first stage April 1992

as a part of Rio 92 works package. The second stage connects Sao Cristovao to Sao Joao de Meriti, passing through Duque de Caxias.

Between the years 1960 and 1970, almost all the public interventions in Rio de Janeiro is reduced to road construction (Bradao, 2006). So many bridges and tunnels are built in this period. For instance, the tunnels Rebouças and Santa Barbara were dug at that time and also the 14 km long bridge Costa e Silva which connects Niteroi to Rio de Janeiro was also constructed.

There were also some urban interventions which were concerning pedestrians as well. 2 projects tried to achieve a fair balance between pedestrians and automobiles (Brandao, 2006). One of them was Flamingo Park designed by the urban architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy and the landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, and built in 1961 - 1965. Burle Marx also designed Copacabana Beach side walks built between 1969 to 1972 by having the pedestrian priority, although the main aim was still to relieve the traffic congestion.

The increasing number of cars on the streets affected the lives of pedestrians substantially. In time, the automobiles kept taking more and more spaces from pedestrians, they were given the first priority in the urban interventions. Inevitably, this situation turned most of the public spaces into undesirable areas, where there is no pedestrian friendly activities or welcoming walking ways; instead the streets and squares consisted of mostly car parking areas or vehicle traffic. Therefore, people were given no reason to go out and spend time on the streets of the city. Before, Rio de Janeiro was promoted by its colorful social life, however, this sceneiro changed in time dramatically. It is a good example of strong correlation between the social life and public space because of the fact that as more public spaces are deteriorated, more people hesitate to go out and use them, which makes citizens disconnected from each other, have a fear of the city and feel hesitation to experience the place they live in.

Worsening of public realm caused the creation of alternative collective spaces by private sectors such as shopping malls, private clubs or condominiums limited in enclosures. The quality of streets and squares are so reduced that they have evolved to spaces people used only for transition areas from home to work or vice versa. Most of the areas for leisure and socialization were privatized, which means people started to be seperated by economical activities.

Between 1960 and 1970, almost all the public interventions in Rio is reduced to road construction. So many brdges and tunnels are built in this period. There were 2 projects concerning pedestrians: Flamingo Park designed by Eduardo Reidy and Copacabana Beach side walks designed by Burle Marx.

The seperation between rich and poor reached worse levels that deteriorated public areas are left for the poor who cannot afford to socialize in private clubs. This situation leaded the creation of "Gated Communities". This seperation reached even worse levels when the number of people who live under poverty line is considered (Please check “economy”). The deteriorated public areas were left for the poor people who cannot afford to socialize in private clubs. This caused middle and high class to perceive public spaces as unsafe areas which they escape to be in it. High social tension started to show itself within the comunity due to the increasing gap between the rich and the poor.

Under these circumstances, the idea of being in a community surrounded by fences, 7/24 security cameras and guards appeared to be very attractive to high and middle stratas (Brandao, 2006). In time, this “architectural urbanism”, as how Zeca Brandao called it, was expanding, as well as confine the city itself inside its walls. Rio has become growth of several isolated indoor “urban spaces” which are linked to each other by highways.

Gated communities are groups of houses, surrounded by fences or walls, that can only be entered by the people who live there. These condominiums provide its residents with a package of everything that one can need in daily life: playgrounds, children’s daycares, spaces to work, pools, saunas, gyms, soc

Figure 1.44. Gated communities in Rio de Janeiro

Figure 1.45. Gated communities in Rio de Janeiro

cer or tennis courts, coffee shops and social lounges. These functions are all supplied together to the families. Living inside this community without a need to leave it and go to the other parts of the city is one of the most attractive features of gated communities. This phenomena earnt reputation especially after several fails of urban interventions which were discussed above, and numbers of gated communities keep raising as the gap between poor and rich increase.

RioOnWatch interviewed with several people who live in gated communities in Barra da Tijuca. The people who were interviewed ranged from a young couple living together in Via Barra; a 35-year-old who lives with his wife (a doctor) in Via Barra too; a married man with a young child and who has lived in the gated community Península all his life; and, a single man in his thirties who moved back into his parents’ house in Atlântico Sul after living abroad for a while. The common answer given to the question of the motivation to live in a gated community was “safety”. According to them, the attractive reasons to choose to live in a gated community is firstly to know that the residents are safe eventhough they go out after a certain time during the evening or letting their children to play within the community without worrying about their safety. However, the fear of security is not solely the reason to live in a gated community for them. Having all the functions for their leisure times just a few floors down from their homes are also other factors that motivate them to live in a gated community.

Another factor is the distance to the city center. Barra da Tijuca is almost 40 km away from the city center and it takes around 1 hour to reach to the center. Most of the people have love and hate relationship with the neighbourhood. While they find the center very crowded and see Barra da Tijuca “an area they can finally breathe”, time to time they complain about the time they would lose to reach the city center.

Up to 1969, the districts developed in 20th century of Rio de Janeiro were designed with both modern and traditional urbanistic approach. In 1969, Lucio Costa’s master plan for the Baixada de Japarepagua changed this and for the first time, a whole district of Rio de Janeiro was designed following the road oriented modernist principles (Brandao 2006). It was actually the last attempt to show that Rio has reached out the absolute modernity with perfect urban environment. This master plan of Costa was a collapse of traditional urban pattern in terms of zoning use and division of land. The plan included clusters connected by wide highways minimum length

The common answer given to the question of motivation for living in gated communities was "safety".

The aim of the Lucio Costa's master plan was to provide socially integrated communities, however, the result was just the opposite. At the end, it became the most segregated urban space in the city. of 1 km. The clusters consisted of residential towers which were connected by small narrow streets, commercial activities and squares in the middle of them. The big green areas were dividing the residentials by proposing no certain activity. To be able to connect those far away clusters, a massive freeway system was designed.

The aim of this master plan was to provide socially integrated community, however, the results were just opposite of what was tried to be achieved. The walls and fences used to define and close certain areas and even public spaces. Eventually, they turned into gated communities. This region of Rio de Janeiro was desired to be socially integrated, however, at the end it became the most segregated urban space in the city (Brandao 2006).

1.3.5. 1977 Basic Urban Development Plan

Rio de Janeiro was generally exposed to massive rational urban plans with no clear applicable design ideas during 1970s and 1980s. They were also quite ambitious in terms of scale and discussing long term solutions, so this make it less effective to solve the immediate problems of the city.

In 1977, The Basic Urban Development Plan (Plano Urbanistico Basico - PUB) executed in order to provide real physical solutions, although it still carries the general characteristics of plans during 70s and 80s explained earlier. This plan created Urban Structural Projects (Projetos de Estruturaçao Urbana - PEUs) and it was an important tool to achieve objective efficient planning.

At those times, there was an uncontroled growth in the city and therefore, planning couldn’t catch the expansion of the city. The important buildings and neighbourhoods were facing the risk of deterioration or disappearance. Therefore, local citizens organized themselves in order to fight for the identity of their hometowns. In this step, PEU projects stepped in and planned to be used in the solution of required urban regulations according to citizen’s desires.

Thanks to those social movements, for the first time in Rio history, historic and ecologic preservation became issues to concern in urban planning which were neglected before (Brandao,2006). It was proved the importance of the participation of local people have a huge role in the applications of the urban projects. The first project implemented with the initiatives of local citizens was Urca Urban Structural Project (PEU - Urca) in 1978. It was due to the protect the region from speculative construction processes (Del rio, 1990.)

Aftter Urca, there were also other projects designed and implemented for the other regions like PEUs Botafogo in 1983 and Santa Teresa in 1985. Those projects were all concerned with the conservation of the city, however, Cultural Corridor Project (Projeto Corredor Cultura) executed by architect Augusto Ivan in 1979 was served as a model in Rio de Janeiro urban planning history due to the fact that it was the first project concerned with the preservation of the whole district of center of Rio rather than revolving aorund only one architectural piece. It was a successful change for Rio because after many years of constant deterioration, central Rio finally went through a transformation economically, physical, social and cultural point of view (Carvalho,1983). During 1980s, Brazilian economy was going through a recession period and therefore there were not so many urban interventions both public and private. However in 1980, the Brazilian government was demilitarise and democracy came back to Brazil.

1.3.6. The Urban Planning of Rio de Janeiro at the end of 20th Century and After

When it comes to the end of the 20th century, city of Rio de Janeiro faced more with the problem of its population getting poor and dilapidation of its public realm. Social gap between people increased rapidly and years of neglection of public facilities reached maximum dimensions. The street crime rates of Rio was the highest in the beginning of the last decade of 20th century.

While the previous urban planning ideologies in 1970s were being criticised for their lack of practical results, an important event occured to change the perception of local government for the city. A global environment forum promoted by the United Nations, 1992 Summit Conference on Sustainable Development of the Earth - Eco 92 held in Rio de Janeiro. Instead of following the previous mistakes, the municipality decided to focus on simple, inexpensive but effective urban programmes for its public space designs.

1992 Summit Conference on Sustainable Development of the Earth held in Rio de Janeiro helped the municipality giving up to follow previous mistakes and they decided to focus on simple, inexpensive but effective urban programmes for its public space designs.

II POVERTY AND SLUMS IN RIO DE JANEIRO

INTRODUCTION

As most of the metropolitan city, Rio de Janeiro is also suffering from the high amount of inequality among its citizens. The unequal distribution of the resources of the city, economic disadvantages or personal mistakes lead people to live in poverty conditions. When poverty merges with wrong urban planning strategies, it becomes inevitable to have informal settlements without proper infrastructure and facilities in the city. Physical inequality generates social inequality, as well as social and physical segregation. While the excluded community increases the tension due to the sense of not belonging, the higher strata feels the necessity to isolate from the city itself. In this chapter, poverty, slums and inequality in the world are analysed firstly. Moreover, the research continues with the deep analysis of Rio de Janerio's informal settlements, their evoluation throughout the history and current situation in terms of physical, social and housing condition.