The TradiTional lebanese house: how To incorporaTe an endangered heriTage inTo Modern day life.

The TradiTional lebanese house: how To incorporaTe an endangered heriTage inTo Modern day life.

Beit tarazi: Creating a new typology of housing to keep the heritage Buildings in Beirut alive.

isabelle Terzi

isabelle Terzi

Ma inTerior and spaTial design 2021/22

Ma inTerior and spaTial design 2021/22

1

Table of ConTenTs

I- HISTORY AND RESEARCH

A - Sequences 6

Sequence 1 : Find / Compare

Sequence 2 : Read / Write

Sequence 3 : Watch / make

Sequence 4 : Analyse /Communicate

Sequence 5 : observe / Record

Sequence 6: Combine / Promote

B - History and development of the Beirut House 22

1- History of Beirut (+ Sequence 5)

2- Urban growth of Beirut : Site Analysis throughout the years

3- Typology of the Traditional Lebanese House (+ Sequence 4) - Tarazi House

- The houses of Lady Cochrane : Carole Schoucair’s interior

4- Construction

II- RECONSTRUCTION PROJECT AND IDENTITY

A - Beirut: Conflicts and Urban development 48

1- Solidere: the aftermath of the Civil War

2- Video: Juliana Issa Tarazi: A mother unfolding her experience during the war

3- August 4th 2020

B - Architectural identity 62

The “Restoration method”

1- Beit Beirut

2- Saifi Village, Beirut

III- BEIT TARAZI

A - Project Analysis 74

1- Site analysis : Saifi, Beirut

2- Intentions : a middle ground between traditional and modern

B - Architecture and Design Process 94

1- Design process and evolution

2- Materiality

C - Final Design 144

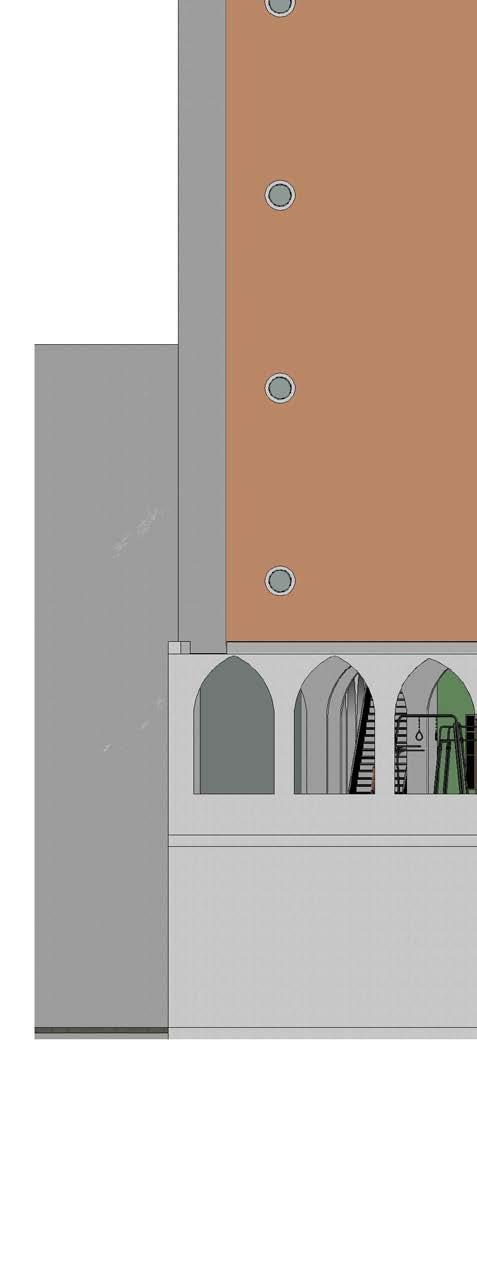

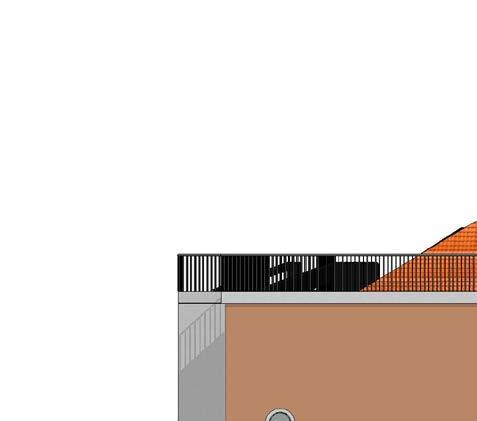

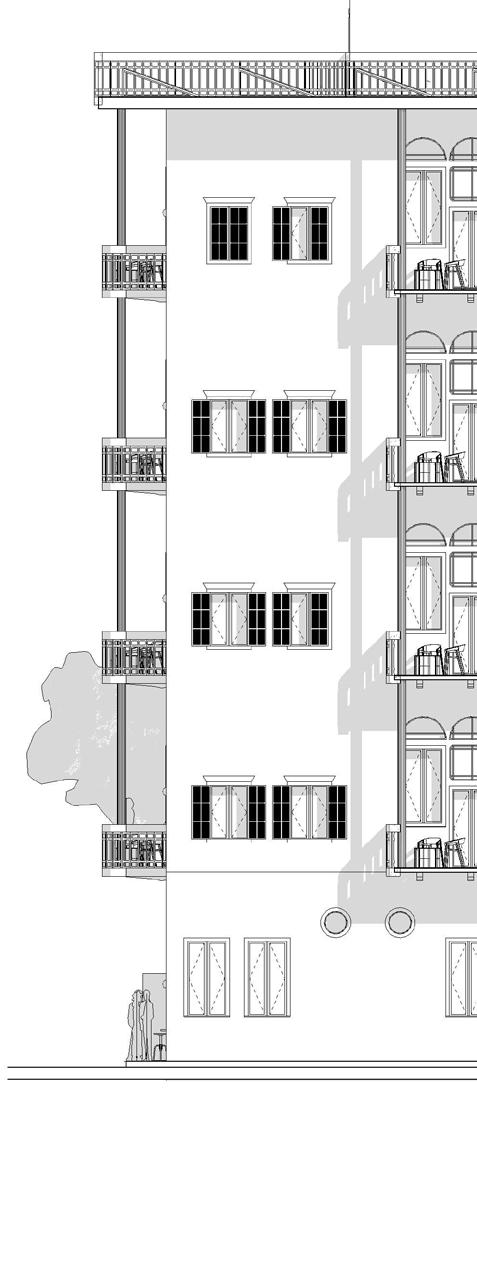

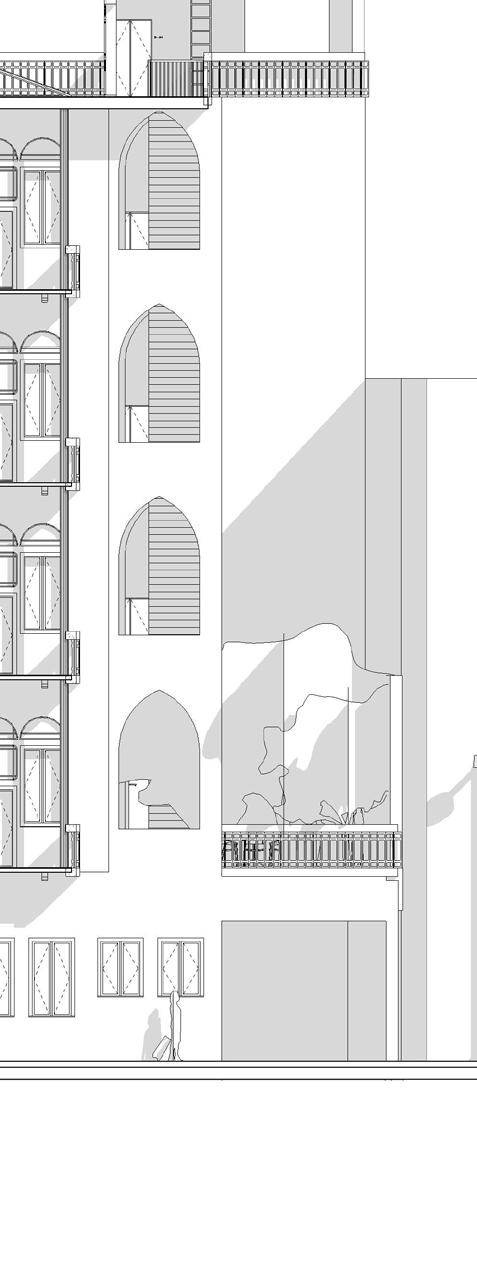

1- Floor plans/ Sections/ Elevations

2- 3D Views and renderings

3- Sobhiye Table

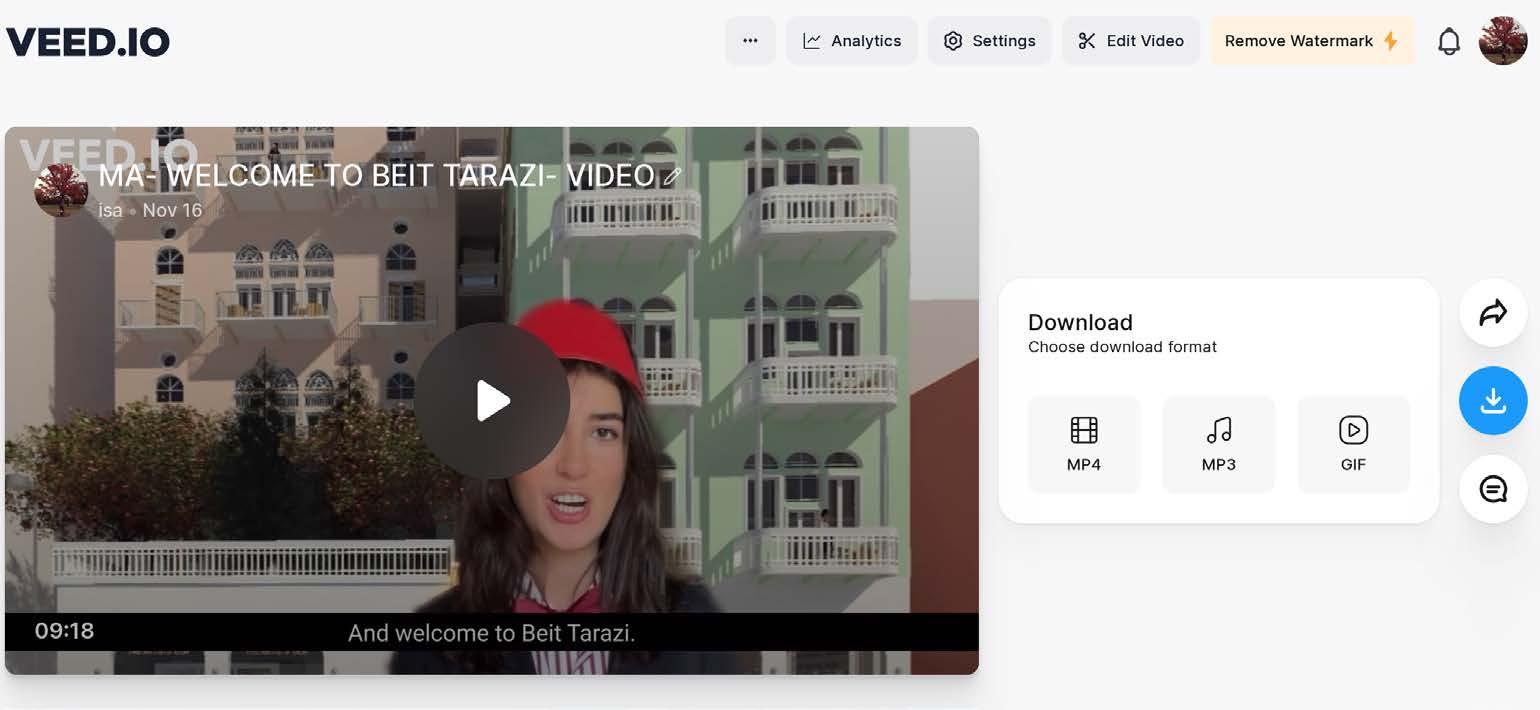

D - Video: Welcome to Beit Tarazi 234

1- Inspiration

2- Concept and link

3- Script

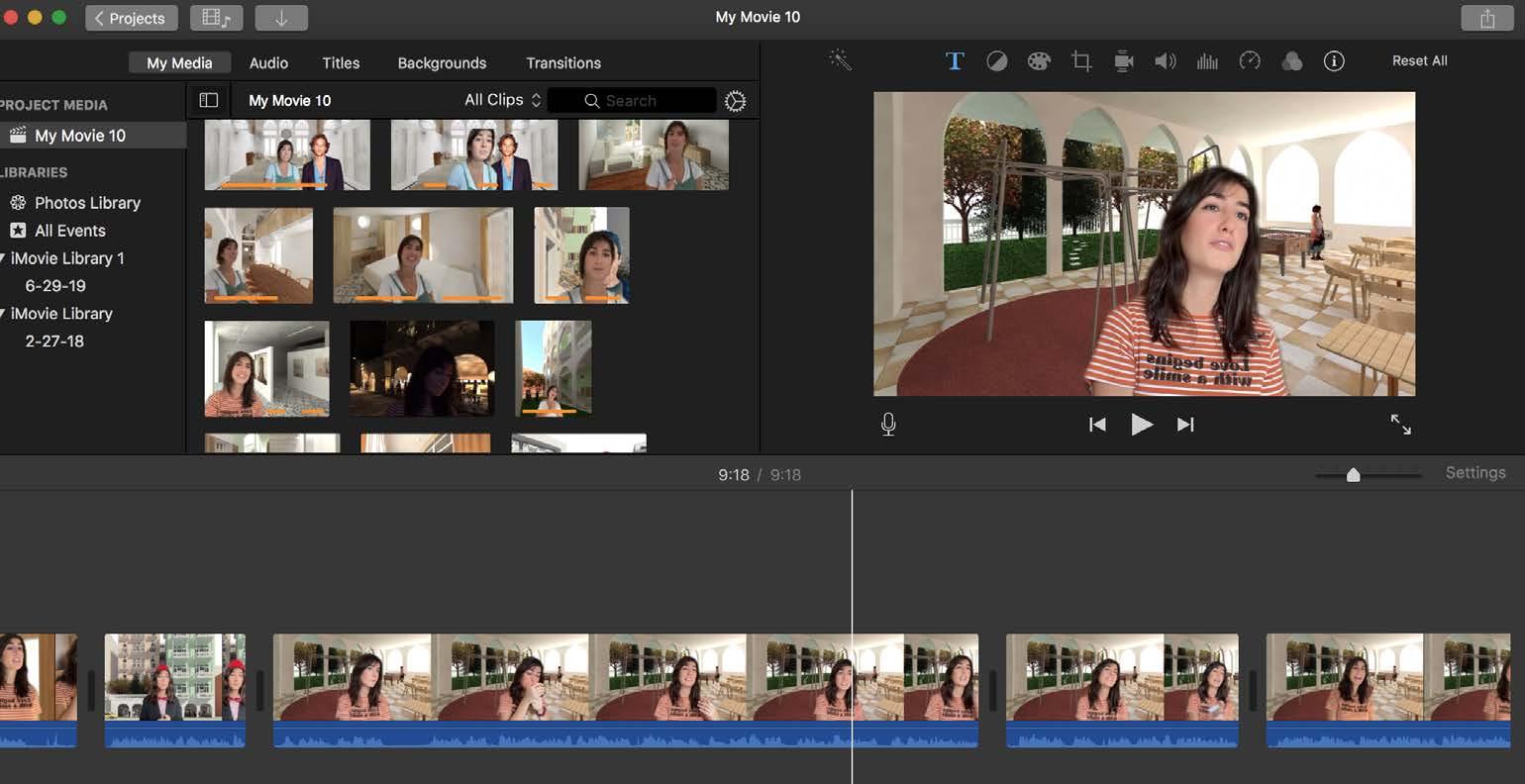

4- Methods

5- Character design

3 2

INTRODUCTION

Beirut is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. The city is situated on a penin sula at the midpoint of Lebanon’s Mediterranean coast. It has been inhabited for more than 5,000 years, and was one of Phoenicia’s most prominent city-states, making it one of the oldest cities in the world. Given this history, we should be able to find numerous footprints that are the mark of the various civilizations that passed through and found refuge in Lebanon. However, very few monu ments were preserved. This lack of cultural preservation is also shown through the rarity of traditional Lebanese houses, which are slowly being destroyed over the years. These houses have a symbolic importance as Lebanon’s archetypal House and a pioneer in the country’s Architecture. Niched in Saifi, in the centre of Beirut, Beit Tarazi (meaning Tarazi House) is a project created to combine the beauty and charm of the Traditional Lebanese Architecture whilst integrating modern construction elements to create a new typology of house for future constructions. The goal of my project is to keep the tradition alive and not loose touch of our identity and history, while taking in consideration modern-day life and the benefits of new methods of constructions and environmental-friendly elements.

5 4

I- A SEQUENCES

6

BILLION EFFORT Recent fighting fails to

Ghattas, Sam F . Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Milwaukee, Wis. [Milwaukee, Wis]. 12 May 1996: 5.

ABSTRACT (ABSTRACT)

Beirut, a city ravaged by a 1975-'90 civil war, is more or less back to normal two weeks after a U.S.-brokered ceasefire halted recent fighting between Israel and Hezbollah guerrillas.

Photo; ASSOCIATED PRESS; Caption: Rebuilding efforts resume in Beirut, Lebanon, after a U.S.-brokered ceasefire halted the April 11-26 fighting between Israel and the Hezbollah guerrillas. This earth mover is working on bridge construction at the capital's southern entrance. Story on 5A

Although the countryside in the south was hit hard, damage in Beirut, the country's economic engine, was largely restricted to two power relay stations blasted by Israeli jets and parts of the southern slums where Hezbollah command centers were rocketed.

FULL TEXT

The pounding of jackhammers has replaced the crackle of anti-aircraft fire. Passenger jets roar overhead instead of Israeli warplanes.

Beirut, a city ravaged by a 1975-'90 civil war, is more or less back to normal two weeks after a U.S.-brokered ceasefire halted recent fighting between Israel and Hezbollah guerrillas.

The worst Israeli-Arab flare-up in nearly 14 years cost millions of dollars in damage to towns and villages in southern Lebanon. But the Lebanese say it caused only a hiccup in their post-civil war reconstruction. "Nothing can make us give up the will to rebuild," Prime Minister Rafik Hariri said after the ceasefire took hold April 27. "No force can stop the Lebanese dream of the nation's revival."

Hariri, a billionaire businessman who has led the reconstruction drive since taking office in 1992, has accused Israel of "trying to jeopardize the work that I've done."

Although the countryside in the south was hit hard, damage in Beirut, the country's economic engine, was largely restricted to two power relay stations blasted by Israeli jets and parts of the southern slums where Hezbollah command centers were rocketed.

During the 16 days of fighting, Beirut residents groused about being without electricity as they started up the diesel-powered generators, just like in the old civil war days.

But though it seemed bad at the time, the conflict caused relatively little damage in Beirut the cancellation of some tourist bookings, the postponement of some business seminars and a general economic slowdown.

Economic confidence didn't seem to suffer: The Lebanese pound held steady at around 1,580 to the U.S. dollar throughout the fighting, according to Marwan Iskandar, a senior economic analyst.

The World Bank, which already has committed $300 million to rebuilding Lebanon, has announced plans to see whether more money is needed in the wake of the Israeli blitz.

Even the capital's power system is working better than expected.

Beirut had only recently returned to a 24-hour electricity supply after the civil war. So after Israeli air raids on two power stations, officials said it could be more than a year before the system was back to normal.

That initial assessment proved far too gloomy, with some neighborhoods already receiving round-the-clock

Document URL : https://www-proquest-com.arts.idm.oclc.org/news papers/8-billion-effort-recent-fighting-fails-stop/ docview/260414667/se-2?accountid=10342

Lebanon as We Once Knew It Is Gone

Mounzer, Lina . The New York Times International edition; New York [New York]. 06 Sep 2021.

ProQuest document link

FULL TEXT

BEIRUT —I never thought I would live to see the end of the world.

But that is exactly what we are living today in Lebanon. The end of an entire way of life. I read the headlines about us, and they are a list of facts and numbers. The currency has lost over 90 percent of its value since 2019; 78 percent of the population is estimated to be living in poverty; there are severe shortages of fuel and diesel; society is on the verge of total implosion.

But what does all this mean? It means days entirely occupied with the scramble for basic necessities. A life reduced to the logistics of survival and a population that is physically, mentally and emotionally depleted.

I long for the simplest pleasures: gathering with family on Sundays for elaborate meals that are unaffordable now; driving down the coast to see a friend, instead of saving my gas for emergencies; going out for a drink in Beirut’s Mar Mikhael strip without counting how many of my old haunts have shut down. I never used to think twice about these things, but now it’s impossible to imagine indulging in any of these luxuries.

I begin my days in Beirut already exhausted. It doesn’t help that there’s a gas station around the corner from my house. Cars start lining up for fuel the night before, blocking traffic, and by 7 a.m. the sound of blaring horns and frustrated shouting from the street is fraying my nerves.

It is nearly impossible to sit down to work. My laptop battery lasts only so long anyway. In my neighborhood, government-provided power comes on for just an hour a day. The UPS battery that keeps the internet router working runs out of juice by noon. I’m behind on every deadline; I’ve written countless shamefaced emails of apology. What am even supposed to say? “My country is falling apart and there’s not a single moment of my day that isn’t beholden to its collapse”? Nights are sleepless in the choking summer heat. Building generators operate for only four hours before going off around midnight to save diesel —if they are turned on at all.

Every few days there’s a new low to get used to. One recent morning needed to exchange some dollars to buy groceries, chiefly bread. At the exchange shop there was a long line of people because the dollar rate was slightly down. There had been rumors that the new prime minister was close to forming a government. At this point such news is like a joke —we’ve been without a government since the cataclysmic port blast on Aug. 4, 2020, and the three prime ministers delegated by Parliament to form a government since then have failed to do so because of infighting between political parties, the same ones who’ve brought this country to ruin. Still, all markets are susceptible to rumor, and whenever the dollar rate goes down, people flock to convert their useless Lebanese lira into dollars.

Once I had my money, I headed to the supermarket, and on my way I encountered a tiny old woman sitting on the pavement. I wanted to give her some money and a bottle of cold water. went to four shops before I found one. This was how I first learned that we are now also facing a shortage of bottled water. The week before, I’d discovered that there was a shortage of cooking gas after our canister ran out and I had to make a dozen calls —and pay five times what it once cost —to replace it. While cooking gas is vital, the shortage of bottled water is an even bigger disaster in a country where most Lebanese believe the tap water isn’t even safe enough to cook with. (Tap water, too, is at risk of being shut down.) read about it later: There isn’t enough fuel to power the machines forming the plastic bottles or the pumps that fill them. No fuel for the trucks making deliveries.

Likewise, there is little bread to be found. There was none at the big supermarket I went to that day, which was

GENERATED BY PROQUEST.COM Page 1 of 4

Document URL : https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/lebanon-aswe-once-knew-is-gone/docview/2569853522/se-2?ac countid=10342

9 8

$8

stop Lebanon's reconstruction Country continues to bounce back from 1975-'90 civil war

ProQuest document link

PDF

PROQUEST.COM

GENERATED BY

Page 1 of 3

SEQUENCE 1 : FIND/ COMPARE

PDF

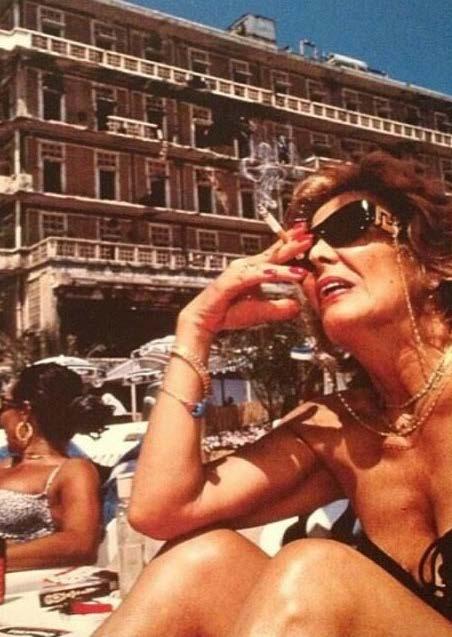

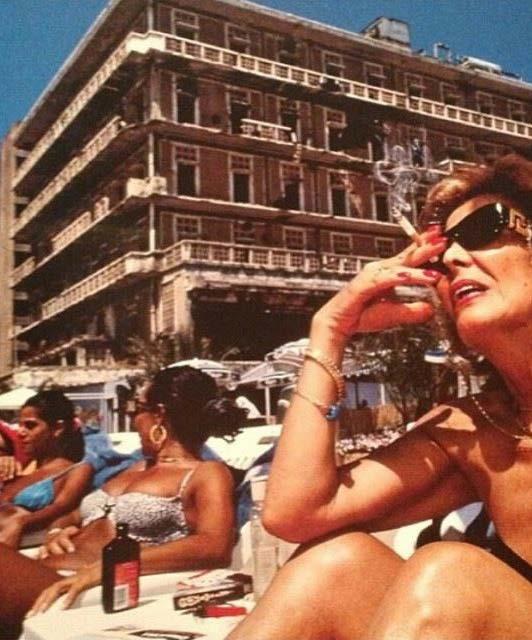

I chose those two articles to talk about the situation in Lebanon, in 1996 and 2021. In 1996, Lebanon was reconstructing and bouncing back from the civil war. It was a period of hope for the Lebanese people, seeing their country living again. The article taken from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel depicts the country “going back to nor mal” ; a country rebuilding its roads, its airport, and aiming towards technological improvement and development. The Lebanese Pound was at a normal rate, and electricity was provided. Little did we know that this uplifting transitional period was going to slowly fade away and lead to the darkest days that Lebanon will face. Politicians blaming other country’s misconducts instead of their own and getting away with it because the population was still in the dark ; slowly stealing from us and instauring an economical system which doesn’t fulfill the basic needs of the people and the country is what led to Lebanon’s utter destruction.

In fact, the recent article from The New York Times is a testimony of what a Lebanese resident is facing daily. Living without electricity, potable water, gas, and even food.

Having endured a cata strophic explosion that wiped half of the city, killed hundreds and injured thousands ; people lost their homes and were left in despair, on top of the un bearable economical crisis and COVID-19 pandemic, and all of that because of an incompetent government, only caring about filling their pockets with millions of dollars whilst more than half of the pop ulation live in poverty. Be ing a Lebanese citizen and growing up there makes it my responsibility to have a glimpse of hope for my country, and contributing to it in any possible way.

As an interior designer, I am able to help through architecture, design and city development, aiming to fill the people’s needs and give them a reason to stay in the country. This is why choosing Lebanon as my MA project location is unquestionable, espe cially Beirut. After the port explosion, hundreds of traditional Lebanese hous es were affected as well, threatening the extinction of our heritage and culture. Working on bringing back the traditional Lebanese architecture is essential, for they have been in ex tinction since the civil war. People destroying them to build skyscrapers for their greedy needs is also one of the reasons why our coun try lost its charm and cul ture.

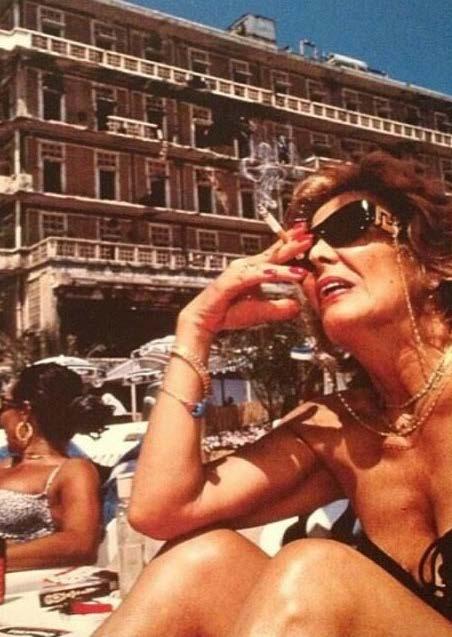

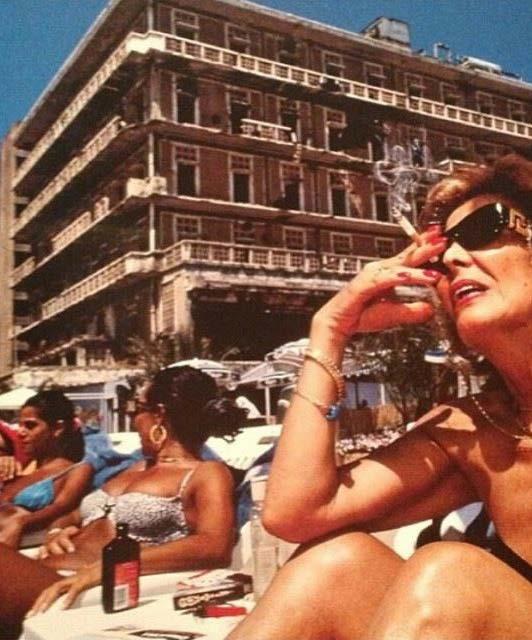

Seeing the change between 1996 and 2021 is flagrant and despairing altogether ; the roads were being built then and now people can’t use their cars and the highways are dark and gloomy, giving place to car accidents of all sorts. Then people were going out and showing off, now the Lebanese citizens are traumatized and desperate, fleeing the country in any possible way. Then they had elec tricity and hot water, now people have approximately 2 hour of government provided electricity per day. This is not the result of conflicts between Lebanon and other countries, this is a result of the incompetence and mismanagement of our government, slowly destroying our heritage and identity, not giving the population basic human needs, like potable water, electricity, transportation, public and green spaces. Stealing from us years after years, they go from millionaires to billionaires, and we move from middle class to scavenging the whole country for a medicine tablet.

11 10

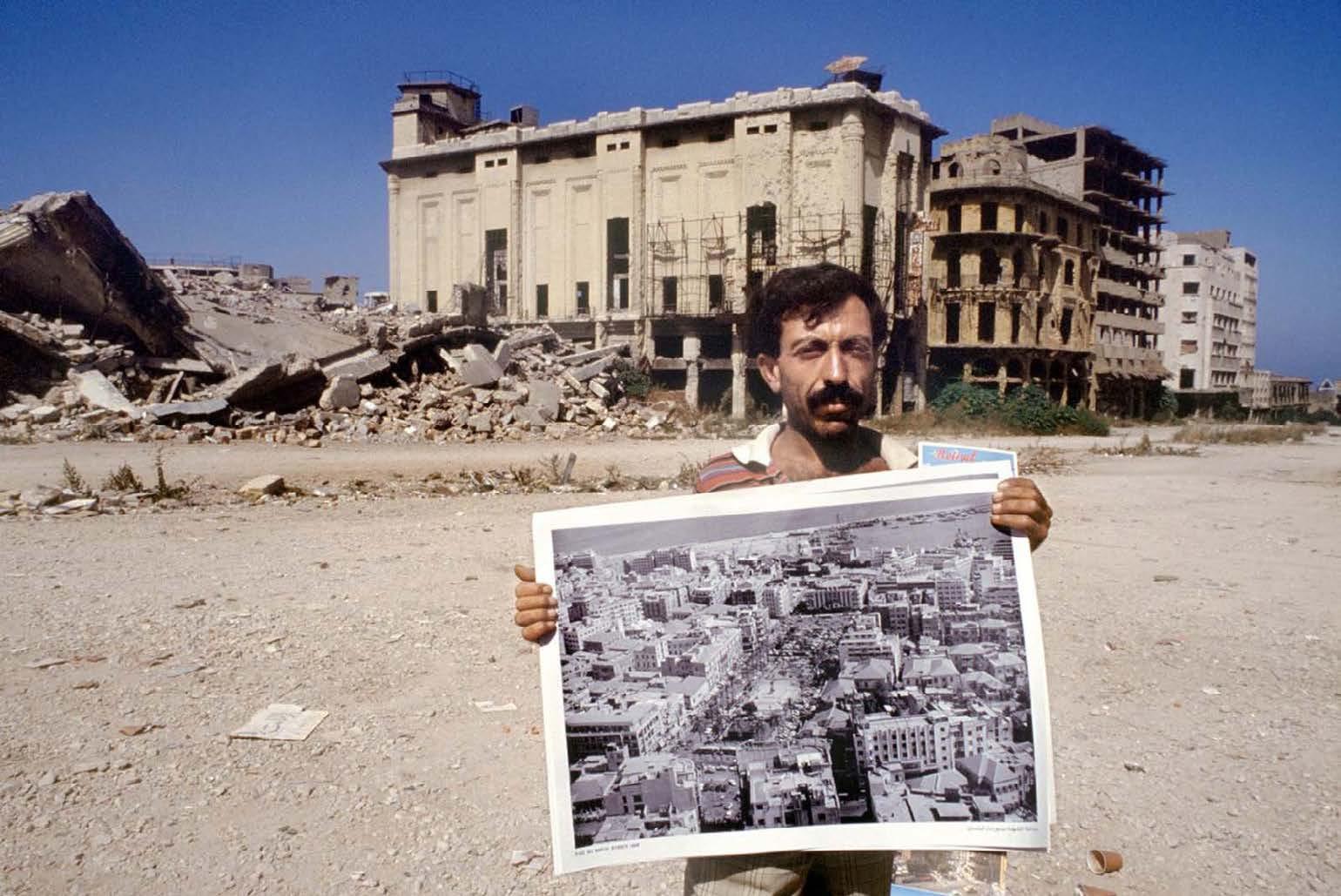

St George Hotel and Marina, 1996, Beirut, Lebanon

A customer pushes her trolley next to near empty shelves, Beirut, Lebanon, Jan. 11, 2021

15 14 SEQUENCE 3 : WATCH / MAKE https://youtu.be/11ibYsIAk2c

17 16 SEQUENCE 4 : ANALYSE / COMMUNICATE

19 18 SEQUENCE 5 : OBSERVE / RECORD https://youtu.be/11ibYsIAk2c

sequenCe 1 sequenCe 2 sequenCe 3

sequenCe 4 sequenCe 5

Introduction of the problematical sub ject that is Lebanon’s mismanagement by its Government : led towards the almost disappearance of the Traditional house of Beirut

Writing exercise: the impact that a room has on peo ple.

1000sec walks : dis covering that all es sential amenities are at a close dis tance from home/ how the Urban de velopment of a City should be

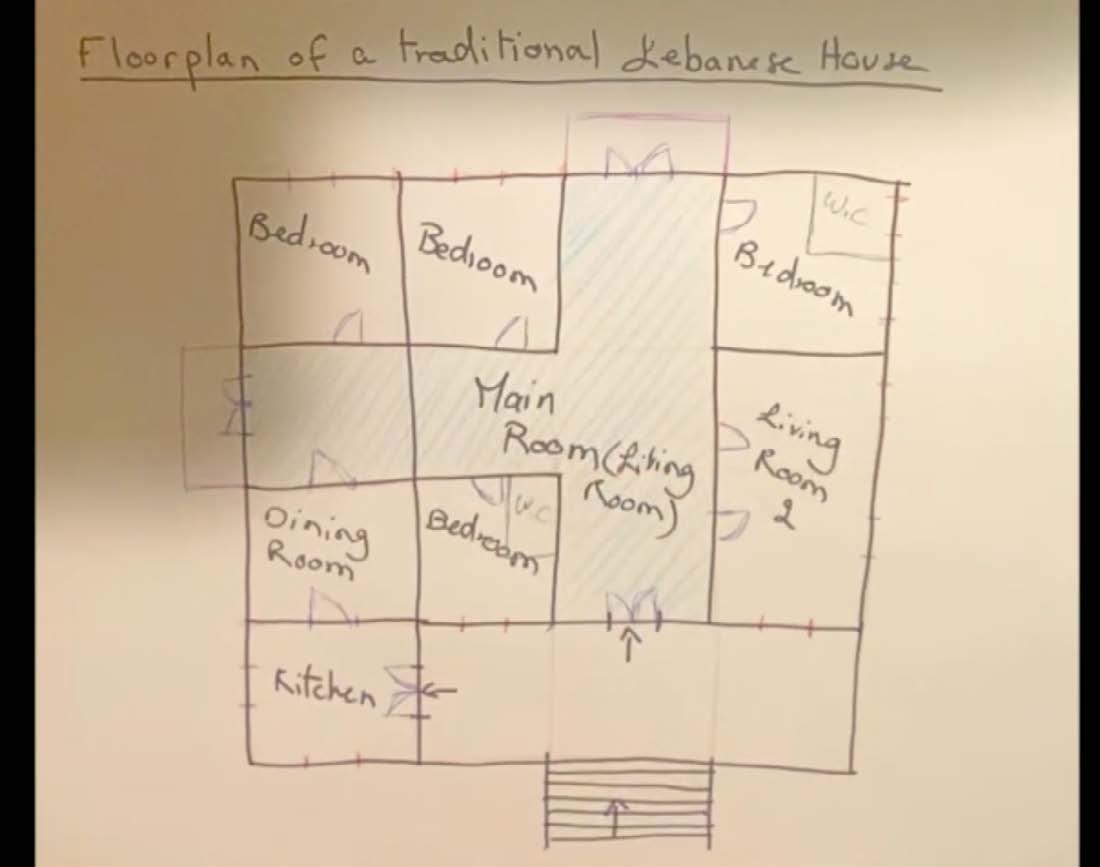

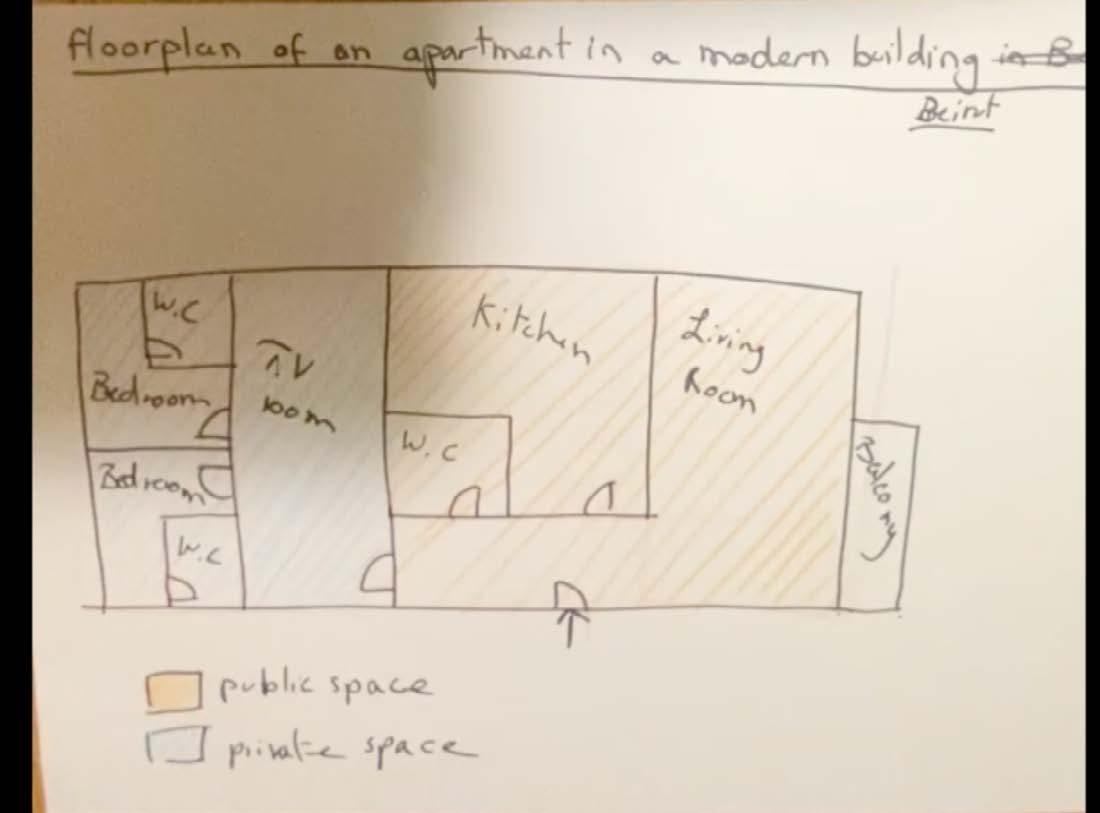

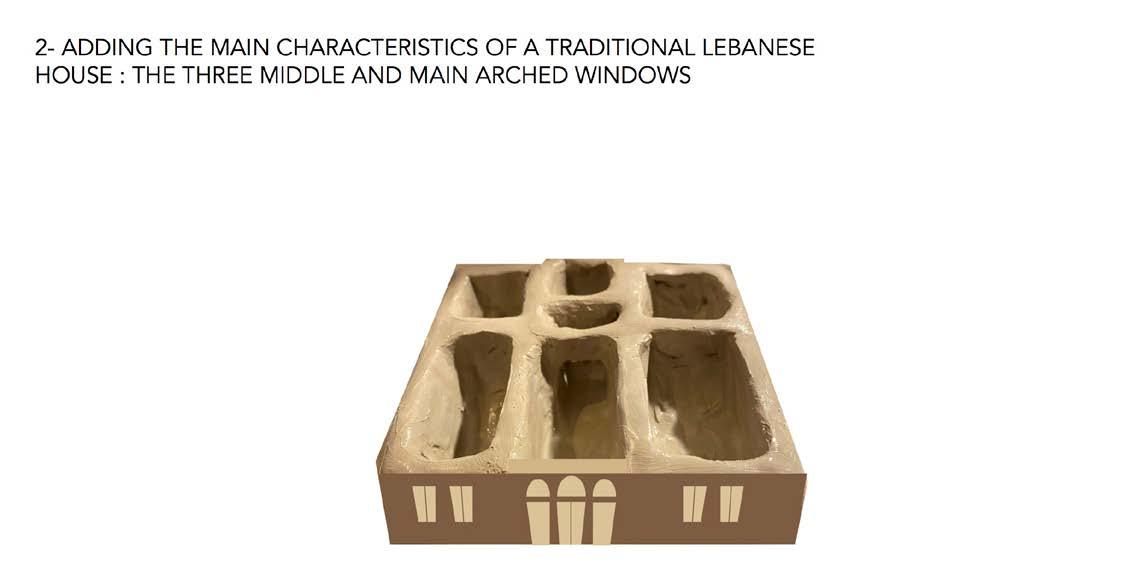

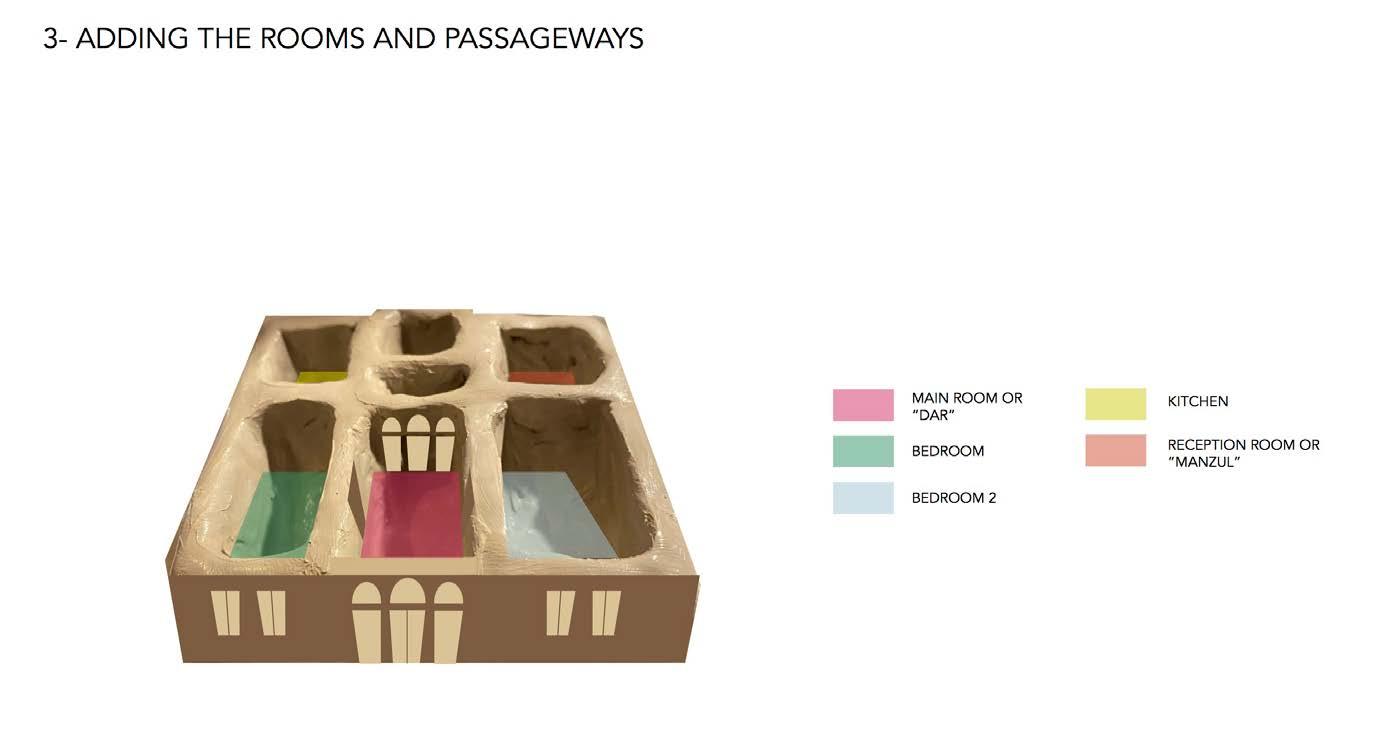

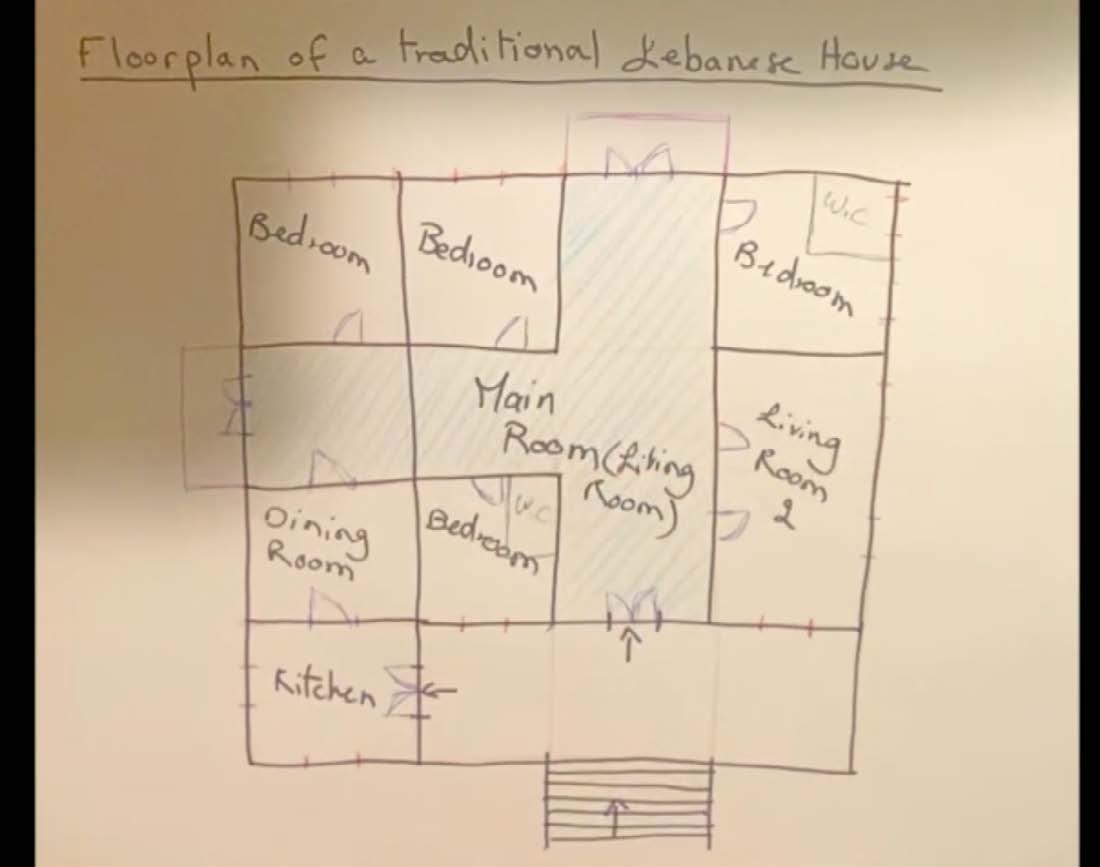

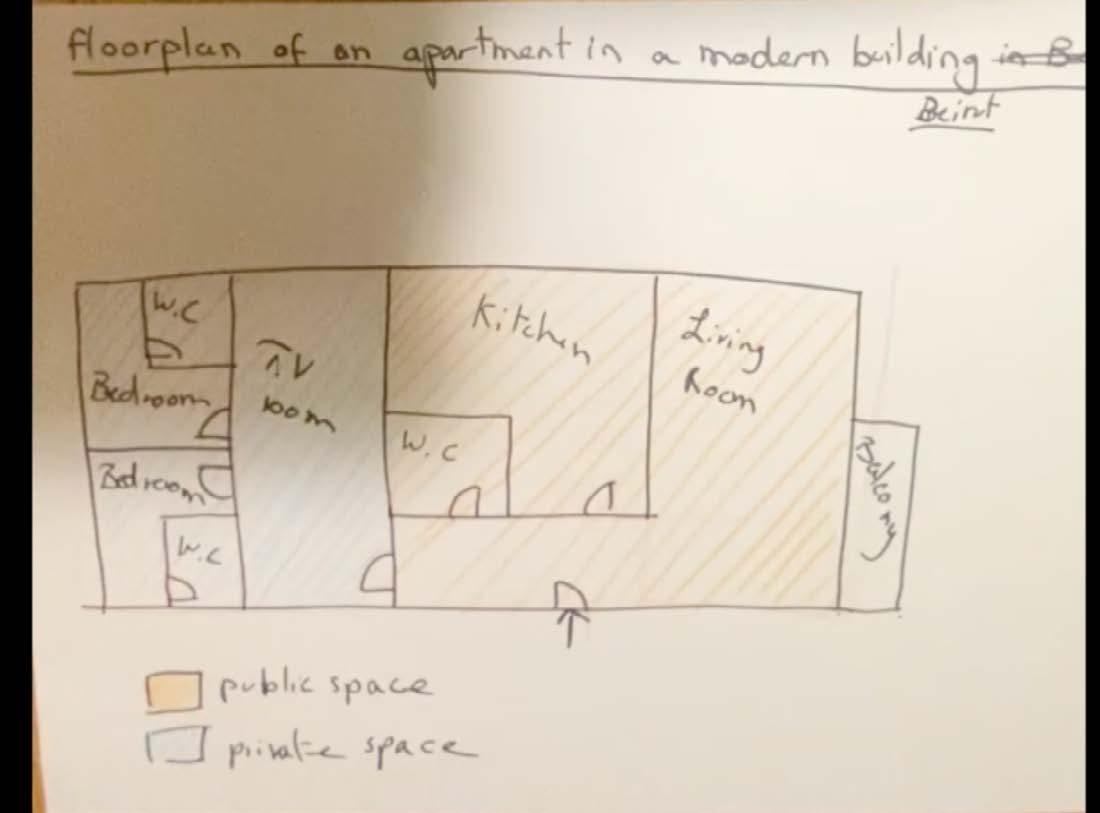

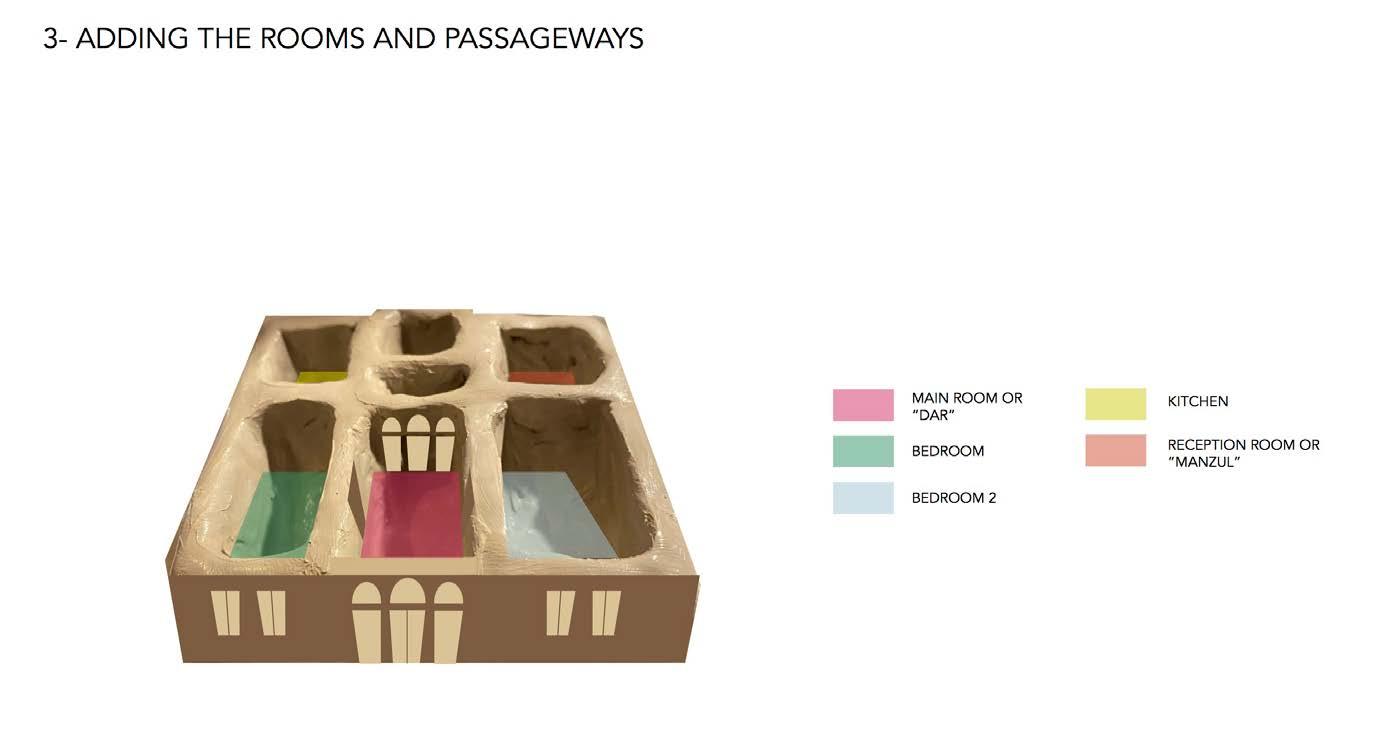

Sketches and mod els of a TLH’s floor plan vs a Modern apartment floorplan : Analysis of each room’s purpose, and the bundary between private and public spaces at Home.

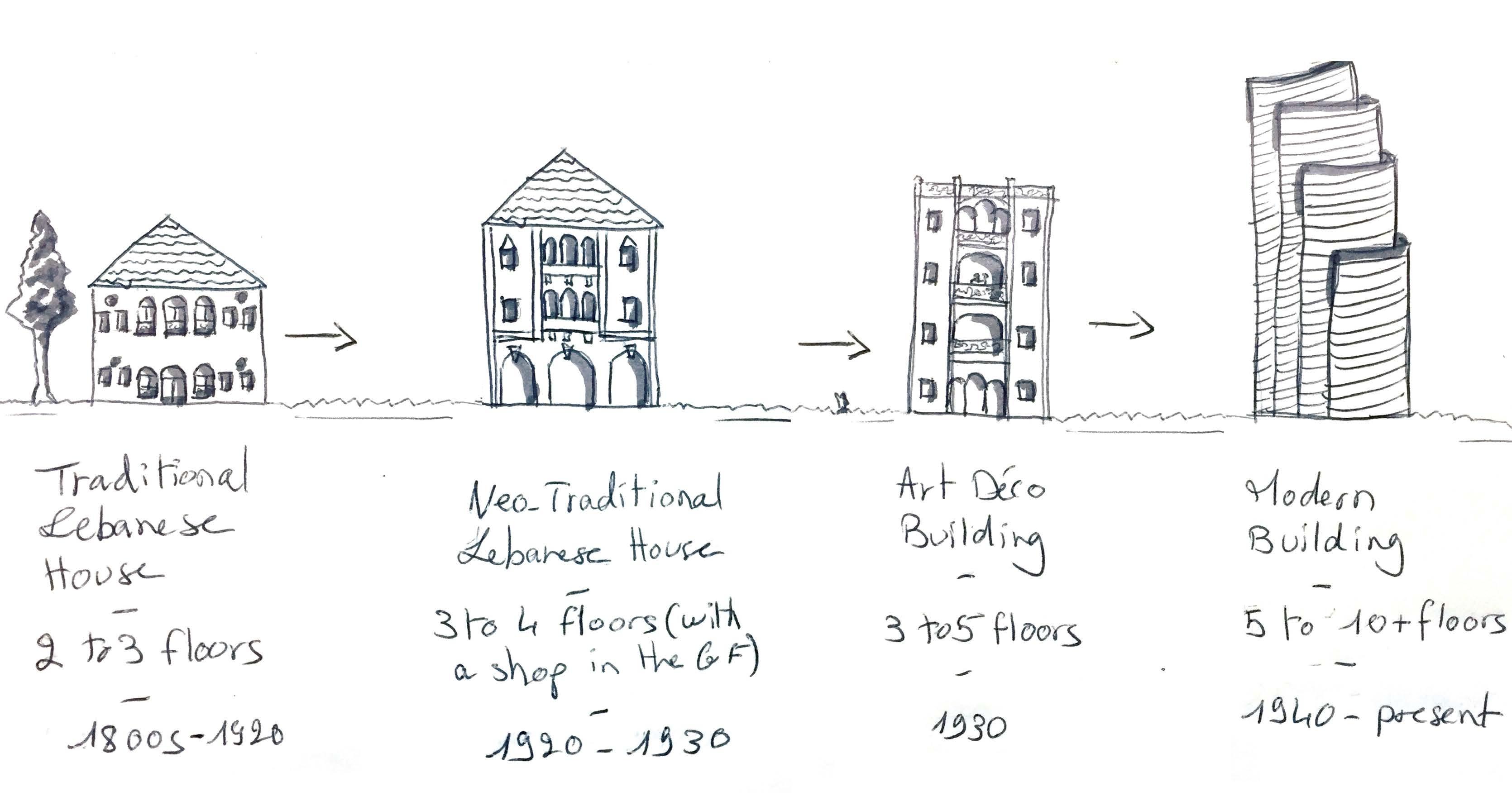

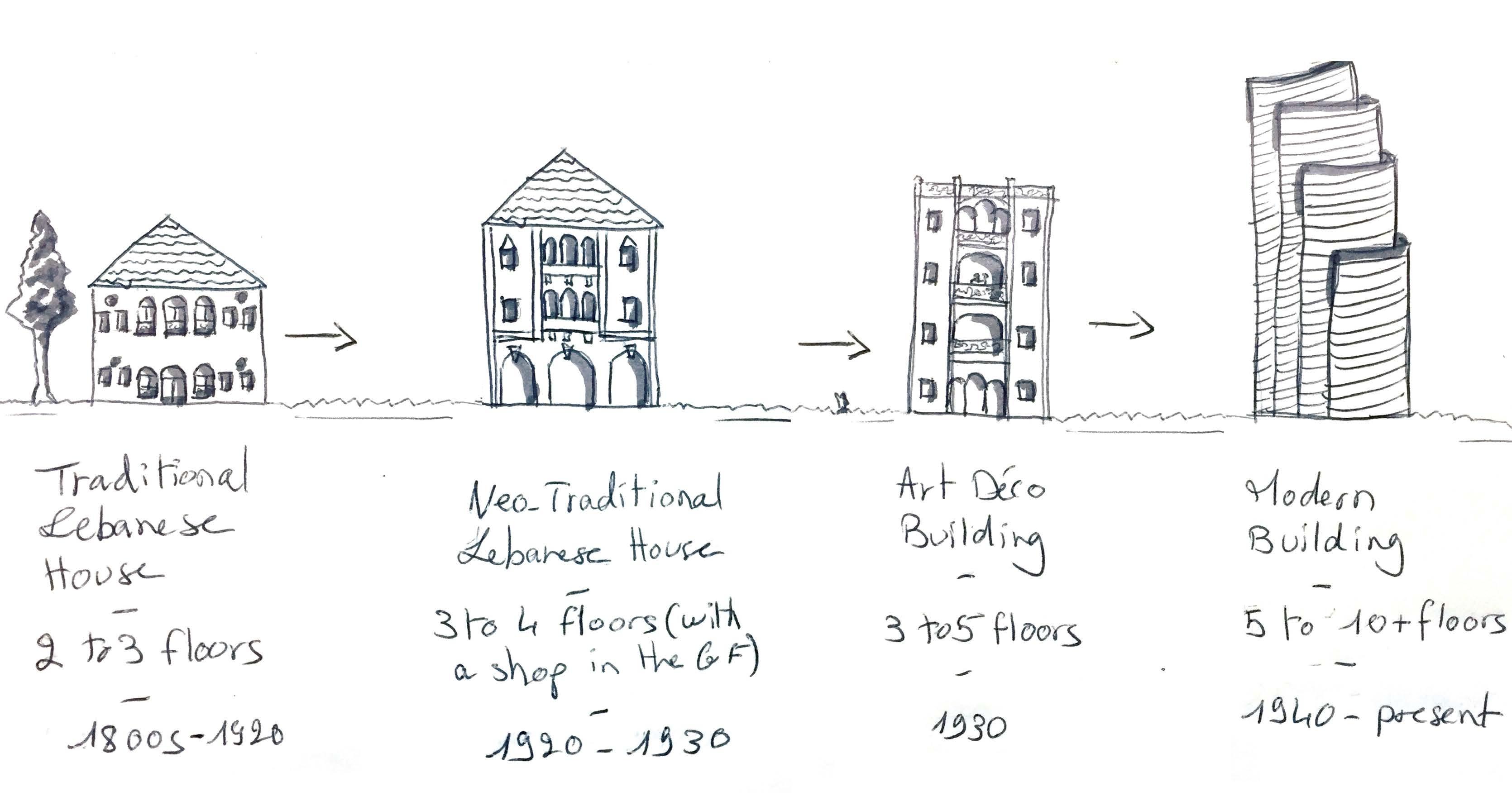

Changes through time, from the 1800s to present time : wit nessing the progres sive expansion of the Beirut house’s architecture that led to its symbolic importance as Leb anon’s archetypal House and a pio neer in the country’s Architecture. Be ing Then damaged during the civil war and consequently entirely destroyed to build modern buildings instead, leading to their ex tinction, therefore a disappearance of Lebanon’s heritage and history : loss of identity?

21 20

I- B

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE BEIRUT HOUSE

22

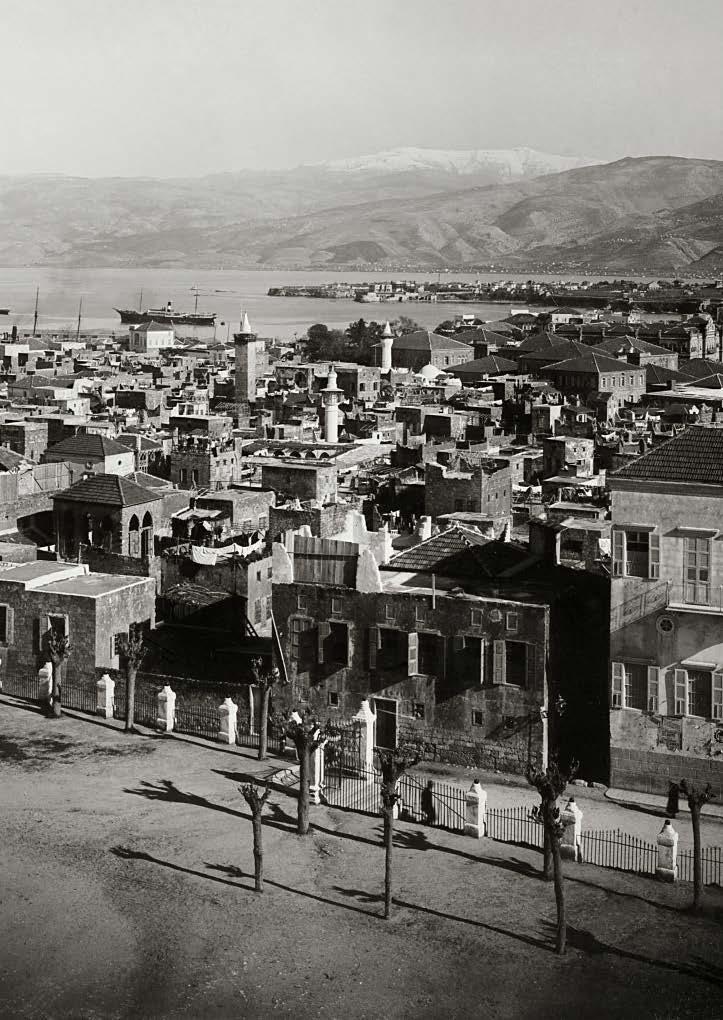

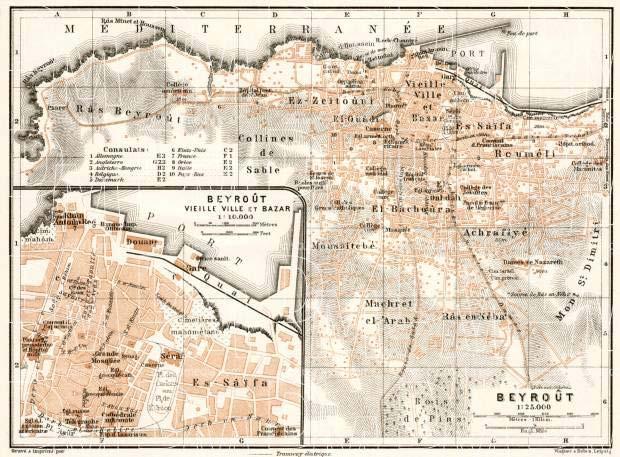

Beirut is a city with over 5,000 years of history. And yet, nowa days, historic houses, including those we call “Beirut houses” , are found located almost exclusively in the pericentral quarters which only began to develop in the 19th century. . This situation, which differs from that of other cities in Lebanon, such as Saïda or Tripo li, whose historic core has been preserved, is due to the profound transformation that Beirut under went in the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century. This transformation has been fu eled by a number of factors. One of these is the political and eco nomic rise of the city, a process that began during the Egyptian occupation (1832-1840) when Beirut assumed the functions for merly occupied by the provincial capitals of Saida and Acre.

It became, in 1841, the official capital of the Ottoman province of Saïda then, in 1888 that of the new province of Beirut (Wilāyat Bayrūt), and finally the capital of the new State of Lebanon under French mandate, created in the 1920s. At the beginning of the 20th century, Beirut had more than 120,000 inhabitants and in 1932, the French census counted 160,000. This demographic growth of the nineteenth century was not only due to people who settled in Beirut in search of economic and social opportunities but also to those who were fleeing socio-economic upheavals, repeated outbursts of violence and civil strife in the Lebanese mountains and cities in Syria like Damascus and Aleppo, especially in the 1840s-1860s. People were struggling to find their place in a growing city and urban society and in a rapidly changing and modernizing world. The houses built at that time were part of this effort.

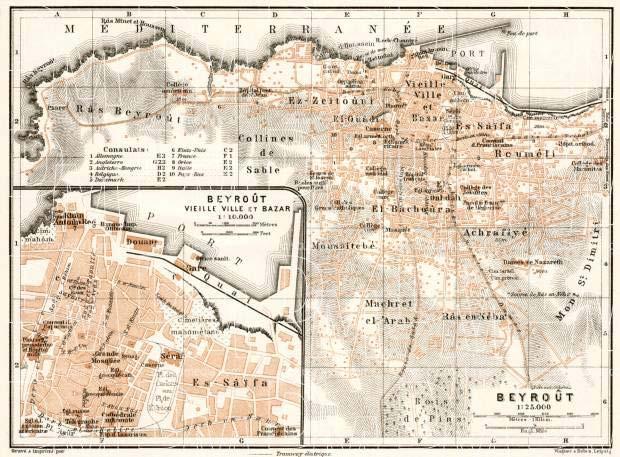

24 1- HISTORY

Be rut c ty mAp 1911 Be rut c ty mAp 2017

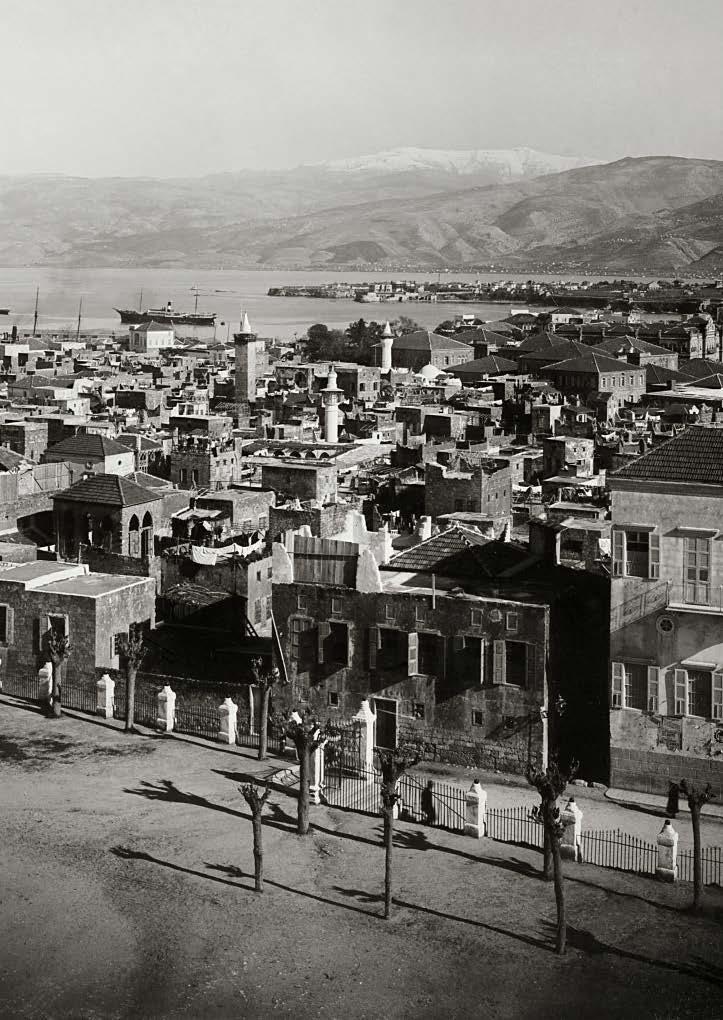

Beirut 1800s

2- URBAN GROWTH OF BEIRUT: SITE ANALYSIS

THROUGHOUT THE YEARS

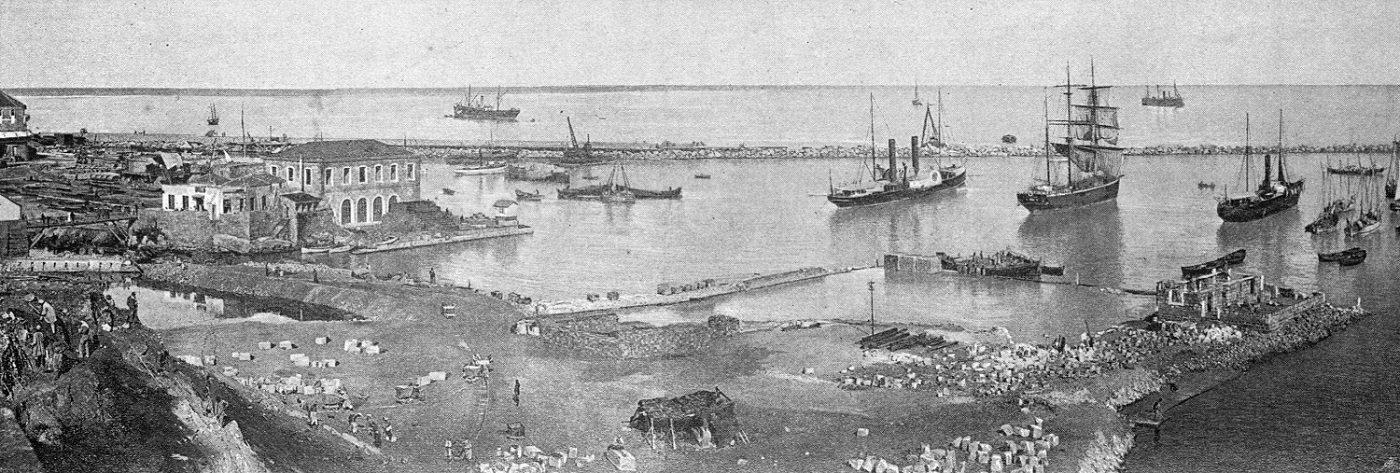

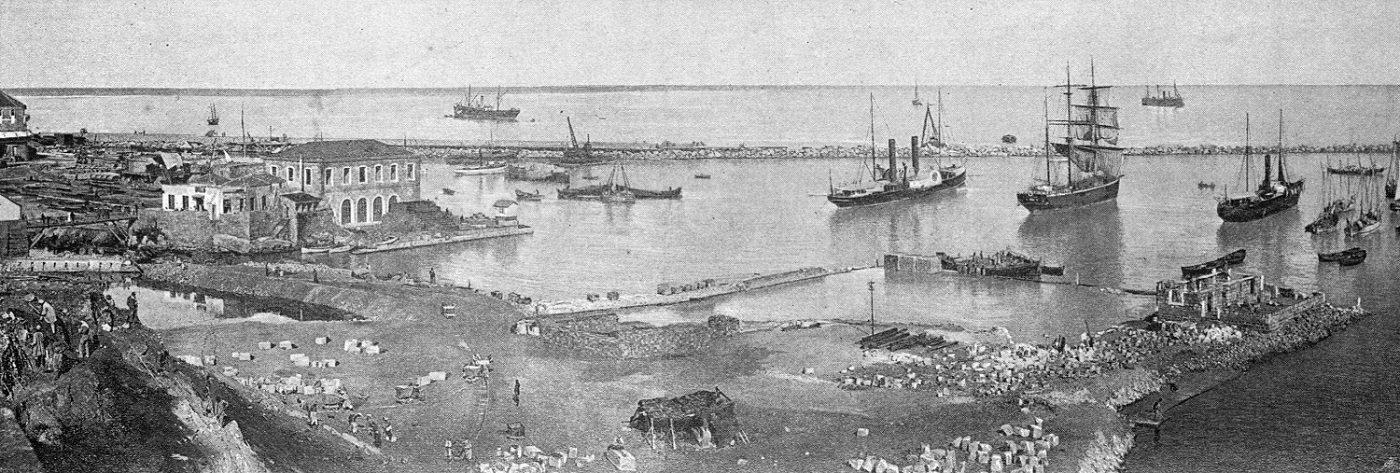

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Beirut witnessed a rapid ur ban transformation, driven by an economical growth due to the expansion of its port that was located strategically on the Mediterranean, serving as a transition between Europe and Syrian hinterland. The city was designated as a provincial capital of the Ottoman Empire and benefited from the Tanzimat (1839 – 1876), a series of governmental reforms meant to modernize the empire and consolidate its social and political foundations. It was then that extra mural expansion be gan: Merchants, bankers, catholic and protestant missionaries moved outside the medieval city walls and on the hills surrounding the old city. The nearby outskirts were the first to be colonized: Mazra’at al Sayfî towards the East, Ghalghoûl/’Ayn al Bâchoûrah, Mazra’at al Qantârî, Santiyyah or Zaytoûnî, towards the South and West. In parallel, the arrival of immigrants taking residence in the old city and along access roads accelerated the densification of the urban fabric, with empty spaces being built up. Consequently, in the remote countryside, localities of more or less significant size appeared timidly then densified and organized themselves: Rmeil, Râs al Nabaa, Moussaytbeh, Jimmayzat al Yammîn, Ras Beirut, Mina al Hosn or Dâr al Mraysah. In the late 1850s, the urbanization of the outskirts had increased significantly that it justified the construction of places of worship which, in turn, stimulated further constructions in what was considered remote areas of the city. For example, the construction of Mar Mikhael church in Rmeil accentuated the urbanization of the eponymous neighborhood.

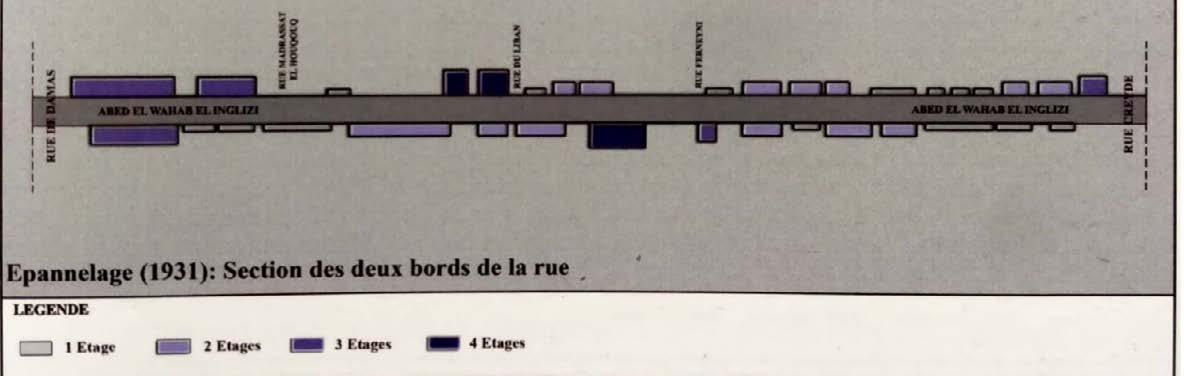

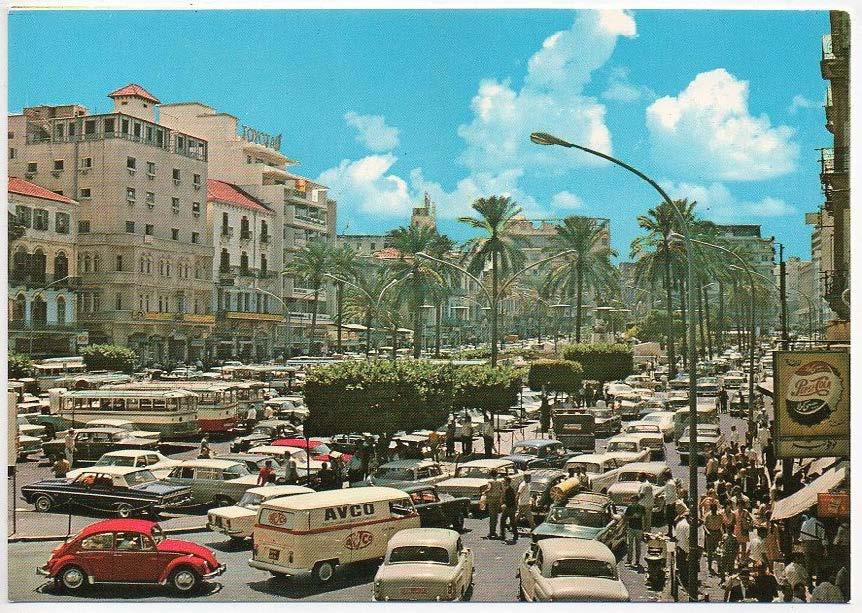

As the city was getting too crowd ed, a second expansion happened towards the east, as the rich bour geoisie sought to build large man sions on the nearby hill, Achrafieh (Mar Mitr hill). It was made possi ble by the continuous progressist planning and modernization works of the city, the most important of which was the completion of Da mascus street in 1863. Around the end of the Ottoman Empire, outside the walls of the medieval city, large houses sur rounded by orchards and gardens reflected an Occidentalized so cio-cultural lifestyle of rich mer chants influenced by their multi ples travels to Europe and by the presence of foreign missionaries, consulates and merchants in Bei rut. Later, during the French Man date, the westernization of Beirut was reinforced and the city played the role of a regional metropole of 300,000 people; Neighborhoods along Damascus street quick ly became urbanized, rich in redroof houses and art deco build ings. Street alignments, building heights and typologies were de fined by the land legislation estab lished by the mandate authorities (1930). It generated a harmoni ous urban fabric in relation to ar chitectural style, integration and street perception.

27 26

conStruct on of the new port n Be rut, leBAnon 1893

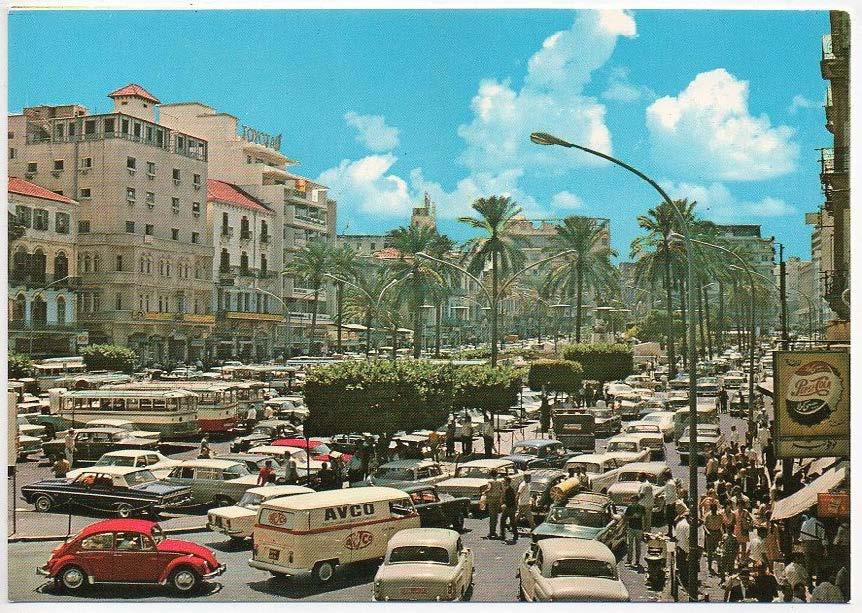

SAhet el-Burj – plAce DeS cAnonS Be rut 1898 (toDAy S mArtyrS SquAre)

mArtyrS SquAre 2019

mArtyrS SquAre 1960S

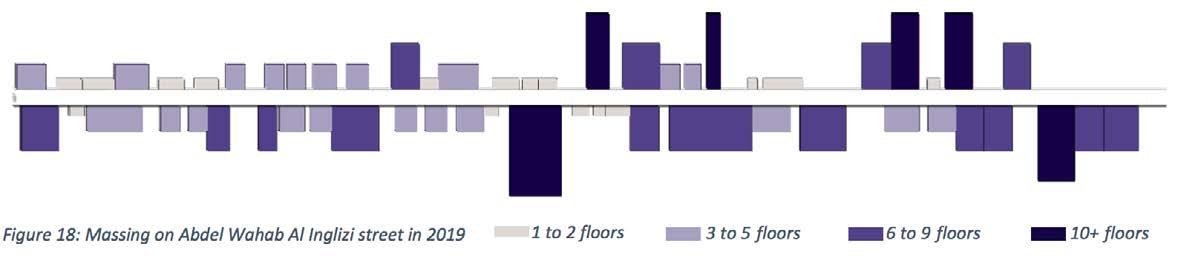

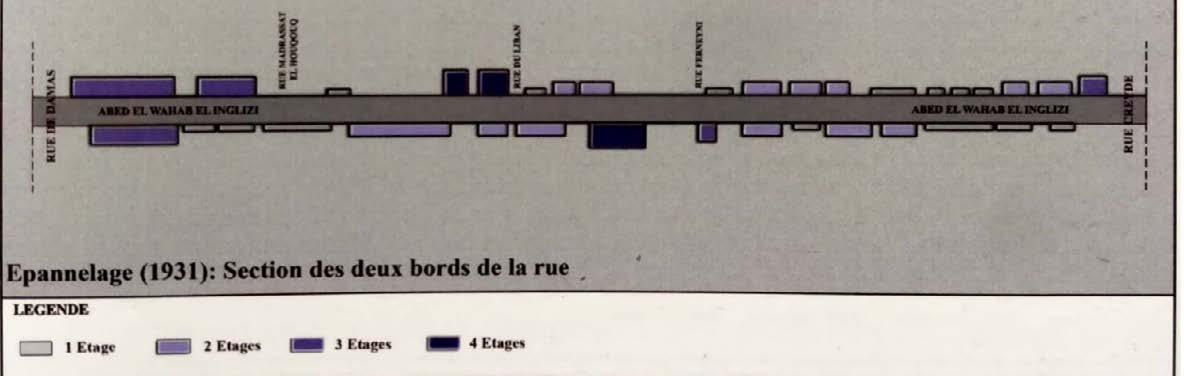

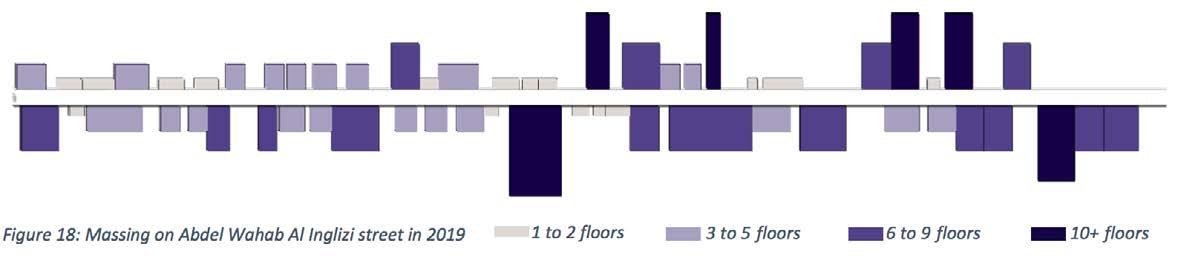

Starting 1940, the adoption of a new building law allowing higher land exploita tion and building heights modified consistently the morphology of the neighbor hoods. In 1954, under the pressure of an intense building boom, Beirut Master Plan divided the city in 10 zones and established a regulation based on densities. The central areas that include the old districts where most of the built heritage is concentrated were affected with the highest exploitation ratios leading to growing land pressure on heritage, mostly consisting of a maximum of 3- floors buildings. In fact, the current ratios for total built-up area (B.U.A) in these sectors allowed an increase in land prices, resulting in a higher risk of demolition for heritage build ings and in a major mutation of the urban fabric. A direct consequence of these rapid transformations materialized in a bigger consumption of city space and in a radical change of people’s lifestyle, driving a flow of diverse activities into his torical centers and traditional neighborhoods, and consequently a densification of their built environment. The need of more space for residents, businesses and activities let to a systematic loading of existing buildings: heightening, addition of staircases, new floors and subdivisions as well as the transformation of gardens and courtyards into garages or workshops. Adaptation to the needs of the modern lifestyle combined with the urban regulation generated an increase in land prices due to their rarity, attracting speculators who replaced old buildings, considered unprofitable due to their rigid stone structure and small dimensions, with high-rise constructions. In all modern buildings, a densification of the ground floor footprint is sought for a maximum profitability of the works done. Consequently, the spon taneous unity of the old historical neighborhoods was broken by the construction of heterogeneous building groups: massive structures interrupting the harmony of the existing urban silhouette. The development of these neighborhoods caused also an influx of traffic which justifies, in turn, the projection of new roads, enlarge ment of streets and creation of parkings, leading to more destruction of heritage buildings.

On the other hand, the morphologi cal changes in the urban fabric of old neighborhoods resulted in the destruc tion of the existing social equilibrium, leading most of the time to the evic tion of people who can’t afford the new living costs and rents, and the arrival of a new, wealthier population. This phenomenon, referred to as “Gentrifi cation”, is not particular to Beirut. The city of Beirut has experienced its own variant of this process: many leisure activities have become high-income directed and more exclusive: shopping malls, restaurants and hypermarkets. Areas outside the city center are be coming more expensive, especially the pericentral areas. A study published by MAJAL2 proposes to use the following definition, adapted to research in Bei rut but still representing the core ideas behind the concept: “Gentrification is a process during which high-income dwellers move into low-income neigh borhoods, economically and physical ly displacing the original residents and economic activities. In Beirut, real es tate developers move in first, acquir ing and demolishing low-rise, low-in come properties and replacing them with luxury residential skyscrapers, thus economically and physically dis placing low and middle-income resi dents. Moreover, an increase in prices surrounding new developments lead to physical and exclusionary displace ment as well. Government agents sup port these developments by not act ing or by enacting legislation in favor of high-rise development”.

29 28

mASSIng on ABDel wAhAB Al Ingl z Street (In AchrAf eh, Be rut) n 1931. (Source fISchfISch 2011) (top v ew) mASSIng on ABDel wAhAB Al Ingl z Street (In AchrAf eh, Be rut) n 2019 (top v ew) (etAge = floor)

Be rut 1950

funerAl In Be rut 1930 Be rut 1950

chrIStIAn

Buildings’ Typologies

The focus area is characterized by the presence of diverse building typologies, reflecting the evolution of residential architecture during the mandate period and the emergence of a new modern language after independence:

i) Classical Mandate buildings before 1920:

- Traditional houses with the classical typology of a triple arcade

- Neo-traditional type with the transformation of the ground-floor from residential to commercial

ii) Transitional mandate buildings between 1920 and 1930

- Buildings with a central bay (triple arcade and its variations)

- Buildings with a veranda

- Buildings with bay windows

iii) Modern buildings between 1940s – 1950s

iv) Modernbuildingsbetween1960s–1980s

31 30

1949 - Beirut - City and port

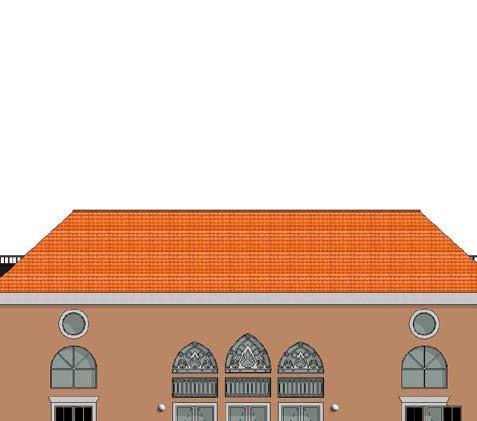

3- TYPOLOGY OF THE TRADITIONAL LEBANESE HOUSE

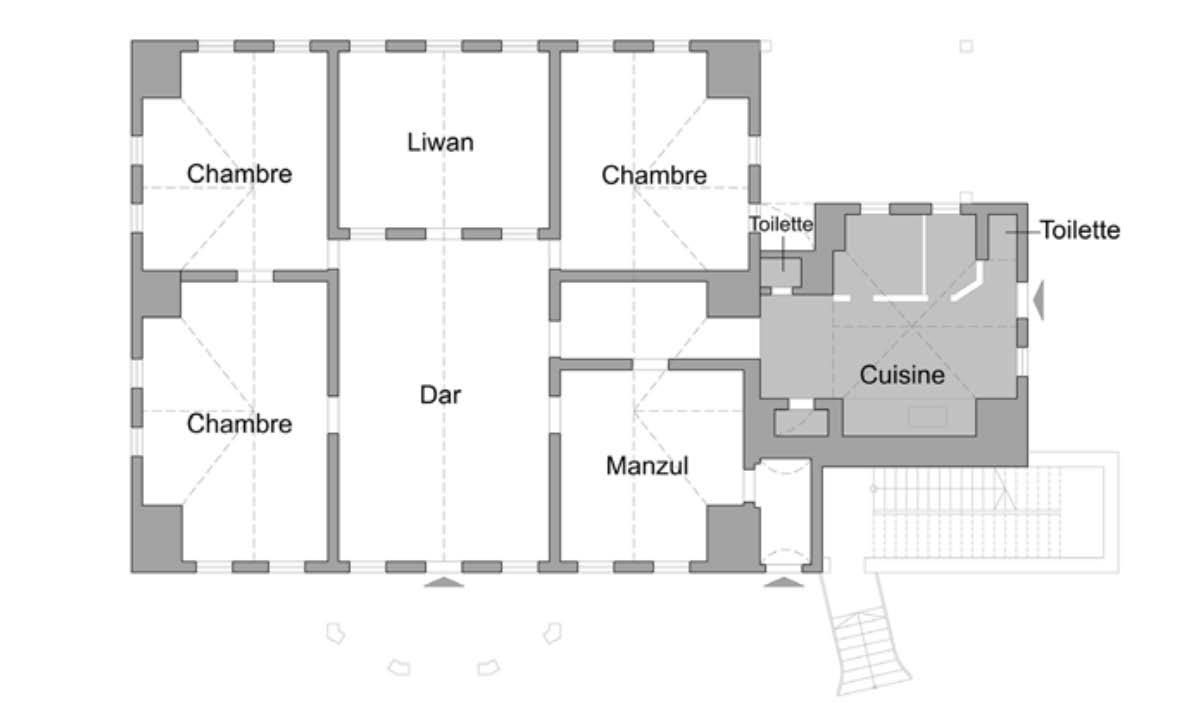

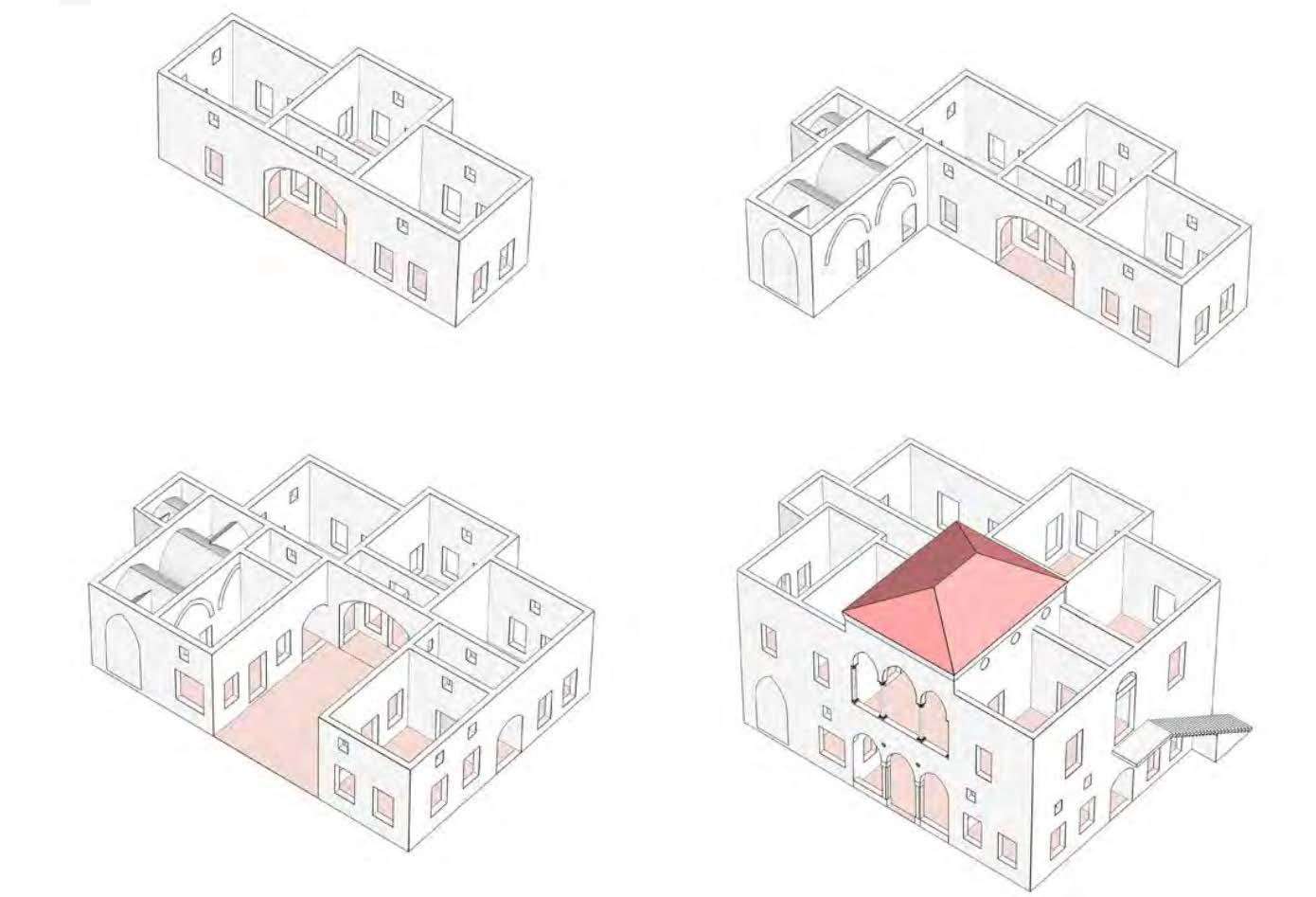

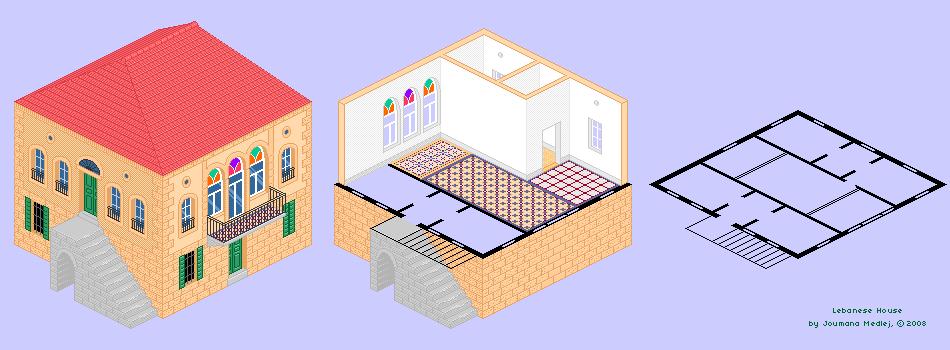

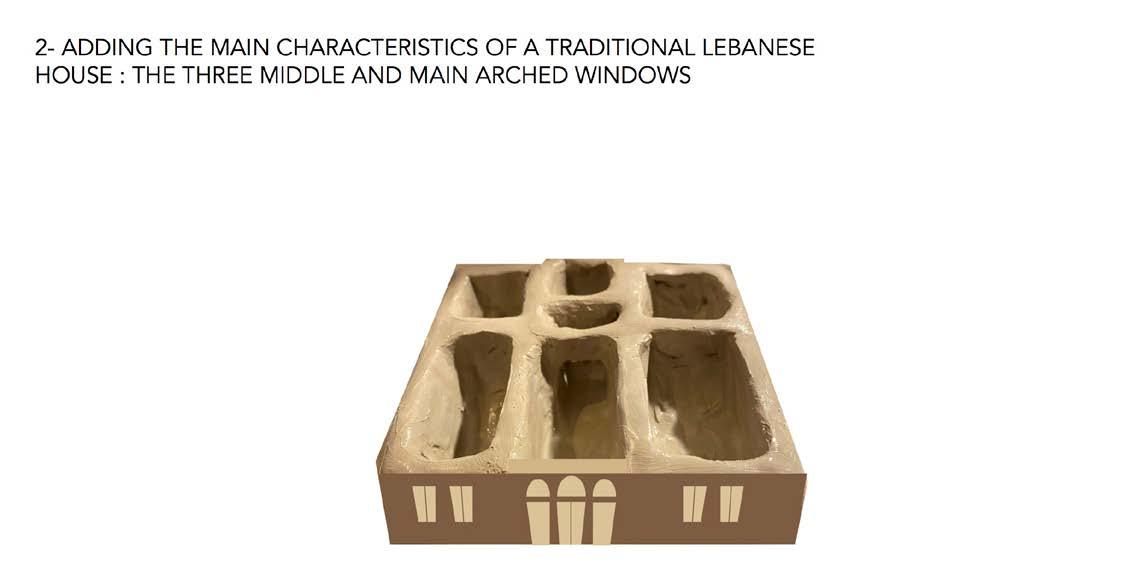

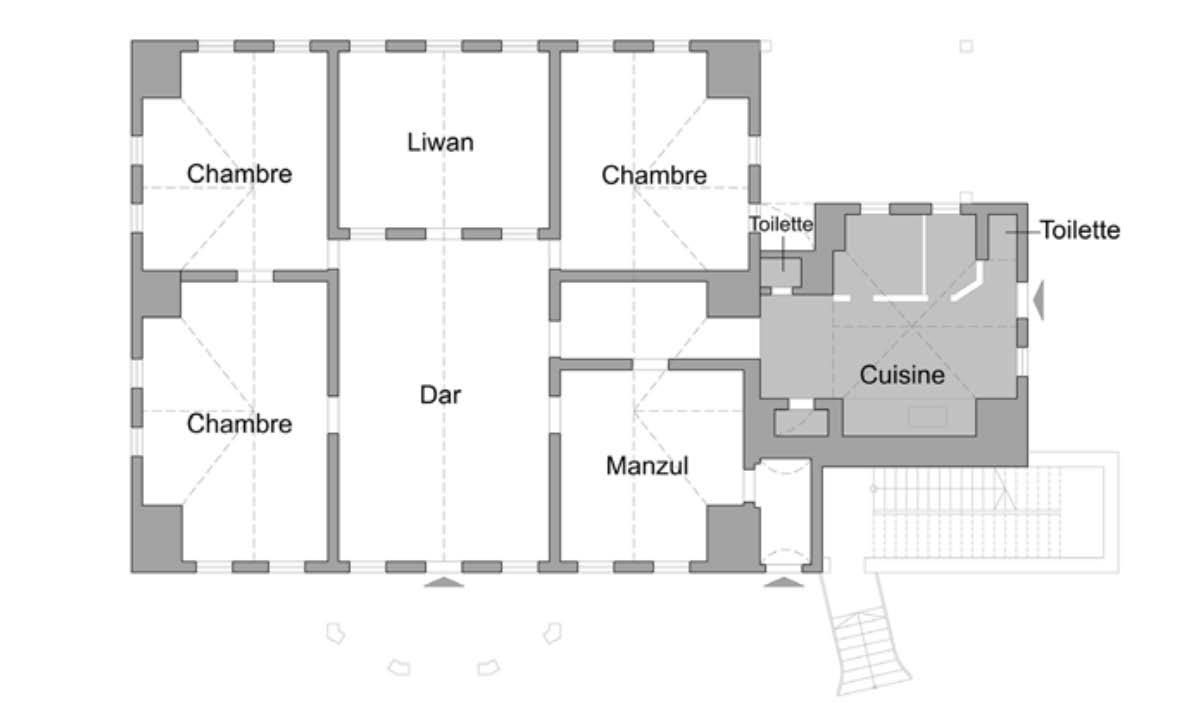

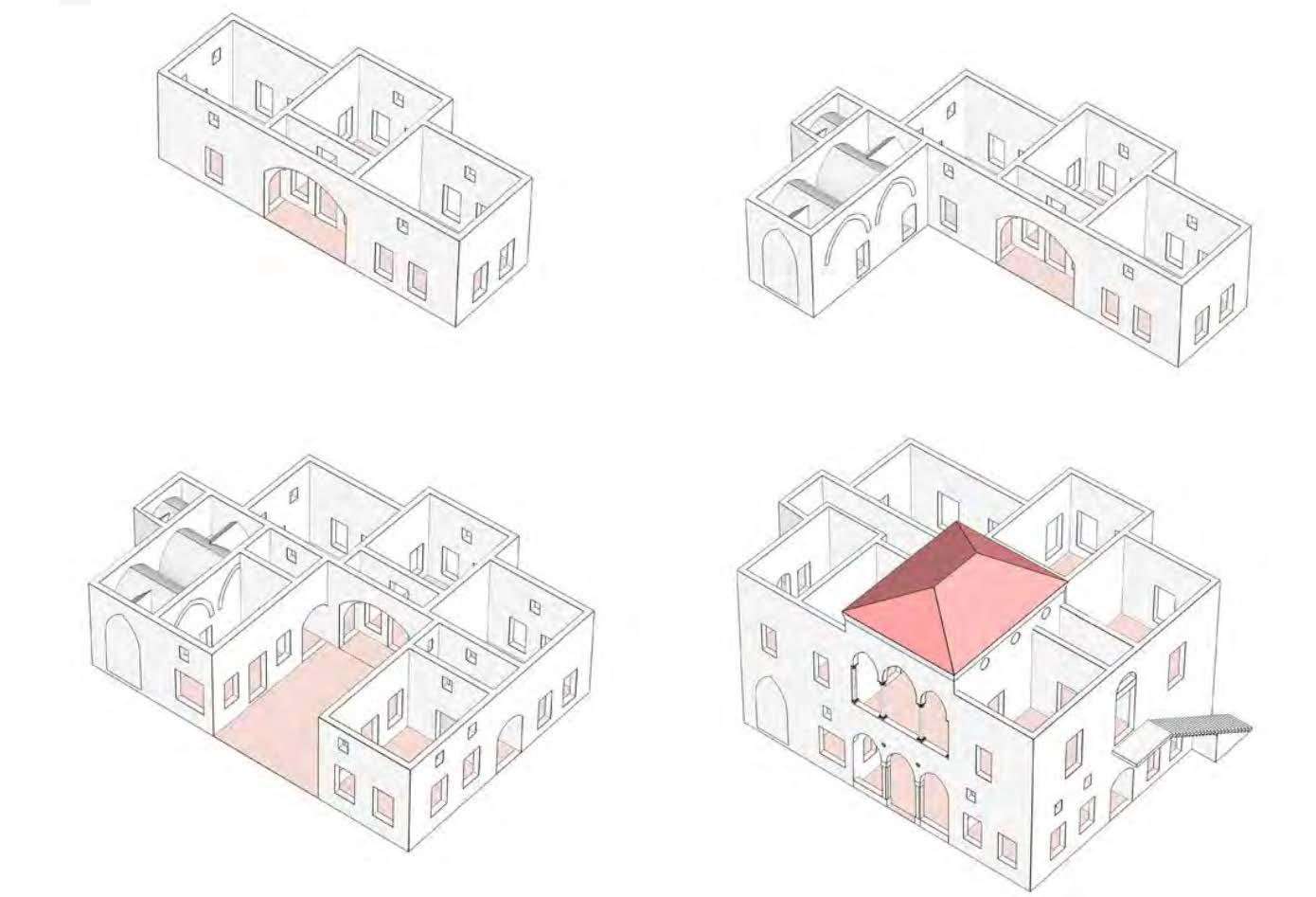

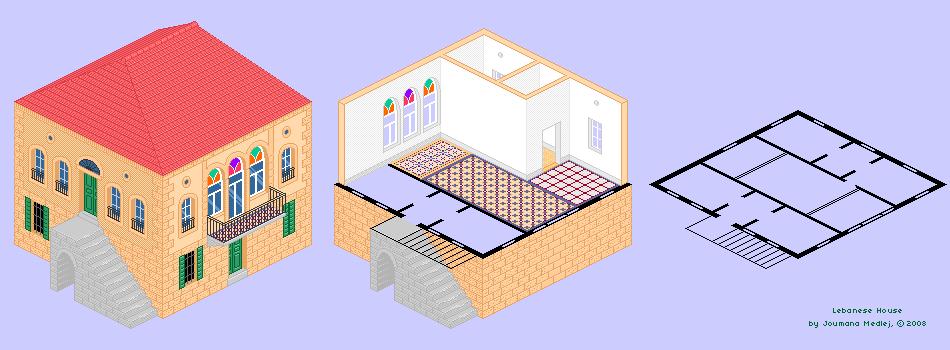

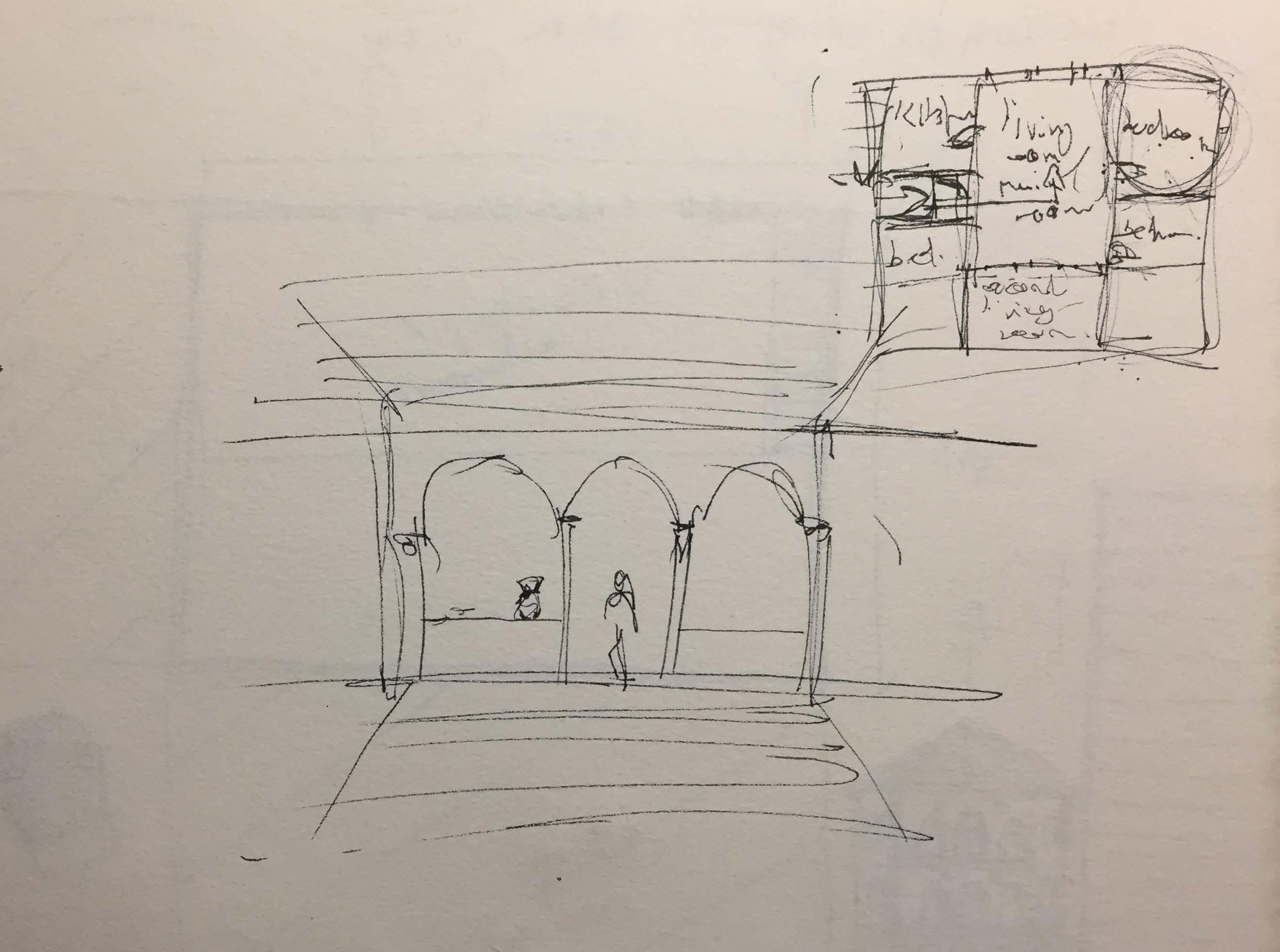

When we speak today of the houses of Beirut, we generally think of the most characteristic typology that developed in the 19th century, commonly called the “house of 3 arches” and referred to as the “house with a central hall” by archi tectural historians. That said, it is important to keep in mind that until the end of the 19th century, houses built extramurally presented a wide variety of types. In the current pericentral districts, various structures sometimes still survive, often integrated into later constructions, which makes them difficult to spot for non-specialist observers. Nevertheless, these material remains together with the historical descriptions and drawings allow us to trace some of the typolog ical diversity and developments which at some point - in the middle of the 19th century - also produced the “central hall house”. Before the city began to expand into the extramural areas, there were already small stone buildings - sometimes vaulted, sometimes with flat wooden and rammed earth roofs - used as ware houses, tool sheds, guard posts and temporary housing for farmers. The first houses built for the summer or as permanent residences often took up these pre-existing rural structures by gradually adding rooms as horizontal and verti cal extensions. In the 1820s-1850s, there were tower houses and multi-storey houses, with vaulted ground floors, as well as single-storey houses with rooms arranged in an L or U shape around them. a forecourt or an inner courtyard. At times the old ground floor vaults were used for storage and stables, while suc cessive additions encompassed the original roof terrace into a dwelling in its own right. Courtyards and roof terraces were important spaces used for household chores, food processing, and the recreation of the family and their guests. Some houses had a room on the roof called ‘aliyya which served as a kind of gazebo and guest room. A typical feature of houses (as in Bilād al-Shām archi tecture more generally) was the īwān, a room facing the courtyard through a wide arch. There existed, in the rural environs of Beirut, a variant where the rear part of the līwān was closed by a wall, thus creating a separate room communicating with the front part by a central door flanked by two windows. This frontal part became a sort of porch with its open arch. These līwāns often appeared in combination with a side room (murabba’) on each side, their doors also open ing onto the porch. The resulting līwān type can be considered as one of the standard modules used for building houses in the extramural areas of Beirut and can constitute a complete dwelling on its own or be integrated into larger structures. The earliest concrete evidence of central hall houses in Beirut date from the mid-19th century and the earliest known descriptions from the early 1850s, meaning they may date back to the late 1840s.

The old preserved specimens can also be dated to the 1850s. Their builders were Beirutis belonging to different faiths - Muslims, Christians and Jews. They had in common the fact of being part of the new wealthy class.

35 34

voûtée elle

(BeDroom) (BeDroom)

(kitchen)

Axonometry of BAyt Aoun (SAifi 614): exAmple of the progreSSive extenSion of A rurAl houSe in līwān And itS

eventuAl trAnSformAtion into A houSe with A centrAl hAll the proceSS took plAce in the mID to lAte 19th century BAyt SAAdeh (ZokAk el-BlAt 122): plAn du reZ de chAuSSée d ’ une mA Son à hAll centrAl Ancienne mAiS déjà complètement Articulée conStruite en Bloc dAnS leS AnnéeS 1850. entièrement

comprend un mAnZūl Avec triple AccèS une cuiSine en Annexe et un module en līwān fA SAnt pArtie intégrAnte de lA nouvelle conStruction

(BeDroom)

This typology is essentially characterized by its fairly symmetrical plan, with a large covered hall (called al-dār) surrounded by rooms on three sides and pre senting large arched openings on the fourth - generally the north side, offering views of the sea and the mountains. The central hall is the main distribution space, giving access to the surrounding rooms. On closer inspection, some of the rooms arranged around the central hall have specific characteristics. One of the two rooms that flank the central hall on the main north facade, called the manzūl, is usually designed to serve as a reception hall and guest bedroom. It is distinguished by its large dimensions, its rich decoration, its many windows and - which is very important - by its multiple access doors: from the outside or the entrance hall, from the central hall, and sometimes also from a service corridor. This arrangement allowed visitors to enter without going through the central hall, and thus protected the privacy of the house. Another element taken up in the central hall house is the līwān module. It was located at the rear of the central hall, either in a closed variant, the līwān com municating with the hall through a central door flanked by interior windows, or in a new open form with three arches replicating those of the front of the central hall. This līwān often functioned as a living space.

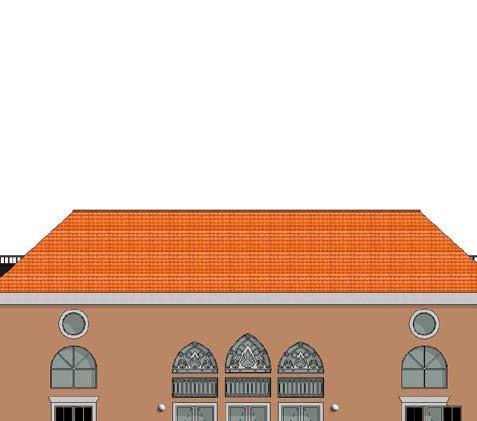

A third constituent element was the kitchen and service area, usually slightly set back from the central hall, located laterally or at the rear at the southeast corner of the house, often forming an annex, with access separate exterior for servants. As a rule, the kitchen was vaulted (at least when it was on the ground floor) and equipped with a wooden mezzanine called titkhīteh intended for storage as well as the accommodation of servants. The service area also contained a small bathroom and toilet, which were originally the only sanitary facilities in the house, used by family and servants. These building blocks remained rela tively stable from the earliest known examples until the 20th century. Other ele ments have undergone modifications: the first specimens had flat roofs, either in wood covered with rammed earth, or completely vaulted. Often the central hall was higher than the surrounding rooms, rising above the roof as a sort of clerestory with circular windows providing additional peripheral lighting. It was not until the late 1850s that we began to observe pyramidal or gabled roofs, covered with red tiles, initially covering only the central hall. The red-tiled roof, which today is considered typical of the Beirut house, only became the norm at the end of the 19th century. The question of exactly how the type of central hall house appeared in Beirut cannot be fully resolved due to the scarcity of pre served period buildings and the absence of ancient sources. It is clear, however, that a major factor has been the continued experimentation with locally developed elements and forms, experimentation motivated by the pressing need felt by Beirut’s old and new elites to build new and prestigious houses as a sign of social distinction. In this context, the model of the houses of the Ottoman upper class, namely the Sofa House, a type of house with a central hall which, at the beginning of the 19th century, became fashionable among the Ottoman and Egyptian elites, had a decisive influence on the formation of these houses. And it’s only once the central hall type established in Beirut that one observes increasingly evident European influences at the end of the 19th century, partic ularly in the exterior and interior decoration. Thus, we first see a strong influ ence of the Ottoman Baroque style until the 1860s, then a gradual shift to more Italianate styles followed by a brief wave of neo-Islamic and neo-Oriental styles in the 1920s, the Art-deco or modernist styles becoming predominant in the 1930s-1940s. In any case, by 1900, the type of Beirut houses with a central hall in its developed form, with two or three floors, a triple arcade and a pyramidal roof with red tiles, had not only become the typical form of the houses of the middle and upper class in Beirut, it had also begun to spread to other coastal towns and the mountains. Contemporary Ottoman observers called it al-tirāz albayrūtī (the Beirut style), as opposed to al-tirāz al-shāmī (the Syrian style), the traditional courtyard townhouse.

37 36

view of ZokAk el-BlAt (Beirut) in the 1890S Showing houSeS of vAriouS typologieS including mAny centrAl hAll houSeS of vAriouS SiZeS And ShApeS

If, once established, the typology of the plan remained relatively stable, the spa tial functioning continued to develop significantly. For example, in the initial model, all the rooms surrounding the central hall had access only to the latter, just as was the case for the rooms surrounding a courtyard. Moreover, until the 1860s-1870s, even in upper-class houses, most rooms were still furnished in the traditional way, with diwans, light tables consisting of a copper top placed on a wooden foot (siniyyeh and kursi khachab) and mattresses that were tempo rarily put up and put away again after use. The rooms were generally multifunc tional. It was the gradual introduction of less flexible European furniture, such as dining tables and box springs, which began to define the functions of rooms in a more lasting or definitive way and led to a functional specialization such as bedroom, dining room etc. Indeed, around the 1880s, certain rooms began to be directly connected by doors in order to allow internal communication with out the need to cross the central hall. The bedrooms were connected by doors and the dining rooms had direct access from the kitchen. Functional groupings began to develop, a process which in the 1920s resulted in the complete articulation of day areas (reception and living room) and night areas (bedrooms coupled with modern bathrooms ) in the plan of large newly built houses. In the older, already existing houses, this process has been reproduced by inserting modern bathrooms in or between the rooms. This clearly indicates a general change in the concepts of domestic comfort and intimacy within families. In smaller houses, however, spatial limitations have reduced the possibilities for functional qualification and grouping. Their plans remained more basic and the uses had to remain flexible. An important and inherent quality of the central hall plan was the possibility of stacking on top of each other floors of almost identical surface and layout, each constituting a potentially independent unit. Already, in the 1860s, there were large houses with a central hall where each of the floors was used by separate households, or rented.

At the turn of the 20th century, apartment buildings, comprising apartments on sever al floors, developed, often consisting of a pairing of two houses with a central hall, each having two or three floors and connected by a common stairwell. These buildings, characteristic of a certain urban typology, were generally located along major arter ies and in central locations. Those of the 1920s and 1930s underwent a further evolution, with the appearance of large verandas using the new technology of reinforced concrete. They were located in pericentral areas, marking a process of urban densi fication. And if these single-storey apartment buildings continued to have a central hall plan, the triple arcade is replaced by large rectangular windows in the Art-Deco or Modernist style. In addition to the Cen tral Hall House, Art Deco buildings of Beirut are a part of our heritage as well; they are a progression of the traditional central hall house, for they incorporate its main typolo gy and floor plan, while adding new design elements. In fact, the architectural element of this period was the use of modern building materials, such as concrete, cast iron, and steel sheeting. In the upper-class, new ly built villas in the expanding suburbs of Beirut, the 1930s already marked the transi tion from the central hall plan to the asymmetrical plans. From then on, houses with a central hall in Beirut went out of fashion. Those that survived the pressures of devel opment and the perils of the following de cades bear witness to the phenomenal rise of Beirut and the many facets of its history in the 19th and early 20th centuries; in this they carry the memory of generations.

39 38

Axonometr c v ew of A Be rut houSe

the wh te houSe IS on rue gourAuD wIth tS hAnD cArveD wooDen w nDowS t over lookS A flouriShing gArden on one Side And the BuStling Beirut trAffic on the other

kettAned Building exAmple of An Art deco Building on mAy Z Ade Streer clemenceAu Be rut

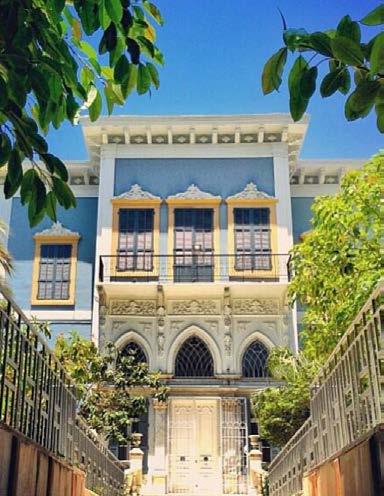

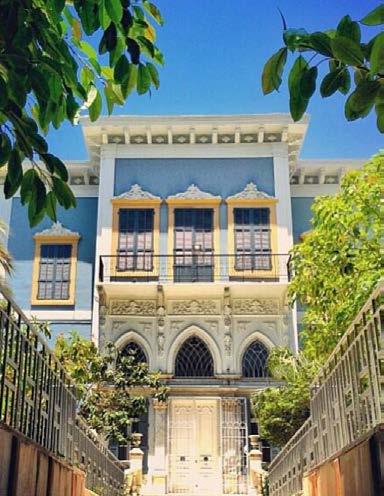

Case sTudy : Tarazi house

This grand, 19th-century tradi tional Lebanese house on Rue Gouraud in Gemmayzeh dis trict was built in 1870 by my great-grandfather in the final decades of the Ottoman Empire. Arranged over three floors, the property has 750m2 of floor space, with an enclosed 700m2 garden to the rear. The ground floor is comprised of open-fronted shops, where his antique shop would be, with the family residing in the two spacious storeys overlooking the street and gardens below.

41 40

p ctureS of the tArAz houSe Be rut

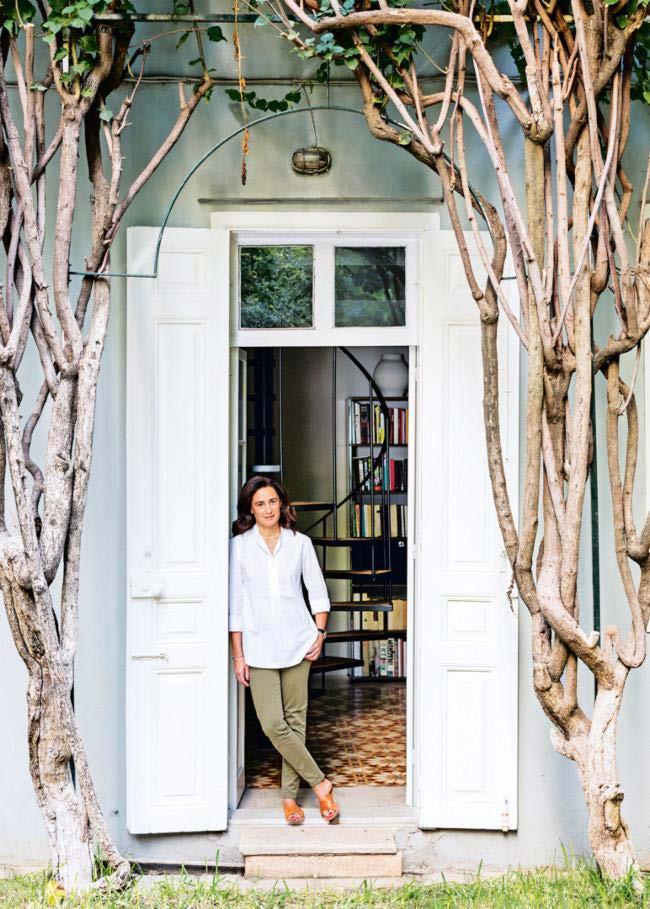

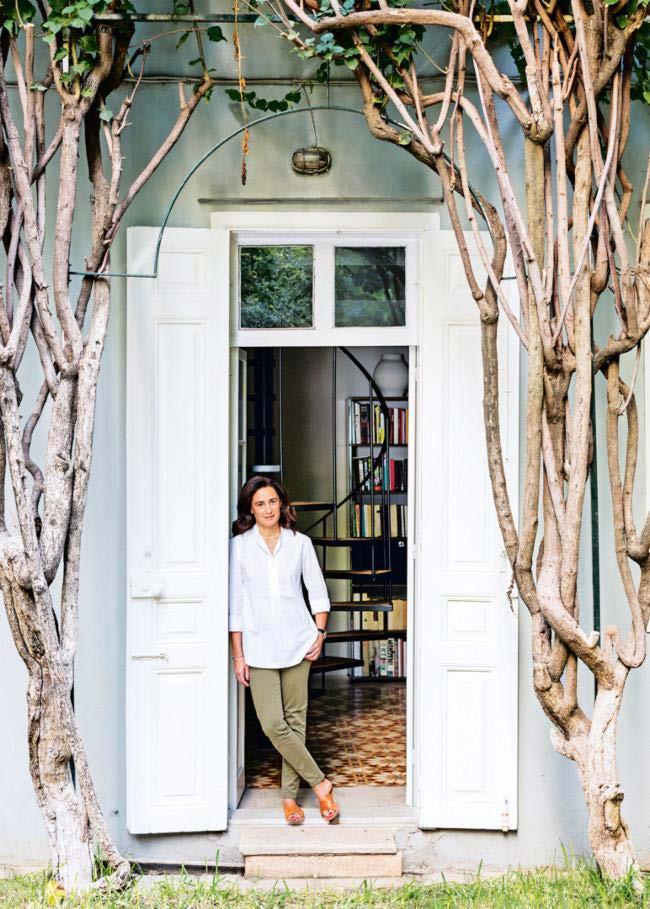

In the Gemmayzeh district of Beirut stand a group of traditional Lebanese res idences known collectively as “the houses of Lady Cochrane”. The country’s most famous fashion designer, Elie Saab, lives in one. Carole Schoucair, a busi ness coach, had long dreamt of renting one, but believed it was almost impossible. “As soon as tenants have the chance to live in them, they’re rarely easy to dislodge,” she says. The Lady Cochrane in question lives in a 19th-century palace just above the houses and is the only daughter of a Lebanese aristocrat. In 1946, she married an Irish lord and has long campaigned for the preservation of Beirut’s architectural heritage. She and her family have steadfastly refused to sell the houses, which they acquired in the 1960s to ensure they wouldn’t be torn down by developers and replaced by high-rises. The one in which Schou cair lives with her film producer husband and their two sons, dates from around 1885 and was temporarily turned into a school in the 1920s. The interiors feature exquisite windows decorated with trefoil motifs, marble flooring and a lofty dou ble-height sitting room that rises to some six metres high. Schoucair changed very little: she simply removed cork panels that had been on the walls, renovated the bathroom and repainted the whole house.

43 42

Case sTudy : The houses of lady CoChrane: Carole sChouCair’s inTerior

p ctureS of the SchoucAIr’S houSe Be rut

45 44

houSe Be rut

p ctureS of the SchoucAIr’S

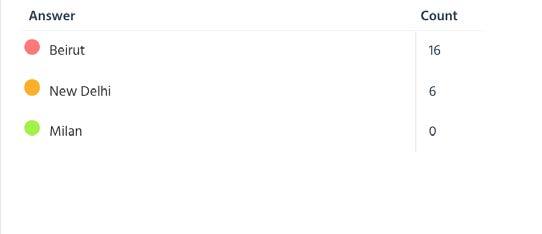

CONSTRUCTION

some of the main arChiteCtural aspeCts of a Beirut house : Masonry :

Masonry is a heterogeneous building material widely used in most of the built heritage but also used for modern structures. Its heterogeneous character is due to the diversity of its components, namely: masonry blocks, dry or mortar joints, filling materials and reinforcements. Among the existing types of masonry, MNR is prevalent in historic buildings that were constructed in the city of Beirut between 1860 and 1925. It was used to build foundations, walls and vaults, mainly executed with blocks of marl or of local sandstone and, at a later stage, it was used for emergency actions applied to heavily damaged buildings. Brick blocks were then introduced in the construction of the slabs, partitions and peripheral load-bearing walls. MNR is sustainable. In addition to its resistance to vertical loads, it has satisfactory properties in terms of fire resistance and sound and thermal insulation. However, it can suffer from several types of anomalies or structural damage.

Walls :

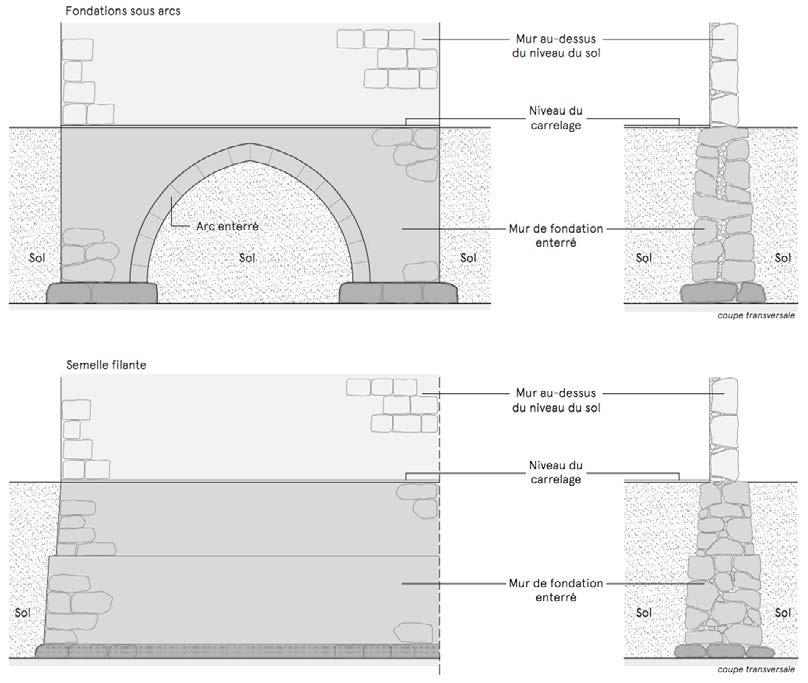

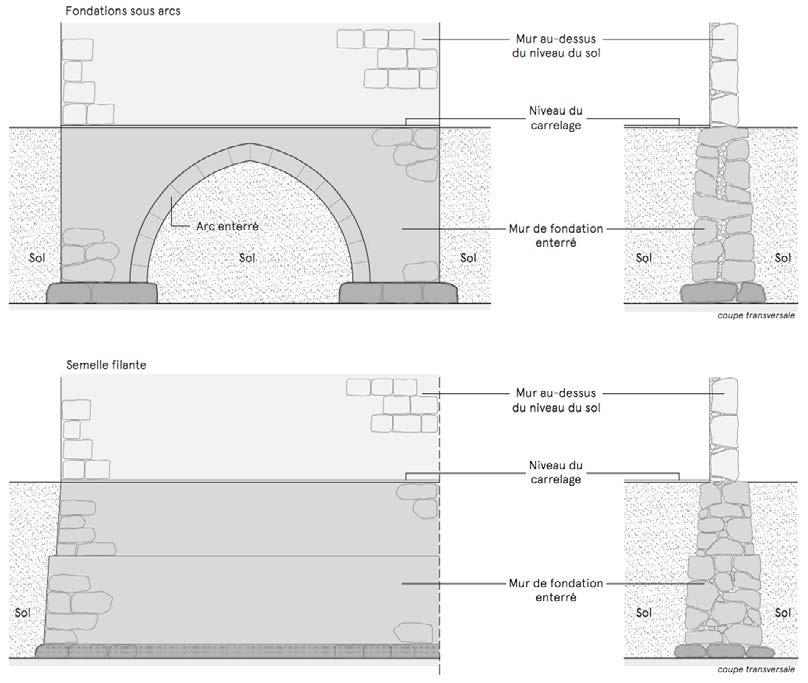

Two main types of foundations can be identified in historic buildings in Beirut. Both are built with stone blocks and lime mortar. Their cross section is stepped. The first type represents a continuous footing supporting a load-bearing wall. The second is a system of isolated foundations linked together by arches made of stone. Remember that the main role of foundations is to transmit the loads of the structure to the ground without exceeding its bearing capacity while re specting an admissible differential settlement.

Vaults :

Several types of vaults are present in the historic buildings of Beirut, among which it is possible to identify barrel vaults and cross vaults. Their presence is limited to the ground floors or to a certain area of the upper floors. Their geo metric shape allows them to withstand high vertical loads. They are also con sidered as rigid elements and resistant to lateral loads induced by earthquakes and explosions.

Foundations :

Two main types of foundations can be identified in historic buildings in Beirut. Both are built with stone blocks and lime mortar. Their cross section is stepped. The first type represents a continuous footing supporting a load-bearing wall. The second is a system of isolated foundations linked together by arches made of stone. Remember that the main role of foundations is to trans mit the loads of the structure to the ground without exceeding its bearing capacity while respecting an admissible differential settlement.

Poles and Arcs :

Unlike structures designed in reinforced concrete, masonry poles and arches are rare in historic buildings in Beirut. The load-bearing walls make up for their ab sence. Very few buildings have simple arches. However, circular marble or local stone posts and pointed arches are frequently present in three-arched houses. They are structurally classified as slender elements due to their great height in relation to their section. The posts support the pointed arches and the vertical continuity of the wall that surmounts them as well as part of the frame. Their ability to withstand vertical loads is acceptable.

47 46

4-

heterogene ty AnD componentS of mASonry StructureS

mAIn typeS of mASonry founDAt onS n hIStor c Bu lDIngS n Be rut founDA on unDer Arche wAll on top of the floor (floor t le level founDAt on wAll ur D groun ) ( rch ur ) groun groun ) groun ) grounD Str founDA on croSS ect on

typ cAl geometry of mASonry wAllS

re nforcement of the upper SurfAce of A vAult BAz pAlAce De r Al qAmAr leBAnon

t pp ng AnD exceSSIve DeformAt on of A pole Support ng the ArcheS of A tr ple ArcADe Be rut

II- A

BEIRUT: CONFLICTS AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

48

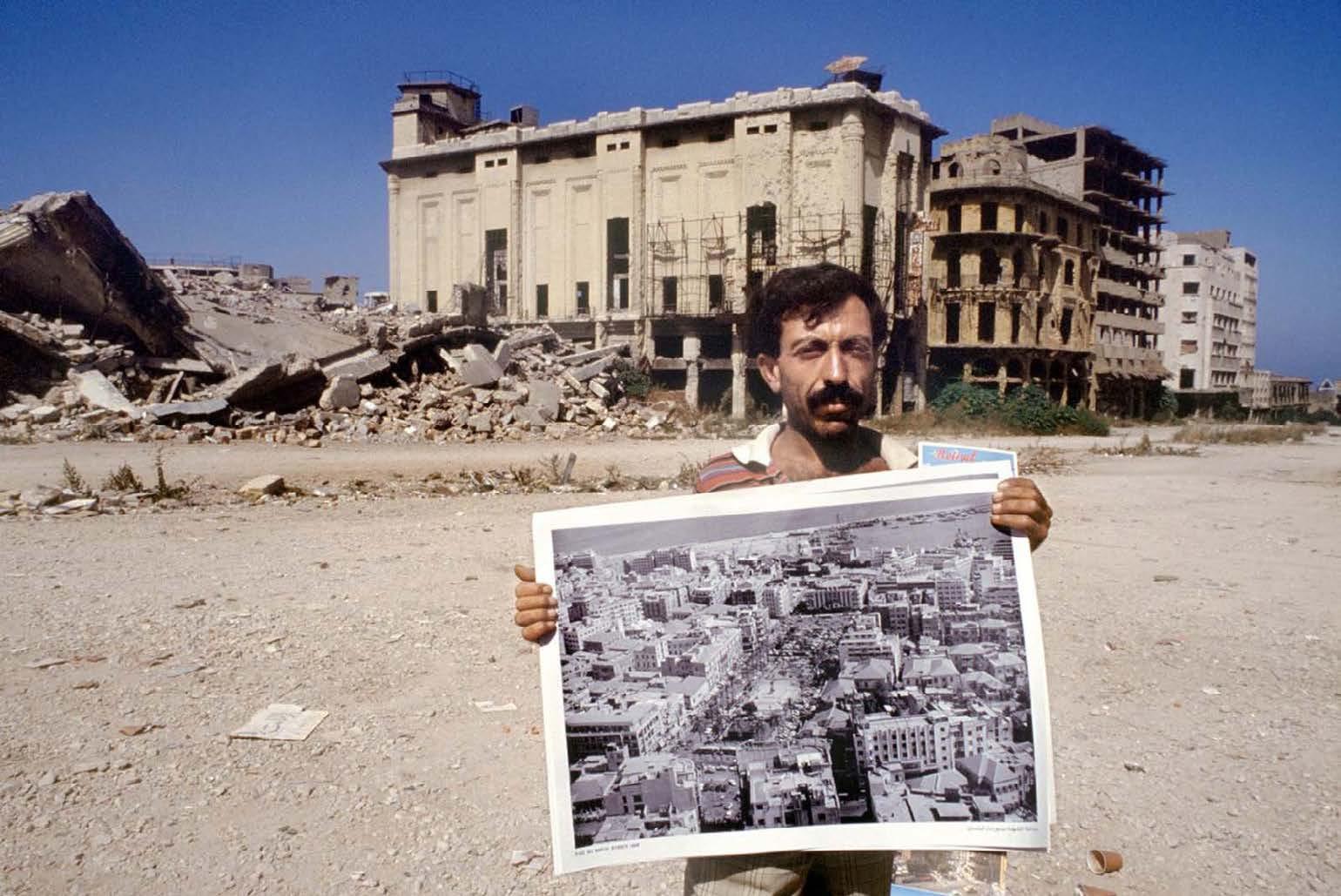

When the civil war was over (1975-1990), Solidere, a joint-stock company, was in charge of rebuilding the city of Beirut. In Reconstructing Beirut, Aseel Sawalha, a Professor of Anthropology, followed the aftermath of the war, interviewing the residents of Beirut, analysing the dynamics of the city and following the reconstruction plan of Solidere, destroying all trace of the past to make place for a new and unknown city for its inhabitants. Intellectuals and historians were against the urban plan presented by the company, as well as the local residents and long-standing tenants. Both groups took it upon themselves to preserve the city’s endangered past and the heritage of its diverse ethnic groups. They doubted Solidere’s promotional motto “Beirut an Ancient City of the Future”. Opponents criticized Solidere for overlooking the needs of the residents of Beirut and destroying the city’s rich heritage. It was rumoured that Hariri (the prime minister of Lebanon a the time) himself owned more than 50 per cent of the company’s shares. Journalist Vanessa Martin described Solidere as “Hari ri’s profit-making puppet” and criticized it for ignoring the city’s rich past by attempting “to build Manhattan-style skyscrapers”.

51 50

1- SOLIDERE: THE AFTERMATH

THE CIVIL

muSl m leBAneSe Army SolDIerS Set up A chrIStmAS tree on the green lIne to celeBrAte the holIDAy w th chrIStIAn SolDIerS on DecemBer 23, 1987. A 1990S mArtyrS’ SquAre Street venDor Sell ng poSterS of the SAme plAce n the lAte SIxtIeS rAS el nABeh 1975 conStruction of Beirut SoukS By Solidere, 2011

OF

WAR

However, Solidere’s plan was celebrated by rich investors and civilians who wanted to move on and erase all trace of the civil war, and was for them a chance to embrace an eminent modernization of the city. Although in a city like Beirut, with over 5,000 years of History, destroying its past should not and cannot be an option. Even though some places can have a negative effect on one’s memory, for it can remind him of a time of war, it must have had, before the eruption of the war, a different and more positive impact on other inhabitants. In fact, this massive destruction provoked many Beirutis to document their personal pre-war and wartime experiences and to express their pain about the damage caused by bulldozers. One writer recalled his childhood memories of walking happily in the old downtown area “[I remember] the alleys where we used to wander around as children, the Kunafa (a traditional Arabic desert) places, the small shops with coloured glass, the Martyr’s Square, and the streets that were crowded with pedestrians”.

53 52

workerS for the Solidere conStruction compAny in the proceSS of renewing Beirut S city centre in 2012. photogrAph ShArif kArim corB S new conStruct on n the ne ghBourhooDS of eASt Be rut v eweD through A hole n A wAr DAmAgeD Bu lDIng photogrAph- joSeph eID/getty

louIS vu tton Store n Downtown Be rut

Downtown-Be rut 2018 Beirut

SoukS

(photogrAphS By BAhAA ghouSSAiny)

VIDEO: JULIANA ISSA TARAZI: A MOTHER

UNFOLDING HER EXPERIENCE DURING THE WAR

When vacationing in Lebanon during the summer 2022, I was sitting in my living room with my mother. She started sectioning the ba2dounis (coriander) for the Tabbouleh, a famous Lebanese salad, and started to talk about the civil war. I found that in that moment, it was a great opportunity to film her, narrating her story while unaware of her being filmed (I then got her consent to show it, of course!).

I wanted to capture her natural emotions and her opening up, without the constraint of a camera. Here she narrates her experience growing up in a village called Jamhour during the Lebanese civil war, and reveals the trauma that the war inflicted on her after all these years.

To watch the video, here is the link below: https://youtu.be/6573kWpa9Rc

55 54 2-

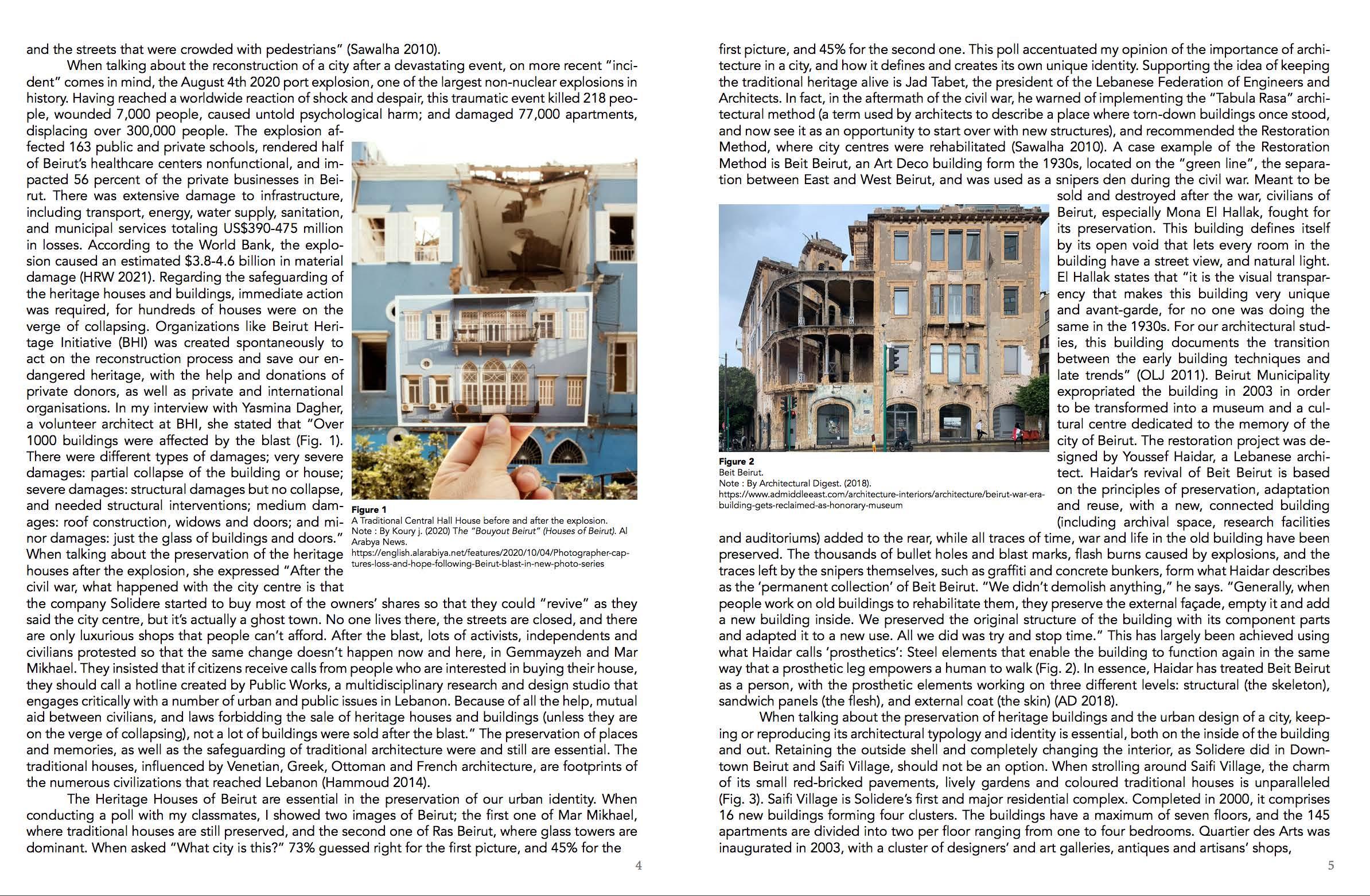

When talking about the reconstruction of a city after a devastating event, on more recent “incident” comes in mind, the August 4th 2020 port explosion, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history. Having reached a worldwide reaction of shock and despair, this traumatic event killed 218 people, wounded 7,000 people, caused untold psychological harm; and damaged 77,000 apart ments, displacing over 300,000 people. The explosion affected 163 public and private schools, rendered half of Beirut’s healthcare centers nonfunctional, and impacted 56 percent of the private businesses in Beirut. There was extensive damage to infrastructure, including transport, energy, water supply, sanitation, and municipal services totaling US$390-475 million in losses. According to the World Bank, the explosion caused an estimated $3.8-4.6 billion in material damage. Regarding the safeguarding of the heritage houses and buildings, immediate action was required, for hundreds of houses were on the verge of collapsing. Organizations like Beirut Heritage Initiative (BHI) was created spontaneously to act on the reconstruction process and save our endangered heritage, with the help and donations of private donors, as well as private and international organ isations.

57 56

3- AUGUST 4TH 2020 A generAl v ew of the Scene of the exploSIon thAt h t the SeAport of Be rut- f le B lAl huSSe n-Ap photo 2020 A mAn StAndS next to grAffiti At the dAmAged port AreA in the AftermAth of A mASSive exploSion. [hAnnAh mckAy/reuterS]

evAcuAte the wounded After the mASSive exploSion in Beirut on AuguSt 4, 2020. [hASSAn AmmAr/Ap

A reScue teAm memBer workS with A SenSor to detect SignS of life Amid the ruBBle of dAmAged BuildingS in gemmAyZe on SeptemBer 4, 2020. [AZ Z tAher/reuterS]

people

photo]

In my interview with Yasmina Dagher, a volunteer architect at BHI, she stated that “Over 1000 buildings were affected by the blast. There were different types of damages; very severe damages: partial collapse of the building or house; severe damages: structural damages but no collapse, and needed structural in terventions; medium damages: roof construction, widows and doors; and minor damages: just the glass of buildings and doors.” When talking about the preservation of the heritage houses after the explosion, she expressed “After the civil war, what happened with the city centre is that the company Solidere started to buy most of the owners’ shares so that they could “revive” as they said the city centre, but it’s actually a ghost town. No one lives there, the streets are closed, and there are only luxurious shops that people can’t afford. After the blast, lots of activists, independents and civilians protested so that the same change doesn’t happen now and here, in Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael. They insist ed that if citizens receive calls from people who are interested in buying their house, they should call a hotline created by Public Works, a multidisciplinary research and design studio that engages critically with a number of urban and public issues in Lebanon. Because of all the help, mutual aid between civilians, and laws forbidding the sale of heritage houses and buildings (unless they are on the verge of collapsing), not a lot of buildings were sold after the blast.” The preservation of places and memories, as well as the safeguarding of traditional architecture were and still are essential. The traditional houses, influenced by Venetian, Greek, Ottoman and French architecture, are footprints of the numer ous civilizations that reached Lebanon.

59 58

BhI - rme l 722 renovAtIon 2020 Bh - rme l 722 After

722

722 Before

BhI rme l

Bh - rme l

61 60 Bh - rme l 722 renovAtIon- three ArcheS DetAIl BhI - rme l 722 renovAtIon- columS DetAIl BhI - rme l 722 renovAt on- roof DetAIl BhI - rme l 722 renovAtIon- Stone DetAIl

II- B

ARCHITECTURAL IDENTITY

62

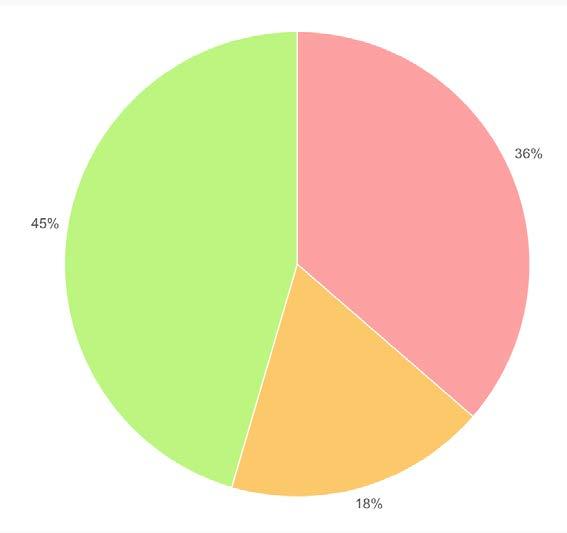

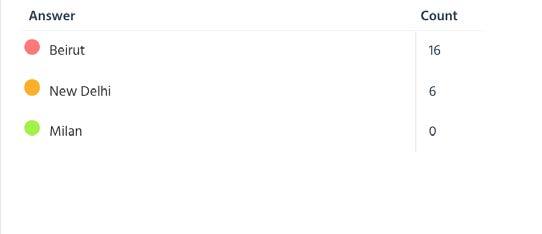

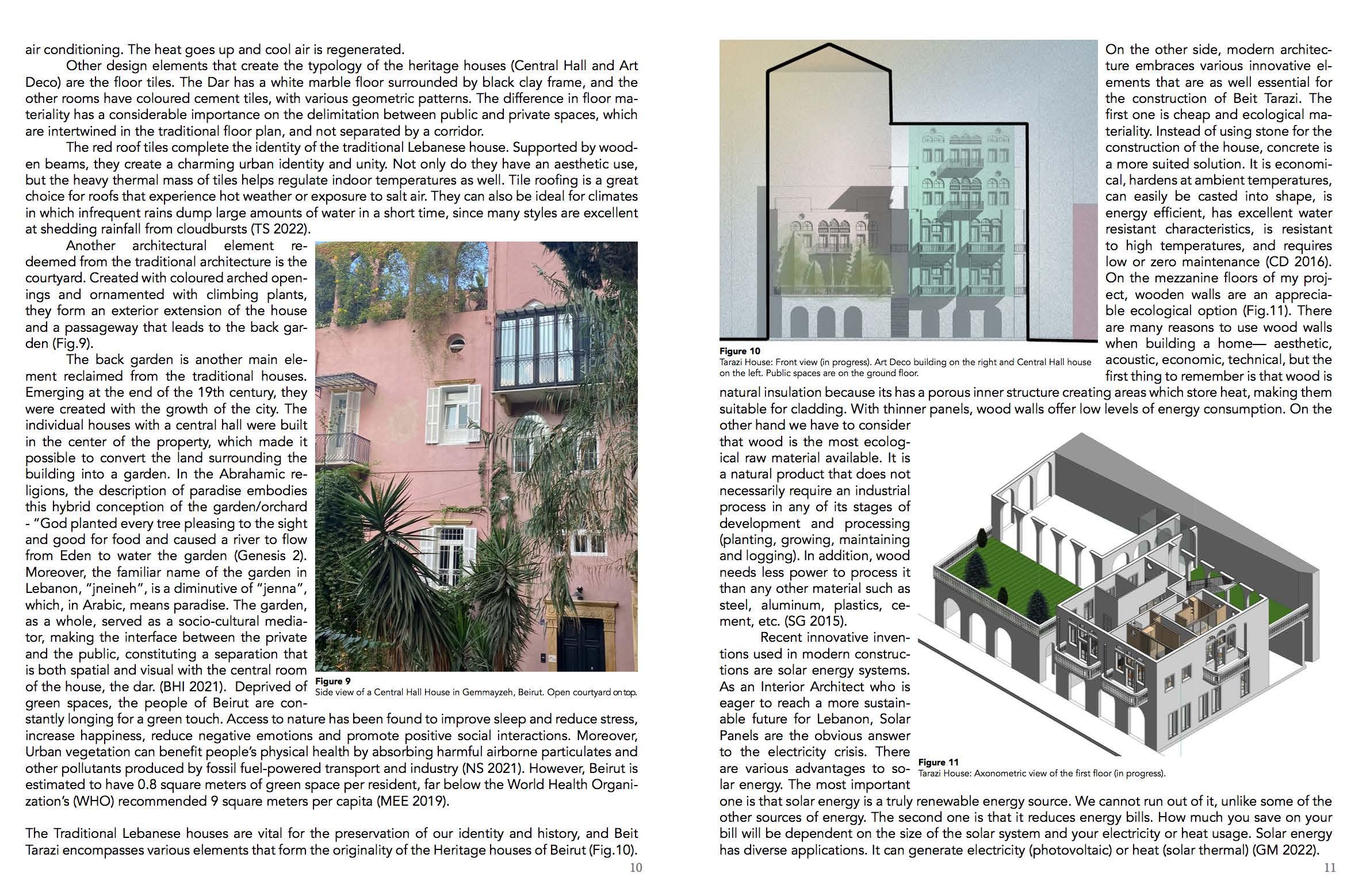

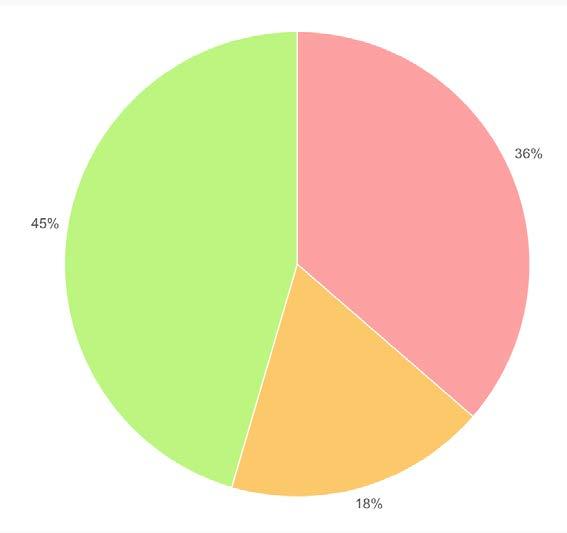

The Central Hall House and Art Deco buildings are essential in the preservation of our urban identity. When conducting a poll with people of my class, I showed two images of Beirut; the first one of Mar Mikhael, where traditional houses are still preserved, and the second one of Ras Beirut, where glass towers are dom inant. When asked “What city is this?” 73% guessed right for the first picture, and 45% for the second one. This poll accentuated my opinion of the importance of architecture in a city, and how it defines and creates its own unique identity. Supporting the idea of keeping the traditional heritage alive is Jad Tabet, the president of the Lebanese Federation of Engineers and Architects. In fact, in the aftermath of the civil war, he warned of implementing the “Tabula Rasa” architectural method (a term used by architects to describe a place where torndown buildings once stood, and now see it as an opportunity to start over with new structures), and recommended the Restoration Method, where city centres were rehabilitated. 73% guessed right

65 64

45% guessed right vs

The “resToraTion Me Thod ”

BEIRUT

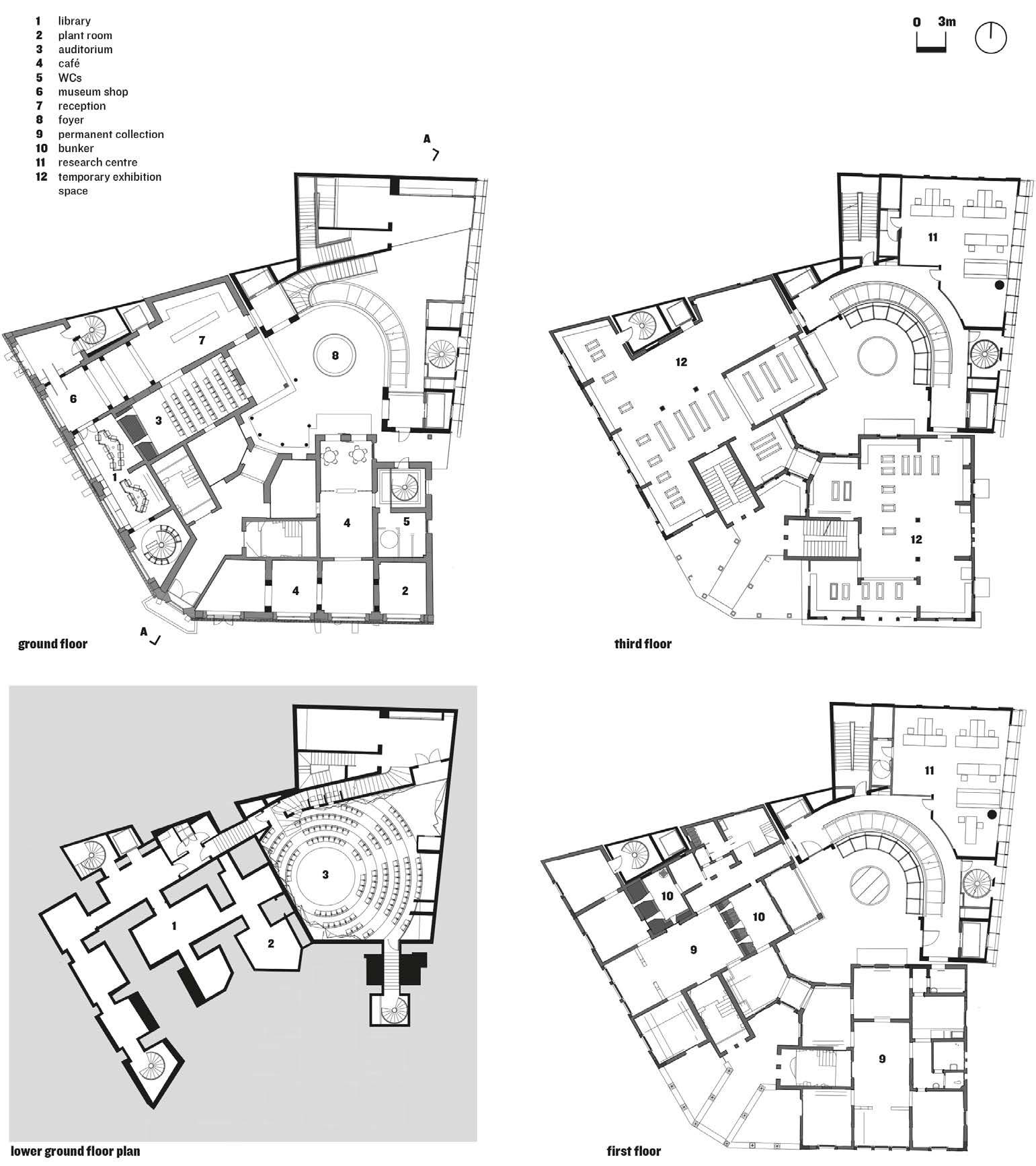

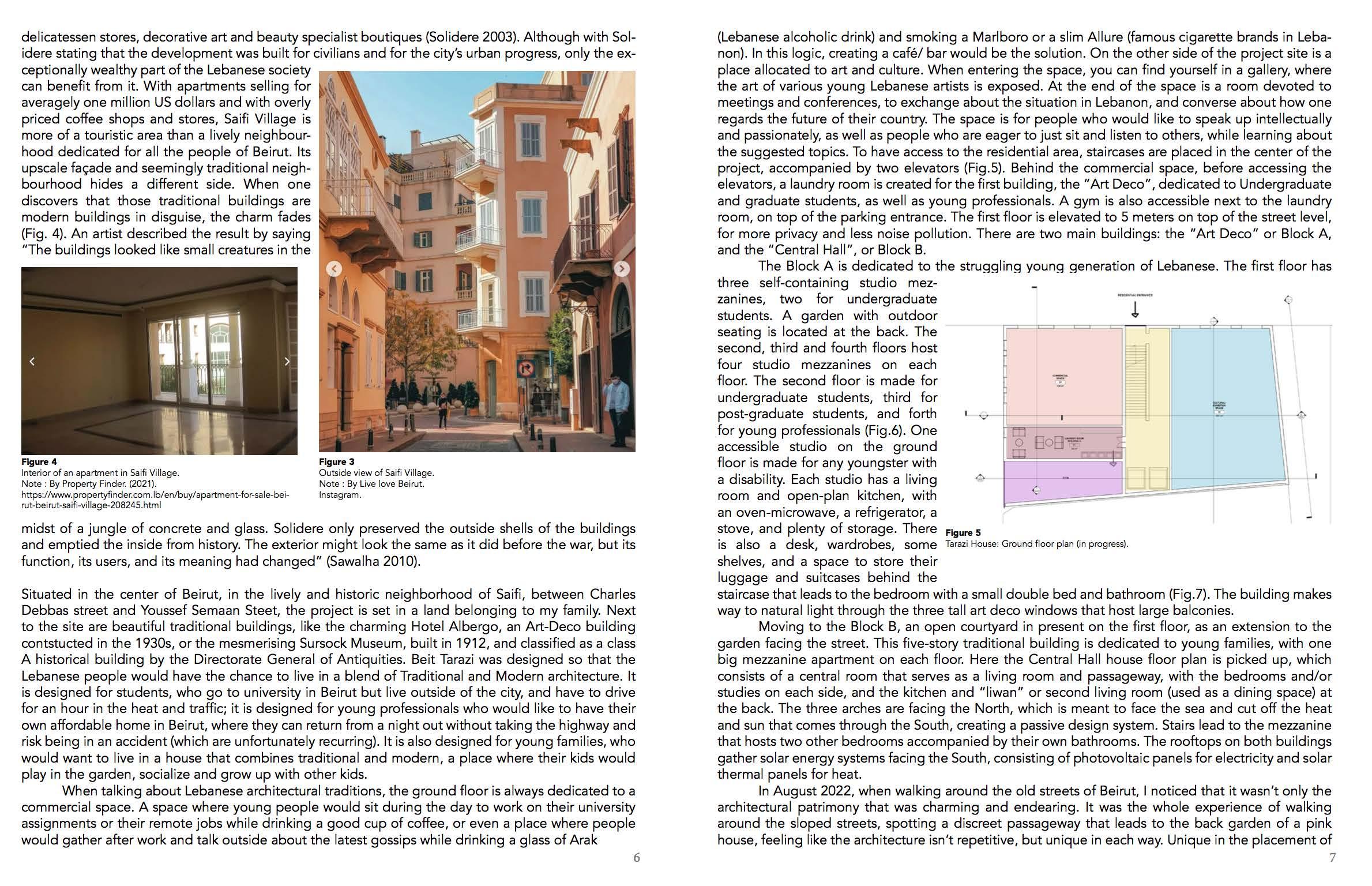

A case example of the Restoration Method is Beit Beirut, an Art Deco building form the 1930s, located on the “green line”, the separation between East and West Beirut, and was used as a snipers den during the civil war. Meant to be sold and destroyed after the war, civilians of Beirut, especially Mona El Hallak, fought for its preservation. This building defines itself by its open void that lets every room in the building have a street view, and natural light. El Hallak states that “it is the visual transparency that makes this building very unique and avant-garde, for no one was doing the same in the 1930s. For our architectural studies, this building documents the transition between the early building tech niques and late trends”. Beirut Municipality expropriated the building in 2003 in order to be transformed into a museum and a cultural centre dedicated to the memory of the city of Beirut. The restoration project was designed by Youssef Haidar, a Lebanese architect. Haidar’s revival of Beit Beirut is based on the prin ciples of preservation, adaptation and reuse, with a new, connected building (including archival space, research facilities and auditoriums) added to the rear, while all traces of time, war and life in the old building have been preserved. The thousands of bullet holes and blast marks, flash burns caused by explosions, and the traces left by the snipers themselves, such as graffiti and concrete bun kers, form what Haidar describes as the ‘permanent collection’ of Beit Beirut. “We didn’t demolish anything,” he says. “Generally, when people work on old buildings to rehabilitate them, they preserve the external façade, empty it and add a new building inside. We preserved the original structure of the building with its component parts and adapted it to a new use. All we did was try and stop time.” This has largely been achieved using what Haidar calls ‘prosthet ics’: Steel elements that enable the building to function again in the same way that a prosthetic leg empowers a human to walk. In essence, Haidar has treated Beit Beirut as a person, with the prosthetic elements working on three different levels: structural (the skeleton), sandwich panels (the flesh), and external coat (the skin).

67 66

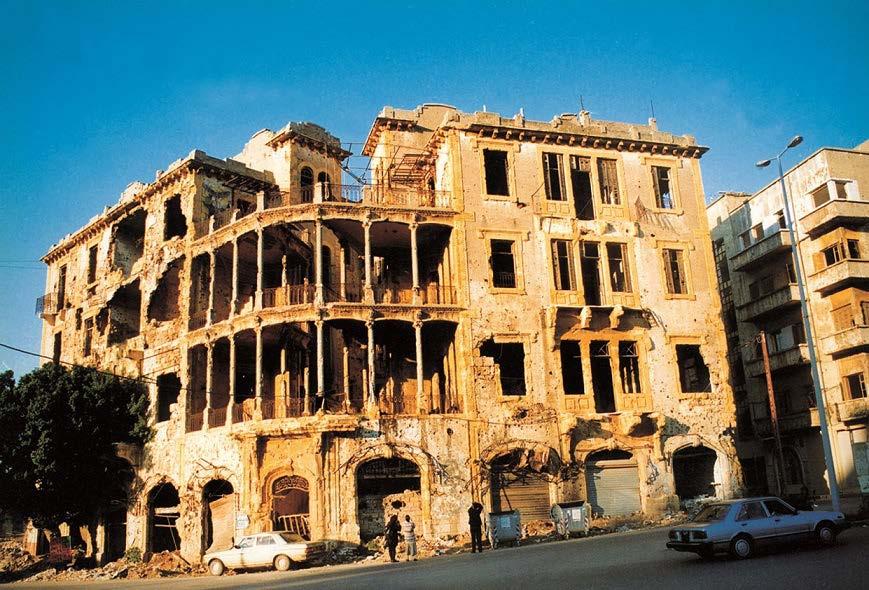

nAt onAl muSeum of Be rut – Be t Be rut 2019 BArAkAt-Building-1994 1- CASE STUDY: BEIT BEIRUT

69 68

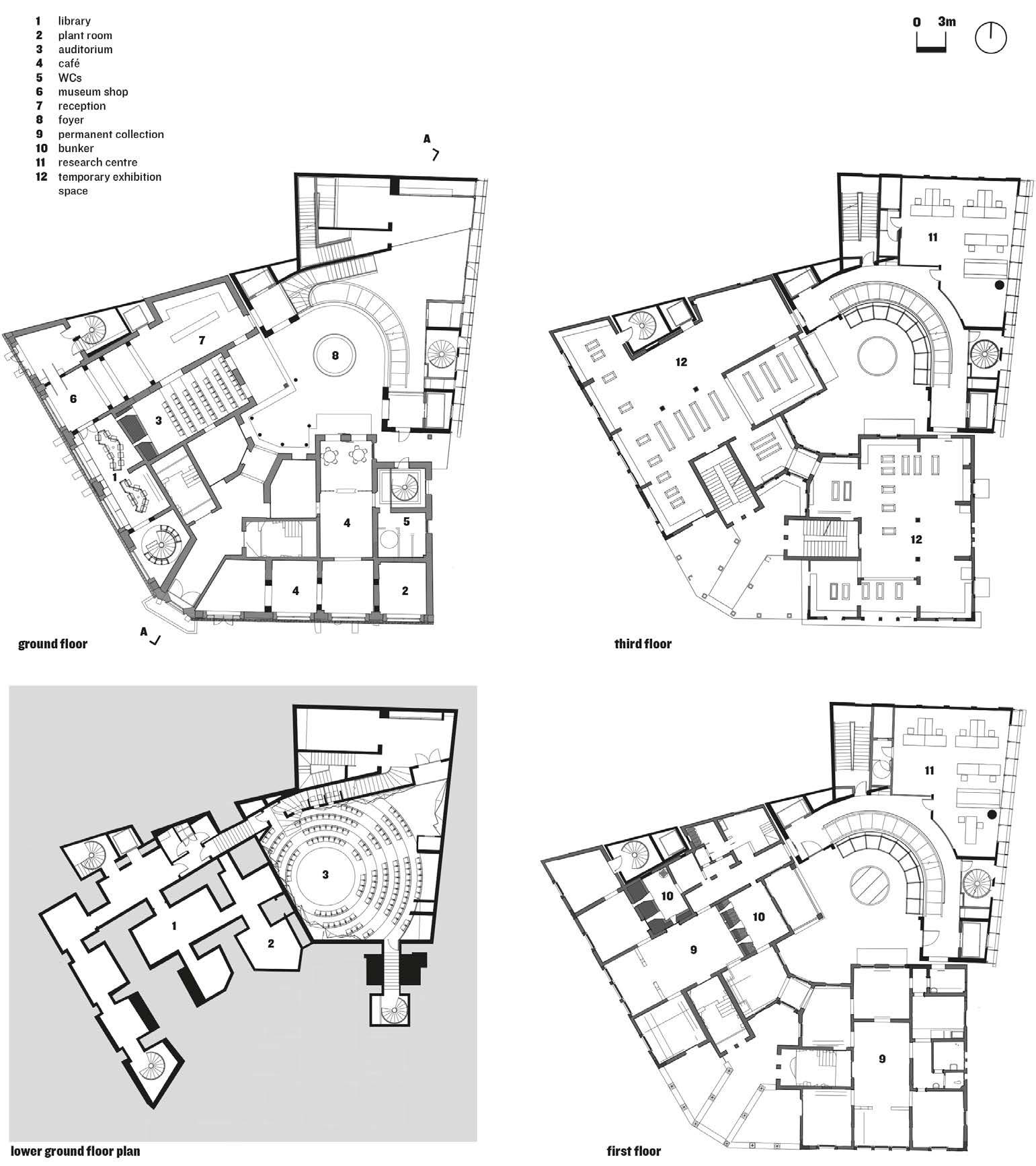

nAt onAl muSeum of Be rut – BeIt Be rut plAnS

Be t Be rut By gerAlDIne Bruneel Beit Beirut leBAnon- BAkArAt

Building By romAn roBroek

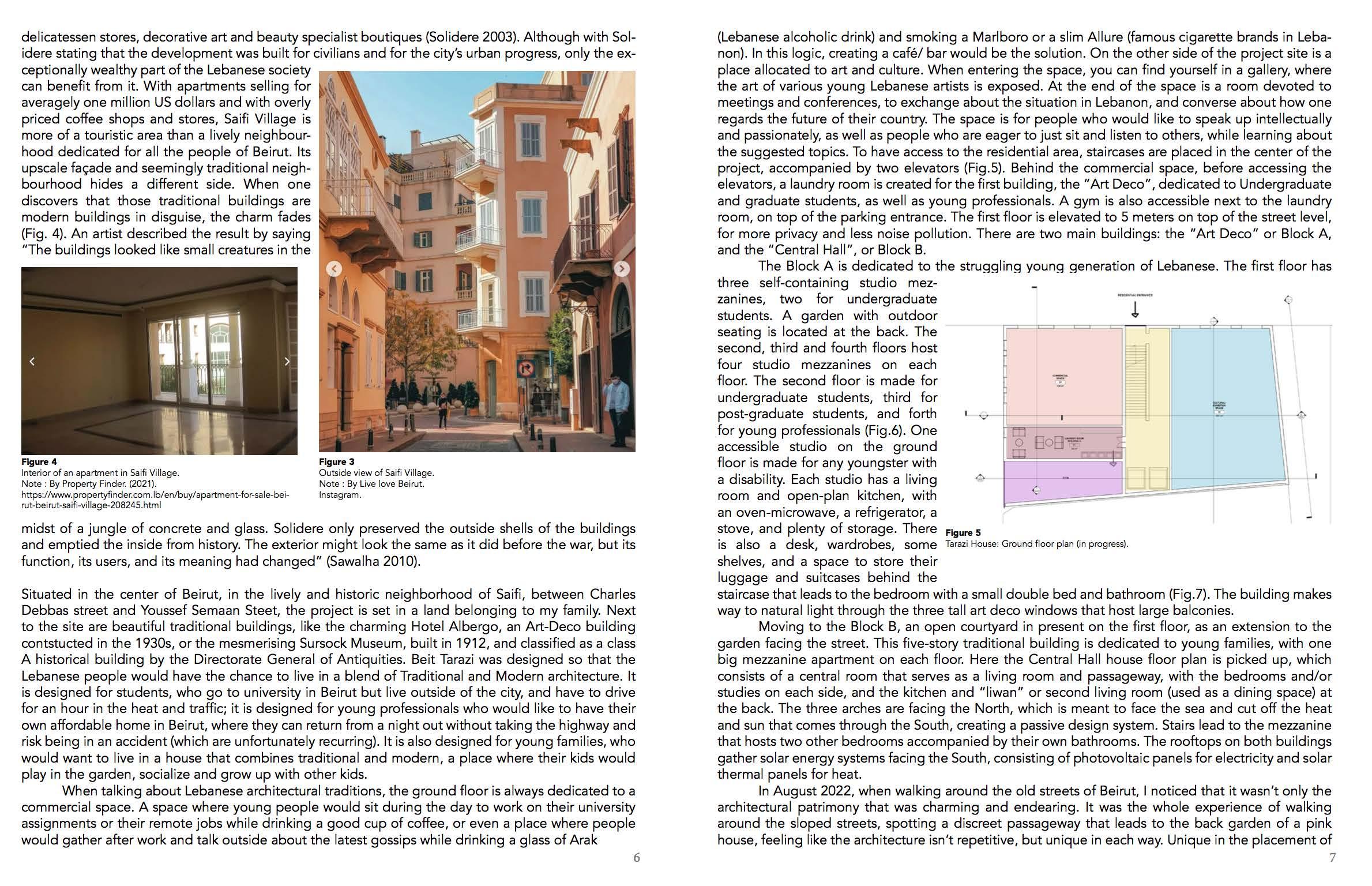

When talking about the preservation of heritage buildings and the urban design of a city, keeping or reproducing its architectural typology and identity is essen tial, both on the inside of the building and out. Retaining the outside shell and completely changing the interior, as Solidere did in Downtown Beirut and Saifi Village, should not be an option. When strolling around Saifi Village, the charm of its small red-bricked pavements, lively gardens and coloured traditional hous es is unparalleled. Saifi Village is Solidere’s first and major residential complex. Completed in 2000, it comprises 16 new buildings forming four clusters. The buildings have a maximum of seven floors, and the 145 apartments are divided into two per floor ranging from one to four bedrooms. Quartier des Arts was in augurated in 2003, with a cluster of designers’ and art galleries, antiques and artisans’ shops, delicatessen stores, decorative art and beauty specialist bou tiques. Although with Solidere stating that the development was built for civilians and for the city’s urban progress, only the exceptionally wealthy part of the Lebanese society can benefit from it. With apartments selling for averagely one million US dollars and with overly priced coffee shops and stores, Saifi Village is more of a touristic area than a lively neighbourhood dedicated for all the people of Beirut. Its upscale façade and seemingly traditional neighbourhood hides a different side.

71 70

the neo trADItIonAl fAcADeS of the SAIfI AreA. (Source SolIDere)- ScAle moDel SAIf v llAge SAIf v llAge 2- CASE STUDY: SAIFI VILLAGE, BEIRUT

When one discovers that those traditional buildings are modern buildings in dis guise, the charm fades. An artist described the result by saying “The buildings looked like small creatures in the midst of a jungle of concrete and glass. Sol idere only preserved the outside shells of the buildings and emptied the inside from history. The exterior might look the same as it did before the war, but its function, its users, and its meaning had changed”.

73 72

plAn of An ApArtment n SAIf v llAge SAifi villAge well Seen cut through the window to mAke plAce for 2 floorS nSIDe A SAIfI v llAge ApArtment low ce l ng he ght leSS nAturAl l ght nSIDe A trADIt onAl houSe of Be rut: he gh ce l ng he ght lotS of nAturAl l ght

III- A

PROJECT ANALYSIS

74

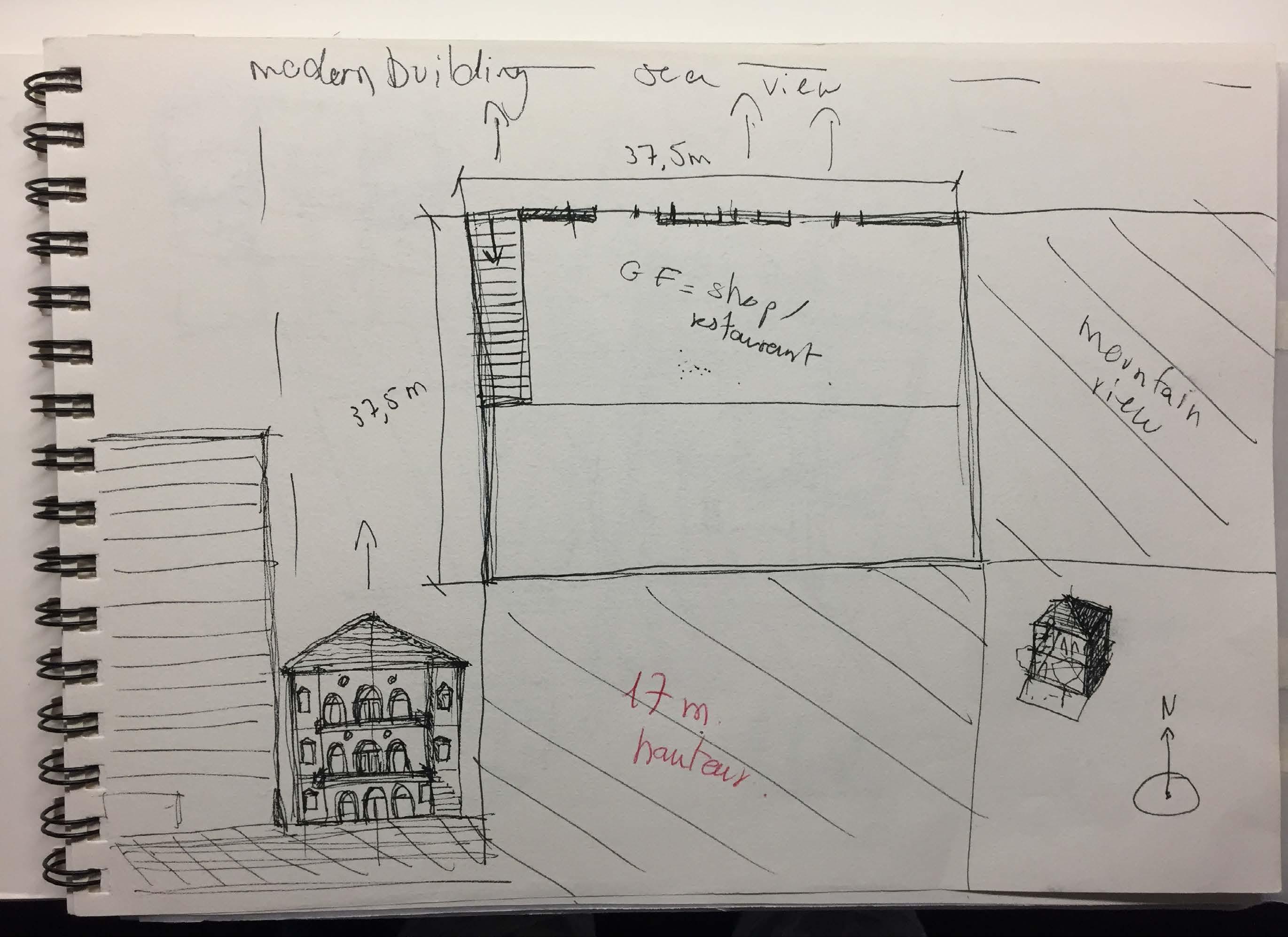

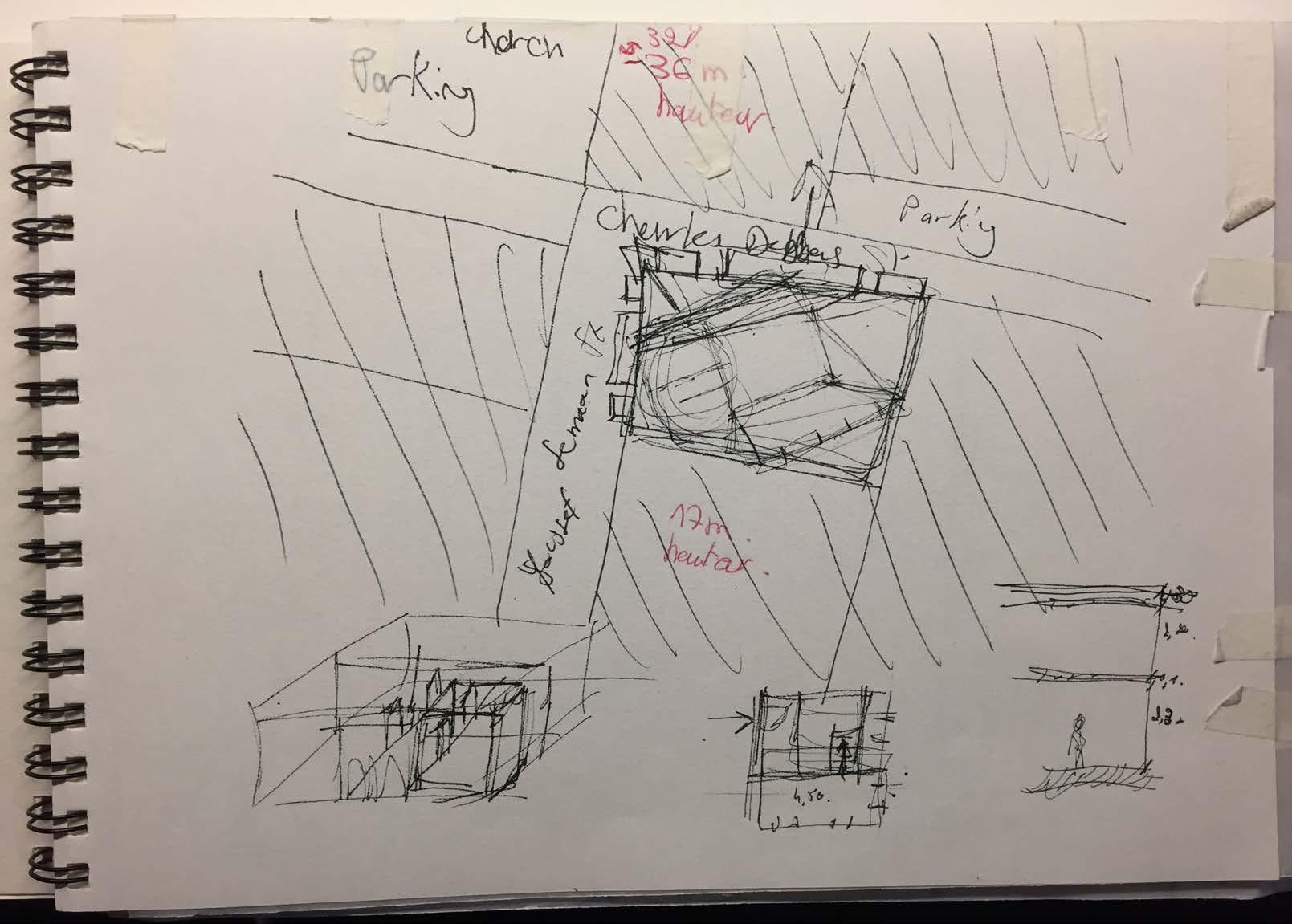

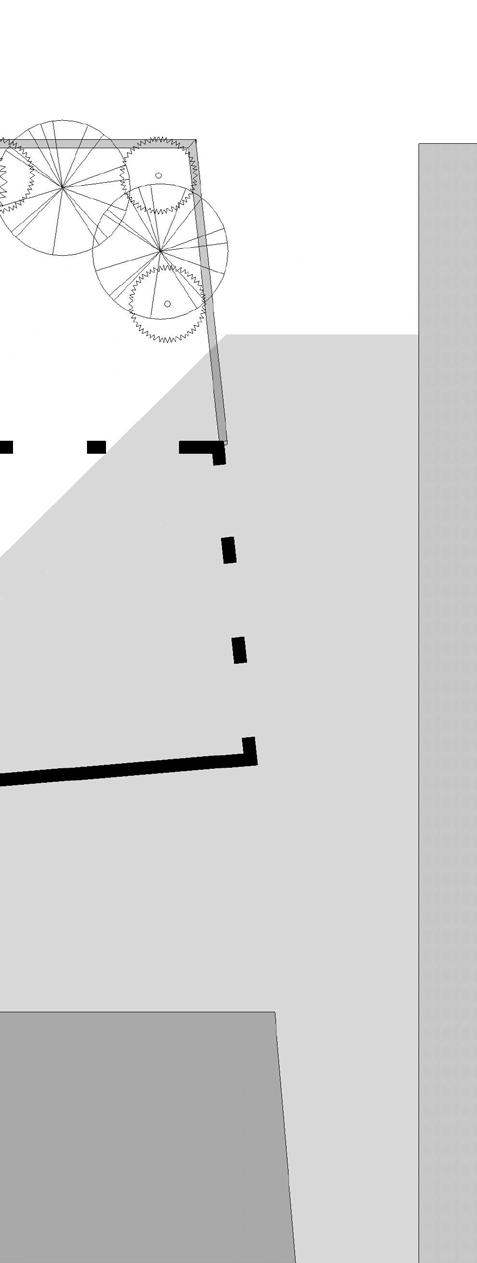

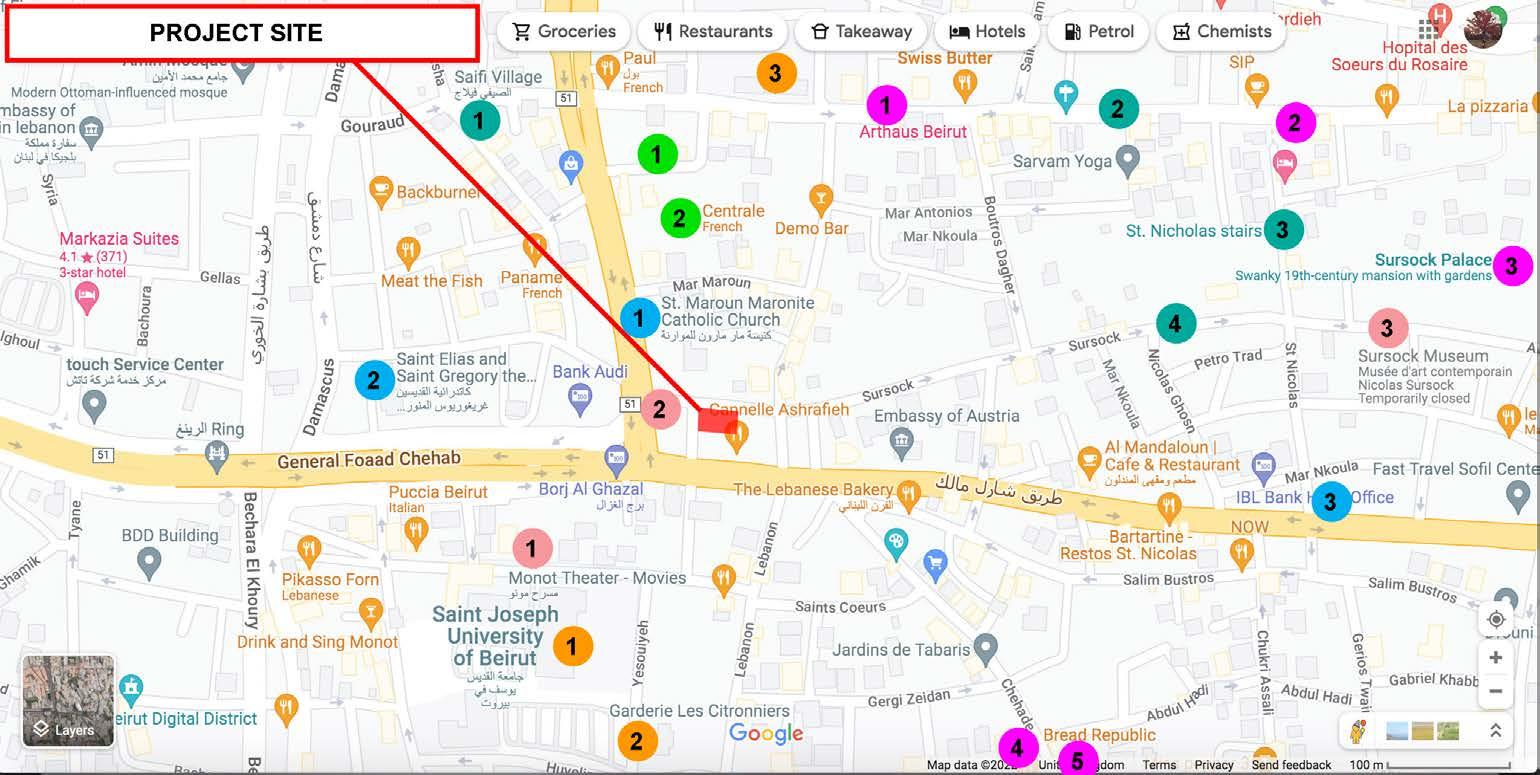

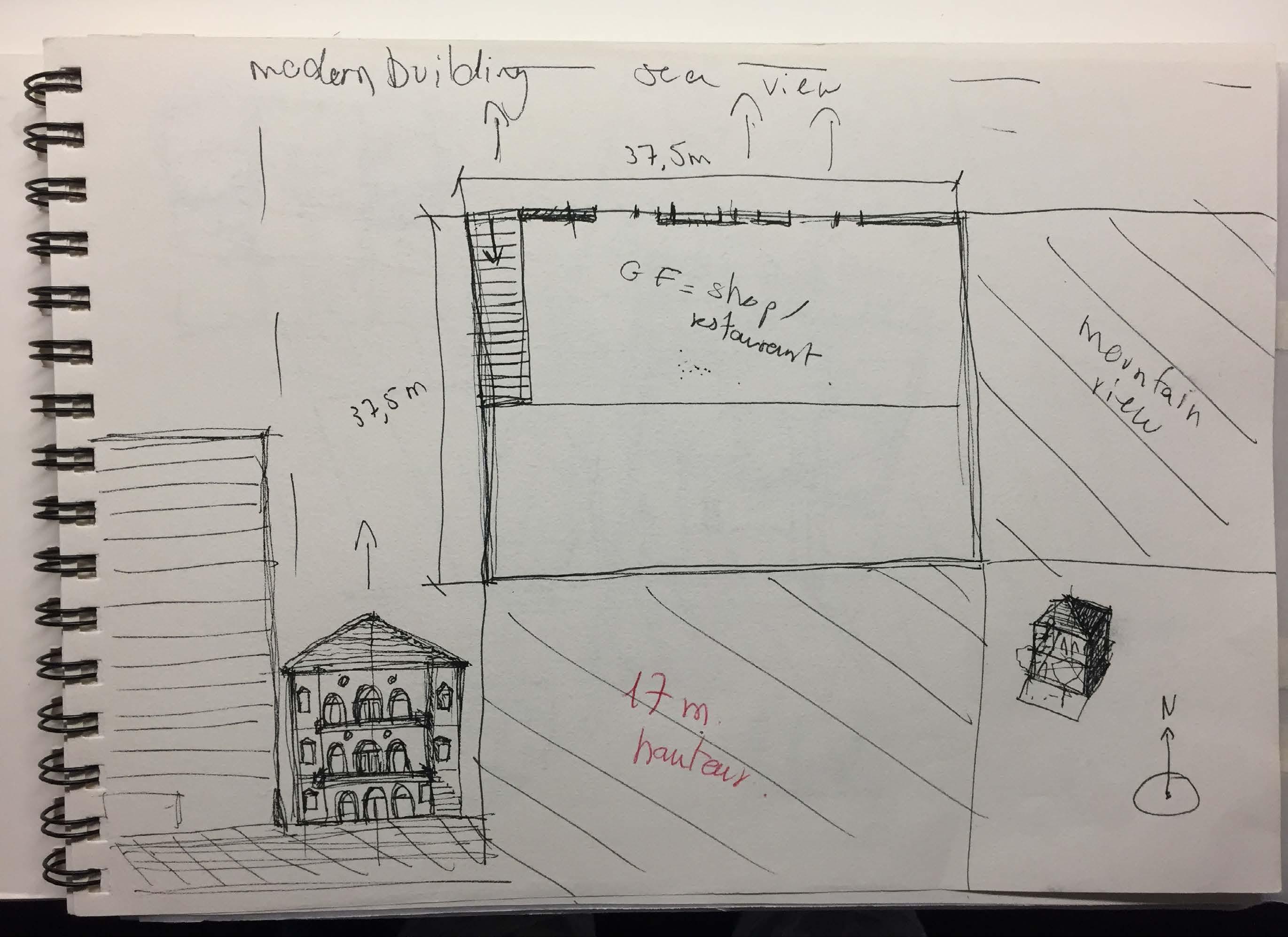

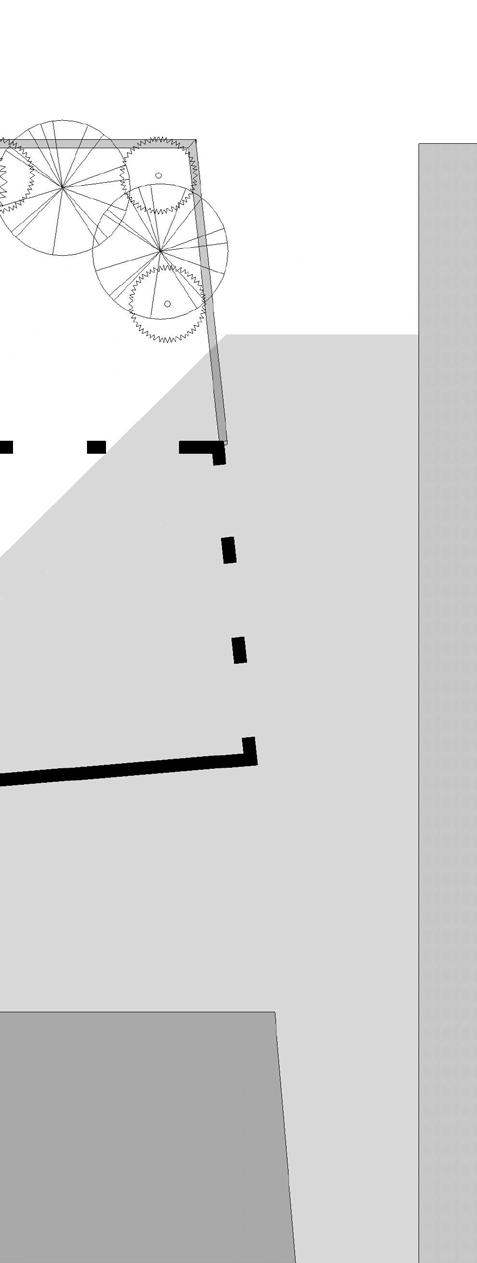

SITE ANALYSIS : SAIFI, BEIRUT LEBANON

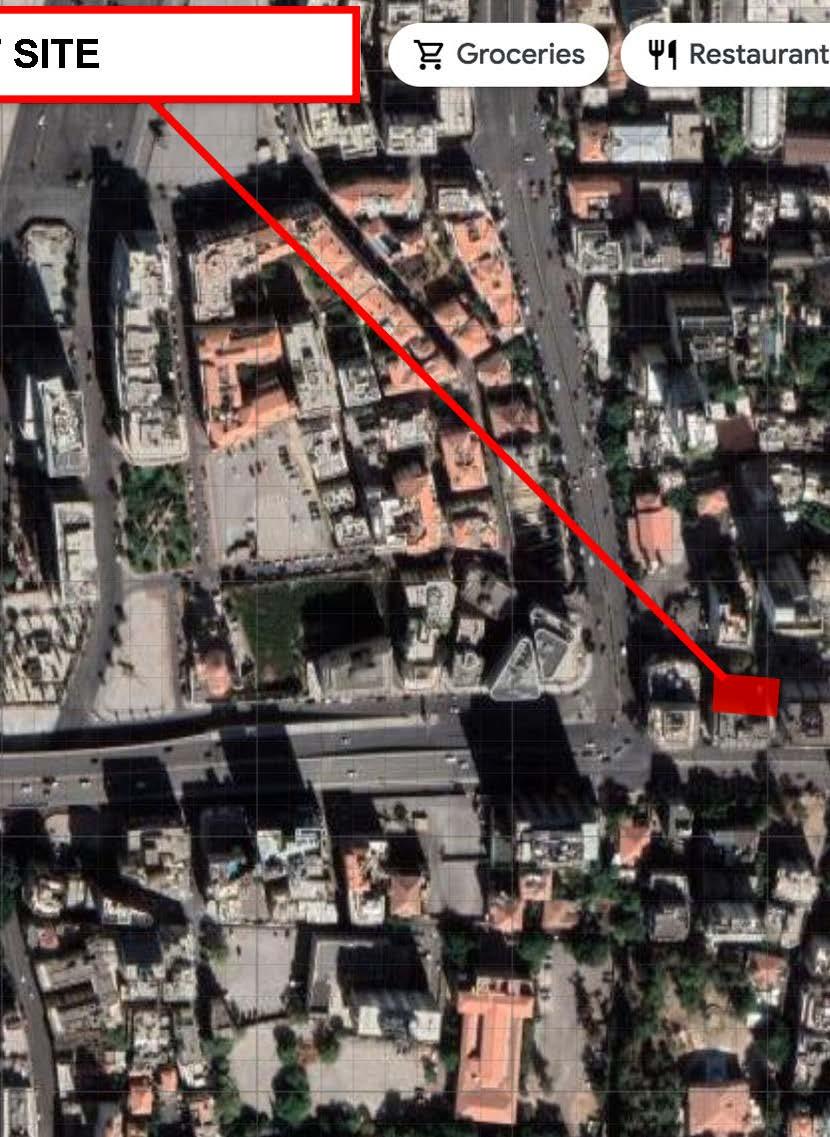

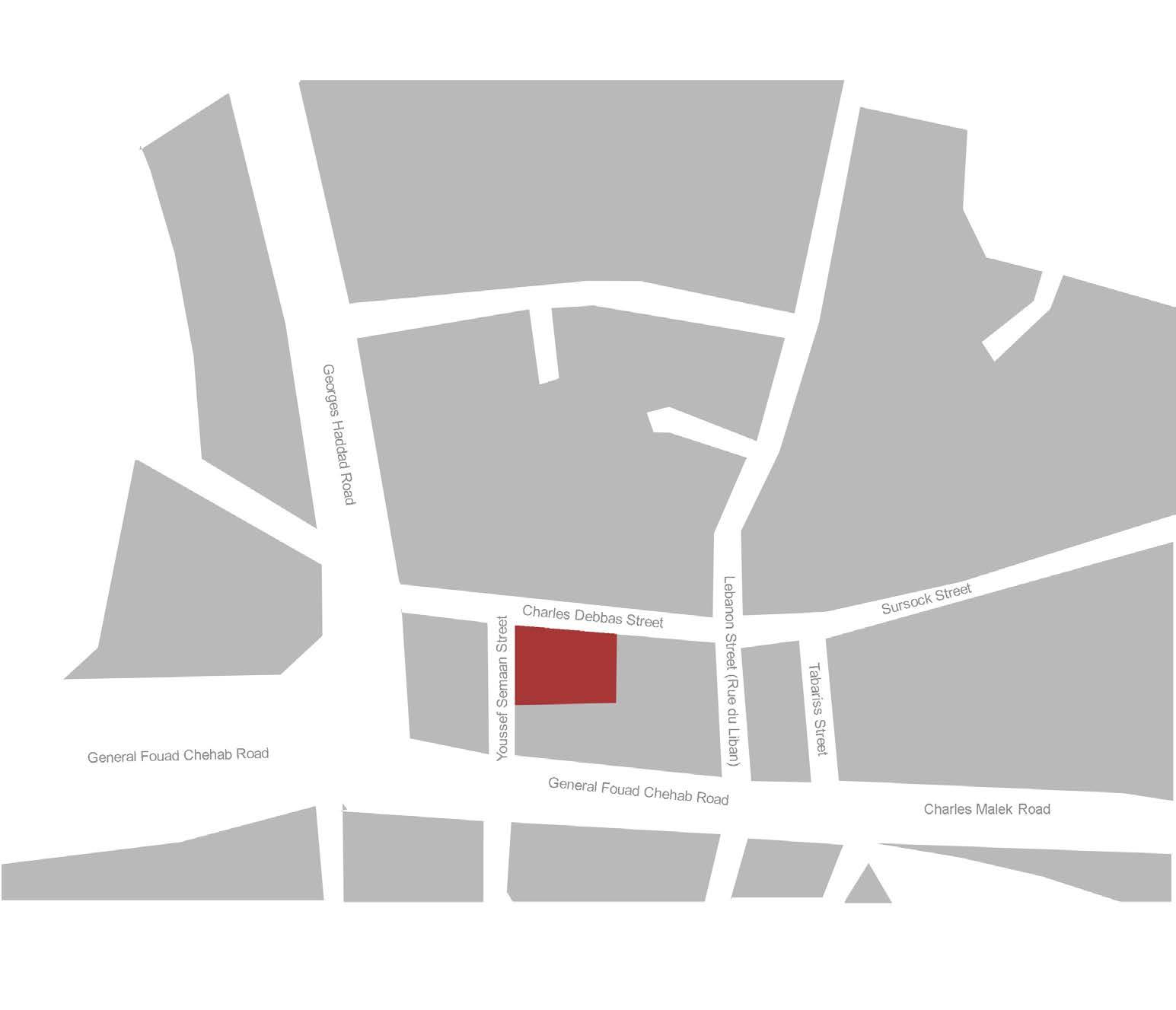

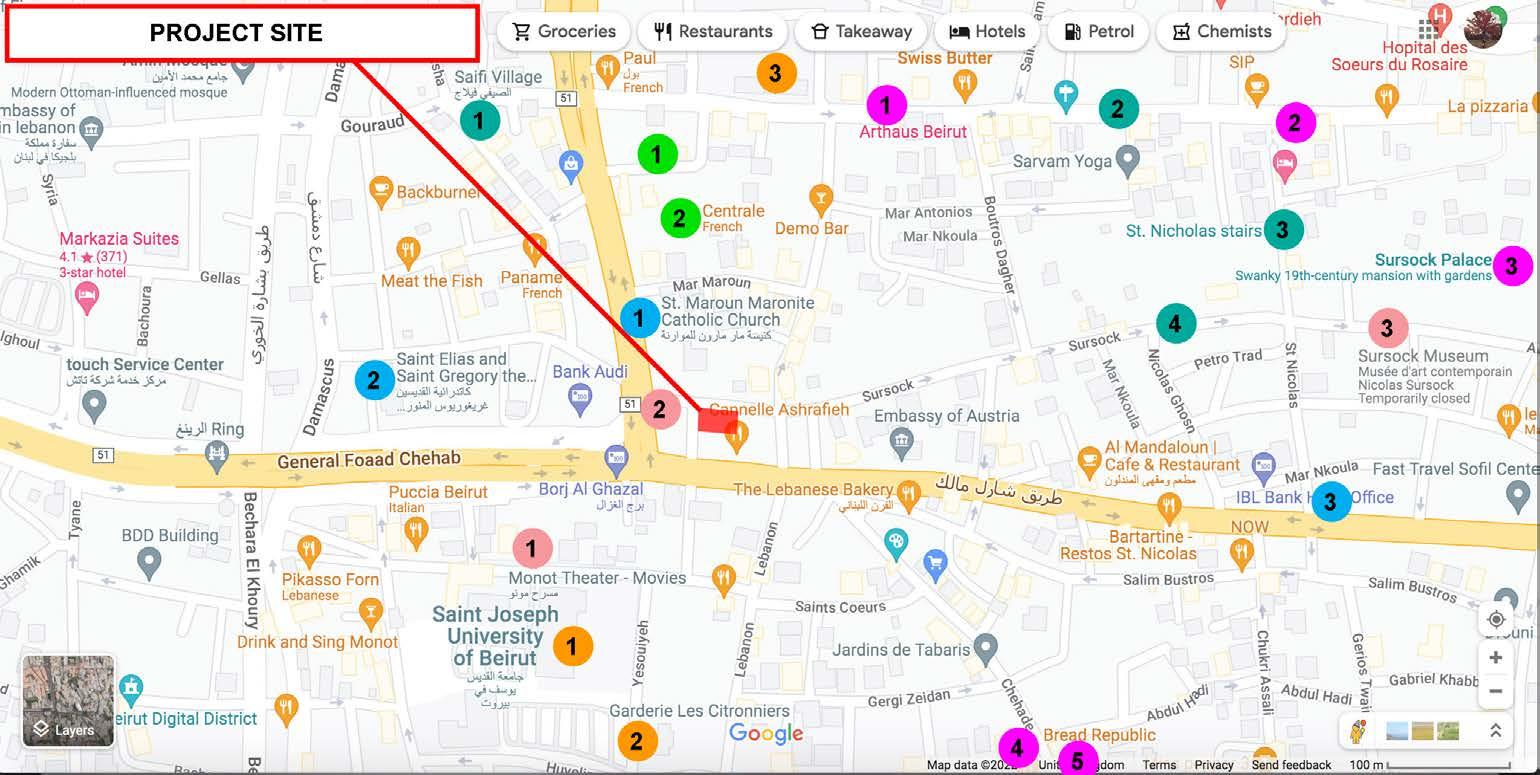

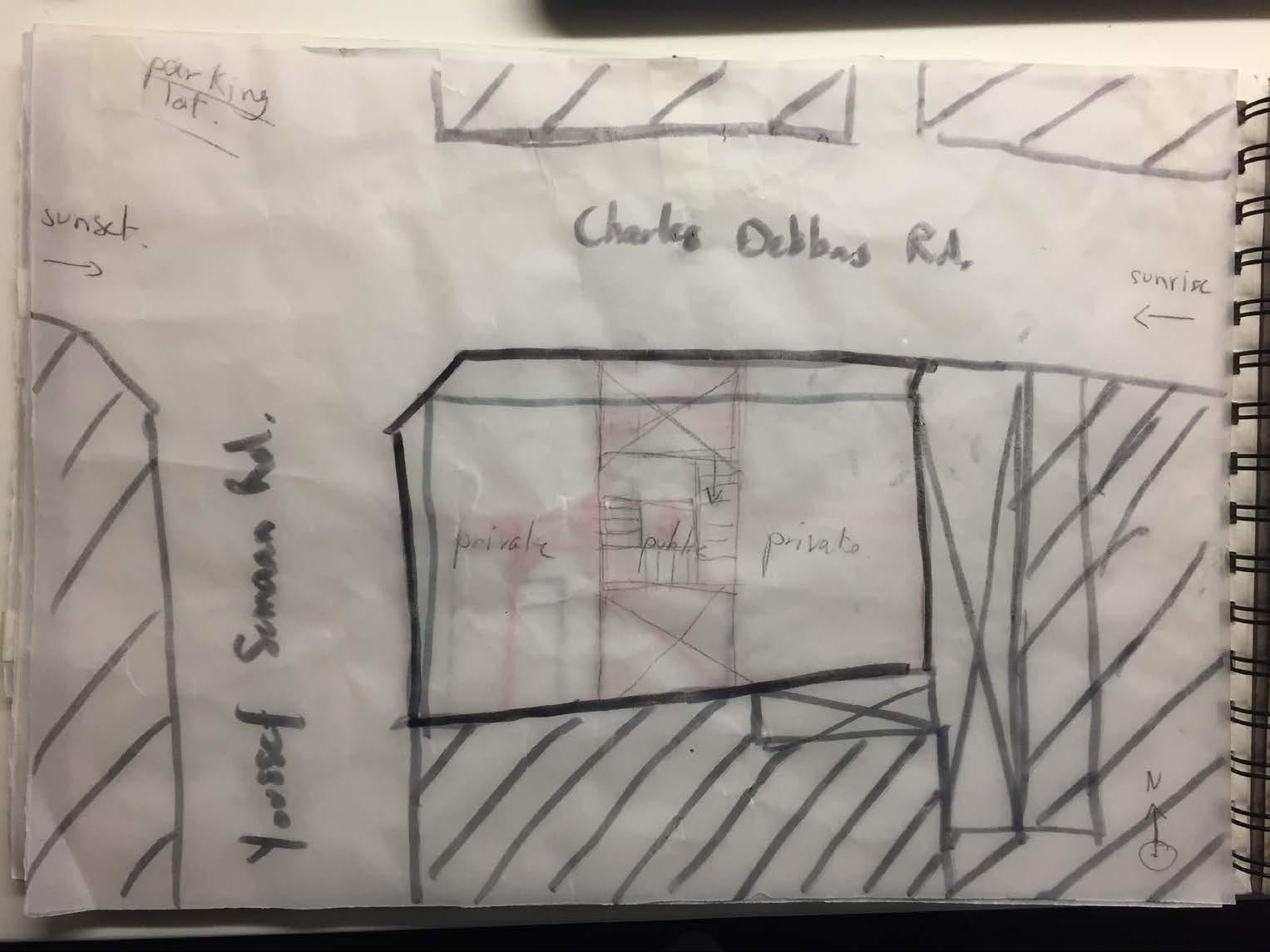

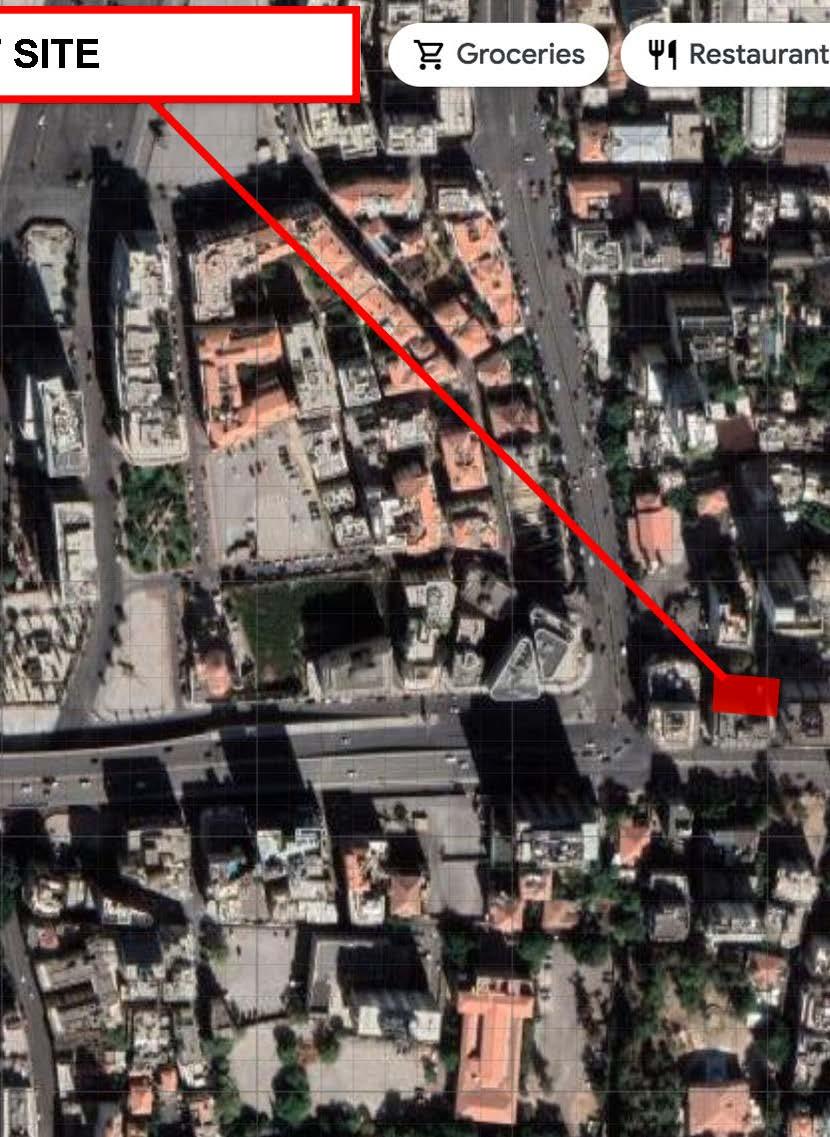

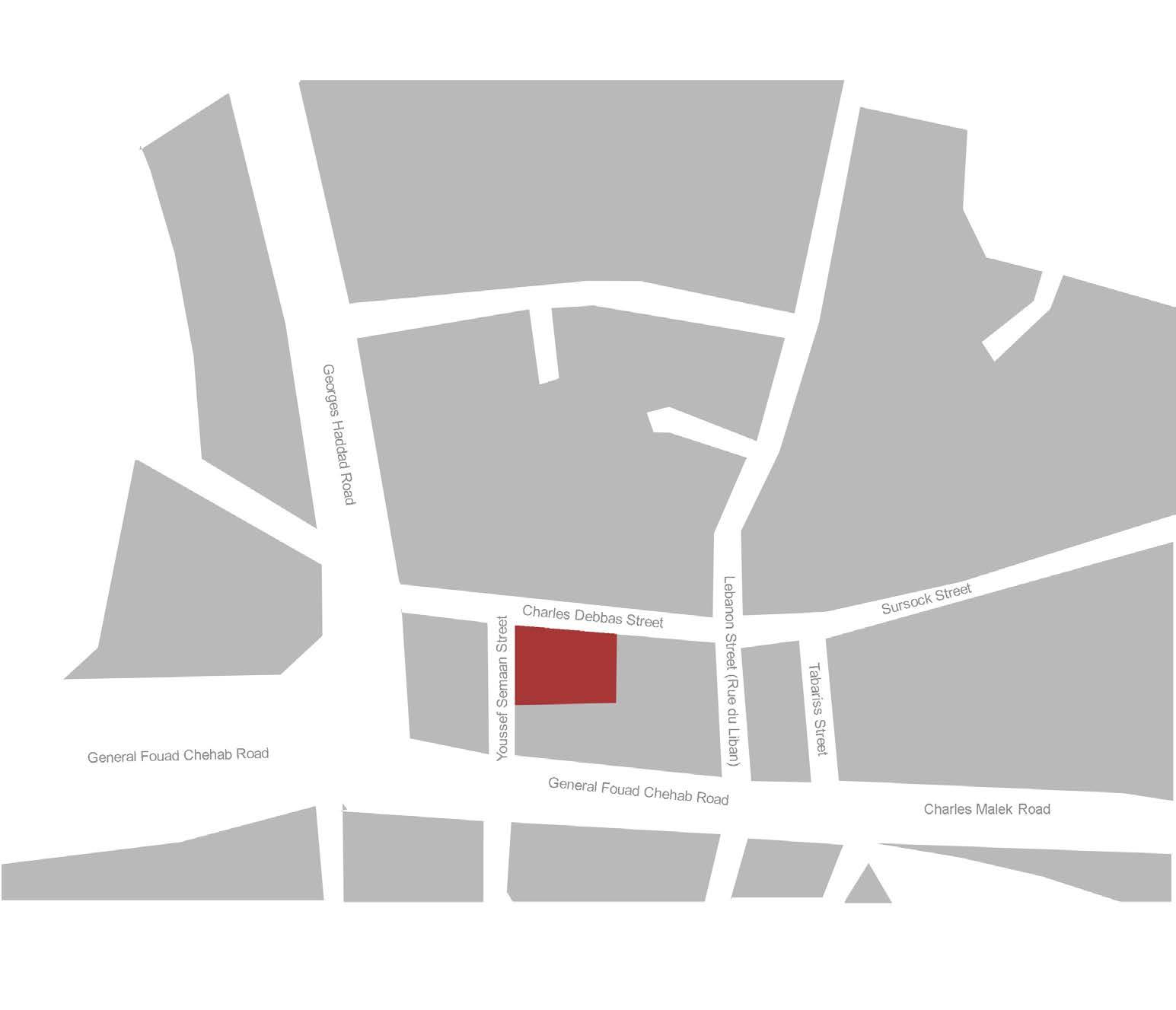

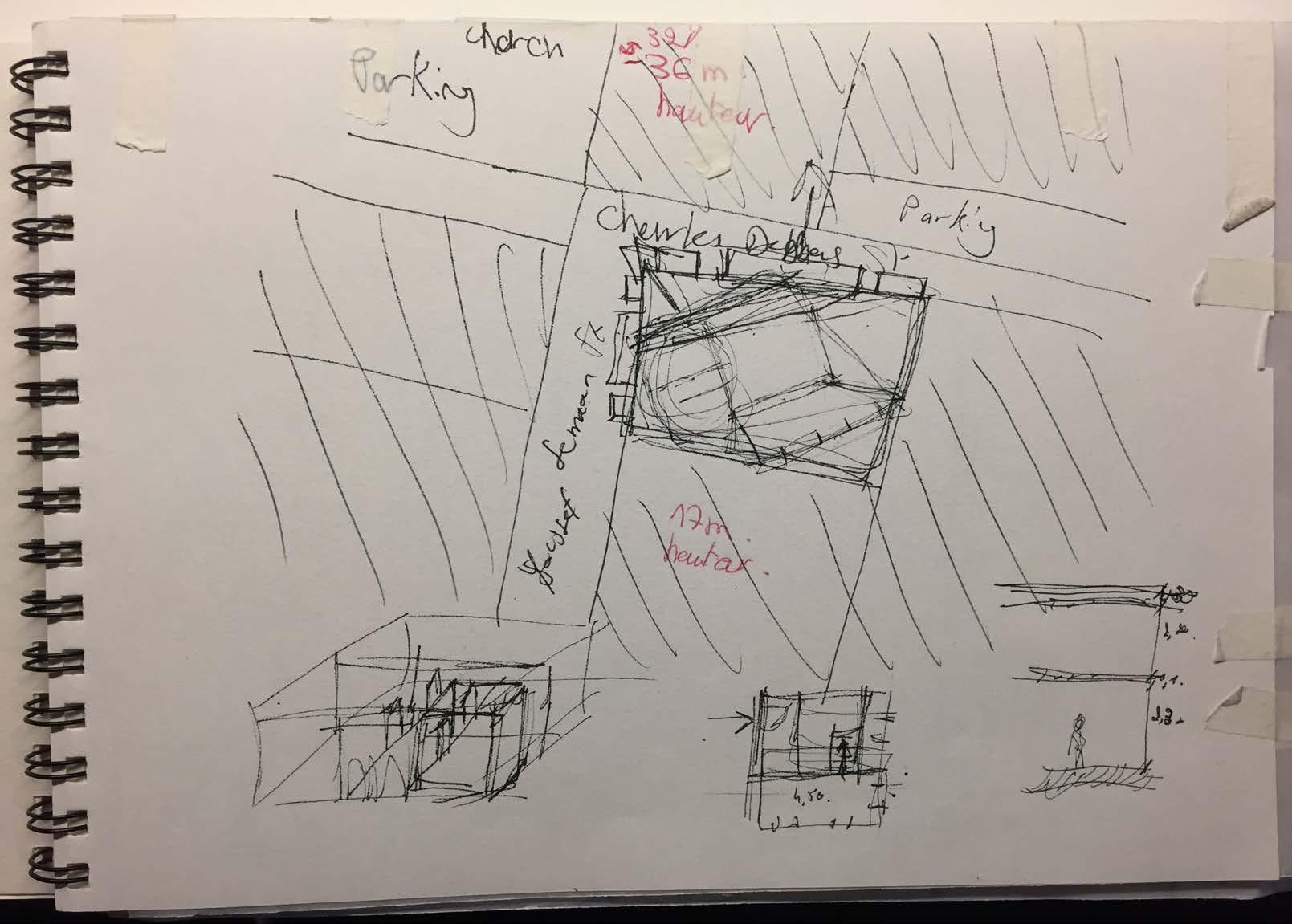

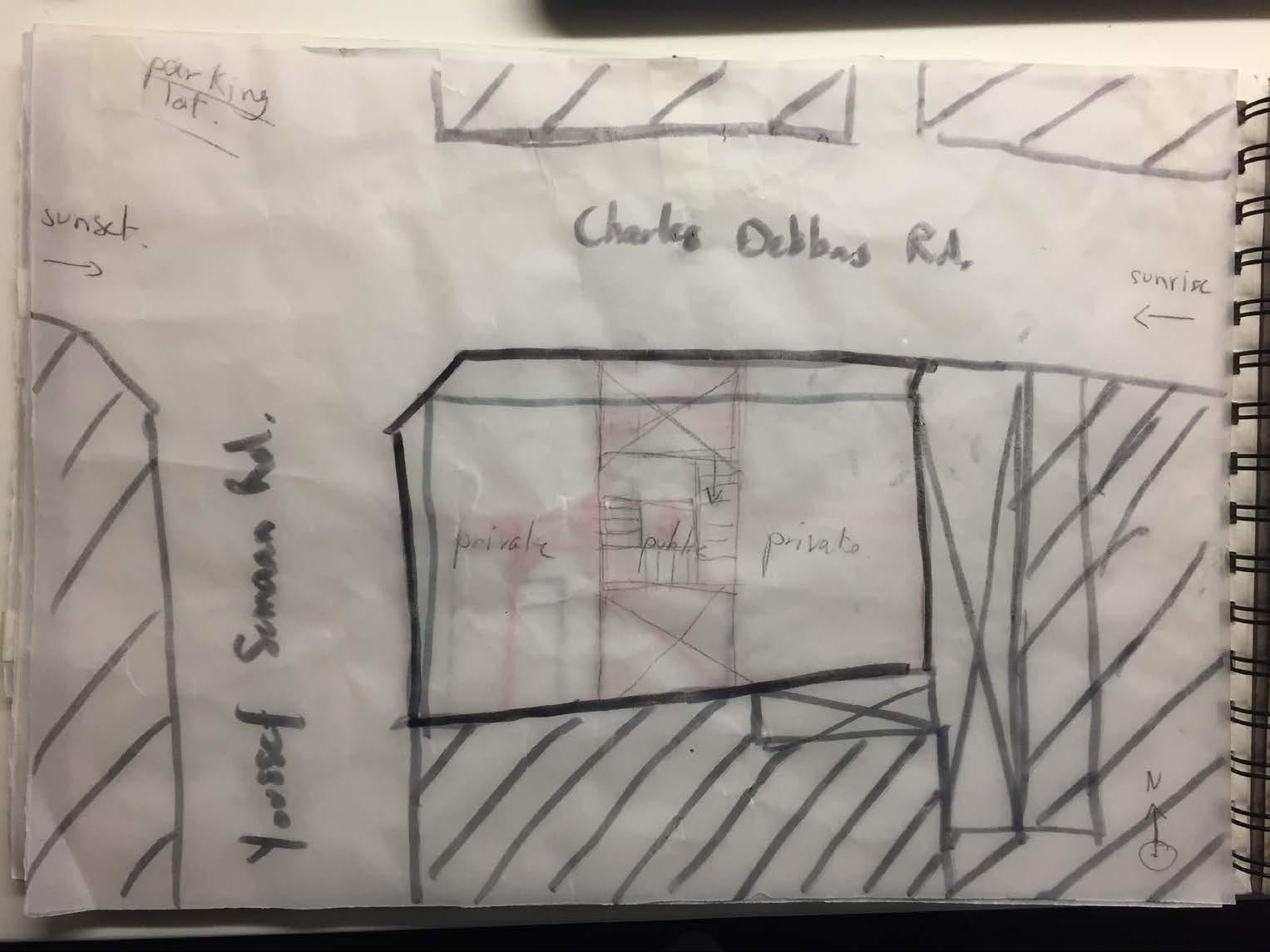

My project follows this ideology of keeping the traditional architecture alive and blending it with modern construction techniques and materiality. Located in Saifi, Beirut, between Charles Debbas street and Youssef Semaan Steet, the project will be set in a land belonging to my family. Next to the site are beauti ful traditional buildings, like the charming Hotel Albergo, an Art-Deco building contstucted in the 1930s, or the mesmerising Sursock Museum, built in 1912, and classified as a class A historical building by the Directorate General of Antiquities.

77 76

1-

3D SIte v ew N

mAp SIte v ew

79 78 siTe Views

81 80

sTree T Views around The siTe

N

83 82 WELL-KNOWN MODERN STRUCTURES 1- Saifi Suites Hotel 2- Centrale restaurant and rooftop bar CULTURAL PLACES 1- Monot Theater and Movies 2- Art Corner (Art Gallery and classes) RELIGIOUS PLACES 1- St. Maroun Maronite Catholic Church 2- Saint Elias and Saint Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Catholic Cathedral 3- Saint Nikolas Geek Orthodox Cathedral 3- Sursock Museum neighbourhood siTes TOURISTIC PLACES 1- Saifi Village 2- Rue Gauraud (Traditional buildings and houses sightseeing Street) 3- St. Nicholas stairs 4- Rue Sursock (Traditional houses and palaces sightseeing Street) EDUCATIONAL PLACES 1- Saint Joseph University of Beirut - Campus of Social Sciences 2- Garderie Les Citronniers (Nursery) 3- Collège Sacré-Cœur Gemmayzeh (School) FAMOUS TRADITIONAL HOUSES SITES 1- Arthaus Beirut (Hotel and restaurant) 2- Maison Tarazi 3- Sursock Palace 4- Liza (Restaurant) 5- Bread Republic (Restaurant)

2- INTENTIONS : A MIDDLE GROUND BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND MODERN

Moodboard

85 84

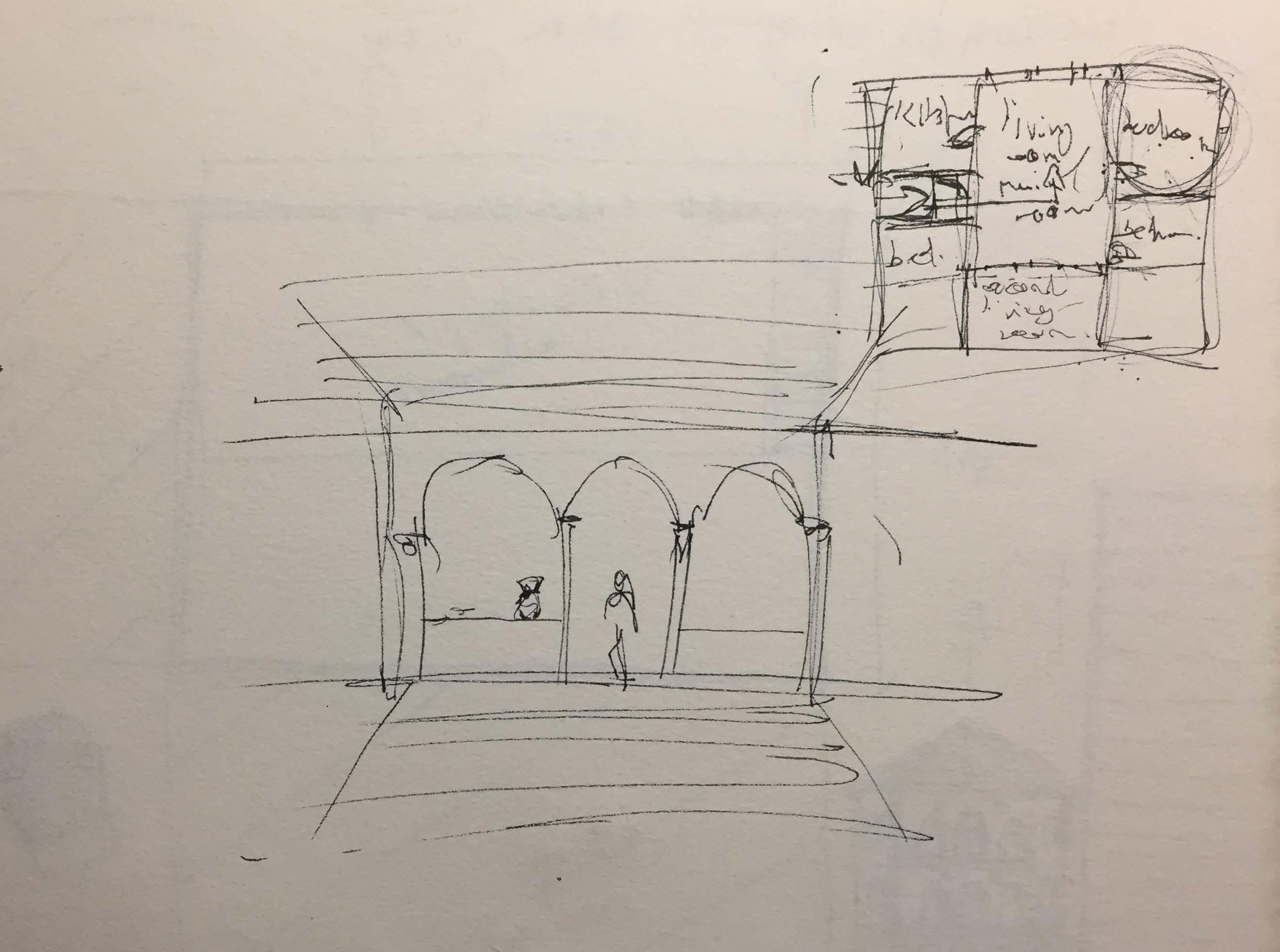

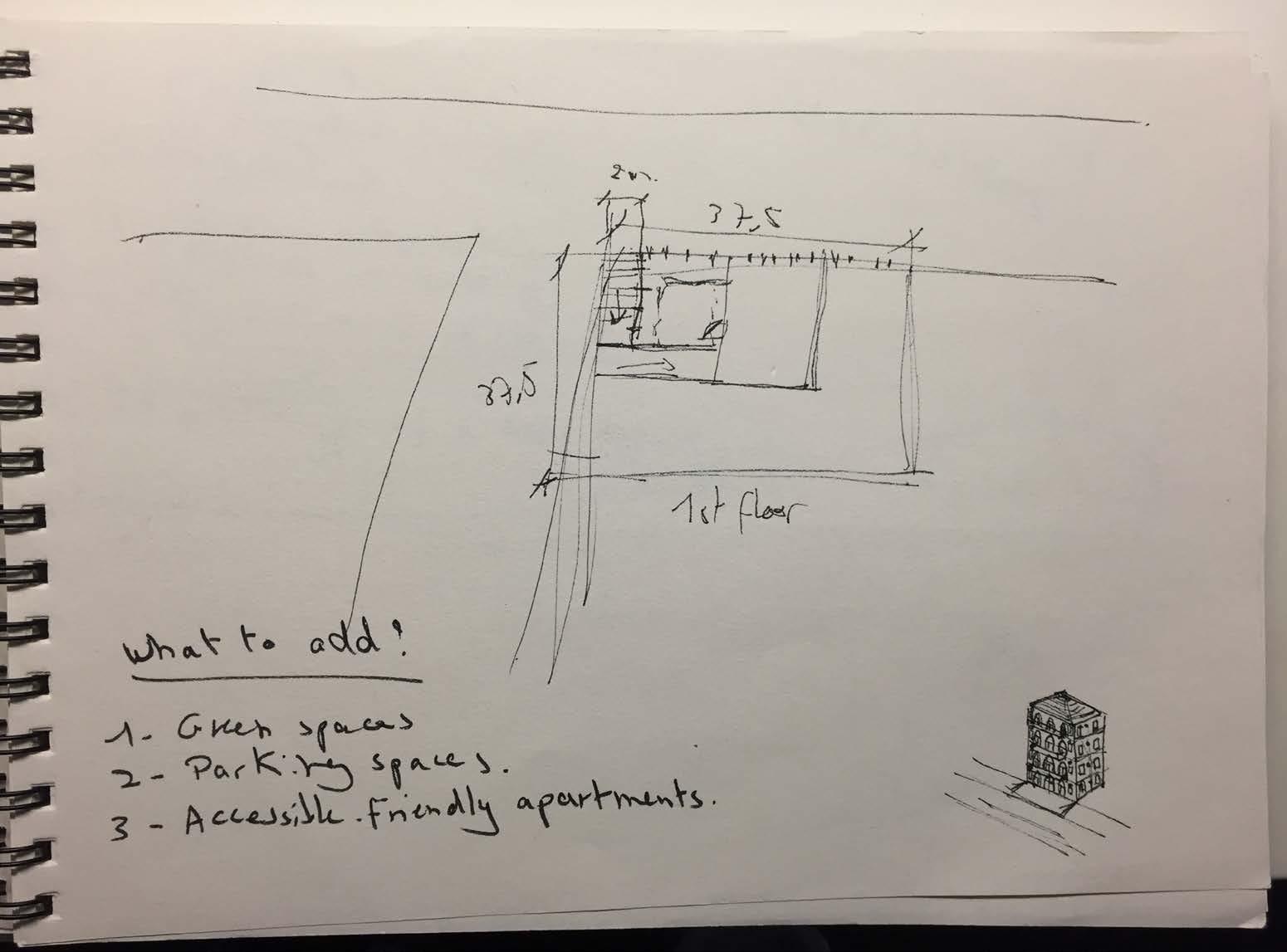

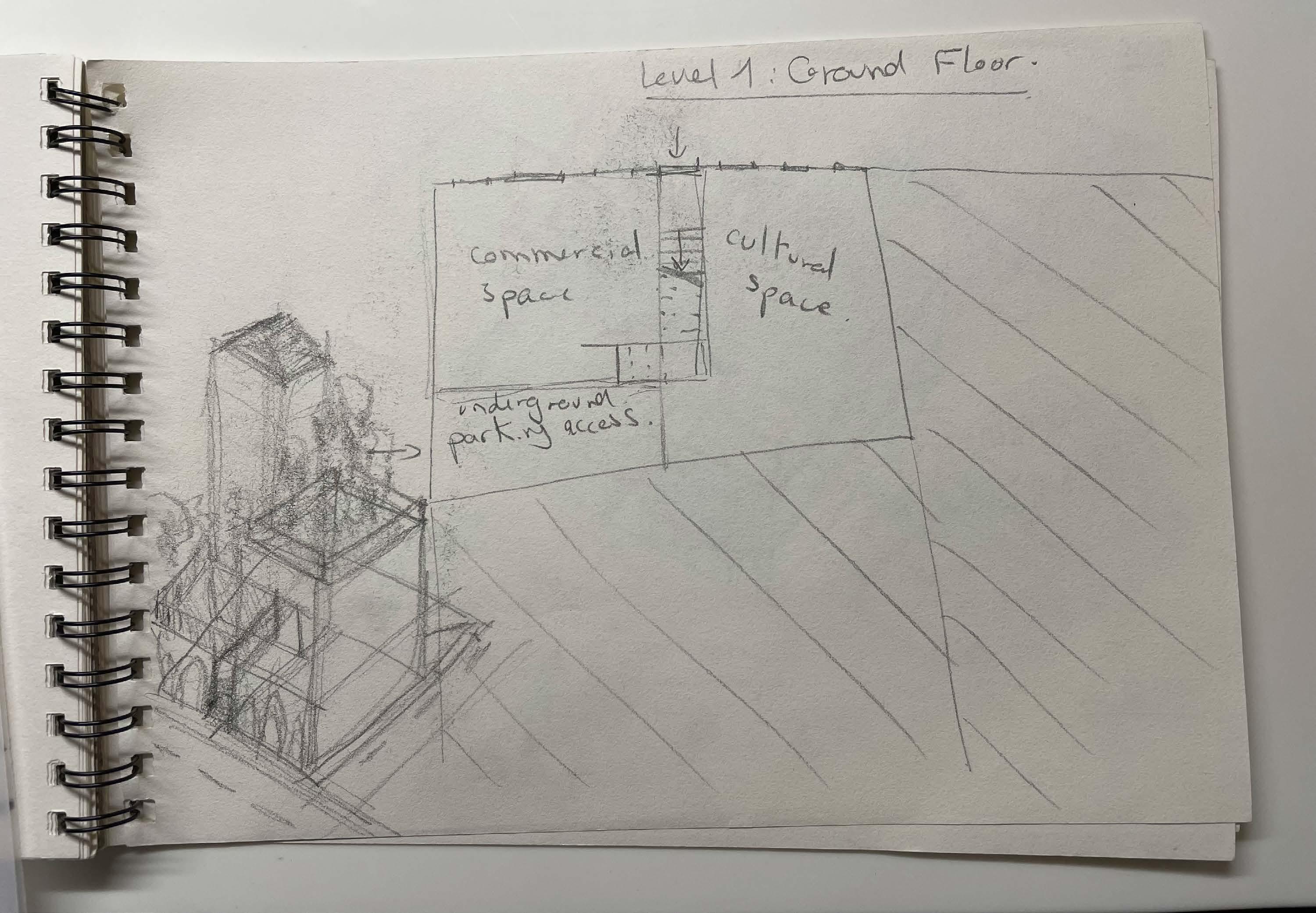

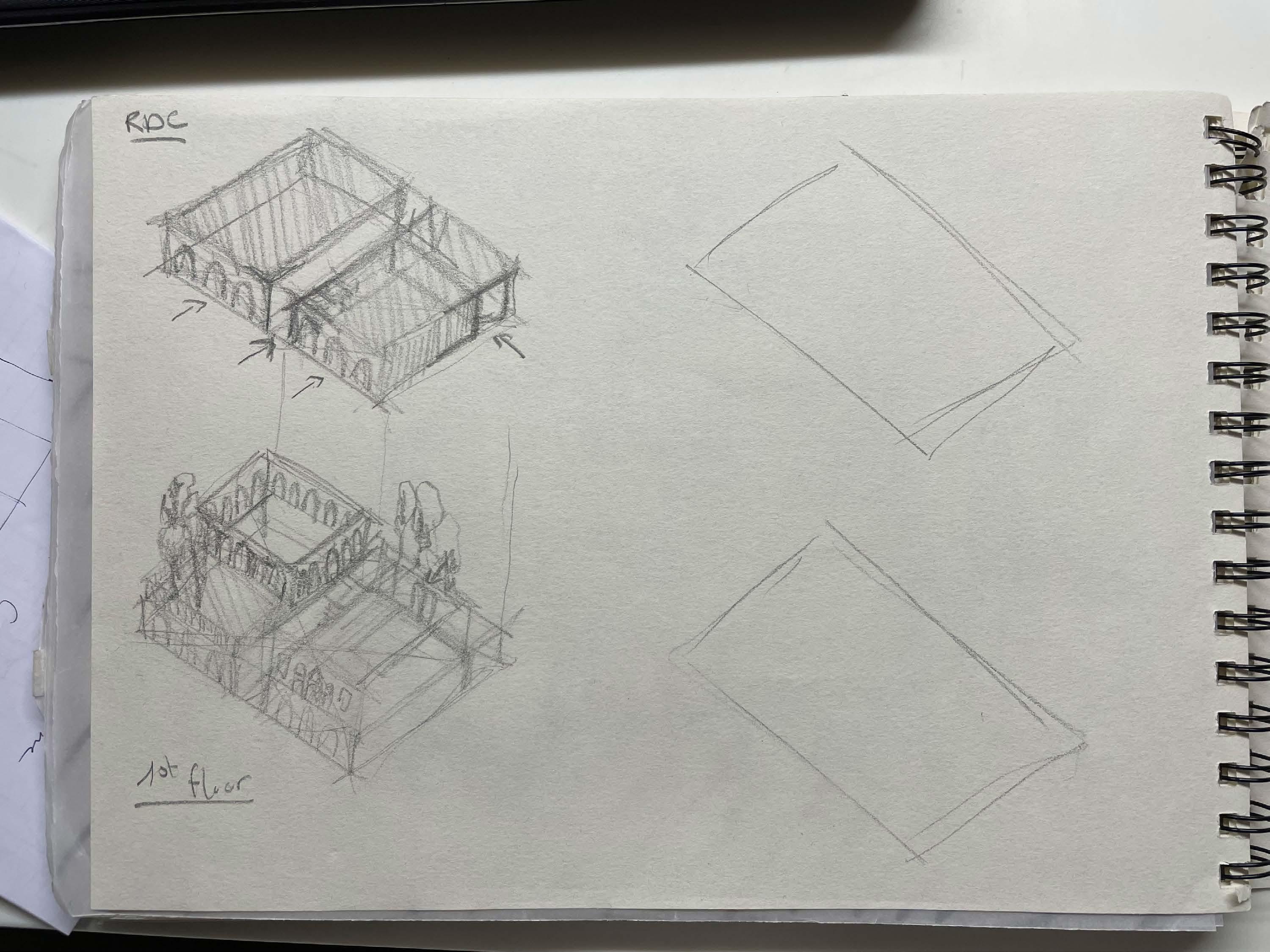

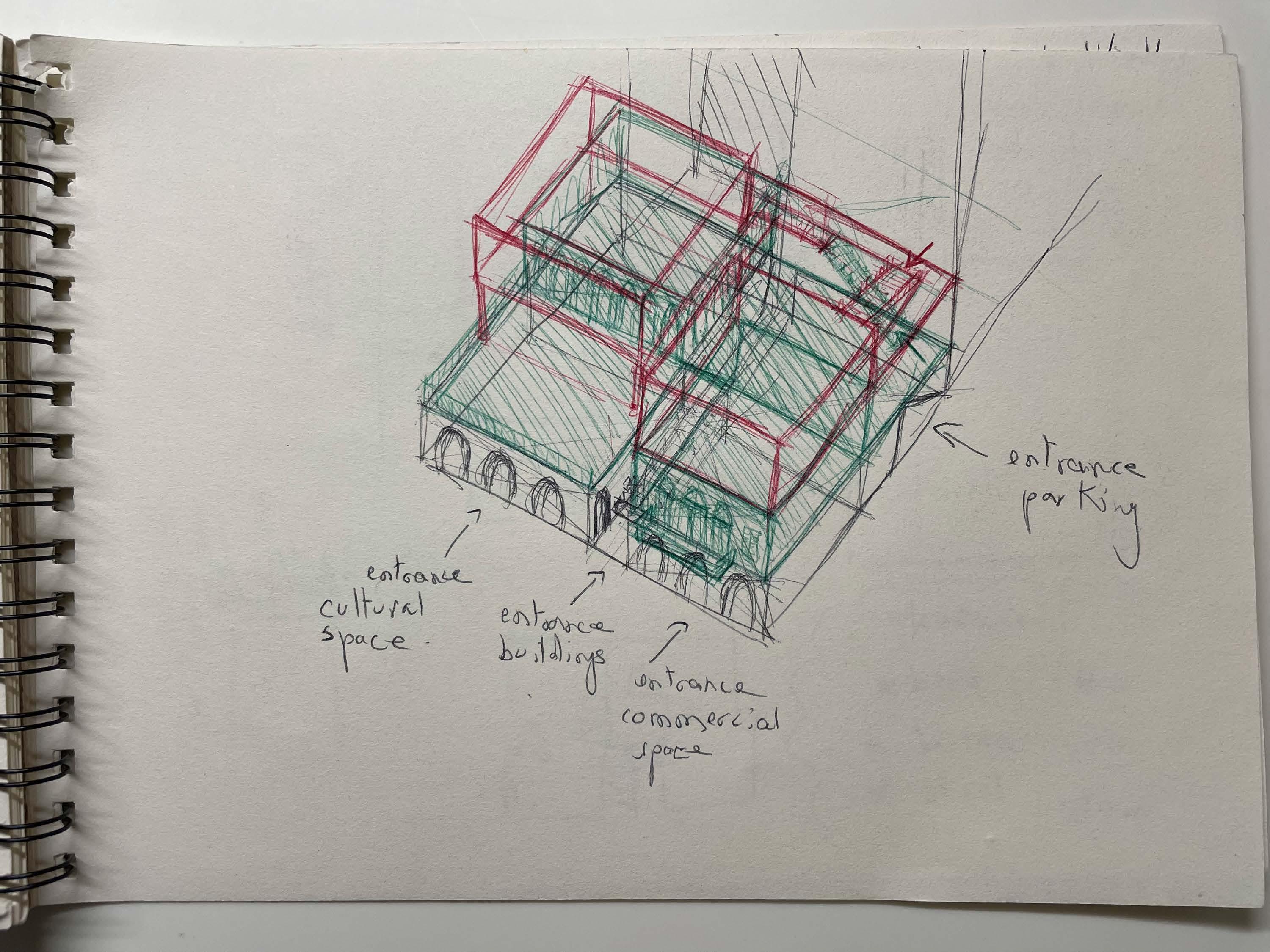

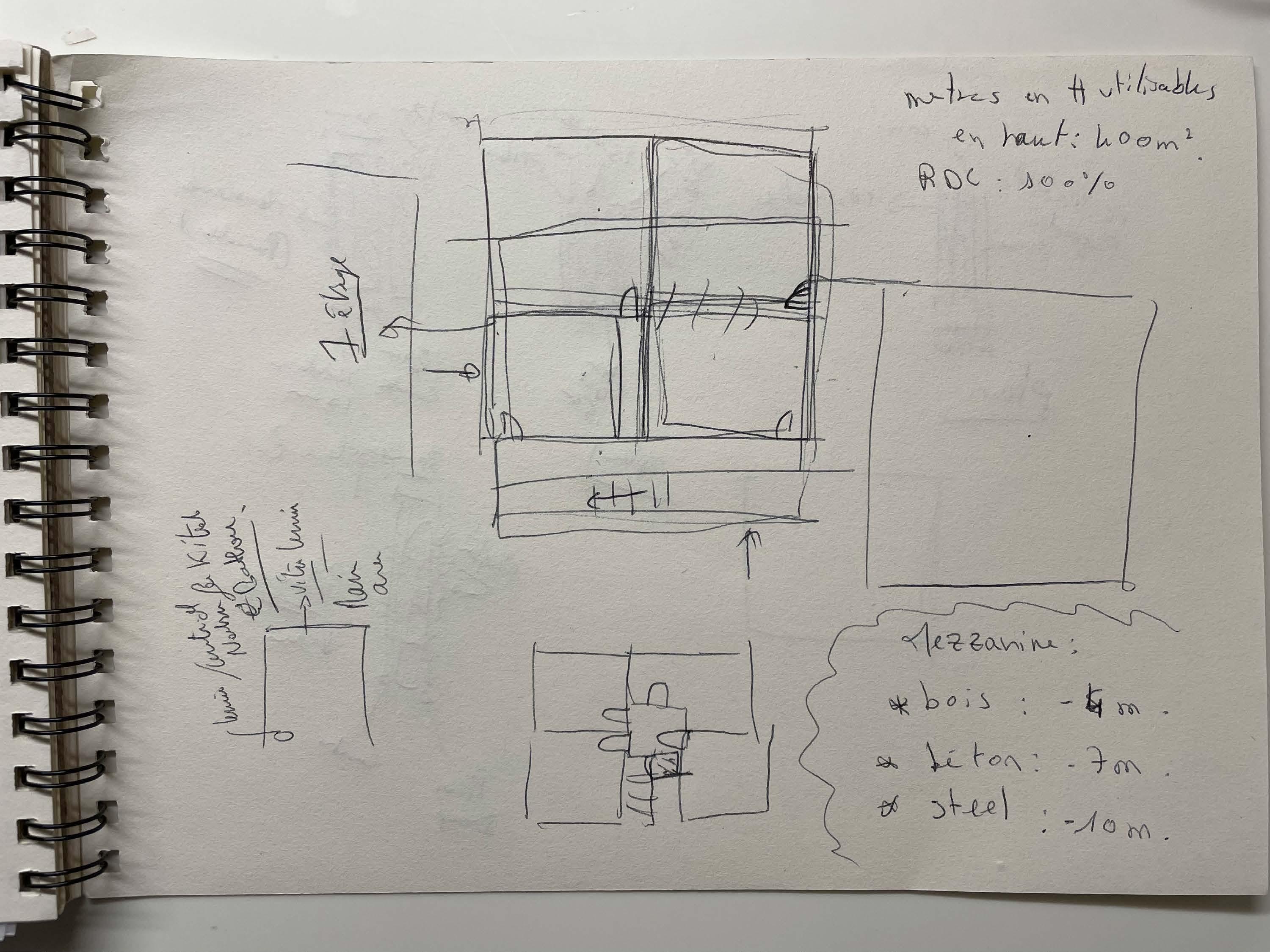

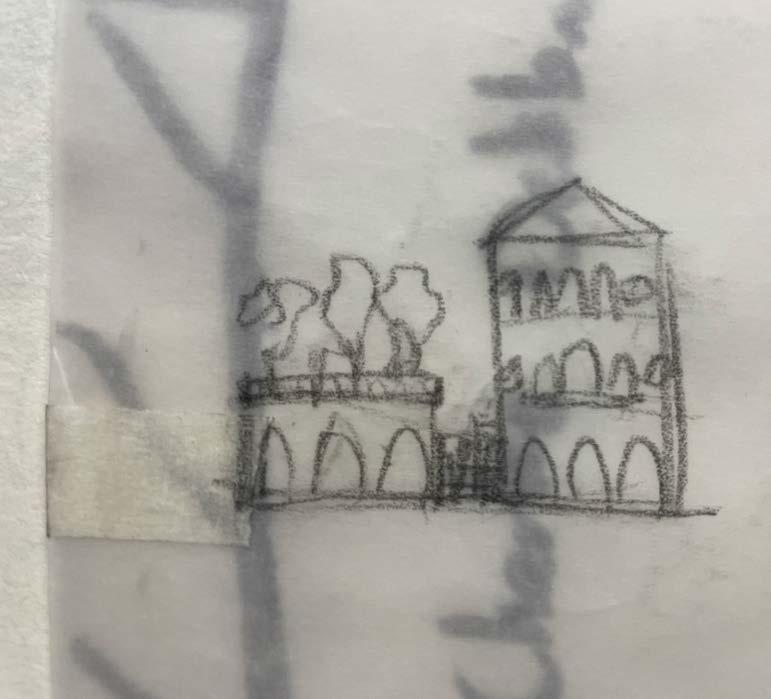

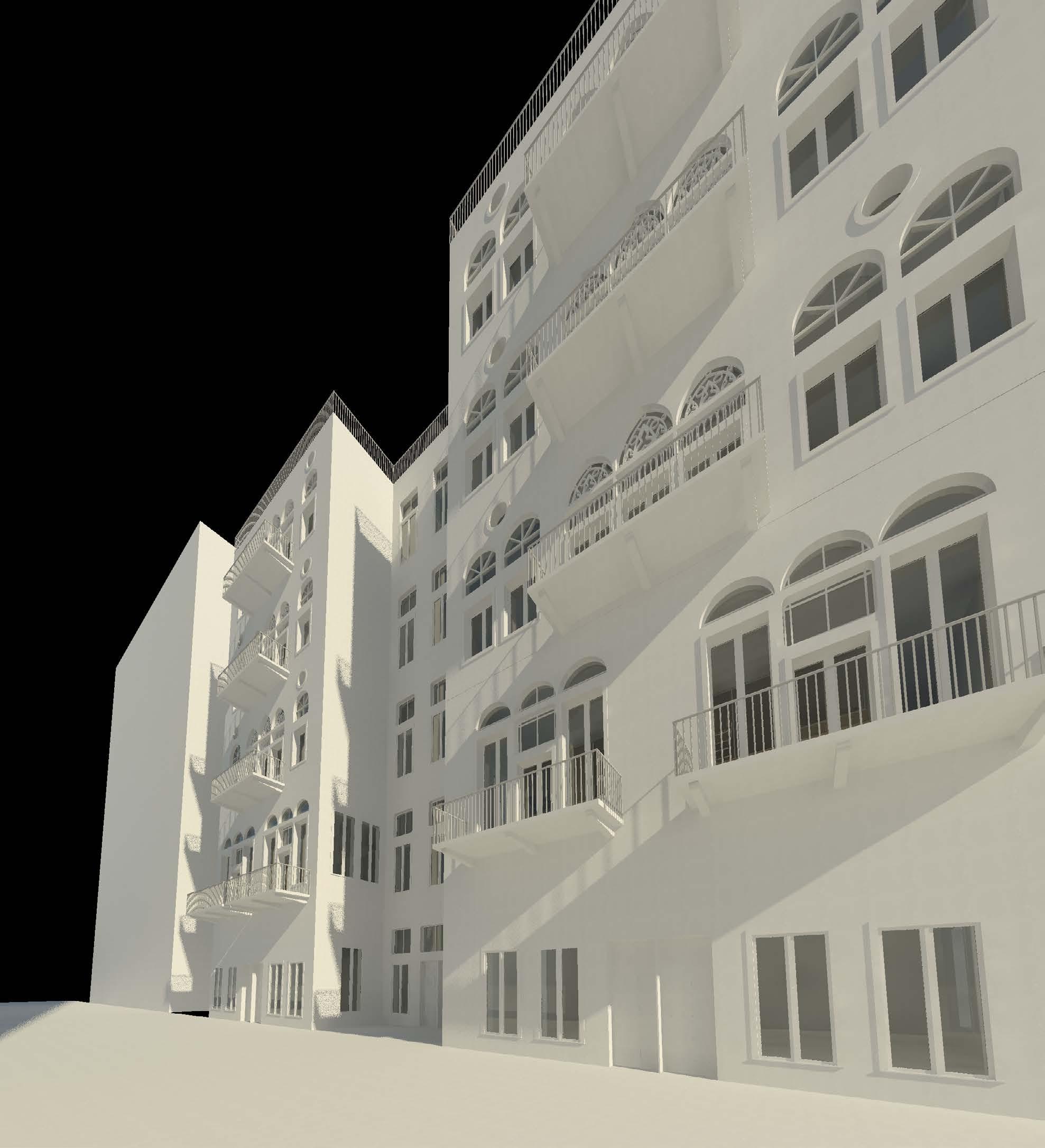

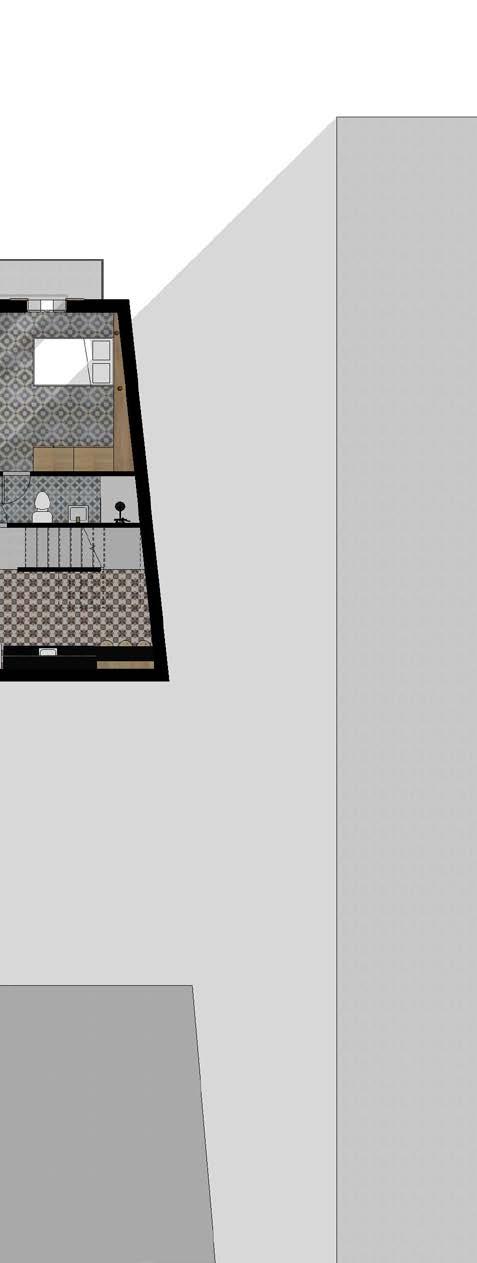

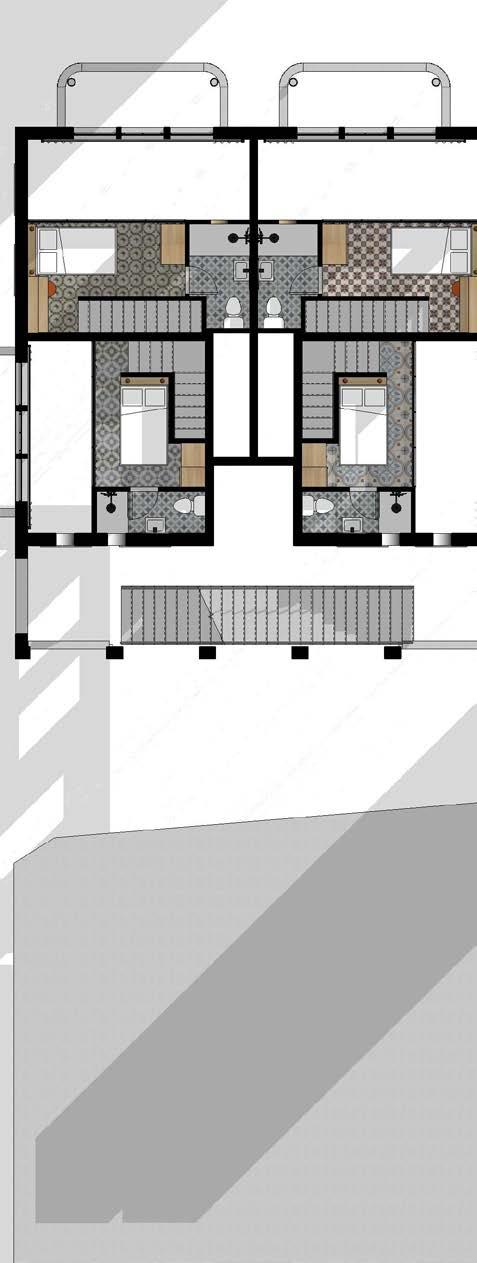

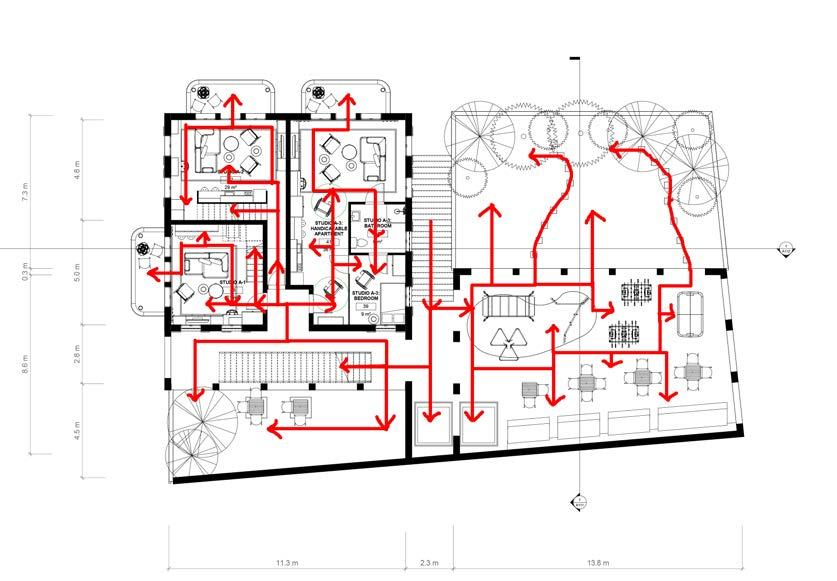

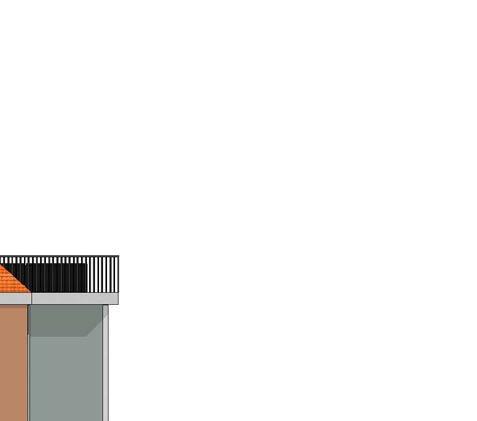

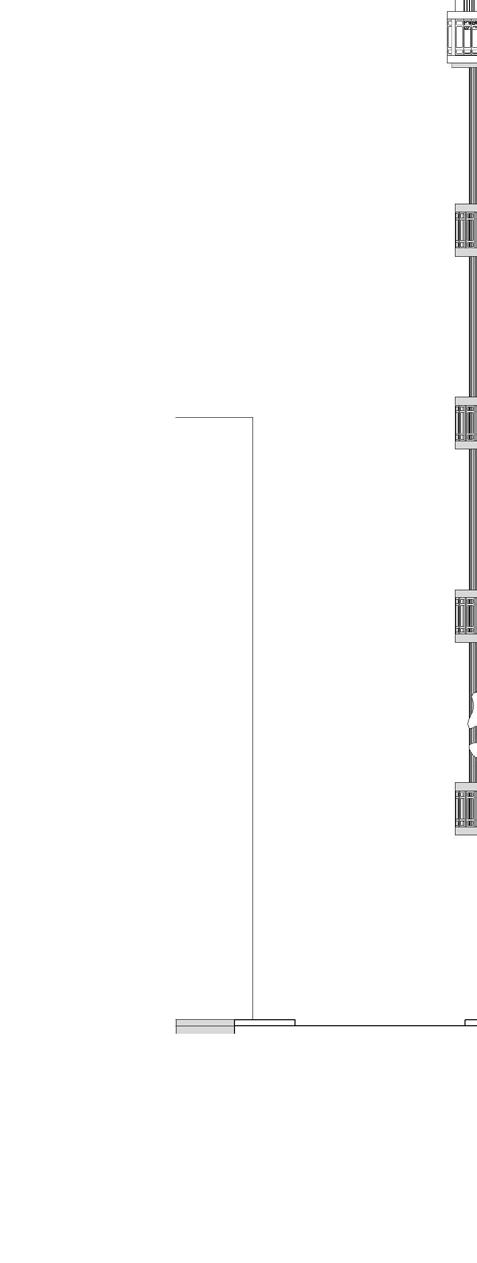

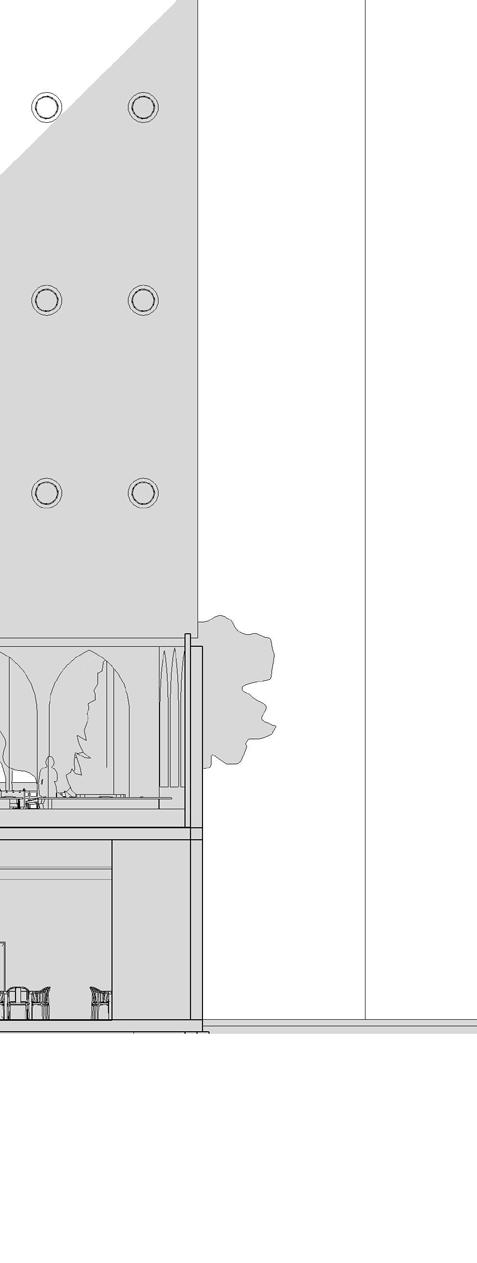

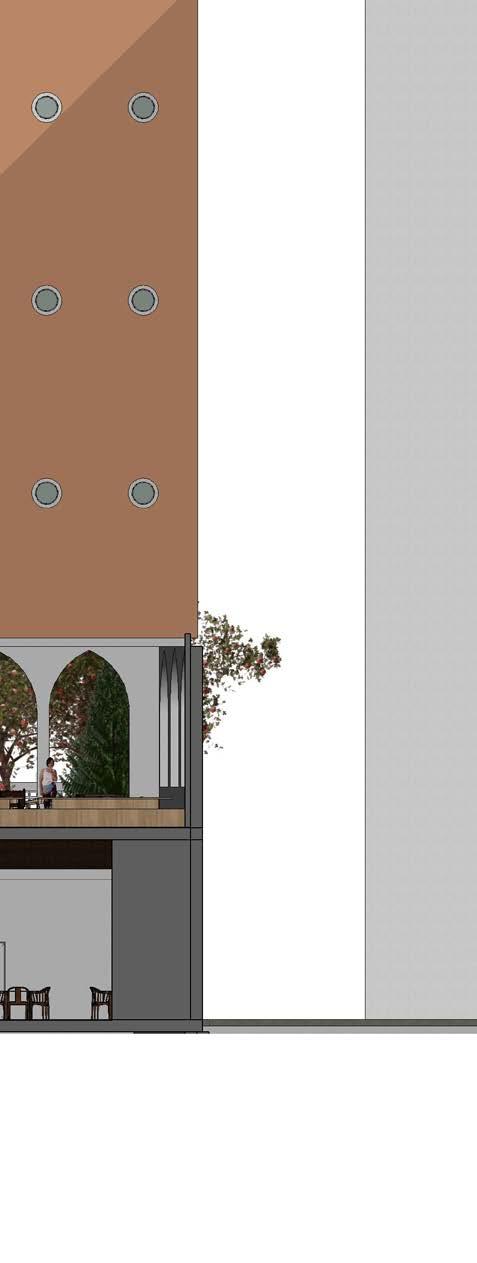

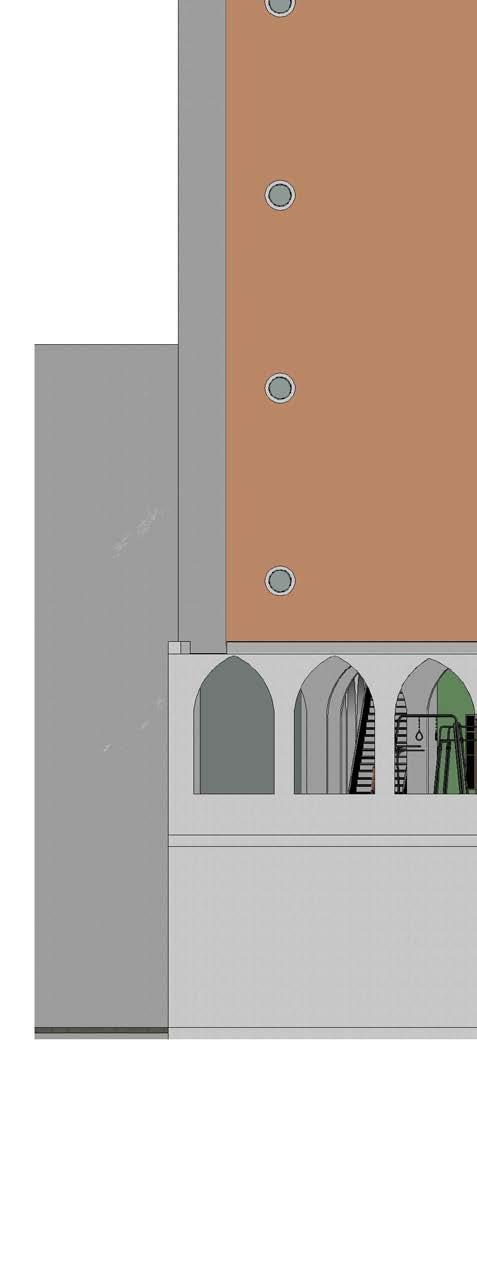

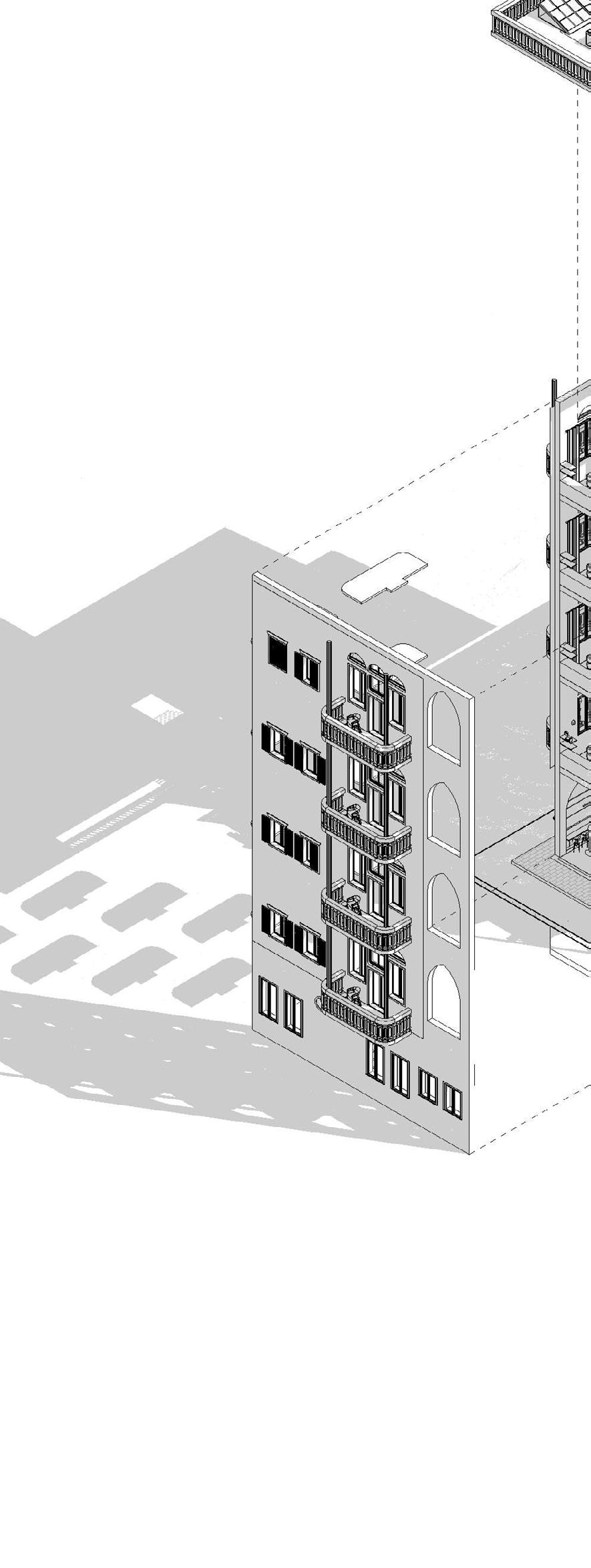

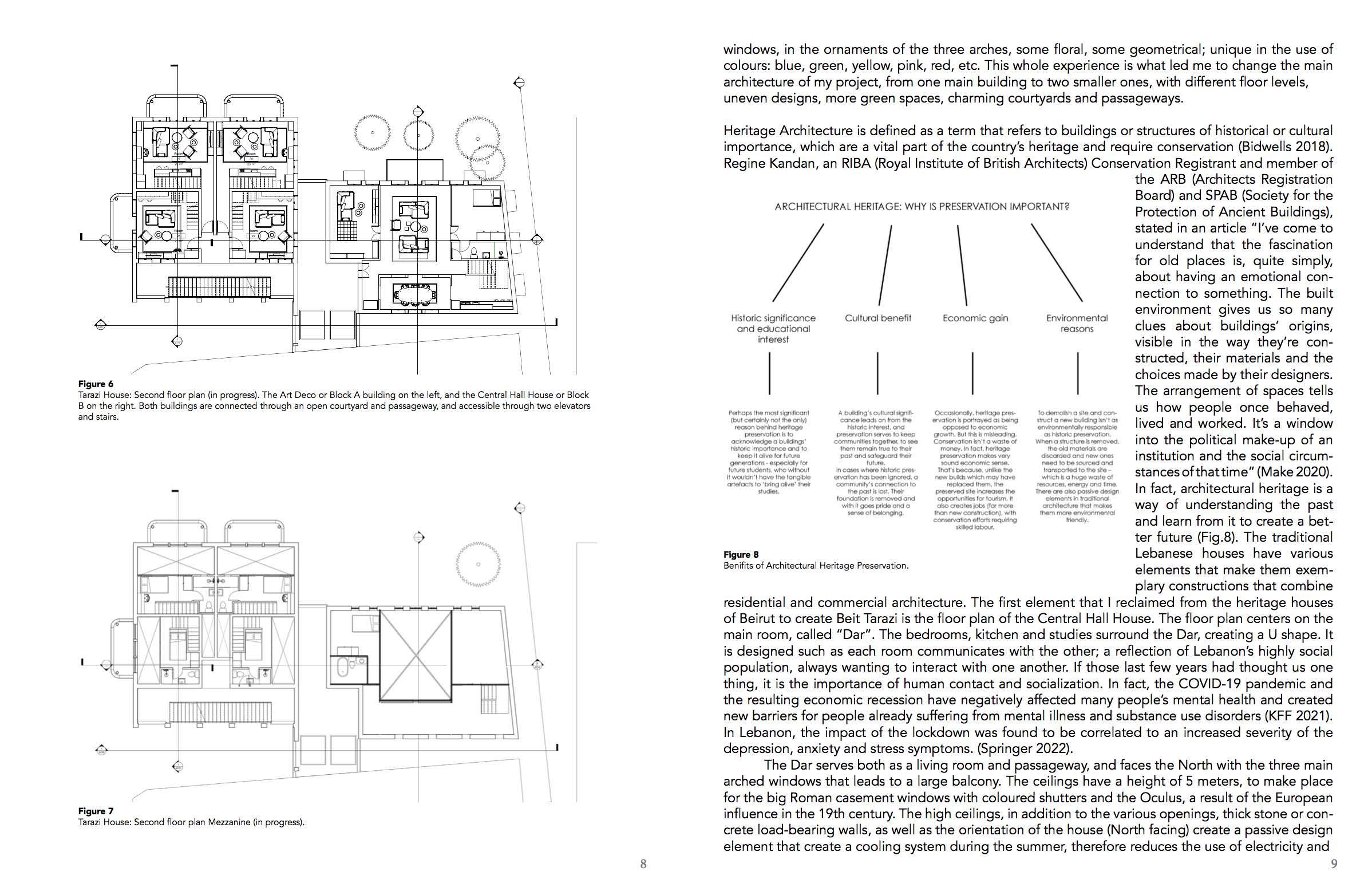

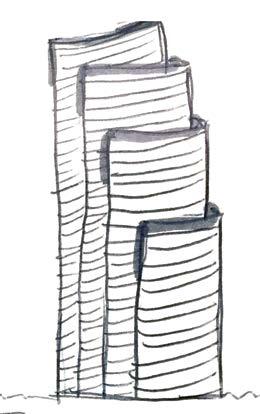

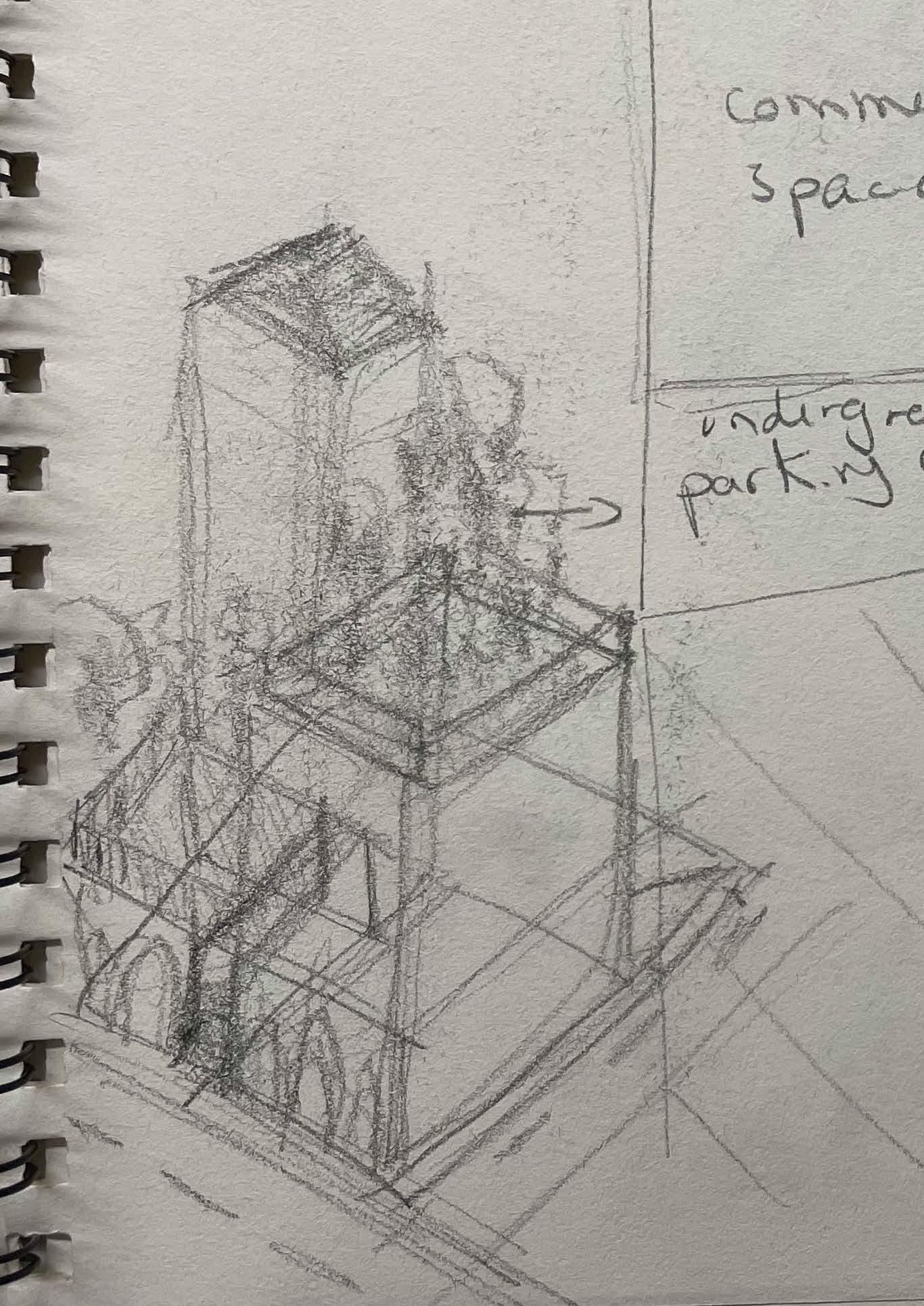

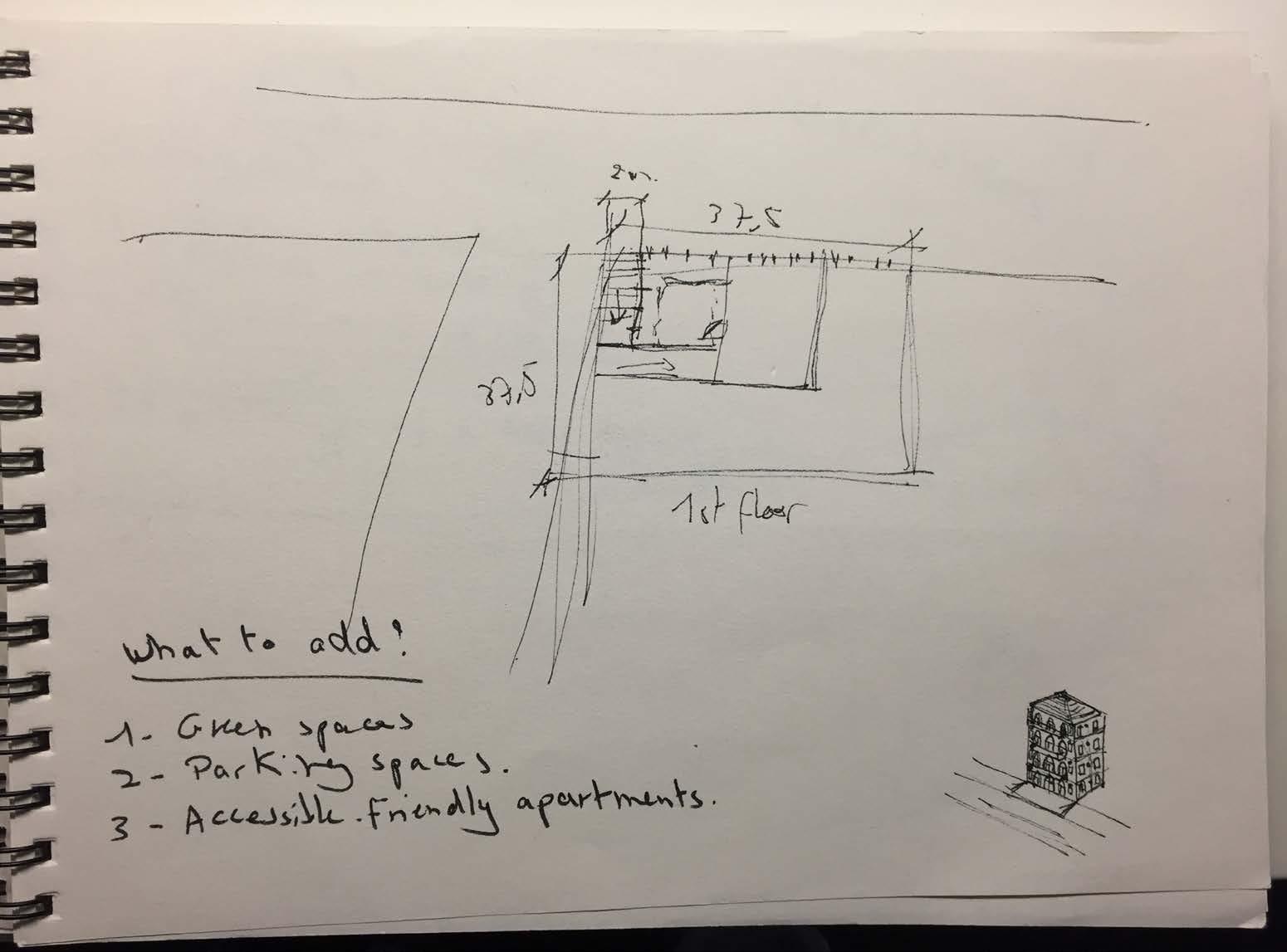

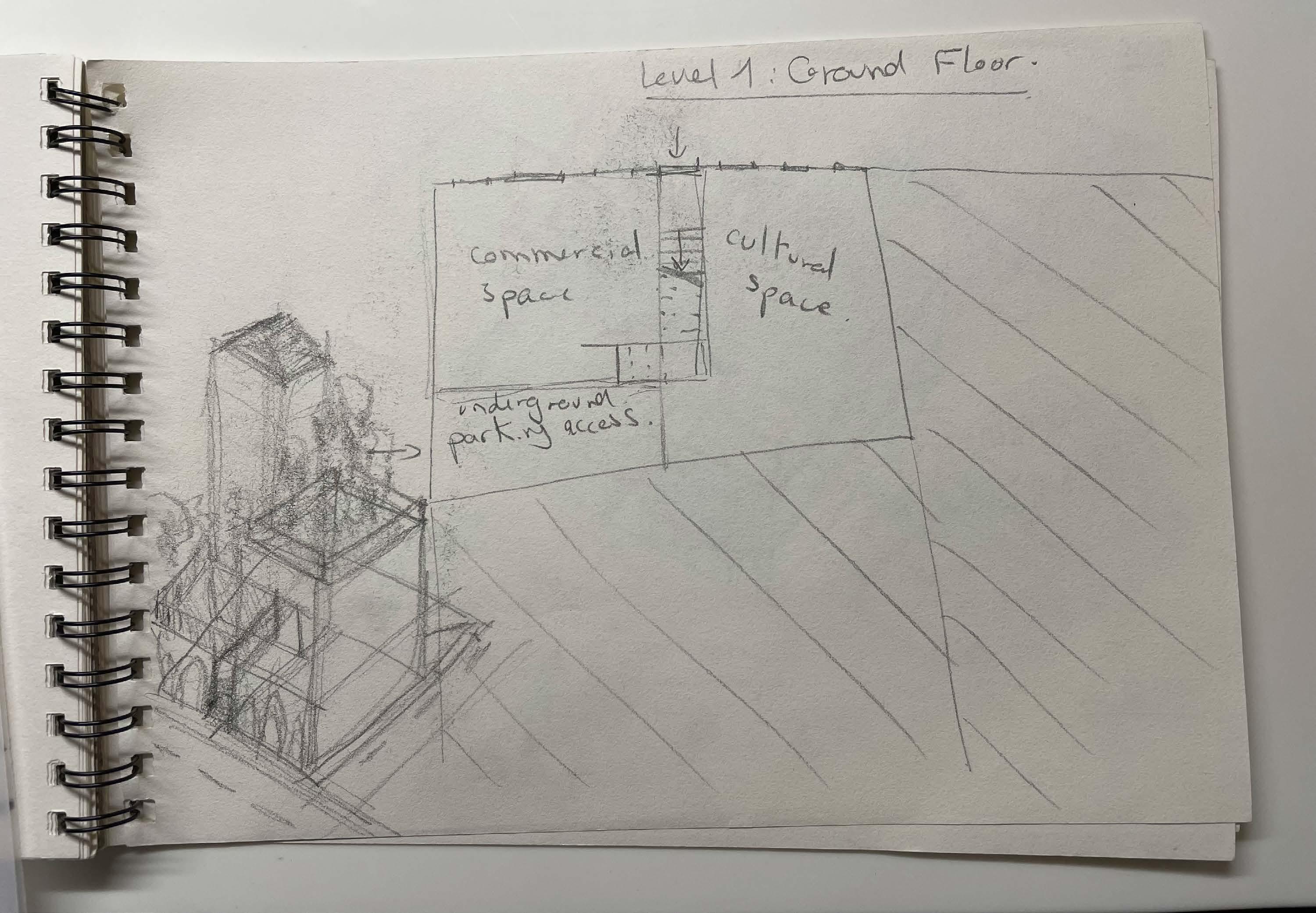

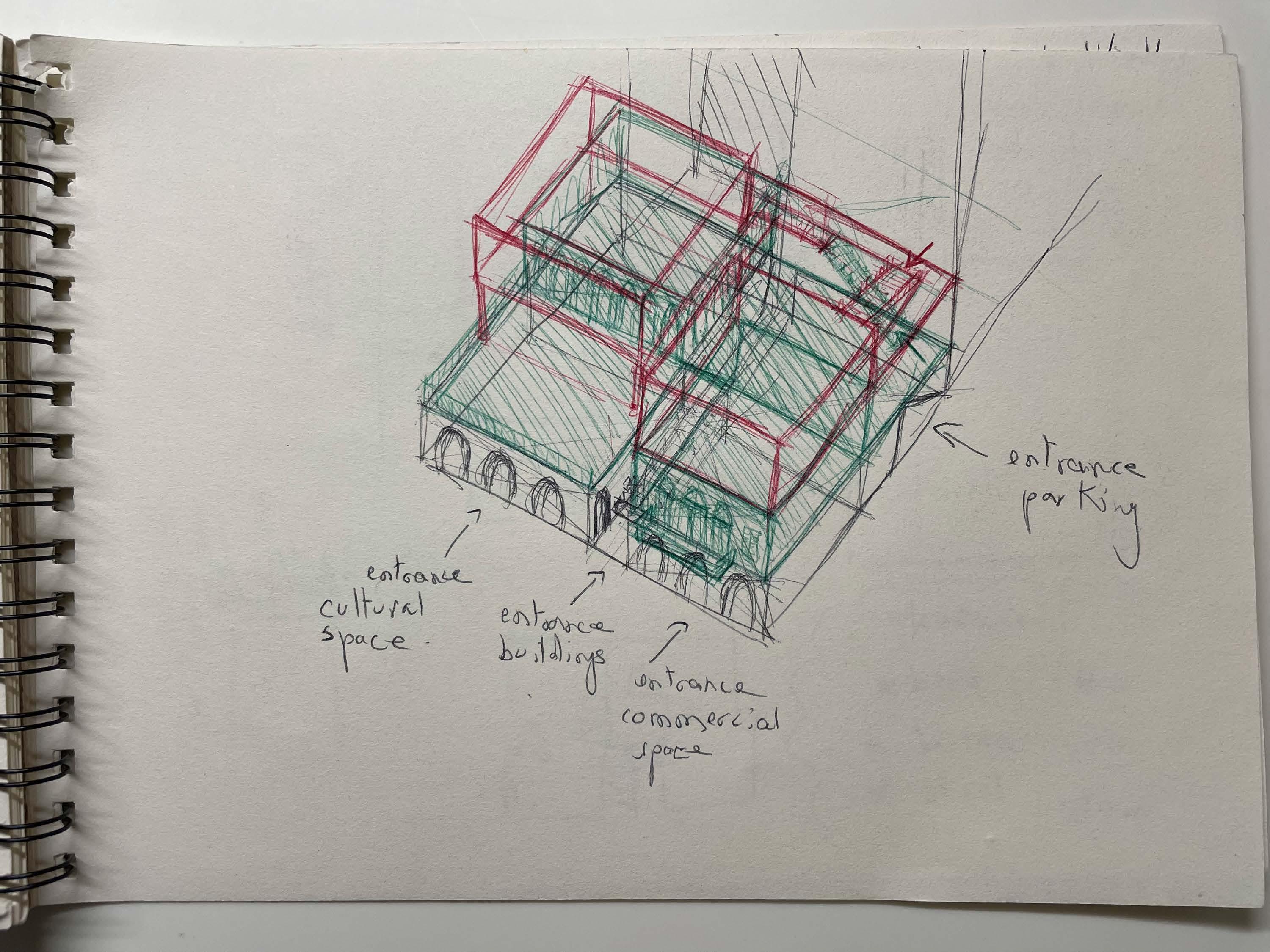

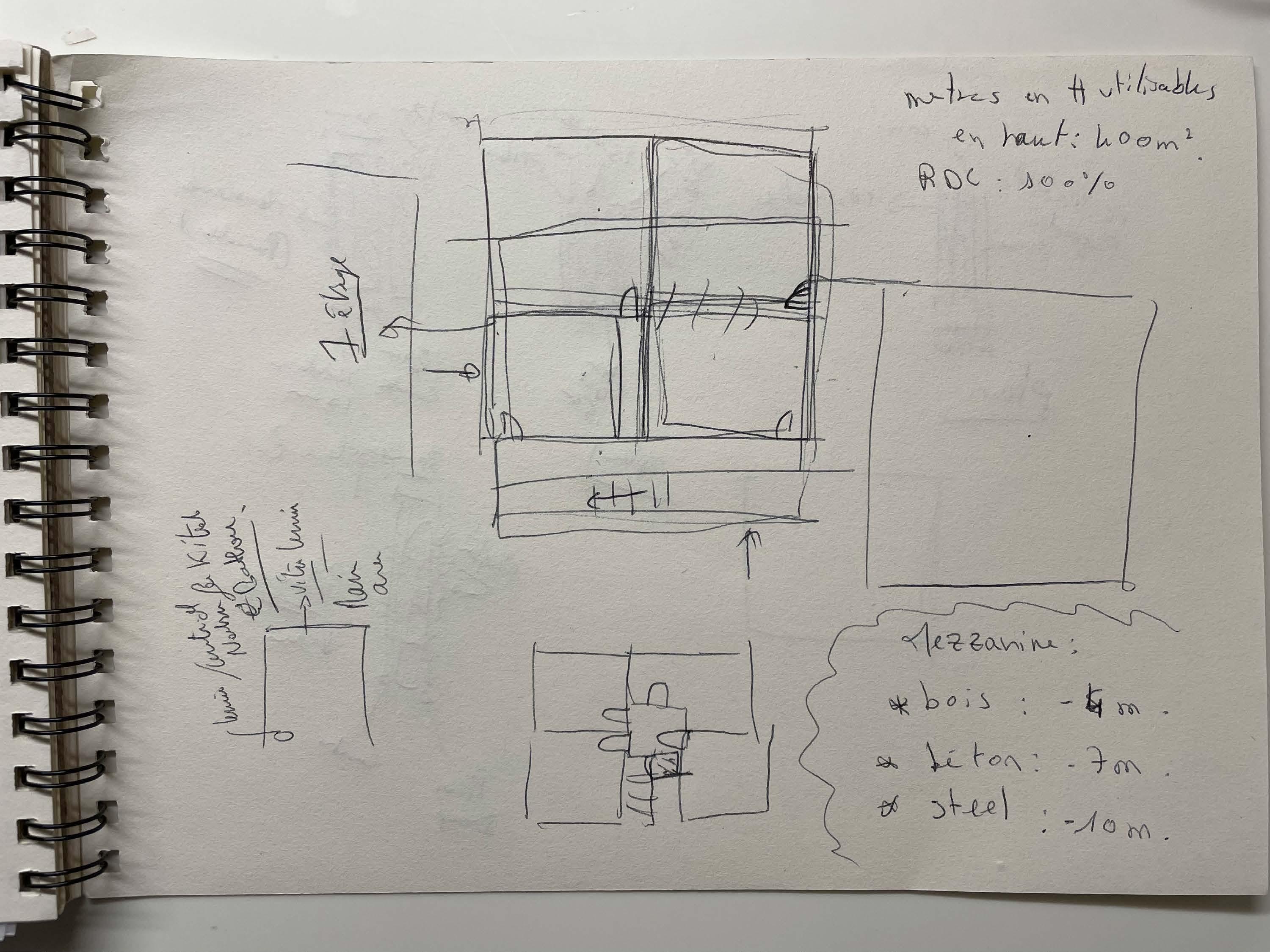

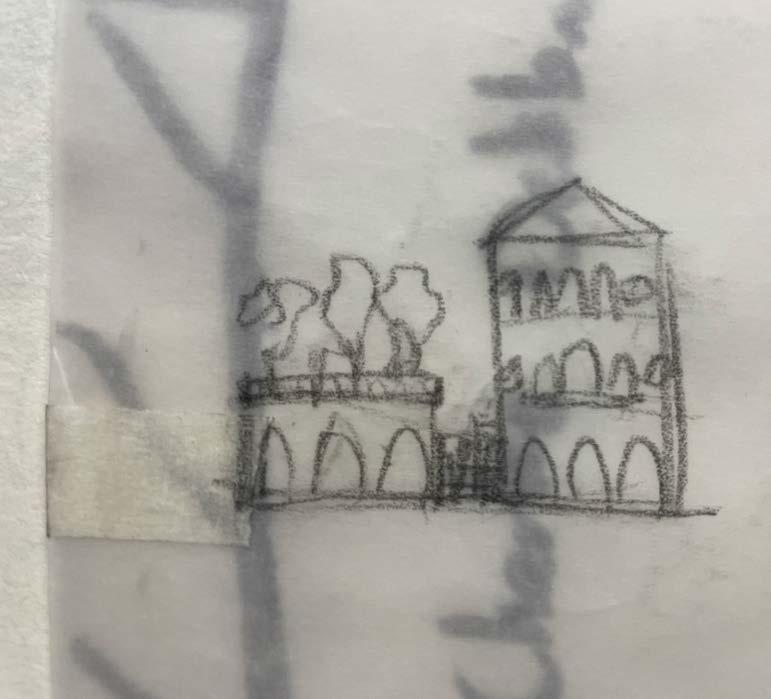

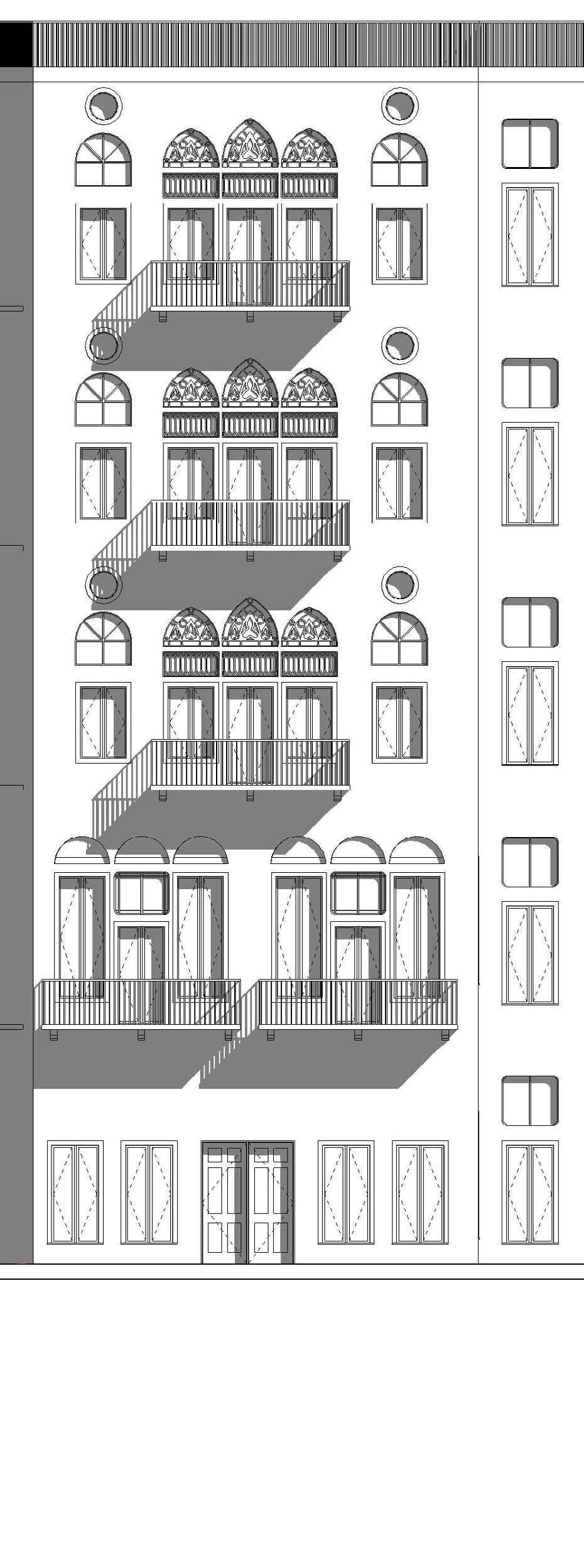

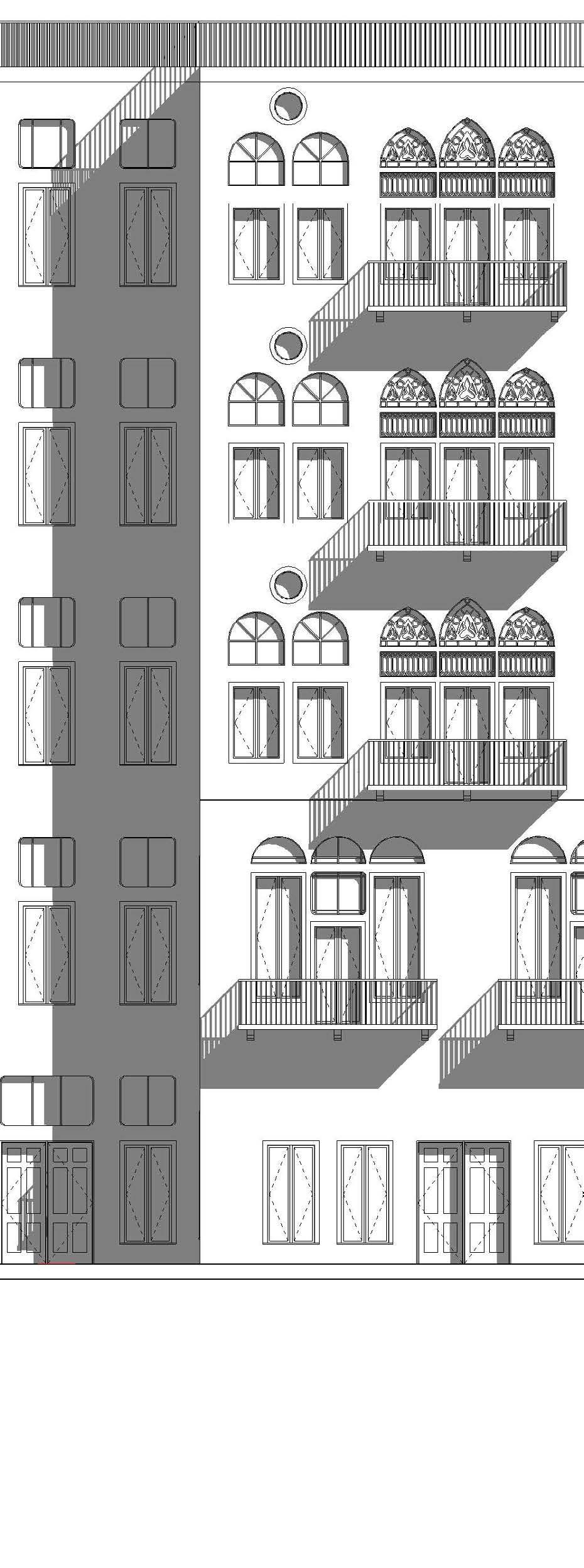

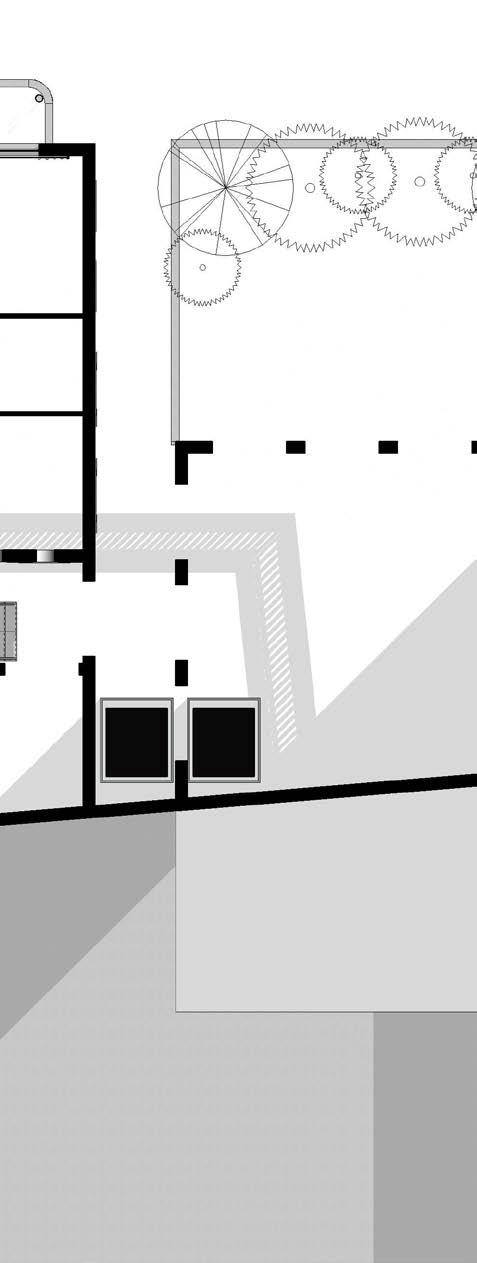

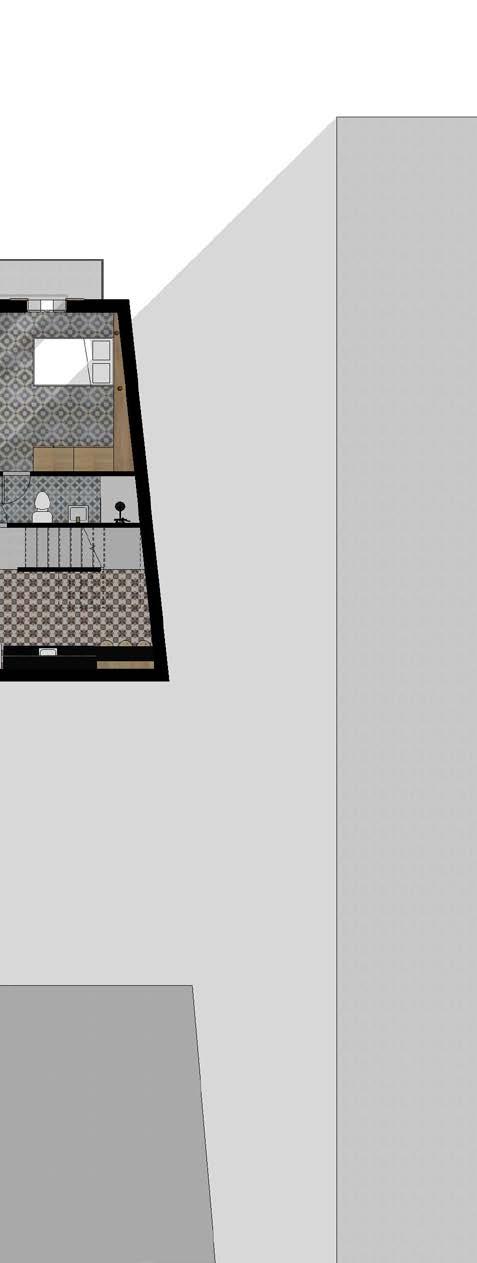

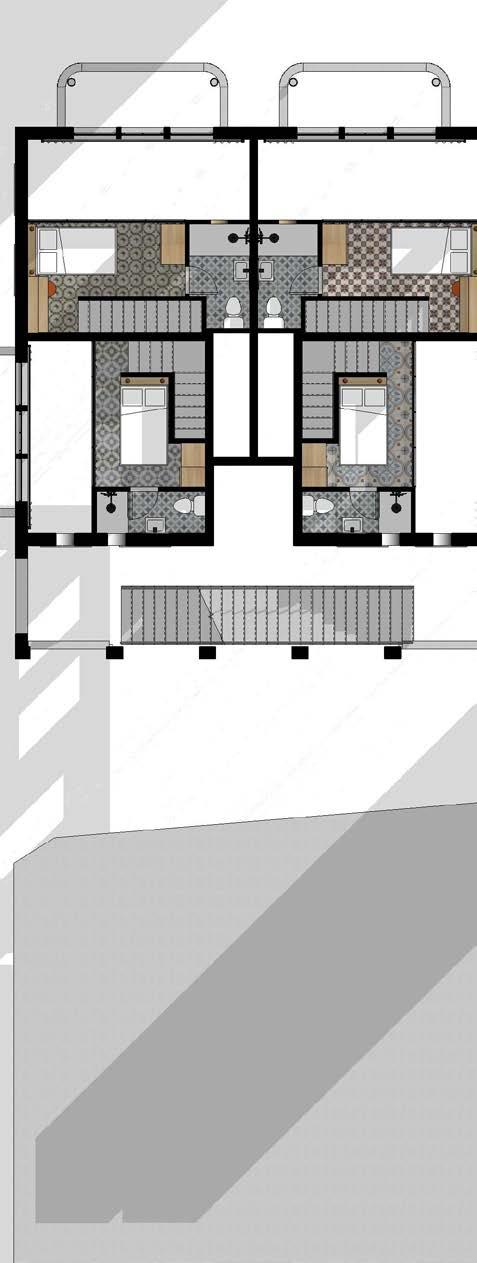

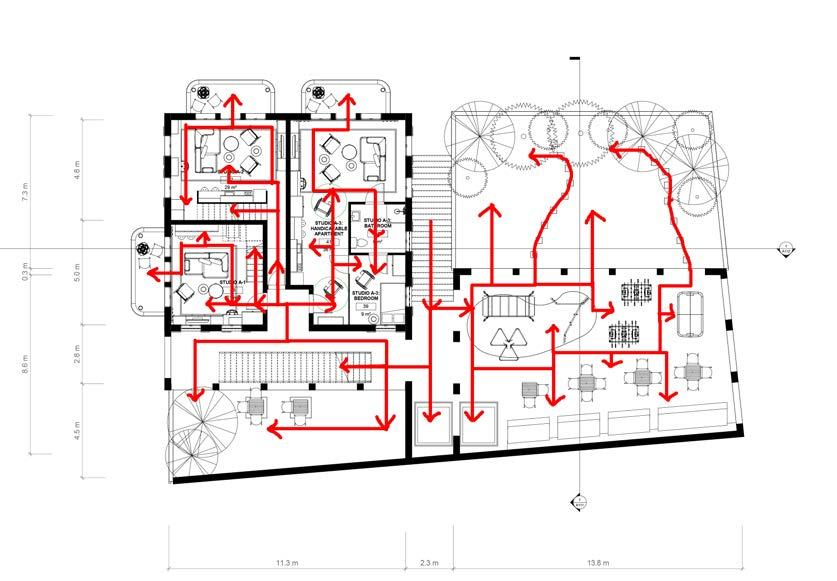

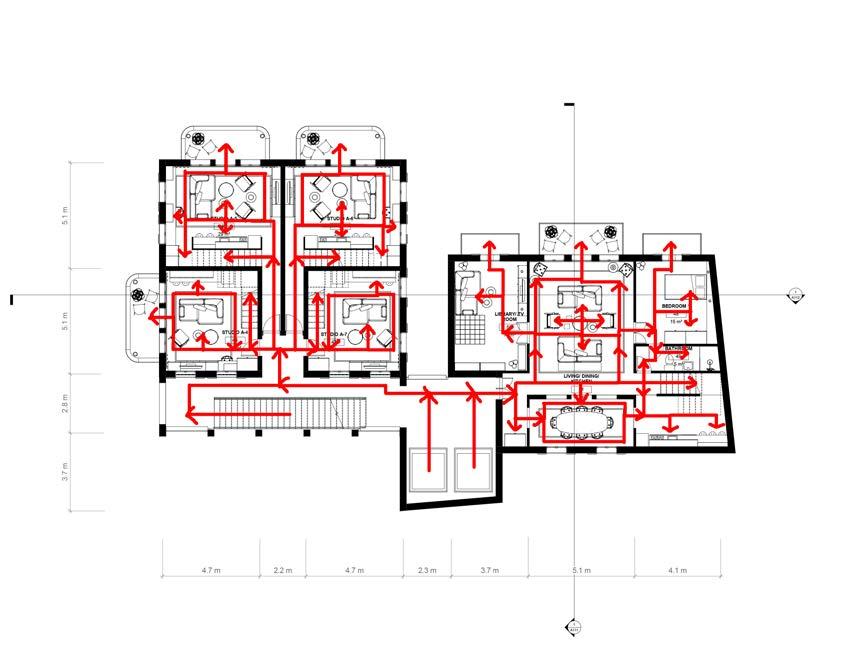

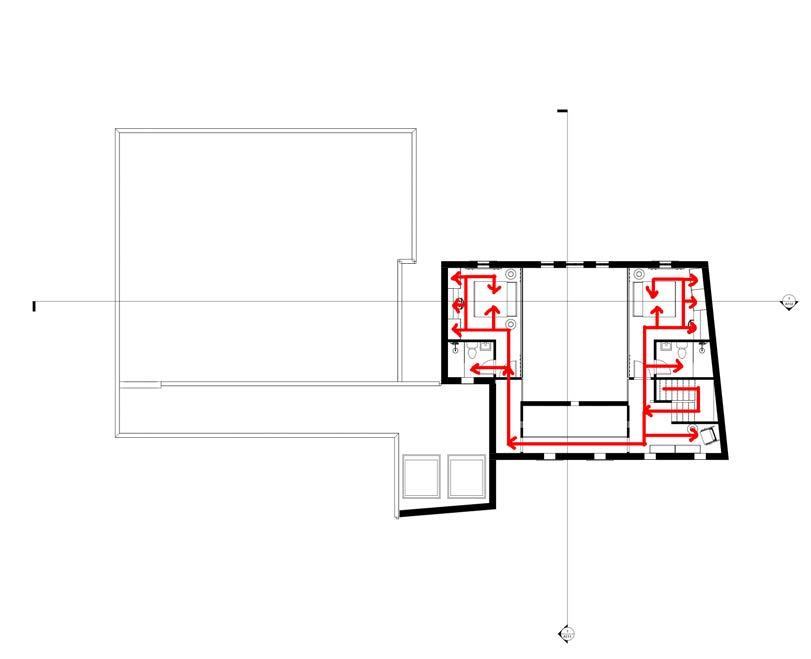

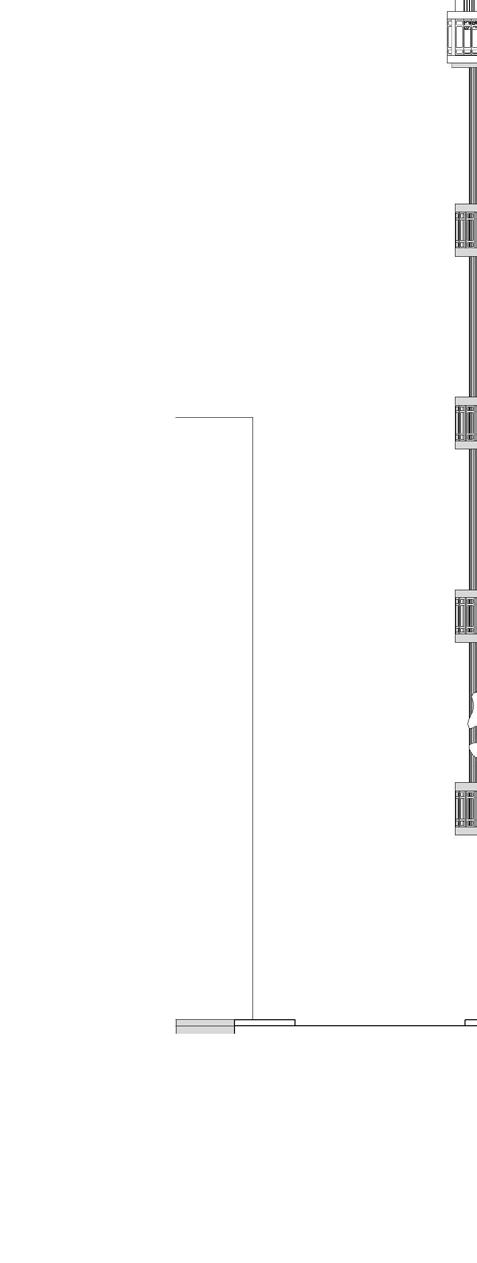

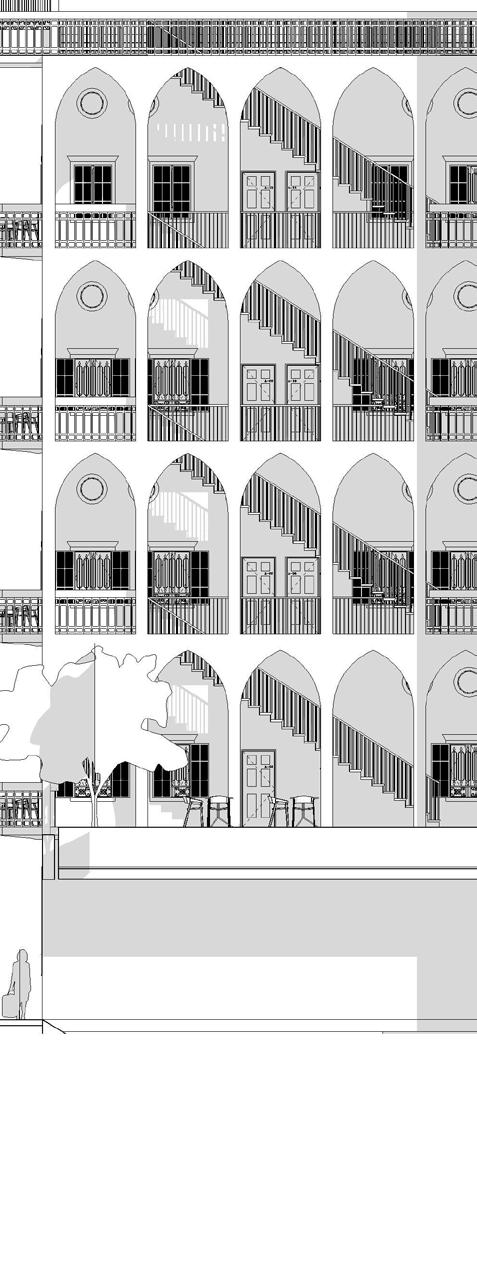

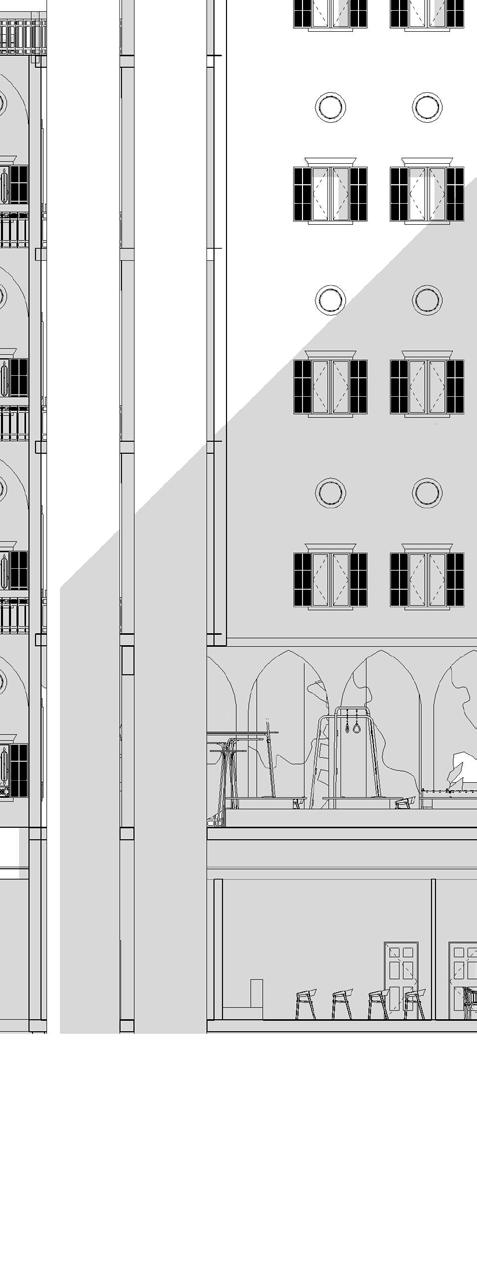

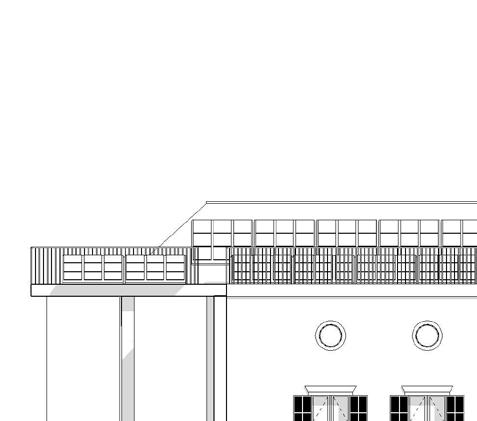

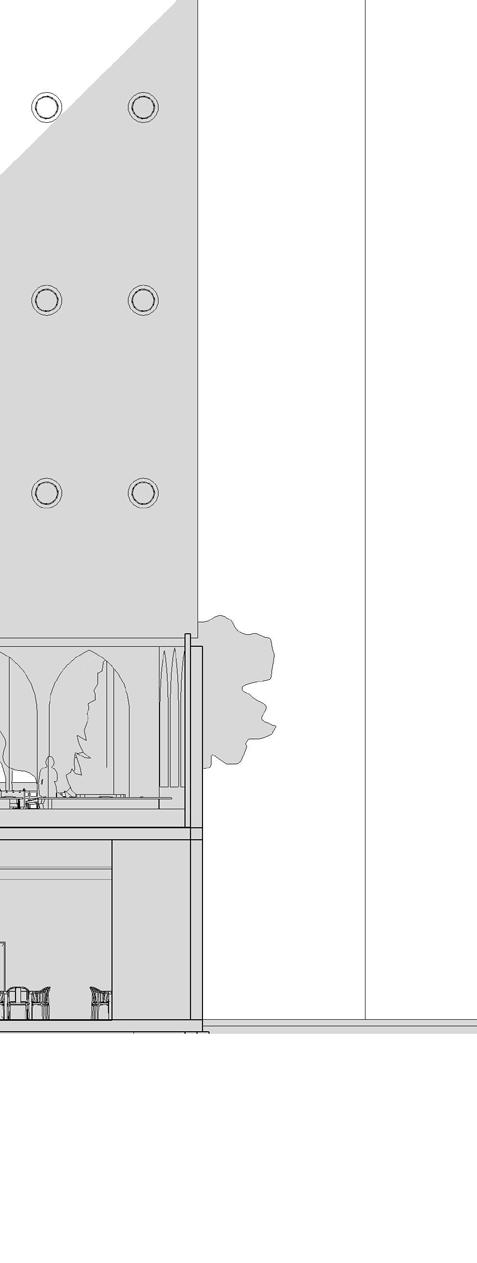

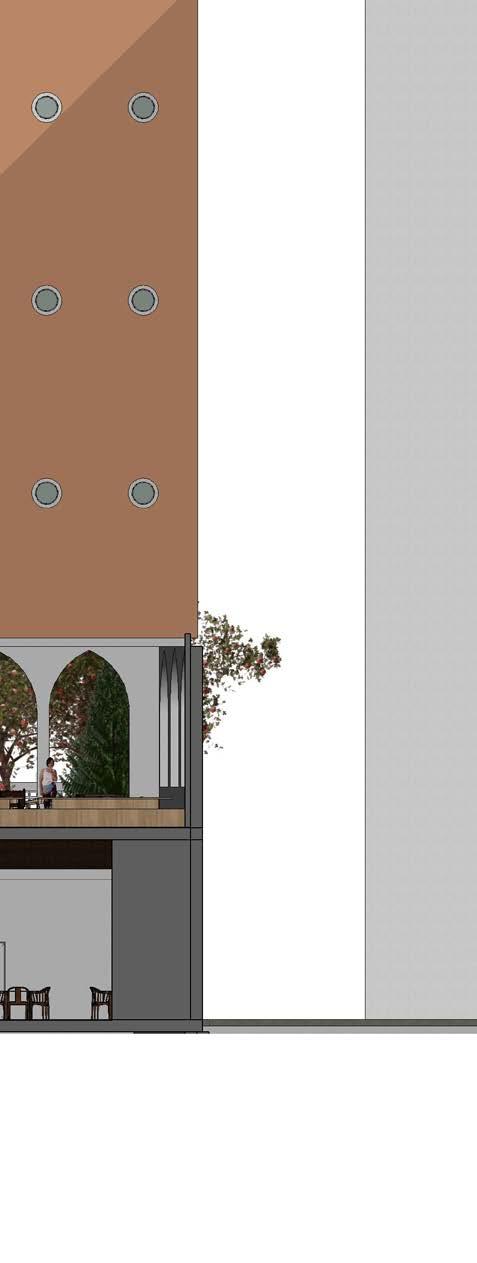

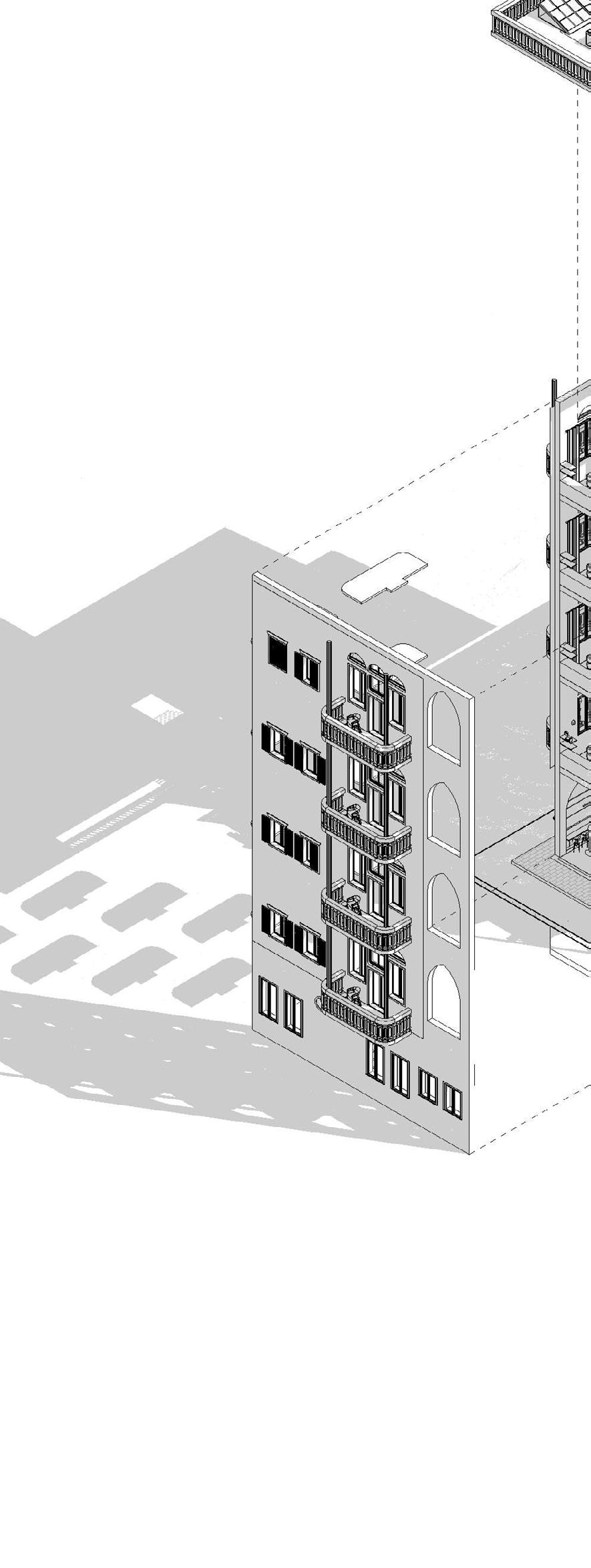

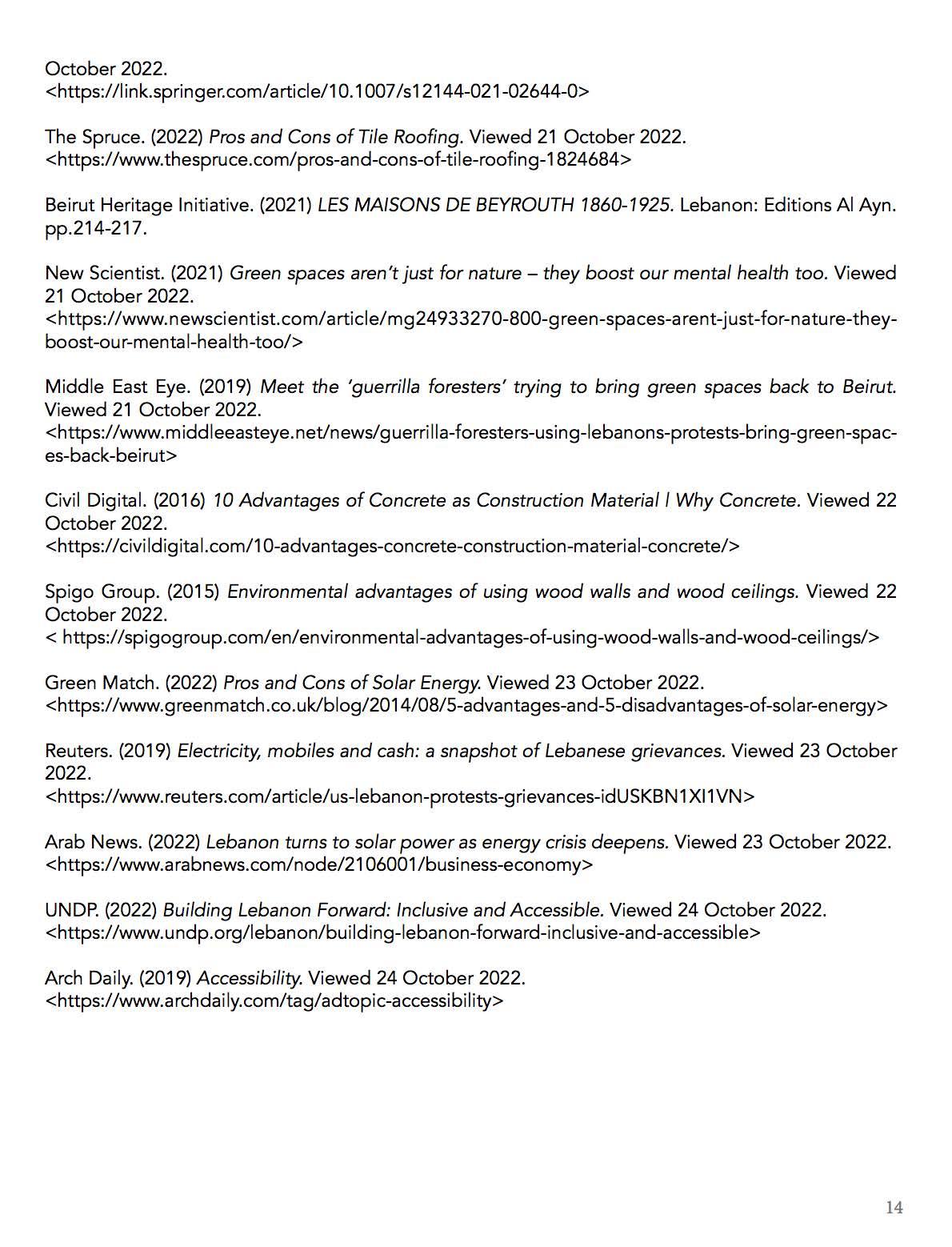

Beit Tarazi was designed so that the Lebanese people would have the chance to live in a blend of Traditional and Modern architecture. It is designed for students, who go to university in Beirut but live outside of the city, and have to drive for an hour in the heat and trafic; it is designed for young professionals who would like to have their own affordable home in Beirut, where they can return from a night out without taking the highway and risk being in an accident (which are unfortunately recurring). It is also designed for young families, who would want to live in a house that combines traditional and modern, a place where their kids would play in the garden, socialize and grow up with other kids. When talking about Lebanese architectural traditions, the ground floor is always dedicated to a commercial space. A space where young people would sit during the day to work on their university assignments or their remote jobs while drink ing a good cup of coffee, or even a place where people would gather after work and talk outside about the latest gossips while drinking a glass of Arak (Lebanese alcoholic drink) and smoking a Marlboro or a slim Allure (famous cigarette brands in Lebanon). In this logic, creating a café/ bar would be the solution. On the other side of the project site is a place allocated to art and culture. When entering the space, you can find yourself in a gallery, where the art of various young Lebanese artists is exposed. At the end of the space is a room devoted to meetings and conferences, to exchange about the situation in Lebanon, and converse about how one regards the future of their country. The space is for people who would like to speak up intellectually and passionately, as well as people who are eager to just sit and listen to others, while learning about the suggested topics. To have access to the residential area, staircases are placed in the center of the project, accompanied by two elevators. Behind the commercial space, before accessing the elevators, a laundry room is created for the first building, the “Art Deco”, dedicated to Undergraduate and graduate students, as well as young professionals. The first floor is elevated to 5 meters on top of the street level, for more privacy and less noise pollution. There are two main build ings: the “Art Deco” or Block A, and the “Central Hall”, or Block B. The Block A is dedicated to the struggling young generation of Lebanese. The first floor has three self-containing studio mezzanines, two for undergraduate students. A garden with outdoor seating is located at the back. The second, third and fourth floors host four studio mezzanines on each foor. The second floor is made for undergraduate students, third for post-graduate students, and forth for young professionals.

One accessible studio on the ground floor is made for any youngster with a dis ability. Each studio has a living room and open-plan kitchen, with an oven-micro wave, a refrigerator, a stove, and plenty of storage. There is also a desk, ward robes, some shelves, and a space to store their luggage and suitcases behind the staircase that leads to the bedroom with a small double bed and bathroom. The building makes way to natural light through the three tall art deco windows that host large balconies.

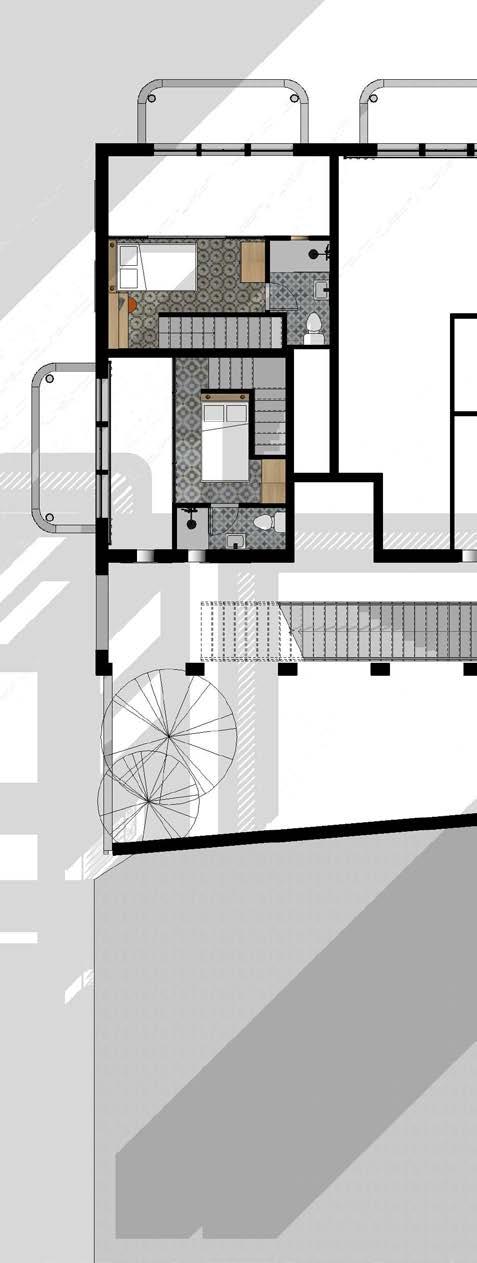

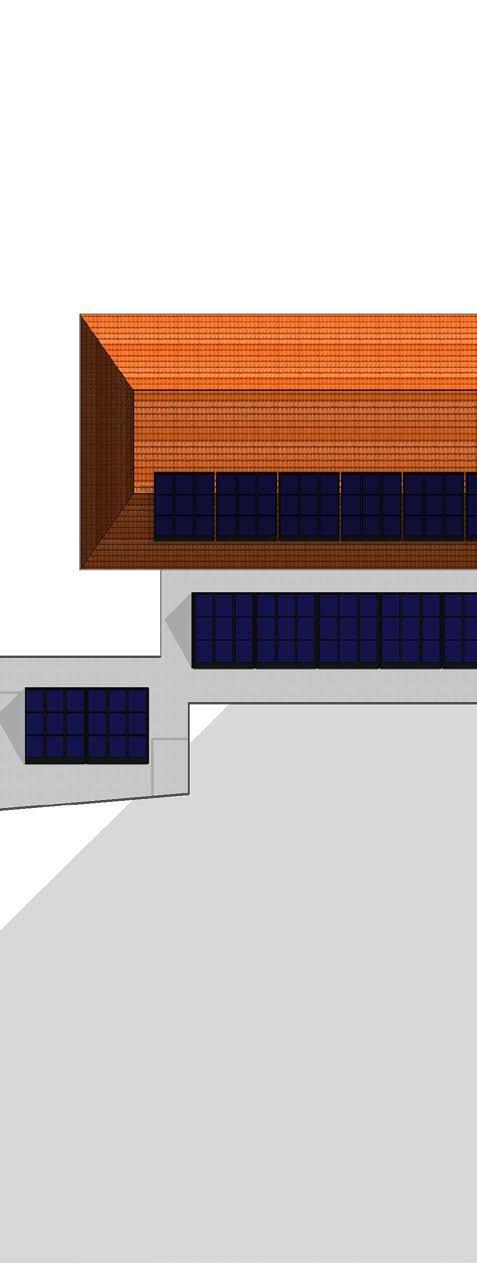

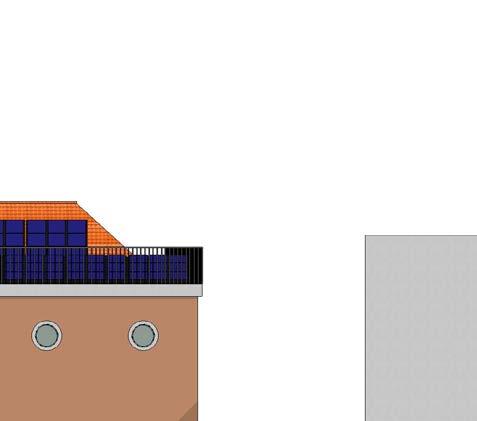

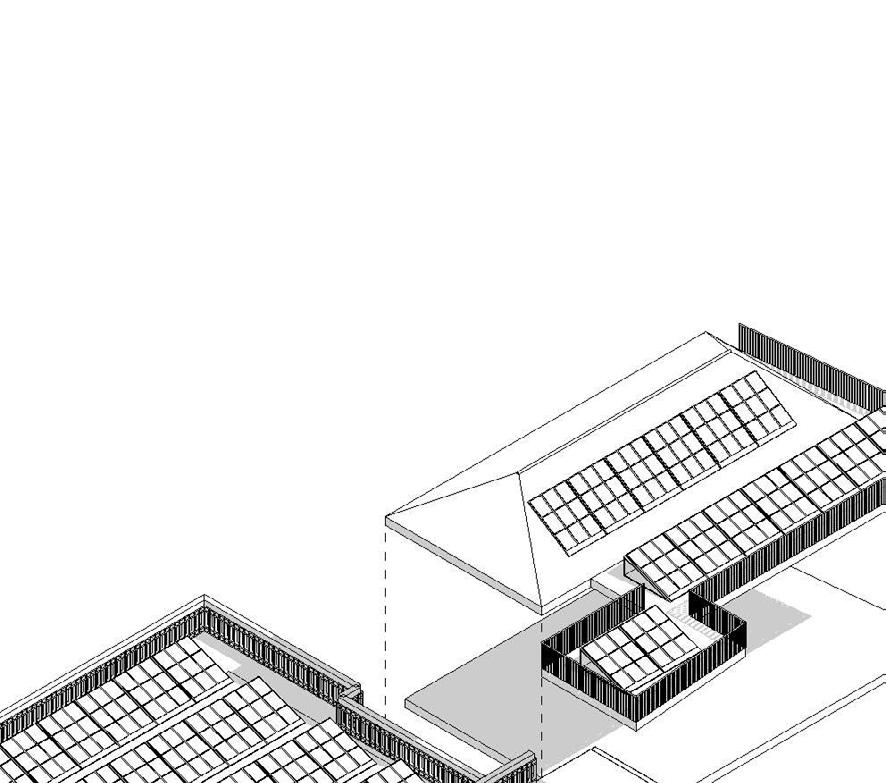

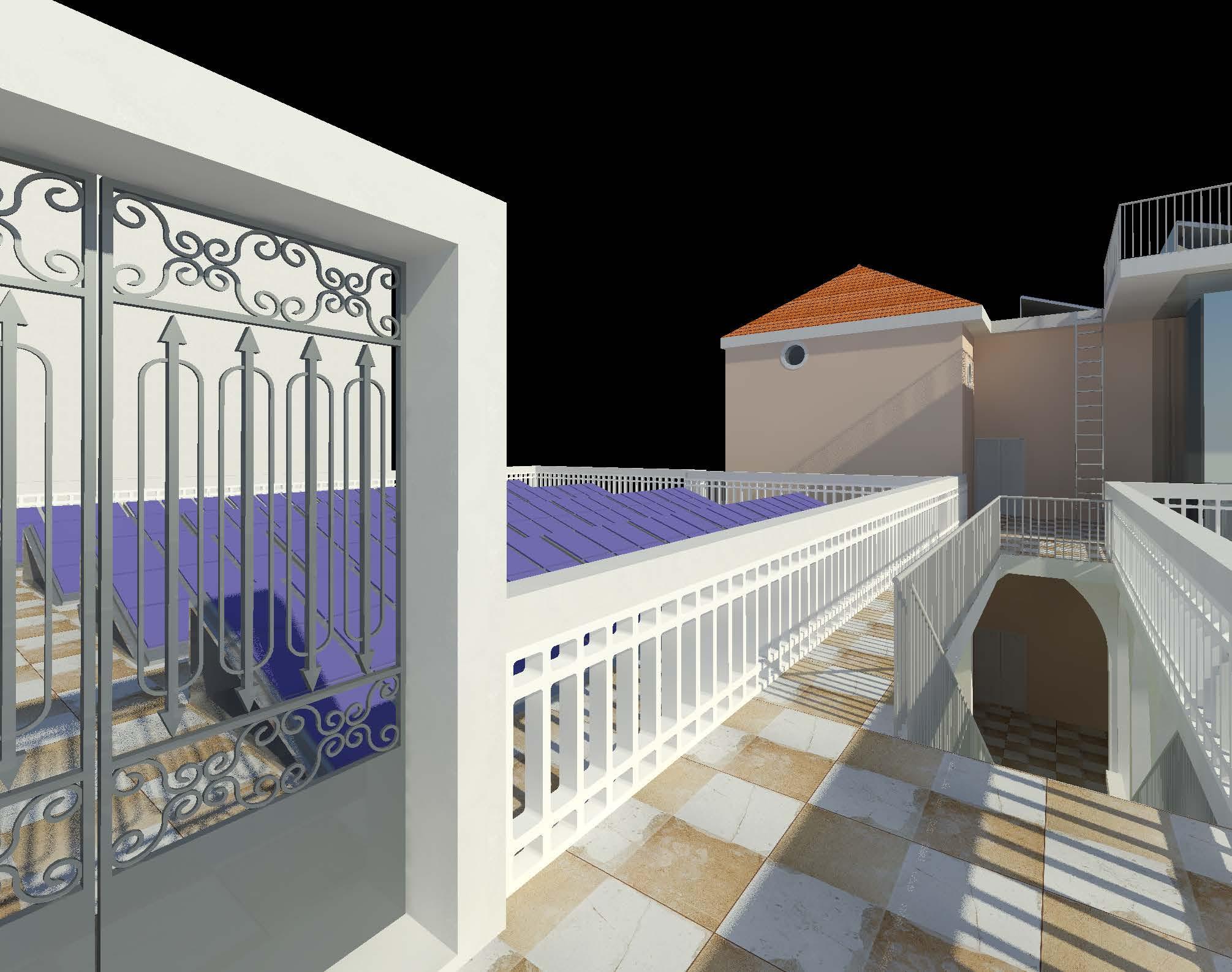

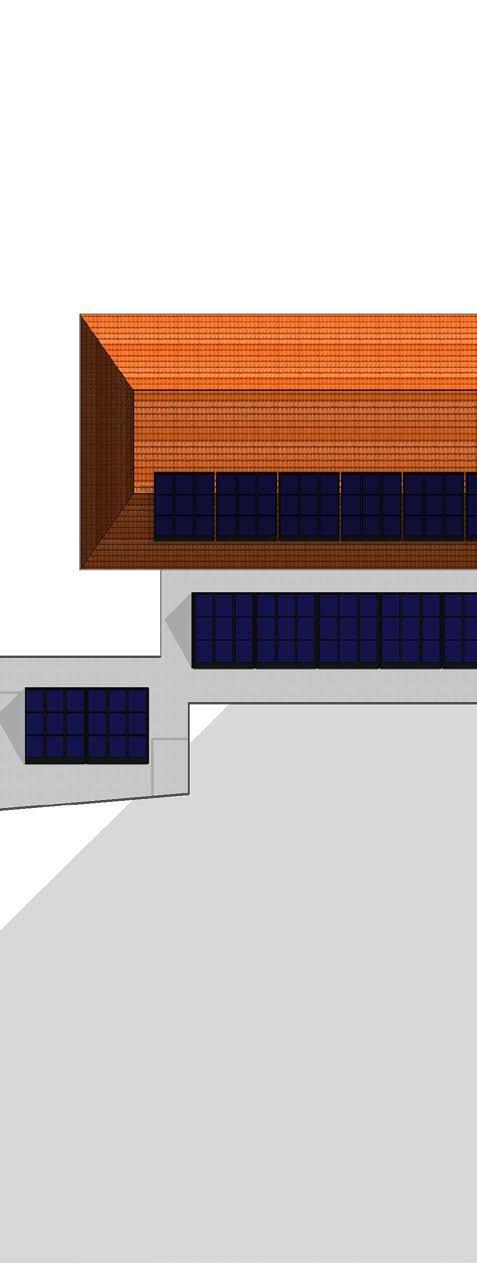

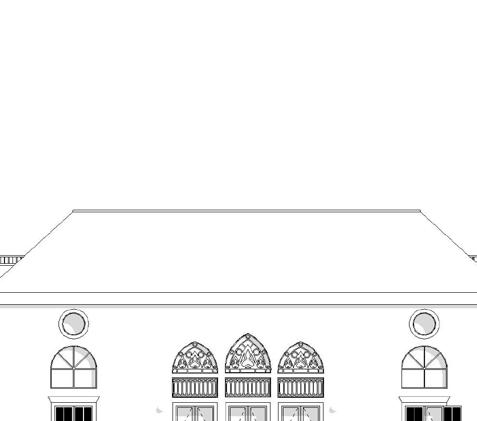

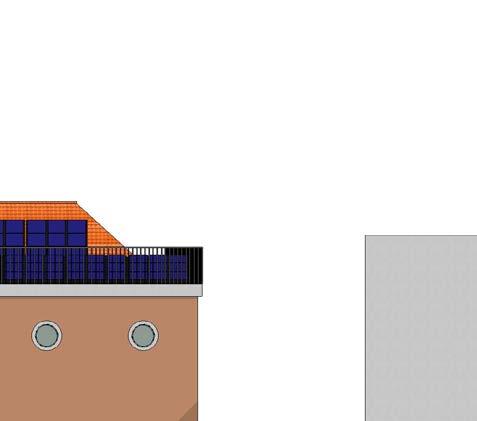

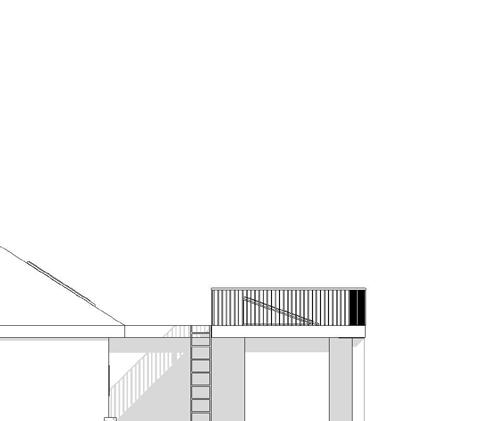

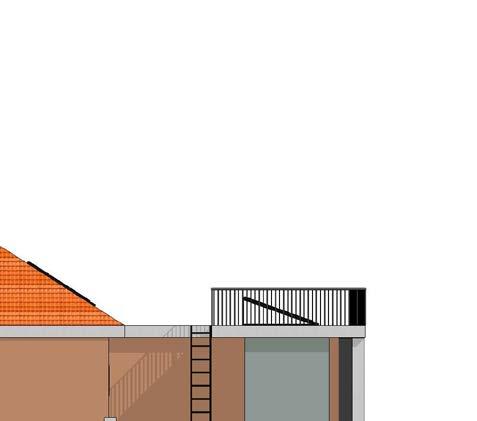

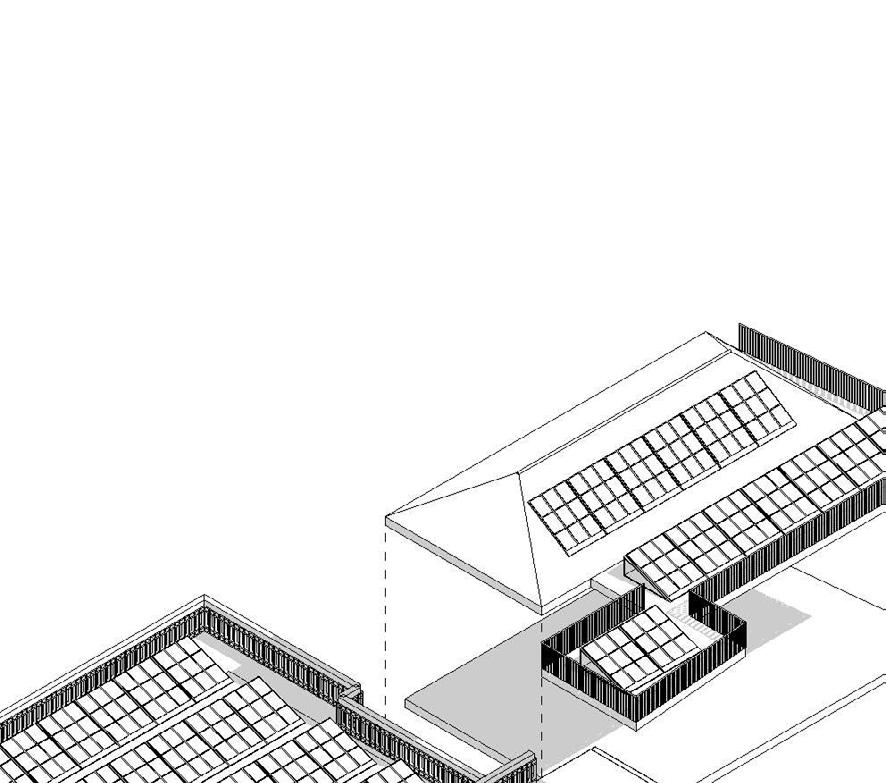

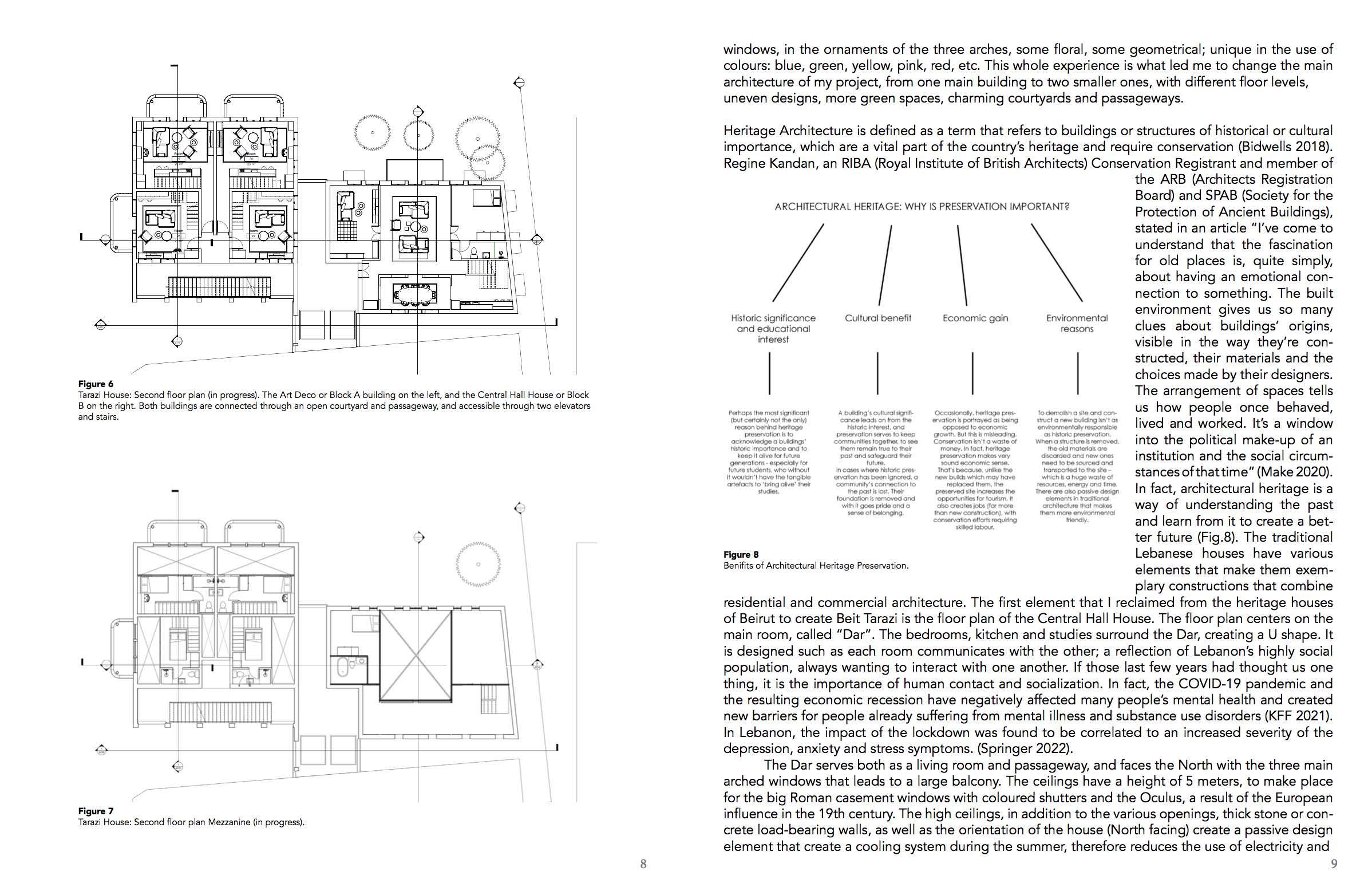

Moving to the Block B, an open courtyard in present on the first floor, as an extension to the garden facing the street. This five-story traditional building is dedicated to young families, with one big mezzanine apartment on each floor. Here the Central Hall house floor plan is picked up, which consists of a central room that serves as a living room and passageway, with the bedrooms and/or studies on each side, and the kitchen and “liwan” or second living room (used as a dining space) at the back. The three arches are facing the North, which is meant to face the sea and cut off the heat and sun that comes through the South, creating a passive design system. Stairs lead to the mezzanine that hosts two other bedrooms accompanied by their own bathrooms. The rooftops of both buildings gather solar energy systems facing the South, consisting of photovoltaic panels for electricity and solar thermal panels for heat.

87 86

inTenTion

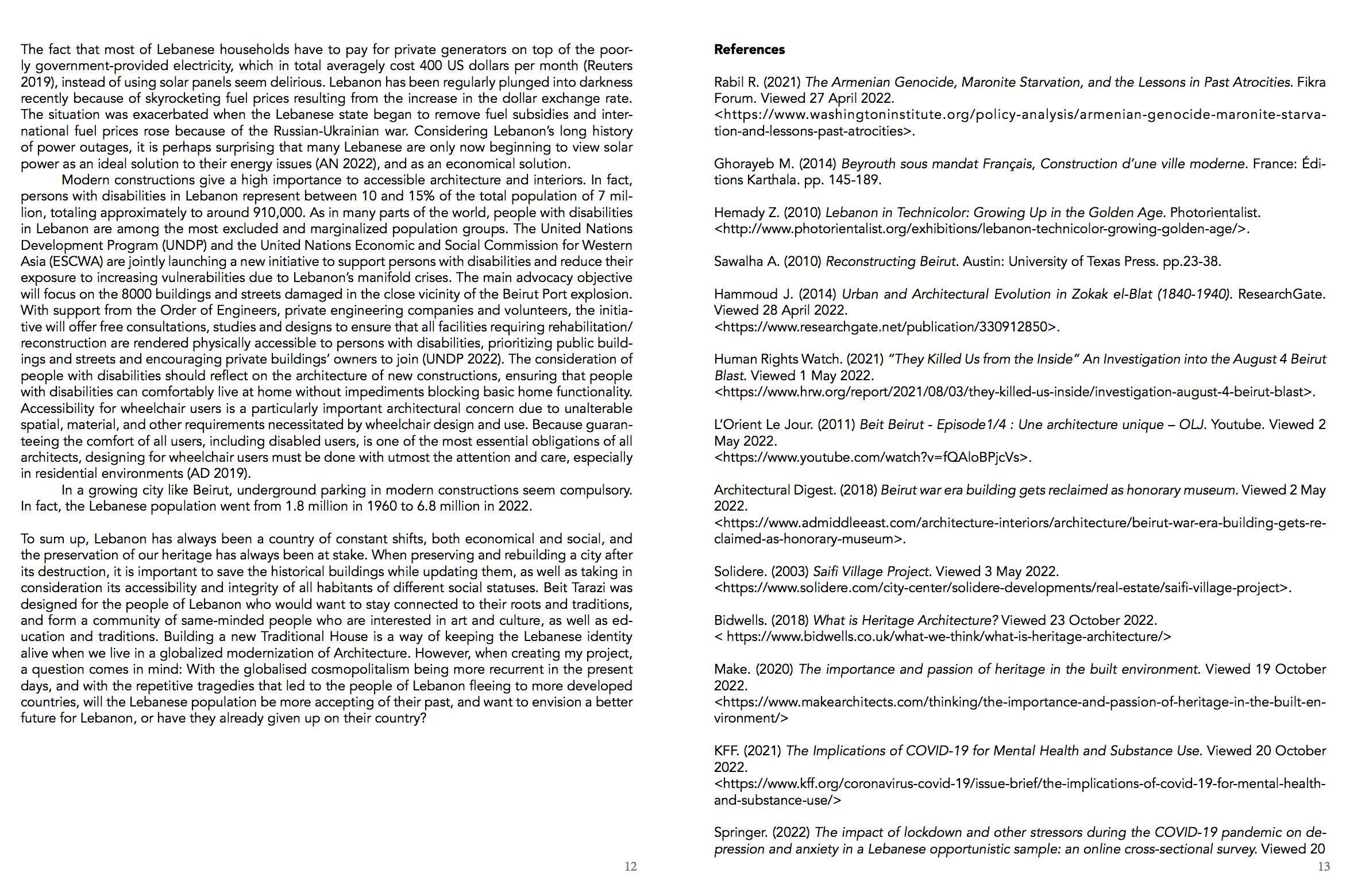

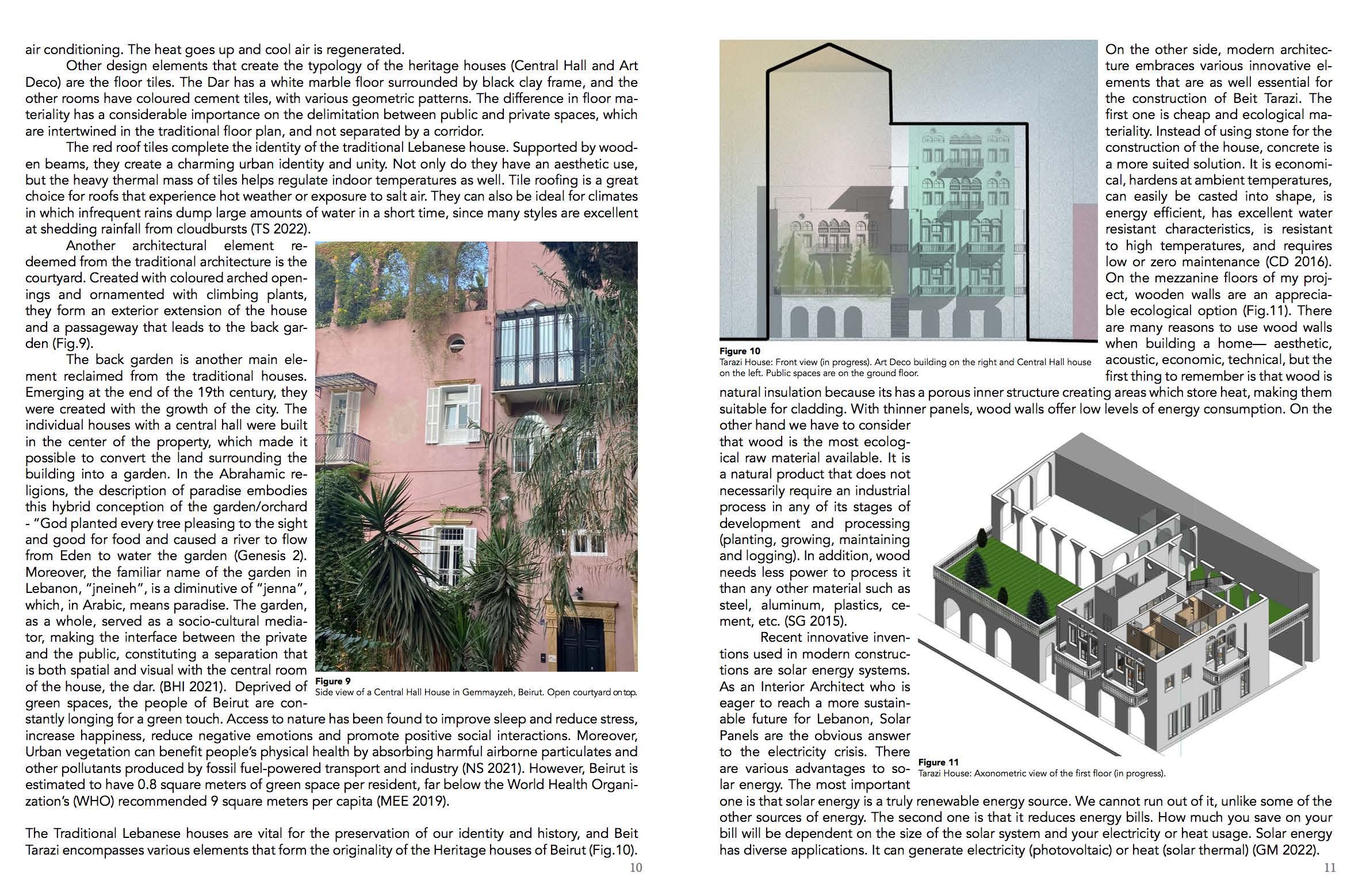

In August 2022, when walking around the old streets of Beirut, I noticed that it wasn’t only the architectural patrimony that was charming and endearing. It was the whole experience of walking around the sloped streets, spotting a dis creet passageway that leads to the back garden of a pink house, feeling like the architecture isn’t repetitive, but unique in each way. Unique in the placement of windows, in the ornaments of the three arches, some floral, some geometrical; unique in the use of colours: blue, green, yellow, pink, red, etc. This whole experience is what led me to change the main architecture of my project, from one main building to two smaller ones, with different floor levels, uneven designs, more green spaces, charming courtyards and passageways.

89 88

saifi neighbourhood in piCTures

inspiraTion:

“Your Lebanon is empty and fleeting, whereas my Lebanon will endure forever.”

- Gibran Khalil Gibran

91 90

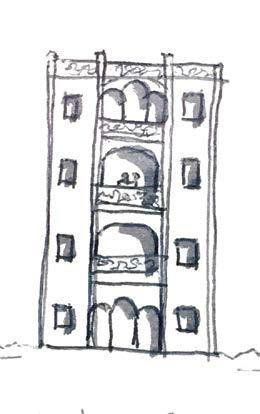

TradiTional and Modern: whaT To Keep

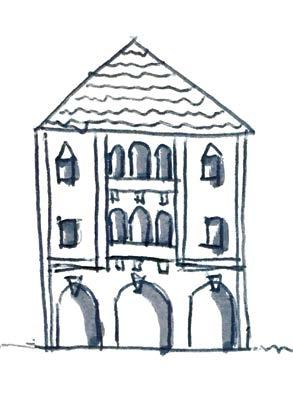

C entral H all H ouse (1850 s - 1920 s )

a rt D e C o B uil D ing (1920 s - 1930 s )

M o D ern B uil D ing (1930 s - present )

WHat to keep :

Main 3 arches in the mid dle of the facade.

- Ground floor used as a commercial space: neigh bourhood dynamics and social interactions.

- Floor plan.

- Orientation/ passive design elements.

- Ceiling height.

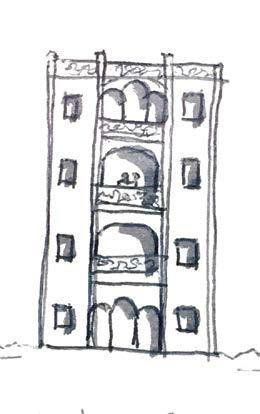

WHat to keep :

- Bigger central balconies.

- Addition of elevators.

- Addition of floors.

- Inner courtyards.

- Concrete structure.

Progression of the tradi tional central hall house: using its main typology while adding new design elements.

WHat to keep :

- Ecological materials (solar panels/ wood ect.).

- Space efficiency + Under ground garage : growth of Bei rut’s opulation over the past years.

- Building safety measures.

- Cheaper materials and con struction alternatives : economi cal crisis.

93 92

III- B

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN PROCESS

94

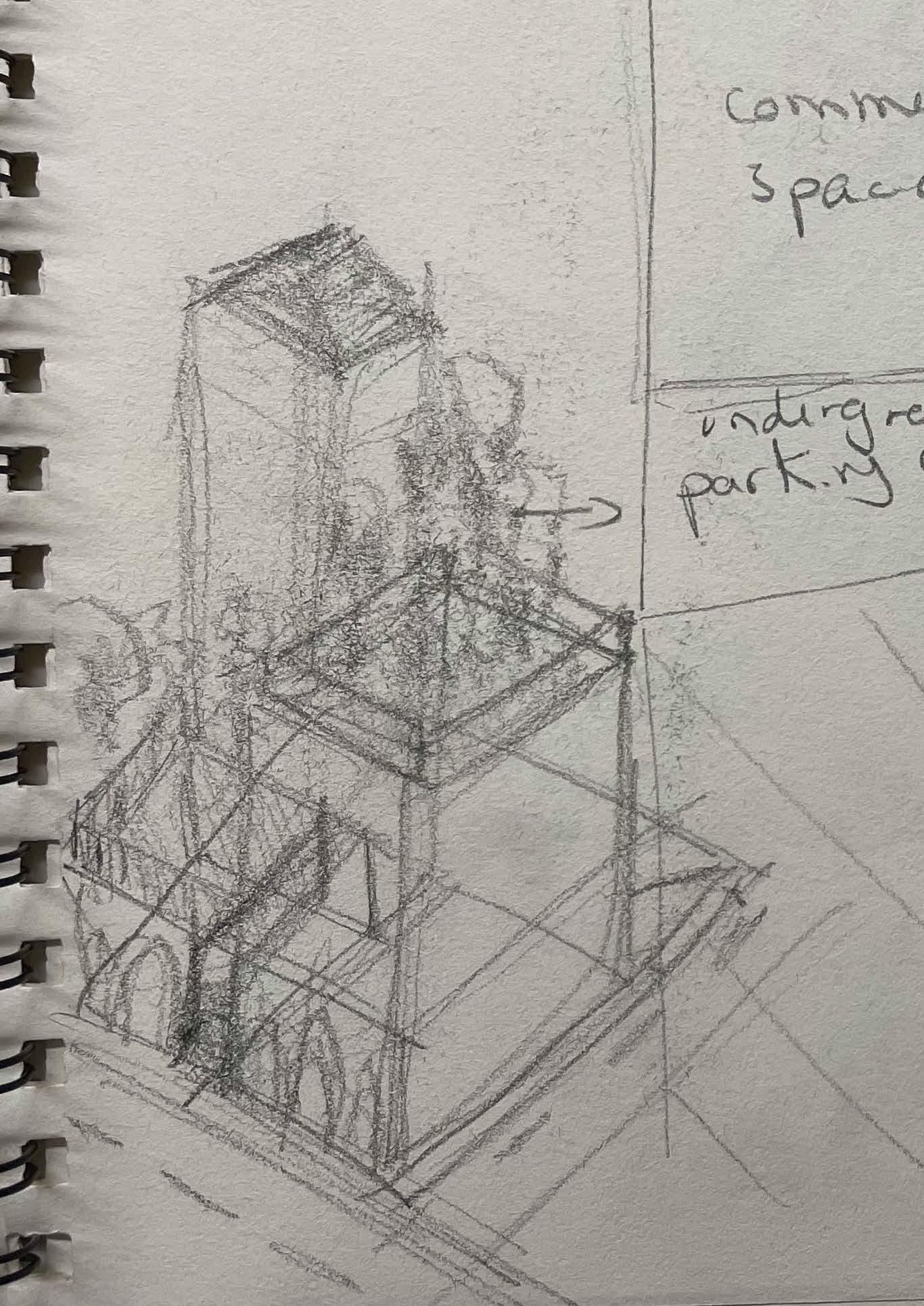

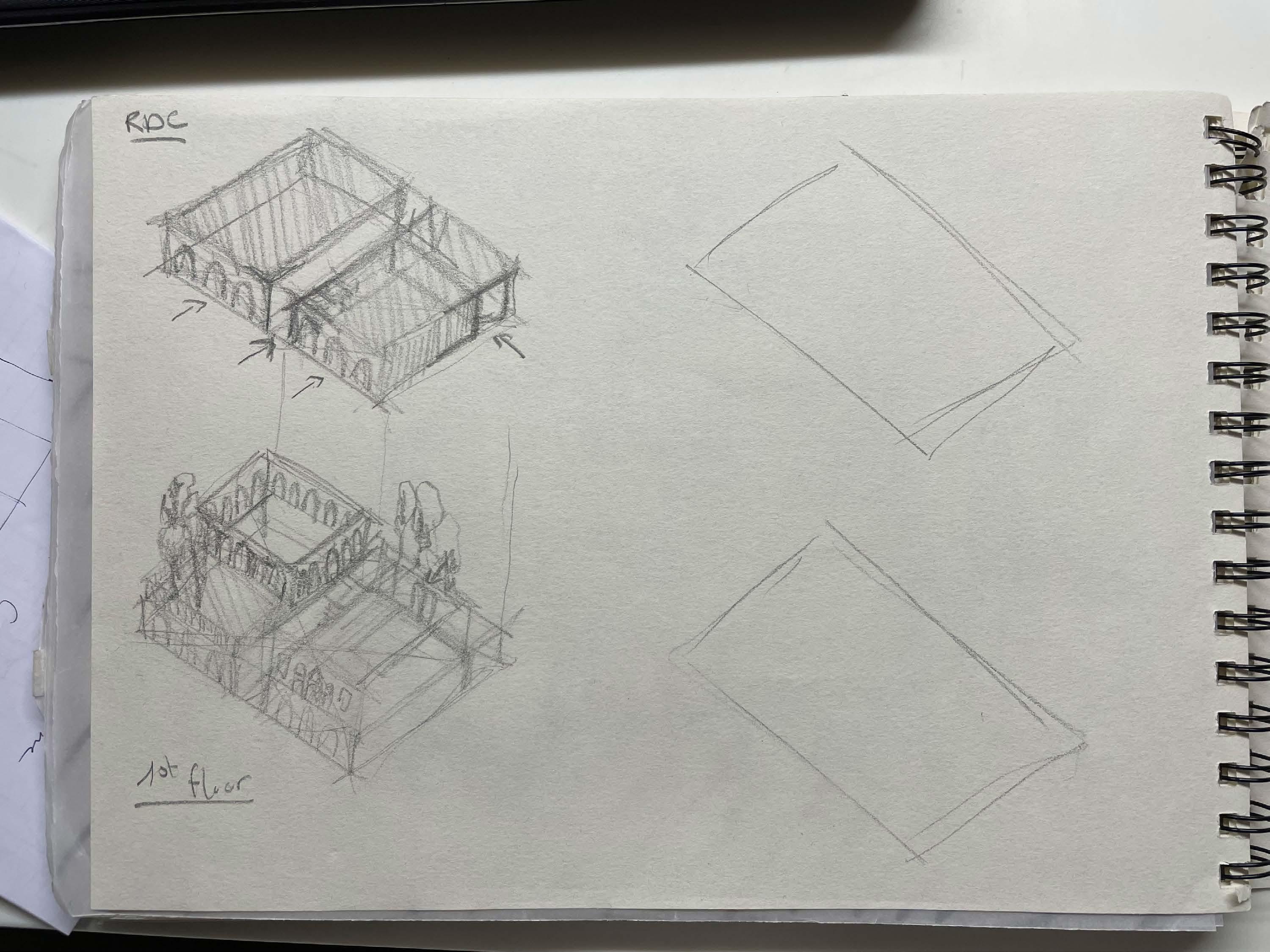

97 96 sKe TChes 1-

DESIGN PROCESS AND EVOLUTION

99 98

101 100

103 102

105 104

107 106

109 108

111 110

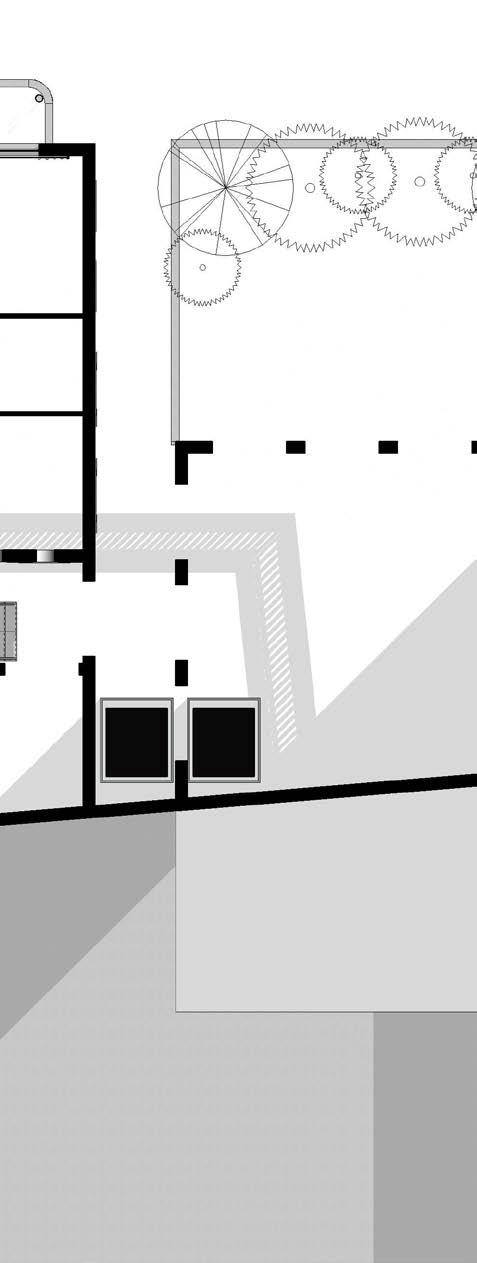

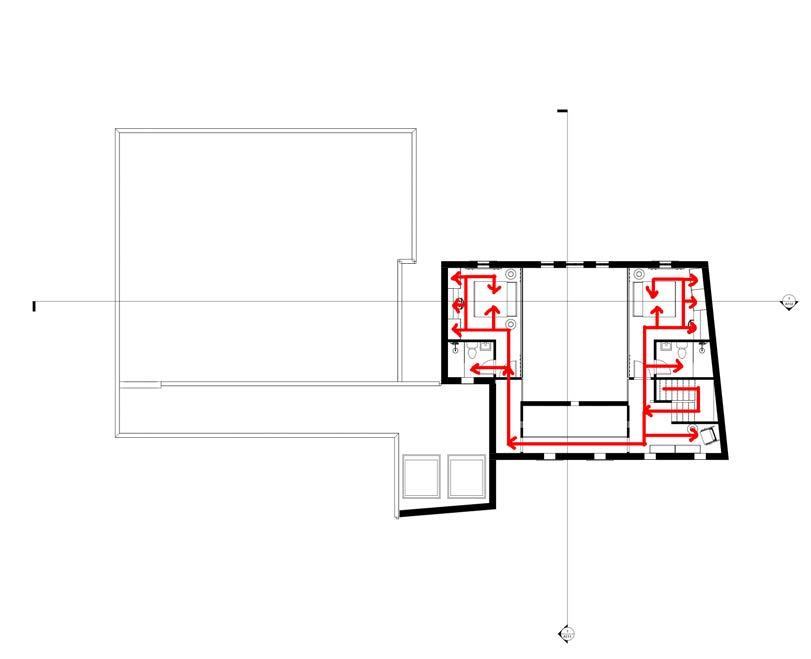

113 112 COMMERCIAL SPACE PARKING ACCESS CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL SPACE COURTYARD RESIDENTIAL ACCESS UP A107 A106 10.6 m 6.5 m 8.9 m 11.6 m 5.7 m www.autodesk.com/revit Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone 1 : 50 6/9/2022 2:25:12 AM A101 RDC Owner Project Name Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate FLOOR PLAN- GROUND FLOOR UP UP UP DN 5.3 m 5.3 m 6.5 m 4.7 m 4.1 m 7.3 m 1.2 m 1.2 m 7.6 m DN DN UP DN 1 A107 A106 1.7 m 3.6 m 5.3 m 3.2 m 4.1 m 1.2 m 6.4 m 2.4 m FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1- MEZZANINE FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1 design eVoluTion

115 114 UP DN DN 3.2 m 4.1 m 3.2 m 3.5 m 1.5 m 1.1 m 1.4 m 1.0 m www.autodesk.com/revit Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone 1 50 6/9/2022 12:01:28 AM A105 LEVEL 2MEZZANINE Owner Project Name Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate UP DN UP 3.2 m 3.2 m 4.2 m 5.0 m 1.1 m 2.4 m 9.1 m 6.5 m 8.9 m www.autodesk.com/revit Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone 1 50 6/8/2022 11:38:53 PM LEVEL 2 Unnamed Owner Project Name Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2- MEZZANINE (Same design plans on floors 2 to 4) FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2 (Same design plans on floors 2 to 4) Level RDC 0 m TOP RDC 5 m Level 2 10 m Level 1 5 m TOP LEVEL 1 9 m TOP LEVEL 2 14 m TOP PARKING 0 m LEVEL 3 14 m TOP LEVEL 3 19 m LEVEL 4 19 m TOP LEVEL 4 24 m LEVEL 5 24 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 1 7 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 2 12 m 1 50 1 Section 3 Level RDC 0 m TOP RDC 5 m Level 2 10 m Level 1 5 m TOP LEVEL 1 9 m TOP LEVEL 2 14 m TOP PARKING 0 m LEVEL 3 14 m TOP LEVEL 3 19 m LEVEL 4 19 m TOP LEVEL 4 24 m LEVEL 5 24 m TOP LEVEL 5 29 m ROOF LEVEL 29 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 1 7 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 2 12 m Scale Date Drawn Checked Project Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone No.DescriptionDate 50 1 Section CROSS SECTION LONGITUDINAL SECTION

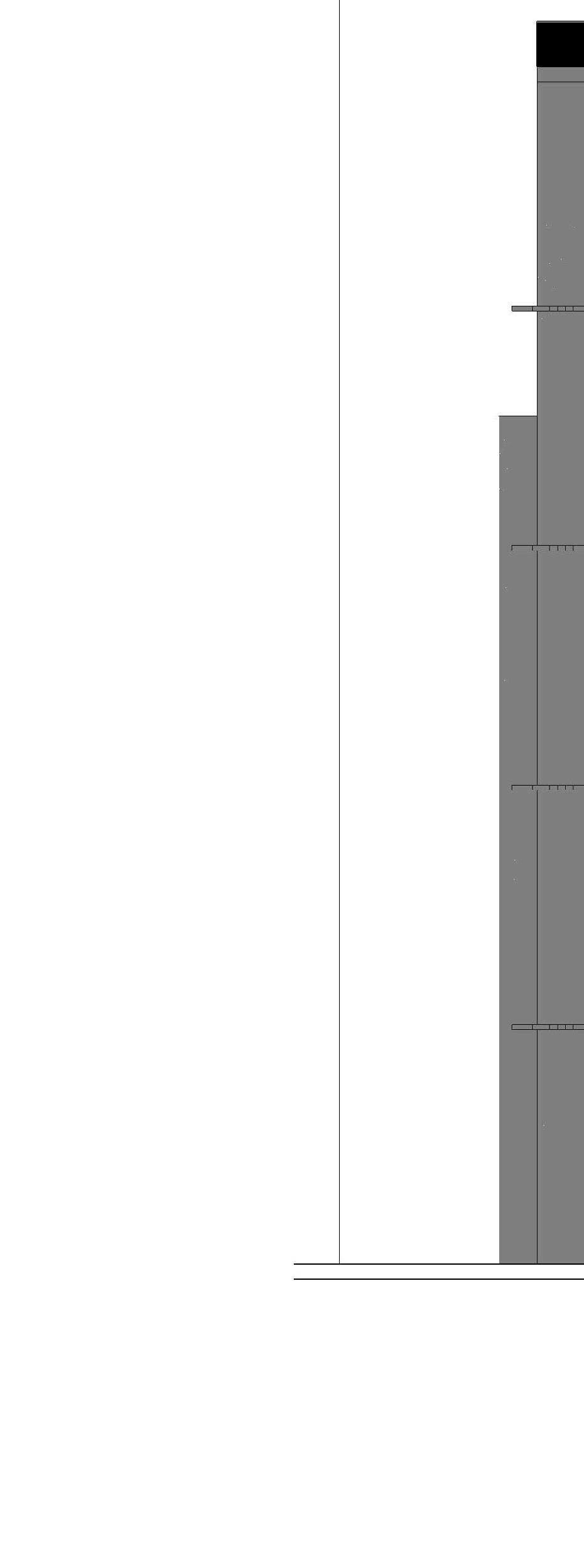

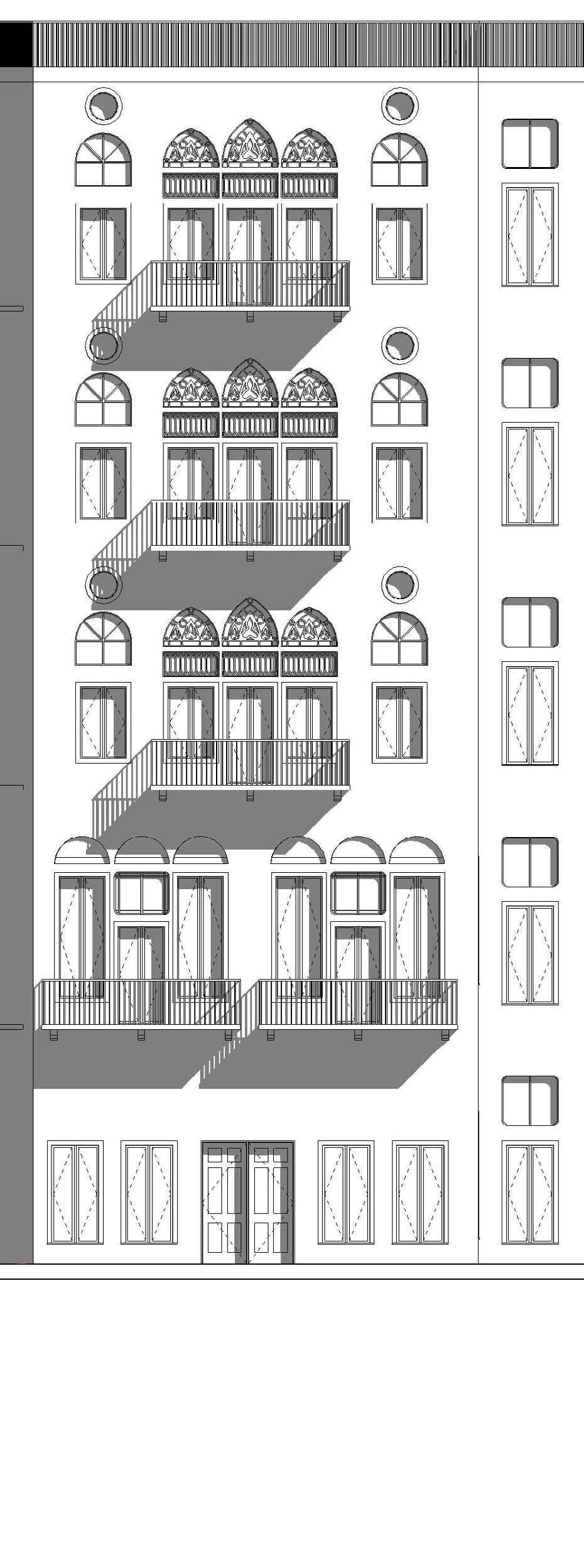

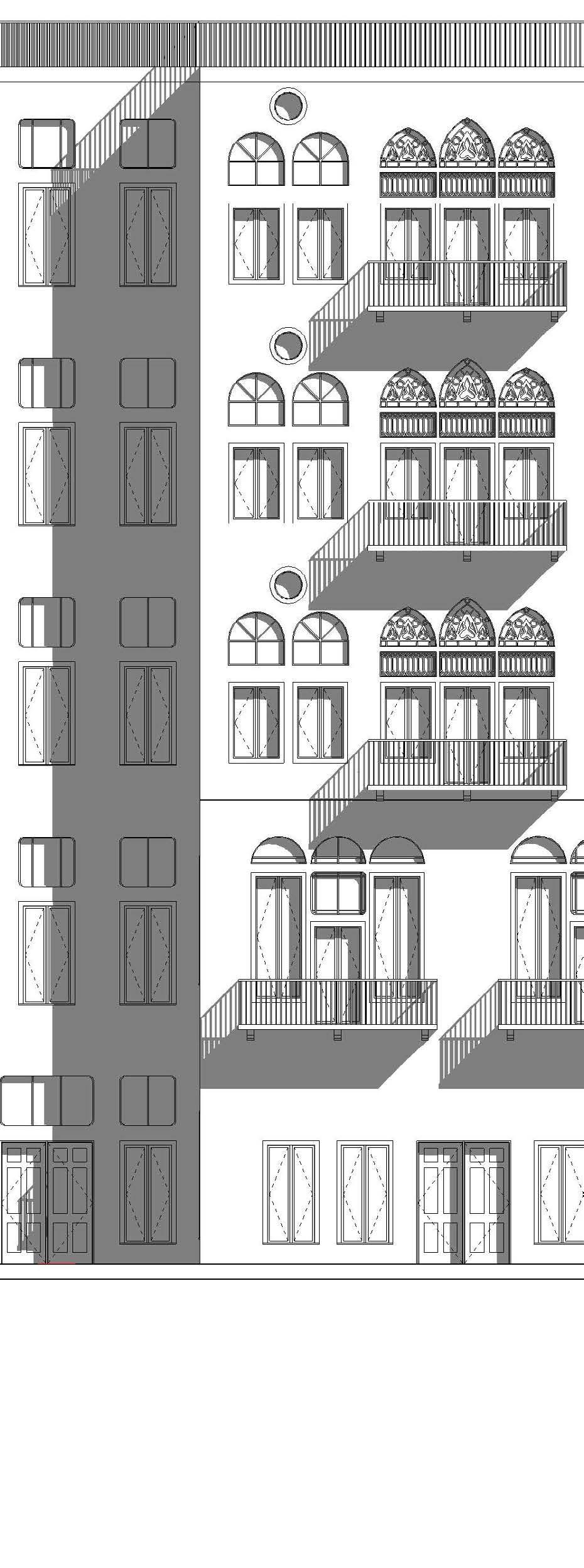

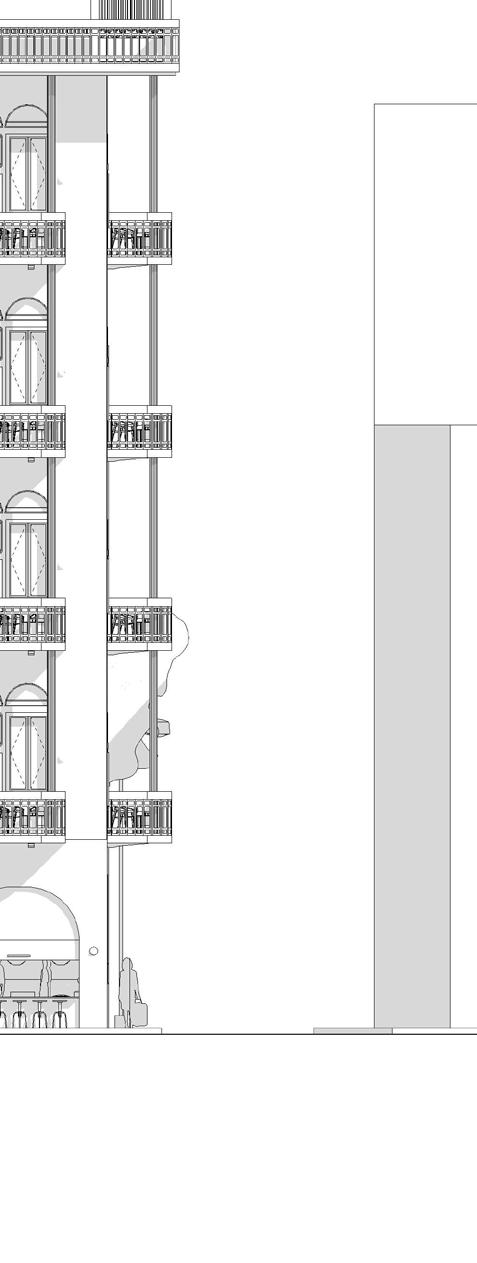

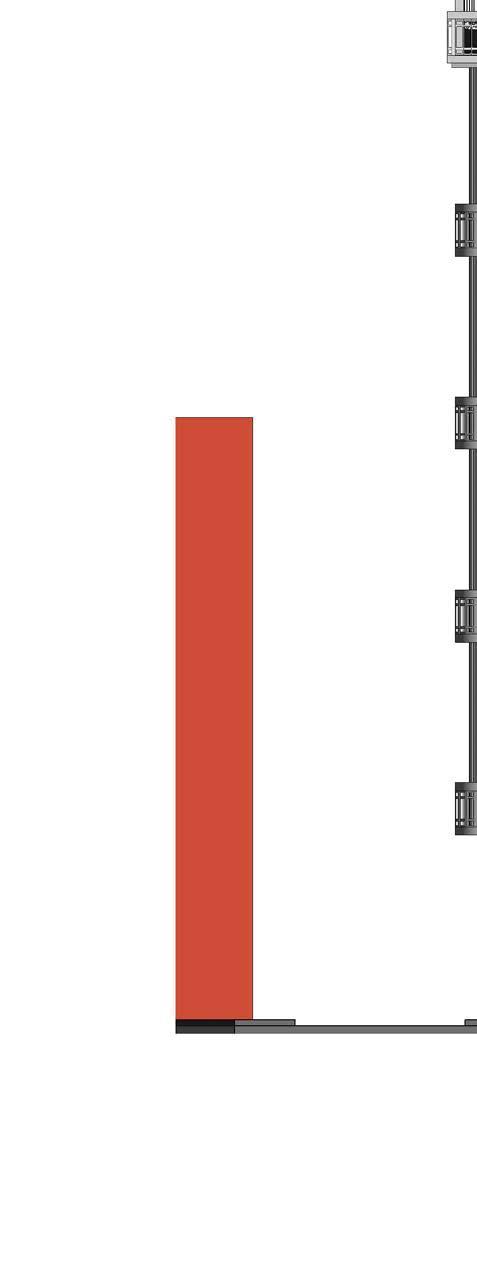

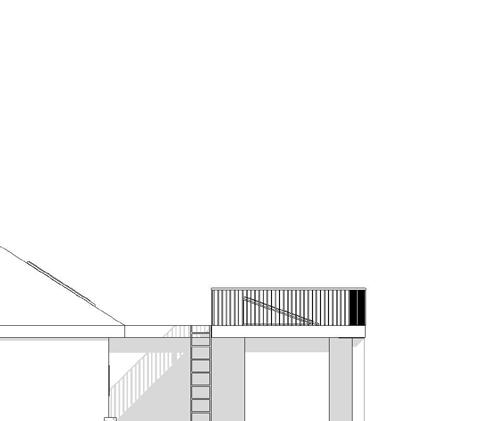

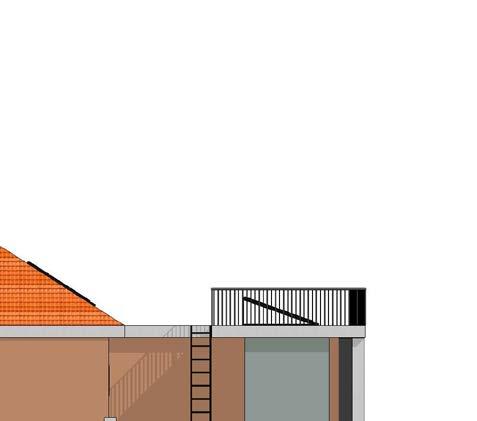

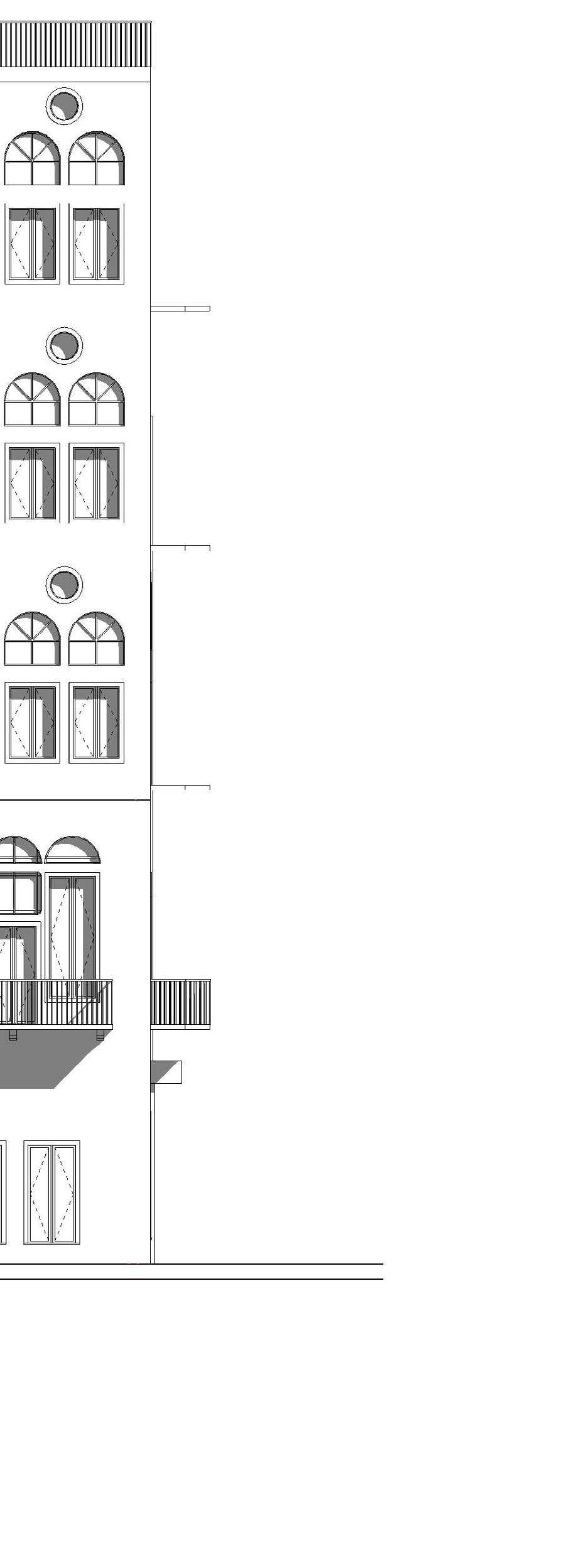

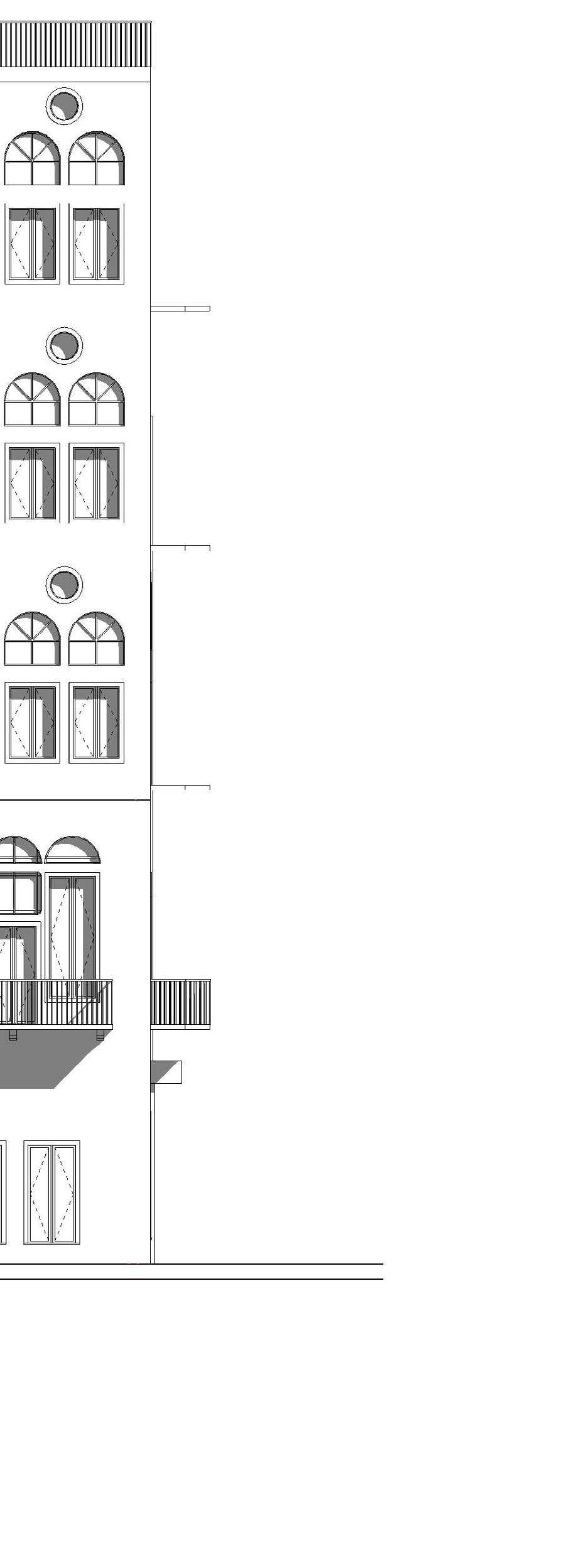

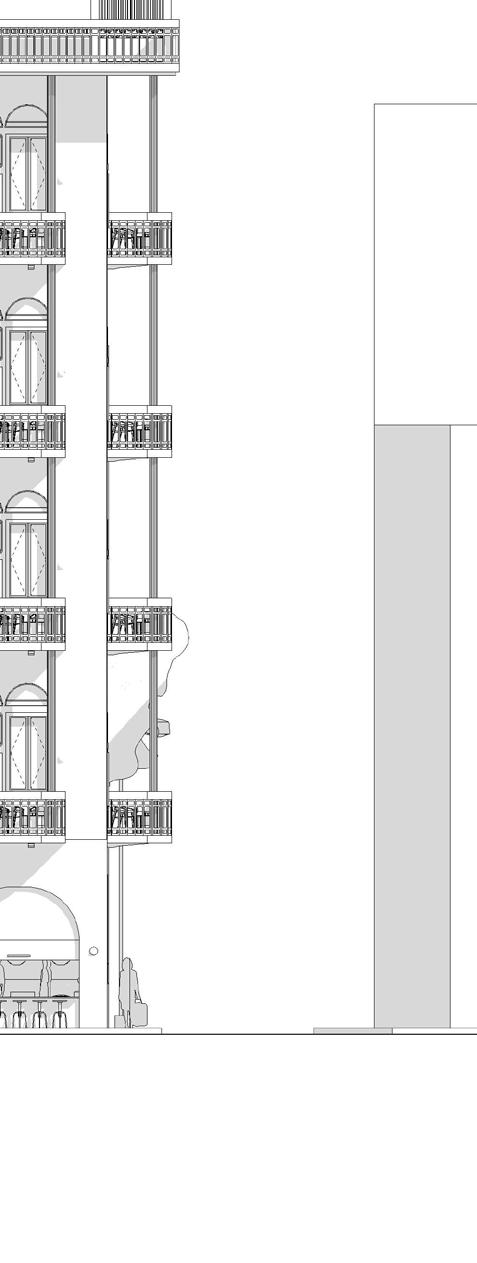

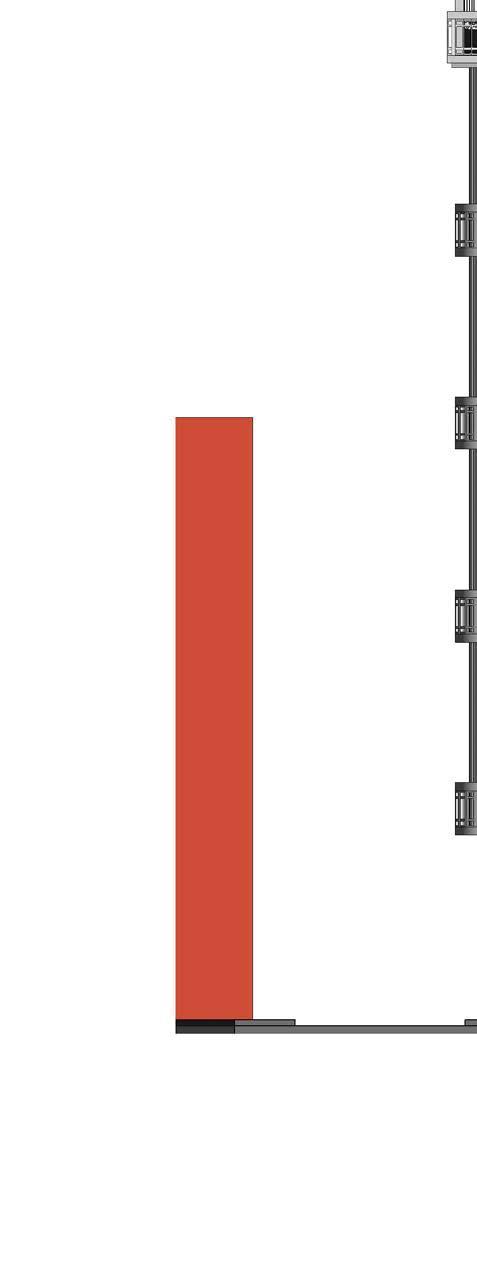

Level RDC 0 m TOP RDC 5 m Level 2 10 m Level 1 5 m TOP LEVEL 1 9 m TOP LEVEL 2 14 m TOP PARKING 0 m LEVEL 3 14 m TOP LEVEL 3 19 m LEVEL 4 19 m TOP LEVEL 4 24 m LEVEL 5 24 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 1 7 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 2 12 m Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone VUE No.DescriptionDate FACADE VIEW

119 118 1sT floor sTudio Views

121 120 2nd floor aparTMenT Views

123 122

125 124 building View

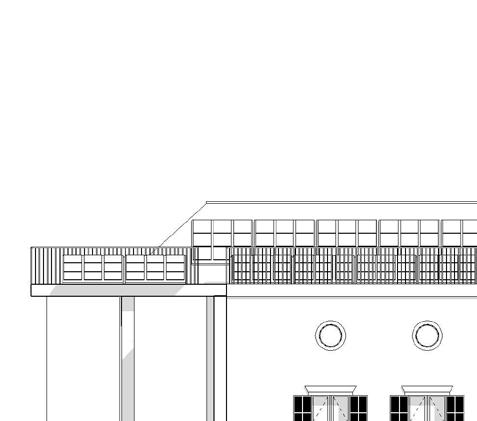

127 Level RDC 0 m TOP RDC 5 m Level 2 10 m Level 1 5 m TOP LEVEL 1 9 m TOP LEVEL 2 14 m TOP PARKING 0 m LEVEL 3 14 m TOP LEVEL 3 19 m LEVEL 4 19 m TOP LEVEL 4 24 m LEVEL 5 24 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 1 7 m MEZZANINE LEVEL 2 12 m www.autodesk.com/revit Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone 1 : 50 6/9/2022 3:13:22 AM A108 VUE FACADE Owner Project Name Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate de Tails Rooftop Venetian Oculi, used in traditional Beirut houses Art Deco window detail inspiration Balcony inspiration Window details inspiration Art Deco window detail inspiration Residential Entrance Commercial Entrance

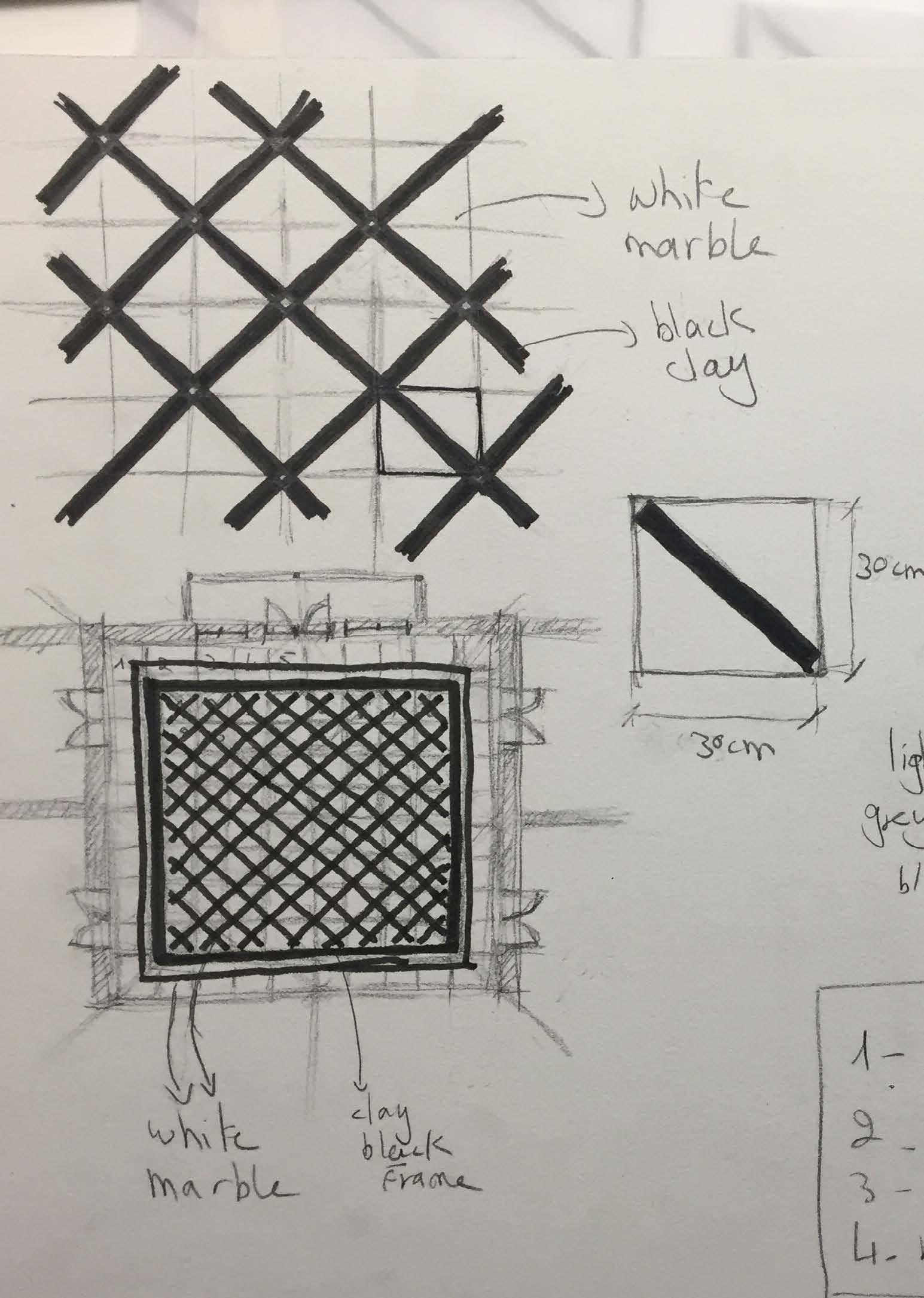

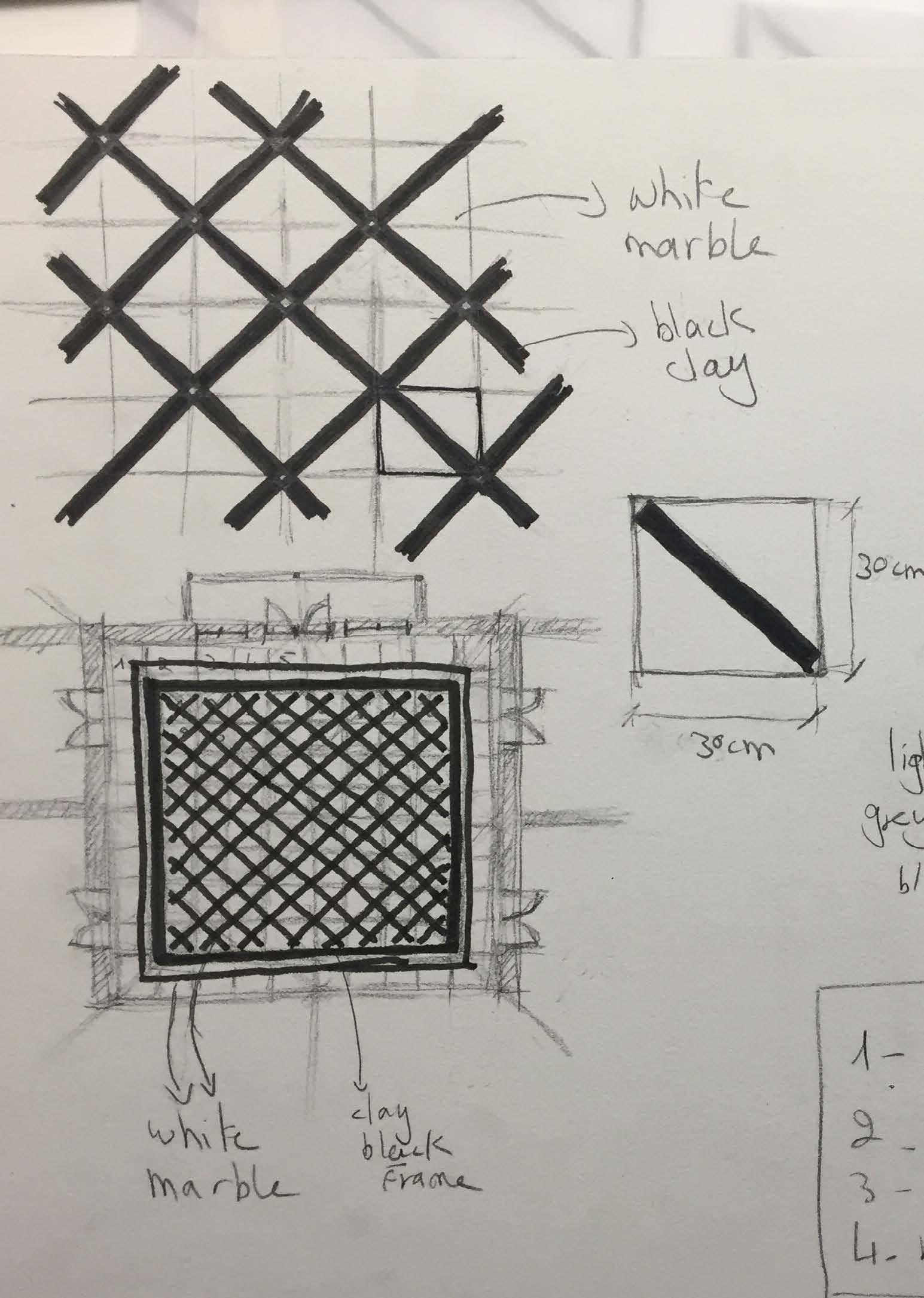

In the early second half of the nineteenth century, the most important space in the houses which is the hall center was tiled by white marble and a surrounded black clay frame as shown in the fig ure. Marble was also used in the sanitary spaces. The marble was installed and pasted by lime cement on the sand screed thickness above the timber joists.

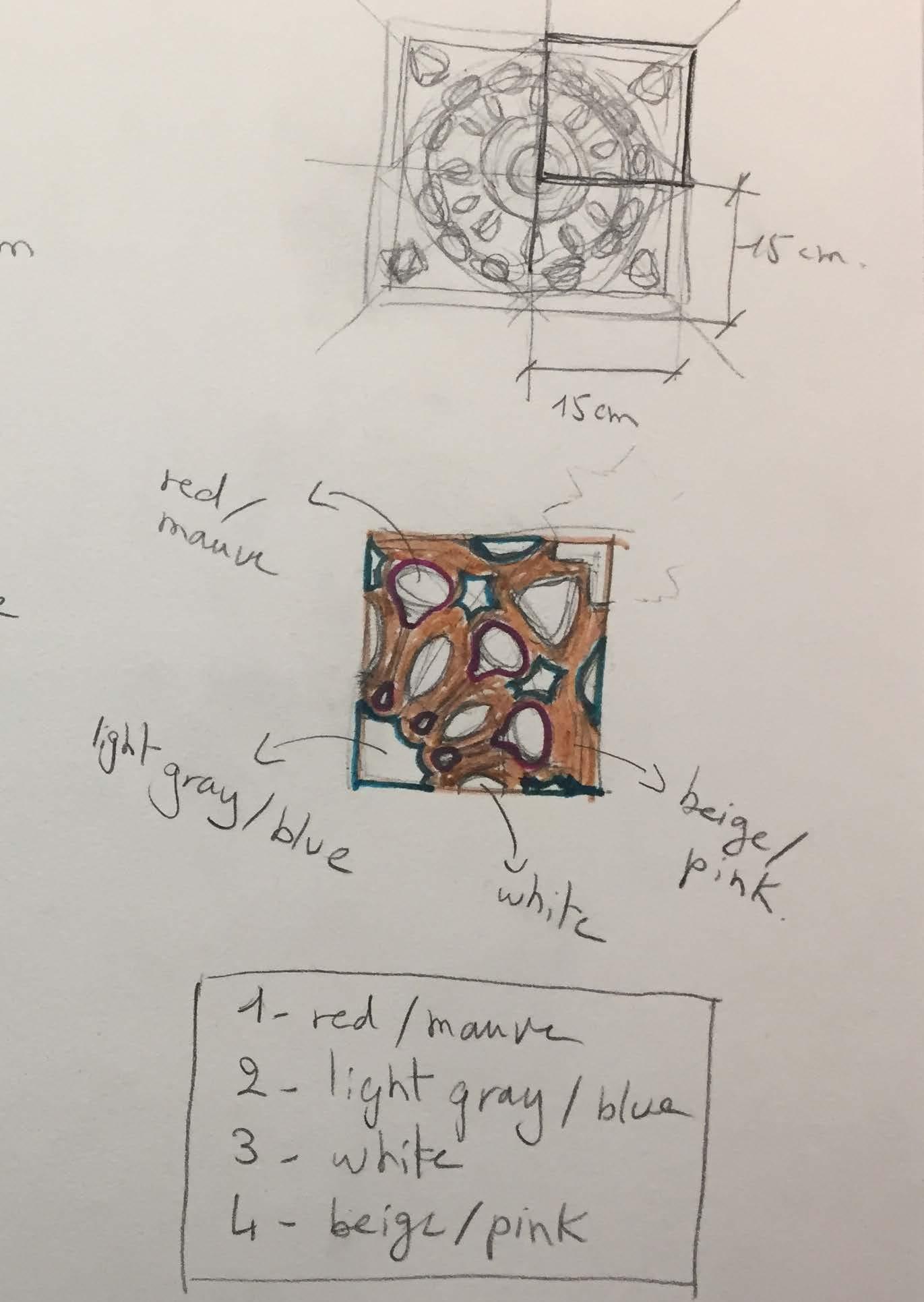

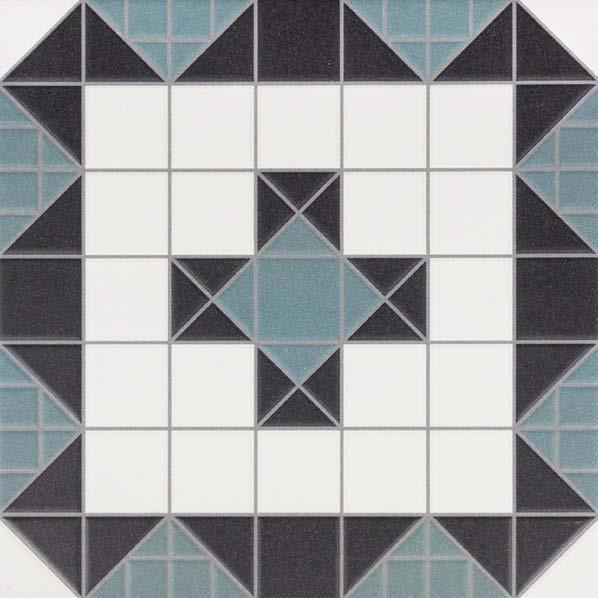

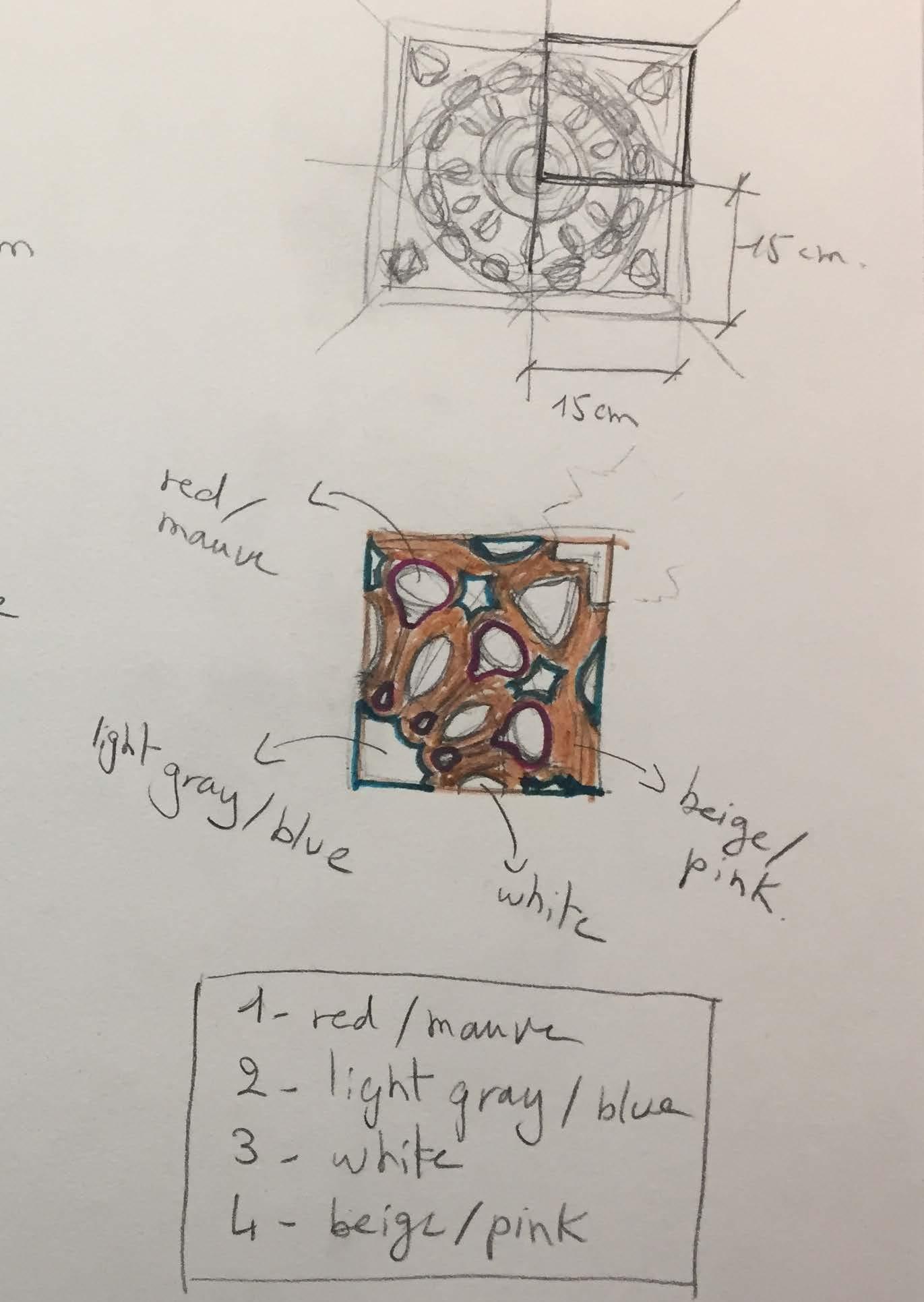

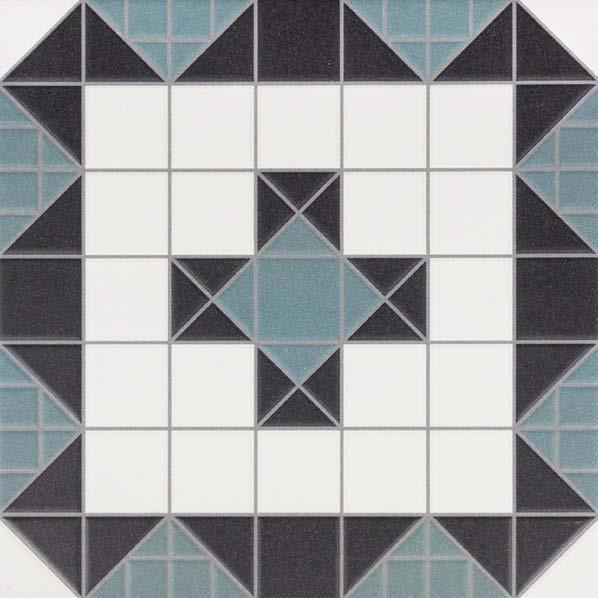

129 128 2- MATERIALITY

flooring : liVing rooM/ CoMMon spaCes

floor mArBle exAmple n leBAneSe houSeS Be rut/ BAtroun tIle AnAlySIS :

CEMENT TILES :

With the increasing of local production, an average of four patterns is found in 1920s building (early Mandate period) where marble remained the primary choice for central hall flooring. The number of colors found in cement tiles varied from one to three colors exposed and on the other hand, geometric patterns maybe divided in two main categories, the body or the infill pattern and the belt patterns. The most popular patterns found were locally manufactured using imported forms from Europe and in limited quantities that were chosen by cli ents. The cement tiles were manufactured from a cement mix with no addition of gravel. They were produced locally by skilled workers using a cast iron mould and a water press. The mould was composed of four parts, the base, the frame, the pattern or forma which was imported from Europe. The face of the tile was made of a cement mix composed of rock powder (boudrat sakhr) or sand, white cement and an artificial color agent (moghra) imported from Italy.

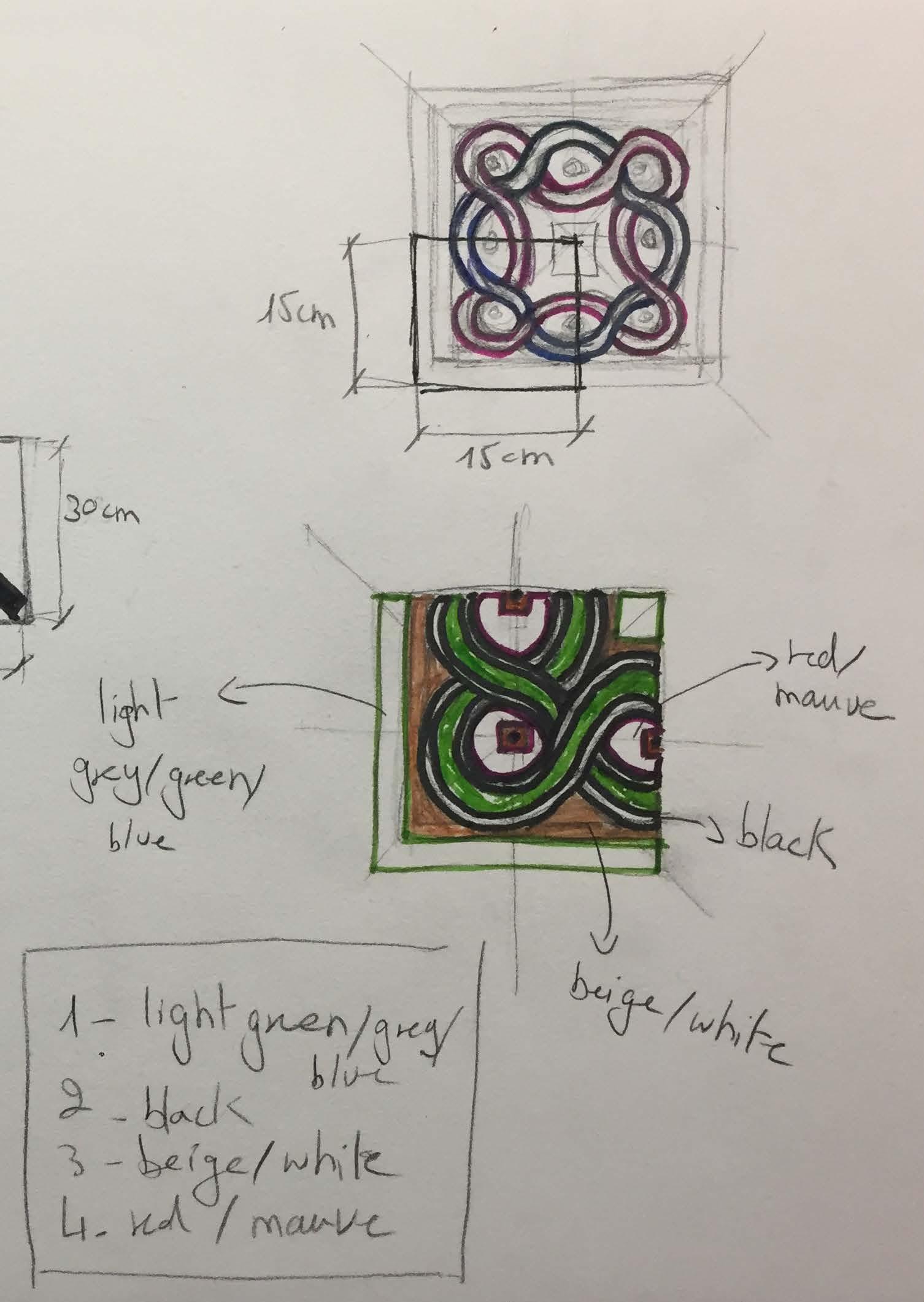

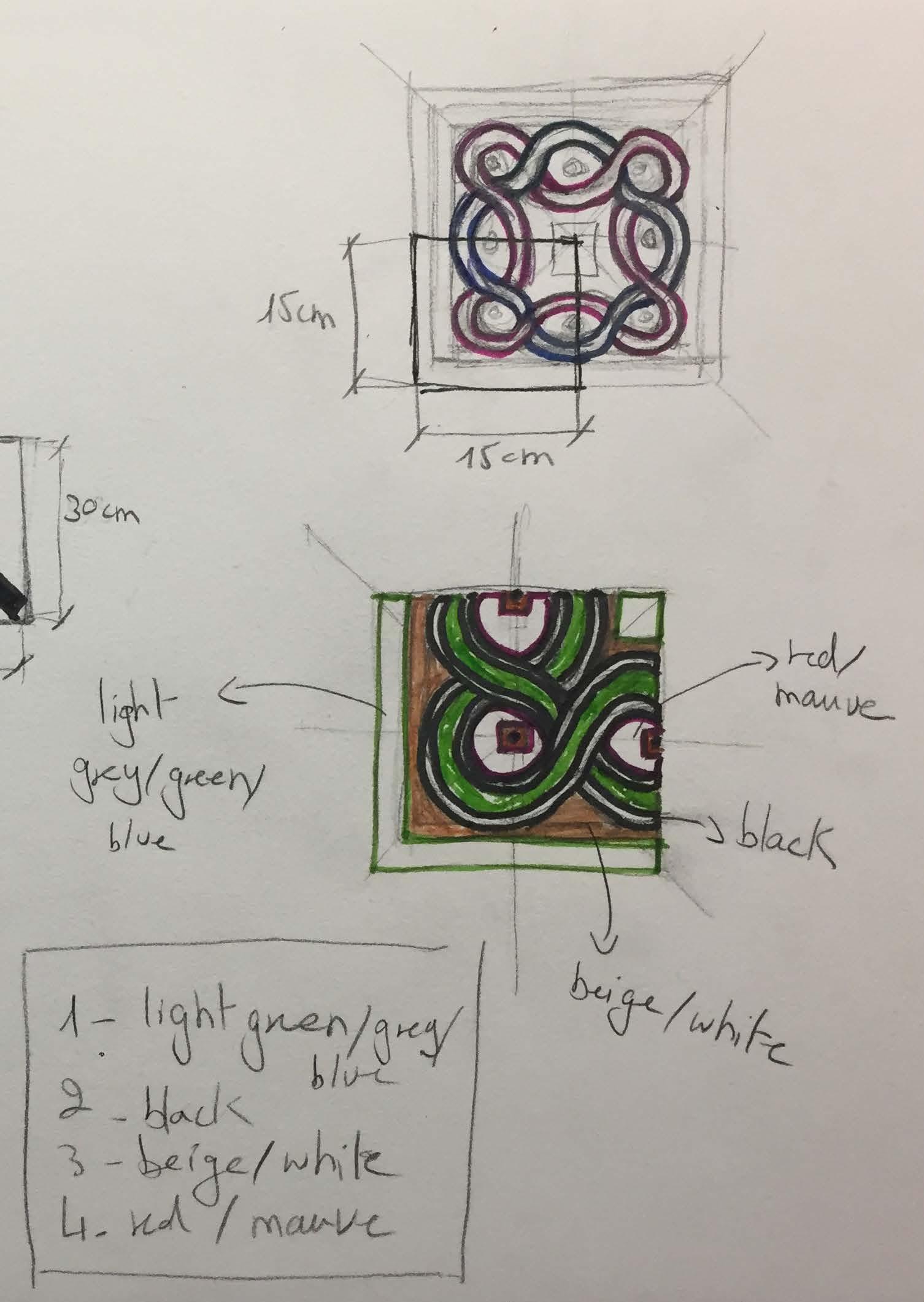

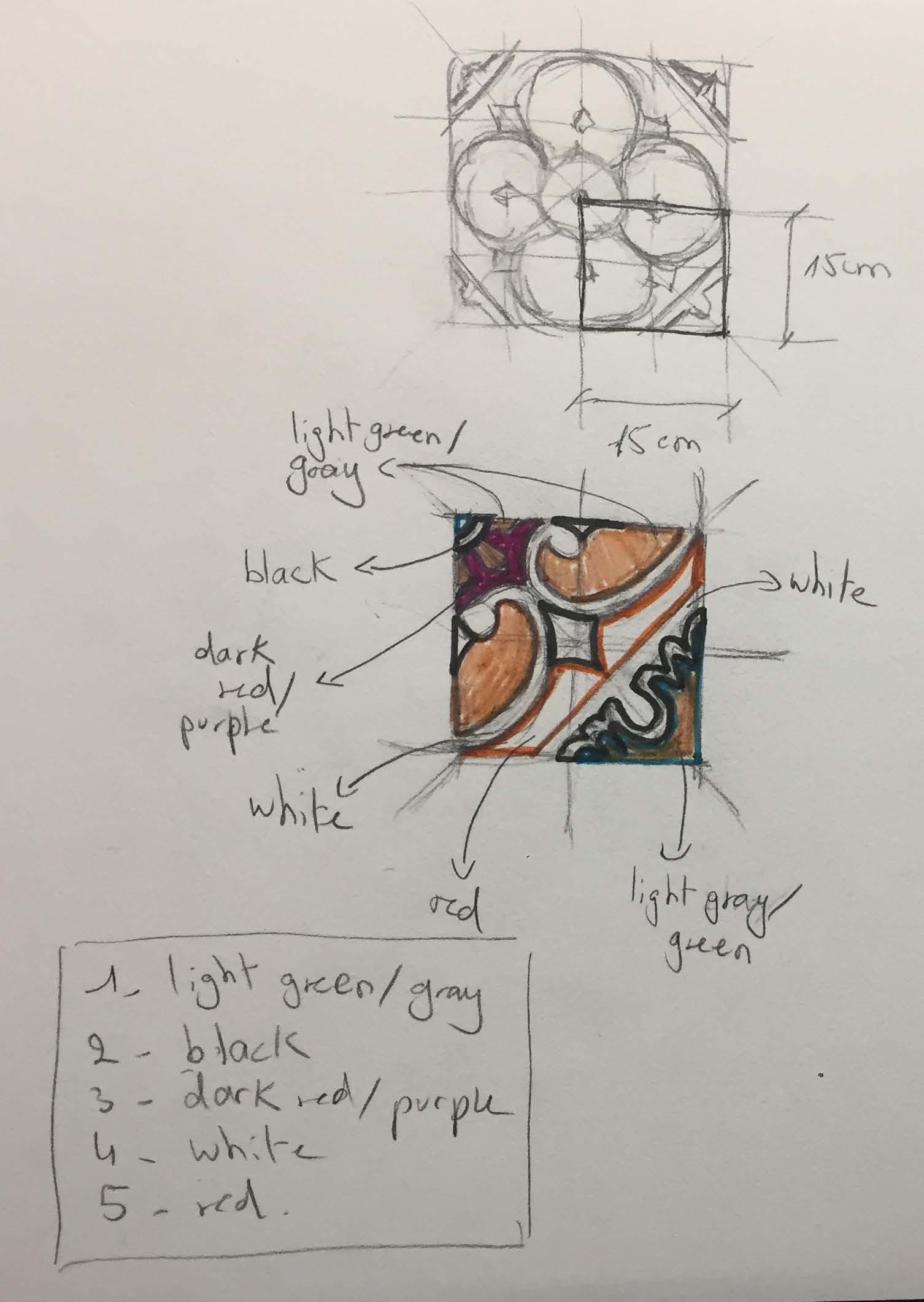

131 130 flooring : priVaTe areas

tIle AnAlySIS :

DINING ROOM TILES IN ONE OF LADY COCHRAIN’S HOUSES IN BEIRUT :

133 132

BEDROOM

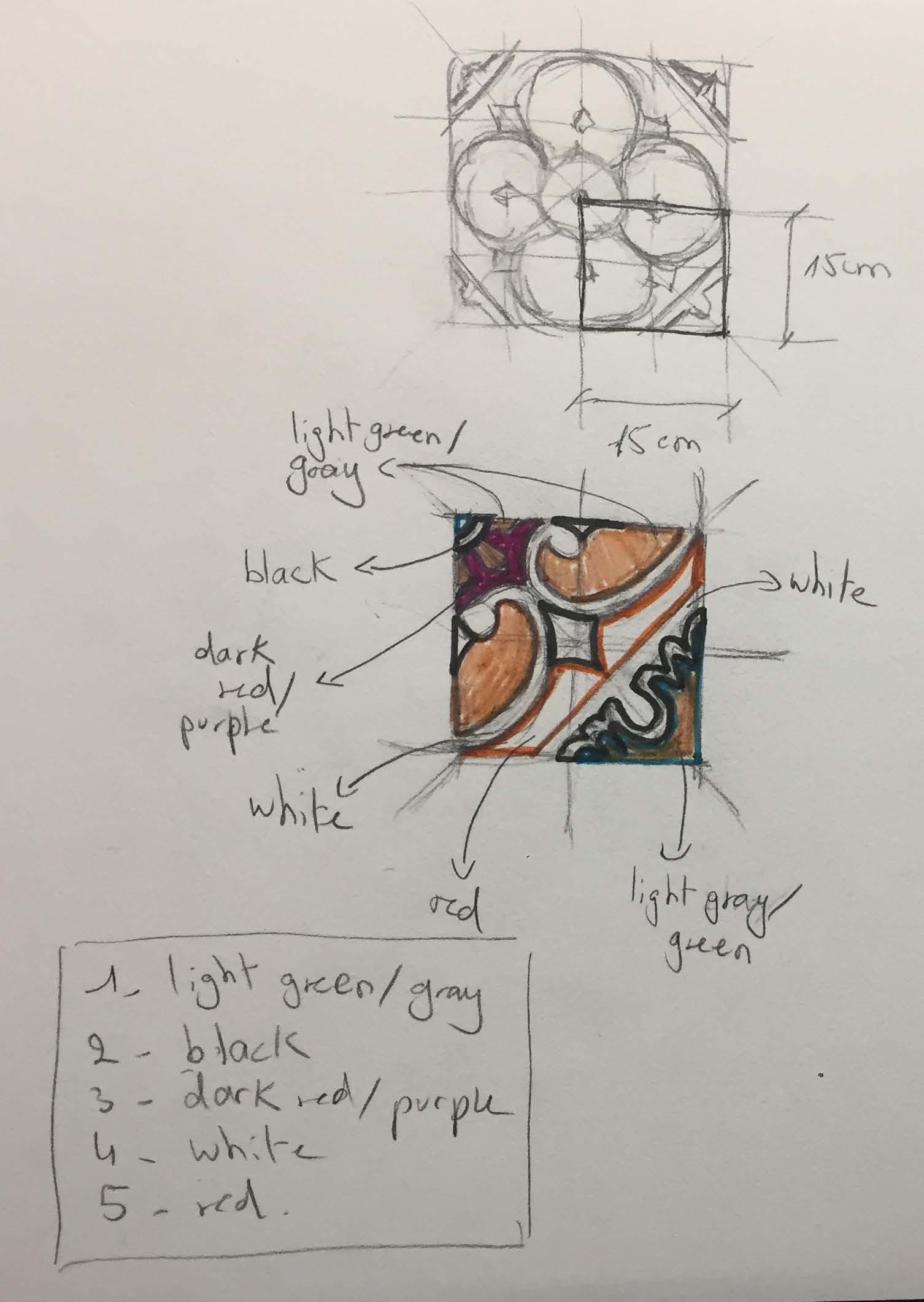

TILES IN ONE OF LADY COCHRAIN’S HOUSES IN BEIRUT : tIle AnAlySIS :

135 134 SIDE ROOM TILES IN ONE OF LADY COCHRAIN’S

IN BEIRUT : tIle AnAlySIS :

HOUSES

137 136 CERAMIC PROJECT TILES

ASSIGNED

Art Deco Bu lDIng BAlcon eS

BAthroomS

courtyArDS

An enormous growth of the paint industry began in the 1860s, encouraged by the invention of a suitable marketing container, the paint box. The first facto ry-made paints in boxes consisted of more finely ground pigments in an oil base. After 1875, factory-made paints were available where greater numbers of people painted and decorated more of their buildings and more frequently. Some conservators collecting paint samples on site.Then, in a laboratory, an ultra violet light microscope will be used to identify pigment and binding media. Mural paintings had become common. Limewash was applied on walls because the stones are absorbent. The mixture of this wash was a volume of lime to 3 or 4 volumes of agregates like sand, earth, stone powder and ashes. It was implemented by specialized craftman called “Mouareq” helped by workmen. Painting was applied on the limewash. To know this kind of painting, we refer to some investigations and contributions and written documentation, verbal research, and visual information about past nineteenth century painting in Middle East.

139 138 walls :

l mewASh lAyer n Be rut houSe pAInt exAmple n tArAz houSe Be rut

INTERIORS/ TILES :

COLOUR PALLETTE TAKEN FROM TRADITIONAL HOUSES EXTERIOR/

for Block B or trAditionAl leBAneSe houre for Block A or Art deco Building

141 140 PROJECT WALL COLOURS

CONCTRETE

143 142 Modern MaTerialiTy

LIGHT OAK WOOD

use : - m ezzanine w alls - d oors - f urniture use : - B uilding C onstru C tion SOLAR PANELS FOR RENEWABLE ENERGY (415 WATT) use : - r oof : B etween and on the red tiles

III- c

FINAL DESIGN

144

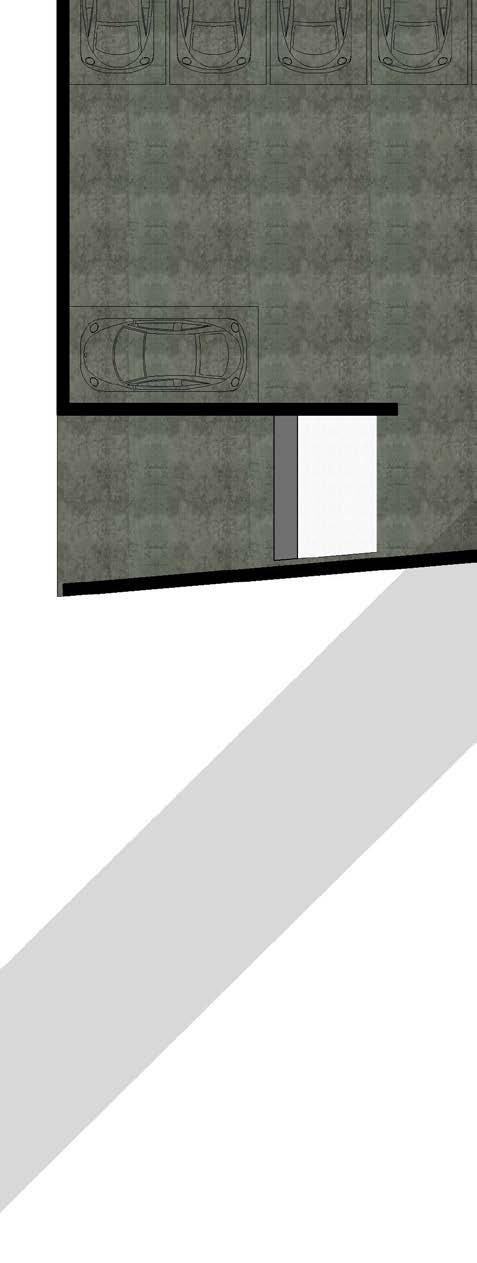

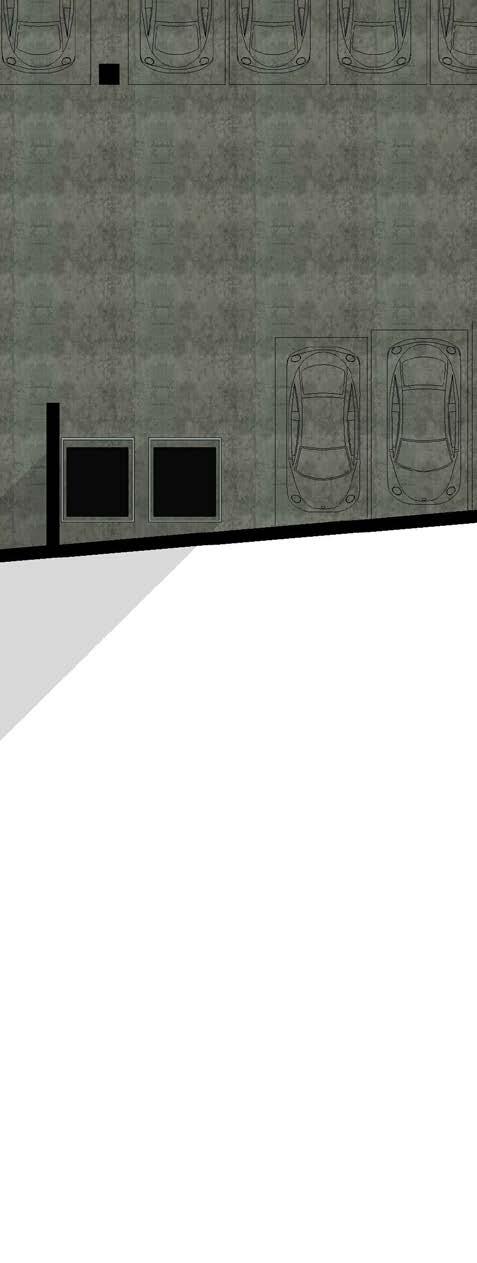

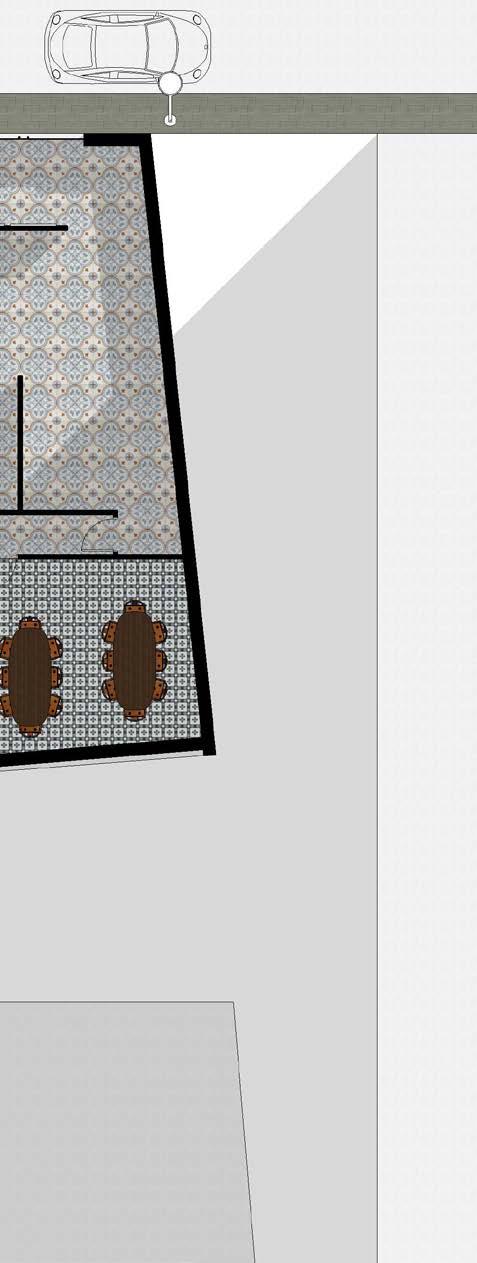

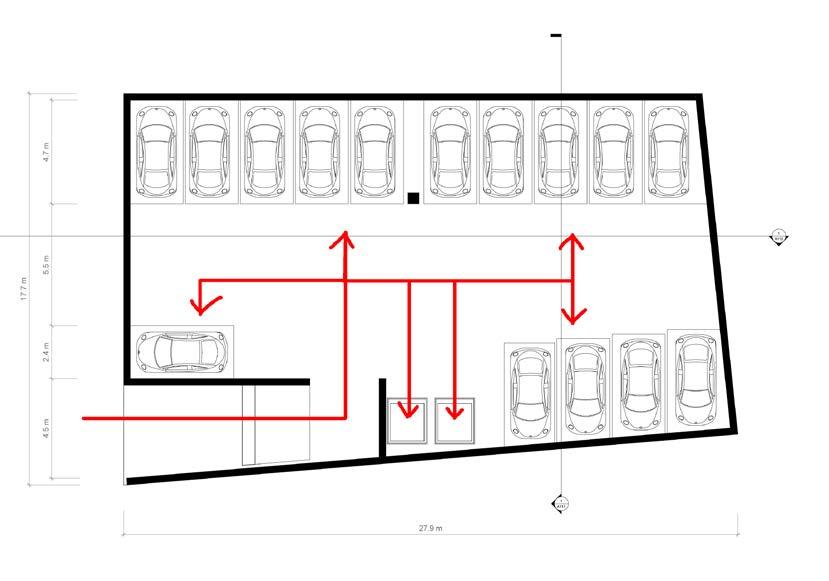

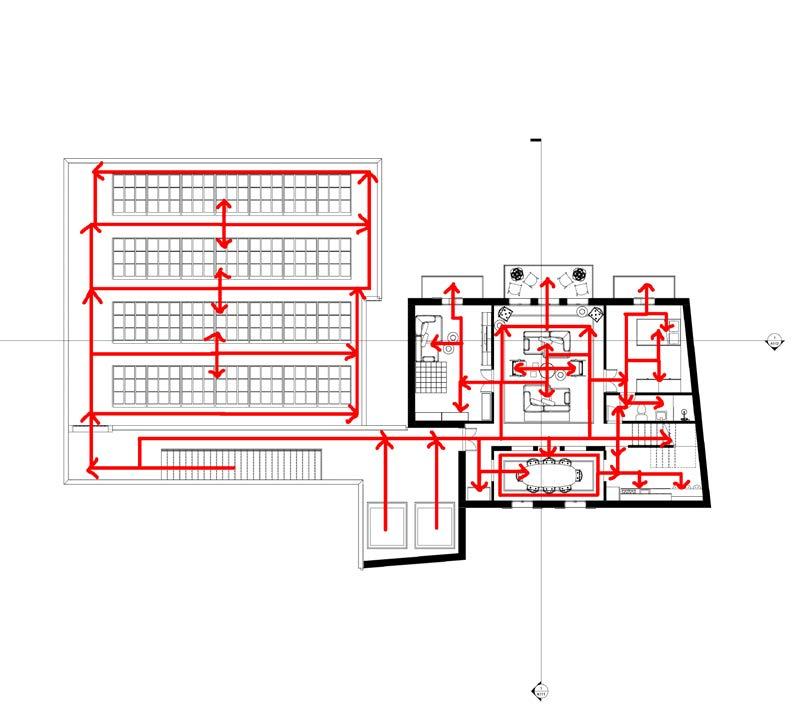

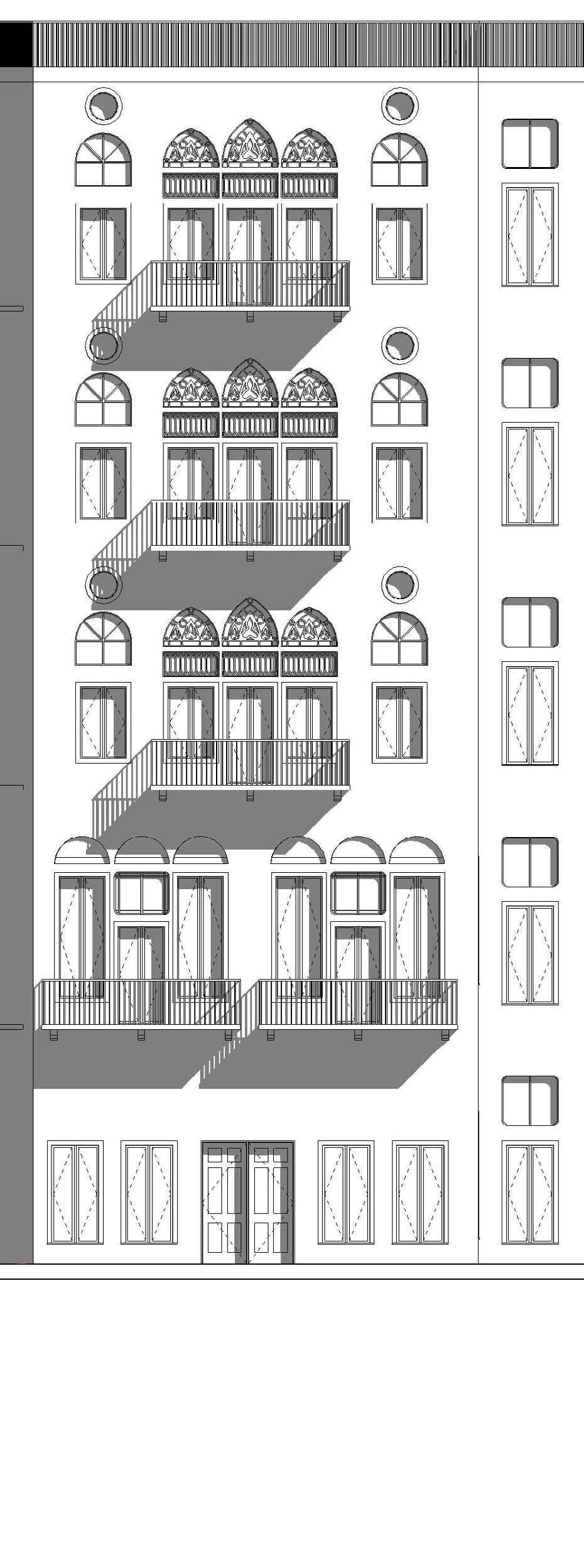

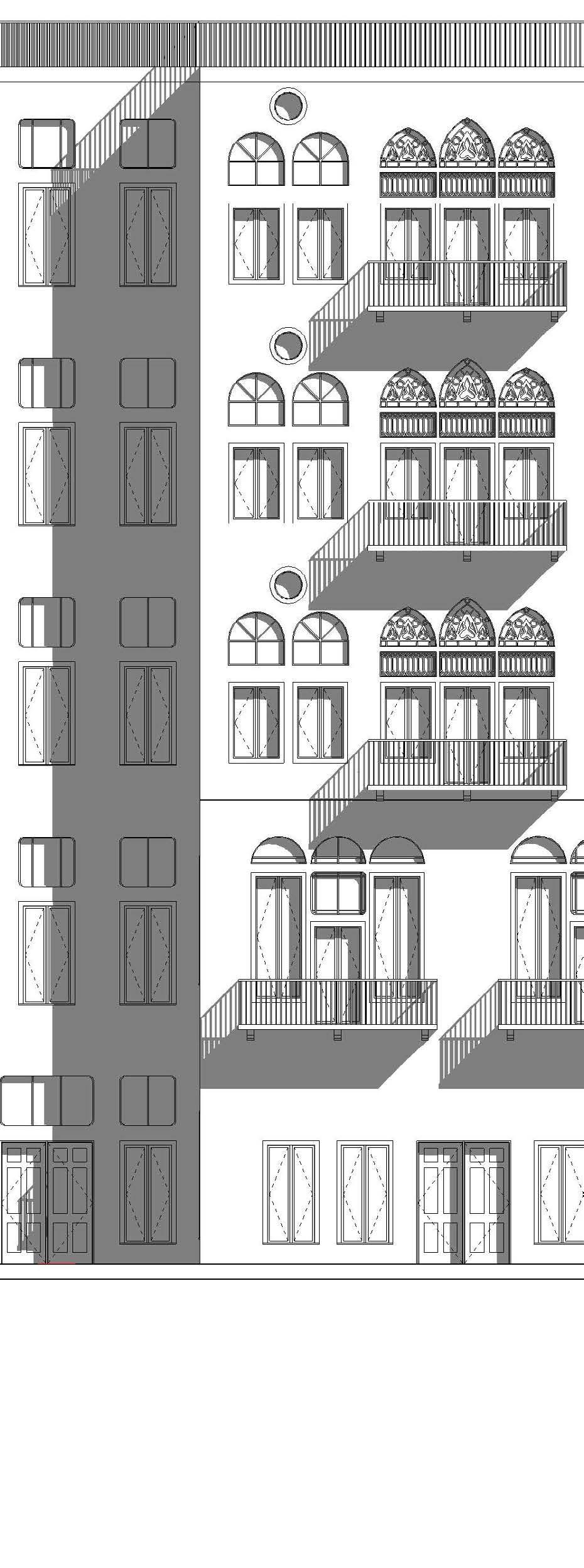

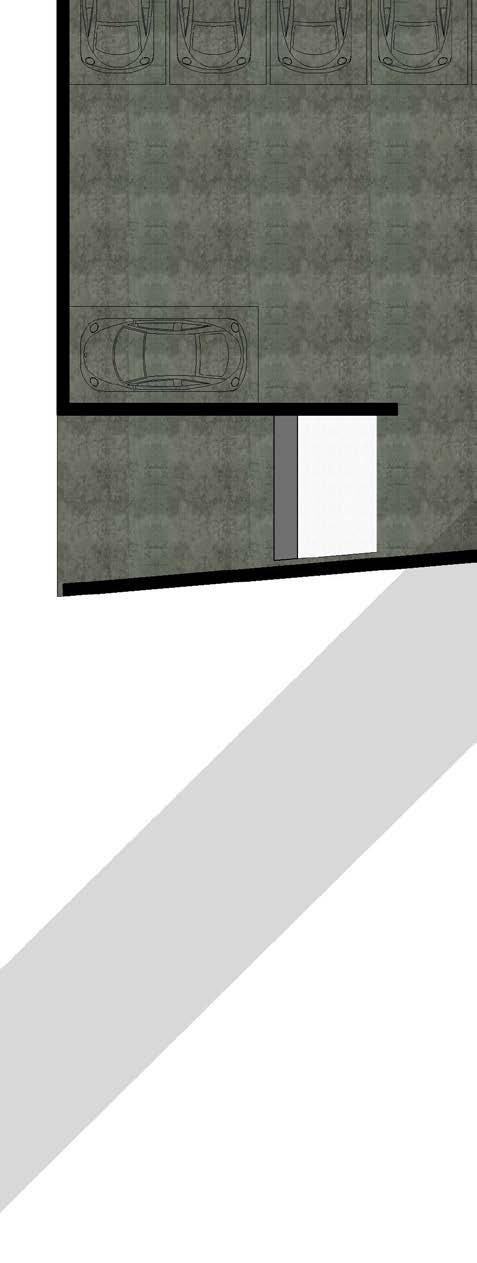

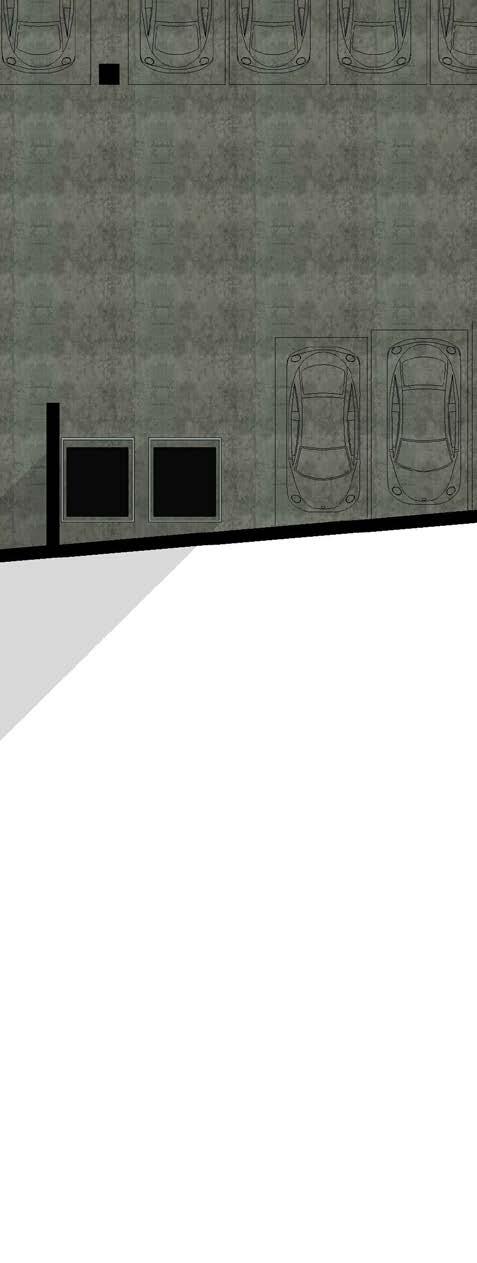

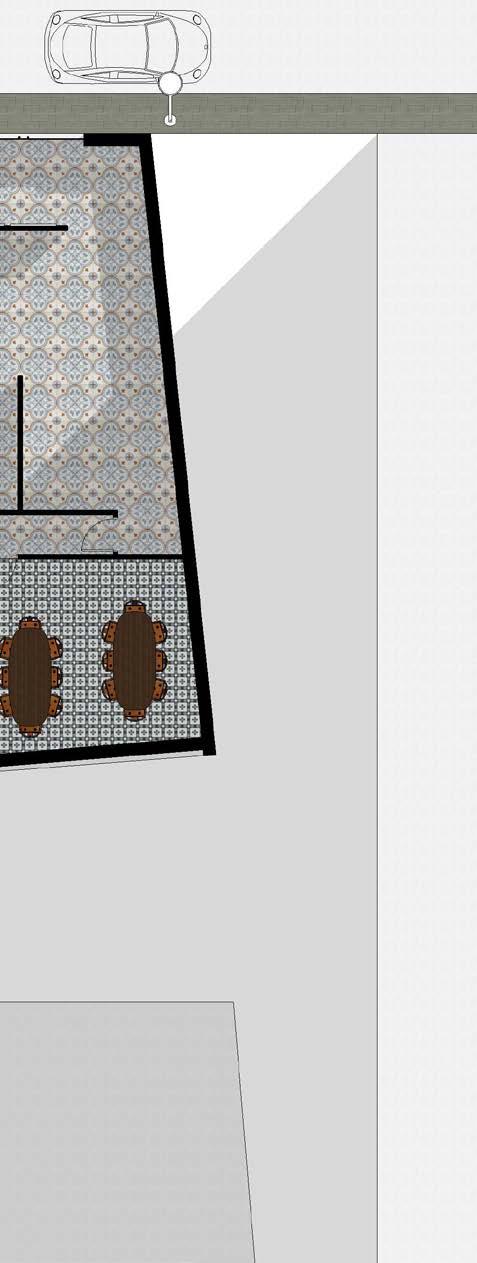

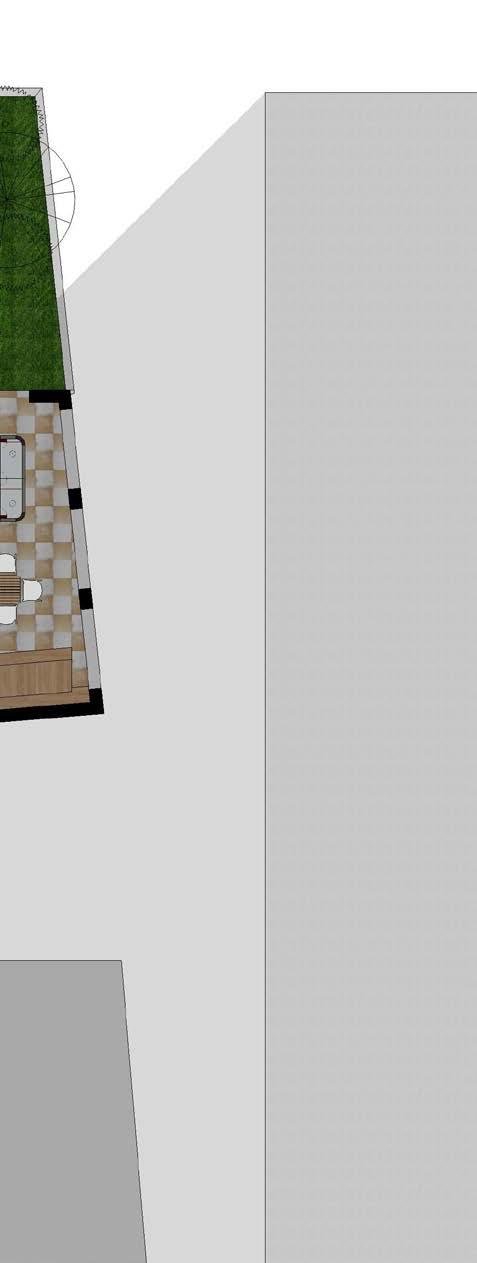

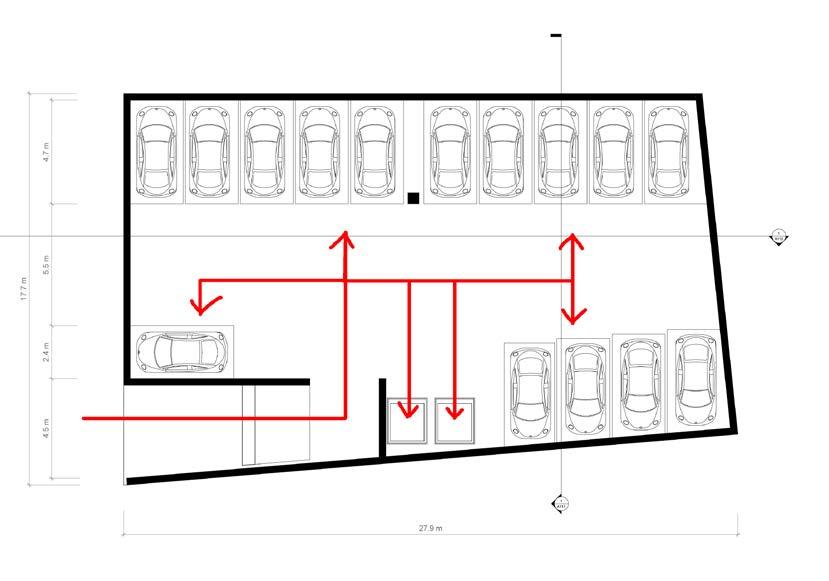

147 146 1- FLOOR PLANS/ SECTIONS/ ELEVATIONS A111 17.7 m 4.5 m 2.4 m 5.5 m 4.7 m 27.9 m Address 1 50 PLAN- PARKING Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 50 1 PARKING FLOOR PLAN- PARKING floor plans A112 A111 17.7 m 4.5 m 2.4 m 5.5 m 4.7 m 27.9 m 1 50 1 PARKING FLOOR PLAN- PARKING- COLOURS

149 148 A111 92 m² CAFE/ BAR 52 34 m² LAUNDRY ROOM 53 80 m² EXHIBITION SPACE 54 27 m² CONFERENCE ROOM 55 26 m² MEETING ROOM 56 8 m² REFUSE ROOM 57 3.3 m 9.6 m 4.5 m 11.7 m 2.3 m 2.3 m 5.3 m 5.8 m 17.5 m 27.4 m www.autodesk.com/revit MONOCHROME Project Name Checker Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 50 1 Level RDC- MONOCHROME FLOOR PLAN- GROUND FLOOR FLOOR PLAN- GROUND FLOOR- COLOURS

151 150 A112 A111 4.8 m 5.0 m 2.8 m 4.5 m 11.3 m 2.3 m 13.8 m 8.6 m 0.3 m 7.3 m 9 m² STUDIO A-3: BEDROOM 39 m² STUDIO A-3: BATHROOM 40 36 m² STUDIO A-3: HANDICAPABLE APARTMENT 41 29 m² STUDIO A-2 42 21 m² STUDIO A-1 43 50 Level 1- MONOCHROME FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1 FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1- COLOURS

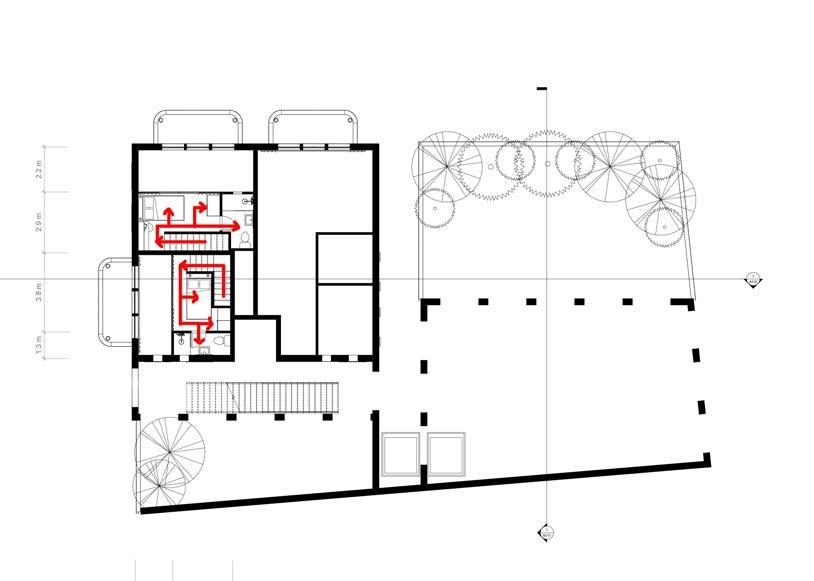

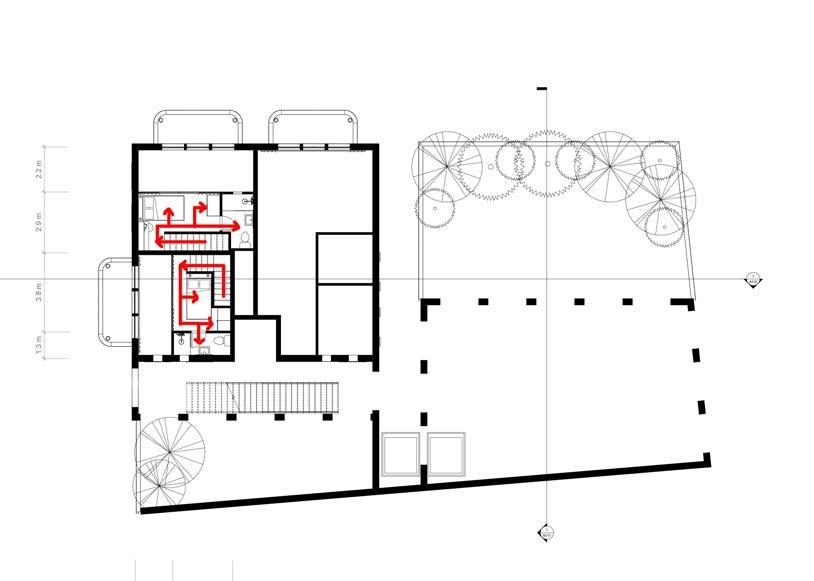

153 152 A111 1.3 m 3.8 m 2.9 m 2.2 m 1.8 m 2.9 m 1 50 1 MEZZANINE LEVEL 1- MONOCHROME FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1- MEZZANINE FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 1- MEZZANINE- COLOURS

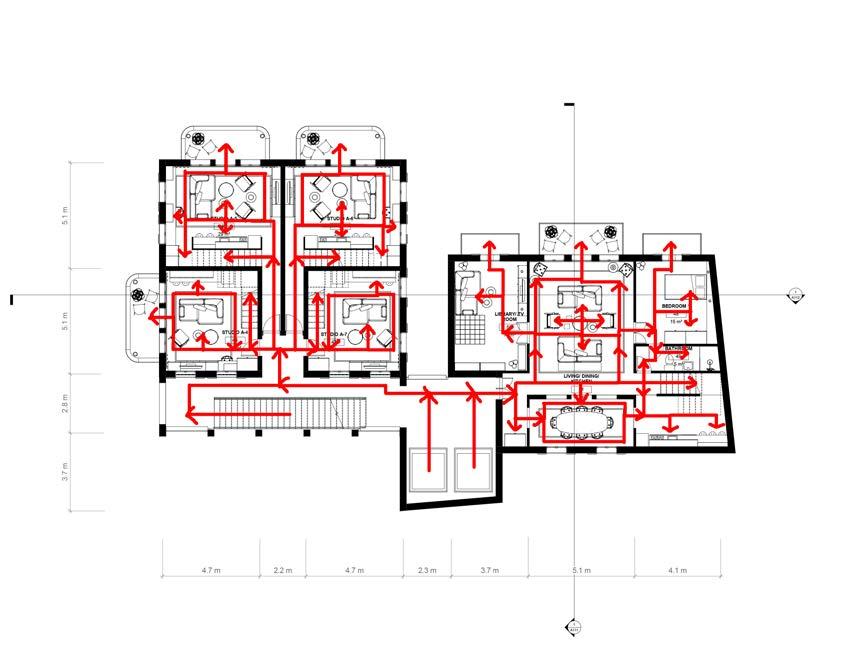

FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2 (same design plans for levels 2 to 4)

FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2- COLOURS (same design plans for levels 2 to 4)

155 154 A111 4.7 m 2.2 m 4.7 m 2.3 m 3.7 m 5.1 m 4.1 m 3.7 m 2.8 m 5.1 m 5.1 m 29 m² STUDIO A-5 44 29 m² STUDIO A-6 45 21 m² STUDIO A-4 46 21 m² STUDIO A-7 47 15 m² BEDROOM 48 m² BATHROOM 49 18 m² LIBRARY/ TV ROOM 50 63 m² LIVING/ DINING/ KITCHEN 51 1 50 Level 2- MONOCHROME

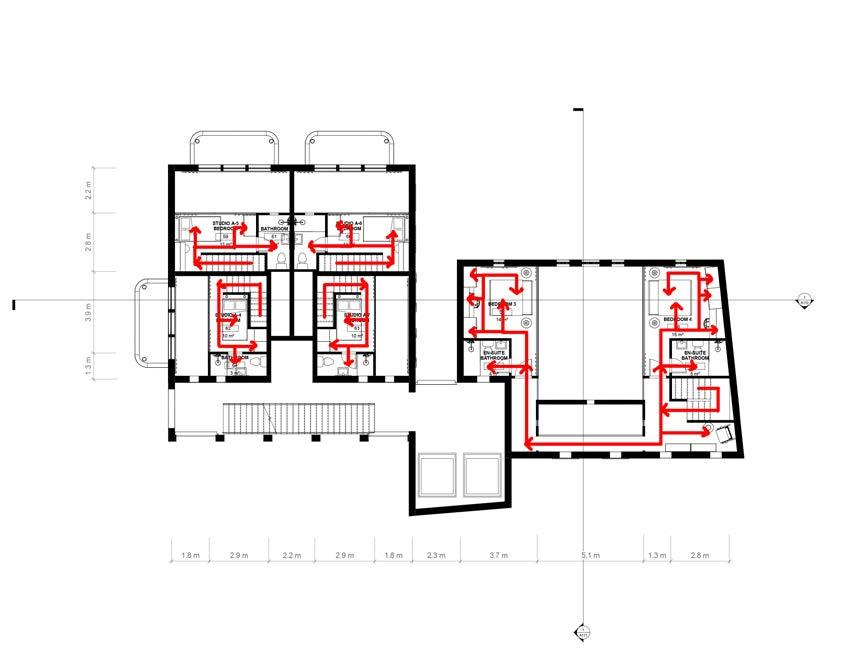

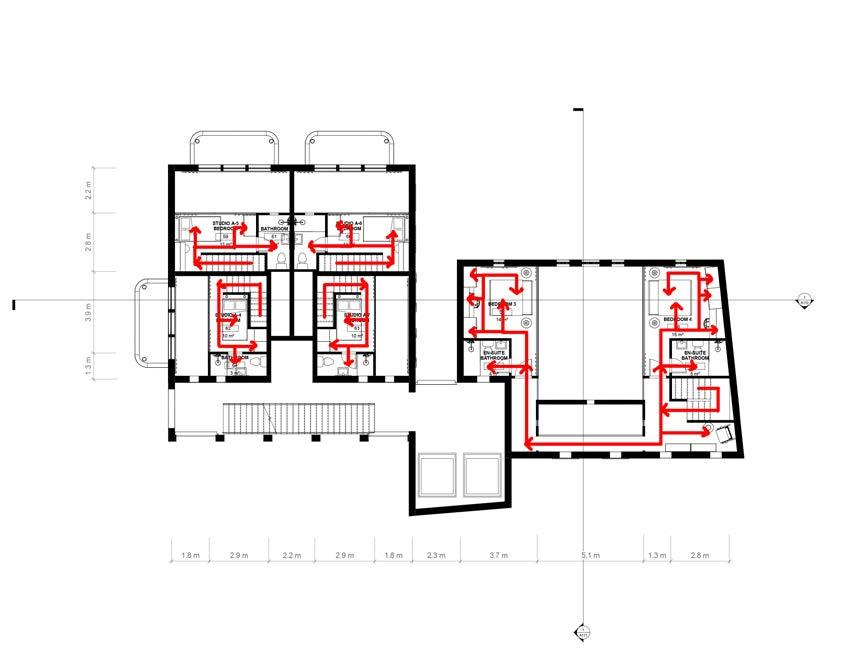

157 156 A111 1.8 m 2.9 m 2.2 m 2.9 m 1.8 m 2.3 m 3.7 m 5.1 m 1.3 m 2.8 m 2.2 m 2.8 m 3.9 m 1.3 m 14 m² BEDROOM 3 58 11 m² STUDIO A-5 BEDROOM 59 11 m² STUDIO A-6 BEDROOM 60 m² BATHROOM 61 10 m² STUDIO A-4 BEDROOM 62 10 m² STUDIO A-7 BEDROOM 63 3 m² BATHROOM 64 4 m² EN-SUITE BATHROOM 65 15 m² BEDROOM 66 5 m² EN-SUITE BATHROOM 67 50 MEZZANINE LEVEL 2- MONOCHROME FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2- MEZZANINE (same design plans for levels

to 4) FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 2- MEZZANINE-

design plans for levels

to 4)

2

COLOURS (same

2

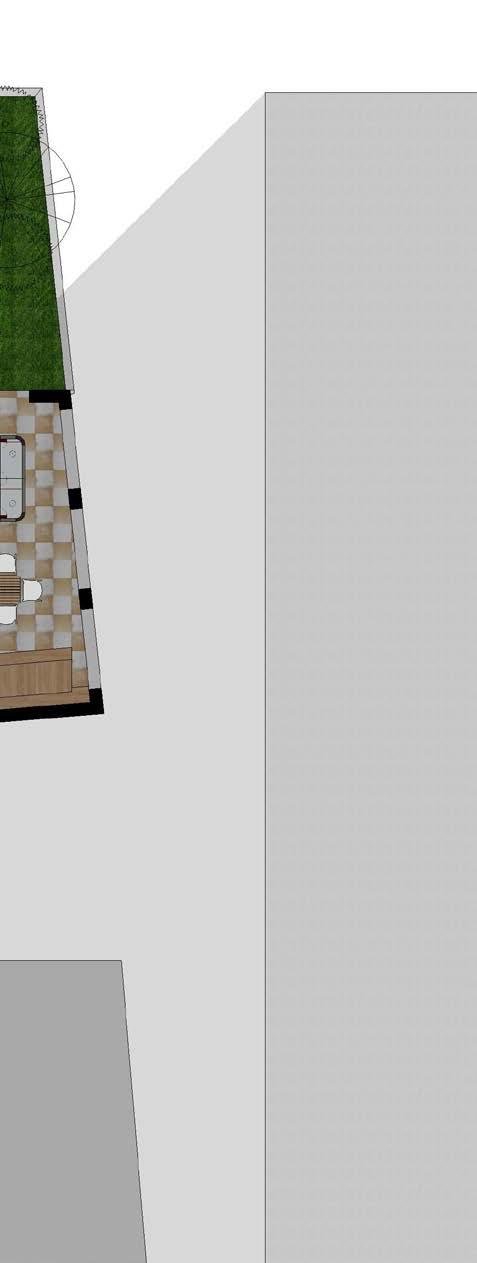

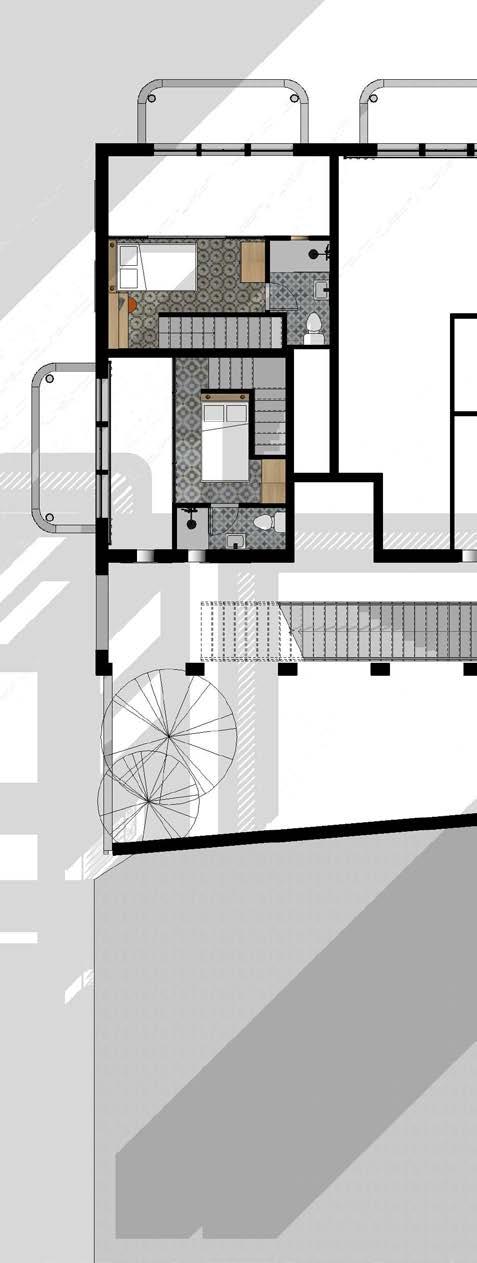

159 158 A112 A111 www.autodesk.com/revit MA- LEVEL 5MONOCHROME Project Name Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 5 FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 5- COLOURS

161 160 A111 1 50 MONOCHROME Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 1 50 MEZZANINE LEVEL 5- MONOCHROME FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 5- MEZZANINE FLOOR PLAN- LEVEL 5- MEZZANINE- COLOURS

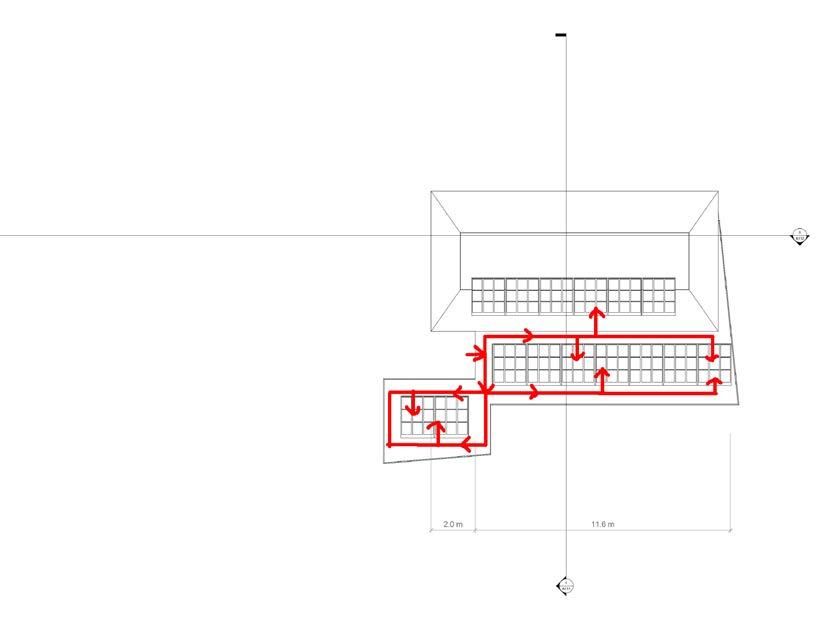

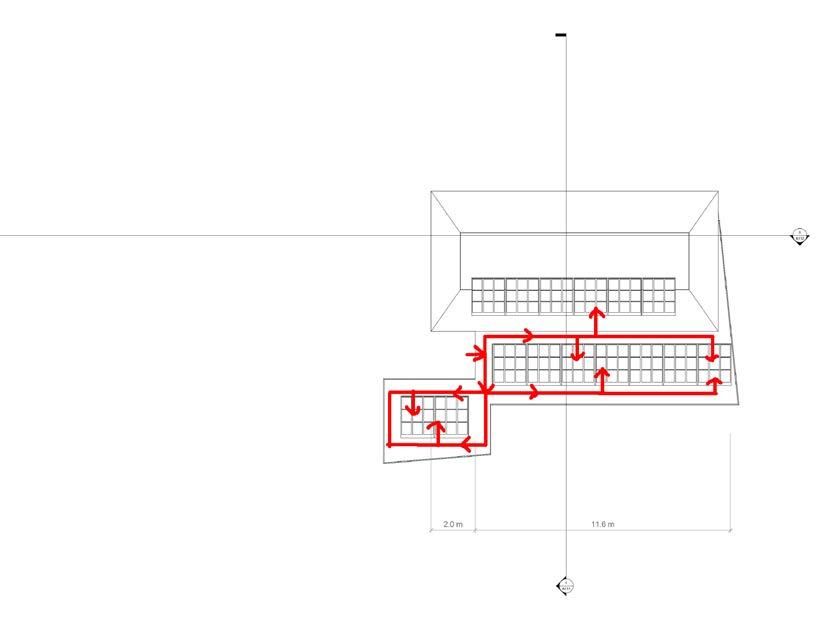

FLOOR PLAN- ROOF

FLOOR PLAN- ROOF- COLOURS

163 162 A111 2.0 m 11.6 m

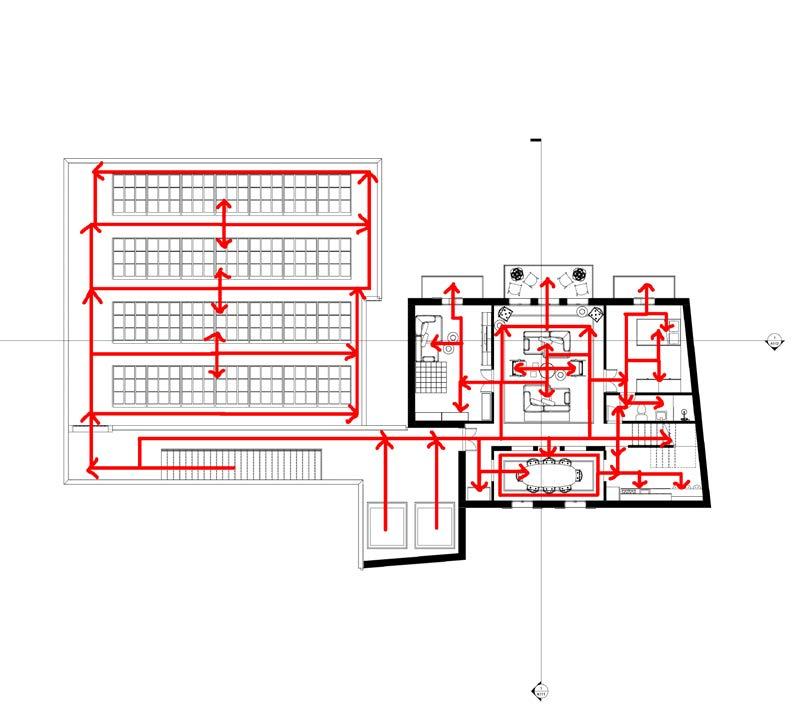

165 164 flow

ROOF

PARKING LEVEL 1 GROUND FLOOR LEVEL 1- MEZZANINE

LEVEL 2 TO 4 LEVEL 5 LEVEL 2 TO 4- MEZZANINE LEVEL 5- MEZZANINE

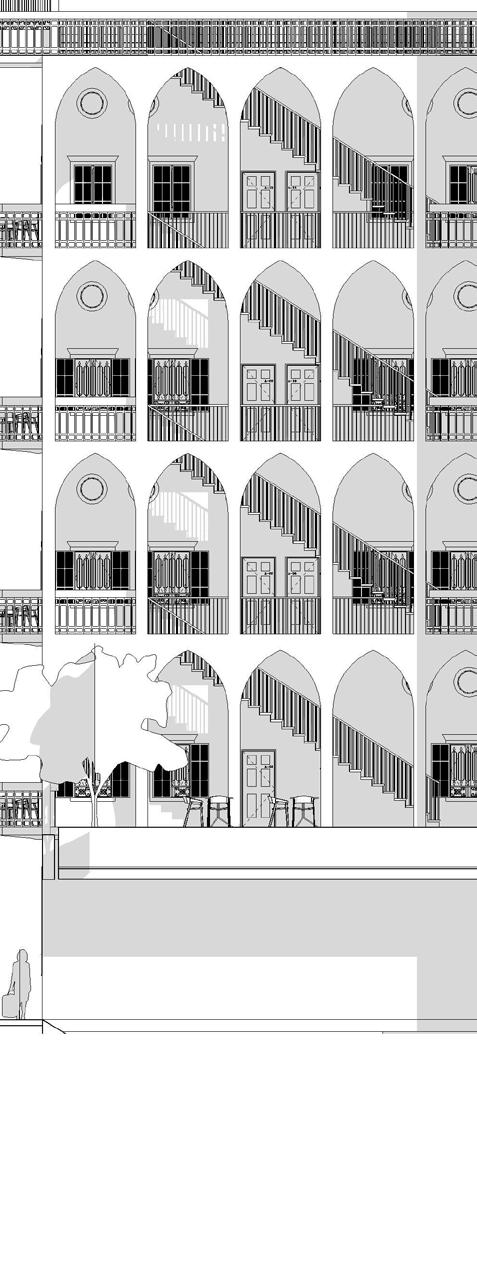

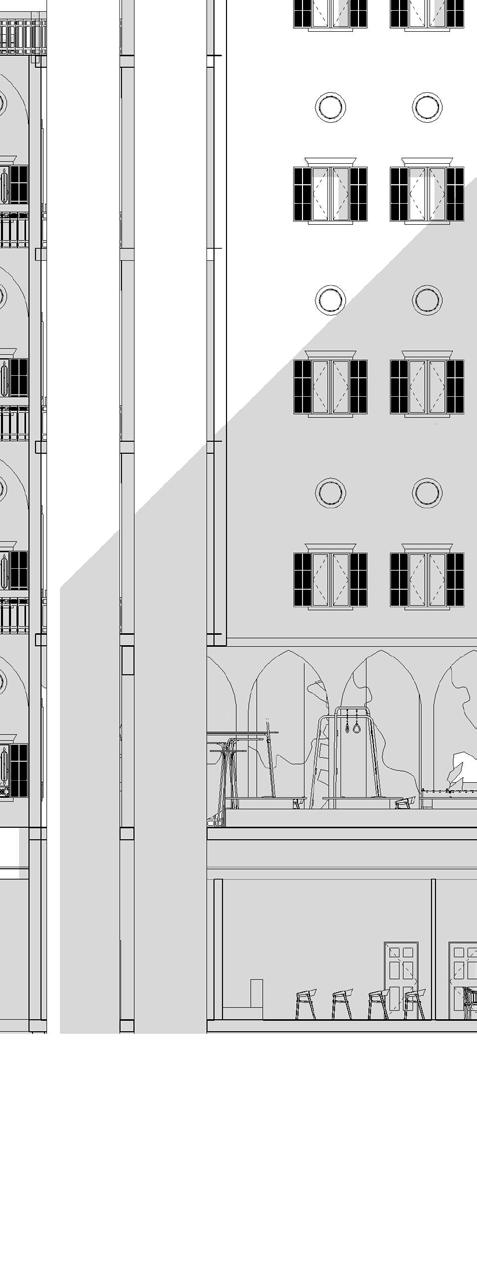

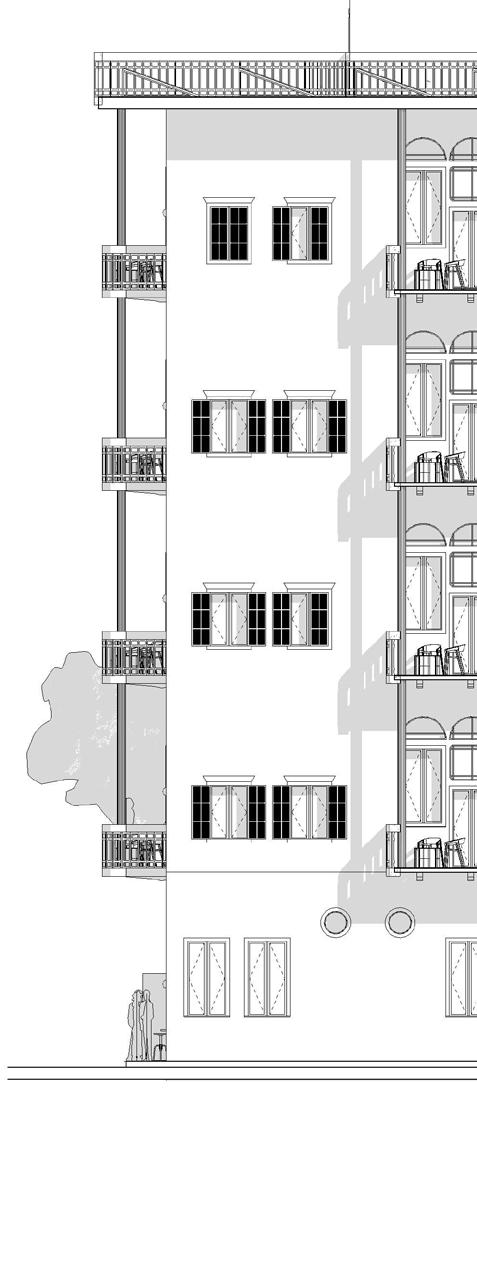

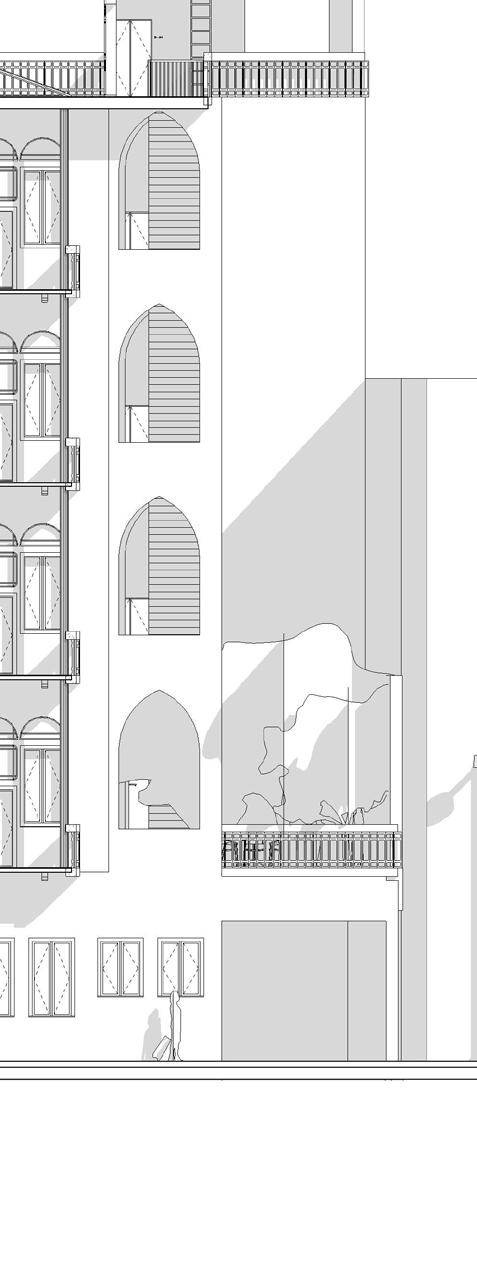

167 166 www.autodesk.com/revit Scale Date Drawn By Checked By Project Number Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone Consultant Address Address Address Phone 1 50 A111 COUPE TRANSVERSALE Owner Project Name Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 50 Section 12 CROSS SECTION seCTions Scale Date Drawn Checked Project 50 1 Section 12 CROSS SECTION - COLOURS

169 168 Address 1 50 LONGITUDINALE Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 50 1 Section 11 LONGITUDINAL SECTION 1 50 Section 11 LONGITUDINAL SECTION- COLOURS

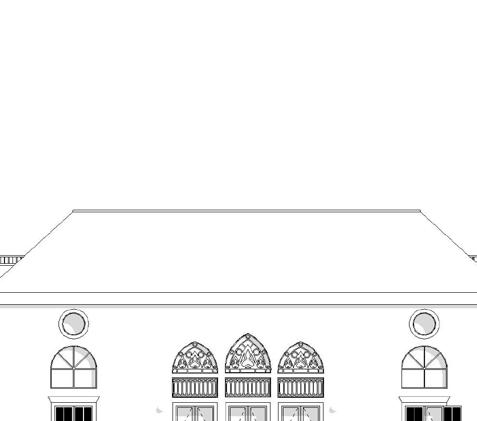

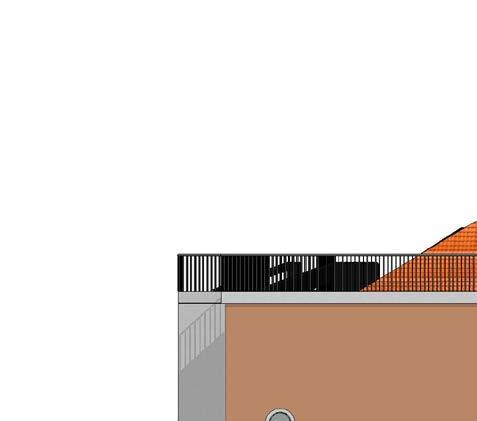

171 170 www.autodesk.com/revit Address A109 VUE FACADEOwner Project Name Project Number No.DescriptionDate FRONT/ NORD VIEW eleVaTions FRONT/ NORD VIEW- COLOURS

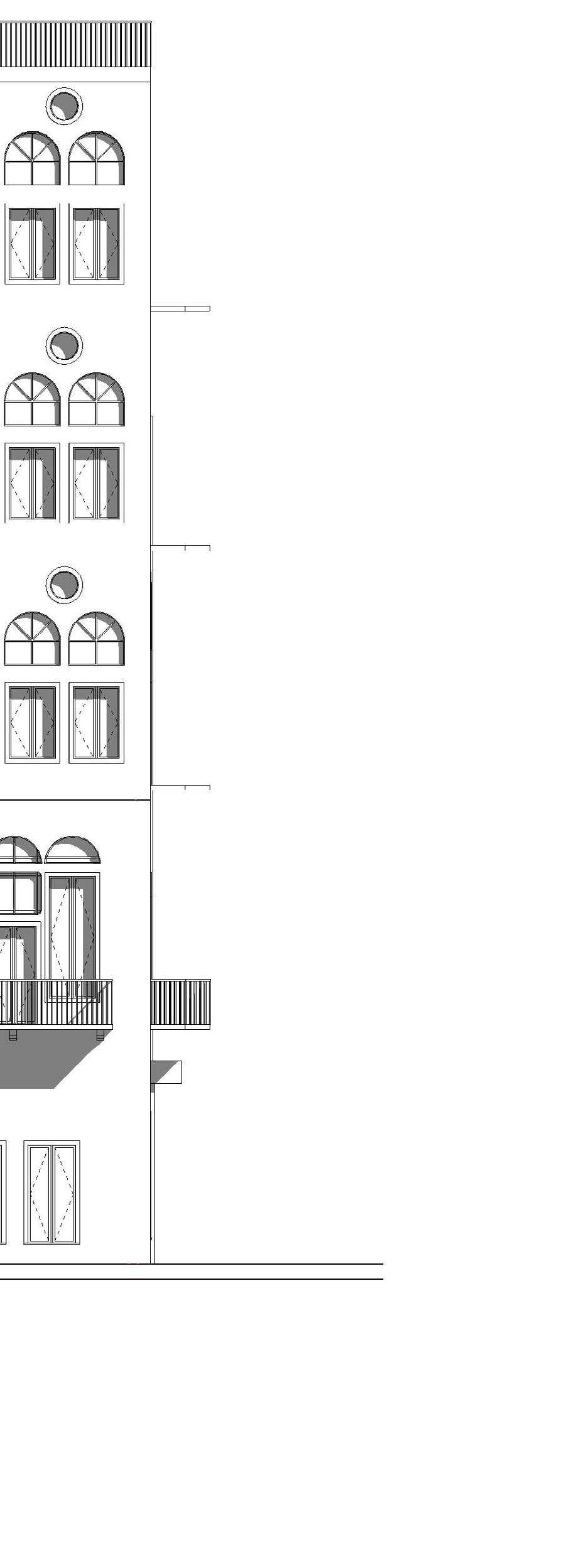

173 172 Address 1 : 50 Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 1 50 Section 10 BACK/ SOUTH VIEW BACK/ SOUTH VIEW- COLOURS

175 174 Address MA- WEST VIEW Checker Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 1 50 Section SIDE/EAST VIEW 50 1 Section 9 SIDE/ EAST VIEW- COLOURS

177 176 Address 1 50 MA- EAST VIEW Checker Author Issue Date Project Number No.DescriptionDate 50 Section SIDE/WEST VIEW 50 Section SIDE/ WEST VIEW- COLOURS

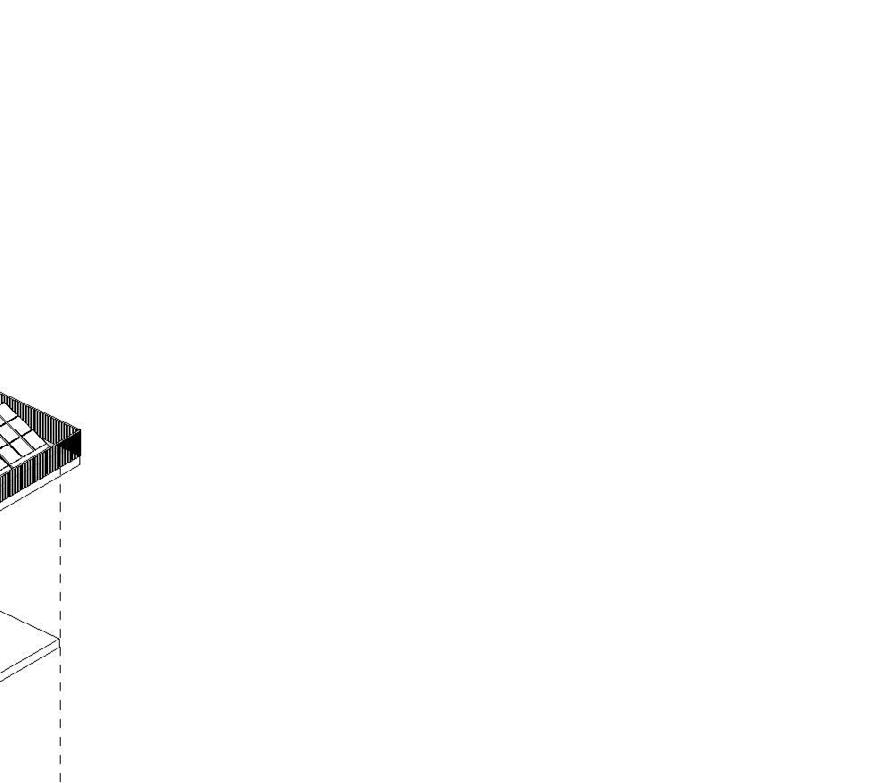

axonoMe TriC Views

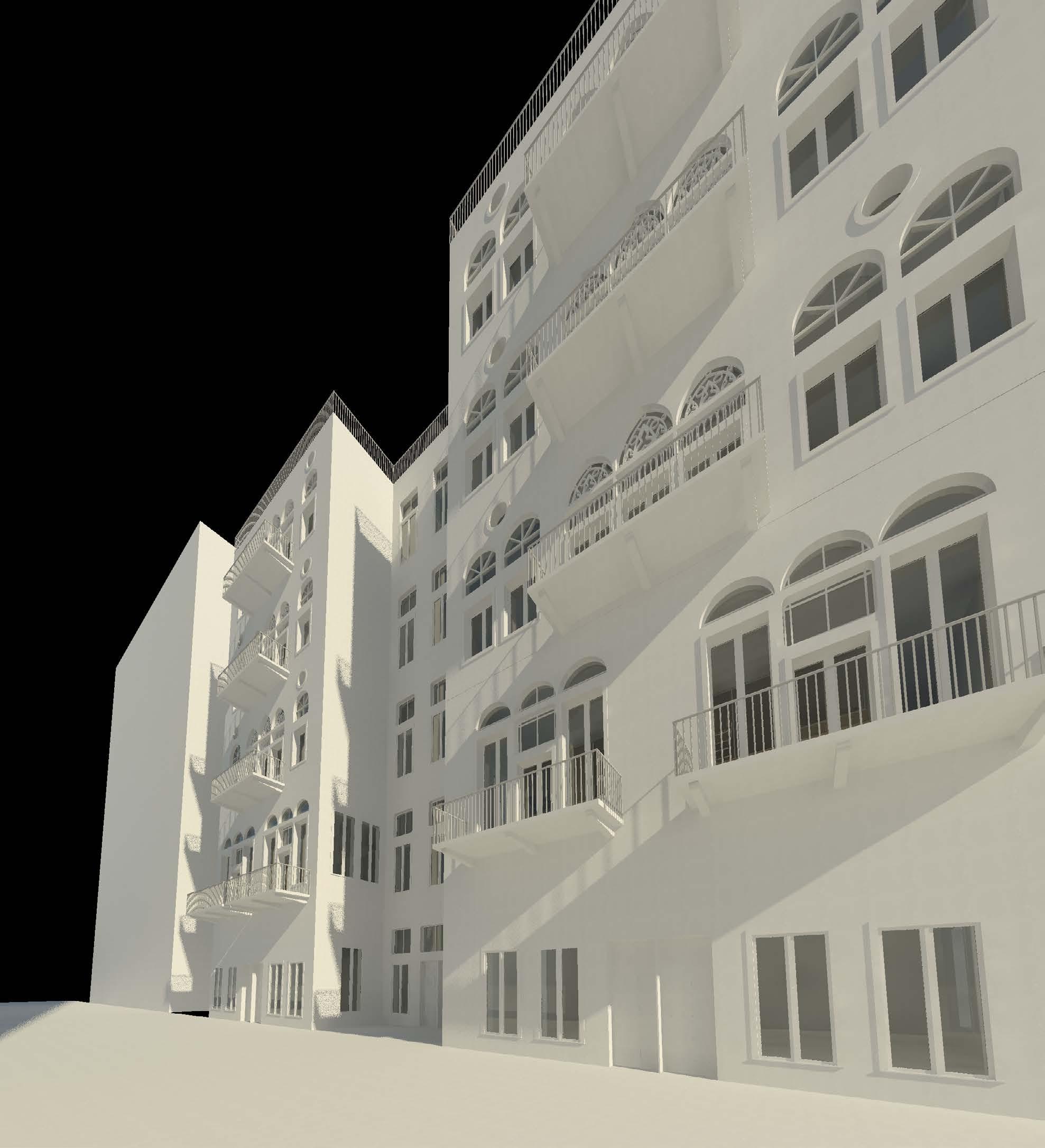

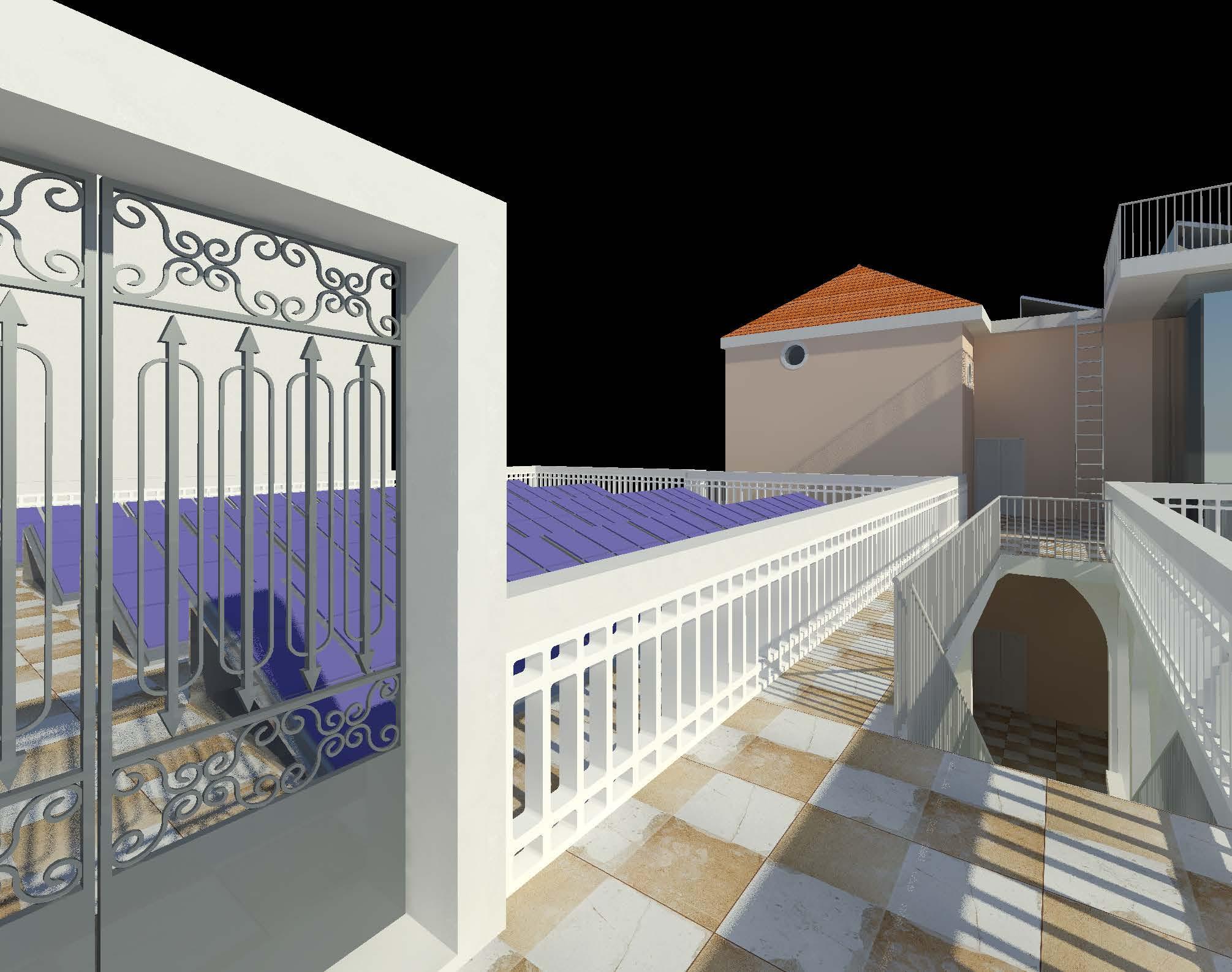

179 178 2- 3D

RENDERINGS

VIEWS AND

AXONOMETRIC VIEW- RENDERED

EXPLODED ANOMOMETRIC VIEW

rendered Views BUILDING VIEW

BUILDING VIEW- BAR- NIGHT

CAFE VIEW

EXHIBITION SPACE VIEW

191 190

MAIN GARDEN VIEW

MAIN COURTYARD VIEW

195 BACK GARDEN VIEW

196 STAIRS/ BLOCK A PASSAGEWAY VIEW

APARTMENT - LIVING ROOM VIEW

201 200 APARTMENT- BALCONY VIEW

203 APARTMENT- DINING ROOM VIEW

205 204

APARTMENT- TV/ LIBRARY ROOM VIEW

APARTMENT- MEZZANINE VIEW

209 208

BEDROOM VIEW

APARTMENT-

STUDIO- LIVING ROOM VIEW

212 STUDIO- LIVING ROOM/ KITCHEN VIEW

215

STUDIO- BEDROOM VIEW

217 216 STUDIO- BATHROOM VIEW

219

STUDIO- BALCONY VIEW

221 ROOFTOP VIEW

whad does “sobhiye” Mean?

Sobhiye doesn’t have a literal translation in English, because it is a concept born in the Middle-East. A sobhiye is sharing a morning coffee and cigarettes with a group of women or men (mainly women)and friends and neighbors. But it is not just restricted to that, it’s also a gossiping session over a freshly brewed pot of coffee. It is important to know that Lebanese have coffee multiple times a day, but only the morning coffee is called a sobhiye, because it comes from the word Sabah which means morning.