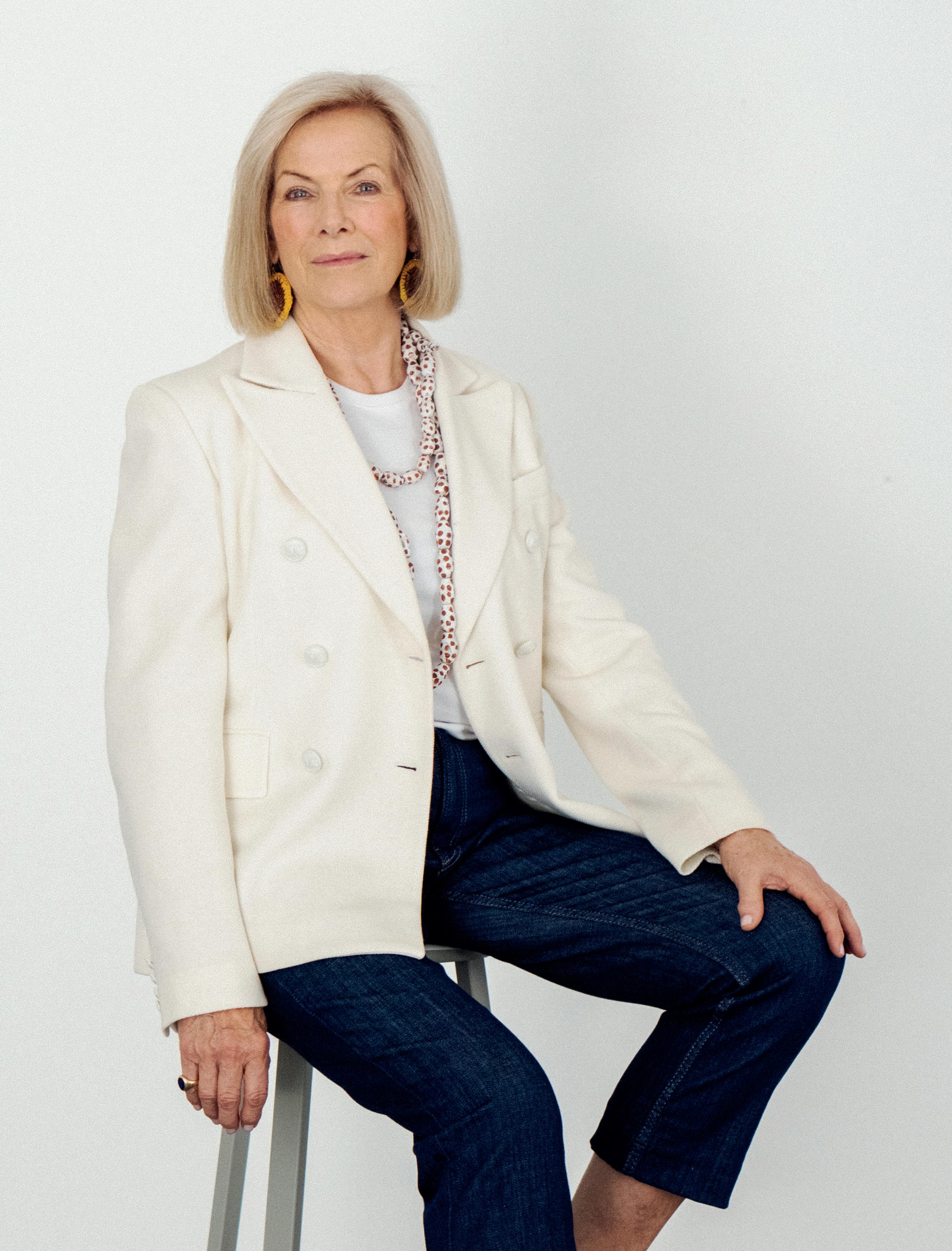

curatorial commentary by julius killerby

JULIUS KILLERBY IS AN ARTIST AND THE ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF JGM GALLERY LONDON. HE HAS PREVIOUSLY HELD POSITIONS AT THE AUSTRALIAN PAVILION (2022 VENICE BIENNALE), METRO GALLERY, SCOTT LIVESEY GALLERY AND FLINDERS LANE GALLERY IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA. WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF HIS OWN PRACTICE, HE HAS EXHIBITED AT THE ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES, THE ART GALLERY OF BALLARAT AND GEELONG GALLERY, AMONGST OTHER SPACES. HIS WORK FOCUSES ON THE PSYCHOLOGICAL RIPPLE EFFECTS OF CERTAIN CULTURAL AND SOCIETAL TRANSFORMATIONS.

Julius Killerby, 2024. Image courtesy of JGM Gallery. 9 10

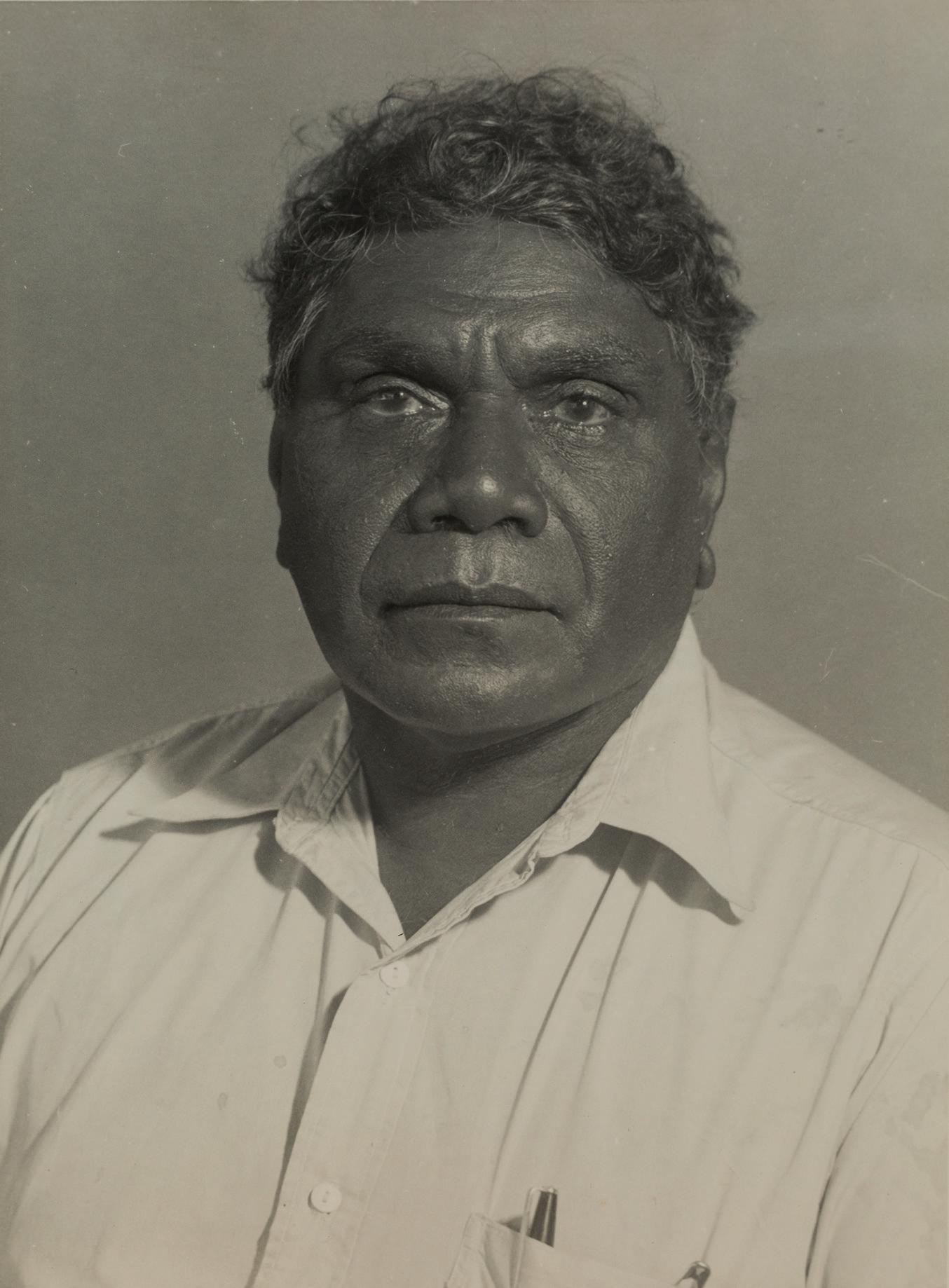

HUBERT PAREROULTJA was born in 1952 on the banks of the Finke river. The local Indigenous people, the Arrernte, call this place Ntaria. It was in this area of central Australia that, almost 80 years earlier, Lutheran Missionaries established the Hermannsburg Mission Before that, the land had been lived on continuously by the Arrernte for more than 30,000 years. By the time of Pareroultja’s birth, both the Mission and the Arrernte had endured and, for the most part, lived together in harmony.

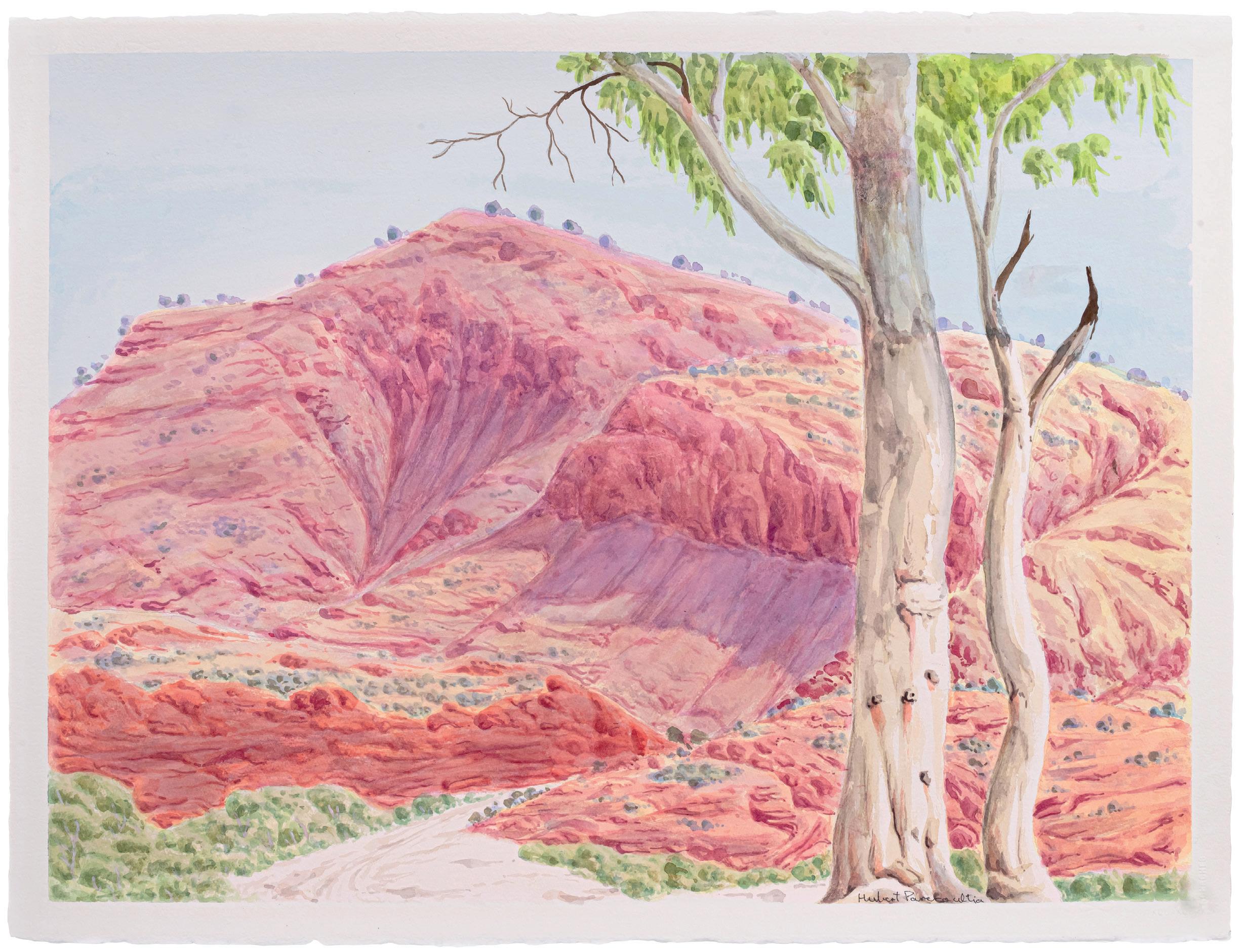

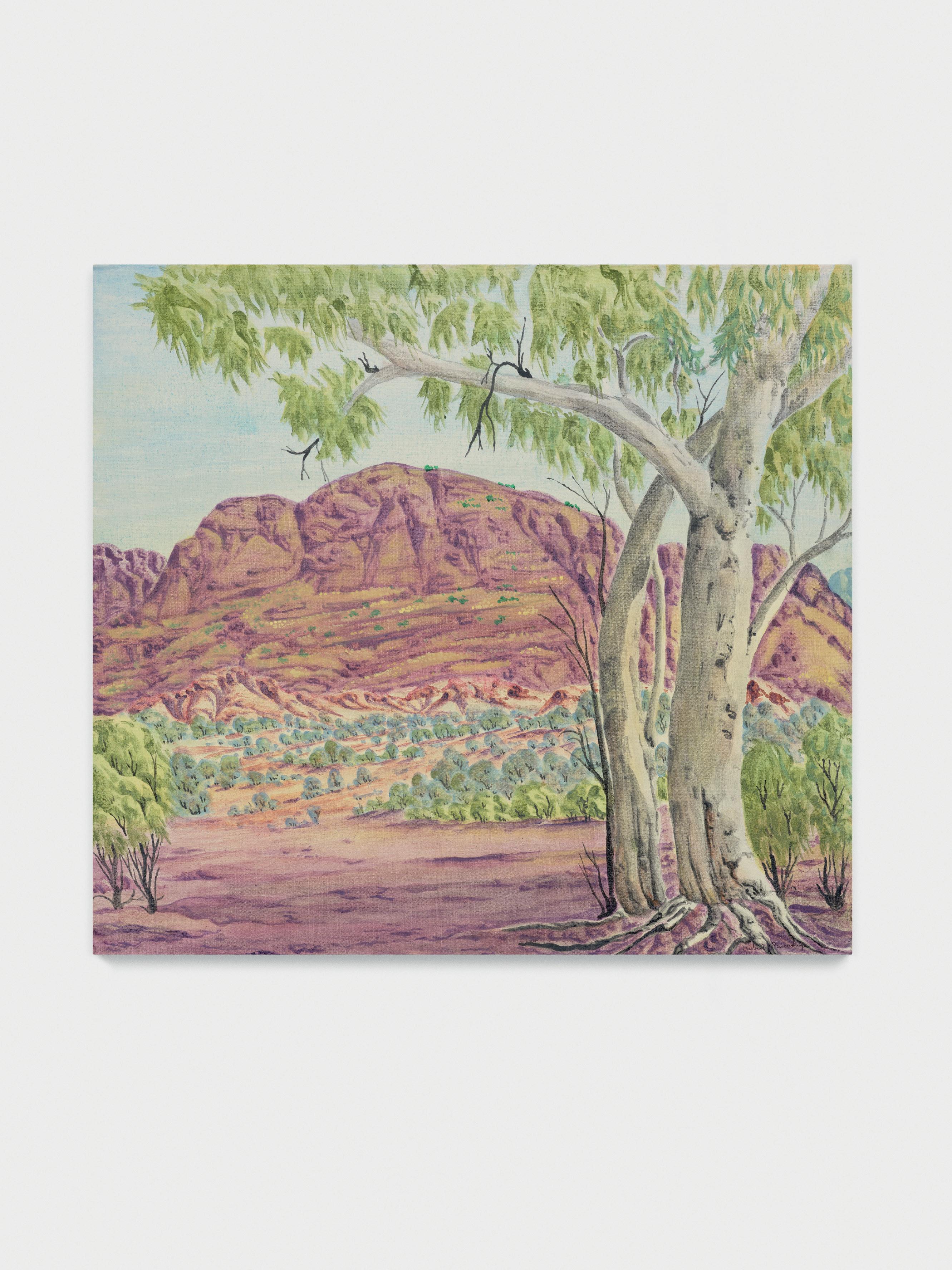

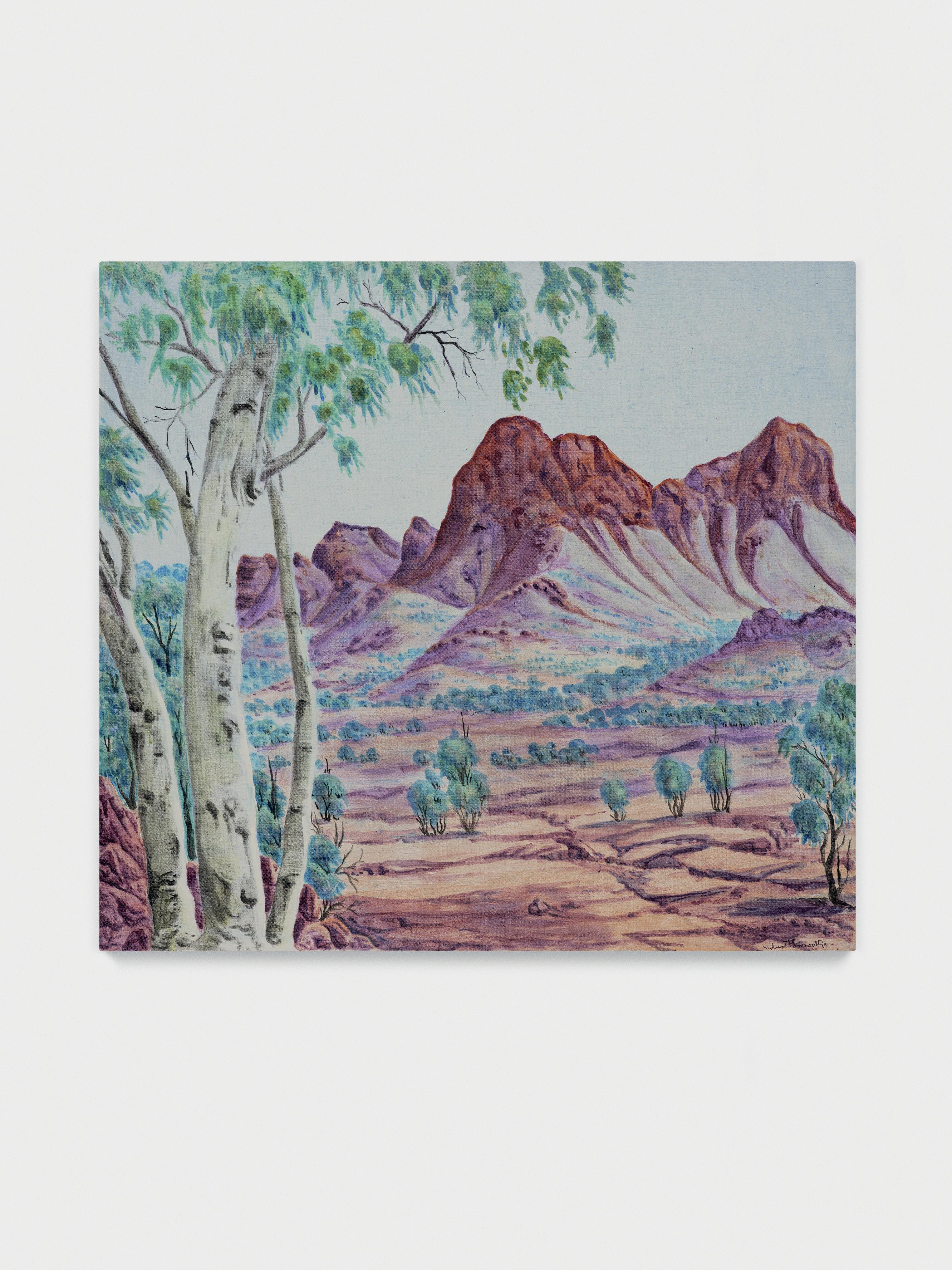

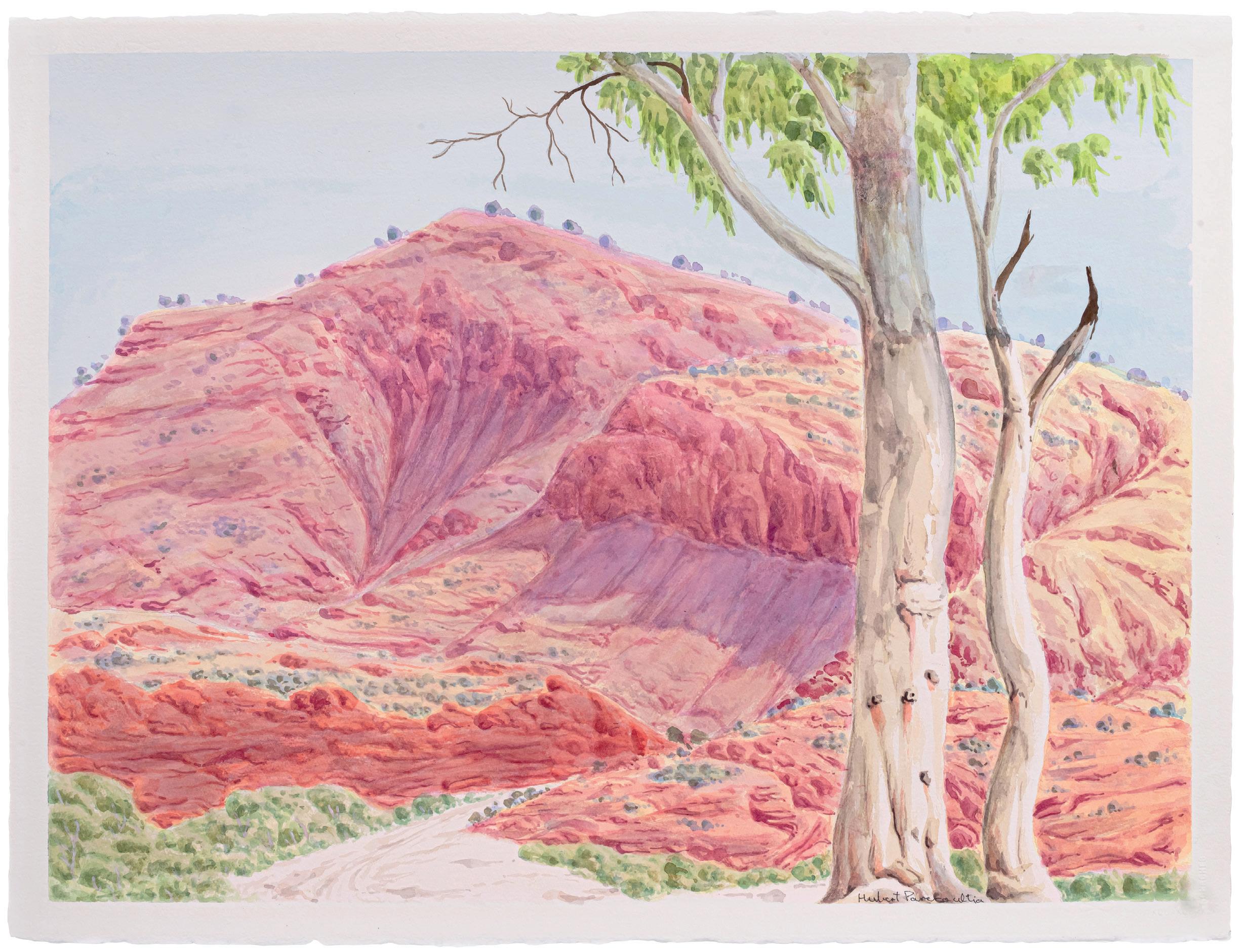

One legacy of this coexistence is the Hermannsburg School, an artistic movement and style of painting pioneered by a non-Indigenous Australian watercolour artist, Rex Battarbee, and Pareroultja’s great grandfather's second wife's grandson, Albert Namatjira. Having seen Battarbee’s paintings in 1934, Namatjira approached the artist, asking for artistic instruction and advice. Battarbee obliged, and Namatjira then rapidly absorbed and developed his own representational style, producing works that now stand as archetypes of the Hermannsburg School. Pareroultja's father and uncles, in turn, received artistic tuition from Namatjira, as did Namatjira's children. Although, of course, each exponent has their own visual lexicon, what unites almost all Hermannsburg practitioners is a hybridity of one-point perspective European landscape painting, and the earth-bound philosophy of the Arrernte. The aesthetic – luminous, almost hallucinatory in its effect, but always representational – is emblematic of the cultural exchange that took place around the Hermannsburg Mission in the early to mid-twentieth century. No known painting by an Indigenous Australian had, until this moment in the 1930s, utilised the one-point perspective of European landscape painting, a compositional framework which eyes adapted to the Western canon perhaps take for granted. Paintings such as Pareroultja’s Ghost Gums & James Range reconcile the perspectives – conceptual and compositional – of two different cultures, and in that hybridity, produce something unique to the Contemporary Indigenous Art Movement.

Within the Hermannsburg School, what perhaps distinguishes Pareroultja most is his palette, and the effects it creates. Unlike artists such as Jillian Namatjira or Herbert Raberaba, who often painted with dark hues of orange, yellow and brown, Pareroultja brightens his tones, representing the land with, amongst other colours, light greens, yellows and blues. Shadows are often painted with variations of these vibrant colours, which adds to the descriptiveness of these pictures, revealing aspects of the land that would otherwise remain obscured and in darkness. The consequent sensation for the viewer is a heightened sense of one’s surroundings, as though Pareroultja’s brush illuminates more than the naked eye can perceive. This combination of colours also contributes to a sense of life and buoyancy, which Pareroultja retains despite much of the hardship he has endured. In Ken McGregor’s recent biography of Pareroultja, the artist describes how the Hermannsburg school principal, Bob Arnold, would whip him if he or any of the other students misbehaved:

“In junior school we would all march to assembly to the beat of a drum and stand in straight lines and sing God Save the Queen.” When it was Hubert’s turn to beat the drum, he would speed the beat up on purpose and have children skipping and falling all over the place, the teachers were not at all amused. “I got into so much trouble playing the drums but I thought it was funny. In the afternoons we would clean the classroom and showers and toilets and when we left school to go back home in the evening, we would change back into our camp clothes.”

Suggestive of Pareroultja's stoicism in the face of such hardship, however, is McGregor's statement that:

“The many forms of violence... Hubert has witnessed during most of his life have not in any way filtered into his paintings.”

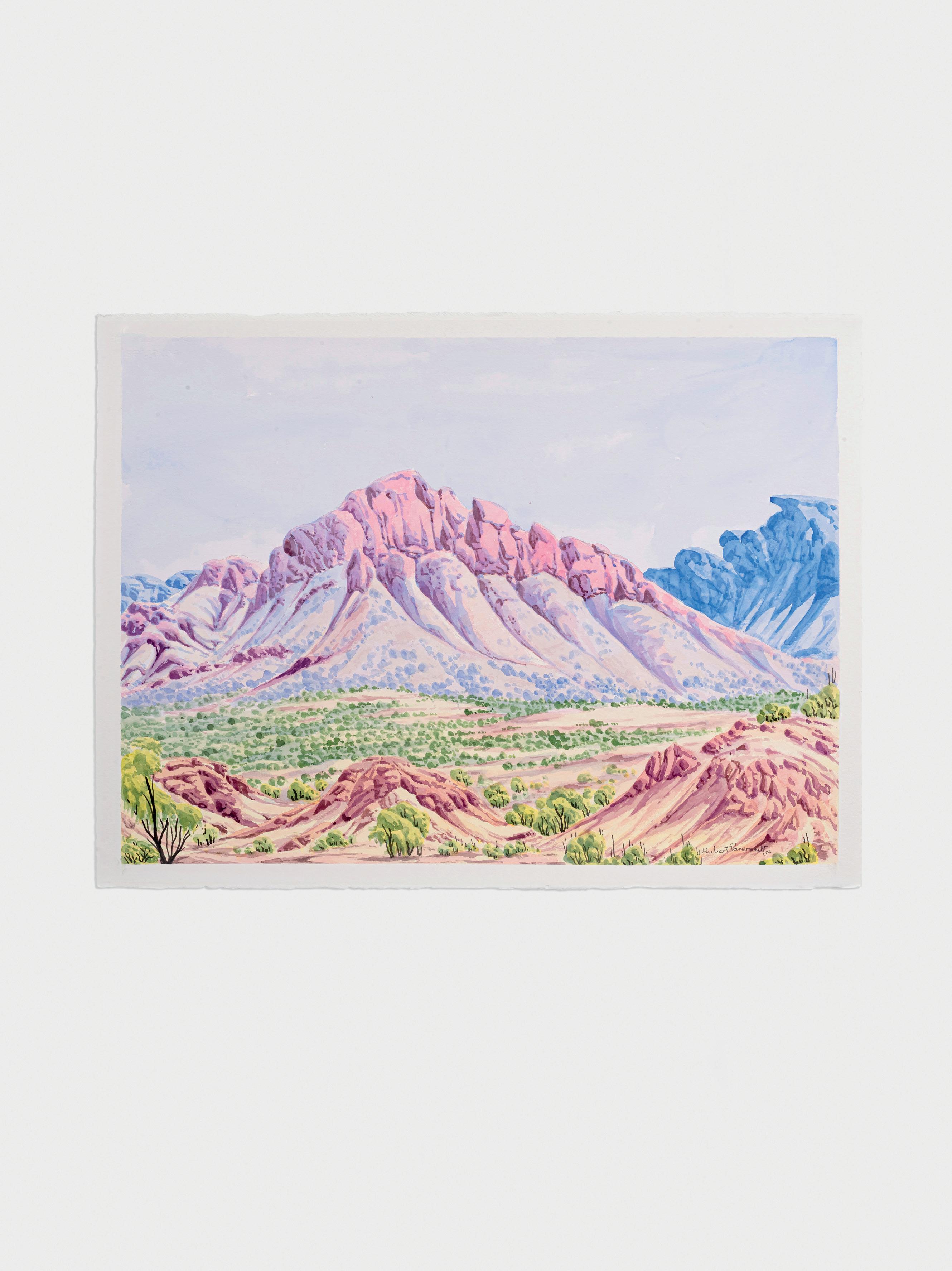

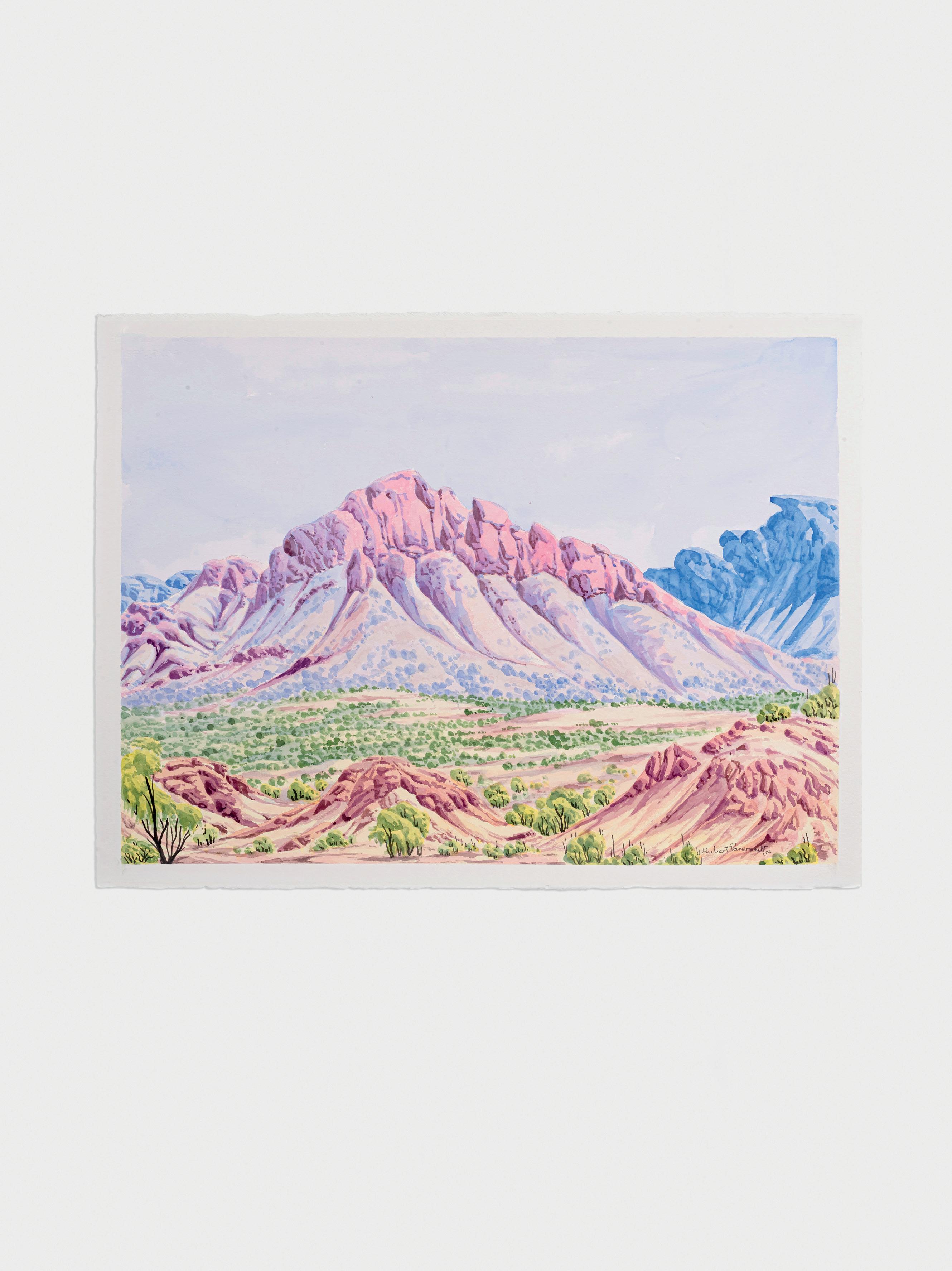

Using this vibrant palette, Pareroultja paints with a masterful economy of brushstrokes and, for the most part, without making preliminary drawings. Consequently, forms lack sharp definition, imbuing the pictures with a lucidity and dynamism that mimics the transient nature of the landscape itself. This is perhaps most clear in the painting, Mount Hermannsburg in which the terrain itself seems to ebb and flow. At the crest of the central mountain, watery pink pigment blurs into the sky above it, and at its base, crimson marks seep into the foregrounded tree. Definition often conveys stagnancy and inertia, whereas this indistinct representative style animates the land and underscores its vitality. The effect is reinforced by the accentuated curve of branches and the angling of horizon lines off their axes, aesthetic decisions which convey a conception of the

land as a living and, within the context of Arrernte culture, familial part of the artist’s life.

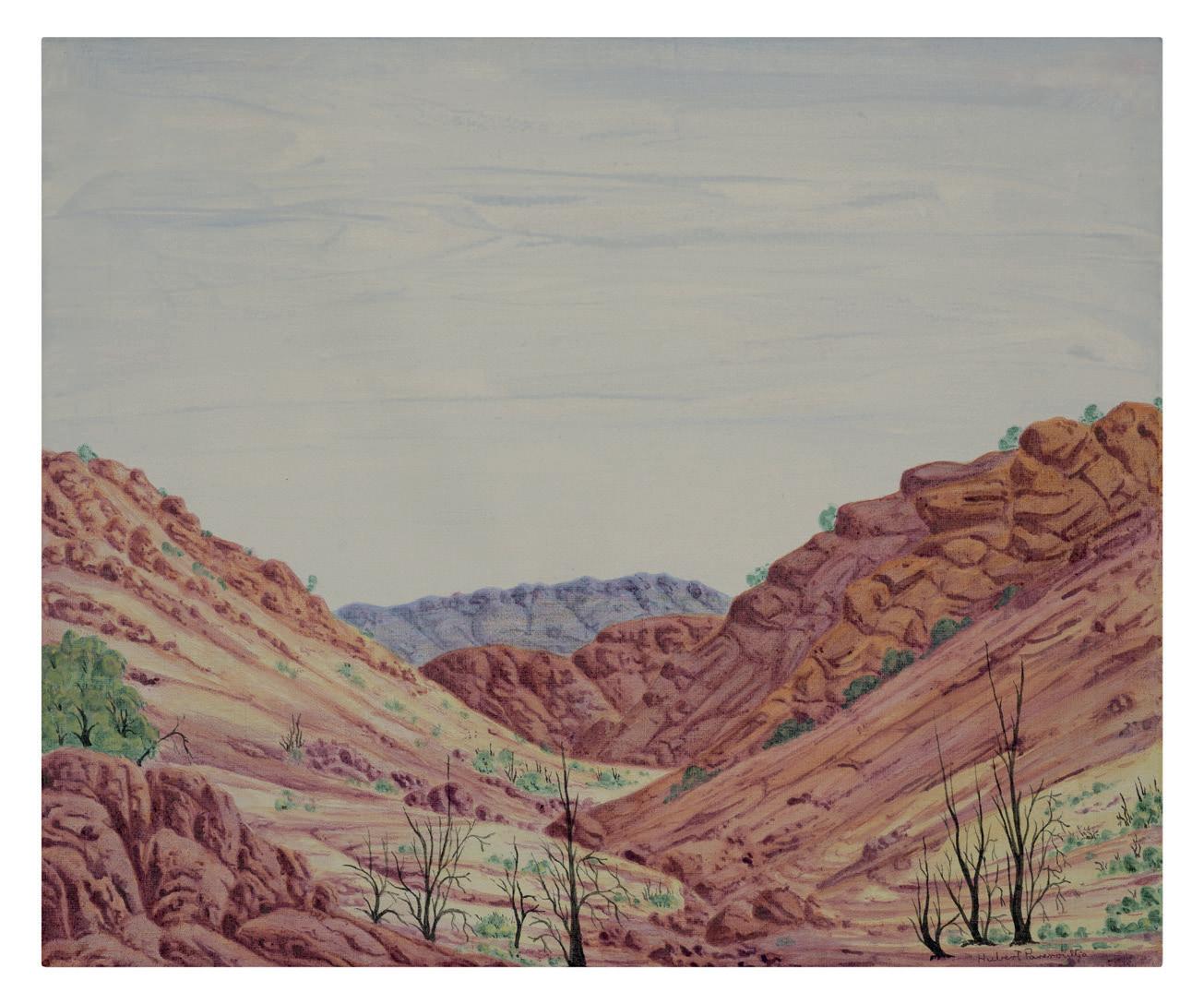

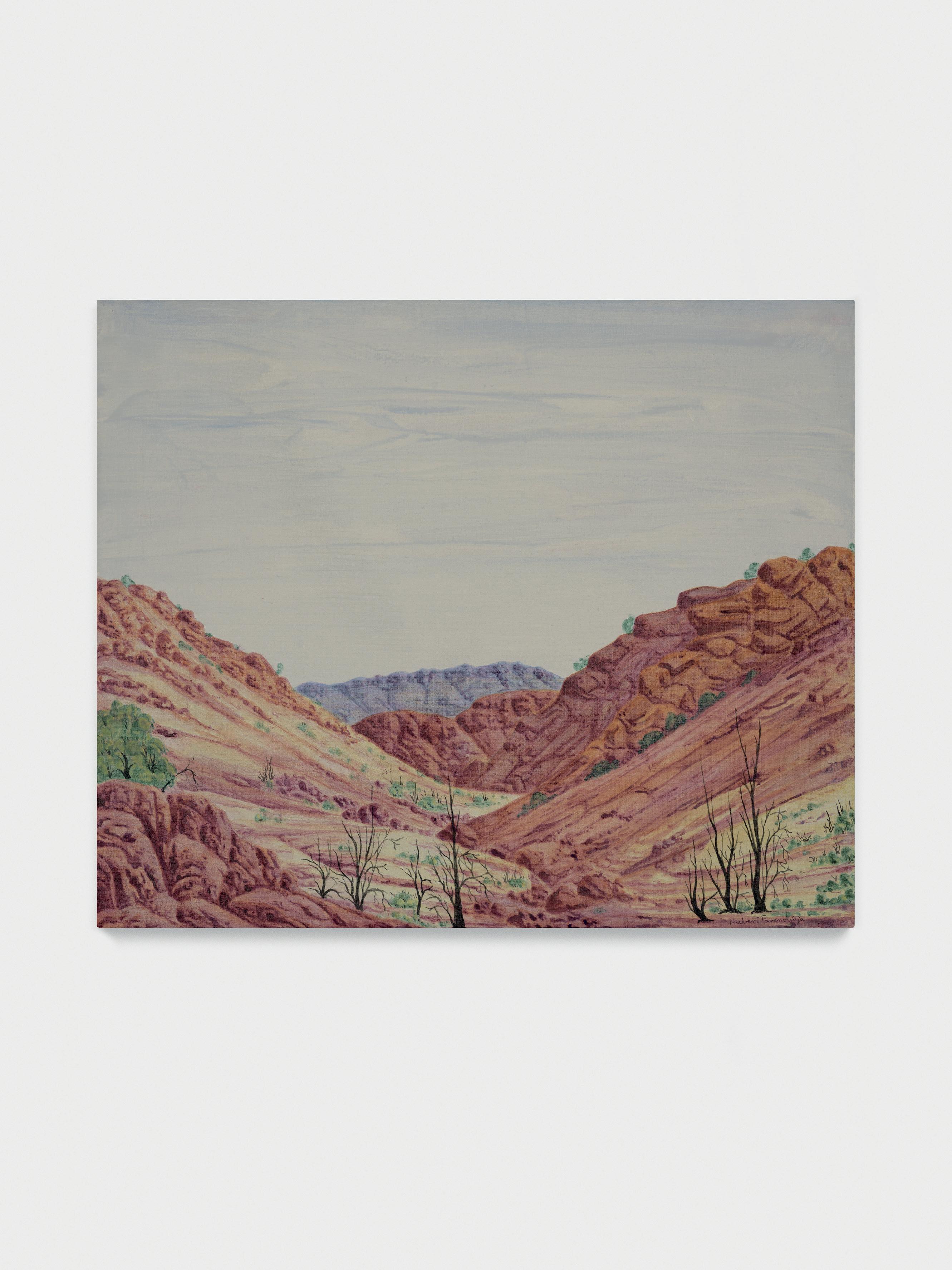

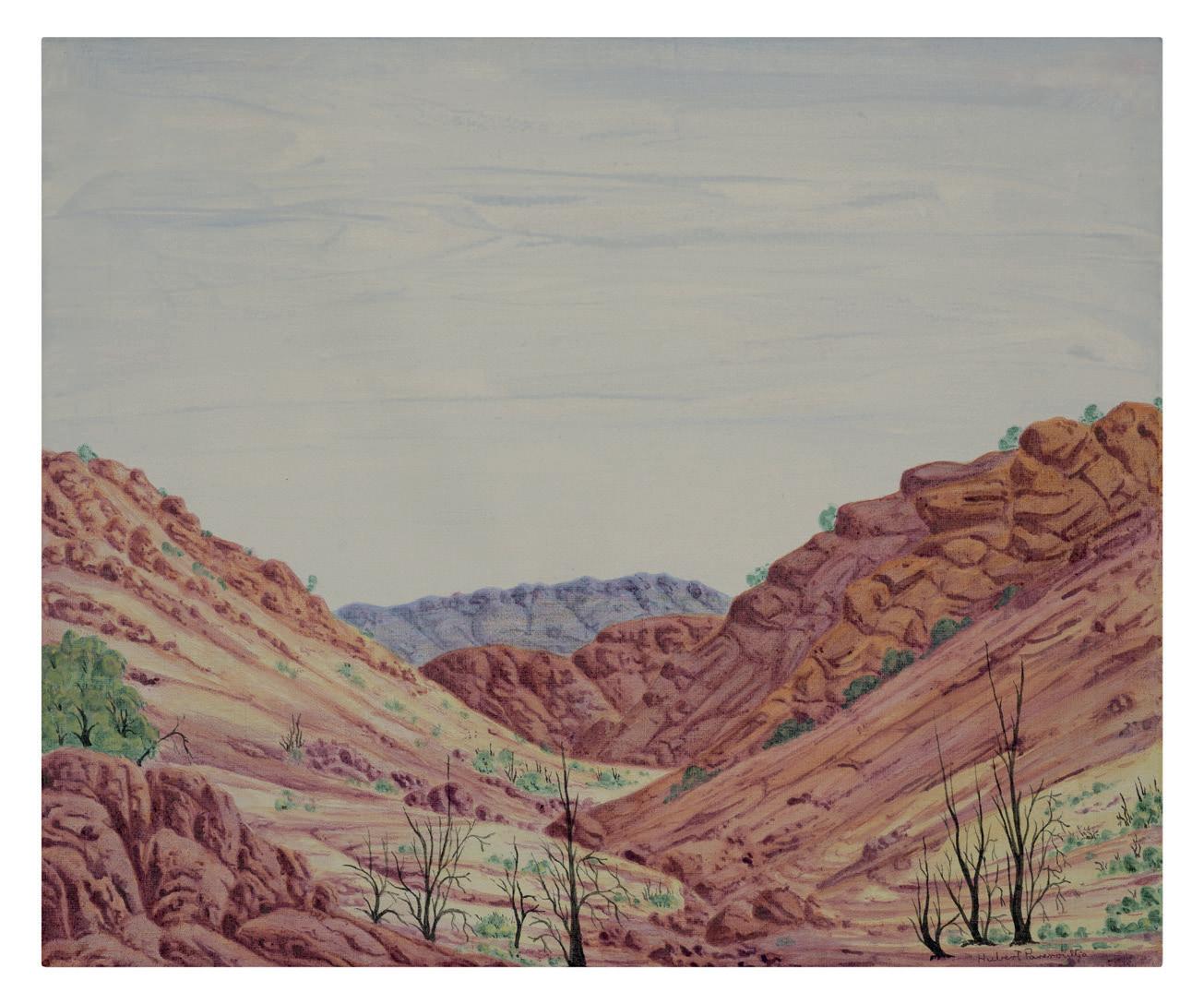

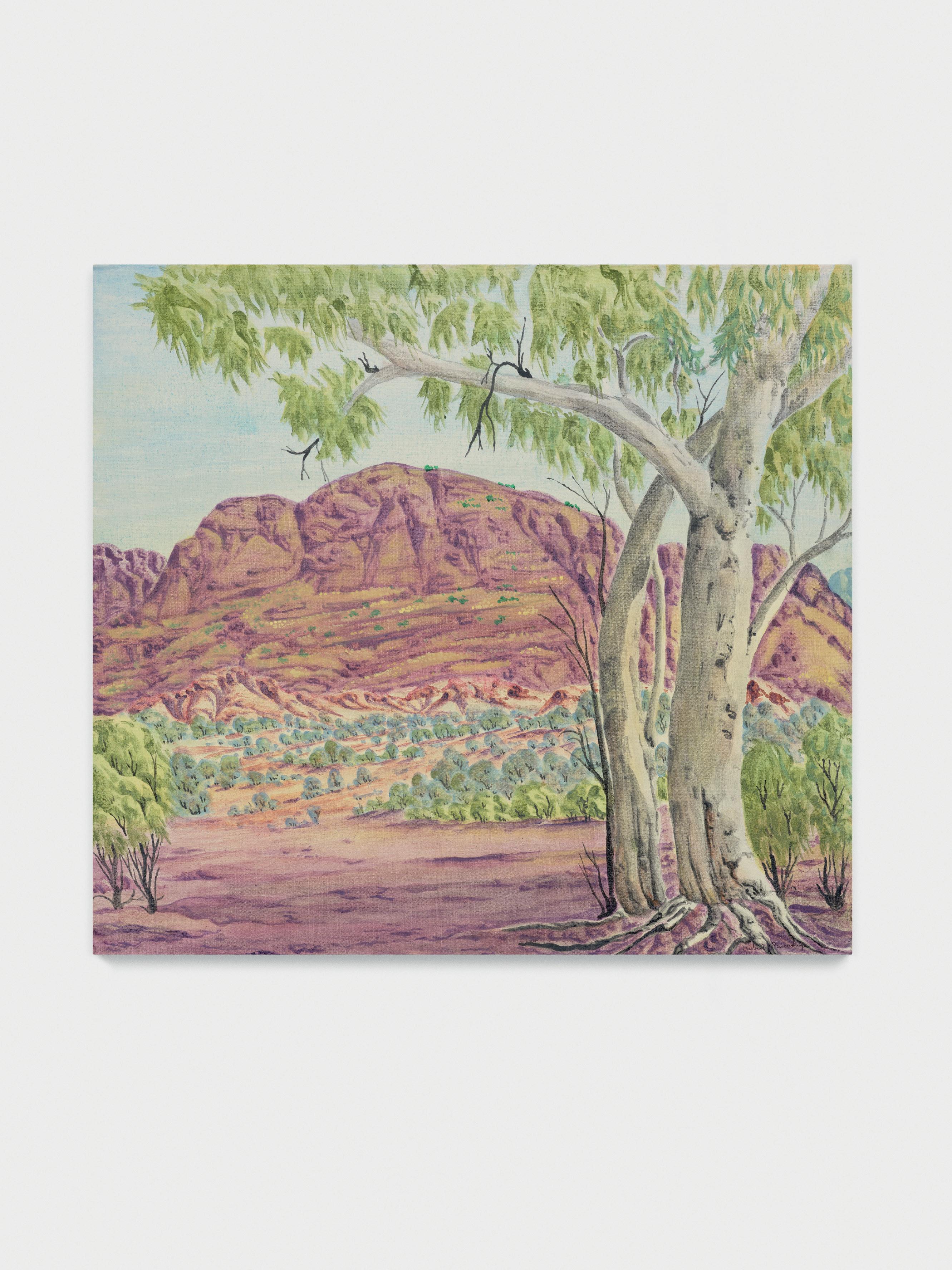

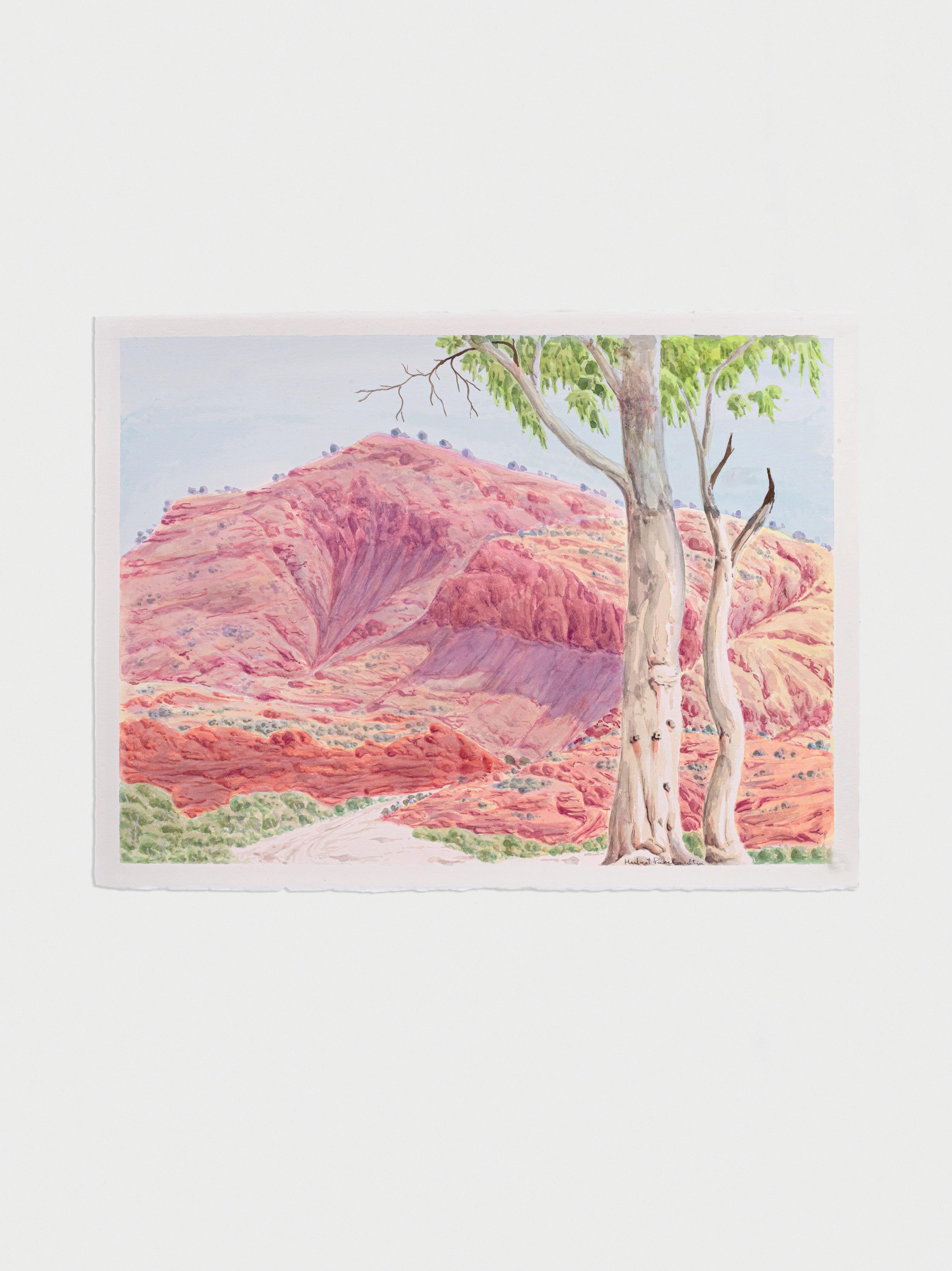

One of the exceptions to the vibrancy of Pareroultja's palette is Looking Towards the James Range, an acrylic depiction of a winding valley path, painted in subdued reds, browns and blues. It is uncertain whether the muted colours reflect morning or late afternoon light. What is clear, however, is that the landscape is in a process of transformation. We see this in the shift from yellow to red as the left slope meets its opposite hill; in the trees, some bare and others flourishing; and the pale blue vapours, which hint at coming rain. Whether or not Pareroultja intended this landscape as a metaphor for his life is unknown, but comparisons between the two seem inevitable: a path forged between two opposing hills, for instance, can be interpreted as a metaphor for a life lived between two worlds, with “... one foot in the Lutheran ways and one foot in the Arrernte culture” or as Pareroultja himself puts it, living “... both ways...”

This connection between the artist and the natural world is reinforced by the exhibition title, which references a large, ground-dwelling bird from Pareroultja's Dreaming. He says that “I hear the sound of the curlew at night on my country... the birds make an unusual sound. They call each other together and celebrate and dance like a sacred ritual and it reminds me of the old Arrernte People who would dance ceremony, which may take the form of a Corroboree.” This underscores the anthropomorphic lens through which Pareroultja views the natural world, but it also situates an interpretation of his paintings within a temporal framework. The early morning or late afternoon light in Looking Towards the James Range, for example, elicits a sense of either anticipation for the nocturnal bird's arrival, or retrospection following its departure.

Weer Loo - e Cry of the Curlew crystallises the artistic exchange that took place around the Hermannsburg Mission in the early to mid-twentieth century, and represents a continuation of that cross-cultural legacy. That it is Pareroultja's first exhibition on the European continent thus makes it all the more significant. Just as Battarbee showed his work to Namatjira, so too does Pareroultja demonstrate his artistic facility and the spirit of the Arrernte to audiences here in London.

REFERENCES:

Ken McGregor, When the Rain Tumbles Down in July (Badger Editions, 2024), 9.

Ibid, 17.

Ibid, 13.

Hubert Pareroultja & Ken McGregor (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Ken McGregor, When the Rain Tumbles Down in July, (Badger Editions, 2024), 125.

Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

1 2 12 11

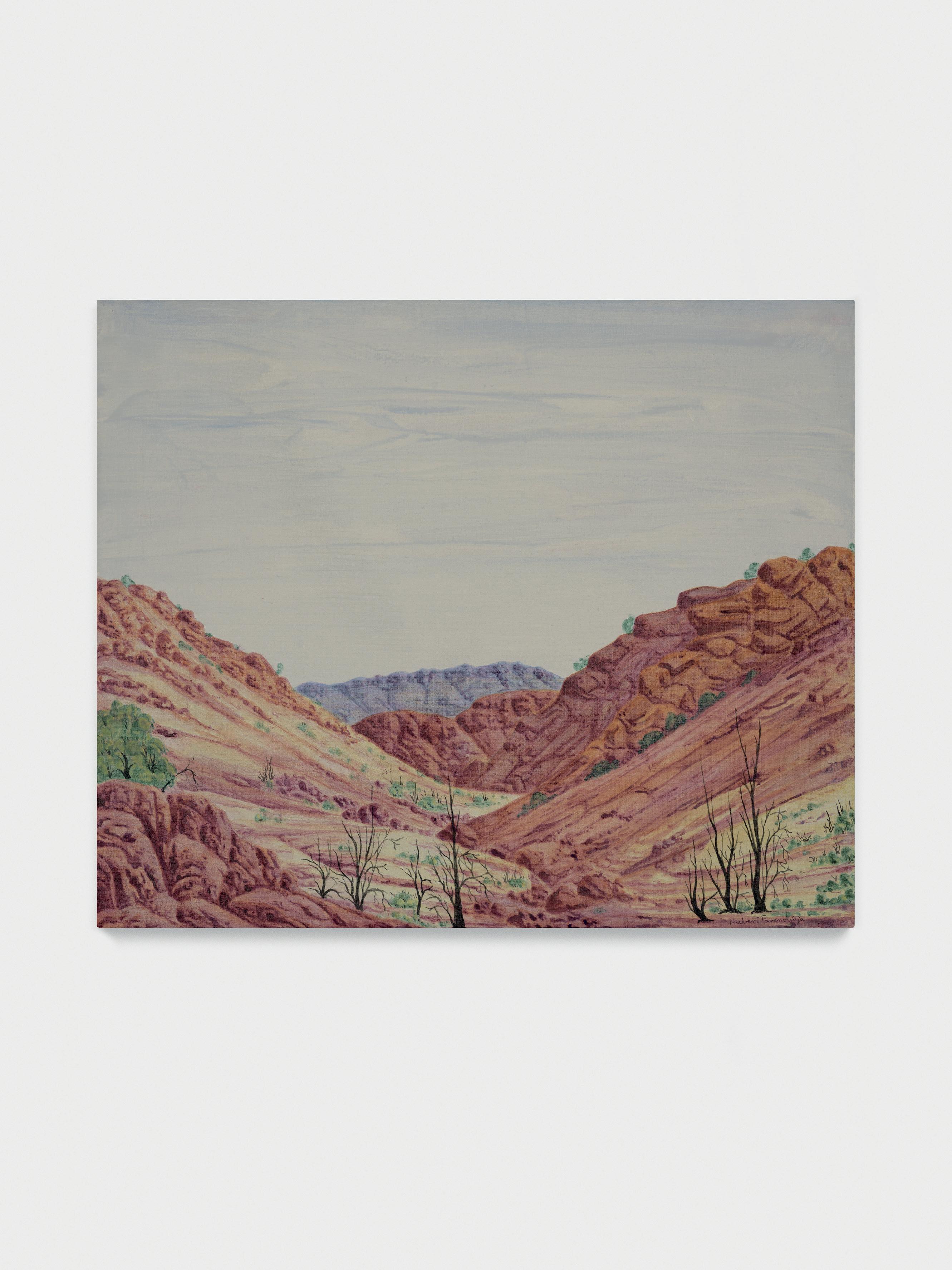

Opposite: Hubert Pareroultja, Looking Towwards The James Range, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 76cm x 90cm Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

in conversation with HUBERT PAREROULTJA & KEN MCGREGOR

CONVENTIONAL HISTORICAL RESEARCH, through its predominant written mode – a textual not an aural instrument – tends to produce an abstraction from the daily life of those whose culture is the under study. The hand of an omniscient narrator, dubbed the historian, often guides the reader through the lives of others in the third person, without adequate consideration given to the hegemony of ideologies reproduced in their own voice (Portelli, 1991). Often, an emphasis is placed not so much on how people feel, experience and create meaning from events and memory as conduits of culture, but on constructing an empirical understanding of a progressive line stamped across time to explain and document specific cultural phenomena. This can result in an anti-empathetical approach. In a time where our knowledge of global happenings is cherry picked from a dense foliage of news headlines, the voices of individuals on the ground often become superimposed and sometimes even lost. Oral sources make opportunities for the local point of view to connect with the global, scientific view. It is on this cross-cultural and experiential meeting ground that a multitude of perspectives and varied socio-linguistic origins are related and undergo a process of self-recognition. The dominance of an external narrator as a mouthpiece is challenged through collective participation and dialogue: the interviewer becomes a subject of the discourse as much as those whom they are investigating. Listening to an audio recording also gives greater space for the receiver’s imagination to construct its own bespoke meaning from the undulance, tone, rhythm and velocity in the speaker’s delivery (McHugh, 2016). Oral histories can be

productive to a culture’s persistence, serving as educational resources to an upcoming generation for its continuation and development. If language and art-making practices are interlocking puzzle pieces of a cultural landscape at large, accumulative documentation and access to the two are vital for the internal preservation and promotion of that culture, as well as its wider understanding, appreciation and politicisation. Oral expression as a means of passing on knowledge has a rooted and inextricable place in Arrernte culture. The following transcript, while being a textual source with the potential to distort the emphases of the spoken word, documents a conversation between Hubert Tjapaltjarri Pareroultja, Ken McGregor, and JGM Gallery's Associate Director, Julius Killerby. Pareroultja is a proud Arrernte man living and working on country in Ntaria. Amongst various artistic achievements, Pareroultja was the recipient of the prestigious Wynne Prize (2020), and the winner of the Wandjuk Marika Memorial 3D Award. Ken McGregor is Hubert Pareroultja and Albert Namatjira's biographer, and author of more than 34 artist monographs and books. In 2016 he received an honorary doctorate from Bond Univeristy “In recognition of his work in promoting the advancement of Indigenous People through their art, his commitment to education, and his work with remote Indigenous Communities. ” The recording of this dialogue is available upon request from JGM Gallery. This transcript is not intended to replace it but is suggested as an intertextual resource.

- Written by Antonia Crichton-Brown

REFERENCES

Siobhan McHugh, ‘How Podcasting Is Changing the Audio Storytelling Genre’, Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media , 2016, 14(1), 65-82.

Looking towards Haasts Bluff. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Alessandro Portelli, The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History (New York: State University of New York Press, 1991).

16 15

JULIUS KILLERBY Hubert, what distinguishes this body of work from previous ones that you have produced?

HUBERT PAREROULTJA Well it's the first time I am showing my work overseas. Before that, I exhibited around Australia, only, and I am proud to be showing depictions of my own country to a new audience. For that reason, I will be showing a mix of my work, with a variety of subjects done in both watercolour and acrylic paint.

JK Could you describe the landscape where you live and work, and what it means to you?

HP I live about two hours from Alice Springs. So a lot of the paintings are of the bush. The landscape is me. I know it so well, every rock, every tree.

KEN MCGREGOR A lot of the time, people will ask Hubert whether he paints from life or from memory. Hubert can paint from both because he knows the land so well.

JK Does painting from memory change the outcome of the finished work, as opposed to when you paint from life?

HP I would just say that it's easier to paint from memory, rather than on location. The last two weeks have been 48 degrees, so it's been im-

possible to paint on location.

JK Ken, could you speak a bit about the history of Ntaria, the Hermannsburg Mission, and the Arrernte?

KM The Arrernte have been living in the area for thousands of years. The Lutheran Missionaries came in the late 1800s from Germany and arrived in Adelaide. They then made the arduous trek for thousands of kilometres through this harsh landscape until they found an area that they thought would be suitable to open a Mission. They did help with the supply of food and water for local Indigenous People. They also certainly helped with medicine, schooling and education. Hubert is the benefactor of that because he was educated at the Mission. However, to a large extent they also destroyed Aboriginal culture by removing sacred objects that were important to them. That was difficult for a lot of people and is still a concern for Hubert today. Those objects were part of their culture and was what made them strong. Hubert has very strong feelings about that, but at the same time he's also happy that he grew up on the Mission, where he had the opportunity to go to school and learn English... Hubert lives in both worlds, having one foot in the Lutheran ways and one foot in the Arrernte culture.

KM Yes, both ways.

JK Would you say that there is a parallel between that history and the Hermannsburg style itself, this blend between the more European representative style and the more Indigenous Australian palette, subject matter and appreciation for the land?

KM Yes, I definitely think so. Many people think that Aboriginal People started what they call the Hermannsburg School of Art, but that's not entirely true. There was an artist named Rex Battarbee, who was a non-Indigenous watercolour artist, and who was travelling in the West MacDonnell Ranges, painting the landscape. He exhibited his works at the Hermannsburg Mission, where they were seen by the Aboriginal People. There was an artist called Albert Namatjira, who was known around the Mission for being good with his hands and making things. He said to Rex Battarbee that he would like to paint with watercolours. A couple of years later when Rex returned to the Mission, he gave Albert tuition. After a couple of weeks, he was painting very, very accomplished works. Albert then taught his children, his brothers, Hubert's father, and this knowledge was then passed down from one generation to another. Today, it is the longest continuous art movement in Australia. As with Hubert, I have spoken with many people who are descended from the original Hermannsburg artists. They were fascinated to see

their country depicted in a realistic way. They'd never seen that before. They'd previously used dots, circles and lines, and visual motifs relating to rituals and ceremonies, so they were quite amazed. What is also interesting is that all of the artists who Albert taught developed their own style. Each of the Hermannsburg artists had such a personal affiliation with the landscape that the paintings they produced were remarkably stylistically unique.

JK Hubert, for the benefit of our audience here in London, you are the nephew and godson of Albert Namatjira, one of Australia's most celebrated artists. Is Namatjira's work a useful reference and inspiration for your own work, and perhaps in answering that could you explain how you found your own artistic voice within the Hermannsburg School?

HP Well, of course, I don't want to copy Albert's work, I want to do it my way. All the work that Albert did has gone, the landscape has changed and the trees have grown. I greatly admired Albert, he was a great man, but I have my own style that I've developed over many years that sets me aside from anybody else.

JK I notice in your work, Hubert, that shadows are suggested with variations in colour, rather than tone. For me, it lends the pictures a sense of vibrancy, and almost a hallucinogenic quality, which I think, amongst other things, distinguishes

it from works by Albert Namatjira and other Hermannsburg artists. I read in Ken's book that you and your family lived in a humpy by the Finke river and that Albert Namatjira lived in the humpy next to you. What memories do you have of him and what was he like?

HP Well, Albert passed away when I was a small boy, but my father used to tell a story about him. He was taught to paint by Albert, and I would watch my father and Albert paint on location, along with the other Pareroultja brothers.

KM Albert was very kind to you wasn't he?

HP Yes, he was very kind. When we used to stay in Alice Springs he would send us parcels with lollies and cold drinks.

KM Yes, Hubert watched Albert work along with his father but, as a child, he was also told not to bother Albert, and to not run around him when he was painting. Albert did not want dust being kicked up and damaging his paintings.

JK Hubert, could you describe your early years around the Mission, and the time you spent exploring your family's country?

HP When I was a kid I used to go out and spend time with my grandfather out bush, learning how to do work. I would learn where the wa-

terholes were. We didn't have many things like electricity, we lived in darkness and by the fire. Sometimes, we had a candle. I learned how to look after animals and build fences. It was fun being on country, but it was also tough in those days in the 1960s.

KM Yes, it was also very hot and would have been a very tough time to grow up in. Looking back on it, it was in some ways a very idyllic childhood. But, as Hubert mentioned, there was no electricity, no light. They had to light fires to keep warm and look after their animals. At one time, Hubert had to roll a 44 galon drum full of water several kilometres to the house where they lived, just so that they could have enough water to drink and to cook with. And that was done in extreme temperatures, so it was a tough, hard lifestyle, but they didn't complain.

HP We had no cars. We could only transport things in wagons, or on donkeys and horses.

JK Yes, and in your book Ken, I certainly get the sense that life around the Mission was idyllic, but also incomprehensibly hard. I am thinking in particular of the project to build the water pipeline, and just the idea of having to build kilometres of pipeline in 45+ degree heat sounds incredibly difficult.

KM Yes, the Kuprilya Springs pipeline was in

HP Both

17

ways.

Left: Hubert Pareroultja, Mount Hermannsburg 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

18

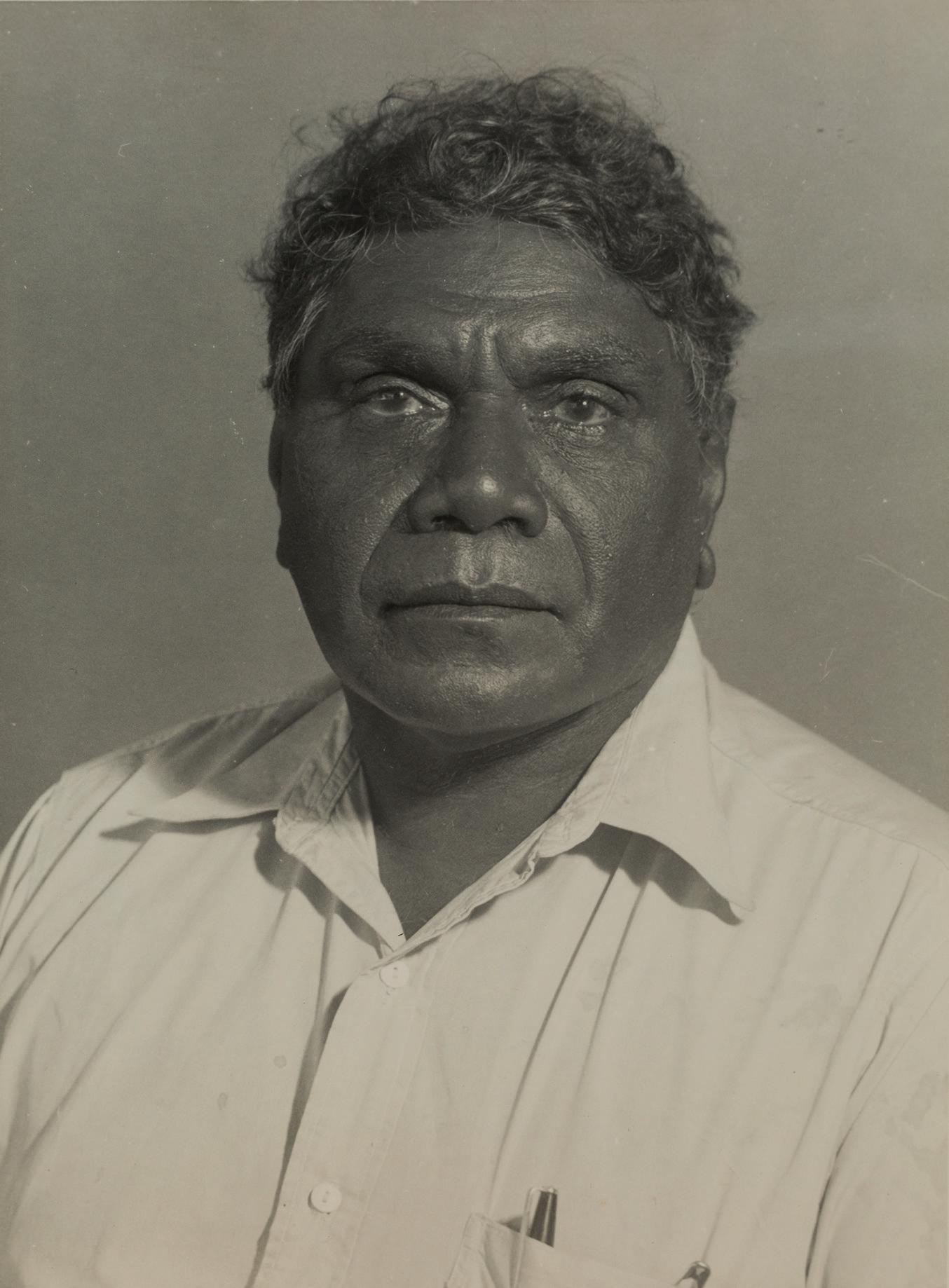

Right: Albert Namatjira, 1950. Image courtesy of the Alice Springs Collection, Northern Territory Library.

fact worked on by Hubert's father and uncles, and it was so hot during the day that they often had to work at night. They were only using crowbars and picts. They didn't have any of the heavy machinery that we use today. The pipeline was essential for the Mission because it allowed them to grow a lot of vegetables and reduce instances of scurvy, amongst other things. So yes, it was essential to the Mission, but an incredibly tough endeavour to build it.

HP There were no pumps in the pipeline either, so sometimes it would take a very long time for the water to flow down. It was gravity fed.

JK As I understand it, money was raised for that project by asking artists from the Hermannsburg Mission to create artworks that could then be sold. Is that correct?

KM Yes, that's correct, but not just artists from the Mission. Artists like Rex Battarbee contacted a lot of friends from Melbourne to donate and they also had coverage in the newspapers. Some artists set up studios and painted portraits. Everything was done to try and raise money for the pipeline, which was absolutely essential.

JK So at what stage did the Hermannsburg School, and Albert Namatjira, become a household name?

KM During the 1930s, artists at the Mission began working on Mulga plaques. They would heat the tip of fencing wire and use that to burn images onto these wooden plaques, it was called poker work. Now, this was partly an idea of Pastor Albricht's, who was the superintendent at the Mission at the time. He thought it was a good idea for these to be produced because there were a lot of tourists coming to Central Australia. During the Second World War, American soldiers stationed in Alice Springs would visit the Mission, as well as other tourists. So it was a great thing to do, to sell these works to raise money for the Mission. All this money was used to help with the supply of water and food to the local Indigenous People. It was difficult times, there were droughts and dust storms, but these “souvenirs” sold really well throughout the 1930s. These “ souvenirs” are now very collectible works of art, and were the first examples of the cultural exchange that took place between Indigenous and non-Indigenous People around the Hermannsburg Mission. Albert Namatjira was originally known just as Albert. His father was Namatjira. When Albert started painting in the mid 1930s, the first works that he produced were signed “Albert” After a couple of months he was signing them “Namatjira Albert” He then settled on “Albert Namatjira” Albert passed away in 1959, but was famous and well known from the early 1940s.

JK Was the Hermannsburg School the first style developed by Indigenous Australians, which utilised one-point perspective, and the more European representative style?

KM I don't like to say that it was started just by the Indigenous People, because it was started by Rex and Albert, who became very close and trusted friends. I would say that it was developed by a combination of great thinkers and great artists, and two people in particular, that being Albert and Rex. They maintained their friendship throughout their lives. I think it is difficult to credit anyone with the development of the Hermannsburg style without mentioning Rex Battarbee, who was the instigator and the first person to teach the style.

JK So it was very much a collaborative art movement, as I suppose almost any artistic movement is.

KM It was, and from there it's been passed down from generation to generation, and that is certainly the Indigenous People doing that. Of course, that's how Hubert learned to paint, from his father. And the Namatjira's taught their children and their relatives.

JK What I find fascinating, then, is that this style, and that period in the early 20th century in particular, provides a glimpse into the Indigenous conception of the land in a way that is seamlessly understood by eyes adapted to the Western canon. It seems to be a fascinating blend of two different cultures.

KM Yes, it definitely is. These paintings possess a spirituality, and they are not just depicting the landscape. Hubert can tell you more about this than I can, but when he goes into the landscape, he doesn't just see the landscape. He sees

his ancestors, he sees the spirit people, and they talk to him. When the wind blows, it's the spirit people telling him stories.

HP Yes, they talk to me a lot.

KM So much goes into these paintings, it's as though Hubert is the landscape himself. In every tree, every rock, every gorge, every waterhole. Not only does he know it so well, but it's part of him. Unless you know this culture well and unless you believe in their spirituality, it's difficult as a Western person to understand that, but he is the landscape and the landscape is him.

JK I find it interesting, Hubert, that in your work there are no people and no indication of people having been in the landscape. But, of course, you see the entire history of your people in the trees, the bush, the animals. You imbue what is ostensibly just a landscape with all the history of the Arrernte.

HP When you walk around in country like this, you can feel some things looking at you, helping you. The trees, rocks, animals, the birds are watching you, and I listen and watch them all.

KM It's often difficult for Western people to understand how Indigenous people think about the land, Julius, but when the wind blows its the old people speaking to them, and when they are walking around the landscape, there's a spirituality that Hubert feels every day. He has painted some works of manmade subjects, such as Areonga Station, and humpies that were there. But usually he just depicts the landscape.

JK There's a passage in Ken's book, Hubert, which I personally found hilarious, if also a bit sad. Ken writes about how when you were at the Hermannsburg primary school, the other children would be made to sing 'God Save The Queen', whilst you beat a drum to keep the timing. There's a quote where you describe how you would deliberately speed up so that everyone was thrown off rhythm and, as you say, “... fall all over the place.” I get the sense that you combatted the disciplinary side of the Lutherans with a kind of stoicism. Would you say that that's accurate?

HP Yes, that's right (Hubert and Ken laugh).

KM That's even true of Hubert today.

JK The seriousness of the missionaries must have seemed quite ridiculous at times, I imagine.

KM Hubert's grandfather Palerula, also known as Kristian, didn't like the rules and regulations of the Mission, and the authoritarian aspect of it. He walked off the Mission several times because he was a tribal man, who lived in tribal ways. He was also a strong man, and the spear was his choice of weapon, which was sometimes used to settle disputes. The missionaries did not like that because they tried to enforce their Western laws on a group of people who had practiced their own ways for thousands of years. There was a bit of conflict there.

JK Did the teachings of the Lutherans have any effect on the Indigenous people's belief system?

HP I believe in Lutheranism, and in my own culture as well.

KM And you attend church every Sunday?

HP Yes, I do.

JK I also imagine, given your relationship to the land, Hubert, that you would never feel lonely in the landscapes you depict. Even if you were ostensibly by yourself.

HP Yes, I never feel alone because the ancestors are watching me, looking after me. I believe in that, and I believe in church. I believe in both ways. In my country, when I walk around, I don't feel fear. They are looking after me. I can feel it.

JK When did you decide that your art was something that you would like to commit to and pursue for the rest of your life?

“I never feel alone because the ancestors are watching me, looking after me... in my country, when i walk around, i don't feel fear. They are looking after me. I can feel it.“

- hubert pareroultja

19

20

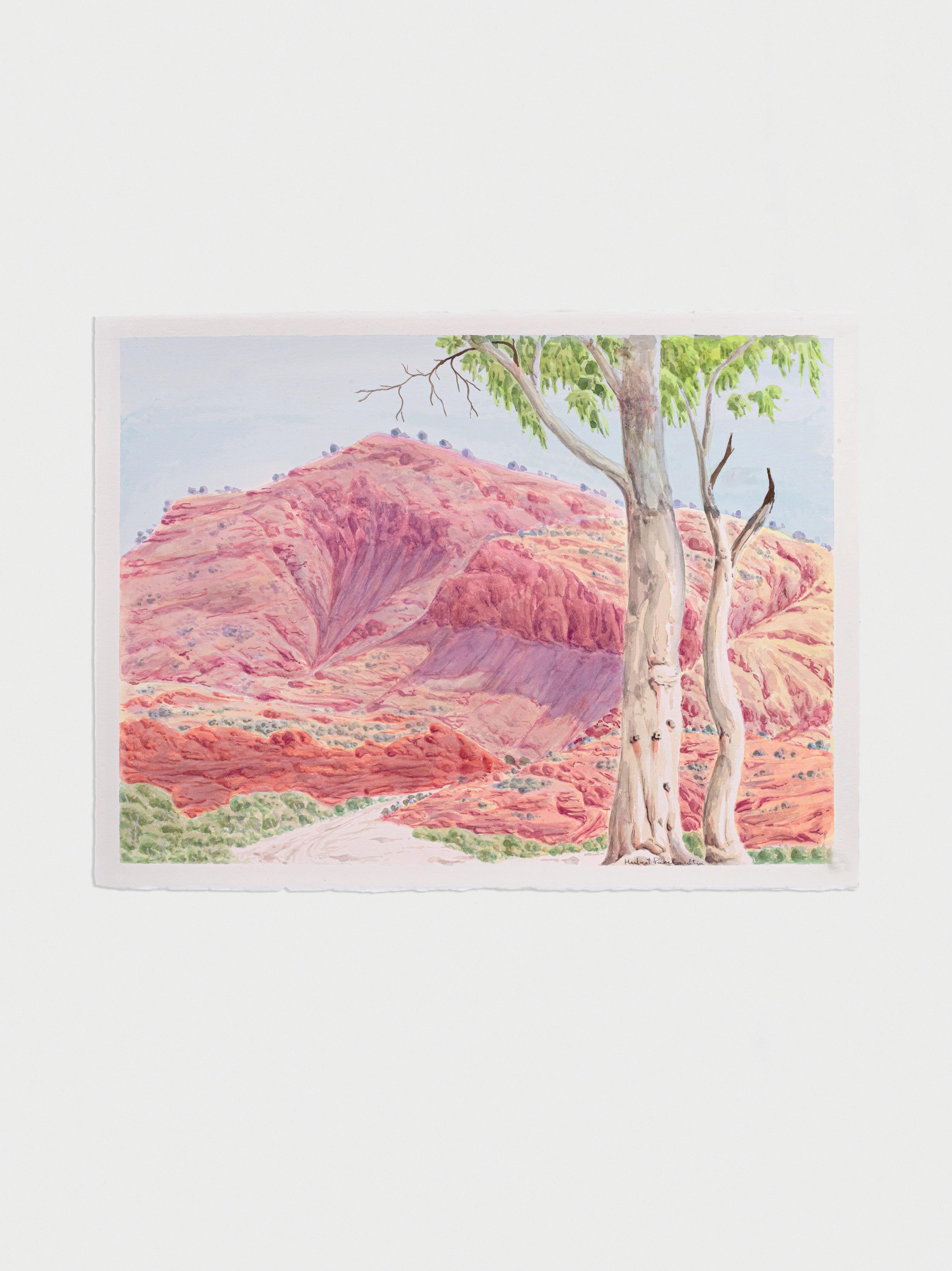

Hubert Pareroultja, Looking Towwards Th James Range, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 76cm x 90cm Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

HP I was a stockman and used to work out on the land for many years. I had always liked making art, so when the stockman work stopped, I went back to the Mission and started to paint again. I also needed to make money to support my family.

KM In those days, a lot of the Indigenous people would be paid in rations. So when people started to see that Hubert was quite an exceptional draftsman and artist, he then realised that he could make a reasonably good living selling his paintings.

JK I get the sense that you have a real affinity for animals, Hubert. Is there one which is particularly dear to you?

HP My favourite animal is the horse. When I was a little boy, my grandfather taught me how to ride one.

KM At his outstation, Hubert's also got emus, chickens, goats...

HP Yes, it's because I love animals.

KM His affinity for animals is quite extraordinary.

JK I get from your work, Hubert, a distinct sense of optimism and obviously beauty which, correct me if I'm wrong, is perhaps at odds with much of the hardship you've endured in your life. Would you agree with that and, if so, what compels you to emphasize the beauty in the world?

HP Because I find the landscape so beautiful. Simple as that. I paint what I see. And my father told me to only paint my own country. I do not paint anywhere else, or I will get punished for it.

JK Could you explain the meaning of the exhibition title, Weer Loo - e Cry of the Curlew?

HP A curlew is a bird that comes out at night time. It calls out and then other curlews join it and dance around. I only hear it at night, and it's part of the Dreaming of my outstation.

KM These birds make an extraordinary and unusual sound and they call each other together to celebrate and dance. It's almost like a sacred ritual and Hubert tells me it reminds him of the old Arrernte people who would dance in ceremonies in the form of a Corroboree. His London exhibition is a comparable celebration and a dance of his own work.

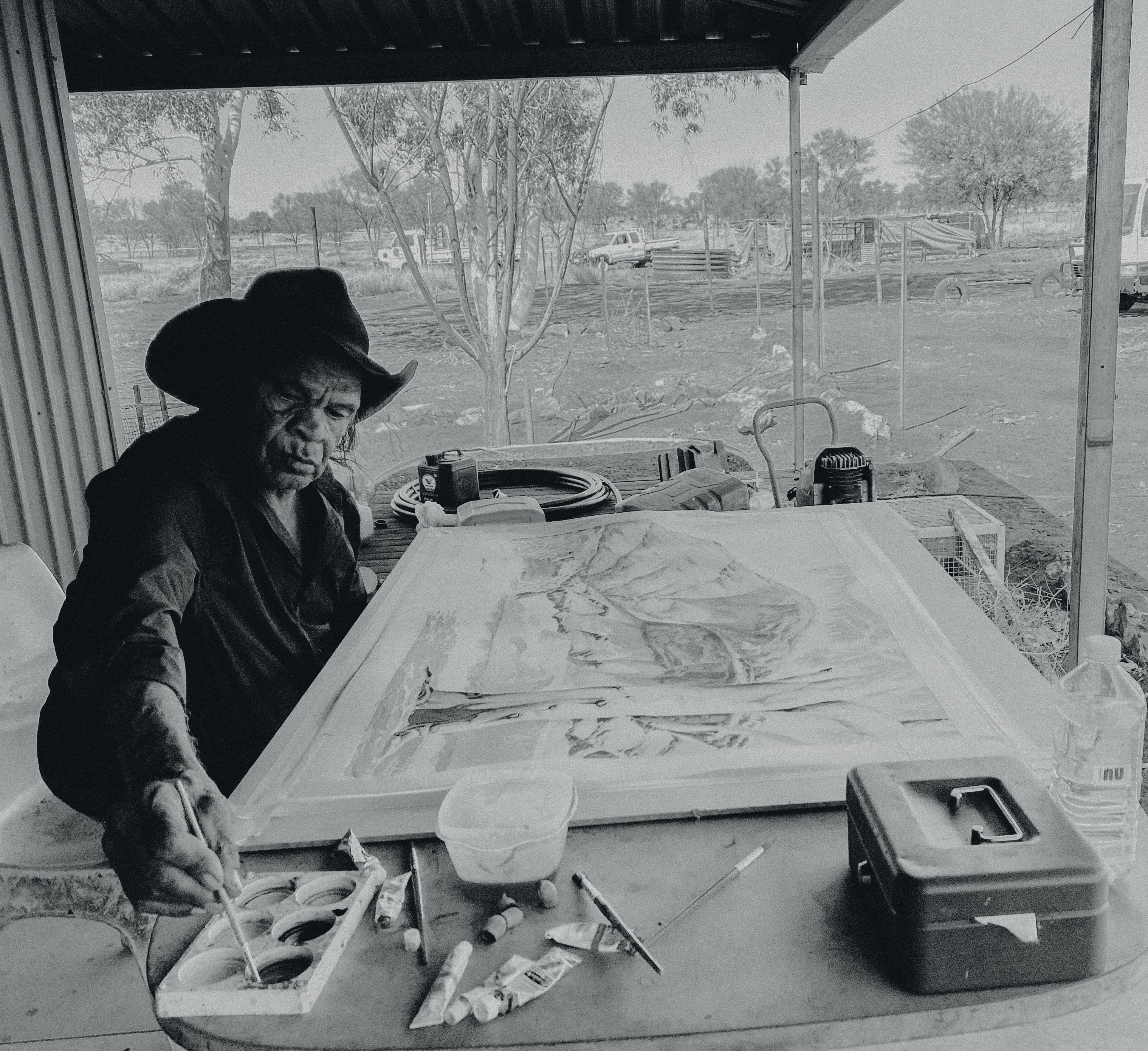

JK Do you make preliminary drawings Hubert? Or do you paint directly onto the paper or canvas?

HP I start off by painting the blue skies. I turn the painting upside down to do this, and then leave it to dry. Then I turn it the right way up and put the yellow down for the hills. Then I put the trees in last.

JK Do you paint quite quickly as well? From looking at your work, it's got this vitality and freshness to it, which is sometimes missing in works that are laboured over.

HP I'm careful with the trees.

KM Hubert has, as he mentioned, a system where he turns the painting upside down to paint the sky, and that's to stop the blue from dripping down. Watercolour, as you know, is a tough medium to use, you can't paint over it like you can with acrylic paint. For the ghost gum trees, Hubert uses the white of the paper itself, and then builds up tone and colour from there. I introduced Hubert to acrylic paints several years ago, and he mastered his technique with them almost straight away. He waters his acrylics down, however, to such an extent that they go onto the canvas almost like watercolour, but the process is a bit more forgiving because Hubert can paint over it.

JK Hubert, what response to the exhibition are you hoping to achieve from your audience here in London?

HP I hope that they love it.

JK I am sure they will.

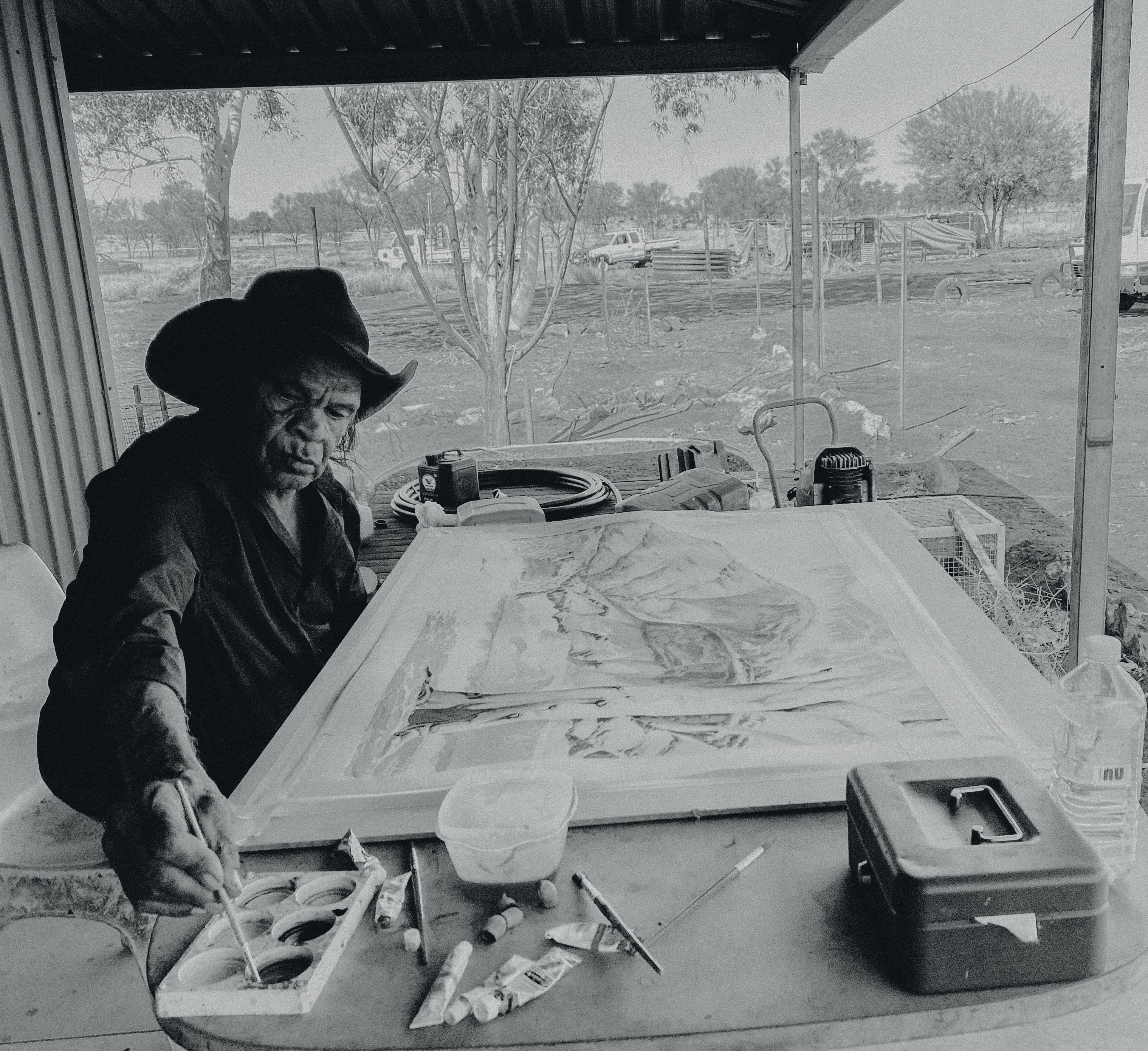

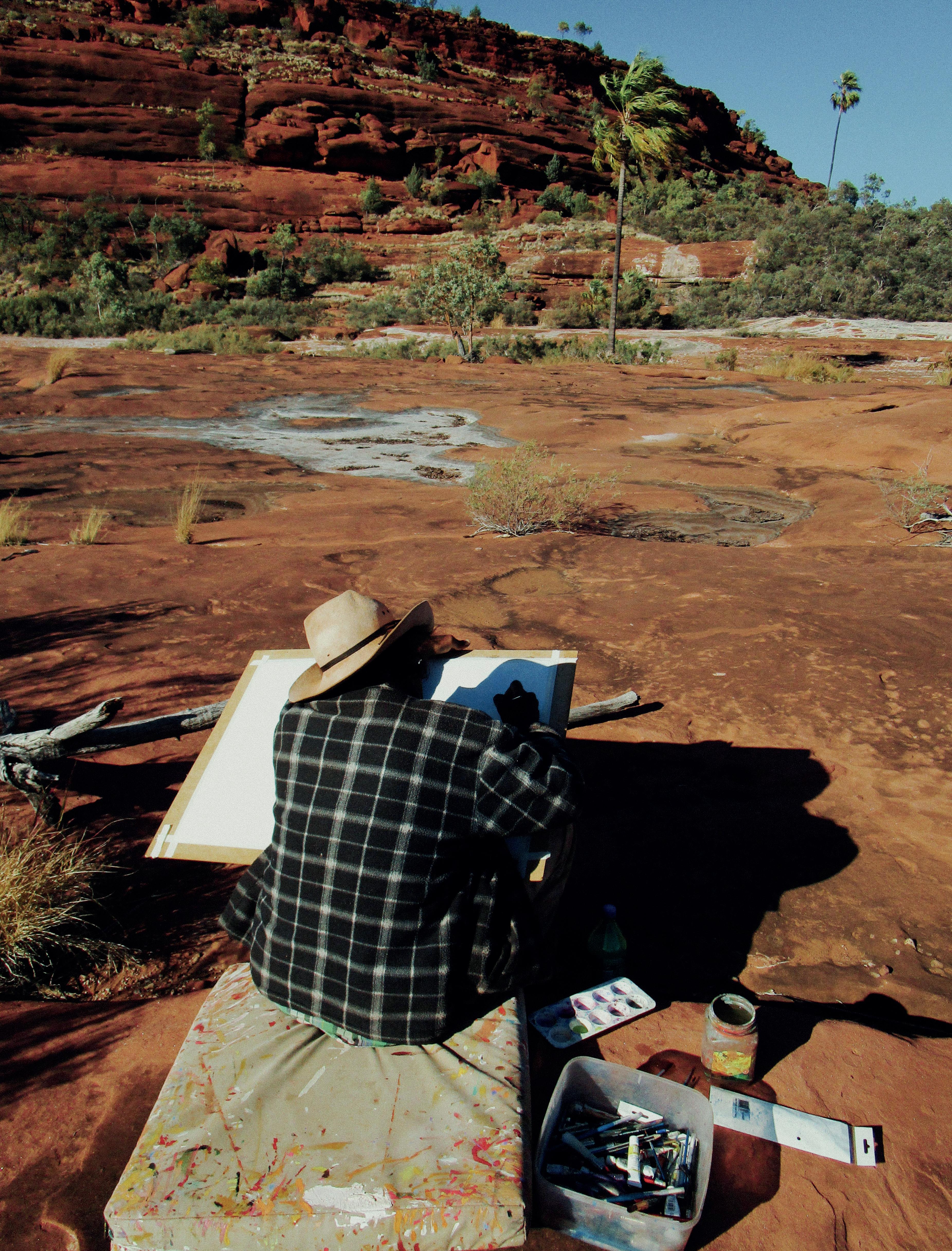

Hubert

at

Image

Ken

Pareroultja working

Luntjatta, 2021.

courtesy of

McGregor.

21 22

23 24

Hubert Pareroultja, Across The Plains 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

25

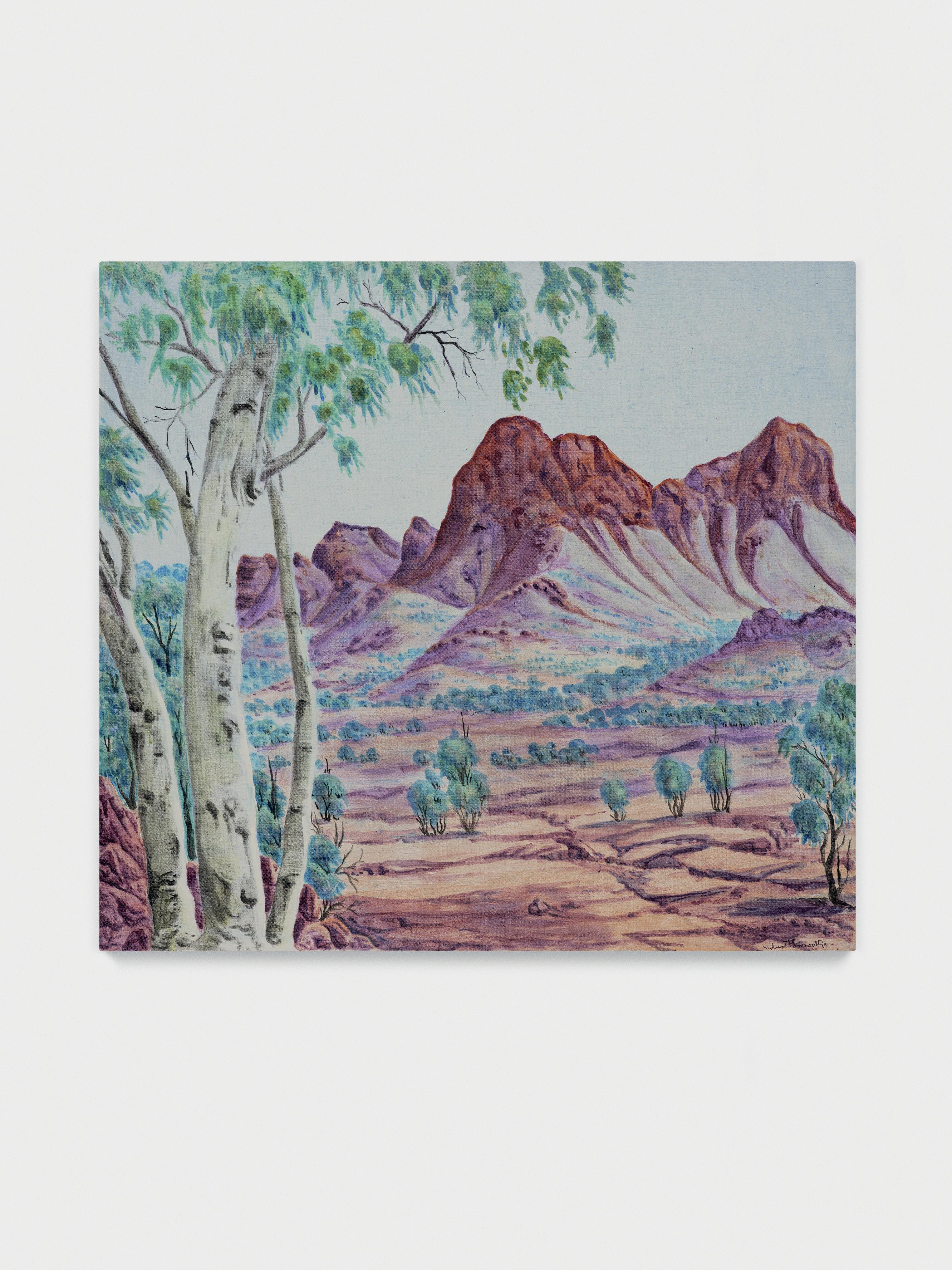

Hubert Pareroultja, Flowers On The James Range, 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 76cm x 83cm

26

Hubert Pareroultja, Looking Towards The James Range, 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 76cm x 90cm

27

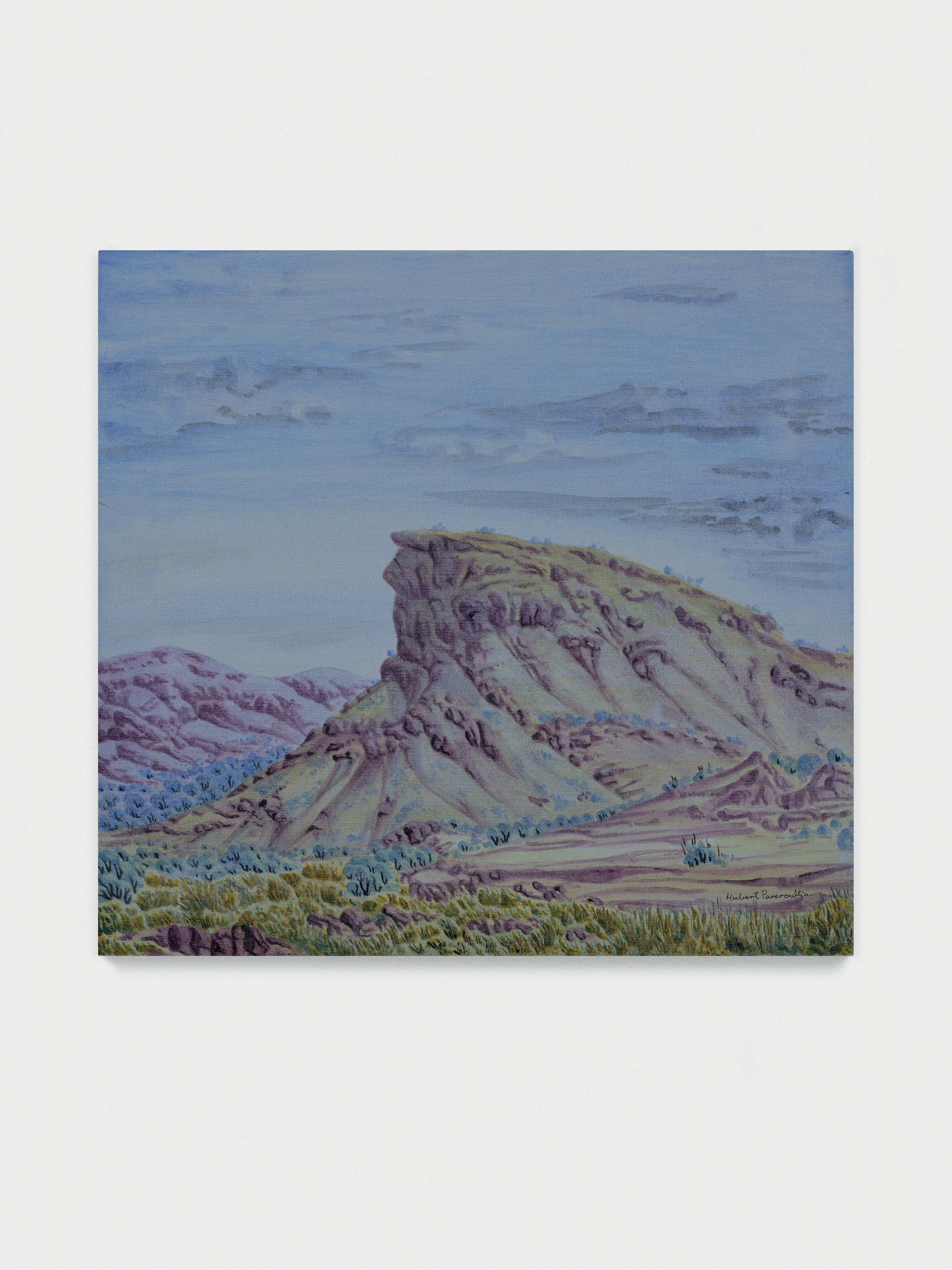

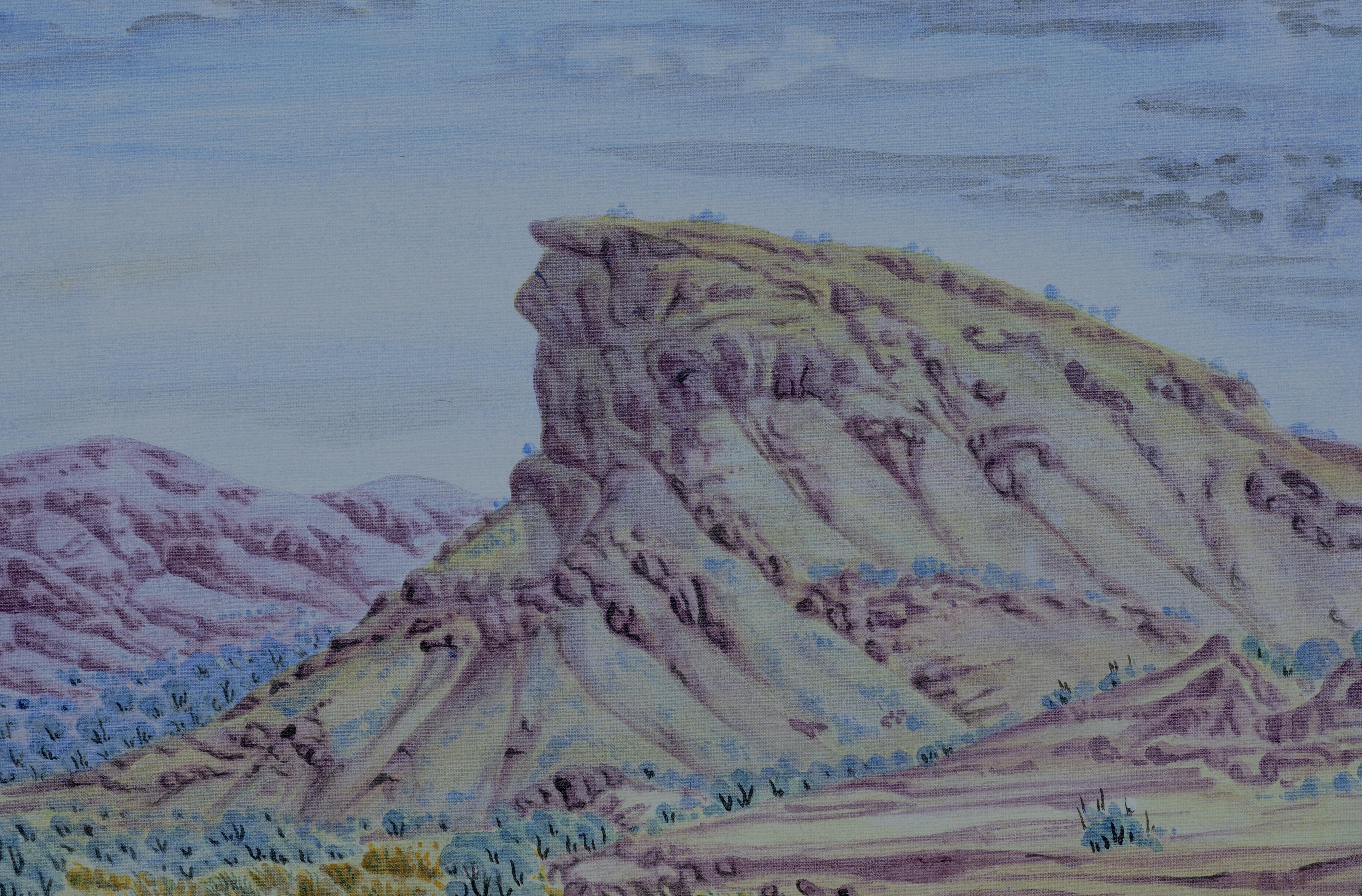

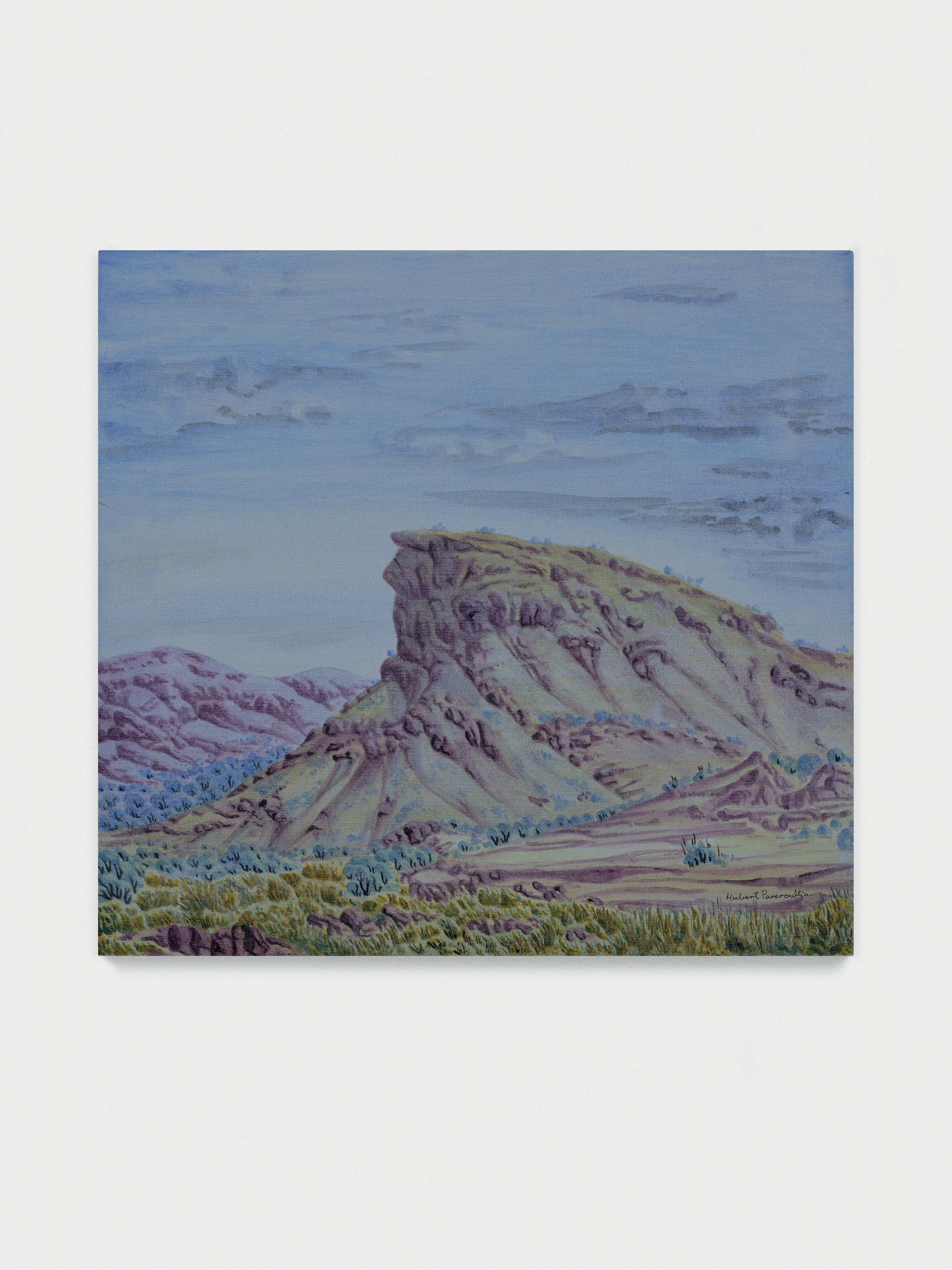

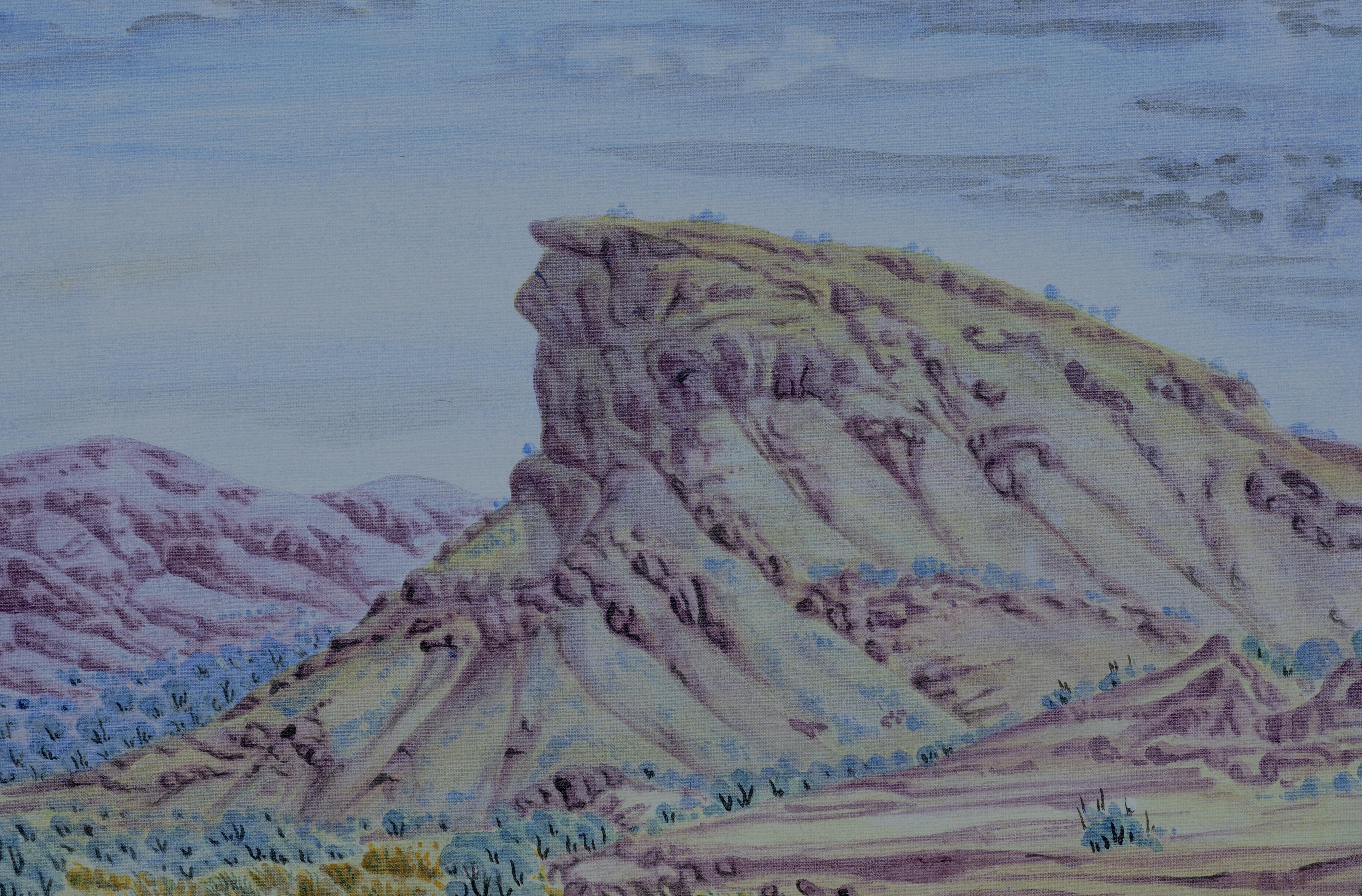

Hubert Pareroultja, Indrai Bluff 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 66cm x 71cm

28

Hubert Pareroultja, Haasts Bluff Country, 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 76cm x 83cm

“when you

walk around in country like this,

you

can feel some things looking at you, helping you. the trees, rocks, animals, the birds... i listen and watch them all.“

- hubert pareroultja

37 38

Hubert Pareroultja, Indrai Bluff 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 66cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

39

Hubert Pareroultja, Mount Hermannsburg, 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm

40

Hubert Pareroultja, Across The Plains, 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm

JGM GALLERY ACKNOWLEDGES THE TRADITIONAL OWNERS AND CUSTODIANS OF COUNTRY

THROUGHOUT AUSTRALIA AND RECOGNISES THEIR CONTINUING CONNECTION TO THE LAND, WATERS AND SKIES, OFTEN EXPRESSED THROUGH ART.

WE PAY OUR RESPECTS TO ARTISTS, ELDERS AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE.

Kwariitnana (Organ Pipes), 2022, Central Australia. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor. 49 50

Front cover: Standley Chasm, 2023. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Back cover: Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Editorial design: Julius Killerby.

Editorial assistant: Chloe Redston.

Photography: Ken McGregor, Julius Killerby.

Front cover: Standley Chasm, 2023. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Back cover: Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Editorial design: Julius Killerby.

Editorial assistant: Chloe Redston.

Photography: Ken McGregor, Julius Killerby.

©

All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-7385394-2-0.

Gallery 24 Howie Street London SW11 4AY info@jgmgallery.com

Artwork Photography: Ken McGregor, Studio Adamson.

2024 JGM Gallery.

JGM

WEER LOO - THE CRY OF THE CURLEW

WEER LOO - THE CRY OF THE CURLEW

Front cover: Standley Chasm, 2023. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Back cover: Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Editorial design: Julius Killerby.

Editorial assistant: Chloe Redston.

Photography: Ken McGregor, Julius Killerby.

Front cover: Standley Chasm, 2023. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Back cover: Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

Editorial design: Julius Killerby.

Editorial assistant: Chloe Redston.

Photography: Ken McGregor, Julius Killerby.