CONTRIBUTORS & TABLE OF CONTENTS

KAROLINA DWORSKA

Karolina Dworska is a London based Polish artist. Her work explores dreams and mythologies, and delves into the subject matter of the ‘in-between’; the grey area between dreams and reality, as well as fantasy spaces, balancing precariously between definitions. Dworska explores these ideas through experimental approaches to rug making and sculpture, and humorous intertextual blending of myth, dream and the mundane everyday.

Dworska has exhibited internationally, has featured in numerous publications and was, in 2021, selected for the Bloomberg New Contemporaries. More recently she was an invited guest lecturer at the University of Lincoln, where she discussed her art practice and research.

Dworska currently works as a Gallery Assistant at JGM Gallery and has previously held a position at Goldsmiths College. She also recently curated a group textile exhibition at JGM Gallery, titled Creature Comforts, which showcased the work of 14 artists working with diverse textile practices.

COMMISSIONED BY JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI

Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi (nee Heathcote) is a leading specialist in the art of First Nations Australians. Following her years as a private dealer, where she exhibited regularly at The Saatchi Gallery and Masterpiece London, amongst others, she founded JGM Gallery in 2017. The gallery has since developed a broad program, exhibiting the work of both British Contemporary artists and Aboriginal Australians.

Guerrini Maraldi was born in Melbourne, Australia where, in the 1970’s, she was the owner and director of the Powell Street Gallery in South Yarra. At Powell Street Gallery she advanced the careers of many artists, placing their work in significant public and private collections, including The National Gallery of Australia and various State Galleries. It was also during this time that she was appointed by the Australian Government as a valuation specialist for Contemporary Australian Art.

3

An examination of recent acquisitions from JGM Gallery’s collection

Julius Killerby analyses recent significant acquisitions by JGM Gallery. These include works by Jimmy Barrmula Yunupingu, The Burton Women’s Collaborative & Mabel Juli.

5

Tim Allen’s The Water In The Well

Matthew Collings analyses the work of Tim Allen in an essay produced on the occasion of the artist’s March 2023 exhibition, The Water In The Well. Titled What Is This Strange Religion?, Colling’s essay examines Allen’s visual cadence, his inspirations and his intentions - or lack thereof - as an artist.

11

MATTHEW COLLINGS

Matthew Collings is an art critic, writer, broadcaster, and artist. Following his studies at Byam Shaw School of Art and Goldsmiths College, London, Collings accepted a position at Artscribe in 1979. He then became the editor of Artscribe, a role which he held between 1983 and 1987. Between 1989 and 1995 Collings worked as a producer and presenter on BBC’s The Late Show, introducing artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst to British television for the first time. In his time at the BBC, Collings also wrote and presented documentary films on artists such as Donald Judd, Georgia O’Keeffe and Willem de Kooning. In 1997 Collings authored Blimey! From Bohemia to Britpop: The London Artworld from Francis Bacon to Damien Hirst, one of the most significant publications to chronicle the rise of the Young British Art (YBA) Movement.

Collings has also written and presented various television series for Channel 4, including Matt’s Old Masters, Impressionism: Revenge of the Nice, The Me Generations: Self Portraits and This Is Modern Art, which won him a Bafta in 2000. Between 1997 and 2005, Collings presented the Channel 4 TV programme on the Turner Prize and in October 2010, he wrote and presented the BBC2 series, Renaissance Revolution. He has been the regular art critic for The Evening Standard since 2015.

JULIUS KILLERBY

Julius Killerby is an artist and the Manager of JGM Gallery. He has more than 7 years of experience working within the Art Industry, including his selection as an assistant for the Australian Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale. He has previously held positions at Metro Gallery, Scott Livesey Gallery and Flinders Lane Gallery in Melbourne, Australia. He has also worked alongside The Torch, an organisation dedicated to the promotion of artworks by incarcerated or ex-incarcerated First Nations Australians. Within the context of his own practice, he has exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, The Art Gallery of Ballarat & Geelong Gallery. His work focuses on the psychological ripple effects of certain cultural and societal transformations. Part of his practice also includes portraiture and an attempt to, piece by piece, sharpen his ability to convey the human condition. Killerby completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2017 and was an Archibald finalist in the same year, the youngest person to achieve this distinction.

Previous sitters for Killerby include the former Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Ron Walker AC CBE, Paul Little AO, Robert Richter QC, Julian Burnside QC & Brendan Murphy QC.

In the studio with Tim Allen

In the weeks preceding Tim Allen’s exhibition, The Water In The Well, Julius Killerby visited the artist in his East London studio. The visit was an opportunity for the two to discuss Allen’s practice generally, and his upcoming exhibition specifically. Both also discuss Allen’s upbringing and his influences - artistic or otherwise. The result of this exchange was a transcript of their conversation, prefaced with a brief written piece by Killerby.

17

Gurrutu: The Art Of Mulkun Wirrpanda

On the occasion of Gurrutu: The Art Of Mulkun Wirrpanda Julius Killerby sat down with William Stubbs (Coordinator of the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre) to discuss the life and work of the late Mulkun Wirrpanda. The conversation casts light, not just on the life of a woman with formidable artistic talent, but also on ‘Gurrutu’ itself, what Stubbs describes as a “...matrix of meaning which is too complex for casual comprehension.”

25 Creature Comforts

Between November of 2022 and January of 2023, JGM Gallery exhibited Creature Comforts, a group show of 14 textile artists, curated by Karolina Dworska. In this issue of the JGM Review, Dworska writes about the show, contextualizing the ideas conveyed by the exhibiting artists.

Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, 2022. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.AN EXAMINATION OF RECENT ACQUISITIONS FROM JGM GALLERY‘S COLLECTION

IN RECENT MONTHS, JGM GALLERY ACQUIRED SEVERAL WORKS OF PARTICULAR SIGNIFICANCE BY FIRST NATIONS ARTISTS. GIVEN THE COLLECTIBLE NATURE OF THESE WORKS, THE GALLERY’S DIRECTOR, JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI, COMMISSIONED THE FOLLOWING WRITTEN PIECE, WITH THE AIM OF ELUCIDATING THE CONCEPTS CONVEYED BY EACH WORK.

ONE OF THE more interesting aspects of Aboriginal Art is that “Country” is often represented with small scale motifs - the serpent, the kangaroo, the goanna - and yet the actions of these small creatures often have far reaching consequences. Amongst the most prominent of the Dreamtime stories, for example, is that of the Rainbow Serpent, whose emergence from beneath the earth created the geographical features of a formerly barren world. The Serpent is believed by some to be the rainbow itself and that, when visible, it signalled the Serpent’s journey from one jila (waterhole) to another. This type of narrative logic - the macro expressed through the micro - is an indication of how profoundly significant the land is to many First Nations Australians.

In Ngayuku Ngura - My Country the Burton Women’s Collaborative have depicted the Serpent’s passage through dozens of jila, activating the full spectrum of colour as it breaches the water’s surface. For the most part, Aboriginal Art utilises both the aesthetics of abstraction and representation, and Ngayuku Ngura is no exception. This is, after all, a topographical landscape, but it has a visceral and psychic intensity that is rarely seen in representative art.

In contrast to Ngayuku Ngura, Garnkiny Ngarranggarni by Mabel Juli is conspicuously monochromatic. Juli is a senior Gija artist from Warmun in the East Kimberley, Western Australia. Amongst various contributions to the development of Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Juli is known for her innovations with the traditional Gija palette. She and her celebrated contemporaries, Queen McKenzie & Madigan Thomas would, in the 1980s, begin mixing ochres without natural pigments. Juli’s work is remarkably minimalistic. Very rarely does she

embellish her subjects and the landscape surrounding them. Instead, she distils them to their spiritual essence as she renders their most pivotal actions in the Ngarranggarni (Juli’s Dreaming and the origin story of the Gija). This piece, titled Garnkiny Ngarranggarni (Moon Dreaming), is an archetypal work by Juli and one of the finest examples of her Garnkiny doo Wardel (Moon & Star) paintings. The Moon and Star are central characters in the Ngarranggarni and through them, Juli explores ideas surrounding forbidden love, kinship and the origins of mortality. She anthropomorphises the moon and the star, depicting their tender embrace in the lonely void that surrounds them.

Jimmy Barmula Yunupingu (1963-2018) grew up in Yirrkala in Northeastern Arnhem Land. As the son of Dhuwarrwarr Marika, his artistic inheritance was rich. Wally Caruana, formerly the curator of Aboriginal Art at the National Gallery of Australia, has drawn parallels, in terms of cultural impact, between the Marika family and the Boyd dynasty. Prior to a sequence of personal tragedies and illnesses, Yunupingu had painted Yalangbara, a land area whose managerial duties he inherited from his mother. Following the death of his wife and certain health complications, however, Yunupingu stopped painting. In a short period of activity before his passing in 2018, he drew a series of poignant and minimal works, depicting his own passage across a body of water. Though a self-portrait, the figuration is stylised such that the viewer can place themself in the artist’s position. Features are muted, universalising Yunupingu’s personal situation and experience.

- Written by Julius Killerby“These recent acquisitions, in combination, dispel the pervasive and misplaced idea that Aboriginal Art is homogeneous. The styles of this movement’s leading figures are as varied, complex and sophisticated as any in the Western Canon. ”

- Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, 2023

The Water In The Well

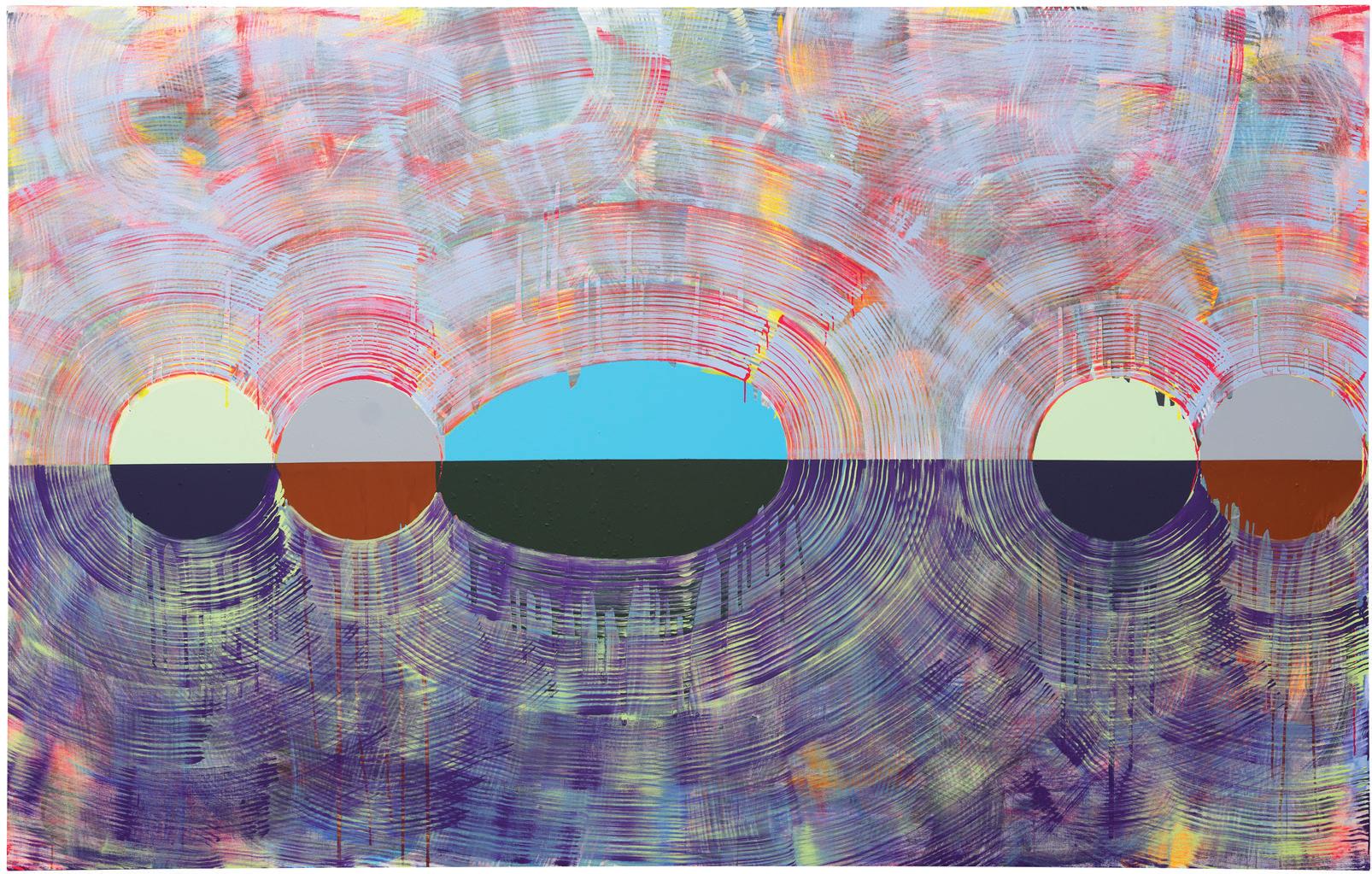

JGM GALLERY IS DELIGHTED TO PRESENT THE WATER IN THE WELL AN EXHIBITION OF WORKS ON CANVAS BY TIM ALLEN, PRODUCED OVER THE LAST DECADE. THE PAINTINGS IN THIS EXHIBITION ARE ARCHETYPAL WORKS BY ALLEN IN THAT THEY ARE VAST AND MESMERIC, STRADDLING THE BORDER BETWEEN ABSTRACTION AND REPRESENTATION.

WHAT SIGNIFIES A NOVEL APPROACH BY THE ARTIST IS THE ADDED EMPHASIS ON TRANSIENCE AND IMPERMANENCE. THIS IS CONVEYED, PRIMARILY, WITH THE USE OF A GRAINER’S BRUSH. THE PARALLEL MARKINGS ACHIEVED WITH THIS TOOL HAVE PREVIOUSLY BEEN USED BY ALLEN TO RENDER A VARIETY OF ATMOSPHERIC EFFECTS: BACON-ESQUE CURTAINS, RIPPLING AIR, REFLECTIVE SURFACES BETWEEN THE VIEWER AND A HORIZON. IN THE WATER IN THE WELL, ALLEN USES THEM TO ESTABLISH ROUNDED APERTURES.

THERE ARE MANY ASSOCIATIONS THAT ONE MIGHT DRAW BETWEEN THESE AND A CLOCK, OR THE ORBIT OF A GLOBE, BUT IT IS THE BRUSHSTROKES THEMSELVES THAT MOST CONVEYS THIS FEELING OF TRANSIENCE AND THE PASSAGE OF TIME. UNLIKE THE REDUCED LANDSCAPE BENEATH, THESE OPENINGS ARE PAINTED IN A WAY THAT EXPOSES THEIR TECHNICAL ARCHITECTURE. AS ALLEN’S BRUSH RUNS OUT OF PAINT, HE CONTINUES TO DRAG IT, CONSPICUOUSLY INDICATING WHERE EACH MARK BEGINS AND ENDS. THAT IS, A CHRONOLOGY OF MOVEMENT AND ACTION IS ESTABLISHED.

IF THE VIEWER IS MADE AWARE OF TIME AND IMPERMANENCE BY THESE SPIRALS, THEN RECTANGLES - USUALLY ESTABLISHED WITH A HORIZONTAL LINE CUTTING THROUGH THE CANVAS - SUGGESTS SOMETHING MORE SPATIAL. THERE IS ALSO A SOLIDITY TO THESE RECTANGULAR AREAS, WHICH CLARIFIES THE COMPOSITIONAL ARRANGEMENT. WITH THESE TWO SHAPES - RECTANGLES AND CIRCLES - ALLEN GENERATES AN AESTHETIC AND CONCEPTUAL TENSION, MASTERFULLY DEMONSTRATING HIS COMPOSITIONAL INSTINCTS.

ON THE OCCASION OF THE EXHIBITION, MATTHEW COLLINGS WROTE AN ESSAY ON ALLEN’S WORK. THE ARTIST ALSO SAT DOWN FOR AN ‘IN CONVERSATION’ WITH JULIUS KILLERBY.

WHAT IS THIS STRANGE RELIGION?

AN EXAMINATION OF TIM ALLEN’S WORK BY MATTHEW COLLINGS.

MATTHEW COLLINGS IS AN ART CRITIC, WRITER, BROADCASTER & ARTIST. HE HAS PREVIOUSLY WRITTEN AND PRESENTED CHANNEL 4’S THIS IS CIVILISATION AND BBC’S RENAISSANCE REVOLUTION. SINCE 2015 HE HAS BEEN A REGULAR ART CRITIC FOR THE EVENING STANDARD.

THESE PAINTINGS are about what they are made of — openings, illusions, circles, lines, horizons, streaks, solid flatness, breaks, continuities. The nature of the illusion is rushing movement, down a hole, through an opening, a cosmic distance, a snapping-to. We go towards ecstasy. We’re transported. If the works are about light and looking, perceptual psychology, visual intelligence, curiosity about looking, they put all this into a certain framework. It is the realm of Big Paintings.

Big and broad, like from long ago, the 1960s and 70s continuing the 1950s. But with a postmodern feel because of the contradiction in each of the paintings between brushy openness and a carefully bounded hard edge. As if a language game is being played. Is it a mere game? The paintings are deep even if they have this device, the use of which could be mistaken for shallowness or a trick or glib. It’s a device yes. But only like masking tape in paintings by Barnett Newman is a device.

Newman said the one great thing of all the many recorded sayings of the Abstract Expressionist painters: “Aesthetics is for artists as ornithology is for the birds.” It’s witty because of the double meaning of “for the birds” (the American idiomatic phrase meant useless, meaningless or only believed by the gullible). And it’s a deep idea, it communicates an important notion about art being an independent mode of knowledge, independent even of the knowledge-system that began to be constructed in the late eighteenth century to explain it.

In our time, no one expects or wants artists to be deep, although we pretend we do. We really want them to be cute and say cute things. Whether they are young or old, they should have the manners — we think — to only say things that anyone not intellectually developed can easily get. Tim’s paintings seem to me to be a playful participant in our own funny and shallow conversations, and at the same time, continuous with the seriousness of the art of the past. With our own seriousness, which we still have somewhere.

Another artist his recent paintings remind me of, is the sculptor Lee Bontecou. Her abstract canvas and metal constructions of the early 60s came out from the wall several feet and presented a black hole, an opening into a void. Sinister, mesmerising, beautiful. If you went through, you’d go into infinity. It was like any black circle in international abstract art, from Kandinsky to Victor Pasmore, but exaggerated and hyperbolised. Maybe a progenitor of Anish Kapoor’s black-void illusions. Anish’s are industrial finish hi tech objects, while Lee’s were industrial-referring but obviously Art. They were deeply “made” objects. You could see everything and feel your way through all the stages. The same with Tim’s streaks and flows, and the maskings and overlays, all his painterly engineering.

He recently titled some paintings after lyrics on Iggy Pop’s American Caesar (it came out exactly thirty years ago). I recognised them immediately and loved their rightness for the mood of Tim’s whole body of work. They make me laugh with delight again looking at his latest pictures. The track, Caesar, is so magnificent and funny. It tells the listener all about movies featuring the Romans when Iggy was young (the Romans in movies always had a soundtrack in a minor key). But it also tells the listener about a new real magnificence. Not just an old camp one. And the two are clearly different as concepts, one silly, one moving, but they are joined in Iggy’s song, and can’t be separated. Just as with Spartacus and Ben Hur there can be an unexpected emotional impact, along with all the absurdity of the scripts.

The Romans is surely also Jesus. And since the “fiery pit” is in Iggy’s narrative (“Throw him in the fiery pit!”) then The Romans is also the Old Testament. Among the earliest known Christian artworks, catacomb graffiti, is a picture of the scene in the Book of Daniel, of Hebrew youths cast into a fiery furnace by Nebuchadnezzar because they refuse to worship a golden idol. The Old Testament appears in Christian Art because the scenes in the New Testament are fulfillments of prophecy. Religion is considered to be for the birds. But all Art comes from it.

Fundamentalist distortions of religion distort our sense of its power as poetry and philosophy. Religion isn’t malignant. We’re all going to die any day now from eco catastrophe, if not before that, from World War III. And both threats came not from religion but from the neoliberal inheritors of the Enlightenment. The vast majority of religious people in the world now, get beauty, spirituality, morality and kindness from it. This magnificent invention.

Tim is funny like Iggy about magnificence. Funny and real. He paints to make you look. Not to prove an academic point from the colour and design class. But so you can be transported by looking.

“... Tim is funny like Iggy (Pop) about magnificence. Funny and real. He paints to make you look. Not to prove an academic point from the colour and design class. But so you can be transported by looking.”

- Matthew Collings, 2023Left (top): Tim Allen, Untitled IV, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 40cm diameter. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne. Left (middle): Tim Allen, Untitled I, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 40cm diameter. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne. Below: Tim Allen, Inside Out, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 213cm x 340cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

IN THE STUDIO WITH TIM ALLEN

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING THE WATER IN THE WELL, JGM GALLERY’S JULIUS KILLERBY VISITED TIM ALLEN IN HIS EAST LONDON STUDIO. THE VISIT WAS AN OPPORTUNITY FOR BOTH TO DISCUSS ALLEN’S WORK & THE UPCOMING EXHIBITION.

AS WE WALK through his East London studio Tim Allen pulls out dozens of canvasses, casually remarking “Oh yeah… this one” and “Ah… that’s where that was”. It’s as though these vast, mesmeric, paintings, mean nothing more to the man who created them, than would a missing pair of socks. We stop this haphazard curation, barely retaining our path back to the studio’s centre. The entrances and exits are almost blocked by this game of Tetris gone awry. One wonders how this seemingly lackadaisical man could be so prolific.

Tim and his work are, on the face of it, rather incongruous. His cadence is soft and steady, though his aesthetic is noisy and electric. His stature is slight and yet much of the work is colossal in scale. Contradictions permeate the work itself. He paints space which is detailed and complex, though it has little relation to the real world - ostensibly at least. That is, representation is the starting point – a landscape or perhaps a building – but once finished, there is little trace of the painting’s representational genesis. Indeed, landscapes and buildings were the artist’s subject earlier in his career. Adrian Searle, the art critic for The Guardian, wrote in 1999 that

“… Tim Allen painted complex, compound buildings, filled with images, imagined places, a dreamy and luminous kind of weather. And then the atmosphere and the evanescent light in the paintings overtook the imagery, until there was nothing recognisable left.”

There is, then, both a sense of place and a sense of oblivion. This ability to make two configurations equally compelling is a compositional tour de force and the key to much of the magic in Tim’s work.

Various effects are achieved with the parallel brush strokes, each carrying their own conceptual implications, none of which Tim is willing to confirm or deny. At a glance, they imbue the work with a melodic quality as they mimic blank musical notation. In a review of Tim’s work, published in 1993, Stuart Morgan made a similar point,

“In a large painting by Tim Allen, it is hard to decide which is more interesting: the intermittent, horizontal striations that look like a jittery musical stave or the effects of colors that never stop trying to break through the surface.”

Whatever is left of the painting then – the solid base colour, the flecks of pigment – can be thought of as musical notes. But something else in the work contradicts this musical levity. There is an opacity to the grainer’s brush markings which overwhelms the landscape underneath. One wonders whether Tim’s childhood years in the polluted streets of Manchester & the Northeast seeped into his visual lexicon. This reading is reinforced by the artificial, almost metallic, palette of many of the paintings. Conventionally, a landscape is detailed and the space between the details and viewer is empty. Tim inverts this convention: a landscape, in his hands, is reduced to a mere horizon, while the air between us and the horizon is made visible by the grainer’s brush marks. Empty space is complexified and, in this, there are similarities with the later, more abstracted, Turners.

In a purely formal sense, the areas of solid colour balance what would otherwise be a noisy and unintelligible surface. They clarify the composition and allow the eye a momentary rest from the hallucinogenic spirals. These areas often include a horizontal line, establishing rectangles on the top and bottom halves of the canvas. Though there are no tonal gradations in these areas, the horizontal line is enough to create a sense of receding space. In fact, without these lines, a landscape might not be implied at all. The only shape that recurs as frequently as the rectangles are the circles which Allen renders with his signature grainer’s brush. The sense of time passing is accentuated by these apertures. There are obvious similarities that one could draw with a clock, or a rotating globe, but more than anything else, the brush strokes themselves convey this feeling of time elapsing. Unlike the uniformly applied areas of solid colour, the grainer’s brushstrokes create a timeline of movement, revealing the chronology of Tim’s process.

- Written by Julius Killerby Opposite page: Tim Allen’s paints, 2023. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.JULIUS KILLERBY Do the marks you make, the parallel brush strokes in particular, do they have any relation to something in the real world? Do they signify something like light or are they pure abstraction?

TIM ALLEN I’m not sure if there is such a thing as pure abstraction, really, but certainly the parallel lines allow for a kind of layering which I hope echoes light effects or spatial effects which you can find in nature.

JK When you say there is no such thing as pure abstraction do you mean that everything is related to the real world in some sense?

TA Yes, I think that’s a good way of putting it. I think the brushstrokes that I use generate something that’s akin to the way that we experience the real world - in a direct kind of way - because they allow a complex layering which is very similar to how we sense depth or sense space. There’s a sense of tracking that maybe allows the viewer to go on a journey with the work which is similar to the way that we experience the world.

JK So they almost mimic the complexity of life without, strictly speaking, representing something?

TA Yes.

JK Is it important to you that your work is correctly interpreted by your audience?

TA Well I’d like my work to be open to interpretation, so although there are maybe clues or aspects to the work which are quite easy to understand or to follow, there are other aspects to it which allow for a very broad range of readings.

JK In your paintings there’s often a small area that’s a very heavily reduced abstraction, usually something geometric and solid in colour, and it seems very different to the grainer’s brush markings, which cover the rest of the canvas. What does the more reduced area signify because, for me, that’s what seems to hint at a landscape?

TA Yes, that’s had quite a genesis. In a very simplistic sense it relates to a lot of hard edge abstractions that I made in the late ‘70s (1976-1979), which were, I hope, not completely generic. But compared to the work I’m making

now they certainly belong to the tradition which was already well established with painters like Ellsworth Kelly or Brice Marden. So, there’s that combined with the fact that from about ‘85 through to ‘90, I began a series of paintings which were either horizon lines, or they featured a kind of aperture or a vignette in the surface of the painting. So, you know, a hole basically in the fabric of the painting. As time went on that vignette which was initially painted in quite an illusionistic way involving something much more soft-edged and atmospheric, gradually became more confrontational and as a result became more hard-edged and I guess simpler in one sense. But the relationship between the surrounding space of the painting and the insert - or the window, if you like - that became more problematic as a result of the pointing up of the difference between the two.

JK It’s almost as if you’ve inverted the conventional approach to landscape. Usually, the landscape itself would be the more detailed area and the air between the viewer and the landscape is empty. Whereas you’ve made the space between complex and you’ve heavily reduced and simplified the landscape underneath.

TA Yes, at one point I used to think of it as being a view, some depth back from the picture plane. In contrast, the ground itself was more like encountering the raw material of what you were viewing at a distance, but seen right up close. It was kind of the raw ingredient of the view. That’s speaking about those paintings from a landscape oriented position though that’s not all there is to them. The way that the images are structured or the way that the images have a conversation internally, inside the painting, I hope allows for quite a broad range of interpretation. What I’m saying now, that’s only my view point. There may be other ways of looking at the paintings. I like the paintings to have an initial punch but I also need for them to render up something much more subtle, complex and slow for the viewer.

JK Do you plan your paintings or are they mostly improvised?

TA They’re always improvised. That’s maybe the only constant thing.

JK So you never go into a painting with an image in mind?

TA Well, I might have a very generalised idea of an image. There might be a particular motif that I’m exploring. All these paintings just start. I just start and see what happens. I’ll lead the audience toward something that I might have

in mind, but it’s very open to change. In fact, the more it changes, the more complex the painting becomes, and the richer the experience is for the viewer. Well, that’s the hope anyway. The improvisation is absolutely crucial. You know, it could start off as something landscape orientated, or it might start off in the complete opposite direction to the eventual outcome, something that’s more abstract, but that can really change enormously in the process of painting. I’m not sure if I could keep my interest with a painting that was completely predictable.

JK The two most common shapes are circles and rectangles. At least for me, the rectangles create a sense of space and the circles make me aware of the passage of time. Would you say that that’s an accurate reading?

TA Yes, I think that’s a very interesting way to put it because, especially with these current paintings, I became very conscious when painting them that for some reason they seemed to generate a more specific sense of time or of time passing. I think the kind of - for want of a better word - rippling quality surrounding the circular forms, in itself generates a feeling that is about locating yourself within the passage of time, and moving across the painting spatially. So you move across the painting and you become aware of the relationship that you are having with time passing; the flow of time, the flow of impermanence.

JK The circles are also painted in a way that you can see the beginning and the end of the brushstroke. The paint, for example, becomes thinner when you reach the end of the stroke. Whereas the solid base layer, which forms the rectangular area, doesn’t give any of the process away, because the paint is applied flatly.

TA I think that’s particularly true of this painting (points to Mirror) but there are other paintings in which the ground is actually quite varied and there are lots of things happening in the ground. So, what’s left to filter through the top layers varies enormously across the picture.

JK Do you paint on a large scale so as to immerse your audience in the world you’ve painted? Do you want your audience to experience the work as much as you want them to analyse it?

TA Yes, I think immersive is the right word for that. I’ve always liked making big paintings.

JK Do you see the smaller works more as conceptual studies, then?

TA No. I think they all work in their own way, but there is something about making a big painting... I’m not sure what it is. It’s just an instinctive thing really. I just enjoy it.

JK Would you agree that there’s a hallucinogenic element to your work?

TA Yeah. Yeah I would say that’s... the problem with the word “hallucino-

genic” is that it seems to imply something that isn’t real, whereas in fact most of one’s experience with making paintings is that you’re trying to convey a real experience. Something which can’t be replicated in any other way. And although, like all experiences, it’s kind of short-lived and moves on very quickly, I would hope that... well I guess that the idea of transport is important, the idea that you can be transported from one state to another. But is that an hallucination, I’m not sure it is. It’s a useful word because it does relate to states of consciousness and I think that’s important in the work. But, as I said earlier, I don’t think it conveys the sense of real experience that I want to convey.

JK Tell me if you agree with this, Tim. I would say that there is a very musical quality to your work. I get that from the parallel lines as well because it reminds me of blank musical notation. Then, for me, the other aesthetic elements in the painting become the musical notes. Is that intentional at all?

TA If you go back quite a long way, a lot of the work was much more like staves, as you suggest, than it is now. There was a review, actually, quite some time ago now, written by Stuart Morgan, where he focused on that aspect of them and made parallels, not just with musical staves, but also written language, different kinds of alphabets and so on. I think it’s definitely an aspect of the work but I wouldn’t have said it was a primary aspect these days. I think my handwriting’s my handwriting and the graining brush mark is being made to do more than it used to.

JK Well what music do you listen to when you paint?

TA All sorts.

JK At least with my own practice I find that you can listen to different songs so as to borrow different kinds of emotions. If you’re needing a bit of an energy kick, play Voodoo Child for example.

TA Yes, I do all that. I can’t envisage working without music actually. These days I tend to listen through wireless headphones.

JK Well given your style is quite improvisational, I imagine the music effects how and what you paint quite a lot.

TA I don’t know... I don’t know if it does or not. It certainly effects how I feel when I’m painting. Sometimes I might be playing something ambient which is almost subconsciously there in the work. I mean once I really start painting I can actually... you know... if something finishes I might not put it on again for a while and just work in silence. I find that the older I get the more often that happens. But yes, music is crucial. My life has revolved around music just as much as art really.

JK You were a musician yourself?

“... at one point I used to think of it as being a view, some depth back from the picture plane. In contrast, the ground itself was more like encountering the raw material of what you were viewing at a distance, but seen right up close. It was kind of the raw ingredient of the view.”

- Tim Allen, 2023Opposite page (left): Tim Allen, Mirror 2013, acrylic on canvas, 195cm x 155cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

TA I did play, yeah.

JK What did you play?

TA Guitar, keyboards, harmonica, writing, singing, you know... the whole lot really. It’s all on Spotify.

JK Under the name, Tim Allen?

TA No it’s under the band’s name, which is Drifting Robots.

JK That’s a good band name. You’ll often have quite suggestive titles for some of your works. The work behind us is titled Mirror, for example. It makes me wonder if there is a narrative element to your work.

TA I talked about this a bit on Gary Mansfield’s podcast, The Ministry Of Art. I talked about writing song lyrics and how that kind of moved into titles and writing for it’s own sake. Kind of poetry I suppose. Certainly with titles I wanted to be able to push something quite complex. So you initially encounter a title with a painting and its problematic. Quite often it’s very difficult to make that relationship between the title and the painting work. It throws you into engaging with a painting in a way that it wouldn’t otherwise and it allows you to interpret it in a way that you might not have done without that title.

JK It pushes the audience along in the interpretive process?

TA Yes, yes I think so. You know you’re looking at them thinking “What does that mean... why is it called that?” And in trying to work that out you live with, or you engage with the painting in a way that you wouldn’t have otherwise been able to. And you can also begin to discern a more complex relationship with what those forms might be leading you to. I was about to say “referring to” but the paintings aren’t symbolic. It’s very hard to explain, which is probably a good sign, but they’re certainly on the border between abstraction and figuration. It’s a kind of shuttling process backwards and forwards and that’s where I like to be, you know, with a foot in both camps.

JK I think having that foot in both camps, at least for the audience, makes you more aware of the paint itself... and the illusionistic qualities of the paint because you can so easily hover between the illusion of representation and straight abstraction. I mean, for me, that’s why I don’t find photorealism too interesting, whereas I find someone like Jenny Saville very interesting because you’re much more aware of the work as a construction.

TA Yeah, thinking about photorealism, I mean it brings to mind someone like Malcolm Morley for me and the way that he began to disrupt what were initially extraordinarily illusionistic paintings and then he began to insist upon their materiality. And of course with him they were kind of mad... I haven’t really thought about him for a while. He’s quite an interesting artist, I think.

JK Who are some of your favourite artists?

TA Well I’ve always rated Brice Marden. It’s one of those questions where, you know, I’d give you a different answer tomorrow... or yesterday.

JK Well my follow on from that was going to be are your favourite artists also the ones who have had the most influence on your work?

TA Hmmm I don’t know. I haven’t really thought about that for a long time. I mean I hope that now the paintings are beginning to establish their own identity. There’s just so many artists really. I think that whole European landscape tradition which then moved out into America and Russia around the late 19th century and then, I suppose, moved into Impressionism... I think that’s still very potent for me. I still love discovering new artists who worked in that tradition that I might not have known. Interestingly, recently one of, I think, the greatest landscape painters, Kuindzhi, who is a Russian... well actually it turns out he wasn’t Russian. He was Ukrainian and there’s a museum which has been really badly damaged and I know that he didn’t do many paintings, just because they took a very long time to paint. I hope that the work has survived. I don’t really know... I just remember reading it in the newspaper where they happened to mention his name. You realise how vulnerable Art is. It’s like going back to the Iraq War and the extraordinary buildings and works of Art that were destroyed by the War.

JK Do you remember which artist was your foot in the door for first getting you into Art?

TA Well, again, I talked about this a little but on Gary’s (Mansfield’s) podcast. It took a while to get past Picasso. And then, when I was about sixteen or seventeen, I saw a reproduction of Woman I, by de Kooning, in Herbert Read’s History of Modern Art and I thought why is that good? It’s so horrible. And I just worked with it, and it obsessed me. I couldn’t get it out of my head even though I didn’t like it at all. And I don’t know what happens, you know, it’s like learning a language. Suddenly you wake up and you can speak it and that’s what happened. I suddenly could understand it and it was one of the greatest paintings, full of incredible stuff. Ever since that experience I’ve never really had a block. I might not like something or I might like something, but that’s not the same as understanding it or being able to see its place in the Pantheon.

JK Well do you think how broadly understood or easily understood an artwork is at least one barometer for its success?

TA Well understanding depends on who’s looking at it doesn’t it? And you get many different kinds of people and different kinds of understanding.

JK No, of course, but I think an artist is always trying to convey an idea, a feeling, an emotion, or something more specific. And I think if the viewer has to labour over a work much longer I wonder how much that’s an indication of the artist falling short of their goal.

TA No it just means some artworks are harder to get to than others. And, you know, this idea that Art has to convey an idea. I mean I’m not sure about any of this. Obviously Art does convey ideas but is that it’s only function? It always seems to me that one of the great things about Art is that it suspends ideation. It opens your mind. That’s not to say that ideas aren’t involved because that’s part of the richness of looking at Art, but it’s not the only thing, it’s something that’s... I nearly said bigger than that but... I don’t know.

JK How do the paintings being exhibited at JGM Gallery this March differ to your previous work, do you think?

TA Well the majority of the work in this show is relatively recent and features a kind of marriage of the horizon line motif with the aperture or vignette. So they’ve been brought together in a way that I hope is new for me. I haven’t quite worked out what they’re about yet really but it does seem that the sensations I get off them are what I was talking about earlier: this relationship with time, that they’re as much to do with time as they are to do with space.

JK Do you generally only see the progression in your work in hindsight?

TA Yeah I think some aspects of the work take years and years to understand. Stuff that you might have rejected once you now look at again and think “That makes sense” or “That’s what that was about”. Or, you know, you can have whole periods of work that you went off for a couple of decades. This is all stuff that I’ve found happens as I’ve got older, that once you’ve been working for a long time, you can move in and out of these different periods and something that you did ten years ago might suddenly come round again. Or twenty years ago or, as it is now, fifty years ago. You know, when you work over a very long period of time your relationship with your work becomes more profound... or at least you understand it more... maybe. But at the same time as saying that, quite often, as I have been in this conversation, I’m at a loss to really be able to understand or explain it. If you could explain everything you wouldn’t paint it. You want to create experiences for other people that can’t be duplicated. Each painting is a unique thing.

JK I guess that gets to what we were saying before. If every painting was just conveying an idea or had a very specific narrative element, why not just write about it, rather than paint it. When we met the other week you were explaining the social and cultural history of Durham to me, which is where you grew up. Could you explain that again?

TA Well it’s quite a complex place. It’s a medieval city. It was, at one point, the greatest pilgrimage centre in Europe until Thomas Becket got whacked in Canterbury. So culturally it was actually a real focus in the North of England and at one point it was a palatinate, which meant that it was ruled by a Prince Bishop who was the only person in the country apart from the King who could print his own money. So it had this kind of independence. Anyway, I don’t know what the relevance of all this is but what is crucial is that I grew up immediately outside one of the greatest buildings in the world and the Cathedral there is probably the best Norman building in the World and certainly one of the greatest Cathedrals. And, as a place to grow up as a child, it was amazing really. Really inspiring and it continues to be inspiring. Also, I guess socially, it was quite

complicated because certainly still as I was growing up it was the headquarters of the mining union. It was at the centre of the Northeastern coalmining industry, which as we know, changed the world, transformed the world via the Industrial Revolution. So the city itself was surrounded by pits which are, of course, closed now. There are villages which are just in dire, dire poverty and that conflicted massively with the university which was obviously one of the most substantial and oldest universities in the country, apart from Oxford and Cambridge. And so, there was that conflict, plus into that is thrown a kind of Church of England hierarchy, second only to Canterbury probably. So, as a social mixture it was really very complicated and confrontational a lot of the time, and that made it a very unique place to grow up.

JK Did it seep into your work at all?

TA Yes, I’m sure it did. Defining how is something else but I’m pretty sure it did.

JK Of course you could over analyze it but for me making the air visible - which is partly what I think you do in your work - seems consistent with an upbringing in a polluted city. The sense of scale, I imagine, was also partly influenced by your upbringing in Durham.

TA I think, yes, definitely the sense of scale. I think visually it was a very powerful place. A very powerful place to live, especially as a teenager.

JK Was it the kind of environment where you were encouraged to be an artist?

TA Yes, it was. I was very lucky in that respect. Both my parents were absolutely encouraging. My

mother had been to art school. She was at Manchester during the Second World War.

JK When did you first want to become an artist?

TA I don’t know. I always knew... well I never really considered anything else. I could’ve written instead maybe, or played music.

JK You’ve previously painted with both oils and acrylics. In relation to your work, what are the pros and cons of both mediums. What do you get from acrylics that you don’t get from oils and vice versa.

TA Well I started with acrylics and then went into oils and then came back to acrylic. Acrylics is about speed. You can work very fast. In a warm temperature you can layer it and layer it, which I like. It makes it closer to calligraphy or something like that where you can work spontaneously and generate quite a speed. With oil paint you kind of have to pace it because of the drying time. It’s a very different approach. The return to acrylic happened quite naturally over quite a long period of time. I had some technical issues with some of the oil paintings from the 1980’s.

JK Did they begin to deteriorate?

TA Yes, it was mostly to do with priming and sizing. I started to use acrylic as a straightforward primer where you don’t have to use conventional or traditional sizing. This was as a result of damage to the paintings incurred with huge temperature changes in the studio I used to be in... it’s actually not totally dissimilar to this one. You’ll have noticed I’m beginning to shiver (both laugh). So massive differences in temperature or humidity. All those things cause a lot of canvas tension and so if you don’t have the primary layer - the sizing - right, then it doesn’t matter what you put on top, it’s going to deteriorate and crack. So I went back to acrylic because it gets rid of that problem. But, you know, I love oil paint. I love all kinds of paint actually. It’s just swings and roundabouts. Who knows, I might get round to using oil paint again.

JK Are you excited to be showing this new body of work in London at JGM Gallery?

TA Yes, I’m very excited. I’m really looking forward to it.

JK And a broad and pretty unfair question Tim, but why do you think Art is important?

TA Because it opens people’s minds. That, in itself, is a crucial part of life.

(Pauses)

JK Well if you were to stop painting today, what would you be losing?

TA Just about everything (laughs). Well, not completely because obviously, you know, you make the best of whatever you can. But I’ve been painting too long now to consider... I’m not going to stop now.

GURRUTU: THE ART OF MULKUN WIRRPANDA

IN JANUARY & FEBRUARY OF THIS YEAR, JGM GALLERY WAS HONOURED TO EXHIBIT THE WORK OF THE LATE MULKUN WIRRPANDA. WORKING PRIMARILY WITH LARRAKITJ (HOLLOWED OUT TREES), BARK, BOARD & PAPER, WIRRPANDA CONVEYED A VISION OF THE WORLD WHERE EVERY ORGANISM LIVES SYMBIOTICALLY TOGETHER.

THOUGH THERE IS CERTAINLY A CONCEPTUAL RICHNESS TO THE WORK, THERE IS A UTILITARIAN ASPECT TO IT ALSO AND IT CAN BE CONCEIVED, AS JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI STATES, AS “... A MANUAL OF SORTS, INTENDED TO INFORM FUTURE GENERATIONS ON THE ECOLOGICAL WISDOM OF THE ARTIST’S ANCESTRY.”

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING GURRUTU: THE ART OF MULKUN WIRRPANDA, JULIUS KILLERBY SAT DOWN WITH WILLIAM STUBBS (COORDINATOR OF THE BUKU-LARRNGGAY MULKA ART CENTRE) TO DISCUSS THE LIFE AND WORK OF WIRRPANDA.

The Art Of Mulkun

THE LATE Mulkun Wirrpanda's (1942-2021) primary subject was the botanical life of her surroundings in Yolnu Country (North Eastern Arnhem Land, Northern Territory). In Wirrpanda's hands, this ostensibly straightforward subject conveyed a rich and ancient cultural inheritance.

A through line in the work of many First Nations Australians is the use of small motifs to convey far reaching concepts of cosmic significance. The story of the Rainbow Serpent, though not an origin story shared by all Indigenous Australians, is the most well-known example of this. This conceptual approach - the macro expressed through the micro - is particularly true of Wirrpanda who, in a blade of grass or the leaf of a tree, conveyed a symbiotic relationship with the land that had sustained her and her ancestors for 65,000 years.

Though not an exact textual equivalent, the verse of William Blake compliments Wirrpanda's conceptual concerns: "To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in an hour" (Auguries of Innocence, 1863).

The term "gurrutu" refers to Wirrpanda and the Yolnu's understanding of the cosmos, what Will Stubbs (Coordinator at the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre) describes as a "... matrix of meaning... which is invisible to us and too complex for casual comprehension." It is perhaps most easily comprehended, however, through the work of Wirrpanda who, with her hatching technique, amongst other aesthetic elements, conveyed an interconnectedness and familial bond with every natural element.

Amongst the works in Gurrutu: The Art Of Mulkun Wirrpanda are various depictions of termite ecosystems. These, and the publication Midawarr | Harvest: The Art Of Mrs Wirrpanda & John Wolsley, were the result of a collaboration in 2019 with the Australian artist & botanist, John Wolseley. In these works Wirrpanda depicts the mounds of 'munyukulunu', magnetic or compass termites, a species of eusocial insect that is endemic to northern Australia. These mounds are populated by the termites' symbiotic partners: 'nadi', or northern meat ants, diverse bird species and their eggs, as well as beehives. Harmonious ecologies such as these exemplify, through a micro example, Wirrpanda's broader societal and world views.

The exhibition culminates in the last artwork Wirrpanda ever made, Untitled II, a series of drawn variations of a void. In the context of Wirrpanda's life and work, the depicted space is imbued with a sense of ancestral communication, rather than morbid contemplation. What is ultimately expressed in all the pieces from this exhibition is a societal and ecological sophistication which is often overlooked.

- Written by Julius

Killerby

Killerby

“Gurrutu:

Wirrpanda stands as a testament to the life of a woman with formidable artistic talent and a symbiotic sensibility.”

- Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, 2023Opposite page (left): Mulkun Wirrpanda, Gan’kurr ga Milinydjura 2018, ‘Larrakitj’ (hollowed out tree), 242cm x 22cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne. Opposite page (bottom): Mulkun Wirrpanda, Nadi ga Gundirr 2020, earth pigment on paper, 76cm x 56cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne. Opposite page (top): Mulkun Wirrpanda, Nambarra II 2017, earth pigment on paper, 67cm x 55cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

“The exhibition culminates in the last work Wirrpanda ever made, ‘Untitled II’, a series of drawn variations of a void. In the context of Wirrpanda’s life and work, the space depicted is imbued with a sense of ancestral communication, rather than morbid contemplation.”

- Julius Killerby, 2023

JULIUS KILLERBY What separates Mulkun Wirrpanda’s conceptual concerns from those of her contemporaries?

WILLIAM STUBBS In the period where she began working on the Harvest series, Ms. Wirrpanda took a novel approach to the topic and the angle. In the Yolnu community people generally paint in line with their identity and they generally refer to sacred designs that encapsulate that identity. Mulkun had a different approach. She was motivated by a desire to educate and entice people into renewing their knowledge and consumption of natural foods that were available - foodstuff. Because the entirety of reality is contained within a matrix of Yolnu cosmology and each element of that reality has a sacred essence assigned to it, she did not have the right to paint all of the various foodstuffs that she was interested in. In order to bypass those conventions she found a way to paint the plants she was referring to without employing their sacred clan design. So in that regard, she had a very novel conceptual framework with which she approached her painting in the period when she was working on the Harvest series and beyond.

JK What was Mulkun’s position within the Yolnu community?

WS Ms. Wirrpanda was a very senior elder. She was held in great regard within the community because of her knowledge and because of her active involvement in every aspect of community life. She attended every ceremony which she was physically able to go to and these ceremonies run for weeks or months at a time and are almost always ongoing in some part of Yolnu land. She attended and directed, managed and choreographed many aspects of those ceremonies. She had a large family which she provided for, and she was a wise and active person who was held in very high regard by her community.

JK How does Mulkun’s aesthetic differ from those of her contemporaries?

WS I have to reiterate that her aesthetic was novel in comparison to her contemporaries, necessarily, because she wasn't allowed to employ sacred design in depicting the wide range of plants and foodstuffs that she wanted to educate people about. Because each one of them would belong to a different clan and would have a specific clan design relating to its identity, she would not have had the authority to paint in many of those areas which have their own autonomous systems of authority. Accordingly, she divined, or sensed the essence of the plant or animals she was depicting and created a design that she felt reflected the natural essence of that plant, independent of the sacred cosmology of Yolnu. In that case, her aesthetic was different from that of her contemporaries.

JK Perhaps to contextualise her work a bit, could you describe Mulkun’s personality?

WS She was clever, she was funny, she was loud. She was strong, tough and she was fearless. But she was warm and soft at the same time. So as you would expect a matriarch to be. She was a genuine leader of the first degree of her clan and her society, and she was able to sustain and buttress that with the fierce power of her intelligence and her curiosity, which allowed her to accumulate so much knowledge over her lifetime.

JK Mulkun was alive throughout the latter half of the ‘Stolen Generation’ and her father, Dhakiyarr, was, it seems, murdered by a group of Australian policemen. Do these traumas make her sharing of knowledge all the more remarkable and generous?

WS All Yolnu who have lived through the 20th and the first part of the 21st century have suffered extreme trauma. The traumas are ongoing as a result of the effects of colonialism and the suppression of their culture and the wilful blindness to the beauty and majesty of their culture. In Mulkun’s case, as in the case of most Yolnu, that trauma is somehow subsumed within a culture that lives in the moment, finds joy in everyday life, and appears in many cases to be unburdened by all of this historical and ongoing trauma.

JK Was there a reconciliatory undertone to her life and work?

WS I don't think she saw herself in a framework of reconciliation between Yolnu and non Yolnu. As with most Yolnu, they are slow to judgment. It's not an inherent part of their cultural background to judge everyone and everything, and particularly not by appearance. She was pretty similar, in that respect, to most Yolnu. They take people as they find them without the inherent concept of a hierarchy or supremacy that Europeans seem to labor with.

JK Just how ancient is the knowledge conveyed in Mulkun’s work?

WS In some of her work relating to the identity of her Dhudi-Djapu clan land, she references landscapes and landmarks that are quite possibly the result of the tsunami or the inundation of the Gulf of Carpentaria, which is likely to have occurred before the last ice age. So the question is unanswerable. But I'm pretty satisfied that we're looking at many, many millennia of knowledge contained in the songs, which eventually reflect in her work.

JK Could you describe what “gurrutu” is and how it relates to Mulkun’s work?

WS “Gurrutu” is not capable of being explained in a short answer, but it is an all encompassing, infinitely repeating framework that allows every element of reality, every person, every place, every animal, plant, bird, fish species and the land itself to trace a direct family relationship between itself and any other element within reality. So it's an overarching matrix that is the main framework which holds human philosophy and society. And it's far too complex to try and understand or explain here. A mistranslation would be kinship, but because our concept of kinship is such a stunted one, it doesn't allow for the fact that we're all actually related to each other and in fact, to all oxygen based life forms. The current system allows you to trace exactly what that family relationship is and give meaning, identity and connection to all things within reality.

JK Could you describe the landscapes Mulkun travelled through and the subjects she depicted in her work?

WS The landscapes that Mulkun travelled within in Northeast Arnhem Land are untouched, fully functioning ecosystems that consists of saltwater, country, beaches and reefs, leading to rivers, which lead to estuaries, which lead to freshwater systems. The plants are in different zones. The bulk of Northeast Arnhem Land is a massive forest of eucalypt, and within that are pockets of mangroves, pockets of monsoonal rainforest and some open grasslands. Some of the shellfish and plants that Mulkun depicted can be found within those various landscapes.

JK What I find remarkable about Mulkun’s work is how she utilized the strengths of abstraction and representation so seamlessly. These images are records of botanical life - ostensibly a rather straightforward subject - but the degree to which they have been stylized imbues them with an intensity that conveys so much more than the subject alone. Would you agree with that?

WS Yes, I would agree with that.

JK In the catalogue text for Midawarr | Harvest you write that the phrase ‘Aborigines ate this’ is often included in the descriptions of plants in botanical text books. You discuss the way in which the tense of this phrase almost pre-supposes the conclusion of Aboriginal culture and is, in your words, “… the assumed tense for Aboriginal occupation.” How does Mulkun’s conception of Yolnu botanical life differ from the attitude of most botanical text books?

WS White supremacist textbook writers prefer to consign Indigenous people to the dustbin of history, but the reality is that that is not accurate. Yolnu people still live off the land with their full knowledge of their history and with full sovereignty.

JK The last artwork Mulkun ever made, Untitled II, will feature in this

exhibition. It strikes me as aesthetically quite distinct from the rest of the works. What is this piece about?

WS It's quite a sad artwork in the sense that there's a person who's been really grossly impaired by the medical issues she was facing. She'd probably suffered multiple strokes at that stage, but her passion and her skill to create was still there. And it's almost a miracle that she could create these works, given how impaired she was. She was happy, she was cheerful. She wanted to come to the Centre even though her capacity to create was impaired, but she continued to create. And this is what came out of it –just a very poignant and beautiful work.

JK “Food security” is a term you bring up in the catalogue text for Midawarr | Harvest, and this term is, especially in recent years, more relevant than ever. The United Nations released a report in October 2022 saying that “A staggering three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet; the war in Ukraine has triggered surging food, fertilizer, and energy prices.” Do these food crises make Mulkun’s work, and the knowledge held within

it, more relevant than ever?

WS Food crises are definitely going to be more prevalent for the industrial people who have been sheltered from it up to this point. Obviously, many people throughout the world have been in an ongoing food crisis, but with the prospect of climate change and war mongering, the occupants of cities may have their access to food more jeopardized than they’re used to.

JK How would you describe the legacy of Mulkun Wirrpanda? What was her impact and how will she be remembered by those who knew her and her work?

WS I feel that Ms. Wirrpanda’s legacy is probably yet to be fully appreciated. As we suffer the loss of ecosystems, which is probably inevitable in the current progression of climate change, and as we lose Indigenous knowledge from all over the world, not just from Australian First Nations People, what she was able to create and capture will be valued even more highly, I would anticipate.

“She (Mulkun) was a genuine leader of the first degree... and she was able to sustain and buttress that with the fierce power of her intelligence and her curiosity, which allowed her to accumulate so much Yolnu knowledge in her lifetime.”

- William Stubbs, 2023

CREATURE COMFORTS

BETWEEN NOVEMBER 2022 AND JANUARY 2023 JGM GALLERY EXHIBITED CREATURE COMFORTS, A GROUP SHOW OF 14 ARTISTS WORKING WITH A VARIETY OF TEXTILE MEDIUMS, CURATED BY KAROLINA DWORSKA.

TEXTILE ART TODAY STRUGGLES TO SHAKE OFF ITS ASSOCIATIONS WITH SENTIMENTALITY, DOMESTICITY AND FEMININITY. THESE COSY CONNOTATIONS, HOWEVER, ALLOW ARTISTS TO DIRECT THEIR AUDIENCE TOWARD UNEXPECTED CONCEPTUAL TERRITORY. CREATURE COMFORTS PRESENTS WORKS BY ARTISTS WHO SUBVERT THE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT TEXTILES, IMBUING THEIR WORK WITH STRANGENESS, ENERGY AND INTENSITY.

THE WORKS WERE MADE USING A VARIETY OF TECHNQIUES, FROM TAPESTRY WEAVING TO KNITTING AND SOFT SCULPTURE. THEY TOUCHED ON THEMES OF THE DOMESTIC AND REINTERPRETED THE TRADITION OF THIS TIMECONSUMING CRAFT. WHAT RESULTED FROM THIS SUBVERSIVE APPROACH WAS SURREAL IMAGERY, LUSCIOUS LANDSCAPES AND DECIDEDLY STRANGE CREATURES.

EXHIBITING ARTISTS INCLUDED ALICE KETTLE, ANDIA NEWTON, ELINA FLYRIN, FREDDIE ROBINS, HAMISH HALLEY, HEIDI PEARCE, KAROLINA DWORSKA, LARA SALOUS, LIZA DICKSON, LOLA PEDERSEN, MARTIN MALONEY, MOLLY KENT, SEBASTIAN SOCHAN & WOO JIN JOO.

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING THE EXHIBITION, KAROLINA DWORSKA PRODUCED A WRITTEN PIECE TO ACCOMPANY THE EXHIBITION.

Opposite: Installation of works from Creature Comforts 2022 2023. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

Opposite: Installation of works from Creature Comforts 2022 2023. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

ALICE KETTLE ANDIA NEWTON

ELINA FLYRIN

FREDDIE ROBINS HAMISH HALLEY

HEIDI PEARCE KAROLINA DWORSKA LARA SALOUS LIZA DICKSON LOLA PEDERSEN

MARTIN MALONEY

TEXTILES ARE SOFT. They are comforting. They are clothes, rugs, blankets, and our favourite plushie toys; they are durable, yet malleable, and ultimately ephemeral. Textiles are “feminine”, knitted by our grandma and repaired by our mother. Textiles are apocalyptic. They portray war, violence, and the rapture. They’re an itchy old dusty carpet. They are precious artefacts that tell us about our past. They are traces of hands, stitches, rips, and careful folds. A million loops, looping in and around each other, looped carefully by a pair of hands.

The idea for Creature Comforts came from a conversation between myself and Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, the Director of JGM Gallery. We were discussing quilts; handmade, traditional, enchanting. Their allure, we thought, was not only their tessellating colourful designs but, on a more basic level, the intricate care that was required in their construction. I remembered a show of Gee’s Bend quilts and how amazed I was by their complexity and by the way the artists had imbued everyday textiles, such as denim trousers, with immense value.

As we discussed quilts, we realised that a group shop of textile work could be used to showcase remarkable talent as well as the medium’s complex context in relation to history, gender and notions of value. Intrinsically, textiles are comforting. They’re soft, and we usually wrap ourselves in them, or sit on them. They have been fundamental to human life since our very beginnings; they furnish our dwellings and keep us warm and comfortable. Yet, historically, these tenderly woven surfaces have been used to showcase a myriad of apocalyptic events. The Bayeux Tapestry details the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The Unicorn Tapestries, resting quietly in the Met Cloisters, present us with a disturbing and perplexing hunt for a mythological beast. The violence of these masterpieces, especially in contrast to the soft material with which they are rendered, never ceases to shock me.

Creature Comforts explores these multifaceted aspects of textiles; of comfort, chaos and conflict. From one side, we have comfort; hanging tufted sculptures of blissful pastels and tender quilts, hand stitched and stuffed with hay. There are embroidered images of the everyday and woven stools which have been hand spun and lovingly made. Then there are depictions of chaos: strange, dog-like creatures clambering out of pillars and embroidered Korean “Dokkaebi” spirits, breathing life into old gloves and socks. And lastly, conflict; woven and knitted tapestries, harbingers of something sinister. Whether it is a mysterious threat, an internal mental conflict, or the suffocating feeling of impending environmental disaster; the soft appeal of the tapestry pulls the viewer into its madness.

Creature Comforts traverses the endless possibilities of the medium and the ways in which its 14 artists embrace and play with its expectations.

- Written by Karolina Dworska

Editorial design: Julius Killerby.

Photography:

©

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-7392905-2-8

JGM Gallery 24 Howie Street London SW11 4AY

info@jgmgallery.com

Front cover: Tim Allen, Silver Train (detail), 2016, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne & Julius Killerby.

Back cover: Freddie Robbins & Karolina Dworska in Robins’ studio, 2022. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.

Julius Killerby & Daniel Browne.

2023 JGM Gallery, Julius Killerby & Daniel Browne.

Front cover: Tim Allen, Silver Train (detail), 2016, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne & Julius Killerby.

Back cover: Freddie Robbins & Karolina Dworska in Robins’ studio, 2022. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.

Julius Killerby & Daniel Browne.

2023 JGM Gallery, Julius Killerby & Daniel Browne.