LOSING THE IMAGE

LOSING THE IMAGE

EXHIBITING AT JGM GALLERY LONDON

10 SEPTEMBER TO 19 OCTOBER 2024

JGM GALLERY PRESENTS LOSING THE IMAGE , AN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY LONDON-BASED ARTIST, KAROLINA ALBRICHT.

TAKING ITS TITLE FROM PHYLLIDA BARLOW'S WORDS, ALBRICHT’S SECOND SOLO EXHIBITION AT JGM GALLERY ENCOURAGES ITS AUDIENCE TO CONSIDER PAINTINGS AS SPATIAL ENVIRONMENTS, WHICH BOTH EVADE DEFINITION AND ILLICIT NOVEL INTERPRETATIONS ON EACH VIEWING. IN BARLOW’S CASE, THE PHRASE, “LOSING THE IMAGE ”, REFERS TO THE PARTICULAR WAY IN WHICH THE VIEWER EXPERIENCES A THREE-DIMENSIONAL OBJECT AS THEY MOVE AROUND IT. FOR ALBRICHT, THIS ALSO OPENS UP AN ENQUIRY INTO WHAT “AN IMAGE ” MEANS AND WHAT ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE WORLD IS. THIS ENQUIRY, AS WELL AS THE PAINTINGS IN THE EXHIBITION, IS INFORMED BY HER INTEREST IN EASTERN ORTHODOX ICON PAINTINGS, AND HER RECENT RESIDENCY IN RURAL NORFOLK, WHICH REAFFIRMED ALBRICHT'S RELATIONSHIP TO NATURE. LOSING THE IMAGE TRACES HER SHIFTS IN PICTORIAL THINKING, “THE IMAGE ” BEING PROGRESSIVELY QUESTIONED AND REPHRASED.

FOR ALBRICHT, AS A PAINTER, ABSOLUTE DISTINCTIONS SURROUNDING OBJECT AND IMAGE BECOME BLURRED. THE PAINTINGS’ SURFACES OFTEN ACCUMULATE THICK LAYERS OF PAINT OF VARYING TONALITIES. OTHERS EMERGE THROUGH SUBTLE GLAZES. REGARDLESS OF HOW THE MARK IS MADE, THE PAINTINGS SEEM TO EXIST NOT ONLY PICTORIALLY BUT ALSO THREE-DIMENSIONALLY. INTERESTED IN THE BODY, ITS MOVEMENT, AND THE SPACE IT OCCUPIES, ALBRICHT TRANSFERS THESE RELATIONSHIPS INTO A PICTORIAL FIELD. AS SUCH, THE MATERIALITY OF THE SURFACE BECOMES AN EXPERIENCE – AN EVENT – BOTH FOR THE ARTIST AND VIEWER, WHICH RECALLS THE IDIOSYNCRASIES OF THE HAND THAT MADE IT.

IN MANY OF THE SMALLER WORKS FROM THIS EXHIBTION, COMPOSITIONAL ELEMENTS EXTEND BEYOND THE CONFINES OF THE SURFACE AND ITS BORDER. THESE PROTRUSIONS FURTHER CHALLENGE THE DEFINITION OF “THE PAINTED IMAGE ” INSTEAD RECALLING PRACTICES REMINISCENT OF SCULPTURE OR COLLAGE. OFFERING VARYING PERSPECTIVES FROM WHICH THEY CAN BE VIEWED AND FUNCTIONING SIMULTANEOUSLY AS BOTH OBJECT AND PAINTING, ALBRICHT’S WORKS PRESENT US WITH A MULTIPLICITY OF READINGS. THE AMBIGUITY OF THE SURFACE CHALLENGES THE URGE OF MIMETIC IMPERATIVE: ALBRICHT DECONSTRUCTS FORM INTO SHIFTING FIELDS OF COLOUR, LIGHT AND SPACE, WHICH MEET WITH AN ANGLED PRECISION AND INTRODUCE A CERTAIN GEOMETRY. YET, RATHER THAN POSSESSING THE GEOMETRICAL SEVERITY OF MINIMALISM, THE RHYTHMIC NATURE OF THE MARKS, THE FLUIDITY OF THE PAINT, AND ORGANIC EXTENSIONS OF THE PICTURE PLANE, DIFFUSE ANY SENSE OF GRAPHIC REGULARITY.

CENTRAL TO THE ATTRACTION OF ALBRICHT'S WORK, IN THE WORDS OF JENNIFER GUERRINIMARALDI, IS “... AN AESTHETIC AND STYLISTIC ORIGINALITY THAT DISTINGUISHES KAROLINA AS AN ARTIST OF GREAT COURAGE AND DARING. ”

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI

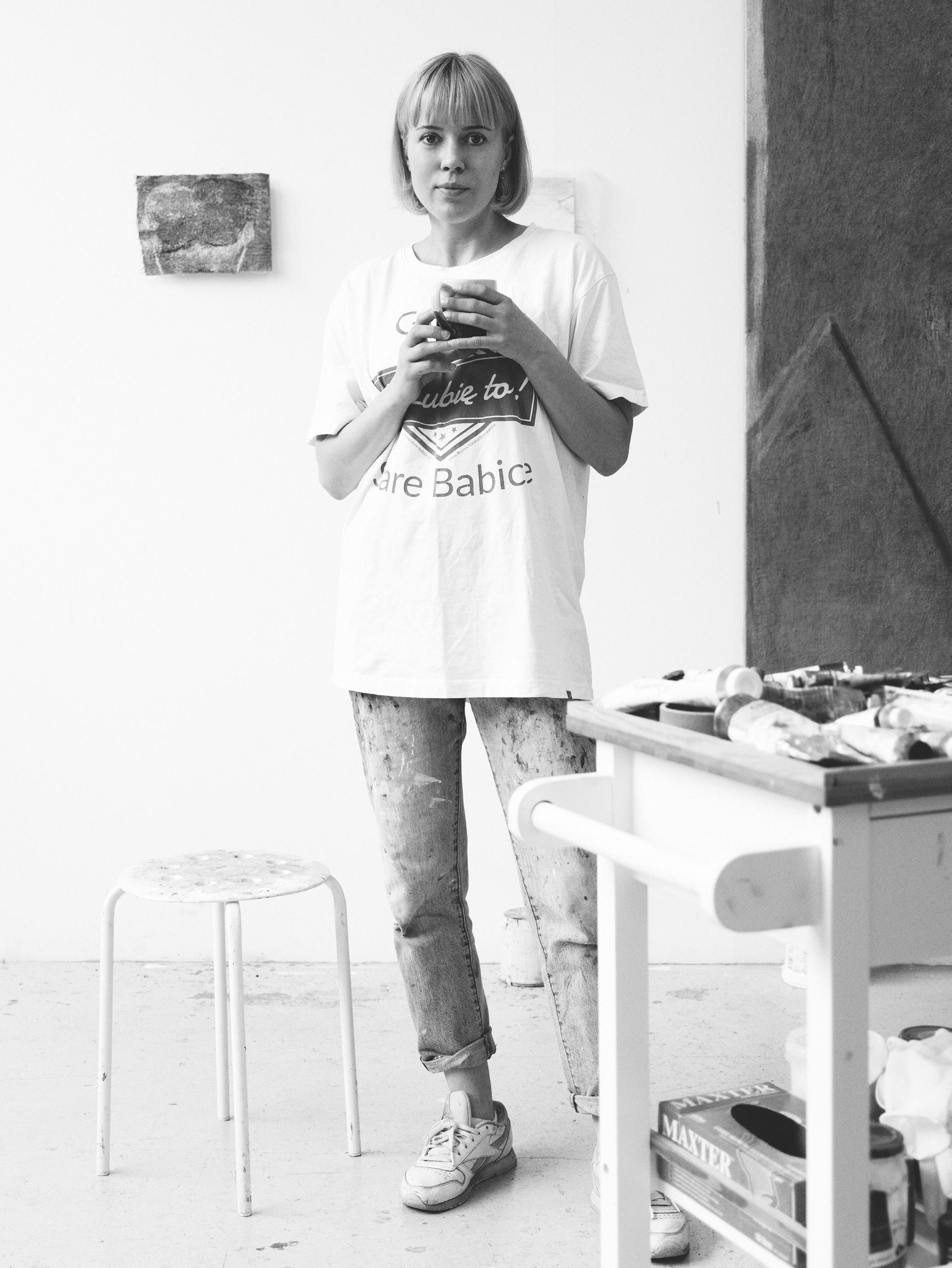

Karolina Albricht in her East London studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Karolina Maria Dudek.

BY JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI FOREWORD

THERE IS in this exhibition a stylistic originality that distinguishes Karolina Albricht as an artist of great courage and daring. I know few artists with such disregard for the trappings of aesthetic politeness. Losing The Image does not coax or seduce, but prompts us to question the very way in which we look at images. Through tears and vaporous coats of paint, these works breach the fabric of our reality, wholly disregarding its rules and conventions.

I have known Karolina for many years and as her gallerist, I have observed her artistic development with great pride and joy. What first struck me about her was the apparent contrast between her genial character, and the fierceness one finds in her work. She is one of those artists who utterly refuses to compromise her vision, and Losing The Image is, to my mind, Karolina's boldest body of work yet.

In many of these works, the painted surface extends beyond the panel's edge, further indication of an artistic vision unbound by orthodoxy. Delightful and unexpected chromatic schemes remind us that the artist is also a masterful colourist. I would say that Karolina is at the height of her powers if she was not still so young. She is destined for, and deserving of, an exceptional future in the world of art.

This is the kind of exhibition that reinvigorates the desire to consume and create art, and I am delighted to introduce it to the JGM Gallery community.

Guerrini Maraldi, 2024.

Killerby.

CAN WE IMAGINE an echo not preceded by a shout or a ripple without a pebble? Karolina Albricht’s considered and dreamlike paintings at least suggest the impossible possibility. Her images must have had a beginning and their minutely enacted, ever-accreting purpose seems to be heading somewhere. But it is as if we encounter them suspended between beginning and end. Suspended yet still active: central to these paintings is a rhythmic fluctuation, as marks coalesce into pattern and patterns turn into shifting assemblages of light and space.

On Albricht’s studio wall is a phrase she picked up from an interview with Phyllida Barlow: “Losing the image”. Around it are reproductions of images by Clyfford Still, by Renoir and by Monet - the intimate curve of a lace-covered profile; the cliff-like massiveness of a cathedral dissolving into light and shade - as well as a number of Eastern Orthodox icon paintings, both ancient and contemporary. Another Post-It reads: “Eternal newness of everything”.

For Barlow, “losing the image” related to the viewer’s movement around the physical bulk of sculpture, and her desire to keep sculpture’s physicality everpresent, free of the potential confinement of singular resemblance and the visual in general. For Albricht, as a painter - a maker of images - the issue is less clearcut. If the goal is to lose the image, then does this imply there was a definitive image there at the start? The impulse behind a picture is just as likely to be a feeling or a sensation of space or light, texture or pattern. It might be more useful to imagine the image as both perpetually found and perpetually lost, a cat and mouse game in which familiarity and singular coherence are constantly approached and constantly moved away from. In this way, Albricht re-enacts a dynamic going back more than a century, to the beginnings of abstract art in its modern form. After all, from Malevich (also inspired by the icon tradition’s claim of direct access to the depicted) onwards, painters tried to escape the image. The result was not the loss of the image but an expansion of what an image could be.

The word, “image”, can imply something clear and apparent; an image can also be vague, nebulous, just out of reach. Sometimes both at once: as when we mentally picture someone, conjuring them in our minds with a strange incorporeal certainty, even as some crucial aspect of their identity remains elusive, beyond our grasp, a few millimetres past the tip of our tongue. This simultaneous nearness and distance is relevant here; as is our habit of describing mental states in tactile, physical terms.

Marks slide and scurry across the surface of Albricht’s paintings, successively bunching together and breaking free of each other. Or more accurately, not so

much across the surface as scooping out an illusionistic space within it, so that the image – or the almost-image – seems to swell and disperse; here drawing nearer, there slipping away. One of the differences between Albricht and many abstract modernists of the second half of the twentieth century – in particular those working in the wake of Abstract Expressionism – is her willingness, especially in her larger works, to employ illusionistic depth and her ability to let virtual space float freely, without feeling the need to control it through strongly asserting the geometric discipline of the picture-plane. In this way, she is perhaps closer to Robert and Sonia Delaunay or Klee; and perhaps also related to this earlier generation in her avoidance of overtly expressive bodily gesture, her willingness to work with very small formats, and her sense of painting as an activity tinged with magic.

Geometry enters Albricht’s paintings obliquely, as drifting fragments rather than governing logic. Lines at odd angles move through her paintings’ spaces, adding bite and a kind of off-beat wit, and moving the viewer more quickly around spaces that otherwise we are encouraged to explore slowly. Disorganisation is as important as organisation. At times it seems as if a diagram of a more conventionally understood geometric figure (triangle or cube say) had been partially disassembled and squeezed into a portion of reality in which it did not quite fit, as if the connections between things were being eased apart. Perhaps this use of structure is partly why Albricht was drawn to the words of a sculptor such as Barlow – I was also reminded of the drawings of Eva Hesse. A process of dissociation can be seen in the paintings’ hard to judge scale, that seems to exist, perhaps, somewhere between the turn of a cheek and the massiveness of a dissolving facade.

Awkward, impossible objectness is especially apparent in some of the small paintings, which with their irregular edges and odd protrusions, present as objects, almost as much as images. Albricht’s attraction to tactility begins with the teeth of the canvas, at times left exposed, and develops through her rhythmic markmaking. There is a consoling aspect to the paintings’ ebb and flow, that creates pulsating cocoon-like environments. Yet Albricht also uses tactility as a tool to punctuate, even to puncture, serenity. Immersion should not be too complete or too cloying. Collaged fragments of diverse materials cut through otherwise woozily shifting areas. Elsewhere, a set of marks congregates around a wound-like hole in the canvas’ surface. Albricht wants to keep us on our toes. Central to the attraction of her paintings, the recent work in particular, is the suggestion of open possibilities, the sense that the echoes of her almost-images could reverberate in many directions, simultaneously.

Opposite: Samuel Cornish, 2024. Image courtesy of Karolina Albricht.

Below: Karolina Albricht, Looked To The River, Looked To The Sky (detail), 2024, oil on panel, 16cm x 23cm. Image courtesy of Benjamin Deakin.

In Conversation with KAROLINA ALBRICHT

Karolina Albricht in her East London studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Karolina Maria Dudek.

JULIUS KILLERBY Karolina, what is the title of this exhibition and, broadly speaking, how does it relate to your work?

KAROLINA ALBRICHT The title of the show is Losing The Image It’s a phrase I heard Phyllida Barlow say in an interview a few years ago. Phyllida’s words stayed with me for several years and as my exhibition with JGM Gallery drew nearer, I almost immediately knew its title had to be Losing The Image Almost as if it was predestined. In the interview, Barlow was describing the viewer as they encounter a three-dimensional object, and how the viewer is then required to move around it. That is, there is a physical activity demanded of them. With each step that the viewer takes, they acquire something new – a new image – whilst simultaneously losing the previous image. This resonated with me as I consider my paintings as spatial environments which one can enter and move around. The question for me is: what is lost and what is acquired? All these “lost images” – do they accumulate and emerge as one entity or do they exist as a fragmentary formation – a broken narrative? And, how can one be continuously losing an image? All this leads to an enquiry into how an image can be defined. It’s something of a certain visual clarity, which one can identify or draw associations, which perhaps has a familiar physical or

"I THINK OF THESE PAINTINGS AS INCUBATED ENERGY, SOMETHING THAT MOVES BUT IN AN ALMOST IMPERCEPTIBLE WAY, A TRANSFER OF ENERGY ON A MOLECULAR LEVEL."

- KAROLINA ALBRICHT

object-like quality. I think that this visual clarity doesn’t have to be lost as the familiarity dissipates – the image becoming fuzzier, more unstable, glitchy. That really interests me.

JK Is the goal, then, simply to remove the two-dimensionality of your paintings, and do you view objects and sculptures as more complex kinds of art than perhaps drawings or paintings?

KA No, that isn’t what I’m aiming for in my work. I would say that each medium has its own set of parameters within which one has to find their own feel of space, shape, colour etc. So, we’re dealing with a different notion of space and, in painting, you have to almost conjure it up. When we’re looking at a flat surface or a sculpture, we experience space differently, but the underlying feeling can be very close, if not the same.

JK Is space, then, perhaps a variable which accentuates the subjective experience of an artwork?

KA Yes, space is certainly one of them. It’s inevitable, because there is no formula for how someone should approach a painting or a sculpture, or any work of art. But, what painting does – and I think that this is rarely discussed – is that it also requires the viewer to be in motion and active.

Some paintings have a very slow unravelling, but that doesn’t mean that the viewer is not required to be in motion: shuffle closer or further from the work, inspect the edges. You can almost map the movements of the viewer as they try to comprehend what is happening, what is emerging.

JK In your work, there are these almost violent wounds, which strike me as piercing into the fabric of our reality. Do you think of these paintings as portals to a higher spiritual or psychological plane?

KA I do think of them as portals, in a sense, yes. Especially the recent paintings. They behave almost like glitches in reality, and I think that the true nature of life can perhaps be closely observed in these glitches. Also, the word “portal” has a particular relationship with icon paintings, which I have been interested in for a few years now. The function of icon paintings is to provide access to divinity for the congregation, and so to act as a kind of a portal. And a wound is a frequent visual shortcut to biblical stories in Christian iconography and it inadvertently started creeping into my work, functioning both as a kind of symbol but also as a formal device.

JK Given your interest in icon paintings, I

suppose my next question would be whether you think of these as secular or religious pictures?

KA Despite having grown up in Poland, where religion has played such a dominant role, my interest in icon paintings doesn't come from a religious point of view. And it started through the work of a Polish painter and theologist, who I greatly admire – Jerzy Nowosielski. His work comprised of both contemporary painting and icon paintings. So, for me it's more to do with the potency of the image – with what it can do. An icon painter follows a specific iconography – a visual formula – to ensure that each image is the same and that subsequently it provides the same access to the divine. They preserve the image. I’m almost operating in the reverse, where I am trying to lose it. The overall objective, however, for myself and the icon painter, is similar, I think. We both want our paintings to transform, and to move.

JK So you are more interested in the mechanisms used by icon painters, rather than the doctrine that grounded their images?

KA Yes. I’m interested in the transformative effects icons can have for the viewer. They are supposed to convey something of the supernatural, or to carry supernatural energy of the proto image,

which is the actual figure of the saint. Some icons are believed to have been created in miraculous circumstances or to have properties similar to those of a guardian spirit. It's just extraordinary that this deeply felt belief accompanies icon paintings. I think that contemporary painting – not all of it of course – has this kind of transformative capacity or magic too.

JK The paintings in Losing The Image were all made in 2023 and 2024. In what ways are they different to previous works you've produced?

KA I would say that these recent paintings talk about time – and, consequently, space – in a different way. The pace is different. Everything has slowed down. They take longer to make, as well. Because time and space have changed, so did the movement. Previously, the pictorial space in my paintings was occupied and structured by shapes that determined spatial relationships in a more distinctive way. This has something to do with how I’d define an image. At the moment, the paintings have more of a sense of a transfer of energy, something which is almost imperceptible, less certain. It's almost as if I’m thinking about a formation, an organism, or an entity that is slowly being developed in all directions, hovering. The paintings in the show trace these slight shifts in my thinking,

the image being progressively questioned and rephrased. Something that has played a central part in these developments is my relationship with nature. I recently spent 6 weeks in rural Norfolk on a residency and something has really changed in my perception of the natural world. For the first time I felt I was able to somehow transfer these experiences to painting. Being in the studio and being out in nature started to overlap and converge, and then they felt like one, the boundaries becoming hazier, blurrier. As did the image. During the last year, I also moved flats and my cycling route to the studio now leads through a section of River Lee. Cycling through this section of the river is incredibly exhilarating for me, in a sensory way… There, I feel completely satiated, as if I’m being continuously filled with something utterly magnificent and infinite. I often take photos of my route to the studio, but that isn’t limited to its greener sections. Architectural details like gates, fences, roofs… anything that has an immediate visual significance. So, these photos are like thoughts and observations which accompany me and which I find interesting. They unlock and develop in me a certain way of thinking about painting. But they don’t really determine anything pictorially, in a conventional way at least. In a sense, thinking about my relationship to my most immediate surroundings, it really comes down to the question: how do you

Above: Jerzy Nowosielski, Villa Dei Misteri, 1975, oil on canvas, 260cm x 500cm. Image courtesy of Karolina Albricht.

Left: Saint Paraskeva the Great Martyr with scenes from her life and passion icon 15th century, tempera on wood, 111cm x 85cm, gift of Stanislaw Zarewicz.

Image courtesy of the laboratory stock, National Museum in Krakow.

THESE PHOTOGRAPHS, TAKEN BY KAROLINA ALBRICHT OVER THE PAST TWO YEARS, ARE OF PLACES AND SIGHTS THAT MOVED HER VISUALLY, AND THE MEMORIES OF WHICH SHE CARRIES WITHIN HER.

ALBRICHT REFERS TO THESE IMAGES AS "... VIEWS OF A WORLD THAT IS MYSTICAL AND GLITCHY, SIMULTANEOUSLY VERY CLOSE AND DISTANT TO ME."

Karolina Albricht, View Of A Gate, Leytonstone 2024. Karolina Albricht, View Of A Roof, Leytonstone 2023.

Karolina Albricht, View Of River Lee, December 2023. Karolina Albricht, Oak Tree Against A Horizon, Norfolk 2024.

Karolina Albricht, The Crown Of A Cedar Tree, Norfolk, 2024. Karolina Albricht, Mile End Station, London 2024.

Karolina Albricht, Cherry Blossom Tree At Dusk, Norfolk 2024. Karolina Albricht, Painting, 'On Shyness Of The Soul', Hung On A Yew Tree, Norfolk 2024.

convey a sense or a feeling of the world? How do you convey its almost inaudible hum?

JK You used the word “hum” and I know of your interest in the “Music of the Spheres”. Just for the readers, could you explain what this is and how it relates to your work?

KA I came across the concept of the music of the spheres whilst listening to a podcast. Another term for it is “Musica Universalis”. It's an ancient philosophical concept and it claims that the proportions in the movements of celestial bodies emit a sound – a kind of music. The concept was developed throughout the following centuries by various philosophers. Kepler had his own take on it, he said that the “Music of the Spheres” is inaudible but can be heard by the soul. I found that so beautiful and moving.

JK Do you think that there is an equivalent to that philosophy in painting? The idea that painted forms, and their relationship to each other, can emit a kind of spiritual vibration?

KA Well, another philosopher named Boethius, from the 6th century AD, divided music into three categories: musica instrumentalis – what you would hear in a concert, musica mundana – music of the spheres, and musica humana – music that is internal, which reverberates in the soul. You can’t turn the volume of the world down, or your own internal musica humana. I think that painting has its own internal hum, its own kind of music. Inaudible to the ear but heard by the soul.

JK I wanted to ask you about those of your paintings which have protrusions and irregular edges. Are the protrusions from the sides of these works intended to encourage the audience to think of them as objects rather than images?

KA The uneven edges are a result of the paintings' development. Whatever relationships are already present and developing within the work, they dictate what else is needed, and whether the edge has to move, or whether a rectangle was ultimately suitable or not for a particular painting. All of that is between myself and the painting, and what happens in the studio is very private, so the audience is never a part of that. The audience's interaction comes later and it is not really a part of the making process for me. That means that some of the paintings will have to expand beyond their physical borders and that the edges might swell or move. There will also be appendages to the edges, and all that would be the result of internal relationships within the painting. So it's all in motion, and doesn't quite sit still.

JK You mentioned that you think of your paintings as spatial environments. Can you talk a bit more about that?

KA Sure. My paintings, to me, speak of time and space and, consequently, of movement. Of course, these concepts are interdependent. Paintings as spatial environments rely on them, but are evoked through formal aspects like colour, mark, texture. The direction of every mark is so important now. After all, the movement of the entire painting is comprised of the movement of each mark. I recently read Carlo Rovelli’s essay, The Order of Time, and it somehow made sense to me in terms of the way I think about painting. Rovelli proposes that the world is made up of events, not things. If you think about the most solid “thing” in the world – a stone – his take on it is that a stone is just a momentary interaction of forces, a vibration. Then, when you start thinking that the world is not made of stones – he actually said something quite poetic about it – he said that the world is not made of stones, but of fleeting sounds. He then continues to talk about the world as a network of events, change and happening. If time is happening, everything is time. So, painting is time too, and painting is made of events. A painting is a network of events. A spatial network of events.

JK That's interesting, because I would say that a consistent characteristic of your work is the lack of solidity in the objects and forms you depict. It's as though you resist giving them that final definition, which I think imbues them with quite a transient quality.

KA Yes, I would definitely agree with that. I think of these paintings as incubated energy, something that moves but in an almost imperceptible way, a transfer of energy on a molecular level. Like the hum of the world that is there in the background and vibrates. I don't think of these paintings as solid blocks.

This is why, perhaps, Rovelli's essay really caught my attention, because of that vibrating, temporal quality.

JK Going back to what you were saying about glitches. I have often wondered how you achieve the disconnect between the space you paint and the objects that occupy it. You know when you see a Photoshopped image and the way light hits one object doesn't quite match up with the lighting in the rest of the image. It doesn't feel like it belongs, but for a reason which is so subtle that you almost cannot put your finger on why. Is it similar in your work, where there is a deliberate aesthetic incoherence in the way some objects are rendered?

KA I always try to keep the process open. Each painting will develop gradually and demand an approach appropriate to itself only. Cracks or glitches are inherent to the experience of reality, they make the reality plausible. These things need to be present in a painting, they need to be felt for the painting to be alive. To test if his painting was successful, Picasso would famously ask Braque: “Is this woman real? Could she go out in the street? Do her armpits smell?” I’ve always liked that idea. A painting having the capacity to sweat… it’s not far from a painting producing its own kind of music.

JK Yes, the great works of art really do have a life to them don't they? You can almost look at them forever. One of my favourite paintings is Velazquez's Las Meninas, and looking at it I've always thought it's bizarre how much life exists beyond the marks on the canvas. It's the same when you hear about Shakespeare's characters and how they seem to exist beyond the words on the page. William Hazlitt I think described Shakespeare's characters as “living persons, not fictions.”

KA And how they continue to be contemporary and relevant to our lives, so that they almost exist outside of time. They are extra-temporal.

JK Sam Cornish, in the catalogue text for Losing The Image writes that “ ... it is as if we encounter these paintings suspended between beginning and end. Suspended, yet still active.” Do you ever think of your works as complete, or do they, at least in your mind's eye, always contain the potential for transformation?

KA I hope that my work continues to be in some kind of motion, and perhaps to catch the right moment and say: “Ok, that’s done” is to know that stopping painting at that point will allow this movement to continue developing. Amy Sillman said something interesting about this. I wholeheartedly agree so I’ll answer with her words. She said that a painting is never finished. It just comes to a point of rest, like a bird on a ship's bow. It could have been a different ship, but it just happened to be that particular ship.

JK Do you struggle to let your paintings go?

KA As I said before, each painting requires a different amount of time so it really depends on the painting. Ironically, some of the small paintings take longer to produce than the larger paintings. Of course, every day is a struggle in the studio. It's mostly torture. And yes, I do struggle letting some of them go. You have to be ruthless about it sometimes and force yourself to stop. It might be that you'll turn the painting around and then look at it again in a couple of months, or a couple of years, and at that point you'll know that it needs this or that amendment or addition. You sometimes just don't know because you are too close to the painting, and the painting needs time, and you as the artist need time.

JK Perhaps to finish with a somewhat impossible question, why do you think art is important?

KA Susanne Langer said that art is the objectification of feeling, where you take feeling out of the flux of life and give it a form outside of yourself. That really hits the nail on the head for me, in terms of what art is. Art returns you to the world and returns you to yourself. How it does it is through a kind of magic, if you define magic as the ability to transform and change. A good painting never stops.

Right: Karolina Albricht's studio wall, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.

Karolina Albricht, Head & Arms That Touched Thunder, 2024, oil on panel, 30cm x 24cm

Karolina Albricht, Double Door Status, 2023, oil on panel, 30cm x 24cm

Karolina Albricht, Ear To Mouth, 2022, oil and other stuff on panel, 18cm x 14cm

Karolina Albricht, As A Mist Magnifies The Moon (J.E.), 2024, oil on panel, 18cm x 14cm

Karolina Albricht in her East London studio, 2024.

courtesy of Karolina Maria Dudek.

Editorial design: Julius Killerby. Photography: Karolina Albricht and Karolina Maria Dudek.

Artwork photography: Benjamin Deakin.

© 2024 JGM Gallery.

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-7385394-4-4.

JGM Gallery

24 Howie Street London SW11 4AY

info@jgmgallery.com