ÖMIE

A GROUP EXHIBITION OF 17 ARTISTS WORKING ON BARKCLOTH

A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO

A GROUP EXHIBITION OF 17 ARTISTS WORKING ON BARKCLOTH

A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO

Front cover: Artists harvesting bark from the forest (detail). Photo by Drusilla Modjeska, courtesy of Ömie Artists.

Back cover: Ömie poster 2023, Barbara Rauno (Inasu), Kukuhon’e soré (nuni’e, taigu taigu’e, jö’o sor’e ohu’o ori sigé) (detail), 2022, natural pigments on barkcloth, 123cm x 59cm. Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

Editorial & graphic design: Julius Killerby.

Photography: Brennan King, Drusilla Modjeska & Julius Killerby.

Artwork Photography: Daniel Browne.

© 2023 JGM Gallery, Ömie Artists, Brennan King, Drusilla Modjeska, Daniel Browne & Julius Killerby. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-7392905-3-5

JGM Gallery 24 Howie Street London SW11 4AY

info@jgmgallery.com

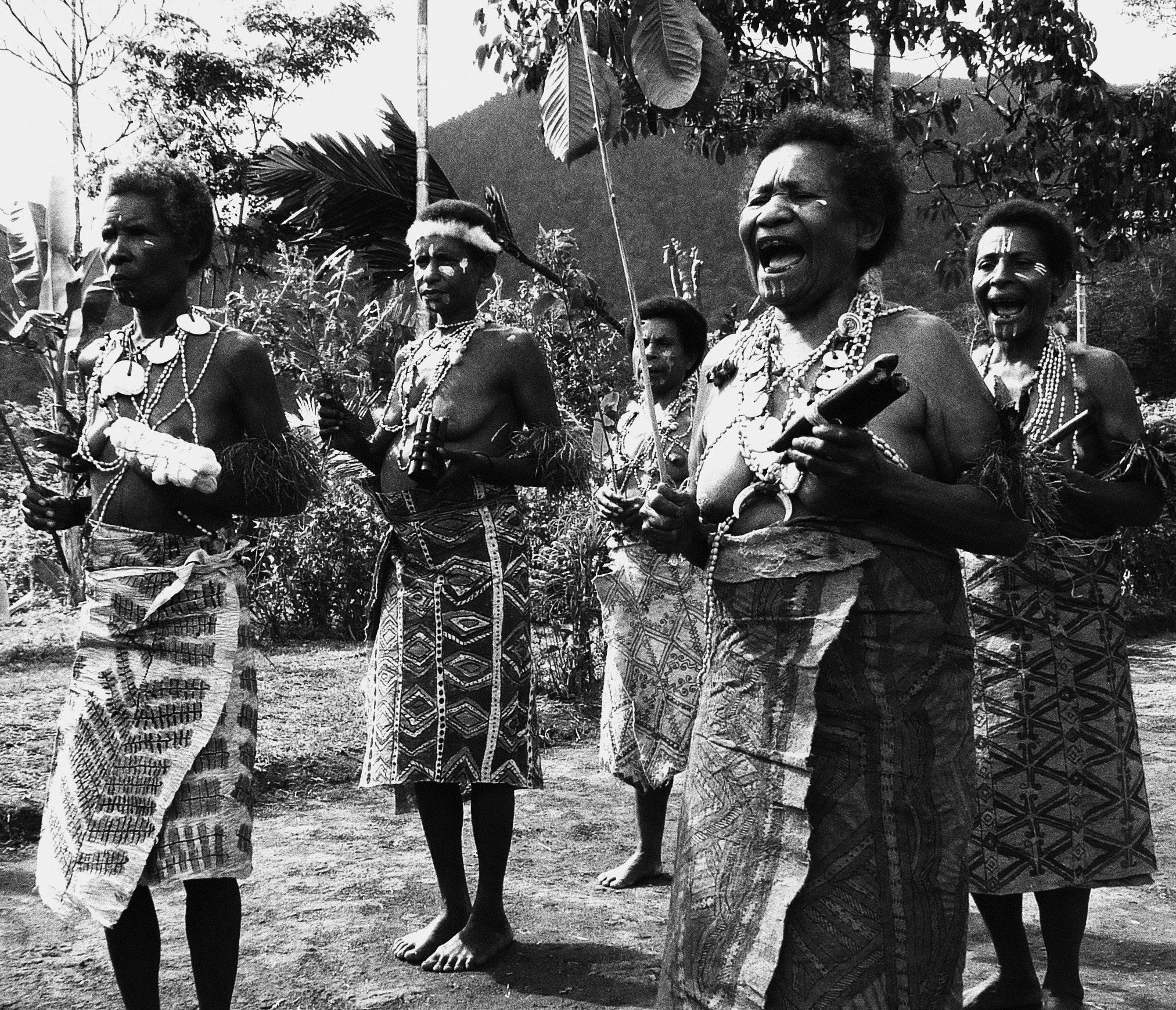

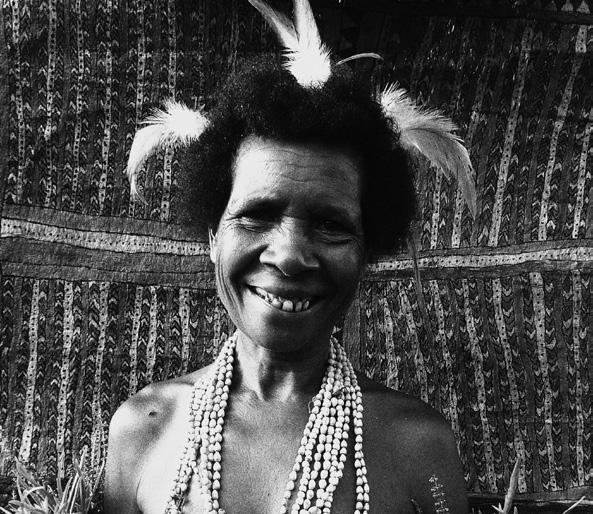

Dance at Duharenu Village.JGM GALLERY PRESENTS ÖMIE A GROUP EXHIBITION OF 17 ARTISTS WORKING ON NIOGE (BARKCLOTH).

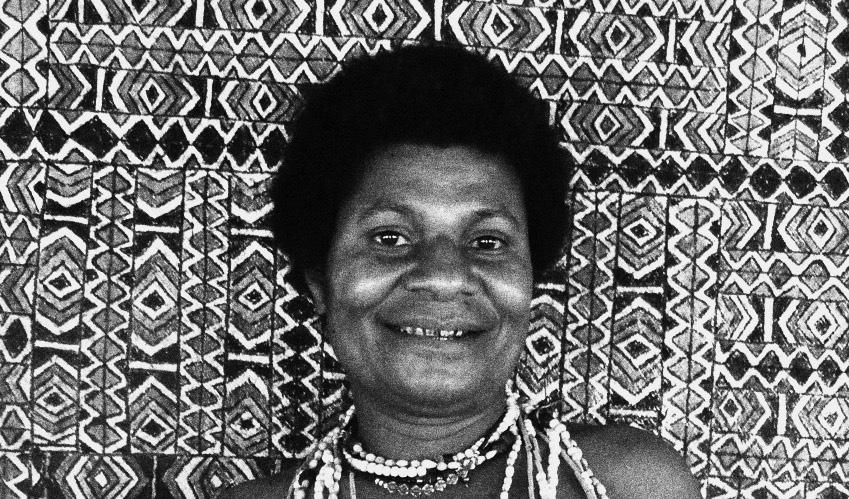

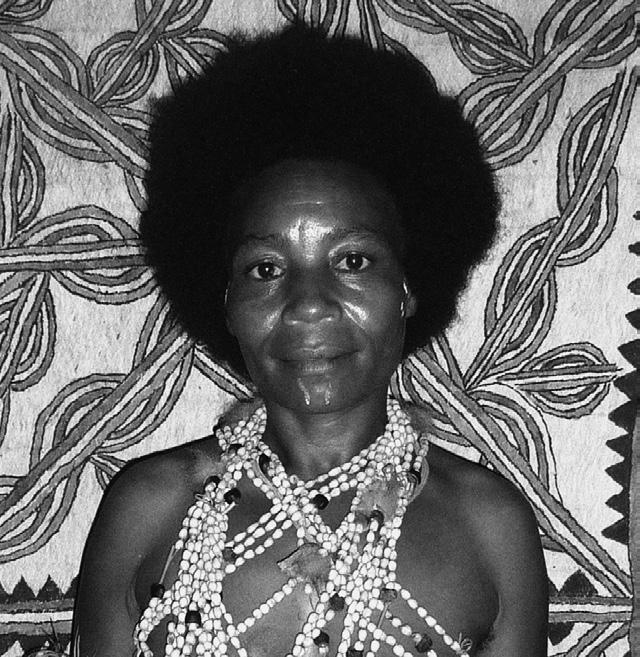

THE ÖMIE RESIDE IN THE REMOTE INLAND MOUNTAINS OF ORO PROVINCE IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA. IT IS HERE THAT THEY CREATE AND DECORATE NIOGE IN A FORM OF EXPRESSION WHERE THE UTILITARIAN, ARTISTIC AND SACRED CO-EXIST. TRADITIONALLY, NIOGE HAVE BEEN USED CEREMONIALLY AND AS EVERYDAY CLOTHING, HOWEVER, IN MORE RECENT YEARS THEY HAVE ALSO BEEN MADE FOR PURELY ARTISTIC APPRECIATION. PRIMARILY, THE ARTISTS ARE WOMEN AND BARKCLOTH PAINTING IS THEIR DOMAIN, HOWEVER, THERE ARE SOME RARE INSTANCES OF MALE PRACTITIONERS WHO WERE FORMALLY TRAINED BY THEIR MOTHERS.

THE PROCESS OF CREATING NIOGE IS A TIME-CONSUMING PROCESS THAT INVOLVES MANY STAGES AND REQUIRES A HIGH DEGREE OF SKILL. FIRST, THE BARK IS COLLECTED FROM CERTAIN TREES, PREDOMINANTLY FROM THE PAPER MULBERRY TREE BUT ALSO FROM FIG AND HIBISCUS SPECIES. THE INNER BARK IS HARVESTED FROM THE TREE AND SEPARATED FROM THE OUTER BARK. THE INNER BARK IS THEN RINSED AND SOAKED IN WATER FOR SEVERAL HOURS, SOFTENING IT BEFORE THE NEXT STAGE. IT IS THEN LAID ON A FLAT SURFACE AND BEATEN WITH A WOODEN MALLET, THIS TIME TO MAKE IT THINNER AND MORE PLIABLE.

THE PIGMENTS AND DYES USED TO PAINT AND DYE THE BARKCLOTHS (PREDOMINANTLY REDS, YELLOWS, GREENS, BLACKS AND DEEP GREYS) ARE ALL PROCURED FROM THE ABUNDANT RAINFORESTS THAT SURROUND THE ÖMIE, SUCH AS FERNS, FRUITS, LEAVES, COCONUT CHARCOAL, TREE SAP AND VOLCANIC MUD. THE INTRICATE DESIGNS ARE EITHER PAINTED ONTO THE BARKCLOTH USING STRONG GRASSES OR FASHIONED WOODEN STICKS (CALLED IJE), WITH FRAYED BETELNUT HUSK BRUSHES. THE COMPLETED NIOGE IS THEN DRIED IN THE SUN, SOMETIMES OVER SEVERAL DAYS. SOME BARKCLOTHS WITH THE MOST ANCIENT ORIGINS HAVE A MINIMAL AESTHETIC, AND THE PROCESS INVOLVES DYEING THE BARKCLOTH IN VOLCANIC RIVER MUD. THE DESIGNS ARE THEN APPLIQUÉD USING A FINE BAT-WING BONE NEEDLE.

THE STYLES OF THE EXHIBITING ARTISTS VARY VASTLY, FROM THE DENSELY PATTERNED AND HALLUCINOGENIC AESTHETIC OF THE LATE ALBERT SIRIMI (NANATI), TO THE MORE REDUCED AND MONOCHROMATIC DESIGNS OF PATRICIA WARERA (MATOMGUO). WHAT UNITES ALL THE WORK, HOWEVER, IS AN EXPRESSION OF ÖMIE CULTURE. AS ÖMIE ARTISTS MANAGER, BRENNAN KING, STATES, THERE IS “... THE SENSE OF ONE UNITED CULTURAL IDENTITY... THIS CAN BE SEEN AND SENSED IN ÖMIE BARKCLOTH PAINTINGS - DESPITE THE GREAT DIVERSITY OF SYMBOLISM THERE IS A DISTINCT ‘ÖMIE ESSENCE’.”

NIOGE CAN BE CONCEIVED AS A LIBRARY OF SORTS, CONTAINING ANCIENT INFORMATION ABOUT ÖMIE COSMOLOGY, THEIR BELIEF SYSTEMS AND THE NATURAL WORLD IN GENERAL. A WESTERN ANALOGUE, THOUGH NOT AN EXACT EQUIVALENT, WOULD BE ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS. THERE IS ALSO A SERIOUSNESS ATTACHED TO THEIR CONSTRUCTION AND ONLY PARTICULARLY REFINED BARKCLOTHS BY ACCOMPLISHED ARTISTS ARE EXHIBITED BY ÖMIE ARTISTS. MOREOVER, THE ARTISTS MUST FIRST MASTER THE INHERITED CLAN DESIGNS OF THEIR ANCESTRAL LINEAGE. UNTIL THEY REACH A CERTAIN LEVEL OF PROFICIENCY AND SOCIAL STATUS, THEY CANNOT USE THEIR UEHORE (WISDOM) TO CREATE NEW DESIGNS. THE ÖMIE’S ARTISTIC PRACTICE IS ALSO, IN PART, INFORMED BY THE ÖMIE CREATION STORY, IN WHICH THE FIRST WOMAN, SUJA, CREATED A BARKCLOTH AND DYED IT WITH RED VOLCANIC RIVER MUD TO CELEBRATE HER NEW-FOUND FERTILITY. THERE IS THUS A RITUALISTIC ASPECT TO THE MAKING OF BARKCLOTHS AND THEIR CREATION IS, IN SOME SENSE, A RE-ENACTMENT OF SUJA’S ACTIONS. IMPLICIT IN THIS IS ALSO A CELEBRATION OF FECUNDITY AND THE CREATIVE FORCES OF NATURE.

EXHIBITING ARTISTS INCLUDE: ALBERT SIRIMI (NANATI) | BRENDA KESI (ARIRÈ) | ELIZABETH GUHO (OWKEJA) FAITH JINA’EMI (IVA) MALA NARI (MATOSI) WILMA RUBUNO (LAMAY) | PAULINE-ROSE HAGO (DERAMI) ROSEMON HINANA JESSIE BUJAVA (KIPORA) DIONA JONEVARI (SUWARARI) | MAGDALENE BUJAVA (KOLAHI) PENNYROSE SOSA | ELVINA NAUMO (EBAHINO) JEAN NIDUVÉ (URIHÖ) BARBARA RAUNO (INASU) MAUREEN SIRIMI (JAFURI) | PATRICIA WARERA (MATOMGUO).

Prior to the first exhibition of their nioge (barkcloths) in 2006, the Ömie had little to no exposure beyond their homeland borders in Oro Province, Papua New Guinea. Though this is an ancient art form, it has been, until recently, relatively unknown. For this reason it is a particular honour and privilege to be entrusted with this exhibition by the Ömie Artists.

These nioge convey something essential to human existence; a deference to elders and ancestry, a respect for the natural world and an interconnectedness with one another. Nioge are not an artefact, or the remnants of an art historical movement, but a dynamic medium with purpose in the day-to-day lives of those who create them. They are interwoven into Ömie culture itself and are used, amongst other things, as day-to-day and ceremonial garments.

This utilitarian aspect of the barkcloths is not separate from their artistic context. Both compliment each other. As Brennan King describes, the act of dancing in nioge, in part, informs the way they are designed. One of the most desirable qualities in a barkcloth is what the Ömie call buriéto’e when the design of the work generates a mesmerising quality, and the nioge “come alive with beauty”.

With this show, JGM Gallery has itself come alive with beauty and we are thrilled to be exhibiting these sublime works.

Nioge (barkcloth) is profoundly sacred to the Ömie of Papua New Guinea. One integral part of their creation story details the first man and woman, Mina and Suja, being clothed in the textile. There is here an interesting connection with Adam and Eve and the wearing of these garments does in some sense symbolise, as it does for the protagonists of Genesis, a transition from innocence. The similarities between the Ömie and societies which, until recently, had not been exposed to their culture, does not stop there. Rather remarkably, there are aesthetic and conceptual similarities between their Art and barkcloth designs from other localities, including the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, Africa and South America, amongst others. Indeed, these may not simply be similarities, but innate ideas that cross-culturally populate the Collective Unconscious.

What does perhaps distinguish the Ömie’s work is its added emphasis on fecundity. Suja, to celebrate her new found fertility, dyed her nioge in red volcanic river mud. The creation of a nioge design, then, is explicitly linked to the creative forces of nature and for the Ömie their construction is a venerated act, equally sublime to the growth of a tree, the crashing of a wave, or the birth of a child. The sihoti’e nioge (mud-dyed barkcloths) on exhibit by artists Brenda Kesi (Ariré), Rosemon Hinana and Patricia Warera (Matomguo) have been dyed in the same way that Suja dyed her barkcloth. Appliquéd using a fine bat-wing bone needle, these pieces, with their contrasting greys and whites, bring the Ömie’s ancestral past into the present. They provide a window through time into the early development of Ömie symbolism, yet with a discernibly contemporary sensibility.

What is remarkable, then, is that these barkcloths are as sacred to the Ömie as the information depicted on them. A Western analogue, though not an exact equivalent, would be the representation of a Biblical narrative on a holy relic. For the Ömie there is thus a parallel between form and content. The medium and the subject are intertwined, imbuing these works with a profound spiritual significance.

Randall Morris, in 2013, wrote of Ömie nioge that “There is a collective genius at work here that allows for iconoclasm and the vision of the individual set into the matrix of the culture itself.” By example, Diona Jonevari’s Se’a hu’e, dahoru’e, bubori anö’e, vë’i ija ahe, odunaigö’e, jö’o sor’e, sabu ahe, vinohu’e ohu’o siha’e is just that; quintessentially “Ömie”, but with a distinctly individual aesthetic cadence. Like many nioge her design is bordered with mountains, a reference to the surroundings in Oro Province, where the Ömie reside. Compositionally, this alpine border emphasizes the centre of the arrangement, as does the red pigment used to paint it. It arrests our attention. The reference to local geographical features also implies that this work will distil something about Ömie culture.

The rest of Jonevari’s nioge is divided into rectangular sections, within which she depicts the beaks of Papuan Hornbills, lizard bones, jungle vine and initiation tattoo designs. Flowing through the composition, and touching each of these symbols, is the red pigment sourced from the skin of the biredihane tree, known to the Ömie as bariré. This colour is a reference, as it was for Suja, to fertility but also, more generally, the fecundity that makes all aspects of Ömie life and culture possible. This is accentuated by the zig-zag lines which suffuse the surface with a sense of interconnectedness and electricity.

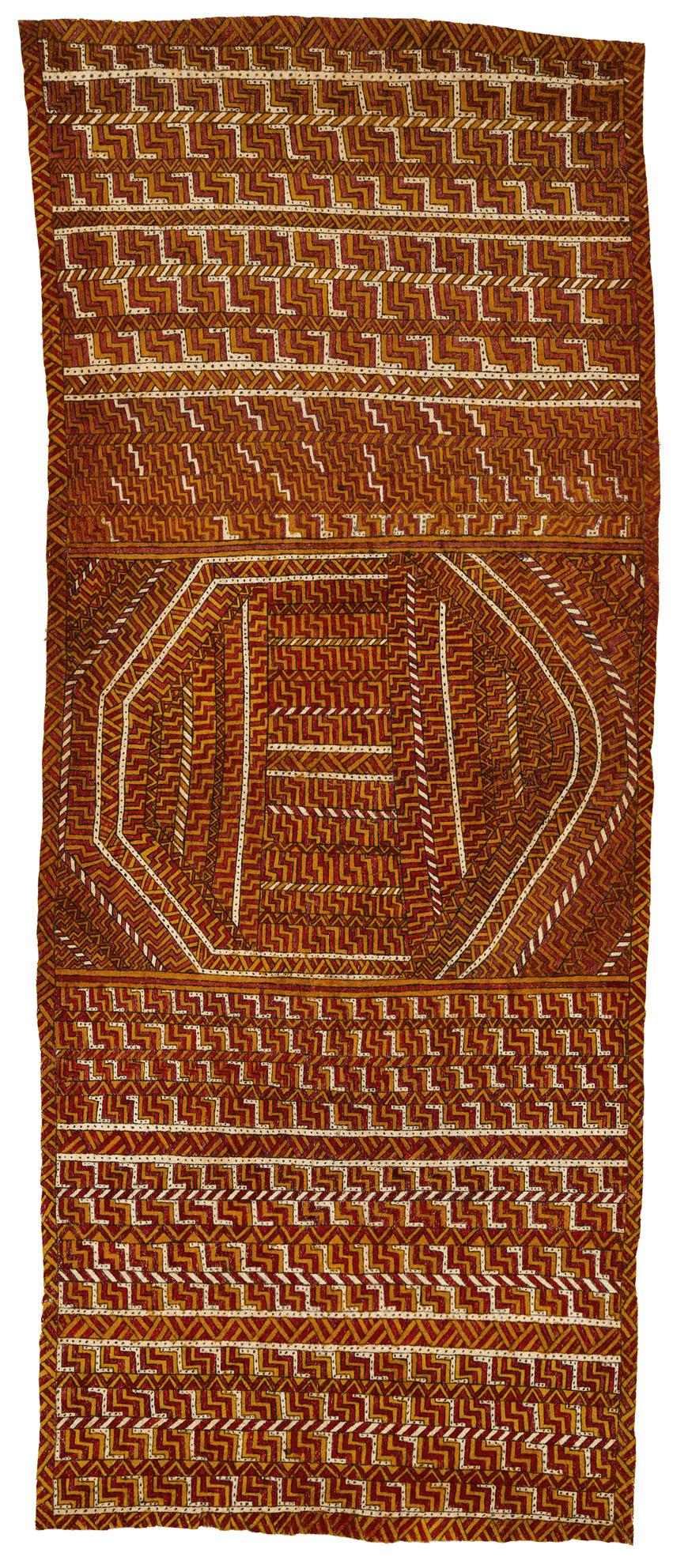

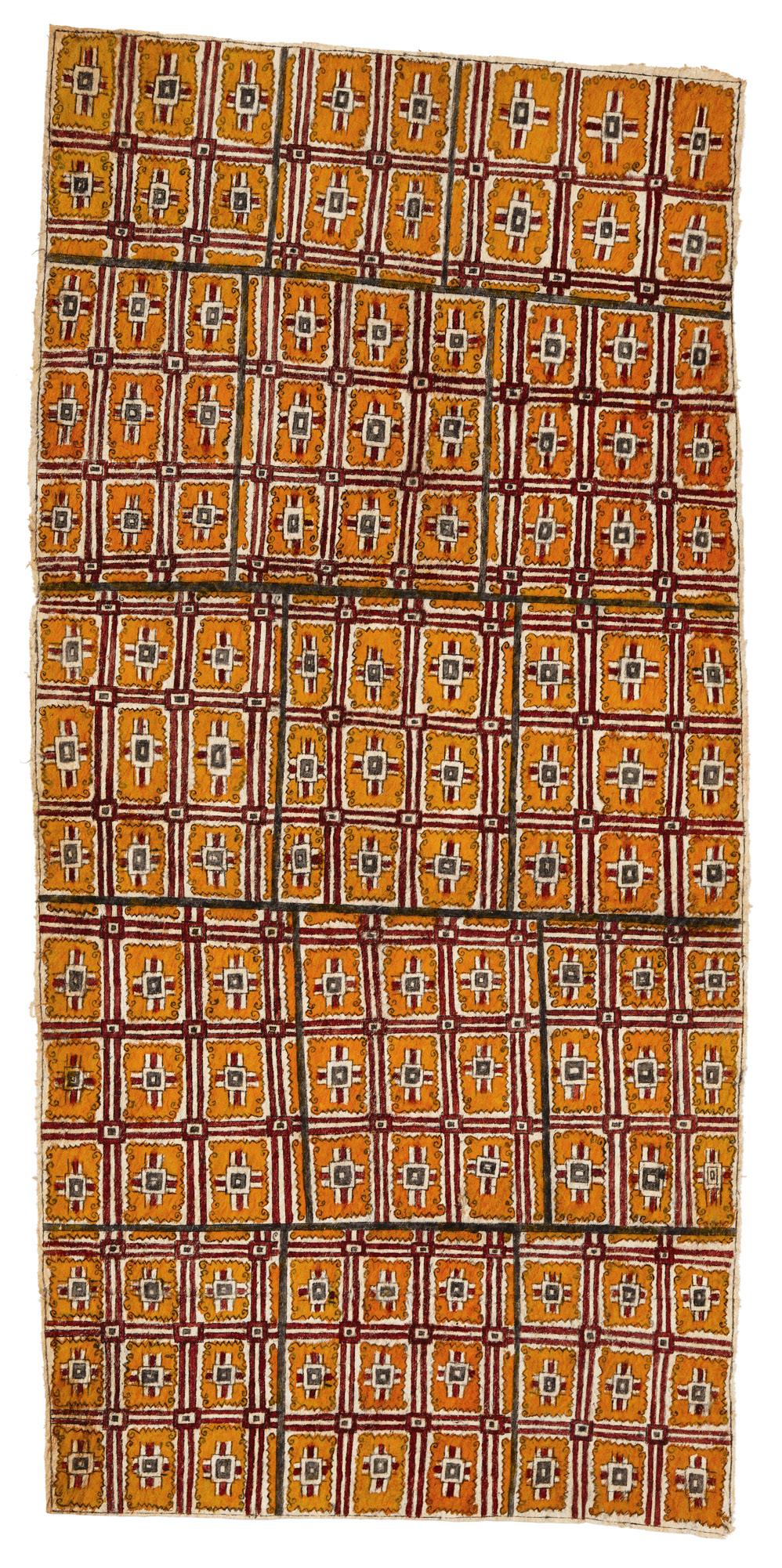

Dazzling optical effects such as these are even more overt in the work of the late Albert Sirimi (Nanati), whose nioge are almost hallucinogenic in quality. Sirimi’s work, Ujavu am’e (guai); taigu taigu’e; juburi anö’e; ahéhuruvë’e; nuni’e; ohu’o sabu ahe, shows how the utilitarian and artistic purposes of these barkcloths compliment each other. Brennan King, the Ömie Artists’ Manager, describes a concept once explained to him by Sirimi, called buriéto’e. “It was used to describe the phenomenal experience when a person looks upon a dancer wearing their barkcloth skirt or loincloth and the painted designs “change” and “come alive with beauty”.” That these patterns “come alive” would also explain why the Ömie see a parallel between their Art and the creative forces of nature. This densely patterned aesthetic is characteristic of what could be called “The School Of Albert Sirimi”, which includes the artists, Jessie Bujava (Kipora), Barbara Rauno (Inasu) and Maureen Sirimi (Jafuri).

The works exhibited in Ömie are exquisite and archetypal examples of an ancient, though recently discovered art form. On display is a hybrid of design, performance and ritual a sublime contribution to the contemporary art world.

“The Spirits of my Ancestors communicate with me directly. They encourage me to paint barkcloth and encourage the other women to paint, to keep the old designs alive so that our culture remains strong. Our Ancestors are taking very good care of us!”

-Mala Nari (Matosi)

BRENDA KESI (ARIRÈ)

Taliobamë’e nioge (Ancestral design of the mud)

2018 Appliquèd mud-dyed nioge (barkcloth) 119cm x 66cm

BRENDA KESI (ARIRÈ)

Wo’ohohe (Ground-burrowing spider)

2018 Appliquèd mud-dyed nioge (barkcloth) 143cm x 82cm

ALBERT SIRIMI (NANATI)

Ujavu am’e (guai); taigu taigu’e; juburi anö’e; ahéhuruvë’e; nuni’e; ohu’o sabu ahe

(Ujawé initiation rite underground tattooing site; Ujawé ceremonial tattoos (jungle vine); design of the orchid-fibre woven waist-belt; design of the chopped tree log in the food garden; design of the eye; and spots of the wood-boring grub)

2012

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 160cm x 65cm

BARBARA RAUNO (INASU)

Kukuhon’e soré (nuni’e, taigu taigu’e, jö’o sor’e ohu’o ori sigé)

(Designs of the bamboo smoking pipe (design of the eye, pattern of a leaf, uncurling fern fronds and pathways)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 123cm x 59cm

DIONA JONEVARI (SUWARARI)

Se’a hu’e, dahoru’e, bubori anö’e, vë’i ija ahe, odunaigö’e, jö’o sor’e, sabu ahe, vinohu’e ohu’o siha’e

(Ancestor’s body designs, Ömie mountains, beaks of the Papuan Hornbill, bone of the lizard, jungle vine, uncurling fern fronds, spots of the wood-boring grub, Ujawé rite initiation tattoo of the navel and fruit of the Sihe tree)

2021

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth)

164cm x 70.5cm

DIONA JONEVARI (SUWARARI)

Dahoru’e, bubori anö’e, vë’i ija ahe, odunaigö’e, jö’o sor’e, sabu ahe, siha’e, taigu taigu’e ohu’o douhia’e soré

(Ömie mountains, beaks of the Papuan Hornbill, bone of the lizard, climbing jungle vine with thorns and tendrils, uncurling fern fronds, spots of the wood-boring grub, fruit of the Sihe tree, leaf pattern, leg tattoo design of the female ancestor (named Kamuola))

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth)

147cm x 83cm

“... This design is the hipbones of the frog. My mother taught me this design before she passed away and now I am the one painting this design for my clan. My mother was the former Chief of Ematé clan women, Mary Naumo. She was a very important barkcloth painter for our clan and village.”

DIONA JONEVARI (SUWARARI)

Dahoru’e, bubori anö’e, jö’o sor’e, sabu ahe, vinohu’e ohu’o siha’e (Ömie mountains, beaks of the Papuan Hornbill, uncurling fern fronds, spots of the wood-boring grub, Ujawé rite initiation tattoo of the navel and fruit of the Sihe tree)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 154cm x 73.5cm

ELIZABETH GUHO (OWKEJA)

Samwé (samu) han’e (Beriirajé/Samwé sub-clan emblem of the leaves of the tree)

2012

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 129cm x 83cm

Vison’e/uge dela, visu anö’e, sabu ahe ohu’o dahoru’e

(Eel-bone jewellery for initiation nasal septum piercings, teeth of the freshwater river fish, spots of the wood-boring grub and Ömie mountains)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 107cm x 55cm

Vison’e/uge dela, sabu ahe ohu’o dahoru’e

(Eel-bone jewellery for initiation nasal septum piercings, spots of the wood-boring grub and Ömie mountains)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 109cm x 46.5cm

ELVINA NAUMO (EBAHINO)

Savani degirani, siha’e ohu’o dahoru’e

(Frog hipbones, fruit of the Sihe tree and Ömie mountains)

2022 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 143cm x 103.5cm

JEAN NIDUVÈ (URIHÖ)

Ijögijegije, dahoru’e ohu’o bubori anö’e

(Ematé clan design of the bare tree branches, Ömie mountains and beaks of the Papuan Hornbill)

2022 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 120cm x 77cm

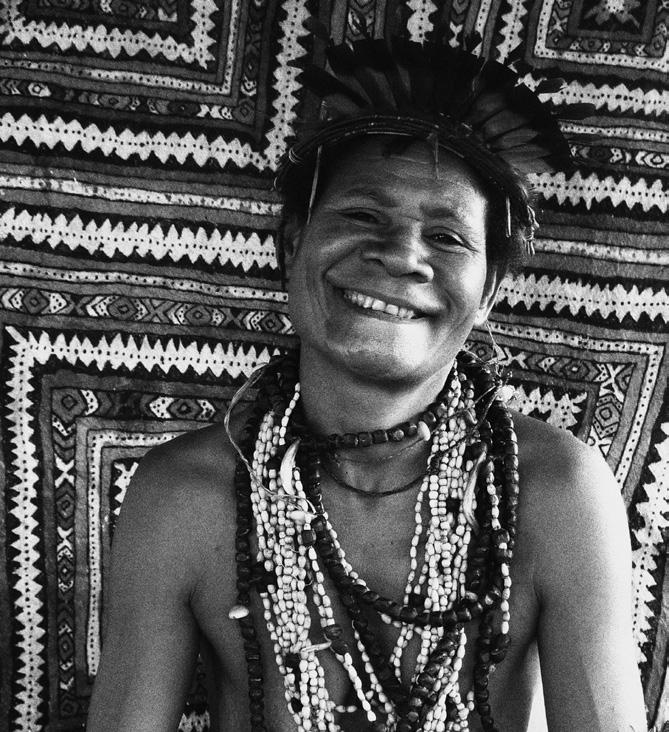

“My mother was Avarro. She was a Chief of Sahouté clan women. When I was a young boy living at old Ab’i village, she taught me how to paint all of her designs onto the barkcloth and all our clan stories. I have been holding everything — all of her knowledge — and now I am teaching my daughters and other women of my clan what my mother taught me. I am old now and when I die, they will be the ones holding our customs and culture.”

JESSIE BUJAVA (KIPORA)

Obohutaigu’e, sin’e soré (siha’e, taigu taigu’e, jö’o sor’e), visu anö’e, vavor’e daje, bubori anö’e ohu’o ori sigé (Ancestors’ tattoo design of the chin (tree bark pattern), Ujawé rite initiation body designs (fruit of the Sihe tree, leaf pattern and uncurling fern fronds), teeth of the freshwater river fish, bush rope (jungle vine with red flowers), beaks of the Papuan Hornbill and pathways)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth)

124cm x 57cm

MAGDALENE BUJAVA (KOLAHI)

Sogua’e (sodireje, siha’u’e, roriré, venimomö’e, uejobibgé, modahisu’e, mahuva’ojé, sin’e sore, jaji’e ohu’o areté) (Ancestor’s customary salt formation process (rock minerals, fruit of the Sihe tree, tail-feathers of the Moustached Tree Swift (Hemiprocne mystacea)in flight, pig hoof-prints of the mischievous pig in the trampled food garden, Ujawé initiation body designs, design of the drum)

2022

Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth)

103cm x 53cm

MALA NARI (MATOSI)

Dahoru’e, bubori anö’e, hurihuri’e, tuböre une ohu’o munë’e

(Ömie mountains, beaks of the Papuan Hornbill, eggs of the Dwarf Cassowary and river stones)

2015 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 106cm x 86cm

MAUREEN SIRIMI (JAFURI)

Vahuhu sin’e, taigu taigu’e, siha’u’e ohu’o ori sigé

(Pattern of the snake skin, leaf pattern, fruit of the Sihe tree and pathways)

2022 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 116cm x 53.5cm

PATRICIA WARERA (MATOMGUO)

Wo’ohohe

(Burrow of the ground-burrowing spider and its tracks)

2021

Appliquéd mud-dyed nioge (barkcloth) 137cm x 79cm

PAULINE-ROSE HAGO (DERAMI)

Amurelavahe’e (Ujawé sin’e sor’e siha’e/vinohu’e, taigu taigu’e, jö’o sor’e ohu’o sabu deje) ohu’o vë’i ija ahe

(Ancestral face paint design for dancing (with initiation rite body designs, fruit of the Sihe tree/design of the navel, pattern of a leaf, uncurling fern fronds and spots of the wood-boring grub), and bone of the lizard)

2022 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 156.5cm x 62cm

“I have been learning Ematé clan designs from the elders of my village. First, my motherin-law, Dapeni Jonevari (Mokokari), Chief of Ematé clan women, taught me how to paint when I first got married to her son. I learnt the old clan stories, and designs from my father-in-law, Emmanuel Jonevari too. Nathan Gama, Chief of Ematé clan men, showed me the old designs on his smoking pipe. Now I also incorporate those into my barkcloth paintings. Nathan grew up in the village of our old clan, Enopé, with barkcloth artist, Brenda Kesi (Ariré). I am painting all of the designs of my Ancestors, all together, in my own way.”

- Diona Jonevari (Suwarari)

PENNY-ROSE SOSA

Hartu’e, sabu ahe ohu’o dahoru’e

(Seashell necklace of the Ancestors, spots of the wood-boring grub and Ömie mountains)

2016 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 106cm x 65.5cm

Jubiri anö’e, bubori anö’e, sabu ahe, buro’ö’e, vinohu’ohu’o ori sigé

(Design of the orchid-fibre woven waist-belt, beaks of the Papuan Hornbill, spots of the wood-boring grub, Ujawé rite initiation tattoo design of the navel and pathways)

2022 Natural pigments on nioge (barkcloth) 129cm x 58cm

ROSEMON HINANA

Jö’o sor’e sihoti’e nioge ohu’o bubori anö’e

(Mudcloth design of the uncurling fern fronds and beaks of the Papuan Hornbill)

2022 Appliquéd mud-dyed nioge (barkcloth) 147cm x 68.5cm

ROSEMON HINANA

Aduvahe sihoti’e nioge ohu’o buborianö’e

(Chief’s prestige mudcloth (the first appliquéd mud-dyed barkcloth design) and beaks of the Papuan Hornbill

2022 Appliquéd mud-dyed nioge (barkcloth) 186.5cm x 78cm

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING ÖMIE JGM GALLERY’S JULIUS KILLERBY & ÖMIE ARTISTS' MANAGER, BRENNAN KING, DISCUSSED THE HISTORY OF THE ÖMIE, THEIR WAY OF LIFE AND THE CONCEPTS CONVEYED IN THEIR ART.

WHAT FOLLOWS IS A TRANSCRIPT OF THEIR CONVERSATION, ACCOMPANIED WITH A PREFACE BY KILLERBY.

JULIUS KILLERBY Just for some context, Brennan, could you describe the area where the Ömie live? What is their everyday life like?

BRENNAN KING The Ömie live in the remote inland mountains of Oro Province in south-eastern Papua New Guinea. Their villages are scattered around the rugged mountains and valleys extending from Huvaimo, the volcano which is the creation site of their first ancestors, Mina and Suja. Huvaimo is a living mountain with an ever-powerful presence and where the Ömie’s ancestors reside in an invisible spirit-village. The Ömie are the traditional custodians of Huvaimo and actively watch over their sacred mountain. Clouds, mist and fog often cloak the mountains due to the high altitude, and monsoon storms and torrential rains are common. All Ömie villages are surrounded by verdant, old growth rainforest stretching as far as the eye can see. This forest is incredibly biodiverse—rich in tropical wildlife such as Birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae), Dwarf Cassowaries, Tree Kangaroos and Cuscus. Waterfalls cascade from the mountains and freshwater rivers and creeks abound.

The majority of Ömie are subsistence farmers and spend much of their day gardening on the outskirts of their villages. Those that are skilled also hunt and gather food from the abundant surrounding rainforest, but with the presence of giant wild boars with dangerous tusks, and cassowaries with giant raptor-like talons, hunting is not for the faint of heart! The Ömie also gather water from the rivers, cook, clean, dance, sing, feast and chew a lot of betelnut. Houses are built predominantly from materials sourced from the forest, but sometimes with modern day tools and construction hardware from the closest town, situated far away in the lowland plains. The most common languages spoken are Ömie and Tok Pisin (a Pidgin/English-based creole language). Some children go to small schools within Ömie territory. Due to the remoteness, there is limited access to medical services, so health emergencies are a constant challenge. Christian missionaries have been present within Ömie homelands since the twentieth century, however, there are many villages, clans and families that have retained most of their cultural beliefs and many practices.

For those Ömie who have held tight to their culture, art is intertwined harmoniously with everyday life and, with this, comes a beauty very rarely witnessed in the modern, globalised world. Different clans, and families within those clans, are landowners, so different villages tend to be strongholds of certain clans. Yet there is one distinguishable unified cultural identity among all Ömie, and this is strongly felt throughout all clans and villages, however distant.

This unified cultural identity also applies to the nioge, or barkcloth art, that the Ömie women create. It can be seen and sensed in all Ömie barkcloth paintings— despite the great diversity of symbolism there is a distinct ‘Ömie essence’. This is one of the incredible mysteries of their art and how this simultaneous diversity and unity is achieved among people living on completely different sides of an enormous region one can only ponder! Even though the painted barkcloth designs can vary considerably between clans, there are common denominators such as dahoru’e (Ömie mountains), buborianö’e (beaks of the Papuan Hornbill) and sabu ahe (spots of the wood-boring grub). Unsurprisingly, these culturally unifying designs have direct correlation to the Ömie’s ancient and collective origin stories.

JK How is nioge made and how does this method differ from the way barkcloths are made elsewhere? Is nioge more of a utilitarian or artistic material

BK Nioge is the name the Ömie use for their traditional textiles—barkcloth skirts and blankets. Men’s barkcloth loincloths are much narrower and are called givai. For the Ömie, barkcloth functions as a utilitarian textile with an integral purpose within social structures, but it is also an artistic medium holding profound cultural and spiritual wisdom, knowledge of the natural world, and jagor’e (customary Ömie law). These qualities, however dissimilar they may seem, are complimentary and only reinforce the importance and centrality of barkcloth for the Ömie.

Barkcloth is a type of non-woven cloth produced by stripping, soaking and beating lengths of the inner bark from trees. Ömie women prepare the barkcloth through an intensive process. First, they harvest the inner bark, also known as bast or phloem, of rainforest trees such as paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) and fig trees (Ficus species). The outer bark is then stripped off. By the river, they rinse the long bark sheet, folding and pounding it on flat stones using a heavy mallet fashioned from dense palm wood, until a strong, fibrous sheet of cloth is produced. The cloth is then left to dry in the sun. Natural coloured pigments such as red, yellow, green and black are created from ferns, fruits, leaves, coconut charcoal and tree sap. Ancient clan designs are painted in freehand onto the cloth or the cloth is dyed in volcanic river mud and the designs are appliquéd. Common painting implements include strong grasses, fashioned wooden sticks (called ije) and frayed betelnut husks. All materials are sourced sustainably from the forest and natural environment, just as the Ömie ancestors produced them thousands of years ago. This natural and sustainable process has immense environmental relevance and significance for the future and is just one of the many reasons why it is critically important that the Ömie’s barkcloth artform is preserved.

The production of barkcloth textiles is, predominantly, a venerable artistic

“... like beautified libraries containing ancient knowledge... they (the barkcloths) maintain and communicate the deep connections their creators have to their origins, ancestors and sense of place...”

- Brennan King, 2023

tradition of many indigenous and tribal cultures primarily from tropical, equatorial regions of the world, sometimes referred to as the ‘barkcloth belt’. This includes the Pacific Islands, Island Southeast Asia, Japan, India, East, Central and West Africa, tropical South and Central America and the Caribbean. Some of the more well-known producers include the Mbuti pygmies of the Congo jungle in Africa, the Toraja of Sulawesi in Indonesia, and the Tukuna of the Amazon.

Barkcloth serves as the medium onto which culturally loaded symbols are painted in freehand, stencilled or sewn/appliquéd. The process of creating a barkcloth is similar throughout the world, however, different tree species are used and pigments for dyeing and painting differ considerably. Though, there does seem to be one intriguing unifying factor found in most painted barkcloth art around the world the predominantly abstract symbolism referencing the natural world, cosmologies, and belief systems. Beyond its utilitarian purpose as a textile, barkcloth and its symbolism has immense spiritual significance to the peoples that produce it and to their cultures. Painted barkcloths are like beautified libraries containing ancient knowledge. They maintain and communicate the deep connections their creators have to their origins, ancestors, and sense of place within their homelands and, in essence, the world. This is also one of the reasons why it is highly valued and often used within sacred ceremonial contexts and as an object of trade and exchange.

Creating barkcloth is a particularly strong tradition for both Melanesian and Polynesian societies across Oceania. Some of the better known barkcloth producing regions include: the Papuan Gulf and New Britain in Papua New

Guinea, Erromango in Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa and Hawaii. In Polynesia, barkcloth is often generically referred to as tapa, but goes by many names such as kapa of Hawaii, masi of Fiji, siapo of Samoa, ngatu of Tonga and hiapo of Niue. Sadly, over the past century barkcloth has become increasingly rare. In many regions it is either being revived, or tragically, has become extinct entirely. The Ömie are among the last peoples of Melanesia preserving this ancient barkcloth artform by way of present-day production.

JK How recently have nioge reached a wider audience, outside of Papua New Guinea?

BK There was incredible excitement when the first exhibition of Ömie barkcloth art opened in Sydney in 2006. The ‘discovery’ of art from this remote region was highly celebrated by the art world, and audiences were captivated by the beauty and raw power of the paintings. Pacific and Papua New Guinean art had been widely documented and published yet—save for a few obscure, unidentified early paintings finding their way into museum collections—the Ömie’s astonishing and captivating barkcloth art managed to slip through the cracks of art history! This was most likely due to the remoteness of their lands. The first Ömie exhibition was an explosive and exhilarating moment and even today, the artists are still relatively recent on the international art stage. After the first exhibition, immediate preparations began for the major dedicated exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, culminating in the landmark show, Wisdom of the Mountain: Art of the Ömie in 2009.

Since then the Ömie women artists have gone on to show their art internationally in exhibitions such as: the 17th Biennale of Sydney, Museum of Contemporary Art in 2010; Paperskin: The Art of Tapa Cloth Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2010; Second Skins: Painted Barkcloth from New Guinea and Central Africa, Fowler Museum at UCLA in 2012; Under the Volcano: Art of Ömie from Papua New Guinea, Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich, Germany in 2015; Shifting Patterns: Pacific Barkcloth Painting, British Museum, London in 2015; and the current 2023 exhibition, Ömie Barkcloth: Pathways of Nioge Chau Chak Wing Museum, Sydney, Australia. However, the story of Ömie art is only just beginning, as the artistic visions of the Ömie women artists are proving to be seemingly boundless. This comes as no surprise when you consider that their creative wellsprings are ancient and come directly from the artists’ ancestral roots and from the natural world around them.

JK As I understand it, one is only allowed to create nioge once they reach a certain level of technical proficiency. There is a seriousness attached to the artform. Could you speak a bit about this? How do the Ömie come up with their designs? Do they have a certain level of freedom with which to interpret their inherited wisdom? Are there any prescribed rules around the designs?

BK Yes, there is a critical hierarchy among barkcloth artist knowledge holders such as Duvahe (Chiefs) and elders, with a passing on of unbroken ancestral knowledge and skills from one generation to the younger generation. Ömie Artists works with artists within this knowledge system as a fundamental act of barkcloth conservation, and furthermore, for: artistic and cultural preservation; maintaining existing clan social structures; accurate cultural representation; environmental sustainability; and future generations of artists. Ömie Artists respects and honours this traditional system, and in keeping with jagor’e (customary Ömie law), only exhibits barkcloths by artists who have reached a certain level of refinement approved and authorised by our cultural leaders and elected female Artist Representatives. Our artists have all learnt their designs, knowledge, or stories within a traceable ancestral lineage, ensuring authenticity and that traditional copyright systems remain perfectly intact. We believe this translates to a perceptible and unmistakeable energy within the works and sets a benchmark in cultural integrity, quality and beauty.

There is an Ömie term, uehore, which is used primarily among only the most senior and respected painters. These highly experienced artists have refined their artistic style to such a degree that they earn the freedom to create new designs. However, even then, this is quite rare. Young artists train under either their or their husband’s grandmother, mother, aunts, or in their absence, under their husband or a male elder who is the knowledge holder of their family’s designs. It takes years of practice to create a painting deemed to have the essential and desirable quality of burito’e—for the designs to “come alive with beauty” when the nioge skirts are danced in. Painters of high regard create optical and visual effects, usually through the repetition of designs, as if the processes of painting and weaving had been perfectly amalgamated—a sort of "painting-weaving" if you like. These designs are not only visually appealing but are also rich in cultural meaning and significance.

Developments within Ömie barkcloth painting also occur within an artist’s unique style and expression, and such idiosyncratic qualities are one of the greatest aspects of all Ömie art. No two painters or their paintings are alike, the sheer diversity is astounding and leaves me without doubt that what we are in fact witnessing is a contemporary art movement playing very much by its own rules. And in a highly globalised art world, what a marvellous and precious thing it is to witness such self-determination! The customary laws that govern the creation of nioge still afford the artists an incredible amount of freedom within their creative practices, and one need only look to this London exhibition to see this in full force.

JK Though the English language is perhaps insufficient to fully convey the concepts surrounding this art form, are the nioge, in some sense, seen as the spiritual descendant of the tree that they were harvested from? In other words, is the barkcloth itself imbued with a spiritual significance?

BK There are many layers to the spiritual aspects of the connection artists have with the tree and barkcloth. And yes, absolutely, the barkcloth is imbued with spiritual significance. The tree, and the barkcloth which is harvested and created from the tree, are inseparable. As an artist harvests the bark there is an invisible thread extending back to when as detailed in the Ömie creation

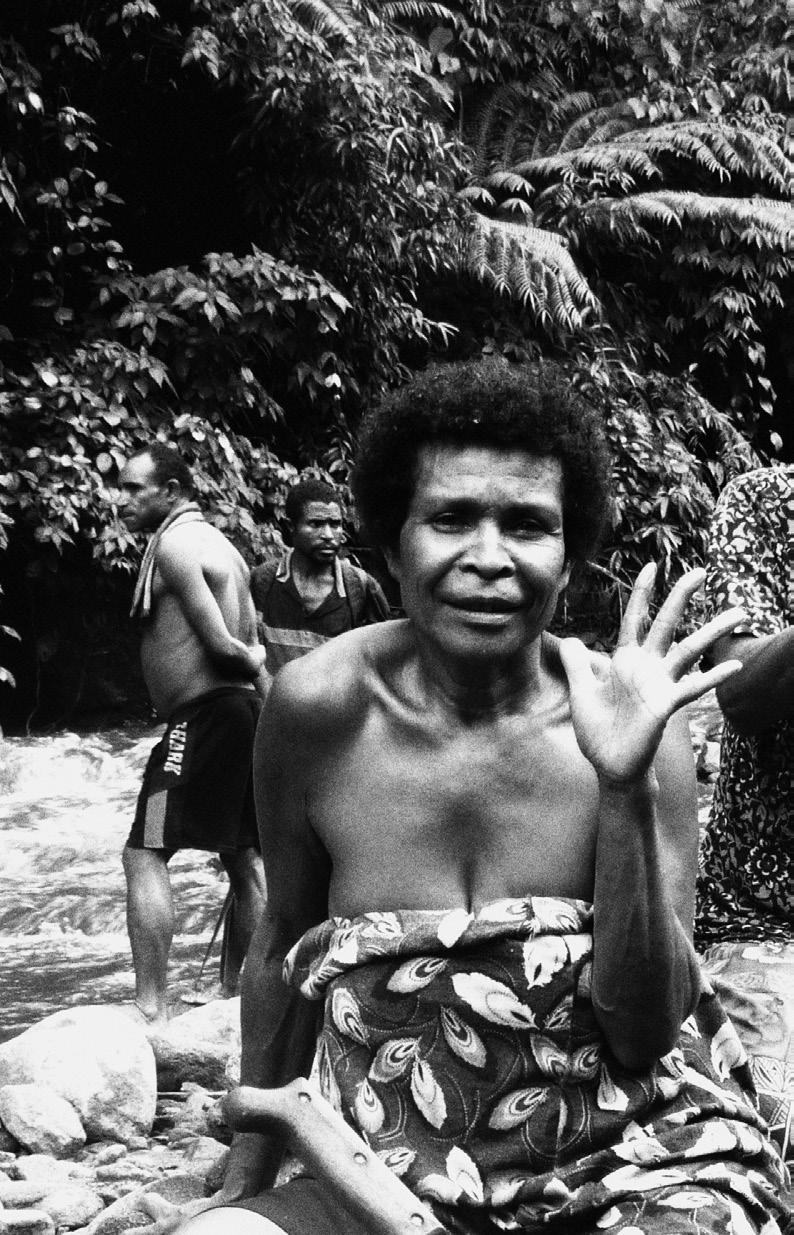

story the first female ancestor, Suja, first menstruated and harvested the tree bark, creating the very first barkcloth to wear. By dyeing it in the river mud, the mud became symbolic of her procreative power as a woman. In this sense, all Ömie artists are the descendants and daughters of Suja, and all steps in the process of creating a barkcloth are a kind of re-enactment of Suja’s original act in the present. This was and still is a critical identity-defining moment to the Ömie as a people and culture, but especially so to Ömie women. Through the processes of barkcloth creation this invisible ancestral thread binds the past to the present and imbues the artist with a strong sense of cultural identity and belonging to her community, people and the environment. The trees and barkcloth are the central and key component in this spiritual act. As artists mirror Suja’s sacred acts of the barkcloth-making process, the artists are very aware that they are keeping their culture alive in the present. So as a time-honoured tradition, there is certainly a ritualistic aspect to barkcloth production also. For Ömie women, and as Drusilla Modjeska so brilliantly identified, barkcloth “... is both a source of their power and a visible manifestation of it.”

The Ömie use tree metaphors to conceptualise society. Ancestors and elders extend from the roots, while children and grandchildren are associated with fine twigs and leaves. For example, the Ömie’s social structure recognises a male and female Duvahe (Chief) for each clan. These are senior and respected community leaders who are knowledge holders and keepers of the culture. The term Duvahe is an adjective for the "... fork of a tree from which the major branches grow." This indicates there has been a reverence for trees even since the inception of the Ömie’s Duvahe social system. Fortunately, there are some beautiful examples of tree designs in this exhibition. Jean Niduvé (Urihö) has painted her ijögijegije design, which is an Ematé clan design of the bare tree branches. Elizabeth Guho (Owkeja)’s painting shows the leaves of the Samu tree, which is the emblem of her Samwé sub-clan. Anie, plant emblems, define social identity and ancestral relationships to hunting and gardening tracts. So as you can see, trees and plants are woven into even the most important aspects of Ömie society as they hold great spiritual significance to them.

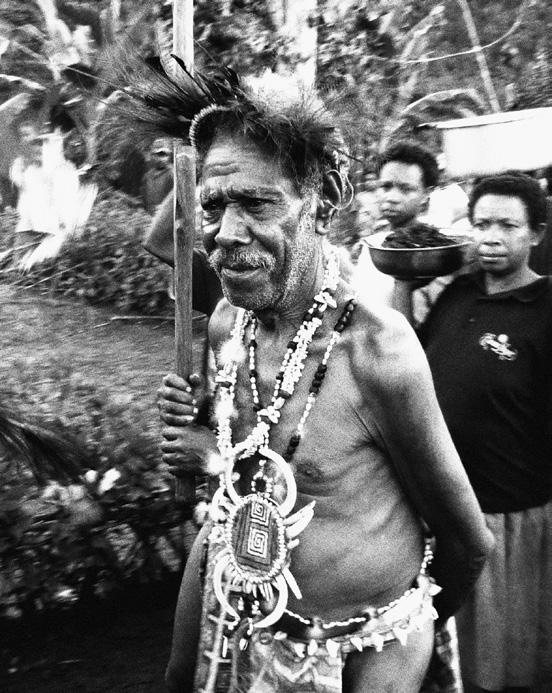

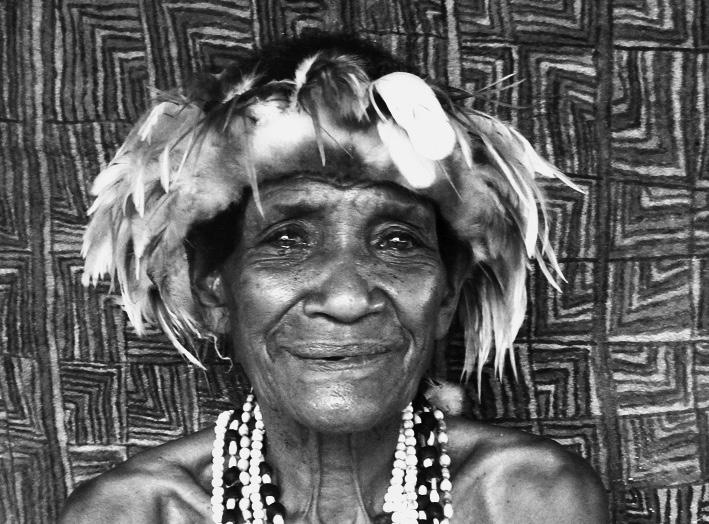

Many of the Ömie’s sor’e (body designs) are based on trees and plants. For example, if you look at Jessie Bujava (Kipora)’s painting you will see the key design of obohutaigu’e, which represents the pattern as inspired by the bark of the Obohe tree. This ancient tree bark pattern design was tattooed on Jessie’s ancestors’ chin during the sacred Ujawé initiation rite. Jessie learnt this design directly from her father, Albert Sirimi (Nanati), who was formally trained in barkcloth painting under his mother, Avarro, in the 1940s. Albert was unique in this regard as he was the only known male barkcloth painter who was formally trained in this way. Albert was very old when he first began painting for Ömie Artists and painted only four paintings before he passed away. As a very special addition to the show, one of Albert’s paintings has been included in this exhibition and it is the largest he produced, as well as his final available work.

JK Artists such as Albert Sirimi (Nanati) and Barbara Rauno (Inasu) seem to have a far more intense and almost hallucinogenic aesthetic compared to the work of artists like Rosemon Hinana, whose designs are far more reduced. Are different concepts conveyed by these opposite aesthetics?

BK I love that word, hallucinogenic! It is actually very fitting, but I will come to why a little later on. The late Albert Sirimi (Nanati) was teaching his daughters, daughter-in-laws, and women members of his clan, the Sahuoté how to paint barkcloth. Anticipating the future, he taught in secret and in private and this act has become his own remarkable (and intensely moving!) legacy to his clan and people. He provided each of his female students with their own designs and encouraged them to practice their designs, overseeing their artistic progress and growth. Now we have what you might call "The School of Albert Sirimi (Nanati)", which consists of six artists: Jessie Bujava (Kipora), Barbara Rauno (Inasu), Maureen Sirimi (Jafuri), Ivy-Rose Sirimi, Petra Ijaja (Jaujé) and Agnes Bujava (Loréma). Many of these artists are included in this exhibition, alongside and complimenting Albert’s work. Their paintings and designs are characterised by either dense, complex interwoven geometries or looser, organic, and naturalistic abstract designs, but all with an emphasis on dazzling optical effects.

Albert taught me about the Ömie ancestors’ concept of the old word buriétö’e. It was used to describe the phenomenal experience when a person looks upon a dancer wearing their

the painted designs “change” and “come alive with beauty” during movement. This mesmerizing sensation of buriétö’e occurs in the moment the designs are animated through dance. From the two-dimensional painted surface, the kaleidoscopic patterns suddenly begin to pulse, radiate and warp. As the designs are kinetic and optimally designed for, and enhanced by, motion, this gives us valuable insight and clues into how the Ömie’s abstract and repeated designs may have come about at the dawn of Ömie creative thought. So, your observation of Albert and Barbara’s work, and that of his other students, being hallucinogenic is absolutely correct! Once this aspect of the repeated designs and compositions within Ömie art is understood by a viewer, the paintings begin to truly reveal themselves and can then be viewed in a whole new light. For added delight, I really encourage exhibition visitors to consider this key to Ömie visual language that Albert has so generously bestowed.

The link between these complex painted designs and the more minimal designs of the appliquéd sihoti’e nioge (mud-dyed barkcloths) becomes apparent when you consider how, in the mud-dyed works, the white and darker grey colours are contrasted to create striking visual patterns. These mud-dyed works, when viewed from a distance, are also capable of producing striking visual effects… and this experience can be transcendental. There is a timeless beauty to these mud-dyed pieces, such as those by artists, Rosemon Hinana and Patricia Warera (Matomguo), and it may not be surprising to discover that these sihoti’e designs were some of the first barkcloth designs created by Ömie ancestors. They are the predecessors of painted barkcloth the foundational and structural bones of nioge and contain a visual template of sorts for the painted abstract proliferation that would follow.

Artists throughout history have long been aware of the dualistic dance of light and dark colour as spiritual symbols for the creation and birth of the Universe. As Australian artist, Diena Georgetti, illuminates, “The origins of colour come from the cosmic beginning of time; there was only dark and light, and colour later formed on the planet as material… black and white… were the first colours denoted by language.” Black and white binaries are present throughout the esoteric, mystical paintings of Swedish abstract artist, Hilma af Klint, as can be seen in her work, No. 2a, The Current Standpoint of the Mahatmas (Nr 2a, Mahatmernas nuvarande ståndpunkt) from Series II (Serie II) 1920. The dark and light abstract paintings of Korean Dansaekhwa artist, Yun Hyong-keun, also come to mind. As do the black and white works of the American colour field painter, Barnett Newman, or those of Dutch Modernist painter, Piet Mondrian. Ömie sihoti’e nioge (mud-dyed barkcloths) speak directly to the earliest origins of the Universe, poetically correlating to a subject some of the greatest artists throughout history have long been fascinated by.

Interestingly, the Ömie Creation Story begins, “At the beginning of time, Uhöeggö’e the lizard lived in a freshwater lake. Uhöeggö’e shed its skin and became a human man, and the world became dark. Uhöeggö’e saw the Sun, Moon and stars reflected in the water, but they were not in the sky. Uhöeggö’e was unhappy living in darkness and thought to himself, “I want brightness!” The water in the lake split down the centre. One half of the water remained as water and also became light. Then Uhöeggö’e said, “But I need darkness!”, and the other half of the water became darkness. The waves of water from the creation of light and darkness created one land called Mt. Ömie. Mt. Ömie gave birth to the mountains A’oji Madorajo’amoho, Uruj’e and Guamo.”

This splitting of darkness and light can be seen in the primordial lake in the painting by Ömie artist, Rex Warrimou (Sabïo), Our Creation (Ömie), and Mina stealing the first fire from Insa on Mt. Madorajo’amoho 2014. This suggests that the

Left: Detail of the primordial Lake Of Light And Darkness at the beginning of time (of The Creator Being and lizard/man, Uhöeggö’e), as depicted in Rex Warrimou’s painting, Our Creation (Ömie) & Mina stealing the first fire from Insa on Mt. Madorajo’amoho, 2014, 88cm x 75cm.

first Ömie artists and creators of sihoti’e nioge were likely to have been acutely aware of the symbolic meaning of the colour polarities of darkness and light. It is possible that these concepts of the Universe and its creation may have informed or inspired their earliest known and most ancient mud-dyed barkcloth artform and are at the very root of the contrasting dark/light appliqué technique, visually echoing their Creation Story.

Furthermore, the Yin and Yang symbol is another pertinent reference to the Ömie’s lake of light and darkness at the beginning of time. The Yin and Yang symbol originates from ancient Chinese philosophy and mythology, and is a circle composed of interlinking black and white colours. This symbol refers to a principle where opposite forces are seen as interconnected, inseparable, and counterbalancing. Yin and Yang were born from chaos when the Universe was first created, and they are believed to exist in harmony at the centre of the Earth. Examples of Yin-Yang dualities are female-male, dark-light, and oldyoung. Despite the great geographic distance between Papua New Guinea and China, there are some intriguing crossovers here pointing to a shared human consciousness, innate human intelligence and Universal Truths. The Ömie’s sihoti’e nioge also has parallels with the black and white ikat, mud-dyed textiles produced by the To Mangki Karautaun people of central Sulawesi, Indonesia. In their Morilotong ceremonial hangings, the oldest ikat motifs known were similarly created in interwoven and striking black and white. Similarly, the natural dyes used were sourced from tree tannins and iron rich mud. The contrasting black and white colours symbolise concepts such as the duality of heaven and earth, with humans living between these worlds. These are just some examples of the multifaceted art historical dialogues to which Ömie sihoti’e nioge speaks to so eloquently, and certainly, further examples can readily be found throughout the diverse art forms of world cultures.

JK Is it correct to view many of these works almost as topographical landscapes?

BK Generally, for most Ömie barkcloth artworks I would say no, they are not topographical landscapes but rather, many are abstracted observations of the natural world, capturing both macrocosms and microcosms. While most contain traditional nioge designs passed down from the ancestors through the generations by way of a highly complex social system, many barkcloths also incorporate sor’e (body tattoo designs) from the Ujawé initiation rites, as well as intricate designs from kuku hon’e (men’s bamboo smoking pipes).

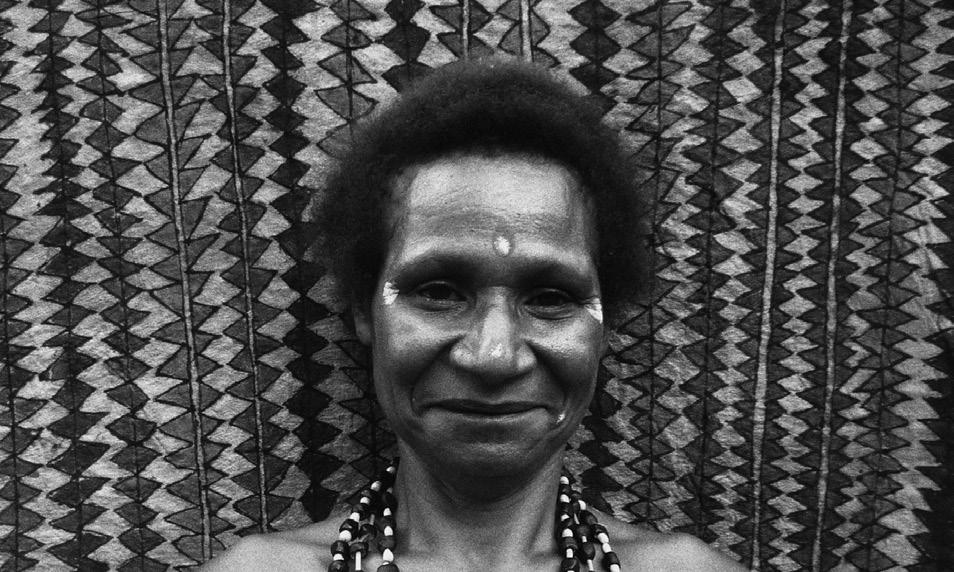

Some designs do have aspects of being topographical landscapes, namely the zigzag design dahoru’e which represents Ömie mountains, and the similar zig-zag design hurihuri’e which are smaller hills (as seen in Mala Nari (Matosi)’s paintings). These zig-zags relate to the visual attributes of mountains, their peaks and valleys and the way mountains repeat to become a mountain range, expanding out to the horizon. But there is also the mind’s perception of the physical experience of traversing these mountains as the body climbs up, down, up, down. Through these designs, the paintings become activated with the experiential feeling of the landscape and environment, rather than being a topographical representation of it. Certainly, upon encountering an Ömie barkcloth painting it is likely that the viewer experiences the beauty of place coming to life through the paintings—we are transported to the wild mountain landscapes of the Ömie, deep into their world among the lush tropical rainforest.

There have been some rare examples of topographical landscapes in Ömie art, and these relate to: sacred creation sites; ancestral stories and their related sites; and remembering, mapping and identifying specific homelands either affectionately, with land ownership objectives or both. But these are singular examples whose visual schema are primarily unrelated to the majority of Ömie barkcloth art.

JK The decoration on the nioge is often asymmetrical. The designs are almost as free and organic as those that one would see in nature. Nothing seems contrived. Would you agree with that?

BK To me, the asymmetrical, free, organic symbolism of Ömie art is a balm for the spirit. This symbolism springs directly from the natural world, and it feels like a natural extension of the natural world. It is a deeply ecological art, soaked with profound wisdom of place. When I walk in nature, especially in a forest, I feel myself begin to relax almost immediately. I feel the same thing when I look upon the asymmetrical Ömie symbolism and compositions. There is something so inviting and comforting about it. I think this comes from a joy and pleasure in

“... remarkably, there are aesthetic and conceptual similarities between Ömie Art and barkcloth designs from other localities, including the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, Africa and South America, amongst others. Indeed, these may not simply be similarities, but innate ideas that crossculturally populate the Collective Unconscious.”

- Julius Killerby, 2023Left: Father & son wearing barkcloth givais (loincloths), painted by Sarah Ugibari, 2010. Photo by Brennan King, courtesy of Ömie Artists.

each artist’s mind and hands as they paint. At the very heart of this artform there seems to be an impulse to harness and capture something of the same beauty and wild forces that exist in nature onto the barkcloth. There is a particular kind of peace in that, some kind of elemental familiarity.

The entire creative process of Ömie barkcloth painting is a tradition imbued with cultural pride and has the ability to connect an artist to the ancestral/spiritual/ divine. These factors may also contribute to how their creative process happens in an uncontrived way. I am endlessly fascinated by the creative mechanisms at work when an Ömie artist first conceives of a painting design, inspired by some aspect of nature or their culture, to when it is painted onto the barkcloth. There is real magic there. I find Ömie iconography highly sophisticated, like a marvellous Universe unto itself. It is like a secret language of the mountain forests… as if they are translating the truths embedded in nature. They seem to draw out the patterns and abstract symbols found within nature, accentuating and articulating them to an entirely new degree of beauty. Each artist then weaves the designs all together in inexhaustible compositions and iterations to mesmerise the eye even further.

JK What are some of your favourite pieces in this new show with JGM Gallery?

BK This is a particularly strong body of work, and it has been a real pleasure to bring these diverse works together for this show. The artists all have their own style and strengths but let me see…

I do have a soft spot for Pauline-Rose Hago (Derami)’s paintings. I think that she could sit alongside any of the great master artists from any era or culture throughout world art history and easily hold her own. Her work needs to be seen in real life in order to be truly appreciated the delicate detail is just extraordinary! It is like some sort of free-spirited, anarchic lacework. Her energetic and wild mark-making is like pure, unbound creative energy itself. She only grows more and more confident and talented with each work she paints, and her progress has been an absolute delight and privilege to watch over the years.

There are so many choices, but I do also adore the wonderful idiosyncrasies within Faith Jina’emi (Iva)’s paintings. She knows exactly how to use her designs to play with composition and the results are unpredictable and always spectacular. This is one of the true signs of an Ömie master painter. She has reached a level of painting skill that situates her in the highest echelon of senior Ömie painters. As the daughter of one the most revered painters in recent history, Filma Rumono, she is essentially Ömie art royalty!

And it would be impossible not to mention Magdalene Bujava (Kolahi)’s painting. When I first saw the work, it took my breath away. It is a Sahuoté clan gem. It looks as though she has reached back into the ancient past while in a dream, had a deep conversation or two with her Duvahe (Chief) ancestors, and then woken up and just started painting. Would you believe she is showing us the process her ancestors used to make salt? Isn’t that sublime! The painting contains everything I love about Ömie art and culture. It is also a spectacular example of how Ömie art and culture has not only survived against all odds to the present day but has done it with gusto and pizazz. She is a real talent to watch! I love hearing how people

respond to Ömie art, it is part of why I love working with the artists so much. Are there any particular paintings that sing out to you Julius?

JK Personally, my favourite pieces are those by Barbara Rauno (Inasu) and Diona Jonevari (Suwarari). I particularly like the intensity of Jonevari's zigzagging lines and colour scheme. The design of Rauno's work, by contrast, seems softer edged. Could you speak a bit about them and their work?

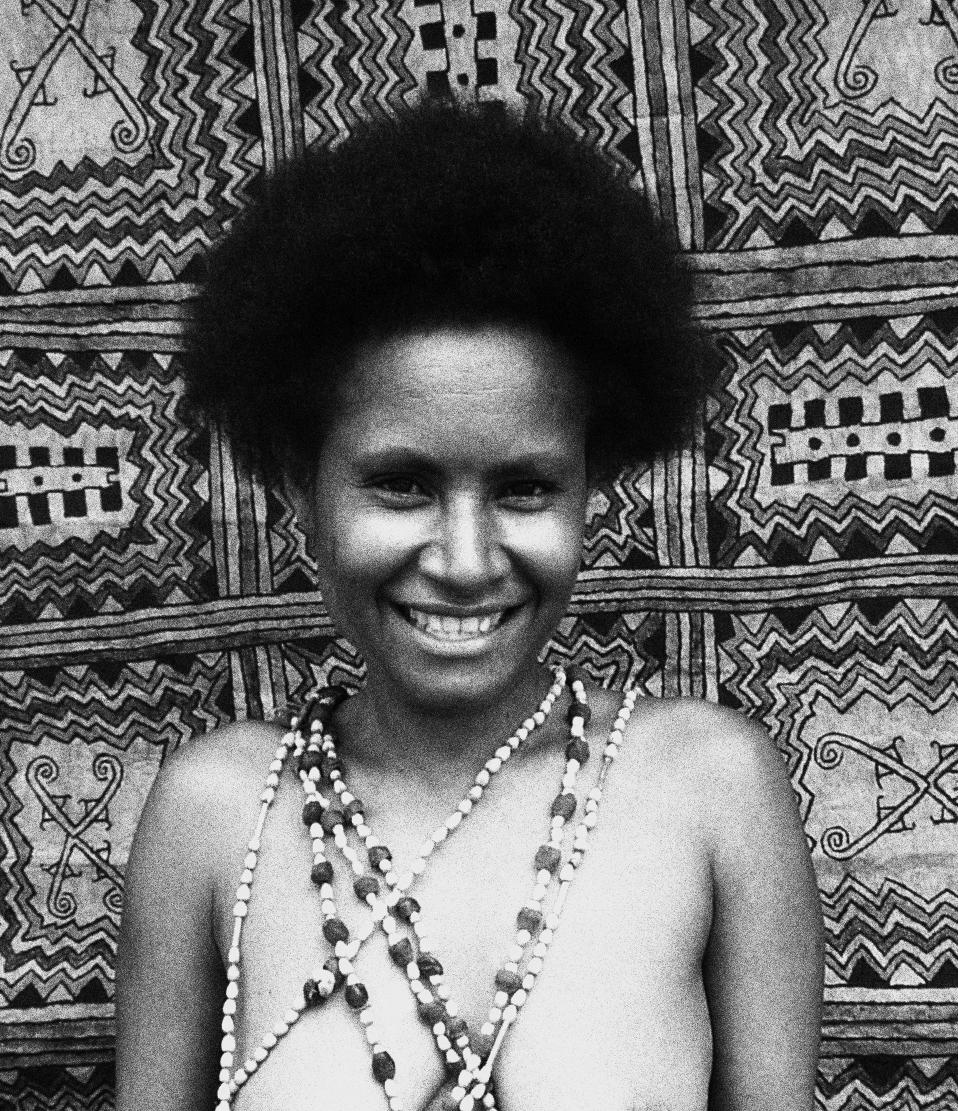

BK Diona Jonevari (Suwarari) is an absolute force of nature. She is leading a new generation of artists and she paints like a Duvahe (Chief). She is most fortunate in that she has not only had one teacher, but three, and all were or are high-ranking Duvahe and respected elders of her clan. This strong foundation, combined with her innate talent as a painter and bold experimentation, has culminated in her particularly arresting and vibrant images which are bursting with every possible aspect of her culture. They are a tour de force to behold.

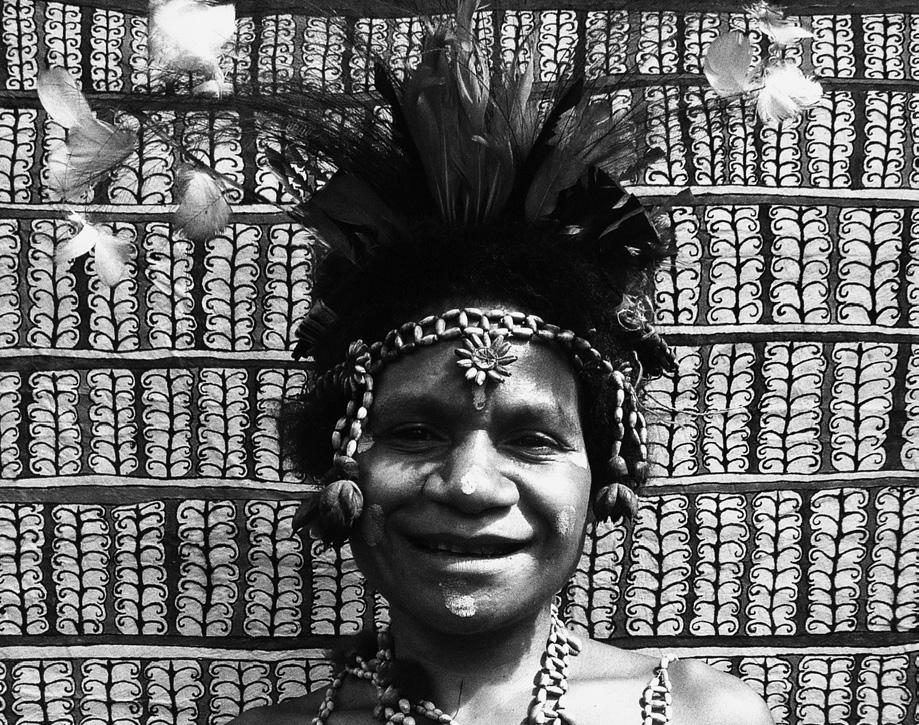

Barbara Rauno (Inasu) is from an entirely different clan and village which tends to lean towards a far more geometric sensibility, yet one that is still loose and organic. The results of such complex compositions can be phenomenal. She was taught to paint by her father, Albert Sirimi (Nanati), and she paints her designs with ever-increasing delicacy and sensitivity. This piece is a fantastic example of recent developments within her painting practice where she has taken nuni'e, the design of the eye, from a man’s bamboo smoking pipe, and then adapted and elaborated it, as if it were unfolding and expanding, and the design has now become a completely new iteration on the barkcloth. Really, she is showing us her culture in a new light.

JK What can one learn from these barkcloths which is unique to Ömie culture and perhaps absent, or at least underappreciated, in the Western World?

BK I think the world needs diverse perspectives and artistic visions from artists that exist outside the cities and urbanised centres, artists that come from well outside the mainstream and the known. I want to live in a world where people don’t just claim to celebrate diversity, but truly celebrate it by engaging with perspectives that may not be quite so familiar. Much can be gained by deeply listening to voices that may differ from our own or from those that may not fit neatly within expected categories. Once we are able to look without discrimination, only then can we truly see.

Viewing the art of the Ömie offers us the perfect opportunity to open our minds and challenge our preconceived expectations. Part of the human story is one of wanting to belong to belong to place and community. To be rooted, grounded and connected is something that many of us long for. That an art and culture as beautiful as the Ömie’s has miraculously risen to meet us within our fragmented modern systems is the greatest of gifts. And, at a time when the world is undergoing environmental catastrophes, it is one with a deep ecological message. Healing from our current ecological dilemma begins with learning to respect nature. When we look upon the art of the Ömie we see even further still beyond the fundamental respect we need. We see how this respect can eventually grow to become an enduring bond, and one with spiritual resonance. Among many things, the Ömie show us that living in balance and harmony with the natural world is indeed possible. And they make it look so good in the process!

Judith, Wisdom of the Mountain: Art of the Ömie, National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne, Australia, 2009, p.27.

1. Drusilla

2. Diena Georgetti, from an interview with Tiarney Miekus for Art Guide Australia (forthcoming 2023).

3. Oil on canvas, 36.5cm x 27cm, as exhibited in Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA, 2018.

4. © Rex Warrimou (Sabïo) & Ömie Artists Inc, orally translated by Raphael Bujava and Didymus Bojugo; transcribed by Brennan King at Savodobehi & Port Moresby, 2009-2015. Brennan King was instructed and authorised/inducted by way of ceremonial ritual by the Dahorurajé clan leaders at Savodobehi village in 2014, tasked to release the Ömie Creation Story to the public. Required in this instance by Ömie jagor'e (law), he carries "... the blessings of the ancestors" to do so. Due to the sacred nature of the story, referencing, copying or appropriating this text in any way is not permitted.

5. 88cm x 75cm | Photo: Brennan King © The artist & Ömie Artists Inc.

6. Threads of Life (Ubud, Indonesia) website.

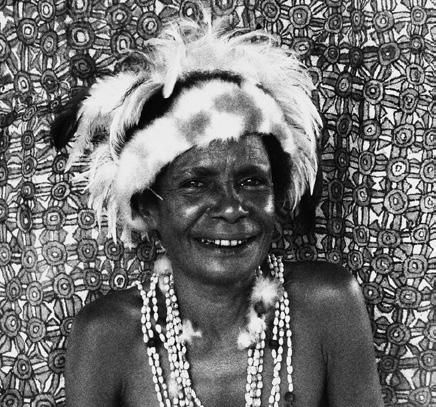

Barbara Rauno’s (c. 1973) father is Albert Sirimi (Nanati), a Sahuoté clanman from Gorabuna village and assistant to his brother, the Paramount Chief of Ömie men, Willington Uruhé. Rauno’s grandmother was Avarro, the former Sahuoté clan chief who is still remembered today as a very important barkcloth painter. Sirimi remembers Avarro’s designs and has been teaching his daughter, Barbara, so that the Sahuoté clan tradition of barkcloth painting will live on long into the future. Barbara and her husband Douglas are the happy parents of seven children.

Albert Sirimi (Nanati), (c. 1937-2012), was a highly respected Sahuoté clan lawman, master songman and the Assistant Paramount Chief of Ömie men. He is the only known Ömie man to have learnt traditional barkcloth painting designs from his mother. Sirimi was one of the last men who remembered the traditional Sahuoté clan funerary rites, which he played an important role in as a young man. He was a young boy living in the old Sahuoté clan village of Ab’i c.1940 when the first white man, Mr. Cook an Australian Patrol officer, accompanied by Orokaivan policemen set up camp at the base of his mountain village on a mission to 'civilize' the Ömie. Sirimi explains how Mr. Cook shot his gun at a tree to assert his power, eventually scaring and coercing Sirimi’s clan down from their village. Mr. Cook gained Sirimi’s people’s trust by giving them sugar, salt, rice, flour, tobacco, matches, clothes, axes and knives. Mr. Cook marked Sirimi’s father, Nanati, as the first village police officer in order to enforce law and stop tribal fighting. Mr. Cook even chose a wife for Sirimi’s father – Avarro, who later became the Chief of Sahuoté clan women and a revered barkcloth painter, and Sirimi’s new mother and painting teacher. Some of Sirimi’s Sahuoté clan designs are shared with artist Celestine Warina (Kaaru), Chief of Sahuoté clan women, as she is the granddaughter of Avarro. Sirimi has achieved the extraordinary by teaching a large group of young women artists the ancestral Sahuoté clan painting designs. This fortunate group includes his daughters and daughter-in-laws, Jessie Bujava (Kipora), Ivy-Rose Sirimi, Maureen Sirimi (Jafuri), Petra Ijaja (Jaujé), Barbara Rauno (Inasu), Agnes Bujava (Loréma) and Audrey Masé (Koren). The spirit of Avarro and Albert Sirimi and their important barkcloth painting legacy lives on through this new generation of artists and their exceptionally beautiful artworks.

Diona Jonevari’s (c. 1979) mother was Delma Iarin of Gora village and her father was Abaho Gugonaymi of old Godibehi village (Ematé clan). When Jonevari married her husband Nathaniel Jonevari in 2002, she began to learn to paint the traditional Ömie designs of his mother Dapeni Jonevari (Mokokari), who was the Chief of Ematé clan women and a highly respected artist. Under Dapeni’s tutelage, Jonevari has become a respected artist in her own right. She incorporates sor’e (tattoo designs) taught to her by other elders of her clan such as her fatherin-law Emmanuel Jonevari (c.1920-2010) and Nathan Gama, Chief of Ematé clan men. As an astute student, Jonevari now draws from a wealth of traditional Ömie designs which she paints in her own innovative and expressive style. Her wealth of knowledge and extraordinary natural talent and skills firmly place her among the most significant Ömie artists.

Elizabeth Guho (c.1958) has been painting for Ömie Artists since 2009. Her mother was Martha Ruruvé of Gorabuna village (Sahuoté clan) and her father was Clement Towora of Enjoro village (Ina’e clan). Her mother taught her the Ömie barkcloth designs of her grandmother such as mahudanö’e - pig’s tusks (traditional Ömie wealth), jov’e avadu avaduvé - ripples of the water, samwé - Beriirajé/Samwé sub-clan emblem of the tree and vinohu’e - design of the bellybutton.

Jessie Bujava’s (c. 1970) father is the Assistant Paramount Chief of Ömie men, Albert Sirimi (Nanati) and her mother was Agnes Sirimi, both Sahuoté clanspeople from Gorabuna village. Bujava was first taught to paint traditional Sahuoté clan designs by both her mother, Agnes, and her grandmother. Later, she was also taught by Albert Sirimi (Nanati). Along with Ömie artists Lillias Bujava (Kausara) and Barbara Rauno (Inasu), Jessie is part of a new and exciting school of Sahuoté clan painters whose designs are characterized by an excess of orriseegé or ‘pathways’. Orriseegé is most often used to provide a compositional framework for Ömie painting designs and it reaches its extreme limit in Bujava’s works where her traditional symbolic designs conform to a tight, yet organic, geometric format. She often paints siha’e, the design of the fruit of the tree and visuanö’e, the design of the teeth of the mountain fish.

Jean Niduvé (c. 1987) is the daughter of Albert Sirimi (Nanati), the Assistant Paramount Chief of Ömie men. She is married to Marumo Niduvé. Ematé clan elder, Brenda Kesi (Ariré), remembered seeing Niduve’s mother-in-law painting barkcloth clan designs, and taught Jean to paint them in 2012. Over the past decade, 2012-2022, Niduvé has developed into an artist of exceptional skill and talent. The emergence and survival of her strong ancestral barkcloth painting designs is quite miraculous for the present day.

Magdalene Bujava (c. 1984) is the daughter of Emily Levoré, former wife of Eric Afukasi and current wife of Raphael Bujava. She began painting for Ömie Artists in 2012 (when she was known as Magdalene Afukasi). Bujava paints designs belonging to her father’s clan, Ematé, as well as her husband’s clan, Sahuoté. She is one of the leading Sahuoté clan painters with knowledge and painting skills directly related to the body designs of the ancient and sacred Ujawé tattooing initiation rite.

Mala Nari’s (c. 1958) mother was Waganami Togarino of Gora village (Saro’ore clan) and her father was A’oji Negunna of Godibehi village (Ematé clan). Nari has three children. Her husband, now passed, was Elo Nari. She was taught to paint Ömie designs by her grandmother and remembers watching her at Kërö village (an old village of Gora) as a young girl. Nari loved to sit with her grandmother and learn about Ömie history, the natural environment and how to nurture the land. Her main designs are: tuböru unö’e - eggs of the Dwarf Cassowary; dahoru’e - Ömie mountains; munë’e/hitai - river boulders; buboriano’e - beaks of the Papuan Hornbill; and odunaigö’e - jungle vines. From 1996 to 2002, before the arrival of David Baker and the formation of the Ömie Artists cooperative, Nari was instrumental in bringing about a revitalisation of barkcloth painting in Jiapa and Duharenu villages. She is a very strong culture woman and is well known across Ömie territory for her powerful singing voice. Her work was exhibited in the 17th Biennale of Sydney at the Museum of Contemporary Art and in the landmark exhibition of Ömie Art, Wisdom of the Mountain: Art of the Ömie at the National Gallery of Victoria International.

Elvina Naumo (c. 1994) is the daughter of Mary Naumo, former Chief of Ematé clan women and a highly respected barkcloth artist. She was taught to paint certain designs from her mother before she passed away. Naumo is becoming an artist of considerable talent and ambition, often painting highly detailed designs on large scales.

Maureen Sirimi (c. 1997) began painting for Ömie Artists in 2021. She is the daughter of esteemed elder, the late Albert Sirimi (Nanati), who was the Assistant Paramount Chief of Ömie men and the only known male artist to have learnt from his mother formally. Albert Sirimi taught Maureen an extraordinary wealth of knowledge and nioge (barkcloth) designs from a very early age. These important designs originate from the former Duvahe (Chief) of Sahuoté clan women, Avarro—Sirimi’s great-grandmother. Sirimi now holds this precious painting lineage and, combined with her natural talent as a painter, she is one of Ömie Artists most exciting new artists carrying the Ömie’s sacred tradition of barkcloth painting into the future.

Faith Jina’emi (c. 1957) began painting for Ömie Arists in 2012. She learnt to paint as a young woman from her mother Filma Rumono, Chief of Sahuoté clan women. Jina’emi is now a leading elder and cultural authority of the central region of Ömie territory. She paints her ever-increasingly complex and diverse ancestral designs with vitality and integrity. Her exquisite work and its recent developments are a very exciting and surprising addition to the unfolding Ömie Art movement.

Patricia Warera (c. 1985) began creating works for Ömie Artists in 2021. She is among the last artists holding knowledge of the ancient method of barkcloth art known as sihoti’e taliobamë’e (designs of the mud). This method of appliquéing mud-dyed barkcloth was first practiced by Suja, the first woman and mother of the world, as told in the Ömie creation story. Her grandmother, Brenda Kesi (Ariré), taught her to sew the ancestral Ömie sihoti’e designs, such as wo’ohohe - the burrow of the groundburrowing spider and its tracks. This precious lineage of sihoti’e nioge (mud-dyed barkcloth skirts) comes from her great-grandmothers, Go’ovino and Munne, who were Ematé clanswoman from old Enopé village between the Jordan and Maruma Rivers.

Pauline-Rose Hago (Derami), (c. 1968), is the daughter of Natalie Juvé, a Sahuoté clanwoman from Duharenu village who was also a barkcloth artist. As a young girl Hago was adopted by Wilington Uruhé, the Paramount Chief of Ömie men. She has been fortunate to have learnt the traditional Sahuoté soru’e (tattoo designs) from her father Willington as she is now the foremost painter of important designs such as: taigu taigu’e - leaf pattern; siha’e - tree fruit; jö’o sor’e - uncurling fern fronds; as well as vë’i ija ahe - bone of the lizard. Her talents as a painter have seen her travel to Sydney, Australia in 2009 with Dapeni Jonevari (Mokokari) to attend an exhibition of Ömie Art. She was married to the late Simon Hago and together they had four children.

Rosemon Hinana began creating works for Ömie Artists in 2022. She is an incredibly special and important artist as she is among the last artists holding knowledge of the ancient method of barkcloth art known as sihoti’e taliobamë’e (designs of the mud). This method of appliquéing mud-dyed barkcloth was first practiced by Suja, the first woman and mother of the world, as told in the Ömie creation story. There is a minimal and elegant restraint to her appliquéd mud designs which sets her work apart from hand-painted designs. She is also adept at painting Ujawé rite initiation body designs.

Pennyrose Sosa (c. 1976) first learnt to paint barkcloth designs from her mother Kiadora, who in turn learnt from her mother Suwo. These Gusi’e clan/Nyoniraje sub-clan designs are rarely seen and Sosa is now the foremost painter of these important designs. She was trained to paint further by the former Chief of Ematé clan women, Mary Naumo, in 2004. Pennyrose married the son of law-man Rex Warrimou and through matrilineal rights has also inherited very rare designs of the Dahoruraje clan, such as those painted by the late master painter Nogi, who is said to have lived for over 100 years.

As a young girl, Wilma Rubuno (c. 1969) was adopted by the late Cecilia Badaru, a Sahuoté clanwoman. Badaru was the daughter-in-law of a very important barkcloth painter, Avarro, who was a former Chief of Sahuoté clanwomen. In 2010 Rubuno’s mother, Cecilia, came to her in a dream, in which she was holding up a barkcloth painting and asking Rubuno “Can you see this design?”...Rubuno replied “Yes” and then her mother told her “This is your design now and you must paint this design”. The next day when Rubuno awoke she began painting the design. When the village Chiefs and elders saw the design she was painting they were very surprised because she was painting one of Avarro’s designs, that is, without ever having met Avarro. Rubuno has been very passionate about painting this important barkcloth design. Her painting style has developed to such intricacy, with a truly breathtaking delicacy, careful complexity and harmonious balance of designs, that her works dazzle the eye. She is the proud mother of six children.

Brenda Kesi (c. 1937) was a young girl during the turmoil of World War II. She also remembers the 1951 eruption of Huvaimo (Mount Lamington). Kesi’s mother was Go’ovino and her father was Valéla, both Ematé clans people from old Enopé village between the Jordan and Maruma Rivers. It was here that her mother taught her how to sew her grandmother, Munne’s, sihoti’e taliobamë’e - designs of the mud. This method of appliquéing mud-dyed barkcloth was first practiced by Suja, the first woman and mother of the world, as told in the Ömie creation story. Kesi has begun to teach her daughter, Patricia Warera (Matomguo) to sew the ancestral Ömie sihoti’e designs such as wo’ohohe - tracks of the ground-burrowing spider and taigu taigu’e - ancestral tattoo designs.

PENNYROSE SOSA

PENNYROSE SOSA

"These nioge convey something essential to human existence; a deference to elders and ancestry, a respect for the natural world and an interconnectedness with one another."

- Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, 2023

19 April to 27 May 2023

A group exhibition of 17 artists working on nioge (barkcloth).

Exhibiting at JGM Gallery | In association with Ömie Artists

Private View

Wednesday April 19 6:00pm - 8:00pm 24 Howie Street, London

Barbara Rauno (Inasu), Kukuhon’e soré (nuni’e, taigu taigu’e, jö’o sor’e ohu’o ori sigé) (detail), 2022, natural pigments on barkcloth, 123cm x 59cm. Photo by Daniel Browne, courtesy of Ömie Artists.