Women’s rights under siege.

Abortion

Abortion

My Facebook profile bio de

scribes me as such: “Lover. Fighter. Feminist Writer.”

The “F” word is the most impor tant in this context. I didn’t know it then, but I’ve been a feminist since kindergarten, when Timmy Carpen ter stomped on my caterpillar. I in turn destroyed his ant farm, which, 50 years later, I still feel guilty about.

I wasn’t about to let some boy push me around.

That’s even more true for me as an adult.

Here’s just one example of the sex ism I’ve fought against in my life:

During an open records project in which “undercover” reporters spread out across Kansas asking for infor mation such as a high school football coach’s salary, minutes of the most recent county commission meeting, a jail log and such, the undersheriff of Harper County detained me.

I had just hopped out of my car to go into the jail when he walked up, his chest puffed out, and asked for my driver’s license. I wasn’t driving. I hadn’t committed any crime. Resi dents of the county seemed to dis agree, I learned.

I was that “girl going around town asking questions.”

The undersheriff took me inside and interrogated me for more than hour. He asked why I wanted the in formation I’d sought. I explained that under the Kansas Open Records Act, I didn’t have to give a reason. He and I went round and round. I asked if I could leave. He said I couldn’t. I told him I’d like to make a call then and slid my editor’s business card across his desk.

“You’re a reporter?” he asked.

“Yes,” I answered.

“Well, why didn’t you just say that?” he quizzed.

“Because we’re trying to find out how Kansans are treated when they request information that belongs to them, and apparently in Harper County they’re detained.”

The undersheriff called my editor, with whom I had worked in Indiana, and uttered these words: “Mr. Lew ers, I’ve got your little gal here.”

The undersheriff found himself without a job about two weeks later. Surprise, surprise ... he had been sex ist to other women, too.

Moving through the world as a woman is exhausting. We’re mans plained, accused of “screaming” when we all we’re doing is speaking directly or standing up for ourselves. We typi cally make less money than men. We’re harassed, diminished, talked over.

I’ve never been so proud of Kansas when voters defeated an amendment that would have stripped reproductive rights from our state Constitution. We were the first state to take up abortion rights since the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal on Roe v. Wade. We not only defeated the amendment but did so by a large margin.

We’re seeing more women run for office. We’re owning our power. We’re speaking up. In this section, you’ll read about a woman who openly talks about her abortions; an analysis of the wage gap in Wyoming; women in leadership; and crones who celebrate the wisdom that comes with age.

Who’s gonna run the world? Wom en. That’s who.

— Deb GruverPublished by PUBLISHER

Kevin Olson

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Adam Meyer EDITOR IN CHIEF

Johanna Love MANAGING EDITOR

Rebecca Huntington

JH WOMAN SECTION EDITOR

Deb Gruver DIGITAL EDITOR: Cindy Harger PHOTOGRAPHERS

Bradly J. Boner, Kathryn Ziesig

EDITORIAL DESIGN

Andy Edwards, Doug Sanders

COPY EDITORS

Jennifer Dorsey, Mark Huffman, Addie Henderson

WRITERS: Billy Arnold, Jeannette Boner, Sophia Boyd-Fliegel, Miranda de Moraes, Kate Ready

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Sarah Wilson

ADVERTISING DESIGN: Lydia Redzich, Luis F. Ortiz, Heather Haseltine, Chelsea Robinson

ADVERTISING SALES: Karen Brennan, Tom Hall, Megan LaTorre

DIGITAL CAMPAIGN AND MULTIMEDIA SALES MANAGER: Tatum Mentzer

PRODUCTION MANAGER: Dale Fjeldsted

PREPRESS SUPERVISOR: Lewis Haddock

PRESS SUPERVISOR: Steve Livingston

PRESS OPERATORS: Robert Heward, Nick Hoskins, Gunner Heller

CIRCULATION MANAGER: Jayann Carlisle

©2022 Teton Media Works

Jackson Hole News&Guide

P.O. Box 7445, 1225 Maple Way

Jackson, WY 83002

Phone: 307-733-2047

Whether a medical need or family need, they were glad to have a choice.

By Kate ReadyAstatewide ban on nearly all abortions was set to go into ef fect in Wyoming on July 27 when lawyers representing six Equal ity State women argued that abortion is health care and banning the procedure would be a “seismic change to women’s health.”

Jackson attorney John Robinson and co-counsel Marci Bramlet argued that the state’s ban should be put on hold while the constitutionality of reversing reproductive rights was decided.

Ninth Judicial District Judge Melissa Owens agreed. She ruled that abortions would remain legal while the merits of the case are decided.

Here we present two personal sto ries of Wyoming women who have had abortions. One story is about a woman who was happily pregnant in the mid1970s when she unexpectedly started hemorrhaging. At the very least her ex perience may leaving you feeling grate ful for modern anesthesia.

The other story is a condensed ver sion of one that was written by Evan Robinson-Johnson and previously appeared in the News&Guide. In it a mother of two details her account of getting an abortion two days before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Renée Carrier, who lives north of Hulett, a town in northeast Wyoming, learned the hard way in 1976 that wom en’s health concerns are not treated equally everywhere.

“My husband and I were living in Cheyenne, and a week after finding out I was pregnant with our first child I started hemorrhaging,” Carrier said.

Carrier, then 23, drove to an area hospital’s emergency room where, af ter examining her, the attending doctor announced that Carrier was having a “threatened abortion.”

“He declared he couldn’t do anything about it and told me to go home,” Car rier said. “I was devastated, naturally, and more than a little confused.”

Carrier called the Planned Parent hood office in Laramie. Carrier remem bers that the British doctor sounded pointedly miffed before telling her to get over there immediately.

Her husband, a school teacher who taught junior high science in Cheyenne, settled her gently into the car before driving the 50 miles west.

“By the time we arrived I was dis traught, and the staff at the facility helped me understand the circumstanc es and, more important, allowed for my emotions,” she said. “The doctor was incredulous I had been dismissed and when asked ‘Which hospital?’ I mut tered ‘DePaul.’ I hadn’t realized that Catholic hospital physicians were not permitted to perform certain proce dures like dilation and curettage, which

this staff prepared to do.”

Doctors these days anesthetize pa tients. But they didn’t back then, and Carrier still recalls the painful process.

“It’s a lot like going through labor,” Carrier said. “You’re basically having your uterus forced open to scrape it out. ... so it’s painful.”

Carrier remembers weeping as the doctor made sure no tissue remained that could have caused sepsis, and in fection that can cause severe illness or even death.

To this day Carrier doesn’t know what caused the hemorrhaging. She

For now, abortion is legal in Wyoming.

The next hearing is scheduled for Oct. 27, when Teton County District Judge Melissa Owens will set the schedule for future hearings.

At that time, the timeline of when the Wyoming Supreme Court will hear the case should become clearer.

The preliminary injunction protecting abortion will likely remain in place until the Wyoming Supreme Court rules on the merits of the case, which could take up to a year.

only knows what the doctor told her that day — that, sadly, this was not un usual, especially in first pregnancies.

“I don’t know if she was merely being kind and didn’t want me bearing undue responsibility for miscarrying, but I do know she attended me with compas sion, care and good sense,” Carrier re called.

Carrier now has two kids — a boy and a girl. Her first baby was born two years after her miscarriage.

“I could have gone into sepsis. I could have died,” Carrier said. “It’s ridiculous. I’ve read enough on women’s health is sues to know that you don’t want to al low something like that to fester.”

In a statement, Carrier wrote the fol lowing:

“Women’s health (including access to safe terminations and birth control) is beyond the purview, moral or other wise, of politicians, male or female, ex cept for their responsibility to guaran tee the right to seek and receive a good ‘standard of care,’ through — it is to be hoped — respectful, honest, and confi dential conversations between practi tioner and patient.

“There exist myriad reasons for ter minations — i.e., miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy — and the circumstance a woman finds herself in with regard to a pregnancy, even apart from incest and rape. These are deeply personal consid erations, and not subject to parsimoni ous analysis by an insensible collective of legislators. Insensible to a particular woman’s situation and consciousness.”

Carrier said she hoped to see the abortion question brought to a statewide vote, “like the referendum held in Kansas.”

For now, she feels grateful for those who helped her in her time of need.

“My sister-in-law drove up from Denver to take care of me after the mis carriage, a kindness I shall never for get,” Carrier remembered. “The help ful, deliberate British doctor, her nurse, and my sister-in-law knew more about women’s health than the present U.S. Supreme Court.”

Two days before the U.S. Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, Jenyka Tapia was sitting in her doctor’s office, making the difficult decision to end her pregnancy.

Tapia, 30, has worked as a barber in Jackson for the past six years. She chose to share her experience with abortion to help normalize the procedure and help other women know they are not alone.

“It’s never just talked about. And if it is, it’s kind of between you and your best friend, or you and your mom behind closed doors. There’s never really a full support system,” she said.

The threat of Roe’s reversal hung over Tapia’s unexpected pregnancy like a heavy cloud, darkening an already fraught decision process. Her ex-boy friend didn’t believe in abortion and used the court’s leaked draft opinion to bolster his case, Tapia said.

It was a big argument between them.

“He wanted me to keep it. I knew it was pretty much not doable,” she said. “He was really heartbroken over it. ... which was also hard for me to deal with.”

“Even now, it’s like, did I make the right decision? And I still sometimes question it. But I’m content with my choice.”

Tapia is grateful she still had a choice to make. If Wyoming’s restrictive abor tion law withstands legal challenges, Jackson patients could be forced to drive

more than six hours away to a clinic in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

As a single mother to two kids, Tapia said crossing state lines for an abortion is a daunting prospect. She began to count up the expenses: gas, food, a ho tel and the procedure itself, which costs $600 to $800.

Even with financial support from non profits such as Chelsea’s Fund, mothers need to time off work and child care for appointments that are expected to be come more difficult to schedule.

“I think I still would have made the drive,” Tapia said. “I would have figured out how to make it work.”

It’s been difficult for Tapia to raise her 8-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son in Jackson. Her “deluxe” studio is about 470 square feet (and costs $1,879 a month). The only available day care

she could find is an hour south in Alpine, so she commutes every day.

Tapia considered adoption, even find ing an Idaho Falls family that does open adoptions so parents can still visit.

“It would have been really perfect,” she said. “But my biggest fear was for my children, especially my daughter.”

Tapia worried her 8-year-old would see that family’s lifestyle — their big, nice house with a fenced backyard — and as sume her mom loved the child she put up for adoption more.

“I could just see those questions com ing up from her,” she said.

She also feared the baby’s father would end up “taking the baby back at the last minute,” as he once suggested.

“There is a domestic violence charge between me and him. So ... I don’t want to put a child into that,” Tapia said.

While her medical abortion was “the most hard emotionally,” it wasn’t her first. She became pregnant with her daughter at age 21 and was still nursing the 1-year-old when she got pregnant again. It was a shock, she said, and defi nitely not the right time.

“There was no way I could have had a 1 1/2-year-old and a newborn at the same time,” she said.

So she made the hard choice to leave her boyfriend’s family home in Utah and drive to Jackson, where her mother lived, for a medical abortion. She was eight weeks pregnant.

Four years later Tapia welcomed a son to the world. Two years after that, in 2020, she accidentally became preg nant again. She took Plan B, a pill de signed to prevent pregnancy the morn ing after unprotected sex, but it didn’t work.

She’ll never forget the “deer in the headlights” look from the other women in that 2020 waiting room.

“The abortion clinic was actually the first place besides the grocery store that I had walked into since COVID-19,” she said. “Everybody was very scared. It was a hard experience to go through. And I felt most alone during that one.”

A similar Plan B failure led to the need for her abortion this year. This time, Tapia said, a doctor told her the emergency contraception pill doesn’t work for her body.

“No woman wants to have an abor tion,” Tapia said. “You don’t get a prize and a sucker.

“We go through pain, we go through bleeding, we go through the questions, the what ifs. I don’t know any woman that would rather have an abortion than use birth control.”

As difficult as those procedures are, Tapia said they beat the possible alterna tive of raising children in poverty or an abusive relationship.

Contact Kate Ready at 732-7076 or kready@jhnewsandguide.com.

Hole

Airport

Experts say forced pregnancy coincides with other forms of intimate partner violence.

By Kate ReadyReproductive coercion happens more in Jackson Hole than most people know.

It’s an issue that’s lacking in aware ness but is a form of intimate partner violence that is not uncommon, said Adrian Croke, the director of educa tion and prevention for the Community Safety Network.

“It’s so, so common within abusive relationships,” Croke said. “People don’t even recognize it as a tactic that’s happening. We’re more quick to rec ognize physical violence. But sexual coercion, reproductive coercion and financial abuse come out as we further develop a relationship with someone.”

Reproductive coercion and abuse indicate any form of behavior that in tentionally controls another person’s reproductive choices. It’s not a pros ecutable offense.

It often coincides with other forms of intimate partner violence, and the methods include pressuring a partner to have unprotected sex, refusing to use a condom, forcing intercourse and lim iting a woman’s access to birth control.

“We see abusers not allowing access to reproductive health care through gynecological visits, limiting access to birth control,” Croke said. “We also see abusers limit access to routine prenatal visits if a woman is pregnant.”

Croke also sees abusers seizing power and control over birth spacing, which re fers to how soon after a prior pregnancy a woman becomes pregnant again.

“It’s very common for women to use

birth control after giving birth,” Croke said. “People might already have one or two children, and there will be pressure from the abuser to have more and not use any type of birth spacing and not have access to medical providers who would support or educate on that.”

Croke added that “it’s very common to get IUDs placed after giving birth.”

“We see clients being shamed for be ing interested in that and being made to feel that’s not an option,” she said. “If they express an interest [in birth spacing], they’re made to feel that they would suffer some sort of abuse.”

Unfortunately, local data around re productive coercion isn’t available.

“We don’t track that,” Croke said. “It’s not a specific ‘grant’ measure re garding the grants we apply to.”

Statistics from the 2005 National

Crime Victimization Survey found that approximately 1 in 5 young women said they experienced pregnancy coercion.

One in 7 young women said they ex perienced active interference with con traception.

A 2010 study of 1,200 sexually active women between the ages of 16 and 29 shows that the rate appears to be grow ing.

“Over one-third of women who re ported experiencing intimate partner violence had also experienced repro ductive coercion and abuse,” the study found.

Another study found that certain ra cial groups disproportionately see their reproductive decisions controlled.

A 2018 study by Grace and Anderson found that in the United States, repro

See COERCION on 8E

If you or someone you know has experienced intimate partner violence, the following organizations may be able to help. Victim Services not affiliated with law enforcement

Community Safety Network

Provides resources for survivors of sexual assault, domestic violence and stalking.

24-hour help line: 733-7233 (SAFE) Office: 733-3711

CSNJH.org

Family Safety Network (Driggs, Idaho) Organization dedicated to eliminating violence, abuse and oppression.

24-hour help line: 208-354-7233 (SAFE) Office: 208-354-8057

Mental health services for everyone in Teton County, regardless of income or ability to pay.

24-hour help line: 733-2046

Office: 733-2046

JHCCC.org

Victim Services affiliated with law enforcement

These organizations may be legally required to report victim statements.

Teton County Victim Services Organization to inform victims of their rights and available services.

An on-call advocate is available 24 hours a day through Teton County Dispatch: 733-2331 Office: 732-8482

JacksonWY.gov/175/victim-services

Jackson Police Department Office: 733-1430

JacksonWY.gov/280/police

Teton County Sheriff’s Office Dispatch: 733-2331

TetonSheriff.org

In an emergency, call 911.

Trained volunteers offer a hand and a heart.

By Kate ReadyWhen a visitor is lost or injured in the vast, mountain ous landscape of Grand Teton National Park, a small and little-known team of park volunteers steps out of the shadows of first responders to lend a hand and a heart.

The seldom-mentioned family liaison officers provide critical support to search and rescue teams by commu nicating with families in the event of a death or crisis in the national park. This year the park’s program inspired Teton County to designate its own team to fill that gap in service.

Elizabeth Maki has been doing the work of a Grand Teton family liaison since 1999.

“We’re not their advocate, we’re their liaison,” Maki said. “We’re here to help them but also allow the rescuers to do their job without the family being in the midst of everything, because that pulls people out of their training and into the emotional side.

“We keep the family informed of what’s happening and try to be as open and honest as we can.”

Grand Teton’s family liaison officers are a volunteer team of specially trained park employees, currently num bering five but soon growing to seven.

The family liaison is triggered if any number of events — if someone dies, if CPR is in progress, if an ambulance has been dispatched or a search is underway and not looking good.

Katie Tozier has been a family liaison for the park since 2015.

“We’ll take the incident commanders’ information and share that with the family so they feel included,” Tozier said.

Families might want to know details, such as what search methods rescuers will use to look for a loved one, she said. The liaisons may tell searchers about family re quests and communicate gratitude from the family to lo cal officials. They also may act as the spokesperson for reporters, connect families with local authorities such as the morgue or the coroner, even work with foreign em bassies to transport bodies home.

Maki and Tozier aren’t able to speak about specific cases they’ve worked on, citing confidentiality, but calls have spanned high-profile incidents with national news coverage to injuries of people hurt by wildlife.

The job requires volunteers to develop trust with a stranger in short order. In those scenarios, both women rely on a two-pronged strategy that, in their experience, helps families most in such tragic situations.

The first principle is “clear, open and timely commu nication.” The second is listening and asking open-ended questions.

“We’re trying to listen and understand their family dy namic, who are they,” Tozier said.

“We refrain from judgment,” Maki said. “We respect who they are and refrain from putting our own morals into their family. We’re trained not to fix it for them or provide solutions so they don’t feel like we’re trying to tell them how to get through this. We just help them move through the process and know what to expect next.”

The language, or “crisis speak,” the liaisons use in these scenarios is critically important.

In a crisis it’s better to be direct. If someone has died, you need to say they’ve died. Softer language may leave room for false hope or misunderstanding.

Another crucial aspect of the role is being compassion ate while retaining emotional boundaries.

“You have to control your own emotions and under stand that their tragedy is not your tragedy,” Maki said.

Katie Tozier and Elizabeth Maki are family liaisons for Grand Teton National Park. The volunteer role, in addition to their duties as “education rangers,” is to be a communications bridge between families and first responders following injuries, traumatic incidents and death in the park.

“You have to learn not to take on their sadness and be that liaison for them but be able to go home and not be sucked into that sadness.”

Both women say they go into “work mode,” which involves compartmentalizing and falling back on their training to follow the next steps.

Part of that boundary is also knowing when to sever communication, for the liaison’s benefit but also for the sake of family members, so they eventually become em powered to move on.

Maki worked as an EMT for Teton County EMS before it combined with the fire department to become Jackson Hole Fire/EMS. She’s always been in the field of helping people.

Tozier has also often found herself in roles that involve tending to people. She has been in the valley nearly 10 years and cited Maki as a mentor.

Both women moonlight as volunteer family liaisons in addition to their main roles. Maki works as the Colter Bay district interpreter. Tozier is the assistant district in terpreter. In Maki’s words, district interpreters are “edu cation rangers.” They manage visitor center operations, hire seasonal staff and coordinate special programs and projects.

For both women the liaison role has brought lessons about grief.

“Sometimes the reactions you get aren’t from the situ ation at the moment but from a tragedy prior that they haven’t healed from,” Maki said. “So that situation can trigger past things that they’ve buried. Sometimes we’re witness to that, too.”

With cultural differences come different requests that the family liaisons field. Even within the same family, a variety of reactions may occur, so both women have learned to be accepting and nonjudgmental.

“I’ve learned that grief looks so different for each per son, each family, each scenario,” Tozier said.

For Maki, that lesson to be less judgmental hit close to home when her own parents died.

“I’m really close with all of my siblings, and we all re acted differently,” Maki said. “We have to give permis sion to people to grieve in whatever way works for them. It doesn’t look the same for everybody. Somebody may be laughing, but that’s what that person needs to do.”

Teton County has taken inspiration from Grand Teton National Park. At the prompting of the Teton County Sheriff’s Office and Teton County Search and Rescue, the county started talking about how to better assist families and bystanders when tragedy strikes.

“We looked at the resources we currently have as a county, and a lot of those resources, services, training

and expertise exist within Teton County Victim Servic es,” Teton County Emergency Management Coordinator Rich Ochs said. “The family liaison in the park is analo gous to our Victim Services. The scope of Victim Services may be a bit wider than the liaison in the park.”

As conversations took place between stakeholders — the Sheriff’s Office, Teton County Search and Rescue, the Jackson Police Department and the National Park Service — Ochs realized the victim advocates had been acting as the go-between for family members and law enforcement, connecting them with support resources, such as shelter or chaplains, communicating law enforce ment information, and holding their hand through the bureaucratic process.

Tracey Trefren, victim coordinator for the county’s Victim Services, said her team had been called out for suicide, death, traumatic loss or injuries, and searches for people in avalanches or rivers.

The victim advocates work for law enforcement agen cies, have access to their dispatch protocols and even un dergo the same background checks as officers.

“Whenever law enforcement needs that empathy piece on a scene or that comforting part, our role is to be there with people,” Trefren said. “We’ll get them tied into their natural support network; we’ll reiterate what the next step is.”

Their training with law enforcement also offers an other inherent strength.

“They’re really good with privacy,” Ochs said.

Finalized in August, the Emergency Operations Plan now incorporates the role of victim services when crises occur in Teton County.

It’s a critical gap to close, especially for families.

“What those families are going to remember is what Tracey and her team did,” Ochs said. “They’re going to remember that personal connection, that someone was there to help me through a tough time.”

Contact Kate Ready at 732-7076 or kready@ jhnewsandguide.com.

ductive coercion and abuse “dispropor tionately affects women experiencing other forms of intimate partner violence, women of low socioeconomic status and women who are Latina, African Ameri can, or multiracial.”

A 2019 PubMed study found the same.

“Examination by race/ethnicity re vealed that non-Hispanic Black women and men had sig nificantly higher lifetime preva lence of both RC types than all other groups,” the study said.

Men also can experience repro ductive coercion.

“In the United States from 2010 to 2012, 9.7% of men and 8.4% of women experi enced reproduc tive coercion by an intimate partner during their lifetime,” the PubMed study found.

“Men reported more commonly than women that a partner tried to get preg nant when the man did not want her to,” the study said. “Women reported higher prevalence of partner condom refusal.”

Reproductive coercion often goes “hand in hand” with other forms of inti mate partner violence.

“We see abusers sexually assaulting their partner and also not allowing them to access reproductive health care,” Croke said. “Unfortunately more often than not, you see all of these different types of abuse in a single relationship. The person wants total power and control.”

It also goes hand in hand with tradi tional societal norms as well as cultural pressure, making it harder to identify.

Researchers in a December 2021

study published out of Australia found “reproductive coercion and abuse can be explained in a social structure where cultural and social norms of male domi nance over women are widely upheld.”

“Gender roles are so wrapped up in gender-based violence,” Croke said. “Abusers will use gender roles as an ex cuse for the abuse, or use religious and cultural beliefs. Many women, regard less of cultural or religious beliefs, feel the pressure of having children. Repro ductive coercion can take advantage of that cultural pres sure and use it to excuse an abuser trying to have more control over someone’s repro ductive health.” Local resources for those experi ence reproductive coercion include the Community Safety Network, which provides individualized op tions.

“We educate people on their options and then empower them and problem solve around the choices they make,” Croke said. “All within exceptional con fidentiality.”

In addition to providing resources, Croke and the Community Safety Net work team is working to bring this is sue out of the dark and facing gray area around the topic.

“A lot of people have had experiences in otherwise happy relationships that brush up on these topics,” Croke said.

“For example, how common it is for women to have to be the ones to take re sponsibility over birth control? That’s so culturally common. We don’t think it’s abuse, but if it’s happening consistently, then why? Who does that serve?”

Contact Kate Ready at 732-7076 or kready@jhnewsandguide.com.

“Unfortunately more often than not, you see all of these different types of abuse in a single relationship.”

Adrian Croke

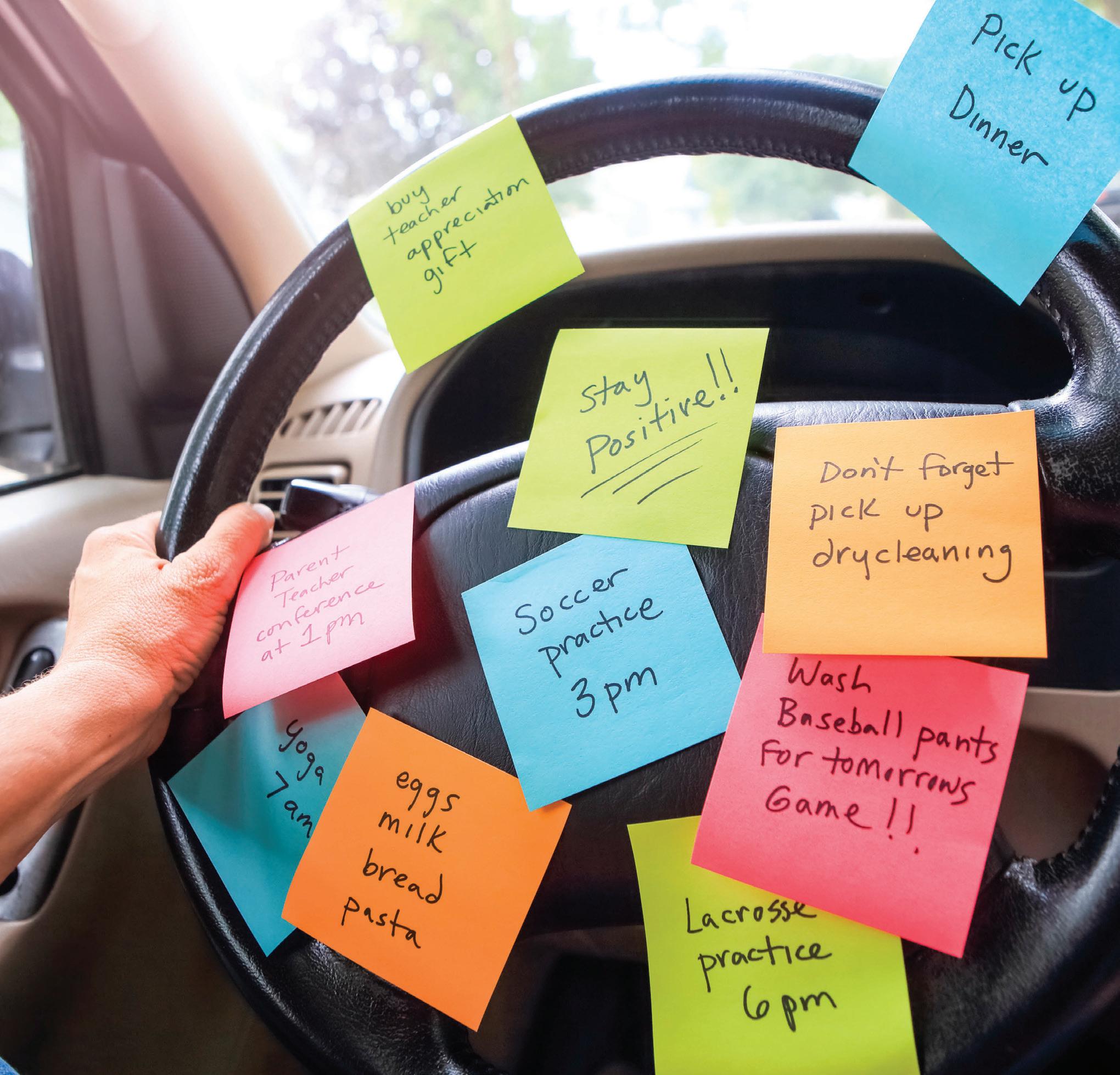

I knew life would change when we had a kid. I was panicky in good and unrea sonable ways about the decision to enter parenthood. To be honest, I was afraid of how my life would be upended. And no matter how progressive I consider my partner, balancing it all is exhausting.

We can debate those statements lat er, because I hear you getting ready to wrangle with me.

We have two kids now, and dammit it is the best, hardest, incredibly challeng ing, self-realizing, bring-you-to-yourknees decision we have never regretted making, save for that one time when we all had that stomach bug…but I digress.

Here’s where I’m going to get selfish. Maybe even a little vain with a hint of self-deprecation. When I became preg nant with my first, I developed a skin condition called melasma.

“Ugh, what’s wrong with your face? Are you wind-burned?” asked my little brother, in his 30s at the time, but still the youngest and self-righteously un aware of how this comment would cut to my core.

The “wind burn” was melasma. Known as “pregnancy mask,” the condi tion is my undeniable mark of mother hood.

I have tried everything to get rid of it, fade it and ignore it.

“I even think your pregnancy mask is beautiful,” my neighbor said, unprompt ed.

That was the first time I heard that term other than “wind-burned” from my brother. Was it beautiful?

It doesn’t hurt. It’s not cancerous. It’s

just there, changing the look of my face, existing as dark brown patches above my eyebrows, along my forehead, around my mouth and ever so slightly around my cheeks. The marks will never go away as I have learned through countless late night web searches coupled with the em barrassing amount of money I’ve spent in dermatologists’ offices trying to recap ture my familiar image in the mirror.

It’s not an uncommon skin condition for a pregnant woman to develop. In most cases, it’s a perfect storm of hor mones that develop during pregnancy matched with the genetic disposition of your skin. I have learned through so many doctors and derms that women who have more melanin in their skin — women of Latino descent and women of Mediterranean descent such as myself — are more likely to develop melasma dur ing pregnancy.

To recapture my face, I started with aloe vera and to this day still use the natural product because it’s just good for you. I cut lemons and rubbed them over the dark patches of my face hoping the citric acid would fade away the uneven patches. Then I moved on to apple cider vinegar. These natural products left me smelling of various salad dressings, and though they are healthy to use on my face, they did little to erase my growing displeasure.

I moved on high-end, prescriptiononly creams. They worked. Until they didn’t. The most commonly prescribed is hydroquinone cream, which is a com bination of skin-lightening agents and sunscreen. I grew so hopeful with each passing week that the dark patches seemed to fade and, combined with makeup, made me feel a little more like “myself.”

But here’s the thing with melasma. It

doesn’t really doesn’t ever “go away.” It lightens with the use of creams infused with Vitamin C — super great for your skin regardless of its condition — but af ter a while, the dark patches come back. I do my best to wear hats even when the sun isn’t out and use moisturizers infused with sunscreen on top of using actual sunscreen, but the dark patches remain.

I soldiered on, escalating in my quest to find my “cure,” moving onto chemical peels. It was a lovely experience to say the least. Working with a dermatologist, the peels did even out my skin tone, pull ing away dead skin and giving my face the chance to rejuvenate with the onset of new cell growth. It was expensive and not covered by my middle-of-the-road health insurance. In fact, most insurance policies won’t cover melasma treatment

because the condition isn’t considered medically necessary. Each peel lightened the dark patches. The doctor cautioned me that I would need to stay the course with the peeling regimen if I were to maintain the new balance of skin tone.

So. I pivoted again. Would a laser work?

Like a jackhammer on the dark patch es of my face, I allowed another derma tologist to burn through this new reality. Laser therapy is intense with time need ed to heal. Much like the peels, the laser brought renewed cell growth and a glow to my face unlike any scrub or lemon wedge could provide.

Mirror, mirror on the wall, I said as I turned and saw that those marks re mained, resurfacing with their familiar pattern.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. I can’t see any of that. I think

In Teton County, women and men

likely paid roughly equally, bucking the statewide trend.

hard to say why that is.

By Billy ArnoldThe Equality State is not so equal. When it comes to wages the medi an woman with a full-time job in Wy oming made roughly 69 cents for every dol lar a man made based on 2020 estimates. In counties such as Campbell County, it’s far less: 61 cents for every dollar a man makes. In others, such as Teton County, it’s a bit more: $1.03 for every dollar a man makes.

But for Teton County women such as Natalia D. Macker, who has spent years ad vocating for equal pay for men and women, that doesn’t meant the fight is over.

“If I only cared about people in Teton County, maybe,” said Macker, the Demo cratic chairwoman of the Teton County Board of County Commissioners who Re publican Gov. Mark Gordon appointed to the Wyoming Council for Women. “But we’re not divorced from everywhere around us.”

The numbers above come from a News&Guide analysis that used U.S. Cen sus Bureau data to compare median wages for men and women working full-time jobs in every county in Wyoming, and every state in the United States. In a nutshell, the difference between men and women’s wages is called the “wage gap.” And, while the gap has narrowed both statewide and nationwide during the past few decades, it remains a somewhat intractable feature of American economies. Wyoming research ers such as Cathy Connolly, a legislator and University of Wyoming gender studies pro fessor, have studied the issue for years. So has the Legislature, which in a 2018 report found that closing the wage gap could yield the state an additional $153 million in la bor income.

“This increase in labor income would in crease state and local taxes by more than $5 million,” the report says.

The News&Guide’s analysis was spurred by an abstract of county profiles released in August by the Wyoming Economic Analysis Division. That analysis, like this paper’s, divided the median women’s wage by the median man’s wage in each of Wyoming’s 23 counties to determine the wage gap. Wenlin Liu, the state’s chief economist, used five-year estimates from 2016 to 2020 released by the U.S. Census Bureau to do the math. The News&Guide did the same, but also looked at five-year estimates from 2006 to 2010 to see how the wage gap had changed in the 10 intervening years — and then did the same for each state in the country.

That analysis generally tracked with the Legislature’s 2018 report and found that, based on 2020 numbers, Wyoming is rock bottom nationwide.

The median woman was paid less in the Equality State, the first state in the country to grant women the right to vote, than in every other state in the nation, and includ ing the territory of Puerto Rico. The me dian woman there was paid slightly more than the median man — the only state or territory in the U.S. where that’s true.

The wage gap is not, however, a cut and

dried issue. Different groups measure it differently — some use an average, a statistical measure that can be more skewed up or down by outliers than a median. Some groups, such as the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, use internal data to calcu late it. But what makes the wage gap particularly tricky to parse is that a number of factors change how much men and women are paid. And while it was possible to determine what ed ucation levels and industries affected men and women’s wages, the Legisla ture’s 2018 report found that roughly 13 cents of the wage gap couldn’t be explained.

That, the report said, could be due to discrimination.

“That’s where the cultural pieces and work that we have to do societally, I think, comes in,” Macker said. “But those are the hard pieces.”

In Teton County the data indicates that the wage gap is closing — in the aggregate.

But it also raises questions for Macker and Jen Simon, the founder of the Wyoming Women’s Action Net work and former senior policy adviser for the Equality State Policy Center. Simon has spent years advocating that the wage gap be understood as a systemic issue, rather than one that comes down to individual choices.

For her the question is: If Teton County’s doing so well, why?

“If we have solutions, how do we identify them not just for us but for other communities?” Simon said. “It’s not a coincidence that our commu nity, at least currently, doesn’t have a gender wage gap and has a thriving economy.”

In 2016 Connolly, the University of Wyoming professor and legislator, used Wyoming Department of Work

force Services data from 2014 — and averages, rather than medians — to calculate the wage gap in all of Wyo ming’s 23 counties. Then, as now, Teton County outperformed every other county in the state. The aver age woman here, Connolly calculated, made 79 cents on the dollar compared to the average man.

Then, in 2018, the Wyoming Department of Workforce Ser vices, again us ing its own data and averages, did a similar calcula tion using 2016 data. The aver age woman in Teton County, the department said, made 93 cents compared with the average man’s $1.

Macker and Simon said the steady increas es don’t mean the work here is done.

They want to understand why Teton County is per forming relatively well — and whether women throughout the local economy are paid equall y to men.

Breaking down Teton County’s median wage by industry shows that might not be the case.

Census Bureau 2020 estimates in dicate that the median woman work ing full-time in the natural resources, construction and maintenance in dustries is pai d by far the most of all women in the county, earning roughly $1.74 for every dollar the median man makes.

That, however, is offset by imbal

ances elsewhere in the data. The me dian woman working full-time in food preparation and serving makes about 4 cents less than the median male. But women in building, grounds cleaning and maintenance? About 30 cents less than men. Women in personal care?

About 70 cents less.

jumping by roughly $15,000 vs. about $8,000. At roughly $65,496, the medi an man’s salary in Lincoln County was above the national median: $61,417. By contrast the median woman in Lincoln County was being paid less than the na tional median: $38,076 vs. $50,982.

Macker and Simon s aid that Teton County’s metrics also raise a number of ques tions for them: Whether educa tion levels play a role in the area’s gap, whether childcare, for all its difficulties in Teton County, is better here than el sewhere in Wyoming, and whether, because of the cost of liv ing here, the peo ple who choose to stay in Teton County tend to have higher in comes altogether than those who commute in from

a place such as Lincoln County or Teton County, Id aho.

“Are we exporting our wage gap to surrounding communities?” Macker asked.

Between 2010 and 2020 in Lin coln County, where Alpine, Etna and Thayne are located, data indicates that the wage gap increased. Census estimates in 2010 indicate that the median woman was being paid 62 cents on the dollar for every dollar a man made. By 2020 that number had dropped to 58 cents.

During that time, men’s wages in Lin coln County rose faster than women’s,

“Jobs typically held by men in Wyo ming such as mining and construction, pay at or above national norms. In con trast, jobs that typically employ women pay significantly below the national norm,” Connolly wrote in her 2016 study. “The combination of better than average pay for jobs held by men with the lower than average wage for jobs held by women explains a good part of the wage gap.”

In Teton County, Idaho, Jackson Hole’s neighbor to the west and an other commuter hot spot, the num bers paint a different story. In 2010 the median Teton County, Idaho, woman made 80 cents for every dol lar a man made. By 2020 she was making $1.03 — the same as in Teton County, Wyoming.

Wage differentials aside, Macker also pointed out that, even for the me dian woman working full-time in Teton County, making $54,242 a year might not cut it.

The Wyoming Women’s Foundation self-sufficiency calculator, which esti mates how much income is required to meet basic needs in each Wyoming county, says that a single parent with an infant and toddler would need an an nual wage of roughly $94,500 to make ends meet in Teton County.

”Even if we close the gap, so what?” Macker said. “In Teton County, specifi cally, because of our high cost of hous ing and our high costs for childcare — those two things paired together really make reaching a self sufficiency wage so challenging.”

Contact Billy Arnold at 732-7063 or barnold@jhnewsandguide.com.

Angelica Jones Galliguez Nieto overcame challenges.

By Miranda de MoraesAt a restaurant, servers usually ask customers ques tions. In the case of Gather, though, one employee de serves the talking stick.

Angelica Jones Galliguez Nieto is a 24-year-old server who emigrated from the Philippines by herself during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ascetic loneliness and existential evaluation dragged Nieto to a tipping point. Handcrafts helped her find her fuel.

Nieto grew up in Pangasinan, the milkfish capital of the Philippines. The trout of Idaho, she said, is nothing compared with delicious milkfish.

She hails from a family of doctors, prominent in Pangasinan, and holds them — especially her eight nieces and nephews — close to her heart. The expecta tion was that she would attend medical school, but as the pink streak in her hair represents, Nieto has never been afraid to stray from tradition.

Fascinated by the color of the world and the unique stories travelers have to share, Nieto chose to study hospitality and tourism instead. After scoring a J-1 visa, she flew 21 hours to Orlando, Florida, to work and study as a culinary student at a Loews Hotel for a year. That was the 21-year-old’s first solo travel.

“My first thought was, ‘Why are people in the mall wearing a bikini?’” Nieto said, laughing. “In my country, you wear a long-sleeve [shirt] and shorts to swim.”

Her program ended in March 2020, which meant she not only would be losing her job and housing but would have to decide if she would stay or go. Her mother has worked for a government hospital in the Philippines, and she was insistent that Nieto not fly back home.

The Philippines, as a developing island nation al ready struggling with economic and political stability, was hit especially hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Community lockdowns ravaged businesses and live lihoods. The infrastructure of the country grew even messier. Hospitals, already short on equipment, strug gled to handle the sudden spike in demand for inten sive care units, protective equipment and staff. Schools, which were under-resourced before the pandemic, fell to the wayside, as online school was not possible for the

Angelica Jones Galliguez Nieto, 24, emigrated from the Philippines by herself in 2020. Since arriving in Jackson, Nieto, a server at Gather, also started making jewelry out of seashells from the Philippines and the tips of elk antlers she bought at the ElkFest. She called her crafts brand “Urduja,” the name of a warrior princess of her hometown.

majority of students, who come from limited resources.

Global shipping disruptions were disastrous for the is land nation, devastating the economy and making vac cine distribution extra challenging.

Nieto felt she had no choice but to make it work to stay in the United States. She called out for help on Facebook, and sure enough, a stranger reached out.

“We had never talked before in person, but she asked me, ‘Are you OK with living in small spaces? I have a job for you,’” Nieto said. “I didn’t know what Jackson was,

and I was like, ‘Oh my god, Wyoming?’”

The stranger turned out to be another J-1-visa-hold er from the Philippines who had lived in Orlando and moved to Jackson. She offered Nieto the same deal, so Nieto hopped on a plane and flew to Jackson Hole. Win ter was in full swing, and snow was a new experience.

The job waiting for her was as a cook at Gather. That is, until the restaurant shut down a few weeks later for a first stage of COVID-19 lockdowns. She lived off rice and soy sauce while scrambling to find work until Gath er reopened in the summertime.

Nieto returned to working as a cook. While on kitch en duty in October she slipped on a rock while carrying a fryer. Hot oil splashed and seared her left foot, which caused an enormous, bloated blister.

From that moment, Nieto was terrified of working in the kitchen. Her employers said she’d have to master hosting and barback service and improve her English to qualify as a server. Both positions were challenging, since she had trained her whole life to be a cook.

On a cold day in October 2020, Nieto silenced the dinner rush at Gather with two bold words: “I quit.”

She fled to a dumpster on West Pearl Avenue and sobbed into her petite palms. A customer whose food took a while had become upset, so Nieto, as a barback at the time, had to take the slack.

“I could never be a server,” Nieto said, sobbing.

Her manager ran out after her.

“It’s not about you; you’re doing a great job,” he said. “Just remember all of your sacrifices.”

She talked herself through it, forced a smile and strode back into the restaurant to complete her shift.

Challenge has worked more as a motivator than as a deterrent for Nieto. That winter of 2020 would be her ultimate test, though, when she came to learn of an ava lanche of disaster that hit her home.

It had been two years since Nieto left the Philip pines. As the pandemic coursed across the world, she had little concept of the realities back home. Struggling with homesickness and the lack of a substantial Fili pino community in Jackson was hard, but a phone call from her sister took her over the edge.

Nieto’s sister said their grandma had died, two other relatives were dying, and their parents were annulling their marriage. (Divorce among Filipino, non-Muslim

citizens is illegal.) Ending a marriage is extremely rare in the Philippines, so the news was bone-shattering for Nieto.

“I cannot be happy when they’re all suffering,” Nieto said, her voice quaking. “Who’s going to benefit when two rela tives are dying, my grandma just died and my parents are divorcing?”

Overwhelmed by the state of the world, her family and her situation in Jackson, Nieto felt drained and doomed. When she was on the brink of giving up, she received a photograph from her sister of a family in her hometown. Six children slept on dried leaves in a hut. The family’s only source of income was selling coconut liquor.

Nieto recognized that she was incred ibly fortunate to have what she does, de spite her struggles. It dawned on her that she could find meaning by supporting her country. The Philippines has high unemployment, especially for women.

“It’s harder for women to get a job in the Philippines because they say, ‘Oh you’re weak,’” Nieto said. “They really un derestimate women there.”

A friend of hers back home hires Fili pino mothers to weave furniture, so Nieto wondered if she could commission these women to make a product that would appeal to the tourist market of Jackson, and combat climate change. The idea was simple: The mothers would repurpose strands of plastic into woven handbags.

Nieto gathered wildlife photos from photographer friends in Jackson and hired a painter in the Philippines to cap ture the photos onto the handbags.

“It’s hard enough not having a job, but being poor while jobless is really hard,” Nieto said about the economic reality of the Philippines. “Homelessness there is not like here in the U.S., where you can be homeless with a car. There, you are with out clothes, food, anything.”

Nieto also started making jewelry out of seashells from the Philippines and the tips of elk antlers she collected at

the ElkFest. She called her crafts brand “Urduja,” the name of a warrior princess of her hometown. Urduja fought invad ers as a single woman, which Nieto feels captures the spirit of the women who weave the handbags.

Twenty percent of sales go to Filipino charities such as an organization that equips children with school supplies. Last August, Nieto donated enough money for 50 students.

At first she was just selling her wares on Instagram, but a co-worker who is well-connected in the community secured her a spot at the People’s Market, which really boosted business. Now Urduja can even be found at the Art Association.

Nieto was promoted to server in Au gust 2021. That allowed her to earn dou ble what she was making each shift in the kitchen. Having more time and money has enabled Nieto to take better care of herself, eating more than rice and soy sauce and putting her extra energy into giving back.

Now she wakes up excited for each day, energized by engaging with custom ers as a server at Gather, fulfilled by her contributions to her home country.

“If you do something good to people, it will come back to you times two,” Nie to said. “And if you can do anything good to people, just do it, because you don’t know how much it can help.”

She rides her electric scooter around town and looks forward to continuing to serve others and travel the world. She has visited half of the states and intends to see them all. She imagines maybe start ing a craft store in Jackson someday and doesn’t plan to return to her country for her family, but rather to see how she can better help Filipinos in the future.

“Now that I’m no longer as concerned about saving money, it’s more about cre ating life,” Nieto said. “Experiences and feelings are so much better than Louis Vuitton.”

Contact Miranda de Moraes at 732-7063 or mdm@jhnewsandguide.com.

Thank you to all of you who help get the news to our community 312 days a year.

Movement began in 1990s with Jackson Hole newsletter.

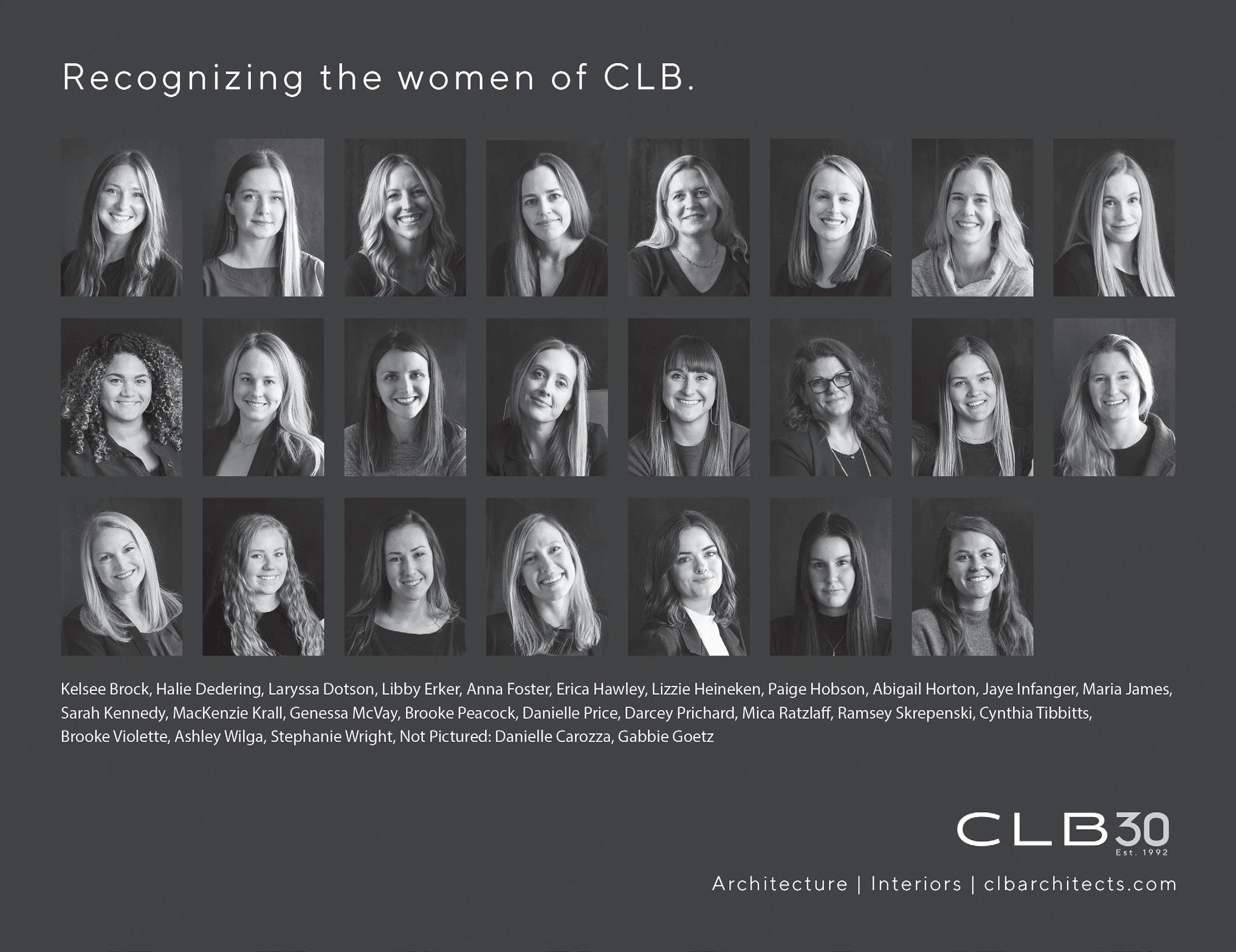

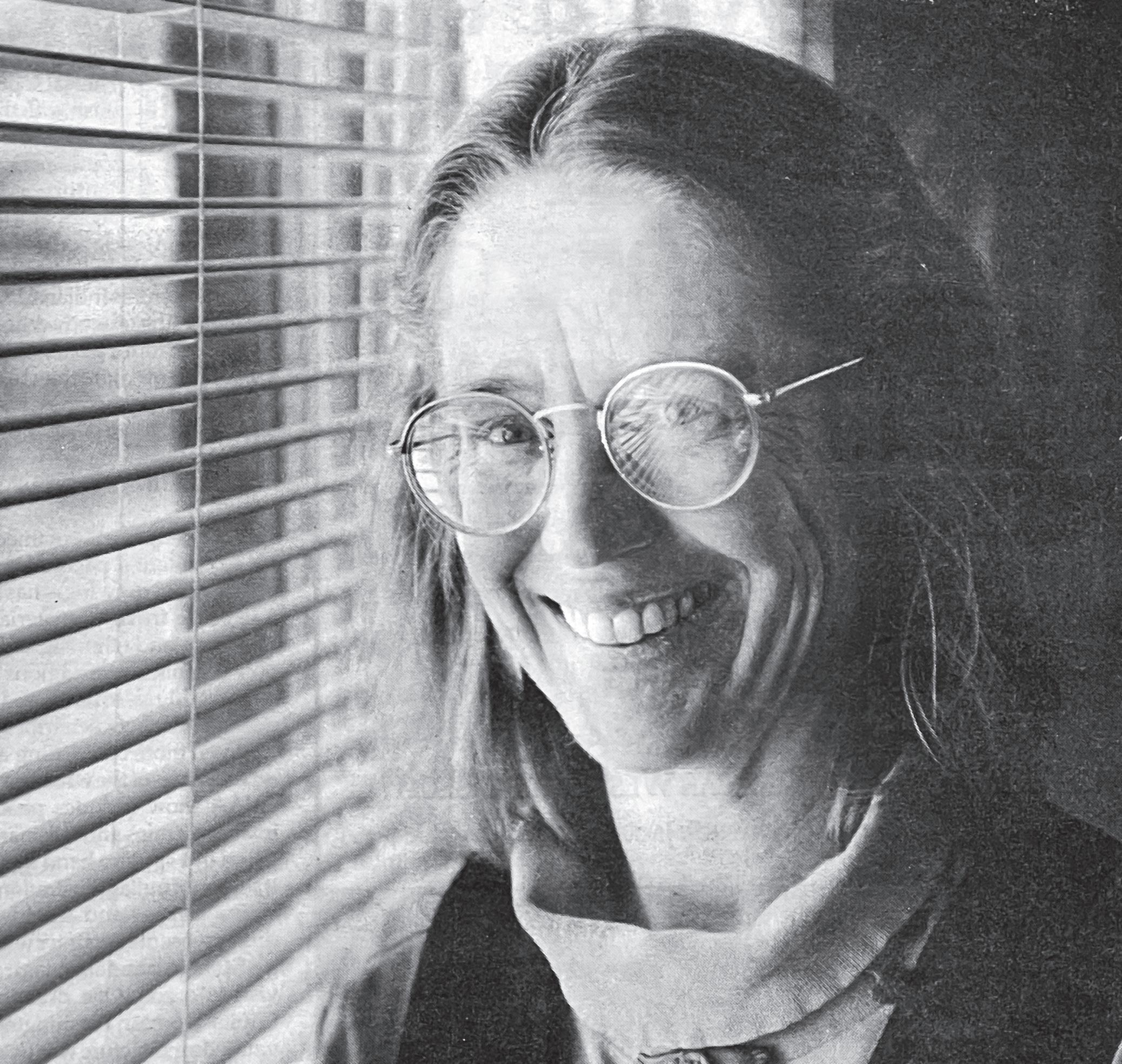

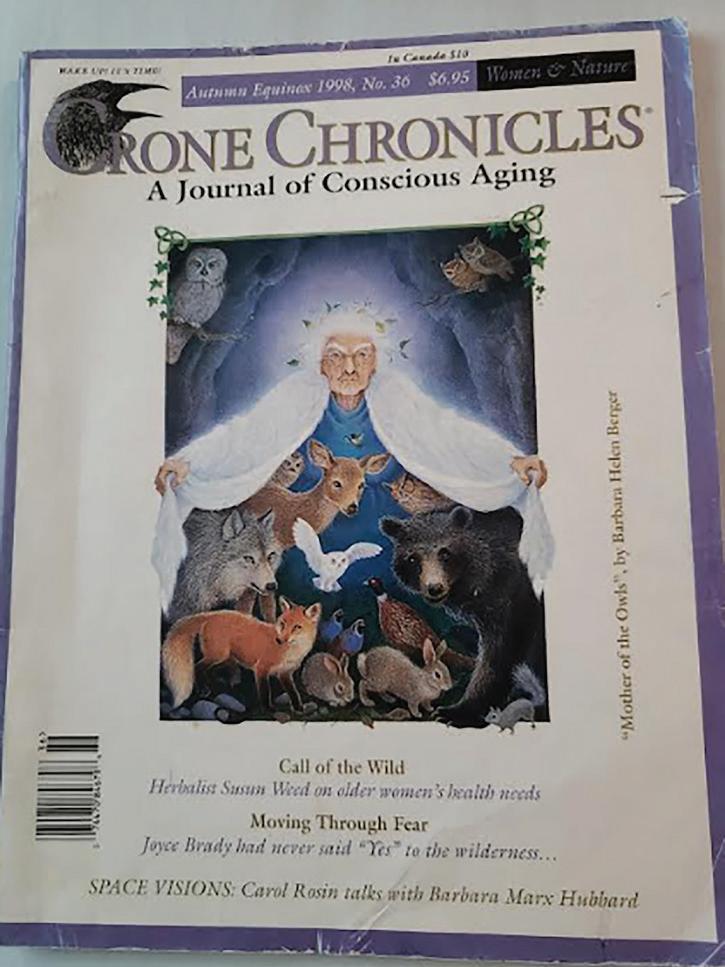

By Deb Gruvermovement that started in the 1990s in Jackson Hole to help women celebrate and honor the wisdom they gain as they age has grown “crone circles” across the country and even has attracted international participants.

Ann Kreilkamp published a small news letter in Jackson titled “Crone Chronicles: A Journal of Conscious Aging” that was resonating with women. She ran an ad in her pho tocopied periodical to see if anyone would be interested in getting together. They were.

About 130 women, ages 42 to 76, met for four days in October 1993. They traveled to Jackson from 16 states.

Crones Counsel still exists today “to empower older women and let them know they are enough,” board president M arga ret Fenton said.

“The core of Crones Counsel is storytell ing. It’s not somebody outside coming in to tell their sto ry. It’s the women telling their own stories.”

Fenton, 73, attended her first gathering when she was 49.

“There was no doubt in my mind, I’m going,” Fenton said. “I learned so much. I wanted to know how to age and do it in an authentic way. Boy did these women teach me. I’ve learned so much from crones.”

Participation in crone circles has “ebbed and flowed in the last five, six, seven years,” Fenton said. “At its peak in the ear ly 2000s, over 300 people attended.

The number of women has decreased, but that’s not surprising, Fenton said.

“Many of them are gone,” she said of longtime members. “They were very pow

erful women. They would drag along five to 10 other women with them. The second reason is when it was started in 1993, it was about the only game in town. There was not much speaking out fo r older women.”

That’s changed with the growth of wise women groups, and that’s good, Fenton said.

Fenton attended her first gathering in 1998. She recalled that there were between 200 and 300 people in atten dance.

“It really is to empower older wom en. That’s the heart of it,” she said.

The group encourages women “to be confident in their own story and to realize that they have accumulated quite a bit of power and wisdom as they’ve lived their lives and help them claim that.”

The word “crone” isn’t a deroga tory term to these women, who live in all 50 states. Women from countries such as England, Spain, Canada and Malawi have at tended crone gath erings.

The majority of women involved in a crone circle are from the West, but New England also is well-represented, Fenton said.

The last in-per son convention was in 2019 in Tucson. About 100 women attended. In 2020, women met twice by Zoom, and in 2021 and this year, met quarterly on line. The gatherings tend to be near the equinox and solstice, said Fenton, who has bee n the board director for

three years and a board member for six.

The next gather ing will be Dec. 17. Registration will open the first week of November at www.cronescoun sel.org . The cost is $25 for Zoom meet ings.

Crones typically met at a re treat center, but “many of them have disap peared or it’s got ten very expensive,” Fenton said.

“We are going to attempt to do one in 2023, but Covid will tell us whether we can or not.”

“I wanted to know how to age and do it in an authentic way. Boy, did these women teach me.”

Margaret Fenton CRONES COUNSEL

Sunflower State native recalls days when anti-choice activists menaced clinics that provided abortions.

By Deb Gruver

Talk about surreal.

By Deb Gruver

Talk about surreal.

Some of the Wichita, Kansas, voters who decided the future of reproductive rights in the Sunflower State cast their ballots in the very church where an antichoice terrorist assassinated Dr. George Tiller.

Scott Roeder shot Tiller on May 31, 2009, as the abortion provider handed out bulletins at Reformation Lutheran Church. Thirteen years later, voters handed a stinging defeat to a proposed amendment that would have stripped the right to abortion from the Kansas Constitution.

Kansas long has been the center of the country’s abortion “debate.” Tiller was one of three doctors who performed socalled “late term abortions” at the time of his murder. Another extremist had once shot him twice in the clinic’s parking lot. Nevertheless, Tiller persisted.

I covered his assassination as a re

porter for The Wichita Eagle. My editor attended Tiller’s church and was there, worshiping with her family, when Ro eder shot the doctor in the head.

I left The Eagle in 2015 to work for a marketing and advertising agency. My heart wasn’t in that industry, so I quit that job and a month later became direc tor of communications for Trust Wom en Foundation, the nonprofit that had opened Tiller’s clinic and, while I was employed there, opened Oklahoma’s first new abortion clinic in 40 years.

My office once was that of Tiller’s phy sician father, who provided abortion care before Roe v. Wade. My office didn’t have air conditioning or heat — at least not reliable temperature control. When you have to constantly spend money building fence to protect patients from protesters, or fix the roof because extremists climbed on top of the building and poked holes in the roof, or keep an armed security guard at the entrance of your workplace, air conditioning and heat seem like a luxury.

Taped near every phone in our offices were bomb threat instructions. In 2017, local and federal law enforcement of ficers spent several days protecting our patients — and those of us who worked there — when anti-choice groups re turned to Wichita for the anniversary of

the so-called “Summer of Mercy.”

Let me tell you, it’s unnerving seeing officers and agents with guns in your lunchroom, outside your office, in the lobby and in the room where women waited to be seen. Those officers stayed in our building 24/7 that week.

Protesters daily recorded the license plate numbers of every vehicle that crossed the gate into the parking lot of our clinic. We always advised patients to drive past the protesters with their win dows rolled up. Employees’ comings and goings were also recorded. We always joked that there was no need for time cards. All the founder and CEO would have to do to find out when we were working would be to ask the protesters to see their notes at the table where they were allowed to set up on the sidewalk outside our building.

The protesters took photos of us and posted them on websites. They published our home addresses. They shouted at us, and called us “baby killers.” They told us we were going to hell.

We underwent training about what to do if we were followed out of the clinic. We varied our routes home. We were al ways on guard.

Nevertheless, we persisted.

Our work was extremely difficult but

next-level rewarding. My job was largely to coordinate interviews between our founder and CEO — and, far more im portant, our patients — and reporters and filmmakers from The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, NPR, the BBC, Rolling Stone, HBO, New York magazine, Glamour, Self, Mother Jones, and the like. I wrote speeches, including one given at the Woman’s National Dem ocratic Club in Washington, D.C. I was proud to work at a national foundation dedicated to providing abortion care.

I came out of the womb a feminist, and my commitment to reproductive rights was unwavering. My husband and our families worried about me, but I nev er once considered quitting out of fear.

On Aug. 2, Kansans — the first in the country to vote on abortion after the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe — which Trump-appointed justices said in their job interviews was “settled law” — sent a clear message that women and other pregnant people should have a choice about whether to continue a pregnancy.

I’ve never been more proud to be a Kansan.

We’ve always been a free state.

Contact Deb Gruver at deb@wordscout. biz.

you’re beautiful,” said my other half, my progressive partner who enters the un graceful fray of parenting with me every day.

Huh. Could I ever really accept this new look?

“Pause and consider taking a selfcompassion approach,” said Tanya Mark, a health and wellbeing coach and

nutrition therapy practitioner in Jack son. “With self-kindness for the desire to ‘correct’ or ‘cure’ your changing body, it makes perfect sense living in a perfec tionist body culture.”

Shifting my focus from looking at this “mark,” to embracing a more full life is, well, difficult. But here’s the thing: I don’t think I’m alone and that is why you are still reading.

“Common humanity means you’re not alone,” Mark told me. “We will all

grapple with aging faces and bodies and make different choices, and they’re all OK. Be mindful, observe how you’re feeling, what you’re experiencing with out judgment.

“Acceptance is a process. You (we), over time, may accept some things about our aging selves, and not others. So meet yourself where you’re at, with self-com passion, curiosity. There are no rights or wrongs. It’s your choice. Self-com passion can help you move through the

shades of acceptance.”

Then, an email hit my inbox declaring “the holy grail” of skin care guaranteed to fix my face and cure the melasma! The HOLY GRAIL! And my face!

I deleted the email, though maybe a few months ago I might have entertained a click on the link. Shades of acceptance. Every pun intended.

Contact Jeannette at schools@ jhnewsandguide.com.

Do you want to heal an injury with a non-surgical approach? Do you want to optimize your health & performance to live your best life?

At Boost, we take a holistic approach - providing you short term relief as well as treating the underlying cause of injury or illness. We offer a range of possible treatments to match your budget, and also provide you support to implement changes in your life. Struggling with nagging injury? Chronic pain? Inflammation? Gut issues? Hormones? Weight gain? Low energy?

We’re here to provide you with support on your wellness journey.

• Non-surgical treatment for acute and chronic pain and injuries

• Ketamine Psychedelic treatments for pain and mental health

• IV nutritional therapy for health, performance and longevity

• Stellate Ganglion Blocks for mental health and Long-COVID

• Ozone therapy for chronic illness, injuries, Long COVID and performance

• Genomics based precision medicine

• Weight loss through health and nutrition coaching

• Strengthen immunity

• PEMF therapy, Shockwave Therapy and Shiftwave Chair

• Infrared light therapy

• Ketamine and Stellate Retreats through mindelevate.me

Allison Mulcahy, MD is double Board Certified in Integrative and Emergency Medicine. She is currently completing fellowships with the Integrative Psychiatry Institute and American Academy of Anti Aging Medicine. She has held academic positions as Assistant/Adjunct Professors of Emergency Medicine at UNM, Univ of Utah and Univ of Washington.

By Sophia Boyd-Fliegel

By Sophia Boyd-Fliegel

At the region’s most prominent hub for arts organizations, 19 of 21 nonprofit and program directors are female.

Many are practicing artists in addition to being dedicated leaders, fostering in clusivity that stretches beyond biological gender.

We asked six directors of organizations housed in the Center for the Arts about the intersection of gender in their leader ship and art.

Interview answers have been edited for clarity.

I remember as a child, my best friend, her dad was a writer. He had this barn — I love barns — and he had this office up stairs. I would watch him walking up, and I knew that he’d be up there writing. All I wanted to do was just sit in there and watch what he did, see how he did it. I wanted so badly to be a writer.

I didn’t know any female writers. The first female writer I knew was Anna Sewell, who wrote “Black Beauty” in 1800s England. She was considered a ren egade for writing that book because it was really about slavery.

Every child needs to be able to see themselves in what somebody else is do ing. It wasn’t until the last 20 years or so that children’s books were really expand ing to have diverse characters.

I made a commitment when I started

working with the Almost Authors pro gram, not only for it to be free, but to have diverse authors. I was never going to have all-white authors.

There’s a higher percentage of women authors for children’s books, but up until probably the last 10 years the people who have been visible have been the white male authors.

We have to fight for visibility.

I think women in Wyoming see them selves as being strong and resilient. Women feel very much part of the deci sion-making. They feel like we’re a small population, which gives us a lot more voice with our legislators than in other places.

At the region’s art organization hub, 19 of 21 executive directors are female.COURTESY PHOTO Nanci T. Steveson of JH Writers

We hope to see you at the 2022 Developing strength, courage & resilience

I think the strength does come from living in a place where places are far apart. You’re a small population, and you have harsh winters. That’s where that spirit of independence comes from.

Why aren’t more women in the Leg islature? What is the reason for that? A lot of it has to do with spending a lot of time in Cheyenne, which is way across the state. We have these long winters and during the winter, that’s when the Legis lature takes place. If you have kids, if you have a family, that’s hard. It’s really hard.

I heard a lot of ranching women say they’re not about “woe is me.” They’re about “everybody’s got to pick themselves up by their bootstraps and get going.” You have to get stronger, get wiser and not walk down that path of “woe is me.” Find that new path, find the new way to do it.

Women are not in as good of a place as

people might think.

I think there’s a photograph that makes it look good, but if you really look, if you were to watch a video — using that as a metaphor — you would see women aren’t getting paid as much. We do more house hold work than men do, in general.

I think in Jackson — just as in other places — there’s also the differentiation between what kinds of jobs are appro priate for women versus not. I’ve also thought it was really interesting that, ba sically, women run the organizations in the Center for the Arts. To some degree I think it’s awesome, but also I think it’s interesting because it means that to some degree you could argue that society sees art as something not worthwhile. So let’s have the women be in charge of it.

But I also think that the trajectory has been good. We were all able to come to gether to support each other and really show how much we respect each other’s disciplines during COVID and helped make sure that we all survived.

At St. John’s Health, we work together as a team with one goal: caring for you. And in the case of a breast cancer diagnosis, that goal is more important than ever.

Every day, our team of breast surgeons collaborate with oncologists, radiologists, and other specialists to provide you with comprehensive diagnosis and treatment plans, designed for your unique needs.

if you require reconstructive surgery, our breast health team is here to help you feel like yourself, while getting you back to the life you love. It’s just one of the ways that St. John’s Health is specializing in Wyoming,

specializing in you.

Continued from 21E

I think it’s more typical for women to be in the nonprofit world.

When I’m thinking about my path to leading the Art Association, it comes much more out of me being an artist first. I’ve been a teacher and a curator and an artist my whole life, and I feel like I come at my position through that before I think about me as a woman doing it.

I feel like the styles and values that I try to aspire to, I don’t think they are just specifically a woman’s leadership style: inclusivity, a flexible work environment, empathy and creativity. I don’t think they are just specifically a woman’s lead ership style.

I feel like it happens in middle school or late, late elementary school, that people just go, “Oh, I can’t draw.” Some

times it’s self imposed. [But] I feel really strongly that people are not born a ge nius creative, it has to do with practice.

Through the arts, education and just accessibility, people can try something and not feel threatened by it.

In the Suzuki program I require parents to come in for an observation. And then we sit down and I say, “As a parent, are you ready to take this on? Are you ready to say I’m going to do this every week with my kids?” So it’s a commitment.

In a lot of families where everybody is working so hard, they have to have child care. They have to figure out what they’re going to do with their kid after school. There are families here that don’t work, but I think a lot of people work. It’s difficult here.

The fact that I’ve had children helps me

The inspiring women of Grand Teton National Park are emboldened by the value of connection. They engage with an intensely proud feeling of female empowerment and support of one another. They respect where they’ve come from, who they are, and the work they do. They build teams, bridges, and relationships with a rich diversity of skills, expertise, and perspectives. The women of Grand Teton are passionate, talented, open-minded, and collaborative. They value relationships and strive to create a culture of inclusion. They are grander together because of their contributions.

Grand Teton National Park would like to celebrate these inspirational women. These amazing women are law enforcement officers, project managers, educators, planners, firefighters, volunteers, vegetation managers, trail workers, administrative professionals, medical providers, business leaders, and often the first person visitors meet.

They are the women who work on trails, perform backcountry search and rescues, and provide bear safety education. They come from a diverse background of biologists, social scientists, budget experts, fire specialists, botanists, educators, writers, and much more.

Wherever you see them, whatever they are doing, they are here in honor of the women of Grand Teton, past, present, and future, the pioneers and trailblazers, whose efforts they highlight by the work they’ve done and continue to do. Why? Because they love this place, this community, the people, and the wildlife. They are all here for the very same reason…to make a difference in this magnificent, wild place.

relate and help other families. Sometimes, I’m in a counseling session. Not that I’m advising people, but, you know, someone will come in and have a middle schooler or an elementary schooler and I’ll be like, ‘Well, when my kid was in fifth grade …”

I’ve had two kids of my own and I’ve had my own trials and tribulations with them. One of my closest colleagues ... has been teaching for 30 years now, and he doesn’t have kids. But he’s been teaching for a lot longer than me. Both of my children I taught violin. I think it gives me an edge.

Natalia Macker, Off Square Theatre Company

Theater as a field has been very maledominated in creative leadership roles. Women-identifying playwrights and di rectors just have less opportunities. There are more parts written in plays for men, there are more male characters.

Shakespeare’s plays don’t have a lot of

women characters and wouldn’t have any women actors. So boys were playing the female parts. For Shakespeare projects all sorts of things are possible. It’s hard to say that there would be a gender normal.

Increasingly, there are more female artistic directors. We’re starting to also see women’s experiences represented in plays. As people are leaving longtime po sitions, those are being filled by people of color, by women of color and by women. And that’s really exciting to see. Twenty years from now, theater in America, gen erally, is going to be different.

As a company, we have inclusion pri orities. We’re making the choice to put underrepresented voices and identities in larger roles.

It has been really remarkable with some of our students, those identifying as girls, those boys and those who are more gender fluid, who’ve come to have the theater as a place where they find their people.

Contact Sophia Boyd-Fliegel at county@ jhnewsandguide or 307-732-7063.

We are proud to support the women who contribute to the creativity and success of businesses in our community.Back,