WILD DEOR INDIGENISM

EDITED BY JONATHAN LEVITSKE

The history of the word wilderness stems from the roots and . meaning plants and animals not subject to the will of the civilized. meaning beast or animal. In the western context wilderness refers to the absence of human civilization. Wilderness was legally defined in the United States with the Wilderness Act of 1964. This act defined wilderness as, “In contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

HOWEVER, MANY CULTURES AND LANGUAGES HAVE NO WORD EQUIVALENT TO WILDERNESS.

Indigenous Peoples do not differentiate between human and non-human environments. They understand land, place, and beings as a reciprocal relationship.

3

1964

CONTENTS BA J A U L A UT 08 NAV IG A TIO N MOBILITY + CLUSTERS 22 MONOXYLE SOUL + SPIRIT MOKEN 36 A DOPTIO N E XCH A NGE S O R A NG L A UT 54 R EL A TEDNES S 840 A.D. 3000 B.C. 1300 PRESENT

CHOREOGRAPHY

SEQUENCE OF ORGANIZED STEPS AND MOVEMENTS

KINSHIP RELATEDNESS

RELATIONSHIP BY NATURE OR THROUGH BLOOD

CONNECTED TO SOMETHING OR SOMEBODY

SOUL

SPIRITUAL ENERGY A PART OF BEINGS AND THINGS

SPIRIT OF PLACE

SYMBOLIC RELATIONSHIP ONE HAS WITH A PLACE

7

LEXICON

MERGUI ARCHIPELAGO CAMBODIA VIETNAM THAILAND LAOS MYANMAR MALAYSIA SINGAPORE BRUNEI

RIAU ISLANDS

MOKEN ORANG LAUT

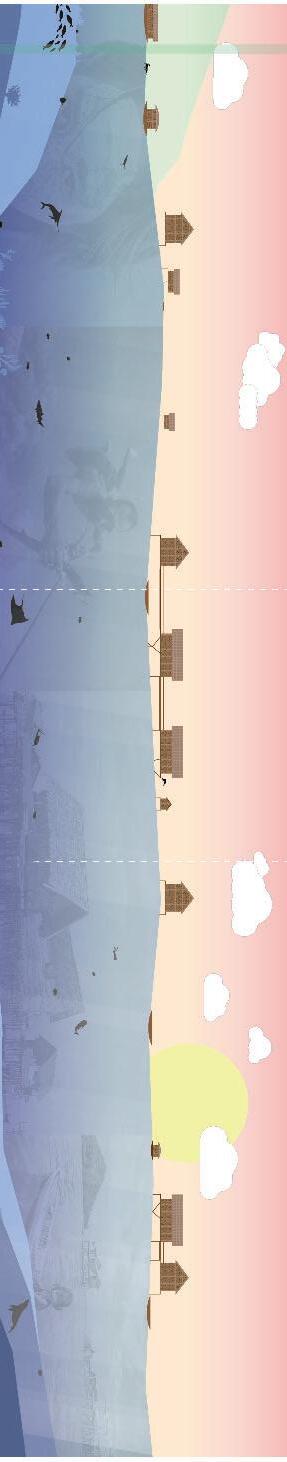

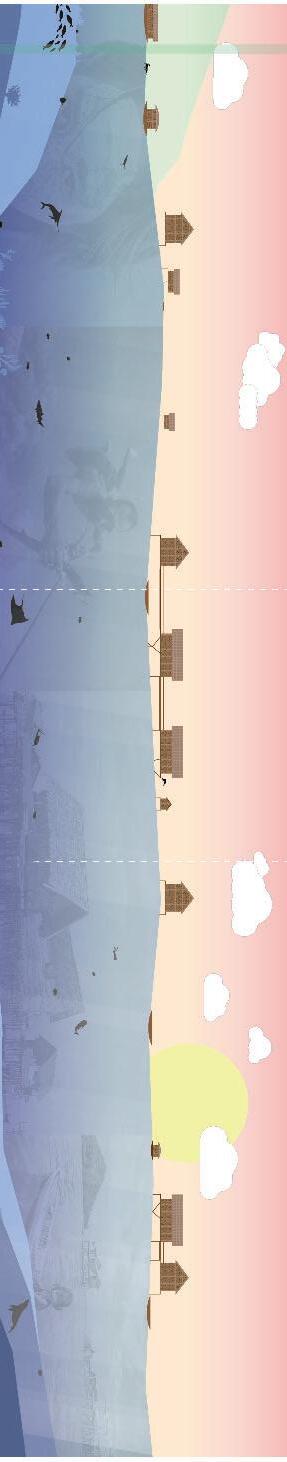

In Southeast Asia, a socio-economic crisis is drastically affecting three indigenous populations within a regional maritime environment: the Bajau Laut, Orang Laut, and Moken peoples. A reef larger than most countries, the Coral Triangle (outlined in red), in the western Pacific Ocean is exploited for economic resources by tourists and commercial fisherman.

BAJAU LAUT

PHILIPPINES SEMPORNA INDONESIA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

TIMOR-LESTE

“We live at sea and won’t survive without these skills, it’s our way of life. When y

THE LAST SEA NOMADS BAJAU LAUT

For centuries, the Bajau Laut people, known as the

“Last Sea Nomads,”

lived completely on the area’s water surface. Consequently, their genetics adapted to the sea and they became heavily reliant on area fishing for income. However, since the mid-1970s, commercial fishers entered the area and outcompeted the Bajau Laut’s passive cultural traditional fishing techniques. Climate change plus the government deeming the Bajau Laut as stateless people, with no recognized legal rights, exacerbated their dilemma.

The indigenous group is dispersed over a maritime environment of 1.25 million square miles. This physical environment dominated by sea and island has an intimate relationship with the Bajau as they are heavily reliant on the sea for food and income. The co-existence of land amongst the vast sea forms the Bajau’s representations of orientation, patterns of navigation, lifestyle, and direction.

11

Loca on Semporna, Malaysia People Sama-Bajau Eleva on 2,642 - 4,094 m Origin 840 A.D. Total Popula on (Present) 750,000 - 1.1 Million

you live at sea you become one with the ocean.”

840 A.D.

SEMPORNA, MALAYSIA SEMPO Semporna Airstrip (WBKA) CONTEXT or

mushroom coral ovulid snails nudibranch

Semporna referred to as “at the end of the forest” by the Bajau is located in Sabah, Malaysia. The peninsula consists of high isolated volcanic peaks, mountains, and rich biodiversity. Some species local to the region are mushroom coral (lithophyllon ranjithi), ovulid snails, and nudibranch.

ORNA

The Bajau’s spleens have grown to be 50% larger than the average spleen for humans which produces more oxygen in the blood allowing them to hold their breath underwater for thirteen minutes.

NAVIGATION

Navigating the sea is primarily determined by tides, wind conditions, and currents. The Bajau begin this unique process by taking a reading of the current by dropping small pieces of wood into the water. Noting the direction in which they are pulled. They then determine a heading to compensate for the currents pull.

Seven cardinal directions were created in reference to winds and sea currents. North (utala’), north-east (utala’ lo’ok), east (timul), south-east (ungala’), south (satan), west (hilaga), north-west (habagat). With the strongest winds in the region blowing from the north-west.

Additionally, their activities on the sea center around a monthly lunar cycle which sets the time to fish within a particular manner or area. For example, as the size of the visible moon increases the nights grow noticeably lighter. And the currents are strongest during the full moon and no moon phases. They distinguish by numerical terms 30 nightly changes in the sea during a single waxing and waning moon.

Therefore, the Bajau have

coexistence with their environment.

16

developed a complex choreography with natural phenomena to inform them of how to passively

lepa boggo’

MOBILITY + CLUSTERS

The Bajau Laut utilize two boat typologies within this maritime environment: the boggo’ and the lepa. All boats are individually owned and serve various functions.

The boggo’, ranging from 3 - 5 meters, is used only inshore as a means to navigate between unconnected villages. The boggo’ only can hold one to two people and is propelled by paddles. However, it can be towed by the lepa.

In contrast, the lepa shown in the diagram to the left is larger at 7 - 12 meters long. The boat is divided into three sections, the midsection is used for living, the stern is used for cooking, and the bow is reserved for fishing, poling, and manning the sails.

Boat construction and care is an intricate process that requires frequent attention. Repairs are typically made from a bark called gellom which grows along the coral line.

During times of marriage, a lepa is built and given to the new couple in order to assure residential independence from their families. Married couples would then set sail to new housing clusters.

REFER TO BAJAU LAUT LEPA DIAGRAM:

1 Teddas (keel)

2 Pangahapit (strake)

3 Tuja’ (bow section with raised poling platform)

4 Jungal (side-pieces ending forward in a projecting bowsprit and aft in a small stern projection)

5 Tuja’ buli’ (stern section)

6 Bengkol (lower sideboard forming fitted gunwale)

7 Kapi kapi (middle sideboard)

8 Koyang koyang (upper sideboard)

9 Dinding (wall of living quarters)

10 Ajong ajong (forward side-piece) fore and aft)

11 Sa’am (cross-beams enclosing living quarters fore and all)

12 Sapau (roof)

13 Lamak (sail)

14 Lantai (deck planks)

15 Panansa’an (bow and stern deck)

16 Patarukan (forward cross-piece and mast support)

17 Sengkol (cros-pieces reinforcing hull and supporting deck planks)

19

Housing clusters form social groups and hierarchy within the Bajau Society. The clusters are typically composed of between seven (50 people) and thirty (200 people) homes. The clusters are composed of close kin and former housemates.

Walking planks and platforms connect clusters together without having to travel with their boggo’. On account of this close relationship between houses neighboring houses are expected to assist with domestic tasks and share food.

cyanide bombing

coral bleaching dynamite

cyanide bombing

coral bleaching dynamite

The Bajau Laut only have participated in passive fishing techniques. They utilize three types of drift-nets crafted from cotton twin, nylon, or locally sourced bark-fibre twine. However, commercial fishing companies are placing economic and nutritional pressures on indigenous peoples. Shown to the left are examples of these activities.

Due to brutal human activity and the fastest growing economy in the Asia-Pacific region, the coral triangle area has lost 40% of its biodiversity.

“The Moken are born, live and die on their boats, and the umbilical cords

WATER PEOPLE MOKEN

of their children plunge into the sea.”

The Moken, meaning water people, live among a string of 800 islands. They believe the sea, the islands, and all entities have spirits. A similar complex choreography, to the Bajau Laut, is conducted with the sea. Where they move toward different fishing ground in conjunction with the wind, current, and the lunar cycle. In contrast to the Bajau, the Moken

only collect what they need from the sea for a day.

They believe that signs of materialism and accumulation of wealth meant that they would settle down and loose their core values. Everything that they own they carry within their, kabang or boat. However, this passive way of living lightly on the land was disrupted in 1945 when the Malaysian government began to insist that the Moken become “civilized citizens” of the country. The government create a village, Pula Nala Island, where the Moken could settle down. The village consisted of souvenir shops, a monastery, a school, a hospital, and a fuel depot.

25

3000 B.C. Loca on Mergui Archipelago People Moken Eleva on 283 - 341 m Origin 3000 B.C. Total Popula on (Present) 2,000 - 3,000

PYINMANA WEATHER STATION

MERGUI ARCHIPELAGO

MERGUI ARCHIPELAGO CONTEXT

MERG

GUI ARCHIPELAGO

The Mergui Archipelago is comprised of 800 islands in the Andaman Sea. Only a small population of people have lived within and around the archipelago which has helped to preserve the biodiversity of the land and sea.

giant oceanic manta

plainpouched hornbill sunda pangolin

giant oceanic manta

plainpouched hornbill sunda pangolin

The Moken use a spear to hunt fish and jump on top of them as they pass by the boat.

The Moken use a spear to hunt fish and jump on top of them as they pass by the boat.

MONOXYLE

The Moken utilize the kabang as their main form of transportation and their home. The hull is composed of two parts a superstructure and a keel carved from the monoxyle dugout. Drawing emphasis to their progression and adaption throughout history from the forest to the vast sea.

Additionally, hunting is the main activity that takes place on the kabang. Since the Moken believe all species posses a soul or spirit; hunting becomes a symbolic and ritual practice.

30

“They form the body of the symbolic technology, firstly because all their components necessary for the realization of a boat have anthropomorphic features. Furthermore, dugouts represent through their assimilation to an ingesting and excreting human body the inability to accumulate.”

SOUL + SPIRIT

Although hunting is a symbolic and spiritual activity; there are a few animals that are hunted that have spirits: the wild pig on land, turtles and manta rays at sea, and some birds in the air. The Moken carve and paint spirit poles, seen to the left, which allow them to summon and connect with their ancestors. The poles are features in a three day festival during the 15th cycle of the moon. Offerings of food are placed on houseboats and launched into the sea for the spirits.

“Dolphins and whales are not harpooned; they have a soul and represent the double of dead shamans and mediumsso their appearance causes a respectful silence. Another species of monkey is considered as a double, probably an ancestor, as it is called Ebab (“grandfather”, “male ancestor”) by the Moken and therefore is not hunted.”

33

The Moken children are born with a genetic adaption that allows them to see underwater with perfect vision. However, as they grow older this genetic adaptation begins to dissipate.

ORANG LAUT

SEA TRIBE PEOPLE

“They would roam their region of the sea in sync in with tide, seasons, and

d the elements.”

The Orang Laut, meaning sea tribe people, of the Indonesian Riau Archipelago similar to the Bajau and Moken possess knowledge related to the intricate navigation of the sea. They were once divided into various suku or clans that served the Sultan. Each clan was assigned various tasks within a territory. In the eighteenth century, the Sultanate began to disintegrate, and the Orang Laut became dispersed throughout the region. They became dispersed among the 1,796 islands of the Riau Archipelago.

The Orang Laut have

developed conceptions of space and place that revolve around a spiritual axis that guides them in patterns of exchange.

These notions inform them of who they can safely exchange items with, how exchanges can be performed, and the effect of exchanges on oneself.

39

Loca on Riau Islands People Orang Suku Laut Eleva on 2,154 - 2,424 m Origin 1300 Total Popula on (Present) 1,000 - 3,000

1300

ZCDY2 WEATHER STATION (MARITIME)

RIAU ISLANDS CONTEXT

RIAU ISLANDS

PULAU S

SERAPAT

PULAU PINANG

The Riau Islands are composed of 1,796 islands and is located within one of the world’s busiest shipping and trading regions.

mangrove crab leaf monkey slow loris

mangrove crab leaf monkey slow loris

ADOPTION

Acts of giving, accepting, and reciprocating ‘gifts’ bring about a certain level of expectations and sometimes fears. Certain objects intrinsically carry with it supernatural powers and therefore cannot be exchanged with others. Therefore, possessions reflect the identify of oneself. Their most important possessions are adopted.

To adopt something means to take care of and protect the object from outside forces. A common object to adopt is their boats.

“By deciding to adopt a thing, is also making a decision to merge the thing with his or her own identity which, in essence, is the soul. Therefore, to fail to adopt these things responsibly also means endangering one’s well being.”

EXCHANGES

Items carry meaning and value to the Orang Laut. There is a one-to-one relationship between belonging to a group and an object. Because of this belief that items reflect oneself certain items may be avoided during exchanges which may signify cultural contrasts between various groups.

“Classify aretfacts and skills into categories to reinforce their material expression and intersubjective order for patterns of interaction. These artefacts and skills have become positional markers to signify their relatedness or difference. They range from items with inherent meanings and values to those whose meanings and values undergo redefinition as they circulate thorough different domains of exchange.

47

”

NATURE IS ME VS MINE

RELATEDNESS: NATURE IS ME VS NATURE IS MINE

The image and video (https://youtu.be/j-eN6unoqpI) displayed examines ours, indigeneity, the land, and architecture’s relationship with the notion of ‘wilderness’. In particular, the concept of nature is mine vs nature is me.

A green line guides a viewer along the video. The plan, nature is mine, is expressed through musical notation which is divided into four section through grid lines. Each object within the image corresponds with specific sounds.

Nature is me is shown within section. We explore the spirit of place of the sea nomads where they understand their relationship within their maritime environment.

Furthermore, if we re-conceptualize architecture and place in terms of relatedness we may be able to reframe our western understanding of ‘wilderness’. In addition, our world is risking climate and ecological impairment through the overuse of our environment. The question becomes how can architecture be utilized to create new non-utilitarian lenses so that the western perspective of ‘Nature is Mine’ acknowledges the Indigenous Perspective of ‘Nature is Ours’?

57

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chou, Cynthia. Indonesian Sea Nomads: Money, Magic and Fear of the Orang Suku Laut. Routledge, 2015. [pg. 42, 43, 45, 46, 47, 49]

The College of Architecture and Design at Lawrence Technological University. CoAD Lecture Series — Chris Cornelius. 18 Mar. 2021, https://youtu.be/j5y1vgz1hLE. Accessed 2021. [pg. 57]

“Dufour 512 - Moken.” Regatta Boat Graphics, https://regattaboatgraphics.com/moken. [pg. 24, 34]

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press, 2015.

Fmh. “The Assimilation of the Orang Suku Laut.” Uniformnovember, 25 July 2019, https://www.uniformnovember.com/single-post/2019/07/25/ The-Assimilation-of-the-Orang-Suku-Laut. [pg. 48, 50, 51]

Gilio-Whitaker, Dina. As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock. Beacon Press, 2020.

Harris, Paul G., and Graeme Lang. Routledge Handbook of Environment and Society in Asia. Routledge, 2015. [pg. 22, 23]

History.com Editors. “Manifest Destiny.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 5 Apr. 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/westward-expansion/manifest-destiny. [pg. 3]

Hope, Sebastian. Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia. HarperCollinsPublishers, 2016. [pg. 17, 18, 19, 20]

Ivanoff, Jacques, and Maxime Bountry. Moken Sea-Gypsies. [pg. 30, 33]

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Tantor Media, Inc., 2016.

Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press, 2021.

M., Nas Peter J, and R. Schefold. Indonesian Houses: Volume 2: Survey of Vernacular Architecture in Western Indonesia. Brill, 2008. [pg. 30]

Marrie, Henrietta L. “Indigenous Coral Reef Tourism: Henrietta L. Marrie.” Taylor & Francis, Taylor & Francis, 30 Aug. 2018, https:// www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315537320-16/indigenous-coral-reef-tourism-henrietta-marrie. [pg. 8, 9, 23]

Sather, Clifford. The Bajau Laut: Adaptation, History, and Fate in a Maritime Fishing Society of South-Eastern Sabah. Oxford University Press, 1997. [pg. 17, 18, 19, 20]

Stacey, Natasha. Boats to Burn: Bajo Fishing Activity in the Australian Fishing Zone. ANU E Press, 2007. [pg. 11, 13]

Stateless at Sea - Backend.hrw.org. http://backend.hrw.org/sites/default/ files/news_attachments/062015_thailand_burma_moken.pdf.

“The Story of Semakau.” Orang Laut, 19 May 2021, https://www.oranglaut.sg/ [pg. 39]

Watson, Julia. Lo-TEK Design By Radical Indigenism. Taschen, 2020

“‘Land of the Burning Ground’: The History and Traditions of Indigenous People in Yellowstone.” “Land of the Burning Ground”: The History and Traditions of Indigenous People in Yellowstone, 26 July 2021, https://www usgs.gov/center-news/land-burning-ground-history-and-traditions-indigenous-people-yellowstone?qt-news_science_products=4#.

cyanide bombing

coral bleaching dynamite

cyanide bombing

coral bleaching dynamite

giant oceanic manta

plainpouched hornbill sunda pangolin

giant oceanic manta

plainpouched hornbill sunda pangolin

The Moken use a spear to hunt fish and jump on top of them as they pass by the boat.

The Moken use a spear to hunt fish and jump on top of them as they pass by the boat.

mangrove crab leaf monkey slow loris

mangrove crab leaf monkey slow loris