Jiayu Sun

University

of Sheffield

Word count: 10948

-- the case of Salford in Greater Manchester

How railway stations contribute to urban regeneration from the perspective of the production of space

University of Sheffield

School of Architecture

ARC6982 Urban Design Project 3: Thesis

Academic Year 2021/22

Module leader: Dr Iulia Statica

How railway stations contribute to urban regeneration from the perspective of the production of space

-- the case of Salford in Greater Manchester

Jiayu Sun

Registration no. 210112179

Supervisor: Iulia Statica

Freya Wigzell

Sergio Poco-Aguilar

Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Urban Design

Sheffield, 1 September 2022

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all of the responders for their feedback and opinions and the material they provided for this study. The ideas upon which this paper is based were from Anji Beautiful High Speed Rail Project Team, which the author was participated in 2018, and the design workshop ‘Rethinking Liverpool’s Railway Heritage’ led by Junjie Xi and Chia-Lin Chen in 2022. This paper could not have been even imagined without the support of Salford Central Station staff and Angel Centre, who provided me great help when I was conducting the physical survey and questionnaires.

The author would like to thank Iulia Statica, Freya Wigzell, and Sergio PocoAguilar for giving me their comments and helping me revise the paper. Many thanks also to Haoqi Liu, Xiaozheng Wang and Siyuan li for their support and encouragement at various stages of the research. I am also grateful to 301 Skills Centre and English Language Teaching Centre at the University of Sheffield for giving me guidance on writing and researching skills.

ii i

Abstract

As the intersection of the railway and the city, the railway station is not merely a place from which people travel but also has a significant impact on the development of the city. Performing as a type of urban infrastructure, the railway station is an opportunity and catalyst for urban regeneration. This paper argues that the research into railway station area urban regeneration may benefit from incorporating spatial production theories based on social interactions and spatial reconfiguration to explore regeneration strategies more comprehensively. Through literary studies, this paper provides an understanding of the theories around spatial production developed by Lefebvre and other philosophers, as well as two theories related to the station-city established by Calthorpe and Bertolini, and explore the practices associated with these theories. Using mixed methods – physical survey, text analysis, questionnaires and case studies – the mechanisms of the physical space and social space levels of the Salford Central Station area are then investigated. The King’s Cross Station urban regeneration project, which integrates transport, industry, architecture and social relations in the city, also sheds light on the regeneration of the Salford Central Area. This paper shows that unlike railway stations in metropolitan areas, which serve the functions of tourism and dissemination, railway stations in small to mediumsized cities are mainly used for commuting, and the station area is dominated by residences and offices. It is found that the regeneration of the railway station area is a spatial production process in which top-down and bottom-up forces interact in a competition for spatial power among multiple subjects motivated by capital. Guidelines from the perspective of multiple actors in the spatial production process are proposed for the development and regeneration of railway station areas similar to the Salford Central Station area.

Keywords: Railway stations, Urban regeneration, Mobility, the Production of space, Urban imaginaries, Transport hubs, Salford Central, Urban infrastructure

This Page Intentionally Left Blank iv iii

1.

6.4

6.5

7.

3.

List of Figures and Tables

Introduction

2. Literature Review

station-oriented urban

on theories

The ‘production of space’ theory

The practice of the production of space in urban studies

2.1 Research on urban regeneration driven by railway stations 2.2 Practice of

development based

2.3

2.4

Research

and

Gaps, Aims

Questions

4. Study Area, Data and Methodology

Methods

Text analysis 4.2.2 Physical survey 4.2.3 Questionnaires 4.2.4 Case study 4.3 Data collection and ethical considerations 4.4 Considerations on and limitations of site and method selection

Explorations

Physical space findings 5.2 Social space findings

Questionnaire findings 5.4 Case study

London King’s Cross regeneration programme 5.4.2 Other developments in the field of railway stations 6. Discussion 6.1 Redevelopment of railway station areas 6.2 Reflecting on spatial production theory in urban regeneration 6.3 Reflections on Salford Central Station Area vii 1 7 8 10 11 12 15 19 20 21 21 22 22 22 23 24 25 26 31 35 39 39 43 45 46 47 50 Contents

4.1 Study area: Salford Central Railway Station area 4.2

4.2.1

5.

5.1

5.3

5.4.1

Guidance for the urban regeneration of the Salford Central Station area

Universality and limitations

Conclusion Bibliography Appendix A. Questionnaire Appendix B. Consent form Appendix C. Information sheet Appendix D. Questionnaire delivery process 52 53 55 59 65 68 69 70 vi v

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1-1 Context of Salford Central Area

Figure 1-2 Location of Salford Central Area

Figure 1-3 Research process map

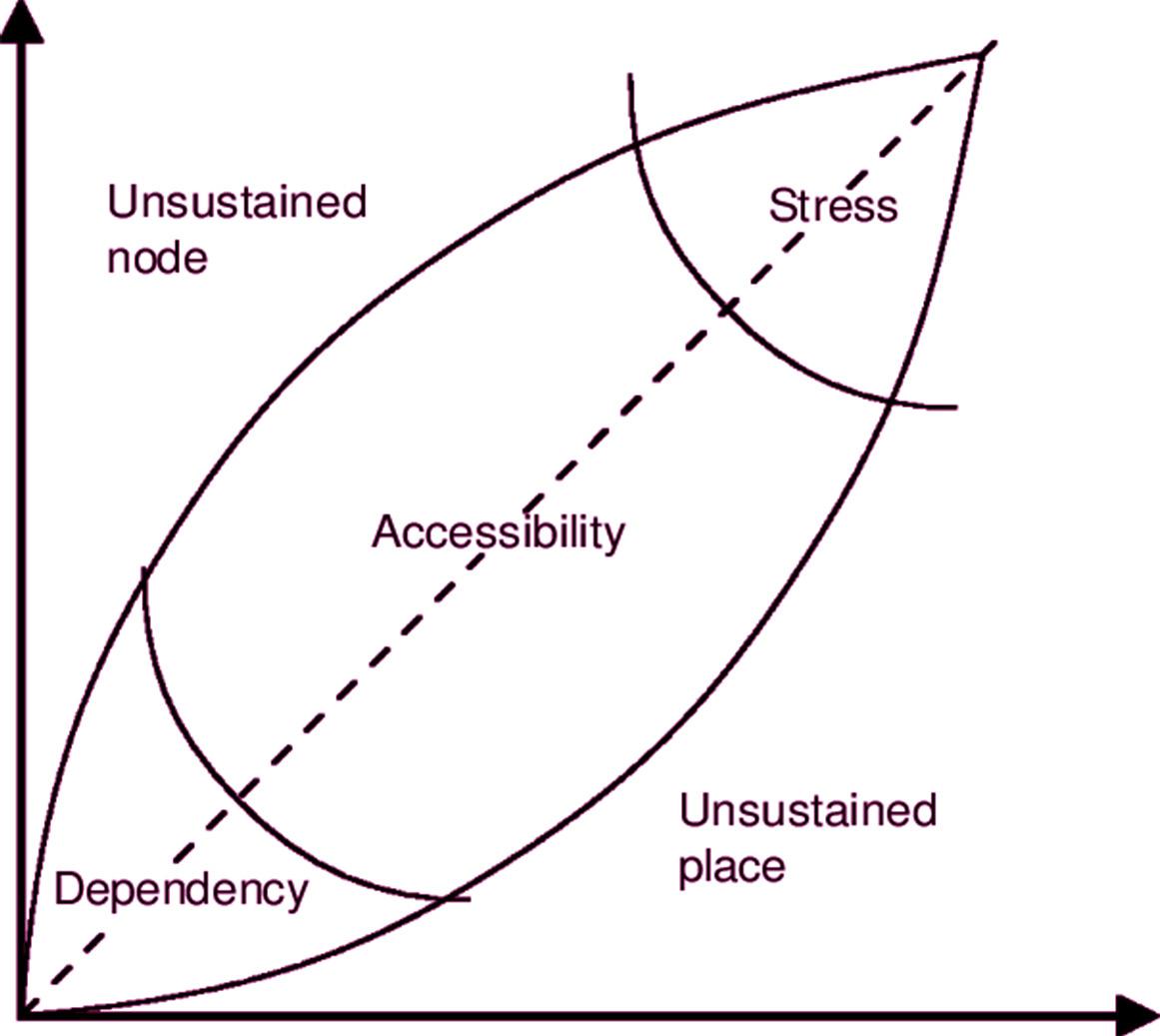

Figure 2.1-1 Node – Place Model by Bertolini

Figure 2.3-1 Thirdspace theoretical framework by Soja

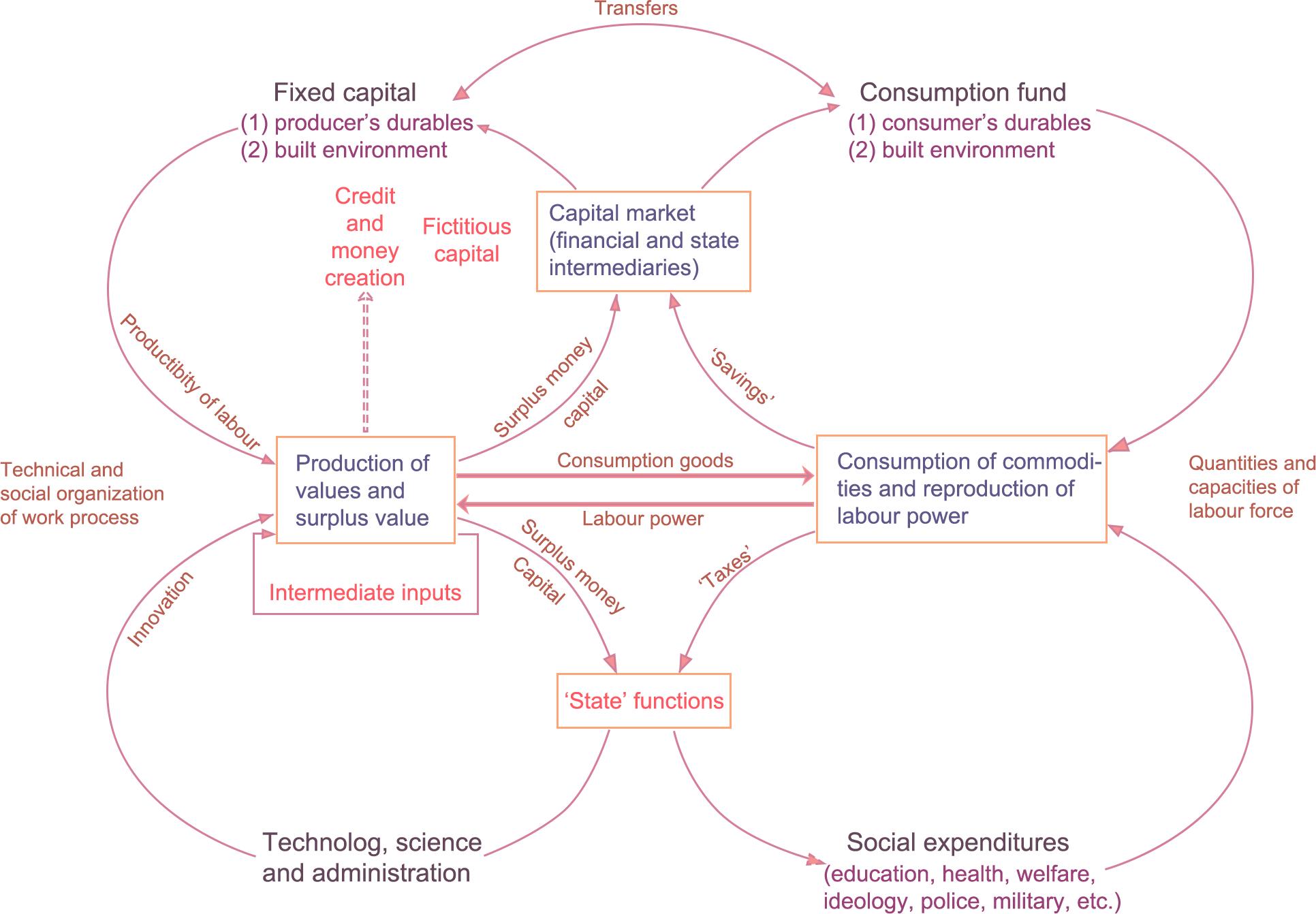

Figure 2.3-2 “Circuit of capital” framework

Figure 3-1 Manifesto

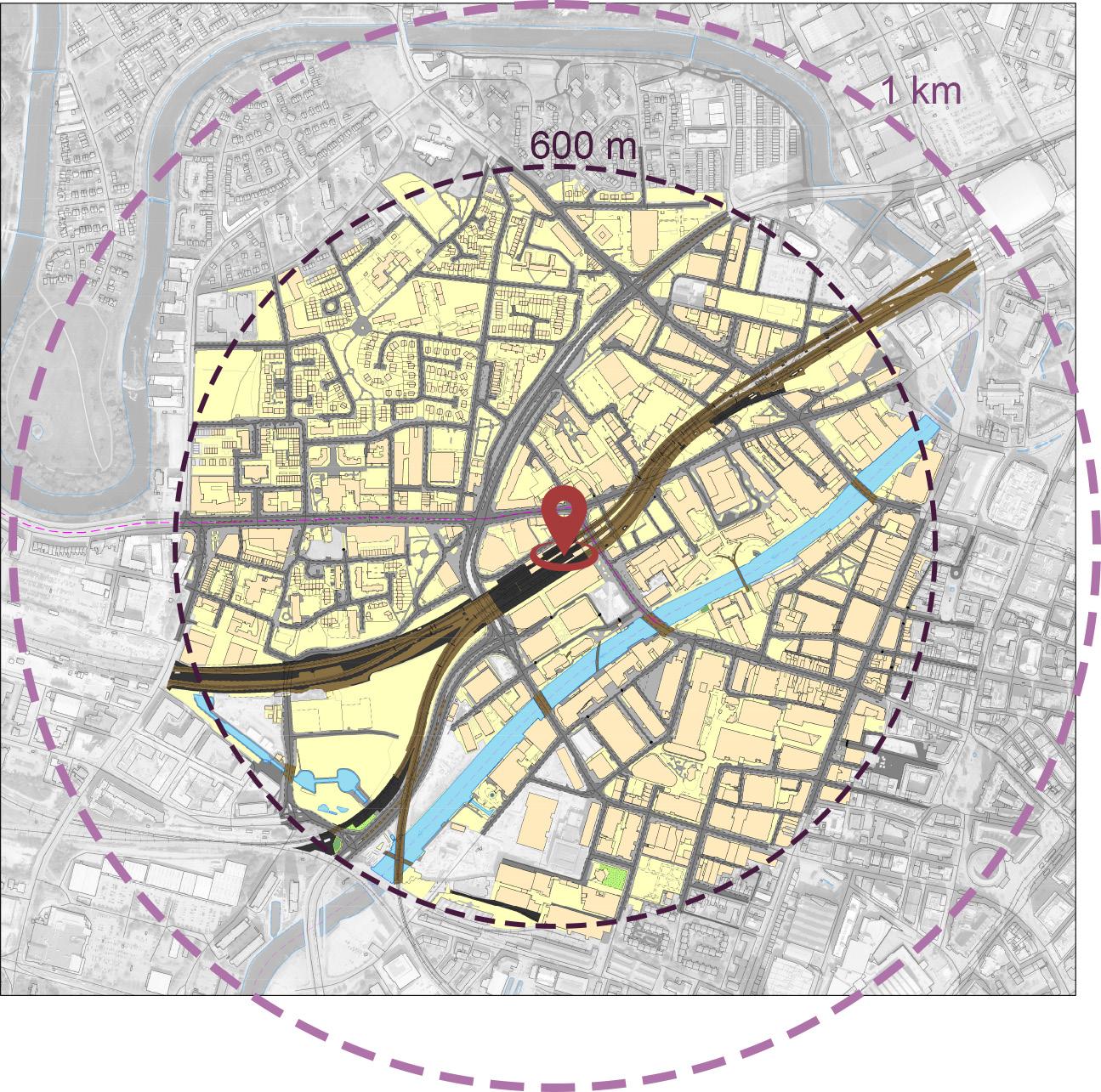

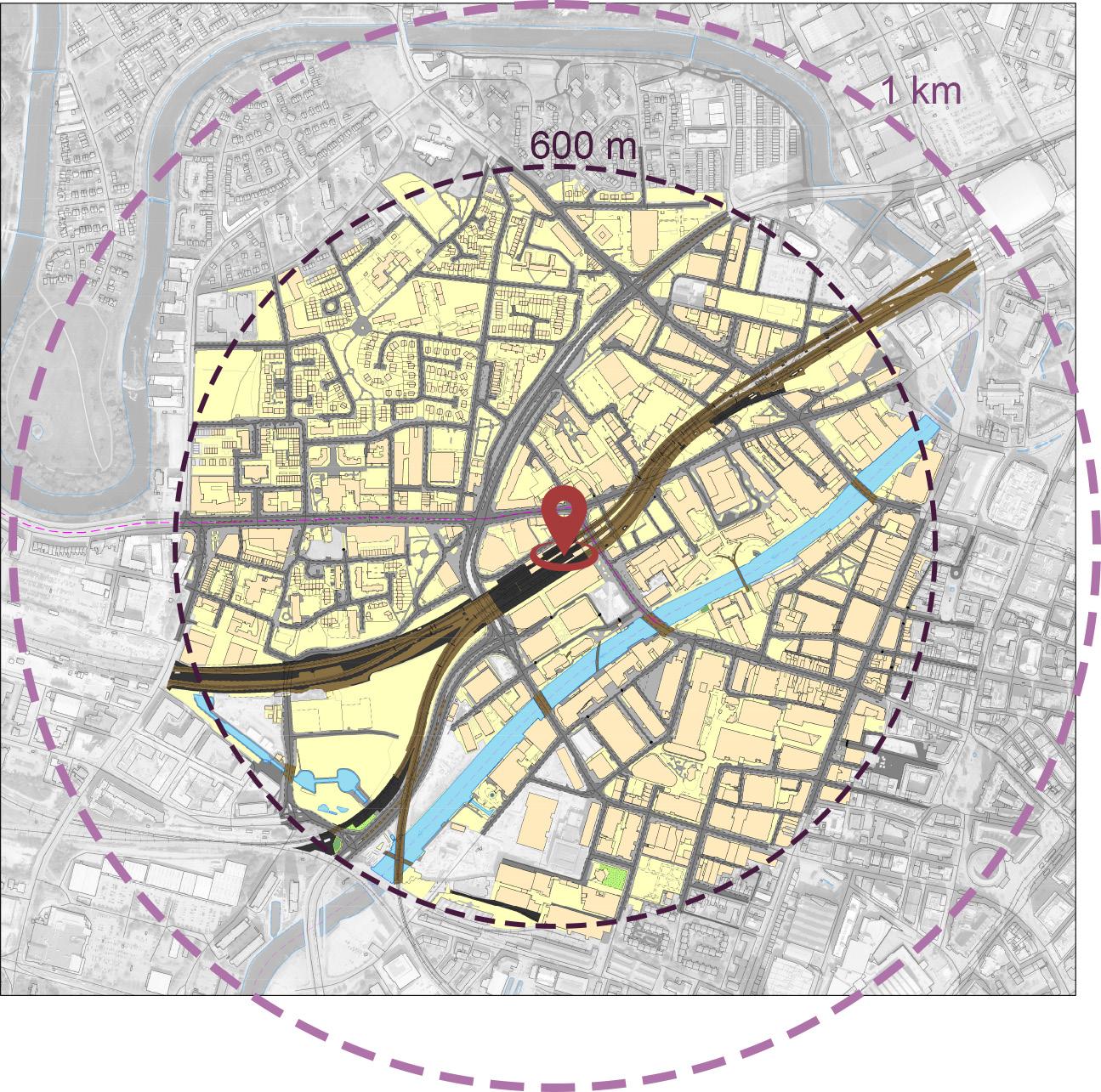

Figure 4.1-1 Research physical space and social space scope

Figure 5.1-1 Bicycle parking area and ramp access in Salford Central Station

Figure 5.1-2 Accessible lifts with negligent management

Figure 5.1-3 Food cart

Figure 5.1-4 Small square outside Salford Central Station

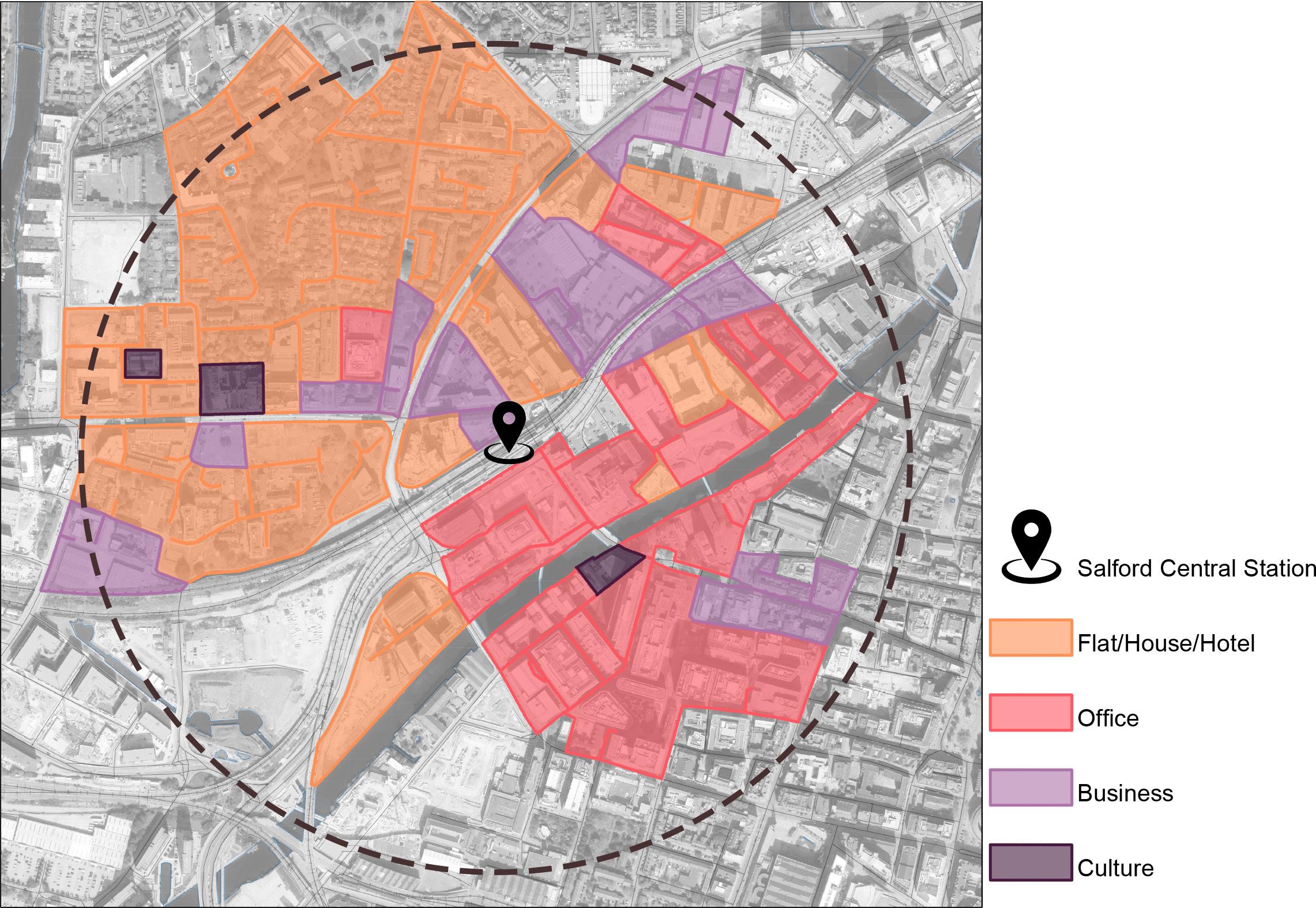

Figure 5.1-5 Distribution of building functions around Salford Central Station

Figure 5.1-6 Office car park

Figure 5.1-7 A view of the buildings surrounding Salford Central Station (with tall buildings in Manchester city in the background)

Figure 5.1-8 All types of POI in the research area

Figure 5.1-9 Building height distribution in the research area

Figure 5.1-10 Kernel density of public transport

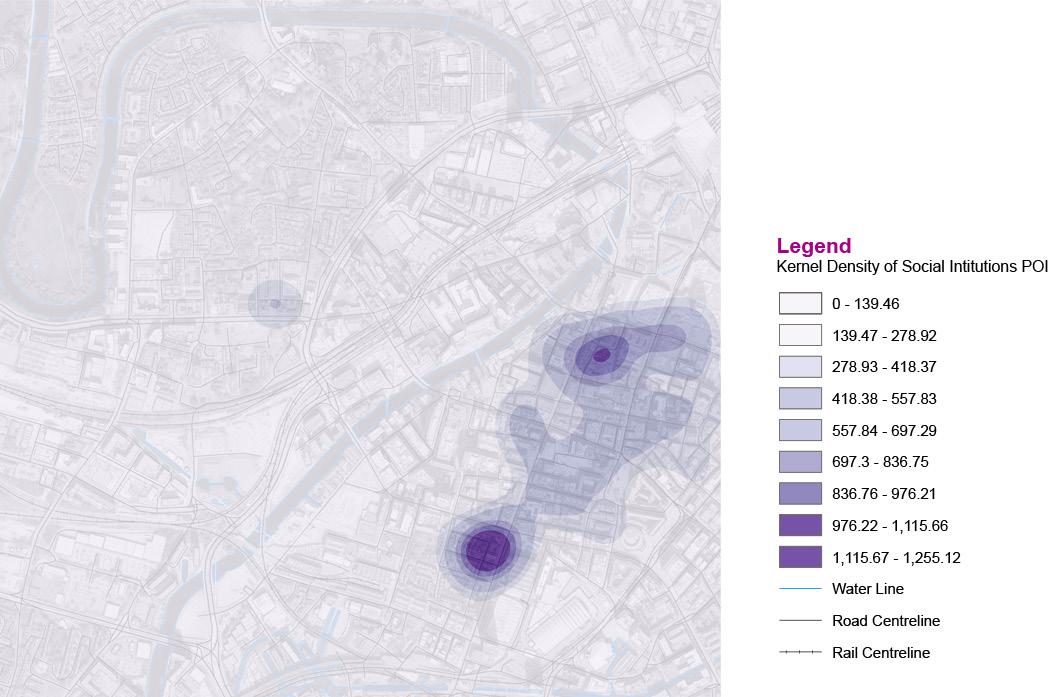

Figure 5.1-11 Kernel density of social institutions

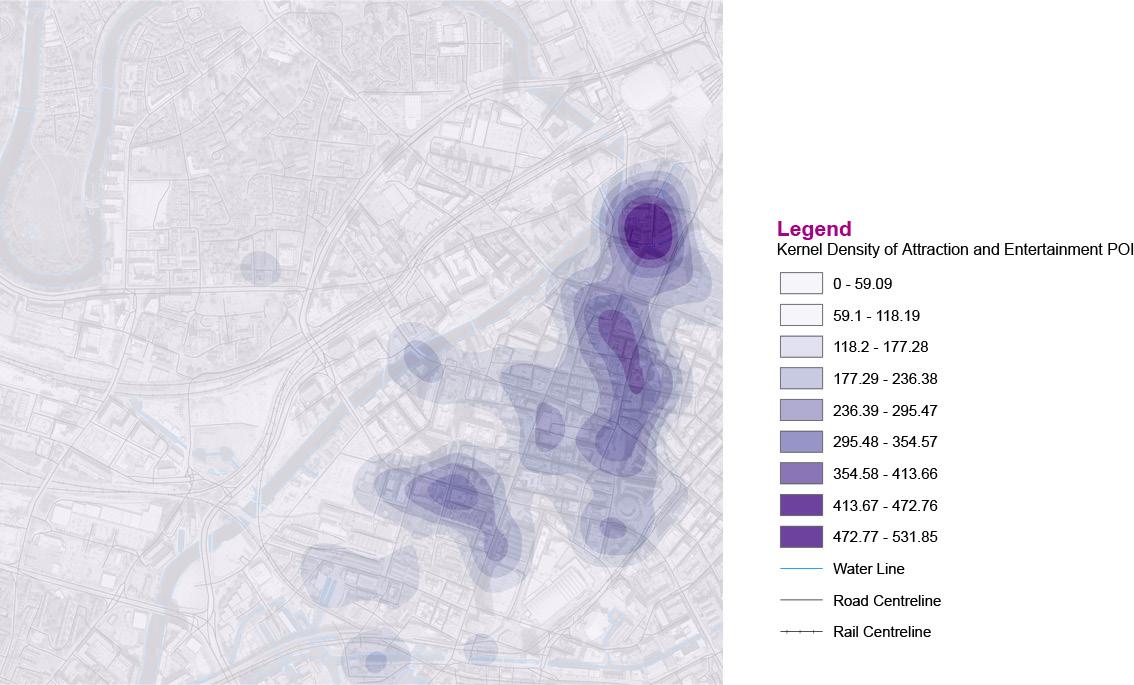

Figure 5.1-12 Kernel density of attractions and entertainment

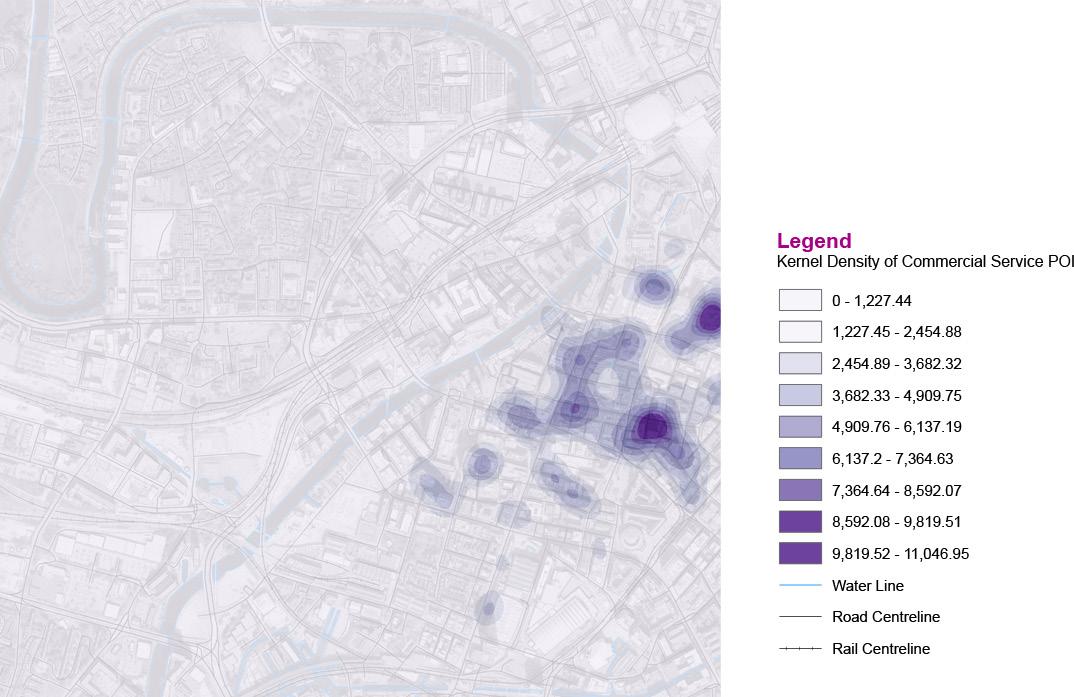

Figure 5.1-13 Kernel density of commercial service

Figure 5.2-1 Percentage of people aging 0-15

Figure 5.2-2 Percentage of people aging 16-34

Figure 5.2-3 Percentage of people aging 35-64

Figure 5.2-4 Percentage of people aging over 65

Figure 5.2-5 Population density

Figure 5.2-6 Employment rates

Figure 5.2-7 Accommodation types

Figure 5.2-8 Percentage of car ownership

Figure 5.2-9 Types of Internet users

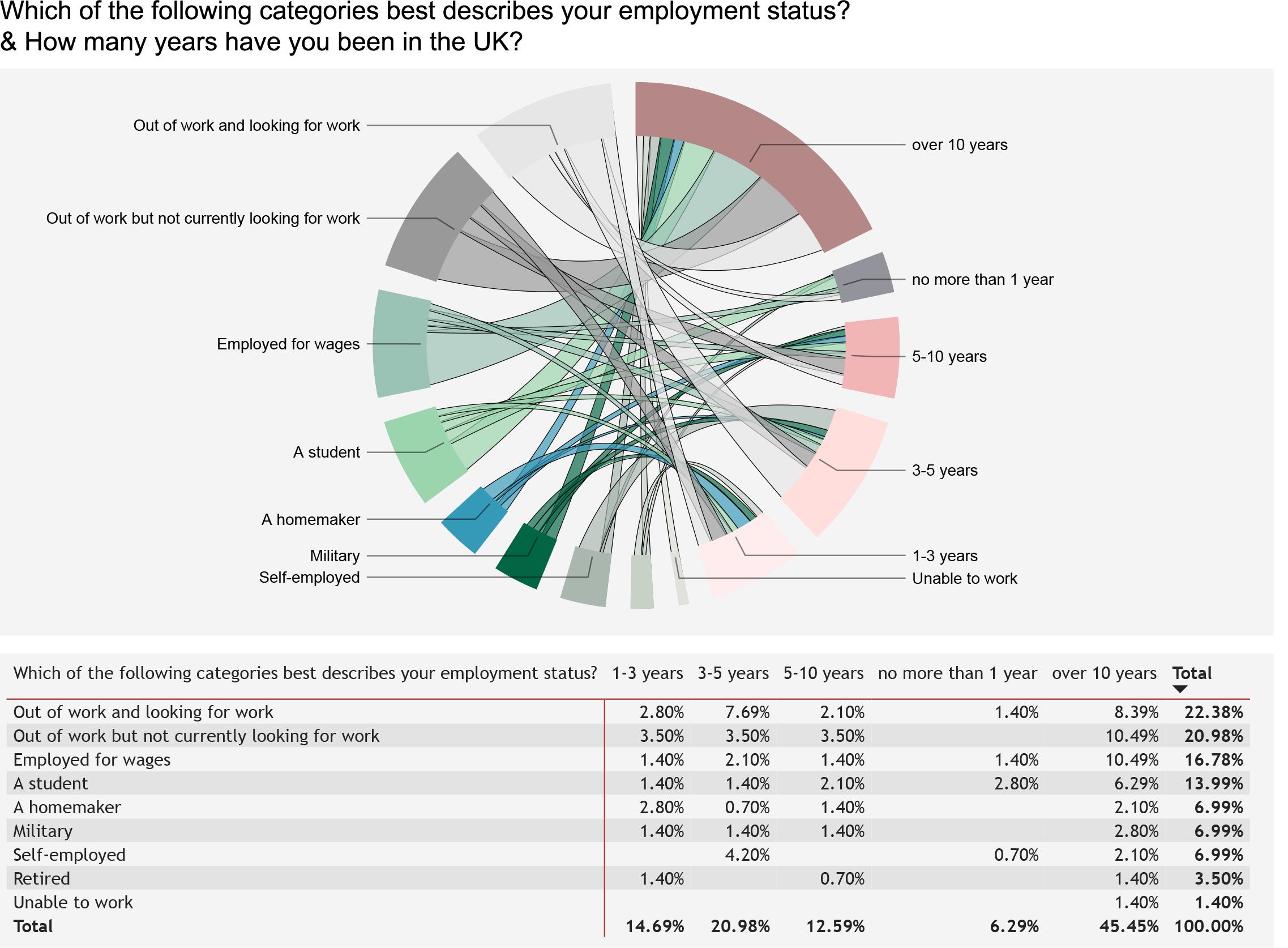

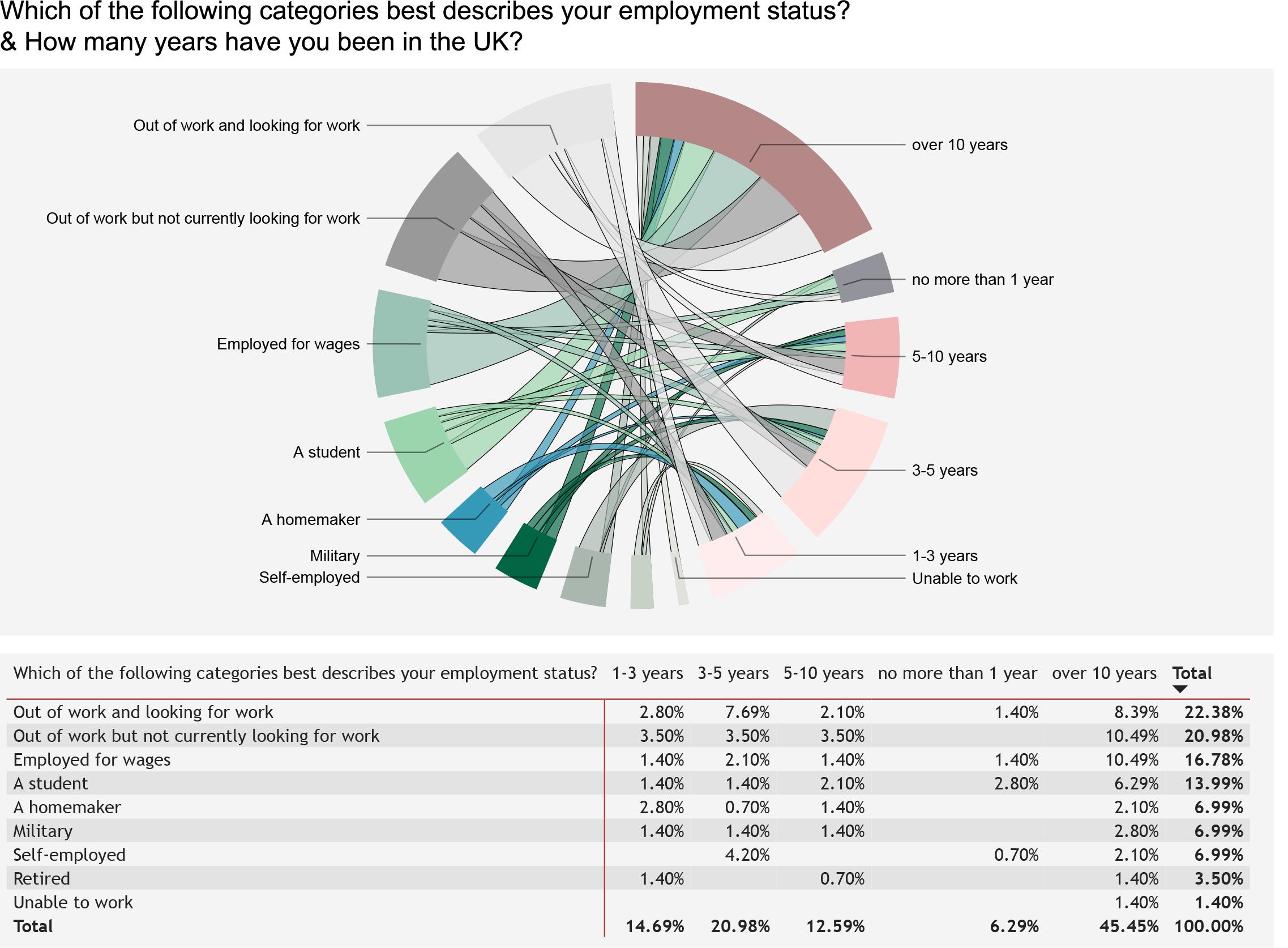

Figure 5.3-1 Results of questionnaires-Years being in the UK and employment status (with statistics)

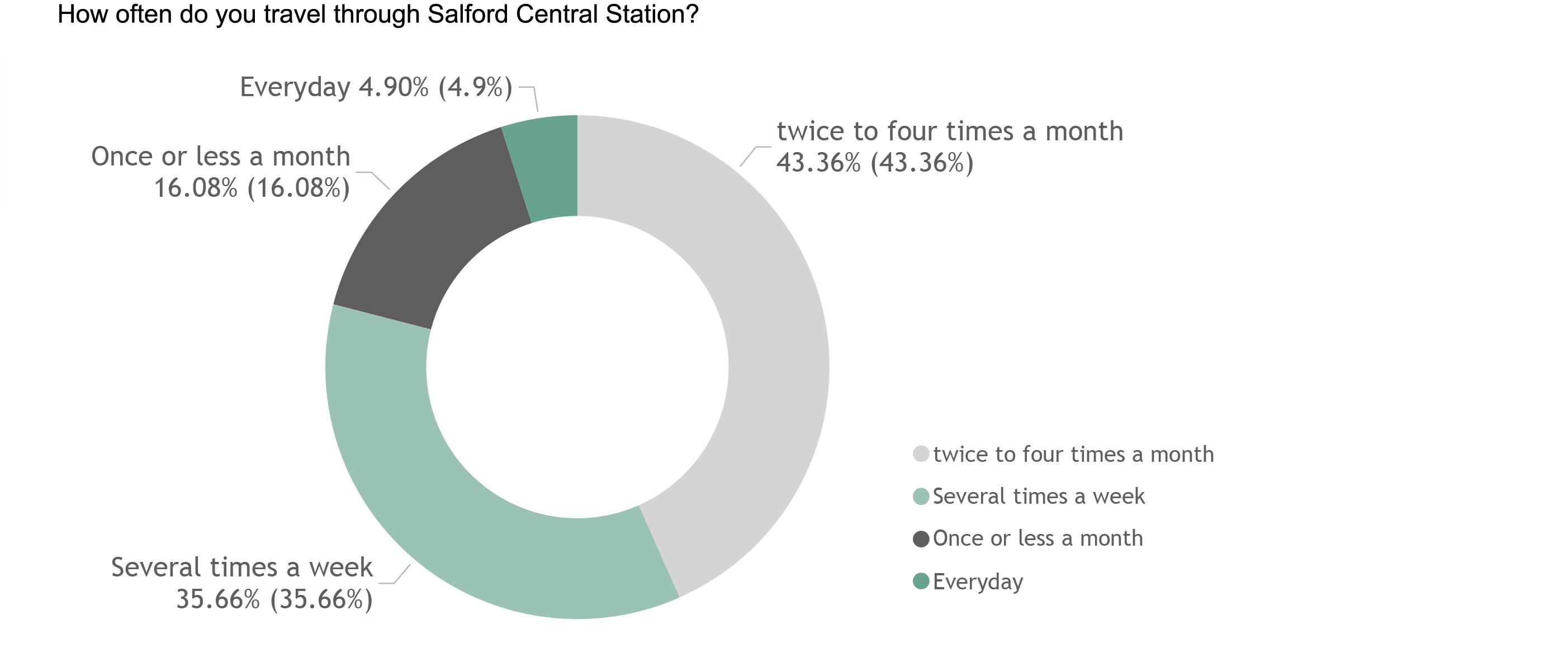

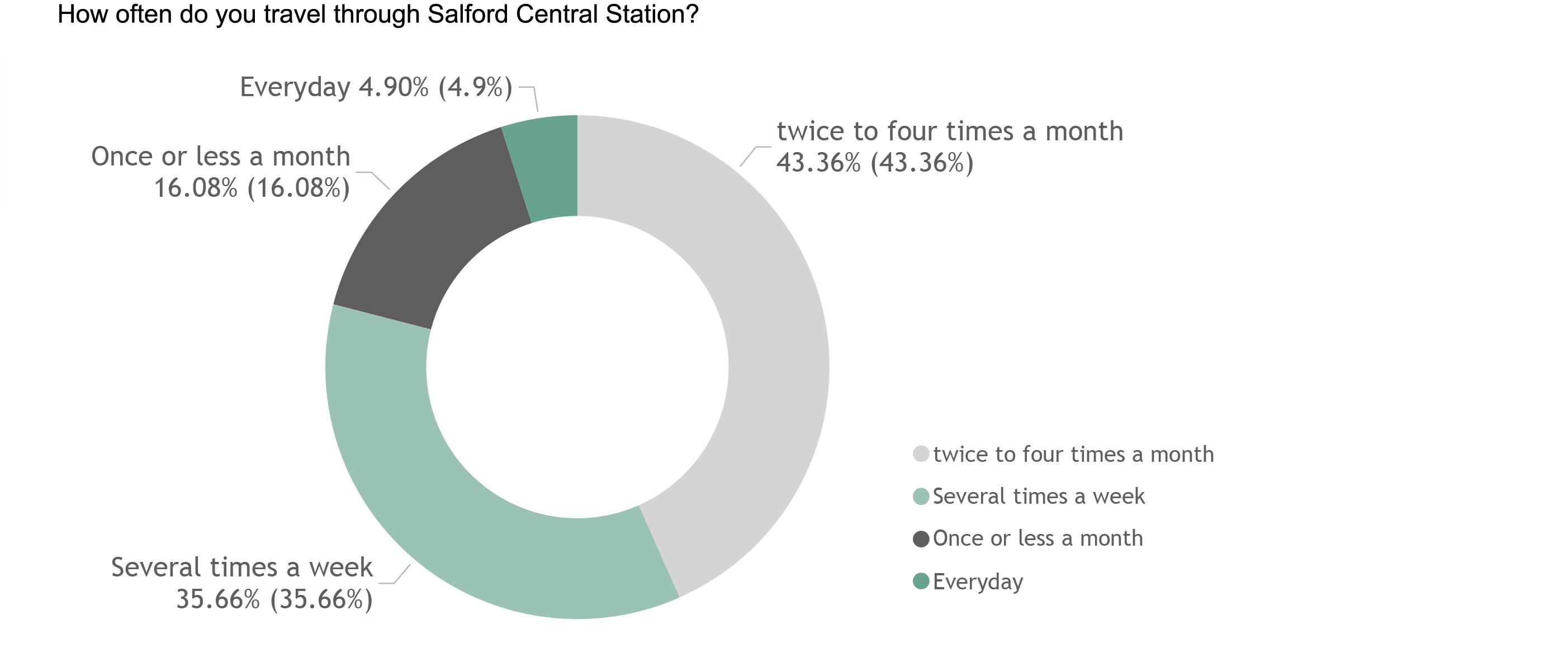

Figure 5.3-2 Results of questionnaires-Frequency traveling through Salford Central Station

Figure 5.3-3 Results of questionnaires-Familiarity with the site of and purpose of the train journey (with statistics)

Figure 5.3-4 Results of questionnaires-Ways to getting platform information

Figure 5.3-5 Results of questionnaires-Reasons people passing through Salford Central Station area

Figure 5.3-6 Results of questionnaires-Earlier arrival time at the station (with statistics)

Figure 5.3-7 Results of questionnaires-Connectivity to other areas, waiting areas, sense of security, clarity of instructions

Figure 5.3-8 Results of questionnaires-Opinions regarding facilities around the site

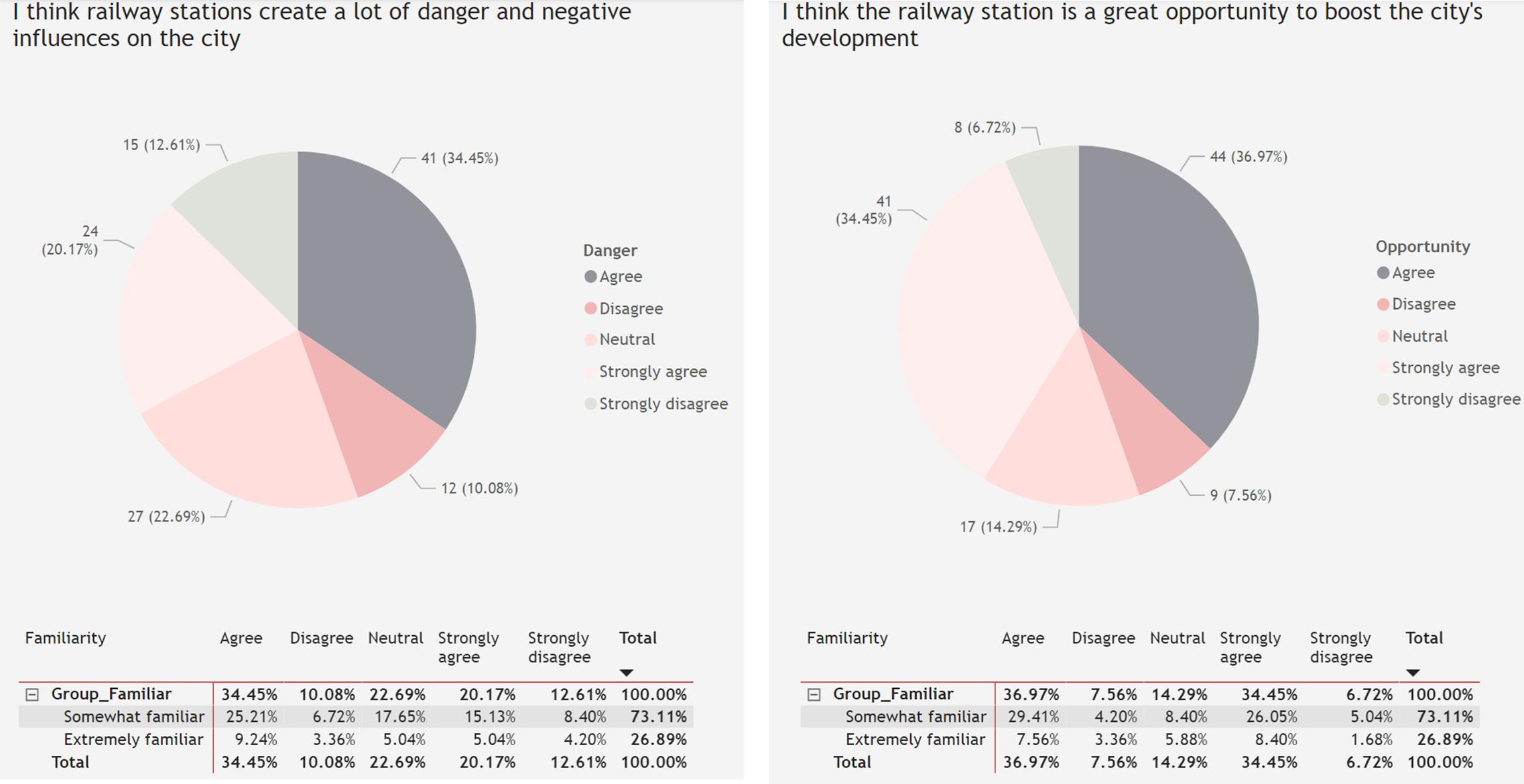

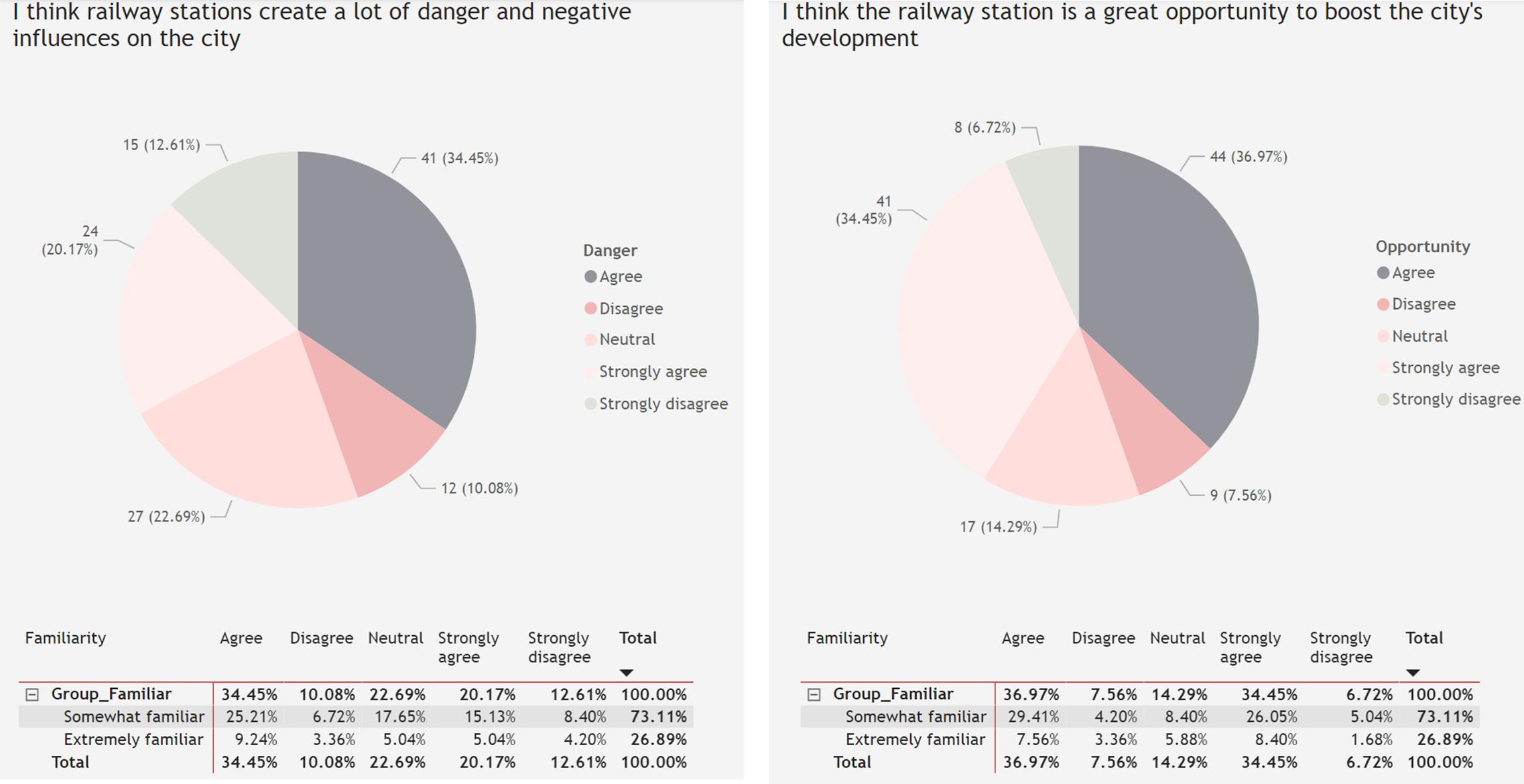

Figure 5.3-9 Results of questionnaires-Opinions about benefits and drawbacks of the train station (with statistics)

Figure 5.4.1-1 King’s Cross in 1899

Figure 5.4.1-2 King’s Cross’ inglorious history

Figure 5.4.1-3 Social relations of the subjects of the King’s Cross regeneration process

Figure 5.4.1-4 Masterplan for King’s Cross regeneration

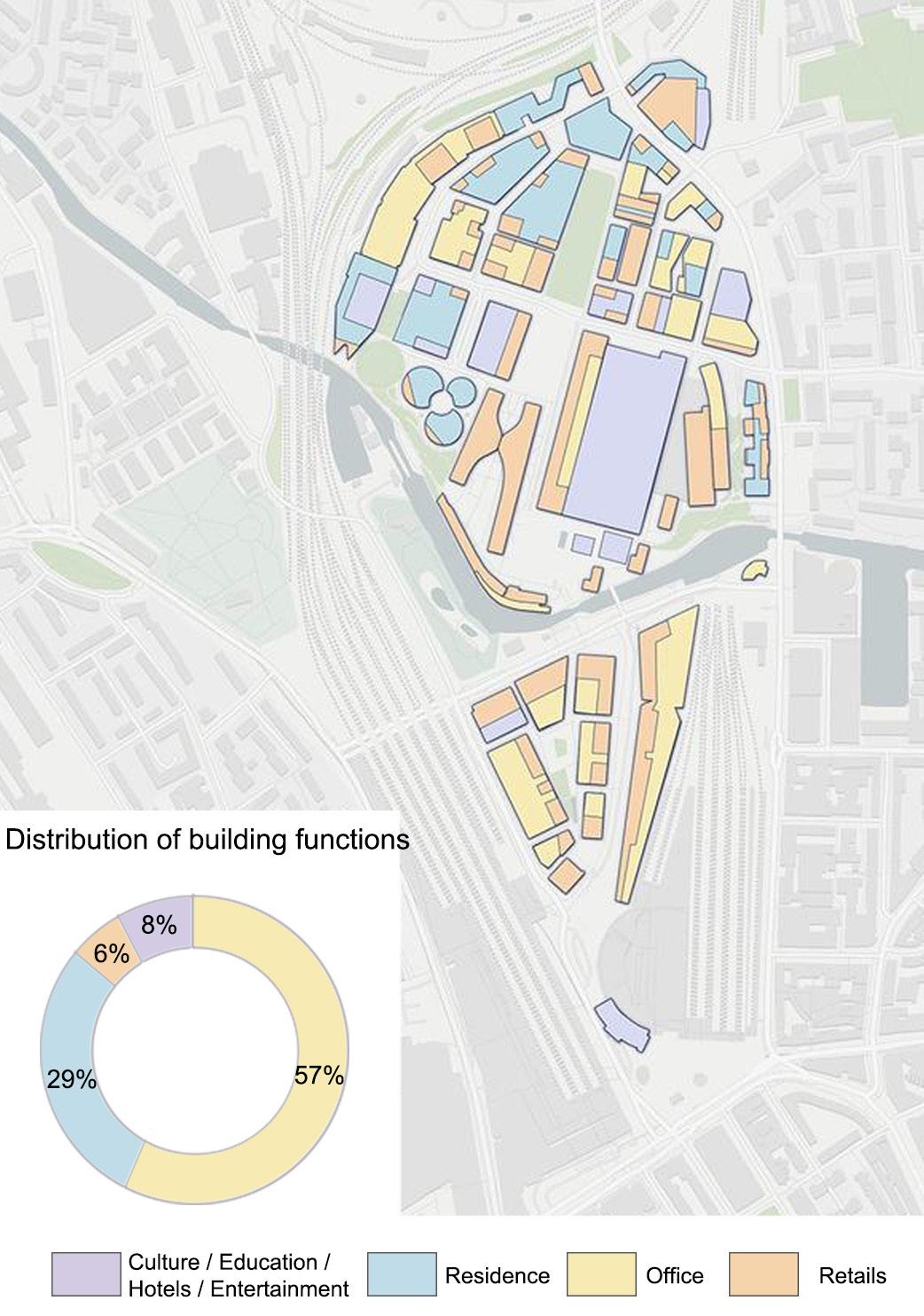

Figure 5.4.1-5 Distribution of building functions in King’s Cross area

Figure 5.4.1-6 Distribution of intellectual institutions and cultural institutions in the King’s Cross neighbourhood

Figure 5.4.1-7 Aerial view of King’s Cross

Figure 5.4.2-1 Visual store in the subway station

Figure 5.4.2-2 Office in the railway station

Figure 6.2-1 ‘Benefit-capital-power’ analytical framework

Figure 6.2-2 Benefit relationships among stakeholders

Figure 6.2-3 Ideal endpoint of the “game” among different subjects (from the perspective of urban regeneration and aspects of economic, cultural, political)

Figure 6.3-1 Negative comments for the previous Salford urban regeneration

Figure 6.4-1 Balance status in the “game” of Salford Central Station area urban regeneration

3 4 5 9 12 13 18 21 27 27 28 28 28 29 29 29 30 30 30 31 31 32 32 32 32 32 33 33 34 34 35 35 36 36 37 37 38 39 39 40 40 41 42 42 43 42 44 44 48 48 49 51 52

of Figures

List

Table 1 Participation and demands among different stakeholders Table 2 Features and proliferation approaches of different types of capital 48 49 viii vii

List of Tables

1. Introduction

As a type of urban infrastructure, railway stations often hold a special position in cities because of their feature in mobility, connecting the outside and inside of the city and gathering people from different places. Being the intersection of the railway and the city, the railway station is a place that travellers and residents are likely to pass through on arrival or departure. In the recent past, the railway station has changed from a simple transportation hub serving passengers to an urban place with considerable commercial, social and recreational attractions, serving a broad range of people from travellers to residents and even visitors passing by. It is recognized as a significant place in the city rather than a mere node in the transport network. Whether in North America as ‘Transit Oriented Development’ (TOD) or as the redevelopment of and around railway stations in Europe, the integration of transit infrastructure and land use development around railway stations is high on the agenda in large cities all over the world (Peek, Bertolini and De Jonge, 2006; QUINN, 2006). In addition, as the negative effects of urbanisation become more evident in cities, there is a growing awareness of the urban environmental degradation caused by cars, which is one reason why railway station-oriented urban regeneration is receiving considerable attention. Consequently, the great value of railway stations and their surroundings in urban regeneration should be acknowledged.

In traditional studies of railway station areas, scholars have focused on the value of such areas, exploring their spatial development and expansion. However, capital, social networks and residents’ views all play an influential role in the game of power and rights among various subjects in the space. The urban regeneration of the railway station area not only involves a change in the form of the physical space of the city but also a rational redistribution of functions and a reorganisation of the social relations in the station surroundings. To create a more humane and inclusive socio-spatial environment in opposition to the rising prioritisation of privatised and commodified public and social space, awareness of Lefebvre’s spatial thinking combined with knowledge of urban design is crucial. Therefore, the theory of spatial production will be introduced to focus on the relationship between society and people in railway station spaces and the relationship between spatial change and capital circulation. Investigating these relationships should greatly contribute to the elucidation of the processes and mechanisms involved in the spatial production of railway station areas.

INTRODUCTION

1 2 1

Introduction Chapter

Moreover, most of the railway station area regeneration projects that have been implemented are focused on metropolitan areas, such as London (Hongya, Yangxiaxi and Gang, 2015), Tokyo (Chorus and Bertolini, 2011) and Amsterdam (Triggianese and Berlingieri, 2014). Not much attention has been paid to the redevelopment of old railway stations in small- and medium-sized cities or satellite cities. As a small city which is affiliated with a large city in Greater Manchester, Salford is a city that grew rapidly in the 19th century as a result of the industrial boom. Located in the east of Salford (Figure 1-1), Salford Central Area is just across the River Irwell from Manchester city centre and has the advantage of railways, history, culture and an important gateway position (Figure 1-2). But a notable recession in the twentieth century and high unemployment, poverty and population loss in the area in the 1990s led the City Council to realise the importance of urban regeneration in the Salford Central Area. Despite more than a decade of trying and failing, the urban regeneration of the Salford Central Area is still being explored. Due to its unique location bordering Manchester, Salford Central Station, as an important element of the area’s infrastructure, seems to be a ideal place to achieve urban regeneration. Hence, this study employs the Salford Central station area as an empirical case to explore the role of railway stations and the application of space production theory in urban regeneration (especially in small to medium-sized cities).

The purpose of this study is to identify the role of railway stations in the urban regeneration of central areas in small to medium-sized cities and explore how spatial production theory can be applied to guide this process. The research

gaps defined in Chapter 3 will be filled by combining interpretations of spatial production theories with case studies of railway station area regeneration projects. Finally, we will derive some insights from the research in Salford that can be applied to other station areas with similar conditions. The subjects involved in the spatial production and social reconfiguration will be defined from the perspective of urban regeneration in railway station areas, and an analytical framework will be proposed that has three dimensions: economic, political and cultural.

The second chapter of this paper is a literature review that introduces theories such as transit-oriented development, the node-place model, the production of space, and the circuit of capital. The research gaps, aims, and questions are set out in chapter 3. In chapter 4, the specific area of the study area is defined, and the Salford Central Station area is investigated through mixed research methods including physical surveys, text analysis, questionnaires and case studies. The results of the survey are presented in chapter 5. Chapter 6 contains a discussion of and reflection on the findings obtained through the research methods. Chapter 7 presents the conclusion.

INTRODUCTION

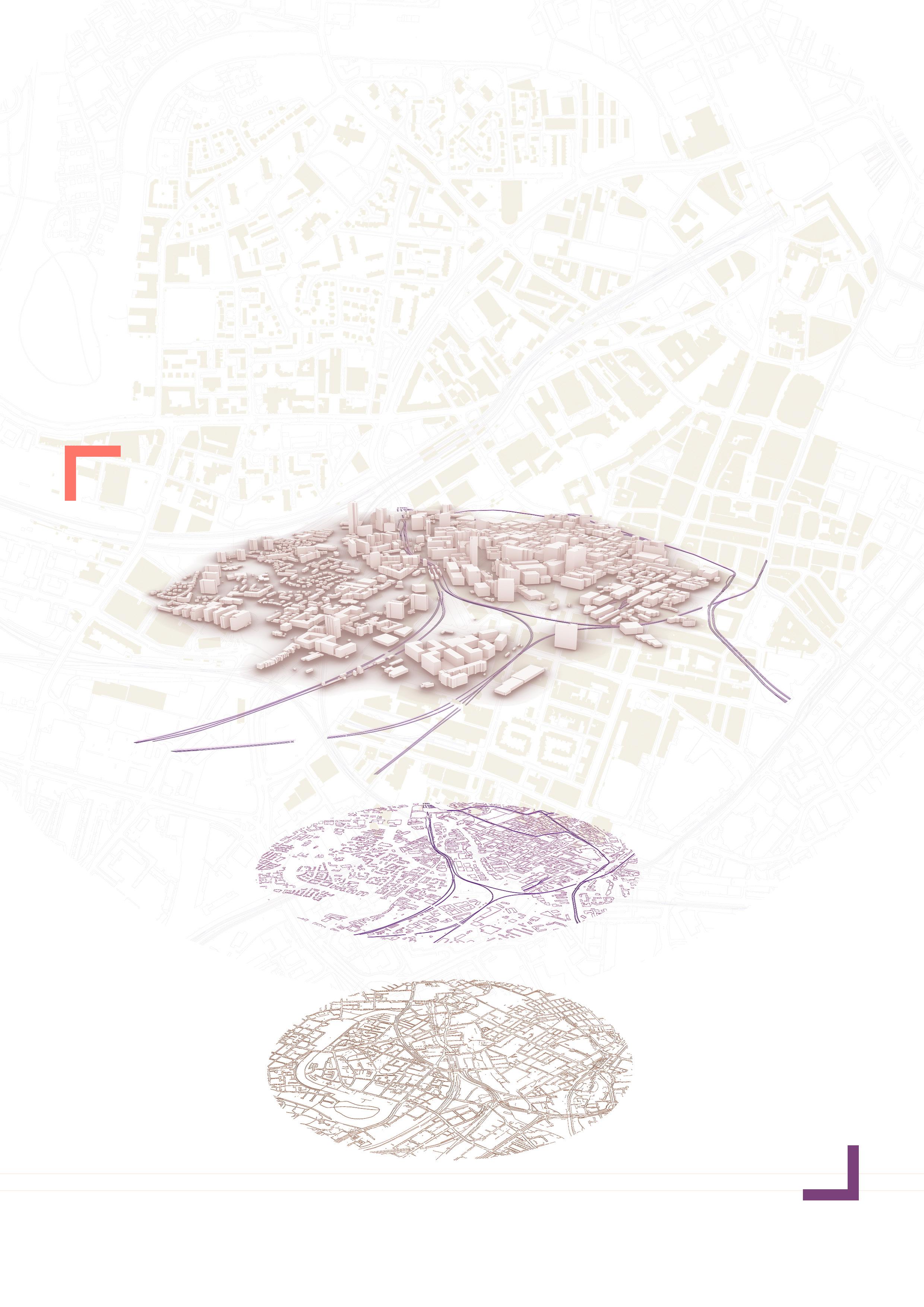

Figure 1-1. Context of Salford Central Area

Source: Reproduced by the author according to Salford Central Development Framework by Salford City Council

Figure 1-2. Location of Salford Central Area

4 3

Source: Salford City Council

6 5

Figure 1-3. Research process map

Literature Review

2.1 Research on urban regeneration driven by railway stations

2.2 Practice of station-oriented urban development based on theories

2.3 The ‘production of space’ theory

2.4 The practice of the production of space in urban studies

2. Literature Review

In this chapter, we will learn about theories associated with railway station-led urban development, including transit-oriented development (TOD) and the nodeplace model and explore the academic research on station-city development studies. Case studies on station-led urban revitalization will also be reviewed. We will then examine the research of other scholars on spatial and social issues by introducing Lefebvre’s “production of space” theory, which explores the philosophical and sociological aspects of space. Finally, we will analyse the application of research on theories connected to spatial production to the study of urban development and assess their connections to this study, thus contributing to the identification of research gaps and questions for the following chapter.

2.1 Research on urban regeneration driven by railway stations

Many urban redevelopment projects focusing on railway areas have succeeded one another over the past few decades (Bertolini, 1996; Bertolini, Curtis and Renne, 2012; Hongya, Yangxiaxi and Gang, 2015; de Wijs, Witte and Geertman, 2016; Diao, Zhu and Zhu, 2017; Yang and Song, 2021; Banerjee and Saha, 2022). To guarantee effective and liveable urban and metropolitan systems, the strategic role of these areas for other urban redevelopment initiatives has been emphasized. Numerous studies have described the role of railway stations in the enhancement of spaces around them (Triggianese and Cavallo, 2019), the maintenance of the urban context, the revitalization of cities (Namseoul Univirsity et al., 2013), the improvement of urban infrastructure (Mota and López, 2014), and the introduction of development opportunities to the housing market and urban economy (Liu and Alain, 2014).

TOD theory concerns major transport hubs and their surroundings. Highly influential on New Urbanism, TOD has been promoted for more than 20 years in cities throughout the world as a sustainable urban mobility strategy. By building mixed-use, dense and walkable communities around public transportation, TOD promotes the integration of land use and transportation (Calthorpe, 1993). Jamme et al. reviewed 25 years of literature on TOD in urban design, policy, planning and implementation (Jamme et al., 2019). They classified, coded and analyzed 344 TOD documents, finding that in addition to being a new mode

LITERATURE REVIEW

8 7

Chapter 2

of development and urbanism, TOD was frequently mentioned and applied theoretically in the planning of public transport hub areas, especially railway stations. Bertolini treated TOD as an approach to station area projects that goes beyond single locations and aims to re-centre whole urban zones around rail transportation and away from the vehicle (Bertolini, Curtis and Renne, 2012). Looking at how cities around the world have overcome obstacles to make TOD happen, Bertolini briefly summarised the transport and land use development challenges to TOD, such as the policies and the environmental specificities of a region. As indicated by Quinn (2006), TOD does not overcome existing “inherited” norms of behaviour. For new projects to be more sustainable than previous projects in their transportation usage, interventionist policy measures are required for the larger region, rather than only for the development itself.

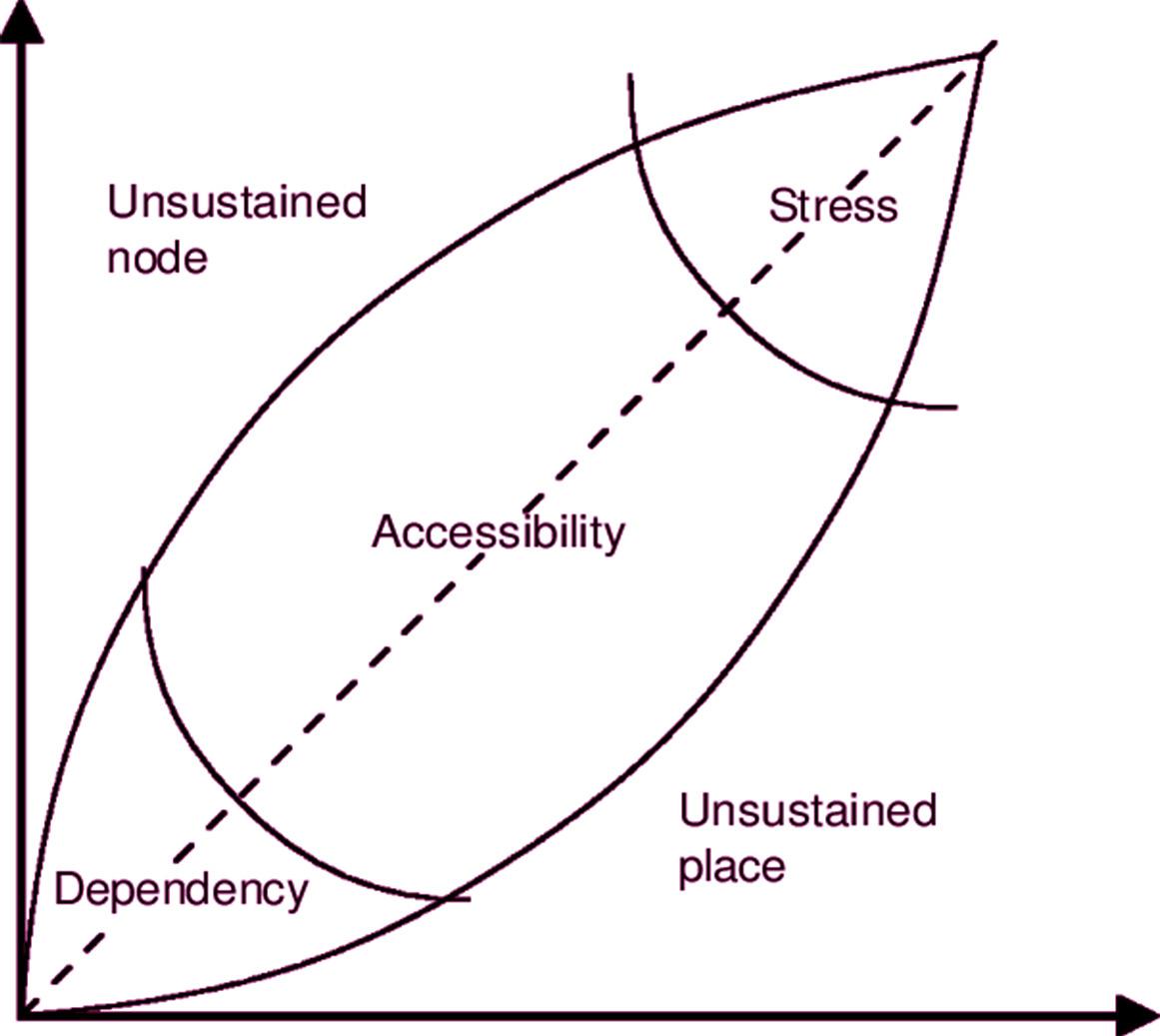

Another important theory of station areas-oriented urban development is Bertolini's node-place model (Figure 2.1-1). This analytical framework for assessing station areas in terms of transport and land use is part of the earliest TOD-influenced research on station areas. Bertolini assumed that increasing transportation at a station site (or its node-value) creates favourable circumstances for future intensification and diversity of activity there (Bertolini, 1996). Due to a rise in demand for connections, increased activity at a station site or an increase in its place value create advantages for additional infrastructure development (Peek, Bertolini and De Jonge, 2006). In addition, improving the transit provision (or the node value) of a site will, by increasing accessibility, provide circumstances favourable to the area's continued growth. Five different "typical" situations of a station area are identified in the node-place model. Depending on the specifics of the case, a station area may be located at a variety of tiers in the metropolitan region's node or location hierarchy (Bertolini, 1999; Chorus and Bertolini, 2011). The "balance" zones are located in the central part of the graph, where node and place coordinates are roughly equivalent. In addition to being a theoretical

model, subsequent academics have investigated the idea and development of the node-place model in reality by analysing real station areas and participants.

2.2 Practice of station-oriented urban development based on theories

Many published studies have built on these two theories and have developed them further. Vale complemented the node-place model with an assessment of the pedestrian connectivity of the Lisbon station area and introduced TOD to assess the station area in terms of land use, access and pedestrian conditions (Vale, 2015). Working with colleagues, he further studied the integration of land-use and transport in Lisbon, finding that a balanced station area does not necessarily add up to TOD (Vale, Viana and Pereira, 2018). This view was echoed by Zhang et al., who suggested that design should be used as a different dimension than node and location when evaluating station area TOD (Zhang, Marshall and Manley, 2019). In another recent study, Saha analysed the place value of railway stations and their neighbourhoods within the urban fabric of a city using the node-place model and discussed integrated transport and land use planning strategies as part of a broad concept of TOD (Banerjee and Saha, 2022).

Scholars have realized that railway stations have a unique advantage in urban regeneration due to the dynamism associated with their role in mobility. In a study of railway station redevelopment in Italy, Conticelli (2011) demonstrated that the redevelopment of railway station areas had the potential to increase the efficiency, liveability and sustainability of urban systems. She proposed an analysis and evaluation methodology to assess the potential for large railway station renewal and identified relevant causes and specific improvement measures, allowing for an integrated assessment of the benefits of policies and actions to achieve a better configuration of the developing urban environment (Conticelli, 2011). Zhang et al. presented some theories on the reuse of abandoned railways and railway stations with the aim of urban regeneration and explored ways to extend urban transformation and urban regeneration in surrounding communities by combining a variety of methods to stimulate urban regeneration (Zhang, Dai and Xia, 2020). With Zhangjiakou as an example, Zhang et al. investigated the practicality of railway-led urban development theory and enriched the literature on urban regeneration from the perspective of transportation infrastructure renewal. Several other scholars have assessed the development potential of regenerating urban railway station areas (Banerjee and Saha, 2022), explored regeneration methods (Namseoul Univirsity et al., 2013) and reflected on social relations by considering examples through the lens of station city theory (Ostanel, 2017;

To sum up, much previous research into railway station area development has concentrated on the place value of railway stations (Banerjee and Saha, 2022), but only a few studies have considered how to use that value – especially the value of old railway stations – to improve the safety and vitality of station areas.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Hickman et al., 2021).

Figure 2.1-1. Node –Place Model by Bertolini

10 9

Source: Bertolini, L., 1999. Spatial development patterns and public transport: the application of an analytical model in the Netherlands. Planning practice and research, 14(2), pp.199-210.

Hence, railway station area development remains severely under-researched, especially in terms of urban regeneration.

2.3 The ‘production of space’ theory

Before the 1970s, space was considered an abstract or physical term separate from social conceptions. However, Lefebvre formulated the concept of "(social) space as a (social) production" in his theory of the production of space; he argued that the relationship between space and society should be re-evaluated (Lefebvre, 1991). The "production of space", a concept of Marxist theory proposed by Lefebvre in his book The production of space, refers to the belief that urban planning and design should value the relationship between space and society. After identifying three elements necessary to the production of space, namely, spatial practices (perceived space), representations of space (conceived space) and spaces of representations (lived space), Lefebvre concluded that space is a tangible product and a tool for the survival of capitalism but also a process that includes social connections between individuals and objects in space (Lefebvre, 1991). Lefebvre regarded space as a product of social practice, not only as an item or commodity but also as the commodity created and the multiple interrelationships surrounding the production of that commodity in the same space and time (Lefebvre and Levich, 1987). According to this idea, space is the product of a succession of activities, and the results of these interactions and actions flow back into space, influencing the behaviour of space and the manner in which it is formed.

Influenced by Lefebvre's philosophical analysis of urban space, a wave of philosophers, sociologists and urban planners have conducted empirical studies and reflected further on urbanisation and the urban environment. Scholars like David Harvey (Harvey, 1978, 1989, 2001, 2012), Edward Soja (Soja, 1996, 2000) and Manuel Castells have refined the dialectical conception of space offered by Lefebvre. Working from Lefebvre’s idea of the trialectic, Soja proposed the notion of “thirdspace” (Figure 2.3-1). The “thirdspace” concept dismantled the duality of space and positioned the idea of space within the context of a “triadic dialectic” relationship (Soja, 1996; Soja and Pratt, 1998). Castells, another Marxist theorist who made an important contribution to the study of space theory, developed the concept of a “space of flows” (Castells, 1977). He combined it with Lefebvre’s idea of spatial production and unpacked the power relations between capital, power and property in a mobile space (Taylor and Derudder, 2022). With the impact of technology on society, Castells’ theory was further developed and continued to be of great value to our discussion of space, digital technology and social development today. Foucault provided an additional significant theoretical perspective on the formation of space. In contrast to the aforementioned researchers, who intellectualised space, he focused on the study of spatial rights and viewed space as a crucial place for the transformation of the discourse of power knowledge (Foucault, 2004; Dufty, 2008). Foucault created the concept of space as "the presence of place" by applying the spatialisation of knowledge and power to the examination of current culture (Foucault, 2001).

Figure

Source: Reproduced by the author according to Soja, E.W., 1998. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Capital & Class, 22(1), pp.137-139.

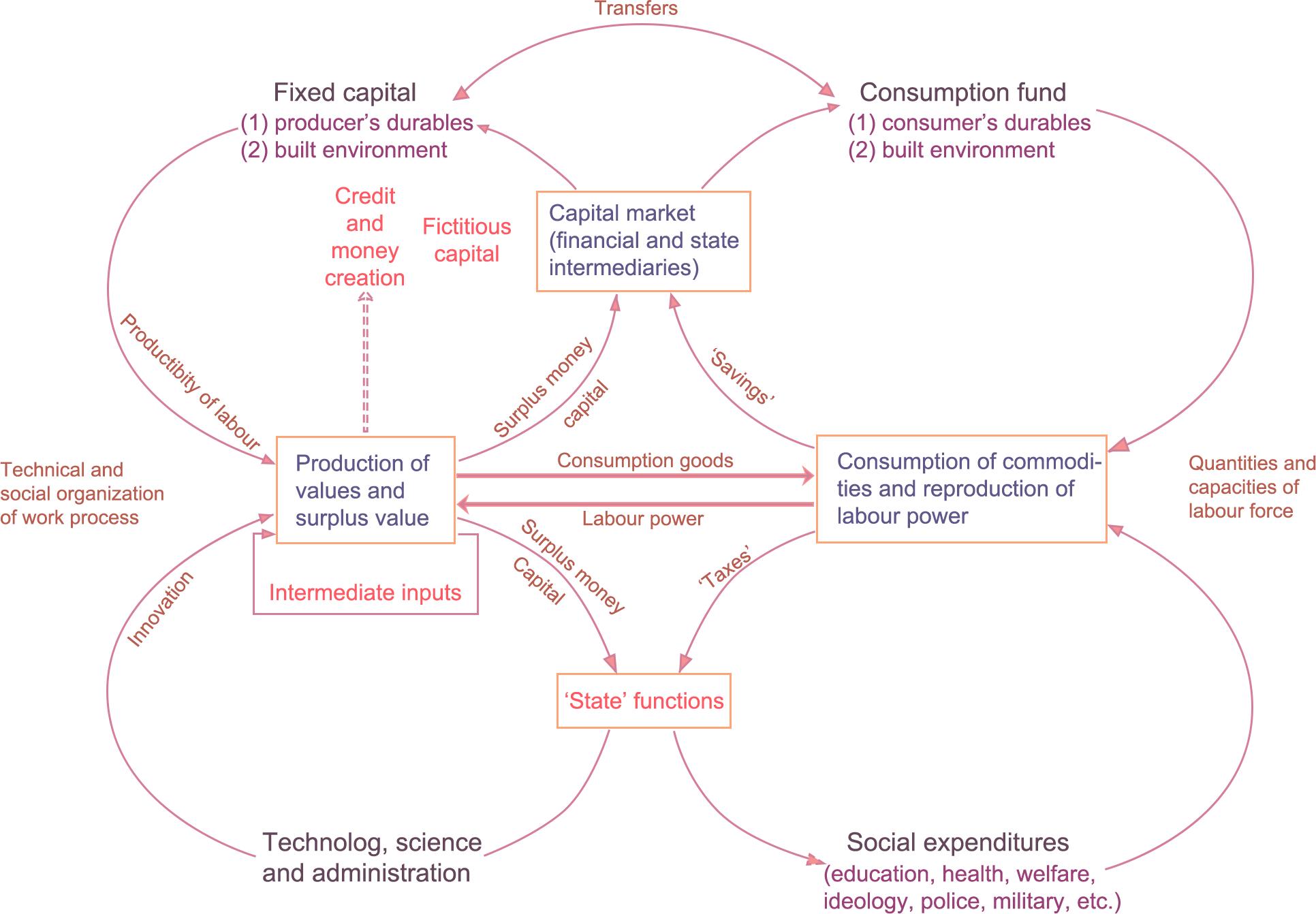

Harvey’s thinking on spatial production theory was significantly affected by Lefebvre, whose theories he expanded (Harvey, 2005). Although he inherited Lefebvre's distinction between “natural space” and “social space”, Harvey argued that the production of space arose with the emergence of capitalism and critiqued the production of space in terms of its operational mechanisms (Harvey, 1990, 2015). An in-depth analysis of spatial development was provided by Harvey and his student Smith, who noted that the imbalance in the production of man-made space is not only a geographical landscape inevitably caused by the process of capitalist accumulation, but also a way to repair the economic crisis caused by the over-accumulation of capital (Smith, 2010). Harvey explained systematically how capitalism survives through spatial production and proposed the theory of the "circuit of capital" (Figure 2.3-2), which constructed a dialectical relationship between capital and space at the macro level (Leary-Owhin and McCarthy, 2019). Neil Smith subsequently offered the “rent gap” theory for the second cycle of capital, resolving the issue of the mechanism and dynamics of capital investment in the built environment, which also provides a micro perspective on the “capital-space” dialectic (Smith, 1987).

2.4 The practice of the production of space in urban studies

As can be seen from section 2.3, the contributions of the philosophers, represented by Lefebvre, to the theory of the production of space have had a profound impact on urban design and urban planning. Merrifield pointed out that Lefebvre's theory is a formula designed to establish a framework for solving spatiallocal problems (Merrifield, 1993). In terms of empirical study, the generation of space in urbanisation has garnered a significant amount of attention, which demonstrates a "scaling impact." By analysing the application of the “production of space” theory in the city from multiple perspectives, Lee critically suggested that urban design theory should play a role in spatial production in the context of existing urban forms (Lee, 2022). Additionally, he argued that we need to generate an integrated vision of spatial production and encourage assemblage thinking in urban design. Similarly, Zieleniec critically reflected on the theory

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.3-1. Thirdspace theoretical framework by Soja

12 11

of the production of space and reconceptualised Lefebvre's spatial thinking by highlighting the complex elements involved in the city and how the “production of space” theory is practised in the field of urban planning and design (Zieleniec, 2018). Combining Lefebvre's theory of spatial production with sustainable urbanism, Wiedmann and Salama proposed three qualities that can maintain sustainable urban development: diversity that can respond to environmental challenges, efficiency rooted in ideology and identity that is recognised over time (Wiedmann and Salama, 2019). As shown, implementing a top-down plan to comprehensively address the relationship between rising global urbanisation and threatened habitats is an approach that must be questioned and evaluated in the context of social, economic and environmental issues.

Source: Reproduced by the author according to Aoyama, Y., Murphy, J. T., & Hanson, S. (2011). Circuits of capital. In Key concepts in economic geography (pp. 129-136). SAGE Publications Ltd, https://dx.doi. org/10.4135/9781446288078. n14

In addition to the scholars who study the production of space at the theoretical level of urban studies, other researchers have been addressing the practical aspects of urban design. Using a framework based on the concept of “production of space,” Zhou and Xiong (2019) explored the processes and mechanisms underlying the development of physical space in a type of urban neighbourhood called a “village resettlement community”. Zhou and Xiong analysed the functioning of physical space production and power-capital operation in the community using data from government institutions as well as the findings of questionnaires and semi-structured field interviews. They reproduced the community's social and

physical spaces, offering important advice on the establishment of new social interactions inside the old physical space in this type of community (Zhou and Xiong, 2019). Sacco et al. proposed a conceptual framework based on the spatial theories of Foucault and Lefebvre that focused on a specific dimension of urban regeneration, namely, the contribution of artistic and cultural activities to the creation of a welcoming urban public space (Sacco et al., 2019). In the framework of heterotopia, the authors claimed that instead of a top-down plan, arts- and culture-driven community development and engagement should be employed to drive urban regeneration. Another application of the “production of space” theory to urban regeneration can be found in Ng's study, which highlights the role of intellectuals in the reconfiguration of urban space. By examining two cases of urban regeneration in Hong Kong and Taipei from the perspective of “the production of space,” he developed a “social engineer-smuggler-expertscritical experts” schema to distinguish the roles of system-maintaining and system-transforming intellectuals in spatial production (Ng, 2014).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Figure 2.3-2. “Circuit of capital” framework

14 13

Research Gaps, Aims and Questions

3. Research Gaps, Aims and Questions

Analysis of the literature on Lefebvre's “production of space" theory and railway station areas demonstrates that urban planners and designers have become aware of the significance of theories relating to spatial production in urban design, even though little related research and practice have been performed during the last five years. As special elements of urban infrastructure with mobility features that can drive urban development, railway stations are recognised and researched extensively by scholars on a theoretical level. However, research gaps remain.

First, the majority of studies on spatial production theory in urban planning are performed from a political economy perspective, emphasising the role of power and capital in the production of space. Very little research relates spatial theory to physical space and applies it to urban design. In addition, empirical studies in the context of urban renewal are uncommon.

Second, in the context of urban regeneration, most studies focus on the renewal of the physical environment of urban areas, with less discussion of the social relationships behind urban infrastructure. Due to the position, historical significance and connection of railway station areas to inner-city neighbourhoods, it is insufficient to emphasize only the regeneration of the physical environment. We should introduce economic and cultural factors, taking into account the key elements involved in the regeneration process.

Third, there have been many studies on how railway station areas can contribute to urban development and urban regeneration, but most scholars have limited their attention to land values, heritage reuse and the impact of urban regeneration on the housing market. At the application level, there is a shortage of research into the spatial design of railway stations and their urban surroundings, and most of these studies focus on major metropolitan areas.

Therefore, this study aims to explore how the design of old railway station areas in small to medium-sized cities can drive the urban regeneration of surrounding areas in combination with the spatial production theory, with the chosen site being Salford Central Station. Informed by the preceding theory and practices, I define "spatial production" in this research as the process of

RESEARCH GAPS / AIMS / QUESTIONS

3 16 15

Chapter

creating, planning, using and modifying space as a commodity, which involves the creation of spatial entities and social interactions.

Hence, the main research question is: What contribution can railway station areas in small to medium-sized cities bring to the urban regeneration of their surrounding neighbourhoods from the perspective of the “production of space”?

The following sub-research questions support the main research question:

1. What are the implications of spatial production theory in the context of urban regeneration?

2. How does the renewal of a railway station lead to urban regeneration? What role does the "production of space" theory play in this?

3. Considering the spatial production theory and cases of railway stationoriented urban regeneration, what issues should be taken into account in designing a regeneration plan for the Salford Central Station area?

4. Does this research on Salford Central Station offer any insights for the regeneration of similar station areas? What are the possible drawbacks in future applications?

RESEARCH GAPS / AIMS / QUESTIONS

18 17

Figure 3-1. Manifesto

Study Area, Data and Methodology

4.1 Study area: Salford Central Railway Station area

4.2 Methods

4.3 Data collection and ethical considerations

4.4 Considerations on and limitations of site and method selection

4. Study Area, Data,

and Methodology

This research takes Salford, in Greater Manchester, as the object of empirical research, demonstrating the influential factors of spatial transformation at the micro level in the Salford railway station area and examining the process and manner of spatial production within the site. Physical surveys, text analysis, questionnaires and case studies are used to obtain primary and secondary data and information on the railway station. Then, from the standpoint of spatial production theory, these data are integrated with elements in the physical space to propose a plan for the regeneration of the station area. In this chapter, I will introduce the study area (Section 4.1). Then, the methods used in this study are described (Section 4.2). Thereafter, the process of data collecting and ethical issues are detailed. (Section 4.3). Finally, considerations on and limitations of the site and method selection are discussed (Section 4.4).

4.1 Study area: Salford Central Railway Station area

The Salford Central Area is situated on the eastern side of Salford, adjacent to Manchester City Centre, a place with a rich history and natural resources that provides multiple opportunities for the development of living, working, shopping and entertainment areas. If the location of the Salford Central area is defined according to the guidance provided by Salford City Council's planning department, the area forms the eastern extent of the city, adjacent to the Castlefield area and the Spinningfields commercial quarter (Figure 1-1, Figure 1-2). The Exchange Greengate area lies to the northeast and the University of Salford immediately to the west. In this study, we adopt the Salford Central Station as the main research site, examining the social and physical spaces surrounding it. Defining the physical extent of a railway station area is the foundation for analysing the social structural relationships within its boundaries and its spatial evolution. Analysis of several studies of the railway station area shows that, depending on the research perspective, some scholars identify the spatial extent of the station area by creating different buffers (del Castillo et al., 2014), others use the distance travelled in a certain period of time as the radius of the station area (Blainey, 2009), and still others derive the appropriate spatial scope for studying the influence of rail transport by analysing the local area (Martínez et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2022). Drawing on other researchers' methods for defining station areas and the context of Salford (Guerra, Cervero

STUDY AREA / DATA / METHDOLOGY

4 20 19

Chapter

and Tischler, 2012), this study identifies a 600m radius around Salford Central Station as the station's spatial scope and uses this area for its investigation into the notion of physical space (Figure 4.1-1).

urban regeneration plans. By collecting articles from newspapers and websites on the core area of Salford, we developed an understanding of public opinions and media coverage of the area's redevelopment.

4.2.2 Physical survey

With the help of satellite maps, I conducted several site studies around Salford Central Station in June and July 2022 and took photographs to document the area. Walking through the physical space of this research site allowed me to recognize the connections between the station and the surrounding area and the links with the city. With the permission of the station staff, I went into the waiting area of the station and onto the platforms to learn the functions of the station and observe the habits of the travellers. The spatial practices and spatial effects of Salford Central Station and the surrounding area were collected and compiled at the physical spatial level in preparation for empirical analysis.

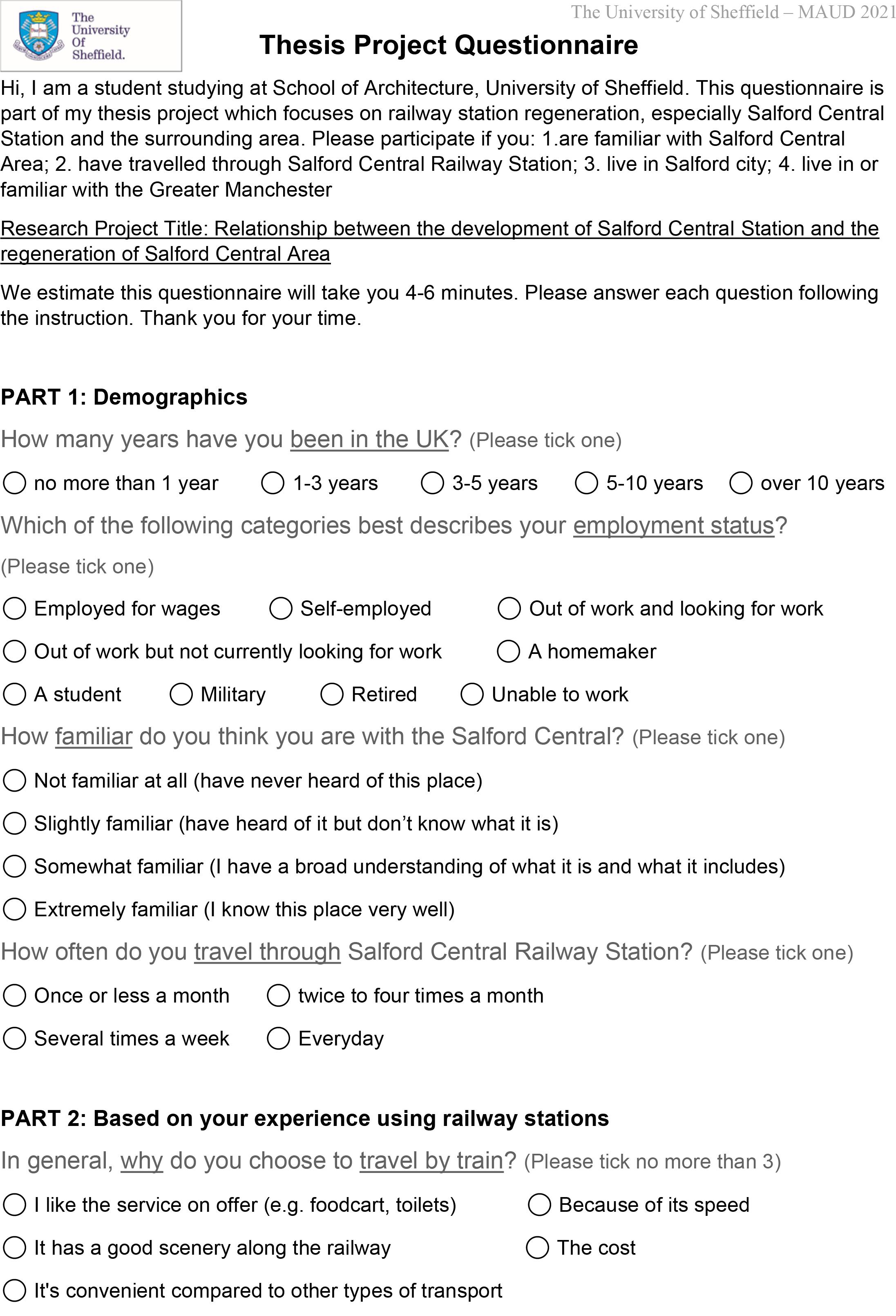

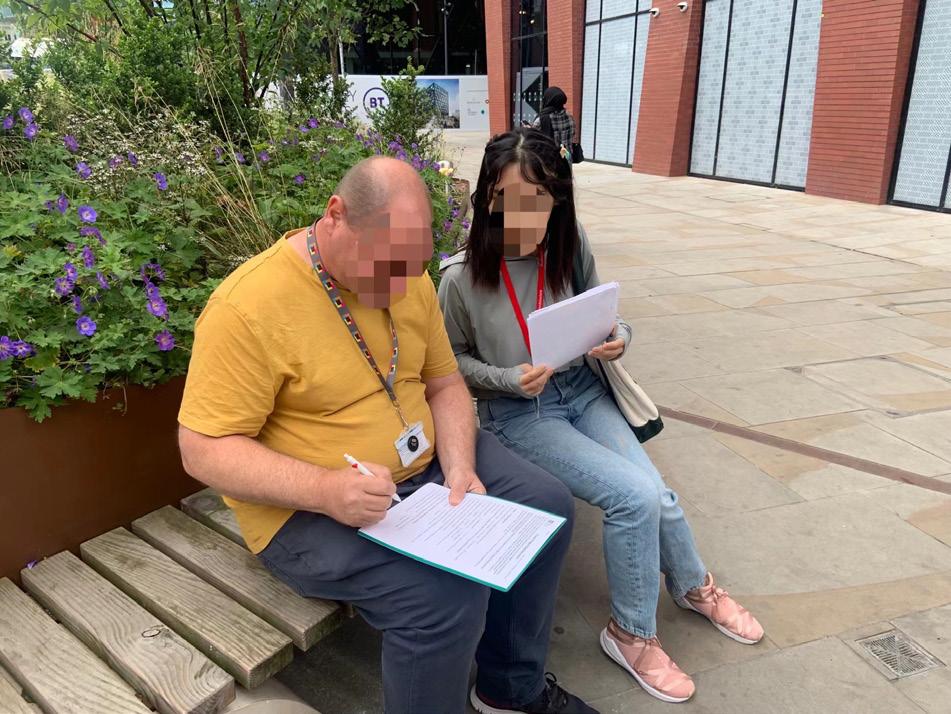

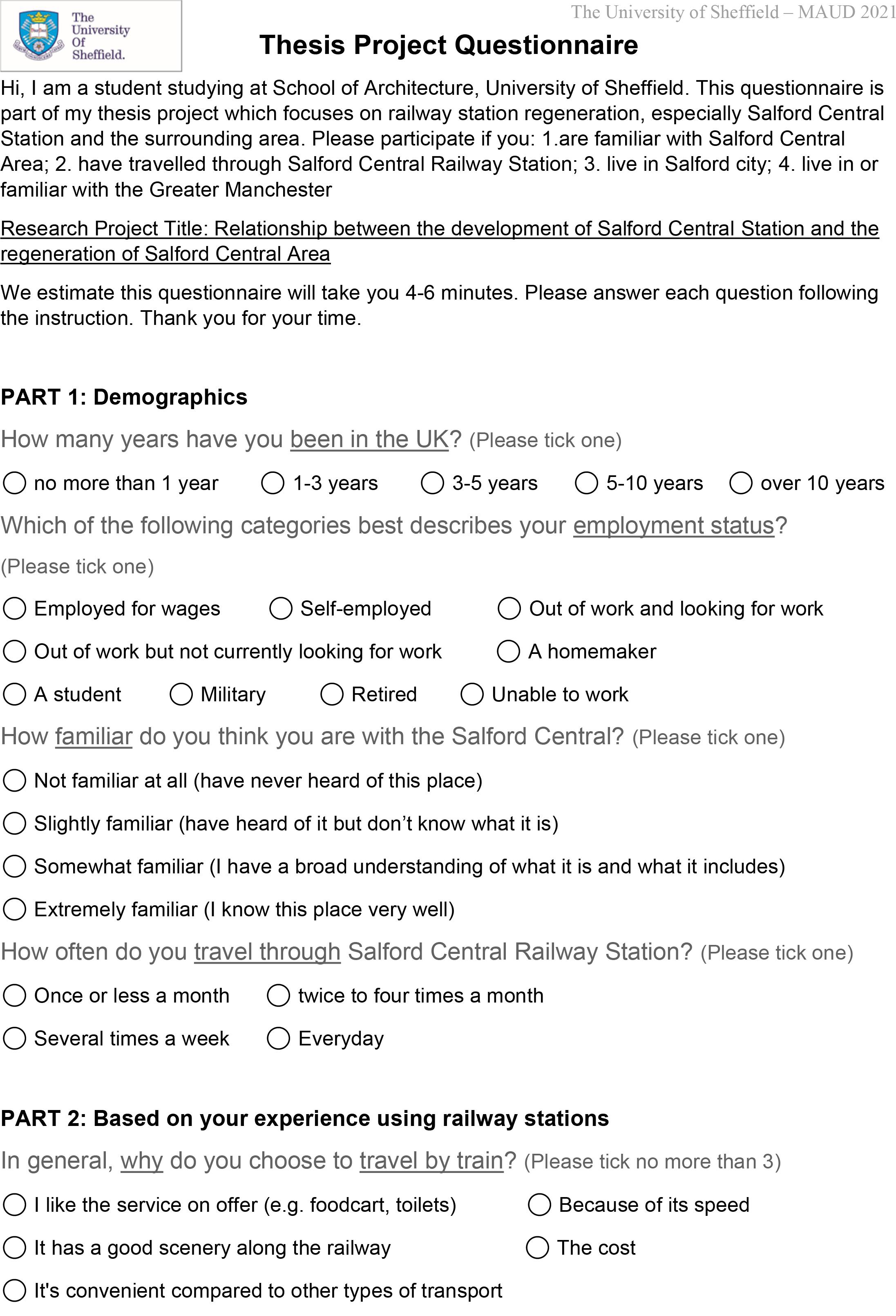

4.2.3 Questionnaires

According to the theory of the production of space, the social groups behind the space are the central element in the urban regeneration process as users and owners of power and capital. To acquire the perspectives and behaviour patterns of the key stakeholders in the study area, the author created and distributed a questionnaire. To increase the response rate and simplify the questionnaire, the majority of questions were multiple-choice, closed-ended questions (Murray, 1999). In the questionnaire, respondents were asked about their living circumstances, views of the station area and suggestions for the region's revitalization.

4.2 Methods

4.2.1 Text analysis

The textual analysis used in this research is primarily content analysis. The texts examined consist mostly of academic literature, essential plans, government documents, neighbourhood histories and relevant news items. The literature review on spatial production theory and the urban renewal of railway station areas has provided the foundation for this study by illuminating the application of the “production of space” theory in the field of urban design and the theoretical and practical advancements that have occurred in railway station-driven urban regeneration.

By examining plans of Manchester and Salford, the UK government's documents on urban regeneration and historical information about Salford, we gained a comprehensive understanding of the historical, social, cultural and economic background of the Salford Central Area and previously implemented

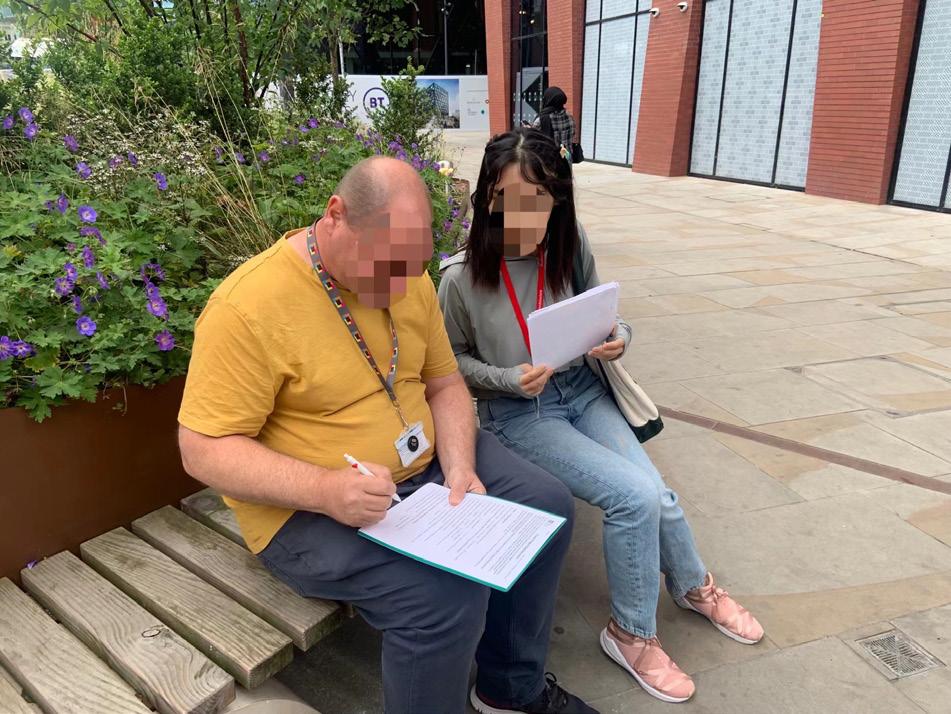

I contacted Northern Rail, the company that administers Salford Central Station, and the Angel Centre, a nearby community centre for permission, and then delivered the questionnaires on the 13th and 26th of July 2022 in the area surrounding Salford Central Station. The physical questionnaire was sent to office workers, residents, train station employees, neighbouring shop owners and frequent passersby in the neighbourhood of Salford Central Station. Due to the limited answers obtained from the physical questionnaire, the author utilised Google Form's ability to triage participants by location and distributed a digital version of the questionnaire through a few Facebook groups associated with this area.

4.2.4 Case study

Case studies illustrate an in-depth knowledge of a specific subject, aid in the comprehension of the context relevant to it and make possible comparisons with similar types of studies. After reviewing a range of methods for selecting cases (Seawright and Gerring, 2008), it seemed most appropriate to examine the development of the King's Cross station area in London to gather context relevant to the study of the Salford Central Station area. Although the area was developed earlier than Salford Central Station and the spatial scale was

STUDY AREA / DATA / METHDOLOGY

22 21

Figure 4.1-1. Research physical space and social space scope

greater, the King’s Cross redevelopment plan had a significant impact on other cases considered in this paper. In addition, the social relations involved in the regeneration of the King's Cross area are more complicated than those in Salford, so it is suitable for use in the analysis to inspire this study.

Given that technological developments may result in subtle changes in the spatial social relations at Salford Central Station, I also investigated the use of new technologies in the transformation of the transport hub, such as visual shopping walls, station office suites and integrated transport apps, in addition to the case mentioned above. The new development possibilities for the station that result from the advent of new technologies will be considered in the development strategies I propose for the Salford Central Station area.

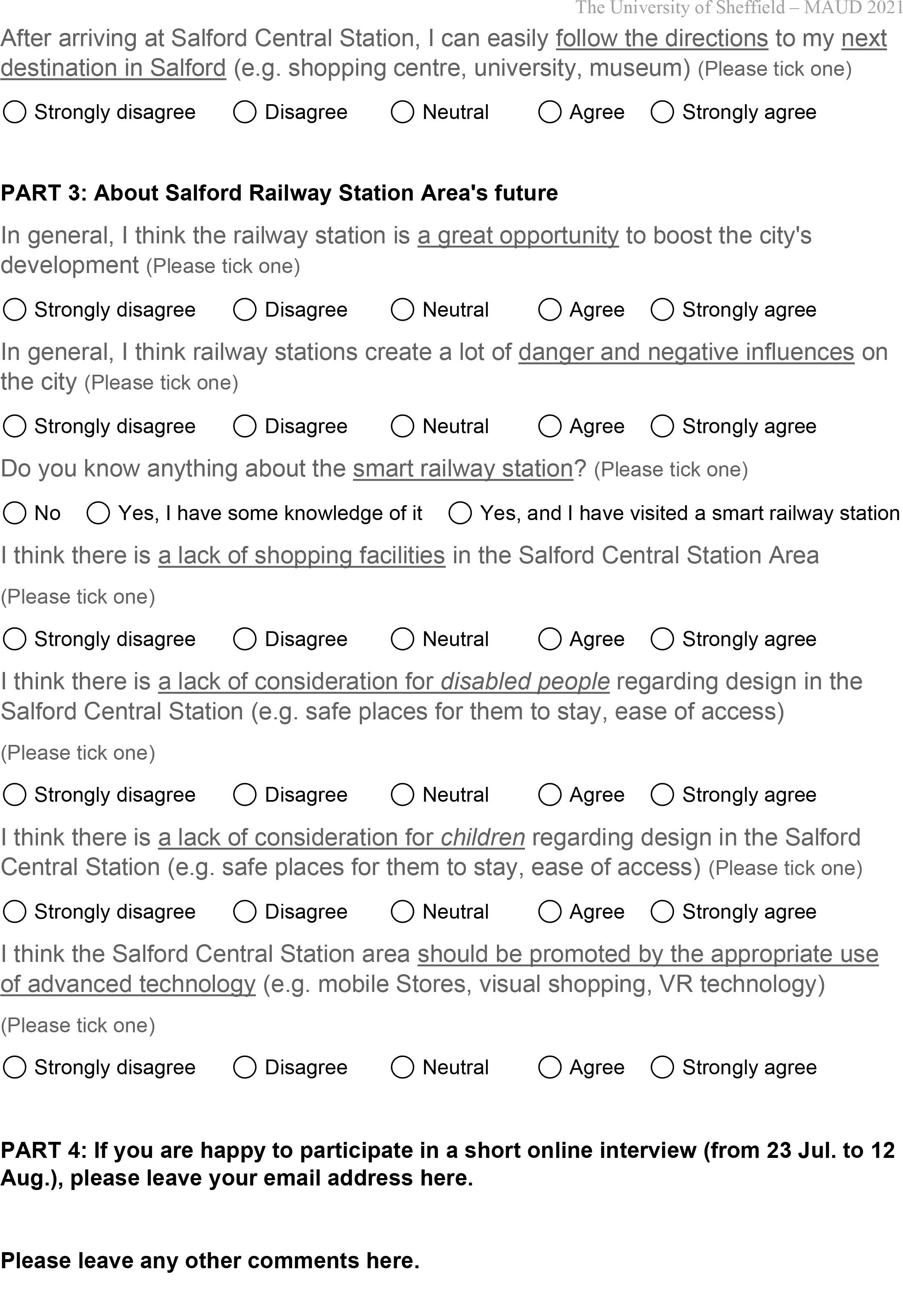

4.3 Data collection and ethical considerations

The data collected for this study at the physical spatial level includes both building data and road data. Building data include building boundaries, building features and building heights. The road data include road centrelines and cross sections of Chapel Street, Gore Street and New Bailey Street. This spatial data was mainly obtained from EDINA Digimap's Ordnance Survey. As the building data provided in Digimap do not include building function or road cross-sections, these two datasets were supplemented by the findings from field studies and data from Google Maps. High-resolution satellite imagery obtained from Google Earth was used in the physical survey and to examine the construction around the station.

Information on the social relations and willingness of the residents was obtained through government census data and the analysis of the questionnaires. The author obtained data on population density, economic activity, car availability, internet usage and age distribution in the study area through the Society Data feature in EDINA Digimap. In addition, the locations of public transport stations, commercial facilities, social institutions and entertainment facilities were obtained through Point of Interest feature in Digimap. Downloading these data and importing them into GIS software for Kernel Density analysis and processing, helped me to understand the social information in the study area, thus laying the foundation for a theoretical framework incorporating spatial production theory and focusing on the Salford Central Station area. The user habits and preferences of key stakeholders were obtained through the paper and online questionnaires. The answers collected were captured in a Google Form and statistically tabulated using an Excel spreadsheet. Some of the answers had clear trends that could provide spatial design insights for the urban regeneration of the Salford Central Station area.

Before the participants filled out the questionnaires, they were given information sheets and consent forms to ensure that they understood the purpose of the study and the meaning of their engagement. The key stakeholders' information

gathered via the questionnaire will be kept confidential by the author and the author's institution and will only be utilised in subsequent studies with the permission of the respondents.

The OS data downloaded using Digimap was provided by EDINA to the author's educational institution for use in this study only. The data used in the analysis of social relations, such as demographic data, were obtained from the Office for National Statistics census database, which the author and the educational institution have the right to use and will not disclose.

4.4 Considerations on and limitations of site and method selection

While researching the relevant literature, it was found that some studies for railway station locations gathered real-time traffic data and analysed it using software such as GIS. However, owing to data gathering restrictions, it was not possible to do real-time traffic calculations for the studied site, and an objective reference indication for traffic density was absent. As theories of spatial production encompass power and capital, urban studies scholars usually interview experts and residents to acquire unpublished information and explore the positions and behaviours of different actors. The author contacted Salford City Council, the planning department and the transport department but received no authorization for interviews or information regarding current plans. Thus, the relevant plans referenced in this paper may no longer apply to the current situation. The questionnaire sample size was small, and the online survey lacked participant identification. Given that questionnaire participants may cheat due to situational conditions, variables and spurious concerns should be addressed.

The generalisability of the case study is subject to certain limitations. London's status as a “world-class city” and its complexity suggest that the conclusions drawn from King's Cross may not be fully applicable to other cities in the UK, let alone small cities such as Salford. However, because of the significant impact of the King's Cross station regeneration project on London, its influence on redevelopment plans elsewhere, the complexity of the project and the diversity of interests involved, it may provide guidance for future practice in other cities. From this perspective, King's Cross is considered a relevant case study.

STUDY AREA / DATA / METHDOLOGY

24 23

Explorations

5.1 Physical space findings

5.2 Social space findings

5.3 Questionnaire findings

5.4 Case study

5. Explorations

In this chapter, we first analyse the physical-spatial results of the information obtained from the field study, OS Digimap and the superordinate planning documents relevant to the surroundings of Salford Central Station. Then, the demographics of the area are analysed (e.g. age distribution, educational attainment and employment rates) using the data collected from the government and Digimap websites. Subsequently, the questionnaire results are presented to highlight station users' habits and key stakeholders' demands for this area’s renewal. Finally, the changes in physical space and social relations resulting from the urban renewal project in the London King's Cross station area are examined. The advanced technologies used in the renovation of stations are also mentioned to explore possibilities for Salford Central Station.

5.1 Physical space findings

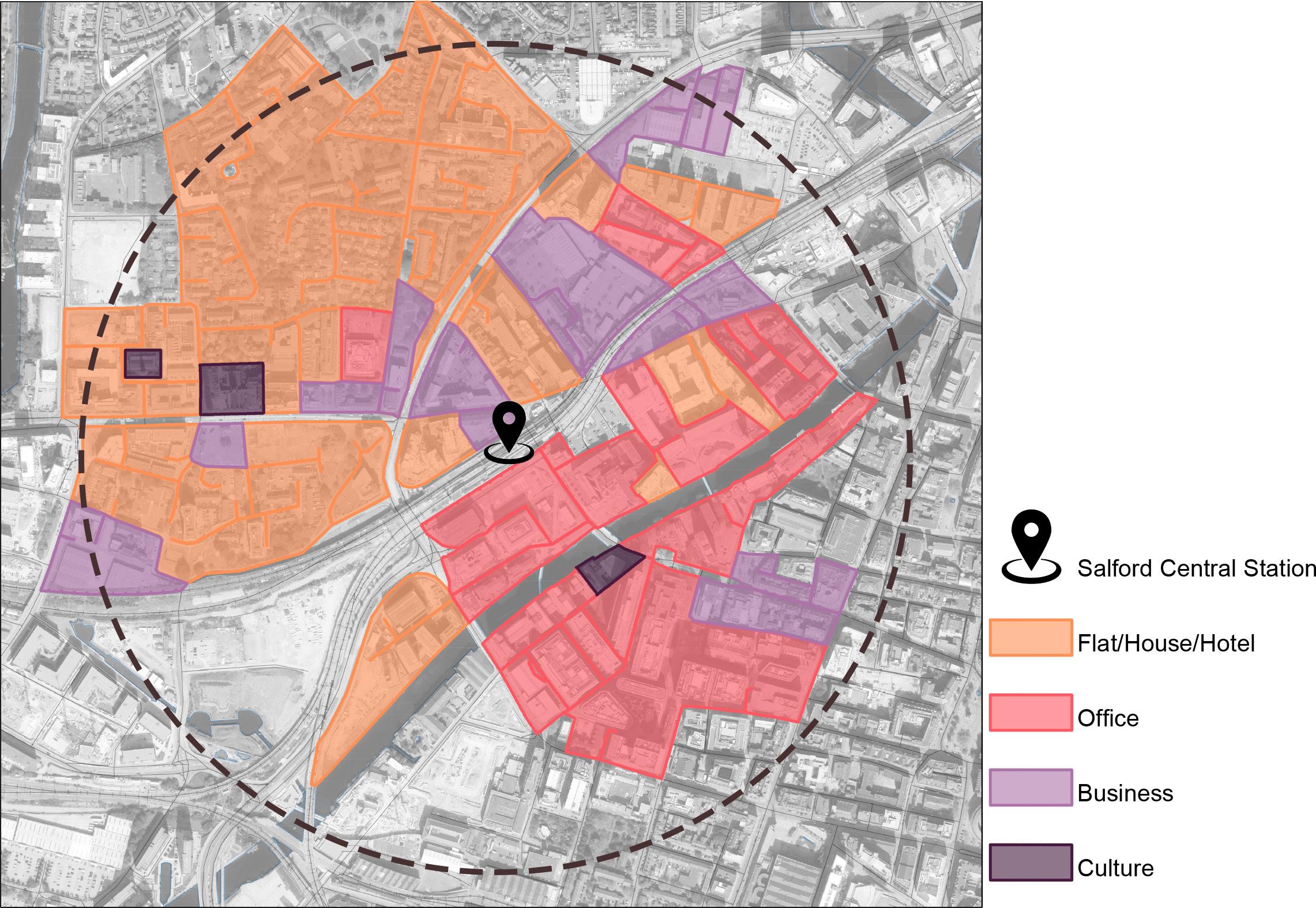

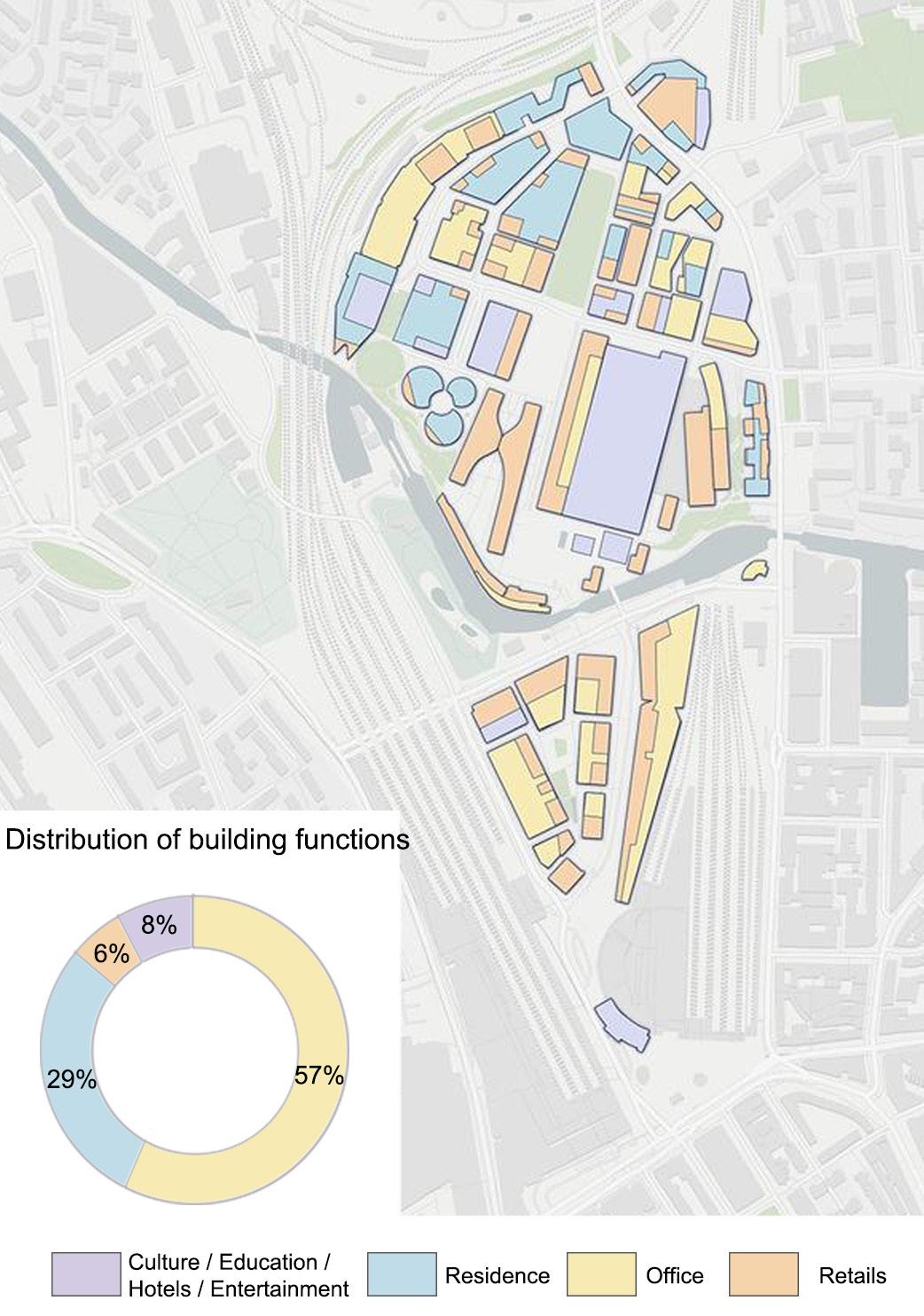

Field survey observations indicate that Salford Central Station is busy between 7 and 9 am and 5 and 7 pm, especially on weekdays. During lunchtime, although there are many people around the station, they visit the area to eat in nearby restaurants or relax rather than travel by train. To find out how Salford Central Station is used as a transport hub, we entered the station and took pictures with the permission of the station staff. Although there is a bicycle parking area and ramp access (Figure 5.1-1), they are not used much due to neglect, and the slope of the ramp is too steep for wheelchair users to use (Figure 5.1-2). There is a large amount of public space inside the station, but the only commercial facility is a food cart (Figure 5.1-3). Although there is no waiting area inside the station, a small square outside the station has many public seating areas (Figure 5.1-4). Combining on-site observations with information from Google Maps, we found that most of the buildings around Salford station contain office space, accommodations and commercial space (Figure 5.1-5). There are four large car parks (Figure 5.1-6) within a 600m radius of the station, of which three are adjacent to the station and office buildings. Salford Central Station is situated across the River Irwell from Manchester city centre and is easily accessible by a bridge. There are many flats and offices on both sides of the river, with a few fast-food chains and convenient services situated on the ground floor of the offices (Figure 5.1-7).

EXPLORATIONS

5 26 25

Chapter

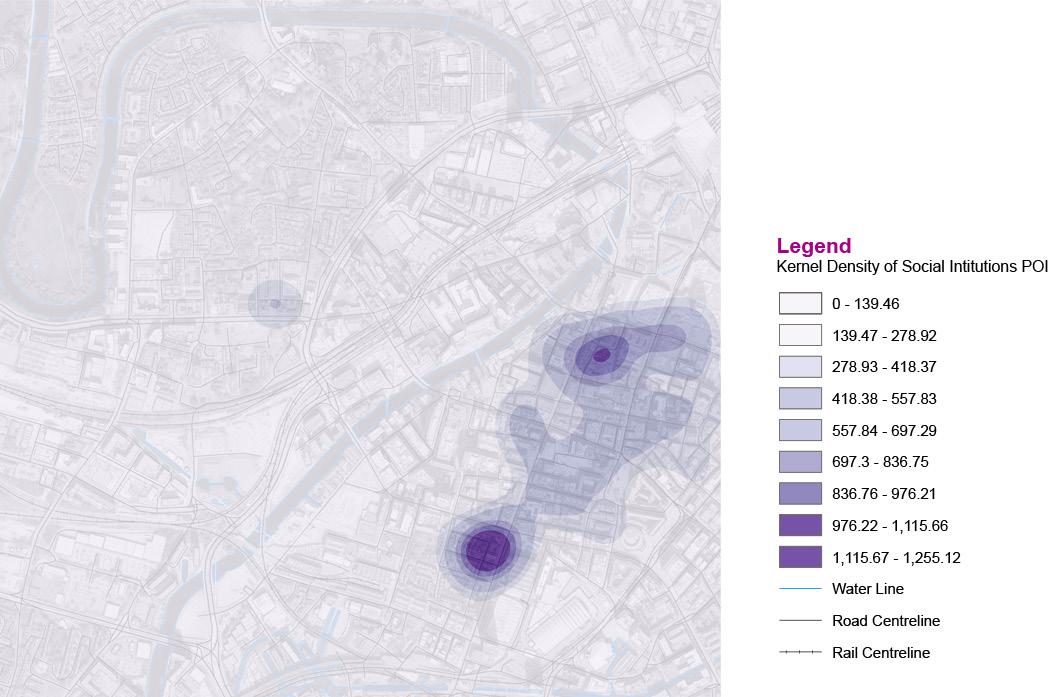

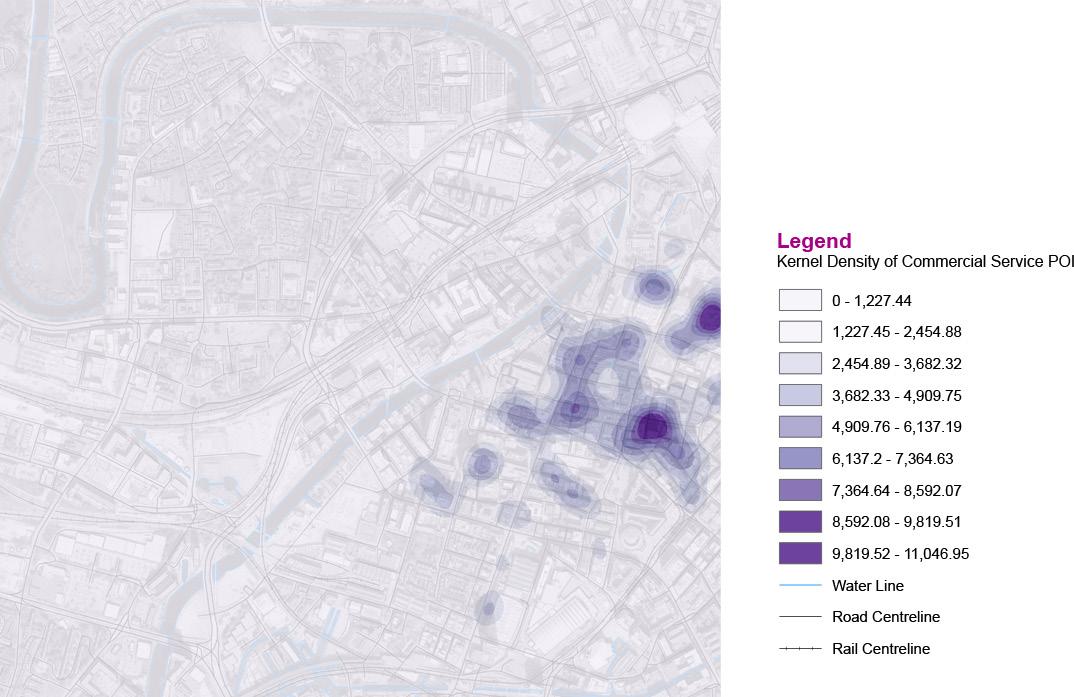

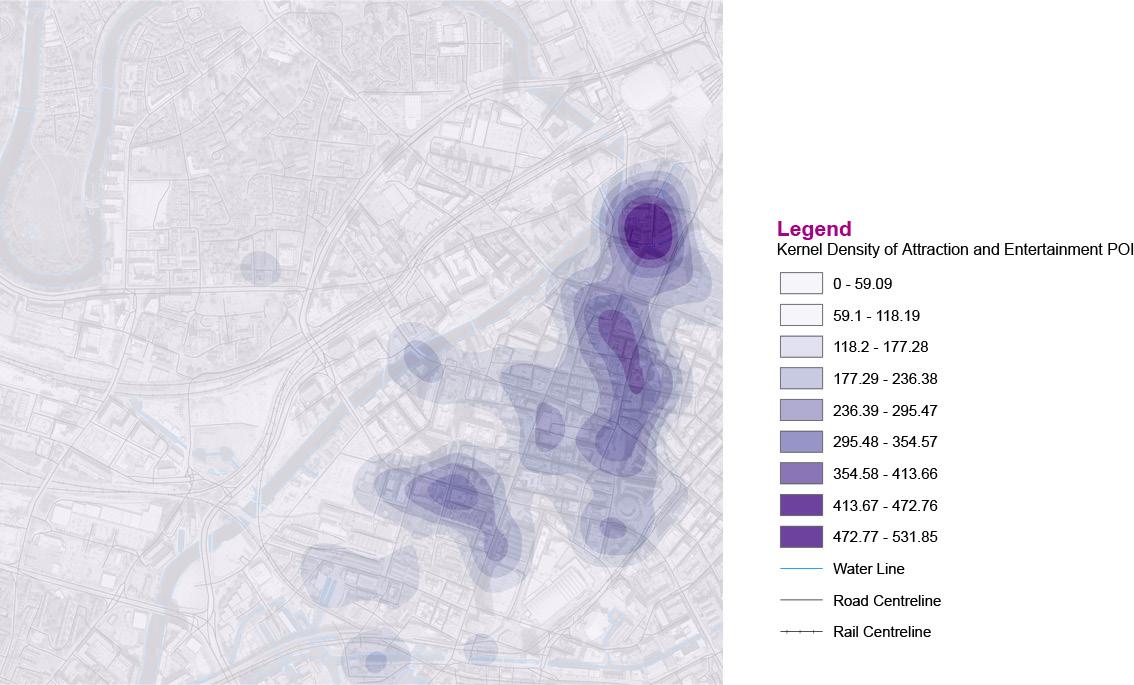

The analysis of the points of interest for transportation, commerce, and accommodation within 600 metres of Salford Central Station (Figure 5.18) reveals that this region is well-served by public transportation and has a decent number of commercial services. Still, the comparison shows a significant disparity in the density of commercial distribution on the two sides of the River Irwell: the Manchester area of the region is far better supplied with all sorts of services. There is a notable disparity in building heights between the two sides of the river, with Manchester having taller and denser buildings than Salford (Figure 5.1-9). The results of the kernel density calculation for public transportation stops, commercial services, recreational facilities and social institutions indicate the facility distribution concentration within the study area. Figure 5.1-10 demonstrates that there is a high concentration of public transportation stations near Salford Central Station, and Chapel Street is easily accessible due to the abundance of stops. The kernel density analysis for social institutions (Figure 5.1-11) and recreational facilities (Figure 5.1-12) indicates that the majority of these facilities are concentrated across the river in the Manchester area, with a small number located in the area near the Salford shopping centre but few in the immediate vicinity of the station. Although there are fewer commercial facilities in the neighbourhood of Salford Central Station than in the Manchester region, the kernel density analysis for commercial services (Figure 5.1-13) suggests that there is still a significant concentration of retail businesses around the railway station.

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.1-1. Bicycle parking area and ramp access in Salford Central Station

Figure 5.1-2. Accessible lifts with negligent management

Figure 5.1-5. Distribution of building functions around Salford Central Station

Figure 5.1-3. Food cart

28 27

Figure 5.1-4. Small square outside Salford Central Station

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.1-6. Office car park

Figure 5.1-7. A view of the buildings surrounding Salford Central Station (with tall buildings in Manchester city in the background)

Figure 5.1-8. All types of POI in the research area

Figure 5.1-9. Building height distribution in the research area

Figure 5.1-10.Kernel density of public transport

30 29

Figure 5.1-11.Kernel density of social institutions

5.2 Social space findings

Based on the UK Census 2021, the age breakdown of the population within 1000m of Salford Central Station was evaluated (Figures 5.2-1, 5.2-2, 5.23, 5.2-4). The largest proportion of the population around the station (more than 45%) consists of people between the ages of 16 and 34. The second most prevalent age group in the station area consists of 35- to 64-year-olds (approximately 20% to 35% of the population. The majority of 0 to 15-yearolds live in bigger communities. The population over the age of 65 is the least prevalent of the four age groups within the socio-spatial context we have defined, accounting for less than 10% of the inhabitants. Working-age adults make up the largest proportion of the population in the research location.

Population density data analysis (Figure 5.2-5) reveals that the population density within the study area is highest in the residential area to the north of the railway station, followed by the area opposite the River Irwell. Overall, the studied region appears to be moderately densely inhabited, with just a few areas being noticeably denser.

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.1-12. Kernel density of attractions and entertainment

Figure 5.1-13. Kernel density of commercial service

Figure 5.2-5. Population density

Figure 5.2-1. Percentage of people aging 0-15

Figure 5.2-3. Percentage of people aging 35-64

Figure 5.2-2. Percentage of people aging 16-34

Figure 5.2-4. Percentage of people aging over 65

32 31

The distribution of employment rates in the research area (Figure 5.2-6) indicates that the vast majority of employment rates are above 50% in station area, with employment rates on both sides of the River Irwell reaching 70% or higher.

An examination of the dwelling types within a 1000-meter radius of Salford Central Station (Figure 5.2-7) shows that flats account for more than 80% of the dwellings in most parts of the area, with the majority being rented. In Salford, the proportion of flats among residential buildings facing the shopping centre is less than 40%.

The household car ownership rate is 30% to 40% in the majority of neighbourhoods in the study area (Figure 5.2-8), but 50% to 60% in neighbourhoods near the Salford Shopping Centre. In contrast to other areas, car ownership rates are lower in areas in which the dwellings are largely flats. The UK Census 2021 data measures the number of internet users and classify them into four groups. Figure 5.2-9 illustrates that the great majority of people in the study area are internet professionals. This means that the great majority of people inside our defined social space have essentially no barriers to internet access.

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.2-6. Employment rates

Figure 5.2-7. Accommodation types

Figure 5.2-8. Percentage of car ownership

Figure 5.2-9. Types of Internet users

34 33

5.3 Questionnaire findings

We visualized and analyzed the data collected from the Google Form through Powerbi. Figure 5.3-1 indicates that almost half of the questionnaire respondents had resided in the UK for more than ten years, and the employment rate of the respondents as a whole was over 30%. These demographics are generally consistent with the findings from the social survey reported in the previous section. Only 16% of the respondents indicated that they passed through Salford Central Station less than once per month, whereas over 40% said they visited the station multiple times per week (Figure 5.3-2), reflecting their good understanding of the research area.

Over 80% of the respondents were either somewhat or very familiar with the Salford Central Area. I divided the respondents into two groups: those familiar with the site (considered to be important stakeholders) and those unfamiliar with the site. By analysing the purpose of train travel, we discovered that those who were familiar with Salford Central primarily travelled for work or study, with leisure travel ranking third. Those unfamiliar with the area used the train primarily for travelling, followed by commuting (Figure 5.3-3).

The two groups did not differ significantly in how they obtained platform information, with the digital departure board being the preferred method. Using a mobile app to obtain information about the platforms was the second most popular option (Figure 5.3-4).

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.3-1. Results of questionnaires - Years being in the UK and employment status (with statistics)

Figure 5.3-3. Results of questionnaires - Familiarity with the site of and purpose of the train journey (with statistics)

Figure 5.3-2. Results of questionnairesFrequency traveling through Salford Central Station

36 35

Figure 5.3-4. Results of questionnaires - Ways to getting platform information (with statistics)

People who were familiar with the Salford Central area were requested to answer more questions about the study area. From Figure 5.3-5, we can see that the top three reasons people visited the Salford Central station area were because they were working nearby, commuting by train or shopping. The majority of respondents stated they usually passed by the station between 12 p.m. and 4 p.m., 10 a.m. and 12 p.m., and/or 6 p.m. and 10 p.m., with nearly the same number of responses for each period. If they were travelling or commuting, the majority of respondents preferred to arrive at the station and the surrounding area between thirty minutes and one hour before departure. But numerous individuals arrived at the station between one and two hours or less than half an hour beforehand. Even though the numbers were small, a few people arrived at the station area more than five hours in advance (Figure 5.36).

More than half of the respondents agreed that Salford station was wellconnected to other public transportation modes and accessible by other means. Nevertheless, some people strongly disagreed and thought that the public transportation facilities surrounding the station could be improved. Similarly, roughly half said that they could follow the directions to the next stop after arriving at Salford Central Station, but a few felt that the signs were not clear enough. Over half of respondents felt that there were sufficient waiting and resting areas near Salford Central Station; however, nearly 20% disagreed. Although 40% of the respondents felt safe and comfortable when travelling around the research area, a considerable number of respondents disagreed. Nearly 30% of the respondents were unaware of the safety concerns existing in the area surrounding the station. (Figure 5.3-7)

In response to questions about the infrastructure surrounding Salford Central Station, 40% of the participants felt that there was a shortage of commercial amenities. More than half believed that the area's infrastructure was not childfriendly enough, and more than 40% felt that there were not enough facilities for disabled people. Other respondents said that they were unconcerned about these issues (Figure 5.3-8). The majority of respondents believed that the Salford Central station area should continue to be developed to foster urban regeneration and that new technologies could be considered to facilitate this.

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.3-5. Results of questionnaires - Reasons people passing through Salford Central Station area

Figure 5.3-6. Results of questionnaires - Earlier arrival time at the station (with statistics)

38 37

Figure 5.3-7. Results of questionnaires - Connectivity to other areas, waiting areas, sense of security, clarity of instructions

As shown in Figure 5.3-9, perceptions of the station did not differ significantly depending on respondents’ familiarity with the location. When the answers of those familiar with the site were analysed separately, more than half described the station as a negative influence on the surrounding area, whereas the majority of respondents viewed the railway station as an opportunity for the city and a positive factor in the city's development.

5.4 Case study

5.4.1 London King’s Cross regeneration programme

With the opening of the Great Northern Railway and the construction of a station in the King’s Cross area of London in the mid-19th century, King's

Cross became an important industrial centre in Britain, including a wholesale potato market, a coal storage yard and a goods yard complex (Figure 5.4.1-1). However, as road transport gradually replaced rail transport after World War II, the role of the transport hub diminished and King's Cross began to show evidence of decline. Factories closed down and the area was transformed from a busy industrial logistics area into a near-derelict industrial brownfield (Figure 5.4.1-2). The area attracted poor people and migrants, and drug dealing, prostitution and street robbery were prevalent (Rodopoulou, 2016). With the introduction of Thatcher's liberal economic theories in the late 1980s and 1990s, the government privatised the railways, and the area around the railway became an appendage of the privatisation process, with the rights to develop the land being handed over to railway companies. Furthermore, the Eurostar established its station in London at King's Cross, enabling it to become the largest transport hub in central London. The clustering of multiple public transportation modes, multi-ethnic populations, housing issues and environmental problems in the King's Cross area provided the impetus for the implementation of an urban regeneration plan.

On a social-spatial level, the King's Cross area integrates a diverse range of individuals, enabling them to share the neighbourhood. As a special government agency, King's Cross Central Limited Partnership (KCCLP) was the only developer of the King's Cross redevelopment project. They believed that in a project of this scale, stakeholders should have the right to express their opinions, resulting in a coordination mechanism to maintain trust between the developer and residents (Jóźwik, 2018). They saw the huge number of individuals served by the transport hub as the most valuable asset to the regeneration of King's Cross. As a result, the space was designed around the concept of "people flow" as a place for people to stay, interact, create and live.

Source: https://flashbak.com/the-inglorious-historyof-kings-cross-and-its-station-a-haunt-of-thieves-

Source: https://flashbak.com/the-inglorious-historyof-kings-cross-and-its-station-a-haunt-of-thievesand-murderers-438629/

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.3-8. Results of questionnaires - Opinions regarding facilities around the site

Figure 5.4.1-1. King’s Cross in 1899

and-murderers-438629/

Figure 5.4.1-2. King’s Cross’ inglorious history

Figure 5.3-9 Results of questionnaires-Opinions about benefits and drawbacks of the train station (with statistics)

40 39

Numerous disputes, negotiations and compromises among local councils, planning authorities, academic organisations, local groups and other bodies eventually ensured the regeneration plan's successful implementation (Figure 5.4.1-3).

On a physical-spatial level, the King's Cross transportation network was redesigned to avoid congestion caused by complex traffic flows. Furthermore, King's Cross station was rearranged and the station concourse moved to prevent conflicts resulting from interchanges. The public areas between the buildings were planned on a human scale to maximise mobility (Figure 5.4.14). Of the neighbourhood’s floor space, 57% is used by company offices, hence the commercial function on the building's first level is well developed (Figure 5.4.1-5). Given the concentration of intellectual institutions in the neighbourhood, King's Cross developed a diverse industrial ecosystem to connect public areas (Figure 5.4.1-6). The redevelopment of the King's Cross station area has contributed to strengthening the urban fabric and restoring lost spatial links. The literature review and field research suggest that the district has exploited the railway development to promote the economic and cultural development of the surrounding communities and overcome the fragmentation of the city produced by the station. The research and discussions conducted during the creation of the redevelopment plan and the monitoring of the investment process led to the success of the plan (Figure 5.4.1-7). The diversity of the urban fabric makes the place more appealing.

Source: https://www.neighbourhoodguidelines.org/ urban-regeneration-kings-cross

Source: https://xueqiu.com/5312790482/136011068

Source: https://irishbuildingmagazine. ie/2019/12/01/big-build-

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.4.1-3. Social relations of the subjects of the King’s Cross regeneration process

Figure 5.4.1-7. Aerial view of King’s Cross

kings-cross-redeveloped/

Figure 5.4.1-4. Masterplan for King’s Cross regeneration

Figure 5.4.1-5. Distribution of building functions in King’s Cross area

42 41

Source: Recreated by the author according to: https://xueqiu. com/5312790482/136011068

5.4.2 Other developments in the field of railway stations

As smartphones and other smart devices become more ubiquitous, the prospects for e- and m-commerce will expand, and virtual supermarkets may become more common, particularly at transportation hubs such as train and metro stations. Homeplus set up the world’s first virtual store along the platform of the Seonreung subway station in Seoul, South Korea, showcasing its most popular items. Smartphone users can scan a product's QR code to order it and arrange for delivery (Figure 5.4.2-1). Similarly, the development of smartphones has resulted in the creation of apps such as TripGo, an integrated transportation application that enables journeys to be chosen based on optimal cost and convenience. Booking and paying for travels across all modes will be feasible in the future, allowing for the development of a unified journey-planning tool. For the convenience of office workers, Regus, the world's leading supplier of flexible workspaces, has set up satellite workspaces at Luxembourg Central Station, Amersfoort Station and Geneva Station. They provide travellers with business lounges and private offices that may be rented flexibly for short periods by those who wish to work quietly while waiting for transport (Figure 5.4.2-2).

Source: https://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/ lbs-case-study/story/ case-study-tesco-virtually-created-new-market-based-on-country-lifestyle-143807-2015-02-06

Source: https://www.reuters.com/news/picture/ office-meets-railwayplatform-meets-servidUSLNE85602320120608

EXPLORATIONS

Figure 5.4.1-6. Distribution of intellectual institutions and cultural institutions in the King’s Cross neighbourhood

Figure 5.4.2-1 Visual store in the subway station

Figure 5.4.2-2. Office in the railway station

44 43

Chapter

6

Discussion

6.1 Redevelopment of railway station areas

6.2 Reflecting on spatial production theory in urban regeneration

6.3 Reflections on Salford Central Station Area

6.4 Guidance for the urban regeneration of the Salford Central Station area

6. Discussion

This chapter will synthesise the previous four chapters and apply the findings from Chapters 2 and 5 to examine how to answer the research questions in this paper. First, we look at the implications of railway station redevelopment for urban regeneration through the lens of the case study and related literature. Second, the theories of spatial production addressed in Chapter 2 and their application to urban design are analysed relative to the railway station area. The results detailed in Chapter 5 are then further discussed to determine what needs to be considered for the future urban regeneration of the Salford Central Station area relative to the theories described earlier in the paper. Finally, we explore whether the study of the railway station area in Salford is relevant to similar areas and reflect on the limitations of this study.

6.1 Redevelopment of railway station areas

As the intersection of transport networks and the city, the railway station has mobility that distinguishes it from other elements of the urban infrastructure. Despite being a physical place, the station generates a more complicated network of social relationships than other built structures in the city due to the presence of people from various places with different travel purposes. This is where the opportunities for the development of the station area exist. The diverse stakeholders in the station area support the existence and interrelationship of various functions in the station area, of which the number and complexity are partially influenced by the size of the city (Zemp et al., 2011). Thus, it seems that integration is needed to optimise the advantages of railway station redevelopments, that is, to integrate development and transit possibilities with liveable, safe and attractive urban environments. Guaranteeing integration between the city and railroad ensures urban sustainability and urban development. To fulfil sustainable urban development objectives, governments (both national and municipal) have generally promoted urban regeneration around transportation hubs. The studies centred on TOD theory and the node-place model that were mentioned in Chapter 2 have explored the way railway stations stimulate urban development. Several examples, including France's Euralille, Sweden's Stockholm Central, the Netherlands' Basel EuroVille and Utrecht and Britain's Kings Cross (Conticelli, 2011), illustrate the importance of railway stations as neighbourhood anchors.

DISCUSSION

6.5 Universality and limitations 46 45

Given the role of railway stations as catalysts in urban development, it is crucial to draw lessons from various research studies and case studies to better utilise the potential of station areas, aid urban regeneration and promote urban economic development, community cohesion and environmental sustainability. Therefore, I propose a few principles for the development of station areas.

First, the borders of the station within the city should be blurred to encourage inclusion and station-city integration. The railway station is no longer only an amenity for travellers. People with diverse identities engage with and influence the station, enhancing its significance to the city. Therefore, railway stations should be redeveloped with a variety of stakeholders in mind, creating a people-centred infrastructure. Second, the railway station area should be used more diversely. Station areas are becoming more valuable and useful due to increasing competition for urban space, with the numbers of both travellers and pedestrians increasing. This provides possibilities for rethinking station space use and the relationship between the station and its contexts, both physical (i.e. above, below and around) and conceptual (i.e. intended users and uses). Third, the majority of old railway stations are situated in densely constructed areas, so it is important to consider the existing infrastructure while undertaking urban renewal. Attention should be paid to integration with the surrounding environment and integration into the physical space and social culture of the community.

6.2 Reflecting on spatial production theory in urban regeneration

As shown in chapter 2, Lefebvre provides a method for dissecting not only how dominant values and ideological norms are maintained in space, but also how we comprehend the spaces created for us and the places we experience in our daily lives. The method involves understanding the city and the urban as forms of functionalized space and the social processes of humans who use space, in addition to an inclusive planning and design process. Lefebvre's trialectic theory and Harvey's "circuit of capital" theory are two of the most widely used concepts in the field of urban studies. These two theories highlight the significance of power, capital and space. Key concepts in urban regeneration include the circulation and multiplication of capital, as well as the function of power in the development process. Based on the notion of "production of space," many social groups achieve "representational space" by controlling the "practise of space" and "representation of space". Thus, different social groups obtain benefits through the process of spatial production, which results in the spatial expression of power and the multiplication of capital. This is expressed in the 'benefit-capital-power' analytical framework shown in Figure 6.2-1.

Benefit is the motivation behind wealth and power. The essence of spatial production is utilizing and redistributing urban space. Those participating in the production of space have diverse interests that interact to enhance the process (Table 1). Therefore, establishing a solid framework for the expression and coordination of benefits and demands (Figure 6.2-2) is important to guarantee the success of urban redevelopment.

DISCUSSION

Figure 6.2-1. ‘Benefit-capital-power’ analytical framework

Figure 6.2-2. Benefit relationships among stakeholders

48 47

Table 1. Participation and demands among different stakeholders

Capital is a tool of spatial production. It profits from the reproduction of urban space, which may lead to the occurrence of gentrification (Hickman et al., 2021). In urban regeneration, the capital involved in the process of spatial production can be divided into financial capital, land capital, technological capital, cultural capital and social capital. All are capable of accumulation and multiplication in the spatial production process, as detailed in Table 2.

Power in the context of spatial production is defined on a sociological level as a subject's domination over or influence on other subjects. Depending on the subjects, the power involved in spatial production may be political, economic or social. The subjects compete with each other for benefits in the process – or “game” – of urban spatial production.

The urban regeneration process is comprised of both top-down and bottomup spatial operations. Multiple stakeholders, often including government, developers, professionals and residents, are constantly engaged in the process of urban regeneration. The mutual game of the different groups contributes to the production of regenerated space. The ideal endpoint of this “game” is a balanced state of cooperation achieved through negotiation between multiple bodies (figure 6.2-3), with each body earning the greatest fair rewards.

6.3 Reflections on Salford Central Station Area

While researching documents about Salford, we concentrated on the Salford Regeneration Masterplan, a major regeneration project that is expected to last 20 years from 2008. Although Salford Quays is an example of successful urban renewal, this is not the case for projects across all areas of Salford. A search of media reports for comments about the plans for the Salford Central Area in this urban regeneration project returned mostly negative results (Figure 6.3-1). The Central Salford Urban Regeneration Company created a plan for the Salford Central Area redevelopment and has been working to improve the neighbourhood around Salford Central Station. Although this planning document stressed the prospects for and challenges of the Salford Central Station area and proposed development around Chapel Street as well as New Bailey Street, including the preservation of historic buildings and a focus on vertical growth, news reports and City Council statistics indicate that this urban renewal has not freed the Salford Central Area from its reputation as a slum. Although the previous regeneration of Salford Central infused physical vitality into the neighbourhood, the reshaping of space led to the reconstruction of social structures and networks in a way that resulted in a diminished sense of community identity.