18 minute read

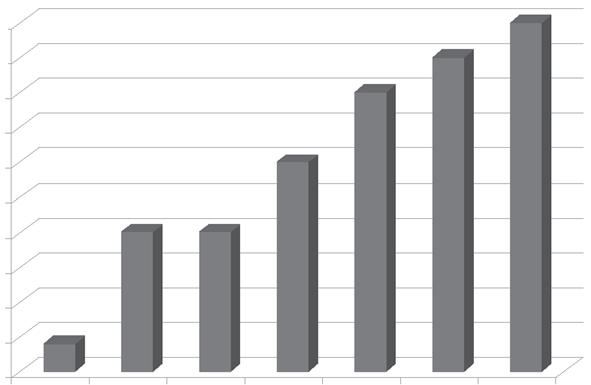

7.1 The percentage of women in the FARC-EP since 1964

Percentage of women in the FARC-EP 50

45

Advertisement

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000 2004 2006 Years since inception

Figure 7.1 The percentage of women in the FARC-EP since 1964

Sources: O’Shaughnessy and Branford, 2005: 27; Marin, 2004; Richani, 2002a: 62; Galdos, 2004; FARC-EP, 2001b: 25.

The percentage of women in the central Colombian government is on average 10 percent, while municipal levels average 5 percent (Cordoba Ruiz, 2002: 3). Looking at the military, only 2 percent of soldiers on average are female while the FARC-EP has a 1:1 sex ratio (Penhaul, 2001: 6).36 It is equally important that not all members trained in combat hold rifles. Both men and women in the movement share roles as “accountants, cooks, fundraisers, logistics specialists, medical doctors, or recruiters” (Hudson, 2002: 18–19). All this is significant, as some “revolutionary” movements have boasted of their female representation but the women’s place in the organization simply reflected conventional roles. They were seen as second-class members, and confined to food production, cooking, cleaning, and other patriarchal duties (see Mies, 1986; Sargent, 1981). This is not the case in the FARC-EP. All members, regardless of gender, share duties – from combat to cleaning. Even civilian women appeared to be well represented in FARC-EP territory. On a number of occasions I found women equaling males at community meetings, guerrilla–civilian open forums, collectives and JACs, and in some cases outnumbering them.

Indigenous relations A discussion concerning indigenous relations with the FARC-EP is greatly needed. As noted, the guerrillas have incorporated people from all regions of the country into their ranks, including members of Colombia’s 84 indigenous groups, to the extent that they make up 12–13 percent of members.37 Historically, the PCC was in close contact with many indigenous communities. Accord-

ing to Paul Oquist (1980: 92), the groups worked closely together dating as far back as the 1920s and 1930s (see LeGrand, 2003: 175; Osterling, 1989: 185). It was this interrelation that facilitated the foundation of the FARC-EP, and later alliances between the guerrillas and indigenous population. For example, take Charro Negro, alias Jacobo Prías Alape, whose civil name was Charry Rincón (see Hyams, 1974: 168n.2). Not only a member of the Central Committee, Charro Negro was an original founder of Marquetalia and one of the first leaders in the FARC-EP (Gott, 1970: 235–6). During the 1960s, the guerrillas obtained large-scale support from various indigenous groups in the southwest, specifically Chaparral, Ortega, Natagaima, and Marquetalia (Gilhodés, 1970: 430). Much of this was due to the organizing efforts of Charro Negro. However, in contrast to this historic relationship, coupled with the fact that indigenous people were some of the insurgency’s first members, the FARC-EP did not always have good relations with all indigenous groups. In fact, in some areas, the FARC-EP was not welcomed by sectors of the population, leading to periods of turbulence between the FARC-EP and a handful of indigenous peoples. During the establishment of the self-defense communities, certain tensions arose between some rural communists (and their peasant supporters) and certain members of the Páez tribe.38 Capitalizing on this, the army strategized a campaign to enhance the frictions by enticing the Páez with economic incentives. It informally enlisted indigenous informers living in or near the self-defense communities who would forward intelligence to the military. In time, this information assisted the historic attack on Marquetalia. Following the offensive on the self-defense communities, the FARC-EP posed several questions. How were these attacks able to take place? From whom was the (poorly39) collected intelligence derived? How did it get to the Colombian military? The answers pointed at members of the Páez.

The army actually recruited informers from FARC regions who had “personal contradictions” with the peasant guerrilla leadership ... the army recruited Páez Indians – who had had conflicts with the “peasant republic’s” leaders – to scout and guide for the military in its campaign against Marquetalia. Their role was crucial in the army’s taking of the region. (Wickham-Crowley, 1992: 146)

Both Russell Crandall (2002: 60) and Dennis Rempe (1995: 321) commented how the state used numerous Páez to help flush out the FARC-EP during the 1964 aggressions. Wickham-Crowley (1992: 56) referred to “the cooperation of the Páez Indians” as helping “the government to subdue the peasant republic of Marquetalia.” Years after the attack, Jacobo Arenas (1972: 107–8) proclaimed that without this sector of the Páez turning on the guerrillas (and the local peasantry), the state would not only have had extreme difficulty finding Marquetalia, they would have experienced significant causalities as the guerrillas would have been more prepared (see also Kirk, 2003: 54). Yet, while some of the Páez jeopardized the security of those living in the self-defense

communities, other indigenous peoples came to the aid of the rebels. Numerous indigenous groups have long supported the PCC, and constructed escape routes in the event of an evacuation of the region. As a result of the cooperative networks that developed between the communists and indigenous people, those within Marquetalia had a venue to flee the bombings (Ruiz, 2001: 110).

Although it is seldom documented, the FARC-EP has long promoted the rights of “native minorities” (Bernard et al, 1973: 316). For the most part, the guerrillas, like the PCC, have coexisted alongside many indigenous communities throughout much of the south, especially Caquetá and Cauca (Findji, 1992: 128). This is likely to be because the guerrillas have supported indigenous self-representation and in no way express an anti-indigenous position (Warren and Jackson, 2002: 82; FARC-EP, 1999: 118–19). It is important to note that issues between the FARC-EP and the Páez40 were not related to the Páez as a people, but rather derive from political ill will as a result of the lives lost at the hands of the state. Tensions then cannot be seen as ethnic-based but rather class-based. During the mid-twentieth century the Páez sought to increase their consolidation of land. Some believed eliminating the guerrillas would facilitate this. The Páez have long populated areas of the southwest (Ortiz, 1971: 324–5). However, during the 1930s, the region saw an influx of poor farmers, small producers, and their families, people who would later form the FARC-EP (Sanchez and Meertens, 2001). While there was some good will and trading between the existing and new residents, a proportion of the Páez felt “foreigners” had intruded on their territory. Cooperating with the military, they hoped to expel these campesinos, which would make it easier for them to increase their landholdings. As a result of this collaboration, historic tensions – even leading to armed confrontations – between the guerrillas and the Páez took root. However, in 1997, the FARC-EP acknowledged that to facilitate change from below they had to improve their relations with the Páez. The FARC-EP established a series of bipartisan meetings with the Páez, and established a commitment to peace with the indigenous group (Richani, 2002a: 188n.15).41 Negotiations commenced and an agreement was signed, ending decades of disagreement. The reality of periodical tensions between the FARC-EP and indigenous groups should not be dismissed; sometimes these have even resulted in deaths, as witnessed in February 2009 when the guerrillas – responding to a request from the indigenous community itself – executed eight Awá members who had been working with the army and established a vigilante group (Vieira, 2009b). In fact, the FARC-EP are responsible for perpetrating a very small percentage of abuse of indigenous groups, yet they appear to be primary culprits because there is such an overemphasis on guerrilla/indigenous confrontations in state and media sources (Leech, 2005a).42 “According to several displaced Awá,” Leech (2006c) said, “it is the army, not the guerrillas, that has threatened them in the past and is primarily responsible for their displacement.” It has been shown that the guerrillas have had a lower rate of aggression toward indigenous peoples than state forces, paramilitaries, or criminal gangs (see

Weekly News Update on the Americas, 2005b). Testimonies I collected also contradicted claims that the FARC-EP threaten indigenous communities. When asked about his community’s position toward the FARC-EP, one indigenous respondent said:

the guerrillas have allowed us to continue our way of life so that we, our children, our families, and our village can exist with less fear; however, things were not always like this. Some indigenous communities have had a difficult past with the guerrillas. For many years some persons in certain communities did not want the FARC anywhere near their towns in fear of being caught in the middle of the war. If the government forces, including the paramilitaries, found out guerrillas were near indigenous communities then they would either be found or assumed to be working with or supporting the guerrillas, making the community a target. Because of this, many communities wanted all its members to separate or not interact with the guerrillas at all.

When asked whether the guerrilla have supported indigenous peoples and whether their community supports the FARC-EP, the same respondent described how the insurgency, over time, adapted its revolutionary strategy to recognize different groups.

I do not think it is necessarily one or the other but a combination of the two. As you know, some indigenous peoples did not get along with the guerrillas during the middle of the twentieth century for many felt that the guerrillas were too violent or were encroaching upon their traditional lands. However, as the repression of the state became too much to bear, many, especially the young, have come to increasingly align themselves, or join, the FARC as a means of fighting against this violence .… Creating a broad revolutionary force against that which commonly and equally represses all peoples in Colombia; not merely blacks, peasants, or members of indigenous tribes. I am not saying I support all their methods but it is time that we as a people [pointing to me and him] resist repression. We are all affected by this injustice; therefore, all must resist in order to build, as they [the guerrilla] say, a new Colombia. This position has taken a long time and some still resist this position but many feel that it is the only answer because the repression is far more violent and ongoing than it was in the past; a violence not only against our people but all those who are not members of the rich.

Rather than taking sides with the guerrillas solely for protection, I have found that a deeper political consciousness has emerged, leading indigenous communities to align with the ideology of the FARC-EP (see also Rizvi, 2006). Researchers have documented how some, seeing no other option but to directly combat state-based reactionism and class repression, are moving away from purely identity/autonomous-based politics to more distal revolutionary movements (Valetta, 2004). The events described by one father from a Wayuu

community in La Guajira help to show why this mode of reasoning has come to fruition.

You can not imagine how it is to have to escape on the run so that they [state and paramilitary forces] won’t kill you, and then hear the cries of the kids, of my two little sons who they burned alive without me being able to do anything .… They burned them alive inside my pick-up. Also, they beheaded my mother and cut my nephews to pieces. They didn’t shoot them, they tortured them so we would hear their screams, and they cut them up alive with a chainsaw.

(quoted in Valetta, 2004)

Others have documented how some groups have not only aimed their sights against the state but have opted to support the FARC-EP as a consequence of the insurgency’s promotion of indigenous rights (coupled by their military capacity to respond to state and paramilitary threats) (Brittain, 2005d; Lobe, 2004). During an interview, a member from one indigenous community acknowledged how people cannot expect change to take place if reformist or non-structural ideas are at the fore.

Many indigenous communities want to remain or struggle for autonomy but many do not know what this word really means. Many want to be left alone by the state, by the paras, by the guerrilla, etc. but the reality is that once the large landowners or the paras want more land they come into our communities. Mind you, this is not a new phenomenon but one which all indigenous peoples have experienced for centuries. In Colombia, many indigenous communities hoped for the day when their individual clans would be left alone and allowed to exist in and of themselves. The last 20 years have shown us that this is not and will never be the case. While the state may not have bothered us in the past, as long as we do not politically organize, our people are witnessing growing violence against our communities for no reason other than to consolidate more land and resources for the rich in this and other countries. This truth has led to many of the young to support, and even join, the guerrillas to stop this from continuing. This is a good thing ... it has brought an increased understanding of indigenous cultures to the guerrillas. With more and more indigenous peoples joining groups like the FARC, the leadership in these organizations has become more familiar with our history, our culture, and our desire for a new Colombia that respects differing peoples and their ways of life.

When asked, “Do you think this has helped relations between the FARC-EP and differing indigenous groups throughout the country?” he immediately responded; “Undoubtedly! With more indigenous peoples joining the guerrillas a broader sense of Colombia’s reality had to come about. There are even elders who now sit and eat with the guerrillas where at one time they would have fled.”

Fine arts

The FARC-EP has viewed imperialism as “an overdeveloped and highly effective machine for manipulating the thinking of large sections of the population” (FARC-EP, 2002a: 13). Capitalism has influenced a culture that has, in many ways, facilitated an “apolitical and apathetic” society “submerged in the notions of individualism and consumerism,” which fractures unified progressive solutions to inhospitable conditions (FARC-EP, 2002a: 14). To offset this manipulation the FARC-EP have tried to nurture an alternative culture outside foreign and domestic class control. Establishing a cultural alternative to imperialism creates the potential for a more collectively conscious opposition to arise. This section examines said alternatives via art, music, and theater. Jacobo Arenas promoted culture as being the common bond that will continue to unite the Colombian people after the guns of revolution fall silent (FARC-EP, 2001–02: 30). Amidst a country in conflict the “cultural hour” acts as a mechanism of expression and enjoyment for and of the guerrillas.

The FARC-EP guerrilleros play, sing, write poetry and books, tell stories, put on plays and paint, etc. The most sensitive men and women, reflecting the reality around us, transform our culture into an orally and visually attractive form, nourishing the patriotic and revolutionary sentiment of thousands of fighters, their friends and thousands of people who today listen to the songs, read books, recite poetry and watch films made by the guerrilleros ... Culture occupies a very large space and plays an important role in the life of each guerrillero in the FARC-EP .… There is a cultural hour from 7 to 8 p.m. in all guerrilla camps, when the public order situation permits. In this hour there may be a book reading, a lecture, the reading of a poem, singing, or a fiesta to dance the current rhythms and compositions of the guerrilleros. This is a space created so that culture is present in the struggles of our people.

(FARC-EP, 2000–01: 30–1)

The “hour” however is not exclusive to the insurgency but has expanded to involve civilians in sharing their own revolutionary ideas and creativity (see FARC-EP, 2001b: 14). Organizing community plays, dances, concerts, and art exhibits has created a medium through which the imaginations of the guerrillas and civilian populace can be expressed (FARC-EP, 2001a: 12). Artists, musicians, playwrights, poets, and writers are frequently asked to voice their feelings and share their gifts with others (see Angel, 2002). In the area of music various composers have emerged from the guerrillas who might otherwise never have had the chance to develop their talent: Luke Iguarán, German Martinez, Cristian Perez, Juan Polo, Camilo Germán Vargas, and Los Compañeros: Jaime Bernardo, Jairo Padilla, and Prudencia Arijuna have recorded dozens of albums in traditional musical styles like Vallenato, Porro and Llanera (see Buch Larsen, 2008; FARC-EP, 2001b: 30). The most famous representative of the FARC-EP’s promotion of culture through music has been

Julián Conrado, a member of the Central High Command who has written and recorded hundreds of songs related to Colombia’s revolutionary struggle.43 A member of the FARC-EP for almost three decades, Conrado was born in 1954 in the town of Turbaco, Bolivar, and established himself as an influential representative of the guerrillas during the 1998–2002 peace negotiations through his activism and community concerts (Semana, 2008a). Conrado’s passionate kind demeanor has promoted this positive alternative culture, leading some to suggest that “the popular and quick-to-smile ‘rebel’ seemed out of place in Latin America’s most brutal civil conflict” (Buch Larsen, 2008). The FARC-EP has also delved into (multi)media as a tool to disseminate its propaganda. For several years informational films have been produced that depict guerrilla campaigns and victories, to respond to false reports of statebased successes propagated by corporate outlets. Beginning in 2006 a news program entitled Revista Resistencia was created and distributed throughout urban areas and rural enclaves via the Bolivarian Movement for a New Colombia (MBNC) and various fronts. It is shown in settings from community halls to individual laptops. A full-length soap opera, El Mito del Hombre Zorro (The Myth of the Fox Man), was released in 2007. The film touches on two issues: first, encouraging peace negotiations alongside a prisoner exchange, and second, demonstrating camaraderie and solidarity between combatants. The FARC-EP has also broadened its long-time use of radio. It changed its old format, Radio Resistencia, transmitted to and easily obtainable in rural locales in Caquetá and Putumayo on 95.9 fm (see Penhaul, 2000), to a more extensive Bolivarian Chain Radio (Cadena Radio Bolivariana, CRB). The CRB or Voice of the Resistance (Voz de la Resistencia), can be heard throughout Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Nariño, and some parts of Caquetá and Putumayo by tuning to 106.8 fm. As preliminary alternative cultural measures are established, a basis for expression is made possible in a country where it is greatly suppressed. The FARC-EP has stated that:

revolutionary culture is present and is nurtured by the people. It is the expression of rebellion charged with social content that has flourished in spite of everything throughout our history – in spite of the massacres, the bullets and the negation with which they think they can silence the voice of the people.

(FARC-EP, 2002a: 31)

As one member of the Secretariat told me, “to have peace a people must also have an environment to express the joys of peace.”

The church

It may seem irrelevant to some to include any discussion of religion when examining a Marxist–Leninist revolutionary movement. The topic did however come up several times when I was interviewing people both within and

outside the guerrilla movement. Obtaining information related to the FARCEP and the (Roman Catholic) church proved to be informative, if nothing else. My research contradicted claims that the guerrillas are anti-religious or violently opposed to the church, and provided an interesting view of those still practicing their faith amidst the civil war. A few years ago, corporate and state media reported news of a tape on which Mono Jojoy (Jorge Briceño), a member of the FARC-EP’s Secretariat, discussed the need for the FARC-EP to target and execute priests throughout the countryside (United Press International, 2005). This claim alarmed many in a country where 90 percent of the population is Roman Catholic. Doubts about the tape’s credibility soon arose, for several reasons. The guerrillas have long encouraged their members to support all “priests sensitive to the cruel arrogance of the powerful” (FARC-EP, 2000b: 14–15). The FARC-EP has also partnered with congregations to construct churches in the countryside, especially during the 1998–2002 peace negotiations (see Otis, 2004).44 Since 2002, sectors of the church have fought for peace talks between the FARC-EP and state. My own research found several cases of FARC-EP members who were once priests but left the institution to struggle alongside the people in a more direct manner, or remained priests keeping their alliances with the insurgency quiet (see Wickham-Crowley, 1992: 214). Former secretary-general of Colombia’s Catholic Bishops Conference, Monsignor Fabian Marulanda Lopez, even questioned the authenticity of the reports demonizing Mono Jojoy. He argued that the tape “should be analyzed because it’s not understood why that group would go after those who are trying to reach them to discuss peace.”45 One person I interviewed was a young man who had recently stopped studying to become a priest. Once stationed in a rural part of one southern department, he vehemently contested all notions that the FARC-EP target members of the church in the countryside. On the contrary, he noted that many guerrillas are quite religious, and some continue to practice their faith even though they are Marxist-Leninists. When asked if he could “talk about the relationship between the guerrillas and the Church in the rural regions” and clarify his position on whether “the FARC-EP are quite repressive toward the religiosity,” he said,

I am always interested in claims of how the guerrillas are in opposition to the church because it demonstrates one of two things: one, how much control there is over information, and two, how little people understand about the guerrillas. I do not really want to talk about the media and how it is controlled by a small few in this country; however, I would like to answer your question concerning this important relationship. As you know, many people in Colombia have a deep devotion to their faith. One can travel throughout the country and see people that are steeped in their affection toward the church, which is practiced by the majority of people in the cities and in the countryside. In understanding this one has to then ask where do the guerrillas come from? Who are the people who have formed the FARC? In answering this question one must then follow with another question, “If the guerrillas come from our towns, villages, cities, which are steeped in the