8 minute read

Between a rock and a hard place: the realities of contemporary global capitalism

enabling the guerrillas to be the ones who win the hearts and minds of the local rural populations (Felbab-Brown, 2005: 104).

What has resulted from these socially supportive activities is a sense of communal alliances between the rural populace and the FARC-EP. Such conditions have led people to view their relationship with the guerrillas as a sociopolitical, economic, and cultural link to their community’s survival, which is sustained by the FARC-EP’s continuity (Ross, 2006: 64).

Advertisement

With the complete failure of the government to even attempt to provide any basic services to the local population, it is the FARC that has filled the void by helping to build roads and provide electricity, law enforcement, judges and other public services traditionally supplied by the state. As one local peasant notes, ‘When farmers or their families get sick and can’t afford medicine, it is the FARC that gives them money to purchase what they need’ .… Until the government offers peasants ... something more than military repression, the local populations ... will continue to see their welfare and survival as inextricably intertwined with that of the FARC. (Leech, 2006b)

As reactionary economic and militaristic state policies take shape, shifts in FARC-EP support and consolidation may take hold. These shifts have the ability to further the revolutionary capacity of the guerrillas in the countryside, leading to an ever-increasing inability of domestic and foreign elites to withstand radical social changes there. This increase in class opposition reveals the frailty of the Colombian state. There are, however, external factors not yet mentioned that have a great effect on the availability of the resources that the state relies on to sustain its stability.

BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE: THE REALITIES OF CONTEMPORARY GLOBAL CAPITALISM

At a time where there has been considerable resurgence in Colombia’s electoral left, alongside muted internal political support from one-time allies, the Colombian state has needed to procure ever more financial resources to keep revolutionary sentiment out of the Plaza de Bolívar. This saw the Uribe administration look to foreign institutions to help it retain or expand its revenue as a means of combating the FARC-EP. Here we look at two examples of this process, and suggest that such external dependencies are unsustainable and only increase the government’s political-economic decline. The FARC-EP’s political-military capacity, coupled with the country’s economy, has placed the state in a very difficult position. Colombia’s civil war, which Uribe said he would end by 2006, is very much alive. In light of this reality, the government cannot increase its already over-reliance on the pocketbooks of the country’s elite or the backs of the working class to help it retain power. As a result, “to finance the war, the Uribe government is running a budget

deficit of 6 percent of the country’s GDP, which is well above the 2.5 percent limit set by the IMF” (Richani, 2005b: 89). The rationale behind increasing Colombia’s long-term debt was to offset political-economic instability, as many Latin American countries have done before. Such a position, however, cannot be prolonged. With the hindsight of the last 30 years, some in the IMF called for a decrease of support for Colombia in order to prevent a problematic debt ratio in the future (Muse, 2004: 22–3). Uribe himself acknowledged that difficulties in acquiring loans, financing, and monetary credit are to appear in the coming years as a result of his military-based security spending (Sáenz V., 2008). The Colombian state is therefore caught between a rock (IMF) and a hard place (a growing opposition to expanded taxation and FTA exploitation). Some have even argued that a potential backlash may arise from Colombia’s elite and leading economic groups23 “against paying any more taxes, thereby increasing the pressure on Uribe to draw foreign reserves to finance his war” (Richani, 2005b: 89–90, 101n.69; see also 2005a: 115). Much of Colombia’s elite has supported an expansion of the country’s debt. It is believed that increased foreign aid and intervention will, first, assist state capacity to combat the FARC-EP, a considerable threat to dominant class interests; and second, decrease the elite’s immediate taxable income by placing partial expenses on the backs of foreign taxpayers (Richani, 2005b: 93). The problem with this line of thinking is that Washington, Colombia’s primary donor, has become economically crippled by its own problematic military campaigns (Iraq and Afghanistan) and domestic economic strife (debt crisis and the $1.5 trillion banking bail-out). As a result of this imperial overstretch, increased military support from the United States is no longer as likely as it once was (Markey, 2008b; Semana, 2008b, 2008c). This gives the Colombian state fewer options, as it continues to exhaust its borrowing opportunities as a result of deficit percentages unacceptable to the IMF (Richani, 2005b: 89–90).24 Reviewing this scenario, Richani wrote:

in light of the current structure of the military and the limited fiscal capacity of the Colombian state, a military build-up needed to match the insurgency’s challenge will not be possible. Preoccupied with its own domestic deficit and the spiraling costs of its Iraq adventure, as well as its commitments to rebuilding Afghanistan, the US is clearly in no position to shoulder more of the burden …. US intervention has not been decisive enough to enable the Colombian military to defeat the guerrillas. Five years after the introduction of Plan Colombia there is no victor in sight, nor have the guerrilla forces shown signs of serious weakening.

(Richani, 2005b: 90)

While neoliberalism has constrained the state’s capacity to confront the FARC-EP, an argument could be made that a reduced state may be just what is needed, as MNCs can provide “extra income to sustain its war against a growing armed insurgency” (Richani, 2005a: 115).25 The use of these private security forces, acting as a mechanism of stability for economic and political

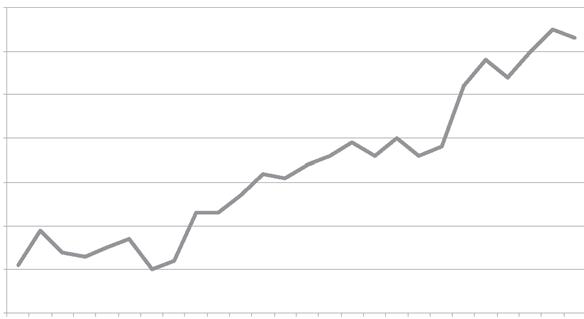

Percentage of GDP reserved for military expenditure 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008

Figure 8.1 Colombia’s military expenditure as a percentage of GDP, 1950–2008

Sources: Adapted from Brockner, 2008; Vieira, 2008b; Avilés, 2006: 84; Bloomberg, 2005; Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, 2005; Richani, 2005b: 94; SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, 2005; Brittain, 2004a; Committee of Government Reform, 2004; UNDP, 2004; US Embassy of Colombia, 2003; World Bank, 2002; Federal Research Division Library of Congress, 1988; Ruhl, 1980: 187.

interests, has risen in recent years (Richani, 2005b: 48; O’Shaughnessy and Branford, 2005: 115, 128–30). However, such mercenaries are not without problems. Private forces will only maintain counter-insurgency activities as long as they remain profitable. The more the Colombian state reduces its economic surplus, through the selling-off of public industries and services alongside greater reductions in foreign-based corporate taxes, the greater the monetary pull on maintaining these private forces. The state, needing to sustain these forces, is therefore forced to increase exploitation over the social relations of production, resulting in greater human and natural resource degradation. This only furthers discontent, which increases state antagonism and can generate even more extreme reactions (such as expanded support for the FARC-EP). With there being a limit to the sustainability of using for-profit private security forces, and the finite realities of human and environmental resources, the state’s withered internal forces will again be faced with little option but to confront the counter-hegemony of a superior armed movement.26 This book demonstrates that a struggle from below is being made real through a united force of the FARC-EP and sectors of the most exploited. This dual power has contributed to a partial breakdown of Colombia’s centralized political-economic paradigm. As the civil war rages on, along with neoliberal economic policies, monetary-driven development, increased deficit spending, and the potential for the United States to draw back its support, a crisis exists that could see Colombia’s conventional politics collapse. The complexity of these conditions may assist the FARC-EP to expand its sociopolitical footing and eventually succeed in bringing about the first Marxist-Leninist revolution

of the twenty-first century. As one campesino succinctly stated when asked if he believes the FARC-EP will succeed in its revolutionary endeavors:

Your question makes it sound as though they are not already [winning] or that their victory is something that will come in the future. The FARC are and have been winning for a long time. Look around ... the paracos are here because the FARC are winning. If the guerrillas and the people who support them were losing the state would not send the paracos to repress us. So many think that if the guerrilla do not take Bogotá they are not winning but they control vast territory throughout the countryside. This is no easy feat, the FARC are winning …. When you look around the southern parts of this country it becomes apparent that the state only exists as an instrument to continue elite rule. Therefore, I think it is very realistic that the guerrillas can preserve control and gain further power over much of the countryside, especially when the United States is so preoccupied with its other wars in the Middle East. Bogotá is a totally different beast …. A few years ago the FARC had the ability to invade Bogotá. They had surrounded it and had people in the barrios ready to fight. For whatever reason, they chose not to do this. Rather the guerrillas have sought to consolidate power in the countryside, where they have the greatest and most open support. Once the guerrillas have consolidated power in the outskirts it will be easier to increase their numbers and march to the Plaza [Plaza de Bolívar]. Bogotá will not be easy but I think they can do it. Support is there, you know. There have been dips here and there, but for the most part, especially here in the south, the FARC cannot be beaten, and the more they try, the stronger the guerrillas will become. The more the paracos come in, the more this forces people into a political and moral corner, leaving them to question, “What else can we do but rebel for a better Colombia?” I do not know if this answers your question. I would never say that the FARC will lose but I will certainly tell you that the state and elite that repress the people of this country will never win.