An Interview with Elsa Mora

6

Elsa Mora working in the studio , Havana, Cuba, 1999

How did your life/art training in Cuba affect your art and life as an artist?

Growing up in Cuba was my boot camp for creativity. Material restrictions forced us to be resourceful and make the most of anything we had. These became valuable lessons in my creative practice later on. Part of the reason why I enjoy working with paper is that it pushes me to explore new ways of transforming a humble material into something unexpected. Our art teachers were very important as well. Dedicated, encouraging, and engaging, they treated us with respect and their sense of humor made of the learning experience something that I was always looking forward to.

Would you describe how artists are trained in Cuba?

Art education in Cuba follows a handson, rigorous approach that gives the students a solid foundation on which to build their careers. There are specialized schools at elementary, intermediate, and advanced stages across the island. The elementary level, called vocational, goes to 9th grade. The subjects covered are art history and the technical aspects of traditional media, such as drawing, painting, printmaking, and sculpture.

The intermediate stage, known as professional or medium-superior, goes from 10th to 12th grade. Here, the student is required to choose a medium to specialize in. During those three years, art history continues to be an important part of the curriculum, and the chosen medium is explored in great depth. Graduating from this level requires a thesis that is usually the creation of a cohesive body of work.

The most advanced level of art education in Cuba has a duration of five years. Known as Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), the main school is located in a historical building in Cubanacán, Havana. At present, the ISA has four schools, three for Art and one for Audiovisual Communication Media. There are also four teaching schools in the provinces, one in Camagüey, two in Holguín, and one in Santiago de Cuba. ISA offers pre-degree and post-degree courses, as well as a wide spectrum of brief and extension courses, including preparation for Cuban and foreign professors for a degree of Doctor of Sciences in Art. Most art teachers in Cuba are also practicing artists.

What was it like making the transition to living in Los Angeles, then New York?

Transitioning from Havana to Los Angeles brought positive change to me. Leaning English and how to drive were my biggest challenges. It was isolating at first because I didn’t know a lot of people there, but then I discovered the Internet, something that was not allowed in Cuba. The fact that I could develop real friendships and professional relationships through a computer was a miracle to me. Another interesting aspect of being in Los Angeles was the opportunity to observe the film world as an outsider

7

through my husband. I met a number of talented writers, directors, producers, and artistic directors who were encouraging and inspiring. Most of them were from different parts of the world.

After our children were older, in 2014, we decided to move to New York, where we still live. We got here right around one of the most extreme winters in the history of the region. My husband, Bill, is from Chicago so snow was part of his system, but it was not part of mine or our children’s. As a kid, I was in love with the idea of snow, which I had seen only in pictures and movies. The closest I got to it back in Cuba was when my younger brother, Alex, and I attempted to make “snowballs” out of frost that we scratched out of our Soviet freezer. We never got to make a real ball because the heat melted the frost too fast. Moving here and having so much material for making snowballs was a dream come true. That made the whole transition fun. Living in the countryside, but still not too far from New York City, has been ideal. We get to enjoy the best of both worlds.

The most remarkable thing to me about moving to New York has been working for ArtYard, a unique arts organization founded by my friends Jill Kearney and her husband, Stephen McDonnell, in Frenchtown, New Jersey. Over there, I wear many hats, but mostly function as artistic director and do curatorial work as well. You can learn more about the organization at www.artyard.org. I truly enjoy working for ArtYard and being part of a team of people that are intelligent, thoughtful, extremely creative, and caring. I appreciate traveling to New Jersey and New York City where we have meetings sometimes. But the best part is interacting with artists from the position of a facilitator. Stepping out of your self-centered world as an artist to

look into other artists’ realms is enriching and revealing, and it gives me perspective on matters that I wouldn’t be able to be exposed to in isolation.

How did your work change when you moved to the States?

I will first give you a little bit on context to answer this question. Before I moved to the U.S. and in terms of what was going on in Cuba in the art world, I was more of an outsider. My first gallery was, in fact, for outsider artists (Phyllis Kind Gallery in New York and Chicago). Back then, in lieu of dealing with matters specific to Cuba, such as the political system and other issues, I was more inclined to exploring personal subjects rooted in universal human experience. The series of photographs that I did based on Belkis Ayón’s death by suicide, for example, was my way to process her loss.

Working with matters that were not necessarily identified as Cuban, left me out of some local and international projects that reflected on Cuban artists working around Cuban issues. But I had plenty of opportunities to exhibit my art in Havana and other provinces, as well as abroad. And I received visitors in my studio weekly; most of them came from the U.S., Italy, Spain, Germany, and some Latin American countries. They were mostly art collectors, curators, or were connected to the academic world in their countries. One thing that they all had in common was their willingness to understanding Cuban artists, how they lived, and how they were building successful careers under difficult circumstances. The support of these visitors by purchasing our work and the opportunities that opened up from these visits were important to many artists living on the island.

8

Once I moved to the U.S., those studio visits stopped, and that was the greatest change at first. Most of the people visiting Cuba were interested in Cuba, specifically, but in Los Angeles, the city where I had just landed, that wasn’t necessarily the case, except for my friend Darrel Couturier from Couturier Gallery on La Brea Avenue, who worked, and still works with Cuban artists.

To summarize the idea of what happened to my work when I moved to the States, I would say that I took it apart and then put back together one piece at a time, in a way that made more sense to the new me. Examining what I had done previously was like opening a machine to see what’s inside and then trying to re-ensemble it, but some pieces didn’t fit and others had to be added to make it work. That’s more or less what happens when you start a new life in a totally new culture.

During that process of reinvention, I became very interested in materials. I spent a great deal of time trying my hands on everything that I could find, such as wool, metal, glass, fabric, paper. Parallel to this and as a way to improve my written English, I started a blog. This combination of exploring new materials and connecting to new people through a language that I didn’t know well was itself the creative “work” that I needed to do back then. Finally, my career started coming back together in a more cohesive way when I became a mother. I reconnected to the subjects that had always fascinated me and started to explore them in more depth from new lenses.

My work continues to change organically. Sometimes in circles of Cuban people I’m considered a Cuban artist and that is nice because my roots will always be there. In other circles, I’m considered an international artist. I believe that at this point I’m a mix of both.

10

When did you start using cut paper in your art, and what are its aesthetic and physical attractions for you?

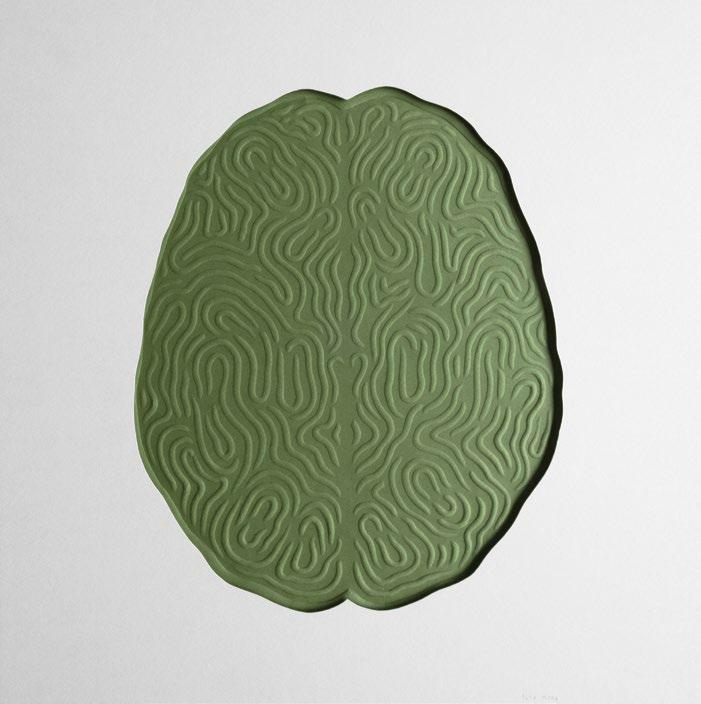

I started exploring paper in 2007, right when my son, Diego, was diagnosed with autism. What attracted me to this material was its unassuming nature. My first tests happened during our son’s therapies. Instead of staying in the waiting room, parents regularly went out for coffee, but making something with my hands at the time was more appealing and comforting. As I played with paper, I heard our son interact with the therapists. The gradual discovery of his potential got interconnected with the hidden possibilities of paper. That’s probably how this material became a metaphor for the mind and its malleability to me. As my son blossomed, so did my relationship with and understanding of paper. Life and art sometimes converge in organic ways, such as in this case.

You mention your son in terms of the work’s inspiration. What about your sister?

My sister was crucial in my understanding of people, the brain, and art. Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at age fifteen, she was my introduction to mental illness and the matters of the brain. It was also through her that I discovered poetry and literature in general. My sister was a gifted artist that showed different talents at an early age, not only for visual arts, but singing and acting. I was fascinated by her wild nature and fearless personality. Watching her draw and paint (sometimes on her own face) was mesmerizing. She talked to me as if I were an adult, and I appreciated that. Her openness helped me see the spectrum of her interior life, from the brightest to the darkest areas. I believe that growing up with her planted the seeds of my interest in human behavior. She’s still alive, but the effects of electroshocks throughout the years, which

at some point she volunteered to take out of desperation, ended up damaging her intellect. Regardless of the limitations, she continues to be creative and lives a highly functional life in Cuba.

Let’s get back to the work itself. Is the image already inside the paper or as you cut, does the design become manifest?

It can go either way. Sometimes I have a concrete idea that I want to materialize, while other times, it’s all about accidents and being open to the unexpected.

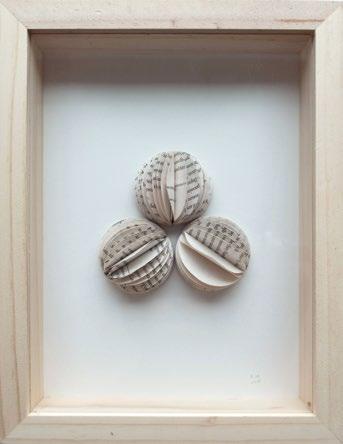

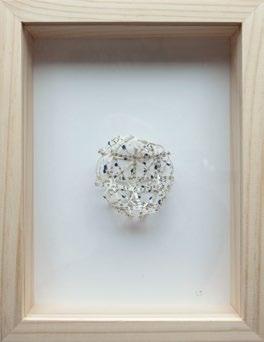

Tell us about your process of moving from twodimensional to three-dimensional cut paper works.

Going from flat surfaces to three-dimensional work was a natural part of the process. After spending enough time in the two-dimensional realm, curiosity kicked in, so I found myself going on an adventure into the sculptural cosmos. For some reason, volume makes everything look and feel more “real.” Think about watching a film on a screen versus experiencing a live play in a theater. Sculptural paper pieces tend to be more satisfying to me, but there are also some two-dimensional works that I truly enjoy making, especially those with repetitive elements where the process becomes meditative.

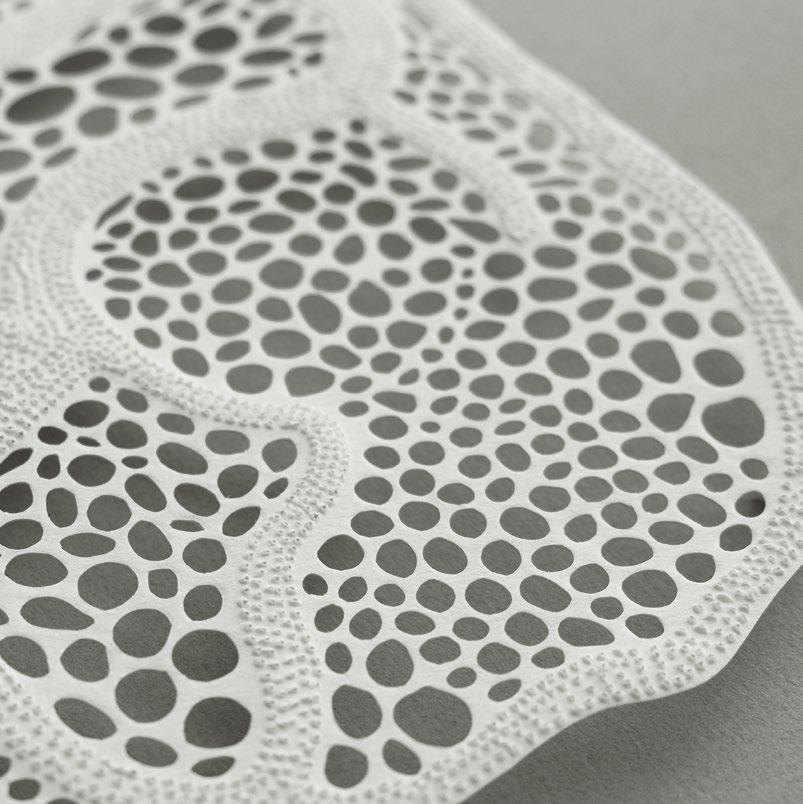

What is informing shape, line, and color in your new body of work? It looks like it could be a combination of abstraction, science, and the subconscious.

Your question pretty much includes the answer. I would say that this new body of work is indeed a combination of abstraction, science, and the subconscious. The shape, line, and color are informed by my observation of nature and sometimes the inner composition of the human body.

11

How did this new body of work challenge you physically and mentally?

Working with a material as simple as paper means that if you want to push the envelope, then you need to push your brain to think outside the box. That can be as exciting as it can be frustrating. Whenever I get stuck, a walk in nature is usually the solution. I’m lucky to live on a farm surrounded by a great variety of vegetation. That has been one of the advantages of moving to Upstate New York.

Does your work with cut paper influence your work in other media? Are you still working in other media?

Working in other media is a necessity to me. Too much of the same thing affects my ability to stay excited and engaged in the creative process. I’m happiest when I give myself the freedom to jump from one medium to the next. While working with paper, I’m sometimes dreaming about other materials and vice versa.

What’s next in your investigation of the intersection of the brain, literature, writers, and the six cognitive faculties that form the mind? Might you explore this in other mediums or material?

Definitely, I want to explore these subjects in other mediums and materials as well as combine them. I’m looking forward to setting up a new studio and finally having the conditions to work in ceramics. Clay is one of my favorite materials; so are fabric, wood, and glass. They all have unique personalities, just like people. What’s coming next, I don’t exactly know, but that’s what makes me want to keep moving forward.

Now that you live in the United States full time, what is your relationship to Cuba, both personally and professionally? How would you characterize the Cuban art scene, perhaps from the time you lived there to now? What should Americans know about Cuban art and artists?

My relationship with Cuba is a long-distance one. I’m connected mostly with my father who lives there, and through him I find out about what’s going on in the country. He visits the U.S. whenever possible, but right at this time it has become harder with the new regulations. I’m also connected to friends with whom I sometimes interact via Facebook. And there is my mother who travels there once a year. She lives in Miami, Florida, and gives me reports on the phone about who has died, who’s had a new baby, who got divorced, etc. More than politics, we talk about people that we know and their lives.

I have noticed that the reports about how things are in Cuba depend on the reporter and their individual situation. Life in the provinces seems to be harder than in Havana, and artists in general seem to have more opportunities to make connections outside of Cuba than people who hold regular jobs. What Americans should know about Cuban artists is that they are like artists anywhere in the world. They want to have opportunities to develop their careers, they want to have their basic needs covered, and they want to contribute something to society through their practice.

12

What do you wish we had asked?

I enjoyed all the questions. I would like to add that Diego is now thirteen, a remarkable artist and an out-of-thebox thinker. His sister, Natalie, fifteen, is my best English teacher and a talented writer, artist, and filmmaker. There is also my stepson, Miro, who is in his twenties. He studied environmental science and with him I have learned to appreciate nature even more. He is also a musician and loves to study and draw specimens with colored pencils. Inspired by them, I recently started an experimental project called The Tiny Gallery. I invite you to visit www.the-tiny-gallery.com to find out more about it. My husband, Bill, continues his career as a film producer from New York and travels back to Los Angeles often.

I can’t end this interview without saying thanks to the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art for opening its doors to my work, to Jill Hartz for her genuine interest in other cultures and her understanding of how people benefit from learning from each other through art. Special thanks to the talented Michael Bragg who designed this book. Thanks to every person who worked on making this exhibition possible. I’m honored to be visiting Eugene, Oregon, for the first time ever with my art.

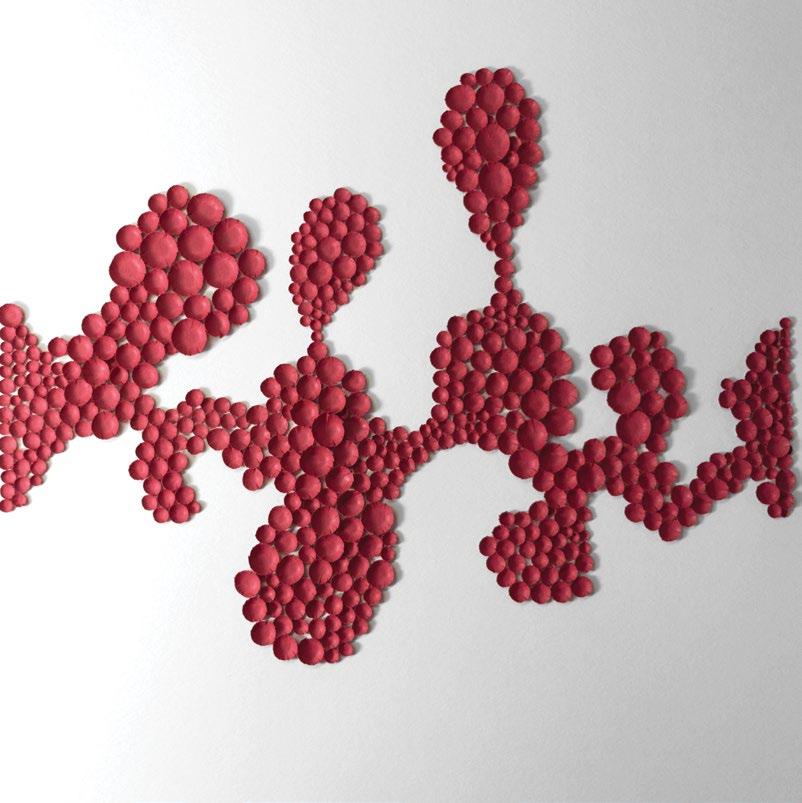

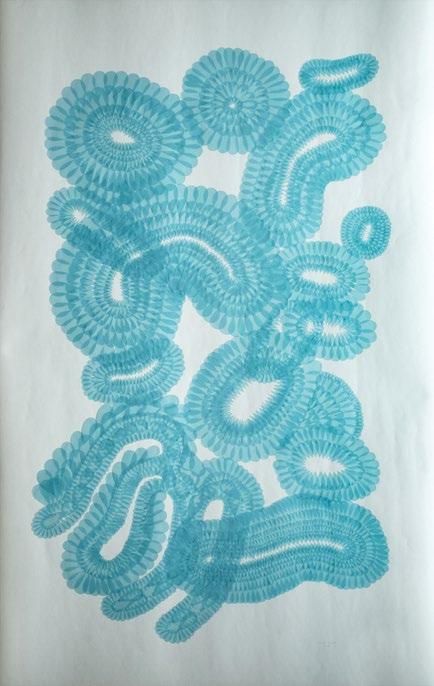

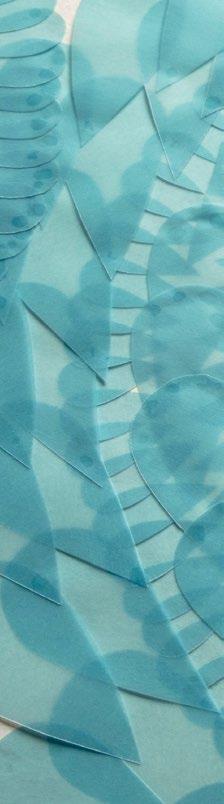

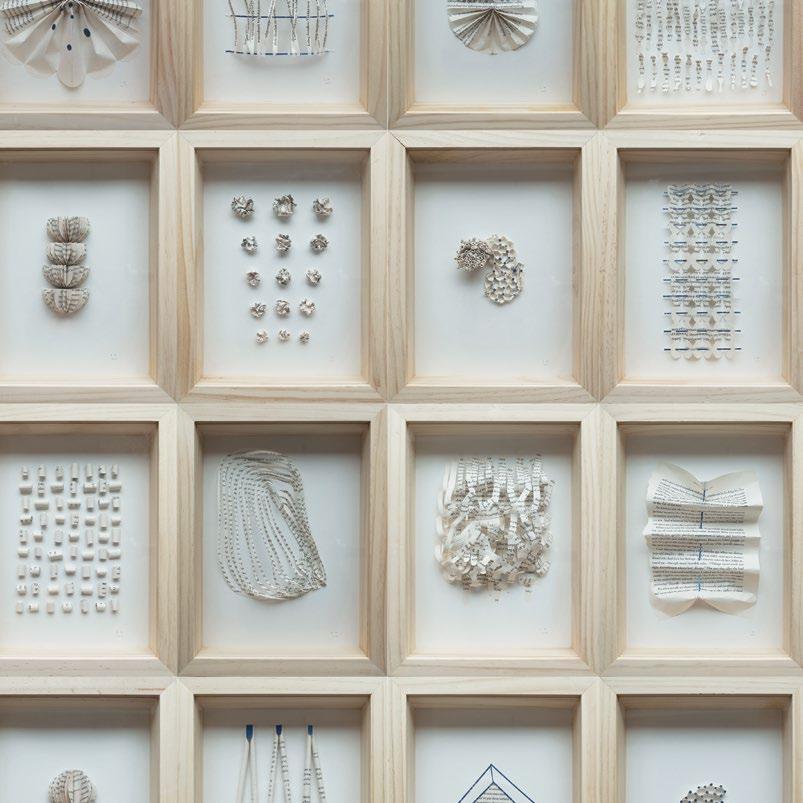

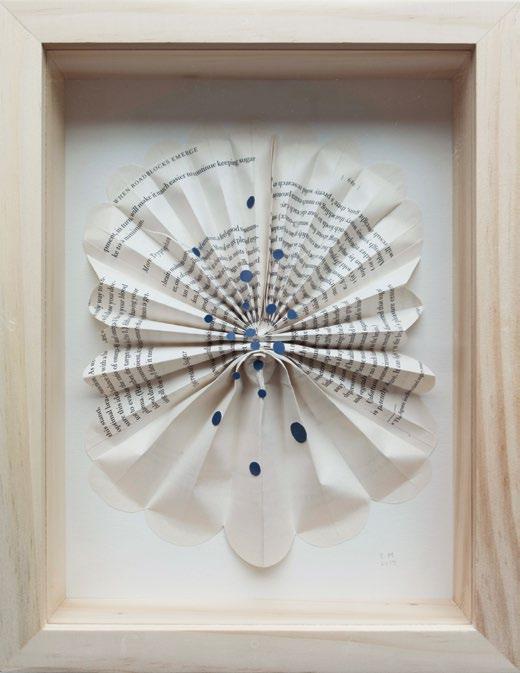

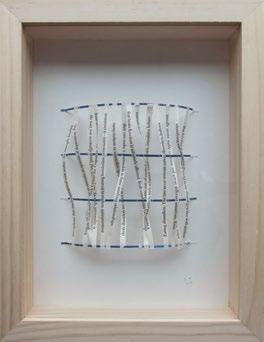

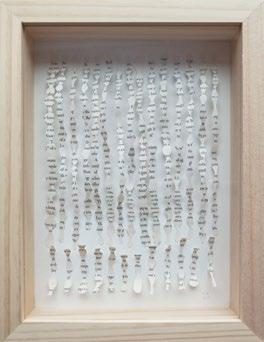

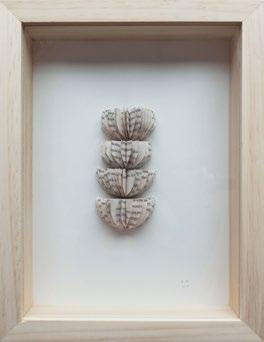

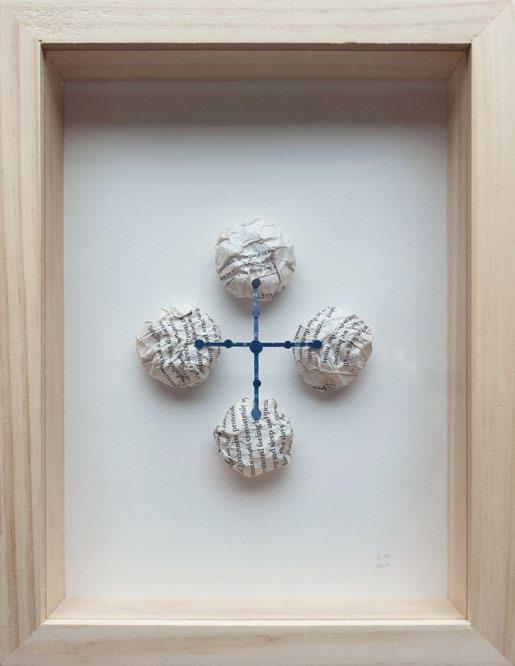

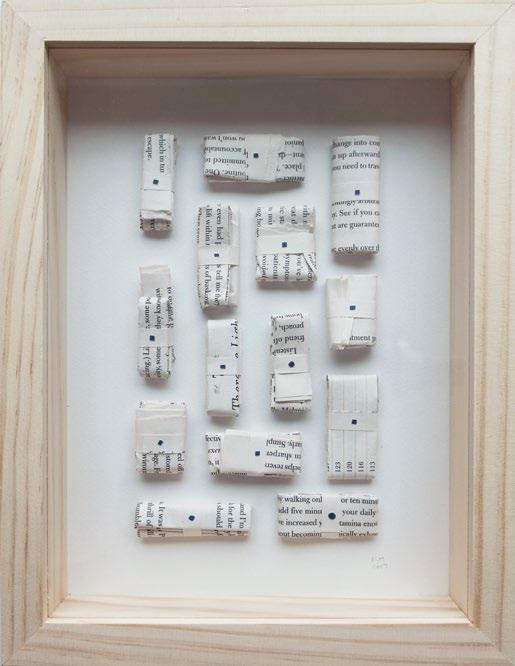

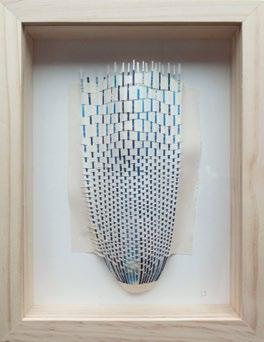

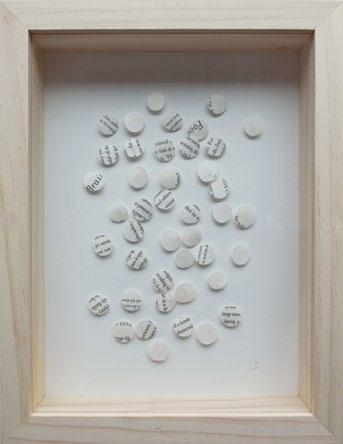

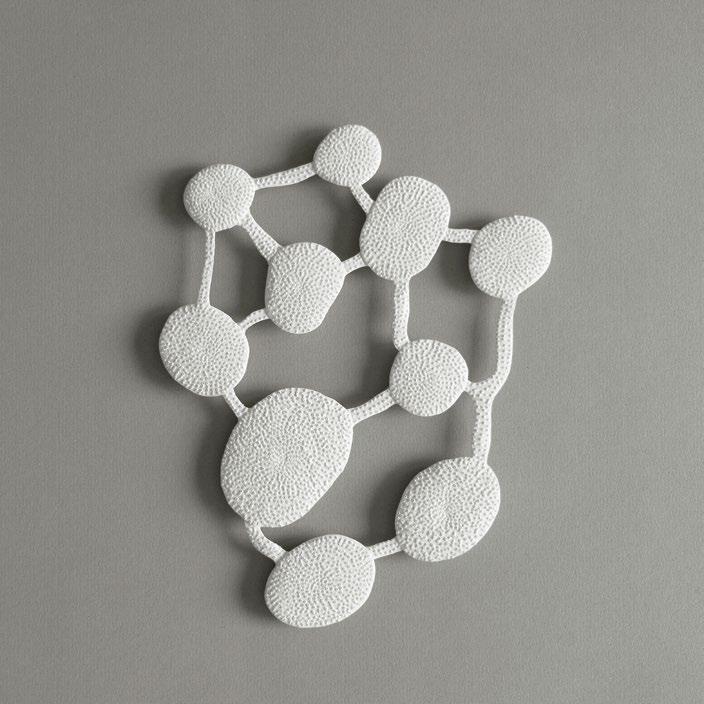

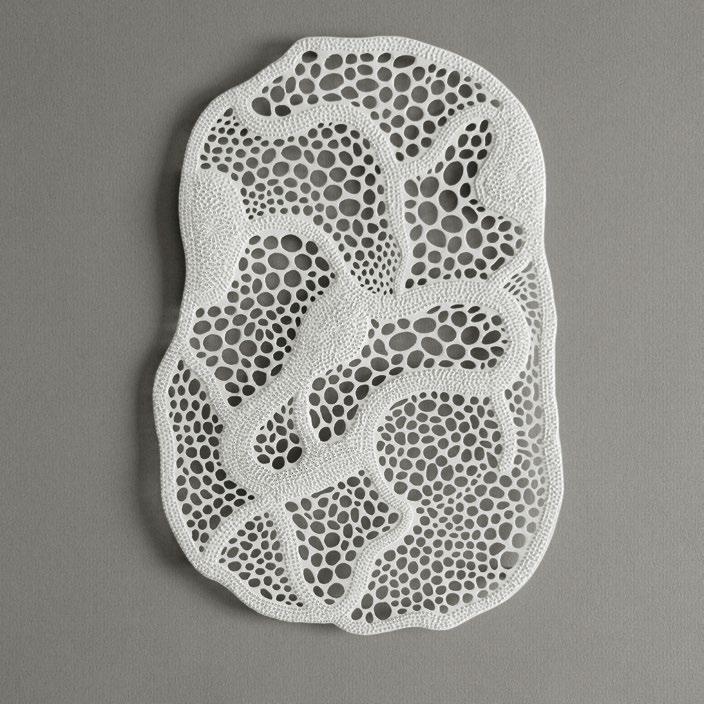

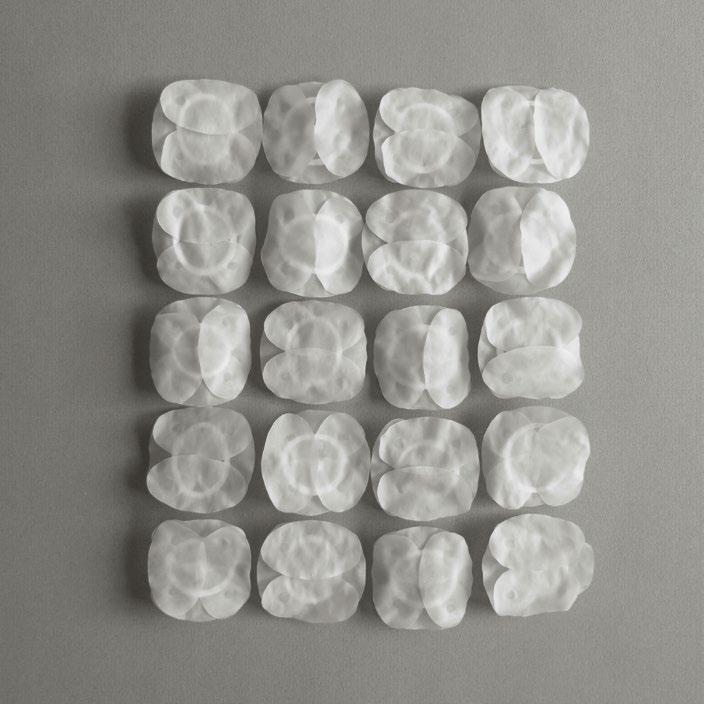

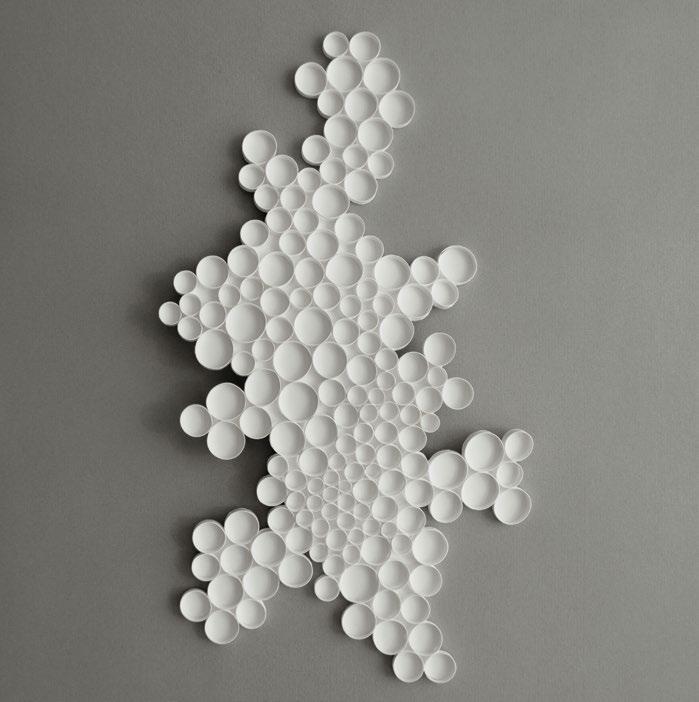

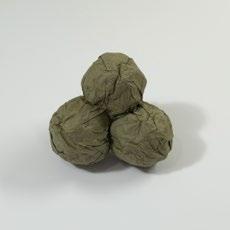

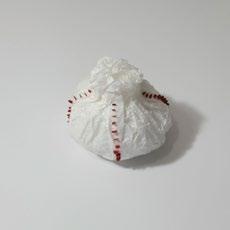

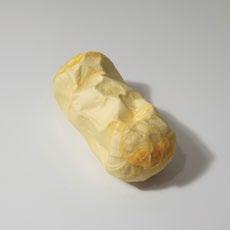

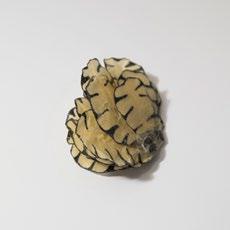

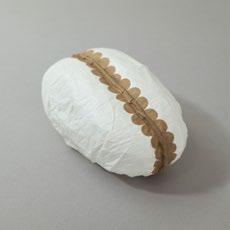

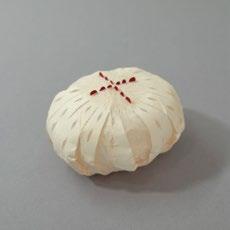

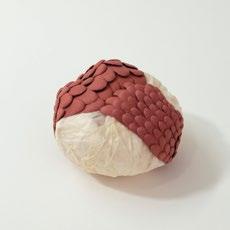

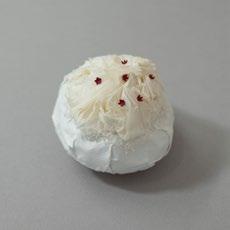

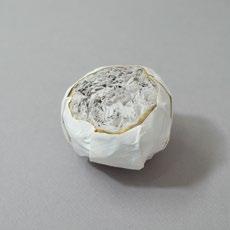

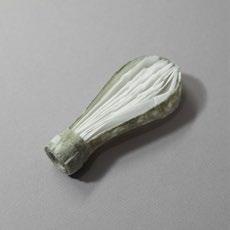

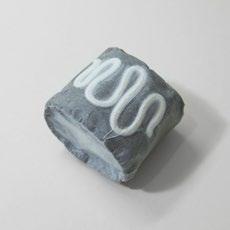

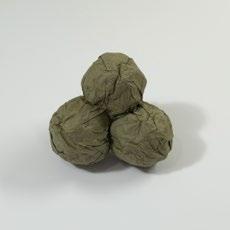

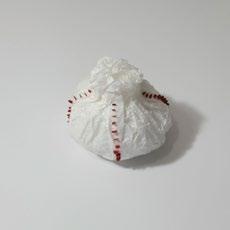

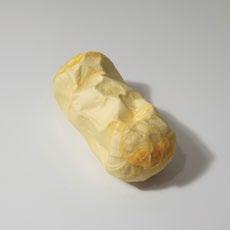

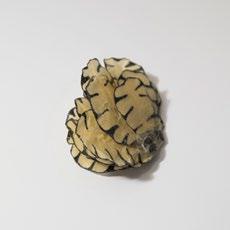

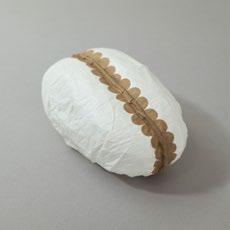

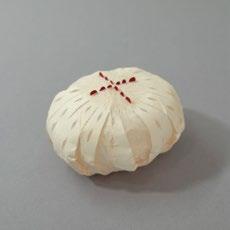

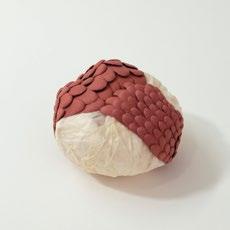

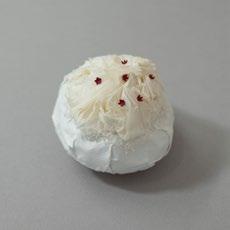

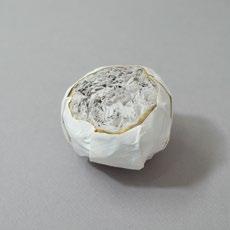

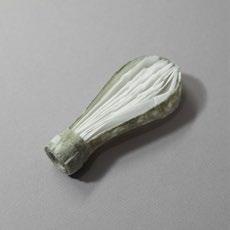

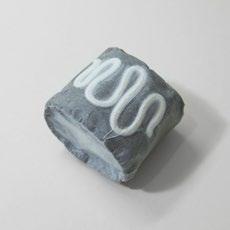

One Hundred and One Notions

Series of 101 small sculptures, 2018 Archival paper and glue Variable dimensions

This series is about perception, and it consists of one hundred and one small paper sculptures, each of them representing a mental disorder. Along the process of creating these pieces, I did research about the different mental disorders, some of which I had never heard of. For example, Fregoli delusion is a rare disorder in which a person holds a delusional belief that different people are in fact a single person who changes appearance or is in disguise. This installation is an homage to the human mind and the endless ways in which it expresses itself. It is about the darkness, light, and mysteries of our human condition.

74 1. Stockholm syndrome 2. Sleep paralysis 3. Agoraphobia 4. Selective mutism 5. Amnestic disorder 6. Schizophrenia 7. Anterograde amnesia 8. Antisocial personality disorder 9. Attention deficit disorder 10. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 11. Autism 12. Autophagia 13. Avoidant personality disorder 14. Atelophobia 15. Bereavement 16. Bibliomania 17. Binge eating disorder 18. Bipolar disorder 19. Body dysmorphic disorder 20. Borderline intellectual functioning 21. Borderline personality disorder 22. Brief psychotic disorder 23. Bulimia nervosa 24. Catatonic disorder 25. Catatonic schizophrenia 26. Circadian rhythm sleep disorder 27. Claustrophobia 28. Communication disorder 29. Conduct disorder 30. Cotard delusion 31. Cyclothymia 32. Delirium tremens 33. Depersonalization disorder 34. Depressive disorder 35. Derealization disorder 36. Dermatillomania 37. Desynchronosis 38. Diogenes syndrome 39. Dispareunia 40. Dissociative identity disorder 41. Dyspraxia 42. Dyslexia 43. Ekbom’s syndrome The Associated Disorders Represented in One Hundred and One Notions

75 44. Encopresis 45. Epilepsy 46. Tourette's syndrome 47. Erotomania 48. Factitious disorder 49. Fregoli delusion 50. Fugue state 51. Ganser syndrome 52. Generalized anxiety disorder 53. General adaptation syndrome 54. Grandiose delusions 55. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder 56. Histrionic personality disorder 57. Huntington’s disease 58. Hypomanic episode 59. Hypochondriasis 60. Hysteria 61. Insomnia 62. Intermittent explosive disorder 63. Lacunar amnesia 64. Maladaptive Daydreaming 65. Malingering 66. Manic episode 67. Mathematics disorder 68. Melancholia 69. Misophonia 70. Mixed episode 71. Munchausen’s syndrome 72. Narcolepsy 73. Narcissistic personality disorder 74. Neurocysticercosis 75. Nightmare disorder 76. Obsessive-compulsive disorder 77. Oneirophrenia 78. Oppositional defiant disorder 79. Orthorexia 80. Ondine’s curse 81. Pain disorder 82. Panic disorder 83. Paranoid personality disorder 84. Parasomnia 85. Persecutory delusion 86. Seasonal affective disorder 87. Phobic disorder 88. Pica (disorder) 89. Kleptomania 90. Korsakoff’s syndrome 91. Psychosis 92. Phonological disorder 93. Polysubstance-related disorder 94. Post-traumatic stress disorder 95. Primary hypersomnia 96. Primary insomnia 97. Pseudologia fantastica 98. Psychogenic amnesia 99. Pyromania 100. Adjustment disorder 101. Relational disorder

1 4 7 2 5 8 3 6 9

10 12 11 13

14

15 18 21 16 19 22 17 20 23

24 26 25 27

28 30 29 31

32 35 38 33 36 39 34 37 40

41 44 47 42 45 48 43 46 49

50 52 51 53

54

55 58 61 56 59 62 57 60 63

64 67 70 65 68 71 66 69 72

73 76 77 74 78 75

79 82 85 80 83 86 81 84 87

88 91 94 89 92 95 90 93 96

97 100 101 98 2 99

Elsa Mora is an artist and curator. A recipient of the UNESCO-Aschberg Bursaries for Artists, she was born and raised in Cuba and moved to Los Angeles in 2001, where she lived until 2014. Mora currently resides in upstate New York with her husband, William Horberg, and their two children. Elsa’s art has been exhibited worldwide in art galleries and museums. She taught at the Vocational School of Arts in Camagüey, Cuba, and has been a visiting artist at the Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco State University, the Art Institute of Boston, the MoMA Design Store, and the National Gallery of Art, among others. Her work is in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.; the Long Beach Museum of Art , California; and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon. Mora has collaborated as an illustrator with such organizations as the Museum of Modern Art, Chronicle Books, The New York Review of Books, Penguin Random House, The Oprah Magazine, Cosmopolitan, and teNeues, among others. She is one of the founding members of ArtYard, a contemporary art center based in Frenchtown, New Jersey, where she is artistic director and curator.

For more information, please see her website: www.elsamora.net

94

My work reflects on universal issues of identity, connectivity, and survival. Through a variety of mediums, I explore philosophical questions associated with isolation, individualism, and disjointed positions as originators of chaos. For the last few years, I have been fascinated by the expressive quality of paper, an unassuming material that I see as a metaphor for transformation and reinvention. Since my childhood, I have also been fascinated by the brain and its intricacies. The fact that some members of my family suffer from mental illnesses made me want to understand the mysteries of an organ that rules a great part of human behavior. My latest work, mostly using paper, associates the versatility of that material with the malleability of the brain.

– Elsa Mora

95

Published by

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

1430 Johnson Lane

1223 University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon 97403-1223

541-346-3027

jsma.uoregon.edu

ISBN-13: 978-0-9995080-4-6

This publication accompanies the special exhibition Paper Weight: Works in Paper by Elsa Mora, on view at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, August 29, 2018 - January 20, 2019

Paper Weight: Works in Paper by Elsa Mora is made possible with the support of the Hartz FUNd for Contemporary Art.

Jill Hartz, Editor

Mike Bragg, Designer

Natalie Horberg, Photographer

The

96

© 2018 Jordan Schnitzer

of Art. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher.

Printed through Four Colour Print Group

Museum

University of

is an equal-opportunity, affirmative-action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the American with Disabilities Act. This publication is available in accessible formats upon request.

Oregon