Social and Cultural Challenges in Interior Architecture

The Ockenburg youth hostel in The Hague, designed by the Dutch architect Frank van Klingeren, is a modular, flexible building made of a dark steel structure. It was built as the extension of a 19th century villa containing three stories with space for 400 beds. The hostel is fallen into abeyance due to its loss of function and was disassembled in 2010 to be re-used at a new location. I chose this building as its history has many similarities with my mission: finding out how I can employ cooperation as a design tool. With a reference to the sociologist Richard Sennett I think people tend to avoid engagement with others with the result that we lead our lives in the city quite independently. By applying Sennett’s view to an interior space I hope to gain social awareness and improvement of social life. For the adaption of ‘a new Ockenburg’ to contemporary society in the neighbourhood Morgenstond in The Hague, I have created a cooperative programme with a focus on social values. It can be described as an urban alternative for the recent phenomenon of wwoofing; instead of paying money for

their stay and make use of hostel services, travellers contribute by working in the hostel and in the surrounding area. In this way the hostel becomes a place where cooperation and sharing knowledge are the moving keys for activities. Also, the local people and travellers will get in touch with each other and learn from each other’s skills; hence it might bring added social benefits to the whole neighbourhood. In line with Van Klingeren’s ideal community building without walls - because only then communication would flourish - the key words for my design research are cooperation, social interaction and transparency. Through a disposition of different activity elements, such as benches, tables, beds, kitchens etc. in the free space of Ockenburg, I will re-use the original structure of the building as the base for my final design.

My research started with my personal observations of idle urban spaces. This inspired me to look into possibilities for temporary transformation. What intrigued me about temporary spaces are the out-of-the-ordinary experiences they evoke and facilitate. The analyses of case studies of temporary projects led me to an in-depth research of the theatrical event as an ultimately timed experience.

My question was how I could translate this physically closed experience to an urban scale and thus link various locations with each other. The analysis of the stages and the process of a performance (script, audition, public discourse, public performance, aftermath) inspired me to curate an urban format for temporary interventions based on the theatrical event – ‘Gastspiel’. ‘Gastspiel’ is a format for a series of temporary interventions offering a diversity of experiences in the urban realm. The Hague serves as a case study. Six idle venues in the city are transformed into spaces of reflection and interaction.

My aim is to appropriate and link these urban idle spaces in order to open up their (hidden) potential to an intense personal experience. Based on the theatrical event each space reflects one stage of performativity : rehearsal, gather, warm-up, performance, cool down, disperse. The ‘rehearsal’ functions as an open workspace that invites the public to participate in workshops held by local artists and designers. The ‘gathering’ is a temporary meeting space on the roof of an idle building. The ‘warm-up’ will become a temporary retreat that facilitates personal concentration and meditation. The ‘performance’ will host scheduled cultural events such as pecha kuchas and debates around themes that are physically discussed in the rehearsal. The ‘cool down’ serves as an experienceable public installation on top of a derelict bridge that calms and cools down. Integrated in a vehicle, the ‘disperse’ changes its location and brings the participants back to their ordinary lives in a literal sense. This multi-locality approach enhances vitality in the urban realm in engaging different audiences and stimulating interactions on different focal points.

Have you ever imagined a space where you would like to be in the final moments of your life? What would you like to see and feel before you close your eyes forever? And how do you picture your final place? Without a doubt, the final moment of life is not very pleasant to think about, but if we do not actively engage ourselves with the idea of death, we will probably end our life in an undefined space. Although people’s expectations and wishes regarding death differ from each other, my intention is to design an “ideal” space that bridges the reality and ideality of the last moments of people’s lives. Herewith I hope to contribute to a sensitive and meaningful journey towards death.

euthanasia usually entails a conscious awareness in which people clearly experience their visual surroundings. I also found out that there are five stages of grief : denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. In my proposal I translated these stages in a spatial way. The final journey of life starts from the ‘Entrance’ where the first step of acceptance starts by facing death. The next space will be the ‘Hall’ where one is encouraged to acknowledge death. Then the ‘Corridor’ will follow which leads a person from the hall to the final room. This is the space to walk through memories and experience a personal moment to gradually accept death. The ‘Final room’ is the most intimate and embracing space. Here a dying person will finally accept death.

For my research I first recalled my grandfather’s death and reflected upon that sad moment. I also visited some hospices and talked to nurses and other caretakers. On the basis of literature I determined two ways of dying : natural death and voluntary death through euthanasia. In the case of ‘natural dying’, the stability of a patient’s physical condition at the dying moment will be the main focus. For ‘euthanasia’ I concentrated primarily on the psychological stage, as

There is a place that I fear the most in The Hague due to a bad memory of being robbed: Muzenplein (the square of Muses). It is a square just around the corner of the Royal Academy in the heart of De Resident: a prestigious high-rise business district close to Central Station, designed by the Luxembourgian architect and urban designer Rob Krier. Was it by accident that the robbery took place here? What are the factors that contribute to the, in my view, uncanniness of the Muzenplein ? I decided to take my personal experience as the starting point of my graduation project and to transform Muzenplein from the place that I feared into a place that I would love to go and feel safe. I studied literature about Krier’s view on urbanism to get to know the ideas behind the project and to find out what he intended with Muzenplein. On the basis of this background information and my observations I could compare the initial ideas with how the area turned out to be. By interviewing people who live and work at Muzenplein I gained insight in how I could improve the area and bring more liveliness for, and interaction between, its residents and the visitors of the area. For my design I decided to use the metaphor of “open house”:

a transformation from an unhomely space into a homely place by adapting the different rooms of a home, like the hallway, the balcony, the living room, into the context of a public interior. This is my design challenge: to translate these homely spaces in response to the existing and in my view complex morphology of De Resident : long alleys, the horse-shoe shaped Muzenplein, the circular-shaped Clioplein, the rectangular garden, and the nearly empty Muzentoren. After all, I believe this area deserves a second chance.

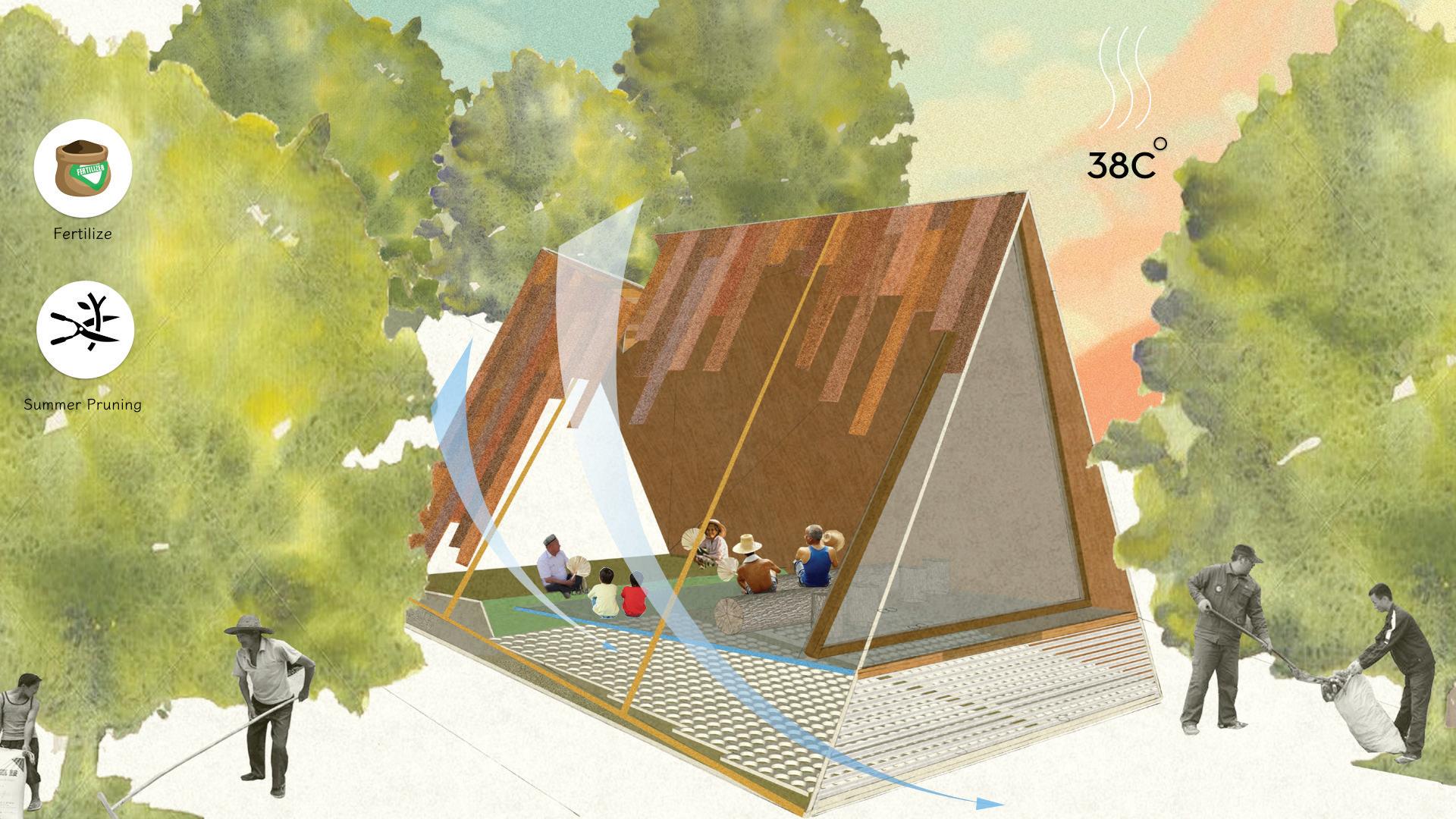

My graduation is based on a personal interest in a current Chinese social issue. Due to China’s urbanization process in the last decade, a large number of villagers moved from the countryside to the city. This phenomenon created a new generation of rural children, the so-called ‘left- behind children’ who stay in their hometown while one or both of their parents have left to live and work in the city. In the Chinese media these children are often called the “orphans of modern China”. At present, there are more than sixty-one million children living in this situation, an equivalent of 20 per cent of all Chinese children !

Through interviews and a research of the daily life in one of these typical left-behind children villages, Yuxian Village in the North of China, I found out that the relationship between the different generations (children, parents, grandparents) is rather weak. The children lack care and love. Although they live together with their grandparents and go to school with other children, they miss the contact with their parents. Therefore my aim is to reconnect

the three generations, and to help enhance the self-esteem of the children. I looked at the activities of all generations, and brooded on moments in which contact would become possible, such as the early morning and early evening, when the grandparents would walk between their homes and the fields where they work, the children would walk between their homes and the school, and the parents would commute between homes and their work facilities. I intend to design a system to allow the left-behind children to contact their parents by phone during these travel moments. Apart from this I intend to design ways for children to help their grandparents in the fields in a playful manner, by which they will be stimulated to learn more about agriculture. These are just a few options to create as many connections as possible between the three generations.

I became interested in the Chinese Hutong due to a personal experience of getting lost in a modern residential Hutong district in Beijing. I did not like the atmosphere with dark alleys and high grey walls, and started to rethink the typology of the Hutong. Through my observations and studies I found out that for me the most attractive aspect of the Hutong district is the diversity of its residents.

locations at the cost of their social housing. As I consider this a great loss, I intend to reactivate the social housing typology of the Hutong and help the original residents to stay. First of all I want to create economic value by employing the skills of the people who live there. By adding workshops in the craftsmen’s living spaces, tourists might watch and learn how traditional products are being made. The numerous residents who offer services to others – like the gardener, cleaning lady and repairman - instead of waiting a call from their neighbors to get a job, I would like to link them with a shop where they can show their horticultural skills and present various products, creating a win — win economy for all involved. Overall it’s my ambition to offer different strategies to the local residents. Through adding, linking, opening, densifying their living spaces and maximizing the spatial qualities, I hope to reactivate the Hutong from the inside.

In the 1950’s, an increasing number of people moved to Beijing and the government transformed some private courtyard buildings into social housing for low-income families, like craftsmen or service personnel. They created a strong social network and coliving and working system inside the Hutong area. However, the government gradually noticed in the last decade that the original Hutong has major potential value, among others as a tourist attraction. Therefore the Hutongs were transformed into attractive

Why are old buildings treated so different in The Netherlands in comparison with Japan? Japanese houses are often demolished after 30 years while in The Netherlands some century-old buildings are still being preserved and in use, sometimes with a different function, like churches. I became very intrigued by this different approach towards the continuity of old buildings and started my research to find out what the reasons are behind these different approaches. I also wondered how old buildings are perceived by the local people and what their influence is on the local identity of cities. My research focused on my hometown, Takasaki, which used to be a vibrant city, but due to the demolishment of a lot of old buildings the streets have become empty and the centre is losing its vibe.

physical and non-physical elements by means of a platform. This platform is both a website and a space where materials of demolished buildings are being presented to the public, who can obtain them for new purposes. The space is located in the city centre of Takasaki, consisting of two former traditional Japanese warehouses (Kura). They are connected by a giant shelf where the local materials are visibly stored and displayed. In these ‘warehouses’ workshops are given to the local people about crafts in order to exchange knowledge and skills and to enhance social interaction.

Through my research I discovered that an old building in The Netherlands is considered an essential element for strengthening a local identity. In Japan, in contrast, non-physical elements (like rituals and skills) play a more significant role in reinforcing local identity. Therefore, I come up with a design strategy to facilitate a (re)generation of local identity in Takasaki by combining both

Overall I hope that through the reuse of materials of old buildings the memory of the history of Takasaki is kept alive and that my platform will nurture the future potential of locality.

In its fifth year INSIDE is proud to say farewell to 7 new masters of interior architecture who graduated with self formulated projects that all relate to the social and cultural challenges that interior architecture faces at this moment.

This years INSIDE graduation shows a large variety of design challenges and approaches. Included in this magazine are proposals to respectfully update a Hutong area in Beijing and to reveal the hidden potentials in vacant buildings in The Hague using elements of the theatre. Buildings are taken apart and stored in a dynamic way in Japan or taken out of the storage and re-used in a cooperative way in The Hague. Besides that the safety in an urban space just around the corner of the Royal Academy was investigated as well as the huge social problem around children in a Chinese village who are left behind with their grandparents because their parents move to the cities for work. One of the graduation students even explored the spatial needs of people who face death. These projects all show challenging opportunities for future interior architects.

Royal Academy of Art, The Hague www.enterinside.nl