Fenna Hup

Sarah van Binsbergen in conversation with Boris van Westering, Lauren Alexander and Niels Schrader

Fenna Hup

Sarah van Binsbergen in conversation with Boris van Westering, Lauren Alexander and Niels Schrader

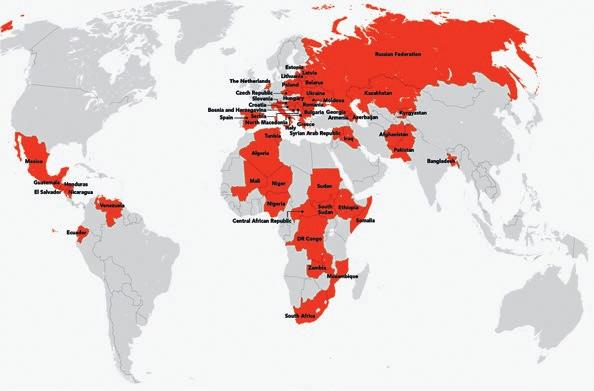

This publication Facts Not Filters is the result of a collaboration between the master programme Non Linear Narrative of the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague and the organisation Free Press Unlimited. Free Press Unlimited is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that supports journalists and media organisations in over fourty countries with training, emergency support and capacity building.

As an art institute with a highly international and diverse studentpopulation the master Non Linear Narrative aims to offer it’s students exploration of urgent, societal issues on an inter national scale. It is a goal to have students gaining attention from a larger audience to these important societal issues from a different, artistic, perspective, thus having an eye-opening function.

Free press is under great strain in many countries and faces major challenges. One example is the safety and protection of journalists, another is guaranteed independance of journalism to enable uncensored journalism. Lastly, the importance of inclusiveness in journalism, enhancing the position of female journalists and reporting by local journalists.

Free Press Unlimited focuses on these challenges and was therefore an ideal partner for the Non Linear Narrative students to work together with in a project from September 2020 until January 2021.

The aims were to investigate different local case studies through the Free Press Unlimited’s inter national partner network and gain a better understanding of how media

functions. The students examined the complexities of culturally rooted and geographically specific nuances related to regional news reporting.

Through these case studies students not only learned how journalists work under difficult conditions, often facing harassment and death threats, but also got an understanding of nuances in reporting due to diverse cultures and geographical locations.

We are proud to present you the artistic outcomes of this project and wish to thank Free Press Unlimited for their meaningful work and collaboration with the Royal Academy of Art (KABK).

Fenna Hup Deputy-Director of Education

Free Press Unlimited operates in countries with limited (press) freedom.

In our ideal world everyone has access to independent, reliable and timely information. To make this possible, Free Press Unlimited supports media and journalists worldwide. Our vision is short and to the point: People deserve to know. All over the world.

Our mission stems from Article 19 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Everyone has the right to independent, reliable and timely

information. People need that information to control their living conditions and to make the right decisions.

To that end, press freedom and freedom of information are indispensable. That is why Free Press Unlimited supports local media professionals and journalists, particularly in countries with limited (press) freedom. They are close to their audience and are the best guarantee for a sustainable, professional and diverse media landscape. We enable them to give people access to the information that helps them survive, to develop themselves, and with which they can monitor their governments.

From September 2020 to January 2021, the Master Non Linear Narrative (NLN) programme at the KABK collaborated with the international NGO based in Amsterdam, Free Press Unlimited. The organisation supports the independent work of journalists and believes in access to information, independent media and freedom of expression for citizens and civil society who work to combat poverty and inequality. Boris van Westering, programme Coordinator of the Middle East and North Africa at Free Press Unlimited, sat down with Niels Schrader and Lauren Alexander from NLN to discuss, with interviewer Sarah van Binsbergen, the results of their partnership. ––––––––– Sarah van Binsbergen: Let’s start at the beginning: how and why did this collaboration come about? ––––––

––– Boris van Westering: For Free Press Unlimited, it was interesting to collaborate with the NLN programme at the KABK because it allowed us to approach the topics we are working on in a different way. We work all over the world and although the circumstances vary from region to region, we see common problems in the newsrooms. The space for dissenting voices in the media is shrinking. There is less time, less money and less space for journalism. In addition to this, the world of media and information has become extremely complex with the current advancements in technology. As a result, the toolbox of journalists is also shrinking. Journalists are under so much pressure that they can hardly be creative. This is why we wanted to work with people from art, design and technology –to explore different forms of story-

telling and their tools to express and tell narratives. So, when NLN reached out to us with the plan to work together, we were very open to collaborate.

––––––––– Niels

Schrader: At the beginning of 2020 we got in touch with Free Press Unlimited (FPU) because one of our former students, a young woman of Iranian descent, was working on a project that took a fierce stance on Iranian politics. We were concerned about the student’s safety and asked her to seek advice from experts at FPU. That’s how we got in touch with their organisation and then, Lauren, Boris and me rather quickly decided that we would love to collaborate on a project together.

––––––––– Lauren Alexander: We have been doing these collaborations with external organisations for a while now because we feel it is a great way for students to learn.

These collaborations are quite open, we try to find a structure that is beneficial and interesting for both parties. In July 2020 we had a meeting to discuss with Boris potential topics and we decided to focus on the issue of censorship and how it plays out in the different countries where Free Press is active. –––––––

–– NS: The NLN programme was developed in 2016 as a response to the dominating rhetoric of political discourse, designed to manipulate people by creating an informational chaos in which the truth is buried. Trump had been elected in the United States, the referendum for Brexit had just happened, Russian disinformation agencies established close ties with Julian Assange to interfere in the presidential election, and so on. There seemed to be a non-linearity in the way that the world was presented in the discus-

sions surrounding these events. This non-linearity, or irrational logic, is of course strongly connected to digital media and how technology alters what people feel, what they believe and how they behave. The ultimate goal is no longer to construct a reasonable argument, but to cause confusion. At NLN we show students why facts matter nevertheless and how we can counter post-truth politics. We aim to create a meeting ground between disciplines, a space where the narratives through which stories are told and information is exchanged are scrutinized. We see the collaborative projects as a place where new knowledge is created by building bridges between disciplines. This approach worked out quite nicely in the past and with FPU it worked out particularly well. ––––––––– LA: There is great urgency in what an organisation like

FPU is doing, and this urgency is something we want to expose the students to. The students come from different backgrounds, both in terms of nationality and education. They come from design but also, for instance, fine art or philosophy. The priority in the first year is to expose them to critical social and political issues. Through working with socially engaged organisations, we can work on topics of relevance, for instance, by understanding Boris’s field and seeing how we as designers and artists can link our practices to that.

BvW: In the collaboration the KABK interacts predominantly with me, but there is in fact a whole team of people behind me. All the cases that I bring forward are peers of my colleagues at FPU who are working in the different regions – sometimes under life-threatening circumstances –

and who stay connected with the local news outlets. Every piece of information I share needs to be approved and every disclosure needs to be considered carefully. My participation in this project is really thanks to all my colleagues and our local media partners.

SvB: If I understand correctly, an important part of this collaboration was that the students would engage on a project related to the issues that FPU is working on. What was the brief that you gave to students? –––––––––

BvW: As Lauren said, we decided to focus on censorship and on the different shapes and forms this takes. All my colleagues collaborates in forty countries with local media partners so the idea was to explore, through different cases, how journalism is increasingly under attack and how censorship manifests itself.

In close coordination with our local partners we offered the different cases as reference material, and students were free to adopt a case or find one themselves. The brief we then gave to students was to “paint the picture”, to visualize the specifics of a given case.

LA: There was a very memorable day in the early stages when students were introduced to the cases. Of course, because of Covid-19, but also because the incidents related to each project took place in different countries, we could not sit with all the journalists in one room. Instead we had a couple of Zoom calls with journalists and organisations from Morocco, Pakistan and Georgia, to name a few. The local journalists explained the issues they were reporting on and challenges they were facing. This was September 2020, after all of us had been inside

for so long due to the pandemic. All of a sudden the students were able to tap into someone else’s life in another part of the world. I think it was an impressive moment for them. –––––––––

BvW: We wanted to introduce them to the topics of censorship and the safety of journalists in different contexts. For instance, we had Paul Vught, crime reporter of Dutch newspaper Het Parool, who talked about media freedom and safety of journalists in the Netherlands. And we had a conversation with Hicham Mansouri from Morocco who talked about the case of Omar Radi, a journalist who was sent to jail for his news reporting. So, students got a sense of what we are working on in different parts of the world. From there on they could dig themselves into the topic and choose an angle, which was sometimes a bit scary. But I see that

as part of my job, to scare the students a little.––––––––– SvB: Could you give an example of how the students proceeded after being given the brief and familiarizing themselves with the cases? ––––

––––– LA: Our student Nelleke Broeze, for example, was very much interested in women’s issues and decided to work on a case connected to Pakistan. Boris then put her in touch with a young journalist working in quite challenging conditions in Pakistan’s rural areas. –––––––

––

BvW: Yes, I connected her to Mamara Afridi. She and her sister are journalists, even though they are only 18 and 19 years old, and to tribal standards they should have already gotten married and stopped working. Their family was very open minded, though. Mamara told Nelleke about the segregation of the domestic space in patriarchal

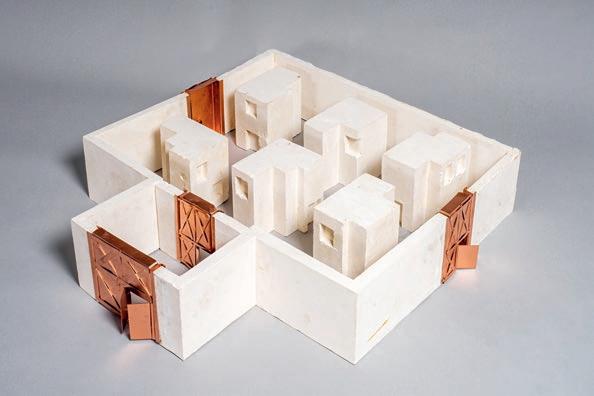

societies and how this affects news reporting. In houses from rural areas, women have no access to the part of the house in which men deliberate and make decisions. They never learn to form an opinion and to be responsible for their own future. Unlike common families, Mamara’s parents allowed the two girls to access this space of decision making and thereby overthrow the general power structures between men and women. Thanks to that, both became journalists, which for women is actually a rather rare occurrence in Pakistan. They literally broke down the walls between men and women and this is what Nelleke’s project focused on.––––––

––– NS: Mamara and Mariam Saeed from the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) also contributed video footage to Nelleke’s work. They filmed the layout of Mamara’s house and

garden and street life and edited this into the film. On top of that Mamara’s voice was used for the voiceover. The final output was in fact a joint work. That was exactly what we imagined the collaboration to be: we wanted to encourage students to not helicopter around an issue but really get embedded – despite all the Covid-19 related challenges. So much of the media we are consuming today comes from a very limited, Western point of view. We want to instill in students a sense that there are many perspectives someone can choose and that any story can be told in many different ways.

BvW: For me it was striking that you can be born at the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, yet speak the same language from the heart as someone from Friesland does. The circumstances of their upbringing

may have been very different and yet there are also many similarities they face: a female journalist in the Netherlands might have easy access to education but she can also be confronted with a misogynist culture or stereotyping. Discovering this connection gives you the opportunity to tell a powerful story. –––––

––––

SvB: Boris, you mentioned earlier that you see it as your job to scare the students a little. What do you mean by that? Why do you need to scare them?––––––––– BvW: This issue of censorship and press freedom is of course a big, serious topic. Working on the cases was challenging because they are real, not hypothetical. It hits close to home when real people are in jail, a real war is unfolding, or actual murders are being committed. And it wasn’t just the cases in faraway countries that were confronting:

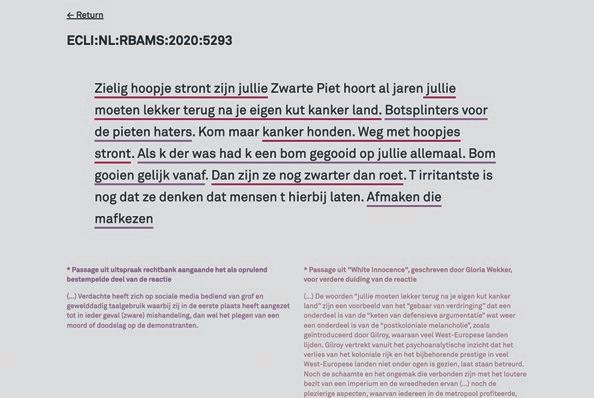

the student who wanted to work on a Dutch case decided to look into the affair around journalist Clarice Gargard who faced threats of racially motivated violence on social media.

––––––––– SvB: What were the challenges for students working with these real-life cases?––––––

––– NS: Students needed to understand the kind of responsibility that comes with investigating and interpreting them. For example, if you focus too much on the offender violating human rights, a lot of attention goes where you don’t want it to go. You start elevating the perpetrator rather than the victim. However careful students are, these things can happen unintentionally. ––––––

––– BvW: This issue of which side of the narrative you focus on also came up in the Morocco case. The students interviewed Hicham Mansouri, a journalist who fled Morocco because

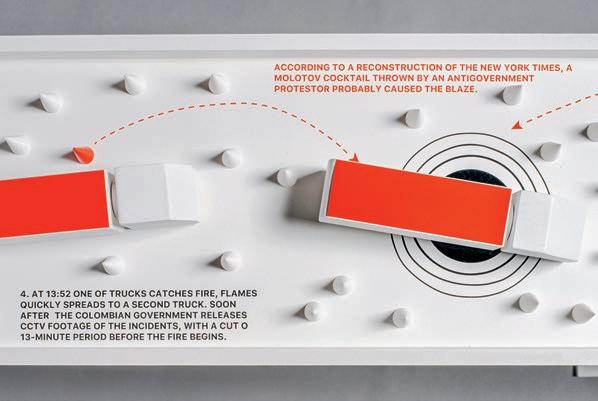

he was prosecuted for his journalistic work. The students ended up analyzing the “Moroccan Press Code”, but they did so solely based on interviews with Hicham. They chose to tell his story and exclude the perspective of the Moroccan government. An example of the opposite approach was the project related to an event that occurred on the Francisco de Paula Santander bridge in Venezuela. There Niels Otterman, Talita Virgínia de Lima and Akina Yoshitake López did a great job in giving a 360-degree view of the story, highlighting all different perspectives.

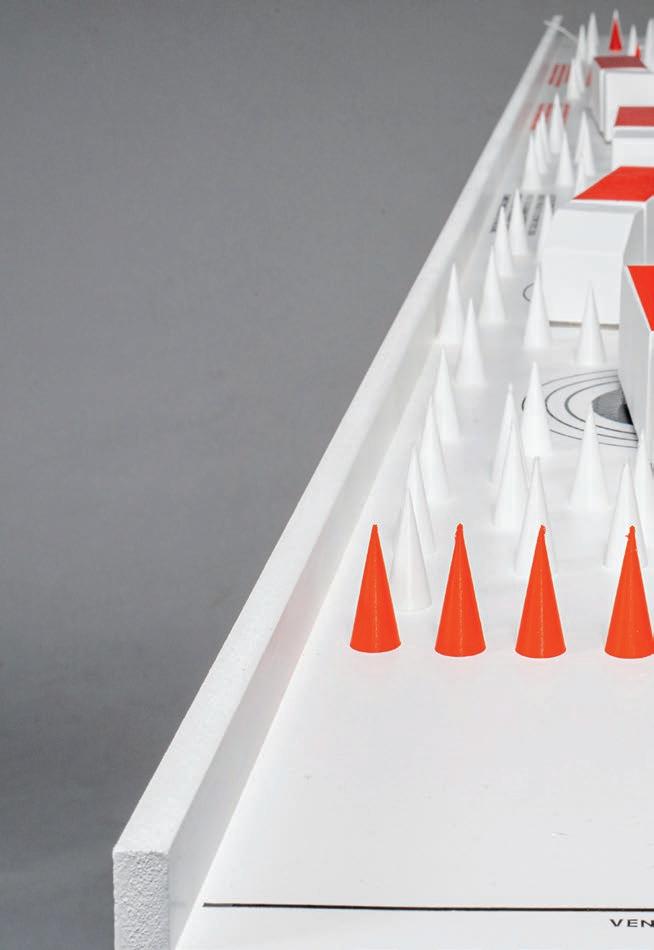

NS: The students made a 3D-model of that particular bridge at the border between Colombia and Venezuela.

On February 23, 2019, a large crowd of volunteers and political activists hoped to deliver over 600 tons of humanitarian aid to Venezuela but

then two of the UN aid trucks were set on fire, presumably by followers of president Nicolás Maduro. Our group of students reconstructed the incident on the bridge and analyzed the different views covered by the news, including not only pro- and anti-Maduro activists but also the report ing of the Columbian and Venezuelan governments. By incorporating these nuanced narratives they recreated the actual cacophony of voices that blurred the line between reality and propaganda.

LA: A lot of students struggled with the question: do I have the right to tell this story? The Moroccan case was interesting in this respect. I think this is where the distinction between art and journalism becomes relevant. As artists, students can afford a certain freedom of interpretation and choose a more personal point of view. If you

are transparent about the fact that your statement is based on a conversation with an individual person, you don’t have to feel the obligation of giving all sides equal attention, whereas in journalism it is very important to consider the different sides. –––––––––

NS: This is one of the details that we as educators often learn along the way. At the beginning of a collaboration, we never have a clear master plan of where we’re heading. Some students engage more easily with the provided content than others. So together with FPU we created space for uncertainty and that in turn led to very surprising results: every project is unique simply because of the varied backgrounds of the students. In the end, we as teachers are learning a lot not only from our partners but also from our students. It’s a fantastic way of exchanging

and producing new knowledge.

–––––

LA: Yes, and it was very valuable for the students to see that. Sometimes it clashed with their expec tations of what education should be. Some even seemed to want a ready-made education where we have all the answers. It is important for students to learn that we as educators have a certain individual approach, but we should not have a one size fitsall formula – especially when dealing with personal expression and storytelling, there are so many approaches. ––––––––– BvW: And each case holds its own challenges, especially in terms of press safety. When talking to the Moroccan journalist Hicham Mansouri, everyone should know he is most likely under surveillance. This is something that most students might not have thought of before. If you talk to him about sensitive issues,

you have to be aware of the risks you might expose him to. You need to establish a safe environment first. The same goes for Pakistan. You have cultural sensitivities: what would happen if the footage that the Pakistani journalist has filmed would be shown in Pakistan. Is it safe to publish it? Or could it come back on the people who contributed? How can you make sure that it doesn’t backfire? Safety is very important, and these are the very real dangers students need to understand.––––––––– SvB: What would you say were the positive outcomes of this collaboration? And how do you see this developing in the future?–––––––––

LA: A very positive outcome of this project, for us as educators, is that students break out of their bubble and get to engage with urgent subject matter in the real world.

The learning curve is incredibly steep because you have to take it very seriously, as you are engaging with real people and real situations. At the same time you have the safety of the school. If you don’t succeed on all levels, that is ok, because you learn through interactions with your classmates and tutors, so that next time you will handle the situation better. –––––––––

NS: Our mission is to connect the students to what is happening outside their personal bubble and for them to look beyond their immediate environment and experience – to encourage them to open their eyes to new possibilities and be aware of incidents and conflicts outside Western Europe.

I think it is important for the upcoming generation of designers to get a grasp of what’s happening throughout the planet and take full advantage of the opportunities

presented in an interconnected globalized world. Much of the information this generation consumes is framed by social media. Ultimately, no matter which career they’ll choose after their study, they will have learned something valuable from these partnerships. –––––––––

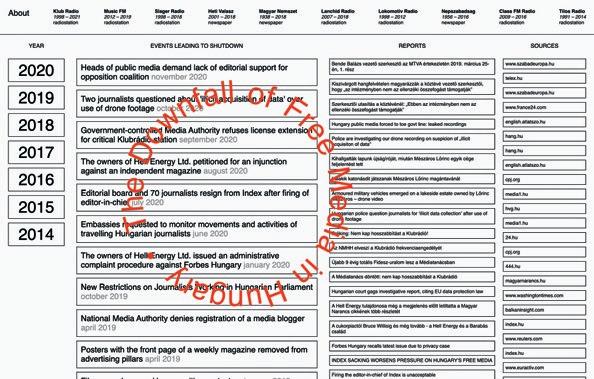

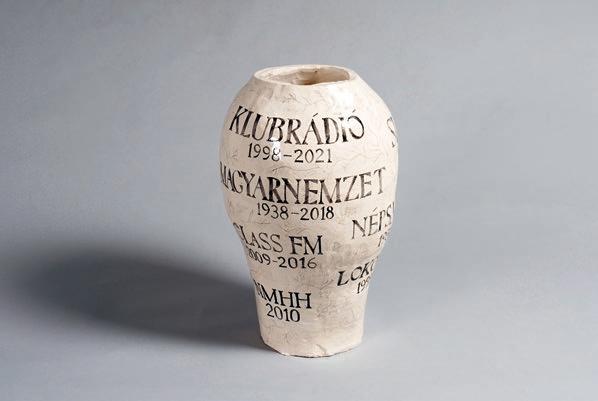

BvW: For FPU, the positive outcome of this collaboration lies in the exchange of knowledge and tools. Very concrete outcomes are the ac tual visualisations the students have been working on. As journalists, we can use these to learn how to tell our stories and how to engage readers. These pieces allow an audience to take in available information in a new and unexpected way. A good example of this is the project made by the student Camilla Kövecses, who focused on Hungary. In Hungary, a lot of radio stations and newspapers have been shut

down under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In response to this, Camilla established a timeline of all the disappearing independent media outlets and she put the names and closure dates on a cremation urn that she designed. During the final presentation, you could hear from the inside of the urn the last minutes of each broadcasting station. This is a moving monument for public radio and a real conversation starter when talking about free press in Hungary. Press freedom is such a complex and abstract concept, you can neither see nor feel it. These visualisations make the issue more tangible and accessible to people. The video that was made for the Pakistan project, for example, I showed to one of our Human Rights Ambassadors who then included it in a talk about press freedom and safety of female jour-

nalists.––––––––– LA: These projects, because they are art projects, also approach the subjects from an angle that allows an audience to see them in a new light. Currently, many people are suffering from news fatigue. We think we already know, for instance, everything about female journalists in danger because we read stories about it. If you offer a new angle you break the tedium of the news.––––––––– BvW: It is really a refreshing new angle. I was also impressed by the positive energy that the students brought to their projects. The stories they told were not just about tragedy and suffering. That was very nice for us to see, because we deal with very bleak topics and people in danger all day long. It is energising to see these fresh takes.–––––––––

NS: It was a fantastic collaboration, despite the struggles with unfore -

seen circumstances. Education was hit incredibly hard by Covid-19 and a lot of plans had to be adjusted. But we at the NLN feel that it was an invaluable experience, the level of commitment and enthusiasm from Boris and his colleague Marieke Le Poole was exceptional. We could share tools, networks and resources to generate new knowledge. We couldn’t be happier with the results and we would definitely like to repeat the experience in the near future. ––––––––– BvW: I really believe in this multidisciplinary approach: combining art and journalism. For me, the next step would be to include students from the regions of interest. There is a lot to gain, I think, by connecting young people from different parts of the world, as we have seen in the collaboration with the Pakistani journalist. We could involve the students

even more than we did now and connect them to individuals in the different regions. To allow students to focus on how to tell a story that others can’t tell. That is in my opinion the most relevant mission: to find a way to tell the stories that cannot be told.

Sarah van Binsbergen Freelance journalist

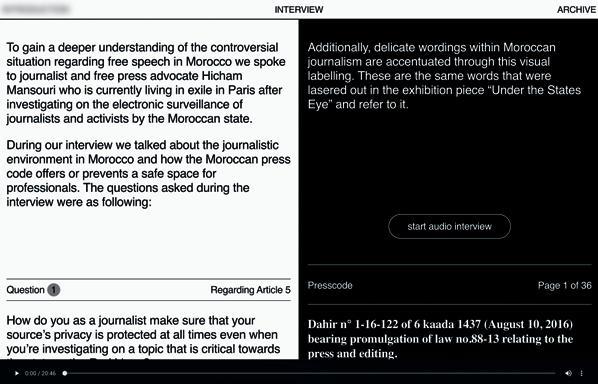

Case presentations at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague.

Pakistan remains in a very difficult position on the press freedom index. Moderate decline of -8 to 157 / 180 in 2022.

The safety situation of women and girls in Pakistan is quite worrisome, especially for women living in more traditional parts of the country and also women who take on a public role, for example becoming a journalist. Female journalists in Pakistan receive multiple forms of pressure; harassment starts in their family life, in the newsroom at work and while reporting in the field. Once female journalists publish their articles they are often trolled online and receive multiple forms of attacks. Digital Rights Foundation from Pakistan supports female journalists in order to increase their safety online. They build networks of journalists, empowering them to address issues of concern related to cyber harassment and online trolling.

Special thanks to Mamara Afridi, Tribal News Network, Mariem Saeed and Nighat Dad, Digital Rights Foundation

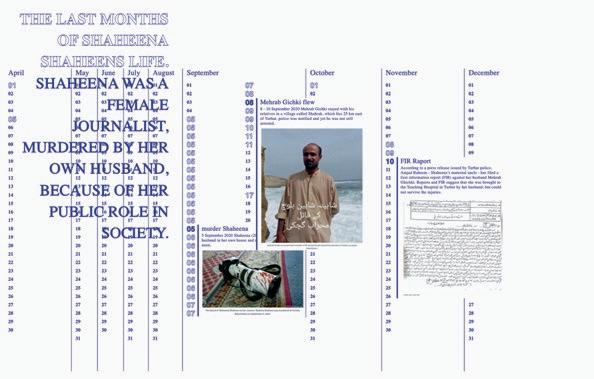

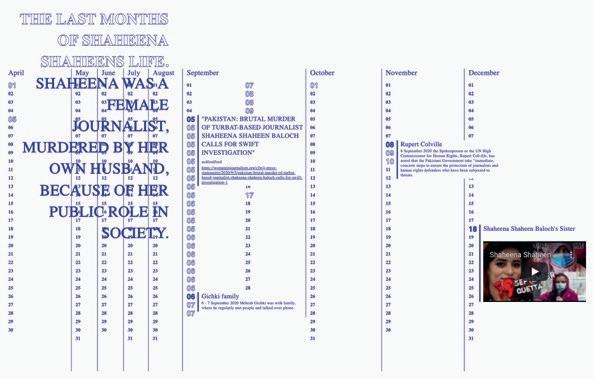

An Area for the Unknown Nelleke Broeze’s project addresses the rights and safety of female journalists in Pakistan. She focuses on how the structure of the patriarchal domestic space affects the mediation of news reporting. As one of her project outcomes Nelleke created a website on which she documents the last months in the life of Shaheena Shaheen Baloch who was murdered because of her work as a journalist in 2020 in Turbat, Pakistan at age 28. The project was inspired by partners Digital Rights Foundation and Tribal News Network.

Interactive timeline documenting the last months in the life of Pakistani journalist Shaheena Shaheen.

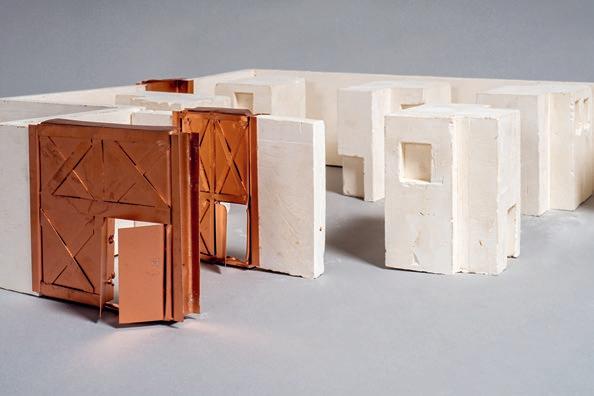

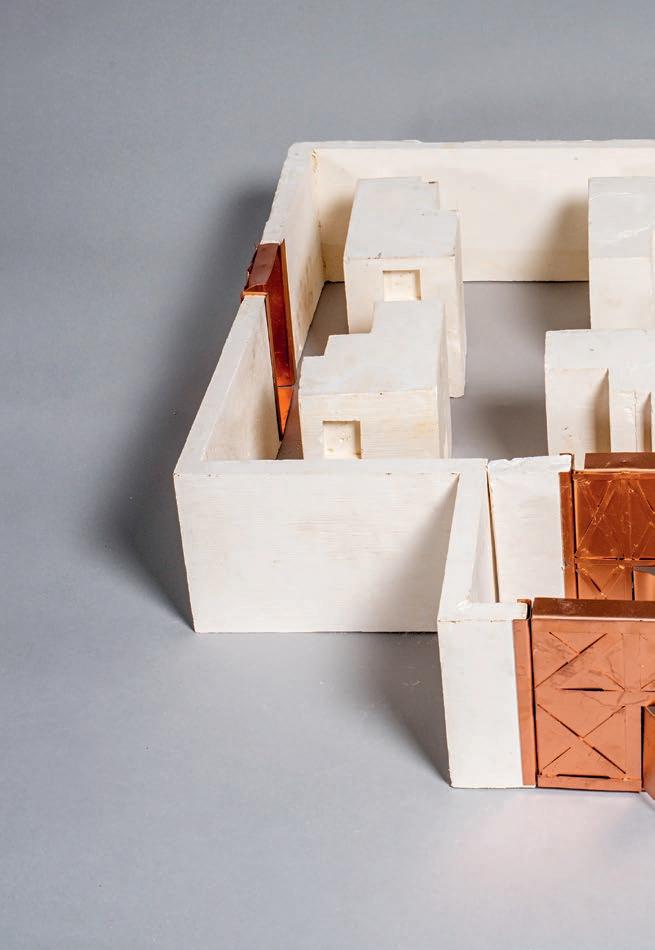

Plaster model of traditional, rural housing in Pakistan.

Tunisia remains in a problematic position on the press freedom index. Sharp decline with -21 to 94 / 180 in 2022.

The structural exclusion of youth from society and massive youth unemployment, especially in the interior parts of Tunisia, has been coupled with corruption and the dictatorship that led to the 2011 revolution. A lot has been done to support the youth, but real systemic change toward inclusiveness of youth and their struggles or vision on the future has not really changed in recent times. Youth, especially young women / girls, deserve a voice in the public domain to define their future. Al Khatt is a Tunisia-based NGO that strives to support media initiatives so they can reach audiences online with meaningful and independent information. The Jaridaty project created by Al Khatt together with youth clubs in the provinces of Tunisia strives to mobilize youth between the ages of 15 and 18 years old to create high

quality cross-media content about topics relevant to the youth and their communities. This effort is highly needed as mainstream media still today applies censorship on specific social taboos (especially related to the role of girls in society). The Tunisian youth needs alternative online and offline spaces to break through these social barriers.

Special thanks to Hazar Abidi, editor in chief, and Raouaa Selmi, Jaridaty, Al Khatt

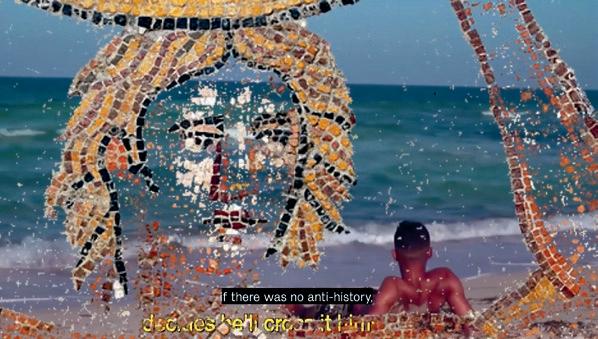

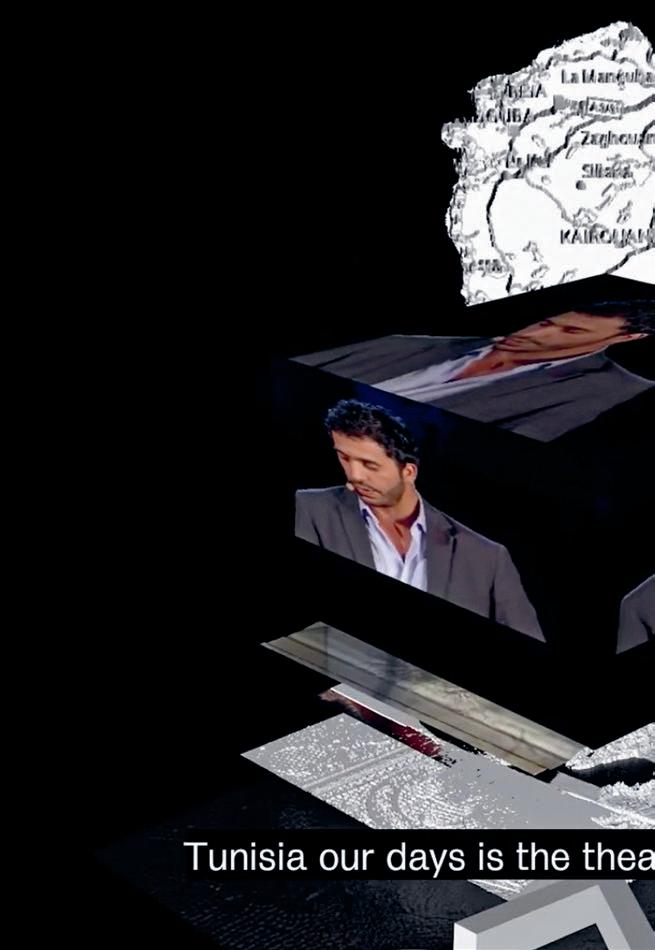

Blandine Molin’s rap and music video share the story of underrepresented youth organisations in Tunisia. The video morphs mosaic elements, drawing on comparisons between contemporary struggles and ancient narratives. This project was inspired by partner Al Khatt in Tunisia.

inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

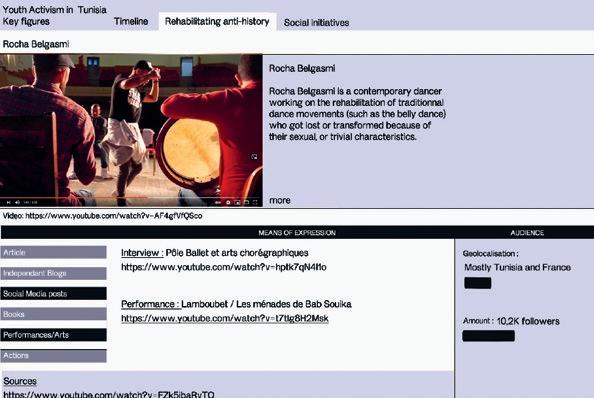

Interactive archive presenting political activism and new forms of engagement of Tunisian youth.

Three minute video clip celebrating the vigour of young Tunisians.

Morocco remains in a difficult position on the press freedom index. Stable with -1 to 136 / 180 in 2022.

Independent and critical journalists have very limited space in Morocco to publish freely. These journalists face multiple forms of harassment from the state that seeks to silence them. Legal harassment of journalists is a very effective technique used by Moroccan authorities. The journalist Omar Radi was charged with multiple charges including rape, sexual assault and spying for a foreign nation. Radi was convicted and sentences to six years prison.

International organisations like Amnesty International and Reporters Without Borders have opposed his conviction as he did not receive a fair trial.

Special thanks to Hicham Mansouri, investigative journalist

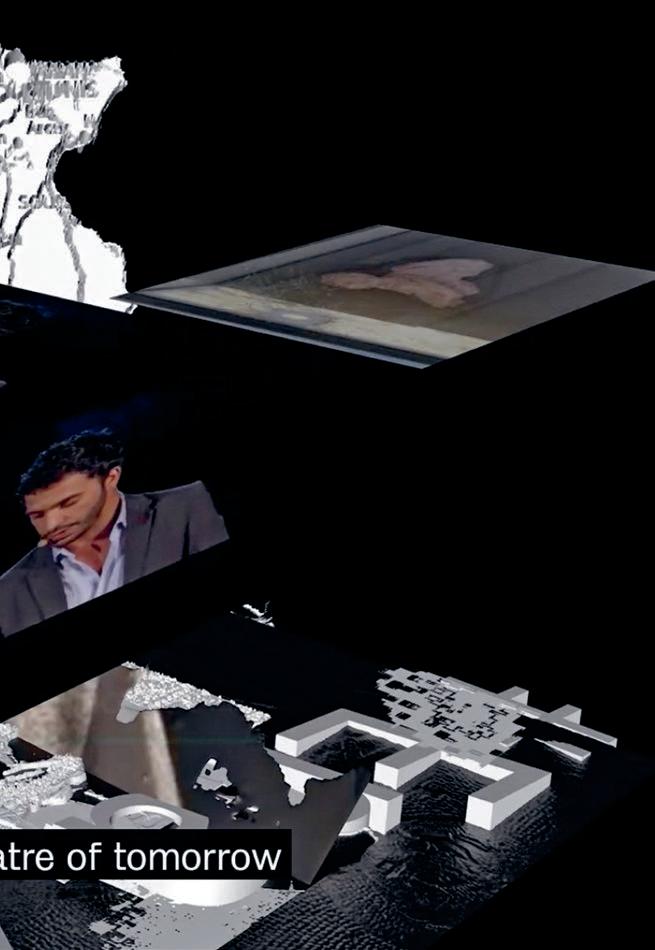

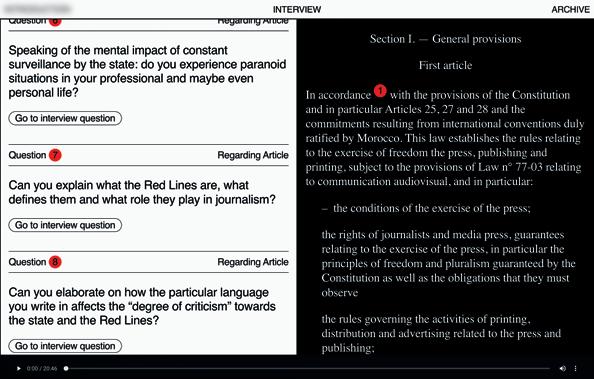

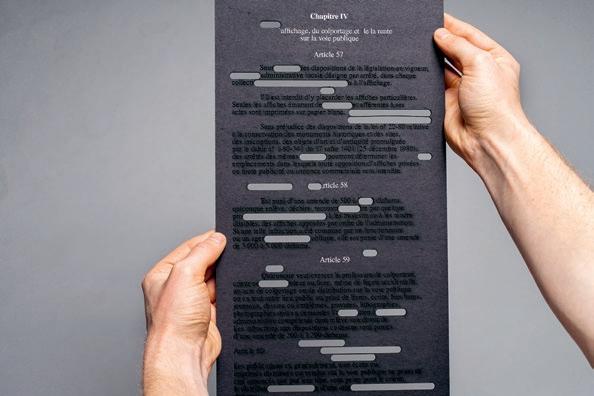

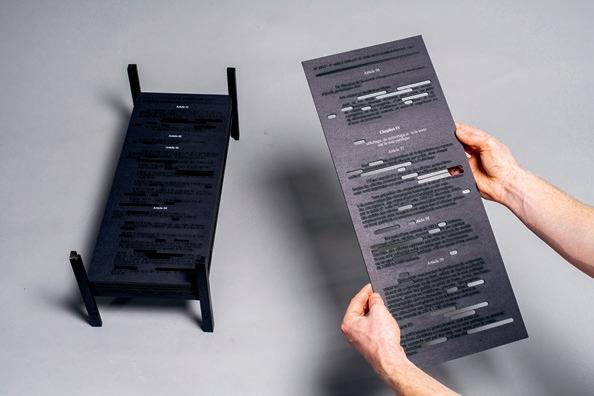

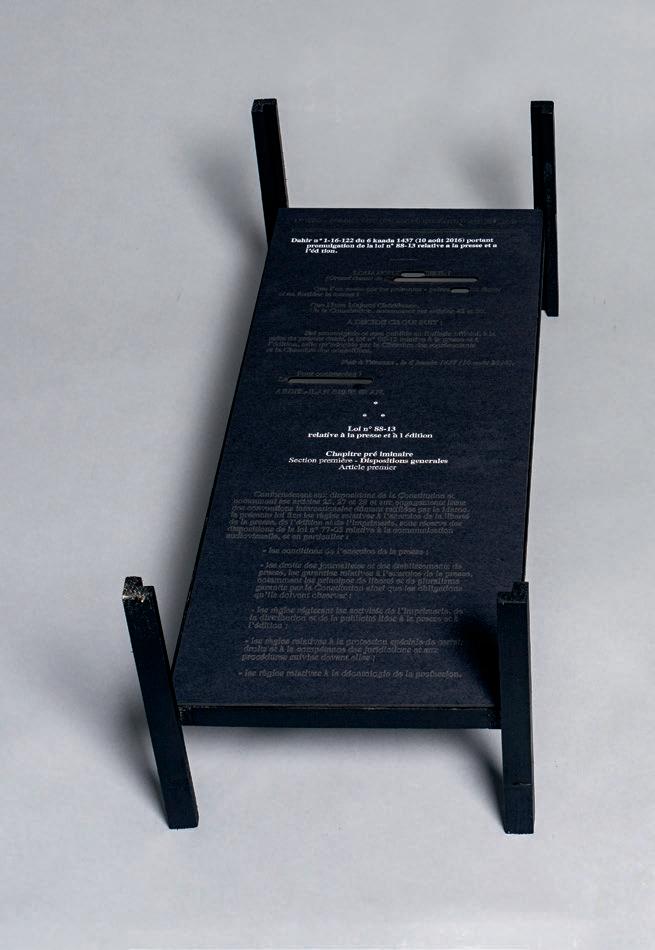

Morocco – Under the State’s Eye

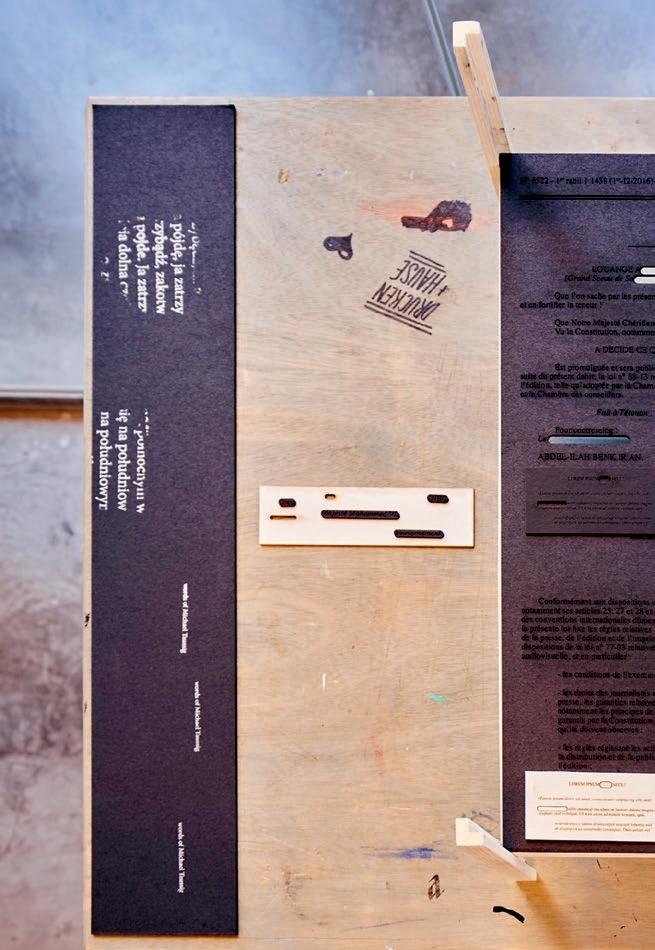

Jeroen van den Bogaert, Jan Johan Draaistra and Coco Maier examine the silencing of Moroccan journalists through government actors by analyzing the “Moroccan Press Code” and constructing a timeline of the case against journalist Omar Radi. They have also interviewed journalist and free press advocate Hicham Mansouri. Using interview material they have developed a website with further information.

Jeroen van den Bogaert, Jan Johan Draaistra and Coco Maier (not in the picture)

Interactive timeline of the Omar Radi espionage case and interview with journalist and free press advocate Hicham Mansouri.

Moroccan Press Code laser cut into 32 pages of cardboard highlighting topics of censorship.

The Netherlands moves from a good to satisfactory position on the press freedom index. Sharp decline of -22 to 28 / 180 in 2022.

The Netherlands has in recent years seen a sharp increase in online and offline intimidation of journalists, especially during protests or other public gatherings. More often than before, regional and national media need to send security for journalists covering these protests. Dutch journalist Clarice Gargard has received many death threats for her recent work. Other violent attacks against journalists relate to organised crime due to their investigative stories. Some crime journalists require constant protection.

Special thanks to Paul Vugts, crime journalist for Het Parool newspaper

s

inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

enes s inclusivinclusiv enes s

i inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s il i inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s il i

enes s inclusivinclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s il i inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s inclusiv enes s

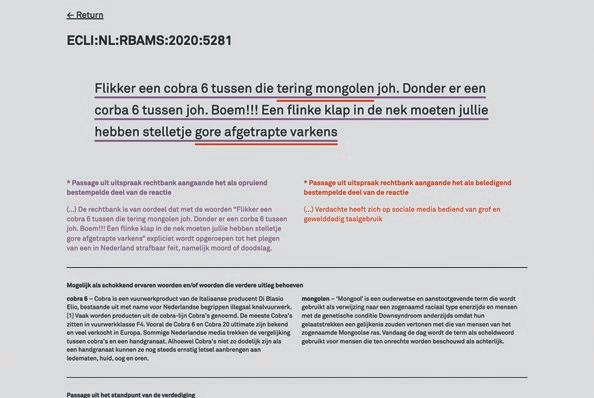

Daan Veerman investigates the 2020 hate speech trial related to Dutch journalist Clarice Gargard, in particular a selection of two hundred racist hate messages on social media. Through an educational game the project aims to understand how those who sent the messages were penalised. Through an interactive website, Daan documented the social media “comments” that were put on trial.

Website listing the criminal offences and sentencing specific to the Clarice Gargard racism case.

Jenga bricks consisting of legal verdicts from the Clarice Gargard case.

Georgia remains in a problematic position on the press freedom index. Sharp decline of -29 to 89 / 180 in 2022.

The media in Georgia is quite pluralist but at the same time quite polarized. Culturally Georgia is rooted in a complex geographic environment. For regional media outlets based in Georgia like JamNews, independent reporting is quite a balancing act, especially when violent regional conflict erupts in the Caucasus region, such as that between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Special thanks to Margarita Akhvlediani, managing editor, JamNews

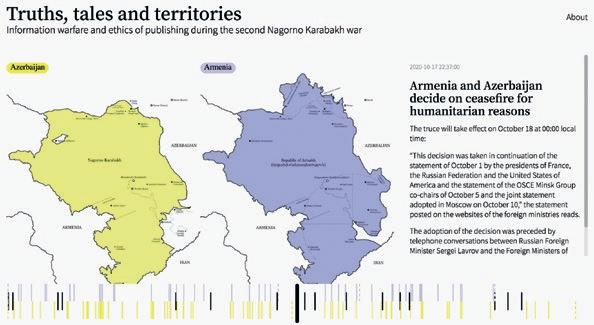

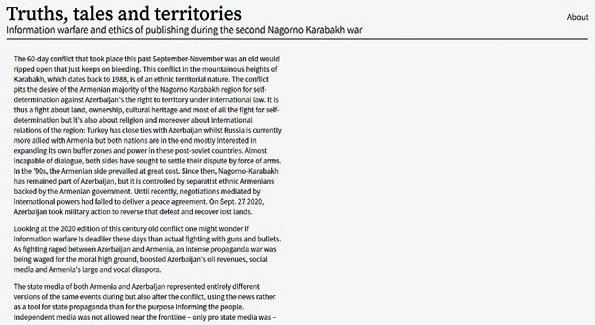

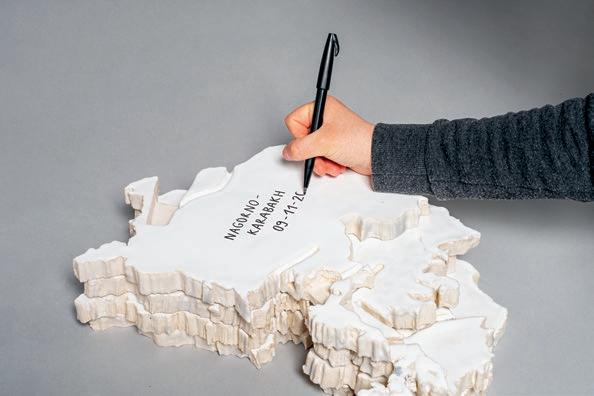

Tales and Territories

Erica Gargaglione, Elvi Kleyn and Paul Mielke investigate local news coverage on the ethnic and territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh in the SouthCaucasus. The project focuses on the role the Georgian independent news platform JamNews in the way people form their opinions.

Paul Mielke, Erica Gargaglione and Elvi Kleyn (not in the picture)

Interactive publishing timeline tracking media coverage on the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.

Clay models visualising the evolution of territorial claims over time.

Venezuela remains in a very difficult position on the press freedom index. Moderate decline of -11 to 159 / 180 in 2022.

Hostile speech, raided homes and offices, arbitrary arrests – the independent media in Venezuela are suffering from a massive crackdown, forcing some to work in exile. Anyone who dares to go outside or questions the state narrative of the Maduro government can expect to be silenced. Despite this hostile environment for independent media, journalists remain determined to provide the public with fact-based investigative pieces, which, for example, reveal corrupt practices of the government.

Special thanks to Mira Chowdhury, programme coordinator at Free Press Unlimited

We Must Have All Options

Niels Otterman, Talita Virgínia de Lima and Akina Yoshitake López reconstruct the political conflict between pro- and anti-Maduro activists on the Francisco de Paula Santander bridge at the border between Venezuela and Colombia.

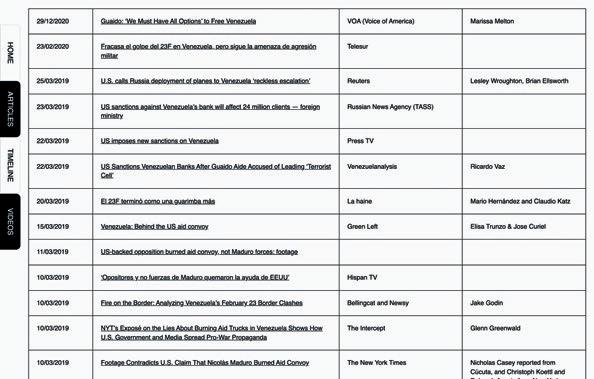

Website with videos reconstructing the political conflict between pro- and anti-Maduro activists.

including brief event descriptions.

Hungary remains in a problematic position on the press freedom index. Moderate improvement with +7 to 85 / 180 in 2022.

Although the Hungarian constitution protects freedom of the press, Victor Orbán’s government has worked very hard to shut down critical media since 2015. Despite being part the European Union in which the core value of freedom of expression is protected, independent media in Hungary are fighting a losing game. To understand the road to closure and especially to pay tribute to independent journalists who had to shut down their media enterprises, this case was picked up by Camilla Kövecses.

Special thanks to Camilla Kövecses, student at the Master Non Linear Narrative

The Downfall of Free Media in Hungary

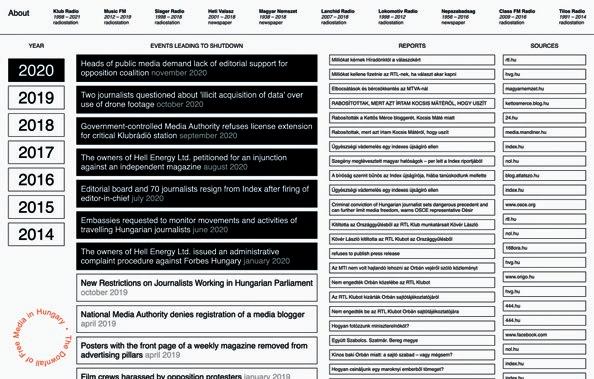

Camilla Kövecses’s research maps the shutdown of independent media in Hungary by means of sound. Camilla carefully draws together and archives the final audio moments of independent radio broadcasters. Camilla has created a website overview as archive.

Interface listing reportings on issues regarding press freedom in Hungary since 2014. By clicking on a date, event, report or source, it is possible to navigate through the content, linking several reports to the same event.

Clay urn with names of independent radio stations shut down by Hungary’s media authority.

\ Lauren Alexander (1983, ZA / NL) is a designer, artist, researcher, co-founder of Foundland Collective, and educator working as tutor at the BA Graphic Design and MA Non Linear Narrative, and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Jeroen van den Bogaert (1995, NL) is a graphic designer, brand designer, co-founder of Fcklck studio and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Nelleke Broeze (1995, NL) is a filmmaker, graphic designer, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Jan Johan Draaistra (1995, NL) is an interaction designer, calligrapher, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Mijke van der Drift (GB / NL) is a choreographer, performer and philosopher, co-founder of Red Forest Assembly, and educator working as tutor at the MA Non Linear Narrative, and Visual Communication at the Royal College of Art, London, and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Camilla Kövecses (1992, SE / HU) is a graphic designer, researcher, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Coco Maier (1994, DE) is a graphic designer, artist, outdoor enthusiast, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Lizzie Malcolm (1987, GB) is a designer and developer, co-founder of Rectangle, tutor at the MA Non Linear Narrative, and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Paul Mielke (1993, DE) is a graphic designer who researches the concept of nation states and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Blandine Molin (1998, FR) is a student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration, interested in contemporary poetry and story telling.

\ Niels Otterman (1996, NL) is a graphic designer, researcher, curator of Van wie is de stad?, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Marieke Le Poole (1967, NL) is Head of Marketing Communication at Free Press Unlimited and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Dan Powers (1983, US) is a designer and developer, co-founder of Rectangle, tutor at the MA Non Linear Narrative, and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Niels Schrader (1977, VE / DE) is an information designer, founder of Mind Design and co-founder of the Queer Computing Consortium (QCC), head of the MA Non Linear Narrative, and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Daan Veerman (1994, NL) is a designer, curator, writer, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Talita Virginia (1986, BR) is a visual storyteller investigating contemporary issues related to power structures, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Boris van Westering (1975, NL / FR) is Programme Coordinator Middle East and North Africa at Free Press Unlimited and supervisor of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

\ Thais Akina Yoshitake López (1993, BR) is a designer, researcher, and student participant of the Facts Not Filters project collaboration.

Facts Not Filters is an educational project between the Master Non Linear Narrative programme at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague and Free Press Unlimited, Amsterdam, lasting from September 2020 to January 2021.

Student participants

Jeroen van den Bogaert, Jan Johan Draaistra, Erica Gargaglione, Elvi Kleyn, Camilla Kövecses, Coco Maier, Paul Mielke, Blandine Molin, Niels Otterman, Daan Veerman, Talita Virgínia de Lima and Thais Akina Yoshitake López

Initiative

Lauren Alexander (tutor MA Non Linear Narrative), Niels Schrader (head MA Non Linear Narrative) and Boris van Westering (programme coordinator Middle East and North Africa at Free Press Unlimited)

Project supervision

Lauren Alexander, Mijke van der Drift, Marieke Le Poole, Lizzie Malcolm, Dan Powers, Louise Rietvink, Niels Schrader, Boris van Westering and Judy Wetters

Case Experts

Pakistan: Mariem Saeed (programme manager Digital Rights Foundation), Sabin Agha (independent journalist) and Umaima Ahmed (independent journalist); Georgia: Margarita Akhvlediani (managing editor, JamNews); Venezuela: Mira Chowdhury (media expert Latin America, Free Press Unlimited); Netherlands: Paul Vughts (crime journalist, Het Parool ); Tunisia: Hazar Abidi (editor in chief, Jaridaty, Al Khatt); Morocco: Hicham Mansouri (investigative journalist); Syria: Shiar Youssef (radio manager, ARTA FM ) and Sherin Ibrahim (journalist, ARTA FM )

Special thanks to Centre for Investigative Journalism, Fenna Hup, Pia Pol, Marieke Le Poole, Jake Charles Rees, Angelina Tsitoura and Boris van Westering

Main editors

Lauren Alexander and Niels Schrader

Interview

Sarah van Binsbergen

Translation

Irene de Craen

Copy editing

Janine Armin

Photography

Roel Backaert, Jodi Hilton (page 173)

Statistics

Reporters Without Borders rsf.org / en / index

Design

Eva van Bemmelen

Printing robstolk ®, Amsterdam

Binding

Patist, Den Dolder

Paper

Maxioffset 90 g and 250 g

ISBN 978-90-72600-58-5

Print run

400

The project is generously supported by Free Press Unlimited, Amsterdam

© 2022

Royal Academy of Art (KABK)

Master Non Linear Narrative

Prinsessegracht 4

NL 2514 AN Den Haag nln.kabk.nl

Facts Not Filters is a research collaboration between the Master Non Linear Narrative programme at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague and Free Press Unlimited, Amsterdam, lasting from September 2020 to January 2021.–––––Inspired by case studies highlighting the need for press freedom all around the world, twelve students examined the complexities of culturally rooted and geographically specific nuances related to regional news reporting and distribution.––––– The artistic results included video works, audio presentations or physical objects highlighting the threats press freedom is exposed to.

ISBN 978-90-72600-58-5