Something we throw

Yet not a ball

Unwanted

Another man’s treasure

Lately I have been thinking about what composes waste

If we repurpose, is it still waste?

Compost composed of waste

Does the rest of ecology even know the notion of ‘waste’?

Or is it more a process of holding on, then letting go

Wasteful thoughts can ll you with worry

Wasting time can make you feel sorry

Yet can you waste what you do not own?

Perhaps there lies the answer to whether the rest of ecology knows waste

Waste implies possession, unwanted ownership

It also implies that there is a distinction between wanted and unwanted, good and bad

Yet how about the grey areas in between

The things you do not need or want but own, the moments spent not doing anything in particular

Waste not now, yet maybe tomorrow

About the collaboration program is collaborative project aimed to bring together students from the KABK and NWO researchers to work together on one or more projects that focus on the communication of research results. By combining the unique artistic skills of KABK students with the in-depth knowledge of academic researchers, NWO aimed to develop innovative and effective methods to present complex ideas visually and understandably to a wider audience.

NWO is convinced that this form of collaboration offers valuable learning opportunities to both KABK students and academic researchers. While students were able to apply and further develop their creative skills within an innovative context, academic researchers gained new insights and perspectives that can help them present their research results in an engaging and understandable way.

Anna, Mayte and Nesie were the three collaborating students within this programme and this publication shows their artistic process and outcomes.

NWO Closed Cycles

NWO encourages research that should lead to the closing of cycles at different levels of scale with the programme ‘Closed Cycles—transition to a circular economy.’

e programme concerns the connections between water, agricultural production, energy and biodiversity in production chains. Closed Cycles is part of the NWO contribution to the Top Sectors Agri & Food, Horticulture & Starting Materials, and Water & Maritime. e principal aim of the programme is to close cycles at various levels of scale within the focus areas water, agriculture, and horticulture.

About NWO

e Dutch Research Council is the most important science funding body in the Netherlands and realises quality and innovation in science. Each year, NWO invests almost 1 billion euros in curiosity-driven research, research related to societal challenges, and research infrastructure.

NWO selects and funds research proposals based on recommendations from expert scientists and other experts in the Netherlands and abroad. NWO encourages national and international collaboration, invests in large research facilities, facilitates knowledge utilisation, and manages research institutes. NWO funds more than 7,200 research projects at universities and knowledge institutions.

About KABK

e Royal Academy of Art, e Hague (KABK) educates students to become independent and self-aware artists and designers with investigative mindsets and unique visual and conceptual abilities. ey are able to produce authentic and in-depth creative work that advances their chosen disciplines and contributes to the well-being of society as a whole.

Assignments, like what the students of Photography did for NWO Life 2024, equip students for real-world projects. It gives the students the opportunity to immerse themselves in societal trends, and seek confrontation with the audience. As an academy, we thank NWO for giving them this opportunity.

Purified residual water for agriculture

Project title

Re-USe of Treated effluent for agriculture RUST

Project leader

Dr. ir. Ruud Bartolomeus

Institution

Wageningen University & Research

Duration

1 March 2018 to 1 December 2022

Irrigation helps combat drought in agriculture. Instead of scarce groundwater, an alternative water source can be used: the purified effluent from water treatment plants. However, this water still contains contaminants. In this research project , Dr. ir. Ruud Bartolomeus and his colleagues investigated two aspects of reuse via ‘reverse drainage’: the dispersal of contamination in the soil and subsoil, and the purifying effect of the soil.

A step towards closing the cycle in water management is the use of water that would normally remain unused. ‘For example, the purified effluent from sewage treatment plants or factories,’ says Bartholomeus. ‘We studied what happens if you add this residual water to the water system beneath the surface. Would this benefit the crops? And if this residual water passes through the soil and the groundwater to the surface water, will it be purified by the soil?’ Effluent may be discharged into surface water in the Netherlands because it meets a number of agreed standards. But this does not mean that it is clean—on the contrary, the researcher emphasises. ‘It still contains quite some micro-pollutants, including certain persistent substances and medicine residues’, he says. ‘Water management is currently focused on discharging these contaminants as quickly as possible via surface water. But what happens if they end up in this slower water system, namely in the soil and in the groundwater? How will they behave there? Will they end up in the crops? We investigated this in a test field, in the lab and using computer models.’

‘Everything we learned feeds into that discussion: Which quality requirements should this effluent meet? Which additional purification steps are needed? But also: should we still be irrigating fields aboveground with surface water that is affected by effluent, which is in fact current practice?’ Many of those questions remain unanswered.

‘Fortunately, this theme is now also being addressed in a wider context,’ says Bartholomeus. ‘For example, in the KWR programme Water in the Circular Economy, which was initiated by water companies and involves various water managers and the Dutch Delta Programme on Freshwater, among others. at is a great development: it means that this subject is getting the attention it deserves. ere is still a lot to be gained when it comes to closing cycles in the water sector.’

Be like water BY Anna Andrejew ere is no new water on this Earth. e air, earth, plants, and water that are available today are all recycled or regenerated from earlier generations of the same. e water cycle—the process by which water circulates on the earth—is a closed system.

e NWO Closed Cycles project investigated the reuse of this residual water for agricultural purposes. For the purpose of this research, corn crops were irrigated with wastewater. e level of contamination of the water and also the movement of water in the soil were studied.

For the artistic interpretation of this project, the paper was made of corn leaves—the residuals of a harvest and the same crop as was used for the research. I was inspired to hear how the movement of water in the soil was studied over time. e photosensitive liquids show the movement of water over time. is references how the effects of watering a crop develop over time and with sunlight.

1 For the purpose of the artwork, Anna dried the leaves of corn. These are the leftovers of a harvest.

2 After drying, cutting the corn leaves is the rst step to turn it into paper pulp.

3 The “Hollander” paper mill processes the corn leaves into pulp.

4 Corn leaf paper pulp ready to be poured.

Flowing Forward in Closed Cycles:

e work resembles watering soil and was made during a performance, it poses the question when water is regarded as ‘clean’. One of these performances took place at the NWO LIFE event on the 21st of May. Paper made from corn leaves, cyanotype, wastewater.

is work would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of several key individuals. I am deeply grateful to Dr. ir. Ruud Bartholomeus for sharing about the research project and his openness to an artistic collaboration. Additionally, my sincere thanks go to Loes Schepens for her expert guidance about the paper-making process.

anna andrejew (based in The Hague, The Netherlands) is a visual artist, writer, and permaculturalist. Through her artistic research, she explores the memory of matter, creating a uid and embodied understanding of ecology. From water to information, what what enters and surrounds our body impacts our emotions.

Her work takes form in the material and immaterial: installations, photography, conversations, performances and writing. The non-linearity of her work shows the making process open-ended ideas and ongoing cycles; an invitation to experience and experiment too—taking part in shared knowledge creation. www.annaandrejew.com

1 Anna pours the corn leaf pulp to make paper.

2 The corn leaf paper is poured and ready to dry.

1

Hydrogen Bonds BY Mayte Breed is year's NWO Life conference takes place in Egmond, coincidentally the village where I was born and lived for 18 years. I still feel a strong connection to Egmond, as my family still resides there, and because of the sense of community often found in smaller towns. After hearing Ruud Bartolomeus share more about his research, coupled with this coincidence, I felt inspired to explore Egmond with fresh eyes and create a site-specific work in my hometown. I grounded my exploration in key concepts such as the soil’s purifying effects, the subsurface water system, groundwater levels, and the local effects of water regulations, drawing from insights discussed in Ruud’s research.

I found this foundation in the valley of the dunes, where locals have cultivated small fields of land to grow their crops for decades. However, currently, the locals experience flooding due to water regulations, which has a significant effect on the community. Without any improvement in sight, this might mean the end of their land. ese areas are steeped in history and community, which made me reconsider the importance of communal feeling in a place like this. I responded by delving into the photo archive and found occasions, big and small, that contribute to these feelings—the annual half marathon, the stranded ship on the shore, the nursing home for children who needed to gain weight or strength.

By documenting the physical stagnated water on the flooded dune lands in Egmond aan Zee, I was able to zoom in on the local effects and consequences. I collected the stagnated water and used this for the process of emulsion lifting with the found archive. It is a technique where water separates the emulsion layer of a polaroid, which can then be transferred onto a new material. By activating this archive with water, I connect this history and the current issue. Water is what made the fishing town stick together in the first place, and now it has the possibility of becoming the factor that drives them apart. e water in both the emulsion lift and the photograph serves as a bonding factor, like a hydrogen bond.

e coastal village Egmond aan Zee is surrounded on all sides: on the west by the North Sea and on the other sides by the dunes. e landscape still bears witness to how the Derpers, the name for the villagers of Egmond aan Zee, have used the dune area for centuries to survive. e high dunes around the village formed because the Derpers had to protect themselves from the blowing sand and pushing sea: they anchored the sea dune with grass, causing the sand to grow in height continuously.

Besides being a protective wall, the dunes also formed a new area to grow crops and combat famine levels. Around 1850, the dune valleys around the village underwent a true transformation, and hundreds of potato fields were cultivated. e crop thrived on poor dune sand, and as a summer fruit, it was less affected by adverse weather and high groundwater levels. By setting aside the topsoil, the fields became deeper, reaching just above the average winter water level. For decades, the villagers cultivated their potatoes and other crops on the so-called Lankies. Today, many of these small fields are still being ‘tended’, although it is more of a hobby than a means of survival. It offers the villagers a place to connect with their community, work with their hands, and it serves as an escape from work and everyday life. In recent years, the villagers have, however, experienced problems with their Lankies.

e dunes are renowned for their purifying effects on drinking water. Infiltrating rainwater, along with additional water, slowly travels through the grains of sand and naturally removes pollutants. e infiltrating water contributes to the freshwater well, which, due to its density, floats on top of the salty seawater. is prevents the soil from being infiltrated with the heavier saltwater coming from the sea and seeping through the dunes into the hinterland. However, due to rising seawater levels, the saltwater well has been growing. To prevent the salty water from infiltrating the soil, the PWN (Puur Water & Natuur), responsible for regulating groundwater levels in the area, decided to increase the freshwater ground levels. is, combined with more intense periods of rain, affects the water level in the dunelands and results in flooded dune lands during the wetter seasons. Visually, the floating remnants of pumpkins, kale tips gasping for breath, and a paddling carpet of algae create a captivating scene. However, this has significant effects on the local community of Egmond aan Zee. Each year, they see their planted crops go to waste, and they have been unable to work on their lands, resulting in a decline in the communal feeling of the villagers. 1

Mayte Breed is a Dutch artist (b. 1997) based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Drawing on her background in biology and climate studies, she approaches photography as her research method of the everyday. Slow observation and natural curiosity allow Mayte to dissect the unnoticed. She zooms in on human interactions with their environment, thereby blending the boundaries between reality and staged moments. Resulting in anonymous images of a world of which others are occasionally aware. Installation, moving-image, and bookmaking come into play to enhance this sense of defamiliarisation. By using multiple layers, the images retain their autonomy which makes them independent. Allowing them to provoke questions rather than provide answers. www.maytebreed.com 1 Archive image of children playing outside in the dunes

A biopolymer from sewage sludge as a basis for high-value materials

Project title

Nature inspired biopolymer nanocomposites towards a cyclic economy (Nanocycle).

Project lead

Prof. dr. Stephen Picken

Institution

Technische Universiteit Delft

Duration

15 September 2018 to 1 October 2022

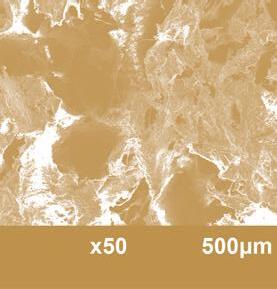

‘Sewage water and industrial wastewater contain various organic compounds’, says Stephen Picken, professor of polymer chemistry at TU Delft. ‘Bacteria can use these as food, and thus help to purify the water.’

An efficient way to do this is via the so-called Nereda technology, developed in Delft. Using natural selection, the bacteria are cultured in such a way that they stick together to form compact granules. ese sink to the bottom, allowing for easy separation of solid matter and water. ‘Compared to traditional water treatment, in which the bacteria form flakes, this method requires much smaller water tanks’, says Picken. ‘Currently, around one hundred water treatment plants worldwide are using Nereda.’

e bacteria stick together because they secrete gelatinous biopolymers—a substance now known as Kaumera. ‘Previously, it was considered waste,’ Picken says. ‘In this project we investigated how to extract the polymers and use them as raw materials in chemistry. For example, they can serve as coatings for seeds, which can be used to ‘glue’ each seed to a grain of artificial fertiliser. e polymer then acts as a sustainable, biodegradable adhesive. It can also serve as a matrix for bioplastics.’

e composition of Kaumera varies with the process conditions, says the professor. ‘We investigated exactly how the bacteria make their polymers’, he says. ‘ is knowledge helps us better understand the polymer structure. is, in turn, gives us clues on how to control those material properties by fine-tuning various process conditions, such as acidity, temperature, or salinity.’

Kaumera Combustions BY Nesie Junyi Wang

Kaumera is an innovative biopolymer harvested from bacteria aggregates that fed on sewage, with untapped potentials. Among its many intriguing properties, one that stands out is its fire retardancy, a focus of research under the NWO Closed Cycles. In collaboration with researchers from TU Delft, my project delves into the unique materiality of Kaumera, experimenting it as a fire-retardant ink for printmaking. is artistic endeavor involves silkscreen prints that are meticulously hand-processed, employing combustion as a pivotal transformative process, redefining the act of creation and destruction.

In conventional waste treatment, the process of combustion condenses the degradation of objects from years into mere seconds. Contrastingly, in urban areas near water bodies, human waste often lingers, floating and decaying. Once discarded by humans, these objects find new life as they are reclaimed by diverse living organisms in the water.

Intrigued by the story behind Kaumera, I've begun to view these discarded objects through a different perspective. What if we perceive these items, traditionally deemed as waste, from the perspective of more-than-human entities? Can the metamorphosis of life forms be discerned through the medium of flames? is work seeks to illuminate the intricate relationship between human waste in water, the materiality of Kaumera, and the transformative art of combustion. It challenges us to reconsider our perception of waste, not as an endpoint but as a part of a broader, more inclusive narrative that encompasses more–than–human perspectives.

is work would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of several key individuals. I am deeply grateful to Prof. dr. Stephen Picken, Dr. Yuemei Lin, Bart Verkooijen, and Dr. Suellen Pereira Espíndola for introducing me to the fascinating world of Kaumera. Additionally, my sincere thanks go to omas Ankum and Guido van der Linden for their expert guidance through the creative and craft processes.

Stories Behind

Known as a biopolymer derived from sewage sludge, Kaumera is a new bio–based raw material from the Nereda® wastewater treatment biotechnology, invented in Professor Mark van Loosdrecht's section. Same age as I, Nerada® has revolutionized waste treatment facilities globally by take maximum advantage of bacteria that feast on sewage.

My introduction to this intriguing substance came through Professor Stephen Picken, who handed me a small bottle of sample as he called ‘a jar of evil stuff ’. I cracked it open, bracing for sensory assault. Instead, I was greeted by a familiar funk, like a drain blocked following an overindulgent feast. I slowly turned the bottle around to observe the material inside. A sluggish brown paste. Despite its odorous familiarity, its appearance seemed strangely fresh—a substance both tempting as chocolate, repulsive as excretion, or indifferent like pond mud.

is mysterious brew has left researchers in wonder, with countless properties waiting to be unveiled. So far, it has already found applications as a bio–stimulant in agriculture, a fire retardant, and as a biodegradable binder. Bart Verkooijen and Suellen Pereira Espíndola showed me their work on enhancing fire retardancy with Kaumera as a binder in gelatin foams within the NWO Closed Cycles project. Its distinctive response to fire, unlike ordinary polymers, inspired my venture of setting Kaumera prints ablaze on steel plates. ese plates, resilient to the ravages of flame, serve as canvases that vividly record the thermal colour transition, a testament to the transformative power of fire.

Alongside Stephen and his colleague Yuemei Lin, I explored Kaumera’s potential as a pigment for printmaking. As a passionate chef in private life, Stephen likes to take analogies from cooking. ‘Chemistry and cooking are close relatives’. Indeed, crafting with Kaumera parallels the culinary arts—mixing, melding, and tweaking, as the paste morphs beneath our touch. It's not glamorous, mind you; there's a fair share of funky smells and accidental splatters. With Yuemei's invaluable support, I dove into refining the ink formula, searching for the optimal blend for both printing and combustion. is quest took us from the lab at TU Delft to the workshops at KABK. rough a relentless process of trial and error, with countless experiments in varied printing techniques and burning methods offered across workshops, we together share the sheer joy that both art and science offer through creativity.

In this collaborative experiment with Kaumera printmaking, the semblance of the world is captured in shades of blended brown, transforming under flames. It’s not just a creative process; it’s like witnessing a story evolve. Out of this, inspirations sprout, flipping our perception of what we used to toss away as mere waste. e microbial world, in its own way, continues to move forward, shaping its unique journey.

Nesie Junyi Wang (b. 1998, China) navigates the boundary between traditional disciplines, utilising photography, interdisciplinary collaborations, and material research to probe the complex interactions between humans and the more-than-human world. Her work is grounded in relational thinking, viewing existence as a uid, interconnected web. This outlook compels her to question established knowledge structures and transcend rigid categorizations, inviting a reconsideration of our place within the broader ecological fabric.

Flowing Forward in Closed Cycles:

A biopolymer from sewage sludge as a basis for high-value materials

Endnote

Nico van Straalen, chair of the Closed Cycles programme committee, stated in the Closed Cycles magazine in 2023: ‘It turned out that there are many unsuspected connections between these topics (of Closed Cycles research), and that there is significant added value in interdisciplinarity: it allows researchers to learn from—and inspire—each other’. Another unsuspected connection was made this year between NWO and KABK. One that sparked interactions between scientists and artists. is publication is the product of their collective efforts in exploring new ways of showcasing science and its impact on practice and society, while also reaching new audiences through art. Most certainly inspiring them.

As we wrap up this publication, I'm taking a moment to look back on our journey with Nesie, Anna, and Mayte. eir work on Closed Cycles has been more than showcasing research, it's been about trying out new things. ey worked together with researchers to come up with new ideas, like making paper from corn, exploring old photo-archives or finding methods for waste sludge to use as a material. eir hard work paid off with a successful NWO LIFE 2024 exhibition and fully-booked creative workshops with circular economy research at its base.

I was impressed to see how the KABK students have collaborated with the Closed Cycles researchers. ey were flexible, enthusiastic and professional. For me, these three aspects are key in a fruitful collaboration. As we say goodbye for now, I cherish the new connections we've made during this project.

A big thanks to everyone who's been part of this adventure. I look forward to future collaboration between our two organisations.

To more unsuspected connections.

Warm regards,

Martijn Bal

Policy O cer, NWO

Project Lead, NWO-KABK collaboration

Colophon

Flowing Forward in Closed Cycles: Exploring the interface of art and science in circular economy research

Texts

Anna Andrejew

Martijn Bal

Mayte Breed

Nesie Junyi Wang

Images

Ruud Bartholomeus (p. 10)

Anna Andrejew (pp. 11-15)

Mayte Breed (pp. 16, 18-21)

Nesie Junyi Wang (pp. 24, 27-29)

Suellen Pereira Espíndola (p. 26)

Graphic Design

Basia Strzeżek

Typefaces

Scala Sans Pro, Pesaro W03, Millettre

Paper

BIO TOP 80g

Printing

This publication is printed on recycled paper. The Riso printer used for this publication produces zero greenhouse gas emissions.

This project has been generously supported by Dutch Research Council (NWO) Domain Science (ENW)

Special thanks to NWO

Martijn Bal, Jos Wendrich, Lisa Slinkert

KABK

Meher Khan Muztar, John Fleetwood, Dirk-Jan Visser, Ari Versluis

Others

Thomas Ankum, Dr. ir. Ruud Bartholomeus, Dr. Yuemei Lin, Guido van der Linden, Dr. Suellen

Pereira Espíndola, Prof. dr. Stephen Picken, Loes Schepens, Bart Verkooijen

Contact

NWO Closed Cycles

Postbus 93460

2509 AL Den Haag Nederland

+31 (0)70 344 07 34 enwkringlopen@nwo.nl

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the authors.

The Hague, 2024. www.nwo.nl/en/researchprogrammes/closed-cycles