28 minute read

1. INTRODUCTION

Light in buildings does not only define how well we can see, it has also been found to affect our mood, motivation, social behaviour, performance, health and general well-being (Boyce, 2014). For educational environments these implications of light have been found to affect pupils’ learning outcomes. This study aims to advance our knowledge about the relationship between light and learning by exploring if exposure to different artificial light conditions in class influences pupils’ behaviour and performance.

Primary education has evolved significantly over the past decades and widely shifted from a teacher-orientated approach to a more student-orientated approach that, amongst others, embraces a more diversified palette of learning activities. This shift has not only changed the instructional and managerial load for teachers; it also sets new requirements for the spaces hosting this new pedagogy. As an architectural lighting designer who advocates light in the built environment should support the occupant’s visual and non-visual needs, my interest became to investigate what role artificial lighting could play in the creation of learning spaces that are supportive of the new pedagogy, and herewith enhances the learning outcomes.

From my professional experience thus far and from conversations with practicing school-designers it appears that attention for light in learning spaces primarily goes out to optimize the natural light conditions, while artificial light is mainly considered an add-on to guarantee good visibility during all hours of use. This approach is also endorsed by most building regulations as these typically focus on visibility aspects. As a result, it appears this approach led to the widespread use of ceiling-based lighting systems that typically illuminate the entire learning space relatively evenly. Although this type of lighting design typically ensures good visibility, it does not offer much prospect to address the changes brought about by the new pedagogy. This research explores whether an alternative lighting design approach could support pupil’s new learning better.

This chapter introduces the research that was undertaken hereto. Section 1.1 describes the context it is situated in, that of the Danish Folkeskole, and outlines a specific challenge it looks to address, namely, to improve quietness during class as advocated by the 2014 reform of the Folkeskole pedagogy. Section 1.2 outlines the twophased research design that has been followed and summarises the different research methods applied per phase. Section 1.3 outlines the contributions this research seeks to make to the academic fields of lighting science and environmental psychology as well as to the practice field of architectural design and the educational community in general. Section 1.4 functions as a reader’s guide and outlines the structure of this thesis further.

1.1 Denmark’s Folkeskole Learning Environment

This research has particular pertinence to Denmark, where a significant reform of the national system for primary and lower secondary education, the Folkeskole, took place in 2014. The reform aims to better pupils’ learning outcomes and introduced amongst others a longer school day and a broader palette of learning activities. It also encourages pupils to be more physically active as part of the overall curriculum. Another focus point of the reform is to improve the indoor conditions of the learning environment to benefit pupils’ well-being in general, and explicitly states the need to improve quietness during class (UVM, 2014). This is specifically addressed by the reform because disturbances, most notably in form of noise, were found prevalent in the Danish Folkeskole (Søndergaard et al., 2014). This is problematic because disturbances interrupt pupils’ attention to their learning, which has been found to negatively affect their performance (Woolner & Hall, 2010; Sala & Rantala, 2016). The aim of this reform point is to reduce class disturbances and herewith better learning outcomes.

1.1.1 Reform’s Implications for School Buildings

The changes brought about by the reform did not only set new challenges for teachers and school management, they also presented new conditions for school-building designers to address. One particular challenge lies in the observation that the longer school days, diversified learning activities and increased physical play are seemingly at odds with the need for creating a calmer or more quiet, learning environment. While the first changes may benefit from spatial flexibility, openness and allowances for (social) interactions, the latter may require a setting that radiates greater intimacy, shielding and privacy. This research seeks to explore in what ways the learning environment itself can support teachers to manage these different learning settings, and specifically looks at how it can assist teachers to improve quietness during class.

1.1.2 The Environment Influences Pupil Behaviour

An important task for teachers is to help pupils concentrate on activities that require sustained focus. These activities are referred to in this research as focussed-learning activities. Typically, pupils’ ability to concentrate is compromised by disturbances occurring during these activities. Disturbances may have various causes, both originating from outside or inside the learning space. Though generally it was found that pupils themselves are the main cause, often expressed in form of noise (Emmer, 1984; Stavnes, 2014). The traditional way for teachers to manage pupil behaviour considered disturbing is through classroom management strategies, which

commonly rely on interactions between teachers and pupils. Most of the critical tools available here are of instructional or procedural nature such as levels of pupil engagement or rules for speaking in class (Simonsen et al., 2008).

However, research has revealed that certain environmental features have the capacity to influence pupil behaviour in various ways too. For example, the type of furniture, the arrangement thereof and the layout of the learning space itself have been found to influence how pupils interact and collaborate (Gifford, 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008; Tanner, 2009). Flexible provisions as movable wall dividers and partition screens were shown to affect pupils’ sense of privacy and shelter, and herewith their level of attention to their task (Gifford, 2007; Tanner, 2009; Cheryan et al., 2014). The sound, light, temperature, and air quality conditions in the learning space were found to particularly affect pupils’ (dis)comfort, mood and academic performance (Küller & Lindsten, 1992; Heschong, 1999; Wargocki & Wyon, 2007; Marchand et al., 2014). These findings imply that besides the teacher (features of) the learning environment itself are also capable of informing pupil behaviour.

Thus far architects have mainly responded to the reform’s demand to improve quietness during class by addressing the symptoms of disturbances, for example by applying sound absorbing materials to mitigate noise. A reason for such symptom approach may be that most of the research exploring the impact of (a feature of) the environment on pupils has focussed on measuring change in their academic performance. Although these studies reveal numerically how the environment may support or hinder learning outcomes, they do not provide insight in underlying behavioural mechanisms such as change in attention, motivation and social behaviour that are incited by these environmental qualities. But in order to design constructive learning spaces that can also be effectively managed, it is critical for designers and school-users to understand those underlying relations. Therefore, advancing our knowledge about the relationship between (features of) the learning environment and pupil behaviour more fundamentally seems highly relevant.

1.1.3 Artificial Lighting as a Behavioural Tool

One particular environmental feature found capable of influencing occupant behaviour is light. Light in the built environment is generally considered to foremost service human vision during all hours of use so that occupants can see their surroundings well, move around safely and perform their tasks. But theoretical models as proposed by Peter Boyce (2014) and Jennifer Veitch (2001) also point towards several non-vision related workings of light, amongst others by stimulating our perceptive-cognitive system. Through this pathway light has been found capable to provoke emotional responses in occupants affecting one’s mood, to influence cognitive processes like attention and motivation, which in turn affect

behavioural outcomes such as task performance (Veitch, 20o1; Boyce, 2014; de Kort, 2014). These findings imply that light, as a feature of the physical environment, has the capacity to influence occupant behaviour.

The light condition in spaces occupied by people during daytime is typically composed of natural and artificial light. A review of literature associated with the fields of lighting science and environmental psychology revealed researchers have been working the past decades towards comprehending the visual and non-visual implications of light (see Chapter 3). Although natural and artificial light have been documented to affect occupants via both pathways, design practitioners appear to typically consider natural light a primary quality of indoor spaces, and to pay significant attention towards optimizing natural condition in their buildings. Artificial light on the other hand is mostly considered complementary to safeguard appropriate visibility when the natural light is lacking.

The latter is an important observation as the availability of natural light is bound to certain hours and weather conditions, and its availability is therefore uncertain. While artificial light is produced by an electrical lighting system and available on-demand; often as simple as flipping a wall switch. Another quality of artificial lighting is that one can precisely define where it is present in a space, and where not. These system design decisions result in a composition of lighter and darker areas in a space, also referred to as a light pattern. In comparison to natural light, artificial lighting thus allows for much greater control over when and where light emitted by the lighting system is present in a space. This control affords to explore how artificial lighting, and the artificial light pattern in particular, could act as a tool to address certain pupil behaviours, and herewith improve quietness during class as advocated by the 2014 reform.

1.1.4 Light Pattern to Improve Quietness in Class

Field studies in six Danish Folkeskole revealed that these learning spaces typically feature the same type of artificial light pattern that can be described as relatively uniform, meaning featuring little variation between darker and lighter areas. This uniform pattern is typically the outcome of a ceiling-based lighting system that distributes the emitted light relatively evenly across the learning space. This type of pattern appears to align well with the design practitioners’ view concerning the purpose for artificial lighting in learning spaces as argued in the previous section, namely, to attend to the visual needs of pupils placed anywhere throughout the space.

Research exploring potential implications of the light pattern for room occupants is still scare, but those available indicate that the light pattern influences the observers’ visual impression of a space, and that certain patterns appear preferred over others (Flynn et al., 1973; Loe et al., 1994). These impressions and preferences appear

to be shared experiences. Findings also suggest that light patterns incite mood responses which in turn affect the observer’s behaviour and performance (Veitch, 2001; Govén et al., 2011). A mechanism that may explain the workings hereof is for example the ability of the light pattern to direct the observer’s attention, particularly towards high-brightness areas. This mechanism may improve the observers’ attention to a task when accentuated relative to its surroundings. These findings inspired this study to explore if exposing pupils to an alternative light pattern could encourage a behavioural change in pupils that reduces disturbances and herewith improve quietness during class.

The alternative light pattern chosen to investigate this proposition is referred to as pools-of-light. The choice for this pattern was informed by beforementioned research findings as well as by observed teaching practices in the visited Folkeskole. The lighting system to create the pools-of-light pattern was developed together with experienced school designers at Henning Larsen. In essence, the pools-of-light pattern features brighter zones (pools) of light set in relatively darker surroundings. The intention with this pattern is to attract pupils into these brighter areas where they would feel safe to withdraw into their own world. It is hypothesized that such stateof-being would direct pupil’s attention inwards and discourage behaviours that typically result in noise or other forms of unrest. As less disturbances equals less interruptions to pupil’s attention, such change could ultimately benefit their learning performance.

1.1.5 Research Question

Central to this research is the quest to create learning environments that are supportive of pupils’ learning performance. It specifically addresses the need to improve quietness during class as called for by the 2014 Folkeskole reform. A quieter environment can be achieved by reducing disturbances, which are found to be mainly caused by pupils. It is hypothesised that the artificial lighting in the learning space, besides enabling good sight, can also act as a tool to reduce the occurrence of disturbing behaviours. In order to test this hypothesis, this research investigates whether exposing pupils to an alternative artificial light pattern, referred to as pools-of-light, elicits desired behavioural change. The questions this research looks to address are therefore formulated as:

Does exposure to the pools-of-light pattern in the Folkeskole learning environment discourage disturbing pupil behaviours and herewith improve quietness during class? And if so, does this change significantly affect pupils’ learning performance?

In order to answer these questions, an experimental field study has been performed in a real-life Folkeskole learning environment. This study explored whether exposure to the pools-of-light pattern affected pupils’ behaviour and learning performance compared to exposure to the standard uniform light pattern.

This research is embedded in the academic fields of environmental psychology and lighting science, and the professional field of architectural lighting design. Methods, tools and techniques from all fields were used to collect the necessary data. The research can be split into two sequential phases of data collection activities:

• Phase I – a first round of data collection that informed the formulation of the research question (preliminary studies).

• Phase II – a second round of data collection that informed the answer to this research question (experimental field study).

Figure 1.1 provides a schematic overview of these two consecutive phases. The following sections will further introduce the two illustrative diagrams presented in this schematic overview and summarize the research methods and techniques used per phase.

Phase I – Preliminary Studies

Research Question Phase II – Experimental Field Study

Treatment Variable

(A) uniform light

(B)

pools of light Folkeskole Learning Environment

(I) noise Outcome Variables

(II) behaviour

(III) performance

(1) architecture

Intervening Variables

(5) activity

(2) interior

(3) climate

(4) pupils Findings

Figure 1.1 Schematic overview of the two-phased research methodology

1.2.1 Phase I – Preliminary Studies

The preliminary studies revolved around exploring two topic-areas within the context of the Folkeskole learning environment:

• the physical environment in which the learning takes place, and specifically the artificial lighting therein; and

• pupil behaviour, and particularly those behaviours found disruptive to or to hinder pupils’ attention to their learning.

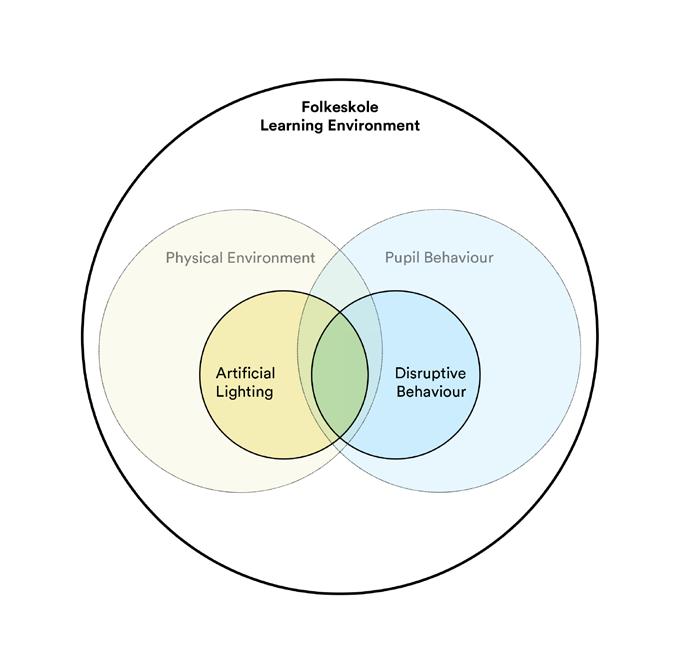

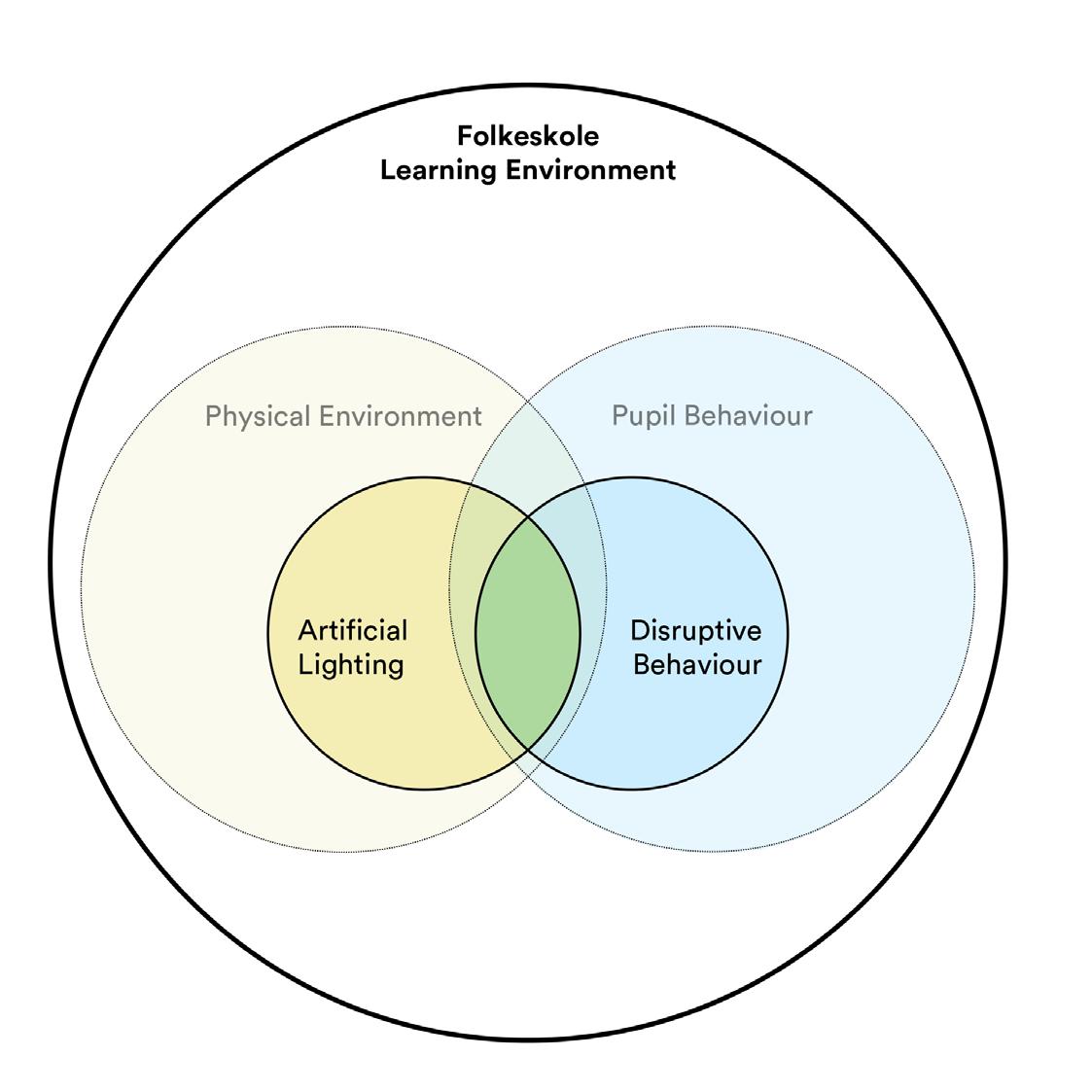

The diagram shown in Figure 1.2 (enlargement of Figure 1.1) serves to illustrate the relationship between these topic-areas.

Figure 1.2 Schematic diagram of the research context and topic areas of interest Note: the size of each circle is illustrative only and not representing any weighting

The diagram in Figure 1.2 is made up out of five circles. The outer circle represents the context of this research: the Folkeskole learning environment. A learning environment as a whole is typically informed by the adhered to pedagogy, the management style and organisational structure, the pupil population as well as the physical context the learning takes place in (Higgins et al., 2005; Barrett et al., 2015). The two medium-sized circles represent the two topic areas of the learning environment this research focusses on:

• The first topic area is the physical environment, which is represented by the light-yellow medium-sized circle in the diagram, and a subtopic area in particular, the artificial lighting, which is represented by a dark-yellow small-sized circle in the diagram.

• The second topic area is pupil behaviour, which is represented by a light-blue medium-sized circle in the diagram. Pupil behaviour may refer to a whole range of ways that pupils can act in a school environment including their (pro)social behaviours, learning behaviours, and disruptive or aggressive behaviours.

The latter, disruptive behaviours, are the type of behaviours of particular interest in this research. This subtopic area is represented by a darker-blue small-sized circle in the diagram.

This research explores the relationship between the two subtopic areas of interest: artificial lighting as a feature of the learning environment, and disruptive pupil behaviour. This relationship is represented in the diagram by a green-coloured area representing the overlap between the two small-sized subtopic circles.

During the preliminary studies the Folkeskole learning environment in general, and the two subtopics artificial lighting and disruptive pupil behaviour in particular, have been studied in order to arrive at a meaningful research question. These studies included three data collection methods: (1) literature review, (2) field studies, and (3) expert interviews.

(1) A review of literature associated with the 2014 Folkeskole reform, the implications of the physical learning environment, and artificial lighting and its effect on building occupants allowed to ground the research in existing knowledge.

(2) Two rounds of field studies in six different Folkeskole further informed the direction of the research. The first round of field studies took place in four newly built or renovated school buildings since the 2014 reform and provided insight into the solutions and responses applied by architects thus far. The second round of field studies took place in two school buildings designed before the 2014 reform, and two school buildings thereafter. All four are in use today. These comparison studies provided insight in the typical condition of the (artificial) lighting in the Folkeskole learning spaces today.

(3) Two rounds of interviews allowed to uncover what is missing or lacking in today’s Folkeskole learning environments. These interviews were held with two types of learning environment experts: teachers and school-designers. The first round of talks included six teachers currently active in the Folkeskole with the purpose of gaining insight into how they use the artificial lighting, how they experience the subsequent lighting conditions, and to uncover what is malfunctioning or lacking in their opinion. The second round of talks included four schoolbuilding architects, with the purpose of gaining insight in their approach to designing the artificial lighting, and the requirements it has to fulfil. Both experts were also consulted about potential alternative artificial lighting designs that could help improve quietness in class.

The findings from these three data sets jointly allowed to formulate the question this study looks to address. Chapters 2,3 and 4 describe these three studies and findings further.

1.2.2 Phase II – Field Experiment

To answer the research question, a full-scale field experiment has been conducted in a live Folkeskole. This method of research was chosen for (1) perceptual, (2) behavioural and (3) temporal reasons:

• Our experience of light conditions in the built environment depends heavily on the complex interactions between the light itself, and the architectural context it is placed in. This experience is not easily replicable in a laboratory or a virtual setting. Experimenting in a full-scale, real-life environment allows to investigate realistic occupant experiences with light.

• Because the interest of this research is to assess inflicted (change in) pupil behaviour, studying pupils in their real habitat while continuing their normal routines allows to reveal realistic behavioural change opposed to simulated ones.

• In order to move beyond the novelty of being exposed to the (temporary) experimental lighting pattern, pools-of-light, a relatively long exposure time to the pattern is necessary, which is most often not feasible in laboratory or virtual setting.

The field experiment took place in four learning spaces of a real Folkeskole environment, namely Frederiksbjerg School located in Aarhus (DK). Three variable-sets have been studied during the experiment: treatment variable, outcome variables, and potentially intervening variables that may confound the research findings.

• The treatment variable in the field experiment, or the variable manipulated, is the artificial light pattern in the learning space.

The two light patterns were compared are: A) standard uniform light pattern and B) experimental pools-of-light pattern.

• The three outcome variables of the field experiment that were respectively monitored, observed or measured for change are: (I) noise levels, (II) disruptive behaviours, and (III) cognitive performance. The first two variables are considered to reveal changes in pupil behaviour that affect quietness in class, most notably vocal change. The third variable reveals any change in pupil’s cognitive performance by means of specialized tests.

This variable was included in the study because ultimately, the purpose of a quieter learning environment is to enable pupils to concentrate better on their learning and perform better.

• Fourteen potentially intervening variables were identified for this experiment. These were grouped into five categories (1 – 5).

Some of these variables were controlled during the experiment, while others had to be monitored for significant change.

Figure 1.3 (enlargement of Figure 1.1) provides a schematic overview of these three types of variables included in this research. In order to collect data on all these variables, the field experiment included a broad range of data collection methods and tools. Chapter 5, 6 and 7 describe the methods used, the context and setup of the experiment, the data collection procedure applied, the processing of this data, and interpretation of the results.

Treatment Variable

(A) uniform light

(B)

pools of light (I) noise Outcome Variables

(II) behaviour

(III) performance

(1) architecture

Intervening Variables

(5) activity

(2) interior

(3) climate

(4) pupils

Figure 1.3 Schematic diagram of the research context and topic areas of interest

1.3 Research Contributions

This research looks to contribute with: (1) new knowledge about how the built environment, and light in particular, influences occupant behaviour; (2) an exemplary design of how artificial lighting may act as a tool for teachers; (3) specific design information for the architectural industry, and (4) a contribution to the broader debate about improving indoor quality of learning environments in general.

1.3.1 New Knowledge

The aim of this research is to add new knowledge to the academic fields of environmental psychology and lighting science about how artificial lighting in the learning environment affects pupil’s learning. It does this by investigating the underlying mechanism through which the artificial light pattern may affect behavioural outcomes in pupils that influence their ability to concentrate on their learning. In addition, the research also provides methodological contributions through learnings from the performed field experiment itself.

1.3.2 Tool for Teachers

The research also revolves around capacitating teachers to use the artificial lighting as a behavioural tool. The fact that the setup of the experiment is not prescriptive in how and when certain lighting features were to be used, allowed to explore how the artificial lighting could be best used as a tool to manage disruptive pupil

behaviours. And because the experimental lighting installation has been kept in place after the experiment, and its design principle extended into other learning spaces of the school too, makes this installation itself also a concrete contribution to a particular learning environment, namely Frederiksbjerg Skole, with the potential to be implemented in other learning environments too.

1.3.3 Enlighten Design Practitioners

Constructive Design Tool

The research, setup as a practice-based research project, directly contributes to Henning Larsen’s ambition to grow their expertise of how their designed environments can (deliberately) affect occupant behaviour. This knowledge will serve the wider architectural community too. In addition, by being embedded in practice this research also allows to exemplify how artificial lighting can be a constructive design tool that the building industry can apply in order to create indoor environments in which occupants can perform their tasks or activities to the best of their abilities.

Building Regulations

The research also points towards adjusting the current building regulations with regards to artificial lighting. Commonly these regulations include recommendations that guide built environment designers towards appropriately configured light applications that, at the very least, ensure minimal visual comfort so that users of these environments can perform their activities as well as possible. Recommendations for learning spaces, as for example provided in European standard EN-12464-1, prescribe average illuminance levels to be maintained across the horizontal working plane, combined with a degree of uniformity. Guidelines like this offer very little room to design anything other than standardized artificial lighting. However, the findings of the field experiment may suggest that doing just that, deviating from the standardized solution, might improve the conditions for learning.

Cost Effective Solution

Another reason to focus on artificial lighting as a means to improve the learning environment, is that it is a relatively (cost) effective tool in comparison to other features of the environment such as those dealing with air quality or noise treatment. This might be particularly relevant for those schools looking to renovate instead of building new. Where a new building naturally allows architects to apply best practices for indoor quality into its design, renovation projects often encounter significant limitations as one has to work with what is already there, and often while being in active use. This is particularly relevant for Denmark, where about 90 percent of the Folkeskole building stock was built before1970, and only about ten

percent thereafter (Kristensen et al., 2004). The consequence is that the majority of school buildings is outdated by today's standards, and upgrading these facilities is desired. For some cases this might involve a completely new building, however for the majority it will likely concern renovations due to governmental budget limitations.

Artificial lighting may be one of the tools through which learning environment improvements may be relatively easily attained in renovation projects. Existing luminaires are often placed in fairly accessible locations and retrofitting these with newer products can be relatively straightforward. Advancements made within the lighting industry for example in light source and control technology and miniaturization also allow for greater efficiency, reduced maintenance and higher durability of artificial lighting in the built environment. These advancements also offer opportunities to expand the capabilities of artificial lighting with features such as intensity and colour control, adaptivity and daylight mimicking. The challenge lies in defining constructive applications for this broadened palette of artificial lighting tools to benefit pupil’s learning performance. This research contributes by exploring one particular type of artificial solution: variability of the light pattern.

1.3.4 Improve the Indoor Quality of Schools

The research also responds to more general call to improve the indoor quality of learning environments as various research has revealed it is inadequate in many of today’s schools. Indoor quality is amongst others linked to the indoor climate variables light, sound, temperature and air quality. These variables have been linked to significantly influence pupils’ learning outcomes. For example, researchers in the UK studied the status of the indoor climate in153 classrooms across 27 very diverse primary schools and compared these against pupils’ academic results (Barrett et al., 2015). This study revealed that these variables are responsible for about eight percent of the variation in learning progress over a year.

Several research initiatives uncovered that the status of the indoor climate in many schools does not meet today’s recommendations. In Denmark, a nation-wide study in 2011 looked at air quality and reported that 56 percent of the 743 measured Folkeskole learning spaces exhibited poor ventilation rates (Toftum et al., 2011). A more extensive follow-up study in 2017 found that of the learning spaces surveyed at some point during use 91 percent exceeded the recommended CO2 level, 63 percent exceeded the recommended maximum sound level, and 49 percent exceeded or fell below the recommended thresholds for lighting levels (Alexandra Institute, 2017; Center for Indeklima og Energi, 2017).

Outside of Denmark similar findings emerged. In Sweden for example, a study including 324 schools exposed the status of the perceived quality of the indoor climate in schools by probing 7000+

teachers for their experiences (Andersson et al., 2008). Findings showed that the most significant complaints concerned noise, dust and “stuffy” bad air, and to a lesser extent, varying temperatures. Fatigue, heavy headedness and headache were frequently reported and often related to both noise and deteriorated indoor air. In the USA the Heschong Group conducted a large study investigating the impact of daylight access in the classroom on pupils’ cognitive performance measured by standardized tests in more than 2000 classrooms (Heschong, 1999, 2003). They found that pupils exposed to higher amounts of daylight would score significantly better than peers in less exposed situations.

These studies expose that the indoor quality of many schools can be considered inadequate, and the authors called for improvements. In Denmark, this has triggered several public and private initiatives encouraging academics and practitioners to collaboratively explore ways to improve the indoor conditions in its schools. Examples thereof are: “Skolernes indeklima” by Realdania, “Den Gode Indeliv” by Sustainable Build, and “Lys i Skole” by Lighting Metropolis / Gate21 * . This research contributes to this call by exploring how artificial light can help improve the overall indoor quality of learning environments.

1.4 Structure of the Thesis

This PhD thesis book comprises eight chapters. Between Chapter 1 Introduction and Chapter 8 Discussion, the thesis is broadly structured in two parts:

• Part I _ Framework – Chapter 2, 3 and 4 provide background and context, and describe the theoretical foundation for this research.

• Part II _Experiment – Chapter 5, 6 and 7 describe the design, execution, data analysis and findings of a field experiment investigating further the relation between light and behaviour.

See Figure 1.4 for an illustration of the overall thesis structure.

Chapter 1 – Introduction, introduces the project, describes the problem it looks to address, and explains why artificial lighting was chosen as a means to explore a solution. This is followed by the formulation of the research question. The chapter then outlines the contributions the research seeks to make to the academic fields of lighting science and environmental psychology as well as towards the practice fields of architectural lighting design and education. The chapter concludes with an overview of the thesis structure.

Ch.1 Introduction

I Framework

Ch.2 The Learning Environment and Pupil Behaviour

Ch.3 Light and Human Behaviour

Ch.4 Artificial Lighting Design for Learning Spaces

II Experiment

Ch.5 The Field Experiment Variables

Ch.6 Experimental Context, Setup and Design

Ch.7 Data Collection, Analysis, Results and Conclusion

Ch.8 Discussion

Figure 1.4 Thesis Structure

Part I: Framework (Chapters 2, 3 and 4)

Chapters 2, 3 and 4 outline the underlying foundations of this study by respectively providing a background setting, theoretical framework and practical context.

Chapter 2 – The Learning Environment and Pupil Behaviour,

outlines the motive for undertaking this research, namely a specific implication of the reform of Denmark’s Folkeskole system in 2014 that requires schools to improve the conditions for undisturbed learning. The main cause of disruptions appears to be the pupils themselves. The approaches taken by architects to help reduce disruptions during class are described, which reveals a missing response. As research revealed the physical environment is capable of influencing pupil behaviour, there is an apparent opportunity for architects to address disruptive behaviours in their building designs, and herewith contribute to a calmer learning environment.

Chapter 3 – Light and Human Behaviour, argues that artificial lighting could be one of the learning environment’s features available to influence pupil behaviour. Hereto, the theoretical context of the research is presented. Most notably, Jennifer Veitch’s work describing the various influences of light on human performance, and Peter Boyce’s conceptual framework outlining three (known) pathways through which lighting conditions influence human performance. A review of associated literature allows to specifically discuss what is known about the effects and workings of light on occupants of learning environments.

Chapter 4 – Artificial Lighting for Learning Spaces, introduces the practice of artificial lighting design, and how it shapes the occupant’s visual impression of physical space. Some practical aspects of lighting design are introduced that inform the research approach, and the design freedom of the lighting designer is sketched as the light pattern–an assemblage of lighting qualities such as intensity, colour and spread. A field study in four representative primary learning environments in Denmark allowed to define the current state of the artificial lighting herein, and how it is experienced by their users, and what is missing. Supported by conversations with educational architects, the idea is presented to investigate whether a non-uniform pools-of-light design may elicit behavioural changes in pupils that benefit their concentration.

Part II: Experiment (Chapters 5, 6 and 7)

Chapters 5, 6 and 7 describe the field experiment itself.

Chapter 5 – The Field Experiment Variables, introduces the field experiment as a method, and outlines the three variable-sets that have been monitored during the study: (1) the treatment variable, constituted by two artificial light patterns pupils have been exposed to in their respective learning spaces; (2) the three outcome variables that were employed to investigate an effect of these light patterns on pupil’s behaviour and learning performance: classroom noise levels, three observable disruptive behaviours, and cognitive performance; and (3) fourteen potentially intervening variables that were identified to potentially contaminate the data. For each variable the method used to collect the necessary data is provided.

Chapter 6 – Experimental Context, Setup and Design, outlines the experimental context, setup and design of the research. It details the conditions of the four learning spaces that hosted the experiment and describes the design and functioning of the lighting system temporarily installed to enable controlled exposure to two different artificial lighting conditions. It also details the research design that was applied, and the protocol followed to collect the data consistently and reliably.

Chapter 7 – Data Collection, Analysis, Results and Conclusion,

covers the data collection itself, the analysis thereof and interpretation of the results for each proxy variable, as well as handling of the fourteen potentially intervening variables. The chapter concludes with relating these findings to the original research question.

Chapter 8 – Discussion. This chapter discusses findings that may not directly be relevant to answer the research question, but are of value to the academic and practice fields this research is associated with. The chapter reviews learnings from the field experiment as a research method, and elaborates on the field experiment’s validity, reliability and replicability. It concludes with suggestions for future research.

Appendix Book

Alongside this thesis book, a complementary appendix book is issued that is supportive to the material presented in this document. Throughout the thesis references are made to the relevant appendix section(s) ranging between A and X.