35 minute read

2 LEARNING SPACES AND PUPIL BEHAVIOUR

This chapter introduces the research context andThis chapter introduces the research context andoutlines outlinesthe the problem it looks to address problem it looks to addresshere.here.The contextThe contextis the Folkeskole—is the Folkeskole— Denmark’s institutions for primary and lower secondary education, Denmark’s institutions for primary and lower secondary education, where in 2014 where in 2014a reform provided fora reform provided forguidelines to improve the guidelines to improve the indoor quality of theseindoor quality of theselearning environments. The reform learning environments. The reform explicitly explicitlyhighlighted the need tohighlighted the need toimprove quietness during class. improve quietness during class. One way to achieve this is to One way to achieve this is toreduce the occurrence of disturbances, reduce the occurrence of disturbances, of which the dominantof which the dominantcause causeis found is foundto be the pupils themselves. to be the pupils themselves. This chapter This chapteroutlines outlinesthe premise that the premise that(features of) the physical(features of) the physical learning learningenvironment could be one of the tools availableenvironment could be one of the tools availableto manage to manage disruptive pupil behavioursdisruptive pupil behavioursand andwherewith attain greater calmness wherewith attain greater calmness during duringclass classas encouraged by the reform. as encouraged by the reform.

Figure 1.1. illustrates the Figure 1.1. illustrates thetwo topic-areas, the physical learning two topic-areas, the physical learning environment environmentand pupil behaviour,and pupil behaviour,discussed in this chapterdiscussed in this chapterwithin within the context of thethe context of theDanish FolkeskoleDanish Folkeskolelearning environment. learning environment.

FigureFigure 2.12.1 Schematic Schematicdiagram of the research context and topic-areas of interestdiagram of the research context and topic-areas of interest

ThisThischapter chapteris structured in five sections. Section 2.1is structured in five sections. Section 2.1outlines outlinesthe the implications of the Folkeskole reform, specifically for school implications of the Folkeskole reform, specifically for school buildings. Section 2.2buildings. Section 2.2presents findings from field studies exploring presents findings from field studies exploring architectural responses to the reform thus far. Section 2.3architectural responses to the reform thus far. Section 2.3describes describes what is understood by disruptive pupil behaviour, the main causer what is understood by disruptive pupil behaviour, the main causer of unrest during class. Section 2.4of unrest during class. Section 2.4defines how the physical learning defines how the physical learning environment could assist with managing these behaviours. Section environment could assist with managing these behaviours. Section 2.5 2.5provides for a summary of the chapter and explainsprovides for a summary of the chapter and explainshow how findings discussed infindings discussed inthe preceding sectionsthe preceding sectionsinformed the problem informed the problem this research looks to address. this research looks to address.

This section introduces the Folkeskole learning environment and describes the ensuing challenges brought about by the 2014 reform that are particularly relevant for school designers. One of these is the improvement of the learning environment by reducing disturbances, in particular from noise. The source of disturbances may reside either outside or inside the classroom, though the dominant cause is found to be the pupils themselves. A potential tool to manage disruptive pupil behaviours may reside in the psychical learning environment itself.

2.1.1 Denmark’s Folkeskole

The learning environment is generally understood to be the whole of social, physical, psychological, and pedagogical aspects that constitute the learning context * . Although this study eventually focusses on one component, namely the physical component, it is important to acknowledge it does not stand-alone but is related to other components of the learning environment too.

The Folkeskole, the specific learning environment this research is addressing, is Denmark’s system for primary and lower secondary education for pupils between the ages of circa 6 and 16. The key motivation to focus on this particular typology is a reform that came in place in 2014. Of a number of changes relative to the Folkeskole before 2014, this reform significantly affected how school buildings should be used, and therefore, designed.

Where a learning environment traditionally is understood to be the domain of teachers that manage classrooms and educate pupils, this reform implicitly reaffirmed the importance of the disciplines that shape the physical learning environment, i.e. the multiple disciplines of building design. The architect Herman Herzberger, known for his work on schools and universities, has compared learning with the creation of architectural space:

As Herzberger suggests, understanding the changes brought about by the reform and interpreting their implications for the physical conditions of the learning environment is an important prerequisite for the reform’s success.

To learn is to create order and coherence in the mind, to form structures where there had been none. Making space is applying structure where emptiness or chaos once prevailed. Learning, then, is a way of creating space in one’s head: space for other aspects, ideas, relations, interpretation, associations. So learning is perhaps the finest imaginable approach to the concept of space. (Herzberger, 2008, p. 67)

The 2014 reform of the Folkeskole was widely supported politically and was initiated to maintain and develop the strengths and academic standards of the primary schools (UVM, 2014). This has brought about significant change in how pupils are being taught, the type of activities that take place, and how a school day is programmed. Not only does this set new challenges for management, teachers and staff, but also for the physical environments, the school buildings that host this new learning.

The 2014 reform was developed around three main goals: (1) improving pupil achievement (or academic level), (2) equity, and (3) well-being. To support these three goals, the ministry of education defined sixteen focus points in which the changes were articulated (UVM, 2013, 2014). These focus points address issues such as pedagogical methods, curricular subjects, a simplification of learning, teacher support, and community engagement.

2.1.3 Three Reform Points relevant for Architects

Three of these focus points bear specific significance for this research, as they raise questions towards the use and design of the physical learning environment that support the new teaching:

• Point 1: A longer and more varied school day,

• Point 3: More physical exercise (PE) and activity; and

• Point 13: Better learning environment and quietness in class.

Point 1 introduces a longer and more varied school day that is characterised by more teaching time, diversified pedagogical methods and more emphasis is placed on catering for individual pupil preferences. This allows teachers to better support the individual academic development of pupils, and to practice more practical, student-led, and application-oriented forms of teaching. One of the consequences of these new methods is that learning and teaching settings now may take many different forms and shapes; ranging from rather traditional ways of individual work and group tutoring, to self-regulating activities requiring pupils to collaborate more and learn-by-doing together. As a consequence, the way that the learning environment is to be used for teaching and learning activities and the needs it should fulfil, has diversified significantly.

Point 3 addresses physical activity during teaching and in breaks. The reform prescribes that pupils need to move, play or otherwise be physically active for at least 45 minutes in total each day. The reasoning behind it is that increased physical activity is found to be related to higher levels of motivation and to improvements in the

overall learning process. The reform is not prescriptive in how physical activity is to be made part of the curriculum. It may take place during fewer longer stretches, such as PE classes or break sessions, but also in multiple shorter intervals with the option of integration in other learning activities. Thus, the learning environment, including the formal teaching areas, needs to accommodate interventions that encourage pupils to be more physically active in-between the formal learning activities.

Point 13 addresses the importance of creating an environment supportive of pupils’ learning, and to specifically improve quietness during class. A supportive learning environment contributes to pupils’ general well-being, their aspiration to learn, and their actual ability to learn in the classroom. Improving quietness during class is specifically emphasised by the reform because disturbances and unrest, particularly in the form of noise, were found prevalent in the Danish Folkeskole (Søndergaard et al., 2014). This is considered a problem because disturbances as noise interrupt pupils’ concentration, which adversely impacts learning performance (Woolner & Hall, 2010; Sala & Rantala, 2016).

Disturbances may present in audible, visual or physical form. They may be environmental disturbances and originate either outside the learning space, for example traffic noise or sun glare, or inside the learning space, for example ventilation system noise or flickering lighting. However, the dominant source of unrest during class is found to be the pupils themselves as they partake in (learning) activities (Emmer, 1984; Stavnes, 2014). In order to attain a quiet learning environment, both environmental as well as behavioural causes of disturbances need to be addressed.

2.1.4 New Challenges for School Designers

Points 1, 3 and 13 prompted significant organisational and pedagogical change, but also set new challenges for school designers (UVM, 2014):

• Point 1: The longer and more-varied school day requires that the physical learning space allows for greater variations of use than was needed before 2014;

• Point 3: The need for the formal learning activities to be alternated frequently with different states of physical activity requires school buildings to facilitate a broader range of play and movement;

• Point 13: The need for the learning environment to support pupil well-being and improve quietness during class, requires comfortable environmental conditions and mitigating or preventing disturbances from occurring, whether caused by environmental sources or pupils.

Considering these three challenges jointly, another overarching challenge surfaces, that of an increased teacher management load. Point 1 and 3 encourage teachers to frequently change between different learning activities as well as movement breaks. This requires the teachers to repeatedly manage their pupils’ state of mind, behaviour and the learning setting to correspond with that specific type of activity, as well as to manage the transitions between these different activity forms effectively. Point 13 advocates to better the learning environment in general, and specially to decrease disturbances during class. As indicated, the dominant causes of disturbances are the pupils themselves. Addressing their behaviour also requires active management by the teacher.

Each of the three challenges (1, 3 and 13) brought about by the reform thus seemingly increase the teachers’ curricular and behaviour management load, indirectly taking time away from their pedagogical tasks and teaching in general. To act upon these challenges, it seems critical that the designers and users—teachers, staff, and perhaps pupils—of school buildings explore together how the physical learning environment may host and serve these diversified curricular and physical activities, while at the same time provide for supportive environmental conditions that help minimise disturbances during class – without the need to significantly increase the teachers’ management load. In order for these goals to be achieved, teachers should be capacitated to easily and effectively manage their learning environments.

2.2 A Field Study of Architectural Responses to the Reform

This section discusses the findings from a field study that was undertaken as part of this research to reveal what architectural responses so far have been implemented to address the reform demands. In three representative school buildings, a range of architectural solutions was identified that were meant to improve the learning environment. These solutions however do not seem to directly address the problem of disturbances caused by pupil’s behaviour; a task apparently left with the teachers. The question then emerges whether the physical learning environment itself could be able to assist teachers in managing these behaviours.

2.2.1 Typical Design Responses by Architects

Even though the 2014 reform itself is relatively young, architectural responses to the specific challenges following point 1, 3 and 13 could be identified in a number of recently built or renovated school buildings. As part of this research, field investigations in three representative school buildings were undertaken, that were

assessed in line with the three focus points of the reform. The first two schools, Frederiksbjerg Skole and Sophieskolen, are newly built, while the third school, Kirkebjerg Skole, includes renovation of an existing building complemented by a newly built extension. See Figures 2.2 – 2.4 for impressions of the three school buildings.

Figure 2.2 Frederiksbjerg Skole (2016) in Aarhus. The new building was designed by Henning Larsen Architects and GPP Arkitekter. The school hosts just under thousand pupils in central Aarhus * (photo credits: Henning Larsen) Figure 2.3 Sophieskolen (2016) in Nykøbing Falster. The new building was designed by TNT Arkitekter and Creo Arkitekter. The school serves circa eight hundred pupils in the Guldborgsund municipality of Falster * (photo credits: Creo Arkitekter) Figure 2.4 Kirkebjerg Skole (2016) in Copenhagen. The renovation design was done by KANT Arkitekter; the new building by Core Arkitekter. The school serve just over thousand pupils in the Vanløse district of Copenhagen * (photo credits: KANT Arkitekter)

From the field observations it was possible to identify four types of architectural responses performed towards reform points 1, 3 and 13. These responses can be loosely defined as: (1) flexible learning units, (2) activity provoking interventions, (3) controlled natural light, and (4) improved acoustics. This section provides for a summary thereof. For an extended discussion on the field study, the school buildings and identified response typologies, see Appendix A.

(1) Flexible learning units are considered the architects response to reform point 1: the longer and more diverse school day. To accommodate and support the diverse curricular activities, the architects of the three field study buildings focussed on creating subject-orientated learning clusters, that are placed throughout the school building. A cluster typically contains multiple spaces, that do not display a predefined use and furniture layout. Instead, the architects employed adaptable spatial provisions, such as retractable walls or moveable space dividers, and flexible furniture, such as movable desks and seats. These design solutions allow teachers and pupils to rearrange their space’s setup quickly, and redistribute pupils easily in different arrangements, for example in small teams, individually or as a larger group, herewith offering significant flexibility and adaptability to address the needs per activity.

(2) Activity provoking interventions are considered the architects response to reform point 3: more PE and physical exercise and activity. In the three school buildings, architects designed and integrated a selection of playful interventions in the school’s premises that encourage pupils to engage in physical activities in and around the learning clusters. These interventions range from dedicated play and activity rooms hosting longerduration, scheduled activities, as well as integrated interventions in hallways or staircases, to provoke physical activity for example when pupils transition between clusters.

The remaining two responses (3) controlled natural light and (4) improved acoustics—deal with the design and quality of the indoor environment as discussed in point 13: better learning environment and quietness in class, and particularly through the indoor climate variables light and sound. In all three field study buildings it appeared specific attention was given to improve natural light intake and bettering the acoustic conditions in the learning spaces.

(3) Ensuring pupils (and teachers) are well exposed to natural light whilst occupying the learning space has been found to positively affect the health and well-being of pupils, and herewith their academic performance (Heschong, 1999, 2003).

Window design optimised for natural light intake at each location has been given significant attention by the architects.

At the same time, provisions such as blinds or shaders to avoid solar glare and internal heat gains were included too, enhancing the quality of the indoor climate as a whole. The artificial lighting appeared to be designed to contribute when natural light would be insufficient to ensure good visibility to all pupils. The two newly built schools featured a control system that would monitor light levels and adapt the output of the light system accordingly, herewith preventing unnecessary energy consumption. Herewith, it appears natural light is commonly considered a dominant light source, both for human comfort and health as well as from a sustainability perspective.

(4) In response to the reform’s request to reduce disturbances during class, the architects seemingly choose to focus on attenuating noise disturbances by optimizing the learning space’s acoustic properties. For example, they attempt to dull sound levels inside a learning space through abundant use of sound-absorbing measures, including the chosen materials, selection of furniture, and use of flexible desk dividers.

Attention also went out to attempt locking out external noise by applying double or triple glazing towards the surrounding environment and using (glazed) separation walls between the different learning spaces to limit noise travel. As well as specifying low sound producing building system such as the ventilation and blinds. Through these measures, architects attempt to reduce the impact of noise inside the learning space.

A critical observation about the solutions applied by architects thus far is that these do not seem to directly address the problem of disturbances caused by pupil’s behaviour; a task apparently left with the teachers. Their solutions focus mostly on attenuating the impact of noise, but seemingly not explore how to prevent noise, or any other types of disturbances for that matter, from occurring. But prevention could arguably be a more effective approach to accomplish quietness during class than only mitigating the impact. Architects have limited scope to avert disturbances from outside the learning space form occurring, but they could explore how the environment itself can assist in preventing disturbances originating inside the learning space. As pupils are found the dominant cause of disturbances, this approach would require that the learning environment assist with addressing disruptive pupil behaviours.

Managing disruptive pupil behaviour is typically a responsibility left with the teacher. The traditional way of influencing pupil’s behaviour is through various classroom management techniques, which predominantly rely on interactions between teachers and pupils. Classroom management can be described as a series of actions aimed at establishing a setting in which pupils engage in learning activities designated by the teacher, and in which disruptive and/or unproductive behaviours (to the learning) are kept to a minimum (Emmer, 1984). Most of the critical tools of classroom management are of instructional or procedural nature, such as varying the levels of pupil engagement or rules for speaking in class (Simonsen et al., 2008). However, these techniques bear heavily on teacher involvement, who already experience an increased management load due to the changes introduced by the reform itself (see section 2.1.3).

In addition, a study initiated by the Danish Ministry of Education, found that disruptive pupil behaviour, and noise in particular, is prevalent in the Danish Folkeskole (Søndergaard et al., 2014). Teachers have said they spend a significant amount of their time addressing pupil behaviours that cause disturbances instead of putting this time towards their teaching, which effectively burdens the management load further (Emmer, 1984; Stavnes, 2014).

Another trend that also amplified the teacher’s management load, is the steady increase of the number of pupils per class over the past years (Clausen et al., 2017). The number of pupils in Folkeskole classes have risen from an average of 20.1 pupils per class in 2009 to 21.5 pupils per class in 2015. Although this is a relatively small increase, it is important to state that the average contains considerable variations. In about 20% of the classes there are now more than 24 students in a single class. This is a significant greater

group management load in comparison to the pre-reform situation. As a result, the teachers management load in the Folkeskole has significantly increased, particularly since the introduction of the new reform. Relying solely on the teacher’s skill to better quietness during class through the traditional management techniques may be insufficient.

This research therefore set out to explore if and how the physical learning environment could assist teachers in the task of managing pupils (disruptive) behaviours instead of solely mitigating disruptive output such as noise. But in order to validate the potency of this premise, it is essential to first establish what constitutes disruptive pupil behaviour, and secondly, how this behaviour is found to implicate the teaching and learning.

2.3 Disturbances Caused by Pupils

This section unpacks how pupil’s attention during class is typically disturbed. Pupil-made disturbances typically manifest in audible (noise), visual or physical form. The behaviours found responsible for many of these disturbances are classified as: (a) irrelevant externalized expressions, (b) non-learning related social interactions, and (c) out-of-seat behaviours. Based hereon, a definition of disruptive pupil behaviour in general is provided which is adhered throughout this research.

2.3.1 Type of Disturbances Caused by Pupils

The attention of the architects for noise attenuation to improve quiet during class as described in the previous section, is not surprising because various studies have found that noise is one of the most significant disruptors during class, preventing pupils to maintain a state of concentration, which negatively impacts their learning performance (Emmer, 1984; Stavnes, 2014). It has also been documented that noise has detrimental effects on pupil’s cognitive performance, for example their language and reading development (e.g. Emmer, 1984; Shield & Dockrell, 2003; Woolner & Hall, 2010; Stavnes, 2014; Sala & Rantala, 2016). These findings, which are mostly attained by means of experimental and observational studies applied either in a laboratory or field setting, are relatively consistent and indicate that noisy conditions are a cause for annoyance and distraction.

Noise is in essence unwanted sound, though it depends upon the listener and circumstances whether sounds are considered noise (Clausen et al., 2017). A study of the perceived quality of the indoor climate in Denmark’s public-school reports that about a third of its pupils’ experience ‘every day’ or ‘almost every day’ problems with noise in their learning environments, and about a fifth report having difficulties to concentrate at school because of that

(Villumsen & Møldrup, 2013). These findings may be further explained by another study reporting that the measured sound levels in Danish classrooms frequently rise above recommended limits (Søndergaard et al., 2014; Clausen et al., 2017; Fangel & Andersen, 2017). Measured sound levels in occupied indoor spaces typically include two type of sound groups: (1) environmental or background sounds and (2) pupil-made sounds.

(1) Environmental or background sounds. All learning environments deal with an accumulation of environmental, or background, sounds which may include external sounds such as from traffic, internal sounds (not by pupils), such as by the ventilation system or teaching appliances (projectors and smartboards), or sounds penetrating from other areas of the building. In principle, these environmental sounds are considered disruptive noise as it does not contribute to the learning. The higher the accumulation, the more disruptive. Importantly, these sounds cannot be directly controlled by the teacher. Often the designers of school buildings will make efforts to mitigate the impact of these sounds as much as possible through their design choices (see section 2.2.1).

(2) Pupil-made sounds. The second group of sounds are those produced by the pupils themselves as they take part in their learning activities. Pupil sounds are often found the most significant contributor to noise experienced during class, and include both vocal sounds and activity sounds as pupils move around the classroom or move learning objects and furniture (Shield & Dockrell, 2003; Woolner & Hall, 2010; Sala & Rantala, 2016). Where the first group, environment or background sounds are generally found to be relatively stable, the level of pupil-made sounds may vary greatly depending on the task or activity at hand. However, in contrast to background noise, not all of these pupil-produced sounds are necessarily considered noise as this is context dependant. Some of the pupil-made sounds may even be imperative to the learning activity at hand.

For example, during collaborative or group exercises where pupils and teacher discuss, explain or question out loud. But at other times, for example during activities that require pupil’s focussed attention or concentration on a task such as mathematics or reading, pupil-made sounds are commonly considered distractive noise.

More broadly considered, noise is only one type of disturbance caused by pupils. In fact, disruptions may also occur in visual or physical format, for example in form of fidgetiness or wandering around. Regardless of the expression, any disturbance diverts pupils’ attention away from their learning activity at hand or averts a teacher from operating effectively in the learning space (Sala & Rantala, 2016). The next section outlines three type of behaviours commonly considered to disrupt pupil’s attention to their learning.

A review of associated literature revealed three types of behaviours that are commonly considered to inflict visual, audible (noise) or physical disturbance to pupils learning attention (Emmer, 1984; Houghton et al., 1988; Stavnes, 2014):

• Externalized expressions by pupils without being relevant or asked for. For example, shouting out loud but not directed at someone, sighing or general laughter. It may also include small, seated physical expressions such as fidgetiness, wobbling on a chair, tapping fingers on a desk, and other forms of restless behaviour.

• Non-learning related forms of social interaction between pupils.

For example, off-topic social talk, joking together, or seeking attention from a peer pupil located elsewhere in- or outside the learning space for example by waving or clapping hands.

• Out-of-seat behaviour such as needlessly wandering around in the classroom. This includes physical actions that take the pupil away from one’s seat or placement, and that are not related to the learning activity or for reasons such as visiting the toilet or taking learning-related materials from a cupboard.

What these behaviours have in common is that they all interrupt pupil’s attention, which has been found to negatively impact learning performance outcomes. However, there is no conclusive way to argue that these behaviours always qualify as disruptive, because this is highly dependent on the context and setting it occurs in (Stavnes, 2014). For example, externalized expressions such as talking out loud may be considered acceptable ‘noise’ during group discussions, but is likely to be experienced disturbing when pupils need to individually focus on a mathematical exercise. Thus, no conclusive list of behaviours can be formulated that is consistently experienced as disruptive. But a general definition of what is understood as disruptive behaviour is feasible.

2.3.3 Definition of Disruptive Pupil Behaviour

Based on the beforementioned descriptions, the definition of disruptive pupil behaviour can be formulated as:

Pupil behaviours considered disruptive are behaviours that cause interruption or diversion of one’s own and/or others’ attention away from the (learning) activity or task at hand.

This study further adheres to this definition when discussing the concept of disruptive pupil behaviour.

2.4 The Physical Environment and Pupil Behaviour

This section outlines current knowledge about the relationship between the physical learning environment and behavioural outcomes in pupils and outlines how this knowledge validates the premise that this environment, as designed by architects, can act as a tool to affect pupils’ behaviour, and ultimately, herewith their learning performance.

2.4.1 The Physical Learning Environment Matters

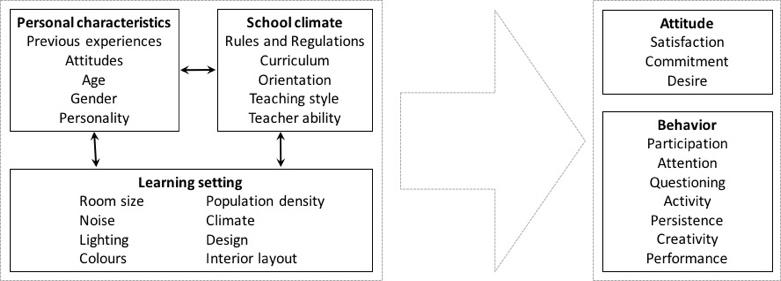

Researchers in fields such as education research, sociology and psychology study pupils’ behaviour. The field of environmental psychology, an interdisciplinary field that can be understood as a sub-field of psychology, addresses in particular the behaviour of pupils in relation to their environment. Environmental psychologist Robert Gifford, the author of a leading publication in this field, reviews a selection of studies situated in educational environments, and based thereon provides a framework for understanding the person-environment relations therein, see Figure 2.5 (Gifford, 2014). In this framework Gifford proposes five factors that are at play in the learning environment: the pupils themselves, the school climate, and features of the physical learning setting. Interactions between these influence pupils’ attitude and behaviour, ultimately affecting the teaching and learning.

Behavioural scientist Rudolf Moos proposed a similar model to understand how the learning environment, or classroom climate as he refers to, is influenced by multiple factors (Moos, 1979). In his model Moos outlines five determinants and relationships between these that are together responsible for the classroom climate. Along with some organisational and human factors, Moos explicitly recognises the physical and architectural features of the environment as a significant factor (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.5 Gifford’s Framework depicting five related factors in the learning environment (2014, p303).

The Moos model displays unidirectional arrows for reasons of simplification, but in the accompanying text Moos articulates various bidirectional relations between these factors. Herewith he suggests that positive choices or changes selected by the teachers and pupils or in the environment tend to cause further positive changes in a ‘virtuous cycle’, whereas negative ones might cause a vicious cycle of decline.

Figure 2.6 Moos’s Model of the determinants of the classroom climate (1979).

What the models by Gifford and Moos share is that both recognise pupil’s learning is influenced by a complex process of contextsensitive interactions, meaning moderated by the situational, social and instructional context of where the learning takes place, and that the physical learning environment is one of these influential factors. However, both stipulate the environment itself usually does not affect the teaching and learning directly, but can facilitate or hinder the effectiveness thereof. Effective learning may thus take place best there where the physical learning setting has been considered similarly mindful as the curriculum, pupils, teachers’ abilities, and other teaching aids. Or in other words, the physical context matters to create optimum learning conditions.

A comprehensive review of studies reporting on behavioural implications associated with (features of) the physical learning environment has already been conducted by Higgins et al. (2005). The authors of this review collected over 200 references, mostly published in journals from the UK, the US and Europe dating back to the 1960s. They organised the behavioural implications discussed in these references into five categories: (1) attainment, (2) engagement, (3) mood and motivation, (4) wellbeing and health, and (5) attendance. These are further described as following:

(1) Attainment. These studies look for measurable change in pupils’ academic achievements, either cognitive or task performance. This is typically measured by standardised tests or exams, or monitored and assessed by teacher observation.

(2) Engagement. These studies typically look for observable changes in pupils’ levels of attention. To collect such data, researchers typically interview pupils and teachers and/or conduct observational studies looking for signs of interrupted concentration by monitoring change in pupils’ on-and-off-task behaviours, distracted or disruptive behaviors, and social behaviours. These studies often take place directly in the field, or by help of video recordings thereof.

(5) Mood and Motivation. These studies look for changes in selfesteem for teachers and pupils or changed levels of academic self-concept. The also look for emotional responses like surprise, excitement, confusion, agitation, fear or boredom.

Typically, these studies apply research methods as self-report surveys, and open or closed questionnaires to collect their data.

(6) Wellbeing and Health. These studies look for changes in the physical self or impacts that relate to (dis)comfort. These studies commonly apply methods as self-report surveys, and open or closed questionnaires to collect data.

(7) Attendance. These studies look for fewer or more instances of lateness or absenteeism by pupils. This data is often drawn from school records and absentees’ lists.

These five categories of behavioural implications are measurable and can be considered either quantitative or qualitative research variables. A critical observation towards Higginswork however is that most of the studies reviewed focussed predominantly on assessing implications of the environment by evaluating change in pupil’s attainment, and to a lesser extent, attendance. This is not surprising as attainment, also referred to as academic performance, and attendance are typically quantitative measurements, and therefore can act as objective assessors of change in pupils that can be applied across different school contexts and generalize findings.

But what these studies do not reveal much about, is the ‘how’ or ‘why’ pupils’ attainment or attendance was affected. Or in other words, what underlying mechanism(s) were responsible for the change. These mechanisms are more closely represented by the other three behavioural implications referenced, namely pupil’s engagement, mood and motivation, and health and wellbeing. The diagram in Figure 2.7 represents an interpretation of how these two categories of behavioural implications may be related.

underlying behavioural implications

Learning Environment

Engagement

Mood & Motivation

Well-being & Health

Attainment

Attendance

Figure 2.7 Diagram of the five environment’s effects on pupils (Higgins et al., 2005).

The input variable in the diagram is (a feature) the physical learning environment. The output variables are the five behavioural changes that can be incited by a change or certain condition of the input variable. These output variables can be split in two categories: (1) the underlying changes in pupil’s engagement, mood and motivation, and health and wellbeing; and (2) the subsequent changes brought about in pupil’s attainment and attendance.

The three underlying behavioural implications, engagement, mood and motivation, and health and wellbeing, appear to be relatively difficult or challenging to study. One reason could be that these are variables typically more qualitative in nature. They also are more context dependant and can be influenced by many more factors than solely the environmental (feature) of interest (Higgins et al., 2005). But to design constructive learning environments that can also be effectively managed, it is critical for the designers of school environments to understand these underlying relations.

This study’s interest is to investigate if (a feature of) the physical learning environment can reduce the occurrence of disruptive pupil behaviours to ultimately better their learning performance. Following Higgins’ categorization, this would entail exploring change in pupil’s engagement and/or mood and motivation brought about by an environmental feature. Changes in either of these two variables may ultimately influence pupil’s attainment. The remaining two variables, well-being and health, and attendance are not directly of interest as these are not related to affect disruptive behaviour. Figure 2.8 provides an illustration of the three behavioural implications of interest in this study.

2.4.3 Three Categories of Environmental Features

This section outlines what features of the learning environment already have been found capable of inflicting change in pupils’ behaviour, mood and performance. Studies by Higgins et al. (2005) and Barrett et al. (2015) have informed this exercise in particular:

underlying behavioural implications

Learning Environment

Engagement

Mood & Motivation

Well-being & Health

Attainment

Attendance

Figure 2.8 Diagram of the specific environment’s effects of interest for this study highlighted.

• Higgins et al. (2005) defines two groups of features. Firstly, the four indoor climate variables light, sound, temperature and air quality, and secondly, three room-design features colour, layout and scale.

• Barrett et al. (2015) documented the impact of six environmental features: the indoor climate variables, space density, room scale, flexibility to re-arrange furniture setup, colour applications and openness/ privacy balance.

Based on these two studies, supplemented by few other studies separately referenced in the text, the environmental features that bring about behavioural implications documented to date are categorized into three groups:

1. Indoor climate features,

2. Temporal features,

3. Architectural features.

These three groups are presented in hierarchical order, indicating their relative capacity for impact. The variables in the first category, indoor climate, are found to have the most profound impact on pupils’ learning and wellbeing, while the impact found for variables in the second and third categories are weaker. For each category examples are provided how architects responded to the respective findings in their school designs to date.

Indoor Climate Features

The set of environmental features found to have the most evident impact on pupils are those referred to as the indoor climate variables – alias the light, sound, temperature and air quality conditions in the learning environment. Researchers exploring their relevance, documented that pupils in learning spaces with

abundant natural light without causing for visual or thermal discomfort, with a high circulation of fresh air, comfortable room temperature, and with good acoustic properties present higher academic performance and increased well-being in general (e.g. Küller & Lindsten, 1992; Heschong, 1999; Wargocki & Wyon, 2007; Tanner, 2009; Shaughnessy et al., 2012; Cheryan et al., 2014; Marchand et al., 2015).

This knowledge inspired architects to explore optimizing building components responsible for attaining and maintaining a supportive indoor climate. Examples hereof are large window surfaces to increase natural light intake combined with deployable shading to prevent for glare or excessive heat, as both a cause for discomfort; a ventilation solution that allows adjusting fresh air circulation, for example to revive sleepy pupils or to eliminate unpleasant smells quickly; or the application of acoustic wall decorations and soft movable furniture to help mitigate the impact of noise. Solutions as these, provided by the architect but managed by the occupant, allow to actively influence pupils’ comfort, behaviour and ultimately, learning performance.

Temporal Features

The category of temporal features refers to elements of the learning environment that can be easily changed or adapted by the teachers and pupils. Most notably, the type and arrangement of seating and desks. Different setups hereof have for example been found to influence the form and level of interactions between pupils. Furniture arranged in small groups was found to encourage collaboration, while single seats or row setups were found to direct a pupil’s attention towards an individual task. The application of desk dividers or partition screens to separate pupils more actively from each other was found to further improve one’s concentration.

Other examples are more of decorative nature. Putting pupils’ works or achievements on display in the learning space has been found to act as a motivator and provoke pro-learning behaviour. The choice of dominant colours in the learning space was found to affect pupils’ behaviour and mood. Significant use of the colour red for instance was found to rouse agitation, while blue was found to ease or unwind pupil’s mood (e.g. Gifford, 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008; Tanner, 2009; Cheryan et al, 2014).

Most of these are examples (except permanent colouring of walls or furniture) of environmental features that teachers can relatively easily change or re-arrange in their learning space to coordinate with the activity, curricular theme or season at hand. These features were found to affect predominantly pupils’ state-of-mind and (social) behaviours and are believed to influence pupils’ overall learning performance.

The architectural features of the learning environment concern permanent elements, incorporated in the design of a learning space by the architect, and were found to affect pupils’ behaviour more indirectly. Examples of architectural choices that could affect behaviour are open versus closed spaces or fixed versus deployable separation walls. While fixed boundaries limit the teacher’s ability to rearrange furniture, movable boundaries allow a space to open up for more arrangement opportunities. And expanding and connecting spaces allows greater freedom to rearrange pupils throughout the learning space. Similarly, the amount of space the architects allocate per pupil defines the range for teachers to move pupils apart. Less space per pupil means less opportunity to vary seating arrangements or levels of privacy (e.g. Gifford, 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008; Tanner, 2009).

Choices towards architectural features as described cannot be (easily) adapted when a building is finished and generally define a teacher’s allowances permanently. Herewith these affect pupils learning long-term.

The Impact of Adequate versus Inadequate Features

Higgins et al. (2005) concluded their review with the notion that the effects of environmental features on pupils’ learning appear most evident when it concerns inadequate environmental features such as loud noise, poor lighting and crowdedness due to lack of space, while positive effects appeared much harder to distil per feature with some degree of unanimity. Higgins provides two reasons for this apparent limitation. The first reason, he states, is that most study’s conclusions tend to be rooted in a particular context. Specific findings from one environment only are difficult to translate, or generalize, to others (see also section 2.4.1). The second reason is that most of the reviewed studies become rather inconclusive when the overall design of the studied learning environment reaches a reasonable standard of quality. If there is not a single environmental factor that performs very poorly, the complexity of environmental interactions comes into play as outlined in section 2.4.1, obscuring cause and effect relations of the various factors.

Nevertheless, researchers exploring person-environment relationships in educational settings have started to uncover how pupils’ behaviour and learning is modulated by the physical environment, as designed by architects and treated by teachers. Advancing our knowledge about these person-environment relations provides a prospect for those designers proactively seeking to help teachers reduce disruptive behaviours from occurring and improve quietness during class with help of features in their learning environments.

The 2014 reform of the Folkeskole has an impact on how school buildings are to be used, and thus designed. This impact has been unpacked in the first section based on three focus points of the reform relevant for architects: (point 1) the need for a more varied school day, (point 3) the need to alternate educational activities with more movement, and (point 13) the need to reduce disturbances including noise during class so that pupils maintain a state of concentration. These demands however imply an inherent friction between the need for more varied activities and the need for a calmer learning environment that is devoid of disturbances, which appear to be largely caused by pupils themselves. This friction in particular has impacted the teachers’ management load notably. To assist teachers in this challenge, the goal for this research became to investigate how architects can capacitate teachers to effectively manage their environments in the post-reform Folkeskole.

A field study has been undertaken to uncover the practical implementation of these reform points thus far in three new and refurbished school buildings. From these observations, it appeared architects integrated several solutions to cater for point 1 and 3, but seemingly dealt with point 13 only by mitigating the impact of noise through sound absorbing measures. Addressing the dominant cause of noise, the pupils themselves, appears left out in their approach thus far. The same accounts for other pupil behaviours identified to cause for distractions. Traditionally, managing pupil behaviours is done through classroom management techniques, which predominantly rely on interactions between teachers and pupils. However, if the environment were to assist in managing disruptive behaviours, calmness may be achieved more effectively.

Literature was consulted on what is already known about these occupant-environment relationships. It appears some environmental features, and particularly inadequate ones, have been found capable to influence pupils in various ways, for example their performance, engagement, behaviour, mood, motivation and health. The type of features found to have such capacity most evidently are the indoor climate variables light, sound, temperature and air quality.

Supported by these findings, this study looks to investigate whether the physical learning environment, or a feature thereof, could become one of the tools at the disposal of teachers to manage disruptive pupil behaviours. Lesser occurrences of disturbances will improve the quality of the learning environment in general, and in particular support pupils to maintain their attention on their learning tasks – ultimately benefitting their learning performance. The following chapter argues that one of the features of the learning environment capable to act as such a tool, is the artificial lighting.