By: Keila Bara

While Godard’s critique of patriarchal capitalism ultimately reproduces it by fusing his characters’ sexual and economic power, Varda effectively plays into the misogyny under capitalism to then skew the narrative and point out the misogyny she pretends to follow at first.

The Female Body As The Ultimate Fetishized Commodity Under Capitalism

un film de AGNÈS VARDA

un film de

JEAN-LUC GODARD

laura lauramulvey mulvey

“woman stands in patriarchal culture as signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his phantasies and obsessions through linguistic command by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning” (Mulvey 834)

Mulvey’s idea of the male gaze refers to the objectification of women in film, specifically visually by the camera’s lens, due largely to the fact that men dominate the film industry and the industry operates under patriarchal capitalism.

“the female figure poses a deeper problem…her lack of a penis [implies] a threat of castration and hence unpleasure” (Mulvey 840). She goes on to explain the ways in which men react to this castration anxiety, the relevant one to this argument being the “complete disavowal of castration by the substitution of a fetish object or turning the represented figure itself into a fetish so that it becomes reassuring rather than dangerous” (Mulvey 840).

“Marx’s analysis of commodities as the elementary form of capitalist wealth can thus be understood as an interpretation of the status of woman in so-called patriarchal societies” (Irigaray 192)

LUCE IRIGARAY LUCE IRIGARAY

Irigaray describes mimesis as the process of “[converting] a form of subordination into an affirmation, and thus [beginning] to thwart it” (Irigaray 76). As Irigaray theorizes, “to play with mimesis is thus, for a woman, to try to rediscover the place of her exploitation by discourse, without allowing herself to be simply reduced to it” (Irigaray 76). She goes on to explain that by mimesis, she means women are to “resubmit herself…to ‘ideas,’ in particular to ideas about herself, that are elaborated in/by a masculine logic, but so as to make ‘visible,’ by an effect of playful repetition, what was supposed to remain invisible” (Irigaray 76).

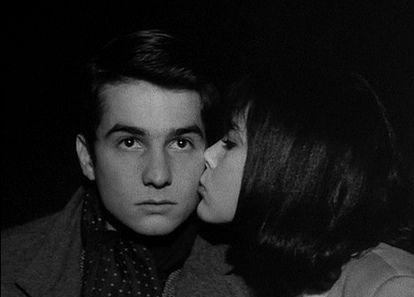

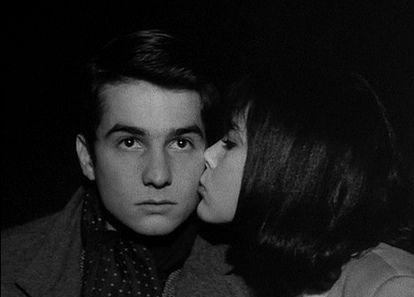

Godard shoots the scene through the male gaze due to the fact that we do not look at anything but Elsa’s face the entire time. Also, Elsa leans against a window, her figure in between the two window frames.

MISS 19

This window literally frames her the entire time; the camera never cuts from this and she never moves her position. The audience has no choice but to only look at Elsa the entire time.

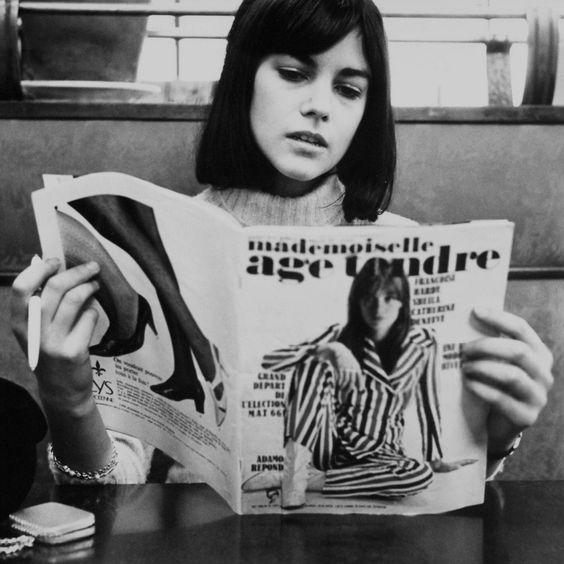

Fifty eight minutes into Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 film Masculin féminin, Godard introduces the intertitle “DIALOGUE WITH A CONSUMER PRODUCT”. In the six-minute scene that follows, the protagonist Paul interviews a woman named Elsa (also known as Miss 19) who recently won a beauty contest hosted by a commercial magazine. With her new status, she receives perks such as a nice car, and she basks in the consumer items she receives for no cost simply because she won this shallow contest. Though Godard attempts a satirical approach to condemning capitalism through labeling Elsa as a “consumer product”, this title ultimately objectifies her further. In this scene, he critiques the way she turns her body into a fetishized commodity while also fetishizing the commodities around her and reaping the benefits of the broken capitalist system.

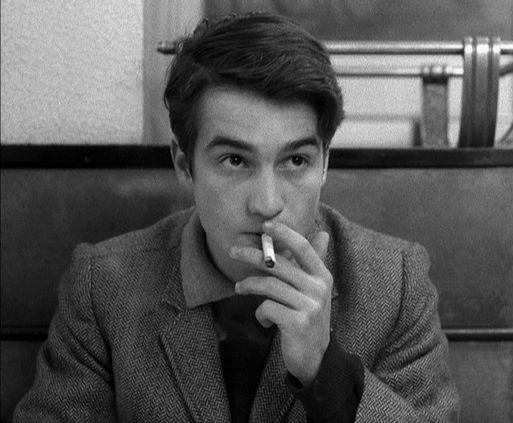

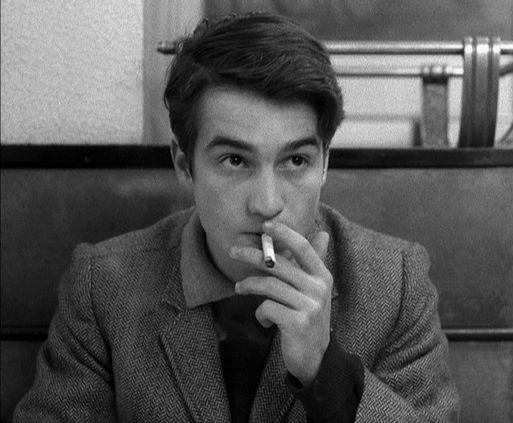

During an early conversation between Paul and Madeleine, Paul flirts as Madeleine combs her hair in a mirror. The use of mirrors is a notable example of a way in which the male gaze visually manifests itself, as the female figure is literally replicated through the image of their reflection.

The castration anxiety a female character’s operating under the male gaze is Paul’s example of a man

During this conversation, we see Madeleine applying lipstick in a compact mirror; Godard portrays her as someone far more interested in herself and her appearance than Paul’s attention.

MADELEINE MADELEINE

Masculin féminin opens with Paul writing in a cafe, looking up immediately entranced by her beauty, and he watches her look mirror after she sits down at a nearby table. Madeleine is objectified

character’s presence invokes in films Paul’s reality, as Paul is the perfect man emasculated.

MADELEINE MADELEINE

Godard’s decision to make Madeleine a pop singer content with the repetitive, uncreative songs her producers tell her to sing shows that he uses Madeleine, the female character, as an outlet for his critiques of capitalist society. This makes for an ineffective critique of patriarchal capitalism – Godard critiques capitalism at the expense of a female character and fails to provide Madeleine with any depth that would help him properly carry out mimesis and make his argument more effective. up to see Madeleine enter. He is look at her reflection in a compact objectified immediately by Paul’s gaze.

While Paul prefers classical music, Madeleine works as a pop singer; this serves as a point of contention in their relationship. Paul clearly sees her music, and all mainstream pop music, as distasteful, but his pretentious comments do not change the fact that Madeleine finds success and operates as a successful capitalist while Paul does not.

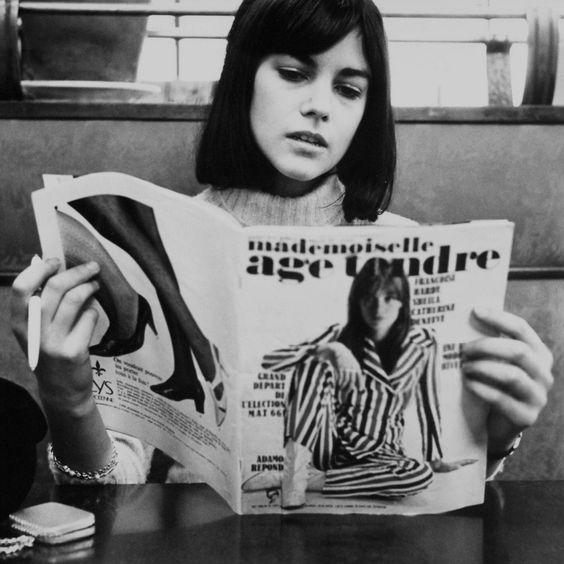

The film opens with Cléo’s tarot reader stating the lines: “A young lover influenced your career…as a result, you met a kind and generous man. He made your artistic career possible.” Already, Varda pokes fun at the patriarchal idea that women can only find success in their career through the help of men.

cléo and mirrors - the male gaze visualized

Cléo ends up going into a hat shop, relaxed by her reflection in the many mirrors throughout the store as she tries on the various hats...The hats Cléo tries on are ridiculous and do not fit her head right for they are so small, and she can barely see her reflection in the tiny mirrors. Yet, she still finds comfort in her reflection, finding these hats stylish because purchasing and wearing them will further turn her into an object desired by the male gaze.

Just as Madeleine is wrapped up in her own vanity, as expressed by her admiring her reflection in a compact mirror, Cléo is drawn to the mirror outside the tarot reader’s office and stops to admire herself. She then utters a line that encapsulates her mindset and shallowness perfectly: “Wait, pretty butterfly. Ugliness is a kind of death. As long as I’m beautiful, I’m even more alive than the rest.”

However, Cléo undergoes a shift halfway through the film. Fed up by the way her lover, music producer, and songwriter (all of whom are men) treat her, she snaps at her producer and songwriter and goes out into Paris on her own. This pivotal moment in the narrative demonstrates where Varda and Godard diverge – with this scene, Varda allows her female character to undergo a change and become a subject, which is an arc Godard does not allow Madeleine to experience.

With this, she switches from playing into these men’s demands to resisting them, yelling, “You make me this way, treating me like an idiot or a china doll! A revolution with macabre words! You tire me! You exploit me! Go away!” At this moment, Cléo realizes these men are exploiting her, and she does not want to comply any longer. Up to this point she enjoyed her pop star status and found joy in people recognizing her (take the woman in the hat store asking for a photo and the taxi driver playing her song, for example). The fusion of her economic and sexual success did not bother her, and she did not care that she was being exploited for she was ultimately benefiting from the system through her fame. However, finally acknowledging the exploitation she experiences by the men in charge of her career, she refuses to comply any longer. This strays from Madeleine’s attitude toward her own career in Godard’s film, for she always remains content with her exploitation, fusing her sexual and economic power to continue to succeed.

Before, she was merely an object of other people’s gaze, prohibiting her from being able to see the world around her because she was preoccupied with the idea of being seen. With her newfound subjecthood, she possesses her own gaze. Her Parisian neighborhood has been transformed in her eyes; “the city street thus becomes a new structuring presence that enables her and those around her to participate in an alternative model of spectatorship not defined by a strict subject/object dichotomy” (Mouton 9).

“a woman who goes from being seen to being able to see”

Both Godard and Varda acknowledge Irigaray’s idea that women exist as commodities under capitalism, however only Varda succeeds at her mimetic attempt to critique this idea, while Godard merely reproduces the misogyny through the objectification of his female characters.

Though Godard was critical of Hollywood, he still created work that was just like it in his misogynistic portrayal of women and tendency to operate under the male gaze. In contrast, Varda’s work serves as the true counterpoint to mainstream cinema’s tendency to reinforce patriarchal capitalism; she succeeds at her mockery of Hollywood’s commodification of women and ultimately creates both a politically and aesthetically avant-garde film.