K. W. Bridges & Nancy Furumoto

K. W. Bridges & Nancy Furumoto

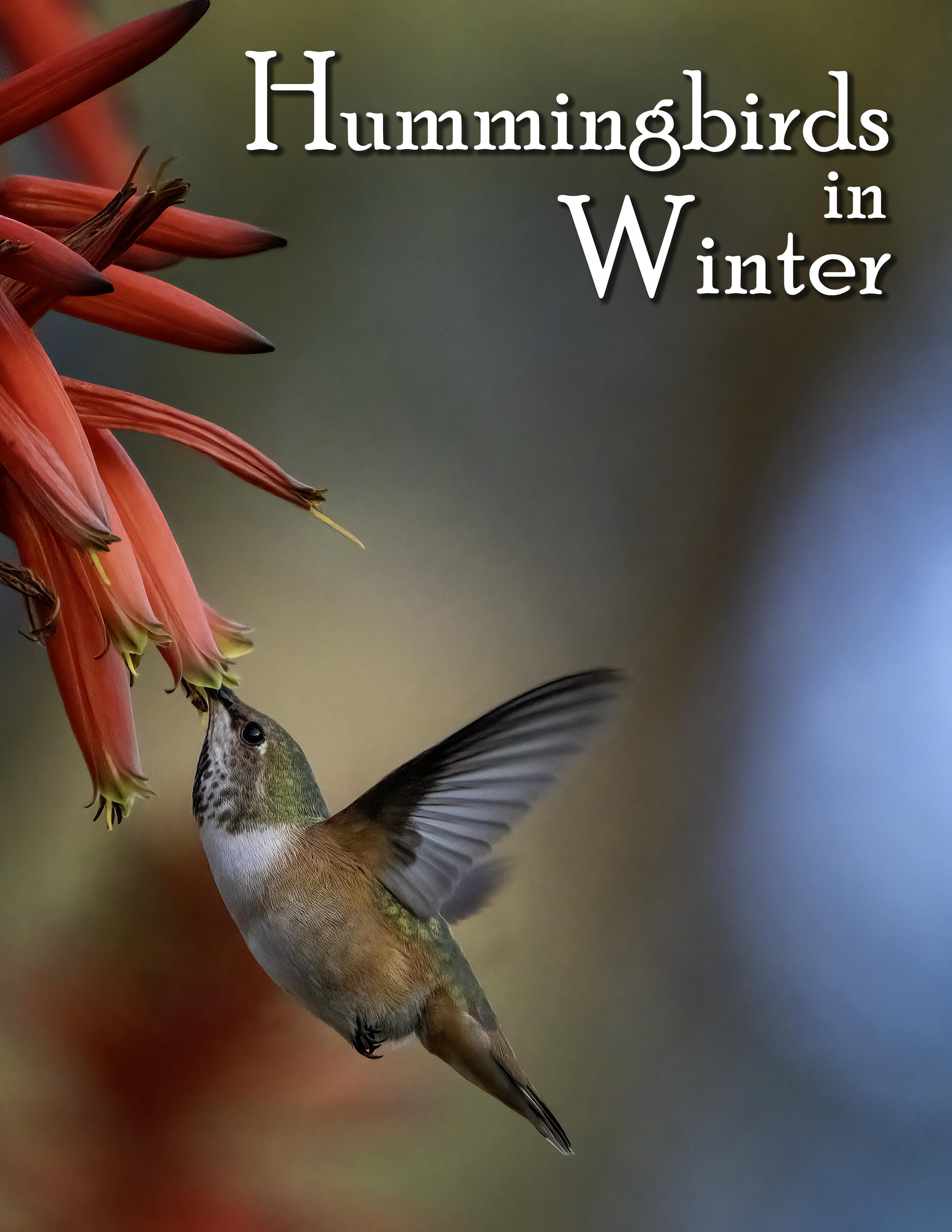

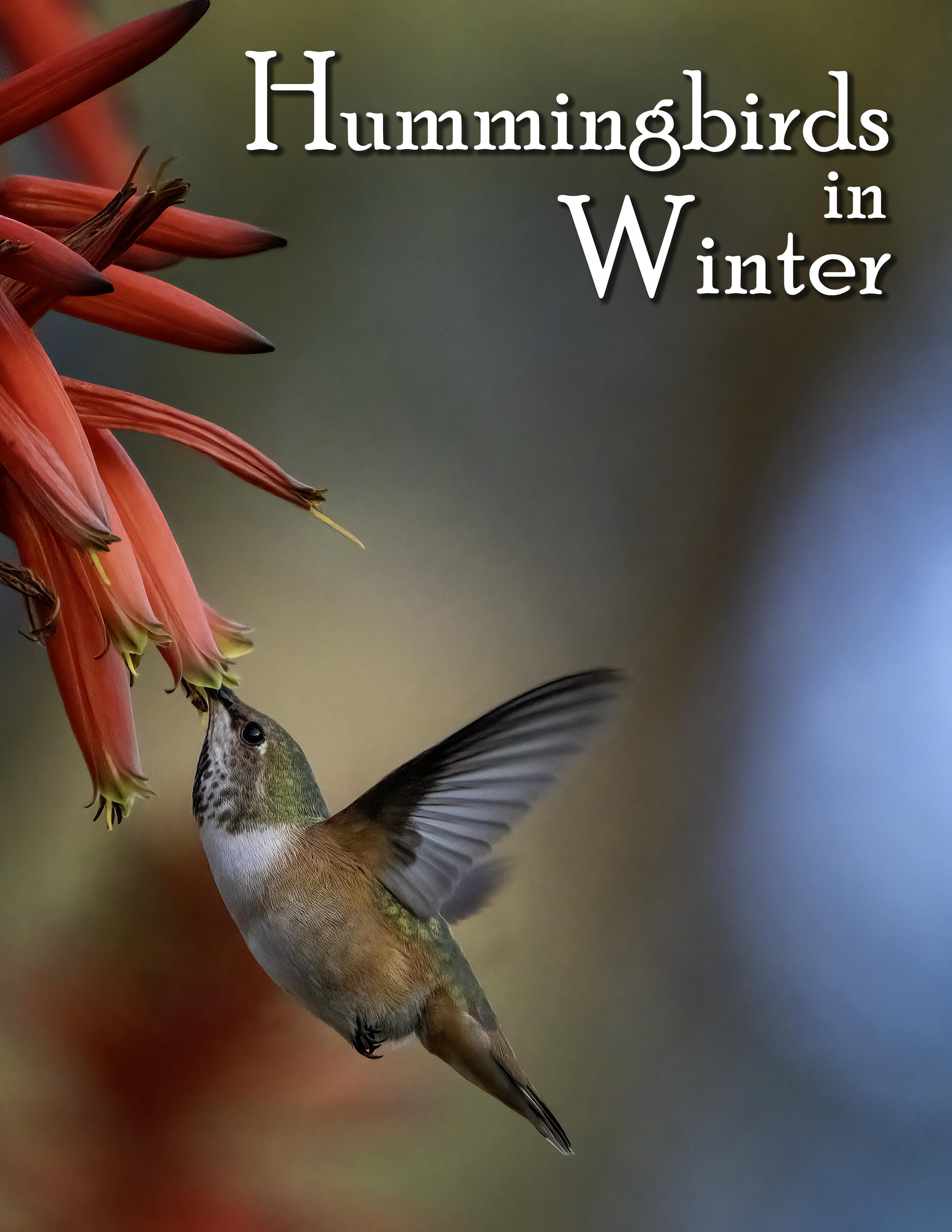

Most of Southern California hummingbirds seasonally migrate, seeking an environment with abundant food resources. A few stay behind and brave the winter months. These are mostly the coastal Allen’s Hummingbirds.

We went bird hunting in January, visiting four excellent botanical gardens: The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, Descanso Gardens, Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden and the South Coast Botanic Garden.

The results of our search for hummingbirds were mixed. Huntington with its massive collection of winter-flowering cactus provided many good opportunities to see the birds. Descanso was the most challenging as there were few food plants to attract the birds. LA Arboretum and South Coast fell somewhere in between, each with enough encounters to make the visit worthwhile.

It’s worth noting that these gardens are a treat in any season, offering far more than just hummingbird watching. Their diverse flora and landscapes provide year-round beauty and many treats for nature enthusiasts.

We’ve organized our photographic captures into three categories: Sitting, Flying, and Feeding, showcasing the varied behaviors of these fascinating animals.

Technical Notes: All photography was done with a Sony Alpha 7R V camera using a Sony EF 100-400 mm f/4.5-5.6 GM OSS lens. Either a Sony FE 1.4x or 2.0x teleconverter was used. With these combinations, the images were taken at either 560 or 800 mm. With only one exception, the shutter speed was 1/1250 seconds. All photographs were taken between January 23 and 27, 2024.

Hummingbirds spend a significant proportion of their time sitting, utilizing plants in their territorial boundaries as observational posts for potential intruders. This sedentary behavior serves a dual purpose: energy conservation and physiological recuperation. The metabolic and structural demands of sustained flight require periods of reduced activity. Perching allows a decrease in metabolic rate and allows for muscle relaxation and recovery. Additionally, this is a time for preening, a crucial maintenance behavior that restores feather integrity. Well maintained feathers contribute to efficient flight. Proper feather arrangement enhances the insulative properties of the plumage, helping to keep the bird warm.

Photographers often enjoy capturing images of perched hummingbirds, as this allows for precise focusing and exposure adjustments. While multiple shots may yield similar results, subtle changes in the bird’s posture or lighting can significantly enhance the image, particularly in showcasing the vibrant iridescence of the gorget.

If you have a long lens, you’re more likely to get the photo you want. Birds sitting on distant perches are the rule, not the exception.

These are the images where it is easier to anthropomorphize the hummingbird’s behavior. But feather ruffling or other postures are natural responses to the environment, not necessarily indicative of the bird’s awareness or reaction to the photographer’s presence.

Hummingbirds exhibit an extraordinary wing-beat frequency, generating a characteristic figure-8 pattern that is imperceptible to the naked eye. Some species achieve rates of 80 to 90 beats per second. This rapid oscillation creates air currents that help the bird to maneuver with remarkable precision, including upward, forward, backward, and hovering flight.

The hummingbird’s capacity for sustained hovering is particularly striking, allowing it to explore flowers for nectar from many directions. This slow maneuvering can be instantaneously replaced by explosive bursts of speed, propelling the bird to a new feeding site or distant perch. This stark contrast between deliberate hovering and rapid transit exemplifies the avian acrobatics characteristic of this group.

Photographing birds in flight presents several technical hurdles. Capturing the bird’s body in sharp focus while allowing some blur in the wings to convey a sense of motion is a common goal. Gathering enough light to enable a fast shutter speed to freeze the motion of the wings generally requires an expensive, high-quality telephoto lens with a wide maximum aperture. This isn’t necessary as some degree of motion blur in the wings can enhance the dynamic feel of the image.

Photographers should anticipate working at the extremes of the exposure triangle - balancing shutter speed, aperture, and ISO sensitivity. High ISO settings may be necessary to attain sufficiently fast shutter speeds, potentially resulting in increased image noise. Post-processing photos with noise reduction software is often essential to improve image quality.

Hummingbirds’ visits to flowers for nectar extraction are well-documented, but this interaction serves a dual purpose. From the plant’s perspective, these avian visitors act as crucial pollen vectors, facilitating cross-pollination. This relationship exemplifies biological mutualism, defined as “an interaction between two or more species that confers reciprocal benefits.” This symbiotic association has been a significant driver of coevolution in both hummingbirds and their preferred floral species.

Natural selection has refined the adaptations of both parties to optimize this mutualistic relationship. Hummingbirds have developed specialized bill shapes and lengths to access nectar from specific flower morphologies, while plants have evolved flower structures and nectar compositions tailored to their avian pollinators.

It’s important to note that nectar isn’t the sole nutritional benefit hummingbirds derive from their floral visits. These birds require protein in their diet, which they obtain primarily by eating small arthropods. Insects and spiders can constitute up to 80% of a hummingbird’s daily nutritional intake. However, the capture of these prey items is rarely observed directly.

An intriguing hypothesis suggests that hummingbirds may opportunistically feed on small insects captured within the flowers during nectar extraction. This behavior, if confirmed, would add another layer to the complexity of hummingbird-flower interactions. However, external photographic evidence is unlikely to provide conclusive proof of this feeding strategy.

Bird photographers generally reject “butt shots.” That’s unfortunate as some of the most interesting action shots show a hummingbird approaching or feeding at a flower. This is also when you might see the flower dabbing pollen on the bird’s head, providing visual evidence of the mutualistic relationship that underpins this fascinating ecological interaction.