Urbanism & Landscape Studio

Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio KTH Arkitekturskolan, Stockholm 2022

Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio KTH Arkitekturskolan, Stockholm 2022

Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio KTH Arkitekturskolan, Stockholm 2022

Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio KTH Arkitekturskolan, Stockholm 2022

RESEARCH (P1)

MEET THE STUDIO

INVITED PARTICIPANTS INTRODUCTION FOUR PRINCIPLES GENERAL STRATEGY P1: RESEARCH AND NARRATIVES

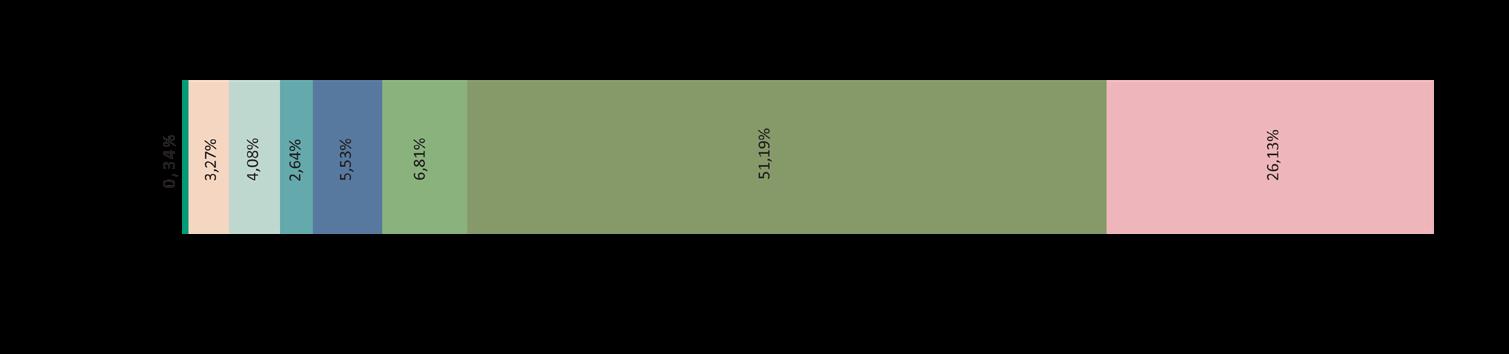

LEGAL INFRASTRUCTURE BLUE INFRASTRUCTURE GREEN INFRASTRUCTUREEARTH, SOIL, FOOD GREEN INFRASTRUCTUREVEGETATION, FOREST

PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE

LIVING CONDITIONS + LIFESTYLE

URBAN ECONOMY

4 6 8 20 24 26 28 36 44 52 60 68 76

P2: A COLLECTIVE STRATEGY

KYMLINGEPARKEN - SOONER AND LATER WEAVING WATERWAYS RETHINKING THE RESERVE LIVING WITH WATER BRIDGING THE BOUNDARIES INTERWEAVING WITH GREEN WORTHMORE

Madeleine Atterhem

Hadi Botoros

Jingkai Chen

Eugénie Deruaz

Agnes Ekbom Aldrin

Lycke Förell

Bingcen Guo

Marcus Johansson

Elizaveta Khamitova

Helena Lecocq

Elina Lejerbäck

Ylva Nissen

Nicole Oliveira

Alhawraa Salman

Beatrice Selander

Wiktoriina Alexandra Setälä

Yifan Su

Çlirimtare Syla

Yves Albert Rico Turmel

Adam Varga

Chiara Vicuna Narvaez

Sébastien Wegmüller

Mandong Zhu

Hanna Erixon Aalto

Francesca Savio

Tor Lindstrand, Architect at Larsson Lindstrand Palme Arkitektkontor and Associate Professor at Konstfack

Andrew Merrie, Research Liaison Officer at Stockholm Resilience Centre and Head of Futures at Planethon

Sherif Zakhour, PhD and Sustainability Specialist at White Arkitekter

Sara Borgström, Associate Professor at KTH

Daniel Koch, Researcher and Docent at KTH

Jonas Torsvall, architect and partner at 2BK Architecture

Francesca Savio, architect and lecturer at KTH

Hanna Erixon Aalto, PhD researcher and lecturer at KTH

Jaime Montes, architect and lecturer at KTH

Nina-Marie Lister, Professor at the School of Urban and Regional Planning, Toronto Metropolitan University

Maria Gregorio, studio lead and urban designer at Warm in the Winter

Anna Sundman, architect and founder at Theory Into Practice

Suzete Tumba Pihl, architect and urban designer at Archus

Jaime Montes, architect and lecturer at KTH

Anders Mårsen, professor at SLU and landscape architect at Landskapslaget

Sara Brolund Fernandes De Carvalho , architect and lecturer at KTH

Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, architect and PhD at KTH

Nina-Marie Lister, Professor at the School of Urban and Regional Planning, Toronto Metropolitan University

Eveliina Hafvenstein Säteri, architect and planning strategist at Stockholms city

Ania Öst, architect and lecturer at KTH

Anders Tranberg, Naturskyddsföreningen

Petter Kvarnbäck, Marketing and Communications manager from Vasakronan

Anna-Maria Larsson, Expert in Green Wedges, Ekologigruppen

Anna Barr, Stockholm University Department of Ecology

Jonas Jernberg, architect/planner expert on urban farming Urbanworks

Ulrika Egerö, ecologist and planning strategist at Stockholm City

Elisabeth Mårell, Regional planner fokus Green Wedges, Länsstyrelsen

Eveliina Hafvenstein Säteri, architect and planning strategist at Stockholms city

Örjan Hultén, Järva Folkets Park

Erik Stenberg, architect and Associate Professor KTH

Anton Botoros, Akalla Native

Amir Sebdani, project manager at BLING

Erik Andersson, Professor and ecologist at the Stockholm Resilience Center and Helsinfors University

Rebecka Milestad, agronomist, doctor in rural development and docent in environmental strategies research at KTH

Kerstin “Piglet” Wikström, Husby konsthall

Anders Berg, city architect Järfalla kommun

Örjan Hultén, Järva Folkets Park

Venue: KTH Library

Address: Osquars backe 31

Date: 16/12/22 - 17/01/23

The Urbanism and Landscape Studio focuses on cities, landscapes and territories in the broader context of the environmental crisis. How can we imagine a sustainable and resilient twenty-first century city? What can designers’ role be in addressing urgent and interconnected problems such as rapid urbanization, biodiversity loss, social inequity and severe global climate changes affecting our cities? This book presents analytical studies and projections made by 23 students from the Urbanism and Landscape Studio at KTH School of Architecture.

In the fall of 2022, the studio has investigated how the Green Wedges of Stockholm can be a catalyst for new resilient urban environments. We have zoomed in on the Järva area, a site that exemplifies a contested planning situation in which the seemingly incompatible endeavors of protecting and maintaining green and open spaces are set against the will of creating a polycentric, dense and more connected urban fabric. The studio aims at challenging this polemic praxis through the exploration of alternative city/nature relationships.

The Urbanism and Landscape Studio focuses on cities, landscapes and territories in the broader context of the environmental crisis. How can we imagine a sustainable and resilient twenty-first century city? What can designers’ role be in addressing urgent and interconnected problems such as rapid urbanization, biodiversity loss, social inequity and severe global climate changes affecting our cities?

Drawing on the nexus of ideas within landscape/ecological urbanism, resilience theory, and the environmental humanities, the studio challenges the modernist idea of the city as a fixed, delimited territory contrasting the ‘natural’ world around us. Instead, we explore landscape and ecology as organizers of urban space; as providers of catalytic urban strategies that can embrace complexity and multi-functionality and change over time.

Stockholm is growing rapidly. This brings with it a number of important challenges, e.g. in building new housing and public infrastructures, as well as strengthening resilience toward climate change and biodiversity loss. In this context, balancing urban growth and development interests against the need to safeguard large-scale urban green structures – the Ten Green Wedges of

Stockholm – has become a key issue. Previous urban development strategies expressed aims to keep the green structure as continuous as possible, by “building the city inwards” and creating a more dense urban core. This has, however, recently shifted towards a desire to expand the city outwards, towards the suburbs, creating a denser, polycentric, locally connected urban fabric across the green wedges that may counter social segregation. At present, the will of achieving a contiguous urban fabric is set against the goal of safeguarding vital ecological services and resilience of the large-scale green structure.

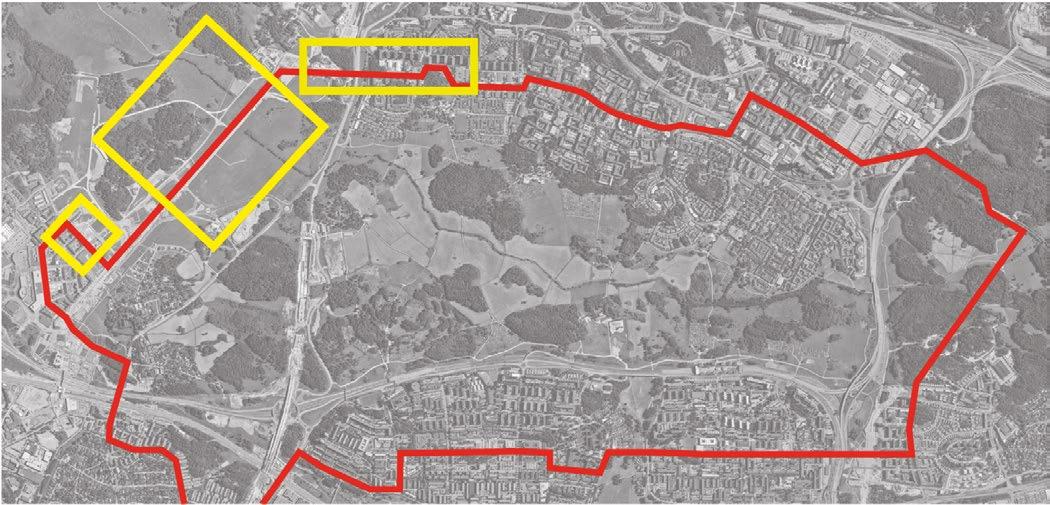

The studio has aimed at challenging this polemic praxis through the exploration of alternative city/nature relationships. How can the Green Wedges of Stockholm be operationalized as a productive, generative landscape that can be a basis for new urban living environments? Must natural values always be sacrificed when the city grows, and, concurrently, must “nature” always be seen as an obstacle to urbanization? We have focused on a suburban section of Järvakilen that includes the municipalities of Järfälla, Stockholm and Sundbyberg. The aim of this studio has been to explore the transformation of existing antagonistic relationships into synergistic ones; they become part of the solution instead of the problem.

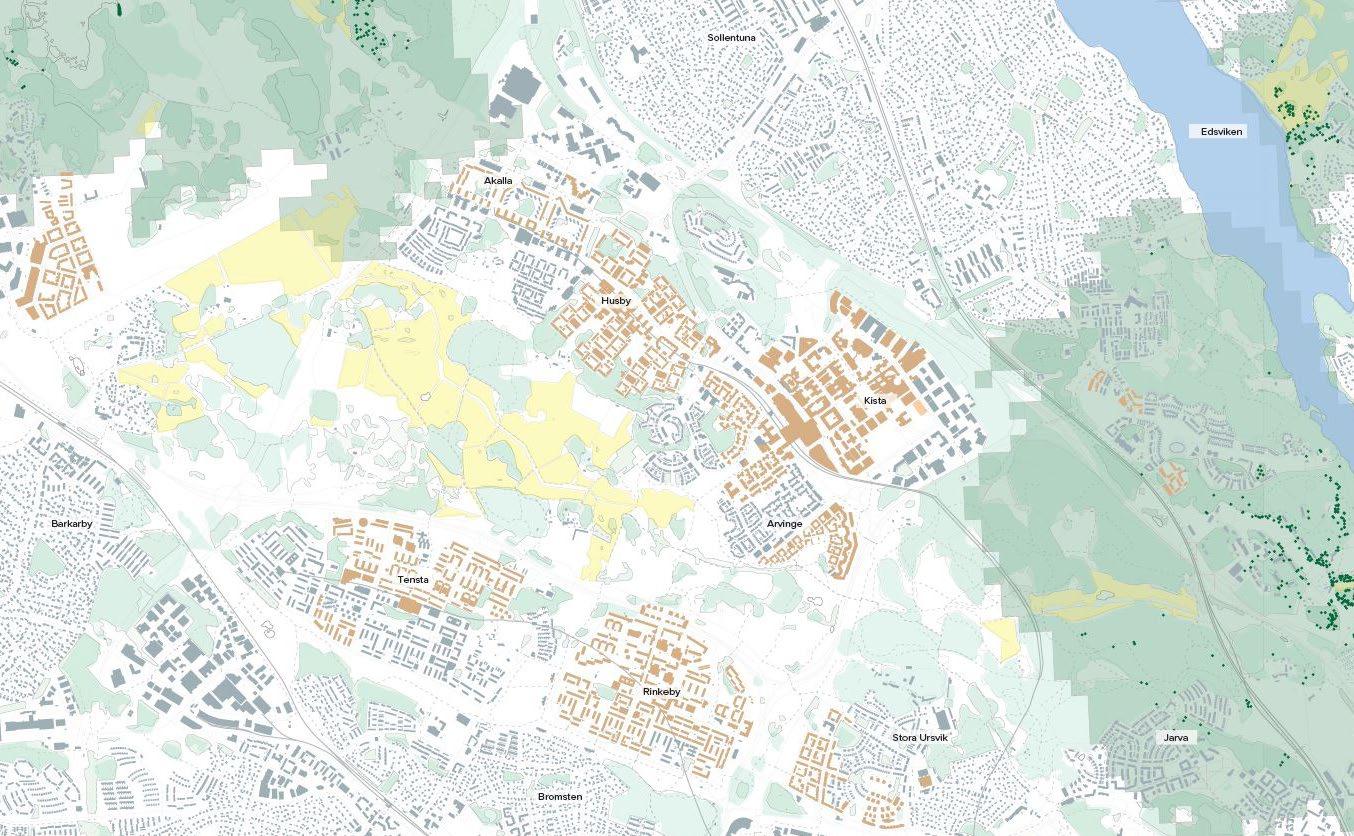

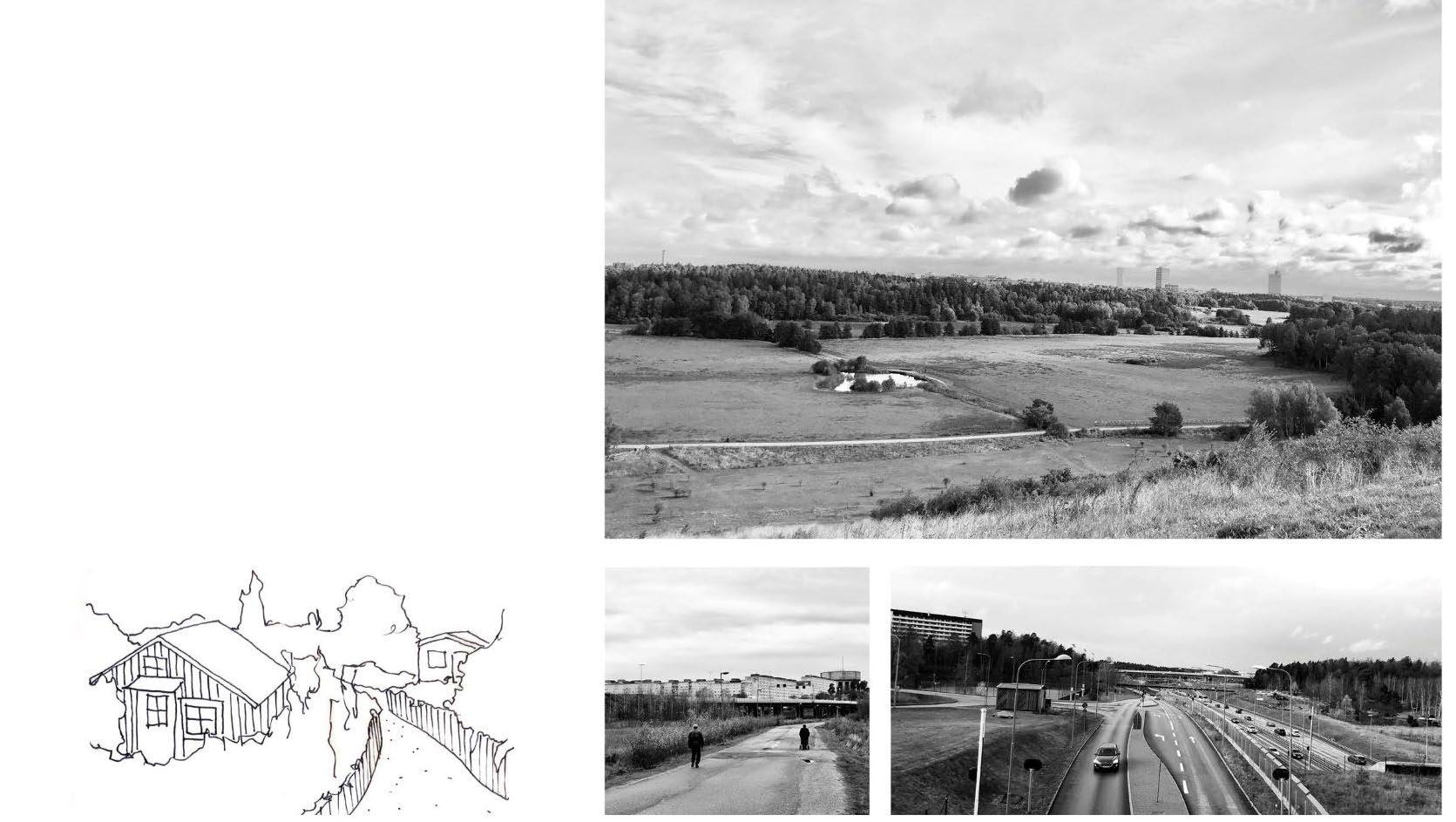

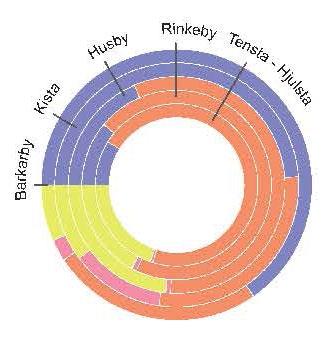

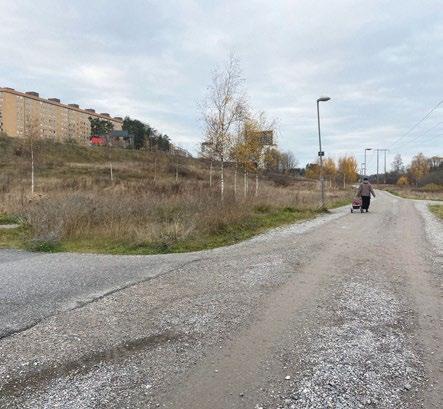

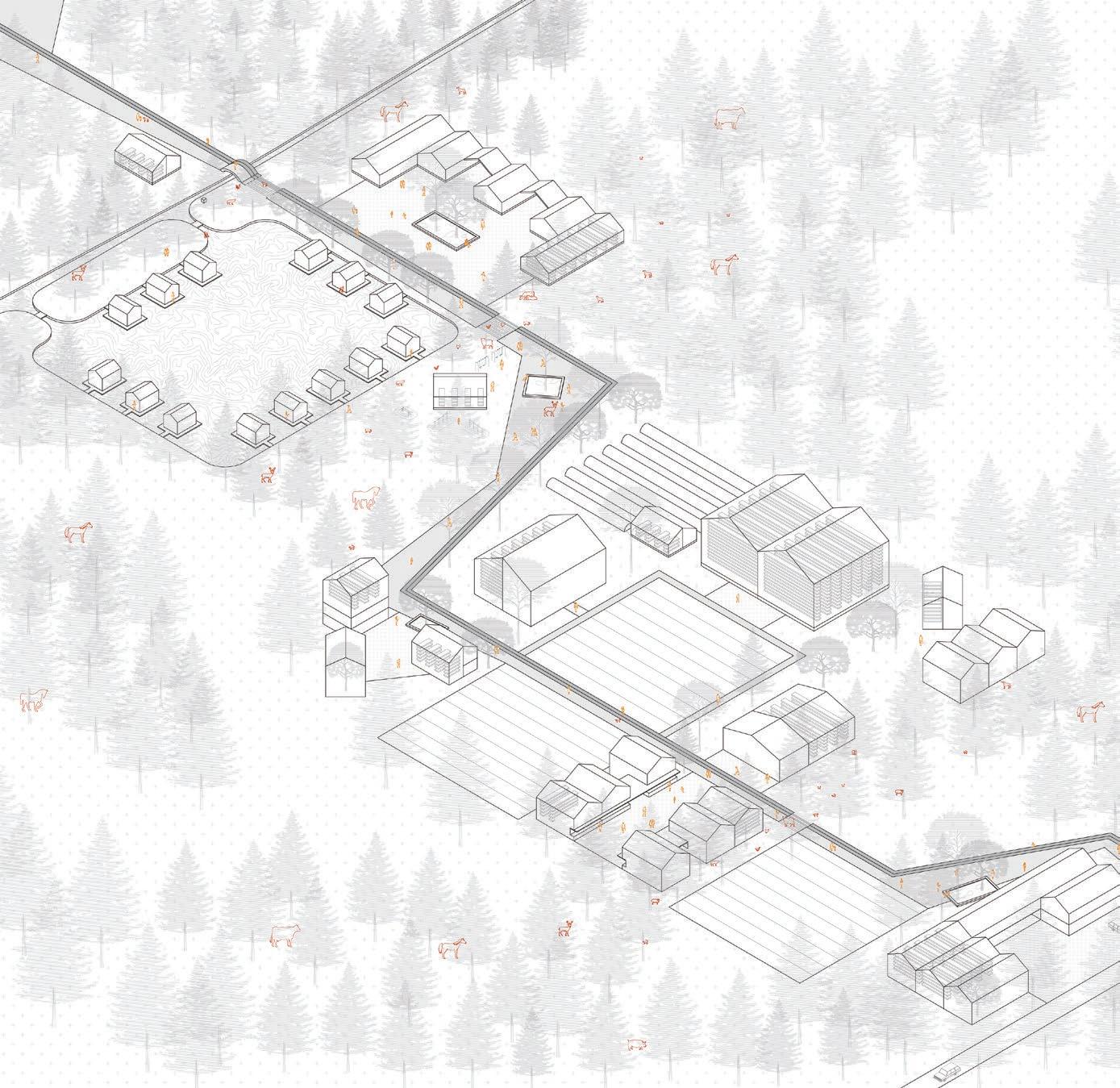

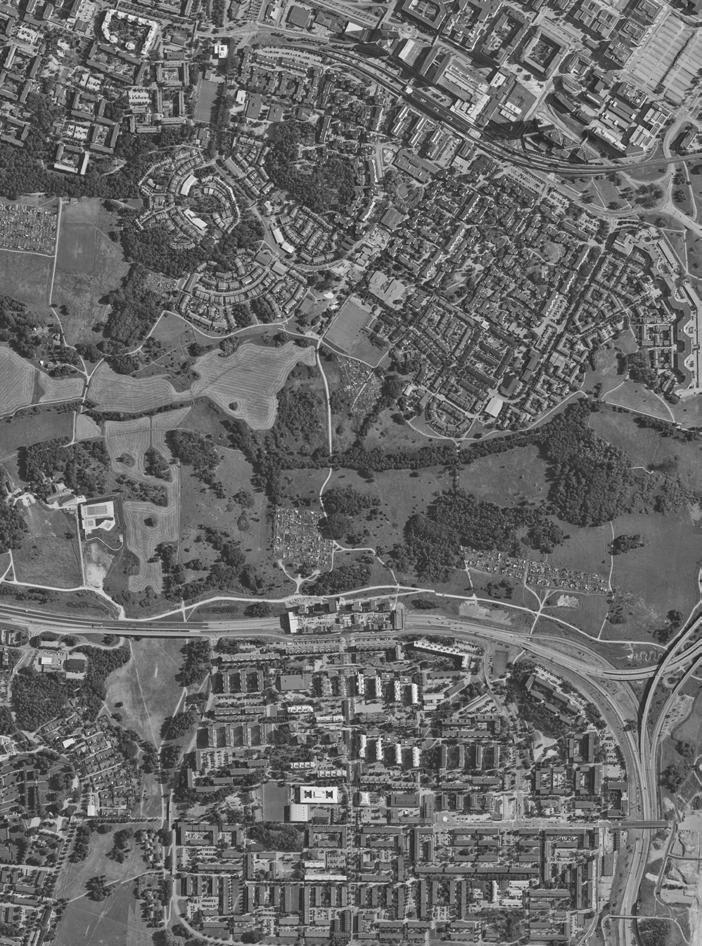

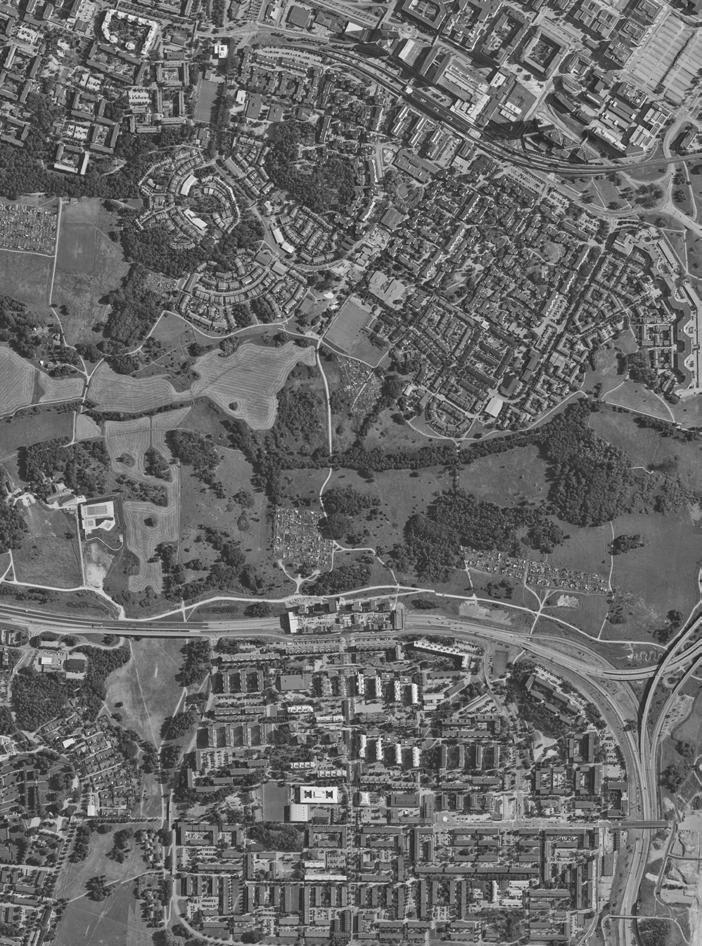

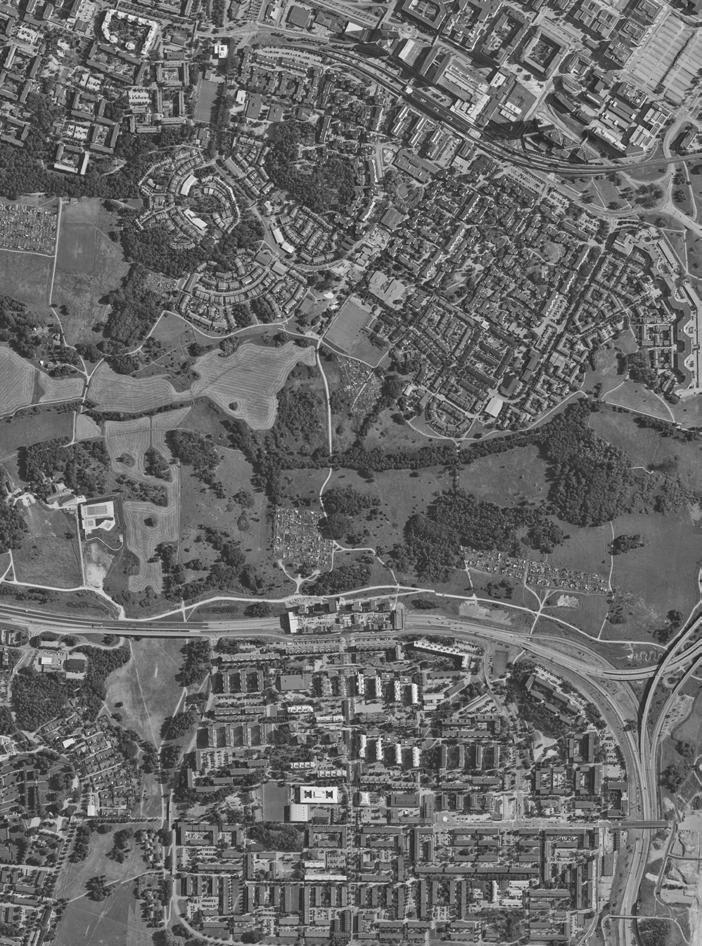

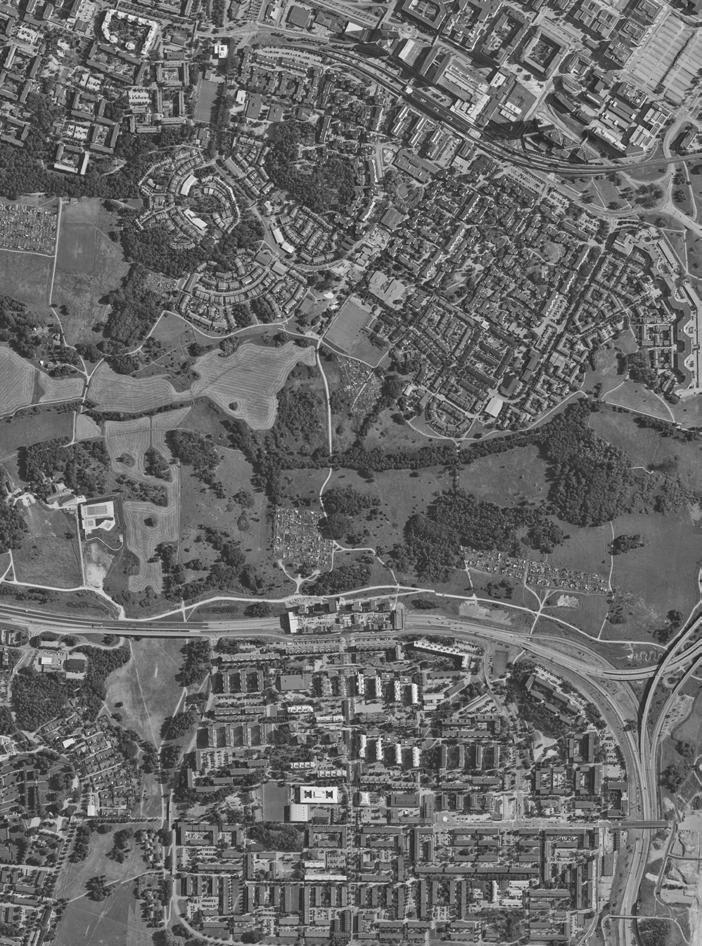

The selected case, the Järva area, is located in the north-western part of Stockholm. The site centers on the Igelbäcken stream and includes a section of the Jäva green wedge and parts of surrounding housing areas that are located to the north and south. These neighborhoods accommodate approximately 60,000 inhabitants (8% of the population of the municipality of Stockholm) and the majority of the land is owned by the municipality and the state. Similar to what is typically found in Swedish cities, the landscape can be characterized as primarily consisting of extensive, cultivated, open areas. About half of the green wedge consists of fields and grazed meadows, which are partly dedicated to active, small-scale agricultural land uses, and partly constitute abandoned and overgrown former agricultural areas. The elevated parts of the landscape support groves of deciduous forests and patches of coniferous forests, and in some lower parts, wetlands have been restored.

Middle-class residential areas characterized predominantly by single-family houses are located at the edge of the study area.

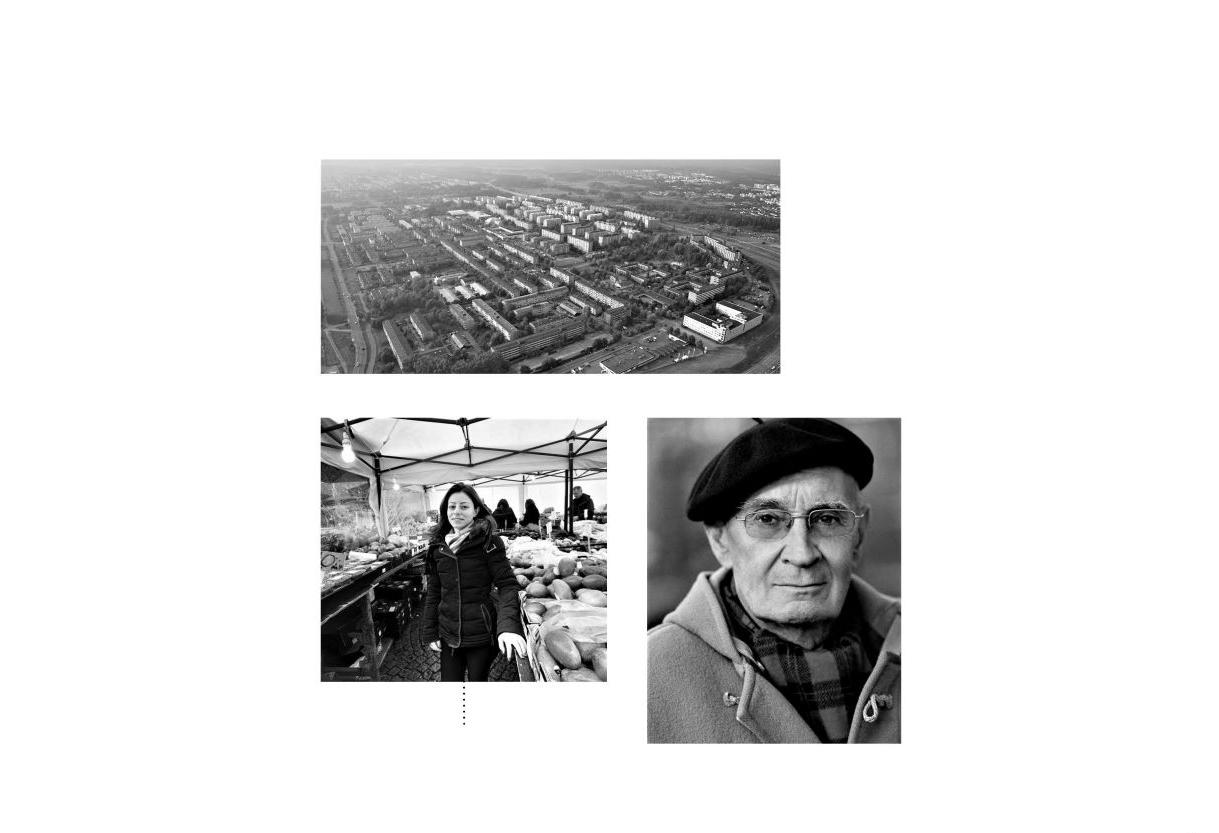

Given these conditions, the study area at large can be said to exhibit socioeconomic and ethnic diversity, but the individual neighborhoods are rather homogenous enclaves, separated by roads and green space – a typical pattern in the suburbs of Stockholm.

The main housing areas surrounding the wedge were planned and built in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, in the spirit of modernist “neighborhood units” and in response to the ideals of traffic and functional separation. These areas are today characterized by a very high proportion of population with foreign background and considered among the most socially segregated suburbs of Stockholm.

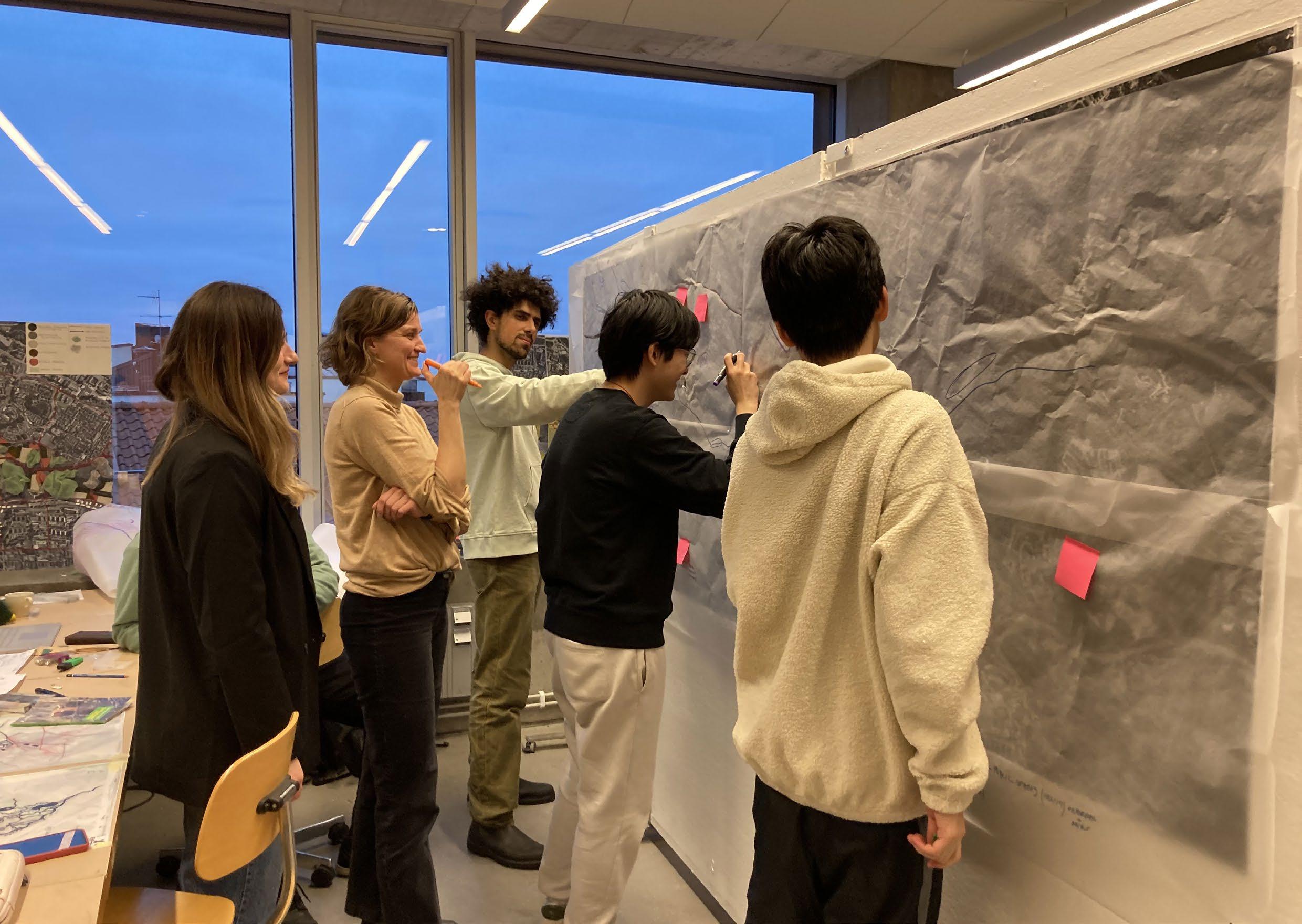

We aim to empower students to develop a critical and systematic outlook to the urban and global problems we face though the study of hands-on, ‘live’ problems grounded in real-world challenges. Urban design is an inclusive, reflective and, by necessity, transdisciplinary practice. The studio supports this by working closely with decision makers, activists, local organizations, and experts. We study international references, learn from invited lecturers, hold literature seminars, perform writing exercises, conduct interviews with relevant actors and arrange expert tutorials and interdisciplinary workshops. Learning from history, we study how the forces of nature, culture and infrastructure have shaped urban life. By combining the critical and the suggestive, analysis and innovation, we develop bold scenarios that reframe the relationship between humans and nature. We see outcomes that reveal unexpected potential ranging in scale from the territorial and the neighbourhood, down to the detail of a living environment.

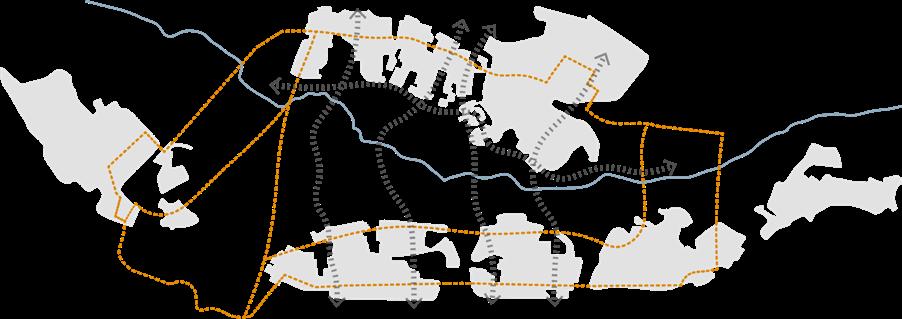

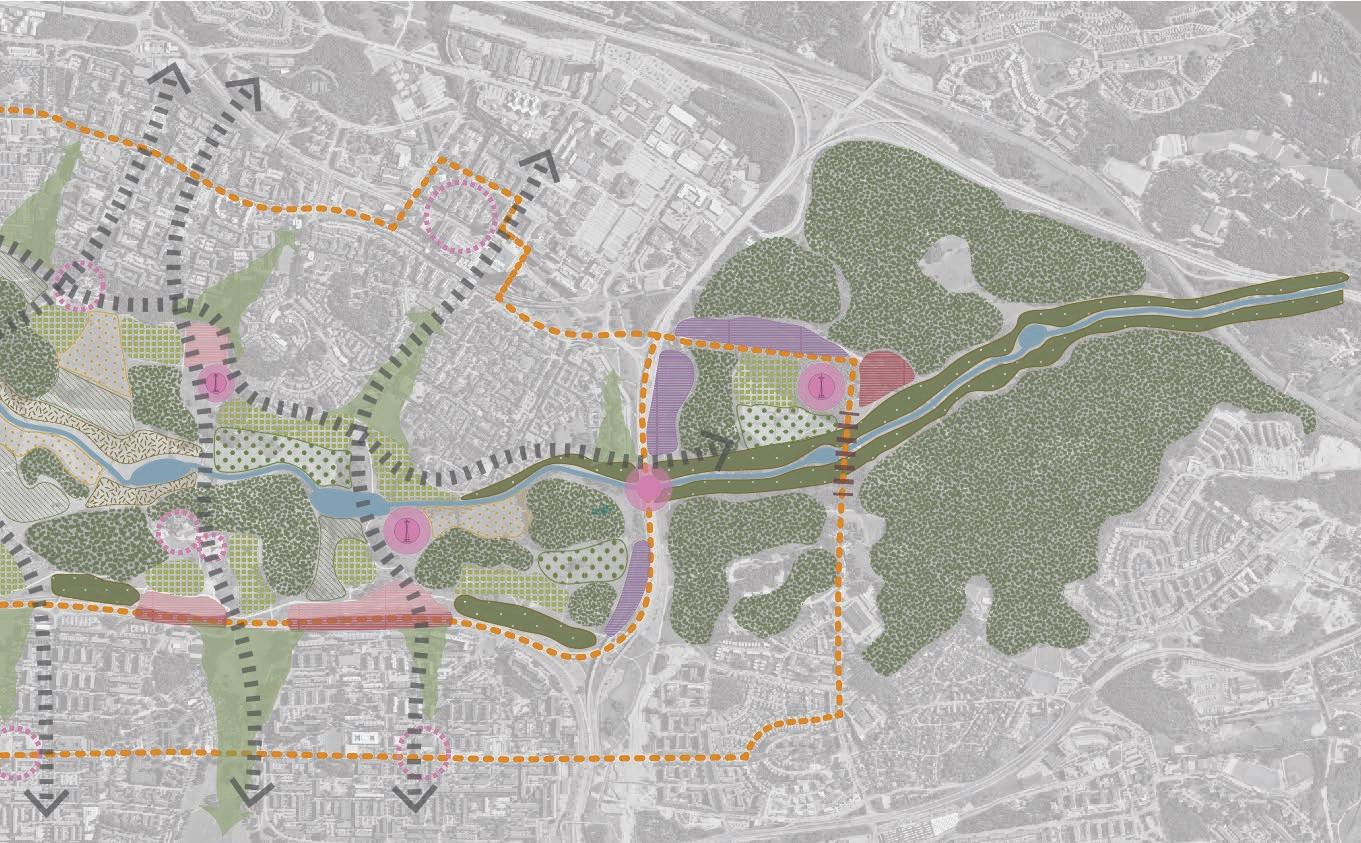

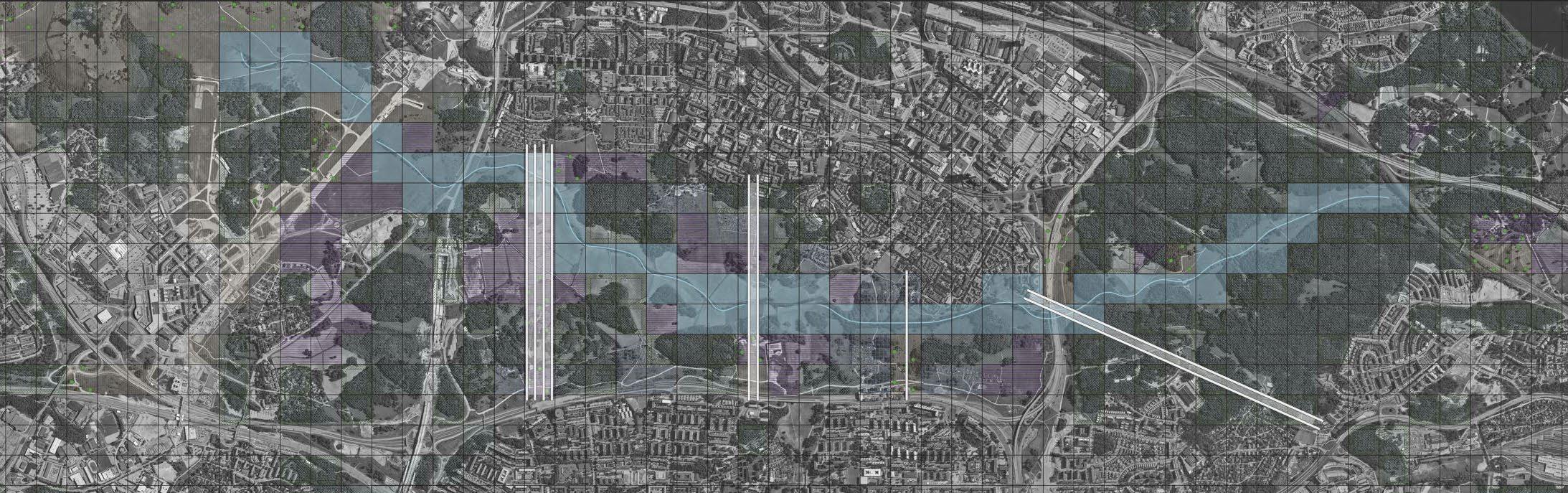

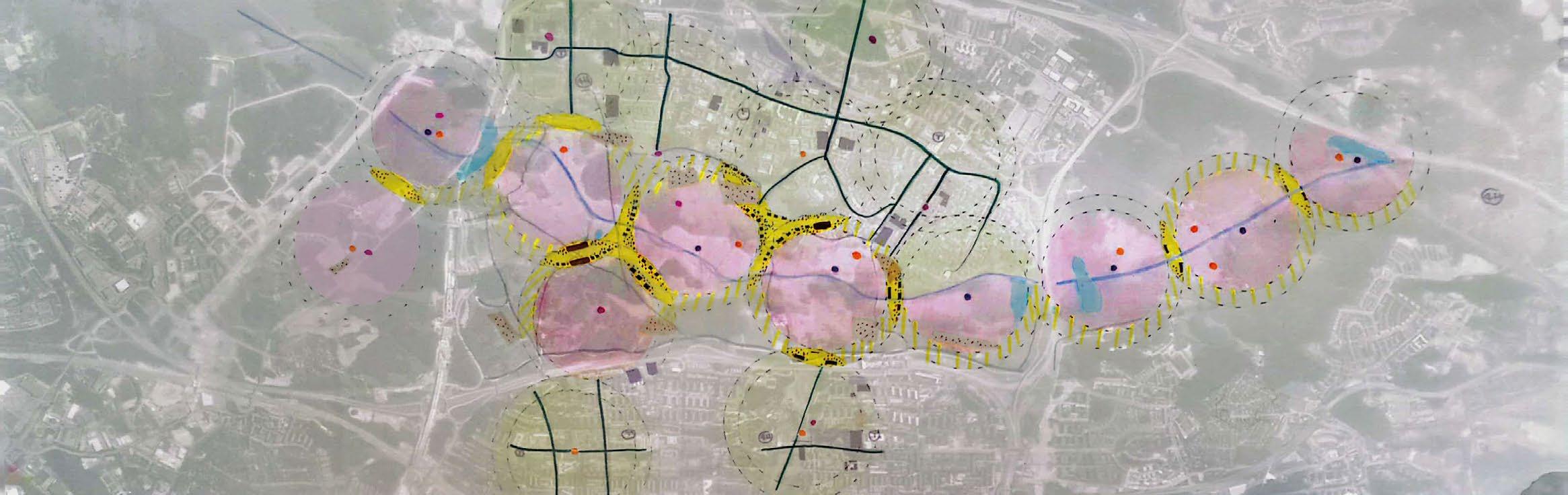

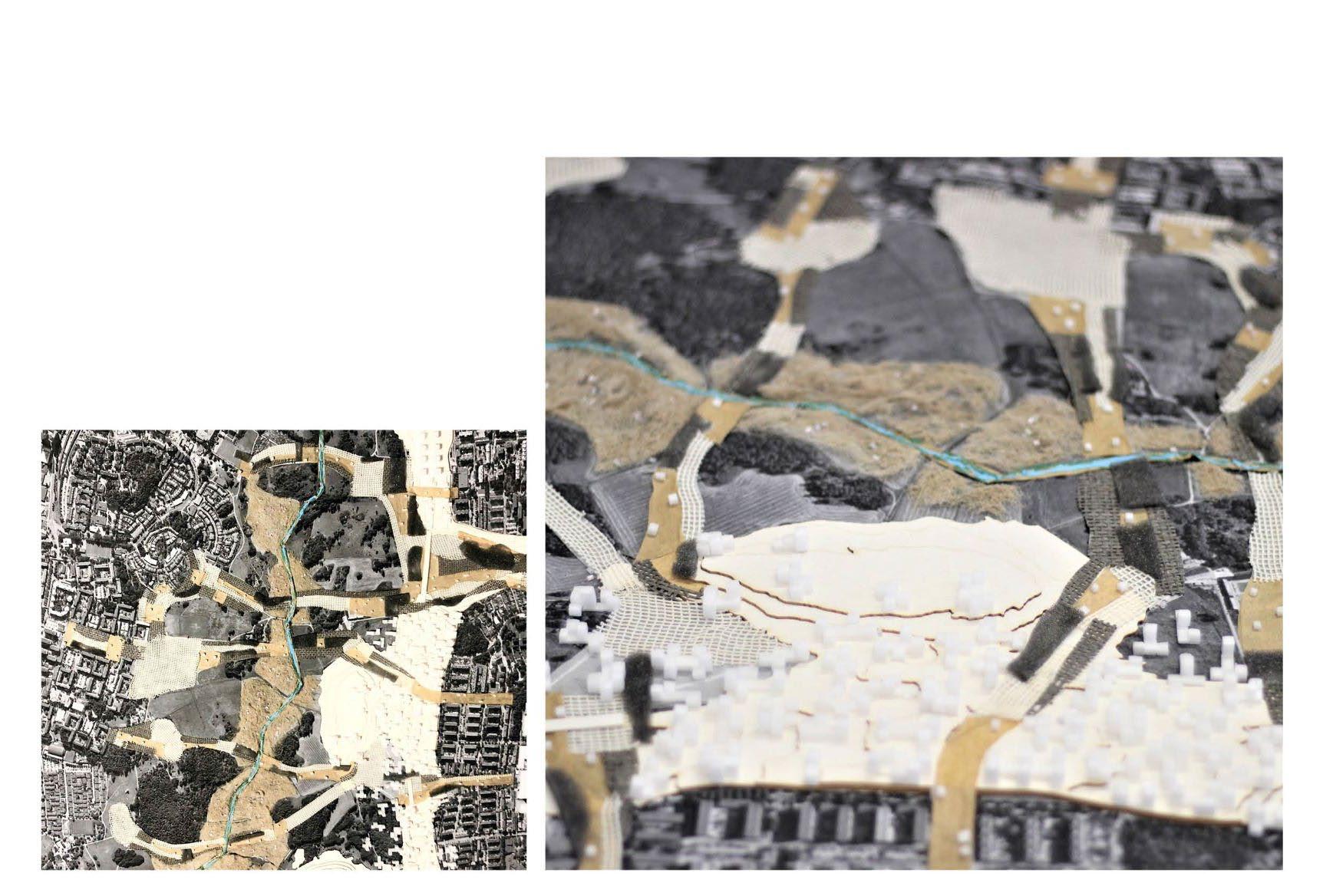

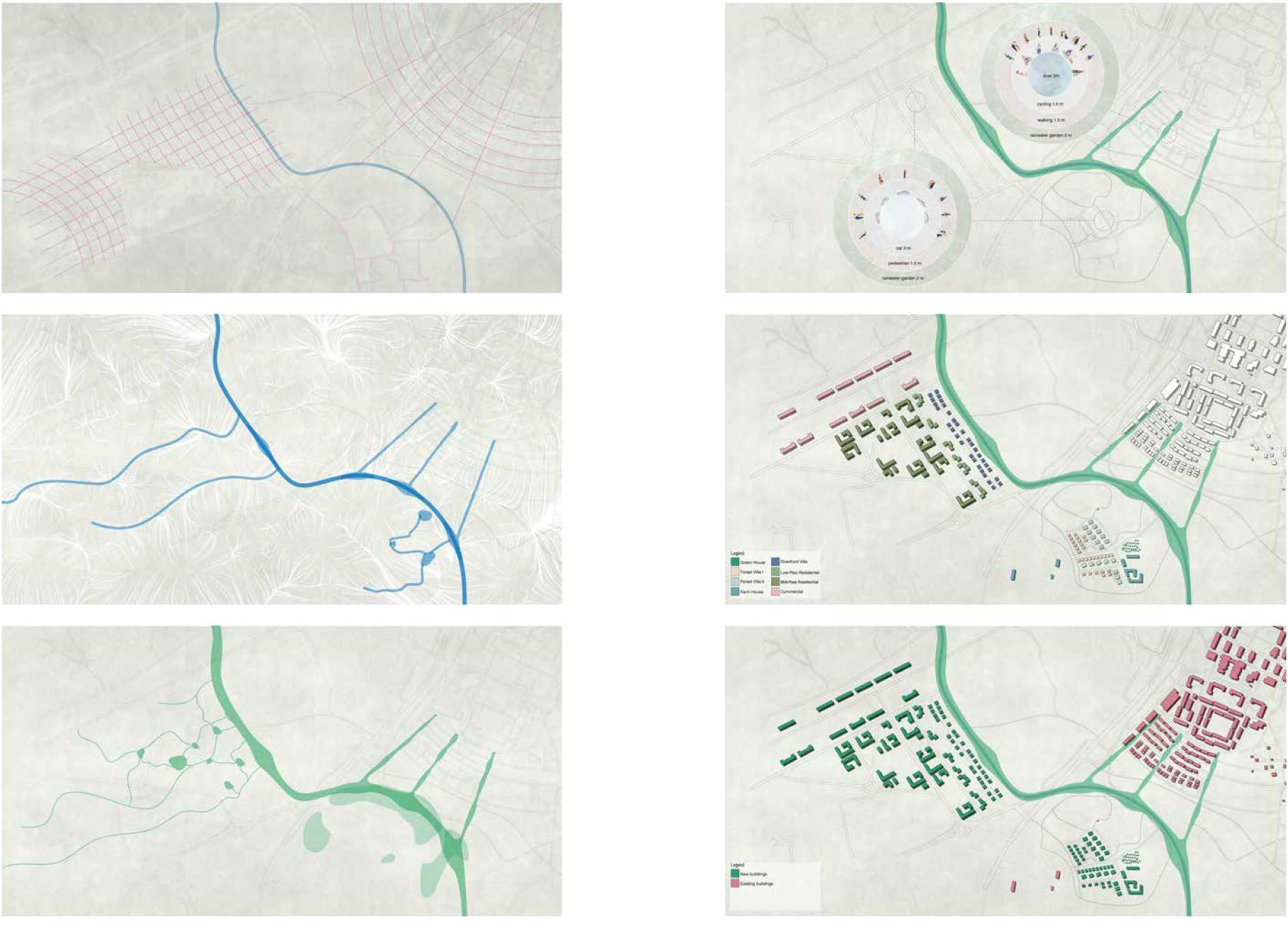

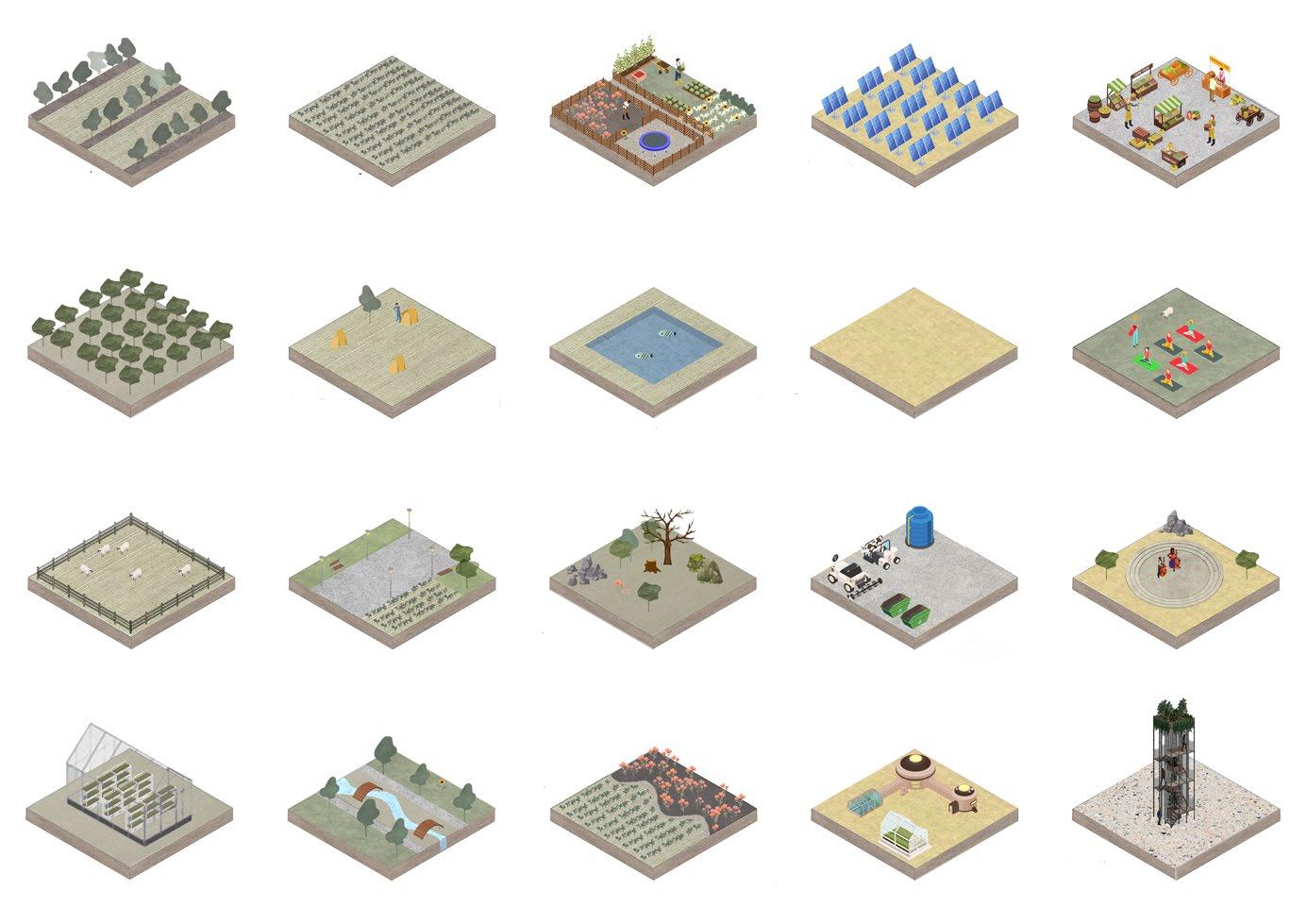

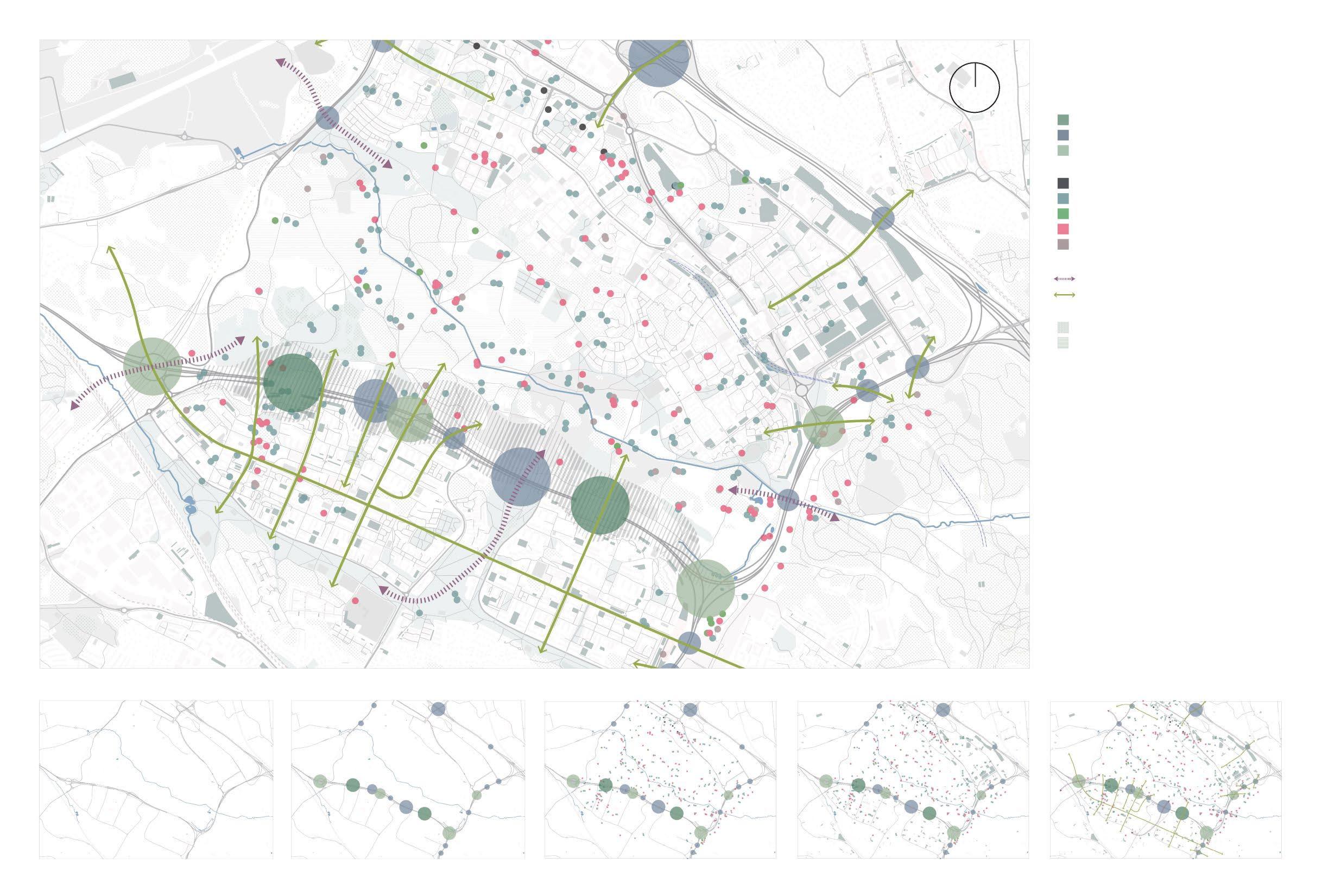

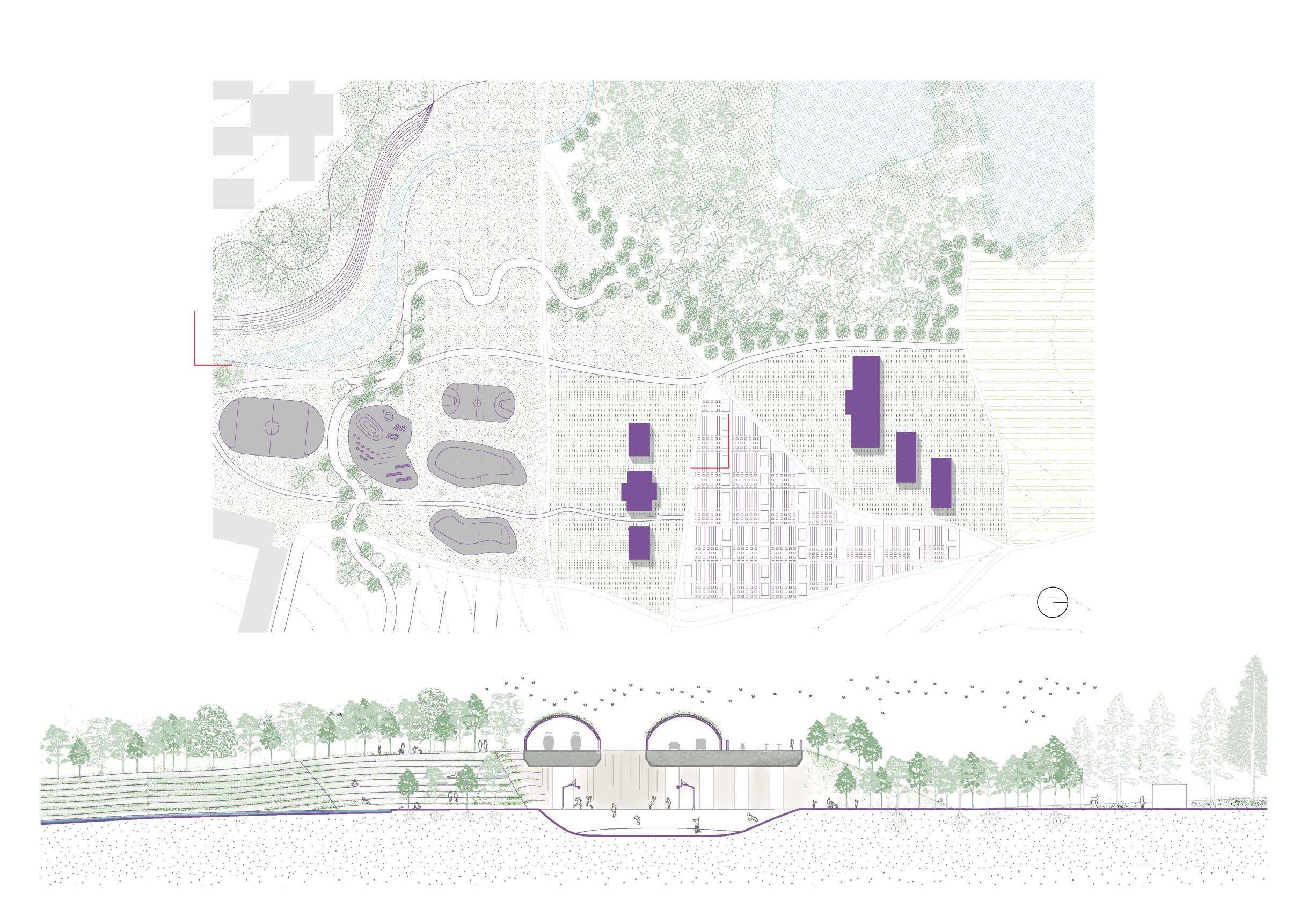

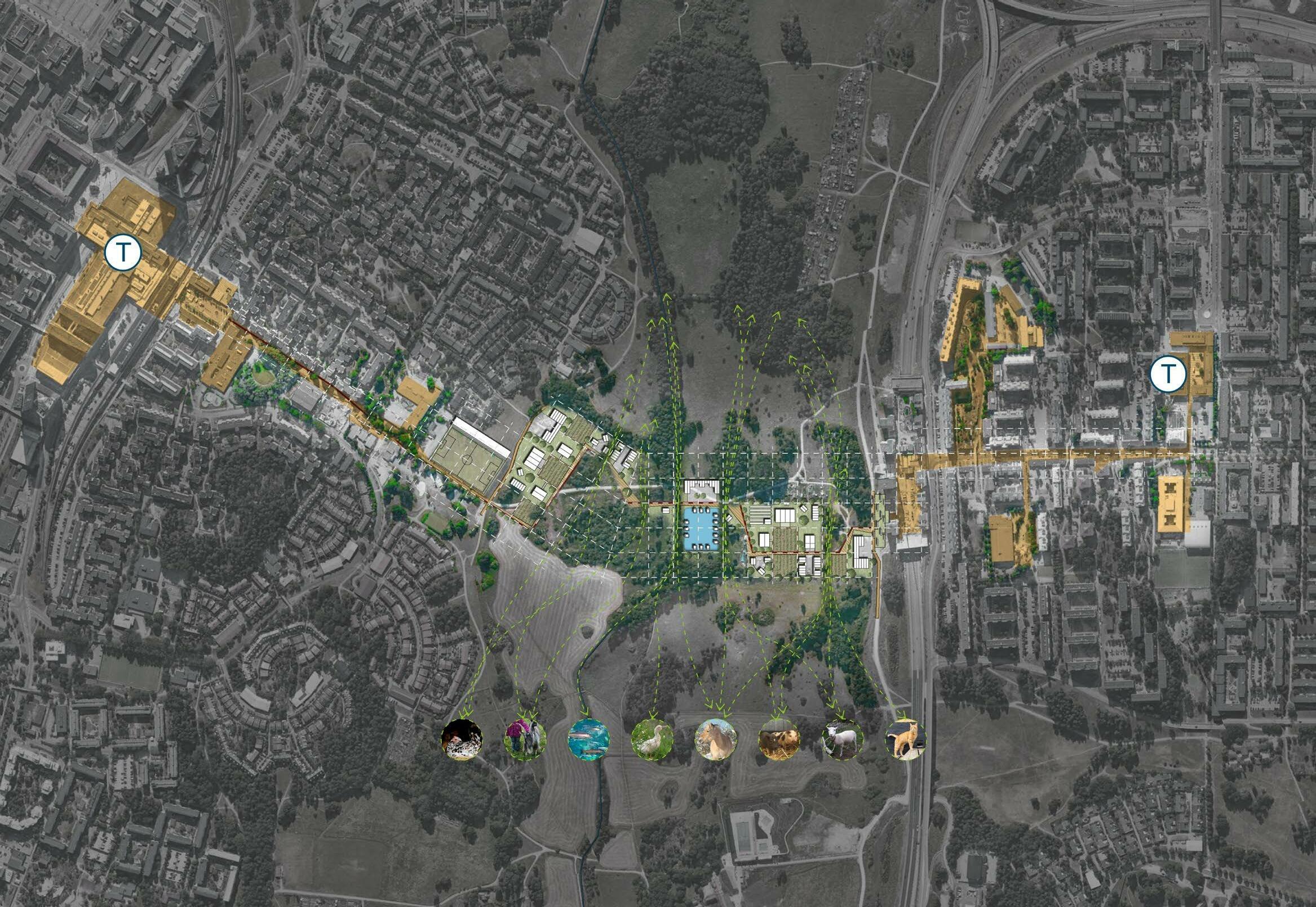

A strategic general plan is developed to establish a holistic view on how the green wedges of Stockholm could be transformed. The map also outlines a set of overarching strategies as well as pointing out the selected sites where the students have developed site specific projections.

A set of maps codifies and illustrates The Jarva Wedge and bring forward various types of boundaries, e.g., political, economic, or physical. The maps also show spatial and statistical relationships that may reflect ecological, physical, social, and economic aspects. We see the maps as subjective abstractions. They can be powerful tools to influence human behavior and decision making. The maps are produced to generate new views on the territory and to bring forward unexpected solutions and effects.

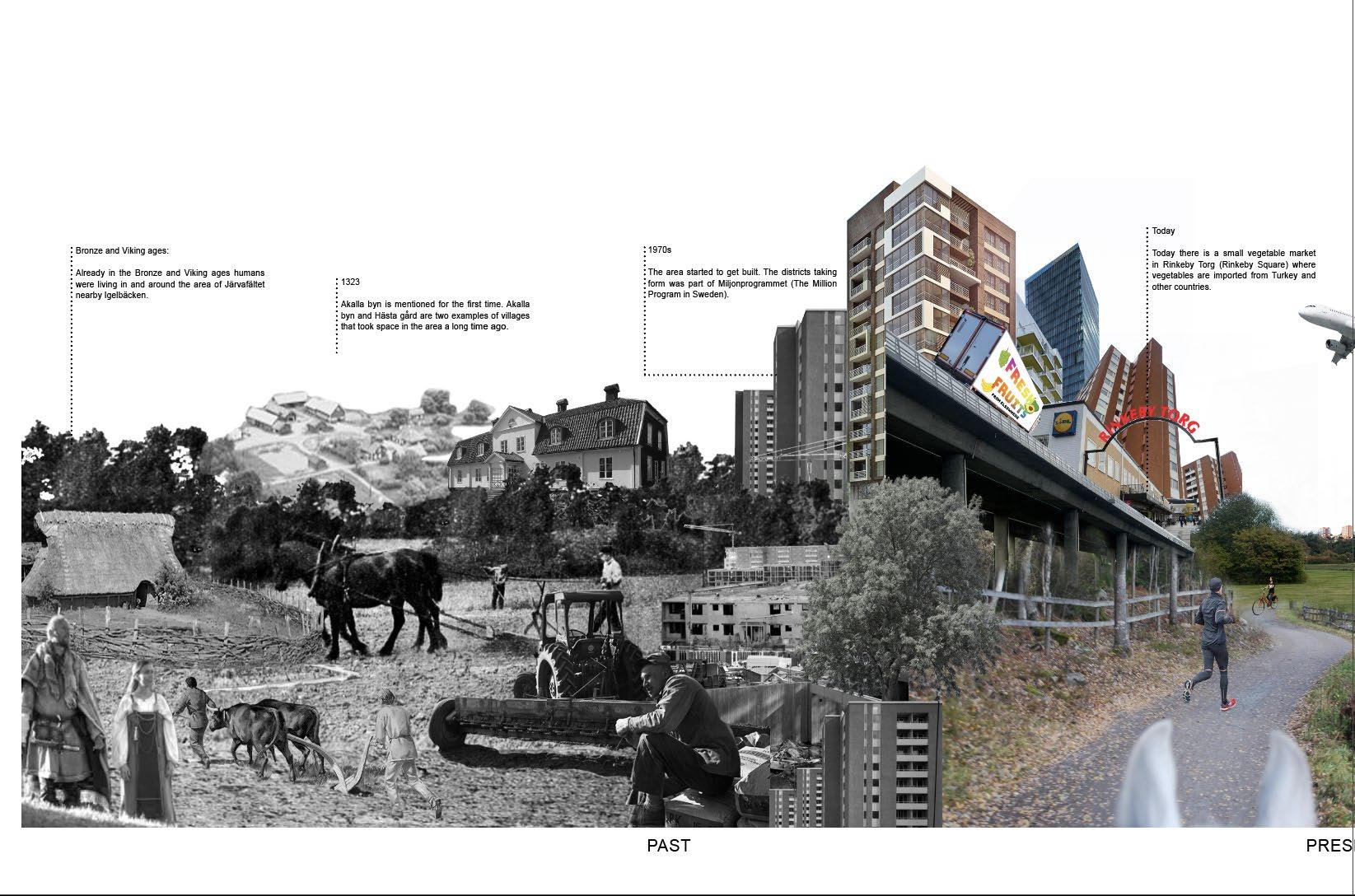

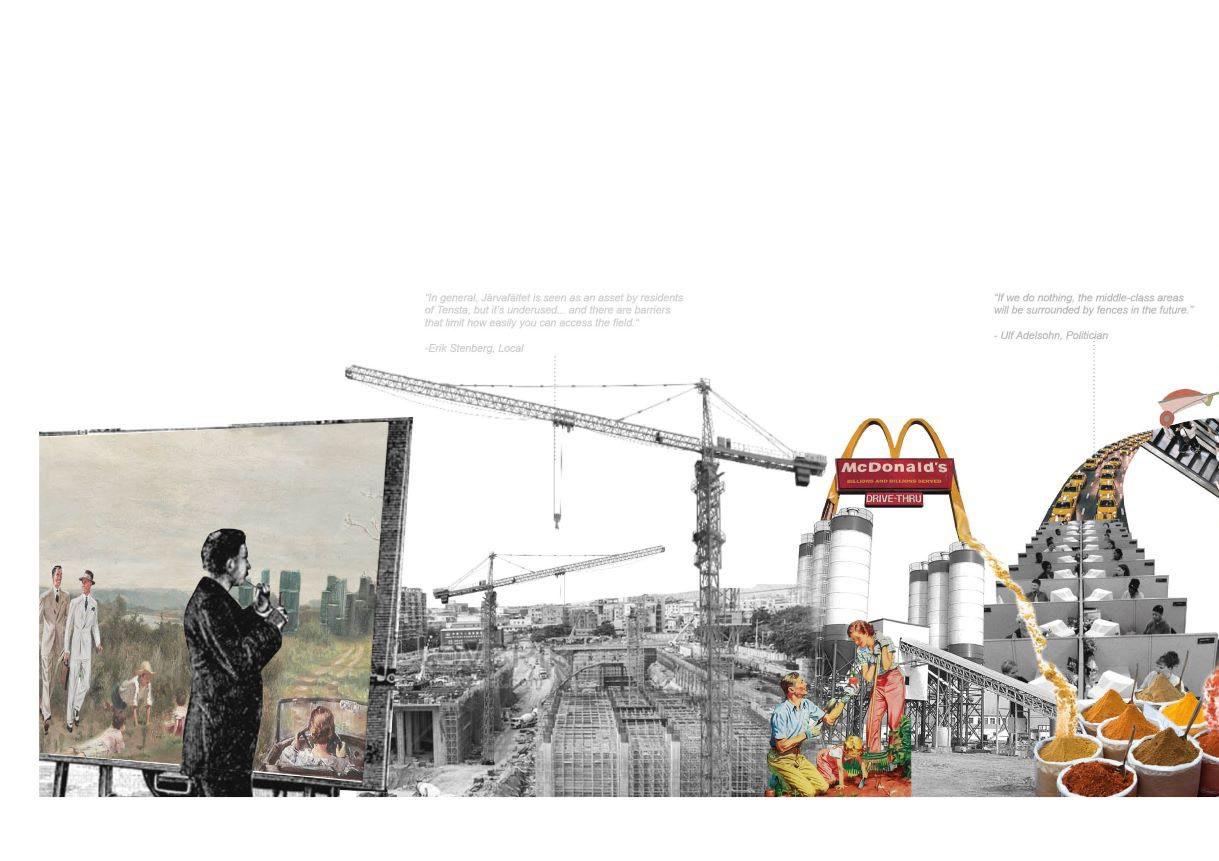

Timeline-collages and interviews present how different relationships between the environment, actors and structures can take on different forms and constitute different living environments. For instance, a farmer can only practice a farmer’s life if he has tools, plants, spaces for storage, structures for selling the crops, and so on. Looking back in history, this practice was associated with one type of living environment; today the practice might look completely different. This leads us to imagine and formulate more resilient future environments and relationships.

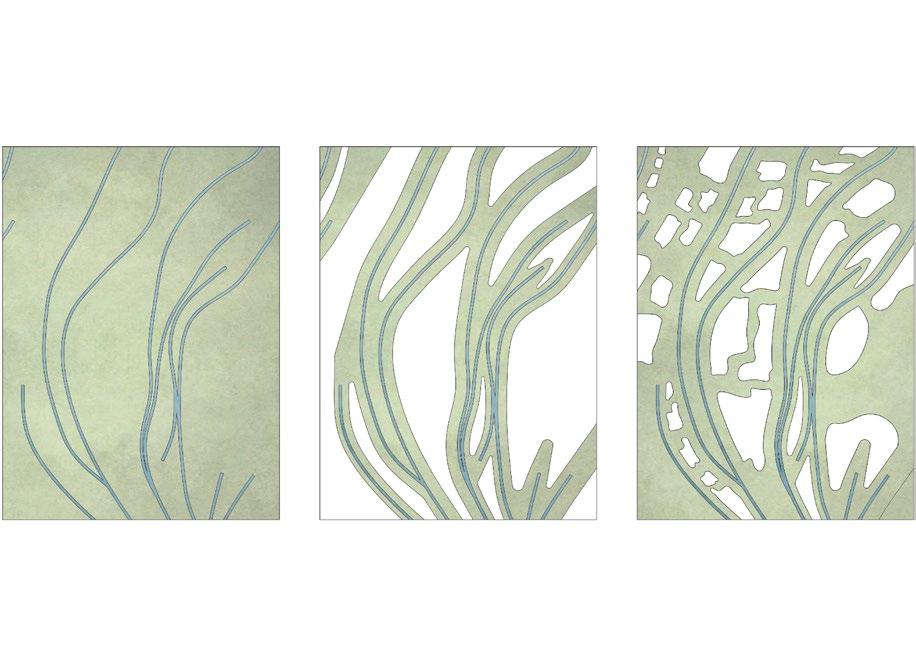

A series of alternative strategies is created with a landscape-first approach by investigating the site in relation to ecosystem services and working with system thinking. In nature, systems think

ing examples include ecosystems in which various elements such as plants, animals, air, water and movement work together to survive or perish. In social and economic systems elements consist of people, structures, and processes that interact and make the system healthy or unhealthy.

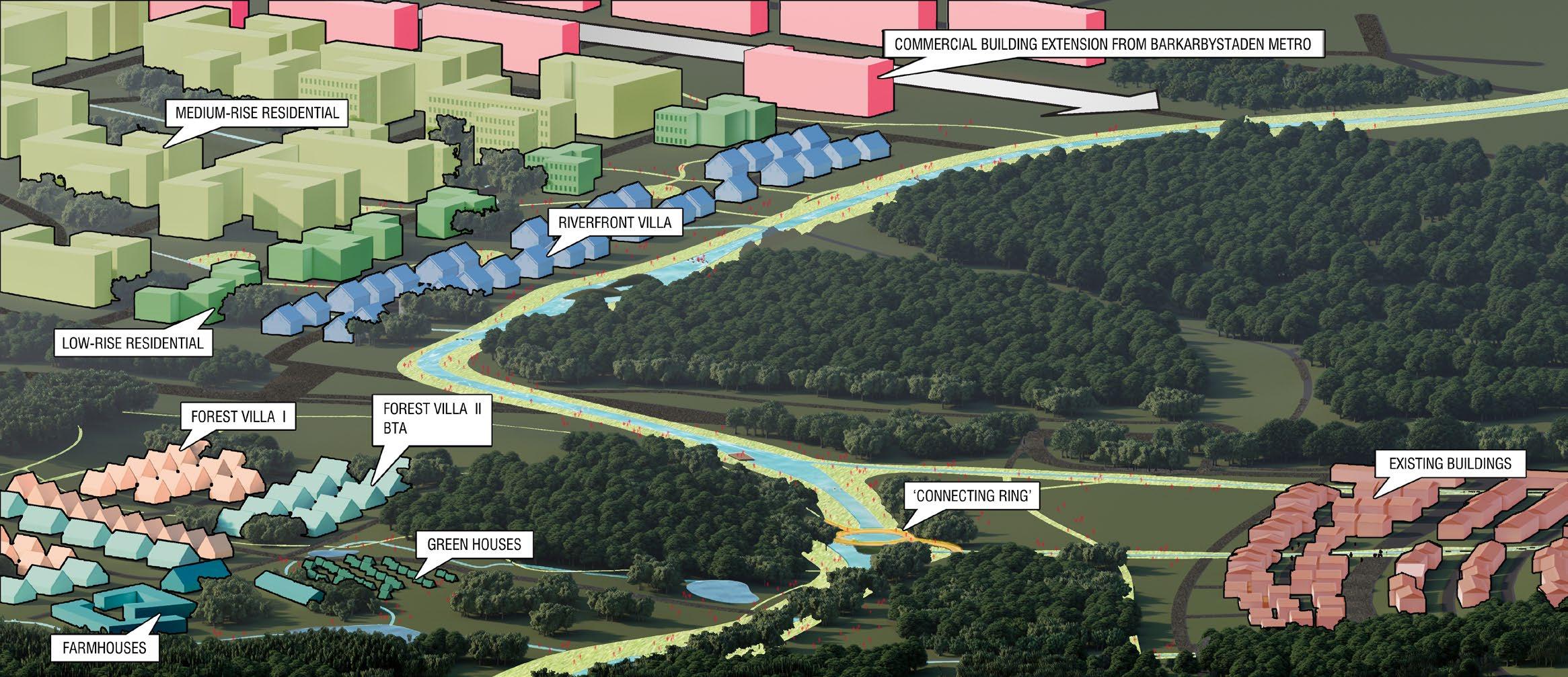

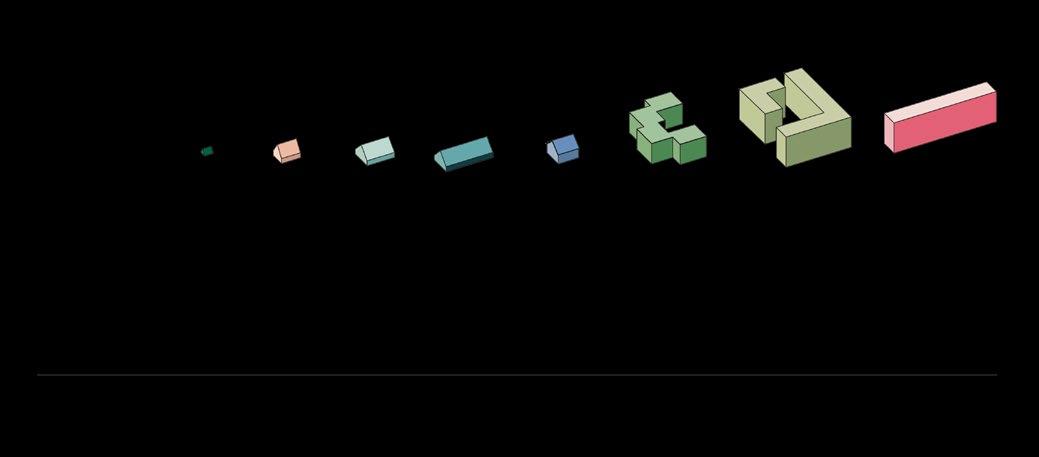

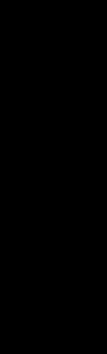

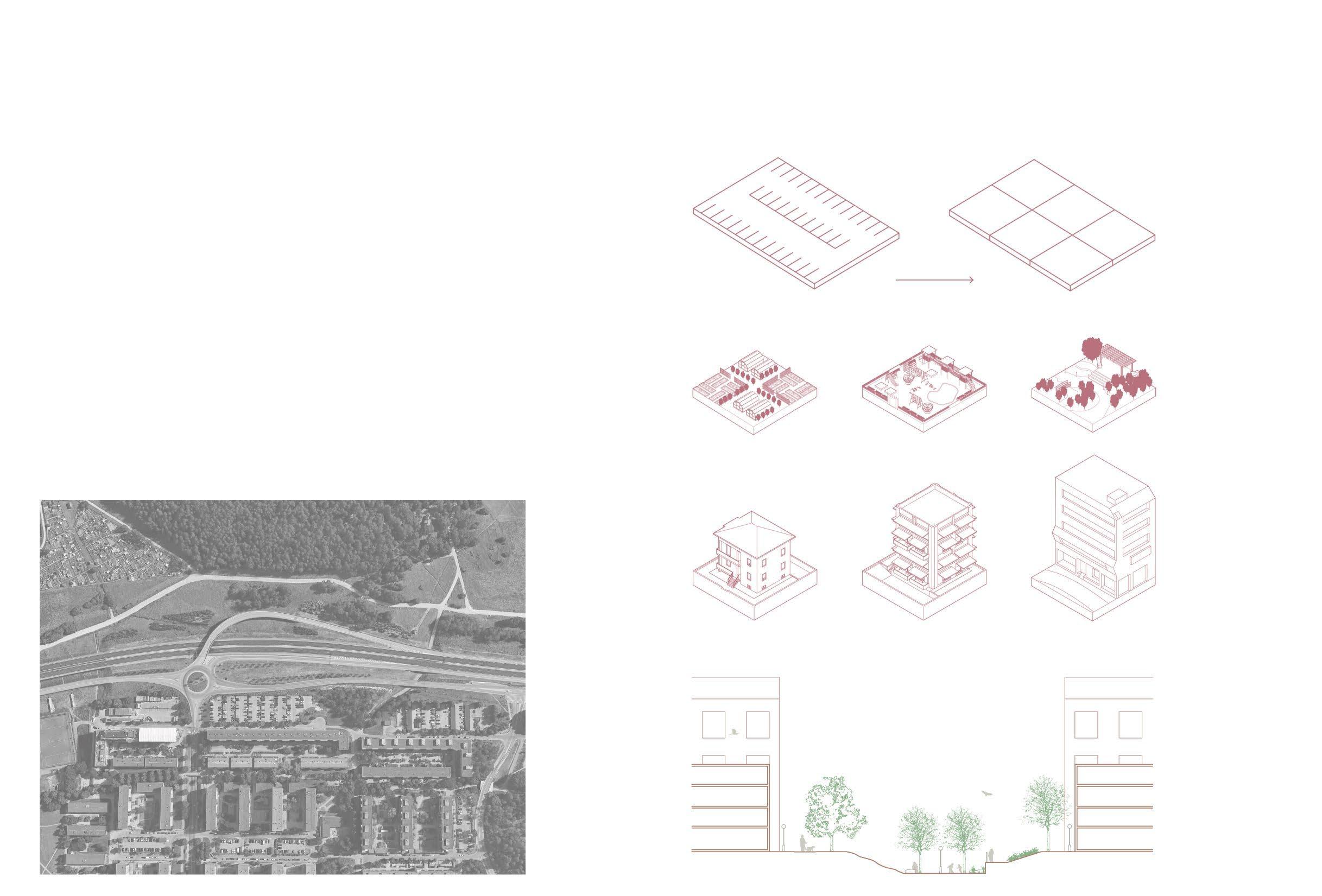

Challenging the idea of the unfeasability of developing in and around the wedge we design different strategies for building and densifying the site. With different density goals we can compare scenarios of development that span from the rural to the ultra urban and exemplifies various approaches to creating density on the sites, by working on the edges, or creating new structures in the core of the park.

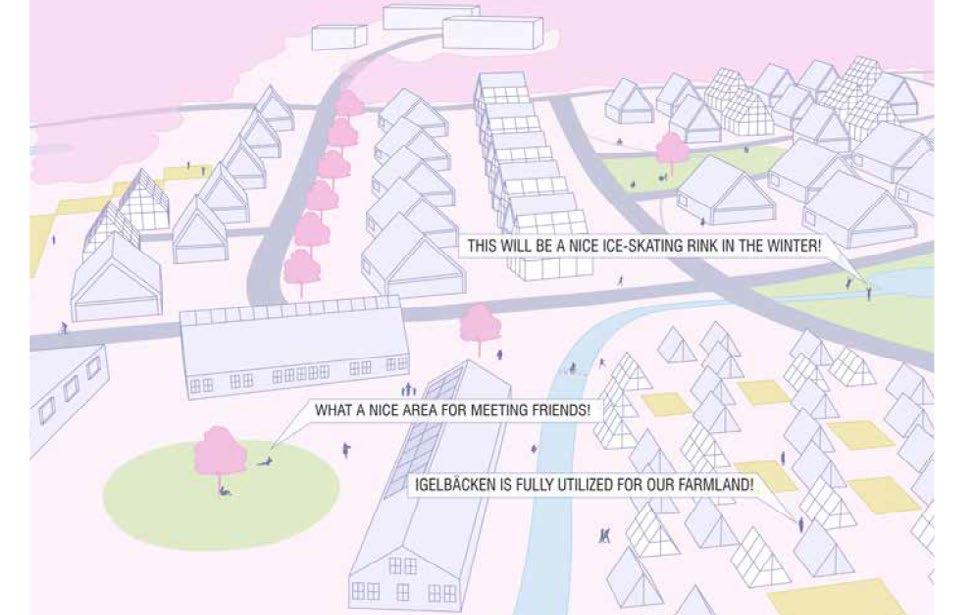

The projections explore the potential of the chosen sites. Projections are estimations or forecasts of future situations based on studies of present trends. The projections are developed as sketches, axonometric drawings, views, and system sections. These projections are tentative, rapid prototypes, through which we explored key aspects and potentials that evoke ideas and reactions for further development. The projections also aim to rouse public opinion about alternative future scenarios.

Four key principles that guide planning and design are developed in the studio. These principles aim to strengthen and support a sustainable and resilient development of Stockholm as well as the city’s relationship to its Green Wedges.

Stockholm is growing rapidly: the city is expected to have a population of 1.3 million by 2040. This entails a number of important challenges, for example, the construction of new buildings, adaptation of transportation- and public infrastructures and strengthening resilience related to climate change and environmental degradation. At present, and in mainstream urban planning strategies, the need to meet the demands of the growing city is often contrasted with the need to safeguard green infrastructures in a dichotomist fashion: landscapes are either ‘spared’ (through reserves) or ‘sacrificed’ (to development) rather than integrated, conceptually, physically, economically and ecologically into the urban structure. Projects within the studio have set out to explore the transformation of these existing antagonistic relationships into synergistic ones, asking – can we preserve, or even strengthen and create, locally generated ecosystem services whilst at the same time developing a more connective urban fabric including modern urban neighborhoods for human and non-human actors alike? Can a more built-in protection of these areas be created through tying people more closely to the green wedge, thus complementing more formal conservation

strategies for safeguarding large urban green structure values? The projects within the studio explore a wide range of strategies including: ● The introduction of a new public connective tissue in the wedge, that activates the landscape and is built on principles of caring and sharing combining urban farming, food production, markets, community buildings whilst supporting ecological connectivity and biodiversity in the landscape ● Creating a framework for experimentation and innovation – a new “Stockholmsutställningen” – that extends the knowledge cluster of Kista out in the wedge towards Barkarby, creating a highly performative and connective landscape where flows of flora and fauna coexists with education, research, commercial and recreational functions.

In recent years, the City of Stockholm has expressed a strong ambition to promote social and physical integration by improving and establishing connections between the neighborhoods in a north–south direction. In the on-going policy discourse, these ambitions are held to conflict with the objective of protecting ecological and recreational values, a task which is tied to the unbroken continuation of the green wedge in an east–west direction. The dualism presented in relation to Järva – which juxtaposes connected, large-scale green structures against a connected

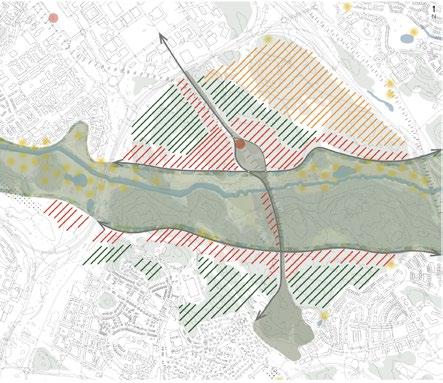

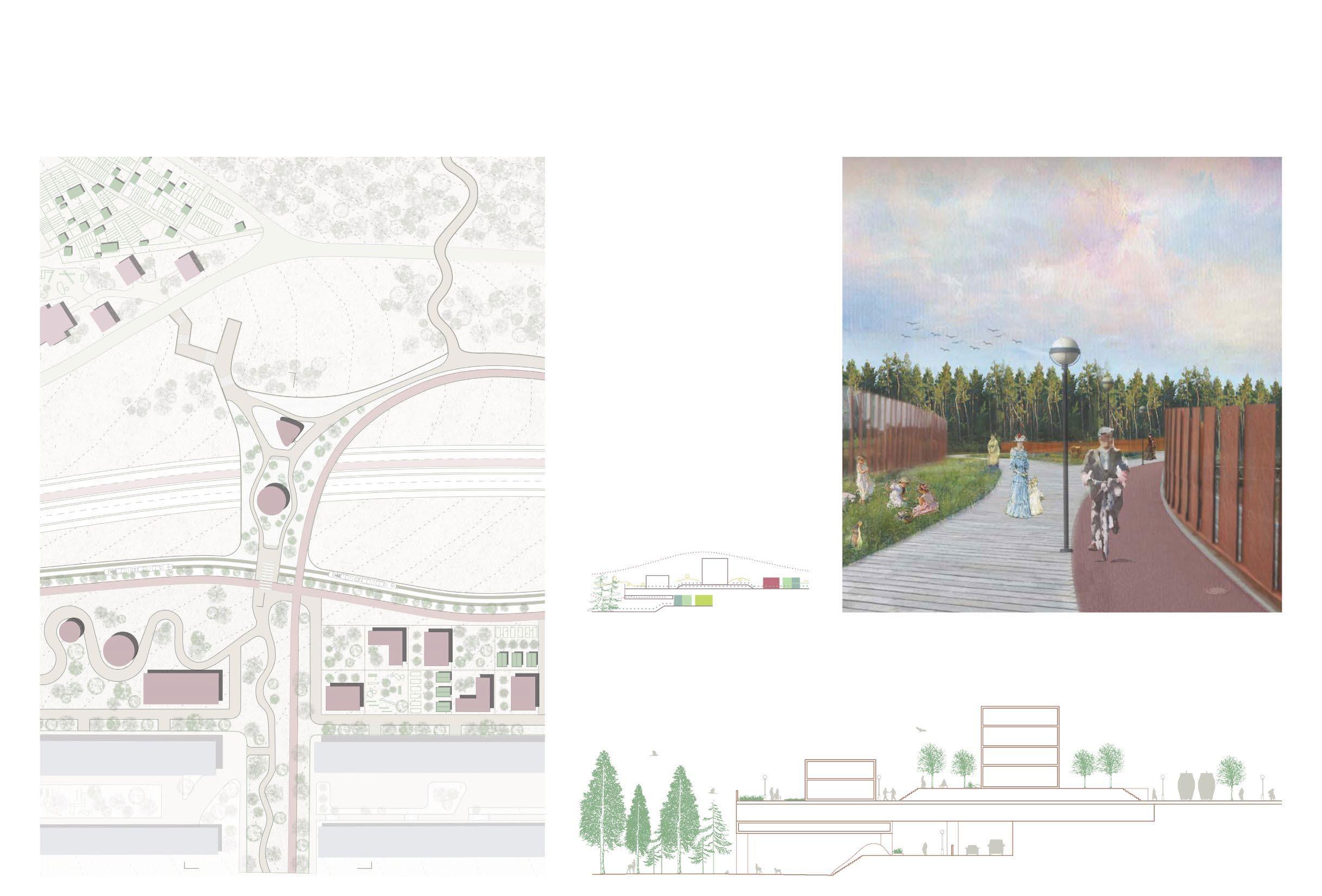

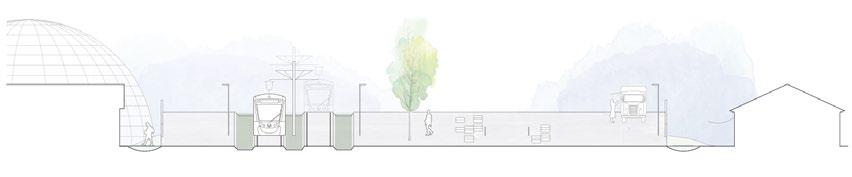

urban fabric – is typical of the Stockholm context and is reflected in both the general planning discourse and in planning practice. In the Urbanism & Landscape Studio we question this polemic thinking and explore the diversity of what it means to “connect”. Strategies proposed within the studio include: ● The introduction of robust public strands that run cross the wedge in strategic locations and weave together people, plants and animals through new symbiotic typologies ● New entrances to the wedge that counter barriers in the landscape and create opportunities for people to live more close to and be a part of Järvafältet ● Enhancing a system of “mini wedges” that connects in to the core of the surrounding neighborhoods through a system of green landscape paths where people, bikers, dog walker, joggers, public transportation etc. can travel around in an uninterrupted flow ● Enabled new connections between the districts and the green with the implementation of a new tram that runs as a ring line between Akalla, Barkarby, Hjulsta, Rinkeby, Ursvik, Kista and Husby.● Staging innovative and playful water spaces and wetland parks that become a public connective tissue for urban development.

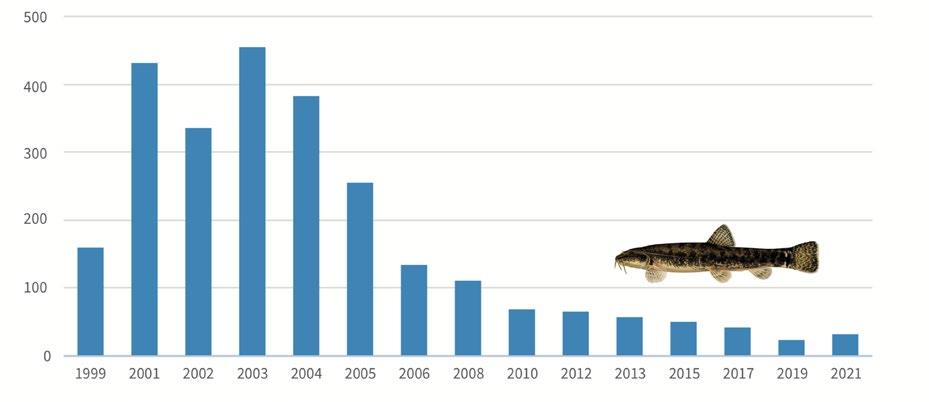

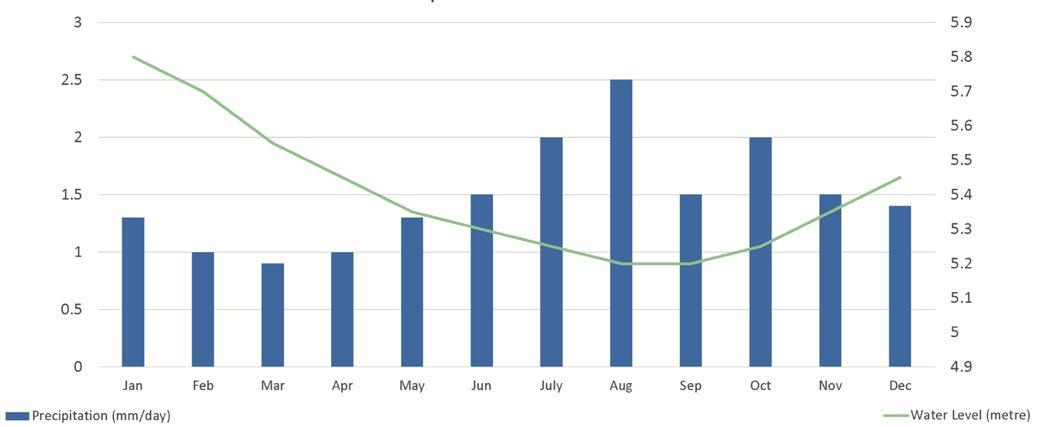

and Sweden. Being our societies and economies dependent on the quality of our ecosystems, we need to start working on enhancing ecological structures and build resilience to safeguard our cities. Climate change is appearing in Sweden in the form of extreme drought and warm weather that have disrupted both agriculture and forestry with, among other climate issues, the lack of water, uncontrollable fires, the strengthening of harmful pests, and unpredictable seasons. In the Järva area, questions of climate change and biodiversity loss are deeply connected to water and blue infrastructures. The Igelbäcken stream that runs from the lake Säbysjön in the North-West to the Edsviken in the East has been suffering from water shortage, lack of connectivity, as well as high amounts of PFOS in water and sediment. The previous vital stream and its surrounding wetlands have been straightened out, buried in artificial tunnels, drained and degraded, just like many other similar areas historically. In Barkarby, issues of water and flooding have even put future development plans on hold, due to projected risks of flooding. In light of this, the studio has set out to take a more holistic approach and explore potential

Extreme weather conditions as a result of climate change have had a global impact that does not spare the Nordic countries

synergies between ecology and its residents. How can we rethink our idea of what is “urban” and “stadsmässigt”, and curate new urbanism cultures that stitch together humans and their green and blue environments? How can we weave together societies with their local resources, and how can we re-imagine new modes of management structures for public green and blue resources? How can we raise human awareness about what is vital for our long-term survival, although it is often invisible? Diverse strategies are proposed within the studio including: ● Robust public spaces that delay storm water through wetlands and softer edges. ● New performative neighborhoods that can simultaneously constitute habitats for humans and non-humans whilst improving biodiversity in the wedge and water quality and flow in Igelbäcken ● The creation of green corridors and connections for flora and fauna to flow through the landscape ● New passages under and over existing barriers in the landscape for both humans and non-humans.

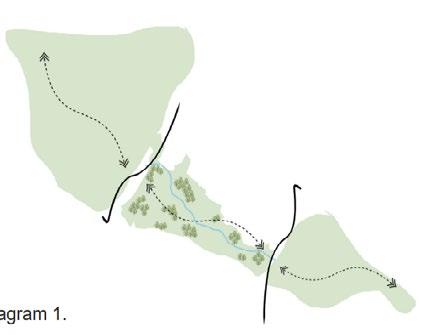

Our site, Järvafältet, is part of the regional green structure and the Järva Green Wedge, which extends from southern Djurgården in the southeast, via Järvafältet, to Sigtuna in the northwest. The wedge structure, compared to for instance a Green Heart or a Green Belt, is beneficial since it allows many people to have

contact with nature close to where they live. As one of the city’s areas of development and expansion, the peri-urban Järva area experiences strong development pressures, with a range of different interests and actors connected to the site and involved in its development. Today, around 50% of new construction in Stockholm takes place on natural land, and piece by piece of the Green Wedge is being chewed away without a clear comprehensive strategy and vision to provide direction. This can be traced back to the market-led “Stockholm model” that today guides urban development, in which long-term planning strategies are replaced by short-term priorities. Furthermore, the very largeness of the green wedge can be identified both as one of the main challenges and main potentials. On the one hand the large scale of the wedge creates conditions for high biodiversity since it allows a dispersal of various species, plants, animals and genes to spread throughout the landscape. On the other hand, the large size, and the fact that the wedge spans over multiple jurisdictional and administrative borders, makes out a challenge to maintain a consistent interpretation of the green structure amongst stakeholders. How can the Järva Green Wedge at large, and the Järva green area in particular, become more legible, as an organizer of space and provider of identity and a sense of belonging? Instead of isolating surrounding neighborhoods, can the green wedge function, as framed by urban theorist Julia Czerniak as a: “social catalysts by providing contact and exchange for people in otherwise disjointed urban environments”? Projects within the studio include proposals for: ● A series of connected identities that tie together as a sequence of parks connected by

a public passage along the stretch of the Igelbäcken stream. ● Amplifying existing social and cultural nodes in the landscape (such as Eggeby gård, Husby gård, Hästa gård), and strategically adding new ones where they seem to be missing. ● Staging innovative and playful water spaces and wetlands parks that become a public connective tissue for urban development. ● A new tram line that strengthens the public transport infrastructure connecting neighborhoods surrounding the wedge in a loop and enhancing local exchanges and accessibility.

While dealing with the Järva area, it is important to realise its great natural and social potentials, which can be segregating barriers, both physical or perceived, but also drivers for future developments. The area suffers from insufficient connectivity between the neighbourhoods, a fragmented relationship with nature and misses common language conveying its qualities into unborn scenarios. Our strategy makes use of the resources and landscapes while maintaining respect and consciousness of the existing conditions and ecosystems. By interpreting our five layers of thinking, we try to imagine Järva as a sustainable and resilient urban area, where large natural green bodies serve as catalysts for creating co-living and co-interacting spaces for future societies and non-human actors.

An essential part of creating a ‘Järva Identity’ is to promote existing landmarks and also create new ones. The celebration of runestones and urban farms cements a pre-existing connection with the area. Bird towers offer vantage points to help locate oneself within the wedge itself while also offering vistas across North East Stockholm.

New infrastructure is to be proposed in the form of a tram operating on two circular lines - connecting neighbouring residential areas. In addition, new roads winding across the green wedge make pedestrian travel safe and public transport on buses easy.

For people to develop closer connections with nature it is important shared spaces such as allotments, farmland and flower gardens thing tangible in return. A range of new public spaces such as markets knowledge to be shared.

important to offer functions that help engagement with it. New gardens offer the chance to work with nature while receiving somemarkets and education centres allow for both produce and

Exsiting public facility Allotment Meadow

New public / meeting space

New public / meeting space / Landmark

Tram

The connection of landscapes can be broadly separated into both green and blue. The Igelbäcken will be used as a carrier for emerging communities, while new wetlands will offer new public space in addition to their ecological benefits. Urban planning and architectural language will be informed by the landscape to create a closer relationship with nature and its human inhabitants.

Main

Bridge

In areas such as Tensta and Rinkeby, the connection to Järvafeltet is inhibited by the highway that acts as a barrier. This edge would be blurred by creating new residential areas that transition from high to low buildings. Furthermore, this will help reduce issues of noise pollution caused by the highway. Areas of new development will have a less explicit distinction between the built and ‘nature’ by introducing mini-wedges that again help blur the line.

In the first part of this studio we study the complexity of the site through combining theory and analysis with artistic and bold explorations. Working closely with actors and experts on the site, we investigated and conceptualized existing and new interfaces for human/nature relations. We divided in groups and specialized in different aspects of landscape and urbanism. The work of each group might overlap but is unique and contributes to an open source knowledge sharing that will

be used by everybody later in the course.

Through the lens of art and architecture we will test and project scenarios for where and how new relations with nature could develop. Our investigation: how can the Green Wedges be operationalized as a productive, generative landscape that can be a basis for new urban living environments?

Grup member, group member, group member

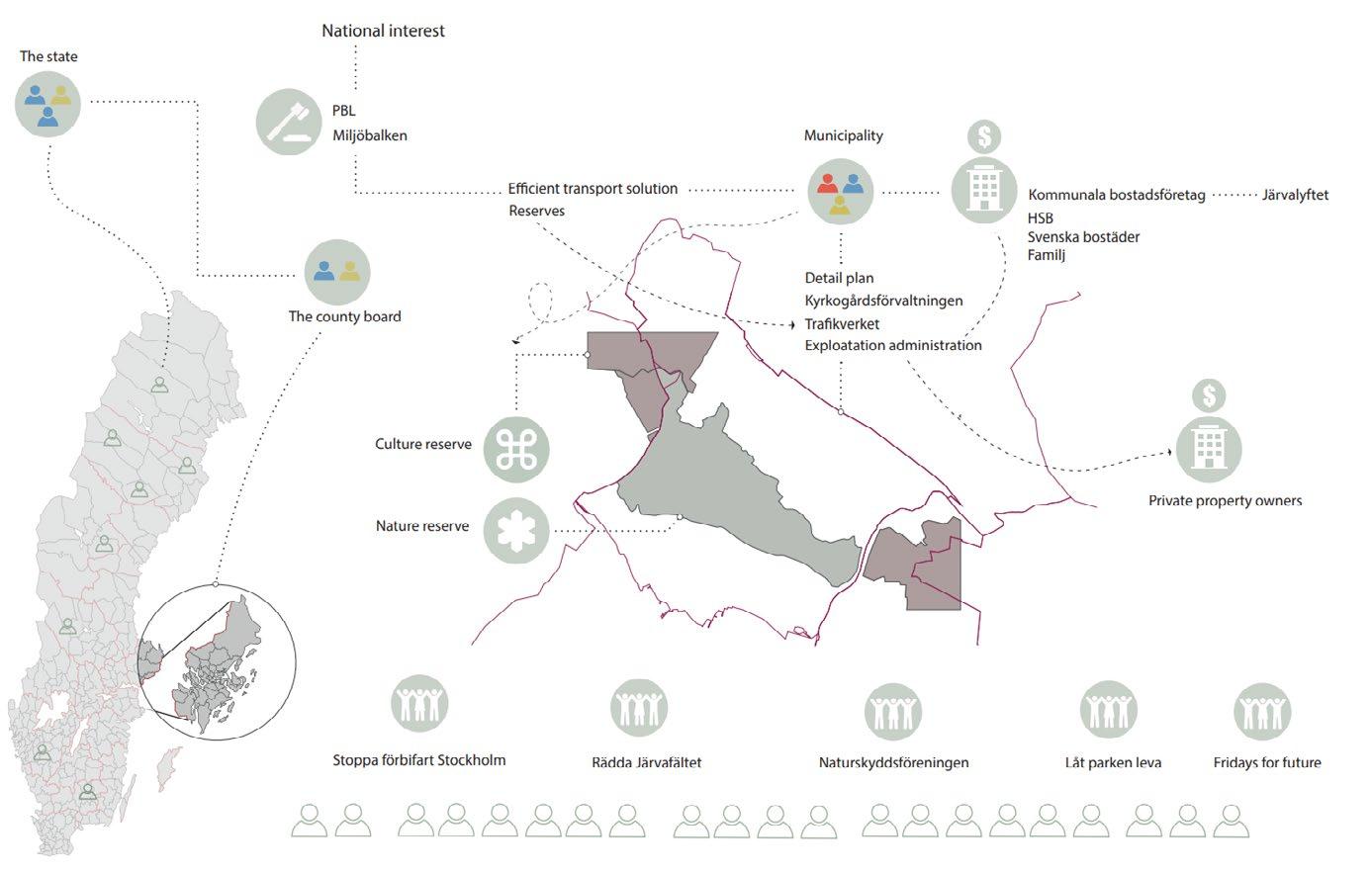

Järvafältet is located northwest of Stockholm and is part of Stockholm’s green wedge, which extends from the inner parts of Stockholm to the more rural parts of the county. The site has great ecological and urban potential but also acts as a barrier for the neighboring areas, which makes the site exciting from several perspectives. We started exploring the site from a legal infrastructure perspective and discovered that the legal conditions dominate the framework for the existence of the site. The legal infrastructure includes physical and administrative borders, but also political visions on both a municipality level and for the country at large. So how could we find a green strategy for this? By expanding the allotment as a principle, we wanted to create collective clusters for food production around the existing arable land. These clusters would stretch the length of Igelböcken and create a legible center that would be beneficial for the entire area.

This is a diagram of how the non-human and human actors would cooperate.With this strategy, we wanted to challenge the view of nature as something separate from us. Could we find a common green infrastructure for both humans and the qualities of the reserve? By bringing different ingredients to the site we could help the ecological actors. The collective clusters would be a new way to organize such a proposal.

Strategic plan for Stockholm - Legal infrastructure

4.

5.

Diagram 1. Urban infrastructure causing fragmentation of the green wedges.

Diagram 2. District segregation due to long distance because of a big conservation.

Graph 1. Number of national parks, nature reserves and nature protected areas divided into total area of sites.6

Graph 2. Protected area of national parks, nature reserves, nature conservation sites and Natura 2000 (habitat directive)

Accumulated area (millions of hectares) per year.7

CATEGORY 1 - LANDMAP

Allotment gardens Culture reserve Nature reserve Borders of municipalities Private owners right to use land

CATEGORY 2 - SYMBOLS

Relation to legal regulation Nature reserve Property owner Municipality Culture reserve Profit interest Associations

1.Nature area and burial ground at Järva

2.Outdoor swimming pool (Järvabadet)

3.Rinkebyterrasen

4.E4 Stockholm Bypass (Förbifart Stockholm)4

5.Possible built area and Kymlinge station

4.

EXPLINATIONS 1. 3.

(1) https://vaxer.stockholm/projekt/jarva-begravningsplats/ (2) https://vaxer.stockholm/projekt/nytt-utomhusbad-pa-jarvafaltet/ (3)https://vaxer.stockholm/projekt/bostadsomradet-rinkebyterrassen/ (4)Trafikverket. E4 The Stockholm bypass. Stockholm, Sweden. (5)https://vaxer.stockholm/projekt/husby-kulturstrak/

(6)Naturvårdsverket. Swedish Nature Conservation 100 years. Stockholm, Sweden

Diagram 2. Graph 2. Diagram 1. Graph 1.

Urbanism & Landscape Studio 2022/2023

Teachers: Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio

Students: Lycke Förell

Çlirimtare Syla

Sébastien Wegmüller

1971

The first protected area is created in Järvafältet by the National Board of Agriculture

1905-1968

The whole field is left by the military, who are using the place as a training area. This particular usage made the place practically untouched.

“Nature has an ecosystem that helps to preserve itself, but we can also as humans take advantage of it.”

“Green infrastructure is very important, both for humans to have green space to walk in, but also for species to be connected between different areas.”

The housing shortage in Sweden and especially in Stockholm has political consequences. The Social Democratic government therefore promises that one million homes will be built between 1965 and 1975.

1999

The cultural reserve protection instrument was introduced by the Environmental Code in 1999. The intention is to enable the care and conservation of valuable cultural landscapes.

The growing population and housing shortage are prompting the city to build more and more homes. The new challenges are defined in the 1999 Stockholm City Plan.

People can have a allotment where can grow food and flowers. No buildings are allowed and the use is restricted.

Few projects are taking agriculture, small communities, sites are the most common The main use is walking,

“Järvafältet is one of these places where there are a lot of people that lose out on the current way of developing it.”

they buildings restricted.

taking place in the protected areas: communities, gardens and rental common activities in these areas. walking, running or cycling.

The boundary between protected areas and built-up areas is very strong. Either the area is protected or you can build whatever you want.

“I think we do need to have sort of boundaries regarding nature, at least perceive certain boundaries as important, especially when we live in this capitalistic society.”

Allotments could be on a much larger scale, with people respecting nature and having a fair division of land.

No more boundaries: nature cohabits with the different buildings, creating a more organic space.

All protected areas are linked, which allows species to move freely, as the buildings are not connected but surrounded by nature.

Activities could be organised to make discover the nature and new dynamic places. The quality of the ecosystem is guaranteed by the people who become part of it.

“I think the clear separation between built-up and protected areas is bad for nature and for the way people look at nature and use it, I don’t think the boundaries need to be so sharp, they can be much more fluid and we need to preserve the best parts of the green spaces.”

One of the interviews that we had was with Petter Kvarnbäck, a Marketing and Communications manager from Vasakronan, which is a commercial real estate company owned in equal shares by the First, Second, Third and Fourth Swedish national pension funds. As answered in the interview the goal of this company is to provide money to pension funds, to allocate some of their means to the company. While asked if it the process is different as a real estate development so close to the nature reserve from other regular real estate developments/city planning, the interviewee said that it is different. He explained that the company develop their property in existing green fields and existing building. And he explained that if they want to build something close to a nature reserve they have to be extra careful on what the border could look like.

He, then told us about the aim of company, that being to be climate neutral as a company. So to be able to do that, they have to work on decreasing the energy consumption, the use of materials and other factors. They have to compensate for the built area otherwise it would be impossible for them to become climate neutral.

He talked about the Kymlinge area where it shows the conflict between Vasakronan and the Sundbyberg municipality since the last mentioned has no interest in the development of this area. This area is part of this municipality so without them settling nothing can start happening in that area. To sum up, it seems that it is not convenient for Sundbyberg to invest something there because it is on the wrong side of the nature reserve which comes to becoming an issue the “strange location” of different services provided by the municipalities while comparing with the other parts of Sundbyberg. But also there would be no business plan for Sundbyberg since Vasakronan owns the land and the when the municipalities develop they sell land and get some money so at this area this wouldn’t be possible for them.

Asked if it is a good or a bad thing this so called separation of nature and the built area of the current organization of nature in the city he depicted that it is bad for the nature and also for the people on how they look at nature or use the nature. His opinion is that the lines don’t have to be so sharp, they could be more fluent while preserving the best parts of the nature and using the not so highly valuable parts for building apartments because of the high demand.

The second person we interviewed was Anders Tranberg from the Stockholm branch of the Swedish Nature Conservation Society. He works to create links between green spaces and protected areas in the city.

Areas are protected, but individual objects can also be protected. The qualities of a nature reserve are protected species, a sensitive environment like wetlands or old forests, and also social values. He thinks that we do not protect nature enough in Sweden, as only 6% of the forests are protected. Industry is the first problem when talking about forests, because the demand for wood is high. For him, it is better to leave the protected areas totally free. If we could build there, it would be difficult to know what to accept or not. Nature needs large spaces, and the soil must also remain intact, which is not compatible with housing foundations for example. Only small constructions could be allowed, and eco-villages could be a possible option.

In the Järvafältet area, the construction of the highway is a big problem for him. The city didn’t want to build a tunnel because it was expensive, even though it was better for the peace and nature. The other problem in Järvafältet is that the area is not welcoming enough for visitors. There are many possibilities to do much more to attract people to the protected area.

He thinks that the way the zones are drawn today is a bit tricky, because often some of the nature has to be preserved for the development of the city. There has to be some balance for the city so that the interests of both parties are respected. He imagines that having a strict limit and a tolerant limit could be interesting. To conclude, he thinks that Stockholm should use the land in an efficient way, for example by having underground infrastructures to let nature develop, and by connecting the different areas by green corridors.

“Green infrastructure is very important, both for humans to have green space to walk in, but also for species to be connected between different areas.”

“When we develop our property we do it in existing green fields or existing buildings. It’s quite rare that we do it in green areas.”Photo: The Stockholm Circle with chairman Anders Tranberg managed to save the endangered old oaks on Kungsholmen

How the “Miljonprogrammet” shaped the landscape of the Stockholm suburbs ?

After World War II, Sweden was characterized by a very strong growth until the 1960s. People left the countryside to find new jobs in the cities. Unfortunately, there was not enough housing for this growing population. The crowding and lack of standards in the inner city neighbourhoods became a symbol of social misery. It was felt that people should instead move to the outskirts of the city to more spacious apartments.

In 1964, the Parliament launched the “Miljonprogrammet” and decided that one million new housing units would be built between 1965 and 1974 to solve the housing shortage for good. The aim was to raise the standard of housing, both in terms of size and equipment. The lack of labor made it difficult to keep up with the high production, so it was necessary to rationalize, standardize, mass produce and use large-scale methods. The confidence in modern methods to solve the housing problem is very high.

During the 1970s, Sweden entered a recession and newly built apartments became empty due to a decline in demand for housing, but many of the original objectives were achieved and the housing shortage was resolved. However, new problems soon emerged and the critical debate began early on.

For many critics, the “Miljonprogrammet” symbolizes the inability of planners and politicians to build the “good society.” The monotony, dullness and large scale of the buildings were often criticized as an attempt to make the largest possible houses in the shortest time and at the lowest cost, with the possibilities offered by technology being poorly exploited. Houses were often depicted as large concrete blocks in contrast to the small human being, and this large scale led to dissatisfaction and lack of social control.

Outdoor environments were often characterized by the same scale and uniformity as the buildings, and quality requirements were often few and imprecise.

This criticism also resulted in problems with empty apartments and relocation. The remaining households had fewer financial resources, and it was easy for social services to place households with social problems in these areas. New immigrants were also often placed in these neighbourhoods, and all of this caused the Miljonprogrammet to develop into underclass communities, which created more and more segregation.

How the Stockholm 1999 General Plan took lessons from the past to set new goals for the future city ?

The plan was created in response to the various problems facing the city, given the population growth that began to increase again in the 1990s. The objective is to achieve the four main goals into which the project is divided by 2040.

A growing city: The first objective is to be an open, tolerant and welcoming city. It should offer housing for all price categories, create an attractive urban environment close to green spaces and bring new concepts that can make the city more dynamic. It should attract businesses with good market conditions and a mixed-use urban environment to accommodate them. Necessary public functions and services should be developed, with an emphasis on building schools.

Good public spaces: The objective is to bring diverse communities together by improving the public space. Each neighborhood should have a dynamic center with access to fundamental urban features in all parts of the city, and housing areas should be transformed into mixed-use urban environments where people live close to their daily activities. New housing should be diversified in size and form, and public spaces should be developed, especially green spaces.

A cohesive city: The goal is for people from different local areas to move through the same public space and see each other throughout their day. The street network must be improved and the street must be used more efficiently. Public transportation needs to be developed to avoid the isolation of areas. Green spaces and parks should be improved to create connections between different neighborhoods, and major attractions should be evenly distributed to encourage people to seek out new destinations.

A climate-smart and resilient city: Urban structure needs to be developed in a way that encourages sustainable travel and lower consumption of resources. Land has to be used effectively and major urban developments should be done in existing poorly developed areas. New buildings must be built with sustainable materials, energy solutions, technology and design to suit future climate change. The infrastructure should be robust enough to cope with new challenges such as heavy rainfall, rising sea levels or heat waves. A network of green spaces must be developed and the green infrastructure should be improved.

“Because of the large scale and uniform design, it could be difficult for many people, especially children, to distinguish their own homes from the ground”

“Approximately 1,600 homes are planned here, with preschools and a school. The area will also be developed to include business premises, parks and a new square.”Photo: Erich Stering, 1972, Kid playing in front of a “Miljonprogrammet” building Photo: Landskapslaget, Kista Äng

Today, the program is seen as a part of the representative history of the housing policy goals of the 1960s and 1970s, and for many people it represents a part of their roots and identity.

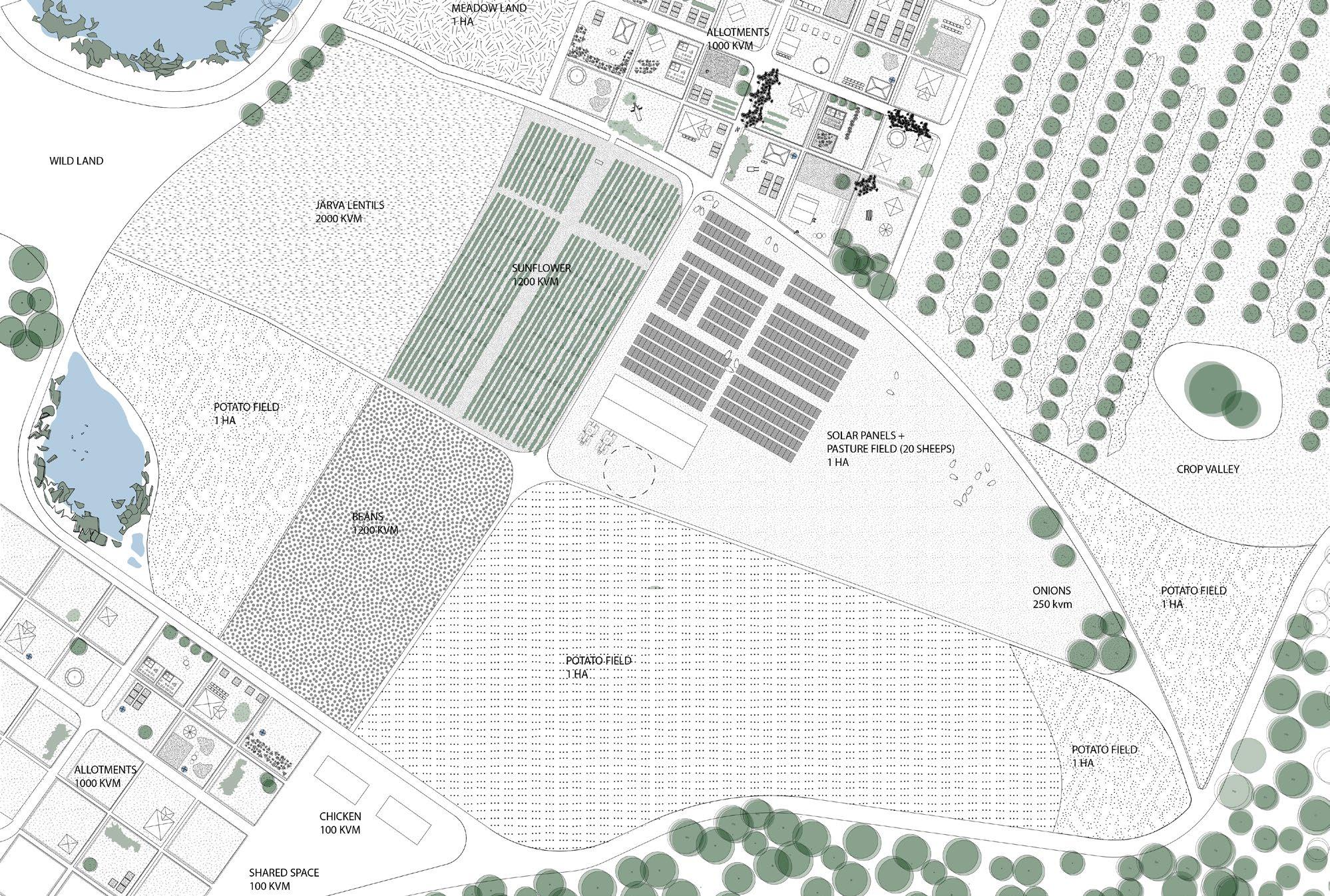

Food production, climate regulation and social ecosystem service.

- Utilization of the allotments and farmlands as a strategy for food production, but also for connecting people and creating different activities (social aspect: physical and mental health, social interaction, knowledge and inspiration).

- Allotments will be the size of 10x10m, which can provide enough product for a person or a small family. They will create the paths around the area and will also be shaping the farmlands which will be positioned inside these allotments.

- The management will be from the municipalities, as they will put a person in charge to manage the area and provide the necessary tools for people to work in the fields.

- As an exchange, the allotments will be given to people who spend their time and bring knowledge, creativity and innovation to the community. This fixes the issue of the long queues to get an allotment. With this idea employment will increase for this area by working at the market place or working in the fields.

- Low-tech green houses will be built, so they can be used during winter time.

- Utilization of the two existing facilities Husby Gård and Eggeby Gård as meeting points, market places and also as cultural, educational and recreational spaces for the residents.

- Along Igelbäcken a path will be created which will be the main connecting path which lies across the field.

Parts of the land will be used as experimenting areas, test gardens or “labs” for institutions related to agriculture.

As a contribution to climate regulation, green roofs can be implemented on the buildings around the area. Revitalized access points or green corridors from each of the districts, as a way to bring nature to the city while at the same time bringing people in to the nature.

Density goal: 200,000-700,000m2

- The area contains: allotment gardens (seasonal gardens and greenhouse allotments), farmlands (food farmlands and livestock), public and institutional spaces.

- Seasonal gardens will be the size of 10x10m, while greenhouse gardens will be the size of 15x15m in which people could also live.

- Public spaces will be used for sports, cultural, recreational, community and academic activities aside from the allotment gardens.

- There can be a possibility of building facilities which can be used for these activities. But always with a focus on sustainability and preserving the nature.

- One way to provide these activities without the need of large buildings could be by building installations or pavilions for different festivals, events, exhibitions, workshop spaces or yoga practice, market places; outdoor cinemas; outdoor sports fields; outdoor fitness equipment.

- Another way of using parts of these lands is for different institutions which can be used as “lab” lands where they can manage and take care of those parts.

- The other built area, which will reach the density goal to around 300,000m2 consists of 3-5 storey apartment buildings and terraced buildings which will have green roofs and green terraces. The higher buildings will be located across the edge which will help reduce noise pollution from the highway. They will be distributed along with the relief by creating a smooth transition from high density to medium density and all the way to the fields and gardens with greenhouses. ( approximately 250 apartment buildings will be built.

- Paths are enriched due to different actions happening all around the field. They welcome the citizens to use the area and contribute positively to the different ecosystems.

- The ideal management of these lands would be a decentralized one, by involving local actors, associations and residents in the decision making and managing of the land use.

During the bronze age the sea level was still high over the Järva field. The area had become a part of the inner archipelago with many islands, one of which was Akalla. During the viking age (around 1000 bc) the bay area had withdrawn so that former sea bottom was now pasture and Igelbäcken a large water source serving as a connection and used to boat transporting.

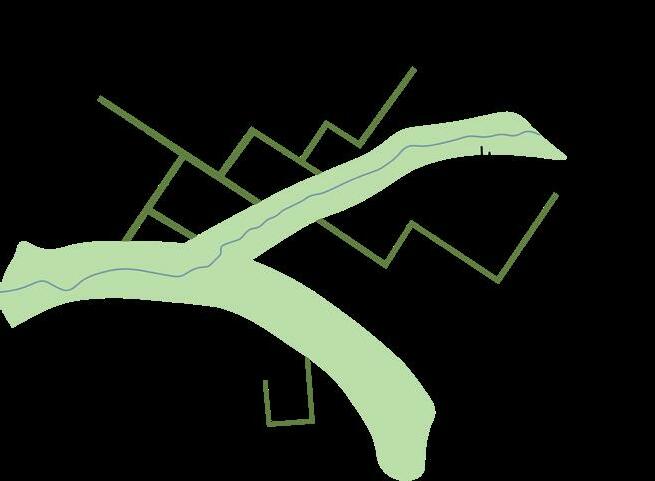

The part of the blue infrastructure in Järva that has our most attention is Igelbäcken; a rather small creek that is running from the lake Säbysjön north-west of Akalla and stretching 10 km east to run into lake Edsviken. On its way through Järva, Igelbäcken is part of several nature reserves divided by the municipalities of Järfälla, Sollentuna, Solna, Stockholm and Sundbyberg.

The creek has a modest ecological status - it is over-nutritioned, but mostly it suffers from water shortage, lack of connectivity and morphology as well as high amounts of PFOS in water and sediment. Stormwater is now run directly to Edsviken, which also contributes to water lack. Climate changes - higher temperature and increased precipitations - impacts the creek area with seasonal flooding but also draught. The hydrological issues effect the connectivity, which we conclude is due to among other reasons the morphological status of the creek. The straightened out parts of the creek, the parts that are led through artificial tunnels and over bridgening by roads.

The Stockholm city ecologist Ulrika Egerö suggested for prior and planned future projects of creating wetlands in the area, as both a way to prevent flooding and draught, while also contributing to biodiversity. Another prominent local actor of Järvafältet is the director of Eggeby gård that is engaged in the local area and is concerned with the lack of connectivity for people in the area, as well as access to the green. The future of Järvafältet has many interests; the different municipalities, the exploitation office, the housing issue if Stockholm, the recreational needs, the residents, the different local organisations.

Our conclusion is that the blue infrastructure has been weakened many times in modern day. There are measurements to be taken. We wonder, how can we strengthen the connection between human and water, how to enhance the recreational aspects for the creek to tie up the communities and attract more people come to the place? And what does the creek want ? If we would give it a voice, a personhood with legal power - would it want us to create more room for the river ?

Amount of the fish Grönlingen (Barbatula Barbatula) / 100m2

Precipitation and water level

“In the Middle Neolithic, most of the Järva field was still under water and only a few small islands emerged, including Hjulsta, Rinkeby, Tensta and Husby.”

“Then, in the Bronze Age, the area around the Järva field became an inland archipelago landscape.”

“Little by little, more and more land became available for people to live on.”

“Currently, as a problem, Igelbäcken has too little water, and the stormwater from the highway is bad for the environment. Anders thinks that the PFOs (toxic chemicals) from Barkarby district are a threat to Igelbacken.”

“The has restoring

Urbanism & Landscape Studio 2022/2023

Teachers: Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio Students: Yifan Su Ylva Nissen Eugénie Deruaz

Urbanism & Landscape Studio 2022/2023

Teachers: Hanna Erixon Aalto & Francesca Savio Students: Yifan Su Ylva Nissen Eugénie Deruaz

activist group “Återställ Våtmarker” existed for many years, they call for restoring wetlands and an immediate stop to using peat in Sweden.”

“A direct consequence of extensive drainage is a dry landscape that has lost its water management and flow equalization function, while the need for water is high.”

“We should make more meeting places in Järvafältet to avoid possible issues of racial disparity and segmentation of different groups of people.”

“Creating more wetlands can help prevent the exposure of old peats that leak out tons of carbon monoxide”

“We should have more open spaces for water in the future, and perhaps adding more ‘Regndiken’ (rain ditches that act as a buffer zone for rainwater to delay the flow) to the site..”

Anders studied at Stockholm University for his Bachelor’s Degree in Human Geography, he focused on understanding the environment and urban development. Now he is the president of Naturskyddsföreningen (Swedish Society for Nature Conservation) since 2005. The company is founded in 1905 since the forest was clear-cut, and the aim for preserving the high natural value of Stockholm.

Anders believes that nowadays many countries are better at protecting than Sweden like Latvia, South America, etc. There is only 5-6% of the forest is being protected because of the industrial background of Sweden, which is not enough. “I could do more in my organization to push Stockholm Stad in preserving natural reserve”, he said, “It has lots of potential and rich resources to be developed”.

Currently, as a problem, Igelbäcken has too little water, and the stormwater from the highway is bad for the environment. Anders thinks that the PFOs (toxic chemicals) from Barkarby district are a threat to Igelbacken. “When you handle the water from Järvafältet, you should have wetlands before the water comes to Igelbäcken. If there are more plants in the area, they can take up and filter the pollution”.

The activist group “Återställ Våtmarker” has existed for many years, they call for restoring wetlands and an immediate stop to using peat in Sweden. “It is very good to restore the old wetland, so the peat will not come to the surface, and the air will not touch the peat. Making more wetlands can help protect the peat”, Ander said. As the president of a legal group, he prefers a more formal way of making action rather than a way of protest, however, he also agrees with the problem of the slow working process for legal groups. “Also there is a lot of money that goes in the wrong direction, we need to tell them to spend money on the wetland instead of the wrong direction”, Anders said.

Anders encourages making more meeting places in Järvafältet to avoid possible issues of racial disparity and segmentation of different groups of people. He believes if we make the green area more interesting, it can change people from different areas. “I do not agree that the green spaces divide people”, he said.

Anna joined Ekologigruppen as a Landscape Architect, who specialized in the research of green wedges. Her research of Järvafältet started in 2006, throughout the time she did interviews with people from different ethnic backgrounds about the use of green wedges. Anna also participated in projects around Järvafältet, like putting up signs for the natural reserves and for Igelbäcken river. She believes that using signs as an information board and directions to guide is really helpful. “People might criticize the use of signs as too traditional, but I am trying to create it as a menu to present information about nature. It can also help people find their way out in nature.” Anna said. Putting signs can help introduce more of the area and educate people about its history.

For the issues of the stormwater and water run-off in Järvafältet, Anna thinks although it is hard to solve the issues, it will be amazing to do more open stormwater solutions which lead the water to Igelbäcken. “It seems everything is working against the Igelbäcken, because throughout history, the water level is decreasing, while the ground level is rising.” We discussed our proposal of expanding the water network by creating more wetlands, which Anna thinks is a good idea. “Creating more wetlands can help prevent the exposure of old peats that leak out tons of carbon monoxide”, Anna said, “We have to accept more chaotic expressions in nature to deal with all the challenges we are meeting in the future and for now”.

As a green wedge expert in Ekologigruppen where they work with restoring wetlands since the early 1980s. Anna has colleagues who struggled with the issues of wetland restoration for many years. “I can see a few of them are really annoyed at the activists when they are using really harsh sentences...It is kind of ironic. We were doing the actual action for restoring the wetland, and we got stuck by a traffic jam that the activist causes”. She believes that the Igelbäcken is needed to be funded by a private landowner for processing the restoration, which should be requested formally through the government.

At last, Anna suggests it is nice to use the grass from the wetland for the growing vegetable since it has many nutrients. “We have to find a circular way of working with the wetland.” It is important to reuse the resources for saving energy consumption and to save the climate.

“We have to find a circular way of working with the wetland. If you want to cut the peat industry, you need to find alternative material as well”

“We could do more in my organization to push Stockholm Stad in preserving natural reserve, where there are lots of pootential and rich resources to be developed”Photo: Online Zoom Interview Process Photos: Anders Tranberg and Anna-Maria Larsson

Igelbäcken and the land uplift in the Järva field

The last ice age ended about 10,000 years ago. The ice cap was so heavy that it pushed the land mass underneath into the sea. Then, as the ice melted, the land began to rise again.

So, little by little, more and more land became available for people to live on.

The first small islands emerged from the sea around 42003300 BC. The sea in which Akalla was located was called the Litorina Sea, which consisted of meltwater from the ice cap.

In the Middle Neolithic, most of the Järva field was still under water and only a few small islands emerged, including Hjulsta, Rinkeby, Tensta and Husby.

Then, in the Bronze Age, the area around the Järva field became an inland archipelago landscape. What had once been sea and open water was transformed into bays. Almost the whole of Akalla emerged from the water and the inhabitants lived from agriculture, livestock, as well as from hunting and fishing.

By the time we reach the Viking Age, the bay has completely disappeared from Akalla. The new land that was previously sunken was used as pasture.

Thereafter, Igelbäcken was a more important watercourse than today, around which farms and villages developed over time. Access to fresh water was a prerequisite for settlement. The inhabitants of Akalla needed drinking water and water for cooking. They could also wash their clothes and bathe.

And later, the remains of a mill and a water saw were found.

Today, Igelbäcken is a small stream in northern Stockholm. Its drainage area is shar ed by the municipalities of Järfälla, Sollentuna, Solna, Stockholm and Sundbyberg. Stretching more than 10 kilometers from west to east, from Säbysjön to Edsviken near Ulriksdal Palace, Igelbäcken is fed mainly by the Djupanbäcken stream, which carries water from the small lake Djupan. Because of its location in the national park and its untouched character, Igelbäcken is considered one of the most valuable bodies of water in Stockholm.

The wetlands: carbon binding and water filtratingand left to dry out

Until the mid-1800s, much of the region was completely, or periodically, a wetland. Industrialization changed the needs of the land - from pasture to agriculture. This led to extensive water drainage in the region in an effort to gain arable land but with the loss of large wetlands.

Water that existed naturally in the landscape was systematically drained, and water sources were maintained, flushed, straightened, deepened and channeled, resulting in lower lake levels and soil drainage. New cropland was then quickly obtained and the effective drainage prevented cropland from being flooded.

Trenching in the forest has a similar history, and has always been used to lower surface groundwater levels to reduce the risk of frost, increase soil oxygenation, and create favorable conditions for forest production. Until the 1920s, there was a widespread belief that virtually all land could become forested if dug to a sufficient depth. In Sweden, the proportion of forest land excavated on peat is about 2.5-5%.

A direct consequence of extensive drainage is a dry landscape that has lost its water management and flow equalization function, while the need for water is high. Another environmental effect is an increased leakage of nutrients that negatively affects lakes, rivers and the Baltic Sea due to the loss of natural filtration in the water landscape. These major changes have also had negative effects on plants and animals, as their living conditions and connectivity have deteriorated. Recently, attention has also been drawn to the fact that large amounts of greenhouse gases are being released from peatland excavation.

During the last two years, more than 22 km² of wetlands in nature reserves throughout Sweden have been restored, measures that have led to a rise in the water table of 7.2 km² of peatlands, with many positive effects on the climate. The County Administrative Board has received from Naturvårdsverket the means to take action in more than 300 wetlands in protected areas across the country. 32 surveys for future actions have also been made, for the coming years.

“Then, as the ice melted, the land began to rise again.

So, little by little, more and more land became available for people to live on.”

“During the last two years, more than 22 km² of wetlands in nature reserves throughout Sweden have been restored, measures that have led to a rise in the water table of 7.2 km² of peatlands, with many positive effects on the climate.”Photos : satellite images showing the water level over time Photo: peat harvesting 4200-3300 BC The Middle Neolithic The Bronze Age Today Year 0 Photo: Hästa pond, a wetland along Igelbacken with rich bird life, 2022

“In Sweden, the proportion of forest land excavated on peat is about 2.5-5%”

Our vision for the project is to bring the water back to Järvafältet, use water as a medium to enhance community engagement, and environmental protection (like lower air pollution), and as a carrier for the experiment of emerging communities on water.

Our strategy will be divided into 3 phases according to importance. The first phase is the ‘purification’ of the beginning part of the river near Säbysjön Lake, and the linkage to the hard surface like the highway, roads, and urban areas. Hence, they are purified before entering Igelbäcken. The second phase is the ‘connection’, where we extend the blue to the metropolitan area through ditches and small ponds. At the same time, activate the waterfront area by creating recreational nodes (the pearl on the necklace) to turn it into a spotlight of the green wedge. The third phase is to ‘develop the beaver area’. The beaver habitation wetlands can increase biodiversity, improve water quality, store water during drought, and minimise flood risk.

Sketch of the blue strategy in relation to the biodivervsity and the purification of water and air

purification Beaver habitation Recreation Culture Living Education

Igelbäcken and its extension

Pedestrian and cycling path Roads

2-step ditch (constructed purificatiob)

Our vision for the project is bringing the water back to Järvafältet, use water as a medium to enhance community engagement, environmental protection, and as a carrier for emerging communities.

In our development strategy, we propose to connect the Igelbacken river with the technological catchment area through a central blue axis, where a new train station Barkarbystaden will be built in the future. It then grows in the form of rib/tree branches, for conveying the water to each neighborhood, and for activating and enlivening each community.

We classified the river into primary, secondary, and tertiary blue spines, where the added river follows the topography and the roads. The primary spine is along the central axis, connecting 3 train stations. It is planned to be a ‘vivid corridor’ with a variety of public buildings and platforms. The secondary spines are carrying the river to the forest and communities, where the tertiary spines are used to further extend it to the residential area. Purifying wetlands in each crossover area on the central corridor are our important nodes, to ensure the water is purified before it enters the community.

Our research into the Järvafältet in North-western Stockholm has centred around the composition of the soil and resultingly in food production too. The green wedge, cutting through two dense residential areas boasts high ecological value.

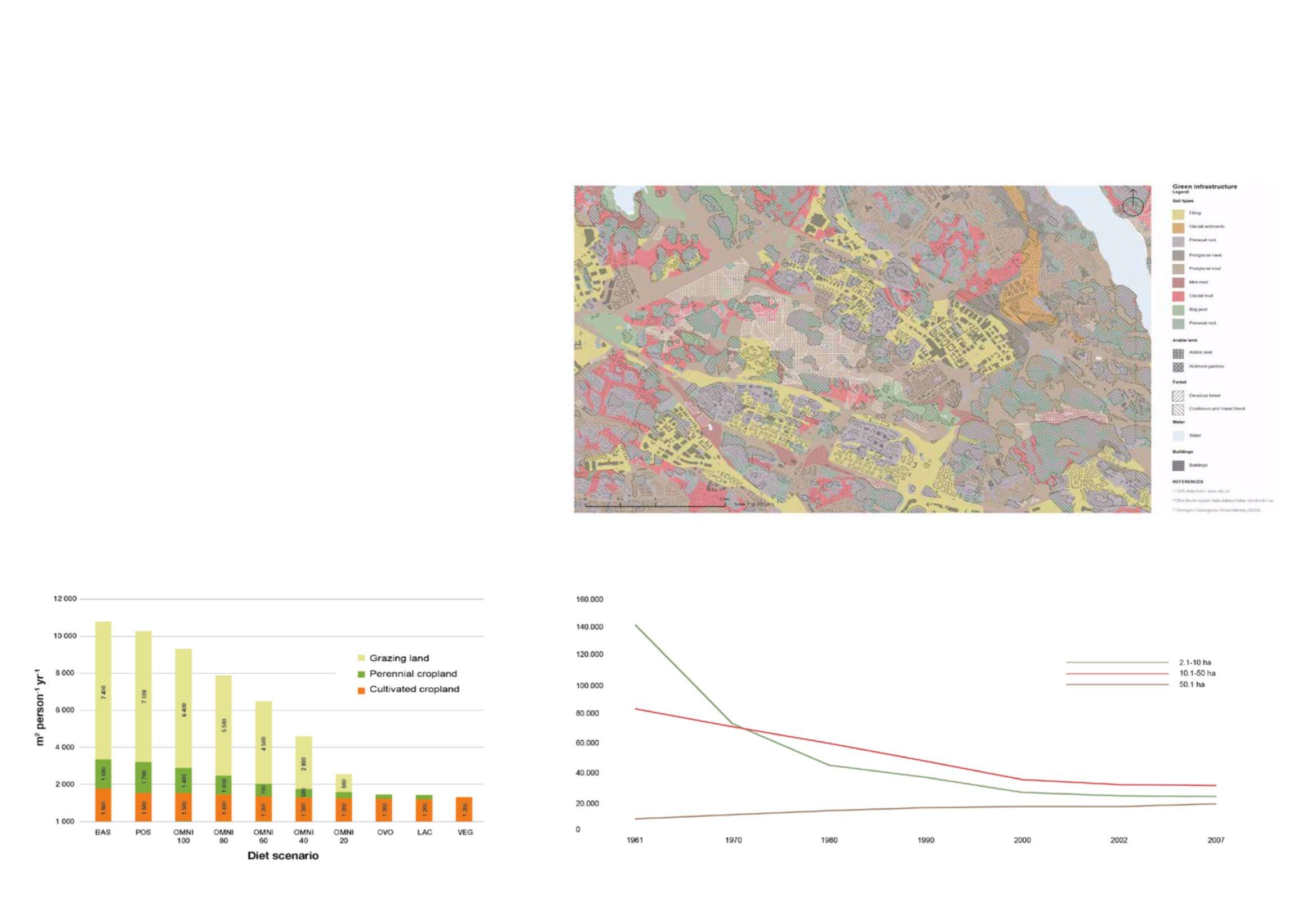

Reading into the history of the site has shown a decline in the use of the arable land as farmland. This echo’s the national trend in the decline of small to mid-scale farms as highlighted in the graph. On a global scale, we are becoming more reliant on large-scale farming to provide us with our daily food. This causes friction with our increased need to reduce our carbon footprint – with the average vegetable travelling 2,400km before being consumed. Today most of the old farmland is used for leisure purposes to serve the very few. A prime example of this is the conversion of working farms into stables for horse riding. By visiting the site, we were able to see that the use of allotments was a popular pastime. Not only does this have a great environmental impact by reducing the carbon footprint of the food consumed – but it is also positive in a social sense – encouraging time spent outside with the community. While still wanting to keep this idea of community in our research, we wanted to delve deeper into what possibilities there were to strengthen the site in an ecological sense as simply reducing food miles was not enough. We then investigated the soil’s ability to absorb carbon in different areas in the site in conjunction with possibilities for rewilding.

Inspired by Effekt’s concept of the ReGen Village, we started to consider the possibility to utilise non-arable land for aquaponic farming. By doing this it could help feed the ever-growing community in Järva while freeing up to 98% more space than traditional farming methods. This saves space and frees up more space for rewilding, encouraging more biodiversity and absorbing more carbon.

Soil types plan

Amount of land to feed a person with different diets

Chart numbers of farms with at least 2 hectares of arable land in Sweden, by arable land.

Jonas Jerberg is an architect and a planner. He’s also an expert on urban farming. Today Jonas has his own practice called Urban Works focusing on urban planning and urban farming.

In his practice Jonas is working with, along other things, urban farming in Enköping and writing a debate article about urban agriculture in Sweden. His knowledge about Järvafältet is quite broad. One of his last projects as an architectural student was in Järvafältet.

During the interview Jonas was talking about how it is important to connect the areas around Järvafältet. Currently the bourders of the area are being even more built but Jonas thinks that Järvafältet also has potentiol. He says that the area should be a green area but built elements could be added, such as housing. A more clear border should also be defined between the built and the non-built areas.

To strengthen the connection between these areas is something that Jonas talks a lot about. Strengthening the physical connections could be a way to work against the ongoing segregation in the area. He also mentions that more public functions should be added in the area and highlights the outdoor swimming pool in the area as a good example.

Regarding urban farming Jonas talks about one of the main challenges being the cost of the electricity needed but also the cost of the maintenance needed for urban farming to work. He continues to explain that a business model and commercial viability are necessary. In the area people are selling vegetables but much of it is not coming from Järvafältet, it would be intresting to connect these aspects Jonas explains. He reminds us that not everyone is good at farming or wants to farm, therefor urban farming should be organized and profferinazied.

Ulrika Egerö is a urban planning strategist (stadsbyggnadsstrateg) and works for the municipality of Stockholm in the planning deparment. She is also a ecologist and has worked with Järvafältet for a long time.

Järvafältet and the housing districts in the area lack a lake nearby. A questionnarie was made for the residents of these areas regarding what activities the residents lacked in the area. Most of the answers conserned a swimming pool. This was the case both in the 1970s and 1990s until an outdoor pool was built in the area. The pool was funded with tax-money because it was considered to be an activitty for the health. A lot of other activities in the area aren’t funded by tax-money beacuse the municipality dosen’t think that those activities will improve the health of the inhabitants. Ulrika disagrees with that and mentions that a lot of other activities could improve the health in the area in different ways. She also mentions that people in these areas usually can’t afford a car which makes it harder for them to travel to different parts of the city and be active.

Regarding the closed farms in the area and how to use the remianing buildings and areas Ulrika talks about the importance of having more activities and places to visit. These closed farms could potentionally be places to visit with different activities, she explains. She also mentions how people’s health could improve if there were more activities in the area. Having cafés or other activities would make people walk more and it would imporve the “social health” Ulrika explains.

Another intresting topic that was brought up in the interview is carbon sinks and sources. Ulrika explains that young forests work better as carbon sinks than old forests and says that the former wetlands act as carbon sources today.

“The former wetlands act as carbon sources.”Photo: Jonas Jerberg, an architect, planner and expert on urban farming.

“The value (of developing Järvafältet) is to dicrease the transport, (strengthen) the social aspect and biodiversity.”Photo: Enköping Stadsjordbruk & Foodtech is a report about Urban Farming and Foodtech as a tool in planning and urbanisation made by Urban Works.

Already in the Bronze and Viking ages humans were living in and around the area of Järvafältet. They were livestock keepers and lived in the area with animals. Today we can see rune stones and grave remains of these times.

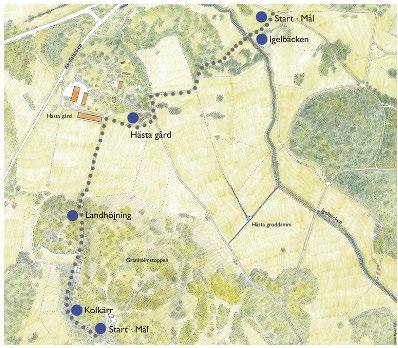

A long time ago Igelbäcken was a miles long waterway. Around it yards and villages sprouted. The water of Igelbäcken worked as a way to connect people. The access to drinking water was a big part of why people were living in this area.

Hästa gård was one of the yards that took form in the area a long time ago, already in the viking age people were living and farming there. Up until recently the farm was Stockholm’s only living agriculture and one of the world’s biggest urban agricultures.

In the 1970s the areas nearby Järvafältet started to be built. The self-sufficiency trend was transformed to a trend of buying your food in a local market. The local market itself could get the food from anywhere in the world. This trend is not specific for Järvafältet or even Sweden, it is an ongoing global trend that is transforming into an issue. Vegetables travel on average 2 400 km from farm to consumer today. This causes a 12% extra emission before consumption.

“Every time you make a decision about food, you are farming by proxy.” is a quote by the American writer Jonathan Saffran Foer. Dijstelbloem (2012) explains that to Foer awareness of what we choose to eat is a moral duty. Even though Dijstelbloem is critical to that statement the quote is really interesting in the context of our group’s narrative. We as planners and architects could also make an effect in how things are produced and what is available for a community. Is it locally produced food or is it transported thousands of kilometers?

Today there is a small vegetable market in Rinkeby Torg (Rinkeby Square) where vegetables are imported from Turkey and other countries. The market is quite popular in the neighborhood. The market seems to be a good thing for the community but as it is today it also awakens a moral question about how far the vegetables are being transported. The vegetables from different parts of the world could be replaced with locally produced vegetables. Dijstebloem (2012) explains that the micro and macro levels in the case of food are linked together. A vegetable-market in Rinkeby is a local actor but it has a global effect too.

(1) Stockholmskällan, Järvafältet (https://stockholmskallan.stockholm.se/teman/Stockholmsplatser/jarvafaltet/)

(2) Stockholmskällan, Tidens väg, en vandring i historien (https://stockholmskallan.stockholm.se/ ContentFiles/SSM/Texter/Text_0001/Skyltar_tidens_vag.pdf)

(3) “Food, A Compromised Issue.” In Food for the city, A Future for The Metropolis, edited by Stroom Den Haag (p.58-64). NAI Publishers, 2012.

Map of a route in Tidens väg (The way of time). Showing among other things Igelbäcken and Hästa gård.

Our development strategy for the Järva area is to explore how current mass and void can be used in the future.

The functions of buildings will change to suit modern, eco-conscious lifestyles; the voids between them will follow suit. Vertical farms will be in current residential areas with markets arising to distribute crops to the dwellers. The land will soften the edges and boost biodiversity between built and wild, through allotments, orchards, new forests, and grazing land.

Approximately 190,000m2 density of new builds will be proposed in hard surfaced areas that already have plans to be built upon, approximately 90,000m2 density will be altered, removing industries that have grown obsolete.

We aim for the mass to become more productive and the void to be less of a chasm between communities and more of a space for joining neighbours and neighbourhoods together.

Sketch of the strategy - Multiple neighbourhoods mixing through multifuction spaces in Järvafältet.

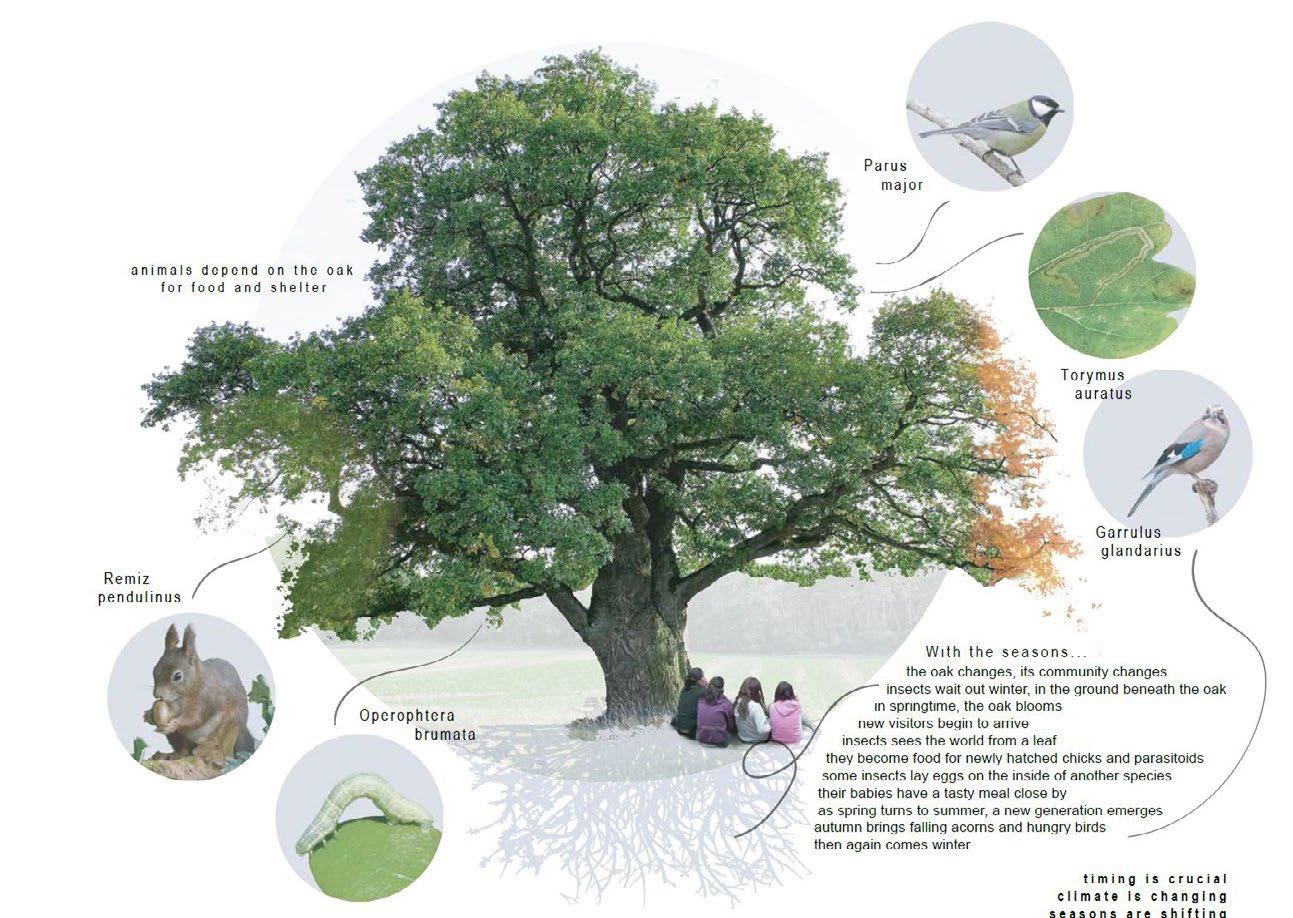

Our research initially focused on the Järva wedges habitats, biotopes and ecological infrastructures. The nature in the Järva wedge is varied and contains everything from deep conifer forests to flowerrich pastures, leaf groves, forest marshes and wetlands. After receiving knowledge about the oak’s importance in ecological infrastructure, we decided to map out oaks in the area. The oak is a vector for biodiversity, a key biotope, home to a large number of species. They function as stepping stones for animals to travel. We have noticed that there is a big gap of oaks in the Järva area. Why can this be?

Oaks can get very old. An oak’s conservation value often comes into play when the tree is about 150 years old. The oak is the tree with the largest number of species associated with it, upwards of 1,500 species, of which approx. 800-900 insects and 400-500 mosses, lichens and mushrooms. The acorns are sought after by many wild animals, such as squirrels, deer and jays (bird). Jays have an important relationship with the oak, through its winter storage of acorns under the grass cover, the acorns spread to new places where they can germinate. Therefore, a good way to spread oaks is to make sure there are optimal living conditions for this bird, and then it’s important to know that these birds nest in coniferous forests, so therefore to get more oaks, we need to make sure there are also other trees like pines.

For a long time the oak was a “royal” tree. The wood was used mainly for boats and larger buildings and was brought to the royals as gifts. When society and agriculture changed, the farmers during the 19th century got the right to rule over the oaks on their lands. It led to large amounts of oaks being cut down.

The greatest threat to oaks is a lack of care so that they are shaded by other trees or buildings. A building with a height of 15 meters must stand more than 32 meters from an oak environment if they are to get sun from morning to afternoon. Other major threats are felling, exploitation, continuity time gaps, isolation of populations and dispersal barriers.

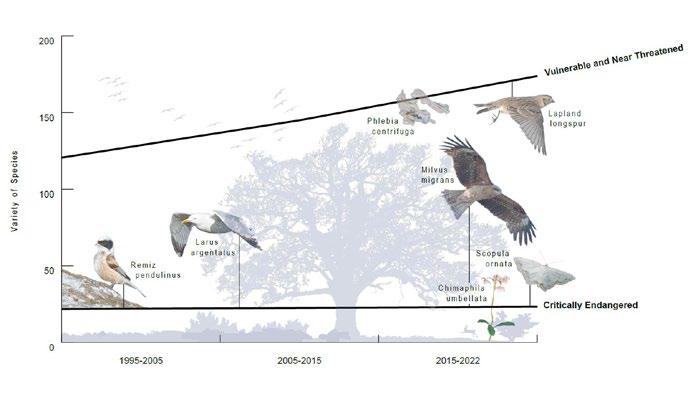

In the graph we have shown the red-listed species that exist and have existed in the area. We wanted to make this graph to show some effects of the changing landscape and furthermore on the biological diversity connected to Järva’s biotopes. What vegetation has disappeared and what ecological values?

(1) City of Stockholm, Vision Jarva 2030. https://international.stockholm.se/ globalassets/rapporter/jarvalyftet_broschyr_en1.pdfv

(2) Lennarth Jonsson, 1966. Oaks in Sweden. Journal of International Oak Society, (7), pp.32 39

Elisabeth Mårell is working as a regional planner in Stockholm. In her role it’s important to have a focus on topics and questions regarding larger areas. Municipalities are responsible for their local contexts, but planning on a regional level deals with the needs that connect over municipalities borders. She says that as a municipality, you can’t only think about the local effects. Changes can create effects in places far away from you, not only in the bordering municipalities but sometimes ever further.

Right now they’re working with the green wedges of Stockholm. The wedges stretch from the inner parts of Stockholm city center, to the more rural areas of Stockholm. Mårell emphasizes awareness when working with these green wedges. When changes are made in these areas, we are potentially risking great functions, both recreational and biological.

In the process of regional planning, the focus is set on the future. In Mårells office, they’re mainly looking towards 2030 but also 2050.

Mårell describes the Järva wedge as a man-made landscape and refers to cultural history. Not only are there nature reserves but also culture reserves. She says it’s important to plan for the maintenance and how to take care of the different parts of the landscape. The wedge is situated between residential areas, with a lot of people living alongside the wedge, which makes it important for different kinds of recreation.

On the regional scale, the effects of climate change are clearly noticeable on the green wedges, which can help mitigate the effects of climate change. Green wedges help with many ecosystem services such as temperature, humidity and flood control.

The Jarva wedge is vital for ecology of the site and Mårell hopes it will stay in tact. However there have already been talks about developing the area for safety and integration reasons by connecting Sollentuna and Rinkeby. If developments as such occur, ecological functions can be put at risk. It’s vital to know the consequences and effects development can cause, on recreational aspects too. Currently a cemetery is being planned, but other recreational functions must move in order for the project to develop.

There is a conflict between cultural and nature based solutions, as they’re incompatible with one another.

Some areas need to be disturbed by humans for values of nature to be kept. Maintenance programs must exist, as there is almost no nature without human interference.

The maintenance is connected to the mankind having used the landscape for a long time. The landscape is affected by for example animal grazing. If the goal is to keep the area the way it is now, the agricultural and forestry maintenance must continue. Otherwise the landscape will change.

“If you want to keep it that way, you need to keep maintaining it and if you stop, the landscape will change. It will not be the same landscape anymore. You may have different values then, but they are not the same values you are trying to protect now.”

“The maintenance is connected to the mankind having used the landscape for a long time. The landscape is affected, for example, by animal grazing.”Photo: Highland cattle (naturskyddsforeningen.se) Photo: Elisabeth Mårell (regionstockholm.se)

For our third interview we interviewed Anna Barr, an oak expert. Anna describes oaks as little islands with animals living on them. They are small worlds in themselves. The oak is providing homes in every part of the tree for different organisms, and it changes during its lifetime. As it gets older, more cracks and cavities arise where species can live.

Anna was interested in the matter of connectivity. She started biking around Stockholm for her master thesis, stopping and looking at a couple hundred old oaks. To be able to measure the connectivity, she created a connectivity

index. She was studying the trees, studying what species were on the oaks, and how many there were. Connectivity was an important factor in how many insects she saw on the trees. She also looked at leaf litter, how much was allowed to stay around the tree. It is very important for small insects and other animals to be able to overwinter and climb up on the trunk.