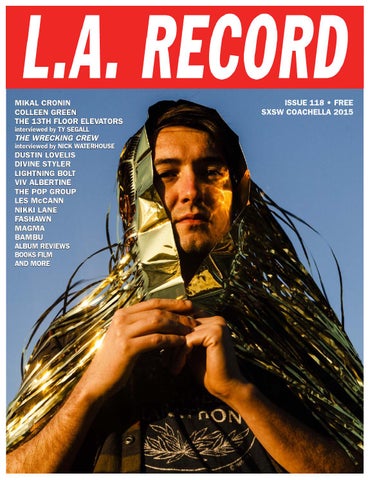

MIKAL CRONIN COLLEEN GREEN THE 13TH FLOOR ELEVATORS interviewed by TY SEGALL

THE WRECKING CREW

interviewed by NICK WATERHOUSE

DUSTIN LOVELIS DIVINE STYLER LIGHTNING BOLT VIV ALBERTINE THE POP GROUP LES McCANN NIKKI LANE FASHAWN MAGMA BAMBU ALBUM REVIEWS BOOKS FILM AND MORE

--1 Ê££nÊUÊ , SXSW COACHELLA 2015

B=07/A 83AA= 8@

/[S`WQO¼a <Sfb 0`O\R <Se 0OU /\R 6S¼a 1O\ORWO\ <Se /ZPc[ 5==< =cb ;O`QV % ]\ B`cS >O\bVS` A]c\Ra

6

ANGEL OLSEN Daiana Feuer

10

DIVINE STYLER sweeney kovar

14

THE POP GROUP David Cotner

36

MAGMA Kristina Benson with Sabrine Mhiri

COLLEEN GREEN Chris Ziegler

40

LES McCANN Ron Garmon

20

NIKKI LANE Frankie Alvaro

42

RUDY De ANDA Desi Ambrozak

24

FASHAWN Rebecca Haithcoat

51

SXSW GUIDE

52

JESSICA PRATT Daiana Feuer

54

LIGHTNING BOLT Zach Mabry

58

BAMBU sweeney kovar

62

DUSTIN LOVELIS Chris Ziegler and Kristina Benson

16

28

32

THE 13th FLOOR ELEVATORS TOMMY HALL Ty Segall RONNIE LEATHERMAN Chris Ziegler FRANK DAVIS Chris Ziegler MIKAL CRONIN Chris Ziegler and Kristina Benson

RUDY DE ANDA BAND BY STEFANO GALLI

ADVERTISE WITH L.A. RECORD

EDITOR — Chris Ziegler — chris@larecord.com PUBLISHER — Kristina Benson — kristina@larecord.com EXECUTIVE EDITOR — Daiana Feuer — daiana@larecord.com CRAFT/WORK EDITOR — Ward Robinson — ward@larecord.com COMICS EDITOR — Tom Child — tom@larecord.com FILM EDITOR — Rin Kelly — rin@larecord.com ASST. ARTS EDITOR — Walt! Gorecki — walt@larecord.com DESIGNER — Sarah Bennett — sarah@larecord.com ONLINE PHOTO EDITOR — Debi Del Grande — debi@larecord.com WRITER AT LARGE — D.M. Collins — danc@larecord.com ACCOUNTS Kristina Benson, Chris Ziegler CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Frankie Alvaro, Desi Ambrozak, Ron Garmon, Jason Gelt, Rebecca Haithcoat, Zachary Jensen, Eyad Karkoutly, sweeney kovar, Zach Mabry, Emily Nimptsch, Ty Segall, Stephen Sigl, Daniel Sweetland and Nick Waterhouse CONTRIBUTING DESIGNERS Kristina Benson, Jun Ohnuki CONTRIBUTING COPY EDITOR Amanda Glassman CONTACT fortherecord@larecord.com

For more information about advertising with L.A. RECORD, please contact us at advertise@larecord.com. ALBUMS, FILMS, BOOKS, ZINES AND OTHER THINGS FOR REVIEW

L.A. RECORD strongly encourages vinyl submissions for review and accepts all physical and digital formats! We also invite submissions by local authors and filmmakers. We review any genre and kind of music and especially try to support local L.A.-area musicians. Send digital music direct at fortherecord@larecord.com. For film—Rin Kelly at rin@larecord.com. For zines—Sarah Bennett at sarah@larecord.com. For books—Kristina at kristina@larecord.com. Any physical copies to:

L.A. RECORD P.O.BOX 21729 LONG BEACH, CA 90801 SUBMISSIONS

L.A. RECORD strongly encourages submissions of all kinds! If you would like to interview, review, illustrate or photograph for us—or help in any other way— please get in touch! Email fortherecord@larecord.com with “submissions” in the subject line and we’ll get you going.

f COLLEEN GREEN PHOTO — Alexandra A. Brown MIKAL CRONIN PHOTO — Ward Robinson DUSTIN LOVELIS POSTER DESIGN — Ward Robinson and Jun Ohnuki All content © 2015 L.A. RECORD and YBX Media, Inc.

LOS ANGELES’ BIGGEST MUSIC PUBLICATION • LARECORD.COM • FORTHERECORD@LARECORD.COM The award-winning L.A. RECORD was started in 2005 on a bedroom floor as a one-page weekly broadsheet dedicated to Los Angeles music of all genres and generations. Now after five years and 100 issues, L.A. RECORD is still a totally independent grassroots print-and-web operation, run and staffed by writers and artists from across the city. “The city’s liveliest bastion of grass-roots, punk rock, seat-of-your-pants music writing ... L.A.’s most formidable music magazine.” — The Los Angeles Times “Make no mistake; the L.A. RECORD is punk rock.” — Huffington Post “Our favorite local music publication.” — L.A. Weekly

4

SUBSCRIPTIONS TO L.A. RECORD Five issues each year of our giant bimonthly with up to 100 pages of homegrown content including definitive and daring interviews; original full-page, full-color art and photography; the most comprehensive compilation of Los Angeles album reviews ever, and our much-loved album-cover-recreation centerfold—suitable for framing if not human consumption. Subscribers may also receive flexi records, discounts, free gifts and luxurious special treatment however we can arrange it.

U.S.A. - $29.99 WORLD - $49.99 L.A. RECORD Subscribe at shop.larecord.com, email kristina@ PO Box 21729 larecord.com to set up PayPal, or cash or check to: Long Beach, CA 90801

ANGEL OLSEN Interview by Daiana Feuer Illustration by Dave Van Patten

It’s the end of February and Angel Olsen will be home in Asheville, North Carolina, for two whole months. It’s been a while. One year ago her second album came out, Burn Your Fire For No Witness—all electrified and with a full band, fulfilling expectations built up after her 2012 solo album Half Way Home. From Bonnie Prince Billy back-up singer to indie folk phenomenon, she started meeting fans when she shopped for toilet paper. As wonderful as that is, it sounds like it doesn’t get easier when people actually like what you do. Olsen gets reflective in this interview. Has touring a lot made your relationship to time and days become more loose? All year it’s been, ‘What day is it? Where are we? Whose time are we on anyway?’ (Laughs) I did this Australia trip recently. I get back home and I’m hyper until 6 am. I can’t sleep! So, that’s cool. I finally get almost two months off now which is really great. In the meantime I want to find an isolated studio. That’s my project, so I don’t go crazy from the contrast of doing a lot at once and then doing nothing. You don’t like doing nothing? I don’t. Especially when I’ve just been doing a lot. I would take a vacation somewhere, but now I travel so much as work that I’m like, ‘Well, if I’m going to be in this weird part of Mexico, why don’t I book a show?’ Maybe that’s just how it goes when that’s what you do for work. It’s also like, ‘Why would I want to get on another plane?’ I want to stay in one place for an extended period of time. But I do like to have stuff do when I’m back home. The contrast is too intense. From working all day, being on call all day. There’s a tour manager but I make the decisions in a lot of cases. If something is wrong, I’m the default person. Whether or not anyone sees it or knows, I’m there making sure everything is going well. This month marks a year since Burn Your Fire For No Witness—are you celebrating or reflecting on its first year of life? Actually a few months ago, I sort of did something commemorative. The artist who drew the cover, her name is Kreh Mellick. She does stuff for The New Yorker. She’s great. I wanted to buy something from her site but she insisted on making something special. So I had this rolled up piece of art in my closet all year and my mom’s like, ‘What are you doing? You need to hang that up!’ But it was kind 6

of weird because I see this thing everywhere I go. It’s on t-shirts, on merch, posters, on everything. But I went to the frame shop and got it framed and we hung it over the fireplace. In that way I have celebrated. It’s there in my living space and it’s something I face and see and know that this is part of my life now. This is something that I’ve done and it’s part of people’s lives in ways I won’t understand and not in any way I can control. The thing that makes it interesting and also frustrating is that even if I have made something I am proud of, there’s this personal pressure that I want to outdo that in some weird way. I want to do something totally different. Then there’s also the fear of ‘What if no one understands the direction I go is better?’ You have to accept that. Right now I just want to get away from watching any press of myself or any footage or knowing anything related to my music so that I can just fully forget about it, and listen to other people’s music and listen to old music and watch movies and just do stuff that has nothing to do with me—so I can remember what it’s like to be in my crappy kitchen in Chicago and not have any money and not have any idea of who is who in the music industry. When I had nothing to really lose or gain, it was just there. That’s what I want to focus on because it’s just all around me in every corner. I want to make sure I’m not trying to recreate the past and it doesn’t continue on someone else’s plan. Once you put a part of you into an object, and the world takes it, it seems like you have to stay connected to yourself as a normal person that isn’t just a walking stage show. Yeah. This last trip we played the St. Jerome’s Laneway Festival in Australia and New Zealand and I got to know all these different

artists. I’d never met St. Vincent but we had a couple run-ins with them because our promoter was the same guy. We started talking about the industry with people who have been doing it fifteen to twenty years. It’s interesting to get perspective from others who have been doing it longer or differently, even people who make completely different types of music. ‘So what about your daughter, how do you see her in nine weeks?’ ‘How do you see your wife?’ ‘Are you on any medications?’ ‘Do you see a therapist?’ ‘Is your PR agent with you all the time?’ ‘Did you make those decisions?’ It’s one thing to come out with a great album and tour and party. When people have been through that a couple times, do they still have really awesome moments with people? And they aren’t completely bitter and jaded about it? I had that opportunity to exchange information with people similar to me and different from me, and to talk about how to stay connected even to each other in all this. After a while it gets to be like you miss these people and don’t know when you’ll see them. You never know how long any of it is going to last. What’s it like to have Internet trolls or sort of stalkers? Some of the commenters on your social media get weird. I really try to make an effort and joke around and interact with people on the page when I can and interact with fan people in general. Even if they’re creepy—and there are definitely some creepers. Just to be like, ‘Hey, I’m a real person. I buy tampons. I go to the doctor. I take care of myself. I have awkward moments like everybody else.’ I don’t mind putting myself out there. I want to project something that’s like, ‘Hey, I’m not only just these songs. I’m trying to interact with people too in a real

way. Not in an “I’m better than anyone because I know how to explain things in songs” way.’ I was at a party and a friend of mine came up to tell me about some year end review she read that basically said ‘Why does Angel Olsen have a Twitter account? That’s insane.’ Basically, my music is so sad and introspective that I don’t have a sense of humor. ‘But her album’s great—blah blah blah, you should check it out.’ I asked my friend, ‘Why are you telling me this at a party?’ In Chicago it was worse because I knew a lot of people that worked for papers and I felt like I was living in the matrix where everyone existed in two personalities. One for interacting with people and one for writing about them. Part of me was like ‘Cool, we’re friends, and I love that you’re a writer, but don’t feel obligated to write about me.’ I’d see things come out and be like, ‘Whoa, I know that writer. I went to school with his roommate. We made out.’ I don’t want to know about a person writing about me when they know all these things about me. I was dating Emmett from Bonnie Prince Billy and it was a private relationship. We never really talked about it. But a friend of ours who wrote for a column was like, ‘We spotted Emmett Kelly and Angel Olsen at such and such restaurant.’ I was like, ‘Why did you do that? You know us. You know it doesn’t matter. Are you doing that because your job makes you do it?’ People will do things sometimes not because they’re being clever and funny but because they’re naively interested in doing them. I had to learn to be less sensitive. But it was everywhere in Chicago. I would have a conversation with someone at a bar and we’d be having a great conversation about politics and at the end of it they would be like, ‘I just want to say, your INTERVIEW

album…’ And I would be like ... oh shit, you’re talking to me because of this thing? You’re not talking to me because we like talking about politics right now? Not that it’s an insult in any way. It’s a compliment. But it makes you feel like you should be unnecessarily prepared for that to happen. But then you’re kind of self-absorbed by preparing for that. It kind of messes with you. I moved to Asheville and it’s a small scene so I’m not as surprised if I run into somebody. People here like to listen to a lot of folk music and Appalachian music and music with a lot of writing in it. I mean— Die Antwoord comes here too. It’s not like just about that stuff. But a lot of people love Bonnie Prince Billy and Bon Iver ... all the Bons. It’s interesting to live here. It doesn’t feel as invasive. I’ve gone to the grocery store and I’m looking at a Neutrogena product or trying to figure out what kind of toilet paper to get and someone comes up and says, ‘Hey that was a really cool show last night.’ I’m like, ‘Cool, thanks! I’m just buying stuff to wipe my butt with later.’ I don’t necessarily have something amazing ready to say. I love hearing stories about Bill Murray. The way he handles his identity for people is to have fun. Immediately have fun. I hope one day when I’m older I can be this crazy weirdo lady who goes with it. I want to. I want to dye my hair smurf blue when I turn 65. Let me ask you something heavy. So your parents are older. Being on tour and doing this career, you don’t see them as much. Do you worry about them dying? Totally. 100%. I think about it a lot. But I thought about it since I was a kid too. I went through this cycle when I was kid, being like, ‘You’re all older than me—why is that? Did I not grow?’ ‘Well, you’re adopted.’ ‘Crap—you mean I have other people? I have other people that look like me?’ I don’t have the actual memory of my birth parents so it didn’t mess me up as much. But it still was weird. Then my mom got sick and had surgery and she lost her mother, and they gave her the wrong medication and it made her sick mentally and physically and she spent some time in the hospital when I was 13 or 14. And I thought, ‘My mom’s never going to be normal.’ And at the time my dad and I didn’t really have that great of a relationship. He was a war dad. He was kind of stiff and unemotional, but when you talked about the right things he would cheer up—like children, and church, and westerns. I would bring a guy home I was dating and say, ‘Dad, this is so-and-so!’ And he would be watching TV and wave at them with the side of his gaze. He would ignore them and turn up the TV. Now when I think about it, it’s sort of sweet. My parents are very old-fashioned in a lot of ways. I’m sure my mother will call me and be like, ‘Well, we’re going to have you for Easter Sunday, aren’t we?’ They’re existing in a different time than me. But I’m not the only one. I have eight brothers and sisters. Some of them are in St. Louis where they live and they see them a lot. There’s less pressure on me to check in on them and see what they’re doing. But honestly my parents have been really responsible with the whole aging thing. I know it sounds weird, but it’s not necessarily 8

the happiest experience to do that. They’re on top of stuff. Which is surprising to me. I love the doctor but I hate the cold-wall cold-floor everyone-is-anonymous feeling. I try to reach out to them. I’ve definitely made more of an effort to be involved in my mom’s life. Whereas when I was in my early 20s it was all, ‘Party, I got away from my parents. I don’t have to take care of them—woohoo!’ But now I’ve changed. Once you really talk to your parents, you realize they’re not idiots—but you were—and they’re smart and someday you will experience the same thing. I was talking to someone in St. Vincent’s band and they were like, ‘I don’t see my mom that much. That’s the one thing about doing this that is a bummer because she’s alone and I feel bad and I try to call her.’ And at least there’s that. You don’t have to be a physical presence as long as you know you’re on the right page with them. This applies to anyone who moves away from their family, whatever their career. Are your parents are proud of you? I think they view this as an Ed Sullivan experience. They think I’m out on stages and people are introducing me like I’m on The Ed Sullivan Show. My mom is like, ‘So, when you get out there, Angel, do they say a couple words aboutcha? Do you do improv duets?’ I’m like, ‘No, not really.’ They definitely know what’s going on but they’re from a different time. Because they’re so different in age and time, I’ve tried to listen to the music they listened to and try to relate in my own way and feel connected to them. Does understanding the world they come from—and these old world ideas that you come into conflict with—give you unique perspective on the world you live in? There’s so many things influencing how people work and how they adjust and form opinions and decide on them forever. It’s interesting to hear a perspective based on the Depression and WWII and not having any money and not ever being out of line because who knows what could happen? The end of the world could happen. What if you got an email today that said, ‘OK, the world is ending tomorrow.’ What would you do today? I’m definitely not the person building a hut to try and survive. I’m just going to go. I will just pass with everyone. I don’t care. I’d probably go roller-skating and try to kiss somebody. Listen to some records, smoke some weed. Call my mother. Probably before the weed, though, because that might be weird for her. I’d try to do as much at once but I’d also like just roller-skating and being with someone romantically. Those two are high up there. ANGEL OLSEN WITH SWANS ON TUE., APR. 14, AT THE EL REY THEATRE, 5515 WILSHIRE BLVD., LOS ANGELES. 9 PM / $30 / ALL AGES. THEELREY.COM, AND ON SUN., APR. 12 AND SUN., APR. 19 AT THE COACHELLA VALLEY MUSIC AND ARTS FESTIVAL IN INDIO. ANGEL OLSEN’S BURN YOUR FIRE FOR NO WITNESS IS AVAILABLE NOW FROM JAGJAGUWAR. VISIT ANGEL OLSEN AT ANGELOLSEN.COM.

l

magic is rea

20

09

FOR THE LOVE OF MUSIC. 6 YEARS & COUNTING

Festival headliners to hometown heroes trust Bedrock.LA for all their rehearsal, recording, gear fixing, gear renting and gear buying needs. Open seven days a week until midnight...give us a call or hit up our website for fast, friendly service.

213.673.1473

WWW.BEDROCK.LA

D

Int Ph

Wo in t era flow ac Fai beh inte Sty

How Con a gru prett livin mus I hav been put I jus para give to m and rock why do y essen then give Wha need The thin who exce be p com hand peop Wha for and conv thin all is and get s plan Why atten like, deals out inde from myse I kn

INTE

DIVINE STYLER Interview by sweeney kovar Photography by B+

Word power, it ignites like the sun. Divine Styler’s verbiage has developed a cult following over the span of 25 years since he first appeared in the late 80s via Ice-T’s Rhyme Syndicate. What appeared initially to be a particularly cerebral iteration of the Afrocentric Native Tongueera styles quickly blossomed into a fiercely iconoclastic voice. Def Mask, his fourth solo LP and his first since 1998, utilizes a voracious flow to craft a dark, affecting cinematic experience centered on a technocratic dystopia—think Aldous Huxley meets Rammelzee. On a cool L.A. winter afternoon, I sat in conversation with Divine Styler inside a private room at the Seventh Letter’s flagship location on Fairfax. With his teen son by his side, the one-of-a-kind MC candidly spoke about his journey through the music industry, the concepts behind his dystopian opus Def Mask, why he rejects the label of Afrofuturism and the guilty pleasures of smartphone art apps. The earnest intensity that has made his music draw in curious minds the world over is just as present in person as on wax. A musical Morpheus, Divine Styler offers up the red pill for those brave enough to take the plunge. How are you feeling these days? Considering the state of the world? I got a grumpy old man thing about me but I’m pretty much at peace. It’s a crazy world we’re living in right now. I had to back up from the music business when everything became free. I haven’t made a record in 14 years but I’ve still been doing music—I just wasn’t [going to] put anything out. Five out of those 14 years I just took to try and understand this new paradigm. People tried to tell me, ‘You gotta give music away.’ That didn’t make any sense to me. I didn’t understand how that worked and why you have to give it away. Pop and rock musicians aren’t giving music away— why do MCs have to give music away? Why do you have to make a free mixtape, which is essentially an album, and give it away? And then put out a free record for download and give it away? And then do shows and so on? What specifically made you feel like you needed to retreat from music for a bit? The Napster thing—the whole download thing. You then had groups like Metallica who spoke out against it, which I thought was excellent. We do this music and we should be paid for it. Just because a new generation comes into play and with the technology at hand people can download shit that other people are hosting doesn’t mean it’s right. What about the artist? The artist don’t work for the fan. The artist works for himself and he should be compensated. Those are conversations that piqued my interest into thinking about what we are getting into. Now all is accessible. Eventually iTunes caught up and other places caught up but you can still get shit for free. You can’t go anywhere on this planet and get shit for free—except music. Why is that? It was an interesting time to pay attention. Then you begin to ask questions like, ‘How do you get a record deal?’ Record deals don’t exist anymore, you have to put it out yourself. What does that mean? I did the independent thing so I know what that means from a wax perspective. I put out Directrix myself and then licensed it to Mo’ Wax. So I know how that process works but people INTERVIEW

are asking you how many Twitter followers you have or how many hits on YouTube you have, because that’s who they’re giving deals to now—people who give away their music. And the more ratchet—the more bullshit it is—the more followers they get because people are more interested in some craziness than then are in anything of substance. And now you have a generation of children that think the crazier the content the better the art. That don’t make sense. Why does it have to be just the worst shit ever to be cool? It’s not adding up. That being followed by the 360 deal—major or independent. There is no difference between a major and an independent company. The indies are backed by the majors and they’re all giving 360 deals. And certain acts are being promoted as indie artists though they’re really backed by a major company via proxy. Yeah. C’mon now—it’s still a billion-dollar industry and one of the most influential industries America has in the world. Who is making money? There is money somewhere. It appears there are fewer people making money so there has to be something deeper. That’s what I’m interested in. How can I do this so it works for me and not against me and I don’t have to make mixtapes and give away content for free? It’s hard to make a record— it’s not easy. You need resources, you need a place, you need to have your bills paid and take care of yourself. How are you going to do that shit? Get an investor who wants 200 per cent return on his investment? You said something really interesting earlier—that the artist doesn’t work for the audience but for himself. I see behavior in hip-hop today that shows the opposite. ‘You gotta give them what they want.’ They don’t know what they want. They want what you give them. When did the psyche flip to where now you’re serving the fan? What does ‘fan’ mean? It came from the word fanatic. Look at the language. I come from a different school. I read. [laughs] I want to understand something before I do it. So how did Def Mask happen?

I made contact with [UK label] Gamma Proforma. I was doing some art on Instagram. Rob [Swain] and I chatted a little bit and he wanted to use some of the art for a show he was doing. I had just started doing hip-hop demos and I gave him a couple of songs. One thing led to another and I started getting back into the swing of things. A year later he hit me up like, ‘You want to make a record?’ The reason I decided to make a record with him is that he follows in the tradition of Mo’ Wax, which is a boutique small indie label that is more art driven than monetarily driven. That always works for me. I’m not the type of artist to do shout-outs, I’m not going to do certain things that now you have to do. I just want to do what the fuck I want to do, which is make music. I have people that like it and people that don’t like it. I’ve earned that over a span of 25 years and I’m cool with that. To have a company that understands that and doesn’t want to bend me to this new system and to have a company that is heavily art influenced also means the packaging is unique in a sense that it’s personal. It’s not a part of the machine. That’s what caused me to really be into it again. Speaking of your Instagram art—how did that begin? It’s pretty amazing. I’ve been writing graff since I was nine or ten in New York. When I started getting into computers I started illustrating on Photoshop. My idea was to take my graff and interpret it through the computer. Then I started my record label so I had to do all my own graphics so I really had to learn Photoshop. Casey ‘Eklips,’ who owns Seventh Letter, started teaching me shit back in the 90s and I’d sit there watching him do his mock-ups for his clothing line and it taught me how to do a lot. Then the apps for phones started to come out. I got this one called Snapseed and I started messing with it and I was like, ‘Damn! It would take you eight hours to do this on Photoshop or Illustrator.’ The technology is mind-bending. That led me to reading up on blogs about art apps and music apps. I downloaded more apps and just started

messing with them and I found a lane to be able to do the art that I like—that I would traditionally do on a wall—on my phone. There was a lot of guilty pleasure in that shit. Graff is all about burners and bombing and getting up and here I am feeling like I’m cheating. That’s how I got into digital art and I’m now heavily into it. That makes me think of some of the themes of Def Mask—how technology can be a tool to link us all as well as being something that isolates us. That lends itself to the age we’re living in. I can put out a record and make a traditional rap record or I can just embrace where things are. I’ve always been a tech head from the beginning of technology, from analog gear into computer recording. I do drum n bass, I do dubstep, I do EDM which is basically disco with bells and whistles on it. I like elements from all of those things and I like pushing envelopes. It’s just a culmination of all the technological capabilities of what is happening on the back end and what is happening sonically on the front end. I could do a traditional record but I’m always going to use the technology and pull from different sources to create a picture to back the concept. For me it’s about creating the music around the concept so it’s more cinematic than a traditional record. It’s more about an experience and the ride than just some headnod shit. People say, ‘Your music makes me think.’ I never intended it to be that way but as I’ve gone along making music I started to realize that I like doing cinematic stuff. Is that the kind of stuff that grabbed you when you were younger? Shit—Rammelzee. Rammelzee was a Five Percenter, he was a graff writer, so he was like a scientist. Between mathematics, science and math there was a school of us in the 80s who followed that route. You had Kase2, the one-armed bomber—he had the computer style. ‘Computer Rock,’ he used to call it. That’s where I was. I was on the Trans-Europe Express. I was into that tech-y sound but I was also into abstract futurism. I wanted to be 11

an architect so I studied Syd Mead, I studied Carl Sagan and shit like that. I was into sci-fi the whole time growing up as a kid. I started to sample those things and reduplicate those things in music. Rammelzee was a super influence on me, just being a graff writer and an MC at the same time who used to rap in graff style—although he had a whole universe backing his movement. He had theorems and treatises and all types of shit. A lot of people say I remind them of him and rightfully so— he’s the father of my style. I see my music in images first. I have the idea and I just see it. Like Directrix—I forget how I came across that word. When I read the definition of it, it said the median line of trajectory of fire. That created the whole landscape for me. That’s the balancing point. They use it for space exploration. I think I was reading something about NASA. The mechanics around directrix is that there will be a launch point and an orbiting point and then you have these geometric lines and you’ll have a directrix, which is a center point on which everything is counter-balancing. That kind of thing is how it works for me musically and visually. The visual is first and then I gather the source material to back the sound. What were some of the visuals you were seeing in Def Mask? As I began to write, I got to the Def Mask—the ‘Mask’ being what you use in opera or a play. In the old world, they would do operas with masks and those masks represent characters, but also a mask has to do with symbolism and the personification behind it. ‘Def’ for me—just being old school—def was the flyest shit ever. Def was the ultimate shit. It could be fresh, it could be funky-fresh, it could be cool ... but when you said it was def? It was untouchable. Once I got that combination then both worlds began to join. As I started to write around the concept of Def Mask and outlining my ideas, this character came and he became Def Mask himself. What does he use the mask for? To protect himself from the pollutants of the environment. Each part of his mask is an element—earth, air, fire, water, ether—each one of those elements have elementals which are creatures or components that adhere to that dimension. So I went way off into the sci-fi thing. I had to pull back and I started to categorize it how I could deliver it. I’m looking out into the world and we’re living in a borderline dystopian science fiction landscape now. This whole technocratic shit we’re moving into where laws are based on technology. In New York they’re trying to pass a law where you can’t text and walk at the same time. That’s technocratic. That’s due to technology being so crazy that they think people are so stupid that they think they’re going to get hurt if they’re texting and walking. It went from ‘you can’t do it in the car’ to now ‘you can’t do it while you’re walking.’ The foundation is being laid for a technocratic society based on data, projections and behaviometrics. Measurable patterns and behavior being compiled by data mining systems. The average citizen hearing this type of language immediately takes the defense and their only come back is conspiracy. Well, in an age where information is more readily 12

available in public domain than ever before, I find it fascinating that most don’t care to be informed except by what directly affects their immediate comfort zone. This is insane. It’s happening all over from the eavesdropping on calls to the collection of emails. Since the Patriot Act it’s been a wrap! Nobody is paying attention to it so I’ll fucking report on that shit. It’s a superimposed interpretation of what’s happening. Some people like to say that is conspiracy-driven and fear-driven paranoia but if you really look at it, a couple of years ago the US government admitted on the news—on CNN—to the Manchurian candidate program, which is called MK Ultra. They made two movies about it—the original and a remake—but it’s not a conspiracy. They want you to think it’s a conspiracy but in an age where information is everywhere, nobody is paying attention to information. I’m taking things I’ve run across, not from my imagination but from reality and weaving it in. Like in ‘Architectonic,’ the narration was a KGB narration from an actual KGB agent that defected in the 70s being interviewed on CBS Tonight. It’s on the Internet. I think Mike Wallace interviewed him—I can’t quite remember the interviewer but everything I said—I just re-recorded it—was everything he said. How am I paranoid? This was on the news in America in the 70s. So again—people don’t want to disrupt the dream, the illusion, that the American Dream is just that. We’re slowly moving into this fascist lock-down by way of convenience. I don’t make this stuff up. I report it. I research and gather legit source material. I think they use the conspiracy term to turn people off—to dismiss it. I don’t get into debates and arguments about it because it’s nothing to debate. Facts are facts. Look it up. So the record started going into an Orwellian dystopian thing, which is nothing new. People been writing about that shit forever. It felt cool and it was something different for me. I thought it was really interesting you included the instrumentals with the release. I like the instrumental version better than the vocal version because it creates a whole other cinematic experience. I was up in Frisco a couple of months ago and I was walking on the streets listening to the instrumental and it was another picture different from the actual content of the vocals but it matched. We did it for no reason other than ‘Why not?’ Did you incorporate electronic elements in the music to fit the concept? Or as a response to the electronic influence that’s so pervasive in music lately? Yeah—it lends itself to the concept more. It’s hard to listen to new music today. I don’t listen to too much rap. If I do listen to it will be my usual suspects, which are Nas, Premier, Ghostface, Raekwon, Death Grips—that’s the closest to me that you’ll get to where the people are today which is just on some ‘burn it down, it’s the fucking end’ shit. That reminds me of a conversation with my friend DJ Sake-One in SF. He was commenting how popular music today reminds him of the fall of the Roman empire because that’s when the empire was most decadent and gratuitous.

It’s a major transition where going through because we’re on the cusp of going from analog music, analog life, analog existence to this digital shit. My son don’t know nothing about analog. He don’t have a clue. Matter of fact, when he was born I purchased my Mackie digital console. I went from my analog Mackie to my digital Mackie. Kids don’t have any clue of that. I say that to say we’re on the cusp of moving into this new paradigm and the average person using the technology because they’re addicted to it but they’re not making the transition mentally. How do you not serve the machine and use it to benefit you to move forward? Instead of buying a $500 iPhone with all the memory you can get on that thing just to play music and to Snapchat and social media bullshit, make the phone work for you. How can you apply it to your daily activity and make it useful for you? It doesn’t matter what it is. Educate yourself on the use of whatever it is that you want to use. You don’t really see that amongst the youth. You see that in other places like TED talks but it doesn’t get reported on a broader scale. If you start to investigate you see how people are using technology to push art, to push social agendas and awareness. I’m into generative art. It’s art you can manipulate through code in real time, like threedimensional projections—like the images you see when you put your computer to sleep. Now it’s so easy you can download scripts and run that shit on a projector and MIDI-map it to your sound to where your kick is creating one design and your snare is creating another. It’s out there but a small percentage is using it. I’ve been following that and using it for a couple of years now. Let the technology serve you. Everybody is serving technology. There was a projection that in 10 years if you don’t know HTML you won’t have a job. I think you go from HTML to Java to CSS to C+ but you have to have HTML as the foundation or you won’t be able to get a job. That’s scary! What are they going to do? People talk about an economy that squeezes certain people out into the margins. That economy is human slave labor at that point. What are you going to do if you can’t read or write? You work at McDonalds. Not literally but I’m saying that in the analog world if you don’t have an education you work construction or you’re a janitor. If you don’t have basic coding skills or a degree what are you going to do? Nobody is paying attention to that shit. Some of the things you’re talking about also make me think of what people describe as Afrofuturism. I just heard that bullshit. That shit is bullshit. It’s just another fucking word for people to coin. I don’t know. If you read the Futurist Manifesto from decades ago that was created by that small group of artists, it has to do with certain things. What they’re coining it into now, it’s really no relation. What’s Afrofuturism—because they’re Black or they’re rapping and using electronic equipment or because it’s minimal? I don’t really see the validity and the connection unless someone who understands Futurism in a traditional sense can point out to me.

The definition I’ve seen is something along the lines of dealing with themes that are connected to the African diaspora through a framework of Futurism. That’s a reach. That’s vague. Why’s it gotta be Afro? Where’s Country-futurism? Better yet, EDM would be house-futurism if that’s the case because it’s just disco melodies—with the 4/4, which is house, which is minimalism. Now they’ve put melodic chords on top. Drum & Bass is pentatonic shit. It’s still disco and house. Should that be Futurism? No, it’s electronic dance music now. I guess my mind wants to know why. I want to understand something before I adhere to it instead of just blindly doing it. That’s where I’m at with it. Again, I’m from the era of reading and wanting to understand and not just do something because it’s cool. I saw some writings where I was put in the Afrofuturism category. I’m not that shit, I’m not Afro nothing. I’m expressing something else. I’ve always broken molds, especially when they’ve tried to put me in them. Why? Why not. It sounds like you don’t relate much with identity politics? No. That is my pet peeve. I understand that system and I’m not against it. But I’ll always buck up against it just for fun. If you don’t speak for yourself and tell your own story, they will. I ask that because I had planned on asking you a question around that track you did years back, ‘Make It Plain.’ You say something to the effect of America living off your blood, sweat and tears. It was on my mind because I’d recently re-read TaNehesi Coates’ ‘A Case For Reparations’ in The Atlantic. His argument was not that the U.S. Government owes X amount of dollars to the descendents of U.S. slaves, but moreso that until there is a very large and wide and public conversation on the vestiges of slavery then America will continue to have these moments of spectacular tragedy. A people can only define who they are, not another source outside of it. That’s the whole problem with the African-American paradigm. The African-Americans were brought over here as property and by law they were three-fifths of a human being because by law they lacked two of their five senses— which by law made them property. That was the first time that slavery was made lawful by ethnicity and not by indentured servitude, conquering people and shit. Now it’s based on ethnicity and after hundreds of years of that being etched and hard-wired into a system, the masters or the conquerors of those people always identify them as property and always identify them from a place where ‘I determine who you are!’ just because it’s so hard-wired. When people say reparations, people usually think about money. I don’t think money is the issue but more about how do you undo that hard-wired psyche that is the foundation of this country? It happened first to Native Americans—the holocaust that began from the day the pilgrims landed. After the Native Americans saved their asses, like five years later they signed a treaty amongst themselves to take their land and eradicate them. That was the Indian Removal Act. How do you fix that? INTERVIEW

You have to change the economic and the mental myth and perception of the relations between the two—the same thing with African-Americans. There is an old saying that however long it took you to become a certain way, it will take you that long to get rid of that. It’s conditioning. Do you see our society progressing towards undoing that psyche? Yes, because it’s getting hot. It’s going to get worse before it gets better. You have to destroy it in order to rebuild it. The destruction is moving slow. I don’t think I’ll see it in my lifetime because it’s a generational thing. I tell my son all the time, ‘If you don’t get your hair cut, I’m going to cut it. You’re not going to walk around here with a nappy Afro dressed like a skater. That’s cool for you but in the world you give a certain image. Keep your hair cut. Look presentable. Wear some clean shoes. Don’t look like a fucking bum. Them whiteboys can do that shit. You can’t do that shit. You’re a Black kid.’ He don’t understand—he just feel like I’m just getting on his ass. We can’t do that. We get choked out and shot. We’re thugs. I don’t think that’s going anywhere in our lifetime unless something cataclysmic happens to the planet that brings us all together and moves us past this shit. But the conversation is on the table in a different way because I don’t think it’s a thing that just Black people or people of color can do as much as it is the people who are in control of institution. That’s where I think the change can be made. There is economic imbalance. There is ethnic imbalance. The myth of everything white being bad and everything Black being bad is a myth—it’s been around for a long time. You got some cultures where it’s the opposite. It’s something systemic in this country that no matter how much you intellectualize it, it gets more complicated and it seems like it just needs to be a simple conversation. How far are we from that simple conversation? Everyone is using the complex intellectual jargon of the day to talk about it but without really addressing it and saying how they really feel in a public forum. We will treat you like a nigga but you can’t say ‘nigga.’ There needs to be some hard conversations. What will get us to that point? It’s like when you have an argument that’s festering with a friend and you say, ‘Fuck it, let’s fight or let’s get it out.’ You yell through it and then everyone calms down and comes to some sensibility about it. That sounds like what we’re living now with some of these more flagrant acts of state violence. It’s coming to the surface. It has to come to the surface. In a time when we are being monitored and everything you’re saying and doing is being recording in infinity, you’re catching people at their best and their worst. That’s revealing. Before there was none of that so everything was behind closed doors. Now it’s out in the open. The one guest on the album, Orko Eloheim—he fits so well. I love that guy. That’s my brother. He was so fucking respectful of the craft and the lineage—he deserved it. Most of these people don’t know what respect is. He was influenced INTERVIEW

by something when he was young. We hooked up and talked and it was nothing but homage. To me, that’s what it’s supposed to be. Quincy Jones wasn’t disrespectful to Coltrane or Miles. Coming up, you make that exchange. Inspiration, influence, whatever it is—there could not be one without the other. For me that’s how it’s handed down. He was so respectful and understands what we do, which is angular to what the general direction is. Out of all the new cats he’s the most respectful cat I’ve met and that’s cause for celebration. Let’s connect and build—ain’t enough of that in the world. Dudes want to hook up to make themselves look good or elevate themselves higher in status from your look, but there is no connection. It’s ‘I can get more fans or more followers if I fuck with you.’ Even in the process of it, people collaborate via email. That’s the norm now. Music is a communal experience—it’s a communion and a communication and a language with a vocabulary. How are we going to express this joyous process when now it’s so far away from the communion aspect of it? It’s all a fame game. I can’t do that. I just can’t do that. That’s okay for other people but not for me. A song on the album that stands out to me is… ‘Pandorum.’ Yes! The rest of the album is very dark and almost claustrophobic at times but this track comes in and it has remnants of the first album from the loop you used to the Wildstyle sample. In the old days, when you would go to the movies there would be an intermission and the movie would stop, the curtains would close, and you would go and get popcorn. That’s kind of what that track is like. That’s the closest I could come to that. There was another track like that that I took off the album because I couldn’t get the beat right. It was paying homage to my graff background and it included Seventh Letter. I had did a record like that already called War Machine Prototype, but this was going to be the remix of that. I couldn’t get the beat right so I took it off the record. I wanted to have something like that so I split the difference on “Pandorum” with the Style Wars sample and the ‘Frisco Disco’ sample, which was a breakbeat we used to B-Boy to. I still kept the Blade Runner-ish soundscape to it though. It’s like an intermission. When did you first come out to L.A.? Some people still don’t know you’re originally from New York. I came out here in ‘83 to go to school for two years because I was getting in too much trouble. I went back to New York in high school. I had met friends out here and I was coming back and forth to do demos from ‘86 to ‘89. I finally got my record deal with Rhyme Syndicate but I was still back and forth until about ‘94. After ‘94 I was pretty much permanently here. It was major culture shock. There was no hip-hop how I knew it out here. There was Ultrawave and Uncle Jamm’s Army and The Time and all of that shit. The gang-banging, that was all culture shock like a motherfucker. I came from New York with

360 waves, Lee’s and British Walkers—they didn’t know what planet I came from. Then Wildstyle came out and that’s when everybody started to put two and two together. I was here during that transition so I started sharing a lot of stuff with a lot of cats. I taught cats graff styles, some B-Boying and just built relationships. Some of the cats I taught graff got down with MSK in the early years. It was a trip watching L.A. define itself in regards to hip-hop. Before graff took hold out here it was just gang writing. I used to do that shit because I hung out because with gangbangers—not because they were gangbangers but because they were the cats from my neighborhood out here. When the bombing came out, then they started to switch and I watched kids like Shaka and all them early dudes, Risky—they developed their own style that was very unlike New York. But the same was with the music. They leaned more towards the bass music, which was more Planet Rock, more T La Rock ‘It’s Yours’—more electronic-based shit which went from N.Y. to Miami to L.A. and less boom-bap shit. Watching that music transition from the Ultrawave and Egyptian Lover to their love for the 808 was interesting because in New York it was all about that dirty kick and snare. What do you think about the gentrification of cities like L.A. and New York? I think the gentrification is the emergence of a younger generation being prepped to be the governing body of the next phase. If you look at the gentrification, it’s all young transplants that are educated and have trust funds and bank accounts. Their lineage is allowing them to go into these places and purchase space and open businesses. The gentrification is not being done by the people who are from these places. It’s being done by people from the outside who are actually building and restructuring the new economic base. It ain’t for the people—it’s for outsiders. It’s like the elite sending their kids out into the world and telling them to make something of themselves. It’s economics. That’s the next phase we’re going into. In the 40s you had the people who came back from World War II, because war builds industry. That was the boom of the middle class. They took precedence over those that didn’t go to war—who were those in the ghettoes and the slums and so on. They were able to build an economic base and establish the suburbs. In the 50s America was perfect based on that happening in World War II. I think it’s just another cycle we’re seeing. How do you stay balanced in the midst of all of this? That’s easy. I don’t care about it. It’s all ideas from our imagination and I’ve dug deep to learn to stand apart from ideas of Self and others. There’s no attachment to this shit. There are discomforts but that too passes. When you see inhumane acts of Americans going down to South America to buy as much land as they can—what does that mean for the people who live there? They’re being tricked or carpet-bagged out of their land. It’s another form of invasion. You have companies like Monsanto that want to outlaw all seeds and put their GMO seeds in place. They want

to make it illegal to grow fucking vegetables. That’s insanity. I can’t turn away from it in the sense of ignoring it, I have to be aware but not attached to it. The attachment to it gives it support. It gives it life. It gives it power. To be detached from it is almost to go towards a place of ‘there’s something bigger going on in the interest of humanity.’ Just because you can’t see it right now don’t mean it ain’t in operation. It’s happening—we just can’t see it. I remain aloof. I don’t let it constrict me mentally. I had my years of that, being angry and shit. Awareness is powerful. What do you do with it? You’re speaking about a crossroads that many of us come to after awareness. Some people feel like you have to tackle these things head on, some hide from it—what is your take? Me, I do it through this music. This is my vehicle. I am not a politician, I am not a speaker, I am not a protester, I am not an activist. That’s not my thing and that’s never been my drive. My drive has been sharing the information through music or some sort of sonic and visual art. I’ve had people try and convince me into the whole activism role and fuck all that. You’re not going to guilt trip me. You do that. That’s what works for you. For all the people that have faith in a deeper power, they understand how it works. Everybody plays a role in the mechanism. It’s a trip becoming aware, remaining aware and then watching everything happen. I read this article about outlawing children playing outside. From something like 5 PM to 8 AM a child can’t be in a park by themselves— and then for teenagers it’s the same thing. It’s fucking insane. How are you going to make it illegal for children to be outside unattended? Now you pose the formula and behind that you create more paranoia, more predatory nature, more dissention. That type of thinking shouldn’t even have a place in the world. What planet is this? They outlawed 20 oz beverages in New York—once they passed that law New York was a wrap. Talking about kids getting too fat. Tell Coke to stop making Coke then! Why make it illegal to drink something that’s legal? You end up with this system that has to contradict itself to stay alive. That’s the end of the world in whatever world that is. It’s the ending of a mental construct— it’s not the end of the trees and the sky. Exactly—people talk about global warming and climate change as if it’s an end to the planet when they really mean it’s an end for us. The planet kicked dinosaurs. It will shake us off—I think George Carlin said it, like a dog shaking off a tick or a flea. We haven’t even been here as long as any race of dinosaur was here and we’ve done worse to it than anything before. When it’s time, it’ll get rid of us before we kill it. What type of world are we living in? It’s all mental, all ideas, all in our imagination—then people give power to it and that power becomes a sub-reality. DIVINE STYLER’S DEF MASK IS AVAILABLE NOW FROM GAMMA PROFORMA. VISIT DIVINE STYLER AT DIVINE-STYLER.COM. 13

THE POP GROUP Interview by David Cotner Illustration by Luke McGarry

If you’re an artist of any conviction, the greatest wealth at your disposal is time. This is a difficult thing to fully grasp in the modern world of lightning-fast paces and instant gratification. Mostly, time means ego death. It means that your fortunes are ultimately not under your own control. You cannot know where your music winds up. You cannot possibly know your ultimate audience. Freeing oneself to whatever comes of the creations an artist makes—precisely because of that surrendering of control—is one of the greatest gifts to creativity itself. The Pop Group began life more than three decades ago as most bands of quality do: without connivances or contrivances. Just a bunch of kids from Brighton—Mark Stewart on words and vocals; Gareth Sager on everything from guitar to saxophone to clarinet and organ; drumming percussionist Bruce Smith; and the trebled bass discourse of John Waddington, Simon Underwood and Dan Catsis. They didn’t know what they wanted to do—but they did know that they didn’t want to be like anyone else. In decades that followed, they lived and struggled and grew as artists and individual adult human beings. When they returned to public view as the Pop Group, interest in what they have to say now was piqued without any sign of peaking. Shows sold out. Wheels began to turn again. Mark Stewart spoke recently about their first-ever U.S. tour and the new album Citizen Zombie, their first record as a band since 1980’s perfectly-titled We Are Time. The Pop Group is nothing if not patient. Why has it taken 35 years for a new Pop Group album? Mark Stewart (vocals): Because I was waiting for your call! [laughs] It’s a funny thing because in one of our songs from back in the day called ‘We Are Time,’ there’s the lyric, ‘Waiting is a crime.’ It’s beyond me, my friend—honestly, this whole experience is something shocking and quite bizarre to me, and the whole thing is very, very strange. For the first time in my life, I’ve got no idea what’s going on. I would have thought that would have been the entire point since the beginning. What you do seems exceptionally spontaneous. Yes—when we were very young, we were really into the Beats, like Gregory Corso, also Michael McClure; and I don’t know if I got it from them or from Alan Watts, and Eno worked it out later on: those things called ‘chance procedures.’ Trying to go against your pre-ordained destiny. The Clash wrote a song called ‘Career Opportunities.’ When we were 12 or 13, we were sat down by the Careers teacher who said, ‘What do you think you want to do? Do you want to work in this factory?’ And in the back of my head, I remember seeing the singer Alvin Stardust on English children’s television. He had a leather glove and all he did was point to the audience. And I thought, ‘You can do something like that!’ And for me, I’m that same 14-year-old kid who went up to his room and lived in a world of music and Andy Warhol’s Interview and Lou Reed records. I’ve never really changed. I’ve never really thought of myself as somebody in a band. To a certain extent, until we went in the studio to make this record, I had some kind of grasp of experiments I wanted to do—things I might throw into the stew that we were going to cook. The whole point of this Pop Group reunion is—we started talking about this over the phone—we said, ‘Look, let’s not have too many preconceptions, let’s not be tethered to anything from the past—although we respect the past—let’s just see what happens.’ As soon as me and Gareth started writing some of these songs, something weird started happening. Like an alchemical golem, something came through a portal—and all I can do is stand back and watch the fireworks. The only thing 14

I know is … sometimes in life, stand back and don’t project any preconceptions or any of these constructs I’ve got in my head onto this thing. It’s good to keep naïve, you know? If we try to cage it or control it or explain it too much … I don’t want to put it in a box at the moment, you know? When you talk about naïveté, I’m reminded of Gavin Bryars’ Portsmouth Sinfonia, an orchestra made of musicians of varying levels of talent. The effort and naïveté in the moment is the thing that’s honored. For sure. Eno [with Peter Schmidt] also developed these cards called Oblique Strategies; Burroughs used chance procedures in cutups. Working with Kenneth Anger a couple of years ago, I’d used chance juxtapositions and the naïveté to throw something that shouldn’t be there into the mix. It’s a portal to the supernatural. I know it sounds a bit pretentious, but my gran was clairvoyant. Each Sunday we used to go around and do table rappings, and sometimes when me and Gareth are experimenting, he’ll go against his own ideas deliberately to see what happens. And then something appears, and it’s bizarre! As you do this more often and go more deeply into it, doesn’t that just seem like the natural order of things? I’m not one to judge things too much. Once, I was involved in a weird kind of psychic procedure, and I saw something. I’m not going to put a face on it; I don’t know how to explain it but it’s part of my punk religious system that you shouldn’t bow down to anything other than yourself. All I know is that there’s something going on which is quite difficult to explain to journalists, but I’m very pleased with the experiments so far and it’s something completely different from what I thought it was going to be. When the first phone call came—when Matt Groening’s people phoned up and said, ‘Can you play at this [All Tomorrow’s Parties] festival?’, we were already talking [about reforming]. I thought, ‘That’s a bit of a weird idea—that’s not very “Pop Group” to perform.’ We’d always been experimenting in our solo careers. And then I thought, ‘Which “me” is saying that?’ I’ve got this concept caged in the form of personal

censorship—so I’ll often try to argue with myself against what I’m thinking I should do. Accepted ideas, or the accepted virtues? And then I flipped it—and I thought, ‘Can I see this as a kind of new condition?’ And my old friends ... because years before, I’d do these collaborations with Richard Hell, Massive Attack or Kenneth Anger, and I thought, ‘Can I work with [the members of The Pop Group] in a different way, and just see it as a new thing?’ None of us wanted to reproduce anything from the past. The coolest thing is that it’s turning into a kind of gathering of freaks. And we really feel part of a community—like the very early Bristol concerts [of The Pop Group], or the very early Clash concerts, the audience is just as important as the people on the stage. So are those chance meetings are as important and strong a phenomena as a mystical experience? There’s a line in an early Pop Group song ‘Don’t Call Me Pain’: ‘Don’t call me Pain / My name is Mystery.’ For me, the mystical is very close to the political. And the idea of love, for me, is a kind of mystical thing that’s bigger than something for one individual. I don’t know how to explain it, but in the 16th century, heretical ideas like politics and mysticism were all mixed. It’s about being a dreamer, really. I don’t necessarily want you to explain it. I want it to be something you and I both think about, but it’s something for which we don’t necessarily have to have answers. Yes! For me, all I’m doing is passing a baton to the listener. For me, the musical process is like the alchemical snake that et its own tail. We set off somewhere with King Tubby or Neu! or whatever and we’re constantly feeding off other forms. I really, really believe in that punk thing where we were kids in the audience and we saw the Clash and then jumped up and had a go. It’s that enabling thing; that spreading of information. What are the plans past the coming tour? Straightaway, we’ve got more material, and it’s going on further. It’s like a wellspring. Today, five new songs appeared. And one of the things that I really missed about being in a band … when you’re a kid back in the day, somebody will bring a bass riff into rehearsal, and that

bass riff will turn into a jam, and you’d work out a chorus at one concert that’d grow over a tour into a song. We haven’t even played the new songs off the album, but I want to get on and make other stuff straightaway! There’s going to be a lot more Pop Group albums. We’re also looking to hook up with loads of other cool filmmakers. Asia Argento made the video for [the first single off Citizen Zombie] ‘Mad Truth,’ and there are all the performance artists out there, mad filmmakers and people on the fringe. We work in a pack—like back in the day, we always used to be package tours with Cabaret Voltaire or Linton Kwesi Johnson. We’re doing this single with these kids called Sleaford Mods. We’re also working with different protest groups all over the place. It’s quite a good time at the moment, but I think people are kind of competing against each other a bit too much. It’s good for people to work together and form package bills and benefits—bring it back to that proper indie spirit. It seems like even after all this time, there are still those barriers—still those walls. It’s becoming even more genre-fied than back in the 1950s, when they used to have race charts [in popular music]. I’m constantly annoyed when people say, ‘Well, you brought funk into punk rock.’ Well, there was a soundsystem on the corner in our part of Bristol. I mean, Elvis was playing R&B. I can’t understand when people make it so genrefied. In my community, growing up, we didn’t see race or class. I don’t understand ‘You’re this, you’re that...’ We’re still in that punky reggae party mode, where everything’s mixed-up and we just want to see what happens. Change is hard. Change hurts. I live off change. THE POP GROUP WITH PEAKING LIGHTS, SEX STAINS AND DJ MICHAEL STOCK (PART TIME PUNKS) ON TUE., MAR. 10, AT THE ECHOPLEX, 1154 GLENDALE BLVD., ECHO PARK. 8 PM / $25-$27 / 18+. THEECHO.COM. THE POP GROUP’S CITIZEN ZOMBIE IS AVAILABLE NOW FROM !K7. THEPOPGROUP.NET. INTERVIEW

MAGMA Interview by Kristina Benson with Sabrine Mhiri Illustration by Bob Kurthy

Christian Vander grew up surrounded by the music of greats like John Coltrane, Clifford Brown and Art Blakey, sitting right up front by the drum kit at jazz clubs when he was as young as four or five years old. As an adult, he created—with godlike vision and acumen—the group called Magma, legendarily known as one of the greatest (even definitive) prog bands, although they actively defy categorization in any genre, with quick-changing unexpected time signatures and operatic Orff-ian backing vocals that result in something evolved from jazz, prog, rock and pure force of will. (Naturally, they invented their own language, too.) The Magma founder joined us to talk about the art of astral projection, the future of artificial intelligence, and the day he realized John Coltrane was going to die. What attracts you to jazz music? What are musicians missing out on if they don’t listen to jazz? Christian Vander: My mother was very musical, my father was a pianist and my step-father, Maurice Vander, was a pianist. So I spent a lot of time in the milieu of jazz. I was very young in these clubs, including in famous clubs in Paris at the time in the 1950s: Club SaintGermain, where I had the chance to see the biggest musicians that passed through Paris, like Art Blakey, people like that. So when I was sitting next to the drum set it was like a dream—I was going to these clubs when I was 3 or 4 years old! I was truly very young when I was introduced to this music, and then afterwords, I took the common path— listening to all these musicians, particularly Clifford Brown, all those guys, and then arrived John Coltrane. And there he was! And then my mom spotted him and was with Miles Davis at the beginning, in the 1950s, especially with the record Cookin’. When you listen to John Coltrane, do you still learn? What can you learn from him after all this time? For me, John Coltrane teaches me every day. I want to say every day and for periods of time too. You see what I’m saying? Every time I hear the configuration of his rhythms, I hear them differently. How he sends out his phrases—it’s never the same. For example, we noticed— me and my mother—that very often in the chorus, on some tracks, he took a breath like that [hums a tune] and we were inspired! But in fact no—in later years, I noticed that when he plays the phrase, he does it differently than we thought he played it when we were so INTERVIEW

inspired—you see? So he even breathes within the interior of the music itself! Yes, there were still things to learn, and to discover in John’s music. He never left us at a dead end. And he has truly opened channels with his music. I think that he has accomplished what he should have, because obviously he died very young, at forty and a half. But he never left a dead end, that’s I would say. How do you pick up where he left off? What did he leave to explore that you’re interested in exploring? In a lot of ways, his entire career. Especially the moment when he began to truly play his music during the 1960s, and, as he said in his famous record A Love Supreme, ‘Seek and ye shall find!’ And we wondered what more there was for him to seek or find! From ’64, that was an extraordinary take-off, and ’65 was an extraordinary year and towards the end, it meant also the end of the quartet with Elvin Jones, McCoy and Jimmy—not Jimmy Garrison, he remained with him and continued on that path with Alice Coltrane, Rashied Ali, and the famous record Expression, which for me is the culmination—truly, like is name indicates, you see! I had a hard time listening to it when he passed away. I listened anyway, but it took me about ten years to be able to truly listen to his records again. It was terrible for me. And in addition, no one had expected him to pass away. He hadn’t said anything, and it’s remarkable that he didn’t tell anyone in his entourage, or confide in anyone, or that no one tried to find out he had cancer until the end, when it was over. And I think that it’s amazing the energy he had and that in his music, he let go. I think that, in fact,

towards the end—I actually call this music a little bit between two worlds: you can really feel that it has a foothold elsewhere, you know what I mean? It’s incredible that he was able to transmit this and at the same time, be aware of it. I understood in the introduction of ‘My Favorite Things’—I understood. I heard, ‘He is going to die’ but I didn’t even know that he was sick. I heard that note, the first note of the introduction of the theme of ‘My Favorite Things,’ I heard a sort of seppuku. I said, ‘He is going to die.’ And in fact, I heard the news ten months later. At that time, Expression hadn’t been released. And so he died before the record came out in France. What are musicians of other genres are missing if they don’t listen to jazz? I regularly practice jazz, independently of the music of Magma, because it’s extraordinary in terms of the level of listening, the speed of expression, the speed of action, to be responsive, to exchange with other forms, or forget the forms and discover other rhythms. Getting to play a structure, as they say, a form, in free time, liberated. John Coltrane did not get on stage to play A-A-B-A—he spoke from inside, he went back and forth with musicians as in a dialogue. He completely abandoned and surpassed the issue of structure. And that’s what we try to do—it’s really opening the ears that makes the music, to me. Does this connect to why you developed your own language Kobaïan—because French seemed to you to be too limited for what you want to express? No, it was not premeditated. The sounds of the new language came along with the music. They could have been love songs or pseudo-

philosophies, or I don’t know—love songs or I don’t know what. The issue of Kobaïan—the sounds arrived alongside and totally together with the music. And then, gradually, I analyzed the sounds that had been conjured, and then I called them Kobaïan because the first song that I composed, ‘Kobaïa’—it has four words: ‘kobaïa, kobaïa, koba shibewa.’ And this was the first sound that came, in fact. It was because of this that I called the language Kobaïan. But they were sounds—vibrations. I’m like a receiver for them. I don’t think that one should seek out a compositions to compose, but I think music should come to you and you should always be ready to receive it, in a state within a state, a state of reception, of receptivity. You’ve said in many interviews that you wish you could have an orchestra as big as Orff’s or Wagner’s to play Magma’s music. For live performances of course, this is difficult. But in the studio, with programs like ProTools and Ableton, it seems like it would be possible to create a virtual orchestra as large as you want. Have computers opened up any opportunities for you that you couldn’t pursue before? I’ve tried with all the possibilities that exist today. For example, on stage there are always three voices, three singers and—rarely—a fourth added as an additional voice,. So if you have three singers, then for sure, if you want to have, say, fifty in the studio, it’s much easier. But I have found that if it’s not fifty real voices, each with its own timbre and expression, the sensitivity of the music and the expression of it is lost. So what happens—for example, with the last record—I tried as always but in the 17

end, I practically always left the arrangement with three voices. And I found that this way, there was much better expression of emotion. I’ve duplicated voices and added six or seven voices at times, because the arrangement with the piano sometimes, was in effect, seven or eight voices and I wanted it to grow. But in the end I decided it loses so much, that using Protools and the like is not a solution. It’s more complicated than that—one must imagine the situations that you can not artificially create. When one takes on a choir of fifty people, there are an enormous amount

not very technical, eh? In any case, it does not slow down, you see. Not one plane allowed him space, so it’s “é-é,” perhaps “thud-e-kee-ding-e-dingédéding” and not “kékeding, kékeding, kékeding” you see? He finished his phrasing and his momentum, his breathing. You see what I mean? It allows [inhales and exhales] lightening, support without weight. Lots of things like that. So this suspension exists, and you sit riveted—for example as a drummer is riveted to his seat, the problem is that in space, it is not there at all. He does not sit in this way, It should really have this

to return to my body. So during these times I had to close the doors to whatever room I was in and if I experienced astral projection, not let anyone disturb me or I wouldn’t be able to return to my body, or so I thought. Gradually, I admit, I became afraid of these things. I thought, ‘I may not be ready to attempt these journeys.’ But on the other hand, I lived through them, and I found out that people who had experienced things like that reflected on them a little in the same way. I got the impression of being like two pieces of wood glued—attached, with filaments.

“And then ... ” [makes noise to describe rejoining with his body] of nuances and differences. But to create that artificially, to me seems impossible. So it is better to actually work with fifty people, that’s certain. Because we are chosen, you see—you can say, ‘Oh it sounds like that—‘ but in a recording session or a performance, there are a number of people, they are alive, and so this version is alive, and there you are. We have been selected in this moment in time, see. You know Miles Davis ‘Kind of Blue’? That version happened on that day. Maybe the next day was not the day, and we would never have had a piece of classic jazz music if they had played the next day, you see. It happened that day. That is all—we are chosen, and after some time, we say, ‘This record there, this version.’ I can tell you, Carl Orff is one of the pianists in a group I discovered early in Magma. I’d never had the opportunity to listen and that’s when I said indeed, this is the ideal training for Magma. With marimbas, vibraphones, all those things, plus chorus, brass, symphony. At times we’ve had offers to play with a symphony orchestra but it never came to be. It was overly complicated, frankly. But this is the dream. Maybe one day it will happen, I dunno. Your music deals a lot with space. Many see it as a void, but you see it as a place with limitless potential. I do a lot of travelling inside the inner world, you see—it’s exactly the same as regular travel but it emits less greenhouse gasses. [laughs] But yes, I think that the inner journey is the same, infinitely. What interests me is infinitely small and exactly the same. I think it’s the center we can see, we can all admire—not the outside— and hence the idea of multimusic, you see. And I work in this way—for example, playing a triplet that is not quite a triplet. While I am quite precise, the problem is that I always leave a space—never maybe. Always! That’s what is very important too. Getting to say the thing at the same time with a side of possibility of very fast response. I think if we just talking about drumming, if one thinks of a rhythmic pattern like, ‘tchenkedé, tchenkedé, tchenkedé, tchenkedé’ you see, well that drummers began to play ‘tché-ke-e ken-keng-ding-kin-da-ke-ke-ke-kedung-deng-é’ for example—to talk, well, it’s INTERVIEW

flexibility to be truly all-round. For example there was a girl who had transcribed a chorus of John Coltrane, and she brought him the score. John Coltrane looked at it and said, ‘I am unable to play such a thing.’ Because in fact between what we decide to do and what actually is ... is something that we’ll never know. These people are nimble enough to make music but that means having sufficient ease in space. To be released fairly rhythmically, because the pace is very important to develop anything. We first develop the part of the rhythm and the melody that leads to more known rhythms, which allows us to create melodies, and then those can be arranged harmonically, if necessary ... or if you can. From the melody comes rhythms. If you have very little rhythm, you tend to overload and overdo it. Otherwise, only the tempo—the rhythm—permits evolution within free space. Plus you have given these spaces precisely the same sensations of weightlessness, too. Do you think that the development of artificial intelligence will be a positive or net negative benefit to humanity? Well, if you think we can look at robots from old science fiction movies and think, ‘Well, we can not get there,’ I think unfortunately we can. We can, and we might get there very soon and quite easily. That’s both exciting and distressing, but it’s where we are today, maybe. And after that, how will it evolve further? Will robots have souls? That’s all that matters, in the end—it’s part of the questions about artificial intelligence, I believe. I believe they will have souls. In any case, I also engage with things besides music— not really spiritualism, you see, but what I want say is that there are forces at work and things. Once, in the past, I had to make a choice—and I decided, ‘I need to focus solely on the music.’ Because I had a kind of gift. I could move objects with my mind, using telekinesis, I think? I’m not sure what people call it, but you know what I mean—there were forces, you see. And other stuff, too—astral travel, where I’d be saying ‘Here, I’ll lie down for five minutes. I want to take a little rest,’ and I’d arrive at a state where I felt my body become detached. Later I studied up on it and I saw that in these cases it was necessary to be very careful to be able