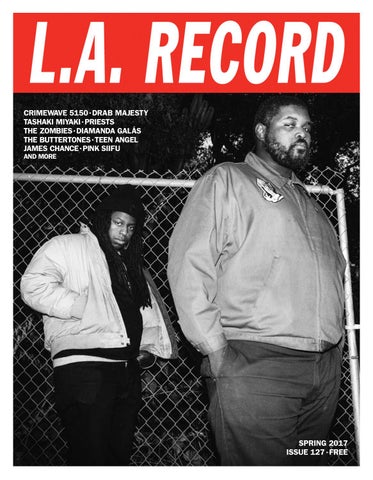

CRIMEWAVE 5150 • DRAB MAJESTY TASHAKI MIYAKI • PRIESTS THE ZOMBIES • DIAMANDA GALáS THE BUTTERTONES • TEEN ANGEL JAMES CHANCE • PINK SIIFU AND MORE

SPRING 2017 ISSUE 127 • FREE

CRIMEWAVE 5150 • DRAB MAJESTY TASHAKI MIYAKI • PRIESTS THE ZOMBIES • DIAMANDA GALáS THE BUTTERTONES • TEEN ANGEL JAMES CHANCE • PINK SIIFU AND MORE

SPRING 2017 ISSUE 127 • FREE