3 minute read

Political

New Census Data: Hispanics may now be the Largest Demographic Group in Texas

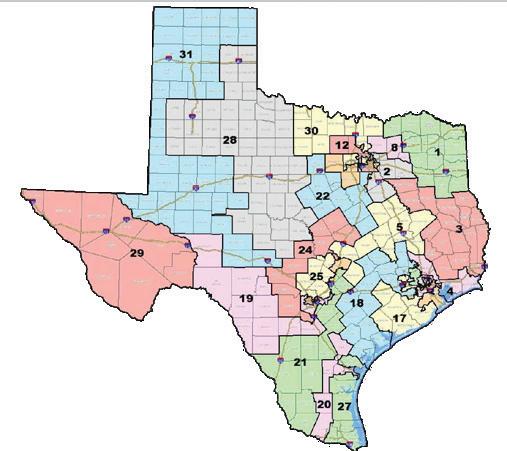

Aclosely watched estimate from the U.S. Census Bureau released last month indicates that Texas may have passed a long-awaited milestone: the point where Hispanic residents make up more of the state’s population than white residents. The new population figures, derived from the bureau’s American Community Survey, showed Hispanic Texans made up 40.2% of the state’s population in 2021 while non-Hispanic white Texans made up 39.4%. The estimates — based on comprehensive data collected over the 2021 calendar year — are not considered official. The bureau’s official population estimates as of July 2021 showed the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white populations virtually even in size. But in designating Hispanics as the state’s largest population group, the new estimates are the first to reflect the foreseeable culmination of decades of demographic shifts steadily transforming the state. The incremental trend demographers have been tracking for years reflects the state’s profound cultural and demographic evolution. The state lost its white majority in 2004. However, the Hispanic population’s relative growth, through both migration and births, has not been reflected in many facets of the state’s economic and political landscape. The 2020 census captured how close the state’s Hispanic and white populations had come, with just half a percentage point separating them at the time. By then, Texas had gained nearly 11 Hispanic residents for every additional white resident over the previous decade. And Hispanics had powered nearly half of the state’s overall growth of roughly 4 million residents since 2010. Hispanic Texans are expected to make up a flat-out majority of the state’s population in the decades to come, but they are already on the precipice of a majority among children. The latest census estimates showed that 49.3% of Texans under the age of 18 are Hispanic. Without corresponding political and economic gains, Hispanic residents’ economic and political reality is captured in the persistent disparities also reflected in the latest census data. Hispanic people living in Texas are disproportionately poor. They are also less likely to have reached the higher levels of education that often serve as pathways to social mobility and greater economic prosperity. The new census estimates showed Hispanic residents are more than twice as likely as white residents to live below the poverty level. Although 14.2% of Texans overall are considered poor, 19.4% of Hispanic residents live below the poverty level, compared with just 8.4% of white residents. Texas households are also divided by significant income inequality. The median income for a white household in 2021 was $81,384, but it was just $54,857 for a Hispanic household, according to the estimates. Up against longstanding educational disparities, Hispanic children have been less likely to graduate college-ready compared with white students and left unprepared to succeed in a flourishing Texas economy that increasingly requires some form of education after high school. The new estimates show that 95% of white adults have at least a high school diploma, compared with only 70% of Hispanic adults. Only 18% of Hispanic adults graduated from college with bachelor’s degrees or higher, compared with 42% of white adults. And while their growing numbers have allowed them to secure local political power in many communities, Texas remains a state governed by primarily white Republican men. Texas lawmakers have a lengthy history of discriminating against Hispanics and other voters of color in pursuit of political control, devising political maps that weaken the impact of their votes. In the face of the growing Hispanic population share that works against their political dominance, the Republicancontrolled Legislature redrew the state’s legislative and congressional districts last year to shore up their hold on state offices. But in the process, they gave white voters greater control of political districts throughout the state, elaborately manipulating district lines in some areas where Hispanics and other voters of color were gaining political ground. The state now faces nearly a dozen consolidated legal challenges — brought by individual voters of color, organizations that serve communities of color and the U.S. Department of Justice — to its four political maps that include allegations of intentional discrimination, vote dilution and racial gerrymandering.