Lambton Musings

www.heritagelambton.ca

www.heritagelambton.ca

David McLean, Forest Museum

For this issue of Lambton Musings we highlight the largest item from our collection: a fanning mill produced by “A. Wren and Company”. Founded in Forest in 1875 by Nova Scotia born Alexander Wren (1835-1894), this local company crafted this impressive machine that is a testament to our community’s industrial and agricultural heritage.

Fanning mills, also known as winnowing machines, played a pivotal role in agricultural history, transforming the labour-intensive process of cleaning grain into a more efficient and effective operation. Invented in the late 18th century, these devices mechanized the separation of grain from chaff, dirt, and other impurities, significantly improving the quality of harvested crops.

Before the invention of fanning mills, farmers relied on manual winnowing—a time-consuming method that involved tossing grain into the air so that wind could blow away the lighter chaff. This process was not only labour-intensive but also inconsistent, as it depended heavily on weather conditions. The advent of fanning mills changed all that, introducing a reliable mechanical solution.

The earliest fanning mills, believed to have originated in Europe, used a hand-cranked mechanism to generate airflow. Grain was poured into a hopper and passed through a series of vibrating sieves or screens. These sieves were designed to separate grains by size while a fan below or within the mill blew away lighter impurities. This combination of sieving and airflow ensured a cleaner, more uniform product and dramatically reduced the time and effort required. By the early 19th century, fanning mills became a staple on farms in Europe and North America. They were particularly valued in wheat-growing regions, where clean grain was essential for milling. As industrialization advanced, the design and efficiency of fanning mills improved. The introduction of power sources such as steam engines and, later, electric motors made the process even faster and less labor-intensive.

The “A. Wren and Company” foundry was the first to be established in Forest and was located on the east side of James Street between Wellington and Jefferson Streets, on the same block as Forest United Church and just a stone’s throw from our museum. The company manufactured a wide range of farm implements and machines, including fanning mills, binders, mowers, and disc harrows. Its products were sought after by farmers as far away as Manitoba, a testament to their quality and innovation.

Our fanning mill was donated to us by Calvin Hill. It is not known who first owned the machine, but Calvin’s grandfather, Arthur Hill (1892-1965), used it on his farm located at the corner of Lakeshore Road and Proof Line in the former Bosanquet Township. The mill had been left behind by the property’s previous owner, Howard Fraleigh (1877-1946). At least one other fanning mill manufactured by Wren’s company is known to still exist. It is in the collection of the Lambton Heritage Museum.

Besides its intriguing inner mechanisms, a delightful feature of the machine is the stencil work on its exterior. The company employed artists, including Stephen Lowe and J.K. Cooke, to paint and decorate their implements.

Unfortunately, a fire broke out at Wren’s foundry in March of 1900, destroying all but its blacksmith and pattern shops. The loss was estimated at $5,000 (about $150,000 in today’s money) and the breadwinners of eight families were left without work. As a result of the fire, the company was dissolved. William Pepper (1866-1949), an employee of the firm, established his own foundry business on the corner of Washington and Clyde Streets. Late in life he sold the foundry to William Hopper (1889-1960). The Hopper Foundry has changed hands a few times over the years (and had to be rebuilt after a devastating fire in 1947) but it is still in business today. Although currently kept in storage, we hope to have our biggest “fan” available for visitors to see in 2025.

Colleen McLean, Lambton County Archives

For this issue of Lambton Musings, we are sharing an Historic Gum Drop Cookies from the 1953 “Cook Book” compiled and published by the C.E.E. Hospital Guild in Petrolia, Ontario. This recipe was shared by Gladys R. (Marriott) Slack.

Gum Drop Cookies Recipe:

Ingredients

½ c. butter

½ c. brown sugar

½ c. gran. sugar

1 c. of flour

½ tsp. baking powder

½ tsp. baking soda

¼ tsp. salt

½ tsp. vanilla

1 egg unbeaten

½ c. coconut

½ c. gumdrops (chopped)

1 c. oatmeal

Instructions

Drop by spoonfuls on cookie sheet. Bake at 400º

Gladys was born to Isaac Marriott and Liela Jessie (Stephens) Marriott on 6 May 1899 in Plympton Township. Gladys was the fifth born child of 10 children. Her siblings were:

• Elmer John Marriott. Born on June 21, 1886, he passed away on November 16, 1974. He was laid to rest in the Forest Cemetery.

• Victoria May Marriott Neely. Born on April 21, 1888, she passed away on March 25, 1919. She is buried in Hillsdale Cemetery, Petrolia.

• Jessie Myrtle Marriott. Born on June 26, 1891, she passed away on January 17, 1892.

• Charles Nelson Marriott. Born on November 10, 1892, he died on September 29, 1918 in France during the First World War. He is buried in France.

• Melvin Edward Marriott. Born on March 25, 1895, he passed away on May 12, 1910.

• Wilfred Henry Marriott. Born on April 19, 1897.

• Stella Irene Marriott Somerville. Born on April 18, 1901.

• Leslie Ashton Marriott. Born on September 28, 1903.

• William Isaac Marriott. Born on March 14, 1906, he died on May 3, 1929.

Gladys married Herbert Austin Slack, the son of Henry and Annie (Edde) Slack and they had four children:

• James Beverly Slack. Born on August 20, 1924, he passed away March 22, 1989. He was laid to rest in Hillsdale Cemetery, Petrolia.

• Donn Raymond Slack. Born on April 26, 1926. He married Vera Geraldine Ford on August 18, 1950 at First Baptist Church, Petrolia. Donn and Gerrie had five children. Donn died in Sudbury on February 19, 2003 and Gerrie passed on February 21, 2011.

• Herbert Clare Slack. Born October 3, 1921. He married Elizabeth Ellen Sanderson (b. September 8, 1922) on July 4, 1942. He died October 25, 2002 and Elizabeth passed away on February 13, 2009. They are buried in Hillsdale Cemetery, Petrolia.

• Gloria L. Slack. Born in 1927. She married Robert Wellington Scruton in 1927. Robert passed away in 2006 and Gloria passed on April 11, 2012.

Gladys was a well known and respected local artist and Herb was a barber in Petrolia for about fifty years. His shop was located downstairs of what is now The Bull Wheel Bar & Grill. The entrance to the Herb’s barber shop was at the front of the building using outside stair. The stairs were closed in several years ago. They also attended St. Paul’s United Church in Petrolia. Gladys passed away on April 10, 1985 and Herb predeceased her on May 23, 1973. They were laid to rest at Hillsdale Cemetery.

Moore Museum Staff

There are many legends surrounding the Great Lakes, what lies within the vast waters and the fates of those who ventured there and never returned. In his 1977 book, The Great Lakes Triangle, Jay Gourley talks about the statistical occurrence of disasters surrounding the Great Lakes being greater than that of the infamous Bermuda Triangle. Many of these tragedies are well known, but there are dozens more that remain unexplained to this day.

In June of 1950, two Wisconsin policemen were working a routine night shift when they saw something neither could explain: a red object hovering in the sky over Lake Michigan. At the risk of sounding ridiculous, they reported the light to the US Coast Guard who went to investigate. They spoke with a US naval research vessel in the area, who reported seeing nothing strange. The Coast Guard may have continued to investigate but they were called away to begin what would be the largest search in the history of Lake Michigan.

Northwest 2501, a flight westbound out of La Guardia headed to Seattle, had failed to report to air traffic control at a regular checkpoint. Having checked in at the previous point recently, the Coast Guard began a search in the area that included anti-submarine experts, sonar, and radar. Interview experts even delved into the personal lives of the crew. The only trace of the plane ever found was a single logbook, floating on the surface of Lake Michigan, east of the policemen’s sighting.

Peculiar, it seems that the logbook didn’t lead to other pieces of the wreckage, but that is not unique to Northwest 2501. A similar search took place with Civil Air Patrol and Royal Canadian Air Force after the disappearance of a small corporate aircraft out of Detroit in 1964, only recovering the wallet of one passenger, 50 miles east of their intended course. Similarly, in 1881, the Jane Miller was spotted near Wiarton, Ontario by a father waiting for his son to arrive at the dock. After looking away for just a moment the ship disappeared, but far too quickly to have sunk, surely. Only the uniform hats of the crew were seen again, floating on the surface of the lake where the ship was last seen. Dozens of planes and ships have disappeared on the Great Lakes without leaving a trace, and even more have met a tragic fate without sounding a warning or call for help.

The Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest vessel on the Great Lakes when it launched at over 700 feet, just one yard shy of the maximum length allowed to pass through the St. Lawrence Seaway. The fate of the ship is well known, though some may not remember that the Fitzgerald had a companion. It was travelling with the Arthur M. Anderson along Lake Superior on its route to a steel mill near Detroit. While the seas were rough and stormy, the Anderson crew’s concerns that the Fitzgerald could have sunk were initially dismissed, as the crew didn’t believe it could have gone down so quickly, and no distress signals were ever activated.

These tragedies are peculiar as many of the ships maintained contact or communication with others until the very moment of disaster, vanishing into seemingly thin air. Radar, radio, or in one case, a tether between two ships travelling in tandem, wasn’t a strong enough connection to warn of the imminent danger.

In 1942, Cleveland Tankers Inc. purchased the Admiral. Its job was to tow their tanker barge, the Clevco, which was loaded with oil. The pair left Toledo, Ohio on December 1st and turned east toward the Pelee Passage as darkness fell over Lake Erie. Crew on the Clevco noticed the lights on the Admiral fade away, thinking it was curious but not overly concerned as the line that connected them still held tight. It wasn’t until later that the lookout noticed the line, while still tight, now stretched downward toward the depths of the lake. No distress signals were sounded, but the Admiral had silently sunk, taking all 14 members of the crew with it.

The Clevco was now anchored in place, held by the sunken Admiral and advised of their position and asked for help. Two tugs were sent to their position to tow the Clevco and two Coast Guard cutters looking for survivors. When they arrived, they found neither ship. The search continued with Civil Air Patrol joining. Eventually, contact was made with the Clevco, now 10 miles North of Cleveland, adrift after curiously cutting their line. In between the sudden onset of flurries, the barge was seen by an aircraft and by one of the Coast Guard vessels, the Ossipee. Crew on

the Clevco abandoned the idea of being towed, and desperately asked to be evacuated before contact with the barge was lost again. The Ossipee replied, instructing the barge to release its cargo, the oil, in the hopes it would lead the rescuers in the right direction. Curiously enough, it was the sheen of oil on the water that led the US Coast Guard to the ship, only in 1994, over 50 years after she was last seen.

While unsuccessful in their rescue mission, the Coast Guard vessels sent after the Clevco were applauded for their bravery and persistence. They encountered harsh weather and strange accidents during their voyage, including a fire breaking out on one, and the gyro compass breaking on the other.

Many theories exist about the happenings on the Great Lakes. They range from natural phenomena like riptides and wind patterns, to the presence of alien life forms sparked by mysterious lights in the sky. Whatever the cause, the Great Lakes persist as a wonder of the world, open yet elusive, munificent but merciless, and just as mysterious as they are beautiful.

For many residents of Lambton County, the end of winter is often associated with the return of the Tundra Swans. Once the Tundra Swans start to arrive, spring is not far behind! These beautiful birds come by the thousands to feed and rest on the Thedford Bog behind Lambton Heritage Museum.

In a good year, there may be 15,000 individual birds resting on the bog, attracted by the melt water of spring and the remnants of the prior year’s corn crop. The first sound to be heard is the soft hoo-hoo-hoo, as the Tundra Swans glide effortlessly down to feed on flooded fields that mark the bottom of a former inland lake called Lake Smith.

The swans migrate north in spring from their wintering grounds on Chesapeake Bay to the Canadian Arctic and return south in the fall. They will travel over 12,000 km per year on this round-trip journey.

Tundra Swans photographed off River Road in March 2023 by Lambton Heritage Museum staff member Colleen Inglis.

A full-grown Tundra Swan boasts a wingspan of between 180 cm and 210 cm. They measure between 120 cm and 148 cm in length and weigh approximately 5 kg to 8.2 kg. They mate for life. They can fly at a top speed of 88 km/h (55 mph). The Tundra Swan holds its neck and head erect while swimming and walking, with the crown and forehead displaying a rounded profile.

Tundra Swans in March 2021, photograph by Lambton Heritage Museum staff member Colleen Inglis.

Early spring is your chance to see these magnificent creatures here in Lambton County! The arrival and departure dates of the Tundra Swans resting on the Thedford Bog varies greatly. Often they are first spotted in late February or early March and they stay for two to three weeks. The peak of swans in the area is usually mid-March, when thousands can be seen flying and feeding.

Once the swans have been spotted in the area, Lambton Heritage Museum staff post regular updates about the number of swans and the best times to see them. Visit our website www.returnoftheswans.com for migration updates and more information about these amazing animals!

Olivia Garva, Sombra Museum

Throughout the 1900s, the St. Clair River was a deadly site for sailors, captains and crew, resulting in the loss of life, goods, and ships. Here are a few of the most well-documented shipwrecks between 1900 and 1909.

Wreck of the schooner Fontana in the St. Clair River - from Sombra Museum’s files

On August 3, 1900, the wooden schooner Fontana was downbound from Michigan to Ohio and in tow of the Kaliyuga. At the same time, the Appomattox was towing the schooner, Santiago. As the vessels passed each other near where the Blue Water Bridge is today, the Santiago struck the Fontana. The Fontana sank immediately, taking the life of one crew member who was asleep at the time. The remaining crew were able to make their escape before the vessel sank.

The stern section of the wreck of the Fontana was still above water and the hull prevented navigation. There were weeks of debating about whether the wreck lay in Canadian or American waters and how it should be removed. Two buoys and two lights were placed around the wreck to identify and warn oncoming ships of the dangers. During this time, disaster struck once again.

On September 22, 1900, the schooner John B. Martin was downbound and the steamer Yuma was upbound heading to western Lake Superior ports. The John B. Martin had barely passed the wreck of the Fontana when the Yuma veered and struck her. The Martin sank to the bottom of the St. Clair River, taking four of her crew with her, including the captain, James Lawless, the mate, William Ross, the cook, Mrs. Bacon, and a Swedish sailor, Charles Reister. Two of the ship’s crew were rescued by a marine reporter and two others were picked up by the Yuma. The Yuma had little damage and was briefly tied up for inspection before continuing her way.

With two wrecks in the St. Clair River at a relatively close distance, navigation became extremely difficult for passing ships. To prevent further wrecks, patrol tugs were stationed in the river to help passing ships navigate the wrecks of the Fontana and the John B. Martin. Before both wrecks were removed, the schooner, A.J. McBrier, veered out of the way of one of the wrecks, launching a sailor into the river to drown and striking the Fontana. After weeks of delay, preparation, and disasters, dynamite was used to remove most of the Fontana from the channel and to remove the spars and rigging off the Martin.

The Swallow was a 133-foot wooden propeller built in 1883 by A. A. Turner in Trenton, Michigan. She was later converted to a bulk freight steamer. On October 5, 1900, she was

heading upbound near Marine City when she was struck by an unidentified steamer, causing a 10-foot hole in her starboard bow. The Swallow sank near the shore and was taken to Detroit to rebuild. The collision was caused by a signal error, with the unidentified steamer maintaining course, not knowing how much damage she had done. The carrier continued to provide service in the lumber and coal trades until 1901 when she sank in a gale near Lake Erie’s Long Point while towing the schooner, Manitou, from Emerson, Michigan to Buffalo. The Manitou rescued the crew of the Swallow and drifted for nearly 40 hours until she was picked up by the steamer, Walter Scranton.

Owned by Sylvester Ray and built by Henry D. Root Shipyard at Black River, Ohio in 1865, the oak-hulled schooner, Fostoria, met her final destiny on May 10, 1901. She was holed by an ice jam and sunk in the St. Clair River near Port Huron, Michigan. The Fostoria and her cargo of coal were deemed total losses as the ship herself had an advanced age and condition and there was little profit to salvaging material as inexpensive as coal.

The George Stauber was a small ferry boat built in 1883 running between Port Huron and Point Edward. On August 21, 1901, the Stauber disappeared on the St. Clair River following a collision with the McDougall. Nine passengers from the ferry stayed alive as they floated in the fast stream. At the time of the disappearance, the George Stauber was not carrying any lights and was only carrying fire insurance, no marine insurance. She was valued at $2,500.

Built at Vicksburg, Michigan in 1870 as a wooden freighter, the Nelson Mills spent her career in the lumber trade. On September 6, 1906, the Mills sunk in a collision with the steamer Milwaukee in the St. Clair River. Two of the crew were lost in this tragedy while Milwaukee and nearby boats rescued the remaining crew. In February 1907, Judge Humphrey of Chicago found boat ships to be at fault. The first mates of the Milwaukee and the Nelson Mills were suspended for six months for cross signalling and failure to reduce speed or reverse the engines. Later, the Nelson Mills was blown up to clear the river for navigation.

Nelson Mills (photo has been digitally remastered from a low-quality copy)

Built by Campbell, Owen & Company in Detroit, Michigan in 1883, the Argonaut was a double-decked schooner until being converted to a powered bulk freighter in Wisconsin in 1881. She was active in the iron ore and coal trades. Docked end to end with the Argonaut at her dock in Marysville, Michigan, was the schooner, Hattie Wells. On October 12, 1906, a fire broke out on the Hattie Wells and spread to the Argonaut. The Hattie Wells was towed away from the dock and extinguished. She had $8,000 worth of damage but had insurance and later rebuilt. The Argonaut, however, burned down and was deemed a total loss.

Underwater wreck of the Hattie Wells, starboard side view courtesy of www.michiganshipwrecks.org

Alan Campbell, Lambton County Branch of the Ontario Genealogical Society

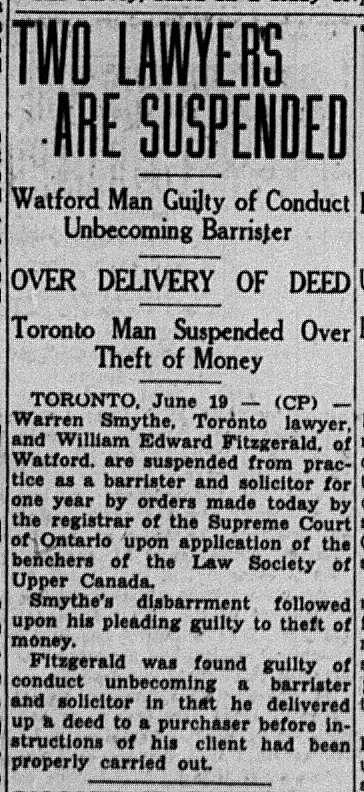

As I was “trolling” through newspapers for information about William Edward Fitzgerald, a second cousin three times removed, my attention was captured by the following article in the June 25, 1936 issue of The Advertiser-Topic (Petrolia):

“Watford Lawyer Suspended

William Edward Fitzgerald of Watford was suspended from practice as a barrister for one year for unethical conduct in that he delivered up a deed to a purchaser before instructions of his client had been properly carried out.”

Ironically, I did not find notice of the suspension in the Watford Guide Advocate.

I did not find any more details about this case but did find a number of articles about another case that could have led to a suspension had it ended differently. An article, Asks Charge be Quashed, dated May 18, 1934, noted that William Edward Fitzgerald presented a motion at Osgoode Hall wanting to upset charges that he and “…his son W.Y. Fitzgerald… obstructed a bailiff in the execution of his duty.” The action had begun at the division court level as the bailiff followed up on those proceedings and attempted to seize a typewriter on the behalf of a Fitzgerald creditor. William Edward, after receiving a summons to Osgoode Hall, placed a motion to have the proceedings set aside. When interviewed, he stated that “The whole thing is bosh …The proceedings are illegal and improper and based on spite.”

The London Free Press, 20 June 1936. p. 12

An article, Won’t Tackle Lawyer’s Case Says Magistrate, published May 28, 1934 provided more information about the case. Magistrate C. S. Woodrow ordered the trial for William Y. and William E. Fitzgerald because of the latter’s profession of barrister. James P. Elliott, division court bailiff at Watford, charged the pair “…with obstructing him in the pursuit of his duties.” Elliott, 83 years old, went to seize a typewriter at the Fitzgerald home May 10, 1934, under “…a writ of replevin…”[based on a $15 bill for typewriter repairs]. He claimed that the Fitzgeralds pushed him into a chair when he went to seize the machine. The image of the claimed assault was made worse by the bailiff’s mention of a missing crutch used

because his foot had been amputated a few years earlier. W. Y. Fitzgerald and his father were released on personal sureties.

An article, Fitzgerald’s Case Deferred, published June 14, 1934, reported that the case against the Fitzgeralds had been deferred because at the General Sessions of the Peace June 12, 1934 they requested a trial without jury and the jury had been brought in already. The case was further laid over until June 27, 1934.

After all the excitement the Fitzgeralds were acquitted July 4, 1934 of charges of obstructing James Elliott, the aged bailiff because of reasonable doubt about the situation. William Edward, who defended himself, was informed by the judge that he could have been more diplomatic. At the time of the attempt to recover the typewriter, a cool-headed Jane Fitzgerald [W. E.’s wife] suggested that the amount owing be paid, $18. A cheque was written at that time. James Blizzard, the county constable who accompanied the bailiff to the Fitzgeralds’ house, claimed that he did not see the alleged assault. William Edward claimed that the bailiff slipped on the waxed hardwood floor. He also indicated that he should be compensated for the costs of the court case but the judge refused to make an order. This led to a lawsuit by the Fitzgeralds seeking damages of $20,000 but that is a story for another day.

How did William Edward’s practice fare after the suspension? According to his obituary published in the Watford Guide Advocate February 22, 1952, he had left Watford to live in London 17 years [1935] before. The first mention of the family in City of London directories actually came in 1937, which captured William Edward as a Barrister, Solicitor, and Notary Public with an office at 12 Market Lane, room 7 with his residence in Watford. It is interesting that his suspension was to end June 17, 1937 yet he had his ad in the 1937 directory which was probably published late in 1936. His son William Young was in Real Estate and Insurance and operating out of 12 Market Lane, room 7. He had already moved to London and was residing at 275 King Street.

Vernon City of London Directory, 1937

By the time of the publication of the 1938 City of London Directory, William Edward had moved to London as Jane, his wife was also listed. He was still operating out of 12 Market Lane and his residence was now recorded as 44 Victor Street, London, also the residence of his son William Young.

Vernon City of London Directory, 1938. Accessed on familysearch.org, 14 Nov 2024

It would appear that William Edward Fitzgerald “landed on his feet” and continued his career. His story as told via newspaper articles is an interesting one and is deserving of the writing of a prequel as he was frequently mentioned in the Watford Guide-Advocate in the years prior to the period about which I have written.

Claire Pidduck, Oil Museum of Canada

At first glance, a connection between ships and the oil industry of Oil Springs may seem to be part of two distinct historical narratives; however, there are many interconnecting threads between the two.

Beginning with an outward look to the Atlantic Ocean, Lambton County oil is linked to arguably the most famous ship in history: the RMS Titanic. The tragedy made headlines across the globe, as demonstrated by an Oil Springs logbook that contains a handwritten note detailing how the ship hit an iceberg and lost 1,600 souls. There is a deeper connection between the doomed liner and the oil industry of southwestern Ontario.

The RMS Titanic as seen in this colour photograph (accessed from World Encyclopedia). The Titanic sank on April 15, 1912. Approximately 1,500 lives were lost, including Sarnia-born international driller, James McCrie.

A logbook from our museum collection featuring a handwritten note about the sinking of the Titanic. This infamous tragedy reached close to home in both the news and the people affected. Image courtesy of the Oil Museum of Canada collection.

A group of international drillers in Borneo, 1907 wearing the customary white suits. Gus Slack, who gave James McCrie the Titanic ticket, instead sailed home on the Lusitania. He sits second from the left, while McCrie himself is fourth from the left. Image courtesy of the Oil Museum of Canada.

A commemorative medal from Lambton Heritage Museum made after the sinking of the Lusitania. This was part of a wider movement with many related propaganda pieces also being made at the time to further stoke anger in the general populace and villainize the Germans.

Image courtesy of Lambton Heritage Museum.

James McCrie was an international driller from Sarnia. While in England after drilling for oil in Egypt, he learned of a family member’s sickness. He presumably obtained ticket #233478 (worth 13 pounds) from his friend, Gus Slack, an international driller originally from Petrolia. James McCrie never made it home, as he was one of over 1,500 people who died that night.

Another key naval vessel of the early 1900s is the Lusitania. In 1912, Gus Slack, who had just avoided catastrophe, boarded this ship and returned home to Canada. This ship is less known in present-day North American memory, but this does not diminish the effect it had on history. In 1915, the ship, which as a passenger presenting ship and therefore protected from wartime attacks, was struck by a German U-boat and sank in 18 minutes with a death toll of 1,200 people. This event stoked the already increasing frenzy of war, partially inspiring American involvement in the First World War. Admittedly, this connection between the Lusitania and international drillers is less dramatic, but it is still crucial. A “hard oiler” was on that great ship, interacting with an environment that, looking back, emerged as a turning point in the First World War.

William McGarvey was a shopkeeper and oilman in Petrolia who eventually moved to Austria, making a name for himself in the oil industry. His daughter married into European nobility. McGarvey was a powerful man who unintentionally advanced the German petroleum industry to a point where they could participate in World War I. He also advised the British Admiralty on how to help convert their battleships from coal to oil-powered technology.

Moving forward in history through the First and Second World Wars, to the advancements in the shipping industry, one arrives at the intersection of oil and maritime history in the present age. Today, many experts are concerned about the amount of oil sitting inside shipwrecks. These ships, spanning from the first use of oil in ships, to the warships used in the great conflicts of the 1900s (many from the Second World War), all the way to the modern era, are decomposing. These ships are becoming ticking time bombs of oil spills in already fragile marine ecosystems.

From the worldwide adventures of “hard oilers” bringing these people into close contact with maritime history, to the World Wars and lasting repercussions today, Lambton County oil and naval history are thoroughly intertwined.

Moore Museum

94 Moore Line, Mooretown, ON N0N 1M0 519-867-2020

Facebook Page

Plympton-Wyoming Museum

6745 Camlachie Road, Camlachie, ON N0N 1E0

Facebook Page

Lambton Heritage Museum

10035 Museum Road, Grand Bend, ON N0M 1T0 519-243-2600

Facebook Page

Oil Museum of Canada

2423 Kelly Road, Oil Springs, ON N0N 1P0 519-834-2840

Facebook Page

Arkona Lions Museum and Information Centre

8685 Rock Glen Road, Arkona, ON N0M 1B0 519-828-3071

Facebook Page

Sombra Museum

3476 St. Clair Parkway, Sombra, ON N0P 2H0 519-892-3982

Facebook Page

Lambton County Archives

787 Broadway Street, Wyoming, ON N0N 1T0

519-845-5426

Facebook Page

Forest-Lambton Museum

8 Main St. North, Forest, ON N0N 1J0

Facebook Page

The Ontario Genealogical Society, Lambton Branch

Facebook Page