WINTER 2020 ISSUE NO. 75

Lincoln Center Theater Review

A publication of Lincoln Center Theater

Winter 2020, Issue Number 75

Lincoln Center Theater Review Staff

Alexis Gargagliano, Editor

John Guare, Executive Editor

Anne Cattaneo, Executive Editor Strick&Williams, Design

David Leopold, Picture Editor

Carol Anderson, Copy Editor

The Vivian Beaumont Theater, Inc.

Board of Directors

Eric M. Mindich, Chairman

Kewsong Lee, President

Marlene Hess, Leonard Tow, and William D. Zabel

Vice Chairmen

Jonathan Z. Cohen, Chairman, Executive Committee

Jane Lisman Katz, Treasurer

John W. Rowe, Secretary

André Bishop

Producing Artistic Director

Annette Tapert Allen

Allison M. Blinken

James-Keith Brown

H. Rodgin Cohen

Ida Cole

Judy Gordon Cox

Ide Dangoor

David DiDomenico

Shari Eberts

Curtland E. Fields

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Cathy Barancik Graham

David J. Greenwald

J. Tomilson Hill, Chairman Emeritus

Judith Hiltz

Linda LeRoy Janklow, Chairman Emeritus

Raymond Joabar

Mike Kriak

Eric Kuhn

Betsy Kenny Lack

Memrie M. Lewis

Ninah Lynne

Phyllis Mailman

Ellen R. Marram

John Morning

Brooke Garber Neidich

Elyse Newhouse

Rusty O'Kelley

Andrew J. Peck

Robert Pohly

Katharine J. Rayner

Richard Ruben

Stephanie Shuman

David F. Solomon

Tracey Travis

Mila Atmos Tuttle

David Warren

Kaily Smith Westbrook

Caryn Zucker

John B. Beinecke, Chairman Emeritus

John S. Chalsty, Constance L. Clapp, Ellen Katz, Augustus K. Oliver, Victor H. Palmieri, Elihu Rose, Daryl Roth, Honorary Trustees

Hon. John V. Lindsay, Founding Chairman

Bernard Gersten, Founding Executive Producer

The Rosenthal Family Foundation— Jamie Rosenthal Wolf, Rick Rosenthal and Nancy Stephens, Directors is the Lincoln Center Theater Review’s founding and sustaining donor.

Additional support is provided by the David C. Horn Foundation.

Our deepest appreciation for the support provided to the Lincoln Center Theater Review by the Christopher Lightfoot Walker Literary Fund at Lincoln Center Theater.

To subscribe to the magazine, please go to the Lincoln Center Theater Review website—lctreview.org.

Front and back cover: MT.2442, a pair of women’s Combinations, circa 1890–1910. Image © The Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum, U.K.

Photo by John Chase Photography

Right: Image © Ellen Gallagher. Detail

series DeLuxe, 2004–2005.

Opposite page Clef Note Pattern

© Zee / Alamy Stock Photo

© 2020 Lincoln Center Theater, a not-for-profit organization. All rights reserved.

from the

AN INTERVIEW WITH LYNN NOTTAGE

PAULA GIDDINGS 5

SOUNDS AN INTERVIEW WITH RICKY IAN GORDON 11 SPECULATION, 1939 NATASHA TRETHEWEY 14

YOUNG IMMIGRANTS ANNELISE ORLECK 14 STEPPING INTO THE SPOTLIGHT CONSTANCE C. R. WHITE 17 SAID AND SUNG 19 SOMETHING NEW AN INTERVIEW WITH ANDRÉ BISHOP, PAUL CREMO, AND PETER GELB 20

Issue 75 REMEMBER ME

AND

LUSH

THE

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Collaboration makes theater possible. There is a special electricity that emerges when a multitude of artists, and ideas, come together to tell a story. They create a whole world that the audience can see, hear, and believe. The opera of Intimate Apparel embodies that collaborative magic. Even its conception was the result of bridge-building—the opera bloomed out of the Metropolitan Opera/ Lincoln Center Theater New Works Program, a groundbreaking enterprise between two constituents here at Lincoln Center Plaza. It champions the creation of new operas by pairing playwrights and composers. The first flower of this collaboration, Nico Muhly’s Two Boys, with a libretto by the playwright Craig Lucas, premiered at the Met in 2011. The next collaboration will be seen at Lincoln Center Theater. Intimate Apparel, like the earlier Two Boys, is directed by Bartlett Sher, Lincoln Center Theater’s resident director, and features music by the celebrated composer Ricky Ian Gordon and a libretto by Lynn Nottage, the Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright whose acclaimed play has been transformed into a mesmerizing opera.

All the characters of Intimate Apparel experience desire and longing, and each of them has dreams much bigger than the world around them can sustain. In this edition, we sought to explore their longings, their limitations, and the world they must navigate. Lynn Nottage sat down with the writer and historian Paula Giddings to discuss the creation of the opera and the necessity of telling the stories of people who would otherwise remain anonymous. Ricky Ian Gordon shared stories about his unusual childhood and his creative process. A poem by the poet laureate Natasha Trethewey takes us inside the dreams of an elevator operator, a working-class African-American woman like the heroine of Intimate Apparel. The historian Annelise Orleck paints a picture of the Lower East Side and the many communities that called it home in the early 1900s. The fashion writer Constance White illuminates the work of

black female designers. André Bishop, the producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater; Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager; and Paul Cremo, its dramaturg, spoke to us about starting the program, their passion for fostering new work, the germination of Intimate Apparel as opera, and the extraordinary collaboration and vision that bring opera and theater to life. Finally, this issue also features the art of Ellen Gallagher, Sanford Biggers, and Titus Kaphar, which invites us to see the world and our history anew.

Alexis Gargagliano

Image © Photographer Name

Image © Photographer Name

Remember Me

were unworthy of notation. Despite an epic search, I found that there was very little information; in the end, it was quite frustrating. My research was very much about trying to piece together the scraps of information that I could conjure from various sources.

PAULA GIDDINGS I was interested in the kinds of things you looked at to bring the history alive.

The Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Lynn Nottage took a break from her work on a Broadway musical to speak with the award-winning writer and historian Paula Giddings, whose books include When and Where I Enter and the biography of the iconic activist Ida B. Wells, Ida. In a quiet lounge above Times Square, the two women spoke with our editor, Alexis Gargagliano, about the history of people who have remained anonymous and undocumented, the power of telling these stories through art, and the dimension that music brings to this adaptation of Lynn Nottage’s beloved play.

ALEXIS GARGAGLIANO Lynn, how did you come to write the play Intimate Apparel?

LYNN NOTTAGE The play really came about after the death of my mother, who died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which is Lou Gehrig’s disease. The disease robs one of the ability to speak. And, just at the moment in my life when I was prepared to ask questions about my family history, my mother was unable to answer them. At the same time my mother was struggling with A.L.S. my grandmother was suffering from alcoholism, which led to her dementia, and so she as well was unable to answer the questions I had about our family.

While we were moving my grandmother from her home in Crown Heights/

Bedford-Stuyvesant to live with my brother, I had the unpleasant task of clearing out her house. I had thrown out a ton of magazines before I realized that my grandmother stored all of her personal photographs between the pages—like she was willing the family to be part of the magazines. In the center of a Family Circle I found a black-andwhite passport photograph of my grandmother and her sister sitting on my great-grandmother’s lap. It was the first time I’d ever seen an image of this striking woman. My great-grandmother was a seamstress from Barbados, and she was taking her children back to the island to visit her relatives. I saw the image and it sparked a million and one questions. The photograph led me on this journey to begin piecing together the history of my great-grandmother, a woman who was basically a stranger to me.

AG Were there things in the research process that really jumped out?

LN One of the things that I encountered when I was doing research is that the lives of “extraordinary/ordinary” AfricanAmerican women at the beginning of the twentieth century were almost completely undocumented. It was very hard to find any periodicals, with the exception of newspaper listings for work or the occasional criminal incident. There were few books written about Black women during this period; it was as if our lives

LN The ads in the newspapers looking for women of color—domestics—were very helpful. I also found descriptions of boardinghouses and the living circumstances to be quite useful, and, because my central character, Esther, is a seamstress, I found myself looking at images of corsets in sources like the Sears catalogs. I spent a lot of time in the New York Public Library, in the visual-arts section, perusing images from that period. My primary research was done at the Schomburg and the main research branch of the New York Public Library, both of which have wonderful photo archives. One of the first things I did was hunt for images of the people like the folks in the play. I found my Esther, I found my Mr. Marks, I found my Mrs. Van Buren, and my George. I pinned those pictures to the wall in my office, and then I went about researching their individual lives.

PG Esther made me think of how the occupation of a seamstress allows a Black woman to navigate not only across race but across class as well.

LN When I was writing the play, I was really interested in that intersection between class and race and gender. I knew when I decided to write about Esther that she was someone who could negotiate nontraditional spaces because of the nature of her work. I also knew that she was someone who could enter with ease the boudoir of a prostitute as well the homes of very wealthy white women. I was interested in what happens when a Black woman who is not empowered enters these different spaces, how her presence shifts the energy within that room.

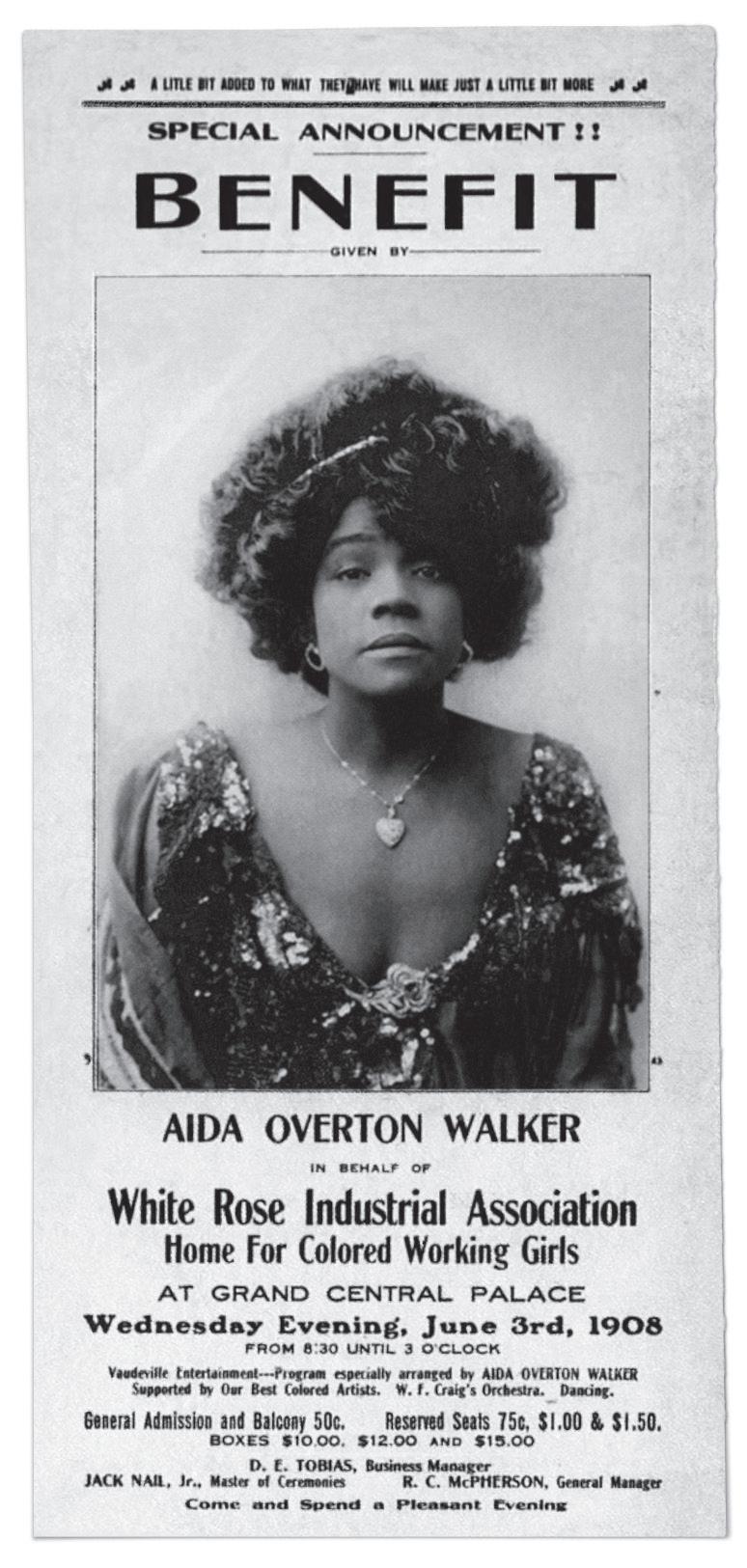

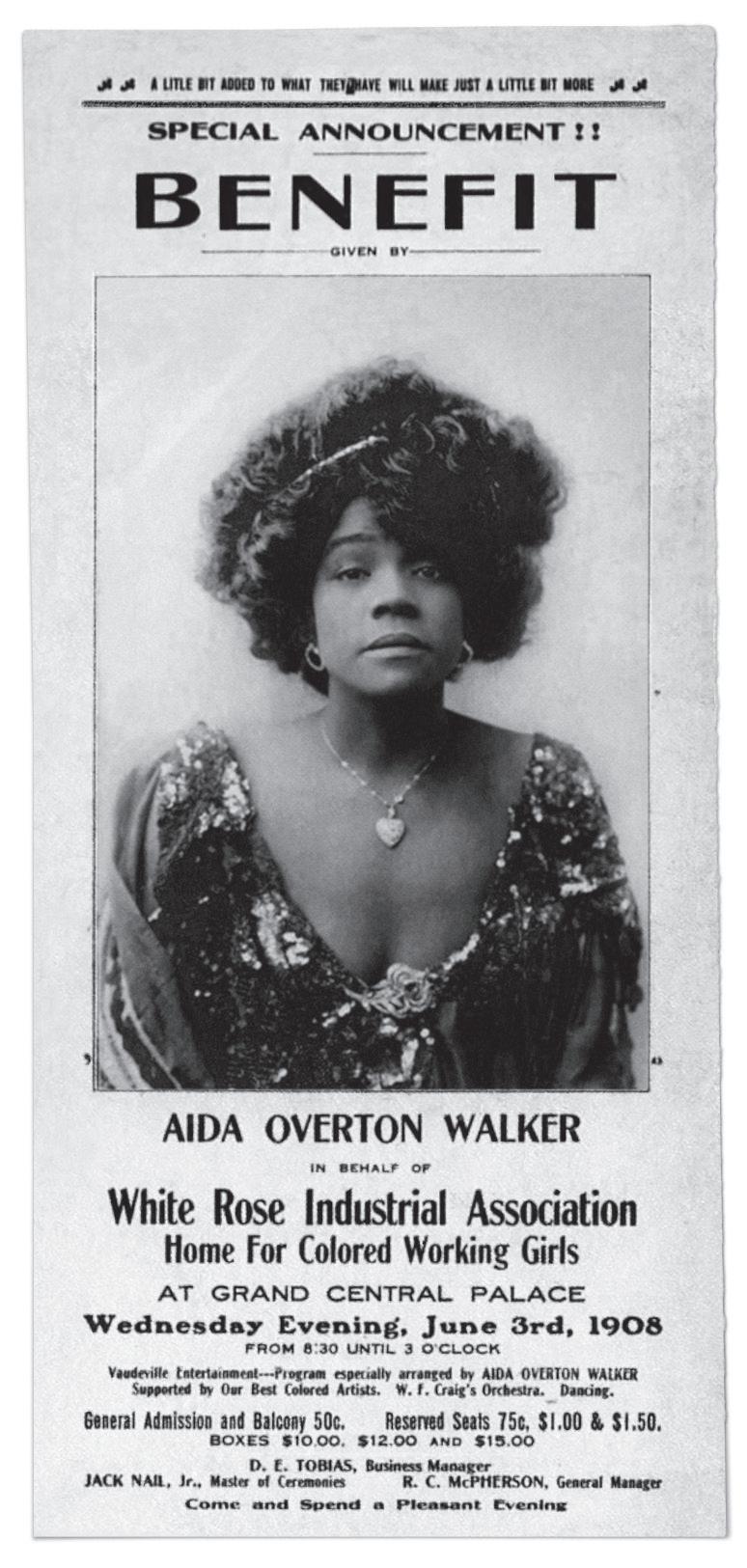

PG Another kind of space was a shelter and protective space for single Black women like that of the White Rose Home for Colored Working Girls, a settlement

Dimensions: frame (each): 389 x 325 x 46 mm Photo

5 LYNN NOTTAGE AND PAULA GIDDINGS

Image © Ellen Gallagher. From the series DeLuxe, 2004–2005. Medium: 60 works on paper, etching, screenprint, lithograph with plastic.

© Tate.

AN INTERVIEW with LYNN NOTTAGE and PAULA GIDDINGS

house in New York during this period. It was founded by Victoria Matthews, a journalist who had been born into slavery in Georgia. She was a friend of Ida B. Wells, the anti-lynching activist, who also founded a settlement house in Chicago. They were protecting Black women, many of whom were coming from the South to find work, like Esther. Esther’s boardinghouse is another protective refuge. I love the sisterhood that’s there and that you talk about.

LN I tried to imagine the first point of contact for a young woman who’s seventeen or eighteen years old upon arrival in New York City. Where would she go? She’d no doubt hunt for someplace that’s familiar. She’d probably seek out other Black women in a similar predicament. And these boardinghouses existed during that period because there was such a massive influx of southern Black women and immigrant women who were coming to New York City at the turn of the century. These women needed safe and inexpensive places to live while forging new lives. My family was part of the wave of Black southerners and West Indians who migrated from the South to the city

during Reconstruction and the early twentieth century.

AG Certainly Mrs. Dixon’s boardinghouse is a safe space. What are these young women facing in this period?

PG Conditions in this period were so perilous for Black women. There were unscrupulous employment agents, con artists, and the proliferation of dancing halls, gambling and prostitution houses helped create what was called a moral panic around young Black women particularly. This resulted in a good deal of surveillance, arrests, and incarceration of Black women, who were always seen as suspect regarding “immoral” activities.

People like Esther, who obviously was brought up in a particular way and was a Christian, would have been very aware of their environment. The whole idea of respectability is also very important in this period, not just for its own sake but because it was evidence that Black women were not inherently immoral and thus undeserving of protection by the state.

AG How would someone like Esther, who couldn’t read or write, have gotten her news?

PG Although Esther was illiterate, she

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 6

Image left: White Rose Industrial Association newspaper clipping. Image above: © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

I was interested in what happens when a Black woman who is not empowered enters these different spaces, how her presence shifts the energy within that room.

LYNN NOTTAGE

probably would have been aware of Black newspapers like the New York Age, which was widely circulated and often read or recounted to those who could not read.

AG What might someone like Esther have known about the activism and reform that were happening at the time?

PG Places like the White Rose Settlement had information sessions and political lectures. This period is the first time Black women were prepared to enter the public sphere and initiate reforms on a large scale. Just eleven years before the play is set, the first national Black women’s organization— the National Association of Colored Women—was founded, with its motto: “Lifting as We Climb.”

AG The presence of the women in the opera is very powerful, and the absence of the men very striking.

PG That’s right. Did you find this absence of men in your family history?

LN Not in my immediate family, because my father was very present, but in the generation before mine there was an absence of men. It’s like the babies were born and then the men disappeared. There was this generation of women who just had to make lives in the absence of male support and companionship.

PG It is amazing how, not to overgeneralize, but how we’re always talking about our making a way out of no way, of overcoming tremendous challenges as Black women, but then the man comes

around and it’s like kryptonite. (Laughter) As Esther shows us, the need to be loved is more important than anything.

LN One of the things I did get to do with the opera that I felt was incomplete in the play was delve more deeply into the character of George, even though he’s meant to be somewhat elusive. I wanted to explore just a little bit more about the nature of his wants and desires when he arrived in a city that was not necessarily a welcoming place for a skilled Black laborer. George, as I understand, is someone who was aspirational. He wasn’t purely mercenary in his intentions. But he came to New York with a mission of self-improvement and betterment, and along the way he also fell victim to con artists. He is at once the exploiter and the exploited.

PG No one can fulfill their dreams in this play. Though no one gets hit with a sledgehammer, their dreams wither before our eyes.

LN They’re people who have these incredible aspirations, and they all become victims of circumstances. I think this is largely due to the way in which racism and classism functioned in New York City at the time. These social barriers were insurmountable for uneducated laborers like Esther and George.

PG Or themselves.

LN Someone like Esther, who’s illiterate and who’s African-American and who’s a woman—there’s only so far that she can climb on the social ladder.

PG And she’s actually done very well for herself.

LN That’s right. She’s heroic. The play begins with Esther sitting at her sewing machine, and when you see that sewing machine it should feel like it’s a symbol of oppression. But by the time she sits at the sewing machine at the end, it should feel like it’s a tool of liberation.

PG It’s interesting, because the play is unfolding around the same time as the shirtmakers’ strike, but Esther transcends the kind of industrial repression that those women experienced.

LN Yes, because she’s entrepreneurial.

AG Paula, there’s a line in your book When and Where I Enter that says, “We became indispensable to everyone but ourselves.” That really resonated for me

with Esther’s journey.

PG We’re very self-confident in many ways and very strong in many ways, but we also tend to think that we are not the ones who are going to shape the race’s future. We tend to think that the race will be saved if men, not us, are saved, but I think the truth may be just the opposite.

When Esther gives up her money and that dream, she is saying Armstrong is the one who’s going to carry us forth, and it was her job to help him do so.

LN Yes. It’s like she’s investing more in his dream than in her own. That somehow she hasn’t placed enough value on her dreams to understand that she can accomplish more if she leans into it.

You made me think of a quote from Ellen Craft, who was a runaway enslaved person in the 1840s. During an abolitionist meeting in Boston a white man stood up and asked, “Well, what makes you think that you can take care of yourself in freedom?” And she said, “I’ve been taking care of white people and myself for all of these years. I am certain I can take care of just myself.” She had been responsible for everyone. I think a lot about that in terms of being a Black woman. One of the reasons it was so hard for us to gain ground during the twentieth century was that we were so busy taking care of the lives of everyone else. Esther is certainly a victim of her own nurturing spirit.

I saw it with my relatives. For generations they took care of white people and then had to come home and feed their kids, and clean the house, and take care of their husbands.

PG That’s right, that’s right. And there are different phases of this, because the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when Black women are coming into the public realm, they’re debating all this. In 1892, the educator and feminist Anna Julia Cooper writes, “When and where I enter”—meaning Black women— “When and where I enter … the whole race enters with me.”

LN One of the things that Black women encountered is that when you’re working that hard you don’t have time for activism. When you’re working just to feed your children and to pay your

7 LYNN NOTTAGE AND PAULA GIDDINGS

Image © Jackson Davis. “Girl Cutting Out Dress Patterns: Hampton Institute.” Jackson Davis Collection of African-American Photographs. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Virginia.

rent, you really don’t have time for all the ancillary things. Think of the suffragist movement; Black women were part of it, but it was, by and large, credited to white women, who had leisure time to march and, importantly, document the history of it.

PG Yes, white women had people to take care of the house and the children. Ida B. Wells figured out that she had to take her children to the scenes of lynching. She said, “Look, I can’t leave them. I will take them with me.”

AG How did you conceptualize having the anonymous photographs at the end of each act?

LN We had done the piece at Baltimore Center Stage, and one of the questions that kept coming up was: Why is this piece relevant today? I thought, Well, it should be obvious, but clearly it was not obvious to a lot of people in the audience. Suddenly, when I bookended the acts with images—“Unidentified Negro Couple,” “Unidentified Negro Seamstress”—people understood why I was telling this story, that it was a reclamation project. I wanted to rescue these working-class people from obscurity.

PG One of the most haunting things I ever came across in doing the research, particularly trying to find names of enslaved people, was a woman, a Black woman, who called herself Rememberme—all one word.

LN That’s amazing. Where did you find that?

PG In a slave census document.

LN That’s beautiful. She understood that she was going to be disappeared and she gave herself the name that you found a century later. She knew that at some point in history someone would read it and hear the message.

PG When Ida B. Wells wrote about the victims of lynching, she made sure they would not be anonymous. She mentioned their names, where they were from, what the community thought of them.

LN Wells is so important. It is only with a generation of Black women who have the power to put pen to paper that she has been resurrected.

AG Yes. Really, a whole swath of history has been disappeared. We are still in a place where “African-American history”

seems to be largely kept separate from what we are taught is “American history,” and without that knowledge it is impossible to understand our country or ourselves.

PG Absolutely. There’s nothing that goes on in this country that’s not shaped by race—and by slavery, specifically. That history is the foundation for everything: not just the founding of the nation on a mega level but our practices, like the advent of the insurance business, which comes out of insuring enslaved people. That our Ivy Leagues were capitalized by those involved in the slave trade at a time when the modern social sciences emerged still has an impact not only on how race but gender is taught in the academy. As Toni Morrison wrote, “If you don’t know Black women’s history you don’t know American history.” Once you understand that history, then you understand race, you understand gender, and you understand sexuality. There’s a glimmer of light: there are scholars doing some great work in this area.

AG Given the dearth of documented histories of Black people at this time, there’s something especially poignant about being able to capture the stories of anonymous people in art.

LN One of the real joys of being an artist is being able to shed light in these spaces where darkness has been. Illuminate.

So often when I was doing my research I’d look at photographs, particularly those of wealthy white families. In the captions, all the white people would be identified, and then where the Black person’s name and title should be it would always say “Unidentified Negro.”

When people look at the images in the production, I really want them to think more thoroughly about the life of someone like Esther, someone who has been disappeared from the public archive. I was at the Brooklyn Museum looking at the art of Titus Kaphar. One of the things he does is examine traditional European painting and, in particular, images that have Black folx who are relegated to the margins. Part of his practice is re-creating these “classical” paintings. However, he shifts the focus, bringing the Black folx to the foreground. He says that his mission is to

shift perspective—so that a Black boy who is hidden in the background, not fully seen, becomes seen. That’s what art can do so beautifully, and that’s what I was hoping to do with Intimate Apparel.

I always felt like its perfect form is an opera. It has sopranos, the alto, the tenor, the baritone. It’s perfectly designed for operatic voices.

AG How has the music opened up the story for you in this adaptation?

LN I was listening to the artist Theaster Gates talk about Black sonic life and how it is music—and not just music but sound—that rescued us and got us through a prolonged period of trauma. We, as Black people in America, have had to suffer through centuries of oppression, and one of the things that permitted us to transcend it was the power to express our trauma through music and through sound.

In Intimate Apparel, in the moment after George has taken all of Esther’s money, she releases this beautiful, tortured sound that Ricky has created. It is a perfect expression of what I wanted to convey. When I heard it, I thought, There is no other way I could have captured the intensity of her despair. It is a perfect marriage between the words and the music. It is beautiful and it is horrifying, and it captures all the complexities of Esther in that moment. That’s the dimension that opera brings. There are layers that, no matter how hard I work, can’t speak as expansively as the marriage between the words and the music.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 8

LYNN NOTTAGE Playwright

PAULA GIDDINGS Writer and historian

Image (top): Lynn Nottage. Image © Lynn Savarese Image (bottom): Paula Giddings.

Image opposite © Titus Kaphar. Darker Than Cotton, 2017. Oil on canvas. 63 x 36 inches.

Photo courtesy of the Artist and the Mississippi Museum of Art.

Lush Sounds

them. It used to be that I could play and sing all my operas just sitting down at the piano, but with Grapes of Wrath my style expanded, and now it’s bigger than my two hands.

JG When I met you, I knew all about you because of this remarkable book, Home Fires, by Don Katz. Katz covered five decades of a “nondescript” American family—just nice people who live in Oceanside, New York. This family was your family. I bring the book up because Intimate Apparel takes a woman who would otherwise be invisible and gives her her full due. Home Fires was a revelation of the chaos, the anguish, and the glory that come out in an American family. What was it like having your life exposed like that?

Our executive editor John Guare sat down with Ricky Ian Gordon, the composer of Intimate Apparel and other celebrated operas and musicals, including Orpheus and Euridice, The Grapes of Wrath, 27, Morning Star, and My Life with Albertine, to talk about craft and Ricky’s unusual life.

JG How did you come to make an opera of Intimate Apparel?

RIG I was commissioned by the Met and Lincoln Center Theater. It was 2007, and it was right after Grapes of Wrath had opened in Minnesota. I wrote that with Michael Korie, so I just assumed he and I would do our next piece. My first idea was Adele Hugo—from Truffaut’s film The Story of Adele H. Michael and I started working on that, but as exigencies in each of our lives happened it turned out that we couldn’t work on that piece together, and I was suddenly left without a collaborator. I didn’t really know Lynn Nottage, but she was on a committee that awarded me an Obie. I read all of her plays, and everything about Intimate Apparel resonated with me.

JG The libretto seems to be a distillation of the play. Did the two of you work very closely on that?

RIG Yes, Lynn had never written an opera libretto. And, of course, the first draft had too many words. But with each draft I got Lynn to trust a little more that a

lot of the drama in an opera happens in the music.

JG Did you play her music as you went along?

RIG Yes. It was really exciting and fun. Lynn is a superb collaborator. She was always open to what I needed or what I didn’t need, and we had a dramaturg at the Met, Paul Cremo, work with us to further distill the play.

It’s always scary for a composer to look at a page and know there might be a problem. If you see too many words on a page, you don’t see music; you just see obligation. There’s something about the way words are spaced out on a page that says possibility or not possibility. Lynn managed to put words on the page that said possibility.

JG Do you write on the piano?

RIG Basically, when I write now everything is mock-orchestrated on my computer. For the first workshop, I brought my computer to the Met and we hooked it up to speakers. I conducted, and the singers sang along with the tracks on the computer.

JG What are the sounds on the computer?

RIG Sampled sounds—piano, strings, reeds. It’s very lush. When André Bishop and Peter Gelb first heard the opera, I made them come over to my apartment and they sat on a piano bench in front of my computer, and I sang the score for

RIG My friend Doug Kennedy, who is Robert Kennedy’s youngest son, read the book and said, “How could you let your family be exploited in that way?” I jokingly said, “Doug, some people crave exploitation.”

On a certain level I didn’t mean that, but there was also something flattering about the attention. It was exciting, and it was painful, too. We all told Don things we didn’t tell each other, especially my dad.

When Home Fires came out, it was right at the time my sister Susan was finishing rehab in Boston. She wrote an article for the Boston Globe about her rehab, and then she wrote a memoir. It was harder for my sisters, because they have more life on the planet than I do, and some of the very painful things that happened to them were deeply described in that book.

JG How did your father and mother react to all this?

RIG My dad would not read it. He didn’t read anything. My sister wrote three memoirs; he never read any of them. Don lost his dad at fifty, so in many ways I think he sort of fell in love with my father. They really bonded. Not that Don glorified my father, but he saw something in my father that we didn’t see. My father was tough and really violent. I think he was so afraid of being exposed.

JG Did your father tell Don things he didn’t tell you?

RIG Absolutely. For one thing, he never

11 RICKY IAN GORDON

Image © Blossom (installation view at the Brooklyn Museum), 2007. Silk steel, wood, MIDI player piano system, Zoopoxy, paint, dirt, modeling clay, polyurethane foam. Courtesy of the artist and the Brooklyn Museum.

Sanford Biggers's sculpture Blossom was inspired by an incident in Louisiana in 2006, when a black high-school student sat beneath a tree that white students had claimed as their own. The next day when he arrived

at school, there were nooses hanging from the tree. Biggers programmed the piece to play, “Strange Fruit,” the song made famous by Billie Holiday.

AN INTERVIEW with RICKY IAN GORDON

talked about his time in World War II with us. Our relationship with my dad was difficult. We were somehow excruciating reflections of him, and so we had difficult relationships with him. When he got older he cried and told my mother, “I feel like I missed my children’s lives.” She wisely said, “You have them now.” So there was reconciliation. But the damage was done, and we were injured and in therapy for four hundred years. It was very complex. It was everything. It was flattering. It was exciting. It was upsetting.

JG You also wrote something autobiographical?

RIG Yes, Sycamore Trees, which we did at the Signature Theatre in Virginia. It was completely about my family. It took years to write. It was so cathartic. For some reason, the thing that allowed me to finish it was that in 1996 my lover, Jeffrey, died of AIDS, and his death came on the heels of me losing, basically, my whole community. I had worked for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and I was really active. When Jeffrey died, I literally fell apart for five years.

JG Who wrote the libretto for Sycamore Trees?

RIG I wrote it, and I worked with a

woman named Nina Mankin, who came on as a dramaturg. But then Nina helped me; we actually wrote a lot of it together, and then I wrote all the lyrics and the score. It was amazing.

JG Was it an opera or a musical?

RIG It was a musical, but it definitely pushed the boundaries in terms of the score, which was complex, and there was a lot of singing. I have a term for my work; I call them “operacals.” I’m a hybrid.

JG Do you have other new work?

RIG Right now, I have three new operas this year. I spent three years setting Frank Bidart’s poem “Ellen West” to music. It’s a poem written in two voices, a doctor and a woman with an eating disorder. It’s a very long narrative poem with a story, and I set it to music. That premiered in Saratoga last summer. Next it goes to Prototype, which is Beth Morrison’s annual contemporaryopera festival. They do new operas all over the city. Then I wrote an opera of The Garden of the Finzi-Continis Really, Home Fires came out before I did anything. All I did was have a big fight with Stephen Sondheim.

JG A fight with Steve?

RIG Oh, you know, it’s so funny to talk about it now, John, because I was a kid. I was twenty-two. When I was about seventeen I was invited to the cast party of Pacific Overtures, at Steve’s house, by my friend Kim Miyori, who was in the show. The moment I arrived, I was scared. I guzzled a huge glass of scotch and then puked all over the place. Kim had to leave the party and get me back to Long Island. (The beginning of my story!) Years later, I recounted that story for Steve and I told him how I loved Merrily We Roll Along and I wrote a funny letter, so he invited me to his house. We were sitting on his terrace drinking. I was drinking plenty of wine, and he was drinking kirs. And at one point I asked him, “Whatever happened with Merrily We Roll Along?”But I asked it in this presumptuous way that was, like, ‘Oh, give me the inside scoop.’ I knew nothing. I was barely a composer yet. Steve asked, “When did you see it?” I said, “The first preview.” He freaked. We just basically screamed at each other. I was screaming, “You’re not my father.” Then we were in

the street yelling at each other and I saw a limo and said, “There’s your car.” He said, “That’s not my car.” It was horrible— having your full-on hero scream at you in the street. It was horrible. It was like having my ideal father figure loathe me. It was a long time before I could think about the incident with any understanding of what had transpired, which was that he was very hurt about what happened with Merrily We Roll Along and I was almost salacious in the way that I asked about it. Now I know what it’s like to write something, and love it, and feel great about it, and have it be trashed by the critics or have the first production not quite get the piece. I pressed the excruciating-pain button, and I reaped the rewards.

JG Have you made up?

RIG Oh, yes. For years I would have dreams about him. Then I heard that Steve had had a heart attack. I made him a watercolor called Stephen Sondheim in Yellow Healing Light. It was Stephen rising out of the ocean with rays of light. I brought it to the hospital and left it for him with the nurse. I never heard from him, so I wrote and asked if he’d got the painting. When he said no, I did the whole painting again and sent it to him. I must have apologized to him four hundred times. I’m sure there’s a part of him that will never forgive me (Laughs), but what can you do? I was a kid. I was insensitive. I had no experience. I was a burgeoning alcoholic and drug addict. I had no boundaries. Reflection is reflection, and we make amends the best way we can.

JG When did your love for opera begin?

RIG When I was eight, I became obsessed with opera. My piano teacher gave me a book called The Victor Book of the Opera Then I started going to the Met and to City Opera every Saturday. When I was twelve, I ran away from home. There was a horrible snowstorm in New York in 1968, one of the biggest snowstorms we’ve ever had, and I ran away because I had a ticket to see Roberta Peters in Lucia at the Met. I did get to the city, but I couldn’t get home, and I called my sister crying, and a friend of hers had to come and get me and take me to her house until the Long Island Railroad was running again. (Laughs)

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 12

There’s something about the way words are spaced out on a page that says possibility or not possibility. Lynn managed to put words on the page that said possibility.

RICKY IAN GORDON

JG When did your formal training as a musician begin?

RIG I started piano lessons when I was five.

JG Did you play by ear?

RIG I played by ear, but then I started taking lessons. In the middle of my senior year of high school, I got into Carnegie Mellon as a pianist. I was obsessed with three pieces: Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 14, Ned Rorem’s Song Cycle Ariel, and Steve Sondheim’s Follies. Soon after I got there, I had a revelation: my main reason for being a pianist was that my hands helped me explore the ideas of all the composers I loved. I thought, Maybe I’m a composer. So I went to the composition department and said, “What do I have to do to get into the composition department?” They said, “Write music.”

On a vacation from Carnegie Mellon, I wrote a hundred pages of music and was accepted into the composition department. Then, after being a composer for a year—I was really a speed freak then—I decided I wanted to be an actor. I quit school and came to New York, and basically bottomed out for about ten years, until I was thirty-three. Then I got sober and everything changed, almost immediately.

JG You didn’t write during that time? RIG I did write. I wrote all the time. But you know what Faye Dunaway says in Barfly when she goes, “Look, I drink. And when I drink, I move in the wrong direction.” That was me. I wrote, and even though people were singing my stuff I could never in a million years have finished an opera. It takes a lot of time and a lot of concentration to do what I do now. You can’t go out drinking every night. After I had thirty days in A.A., Terry McCarthy brought me over to Adam Guettel’s house to record some of my songs. Adam liked my music, and said, “I’m about to do a benefit for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and I want to present four composers. Would you be one of them?” I didn’t even know who he was, but I was flattered. So he presents me last at his loft, which seated, like, five thousand people. When I was done playing, Mary Rodgers and Sheldon Harnick and all these people were asking me, “Who are you? How come we don’t know who you are?” I couldn’t really tell them I was sort of hiding under a rock with various substances!

JG What was the piece you wrote for it?

RIG There was a soprano, who was singing at the Met at the time, named Patricia Schuman. She was incredible.

She was Peter Brook’s Carmen, the first Carmen.

JG She was the best. I remember her rolling the cigar on her thigh. RIG I wrote her a cycle using poems by May Sarton, Stevie Smith, e. e. cummings, and Frank O’Hara. The cycle was called I Was Thinking of You. Because of that poem by Frank O’Hara: “Did you see me walking by the Buick repairs? / I was thinking of you.” Within a couple of weeks, I had a full-on publishing contract with Rodgers & Hammerstein, where for four years they paid for me to live and write, and then, soon after, I had a recording contract with RCA for a huge cycle that I wrote for Harolyn Blackwell called Genius Child. It all happened immediately.

JG Does your life surprise you?

RIG Yes, it does—a lot, John. I am who I wanted to be, doing what I wanted to do in the world. And, you know, that could not have happened if I hadn’t got sober. Frankly, my biggest fear about my own drug and alcohol abuse wasn’t dying but that I wouldn’t fulfill my dreams.

13 RICKY IAN GORDON

Image: Four albums by Ricky Ian Gordon.

Image: Ricky Ian Gordon. Photograph © 2020 Gregory Downe.

RICKY IAN GORDON Composer of Intimate Apparel

The Young Immigrants

First, the moles on each hand— That’s money by the pan—

and always the New Year’s cabbage and black-eyed peas. Now this, another remembered adage, her palms itching with promise,

she swears by the signs—Money coming soon. But from where? Her left-eye twitch says she’ll see the boon. Good—she’s tired of the elevator switch, those closed-in spaces, white men’s sideways stares. Nothing but time to think, make plans each time the doors slide shut.

What’s to be gained from this New Deal? Something finer like beauty school or a milliner’s shop—she loves the feel of marcelled hair, felt and tulle, not this all-day standing around, not that elevator lurching up, then down.

NATASHA TRETHEWEY, a two-term U.S. poet laureate, Pulitzer Prize winner, and 2017 Heinz Award recipient, has written five collections of poetry and one book of nonfiction. An American Academy of Arts and Sciences fellow, she is currently Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University. Natasha Trethewey, “Speculation, 1939," from Domestic Work. Copyright © 1994, 2000 by Natasha Trethewey. Reprinted with permission of the Permissions Company, LLC, on behalf of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, graywolfpress.org.

NEW YORK WAS A CITY OF POSSIBILITY IN 1905, and also a place where the dreams of its many newcomers were as likely to be smashed as realized. It was a city of people who migrated when they were young and lived far from their parents and siblings, far from the villages and little corners of the world where they had been born.

The “Jewish ghetto”where Mr. Marks lived amid his piles and bolts of fabric was the Lower East Side, in 1905 the most crowded square mile on earth— alongside one ancient neighborhood in Beijing. In the years during which this opera is set, the city felt more crowded than ever. Thousands of people were displaced by demolition done to prepare for the construction of the Williamsburg Bridge, begun in 1896 and opened in 1903, and the Manhattan Bridge, begun in 1901 and not completed until 1912. During the Panic of 1907, thousands were evicted, and one group of four hundred young female garment workers spent a summer camped on the Hudson River Palisades as they prepared for a Lower East Side rent strike to protest sudden and dramatic rent increases.

Sometime between the 1960s and the 1980s— when New York’s Jewish population halved from 2,000,0000 to 1,000,000 because of the low birth rate and migration to the suburbs of Long Island and Westchester County, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Florida—the Lower East Side began to be portrayed in literature, film, and song through a nostalgic lens. A sepia-colored vision of Bubbe and Zayde (Grandma and Grandpa) taking in boarders, walking to a storefront synagogue, buying smoked fish and meat from kosher delis that cut

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW

ANNELISE ORLECK

NATASHA TRETHEWEY

from the bone, fishing pickles from barrels, steaming in mikvehs, the ritual bath performed, for example, in preparation for the Sabbath. All that was true, but it was not the whole story.

New York’s Jewish population certainly exploded between 1880 and 1920—from 80,000 to 1,600,000, and the city became home to forty-five percent of Jews in the United States. But this era was one of the two largest immigration eras in U.S. history; the other came in the 1990s. The Lower East Side was never exclusively the place of one people. There were different ethnic and racial groups living in different quarters and on different blocks. There were gangs of young boys who patrolled their turf, bullying anyone who didn’t belong. Lower Manhattan in 1905 was home not only to recently immigrated East European Jews but also to immigrants of Chinese, Irish, Italian, and Slavic descent. It was also home to many blacks, some born in New York and others who had migrated from the cotton-growing South or immigrated from the Caribbean.

In later years, when the Lower East Side and Chinatown and Little Italy became tourist destinations, we would be led to believe that they had always been distinct,“authentic” ethnic enclaves. But in truth people of various backgrounds existed cheek by jowl. Yiddish vaudeville and Chinese theater. And sometimes, sometimes, people fell in love across those lines of difference.

In the mid-nineteenth century—especially the 1840s, ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s—interracial living, loving, and marriage were not common in New York, but neither were they unheard of. According

to studies and census surveys from those years, there were hundreds of interracial marriages in the city—mostly Chinese and Euro-American but also marriages of African-American or Afro-Caribbean migrants and Irish, Scottish, or English immigrants. The vast majority of these marriages involved men of color marrying women who would now—but weren’t always then—be considered white. There were interracial marriages, too, in the first half of the twentieth century, but black and Jewish men married “outside the race” at twice the rate that black and Jewish women did. That would change, but not in Esther’s day.

So what Esther and Mr. Marks flirted with, a black-white love, a Jewish-Christian love, would have been possible but rare. And frightening. Interestingly, since Jews in that time and place were considered to be only “slightly white,” it was probably the religious divide that would have stopped these two lonely people from finding love and companionship in each other. At least where Mr. Marks was concerned. A study of 170,000 New York marriages that took place from 1908 to 1912 found that black and Jewish New Yorkers intermarried less frequently than any other groups in the city—at a rate of only one to two percent.

Even if some New Yorkers in the nineteenth century had cohabited with and married people of other races, that did not mean there were no racial fault lines or tensions. Violence was one route taken by various immigrant groups to claim their place in the city, to establish themselves as white. In 1834 and in 1863, there were outbreaks of terrible violence in which mobs of hundreds roved the city beating black men, women, and children, and also white women living with men of color. Windows were smashed, stores and homes burned, men and women murdered.

The New York of the early twentieth century was also a city rife with anti-Semitism, where stories abounded of Irish or German youths jumping older Jewish men and pulling or cutting off their beards, where newspapers ran anti-Semitic cartoons, and where candidates sold themselves on antiJewish and anti-immigrant rhetoric. (Maybe it isn’t really so long ago, after all.)

In 1900, five years before Intimate Apparel is set, and in the Tenderloin, where Mayme lives, there was a two-week riot in which police officers and Irish immigrant workers mercilessly beat black New Yorkers. It began with the attempted arrest of a black sex worker. Her boyfriend fought and ended up fatally stabbing the arresting officer. At the officer’s funeral, the violence began. What would

ANNELISE ORLECK

Photograph © 2007

Gordon Fikes

come to be known as the Race Riot of 1900 was a turning point in the city’s history. Black New Yorkers left midtown en masse and began to move uptown, to new housing in Harlem.

New York’s black population was growing, too, then, not in such dramatic fashion as that of the Jewish immigrant population, although it would eventually be twice as large. Between 1900 and 1920, the city’s black population increased from 60,666 to 152,457. Harlem, given its growth, was soon dubbed “the race capital.” As the Harlem Renaissance writer Alain Locke put it, New York boasted “the first concentration in history of so many elements of Negro life.” It became the epicenter of African-American art, music, dance, and literature. And so the New York where Mayme and Mrs. Dickson and Esther lived was both a terrifying and an exciting, promising place.

The Tenderloin was a red-light district that ultimately spanned the area from Twenty-fourth to Forty-second Street and eventually up to the West Sixties, where Lincoln Center now stands. There were theaters and music halls, too, especially on the main thoroughfare: Broadway.

The city was full of young men on their own: Italians and Irish and Germans and Greeks and Slavs and African-Americans from the South, as well as Chinese. (Chinese women were banned by the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s.) These young men had left without their families to seek golden fortunes in a burgeoning, booming, buzzing New York, and to try to save enough to bring their wives and children, brothers and sisters, and parents. One by one.

The city was also full of young women— African-American and Irish and Jewish—who had migrated on their own, bursting with ambition, like the young men but different, too. They wanted to learn to read. They wanted to go to school, to make the most of themselves, to have the kinds of freedom that women might not have had in the old country, or in “the rurals,” as some southerners referred to the farmlands from which they came.

The city was teeming with a youth culture— dance halls and theaters and chaotic intermixings of people on the streets. Amusement parks at the end of subway lines: Coney Island, with its pleasure parks—Steeplechase, Dreamland, and Luna Park. There were plenty of spots where young men and women might meet away from the prying eyes of parents, police, ministers, or rabbis and social workers.

The city’s young immigrant garment workers were beginning to organize unions and to strike for better wages, safer working conditions, shorter hours. But there were still few spots for AfricanAmerican seamstresses. They were legally banned, for a time, from the kinds of domestic work that so many Jewish and Italian women did—sewing artificial feathers and hats. It was difficult for them to find jobs. To open a private business sewing special garments for the wealthy, as Esther did, you had to be gifted and bold, and still it was hard to keep body and soul together.

New York had a way of wearing on many who came here alone, eyes bright with dreams of successful careers in business, or the arts or politics, or the trades. Then, as now, it was expensive and sometimes personally isolating. So many people—so hard to meet one. So difficult to cross those lines of difference—invisible and yet impossible to ignore.

ANNELISE ORLECK is Brooklyn born and bred. She is the author of five books, including Common Sense and a Little Fire, The Soviet Jewish Americans, Storming Caesars Palace, Rethinking American Women’s Activism, and We Are All Fast-Food Workers Now. She teaches history at Dartmouth College and lives in Vermont.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 16

The “Jewish ghetto” where Mr. Marks lived amid his piles and bolts of fabric was the Lower East Side, in 1905 the most crowded square mile on earth—alongside one ancient neighborhood in Beijing.

Stepping Into the Spotlight

BLACK FEMALE DESIGNERS FACE DOUBLE the trouble of other groups on their journey through the pintucked halls of fashion by virtue of being both black and female.

Historically, the rag trade has been dominated by men, a counterintuitive state of affairs, since women make up fashion’s biggest market by far. This lack of diversity on Seventh Avenue underscores the barriers faced by African-American female designers. Of the more than one hundred shows presented at New York Fashion Week twice a year, you can count on one hand the number produced by black women.

But change is coming, even if it is at a pace that a tortoise would have no problem keeping up with. Black women have made room for themselves as designers in the past three decades, led by such talents as Tracy Reese, Felicia Farrar, Constance Saunders, and April Walker. And joining them is a new generation, most notably Carly Cushnie, Aurora James, Felisha Noel, Terese Sydonna, Marie Jean-Baptiste, and Korto Momolu. Across the Atlantic, Grace Wales Bonner and Stella Jean are blowing up classic notions of European-centered design.

Black women have always been a central part of the world’s fashion story. But they have operated behind the scrim, with little reward or acknowledgment, even as early as the fifteenth century, when the first known Africans arrived in America. Elizabeth Keckley was a seamstress who worked for Mary Todd Lincoln, the wife of President Abraham Lincoln. Keckley was gifted. She is said to have made all the First Lady’s clothes.

Born into slavery, in Virginia, she was also an author, and was successful enough to purchase her freedom in 1855.

It was common, during this period, for black women, both free and enslaved, to assume a large share of the dressmaking for white women and their households, as well as for themselves and their own families.

Few know that it was a black woman who created Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress. Her name is Ann Lowe, and her garments sometimes carried her label. Lowe was a go-to fashion resource among socialites of the day, when she was tapped to design the gown for Jacqueline Bouvier’s September 12, 1953, wedding to Senator John F. Kennedy. The creation incorporated Lowe’s signatures, including lush handiwork and a defined waist.

Lowe was an anomaly. The practice of recognizing black women as seamstresses, but not as designers, persisted for decades. The legendary designer Stephen Burrows recalled how his mother worked as a seamstress in the 1940s and 1950s for designers like Hattie Carnegie.

Inclusivity started to increase in the sixties and seventies, but only in the past two decades has there been a noticeable change in numbers and impact. Reese burst onto the scene after stints with the French designer Martine Sitbon and the upscale brand Magaschoni before introducing her own, eponymous successful line for women. Recently, Reese returned to her native Detroit to unveil Hope for Flowers, a new sustainable fashion label, featuring the same feminine flourishes that her fans know and love.

17

CONSTANCE C.R. WHITE

Image: Ann Lowe, 1964.

CONSTANCE C. R. WHITE

Saunders parlayed her eye for the kinds of power suits favored by eighties women in the C-suite and on the lunch circuit, and Felicia Farrar, after paying her dues in the back rooms of New York garment manufacturers, decamped to Paris, producing sexy, feminine luxury looks. She’s now doing interiors in Durham, North Carolina.

Still, it isn’t easy for the new flock, but they’re doing well, garnering more than succès d’estime. These women have established financial footholds as retailers, and consumers warm to their designs. Carly Cushnie has attracted well-deserved attention for her sleek, contemporary looks with a rakish dash and is expanding her Cushnie brand. Noel, a Brooklynite, designing under her Fe Noel label, has sold in Bloomingdale’s, and she recently landed a coveted spot in the Workshop at Macy’s, a boot camp of sorts for aspiring fashion designers of color and for women-owned businesses.

Not confining themselves to clothing, black women designers have paved a way for themselves in accessories. Aurora James creates the most beautiful and visionary footwear for her New Yorkbased Brother Vellies brand. Observing the need for fashionable stilettos at the luxury level, Marcella Gift introduced Emme Cadeau, designed in New York and made in Portugal.

Two of the most successful people in the jewelry game are Monique Péan and Crystal Streets, who got a boost from an early fan, Jay-Z.

And then there’s Rihanna, her superstar status putting her in her own vibration frequency. Her entry into fashion as a designer along with the arrival of these other black women is significant as it opens the door to so many women of color who were denied entry.

That they have all been able to attract financing and generate sales revenues is notable. Lack of funds is cited as the number one deterrent for African-Americans trying to establish a fashion business.

Rihanna is backed by French luxury behemoth LVMH, Tracy Reese’s father, Claude Reese, seeded her business.

A company man who rose through the ranks in the automobile industry, Reese nevertheless recognized the glorious spirit of entrepreneurship and self-determination in his daughter.

Reese’s runway shows have long been among the most diverse. With an increased number of Black women in design seats, will come a more inclusive view of the world vis-à-vis beauty standards, body diversity, cultural appreciation and ageism.

Fashion sorely needs Black women to help recalibrate an industry that feels off-kilter with its homogeneity in body size, race and age.

There are still horrifyingly few women of color at brands like H & M, Gucci and Ted Baker. Had a black woman designer been on board, H&M would never have shown a photo of a black girl that many found offensive both in America and in Europe. These are painful ways to speak to the value of having a black woman’s voice in deciding what is beautiful, what is acceptable.

Historically, black women have been a force in fashion precisely because they’ve been pushed outside the boundaries of decision-making and power. With more black women taking the reins as designers and self-employed seamstresses, they increasingly determine their own message and change the wider conversation.

CONSTANCE C. R. WHITE is an award-winning journalist and author of the popular Rizzoli coffee table book How to Slay. Constance has helped steer brand and editorial direction for some of the most exciting companies, from magazines like Essence and Elle to the New York Times and eBay.

Image

of Division of

and

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW

courtesy

Cultural

Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Something New

as head of the Metropolitan Opera, we met for the first time to discuss this idea. I wanted to develop a whole program of ways to reenergize the Met. One avenue was to create new work. We were intrigued by the idea of developing work with librettists from the world of theater and bringing stage directors into the development process from the onset. André and I both felt that we could help improve the odds for success with new works by nurturing these collaborations at a very early stage.

AG Had you seen something at Lincoln Center Theater that sparked this idea?

PG Seeing things like Contact made me realize that André was encouraging the creation of work outside traditional bounds.

Our editor, Alexis Gargagliano, spoke with André Bishop, the producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater; Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager; and Paul Cremo, its dramaturg and the director of the opera-commissioning program. In Gelb’s handsomely appointed office, they discussed the creation of the opera Intimate Apparel, the Metropolitan Opera/Lincoln Center Theater New Works Program, and the burgeoning of

contemporary operas in the United States.

ALEXIS GARGAGLIANO How was the New Works Program started?

ANDRÉ BISHOP It was Peter’s idea. He was interested in developing new work— the Met could bring many musical forces to the table, and Lincoln Center Theater could bring accomplished playwrights. That was the beginning.

PETER GELB Shortly after I was appointed

AB We had done a couple of sung-through musicals. So doing something sung through with no dialogue, or hardly any dialogue, was not new to us or to our audience.

AG Had there been much crosspollination among the institutions at Lincoln Center?

AB There has been very little collaboration, and certainly not like this. We wanted to show that companies on this campus could actually work together and learn from one another.

PG The key ingredient in the collaboration was the arrival of Paul Cremo, our dramaturg. He’s been the field general of this whole project.

PAUL CREMO I think your initial conversations happened in 2005, and I came on board in 2007. You decided not to give commissions with a guaranteed premiere date; instead, it was a more theatrical model, where the end result of the program is the workshop. This allows the pieces to develop freely, without the pressures of a production looming.

AG How did you begin?

AB Once we had raised the money, we matched ten composers with librettists. Some fell away and we added a few more. The other rule we created was not to decide whether a work was appropriate for Lincoln Center Theater or for the Metropolitan Opera until after the workshop.

PG At the workshop, each piece is performed with a piano and singers.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 20

Image: Viola Davis as Esther and Lauren Vélez as Mamie © Joan Marcus.

AN INTERVIEW with ANDRÉ BISHOP, PAUL CREMO, and PETER GELB

If we’re going to do a full production, we collectively decide whether it’s a chamber-sized work or a grandopera-sized work. One of the challenges that we face all the time, when I talk to directors who are working here, is how do you connect the audience to the stage? That problem doesn’t exist with the Mitzi. The audience and the stage are one.

AB It’s because it’s small—there are only 290 seats—and it has a thrust stage, which means the last row is only seven rows back. If a director and a designer know how to use that configuration, it’s a wonderful thing. On a larger scale, this is true in the Beaumont as well. That’s why I think these musicals we’ve done in the Beaumont seem so refreshed. Part of it is that the productions, if I can say this, are good productions, but part of it is that the audience is suddenly seeing South Pacific or My Fair Lady on a stage, in a pattern of movement and scenery they’ve never seen before—and the last seat is only thirteen rows back.

PG André is too modest to say it himself, but if not for him the Beaumont would never have been successfully harnessed theatrically. It wasn’t until you took over that the possibility of its really being successfully utilized was achieved. AB When Jerry Zaks was resident director, he did some very good shows there before my time. But when I arrived we put in the orchestra pit, because I very badly wanted to do musicals.

PG The directors who staged these wonderfully successful musicals, particularly someone like Bartlett Sher, have become masters of moving action around in a way that the audience can appreciate from all sides.

When Bart made his debut at the Met with The Barber of Seville we didn’t have a thrust stage to offer him, so he did the next best thing—he created a passerelle, which brought the action of the stage around and beyond the orchestra pit and literally into the audience.

AG Were there writers creating new works, too, or was it all adaptation, like Intimate Apparel?

PG It varied. The young composer Matthew Aucoin wanted to write an opera based on the Orpheus myth. André suggested that we pair him with Sarah Ruhl, who had written one of the great plays based on the Orpheus legend, Eurydice. Matt and Sarah hit it off amazingly well. The opera will have its premiere this season at the L.A. Opera. They joined us as a commissioning partner once we went beyond the workshop stage, and it will play at the Met two seasons from now. On the other hand, the opera Two Boys, which Nico Muhly composed, had an original libretto by Craig Lucas, and Bart Sher directed.

AB Craig had written the book to The Light in the Piazza, which was the first show Bart did at the Beaumont.

AG How did the Intimate Apparel conversation start?

PC I had been speaking with Ricky Ian Gordon about possible writers to work with. I suggested Lynn, and Ricky said, “I’ll read her stuff.” We initially planned to have Lynn write something original, but after Ricky read Intimate Apparel he fell in love with it, and Lynn agreed to adapt it.

AG André, what did Lynn tell you about her original conception of Intimate Apparel?

AB My memory is of her telling me that she had originally thought of Intimate Apparel as a musical or an opera, but that she was unknown then and it would have been a bigger, more expensive production and she was afraid that nobody would produce it. So she wrote it as a play.

PC Her father had loved opera. In Lynn’s play Ruined, there are monologues that are like arias. We talked about ways to sort of expand the play a bit, adding a chorus, ensembles. Lynn’s an avid student, and read a bunch of librettos. Ricky talked her through what he needed. He started writing the first notes in April 2012.

PG The development of an opera or a musical is much longer than that of a play. There are more moving parts and it requires more development, more workshops—Intimate Apparel had four. The first workshop was in 2015.

AG How did it change?

PG It got better. (Laughter)

PC The basic bones and the structure were always there because the play existed. But Bart, for instance, after the first workshop said that the boundaries between scenes could blur a little and be more fluid. The opening of the piece also changed. We were trying to get the main character, the seamstress Esther, and

21 ANDRÉ BISHOP,

AND

GELB

PAUL CREMO,

PETER

Sometimes even experienced composers forget the capabilities of a human voice, and the workshop will remind them of what’s possible and what isn’t.

PETER GELB

Some of the better pieces that have come out of our program so far have been good not only because the composer is good . . . but because the libretto was so strong.

ANDRÉ BISHOP

her situation clearly established up front. And, in terms of the music, there has been some tightening, shortening, making things more efficient. In the third workshop, Ricky discovered the possibilities of the chorus and started using them in different ways, almost like underscoring.

PG When a composer hears his or her work performed, it’s different from just looking at the notes. It inspires him or her to do more.

AG Does that also change the conversation between the librettist and the composer?

PC They work hand in hand. Their collaboration is the key to it all.

AB Some of the better pieces that have come out of our program so far have been good not only because the composer is good—and it is a world of the composer, really, the opera world—but because the libretto was so strong. In the case of Eurydice and Intimate Apparel, they’re both extremely powerful pieces of writing, adapted by the playwrights from their own plays.

AG What challenges do the playwrights face?

PC Playwrights have a learning curve adapting an existing piece. They first have to throw out nearly half of their text, and that’s challenging (it takes longer to sing something than to say it). This play was very close to Lynn’s heart. She wrote it after her mother died, and she felt that it was a way of communing with her ancestors. She found it really

difficult to cut out so much of the great detail that was in the play, but we worked together to isolate the most important text. Then Ricky could show Lynn how the music could tell that story to fill in some of the colors and details that were cut from the text. It’s hard, I think, for any writer. In the theater world, the playwright rules; in the opera world, the composer rules. So the playwright has to step back a bit and hand it over and let the composer run with it.

PG There’s also a technical aspect of a playwright’s learning to write a libretto, of writing words that can be sung. Not only does there have to be fewer of them; they also have to be fit, in the right way, into a singer’s voice.

AG I marveled at the libretto—how Lynn could write such a complex play and then distill it into essentially a poem that can be sung.

PC That’s something else that changed. Hearing the workshops, Ricky got to see where singers were struggling with certain things—like particular words on high notes—and he could lower them or change the emphasis in a line to make it sound more natural.

PG Sometimes even experienced composers forget the capabilities of a human voice, and the workshop will remind them of what’s possible and what isn’t.

AG Was there a moment in one of the first workshops where you felt a particular electricity?

PG I thought it had great potential and was excited by it from the very first workshop—I think we all felt it. We knew it was something special.

AG How did you decide that it was going to be at the Mitzi?

AB I had assumed this would be for the Beaumont, with a full orchestra. It wasn’t until the third workshop that Bart said, “I think we should do it in the Mitzi Newhouse with two pianos.” He was right. In the Mitzi, the words and the music are just right there. You don’t have to strain. We have these incredible singers in this relatively small theater. It’s going to blow the roof off it.

AG How often are new operas produced?

PC Well, during the thirteen years that

this program has been in existence there’s been an explosion of contemporary opera in the U.S. Back then, maybe between two and five new operas premiered in a year. At the Met, prior to this program, there would be years between the premieres of original operas. But in 2018 over forty new operas premiered in the U.S. Opera was seen as this sort of faroff, grand thing, and too conservative. But younger composers have seen what’s possible. They don’t have to compromise their musical style or values, and they see that new dramatic subjects can be embraced. And opera companies have been inspired by the idea that new operas can bring in new audiences.

AG What are your hopes for the program in the future?

PG There are a couple of projects still in the pipeline that are coming along really nicely. And André and I have been in discussion on adding composers, and Paul’s been vetting them.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 22

Image opposite © Ellen Gallagher. Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, 2019. Oil, ink, gold leaf, and paper on canvas, 97 5/8 x 79 1/2 inches, 248 x 201.9 cm. (GALLA 2019.0002). © Ellen Gallagher.

Photo: Thomas Lannes. Courtesy Gagosian.

Opera was seen as this sort of far-off, grand thing, and too conservative. But younger composers have seen what’s possible.

PAUL CREMO

ANDRÉ BISHOP Producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater

PAUL CREMO Dramaturg at the Metropolitan Opera

PETER GELB General manager of the Metropolitan Opera

Image top: André Bishop © Chasi Annexy Image middle: Peter Gelb © Associated Press Image bottom: Courtesy of Paul Cremo

Lincoln Center Theater Review

Vivian Beaumont Theater, Inc.

150 West 65 Street

New York, New York 10023

NON PROFIT ORG U.S. POSTAGE PAID NEW YORK, NY PERMIT NO. 9313

Image © Photographer Name

Image © Photographer Name