October 31, 2024

Jim Duncan, AICP, Director

Kimberlyn Caywood*

Sylvia Schmonsky

Chris Taylor, Deputy Director

LONG RANGE PLANNING

Hal Baillie, AICP, Acting Manager

Rachael Lay

Valerie Friedmann*

Eve Miller

Quinn Mulholland

Boyd Sewe

SB Stroh

Traci Wade, AICP, Manager

Dalton Belcher

Chris Chaney

Daniel Crum, AICP

Stephanie Cunningham

Cheryl Gallt

Autumn Goderwis, AICP*

James Mills

Meghan Jennings*

Donna Lewis

Tom Martin, AICP*

Paula Schumacher

Bill Sheehy

TRANSPORTATION PLANNING

Chris Evilia, AICP, Manager

Hannah Crepps

Joseph David

Kenzie Gleason

Sam Hu

Stuart Kearns

Scott Thompson

Debbie Woods

Ivy Barksdale

Jonathan Davis

Zach Davis

Larry Forester, Chair

Janice Meyer*

Robin Michler

Bruce Nicol

Mike Owens

Frank Penn

Graham Pohl

William Wilson

Judy Worth

URBAN GROWTH MANAGEMENT

MASTER PLAN ADVISORY COMMITTEE

James Brown, Council-at-Large

Todd Clark, Fayette County Extension Office

Alison Davis, University of Kentucky

Chuck Ellinger, Council-at-Large

Larry Forester, Planning Commission, Chair

Andi Johnson, Commerce Lexington

Todd Johnson, Building Industry Association

PG Peeples, Urban League

John Phillips, Darby Dan Farm

Kathy Plomin, 12th District Councilmember

William Wilson, Planning Commission

Zach Worsham, Winterwood Inc.

Judy Worth, Planning Commission

Dan Wu, Vice Mayor

COMMISSIONERS OFFICE

Keith Horn, Commissioner of Planning, Preservation & PDR

Joe Black

Shaun Denney

Albulena Gjoshi

LAW DEPARTMENT

Tracy Jones

Brittany Smith

*Denotes former staff/ Planning Commission/ Urban County Council members PHOTO CREDITS All photos courtesy of LFUCG except where noted.

Special thanks to the following departments and agencies for their expertise and input in the master plan process:

AGING AND DISABILITY SERVICES

Kristy Stambaugh, Director of Aging and Disability Services

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Kevin Adkins, Chief Development Office

Craig Bencz

ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND PUBLIC WORKS

Nancy Albright, Commissioner of Environmental Quality and Public Works

Brandi Peacher, Complete Streets Coordinator

Doug Burton, Director of Engineering

Jennifer Carey, Director of Environmental Services

Jada Griggs

Demetria Kimball Mehlhorn

Jeff Neil, Director of Traffic Engineering

David Filiatreau

Charles Martin, Director of Water Quality

Chris Dent

Erin Hensley, Commissioner of Finance

Ashley Simpson, Deputy Chief Finance

Melissa Lueker, Director of Budget

GENERAL SERVICES

Chris Ford, Commissioner of General Services

Monica Conrad, Director of Parks

Tim Joice

Michelle Kosieniak

HOUSING ADVOCACY AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Charlie Lanter, Commission of Housing Advocacy and Community Development

PLANNING AND PRESERVATION

Beth Overman, Director of PDR

PUBLIC SAFETY

Ken Armstrong, Commissioner

Lawrence Weathers, Police Chief

Jason Wells, Fire Chief

Marilyn Clark, FCPS Board of Education

Amy Green, FCPS Board of Education

Melinda Joseph-Dezarn, FCPS

Myron Thompson, FCPS

ACCESS LEXINGTON COMMISSION

BLUEGRASS GREENSOURCE

LEXTRAN

Fred Combs, General Manager

Emily Elliott, Director of Planning and Community Development

YMCA OF CENTRAL KENTUCKY

Keith Gallagher, COO

TSW | TUNNELL SPANGLER

WALSH & ASSOCIATES

Samantha Castro, AICP, LEED-ND

Caleb Racicot, AICP

Thomas Walsh, PLA

Allison Stewart-Harris, AICP

Jia Li, AICP

Nick Johnson, AICP

Saloni Shah

Christopher Myers

GRESHAM SMITH

Louis R. Johnson, PLA, ASLA

Erin Masterson, PLA, ASLA

Katie Rowe, P.E., AICP

Andrea Cull, P.E.

Matt Maclaren, P.E.

Amanda C. Deatherage, AICP

Morgan Dunay

PARTNERS FOR ECONOMIC

Anita Morrison

Abigail Ferretti

CIVICLEX

Richard Young

Kit Anderson

Megan Gulla

Noel Osborn

Stephanie Mobley

Adrian Paul Bryant

Haley Wartell

Lilly Bramley

SOUTHFACE INSTITUTE

Robert E. Reed, III

Executive summary

Market

Guiding principles and benchmarks

Public and stakeholder engagement Sustainability

Existing conditions inventory and analysis Regulatory framework for implementation

Land use and transportation regulating plans Infrastructure costs and fiscal impact

Appendices

A: Imagine: Lexington

B: Community voices

C: Concept plans

D: Market analysis data

E: Funding mechanisms

The following is a synopsis of the major elements and key aspects found throughout the Lexington Urban Growth Master Plan (UGMP).

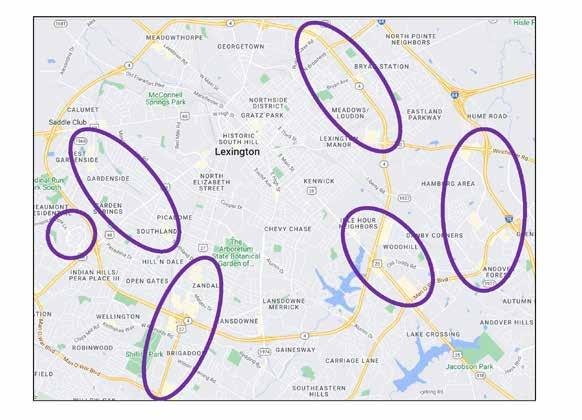

In 2023, Lexington’s Planning Commission recommended a 2,800 acre expansion of its Urban Service Boundary in five locations across Fayette County.

In a year’s time this Master Plan was created through intense research, analysis, and community and stakeholder engagement to create a plan for urban development, transportation, parks, infrastructure, and more in the identified expansion areas.

■ Identified by the Planning Commission on October 26, 2023

■ Total acreage of 2,833 acres

■ Spread across 5 Approved Areas, in three geographic edges of the Urban Service Area

■ Along major corridors

■ Potential as ‘gateway’ moments into the city

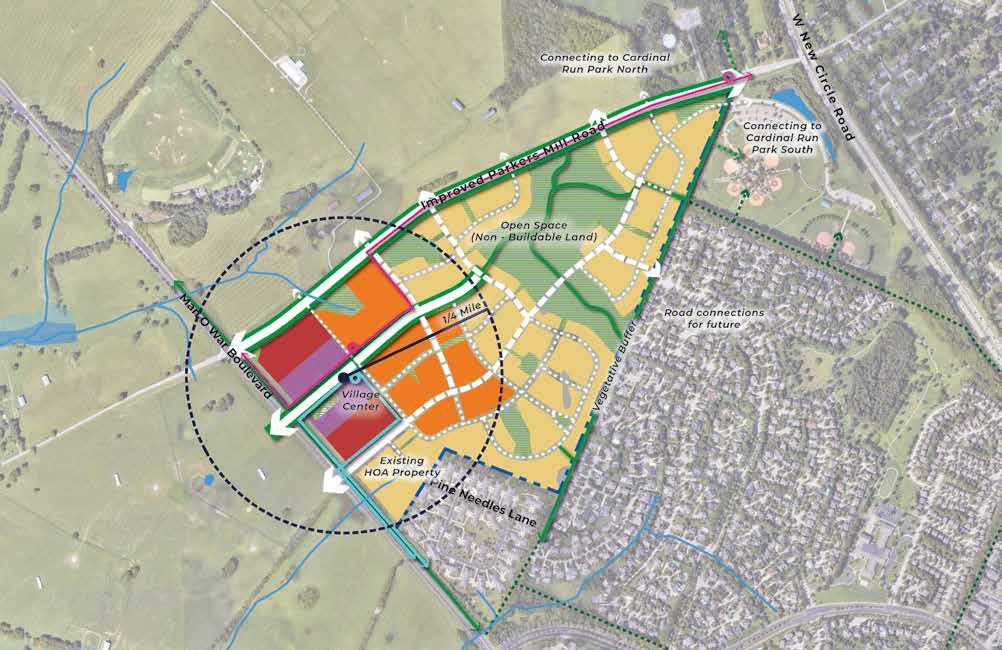

Area 1 is the smallest of the five areas. The land is currently being used for cattle and horse pastures with paddocks for horses and areas for grazing animals. There are several associated barns, outbuildings, and the original farmhouse on site.

The vegetated entry to Pine Needles Lane is included in Area 1. This parcel is owned and maintained by the Heritage Place HOA, which is the adjoining active adult community.

Area 2 is the largest of the five areas. It includes a cluster of single-family homes along Hume Road and Ami Lane. Several large lot rural residential homes are scattered throughout the site.

There are several actively managed farms, which include a residence and multiple barns or outbuildings. Non-residential uses include WKYT News station, and part of a power sub-station.

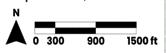

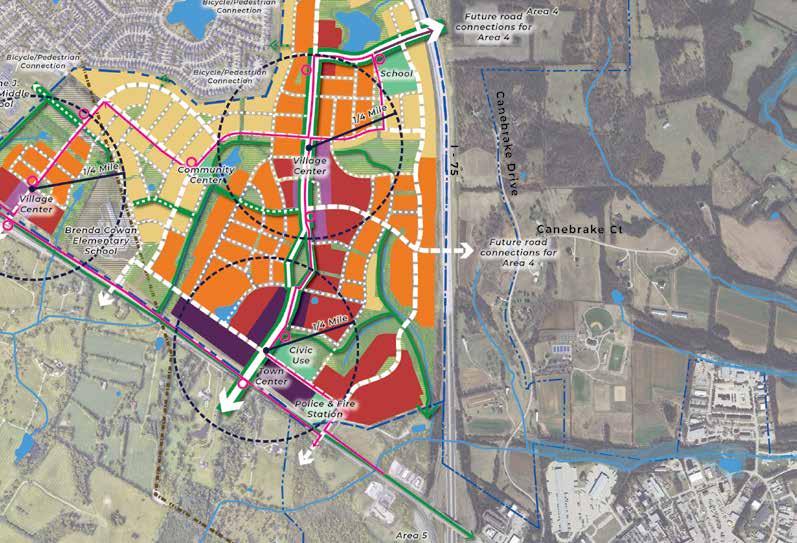

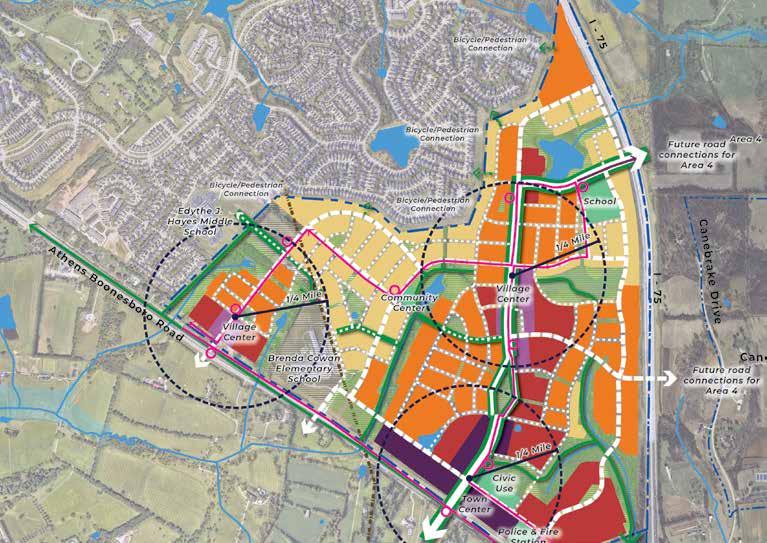

Area 3 is sparsely developed, other than a single operational farm west of Brenda Cowan Elementary. The remainder of the land is unoccupied and used for crop rotations. The northernmost portion of the site is bound by I-75 to the east. Additionally, due to the required agricultural buffer from the 1996 Expansion, there is no vehicular access to the adjacent neighborhood and limited bicycle and pedestrian access through a temporary easement. Access to these parcels would need to be reevaluated depending on any future development.

Non-residential uses include: two public schools, Brenda Cowan Elementary School and the back portion of Edythe J. Hayes Middle School.

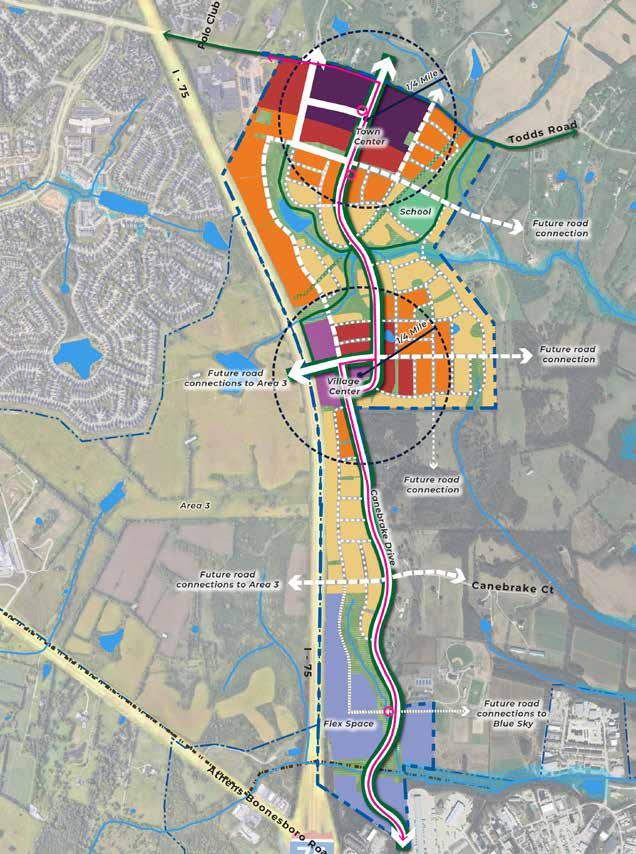

Area 4 consists of a few large agricultural tracts along Todds Road. The farmland has a mix of row crops and pasture.

There are a series of 10-acre lots along Canebrake, which were subdivided in 1987, a few of which have dwellings on them.

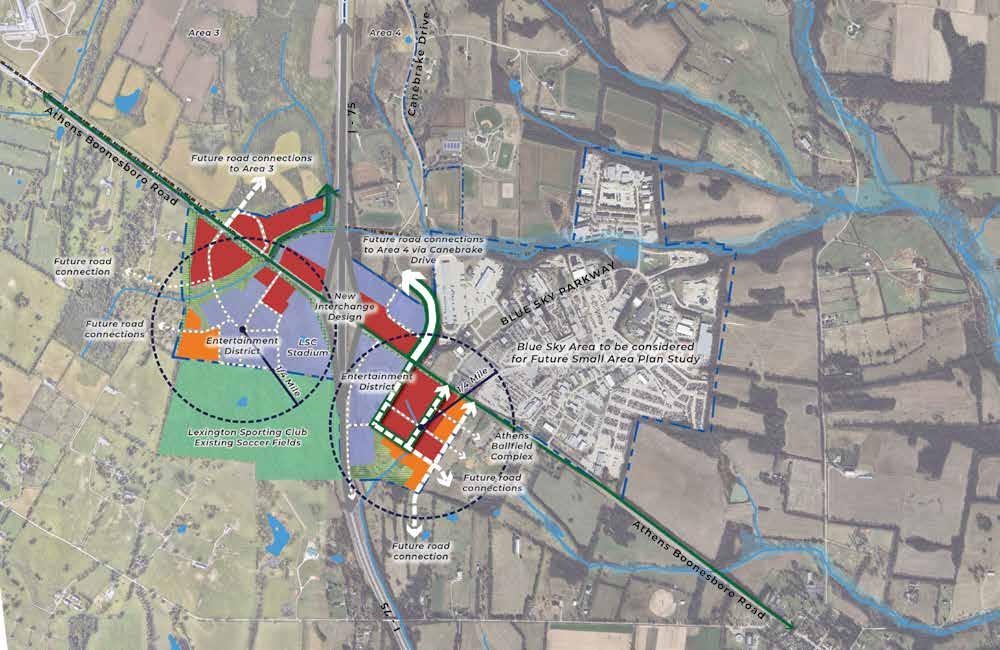

Area 5 is the most developed of the 5 sites. The Blue Sky Rural Activity Center, centered around the Blue Sky Parkway, hosts a wide variety of industrial sites, including freight, light manufacturing, and construction services.

The Blue Sky Rural Activity Center also contains several hotels clustered at the I-75 interchange with Athens Boonesboro Road. The remainder of the areas at the corners of Athens Boonesboro Road and I-75 are highway-serving businesses such as fast food restaurants, gas stations, convenience stores, and adult entertainment.

The southwest portion of the Blue Sky Rural Activity Center has experienced significant changes between 2023 and 2024. These changes have been spurred by the construction of the Lexington Sporting Club soccer fields and stadium. The owner of the property has indicated that future construction of the undeveloped parcels will complement the sports complex to create an entertainment district within Lexington.

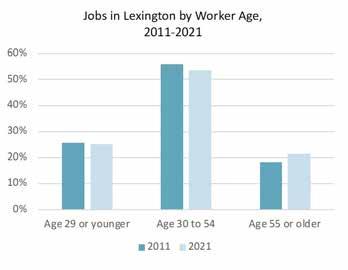

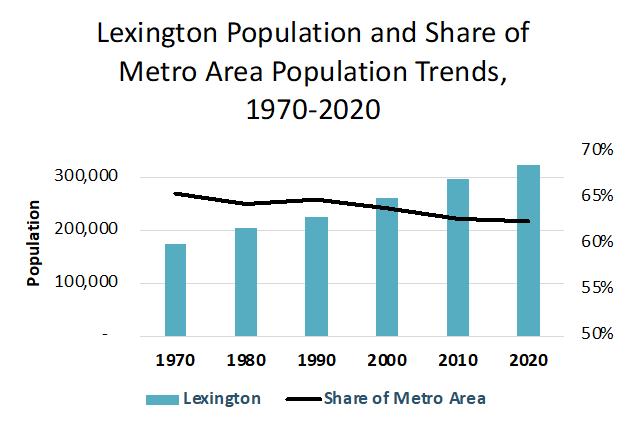

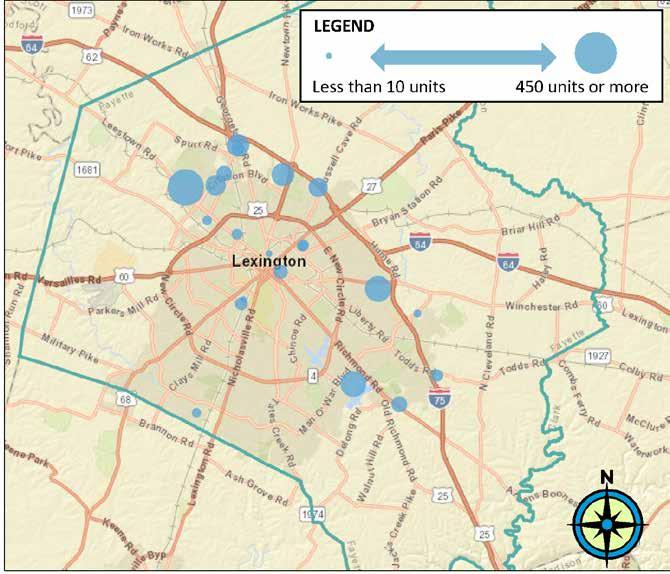

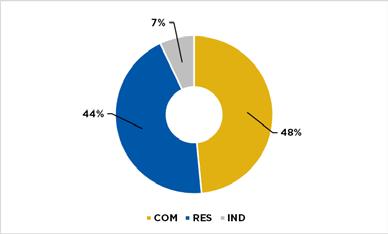

This section reviews local demographics, housing needs, and market conditions to be used as a foundation for a master plan to incorporate land in the Urban Growth Management area. The analysis focuses on Lexington-Fayette Urban County in comparison with the Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA).

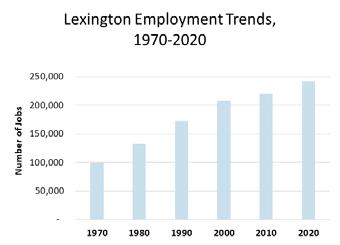

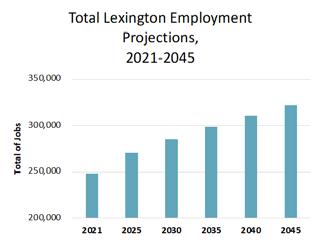

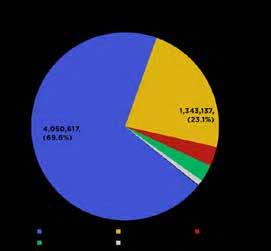

The market analysis reviews trends and potentials for residential, office, industrial, flex space, retail, and hotel development through 2045. As the economy in the Lexington-Fayette MSA steadily expands, population growth continues but at a slower pace than in recent years. The City of Lexington’s population is projected

to grow by 14.8 percent from 327,388 in 2023 to 375,774 by 2045 according to the University of Louisville. Additionally, the number of households in Lexington will grow somewhat more quickly, by 18.2 percent, to a total 161,776 by 2045. That represents an increase of roughly 48,400 residents and 24,900 households.

26,500

projected new housing units based on growth trends

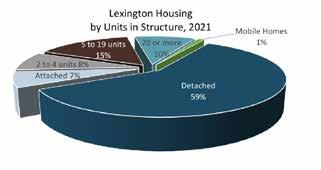

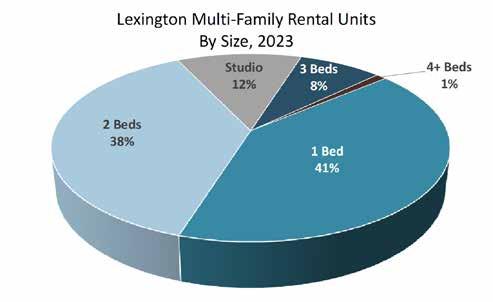

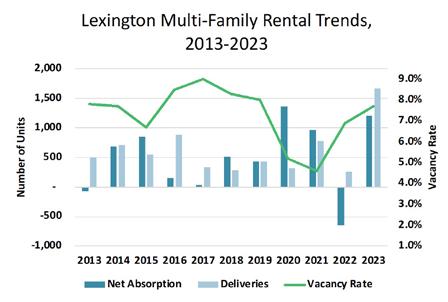

Historically, Lexington’s housing development has focused on singlefamily houses – 50 percent of which were built from 2013 to 2022. The focus on larger, single-family detached homes has left a gap in the market for options that meet the needs of smaller households at prices they can afford. With increased costs, homeownership has become less attainable, fueling an increase in the development of townhouses and rental housing. The demand for attainable housing for households across the income spectrum continues to climb as housing costs increase at a greater pace than income.

Lexington needs a greater variety of housing types to address the diverse housing needs of households at different sizes, incomes, and life stages. Mixeduse development that blends large and small units in a variety of styles along with both ownership and rental units could create opportunities for balanced and sustainable communities. It would also provide a faster development cycle by appealing to multiple markets at the same time.

Based on the population growth

50%

housing units built between 2013-2022 that were single-family residential

projections and historic trends, Lexington could support the development of roughly 25,600 new housing units by 2045.

New development needs to achieve higher densities to support a mix of uses, create active and vibrant places, make better use of land, and preserve agricultural and other rural lands. A mix of offerings that range from an average of 8 to 20 units per acre would offer more options than self-contained subdivisions at 3 to 4 units per acre dominated by a single housing type.

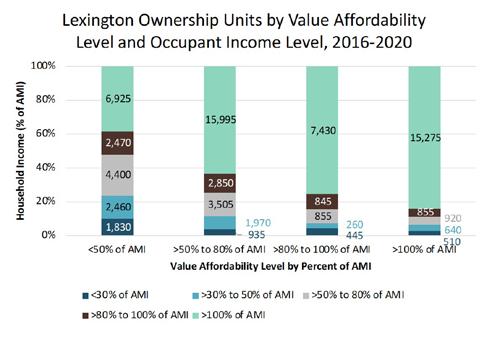

Housing data from 2016-2020 indicate that housing affordability problems impacted 59 percent, or 23,115, of Lexington’s renter households with incomes up to 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI). These households exceeded the U.S. Department of

59%

Lexington renters who spend 30% or more of their income on housing

8-20 units/acre

recommended approximate density for new construction to meet city affordability and quality of life goals

Housing and Urban Development’s standard that a household should not spend more than 30 percent of its income for gross housing costs to preserve enough money for food, transportation, health care and other basic needs. Fiftythree percent of those renter households, constituting 12,240 households, were severely cost burdened, spending more than half of their income for housing. Among owner households with incomes up to 80 percent of AMI, 3,725 households spent more than half of their income for housing.

Housing problems were even more significant for seniors. Thirty-one percent of renter householders age 65 or older spent more than half their incomes on rent. Among owner householders age 65 or older, severe cost burdens impacted 19 percent.

A precept in the retail industry is that new retail follows rooftops or increases in population. Lexington continues to add new residents, driving retail demand. Over the next two decades, many existing retail spaces will likely be demolished or converted to new uses as new shopping corridors and clusters or nodes of activity create opportunities to better meet modern retailers’ needs. Many of today’s modern retailers rely on placemaking to create walkable environments that draw customers for the experience as well as the retail offerings. Mixed-use developments offer daytime, evening, and weekend support from both nearby workers and residents.

Prior to the planning workshop recommendations for Expansion Area development scale, it is too early to estimate the scale of supportable commercial development. Currently, none of the Expansion Areas are well located to serve as regional activity centers, hindering the ability to attract significant numbers of existing residents. As none of the areas are strategically located to serve as regional activity centers, attracting significant numbers of existing residents.

22.7 million

total retail square footage in Lexington 3.7%

retail vacancy rate as of January 2024

67.8%

share of the Lexington-Fayette Metro Area (Bourbon, Clark, Fayette, Jessamine, Scott and Woodford Counties) retail that is located in Lexington

44,300 sq ft

average annual delivery of new retail between 2018 - 2023

75,00095,000 sq ft

potential new retail that growth within proposed expansion areas could support

In the mid- to long-term, Expansion Area 3 and Area 5 provide the most competitive opportunity for new retail development that serves primarily the new community. The new retail development in Expansion Area 3 will depend on the future scale of residential development as well as designating a visible and accessible site that allows retailers to attract customers from the larger southeast Lexington area and not just the adjacent residential development. Expansion Area 5’s retail growth depends on the plans for the new

Lexington Sporting Club soccer stadium and the visibility offered by sites at the I-75 interchange. It is likely that growth west of I-75 will support between 40,000 to 50,000 square feet and east of I-75 in Expansion Area 5 will support 25,000 to 30,000 square feet.

Finally, Expansion Area 4 could support development of a few new food outlets or ancillary retail of 10,000 to 15,000 square feet of new retail demand by 2045.

Historically, the major drivers of office demand for Lexington have been byproducts from University of Kentucky research initiatives, medical office space related to the region’s major medical centers, and the sporadic attraction of new corporate facilities. Demand and development have been focused on downtown Lexington, Coldstream Research Campus and other business parks. Separate neighborhood-serving offices have developed on independent parcels along major thoroughfares.

Office occupancies in both Lexington and the region remain relatively healthy with occupancies around 92 percent. With the minimal amount of new office space developed during the last four years, the region has avoided the doubledigit vacancy rates that have plagued many major office markets. Office space construction has averaged 137,900 square feet annually over the last decade and 67,800 square feet per year over the last four years during the pandemic in the region. However, it is likely that future demand will slow as larger tenants shrink footprints due to work-from-home and space efficiency trends result in less space per employee. In this transitional

67,800 sq ft

average annual delivery of new office space between 2018 - 2023

50,00080,000 sq ft

potential annual growth of new office space through 2045

period for the office market, as it strives to adjust to the new normal following the Covid-19 pandemic, it is not yet clear whether greater working from home will translate into a reduced demand for space, but it looks as though space per employee may decline 10 to 20 percent.

Based on historic trends and continued employment growth among Lexington’s office-using industries, demand for additional facilities will support development of 50,000 to 80,000 square feet annually by 2045, or a total of 1.0 to 1.7 million square feet of new office space. That demand is anticipated to continue to be concentrated in Lexington's downtown, business parks and neighborhood office clusters.

Office tenants typically make their location decisions based on a mix of

criteria, including accessibility, proximity to institutions and other clients, proximity to similar businesses, building quality, visibility, and availability of support services and retail. Increasingly, in today’s tight labor market, businesses are using their office locations as a recruiting tool. That has meant placing a high premium on walkable, mixed-use districts that provide a mix of restaurants, cafes, service businesses, and housing in close proximity. This is particularly true as companies work to offer their workers a reason to come to the office.

Among the five expansion areas, only the sports complex site in Expansion Area 5 could possibly offer the type of business setting and clustering that could compete for major businesses not focused on serving the local population. Demand in that area will depend on recruitment. The opening of the new Baptist Health medical campus south of Winchester Road will likely generate demand for new medical office buildings and space for related businesses; however, that demand is likely to focus primarily in the area surrounding the medical center rather than in Expansion Area 2. Expansion Area 3 could potentially support a small increment of office space for neighborhood-serving businesses attracted by the new residential base, as much as 10,000 to 20,000 square feet if developed in a retail cluster with visibility and access from Athens Boonesboro Road.

Development of industrial and flex space in Lexington and the nation over the last decade has reflected major shifts in the logistics industry with the majority of new space developed for distribution facilities. As the industry has recovered from major supply chain problems during the Covid-19 pandemic, growth has slowed significantly. Beyond distribution, the Lexington-Fayette MSA has benefited from Toyota’s growing manufacturing base in Scott County and related suppliers and manufacturers.

The Lexington-Fayette MSA has 60.5 million square feet of industrial and flex space, which is up by 2.7 million square feet since 2014. Of the regional total, Lexington accounts for 32.8 million square feet or 54 percent, and 1.7 million square feet or 52 percent of the growth over the last decade. The higher cost of land in Lexington has reduced its competitive position for warehouse space relative to other MSA counties. Lexington is now most competitive for higher-end research and development labs and other businesses that benefit from Lexington’s

2.7 million industrial/flex square feet added throughout Lexington-Fayette MSA between 2014 - 2023

200,000275,000 sq ft potential annual addition of new industrial/flex through 2045

Areas. The largest potential for future industrial development remains in Expansion Area 5 which has the only sites suitable and competitive for such uses. New industrial and flex space development in Expansion Area 5 could reach 65,000 to 130,000 square feet by 2045.

educated workforce and the potential for collaborations with the University of Kentucky.

Projected employment growth in industries that rely on industrial and flex space coupled with historic trends data suggest that the region will develop an average of 200,000 to 275,000 square feet of space annually to 2045 for a total of 4.2 to 5.8 million square feet. Lexington is projected to capture 35 to 40 percent of the region’s future industrial and flex space construction for a total of 1.5 to 2.3 million square feet of new space.

Land costs will hinder industrial and flex space development in the Expansion

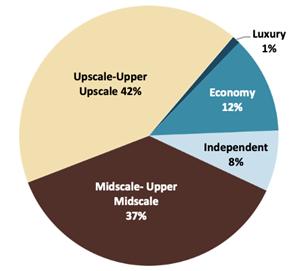

Lexington’s hotel inventory provides 9,018 rooms across 82 hotels, clustered along major thoroughfares, near area attractions, and in close proximity to University of Kentucky and downtown Lexington. The existing inventory of hotel rooms consists of a wide variety of options encompassing independent operators (8 percent of room supply) economy (12 percent), mid-level hotels without food and beverage service, upper mid-scale with limited food service and high-end alternatives in upper upscale or luxury segments. Occupancy has largely recovered from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the travel industry,

9,018 hotel rooms throughout Lexington 9.4%

increase in room-night demand from 2019 - 2023

12%

increase in number of hotels from 2018 - 2023

averaging 61 percent in 2023. Annual room-night demand in 2023 was up 9.4 percent above the 2019 total. Over the last five years, Lexington’s market has increased with 9 new hotels with a total of 964 rooms (a 12-percent increase).

Construction of new hotels will continue with the region’s population growth, the addition of new attractions such as the new soccer stadium, and replacement of older, obsolete hotels.

Expansion Area 5 offers competitive highway locations on either side of I-75 for two to three new hotels by 2045. If a mixed-use retail/restaurant cluster is developed in Expansion Area 3, it could attract a hotel. However, the viability of these sites will depend on the extent of new hotels being developed as part of the new sports complex.

New development in the Expansion Areas will be primarily comprised of residential development. Commercial development has not generally occurred in southeast Lexington, and none of the Expansion Areas have the potential to develop into major activity centers that will attract visitors from around the region. Only the new sports complex offers near-term potential for significant commercial development. Because commercial development in the other Expansion Areas will serve primarily the new Expansion Area households, supportable retail, restaurant, service and office development will likely be delayed by at least a decade while waiting for the household base to reach a level sufficient to support these new businesses.

The value of the properties to their owners and the larger community would be maximized by the development of diverse neighborhoods offering a variety of housing units of different types, sizes, and price/rent ranges. This would allow the development to address multiple market segments at one time and to address gaps in the current housing supply – smaller units at greater densities to meet the housing needs of current and future Lexington households. Higher densities would allow greater potential to support local businesses and create walkable places to gather and interact with neighbors. A greater number of new units also will reduce the costs of needed infrastructure development per unit by spreading the costs.

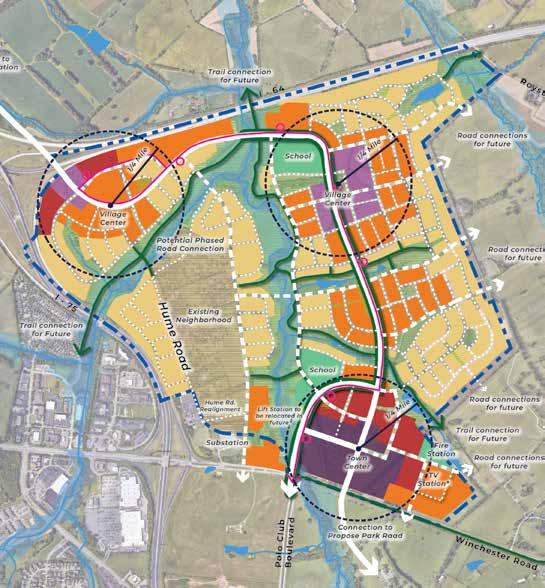

Following the project’s Guiding Principles, a Regulating Plan was created for each Expansion Area.

The process for each plan was as follows:

1. Non-buildable areas, such streams and ponds, floodplains, steep slopes of 15 percent or greater, or sinkhole risks were identified and set aside for protection based on Existing Conditions analysis.

2. Town and Village Centers were designated along the limited frontage of major arterial roads to serve as gateways.

3. A network of boulevards and avenues was laid out from these hubs, aligning with the terrain.

4. Additional hubs were placed to ensure residents were within 1/2-mile, ideally 1/4-mile, of these focal points.

5. A modified grid of local streets was designed for walkability and long-term development flexibility.

6. Off-road bicycle and pedestrian routes were added for connectivity.

7. Potential transit routes for future Lextran expansion were identified.

Enable a mix of housing options that can serve multiple needs and market sectors

Encourage a variety of uses to meet people’s needs and preferences within their own neighborhoods

Allow modest density increases to drive community improvements and support greater amenities, like retail and public spaces

Provide multiple routes to reduce: congestion, travel distance, travel time, emergency response time, social isolation, and reduce social isolation

Encourage safe alternatives to driving, offering more choices for travel

Respect the natural world and incorporate water, trees, and open space throughout designs

As outlined in the Chapter 4 - Public & Stakeholder Engagement, the Regulating Plans were available for review and feedback by the public and developers at several points throughout the process.

The Regulating Plans outline the development of streets, land use, open spaces, and additional regulations to ensure integrity in land planning. It prioritizes protecting natural features, establishing town and village centers, and creating transportation networks that are walkable and adaptable to future growth.

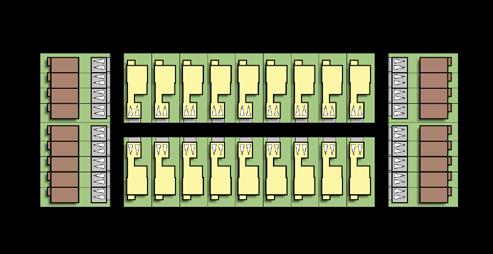

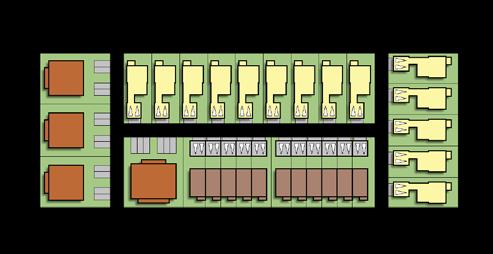

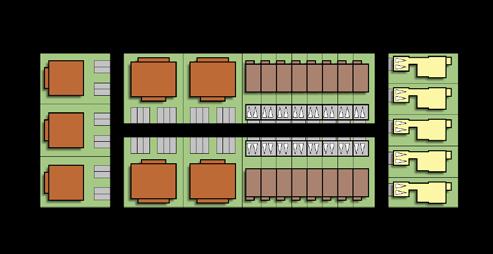

Each typology is designed to accommodate various needs, ranging from residential communities to mixed-use urban hubs

Primarily single-family dwellings, some multifamily units (up to 8 units), and corner stores.

Density: 7-13 net dwelling units/acre.

A mix of retail, restaurant, office, and residential uses, with primarily townhouses and multiple-family dwellings.

Density: 20+ net dwelling units/acre.

A mix of single-family homes, townhouses, and multiple-family dwellings (up to 10 units), with corner stores as secondary uses.

Density: 11-25 net dwelling units/acre.

A mix of retail, restaurant, office, and residential uses within attached buildings, serving both adjacent and wider neighborhoods.

Density: 30+ net dwelling units/acre.

Primarily multiple-family dwellings, with some commercial use.

Density: 23+ net dwelling units/acre.

Primarily retail, restaurant, office, entertainment, industry, or recreation, with secondary residential uses.

Density: Varies based on use.

As noted in Theme E - Goal 3 of the 2045 Comprehensive Plan, Lexington continues to support new and robust economic development through the inclusion of land for new jobs. The UGMP has not identified specific acreage for a Regional or Local Business or Industrial Park. However, nothing in this plan is intended to prevent a property owner from bringing forward a proposed Regional or Local Business or Industrial Park. While the UGMP did not identify a specific location for such a use, economic growth remains a priority for the community. Should a Regional or local Business or Industrial user identify land that is within the UGMP area, appropriate flexibility is important to allow for significant job opportunities within Lexington’s Urban Service Area.

The UGMP emphasizes a modified street grid to enhance walkability, flexibility, and connectivity. The grid adapts to the terrain while maintaining small, walkable blocks that balance the needs of local and through traffic. Key street typologies include:

• Alley Shared space for vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians ,usually serving garages and loading zones.

• Neighborhood Street Low-traffic street with shared lanes for bicycles and vehicles. Designed for slower speeds (20 mph) and appropriate for residential areas.

• Avenue Minor collector street, usually with bike lanes, providing more connectivity between neighborhoods and destinations.

• Boulevard Major collector street with more traffic capacity, separated bike lanes, and pedestrian-friendly designs.

• Single-Loaded Street Street with development on only one side, providing open space views and connections to parks or public spaces.

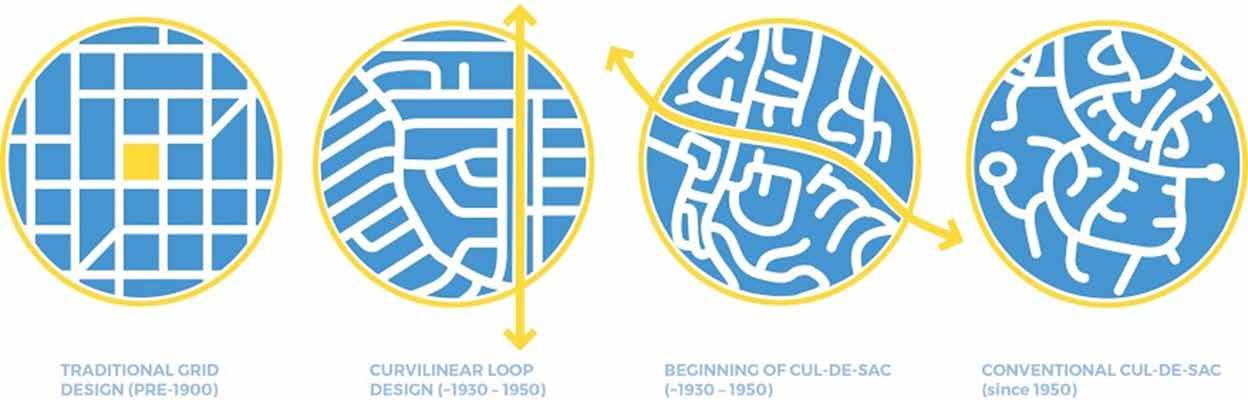

Modified Grid. The Curvilinear Loop Design should be prioritized when designing the Areas in order to add redundancy in the network and create a human-scale street network. Source: Congress for New Urbanism Street Networks 101 | CNU

• Traffic volumes vary based on street types, with higher volumes on boulevards and avenues, and lower volumes on neighborhood streets.

• Speeds are intentionally limited, with boulevards and avenues targeting 25 mph, neighborhood streets at 20 mph, and alleys at 10 mph, ensuring safety for pedestrians and cyclists.

Traditional signalized intersections are minimized in favor of alternative intersections that improve safety and traffic flow:

• Roundabouts and mini-roundabouts are used to reduce delays, congestion, and maintenance costs while accommodating large vehicles like buses and delivery trucks.

• Reduced Conflict U-turns (RCUTs) improve safety by reducing conflict points at busy intersections, especially along divided highways.

• Continuous Flow Intersections (CFIs) allow for more efficient left turns at high-traffic areas, although special attention is needed to ensure pedestrian safety.

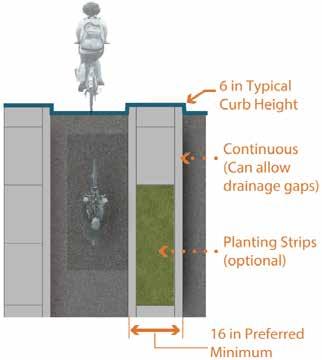

• The plan prioritizes creating a safe, connected bicycle and pedestrian facilities. It includes shared-use paths or protected bike lanes that are separated from vehicle traffic along major roads like boulevards, and bike lanes on minor collectors.

• Greenway trails are incorporated for recreational use, designed to follow natural features like water bodies, while bike lanes are intended for more direct commuting and travel.

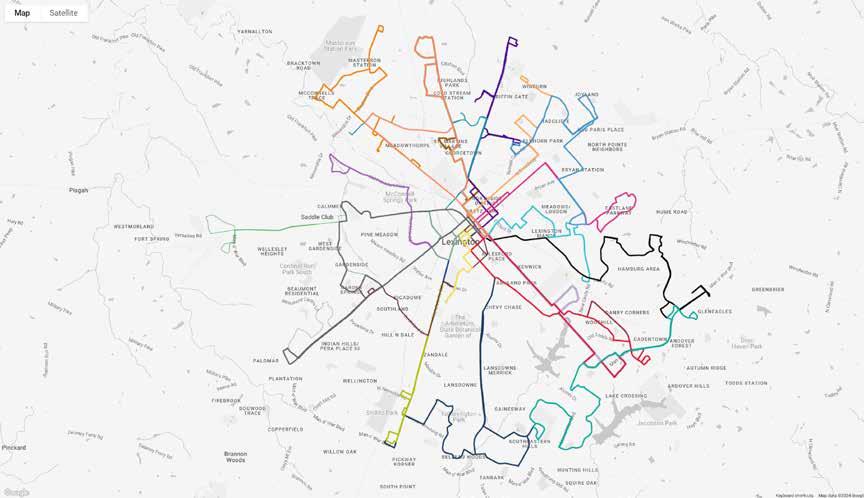

• The plan anticipates the expansion of Lextran bus routes into new development areas, prioritizing stops at Town Centers and Village Centers to serve dense mixed-use areas.

• Transit stops are designed with accessibility in mind, connecting pedestrians and cyclists via quality bicycle and pedestrian facilities. Stops will include shelters and amenities like benches and trash receptacles.

• Transit routes will focus on boulevards and avenues integrating with planned roundabouts and alternative intersections to ensure smooth operation for buses.

The transportation framework is underpinned by Complete Streets principles, ensuring that all streets are designed for safe use by people of all ages and abilities. This includes prioritizing sidewalks on both sides of the street, bike lanes, and traffic-calming features like curb extensions and narrower lane widths to slow down traffic and enhance pedestrian safety.

This framework is built to create a multimodal, connected, and sustainable urban environment in Lexington.

Hand-in-hand with the Regulating Plans are the supportive policy work to ensure that the long-term vision established in this Master Plan is realized. The key aspects are divided into development criteria and proposed regulations, which focus on zoning updates, infrastructure needs, land use guidelines, and development criteria for the City of Lexington.

Rezone sites to align with UGMP land uses, such as village and town centers. It emphasizes low, medium, and high-density land use configurations, promoting flexibility while maintaining UGMP goals.

Establish a concurrency requirement where residential developments must match commercial occupancy, ensuring balanced growth in mixed-use areas.

Propose strict street design standards in alignment with the Lexington Complete Streets Policy, encouraging walkability

and multimodal transportation, along with block sizing to foster connectivity.

Recommend including buffer zones between developments and rural areas, parking and garage placement, to ensure that retail-ready spaces meet specified design standards (e.g., active depths and transparency for pedestrian engagement).

Support sustainable design by offering bonuses for LEED-certified buildings and encourages innovation by supporting low-impact manufacturing and microdistribution hubs, subject to specific active depth requirements.

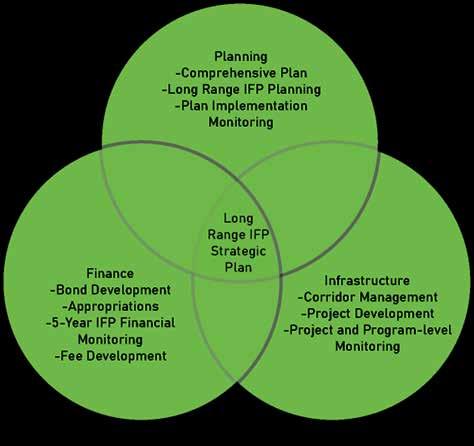

Coordinate efforts to ensure public infrastructure like roads and sanitary sewers and public services such as waste collection, emergency response, and transit can support new development. It advocates for the creation of an Infrastructure Funding Plan and Parkland Dedication Ordinance by 2025.

Identify the need for additional studies on intersection design, transit service feasibility, and roadway connectivity,

particularly in areas like Athens Boonesboro Road.

This regulatory framework is integral to ensuring that development aligns with the broader goals of sustainable, walkable, and mixed-use urban growth.

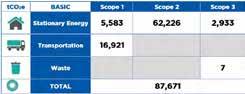

The key aspects to the fiscal impacts of infrastructure improvements and costs required for the Lexington UGMP include the following, all of which are in 2024 dollars:

• Capital Costs: A total of $569.5 million is estimated, including public and developer-funded infrastructure such as roads, trails, intersections, sewers, parks, police, and fire stations.

• Roadways, Trails, and Intersections: The bulk of the infrastructure costs ($510 million) are related to roadways, trails, intersections, and stream crossings. Maintenance is estimated at $525,500 annually.

• Sewer, Police, and Fire Services: Significant sewer upgrades are required, particularly in Expansion Area 2, costing $54.3 million. New police roll call centers and fire stations will be built to meet growing demands, costing $7.5 million and $22.5 million respectively.

• Parks and Libraries: 16 new neighborhood parks and library expansions are planned, with an estimated cost of $22.5 million and $17.0 million, respectively.

• Operating and Maintenance Costs: At build-out, operating and maintenance costs will reach $8.5 million annually.

• Funding Strategies: The plan includes a fiscal impact model to measure the effects of development on Lexington’s General Fund and explores innovative funding strategies to ensure infrastructure funding aligns with future growth.

While a more traditional inventory and analysis is contained in Chapter 2, this Chapter focuses on setting the stage for this project. The UGMP emerged as a priority project coming out of the adoption of the Goals and Objectives of Imagine Lexington 2045. Therefore, the process and the stated community values that led up to Imagine Lexington 2045 should be considered as part of the UGMP.

Chapter 01 covers the following:

■ Origins in Imagine Lexington 2045

■ On The Table Principles

The Lexington UGMP draws directly from the policies and pillars of the Imagine Lexington 2045 Comprehensive Plan. Appendix A – Imagine Lexington 2045 Survey designates each policy that applies to the Master Plan, and whether it manifests through design in the Regulating Plans, or through regulation and policy implications.

The following is a summary of how each Comprehensive Plan pillar has been applied within the Master Plan.

Design 1 Utilize a people-first design, ensuring that roadways are moving people efficiently & providing equitable pedestrian infrastructure.

Design 2 Ensure proper road connections are in place to enhance service times & access to public safety, waste management and delivery services for all residents.

Design 3 Design policy #3: Multi-Family residential developments should comply with the Multi-Family Design Standards

Design 4 Provide development that is sensitive to the surrounding context.

Design 5 Provide pedestrian-friendly street patterns & walkable blocks to create inviting streetscapes.

Design 6 Adhere to the recommendations of the 2018 Lexington Area Bicycle & Pedestrian Master Plan.

Design 7 Design car parking lots and vehicular use areas to enhance walkability and bikability.

Design 8 Provide varied housing choice.

Design 9 Design policy #9: Provide neighborhood-focused open spaces or parks within walking distance of residential uses.

Design 10 Design policy #10: Reinvest in neighborhoods to positively impact Lexingtonians through the establishment of community anchors.

Design 11 Design policy #11: Street layouts should establish clear public access to neighborhood open space and greenspace.

Design 12 Support neighborhood-level commercial areas.

Design 13 Development should connect to adjacent stub streets & maximize the street network.

Density 1 Locate high density areas of development along higher capacity roadways (minor arterial, collector), major corridors & downtown to facilitate future transit enhancements.

Density 2 Infill residential can & should aim to increase density while enhancing existing neighborhoods through context sensitive design.

Density 3 Provide opportunities to retrofit incomplete suburban developments with services and amenities to improve quality of life and meet climate goals.

Density 4 Allow & encourage new compact single family housing types.

THEME A: BUILDING AND SUSTAINING SUCCESSFUL NEIGHBORHOODS

Pillar 1: Design

The application of the policies within the Design pillar of the Master Plan focuses on the layout of the circulation network, ensuring multi-modal transportation options are at the forefront while highlighting and framing community anchors and neighborhoodfocused commercial uses/developments, open space, and parks. The Master Plan utilizes a modified street grid system to the extent possible, while being sensitive to topography and natural features. Connectivity beyond the Growth Areas is stressed where those connections are possible into the existing Urban Service Area (USA), including streets stubbed out along the edges of development at regular intervals to ensure potential future growth has more opportunity for connectivity.

While the Master Plan outlines a preferred mix of housing types or uses, the eventual design of those structures is up to the developer and subject to current regulations.

Pillar 2: Density

Each of the Growth Areas is located along one of the city’s major corridors, and the Master Plan leverages that fact to focus the most intense portions of development close to the major roadways to encourage future transit access points and to make any potential commercial uses as viable as possible. Density will then decrease from the major corridors towards established neighborhoods or areas remaining as agricultural land.

To ensure the Master Plan is using all the ‘tools’ available to provide a wide range of housing types, new compact styles of housing will be shown in the plan and supported in regulations.

Pillar 3: Equity

While the ‘ensuring equitable development' policy focuses on existing neighborhoods, it is important to note that the creation of this Master Plan is being done through the lens of providing and planning for all members of the community. In that vein, attainable housing and the provision of affordable housing are part of the regulatory approach. These housing options show up in the Master Plan at all scales of residential.

Community facilities, such as schools, libraries, and parks, are an integral part of the civic infrastructure, which the master plan prioritizes as a key building block from which the rest of any development should radiate.

The Master Plan looks at accessibility at a site level, but the merits of universal design and standards of accessibility to and within buildings should become a major topic of discussion and approval when developers bring projects for approval.

While the Regulating Plans establish what land is buildable, the Master Plan works to protect existing areas of environmental sensitivity and rich biodiversity. These areas may be near streams or ponds, but they may also coincide with existing stands of trees.

The sustainable/net zero guidelines created for this project help ensure that the Growth Areas are in line with the goal of the City to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Both the master plan and the regulatory approach establish compact development patterns and a complete streets approach to encourage multimodal transportation and avoid reliance on single occupancy vehicles. The concept plans reinforce through design the reduction of impervious surface relative to a traditional development, the use of green stormwater infrastructure and low impact design, and the use of native plants, and regulations of these sustainability measures would be included in future studies.

The master plan and related implementation plan for the Growth Areas sets aside space for performative landscapes, while leveraging greenways and natural areas for passive recreation and trails. Waterway quality and watershed management can be improved when tied to development and investment in greenway infrastructure and maintenance.

While the master plans does not get down to the level of detail of showing parking for electric vehicles, the sustainable/net zero guidelines will discuss options for greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

Each of the Growth Areas are located along, and will have its primary access on, a major corridor heading into town. The master plan weighs the need for visibility of future development with the desire to create gateway moments between urban areas and the bluegrass landscape.

Planning for entertainment districts is a key consideration for the Growth Areas, whether it be enhancing existing sports facilities or shaping and providing supportive uses for future venues.

Pillar 1: Livability

Pillar 2: Diversity

The entire concept of the Growth Areas hinges upon the idea of creating more opportunities for attainable housing, varying in type and price point. These residential areas need to be supported by civic infrastructure and a mix of uses that help to retain and attract a vibrant workforce. These areas will be further bolstered and be attractive to a wider range of residents by being well-served by transit.

The Blue Sky Activity Center will continue to be a highlyfunctional industrial center, but the ability to take advantage of new town centers nearby with workforce housing will open up opportunities for the job force. The Blue Sky area will be fully analyzed through a future small area plan.

Pillar 3: Prosperity

Several of the Growth Areas include ‘Flex Space’ and even more have the opportunity for mixed-use development. Flex Space provides a wide array of spaces, including small-scale brick and mortar and incubator spaces, for businesses to locate. This allows for a more diverse economic base, which could include smallscale brick and mortar and incubator space.

The viability of creating walkable neighborhoods in the expansion area is greatly improved by the minimization of the amount of surface parking. Through design and regulations, developers are encouraged to get creative with how they think about parking, including through flexible and shared parking arrangements.

While forcing grocery chains to build in certain areas is impossible, the plans allow for opportunity to include everything from grocery chains down to small farmers markets.

Pillar 1: Connectivity

The basic principles of a highly functioning and well-connected multi-modal transportation network are the backbone of each of the Growth Areas. The City’s adopted Complete Streets Policy is demonstrated in the Regulating Plans and reinforced in the regulations. Knowing that the Complete Streets Design Manual follows on the heels of this project, many of the details of the transportation network are roughly sketched out during this project, with the opportunity for refinement once the Complete Streets Design Manual is finished. While the Growth Areas are all relatively far away from the existing transit network, the designs for each will start with a strong bicycle/pedestrian network. This ensures people who cannot, or choose not to, take personal vehicles have an option that gets them around their community. The idea being that eventually this already strong system can connect to Lextran. The design of streets and roads will focus on safety and accessibility for all modes. This includes designing for desired speeds, using traffic control measures, and utilizing alternative, safer intersections throughout.

Pillar 2: Placemaking

Each of the Growth Areas builds off the protection of each site’s unique natural resources and key features, such as streams, water bodies, and groupings of trees, to help develop a sense of place. These natural areas become the location of numerous off-road trails and greenways, making them an amenity for use by the community. The regulatory elements being created as part of this project will help the city establish better standards and guidelines for creating walkable communities.

As part of key civic infrastructure, and as a built-in way to ensure vibrancy of place, potential school sites will be shown in several of the Growth Areas where the number of households will be able to support them.

The ability to age in place in a vibrant community is an evergrowing need. By requiring a specific minimum density and allowing for a diversity of housing options, including cohousing, the Master Plan increases Lexington's ability to serve an aging population.

Street trees as essential infrastructure are at the forefront of the design of a walkable community and the Complete Streets effort and will be included in the design and regulations.

THEME E: URBAN AND RURAL BALANCE

Pillar 1: Accountability

The Lexington UGMP project is a large step towards achieving several of the accountability policies listed, including expanding the Urban Service Area.

Pillar 2: Stewardship

Pillar 3: Growth

One of the main goals of this project is to plan the Growth Areas in such a way that maximizes this opportunity and accommodates the need for development and housing in a significant way.

By showcasing portions within and surrounding the Blue Sky Activity Center for use as an Entertainment District with a regional draw by the Lexington Sporting Club and others, tourism and development remains prioritized.

This pillar covers the adoption of this project, which works to create more dense residential developments, missing middle and attainable housing, walkability, and transitoriented development. Incorporating thoughtful design and placement of infrastructure, including roads, stormwater, and sewer, keeps the cost of development down.

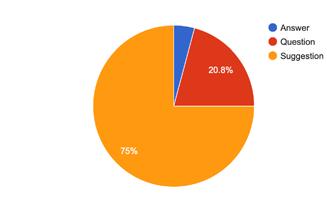

The On The Table database CivicLex and the Division of Planning created provides the Project Team with a better picture of what the public wants to see as the City grows. It effectively ties those desires to specific geographical locations within the City based on the respondents’ identified neighborhood. This creates a unique baseline for our understanding of the community’s needs and wants prior to any outreach being done.

On the Table 2022 was an unprecedented opportunity for everyday Lexington residents to get engaged on land use and the Comprehensive Planning process. Across a week of conversations, 2,412 participants filled out the On the Table Survey, a combination of qualitative and quantitative questions about how they want to see Lexington grow and change. This survey resulted in a database of over 15,000 open-ended responses about land use in Lexington-Fayette County, which was coded by CivicLex and the Division of Planning to use in the development of Imagine Lexington 2045 and other land use decisions.

The initial coding process, developed in partnership with the University of Kentucky’s Martin School of Public

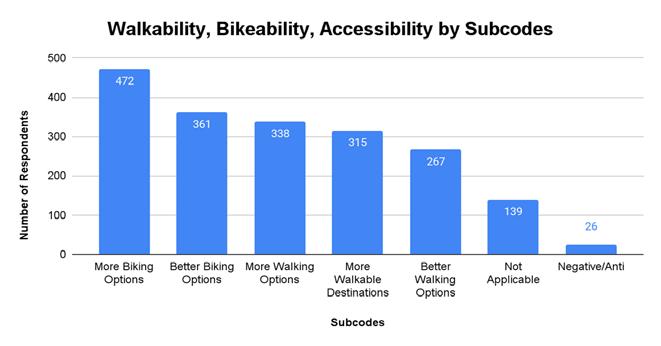

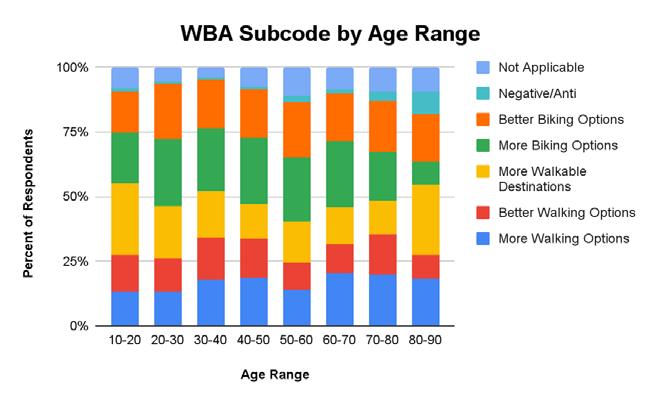

The most popular code was “Walkability, Bikeability, and Accessibility,” with 1,731 comments tagged with this code (8% of the total 15,000 comments). A total of 1,134 survey respondents spoke to this issue (some brought up the issue multiple times in response to the different open-ended survey questions). Walkability, Bikeability, and Accessibility refers to comments that mentioned walking or biking trails, sidewalks, bike lanes, or physical accessibility to walking or biking for people with disabilities (i.e., sidewalk conditions, ramps, and curb heights).

The second most popular code in the On the Table dataset was Public Transportation, with 1,744 comments (11% of all OTT responses). A total of 1,163 unique respondents mentioned Public Transportation, 48% of all survey takers. The neighborhoods that mentioned public transportation most frequently were Picadome, Kenwick, Woodland, and Cardinal Valley.

Amenities and Quality of Life (AQL) was the third most popular code. Within AQL, which was mentioned in 1,567 of the gathered respondents' comments, More Things to Do, Commerce/Retail/Restaurant, and Quality of Life were the top three priorities highlighted by participants.

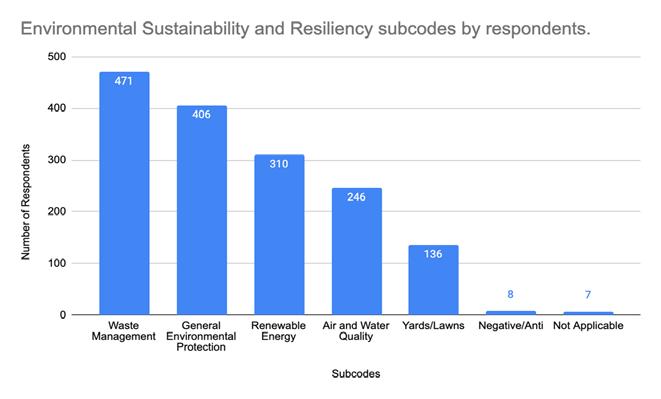

Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency (ESR) is the fourth most popular code. Within ESR, which was mentioned in 1,000 of the gathered comments, Waste Management, General Environmental Protection, and Renewable Energy are the top three priorities highlighted by participants.

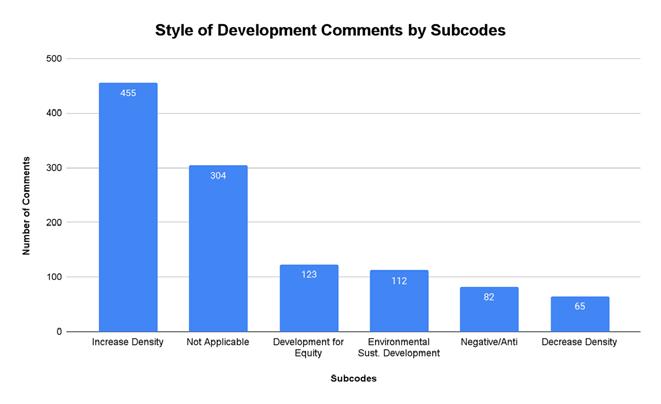

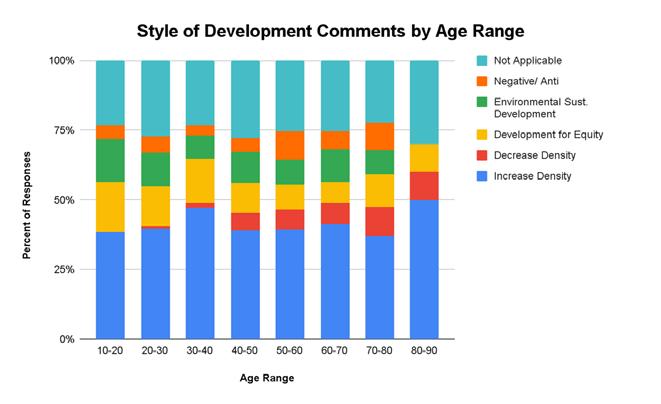

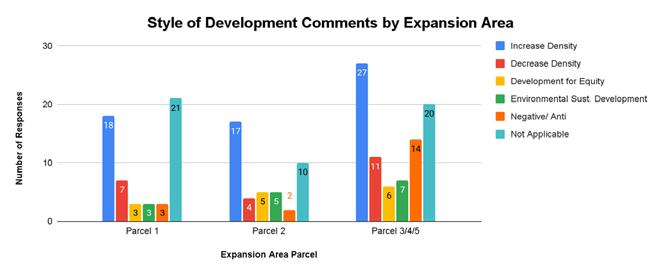

The fifth most popular code was “Style of Development,” with 1,137 comments tagged with this code (7.5% of the total 15,000 comments). Style of Development refers to comments that mentioned any of the following: density/intensity, aesthetics, context, housing options/ types, sprawl, missing middle housing, mixed use, or low-density or single-family development.

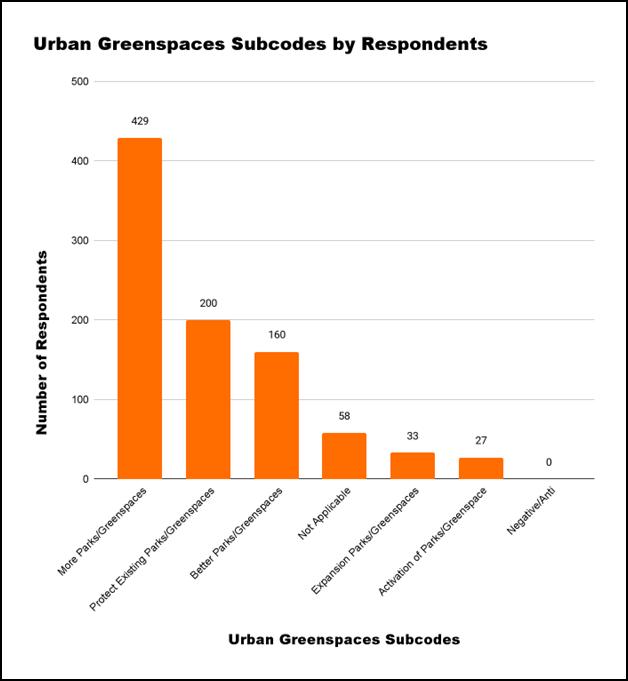

The sixth most popular code was “Urban Greenspaces,” with 962 comments tagged with this code (4% of the total 15,000 comments). More Parks/Greenspaces, Protecting Existing Parks/Greenspaces, Better Parks/Greenspaces were the top three priorities among those who mentioned UG concerns. Even though most people wanted more parks, there were many mentions of keeping existing parks better maintained and accessible. Additionally, many respondents commented on increasing the usefulness of parks and greenspaces through increased activities and events at parks to bring people and communities together.

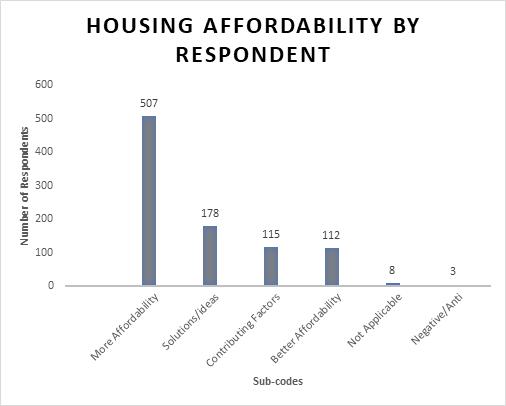

The seventh most popular code was “Housing Affordability,” with 646 respondents mentioning the topic in their open-ended responses. This category refers to responses that mention the need for safe, affordable housing, with many indicating how improved housing affordability would impact their quality of life. Responses in this category also included those related to the quality of available affordable housing, commentary about the contributing factors or justifications for why housing affordability is so difficult for Lexingtonians, and specific ideas, policies, or solutions that might increase housing affordability in Lexington.

It is important to note that this emerged as a common topic even though there were no specific questions within the OTT survey that asked directly about housing. While many codes correspond directly to specific survey questions, this theme bubbled up from the data as a significant number of respondents brought up the issue in their openended responses, most often in relation to questions asking about jobs or prosperity.

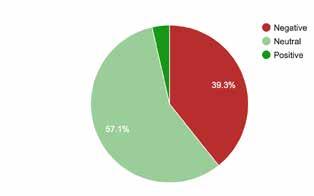

Policy, involved reading every open response question for mention of 32 key themes, or “codes.” These include topics like public transportation, housing affordability, traffic congestion, water infrastructure, and safety. This coding process was essential to organizing the overwhelming amount of qualitative and quantitative data. The On the Table database can be filtered by any of the 32 codes, leading to insight about the most popular codes by Comprehensive Plan theme, demographic, neighborhood, and sentiment. However, there were two key drawbacks of the initial coding process.

First, the coding did not capture the sentiment of the responseswhether a participant wrote “I love my neighborhood because of all the trees along the sidewalks” or “The trees in my neighborhood make it difficult to see around corners while driving and have caused accidents”, the response was simply tagged with the “trees” code.

Second, the coding did not capture a high level of detail within the responses. A code like “style of development” includes a variety of subjects, including the density, aesthetics, and types of housing, commercial development, and industry.

Both of these drawbacks were necessary choices within the timeframe of On

the Table and the creation of Imagine Lexington 2045. The UGMP presented an exciting opportunity to revisit the On the Table data and dive deeper into resident sentiment and responses, gaining an even clearer picture of how Lexington’s residents want to see our city grow.

As part of the public engagement work for the UGMP, CivicLex staff and the University of Kentucky’s Department of Community Leadership and Development re-investigated the On the Table data and subcoded the most popular concepts. CLD 670: Community Engagement led by CivicLex Staff, Professor Nicole Breazeale, and Professor Karen Rignall, with graduate students Jason Schubert, Jamari Turner, Himika Akram, Tanya Whitehouse, Lindsey Windland, Reba Prather, Ruth Toole, and Brock Vandagriff executed an in depth research and sub coding process for the top six codes in the On the Table dataset.

In teams of two or three, students (with a staff/faculty leader), selected a code, read all open responses tagged with that code, and followed the initial OTT process for developing a code book as described in the Imagine Lexington Public Input Report. With the narrower focus of a single subject (for example,

walkability/bikeability), students were able to create subcodes that captured sentiment and increased detail - e.g., residents asking for more biking infrastructure versus residents frustrated with bike paths being developed instead of additional driving lanes. The results of this subcoding process are included in Appendix B Community Voices.

This UGMP for Lexington's future is grounded in an inventory and analysis of the conditions that shape the county today, including:

■ Existing land uses and densities

■ Zoning and permitted land uses

■ Agricultural land

■ Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) land

■ Environmental features (i.e., soils, topography and steep slopes, waterways)

■ Vehicular infrastructure

■ Multimodal infrastructure (i.e., pedestrian, bicycle, transit)

■ Utilities (i.e., electric, water, gas, telecommunications, sanitary sewer)

The current planning study uses the areas recommended for potential growth as identified by the Planning Commission on October 26, 2023.

The following pages introduce each planning area, its context, and the issues and opportunities identified that it currently faces or may face in coming decades.

Between differences in size, existing land use and current management, zoning, topography, drainage patterns, and more, each area presents unique opportunities and constraints for development.

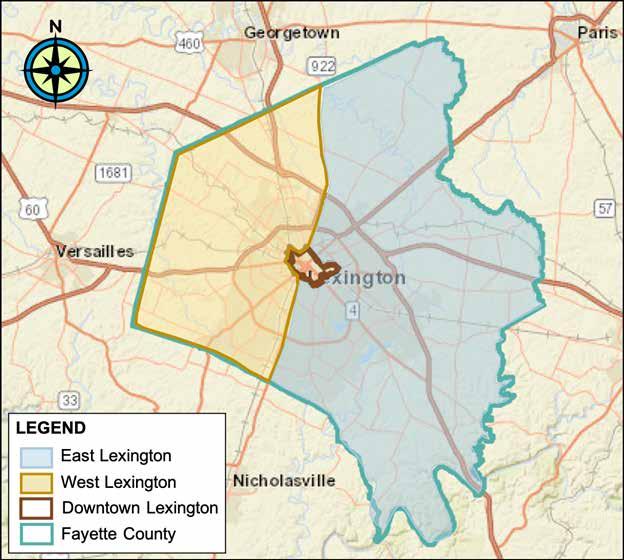

Area 1 is located along the western edge of the Urban Service Area. The smallest of the five sites included in this study, it is bounded by Parkers Mill Road to the north and Man O' War Boulevard to the southwest. Its southeastern edges border Heritage Place, a subdivision of two-family dwellings, and The Reserve, a large single family detached subdivision that spans approximately 132 acres, not including the 78.5-acre Beaumont Preserve.

Area 2 is located to the northeast of Lexington’s Urban Service Area and forms the largest of this study’s five sites. The site is situated between two Interstate Highways—I-64 to the north and I-75 to the west—and Winchester Road to the south. The site’s eastern boundary is agricultural land.

Areas 3, 4, and 5 are often shown together for the purposes of this Chapter since they are all adjacent to one another and share many of the same characteristics.

Area 3 is located adjacent to the Urban Service Area’s southeastern corner. It is bounded by Athens Boonesboro Road to the south and I-75 to the east. Area 4 is immediately adjacent to the east, but I-75 acts as a major barrier, while Area 5 is also nearby to the southeast. Several subdivisions form this site’s northern and western boundaries, including Walnut Creek and Chilesburg, two dense single-family subdivisions. Area 3 also includes Brenda Cowan Elementary School and the undeveloped portion of land attached to Edythe Jones Hayes Middle School.

Located immediately to the east of Area 3, Area 4 is bounded by Todds Road to the north, I-75 to the west, and portions of Canebrake Drive to the east. The cluster of hotels and highwayservice businesses located where Athens Boonesboro Road crosses I-75 forms the site’s southern boundary.

Athens Boonesboro Road forms the spine of Area 5. The boundary extends between 1/8-mile and 1/3-mile on either side of Athens Boonesboro Road site and mostly includes this area’s non-residential uses: the hotel and highway-service businesses adjacent to I-75 and the industrial uses along Blue Sky Parkway.

■ Identified by the

■ Total acreage of 2,833

■ Spread across 5 approved areas, in three geographic edges of the

■ Along major corridors

■ Potential as ‘gateway’ moments into the

Given that all of the proposed areas of future growth are outside of the existing Urban Service Area, the majority of the sites are low density and used mostly for agricultural purposes.

Area 1 is the smallest of the five areas. The land is currently being used for cattle and horse pastures with seven paddocks for horses and areas for grazing animals. There are several associated barns, outbuildings, and the original farmhouse on site.

The vegetated entry to Pine Needles Lane is included in Area 1. This parcel is owned and maintained by the Heritage Place HOA, which is the adjoining community.

Area 2 is the largest of the five areas. It includes a cluster of single-family homes along Hume Road and Ami Lane. Several large lot rural residential homes are scattered throughout the site.

There are several actively managed farms, which include a residence and multiple barns or outbuildings. Non-residential uses include WKYT News

station, and part of a power sub-station.

Area 3 is sparsely developed, other than a single operational farm west of Brenda Cowan Elementary. The remainder of the land is unoccupied and used for crop rotations. The northernmost portion of the site is landlocked and has access through a temporary easement into the adjacent neighborhood to the west. Access to these parcels would need to be reevaluated depending on any future development.

Non-residential uses include: two public schools, Brenda Cowan Elementary School and the back portion of Edythe J. Hayes Middle School.

Area 4 consists of several large agricultural tracts along Todds Road. The farmland has a mix of row crops and pasture.

There are a series of 10-acre lots along Canebrake which were subdivided in 1987, a few of which have dwellings on them.

Area 5 is the most developed of the 5 sites. The Blue Sky Rural Activity Center, centered around the Blue Sky Parkway, hosts a wide variety of industrial sites, including freight, light manufacturing, and construction services.

The Blue Sky Rural Activity Center also contains several hotels clustered at the I-75 interchange with Athens Boonesboro Road. The remainder of the areas at the corners of Athens Boonesboro Road and I-75 are highway-serving businesses such as fast food restaurants, gas stations, convenience stores, and an adult entertainment venue.

The land surrounding the recently constructed Lexington Sporting Club soccer fields and future stadium has seen huge changes since 2023, transitioning from being a hilly forested piece of unused land to major earth movement to make way for new fields, parking, and infrastructure. The stated goal is to create an entertainment district based on the new sports complex, but not all of the components have been decided yet.

Source: Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government GIS (LFUCG), 2023

The zoning that regulates development on each site does not immediately offer insight into what types of development and uses are appropriate for future development outside of the existing Urban Service Area. This section describes the current zoning for each area—but perhaps more importantly, the zoning around each site—to reveal what built form and character might fit within each one.

Areas 1, 3, and 4 are exclusively comprised of land zoned Agricultural - Rural (A-R). This category is reserved for agricultural

operations, including crop production, pastureland, and equine-related facilities. Single-family detached residential is also permitted within the zone. Agricultural tracts within Areas 1 and 3 are quite large. Area 4 also features large tracts, along with a series of smaller agricultural lots (a minimum of 10 acres each) along Canebrake Drive that have been subdivided into lots for single-family homes.

Area 2 mostly consists of land zoned A-R, similarly organized into large agricultural holdings. A small, single-family neighborhood (zoned R-1A) extends along

Hume Road and Ami Lane.

Area 5’s zoning is the most distinct of the five sites. While some small pockets of A-R remain, the majority of Area 5 is zoned Light Industrial (I-1). Land immediately adjacent to I-75 is zoned commercial (B-3 and B-5P), which permits auto-centric businesses including hotels, quick service restaurants, gas stations, and other such uses.

5 4 3 2 1

When considering adjacent zoning, much of the five areas are surrounded by land outside of the Urban Service Area, zoned A-R. Areas 1, 2, and 3 also share significant edges bordering areas of Lexington within the Urban Service Area, which fall under a variety of the City’s standard urbanized zones.

To the southeast of Area 1 are multiple single-family subdivisions, mostly zoned R-1C. Conforming lots in R-1C are a minimum of 8,000 square feet, and with 1 dwelling unit per acre, R-1C zones reach a maximum density between 5-6 units per acre. Also, immediately adjacent to Area 1’s boundary is a small multifamily development zoned R-3. Immediately north of Area 1 is an A-R tract and a park that is zoned R-1A (Cardinal Run North). There are two Agricultural - Urban (AU) districts adjacent to Area 1, which are available for an urbanized use. A small sliver is situated between Area 1 and R-3, while the larger A-U district is currently used as a park (Cardinal Run South).

I-75 forms the western boundary of Area 2, as well as the eastern boundary of the Urban Service Area. Across I-75 from the site are several districts zoned B-3, B-5P, and B-6P, all permissive of auto-oriented businesses. These non-residential districts back up to single-family (R-1C,

R-1D, R-1E) and multifamily districts (R3). Between I-75 and Area 2’s boundary are two “expansion area zones” - EAR-1 and ED. EAR-1 is reserved for low-density residential, while the ED zone is reserved for job production

To the north of Area 3 are several new subdivisions that fall under Expansion Area Zones (EAR-2 and CC). These zones are intended to provide a well-managed transition in density between the urban area of the city to its agricultural surroundings.

Standard Zones

A-R Agricultural - Rural Agricultural land (crops, pasture) and limited single family dwellings

A-U Agricultural - Urban Undeveloped land within urban growth boundary, with restrictions on development until infrastructure and services are provided

R-1A Single-Family Residential (SFR)

R-1B SFR

R-1C SFR

R-1D SFR

R-1E SFR

Detached homes on 25,000 sf lots

Detached homes on 15,000 sf lots

Detached homes on 8,000 sf lots

Detached homes on 6,000 sf lots

Detached homes on 4,000 sf lots

R-1T Townhome Residential Attached homes, minimum lot size 1500 (maximum 12 attached)

R-3 Planned Neighborhood Residential Mixed residential district (multifamily, townhomes, and single-family detached)

B-1 Neighborhood Business Commercial district catering to businesses that serve residential neighborhoods

B-3 Highway Service Business Commercial district catering to auto-oriented businesses appropriate for highways

B-5P Interchange Service Business Commercial district catering to businesses appropriate for interstate interchanges

B-6P Commercial Center District intended to create walkable retail and business developments

I-1 Light Industrial Manufacturing, logistics, and other industrial without nuisances

P-1 Professional Office Offices and professional uses

Expansion Area Zones

EAR-1 Expansion Area Residential Low density residential, mixed type (3 units/acre maximum)

EAR-2 Expansion Area Residential Low density residential, mixed types (9 units/acre maximum with density transfer rights)

CC Community Center Mixed use district that permits residential, retail, and office

ED Economic Development Non-residential district that permits office and industrial uses

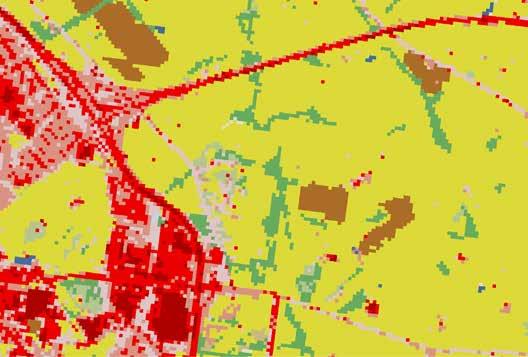

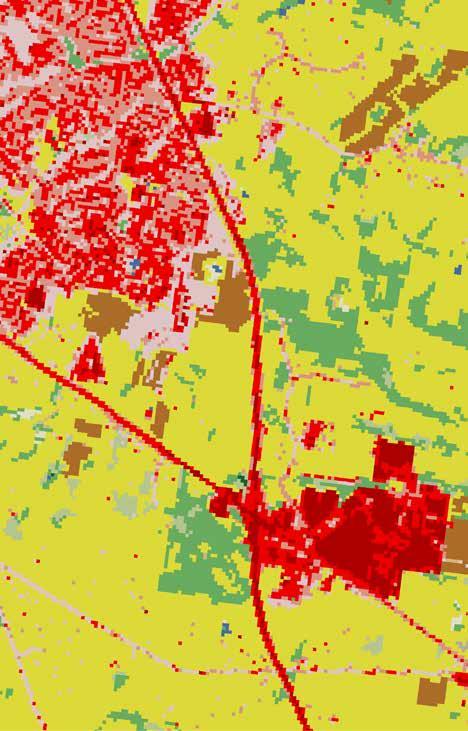

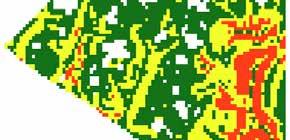

In early 2024 when the Project Team reviewed each area of study in person and from aerial imagery, each area of study, with the exception of Area 5, contains significant portions of agricultural land. The use of the agricultural land differs across the landscape and use is challenging to discern from aerial imagery alone. Data from the National Land Cover Database (NLCD), shown in the following maps, provides an additional layer of detail but still contains a margin of error. For instance, there is a portion of land in Area 3 which is existing agriculture being shown as ‘Developed Open Space’, most likely as a result of being heavily disturbed. The NLCD data is taken at a zoomed out scale, providing a good, but not very specific, idea of what may be happening on th ground.

Almost all of Area 1 is occupied by grazing land, labeled “hay/pasture” by the NLCD. From aerial and street-view imagery, there appear to be seven pastures or paddocks total within this area, used primarily for cattle grazing and equine turnout. The NLCD data shows how suburban development has altered land cover up to the boundary of Area 1.

There is also a small parcel of land included within Area 1, which acts as the

landscaped entry of Pine Needles Lane into the neighborhood.

Similar to Area 1, the majority of Area 2 contains grazing land, with some agricultural land devoted to cultivated crops in the eastern portion of the study area. These grazing tracts are divided by riparian zones lining North Elkhorn Creek and its smaller tributaries. The limited amount of developed land in Area 2 can be found in the single-family neighborhood extending along Hume Road and Ami Lane.

Area 3 features large agricultural holdings of hay/pasture, especially toward I-75 to the east and Athens Boonesboro Road to the south. Some plots of cultivated crops are also captured in the land cover data. This area features significantly more developed land cover than Areas 1 and 2. The “medium intensity” and “high intensity” land cover represents Brenda Cowan Elementary School. The large swath of land identified as “developed, open space” adjacent to the recent subdivision development to the north could indicate a few things. Aerial imagery shows this area as grazing land, although the area is dotted with clear,

circular patches of green which could indicate a different land use. Still, most of the land identified as “developed, open space” appears to be for agricultural use.

Area 4 includes several large agricultural holdings, as well as a handful of smaller agricultural tracts along Canebrake Drive. Most of these holdings are being used for grazing land or crop rotations. However, a sizable portion of them are forested, especially those farther north along Canebrake Drive, and many do not have an active agricultural use.

Area 5 is the most distinct from the other four study areas. While the far western portion of the study area was characterized by forested land cover, the current development of the soccer complex has since removed the majority of the treed portions of the site. The remaining bulk of Area 5 has been developed to a relatively high intensity. Land cover data shows how this development had been limited to Blue Sky Parkway and the four corners of the I-75 on-ramps.

Hay/Pasture

Cultivated Crops

Deciduous Forest

Mixed Forest

Developed, Open Space

Developed, Low Intensity

Developed, Medium Intensity

Developed, High Intensity

Open Water

Site Boundaries

Parcels

Parks Interstates Main Arterials Other Streets

Source: National Land Cover Database (NLCD), 2021 NLCD data is provided at 30-meter resolution, meaning that each pixel has a width of 30 meters.

Land preserved under Lexington-Fayette County’s Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) program can be found near the five areas of study. Because these lands cannot be developed due to legally binding conservation easements. Any development projects occurring within these five areas must consider how to buffer or transition between developed neighborhoods or districts and conservation areas.

The tracts closest to Area 1 that are protected under PDR are located about one mile to the south, along Bowman Mill Road where it meets South Elkhorn Creek (not shown in map extents).

Two PDR tracts are located close to Area 2’s boundary, one immediately adjacent to the area’s northeastern corner across Royster Road (approximately 40 feet) and another to the north across I-64 (approximately 250 feet). Both of these tracts appear to be utilized for agricultural operations, mostly pasture.

PDR land is clustered to the south and east of Areas 3, 4, and 5. The southern tracts consist of smaller agricultural holdings, mostly used for pasture, while the eastern tracts are larger and appear to be used for a variety of agricultural production, including both pasture and cultivated crops.

Example of Agrucltural Uses - Equine and Hay

While Fayette County is known for its karst* landscape, it is important to note that specific karst features have been identified as either existing sinkholes, or areas of potential future karst features, including sinkholes, caves, springs, etc. It may be advisable to avoid high density development in areas known to have problems.

Area 1 is characterized by rolling terrain of 10% or less slope. The site falls from east to west with two drainage features leaving the site, one under Parkers Mill Rd and the other under Man O' War Boulevard.

While not impeded by existing drainage channels, floodplain, or steep slopes, the identified existing and potential karst features will present challenges to the overall development due to issues with building foundations and other structural concerns.

Area 2 has two distinct regions, the neighborhood development along Hume Road with slopes in the 10% - 20% range and the undeveloped portions which area predominately 10% or less with pockets of steeper slopes.

Areas 3, 4, and 5 have more topographic relief than the other Areas, with substantial portions of land that is undesirable or unsuitable for development (slopes over 20% and some in the 10% - 20% range). The northern region of Area 4 has significant portions of gentle slopes of 10%.

Area 3 has pockets of mapped karst / sinkholes, but additional areas may be present beyond those mapped given the expected site geology and topography.

In general, much of the undeveloped portions of Area 3, 4, and 5 would require minimal earth movement and would

lend themselves to development given that design respects the topography. Care should be taken to avoid the areas with steep slopes and known karst areas, and developers should be cognizant that additional unmapped areas may be present.

* Karst – a type of landscape formed when the earth's bedrock dissolves, leading to features like sinkholes, caves, and springs. It usually occurs in areas with soluble rocks like limestone, marble, and gypsum. In a typical karst landscape, rainwater seeps into the ground through cracks and holes in the rock. This water can travel underground for long distances before it comes back to the surface through springs, often found at cave entrances.

<3% Slope- Suitable for Building

3-10% Slope- Suitable for Building

10-15% Slope- Suitable for Building with Restrictions

>15% Slope- Not Desirable for Building

Sinkhole / Karst

Source: Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government (LFUCG) GIS, 2023

When imagining how these areas could accommodate thoughtful development, it is important to note environmental and geological features that should be protected from negative impacts.

Areas 2 and 4 both feature prominent waterways that would affect the shape and orientation of development plans. The tributaries shown on the maps without floodways or FEMA floodplains are classified by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) as intermittent streams, which may not have flowing surface water and which flow during certain times of the year when smaller upstream waters are flowing and when groundwater provides enough water for stream flow.

While two small streams begin within Area 1, ultimately draining to Cave Creek southwest of Man O' War Boulevard, Area 1 otherwise does not experience many challenges with existing waterways. The features drain into Manchester Branch, Wolf Run, and Cave Creek, and none have mapped FEMA floodplains within Area 1. A jurisdictional determination has not been made on these features. Based on the Kentucky Water LiDAR Analysis, numerous sinkholes / karst features are present on the site.

Area 2 has multiple drainage features (streams and ponds), some of which are jurisdictional, and some have not been classified. All water flows south to north and discharges under I-64. North Elkhorn Creek bisects Area 2 from I-64 to the north to Winchester Road to the south. There are approximately 18 acres of floodplains within Area 2, comprising just under 2 percent of the study area. The mainstream sections through the center of the site have both FEMA mapped floodplain and floodways which will create challenges with roadway connections within the site.

While no karst features are presently mapped, they could be present given the geology of central Kentucky. Given the existing FEMA floodplains and floodway dividing the site, multiple road crossings will be challenging. Larger than typical drainage structures or lengthy permitting associated with the FEMA process to allow flood impacts may be required. Additionally, if structures are selected that impact the stream channels, an individual permit through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) may be triggered depending on the number of crossings that would exceed the Nationwide Permitting thresholds.

Areas 3 and 5 are less affected by streams and floodplains, though several waterways still appear within their boundaries. Area 3 features no floodplains, though several streams drain to the south.

Area 3 drains into three separate drainage basins with a high point in the center of the site. Additionally, there are existing ponds on site. To the northeast, the site drains under I-75 and to the southwest, it drains under Athens Boonesboro Road. To the southeast, flows drain into Area 5 and then under I-75.

Area 4 is broken into two distinct drainage basins, one to the north and one to the south. In Area 4, the Baughman Fork of Boone Creek begins in the northern portion of the study area, draining away from I-75 toward Boone Creek to the East. Neither of the drainage features have mapped floodplains. Ponds are also present on site in the northern region.

In Area 5, a sizable floodplain is situated on the northern edge of the industrial area along Blue Sky Parkway, ultimately draining to Boone Creek as well. Area 5 drainage connects with both Area 3 and Area 4 features but does not have mapped floodplains; however, just off-site to the east of the Area 5 limit, floodplains are present.

Although a formal assessment has not yet been completed by the state government, it's likely that many of these areas will be identified as intermittent or perennial streams, and their surface waters will be considered state waters.

As roadway networks are developed, staying below the Nationwide Permit thresholds with the USACE for stream and open water impacts should be considered to avoid the Individual Permitting process. While steep slopes are present in Area 4, avoiding impacts to the channels should limit development in those areas. Alternatively, if the channels are either unregulated or permitted to be filled, large scale earth moving will alleviate the limitations with the slopes.

Currently, there is a delay at the traffic light on Lane Allen Road and Parkers Mill Road, where drivers often wait for more than one signal cycle to get through the intersection in the morning. Queues in the morning can reach up to 25 vehicles on Lane Allen Road. When this happens, only a third of the vehicles can clear the intersection during the green phase of the cycle. The intersection does not experience the same level of queuing outside of the AM or PM peak periods. At the Parkers Mill Road at Man O' War Boulevard intersection, the traffic signal

appears to be sufficiently managing traffic flow. Despite the maximum queue length of 15 vehicles in the evening, queues are flushed each cycle. Operations are consistent and under capacity, given the current demand.

Finally, the Man O' War Boulevard at Beaumont Centre Lane intersection is busy during peak hours, with Beaumont Centre Lane having a typical queue of 15-20 vehicles. However, queues are successfully cleared each cycle and the intersection appears to efficiently manage the demand. Nearby Dunbar

High School does generate additional traffic during the school year. The additional traffic results in an increase in delay experienced at the intersection; however, the overall impact is restricted to school arrival and release.

Average Daily Traffic (ADT) –the average number of vehicles passing a specific point on a roadway on an average day.

K factor – the proportion of annual average daily traffic occurring in an hour.

D factor – the proportion of traffic traveling in the peak direction during a selected hour.

Station data is collected on a three year cycle, data is from 2021 - 2023.