Appendix: Imagine Lexington 2045 Survey A

Words

The Lexington Urban Growth Master Plan draws directly from the policies and pillars of the Imagine Lexington 2045 Comprehensive Plan. The following table designates each policy that applies to the Master Plan (MP), and whether it manifests itself through design in the Regulating Plans (REG), or through regulation and policy implications.

THEME A: BUILDING AND SUSTAINING SUCCESSFUL NEIGHBORHOODS

PILLAR I: DESIGN

Design 1 Utilize a people-first design, ensuring that roadways are moving people efficiently & providing equitable pedestrian infrastructure.

Design 2 Ensure proper road connections are in place to enhance service times & access to public safety, waste management and delivery services for all residents.

Design 3 Design policy #3: Multi-Family residential developments should comply with the Multi-Family Design Standards

Design 4 Provide development that is sensitive to the surrounding context.

Design 5 Provide pedestrian-friendly street patterns & walkable blocks to create inviting streetscapes.

Design 6 Adhere to the recommendations of the 2018 Lexington area MPO bike/ Pedestrian Master Plan.

Design 7 Design car parking lots and vehicular use areas to enhance walkability and bikability.

Design 8 Provide varied housing choice.

Design 9 Design policy #9: Provide neighborhood-focused open spaces or parks within walking distance of residential uses.

Design 10 Design policy #10: Reinvest in neighborhoods to positively impact Lexingtonians through the establishment of community anchors.

Design 11 Design policy #11: Street layouts should establish clear public access to neighborhood open space and greenspace.

Design 12 Support neighborhood-level commercial areas.

Design 13 Development should connect to adjacent stub streets & maximize the street network.

PILLAR II: DENSITY

Density 1 Locate high density areas of development along higher capacity roadways (minor arterial, collector), major corridors & downtown to facilitate future transit enhancements.

Density 2 Infill residential can & should aim to increase density while enhancing existing neighborhoods through context sensitive design.

Density 3 Provide opportunities to retrofit incomplete suburban developments with services and amenities to improve quality of life and meet climate goals.

Density 4 Allow & encourage new compact single family housing types.

PILLAR III: EQUITY

Equity 1 Ensure equitable development and address Lexington’s segregation resulting from historic planning practices and policies: rectify the impact of redlining and discrimination based on race and socioeconomic status.

Equity 2 Provide an ongoing and contextualized educational curriculum on historical planning practices and policies acknowledging their impact on marginalized neighborhoods in Lexington.

Equity 3 Meet the demand for housing across all income levels.

Equity 4 Provide affordable housing across all areas, affirmatively furthering fair housing, complying with HUD guidance.

Equity 5 Add residential opportunities by proactively up-zoning areas near transit for populations who rely solely on public transportation.

Equity 6 Preserve & enhance existing affordable housing through the Land Bank, Community Land Trust & Vacant Land Commission.

Equity 7 Protect affordable housing tenants through improved code enforcement policies.

Equity 8 Improve access to and promote accessory dwelling units as a more affordable housing option in Lexington.

Equity 9 Community facilities should be well integrated into their respective neighborhoods.

Equity 10 Housing developments should implement universal design principles on a portion of their units.

Equity 11 Ensure stable housing. Empower individuals through shelter, and provide housing security through permanent residences and comprehensive assistance programs.

Protection 1 Continue the Sanitary Sewer Capacity Assurance Program (CAP) and encourage the Stormwater Incentive Grant Program to reduce impacts of development on water quality.

Protection 2 Conserve and protect environmentally sensitive areas, including sensitive natural habitats, greenways, wetlands and water bodies.

Protection 3 Continue to implement the PDR program to safeguard Lexington’s rural land.

Protection 4 Conserve active agriculture land in the Rural Service Area while promoting sustainable food systems.

Protection 5 Promote and connect local farms with the community through integrated partnerships.

THEME B: PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT

PILLAR I: PROTECTION

Protection 6 Promote context-sensitive agritourism in the Rural Service Area.

Protection 7 Protect the urban forest and significant tree canopies.

Protection 8 Protect and enhance biodiversity in both the Urban and Rural Service Areas.

Protection 9 Respect the geographic context of natural land, encourage development to protect steep slopes, and locate building structures to reduce unnecessary earth disruption.

Protection 10 Reduce light pollution to protect dark skies.

PILLAR II: SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainability 1 Establish a plan to reduce community-wide greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

Sustainability 2 Establish a plan to reduce all LFUCG facilities, operations, and fleets to net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

Sustainability 3 Reduce air pollution and greenhouse gasses through compact development and complete streets that encourage multimodal transportation options.

Sustainability 4 Reduce and mitigate negative environmental impacts of impervious surfaces and vehicle use areas.

Sustainability 5 Expand and promote energy efficiency, renewable energy, and electrification initiatives.

Sustainability 6 Apply for LEED for Cities certification to track progress toward sustainability, greenhouse gas emissions reduction, and environmental equity objectives.

Sustainability 7 Develop and proactively share educational materials and programs to increase public awareness of energy efficiency benefits and services.

Sustainability 8 Sustainability policy #8: Enhance Lexington’s recycling, composting, and waste management programs.

Sustainability 9 Incentivize green stormwater infrastructure beyond regulatory requirements.

Sustainability 10 Develop incentives for Green Building Practices and Sustainable Site Design.

Sustainability 11 Require low impact landscaping and native plants species.

PILLAR III: RESTORATION

Restoration 1 Implement the LFUCG urban forestry management plan to restore and grow Lexington’s urban forest.

Restoration 2 Identify opportunities to strategically link parks, trails, complete streets, greenways, and natural areas to advance Lexington’s green infrastructure network.

Restoration 3 Support community gardens and urban agriculture to restore natural resources within the Urban Service Area.

Restoration 4 Improve public health and reduce the regional carbon footprint by decreasing vehicle emissions through the use of alternative fuel vehicles.

Restoration 5 Improve watershed management and waterway quality.

Restoration 6 Coordinate to address litter abatement.

Restoration 7 Support Environmental Justice and equity.

THEME C: CREATING JOBS AND PROSPERITY

PILLAR I: LIVABILITY

Livability 1 Encourage economic opportunities for a wide array of agritourism while preserving the Bluegrass identity.

Livability 2 Emphasize the preservation, protection, & promotion of the iconic Bluegrass landscape along rural gateways & roadways serving as primary tourist routes.

Livability 3 Promote sports tourism through the development of athletic complexes & enhance Lexington’s existing facilities.

Livability 4 Promote economic development through improving the livability of downtown to support more residents and community serving businesses.

Livability 5 Enhance programs & activities by Lexington’s Parks & Recreation department, & support public event planning, community events, & festivals.

Livability 6 Attract & retain a vibrant workforce by improving affordable housing opportunities, amenities, & entertainment options.

Livability 7 Create a walkable city with quality transit that is attractive to new businesses and residents.

Livability 8 Promote quality of life aspects, including investment in public space, as an attraction to new businesses & residents.

Livability 9 Promote economic development through the preservation of strategically & appropriately located industrial & production zoned land.

PILLAR II: DIVERSITY.

Diversity 1 Create opportunities for incubators. Seek incentives for owners of vacant office/laboratory space, & for developers who build incubator space for startups & for growing businesses.

Diversity 2 Encourage a diverse economic base to provide a variety of job opportunities, allowing upward mobility for lower income residents of Fayette County.

Diversity 3 Support full funding & adequate staff for the Minority Business Enterprise Program (MBEP) which increases diversification of city vendors through promoting an increase in minority, veteran, & womenowned companies doing business with the city.

Diversity 4 Encourage training, programs, access, & inclusion to employment opportunities.

Diversity 5 Maximize context sensitive employment opportunities within the opportunity zone tracts, providing equitable community development, & prioritizing local residents for advancement opportunities.

Diversity 6 Increase flexibility on types of home occupations allowed.

PILLAR III: PROSPERITY.

Prosperity 1 Promote hiring local residents, & recruit employees living in areas of construction projects.

Prosperity 2 Support continued funding for economic development.

Prosperity 3 Continue to protect the agricultural cluster & equine industry, & support existing agricultural uses, while promoting new innovative agricultural uses in the Rural Service Area.

Prosperity 4 Encourage installation of fiber-optic broadband infrastructure for high-tech & other industries.

Prosperity 5 Continue to raise awareness of farms & farm tours.

Prosperity 6 Promote Kentucky Proud & local Lexington products using unified branding.

Prosperity 7 Support & increase networking opportunities for career related institutions, organizations, & agencies.

Prosperity 8 Provide employment opportunities that match the graduating majors from local colleges & vocational training institutions.

Prosperity 9 Recruit professional services that utilize vacant office space.

Prosperity 10 Encourage flexible parking & shared parking arrangements.

Prosperity 11 Expand job opportunities through education & training to retain existing businesses & attract new ones.

Prosperity 12 Implement the Legacy Business Park Master Plan for the 250 acres of publicly-controlled economic development land at Coldstream research campus.

Prosperity 13 Promote increasing the supply of farm workers, & the availability & affordability of using agricultural technology, & agricultural equipment.

Prosperity 14 Create and implement mechanisms for low, moderate, and middle income residents to access affordable and equitable home financing options to enable them to “get on the property ladder” and accumulate intergenerational wealth.

Prosperity 15 Collaborate with developers, commercial entities, and non-profits to eliminate food deserts throughout the county and ensure that all residents have easy access to affordable and nutritious food.

Prosperity 16 Create a central coordinating function for all social services in the county, including non-profit, faithbased, and governmental services.

THEME D: IMPROVING A DESIRABLE COMMUNITY.

PILLAR I: CONNECTIVITY.

Connectivity 1 Street design should reflect & promote the desired place-type.

Connectivity 2 Create multi-modal streets that satisfy all user needs and provide equitable multi-modal access for those who do not drive due to age, disability, expense, or choice.

Connectivity 3 Connectivity policy #3: Encourage Transit-Oriented Development, increase density along major corridors, and support transit ridership, thus reducing Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT).

Connectivity 4 Design street networks that provide alternative route options and reduce traffic congestion.

Connectivity 5 Streets should be designed for the desired speed, using built-in traffic calming measures such as roundabouts, narrower street widths, chicanes, medians, etc.

Connectivity 6 Develop a multi-modal transportation network and infrastructure; seek collaboration with regional transit partners for the commuting public.

Connectivity 7 Plan for the long-term land use and transportation impacts of connected and autonomous vehicles (CAV).

PILLAR II: PLACEMAKING.

Placemaking 1 Create development standards and best practices for land adjacent to shared use trails and trail corridors.

Placemaking 2 Activate built and natural environments to promote economic development and create safer spaces.

Placemaking 3 Establish design standards for placemaking.

Placemaking 4 Create quality & usable open space for all developments.

Placemaking 5 Review zoning ordinance & subdivision regulations to create more walkable places.

Placemaking 6 Promote a more resilient power grid while maintaining urban canopy and enhancing the visible characteristics of Lexington.

Placemaking 7 Cultivate a more collaborative predevelopment process by implementing the recommendations of the Public Engagement Toolkit.

Placemaking 8 Develop a tactical placemaking program within the Division of Planning to work with interested neighborhoods & aid in the organization of activities.

Placemaking 9 Honor Lexington’s history by requiring new development & redevelopments to enhance the cultural, physical, & natural resources that have shaped the community.

Placemaking 10 Coordinate with non-profit organizations to designate public art easements on new development.

Placemaking 11 Update the adaptive reuse ordinance.

Placemaking 12 Analyze underutilized commercial property through corridor land use & transportation studies.

Placemaking 13 Update the Downtown Master Plan.

Placemaking 14 Develop a new citywide festival to entice visitors & provide additional draw during the tourism offseason.

Placemaking 15 Reduce/discourage vehicle-oriented development patterns, such as drive through businesses and gas stations, within neighborhoods and the urban core.

Support 1 Ensure school sites are designed to integrate well into the surrounding neighborhood.

Support 2 Incorporate natural components into school site design to further the goals of Theme B (Protecting the Environment), but also to provide calming elements that reduce student stress & anxiety.

Support 3 Support the maintenance & expansion of a robust wireless communications network creating reliable service throughout Lexington’s urban & rural areas.

Support 4 Provide equitable healthcare opportunities throughout Lexington to allow for the wide range of medical needs of everyone.

Support 5 Provide equity in social services by ensuring those in need are served by social service community facilities that address homelessness, substance abuse, mental health, & other significant issues.

Support 6 Ensure all social service & community facilities are safely accessible via mass transit, bicycle, & pedestrian transportation modes.

Support 7 Protect and promote social services and take active measures to reduce homelessness.

Support 8 Build upon the success of the Senior Citizens’ Center to provide improved quality of life opportunities for the largest growing population demographic.

Support 9 Implement additional creative cohousing opportunities that are both accessible & affordable for seniors & people with disabilities.

Support 10 Incorporate street trees as essential infrastructure.

Support 11 Develop a climate adaptation plan.

Support 12 Support programs that protect the rights of tenants during the eviction process.

PILLAR III: SUPPORT.

PILLAR I: ACCOUNTABILITY.

Accountability 1 Complete the new process for determining longterm land use decisions involving the Urban Service Area and Rural Activity Centers.

Accountability 2 Develop growth benchmarks and determine best measurable methods to monitor them and report progress on a regular basis.

Accountability 3 Implement the Placebuilder to ensure development compliance with the goals, objectives, and policies of the Comprehensive Plan.

Accountability 4 Modernize the Zoning Ordinance to reflect the direction of the 2045 Comprehensive Plan.

Accountability 5 Redesign and retrofit the Lexington roadway network to safely and comfortably accommodate all users so as to encourage walking, bicycling and transit usage.

Accountability 6 Partner with other agencies and organizations to create public education and outreach opportunities.

Accountability 7 Establish a coordinating office to advance climate action and sustainability planning efforts.

Accountability 8 Establish a coordinating office to implement recommendations of the mayor’s Commission For Racial Justice And Equality.

Accountability 9 Enhance diversity in Lexington’s boards and commissions.

PILLAR

II: STEWARDSHIP.

Stewardship 1 Uphold and modernize the Urban Service Area concept.

Stewardship 2 Capitalize on the diverse economic development, housing, and tourism opportunities throughout the Bluegrass region and engage in discussions to further connect regional economic hubs.

Stewardship 3 Increase regional transportation cooperation and pursue multimodal transportation options to facilitate inter-county connectivity.

Stewardship 4 Coordinate with surrounding counties to capitalize on the inherent tourism draws of the Bluegrass region.

Stewardship 5 Fully realize the development potential within Lexington’s Rural Activity Centers while avoiding negative impacts to surrounding agriculture, rural settlements, and scenic resources.

Stewardship 6 Identify new compatible rural land uses that would enhance Lexington’s economy and provide additional income-generating possibilities for local farmers.

Stewardship 7 Enhance regional collaboration for coordinated planning efforts.

Stewardship 8 Ensure future development is economically, environmentally, and socially sustainable.

Stewardship 9 Follow and implement the recommendations of the 2007 study of Fayette County’s small rural communities and the 2017 Rural Land Management Plan to protect and preserve Lexington’s rural settlements.

PILLAR III: GROWTH.

Growth 1 Modernize regulations that support infill and redevelopment.

Growth 2 Identify and enhance opportunities for infill and redevelopment in downtown areas.

Growth 3 Implement the recommendations of the 2018 Your Parks, Our Future Master Plan.

Growth 4 Promote the adaptive reuse of existing structures.

Growth 5 Identify and preserve Lexington’s historic assets, while minimizing unsubstantiated calls for preservation that can hinder the city’s future growth.

Growth 6 Address new development context along the boundaries of existing historic districts while encouraging infill and redevelopment.

Growth 7 Ensure stormwater and sanitary sewer infrastructure is placed in the most efficient and effective location to serve its intended purpose.

Growth 8 Identify catalytic redevelopment opportunities to proactively rezone properties, clear regulatory hurdles, and expedite redevelopment.

Growth 9 Support missing middle housing types throughout Lexington.

Growth 10 Establish Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) for new development and infill along major corridors.

Growth 11 Imagine Lexington 2045 anticipates a variety of land use changes will occur throughout the Urban Service Area and recommends those that are in agreement with the goals, objectives, and policies within this comprehensive plan. Land use changes alone in an area are not sufficient to constitute major changes of an economic, physical, or social nature as provided in state statute for the approval of a zone map amendment.

Growth 12 Adopt a Master Plan for the expansion of the Urban Service Area that addresses Lexington’s growth needs through sustainable and equitable development.

Growth 13 Establish minimum residential densities and commercial intensities for new growth areas so that development covers the cost of the provision of infrastructure, community services, and facilities.

Growth 14 Identify and provide mechanisms that produce affordable housing.

Appendix: Community Voices B

Words

On the Table 2022 provided everyday Lexington residents with an opportuntiy to provide qualitative and quantitative feedback about how Lexington should grow and change. Over 2,400 individuals completed the extensive On The Table survey, resulting in over 15,000 open-ended responses. After reading through and grouping these responses, CivicLex developed 32 codes that captured the major topics that people mentioned and then manually went through and applied the codes to the open response comments.

The On The Table database CivicLex and the Division of Planning created provides the Project Team with a better picture of what the public wants to see as the City grows. It effectively ties those desires to specific geographical locations within the City based on the respondents identified neighborhood. This creates a unique baseline for our understanding of the community’s needs and wants prior to any outreach being done.

Walkability, Bikeability, & Accessibility

biking trails, sidewalks, bike lanes, or physical accessibility to walking or biking for people with disabilities (ie, sidewalk conditions, ramps, and curb heights).

The neighborhoods that mentioned this code the most frequently were Picadome/Pensacola (20% of comments), Woodland/Chevy Chase (20% of comments), Kenwick/Bell Court (19% of comments), Liberty (18% of comments), Lakeview/Chinoe (15% of comments), Cardinal Valley/Alexandria (14% of comments), and Northside (14% of codes). Most of the comments (37%) were

the theme or topic was raised in the response, not how people actually felt about it. For example, “I want more bike lanes” and “We have too many bike lanes” would both be tagged as “Walkability, Bikeability, and Accessibility.

To better understand the sentiment included in each comment, the team conducted a more robust analysis and deep dive into the “Walkability, Bikeability, and Accessibility” (WBA) code. Open comments with the WBA code were read thoroughly to identify recurring themes. The 7 themes, or subcodes, included:

More Sidewalks, Better Sidewalks, More Walkable Destinations, More Bike Lanes, Better Bike Lanes, Negative/Anti, and Not Applicable. The table to the right lists these codes and their criteria.

The team then went through and coded the 1,731 comments using this list of subcodes. Note that each open-ended comment could be coded with more than one subcode. For example, if a response mentioned the need for “more bike lanes that are protected from passing vehicles” it would be coded as both More Biking Options and Better Biking Options. Data was coded in AirTable, a cloudbased collaborative spreadsheet. Upon completion of individual assignments, coders regrouped to review and resolve any discrepancies.

We then created a single column for each survey respondent that included the combined subcodes for WBA across all six open-ended questions. Again, a total of 1,134 people commented on WBA

Table B-1. Walkability, Bikeability, Accessibility Subcodes and Definitions

SUBCODE SUMMARY

1 - More Walking Options

2 - Better Walking Options

3- More Walkability/ Walkable Destinations

4 - More Biking Options

5 - Better Biking Options

6 - Negative/Anti

7- Not Applicable

More sidewalks, add sidewalks, more walking connectivity, walking trails.

Safer, better maintained, better protected, safer crosswalks, less barriers, with landscaping, ADA compliant.

Businesses, parks, neighborhoods, “more walkability.”

More bike lanes, bike trails, bike paths.

More protected, better maintained, with landscaping, more accessible/connected, “more bikeability.”

Less/against any above codes, Prioritize other things over above codes.

Response does not qualify for any other codes.

issues. This means that the code counts used in this report represent individuals who mentioned this topic at some point in their commentary. For example, Figure B-2 (pg. 290) shows 472 respondents mentioned More Biking Options. This means that 472 people who took the survey mentioned More Biking Options as important in one or more of their open-ended responses.

During the initial coding, we used the

terms “sidewalks” and “bike lanes” (e.g. More Sidewalks, Better Sidewalks, More Bike Lanes, Better Bike Lanes). However, after completing the coding, these terms were changed to “walking options” and “biking options” to reflect the sentiments of the respondents. Respondents highlighted the need for paths and trails throughout the city, which was not reflected in the initial terms of “sidewalks” and “bike lanes.”

Walkability, Bikeability, & Accessibility

RESULTS

Results from subcoding under Walkability, Bikeability, Accessibility are included in Figure B-2. Overall, there was a lot of passion around more and better pedestrian infrastructure motivated by concerns of safety. Many respondents highlighted the importance of separation between sidewalks or bike paths and roads, improved visibility at crosswalks, increased number of crosswalks, and education for both drivers and pedestrians within their comments.

Biking comments were more common than walking comments, with many respondents articulating their desire to commute via bike but not feeling safe to do so or their desire to use biking as a form of exercise more often.

This created a unique overlap between “negative/anti” and “more biking options.” There were a number of responses that were against bike lanes on main roads,

but included in their response they would prefer grade separated bike lanes to improve safety for drivers, bikers, and other pedestrians.

More Biking Options was the most popular response, representing 25 percent of respondents. This subcode focused on creating more biking options (either through additional bike lanes or bike paths) as well as connecting existing bike infrastructure together. Many respondents highlighted the gaps within the city’s biking infrastructure. Respondents also advocated for more biking specific trails throughout the community. A popular request was a rail trail along the Norfolk Southern and RJ Corman train tracks that run through town.

Better Biking Options was the second most popular response, representing 19 percent of respondents. This subcode focused on the improvement of existing bike infrastructure or making new bike infrastructure better, and generally respondents were focused on safety. Comments included requests for gradeseparated bike lanes or mixed use paths along major roadways (e.g. the planned mixed use path along Alumni Drive). Some respondents also requested biking safety courses to enable residents to feel more comfortable commuting via bike instead of in their personal vehicles.

More Walking Options was the second most popular response, representing 18 percent of respondents. This subcode

Figure B-2. Walkability, Bikeability, Accessibility Responses by Subcodes

focused on building more sidewalks, more walking paths, and connecting new or existing sidewalks together. A common theme in this subcode was having sidewalks along every road in the city. Specifically, along major transportation corridors that are currently missing sidewalks (e.g. Tates Creek Road and Richmond Road).

More Walkability/Walkable

Destinations represented 16 percent of respondents. This subcode highlighted the need for creating neighborhoods that are walkable. A common phrase within this subcode was the use of “15 minute city” meaning all basic needs (work, shopping, parks, restaurants, etc.) should be within a 15 minute walk from one’s house. In this subcode, many respondents highlighted the high quality of life experienced by residents living in areas like Chevy Chase and Southland and expressed a strong desire to have those benefits replicated in other areas of the city.

Better Walking Options represented 14 percent of respondents. This subcode focused exclusively on safety, with respondents commenting on the need for improved pedestrian safety. This included more crosswalks, better signaling at crosswalks, improved ADA accessibility, and grade separation for sidewalks. Also included in this code was general improvements to sidewalks, highlighting needs like connectivity, wider sidewalks, and fixing broken sidewalks. Consider the following quotes:

• “I can walk all day long for exercise or recreation, but that choice is a privilege. District 2 needs more intentional neighborhood planning.” Female, White, 40-50, Masterson Station / McConnell’s Trace / Coldstream neighborhood cluster.

• “I think making a more walkable city, with more restaurants, lifestyle businesses, and stores of necessity in close proximity would be nice. It would shorten the time necessary to get from one place to another in the city.” Male, White, 20-30, Downtown neighborhood cluster.

• “I think the best way to improve transportation in Lexington is to encourage construction of buildings and services within walking distance of each other. By making everything closer, the need for cars is lessened. Another major issue is free/cheap meeting areas for socialization. Many of the younger generation are staying inside because places they can go with friends are expensive or unwelcoming. By creating more welcoming spaces people will be out and about more.” No demographic information provided, Tates Creek neighborhood cluster.

Negative/Anti represented 1 percent of respondents. Though the smallest number of respondents, there was wide diversity in the opinions expressed here. Some respondents were more concerned about the safety of people using bike paths. Other respondents articulated that Lexington is a car city

and bike infrastructure should not be a priority. Particularly in the Old Richmond Road/Rural South neighborhood cluster, respondents were concerned about the safety of bikers on rural roads, with at least one respondent advocating for banning bikers on those roads. Consider the following quotes:

• “The Mayor has done well in promoting bike trails and lanes. Although bikes are a major hazard on rural roads.” Female, White, Age 6070, Old Richmond Road/Rural South neighborhood cluster.

• “The bike trails on the side of the road are completely inefficient and dangerous. I wouldn’t put anyone I love on that. People text and drive and if we have bike trails they need to be through parks and for leisure. This is a car city.” Other Gender, White, Age 4050, Idle Hour / Woodhill neighborhood cluster.

• “Biking involves a minuscule minority of people, and is dangerous and divisive. Better walking routes would be good - including safe ways to cross busy streets full of distracted drivers, and walker- friendly amenities such as simple rest area (like a bus bench, but for walkers). Lexington should prioritize cars!” Female, White, Age 30-40, Stonewall neighborhood cluster.

Not Applicable represented 7 percent of respondents. This is reflective of the focus of our coding.

Walkability, Bikeability, & Accessibility

Some respondents commented on walking paths or bike paths, but did not give guidance on whether they wanted more, fewer, or safer options. Other respondents commented on the condition of pedestrian infrastructure, but did not include comments about fixing the infrastructure. A few respondents were complimentary of the city’s efforts to increase pedestrian infrastructure through options like The Legacy Trail, but did not include if they wanted more options like this. Finally, some respondents included references to accessibility (e.g. ADA), which was not included in our subcodes.

ADDITIONAL DATA VIEWS

Another unique way to look at the Style of Development sub coded data is by age range, displayed in the figure to the right. Only 1,918 of the 2,416 respondents included their age, so this is not a complete data set. Any respondent with an empty value in their age range has been removed.

Overall, a desire for a more walkable community with better and more walking options and biking options is evident across all age groups. As respondents grew older, they tended to have more negative views of these subcodes.

An important piece of On The Table and CivicLex’s work is facilitating the master plan for the expansion areas to the Urban Service Boundary. The LFUCG City Council approved the addition of five parcels in late 2023.

One question respondents could complete in the On The Table survey was their neighborhood. These neighborhoods were then combined into clusters. Utilizing information from LFUCG and CivicLex, the team studied the neighborhood clusters that are directly connected to the expansion areas. Any respondent that did not give their neighborhood was not included.

• Beaumont

• Gardenside, Cardinal Valley / Alexandria

B-3. Walkability, Bikeability, Accessibility Responses by Subcode and Age

Parcel 1

Figure

Parcel 2:

• Bryan Station / Eastland

• Hamburg / Greenbriar

Parcel 3/4/5:

• Old Richmond Road / Rural South

• Andover

• Hamburg / Greenbriar

For Parcel 2, Rural North is connected to the expansion area, but that was not a neighborhood code in On The Table. For Parcel 2 and Parcel 3/4/5, Hamburg / Greenbriar touch both parcels. Accordingly, their comments have been included in both parcels.

Again, more biking options is the most popular subcode in all three parcels.

Finally, grouped by race/ethnicity. Again, a desire for a more walkable community with better and more walking options and biking options is evident across all races/ethnicities.

However, these numbers are heavily skewed towards White respondents. 1,472 respondents categorized themselves as White. All other races/ethnicities had fewer than 100 respondents. This causes skew within the data. For example, in American Indian / Alaskan Native, it appears a large percentage of respondents were negative/anti. However, this represents one respondent of the total seven respondents for that race/ ethnicity.

Figure B-4. Walkability, Bikeability, Accessibility Responses by Expansion Area

Public Transportation

The protocol and subcoding for the Public Transportation code was completed in 2023, as a part of the On the Table Microgrants project. Lexington resident Krasi Staykov applied for an On the Table microgrant to perform a deeper dive into the public transportation code, and was given a $250 stipend for their work.

The second most popular code in the On the Table dataset was Public Transportation, with 1,744 comments tagged with this code (11 percent of all responses). A total of 1,163 unique respondents mentioned Public Transportation, 48 percent of all survey takers. The neighborhoods that mentioned public transportation most frequently were Picadome, Kenwick, Woodland, and Cardinal Valley.

The subcoding process for Public Transportation is different and more detailed than the other On the Table principles. Each public transportation response was reviewed for mention of six broad subjects, and then coded with a more exact sentiment related to those subjects. This was accomplished by assigning the six major subjects a number, and each subcode a number letter combination. For example, “Bus” was code 1, with “add stops”, “upgrade existing stops”, and “increase frequency” as codes 1A, 1B, and 1C.

This methodology creates a specific understanding of what exactly residents are talking about when they mention Public Transportation in the On the Table survey. The six major topics were:

KEY FINDINGS

Favorability: Respondents were overwhelmingly supportive of greater public transit. 16 of the 1,587 coded responses advocated for a reduction or removal of bus infrastructure in Lexington (0.05 percent of all responses). Six advocated for a reduction or removal of bike infrastructure in Lexington.

Improvements: The most popular suggestions to improve public transit were:

• Additional routes, particularly routes that would avoid downtown transfers.

• Additional stops along existing routes, particularly within New Circle.

• Improvements of stops and the transit center—seating, covered waiting areas, sidewalk access, lighting.

• Increased frequency of existing routes.

Environment: Many individuals suggested smaller buses due to environmental concerns, a low ridership rate, and the hopes that the savings on energy would allow greater route frequency or an addition of routes/stops.

Safety: Safety on the bus was a very low concern for individuals; only 14 responses noted safety as an issue on the bus, many more noted feeling unsafe due to the bus stops with low visibility and accessibility. Additional sidewalks and bike lanes were highly demanded, but safety of existing routes was also essential. Safe crosswalks, safe sidewalks, and protected bike lanes were common requests.

Other Public Transportation:

Respondents also expressed interest in public transportation beyond buses—4.35 percent of respondents mentioned either trolley, light rail, or both. These responses were concentrated in people who had higher education degrees; 48 percent had a Master’s degree or more, and 36.5 percent had a Bachelor’s degree.

Table B-5. Public Transportation Major Codes and Subcodes

SUBJECT SUBCODES

1A. Add stops

1B. Upgrade existing stops

1C. Increase frequency

1D. Increase reliability

1E. Add routes

1F. Add houses

1. Bus

2. Walkability

3.

Cars

4. Biking

5. Parking

6. Other codes

1G. Access

1H. Efficiency

1J. Electricity

1K. Affordability

1L. Smaller buses

1S. Safety

1X. Other

2A. Add sidewalks or walking paths

2B. Connecting sidewalks

2C. Sidewalk maintenance

2D. Add crosswalks

2E. Safety pedestrian options

2X. Other

3A. Non-car centric

3B. Connecting sidewalks

3C. Traffic management: speed limit, slowing, calming

3X. Other

4A. Add bike lanes

4B. Connect bike trails to bike lanes

4C. Safer bike lanes

4X. Other

5A. Limit parking

5B. Add parking

5X. Othe

6A. Trolley

6B. Light rail

6C. Road upkeep

6D. Scooters

6E. Electric vehicle charging stations/ incentives

6X. Other

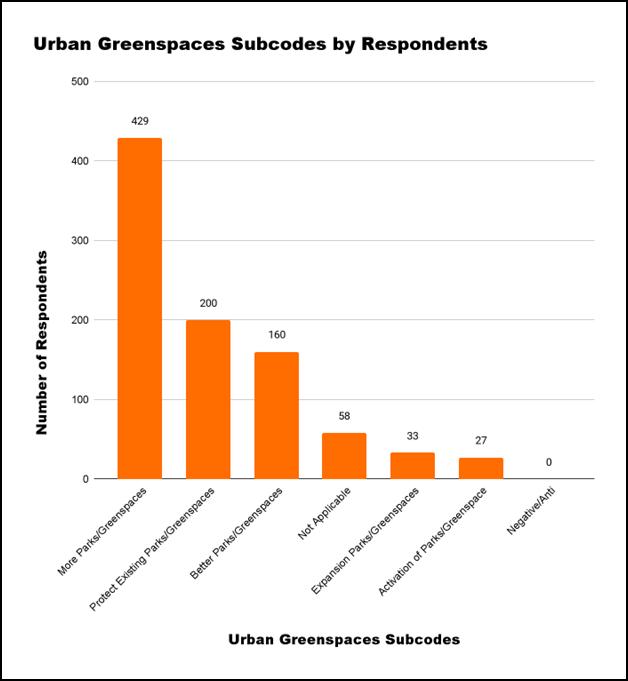

Amenities & Quality of Life

The third most popular code was “Amenities and Quality of Life,” with 1567 comments tagged with this code (7 percent of the total 15,000 comments). A total of 1,142 survey respondents spoke to this issue (some brought up the issue multiple times in response to the different open-ended survey questions). Amenities & Quality of Life refers to comments that mentioned neighborhood facilities, entertainment opportunities, restaurants and retail, cultural events, sense of community, and so forth. City parks and trails were not included in this code as there is a separate code specifically for these topics.

In response to the question, “What do you think would make Lexington a better place to live or spend time in?,” one third of the open-ended comments referenced Amenities & Quality of Life issues. In response to the question, “What do you think would make your neighborhood a better place to live?,” approximately one fourth of the comments spoke to

Amenities & Quality of Life concerns. A small percentage (5 percent) of the responses to the question, “Where and how do you think new growth should happen in Lexington?” were also coded as “Amenities & Quality of Life.”

Importantly, however, coded responses only indicate that the theme or topic was raised in the comment – not how people actually felt about it. For example, both “I want more restaurants and shopping malls” and “We have too many restaurants and shopping malls” would be tagged with the “Amenities & Quality of Life” code.

To better understand the sentiment included in each comment, the team conducted a more robust analysis and deep dive into the “Amenities & Quality of Life” (AQL) code. Open comments with the AQL code were read thoroughly to identify recurring themes. The 10 themes, or subcodes, included: More Things to Do, Commerce/Retail/Restaurant, Affordable/

Low Income/Free, Arts/Culture, Diversity/ Equity/Unity, Sense of Community, Basic Needs, Quality of Life (other), No Improvements, and Not Applicable. The figure to the right lists these codes and their criteria.

The team then went through and coded the 1,567 comments using this list of subcodes. Note that each openended comment could be coded with more than one subcode. For example, if a response mentioned the need for more recreational activities, particularly those that are free to the public, it would be coded with “More Things To Do” and “Affordable/Low Cost/Free.” Every comment was coded twice–by a different coder each time. Data was coded in AirTable. Upon completion of individual assignments, coders regrouped to review and resolve any discrepancies.

Table B-6. Amenities and Quality of Life Major Codes

and Subcodes

SUBCODE SUMMARY

More Things to Do

Commerce/Retail/ Restaurant

Affordable/ Low Cost/ Free

Advocating for more things to do, events, activities, festivals, entertainment, attractions, etc.

Asking for more retail/restaurant/commerce opportunities, including amenities such as shopping malls, local businesses, restaurants, retail, and nightlife options.

Specifically referencing free, affordable, or low-cost amenity options or specific places that are known to be free (libraries, community centers, playgrounds).

Arts/Culture

Diversity/ Equity/ Unity

Sense of Community

Basic Needs

Asking for more arts and cultural activities, events, and venues, including concerts, public art, theaters, and museums.

Responses that reference wanting to celebrate or increase diversity, equity, and unity.

Responses emphasizing the importance of increasing feelings of belonging or connection in their community.

Asking for more basic needs amenities, such as grocery stores, healthcare, or childcare options.

Quality of Life (other)

No Improvements

Not Applicable

Covers QOL conditions not covered by other codes, including noise complaints, the need for better communication about events, etc.

Responses noting that everything is good and needs no improvement.

Responses that don’t qualify for previous subcodes.

Amenities & Quality of Life

The team then created a single column for each survey respondent that included the combined subcodes for AQL across all six open-ended questions. A total of 1,142 people commented on AQL issues. This means that the code counts used in this report represent individuals who mentioned this topic at some point in their commentary. For example, in the chart below you can see 183 respondents mentioned “Basic Needs.” This means that 183 people who took the survey mentioned basic need amenities as important in one or more of their openended responses.

First, of the 1,142 participants whose comments were coded as “Amenities & Quality of Life,” almost half (48 percent, or 542 respondents) were asking for “More things to do.” As one Heartland resident explained, “We need more attractions or something to do. There is nothing to do down here.” Another resident living in Bryan Station agreed, “More activities. More places to hang out with friends.”

While the team did not have a subcode for comments that specifically referenced the need for “things to do” for young Lexingtonians, this response was frequent. For example, one comment by a Lexington teenager stated: “I think there could be things done to make it more fun and accessible for high schoolers and young adults. I feel like either entertainment is catered to adults or children and it’s either not safe enough or not mature enough for the middle, being high schoolers and younger adults below the age of 21.” In the words of another respondent, “We need more attractions that aren’t just for tourists but also for its citizens. Being a teenager in Lexington can be so boring because there is not much to do here.”

Commerce/Retail/Restaurant

was the second most popular AQL subcode. Some residents asked for more bars or nightlife opportunities downtown while others wanted to see small retailers in their neighborhoods. Lexingtonians asked for amusement parks, bowling alleys, soccer stadiums, water parks, malls, international food, and so much more.

Consider the following quotes:

• “We need a waterfront but that’s not easily accomplished. Fun cities often have waterfront areas where people can dine & shop. We need things for teens & the new movie theater & bowling alley across from Rupp Arena is a great addition. It will also be great if the soccer stadium is added beside it

& can be utilized for outdoor concerts. The Distillery District is wonderful & a great example of revitalizing what we have vs. building new, & incentives should be given to entrepreneurs to do so.” (Idlehour)

• “More opportunities (restaurants, entertainment) on my side of town.” (Masterson Station)

Other Quality of Life issues were included in the third most common AQL subcode, which 219 individuals spoke to. Many of these respondents wrote about their struggle to find information about what was happening in Lexington. For example, one respondent explained: “Me encantaría mas información de dónde ir en fines de semana para mi familia y disfrutar de Lexington.” Translation: “I would love more information on where to go for weekends for my family to enjoy Lexington.” Others struggled with their HOAs or had noise complaints. Consider the following comment from a middleaged resident: “We need better reporting and enforcement of noise violations by neighbors especially in the late night and early morning hours.”

Basic Needs amenities were highlighted by 183 people, which is 16 percent of the respondents who spoke about AQL needs. Lexingtonians spoke passionately about the need for grocery stores near their neighborhood as well as other local basic need amenities such as childcare, healthcare, etc. As an older resident from the East End described: “Better parks

• “Improve the arts! More galleries. Large/significant outdoor concerts. More activities downtown and in parks.” (Old Richmond Road, 20-30 year old)

• “There needs to be more things for people to do, more plays to include people of color, gospel concerts, museums.” (Georgetown, 70-80 year old)

(some are awesome; some, like Duncan Park in my neighborhood, could be better), safer biking, more trees, less air pollution (coal heat generation is still happening in town??), more walkable neighborhoods with amenities like grocery stores in all neighborhoods.”

Another resident noted his desires: “Closer proximity and access to essential

services and stores for basic needs.”

Arts/Culture was the next most noted subcode, with 177 people writing about this amenity. Residents provided long lists of cultural amenities that they desired in Lexington, including museums, concerts, plays, public art, and so much more. Consider the following two responses:

Free/Low Cost amenities was another important subcode, with 174 respondents highlighting this issue. These were comments that referenced the importance of having things to do that were affordable and low-cost, so that all Lexingtonians could participate, regardless of income. One young (10-20 year old) resident from Cardinal Valley explained her needs: “I think it would be better if they had more activities to do that weren’t expensive or cost money. Maybe we could have stuff like free museums.” A 30-40 year old Glendover resident explained, “Build some indoor public activity centers for kids to support families during the winter. Not all of us have the means to ‘winter’ in Florida.” This code also included wanting more places that are widely known to be free, such as libraries, community centers, and so forth. One resident asked for “A large new Village Branch Public Library!”

Sense of Community was mentioned by 166 survey participants. Many residents want opportunities to interact more deeply with others in their

Figure

Amenities & Quality of Life

neighborhoods and across the city and to do so in ways that foster a sense of solidarity and community. Consider the following quotes from various neighborhoods:

• “More events where folks can meet their neighbors. I love that my neighborhood is racially diverse, but I think there is a feeling of in-group, outgroup.” (Castlewood)

• “In general, it’s been really difficult to find a sense of community. Even living in a dorm, I don’t feel like I know my neighbors. I wish there were more ways for me to get to know the people who live in such close proximity to me.” (UK Campus)

• “Community involvement to take more pride in the city.”

Diversity, Equity, and Unity was mentioned as important by 81 survey respondents. For these residents, it is imperative that Lexington provides equal access to quality amenities,

especially for groups that have been historically marginalized on the basis of race, disability, sexual orientation, and so forth. For example, one respondent in Tates Creek noted, “This neighborhood is majority Black and Brown population and has been historically excluded and under-resourced. I believe neighborhoods like mine should be prioritized with investments towards revitalizing the people (e.g. easy access to culturally responsive mental health supports, education, and child care) and spaces (e.g. green spaces, clean/green energy investments, easy access to fresh food) that have existed there historically (not gentrification). A trickle up approach towards community.” A resident of Woodland provides her perspective: “Growth doesn’t have to mean financial. Growth can mean environmental, (the city that has the most rooftop gardens in america or has planted the most trees), artistic growth (more sculptures, street musicians nights, theater in the park), empathetic growth ( crosswalks for the blind, parking for veterans, disabled and pregnant women, ramps for those in wheelchairs, benches for the elderly to take a break)With all growth, get the community involved including all ages, races, and family styles.”

Finally, this code also captures those comments that highlight the need to increase and celebrate diversity in this community. For example, “Doing what it takes to keep Lexington friendly. One way is to increase the frequency of festivals celebrating ethnic and racial

groups. Diverse activities that bring people of many different backgrounds and ages together.” and “Equity, inclusion and coming together of all communities. Analyze which events/festivals are most diverse and plan ways to bring more diversity to the ones that are EXclusive. Workplaces that are exclusive need diversity.”

The final subcode captured the 38 respondents that indicated No Improvements are necessary. As one resident in the Old Richmond Road areas argues, “I think Lexington has enough to do if you get tired of the area you can always go vacation somewhere and then come back but overall Lexington is a clean safe town and a great place to live in.”

Environmental Sustainability & Resiliency

The fourth most popular code was “Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency,” with 1,224 mentions tagged with this code (6 percent of the total 15,000 comments). A total of 1,000 survey respondents spoke to this issue (some brought up the issue multiple times in response to the different open-ended survey questions).

Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency refers to comments that mentioned municipal recycling and composting, cleaning up litter and trash, construction and pavement sustainability efforts, protecting natural habitats and ecosystems, reducing emissions, controlling harmful soil amenities, and education surrounding these topics. Comments concerning trees were not included in this code as there is a separate code specifically for these topics. We also did not include comments about noise or light pollution as these topics are covered under a different code.

In response to the question, “What do you think should be done to protect the environment in Lexington?” one half of the comments spoke to Environmental Sustainability and Resilience concerns. A small percentage (5 percent) of the responses to the question, “What do you think would make your neighborhood a better place to live?,” were also coded as “Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency.”

Importantly, however, coded responses only indicate that the theme or topic was raised in the comment – not how people actually felt about it. Think about it this way – both “I want more recycling and composting” and “We are too focused on recycling and composting” would be tagged with the “Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency” code.

To better understand the sentiment included in each comment, we did a more robust analysis and deep dive into

the “Environmental Sustainability and Resilience” (ESR) code. Open comments with the ESR code were read thoroughly to identify recurring themes. The eight themes, or subcodes, included: General Environmental Protection, Air and Water Quality, Waste Management, Renewable Energy, Yards/Lawns, Negative/Anti, No Improvements, and Not Applicable. The figure to the right lists these codes and their criteria.

The team then went through and coded the 1,567 comments using this list of subcodes. Each open-ended comment could be coded with more than one subcode. For example, if a response requests wildlife protection educational programs, particularly with a goal to preserve and increase biodiversity in residents’ yards, it would be coded with “General Environental Protection” and “Yards/Lawns”. Every comment was coded twice–by a different coder each time. Data was coded in AirTable, a cloudbased collaborative spreadsheet.

Table B-8. Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency Major Codes and Subcodes

SUBCODE SUMMARY

General Environmental Protection

Air and Water Quality

Waste

Management

Renewable Energy

Yards/Lawns

Negative/Anti

No Improvements

Not Applicable

Asking for more environmentally friendly practices; and education on climate change, wildlife protection, “going green."

Asking for more protections against pollution and harmful materials and chemicals; waterway preservation; clean water and air; water runoff; stormwater management.

Responses that reference recycling, composting, litter cleanups, education on recycling/composting.

Asking for more solar panels, incentives for renewable energy (RE), electric vehicles (EV), investments in renewable energy, less fossil fuels.

Responses that reference pollinator friendly yards, eco friendly fertilizers, grass alternatives, gardens, native plants, landscaping.

Responses that ask for a decrease in efforts or are against previous subcodes.

Responses noting that everything is good and needs no improvement.

Responses that don’t qualify for previous subcodes.

Environmental Sustainability & Resiliency

Upon completion of individual assignments, coders regrouped to review and resolve any discrepancies in their coding.

We then created a single column for each survey respondent that included the combined subcodes for ESR across all six open-ended questions. Again, a total of 1,142 people commented on ESR issues. This means that the code counts used in this report represent individuals who mentioned this topic at some point in their commentary. For example, in the chart below you can see 310 respondents mentioned “Renewable Energy.” This means that 310 people who took the survey mentioned renewable energy as important in one or more of their openended responses.

First, of the 1,000 participants whose comments were coded as “Environmental Sustainability and Resilience,” 47 percent (471 respondents) indicated “Waste Management” is a priority. As one

Richmond Road resident explained, “Make sure the recycling programs are available in all neighborhoods. Our previous location had no provisions for recycling at all. Adopt a street, community service hours for high school students if they take on a neighborhood cleanup project.” A Landsdowne/ Glendover resident concurred, “Update recycling by making it more accessible to more people. Communicate the need for environmental stewardship.”

While we did not have a subcode for comments that specifically referenced the categories of recycling available in Lexington, this did come up a lot. Take, for example, a comment by a Hartland resident: “All numbers of recycling should be accepted.” Regarding the cessation of paper recycling because of machinery repair, a resident of the Gardenside neighborhood responded, “Ensure plant parts stay working. Over a year without paper recycling was unacceptable. Improve education around recycling & compost. Encourage community gardens and biocompostable materials.”

Another theme which did not have a subcode includes composting. At least 42 respondents mentioned composting or municipally managed composting including the comment from this Picadome dweller, “Municipal or city run compost program. All food waste from restaurants and groceries, then for a small charge or free to taxpayers.”

General Environmental Protection was the second most popular ESR subcode. Within this code commenters listed priorities such as education about climate change, city-level changes or municipal investments, watersheds, emissions, and energy updates.

Consider the following quotes:

• “Educar y poner el ejemplo a los demás sobre todo a las nuevas generaciones Translation: Educate and set an example for others, especially the new generation” (Winburn/Radcliffe)

• “Lexington should set a Big Picture Vision for our city/county across all climate change + environmental + sustainability issues..... to be used in considering and addressing complex community-wide decisions with both short-term implications and longer view sustainability. How do we protect out families for now and into the upcoming future? How do we protect our water, our air, our land, our economy” (Wyndham Downs)

• “We need to get a handle on our water quality in urban streams that run through our neighborhoods. They become water features and amenities instead of polluted ditches if you plant trees, shrubs and perennial plants along them. Also, public works projects operated by LFUCG need to do a better job of their construction pollution control. Those are usually a mess. They thumb their noses at their own rules, making it hard to maintain

better standards.” (Southland)

• “To get more people being less car dependent start putting in other things that do not rely on gas. Seriously look into light rail, require new developments to plant street trees and improve their sidewalks, so people have shade and protection from cars. Have give back programs for resi. solar panels. Install more elec. charging stations.” (Picadome)

Renewable Energy issues were included in the third most common ESR subcode, which 310 individuals spoke to. Many of

these respondents wrote about their desire to see renewable, most commonly, solar energy embraced in Lexington. For example, one respondent suggested: “Clean energy - decentralized solar (meaning solar on every roof, not just in large scale solar farms)” Another respondent said, “Add solar collectors to all publilc buildings, including shelters at parks.”

Often times respondents suggest incentives to encourage the change, “Subsidize the installation of solar panels on low-income, senior, group housing.” and, “Give incentives private homeowners

to install renewable energy sources. Incentivize small-businesses that are generally associated with being good for the environment, like vegan restaurants.”

Air and Water Quality concerns were highlighted by 246 people, which is 25 percent of the respondents who spoke about ESR needs. Lexingtonians spoke passionately about the need for better maintenance of storm drains and protection of waterways. As a Hartland resident explained: “Better stormwater management and larger greenways and buffers around our floodplains.

Continuing education effort around the importance of keeping Lexington green. Work harder to increase tree canopy in our built environment. Continue the work on making our sanitary sewers sealed and prevent contamination of our streams from sewage overflows. Better management of private lawn fertilizer companies and the impacts of lawn maintenance. Encourage natural landscapes in neighborhoods.” To reduce emissions and air pollution, another Cardinal Valley resident suggested, “Adopt idle-free zones around businesses and schools to reduce exposure to vehicle emissions; pay more attention to zoning issues when neighborhoods butt up against industrial areas whose practices impact residents living nearby.” Specifically addressing the efforts of Lexington regarding this issue, and older Lakeview resident commented, “It is my understanding that Lexington now has a sustainability coordinator. That is a good step in the right direction. Lexington

Environmental Sustainability & Resiliency

needs a clear, overarching vision of how we are going to protect the environment, and that needs to be central to all city decisions. For every decision, the Urban County Council needs to ask, how does this affect our water? Our trees? Our air quality?”

The fifth most assigned subcode was Yards/Lawns, garnering mentions from 136 people. Numerous residents highlighted the potential ecological benefits of encouraging residents to turn away from traditional frontyard landscaping to pollinator and native gardens. Consider the following responses:

• “Small yards that are being made into native plant gardens instead of labor and resource intensive lawns.”

• “Educate homeowners as to what plants attract butterflies, birds, and other desirable species; encourage planting, subsidize rain gardens, rain barrels; bird houses, bird baths,

and accommodations that foster Encourage wildlife.”

• “Education about alternatives to lawns, like moss or gardens.”

Conclusion

From the data set, it is apparent that the residents of Lexington are concerned about the environmental impacts within their community. There is a clear consensus among respondents regarding the need for proactive measures to address various environmental issues, ranging from litter cleanup initiatives to the reduction of single-use plastics and runoff pollution prevention strategies. Residents emphasize the importance of transparency in recycling processes and advocate for expanded recycling services.

As the urban service boundary expands, residents want the environment to be considered integral in urban planning and development. This includes prioritizing sustainable construction practices, energy-efficent designs, and incorporation of renewable materials. There is a desire to instill environmental consciousness in future generations through education on waste reduction, recycling, renewable energy, and resource management.

Waste management is a significant concern, with calls for expansion of recycling infrastructure and accessibility–residents express frustration with existing program limitations and suggest a need for supplemental efforts like

coordinating neighborhood cleanups and recycling education efforts. The push for decentralized solar energy and incentivized renewable energy installations, and sustainable residential landscaping practices reflects a collective value for individual and communitydriven stewardship of the environment.

Disparities among Lexington neighborhoods raise questions about the distribution of responsibility for sustainability between individuals and city authorities. A comprehensive approach by the city council, one tailored to address neighborhood-specific needs, may be essential to effectively meet residents’ desires. This approach considers that some neighborhoods require minimal intervention while others may need more support. Environmental sustainability and resiliency issues are at the forefront of Lexingtonian’s minds when considering urban development and community engagement.

Style of Development

The fifth most popular code was “Style of Development,” with 1,137 comments tagged with this code (7.5 percent of the total 15,000 comments). Style of Development refers to comments that mentioned any of the following:

• Density/Intensity

• Aesthetics

• Context

• Housing Options/ Types

• Sprawl

• Missing Middle Housing

• Mixed Use

• Low Density / Single Family

For each question in the On The Table survey, we can show a breakdown of how many open-ended comments were tagged with Style of Development. The question with the highest number of comments was related to new growth in Lexington, with 48 percent of comments being coded as Style of Development.

• What do you think would make your neighborhood a better place to live?159 comments

• What do you think should be done to protect the environment in Lexington? - 202 comments

• What do you think would help make Lexington a place where everyone can have financial success? - 50 comments

• What do you think should be done to improve transportation in Lexington?53 comments

• Where and how do you think new growth should happen in Lexington?548 comments

• What do you think would make Lexington a better place to live or spend time in? - 125 comments

Importantly, however, coded comments only indicate that the theme or topic was raised in the response—not how people actually felt about it. For example, both “I want more density” and “I want

less density” would be tagged with Style of Development. Respondents did not speak exclusively to the Style of Development they would like to see in the new areas of expansion for the Urban Service Boundary, but rather a guiding approach to development that would apply to the city as a whole.

To better understand the sentiment included in each comment, the team did a more robust and detailed analysis of the “Style of Development” code. Open-ended comments with the Style of Development code were read thoroughly to identify recurring themes. The six themes, or subcodes, included: Increase Density, Decrease Density, Development for Equity, Environmentally Sustainable Development, Negative/Anti, and Not Applicable. The table to the right lists these codes and their criteria.

Each response was read by two coders who assigned a subcode to the response. Comments could receive more than one code. For example, a response could be coded as both “Increase Density” and “Development for Equity” if the response advocated for more housing and more housing that was affordable or lowincome. Anything that appeared unclear was flagged for review later.

Once the initial round of coding was completed, coders met to discuss any differences in their coding and resolve any flagged comments.

Table B-10. Style of Development Major Codes and Subcodes

SUBCODE SUMMARY

1

- Increase Density

2 - Decrease Density

Any response advocating for more, denser development, such as infill, redevelopment, using vacant areas, adaptive reuse, smart growth, and “building up.”

Any response with concerns about overdevelopment or overly dense development, including overcrowding, concerns about neighborhood character that specifically cite the need to decrease density (see note below about historic preservation), and decreasing high density housing such as apartments or multi-family homes.

3- Development for Equity

Any response referencing development with the purpose of increasing equity in Lexington; this refers to racial, income, and other forms of past inequality as well as disability access; also includes affordable houses with equity in mind.

4 - Environmentally Sustainable Development

5 - Negative/Anti

Any response referencing development that is environmentally sustainable/eco friendly, such as green building, concern for environmental impacts and maintaining natural spaces.

Comments against the concept of development of any kind, regardless of location, characteristics, context, including specific mention of decreasing or slowing all development; also includes calls to prioritize other issues over the above codes.

6- Not Applicable Response does not qualify for any other codes.

Results

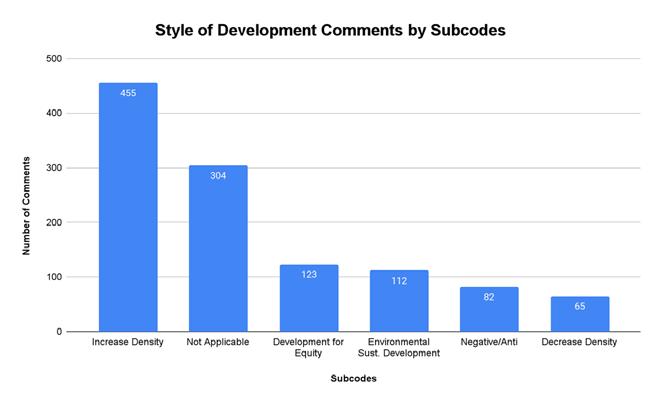

Results from subcoding under Style of Development are included in Figure B-11 (pg. 310) below. Because comments could receive more than one code, a total of 1,141 open-ended comments were recorded.

A total of 851 individuals had comments that were coded as Style of Development. Overall, there is a lot of passion around how Lexingtonians see development and how it affects their experience of the city.

Style of Development

conclusion and rather points to the need for a holistic approach to development and how growth or increased density in one area affects other areas.

properties here. “ (respondent: 50-60 years old, 40508)

Increase Density was the most popular subcode, representing about 40 percent of comments. Comments in this subcode identified walkable communities as a priority, but also proposed nuanced ideas of where and how density should be increased, and in some places, decreased. Across the board, residents advocated for dense and mixed use development within the existing Urban Service

Boundary as a way to increase housing supply, support positive environmental outcomes, promote social equity, and improve overall quality of life.

Few comments advocated for decreased density across the board, but many expressed sentiments about increasing density in some locations in Lexington so that open spaces (for green space, for example, or single family homes) could be maintained elsewhere. While this could be considered a form of NIMBYism (the idea that a certain kind of development should happen, but not in my area), our data could not support this

“I think growth is good. It’s a sign that people are interested in living in our city because there is opportunity here. I do, however, think that part of the appeal of living in Lexington is that we have green space. Urban planners need to be more creative in the use of space. We need to have more single family dwellings that take up less space. Building upwards instead of outwards is an underused concept here. Also, we need to make more use of the multiple abandoned

“Infill. I always feel kind of horrified driving through the sprawl of South Lexington. So much land is wasted in distance between houses and on expansive lawns. Some of Lexington’s historic neighborhoods show how people can live well in denser settings while still being able to create intimate spaces and maintain privacy. In 2022, there is no good reason for so much land in Lexington to be used as lawns that require obscene amounts of chemical fertilizer, or as impermeable surface parking lots.” (respondent: 30-40 years old, 40507)

Figure B-11. Style of Development Responses by Subcodes

“Infill, infill, infill. Quit allowing private developers to tear down historical buildings, especially former private homes, without thorough investigation into how the structure could be utilized within the planned development. Quit allowing UK to buy private homes, rent them to students for a few years, never maintain them, then say they have to be torn down because they’re in too bad shape & too expensive to rehab. UK is the biggest, single cause of the destruction of historic neighborhoods!” (respondent: 60-70 years old, 40517)

Not Applicable represented the second largest subcode, with nearly 27 percent of comments. This is reflective of the focus of the coding. Many comments focused on green spaces and parks, which are being captured in other sub coding efforts. Others were comments that indicated a need for careful or deliberate planning, which is important, but did not give guidance on the particular style of development that should happen.

Historic preservation and maintaining the character of Lexington was a priority for many respondents, but because they do not specifically address the style of new development that should happen, we did not code historic preservation as either for/against increased density. Many respondents did specifically mention the outsized power they saw developers as having in decision making around styles of development.

Negative/Anti and Decrease Density each represented about 13 percent of comments. Both groups expressed strong sentiments regarding growth, with all being anti-growth in their comments. These comments represented a desire to keep Leixngton’s existing identity and historic preservation.

“Lex is starting to look like any over-built town in the country with poorly planned development along busy roads. The town was built on horses, charm and historic character is a huge pull but we’re on the brink of losing that because we’re pushing horse farmers out for Walmart. We’re doing a terrible job of planning, zoning, and preservation which is sad bc I know how much tourism is built around distilleries, horse tracks, horse farms. Outsiders are attracted to the charm we’re killing.” (respondent: 50-60 years old, neighborhood not specified).

“It needs to be planned carefully, with the expansion in Hamburg, south Lexington, brewery district, you see immediate impacts both positive and negative. Growth for growths sake will benefit no one but land and building owners.” (respondent: 20-30 years old, 40504)

“Growth is good ONLY if contextual. Suddenly adding a multi-story apartment building next to single family homes is out of context. Adding ADU’s is out of context. Doing these would further crowd narrow streets, add to ground

water flooding problems, overburden sewer lines and electrical, leading to a reduction of home values and a reduction of tax revenue.” (respondent: no demographic information, 40513, Beaumont neighborhood cluster).

In response to the question How should growth happen in Lexington, one respondent commented, “Very difficult answer. Vacant land. Slowly. All kinds of factors are involved. I don’t know too many people who like being crammed on top of each other.” (respondent: male, 70-80, white, 40503, Picadome/Pensacola neighborhood cluster).

“I think the best ides would be towards working on renovations in the Tates Creek and Versailles areas of the city demolishing multifamily housing and creating better single family home options” (respondent: male, 40-50, other, 40515, Hartland/Squires neighborhood cluster)

“Stop over developing and over crowding already crowded roads like Nicholasville.” (respondent: female, white, 40515, Veterans neighborhood cluster).

“I don’t like the present “in-fill” approach which rapes the integrity of older neighborhoods.” (respondent: female, white, 70-80, 40503, Southland neighborhood cluster).

Style of Development

used a narrow definition of sustainability in this subcode, focusing specifically on the built environment, the environmental implications of certain building styles, and a specific mention of sustainable development. We did not include mention of greenspaces, tree cover, or parks, as these are coded for separately.

support to the city’s environmental services and education programs.” (respondent: 30-40 years old, 40505)

Additional Data Views

Development for Equity subcode represented about 11 percent of comments. Many respondents articulated the throughline of race-based housing and planning policies of the 20th century to the current housing crisis in Lexington. Respondents advocated for affordable housing as part of addressing this legacy of inequality. This subcode also included comments about accessibility (such as ADA).

“New growth should be strategic and affordable. I am not for the gentrification of urban areas as it kicks out current residents. However, affordable housing is really important and it is also important to make “urban” spaces aesthetically and culturally/socially pleasing. New growth should occur within the lens of making Lex affordable for all and nice for all.” (respondent: 20-30 years old, 40515)

Environmentally Sustainable Development subcode represented about 10 percent of comments. The team

“...define strict sustainability requirements for new development to ensure green space is preserved/restored; increase public access to green spaces by creating and connecting more bike paths like the Legacy Trail, thereby increasing awareness/appreciation of natural spaces within Lexington; increase

Another unique way to look at the Style of Development sub coded data is by age range, displayed in Figure B-12. Only 730 of the 851 respondents included their age, so this is not a complete data set. Any respondent with an empty value in their age range has been removed from Figure B-12.

In this view, it is clear that the desire to increase density within Lexington is shared among all age groups.

Figure B-12. Style of Development Responses by Subcode and Age

An important piece of On The Table and CivicLex’s work is facilitating the master plan for the expansion areas to the Urban Service Boundary. The LFUCG city council approved the addition of five parcels in late 2023.