KEVIN CASEY

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF

The Unique History of Golf in the Garden State

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © 2022 ISBN: FirstPrintedWritten978-0-578-95763-0byKevinCaseyinChinaPrinting,2022,Allrights

Published by Legendary Publishing & Media Group

President, Business Development: William Green

Produced by Legendary Publishing & Media Group

Editor: Debbie Falcone

FRONT ENDPAPER: Caddies ready to loop at Baltusrol Golf Club, circa 1908.

President561-309-0229Legendarypmg.comandCreative

reserved.

Consulting Editors: David Barrett, Thomas Dunne Art Director/Prepress Specialist: Matt Ellis

Director: Larry Hasak

Senior Art Director: Susan Balle

Business Manager: Melody Manolakis

KEVIN CASEY

The Unique History of Golf in the Garden State

PUBLISHING & MEDIA GROUP

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF

The Birdie: First Shot in Atlantic City: 80

Keepers of Golf’s Flame: 106

An Auspicious Start at Morris County Golf Club: 36

THE GREATEST GENERATION: 1925–1955: 84

The Unlikely Inspiration for the Tour: 4

New Jersey Golf’s Early Adopters: 12

PART TWO

A Portrait of the Player of the Century: 88

The 1930s: When the Stars Descended On the New Jersey Open: 92

PREFACE: VIII

PART ONE

The Quadrangular Team Matches: 100

Baltusrol and the U.S. Open–1936 and 1954: 110

Shady Rest Golf and Country Club: 122

The Original Mulligan—The New Jersey Version: 126

THE START OF SOMETHING GRAND: 1890–1925: 1

The First Garden State U.S. Opens: 26

Teeing Up the Golf Tee: 34

The Artists of New Jersey’s Golden Age of Golf Course Design: 42

CONTENTS

VI

PART THREE

The Record Book: 228

Baltusrol and the U.S. Open–1993: 210

Index: 241 Acknowledgments: 243

Modern Era Contributors: 206

Baltusrol and the U.S. Open–1967 and 1980: 136

THE MODERN GAME—SINCE 1990: 184

The Popularity of Interclub Team Matches: 214

The Garden State’s Second Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture?: 188

The New Jersey State Open’s Big Three: 218 Somerset Hills Country Club: 220

VII

Hosted in New Jersey: 172

New Jersey, Home State of the USGA: 174

THE WONDER YEARS: 1955–1990: 128 Excellence, Determination, and Grit: 132

PART FOUR

There’s No Keeping Up With These Joneses: 148 Representing Something Bigger: 162

CHAPTER HEADER VIII

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 1 PART ONE THE START OF1890–1925SOMETHINGGRAND

At that same time, across the Hudson River from New Jersey in Yonkers, New York, a transplanted Scotsman named John Reid laid out three short holes in a nearby pasture. Using clubs and gutta-percha balls just delivered from Old Tom Morris’s pro shop in St. Andrews, Scotland, Reid and several of his buddies took turns hitting shots in the pasture. After a summer of playing this new game every weekend, Reid’s gang formed a club, named Saint

New Jersey was also home to the first club created and man aged by women. This same club was also quite possibly the site of American golf’s first coup d’état.

It must have been exciting to be there at the beginning,

At that moment, Saint Andrew’s was the only continuously exist ing golf club in the U.S. But that wouldn’t last long. In New Jersey, for example, Essex County Country Club and Plainfield Country Club had already incorporated and were developing plans for their golf courses. Within a few years, there were a half-dozen courses in New Jersey, and by 1900, ten of the most prominent came together to form the New Jersey State Golf Association (NJSGA), the second-oldest state golf asso ciation in the U.S. The new sport had taken hold and the Garden State was in the vanguard.

2 THE START OF SOMETHING GRAND: 1890–1925

to sense that a fascinating new sport had hit America’s shores. In 1890, it would have been hard to imagine that this ancient sport called golf would eventually generate billions of dollars of capital and become a major source of recreation in America.

ABOVE: Members play golf at Saint Andrew’s Golf Club in Yonkers, New York, circa 1899.

Great wealth was being created, and there was a growing appe tite to see that its benefits were equitably spread. The country was ripe for recreation, as baseball became the national pastime, col lege football was gaining traction, and a growing interest in track and field found a focus with the first Olympics in 1896. But these were largely spectator sports. There were few channels available for outdoor, vigorous recreation that didn’t demand youth, strength, speed, and exceptional coordination to enjoy.

Andrew’s Golf Club, paying homage to the game’s most hallowed Scottish ground. Forming the club not only strengthened the bond they had developed, but provided funds for maintenance of their beloved new sport—golf.

One of the best indicators of New Jersey leadership was that between 1896 and 1906, the state hosted four of the first twelve U.S. Amateur championships, the most important competition in the country at the time. In 1898, Lakewood, New Jersey, was the site of a prototype tournament for the events that led to the formation of the first tour for professional golfers. New Jersey clubs were the venues for three early U.S. Opens (1903, ’09, and ’15), and one Open win ner, New Jersey amateur Jerry Travers, was so good that the United States Golf Association (USGA) based its handicap system—devel oped by a son of Plainfield Country Club—on his prowess.

Finally, one need not look further to determine the importance of New Jersey to early golf in America than to note the attention lav ished on the Garden State by the country’s best architects. New Jersey was at the epicenter of the Golden Age of golf course architecture.

One had to be in the right places, at the right times, to get a perspective of what was happening. But the country was ripe for change. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the United States stood on the threshold of the greatest era of expansion and development in its history. Railroads were moving goods and peo ple across the continent, while Alexander Graham Bell’s tele phone was helping spread new ideas. New Jersey’s (and Essex County Country Club’s) Thomas Edison was bringing not just light to America, but electricity. Henry Ford would start to produce the first of his automobiles by 1900, and engineering was catching up with theory, allowing the Wright brothers to soon take flight.

OPPOSITE: Essex County Country Club member Thomas A. Edison photographed in his laboratory in 1911.

A better-known resort competitor for the winter golf crowd sixty miles to the south, Atlantic City, welcomed a train from Phil adelphia every Saturday through the winter, laden with golfers to take on Atlantic City Country Club and Seaview Golf Club.

It happened on New Year’s Day 1898, in weather typical for a Jersey January: “Light snow in morning, followed by fair, cold wave, north to northwest gales.” Not the ideal forecast for a golf tourna ment, but good enough for seventeen, longjohns-clad golf profes sionals hailing from a region stretching from Long Island to upstate New York to Philadelphia to meet on the first tee at Lakewood’s Ocean County Hunt and Country Club. They went at it for two frigid, wind-blown days, all for a $150 purse.

THE UNLIKELY INSPIRATION FOR THE TOUR

P

As global as it is in its reach and financial influ ence today, the Tour’s origins are much more pedestrian. In his book The History of the PGA Tour, Al Barkow credits an event in Lakewood, New Jersey, with creating the template for what would become a typical tour event.

This idea of a winter golf resort reflects the axis of America’s golf in 1898 relative to New York City and Philadelphia. Lakewood was not quite a day’s train ride away from these two golf centers, so golfers could hop on the train and get in some same-day play in slightly better weather than they were suffering through at home.

gathering places. In those days, golfers visiting Lakewood had their choice of two resort courses whose prime season lasted from October to June.

OPPOSITE: The Golf Club of Lakewood was incorporated in 1898.

Beyond the presence of frozen turf and the absence of GORE-TEX and handwarmers, this event was remarkable for several reasons. For one, by the late 1800s, Lakewood was devel oping a reputation—counterintuitive as it may seem today—as a winter tourist destination, one of golf’s first popular off-season

Ocean County Hunt and Country Club was one of the town’s first resorts. The club was organized in December 1895 and became

FOLLOWING PAGES: Lakewood society at the polo grounds at Georgian Court, Lakewood, circa 1900

Lakewood, New Jersey—Home of the First “Tour” Event

ABOVE: A postcard dated 1907 of the Lakewood Hotel

However, Lakewood had a differentiator—a Gilded Age social register, impressive and growing with Rockefellers, Goulds, Ham iltons, and others of that era’s wealthy elite. The social set loved spending time in Lakewood, filling the non-golf hours with polo, tennis, hunting, and just plain socializing. John D. Rockefeller Sr., considered by many the wealthiest American at that time, expressed a love for the pine scents that wafted through every breeze and spent months on end in the community. Clearly, money was flow ing freely through Lakewood.

4 THE START OF SOMETHING GRAND: 1890–1925

GA TOUR players today can pick and chose from among a schedule of about forty-five tournaments, some of them in countries outside the U.S., for a total (in 2021) of approximately $430 million in prize money and season-long bonuses.

Over those frigid two days in Ocean County, Val Fitzjohn shot 92-88, well enough ahead of most of the field, but only good enough for a tie with brother Ed. In what must have been a tough decision to go back out into the deep freeze, Val bested Ed on the first playoff hole and pocketed the seventy-five dollar first prize.

As prosperous as the PGA Tour is today, it’s hard to imagine a more modest origin story. Nonetheless, this event laid the

INSET: An advertisement for brothers Val and Ed Fitzjohn who finished first and second, respectively, in the New Year’s Day tournament playoff.

foundation for the massive industry the various worldwide tours have become.

one of the first forty allied members of the USGA. By 1897, it sported a nine-hole course designed by Horace Rawlins, winner of the first U.S. Open in 1895.

This little tournament contested in the middle of a frigid New Jersey winter, said Barkow, “was, and remains, the founda tion of professional golf tours.” In a lingo understood by pros like Fitzjohn back then and Phil Mickelson today, professional golf is, as Barkow observed, “a great way to drum up business, and not just golf business.”

Golf historian Barkow explained in his book, The Golden Era of Golf, that “The Lakewood tournament was staged by the hoteliers as a way to entertain their current patrons and, by word of mouth and newspaper reports, attract new customers.” The objective of the Ocean County event was not as straightforward as the USGA’s and WGA’s goal: to identify the best players. The reason for this event was to entertain guests, rent out Lakewood’s hotel rooms, and sell Ocean County real estate.

OPPOSITE: Horace Rawlins designed the first nine holes at the Ocean County Hunt and Country Club course and tied for fourth in the first event at the club.

Among the ten pros who competed val iantly in harsh conditions over two days was the course’s designer and former U.S. Open champ Rawlins, Shinnecock Hills Golf Club’s John Shippen, and twentynine-year-old Val Fitzjohn, who was at the time the professional at Otsego Golf Club, near Cooperstown, New York.

With a century’s worth of hindsight, we would not describe any of the competitors as golfing “giants.”

The Importance of This Competition

Fitzjohn was a Scottish émigré who had learned the game cad dying and helping his father tend to North Berwick Golf Club and to the Honorable Company of Edinburgh Golfers. Fitzjohn and his youngest brother Ed came to America in 1890, enticed by its almost faddish growth of golf. By 1898, Val was nearing the peak of what we would today call a journeyman pro’s career, highlighted by a T-2 in the 1899 U.S. Open at Baltimore Country Club.

Golf resorts already existed in the north: Poland Spring, Maine; New Hampshire’s White Mountains; Lake Placid, New York; and even Water Gap, Pennsylvania. But the concept was moving south. Within a few years, golf resorts in places like Pinehurst, North Carolina, and Florida were opening everywhere, and some prop erties picked up on Lakewood’s idea of using professional golf as a way to attract interest. As Barkow put it, “Eventually, chambers of commerce around the country began putting on tournaments for pros as a way to get publicity for their towns and cities and attract people to live, work and play there.”

Before Lakewood, the only American compe tition staged for golf professionals to vie for a purse was the USGA’s U.S. Open, which started in 1895. The Ocean County tournament predated the third such event—the Western Golf Association (WGA)’s West ern Open—by a year. These three tournaments became the foundational competitions in what would be even tually become the professional golf tours we see today.

ABOVE: The first U.S. Open medal was given to Rawlins for winning the championship in 1895.

As young as golf was in America, wily marketeers saw an opportunity to draw attention to Lakewood and its still-young tourist industry by putting on a profes sional golf tournament. In the process, they focused on cultivating what would become a central part of the tour: the resort business.

The First Polar Bear Tournament?

9 REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF

However, the club didn’t last long. Its property was bought by Rockefeller in 1903. Presumably in honor of his property’s origin, Rockefeller named his manor “Golf House.”

In keeping with the hype leading up to the New Year’s Day tournament, the New York Times described the event as “one of golfing giants, to each of whom was granted an unknown degree of skill and each of whom had their partisans.” The partisans—today, we would call them gal lery—were fired up by the pre-tournament publicity and esti mated to number about one hundred; an impressive count consid ering the frigid temperatures that surely affected the quality of play.

ESSEX COUNTY COUNTRY CLUB WEST ORANGE • HOLE 9

84

85 PART GENERATIONGREATESTTHETWO1925–1955

REMARKABLE STORIES OF JERSEY GOLF

NEW

Sociologists refer to Americans born between 1901 and 1927

as members of the Greatest Generation. In his popular 1998 book of the same name, Tom Brokaw profiled American members of this generation who came of age during the Great Depression and went on to fight in World War II or otherwise contributed to the war effort.

87

We’ll see how, when, and why New Jersey was invaded by some of the biggest names in golf; how some of the most unlikely winners in U.S. Open history finally had their day; what it takes to be considered the “Player of the Century;” how Baltusrol’s fourth U.S. Open may have been the tipping point that introduced the world to the future of big-time golf; and how one club just six miles down Route 22 from Baltusrol defied gravity to become a cultural icon, if only for a few years. Finally, we’ll see how four clubs insist, thankfully, on committing to 120 years of tradition.

OPPOSITE: In a famous expression of an exuberant time, two strangers kiss in New York City’s Times Square on V-J Day, August 14, 1945.

The people, places, and events described in this chapter were shaped by the most difficult set of circumstances the United States had faced, certainly since the Civil War. Like the subjects of Brokaw’s book, these New Jerseyans were forged by year upon year of the hardships created by two world wars, the Great Depression, and two massive epidemics—but most by an ability to solve problems.

Maureen Orcutt (1907–2007)

For your consideration, meet New Jersey’s Maureen Orcutt, named in 1998 by the Women’s Metropolitan Golf Association as its “Player of the Century.” The WMGA, formed in 1899, was impressed by Orcutt’s ten WMGA Championships (over a forty-two-year span); twenty-eight total WMGA titles; her sixty-five notable, national, and regional-level tournament championships; and her international tournament

W

From great players starting with the nineteenth century’s Old Tom Morris through Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods, not the USGA, not the R&A, not the PGA Tour—not any major golf association—has credibly placed such a title on the shoulders of one of their competitors.

For a golfer to be plausibly named “Player of the Century,” a few con ditions should be satisfied. One, the organization issuing the moniker should have a history that spans that century. Two, the golfer should have exhibited exceptional feats of golfing prowess, feats that eclipse those of anyone else involved. Three, the player’s champion ship record should traverse several decades— no shooting stars need apply. And, four, the golfer should embody the ideals that the orga nization values.

As if golf and a pioneering journalism career were not enough,

In the USGA’s Golf Journal (January 2007), historian Rhonda Glenn observed that, “Orcutt was a working girl and her reporting career helped finance her amateur golf. Over the years she was part of a group of elite players, Glenna Col lett Vare, Virginia Van Wie, Alexa Stirling, Pam Barton, and she beat most of them at one time or another.

It’s understandable why—few, if any, players would begin to qualify.

Orcutt’s writing offered her readers uncommon insight into the sport she knew so thoroughly. In 1969, she received the first Tanqueray Award for contributions to amateur sports and was elected to the New York Sports Hall of Fame in 1991. A publica tion Orcutt worked for, the New York Evening Journal, wrote that “Miss Orcutt has the unique distinction of being able to write as well as she plays championship golf.”

88 THE GREATEST GENERATION: 1925–1955

presence over nearly seven decades of a ninety-nine-year life. As important, Orcutt was a stellar WMGA ambassador—a quality individual, fierce competitor, and champion who inspired admi ration and respect from generations of golfers around the world.

More than simply a fabulous golfer, Orcutt was, starting in 1937, just the second-ever female sports journalist at the New York Times, and over her career, covered women’s golf for the New York World and wrote a sports column for the New York Journal

ABOVE: Bobby Jones and the Women’s Metropolitan Golf Association’s “Player of the Century,” Maureen Orcutt, circa 1920.

A PORTRAIT OF THE PLAYER OF THE CENTURY

HAT KIND OF GOLFER would it take to be talented enough, durable enough, and respected enough to deserve the title, “Player of the Century?”

OPPOSITE: Orcutt, circa 1931

“Several times Orcutt’s excellent tournament play conflicted with her reporting duties. In 1968, she made the final of the WMGA championship. ‘When I got into the finals, I called the office and said, ‘I’m not covering the final, send somebody.’ ” They did, and her replacement was able to report on Orcutt’s latest championship.

Runner-up Marueen Orcutt (left) with winner Pam Barton at the 1936 U.S. Women’s Amateur held at Canoe Brook Country Club

MAUREEN ORCUTT—PORTRAIT OF THE “PLAYER OF THE CENTURY” NOTABLE FINISHES YEARS

New Jersey Women’s Amateur Champion 1924, ’25, ’33, ’42, ’54, ’67

U.S. Women’s Amateur Runner-up 1927, ’36 U.S. Women’s Amateur Medalist 1928, ’31(T), ’32(T) U.S. Senior Women’s Amateur Champion 1962, ’66 WMGA Amateur Champion 1926, ’27, ’28, ’29, ’34, ’38, ’40, ’46, ’59, ’68

90

Canadian Women’s Amateur Champion 1930, ’31 North and South Women’s Amateur Champion 1931, ’32, ’33 North and South Senior Women’s Amateur Champion 1960, ’61, ’62

Women’s Eastern Amateur Champion 1925, ’28, ’29, ’34, ’38, ’47, ’49

Curtis Cup teams 1932, ’34, ’36, ’38

greatest amateurs of the 1920s and 1930s, including Bob Jones, Joyce Wethered, and Glenna Collett Vare. Later on, she played and became friends with Walter Hagen, Gene Sarazen, Marion Hollins, Babe Zaharias, and Sam Snead.

Orcutt won her first important championship, the 1925 East ern Women’s Amateur, at Connecticut’s Greenwich Country Club. The last of her two USGA championships came at the 1966 U.S. Senior Women’s Amateur in New Orleans. In between those book ends was the stuff of history.

Maureen Orcutt hits a drive at a 1941 exhibition match for the benefit of the British War Relief played at Glen Ridge Country Club.

A lifelong member of White Beeches Golf & Country Club in Haworth, Orcutt’s mother introduced her ten-year-old daughter to golf to avoid the conditions she felt exposed her children to the era’s polio and Spanish influenza epidemics. By the time she was seventeen, Orcutt had improved to the point that she finished sec ond in White Beeches’s men’s club championship. Soon, Maureen won her first WMGA title, the Junior Girls Championship, the first of twenty-eight WMGA winner’s trophies she would amass.

When she was inducted into the New York State Hall of Fame in 1991, the program noted that, “Perhaps no competitor in any major sport has been a significant factor for so long in top level play.”

The WMGA got it right. “Player of the Century” describes Maureen Orcutt perfectly.

91 REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF

Orcutt—a resident of Englewood—won the 1934 Democratic Party nomination for the New Jersey General Assembly to rep resent Bergen County. According to the New York Times, despite running unopposed, her name still appeared on almost all the written ballots.

At the 1990 Curtis Cup, held at Somerset Hills County Club in Bernardsville, Orcutt (who was on the original Curtis Cup team in 1932) was an honored guest. She loved being around the competitors. According to the USGA’s Rhonda Glenn, “the then 83-year-old Orcutt sat in the grass on a hillside near the 18th green, cheerfully chatting with the young American players Vicki Goetze and Brandie Burton as the network television cameras rolled.” Her impact bridged the generations.

Orcutt was inducted into the inaugural NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2018.

Orcutt’s amateur playing career included matches against the

Classic.”It was tough sledding, especially in the first few years of the Depression. By 1931, the year’s total of all the purses managed by Harlow and contested by his gladiators was $77,000. In 2021 dollars, that’s $1,363,685— equivalent to a typical weekly first prize offered on the 2021 PGA Tour.

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 93

role was assumed by Robert “Bob” Harlow, who became the first full-time PGA tournament manager. His main job was to cajole enough money out of local chambers of commerce and Rotary Clubs, the occasional resort or local businesses and often the Golf Ball and Golf Club Manufacturers Association to put on a 72-hole “(fill in the town)

THE 1930s: WHEN THE STARS DESCENDED ON THE NEW JERSEY OPEN

Professional Golf and the Great Depression

U

The reason for all the attention on New Jersey was pretty clear—during the Great Depres sion, more opportunity existed for golf pro fessionals in the New York metropolitan region than anywhere in the nation.

The 1929 Wall Street collapse had spread quickly to Main Street, and golf understand ably took a back seat across America. The Great Depression took its toll not only on golf, but on what was loosely referred to as the professional golf tour.

NLIKE ANY OTHER PERIOD in the New Jersey Open’s century-long existence, some of the game’s biggest stars—Byron Nelson, Craig Wood, Long Jim Barnes, just to name a few—participated in that event in the 1930s. A few of them actually won.

ABOVE: Robert “Bob” Harlow, Walter Hagen’s manager, was a key figure in the development of the professional golf tour.

While important, warm-weather events such as the U.S. Open, the Western Open, the North and South Open, and the Met Open continued to be held along with various state Opens, the organized professional tour in the 1920s and early 1930s was pri marily a wintertime collection of golf tournaments in California, Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and Florida. Most of the players would caravan from event to event, with some reportedly earning more on side bets, skins, and poker than in official winnings.

Eventually with Eighteen Major Titles Among Them, These Stars Dominated the State Open—Almost

In fact, many of those touring stars had club professional jobs in New Jersey, attracted by the state’s high density of relatively prosperous clubs and the quality of their courses. As a result, many of the best players in America found the opportunity to

A winter tour supplemented by a slowly coalescing summer tour still did not provide a livable income, which meant that all of those touring pros needed to make money somewhere else. To stay close to the game, almost all the pros took club professional jobs for income between tournaments. Many of those were in the relatively pros perous metropolitan New York City area. It was no accident that many of the biggest (or up and coming) names in the game—Gene Sarazen, Walter Hagen, Jim Barnes, Johnny Farrell, Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Ralph Guldahl, Paul Runyan, Craig Wood—all had affiliations (usually summer club jobs) in the region.

OPPOSITE: Paul Runyan, known for his legendary short game, won the 1930 New Jersey State Open and two PGA Championships, in 1934 and 1938.

In the 1928–1929 winter season, tournament sponsors and purses were cobbled together by East Orange resident Hal Sharkey, a sportswriter for the Newark News. The next year, the

(From left) Johnny Revolta, good friends Tony Manero and Gene Sarazen, and Walter Hagen at the 1936 PGA Championship at Pinehurst Resort in North Carolina

114

THE FIRST U.S. OPEN OF A NEW ERA

Or so it seemed. Right after the tournament ended, an unnamed

And Harry Cooper tore up the cablegram to his mom.

*****

ABOVE: Despite setting a new U.S. Open record of 284, Harry Cooper finished second in the 1936 championship.

Still, his total of 284 broke the U.S. Open record by two, and Cooper was feeling the love and accepting the applause accorded a champion. He even composed a cablegram to his mother in Great Britain announcing his victory.

1954

FOLLOWING PAGES: Tony Manero and Gene Sarazen on Baltusrol’s 18th green during the 1936 U.S. Open.

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 115

Meanwhile, playing several holes ahead of Manero, Cooper was channeling his best “Pipeline.” He reached No. 14 at 2 under for the day. By simply parring in, Cooper would shoot a 70 and set a new U.S. Open record of 281. But, “simply parring in” on the last nine of the Open can be a tall order. Cooper would go on to bogey three of the last five holes, punctuated by a 3-putt on the home green.

The largest-ever gallery to watch a U.S. Open—39,600 over three days—required special attention. Until 1954, the fans had almost unfettered access to the players for the entire event. For the first time in the U.S. Open, ropes lined the fairways to keep the spectators back, a commonsense restraint that reflected a growing interest in the game.

Still on the course, Manero knew he was getting close to Cooper, even though there were no scoreboards on the course in those days. Then, coming in, he buried a twelve footer for birdie on No. 16 and narrowly missed an eight footer for birdie on 17. Finally, on 18, in front of galleries unseen since the years of Bobby Jones, Manero struck a 2-iron to forty feet on the long par 4, and took two putts for a par to shoot a 67 and win the Open by two strokes.

person—some say a fellow competitor, others a reporter—filed a protest with the USGA, alleging that Sarazen had given his playing partner advice throughout the final round, a violation of the rules.

In retrospect, this U.S. Open was a three-ring circus that—more than most Opens—successfully blended older, established players with a mix of young, ambitious professionals and talented amateurs. It introduced new, enduring ideas, an unlikely champion, and an exciting communication medium that would forever change the face of golf. As though the Fates had conspired to make Baltusrol the agent of change, the 1954 U.S. Open was the dawn of an exciting, transformative era of golf.

That change paled in comparison to the epic innovation of this U.S. Open—the National Broadcasting Company’s national cover age of the championship. For the first time, television brought the championship into homes across the entire country (for one hour) and set the stage for an explosion of interest in the game in the late 1950s. The purse for this Open (first prize of $6,000) was 20 per cent larger than at Oakmont just the year before.

In terms of expectations, Ben Hogan came to Baltusrol riding an amazing U.S. Open streak, with wins in 1948, 1950, 1951, and

New ideas? Consider the venue. Baltusrol is blessed with two exceptional tracks, the Upper Course and the Lower Course. Today’s fans might assume that Baltusrol’s Lower Course had always been the venue of Baltusrol’s four previous U.S. Opens, but the 1954 event was the Lower’s first of many voyages as the featured route. It was the longest par 70 in Open history, at 7,027 yards, a combination that took its toll on the best players in the world.

The USGA investigated on the spot, holding an hour-long meeting with both golfers. After some deliberation, the USGA ruled that there was no evidence of any wrongdoing. Manero was allowed to keep his trophy.

CHAPTER HEADER 128

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 129 PART1955–1990WONDERTHETHREEYEARS

In 1955 we were introduced by television to Arnold Palmer, followed shortly thereafter by Gary Player, Billy Casper, and in 1960, an amateur by the name of Jack Nicklaus. The table had been set by the greatest generation, and the game of golf was about to take off.

New Jersey was primed to participate.

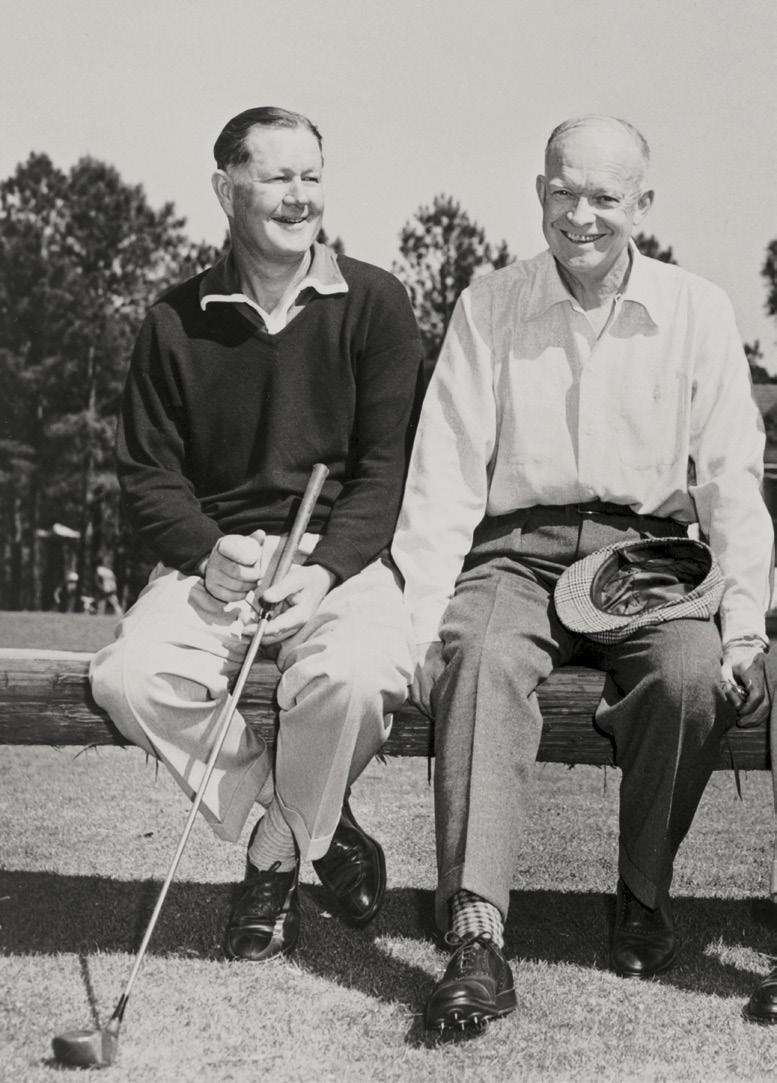

(From left): Byron Nelson, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ben Hogan, and Clifford Roberts at Augusta National Golf Club, 1953

During this period, we saw an astonishing diversity of excellent golfers, including some of the most interesting personalities in the game. We witnessed first hand the greatness of Nicklaus with his two U.S. Open triumphs at Baltusrol Golf Club as the Township of Montclair served as home base to two of the most important golf course architects of the era. We also experienced the value of team compe titions, where golfers had an opportunity to compete for something bigger than themselves. Finally, New Jersey became an all-in partner with the USGA.

This was a good time to be a golfer in New Jersey.

The country had emerged from World War II

as the premier superpower. General Dwight Eisenhower was elected by voters to the presidency in 1952, where he oversaw an economic boom. His vision and construction of the Interstate Highway System completely changed people’s ideas about what an automobile trip could mean, and many noticed that golf courses were suddenly not so far away. Eisenhower also carried on a public love affair with the game of golf, and people took notice.

132

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 133

T

CAROLYN1918–2009CUDONE

From 1968 through 1972, Carolyn Cud one won five straight U.S. Women’s Senior Amateur titles, becoming the only golfer, male or female, to win five consecutive U.S. national golf titles. Cudone appeared to own the championship, not once finish ing out of the top five in her ten appear ances. Her five Women’s Senior Amateur championships exceed the total of any otherPlayinggolfer. primarily out of Montclair Golf Club, Cudone also won the NJSGA Women’s Championship in 1955, ’56, ’59, ’60, ’63, and ’65. As for the Women’s Met ropolitan Golf Association, she won its Amateur Championship five times (1955, ’61, ’63, ’64, and ’65).

MICHAEL1904–1988CESTONE

Cestone’s greatest year was 1960 when, at age fifty-six, the Upper Montclair resi dent won an unprecedented hat trick: the NJSGA Senior Amateur, the Met Senior Amateur, and the U.S. Senior Amateur.

He captured four NJSGA Four-Ball tri umphs with four different partners (1935, ’37, ’38, and ’47) and six NJSGA Father and Son titles (with son Michael in 1949, ’50, ’56, and ’59, and with son Alan in 1953 and 1960). He won the NJSGA Caddie (1923) and the New Jersey Public Links (1938) championships and served as a member of six winning NJSGA Stoddard Trophy teams.

On a more national level, besides her success in the U.S. Women’s Senior Amateur, she captured the 1958 North and South Women’s Amateur Champion ship, the 1960 Women’s Eastern Amateur and competed in the 1956 Curtis Cup. In 1970, Cudone was asked to serve as non-playing Curtis Cup captain on the victorious American squad.

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT: New Jersey’s Michael Cestone (left), winner, and David Rose (runner-up) with the 1960 U.S. Senior Amateur trophy; Atlantic City Country Club portrait of Leo Fraser, president of the PGA of America from 1969-’70; winner Carolyn Cudone holds the trophy for the 1970 U.S. Senior Women’s Amateur.

All members of the NJSGA Hall of Fame, here’s just a little more about these exceptional contributors.*****

Cestone is a member of the 2020 NJSGA Hall of Fame class of inductees.

DETERMINATION,EXCELLENCE,AND GRIT

U.S. Senior Amateur, he became only the second New Jersey-born player to win a USGA championship (the 1933 U.S. Amateur champion, George Dunlap, was the Hisfirst).most significant local champion ships included the MGA’s Met Amateur (1941), the NJSGA Senior Amateur (1960 and 1963), the Met Senior Amateur (1960), and the Met Public Links (1937). Addition ally, Cestone came in second at the NJSGA Open (1944, to PGA of America champion Vic Ghezzi), and tallied four runner-up finishes in the NJSGA Amateur (1938, ’43, ’44, and ’45).

Playing out of Branch Brook (now Hen dricks Field) Golf Course in Belleville, as well as Jumping Brook Golf Course, Crestmont Country Club, and Forsgate Country Club, Michael Cestone was one of the most successful amateur golfers in state history. When he won the 1960

*****

In 1961, at the age of forty-two, she finished T-9 as second low amateur in the

HE WAR WAS OVER, the GI Bill was fulfilling its promise, and the country was bursting with energy. The pieces were coming together for the game to explode, and it did.

While Arnold Palmer became the nation’s king of golf, New Jersey resident Babe Lichardus made the state’s courses of the 1950s and 1960s his personal fiefdom. From Atlantic City, Leo Fraser collaborated with Palmer, Nicklaus, and other touring professionals to tee up the future of what we know today as the PGA Tour. Garden Staters Carolyn Cudone, Michael Cestone, and Dot Porter became national cham pions. Immigrant businessman Nestor Macdonald put in motion a college cad die scholarship foundation that today has distributed $15 million to over three thous dand New Jersey student caddies.

A postman by trade, it was typical for Cestone to play five rounds of golf every weekend, not to mention eighteen holes at Branch Brook on weekdays when he was finished with his mail route.

The Pilots When the Game Took Off

134 THE WONDER YEARS: 1955–1990

agreement between the PGA’s touring pros and the organization’s rank-and-file club professionals. Without Fraser’s guidance, the PGA of America and the PGA Tour might not be the thriving organizations they are

Duringtoday.his term as president of the PGA of America in 1969-’70, Fraser helped bridge the gap between club professionals and touring pros over a long-running dis pute that centered on distribution of the tour’s rapidly growing television revenue. As part of this reconciliation, Fraser hired Joseph Dey Jr., the highly respected former Executive Secretary of the USGA, as the first commissioner of the Tournament Players Division of the PGA, known today as the

Leo Fraser played an iconic role in profes sional golf in America. As president of the PGA when the organization was faced by the threat of fracture, Fraser engineered an

LEO1910–1986FRASER

Locally, Fraser purchased one of New Jersey’s most storied golf venues, Atlantic City Country Club, which he managed from 1945 until his death in 1986. During his ownership, Fraser was instrumental in attracting three U.S. Women’s Opens (1948, ’65, and ’75) to Atlantic City. In addition, Fraser and the club hosted the 1967 U. S. Senior Women’s Amateur. In 1980, the first tournament of what would become the PGA Tour Champions (then known as the Senior PGA Tour) was held at Atlantic City.

PGA Tour. The successful results of Fraser’s work are seen every week on television.

Cudone retired to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where she founded the Myrtle Beach Junior Golf Program in 1981 and led the organization for twenty-one years. Cudone was inducted into the inaugural NJSGA Hall of Fame in *****2018.

Babe Lichardus (center) shakes hands with winner Billy Ziobro at the 1971 Dodge Open, at the time a New Jersey PGA major event.

U.S. Women’s Open held at Baltusrol Golf Club. In 1970, Cudone was named Golf magazine’s Amateur of the Year.

For his impact on both New Jersey and national-level golf, Fraser was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2019.

NESTOR J. 1895–1991MACDONALD

MacDonald, a native Scotsman, enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force at the out break of World War I, became a fighter pilot

MacDonald became a member of the inaugural NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2018.

1948–

Ziobro became a member of the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2019.

Babe Lichardus was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in *****2019.

He won four NJSGA Open titles (1952, ’65, ’69, and ’71), the last at age forty-five. When Lichardus won in 1971 at Montclair Golf Club, he shot 72 in an 18-hole play off to defeat Bob Benning of Plainfield Country Club by six shots. At the time, he became the first player to win four New Jersey Open championships. He was also the New Jersey Open runner-up on three occasions (1950, ’63, and ’68).

Nestor MacDonald was an original founder of the NJSGA Caddie Scholarship Founda tion (CSF) and its chairman from 1957 to 1967. A member of the Rock Spring Club and Baltusrol Golf Club, MacDonald and his colleagues started the CSF in 1947. Since then, it has provided more than $15 million in college scholarships to more than three thousand New Jersey caddies.

Born in Philadelphia in 1924, Dot Porter lived the majority of her adult life in south ern New Jersey, playing out of Riverton Country Club in Cinnaminson until her death. With five USGA national cham pionships to her credit, Porter is tied for seventh-most wins among women in a rather exclusive club.

A member of the victorious 1950 Cur tis Cup team, she was captain of the alsosuccessful 1966 Curtis Cup squad. Porter was low amateur in the 1952 U.S. Women’s Open and hoisted the winner’s trophy at the Western Amateur (1943, ’44, and ’67) and the 1969 Eastern Amateur championships.

Porter won the 1964 NJSGA Women’s Amateur and the Pennsylvania Amateur (1946, ’52, and ’55) Championships. As yet

MacDonald is remembered as one of the greatest benefactors in New Jersey golf history. Today a full four-year scholarship to Rutgers University is named in his honor.

Porter was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2019.*****

WILLIAM “BILLY” ZIOBRO

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 135 *****

Billy Ziobro’s amateur golf career reached its zenith at the tender age of twenty-one when he won both the NJSGA Amateur and Open in 1970. At the Amateur, Ziobro played the final 18 holes in 7 under par coming from 6 down to beat Jeff Alpert in the final match.

In a professional career that spanned more than fifty years, Babe Lichardus compiled one of the greatest playing records of any New Jersey club professional.

in England and was shot down, surviving the crash, but suffering multiple injuries. He was later a recipient of the British Royal Order of Merit.

another measure of her endurance, she cap tured the first of her three Women’s Golf Association of Pennsylvania Junior Cham pionships in 1939, then won the last of her nine WGAP Amateur Championships fifty-three years later in 1992.

In addition to playing often on the PGA Tour with moderate success, Lichardus won five New Jersey PGA Section cham pionships (1953, ’65, ’66, ’77, and ’78), two NJPGA Clambake titles (1966 and 1968), and numerous other events. In recogni tion of his spectacular record, Lichardus was named New Jersey PGA Player of the Decade for both the 1950s and the 1960s.

In 1920, he joined the firm Thomas & Betts, producers of electric connectors and accessories. Starting as a salesman, he rose to become the company’s president (1955), CEO (1960), and board chairman (1965).

Playing out of Ash Brook Golf Course, he is the first player in NJSGA history to win its Amateur, Open, and Junior champion ships. Ziobro is one of only two golfers (the other being Charley Whitehead in 1942) to win the NJSGA Amateur and Open in the same

MILTONLICHARDUS“BABE”1926–2007

Ziobro went on to have a very success ful club professional career, first in Mas sachusetts and later in New Jersey, where he developed a great reputation for devel oping young professionals. In 1998 he was tapped by Caesars Entertainment to man age its extensive golf properties, including Atlantic City Country Club.

A truly national-level competitor, Porter won the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1949 and four U.S. Senior Women’s Ama teur titles (1977, ’80, ’81, and ’83). The thirty-four-year span between her first and last USGA championship is, by one year, the second-longest in USGA history for women, behind Anne Quast Sander.

Heyear.won his first professional event, the Dodge Open, at Rockaway River Country Club in 1971. Ziobro has competed in five U.S. Opens, making two cuts, and played on the PGA Tour from 1972–1975, where he collected six top-ten finishes. He made the cut at The Players Championship and has played in the Senior PGA Champion ship. Ziobro has also won the New Jersey PGA Section Championship, two Dodge Opens, and the Vermont Open.

DOROTHY GERMAIN “DOT”1924–2012PORTER

*****

BALTUSROL AND THE U.S. OPEN: 1967 AND 1980

Nicklaus did it his way, setting U.S. Open scoring records both times. But that’s not to say he did it the easy way. The first time, he had to overcome the gallery’s palpable pref erences for the King—Arnold Palmer—and, in 1980, he barely escaped the putting wiz ardry of Isao Aoki.

*****

1967

ARNIE, JACK, AND WHITE FANG

HERE MAY BE NO BETTER WAY to determine the greatness of a course than to see which golfers triumph on its fairways. On that basis alone, Baltusrol Golf Club’s Lower Course is clearly among the elite few, for Jack Nicklaus rose to the top in its 1967 and 1980 U.S. Opens.

YEAR COURSE WINNER SCORE RUNNER-UP

Nicklaus had designs of his own. A Wednesday prac tice-round match with Palmer yielded a 62, fifteen dollars as

And, for Jack, it wasn’t always pleasant. Some members of the Jersey brigade of Arnie’s Army were vocal, for example, suggesting Nicklaus hit the ball into the rough. Palmer would get roars of approval for hitching his pants, while Nicklaus would often only receive polite applause for moments of bril liance. On this day, Nicklaus was having to deal with more than the course and the field.

1980 Baltusrol GC (Lower) Jack Nicklaus 272 Isao Aoki

T

OPPOSITE: Jack Nicklaus and his wife Barbara hold the trophy after his win at the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol.

Nicklaus and Baltusrol—a

This was the year Jack Nicklaus, armed with his new putter, White Fang, took on the most popular golfer of the era, Arnold Palmer. Palmer had not won a major since the 1964 Masters and was, by all accounts, overdue. He had captured two events earlier in 1967 but had notably collapsed in a duel with Billy Casper for the title at the 1966 U.S. Open at The Olympic Club. Palmer yearned for another major; it surely occurred to him that Baltusrol in June would be the place and time.

Marriage Made in Heaven

Palmer’s second-round 68 (with seventeen greens hit in reg ulation) captured the lead at 137, just one ahead of Nicklaus, whose 67 featured several clutch, White Fang-produced putts. While other players—Fleckman, Casper, Deane Beman, Don January, and newcomer Lee Trevino—lurked in the shadows, to the casual fan the U.S. Open had become a “King Arnie vs. Jack the Pretender” title match.

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 137

1967 Baltusrol GC (Lower) Jack Nicklaus 275 Arnold Palmer

In the third round, as so often happens in anticipated head-to-head matches, both players didn’t fare well. Nicklaus’s 72 bested Arnie’s 73, leaving them both at even-par 210. However, their sloppy play allowed amateur Fleckman (69) to take the lead by one and defending champ Billy Casper (71) to join them at even par. An amateur one shot clear of three of the greatest golfers who ever lived—this was an U.S. Open leaderboard for the ages.

In the final round, Nicklaus and White Fang regained their

But there were 148 other players in the event. One of them, Marty Fleckman, an amateur bomber from Texas, stole the show with a first-round 67, two ahead of Palmer and U.S. Open defender Casper. Nicklaus signed for a 1-over 71, a round he considered satisfactory.

a result of their Nassau, and gave Nicklaus the confidence that Baltusrol could be conquered. White Fang, an Acushnet Bulls eye putter custom-painted white then christened by Nicklaus, yielded nine 1-putt greens in that practice round and was soon to make U.S. Open headlines throughout the country.

NEW JERSEY’S U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIPS 1967, 1980

138

ABOVE AND INSET: Nicklaus won the championship using a Bullseye putter painted white that he named “White Fang.”

In the end, Nicklaus (275, -5) and Palmer (279, -1) were the only players to finish under par. Nicklaus owned a new U.S. Open scoring record. His 1967 title was the second of an eventual four U.S. Open wins and the seventh of his record career eighteen major championships. This win also had the effect of quieting most of the anti-Nicklaus chatter.

FOLLOWING PAGES: Nicklaus and Palmer were the only players to finish under par during the championship.

Palmer remained a huge force in the game, but never won another major championship.

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 139

practice-round form. Playing with Palmer in the second-to-last pairing, Nicklaus birdied five of his first eight holes and went on to card a 65 to Palmer’s otherwise fine 69. Nicklaus posted an exclamation point on the round with a 230-yard 1-iron third shot on the par-5 18th hole to set up a birdie and a four-shot win. That 1-iron shot was commem orated by Baltusrol with a plaque on the site of Nicklaus’s divot and has been slowing down play on No. 18 fairway ever since.

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT: The crowd shows support for Arnold Palmer; Marty Fleckman signs autographs; Nicklaus’s final-round 65 helped set a new U.S. Open record.

Playing from the 165-yard members tee, Mr. Farrell and the two members each hit balls on the green. Mr. Jones stepped up and swung his 4-iron. His ball landed on the green and rolled into the cup for a hole in one. Turning to the assembled members, he said: ‘Gentlemen, the hole is fair. Eminently fair.’ ”

Robert Trent Jones Sr. had a knack for the dramatic. As noted New York Times sports columnist Dave Anderson mentioned, Jones was fond of saying “The sun never sets on a Robert Trent Jones golf course.’’

Anderson also recalled that, “When Mr. Jones redesigned the fourth hole at the Baltusrol Golf Club’s Lower Course in Springfield, N.J., before the 1954 United States Open, some members thought the par 3 over a pond was unfair.”

Jones had lengthened the hole’s original Tillinghast yard age of 125 yards to 165 yards. But he had also enlarged the green, making it more receptive to long-iron shots, thereby compensating for the new length.

A CERTAIN FLAIR

BACKGROUND PHOTO: Not only is the fourth hole at Baltusrol (Lower), “eminently fair,” it is one of the game’s most photographed holes.

“He offered to play the hole along with Johnny Farrell, the club pro, and two members while other members watched.

CHAPTER HEADER 184

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 185 PART SINCEMODERNTHEFOURGAME1990

In that time, New Jersey golf evolved as well. In the space of fewer than ten years, New Jersey experienced a renaissance in golf course architecture, often facilitated by modern-day visionaries who must have been

the popularity of golf rose and fell with movement in the economy, seemingly immune to war, politics, and climate change—even to pandemics.

We’re talking about a lot of change.

Since 1990, we golfers noticed: the last professionals using persimmon drivers; Greg Norman’s penchant for losing the big one; the emergence of Augusta National Golf Club as more than just the site of a great golf tournament; Tiger Woods winning so often and so convincingly that he seems on his way to demolishing any argument about who is golf’s greatest—then seemingly blows it; the Ryder Cup become absolutely huge; the passing of the game’s most beloved general, Arnold Palmer; each of our five American presidents during this time displaying a love of golf, while playing it five different ways; a thirty-four-yard increase in the distance PGA Tour players smack their drives; and the proliferation of good greens everywhere.

As America entered the 21st century,

186

187

inspired by their predecessor, Pine Valley Golf Club’s George Crump. The finest players in the state racked up impressive wins (including a national championship), but New Jersey’s best amateur since Jerry Travers tragically died early. The scribe of New Jersey golf—who had become a bit of a legend himself—died, but his decades of work have been memorialized in what has quickly become an institution in New Jersey—inter club team competitions. What may have been Baltusrol Golf Club’s last U.S. Open cleared the decks for what appears to be a new series of championships with the PGA of America. And a pro’s pro, Ed Whitman, became just the third four-time winner of the New Jersey Open.

While so much is changing, one of golf’s most basic appeals is its timelessness. The objective—to get the ball in the cup in the fewest number of strokes—hasn’t changed in centuries. The rules are, at their essence, what they were in 1900. New Jersey is blessed with clubs that place golf at their core, that strive to achieve a sense of timelessness while maintaining relevance in a fast-paced world. As you’ll see, Somerset Hills Country Club is one of those places.

Bayonne Golf Club, designed by Eric Bergstol, opened in 2006.

THE GARDEN STATE’S SECOND GOLDEN AGE OF GOLF COURSE ARCHITECTURE?

A WELL-SET TABLE

The 1990s were a special time in America—a period of growth, optimism, and great prosperity in the United States. The largely

unexpected development of the internet and the explosion of tech nology that came with it fueled this expansive view, as did our country’s emergence in the early 1990s from the Cold War as the world’s lone superpower.

Starting in 1991, the U.S. economy experienced a record period of peacetime economic expansion. Personal income was up 20 percent from the 1990 recession to 2000 and there was higher productivity overall. Life was good, so much so the Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan applied the term “irrational exuberance” in late 1996 to the U.S. economy.

Golf benefited from these heady times. By the late 1990s, the “Tiger Effect” was starting to be felt as young Tiger Woods came into his own. In 2000, his most productive year, the highest-ever number of beginners—2.4 million—took up the game. The number

OPPOSITE: Plainfield Country Club’s 2nd hole

188 THE MODERN GAME: SINCE 1990

ABOVE: The “Tiger Effect,” started to build momentum with Tiger Woods’s win at the 1997 Masters Tournament.

*****

N UNPRECEDENTED NUMBER of quality New Jersey courses have recently come to life at a time when more austerity might have been expected. This burst of creative brilliance is still too fresh to determine if it is as auspicious as it appears. Look back in thirty or forty years and we’ll know definitively whether a compact span of time—1998 to 2006—was New Jersey’s second Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture.

1990s

“It’s déjà vu all over again!” —Yogi Berra, member, Montclair Golf Club

A

FOUR-TIME CHAMPIONS’ CLUB StateNewTheJerseyOpen’sBigThree

OPPOSITE: The New Jersey State Open C. W. Badenhausen trophy.

Whitman carried his success into the new millennium, with his fourth Open at Crestmont Country Club in 2004 at age fifty-two. Whitman has been named NJPGA Player of the Year five times, won over 225 professional tournaments, and captured twenty Garden State major titles. Recognized as both a great golfer and a consummate golf professional, Whitman was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2022.

ABOVE: New Jersey State Open winners: (top) Babe Lichardus, (1952, ’65, ’69 and ’71); (left) David Glenz (1984, ’86, ’88, and ’90); (right) Ed Whitman (1991, ’95, ’96, and 2004)

219

N THE ONE HUNDRED-YEAR history of the New Jersey State Open, only three players—all professionals—have won the event a total of four times. Milton “Babe” Lichar dus was the first quadruple winner of the most difficult con test the NJSGA has to offer, followed by David Glenz, then Ed Whitman. These gentlemen each deserve a special place in the roll call of New Jersey’s top players ever.

ica’s finest instructors. In the early 1990s, Glenz opened up his own instruction school in Crystal Springs and, in 1998, was rec ognized by the PGA of America as National PGA Teacher of the Year. Glenz has continued to grow, becoming a principal behind the decade-long creation of impressive Black Oak Golf Club over the early 2000s.

Nearly as impressive as Glenz’s 1980s Open dominance was Ed Whitman and his three ’90s Open wins (1991 at Rock Spring Club, ’95 at North Jersey Coun try Club, and ’96 at Essex Fells Country Club). The head professional at Knick erbocker Country Club for more than three decades (and now its pro emeri tus), Whitman’s triumph at Rock Spring was truly that, posting an Open 72-hole record 17-under-par 267.

I

The Opens of the 1980s were dominated by David Glenz, who won the Open four times (1984, ’86, ’88, and ’90) in just seven years. His play was special enough here and in other professional state events that he was voted the NJPGA’s Player of the Decade. By the mid-1980s, Glenz was head professional at Morris County Golf Club and was also developing a reputation as one of Amer

For contributions to New Jersey golf that went beyond his exceptional golf, Glenz was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2022. In a telling moment, he shared the HoF dais with his protégé, Karen Noble, who credits Glenz for guiding her development as a top amateur, tour ing professional and now, instructor.

Lichardus won his first Open in 1952 at storied Plainfield Country Club. A Baltusrol Golf Club assistant professional at the time, this was Lichardus’s first step on his way to being named the 1950s Player of the Decade by his club professional peers and etching his name onto the Open’s C. W. Badenhausen champions’ trophy four times before he sank his last putt.

Babe was reanointed by his NJPGA peers as the 1960s Player of the Decade. With Open wins in 1965 (Spring Brook Country Club) and 1969 (Rockaway River Country Club) supported by sec ond-place silver in 1963 and 1968, he seemed omnipresent. Hanging his hat at several clubs over the span of the decade, he also found himself on and off the PGA Tour, befriending Sam Snead, Tony Lema, and others with his charismatic but irreverent ways. In 1971, Lichardus became the first player to win four New Jersey Opens, taking his time in the process. He won his last Open at Montclair Golf Club, almost twenty years after his initial 1952 Open victory.

His colleagues have taken note, voting him into the NJPGA Hall of Fame in 1996. Word is, they might have also passed the hat several times in a bid to get Whitman to retire from competition. That’s quite likely another experience that all three of these fourtime champions have in common.

As grand as some of the other A-list clubs in New Jersey are, Somerset Hills revels in a lack of glitter. No pretense and a studied casualness make the club a comfortable, always-friendly place to visit.

SOMERSET HILLS COUNTRY CLUB

*****

OPPOSITE: Somerset Hills Country Club’s 11th and 12th greens

S

A Special Place

Somerset Hills dates its origins to 1896, when a group of local land owners with close ties to New York City formed the Ravine Lake and Game Association. The club itself was started in 1899. Its early nine-hole course was considered good for the day, but by 1916, the club moved to the 190-acre Frederic Olcott estate in the hills just

ABOVE: The 16th hole at Somerset Hills in September 1927

OMERSET HILLS COUNTRY CLUB, in Bernardsville, was once described by Frank Hannigan, a longtime member and former USGA executive director, simply as “a special Hanniganplace.”was a golf administrator, sportswriter, and television commentator whose long involvement in golf took him to virtually every sanctuary of the game. In that context, he used his three-word description in the strictest, most exacting sense. Somerset Hills’s members, struck by the under stated relevance of Hannigan’s phrase, embraced it as the title of their 1990 club history book. It fits perfectly.

REMARKABLE STORIES OF NEW JERSEY GOLF 221

The clubhouses at Shinnecock Hills, Cypress Point, and Somer set Hills are in the same genre in that each reflects a perspective that seemed to be important to their respective founders: If you decide to do something, do it right, with grace and respect. Somerset Hills’s clubhouse, now over one hundred years old, exemplifies that idea. It is a cozy, comfortable place to gather after a round of golf or a tennis match on its grass courts.

This is not what you’d necessarily expect when you learn about the membership. Gaze at the numerous club champion plaques and you’ll see last names of the hardy souls that first shaded North American soil centuries ago, led some of the most important companies in history, served our country at the highest levels in Washington or in the military, governed our state or—as previ ously noted—led the USGA.

Do It Right, With Grace and Respect

outside Bernardsville, which included a private horse racetrack and remains its home today.